The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of Opal, by Opal Whiteley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Story of Opal

The Journal of an Understanding Heart

Author: Opal Whiteley

Contributor: Ellery Sedgwick

Release Date: September 26, 2013 [EBook #43818]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF OPAL ***

Produced by Marie Bartolo from page images made available

by the Internet Archive: American Libraries

The Story of Opal

The Journal of

An Understanding Heart

With Illustrations

The Atlantic Monthly Press

Boston

Copyright, 1920, by The Atlantic Monthly Company

Copyright, 1920, by the Atlantic Monthly Press

All rights reserved

For those whom Nature loves, the Story of Opal is an open book. They need no introduction to the journal of this Understanding Heart. But the world, which veils the spirit and callouses the instincts, makes curiosity for most people the criterion of interest. They demand facts and backgrounds, theories and explanations, and for them it seems worth while to set forth something of the child’s story undisclosed by the diary, and to attempt to weave together some impressions of the author.

Last September, late one afternoon, Opal Whiteley came into the Atlantic’s office, with a book which she had had printed in Los Angeles. It was not a promising errand, though it had brought her all the way from the Western coast, hoping to have published in regular fashion this volume, half fact, half fancy, of The Fairyland Around Us, the fairyland of beasts and blossoms, butterflies and birds. The book was quaintly embellished with colored pictures, pasted in by hand, and bore a hundred marks of special loving care. Yet about it there seemed little at first sight to tempt a publisher. Indeed, she had offered her wares in vain to more than one publishing house; and as her dollars were growing very few, the disappointment was severe. But about Opal Whiteley herself there was something to attract the attention even of a man of business—something very young and eager and fluttering, like a bird in a thicket.

The talk went as follows:—

“I am afraid we can’t do anything with the book. But you must have had an interesting life. You have lived much in the woods?”

“Yes, in lots of lumber-camps.”

“How many?”

“Nineteen. At least, we moved nineteen times.”

It was hard not to be interested now. One close question followed another regarding the surroundings of her girlhood. The answers were so detailed, so sharply remembered, that the next question was natural.

“If you remember like that, you must have kept a diary.”

Her eyes opened wide. “Yes, always. I do still.”

“Then it is not the book I want, but the diary.”

She caught her breath. “It’s destroyed. It’s all torn up.” Tears were in her eyes.

“You loved it?”

“Yes; I told it everything.”

“Then you kept the pieces.”

The guess was easy (what child whose doll is rent asunder throws away the sawdust?), but she looked amazed.

“Yes, I have kept everything. The pieces are all stored in Los Angeles.”

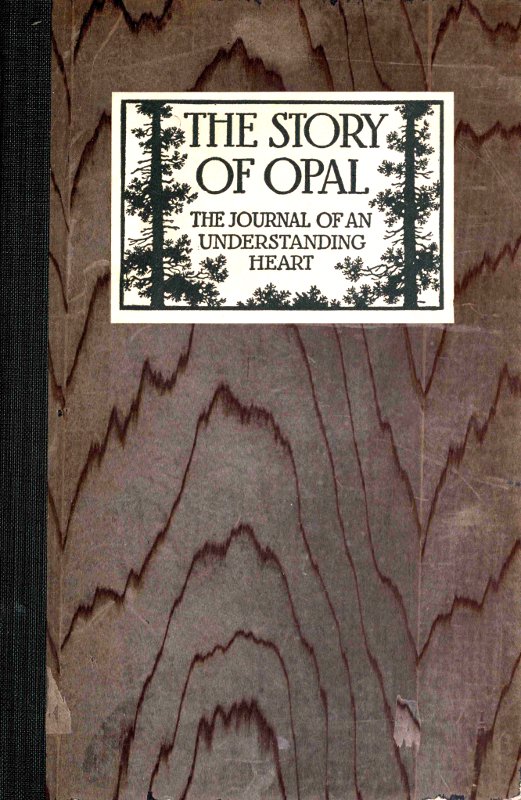

We telegraphed for them, and they came, hundreds, thousands, one might almost say millions of them. Some few were large as a half-sheet of notepaper; more, scarce big enough to hold a letter of the alphabet. The paper was of all shades, sorts, and sizes: butchers’ bags pressed and sliced in two, wrapping-paper, the backs of envelopes—anything and everything that could hold writing. The early years of the diary are printed in letters so close that, when the sheets are fitted, not another letter can be squeezed in. In later passages the characters are written with childish clumsiness, and later still one sees the gradually forming adult hand.

The labor of piecing the diary together may fairly be described as enormous. For nine months almost continuously the diarist has labored, piecing it together sheet by sheet, each page a kind of picture-puzzle, lettered, for frugality (the store was precious), on both sides of the paper.

The entire diary, of which this volume covers but the two opening years, must comprise a total of a quarter of a million words. Upwards of seventy thousand—all that is contained in this volume—can be ascribed with more than reasonable definiteness to the end of Opal’s sixth and to her seventh year. During all these months Opal Whiteley has been a frequent visitor in the Atlantic’s office. With friendliness came confidence, and little by little, very gradually, an incident here, another there, her story came to be told. She was at first eager only for the future and for the opportunity to write and teach children of the world which she loved best. But as the thread of the diary was unraveled, she felt a growing interest in what her past had been, and in what lay behind her earliest recollections and the opening chapters of her printed record.

Her methods were nothing if not methodical. First, the framework of a sheet would be fitted and the outer edges squared. Here the adornment of borders in childish patterns, and the fortunate fact that the writer had employed a variety of colored crayons, using each color until it was exhausted, lent an unhoped-for aid. Then, odd sheets were fitted together; later, fragments of episodes. Whenever one was completed, it was typed by an assistant on a card, and in this way there came into being a card-system that would do credit to a scientific museum of modest proportions. Finally the cards were filed in sequence, the manuscript then typed off and printed just as at first written, with no change whatever other than omissions, the adoption of reasonable rules of capitalization (the manuscript for many years has nothing but capitals), and the addition of punctuation, of which the manuscript is entirely innocent. The spelling—with the exception of occasional characteristic examples of the diarist’s individual style—has, in the reader’s interest, been widely amended.

Opal Whiteley—so her story runs—was born about twenty-two years ago—where, we have no knowledge. Of her parents, whom she lost before her fifth year, she is sure of nothing except that they loved her, and that she loved them with a tenacity of affection as strong now as at the time of parting. To recall what manner of people they were, no physical proof remains except, perhaps, two precious little copybooks, which held their photographs and wherein her mother and father had set down things which they wished their little daughter to learn, both of the world about her and of that older world of legend and history, with which the diarist shows such capricious and entertaining familiarity. These books, for reasons beyond her knowledge, were taken away from Opal when she was about twelve years of age, and have never been returned, although there is ground for believing that they are still in existence.

Other curious clues to the identity of her father and mother come from the child’s frequent use of French expressions, and sometimes of longer passages in French, and from her ready use of scientific terms. It is, perhaps, a fair inference that her father was a naturalist by profession or native taste, and that either he or her mother was French by birth or by education.

After her parents’ death, there is an interlude in Opal’s recollection which she does not understand, remembering only that for a brief season the sweet tradition of her mother’s care was carried on by an older woman, possibly a governess, from whom, within a year, she was taken and, after recovering from a serious illness, given to the wife of an Oregon lumber-man, lately parted from her first child,—Opal Whiteley,—whose place and name, for reasons quite unknown, were given to the present Opal.

From some time in her sixth year to the present, her diary has continued without serious interruption; and from the [ix]successive chapters we shall see that her life, apart from the gay tranquillity of her spirit, was not a happy one. Her friends were the animals and everything that flies or swims; her single confidant was her diary, to which she confided every trouble and every satisfaction.

When Opal was over twelve years old, a foster-sister, in a tragic fit of childish temper, unearthed the hiding-place of the diary and tore it into a myriad of fragments. The work of years seemed destroyed, but Opal, who had treasured its understanding pages, picked up the pitiful scraps and stored them in a secret box. There they lay undisturbed for many years.

