Transcriber’s Note: The original publication has been replicated faithfully except as listed here.

In most web browsers the text conforms to changes in window size.

A volume of travel, exploration and adventure is never without instruction and fascination for old and young. There is that within us all which ever seeks for the mysteries which are bidden behind mountains, closeted in forests, concealed by earth or sea, in a word, which are enwrapped by Nature. And there is equally that within us which is touched most sensitively and stirred most deeply by the heroism which has characterized the pioneer of all ages of the world and in every field of adventure.

How like enchantment is the story of that revelation which the New America furnished the Old World! What a spirit of inquiry and exploit it opened! How unprecedented and startling, adventure of every kind became! What thrilling volumes tell of the hardships of daring navigators or of the perils of brave and dashing landsmen! Later on, who fails to read with the keenest emotion of those dangers, trials and escapes which enveloped the intrepid searchers after the icy secrets of the Poles, or confronted those who would unfold the tale of the older civilizations and of the ocean’s island spaces.

Though the directions of pioneering enterprise change, yet more and more man searches for the new. To follow him, is to write of the wonderful. Again, to follow him is to read of the surprising and the thrilling. No prior history of discovery has ever exceeded in vigorous entertainment and startling interest that which centers in “The Dark Continent” and has for its most distinguished hero, Henry M. Stanley. His coming and going in the untrodden and hostile wilds of Africa, now to rescue the stranded pioneers of other nationalities, now to explore the unknown waters of a mighty and unique system, now to teach cannibal tribes respect for decency and law, and now to map for the first time with any degree of accuracy, the limits of new dynasties, make up a volume of surpassing moment and peculiar fascination.

All the world now turns to Africa as the scene of those adventures which possess such a weird and startling interest for readers of every class, and which invite to heroic exertion on the part of pioneers. It is the one dark, mysterious spot, strangely made up of massive mountains, lofty and extended plateaus, salt and sandy deserts, immense fertile stretches, climates of death and balm, spacious lakes, gigantic rivers, dense forests, numerous, grotesque and savage peoples, and an animal life of fierce mien, enormous strength and endless variety. It is the country of the marvelous, yet none of its marvels exceed its realities.

And each exploration, each pioneering exploit, each history of adventure into its mysterious depths, but intensifies the world’s view of it and enhances human interest in it, for it is there the civilized nations are soon to set metes and bounds to their grandest acquisitions—perhaps in peace, perhaps in war. It is there that white colonization shall try its boldest problems. It is there that Christianity shall engage in one of its hardest contests.

Victor Hugo says, that “Africa will be the continent of the twentieth century.” Already the nations are struggling to possess it. Stanley’s explorations proved the majesty and efficacy of equipment and force amid these dusky peoples and through the awful mazes of the unknown. Empires watched with eager eye the progress of his last daring journey. Science and civilization stood ready to welcome its results. He comes to light again, having escaped ambush, flood, the wild beast and disease, and his revelations set the world aglow. He is greeted by kings, hailed by savants, and looked to by the colonizing nations as the future pioneer of political power and commercial enterprise in their behalf, as he has been the most redoubtable leader of adventure in the past.

This miraculous journey of the dashing and intrepid explorer, completed against obstacles which all believed to be insurmountable, safely ended after opinion had given him up as dead, together with its bearings on the fortunes of those nations who are casting anew the chart of Africa, and upon the native peoples who are to be revolutionized or exterminated by the last grand surges of progress, all these render a volume dedicated to travel and discovery, especially in the realm of “The Dark Continent,” surprisingly agreeable and useful at this time.

5

Stanley is safe; the world’s rejoicings; a new volume in African annals; who is “this wizard of travel?” story of Stanley’s life; a poor Welsh boy; a work-house pupil; teaching school; a sailor boy; in a New Orleans counting-house; an adopted child; bereft and penniless; a soldier of the South; captured and a prisoner; in the Federal Navy; the brilliant correspondent; love of travel and adventure; dauntless amid danger; in Asia-Minor and Abyssinia; at the court of Spain; in search of Livingstone; at Ujiji on Tanganyika; the lost found; across the “dark continent;” down the dashing Congo; boldest of all marches; acclaim of the world.

A Congo’s empire; Stanley’s grand conception; European ambitions; the International Association; Stanley off for Zanzibar; enlists his carriers; at the mouth of the Congo; preparing to ascend the river; his force and equipments; the river and river towns; hippopotamus hunting; the big chiefs of Vivi; the “rock-breaker;” founding stations; making treaties; tribal characteristics; Congo scenes; elephants, buffaloes and water-buck; building houses and planting gardens; making roads; rounding the portages; river crocodiles and the steamers; foraging in the wilderness; products of the country; the king and the gong; no more war fetish; above the cataracts; Stanley6 Pool and Leopoldville; comparison of Congo with other rivers; exploration of the Kwa; Stanley sick; his return to Europe; further plans for his “Free State;” again on the Congo; Bolobo and its chiefs; medicine for wealth; a free river, but no land; scenery on the upper Congo; the Watwa dwarfs; the lion and his prey; war at Bolobo; the Equator station; a long voyage ahead; a modern Hercules; tropical scenes; a trick with a tiger skin; hostile natives; a canoe brigade; the Aruwimi; ravages of slave traders; captive women and children; to Stanley Falls; the cataracts; appointing a chief; the people and products; wreck of a steamer; a horrible massacre; down the Congo to Stanley Pool; again at Bolobo; a burnt station; news from missionaries; at Leopoldville; down to Vivi; the treaties with chiefs; treaty districts; the Camaroon country; oil river region; Stanley’s return to London; opinions of African life; thirst for rum; adventures and accidents; advice to adventurers; outlines of the Congo Free State; its wealth and productions; commercial value; the Berlin conference; national jurisdiction; constitution of the Congo Free States; results.

Stanley’s call; the Belgian king; the Emin Pasha relief committee; Stanley in charge of the expedition; off for Central Africa; rounding the cataracts; the rendezvous at Stanley Pool; who is Emin? his life and character; a favorite of Gordon; fall of Khartoum; Emin cut off in equatorial Soudan; rising of the Mahdi; death of Gordon; Emin lost in his equatorial province; his capitals and country; Stanley pushes to the Aruwimi; Tippoo Tib and his promises; Barttelot and the camps; trip up the Aruwimi; wanderings in the forest; battles with the dwarfs; sickness, starvation and death; lost in the wilds; the plains at last; grass and banana plantations; arrival at Albert Nyanza; no word of Emin; back to the Aruwimi for boats; another journey to the lake; Emin found; tantalizing consultations; Stanley leaves for his forest stations; treachery of Tippoo Tib; massacre of Barttelot; the Mahdi influence; again for the Lake to save Emin; willing to leave Africa; the start for Zanzibar; hardships of the trip; safe arrival at Zanzibar; accident to Emin; the world’s applause; Stanley a hero.

7

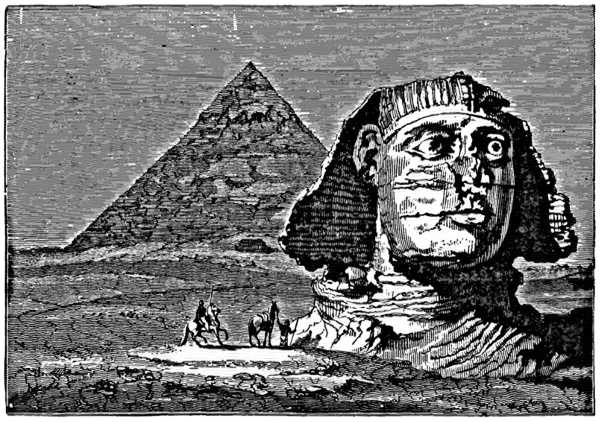

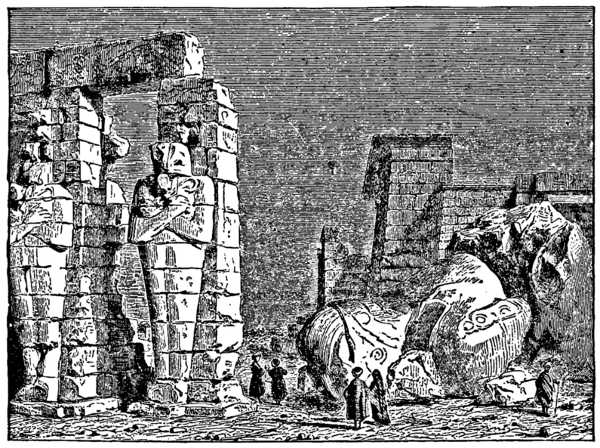

Shaking hands at Ujiji; Africa a wonderland; Mizriam and Ham; Egypt a gateway; mother of literature, art and religion; the Jews and Egypt; mouths of the Nile; the Rosetta stone; Suez Canal; Alexandria; Pharos, a “wonder of the world;” Cleopatra’s needles; Pompey’s Pillar; the catacombs; up the Nile to Cairo; description of Cairo; Memphis; the Pyramids and Sphinx; convent of the pulley; Abydos its magnificent ruins; City of “the Hundred Gates;” temple of Luxor; statues of Memnon; the palace temple of Thebes; the old Theban Kings; how they built; ruins of Karnak; most imposing in the world; temples of Central Thebes; wonderful temple of Edfou; the Island of Philæ; the elephantine ruins; grand ruins of Ipsambul; Nubian ruins; rock tomb at Beni-Hassan; the weird “caves of the crocodiles;” horrid death of a traveler; Colonel and Lady Baker; from Kartoum to Gondokoro; hardships of a Nile expedition; the “forty thieves;” Sudd on the White Nile; adventures with hippopotami; mobbing a crocodile; rescuing slaves; at Gondokoro; horrors of the situation; battles with the natives; night attack; hunting elephants; instincts of the animal; natural scenery; different native tribes; cruelty of slave-hunters; ambuscades; annexing the country; hunting adventures; the Madhi’s rebellion; death of Gordon.

