| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through

Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/lettersofsamuelt01coleuoft Project Gutenberg has the other volume of this work. Volume II: see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/44554/44554-h/44554-h.htm |

LETTERS

OF

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

EDITED BY

ERNEST HARTLEY COLERIDGE

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1895

[All rights reserved.]

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton and Company.

Hitherto no attempt has been made to publish a collection of Coleridge’s Letters. A few specimens were published in his lifetime, both in his own works and in magazines, and, shortly after his death in 1834, a large number appeared in print. Allsop’s “Letters, Conversations, and Recollections of S. T. Coleridge,” which was issued in 1836, contains forty-five letters or parts of letters; Cottle in his “Early Recollections” (1837) prints, for the most part incorrectly, and in piecemeal, some sixty in all, and Gillman, in his “Life of Coleridge” (1838), contributes, among others, some letters addressed to himself, and one, of the greatest interest, to Charles Lamb. In 1847, a series of early letters to Thomas Poole appeared for the first time in the Biographical Supplement to the “Biographia Literaria,” and in 1848, when Cottle reprinted his “Early Recollections,” under the title of “Reminiscences of Coleridge and Southey,” he included sixteen letters to Thomas and Josiah Wedgwood. In Southey’s posthumous “Life of Dr. Bell,” five letters of Coleridge lie imbedded, and in “Southey’s Life and Correspondence” (1849-50), four of his letters find an appropriate place. An interesting series was published in 1858 in the “Fragmentary Remains of Sir H. Davy,” edited by his brother, Dr. Davy; and in the “Diary of H. C. Robinson,” published in 1869, a few letters from Coleridge are interspersed. In 1870, the late Mr. W. Mark W. Call printed in the “Westminster Review” eleven [Pg iv]letters from Coleridge to Dr. Brabant of Devizes, dated 1815 and 1816; and a series of early letters to Godwin, 1800-1811 (some of which had appeared in “Macmillan’s Magazine” in 1864), was included by Mr. Kegan Paul in his “William Godwin” (1876). In 1874, a correspondence between Coleridge (1816-1818) and his publishers, Gale & Curtis, was contributed to “Lippincott’s Magazine,” and in 1878, a few letters to Matilda Betham were published in “Fraser’s Magazine.” During the last six years the vast store which still remained unpublished has been drawn upon for various memoirs and biographies. The following works containing new letters are given in order of publication: Herr Brandl’s “Samuel T. Coleridge and the English Romantic School,” 1887; “Memorials of Coleorton,” edited by Professor Knight, 1887; “Thomas Poole and his Friends,” by Mrs. H. Sandford, 1888; “Life of Wordsworth,” by Professor Knight, 1889; “Memoirs of John Murray,” by Samuel Smiles, LL. D., 1891; “De Quincey Memorials,” by Alex. Japp, LL. D., 1891; “Life of Washington Allston,” 1893.

Notwithstanding these heavy draughts, more than half of the letters which have come under my notice remain unpublished. Of more than forty which Coleridge wrote to his wife, only one has been published. Of ninety letters to Southey which are extant, barely a tenth have seen the light. Of nineteen addressed to W. Sotheby, poet and patron of poets, fourteen to Lamb’s friend John Rickman, and four to Coleridge’s old college friend, Archdeacon Wrangham, none have been published. Of more than forty letters addressed to the Morgan family, which belong for the most part to the least known period of Coleridge’s life,—the years which intervened between his residence in Grasmere and his final settlement at Highgate,—only two or three, preserved in the MSS. Department of the British Museum, have been published. Of numerous letters written in later life to his friend and amanuensis, Joseph Henry Green; to Charles Augustus[Pg v] Tulk, M. P. for Sudbury; to his friends and hosts, the Gillmans; to Cary, the translator of Dante, only a few have found their way into print. Of more than forty to his brother, the Rev. George Coleridge, which were accidentally discovered in 1876, only five have been printed. Of some fourscore letters addressed to his nephews, William Hart Coleridge, John Taylor Coleridge, Henry Nelson Coleridge, Edward Coleridge, and to his son Derwent, all but two, or at most three, remain in manuscript. Of the youthful letters to the Evans family, one letter has recently appeared in the “Illustrated London News,” and of the many addressed to John Thelwall, but one was printed in the same series.

The letters to Poole, of which more than a hundred have been preserved, those addressed to his Bristol friend, Josiah Wade, and the letters to Wordsworth, which, though few in number, are of great length, have been largely used for biographical purposes, but much, of the highest interest, remains unpublished. Of smaller groups of letters, published and unpublished, I make no detailed mention, but in the latter category are two to Charles Lamb, one to John Sterling, five to George Cattermole, one to John Kenyon, and many others to more obscure correspondents. Some important letters to Lord Jeffrey, to John Murray, to De Quincey, to Hugh James Rose, and to J. H. B. Williams, have, in the last few years, been placed in my hands for transcription.

A series of letters written between the years 1796 and 1814 to the Rev. John Prior Estlin, minister of the Unitarian Chapel at Lewin’s Mead, Bristol, was printed some years ago for the Philobiblon Society, with an introduction by Mr. Henry A. Bright. One other series of letters has also been printed for private circulation. In 1889, the late Miss Stuart placed in my hands transcriptions of eighty-seven letters addressed by Coleridge to her father, Daniel Stuart, editor of “The Morning Post” and[Pg vi] “Courier,” and these, together with letters from Wordsworth and Southey, were printed in a single volume bearing the title, “Letters from the Lake Poets.” Miss Stuart contributed a short account of her father’s life, and also a reminiscence of Coleridge, headed “A Farewell.”

Coleridge’s biographers, both of the past and present generations, have met with a generous response to their appeal for letters to be placed in their hands for reference and for publication, but it is probable that many are in existence which have been withheld, sometimes no doubt intentionally, but more often from inadvertence. From his boyhood the poet was a voluminous if an irregular correspondent, and many letters which he is known to have addressed to his earliest friends—to Middleton, to Robert Allen, to Valentine and Sam Le Grice, to Charles Lloyd, to his Stowey neighbour, John Cruikshank, to Dr. Beddoes, and others—may yet be forthcoming. It is certain that he corresponded with Mrs. Clarkson, but if any letters have been preserved they have not come under my notice. It is strange, too, that among the letters of the Highgate period, which were sent to Henry Nelson Coleridge for transcription, none to John Hookham Frere, to Blanco White, or to Edward Irving appear to have been forthcoming.

The foregoing summary of published and unpublished letters, though necessarily imperfect, will enable the reader to form some idea of the mass of material from which the present selection has been made. A complete edition of Coleridge’s Letters must await the “coming of the milder day,” a renewed long-suffering on the part of his old enemy, the “literary public.” In the meanwhile, a selection from some of the more important is here offered in the belief that many, if not all, will find a place in permanent literature. The letters are arranged in chronological order, and are intended rather to[Pg vii] illustrate the story of the writer’s life than to embody his critical opinions, or to record the development of his philosophical and theological speculations. But letters of a purely literary character have not been excluded, and in selecting or rejecting a letter, the sole criterion has been, Is it interesting? is it readable?

In letter-writing perfection of style is its own recommendation, and long after the substance of a letter has lost its savour, the form retains its original or, it may be, an added charm. Or if the author be the founder of a sect or a school, his writings, in whatever form, are received by the initiated with unquestioning and insatiable delight. But Coleridge’s letters lack style. The fastidious critic who touched and retouched his exquisite lyrics, and always for the better, was at no pains to polish his letters. He writes to his friends as if he were talking to them, and he lets his periods take care of themselves. Nor is there any longer a school of reverent disciples to receive what the master gives and because he gives it. His influence as a teacher has passed into other channels, and he is no longer regarded as the oracular sage “questionable” concerning all mysteries. But as a poet, as a great literary critic, and as a “master of sentences,” he holds his own and appeals to the general ear; and though, since his death, in 1834, a second generation has all but passed away, an unwonted interest in the man himself survives and must always survive. For not only, as Wordsworth declared, was he “a wonderful man,” but the story of his life was a strange one, and as he tells it, we “cannot choose but hear.” Coleridge, often to his own detriment, “wore his heart on his sleeve,” and, now to one friend, now to another, sometimes to two or three friends on the same day, he would seek to unburthen himself of his hopes and fears, his thoughts and fancies, his bodily sufferings, and the keener pangs of the soul. It is, to quote his own words, these “profound touches of[Pg viii] the human heart” which command our interest in Coleridge’s Letters, and invest them with their peculiar charm.

At what period after death, and to what extent the private letters of a celebrated person should be given to the world, must always remain an open question both of taste and of morals. So far as Coleridge is concerned, the question was decided long age. Within a few years of his death, letters of the most private and even painful character were published without the sanction and in spite of the repeated remonstrances of his literary executor, and of all who had a right to be heard on the subject. Thenceforth, as the published writings of his immediate descendants testify, a fuller and therefore a fairer revelation was steadily contemplated. Letters collected for this purpose find a place in the present volume, but the selection has been made without reference to previous works or to any final presentation of the material at the editor’s disposal.

