Project Gutenberg's The Sea-beach at Ebb-tide, by Augusta Foote Arnold

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Sea-beach at Ebb-tide

A Guide to the Study of the Seaweeds and the Lower Animal

Life Found Between Tide-marks

Author: Augusta Foote Arnold

Release Date: October 13, 2013 [EBook #43946]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEA-BEACH AT EBB-TIDE ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, RichardW and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

And hath been tutor'd in the rudiments

Of many desperate studies.

Shakspere.

This volume is designed to be an aid to the amateur collector and student of the organisms, both animal and vegetable, which are found upon North American beaches. In it are described many invertebrates and some of the more notable varieties of seaweeds, and each individual is given its proper place in the latest classification.

The technicality of classification or scientific grouping may at first seem repellent, but it in reality makes the study of these objects more simple; and a systematic arrangement has been adopted in the belief that it is the easiest as well as the only satisfactory way of becoming familiar with the organisms described. Without it a very confused picture of separate individuals would be presented to the mind, and a book like the present one would become a mere collection of isolated scraps of information. Morphology, or the study of structure, has been touched upon just enough to show the objects from the biologist's point of view and to enable the observer to go a little beyond the bare learning of names.

Scientific names have been used from necessity, for the plants and animals of the beach are so infrequently observed, except by scientific people, that but few of them have common names; and, as a matter of fact, the reader will find that a scientific name is as easily remembered as a common one. Technical phraseology has, however, been avoided as much as possible, even at the expense of conciseness and precision; where it has been used, care has been taken to explain the terms so that their meaning will be plain to every one. A general glossary has been omitted, but the technical terms used have been indexed. The illustrations will bear the use of a hand-glass, and this will often bring out details which cannot well be seen by the unaided eye.

The systematic table of the marine algæ, as given in Part I, and followed in the text, will be of use to collectors who wish to make herbaria. In order to name and group specimens such a guide is necessary. Should specific names lead to embarrassment, many of them can be neglected, for the names of genera are often a sufficient distinction.

Since so many species of invertebrates are found on the beach that a complete enumeration of them is impracticable, only the most conspicuous ones have been selected for description in Part II; but the attempt has been made to designate the various classes and orders with sufficient clearness to enable the collector to identify the objects commonly found on the shore, and to follow the subject further, if he so desires, in technical books.

It is hoped that this book will suggest a new interest and pleasure to many, that it will encourage the pastime of collecting and classifying, and that it will serve as a practical guide to a better acquaintance with this branch of natural history, without necessitating serious study. Marine organisms are interesting acquaintances when once introduced, and the real purpose of the author is to present, to the latent naturalist, friends whom he will enjoy.

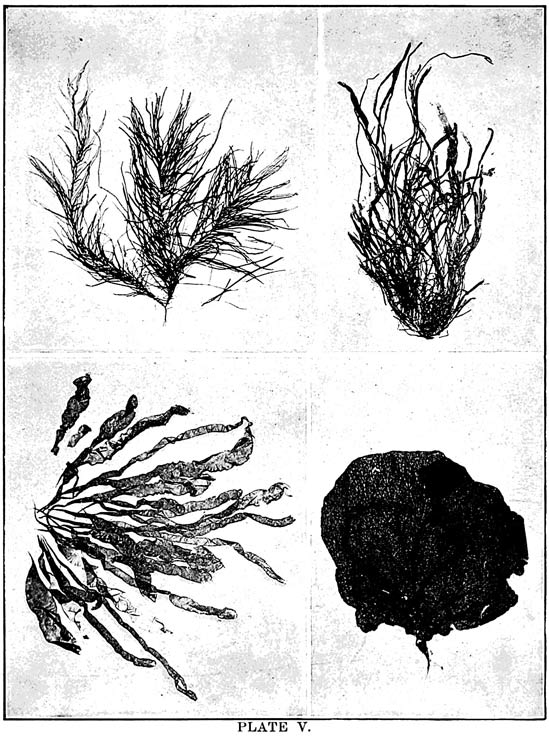

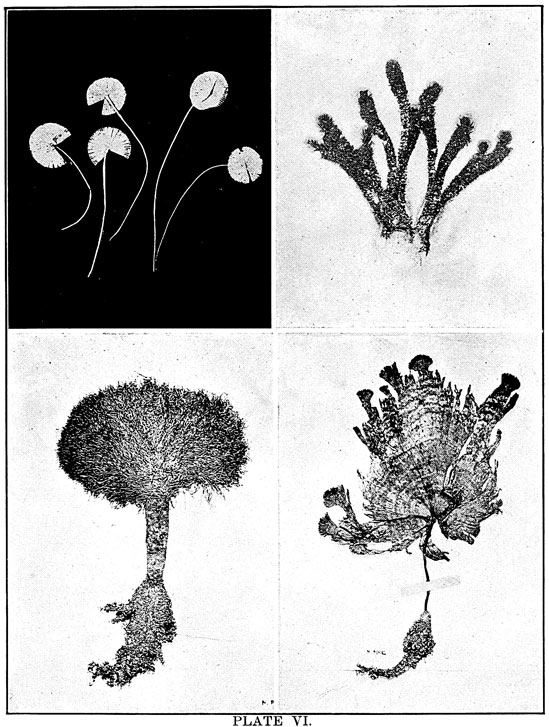

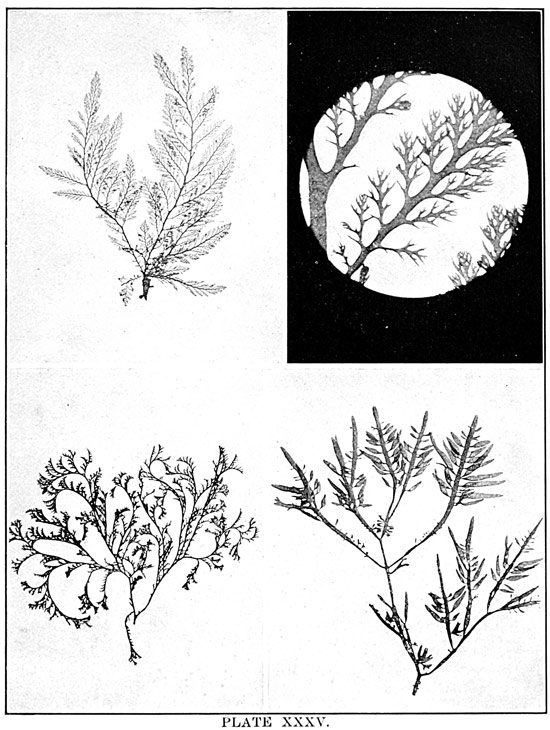

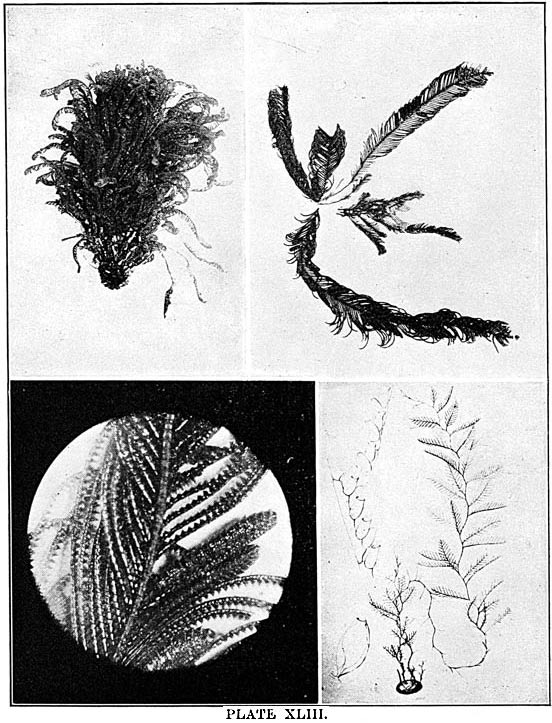

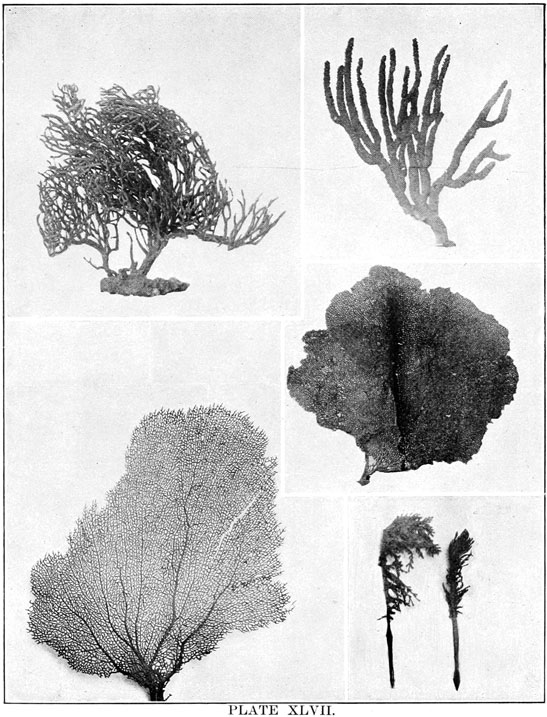

Grateful acknowledgment is here made to the following persons who have kindly assisted and advised the author and have also extended valued courtesies to her in the preparation of this book: Smith Ely Jelliffe, M.D., Ph.D.; Herbert M. Richards, A.B., Ph.D., Professor of Botany in Barnard College; Marshall A. Howe, A.B., Ph.D.; the Rev. George A. Holst; the Long Island Historical Society of Brooklyn for the use of its fine herbarium, containing the collections of Mr. John Hooper, Mr. A. R. Young, and others, from which most of the illustrations of algæ in this book were photographed; Miss Toedtleberg, Librarian of the Long Island Historical Society; Miss Ingalls, in charge of the Museum of the Long Island Historical Society; Dr. Theodore Gill; James A. Benedict, Ph.D., Assistant Curator of Marine Invertebrates in the Smithsonian Institution; Miss Mary J. Rathbun, second Assistant Curator of Marine Invertebrates in the Smithsonian Institution; Miss Harriet Richardson; and especially to Mr. John B. Henderson, Jr.

