LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

JANUARY 15 1917

SERIAL NO. 123

THE

MENTOR

AMERICAN

MINIATURE

PAINTERS

By MRS. ELIZABETH LOUNSBERY

Author

DEPARTMENT OF

FINE ARTS

VOLUME 4

NUMBER 23

FIFTEEN CENTS A COPY

Art and Life

We are close to realizing the greatest joys to be found in this workaday world when we accept art as a vital part and not a thing separate and distinct from our daily lives. Then we come to know the true values of things—to "find tongues in trees, books in running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything."

"Art, if we so accept it," says William Morris, "will be with us wherever we go—in the ancient city full of traditions of past time, in the newly cleared farm in America or the colonies, where no man has dwelt for traditions to gather round him; in the quiet countryside as in the busy town—no place shall be without it.

You will have it with you in your sorrow as in your joy, in your working hours as in your leisure. It will be no respecter of persons, but be shared by gentle and simple, learned and unlearned, and be as a language that all can understand. It will not hinder any work that is necessary to the life of man at the best, but it will destroy all degrading toil, all enervating luxury, all foppish frivolity.

It will be the deadly foe of ignorance, dishonesty, and tyranny, and will foster good-will, fair dealing, and confidence between man and man. It will teach you to respect the highest intellect with a manly reverence, but not to despise any man who does not pretend to be what he is not."

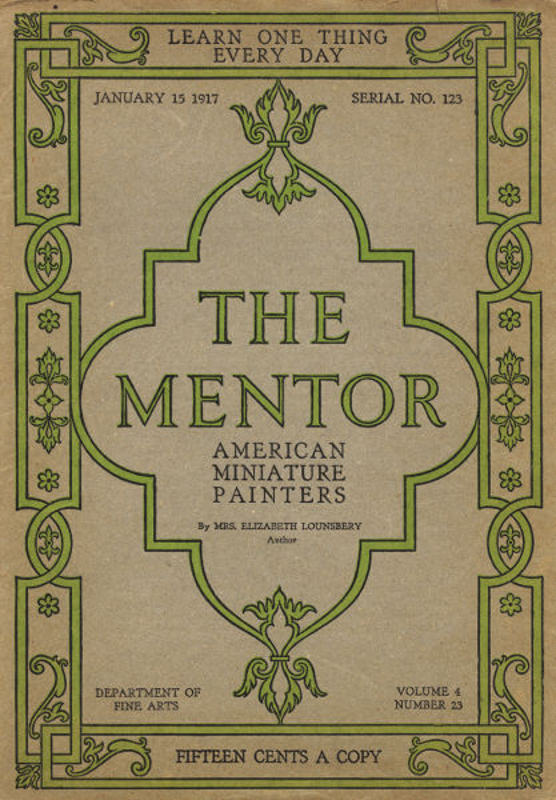

Actual size 3-3/4 inches high.

IN THE POSSESSION OF

THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

ONE

![]() THE work of

John Trumbull as a historical painter has already been

considered in The Mentor (No. 45), and in that number, too, the main

facts of his life are told. John Trumbull was a patriotic American and

a leader in the artistic and public life of his day, both in England

and in America. His position was much more than that of a painter.

His attitude toward painting was not one of complete and whole souled

devotion. "I am fully sensible," he wrote at one time, "that the

profession of painting as it is generally practised is frivolous,

and unworthy a man who has talents for more serious pursuits. But to

preserve and diffuse the memory of the noblest series of actions which

have ever presented themselves in the history of man is sufficient

warrant for it." We see accordingly that John Trumbull's idea of the

work of a painter was to write history on canvas with a brush—and

his pictures bear out his idea.

THE work of

John Trumbull as a historical painter has already been

considered in The Mentor (No. 45), and in that number, too, the main

facts of his life are told. John Trumbull was a patriotic American and

a leader in the artistic and public life of his day, both in England

and in America. His position was much more than that of a painter.

His attitude toward painting was not one of complete and whole souled

devotion. "I am fully sensible," he wrote at one time, "that the

profession of painting as it is generally practised is frivolous,

and unworthy a man who has talents for more serious pursuits. But to

preserve and diffuse the memory of the noblest series of actions which

have ever presented themselves in the history of man is sufficient

warrant for it." We see accordingly that John Trumbull's idea of the

work of a painter was to write history on canvas with a brush—and

his pictures bear out his idea.

His life governed and controlled his art. He was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1756, a son of the Colonial governor of that State, and from early years he revealed a mental vigor that was extraordinary. He was an infant prodigy in learning. He entered Harvard College in the junior year at the age of fifteen, and the time he spent there was occupied in omniverous reading and study—which finally came near wrecking his health. When he was a student he visited the great painter John Singleton Copley, and became impressed with that great painter's idea of the dignity of an artist's life. He determined to study art, and he was learning to paint when the War of the Revolution began. This event determined the character of his art life. His skill in drawing being noted by General Washington, he was set to work making plans of the enemy's works. He was then promoted to a position on the general staff, and, afterward, served as colonel under Gates. But aggrieved at what he considered a tardy recognition of himself by Congress, he resigned from the army, went to England and there, meeting the distinguished artist, Benjamin West, took up under him the study of painting. When Major André was executed there was a spirit of retaliation aroused in England, and Trumbull was arrested and imprisoned as a spy. It was only the intercession of Benjamin West that saved his life. After seven months' imprisonment he was released, on condition that he leave the country. He did not leave, however, but continued his studies with West, and did not return to the United States until 1789.

And so we see that Trumbull's life was more that of a patriot than a painter. Art was not the controlling factor with him, but the servant. He devoted his brush to the commemoration of great historical events, such as the battles of Bunker Hill and Trenton. And when he painted portraits he selected the prominent patriotic figures in the public life of his time—Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and others of like importance.

It was only natural then that he should turn with an interest little short of enthusiasm to the portrait of that brave and gallant officer, Captain Lawrence. The face of Lawrence, as shown in Trumbull's miniature, is more rotund, more genial—not to say jovial—than we are led to believe it to be from other portraits. John Trumbull knew Lawrence, however, and found great satisfaction in this portrait. The special interest to us that distinguishes the portrait from others of Lawrence, is that it imparts a sense not so much of the military as of the personal character of the man. As pictured here, by Trumbull, he is a very human hero. In studying this portrait, we feel anew the gripping pathos of Lawrence's tragic end.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

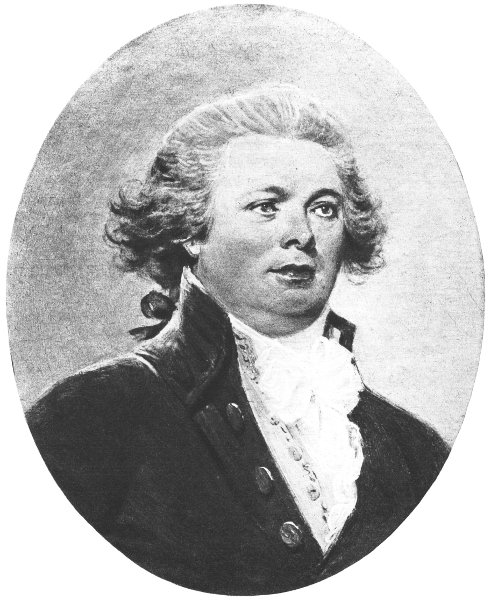

Actual size: 7 inches high, 6 inches wide.

