*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 43110 ***

Mrs Molesworth

"Tell me a Story"

Chapter One.

Introduction.

The children sat round me in the gloaming. There were several of them; from Madge, dear Madge with her thick fair hair and soft kind grey eyes, down to pretty little Sybil—Gipsy, we called her for fun,—whom you would hardly have guessed, from her brown face and bright dark eyes, to be Madge’s “own cousin.” They were mostly girls, the big ones at least, which is what one would expect, for it is not often that big boys care much about sitting still, and even less about anything so sentimental as sitting still in the twilight doing nothing. There were two or three little boys however, nice round-faced little fellows, who had not yet begun to look down upon “girls,” and were very much honoured at being admitted to a good game of romps with Madge and her troop.

It was one of these—the rosiest and nicest of them all, little Ted—who pulled my dress and whispered, but loud enough for every one to hear, with his coaxingest voice—“Tell me a story, aunty.” And then it came all round in a regular buzz, in every voice, repeated again and again—“O aunty! do; dear, dear aunty, tell us a story.”

I had been knitting, but it had grown too dark even for that. I could not pretend to be “busy.” What could I say? I held up my hands in despair.

“O children! dear children!” I cried, “truly, truly, I don’t know what stories to tell. You are such dreadfully wise people now-a-days—you have long ago left behind you what I used to think wonderful stories—‘Cinderella,’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ and all the rest of them; and you have such piles of story-books that you are always reading, and many of them too written for you by the cleverest men and women living! What could I tell you that you would care to hear? Why, it will be the children telling stories to amuse the papas and mammas, and aunties next, like the ‘glorious revolution’ in ‘Liliput Levée!’ No, no, your poor old aunty is not quite in her dotage yet. She knows better than to try to amuse you clever people with her stupid old hum-drum stories.”

I did not mean to hurt the poor dear little things—I did not, truly—I spoke a little in earnest, but more in jest, as I shook my head and looked round the circle. But to my surprise they took it all for earnest, and the tears even gathered in two or three pairs of eyes.

“Aunty, you know we don’t think so,” began Madge, gentle Madge always, reproachfully.

And “It’s too bad of you, aunty, too bad,” burst out plain-speaking Dolly. And worst of all, Ted clambered manfully up on to my knees, and proceeded to shake me vigorously. “Naughty aunty,” he said, “naughty, naughty aunty. Ted will shake you, and shake you, to make you good.”

What could I do but cry for mercy? and promise anything and everything, fifty stories on the spot, if only they would forgive me?

“But, truly children,” I said again, when the hubbub had subsided a little, “I am afraid I do not know any stories you would care for.”

“We should care for anything you tell us,” they replied, “about when you were a little girl, or anything.”

I considered a little. “I might tell you something of that kind,” I said, “and perhaps, by another evening, I might think over about some other people’s ‘long agos’—your grandmother’s, for instance. Would that please you?”

Great applause.

“And another thing,” I continued, “if I try to rub up some old stories for you, don’t you think you might help? You, Madge, dear, for instance, you are older than the others—couldn’t you tell them something of your own childish life even?”

I was almost sorry I had suggested it; into Madge’s face there came a look I had seen there before, and the colour deepened in her cheeks. But she answered quite happily.

“Yes, aunty, perhaps they would like to hear about—you know who I mean, and my other aunties, who are mammas now as well; if you wouldn’t mind writing it down—I don’t think I could tell it straight off.”

“Very well,” I said, “I’ll remember. And if, possibly, some not real stories come into my head—there’s no saying what I can do till I try,” for I felt myself now getting into the spirit of it,—“you won’t object, I suppose, to a fairy tale, or an adventure, for instance—just by way of a change you know?”

General clapping of hands.

“Well then,” I said, “to begin with, I’ll tell you a story which is—no, I won’t tell you what it is, real or not; you shall find out for yourselves.”

And in this way it came to pass, you see, that there was quite a succession of “blind man’s holidays,” on which occasions poor aunty was always expected to have a story forthcoming.

Chapter Two.

The Reel Fairies.

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

Louisa was a little girl of eight years old. That is to say, she was eight years old at the time I am going to tell you about. She was nothing particular to look at; she was small for her age, and her face was rather white, and her eyes were pretty much the same as other people’s eyes. Her hair was dark brown, but it was not even curly. It was quite straight-down hair, and it was cut short, not quite so short as little boys’ hair is cut now-a-days, but not very much longer. Many little girls had quite short hair at that time, but still there was something about Louisa’s that made its shortness remarkable, if anything about her could have been remarkable! It was so very smooth and soft, and fitted into her head so closely that it gave her a small, soft look, not unlike a mouse. On the whole, I cannot describe her better than by saying she was rather like a mouse, or like what you could fancy a mouse would be if it were turned into a little girl.

Louisa was not shy, but she was timid and not fond of putting herself forward; and in consequence of this, as well as from her not being at all what is called a “showy” child, she received very little notice from strangers, or indeed from many who knew her pretty well. People thought her a quiet, well-behaved little thing, and then thought no more about her. Louisa understood this in her own way, and sometimes it hurt her. She was not so unobservant as she seemed; and there were times when she would have very much liked a little more of the caressing, and even admiration, which she now and then saw lavished on other children; for though she was sensible in some ways, in others she was not wiser than most little people.

Her home was not in the country: it was in a street, in a large and rather smoky town. The house in which she lived was not a very pretty one; but, on the whole, it was nice and comfortable, and Louisa was generally very well pleased with it, except now and then, when she got little fits of wishing she lived in some very beautiful palace sort of house, with splendid rooms, and grand staircases, and gardens, and fountains, and I don’t know all what—just the same sort of little fits as she sometimes had of wishing to be very pretty, and to have lovely dresses, and to be admired and noticed by every one who saw her. She never told any one of these wishes of hers; perhaps if she had it would have been better, but it was not often that she could have found any one to listen to and understand her; and so she just kept them to herself.

There was one person who, I think, could have understood her, and that was her mother. But she was often busy, and when not busy, often tired, for she had a great deal to do, and several other little children besides Louisa to take care of. There were two brothers who came nearest Louisa in age, one older and one younger, and two or three mites of children smaller still. The brothers went to school, and were so much interested in the things “little boys are made of,” that they were apt to be rather contemptuous to Louisa because she was a girl, and the wee children in the nursery were too wee to think of anything but their own tiny pleasures and troubles. So you can understand that though she had really everything a little girl could wish for, Louisa was sometimes rather lonely and at a loss for companions, and this led to her making friends in a very odd way indeed. If you guessed for a whole year I do not think you would ever guess whom, or I should say what, she chose for her friends. Indeed, I fear that when I tell you you will hardly believe me; you will think I am “story-telling” indeed. Listen—it was not her doll, nor a pet dog, nor even a favourite pussy-cat—it was, they were rather, the reels in her mother’s workbox.

Can you believe it? It is quite, quite true. I am not “making up” at all, and I will tell you how it came about. There was one part of the day, I daresay it was the hour that the nursery children were asleep, when it was convenient for Louisa to be sent down-stairs to sit beside her mother in the drawing-room, with many injunctions to be quiet. Her mother was generally writing or “doing accounts” at that time, and not at leisure to attend to her little girl; but when Louisa appeared at the door she would look up and say with a smile, “Well, dear, and what will you have to amuse yourself with to-day?” At first Louisa used to consider for a minute, and nearly every day she would make a different request.

“A piece of paper and a pencil to write,” she would say on Monday perhaps, and on Tuesday it would be “The box with the chess, please,” and on Wednesday something else. But after a while her answer came to be always the same—“Your big workbox to tidy, please, mamma.”

Mamma smiled at the great need of tidying that had come over her big workbox, but she knew she could certainly trust Louisa not to un-tidy it, so she used just to push it across the table to her without speaking, and then for an hour at least nothing more was heard of Louisa. She sat quite still, fully as absorbed in her occupation as her mother was in hers, till at last the well-known tap at the door would bring her back from dream-land.

“Miss Louisa, your dinner is waiting,” or “Miss Louisa, the little ones are quite ready to go out;” and, with a deep sigh, the workbox would be closed and the little girl would obey the unwelcome summons.

And next day, and the day after, and a great many days after that, it was always the same thing. But nobody knew anything about these queer friends of hers, except Louisa herself.