Thanks, also, are due to Messrs. Macmillan & Co. for permission to use cuts from the "Cambridge Natural History," Parker and Haswell's "Zoölogy", and Murray's "Introduction to the Study of Seaweeds"; to Swan Sonnenschein & Co. for the use of cuts from Sedgwick's "Student's Text-book of Zoölogy"; to Wilhelm Engelmann for a cut from "Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien" of Engler and Prantl; to Little, Brown & Co. for permission to reproduce illustrations from Agassiz's "Contributions to the Natural History of the United States"; to Henry Holt & Co. for a cut from McMurrich's "Invertebrate Morphology"; to Houghton, Mifflin & Co. for cuts from the "Riverside Natural History" and Agassiz's "Seaside Studies in Natural History"; to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the use of illustrations from Verrill's "Report upon the Invertebrate Animals of Vineyard Sound and the Adjacent Waters," Gould's "Invertebrata of Massachusetts" (ed. Binney), and certain fisheries reports; and to the United States government for illustrations taken from Bulletin 37 of the Smithsonian Institution and from reports of the United States Fish Commission.

CONTENTS | ||

| Introduction | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I | Signs on the Beach | 1 |

| II | Collecting | 6 |

| III | Classification | 19 |

| IV | Animal Life in its Lowest Forms | 21 |

| V | Distribution of Animal Life in the Sea | 23 |

| VI | Some Botanical Facts about Algæ | 25 |

| VII | Naming of Plants | 28 |

| VIII | Distribution of Algæ | 30 |

| IX | Some Peculiar and Interesting Varieties of Algæ | 32 |

| X | Uses of Algæ | 37 |

| XI | Collecting at Bar Harbor | 40 |

| PART I | ||

| Marine Algæ | ||

| I | Blue-Green Seaweeds (Cyanophyceæ) | 47 |

| Grass-Green Seaweeds (Chlorophyceæ) | 47 | |

| II | Olive-Green and Brown Seaweeds (Phæophyceæ) | 61 |

| III | Red Seaweeds (Rhodophyceæ or Florideæ) | 75 |

| PART II | ||

| Marine Invertebrates | ||

| I | Porifera (Sponges) | 99 |

| II | Cœlenterata (Polyps) | 111 |

| III | Worms (Platyhelminthes, Nemathelminthes, Annulata) | 159 |

| IV | Molluscoida | 187 |

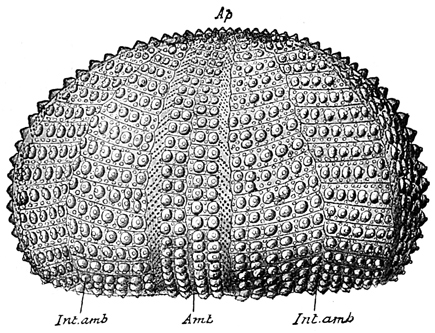

| V | Echinodermata | 199 |

| VI | Arthropoda | 237 |

| VII | Mollusca | 299 |

| VIII | Chordata | 471 |

| Index | 479 | |

In vain through every changeful year

Did nature lead him as before;

A primrose by a river's brim,

A yellow primrose was to him,

And it was nothing more.

At noon, when by the forest's edge

He lay beneath the branches high,

The soft blue sky did never melt

Into his heart; he never felt

The witchery of the soft blue sky.

Wordsworth.

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language.

Bryant.

The sea-shore, with its stretches of sandy beach and rocks, seems, at first sight, nothing but a barren and uninteresting waste, merely the natural barrier of the ocean. But to the observant eye these apparently desolate reaches are not only teeming with life; they are also replete with suggestions of the past. They are the pages of a history full of fascination for one who has learned to read it.

In this history even the grains of sand have a part. Though so humble now, they once formed the rocky barriers of the shore. They stood as do the rocks of to-day, defiant and seemingly everlasting, but the fury of the sea, which knows no invincible adversary, has laid them low. Every coast-line shows the destructive effects of the sea, for the bays and coves, the caves at the bases of the cliffs, the buttresses, stocks, needles, and skerries, are the work of the waves. And this work is constantly going on.

Even a blind man could not stand long upon a shingly beach without knowing that the sea was busily at work. Every wave that rolls in from the open ocean hurls the pebbles up the slope of the beach, and then as soon as the wave has broken and the water has dispersed, these pebbles come rattling down with the currents that sweep back to the sea. The clatter of the beach thus tells us plainly that as the stones are being dragged up and down they are constantly knocked against each other; and it is evident that by such rough usage all [pg002] angular fragments of rock will soon have their corners rounded off and become rubbed into the form of pebbles. As these pebbles are rolled to and fro upon the beach they get worn smaller and smaller, until at length they are reduced to the state of sand. Although this sand is at first coarse, it gradually becomes finer and finer as surely as though it were ground in a mill; and ultimately it is carried out to sea as fine sediment and laid down upon the ocean floor. [1]

The story of the sands is not only one of the conflict of the sea and rocks; it is also a story of the winds. It is the winds that have rescued them from the waves and driven them about, sifting and assorting them, arranging them in graceful forms, and often heaping them up into dunes which, until fastened by vegetation, are themselves ever moved onward by the same force, sometimes burying fertile lands, trees, and even houses in their march. The sands, moreover, are in turn themselves destructive agents, to whose power the many fragments which strew the beach and dunes bear ample witness. The knotty sticks so commonly seen on the beach are often the hearts of oak- or cedar-trees from which the tiny crystals of sand have slowly cut away their less solid outer growth. Everything, in fact, upon the sands is "beach-worn," even to the window-glass of life-saving stations, which is frequently so ground that it loses its transparency in a single storm.

The beach is also a vast sarcophagus holding myriads of the dead. "If ghosts be ever laid, here lie ghosts of creatures innumerable, vexing the mind in the attempt to conceive them." And there are certain sands which may be said to sing their requiem, the so-called musical sands, like the "Singing Beach" at Manchester-by-the-Sea, which emit sounds when struck or otherwise disturbed. On some beaches these sounds resemble rumbling, on others hooting; sometimes they are bell-like and even rhythmical. The cause of this sonorous character is not definitely known, but it is possibly due to films of compressed gases which separate each grain as with a cushion, and the breaking of which [pg003] causes, in the aggregate, considerable vibrations. Such sands are not uncommon, having been recorded in many places, and they exist probably in many others where they have escaped observation. They may be looked for above the water-line, where the sand is dry and clean.

We have to do, however, in this volume, not with the history of the past, nor with the action of physical forces, but with the life of the present, and to find this, in its abundance, one must go down near the margin of the water, where the sands are wet. There is no solitude here; the place is teeming with living things. As each wave retreats, little bubbles of air are plentiful in its wake. Underneath the sand, where each bubble rose, lives some creature, usually a mollusk, perhaps the razor-shell Solen ensis. By the jet of water which spurts out of the sand, the common clam Mya arenaria reveals the secret of its abiding-place. A curious groove or furrow here and there leads to a spot where Polynices heros has gone below; and the many shells scattered about, pierced with circular holes, tell how Polynices and Nassa made their breakfast and their dinner. Only the lifting of a shovelful of sand at the water's edge is needed to disclose the populous community of mollusks, worms, and crustaceans living at our feet, just out of sight.

Even the tracks and traces of these little beings are full of information. What may be read in the track of a bird on the sand is thus described by a noted ornithologist:

Here are foot-notes again, this time of real steps from real feet. . . . The imprints are in two parallel lines, an inch or so apart; each impression is two or three inches in advance of the next one behind; none of them are in pairs, but each one of one line is opposite the middle of the interval between two of the other line; they are steps as regular as a man's, only so small. Each mark is fan-shaped; it consists of three little lines less than an inch long, spreading apart at one extremity, joined at the other. At the joined end, and also just in front of it, a flat depression of the sand is barely visible. Now following the track, we see it run straight a yard or [pg004] more, then twist into a confused ball, then shoot out straight again, then stop, with a pair of the footprints opposite each other, different from the other end of the track, that began as two or three little indistinct pits or scratches, not forming perfect impressions of a foot. Where the track twisted there are several little round holes in the sand. The whole track commenced and finished upon the open sand. The creature that made it could not, then, have come out of either the sand or the water; it must have come down from the air—a two-legged flying thing, a bird. To determine this, and, next, what kind of bird it was, every one of the trivial points of the description just given must be taken into account. It is a bit of autobiography, the story of an invitation to dine, acceptance, a repast, an alarm at the table, a hasty retreat. A bird came on wing, lowering till the tips of its toes just touched the sand, gliding half on wing, half afoot, until the impetus of flight was exhausted; then folding its wings, but not pausing, for already a quick eye spied something inviting; a hasty pecking and probing to this side and that, where we found the lines entangled; a short run after more food; then a suspicious object attracted its attention; it stood stock-still (just where the marks were in a pair), till, thoroughly alarmed, it sprang on wing and was off.[2]

Following the key further, he draws more conclusions. The tracks are not in pairs, so the bird does not belong to the perchers; therefore it must be a wader or a swimmer. There are no web-marks to indicate the latter; hence it is a three-toed walking or wading bird. It had flat, long, narrow, and pointed wings because it came gliding swiftly and low, and scraped the sand before its wings were closed. This is shown by the few scratches before the prints became perfect. A certain class of birds thus arrests the impetus of flight. It had a long feeling-bill, as shown by the little holes in the sands where the marks became entangled; and so on. These combined characteristics belong to one class of birds and to no other; so he knows as definitely as [pg005] though he had seen the bird that a sandpiper alighted here for a brief period, for here is his signature.