COPYRIGHT, 1895, BY THE PROVIDENCE ATHENAEUM

IN THE PROVIDENCE ATHENAEUM

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

TWO

EDWARD GREENE MALBONE was born in Newport, Rhode Island, August 17,

1777, and died in Savannah in 1807. While a boy he frequently visited

the local theater in his native town to watch the process of scene

painting, and, later, tried his hand at this work—attaining what

was considered by the townspeople great success. As a child he was

quiet, reserved and self-absorbed. At sixteen he showed an indication

of great talent in his first portrait miniature. Encouraged in his

efforts by the English Consul at Providence, he devoted himself to the

study of drawing heads and painting miniatures, and, at seventeen,

he became professionally identified with miniature painting in

Providence, and, in 1796, fairly established as a miniature painter in

Boston.

EDWARD GREENE MALBONE was born in Newport, Rhode Island, August 17,

1777, and died in Savannah in 1807. While a boy he frequently visited

the local theater in his native town to watch the process of scene

painting, and, later, tried his hand at this work—attaining what

was considered by the townspeople great success. As a child he was

quiet, reserved and self-absorbed. At sixteen he showed an indication

of great talent in his first portrait miniature. Encouraged in his

efforts by the English Consul at Providence, he devoted himself to the

study of drawing heads and painting miniatures, and, at seventeen,

he became professionally identified with miniature painting in

Providence, and, in 1796, fairly established as a miniature painter in

Boston.

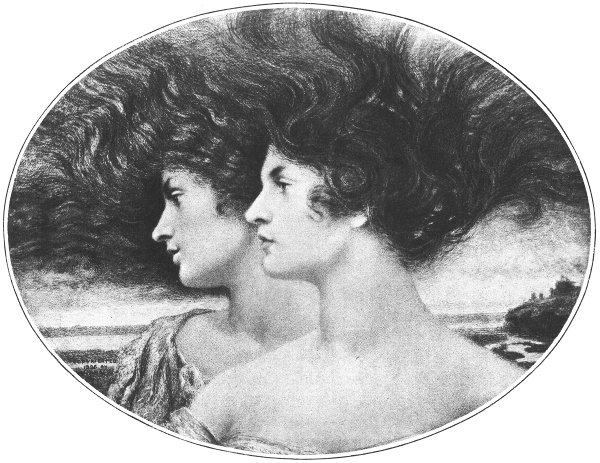

In 1800 he accompanied his friend and fellow artist, Washington Allston, to Charleston, and the following year the two went together to Europe. It was during his stay in London that Malbone painted his most important miniature, "The Hours," now owned by the Providence Athenæum. This shows, at three-quarter length, the figures of three beautiful women, who represent, as the Greeks personified them, Eunomia, Dice (die´-see) and Irene—the Past, the Present and the Coming Hour. They have a general resemblance and seem as if they might represent the same individual in different moments of emotion and development.

On the left is seen Eunomia or the Past, with an expression of pensive reluctance rather than regret. The central figure is Dice, or the Present—looking straight out from the picture. Her right arm is slightly raised toward Eunomia, at the left, while the left hand reaches half deprecatingly toward the Coming Hour. Irene, or the Coming Hour, is shown leaning upon the left shoulder of the Present.

This miniature was given to his sister by the painter during his lifetime, and, later, was purchased from the family by the subscription of twelve hundred dollars for the Providence Athenæum.

Although urged by Benjamin West to remain in England, where his art would win him ample appreciation and employment, Malbone preferred to return to America, and on his arrival traveled for several years—stopping in the principal cities to paint miniatures. "These," to quote Tuckerman, "are among the few pleasant and precious artistic associations with the past in this country."

Ill health finally took Malbone to Jamaica, but finding that his illness was incurable he left there, with the intention of returning to New England, but died in Savannah—in the prime of his life and success—before he could reach the North. Malbone is now considered the most important of all miniaturists of his time.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

Actual size. 4 inches high, 5 inches wide.

COPYRIGHT. 1896, BY W. J. BAER

IN THE POSSESSION OF

MR. ROBERT S. CLARK, NEW YORK CITY

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

THREE

ART beckons and the artist follows. Only an artist knows what the lure

of art is. The field of art is full of enticements. Little incidents,

apparently insignificant, have sometimes been sufficient to change an

artist's career and direct him toward his most brilliant achievements.

ART beckons and the artist follows. Only an artist knows what the lure

of art is. The field of art is full of enticements. Little incidents,

apparently insignificant, have sometimes been sufficient to change an

artist's career and direct him toward his most brilliant achievements.

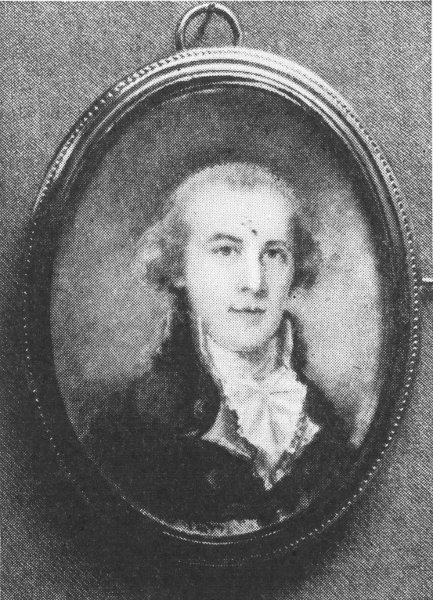

William J. Baer was thirty years of age before he painted a miniature. More than that, he had never seen a miniature that interested him, and he believed that miniature painting had limitations that precluded it from serious consideration. He was an instructor of drawing at Cooper Institute, New York City, an illustrator for magazines, and a painter of portraits, and had no thought of painting miniatures when, in 1892, he finished a very successful portrait of the late Alfred Corning Clark of New York. Mr. Clark was so pleased with the painting that he expressed a desire to have a copy of it in miniature. Mr. Baer did not believe that a result could be obtained worthy of the effort, so he refused to try it. Mr. Clark renewed his request, and Mr. Baer again refused. A short time after, however, having some leisure, his mind turned back to Mr. Clark's request, and, upon consideration, he was prompted to make a quiet attempt at miniature painting. He supplied himself with the necessary materials, and made his first experiment by copying a head from one of his own pictures, a profile of a young woman. The result was surprising to him—detail, patience, eyesight and hand served him well. In another week he had painted the miniature of Mr. Clark from his original sketch in oil colors. When Mr. Clark saw it he was delighted and asked for another. And so, out of what was at first a mere diversion, Mr. Baer developed a perfected art.

