THE HUNDREDTH CHANCE

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Hundredth Chance

Author: Ethel M. Dell

Release Date: June 30, 2013 [EBook #43069]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HUNDREDTH CHANCE ***

Produced by Al Haines.

The

Hundredth Chance

BY

ETHEL M. DELL

AUTHOR OF

THE LAMP IN THE DESERT,

THE SWINDLER, ETC.

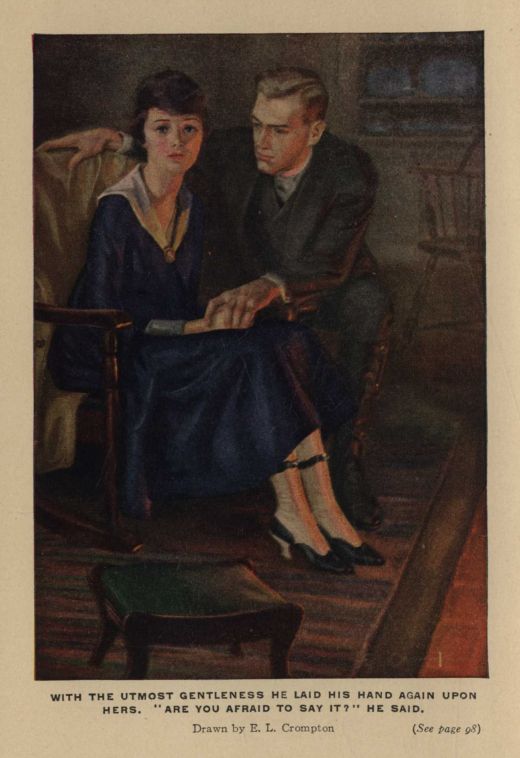

FRONTISPIECE BY

EDNA CROMPTON

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

COPYRIGHT. 1917

BY

ETHEL M. DELL

The Way of an Eagle

The Knave of Diamonds

The Rocks of Valprê

The Swindler

The Keeper of the Door

Bars of Iron

Rosa Mundi

The Hundredth Chance

The Safety Curtain

Greatheart

The Lamp in the Desert

The Tidal Wave

The Top of the World

The Obstacle Race

This edition is issued under arrangement with the publishers

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS, NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

I Dedicate This Book

to

My Old Friend

W. S. H.

In Affectionate Remembrance of Many Kindnesses

"The plowman shall overtake the reaper,And the treader of grapes him that soweth seed."Obadiah 9-13.

CONTENTS

PART 1

THE START

I.--Beggars

II.--The Idol

III.--The New Acquaintance

IV.--The Accepted Suitor

V.--In the Dark

VI.--The Unwilling Guest

VII.--The Magician

VIII.--The Offer

IX.--The Real Man

X.--The Head of the Family

XI.--The Declaration of War

XII.--The Reckoning

XIII.--The Only Port

XIV.--The Way of Escape

XV.--The Closed Door

XVI.--The Champion

XVII.--The Wedding Morning

XVIII.--The Wedding Night

XIX.--The Day After

XX.--A Friend of the Family

XXI.--The Old Life

XXII.--The Faithful Widower

XXIII.--The Narrowing Circle

XXIV.--Brothers

XXV.--Misadventure

XXVI.--The Word Unspoken

XXVII.--The Token

XXVIII.--The Visitor

XXIX.--Her Other Self

XXX.--The Rising Current

XXXI.--Light Relief

XXXII.--The Only Solution

XXXIII.--The Furnace

XXXIV.--The Sacrifice

XXXV.--The Offer of Freedom

XXXVI.--The Bond

PART II

THE RACE

I.--Husks

II.--The Poison Plant

III.--Confidences

IV.--The Letter

V.--Rebellion

VI.--The Problem

VII.--The Land of Moonshine

VIII.--The Warning

IX.--The Invitation

X.--The Mistake

XI.--The Reason

XII.--Refuge

XIII.--The Lamp before the Altar

XIV.--The Open Door

XV.--The Downward Path

XVI.--The Revelation

XVII.--The Last Chance

XVIII.--The Whirlpool

XIX.--The Outer Darkness

XX.--Deliverance

XXI.--The Poison Fruit

XXII.--The Loser

XXIII.--The Storm Wind

XXIV.--The Great Burden

XXV.--The Blow

XXVI.--The Deed of Gift

XXVII.--The Impossible

XXVIII.--The First of the Vultures

XXIX.--The Dutiful Wife

XXX.--The Lane of Fire

XXXI.--The New Boss

XXXII.--Old Scores

Epilogue: The Finish

The Hundredth Chance

PART I

THE START

CHAPTER I

BEGGARS

"My dear Maud, I hope I am not lacking in proper pride. But it is an accepted--though painful--fact that beggars cannot be choosers."

Lady Brian spoke with plaintive emphasis the while she drew an elaborate initial in the sand at her feet with the point of her parasol.

"I cannot live in want," she said, after a thoughtful moment or two. "Besides, there is poor little Bunny to be considered." Another thoughtful pause; then: "What did you say, dear?"

Lady Brian's daughter made an abrupt movement without taking her eyes off the clear-cut horizon; beautiful eyes of darkest, deepest blue under straight black brows that gave them a somewhat forbidding look. There was nothing remarkable about the rest of her face. It was thin and sallow and at the moment rather drawn, not a contented face, and yet possessing a quality indefinable that made it sad rather than bitter. Her smile was not very frequent, but when it came it transfigured her utterly. No one ever pictured that smile of hers beforehand. It came so brilliantly, so suddenly, like a burst of sunshine over a brown and desolate landscape, making so vast a difference that all who saw it for the first time marvelled at the unexpected glow.

But it was very far from her face just now. In fact she looked as if she could never smile again as she said: "Bunny would sooner die of starvation than have you do this thing. And so would I."

"You are so unpractical," sighed Lady Brian. "And really, you know, dear, I think you are just a wee bit snobbish too, you and Bunny. Mr. Sheppard may be a self-made man, but he is highly respectable."

"Oh, is he?" said Maud, with a twist of the lips that made her look years older than the woman beside her.

"I'm sure I don't know why you should question it," protested Lady Brian. "He is extremely respectable. He is also extremely kind,--in fact, a friend in need."

"And a beast!" broke in her daughter, with sudden passionate vehemence. "A hateful, familiar beast! Mother, how can you endure the man? How can you for a single moment demean yourself by the bare idea of--of marrying him?"

Lady Brian sighed again. "It isn't as if I had asked you to marry him," she pointed out. "I never even asked you to marry Lord Saltash, although--as you must now admit--it was the one great chance of your life."

Again Maud made that curious, sharp movement of hers that was as if some inner force urged her strongly to spring up and run away.

"We won't discuss Lord Saltash," she said, with lips that were suddenly a little hard.

"Then I don't see why we should discuss Giles Sheppard either," said Lady Brian, with a touch of querulousness. "Of course I know he doesn't compare well with your poor father. Second husbands so seldom do--which to my mind is one of the principal objections to marrying twice. But--as I said before--beggars cannot be choosers and something has got to be sacrificed, so there is an end of the matter."

Maud turned her eyes slowly away from the horizon, swept with them the nearer expanse of broad, tumbling sea, and finally brought them to rest upon her mother's face.

Lady Brian was forty-five, but she looked many years younger. She was a very pretty woman, delicate-featured, softly-tinted, with a species of appealing charm about her that all but the stony-hearted few found it hard to resist. She put her daughter wholly in the shade, but then Maud never attempted to charm anyone. She had apparently no use for the homage that was as the very breath of life to her mother's worldly little soul. She never courted popularity. All her being seemed to be bound up in that of her young brother who had been a helpless cripple from his babyhood, and dependent upon her care. The ten years that stretched between them were as nought to these two. They were pals; and if the boy tyrannized freely over her, she was undoubtedly the only person in the world for whom he entertained the smallest regard. She had lavished all a mother's love upon him during the whole of his fifteen years, and she alone knew how much had been sacrificed before the shrine of her devotion. He filled all the empty spaces in her heart.

But now--now that they were practically penniless--the great question arose: Who was to provide for Bunny? Lady Brian had lived more or less comfortably upon credit for the past five years. It was certainly not her fault that this bruised reed had broken at last in her hand. She had tried every device to strengthen it. And then too there had always been the possibility that Maud might marry Lord Saltash, who was extremely wealthy and--by fits and starts--very sedulous in his attentions.

