Transcriber's Note: Chapter VI is succeeded by Chapter VIII without a designated intervening Chapter VII. DW

CONTENTS

XII. THE RETURN OF “OLD KAZOOZER”

PETER LANE GEORGE RAPP, the red-faced livery-man from town, stood with his hands in the pockets of his huge bear-skin coat, his round face glowing, looking down at Peter Lane, with amusement wrinkling the corners of his eyes.

“Tell you what I'll do, Peter,” he said, “I'll give you thirty-five dollars for the boat.”

“I guess I won't sell, George,” said Peter. “I don't seem to care to.”

He was sitting on the edge of his bunk, in the shanty-boat he had spent the summer in building. He was a thin, wiry little man, with yellowish hair that fell naturally into ringlets: but which was rather thin on top of his head. His face was brown and weather-seamed. It was difficult to guess just how old Peter Lane might be. When his eyes were closed he looked rather old-quite like a thin, tired old man-but when his eyes were open he looked quite young, for his eyes were large and innocent, like the eyes of a baby, and their light blue suggested hopefulness and imagination of the boyish, aircastle-building sort.

The shanty-boat was small, only some twenty feet in length, with a short deck at either end. The shanty part was no more than fifteen feet long and eight feet wide, built of thin boards and roofed with tar paper. Inside were the bunk—of clean white pine—a home-made pine table, a small sheet-iron cook-stove, two wooden pegs for Peter's shotgun, a shelf for his alarm-clock, a breadbox, some driftwood for the stove, and a wall lamp with a silvered glass reflector. In one corner was a tangle of nets and trot-lines. It was not much of a boat, but the flat-bottomed hull was built of good two-inch planks, well caulked and tarred. Tar was the prevailing odor. Peter bent over his table, on which the wheels and springs of an alarm-clock were laid in careful rows.

“Did you ever stop to think, George, what a mighty fine companion a clock like this is for a man like I am?” he asked. “Yes, sir, a tin clock like this is a grand thing for a man like me. I can take this clock to pieces, George, and mend her, and put her together again, and when she's mended all up she needs mending more than she ever did. A clock like this is always something to look forward to.”

“I might give as much as forty dollars for the boat,” said George Rapp temptingly.

“No, thank you, George,” said Peter. “And it ain't only when you 're mending her that a clock like this is interesting. She's interesting all the time, like a baby. She don't do a thing you'd expect, all day long. I can mend her right up, and wind her and set her right in the morning, and set the alarm to go off at four o'clock in the afternoon, and at four o'clock what do you think she'll be doing? Like as not she'll be pointing at half-past eleven. Yes, sir! And the alarm won't go off until half-past two at night, maybe. Why I mended this clock once and left two wheels out of her—”

“Tell you what I'll do, Peter,” said Rapp, “I'll give fifty dollars for the boat, and five dollars for floating her down to my new place down the river.”

“I'm much obliged, but I guess I won't sell,” said Peter nervously. “You better take off your coat, George, unless you want to hurry away. That stove is heating up. She's a wonderful stove, that stove is. You wouldn't think, to look at her right now, that she could go out in a minute, would you? But she can. Why, when she wants to, that stove can start in and get red hot all over, stove-pipe and legs and all, until it's so hot in here the tar melts off them nets yonder—drips off 'em like rain off the bob-wires. You'd think she'd suffocate me out of here, but she don't. No, sir. The very next minute she'll be as cold as ice. For a man alone as much as I am that's a great stove, George.”

“Will you sell me the boat, or won't you?” asked Rapp.

“Now, I wish you wouldn't ask me to sell her, George,” said Peter regretfully, for it hurt him to refuse his friend. “To tell you the honest truth, George, I can't sell her because it would upset my plans. I've got my plans all laid out to float down river next spring, soon as the ice goes out, and when I get to New Orleans I'm going to load this boat on to a ship, and I'm going to take her to the Amazon River, and trap chinchillas. I read how there's a big market for chinchilla skins right now. I'm goin' up the Amazon River and then I'm goin' to haul the boat across to the Orinoco River and float down the Orinoco, and then—”

“You told me last week you were going down to Florida next spring and shoot alligators from this boat,” said Rapp.

Peter looked up blankly, but in a moment his cheerfulness returned.

“If I didn't forget all about that!” he began. “Well, sir, I'm glad I did! That would have been a sad mistake. It looks to me like alligator skin was going out of fashion. I'd be foolish to take this boat all the way to Florida and then find out there was no market for alligator skins, wouldn't I?”

“You would,” said Rapp. “And you might get down there in South America and find there was no market for chinchillas. It looks to me as if the style was veering off from chinchillas already. You'd better sell me the boat, Peter.”

“You know I'd sell to you if I would to anybody, George,” said Peter, pushing aside the works of the clock, “but this boat is a sort of home to me, George. It's the only home I 've got, since Jane don't want me 'round no more. You're the best friend I've got, and you've done a lot for me—you let me sleep in your stable whenever I want to, and you give me odd jobs, and clothes—and I appreciate it, George, but a man don't like to get rid of his home, if he can help it. I haven't had a home I could call my own since I was fourteen years old, as you might say, and I'm going on fifty years old now. Ever since Jane got tired havin' me 'round I've been livin' in your barn, and in old shacks, and anywheres, and now, when I've got a boat that's a home for me, and I can go traveling in her whenever I want to go, you want me to sell her. No, I don't want to sell her, George. I think maybe I'll start her down river to-morrow, so as to be able to start up the Missouri when the ice goes out—”

“I thought you said Amazon a minute ago,” said Rapp.

“Well, now, I don't know,” said Peter soberly. “The fevers they catch down there wouldn't do my health a bit of good. Rocky Mountain air is just what I need. It is grand air. If I can get seventy or eighty dollars together, and a good rifle or two, I may start next spring. I always wanted to have a try at bear shootin'. I've got sev'ral plans.”

“And somehow,” said Rapp, who knew Peter could no more raise seventy dollars than freeze the sun, “somehow you always land right back in Widow Potter's cove for the winter, don't you? She'll get you yet, Peter. And then you won't need this boat. All you got to do is to ask her.”

Peter pushed the table away and stood up, a look of trouble in his blue eyes.

“I wish you wouldn't talk like that, George,” he said seriously. “It ain't fair to the widow to connect up my name and hers that way. She wouldn't like it if she got to hear it. You know right well she don't think no more of me than she does of any other river-rat or shanty-boatman that hangs around this cove all summer, and yet you keep saying, 'Widow, widow, widow!' to me all the time. I wish you wouldn't, George.” He opened the door of his shanty-boat and looked out. The cove in which the boat was tied was on the Iowa side of the Mississippi, and during the summer it had been crowded with a small colony of worthless shanty-boatmen and their ill-kempt wives and children, direly poor and afflicted with all the ills that dirt is heir to. Here, each summer, they gathered, coming from up-river in their shanty-boats and floating on downriver just ahead of the cold weather in the fall. All summer their shanty-boats, left high and dry by the receding high water of the June flood, stood on the parched mud, and Peter looked askance on all of them, dirty and lazy as they were, but somehow—he could not have told you why—he made friends with them each summer, lending them dimes that were never repaid, helping them set their trot-lines that the women might have food, and even aiding in the caulking of their boats when his own was crying to be built.

All summer and autumn Peter had been building his shanty-boat, rowing loads of lumber in his heavy skiff from the town to the spot he had chosen on the Illinois shore, five miles above the town. He had worked on the boat, as he did everything for himself, irregularly and at odd moments, and the boat had been completed but a few days before George Rapp drove up from town, hoping to buy it. Peter believed he loved solitude and usually chose a summer dwelling-place far above town, but if he had gone to the uttermost solitudes of Alaska he would have found some way of mingling with his fellow-men and of doing a good turn to some one.

He never dreamed he was associating with the worthless shanty-boatmen, yet, somehow, he spent a good part of his time with them. They were there, they were willing to accept aid of any and all kinds, and on his occasional trips to town Peter passed them. This was enough to draw him into the entanglement of their woes, and to waste thankless days on them. Yet he never thought of making one of their colony. He would row the two miles to reach them, but he rowed back again each evening. It was because he was better at heart, and not because he thought he was better, that he remained aloof to this extent. In his own estimation he ranked himself even lower than the shanty-boatmen, for they at least had the social merit of having families, while he had none. His sister Jane had told him many times just how worthless he was, and he believed it. He was nothing to anybody—he felt—and that is what a tramp is.

Once each week or so Peter rowed to town to sell the product of his jack-knife and such fish as he caught. He was not an enthusiastic fisherman, but his jack-knife, always keen and sharp, was a magic tool in his hand. When he was not making shapely boats for the shanty-boat kids, or whittling for the mere pleasure of whittling, his jack-knife shaped wooden kitchen spoons and other small household articles, or net-makers' shuttles, out of clean maplewood, and these, when he went to town, he peddled from door to door. What he could not sell he traded for coffee or bacon at the grocery stores.

With the coming of cool weather and the “fall rise” of the river the shanty-boat colony left the cove, to float down-river ahead of the frost, and Peter hurried the completion of his boat that he might float it across to the cove. Rheumatism often gave him a twinge in winter and when the river was “closed” the walk to town across the ice was cold and long. The Iowa side was more thickly populated, too, for the Iowa “bottom” was narrow, the hills coming quite to the river in places, while on the Illinois side five or six miles of untillable “bottom” stretched between the river and the prosperous hill farms. The Iowa side offered opportunities for corn-husking and wood-sawing and other odd jobs such as necessity sometimes drove Peter to seek. These opportunities were the reasons Peter gave himself, but the truth was that Peter loved people. If he was a tramp he was a sedentary tramp, and if he was a hermit he was a socialistic hermit. He liked his solitudes well peopled.

This early November day Peter had brought his shanty-boat across the river to the cove. A fair up-river breeze and his rag of a sail had helped him fight the stiff current, but it had been a hard, all-day pull at the oars of his skiff, and when he had towed the boat into the cove and had made her fast by looping his line under the railway track that skirted the bank, he was wet and weary. His tin breadbox was empty and he had but a handful of coffee left, but he was too tired to go to town, and he had nothing to trade if he went, and he knew by experience that an appeal to a farmer—even to Widow Potter—meant wood-sawing, and he was too tired to saw wood. But he was accustomed to going without a meal now and then, and there being nothing else to do, he tightened his belt, made a good fire, took off his shoes, and dissected his alarm-clock. He was reassembling it when George Rapp arrived.

George Rapp was a bluff, hearty, loud-voiced, duck-hunting liveryman. He ran his livery-stable for a living and, like many other men in the Mississippi valley, he lived for duck-hunting. He owned the four best duck dogs in the county. He had traded a good horse for one of them. Although George Rapp would not have believed it, it was a blessing that he could not hunt ducks the year around. The summer and winter months gave him time to make money, and he was making all he needed. Some of his surplus he had just paid for a tract of low, wooded bottom-land, in the section where ducks were most plentiful in their seasons. The land was swamp, for the most part, and all so low that the river spread over it at every spring “rise” and often in the autumn. It was cut by a slough (or bayou, as they are called farther south) and held a rice lake which was no more than a widening of the slough. This piece of property, far below the town, Rapp had bought because it was a wild-duck haunt, and for no other reason, and after looking it over he wisely decided that a shanty-boat moored in the slough would be a better hunting cabin than one built on the shore, where it would be flooded once, or perhaps twice a year, the river leaving a deposit of rich yellow mud and general dampness each time. But Peter would not sell his boat, and Peter's boat, new, clean and sturdy of hull, was the boat Rapp wanted.