African mysteries; early adventures; the wonderful lake regions; excitement over discovery; disputed points; the wish of emperors; journey through the desert; Baker and Mrs. Baker; M’dslle Tinne; Nile waters and vegetation; dangers of exploration; from Gondokoro to Albert Nyanza, native chiefs and races; traits and adventure; discovery of Albert Nyanza; King Kamrasi; his royal pranks; adventures on the lake; a true Nile source; Murchison Falls; revelations by Speke and Grant; Victoria Nyanza; another Nile source; Stanley on the scene; his manner of travel; trip to Victoria Nyanza; voyage of the “Lady Alice;” adventures on the lake; King Mtesa and his empire; wonders of the great lake; surprises for Stanley; in battle for King Mtesa; results of his discoveries; native traditions; demons and dwarfs; off for Tanganyika.

8

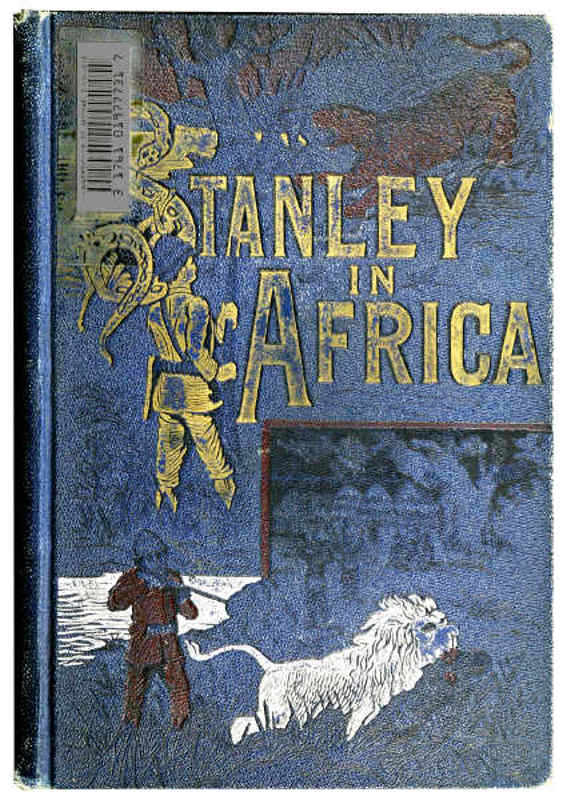

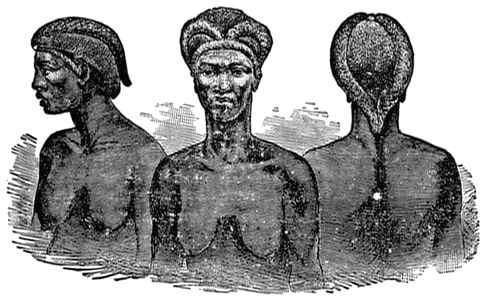

Livingstone on the scene; how he got into Africa; his early adventures and trials; wounded by a lion; his marriage; off for Lake Ngam; among the Makololo; down the Chobe to the Zambesi; up the Zambesi; across the Continent to Loanda; discovery of Lake Dilolo; importance of the discovery; description of the lake; its wonderful animals; methods of African travel; rain-makers and witchcraft; the magic lantern scene; animals of the Zambesi; country, people and productions; adventures among the rapids; the Gouye Falls; the burning desert and Cuando river; an elephant hunt; the wonderful Victoria Falls; sounding smoke; the Charka wars; lower Zambesi valley; wonderful animal and vegetable growth; mighty affluents; escape from a buffalo; slave hunters; Shire river and Lake Nyassa; peculiar native head-dresses; native games, manners and customs; Pinto at Victoria Falls; central salt pans.

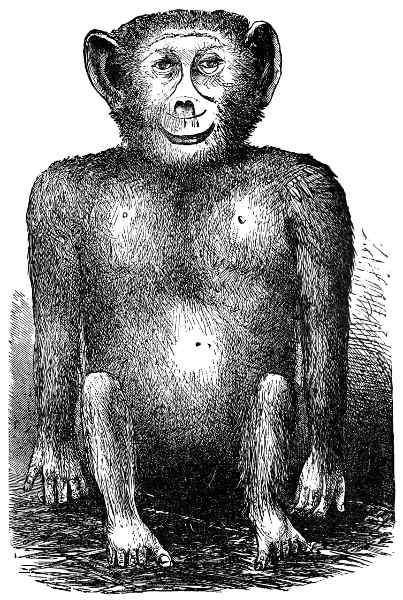

Discovery of the wonderful Lake Tanganyika; Burton and Speke’s visit; Livingstone’s trials; his geographical delusions; gorilla and chimpanzee; Livingstone at Bangweola; on the Lualaba; hunting the soko; thrilling adventure with a leopard; the Nyangwe people; struggle back to Ujiji; meeting with Stanley; joy in the wilderness; exploration of Tanganyika; the parting; Livingstone’s last journey; amid rain and swamps; close of his career; death of the explorer; care of his body; faithful natives; Stanley’s second visit; what he had done; strikes the Lualaba; descends in the “Lady Alice;” fights with the natives; ambuscades and strategies; boating amid rapids; thrilling adventures amid falls and cataracts; wonderful streams; the Lualaba is the Congo; joy over the discovery; gauntlet of arrows and spears; loss of men and boats: death of Frank Pocock; the falls become too formidable; overland to the Atlantic; at the mouth of the mighty Congo; return trip to Zanzibar; the Congo empire; Stanley’s future plans.

Discovery of the Cape; early settlers; table mountain; Hottentot and Boer; the diamond regions; the Zulu warriors; the Pacific republics; natal and the transvaal; manners, customs, animals and sports; climate and resources.

9

A disputed possession; the beautiful Shiré; rapids and cataracts; mountain fringed valleys; rank tropical vegetation; magnificent upland scenery; thrifty and ingenious natives; cotton and sorghum; the Go-Nakeds; beer and smoke; geese, ducks and waterfowls; Lake Shirwa; the Blantyre mission; the Manganja highlands; a village scene; native honesty; discovery of Lake Nyassa; description of the Lake; lofty mountain ranges; Livingstone’s impressions; Mazitu and Zulu; native arms, dresses and customs; slave-hunting Arabs; slave caravans; population about Nyassa; storms on the lake; the first steamer; clouds of “Kungo” flies; elephant herds; charge of an elephant bull; exciting sport; African and Asiatic elephants; the Scottish mission stations; great wealth of Nyassaland; value to commerce; the English and Portuguese claims.

African coasts and mysteries; Negroland of the school-books; how to study Africa; a vast peninsula; the coast rind; central plateaus and mountain ranges; Stanley’s last discoveries; a field for naturalists; bird and insect life; wild and weird nature; vast area; incomputable population; types of African races; distribution of races; African languages; character of the human element; Africa and revelation; tribes of dwarfs; “Africa in a Nutshell”; various political divisions; variety of products; steamships and commerce; as an agricultural field; the lake systems; immense water-ways; internal improvements; Stanley’s observations; features of Equatorial Africa; extent of the Congo basin; the Zambesi and Nile systems; the geographical sections of the Congo system; the coast section; cataracts, mountains and plains; affluents of the great Congo; tribes of lower Congo; length of steam navigation; future pasture grounds of the world; the Niam-Niam and Dinka countries; empire of Tippoo Tib; richness of vegetable productions; varieties of animal life; immense forests and gigantic wild beasts; oils, gums and dyes; hides, furs, wax and ivory; iron, copper, and other minerals; the cereals, cotton, spices and garden vegetables; the labor and human resources; humanitarian and commercial problems; the Lualaba section; size, population and characteristics; navigable waters; Livingstone’s observations; tracing his footsteps; animal and vegetable life; stirring scenes and incidents; the Manyuema country; Lakes Moero and Bangweola; resources of forest and stream; climate and soil; a remarkable land;10 customs of natives; village architecture; river systems and watersheds; Stanley and Livingstone in the centre of the Continent; the Chambesi section; head-rivers of the Congo; the Tanganyika system; owners of the Congo basin; Stanley’s resume of African resources; a glowing picture.

Egyptian and Roman Colonists; Moorish invasion; Portugese advent; the commercial and missionary approach; triumphs of late explorers; can the white man live in Africa?; colonizing and civilizing; Stanley’s personal experience; he has opened a momentous problem; Stanley’s melancholy chapters; effect of wine and beer; the white man must not drink in Africa; must change and re-adapt his habits; visions of the colonists; effect of climate; kind of dress to wear; the best house to build; how to work and eat; when to travel; absurdities of strangers; following native examples; true rules of conduct; Stanley’s laws of health; African cold worse than African heat; guarding against fatigue; Dr. Martins code of health; the white man can live in Africa; future of the white races in the tropics; the struggle of foreign powers; missionary struggles; political and commercial outlook.

Africa for the Christian; Mohammedan influences; Catholic missions; traveler and missionary; the great revival following Stanley’s discoveries; Livingstone’s work; perils of missionary life; history of missionary effort; the Moors of the North; Abyssinian Christians; west-coast missions; various missionary societies; character of their work; Bishop Taylor’s wonderful work in Liberia, on the Congo, in Angola; nature of his plans; self-supporting churches; outline of his work; mission houses and farms; vivid descriptions and interesting letters; cheering reports from pioneers; South African missions; opening Bechuana-land; the Moffats and Coillards; Livingstone and McKenzie; the Nyassa missions; on Tanganyika; the Church in Uganda; murder of Harrington; the gospel on the east coast; Arabs as enemies; religious ideas of Africans; rites and superstitions; fetish and devil worship; importance of the mission field; sowing the seed; gathering the harvest.