There were several families of them, and their names were as original as themselves. There were the Browns, reels of brown wood wound with white cotton; as far as I remember there were a Mr and Mrs Brown and three children; the Browns were supposed to be quiet, respectable people, who lived in a large house in the country, but had nothing particularly romantic or exciting about them. There were the De Cordays, so named from the conspicuous mark of “three cord” which they bore. They were a set of handsome bone, or, as Louisa called it, ivory reels, and she added the “De” to their name to make it sound grander. There were two pretty little reels of fine China silk, whom she distinguished as the Chinese Princesses. Blanche and Rose were their first names, to suit the colours they bore, for Louisa, you see, had learnt a little French already; and there were some larger silk reels, whom she called the “Lords and Ladies Flossy.” Altogether there were between twenty and thirty personages in the workbox community, and the adventures they had, the elegance and luxury in which they lived, the wonderful stories they told each other, would fill more pages than I have time to write, or than you, kind little girls that you are, would have patience to read. I must hasten on to tell you how it came to pass that this queer fancy of Louisa’s was discovered by other people.

One morning when she was sitting quietly, as usual, beside her mother, a friend of Mrs no, we need not tell her name, I should like you best just to think of her as Louisa’s mamma—well then, a friend of Louisa’s mamma’s came to call. She was a lady who lived in the country several miles away from Smokytown, but she was very fond of Louisa’s mamma, and whenever she had to come to Smokytown to shop, or anything of that kind, perhaps to take her little girl (for she too had a little girl as you shall hear) to the dentist’s, she always came early to call on her friend. Louisa’s mamma jumped up at once, when the servant threw open the door and announced the lady by name, and then they kissed each other, and then Louisa’s mamma stooped down and kissed the lady’s little girl who was standing beside her, but Louisa sat so quietly at her corner of the table, that for a minute or two no one noticed her. She was just thinking if she could manage to creep down under the table and slip away out of the room without being seen, when her mamma called her.

“Louisa, my dear,” she said, “come here and speak to Mrs Gordon and to Frances. You remember Frances, don’t you, dear?”

Louisa got down slowly off her chair and came to her mamma. She stood looking at Frances for a minute or two without speaking.

“Don’t you remember Frances?” said her mamma again.

“No,” said Louisa at last, “I don’t think I do.” Then she turned away as if she were going back to her place at the table. Her mamma looked vexed.

“Poor little thing,” said Mrs Gordon, “she is only rather shy. Frances, you must make friends with her.”

“Louisa, I am not pleased with you,” said her mamma gravely, and then she went on talking to Mrs Gordon.

Frances followed Louisa to the table, where all the reels were arranged in order. There was a grand feast going on among them that day: one of the Chinese princesses was to be married to one of the Lords Flossy, and Louisa had been smartening them up for the occasion. But she did not want to tell Frances about it.

“I am only playing with mamma’s workbox things,” she said, looking up at Frances, and wishing she had not come. She had taken a dislike to Frances, and the reason was not a very nice one—she was envious of her because she had such a pretty face and was very beautifully dressed. She had long curls of bright light hair, and large blue eyes, and she had a purple velvet coat trimmed with fur, and a sweet little bonnet with rosebuds in the cap, and Louisa’s mamma would never let her have rosebuds or any flowers in her bonnets. To Louisa’s eyes she looked almost as beautiful as a fairy princess, but the thought vexed her.

“Playing with your mamma’s workbox things,” said Frances, “how very funny! You poor little thing, have you got nothing else to play with?”

She spoke as if she were several years older than Louisa, and this made Louisa still more vexed.

“Yes,” she answered, “of course I have got other things, but I like these. You can’t understand.” Frances smiled. “How funny you are!” she said again, “but never mind. Let us talk of something nice. Perhaps you would like to hear what things I have got to play with. I have a room all for myself, filled with toys. I have got a large doll-house, as tall as myself, with eight rooms; and I have sixteen dolls of different kinds. They were mostly birthday presents. But I am getting too big to care for them now. My birthday was last week. What do you think papa gave me? Something so beautiful that I had wanted for such a long time. I don’t think you could guess.”

In spite of herself Louisa was becoming interested. “I don’t know, I’m sure,” she said; “perhaps it was a book full of stories.”

Frances shook her head. “O no,” she answered, “it wasn’t. That would be nothing particular, and my present was something particular, very particular indeed. Well, you can’t guess, so I’ll tell you—it was a Princess’s dress; a real dress you know; a dress that I can put on and wear.”

“A Princess’s dress!” repeated Louisa, opening her eyes.

“Yes, to be sure,” said Frances. “I call it a Princess’s dress, because it is copied from one the Princess Fair Star wore at the pantomime last Christmas. It was there I saw it, and I have teased papa ever since till he got it for me. And it is so beautiful; quite beautiful enough for a queen for that matter. My papa often calls me his queen, sometimes he says his golden-haired queen. Does yours?”

“No,” said Louisa sadly; “my papa sometimes calls me his pet, and sometimes he calls me ‘old woman,’ but he never says I am his queen. I suppose I am not pretty enough.”

“I don’t know,” said Frances, consideringly, “I don’t think you’re ugly exactly. Perhaps if you asked your papa to get you a Princess’s dress—”

“He wouldn’t,” said Louisa decidedly, “I know he wouldn’t. It would not be the least use asking him. Tell me more about yours—what is it like, and does it make you feel like a real princess when you have it on?”

“I suppose it makes me look like one,” replied Frances complacently, “and as for feeling, why one can always fancy, you know.”

“Fancying isn’t enough,” said Louisa. “I know I should dreadfully like to be a princess or a queen. It is the first thing I would ask a fairy. Perhaps you don’t wish it so much because every one pets you so, and thinks you so pretty. Has your dress got silver and gold on it?”

“O yes, at least it has silver—silver spots,” began Frances eagerly, but just then her mamma turned to tell her that they must go. “The little people have made friends very quickly after all, you see,” she said to Louisa’s mamma. “Some day you must really bring Louisa to see Frances—it has been such an old promise.”

“It is not often I can leave home for a whole day,” said Louisa’s mamma; “and then, dear, you must remember not having a carriage makes a difference.”

Louisa’s cheeks grew red. She felt very vexed with her mamma for telling Mrs Gordon they had no carriage, but of course she did not venture to say anything, so no one noticed her. She was not sorry when Mrs Gordon and Frances said good-bye and went away.

That same evening, a little before bed-time, Louisa happened to be again in the drawing-room alone with her mother.

“Louisa,” said her mother, who was sewing at the table, “you did not leave my workbox as neat as usual this morning. I suppose it was because you were interrupted by Frances Gordon. Come here, dear, and take the box and put it on a chair near the fire and arrange it rightly. Here is a whole collection of reels rolling about. Put them all in their places.”

Louisa did as she was told, but without speaking. Indeed she had been very silent all day, but her mother had been occupied with other things and had not noticed her particularly. Louisa quietly put the reels into their places, giving the most comfortable corners to her favourites as usual, and huddling some of the others together rather unceremoniously. Then she sat down on the hearth-rug, and began to think of what Frances Gordon had said to her, and to wish all sorts of not very wise things. She felt herself at last growing drowsy, so she leant her little round head on the chair beside her, and was almost asleep, when she heard her mother say, “Louisa, my dear, you are getting sleepy, you must really go to bed.”

“Yes, mamma,” she said, or intended to say, but the words sounded faint and dreamlike, and before they were fully pronounced she was fairly asleep!

She remembered nothing more for what seemed a very long time—then to her surprise she found herself already undressed and in her own little bed! “Nurse must have carried me upstairs and undressed me,” she thought, and she opened her eyes very wide to see if it was still the middle of the night. No, surely it could not be; the room was quite light, yet where was the light coming from? It was not coming in at the window—there was no window to be seen; the curtains were drawn across, and no tiny chink even was visible; there was no lamp or candle in the room,—the light was simply there, but where it came from Louisa could not discover. She got tired of wondering about it at last, and was composing herself to sleep again, when suddenly a small but very clear voice called her by name. “Louisa, Louisa,” it said. She did not feel at all frightened. She half raised herself in bed and exclaimed, “Who is speaking to me? what do you want?”

“Louisa, Louisa,” the voice repeated, “would you like to be a queen?”

“Very much indeed, thank you,” Louisa replied promptly.

“Then rub your eyes and look about you,” said the voice.

