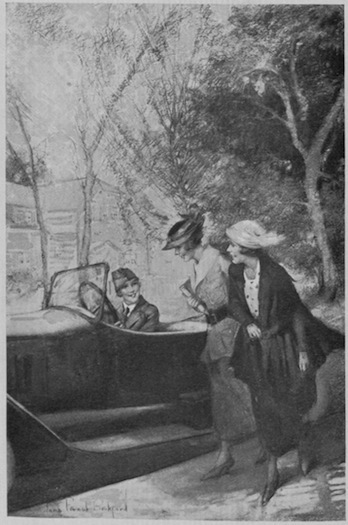

“Ah there, girls! How are you?”—Page 11.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | “God Speed You” | 11 |

| II | Giving Her Best | 28 |

| III | The Liberty Girls | 46 |

| IV | The Liberty Garden | 60 |

| V | The Liberty Pageant | 73 |

| VI | The Strange Letter | 89 |

| VII | The Visit to Camp Mills | 106 |

| VIII | Seven Pillars | 121 |

| IX | The Little Old Lady in the Red House | 133 |

| X | The Sweet-Pea Ladies | 147 |

| XI | The Ride Through the Notch | 164 |

| XII | Nathalie’s Liberty Boys | 179 |

| XIII | “The Mountains with the Snowy Foreheads” | 194 |

| XIV | “Sons of Liberty” | 211 |

| XV | The Gallery of the Gods | 222 |

| XVI | Butternut Lodge | 238 |

| XVII | The Cabin on the Mountain | 256 |

| XVIII | The Liberty Cheer | 275 |

| XIX | “The White Comrade” | 288 |

| XX | The Liberty Tea | 302 |

| XXI | The Funnies | 322 |

| XXII | The Man in the Woods | 334 |

| XXIII | A Mystery Solved | 348 |

| XXIV | The Winner of the Prize | 362 |

| “Ah there, girls! How are you?” (Page 11) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “My name is Liberty, My throne is Law” | 76 |

| “Is that your dog? Oh, I love dogs!” | 184 |

| The girl found herself gazing into the sun-tanned face of a young man in khaki | 232 |

| Nathalie bent over in anxious solicitude | 260 |

| “Oh, it is Philip, my son!” | 376 |

“Oh, Nathalie, I do believe there’s Grace Tyson in her new motor-car,” exclaimed Helen Dame, suddenly laying her hand on her companion’s arm as the two girls were about to cross Main Street, the wide, tree-lined thoroughfare of the old-fashioned town of Westport, Long Island.

Nathalie Page halted, and, swinging about, peered intently at the brown-uniformed figure of a young girl seated at the steering-wheel of an automobile, which was speeding quickly towards them.

Yes, it was Grace, who, in her sprightliest manner, her face aglow from the invigorating breezes of an April afternoon, called out, “Ah there, girls! How are you? Oh, my lucky star must have guided me, for I have something thrilling to tell you!” As she spoke the girl guided the car to the curb, and the next moment, with an airy spring, had landed on the ground at their side.

12 With a sudden movement the uniformed figure clicked her heels together and bent stiffly forward as her arm swung up, while her forefinger grazed her forehead in a military salute. “I salute you, comrades,” she said with grave formality, “at your service as a member of the Motor Corps of America.

“Yes, girls,” she shrilled joyously, forgetting her assumed rôle in her eagerness to tell her news, “I’m on the job, for I’m to see active service for the United States government. I’ve just returned from an infantry drill of the Motor Corps at Central Park, New York.

“No, I’ll be honest,” she added laughingly, in answer to the look of amazed inquiry on the faces of her companions, “and ’fess’ that I didn’t have the pleasure of drilling in public, for I’m a raw recruit as yet. We recruits go through our manual of arms at one of the New York armories, drilled by a regular army sergeant. Oh, I’ve been in training some time, for you know I took out my chauffeur’s and mechanician’s State licenses last winter.

“One has to own her car at this sort of government work,”—Grace’s voice became inflated with importance,—“and be able to make her own repairs on the road if necessary. But isn’t my new car a Jim Dandy?” she asked, glancing with keen pride at the big gray motor, purring contentedly at the curb. “It was a belated Christmas gift from grandmother.

