"The Female Ostrich at the Zoo is dead."

["The unbridled greediness of some authors."—Mr. Gosse.]

Publisher (nervously). And what will your terms be for a short story, in your best style?

Author (loftily). I have only one style, and that is perfection. I couldn't think of charging less than fifty guineas a page.

Publisher (aghast). Fifty guineas a page! But are you aware that Lord Macaulay got only ten thousand for the whole of his history, and that Milton——

Author (rudely). Hang Macaulay and Milton! Surely you would not compare those second-rate writers with myself! If they were content to work for starvation wages, I am not.

Publisher. But, say your story runs to twenty pages, as it probably will, I shall have to pay you for that one short tale the really ridiculous sum of a thousand pounds!

Author (coolly). Yes, it is rather ridiculous—ridiculously small, I mean. Still, out of regard to your pocket, I am willing to accept that inadequate remuneration. Is it a bargain?

Publisher (with a groan). It must be. The public demands your work, and we have no option. But allow me to remark that your policy is——

Author (gaily). A Policy of Assurance, on which you have to pay the premium. Ha, ha!

A Year Or Two Later.

Author (deferentially). I have a really capital idea for a work of fiction, on a subject which I believe to be quite original. What—ahem!—are you prepared to offer for the copyright?

Publisher. Couldn't think of making an offer till we saw the work. It might turn out to be worth nothing at all.

Author. Nothing at all! But you forget how my fame——

Publisher. Disappeared when we were obliged to charge the public six shillings for a story of yours about the size of an average tract. Other writers have come to the front, you know. Still, if there's anything in your novel, when it's finished, we should, I daresay, be prepared to offer you a couple of guineas down, and a couple more when—say—a thousand copies had been sold. Is it a bargain?

Author (sadly). I suppose it must be! Yet I can hardly be said to be paid for my work.

Publisher. Perhaps not. But you can be said to be paid out!

The stately streets of London

Are always "up" in Spring,

To ordinary minds an ex-

traordinary thing.

Then cabs across strange ridges bound,

Or sink in holes, abused

With words resembling not, in sound,

Those Mrs. Hemans used.

The miry streets of London,

Dotted with lamps by night;

What pitfalls where the dazzled eye

Sees doubly ruddy light!

For in the season, just in May,

When many meetings meet,

The jocund vestry starts away,

And closes all the street.

The shut-up streets of London!

How willingly one jumps

From where one's cab must stop, through pools

Of mud, in dancing pumps!

When thus one skips on miry ways

One's pride is much decreased,

Like Mrs. Gilpin's, for one's "chaise"

Is "three doors off" at least.

The free, fair streets of London!

Long, long, in vestry hall,

May heads of native thickness rise,

When April showers fall;

And green for ever be the men

Who spend the rates in May,

By stopping all the traffic then

In such a jocose way!

In Bloom.—On Saturday last there was a letter in the Daily Telegraph headed "Trees for Londoners." The lessee and manager of the Haymarket Theatre thinks that for Londoners two Trees are quite sufficient, i.e. his wife and himself.

First Man. What rot it is to keep this tax on beer!

Second Man. Well, it's better than spirits, anyhow.

First Man. Of course you say that as you've got those shares in that Distillery Company.

Second Man. Well, you needn't talk, with your Allsopp Debentures.

First Man. Come to that, personally I take no interest in beer. It's poison to me.

Second Man. It's the finest drink in the world. I never touch spirits.

First Man. They're much more wholesome. I wonder what the Government will do about Local Veto and Compensation. I suppose, as I'm a Liberal——

Second Man. So am I. But I respect vested interests. Now, in theory, teetotalism, especially for the masses——

First Man. Waiter, bring me a whiskey and soda.

Second Man. And bring me a glass of bitter.

First Man. As for Wilfrid Lawson, he's an utter——

Second Man. Oh, Wilfrid Lawson! He's a downright——

[They drink—not Sir Wilfrid's health.

(A Fragment from the Chronicles of St. Stephen's.)

"But must I give up this comfortable furniture?" asked the poor person, looking at the venerable chairs, some of which were distinctly rickety.

"You must, indeed," replied firmly, but still with a certain tenderness, the stern official.

"But I can nearly hear what they are saying," urged the fair petitioner.

"I cannot help it."

"And all but see them," and once again she peered through the grille.

"I am forced to obey my orders," returned the official. "You applauded. You clapped your hands—and you must retire."

"And for that little burst of enthusiasm," almost wept the person, "I am to lose all this happiness! To be stopped from hearing an indistinct murmur, seeing a blurred picture, resting on rickety seats, and breathing a vitiated atmosphere! Am I to lose all these comforts and pleasures and advantages?"

"I am afraid so," was the answer. And then the official opened the door of the Ladies' Gallery of the House of Commons, and the person passed out.

Lord W-ls-l-y (to Commander-in-Chief). "In September I have to retire from my Command."

Duke. "Dear me! I haven't!"

Seniores priores? Rude Rads, and some Tories,

Would make that apply to mere manner of exit.

If the "Spirit of Eld" is in charge of our glories,

Why wantonly vex it?

That Spirit of Eld is the "note" of our era.

Grand old men—and women—at bossing are busy.

Youth? Stuff! Callow youth was indeed the chimera

Of dandyish Dizzy.

But that was when Dizzy, himself young—and curly—

Was Vivian Grey, not the Primrose Dames' darling.

The Great Earl himself did not dominate early.

Oh, out on such snarling!

Old ways, and old wines, and old warriors for ever!