Such in briefest outline is the story Opal told; and month after month, while chapters of the diary were appearing in the Atlantic, snatches of the same history, together with descriptions of many unrecorded episodes, came in the editor’s mail; and though the weaving is of very different texture, the pattern is unmistakably the pattern of the diary. Dates and names, peregrinations and marriages, births, deaths, and adventures less solemn and less apt to be accurately recollected, occurred just as the diary tells them. The existence of the diary itself was well remembered, though for many years Opal had never spoken of it; a friend recalled the calamitous day when the abundant chronicle of six years was destroyed; and a cloud of witnesses bore testimony to the multitudinous family of pets, and some even to the multicolored names they bore. There were many letters besides, which came not to the Atlantic at all, but were part of Opal’s own correspondence with people “of understanding,” members by instinct of that free-masonry which, as she learned long ago, binds folk of answering hearts and minds. Many of these letters (which rest for safety in the Atlantic’s treasury) are messages of thanks for copies of that first book of Opal’s—[x]engaging letters, very personal most of them, bearing signatures to delight the eyes of collectors of autographs: M. Clemenceau, M. Poincaré, Lord Rayleigh, Lord Curzon, members of the French cabinet, scientists, men of letters, men of achievement. Opal has sought her friends all through the world; but her lantern is bright and she has found them. Her old Oregon teachers also have been quick to bear witness to her talents, and to recall the formal lessons which often she would not remember, and the other more necessary lessons which she could not forget. They would ask too whence came the French which they had never taught her. An attempt to answer that would take us far afield. All we need do here is to recall that first time, when Opal, full of puzzlement over letters that simply would not shape themselves into familiar phrases, turned to her editors and was told that they were French.

“But they can’t be French! I never studied French.”

But French they are, nevertheless.

If the story of Opal were written by another hand than her own, the central theme of it would be faith. No matter how doubtful the enterprise, the issue she always holds as certain, simply because the world is good and God loves his children. Loving herself all created things, from her barrel-full of caterpillars, whose evolution she would note and chronicle from day to day, to the dogs and horses, squirrels, raccoons, and bats which peopled the world she lived in, she would thank God daily for them, and very early in her life determined to devote the rest of it to spreading knowledge of them and of their kind far and wide among little children.

To accomplish this, needed education, and an education she would have. Those about her showed no interest; but by picking berries, washing, and work of all rough sorts, Opal paid for the books which the high school required. But she [xi]must do more than this. She must go to college. To the State University she went, counting it nothing that she should live in a room without furniture other than a two-dollar cot, and two coats for blankets. Family conditions, however, made college impossible for her. After the illness and death of Mrs. Whiteley, Opal borrowed a little money from friends in Cottage Grove, Oregon, and started alone for Los Angeles, determined to seek her livelihood by giving nature lessons to classes of children.

The privations and disappointments of the next two years would make an heroic tale; but she persevered, and her classes became successful. The next step was her nature book, for which, by personal canvass for subscriptions, she raised not less than the prodigious sum of $9400. But the printers with a girl for a client, demanded more and still more money, and when the final $600 necessary to make the booty mount to $10,000 was not forthcoming, with a brutality that would do credit to a Thénardier, first threatened, and then destroyed the plates.

A struggle for mere existence followed, but gradually Opal triumphed, when she was overtaken by a serious illness and taken to the hospital. New and merciful friends, such as are always conjured up by such a life as Opal’s, came to her assistance, and after her recovery she soon started eastward, to find a publisher for her ill-fated volume. The rest we know.

Yet, after all, our theme should not be Opal, but Opal’s book. She is the child of curious and interesting circumstance, but of circumstance her journal is altogether independent. The authorship does not matter, nor the life from which it came. There the book is. Nothing else is like it, nor apt to be. If there is alchemy in Nature, it is in children’s hearts the unspoiled treasure lies, and for that room of the treasure-house, the Story of Opal offers a tiny golden key.

Ellery Sedgwick.

The Atlantic Office, June, 1920.

How Opal Goes along the Road beyond the Singing Creek, and of all she Sees in her New Home 5

How Lars Porsena of Clusium Got Opal into Trouble, and how Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael and Sadie McKibben Gave her Great Comfort 9

Of the Queer Feels that Came out of a Bottle of Castoria, and of the Happiness of Larry and Jean 14

How Peter Paul Rubens Goes to School 21

How Opal Comforted Aphrodite, and how the Fairies Comforted Opal when there Was Much Sadness at School 25

Opal Gives Wisdom to the Potatoes, Cleanliness to the Family Clothes, and a Delicate Dinner to Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus 35

The Adventure of the Tramper; and what Happens on Long and on Short Days 47

How Opal Takes a Walk in the Forest of Chantilly; she Visits Elsie and her Baby Boy, and Explains Many Things to the Girl that Has no Seeing 55

Of an Exploring Trip with Brave Horatius; and how Opal Kept Sadness away from her Animal Friends 69

How Brave Horatius is Lost and Found again, but Peter Paul Rubens is Lost Forever 75

How Opal Took the Miller’s Brand out of the Flour-Sack, and Got Many Sore Feels thereby; and how Sparks Come on Cold Nights; and how William Shakespeare Has Likings for Poems 81

Of Elsie’s Brand-New Baby, and all the Things that Go with it; and the Goodly Wisdom of the Angels, who Bring Folks Babies that Are like them 91

How Felix Mendelssohn and Lucian Horace Ovid Virgil Go for a Ride; William Shakespeare Suffers One Whipping and Opal Another 100

How Opal Feels Satisfaction Feels, and Takes a Ride on William Shakespeare; and all that Came of it 104

Of Jenny Strong’s Visit, its Gladness and its Sadness 114

Of the Woods on a Lonesome Day, and the Friendliness of the Wood-Folks on December Days when you Put your Ears Close and Listen 122

Of Works to be Done; and how it Was that a Glad Light Came into the Eyes of the Man who Wears Gray Neckties and Is Kind to Mice 127

How Opal Pays One Visit to Elsie and Another to Dear Love, and Learns how to Mend her Clothes in a Quick Way 131

Of the Camp by the Mill by the Far Woods; of the Spanking that Came from the New Way of Mending Clothes; and of the Long Sleep of William Shakespeare 138

Of the Little Song-Notes that Dance about Babies; and of the Solemn Christening of Solomon Grundy 146

How Opal Names Names of the Lambs of Aidan of Iona, and Seeks for the Soul of Peter Paul Rubens 158

How Solomon Grundy Falls Sick and Grows Well again; and Minerva’s Chickens are Christened; and the Pensée Girl, with the Far-Away Look in her Eyes, Finds Thirty-and-Three Bunches of Flowers 165

How Opal and Brave Horatius Go on Explores and Visit the Hospital.—How the Mamma Dyes Clothes and Opal Dyes Clementine 177

How the Mamma’s Wish Came True, and how Opal was Spanked for it; and of the Likes which Aphrodite Had for a Clean Place to Live in 185

Of Many Washings and a Walk 193

Why it Was that the Girl who Has no Seeing Was not at Home when Opal Called 197

Of a Cathedral Service in the Pig-Pen.—How the World Looks from a Man’s Shoulder 204

How Opal Piped with Reeds, and what a Good Time Dear Love Gave Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus 212

How Opal Feels the Heat of the Sun, and Decorates a Goodly Number of the White Poker-Chips of the Chore Boy 218

How Opal and the Little Birds from the Great Tree Have a Happy Time at the House of Dear Love 226

How Lola Wears her White Silk Dress at Last 231

Of the Ways that Fairies Write, and the Proper Way to Drink in the Song of the Wood 234

Of the Death of Lars Porsena of Clusium, and of the Comfort that Sadie McKibben can Give 242

Of the Fall of the Great Tree, and the Funeral of Aristotle 249

How the Man of the Long Step that Whistles Most of the Time Takes an Interesting Walk 253

Of Taking-Egg Day, and the Remarkable Things that Befell thereon 259

Of the Strange Adventure in the Woods on the Going-Away Day of Saint Louis 270

How Opal Makes Prepares to Move. How she Collects all the Necessary Things, Bids Good-bye to Dear Love, and Learns that her Prayer has been Answered 275

The Story of Opal

The Journal of

An Understanding Heart

THE STORY OF OPAL

Of the days before I was taken to the lumber camps there is little I remember. As piece by piece the journal comes together, some things come back. There are references here and there in the journal to things I saw or heard or learned in those days before I came to the lumber camps.

There were walks in the fields and woods. When on these walks, Mother would tell me to listen to what the flowers and trees and birds were saying. We listened together. And on the way she told me poems and other lovely things, some of which she wrote in the two books and also in others which I had not with me in the lumber camps. On the walks, and after we came back, she had me to print what I had seen and what I had heard. After that she told me of different people and their wonderful work on earth. Then she would have me tell again to her what she had told me. After I came to the lumber camp, I told these things to the trees and the brooks and the flowers.