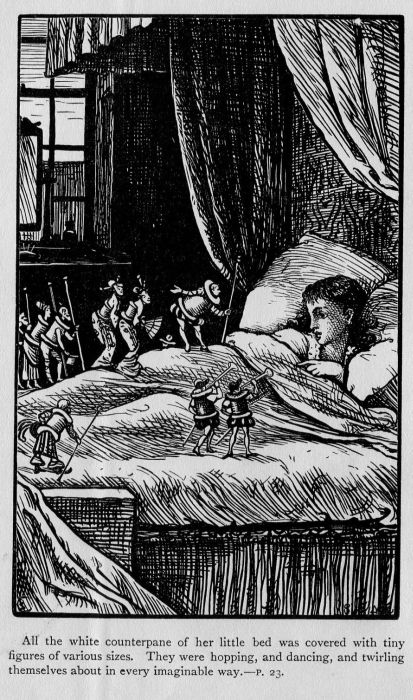

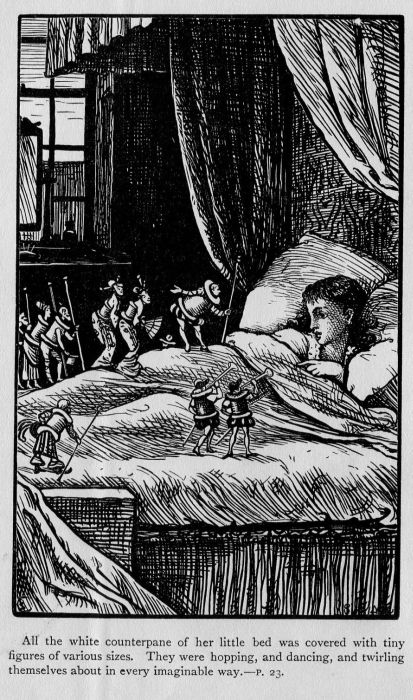

Louisa rubbed her eyes and looked about her to some purpose, for what do you think she saw? All the white counterpane of her little bed was covered with tiny figures, of various sizes, from one inch to three or four in height. They were hopping, and dancing, and twirling themselves about in every imaginable way, like nothing anybody ever saw before, or since, or ever will again.

“Fairies!” thought Louisa at once, and without any feeling of overwhelming surprise, for, like most children, she had always been hoping, and indeed half expecting, that some day an adventure of this kind would fall to her share.

“Yes, fairies,” said the same voice as before, which seemed to hear her thoughts as distinctly as if she had spoken them; “but what kind of fairies? Look at us again, Louisa.”

Louisa opened her eyes wider and stared harder. There were all kinds of fairies, gentlemen and ladies, little and big; but as she looked she saw that every one of them, without exception, wore a curious sort of round stiff jacket, more like a little barrel than anything else. It gave them a queer high-shouldered look, very like the little figures of Noah and his family in toy arks; but as Louisa was staring at them the mystery was explained. A big, rather clumsy-looking gentleman fairy, stopped for a moment in his gymnastics, and Louisa read on the ledge round his shoulders the familiar words “Clarke and Company’s best six-cord, extra quality, Number 12.”

“I know,” she cried, clapping her hands; “you’re mamma’s reels!”

At these words a sensation ran through the company; they all stood stock-still, and Louisa began to feel a little afraid.

“She says,” exclaimed the voice, “she says we’re her mamma’s reels!”

There fell a dead silence; Louisa expected to be sentenced to undergo capital punishment on the spot. “It’s too bad,” she said to herself, “it’s too bad; they asked me to guess who they were.”

“She says,” continued the voice, “she says ‘it’s too bad.’ What is too bad? My friends, let the deputation stand forward.”

Instantly about a dozen fairies separated themselves from the others and advanced, slowly marching two and two up the counterpane, till having made their way across the various hills and valleys formed by Louisa’s little figure under the bedclothes, they drew up just in front of her nose. Foremost of the deputation she recognised, the one clad in pink satin, the other in glistening white, her two favourites the Princesses Blanche and Rose.

“Beautiful Louisa,” said the deputation, all speaking at once, “we have come to ask you to be our queen.”

“Thank you,” said Louisa, not knowing what else to say.

“She consents!” exclaimed the deputation, “let the royal chariot appear.”

Thereupon there suddenly started up in the middle of the bed, as large as life, but no larger, her mamma’s big workbox! The fairies all clambered on to it with a rush, and hung upon it in every direction, like bees on a hive, or firemen on a fire-engine; and no sooner were they all mounted than the workbox slowly glided along till it was close to Louisa’s face.

“Will your majesty please to get in?” said one of the fairies, “Clarke’s Number 12, extra quality,” I think it was.

“How can I?” said Louisa piteously, “how can I? I’m far too big. How can I get into a workbox?”

“Please to rub your eyes and try,” said the big fairy, “right foot foremost, if you please.”

Louisa rubbed her eyes, and pulling her right foot out from under the clothes, stepped on to the workbox.

To her surprise, or rather not to her surprise, everything seemed to come quite naturally, she found that she was not at all too big, and she settled herself in the place the fairies had kept for her, the nice little division lined with satin, in which her mamma’s thimble and emery cushion always lay. It was pretty comfortable, only rather hard, but Louisa had no time to think about that, for no sooner was she seated than off flew the workbox, that is to say the royal chariot, away, away, Louisa knew not where, and felt too giddy to try to think. It stopped at last as suddenly as it had started, and quick as thought all the fairies jumped down. Louisa followed them more deliberately. She found herself in a great shining hall, the walls seemed to be of looking-glass, but when she observed them more closely she found they were made of innumerable needles, all fastened together in some wonderful fairy fashion, which she had not time to examine, for just then the Chinese princesses approached her, carrying between them a glistening dress, which they begged her to put on. They were quite as tall as she by-the-by, so she allowed them to dress her, and then examined herself with great satisfaction in the looking-glass walls. The dress was lovely, of that there was no doubt; it was just such a one, curiously enough, as Frances Gordon had described; the only drawback was her short hair, which certainly did not add to her regal appearance.

“It won’t show so much when your majesty has the crown on,” said the Chinese princesses, answering as before to Louisa’s unspoken thoughts. Then some gentlemen fairies appeared with the crown, which fitted exactly, only it felt rather heavy. But it would never do for a queen to complain, even in thought, of so trifling a matter, so with great dignity Louisa ascended the throne which stood at one end of the hall, and sat down upon it to see what would come next.

The Fairies came next. One after the other, by dozens, and scores, and hundreds, they passed before her, each as he passed making the humblest of obeisances, as if to the great Mogul himself. It was very fine indeed, but after a while Louisa began to get rather tired of it, and though the throne was very grand to look at, it too felt rather hard, and the crown grew decidedly heavier.

“I think I’d like to come down for a little,” she said to some of the ladies and gentlemen beside her, but they took no notice. “I’d like to get down for a little and to take off my crown—it’s hurting my head, and this spangly dress is so cold,” she continued. Still the fairies took no notice.

“Don’t you hear what I say?” she exclaimed again, getting angry; “what’s the use of being a queen if you won’t answer me?”

Then at last some of the fairies standing beside the throne appeared to hear what she was saying.

“Her majesty wishes to take a little exercise,” said “Clarke’s Number 12,” and immediately the words were repeated in a sort of confusing buzz all round the hall. “Her majesty wishes to take a little exercise”—“her majesty wishes to take a little exercise,” till Louisa could have shaken them all heartily, she felt so provoked. Then suddenly the throne began to squeak and grunt (Louisa thought it was going to talk about her taking exercise next), and after it had given vent to all manner of unearthly sounds it jerked itself up, first on one side and then on the other, like a very rheumatic old woman, and at last slowly moved away. None of the fairies were pushing it, that was plain; and at first Louisa was too much occupied in wondering what made it move, to find fault with the mode of exercise permitted to her. The throne rolled slowly along, all round the hall, and wherever it appeared a crowd of fairies scuttled away, all chattering the same words—“Her majesty is taking a little exercise,” till at last, with renewed jerks and grunts and groans, her queer conveyance settled itself again in its old place. As soon as it was still, Louisa tried to get down, but no sooner did she put one foot on the ground than a crowd of fairies respectfully lifted it up again on to the footstool. This happened two or three times, till Louisa’s patience was again exhausted.

“Get out of my way,” she exclaimed, “you horrid little things, get out of my way; I want to get down and run about.”

But the fairies took no notice of what she said, till for the third time she repeated it. Then they all spoke at once.

“Her majesty wants to take a little more exercise,” they buzzed in all directions, till Louisa was so completely out of patience that she burst into tears.

“I won’t stay to be your queen,” she said, “it’s not nice at all. I want to go home to my mamma. I want to go home to my mamma. I want to go home to my mamma.”

“We don’t know what mammas are,” said the fairies. “We haven’t anything of that kind here.”

“That’s a story,” said Louisa. “There—are mammas here. I’ve seen several. There’s Mrs Brown, and there’s Lady Flossy, and there’s—no, the Chinese princesses haven’t a mamma. But you see there are two among my mamma’s own reels in her workb—.”

But before she could finish the word the fairies all set up a terrific shout. “The word, the word,” they cried, “the word that no one must mention here. Hush! hush! hush!”

They all turned upon Louisa as if they were going to tear her to pieces. In her terror she uttered a piercing scream, and—woke.