(Or, if not for ever, a whacking big slice of it.)

Great Senex from service 'twere folly to sever,

Whilst winning the price of it.

Retirement is not your true militaire's virtue;

To "beat the retreat" irks us all, dukes or drummers.

Let Winter hold sway, then—it cannot much hurt you—

For—say x—more summers!

True Hannibal, Gaston de Foix, Alexander,

Napoleon, Don John, the Great Condé, and Cortes

Were types of the true, adolescent commander,

And swayed ere their forties.

Still, they were god-loved and died young, like our Sidney,

But Genius is versatile, Nature is various;

All heroes are not of the same "kiddish" kidney,

Ask—say—Belisarius!

To grudge him his obolus ("screw" as we name it)

Because he has drawn it a few years—say fifty—

If Rads had a conscience at all, Sir, would shame it!

But Rads are so—thrifty!

For fellows like Wolseley or Roberts, retirement

Is all very well; they've no call for to stop, Sir.

But oh! for an Army the master requirement

Is grey hairs—a-top, Sir!

Robinson. "Well, old Chap, how did you sleep last Night?"

Smith (who had dined out). "'Like a Top.' As soon as my Head touched the Pillow, it went round and round!"

["In the retrospect of ninety years there is a pathetic mixture of gratitude for ample opportunities, and humiliation for insignificant performances."—Dr. James Martineau, on his Ninetieth Birthday.]

Air—Thackeray's "Age of Wisdom"

Ho! petty prattler of sparkling sin,

Paradox-monger, slave of the queer!

All your wish is a name to win,

To shook the dullards, to sack the tin,—

Wait till you come to Ninety Year!

Curled locks cover your shallow brains,

Twaddle and tinkle is all your cheer.

Sickly and sullied your amorous strains,

Pessimist praters of fancied pains,—

What do you think of this Ninety Year?

Ninety times over let May-day pass

(If you should live, which you won't I fear),

Then you will know that you were but an ass,

Then you will shudder and moan, "Alas!

Would I had known it some Ninety Year!"

Pledge him round! He's a Man, I declare;

His heart is warm, though his hair be grey.

Modest, as though a record so fair,

A brain so big, and a soul so rare,

Were a mere matter of every day.

His eloquent lips the Truth have kissed,

His valiant eyes for the Right have shone.

Pray, and listen—'twere well you list—

Look not away lest the chance be missed,

Look on a Man, ere your chance be gone!

Martineau lives, he's alive, he's here!

He loved, and married, seventy years' syne.

Look at him, taintless of fraud or fear,

Alive and manful at Ninety Year,

And blush at your pitiful pessimist whine!

Hamlet (amended by Lord Farrar).—"In my mind's eye, O ratio!"

(I.e., A Representative at the Royal Academy.)

Anyone arriving at Burlington House so early as to be the first person to pay his money and take his choice, will probably look straight before him, and will feel somewhat confused at seeing in the distance, but exactly opposite him, a dignified figure wearing a chain of office, politely rising to receive the early visitor. "It can be no other than the President himself," will at once occur to the stranger within the gates; "and yet, did I not hear that he was abroad for the benefit of his health?" Then, just as he is about to bow his acknowledgments of the courtesy extended to him personally by the Chief Representative of Art in this country, he will notice seated, at the President's left hand, and staring at him, with a pen in his hand, ready either to take down the name of the visitor, or to make a sketch of him, a gentleman in whose lineaments anyone having the pleasure of being personally acquainted with Mr. Stacy Marks, R.A., would at once recognise those of that distinguished humourist in bird-painting. "Is there wisions about?" will the puzzled visitor quote to himself, and then boldly advancing, hat in hand, to be soon replaced on head, he will come face to face with the biggest picture in the Academy, covering almost the entire wall.

The stately figure is not Sir Frederic Leighton, P.R.A., who unfortunately has been compelled to go abroad for the benefit of his health—prosit!—nor is the seated figure Mr. S. Marks; but the former is "The Bürgermeister of Landsberg, Bavaria," and the latter is his secretary, while the other figures, all likenesses, are "his Town Council" in solemn deliberative assembly. The picture, an admirable one, and, as will be pretty generally admitted, a masterpiece of the master's, is No. 436 in the book, the work of Meister Hubert Herkomer, R.A.

But as this is in Gallery No. VI., and as it is not every one who will be [pg 221] privileged to see the picture as the early bird has seen it, and as some few others may, perhaps, see it during the season, this Representative retraces his steps from No. VI., and commences de novo with No. 1.

No. 17. "Finan Haddie," fresh as ever, caught by J. C. Hook, R.A. Title, of course, should have been "Finan Haddie Hook'd."

Sir John Millais' St. Stephen (not a parliamentary subject), showing that Good Sir John's hand has lost none of its cunning, is No. 18; and after bowing politely to Mrs. Johnson-Ferguson, and pausing before this charming picture by Luke Fildes, R.A., to take a last Luke at her, you will pass on, please, to No. 25, "The Fisherman and the Jin," and will wonder why Val. C. Prinsep, R.A., spells the cordial spirit with a "J" instead of a "G." It is a spirited composition.

No. 31. Mr. John S. Sargent, A., let "Mrs. Ernest Hills" go out of his studio in a hurry. She is evidently "to be finished in his next."

No. 34. "A Quiet Rehearsal." Lady Amateur all alone, book in hand, to which she is not referring, trying to remember her part and say it off by heart. It is by W. B. Richmond, A. To quote a cigarette paper, this work may be fairly entitled "A Richmond Gem."