There were five words my mother said to me over and over again, as she had me to print what I had seen and what I had heard. These words were: [2]What, Where, When, How, Why. They had a very great influence over all my observations and the recording of those observations during all the days of my childhood. And my Mother having put such strong emphasis on these five words accounts for much of the detailed descriptions that are throughout my diary.

No children I knew. There were only Mother and the kind woman who taught me and looked after me and dressed me, and the young girl who fed me. And there was Father in those few days when he was home from the far lands. Those were wonderful days—his home-coming days. Then he would take me on his knee and ride me on his shoulder and tell me of the animals and birds of the far lands. And we went for many walks, and he would talk to me about the things along the way. It was then he taught me comparer.

There was one day when I went with Mother in a boat. It was a little way on the sea. It was a happy day. Then something happened and we were all in the water. Afterward, when I called for Mother, they said the sea waves had taken her and she was gone to heaven. I remember the day because I never saw my Mother again.

The time was not long after that day with Mother in the boat, when one day the kind woman who taught me and took care of me did tell me gently that Father too had gone to heaven while he was away in the far lands. She said she was going to [3]take me to my grandmother and grandfather, the mother and father of my Father.

We started. But I never got to see my dear grandmother and grandfather, whom I had never seen. Something happened on the way and I was all alone. And I did n’t feel happy. There were strange people that I had never seen before, and I was afraid of them. They made me to keep very still, and we went for no walks in the field. But we traveled a long, long way.

Then it was they put me with Mrs. Whiteley. The day they put me with her was a rainy day, and I thought she was a little afraid of them too. She took me on the train and in a stage-coach to the lumber camp. She called me Opal Whiteley, the same name as that of another little girl who was the same size as I was when her mother lost her. She took me into the camp as her own child, and so called me as we lived in the different lumber camps and in the mill town.

With me I took into camp a small box. In a slide drawer in the bottom of this box were two books which my own Mother and Father, the Angel Father and Mother I always speak of in my diary, had written in. I do not think the people who put me with Mrs. Whiteley knew about the books in the lower part of the box, for they took everything out of the top part of the box and tossed it aside. I picked it up and kept it with me, and, being as I was more quiet with it in my arms, they [4]allowed me to keep it, thinking it was empty. These books I kept always with me, until one day I shall always remember, when I was about twelve years old, they were taken from the box I kept then hid in the woods. Day by day I spelled over and over the many words that were written in them. From them I selected names for my pets. And it was the many little things recorded there that helped me to remember what my Mother and Father had already told me of different great lives and their work; and these books with these records made me very eager to be learning more and more of what was recorded in them. These two books I studied much more than I did my books at school. Their influence upon my life has been great.

To-day the folks are gone away from the house we do live in. They are gone a little way away, to the ranch-house where the grandpa does live. I sit on our steps and I do print. I like it—this house we do live in being at the edge of the near woods. So many little people do live in the near woods. I do have conversations with them. I found the near woods first day I did go explores. That was the next day after we were come here. All the way from the other logging camp in the beautiful mountains we came in a wagon. Two horses were in front of us. They walked in front of us all the way. When first we were come, we did live with some other people in the ranch-house that was n’t all builded yet. After that we lived in a tent, and often when it did rain many raindrops came right through the tent. They did fall in patters on the stove and on the floor and on the table. Too, they did make the quilts on the beds some damp—but that did n’t matter much because they soon got dried hanging around the stove.

By and by we were come from the tent to this lumber shanty. It has got a divide in it. One room we do have sleeps in. In the other room we do [6]have breakfast and supper. Back of the house are some nice wood-rats. The most lovely of them all is Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus. By the wood-shed is a brook. It goes singing on. Its joy song does sing in my heart. Under the house live some mice. I give them bread-scraps to eat. Under the steps lives a toad. He and I—we are friends. I have named him. I call him Lucian Horace Ovid Virgil.

Between the ranch-house and the house we live in is the singing creek where the willows grow. We have conversations. And there I do dabble my toes beside the willows. I feel the feels of gladness they do feel. And often it is I go from the willows to the meeting of the road. That is just in front of the ranch-house. There the road does have divides. It goes three ways. One way the road does go to the house of Sadie McKibben. It does n’t stop when it gets to her house, but mostly I do. The road just goes on to the mill town a little way away. In its going it goes over a hill. Sometimes—the times Sadie McKibben is n’t at home—I do go with Brave Horatius to the top of the hill. We look looks down upon the mill town. Then we do face about and come again home. Always we make stops at the house of Sadie McKibben. Her house—it is close to the mill by the far woods. That mill makes a lot of noise. It can do two things at once. It makes the noises and also it does saw the logs into boards. About the mill do live some people, mostly [7]men-folks. There does live the good man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice.

Another way, the road does go the way I go when I go to the school-house where I go to school. When it is come there, it does go right on—on to the house of the girl who has no seeing. When it gets to her house, it does make a bend, and it does go its way to the blue hills. As it goes, its way is near unto the way of the rivière that sings as it comes from the blue hills. There are singing brooks that come going to the rivière. These brooks—they and I—we are friends. I call them Orne and Loing and Yonne and Rille and Essonne.

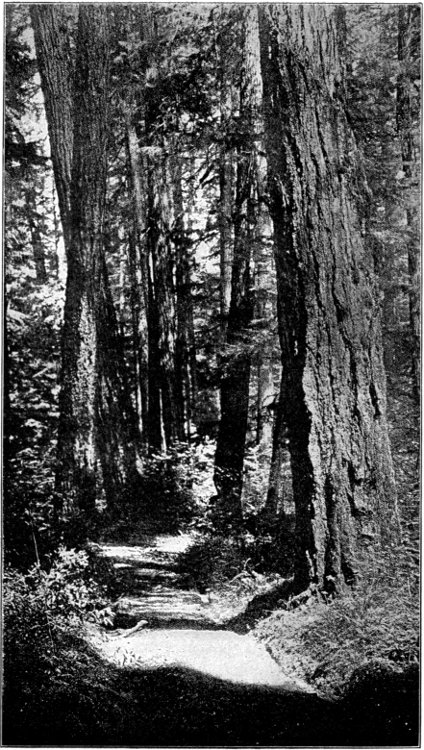

Near unto the road, long ways between the brooks, are ranch-houses. I have not knowing of the people that do dwell in them. But I do know some of their cows and horses and pigs. They are friendly folk. Around the ranch-houses are fields. Woods used to grow where now grows grain. When the mowers cut down the grain, they also do cut down the cornflowers that grow in the fields. I follow along after and I do pick them up. Of some of them I make a guirlande. When the guirlande is made, I do put it around the neck of William Shakespeare. He does have appreciations. As we go walking down the lane, I do talk with him about the one he is named for. And he does have understanding. He is such a beautiful gray horse, and his ways are ways of gentleness. Too, he does have likings like the likings I have for the hills that are [8]beyond the fields—for the hills where are trails and tall fir trees like the wonderful ones that do grow by the road.

So go two of the roads. The other road does lead to the upper logging camps. It goes only a little way from the ranch-house and it comes to a rivière. Long time ago, this road did have a longing to go across the rivière. Some wise people did have understandings and they did build it a bridge to go across on. It went across the bridge and it goes on and on between the hills—the hills where dwell the talking fir trees. By its side goes the railroad track. Its appears are not so nice as are the appears of the road, and it has got only a squeaky voice. But this railroad track does have shining rails—they stretch away and away, like a silver ribbon that came from the moon in the night. I go a-walking on these rails. I get off when I do hear the approaches of the dinky engine. On this track on every day, excepting Sunday, comes and goes the logging train. It goes to the camps and it does bring back cars of logs and cars of lumber. These it does take to the mill town. There engines more big do take the cars of lumber to towns more big.

Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus has been waiting in my sunbonnet a long time. He wants to go on explores. Too, Brave Horatius and Isaiah are having longings in their eyes. And I hear Peter Paul Rubens squealing in the pig-pen. Now I go. We go on explores.

To-day was a warm, hot day. It was warm in the morning and hot at noon. Before noon and after noon and after that, I carried water to the hired men in the field in a jug. I got the water out of the pump to put into the jug. I had to put water in the pump before any would come out. The men were glad to have that water in the jug.

While I was taking the water in the jug to the men in the field, from her sewing-basket Lars Porsena of Clusium took the mamma’s thimble, and she did n’t have it and she could n’t find it. She sent me to watch out for it in the house and in the yard and everywhere. I know how Lars Porsena of Clusium has a fondness for collecting things of bright colors, like unto my fondness for collecting rocks; so I ran to his hiding-place in the old oak tree. There I found the mamma’s thimble; but she said the pet crow’s having taken it was as though I had taken it, because he was my property; so I got a spanking with the hazel switches that grow near unto our back steps. Inside me I could n’t help feeling she ought to have given me thanks for finding the thimble.