She wasn’t in bed; where was she? Could she be in the workbox? Wherever she was it was quite dark and cold, and something was pressing against her head, and her legs were aching. Suddenly there came a flash of light. Some one had opened the door, and the light from the hall streamed in. The some one was Louisa’s mamma.

“Who is in here? Did I hear some one calling out?” she exclaimed anxiously.

Louisa was slowly recovering her wits. “It was me, mamma,” she answered; “I didn’t know where I was, and I was so frightened and I am so cold. Oh mamma!”

A flood of tears choked her.

“You poor child,” exclaimed her mamma, hurrying back to the hall to fetch a lamp, as she spoke, “why, you have fallen asleep on the hearth-rug, and the fire’s out; and my workbox—what is it doing here? Were you using it for a pillow?”

“No,” said Louisa, eyeing the workbox suspiciously, “it was on the chair, and the corner of it has hurt my head, mamma; it was pressing against it.” Her mamma lifted the box on to the table.

“Are they all in there, mamma?” whispered Louisa, timidly.

“All in where? All who? What are you speaking about, my dear?”

“The fairies—the reels I mean,” replied Louisa. “My dear, you are dreaming still,” said her mamma, laughing, but seeing that Louisa looked dissatisfied, “never mind, you shall tell me your dreams to-morrow. But just now you must really go to bed. It is nine o’clock—you have been two hours asleep. I went out of the room in a hurry, taking the lamp with me because it was not burning rightly, and then I heard baby crying—he is very cross to-night—and both nurse and I forgot about you. Now go, dear, and get well warmed at the nursery fire before you go to bed.”

Louisa trotted off. She had no more dreams that night, but when she woke the next morning, her poor little legs were still aching. She had caught cold the night before, there was no doubt, so her mamma, taking some blame to herself for her having fallen asleep on the floor, was particularly kind and indulgent to her. She brought her down to the drawing-room wrapped in a shawl, and established her comfortably in an arm-chair.

“What will you have to play with?” she asked. “Would you like my workbox?”

“I don’t know,” said Louisa, doubtfully. “Mamma,” she continued, after a moment’s silence, “can queens never do what they like?”

“Very often they can’t,” replied her mamma. “What makes you ask?”

“I dreamt I was a queen,” said Louisa.

“Did you? What country were you queen of?”

“I was queen of the reel fairies,” replied the child gravely. Her mother looked mystified “Tell me what you mean, dear,” she said. “Tell me all about it.”

So bit by bit Louisa explained the whole, and her mamma had for once a peep into that strange, fantastic, mysterious world, which we call a child’s imagination. She had a glimpse of something else too. She saw that her little girl was in danger of getting to live too much alone, was in need of sympathy and companionship.

“I think it was what Frances Gordon said that made me dream about being a queen,” she said.

“And do you still wish you were a queen?” said her mamma.

“No,” said Louisa.

“A princess then?”

“No,” she replied again. “But, mamma—”

“Well, dear?”

“I do wish sometimes that I was pretty, and that—that—I don’t know how to say it—that people made a fuss about me sometimes.”

Her mamma looked a little grave and a little sad; but still she smiled. She could not be angry—thought Louisa.

“Is it naughty, mamma?” she whispered.

“Naughty? No, dear; it is a wish most little girls have, I fancy—and big ones too. But some day you will understand how it might grow into a wrong feeling, and how on the other side a little of it may be useful to help good feelings. And till you understand better, dear, doesn’t it make you happy to know that to me you could not be dearer if you were the most beautiful little princess in the world.”

“As beautiful as Princess Fair Star, mamma?”

“Yes, or any other princess you can think of. I would rather have my little mouse of a girl than any of them.”

Louisa nestled closer to her mamma with great satisfaction. “I like you to call me your mouse, mamma; and do you know I almost think I like having a cold.”

Her mother laughed. “Am I making a little fuss about you? Is that what you like?”

Louisa laughed too.

“Do you think I should leave off playing with the reels, and making stories about them, mamma? Is it silly?”

“No, dear, not if it amuses you,” said her mother.

But though Louisa did not leave off playing with the reels altogether, she gradually came to find that she preferred other amusements. Her mother taught her several pretty kinds of work, and read aloud stories to her more often than formerly. And, somehow, Louisa never again cared quite as much for her old friends. She thought the Chinese princesses had grown rather “stuck-up” and affected, and she could not get over a strong suspicion that “Clarke’s Number 12” was very ready to be impertinent, if he could ever again get a chance.

Chapter Three.

Good-Night, Winny.

“Say not good-night—but, in some brighter clime,

Bid me good-morning!”

When I was a little girl I was called Meg. I do not mean to say that I have got a different name now that I am big, but my name is used differently. I am now called Margaret, or sometimes Madge, but never Meg. Indeed I do not wish ever to be called Meg, for a reason you will quite understand when you have heard my story. But perhaps I am wrong to call it a “story” at all, so I had better say at the beginning that what I have to tell you is only a sort of remembrance of something that happened to me when I was very little—of some one I loved more dearly, I think, than I can ever love any one again. And I fancy perhaps other little girls will like to hear it.

Well then, to begin again—long ago I used to be called Meg, and the person who first called me so was my sister Winny, who was not quite two years older than I. There were four of us then—four little sisters—Winny, and I, and Dolly, and Blanche, baby Blanche we used to call her. We lived in the country in a pretty house, which we were very fond of, particularly in the summer time, when the flowers were all out. Winny loved flowers more dearly than any one I ever knew, and she taught me to love them too. I never see one now without thinking of her and the things she used to say about them. I can see now, now that I am so much older, that Winny must have been a very clever little girl in some ways, not so much in learning lessons as in thinking things to herself, and understanding feelings and thoughts that children do not generally care about at all. She was very pretty too, I can remember her face so well. She had blue eyes and very long black eyelashes—our mamma used to teaze her sometimes, and say that she had what Irish people call “blue eyes put in with dirty fingers”—and pretty rosy cheeks, and a very white forehead. And her face always had a bright dancing look that I can remember best of all.

We learnt lessons together, and we slept together in two little beds side by side, and we did everything together, from eating our breakfast to dressing our dolls—and when one was away the other seemed only half alive. All our frocks and hats and jackets were exactly the same, and except that Winny was taller than I, we should never have known which was which of our things. I am sure Winny was a very good little girl, but when I try to remember all about her exactly, what seems to come back most to me is her being always so happy. She did not need to think much about being good and not naughty; everything seemed to come rightly to her of itself. She thought the world was a very pretty, nice place; and she loved all her friends, and she loved God most of all for giving them to her. She used to say she was sure Heaven would be a very happy place too, only she did so hope there would be plenty of flowers there, and she was disappointed because mamma said it did not tell in the Bible what kinds of flowers there would be. Almost the only thing which made her unhappy was about there being so many very poor people in the world. She used to talk about it very often and wonder why it was, and when she was very, very little, she cried because nurse would not let her give away her best velvet jacket to a poor little girl she saw on the road.

But though Winny was so sweet, and though we loved each other so, sometimes we did quarrel. Now and then it was quite little quarrels which were over directly, but once we had a bigger quarrel. Even now I do not like to remember it; and oh! how I do wish I could make other boys and girls feel as I do about quarrelling. Even little tiny squabbles seem to me to be sorrowful things, and then they so often grow into bigger ones. It was generally mostly my fault. I was peevish and cross sometimes, and Winny was never worse than just hasty and quick for a moment. She was always ready to make friends again, “to kiss ourselves to make the quarrel go away,” as our little sister Dolly used to say, almost before she could speak. And sometimes I was silly, and then it was right for Winny to find fault with me. My manners used occasionally to trouble her, for she was very particular about such things. One day I remember she was very vexed with me for something I said to a gentleman who was dining with our papa and mamma. He was a nice kind gentleman, and we liked him, only we did not think him pretty. Winny and I had fixed together that we did not think him pretty, only of course Winny never thought I would be so silly as to tell him so. We came down to dessert that evening—Winny sat beside papa, and I sat between Mr Merton and mamma, and after I had sat quite still, looking at him without speaking, I suddenly said,—I can’t think what made me—“Mr Merton, I don’t think you are at all pretty. Your hair goes straight down, and up again all of a sudden at the end, just like our old drake’s tail.”

Mr Merton laughed very much, and papa laughed, and mamma did too, though not so much. But Winny did not laugh at all. Her face got red, and she would not eat her raisins, but asked if she might keep them for Dolly, and she seemed quite unhappy. And when we had said good-night, and had gone upstairs, I could see how vexed she was. She was so vexed that she even gave me a little shake. “Meg,” she said, “I am so ashamed of you. I am really. How could you be so rude?”