It is plain that tracks in the sand mean as much to the naturalist as do tracks in the snow to the hunter, and trails on the land to the Indian who follows his course by signs not seen by an untrained eye.

The tide effaces much that is written by foot and wing, but sometimes such signs are preserved and become veritable "footprints on the sands of time." In the Museum of Natural History in New York is a fossil slab, taken from the Triassic sandstone, showing the footprints of a dinosaurian reptile now extinct, which, in that long ago, walked across a beach—an event unimportant enough in itself, but more marvelous than any tale of imagination when recorded for future ages. From such tracks, together with fragments of skeletons, the dinosaur has been made to live again, and its form and structure have been as clearly defined as those of the little sandpiper of Dr. Coues. [pg006]

It has been said that everything on the land has its counterpart in the sea. But all land animals are separate and independent individuals, while many of those of the sea are united into organic associations comprising millions of individuals inseparably connected and many of them interdependent, such as corals, hydroids, etc. These curious communities can be compared only to the vegetation of the land, which many of them resemble in outer form. Other stationary animals, such as oysters and barnacles, which also depend upon floating organisms for their food, have no parallel on the land.

The water is crowded with creatures which prey upon one another, and all are interestingly adapted to their mode of life. Shore species are exceedingly abundant, and the struggle for life is there carried on with unceasing strife. In the endeavor to escape pursuers while they themselves pursue, these animals have various devices of armature and weapons of defense; they have keen vision, rapid motion, and are full of arts and wiles. One of the first resources for safety in this conflict is that of concealment. This is effected not only by actual hiding, but very generally by mimicry in simulating the color of their surroundings, and often by assuming other forms. Thus, for instance, the sea-anemone when expanded looks like a flower and is full of color, but when it contracts becomes so inconspicuous as to be with difficulty distinguished from the rock to which it is attached. Anemones also have stinging threads (nematophores), which they dart out for further defense. [pg007]

The study of biology has great fascination, and the subject seldom fails to awaken interest as soon as the habit of observation is formed. Jellyfishes, hardly more dense than the water and almost as limpid, swimming about with graceful motion, often illuminating the water at night with their phosphorescence, showing sensitiveness, volition, and order in their lives, cannot fail to excite wonder in even the most careless observer. Not less interesting are the thousands of other animals which crowd the shores, lying just beneath the surface of the sand, filling crevices in the rocks, hiding under every projection, or boldly—perhaps timidly, who shall say?—lying in full view, yet so inconspicuous that they are easily passed by unnoticed.

To find these creatures, to study their habits and organization, to consider the wonderful order of nature, leads through delightful paths into the realms of science. But even without scientific study the simple observation of the curious objects which lie at one's feet as one walks along the beach is a delightful pastime.

The features which separate the classes and the orders of both the plant and the animal life are so distinctive that it requires but very superficial observation to know them. It is easy to discriminate between mollusks, echinoderms, and polyps, and to recognize the relationship between univalves and bivalves, sea-urchins and starfishes, sea-anemones and corals. The equally plain distinctions between the branched, unbranched, tubular, and plate-like green algæ make them as easy to separate.

The pleasure of a walk through field or forest is enhanced by knowing something of the trees and flowers, and in the same way a visit to the sea-shore becomes doubly interesting when one has some knowledge, even though it be a very superficial one, of the organisms which inhabit the shore.

Rocky shores furnish an abundance and great variety of objects to the collector. The seaweeds here find places of attachment, and the lee and crevices of the rocks afford shelter to many animals which could not live in more open and exposed places. The [pg008] rock pools harbor species whose habitat is below low-water mark and which could not otherwise bear the alternation of the tides.

The first objects on the rocky beach to attract attention are the barnacles and rockweeds. They are conspicuous in their profusion, the former incrusting the rocks with their white shells, and the latter forming large beds of vegetation; yet both are likely to be passed by with indifference because of their plentifulness. They are, however, not only interesting in themselves, but associated with them are many organisms which are easily overlooked. The littoral zone is so crowded with life that there is a constant struggle for existence,—even for standing-room, it may be said,—and no class of animals has undisputed possession of any place. Therefore the collector should carefully search any object he gathers for other organisms which may be upon it, under it, or even in it, such as parasites, commensals, and the organisms which hide under it or attach themselves to it for support. Let the rockweed (Fucus) be carefully examined. Among the things likely to be found attached to its fronds are periwinkles (Littorina litorea), which simulate the plant in color, some shells being striped for closer mimicry. Sertularian hydroids also are there, zigzagging over the fronds or forming tufts of delicate horny branches upon them. Small jelly-like masses at the broad divisions of the fronds may be compound ascidians. Calcareous spots here and there may be polyzoans of exquisite form, while spread in incrusting sheets over considerable spaces are other species of Polyzoa. Tiny flat shelly spirals are the worm-cases of Spirorbis. A pocket-lens is essential to enable one to appreciate the beauty of these minute forms. Under the rockweeds are many kinds of crustaceans; perhaps there will also be patches of the pink urn-like egg-capsules of Purpura at the base of the fucus.

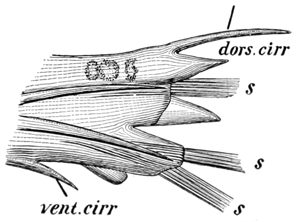

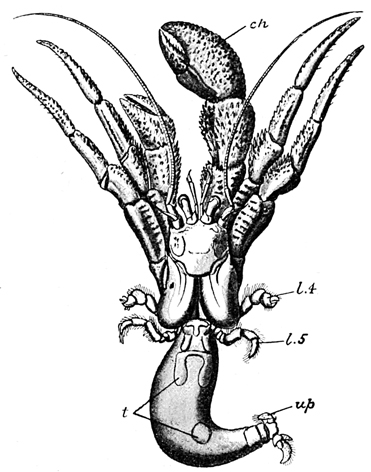

Various kinds of seaweed abound in the more sheltered parts of the rocks, and among them will be found amphipods and isopods, many of which are of species different from those of the sandy beaches. Here, too, is the little Caprella, imitating the seaweed in form, and swaying its lengthened body, which is attached to the plant only by its hind legs. On the seaweeds, as well as in the tide-pool, may be found beautiful hydroids, and on [pg009] them the curious little sea-spiders (Pycnogonidæ), animals which seem to be all legs.

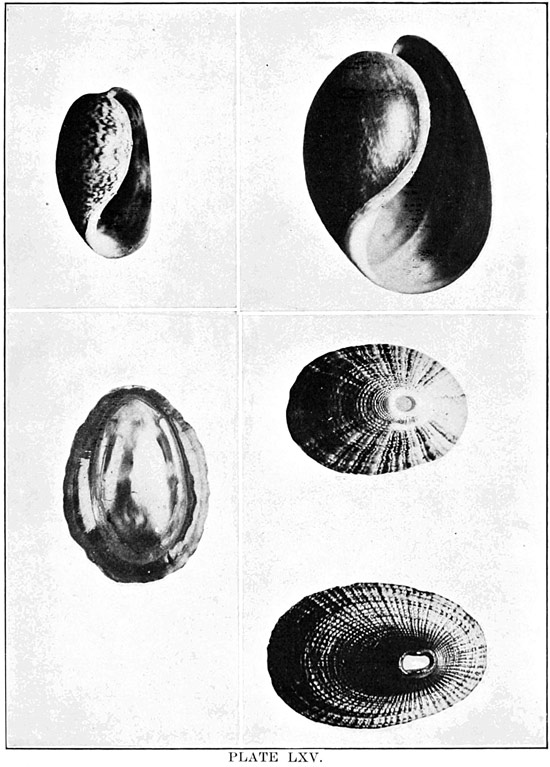

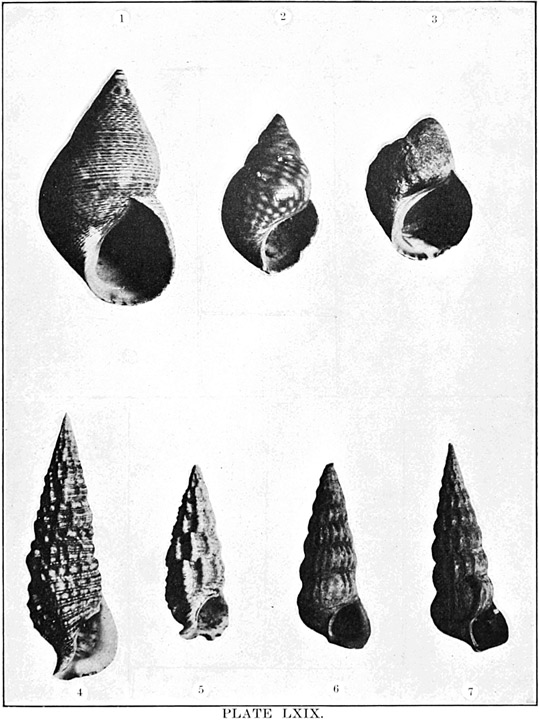

Mollusks, and other classes as well, differ in different latitudes. On the rocks of the Northern shores Littorina and Purpura shells are very abundant, the latter in various colors and beautifully striped. Limpets are also plentiful, but are not as conspicuous, since they have flat, disk-shaped shells. When their capture is attempted, they must be taken unawares and pushed quickly aside, else they take such a firm hold of the rock that it is difficult to dislodge them. Near low-water mark under ledges will perhaps be found chitons, which are easily recognized by their oval, jointed shells. On the California coast in like localities will be found the beautiful Haliotis, Acmæa, and chitons. Every stone that is lifted will disclose numbers of little amphipods (Gammarus), which will scuttle away on their sides to other shelter; worms will suddenly disappear into the mud, and perhaps a crab, here and there, having no alternative, will make a stand and fight for his liberty. Flat against the stone and not easily perceived may be a chiton, a planarian worm, or a nudibranch. And just below the water's edge are sea-urchins and starfishes, which grow in numbers as the eye becomes accustomed to the search.