11

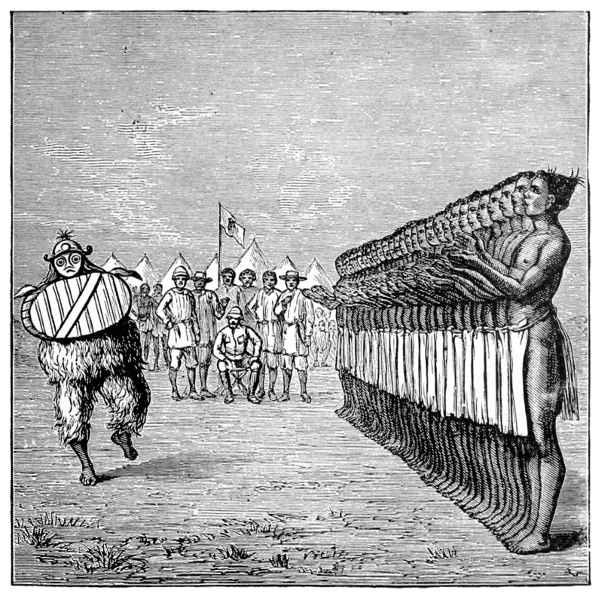

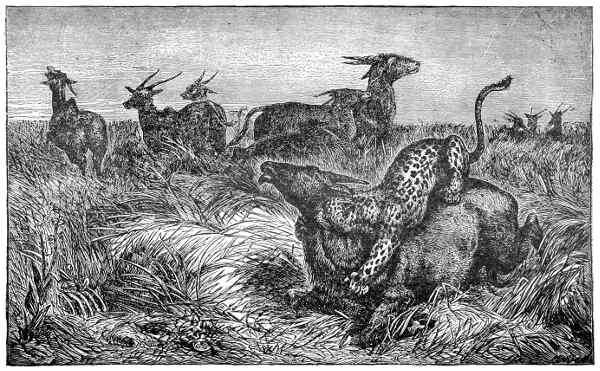

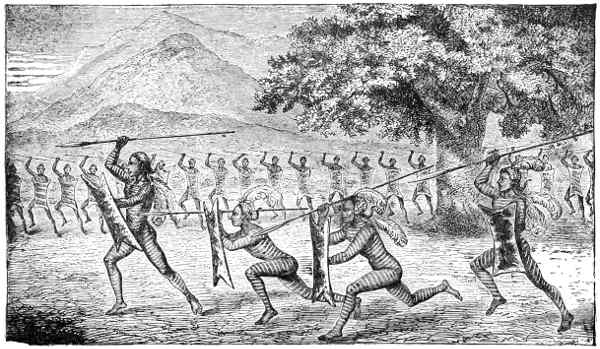

Arnot’s idea of Central Africa; killed by an elephant; the puff adder; the Kasai region; bulls for horses; a Congo hero; affection for mothers; caught by a crocodile; decline of the slave trade; the natives learning; books in native tongues; natives as laborers; understanding of the climate; Stanley on the Gombe; the leopard and spring-bock; habits of the antelope; Christian heroes in Africa; the boiling pot ordeal; adventures of a slave; Arab cruelties; a lion hunt; Mohammedan influence; a victim of superstition; Hervic women; Tataka mission in Liberia; a native war dance; African game laws; Viva on the Congo; rum in Africa; palavering; Emin Pasha at Zanzibar; the Sas-town tribes; an interrupted journey; in Monrovia; a sample sermon; the scramble for Africa; lions pulling down a giraffe; Kilimanjars, highest mountains in Africa; the Kru-coast Missions; a desperate situation; Henry M. Stanley and Emin Pasha; comparison of the two pioneers. pp. 800.