With the showing of Mr. Baer's miniatures at the First Portrait Show in 1894, his success was definitely assured.

In 1896 he painted his first ideal miniature, "The Golden Hour," now owned by Mr. Robert S. Clark of New York City. The idea of this exquisite picture developed from an effort of Mr. Baer's to paint in profile from memory the head of an auburn-haired girl that he had seen. A well-known English girl who had posed for Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Sir Frederick Leighton, happened then to call at his studio. Several sittings, in which a number of pencil and red chalk drawings were made, gave him an entirely different idea. The profile developed into a lovely dream picture, in which woman's crowning glory, her glowing hair, was poetically idealized. The picture shows two profiles, like twin sisters—the first with hair of dark copper tinge, the second at the left with hair of brilliant auburn, melting into the sunset colors of the sky.

This was the first of a number of ideal works by Mr. Baer, and was followed at intervals by others of like charm. "Primevera," painted in 1908, which is Mr. Baer's most important and ambitious endeavor, represents Flora, the handmaiden of spring, and is a delicate color poem.

Mr. Baer was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on January 29, 1860. He studied art in Cincinnati and in Munich. He returned to America in 1885, and for several years was an instructor in various art institutions. In 1897 he received the first-class medal for miniature and ideal subjects in New York, and he was an organizer and a former president of the American Society of Miniature Painters. Mr. Baer is at present treasurer of that society and an associate of the National Academy.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

Actual size: 5-1/4 inches high, 4-3/8 inches wide.

IN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK CITY

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

FOUR

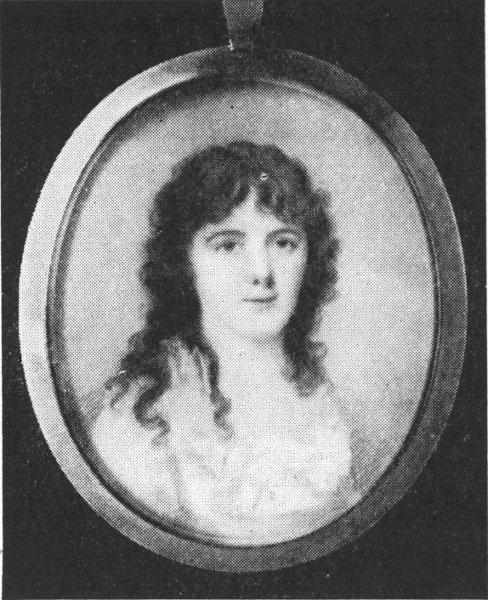

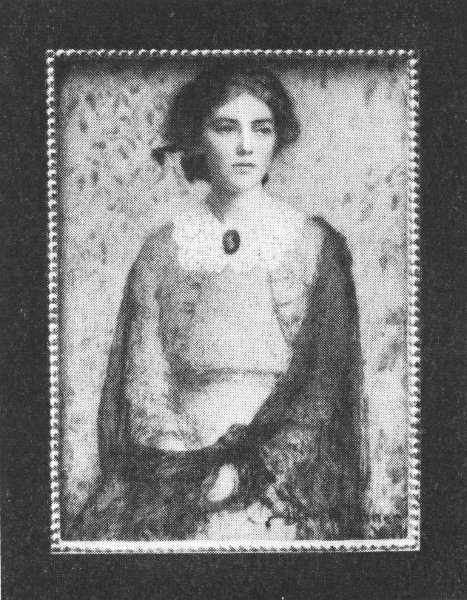

ALICE BECKINGTON is one of the leading members of the American Society

of Miniature Painters, and she now holds the office of vice-president.

She was born in St. Charles, Missouri, on July 30, 1868. She was

a pupil at the Art Students' League in New York under Carroll

Beckwith—after that she studied in Paris with Benjamin Constant.

Miss Beckington was a close friend of Miss Thayer's, and the work of

the two shows a sympathetic understanding. Miss Beckington's work is

serious, fine in taste, and dignified in character. She does not play

lightly with her art. Her pictures have a pleasing warmth of color;

that is to say, blacks and browns, golden flesh colorings, and grays

that are never cold. Occasional cool effects are, however, to be

found in her work, for Miss Beckington has a full appreciation of the

value of harmoniously contrasting color. The picture reproduced on

the reverse side of this sheet is taken from an original miniature in

the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is a portrait of Miss Beckington's

mother, the original ivory plate being slightly smaller than the

reproduction here given.

ALICE BECKINGTON is one of the leading members of the American Society

of Miniature Painters, and she now holds the office of vice-president.

She was born in St. Charles, Missouri, on July 30, 1868. She was

a pupil at the Art Students' League in New York under Carroll

Beckwith—after that she studied in Paris with Benjamin Constant.

Miss Beckington was a close friend of Miss Thayer's, and the work of

the two shows a sympathetic understanding. Miss Beckington's work is

serious, fine in taste, and dignified in character. She does not play

lightly with her art. Her pictures have a pleasing warmth of color;

that is to say, blacks and browns, golden flesh colorings, and grays

that are never cold. Occasional cool effects are, however, to be

found in her work, for Miss Beckington has a full appreciation of the

value of harmoniously contrasting color. The picture reproduced on

the reverse side of this sheet is taken from an original miniature in

the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is a portrait of Miss Beckington's

mother, the original ivory plate being slightly smaller than the

reproduction here given.

As may be seen, it is a work of distinction. The character of this refined woman is portrayed with simple eloquence. The pale blue of the dress and the delicately toned background set off in a poetic and sympathetic manner the character of this fine gentlewoman. The picture is thoroughly representative of Miss Beckington's work, and amply explains her high standing among our miniature painters. Just as many persons in social life who are assured in their exclusive positions dress simply and unaffectedly, so Miss Beckington paints—with directness and sincerity, without display or striving for effect.