“I wish you wouldn't talk that way about the widow, George,” said Peter, looking out of the open door. The liveryman's team was tied to a fence at the foot of the hills, and between the road and the railway tracks that edged the river a wide corn-field extended. A cold drizzle half hid the hillside where Widow Potter's low, white farmhouse, with its green shutters, stood in the midst of a decaying apple orchard. “I wisht the widow lived farther off. There ain't no place like this cove to winter a boat, and when I'm here I've got to saw wood for her, and shuck corn, and do odd jobs for her, and then she lights into me. I don't say I'm any better than a tramp, George, but the way the widow jaws at me, and the things she calls me, ain't right. She thinks I'm scum—just common, low-down, worthless scum! So that's all there is to that.”

“Oh, shucks!” said George Rapp.

But Peter believed it. For five years the Widow Potter had kept a jealous eye on Peter Lane. Tall and thin, penny-saving and hard-working, she had been led a hard life by the late Mr. Potter, who had been something rather worse than a brute, and since death had removed Mr. Potter the widow had given Peter Lane the full benefit of her experienced tongue whenever opportunity offered. It was her way of showing Peter unusual attention, but Peter never suspected that when she glared at him and told him he was a worthless, good-for-nothing loafer and a lazy, paltering, river-rat, and a no-account, idling vagabond she was showing him a flattering partiality. He knew she could make him squirm. It was Love-in-Chapped-Hands, but Mrs. Potter herself did not know she scolded Peter because she liked him. She counted him as a poor stick, of little account to himself or to any one else, but what her mind could not, her heart did recognize—that Peter was Romance. He was a whiff of something that had never come into her life before; he was a gentleman, a chivalrous gentleman, a gentleman down at the heel, but a true gentleman for all that.

“The way me and her hates each other, George, is like cats and dogs,” said Peter. “I don't go near her unless I have to, and when I do she claws me all up.”

“All right,” said Rapp, laughing, “but you could do a lot worse than tie up to a good house and cook-stove. If you make up your mind to go housekeeping and to sell the boat, let me know. I'll get along home. It is going to be a dog of a night.”

“I won't change my mind about the boat, George,” said Peter. “Good night.”

He closed the door and bolted it.

“George means all right,” he said, settling himself to his task of reassembling his clock, “but he's sort of coarse.”

The storm, increasing with the coming of night, darkened the interior of the cabin, and Peter lighted his lamp. As he worked over the clock the drizzle turned into a heavy rain through which damp snowflakes fluttered, and the wind strengthened and turned colder, slapping the rain and snow against the small, four-paned window and freezing it there. It was blowing up colder every minute and Peter put his handful of coffee in his coffee-pot and set it on the stove to boil while he completed his clock job. He tested the clock and found that if he set the alarm for six o'clock it burst into song at seventeen minutes after three. A thin smile twisted the corners of his mouth humorously.

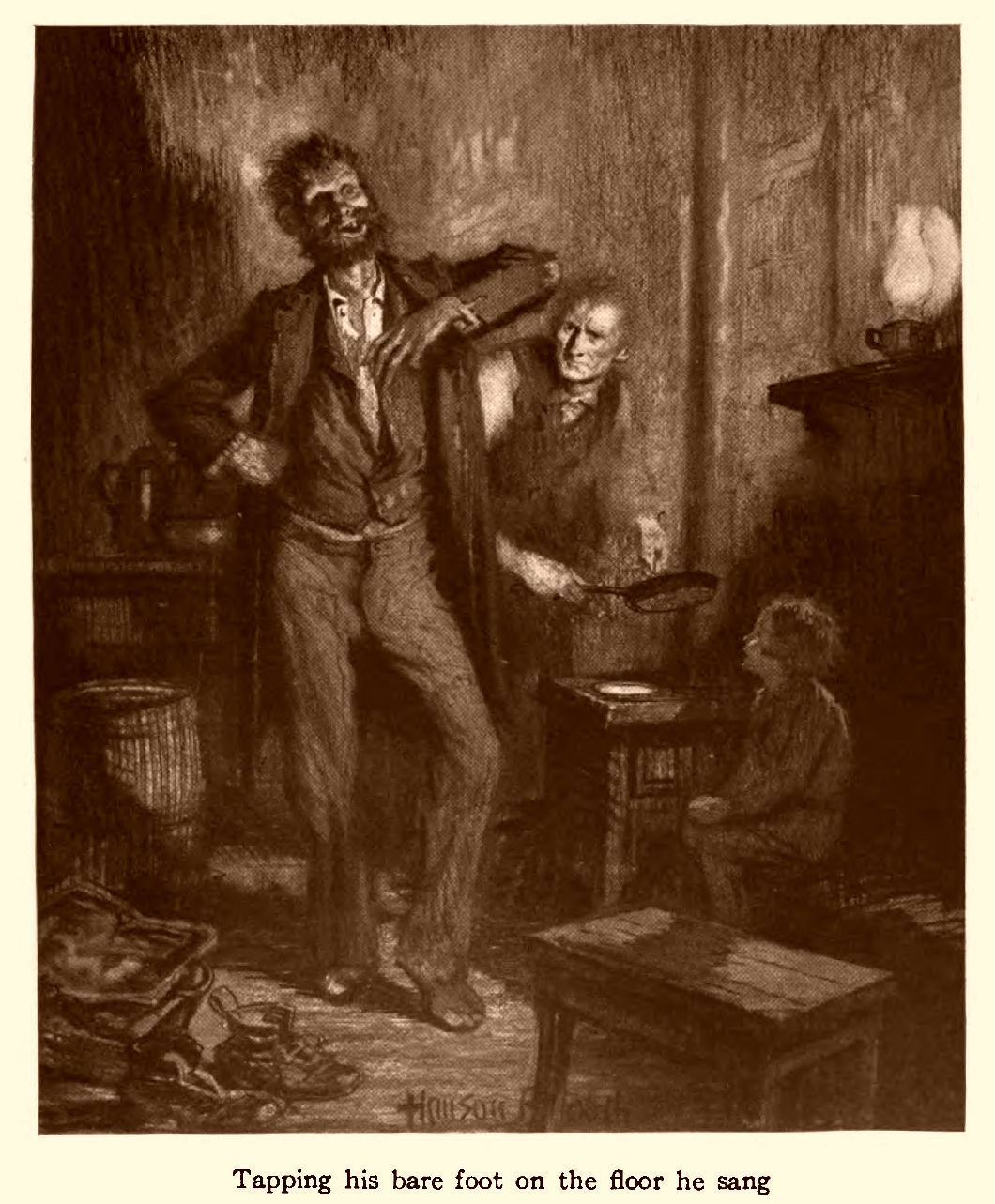

“You skeesicks! You old skeesicks!” he said affectionately. “Ain't you a caution!” He set the clock on its shelf where it ticked loudly while he drew his table closer to the bunk, his only seat, and put his coffeepot and tin cup on the table.

“Well, now,” he said cheerfully, “as long as there ain't anything to eat I might as well whet up my jack-knife.”

He whetted the large blade of his knife while he sipped the coffee. From time to time he put down the tin cup and tried the blade of the knife on his thumb, and when he was satisfied it was so sharp any further whetting meant a wire edge, he took a crumpled newspaper from under the pillow of his bunk and read again the article on the increased demand for chinchilla fur, but it had lost interest. The wind was slapping against the side of the boat in gusts and the frost was gathering on his windows, but Peter replenished his fire and lighted the cheap cigar George Rapp had left on the clock shelf.

What does a hermit do when he is shut in for a long night with a winter storm raging outside? Peter put his newspaper back under the pillow and hunted through his driftwood for a piece that would do to whittle, but had to give that up as a bad job. Then his eyes alighted on the wooden pegs on which his shot-gun lay, and he took down the gun and pulled one of the pegs from its hole. He looked out of the door, to see that his line was holding securely, and slammed the door quickly, for the night was worse, the rain freezing as it fell and the wind howling through the telegraph wires. With a sigh of satisfaction that he was alone, and that he had a snug shanty-boat in which to spend the winter, Peter propped himself up in his bunk and began carving the head of an owl on the end of the gun peg, screwing his face to one side to keep the cigar smoke out of his eyes. He was holding the half-completed carving at a distance, to judge of its effect, when he heard a blow on his door. He hesitated, like a timid animal, and then slipped from the bunk and let his hand glide to the shot-gun lying on his table. Quietly he swung the gun around until the muzzle pointed full at the door, and with the other hand he grasped his heavy stove poker, for he knew that tramps, on such a night, are not dainty in seeking shelter, and he had no wish to be thrown out of his boat and have the boat floated away from him.

