Bobby North went out into the front yard by the iron gate between the two tall stone columns to watch the horses and wagons and 'mobiles traveling up and down that invitingly dusty and mysterious road that he was forbidden ever to set foot upon.

He knew he could crawl under the gate, he was so little, and raise clouds of dust by dragging his feet in the road as two small boys did who passed by and stopped to gaze in wonder at Bobby and at the big brick house set back in the yard among some trees. He wondered if the Supe'tendent would really send him to bed without anything to eat if he disobeyed her just this once and slipped under the gate, out into the road for as many as forty or a dozen minutes.

He was afraid she really might, and was standing with face pressed against the iron bars of the gate when a man drove up back of him with a buggy jammed as full as it would hold of boys and girls from the Home.

"Bobby North!" cried the sharp, irritated voice of the Supe'tendent. "How many times must I tell you to keep away from that gate!"

He turned clear around and saw on the porch the tall, thin figure of the Supe'tendent. The man in the buggy jumped out to open the gate. Bobby stepped back from the graveled road, for he knew by experience that it is always safer, if you are a small boy, to keep out of the way of grown-up folks—then they can't scold you for doing something you mustn't, or not doing something you should, even when you had never thought of doing either one.

He looked up longingly at the buggy load of boys and girls who were going to explore the mysteries of that delightfully dusty road and not coming back for maybe forty or a dozen days. Bobby was used to being left behind and stepped further away, but without taking his lonely eyes off those more fortunate children.

When the man had opened the gate, he stopped and looked at Bobby and then at the Supe'tendent on the porch. He came[9] directly towards Bobby as he kept backing away, caught him up in his arms and tossed him into the lap of the lady who sat on the front seat!

"You'd like a whole week in the country, too, wouldn't you?" said the man.

"Yes'm."

Bobby was so surprised that that was all he could think of to say.

"I'm afraid he will be too much trouble for you," called the Supe'tendent. "He's so young."

Bobby steeled his heart and started to climb down from the lady's lap, but his lower lip twitched in spite of his effort to keep it steady.

"Nonsense!" exclaimed the man, as he led the horses out into the road, shut the gate, jumped into the seat by the woman and drove off in a cloud of dust. He didn't seem to be at all afraid of the much-to-be-feared Supe'tendent!

Bobby was so glad to be riding away from the Home that he thought he almost liked the Supe'tendent this once, and looked back and waved good-bye to her. She stood there stiff and angry and did not reply.

Thus it came about that Bobby North had his first trip away from the Home that he[10] could remember. The week at Mr. and Mrs. Robert Eller's in the country was a glorious time—days to be remembered by all the red letters on the playing blocks that were sometimes given him on a Sunday to keep him quiet.

Besides the calves and little pigs, the clover field and the daisies in the yard, there was the two-months' old puppy that Mr. Eller's little boy told him was a St. Bernard. It soon became the chief delight of this puppy to chase Bobby about the yard and trip him and then, when he fell headlong, to lick his hands and face affectionately with a moist, red tongue. The man never once objected to his playing with the awkward and much-to-be-desired puppy all day long.

He was an answer to ardent and secret prayer, this Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy, and Bobby looked up to him with a great deal of awe; his words carried the weight of authority. He seemed to understand what small boys want, to know that the greatest of all treasures, a real live puppy, is good for them.

Thus the happy days in the country passed like magic.

One afternoon the puppy was not to be found anywhere. Bobby returned to the front yard at Mr. Eller's, after a vain search for his playmate, and found that that day was a very special occasion.

The grown-ups, and the children, too, were celebrating something which seemed to be called a "birthdays." It belonged to Richard, the small son of the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy. It was the boy's eighth birthdays, and he was very proud of that fact.

There was ice-cream—enough so that Bobby's dish was heaped full a second time[12] without asking and before he had quite finished the first helping—and cake and two big red and white apples for each child. Bobby was still munching contentedly away at his first apple, the other clutched tightly in his left hand, when Richard's mothers led the children into the house to see the "presents."

There was quite an array of them—enough Bobby decided for all eight birthdays and he vaguely wondered if all eight of them had come on that one day. There was a baseball, and a bat, a dozen marbles—"glassies" Richard called them, presents it seemed from his fathers; a nice, new, starchy white blouse with blue trousers, a gift from his mothers. Then there was a pair of high boots with a copper plate on the point of each toe, sent him by his Uncle John in the city.

Last of all there was something out at the barn which was to be sold when "they" grew up and help to buy something for Richard some day which his fathers never had—"an edge-cation."

"They" proved to be six little pigs with curly tails and squealy voices. Bobby wondered if Richard wouldn't grow up before they did, he was so much bigger, and then what would become of his edge-cation?

He fell to wondering about this thing called a birthdays. As near as he could make out, it was a very special day on which everybody—at least your fathers and mothers, if you had such possessions—unaccountably gave you playthings that you had always wanted, such as "glassies" and baseballs and, yes, little curly-tailed pigs that were to help buy you an edge-cation.

He decided he wanted a birthdays, but didn't know the least thing about how to go about it to get one. He determined to ask and went immediately to Richard who, having eight birthdays of his own, must be an authority on the matter.

"Where did you get your birthdays?" he asked in what he thought was a very loud voice, but apparently it wasn't for Richard said "Huh?" and for a moment stopped trying to straighten the curls out of the tails of the little pigs. Bobby repeated his question and added wistfully:

"Never had none."

"You have, too," said Richard.

"Ain't not," said Bobby resolutely.

"You have, too," repeated Richard.

Bobby fell silent under that assertion and tried to remember when anybody had ever given him presents. He could recall no[14] such occasion. Then an explanation came to him.

"P'raps," he suggested timidly, "you only have birthdays when you have fathers and mothers and things like that."

"Everybody has birthdays," said Richard from the lofty peak of his superior years.

Bobby again remained silent and Richard, to add the final, crushing blow, gave further information.