It was of course very unfortunate that he should have been connected with that unfortunate scandal in the Divorce Court; but then everyone knew that he had led a somewhat giddy life ever since his succession to the title. Besides, nothing had been proved, and the unlucky affair had fallen through in consequence. It was really too absurd of Maud to treat it seriously, if indeed she had treated it seriously. Not being in her daughter's confidence, Lady Brian was uncertain on this point. But, whatever the circumstances, Charlie Saltash had obviously abandoned his allegiance. And Maud--poor girl!--had no one else to fall back upon. Of course it was very sweet of her to devote herself so unsparingly to dear little Bunny, but Lady Brian was privately of the opinion that she wasted a good deal of valuable time in his service. She was twenty-five already, and--now that the crash had come--little likely to find another suitor.

They had come down to this cheery little South Coast resort to recruit and look around them. Obviously something would have to be done, and done very quickly, or they would end their days in the workhouse.

Lady Brian had relations in the North, but, as she was wont to express it, they were not inclined to be kind to her. Her runaway marriage with Sir Bernard Brian in her irresponsible girlhood had caused something of a split between them. The wild Irish baronet had never been regarded with a favourable eye, and her subsequent sojourn in Ireland had practically severed all connection with them.

Sir Bernard's death and her subsequent migration to London had not healed the breach. She was regarded as flighty and unreliable. There was no knowing what her venture might be, and, save for a very occasional correspondence with an elderly bachelor uncle who was careful not to betray too keen an interest in her affairs, she was left severely alone.

Therefore she had too much pride to ask for help, sustaining herself instead upon the kindness of friends till even this prop at length gave way; and she, Maud and poor little Bunny (whose very empty title was all he possessed in the world) found themselves stranded at Fairharbour at the dead end of the season with no means of paying their way even there.

Not wholly stranded, however! Lady Brian had stayed at Fairharbour before at the Anchor Hotel down by the fishing-quay--"the Anchovy Hotel" Bunny called it on account of its situation. It was not a very high-class establishment, but Lady Brian had favoured it on a previous occasion because Lord Saltash had a yacht in the vicinity, and it had seemed such a precious opportunity for dear Maud. He also had large racing-stables in the neighbourhood of the downs behind the little town, and there was no knowing when one or other of his favourite pastimes might tempt him thither.

Nothing had come of the previous visit, however, save a pleasant, half-joking acquaintance with Mr. Sheppard, the proprietor of the Anchor Hotel, during the progress of which Lady Brian's appealing little ways had laid such firm hold of the worthy landlord's rollicking fancy that she had found it quite difficult to tear herself away.

Matters had not then come to such a pass, and she had finally extricated herself with no more than a laughing promise to return as soon as the mood took her. Maud had been wholly unaware of the passage between them which had been of a very slight and frothy order; and not till she found herself established in some very shabby lodgings within a stone's throw of the Anchor Hotel did the faintest conception of her mother's reason for choosing Fairharbour as their city of refuge begin to dawn in her brain.

She was very fully alive to it now, however, and hotly, furiously resentful, albeit she had begun already to realize (how bitterly!) that no resentment on her part could avert the approaching catastrophe. As Lady Brian pathetically said, something had got to be sacrificed.

And there was Bunny! She could not leave Bunny to try to earn a living. He was utterly dependent upon her--so dependent that it did not seem possible that he could live without her. No, she could see no way of escape. But it was too horrible, too revolting! She was sure, too, that her mother had a sneaking liking for the man, and that fact positively nauseated her. That awful person! That bounder!

"So, you see, dear, it really can't be helped," Lady Brian said, rising and opening her sunshade with a dainty air of finality. "Why his fancy should have fallen upon me I cannot imagine. But--all things considered--it is perhaps very fortunate that it has. He is quite ready to take us all in, and that, even you must admit, is really very generous of him."

Maud's eyes travelled again to the far sky-line. They had a look in them as of a caged thing yearning for freedom.

"It is getting late," said Lady Brian.

Sharply she turned. "Mother," she said, "I shall write to Uncle Edward. This is too much. I am sure he will not condemn us to this."

Lady Brian sighed a trifle petulantly. "You will do as you like, dear, no doubt. But pray do not write on my account! Whatever he may be moved to do or say can make no difference to me now."

"Why not?" Curtly her daughter put the question. The beautiful brows were painfully drawn.

"Because," said Lady Brian plaintively, "it will be too late--so far as I am concerned."

"What do you mean?" Again, almost like a challenge, the girl flung the question.

Lady Brian began to walk along the beach. "I mean, dear, that I have promised to give Mr. Sheppard his answer to-night."

"But--but--Mother--" there was almost a cry in the words, "you can't--you can't have quite decided upon what the answer will be!"

Lady Brian sighed again. "Oh, do let us have a little common-sense!" she said, with just a touch of irritation. "Of course I have decided. The decision has been simply thrust upon me. I had no choice."

"Then you mean to say Yes?" Maud's voice fell suddenly flat. She turned her face again to the open sea, a glint of desperation in her eyes.

"Yes," said Lady Brian very definitely. "I mean to say Yes."

"Then Heaven help us!" said Maud, under her breath.

"My dear, don't be profane!" said Lady Brian.

CHAPTER II

THE IDOL

"I say, Maud, what a dratted long time you've been! What on earth have you and the mother been doing?" Young Bernard Brian turned his head towards his sister with the chafing, impatient movement of one bitterly at variance with life. "You swore you wouldn't be long," he said.

"I know. I'm sorry." Maud came to his side and stooped over him. "I couldn't help it, Bunny," she said. "I haven't been enjoying myself."

He looked up at her suspiciously. "Oh, it's never your fault," he said, with dreary sarcasm.

Maud said nothing. She only laid a smoothing hand on his crumpled brow, and after a moment bent and kissed it.

He jerked his head away from her caress, opening and shutting his hands in a nervous way he had acquired in babyhood. "I've had a perfectly sickening time," he said. "There's a brute with a gramophone upstairs been driving me nearly crazy. For goodness' sake, see if you can put a stop to it before to-night comes! I shall go clean off my head if you don't!"

"I'll do my best, dear," Maud promised.

"I wish to goodness we could get away from this place," the boy said restlessly. "Even the old 'Anchovy' was preferable. I loathe this hole."

"Oh, so do I!" said Maud, with sudden vehemence. And then she checked herself quickly as if half-ashamed. "Of course it might be worse, you know, Bunny," she said.

Bunny curled a derisive lip, and looked out of the window.

"Did you really like 'The Anchor' better?" Maud asked, after a moment.

He drew his brows together--beautiful brows like her own, betraying a sensitive, not too well-balanced temperament. "It was better," he said.

Maud sat down beside his sofa with a slight gesture of weariness. "You would like to go back there?" she asked.

He looked at her sharply. "We are going?"

She met his look with steady eyes. "Mr. Sheppard has offered to take us in," she said.

The boy frowned still more. "What! For nothing?" he said.

"No; not for nothing." The girl was frowning too--the frown of one confronted with a difficult task. "Nobody ever does anything for nothing," she said.

"Well? What is it?" Bunny's eyes suddenly narrowed and became shrewd. "He doesn't want you to marry him, I suppose?"

"Good gracious, Bunny!" Maud gasped the words in sheer horror. "What ever made you think of that?"

Bunny laughed--a cracked, difficult laugh. "Because he's bounder enough for anything; and you're so beastly fond of him, aren't you?"

"Oh, don't!" Maud said. "Really don't, Bunny! It's too horrible to joke about. No, it isn't me he wants to marry. It's--it's----"

"The mother?" queried Bunny, without perturbation. "Oh, he's quite welcome to her. It's a pity he's been such a plaguey time making up his mind. He might have known she'd jump at him."

"But, Bunny--" Maud was gazing at him in utter amazement. There were times when the working of her young brother's brain was wholly beyond her comprehension. "You can't be--pleased!" she said.

"I'm never pleased," said Bunny sweepingly. "I hate everything and everybody--except you, and you don't count. The man's a brute of course; but if the mother has a mind to marry him, why on earth shouldn't she? Especially if it's going to make us more comfortable!"

"Comfortable on his money!" There was scorn unutterable in Maud's voice. Her eyes were tragically proud.

"But, why not?" said Bunny, with cynical composure. "We shall never be comfortable on our own, that's certain. If the man is fool enough to want to lay out his money in that way, why, let him!"

"Live on his--charity!" said Maud very bitterly.