I began to cry, and I said I did not mean to be rude; and I promised that I would never say things like that again; and then Winny forgave me; but I never forgot it. And once I remember, too, that she was vexed with me because I would not speak to a little girl who came to pay a visit to her grandfather, who lived at our grandfather’s lodge. Winny stopped to say good-morning to her, and to ask her if her friends at home were quite well; and the little girl curtseyed and looked so pleased. But I walked on, and when Winny called to me to stop I would not; and then, when she asked me what was the matter, I said I did not think we needed to speak to the little girl, she was quite a common child, and we were ladies. Winny was vexed with me then; she was too vexed to give me a little shake even. She did not speak for a minute, and then she said, very sadly, “Meg, I am sorry you don’t know better than that what being a lady means.”

I do know better now, I hope; but was it not strange that Winny always seemed to know better about these things? It came of itself to her, I think, because her heart was so kind and happy.

Winny was very fond of listening to stories, and of making them up and telling them to me; but she was not very fond of reading to herself. She liked writing best, and I liked reading. We used to say that when we were big girls, Winny should write all mamma’s letters for her, and I should read aloud to her when she was tired. How little we thought that time would never come! We were always talking about what we should do when we were big; but sometimes when we had been talking a long time, Winny would stop suddenly, and say, “Meg, growing big seems a dreadfully long way off. It almost tires me to think of it. What a great, great deal we shall have to learn before then, Meg!” I wonder what gave her that feeling.

Shall I tell you now about the worst quarrel we ever had? It was about Winny’s best doll. The doll’s name was “Poupée.” Of course I know now that that is the French for all dolls; but we were so little then we did not understand, and when our aunt’s French maid told us that “poupée” was the word for doll, we thought it a very pretty name, and somehow the doll was always called by it. Grandfather had given “Poupée” to Winny—I think he brought it from London for her—and I cannot tell you how proud she was of it. She did not play with it every day, only on holidays and treat-days; but every day she used to peep at “Poupée” in the drawer where she lay, and kiss her, and say how pretty she looked. One afternoon Winny was going out somewhere—I don’t remember exactly where; I daresay it was a drive with mamma—and I was not to go, and I was crying; and just as Winny was running down-stairs all ready dressed to go, she came back and whispered to me, “Meg, dear, don’t cry. It takes away all my pleasure to see you. Will you leave off crying and look happy if I let you have ‘Poupée’ to play with while I am out?”

I wiped away my tears in a minute, I was so pleased. Winny ran to “Poupée’s” drawer and got her out, and brought her to me. She kissed her as she put her into my arms, and she said to her, “My darling ‘Poupée,’ you are going to spend the afternoon with your aunt. You must be a very good little girl, and do exactly what she tells you.”

And then Winny said to me, “You will be very careful of her, won’t you, Meg?” and I promised, of course, that I would.

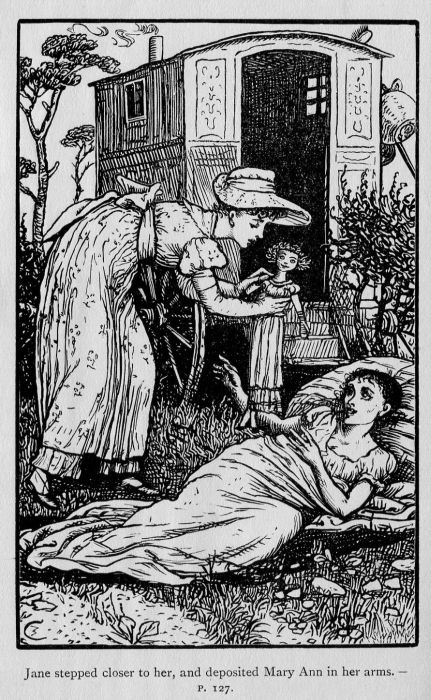

I did mean to be careful, and I really was; but for all that a sad accident happened. I had been very happy with “Poupée” all the afternoon, and I had made her a new apron with a piece of muslin nurse gave me, and some ribbon, which did nicely for bows; and I was carrying her along the passage to show nurse how pretty the apron looked, when the housemaid, who was coming along with a trayful of clean clothes from the wash in her arms, knocked against me, and “Poupée” was thrown down; and, terrible to tell, her dear, sweet little right foot was broken. I cannot tell you how sorry I was, and nurse was sorry too, and so was Jane; but all the sorrow would not mend the foot. I was sitting on the nursery floor, with “Poupée” in my lap, crying over her, as miserable as could be, when Winny rushed in, laden with parcels, in the highest spirits.

“O! I have had such a nice drive, and I have brought some buns and sponge-cakes for tea, and a toy donkey for Blanche. And has Poupée been good?” she exclaimed. But just then she caught sight of my face. “What is the matter, Meg? What have you done to my darling, beautiful Poupée? O Meg, Meg, you surely haven’t broken her?”

I was crying so I could hardly speak.

“O Winny!” I said, “I am so sorry.”

But Winny was too vexed to care just at first for anything I could say. “You naughty, naughty, unkind Meg,” she said, “I do believe you did it on purpose.”

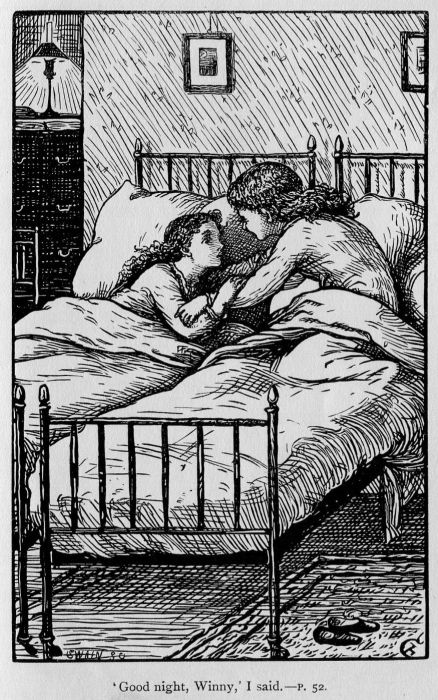

I could not bear that. I thought it very hard indeed that she should say so, when any one could see how miserable I was. I did not answer her; I ran out of the nursery, and though Winny called to me to come back (for the moment she had said those words she was sorry for them), I would not listen to her. Nurse fetched me back soon, however, for it was tea-time, but I would not speak to Winny. We never had such a miserable tea; there we sat, two red-eyed, unhappy little girls, looking as if we did not love each other a bit. If mamma had come up to the nursery she would have put it all right—she did put Poupée’s foot right the very next day, she mended it so nicely with diamond cement, that the place hardly showed at all—but she was busy that evening, and did not happen to come up. So bed-time came, and still we had not made friends, though I heard Winny crying when she was saying her prayers. After we were in bed, and nurse had gone away, Winny whispered to me, “Meg, won’t you forgive me for saying that unkind thing? Won’t you kiss me and say good-night, Winny?”

A minute before, I had been feeling as sorry as could be, but when Winny spoke to me, a most hard, horrid, unkind feeling seemed to come back into my heart, and I would not answer. I breathed as if I were asleep, pretending not to hear. I think Winny thought I was asleep, for she did not speak again. I heard her crying softly, and then after a while I heard by her breathing that she had really gone to sleep. But I couldn’t. I lay awake a long time, I thought it was hours and hours, and I tossed and turned, but I couldn’t go to sleep. I listened but I could not hear Winny breathing—I put my hand out of my cot, and stretched across to hers to feel for her; she seemed to be lying quite still. Then a dreadful feeling came into my mind—suppose Winny were dead, and that I had refused to make friends and say good-night! I must have got fanciful with lying awake, I suppose, and you know I was only a very little girl. I could not bear it—I stretched myself across to Winny and put my arms round her.

“Winny! Winny!” I said, “wake up, Winny, and kiss me, and let us say good-night.”

Winny woke up almost immediately, and she seemed to understand at once.

“Poor little Meg,” she said, “poor little Meg. We will never be unkind to each other again—never. Good-night, dear Meg.”

“Good-night, Winny,” I said. And just as I was falling asleep I whispered to her—“I will never let you go to sleep again, Winny, without saying good-night.” And I never did, never except once.

I could tell you ever so many other things about Winny, but I daresay you would be tired, for, of course, they cannot be so interesting to any other little girls as to me. But I think you will wish to hear about our last good-night.

Have I told you about our aunts at all? We had two aunties we were very fond of. They were young and merry and so kind to us, and there was nothing we liked so much as going to stay with them, for their home—our grandfather’s—was not far away. We generally all went there to spend Christmas, but one year something, I forget what, had prevented this, so to make up for it we were promised to spend Easter with them. We did so look forward to it—we were to go by ourselves, just like young ladies going to pay a visit, and we were to stay from Saturday till Easter Monday or Tuesday.