My acknowledgments are due to many still living, and to others who have passed away, for their generous permission to print unpublished letters, which remained in their possession or had passed into their hands.

For the continued use of the long series of letters which Poole entrusted to Coleridge’s literary executor in 1836, I have to thank Mrs. Henry Sandford and the Bishop of Gibraltar. For those addressed to the Evans family I am indebted to Mr. Alfred Morrison of Fonthill. The letters to Thelwall were placed in my hands by the late Mr. F. W. Cosens, who afforded me every facility for their transcription. For those to Wordsworth my thanks are due to the poet’s grandsons, Mr. William and Mr. Gordon Wordsworth. Those addressed to the Gillmans I owe to the great kindness of their granddaughter, Mrs. Henry Watson, who placed in my hands all the materials at her disposal. For the right to publish the letters to H. F. Cary I am indebted to my friend the Rev. Offley[Pg ix] Cary, the grandson of the translator of Dante. My acknowledgments are further due to the late Mr. John Murray for the right to republish letters which appeared in the “Memoirs of John Murray,” and two others which were not included in that work; and to Mrs. Watt, the daughter of John Hunter of Craigcrook, for letters addressed to Lord Jeffrey. From the late Lord Houghton I received permission to publish the letters to the Rev. J. P. Estlin, which were privately printed for the Philobiblon Society. I have already mentioned my obligations to the late Miss Stuart of Harley Street.

For the use of letters addressed to his father and grandfather, and for constant and unwearying advice and assistance in this work I am indebted, more than I can well express, to the late Lord Coleridge. Alas! I can only record my gratitude.

To Mr. William Rennell Coleridge of Salston, Ottery St. Mary, my especial thanks are due for the interesting collection of unpublished letters, many of them relating to the “Army Episode,” which the poet wrote to his brother, the Rev. George Coleridge.

I have also to thank Miss Edith Coleridge for the use of letters addressed to her father, Henry Nelson Coleridge; my cousin, Mrs. Thomas W. Martyn of Torquay, for Coleridge’s letter to his mother, the earliest known to exist; and Mr. Arthur Duke Coleridge for one of the latest he ever wrote, that to Mrs. Aders.

During the preparation of this work I have received valuable assistance from men of letters and others. I trust that I may be permitted to mention the names of Mr. Leslie Stephen, Professor Knight, Mrs. Henry Sandford, Dr. Garnett of the British Museum, Professor Emile Legouis of Lyons, Mrs. Henry Watson, the Librarians of the Oxford and Cambridge Club, and of the Kensington Public Library, and Mrs. George Boyce of Chertsey.

Of my friend, Mr. Dykes Campbell, I can only say that[Pg x] he has spared neither time nor trouble in my behalf. Not only during the progress of the work has he been ready to give me the benefit of his unrivalled knowledge of the correspondence and history of Coleridge and of his contemporaries, but he has largely assisted me in seeing the work through the press. For the selection of the letters, or for the composition or accuracy of the notes, he must not be held in any way responsible; but without his aid, and without his counsel, much, which I hope has been accomplished, could never have been attempted at all. Of the invaluable assistance which I have received from his published works, the numerous references to his edition of Coleridge’s “Poetical Works” (Macmillan, 1893), and his “Samuel Taylor Coleridge, A Narrative” (1894), are sufficient evidence. Of my gratitude he needs no assurance.

ERNEST HARTLEY COLERIDGE.

Born, October 21, 1772.

Death of his father, October 4, 1781.

Entered at Christ’s Hospital, July 18, 1782.

Elected a “Grecian,” 1788.

Discharged from Christ’s Hospital, September 7, 1791.

Went into residence at Jesus College, Cambridge, October, 1791.

Enlisted in King’s Regiment of Light Dragoons, December 2, 1793.

Discharged from the army, April 10, 1794.

Visit to Oxford and introduction to Southey, June, 1794.

Proposal to emigrate to America—Pantisocracy—Autumn, 1794.

Final departure from Cambridge, December, 1794.

Settled at Bristol as public lecturer, January, 1795.

Married to Sarah Fricker, October 4, 1795.

Publication of “Conciones ad Populum,” Clevedon, November 16, 1795.

Pantisocrats dissolve—Rupture with Southey—November, 1795.

Publication of first edition of Poems, April, 1796.

Issue of “The Watchman,” March 1-May 13, 1796.

Birth of Hartley Coleridge, September 19, 1796.

Settled at Nether-Stowey, December 31, 1796.

Publication of second edition of Poems, June, 1797.

Settlement of Wordsworth at Alfoxden, July 14, 1797.

The “Ancient Mariner” begun, November 13, 1797.

First part of “Christabel,” begun, 1797.

Acceptance of annuity of £150 from J. and T. Wedgwood, January, 1798.

Went to Germany, September 16, 1798.

Returned from Germany, July, 1799.

First visit to Lake Country, October-November, 1799.

Began to write for “Morning Post,” December, 1799.

Translation of Schiller’s “Wallenstein,” Spring, 1800.

Settled at Greta Hall, Keswick, July 24, 1800.

Birth of Derwent Coleridge, September 14, 1800.

Wrote second part of “Christabel,” Autumn, 1800.

Began study of German metaphysics, 1801.

Birth of Sara Coleridge, December 23, 1802.

Publication of third edition of Poems, Summer, 1803.

Set out on Scotch tour, August 14, 1803.

Settlement of Southey at Greta Hall, September, 1803.

Sailed for Malta in the Speedwell, April 9, 1804.

Arrived at Malta, May 18, 1804.

First tour in Sicily, August-November, 1804.

Left Malta for Syracuse, September 21, 1805.

[Pg xii]Residence in Rome, January-May, 1806.

Returned to England, August, 1806.

Visit to Wordsworth at Coleorton, December 21, 1806.

Met De Quincey at Bridgwater, July, 1807.

First lecture at Royal Institution, January 12, 1808.

Settled at Allan Bank, Grasmere, September, 1808.

First number of “The Friend,” June 1, 1809.

Last number of “The Friend,” March 15, 1810.

Left Greta Hall for London, October 10, 1810.

Settled at Hammersmith with the Morgans, November 3, 1810.

First lecture at London Philosophical Society, November 18, 1811.

Last visit to Greta Hall, February-March, 1812.

First lecture at Willis’s Rooms, May 12, 1812.

First lecture at Surrey Institution, November 3, 1812.

Production of “Remorse” at Drury Lane, January 23, 1813.

Left London for Bristol, October, 1813.

First course of Bristol lectures, October-November, 1813.

Second course of Bristol lectures, December 30, 1813.

Third course of Bristol lectures, April, 1814.

Residence with Josiah Wade at Bristol, Summer, 1814.

Rejoined the Morgans at Ashley, September, 1814.

Accompanied the Morgans to Calne, November, 1814.

Settles with Mr. Gillman at Highgate, April 16, 1816.

Publication of “Christabel,” June, 1816.

Publication of the “Statesman’s Manual,” December, 1816.

Publication of second “Lay Sermon,” 1817.

Publication of “Biographia Literaria” and “Sibylline Leaves,” 1817.

First acquaintance with Joseph Henry Green, 1817.

Publication of “Zapolya,” Autumn, 1817.

First lecture at “Flower-de-Luce Court,” January 27, 1818.

Publication of “Essay on Method,” January, 1818.

Revised edition of “The Friend,” Spring, 1818.

Introduction to Thomas Allsop, 1818.

First lecture on “History of Philosophy,” December 14, 1818.

First lecture on “Shakespeare” (last course), December 17, 1818.

Last public lecture, “History of Philosophy,” March 29, 1819.

Nominated “Royal Associate” of Royal Society of Literature, May, 1824.

Read paper to Royal Society on “Prometheus of Æschylus,” May 15, 1825.

Publication of “Aids to Reflection,” May-June, 1825.

Publication of “Poetical Works,” in three volumes, 1828.

Tour on the Rhine with Wordsworth, June-July, 1828.

Revised issue of “Poetical Works,” in three volumes, 1829.

Marriage of Sara Coleridge to Henry Nelson Coleridge, September 3, 1829.

Publication of “Church and State,” 1830.

Visit to Cambridge, June, 1833.

Death, July 25, 1834.

1. The Complete Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. New York: Harper and Brothers, 7 vols. 1853.

2. Biographia Literaria [etc.]. By S. T. Coleridge. Second edition, prepared for publication in part by the late H. N. Coleridge: completed and published by his widow. 2 vols. 1847.

3. Essays on His Own Times. By Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Edited by his daughter. London: William Pickering. 3 vols. 1850.

4. The Table Talk and Omniana of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Edited by T. Ashe. George Bell and Sons. 1884.

5. Letters, Conversations, and Recollections of S. T. Coleridge. [Edited by Thomas Allsop. First edition published anonymously.] Moxon. 2 vols. 1836.