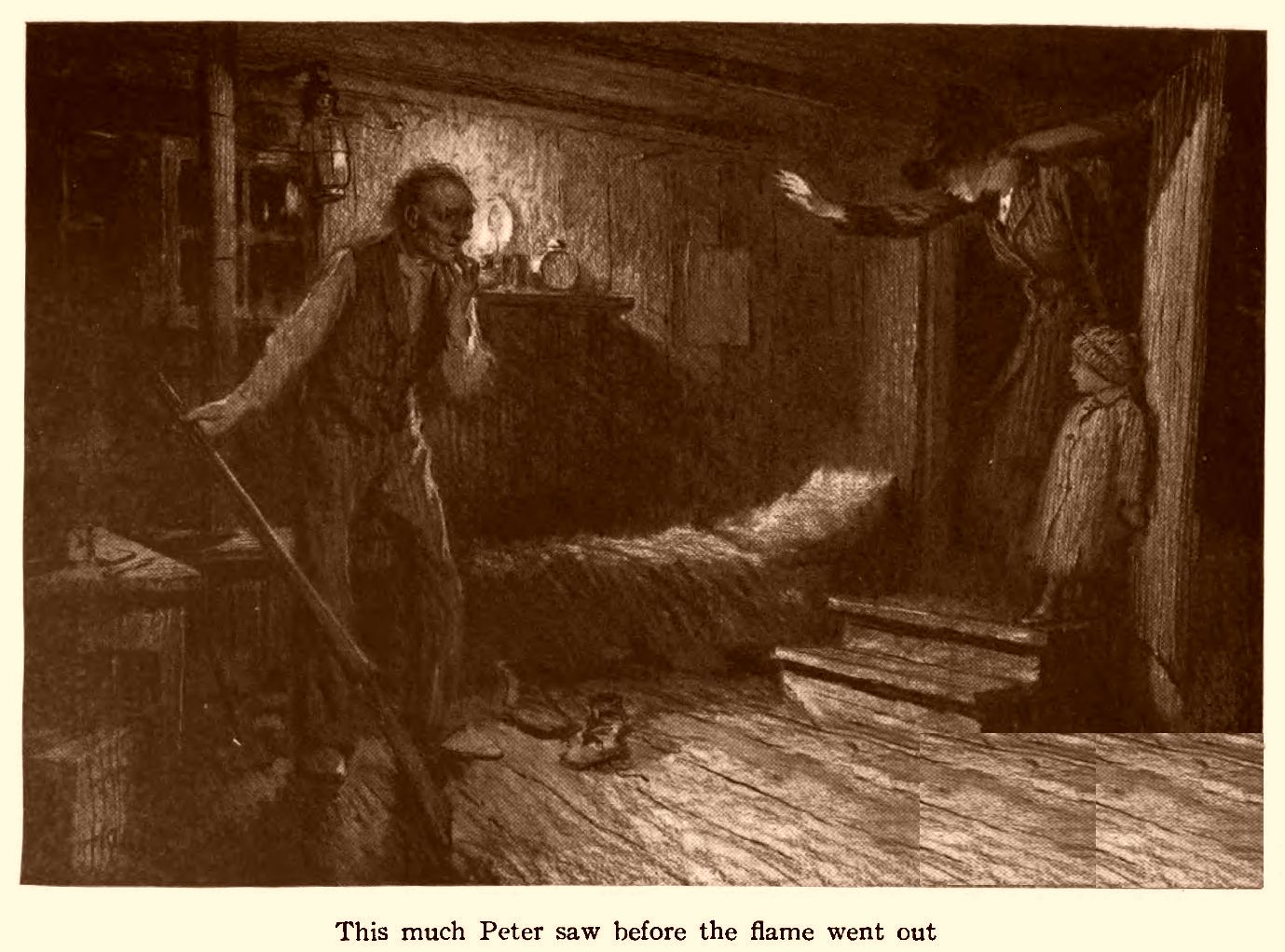

“Who's out there?” he shouted, but before he could step forward and bolt the door, the latch lifted and the door, forced violently inward by a gust of wind, clattered against the cabin wall. A woman, one hand extended, stood in the doorway. Her face was deathly white, and her left hand held the hand of a three-year-old boy. This much Peter saw before the flame of his lamp flared high in a smoky red and went out, leaving utter darkness.

COME right in, ma'am,” said Peter.

“Step inside and close the door. Nobody here's going to hurt you. I'll put my shoes on in a minute—”

He was feeling for the matches on his clock shelf, but he hardly knew what he was doing or saying. The ghastly white face of the woman was still blazed on his mind.

“Excuse me for being bare foot; I wasn't looking for callers,” he continued nervously, but he was interrupted by the sound of a falling body and a cry. He pushed one of the stove lids aside, letting a glare of red light into the room. The woman had fallen across his doorsill and lay, half in and half out of the boat, with the boy crying as he clung to her relaxed fingers.

“Don't, Mama! don't!” the small boy wailed, not understanding.

Peter stood, irresolute. He was a coward before women; they drove his wits away, and his first wild thought was of flight—of leaping over the fallen body—but, as he stood, the alarm-clock, after a preliminary warning cluck, burst into a loud jangling clatter and the boy, sore frightened, howled with all his strength. That decided for Peter.

“There, now, don't you cry, son!” he begged, on his knees beside the boy in an instant. “Don't you mind the racket. It ain't nothing but my old funny alarm-clock. She goes off that way sometimes, but she don't mean any harm to anybody. No, sir! Don't you cry.”

The boy wailed, more wildly than ever, calling on his mother to get up.

“Don't cry, your ma will be all right!” urged Peter. “That clock will stop right soon, and she won't begin again—not unless she takes a notion.”

The clock stopped ringing abruptly, the boy stared at it open-mouthed.

“That's a big boy!” said Peter approvingly. “And don't you worry about your ma. I guess she'll be all right in a minute. You go over by that stove and warm yourself, and I'll help your ma in, so this rain won't blow on her.”

Peter led the boy to the stove, and lighted his lamp. He put the peg back in the wall, and placed the gun behind the boy's reach before he turned to the woman.

She was neither young nor old, but as she lay on the floor she was ghastly white, even in the glare from the smoking oil lamp, and her lips were blue. Her cheap hat was wet and weighted down with sleet, and the green dye from the trimmings had run down and streaked her face. She was fairly well clad, but not against the winter rain, and her shoes were too light and too high of heel for tramping a railway track. Peter saw she was wet to the skin. He bent down and with his knee against her shoulder moved her inside the door and closed it.

“That's hot in there,” said the boy, who had been staring into the glowing coals of the opened stove. “I better not put my hand in there. I'll burn my hand if I put it in there, won't I?”

“Yes, indeedy,” said Peter, “but now I got to fix your ma so's she will be more comfortable.”

“I wish I had some liquor or something,” he said, looking at the woman helplessly. “Brandy or whisky would be right handy, and I ain't got a drop. This ain't no case for cold water; she's had too much cold water already. I wonder what coffee would do?”

He put his coffee-pot down among the coals of his fire and while he waited for it to heat, he drew on his shoes.

“I guess your ma will feel sort of sick when she wakes up,” he told the boy, “and I guess she'd be right glad if we took off them wet shoes and stockings of yours and got your feet nice and warm. You want to be ready to help look after your ma. You ain't going to be afraid to let me, are you?”

“No,” said the boy promptly, and held out his arms for Peter to take him. He was a solid little fellow, as Peter found when he picked him up, and his hair was a tangled halo of long, white kinks that burst out when Peter pulled off the red stocking-cap into which they had been compressed. From the first moment the boy snuggled to Peter, settling himself contentedly in Peter's arms as affectionate children do. He had a comical little up-tilt to his nose, and eyes of a deeper blue than Peter's, and his face was white but covered with freckles.

“That's my good foot,” said the boy, as Peter pulled off one stocking.

“Well, it looks like a mighty good one to me, too,” said Peter. “So far as I can see, it is just as good as anybody'd want.”

“Yes. It's my hop-on-foot,” explained the boy. “The other foot is the lame one. It ain't such a good foot. It's Mama's honey-foot.”

“Pshaw, now!” said Peter gently. “Well, I'll be real careful and not hurt it a bit.” He began removing the shoe and stocking from the lame foot with delicate care, and the boy laughed delightedly.

“Ho! You don't have to be careful with it,” he laughed, giving a little kick. “You thought it was a sore foot, didn't you? It ain't sore, it's only lame.”

Peter put the barefoot boy on the edge of the bunk and hung the wet stockings over his woodpile. The boy asked for the jack-knife again, and Peter handed it to him.

“You just set there,” he told the boy, “and wiggle your toes at the stove, like they was ten little kittens, and I'll see if your ma wants a drink of nice, hot coffee.”

He poured the coffee into his tin cup and went to the woman, raised her head, and held the hot coffee to her lips. At the first touch of the hot liquid she opened her eyes and laughed; a harsh, mirthless laugh, which made her strangle on the coffee, but when her eyes met Peter's eyes, the oath that was on her lips died unspoken. No woman, and but few men, could look into Peter's eyes and curse, and her eyes were not those of a drunkard, as Peter had supposed they would be.

“That's all right,” she said. “I must have keeled over, didn't I? Where's Buddy?”

“He's right over there warming his little feet, as nice as can be,” said Peter. “And he was real concerned about you.”

“I wouldn't have come in, but for him,” said the woman, trying to straighten her hat. “I thought maybe he could get a bite to eat. It don't matter much what, he ain't eat since noon. A piece of bread would do him 'til we get to town.” She leaned back wearily against the pile of nets in the corner.

“I want butter on it. Bread, and butter on it,” said Buddy promptly.

“There, now!” said Peter accusingly. “I might have knowed it was foolish to let myself run so low on food. A man can't tell when food is going to come in handiest, and here I went and let myself run clean out of it. But don't you worry, ma'am,” he hastened to add, “I'll get some in no time. Just you let me help you over on to my bunk. I ain't got a chair or I'd offer it to you whilst I run up to one of my neighbors and get you a bite to eat. I've got good neighbors. That's one thing!”

The woman caught Peter by the arm and drew herself up, laughing weakly at her weakness. She tottered, but Peter led her to the bunk with all the courtesy of a Raleigh escorting an Elizabeth, and she dropped on the edge of the bunk and sat there warming her hands and staring at the stove. She seemed still near exhaustion.

“If you'll excuse me, now, ma'am,” said Peter, when he had made sure she was not going to faint again, “I'll just step across to my neighbor's and get something for the boy to eat. I won't probably be gone more than a minute, and whilst I'm gone I'll arrange for a place for me to sleep to-night. You hadn't ought to make that boy walk no further to-night. It's a real bad night outside.”

“That's all right. I don't want to chase you out,” said the woman.

“Not at all,” said Peter politely. “I frequently sleep elsewheres. It'll be no trouble at all to make arrangements.”

He put more wood in the stove, opened the dampers, and lighted his lantern. Then he pinned his coat close about his neck with a blanket pin, and, as he passed the clock shelf, slipped the alarm swiftly from its place and hid it beneath his coat.

“I'll be right back, as soon as I can,” he said, and, drawing his worn felt hat down over his eyes, he stepped out hastily and slammed the door behind him.

“Why did the man take the clock?” asked the boy as the door closed.

“I guess he thought I'd steal it,” said the woman languidly.

“Would you steal it?” asked the boy.

“I guess so,” the woman answered, and closed her eyes,

AS Peter crossed the icy plank that led from his boat to the railway embankment he tried to whistle, but the wind was too strong and sharp, and he drew his head between his shoulders and closed his mouth tightly. He had understated the distance to Widow Potter's when he had said it was “just across.” In fair weather and daylight he often cut across the corn-field, but on such a night as this the trip meant a long plod up the railway track until he came to the crossing, and then a longer tramp back the slushy road, a good half mile in all. When he turned in at Widow Potter's open gate a great yellow dog came rushing at him, barking, but a word from Peter silenced him and the dog fell behind obediently but watchfully, and followed Peter to where the light shone through the widow's kitchen window. Peter rapped on the door.

“Who's out there?” Mrs. Potter called sharply. “I got a gun in here, and I ain't afraid to use it If you 're a tramp, you'd better git!”

“It's Peter Lane,” Peter called, loud enough to be heard above the wind. “I want to buy a couple of eggs off you, Mrs. Potter.”

The door opened the merest crack and Mrs. Potter peered out. She did not have a gun, but she held a stove poker. When she saw Peter she opened the door wide. It was a brusk welcome.

“Of all the shiftlessness I ever heard of, Peter Lane,” she said angrily, “you beat all! Cormin' for eggs this time of night when your boat's been in the cove nobody knows how long. I suppose it never come into your head to get eggs until you got hungry for them, did it?”

Peter closed the door and stood with his back to it. At all times he feared Mrs. Potter, but especially when he gave her some cause for reproof.

“I had some company drop in on me unexpected, Mrs. Potter,” he said apologetically. “If I hadn't, I wouldn't have bothered you. I hate it worse'n you do.”

“Tramps, I dare say,” said the widow. “You 're that shiftless you'd give the shoes off your feet and the food out of your mouth to feed any good-for-nothing that come camping on you. You don't get my good eggs to feed such trash, Peter Lane! Winter eggs are worth money.”

“I thought to pay for them,” said Peter meekly. “I wouldn't ask them of you any other way, Mrs. Potter.”