"Everybody has fathers and mothers, some time."

"P'raps I'm not big enough yet to have fathers and mothers and birthdays. How big will I have to be?"

Richard snorted in derision.

"They have you," he said and turned his attention to straightening out the curls from his pigs' tails.

Bobby did not understand, but felt that somehow he was in the wrong, and he went off a ways by himself and took the first comforting bite out of his other apple, carefully choosing the side with the most red on it.

After a time Richard convinced himself that the kink was a part of the pig's tail and stopped trying to uncurl it. Then his eye fell on Bobby and he scowled fiercely.

"Everybody has birthdays," he said. "What you done with yours?"

"Not done nothing with it," replied Bobby. Then, after a time, "Never had none."

"Papa," called Richard to the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy, "Bobby says he hasn't got a birthday. Everybody has birthdays, haven't they, papa?"

Mr. Eller was talking with his wife and paid no attention.

"Everybody has birthdays, haven't they, papa?" This time Richard yelled so loud his father couldn't help hearing.

"Yes, of course," he replied carelessly.

"There, I told you so!" said Richard.

"Ain't not," insisted Bobby stubbornly, and hunted out another red spot on his apple.

Richard seemed to take Bobby's words as a personal affront.

"Papa, he has too, hasn't he, papa?"

"Has what?" asked Mr. Eller impatiently.

"Bobby has too a birthday, hasn't he?"

"Everybody has a birthday," replied his father.

"I told you so! I told you so!" chanted Richard, skipping about. "Bobby North has lost his birthday! Bobby North has lost his birthday and don't know where to find it!"

"Ain't not," repeated Bobby and his lower lip began to twist up. "Wouldn't lose a 'portant thing like a birthdays."

Mr. Eller and his wife approached the children. That capable woman put her hand on Bobby's head.

"Haven't they ever celebrated your birthday at the Home?" she asked.

"Perhaps they don't know when it is," Mr. Eller suggested in a low voice to his wife.

"Couldn't lose it, could I?" appealed Bobby to the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy.

"Some children lose their birthday before they are big enough to know what it is," comforted Mr. Eller.

"Bobby North has lost his birthday and don't know where to find it!" chanted Richard in derision.

"Ain't not," repeated Bobby dismally.

"That will do, Richard," said Mr. Eller severely. "Go and play pump-pump-pull-away with the other children."

"Yes, sir," said Richard and went obediently off, turning back only once to make a face at the boy who had lost his birthday.

"Never mind, Bobby," said Mr. Eller. "You'll find it some day."

"When I get growed up?"

"Perhaps sooner. I'll see the Superintendent. We may be able to find it for you."

"Could I find it if I hunted and hunted all day long, like the spoon?" queried Bobby eagerly.

The Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy laughed.

"Don't worry about your birthday, Bobby. You'll stumble across it some day when you are walking along and not thinking about it."

"It won't matter if you don't, dear," said Mrs. Eller. "Folks will love you just the same."

"No'm," said Bobby skeptically, replying to her first statement, and retiring under a tree to puzzle over the matter and consume the rest of the apple. The other children were playing their games and Mr. and Mrs. Eller soon went into the house.

Bobby decided that the lady, Richard's mothers, didn't know the importance of a birthdays, whereas nothing could be more important. Birthdays brought little boys all the things they had always wanted, like "glassies" and baseball bats and little pigs. He knew he wanted the "glassies" and the bat and wasn't quite sure but that he might want the pigs to help buy an edge-cation[18] when he grew to be as big as Richard's fathers who said he wished that he had one.

If he had really lost his birthdays himself, he might find it as he did the spoon which he lost in the yard one day. The Supe'tendent made him hunt and hunt for it till he couldn't see for the water in his eyes. And then, suddenly, he stepped on it when he wasn't thinking about it and bent it all twisty-like. What if he should step on his birthdays and bend it just as he had the spoon? He must be very careful where he stepped. Didn't the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy say he would find his birthdays some time when he was walking along and not thinking about it?

He wanted very much to find his birthdays; so he must be up and about it. He would start at once; he might find it before night and would show that Richard that he did know where to find his birthdays. He knew that he could walk ever so far, but was not so sure that he could keep from thinking about what he was looking for. It was worth trying anyway. If only he might step on his birthdays! He must be careful though not to step on it with all his weight and bend it as he did the spoon—it might be harder to straighten it out.

He rose and started for the road. The other children were too busy with their playing to notice him. Stepping lightly, with eyes fixed on the ground, Bobby trudged out through the yard into the road.

So he started out on his strange quest.

When he had gone a long way, Bobby crossed the road and crawled under the fence into the field beyond. He tried so hard not to think about the thing he was searching for that he forgot all about the fact that it had been hours since dinner and that the sun's bedtime could not be so very far off. One can't remember everything when trying so hard not to think of one thing. He wasn't thinking of that—only of the presents Richard had received, and that wasn't the same!

He trudged on till his short legs grew weary, always looking down at the ground[21] and stepping, oh, so lightly! He was startled when a big gruff voice suddenly boomed out right in front of him:

"Hullo, Bub! What're you doin' out here?"

Bobby was so astounded that he blurted out the truth without thinking.

"Hunting for my birthdays."

"Huntin' for your birthday, huh? Well, now, what do you think of that, Steve?" And the rough, bearded man who had spoken to him, winked prodigiously at the youth who was helping him mend a broken place in the fence.

"Where'd-ja lose it?" asked the youth.

"Don't know," confessed Bobby.

"That's a funny thing to lose," said the rough, bearded man. "Sure you had one?"

"Don't perzactly 'member," replied Bobby. Then a dreadful thought came to him: he was thinking about his birthdays! "Please, I musn't not think about it."

The bearded man burst out laughing.

"You're a funny codger! Huntin' for something you mustn't think about! What do you think of that, Steve?"

Steve didn't think very highly of the matter, Bobby was sure from the way he laughed.