The rock pools are natural aquaria, more interesting by far than any prepared by man. The possibilities of these little sea-gardens are beyond enumeration. The longer one studies them the more one finds. In them all classes of seaweeds and marine invertebrates may be found and their habits watched. The great beauty of these pools gives them an esthetic charm apart from the scientific interest they excite. Perhaps one may find here a sponge, and removing it to a shallow vessel of sea-water can watch the currents of water it creates. Several sponges of the same species placed in contact will at the end of two days be closely united. If the sponges are of different species they will not coalesce.

In the clefts and crannies of the rocks are various fine seaweeds, often of the red varieties, sea-anemones, hydroids, polyzoans, crustaceans, mollusks, and ascidians. Crabs will be snugly [pg010] ensconced under projecting surfaces. Most species are more plentiful at the lowest-water mark, and many are found only at this point and below.

On sandy shores the greater part of the inhabitants live under the surface. Many give evidence of their presence by the open mouths of their burrows, and some distinctly point out these places by piles of sand or mud in coils at the opening. Some tubicolous worms have their tubes projecting above the surface. The tubes of Diopatra are hung with bits of shells, seaweeds, and other foreign matter. Some mollusks announce themselves by spurting jets of water or sending bubbles of air from the sand. The majority of the underground species, however, give no sign of their presence on the surface, and must be found by digging. Many of them go deep into the sand, and in searching for worms the digger must be quick- and expert, or he will lose entirely or cut in two many of the most beautiful ones, which retreat quickly and to the extremity of their holes at the least alarm. One can be a rambler on the sandy beach for a long time without being aware of the many beautiful objects which inhabit the subsurface of the sand. The curious crab Hippa will disappear so quickly into the sand that one is hardly sure he has really seen it. The vast number of worms will surprise any one who searches for them by their variety, their beautiful color, and their interesting shapes. Here again a glass is requisite to appreciate the delicacy and beauty of their locomotive organs, their branchiæ, and so on. The most common of the gasteropod mollusks on sandy shores are Nassa obsoleta, Nassa trivittata, and Polynices (Lunatia) heros. The last are detected by the little mounds of sand which they push before them as they plow their way just below the surface. On more southern beaches, Fulgur, Strombus, and Pyrula are the common varieties. Olivella, Oliva, and Donax, also inhabitants of sandy beaches, will quickly disappear when uncovered by the waves, being rapid burrowers. Most of the many dead shells on the beach will be found to be pierced with a round hole, which is [pg011] drilled by the file-like tongue, or lingual ribbon, of Polynices, Urosalpinx, or Nassa, which thus reach the animal within and suck out its substance. Another similar species is Polynices (Neverita) duplicata, which extends to the Gulf of Mexico, while P. heros is not commonly found below Hatteras. Crustaceans are abundant on the sandy beach over its whole breadth. Some of the sand-crabs live above tide-mark. Among these is the fleet-footed Ocypoda, which is interesting to watch. Often they go in numbers to the water's edge and throw up mounds, behind which they crouch like cats, watching for whatever prey the tide may bring up. When unable to outrun a pursuer they rush into the surf and remain there until the danger is past. The wet sand is often thickly perforated with the burrows of the sandhoppers (Orchestia). These often rise about the feet as do grasshoppers in the fields.

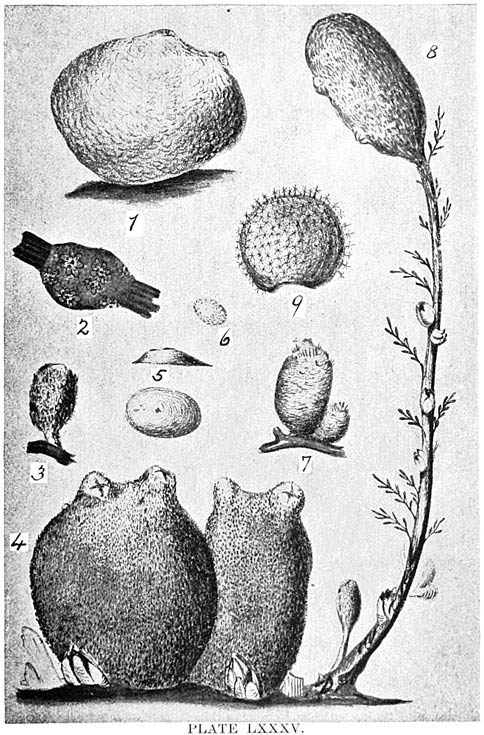

| PLATE I. | |

|---|---|

| Egg-capsules of Purpura lapillus. | Egg-case of Polynices heros. |

| Egg-capsules of Buccinum undatum. | Egg-case of the skate. |

| Fulgur canaliculata (whelk) and egg-cases. | |

Hippa talpoida is a remarkable crab, somewhat resembling an egg. It is not likely to be seen unless searched for by digging at the water's edge. It burrows so rapidly that one must be quick to catch it after it is exposed by the shovel. In some places the tests of "sand-dollars" are common. The living animal may be found buried just below the surface at extreme low-water mark.

The sea-wrack drifted in lines along the shore will repay careful examination, for here will be found many things belonging to other shores and deep water. It is often alive with sandhoppers, which hop away while one searches for less common things. Often the most delicate seaweeds, numerous small shells, worms, polyzoans, etc., will be found there.

The surface of the sand-beach is strewn with remains of many species, usually beach-worn, but interesting nevertheless as examples of species one would like to find in better condition, but good specimens of which elude ordinary search or are unobtainable except by dredging.

Egg-cases form another class of objects which are often gathered with no idea of their identity. Of these the most common are the long strings of saucer-like capsules which contain the eggs of the mollusk Fulgur, those having square edges being [pg012] the egg-cases of F. carica, and those having sharp edges those of F. canaliculata. Collar-like sandy rings contain the eggs of Polynices (Lunatia), which are cemented together in this shape. The boys of Cape Cod call them "tommy-cod houses." Cylindrical piles of little capsules, sometimes called "ears of corn," hold the eggs of Chrysodomus. The irregular masses of small hemispherical capsules are those of the common whelk (Buccinum). The so-called "Devil's pocket-books" are the egg-cases of the skate.

On muddy shores the eel-grass (Zostera marina) grows abundantly, giving an appearance of submerged meadows. It is one of the very few flowering plants which live in salt water. In summer its little green blossoms may be seen in grooves on the leaf-like blades. Many animals live on and among eel-grass. Found upon it is the delicate gasteropod mollusk Lacuna vincta, and its eggs in little rings; the iridescent Margarita helicina, and Nassa, with its bright-yellow eggs in small gelatinous masses; also little worms (Spirorbis) in tiny flat spiral shells, compound ascidians in jelly-like masses, clusters of shelly or horny polyzoans, isopods, planarian worms, and so on. Scallops (Pecten) will be found at the base of the plants, and the common prawns are very numerous, swimming freely about. Mud flats and shores are the homes of many mollusks, especially of Nassa obsoleta,—which is the most abundant shell of any considerable size from Cape Cod to the Gulf of Mexico,—and of vast numbers of the tiny Littorinella minuta, which serve as food for fishes and aquatic birds. Clams and worms of all varieties are also abundant.

There are many varieties of mud-crabs, of which the most common are the "fiddlers," which honeycomb the banks and the surface of salt-marshes with their burrows. The common edible crab Callinectes hastatus is plentiful in bays and estuaries. The sluggish spider-crabs hide beneath the surface of the mud and in decaying weeds and eel-grass. Hermit-crabs are plentiful here as well as elsewhere. Panopeus is a sluggish crab found in shallow water and in all sorts of hiding-places along the shore. It [pg013] may often be found in dead shells, and, in the South, in holes in the banks. This genus is represented by a number of species, some of which are quite pretty.

On the piles of wharves and bridges may often be found beautiful tubularian hydroids in large tufts just below low-water mark, branched hydroids looking like little shrubs, polyzoans, sea-anemones, mollusks, and ascidians. The species peculiar to these localities are the boring mollusk Teredo navalis, or ship-worm, the boring isopod Limnoria lignorum, and the boring amphipod Chelura terebrans, all of which penetrate the wood and are most destructive.

The animals and plants of tropical beaches and coral reefs are so various and abundant, so curious and beautiful, as to make a description or even an enumeration of them in a brief space difficult. The collector is bewildered and excited when he first views the profusion of the wonderful forms there found.