No. 43. "Evening." By B. W. Leader, A. Delightful. Artistic aspirants in this line cannot play a better game than that of "Follow my Leader."

This Representative recognised "Dr. Jameson, C.B.," by Herkomer, at a glance. If you are asked by anyone to look at "Hay Boat" do not correct him and say "You mean A Boat," or you will find yourself in the wrong boat, but admire Hilda Montalba's painting, and pass on to Ouless, R.A.'s, excellent portrait of "J. J. Aubertin" (a compound name, whose first two syllables suggest delightful music while the last syllable means money); thence welcome our old friend Frith, R.A., who, in 67, [and a trifle over, eh?] shows us "Mrs. Gresham and Her Little Daughter." From the "little D.'s" expressive face may be gathered that she has just received a "Gresham Lecture." After noting No. 73 and 83 (the unhappily separated twins) together, you may look on No. 126. Two fierce animals deer-stalking in a wild mountainous region, painted by Arthur Wardle. Only from what coign of vantage did Mr. Wardle, the artist, make this life-like sketch? However, he came out of the difficulty safe and sound, and we are as glad to welcome a "Wardle" as we should be to see his ancient associate "Pickwick," or a "Weller," in Burlington House.

No. 139. Charming is Sir F. Leighton's "Fair One with the Golden Locks." To complete the picture the hairdresser should have been thrown in. She is en peignoir, and evidently awaiting his visit. This is the key to these locks.

No. 242. Mr. Andrew C. Gow, R.A., gives us Buonaparte riding on the sands with a party of officers, "1805." The Emperor is cantering ahead of the staff. Another title might be "Going Nap at Boulogne."

No. 160. "A Lion Tamer's Private Rehearsal." But Briton Rivière, R.A., calls it "Phœbus Apollo."

No. 251. Queer incident in the life of a respectable middle-aged gentleman. Like Mr. Pickwick, he has mistaken his room in the hotel, and has gone to bed. Suddenly, lady, in brilliant diamond tiara, returns from ball, and finds him there. The noise she makes in opening the curtains awakes him. He starts up alarmed. "Hallo!" he cries, and for the moment the ballad of "Margaret's Grim Ghosts" recurs to his mind. His next thought is, "How fortunate I went to bed in my copper-coloured pyjamas, with a red cummerbund round me." Of course he apologised, and withdrew. What happened subsequently is not revealed by the artist who has so admirably depicted this effective scene, and whose name is Sir John Millais, Bart., R.A.

No. 368. Excellent likeness, by Mr. Arthur S. Cope, of the well-known and popular parson Rogers. A Parsona Grata. This typical old-fashioned English clergyman, who, in ordinary ministerial functions, would be the very last person to be associated with a "chasuble," will henceforth never be dissociated from a "Cope."

No. 491. A picture by Mr. Fred Roe. If Nelson's enemies had only known of this incident in his lifetime!! Here is our great naval hero, evidently "half seas over," being personally conducted through some by-streets of Portsmouth, on his way back to the Victory, in order to avoid the crowd. Rather a hard Roe, this.

No. 767. Congratulations to T. B. Kennington on his "Alderman George Doughty, J.P.," or, as the name might be from the characteristic colouring, Alderman Deorge Gouhty, which is quite in keeping with the proverbial aldermanic tradition.

A Little Mixed.—In its account of the private view at the Royal Academy the Daily News says:—"The Countess of Malmesbury studied the sculpture in a harmonious costume of striped black and pink, and a picture hat trimmed with pink roses." This is presumably the result of the influence of Mr. Horsley. But isn't it going a little too far, at least to begin with? A piece of sculpture—say, a Venus—in a harmonious costume of striped black and pink might pass. But the addition of a picture hat trimmed with pink roses is surely fatal.

Disgusted Sculptor. "So you've got the Line in Two Places, have you? Hang me if I don't give up Art, and go in for Painting!"

Chair of absent President ably filled by Sir John Millais, who, pluckily struggling against evidently painful hoarseness, made, in returning thanks, an exceptionally graceful, touching, and altogether memorable speech. Odd to note that, had Sir John, speaking hoarsely, broken down, we should have heard his remplaçant Horsley speaking. The incident, however, which will mark this banquet as unique in Academical records, was Sir John's mistaking one Archbishop for the other, and, in consequence, pleasantly indicating by a polite bow to the prelate on his left, that he called upon him, the Archbishop of York, to reply for the visitors. "York, you're wanted," said, in effect, the genial Sir John, utterly ignoring the presence of His Grace of Canterbury. Whereupon, Canterbury collapsed, while the Northern Primate, vainly attempting to dissemble his delight, professed his utter surprise, his total unpreparedness, and straightforth hastened to improve the occasion. But before fifty words had passed the jubilant Prelate's lips, Sir John, having discovered his mistake, rose quickly in his stirrups, so to speak, and pulled up the impetuous York just then getting into his stride. Genially beaming on the slighted Canterbury, Sir John called on "The Primate of All England" (a snub this for York) to return thanks. "One Archbishop very like another Archbishop," chuckled the unabashed Sir John to himself, as he resumed his seat, "but quite forgot that York as Chaplain to Academy is 'His Grace before dinner,' and Canterbury represents 'Grace after dinner.'" "'Twas ever thus," muttered York, moodily eyeing the last drop in his champagne-glass, as he mentally recalled ancient ecclesiastical quarrels between the two provinces, from which the Southern Prelate had issued victorious. Canterbury flattered, but, fluttered, lost his chance. His Royal Highness's speech brief, comprehensive, effective. Lord Rosebery entertaining. "The rest is silence," or better if it had been. No more at present. Good luck to the Academy Show of 1895.