"Does your mother know you're out?" asked Steve, and in turn exchanged another prodigious wink with the man with whiskers.

"Ain't not got any mothers," said Bobby.

"Oh," said the bearded man in a different voice, "you're one of the kids old man Eller has out to his place."

"Yes'm," Bobby admitted and began to back away. These men were making fun of him and he felt uncomfortable, and they had made him think of his birthdays! He had taken only a few backward steps when a big pleasant voice behind him made him jump.

"Quite a ways from home, aren't you, son?"

"I'm hunting my——," but Bobby remembered just in time and stopped. "Yes'm," he added and turned to look up into a pair of friendly blue eyes and at lips that smiled under a blond mustache that curled up at the ends. The man put a hand on Bobby's shoulder and drew him closer.

"Lost, are you? Well, we'll soon fix that. What is your name?"

"No'm," said Bobby, trying to answer the man's questions in order.

"No'm! That's a funny name!" exclaimed the man and laughed till his eyes all crinkled up.

"No'm's not my name!" laughed Bobby. "No'm, I'm not lost, I'm hunting——" Again he remembered just in time and stopped.

"That's a secret, is it? Is your name, too?"

"Bobby North," he replied and smiled up at this man who laughed at him without making fun of him.

"Where do you live?"

"Way off—there," replied Bobby, pointing over the tops of the trees.

"Oh, up there! You've chosen a fine home—"

"He's one of the kids at Eller's place, Mr. Anning," interrupted the man with the whiskers.

"He's huntin' for his birthday which he was careless enough to lose," added Steve.

"Was not care-less!" Denied Bobby and that unsteady lower lip began to tremble.

"Of course you were not careless," said the man with the mustache. "Somebody just forgot to tell you. Here, take this."

He put his hand in his pocket and drew it out full of money. He selected a large shining white piece and put it in Bobby's hand.

"Here's a quarter for you. Now it will soon be sundown and you'd better make[24] tracks for Mr. Eller's. Know how to find it?"

"Thank you," said Bobby, clutching the quarter and not forgetting what the Supe'tendent told him to say whenever anybody gave him anything. Then, after a time, he remembered the man's question and he replied to it. "Yes'm."

"That's it—that house way over there on the other side of the road," said the man. "Keep your eyes on the house and you can't miss it."

"Yes'm," said Bobby and started off.

"Here," called the man, "Wait a minute. Here's a quarter for you." He drew out another handful of money and selected another shining white quarter, only it was not so shiny as the other one. "Now skeedaddle for Mr. Eller's."

Forgetting to thank the man for the second quarter, Bobby started off, keeping his eyes fixed on the house. When he had gone a long ways he turned and looked back. The Man with the Pocketful of Quarters waved to him, and Bobby, after waving, too, set resolutely onwards for the house far off across the road.

Now it's hard to remember just what you a going to do when one is a very little boy[25] and has just been given two whole quarters all for his very own, particularly if the disturbing thought will come to you that you can have lots and lots of quarters and other things given to you if you have birth—the thing you musn't think about.

That reminded Bobby; he was sure that he hadn't stepped on It while he wasn't thinking or he would have felt it under his foot as he did the spoon. Perhaps it might be somewhere along this mysterious, inviting white road, all covered with dust and lined with trees and bushes, that wound away further than anyone could see. It might be just beyond that turn; there where the meadow lark went sailing happily up into the sky. He would go there and look.

Dragging his toes in the dust to see if his lost birthdays might be covered up there, Bobby gained the turn in the road, and the next one, and the one beyond that, and still trudged on, his short legs aching and stumbling. He wasn't thinking about the thing he musn't think about! Why didn't he feel it under his feet? Perhaps because the water wasn't in his eyes so he couldn't see, as it had been when he stepped on the spoon. He began to fear he couldn't go much farther. Still he kept on.

Then suddenly the sun went entirely to bed. Bobby began to be frightened for he had never been out all alone with the darkness. When it's all dark, little boys can't tell what other things may be about. His lip began to tremble and now the water did come into his eyes. That interested him; it was so when he stepped on the spoon; it might be that he would find his—what he was looking for—now, and he stumbled on through the dust and the gathering darkness towards the next turn in the road.

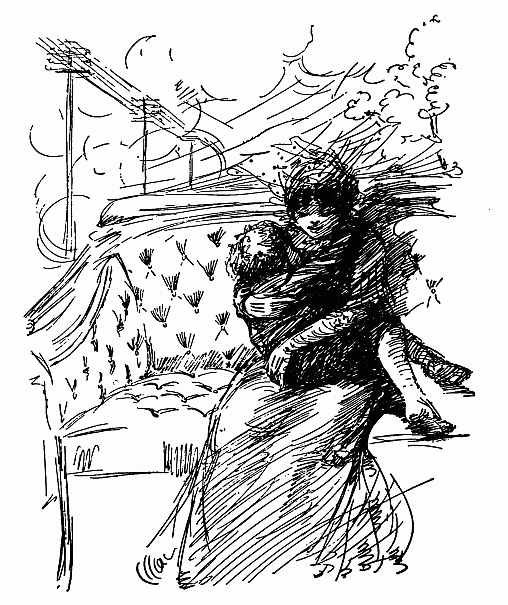

As he toiled on, he became conscious of a gentle purring sound behind him that kept getting louder and louder. He was almost at the turn when there came a fierce honking right behind him. Blinded by the water in his eyes, he could but dimly see a great black mysterious object almost on him when he turned. He was too frightened to move. The thing came to a sudden stop just a few feet from him and he saw that it was only a 'mobile. A rough, young voice cried:

"Don't you know enough to get out of the road when you hear a car coming, you little—"

"James! You might have struck him!" cried a sweet, frightened voice from the body of the 'mobile. "We ought not to have tried to make home without having the lights on."

"Don't stand there in the way like a——" the rough, young voice began, but the woman's voice interrupted:

"The child is crying! Open the door, James."