It is not generally known that a fine species of "stony coral" is common from Cape Cod southward, growing in clear water as an incrustation on rocks, and developing little spires as it advances in age. This species, the Astrangia danaë, is especially interesting, since it will live in a dish of clear sea-water, and the polyps will expand, showing a very close relationship to the sea-anemone. With care in changing the water this coral will live for days, and may be examined in its expanded condition with a lens of moderate power.

The most favorable time for collecting on any beach is at the lowest tide, many objects being then uncovered which do not appear higher up on the beach. At the spring-tides, which occur twice a month, at the period of the new and that of the full moon, the ebb is especially low, and affords an opportunity to search for forms whose habitat is below ordinary low-water mark. During storms deep-water forms are often torn from their beds and cast upon the beach. Shore-collecting at these times is often very interesting. [pg014]

The equipment for collecting upon sandy beaches is a shovel, a sieve, and a net. Numerous trials should be made with the shovel from about half-tide mark to as deep as one cares to wade, and the sand raised should be carefully searched for shells, crustaceans, and worms. By washing out the sand in the sieve the smallest specimens, which might otherwise escape notice, may be secured. On a rocky beach a strong knife and a net are sufficient. It is well to have a number of homeopathic vials for small specimens, which will be injured by contact with larger forms, and jars for holding the general collection.

To preserve specimens, they should first be placed in a weak solution of alcohol, the strength of which should be increased gradually until the animal is entirely free from water and is hardened throughout. If the alcohol becomes colored and sediment falls to the bottom of the jar, the animal is degenerating, and the alcohol should be changed. Specimens for transportation can be packed by wrapping each one in a bit of cheese-cloth and then placing them together in a large receptacle. Care should be taken to keep the fragile specimens separate. Sand-dollars possess a pigment which discolors and soon vitiates alcohol, and consequently these should be separated from the other forms and placed where the alcohol may be changed from time to time as appears necessary. The homeopathic vials containing small specimens may be put into the can without injury to the other specimens. Special cans of various sizes, with handles and screw covers, are made for naturalists. One of these cans is a convenient receptacle for carrying the alcohol to the station and for receiving the collection for transportation. Careful notes should be made on the spot of the conditions under which the species are found. One is likely to forget details if this is delayed until one reaches home. Labels should be used, giving name when known, or a number when the name is not known, [pg015] corresponding with the note-book. Names written with lead-pencil on a slip of paper will not be defaced by or injure the alcohol. Collections when arranged permanently should be placed in glass jars, the species being kept separate.

To collect seaweeds one must search for them on rocks, in tide-pools, in the sea-wrack upon the beach, on piles of wharves, on eel-grass, and on the surface of incoming waves. It is well to follow the receding tide and take advantage of its lowest ebb (especially of that of the spring-tides, as mentioned above) to search the extreme limit of the beach in the short time it is exposed. Many of the red seaweeds are found there.

The equipment for collecting consists of a basket, two small tin pails, one small enough to be carried within the other, a staff with an iron edge at one end and a small net at the other, and a pocket-lens. Rockweeds (Fucus) or other coarse gelatinous seaweeds should be put into the basket. The pails, half filled with sea-water, will receive the other specimens, fine and delicate algæ being put into the smaller pail. It is well to have a second small receptacle for Callithamnion and Griffithsia, if one can be further burdened. Desmarestia should be kept apart, if possible, since it discolors and decomposes other algæ; it should also have the earliest attention when the time comes for mounting, and salt water should be used for floating it upon the mount, otherwise the beauty of the specimen will be impaired.

Besides its use as a support, the staff is needed to dislodge specimens from the rocks, and the net to secure those that are floating just out of reach. When possible, it is desirable to secure the whole plant, including the holdfast, and to gather several plants of the same species, since they vary with age and other conditions, and it is also well to have duplicates for exchange. It is particularly desirable to obtain plants which are in fruit. Each specimen as it is taken should be rinsed in the sea-water to free it from sand.

Collections should be mounted as soon as convenient, and [pg016] especial care in this respect should be taken with red algæ, as they decompose quickly. The requisites for mounting are blotters, pieces of muslin, two or more smooth boards, weights, a basin, and several shallow dishes containing water. Fresh water has a strong action on the color and substance of seaweeds, and specimens should not be left in it for any length of time.

Lift a specimen from the general collection, and in a basin of deep water carefully wash off all superfluous matter; then place it in shallow water and spread it out, trimming it judiciously, so that when mounted it will not be too thick and the characteristics be hidden. Specimens are more interesting and their species more easily determined when laid out rather thin, showing their branching and fruit. After the specimen is thus prepared, place it in a second shallow dish of water. It should now be perfectly clean. Float it out into the desired position, spreading it well, letting some parts show the details of the branching, and other parts the general natural effect of the mass. Run under it a rather heavy sheet of white paper, and lift it carefully from the water. If raised from the center, it is easier to let the water subside evenly and gradually without disarranging the parts. Some collectors find it better to float the specimen in water deep enough to allow the left hand to be placed under the sheet to raise it. Lay the sheet on a plate, and with a needle or forceps rearrange any of the delicate parts which have fallen together. A few drops of water placed on any portion will usually be sufficient to enable one to separate the branchlets or ultimate ramifications. A magnifying-glass will be useful in this work.

Cover a blotter with mounted specimens, spread over them a piece of cotton cloth, and on this place another blotter, upon which lay more mounted specimens and a cloth. Proceed in this way until all the specimens are used. Lay the pile of blotters between boards, and on them place the weights. The weights should not be very heavy. Judgment must be used in assorting the specimens, those that are fine being placed together. Those that are coarse and likely to indent the blotters should be placed between separate boards. In this way a flat surface and an even pressure will be obtained. The blotters and cloths should be [pg017] changed twice each of the first two days, then the cloths should be removed and the specimens left in press for a week, the blotters being changed daily. Be sure that the specimens are perfectly dry before placing them in the herbarium. Label each specimen with the name and the date and place of collection.

There are some seaweeds which cannot be treated in the above manner. Fucus if placed in fresh water soon becomes slimy. It is so full of gelatine that it soon destroys blotters; therefore it is well to hang it up for several hours and then place it between newspapers, which should be frequently changed, and as the plant becomes pliable it should be arranged in proper position.

Those specimens which do not adhere to paper in drying should be secured with gum. When it is impossible to mount specimens at the time they are collected, they can be preserved by drying; afterward they can be soaked and mounted in the usual manner. To dry the plants, lay them separately upon boards without pressing out the sea-water, and leave them in an airy, shaded place until thoroughly dry; then pack them loosely into boxes and label, giving date and locality. Blotters or driers can be obtained at botanical-supply stores at thirty-five cents per quire.

The standard herbarium-paper is sixteen by eleven and a half inches. The sheets are single, white, smooth, and quite heavy. These, together with folded sheets of yellow manila paper, called genus-covers, are the only requisites. It is desirable to have also a case of shelves protected by glass doors. The shelves should be twelve by eighteen inches, and four to six inches apart. They are more convenient when made to slide like drawers.

The different species of one genus are gummed on one or more of the white sheets and placed within the folded manila paper, which serves as a cover. Each specimen should be signed with its name, place, and date of collection, thus:

C. rubrum. Bar Harbor. Aug. 12, 1899,

the generic name being indicated by its initial capital letter and the specific name written in full. To this are often added the [pg018] name of the collector and some interesting comment. On the lower left-hand corner of the genus-cover is written the generic name in full and the species of that genus which the cover contains, thus:

| Ceramium | C. rubrum | |

| C. strictum | ||

| C. diaphanum |

The genera of an order are then placed within a cover and labeled in the same way, the legend then having the name of the order on the left and the genera on the right of the bracket,[†] thus:

| Rhodymeniaceæ, suborder Ceramieæ |

Callithamnion | |

| Griffithsia | ||

| Ceramium |

When the order is a large one the genera are distributed through as many covers as may be necessary. The covers are then arranged on shelves in the regular order of their classification, and each shelf is labeled with the order it contains. Herbarium-sheets cost at retail one dollar per hundred. Genus-covers cost at retail one dollar and eighty cents per hundred. [pg019]

The first great biological division is into kingdoms, namely, the animal kingdom and the vegetable kingdom. Then by classification the vast number of existing animals and plants are grouped so as to give each individual a definite place. By this system a beautiful order is established, which enables the student to find any particular animal or plant he may wish to study, and also to know its general characteristics from the name of the group to which it belongs.

In broad generalization, objects of wide dissimilarity are recognized as belonging to the same kingdom, as do trees and grasses, or as do birds and fishes. Certain trees or grasses and certain birds or fishes have such points of resemblance that they plainly show that they belong to subdivisions. The most untutored people recognize these distinctions, but the naturalist goes further and finds points of distinction which the casual observer overlooks.

The animal kingdom has a varying number of divisions, called branches, subkingdoms, or phyla. Some late authors have admitted twelve divisions, and have given them the name phyla. Each phylum is composed of a group of animals with a plan of structure which is common to themselves, but differs from that of the animals of all other phyla.

The higher animals begin with the twelfth phylum, namely, the Chordata, or vertebrates. These animals have a spinal column, or series of vertebræ, while the lower animals, or invertebrates are without a spinal column, and depend for stability [pg020] upon muscles or coriaceous or calcareous coverings. The vertebrates are first represented in the fish-like forms. Bilateral symmetry, however, or the uniform arrangement of parts on each side of a central axis, exists in several groups which are below the vertebrates, the first pronounced example being found in worms. Groups lower than worms have their organs arranged around a central axis or radiating from it, and were once all classed as radiates.