Afterwards I made little vases out of clay. I put them in the oven to bake. The mamma found my vases of clay. She threw them out the window. When I went to pick them up, they were broken. I felt sad inside. I went to talk things over with my chum, Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael. He is that most tall fir tree that grows just back of the barn. I scooted up the barn door. From there I climbed onto the lower part of the barn roof. I walked up a ways. Up there I took a long look at the world about. One gets such a good wide view of the world from a barn roof. After, I looked looks in four straight ways and four corner ways. I said a little prayer. I always say a little prayer before I jump off the barn into the arms of Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael, because that jump is quite a long jump, and if I did not land in the arms of Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael, I might get my leg or neck broken. That would mean I’d have to keep still a long time. Now I think that would be the most awful thing that could happen, for I do so love to be active. So I always say a little prayer and do that jump in a careful way. To-day, when I did jump, I did land right proper in that fir tree. It is such a comfort to nestle up to Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael when one is in trouble. He is such a grand tree. He has an understanding soul.

After I talked with him and listened unto his voice, I slipped down out of his arms. I intended to slip into the barn corral, but I slid off the wrong [11]limb in the wrong way. I landed in the pig-pen on top of Aphrodite, the mother-pig. She gave a peculiar grunt. It was not like those grunts she gives when she is comfortable.

I felt I ought to do something to make up to her for having come into her home out of the arms of Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael instead of calling on her in the proper way. I decided a good way to make it up to her would be to pull down the rail fence in that place where the pig-pen is weak, and take her for a walk. I went to the wood-shed. I got a piece of clothes-line rope. While I was making a halter for the mother-pig, I took my Sunday-best hair-ribbon—the blue ribbon the Uncle Henry gave to me. I made a bow on that halter. I put the bow just over her ears. That gave her the proper look. When the mamma saw us go walking by, she took the bow from off the pig. She put that bow in the trunk; me she put under the bed.

By-and-by—some time long it was—she took me from under the bed and gave me a spanking. She did not have time to give me a spanking when she put me under the bed. She left me there until she did have time. After she did it she sent me to the ranch-house to get milk for the baby. I walked slow through the oak grove, looking for caterpillars. I found nine. Then I went to the pig-pen. The chore boy was fixing back the rails I had pulled down. His temper was quite warm. He was saying prayer words in a very quick way. I went not near [12]unto him. I slipped around near Michael Angelo Sanzio Raphael. I peeked in between the fence-rails. Aphrodite was again in the pig-pen. She was snoozing, so I tiptoed over to the rain-barrel by the barn. I raised mosquitoes in the rain-barrel for my pet bats. Aristotle eats more mosquitoes than Plato and Pliny eat.

On my way to the house I met Clementine, the Plymouth Rock hen, with her family. She only has twelve baby chickens now. The grandpa say the other one she did have died of new monia because I gave it too many baths for its health. When I came to the house one of the cats, a black one, was sitting on the doorstep. I have not friendly feelings for that big black cat. Day before the day that was yesterday I saw him kill the mother hummingbird. He knocked her with his paw when she came to the nasturtiums. I did n’t even speak to him.

Just as I was going to knock on the back door for the milk, I heard a voice on the front porch. It was the voice of a person who has an understanding soul. I hurried around to the front porch. There was Sadie McKibben with a basket on her arm. She beamed a smile at me. I went over and nestled up against her blue gingham apron with cross stitches on it. The freckles on Sadie McKibben’s wrinkled face are as many as are the stars in the Milky Way, and she is awful old—going on forty. Her hands are all brown and cracked like the dried-up mud-puddles [13]by the roadside in July, and she has an understanding soul. She always has bandages ready in her pantry when some of my pets get hurt. There are cookies in her cookie-jar when I don’t get home for meals, and she allows me to stake out earthworm claims in her back yard.

[Photograph: A SPECIMEN PAGE OF OPAL’S DIARY WRITTEN ON A PAPER BAG]

She walked along beside me when I took the milk home. When she came near the lane, she took from her basket wrapping-papers and gave them to me to print upon. Then she kissed me good-bye upon the cheek and went her way to her home. I went my way to the house we live in. After the mamma had switched me for not getting back sooner with the milk, she told me to fix the milk for the baby. The baby’s bottle used to be a brandy bottle, but it evoluted into a milk bottle when they put a nipple onto it.

I sit here on the doorstep printing this on the wrapping-paper Sadie McKibben gave me. The baby is in bed asleep. The mamma and the rest of the folks is gone to the ranch-house. When they went away, she said for me to stay in the doorway to see that nothing comes to carry the baby away. By the step is Brave Horatius. At my feet is Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus. I hear songs—lullaby songs of the trees. The back part of me feels a little bit sore, but I am happy listening to the twilight music of God’s good world. I’m real glad I’m alive.

A SPECIMEN PAGE OF OPAL’S DIARY WRITTEN ON A PAPER BAG [Return to text]

The colic had the baby to-day, and there was no Castoria for the pains; there was none because yesterday Pearl[1] and I climbed upon a chair and then upon the dresser and drank up the new bottle of Castoria; but the bottle had an ache in it and we swallowed the ache with the Castoria. That gave us queer feels. Pearl lay down on the bed. I did rub her head. But she said it was n’t her head—it was her back that hurt. Then she said it was her leg that ached. The mamma came in the house then, and she did take Pearl in a quick way to the ranch-house.

[1] A foster-sister.

It was a good time for me to go away exploring, but I did n’t feel like going on an exploration trip. I just sat on the doorstep. I did sit there and hold my chin in my hand. I did have no longings to print. I only did have longings not to have those queer feels. Brave Horatius came walking by. He did make a stop at the doorstep. He wagged his tail. That meant he wanted to go on an exploration trip. Lars Porsena of Clusium came from the oak tree. He did perch on the back of Brave Horatius. He gave two caws. That meant he [15]wanted to go on an exploration trip. Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus came from under the house. He just crawled into my lap. I gave him pats and he cuddled his nose up under my curls. Peter Paul Rubens did squeal out in the pig-pen. He squealed the squeals he does squeal when he wants to go on an exploration trip.

Brave Horatius did wait and wait, but still those queer feels would n’t go away. Pretty soon I got awful sick. By-and-by I did have better feels. And to-day my feels are all right and the mamma is gone a-visiting and I am going on an exploration trip. Brave Horatius and Lars Porsena of Clusium and Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus and Peter Paul Rubens are waiting while I do print this. And now we are going the way that does lead to the blue hills.

Sometimes I share my bread and jam with Yellowjackets, who have a home on the bush by the road, twenty trees and one distant from the garden. To-day I climbed upon the old rail fence close to their home with a piece and a half of bread and jam and the half piece for them and the piece for myself. But they all wanted to be served at once, so it became necessary to turn over all bread and jam on hand. I broke it into little pieces, and they had a royal feast there on the old fence-rail. I wanted my bread and jam; but then Yellowjackets are such interesting fairies, being among the world’s first paper-makers; and baby Yellowjackets are [16]such chubby youngsters. Thinking of these things makes it a joy to share one’s bread and jam with these wasp fairies.

When I was coming back from feeding them I heard a loud noise. That Rob Ryder was out there by the chute, shouting at God in a very quick way. He was begging God to dam that chute right there in our back yard. Why, if God answered his prayer, we would be in an awful fix. The house we live in would be under water, if God dammed the chute. Now I think anger had Rob Ryder or he would not pray kind God to be so unkind.

When I came again to the house we live in, the mamma was cutting out biscuits with the baking-powder can. She put the pan of biscuits on the wood-box back of the stove. She put a most clean dish-towel over the biscuits, then she went to gather in clothes. I got a thimble from the machine drawer. I cut little round biscuits from the big biscuits. The mamma found me. She put the thimble back in the machine drawer. She put me under the bed. Here under the bed I now print.

By-and-by, after a long time, the mamma called me to come out from under the bed. She told me to put on my coat and her big fascinator on my head. She fastened my coat with safety-pins, then she gave me a lard-pail with its lid on tight. She told me to go straight to the grandpa’s house for the milk, and to come straight home again. I started to go straight for the milk. When I came near the [17]hospital, I went over to it to get the pet mouse, Felix Mendelssohn. I thought that a walk in the fresh air would be good for his health. I took one of the safety-pins out of my coat. I pinned up a corner of the fascinator. That made a warm place next to my curls for Felix Mendelssohn to ride in. I call this mouse Felix Mendelssohn because sometimes he makes very sweet music.