Before he knew what she was going to do, the lady was kneeling right in the dust of the road by his side. She put her arms about him and drew his head against her breast. It was so soft and warm there and so safe that Bobby cried all the harder for very relief and his arms stole about the neck of the lady until his fingers got tangled in her soft hair.

"I do believe the child is lost," said the lady and gathered Bobby up in her arms and carried him into the 'mobile. "Light the lamps, James," she added from the depths of the black-cushioned seat.

James, who wore a pair of big glasses that almost hid his face, turned on the lights, and, through his tears, Bobby soon saw two beams of light spurt out on the road ahead.

"Tell me your name, won't you?" begged a low voice close to Bobby's ear.

He struggled to control his sobs enough to answer.

"I like little boys," added the voice coaxingly.

"B-B-Bob-b-by," he said at last, nestling closer in those protecting arms.

"He's so tired he's falling asleep," said the voice which was the sweetest Bobby had ever heard.

The next thing Bobby knew, he woke up to find himself sitting in a great big, soft red chair in a great big, red room with as many as forty or a dozen red-shaded lights, with a strange lady kneeling in front of him. He looked into her eyes, puzzled at finding she was not the Supe'tendent.

"You don't remember one thing that happened, do you?" laughed the lady.

"Yes'm," said Bobby after a pause, smiling sleepily back at her. "You're the Lady Who Likes Little Boys."

"You darling!" murmured the lady and[30] squeezed Bobby until he could hardly breathe. "Tell me where you live."

"There," and he pointed hesitatingly towards the top of the door. "N-No, that way. Don't know." The knowledge that he was lost came to him and that lower lip began to twitch tremulously.

"Never mind, dear, I'll find your home. What is your father's name?"

Bobby's big brown eyes opened wide and he stared at her unblinking for a while.

"Got none," he answered at last.

"Then your mother. What is her name?"

"Got none," he repeated.

"But she must have a name. Tell me what you call her when she sits by your bed at night and kisses you and tucks you in," coaxed the lady.

Bobby sat up straight.

"Do mothers do that?"

"Why, yes. Don't you know?" And the lady kissed Bobby.

"No'm," said Bobby wistfully.

"She must be worried frantic because you don't come home. Tell me about her so I can find her and tell her you are not lost."

"Got no mothers," said Bobby after a long pause.

"Who are you? What's the rest of your name?"

"Bobby North, little imp."

The lady didn't like that: she almost frowned.

"You're not that at all. Who ever told you so?"

"Supe'tendent at the Home said so."

"Oh," said the lady, taking in her breath quickly, "then you're—"

The Lady Who Likes Little Boys stopped: then she put her arms about Bobby and squeezed till he squirmed.

"Yes'm," said Bobby timidly, trying to breathe.

"How did you come to be wandering alone along the road?"

Bobby looked at her for a long time without moving an eyelash.

"Please, will telling be thinking about it?"

"Not if you whisper it close in my ear."

Bobby took his courage in both hands, placed his lips close to her ear, shut both eyes tight, and whispered all in a breath:

"Wanted to find my birthdays which I lost before when I was too little to know what it was."

"Your birthdays!" The lady was so surprised[32] that the smile faded from her lips. "Have you lost that?"

"Hunted and hunted all day," said Bobby. "And I didn't think about it——Not very much."

"Why didn't you think about it? Can't you tell me?"

Bobby opened his eyes wide.

"'Cause if you don't think about it maybe I'll step on it like the spoon."

"Who told you that?"

"The Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy."

"Who is he? Don't you remember his name?"

"No'm," said Bobby after a long struggle to think. "To-day is his birthdays."

"The Man's Who Lets You Play with the Puppy?"

"His little boy's. He has eight of them and presents, glassies, and a bat, and little pigs to help buy you an edge-cation."

A delicious drowsiness crept all over Bobby till his eyelids went all tickly and prickly and he rubbed both fists into them.

"You're all tired out," said the lady, "and hungry, too. I'm going to get you something to eat and put you to bed. Would you like to be my little boy tonight?"

For reply, Bobby flung both arms about her neck and squeezed with all his might until he squeezed a sob right out of her throat. She took him up in her arms and carried him out into a room with a big shiny red table with two red chairs by it. Then she rang a bell and soon a girl with a little white apron came in.

"Sarah, bring me a glass of milk, some bread and butter and jam."

"Why does that girl wear a little white apron?" asked Bobby. "Is she a 'tendant?"

"No, she's the maid," replied the lady.

The girl seemed hardly to have had time to leave the room before she was back, bringing on a tray the bread, the milk, two little cakes of butter and a dish all ready to run over with red jam. The lady put lots and lots of butter on the bread, besides all the jam it could hold without running over the edges, and watched Bobby eat it all up. She didn't tell him to pick up the crumbs,—just kept smiling at him and asked if he could eat another piece. Of course he could! But, as it happened, he couldn't, for he hadn't eaten half of it when the prickling in his eyelids got so bad he had to close them.

When he opened his eyes again, he was in a little white bed in a little white room,[34] and there—it couldn't be! He rubbed the sleep out of his eyes. Yes, it was! A little train with an engine and a whole string of cars! He looked around.

In one corner of the room stood a baseball bat with a catcher's glove, and there on the little stand by the window was a box all full of marbles, "glassies" and agates and many other kinds. He felt queer and looked down at himself and found he no longer had on his own clothes but a nice clean nighty.

"What made you wake, dear?"

He twisted his head and there sat the Lady Who Likes Little Boys, smiling at him.

It took him a long time to think of the reason.

"Please, I forgot 'Now I lay me'."

"Will you say it to me, right here at my knees?"

Bobby climbed out of the bed, knelt by the lady, laid his head on her knees and repeated the sleep-forgotten prayer. He looked up when he had finished and found the lady had covered her face with both hands. Perhaps she was saying her "Now I lay me," and Bobby kept still for a long time. Finally he squirmed around for another look at the train of cars.