An animal is classified in accordance with its morphology, anatomy, histology, and embryology. Morphology determines its general shape, the position of its limbs, eyes, and mouth, and the covering of its body; anatomy, the arrangement of its internal organs, such as the position of its heart, lungs, stomach, etc.; histology, the character of the tissues of the body; and embryology, the method of the development of the animal from the embryo to maturity. It is only after these exact discriminations have been made that the groups are arranged. Owing to the greater accuracy resulting from histology and embryology (methods which have been employed only in later years), many changes in classification have been made, and as science advances will continue to be made.

The primary groups are based on broad general characteristics, but their divisions and subdivisions are determined by closer distinctions. Animals having shells differ from those having a cartilaginous or those having a crustaceous covering, and are placed in different groups. Yet mollusks having a single or a double shell, having spiral or flat forms, living on land, in fresh water, or in the sea, while differing from one another, are all of one group. Lobsters and crabs, although both have crustaceous coverings, are very unlike; and again, there are many species of both lobsters and crabs.

To group individuals, noting resemblances as well as differences, a system of classification has been arranged with the following divisions:

Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family (or Suborder), Genus, Species. [pg021]

The biological division, or discrimination, between animal and vegetable life, is based on the manner of assimilating food. Plants feed upon mineral substances, or, in other words, assimilate inorganic matter, while animal life requires for its support vegetable or some other organic matter.

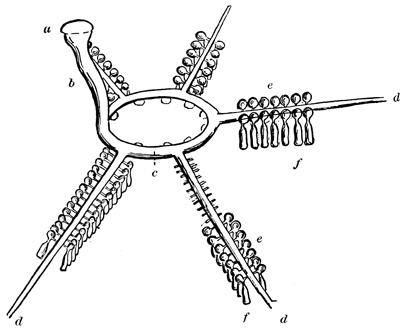

Animal as well as vegetable life in its lowest forms begins with one-celled organisms, which are called respectively Protozoa (first animals) and Protophyta (first plants). Both of these divisions are composed mostly of microscopic objects, and, together with other minute forms of life of the marine species, constitute a great part of the plankton, or free-floating organisms of the sea. These minute organisms seem like connecting-links between the two kingdoms. They were claimed by both botanists and zoölogists until the use of the microscope made close observation of minute structure possible.

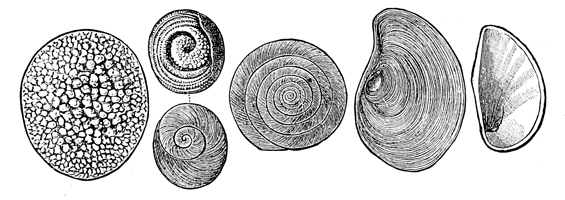

Among the small animalcules of the phylum Protozoa are some which are familiar to all by name, such as the Infusoria, which are most interesting creatures to examine in a drop of water under the microscope. A more tangible example of the Protozoa are the Foraminifera. Foraminifera, like diatoms, have a shell-like covering, and these shells, among the most plentiful of which are those of the genus Globigerina, fall, as do those of diatoms, in immense numbers to the bottom of the ocean, and form respectively what are known as Globigerina and diatomaceous ooze. In course of time the sedimentary strata become fossilized; thus, the stone of which the city of Paris is built consists of fossilized [pg022] foraminifers, and the pyramids of Egypt are built of nummulites, another genus of Foraminifera. It is estimated that an ounce of this deposit contains four millions of these protozoans, so it is impossible to conceive the numbers of once living animals represented in the tombs of the Pharaohs. Telegraph-cables raised from the depth of two miles bring the message to naturalists that the bottom of the ocean at that depth is composed of little else than the calcareous shells of Foraminifera.

Many of the lower animals resemble plants in form. Hydroids and polyzoans are often gathered and preserved as seaweeds. Corals, sea-anemones, and holothurians are curiously like plants. For a time the confusion about the division of animals and plants was partly owing to this resemblance of forms, and the theory of the animal nature of corals was for a long time considered to be refuted by the testimony of a naturalist who declared that he had seen them in bloom. Later this class of animals was believed to occupy an intermediate sphere and partake of the characteristics of both kingdoms. The name zoöphyte, meaning "animal-plant" or "mingled life," was adopted because of these resemblances and was formerly applied to these forms only. To-day it has a broader application. There is still a neutral class, called Protista, comprising organisms which have not yet been classified as plants or animals. [pg023]

All living things which inhabit the sea have their appointed boundaries, and the localization of marine life is as distinct as is that of terrestrial life. Each kind of beach has forms of life peculiar to itself. Those animals which inhabit rocky shores or stony beaches or sand or mud may be looked for anywhere under similar physical surroundings. They are, however, modified by climatic conditions, and in wide ranges differ in genera and species. The rocky coast of Maine has a class of sea-urchins and starfishes which are different from those which live on the rocky shores of the northern Pacific coast, yet they are all easily recognized as belonging to the same family, and a description of typical forms is a sufficient guide to the recognition of their relationships.

A bathymetrical division defines the classes of animals according to the depth of water in which they live. Those which live near the shore are littoral species, those of the broad sea are pelagic, while those living at great depths are abyssal.

Their modes of life are distinguished by other terms. Those which float at or near the surface and are carried about by the currents, like the jellyfishes and the minute organisms mentioned elsewhere, are plankton. Strong swimming animals which move about at will are nekton. Those which are fixed, like oysters, sponges, etc., and those which crawl on the bottom, like crabs, echinoderms, etc., are benthos.

Again, geographical divisions are named, in recognition of climatic influences. The boreal fauna and flora on the Atlantic [pg024] coast extend from Cape Cod northward; the American, from Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras; the West Indian, from Cape Hatteras southward. On the Pacific coast the divisions, without definite names, are from the Isthmus to Acapulco, Acapulco to the Gulf of California, Cape Lucas to the Strait of Fuca. These divisions merge at indefinite lines, but the above limits are generally accepted as the points of broad division.

The shore or littoral fauna is especially abundant and comprises more species that are curious in form and beautiful in color than the others. The invertebrates of the deep sea are mostly transparent and of a blue or violet tint, while the fishes are gray or bluish above and white beneath, which renders them inconspicuous to their enemies. [pg025]

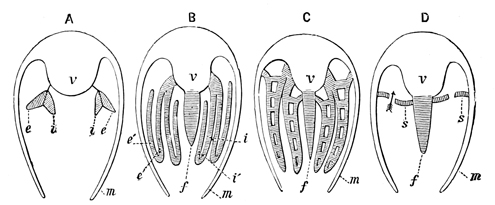

The vegetable world is separated into two great divisions: thallophytes, or plants having no distinction of leaf or stem, and cormophytes, or plants which have leaves and stems. All thallophytes that live in the water and are nourished wholly by water are called algæ.

A second great division of plants is into cryptogams, or those that have no flowers, and phanerogams, or those that have flowers, by means of which seeds are produced and successive generations of plant life continued.

Thallophytes and cryptogams comprise the lowest and simplest vegetable organisms. Algæ belong to both these divisions; to the first because they have neither stems nor leaves, and to the second because they have no flowers.

The lowest forms of algæ are microscopic in size, each individual being a single cell; but in the ascending scale they attain curious and beautiful shapes, some growing to a gigantic size and in forms that resemble shrubs and trees. The green surface commonly seen on the shady side of trees, on stone steps, and in other damp places is one of the species of algæ which consist of a single cell. This plant or cell divides, and the separate divisions divide and subdivide again and again, and in time the aggregate number is great enough to spread over a comparatively large surface, and thus become visible to the naked eye. This plant, the Pleurococcus vulgaris, is a fresh-water alga. The Protococcus nivalis, or red snow, described on page 33, is a closely allied species. The green and blue-green scums and slimes on [pg026] brackish ditches and on the stones and woodwork of wharves are also species of the lowest orders of algæ and increase by cell-division. Many of them are in colonies incased in gelatinous matter. These, together with plants of a little higher order, though still of low organization, the Confervaceæ, form a large part of the green vegetation between tide-marks.

The vegetative body of a thallophyte is a thallus, and corresponds to stem and leaf. It is also called a frond. What corresponds to the root of flowering plants is in algæ a disk or conical expansion of the base of the plant. It is simply a holdfast by which the frond attaches itself to any submerged material. The algæ which grow on sandy shores and on corals have holdfasts which branch like fibrous roots and penetrate porous substances in all directions; but this is only for greater stability, and is an adaptation to the habitat. Holdfasts do nothing for algæ other than the name implies, whereas real roots absorb the nourishment upon which plants live. Algæ are nourished by the substances held in solution by the water which surrounds them.

Algæ are the lowest and simplest in organization of all plants, because they are composed of but one class of cells, such as in flowering plants are called the parenchyma, or soft cells, these being the ones which compose the pulp of the leaf. In the lowest orders of algæ single cells constitute individual plants, as in Pleurococcus; but in the higher forms, such as Sargassum, they arrange themselves in such a variety of combinations as to resemble plants which have leaf and stem. The botanical distinction is that in leaf and stem there would exist the woody and the vascular cells as well as the parenchyma cells.