| PAGE. | |

| COLUMBIA PRESENTING STANLEY TO EUROPEAN SOVEREIGNS, Colored Plate |

Frontis- piece |

| MARCHING THROUGH EQUATORIAL AFRICA | 4 |

| MAP OF CENTRAL AFRICA | 16 and 17 |

| HENRY M. STANLEY | 18 |

| THE BELLOWING HIPPOPOTAMI | 23 |

| SCENE ON LAKE TANGANYIKA | 29 |

| GATHERING TO MARKET AT NYANGWE | 31 |

| A SLAVE-STEALER’S REVENGE | 34 |

| BUFFALO AT BAY | 38 |

| FIGHT WITH AN ENRAGED HIPPOPOTAMUS | 40 |

| ROUNDING A PORTAGE | 44 |

| A NARROW ESCAPE | 45 |

| WHITE-COLLARED FISH-EAGLES | 48 |

| A TEMPORARY CROSSING | 49 |

| WEAVER-BIRDS’ NESTS | 51 |

| NATIVES’ CURIOSITY AT SIGHT OF A WHITE MAN | 56 |

| CAPTURING A CROCODILE | 58 |

| LIONS DRAGGING DOWN A BUFFALO | 62 |

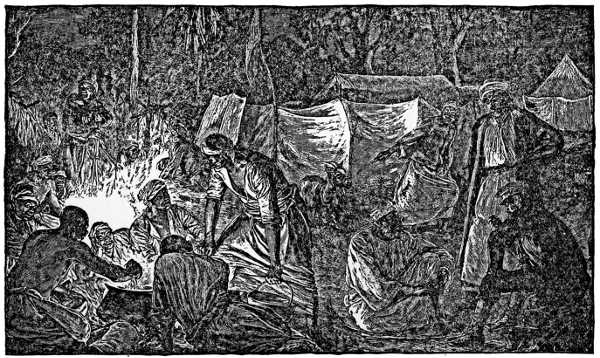

| A FUNERAL DANCE | 66 |

| STANLEY’S FIGHT WITH BENGALA IN 1877 | 67 |

| AFRICAN BLACK-SMITHS | 71 |

| AFRICAN HEADDRESSES | 72 |

| ORNAMENTED SMOKING PIPE | 75 |

| NIAM-NIAM HAMLET ON THE DIAMOONOO | 76 |

| NIAM-NIAM MINSTREL | 79 |

| NIAM-NIAM WARRIORS | 79 |

| RECEIVING THE BRIDE | 81 |

| A BONGO CONCERT | 82 |

| THE MASSACRE AT NYANGWE | 90 |

| KNIFE-SHEATH, BASKET, WOODEN-BOLSTER AND BEE-HIVE | 96 |

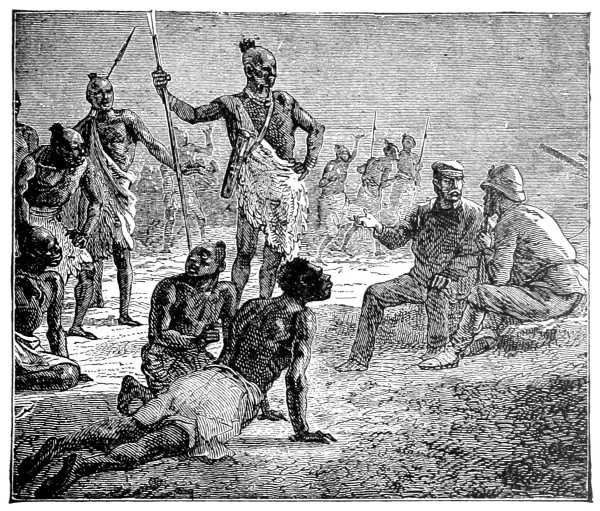

| RECEPTION BY AN AFRICAN KING | 99 |

| SACRIFICE OF SLAVES, Colored Plate | 100 |

| TIPPOO TIB’S GRAND CANOES GOING DOWN THE CONGO, FRONT | 136 |

| TIPPOO TIB’S GRAND CANOES GOING DOWN THE CONGO, REAR | 137 |

| HENRY M. STANLEY. From a Late Portrait | 138 |

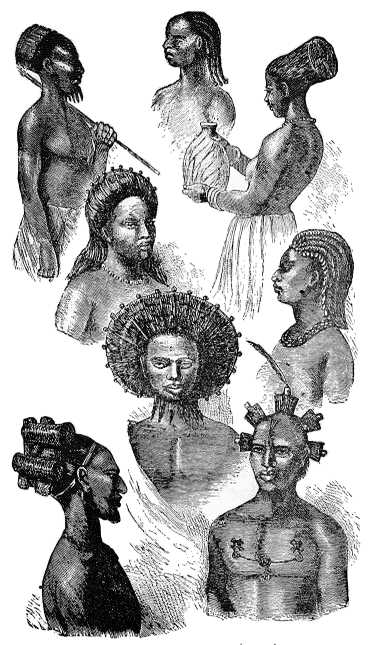

| EMIN PASHA IN HIS TENT | 142 |

| NIAM-NIAM VILLAGE | 146 |

| CUTTING WOOD AT NIGHT FOR THE STEAMERS | 149 |

| INTERVIEW OF MAJOR BARTTELOT AND MR. JAMESON WITH TIPPOO TIB | 149 |

| AN AMBUSCADE | 151 |

| ELEPHANTS DESTROYING VEGETATION | 157 |

| THE CAPTURED BUFFALO | 159 |

| AFRICAN WARRIORS | 159 |

| ATTACK ON THE ENCAMPMENT | 161 |

| BEGINNING A HUT | 164 |

| STANLEY’S FIRST SIGHT OF EMIN’S STEAMER | 165 |

| THE SECOND STAGE | 165 |

| HUT COMPLETED IN AN HOUR | 166 |

| CAMP AT KINSHASSA, ON THE CONGO, WITH TIPPOO TIB’S HEADQUARTERS |

170 |

| SLAVE MARKET | 180 |

| LIVINGSTONE AND STANLEY | 185 |

| THE ROSETTA STONE | 188 |

| DE LESSEPS | 190 |

| CLEOPATRA | 191 |

| PHAROS LIGHT | 192 |

| ALEXANDER, THE GREAT | 193 |

| CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE | 193 |

| THE SERAPEION | 195 |

| EGYPTIAN GOD | 196 |

| ROMAN CATACOMBS | 196 |

| MASSACRE OF MAMELUKES | 199 |

| VEILED BEAUTY | 200 |

| PYRAMIDS OF EGYPT | 203 |

| INTERIOR OF GREAT PYRAMID | 204 |

| THE SPHINX | 206 |

| STATUES OF MEMNON | 210 |

| RUINS IN THEBES | 211 |

| OBELISK OF KARNAK | 213 |

| SPHINX OF KARNAK | 214 |

| GATEWAY AT KARNAK | 215 |

| A MUMMY | 216 |

| TEMPLE AT EDFOU | 217 |

| ISIS ON PHILÆ | 218 |

| TEMPLE COURT, PHILÆ | 220 |

| TEMPLE AT IPSAMBUL | 221 |

| TEMPLE OF OSIRIS | 222 |

| TEMPLE OF ATHOR | 224 |

| ROCK TOMB OF BENI-HASSAN | 226 |

| EGYPTIAN BRICK FIELD | 227 |

| GROTTOES OF SAMOUN | 228 |

| A CHIEF’S WIFE | 231 |

| THE “FORTY THIEVES” | 232 |

| MOBBING A CROCODILE | 234 |

| RELEASING SLAVES | 236 |

| ATTACKED BY A HIPPOPOTAMUS | 237 |

| A SOUDAN WARRIOR | 239 |

| A NIGHT ATTACK | 241 |

| ELEPHANTS IN TROUBLE | 242 |

| SHAKING FRUIT | 244 |

| TABLE ROCK | 245 |

| NATIVE DANCE | 246 |

| ATTACK BY AMBUSCADE | 248 |

| HUNTING WITH FIRE | 251 |

| RESULTS OF FREEDOM | 251 |

| GORDON AS MANDARIN | 253 |

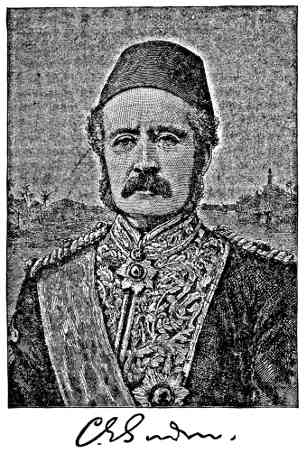

| PORTRAIT OF GORDON | 256 |

| PORTRAIT OF COLONEL BAKER | 266 |

| MAD’MLLE TINNE | 268 |

| LADY BAKER | 270 |

| SLAVE HUNTER’S VICTIM’S | 271 |

| WHITE NILE SWAMPS | 274 |

| CROSSING A SPONGE | 276 |

| PREPARING TO START | 279 |

| A ROYAL JOURNEY | 291 |

| MURCHISON FALLS | 298 |

| HENRY M. STANLEY | 303 |

| STANLEY ON THE MARCH | 304 |

| RUBAGA | 314 |

| SHOOTING A RHINOCEROS | 328 |

| LIVINGSTONE | 330 |

| LION ATTACKS LIVINGSTONE | 333 |

| CUTTING A ROAD | 334 |

| A BANYAN TREE | 338 |

| ANIMALS ON THE ZAMBESI | 343 |

| THE GONYE FALLS | 344 |

| HUNTING THE ELEPHANT | 345 |

| IN THE RAPIDS | 348 |

| VICTORIA FALLS | 351 |

| CHARGE OF A BUFFALO | 355 |

| NATIVE SLAVE HUNTERS | 356 |

| HUAMBO MAN AND WOMAN | 359 |

| SAMBO WOMAN | 359 |

| GANGUELA WOMEN | 359 |

| BIHE HEAD DRESS | 361 |

| QUIMBANDE GIRLS | 361 |

| CUBANGO HEAD-DRESS | 361 |

| LUCHAZE WOMAN | 362 |

| AMBUELLA WOMAN | 362 |

| SOVA DANCE | 363 |

| FORDING THE CUCHIBI | 363 |

| VICTORIA FALLS (BELOW) | 365 |

| ON TANGANYIKA | 368 |

| ANT HILL | 371 |

| GORILLAS | 371 |

| A SOKO HUNT | 374 |

| A DANGEROUS PRIZE | 375 |

| NYANGWE MARKET | 378 |

| STANLEY AT TANGANYIKA | 380 |

| STANLEY MEETS LIVINGSTONE | 381 |

| AFLOAT ON TANGANYIKA | 382 |

| DEEP-WATER FORDING | 386 |

| LAST DAY’S MARCH | 388 |

| DEATH OF LIVINGSTONE | 389 |

| THE KING’S MAGICIANS | 390 |

| A WEIR BRIDGE | 395 |

| FIGHTING HIS WAY | 398 |

| RESCUE OF ZAIDI | 403 |

| ATTACK BY THE BANGALA | 405 |

| IN THE CONGO RAPIDS | 408 |

| DEATH OF FRANK POCOCK | 411 |

| ZULUS | 418 |

| MY CATTLE WERE SAVED | 420 |

| BUFFALO HUNTERS | 421 |

| VILLAGE SCENE ON LAKE NYASSA | 426 |

| STORM ON LAKE NYASSA | 434 |

| AN ELEPHANT CHARGE | 436 |

| NATIVE HUNTERS KILLING SOKOS | 446 |

| AFRICAN ANT-EATER | 446 |

| TERRIBLE FIGHT OF AFRICAN MONARCHS, Colored Plate | 446 |

| QUICHOBO | 446 |

| THE “DEVIL OF THE ROAD,” ETC. | 450 |

| BUSH-BUCKS | 450 |

| NATIVE TYPES OF SOUTHERN SOUDAN | 451 |

| BARI OF GONDOKORO | 453 |

| CHASING GIRAFFES | 457 |

| NATIVE RAT-TRAP | 463 |

| AFRICAN HATCHET | 464 |

| NATIVES RUNNING TO WAR | 466 |

| UMBANGI BLACKSMITHS | 469 |

| NATIVES KILLING AN ELEPHANT | 472 |

| ON A JOURNEY IN THE KALAHARI DESERT | 480 |

| WOMEN CARRIERS | 481 |

| DRIVING GAME INTO THE HOPO | 483 |

| PIT AT END OF HOPO | 483 |

| CAPSIZED BY A HIPPOPOTAMUS | 487 |

| HUNTER’S PARADISE | 488 |

| BATLAPIN BOYS THROWING THE KIRI | 492 |

| PURSUIT OF THE WILD BOAR | 492 |

| RAIDING THE CATTLE SUPPLY | 494 |

| HUNTING ZEBRAS | 497 |

| DANGEROUS FORDING | 503 |

| A YOUNG SOKO | 506 |

| MANYUEMA WOMEN | 510 |

| TYPES OF AFRICAN ANTELOPES | 515 |

| BINKA CATTLE HERD | 518 |

| AFRICAN RHINOCEROS | 534 |

| ELEPHANT UPROOTING A TREE | 540 |

| COL. BAKER’S WAY OF REACHING BERBER | 553 |

| AFRICA METHODIST CONFERENCE | 564 |

| CHUMA AND SUSI | 568 |

| KING LOBOSSI | 568 |

| WEST AFRICAN MUSSULMAN | 579 |

| AN AFRICAN CHIEF | 587 |

| PORT AND TOWN OF ELMINA | 592 |

| COOMASSIE, THE CAPITAL OF ASHANTI | 594 |

| CANOE TRAVEL ON THE NIGER | 598 |

| MAP OF LIBERIA | 604 |

| METHODIST PARSONAGE OF AFRICA | 606 |

| AFRICAN VILLAGE AND PALAVER TREE | 611 |

| ST. PAUL DE LOANDA | 618 |

| FOREST SCENE IN ANGOLA | 621 |

| MUNDOMBES AND HUTS | 626 |

| NATIVE GRASS-HOUSE ON THE CONGO | 629 |

| SOME OF BISHOP TAYLOR’S MISSIONARIES | 635 |

| GARAWAY MISSION HOUSE | 643 |

| MAP OF ANGOLA | 647 |

| STEAM WAGONS FOR HAULING AT VIVI | 659 |

| REED DANCE BY MOONLIGHT | 676 |

| MISSION HOUSE AT VIVI | 692 |

| HUNTING THE GEMBOCK | 696 |

| BISHOP TAYLOR’S MISSIONS | 699 |

| A NATIVE WARRIOR | 706 |

| THE COILLARD CAMP | 709 |

| AT HOME AFTER THE HUNT | 711 |

| MOFFAT INSTITUTION—KURUMAN | 713 |

| MOFFAT’S COURAGE | 715 |

| NATIVES OF LARI AND MADI IN CAMP AT SHOO | 719 |

| TINDER-BOX, FLINT AND STEEL | 726 |

| A CARAVAN BOUND FOR THE INTERIOR | 728 |

| TRAVEL ON BULL-BACK AND NATIVE ESCORT | 739 |

| LEOPARD ATTACKING A SPRINGBOCK | 747 |

| A LION HUNT | 757 |

| NATIVE WAR DANCE | 764 |

| BUFFALO DEFENDING HER YOUNG | 770 |

| SEKHOMS AND HIS COUNSEL | 774 |

| AN INTERRUPTED JOURNEY | 779 |

| LIONS PULLIN DOWN A GIRAFFE | 786 |

| HUNTING LIONS | 794 |

| A DESPERATE SITUATION | 797 |

| DINING ON THE BANKS OF THE SHIRE | 800 |

The news rang through the world that Stanley was safe. For more than a year he had been given up as lost in African wilds by all but the most hopeful. Even hope had nothing to rest upon save the dreamy thought that he, whom hardship and danger had so often assailed in vain, would again come out victorious.

The mission of Henry M. Stanley to find, succor and rescue Emin Pasha, if he were yet alive, not only adds to the life of this persistent explorer and wonderful adventurer one of its most eventful and thrilling chapters, but throws more light on the Central African situation than any event in connection with the discovery and occupation of the coveted areas which lie beneath the equatorial sun. Its culmination, both in the escape of the hero himself and in the success of his perilous errand, to say nothing of its far-reaching effects upon the future of “The Dark Continent,” opens, as it were, a new volume in African annals, and presents a new point of departure for scientists, statesmen and philanthropists.

Space must be found further on for the details of that long, exciting and dangerous journey, which reversed all other tracks of African travel, yet redounded more than all to the glory of the explorer and the advancement of knowledge respecting hidden latitudes. But here we can get a fair view of a situation, which in all its lights and shadows, in its many startling outlines, in its awful suggestion of possibilities, is perhaps the most interesting and fateful now before the eyes of modern civilization.

It may be very properly asked, at the start, who is this wizard of travel, this dashing adventurer, this heroic explorer and rescuer, this20 pioneer of discovery, who goes about in dark, unfathomed places, defying flood and climate, jungle and forest, wild beast and merciless savage, and bearing a seemingly charmed life?

Who is this genius who has in a decade revolutionized all ancient methods of piercing the heart of the unknown, and of revealing the mysteries which nature has persistently hugged since “the morning stars first sang together in joy?”