Miss Beckington, referring to her early efforts in miniature painting, says that it was during the four years when she was working in oils in Paris that she became interested in miniature painting—and that in this work she was self-taught. Her first portrait of her mother was accepted by the Salon in Paris in 1894, and upon her return to New York she exhibited pictures annually at the National Academy. She believes that the great principles of art that obtain in oil painting should apply to miniature work as well; and she paints her miniatures in the same manner as she would paint in oils—with only the difference in treatment required by the conditions of a small sized picture.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

IN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM

OF ART NEW YORK CITY

Actual size: 6-3/4 inches high, 5-1/16 inches wide.

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

FIVE

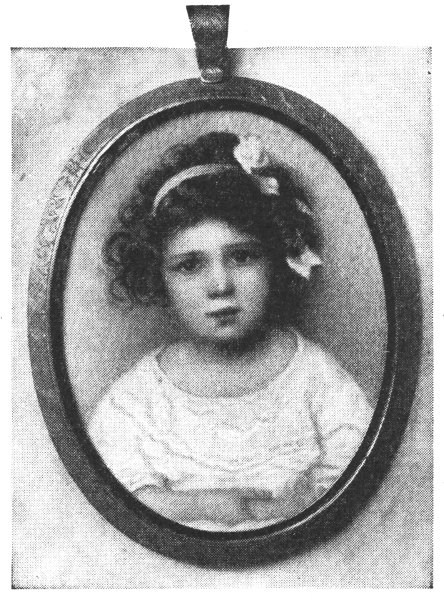

LAURA COOMBS HILLS is a favorite of lovers of miniature painting. She

has a fine, fresh style of her own. Her spirit is buoyant, natural,

and without affectation. She is a craftsman of extraordinary talent.

No difficulties seem to daunt her. Her coloring is positive, and she

seems undismayed in rendering any tone of dress or background or

face. Her painting of flesh color, particularly, is just and true.

Temperamentally, Miss Hills must be counted as one of the soundest and

truest of miniature painters, by which is meant that she looks at life

with clear seeing eyes, and records what she sees truthfully and with

sympathetic understanding. The accompanying picture, Persis, is a good

example of Miss Hills' work. It shows a child with brownish-red hair,

wearing a dark shade of pink ribbon. Her dress, of the faded pink

variety, wherein the lights approach flesh coloring and the shadows

are silvery, merges into golden tints. The background of sofa and

tapestry offers a variety of greens throughout, with a note of clear

orange in the bit of cushion to the left of the child's right arm.

The floor and the arm of the sofa repeat the color of the hair. A few

patches of blue and blue-green in the tapestry supply a relief for the

colors of the figure and the cushions.

LAURA COOMBS HILLS is a favorite of lovers of miniature painting. She

has a fine, fresh style of her own. Her spirit is buoyant, natural,

and without affectation. She is a craftsman of extraordinary talent.

No difficulties seem to daunt her. Her coloring is positive, and she

seems undismayed in rendering any tone of dress or background or

face. Her painting of flesh color, particularly, is just and true.

Temperamentally, Miss Hills must be counted as one of the soundest and

truest of miniature painters, by which is meant that she looks at life

with clear seeing eyes, and records what she sees truthfully and with

sympathetic understanding. The accompanying picture, Persis, is a good

example of Miss Hills' work. It shows a child with brownish-red hair,

wearing a dark shade of pink ribbon. Her dress, of the faded pink

variety, wherein the lights approach flesh coloring and the shadows

are silvery, merges into golden tints. The background of sofa and

tapestry offers a variety of greens throughout, with a note of clear

orange in the bit of cushion to the left of the child's right arm.

The floor and the arm of the sofa repeat the color of the hair. A few

patches of blue and blue-green in the tapestry supply a relief for the

colors of the figure and the cushions.

It was somewhat over twenty years ago that Miss Hills began to paint miniatures. Up to that time she had done some illustrating and decorative painting, worked on china, and some commercial designing. She was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, September 7, 1859, and was a pupil of Helen M. Knowlton, of the Cowles Art School in Boston, and also of the Art Students' League in New York. She was in England on a visit when a girl friend of hers remarked on her work, and asked her why she did not turn her brush to miniature painting. Miss Hills was at first reluctant to attempt a new line of art. But after some consideration she got several pieces of ivory, persuaded some young girls to sit for her, and in a short time turned out seven miniatures. She was surprised to find how easy the work appeared to be. She had understood that miniature painting was difficult and required a special talent. She was not wrong about that, but until she undertook the work she was not aware that this special talent was hers. She was delighted. Her outlook was clear and full of promise. She had a work of beauty to do and she knew that she could do it well.

People interest Miss Hills, and the picturing of people, especially young people, is a delight to her. The people she paints are very real, and they are distinct and individual. She has painted over 200 miniatures, and they are something more than portraits. They have a pictorial quality that gives them a very special charm and distinction. It has been observed that if the subjects that she has pictured in her miniatures had been rendered in oils on large canvases, "they would be found decorative and impressive." Miss Hills was a member of the Society of American Artists in 1897, and was made an associate of the National Academy in 1906. She is a member of the Boston Water Color Club, Copley Society, New York Woman's Art Club, and the American Society of Miniature Painters. She has exhibited in several of the world expositions, and has received a number of medals for merit.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

Actual size: 5 inches high, 3-3/16 inches wide.

IN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK CITY

AMERICAN MINIATURE PAINTERS

SIX

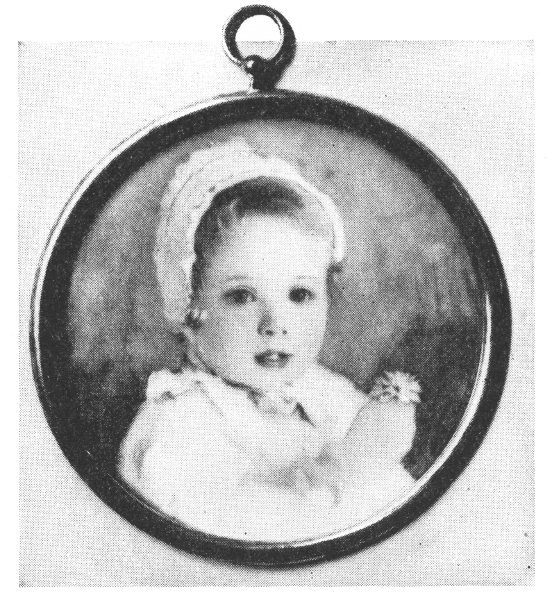

THE miniature work of Mrs. Fuller, like that of Miss Thayer and Miss

Hills, came close after that of Mr. Baer. These artists were each

independent of the other, and in the history of the modern revival

of miniature painting they stand simply as remarkable coincidences

in taste and inclination. Miss Fuller's miniature work is full of

intimate feeling, reflecting the charm of affectionately considered

detail and giving out an impression that her subjects must have been

near and dear to her. Her work is distinguished for its delicate grace

and simple charm. The picture on the reverse side of this sheet is a

portrait of a child—a very real child. The composition is beautiful

in line as well as in pattern. The human interest predominates,

without sacrifice of fine workmanship. It is not simply a "prettified"

picture, such as we find so often in the shops and soon tire of. It

is a work that attracts the painter, as well as the layman, by its

sympathetic appeal. "Delightful!" we exclaim. A masterpiece of child

life painting is this little girl in her "nightie" holding her doll.