Aunt Phillida. "The last time I went to a grown-up Fancy Ball, I went as a Wasp. That was only Ten Years ago. I don't suppose I shall ever again go to a Fancy Ball as a Wasp!"

[Sighs deeply.

Mary. "Hardly as a Wasp, Aunt Phillida. But you'd look very splendid as a Bumble-Bee!"

(A Fable.)

A Duck that had lately succeeded in hatching a fine brood of ducklings, and was much concerned on the point of their polite education, took them down to the river one day in order to teach them to swim.

"See, my dears!" she said when they were all got to the bank, addressing her brood in encouraging accents, "this is the way to do it," and so saying the old duck pushed off from the land, in evident expectation that her young ones would follow her.

The Ducklings, however, instead of coming after their mother, remained on the bank, talking and laughing and whispering among themselves in a very knowing manner; until at last the old bird, provoked by their levity and wondering what ailed them, called out sharply to them from mid-stream to come into the water at once; upon which one of the Ducklings, who had evidently been constituted spokesman for the rest, made bold to address his mother in the following words.

"You must be a simpleton indeed, Madam," said he, "to imagine that we are going to do anything so foolish as to endanger our lives in the reckless fashion in which you are now exposing yours; for though it may be true that in obedience to some unwritten law of nature (unknown at present to us) you are floating securely upon the surface of the stream, instead of sinking to the bottom of it, yet it by no means follows from thence that we should do the same thing, supposing we were so foolish as to follow your example. Rest assured, dear Madam," continued the Duckling, "that so soon as we have sifted this matter to the bottom for ourselves, we shall act on the knowledge of it, according as our experience may suggest to us; but for the present, at any rate, we prefer to remain where we are."

And so saying, the Duckling, accompanied by the rest of the brood, turned his back on his natural element, and returned forthwith to the poultry-yard.

Or, The Triumph of the Timid One.

At last! I see signs of a turn in the tide,

And O, I perceive it with infinite gratitude.

No more need I go with a crick in my side

In attempts to preserve a non-natural attitude.

Something has changed in the season, somewhere;

I'm sure I can feel a cool whiff of fresh air!

Mental malaria worse than the grippe

Has asphyxiated my mind, or choke-damped it.

The plain honest truth has been strange to my lip;

I've shammed it, and fudged it, humbugged it and vamped it

Till I wasn't I, self-respect was all gone,

And I hadn't a taste that I dared call my own.

I do not love horror. I do not like muck;

And mystical muddle to me is abhorrent.

In Stygian shallows long time I have stuck,

Or, like a dead dog on a sewage-fouled torrent,

Have gone with the stream; but beyond the least doubt

I'm grateful—so much—for a chance to creep out.

Egomania it seems then is not the last word

Of latter-day wisdom! By Jove I am glad!

I always did feel it was highly absurd

To worship the maudlin, and aim at the mad;

And now, there's a chance for the decent again,

One may relish one's Dickens, yet not seem insane!

The ghoulish-grotesque, and the grimy-obscure,

I have tried to gloat on in poem and prose,

But oh! all the while there seemed something impure

In the sniff of the thing that tormented my nose;

And as to High Art—well, to me it seemed high,

Like an over-hung hare—only food for the fly.

Yet I didn't dare say that I felt it to be

Pseudo-sphinxian fudge, and sheer Belial bosh;

Or that after Art-babble at five o'clock tea,

I felt that the thing I most craved was—a wash;

Because in the view of the Mystical School,

That would just write you down a mere Philistine fool.

I am not quite sure that I quite understand

How they've suddenly found all our fads are degenerate;

Why Maeterlinck, Ibsen, Verlaine, Sarah Grand,

Tolstoi, Grant Allen, Zola, are "lumped"—but, at any rate,

I know I'm relieved from one horrible bore,—

I need not admire what I hate any more.

Mr. J-s-ph Ch-mb-rl-n (as "Benedick"). "DOTH NOT THE APPETITE CHANGE? A MAN LOVES THE MEAT IN HIS YOUTH THAT HE CANNOT ENDURE IN HIS AGE.... WHEN I SAID I WOULD DIE AN INDEPENDENT RADICAL, I DID NOT THINK I SHOULD LIVE TO BE ALLIED WITH A TORY PARTY."

Much Ado About Nothing, Act II., Sc. 3 (slightly "modified").

By Dunno Währiar.

(Translated from the original Lappish by Mr. Punch's own Hyperborean Enthusiast.)

I sat on the beach one forenoon in midsummer. A great number of people were doing much the same. The rhapsodists and orators, the blameless Ethiopians with their barbaric instruments of music, the itinerant magicians with their wands, the statuesque groups posed before the tripod of the photographer, the snow-white sea-chariots with crimson wheels, the bare-legged riders on antique steeds, made me fancy I was gazing at a scene of Southern Hellenic life. Why I know not—for it was not in the least like.

Then I saw an enormous black hand stretch down over the fjord. I was not alarmed, for I am becoming accustomed to apparitions of this kind.

It set weird signs and black marks upon the railings of the jetty, and on the white sides of the bathing machines, and on the sails of the fishing-boats, and when I turned about, the parade itself was plastered with tablets.

And on all things had the New Lawgiver incised in letters of gold

and azure and purple upon shining tables the new commandments:

"Use Skäuerskjin's Soap!"; "Try Tommeliden Tonic!"; "Buy

Boömpvig's Pills!"; "Ask for Baldersen's Hairwash!"