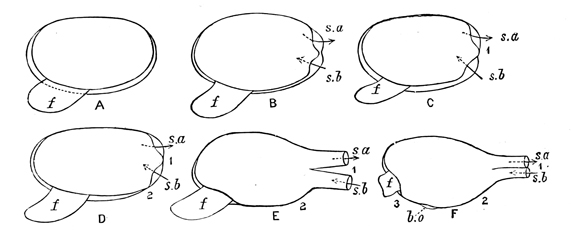

Beginning with plants composed of a single cell, the next development is into filamentous plants, which are single thread-like rows of cells, as in Cladophora. In Ulva is seen the earliest type of an expanded leaf. The cells are here arranged in a horizontal surface of plate-like or ribbon-like shape.

In Ulva there is a double layer of cells. The layers separate in Enteromorpha, giving a hollow or tubular form. In Monostroma a double layer is opened or torn apart, giving a frond with a single layer of cells. [pg027]

The stem-like forms of certain algæ are composed of cylindrical cells which combine or grow in a longitudinal direction chiefly. Sometimes the cells are arranged evenly, in which case the stem seems articulated, as in some species of Ceramium. Again, they are irregularly placed, so that the stem appears solid.

The highest types of algæ in the differentiation of parts, or vegetative forms, are to be found in the Fucaceæ, of the brown seaweeds; the highest in the reproductive development, in the red class.

Reproduction by cell-division, in which the organism itself breaks up into two or more individuals, is called vegetative reproduction. Higher forms reproduce by spores, or germ-cells, which give rise to new individuals on germination.

The substance of an alga is more or less firm, according as the vegetable mucus or gelatinous matter it contains has more or less consistency; it is membranaceous when the gelatine is scant and glossy, gelatinous when it is abundant and fluid, and cartilaginous when it is hard.

Some algæ are annuals; a few are perennials, and cast off and renew their laminæ every season. Many plants present quite a different appearance at different seasons of the year, and so are often difficult to identify. Those which form spores throw off these isolated cells, which sink or are washed to positions where they germinate and begin their cycle of life. Many of the spores begin their growth at once, without regard to season, so the species is ever present. [pg028]

The real or technical names of plants, which at first appear long and unpronounceable, are in reality simple when the system of naming is understood. Every plant has a generic and a specific name. The generic name is analogous to the surname of a person, such as Smith or Jones. The specific name is analogous to the Christian name of a person, such as John or James. The specific name never stands alone, and would have as little designating character as John —— or James ——.

This is called the binomial (two-name) nomenclature. It was introduced by Linnæus, and greatly simplified the system of naming. The rule in scientific nomenclature is that all names must be Latin or Latinized. This gives a universal language by which scientists of all countries understand one another.

The names of classes (the highest groups) and subclasses are adjectives or adjective nouns, expressing the most prominent characteristic of the class or subclass. Thus the four subclasses of the class Algæ are:

Cyanophyceæ (subclass of blue-green algæ).

Chlorophyceæ (subclass of grass-green algæ).

Phæophyceæ (subclass of dusky-brown or olive-green algæ).

Rhodophyceæ or Florideæ (subclass of red algæ).

Orders are, with few exceptions, the names of genera with the termination -aceæ, as:

Ulvaceæ, from the genus Ulva.

Ectocarpaceæ, from the genus Ectocarpus.

Gigartinaceæ, from the genus Gigartina. [pg029]

Suborders, or groups between orders and genera, terminate in -eæ. Names of genera are nouns or words taken as nouns. They are derived from any source,—from prominent or peculiar characteristics, from localities, or from names of botanists,—or they may be wholly arbitrary. Personal generic names are divested of titles and take a final a, or, in many cases, for euphony, ia. Thus, Ulva is the Latin for "sedge"; Ectocarpus is from two Greek words meaning "fruit outside"; Corallina means "coral-like"; Grinnellia is named for Mr. Henry Grinnell.

The specific names are commonly adjectives, but sometimes they are nouns, and occasionally are the names of the botanists who first described the plants, in which case the name terminates in -i or -ii. The specific name always follows the generic name, thus:

Ectocarpus Hooperi, a species of Ectocarpus, first described by Mr. Hooper.

Grinnellia Americana, a species, peculiar to America, of a genus named for Mr. Grinnell.

Griffithsia corallina, a species resembling coral, and belonging to a genus named for Mrs. Griffiths.

With regard to the four subclasses mentioned above, it should be said that algæ are strictly classified in accordance with their methods of reproduction; but since allied species have, with few exceptions, the same color, the classification by colors is generally adopted as convenient and sufficiently precise.

Familiar, or, in technical language, "vulgar," names are very generally given to land plants, and especially to flowers; but seaweeds are less in sight than flowers are, and so, save in a few instances, have not been named except by the man of science. To remember the scientific names will not be found difficult, for without effort or special pains to acquire the new vocabulary, the names, like those of new personal friends, will insensibly become fixed in the memory.

In the body of this work each of the groups (class, subclass, order, etc.), in the classification of both animals and plants, is indicated by a special kind of type. [pg030]

The eastern coast of North America has been divided into four sections, which correspond to the distribution of the algæ which are characteristic of each section. The boundary-lines are not precise, since some species of each section extend beyond the defined limits; but arctic forms are not generally found south of Cape Cod, nor can tropical varieties be expected north of Cape Hatteras. On the intervening coast, however, there are some species common to both sections. The divisions are:

On the Pacific coast such distinct lines of demarcation do not exist, there being no such natural barriers as are formed on the eastern coast, first by Cape Cod, and, second, by the stretch of sand-beach which extends from New York to Charleston, and which divides sharply the climatic varieties.

The whole shore is again divided laterally into three distinct belts, called the littoral, the laminarian, and the coralline zones. The first or littoral zone covers the space between tide-marks. Vegetable life in this zone is subjected first to exposure to the sun and air, and even to desiccation, and then to entire submergence at constantly recurring periods. The rockweeds (Fucus), which are so plentiful in this zone, are very gelatinous, nature having apparently provided the gelatine to protect the cells of the plant from the effects of the alternating extreme conditions. Fucus and Enteromorpha predominate in this zone. [pg031]

The laminarian zone extends from low-water mark to the depth of fifteen fathoms. The Laminariaceæ and the beautiful red algæ (Florideæ) grow here.

The third or coralline zone extends to the depth of about fifty fathoms. The algæ of this zone, the nullipores, are incrusted with a deposit of lime which gives them the appearance of corals; and, singularly enough, the corals, which are animal forms, simulate plant life.

Again, algæ have special habits and demand certain climates and seasons for their growth. Algologists register the place where a specimen is found, and in this way localities have been pretty well determined. However, great exactness has not been reached, and the collector is ever watchful to find an alga in some undiscovered home within the given range. Although algæ grow from extreme high-water mark to the depth of fifty fathoms, almost every variety may be found on the beach, those growing in deep water being frequently torn off and washed ashore by the waves. The heaps of sea-wrack will often reward one who examines them carefully for deep-water species. Seaweeds are most abundant on rocky shores, particularly where there are stratified rocks with crevices, which afford shelter from the waves. Rock pools often contain beautiful varieties of the more delicate species. Red algæ will sometimes be found on the shady side of these pools. Sand-beaches are unfavorable to the growth of seaweeds, but fronds which have been carried long distances by the currents will frequently be found on such shores. [pg032]

The species of seaweeds that are known and classified are said to number several thousands. These plants, which have neither vessels for the conduction of fluids, nor fibers, consisting simply of the first vegetable element, the cell, have, notwithstanding this limitation, assumed a great variety of forms. In size they vary from one one-thousandth of an inch in diameter, the smallest green plants known, to those which exceed in length the height of the tallest trees and form dense submarine forests, which in places make comparatively deep water impassable for boats. In texture they vary from a jelly- to a paper- and a leather-like consistency. In color they have all the shades of green, brown, and red.

Among the smallest algæ are diatoms. They are microscopic in size, but exist everywhere in both salt and fresh water, and are infinite in variety as well as in numbers. They have a silicious, shell-like covering, which divides and subdivides in their reproductive growth, forming varied shapes which are exceedingly beautiful and interesting to examine under the microscope. In vast numbers they float on the surface of the sea, and, together with other minute free-floating organisms, form the basis of food-supply for fishes. Their indestructible shells fall to the bottom of the sea, forming large deposits, which in time become fossilized. The city of Richmond, Virginia, is built upon [pg033] a fossiliferous bed of diatoms, which measures twenty to eighty feet in depth and several miles in length.

Associated with diatoms, in fresh water, are desmids, which are green in color and resemble the diatoms except in having a cartilaginous instead of a silicious covering. Another minute organism, Pyrocystis noctiluca, is luminous and is said to produce the beautiful phosphorescent effects seen in tropical seas. Trichodesmium is a little alga which periodically occurs in great numbers, giving the water a red appearance, as in the Red Sea, which is said to derive its name from this circumstance.

In the high latitudes of the arctic regions, also on snowy mountains at altitudes where all vegetable life is supposed to be extinguished, there sometimes appears a redness on the surface of the snow, which in some cases extends for many miles. At a certain place in Greenland the color was so vivid that an arctic voyager named the locality the Crimson Bluffs.

The strangeness and almost sudden appearance of this color in the snow have been so unaccountable to uninformed observers that it has been ascribed by them to the falling of bloody snow and has been regarded with superstition. The redness is caused by the growth of one of the smallest of plants, the Protococcus nivalis. It is a simple one-celled alga containing protoplasm and endochrome (red coloring-matter). It grows by cell-division, the cell dividing into four, eight, or sixteen parts on a quaternary scale. Each part acquires a new covering while within the mother cell, and when it emerges it is a complete individual and ready to repeat the process. Only a few hours are required for its growth and development; hence its increase is rapid, and it requires but a little time to make itself manifest in those places where the conditions are favorable to its existence.