The coloring is tender and fine. The background is a pale blue, under

which the baseboard and floor show a pale golden color, harmonizing

with the child's blond hair. The little print on the wall also makes a

"repeat" of the warm color.

THE miniature work of Mrs. Fuller, like that of Miss Thayer and Miss

Hills, came close after that of Mr. Baer. These artists were each

independent of the other, and in the history of the modern revival

of miniature painting they stand simply as remarkable coincidences

in taste and inclination. Miss Fuller's miniature work is full of

intimate feeling, reflecting the charm of affectionately considered

detail and giving out an impression that her subjects must have been

near and dear to her. Her work is distinguished for its delicate grace

and simple charm. The picture on the reverse side of this sheet is a

portrait of a child—a very real child. The composition is beautiful

in line as well as in pattern. The human interest predominates,

without sacrifice of fine workmanship. It is not simply a "prettified"

picture, such as we find so often in the shops and soon tire of. It

is a work that attracts the painter, as well as the layman, by its

sympathetic appeal. "Delightful!" we exclaim. A masterpiece of child

life painting is this little girl in her "nightie" holding her doll.

The coloring is tender and fine. The background is a pale blue, under

which the baseboard and floor show a pale golden color, harmonizing

with the child's blond hair. The little print on the wall also makes a

"repeat" of the warm color.

Lucia Fairchild Fuller is the wife of the well known artist, Henry Brown Fuller. She was born in Boston on December 6, 1872. She was a pupil of Dennis M. Banker, and studied at the Cowles Art School and at Mrs. Shaw's in Boston—likewise with Siddons Mowbray, and William M. Chase in New York. As a member of the Society of American Artists she became an associate of the National Academy in 1906, and was likewise one of the founders of the American Society of Miniature Painters, of which she is now president. Her work has not only won popular appreciation, but has secured distinguished recognition in the form of medals awarded at various expositions in Paris and in the United States.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 4, No. 23, SERIAL No. 123

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE MENTOR . DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS

JANUARY 15, 1917

By ELIZABETH LOUNSBERY

Author and Critic

By courtesy of Mrs. Frank Ralston, New York

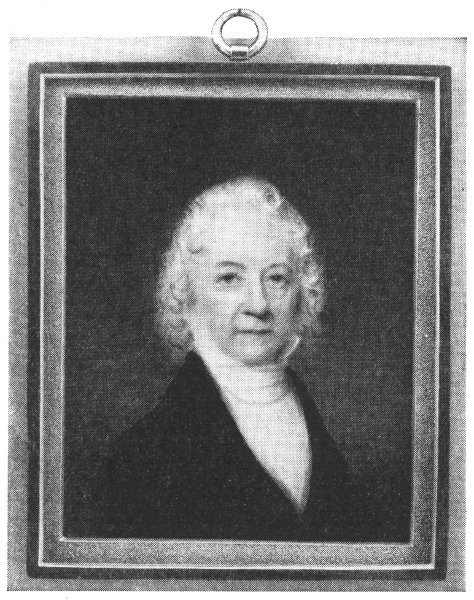

Attributed to Charles Willson Peale

MENTOR GRAVURES

THE revival of miniature painting in America in the last twenty-five

years has awakened interest in its past history. The installation in

the Metropolitan Museum of Art of the comprehensive collection of

miniatures owned by the estate of the late J. Pierpont Morgan has no

doubt done much to increase this, and inspire the purchase and gifts

of examples by American painters, for the Museum collection, that are

now on permanent exhibition there.

THE revival of miniature painting in America in the last twenty-five

years has awakened interest in its past history. The installation in

the Metropolitan Museum of Art of the comprehensive collection of

miniatures owned by the estate of the late J. Pierpont Morgan has no

doubt done much to increase this, and inspire the purchase and gifts

of examples by American painters, for the Museum collection, that are

now on permanent exhibition there.

Just when the art had its beginning has never been definitely determined, but its evolution from the portrait painting in illuminated manuscripts and parchments of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is generally accepted. In these, small heads and portraits were painted into the text and often in the first letter of the first word of a paragraph. This was extensively practiced in Italy, where this work assumed a necessarily religious character, being executed almost exclusively in the monasteries, for ecclesiastical use.

Minium, the Latin name for a red mineral coloring matter, was the pigment used by the early scribes for the initial letters and headings of these manuscripts. Thus, the term "miniatura" generally came to be applied to these portraits, which later became known as "miniatures." Miniature painting on ivory, or paintings "in little," as they have been called, gradually developed into a "personal" art, because of their peculiar appeal to the sentiments and affections, and for their "companionable proportions." They were often framed in black wood, usually in gold, however, sometimes mounted in jewels or set in a locket that could be readily worn on a chain or ribbon about the neck, or kept in intimate touch upon the dressing table or desk. In them the fashions and vanities of costume and head-dress of all periods have been recorded in the daintiest and most minute detail.

The history of miniature painting, however, is not complex—the methods and materials being much the same throughout its development or decline. The art is largely confined to the simple portrayal of heads, with only occasional contributions of fanciful subjects. Were it not, therefore, for the changes of fashion, one would have difficulty in remembering the painters, and an approach to monotony would result.

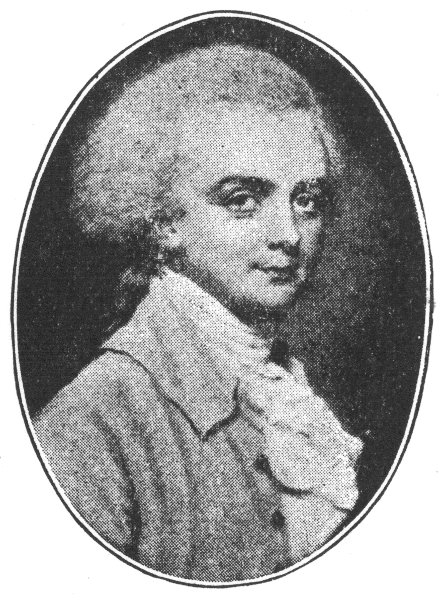

Curiously enough, the first notable miniature painter, Hans Holbein, has remained the undisputed prince of miniature painters. Indeed, it may be said that the birth of miniature painting as an enduring means of expression in art dates from the time of Holbein's arrival in England, in 1526. Following Holbein, Nicholas Hilliard became England's most distinguished exponent of the art—then Richard Cosway and his contemporaries in England, France and Italy. This period, the eighteenth century, marks the introduction of miniature painting into America, where it became popular as an expression of art during and after the Revolution, as large oil portraits had been before.