And I heard the voice of the wild waves saying, as they lapped up over the cheap sandshoes and saturated paper bags full of gingerbread nuts:

"This is the new moral law. That men should cherish the outside and insides of their bodies, and keep them clean, like precious vessels of brass and copper. Rather to let the picturesque perish than forget for a moment which is the best soap for the complexion, and which will not wash clothes. Never to see a ship spreading her canvas like a sea bird without associations of a Purifying Saline Draught or a Relishing Pickle. To ask and see that ye procure!"

Then I looked into the heavens above me, and behold, high above the esplanade hung a hand, enormous as the one that had set its marks on everything below, but white, white; and it held a brush and wrote until the sky was full of signs, and they had form and colour, but not of this world, and those who ran could read them.

And I bought a shell-box and a bath bun, and closed my eyes, and lay musing in an agony of soul. Suddenly I felt the pain snap, and something grow in me, and I saw in my soul's dawning the great half-opened shell of a strange oyster.

And this oyster has its bed on my very heart, and it is my salt tears that nourish it, and it grows inside, invisible to all but me.

But I know that, when the oyster opens, I shall find within its shell, like a gleaming dove-coloured pearl, the great Panacea of the To Be; and, if you ask me to explain my meaning more fully, I reply that the bearings of this blind allegory lie in the application thereof, and that ye are a blow-fly brood of dull-witted hucksters.

(Under the guidance of Herr Goethemann.)

"Afternoon. Two-pair suburban back. Upright piano. High-minded table. Henry (dramatic author and host) under it, heavy with wine. Romeo (his friend and Town Blood) communing with Mary Ann (local ingénue). Eliza (her sister and hostess) outside just now, making coffee. She will come in presently, and realise Dramatic Moment.

Mary Ann. Get up, Henry, and give us a regular old rousing tune.

Henry (huskily, emerging from retreat). What shall it be?

Romeo. Oh, anything. Wagner for choice.

[Gifted musician obliges with a pot pourri of 'Parsifal,' Romeo absently whistling the trombone part.

Mary Ann. Ripping! Now something classical. Let's have 'After the Ball.' Come on, Romeo, we'll waltz; push back the fire-place. (They push back the fire-place; Romeo grasps Mary Ann, and they revolve. He kisses her on the cheek l. c.) Well, I never did! For shame! I decline to dance with you. There!

[Declines to dance with him.

Henry. One for you, my buck! Cheer up, Mary Ann; I'll give you a turn.

[Pirouettes twice with her, humming suitable air.

Mary Ann (rendered completely breathless). It's not like real dancing when you only hum!

Henry. Can't play and dance at same time, you know. Piano too stationary. So you must take Romeo on again, or go without.

Eliza (entering with coffee-tray and realising situation). Well, I declare! Having high jinks while I was making the coffee. What dramatic irony!

[Romeo gallantly invites her to join the giddy throng. They dance.

Eliza (rendered completely breathless). My soul! I'm in bad training!

Mary Ann (having got her second wind). Have a turn with me, Eliza! Romeo 's no good; he misses out every other bar.

Eliza. Want my coffee. No wind left.

[Henry spontaneously sings a Lullaby of Brahms'. Stops in middle to see what they all think of it. They all think a lot of it. Goes on singing. Only Eliza goes on thinking a lot of it. Others talk quite loud, Romeo being a Town Blood. Henry finishes, under conviction that they have no manners to speak of. Mind wanders off to the leading lady in his new piece, and he drops inadvertently into 'Daisy' waltz. Eliza waits for second wind. Romeo grapples with Mary Ann, the latter reluctant. She is rapt away in mazy whirl, kicking feebly. He again kisses her on the cheek, this time r. c.

Eliza. Man! I saw you! It was a wanton act.

Henry (casually). Anything broken?

Eliza. Oh, Henry! He went and kissed my Mary Ann, my own sister!

Romeo (with easy bravado). A mere nothing, I assure you. She's so provoking, don't you know? Had to do it in self-defence.

Eliza. It is contrary to established etiquette in our circles. Mary Ann, how could you?

Mary Ann. I didn't. It was him. I shall scream another time.

Eliza. Man, you will oblige me by treating my sister as you would your own.

[Exit with crushing expression which leaves Romeo intact.

Mary Ann. Eliza talks rot. (To Romeo.) Not that you're not a beast, all the same.

[Exit in two frames of mind. Henry laughs and makes light of osculation. The men converse. The plot becomes even more intricate. The end is nigh."

Cheering.—Liberal Party much encouraged by East Wicklow and East Leeds. "Wisdom from the East," they call it.

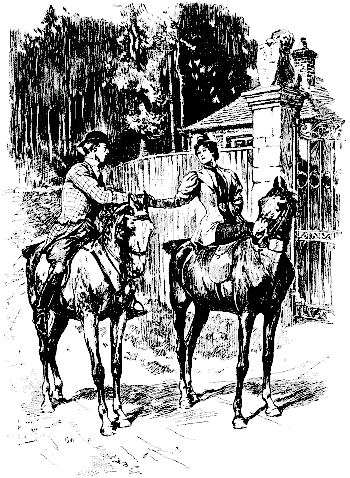

Nervous Youth. "Well—er—good-bye, Mrs. Thomas. Awfully glad I met you! Er—so good of you—so much pleasanter than Riding alone!"

[Shuts up.

(An Anglo-Nicaraguan Parallel.)