The story of his life may be condensed into a brief space—brief yet eventful as that of a conqueror, moved ever to conquest by sight of new worlds. Henry M. Stanley was born in the hamlet of Denbigh, in Wales, in 1840. His parents, who bore the name of Rowland, were poor; so poor, indeed, that the boy, at the age of three years, was virtually on the town. At the age of thirteen, he was turned out of the poor-house to shift for himself. Fortunately, a part of the discipline had been such as to assure him the elements of an English education. The boy must have improved himself beyond the opportunities there at hand, for in two or three years afterwards, he appeared in North Wales as a school-teacher. Thence he drifted to Liverpool, where he shipped as a cabin-boy on a sailing-vessel, bound for New Orleans. Here he drifted about in search of employment till he happened upon a merchant and benefactor, by the name of Stanley. The boy proved so bright, promising and useful, that his employer adopted him as his son. Thus the struggling John Rowland became, by adoption, the Henry M. Stanley of our narrative.

Before he came of age, the new father died without a will, and his business and estate passed away from the foster child to those entitled at law. But for this misfortune, or rather great good fortune, he might have been lost to the world in the counting-room of a commercial city. He was at large on the world again, full of enterprise and the spirit of adventure.

The civil war was now on, and Stanley entered the Confederate army. He was captured by the Federal forces, and on being set at liberty threw his fortunes in with his captors by joining the Federal navy, the ship being the Ticonderoga, on which he was soon promoted to the position of Acting Ensign. After the war, he developed those powers which made him such an acquisition on21 influential newspapers. He was of genial disposition, bright intelligence, quick observation and surprising discrimination. His judgment of men and things was sound. He loved travel and adventure, was undaunted in the presence of obstacles, persistent in every task before him, and possessed shrewd insight into human character and projects. His pen was versatile and his style adapted to the popular taste. No man was ever better equipped by nature to go anywhere and make the most of every situation. In a single year he had made himself a reputation by his trip through Asia Minor and other Eastern countries. In 1866 he was sent by the New York Herald, as war correspondent, to Abyssinia. The next year he was sent to Spain by the same paper, to write up the threatened rebellion there. In 1869 he was sent by the Herald to Africa to find the lost Livingstone.

A full account of this perilous journey will be found elsewhere in this volume, in connection with the now historic efforts of that gallant band of African pioneers who immortalized themselves prior to the founding of the Congo Free State. Suffice it to say here, that it took him two years to find Livingstone at Ujiji, upon the great lake of Tanganyika, which lake he explored, in connection with Livingstone, and at the same time made important visits to most of the powerful tribes that surround it. He returned to civilization, but remained only a short while, for by 1874 he was again in the unknown wilds, and this time on that celebrated journey which brought him entirely across the Continent from East to West, revealed the wonderful water resources of tropical Africa and gave a place on the map to that remarkable drainage system which finds its outlet in the Congo river.

Says the Rev. Geo. L. Taylor of this march: “It was an undertaking which, for grandeur of conception, and for sagacity, vigor, and completeness of execution, must ever rank among the marches of the greatest generals and the triumphs of the greatest discoverers of history. No reader can mentally measure and classify this exploit who does not recall the prolonged struggles that have attended the exploration of all great first-class rivers—a far more difficult work, in many respects, than ocean sailing. We must remember the wonders and sufferings of Orellana’s voyages (though in a brigantine,22 built on the Rio Napo, and with armed soldiers) down that “Mediterranean of Brazil,” the Amazon, from the Andes to the Atlantic, in 1540. We must recall the voyage of Marquette and Joliet down the Mississippi in 1673; the toils of Park and Landers on the Niger, 1795-1830; and of Speke and Baker on the Nile, 1860-1864, if we would see how the deed of Stanley surpasses them all in boldness and generalship, as it promises also to surpass them in immediate results.

The object of the voyage was two-fold: first, to finish the work of Speke and Grant in exploring the great Nile lakes; and, secondly, to strike the great Lualaba where Livingstone left it, and follow it to whatever sea or ocean it might lead.”

And again:—“The story of the descent of the great river is an Iliad in itself. Through hunger and weariness; through fever, dysentery, poisoned arrows, and small-pox; through bellowing hippopotami, crocodiles, and monsters; past mighty tributaries, themselves great first-class rivers; down roaring rapids, whirlpools, and cataracts; through great canoe-fleets of saw-teethed, fighting, gnashing cannibals fiercer than tigers; through thirty-two battles on land and river, often against hundreds of great canoes, some of them ninety feet long and with a hundred spears on board; and, at last, through the last fearful journey by land and water down the tremendous cañon below Stanley Pool, still they went on, and on, relentlessly on, till finally they got within hailing and helping distance of Boma, on the vast estuary by the sea; and on August 9, 1877, the news thrilled the civilized world that Stanley was saved, and had connected Livingstone’s Lualaba with Tuckey’s Congo! After 7,000 miles’ wanderings in 1,000 days save one from Zanzibar, and four times crossing the Equator, he looked white men in the face once more, and was startled that they were so pale! Black had become the normal color of the human face. Thus the central stream of the second vastest river on the globe, next to the Amazon in magnitude, was at last explored, and a new and unsuspected realm was disclosed in the interior of a prehistoric continent, itself the oldest cradle of civilization. The delusions of ages were swept away at one masterful stroke, and a new world was discovered by a new Columbus in a canoe.”

24

It was on that memorable march that he came across the wily Arab, Tippoo Tib, at the flourishing market-town of Nyangwe, who was of so much service to Stanley on his descent of the Lualaba (Congo) from Nyangwe to Stanley Falls, 1,000 miles from Stanley Pool, but who has since figured in rather an unenviable light in connection with efforts to introduce rays of civilization into the fastnesses of the Upper Congo. This, as well as previous journeys of Stanley, established the fact that the old method of approaching the heart of the Continent by desert coursers, or of threading its hostile mazes without armed help, was neither expeditious nor prudent. It revolutionized exploration, by compelling respect from hostile man and guaranteeing immunity from attack by wild beast.

For nearly three years Stanley was lost to the civilized world in this trans-continental journey. Its details, too, are narrated elsewhere in this volume, with all its vicissitude of 7,000 miles of zigzag wandering and his final arrival on the Atlantic coast—the wonder of all explorers, the admired of the scientific world.

Such was the value of the information he brought to light in this eventful journey, such the wonderful resource of the country through which he passed after plunging into the depths westward of Lake Tanganyika, and such the desirability of this new and western approach to the heart of the continent, not only for commercial but political and humanitarian purposes, that the cupidity of the various colonizing nations, especially of Europe, was instantly awakened, and it was seen that unless proper steps were taken, there must soon be a struggle for the possession of a territory so vast and with such possibilities of empire. To obviate a calamity so dire as this, the happy scheme was hit upon to carve out of as much of the new discovered territory as would be likely to embrace the waters of the Congo and control its ocean outlet, a mighty State which was to be dedicated for ever to the civilized nations of the world.

In it there should be no clash of foreign interests, but perfect reciprocity of trade and free scope for individual or corporate enterprise without respect to nationality. The king of Belgium took a keen interest in the project, and through his influence other powers of Europe, and even the United States, became enlisted. A25 plan of the proposed State was drafted and it soon received international ratification. The new power was to be known as the Congo Free State, and it was to be, for the time being, under control of an Administrator General. To the work of founding this State, giving it metes and bounds, securing its recognition among the nations, removing obstacles to its approach, establishing trading posts and developing its commercial features, Stanley now addressed himself. We have been made familiar with his plans for securing railway communication between the mouth of the Congo and Stanley Pool, a distance of nearly 200 miles inland, so as to overcome the difficult, if not impossible, navigation of the swiftly rushing river. We have also heard of his successful efforts to introduce navigation, by means of steamboats, upon the more placid waters of the Upper Congo and upon its numerous affluents. Up until the year 1886, the most of his time was devoted to fixing the infant empire permanently on the map of tropical Africa and giving it identity among the political and industrial powers of earth.

In reading of Stanley and studying the characteristics of his work one naturally gravitates to the thought, that in all things respecting him, the older countries of Europe are indebted to the genius of the newer American institution. We cannot yet count upon the direct advantages of a civilized Africa upon America. In a political and commercial sense our activity cannot be equal to that of Europe on account of our remoteness, and because we are, as yet, but little more than colonists ourselves. Africa underlies Europe, is contiguous to it, is by nature situated so as to become an essential part of that mighty earth-tract which the sun of civilization is, sooner or later, to illuminate. Besides Europe has a need for African acquisition and settlement which America has not. Her areas are small, her population has long since reached the point of overflow, her money is abundant and anxious for inviting foreign outlets, her manufacturing centres must have new cotton and jute fields, not to mention supplies of raw material of a thousand kinds, her crowded establishments must have the cereal foods, add to all these the love of empire which like a second nature with monarchical rulers, and the desire for large landed estates which is a characteristic of titled nobility, and26 you have a few of the inducements to African conquest and colonization which throw Europe in the foreground. Yet while all these are true, it is doubtful if, with all her advantages of wealth, location and resource, she has done as much for the evangelization of Africa as has America. No, nor as much for the systematic and scientific opening of its material secrets. And this brings us to the initial idea of this paragraph again. Though Stanley was a foreign waif, cast by adverse circumstances on our shores, it seemed to require the robust freedom and stimulating opportunities of republican institutions to awaken and develop in him the qualities of the strong practical and venturesome man he became. Monarchy may not fetter thought, but it does restrain actions. It grooves and ruts human energy by laws of custom and by arbitrary rules of caste. It would have repressed a man like Stanley, or limited him to its methods. He would have been a subject of some dynasty or a victim of some conventionalism. Or if he had grown too large for repressive boundaries and had chosen to burst them, he would have become a revolutionist worthy of exile, if his head had not already come to the block. But under republican institutions his energies and ambitions had free play. Every faculty, every peculiarity of the man grew and developed, till he became a strong, original and unique force in the line of adventure and discovery. This out-crop of manhood and character, is the tribute of our free institutions to European monarchy. The tribute is not given grudgingly. Take it and welcome. Use it for your own glory and aggrandizement. Let crowned-heads bow before it, and titled aristocracy worship it, as they appropriate its worth and wealth. But let it not be forgotten, that the American pioneering spirit has opened Africa wider in ten years than all the efforts of all other nations in twenty.