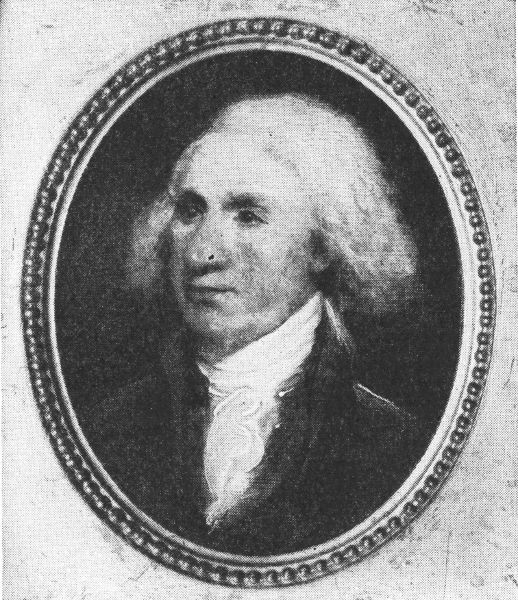

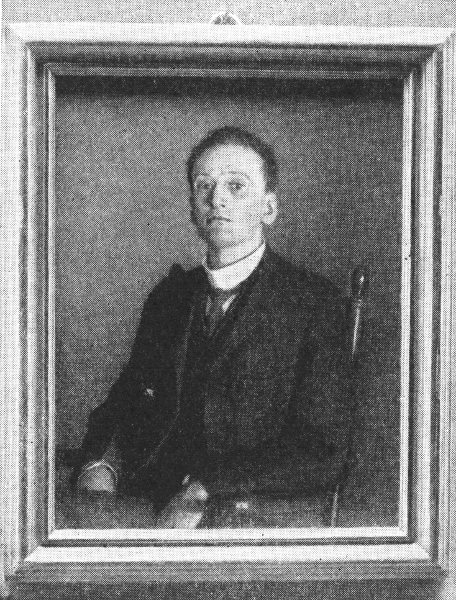

Charles Willson Peale, the famous painter of George Washington (of whom Peale is said to have painted fourteen portraits) was the best known of his era, many of his miniatures being painted while in camp on the battlefield. His brother James, likewise won a reputation in miniature painting, his work being notable for its extreme delicacy and beauty. We are told that starting life as a carpenter, he was able to make the frames used by both his brother and himself for their portraits and miniatures.

John Singleton Copley was another famous artist of this period. He was renowned for his large portraits in oil, which were characterized by a skilful treatment of silks and rich fabrics for both costumes and elaborate backgrounds, and yet he painted many miniatures. John Trumbull, known chiefly as a painter of stirring historical subjects of the Revolutionary era and for his portraits of Washington, also worked in miniatures, as did John Hesselius, in Annapolis. Gilbert Stuart, while a prolific painter of portraits, is not said by his biographers to have painted miniatures, although several have been attributed to him.

The fact that many miniatures, even by the greater artists, were not signed or dated, has made it difficult to determine the origin of some of the most beautiful examples, or to place them definitely as the work of American painters. Moreover, miniatures brought back as souvenirs by those who were able to travel abroad in those days introduced the work of foreign artists, often unsigned, among American miniatures, thus making identification more difficult.

Edward G. Malbone, born in Newport, R.I., in 1777, was destined to become the most important miniature painter of his time in America. Malbone had the gift of realism; of simple, unaffected grace and a sureness of rendition that compelled attention. His portraits were likenesses of intimate and convincing truth. "The Hours," Malbone's most famous work, a fanciful subject depicting the past, present and future hour and painted in 1801, after a short period of study in England, is now the property of the Providence Athenæum. Many of his portrait miniatures are owned by individuals throughout the South, where he spent several years, and prematurely died in the height of his career, at the age of thirty. A group of his portraits is also included in the Metropolitan Museum collection.

Charles Fraser, Malbone's contemporary and friend, likewise excelled, especially in male portraiture. Others of this period and men who afterwards forsook their art for other interests, but who were recognized as successful miniature painters, were Robert Fulton (1765-1815) the inventor of the steamboat, and Alvan Clark, the most notable of all lens grinders. John Ramage, an Irishman by birth, became a well known miniature painter in Boston and New York about this time, and also Richard M. Staigg, who, though born in England, was prominently identified with American art as one of the original members of the National Academy of Design and a miniature painter of distinction, strongly influenced by Malbone. Benjamin Trott was a contemporary of Malbone's and Fraser's, whose painting was characterized by strength and delicacy.

Anson Dickinson, John Wesley Jarvis, Joseph Wood, Henry Inman of Philadelphia, and Charles Cromwell Ingham, may also be mentioned among the miniature painters of the early nineteenth century, together with Sarah Goodridge, a protégé of Gilbert Stuart's, and whose work reached a great degree of excellence about 1840, and later John Henry Brown.

About this time miniature painting began to decline, owing to the introduction of the daguerreotype and the photograph. Such American artists as devoted their efforts to miniature painting struggled on without sufficient recognition until, feeling the need of organization and the encouragement in this branch of art that an association would lend, the American Society of Miniature Painters was founded in 1899 by William J. Baer, Alice Beckington, Lucia Fairchild Fuller, Laura Coombs Hills, John A. McDougall, Virginia Reynolds, Theodora M. Thayer, and William J. Whittemore. It was the intention of the Society to hold annual exhibitions, where the work of all American miniaturists could be passed upon by a competent jury and then be seen by the public. The first annual exhibition was held in January, 1900, at the Galleries of Messrs. Knoedler & Co., New York City. Isaac A. Josephi, prominent as a miniaturist at this time, became its first president, and is accredited with the conception of the Society. William J. Baer, sometime president and afterwards treasurer of the Society, contributed largely through his efforts to make the Society the factor that it has since become in the art world.