The boy's mouth twisted. "We've got to live on someone's," he said. "There's nothing new in that. I think you're rather an ass, Maud. It's no good being proud when you can't afford it. We can't earn a living for ourselves, so someone must do it for us, that's all."

"Bunny!" There was passionate protest in the exclamation; but he passed it by.

"What's the good of arguing?" he said irritably. "We can't help ourselves. If the mother would rather marry that bawling beast Sheppard than starve on a doorstep with us, who's to blame her? I suppose we're included in the bargain for good, are we?"

Maud nodded mutely, her fingers locked and straining against each other.

Bunny screwed his face up for a moment. Then: "There's that filthy gramophone again!" he suddenly exclaimed. "Go and stop it, I say! I can't bear the noise! I won't bear it! It's--it's--it's infernal! That's what it is!" He flung his arms up frenziedly above his head, and then suddenly uttered an anguished cry of pain.

Maud was on her feet on the instant. She caught the arms, drew them firmly down again. "Oh, don't, dear, don't!" she said. "You know you can't!"

The boy's face was convulsed. "I didn't know! I can sometimes! Oh, Maud, I hate life! I hate it! I hate it!"

His voice choked, became a gasping moan, ceased altogether.

Maud stooped over him. His eyes were shut, his face white as death. "Bunny, Bunny darling!" she whispered passionately. "I would give--all the world--to make it better for you!"

There fell a silence, while gradually the awful paroxysm began to pass.

Then very abruptly Bunny opened his eyes. "No, you wouldn't!" he said unexpectedly.

"Indeed I would!" she said very earnestly.

"You wouldn't!" he reiterated, with the paralysing conviction that refuses to hear any reasoning. "If you would, you'd have married Lord Saltash years ago, and been rich enough to pay one of the big men to put me right."

She winced sharply. "Bunny! You're not to talk to me of Lord Saltash. It isn't kind. He is the one man in the world I--couldn't marry."

"Rot!" said Bunny. "You know you're in love with him."

"I know I couldn't marry him," she said, a piteous quiver in her voice. "It is cruel to--to--" She broke off.

"All right," said Bunny waiving the point. "Find some other rich man then! I don't care who it is. You'll have to pretty soon. We shall neither of us stand this Sheppard person for long."

"If I could only--somehow--make a living for the two of us!" the girl said.

"You can't!" Again deadly conviction swept aside argument. "You're not clever enough, and you haven't time--unless you propose to leave me to the tender mercies of the Sheppard. It would be a quick way out of the difficulty so far as I am concerned anyway."

"Of course I could never leave you!" Maud said quickly.

"All right then. Marry--and be quick about it!" said Bunny.

He turned his drawn, white face to the window--a face of unconscious pathos that often stirred his sister to the depths. Youth--and the gladness of youth--had never existed for Bunny Brian. Life for so long as he could remember had always been a long, dreary round of pain and disappointment, of restless nights and dragging, futile days. Only Maud, who shared them all, knew to the uttermost the woeful bitterness of the lad's existence. It hurt her cruelly, that bitterness, moving her to a perpetual self-sacrifice, of the extent of which even Bunny had small conception.

She identified herself completely with him, and had so done since the tenth year of her life when he had come--a puny, wailing baby--into the world to fill the void of her childish heart. She had, as it were, grown up in his service, worn and sallow and thin, with the sharp edges of nerves that were always strung up to too high a pitch--the nerves of one who scarcely ever knew a whole night of undisturbed rest. They had told upon her, those years of anxiety and service; they had shorn away her youth also. Only once--and that for how short a time!--had life ever seemed desirable in her eyes. A brief and splendid dream had been hers, spreading like a golden sunrise over her whole horizon. But the dream had faded, the sunrise had been extinguished in heavy clouds that had never again parted. She knew life now for a grey, grey dreariness on which no light could ever shine again. She was tired--tired to the soul of her; and she was only twenty-five.

"Maud!" Bunny's voice half-irritable, half-eager, broke in upon her. "See that fellow down there trying to make his nag go into the sea? It's going to be a big job. Let's go down and see it done!"

Bunny's long chair was in a corner of the room. It was no light task to get it in and out of the house; but Maud was used to the management of it. The weight of it went in with the other burdens of life. She was used also to lifting Bunny's poor little wasted body, and no wish of his that she could gratify was ever left neglected. Moreover, the offensive clamour of the gramophone overhead added to her alacrity to obey his behests. And the day was bright and warm, with a south wind blowing over a sparkling sea.

It would do Bunny good to go out, especially if he desired to go. It was not always that he would consent to do so after a sleepless night. But there was an extraordinary vitality in the meagre frame, a fevered, driving force that never seemed to be wholly exhausted. There were times when inaction was absolute torture to him, and Maud was ready to go until she dropped if only she could in some measure alleviate that chafing restlessness. She counted it luck indeed if these moods of fret and turmoil raged during the day. She was better able to cope with them then, and it gave the night a better chance. Poor lad! He could fight his own way through the days, but the long-drawn-out misery of nights of incessant pain broke him down--how completely only Maud ever knew.

So, gladly she wheeled him forth on that afternoon of late October, down the hill to the sun-bathed shore.

That hill taxed her physical powers to the uttermost. Secretly she dreaded the ascent, but not for worlds would she have had Bunny know it--Bunny who depended solely upon her for the very few pleasures that ever came his way. To the last ounce of her strength she was dedicated to the service of her idol.

CHAPTER III

THE NEW ACQUAINTANCE

They reached the sunny stretch of parade in time to see the young chestnut that had excited Bunny's interest being coaxed along the edge of the water by his rider. The animal was covered with froth, and evidently in a ferment of nervous excitement. The man who rode him sat loosely in the saddle as if the tussle in progress were of very minor importance in his estimation. He kept the fretting creature's head turned towards the water, however, and at intervals he patted the streaming neck and spoke a few words of encouragement.

At Bunny's request his chair was drawn to the edge of the parade, and from here he and Maud watched the progress of the battle. A battle of wills it undoubtedly was, though there was nothing in the man's attitude to indicate any strain. He was obviously one who knew how to bide his time, thick-set, bull-necked, somewhat bullet-headed, with a face of even redness and a short, blunt nose that looked aggressively confident.

"Wonder if he'll do it," said Bunny.

Maud wondered too, realizing that the task would be no easy one. The horse was plainly on edge with apprehension, and her sympathies went out to him. Somehow she did not want to see him conquered. In fact, not greatly admiring the physiognomy of his rider, she hoped the horse would win.

Stepping with extreme daintiness, as if he expected the ground to open and swallow him, the animal sidled past, and she caught the gleam of a wicked eye as he went. There was mischief mingled with his fear. He evidently was not feeling particularly kindly disposed towards the man who rode him. The loose seat of the latter made her wonder if he were wholly aware of this.

"He'll be thrown if he isn't careful," she said, half to herself and half to Bunny, who was watching with the keenest interest.

"Hope he'll tumble into the water," said Bunny, who enjoyed dramatic situations.

The pair had passed them and were continuing their sidling progress along the beach. The man still appeared preoccupied, the horse still half-frightened, half-mischievous. Some fifty yards they covered thus; then the figure in the saddle slowly stiffened. Aware of an impending change of treatment, the animal began to jib with his head in the air. An odd little thrill went through Maud, a feeling as of electricity in the air. It was almost a sensation of foreboding. And then clean and grim as a pistol-shot, she heard the crack of a whip on the creature's quivering flank.

It was a well-earned correction, deliberately administered, one stinging cut, delivered with a calculation that knew exactly where to strike. But the horse, a young animal, leapt into the air as if he had been shot indeed, and landing again almost on the same spot began forwith to buck-jump in frenzied efforts to free himself of the task-master whose lash was so unerring.

The whip descended again with absolute precision. It looked almost like a feat of jugglery to Maud's fascinated eyes. The horse uttered a furious squeal. He was being forced, literally forced, into the hated water, and he knew it, set himself with all the fiery unreason of youth to resist, and incidentally to receive a punishment none the less painful on account of its extreme deliberation.

As for his rider, he kept his seat without apparent effort. He kept his temper also to all outward appearance. He even in the thick of the struggle abandoned force and tried coaxing again. It was only when this failed that it seemed to the watching girl that a certain quality of implacability began to manifest itself. His movements were no less studied, but they seemed to her to become relentless. From that moment she knew with absolute certainty that there could be but one end to the struggle.