6. The Life of S. T. Coleridge, by James Gillman. In 2 vols. (Vol. I. only was published.) 1838.

7. Memorials of Coleorton: being Letters from Coleridge, Wordsworth and his sister, Southey, and Sir Walter Scott, to Sir George and Lady Beaumont of Coleorton, Leicestershire, 1803-1834. Edited by William Knight, University of St. Andrews. 2 vols. Edinburgh. 1887.

8. Unpublished Letters from S. T. Coleridge to the Rev. John Prior Estlin. Communicated by Henry A. Bright (to the Philobiblon Society). n. d.

9. Letters from the Lake Poets—S. T. Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Robert Southey—to Daniel Stuart, editor of The Morning Post and The Courier. 1800-1838. Printed for private circulation. 1889. [Edited by Mr. Ernest Hartley Coleridge, in whom the copyright of the letters of S. T. Coleridge is vested.]

10. The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Edited, with a Biographical Introduction, by James Dykes Campbell. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. 1893.

11. Samuel Taylor Coleridge. A Narrative of the Events of His Life. By James Dykes Campbell. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. 1894.

12. Early Recollections: chiefly relating to the late S. T. Coleridge, during his long residence in Bristol. 2 vols. By Joseph Cottle. 1837.

13. Reminiscences of S. T. Coleridge and R. Southey. By Joseph Cottle. 1847.

14. Fragmentary Remains, literary and scientific, of Sir Humphry Davy, Bart. Edited by his brother, John Davy, M. D. 1838.

15. The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt. London. 1860.

[Pg xiv]16. Diary, Reminiscences, and Correspondence of Henry Crabb Robinson. Selected and Edited by Thomas Sadler, Ph.D. London. 1869.

17. A Group of Englishmen (1795-1815): being records of the younger Wedgwoods and their Friends. By Eliza Meteyard. 1871.

18. Memoir and Letters of Sara Coleridge [Mrs. H. N. Coleridge]. Edited by her daughter. 2 vols. 1873.

19. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the English Romantic School. By Alois Brandl. English Edition by Lady Eastlake. London. 1887.

20. The Letters of Charles Lamb. Edited by Alfred Ainger. 2 vols. 1888.

21. Thomas Poole and his Friends. By Mrs. Henry Sandford. 2 vols. 1888.

22. The Life and Correspondence of R. Southey. Edited by his son, the Rev. Charles Cuthbert Southey. 6 vols. 1849-50.

23. Selections from the Letters of R. Southey. Edited by his son-in-law, John Wood Warter, B. D. 4 vols. 1856.

24. The Poetical Works of Robert Southey, Esq., LL.D. 9 vols. London. 1837.

25. Memoirs of William Wordsworth. By Christopher Wordsworth, D. D., Canon of Westminster [afterwards Bishop of Lincoln]. 2 vols. 1851.

26. The Life of William Wordsworth. By William Knight, LL.D. 3 vols. 1889.

27. The Complete Poetical Works of William Wordsworth. With an Introduction by John Morley. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. 1889.

Note. Where a letter has been printed previously to its appearance in this work, the name of the book or periodical containing it is added in parenthesis.

| Page | ||

| CHAPTER I. STUDENT LIFE, 1785-1794. | ||

| I. | Thomas Poole, February, 1797. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 313) | 4 |

| II. | Thomas Poole, March, 1797. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 315) | 6 |

| III. | Thomas Poole, October 9, 1797. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 319) | 10 |

| IV. | Thomas Poole, October 16, 1797. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 322) | 13 |

| V. | Thomas Poole, February 19, 1798. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 326) | 18 |

| VI. | Mrs. Coleridge, Senior, February 4, 1785. (Illustrated London News, April 1, 1893) | 21 |

| VII. | Rev. George Coleridge, undated, before 1790. (Illustrated London News, April 1, 1893) | 22 |

| VIII. | Rev. George Coleridge, October 16, 1791. (Illustrated London News, April 8, 1893) | 22 |

| IX. | Rev. George Coleridge, January 24, 1792 | 23 |

| X. | Mrs. Evans, February 13, 1792 | 26 |

| XI. | Mary Evans, February 13, 1792 | 30 |

| XII. | Anne Evans, February 19, 1792 | 37 |

| XIII. | Mrs. Evans, February 22 [1792] | 39 |

| XIV. | Mary Evans, February 22 [1792] | 41 |

| XV. | Rev. George Coleridge, April [1792]. (Illustrated London News, April 8, 1893) | 42 |

| XVI. | Mrs. Evans, February 5, 1793 | 45 |

| XVII. | Mary Evans, February 7, 1793. (Illustrated London News, April 8, 1893) | 47 |

| XVIII. | Anne Evans, February 10, 1793 | 52 |

| XIX. | Rev. George Coleridge, July 28, 1793 | 53 |

| XX. | Rev. George Coleridge [Postmark, August 5, 1793] | 55 |

| XXI. | G. L. Tuckett, February 6 [1794], (Illustrated London News, April 15, 1893) | 57 |

| [Pg xvi]XXII. | Rev. George Coleridge, February 8, 1794 | 59 |

| XXIII. | Rev. George Coleridge, February 11, 1794 | 60 |

| XXIV. | Capt. James Coleridge, February 20, 1794. (Brandl’s Life of Coleridge, 1887, p. 65) | 61 |

| XXV. | Rev. George Coleridge, March 12, 1794. (Illustrated London News, April 15, 1893) | 62 |

| XXVI. | Rev. George Coleridge, March 21, 1794 | 64 |

| XXVII. | Rev. George Coleridge, end of March, 1794 | 66 |

| XXVIII. | Rev. George Coleridge, March 27, 1794 | 66 |

| XXIX. | Rev. George Coleridge, March 30, 1794 | 68 |

| XXX. | Rev. George Coleridge, April 7, 1794 | 69 |

| XXXI. | Rev. George Coleridge, May 1, 1794 | 70 |

| XXXII. | Robert Southey, July 6, 1794. (Sixteen lines published, Southey’s Life and Correspondence, 1849, i. 212) | 72 |

| XXXIII. | Robert Southey, July 15, 1794. (Portions published in Letter to H. Martin, July 22, 1794, Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 338) | 74 |

| XXXIV. | Robert Southey, September 18, 1794. (Eighteen lines published, Southey’s Life and Correspondence, 1849, i. 218) | 81 |

| XXXV. | Robert Southey, September 19, 1794 | 84 |

| XXXVI. | Robert Southey, September 26, 1794 | 86 |

| XXXVII. | Robert Southey, October 21, 1794 | 87 |

| XXXVIII. | Robert Southey, November, 1794 | 95 |

| XXXIX. | Robert Southey, Autumn, 1794. (Illustrated London News, April 15, 1893) | 101 |

| XL. | Rev. George Coleridge, November 6, 1794 | 103 |

| XLI. | Robert Southey, December 11, 1794 | 106 |

| XLII. | Robert Southey, December 17, 1794 | 114 |

| XLIII. | Robert Southey, December, 1794. (Eighteen lines published, Southey’s Life and Correspondence, 1849, i. 227) | 121 |

| XLIV. | Mary Evans, (?) December, 1794. (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, A Narrative, 1894, p. 38) | 122 |

| XLV. | Mary Evans, December 24, 1794. (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, A Narrative, 1894, p. 40) | 124 |

| XLVI. | Robert Southey, December, 1794 | 125 |

| CHAPTER II. EARLY PUBLIC LIFE, 1795-1796. | ||

| XLVII. | Joseph Cottle, Spring, 1795. (Early Recollections, 1837, i. 16) | 133 |

| XLVIII. | Joseph Cottle, July 31, 1795. (Early Recollections, 1837, i. 52) | 133 |

| XLIX. | Joseph Cottle, 1795. (Early Recollections, 1837, i. 55) | 134 |

| L. | Robert Southey, October, 1795 | 134 |

| LI. | Thomas Poole, October 7, 1795. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 347) | 136 |

| LII. | Robert Southey, November 13, 1795 | 137 |

| [Pg xvii]LIII. | Josiah Wade, January 27, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 350) | 151 |

| LIV. | Joseph Cottle, February 22, 1796. (Early Recollections, 1837, i. 141; Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 356) | 154 |

| LV. | Thomas Poole, March 30, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 357) | 155 |

| LVI. | Thomas Poole, May 12, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 366; Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 144) | 158 |

| LVII. | John Thelwall, May 13, 1796 | 159 |

| LVIII. | Thomas Poole, May 29, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 368) | 164 |

| LIX. | John Thelwall, June 22, 1796 | 166 |

| LX. | Thomas Poole, September 24, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 373; Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 155) | 168 |

| LXI. | Charles Lamb [September 28, 1796]. (Gillman’s Life of Coleridge, 1838, pp. 338-340) | 171 |

| LXII. | Thomas Poole, November 5, 1796. (Biographia Literaria, 1847, ii. 379; Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 175) | 172 |