The young Midshipman looked towards Corinto. The public buildings were still within range of the monster guns. The select army of one hundred and fifty had retired before the advance of the blue jackets and marines. All was tranquil, and, as he gazed upon the Nicaraguan capital, his eyes closed, and he dreamed a dream.

He was once more in England. He was at the seaside. Here in front of him were bathing-machines. There, to his right, was a circulating library. He could see a clock-tower and a shortened pier. Then he laughed in his glee. He was at Herne Bay! Close to the Isle of Thanet—within sight of the Reculvers!

He had scarcely realised his happiness, when he noticed on the ocean a flotilla. Three gigantic ironclads were approaching the tranquil town!

"The Nicaraguan fleet!" he murmured in his sleep.

It, alas! was too true! The Central American Admiral had sent an ultimatum. The news had run from one end of Herne Bay to the other that, unless the sum demanded were paid at once, the as-yet-unconquered watering-place would be "ploughed," as the Poet Bunn would have put it, "by the hoof of the ruthless invader."

Then there was a hurried consultation. What could be done with that overpowering fleet? It was useless to defend the bathing-machines; the donkeys and their drivers were no match for heavy ordnance. What could the few coast-guardsmen do when threatened by five hundred Nicaraguans?

"Herne Bay must surrender!" murmured the Midshipman in his sleep. "There is no help for it."

And then came a strange sight. The search-lights of the Nicaraguan fleet played upon the sea front, and the little garrison of Herne Bay retired towards Birchington and Margate. The Band (lent from the Militia) marched away, followed by the heavy cavalry of the bathers, and the Uhlan-like donkeys of the sands. The representatives of the Navy (carrying their look-out telescopes) brought up the rear.

Then, when all had gone, the sailors and marines of the Nicaraguan fleet landed. The British flag was hauled down, and replaced by the colours of the enemy.

Herne Bay was conquered!

At this point the Midshipman awoke with a start. He looked round, and sighed a great sigh of relief.

"How fortunate it is that the English fleet have conquered Corinto and not the Nicaraguan fleet Herne Bay!" he cried in an ecstacy of patriotic fervour. Then he performed for hours the duties of his command. Towards the close of day he again casually glanced at Corinto and once more was involuntarily reminded of Herne Bay. And as he gazed upon the Central American town he came to the conclusion that it was about as formidable and about as well defended as the Kentish watering-place. And having arrived at this opinion he determined in his own mind that the taking of Corinto, as a feat of arms, was scarcely on a par with the Victory of Trafalgar.

(On his Seventieth Birthday.)

To Manns of Crystal Palace fame,

Punch sends his kindly greeting.

The ever keen, the never tame,

Time may he long be beating

(For Time it seems cannot beat him).

Time's darts may he resist all

With bâton brisk and eyes un-dim.

Beneath that dome of Crystal—

For many a year! And decades hence

Punch hopes it may befa' that

He'll shout, before that choir immense,

"A Manns' a Man for a' that!"

A Classic Candidate.—Mr. Homer in West Dorset is the Independent Farmers' Candidate. He is, of course, more than a positive "Home Ruler," being a comparative hopeful "Homer Ruler." But surely the language of Homer must be Greek to most of his hearers, even at Bridport, and in view of the poluphoisboio thalasses.

(On the Humdrum Budget.)

Just "As you were"! Ingenious, fair,

And all that, I've no doubt;

But titled swells you do not scare,

Nor rich monopolists flout.

I tolerate where I would praise.

Reform is a slow grower!

My spirits, Will, it will not raise,

To see your spirits lower!

Free Breakfast Table? Graduation?—

Chances seem getting fewer:

Well Will, my only consolation

Is this—you've "copped the brewer!"

In the title of his new book, "Anthony Hope" has taken the Roman prénom which evidently by right belonged to him. There is no comma, nor introduction of "by," and so straight off we read in golden letters on the back, "A Man of Mark Anthony Hope." O Brave Mark Anthony! His readers have great faith in Hope.

Parliamentary.—The nearest approach to a dead-lock is a live (J. G.) Weir.

Is Mr. Hitchcock's "Flight into Egypt" a view of Dartmoor? and what are all those blue flowers? Borage, blue currants, corn-flowers, "new broom," gorse dyed blue for this occasion only, or what? I have been offered all these random suggestions by distinguished critics, but they somehow don't seem convincing.

Why are the competitors in the charming swimming-match between Mermaids and Tritons so remarkably dry in the upper parts? I always get decidedly damp when I enter the sea, but these ladies take to it like ducks—"Dux fœmina facti" (as said an ancient poet in anticipation)—and so I suppose the water rolls off their backs.

Will "Her First Offering" of grass and daisies go far towards softening the heart of a statuette? Her sister, last year, had a much more tempting "Gift for the Gods," but there is no accounting for divinities' tastes.

What does Mr. Kpoffnh—dear me, I can not get his name right?—mean by "Sous les Arbres?" Is it a man or a statue, a spook or a symbol? Why does he wear a marble wig? Why does his brown hair show underneath it? Why has he got a wall eye? Why is he "under the trees?" Why is he at large at all? Why—— But there, I give it up! I don't believe there are any answers to these conundrums!

How is it I've been looking at "Kit" for two whole minutes before realising that there's a Persian cat in the composition? But she's a real beauty, when you do coax her out of this "puzzle picture."