13 “But I tell you what, girls,” she rattled on, “I’ve been put through the paces all right, but I’ve passed my exams with flying colors. Phew! wasn’t the physical exam stiff!—before a regular high official of the army medical corps. I was inoculated for typhoid, and for paratyphoid. I’ll secretly confess that I don’t know what the last word means. Yes, and I took the oath of allegiance to the United States Government, administered by another army swell,—and that’s where my Pioneer work proved O. K. And then we had the First Aid course, too, at St. Luke’s. The head nurse, who gave us special lessons in bandaging, said I was A No. 1; and in wigwagging, oh, I did the two-flag business just dandy.”

“But what is your special work?” asked Nathalie, for the two girls were somewhat surprised and bewildered by all these high-sounding, official-like terms. To be sure, Grace had long been known as an expert driver, but she had never shown her efficiency in any way but by giving the girls joy-rides once in a while; yes, and once she had driven her father to New York.

But war work, thought Nathalie, for this aristocratic-looking, sweet-faced young girl, whose eyes gleamed merrily at you from under the peaked army cap—with its blue band and the insignia of the Corps, a tire surmounted by Mercury’s wings—set so jauntily on the fluffy hair. To be sure the slim, trim figure in the army jacket, short skirt over trousers, and high 14 boots did have a warlike aspect, but it was altogether too girlish and charming to be suggestive of anything but a toy soldier, like one of the tiny painted tin things that Nathalie used to play with when a wee tot.

“Do? Why, I am a military chauffeur,” returned Grace patronizingly, “and in the business of war-relief work for the Government. At present I’m to act as chauffeur to one of our four lieutenants, Miss Gladys Merrill. Oh, she’s a dear! I have to drive her all over the city when she is engaged on some Government errand. You should see me studying the police maps, and then you would know what I do. Sometimes we are called to transport some of the army officers from the railroad station to the ferry, or to headquarters. Then we do errands for the Red Cross, too.

“Why, the other day I helped to carry a lot of knitted things down on the pier, to be packed in a ship bound for the other side; they were for the soldiers at the front. We do work for the National Defense, and for the Board of Exemption. I’m doing my ‘bit,’ even if it is a wee one, towards winning the war,” ended the girl, with a note of satisfaction in her voice.

“O dear, but wouldn’t I like to drive an ambulance in France! But I’ve got to be twenty-one to do that sort of work,”—the girl sighed. “But did I tell you that brother Fred is doing American Field Service? I had a letter from him yesterday, and he said that he and a lot of American boys have established a little encampment 15 of ambulances not far from the front-line trench. They live in what was once a château belonging to Count Somebody or Another, but now it is nothing but a shell.

“Oh, Fred thinks it is glorious fun,” cried the girl, with sparkling eyes. “He has to answer roll-call at eight in the morning, and then he eats his breakfast at a little café near. He has just black bread,—think of that, coffee, and, yes, sometimes he has an egg. Then he has to drill, clean his car, and—oh, but he says it’s a great sight to see the aëroplanes constantly flying over his head, like great monsters of the air. And sometimes he goes wild with excitement when he sees an aërial battle between a Boche and a French airman.

“Yes, he declares it is ‘some’ life over there,” animatedly continued Grace, “for even his rest periods are thrilling, for they have to dodge shells, and sometimes they burst over one’s head. Several times he thought he was done for. And at night the road near the château is packed with hundreds of marching guns, trucks of ammunition, and war supplies and cavalry, all on their way to the front.

“But when he goes in his ambulance after the blessés—they are the poor wounded soldiers—it is just like day, for the sky is filled with star-shells shooting around him in all colors, and then there is a constant cannonading of shells and shot of all kinds. When he hears a purr he knows it’s a Boche plane and 16 dodges pretty lively, for if he doesn’t ‘watch out’ a machine-gun comes sputtering down at him. He’s awfully afraid of them because they drop bombs.

“But he says it would make your heart ache to see him when he carries the blessés. He has to drive them from the postes de secours—the aid-stations—to the hospitals. He has to go very slowly, and even then you can hear the poor things groan and shriek with the agony of being moved. And sometimes,” Grace lowered her voice reverently, “when he goes to take them out of the ambulance he finds a dead soldier.