In 1877, Stanley wrote to the London Daily Telegraph as follows:—

“I feel convinced that the question of this mighty water-way (the Congo) will become a political one in time. As yet, however, no European power seems to have put forth the right of control. Portugal claims it because she discovered its mouth; but the great powers, England, America, and France, refuse to recognize her right. If it were not that I fear to damp any interest you may have in Africa, or in this magnificent stream, by the length of my letter, I could show you very strong reasons why it would be a politic deed to settle this momentous question immediately. I could prove to you that the power possessing the Congo, despite the cataracts, would absorb to itself the trade of the whole enormous basin behind. This river is and will be the grand highway of commerce to West Central Africa.”

When Stanley wrote this, with visions of a majestic Congo Empire flitting through his brain, he was more than prophetic; at least, he knew more of the impulse that was then throbbing and permeating Europe than any other man. He had met Gambetta, the great French statesman, who in so many words had told him that he had opened up a new continent to the world’s view and had given an impulse to scientific and philanthropic enterprise which could not but have material effect on the progress of mankind. He knew what the work of the International Association, which had his plans for a Free State under consideration, had been, up to that hour, and were likely to be in the future. He was aware of the fact that the English Baptist missionaries had already pushed their way up the Congo to a point beyond the Equator, and that the American Baptists were working side by side with their English brethren. He29 knew that the London and Church Missionary Societies had planted their flags on Lakes Victoria and Tanganyika, and that the work of the Free Kirk of Scotland was reaching out from Lake Nyassa to Tanganyika. He had seen Pinto and Weissman crossing Africa and making grand discoveries in the Portuguese possessions south of the Congo. De Brazza had given France a West African Empire; Germany had annexed all the vacant territory in South-west Africa, to say nothing of her East African enterprises; Italy had taken up the Red Sea coast; Great Britain had possessed the Niger delta; Portugal already owned 700,000 square miles south of the Congo, to which no boundaries had been affixed.

SCENE ON LAKE TANGANYIKA.

SCENE ON LAKE TANGANYIKA.

Stanley knew even more than this. His heroic nature took no stock in the “horrible climate” of Africa, which he had tested for so many years. He was fully persuaded that the plateaus of the Upper Congo and the central continent were healthier than the lands of Arkansas, which has doubled its population in twenty-five years. He treated the coast as but a thin line, the mere shell of an egg, yet he saw it dotted with settlements along every available water-way—the Kwanza, Congo, Kwilu, Ogowai, Muni, Camaroon, Oil, Niger, Roquelle, Gambia and Senegal rivers. He asked himself, What is left? And the answer came—Nothing, except the basins of the four mighty streams—the Congo, the Nile, the Niger and the Shari (Shire), all of which require railways to link them with the sea. His projected railway from Vivi, around the cataracts of the Congo, to Stanley Pool, 147 miles long, would open nearly 11,000 miles of navigable water-way, and the trade of 43,000,000 people, worth millions of dollars annually.

The first results of Stanley’s efforts in behalf of a “Free Congo State” were, as already indicated, the formation of an international association, whose president was Colonel Strauch, and to whose existence and management the leading powers of the world gave their assent. It furnished the means for his return to Africa, with plenty of help and with facilities for navigating the Congo, in order to establish towns, conclude treaties with the natives, take possession of the lands, fix metes and bounds and open commerce—in a word, to found a State according to his ideal, and firmly fix it among the recognized empires of the world.

30

In January, 1879, Stanley started for Africa, under the above auspices and with the above intent. But instead of sailing to the Congo direct, he went to Zanzibar on the east coast, for the purpose of enlisting a force of native pioneers and carriers, aiming as much as possible to secure those who had accompanied him on his previous trips across the Continent and down the river, whose ascent he was about to make. Such men he could trust, besides, their experience would be of great avail in so perilous an enterprise. A second object of his visit to Zanzibar was to organize expeditions for the purpose of pushing westward and establishing permanent posts as far as the Congo. One of these, under Lieut. Cambier, established a line of posts stretching almost directly westward from Zanzibar to Nyangwe, and through a friendly country. With this work, and the enlistment of 68 Zanzibaris for his Congo expedition, three-fourths of whom had accompanied him across Africa, he was engaged until May, 1879, when he sailed for the Congo, via the Red Sea and Mediterranean, and arrived at Banana Point at the mouth of the Congo, on Aug. 14, 1879, as he says, “to ascend the great river with the novel mission of sowing along its banks civilized settlements, to peacefully conquer and subdue it, to mold it in harmony with modern ideas into national States, within whose limits the European merchant shall go hand in hand with the dark African trader, and justice and law and order shall prevail, and murder and lawlessness and the cruel barter of slaves shall forever cease.”

Once at Banana Point, all hands trimmed for the tropical heat. Heads were shorn close, heavy clothing was changed for soft, light flannels, hats gave place to ventilated caps, the food was changed from meat to vegetable, liquors gave place to coffee or tea—for be it known a simple glass of champagne may prove a prelude to a sun-stroke in African lowlands. The officers of the expedition here met—an international group indeed,—an American (Stanley), two Englishmen, five Belgians, two Danes, one Frenchman. The steamer Barga had long since arrived from Europe with a precious assortment of equipments, among which were building material and a flotilla of light steam launches. One of these, the En Avant was the first to discover Lake Leopold II, explore the Biyeré and reach Stanley Falls.

32

In seven days, August 21st, the expedition was under way, braving the yellow, giant stream with steel cutters, driven by steam. The river is three miles wide, from 60 to 900 feet deep, and with a current of six miles an hour. On either side are dark walls of mangrove and palm, through which course lazy, unknown creeks, alive only with the slimy reptilia of the coast sections. For miles the course is through the serene river flood, fringed by a leafy, yet melancholy nature. Then a cluster of factories, known as Kissinga, is passed, and the river is broken into channels by numerous islands, heavily wooded. Only the deeper channels are now navigable, and selecting the right ones the fleet arrives at Wood Point, a Dutch trading town, with several factories. Up to this point, the river has had no depth of less than 16 feet, increased to 22 feet during the rainy season. The mangrove forests have disappeared, giving place to the statelier palms. Grassy plains begin to stretch invitingly down to the water’s edge. In the distance high ridges throw up their serrated outlines, and seemingly converge toward the river, as a look is taken ahead. Soon the wonderful Fetish Rocks are sighted, which all pilots approach with dread, either through superstition or because the deep current is broken by miniature whirlpools. One of these granite rocks stands on a high elevation and resembles a light-house. It is the Limbu-Li-Nzambi—“Finger of God”—of the natives.

Boma is now reached. It is the principal emporium of trade on the Congo—the buying and selling mart for Banana Point, and connected with it by steamers. There is nothing picturesque hereabouts, yet Boma has a history as old as the slave trade in America, and as dark and horrible as that traffic was infamous. Here congregated the white slave dealers for over two centuries, and here they gathered the dusky natives by the thousand, chained them in gangs by the dozen or score, forced them into the holds of their slave-ships, and carried them away to be sold in the Brazils, West Indies and North America. Whole fleets of slave-ships have anchored off Boma, with their loads of rum, their buccaneer crews and blood-thirsty officers, intent on human booty. Happily, all is now changed and the Arab is the only recognized slave-stealer in Africa. Boma has several missions, and her traders are on good terms with the surrounding tribes. Her market is splendid, and here may be found34 in plenty, oranges, citrons, limes, papaws, pine-apples, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, onions, turnips, cabbage, beets, carrots and lettuce, besides the meat of bullocks, sheep, goats and fowls.

A SLAVE-STEALER’S REVENGE.

A SLAVE-STEALER’S REVENGE.

After establishing a headquarters at Boma, under the auspices of the International Commission, the expedition proceeded to Mussuko, where the heavier steamer, Albion, was dismissed, and where all the stores for future use were collected. This point is 90 miles from the sea. River reconnoissances were made in the lighter steamers, and besides the information picked up, the navigators were treated to a hippopotamus hunt which resulted in the capture of one giant specimen, upon whose back one of the Danish skippers mounted in triumph, that he might have a thrilling paragraph for his next letter to Copenhagen.

Above Boma the Congo begins to narrow between verdure-clad hills rising from 300 to 1100 feet, and navigation becomes more difficult, though channels of 15 to 20 feet in depth are found. Further on, toward Vivi is a splendid reach of swift, deep water, with an occasional whirlpool, capable of floating the largest steamship. Vivi was to be a town founded under the auspices of the International Commission—an entrepôt for an extensive country. The site was pointed out by De-de-de, chief of the contiguous tribe, who seemed to have quite as keen a commercial eye as his European visitors. Hither were gathered five of the most powerful chiefs of the vicinity, who were pledged, over draughts of fresh palm-juice, to recognize the newly established emporium. It is a salubrious spot, surrounded by high plateaus, affording magnificent views. From its lofty surroundings one may sketch a future, which shall abound in well worn turnpike roads, puffing steamers, and columns of busy trades-people. As Vivi is, the natives are by no means the worst sort of people. They wear a moderate amount of clothing, take readily to traffic, keep themselves well supplied with marketing, and use as weapons the old fashioned flint-lock guns they have secured in trade with Europeans. At the grand assemblage of chiefs, one of the dusky seniors voiced the unanimous sentiment thus:—“We, the big chiefs of Vivi are glad to see the mundelé (trader). If the mundelé has any wish to settle in this country, as Massala (the interpreter) informs us, we will welcome35 him, and will be great friends to him. Let the mundelé speak his mind freely.”

Stanley replied that he was on a mission of peace, that he wanted to establish a commercial emporium, with the right to make roads to it and improve the surrounding country, and that he wanted free and safe intercourse with the people for all who chose to come there. If they would give guarantees to this effect, he would pay them for the right. Then began a four hour’s chaffer which resulted in the desired treaty. Apropos to this deal Stanley says:—“In the management of a bargain I should back the Congo native against Jew or Christian, Parsee, or Banyan, in all the round world. I have there seen a child of eight do more tricks of trade in an hour than the cleverest European trader on the Congo could do in a month. There is a little boy at Bolobo, aged six, named Lingeuji, who would make more profit out of a pound’s worth of cloth than an English boy of fifteen would out of ten pound’s worth. Therefore when I write of the Congo natives, Bakougo, Byyanzi or Bateke tribes, I associate them with an inconceivable amount of natural shrewdness and a power of indomitable and untiring chaffer.”