| LXIII. | Thomas Poole, November 7, 1796 | 176 |

| LXIV. | John Thelwall, November 19 [1796]. (Twenty-six lines published, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, A Narrative, 1894, p. 58) | 178 |

| LXV. | Thomas Poole, December 11, 1796. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 182) | 183 |

| LXVI. | Thomas Poole, December 12, 1796. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 184) | 184 |

| LXVII. | Thomas Poole, December 13, 1796. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 186) | 187 |

| LXVIII. | John Thelwall, December 17, 1796 | 193 |

| LXIX. | Thomas Poole [? December 18, 1796]. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 195) | 208 |

| LXX. | John Thelwall, December 31, 1796 | 210 |

| CHAPTER III. THE STOWEY PERIOD, 1797-1798. | ||

| LXXI. | Rev. J. P. Estlin [1797]. (Privately printed, Philobiblon Society) | 213 |

| LXXII. | John Thelwall, February 6, 1797 | 214 |

| LXXIII. | Joseph Cottle, June, 1797. (Early Recollections, 1837, i. 250) | 220 |

| LXXIV. | Robert Southey, July, 1797 | 221 |

| LXXV. | John Thelwall [October 16], 1797 | 228 |

| LXXVI. | John Thelwall [Autumn, 1797] | 231 |

| [Pg xviii]LXXVII. | John Thelwall [Autumn, 1797] | 232 |

| LXXVIII. | William Wordsworth, January, 1798. (Ten lines published, Life of Wordsworth, 1889, i. 128) | 234 |

| LXXIX. | Joseph Cottle, March 8, 1798. (Part published incorrectly, Early Recollections, 1837, i. 251) | 238 |

| LXXX. | Rev. George Coleridge, April, 1798 | 239 |

| LXXXI. | Rev. J. P. Estlin, May [? 1798]. (Privately printed, Philobiblon Society) | 245 |

| LXXXII. | Rev. J. P. Estlin, May 14, 1798. (Privately printed, Philobiblon Society) | 246 |

| LXXXIII. | Thomas Poole, May 14, 1798. (Thirty-one lines published, Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 268) | 248 |

| LXXXIV. | Thomas Poole [May 20, 1798]. (Eleven lines published, Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 269) | 249 |

| LXXXV. | Charles Lamb [spring of 1798] | 249 |

| CHAPTER IV. A VISIT TO GERMANY, 1798-1799. | ||

| LXXXVI. | Thomas Poole, September 15, 1798. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 273) | 258 |

| LXXXVII. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, September 19, 1798 | 259 |

| LXXXVIII. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, October 20, 1798 | 262 |

| LXXXIX. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, November 26, 1798 | 265 |

| XC. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, December 2, 1798 | 266 |

| XCI. | Rev. Mr. Roskilly, December 3, 1798 | 267 |

| XCII. | Thomas Poole, January 4, 1799 | 267 |

| XCIII. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, January 14, 1799 | 271 |

| XCIV. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, March 12, 1799. (Illustrated London News, April 29, 1893) | 277 |

| XCV. | Thomas Poole, April 6, 1799 | 282 |

| XCVI. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, April 8, 1799. (Thirty lines published, Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 295) | 284 |

| XCVII. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, April 23, 1799 | 288 |

| XCVIII. | Thomas Poole, May 6, 1799. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, i. 297) | 295 |

| CHAPTER V. FROM SOUTH TO NORTH, 1799-1800. | ||

| XCIX. | Robert Southey, July 29, 1799 | 303 |

| C. | Thomas Poole, September 16, 1799 | 305 |

| CI. | Robert Southey, October 15, 1799 | 307 |

| CII. | Robert Southey, November 10, 1799 | 312 |

| CIII. | Robert Southey, December 9 [1799] | 314 |

| CIV. | Robert Southey [December 24], 1799 | 319 |

| CV. | Robert Southey, January 25, 1800 | 322 |

| CVI. | Robert Southey [early in 1800] | 324 |

| CVII. | Robert Southey [Postmark, February 18], 1800 | 326 |

| CVIII. | Robert Southey [early in 1800] | 328 |

| CIX. | Robert Southey, February 28, 1800 | 331 |

| [Pg xix] | ||

| CHAPTER VI. A LAKE POET, 1800-1803. | ||

| CX. | Thomas Poole, August 14, 1800. (Illustrated London News, May 27, 1893) | 335 |

| CXI. | Sir H. Davy, October 9, 1800. (Fragmentary Remains, 1858, p. 80) | 336 |

| CXII. | Sir H. Davy, October 18, 1800. (Fragmentary Remains, 1858, p. 79) | 339 |

| CXIII. | Sir H. Davy, December 2, 1800. (Fragmentary Remains, 1858, p. 83) | 341 |

| CXIV. | Thomas Poole, December 5, 1800. (Eight lines published, Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, ii. 21) | 343 |

| CXV. | Sir H. Davy, February 3, 1801. (Fragmentary Remains, 1858, p. 86) | 345 |

| CXVI. | Thomas Poole, March 16, 1801 | 348 |

| CXVII. | Thomas Poole, March 23, 1801 | 350 |

| CXVIII. | Robert Southey [May 6, 1801] | 354 |

| CXIX. | Robert Southey, July 22, 1801 | 356 |

| CXX. | Robert Southey, July 25, 1801 | 359 |

| CXXI. | Robert Southey, August 1, 1801 | 361 |

| CXXII. | Thomas Poole, September 19, 1801. (Thomas Poole and his Friends, 1887, ii. 65) | 364 |

| CXXIII. | Robert Southey, December 31, 1801 | 365 |

| CXXIV. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge [February 24, 1802] | 367 |

| CXXV. | W. Sotheby, July 13, 1802 | 369 |

| CXXVI. | W. Sotheby, July 19, 1802 | 376 |

| CXXVII. | Robert Southey, July 29, 1802 | 384 |

| CXXVIII. | Robert Southey, August 9, 1802 | 393 |

| CXXIX. | W. Sotheby, August 26, 1802 | 396 |

| CXXX. | W. Sotheby, September 10, 1802 | 401 |

| CXXXI. | W. Sotheby, September 27, 1802 | 408 |

| CXXXII. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, November 16, 1802 | 410 |

| CXXXIII. | Rev. J. P. Estlin, December 7, 1802. (Privately printed, Philobiblon Society) | 414 |

| CXXXIV. | Robert Southey, December 25, 1802 | 415 |

| CXXXV. | Thomas Wedgwood, January 9, 1803 | 417 |

| CXXXVI. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, April 4, 1803 | 420 |

| CXXXVII. | Robert Southey, July 2, 1803 | 422 |

| CXXXVIII. | Robert Southey, July, 1803 | 425 |

| CXXXIX. | Robert Southey, August 7, 1803 | 427 |

| CXL. | Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, September 1, 1803 | 431 |

| CXLI. | Robert Southey, September 10, 1803 | 434 |

| CXLII. | Robert Southey, September 13, 1803 | 437 |

| CXLIII. | Matthew Coates, December 5, 1803 | 441 |

| Page | |

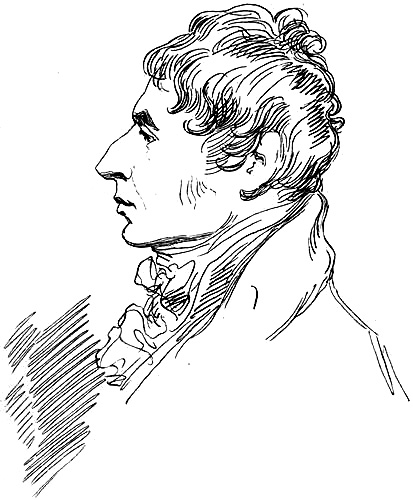

| Samuel Taylor Coleridge, aged forty-seven. From a pencil-sketch by C. R. Leslie, R. A., now in the possession of the editor. |

Frontispiece |

| Colonel James Coleridge, of Heath’s Court, Ottery St. Mary.

From a pastel drawing now in the possession of the Right Honourable Lord Coleridge |

60 |

| The Cottage at Clevedon, occupied by S. T. Coleridge, October-November, 1795. From a photograph |

136 |

| The Cottage at Nether Stowey, occupied by S. T. Coleridge,

1797-1800. From a photograph taken by the Honourable Stephen Coleridge |

214 |

| Samuel Taylor Coleridge, aged twenty-six. From a pastel sketch

taken in Germany, now in the possession of Miss Ward of Marshmills, Over Stowey |

262 |

| Robert Southey, aged forty-one. From an etching on copper. Private plate | 304 |

| Greta Hall, Keswick. From a photograph | 336 |

| Mrs. S. T. Coleridge, aged thirty-nine. From a miniature by Matilda Betham, now in the possession of the editor |

368 |

| Sara Coleridge, aged six. From a miniature by Matilda Betham, now in the possession of the editor |

416 |

LETTERS

OF

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

CHAPTER I

STUDENT LIFE

1785-1794

The five autobiographical letters addressed to Thomas Poole were written at Nether Stowey, at irregular intervals during the years 1797-98. They are included in the first chapter of the “Biographical Supplement” to the “Biographia Literaria.” The larger portion of this so-called Biographical Supplement was prepared for the press by Henry Nelson Coleridge, and consists of the opening chapters of a proposed “biographical sketch,” and a selection from the correspondence of S. T. Coleridge. His widow, Sara Coleridge, when she brought out the second edition of the “Biographia Literaria” in 1847, published this fragment and added some matter of her own. This edition has never been reprinted in England, but is included in the American edition of Coleridge’s Works, which was issued by Harper & Brothers in 1853.