“Well, if you 've got the money I suppose I've got to let you have them,” said the widow grudgingly. “Eggs is worth three cents apiece, and I hate to have 'em fed to tramps. How many do you want to buy?” Peter shifted from one foot to another uncomfortably. “Well, now, I'm what you might call a little short of ready money tonight,” he said. “I thought maybe I might come over and saw some wood for you tomorrow—”

“And so you can,” said Mrs. Potter promptly, “and when the wood is sawed they will be paid for, in eggs or money, and not until it is sawed. I'm not going to encourage you to run into debt. You 're shiftless enough now, goodness knows.”

Peter tried to smile and ignored the accusation.

“There couldn't be anything fairer than that,” he said. “Nobody ought to object to that sort of arrangement at all. That's real business-like. Only, there's a small boy amongst the company that dropped in on me and he's only about so high—” Peter showed a height that would have been small for an infant dwarf. “He's a real nice little fellow, and if you was ever a boy that high, and crying because you wanted something to eat—”

“I don't believe a word of it!” snapped Mrs. Potter. “If there is a child down there he ought to be in bed long ago.”

“Yes'm,” agreed Peter meekly. “That's so. You wouldn't put even a dog that size to bed hungry. So, if you could let me have about half-a-dozen eggs, I'll go right back.”

“Six eggs at three cents is eighteen cents,” said Mrs. Potter firmly, looking Peter directly in the eye. She was not bad looking. Her cheek bones were rather high and prominent and her cheeks hollow, and she had a strong chin for a woman, but the downward twist of discouragement that had marked her mouth during her later married years had already disappeared, giving place to a firmness that told she was well able to manage her own affairs. Peter drew his alarm-clock from beneath his coat and stood it on the kitchen table.

“I brought along this alarm-clock,” he said, “so you'd know I'd come back like I say I will. She's a real good clock. I paid eighty cents for her when she was new, and I just fixed her up fresh to-day. She's running quite—quite a little, since I fixed her.”

Mrs. Potter did not look at the clock. She looked at Peter.

“So!” she exclaimed. “So that's what you've come to, Peter Lane! Pawnin' your goods and chattels! That's what shiftless folks always come to in the end.”

“And so, if you'll let me have half-a-dozen eggs, and maybe some pieces of bread and butter and a handful of coffee,” said Peter, “I'll leave the clock right here as security that I'll come up first thing in the morning and saw wood 'til you tell me I've sawed enough.”

Mrs. Potter took the clock in her hand and looked at Peter.

“How old did you say that boy is?” she asked.

“Goin' on three, I should judge. He's a real nice little feller,” said Peter eagerly.

Mrs. Potter put the clock on her kitchen table.

“Fiddlesticks! I don't believe a word of it. Who else have you got down there?”

“Just his—his parent,” said Peter, blushing. “I wisht you could see that little feller. Maybe I'll bring him up here to-morrow and let you see him.”

“Maybe you won't!” said the widow. “If you 're hungry you can set down and I'll fry you as many eggs as you want to eat, but you can't come over me with no story about visitors bringin' you children on a night like this! No, sir! You don't get none of my eggs for your worthless tramps. Shall I fry you some?”

Peter looked down and frowned. Then he raised his head and looked full in the widow's eyes and smiled. Nothing but the direct need could have induced him to smile thus at the widow for he knew and feared the result. When, once or twice before, he had looked into her eyes and smiled in this way—unthinkingly—she had fluttered and trembled like a bird in the presence of an overmastering fascination, and Peter did not like that. Such power frightened him. The widow, scolding and condemning, he could escape, but the widow fluttering and trembling, was a thing to be afraid of. It made him flutter and tremble, too.

When Peter smiled the widow drew in her breath sharply.

“Six—six eggs—will six eggs be all you want?” she asked hurriedly.

“Yes'm,” said Peter, still smiling, “unless you could spare some bread and butter. He 'specially asked for butter,” and then he looked down. The widow drew another long breath.

“I don't believe you've got a boy down there, and I don't believe you've got a visitor that deserves nothing,” she said crossly. She was herself again. “I know you from hair to sole-leather, Peter Lane, and if any worthless scamp came and camped on you, you'd lie your head off to get food for him, and that's what I think you 're doing now, but there ain't no way of telling. If so be you have got a boy down there I don't want him to go hungry, but if it's just some worthless tramp, I hope these eggs choke him. You ain't got a mite of common sense in you. You 're too soft, and that's why you don't get on. You'd come up here to-morrow and do a dollar's worth of wood sawing for eighteen cents' worth of eggs, and then give the eggs to the first tramp that asked you. What you ought to have is a wife. You ought to have a wife with a mind like a hatchet and a tongue like a black-snake whip, and you might be worth shucks, anyway. You just provoke me beyond patience.”

“Yes'm,” said Peter nervously.

Mrs. Potter was cutting thick, enticing slices from a big loaf and spreading them with golden butter.

“I reckon you want jam on this bread?” she asked suddenly.

“Yes, thank you!” said Peter.

“Well, maybe you have got a boy down there,” said Mrs. Potter reluctantly. “You'd be ashamed to ask for jam if you hadn't. If you had a wife and she was any account you'd have bread and jam when boys come to see you. But I do pity the woman that gets you, Peter Lane! No woman on this earth but a widow that has had experience with men-folks could ever make anything out of you.”

Peter put his hand on the door-knob, ready for instant flight. When he smiled on Mrs. Potter something like this usually resulted and that was why he tried it so seldom. It was he, now, who trembled and fluttered.

“I'm not thinking of getting married at all,” he said. “I couldn't afford to, anyway.”

“You needn't think, just because you are no-account, some fool woman wouldn't take you,” snapped Mrs. Potter. “Look at what my first husband was. Women marry all sorts of trash.”

Peter watched the progress of the bread and jam, trusting its preparation would not be delayed long.

“If they're asked,” said Mrs. Potter. She seemed very cross about something. She wrapped the slices of bread in a clean sheet of paper from her table drawer, folding in the ends of the paper angrily. “But they don't do the asking,” she added.

Peter took the parcel, and slipped the six clean white eggs into his pocket. He wanted to get away, but Mrs. Potter stopped him.

“I suppose, if there is a boy down there, I've got to give you what's left of my roast chicken,” she grumbled, “or you'll be coming up here about the time I get into bed, routing me out for more victuals. If I had a husband, and he was like you, and he had a mind to feed all the tramps in the county, he wouldn't have to rout me out of bed to do it. He could go to the cupboard himself, and feed them.”

“Now, that clock,” said Peter hastily, “if I was you I wouldn't depend too much on her alarm to get you up. I can't say she's regulated just the way I'd like to have her yet. And I'm much obliged to you.”

“I don't want your clock!” said Mrs. Potter, but Peter had slipped out of the door, closing it behind him. The widow held the clock in her hand for a full minute, and then set it gently beside her own opulent Seth Thomas.

“I dare say you 're about as well regulated as he is,” she said, “and that ain't saying much for either of you. He ain't got the eyes to see through a grindstone!”

When Peter returned to the boat, the boy was busily trying to work one of the trot-line hooks out of the sleeve of his jacket, but the woman had dropped back on the bunk and her eyes were closed. She opened them when the rush of cold air from the door struck her face, and looked at Peter listlessly.

“I guess you don't feel like cooking a couple of eggs,” said Peter, “so if you'll excuse me remaining here awhile, I'll do it for you. I'm a fair to middling fried-egg cook. Son, you let me get that hook out of you, and then see if you can eat five or six of these pieces of bread and jam. I could when I was a boy, and then I could wind up with a piece of chicken like this.”

“I hooked myself,” the boy explained.

“I should say you did,” said Peter. “You want to look out for these hooks, they bite a boy like a cat-fish stinger, and that ain't much fun. I'm right glad you dropped in,” he said to the woman, “because I've got such good neighbors. It's almost impossible to keep them from forcing more eggs and butter and such things on me than I'd know what to do with. 'Just come on up when you want anything,' they are always saying, 'and help yourself.' So it's quite nice to have somebody drop in and give me a chance to show my neighbors I ain't too proud to take a few eggs and such. It would surprise you to see how eager they are that way.”

He scraped the butter from one of the pieces of bread, needing it to fry the eggs in, and he worked as he talked, breaking the eggs into the frying-pan and watching that they were cooked to a turn.

“I certainly am blessed with nice neighbors,” he said. “There's a widow lady lives a step or two beyond the railroad, and seems as if she couldn't do enough for me. She just lays herself out to see that I'm overfed. Do you feel like you could eat a small part of chicken?”

The woman let her eyes rest on Peter some time before she spoke.

“I ought to feel hungry, but I don't,” she said.

“Well, maybe a soft-boiled egg would be better. I ought to have thought of that,” said Peter as if he had been reproved. “You'll have to excuse me for boiling it in the coffee-pot, I've been so busy planning a trip I'm going to take I haven't had time to lay in much tinware yet.”

“Where did you take the clock?” asked the boy suddenly.

Peter reddened under his tan.

“That clock?” he said hesitatingly. “Where did I take that clock? Well, the fact is—the fact is that clock is a nuisance. That's it, she's a nuisance.' I been meaning to throw that clock into the river for I don't know how long. Unless you are used to that clock you just can't sleep where she is. 'Rattelty bang!' she goes just whenever she takes a notion, like a dish-pan falling downstairs, all times of the night. So I just thought, as long as I was going out anyway, 'Now's a good time to get rid of the old nuisance!'”

“Mama would steal the clock,” said the boy.

“Oh, you mustn't say that!” said Peter. “You come here and eat these two nice eggs. I hope, ma'am, you don't think I had any such notion as that. When I have visitors they can steal everything in the boat, and welcome. I mean—”

“I know what you mean,” said the woman. “You 're the white kind.”

“I'm glad you look at it that way,” said

Peter. “The boy, he don't understand such things, he's so young yet. Maybe you'd feel better if I propped you up with the pillow a little better. I'll lay this extry blanket on the foot of the bunk here in case it should get cold during the night. You look nice and warm now.”

“I'm burning up,” said the woman.

“I judge you've got a slight fever,” said Peter. “I often get them when I get overtook by the rain when I'm out for a stroll.”

“I'll be all right if I can lie here for an hour or so,” said the woman listlessly. “Then Buddy and me will get on. Is it far to town?”

“Now, you and that boy ain't going another step to-night,” said Peter firmly. “You 're going to stay right here. You won't discommode me a bit for I've made arrangements to sleep elsewhere, like I often do.”

He gave the woman the egg in his tin cup, and while she ate he put his trot-lines outside on the small forward deck so the boy might get in no more trouble with the hooks. Then he removed the shells from his shotgun, put the remaining eggs and bread and butter and chicken in his tin box, and pinned his coat collar.

“I'm going up to the place I arranged to sleep at, now,” he said, “and I hope you'll find everything comfortable and nice. There's more wood there by the stove, and before I come in in the morning I'll knock on the door, so I guess maybe you'd better take off as many of them wet clothes as you wish to. You'll take a worse cold if you don't.”