The lady must have known that he was through, for he felt gentle hands on his shoulders.

"Who taught you that?" she asked.

"The 'tendant with the blue and white dress."

"It's—it's beautiful," said the lady in a voice that sounded very much like Bobby's when he had water in his eyes.

He looked up and saw there was water in her eyes! Suddenly he felt queer inside and knew something without having been told.

"Is the train your little boy's?"

"Yes, dear. This was his room."

"And his bed?"

"Yes; everything in the room was his."

"Where is your little boy?"

It was quite a long time before she replied and then it was so low Bobby scarcely heard.

"He's gone away."

"When did he go away?"

That seemed a very hard question to answer.

"Three months ago," said the lady at last, her fingers at her throat as though to help the words come out.

"When's he coming back?"

The question this time was still harder to answer.

"He's never coming back . . . never till I . . . go for him. He was sick a long time . . . until God had pity on him and took him home."

"Are you going for him tonight?" asked Bobby in that new, diffident voice.

"No, dear. I can't go for a long, long time."

"Not till he gets growed up?"

The Lady Who Likes Little Boys put a handkerchief to her eyes before she answered.

"Not . . . not till God sends for me."

Bobby remained silent till his eyes fell on the box of marbles.

"Can I play with the marbles till he comes back?"

"Yes, dear, tomorrow when you've had your sleep out."

Then Bobby looked at the little train again and fell to wondering; perhaps this boy, too, had birthdays. He turned to the lady.

"Did your little boy have birthdays?"

"Yes, dear. Day after tomorrow is his birthday."

"Are you going to cel'brate it?"

"Yes . . . in my heart." It was just a whisper that Bobby barely heard.

"How many birthdays did he have?"

"Seven."

Bobby considered that. The little boy whose fathers was the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy had eight birthdays and the little boy whose mothers was the Lady Who Likes Little Boys had seven. But her little boy had gone away. Perhaps he wouldn't mind letting him have just one of his birthdays.

"Would he let me have just one of his birthdays?"

The lady remained perfectly still and did not answer. Bobby added wistfully:

"Just till I see what it's like? P'raps I wouldn't want it any more. If I did like it, then I could go on hunting for the birthdays I lost."

He knew before she spoke that her little boy wouldn't let him have one of his birthdays.

"Not his. I couldn't. Don't. . . . There, dear, go to sleep now and I'll. . . ."

She didn't finish what she was saying, but went quickly out, carrying her handkerchief to her face. Bobby was too tired to be very much disappointed, so tired that he fell asleep almost before the swishing of her dress had ceased to sound in his ears.

The Lady Who Likes Little Boys went quickly into another room and took down from a closet shelf a little suit of clothes and gave way to tears, hugging the empty clothes desperately to her heart.

After a time, a big man with a brown mustache whose ends curled up, came into the room, looked down pityingly at her, then took her up in his arms like a little tired child and held her silently while she wept her heart out.

"You mustn't take his things out, Alice," said the man. "Not yet."

"I can't bear it, Alfred. I want him! I won't try not to think of him!"

Mr. Anning placed his wife gently in a chair and began to tell her about meeting a small boy in the field who was hunting for something he must not think about.

"For the birthdays he lost before he was big enough to know what it was?" said his wife smiling through her tears.

"Do you know him? Who is he?" asked Mr. Anning eagerly.

For answer, his wife took him by the hand and led him into the little white room where Bobby lay fast asleep. Mr. Anning bent quickly over him and exclaimed:

"Why, it's the very same! The little fellow who lost his birthdays! And in Edward's room. Now I understand, dear, why——"

"It was not that," interrupted his wife, and covered her eyes with her hand. "He asked for just one of Edward's birthdays so he could find out what it was like. And I couldn't give it to him, Alfred! I couldn't!"

"Poor little chap," said her husband. Then he took his wife by the hand and led her out of the little white room.

They entered the red room just as Sarah, the maid, ushered in Mr. Eller. He was very much disturbed and spoke quickly.

"I'm sorry to trouble you, Mr. Anning, but one of the children from the Home is lost. I wonder if you would take your car and——"

"Was he a little boy of five?" interrupted Mrs. Anning.

"The boy who had lost his birthdays?" questioned her husband.

"Yes," replied Mr. Eller. "Have you found him?"

"He is upstairs fast asleep."

"You don't know what a relief that is!" sighed Mr. Eller. "My wife is nearly distracted at the thought that he may be wandering about in the woods or the fields."

"We'll bring him over in the morning," said Mr. Anning.

"I think I'd better take him with me," said Mr. Eller. "It will calm Mary to have him right under her eyes with the other children."

"I know how she feels," said Mrs. Anning. "I will get him ready."

After he had been asleep for a long, long while, Bobby woke to find himself dressed in his own clothes and in the arms of the Lady Who Likes Little Boys. She was speaking.

"He is so tired and sleepy, Mr. Eller. It's a pity to wake him. I wish you would let me have him until morning."

"My wife's worried sick by his disappearance," replied a voice that was familiar to Bobby. He turned his head about to see. It was the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy. In the doorway stood another man, a big man with a mustache whose ends curled up. He came forward, smiling at Bobby, and held out his hand.

"Well, young man, I didn't expect to see you again so soon, and in my own house, too."

Bobby didn't know quite what to say to that although he was sure the man was not making fun of him, so he said nothing.

"You haven't forgotten me already, have you?" continued the man.

"No'm," smiled Bobby. "You're the Man with the Pocketful of Quarters."

"Right you are!" laughed the man and, to prove it, drew out a handful of coins from his pocket, selected a quarter and pressed it into Bobby's palm.

The lady kissed Bobby good-bye while the man looked pleadingly at her.

"I can't, Alfred! I can't!" she said all choked up, and Bobby wondered what had made her cry.

"No, of course, you can't, Alice, I understand."

The Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy took Bobby from the Lady and carried him out. Bobby looked back and saw the Man with the Pocketful of Quarters put his arm about the Lady Who Likes Little Boys.