Some dim suspicion of the same thing must have penetrated the animal's intelligence also, for almost from the same moment he seemed to lose heart. He still bucked away from the water and leapt in futile frenzy under the unsparing whip; but his fury was past. He no longer tried to fling his rider over his head. He seemed to be fighting to save his pride rather than for any other reason.

But his pride had to go. Endurance had its limits, and his smooth, clipped flanks were smarting intolerably. Very suddenly he gave in and walked into the water.

It foamed alarmingly round his legs, and he started in genuine terror and tried to turn; but on the instant a hand was on his neck, a square, sustaining hand that patted and consoled.

"Now, don't be a fool horse any longer!" said his conqueror. "Don't you know it's going to do you good? Go on and face it!"

He went on, splashing his rider thoroughly, first in sheer nervousness, later in undisguised content.

He came out of the water some five minutes later, a wiser and considerably less headstrong youngster than he had entered it, and walked serenely along the edge as if he had been accustomed to it all his life. When the spreading foam washed round his hoofs, he did not so much as lay an ear. He had surrendered his pride, and he did not seem to feel the sacrifice.

"A beastly tame ending!" said Bunny in frank disappointment. "I hoped the fellow was going to break his neck."

The horseman was passing immediately below them. He looked up, and Maud coloured a guilty scarlet, realizing that he had overheard the remark. He had the most startlingly bright eyes she had ever seen. They met hers with a directness that seemed to pierce straight through her, and passed on unblinkingly to the boy in the long chair. There was something lynx-like in the straight regard, something so deliberately intent that it seemed formidable. His clean-shaven, weather-beaten face had an untamed, primitive look about it, as of one born in the wilderness. His mouth was rugged rather than coarse, but it was not the mouth of civilization.

Bunny, who was not easily daunted, looked hard back at him, with the brazen expression of one challenging a rebuke. But the horseman refused the challenge, passing on without a word.

"I'm tired," said Bunny, in sudden discontent. "Let's go back!"

When he spoke in that tone, he was invariably beyond coaxing. Maud turned the chair without protest, and prepared to make that exhausting ascent.

"How slow you are to-day!" said Bunny peevishly. "I hate this beastly hill. You make me go up it on my head!"

The slant was certainly acute. Maud murmured sympathy. "I would pull you up if I could," she said.

"You've never even tried," said Bunny.

He was plainly in an exacting mood. Her heart sank a little lower. "It's no use trying, darling," she said. "I know I can't. But I won't take a minute longer over it than I can help."

"You never do anything decently," said Bunny in disgust.

Maud made no rejoinder. She bent in silence to her task.

Bunny could not see her face, and she strove desperately to control her panting breath.

"You puff like a grampus," the boy said discontentedly.

There came the quick fall of a horse's hoofs behind them, and Maud bent her flushed face a little lower. She did not want to meet that piercing regard again. But the hoof-beats slackened behind her, and a voice spoke--a voice so curiously soft that at the first sound she almost believed it to be that of a woman.

"Say! That's too heavy a job for you."

She paused--it was inevitable--and looked round.

In the same moment he slid to the ground--a square, sturdy figure, shorter than she had imagined him when he was in the saddle, horsey of aspect, clumsy of build, possessing a breadth of chest that seemed to indicate vast strength.

Again those extremely bright eyes met hers, red-brown, intensely alive. She felt as if they saw too much; they made her vividly conscious of her hot face and labouring heart. They embarrassed her, made her resentful.

She was too breathless to speak; perhaps she might not have done so in any case. But he did not wait for that. He pushed forward till he stood beside her.

"You take my animal!" he said. "He's quiet enough now."

She might have refused, had she had time to consider. But he gave her none. He almost thrust the bridle into her hands, and the next moment he had taken her place behind the invalid-chair and begun briskly to push it up the hill.

Maud followed, leading the now docile horse, divided between annoyance and gratitude. Bunny seemed struck dumb also, though whether with embarrassment or merely surprise she could not tell.

At the top of the steep ascent the stranger stopped and faced round. "Thanks!" he said briefly, and took his horse back into his own keeping.

Maud stood, feeling shy and awkward, while he set his foot in the stirrup. Then, ere he mounted, with a desperate effort she spoke.

"It was very kind of you. Thank you very much."

Her voice sounded coldly formal by reason of her extreme discomfiture. She would have given a good deal to have avoided speaking altogether. But the man stopped dead and looked at her as though she had attempted to detain him.

"You've nothing to thank me for," he said, in that queer, soft voice of his. "As I said before, it's too heavy a job for you. You'll get a groggy heart if you keep on with it."

There was no intentional familiarity in the speech; but it made her stiffen instinctively.

"It was very kind of you," she repeated, and with a bow that was even more freezingly polite than her words she turned to the chair and prepared to walk on.

But at this point Bunny suddenly found his voice in belated acknowledgment of the service rendered. "Hi! You! Stop a minute! Thanks for pushing me up this beastly hill!"

The stranger was still standing with his foot in the stirrup; but at the sound of Bunny's voice he took it out again and came to the boy's side, leading his horse.

"What a beauty!" said Bunny, admiringly. "Let me touch him, I say!"

"Oh, don't!" Maud said nervously. "He looked so savage just now."

"He's not savage," said the horse's owner, and pulled the animal's nose down to Bunny's eager, caressing hand.

The creature was plainly suspicious. He tried to avoid the caress, but his master and Bunny were equally insistent, and he finally submitted.

"He's not savage," his rider said again. "He's only young and a bit heady; wants a little shaping--like all youngsters."

Bunny's shrewd eyes flashed him a rapid glance, meeting the red-brown eyes deliberately scrutinizing him. With a certain blunt courage that was his, he tackled the situation.

"I say, did you hear what I said down on the parade?"

The man smiled a little, still watching Bunny's red face. "Did you mean me to hear?" he enquired.

"No," said Bunny, staring back, half-fascinated and half-defiant.

"All right then. I didn't," the horseman said.

Bunny's expression changed. He smiled; and when he smiled his lost youth looked out of his worn face. "Good for you!" he said. "I say, I hope we shall see you again some time."

"If you are here for long, you probably will," the man made answer.

"Do you live here?" Bunny's voice was eager. His eyes sparkled with interest.

The man nodded. "Yes, I'm a fixture. And you?"

"Oh, we're going to be fixtures too," said Bunny. "This is my sister Maud. I am Sir Bernard Brian."

Maud's ready blush rose burningly. She fidgeted to be gone. Bunny's swaggering announcement made her long to sink through the earth. She dreaded to hear his listener laugh, even looked up in surprise when no laugh came.

He was surveying Bunny with that same unblinking regard that had disconcerted her. The slight smile was still on his face, but it was not a derisive smile.

After a moment he said, "My name is Bolton--Jake Bolton. Think you can remember that?"

"What are you?" said Bunny, with frank curiosity.

"I?" The faint smile suddenly broadened, showing teeth that were large and very white. "I am a groom," the horseman said.

"Are you?" The boy's eyes opened wide. "Then you're not a mister!" he said.

"Oh no, I'm not a mister!" There was certainly a laugh in the womanish voice this time, but it held no open ridicule. "I'm plain Jake Bolton. You can call me Bolton or Jake--which ever you like. Good day, Sir Bernard!"

He backed his horse with the words, and mounted.

Maud did not look at him. She felt too overwhelmed. Moreover, she was sure--painfully sure--that he looked at her, and she thought there must be at least amusement in his eyes.

With relief she heard him turn his horse and trot down the hill. He had not even been going their way, then. Her face burned afresh.

"What a queer fish!" said Bunny. "Hullo! What are you so red about?"

"I wish you wouldn't tell people your title," she said. "They only laugh."

"He didn't laugh when I told him," said Bunny. "And why shouldn't I? I've a right to it."

He would not see her point she knew. But she made an attempt to explain. "He would have liked to call himself a gentleman," she said. "But--he didn't."

"That's quite different," said Bunny loftily. "He knows he isn't one."

Maud abandoned the argument then, because--though it was against her judgment--she found that she wanted to agree.

CHAPTER IV

THE ACCEPTED SUITOR

"Hark to the brute!" said Bunny.

A long, loud peal of laughter was echoing through the house. Maud shuddered at the sound. The noisy wooing of her mother's suitor made her feel physically sick. But for Bunny, she would have fled incontinently from the man's proximity. Because of Bunny, she sat at a rickety writing-table in a corner of the room and penned an urgent, almost a desperate, appeal to the bachelor uncle in the North to deliver them from the impending horror. No other consideration on earth would have forced such an appeal from her. She felt literally distraught that night. She was being dragged, a helpless prisoner, to the house of bondage.