“I'm afraid I'm too weak,” said the woman. “If you will just give me some help with my dress—”

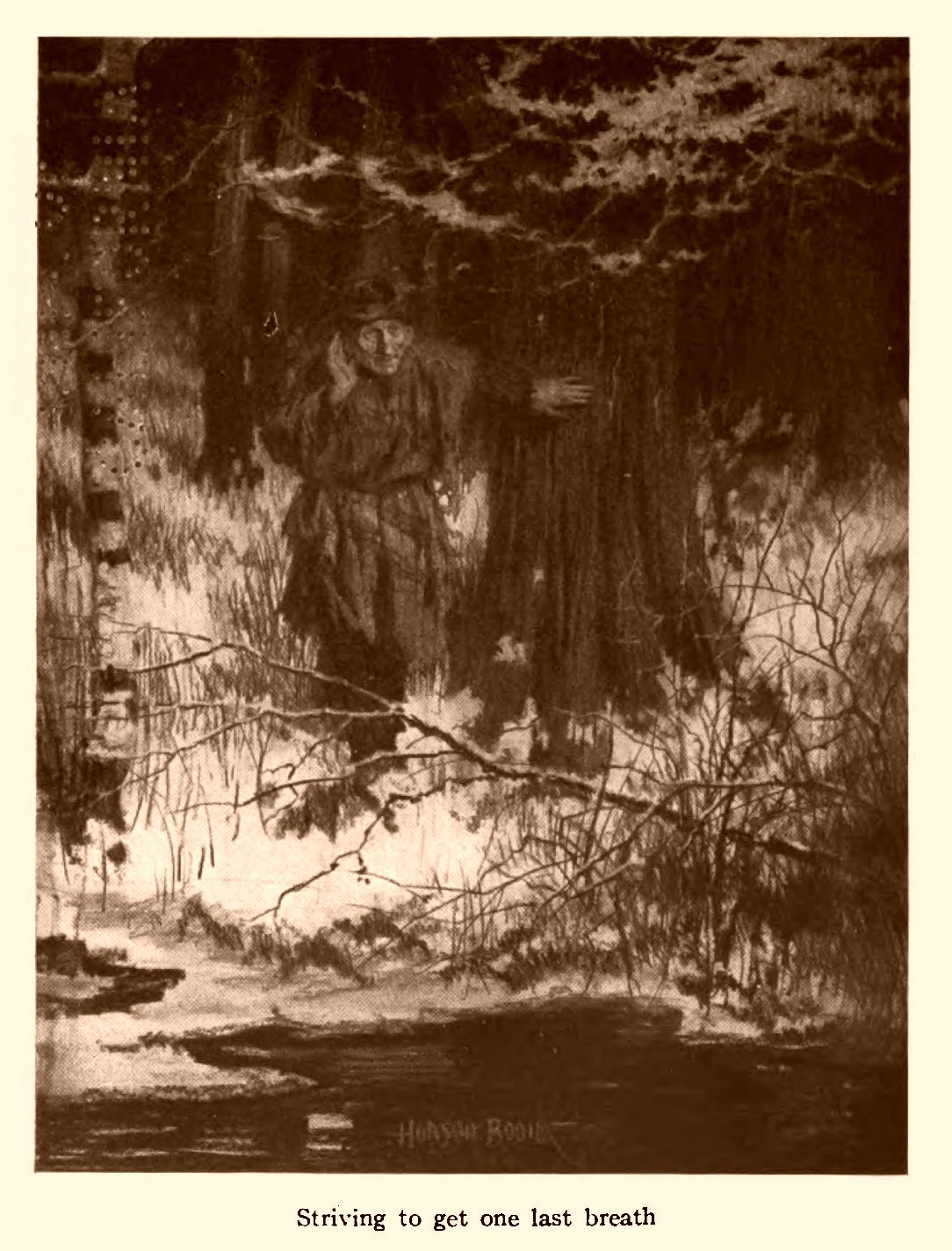

But Peter fled. He was a strange mixture, was Peter, and he fled as a blushing boy would have fled, not to stop running until he was far up the railway track. Then he realized, by the chill of the sleety rain against his head where the hair was thinnest, that he had forgotten his hat, and he laughed at himself.

“Pshaw, I guess that woman scared me,” he said.

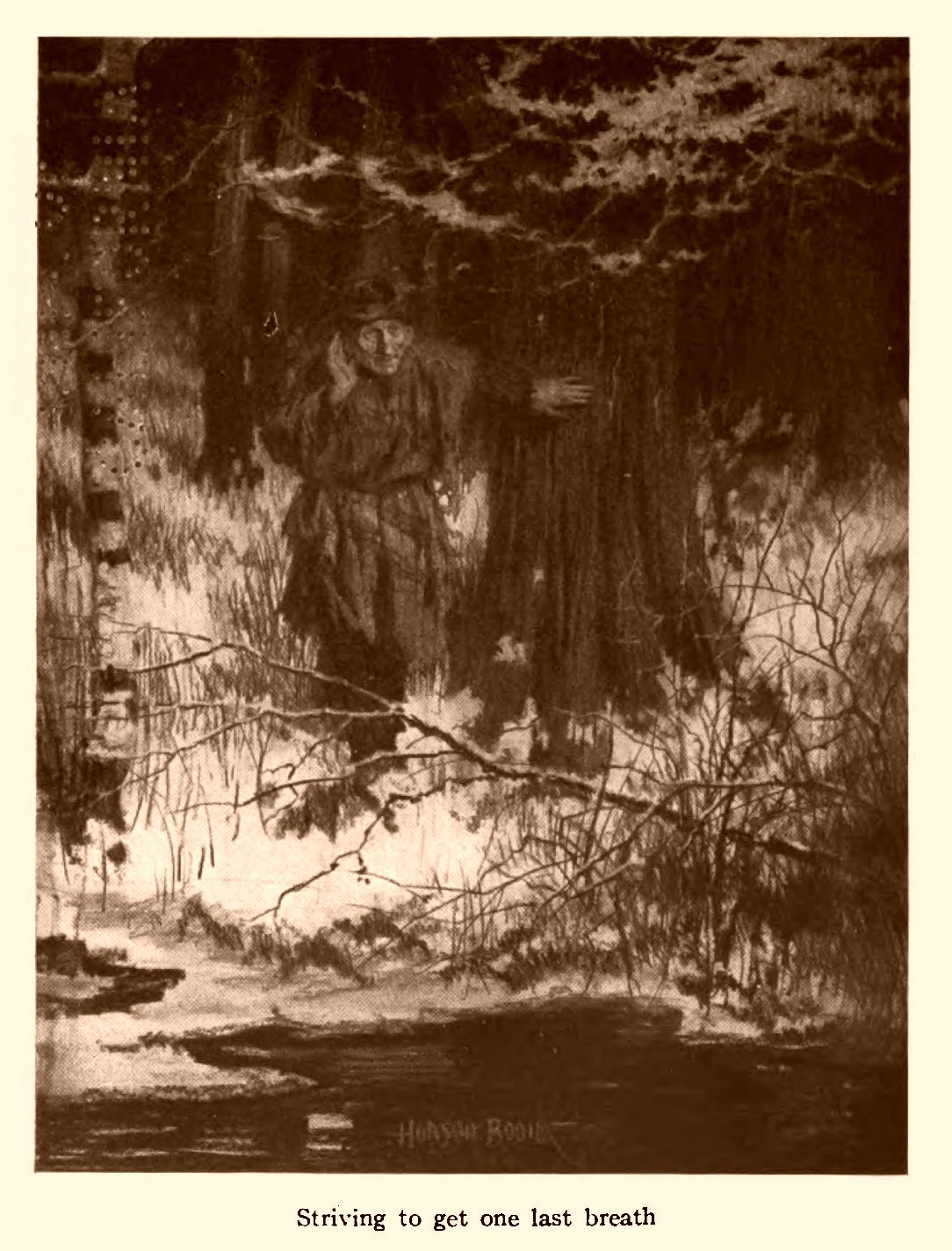

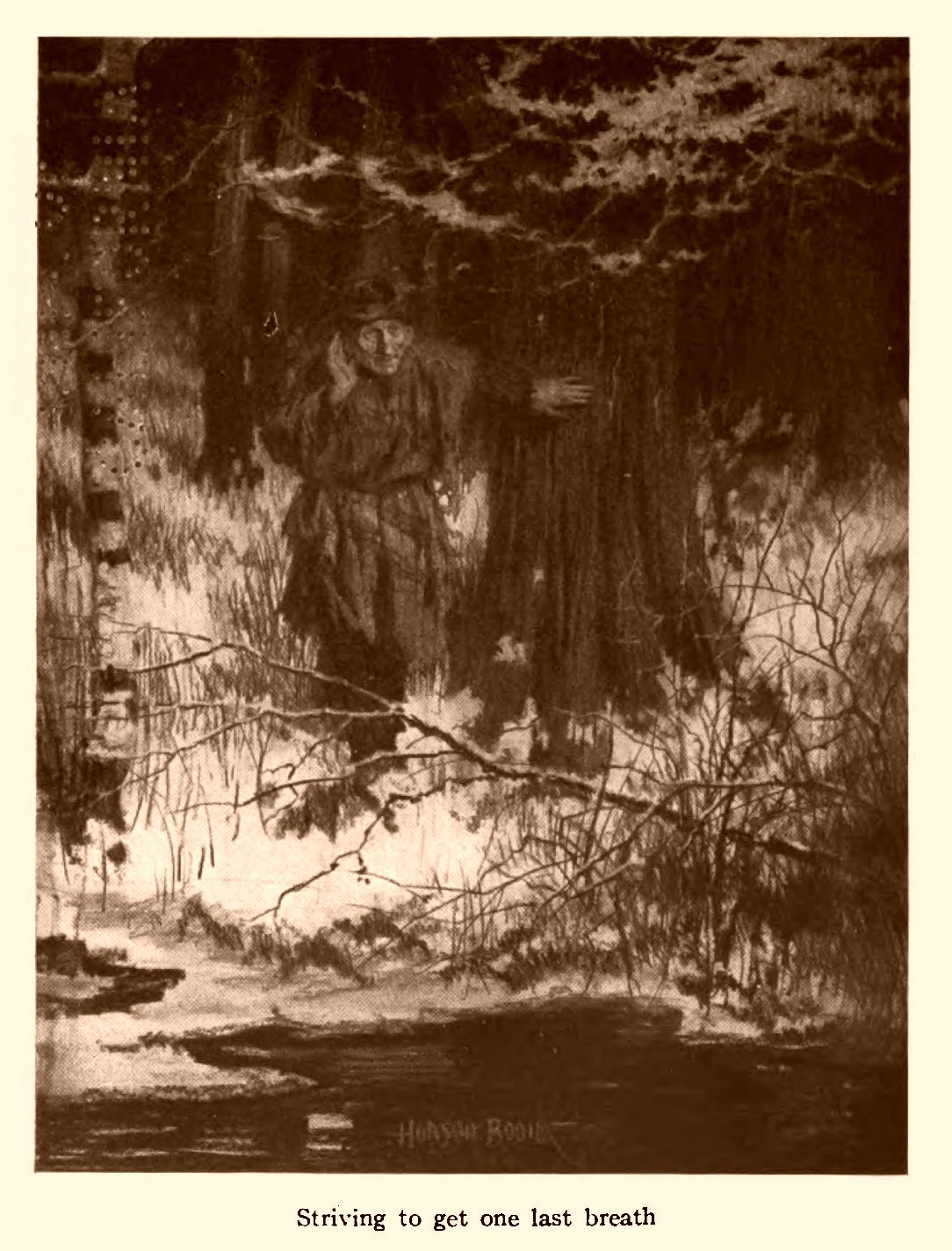

He did not follow the path to Mrs. Potter's kitchen door this time, but skirted the orchard and climbed a rail fence into the cow pasture. He made a wide circle through the pasture and climbed another fence into the yard behind the barn, where a haystack stood. He was trembling with cold by this time, and wet through, and the water froze stiff in his coat cuffs, but he dug deep into the base of the haystack and crawled into its shelter, drawing the sweet hay close around him. For awhile he lay with chattering teeth, his knees close under his chin, and then he felt warmer, and straightened his knees. The next moment he was asleep.