Then I crossed to the cornfield. A cornfield is a very nice place, and some days we children make hair for our clothes-pin dolls from the silken tassels of the corn that grow in the grandpa’s cornfield. Sometimes, which is quite often, we break the cornstalks in getting the silk tassels. That makes bumps on the grandpa’s temper.

To-night I walked zigzag across the field to look for things. Into my apron pocket I put bits of little rocks. By a fallen cornstalk I met two of my mouse friends. I gave them nibbles of food from the other apron pocket. I went on and saw a fat old toad by a clod. Mice and toads do have such beautiful eyes. I saw two caterpillars on an ear of corn after I turned the tassels back. All along the way I kept hearing voices. Little leaves were whispering, “Come, petite Françoise,” over in the lane. I saw another mouse with beautiful eyes. Then I saw a man and woman coming across the field. The man was carrying a baby.

Soon I met them. It was Larry and Jean and their little baby. They let me pat the baby’s hand [18]and smooth back its hair, for I do so love babies. When I grow up I want twins and eight more children, and I want to write outdoor books for children everywhere.

To-night, after Larry and Jean started on, I turned again to wave good-bye. I remembered the first time I saw Larry and Jean, and the bit of poetry he said to her. They were standing by an old stump in the lane where the leaves whispered. Jean was crying. He patted her on the shoulder and said:—

And he did. And the angels looking down from heaven saw their happiness and brought a baby real soon, when they had been married most five months; which was very nice, for a baby is such a comfort and twins are a multiplication table of blessings. And Felix Mendelssohn is yet so little a person, and the baby of Larry and Jean is growed more big. On the day I did hear him say to her that poetry—it was then I did find Felix Mendelssohn there in the lane near to them. He was only a wee little mouse then. And every week that he did grow a more week old, I just put one more gray stone in the row of his growing. And there was nineteen more gray stones in the row when the Angels did bring the dear baby to Larry and Jean than there was stones in the row when they was married. And now there are a goodly number more stones in [19]the row of Felix Mendelssohn’s weeks of growing old. I have feels that there will be friendship between the dear mouse Felix Mendelssohn and the dear baby of Larry and Jean. For by the stump where he did say that poetry to her was the abiding place of Felix Mendelssohn when I did have finding of him. This eventime he did snuggle more close by my curls. I have so much likes for him. I did tell him that this night-time he is to have sleeps close by. When we were gone a little way, I did turn again to wave good-bye to the baby of Larry and Jean.

After I waved good-bye to the dear baby, I thought I’d go around by the lane where I first saw them and heard him say to her that poetry. It is such a lovely lane. I call it our lane. Of course, it does n’t belong to Brave Horatius and Lars Porsena of Clusium and Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus and I and all the rest of us. It belongs to a big man that lives in a big house, but it is our lane more than it is his lane, because he does n’t know the grass and flowers that grow there, and the birds that nest there, and the lizards that run along the fence, and the caterpillars and beetles that go walking along the roads made by the wagon wheels. And he does n’t stop to talk to the trees that grow all along the lane.

All those trees are my friends. I call them by names I have given to them. I call them Hugh Capet and Saint Louis and Good King Edward I; [20]and the tallest one of all is Charlemagne, and the one around where the little flowers talk most is William Wordsworth, and there are Byron and Keats and Shelley. When I go straight for the milk, I do so like to come around this way by the lane and talk to these tree friends. I stopped to-night to give to each a word of greeting. When I got to the end of the lane, I climbed the gate and thought I had better hurry straight on to get the milk.

When I went by the barn, I saw a mouse run around the corner and a graceful bat came near unto the barn-door. I got the milk. It was near dark time, so I came again home by the lane and along the corduroy road. When I got most home, I happened to remember the mamma wanted the milk in a hurry, so I began to hurry.

I don’t think I’ll print more to-night. I printed this sitting on the wood-box, where the mamma put me after she spanked me after I got home with the milk. Now I think I shall go out the bedroom window and talk to the stars. They always smile so friendly. This is a very wonderful world to live in.

In the morning of to-day, when I was come part way to school, when I was come to the ending of the lane, I met a glad surprise. There was my dear pet pig awaiting for me. I gave him three joy pats on the nose, and I did call him by name ten times. I was so glad to see him. Being as I got a late start to school, I did n’t have enough time to go around by the pig-pen for our morning talk. And there he was awaiting for me, at the ending of the lane. And his name it is Peter Paul Rubens. His name is that because the first day I saw him was on the twenty-ninth of June. He was little then—a very plump young pig with a little red ribbon squeal and a wanting to go everywhere I did go. Sometimes he would squeal and I would n’t go to find out what he wanted. Then one day, when his nose was sore, he did give such an odd pain squeal. Of course I run a quick run to help him. After that, when he had a chance he would come to the kitchen door and give that same squeal. That Peter Paul Rubens seemed to know that was the only one of all his squeals that would bring me at once to where he was.

And this morning, when I did start on to school, [22]he gave that same squeal and came a-following after. When he was caught up with me he gave a grunt, and then he gave his little red ribbon squeal. A lump came up in my throat and I could n’t tell him to turn around and go back to the pig-pen. So we just went along to school together.

When we got there school was already took up. I went in first. The new teacher came back to tell me I was tardy again. She did look out the door. She saw my dear Peter Paul Rubens. She did ask me where that pig came from. I just started in to tell her all about him, from the day I first met him. She did look long looks at me. She did look those looks for a long time. I made pleats in my apron with my fingers. I made nine on one side and three on the other side. When I was through counting the pleats I did make in my apron, I did ask her what she was looking those long looks at me for. She said, “I’m screwtineyesing you.” I never did hear that word before. It is a new word. It does have an interest sound. I think I will have uses for it. Now when I look long looks at a thing I will print I did screwtineyes it.

After she did look more long looks at me, she went back to her desk by the blackboard. She did call the sixth grade fiziologie class. I went to my seat. I only sat half way in it. I so did so I would have seeing of my dear Peter Paul Rubens. He did wait at the steps. He looked long looks toward the door. It was n’t long until he walked right in. I [23]felt such an amount of satisfaction having him at school. Teacher felt not so. Now I have wonders about things. I wonder why was it teacher did n’t want Peter Paul Rubens coming to school. Why, he did make such a sweet picture as he did stand there in the doorway looking looks about. And the grunts he gave, they were such nice ones. He stood there saying: “I have come to your school. What class are you going to put me in?” He said in plain grunts the very same words I did say the first day I came to school. The children all turned around in their seats. I’m sure they were glad he was come to school—and him talking there in that dear way. But I guess our teacher does n’t have understanding of pig-talk. She just came at him in such a hurry with a stick of wood. And when I made interferes, she did send us both home in a quick way.

We did have a most happy time coming home. We did go on an exploration trip. Before we were gone far, we did have hungry feels. I took the lid off the lard-bucket that my school lunch was in. I did make divides of all my bread and butter. Part I gave to Peter Paul Rubens and he did have appreciations. He did grunt grunts for some more. Pretty soon it was all gone. We did go on. We went on to the woods. I did dig up little plants with leaves that do stay green all winter. We saw many beautiful things. Most everything we did see I did explain about it to Peter Paul Rubens. I [24]told him why—all about why I was digging up so many of the little plants. I did want him to have understanding that I was going to plant them again. When I did have almost forty-five, and it was come near eventime, Brave Horatius and Lars Porsena of Clusium did come to meet us. When I did have forty-five plants, we all did go in the way that does lead to the cathedral, for this is the borning day of Girolamo Savonarola. And in the cathedral I did plant little plants as many years as he was old. Forty-five I did so plant. And we had prayers and came home.

Aphrodite has got a nice blue ribbon all her very own, to wear when we go walking down the lane and to services in the cathedral. The man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice did give to Sadie McKibben the money to buy it last time she went to the mill town. That was on the afternoon of the day before yesterday. On yesterday, when I was coming my way home from school, I did meet with Sadie McKibben. It was nice to see her freckles and the smiles in her eyes. She did have me to shut my eyes, and she did lay in my hand the new blue ribbon for Aphrodite that the man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice did have her to get. I felt glad feels all over. I gave her all our thanks. I did have knowing all my animal friends would be glad for the remembers of the needs of Aphrodite, for a blue ribbon.