Thus Vivi was acquired, and Stanley brought thither all his boats and supplies. He turned all his working force, a hundred in number, to laying out streets to the top of the plateau, where houses and stores were erected. The natives rendered assistance and were much interested in the smashing and removal of the boulders with the heavy sledges. They called Stanley Bula Matari—Rock Breaker—a title he came to be known by on the whole line of the Congo, up to Stanley Falls. Gardens were planted, shade trees were set out, and on January 8, 1880, Stanley wrote home that he had a site prepared for a city of 20,000 people, at the head of navigation on the lower Congo, and a center for trade with a large country, when suitable roads were built. He left it in charge of one of his own men, as governor, or chief, and started on his tedious and more perilous journey through the hills and valleys of the cataract region. This journey led him through various tribes, most of whom lived in neat villages, and were well supplied with live animals, garden produce and cotton clothing. They were friendly and disposed to encourage him in his enterprise of making a good commercial road36 from Vivi, around the cataracts, to some suitable station above, provided they were well paid for the right of way. A melancholy fact in connection with many of these tribes is that they have been decimated by internecine wars, mostly of the olden time, when the catching and selling of slaves was a business, and that thereby extensive tracts of good land have been abandoned to wild game, elephants, buffaloes, water-buck and antelopes, which breed and roam at pleasure. It was nothing unusual to see herds of half a dozen elephants luxuriously spraying their sunburnt backs in friendly pools, nor to startle whole herds of buffaloes, which would scamper away, with tails erect, for safety—cowards all, except when wounded and at bay, and then a very demon, fuller of fight than a tiger and even more dangerous than the ponderous elephant.

Owing to the fact that the Congo threads its cataract section with immense falls and through deep gorges, this part of Stanley’s journey had to be made at some distance from its channel, and with only glimpses of its turbid waters, over lofty ridges, through deep grass-clothed or densely forested valleys, and across various tributaries, abounding in hippopotami and other water animals. Many fine views were had from the mountains of Ngoma. He decided that a road could be made from Vivi to Isangila, a distance of 52 miles, and that from Isangila navigation could be resumed on the Congo. And this road he now proceeded to make, for, though years before in his descent of the river he had dragged many heavy canoes for miles overland, and around similar obstructions, he now had heavier craft to carry, and objects of commerce in view. He had 106 men at his disposal at Vivi, who fell to work with good will, cutting down the tall grass, removing boulders, corduroying low grounds, bridging streams, and carrying on engineering much the same as if they were in a civilized land—the natives helping when so inclined. The workmen had their own supplies, which were supplemented by game, found in abundance, and were molested only by the snakes which were disturbed by the cutting and digging; of these, the spitting snake was the most dangerous, not because of its bite, but because it ejects its poison in a stream from a distance of six feet into the face and eyes of its enemy. The ill effects of such an injection lasts for a week or more. The tall grass was infested38 with the whip-snake, the bulky python was found near the streams, while a peculiar green snake inhabited the trees of the stony sections and occasionally dangled in unpleasant proximity to the faces of the workmen.

BUFFALO AT BAY.

BUFFALO AT BAY.

As this road-making went on, constant communication was kept up with Vivi. The steamers were mounted on heavy wagons, and were drawn along by hand-power as the road progressed. Stores and utensils of every kind were similarly loaded and transported. The mules and asses, belonging to the expedition, were of course brought into requisition, but in nearly all cases their strength had to be supplemented by the workmen. Accidents were not infrequent, but fatal casualties were rare. Some died of disease, yet the general health was good. One of the coast natives fell a victim to an enraged hippopotamus, which crushed him and his bark as readily as an egg-shell.

Thus the road progressed to Makeya Manguba, a distance of 22 miles from Vivi, and after many tedious trips to and fro, all the equipments of the expedition were brought to that point. The time consumed had been about five months—from March to August. Here the steel lighters were brought into requisition, and the equipments were carried by steam to a new camp on the Bundi river, where road making was even more difficult, because the forests were now dense and the woods—mahogany, teak, guaiacum and bombax—very hard. Fortunately the natives kept up a fine supply of sweet potatoes, bananas, fowls and eggs, which supplemented the usual rice diet of the workmen. It was with the greatest hardship that the road was completed between the Luenda and Lulu rivers, so thick were the boulders and so hard the material which composed them. The Europeans all fell sick, and even the natives languished. At length the Bula river was reached, 16 miles from the Bundi, where the camp was supplied with an abundance of buffalo and antelope meat.

The way must now go either over the steep declivities of the Ngoma mountains, or around their jagged edges, where they abut on the roaring Congo. The latter was chosen, and for days the entire force were engaged in cutting a roadway along the sides of the bluffs. This completed, a short stretch of navigable water brought40 them to Isangila, 52 miles from Vivi. It was now January 2, 1881. Thither all the supplies were brought, and the boats were scraped and painted, ready for the long journey to Manyanga. Stanley estimated that all the goings and comings on this 52 miles of roadway would foot up 2,352 miles of travel; and it had cost the death of six Europeans and twenty-two natives, besides the retirement of thirteen invalids. Verily, it was a year dark with trial and unusual toil. But the cataracts had been overcome, and rest could be had against further labors and dangers.

FIGHT WITH AN ENRAGED HIPPOPOTAMUS.

FIGHT WITH AN ENRAGED HIPPOPOTAMUS.

The little steel lighters are now ready for their precious loads. In all, there has been collected at Isangila full fifty tons of freight, besides wagons and the traveling luggage of 118 colored carriers and attendants and pioneers. It is a long, long way to Manyanga, but if the river proves friendly, it ought to be reached in from seventy to eighty days. The Congo is three-quarters of a mile wide, with rugged shores and tumultuous currents. The little steamers have to feel their way, hugging the shores in order to avoid the swift waters of the outer channels, and starting every now and then with their paddles the drowsy crocodiles from their habitat. The astonished creatures dart forward, at first, as if to attack the boats, but of a sudden disappear in the flood, to rise again in the rear and give furious chase at a distance they deem quite safe. This part of the river is known as Long Reach. These reaches, or stretches, some of them five miles long, are expansions of the river, between points of greater fall, and are more easily navigable than where the stream narrows or suddenly turns a point. The cañon appearance of the shores now begins to disappear, and extensive grass-grown plains stretch occasionally to the water’s edge.

At the camp near Kololo Point, where the river descends swiftly, the expedition was met by Crudington and Bentley, two missionaries, who were fleeing in a canoe from the natives of Kinshassa, where they had been surrounded by an armed mob and threatened with their lives. They were given protection and sent to Isangila. Stanley had now to mourn the loss of his most trustworthy messenger, Soudi. He had gone back to Vivi for the European mail and on the way had met a herd of buffaloes; selecting the finest, he discharged his rifle at it and killed it, as he thought. But when he41 rushed up to cut its jugular vein, the beast arose in fury, and tossed and mangled poor Soudi so that he died soon after his companions came to his rescue.

Stretch after stretch of the turbulent Congo is passed, and camp after camp has been formed and vacated. At all camps, where practicable, the natives have been taken into confidence, and the intent of the expedition made known. With hardly an exception they fell into the spirit of the undertaking, and gladly welcomed the opportunity to open commerce with the outer world. The Nzambi rapids now offer an obstacle to navigation, but soon a safe channel is found, and a magnificent stretch of water leads to a bay at the mouth of the Kwilu river, a navigable stream, with a depth of eight feet, a width of forty yards and a current of five miles an hour. The question of food now became pressing. Each day the banks of the river were scoured for rations, by gangs of six men, whose duty it was to purchase and bring in cassava, bread, bananas, Indian corn, sweet potatoes, etc., not forgetting fowls, eggs, goats, etc., for the Europeans. But these men found it hard work to obtain fair supplies.

By April 7th the camp was at Kimbanza opposite the mouth of the Lukunga and in the midst of a land of plenty, and especially of crocodiles, which fairly infest the river and all the tributaries thereof. Here, too, are myriads of little fish like minnows, or sardines, which the natives catch in great quantities, in nets, and prepare for food by baking them in the sun. The population is quite dense, and of the same amiable mood, the same desire to traffic, and the same willingness to enter into treaties, as that on the river below.

Further up are the Ndunga people and the Ndunga Rapids, where the river is penned in between high, forbidding walls and where nature has begrudged life of every kind to the scene. But out among the villages all is different. The people are thrifty and sprightly. Their markets are full of sweet potatoes, eggs, fish, palm-wine, etc., and the shapely youths, male and female, indulge in dances which possess as much poetry of motion as the terpsichorean performances of the more highly favored children of civilization.

42

The next station was Manyanga, a destination indeed, for here is a formidable cataract, which defies the light steamers of the expedition, and there will have to be another tedious portage to the open waters of Stanley Pool. It was now May 1, 1881. Manyanga is 140 miles from Vivi. The natives were friendly but adverse to founding a trading town in their midst. Yet Stanley resolved that it should be a station and supply point for the 95 miles still to be traversed to Stanley Pool. He fell sick here, of fever, and lay for many days unconscious. Such was his prostration, when he returned to his senses, that he despaired of recovery, and bade his attendants farewell.

In the midst of hardship which threatened to break his expedition up at this point, he was rejoiced to witness the arrival of a relief expedition from below, other boats, plenty of provisions and a corps of workmen. Then the site of the town of Manyanga was laid out, and a force of men was employed to build a road around the cataract and haul the boats over it. This point is the center of exchange for a wide territory. Slaves, ivory, rubber, oil, pigs, sheep, goats and fowls are brought in abundance to the market, and it is a favorite stopping-place for caravans from the mouth of the Congo to Stanley Pool. But the natives are crusty, and several times Stanley had to interfere to stop the quarrels which arose between his followers and the insolent market people. At length the town was fortified, provisioned and garrisoned, and the expedition was on its way to Stanley Pool, around a portage of six miles in length, and again into the Congo; then up and up, with difficult navigation, past the mouths of inflowing rivers, around other tedious portages, through quaint and curious tribes, whose chiefs grow more and more fantastic in dress and jealous of power, till they even come to rival that paragon of strutting kingliness, the famed Mtesa of Uganda. Though not hostile, they were by no means amiable, having made a recent cession of the country on the north of the Congo to French explorers. King Itsi, or Ngalyema, was among the most powerful of them and upon him was to turn the fortune of the expedition in the waters of the upper Congo. Stanley made the happy discovery that this Ngalyema was the Itsi, of whom he had made a blood brother on his descent of the river,44 and this circumstance soon paved the way to friendship and protection, despite the murmurs and threats of neighboring chiefs.