The letters may be compared with an autobiographical note dated March 9, 1832, which was written at Gillman’s request, and forms part of the first chapter of his “Life of Coleridge.”[1] The text of the present issue of the autobiographical letters is taken from the original MSS., and differs in many important particulars from that of 1847.

Monday, February, 1797.

My dear Poole,—I could inform the dullest author how he might write an interesting book. Let him relate the events of his own life with honesty, not disguising the feelings that accompanied them. I never yet read even a Methodist’s Experience in the “Gospel Magazine” without receiving instruction and amusement; and I should almost despair of that man who could peruse the Life of John Woolman[2] without an amelioration of heart. As to my Life, it has all the charms of variety,—high life and low life, vices and virtues, great folly and some wisdom. However, what I am depends on what I have been; and you, my best Friend! have a right to the narration. To me the task will be a useful one. It will renew and deepen my reflections on the past; and it will perhaps make you behold with no unforgiving or impatient eye those weaknesses and defects in my character, which so many untoward circumstances have concurred to plant there.

My family on my mother’s side can be traced up, I know not how far. The Bowdons inherited a small farm in the Exmoor country, in the reign of Elizabeth, as I have been told, and, to my own knowledge, they have inherited nothing better since that time. On my father’s side I can rise no higher than my grandfather, who was born in the Hundred of Coleridge[3] in the county of Devon,[Pg 5] christened, educated, and apprenticed to the parish. He afterwards became a respectable woollen-draper in the town of South Molton.[4] (I have mentioned these particulars, as the time may come in which it will be useful to be able to prove myself a genuine sans-culotte, my veins uncontaminated with one drop of gentility.) My father received a better education than the others of his family, in consequence of his own exertions, not of his superior advantages. When he was not quite sixteen years old, my grandfather became bankrupt, and by a series of misfortunes was reduced to extreme poverty. My father received the half of his last crown and his blessing, and walked off to seek his fortune. After he had proceeded a few miles, he sat him down on the side of the road, so overwhelmed with painful thoughts that he wept audibly. A gentleman passed by, who knew him, and, inquiring into his distresses, took my father with him, and settled him in a neighbouring town as a schoolmaster. His school increased and he got money and knowledge: for he commenced a severe and ardent student. Here, too, he married his first wife, by whom he had three daughters, all now alive. While his first wife lived, having scraped up money enough at the age of twenty[5] he[Pg 6] walked to Cambridge, entered at Sidney College, distinguished himself for Hebrew and Mathematics, and might have had a fellowship if he had not been married. He returned—his wife died. Judge Buller’s father gave him the living of Ottery St. Mary, and put the present judge to school with him. He married my mother, by whom he had ten children, of whom I am the youngest, born October 20, 1772.

These sketches I received from my mother and aunt, but I am utterly unable to fill them up by any particularity of times, or places, or names. Here I shall conclude my first letter, because I cannot pledge myself for the accuracy of the accounts, and I will not therefore mingle them with those for the accuracy of which in the minutest parts I shall hold myself amenable to the Tribunal of Truth. You must regard this letter as the first chapter of an history which is devoted to dim traditions of times too remote to be pierced by the eye of investigation.

Yours affectionately,

S. T. Coleridge.

Sunday, March, 1797.

My dear Poole,—My father (Vicar of, and Schoolmaster at, Ottery St. Mary, Devon) was a profound mathematician, and well versed in the Latin, Greek, and Oriental Languages. He published, or rather attempted to publish, several works; 1st, Miscellaneous Dissertations arising from the 17th and 18th Chapters of the Book of Judges; 2d, Sententiæ excerptæ, for the use of his own school; and 3d, his best work, a Critical Latin Grammar; in the preface to which he proposes a bold innovation in the names of the cases. My father’s new[Pg 7] nomenclature was not likely to become popular, although it must be allowed to be both sonorous and expressive. Exempli gratiâ, he calls the ablative the quippe-quare-quale-quia-quidditive case! My father made the world his confidant with respect to his learning and ingenuity, and the world seems to have kept the secret very faithfully. His various works, uncut, unthumbed, have been preserved free from all pollution. This piece of good luck promises to be hereditary; for all my compositions have the same amiable home-studying propensity. The truth is, my father was not a first-rate genius; he was, however, a first-rate Christian. I need not detain you with his character. In learning, good-heartedness, absentness of mind, and excessive ignorance of the world, he was a perfect Parson Adams.

My mother was an admirable economist, and managed exclusively. My eldest brother’s name was John. He went over to the East Indies in the Company’s service; he was a successful officer and a brave one, I have heard. He died of a consumption there about eight years ago. My second brother was called William. He went to Pembroke College, Oxford, and afterwards was assistant to Mr. Newcome’s School, at Hackney. He died of a putrid fever the year before my father’s death, and just as he was on the eve of marriage with Miss Jane Hart, the eldest daughter of a very wealthy citizen of Exeter. My third brother, James, has been in the army since the age of sixteen, has married a woman of fortune, and now lives at Ottery St. Mary, a respectable man. My brother Edward, the wit of the family, went to Pembroke College, and afterwards to Salisbury, as assistant to Dr. Skinner. He married a woman twenty years older than his mother. She is dead and he now lives at Ottery St. Mary. My fifth brother, George, was educated at Pembroke College, Oxford, and from there went to Mr. Newcome’s, Hackney, on the death of William. He stayed there fourteen years,[Pg 8] when the living of Ottery St. Mary[6] was given him. There he has now a fine school, and has lately married Miss Jane Hart, who with beauty and wealth had remained a faithful widow to the memory of William for sixteen years. My brother George is a man of reflective mind and elegant genius. He possesses learning in a greater degree than any of the family, excepting myself. His manners are grave and hued over with a tender sadness. In his moral character he approaches every way nearer to perfection than any man I ever yet knew; indeed, he is worth the whole family in a lump. My sixth brother, Luke (indeed, the seventh, for one brother, the second, died in his infancy, and I had forgot to mention him), was bred as a medical man. He married Miss Sara Hart, and died at the age of twenty-two, leaving one child, a lovely boy, still alive. My brother Luke was a man of uncommon genius, a severe student, and a good man. The eighth child was a sister, Anne.[7] She died a little after my brother Luke, aged twenty-one;

Rest, gentle Shade! and wait thy Maker’s will;

Then rise unchang’d, and be an Angel still!

The ninth child was called Francis. He went out as a midshipman, under Admiral Graves. His ship lay on the Bengal coast, and he accidentally met his brother John, who took him to land, and procured him a commission in the Army. He died from the effects of a delirious fever brought on by his excessive exertions at the siege of Seringapatam, at which his conduct had been so gallant, that Lord Cornwallis paid him a high compliment in the presence of the army, and presented him with a[Pg 9] valuable gold watch, which my mother now has. All my brothers are remarkably handsome; but they were as inferior to Francis as I am to them. He went by the name of “the handsome Coleridge.” The tenth and last child was S. T. Coleridge, the subject of these epistles, born (as I told you in my last) October 20,[8] 1772.

From October 20, 1772, to October 20, 1773. Christened Samuel Taylor Coleridge—my godfather’s name being Samuel Taylor, Esq. I had another godfather (his name was Evans), and two godmothers, both called “Monday.”[9] From October 20, 1773, to October 20, 1774. In this year I was carelessly left by my nurse, ran to the fire, and pulled out a live coal—burnt myself dreadfully. While my hand was being dressed by a Mr. Young, I spoke for the first time (so my mother informs me) and said, “nasty Doctor Young!” The snatching at fire, and the circumstance of my first words expressing hatred to professional men—are they at all ominous? This year I went to school. My schoolmistress,[Pg 10] the very image of Shenstone’s, was named Old Dame Key. She was nearly related to Sir Joshua Reynolds.

From October 20, 1774, to October 20, 1775. I was inoculated; which I mention because I distinctly remember it, and that my eyes were bound; at which I manifested so much obstinate indignation, that at last they removed the bandage, and unaffrighted I looked at the lancet, and suffered the scratch. At the close of the year I could read a chapter in the Bible.

Here I shall end, because the remaining years of my life all assisted to form my particular mind;—the three first years had nothing in them that seems to relate to it.

(Signature cut out.)

October 9, 1797.

My dearest Poole,—From March to October—a long silence! But [as] it is possible that I may have been preparing materials for future letters,[10] the time cannot be considered as altogether subtracted from you.