I did have beginnings of hurry feels to go to the pig-pen. I have thinks Sadie McKibben saw the hurrys in my eyes. She said she would like to go hurrys to the pig-pen too, but she was on her way to the house of Mrs. Limberger. She did kiss me good-bye—two on the cheeks and one on the nose. [26]I run a quick run to the pig-pen to show it to Aphrodite. I gave her little pats on the nose and long rubs on the ears, and I did tell her all about it. I did hold it close to her eyes so she could have well seeing of its beautiful blues like the blues of the sky. She did grunt thank grunts, and she had wants to go for a walk right away. I did make invest tag ashuns where there used to be a weak place in the pig-pen. It was not any more. I did look close looks at it. I made pulls, but nothing made little slips. Before it was not like that. I have thinks that chore boy is giving too much at ten chuns to the fence of this pig-pen that Aphrodite has living in all of the time I am not taking her on walks. I did feel some sad feels when I could not take her walking down the lane with her nice new blue ribbon on. While I did feel the sad feels so, I did carry bracken ferns to make her a nice bed. It brought her feels of where we were going for walks where the bracken ferns grew.

When I did have her a nice bed of bracken fern and some more all about her, I went goes to get the other folks. Back with me came Brave Horatius and Lars Porsena of Clusium and Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus and Lucian Horace Ovid Virgil and Felix Mendelssohn and Louis II, le Grand Condé. When we were all come, I did climb into the pig-pen and I did tie on Aphrodite’s new ribbon so they all might have seeing of its blues like the sky. I sang a little thank song, and we had prayers, [27]and I gave Aphrodite little scratches on the back with a little stick, like she does so like to have me do. That was to make up for her not getting to go for a walk where the bracken ferns grow.

Now teacher is looking very straight looks at me. She says, “Opal, put that away.” I so do.

To-day it is I do sit here at my desk while the children are out for play for recess-time. I sit here and I do print. I cannot have goings to talk with the trees that I do mostly have talks with at recess-time. I cannot have goings down to the rivière across the road, like I do so go sometimes at recess-time. I sit here in my seat. Teacher says I must stay in all this whole recess-time.

It was after some of our reading lessons this morning—it was then teacher did ask questions of all the school. First she asked Jimmy eight things at once. She did ask him what is a horse and a donkey and a squirrel and a engine and a road and a snake and a store and a rat. And he did tell her all. He did tell her in his way. They she asked Big Jud some things, and he got up in a slow way and said, “I don’t know,”—like he most always does,—and he sat down. Then she asked Lola some things, and Lola did tell her all in one breath. And teacher marked her a good mark in the book and she gave Lola a smile. And Lola gave her nice red hair a smooth back and smiled a smile back at teacher.

Then it was teacher did call my name. I stood up real quick. I did have thinks it would be nice to get a smile from her like the smile she did smile upon Lola. And teacher did ask me eight things at once. She did ask me what is a pig and a mouse and a baby deer and a duck and a turkey and a fish and a colt and a blackbird. And I did say in a real quick way, “A pig is a cochon and a mouse is a mulot and a baby deer is a daine and a duck is a canard and a turkey is a dindon and a fish is a poisson and a colt is a poulain and a blackbird is a merle.” And after each one I did say, teacher did shake her head and say, “It is not”; and I did say, “It is.”

When I was all through, she did say, “You have them all wrong. You have not told what they are. They are not what you said they are.” And when she said that I did just say, “They are—they are—they are.”

Teacher said, “Opal, you sit down.” I so did. But when I sat down I said, “A pig is a cochon—a mouse is a mulot—a baby deer is a daine—a duck is a canard—a turkey is a dindon—a fish is a poisson—a colt is a poulain—a blackbird is a merle.” Teacher says, “Opal, for that you are going to stay in next recess and both recess-times to-morrow and the next day and the next day.” Then she did look a look at all the school, and she did say as how my not getting to go out for recess-times would be an egg sam pull for all the other children in our school.

They are out at play. It is a most long recess, but I do know a pig is a cochon, and a mouse is a mulot and a baby deer is a daine and a duck is a canard and a turkey is a dindon and a fish is a poisson and a colt is a poulain and a blackbird is a merle. So I do know, for Angel Father always did call them so. He knows. He knows what things are. But no one hereabouts does call things by the names Angel Father did. Sometimes I do have thinks this world is a different world to live in. I do have lonesome feels.

This is a most long recess. While here I do sit I do hear the talkings of the more big girls outside the window most near unto my desk. The children are playing Black Man and the ones more little are playing tag. I have thinks as how nice it would be to be having talks with Good King Edward I and lovely Queen Eleanor of Castile and Peter Paul Rubens and Brave Horatius and Lars Porsena of Clusium and Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus and Aphrodite. And I do think this is a most long recess.

I still do have hearings of the talkings of the girls outside the windows. The more old girls are talking what they want. Martha says she wants a bow. I don’t have seeings why she wants another one. Both her braids were tied back this morningtime with a new bow, and its color was the color of the blossoms of camarine. Lola says she wants a white silk dress. She says her life will be complete [30]when she does have on a white silk dress—a white silk dress with a little ruffle around the neck and one around each sleeve. She says she will be a great lady then; and she says all the children will gather around her and sing when she has her white silk dress on. And while they sing and while she does have her white silk dress on, she will stand up and stretch out her arms and bestow her blessing on all the people like the deacon does in the church at the mill town.

Now teacher is come to the door. She does say, “Opal, you may eat your lunch—at your desk.” I did have hungry feels and all this is noon-time instead of short recess-time. It so has been a long recess-time. I did have thinks when came noon-time of all the things I would do down by the rivière.

Now I do gather seeds along the road and in the field. I lay in rows side by side the seeds I gather. With them I do play comparer. I look near looks at them. I do so to see how they look not like one another. Some are big and some are not so. And some are more large than others are large. And some do have wrinkles on them. And some have little wings and some do have silken sails. Many so of all I did see on my way coming home from school on this eventime, and too I did see four gray squirrels and two chipmunks; and when I was come near the meeting of the roads I saw a tramper [31]coming down the railroad track where the dinky engine comes with cars of lumbers from the upper camps.

This tramper—he did have a big roll on his back and he walked steps on the ties in a slow tired way. When I was come more near to the track, I did have thinks he might have hungry feels. Most trampers do. While I was having thinks about it, I took the lid off my dinner-pail. There was just a half a piece of bread and butter left. I was saving that. I was saving it to make divides between Peter Paul Rubens and Aphrodite and Felix Mendelssohn and Louis II, le Grand Condé, and the rest of us. I did look looks from that piece of bread and butter in the dinner-pail to the tramper going down the railroad track. I did have little feels of the big hungry feels he might be having. I ran a quick run to catch up with him.

He was glad for it. He ate it in two bites, and I came a quick way to our lane. I went along it. I made a stop by a hazel bush. I did stop to watch a caterpillar making his cradle. He did not move about while he did make it. He did roll himself up in a leaf. That almost hid him. He did weave white silk about him. I think it must be an interesting life to live a caterpillar life. Some days I do think I would like to be a caterpillar and by-and-by make a silk cradle. The silk a caterpillar makes its cradle from does come from its mouth. I have seen it so. But not so have I seen come the silk the spider does [32]make its web of. This silk does come from the back part of the back of the spider.

When I was come to the house we live in, I did do the works the mamma did have for me to do. Then I made begins to fill the wood-box. When I did have ten sticks piled on its top, I looked to the door where the mamma was talking with Elsie. I did have sorry feels for the mamma. I heard her say she lost ten minutes. I did have wants to help her find them. I looked looks under the cupboard, and they were not there. I looked looks in the cook-table drawers, and they were not there. I looked looks into every machine-that-sews drawer, and I did n’t find them. I crawled under the bed, but I had no seeing of them. Then I did look looks in all the corners of the house that we do live in. I looked looks all about. But I did n’t find them. I have wonders where those ten minutes the mamma lost are gone. While I did look more looks about for them, she did say for me to get out of her way. I so did.

I went to look for the fairies. I went to the near woods. I hid behind the trees and made little runs to big logs. I walked along the logs and I went among the ferns. I did tiptoe among the ferns. I looked looks about. I did touch fern-fronds and I did have feels of their gentle movements. I came to a big root. I hid in it. I so did to wait waits for the fairies that come among the big trees.

While I did wait waits, I did have thinks about [33]that letter I did write on the other day for more color pencils that I do have needs of to print with. I thought I would go to the moss-box by the old log. I thought I would have goes there to see if the fairies yet did find my letter. I went. The letter—it was gone. Then I did have joy feels all over. The color pencils—they were come. There was a blue one and a green one and a yellow one. And there was a purple one and a brown one and a red one. I did look looks at them a long time. It was so nice, the quick way the fairies did bring them.