The impetus thus given to miniature painting led, unfortunately, to the production of cheap substitutes of artistic work in the form of colored photographs made to simulate miniatures. These tawdry imitations were sold broadcast to undiscriminating persons, and did much toward creating the opinion that a miniature could not be a serious work of art. Some merely regarded miniature painting as a remarkable feat of technical skill—a "stunt," in which the feature of interest was the astonishing minuteness of detail that could be introduced on a very small area. It was to counteract this popular fallacy and encourage the work of really good artists that the American Society of Miniature Painters lent its best efforts—with the coöperation of the Pennsylvania Society of Miniature Painters,—an offshoot from the older organization.

These exhibitions revealed a miniature art of a high order of merit. But even among examples supremely fine in quality there are to be found many productions that were simply good, honest workmanship, without inspiration. Painting on ivory is not easy of control, and it is unresponsive to the intention of the hand. The colors wash up readily, or at best are apt to be spotty and unmanageable. In consequence, the painter must resort to stippling (a process of drawing by means of dots) and repeated light touches to produce the required flow of form or surface. The results, therefore, except under the hand of a master, are apt to run to labored effects, due to the loss of freshness and directness. The expression, "It is art to hide art," may be taken to mean that an artist's results should appear comfortable, spontaneous and unrestrained.

In these characteristics there is no more proficient exponent than William J. Baer, although his earlier efforts in art were devoted to magazine illustrating, painting in oil and teaching drawing at the School of Applied Design for Women, Cooper Institute and Chatauqua. It may be interesting to note here how circumstances often cause the door of opportunity to open for a man, in fields quite different from those to which he dedicated himself. For example, S. F. B. Morse (1791-1872) who was the most able portrait painter in the United States in his time, found his place in the Hall of Fame as the inventor of the telegraphic code.

So Mr. Baer's activities as a portrait painter were turned into another field of art. Having painted a successful portrait of the late Alfred Corning Clark, of New York City, in 1892, and afterwards a replica in a miniature, Mr. Baer began his career as a miniature painter, showing unrivalled skill and an acknowledged excellence of conception, character, color and suggestion of detail. In 1896 he painted his first ideal subject,—"The Golden Hour," and in 1908 what he considers his most important and ambitious endeavor, "Primavera," representing "Flora," the handmaiden of spring, in which the color scheme is rendered in delicate pinks, blues, greens and grays. "Aurora," owned by Mr. Henry Walters of Baltimore; "Daphne," a charming conception of the nude; "Summer"; "Mildred," a fancy head representing spring; "Doris," another female nude, and "Young Diana," are also among the ideal subjects for which Mr. Baer has become famous, while the portrait miniatures of many prominent persons can be numbered as the result of his able brush.

In freshness and brilliancy of rendition Laura Coombs Hills, of Boston, is a recognized leader among living miniaturists. Her work is charmingly natural and unaffected, with vivacity evident in every essential part of her work. Especially true is this of her miniature entitled "Persis," in the Metropolitan Museum, a "5 x 6-1/2" oval. In this a child with brownish red hair, dressed in faded pink, is seated in relief against the reds and blues of the background. "The Goldfish" is another beautiful miniature by Miss Hills, in which her treatment of the bright golden tresses of a girl, her gown and the illusive tones of the background, denote the artist to be a colorist of the first rank. "The Bride," a harmony of gray, gold and blue, is also a notable example of her work that marks her as a craftsman of great talent.

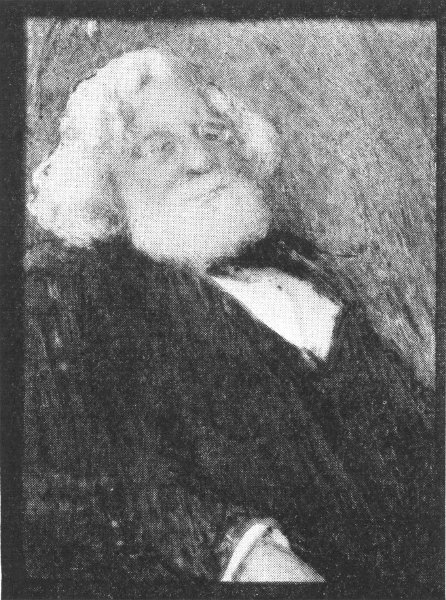

Theodora W. Thayer's short career (1868-1905) as a miniature painter measures well up to that of Malbone's in its quality and good art. Perhaps Malbone will be more popularly remembered by reason of the fact that he painted a number of works, whereas the available works of Miss Thayer are few. The latter artist had the distinction of being "different" from other miniaturists, although quite without eccentricity.

In her portrait of Parke Godwin, at the Metropolitan Museum, we see a person we should like to know. A charming portrait of an old gentleman, with a mass of white hair that dominates the picture. This is not only a characteristic example of Miss Thayer's art, but is an eloquent portrayal of fine manhood. In the profile portrait of Miss Gray the genius of this artist is again seen, also in her portrait of Bliss Carman, the poet, in profile.

The successes of Lucia Fairchild Fuller, like those of Miss Hills and Miss Thayer, followed immediately upon Mr. Baer's. Mrs. Fuller's painting, like Mr. Baer's, is full of tenderness, reflecting sympathetically and affectionately the details of her subjects. Feminine grace and the charm of child life are special qualities of her work. In the Metropolitan Museum may be seen a masterpiece of child portraiture—a little girl standing in her nightgown, caressing her doll. In this the color scheme is delicate throughout—in the tender pearly flesh and the pale blue background. In "Mother and Child," the portrait of a woman with a classic profile, dressed in red brocade with ivory white draperies over her shoulders, upholding the nude figure of a little girl with outstretched arms, is again seen a perfection of arrangement, line and fine color, and a predominating human interest that attracts by its sympathy.

Alice Beckington, like the other miniaturists just referred to, was one of the original members of the American Society of Miniature Painters. A close friend of Miss Thayer's in the latter's lifetime, she profited much by that influence. Her work is distinguished by its dignity and reserve. Her most successful miniatures tend to warm schemes of color. In her portrait of her mother ("Portrait of Mrs. Beckington") in the Metropolitan Museum, the coloring of the dress is of a faded blue, against a background of a warm, dull coloring—not gray, not brown, while the reddish color of the chair provides the only note of difference needed to satisfy the eye. This picture is essentially characteristic of Miss Beckington's art, representing her straightforward and sincere simplicity, combined with an appreciation of subdued color harmonies.

William J. Whittemore is well known as a painter in oils and in water color—one who essayed miniature painting without ever deserting the other mediums. His work is marked by a fondness for completeness of beauty and fineness of finish, whether in oil or miniature. As a master of form and an excellent painter of likenesses, Mr. Whittemore has executed a great number of portrait miniatures. His "Burgomeister," in which an old man wearing a ruff appears against a somber background, is a fine bit of characterization, strongly expressed.