WHEN Peter crawled out of his haystack the next morning the weather was intensely cold and the wind was gone. Every twig and weed sparkled with the ice frozen upon it. He had needed no alarm-clock to awaken him, for an uneasy sense of discomfort gradually opened his eyes, and he found his knees aching and his whole body chilled and stiff. He climbed the fence into the farm-house yard. He had no doubt now that he was hungry, and he was well aware that his head was cold where the hair was thin. Indeed, his hands and feet were cold too. But he tightened his belt another hole and made for Mrs. Potter's woodshed. Among the chips and sawdust he found a piece of white cloth which, had he known it was the remains of one of Mrs. Potter's petticoats, he would have left where it lay, but not knowing this he made a makeshift turban by knotting the corners, and drew it well down over his ears, like a nightcap. It was more comfortable than the raw morning air, and Peter had no more pride than a tramp.

He found the wood saw hanging in the shed, a piece of bacon-rind on the windowsill, and the ice-covered sawbuck in the yard, and he set to work on the pile of pin-oak as if he meant to earn his clock, his breakfast and a full day's wages before Mrs. Potter got out of bed. The exercise warmed him, but he kept one eye on the top of Mrs. Potter's kitchen chimney, looking for the thin smoke signal telling that breakfast was under way. The pile of stove-wood grew and grew under his saw but still the house gave no sign of life. The sun climbed, making the icy coating of trees and fences glow with color, and still Mrs. Potter's kitchen chimney remained hopelessly smokeless.

“That woman must have a good, clear conscience or she couldn't sleep like that,” said the hungry Peter, “but I've got folks on my hands, and I've got to see to them. If this ain't enough wood to satisfy her I'll saw some more when I come back.”

He was worried, for no smoke was coming from the stovepipe that protruded from the roof of his shanty-boat. When he reached the boat he knocked three times without answer before he opened the door cautiously and peered in, ready to retreat should his entrance be inopportune. The woman was lying where he had left her, still in her wet clothes, and the cabin was icy cold. The boy, when Peter opened the door, was standing on the table trying to lift the shot-gun from its pegs. His face showed he had made a trip to the bread and jam. He looked down at Peter as the door opened.

“Mama's funny,” he said, and reached for the gun again.

The woman was indeed “funny.” She was in the grip of a raging fever. Her cheeks were violently red and against them the green dye from her hat made hideous streaks. Her hair had fallen and lay in a tangle over the pillow, with the rain-soaked hat still clinging to a strand. As she moved her head the hat moved with it, giving her a drunken, disreputable appearance. She talked rapidly and angrily, repeating the names of men, of “Susie” and “Buddy,” stopping to sing a verse of a popular song, breaking into profanity and laughing loudly. All human emotions except tears flowed from her, and Peter stood with his back against the door, uncertain what to do. The table, tipping suddenly and throwing the boy to the floor, decided him.

“There, now, you little rascal!” he said, gathering the weeping boy in his arms.

“You might have broke your arm, or your leg. You oughtn't to stand on a table you ain't acquainted with, that way.”

“I wanted to fall down,” said the boy, ceasing his tears at once. “I like to fall off tables I ain't 'quainted with.”

“Well, I just bet you do!” said Peter. “You look like that sort of a boy to me. Does your ma act funny like this often? You poor young 'un, I hope not!”

“No,” said Buddy.

Peter looked at the woman, studying her. It might have been possible that she was insane, but the vivid red of her cheeks convinced him she was delirious with fever. Her hat, askew over one ear, gave Peter a feeling of shame for her, and he put Buddy down and walked to the bunk. He saw that the hat pin had made a cruel scratch along her cheek.

“Now, ma'am,” he said, “I'm just going to help you off with this hat, because it's getting all mashed up, and it ain't needed in the house.”

He put out his hand to take the hat, but the woman raised herself on one arm, and with the other fist struck Peter full in the face, so that he staggered back against the table, while she swore at him viciously.

“You hadn't ought to do that,” he said reprovingly; “I wasn't going to hurt you.”

“I know you!” shouted the woman in a rage. “I know you! You can't come any of that over me! You took Susie, you beast, but you don't get Buddy. Let me get at you!”

She tried to clamber from the bunk, but fell back coughing.

“Now, you are absolutely wrong, ma'am,” said Peter earnestly. “You've got me placed entirely wrong. I ain't the man you think I am at all. I'm the man that got something for Buddy to eat last night. You recall that, don't you?”

The woman looked at him craftily.

“Where's Buddy?” she asked.

“I'm—I'm cooking eggs, Mama,” said Buddy promptly, and Peter turned.

“Well, you little rascal!” cried Peter. “You must be hungry.”

The boy had put the frying-pan on the floor while Peter's back was turned, and had broken the remaining eggs in it. Much of the omelet had missed the pan, decorating Buddy's clothes and the floor. The woman seemed satisfied when she heard the boy's voice, and closed her eyes, and Peter took the opportunity to kindle the fire and start the breakfast. He cooked the omelet, the condition of the eggs suggesting that as the only method of preparing them. The woman opened her eyes as the pleasant odor filled the cabin, and followed every movement Peter made.

“I know you! You'll run me out of town, will you?” she cried suddenly. “All right, I'll go! I'll go! That's what I get for being decent. You know I 've been decent since you took Susie away from me, and that's what I get. Run me out—what do I care! I'll go.”

She put her feet to the floor, but another coughing fit threw her back against the pillow, and when she recovered she burst into tears.

“Don't take her!” she pleaded. “I'll be decent—don't! I tell you I'll be decent. Don't I feed her plenty? Don't I dress her warm? Ain't she going to school like the other kids? Don't take her. Before God, I'll be decent. Come here, Susie!”

“Now, that's all right, ma'am,” said Peter, as she began coughing again. “Nobody's going to take nobody whilst I'm in this boat, and you can make your mind up to that right off. Here's Buddy right here, eating like a little man, ain't you, Buddy?”

“Poor baby!” said the woman. “Come and let Ma try to carry you again. Your poor little leg's all tired out, ain't it?”

“It's rested,” said Buddy, “it ain't tired.”

“Tired, oh, God, I'm tired!” she wept. “You'll have to get down, Buddy. Ma can't carry you another step. God knows when I get to Riverbank I'll be straight. I've got enough of this. Where's Susie?”

“Now, I wisht, if you can, you'd try to lie quiet, ma'am,” said Peter, “for you ain't well. Try lying still, and I'll go right to town and get a doctor to come out and see you. I didn't mean you no harm at all.”

“I know you, you snake!” she cried. “You 're from the Society. You took my Susie, and you want Buddy. I'll kill you first. Come here, Buddy!”

The boy went to her obediently, and she drew him on to the bunk and ran her hand through his white kinks of hair. It seemed to quiet her to feel him in her arm.

“Now, ma'am,” said Peter, “you see nobody's going to take Buddy at all, and you can take my word I won't let anybody take him whilst I'm around. You can depend on that, I'm going to town, now, and I guess I'd better leave Buddy right here, for you'll be more comfortable knowing where he is. Don't you worry about nothing at all until I get back, and if you find the door locked it's just so nobody can't get in and bother you.”

He looked about the cabin. It was comfortably warm, and he poured water on the fire. He wished to take no chances with the woman in her present state. He even took his shot-gun and the heavy poker as he went out. Buddy watched him with interest.

“Are you stealing that gun?” he asked.

“No, son,” said Peter gravely. “Nobody's stealing anything. You want to get that idea out of your head. Nobody in this cabin—you, nor me, nor your ma, would steal anything. Your ma's sick and don't know what she's doing, but she don't mean no real harm. I guess she ain't been treated right, and she feels upset about it, but a boy don't want, ever, to say anything bad about his ma.”

He went out and closed and locked the door. Involuntarily he glanced at Widow Potter's chimneys. No smoke came from any of them.

“Now, I just bet that woman has gone and got sick, just when I've got my hands plumb full!” he said disgustedly. “I've got to go up and see what's the matter with her, or she might lie there and die and nobody know a thing about it.”

The cold had frozen the slush into hardness, and Peter cut across the corn-field. He tried Mrs. Potter's doors and found them all locked—which was a bad sign, unless she had gone to town while he was in the shanty-boat—but he knocked on the kitchen door noisily, and was rewarded after a reasonable wait, by hearing the widow dragging her feet across the kitchen.

“Is that you, Peter Lane?” she asked.

“Yes'm,” Peter answered.

“Well, it's time you come, I must say,” said the widow, between groans. “You the only man anywheres near, and you'd leave me die here as soon as not. You got to feed the cows and the horse and give the chickens some grain and then hitch up and fetch a doctor as fast as he can be fetched. I might have laid here for weeks, you 're that unreliable. I'll put the barn key on the kitchen table, and when the doctor comes I'll be in my bed, if the Lord lets me live that long. I'll be in it anyway, I dare say, dead or alive, if I can manage to get to it. And don't you come in until I get out of the way, for I ain't got a stitch on but my night-gown.”

“I won't,” said Peter, and he didn't. He gave Mrs. Potter time to get into twenty beds, if she had been so minded, before he opened the kitchen door a crack and peeped in. He hurried through the chores as rapidly as he could, feeding the stock and the chickens and milking the cows. He had eaten part of the omelet Buddy had commenced, but he thought it only right he should have a satisfying drink of the warm milk, and he took it. He made a fire in the kitchen stove and saw that the iron tea-kettle was full of water, and then he harnessed the horse and drove briskly to town and sought a doctor.

It was the hour when physicians were making their calls and the first two Peter sought were out, but Dr. Roth, the new doctor who had come from Willets to build a practice in the larger town, happened to be in his office over Moore's Drug Store, and he drew on his coat and gloves while Peter explained the object of his visit.

“I ain't running Mrs. Potter's affairs,” said Peter, “for there ain't no call for her to have nobody to run them, but, if I was, I'd get a sort of nurse-woman to go up and take care of her. She's all alone, and I don't know how sick she is.”

“Then you are not Mr. Potter?” asked the doctor.

“I ain't nothing at all like that,” said Peter. “I'm a shanty-boatman and my boat is right near the widow's place, and I do odd chores for her. Old Potter died and went where he belongs quite some time ago.”

The doctor agreed to pick up Mrs. Skinner on his way, Mrs. Skinner being one of those plump, useful creatures that are willing to do nursing, washing, or general housework by the day.

“And another thing, doctor,” said Peter, as the doctor closed his office door, “whilst you are out there I want you to drop down to the cove below the widow's house, to a shanty-boat you'll see there, and take a look at the woman I've got in it. So far as I can make out she's a mighty sick woman. I'll try to get back before you get through with the widow, but you'd better take my key, if I shouldn't. I'll pay whatever it costs to treat her. I'm quite ready to do that.”