While I was looking more looks at them, some one did come near the old root. It was my dear friend Peter Paul Rubens. I gave him four pats and I showed him all the color pencils. Then I did make a start to go to the mill by the far woods. Peter Paul Rubens went with me and Brave Horatius came a-following after. All the way along I did feel glad feels, and I had thinks how happy the man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice would be when he did see how quick the fairies did answer my letter and bring the color pencils.

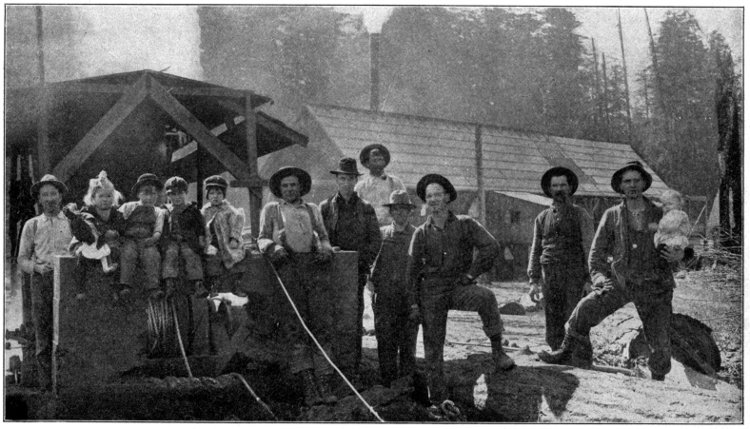

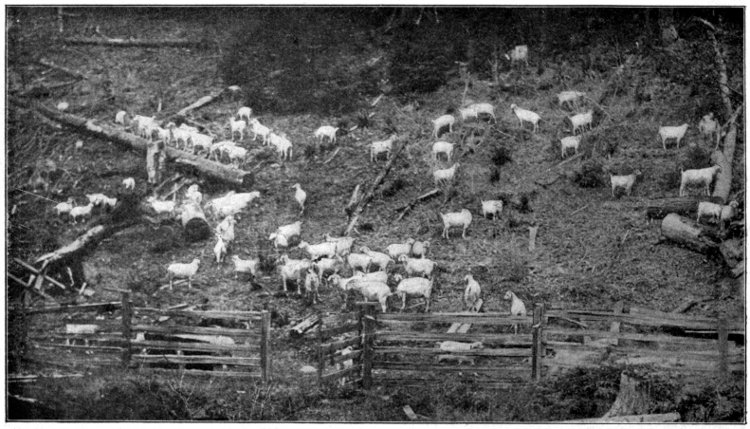

[Photograph: LUMBER-CAMP FOLK]

When we were come near the mill by the far woods, it was near gray-light-time. The lumber men were on their home way. They did whistle as they did go. Two went side by side, and three came after. And one came after all. It was the man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice. Brave Horatius made a quick run to meet him, and I did follow after. I did have him guess what it was the [34]fairies did bring this time. He guessed a sugar-lump for William Shakespeare every day next week. I told him it was n’t a right guess. He guessed some more. But he could n’t guess right, so I showed them all to him.

He was so surprised. He said he was so surprised the fairies did bring them this soon. And he was so glad about it. He always is. He and I—we do have knows the fairies walk often in these woods, and when I do have needs of more color pencils to make more prints with, I do write the fairies about it. I write to them a little letter on leaves of trees and I do put it in the moss-box at the end of the old log. Then, after they do come walking in the woods and find the letter in the moss-box, they do bring the color pencils, and they lay them in the moss-box. I find them there and I am happy.

No one does have knowing of that moss-box but one. He is the man that wears gray neckties and is kind to mice. He has knowings of the letters I do print on leaves and put there for the fairies. And after he does ask me, and after I do tell him I have wrote to them for color pencils that I have needs of—he does take a little fern plant and make a fern wish with it that the fairies will bring to me the color pencils I have needs of. Then we do plant the little fern by the old log. And the time is not long until I do find the color pencils in the moss-box by the old log. I am very happy.

LUMBER-CAMP FOLK [Return to text]

To-day the grandpa dug potatoes in the field. Too, the chore boy did dig potatoes in the field. I followed along after. My work was to pick up the potatoes they got out of the ground. I picked them up and piled them in piles. Some of them were very plump. Some of them were not big. All of them wore brown dresses. When they were in piles, I did stop to take looks at them. I walked up close. I looked them all over. I walked off and took a long look at them. Potatoes are very interesting folks. I think they must see a lot of what is going on in the earth; they have so many eyes. And after I did look those looks as I did go along, I did count the eyes that every potato did have, and their numbers were in blessings.

To some piles I did stop to give geology lectures, and some I did tell about the nursery and the caterpillars in it—the caterpillars that are going to hiver sleep in silken cradles, and some in woolen so go. To more potatoes I did tell about my hospital at St.-Germain-en-Laye in the near woods, and all about the folks that were in it and that are in it, [36]and how much prayers and songs and mentholatum helps them to have well feels.

And to some other potatoes I did talk about my friends—about the talks that William Shakespeare and I do have together; and about how Lars Porsena of Clusium does have a fondness for collecting things, and how he does hide them in the oak tree near unto the house we live in; and about Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the poetry in her tracks. And one I did tell about the new ribbon Aphrodite has to wear, and how she does have a fondness for chocolate creams. To the potato most near unto it I did tell of the little bell that Peter Paul Rubens does wear to cathedral service. To the one next to it I did tell how Louis II, le Grand Condé, is a mouse of gentle ways, and how he does have likings to ride in my sleeve.

And all the times I was picking up potatoes I did have conversations with them. Too, I did have thinks of all their growing days there in the ground, and all the things they did hear. Earth-voices are glad voices, and earth-songs come up from the ground through the plants; and in their flowering and in the days before these days are come, they do tell the earth-songs to the wind. And the wind in her goings does whisper them to folks to print for other folks. So other folks do have knowing of earth’s songs. When I grow up I am going to write for children—and grown-ups that have n’t grown up too much—all the earth-songs I now do hear.

I have thinks these potatoes growing here did have knowings of star-songs. I have kept watch in the field at night and I have seen the stars look kindness down upon them. And I have walked between the rows of potatoes, and I have watched the star-gleams on their leaves. And I have heard the wind ask of them the star-songs the star-gleams did tell in shadows on their leaves. And as the wind did go walking in the field talking to the earth-voices there, I did follow her down the rows. I did have feels of her presence near. And her goings by made ripples on my nightgown. Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus did cuddle more close up in my arms. And Brave Horatius followed after.

Sometimes, when a time long it is I have been walking and listening to the voices of the night, then it is Brave Horatius does catch the corner of my nightgown in his mouth and he pulls—he pulls most hard in the way that does go to the house we live in. After he does pull, he barks the barks he always does bark when he has thinks it is home-going time. I listen. Sometimes I go back. He goes with me. Sometimes I go on. He goes with me. And often it is he is here come with me to this field where the potatoes grow. And he knows most all the poetry I have told them.

On the afternoon of to-day, when I did have a goodly number of potatoes in piles, I did have thinks as how this was the going-away day of Saint François of Assisi and the borning day of Jean [38]François Millet; so I did take as many potatoes as they years did dwell upon earth. Forty-four potatoes I so took for Saint François of Assisi, for his years were near unto forty-four. Sixty potatoes I so took for Jean François Millet, for his years were sixty years. All these potatoes I did lay in two rows. In one row was forty-four and in the other row was sixty.

And as I had seeing of them all there, I did have thinks to have a choir. First I did sing, “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus.” After I did sing it three times, I did have thinks as how it would be nice to have more in the choir. And I did have remembers as how to-morrow is the going-away day of Philippe III, roi de France; and so for the forty years that were his years I did bring forty more potatoes in a row. That made more in the choir. Then I did sing three times over, “Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritu Sancto. Hosanna in excelsis.” Before I did get all through the last time with Hosanna in excelsis, I did have thinks as how the next day after that day would be the borning day of Louis Philippe, roi de France, and the going-away day of Alfred Tennyson. And I did bring more potatoes for the choir. Seventy-six I did so bring for the years that were the years of Louis Philippe, roi de France. Eighty-three I so did bring for the years that were the years of Alfred Tennyson. And the choir—there was a goodly number of folks in it—all potato folks wearing brown robes. Then I did sing one “Ave Maria.”