Bobby did not see the 'mobile drive up toward evening of the next day for he was out in the yard at Mr. Eller's playing with the St. Bernard puppy. He was running with all his might, the puppy right at his heels, when he looked up and saw the Lady Who Likes Little Boys coming swiftly towards him. He stopped quite still for a time, then ran with all his might right into her arms and tangled his fingers among the soft hair at the back of her neck.

"Oh, Bobby, I just can't let you go back to the . . . Home, without your first knowing what a birthdays is."

"Have you found it? Is it mine?" asked Bobby eagerly.

"Not yours, Bobby. My little boy is going to lend you—one of his."

Bobby squirmed in delight.

"Day after tomorrow?"

"Tomorrow," smiled the lady.

"When will that be?"

"Soon, dear. I'll tell you when it comes."

Bobby remained in thought for a long while.

"Your little boy won't be mad at you?"

"No, Bobby. He was always generous—just like his father." Then she said something that Bobby decided was addressed to herself and not to him. "I can't be less generous."

Bobby squeezed her neck until his arms ached. Then he remembered something she had just said.

"Did your little boy have fathers, too?"

"Yes. He's waiting in the car. Let's go to him, will you? Mrs. Eller is going to let you spend the night with us."

Holding hands, they went out through the yard, while the deserted puppy sat on his haunches and stared forlornly after his little playmate who did not even look back.

When they got to the car, there sat the Man With the Pocketful of Quarters! So that was the fathers of the little boy who was going to lend him a birthdays!

"Well, son," said the man as they solemnly shook hands, "we're going to show you what a real birthdays is."

"Yes'm?" queried Bobby as he was lifted into the 'mobile.

"Sure thing. It will be birthday all day[44] long, from the moment you open your eyes until the Sandman comes."

Bobby snuggled happily at the side of the lady in the back seat, while the car sped swiftly on towards the house with the little white room with the little train and a whole string of little cars.

"Is it tomorrow now?" asked Bobby eagerly as he awoke the next morning in the little white room and found the Lady Who Likes Little Boys bending over him.

"Yes, this is day-after-tomorrow."

"Your little boy's birthday?"

The reply was a long time in coming.

"It's your birthday this time, dear."

"For all day and always?"

"For all day long."

Bobby felt of himself all over and then announced wistfully:

"It doesn't not feel any different, having birthdays—not yet."

"Wait, Bobby, until you have had your bath and breakfast, then maybe it will be different."

Bobby didn't mind the bath this time at all, only he was in a tremendous hurry to get through with it, and when he was seated at the table he scampered through breakfast very quickly without being scolded once. He did not even notice that the girl with the little white apron did not bring him things to eat as she had the night before. He was back in the red room with the forty or a dozen red-shaded lights, now all put out, shaking hands with the Man With the Pocketful of Quarters, when the maid came into the room and said:

"It's all ready now, sir."

"All right, Sarah," replied the man and the girl left the room.

"We're going to start out this birthday right, son."

"Yes'm," said Bobby, watching him with eyes that sparkled expectantly.

"Up in the room where you slept," continued the man, "are a lot of things that small boys like. I want you to go up there alone and look them over. Then you are[47] to pick out the one thing that you want most of all—just one. That will be yours for keeps."

"'Glassies' or the bat or the train?" asked Bobby.

"It's just one thing for now," interposed the lady. "There will be—"

"Don't give me away, Alice," pleaded the man.

Bobby wondered how she could give away the Man With the Pocketful of Quarters, but soon forgot that thinking about more important matters.

"Or little pigs to buy an edge-cation with curly tails?" pursued Bobby.

The man burst out into a big laugh that filled the room.

"I haven't a doubt but what you'll have a curly-tailed edge-cation all right, Bobby, when the time comes, pigs or no pigs."

"Yes'm," smiled Bobby not knowing quite what the man meant.

"Come," said the lady. "I'll go as far as the door with you."

And that was as far as she did go. Her hand slipped gently over Bobby's straight blond hair and lingered there before she pushed him into the room and closed the door between them.

Bobby stopped at the head of the little bed which had already been made up, and looked carefully about the room. There was the enchanting train all ready to get up steam to carry him away into that strange land where red Indians tomahawk little boys, or where pirates dig all day in the white sand making places to hide yellow gold in. And there on the bed was the box of marbles, "glassies," agates and all, and a little blue sailor suit, and a baseball bat, and a whole row of quarters, and there—

Bobby's eyes opened wide and he made a jump for the thing that was almost hidden in the pocket of the sailor suit. It couldn't be, and yet it was! The shiningest, white-handled pocket knife a boy ever had! He counted the blades; there were three of them, but not one of them could he open. He sat down on the floor and tried and tried to open those blades, oblivious to everything else.

Before very long he became aware of a barely audible scratching sound. It was soon followed by a high-pitched whine. Bobby looked eagerly all about; a strange excitement thrilled his blood, but didn't see anything that could make such a noise.

At last he leaned clear over until his head almost touched the floor and looked under[49] the bed. Way down at the foot of it was something in a basket, that moved. Bobby watched fascinated, hardly daring to breathe. The whining came again. Then the dearest little black nose was lifted above the edge of the basket and two soft brown eyes looked into Bobby's.

Bobby shouted and the puppy yelped at the same instant. Bobby, forgetting that he could walk around the bed, crawled under it. The puppy tried just as hard to come to him. It managed to get half way out of the basket when Bobby's face came down against its black nose. Puppy and boy mingled affection and gratitude.

The puppy's ugly face and wide-apart bow-legs were at that moment the most beautiful things in the world to Bobby. Even birthdays were forgotten and he hugged and patted that worshipping creature for a long, long time before recollection of the Lady Who Likes Little Boys caused him to crawl hastily out from under the bed, burst through the door, and tear wildly downstairs to the red room, the puppy clutched to his heart.