From October, 1775, to October, 1778. These three years I continued at the Reading School, because I was too little to be trusted among my father’s schoolboys. After breakfast I had a halfpenny given me, with which I bought three cakes at the baker’s close by the school of my old mistress; and these were my dinner on every day except Saturday and Sunday, when I used to dine at home, and wallowed in a beef and pudding dinner. I am remarkably fond of beans and bacon; and this fondness I attribute to my father having given me a penny for[Pg 11] having eat a large quantity of beans on Saturday. For the other boys did not like them, and as it was an economic food, my father thought that my attachment and penchant for it ought to be encouraged. My father was very fond of me, and I was my mother’s darling: in consequence I was very miserable. For Molly, who had nursed my brother Francis, and was immoderately fond of him, hated me because my mother took more notice of me than of Frank, and Frank hated me because my mother gave me now and then a bit of cake, when he had none,—quite forgetting that for one bit of cake which I had and he had not, he had twenty sops in the pan, and pieces of bread and butter with sugar on them from Molly, from whom I received only thumps and ill names.

So I became fretful and timorous, and a tell-tale; and the schoolboys drove me from play, and were always tormenting me, and hence I took no pleasure in boyish sports, but read incessantly. My father’s sister kept an everything shop at Crediton, and there I read through all the gilt-cover little books[11] that could be had at that time, and likewise all the uncovered tales of Tom Hickathrift, Jack the Giant-killer, etc., etc., etc., etc. And I[Pg 12] used to lie by the wall and mope, and my spirits used to come upon me suddenly; and in a flood of them I was accustomed to race up and down the churchyard, and act over all I had been reading, on the docks, the nettles, and the rank grass. At six years old I remember to have read Belisarius, Robinson Crusoe, and Philip Quarles; and then I found the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, one tale of which (the tale of a man who was compelled to seek for a pure virgin) made so deep an impression on me (I had read it in the evening while my mother was mending stockings), that I was haunted by spectres, whenever I was in the dark: and I distinctly remember the anxious and fearful eagerness with which I used to watch the window in which the books lay, and whenever the sun lay upon them, I would seize it, carry it by the wall, and bask and read. My father found out the effect which these books had produced, and burnt them.

So I became a dreamer, and acquired an indisposition to all bodily activity; and I was fretful, and inordinately passionate, and as I could not play at anything, and was slothful, I was despised and hated by the boys; and because I could read and spell and had, I may truly say, a memory and understanding forced into almost an unnatural ripeness, I was flattered and wondered at by all the old women. And so I became very vain, and despised most of the boys that were at all near my own age, and before I was eight years old I was a character. Sensibility, imagination, vanity, sloth, and feelings of deep and bitter contempt for all who traversed the orbit of my understanding, were even then prominent and manifest.

From October, 1778, to 1779. That which I began to be from three to six I continued from six to nine. In this year [1778] I was admitted into the Grammar School, and soon outstripped all of my age. I had a dangerous putrid fever this year. My brother George lay ill of the same fever in the next room. My poor brother Francis, I[Pg 13] remember, stole up in spite of orders to the contrary, and sat by my bedside and read Pope’s Homer to me. Frank had a violent love of beating me; but whenever that was superseded by any humour or circumstances, he was always very fond of me, and used to regard me with a strange mixture of admiration and contempt. Strange it was not, for he hated books, and loved climbing, fighting, playing and robbing orchards, to distraction.

My mother relates a story of me, which I repeat here, because it must be regarded as my first piece of wit. During my fever, I asked why Lady Northcote (our neighbour) did not come and see me. My mother said she was afraid of catching the fever. I was piqued, and answered, “Ah, Mamma! the four Angels round my bed an’t afraid of catching it!” I suppose you know the prayer:—

“Matthew! Mark! Luke and John!

God bless the bed which I lie on.

Four angels round me spread,

Two at my foot, and two at my head.”

This prayer I said nightly, and most firmly believed the truth of it. Frequently have I (half-awake and half-asleep, my body diseased and fevered by my imagination), seen armies of ugly things bursting in upon me, and these four angels keeping them off. In my next I shall carry on my life to my father’s death.

God bless you, my dear Poole, and your affectionate

S. T. Coleridge.

October 16, 1797.

Dear Poole,—From October, 1779, to October, 1781. I had asked my mother one evening to cut my cheese entire, so that I might toast it. This was no easy matter, it being a crumbly cheese. My mother, however, did it. I went into the garden for something or other, and in[Pg 14] the mean time my brother Frank minced my cheese “to disappoint the favorite.” I returned, saw the exploit, and in an agony of passion flew at Frank. He pretended to have been seriously hurt by my blow, flung himself on the ground, and there lay with outstretched limbs. I hung over him moaning, and in a great fright; he leaped up, and with a horse-laugh gave me a severe blow in the face. I seized a knife, and was running at him, when my mother came in and took me by the arm. I expected a flogging, and struggling from her I ran away to a hill at the bottom of which the Otter flows, about one mile from Ottery. There I stayed; my rage died away, but my obstinacy vanquished my fears, and taking out a little shilling book which had, at the end, morning and evening prayers, I very devoutly repeated them—thinking at the same time with inward and gloomy satisfaction how miserable my mother must be! I distinctly remember my feelings when I saw a Mr. Vaughan pass over the bridge, at about a furlong’s distance, and how I watched the calves in the fields[12] beyond the river. It grew dark and I fell asleep. It was towards the latter end of October, and it proved a dreadful stormy night. I felt the cold in my sleep, and dreamt that I was pulling the blanket over me, and actually pulled over me a dry thorn bush which lay on the hill. In my sleep I had rolled from the top of the hill to within three yards of the river, which flowed by the unfenced edge at the bottom. I awoke several times, and finding myself wet and stiff and cold, closed my eyes again that I might forget it.

In the mean time my mother waited about half an hour,[Pg 15] expecting my return when the sulks had evaporated. I not returning, she sent into the churchyard and round the town. Not found! Several men and all the boys were sent to ramble about and seek me. In vain! My mother was almost distracted; and at ten o’clock at night I was cried by the crier in Ottery, and in two villages near it, with a reward offered for me. No one went to bed; indeed, I believe half the town were up all the night. To return to myself. About five in the morning, or a little after, I was broad awake, and attempted to get up and walk; but I could not move. I saw the shepherds and workmen at a distance, and cried, but so faintly that it was impossible to hear me thirty yards off. And there I might have lain and died; for I was now almost given over, the ponds and even the river, near where I was lying, having been dragged. But by good luck, Sir Stafford Northcote,[13] who had been out all night, resolved to make one other trial, and came so near that he heard me crying. He carried me in his arms for near a quarter of a mile, when we met my father and Sir Stafford’s servants. I remember and never shall forget my father’s face as he looked upon me while I lay in the servant’s arms—so calm, and the tears stealing down his face; for I was the child of his old age. My mother, as you may suppose, was outrageous with joy. [Meantime] in rushed a young lady, crying out, “I hope you’ll whip him, Mrs. Coleridge!” This woman still lives in Ottery; and neither philosophy or religion have been able to conquer the antipathy which I feel towards her whenever I see her. I was put to bed and recovered in a day or so, but I was certainly injured. For I was weakly and subject to the ague for many years after.

[Pg 16]My father (who had so little of parental ambition in him, that he had destined his children to be blacksmiths, etc., and had accomplished his intention but for my mother’s pride and spirit of aggrandizing her family)—my father had, however, resolved that I should be a parson. I read every book that came in my way without distinction; and my father was fond of me, and used to take me on his knee and hold long conversations with me. I remember that at eight years old I walked with him one winter evening from a farmer’s house, a mile from Ottery, and he told me the names of the stars and how Jupiter was a thousand times larger than our world, and that the other twinkling stars were suns that had worlds rolling round them; and when I came home he shewed me how they rolled round. I heard him with a profound delight and admiration: but without the least mixture of wonder or incredulity. For from my early reading of fairy tales and genii, etc., etc., my mind had been habituated to the Vast, and I never regarded my senses in any way as the criteria of my belief. I regulated all my creeds by my conceptions, not by my sight, even at that age. Should children be permitted to read romances, and relations of giants and magicians and genii? I know all that has been said against it; but I have formed my faith in the affirmative. I know no other way of giving the mind a love of the Great and the Whole. Those who have been led to the same truths step by step, through the constant testimony of their senses, seem to me to want a sense which I possess. They contemplate nothing but parts, and all parts are necessarily little. And the universe to them is but a mass of little things. It is true, that the mind may become credulous and prone to superstition by the former method; but are not the experimentalists credulous even to madness in believing any absurdity, rather than believe the grandest truths, if they have not the testimony of their own senses in their favour? I have known some who have[Pg 17] been rationally educated, as it is styled. They were marked by a microscopic acuteness, but when they looked at great things, all became a blank and they saw nothing, and denied (very illogically) that anything could be seen, and uniformly put the negation of a power for the possession of a power, and called the want of imagination judgment and the never being moved to rapture philosophy!