On the Saturday morning we woke up so early—hours before it was time to be dressed—we were so excited about our visit. But somehow Winny did not seem quite as happy about it as I wanted her to be. I asked her what made her dull, and she said it was because she did not like leaving papa and mamma, and Dolly and Blanche, not even for two or three days. And when we went into mamma’s room to say good-morning as usual, Winny said so to her too. Mamma laughed at her a little, and said she was a great baby after all; and Winny smiled, but still she seemed dull, and I shall never forget what a long long kiss she gave mamma that morning, as if she could When we went to the nursery for breakfast, baby Blanche was crying very much, and nurse said she was very cross. She did not think she was quite well, and we must be good and quiet. After breakfast, when mamma came to see baby, she seemed anxious about her, but baby went to sleep before long quite comfortably, and then nurse said she would be better when she awoke; it was probably just a little cold. And very soon the pony carriage was ready for Winny and me, and we kissed them all and set off on our visit. I was in high spirits, but as we drove away I saw that Winny was actually crying a little, and she did not often cry.

When we got to our aunties’, however, she grew quite happy again. We were very happy indeed on Sunday, only Winny kept saying how glad she would be to see them all at home again on Monday or Tuesday. But on Monday morning there came a letter, which made our aunties look grave. They did not tell us about it till Winny asked if we were to go home “to-day,” and then they told us that perhaps we could not go home for several days—not for two or three weeks even, for poor baby Blanche was very ill, and it was a sort of illness we might catch from her if we were with her.

“And that would only add to your poor mamma’s trouble,” said our aunties; “so you see, dears, it is much the best for you to stay here.”

I did not mind at all; indeed I was pleased. I was sorry about baby, but not very, for I thought she would soon be better. But Winny looked very sad.

“Aunty,” she said, “you don’t think poor baby will die, do you?”

“No, dear; I hope she will soon be better,” said aunty, and then Winny looked happier.

“Meg,” she whispered to me, “we must be sure to remember about poor baby being ill when we say our prayers.” And we fixed that we would.

After that we were very happy for two or three weeks. Sometimes we were sorry about baby and Dolly, for baby was very ill we were told, and Dolly had caught the fever too. But after a while news came that they were both better, and we began to look forward to seeing papa and mamma and them again. We used to write little letters to them all at home, and that was great fun; and we used to go such nice walks. The fields and lanes were full of daffodils, and soon the primroses came and the violets, and Winny was always gathering them and making wreaths and nosegays. It was a very happy time, and it all comes back into my mind dreadfully, when I see the spring flowers, especially the primroses, every year.

One day we had had a particularly nice walk, and when we came in Winny seemed so full of spirits that she hardly knew what to do with herself. We had a regular romp. In our romping, by accident, Winny knocked me down, for she was very strong, and I hurt my thumb. I was often silly about being hurt even a little, and I began to cry. Then Winny was so sorry; she kissed me and petted me, and gave me all her primrose wreaths and nosegays, so I soon left off crying. But somehow Winny’s high spirits had gone away. She shivered a little and went close to the fire to get warm, and soon she said she was tired, and we both went to bed. I remember that night so well. Winny did not seem sleepy when she was in bed, and I wasn’t either. She talked to me a great deal, and so nicely. It was not about when we should be big girls; it was about now things; about not being cross ever, and helping mamma, and about how pretty the lowers had looked, and how kind every one was to us, and how kind God must be to make every one so, and just at the last, as she was falling asleep, she said, “I do wonder so if there are primroses in heaven?” and then she fell asleep, and so did I.

When I woke in the morning, I heard voices talking beside me. It was one of our aunties. She was standing beside Winny, speaking to her. When she looked round and saw that I was awake, she said to me in a kind but rather a strange voice, “Meg, dear, put on your dressing-gown and run down to my room to be dressed. Winny has a headache, and I think she had better not get up to breakfast.”

I got up immediately and put on my slippers, and I was running out of the room when I thought of something and ran back. I put Winny’s slippers neatly beside her crib, and I said to her, “I have put them ready for you when you get up, Winny.” I wanted to do something for her you see, because I was so sorry about her headache. She did not speak, but she looked at me with such a look in her eyes. Then she said, “Kiss me, Meg, dear little Meg,” and I was just going to kiss her when she suddenly seemed to remember, and she drew back. “No, dear, you mustn’t,” she said; “aunty would say it was better not, because I’m not well.”

“Could I catch your headache, Winny?” I said, “or is it a cold you’ve got? You are not very ill, Winny?”

She only smiled at me, and just then I heard aunty calling to me to be quick. Winny’s little hand was hanging over the side of the bed. I took it, and kissed it—poor little hand, it felt so hot—“I may kiss your hand, mayn’t I?” I said, and then I ran away.

All that day I was kept away from Winny, playing by myself in rooms we did not generally go into. Sometimes my aunties would come to the door for a minute and peep at me, and ask me what I would like to play with, but it was very dull. My aunties’ maid took me a little walk in the garden, and she put me to bed, but I cried myself to sleep because I had not said good-night to Winny.

“Oh how I wish I had never been cross to her!” I kept thinking; and if only I could make other children understand how dreadful that feeling was, I am sure, quite sure, they would never, never quarrel.

The next day was just the same, playing alone, dinner alone, everything alone. I was so lonely. I never saw aunty till the evening, when it was nearly bed-time, and then she came to the room where I was, and I called out to her immediately to ask how Winny was.

“I hope she will soon be better,” she said. “And, Meg, dear, it is your bed-time now.”

The thought of going to bed again without Winny was too hard. I began to cry.

“O aunty!” I said, “I do so want to say good-night to Winny. I always say good-night, and last night I couldn’t.”

Aunty thought for a minute. She looked so sorry for me. Then she said, “I will see if I can manage it. Come after me, Meg.” She went up through a part of the house I did not know, and into a room where there was a closed door. She tapped at it without opening, and called out. “Meg has come to say good-night to you, through the door, Winny dear.”

Then I heard Winny’s voice say softly, “I am so glad;” and I called out quite loud, “Good-night, Winny,” but Winny answered—I could not hear her voice without listening close at the door—“Not good-night now, Meg. It is good-bye, dear Meg.”

I looked up at aunty. It seemed to me her face had grown white, and the tears were in her eyes. Somehow, I felt a little afraid.

“What does Winny mean, aunty?” I said in a whisper.

“I don’t know, dear. Perhaps being ill makes her head confused,” she said. So I called out again, “Good-night, Winny,” and aunty led me away.

But Winny was right. It was good-bye. The next morning when aunty’s maid was dressing me, I saw she was crying.

“What is the matter, Hortense?” I said. “Why are you unhappy? Is any one vexed with you?”

But she only shook her head and would not speak.

After I had had my breakfast, Hortense took me to my aunties’ sitting-room. And when she opened the door, to my delight there was mamma, sitting with both my aunties by the fire. I was so pleased, I gave quite a cry of joy, and jumped on to her knee.

“Does Winny know you’ve come?” I cried, “dear mamma.”

But when I looked at her I saw that her face was very white and sad, and my poor aunties were crying. Still mamma smiled.

“Poor Meg!” she said.

“What is the matter? Why is everybody so strange to-day?” I said.

Then mamma told me. “Meg, dear,” she said, “you must try to remember some of the things I have often told you about Heaven, what a happy place it is, with no being ill or tired, or any troubles. Meg, dear, Winny has gone there.”

For a minute I did not seem to understand. I could not understand Winny’s having gone without telling me. A sort of giddy feeling came over me, it was all so strange, and I put my head down on mamma’s shoulder, without speaking.

“Meg, dear, do you understand?” she said.

“She didn’t tell me she was going,” I said, “but, oh yes, I remember she said good-bye last night. Did she go alone, mamma? Who came for her? Did Jesus?” Something made me whisper that.

Mamma just said softly, “Yes.”

“Had she only her little pink dressing-gown on?” I asked next. “Wouldn’t she be cold? Mamma, dear, is it a long way off?”

“Not to her,” she said. She was crying now.

“Do you think if I set off now, this very minute, I could get up to her?”

But when I said that, mamma clasped me tight.

“Not that too,” she whispered. “Meg, Meg, don’t say that.”

I was sorry for her crying, and I stroked her cheek, but still I wanted to go.

“Heaven is such a nice place, mamma. Winny said so, only she wondered about the primroses. Why won’t you let me go, mamma?” And just then my eyes happened to fall on the little piece of black sticking-plaster that Winny had put on my thumb only two evenings before, when she had hurt it without meaning. “Mamma, mamma,” I cried, “I can’t stay here without Winny.”