When the voyager reaches a certain region of the North Atlantic, called the Sargasso Sea, he sails into a vast undulating marine [pg034] prairie. Farther than the eye can reach is spread a yellowish-brown vegetation which covers the water as grass covers the plain. Sometimes these weeds are so thick as to impede navigation, and, seen from a little distance, seem substantial enough to walk upon. At other times, according to seasons and conditions of storm and wind, they are divided into strips or into island-like masses, with spaces of clear water between. If the sailor did not know the special conditions existing here he might suppose he had come upon dangerous shallows; or were the waters less turbulent he might dream that he was floating among the water-weeds of an inland lake.

This vast acreage of vegetation, as large as the continent of Europe, lying southwest of the Azores and extending between the Canary and the Cape Verde Islands, was first reported by Columbus, and takes its name from the floating plant of which it is composed, the Sargassum bacciferum, a species of the order Fucaceæ, commonly known as gulfweed. Columbus's sailors took fright at the marvelous appearance and wished to turn back, thinking they had reached the end of the navigable ocean. They thought, if land were beyond, it was guarded by shoals, and that the weeds concealed dangerous rocks. Columbus threw out two hundred fathoms of line, but did not reach bottom, and continued on his course for fifteen days before emerging into clear water. From that day to this the Sargasso Sea has attracted the attention of all navigators. It is especially interesting to scientists. The physicist finds there the phenomenon of the ocean currents holding in a vortex this immense mass of seaweed, the zoölogist finds a great pasture in whose protecting shelter are living and breeding countless numbers of marine animals, and the botanist is puzzled because the source of this species of plant is clouded with doubt.

According to one theory, the plants are dislodged by the tempests from terrestrial beds and carried by the Gulf Stream into the huge eddy; but since there does not exist enough of the attached plants of this species to supply the vast accumulation, another and more generally accepted theory is that the gulfweed lives also a pelagic life and adapts itself to the conditions of the [pg035] floating state, thus dispensing with the disk-like root, as it needs no holdfasts, and propagating solely by lateral and axillary ramification.

There are said to be one hundred and fifty species of Sargassum, but S. bacciferum alone constitutes the beds of the Sargasso Sea. The plant is the most highly differentiated of any seaweed, in that it more nearly approaches the true leaf and stem, and is described botanically as follows: Frond furnished with distinct, stalked, nerveless leaves and simple, axillary, stalked air-vessels. The integument is leathery, and the color brown of varying shades. The most striking peculiarity is the abundance of globular cells. These berry-like air-bladders give the plant buoyancy enough to support the weight of its innumerable guests. (Plate XVI.)

In the laminarian zone, described above, grow the Laminariaceæ, an order of brown seaweeds, some of whose genera grow to enormous size, and in some places form dense submarine forests. Darwin speaks of the good service rendered by these plants to vessels navigating stormy coasts, where often they act as natural breakwaters, and again as buoys designating dangerous rocks near the shore on which they grow. The seaweeds belonging to this order, commonly known as oarweeds, tangle, devil's-apron, and sea-colander, are frequently seen twelve to twenty feet in length, and others are measured by fathoms. One of the giant plants is Nereocystis Lütkeana, which occurs on the northwest coast. It has a stalk, sometimes three hundred feet in length, which bears on its extremity a barrel- or cask-shaped air-vessel, six or seven feet long, from the surface of which a tuft of fifty or more forked laminæ grows to a length of thirty or forty feet. The stem which anchors this immense frond is so small that the Aleutian Indians use it for fishing-lines. The sea-otter makes his home on its huge air-vessel, and the plant is called by the Russians the "sea-otters' cabbage."

But the longest of all known plants is the alga Macrocystis. Its thin naked stem, the diameter of which seldom exceeds one quarter [pg036] of an inch, is reported by one author to be seven hundred feet in length, by another fifteen hundred feet. It is terminated by a lamina fifty feet long, resembling a pinnatifid leaf, each leaflet of which, at its point of division on the stem, expands into an air-vessel as large as an egg. These air-vessels sustain the immense frond which floats on the surface of the water, its leaflets depending in a vertical position from the stem. M. pyrifera, the only species, is found in the Southern oceans and on the Pacific coast of North America.

Lessonia, another genus, resembles a palm-tree. It grows erect to a great height and has a stem like the bole of a tree. It branches in a forking manner and has depending from its branches laminæ two or three feet long. The large stems from which the laminæ have been torn by the storms, and which have been cast ashore on the Falkland Islands, as described by Sir Joseph Hooker, resemble driftwood, as they lie in piles three or four feet high and extending for many miles.

Agarum and Thalassiophyllum are arctic genera, but they are found within our limits, the former in the North Atlantic. It has a simple but enormous leaf-like frond. The latter, which is found on the North Pacific coast, has a compound frond. Both are characterized by their fronds being perforated throughout with holes, giving them the name of sea-colander. [pg037]

Water covers two thirds of the surface of the earth, and algæ, with a very few exceptions, constitute the whole vegetation which exists in that enormous area. They have, therefore, an important part to perform in the economy of nature. Algæ do not, like land plants, derive their nourishment from the soil to which they are attached, but from substances held in solution by water. In their growth they effect changes in the water analogous to those effected by land plants in the air; that is, they change so-called impurities in the water into materials essential to animal life. The function of plants is that of transforming or manufacturing inorganic matter, which they assimilate, into organic matter (such as starch, albumen, sugar), which forms their own structure and which is the food essential to animals. In this process, plants inhale carbonic acid gas which animals breathe out, and exhale oxygen which animals breathe in. Plants feed on mineral substances and furnish vegetable food, thus keeping up the balance of life.

Fresh-water algæ have a like economic value. The green surface on stagnant pools is a vegetable growth whose function is to assimilate the matter which makes the pool offensive. A submerged district soon becomes covered with scum, or minute plants (Sphæoplea annulina), which grow with great rapidity, using up the materials of the decaying vegetation, and in great measure counteracting the ill effects, in the atmosphere, of such decay. When the waters subside, the plants shrivel up and appear like thin paper covering the ground. This ephemeral substance soon [pg038] disappears, without giving evidence of its nature in dust or gases, its body seeming to be a machine which transmutes, but does not hold, the substances on which it grows.

Algæ, as has been said above, grow in definite zones, and each zone has also a definite animal life which finds there its food. Darwin says: "In all parts of the world a rocky and partially protected shore perhaps supports in a given space a greater number of individual animals than any other station." And speaking of the Laminariaceæ, he adds: "I can only compare these great aquatic forests of the southern hemisphere with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions. Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here from the destruction of the kelp." The same may be said of the Sargasso Sea, where millions of living creatures make their home. In every kind of marine fauna there are species which derive, if not the whole, at least a part of their nourishment from the seaweeds.

The vegetation in the narrow boundary of the three zones is palpably inadequate to supply the needs of the animal life which exists in deeper waters. But over the broad area of the ocean there exists a vast number of pelagic, free-floating algæ, which, although microscopical in size, are almost infinite in numbers. In illustration of this it has been estimated that, although they are not especially numerous in the Sargasso Sea, yet if all the seaweed there were gathered into one mass and the free-floating algæ into another, the bulk of the latter would exceed that of the former. The pelagic flora consists of Diatomaceæ, Protococcaceæ, Peridinieæ, and others. Undoubtedly it is on these pastures that fishes feed, as well as other organisms which in turn are food for fishes.

Fucus and Laminaria constitute the kelp from which iodine is obtained, and were at one time the source of the potash of commerce. Fucus vesiculosus is a constituent of a medicine used as a cure for obesity. Chondrus crispus, commonly known as Irish moss, was a few years ago generally used as an article of diet. Porphyra vulgaris (laver) is used by the Chinese for soups. Rhodymenia palmata (dulse) is an article of food in Ireland and Scotland. [pg039] Gracilaria spinosa is used by birds, allied to the swallows, for making their nests—the edible nests found in large numbers on the islands of the Indian Archipelago, especially in the caves on the shores of Java, and gathered and sent to China, where they bring large prices and are used in making the famous birds'-nest soup. Gracilaria lichenoides, also a species of the Eastern seas, is the source of agar-agar, a preparation used in laboratories as a culture-medium for bacteria. Fossil diatoms are ground and used for polishing-powders. Seaweeds are everywhere used by farmers on the coasts as fertilizers. [pg040]

The beautiful coast of Maine is a particularly good field for shore-collecting. The rocky coast harbors the boreal fauna and flora which depend upon such physical conditions, and the shores at Bar Harbor are typical of those found elsewhere in northern New England. The rocks give shelter from the beating surf, while life has exposure to the cold, pure waters of the arctic current. Everywhere along the shore, rock pools are to be found. These are perhaps the most fascinating of all spots to the collector. They are veritable gardens of the sea, where species flourish which naturally belong to deeper water, but which find in such pools conditions suitable to their existence.

At Bar Harbor one well-known and frequently visited rock pool is found in Anemone Cave. Entering a field at Schooner Head, one turns to the right and follows the rocky shore for two or three hundred feet. It is difficult to take this short walk without being constantly diverted and delayed by the various attractions one meets, such as the tide-pools, the barnacles which in places whiten the rocks, the periwinkles, the purpura shells, and the curious algæ; but at last one arrives at a cavern under an overhanging rock. Here is a large tide-pool which at first sight displays only a beautiful scheme of color. It is carpeted with a bright-pink alga, Hildenbrandtia rosea, which incrusts the basin of the pool.