Towards the latter end of September, 1781, my father went to Plymouth with my brother Francis, who was to go as midshipman under Admiral Graves, who was a friend of my father’s. My father settled my brother, and returned October 4, 1781. He arrived at Exeter about six o’clock, and was pressed to take a bed there at the Harts’, but he refused, and, to avoid their entreaties, he told them, that he had never been superstitious, but that the night before he had had a dream which had made a deep impression. He dreamt that Death had appeared to him as he is commonly painted, and touched him with his dart. Well, he returned home, and all his family, I excepted, were up. He told my mother his dream;[14] but he was in high health and good spirits, and there was a bowl of punch made, and my father gave a long and particular account of his travel, and that he had placed Frank under a religious captain, etc. At length he went to bed, very well and in high spirits. A short time after he had lain down he complained of a pain in his bowels. My mother got him some peppermint water, and, after a pause, he said, “I am much better now, my dear!” and lay down again. In a minute my mother heard a noise in his throat, and spoke to him, but he did not answer; and she spoke repeatedly in vain. Her shriek awaked me, and I said, “Papa is dead!” I did not know of my father’s return,[Pg 18] but I knew that he was expected. How I came to think of his death I cannot tell; but so it was. Dead he was. Some said it was the gout in the heart;—probably it was a fit of apoplexy. He was an Israelite without guile, simple, generous, and taking some Scripture texts in their literal sense, he was conscientiously indifferent to the good and the evil of this world.

God love you and

S. T. Coleridge.

February 19, 1798.

From October, 1781, to October, 1782.

After the death of my father, we of course changed houses, and I remained with my mother till the spring of 1782, and was a day-scholar to Parson Warren, my father’s successor. He was not very deep, I believe; and I used to delight my mother by relating little instances of his deficiency in grammar knowledge,—every detraction from his merits seemed an oblation to the memory of my father, especially as Parson Warren did certainly pulpitize much better. Somewhere I think about April, 1782, Judge Buller, who had been educated by my father, sent for me, having procured a Christ’s Hospital Presentation. I accordingly went to London, and was received by my mother’s brother, Mr. Bowdon, a tobacconist and (at the same time) clerk to an underwriter. My uncle lived at the corner of the Stock Exchange and carried on his shop by means of a confidential servant, who, I suppose, fleeced him most unmercifully. He was a widower and had one daughter who lived with a Miss Cabriere, an old maid of great sensibilities and a taste for literature. Betsy Bowdon had obtained an unlimited influence over her mind, which she still retains. Mrs. Holt (for this is her name now) was not the kindest of daughters—but, indeed, my poor uncle would have wearied the patience and affection of an Euphrasia. He received me with great affection,[Pg 19] and I stayed ten weeks at his house, during which time I went occasionally to Judge Buller’s. My uncle was very proud of me, and used to carry me from coffee-house to coffee-house and tavern to tavern, where I drank and talked and disputed, as if I had been a man. Nothing was more common than for a large party to exclaim in my hearing that I was a prodigy, etc., etc., etc., so that while I remained at my uncle’s I was most completely spoiled and pampered, both mind and body.

At length the time came, and I donned the blue coat[15] and yellow stockings and was sent down into Hertford, a town twenty miles from London, where there are about three hundred of the younger Blue-Coat boys. At Hertford I was very happy, on the whole, for I had plenty to eat and drink, and pudding and vegetables almost every day. I stayed there six weeks, and then was drafted up to the great school at London, where I arrived in September, 1782, and was placed in the second ward, then called Jefferies’ Ward, and in the under Grammar School. There are twelve wards or dormitories of unequal sizes, beside the sick ward, in the great school, and they contained all together seven hundred boys, of whom I think nearly one third were the sons of clergymen. There are five schools,—a mathematical, a grammar, a drawing, a reading and a writing school,—all very large buildings. When a boy is admitted, if he reads very badly, he is either sent to Hertford or the reading school. (N. B. Boys are admissible from seven to twelve years old.) If he learns to read tolerably well before nine, he is drafted into the Lower Grammar School; if not, into the Writing School, as having given proof of unfitness for classical attainments. If before he is eleven he climbs up to the first form of the Lower Grammar School, he is drafted into the head Grammar School; if not, at eleven years old, he is sent[Pg 20] into the Writing School, where he continues till fourteen or fifteen, and is then either apprenticed and articled as clerk, or whatever else his turn of mind or of fortune shall have provided for him. Two or three times a year the Mathematical Master beats up for recruits for the King’s boys, as they are called; and all who like the Navy are drafted into the Mathematical and Drawing Schools, where they continue till sixteen or seventeen, and go out as midshipmen and schoolmasters in the Navy. The boys, who are drafted into the Head Grammar School remain there till thirteen, and then, if not chosen for the University, go into the Writing School.

Each dormitory has a nurse, or matron, and there is a head matron to superintend all these nurses. The boys were, when I was admitted, under excessive subordination to each other, according to rank in school; and every ward was governed by four Monitors (appointed by the Steward, who was the supreme Governor out of school,—our temporal lord), and by four Markers, who wore silver medals and were appointed by the Head Grammar Master, who was our supreme spiritual lord. The same boys were commonly both monitors and markers. We read in classes on Sundays to our Markers, and were catechized by them, and under their sole authority during prayers, etc. All other authority was in the monitors; but, as I said, the same boys were ordinarily both the one and the other. Our diet was very scanty.[16] Every morning, a bit of dry[Pg 21] bread and some bad small beer. Every evening, a larger piece of bread and cheese or butter, whichever we liked. For dinner,—on Sunday, boiled beef and broth; Monday, bread and butter, and milk and water; on Tuesday, roast mutton; Wednesday, bread and butter, and rice milk; Thursday, boiled beef and broth; Saturday, bread and butter, and pease-porritch. Our food was portioned; and, excepting on Wednesdays, I never had a belly full. Our appetites were damped, never satisfied; and we had no vegetables.

S. T. Coleridge.

February 4, 1785 [London, Christ’s Hospital].

Dear Mother,[17]—I received your letter with pleasure on the second instant, and should have had it sooner, but that we had not a holiday before last Tuesday, when my brother delivered it me. I also with gratitude received the two handkerchiefs and the half-a-crown from Mr. Badcock, to whom I would be glad if you would give my thanks. I shall be more careful of the somme, as I now consider that were it not for my kind friends I should be as destitute of many little necessaries as some of my schoolfellows are; and Thank God and my relations for them! My brother Luke saw Mr. James Sorrel, who gave my brother a half-a-crown from Mrs. Smerdon, but mentioned not a word of the plumb cake, and said he would call again. Return my most respectful thanks to Mrs. Smerdon for her kind favour. My aunt was so kind as to accommodate me with a box. I suppose my sister Anna’s beauty has many[Pg 22] admirers. My brother Luke says that Burke’s Art of Speaking would be of great use to me. If Master Sam and Harry Badcock are not gone out of (Ottery), give my kindest love to them. Give my compliments to Mr. Blake and Miss Atkinson, Mr. and Mrs. Smerdon, Mr. and Mrs. Clapp, and all other friends in the country. My uncle, aunt, and cousins join with myself and Brother in love to my sisters, and hope they are well, as I, your dutiful son,

S. Coleridge, am at present.

P. S. Give my kind love to Molly.

Undated, from Christ’s Hospital, before 1790.

Dear Brother,—You will excuse me for reminding you that, as our holidays commence next week, and I shall go out a good deal, a good pair of breeches will be no inconsiderable accession to my appearance. For though my present pair are excellent for the purposes of drawing mathematical figures on them, and though a walking thought, sonnet, or epigram would appear on them in very splendid type, yet they are not altogether so well adapted for a female eye—not to mention that I should have the charge of vanity brought against me for wearing a looking-glass. I hope you have got rid of your cold—and I am your affectionate brother,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

P. S. Can you let me have them time enough for re-adaptation before Whitsunday? I mean that they may be made up for me before that time.

October 16, 1791.

Dear Brother,—Here I am, videlicet, Jesus College. I had a tolerable journey, went by a night coach packed[Pg 23] up with five more, one of whom had a long, broad, red-hot face, four feet by three. I very luckily found Middleton at Pembroke College, who (after breakfast, etc.) conducted me to Jesus. Dr. Pearce is in Cornwall and not expected to return to Cambridge till the summer, and what is still more extraordinary (and, n. b., rather shameful) neither of the tutors are here. I keep (as the phrase is) in an absent member’s rooms till one of the aforesaid duetto return to appoint me my own. Neither Lectures, Chapel, or anything is begun. The College is very thin, and Middleton has not the least acquaintance with any of Jesus except a very blackguardly fellow whose physiog. I did not like. So I sit down to dinner in the Hall in silence, except the noise of suction which accompanies my eating, and rise up ditto. I then walk to Pembroke and sit with my friend Middleton. Pray let me hear from you. Le Grice will send a parcel in two or three days.

Believe me, with sincere affection and gratitude, yours ever,

S. T. Coleridge.

January 24, 1792.