Again came that loud, coarse laugh, and with it the opening of a door on the other side of the passage.

"Watch out!" warned Bunny. "They're coming!"

There was a hint of nervousness in his voice also. She heard it, and swiftly rose. When their own door opened, she was standing beside him, very upright, very pale, rigidly composed.

Her mother entered, flushed and smiling. Behind her came her accepted lover,--a large, florid man, handsome in ascertain coarse style, with a dissipated look about the eyes which told its own tale. Maud quivered in impotent resentment whenever she encountered those eyes. They could not look upon a woman with reverence.

He strolled into the room in her mother's wake, fondling a dark moustache, in evident good humour with himself and all the world.

Lady Brian ran to her daughter with all a girl's impetuosity. "My dear, it's all settled!" she declared. "Giles and I are going to be married, and we're all going to live at "The Anchor" with him. And dear little Bunny is to have the best ground-floor rooms. Now, isn't that kind?"

It was kind. Yet Maud stiffened to an even icier frigidity at the news, and dear little Bunny's nose turned up to an aggressive angle.

After a distinct pause, Maud bent her long neck and coldly kissed her mother's expectant face. "I hope you--and Mr. Sheppard will be very happy," she said.

The happy suitor broke into his loud, self-satisfied laugh. "Egad, what an enthusiastic reception!" he cried. "Have you got a similar chaste salute for me?"

He swaggered towards her, and Maud froze as she stood. Her eyes shot a blue flare of open enmity at him; and--almost in spite of himself--Giles Sheppard paused.

"By Jove!" he said. "You've got a she-wolf here, madam."

Lady Brian turned. "Oh, Giles, don't be absurd! Maud is not like me, you know. She was never demonstrative as a child. She was always shy and quiet. They are not quite used to the idea of you yet. You must give them time. Bunny darling, won't you give Mother a kiss?"

"What for?" said Bunny.

He was tightly gripping Maud's cold hand with fingers that were like tense wire. His eyes, very wide and bright, defied the whole world on her behalf.

"I'm not going to kiss anyone," he said. "Neither is Maud. I don't know what there is to make such a fuss about. You've both been married before."

The landlord of "The Anchor" gave a great roar of laughter. "Not bad for a bantling, eh, Lucy? Didn't know I was to have a sucking cynic for a step-son. You're quite right, my boy; there is nothing to make a fuss about. And so we shan't ask you to dance at the wedding. Not that you could if you tried, eh? And my Lady Disdain there won't be invited. We are going to be married by special licence to-morrow afternoon, and you can take possession of your new quarters while the knot is being tied. How's that appeal to you?"

Bunny looked at him with a certain grim interest. "It'll suit me all right," he said. "But I'm hanged if I can see where you come in."

Giles Sheppard laughed again with his tongue in his cheek. "Oh, I shall have my picking at the feast, old son," he declared jovially. "I've had my eye on your mother for a long time. Pretty piece of goods she is too. You're neither of you a patch on her. They don't do you credit, Lucy, my dear. Sure they're your own?"

"The man's drunk!" said Maud suddenly and sharply.

"My dear! My dear!" cried Lady Brian, in dismayed protest.

The girl bit her lip. The words had escaped her, she knew not how.

Giles Sheppard however only laughed again, and seated himself on the edge of the table to contemplate her.

"We shall have to try and find a husband for you, young woman," he said, "a husband who'll know how to bring you to heel. It'll be a tough job. I wonder who'd like to take it on. Jake Bolton might do the trick. We'll have Jake Bolton to dine with us to-morrow. He knows how to tame wild animals, does Jake. It's a damn' pretty sight to see him do it too. Gosh, he knows how to lay it on--just where it hurts most."

He chuckled grimly with his eyes on Maud's now crimson face.

"Now, Giles," protested Lady Brian, "you've promised to be good to my two children. I'm sure we shall all shake down comfortably presently. Dear Maud has a good deal to learn yet, so you must be patient with her. We were foolish ourselves at her age, I have no doubt."

"Oh, no doubt," said her fiancé, with his thick-lidded eyes still mocking the girl's face of outraged pride. "We've all been foolish in our time. But there's only one treatment for that complaint in the female species, my lady; and that is a sound good spanking. It does a world of good, takes the stiffening out of a woman in no time. I've had a daughter of my own--a decent little filly she was too. Married now and gone to Canada. But I had to keep her in order, I can tell you, before she went. I gave her many a slippering, and she thought the better of me for it too. She knew I wouldn't stand any of her nonsense."

"Oh, well," smiled Lady Brian, "we are not all alike, you know; and that sort of treatment doesn't suit everybody. Now I think we all know each other, and my little Bunny is looking rather tired. I think we won't stay any longer. It means a bad night if he gets excited."

"Wait a minute!" interposed Bunny. "That man you were talking about just now--Jake Bolton. Who is he? Where does he live?"

"Who is he?" Giles Sheppard slapped his thigh and rose. "He's one of the best-known fellows about here--a bit of a card, but none the worse for that. He's the trainer up at the stables--Lord Saltash's place. Never heard of him? He's known as 'The Lynx' on the turf, because he's so devilish shrewd. Oh yes, he's quite a card. And to see him break one of them youngsters--well, it's a fair treat."

Mr. Sheppard's grammar was apt to lapse somewhat when his enthusiasm was kindled. Maud shivered a little. Lady Brian smiled indulgently. Poor Giles! He was a rough diamond. She would have to do a little polishing; but she was sure he would become quite a valuable gem when polished.

"Oh, he's Lord Saltash's trainer is he?" she said. "Lord Saltash is a very old friend of ours. Is he--does he ever come down here?"

"Who? Lord Saltash? He has a place here. You couldn't have been very intimate with him if you didn't know that. Just as well p'raps with a man of his tendencies." Sheppard laughed in a fashion that sent the hot blood back to Maud's face. "A bit too fond of his neighbour's wife--that young man. Lucky thing for him that he didn't have to pay heavy damages. More luck than judgment, to my thinking."

"Oh, Giles!" protested Lady Brian. "How you do run on! I did know that he had an estate here. That was why I asked if he still came down. You really mustn't blacken the young man's character in that way. We are all very fond of him."

"Are you though!" Sheppard's laugh died; he looked at Maud with a hint of venom. "Like the rest of your charming sex, eh? Well, we don't see much of the gay Lothario in these parts. If that was your little game, you'd better have stopped in town."

Maud's lips said, "Cad!", but her voice made no sound.

He bowed in ironical acknowledgment and turned to her mother. "Now, my lady, having received these cordial congratulations, I move an adjournment. As you have foretold, we shall doubtless all shake down together very comfortably in the course of a few weeks. But in the meantime I should like to inform all whom it may concern that I am master in my own house, and I expect to be treated as such."

Again his insolent eyes rested upon Maud's proud face, and her slight form quivered in response though she kept her own rigidly downcast.

"Of course that is understood," said Lady Brian, with a pacific hand on his arm. "There! Let us go now! I am sure we are all going to be as happy as the day is long."

She looked up at him with persuasive coquetry, and he at once succumbed. He pulled her to him roughly and bestowed several resounding kisses upon her delicate face, not desisting until with laughing remonstrance she put up a protesting hand.

"Giles, really--really--you mustn't be greedy!" she said, and drew him to the door with some urgency.

He went, his malignancy for the moment swamped by a stronger emotion; and brother and sister were left alone.

"What a disgusting beast!" said Bunny, as the door closed.

Maud said nothing. She only went to the window, and flung it wide.

CHAPTER V

IN THE DARK

Black night and a moaning sea! Now and then a drizzle of rain came on a gust of wind, sprinkling the girl's tense face, damping the dark hair that clustered about her temples. But she did not so much as feel it. Her passionate young spirit was all on fire with a fierce revolt against the destinies that ruled her life. She paced the parade as one distraught.

Only for a brief space could she let herself go thus,--only while Bunny and their mother played their nightly game of cribbage. They did not so much as know that she was out of the house. She would have to return ere she was missed, and then would follow the inevitable ordeal of putting Bunny to bed. It was an ordeal that seemed to become each night more difficult. In the morning he was easier to manage; but at night when he was tired out and all his nerves were on edge she sometimes found the task almost beyond her powers. When he was in pain--and this was not infrequently--it took her hours to get him finally settled.