It all seemed to come into my mind then what it would really be to be without her, and I cried and cried till my face ached with crying. I can’t remember much of that day, nor of several days. I did not get ill, the fever did not come to me somehow, but I seemed to get stupid with missing Winny. Mamma and my aunties talked to me, but it did not do any good. They could not tell me the only things I cared to hear—all about Winny, what she was doing, what lessons she would have, if she would always wear white frocks, and all sorts of things, that I must have sadly pained them by asking. For I did not then at all understand about death. I thought that Winny, my pretty Winny, just as I had known her, had gone to Heaven. I did not know that her dear little body had been laid to rest in the quiet churchyard, and that it was her spirit, her pure happy spirit, that had gone to heaven. It was not for a long time after that, that I was old enough to understand at all, and even now it is hard to understand. Mamma says even quite big, and very, very clever people find it hard, and that the best way is to trust to God to explain it afterwards. But still I like to think about it, and I like to think of what my aunties told me of the days Winny was ill—how happy and patient she was, how she seemed to “understand” about going, and how she loved to have fresh wreaths of primroses about her all the time she was ill.

I am a big girl now—nearly twelve. I am a good deal bigger than Winny was when she died, even Blanche is now as big as she was—is that not strange to think of? Perhaps I may live to be quite, quite an old woman—that seems stranger still. But even if I do I shall never forget Winny. I shall know her dear face again, and she will know mine—I feel sure she will, in that happy country where she has gone. But I will never again say “good night” to my Winny, for in that country “there is no night—neither sorrow nor weeping.”

Chapter Four.

Con and the Little People.

“They stole little Bridget

For seven years long;

When she came home again

Her friends were all gone.”

There was once a boy who was a very good sort of a boy, except for two things; or perhaps I should say one thing. I am really not sure whether they were two things, or only two sides of the same thing; perhaps, children, you can decide. It was this. He could not bear his lessons, and his head was always running on fairies. You may say it is no harm to think about fairies, and I do not say that in moderation it is. But when it goes the length of thinking about them so much that you have no thought for anything else, then I think it is harm—don’t you? and I daresay that this had to do with Con’s hating his lessons so. Perhaps you will think it was an odd fancy for a boy: it is more often that girls think about fairies, but you must remember that there are a great many kinds of fairies. There are pixies and gnomes, and brownies and cobs, all manner of queer, clever, mischievous, and kindly creatures, besides the pretty, gentle, little people whom one always thinks of as haunting the woods in the summer time, and hiding among the flowers.

Con knew all about them; where he got his knowledge from I can’t say, but I hardly think it was out of books. However that may have been, he did know all about the fairy world as accurately as some boys know all about birds’ nests, and squirrels, and field mice, and hedgehogs. And there was one good thing about this fancy of Con’s; it led him to know a great many queer things about out-of-door’s creatures that most boys would not have paid attention to. He did not care to know about birds’ nests for the sake of stealing them for instance, but he had fancies that some of the birds were special favourites of the fairies, and it led him to watch their little ways and habits with great attention. He knew always where the first primroses were to be found, because he thought the fairies dug up the earth about their roots, and watered them at night, when every one was asleep, with magic water out of the lady well, to make them come up quicker, and many a morning he would get up very very early, in hopes of surprising the tiny gardeners at their work before they had time to decamp. But he never succeeded in doing so; and, after all, when he did have an adventure, it came, as most things do, just exactly in a way he had never in the least expected it.

Con’s home had something to do with his fancifulness perhaps. I won’t tell you where it was, for it doesn’t matter; and though some of the wiser ones among you may think you can guess what country he belonged to when I tell you that his real name was not Con, but Connemara, I must tell you you are mistaken. No, I won’t tell you where his home was, but I will tell you what it was. It was a sort of large cottage, and it was perched on the side of a mountain, not a hill, a real mountain, and a good big one too, and there were ever so many other mountains near by. There was a pretty garden round the cottage, and at the back a door opened in the garden wall right on to the mountain. Wasn’t that nice? And if you climbed up a little way you had such a view. You could see all the other mountains poking their heads up into the sky one above the other—some of them looked bare and cold, and some looked comfortable and warmly clad in cloaks of trees and shrubs and furze, but still they all looked beautiful. For the sunshine and the clouds used to chase each other over the heights and valleys so fast it was like giants playing bo-peep; that was on fine days of course. On foggy and rainy days there were grand sights to be seen too. First one mountain and then another would put on a nightcap of great heavy clouds, and sometimes the night-caps would grow down all over them till they were quite hidden; and then all of a sudden they would rise off again slowly, hit by bit, till Con could see first up to the mountain’s waist, then up, up, up to the very top again. That was another kind of bo-peep.

Summer and winter, fine or wet, cold or hot, Con used to go to school every day. He was only seven years old, and there was a good way to walk, more than a mile; but it was very seldom, very, very seldom, that he missed going. There were reasons why it was best for him to go; his father and mother knew them, and he was too good not to do what they told him, whether he liked it or not. But he was like the horse that one man led to the water, but twenty couldn’t make drink. There was no difficulty in making Con go to school; but as for getting him to learn once he was there—ah, no! that was a different matter. So I fear I cannot say that he was much of a favourite with his teachers. You see they didn’t know that his little head was so full of fairies that it really had no room for anything else, and it was only natural that they should think him inattentive and even stupid, and their thinking so did not make Con like his lessons any better. And with his playmates he was not a favourite either. He never quarrelled with them, but he did not seem to care about their games, and they laughed at him, and called him a muff. It was a pity, for I believe it was partly to make him play with other boys that his father and mother sent him to school; and for some things the boys couldn’t help liking him. He was so good-natured, and, for such a little fellow, so brave. He could climb trees like a squirrel, and he was never afraid of anything. Many and many a short winter’s afternoon it was dark before Con left school to come home, but he did not mind at all. He would sling his satchel of books across his shoulders, and trudge manfully home—thinking—thinking. By this time I daresay you can guess of what he was thinking.

There were two ways by which he could come home from school—there was the road, really not better than a lane, and when he came that way you see he had to do all his climbing at the end, for the road was pretty level, winding along round the foot of the mountain, perched on the side of which was Con’s home; and there was what was called the hill road, which ran up the mountain behind the village, and then went bobbing up and down along the mountain side still gradually ascending, away, away, I don’t know where to—up to some lonely shepherds’ huts I daresay, where nobody but the shepherds and the sheep ever went. But on its way it passed not very far from Con’s home. I need hardly say that the hill road was the boy’s favourite way. He liked it because it was more “climby,” and for another reason too. By this way, he passed the cottage of an old woman named Nance, of whom he was extremely fond, and to whom he would always stop to speak if he possibly could.

I don’t know that many boys and girls would have taken a fancy to Nance. She was certainly not pretty, and what is more she was decidedly queer. She was very very small, indeed the smallest person I ever heard of, I think. When Con stood beside her, though he was only seven, he really looked bigger than she did, and she was so funnily dressed too. She always wore green, quite a bright green, and her dresses never seemed to get dull or soiled though she had all her housework to do for herself, and she had over her green dress a long brown cloak with a hood, which she generally pulled over her face to shield her eyes from the sun, she said. Her face was very small and brown and puckered-up looking, but she had bright red cheeks, and very bright dark eyes. She was never seen either to laugh or cry; but she used to smile sometimes, and her smile was rather nice.

The neighbours—they were hardly to be called her neighbours, for her house was quite half-a-mile from any other—all called her “uncanny,” or whatever word they used to mean that, and they all said they did not know anything of her history, where she had come from, or anything about her. And once when Con repeated to her some remarks of this kind which he had heard at school, Nance only smiled and said, “no doubt the people of Creendale”—that was the name of the village—“were very wise.”

“But have you always lived here, Nance?” asked Con.

“No, Connemara,” she answered gravely, “not always.”

But that was all she said, and somehow Con did not care to ask her more.

It was not often he asked her questions; he was not that sort of boy for one thing, and besides, there was something about her that forbade it. He used to sit at one side of the cottage fire, or, in summer, on the turf seat just outside the door, watching Nance’s tiny figure as she flitted about, or sometimes just staring up at the sky, or into the fire without speaking. Nance never seemed to mind what he did, and he in no way doubted that she was glad to see him, though by words she had never said so. When he did speak it was always about one thing—what, you can guess, it was always about fairies. It was through this that he had first made friends with Nance. She had found him peering into the hollow trunk of an old solitary oak-tree that stood farther down the hill, not very far from her dwelling.

“What are you doing there, Connemara?” she said.

“I was thinking this might be one of the doors into fairyland,” he answered quietly, without seeming surprised at her knowing his name.