Why (this is no new query!) have Sir Edward Burne-Jones' Luciferians and Sleeping Beauties and peeresses and children and brides one and all the same world-weary expression? Why do they, without exception, look as if they were off to a funeral, or had just seen themselves in the glass? Are there no other colours in the land but dull green, steel-blue, ink-purple, and brick-red? Why do I immediately want to commit suicide after studying these masterpieces? Why doesn't Psyche cheer up a bit, even though she is going to be married? She wasn't a νέα γυνή, I'm sure!

Why does the dog in Mr. Holman Hunt's picture look as if it had softening of the brain? and why do I pass on hurriedly to the next picture?

Will Miss Rehan's left shoulder hold up her dress much longer, I wonder, in Mr. Sargent's portrait? I don't know, but I have fears!

Is the lady in Mrs. Swynnerton's "Sense of Sight" preparing to catch a cricket ball, or cutting an acquaintance, or going to recite something? I should like to know.

Why couldn't some enterprising dentist supply the ladies in "Echoes" with false teeth, and why weren't they taken away quietly home, and not allowed to exhibit their other anatomical innovations? Echo answers to these and all my queries, "Why, indeed?"

"By the way, Doctor, the 'New Woman,' don'tcherknow—what'll she be like, when she's grown old?"

"My dear Colonel, she'll never grow old!"

"Great Scott! You don't mean to say she's going to last for ever!"

"She won't even last out the Century! She's got every Malady under the Sun!"

The Rock Dove don't pooh-pooh,

A dove can make a coup;

The odds? You yet may nobble 'em.

'Tis four to one

'Gainst Son of a Gun,

But Euclid is a problem.

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, April 29.—When Mr. Toots, in agony of perturbed bashfulness, sat down on Florence Dombey's best bonnet, he murmured, "Oh, it's of no consequence." Squire of Malwood does not resemble Mr. Toots in any respect, not even that of bashfulness. But he has a way, when taking important move, of studiously investing it with appearance of "no consequence." Thus to-night, asking for lion's share of time for remaining portion of Session, he could hardly bring himself to uplift his voice: mumbled over phrases; coughed at conjunctions; half paralysed by prepositions; looked round with pained astonishment when Members behind cried, "Speak up!" Why should he trouble to speak up on so immaterial a matter? Still, to oblige, he would say all he wanted was to take for Government purposes, for rest of Session, all the time of House, save the inconvenient Wednesday afternoon sitting, and the inconsiderable Friday night.

More marked this cultured mannerism when announcing immediate introduction of Bill prohibiting plural voting. This a genuine surprise. Not been talked of since House met. Nobody thinking of it. Squire in almost whisper announced its introduction to-morrow. Astonished beyond measure at commotion created; the boisterous cheers of Liberals, the uneasy laughter of Opposition.

"Most remarkable place this House of Commons," he said afterwards, gazing over my head into the infinite horizon, where shadowy figure of Local Veto Bill is visible to the eye of faith. "Always full of surprises even for old practitioners like you and me."

Prince Arthur, much relishing this subtle humour, was himself in sprightliest mood. The whole business of Session, he protested, was an elaborate joke. If they were there to work, he would take off his coat and ding on with the best of them. But they were there to play. "Well, let us play," he said, holding out both hands with gesture of invitation to Treasury Bench.

Proposal irresistible. House divided forthwith; Squire's motion carried by majority of 22; then, whilst half a dozen naval men talked water-tube boiler, Prince Arthur, Squire of Malwood, and picked company from either side went out behind Speaker's Chair to play. Such larks! To see Prince Arthur take in a stride "the backs" given him by the Squire of Malwood, with Cawmel-Bannerman next; to see John Morley seriously whipping a top; to watch Bryce breathless behind the nimble hoop; to look on while Edward Grey, forgetful of China and Japan, thinking nothing of Nicaragua, played a game of marbles with Hart Dyke; to see Lockwood trying a spurt with Dick Webster, the course being twice round the Division Lobby, Asquith, fresh from the Cab-arbitration, having handicapped them—to see this, and much else, was a spectacle wholesome for those engaged in it, interesting for the solitary spectator.

Business done.—Shipbuilding Vote in Navy Estimates agreed to.

Tuesday.—Odd thing that on this particular night, when Government bring in Bill prohibiting plurality of voting, Bill should bring in a Bill. His first and only Bill. Of course he might argue if we have one man one vote, one Bill one Bill is all right. Yes; but, as Sark with his keen mathematical instinct points out, this is a case of two Bills—Bill, the Member for Leek, and a Bill to empower magistrates to prohibit the sale of intoxicating liquors to persons previously convicted of drunkenness. That is obviously a plurality of Bills. But we are getting hopelessly mixed. The only man among us who sees clear is John William. Deep pathos in his voice as he says the time is near at hand when a tyrannical Government will attempt to enforce principle of "One Man One Drink."

Cap'en Tommy Bowles had best of dreary evening. Mentioned yesterday, with tears from his honest blue eyes coursing down his [pg 228] rugged, weather-beaten cheek, fresh infamy on part of Squire of Malwood. Had announced on Thursday that, at Monday's sitting, Naval Works Loan Bill would be proceeded with. Tommy accordingly clewed up, and ran for port; laying to for forty-eight hours, prepared speech on Naval Works. Now Squire calmly announced that Shipbuilding Vote was to be taken. What was Tommy to do with speech prepared on Naval Works Loans?