She was sure that it would be no easy task to-night. He had had bouts of severe neuralgia during the day, and his flushed face and irritable manner warned her that there was a struggle in store. She had sometimes sat waiting till the small hours of the morning before he would permit her to move or undress him. She felt that some such trial was before her now, and her heart was as lead.

The house had seemed to stifle her. She had run out for a breath of air; and then something about that moaning shore had seemed to draw her. She had run down to the parade, and now she paced along it, staring down into the fathomless dark below her where the deep water rose and fell with a ceaseless moaning, thumping the well beneath in sullen impotence.

There was no splash of waves, only that dumb striving against a power it could not overthrow. It was like her own mute rebellion, she thought to herself miserably, as persistent and as futile.

She reached the end of the parade. The hour was late; the place deserted. There was a shelter here. She was sure it would be empty, but it did not attract her. She wanted to get as close as possible to that moaning, mysterious waste of water. It held a stark fascination for her. It drew her like a magnet. She stood on the very edge of the parade, facing the drift of rain that blew in from the sea. How dark it was! The nearest lamp was fifty yards away! The thought came to her suddenly, taking form from the formless deep: how easy to take one single false step in that darkness! How swift the consequence, and how complete the deliverance!

A short, inevitable struggle in the dark--in the dark; and then a certain release from this hateful chain called life. It would be terrible, but so quickly over! And this misery that so galled her would be for ever past.

She beat her foot on the edge with a passionate impatience. What a fool she was to suffer so--when there was nothing (never had been any thing) in life worth living for!

Nothing? Well, yes, there was Bunny. She was an absolute necessity to him. That she knew. She was firmly convinced that he would die without her. And though he would be far, far happier dead, poor darling, she couldn't leave him to die alone.

She lifted her clenched hands above her head in straining impotence. For one black moment she almost wished that Bunny were dead.

And then very suddenly, with staggering unexpectedness she received the biggest shock of her life. Two hands closed simultaneously upon her wrists, and she was drawn into two encircling arms.

She uttered a startled outcry, and in the same moment began a wild and flurried struggle for freedom. But the arms that held her closed like steel springs. A man's strength forced her steadily away from the yawning blackness that stretched beyond the parade.

"It's no good kicking," a soft voice said. "You won't get away."

Something in the voice reassured her. She ceased to struggle. "Oh, let me go!" she said breathlessly. "You--you don't understand. I--I--only----"

"Came out for a breath of air?" he suggested. "Of course--I gathered that."

He took his arms away from her, but he still kept one of her wrists in a strong grasp. She could not see his face in the darkness, only his figure, which was short and stoutly built.

"Do you know," he said, "when people take the air like that, I always have to hold on to 'em tight till they've had all they want. It's damn' cheek on my part, as you were just going to remark. But, my girl, it's easier than mucking about in a dark sea looking for 'em after they've lost their balance."

He had led her to the shelter. She sat down rather helplessly, wondering if it would be possible to conceal her identity from him since it was evident that so far he had not recognized her.

He stood in front of her, squarely planted, his hand still locked upon her wrist. She had known him from the first word he had spoken, and, remembering those startling lynx eyes of his, she felt decidedly uneasy. She was sure they could see in the dark.

She spoke after a moment with slight hesitation. "I shouldn't have lost my balance. And if I had meant to jump over, as you imagined, I shouldn't have stood so long thinking about it."

"Sure you're not thinking about it now?" he said.

"Quite sure," she answered.

He bent down, and she was sure--quite sure--that his eyes scrutinized her and took in every detail.

The next moment he released her wrist also. "All right, my girl," he said. "I believe you. But--don't do it again! Accidents happen, you know. You might have had one then; and I should still have had to flounder around looking for you."

Something in his tone made her want to smile, and yet she felt so sure--so sure--that he knew her all the time. And she wanted to resent his familiarity at the same moment. For if he knew her, it was rank presumption to address her so.

She rose at length and faced him with such dignity as she could muster. "I am obliged to you," she said, "but I fail to see why your responsibility should extend so far. If I had fallen over, the chances are that you could never have found me--or saved me if you had."

"Ninety-nine to one!" he said coolly. "But, do you know, I rather count on the hundredth chance. I've taken it--and won on it--before now."

He was not to be disconcerted, it was evident. He was plainly a difficult man to rout, one accustomed to keep his head in any emergency. And she--she was but a slip of a girl in his estimation, and he had her at a disadvantage already.

She felt her face begin to burn in the darkness. She shifted her ground. "I don't see why anyone should be made to live against his will," she said, "why it should be anyone's business to interfere."

"That's because you're young," he said. "You haven't yet got the proper hang of things. It only comes with practice--that."

Her face burned more hotly. He was actually patronizing her!

She turned abruptly. "Good evening," she said, and began to walk away.

But he fell in beside her at once. "I'm going your way," he observed. "May as well see you past the bar of 'The Anchor.' They get a bit lively there sometimes at this end of the day."

He walked with the slight roll of a man accustomed to much riding. She imagined that he never appeared in anything but breeches and gaiters. But his tread was firm and purposeful. Quite obviously it never entered his head that she might not desire his company.

For that reason she had to submit to the arrangement though she felt herself grow more and more rigid as they neared the circle of light cast by the street-lamp. Of course he was bound to recognize her now.

But they reached and passed the lamp, and he tramped straight ahead without looking at her, after the square fashion that she had somehow begun to associate with him.

They reached and passed "The Anchor" also, with its lighted bar and coarse voices and lounging figures. They began the steep ascent up which he had pushed Bunny that afternoon. It was dark enough here at least, and her self-confidence began to revive. She would put him to the test. She would pass the gate that he had seen her enter earlier in the day. If he displayed surprise or hesitation she would know that he had recognized her.

But yet again he baffled her. He tramped steadily on.

She began to get a little breathless. There was another lamp at the top of the road. She did not want to reach that.

In desperation she paused. "Good evening!" she said again.

He stopped at once, and she thought she caught the glitter of his eye, seeking her own in the darkness.

"You're going in now?" he asked.

"Yes," she said.

He came a step nearer, and laid one finger on her arm. "Look here, my girl! You take a straight tip from me! If you're in any sort of trouble, go and tell someone! Don't bottle it in till it gets too big for you! And above all, don't go step-dancing on the edge of the parade in the dark! It's a fool thing to do."

He emphasized his points with impressive taps upon her arm. She felt absurdly small and meek.

"Suppose I haven't anyone to tell?" she said, after a moment.

He rose to the occasion instantly. "I'm sound," he said. "Tell me!"

She had not expected that. He seemed to disconcert her at every turn.

"Thank you," she said, taking refuge in extreme frigidity. "I think not."

"As you like," he said. "I daresay I shouldn't in your place. I only suggested it because I can't see a girl in trouble and pass by on the other side."

He spoke quite quietly, but there was a quality in the soft voice that stirred her very strangely, something that made her for the moment forget the man's dominant personality, and feel as if a woman had uttered the words.

She put out a groping hand to him, obeying a curious impulse that would not be denied.

"Thank you," she said again.

He kept her hand for a second or two, holding it squarely, almost as if he were waiting for something.

Then, without a word, he let it go. She turned back; and he went on.

CHAPTER VI

THE UNWILLING GUEST

"But, my dear child, you must appear!" urged the bride, with a piteous little twist of the lips. "I can't go unsupported into that dreadful crowd."

"Oh, Mother!" Maud said. And that was all; for what was the good of saying more? Her mother had made the choice, and there was no turning back. They could only go forward now along the new course, whithersoever it led. "I'll come," she said, after a moment.

Her mother's smile was full of pathos. "We must all make sacrifices for one another, darling," she said. "I have made a very big one for you and Bunny. He--poor little lad--isn't old enough to understand. But surely, you, at least can appreciate it."

She looked so wistful as she spoke that in spite of herself Maud was moved to a very unusual show of tenderness. She turned and kissed her. "I do hope you will be happy," she said. "I expect you will, you know, when you are used to it."

She spoke out of a very definite knowledge of her mother's character. She knew well the yielding adaptability thereof. Giles Sheppard's standards would very soon be hers also, and she would speedily cease to find anything wanting in his friends.

She turned with a sigh. "Let's go and get it over!" she said. "But I can't stay long. I shall have to get back to Bunny."