“Why not drive out with me?”

“I got some business to transact,” said Peter. “But mebby it might be just as well to wait till I do get there. She's sort of out of her mind, and she might think you had come to do her some harm if I wasn't there.” The business Peter had to transact took him to George Rapp's Livery, Sale and Feed Stable, and by good luck he found George in his stuffy, over-heated office, redolent of tobacco smoke, harness soap and general stable odors. Like all men who brave cold weather at all hours George liked to be well baked when in-doors.

“Well, George,” said Peter, “since I seen you yesterday circumstances has occurred to change my mind about making any trips this year in my boat. For a man of my constitution I've made up my mind it would be just the worst thing to go south at all. It ain't the right air for my lungs, and when you got to talking about chinchillas going out of fashion, I seen it wasn't worth the risk. What I need is cold climate, George, and it's an unfortunate thing this here Mississippi River don't run any way but south, because there's one fur never does go out of style, and that's arctic fox—.”

“All right, I'll give you forty dollars for the boat,” laughed Rapp, putting his hand in his pocket.

“Now, wait!” said Peter. “I don't want you to think I'm doing this just because I want to sell the boat, George. That ain't so. I guess maybe I could raise what money I need to outfit, one way or another, but I can't afford to pay a caretaker to take care of that boat whilst I'm away up in Labrador, or Alaska, or wherever I'm going, and it ain't safe to leave a shanty-boat vacant. Tramps would run away with her.”

“When do you aim to start north?” asked Rapp, grinning.

“My mind ain't quite made up to that,” said Peter. “I want to look over a map and see where Labrador is before I start out. I thought maybe you'd let me remain in the shanty-boat awhile, George.”

“Stay on her as long as you like,” said Rapp. “You can live right in her all winter. All I want is to get her down to my place right away before the river closes, so she'll be there when the ducks fly next spring.”

“Now, that's another thing,” said Peter uneasily. “With all the preparations I have to make for my trip I'll have to be round town more or less this winter, and as your place is a long way down river, I thought maybe you might let the boat stay where she is this winter, George?”

“You can sleep in my barn any time you want to, Peter,” said Rapp. “I might as well let that boat lie where she is forever as leave her there all winter. I want her down there when the ducks fly north. I'll give you five dollars extra for floating her down, and a dollar or so a week for taking care of her, but if she can't go down she ain't any use to me.”

“The way the ice is beginning to run I'd have to start her down to-day or to-morrow,” said Peter regretfully. “It upsets my plans, but I got to have some ready cash. If the wind shifts your slough will be ice-blocked, and there ain't no other safe place to winter a boat down there.”

“You don't have to sell her if you don't want to,” said Rapp. “You can put off your trip. Seems like I've heard you put off trips before now, Peter.”

“Well, I guess I'll sell, George,” said Peter. “Maybe I can trap muskrats or something down there, I'll make out some how.”

He took the money Rapp handed him and once more Peter was homeless. He was no better than a tramp now. His plans were vague as to the sick woman, but forty-five dollars seemed a great deal of money to Peter. He might hire a room from Mrs. Potter, if that lady would permit, and have the sick woman cared for there, or he might, have her brought to town and lodged somewhere, if any one would take her in. There was no hospital in Riverbank. But he was happy. Somehow, he did not doubt he could care for the woman, for he had money in his pocket. To turn her over to the county poor-farm did not enter his mind. He would not have given a dog that fate.

He drove to Main Street first and tied his horse before the grocery that received his infrequent patronage. Here he bought a bag of flour and six packages of roasted coffee, some bacon and beans, condensed milk and canned goods, sugar and other necessities, and then let his eyes wander over the grocer's shelves. He had about decided to buy a can of green gage plums, as a dainty he loved and never indulged in, and therefore suitable to buy for the sick woman, when he saw the small white jars of beef extract, and he bought one for the sick woman.

While his parcels were being wrapped he picked up the copy of the Riverbank News that lay on the counter and glanced over it, for a newspaper was a rare treat for Peter. On the first page his eye caught the headline “Pass Her Along.” It was at the head of an article in the News reporter's best humorous style, and told how Lize Merdin, a notorious character, had been run out of Derlingport, the next town up the river, and ordered never to return under pain of tar and feathers. “The gay girl hit the ties in the direction of Riverbank at a Maud S. pace, yanking her young male offspring after her by the arm,” wrote the reporter, “and when last seen seemed intending to favor River-bank with her society, but up to last reports nothing has been seen of her there. It is a two days' jaunt for a gentle creature like Lize, but when she hits the River Street depot she will find Riverbank a regular springboard, and the bounce she will get here will impress on her receptive mind the fact that Riverbank is not hankering for her company. Pass her along!”

Peter folded the paper and laid it on the counter. So that was who his visitor was, and how she came to be tramping the railway track! He walked to where great golden oranges glowed in a box, near the door, and chose half a dozen and laid them beside his other purchases. These too were for the sick woman. Then he selected a dozen big, red apples and laid them beside the oranges. They were for Buddy. It was Peter's method of showing his disapproval of the bad taste of the News'' article.

When Peter reached the widow's farmhouse the doctor's horse still stood in the bam-yard, and Peter put up his own horse, while waiting for the doctor to come out.

“How is the widow? Is she bad off?” he asked when the doctor appeared.

“Mrs. Potter thinks she is a very sick woman, and she isn't a well one,” said the doctor. “She'll stay in bed a week, anyway. That's some woman. She has Mrs. Skinner hopping around like a toad in a skillet already, and she sent orders by me that you are to come and sleep in the kitchen, to be handy if she has a relapse in the night. You are to take care of her stock, and saw the rest of her cord wood, and do the odd chores, and if the pump freezes thaw it out, before it gets frozen any worse.”

“Now, ain't that too bad!” said Peter. “Just when I've got to get started down river this afternoon. Things always happen like that, don't they?”

He led the way across the frozen corn-field to his shanty-boat, and opened the door. Buddy had managed to turn the table upside down and was “riding a boat” in it. The doctor gave the boy and the cabin one glance and had Peter classed as one of the shiftless shanty-boatmen before he had pulled off his fur gloves. Then he turned to the woman. She was lying with her face toward the wall. He bent over her, and when he straightened his back and turned to Peter his face was very serious.

“Your wife is dead,” he said.

Peter's pale blue eyes stared at the doctor vacantly.

“Dead?” he stammered. “My wife? Why, doctor, she ain't—”

“Yes,” said the doctor, not waiting to hear the conclusion of Peter's sentence. “She has been dead an hour, at least. A weak heart, overtaxed, I should say. What do you mean by leaving her in these damp clothes? I should have been called long ago.”

“Now, ain't that too bad! Ain't that too bad!” said Peter regretfully. “It ain't nobody's fault but mine. I ought to have gone for you last night, and there I was, a-sleepin' away as comfortable as could be!”

“She should have been under treatment for some time,” said the doctor severely. He was a young doctor, and important, and not inclined to spare the feelings of a mere shanty-boatman. Here he could be severe, who had to be suave and politic with better people. He told Peter brutally that the woman had not been properly cared for; that with her constitution, she should have had delicacies and comforts and kindness. “If you want my candid opinion, you as much as killed her,” said Dr. Roth.

He was nettled by Peter's apparent heartlessness, for while Peter showed that the death had shocked him, he gave way to no outburst of sorrow such as might be expected from a bereaved husband. But now deep regret in Peter's eyes touched him.

“I shouldn't have said that,” he said more kindly. “I might not have been able to do anything. Probably not much after all. But if you don't want the boy to go the same way, treat him better. You have him left.”

Peter turned and looked at Buddy who, all unconscious, was rowing his table boat with a piece of driftwood for oar.

“That's so, aint it?” said Peter. “She's left the boy on my hands, ain't she? I guess I got to take care of him. Yep, I guess I have!”

When the doctor left the boat, half an hour later, he shook his head as he closed the door.

“Shiftless and unfeeling!” he muttered to himself. “'Left the boy on my hands!' Poor boy, I'm sorry for you, with a father like that.”

For he did not see Peter drop on his knees beside the curly headed child as soon as the door was closed, and he did not see how Peter took the boy in his arms. He could not hear what Peter said.

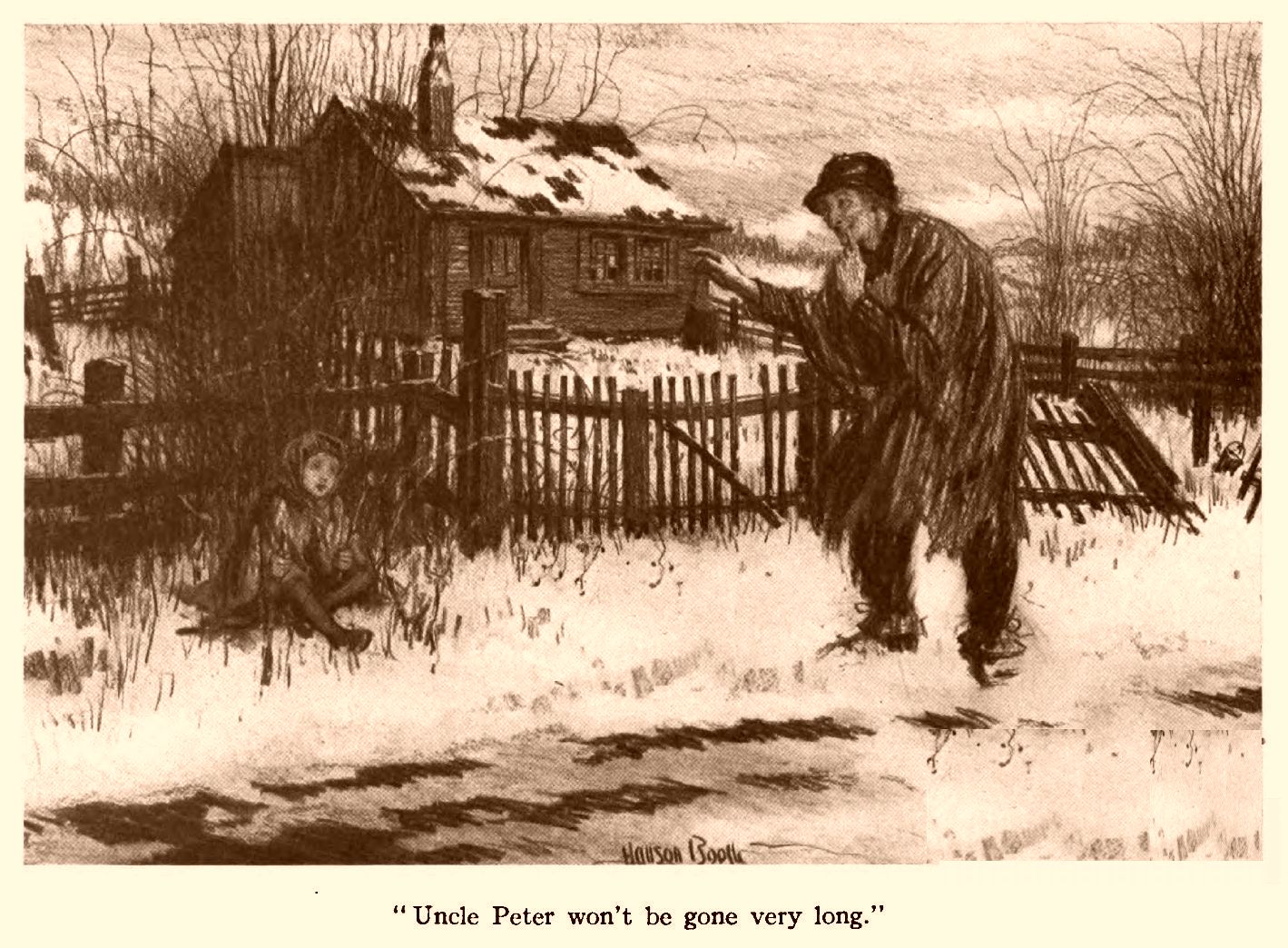

“Buddy boy,” said Peter, “how'd it be if you and Uncle Peter just sort of snuggled up close and—and et a big, red apple?”