The last king of note, before reaching Stanley Pool, was Makoko, who favored the breaking of rocks and the cutting down of trees in order to pass boats over the country, but who wanted it understood that his people owned the country and did not intend to part with their rights without due consideration. Scarcely had a treaty been struck with him when Stanley was informed that Ngalyema was on his track with two hundred warriors, and determined to wipe out his former negotiations with blood. Already the sound of his war-drums and the shouts of his soldiers were heard in the distance. Stanley ordered his men to arm quickly and conceal themselves in the bush, but to rush out frantically and make a mock attack when they heard the gong sounding. Ngalyema appeared upon the scene with his forces and informed Stanley that he could not go to Kintamo, for Makoko did not own the land there. After a long talk, the stubborn chief left the tent in anger and with threats of extermination on his lips; but as he passed the inclosure, he was attracted by the gong, swinging in the wind.

“What is this?” he asked.

“It is fetish,” replied Stanley.

“Strike it; let me hear it,” he exclaimed.

“Oh, Ngalyema, I dare not; it is the war fetish.”

“No, no, no! I tell you to strike.”

“Well, then!”

Here Stanley struck the gong with all his force, and in an instant a hundred armed men sprang from the bush and rushed with demoniac yells upon the haughty chief and his followers, keeping up all the while such demonstrations as would lead to the impression that the next second would bring an annihilating volley from their guns. The frightened king clung to Stanley for protection. His followers fled in every direction.

“Shall I strike the fetish again?” inquired Stanley.

“No, no! don’t touch it!” exclaimed the now subdued king; and the broken treaty was solemnized afresh over a gourd of palm-wine. Makoko was jolly over the discomfiture of his powerful rival.

A NARROW ESCAPE.

A NARROW ESCAPE.

46

These Kintamo people, sometimes called the Wambunda, now gave to Stanley some 78 carriers and greatly assisted him in making his last twelve miles of roadway and in conveying his boats and wagons over it. The expedition was now in sight of Stanley Pool, beyond the region of the cataracts, and at the foot of navigation on the upper Congo. It was now Dec. 3, 1881, the boats were all brought up and launched in smooth water, a station was founded, and the expedition prepared for navigation on that stupendous stretch of water between Stanley Pool and Stanley Falls.

The Kintamo station was called Leopoldville, in honor of king Leopold of Belgium, European patron of the Congo Free State, and to whose generosity more than that of any other the entire expedition was due. It was the most important town thus far founded on the Congo, for it was the center of immense tribal influence, a base of operations for 5000 miles of navigable waters, and a seat of plenty if the chiefs remained true to their concessions. It was therefore well protected with a block-house and garrison, while the magazine was stocked with food and ammunition. Gardens were laid out and planted, stores were erected in which goods were displayed, and soon Stanley had the pleasure of seeing the natives bringing ivory and marketing for traffic. The stay of the expedition at Leopoldville was somewhat lengthy and it was April, 19, 1882, before it embarked for the upper Congo, with its 49 colored men, four whites, and 129 carrier-loads of equipments.

The boats passed Bamu Island, 14 miles in length, which occupies the center of Stanley Pool, the stream being haunted by hippopotami and the interior of the island by elephants and buffaloes, adventures with which were common. The shores are yet bold and wooded, monkeys in troops fling themselves from tree to tree, white-collared fish eagles dart with shrill screams across the wide expanse of waters, and crocodiles stare wildly at the approaching steamers, only to dart beneath them as they near and then to reappear in their wake. Says Stanley, of this part of the river:

“From the Belize to Omaha, on the line of the Mississippi, I have seen nothing to excite me to poetic madness. The Hudson is a trifle better in its upper part. The Indus, the Ganges, the Irrawaddy, the Euphrates, the Nile, the Niger, the La Platte, the48 Amazon—I think of them all, and I can see no beauty on their shores that is not excelled many fold by the natural beauty of this scenery, which, since the Congo highlands were first fractured by volcanic caprice or by some wild earth-dance, has remained unknown, unhonored and unsung.”

WHITE-COLLARED FISH EAGLES.

WHITE-COLLARED FISH EAGLES.

From Stanley Pool to Mswata, a distance of 64 miles, the river has a width of 1500 yards, a depth sufficient to float the largest steamer, and heavily wooded banks. The people are of the Kiteké tribes and are broken into many bands, ruled by a high class of chieftains, who are not averse to the coming of the white man. The Congo receives an important tributary near Mswata, called the Kwa. This Stanley explored for 200 miles, past the Holy Isle, or burial place of the Wabuma kings and queens, through populous and pleasantly situated villages and onward to a splendid expanse of water, which was named Lake Leopold II.

It was during his exploration of the Kwa that Stanley fell sick; and on his return to Mswata, was compelled to return to Leopoldville and so back to Manyanga, Vivi, and the various stations he had founded, to the coast, whence he sailed for Loando, to take a steamer for Europe. The three-year service of his Zanzibaris was about to expire; and when he met at Vivi, the German, Dr. Peschnel-Loeche, with a large force of men and a commission to take charge of the expedition, should anything happen to him (Stanley), he felt that it was in the nature of a reprieve.

On August 17, 1882, he sailed from Loando for Lisbon. On his arrival in Europe, he laid before the International Association a full account of the condition of affairs on the Congo. He had founded five of the eight stations at first projected, had constructed many miles of wagon road, had left a steamer and sailing vessels on the Upper Congo, had opened the country to traffic up to the mouth of the Kwa, a distance of 400 miles from the coast, had found the natives amiable and willing to work and trade, and had secured treaties and concessions which guaranteed the permanency of the benefits sought to be obtained by the expedition and the founding of a great Free State. Yet with all this he declared that “the Congo basin is not worth a two-shilling piece in its present state, and that to reduce it to profitable order a railroad must be built from the lower to the49 upper river.” Such road must be solely for the benefit of Central Africa and of such as desire to traffic in that region. He regarded the first phase of his mission as over—the opening of communication between the Atlantic and Upper Congo. The second phase he regarded as the obtaining of concessions from all the chiefs along the way, without which they would be in a position to force an abandonment of every commercial enterprise.

The International Association heard him patiently and offered to provide funds for his more extensive work, provided he would undertake it. He consented to do so and to push his work to Stanley Falls, if they would give him a reliable governor for the establishments on the Lower Congo. Such a man was promised; and after a six weeks’ stay in Europe, he sailed again for Congo-land on November 23, 1882.

He found his trading stations in confusion, and spent some time in restoring order, and re-victualling the empty store-houses. The temporary bridges on his hastily built roads had begun to weaken and one at the Mpalanga crossing gave way, compelling a tedious delay with the boats and wagons he was pushing on to the relief of Leopoldville. Here he found no progress had been made and that under shameful neglect everything was going to decay. Even reciprocity with the natives had been neglected, and garrison and tribes had agreed to let one another severely alone. To rectify all he found wrong required heroic exertion. He found one source of gratification in the fact that two English religious missions had been founded on the ground of the Association, one a Baptist, the other undenominational. Dr. Sims, head of the Baptists, was the first to navigate the waters of the Upper Congo, and occupy a station above Stanley Pool, but soon after the Livingstone, or undenominational mission, established a station at the Equator. Both missions now have steamers at their disposal, and are engaged in peaceful rivalry for moral conquest in the Congo Basin.

A TEMPORARY CROSSING.

A TEMPORARY CROSSING.

The relief of Leopoldville accomplished, Stanley started in his steam-launches, one of which was new (May 9, 1883), for the upper waters of the Congo, with eighty men. Passing his former station at Mswata, he sailed for Bolobo, passing through a country with few villages and alive with lions, elephants, buffaloes and antelopes,51 proof that the population is sparse at a distance from the river. Beyond the mouth of the Lawson, the Congo leaves behind its bold shores and assumes a broader width. It now becomes lacustrine and runs lazily through a bed carved out of virgin soil. This is the real heart of equatorial Africa, rich alluvium, capable of supporting a countless population and of enriching half a world.

WEAVER-BIRD’S NEST.

WEAVER-BIRD’S NEST.

The Bolobo country is densely populated, but flat and somewhat unhealthy. The villages arise in quick succession, and perhaps 10,000 people live along the river front. They are peaceful, inclined to trade, but easily offended at any show of superiority on the part of white men. Ibaka is the leading chief. He it was who conducted negotiations for Gatula, who had murdered two white men, and who had been arraigned for his double crime before Stanley,

52

The latter insisted upon the payment of a heavy fine by the offending chief—or war. After long deliberation, the fine was paid, much to Stanley’s relief, for war would have defeated the whole object of his expedition. Ibaka’s remark, when the affair was so happily ended, was: “Gatula has received such a fright and has lost so much money, that he will never be induced to murder a man again. No, indeed, he would rather lose ten of his women than go through this scene again.” A Bolobo concession for the Association was readily obtained in a council of the chiefs.

And this station at Bolobo was most important. The natives are energetic traders, and have agents at Stanley Pool and points further down the river, to whom they consign their ivory and camwood powder, very much as if they were Europeans or Americans. They even acquire and enjoy fortunes. One of them, Manguru, is a nabob after the modern pattern, worth fully $20,000, and his canoes and slaves exploit every creek and affluent of the Congo, gathering up every species of merchandise available for the coast markets. Within two hours of Bolobo is the market place of the By-yanzi tribe. The town is called Mpumba. It is a live place on market days, and the fakirs vie with each other in the sale of dogs, crocodiles, hippopotamus meat, snails, fish and red-wood powder.