She and Bunny had spent all the afternoon and evening settling into their new quarters at the Anchor Hotel, and it had been a tiring task. The bride and bridegroom had gone straight from the registry-office where the ceremony had been performed to the county town some thirty miles distant, in the one ramshackle little motor that the hotel possessed, and had returned barely in time to receive the guests whom Sheppard had invited to his wedding-feast.

Neither Maud nor her mother had been told much of the forthcoming festivity, and the girl's dismay upon learning that she was expected to attend it was considerable. She was feeling tired and depressed. Bunny was in a difficult mood, and she knew that another bad night lay before them. Still it was impossible to refuse. She could only yield with as good a grace as she could muster.

"Make yourself pretty, won't you, dear?" said Mrs. Sheppard as, her point gained, she prepared smilingly to depart. "Wear your white silk! You look charming in that."

Maud had not the faintest wish to look charming, but yet again she could not refuse to gratify a wish so amiably expressed. She donned the white silk, therefore, though feeling in any but a festive mood, and prepared herself for the ordeal with a grim determination to escape from it as soon as possible.

She was not tall, but her extreme slenderness gave her a decidedly regal pose. She held her head proudly and bore herself with distinction. Her eyes--those wonderful blue-violet eyes--had the aloof expression of one whose soul is far away.

Giles Sheppard watched her enter the drawing-room behind her mother, and a bitter sneer crossed his bloated face. He was utterly incapable of appreciating that innate pride of race that expressed itself in every line of her. He read only contempt for him and his in the girl's still face, and the deep resentment kindled the night before began to smoulder within him with an ever-increasing heat. How dared she show her airs and graces here?-- She, a penniless minx dependent now upon his charity for the very bread she ate!

He turned with an ugly jest at her expense upon his lips to the man with whom he had been talking at her entrance; but the jest was checked unuttered. For the man, square, thickset as a bulldog, abruptly left his side and moved forward.

The quick blood mounted in Maud's face as he intercepted her. She looked at him for a second as if she would turn and flee. But he held out a steady hand to her, and she had to place hers within it.

In a moment his peculiar voice accosted her. "You remember me, Miss Brian? I'm Jake Bolton--the horse breaker. I had the pleasure of doing your brother a small service yesterday."

Both hand and voice reassured her. She had an absurd feeling that he was meting out to her such treatment as he would have considered suitable for a nervous horse. She forced herself to smile upon him; it was the only thing to do.

He smiled in return--his pleasant open smile. "Remember me now?" he said.

"Quite well," she answered.

"Good!" he said briefly. "Let me find you a chair! I don't suppose you know many of the people here."

She did not know any of them, and as Sheppard had seized upon his bride, and was presenting her in rude triumph to each in turn with much noisy laughter and coarse joking it was not difficult to slip into a corner with Jake Bolton without attracting further attention.

He stood beside her for a space while covertly she took stock of him.

Yes, he actually had discarded his gaiters and was wearing evening dress. It did not seem a natural garb for him, but he carried it better than she would have expected. He still reminded her very forcibly of horses, though she could not have definitely said wherein this strong suggestion lay. His ruddy face and short, dominant nose might have belonged to a sailor. But the brilliant chestnut eyes with their red-brown lashes were somehow not of the sea. They made her think of the reek of leather and the thud of galloping hoofs.

Suddenly he turned and caught her critical survey. She dropped her eyes instantly in hot confusion, while he, as if he had just made up his mind, sat down beside her.

"So you and your brother are going to live here?" he said.

She answered him in a low voice; the words seemed to leap from her almost without her conscious volition. "We can't help ourselves."

He gave a short nod as of a suspicion confirmed, and sat in silence for a little. The loud laughter of Giles Sheppard's guests filled in the pause.

Maud held herself rigidly still, repressing a nervous shiver that attacked her repeatedly.

Suddenly the man beside her spoke. "What's the matter with that young brother of yours?"

With relief she came out of her tense silence. "It is an injury to the spine. He had a fall in his babyhood. He suffers terribly sometimes."

"Nothing to be done?" he asked.

She shook her head. "No one very good has seen him. He won't let a doctor come near him now."

"Oh rats!" exclaimed Jake Bolton unexpectedly.

She felt her colour rise as he turned his bright eyes upon her.

"You don't say that a kid like that can get the better of you?" he said.

She resented the question; yet she answered it. "Bunny has a strong will. I never oppose it."

"And why not?" He was looking directly at her with a comical smile as if he were inspecting some quaint object of interest.

Again against her will she made reply. "I try to give him all he wants. He has missed all that is good in life."

He wrinkled his forehead for a moment as if puzzled, then broke into a laugh. "Say, what a queer notion to get!" he said.

She stiffened on the instant, but he did not seem to notice it. He leaned towards her, and laid one finger--a short, square fore-finger--on her arm.

"Tell me now--what are the good things in life?"

She withdrew her arm from his touch, and regarded him with a hauteur that did not wholly veil her embarrassment.

"You don't know!" said Jake. "Be honest and say so!"

But Maud only retired further into her shell. "I think we have wandered rather far from the subject," she said coldly. "My brother is unfortunately the victim of circumstance, and no discussion can alter that fact."

He accepted the snub without a sign of discomfiture. "Is he here now?" he asked.

She bent her head. "In this house--yes."

"Will you let me see him presently?" he pursued.

Distantly she made reply. "I am afraid that is impossible."

"Why?" he said.

She raised her dark brows.

"Tell me why!" he insisted.

Calmly she met his look. "It is not good for him to see strangers at night. It upsets his rest."

"You think it would be bad for him to see me?" he questioned.

His voice was suddenly very deliberate. He was looking her full in the face.

A curious little tremor went through her. She felt as if he had pinioned her there before him.

Her reply astounded herself. "I don't say it would be bad for him,--only--inadvisable. He is rather excited already."

"Will you ask him presently if he would cane to see me?" said Jake Bolton steadily.

She bit her lip, hesitating.

"I shan't upset him," he said. "I won't excite him. I'll quiet him down."

She did not want to yield--yet she yielded. "I will ask him--if you wish," she said.

He smiled. "Thank you, Miss Brian. You didn't want to give in, did you? But I undertake that you will not be sorry."

"Hullo, Jacob!" blared Sheppard's voice suddenly across the room. "What are you doing over there, you rascal? Thought I shouldn't see you, eh? Ah, you're a deep one, you are! I daresay now you've made up your mind that that young woman is a princess in disguise. She isn't. She's just my step-daughter, and a very cheap article, I assure you, Jake,--very cheap indeed!"

The roar of laughter that greeted this sally filled the room, drowning any further remarks. Sheppard stood in the centre, swaying a little, looking round on the assembled company with a facetious grin.

Jake Bolton rose and went to him. He stood with him for a moment, and Maud, shivering in her corner, marvelled that he did not look mean and insignificant beside the other's great bulk. She wondered what he said. It was only a few words, and they were not apparently uttered with much urgency. But Sheppard's grin died away, and she fancied that for a moment--only for a moment--he looked a little sheepish. Then he clapped a great hand upon Bolton's shoulder.

"All right. All right. It's for you to make the running. Come along, ladies and gentlemen! Let us feed!"

There was a general move, and a tall, lanky young man with a white face and black hair that shone like varnish slouched up to Maud.

"I don't see why Bolton should have all the plums," he said. "May I have the honour of conducting you to the supper table?"

She was on her feet. She looked at him with a disdain so withering that the young man wilted visibly before her.

"No offence meant, I'm sure," he said, shuffling his feet. "But I thought--as you were being so pally with Jake Bolton--you wouldn't object to being pally with me."

Maud said nothing. She was in fact so quivering with rage that speech would have been difficult.

A very stout elderly lady, with a neck and arms that were hardly distinguishable from the red silk dress she wore, sailed up to them. "Come, come, Miss!" she said, beaming good-temperedly upon Maud's pale face. "We're not standing on ceremony to-night. We're all friends here. You won't mind going in with my boy Tom, I'm sure. He's considered quite the ladies' man, I can assure you."

"Oh, excuse me, Mrs. Wright? Miss Brian is going in with me," said Jake Bolton's smooth voice behind her. "Tom, you git!"

Somehow--before she knew it--the black-haired young man was gone from her path, and her hand lay trembling within Bolton's arm.

She did not utter a word, she could not. She felt choked.

Jake Bolton said nothing either. He only piloted her through the crowd with the smile of the winner curving the corners of his mouth.

They readied the dining-room, and people began to seat themselves around a long centre table. There was no formal arrangement, and some confusion ensued in consequence.