NOW, don't you fret, Buddy-boy,” said Peter Lane with forced cheerfulness, “because I'm going to let you do something you never did before, and that I wouldn't let many boys do. You are going to help Uncle Peter steer this boat, just like you was a big man.”

Buddy stood in the skiff which was drawn up on the bank. Peter, with a rock and his stove-poker, was undoing the frozen knot that held his shanty-boat to the Rock Island Railway System, and by means of that to the State of Iowa. He was preparing to take the shanty-boat down the river to George Rapp's place. His provisions were aboard, the rag of a sail lay ready to raise should the wind serve—but it promised not to—and the long sweep that had reposed on the roof of the boat was on its pin at the bow, if a boat, both ends of which were identical, could be said to have a bow.

“I like to steer boats,” said Buddy out of his boyish optimism.

“I bet you do,” said Peter, “and a mighty good steerer you'll make. I don't know how Uncle Peter could get down river if he didn't have somebody to steer for him. Now, you let me push that skiff into the water, and we'll row around the boat, and before you know it you'll be steering like a regular little sailor.”

He threw the mooring rope on to the stern deck of the shanty-boat, pushed the skiff into the water and poled to the other end of the boat where the long sweep was held with its blade suspended in the air, the handle caught under a cleat on the deck. Peter lifted Buddy to the deck, made the skiff's painter fast, and climbed to the deck after the boy.

“Now, Buddy, we'll be off in a minute and a half,” he said, “just as soon as I fix you the way they fix sailors when they steer a ship in a big storm.”

He drew a ball of seine twine from his pocket, knotted one end about Buddy's waist, cut off a generous length, and tied the other end to the cleat.

“Don't!” said Buddy imperatively. “I don't want to be tied, Uncle Peter.”

“Oh, yes, you do!” said Peter. “Why, a sailor-man couldn't think of steering a great boat like this unless he was tied to it.”

“No!” shouted Buddy, and Peter stood, holding his end of the cord, studying the boy.

“Now, Buddy-boy,” he said appealingly. “Don't holler like that. Ain't I told you we must keep right quiet, because your ma is asleep in there.”

“But I don't want to be tied!” cried the boy.

“But Uncle Peter's going to be tied, too,” said Peter. “Yes, siree, Bob! Just as soon as I get this boat out into the river, I'm going to be tied like you are, and no mistake. You didn't know that, I guess, did you?”

The boy looked at him doubtfully.

“Are you?” he asked.

“If I say I am, I am,” said Peter. “You can always be right sure that when Uncle Peter says a thing, he ain't trying to fool you, Buddy. No, sir! You can just believe what Uncle Peter says, with all your might. I might lie to grown folks now and then, but I wouldn't lie to a little boy. No, sir!”

“I ain't a little boy. I'm a big sailor-man!” said the boy. “And you said I could steer, and I want to steer.”

“Right away you can,” said Peter. “You're going to steer with one of them skiff oars, but first I've got to row this boat out into the river a ways so you'll have plenty of room. So don't you fret. You watch Uncle Peter.”

He made the skiff fast to the boat with a length of rope, took the oars, and as he rowed, the heavy boat moved slowly from behind the point out into the river current. Peter towed her well out into the river before he let the skiff drop back. He meant the shanty-boat to float sweep first—it was all the same to her—and he fastened the painter of the skiff to the shanty-boat's stern, and edged his way along the narrow strip of wood that marked the division between the hull and the superstructure, holding himself by clasping the edge of the roof with his cold fingers, and sliding an oar along the roof as he went. It would have been much simpler and safer to have passed through the cabin.

To satisfy Buddy, he tied a length of seine cord about his own waist and fastened the end to the deck ring, and then he lashed Buddy's oar to a small iron ring. The boy could take a few steps and splash the water with the oar without falling into the river. Then Peter took the heavy sweep handle in his hands and the shanty-boat was under way.

It was time. The rising water had dislodged heavier ice than had yet come down, and the river was filling with it. The wind, such as there was, while it blew almost dead upstream, was an aid in that it swept the floating ice toward the Illinois shore, leaving Peter's course clear, and an occasional dip of the sweep was sufficient to keep the boat head-on in the current. The wind made the river choppy, but the shanty-boat, not having had time to water-log since Peter put her in the water, floated high.

For a while Buddy steered energetically, splashing the water with the blade of his oar, but Peter was ready for the first sign of weariness.

“My! but you are a fine steerer!” he said approvingly. “When you grow just a bit bigger, Uncle Peter is going to teach you how to row a boat, and a song to sing while you row it. Hurry up, now, and help Uncle Peter steer.”

“Let's sing a song to steer a boat,” said Buddy.

“No, I guess we won't sing to-day,” said Peter. “Some other day we'll sing.”

For Peter and Buddy were not taking the voyage alone. When Peter, assisted by Mrs. Skinner, had completed the preparations he felt were due any woman who is making the Great Journey, he found his money too little to afford her a resting-place in the town, but Peter Lane could not let one who had knocked at his door, seeking shelter, go from there to the potter's field, any more than he could let her boy go to the county farm. While the smart reporter was wondering whether the power of the press, in his article “Pass Her Along,” had warned Lize Merdin to take the road to some other town, and while Dr. Roth was telling of the shanty-boatman whose wife had died without medical attendance, Peter, by roundabout questions regarding George Rapp's place, learned of a small country burying ground not too far from the spot where the shanty-boat was to be moored for the winter. There he was taking Lize Merdin who, “decent” at last and forever, lay within the cabin.

Through the long forenoon Peter leaned on the handle of his sweep, pressing his breast against it now and then to swing the shanty-boat into the full current. There was no other large boat on the river. Here and there a fisherman pulled at his oars in a heavy skiff, or moved slowly from hook to hook of his trot-line, lifting from time to time a flop-pily protesting fish, but gave the shanty-boat no more than a glance.

The boat floated past the empty log-boom of the upper mill—silent for the winter—and past the great lumber piles, still bearing their covering of sleet. Peter could hear the gun-like slap of board on board coming from where some man was loading lumber in a freight car, and occasionally a voice came across the water with startling distinctness:

“I told him he could chop his own wood, I wouldn't do it.”

“What did he say to that?”

“He said he could get plenty of men that would do it.” He knew the men must be sitting close to the water's edge, and finally his sharp eyes made them out below the railway embankment—two black specks crouched over a small, yellow blaze. He recognized one voice, the voice of one of the town loafers. The other was strange to him, probably that of some tramp.

Below that, dwellings fronted the river and the streets of the town opened in long vistas as the boat came to them, closing again immediately as it passed. The hissing of a switch-engine, sidetracked to await the passing of a train soon due, and the clanking of a poker on the grate bars as the fireman dislodged the clinkers, came to Peter's ears distinctly. Then the boat slipped past George Rapp's stable, with its bold red brick front, and as he passed the door, Peter could hear for an instant the scrape of a horse's hoof in the stall, although the boat was a good half mile out in the river. Beyond the stable was the low-lying canning factory, and the row of saloons, and the hotel, and the wholesale houses, partly hidden by the railway station on the river side of Front Street, and the packet warehouse on the river's edge. Then the low rumbling of the dusty oatmeal mill, cut by the excited voices of small children playing at the water's edge, became the prominent voice of the town.

From the edge of the river the town rose on two hills, showing masses of gray, leafless trees, with here and there a house peeping through. From Peter's boat it looked like the dead corpse of a town, but he knew every street of it, and he knew Life, with its manifold business of work and play, was hurrying feverishly there, and he knew, too, that not one of all those so busy with Life knew he was floating by, or if knowing it, would have cared.

“That there is a town, Buddy,” said Peter. “That's Riverbank.”

“Is it?” said Buddy, without interest. He gave it but a glance.

“Yes, sir!” said Peter. “That's the town. And it's sort of funny to think of that whole townful of people rushing around, and going and coming, and doing things that seem mighty important to them whilst your—whilst this boat goes floating down this river as calm and peaceful as if the day of judgment had come and gone again. It's funny! Probably there ain't man or woman in that whole town but, a couple of days ago, was better and whiter than—than a certain party; and now there ain't one of 'em but is all smudgy and soiled if compared with her. Yes, sir, it's funny!”

He worked his sweep vigorously to carry the shanty-boat to the east of the large island—the Tow-head—that lay before the lower-town. The screech of boards passing through the knives of a planing-mill drowned the rumble of the oatmeal mill. A long passenger train hurried along the river bank like a hasty worm, and stopped, panting, at the water tank, and went on again. The boat, as it passed on the far side of the island, seemed to drop suddenly into silence, and the chopping of the waves against the hull of the boat made itself heard.

“Yes, sir, towns is funny!” said Peter. “Now, take the way going behind this island has wiped that one out. So far as you and me are concerned, Buddy, that town might be wiped off the earth, and we wouldn't know. We wouldn't hardly care at all. The folks in it ain't nothing to us at all, right now. And yet, if I go into that town, I'm interested in every one of the folks I meet, and it makes me sort of sick to see any of them cold and hungry. Maybe that's what towns is for. Maybe I live alone too much. I get so all I think about is sleep and eat. And eating ain't a bad habit. How'd you like to?”

Buddy was willing. He was willing to eat any time. He ate two apples and eight crackers, and watched the apple cores float beside the boat.

“Now, you 're going to fish,” said Peter. “Right here looks like a good place to fish. Maybe you'll catch a whale. You're just as apt to catch a whale here as anything else.”

“Ain't Mama hungry?” asked Buddy so suddenly that Peter was startled.

“Now, hear that!” he said. “Ain't you just as thoughtful! Why, no, Buddy. It's real nice for you to think of that, but your ma ain't hungry. She ain't going to be hungry or cold or wet any more, so don't you bother your little head about it one bit. She don't want anything but that you should grow up and be a big, fine man.”

“Like you, Uncle Peter?” asked Buddy. “My land, no!” said Peter impulsively. “I mean, no, indeed. Don't you take me for no model, Buddy. You want to grow up and be—I'll explain when you get older. I want you to grow up to be a good man; the kind of man that takes some interest in other folks. You don't want to be a dried-up old codger like me.”

“What's a codger?” asked Buddy.

“A codger is a stingy, old, hard-shell cuss—” Peter began. “I guess you could eat another apple,” he finished, and Buddy did.