The Man with the Pocketful of Quarters sat at the table in the corner, talking to the Lady. They both looked up.

"Well, son, is that what you want most?"

"Yes'm," smiled Bobby. "Is it all mine?"

"Head, body and tail," replied the man.

"It knew me!" exulted Bobby.

The man and the lady exchanged laughs.

"He's all boy," said the man. "Made of the right stuff."

The lady patted the man's shoulder and looked away.

"Come here, son, and tell me what you think about birthdays."

Bobby marched close up to the man.

"Wish it was mine."

The wistful note in his voice made the lady's hands fly out to him.

"Oh, you like it, do you?" asked the man. "Well, this birthday has only just started."

"Yes'm," said Bobby and hugged the squirming puppy till it licked his ear.

"Here's another quarter for you. That's four quarters—quite a sum for a small boy."

Bobby took one hand off the puppy long enough to accept the quarter.

"What have you done with the others, Bobby?" asked the lady.

He fished them out of the pocket of his blouse and held all four out in the palm of his hand.

"That makes a dollar, son. That's a whole lot of money for a boy only five years old."

That set Bobby to wondering.

"Is it lots of money for a little boy with seven birthdays?" he asked.

"You can just bet your boots it is. A boy can buy all sorts of things with a dollar."

As he spoke, the man pulled a great, round white piece of money out of his pocket, thereby revealing to Bobby that his pockets contained other things besides quarters, and making him forget that four quarters is an awful lot of money even for a boy with seven birthdays.

"Know what this is?" asked the man.

"Money," replied Bobby.

"How much money?"

"A grown-up quarter," hazarded Bobby at length.

"It's a dollar," replied the man, "and is worth just as much as the four quarters. Would you rather have your money all in one piece? I'll give you the dollar for the four quarters."

Bobby hesitated in perplexity and the Lady came to his rescue.

"Take the big piece, Bobby. It's not so easy to lose and easier to find if you do lose it."

Bobby obediently exchanged the four quarters for the dollar despite the frantic efforts of the puppy to see what was going on. The dollar was heavy in his hand and it was very thick. Bobby felt quite wealthy, able to buy all sorts of things, an edge-cation or . . . or perhaps even birthdays! His eyes grew big and round.

The Man with the Pocketful of Quarters had just said a moment before that a boy could buy all sorts of things with a dollar. And a dollar is lots of money even to a boy with seven birthdays! In his excitement[53] Bobby almost dropped the puppy, retaining his hold on that delight by one leg only. His eyes sparkled with the intensity of the desire lighted in them.

"Is it enough to buy a birthdays?" he asked, stammering in his eagerness.

The lady gasped at the question and the man was too staggered to do anything at first; finally he exploded into that huge laughter which always seemed to Bobby to fill the room. He didn't mind the laughter for he knew the man was not making fun of him.

"I don't know, Bobby," said the man when he had stopped laughing. "I've never heard of anybody selling his birthday. You might try and see."

Bobby turned at once to the Lady Who Likes Little Boys.

"Your little boy ain't not never coming back," he fairly stammered in his excitement. "Would he sell me a birthdays?"

And he held out the round, shining dollar.

The lady shrank back from him and went suddenly all white. Bobby knew he had done something wrong, but couldn't for the life of him imagine what it was.

The father of the boy with seven birthdays went quickly to his wife.

"He's got grit and perseverance," said the man. "A birthday looks good to him and he won't give up till he gets one. It would make him happy as a king, Alice."

She hid her face on his shoulder.

"I can't, Alfred. Don't ask that."

Bobby didn't understand what it was she couldn't do, but felt that he had in some way hurt her and his lower lip began to move unsteadily.

"It's only day-after-tomorrow, Alice," pleaded the man.

"It's Edward's," replied the Lady. "You have no heart or you couldn't. . . ."

The man looked at Bobby and then said in a low voice to his wife:

"Day-after-tomorrow is never to-day."

Bobby's heart smote him anew, for he saw water running down the Lady's face as she lifted her head. It had all been caused by his wanting a birthdays. Very well, he would pretend he didn't want a birthdays any more; then perhaps the water would go out of the Lady's eyes.

"Don't want a birthdays," he announced with a suspicious dolefulness in his voice. "It doesn't not feel good."

"Look at him, Alice," said the man.

Bobby didn't want the Lady to see the[55] water in his eyes, so he tried to rub it out, but the tightly clutched dollar got in the way, and the lady must have seen what he was doing, for she simply rushed at Bobby and gathered him, puppy, dollar and all, into her arms and kissed him forty or a dozen times and held his face against her wet cheek.

"Birthdays can't be bought, Bobby, but you shall have one all of your very own. I'll give you one."

"Don't not want any," whimpered Bobby.

"Not if I give you one?" asked the lady, wiping the water out of her eyes. "We'll give you our little boy's."

Bobby kept perfectly still and in that stillness a miracle was performed; that trembling lip of his, without stopping its trembling, was transformed into a joyful smile. And when the Lady saw it, she smiled too.

"I've been selfish and . . . rebellious," said her sweet, low voice right at his ear, but she was looking up at the Man with the Pocketful of Quarters when she said it.

The man blew his nose and made such a loud noise that it startled Bobby and the Lady. They looked into one another's face and then began to smile like persons sharing a happy secret that no one else knew.

"I'll draw it up on paper, son," said the man, "and then if you ever lose it again, whoever finds the paper will know that birthday belongs to you and return it."

He went to the writing desk in one corner of the room, took paper, pen and ink and began to write. When all the water had gone out of the eyes of Bobby and the Lady, they went over to watch the man who was writing away rapidly and smiling to himself.

"There you are," he said at last, with a concluding flourish, and handed the paper to his wife. She smiled as if it hurt her to read what he had written, and pressed Bobby more closely to her.

"Now we must sign it," said the man.

With another flourish, he wrote his name on the paper. His wife's lip trembled just like Bobby's as she signed it. Then the man took Bobby on his lap and guided his hand in making a big cross, and then wrote something himself above and below the mark Bobby made.