“And what should you know about that place?” she said again.

And Con turned towards her his earnest blue eyes, and told her all his thoughts and fancies. It seemed easier to him to tell Nance about them than it had ever seemed to tell any one else—his feelings seemed to put themselves into words, as if Nance drew them out.

Nance said very little, but she smiled. And after that Con used to stop at her cottage nearly every day on his way home—he dared not on his way to school, for fear of being late, for almost the only thing he always did get was good marks for punctuality. His people at home did not know much about Nance. He told his mother about her once, and asked if he might stay to speak to her; and when his mother heard that Nance’s cottage was very clean, she said, “Yes, she didn’t mind,” and, after that, Con somehow never mentioned her again. He came to have gradually a sort of misty notion that Nance had had something to do with him ever since he was born. She seemed to know everything about him. From the very first she called him by his proper name—not Con or Master Con, but Connemara, and he liked to hear her say it.

One winter afternoon, it was nearly dark though it was only half-past three, Con coming home from school (the master let them out earlier on the very short days), stopped as usual at Nance’s cottage. It was very, very cold, the fierce north wind came swirling down from the mountains, round and round, here, there, and everywhere, till, but for the unmistakable “freeze” in its breath, you would hardly have known whence it blew.

“It is so cold, Nance,” said the boy, as he settled himself by the fire. Nance’s fires always burnt so bright and clear.

“Yes,” said Nance, “the snow is coming, Connemara.”

“I don’t care,” said Con, shaking his shaggy fair hair out of his eyes, for the heat was melting the icicles upon it. “I’m not going to hurry. Father and mother are away for two days, so there’s no one to miss me. Mayn’t I stay, Nance?”

Nance did not answer. She went to the door and looked out, and Con thought he heard her whisper something to herself. Immediately a blast of wind came rushing down the hill, into the very room it seemed to Con. Nance closed the door. “Not long; the storm is coming,” she said again, in answer to his question.

But in the meantime Con made himself very comfortable by the fire, amusing himself as usual by staring into its glowing depths.

“Nance,” he said at last, “do you know what the boys at school say? They say they wonder I’m not afraid of you! They say you’re a witch, Nance!”

He looked up in her face brightly with his fearless blue eyes, and laughed so merrily that all the corners of the queer little cottage seemed to echo it back. Nance, however, only smiled.

“If you were a witch, Nance, I’d make you grant me some wishes, three anyway,” he went on. “Of course you know what the first would be, and, indeed, if I had that, I don’t know that I would want any other. I mean, to go to fairyland, you know.”

Nance nodded her head.

“The other two would be for it to be always summer, and for me never, never, never to have any lessons to learn,” he continued.

“Never to grow a man?” said Nance.

“I don’t know,” answered Con. “Lessons don’t make boys grow; but still I suppose they have to have them sometime before they are men. But I shouldn’t care if I could go to fairyland, and if it would be always summer; I don’t think I would care about ever being a man.”

As he said these words the fire suddenly sent out a sputtering blaze. It jumped up all at once with such a sort of crackle and fizz, Con could have fancied it was laughing at him. He looked up at Nance. She was not laughing; on the contrary, her face looked very grave, graver than ever he had seen it.

“Connemara,” she said slowly, “take care. You don’t know what you are saying.”

But Con stared into the fire again and did not answer. I hardly think he heard what she said; the warm fire made him drowsy, and the brightness dazzled his eyes. He was almost beginning to nod, when Nance spoke again to him, rather sharply this time.

“My boy, the snow is beginning; you must go.” Con’s habit of obedience made him start up, sleepy though he was. Nance was already at the door looking out.

“Do not linger on the way, Connemara,” she said, “and do not think of anything but home. It will be a wild night, but if you go straight and swift you will reach home soon.”

“I’m not afraid,” said Con stoutly, as he set off.

“I could wish he were,” murmured Nance to herself, as she watched the little figure showing dark against the already whitening hill side, till it was out of sight.

Then she came back into the cottage, but she could not rest.

Con strode on manfully; the snow fell thicker and thicker, the wind blew fiercer and fiercer, but he had no misgiving. He had never before been out in a snow-storm, and knew nothing of its special dangers. For some time he got on very well, keeping strictly to the path, but suddenly, some little way up the mountain to his right, there flashed out a bright light. It jumped and hopped about in the queerest way. Con stood still to watch.

“Can it be a will-o’-the-wisp?” thought he, in his innocence forgetting that a bleak mountain side in a snow-storm is hardly the place for jack-o’-lanterns and such like.

But while he watched the light it all at once settled steadily down, on a spot apparently but a few yards above him.

“It may be some one that has lost their road,” thought Con; “I could easily show it them. I may as well climb up that little way to see;” for strangely enough the thought of the fairies having anything to do with what he saw never once occurred to him.

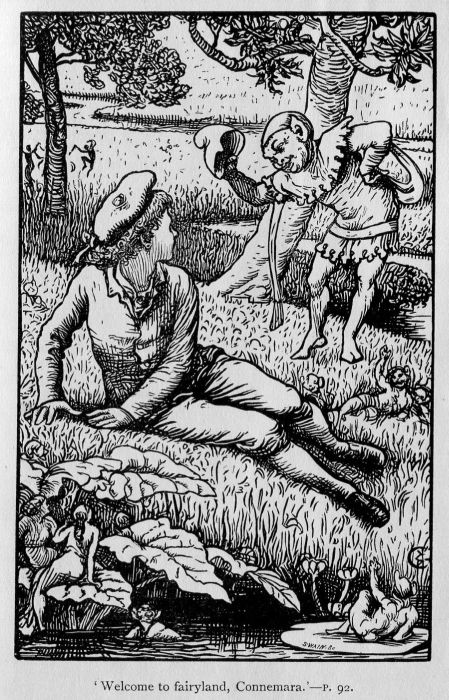

He left the path and began to climb. There, just above him, was the light, such a pretty clear light, shining now so steadily. It did not seem to move, but still as fast as he thought he had all but reached it, it receded, till at last, tired, and baffled, he decided that it must be a will-o’-the-wisp, and turned to regain the road. But like so many wise resolutions, this one was more easily made than executed; Con could not find the road, hard though he tried. The snow came more and more thickly till it blinded and bewildered him hopelessly. Con did his utmost not to cry, but at last he could bear up no longer. He sank down on the snow and sobbed piteously; then a pleasant resting feeling came over him, gradually he left off crying and forgot all his troubles; he began to fancy he was in his little bed at home, and remembered nothing more about the snow or anything.

Nance meanwhile had been watching anxiously at her door. She saw that the snow was coming faster, and that the wind was rising. Every now and then it seemed to rush down with a sort of howling scream, swept round the kitchen and out again, and whenever it did so, the fire would leap up the chimney, as if it were laughing at some one.

“Frisken is at his tricks to-night,” said Nance to herself, and every moment she seemed to grow more and more anxious. At last she could bear it no longer. She reached a stout stick, which stood in a corner of the room, drew her brown cloak more closely round her, and set off down the path where she had lost sight of Con. The storm of wind and snow seemed to make a plaything of her; her slight little figure swayed and tottered as she hastened along, but still she persevered. An instinct seemed to tell her where she should find the boy; she aimed almost directly for the place, but still Connemara had lain some time in his death-like sleep before Nance came up to him. There was not light enough to have distinguished him; what with the quickly-approaching darkness and the snow, which had already almost covered his little figure, Nance could not possibly have discovered him had she not stumbled right upon him. But she seemed to know what she was about, and she did not appear the least surprised. She managed with great difficulty to lift him in her arms, and turned towards her home. Alas, she had only staggered on a few paces when she felt that her strength was going. Had she not sunk down on to the ground, still tightly clasping the unconscious child, she would have fallen.

“It is no use,” she whispered at last; “they have been too much for me. The child will die if I don’t get help. The only creature that has loved me all these long, long years! Oh, Frisken, you might have played your tricks elsewhere, and left him to me. But now I must have your help.”

She struggled again to her feet, and, with her stick, struck sharply three times on the mountain side. Immediately a door opened in the rock, revealing a long passage within, with a light, as of a glowing fire, at the end, and Nance, exerting all her strength, managed to drag herself and Con within this shelter. Instantly the door closed again.

No sooner had it done so, no sooner was Nance quite shut out from the outside air, than a strange change passed over her. She grew erect and vigorous, and the weight of the boy in her arms seemed nothing to her. She looked many years younger in an instant, and with the greatest ease she carried Con along the passage, which ended in a small cave, where a bright fire was burning, in front of which lay some soft furry rugs, made of the skins of animals. With a sigh Nance laid Con gently down on the rugs. “He will do now,” she said to herself.