In despair yesterday; to-day bright idea struck him. Shaw-Lefevre had moved to introduce One Man One Vote Bill. Why shouldn't Tommy, flying that flag, run in and deliver his speech on Naval Works? A bold experiment; only hope of success was that House, being in almost comatose state, wouldn't notice ruse if cleverly managed. Trust Tommy for clever management. Holding sheaf of notes firmly in left hand, deftly turning them over with the hook that serves him for right hand, the old salt read his speech on Naval Works Loan Bill. Here and there, when he observed restless movement in any part of House, fired off phrase about "forty-shilling freeholder," "occupation votes," "rural constituencies," "re-distribution," "country going to the dogs," "jerrymandering," and "right hon. gentleman opposite." Scheme worked admirably; speech reeled off, and Squire of Malwood's knavish trick confounded.

Business done.—One Man One Vote Bill brought in.

Thursday.—House not to be moved to evidence of excitement even by prospect of Budget night. On such occasion in ordinary times attendance at prayer-time most encouraging to Chaplain. Begins to think that at last his ministrations are bearing fruit. This afternoon congregation not much above average. No rush for tickets for seats. When Squire rose to open his statement, great gaps below Gangway on Ministerial side. The Squire, recognising situation, refrained from heroics, content to deliver plain business speech. No exordium; no peroration; no flight into empyrean heights of eloquence as was the wont of Mr. G. Some sympathetic movement when Squire, with momentarily increased briskness of manner, spoke of snap of cold weather in February, with its accompaniment of influenza, increased death-rate, and fuller flow of death duties into National coffers. The quality of this mercy was not quite unstrained. Not dropping, like the gentle dew from heaven, till February, increased death rates will not come into account till succeeding year. Still, there was rum. As thermometer fell rum went up with a rush.

Fifteen men on a dead man's chest.

High ho! and a bottle of rum.

What with comforting the mourners, and imbibed as a preventive, rum brought a windfall of £100,000 into the Treasury.

That was well in its way. But then there were those 75,000 mean-spirited people who ought to have died last year, their estates paying tribute to Chancellor of Exchequer, and who positively insisted upon living. The long-trained fortitude of the Squire nearly broke down when he mentioned this circumstance. Pretty to see how it also touched Jokim. The wounds of riven friendship temporarily closed up; the rivalry of recent years forgotten in contemplation of these 75,000 reckless, ruthless people, who, in defiance of law of average, didn't die in financial year ending March 31, 1895. The past Chancellor of Exchequer and his successor in office mingled their tears. But for intervention of table they would probably have flung themselves into each other's arms and sobbed aloud.

"Thus," said Prince Arthur, himself not unaffected by the scene, "doth one touch of nature make Chancellors of the Exchequer kin."

Business done.—Budget brought in.

Friday Night.—Alpheus Cleophas submitted proposal to dock payment of £10,000 annuity to Duke of Coburg. Thinks H.R.H. might, in circumstances, get along nicely without it. Sage Of Queen Anne's Gate agrees. T. H. Boltonparty, on the other hand, gravely differs. Folding his arms as was his wont on eve of Austerlitz, he regards Alpheus Cleophas with awful frown. Imperial instincts naturally wounded. "No trifling with the personal revenues of our Royal cousins, whether at home or abroad," said T. H. Boltonparty in the voice of thunder that once reverberated across the shivering chasms of the Alps.

Business done.—Proposal to cut off Duke of Coburg's pension negatived by 193 votes against 72.

From the Representative of Her Britannic Majesty's Government to the —— Minister for Foreign Affairs.

January 1, 18-0.

I have the honour to inform your Excellency that I am instructed by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs that Her Britannic Majesty's Government has reason to complain of the conduct of the Government of which your Excellency is the representative. I have the honour to say that it will be advisable for your Excellency to urge upon the Government of which your Excellency is the representative the necessity of inquiry into the matter as speedily as possible. I have further the honour to add that it will be gratifying to Her Britannic Majesty's Government if the Government of which your Excellency is a representative will give the matter to which I refer the earliest attention.

From the Representative, &c., to the —— Minister, &c.

January 1, 18-1.

I have the honour to call the attention of your Excellency to the long and unsatisfactory correspondence that has passed during the last year between your Excellency as representing the Government of which you are the representative and the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs upon the matter of the despatch I had the honour to forward to your Excellency dated January 1, 18-0. I am directed to have the honour of requesting your Excellency to urge upon the Government of which your Excellency is a representative the necessity of a speedy settlement of the matter in dispute.

From the Representative, &c., to the —— Minister, &c.

January 1, 18-2.

I have again the honour to call the attention of your Excellency to, &c. &c.

(Rather longer than the foregoing one. Then follow two more "from the same to the same" in 18-3 and 18-4. This is the first way.)

From British Admiral to —— Minister.

January 1, 18-5, 12 Noon.

If you don't pay up within a quarter of an hour, I will bombard your capital, seize your country, and imprison the Government of which you are the representative.

From —— Minister, &c., to British Admiral.

January 1, 18-5, 12.10 P.M.

Don't fire. Have sent money demanded by P.O.O.

'Tis to the "New National Party," 'tis clear,

That Chamberlain swears his affiance.

The Triple Alliance? Why, no, 'twould appear

The third, and predominant partner, is Beer,

So let's call it "The Tipple Alliance."

Our Booking-Office.—To all, and especially to all travellers, on account of its portable size, the Baron begs to recommend a charming novelette written by Guy Boothaby, entitled A Lost Endeavour, published by Dent of Aldine House. When Mr. Guy Boothaby brings out another story equal to this, the Baron will be delighted to draw public attention to it by saying, "Here's another Guy—Boothaby."

An awful Monster recently let out in a Church!—A second-hand sermon with eight heads.

Motto for the Lord Chief Justice.—"Quantum snuff."