"Is that a birthdays?" asked Bobby.

"No," replied the Lady, "it's just proof that we have given you a birthday. If anybody ever doesn't believe you have one, just show him that, and he'll know that you have."

"I'll read it to you, son," said the man and proceeded to read in a big, booming voice:

"Done at Our House this Second Day of August, 1916. We, Alfred and Alice Anning, do hereby and herewith give and convey to Bobby North, Day-After-Tomorrow, which on every Second Day of August becomes To-Day, to be his very own birthday forever. This Day-After-Tomorrow is his fifth birthday; the next one will be his sixth. No one can take this birthday from him because it is ours to give. Whenever Day-After-Tomorrow comes, the aforesaid Bobby North is to have his birthday with a celebration and all the perquisites pertaining thereto. In witness whereof our signatures are herewith attached.

"There, I guess that's all ship-shape and tight enough so water can't leak through," said the man and offered the paper to Bobby. He accepted it gravely, as one should in such important matters, then smiled up at the[58] Lady whose lip still twitched curiously. He looked thoughtfully at the paper in his hand.

"A birthdays and perk—perk—"

"And all the perquisites pertaining thereto," said the man, helping him out.

"What is perk-wizits?" Bobby asked.

"Perk-wizits," replied the man gravely, "are the things that go with birthdays, a celebration, marbles, cake and ice cream, pocket knives, pigs and pups. Why, look at that pup!"

Bobby looked and the puppy had the precious bit of paper in his mouth and was trying to swallow it!

The man opened the puppy's mouth and rescued Bobby's birthdays.

"I was only just in time," he confided to Bobby. "A second later and that dog would have swallowed it. Then where would your birthdays have been?"

Bobby took time to consider. In due course he arrived at a decision.

"Long's the puppy's mine, I'd have the birthdays, too."

He joined in the laughter of his two friends without quite knowing why.

"Keep the paper in your pocket, Bobby. If the dog eats it you couldn't prove to anybody that you had a birthday. Now we are going to continue the celebration."

All day long that celebration lasted and Bobby was so happy and excited and had so many good things to eat and so many wonderful things to do that he didn't know where the hours had gone when the man said the day was almost over and that it was time to take him back to Mr. Eller's.

The Lady Who Likes Little Boys took Bobby into the house to get him ready while the man was bringing the 'mobile out to the gate. The car was waiting long before the Lady had Bobby ready. She was very slow about it; first she held him tight and ran her fingers through his hair; then she put his hat on, and took it off to smooth his hair again. Next she brushed his clothes. Finally she put the puppy in his arms and gathered up all the presents which Bobby was to take with him.

There came a sudden honking from the[61] waiting 'mobile, the Lady hastily kissed Bobby, put on his hat for the last time, and led him out of the house. She helped Bobby into the car and very slowly arranged his presents about him in the back seat. Then, reluctantly, she closed the door.

"Aren't you coming with us, Alice?" asked the man. "The ride will do you good."

"No," she replied, "the day is over for me.

"Why, the sun hasn't not gone to bed—quite," said Bobby, for the edge of the round, red ball in the West had not yet touched the horizon.

"All right, son, we're off," said the man and honked the horn, and the wheels began to go slowly 'round.

"Wait, Alfred!" called his wife in an unsteady voice and her hands went out quickly towards Bobby.

The 'mobile came to a sudden stop, the Lady opened the door and snatched Bobby out and to her breast.

"I can't let you go, Bobby. They wouldn't celebrate your birthday at the Home. They wouldn't know how."

"I'm afraid it wouldn't be much like a birthday there; not after this one," said the man.

The Lady put Bobby down and he seized the opportunity to readjust his hold on the puppy and to look into his blouse pocket to see if the precious bit of paper was still there.

"May I, Alfred?" he heard the Lady Who Likes Little Boys saying to the man in the 'mobile.

"Alice!" cried the man. "I love you a thousand times better than ever!"

That seemed a very funny sort of answer to Bobby; there was no sense in it. He looked up and found the Lady's arms held out to him.

"Bobby, would you like to stay with us and be my little boy? Then, every year when your birthday comes, we could celebrate it together."

Bobby's eyes glistened. He looked from her to the man and back again. They were both smiling at him.

"Will you be my mothers, then?"

"Yes, dear, I'll be your mother."

Then, forgetting all about the puppy, which fell to the ground with a surprised little yelp, Bobby rushed to the Lady Who Likes Little Boys and threw his arms passionately about her neck as she knelt to receive him. They both squeezed just as[63] hard as they could and the Lady laughed and cried and then laughed again.

Bobby sighed with complete happiness. He had found a birthdays and already that magical thing was bringing him all sorts of presents—puppies and perk-wizits and "glassies" and mothers and perhaps curly-tailed little pigs to buy him an edge-cation. He hugged the Lady again.

"Well, son, you seem to like mothers."

Bobby looked up and saw that the Man with the Pocketful of Quarters had climbed out of the 'mobile and was standing over them.

"Yes'm," replied Bobby and twined his fingers in the soft hair at the back of the Lady's neck.

"And fathers, too?" smiled the lady.

Bobby drew back and looked at her with shining eyes.

"Have I fathers, too?"

"Yes, dear. You will love him because he likes little boys, too."

Bobby thought that over, then looked up with a shy smile at the man.

"The Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy?" he asked.

"No, dear," said his mothers, "not that man—The Man with the Pocketful of[64] Quarters. Will you shake hands with him?"

"Why he's the Man Who Lets You Play with the Puppy, too!" said Bobby, anticipating the fact.

"Already he's found me out!" laughed the man.

Smilingly, Bobby held out his hand to his fathers.

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

Page 32, "did'nt" changed to "didn't" (I didn't think about)

Page 52, "and" changed to "an" (things, an edge-cation)

Page 53, "fathers" changed to "father" (The father of the boy)