Among other artists who are now prominently identified with American miniature painting may be mentioned Elsie Dodge Pattie, whose work is represented in the larger type of miniature, rendered with much tenderness and directness, as in the portrait heads of her own children. Also Margaret F. Hawley, of Boston, a thorough craftsman, as is evidenced in her fine portrait of Alexander Petrunkevitch. The work of Heloise G. Redfield, who has had a Paris training, is characteristic of the method of the French school (a method which has found little favor with American miniaturists generally) wherein there is a free wash of color on the surface of the miniature instead of the granulated appearance of stipple work. The work of Katherine Smith Myrick is in direct contrast, being entirely of stipple-producing qualities, while Mabel R. Welch uses free washes, qualified with delicate and well controlled stipple that never obtrudes in her finished work. The miniatures of Lucy M. Stanton, a southern painter, now in New York, are rendered rather in the manner of the late Theodora W. Thayer, and are strong in characterization. Those of Margaret Kendall are virile and natural, and her portraits of children are always charming. Maria Judson Strean's portraits are refined, and painted, with lightness and freedom. The work of Lydia E. Longacre is personal and has much charm. Harry L. Johnson, of Philadelphia, known as a miniaturist but a few years, has painted effectively both landscapes and figures on a diminutive scale. W. Sherman Potts is a competent and scholarly craftsman, who has established a summer school in miniature painting in Connecticut. Emily Drayton Taylor, who has been president of the Philadelphia Society of Miniature Painters since its organization, has been a prolific worker in the field.

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright 1917, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

PORTRAIT MINIATURES By George C. Williamson

MINIATURES, ANCIENT AND MODERN By C. J. H. Davenport

MINIATURES By D. Heath

HISTORY OF PORTRAIT MINIATURES (two vols.) By George C. Williamson

HOW TO IDENTIFY PORTRAIT MINIATURES By George C. Williamson

CHATS ON OLD MINIATURES By J. J. Foster

⁂ Information concerning the above books may be had on application to the Editor of The Mentor.

Miniatures are painted in water color and in oil—more commonly the former. Some of the early Dutch and German miniatures were painted in oil, and, as a rule, on copper. The miniatures painted during the eighteenth century were chiefly in water color, and on ivory. It is said that ivory came into general use during the reign of William III (1689-1702). Miniatures before that time were painted on vellum or cardboard.

The development of miniature painting, especially as it is applied to portraits, is largely English, and our early American miniaturists drew their art from English painters. We present on this page reproductions of the work of four of the most famous early English miniature painters. The first of whom anything definite is known was Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619). His work shows a close observation of the art of Hans Holbein. His little portraits look as if they had been taken out of illuminated manuscripts. His colors are solid, and gold is used to heighten the effect. Some of his pictures, moreover, are accompanied by Latin mottoes. Nicholas Hilliard had a son, Lawrence, whose work was similar to that of his father, but a little bolder in treatment and richer in color. Some years later came Samuel Cooper (1609-1672), reckoned by some the greatest English miniaturist. His work was broad and dignified, and has been referred to as "life-size work in little." His portraits of the prominent men of the Puritan period are vigorous, and true to life. The picture of Colonel Sidney, printed herewith, is interesting as showing the photographic fidelity of Cooper's work. There were many miniature painters during the eighteenth century, among whom Richard Cosway (1742-1821) stands prominent. His works were greatly admired for their smartness and brilliancy. In miniature form he pictured the pretty girl of the day. There were many people, however, of that same time that preferred the work of John Smart (1741-1811), for while he lacked the dashing style of Cosway, he excelled in refinement, power and delicacy—in "silky texture and elaborate finish." Smart's work was very popular, for he pictured fine people in fine style. The little portrait of Sir Charles Oakeley, printed here, is a typical example of Smart's work.

The Cosway and Smart miniatures on this page are taken from the collection of Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan; the Hilliard and Cooper miniatures from the collection of the Duke of Portland.

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

CONTRIBUTORS—PROF. JOHN C. VAN DYKE, HAMILTON W. MABIE, PROF. ALBERT BUSHNELL HART, REAR ADMIRAL ROBERT E. PEARY, WILLIAM T. HORNADAY, DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF, HENRY T. FINCK, WILLIAM WINTER, ESTHER SINGLETON, PROF. G. W. BOTSFORD, IDA M. TARBELL, GUSTAV KOBBÉ, DEAN C. WORCESTER, JOHN K. MUMFORD, W. J. HOLLAND, LORADO TAFT, KENYON COX, E. H. FORBUSH, H. E. KREHBIEL, SAMUEL ISHAM, BURGES JOHNSON, STEPHEN BONSAL, JAMES HUNEKER, W. J. HENDERSON, AND OTHERS.

The purpose of The Mentor Association is to give its members, in an interesting and attractive way, the information in various fields of knowledge which everybody wants to have. The information is imparted by interesting reading matter, prepared under the direction of leading authorities, and by beautiful pictures, produced by the most highly perfected modern processes.

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., AT 52 EAST NINETEENTH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. SUBSCRIPTION, THREE DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES FIFTEEN CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, ROBERT M. DONALDSON; ASST. TREASURER AND ASST. SECRETARY, J. S. CAMPBELL

COMPLETE YOUR MENTOR LIBRARY

Subscriptions always begin with the current issue. The following numbers of The Mentor Course, already issued, will be sent postpaid at the rate of fifteen cents each

Serial

No.

NUMBERS TO FOLLOW

February 1. GEMS. By Esther Singleton, Author.

February 15. THE ORCHESTRA. By W. J. Henderson, Author and Music Critic.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc.

52 EAST 19th STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y.

THE MENTOR

LITTLE VISITS TO THE

BEAUTY SPOTS OF THE WORLD

Nothing is more broadening than travel. To see foreign lands, to study individual characters, their manners, their mode of living, means a wider appreciation of the world, a broadening of your view-point of life. These particular Mentors, therefore, are extremely valuable.

SEND AT ONCE FOR THIS TRAVEL SET

This set will be sent you upon receipt of request. They cost $2.10. Send no money, merely a post card indicating that you desire this Travel Set. A bill will follow in due course. Address your request to

SECRETARY, THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

52 East Nineteenth Street . . New York City

MAKE THE SPARE MOMENT COUNT

Transcriber's Notes

Last Page: Changed "Elmdneorf" to "Elmendorf."

(Orig: CHINA By Dwight L. Elmdneorf)

Page Two: Changed "amployment" to "employment."

(Orig: ample appreciation and amployment,)