"Fight it out among yourselves!" yelled Sheppard above the din of laughter and movement. "Make yourselves at home!"

Bolton glanced round. "There's a table for two in that alcove," he said. "Shall we make for that?"

"Anywhere!" she said desperately.

He elbowed a way for her. The table was near a window, the alcove draped with curtains. He put her into a chair where she was screened from the eyes of those at the centre table. He seated himself opposite to her.

"Don't look so scared!" he said.

She smiled at him faintly in silence.

"I gather you don't enjoy this sort of bear-fight," he said.

She remained silent. The man disconcerted her. She was burningly conscious that she had not been too discreet in taking him even so far into her confidence.

He leaned slowly forward, fixing her with those relentless, lynx-like eyes. "Miss Brian," he said, his voice very level, faultlessly distinct. "I'm rough, no doubt, but please believe I'm white!"

She looked at him, startled, unhappy, not knowing what to say.

He nodded, still watching her. "Don't you forget it!" he said. "There are plenty of beasts in the world, but I'm not one of 'em. You'll drink champagne, of course."

He got up to procure it, and Maud managed in the interval to recover some of her composure.

When he came back, she mustered a smile and thanked him.

"You look fagged out," he said, as he filled her glass. "What have you been doing?"

"Getting straight in our new quarters here," she answered. "It takes some time."

"Where are your rooms?" he asked.

She hesitated momentarily. "It is really only one room," she said. "But it is a fine one. I have another little one upstairs; but it is a long way off. Of course I shall sleep downstairs with Bunny."

"Do you always sleep with him?" he asked.

She coloured a little. "Yes."

"Is he a good sleeper?" He had moved round and was filling his own glass.

She watched his steady hand with a touch of envy. She would have given much for as cool a nerve just then.

"Is he a good sleeper?" He repeated the question as he set down the bottle.

She answered it at once. "No; a very poor one."

"And you look after him night and day?" Bolton's eyes suddenly comprehended her. "I guess that accounts for it," he said, in a tone of enlightenment.

"For what?" She met his look haughtily, determined to hold her own.

But he smiled and refused the contest. "For much," he said. "Now, what will you eat? Lobster? That's right. I want to see you started. What a filthy racket they are making! I hope it won't upset your appetite any."

She had never felt less hungry in her life, but out of a queer sensation of gratitude she tried to eat what he put before her. He had certainly done his best to shield her from that objectionable crowd, but she was still by no means certain that she liked the man. He was too much inclined to take her friendship for granted, too ready to presume upon a very short acquaintance. And she was sure--quite sure now--that he had recognized her from the very first moment, down on the parade the night before. The knowledge was very disquieting. He was kind--oh, yes, he was kind. But she felt that he knew too much.

And so a certain antagonism warred against her gratitude, and prevented any gracious expression thereof. She only longed--oh, how desperately!--to flee away from this new and horrible world into which she had been so ruthlessly dragged and to see no more of its inhabitants for ever.

Vain longing! Even then she knew, or shrewdly suspected, that her lot was to be cast in that same world for the rest of her mortal life.

CHAPTER VII

THE MAGICIAN

"Oh, Maud! I thought you were never coming!"

Bunny's face, pale and drawn, wearing the irritable frown so habitual to it, turned towards the opening door.

"I have brought you a visitor," his sister said.

Her voice was low and nervous. She looked by no means sure of Bunny's reception of the news. Behind her came Jake Bolton the trainer, alert and self-assured. It was quite evident that he had no doubts whatever upon the subject. His thick mat of chestnut hair shone like copper in the brilliant electric light, such hair as would have been a woman's glory, but that Jake kept very closely cropped.

"What on earth for?" began Bunny querulously; and then magically his face changed, and he smiled. "Hullo! You?" he said.

Bolton came to his side and took the small, eager hand thrust out to him. "Yes, it's me," he said. "No objection, I hope?"

"I should think not!" The boy's face was glowing with pleasure. "Sit down!" he said. "Maud, get a chair!"

Bolton turned sharply, found her already bringing one and took it swiftly from her.

He sat down by Bunny's side, and took the little thin hand back into his. "Do you know, I've been thinking a lot about you," he said.

Bunny was vastly flattered. He liked the grasp of the strong fingers also, though he would not probably have tolerated such a thing from any but this stranger.

"Yes," pursued Jake, in his soft, level voice. "I reckon I've taken a fancy to you, little chap--I beg your pardon--Sir Bernard. How have you been to-day?"

"Don't call me that!" said Bunny, turning suddenly red.

"What?" Jake smiled upon him, his magic, kindly smile. "Am I to call you Bunny--like your sister--then?"

"Yes. And you can call her Maud," said Bunny autocratically. "Can't he, Maud?"

Jake turned his head and looked at her. She was standing before the fire, the red glow all about her, very slim, very graceful, very stately. She did not so much as glance at Jake, only bent a little towards the blaze so that he could not see her face.

"I don't think I dare," said Jake.

"Maud!" Peremptorily Bunny's voice accosted her. "Come over here! Come and sit on my bed!"

It was more of a command than an invitation. Maud straightened herself and turned.

But as she did so, their visitor intervened. "No, don't!" he said. "Sit down right there, Miss Brian, in that easy-chair, and have a rest!"

His voice was peremptory too, but in a different way. Bunny stared at him wide-eyed.

Jake met the stare with an admonitory shake of the head. "Guess Bunny's not wanting you," he said. "Don't listen to anything he says!"

Bunny's mouth opened to protest, remained open for about five seconds, and finally he said, "All right, Maud. You can stay by the fire while we talk."

And Maud, much to her own surprise, sat down in the low chair on the hearth and leaned her aching head back upon the cushion.

She had her back to Bunny and his companion, and the soft murmur of the latter's voice held nought disturbing. It seemed in fact to possess something of a soothing quality, for very soon her heavy eyelids began to droop and the voice to recede into ever growing distance. For a space she still heard it, dim and remote as the splash of the waves on the shore; then very softly it was blotted out. Her cares and her troubles all fell away from her. She sank into soundless billows of sleep.

It was a perfectly dreamless repose, serene as a child's and it seemed to last indefinitely. She lay in complete content, unconscious of all the world, lapped in peace and blissfully free from the goading anxiety that usually disturbed her rest. It was the calmest slumber she had known for many years.

From it she awoke at length with a guilty start. The fall of a piece of coal had broken the happy spell. She sat up, to find herself in firelight only.

Her first thought was for Bunny, and she turned in her chair and looked across the unfamiliar room. He was lying very still in the shadows. Softly she rose and stepped across to him.

Yes, he was asleep also, lying among his pillows. The chair by his side was empty, the visitor vanished.

Very cautiously she bent over him. He had been lying dressed outside the bed. Now--with a thrill of amazement she realized it--he was undressed and lying between the sheets. He was breathing very quietly, and his attitude was one of easy rest. Surely some magic had been at work!

On a chest of drawers near stood a glass that had contained milk. He always had some hot milk last thing, but she had not procured it for him. She had in fact been wondering how she would obtain it to-night.

Another coal fell, and she crept back to replace it. Stooping she caught sight of another glass in the fender, full of milk. It must have been there a long time, for it was barely warm. Clearly it had been intended for her. She put it to her lips and drank.

Who could have put it there? Her mother? No; she was sure that her mother would have roused her from her sleep if she had entered. She was moreover quite incapable of getting Bunny to bed now that he had grown out of childhood.

The house was very quiet. She wondered if the guests had all gone. The room was situated at the end of a long passage, so that the noise of the party had scarcely reached it. But the utter silence without as well as within made her think that it was very late.

She dared not switch on the light, but as the fire burned up again she held her watch to the blaze. Half-past two!

In utter amazement she began to undress.

There was no second bed in the room; only a horse-hair sofa that was far less comfortable than the chair by the fire. She lay down upon it, however, pulling over her an ancient fur travelling-rug belonging to her mother, and here she lay dozing and waking, turning over the mystery in her mind, while another quiet hour slipped away.

Then there came a movement from Bunny, and she sat up.

"Are you awake, Maud?" asked his voice out of the shadows. "Has Jake gone?"

"Yes, darling," she made answer. "Are you wanting anything?"

She was by his side with the words; she bent over him. He wanted his pillows rearranged, and when she had done it he said, "I say, when did you wake up?"

"About an hour ago," she said.

He chuckled a little. "Weren't you surprised to find me in bed?"

"Yes, I was," she said. "How did you get there?"