Dear Brother,—Happy am I, that the country air and exercise have operated with due effect on your health and spirits—and happy, too, that I can inform you, that my own corporealities are in a state of better health, than I ever recollect them to be. This indeed I owe in great measure to the care of Mrs. Evans,[18] with whom I spent a fortnight at Christmas: the relaxation from study coöperating with the cheerfulness and attention, which I met[Pg 24] there, proved very potently medicinal. I have indeed experienced from her a tenderness scarcely inferior to the solicitude of maternal affection. I wish, my dear brother, that some time, when you walk into town, you would call at Villiers Street, and take a dinner or dish of tea there. Mrs. Evans has repeatedly expressed her wish, and I too have made a half promise that you would. I assure you, you will find them not only a very amiable, but a very sensible family.

I send a parcel to Le Grice on Friday morning, which (you may depend on it as a certainty) will contain your sermon. I hope you will like it.

I am sincerely concerned at the state of Mr. Sparrow’s health. Are his complaints consumptive? Present my respects to him and Mrs. Sparrow.

When the Scholarship falls, I do not know. It must be in the course of two or three months. I do not relax in my exertions, neither do I find it any impediment to my mental acquirements that prudence has obliged me to relinquish the mediæ pallescere nocti. We are examined as Rustats,[19] on the Thursday in Easter Week. The examination for my year is “the last book of Homer and Horace’s De Arte Poetica.” The Master (i. e. Dr. Pearce) told me that he would do me a service by pushing my examination as deep as he possibly could. If ever hogs-lard is pleasing, it is when our superiors trowel it on. Mr. Frend’s company[20] is by no means invidious. On the contrary, Pearce himself is very intimate with him. No![Pg 25] Though I am not an Alderman, I have yet prudence enough to respect that gluttony of faith waggishly yclept orthodoxy.

Philanthropy generally keeps pace with health—my acquaintance becomes more general. I am intimate with an undergraduate of our College, his name Caldwell,[21] who is pursuing the same line of study (nearly) as myself. Though a man of fortune, he is prudent; nor does he lay claim to that right, which wealth confers on its possessor, of being a fool. Middleton is fourth senior optimate—an honourable place, but by no means so high as the whole University expected, or (I believe) his merits deserved. He desires his love to Stevens:[22] to which you will add mine.

At what time am I to receive my pecuniary assistance? Quarterly or half yearly? The Hospital issue their money half yearly, and we receive the products of our scholarship at once, a little after Easter. Whatever additional supply you and my brother may have thought necessary would be therefore more conducive to my comfort, if I received it quarterly—as there are a number of little things which require us to have some ready money in our pockets—particularly if we happen to be unwell. But this as well as everything of the pecuniary kind I leave entirely ad arbitrium tuum.

I have written my mother, of whose health I am rejoiced to hear. God send that she may long continue to recede[Pg 26] from old age, while she advances towards it! Pray write me very soon.

Yours with gratitude and affection,

S. T. Coleridge.

February 13, 1792.

My very Dear,—What word shall I add sufficiently expressive of the warmth which I feel? You covet to be near my heart. Believe me, that you and my sister have the very first row in the front box of my heart’s little theatre—and—God knows! you are not crowded. There, my dear spectators! you shall see what you shall see—Farce, Comedy, and Tragedy—my laughter, my cheerfulness, and my melancholy. A thousand figures pass before you, shifting in perpetual succession; these are my joys and my sorrows, my hopes and my fears, my good tempers and my peevishness: you will, however, observe two that remain unalterably fixed, and these are love and gratitude. In short, my dear Mrs. Evans, my whole heart shall be laid open like any sheep’s heart; my virtues, if I have any, shall not be more exposed to your view than my weaknesses. Indeed, I am of opinion that foibles are the cement of affection, and that, however we may admire a perfect character, we are seldom inclined to love and praise those whom we cannot sometimes blame. Come, ladies! will you take your seats in this play-house? Fool that I am! Are you not already there? Believe me, you are!

I am extremely anxious to be informed concerning your health. Have you not felt the kindly influence of this more than vernal weather, as well as the good effects of your own recommenced regularity? I would I could transmit you a little of my superfluous good health! I am indeed at present most wonderfully well, and if I continue so, I may soon be mistaken for one of your very children:[Pg 27] at least, in clearness of complexion and rosiness of cheek I am no contemptible likeness of them, though that ugly arrangement of features with which nature has distinguished me will, I fear, long stand in the way of such honorable assimilation. You accuse me of evading the bet, and imagine that my silence proceeded from a consciousness of the charge. But you are mistaken. I not only read your letter first, but, on my sincerity! I felt no inclination to do otherwise; and I am confident, that if Mary had happened to have stood by me and had seen me take up her letter in preference to her mother’s, with all that ease and energy which she can so gracefully exert upon proper occasions, she would have lifted up her beautiful little leg, and kicked me round the room. Had Anne indeed favoured me with a few lines, I confess I should have seized hold of them before either of your letters; but then this would have arisen from my love of novelty, and not from any deficiency in filial respect. So much for your bet!

You can scarcely conceive what uneasiness poor Tom’s accident has occasioned me; in everything that relates to him I feel solicitude truly fraternal. Be particular concerning him in your next. I was going to write him an half-angry letter for the long intermission of his correspondence; but I must change it to a consolatory one. You mention not a word of Bessy. Think you I do not love her?

And so, my dear Mrs. Evans, you are to take your Welsh journey in May? Now may the Goddess of Health, the rosy-cheeked goddess that blows the breeze from the Cambrian mountains, renovate that dear old lady, and make her young again! I always loved that old lady’s looks. Yet do not flatter yourselves, that you shall take this journey tête-à-tête. You will have an unseen companion at your side, one who will attend you in your jaunt, who will be present at your arrival; one whose[Pg 28] heart will melt with unutterable tenderness at your maternal transports, who will climb the Welsh hills with you, who will feel himself happy in knowing you to be so. In short, as St. Paul says, though absent in body, I shall be present in mind. Disappointment? You must not, you shall not be disappointed; and if a poetical invocation can help you to drive off that ugly foe to happiness here it is for you.

TO DISAPPOINTMENT.

Hence! thou fiend of gloomy sway,

Thou lov’st on withering blast to ride

O’er fond Illusion’s air-built pride.

Sullen Spirit! Hence! Away!

Where Avarice lurks in sordid cell,

Or mad Ambition builds the dream,

Or Pleasure plots th’ unholy scheme

There with Guilt and Folly dwell!

But oh! when Hope on Wisdom’s wing

Prophetic whispers pure delight,

Be distant far thy cank’rous blight,

Demon of envenom’d sting.

Then haste thee, Nymph of balmy gales!

Thy poet’s prayer, sweet May! attend!

Oh! place my parent and my friend

’Mid her lovely native vales.

Peace, that lists the woodlark’s strains,

Health, that breathes divinest treasures,

Laughing Hours, and Social Pleasures

Wait my friend in Cambria’s plains.

Affection there with mingled ray

[Pg 29]Shall pour at once the raptures high

Of filial and maternal Joy;

Haste thee then, delightful May!

And oh! may Spring’s fair flowerets fade,

May Summer cease her limbs to lave

In cooling stream, may Autumn grave

Yellow o’er the corn-cloath’d glade;

Ere, from sweet retirement torn,

She seek again the crowded mart:

Nor thou, my selfish, selfish heart

Dare her slow return to mourn!

In what part of the country is my dear Anne to be? Mary must and shall be with you. I want to know all your summer residences, that I may be on that very spot with all of you. It is not improbable that I may steal down from Cambridge about the beginning of April just to look at you, that when I see you again in autumn I may know how many years younger the Welsh air has made you. If I shall go into Devonshire on the 21st of May, unless my good fortune in a particular affair should detain me till the 4th of June.

I lately received the thanks of the College for a declamation[23] I spoke in public; indeed, I meet with the most pointed marks of respect, which, as I neither flatter nor fiddle, I suppose to be sincere. I write these things not from vanity, but because I know they will please you.

I intend to leave off suppers, and two or three other little unnecessaries, and in conjunction with Caldwell hire a garden for the summer. It will be nice exercise—your advice. La! it will be so charming to walk out in one’s own garding, and sit and drink tea in an arbour, and[Pg 30] pick pretty nosegays. To plant and transplant, and be dirty and amused! Then to look with contempt on your Londoners with your mock gardens and your smoky windows, making a beggarly show of withered flowers stuck in pint pots, and quart pots menacing the heads of the passengers below.

Now suppose I conclude something in the manner with which Mary concludes all her letters to me, “Believe me your sincere friend,” and dutiful humble servant to command!

Now I do hate that way of concluding a letter. ’Tis as dry as a stick, as stiff as a poker, and as cold as a cucumber. It is not half so good as my old

God bless you

and

Your affectionately grateful

S. T. Coleridge.

February 13, 11 o’clock.

Ten of the most talkative young ladies now in London!