I was going to sing one more, when I did have thinks as how the next day after the next day after the next day would be the going-away day of Sir Philip Sidney; so I did bring thirty-one more potatoes for the choir. It did take a more long time to bring them, because all the potatoes near about were already in the choir. Brave Horatius did walk by my side, and he did have seeing as how I was bringing potatoes to the choir. And so he did bring some—one at a time he did pick them up and bring them, just like he does pick up a stick of wood in his mouth when I am carrying in wood. He is a most helpful dog. To-day I did have needs to keep watches. I did so have needs to see that he put not more potatoes in the other choir-rows. First time he did bring a potato, he did lay it down by the choir-row of Alfred Tennyson. Next potato he did bring he did lay it by the choir-row of Jean François Millet. Next time I made a quick run when I did have seeing of him going to lay it down by the choir-row of Philippe III, roi de France. I did pat my foot and tell him where to lay it for the choir-row of Sir Philip Sidney. He so did. We did go for more.

When there were thirty-one potatoes in the choir-row of Sir Philip Sidney, we did start service again. I did begin with “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus.” And Brave Horatius did bark Amen. Then I did begin all over, and he did so again. After we had prayers, I did sing one more [40]“Ave Maria.” Then I did begin to sing “Deo Gratias, Hosanna in excelsis,” but I came not unto its ending. Brave Horatius did bark Amen before I was half done. I just went on. He walked in front of me and did bark Amen three times.

I was just going to sing the all of it. I did not so. I so did not because the chore boy did have steps behind me. He gave me three shoulder-shakes, and he did tell me to get a hurry on me and get those potatoes picked up. I so did. I so did in a most quick way. The time it did take to pick them up—it was not a long time. And after that there was more potatoes to pick up. Brave Horatius did follow after. He gave helps. He did lay the potatoes he did pick up on the piles I did pick up. He is a most good dog. When near gray-light-time was come, the chore boy went from the field. When most-dark-time was come Brave Horatius and I so went. When we were come to the house we live in, the folks was gone to visit at the house of Elsie. I did take my bowl of bread and milk, and I did eat it on the back steps. Brave Horatius ate his supper near me. He did eat his all long before I did mine. So I did give him some of mine. Then we watched the stars come out.

I did not have goings to school to-day, for this is wash-day and the mamma did have needs of me at home. There was baby clothes to wash. The mamma does say that is my work, and I do try to do it in [41]the proper way she does say it ought to be done. It does take quite a long time, and all the time it is taking I do have longings to go on exploration trips. And I do want to go talk with William Shakespeare there where he is pulling logs in the near woods. And I do want to go talk with Elizabeth Barrett Browning in the pasture, and with Peter Paul Rubens and Aphrodite in the pig-pens. All the time it does take to wash the clothes of the baby—it is a long time. And I do stop at in-between times to listen to the voices. They are always talking. And the brook that does go by our house is always bringing songs from the hills.

When the clothes of the baby were most white, I did bring them again to the wash-bench that does set on the porch that does go out from our back door. Then there was the chickens to feed, and the stockings were to rub. Stockings do have needs of many rubs. That makes them clean. While I did do the rubs, I did sing little songs to the grasses that grow about our door. After the stockings did have many rubs, the baby it was to tend. I did sing it songs of songs Angel Mother did sing to me. And sleeps came upon the baby. But she is a baby that does have wake-ups between times. To-day she had a goodly number.

By-and-by, when the washing was part done, then the mamma went away to the grandma’s house to get some soap. When she went away she did say she wished she did n’t have to bother with [42]carrying water to scrub the floor. She does n’t. While she has been gone a good while, I have plenty of water on the floor for her to mop it when she gets back. When she did go away, she said to me to wring the clothes out of the wash. There were a lot of clothes in the wash—skirts and aprons and shirts and dresses and clothes that you wear under dresses. Every bit of clothes I took out of the tubs I carried into the kitchen and squeezed all the water out on the kitchen floor. That makes lots of water everywhere—under the cook-table and under the cupboard and under the stove. Why, there is most enough water to mop the three floors, and then some water would be left over. I did feel glad feels because it was so as the mamma did want it.

While I did wait for her coming, I did make prints and mind the baby. When the mamma was come, she did look not glad looks at the water on the floor. She did only look looks for the switches over the kitchen window. After I did have many sore feels, she put me out the door to stay out. I did have sorry feels for her. I did so try hard to be helps.

When a little way I was gone from the door, I did look looks about. I saw brown leaves and brown birds. Brown leaves were érable leaves and chêne leaves, and the brown birds were wrens. And all their ways were hurry ways. I did turn about and I did go in a hurry way to a root in the near woods. [43]I so went to get my little candle. Then I did go to the Jardin des Tuileries. Often it is I do go there near unto the near woods. Many days after I was here come, I did go ways to look for Jardin des Tuileries. I found it not. Sadie McKibben did say there is none such here. Then being needs for it and it being not, I did have it so. And in it I have put statues of hiver and all the others, and here I do plant plants and little trees. And every little tree that I did plant it was for someone that was. And on their borning days I do hold services by the trees I have so planted for them.

To-day I did go in quick steps to the tree I have planted for Louis Philippe, roi de France, for this is the day of his borning in 1773. I did have prayers. Then I did light my little candle. Seventy-six big candles Angel Father did so light for him, but so I cannot do, for only one little candle I have. It did burn in a bright way. Then I did sing “Deo Gratias.” I so did sing for the borning day of Louis Philippe, roi de France. Then I did sing “Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus.”

Afterwards I did have thinks about Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus—about his nose, its feels. I so went in the way that does go to the hospital. That dear pet rat’s nose is getting well. Some way he got his nose too near that trap they set for rats in the barn. Of course, when I found him that morning I let him right out of the trap. He has a ward all to himself in the hospital. For breakfast [44]he has some of my oatmeal. For dinner he has some of my dinner. And for supper I carry to him corn in a jar lid. Sadie McKibben, who has on her face many freckles and a kind heart, gives me enough mentholatum to put on his nose seven times a day. And he is growing better. And to-day when I was come to the hospital, I took him in my arms. He did cuddle up.

Too, he gave his cheese squeak. That made me have lonesome feels. I can’t carry cheese to him any more out of the house we live in. I can’t because, when the mamma learned that I was carrying cheese to Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus, she said to me while she did apply a kindling to the back part of me: “Don’t you dare carry any more cheese out to that rat.” And since then I do not carry cheese out to Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus, but I do carry him into the kitchen to the cheese. I let him sniff long sniffs at it. Then I push his nose back and I cut from the big piece of cheese delicate slices for Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus. This I do when the mamma is n’t at home.

To-day, she being come again to the house we live in, I could not have goings there for Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus to the cheese. I did go the way that goes to the house of Sadie McKibben. I did go that way so she might have knowings of the nose-improvements of Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus. When I was most come here he did squeak more of his cheese squeaks. It was most hard—[45]having hearing of him and not having cheese for him. I could hardly keep from crying. He is a most lovely wood-rat, and all his ways are ways of gentleness. And he is just like the mamma’s baby—when he squeaks he does have expects to get what he squeaks for. I did cuddle him up more close in my arms. And he had not squeaks again for some little time. It was when I was talking to Sadie McKibben about the château of Neuilly that I do have most part done—it was then he did give his squeaks. He began and went on and did continue so. I just could n’t keep from crying. His cheese longings are like my longings for Angel Mother and Angel Father. He did just crawl up and put his nose against my curls. I did stand first on one foot and then on the other. The things I was going to say did go in a swallow down my throat.

Sadie McKibben did wipe her hands on her blue gingham apron with cross stitches on it. She did have askings what was the matter with Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus. And I just said, “O Sadie McKibben, it’s his cheese squeak.” And she said not a word, but she did go in a quick way to her kitchen. She brought back a piece of cheese. It was n’t a little piece. It was a great big piece. There’s enough in it for four breakfasts and six dinners. When Sadie McKibben did give it to me for him, she did smooth back my curls and she did give me three kisses—one on each cheek and one on the nose. She smiled her smile upon us, and we [46]were most happy, and we did go from her house to the cathedral. There I did have a thank service for the goodness of God and the goodness of Sadie McKibben, and the piece of cheese that did bring peace to the lovely Thomas Chatterton Jupiter Zeus.

To-day was a fall-time-is-here day. I heard the men say so that were talking at the meeting of the roads. From the meeting of the roads I did hurry on. I so did in a quick way because, when I was come to the meeting of the roads, I did have remembers as how the mamma did say at morningtime there was much work to be done before eventime.