“But dear me,” she continued in a more cheerful tone, “he seems to like the life and is constantly hoping—I believe he dreams about it in his sleep—that he’ll soon have a shot at one of those German fiends. Yes, I think it would be gloriously exciting,” ended Grace with a half sigh of envy.

“Gloriously exciting?” repeated Nathalie with a shudder. “Oh, Grace, I should think you would be frightfully worried. Suppose he should lose his life some time in the darkness of the night, alone with those wounded soldiers? O dear,” she ended drearily, “I just wish some one would shoot or kill the Kaiser! Sometimes I wish I could be a Charlotte Corday. Don’t you remember how she killed Murat for the sake of the French?”

“Why, Nathalie,” cried Helen with amused eyes, 17 “I thought you were a pacifist, and here you are talking of shooting people.” And the girl’s “Ha! ha!” rang out merrily.

Nathalie’s color rose in a wave as she cried decidedly, “Helen, I’m not a pacifist. Of course I want the Allies to win. I believe in the war—only—only—I do not think it is necessary to send our boys across the sea to fight.”

“But I do,” insisted Helen, “for this is God’s war, a war to give liberty to everybody in the world, and that makes it our war. We should be willing to fight, to give the rights and privileges of democracy to other people, and our American boys are not slackers who let some one else do their work.”

“Our boys! You mean my boy,” said Nathalie, with sudden bitterness. “It’s all right for you to talk, Helen, but you haven’t a brother to go and stand up and be mercilessly bayoneted by those Boches. And that is what Dick will have to do.” Nathalie choked as she turned her head away.

“Yes, Nathalie dear,” replied Helen in a softened tone, “I know it is a terrible thing to have to give up your loved ones to be ruthlessly shot down. But what are we going to do?” she pleaded desperately, “we must do what is right and leave the rest to God, for, as mother says, ‘God is in his Heaven.’ And Dick wants to go,” she ended abruptly, “he told me so the other day.”

18 “Yes, that is just it,” cried Nathalie in a pitifully small voice, “and he says that he is not going to wait to be drafted. Oh, Helen, mother and I cannot sleep at night thinking about it!” Nathalie turned her face away, her eyes dark and sorrowful. No, she did not mean to be a coward, but it just rent her heart to picture Dick going about armless, or a helpless cripple shuffling along, with either she or Dorothy leading him.

“Oh, I would like to be a Joan of Arc,” interposed Grace at this point, her blue eyes suddenly afire. “I think it would be great to ride in front of an army on a white charger. And then, too,” she added more seriously, “I think it takes more bravery to fight than to do anything else.”

“Perhaps it does, Grace,” remarked Helen slowly, “but when it comes to heroism, I think the mothers who give their boys to be slaughtered for the good of their fellow-beings are the bravest—” The girl paused quickly, for she had caught sight of Nathalie’s face, and remorsefully felt that what she had just said only added to her friend’s distress. “But, girls,” she went on in a brighter tone, “I have something to tell you. I’m going to France to do my ‘bit,’ for I’m to be stenographer to Aunt Dora. We expect to sail in a month or so. You know that she is one of the officials in the Red Cross organization.”

There were sudden exclamations of surprise from the girl’s two companions, as they eagerly wanted to 19 know all about her unexpected piece of news. As Helen finished giving the details as to how it had all come about, she exclaimed, with a sudden look at her wrist-watch: “Goodness! Girls, do you know it is almost supper-time? I’m just about starved.”

“Well, jump into the car, then,” cried Grace Tyson, “and I’ll have you home in no time.” Her companions, pleased at the prospect of a whirl in the new car, gladly accepted her invitation, and a few minutes later were speeding towards the lower end of the street where Helen and Nathalie lived.

After bidding her friends good-by, Nathalie, with a tru-al-lee, the call-note of their Pioneer bird-group, ran lightly up the steps of the veranda. Yes, Dick was home, for he was standing in the hall, lighting the gas. With a happy little sigh she opened the door.

“Hello, sis,” called out Dick cheerily,—a tall well-formed youth, with merry blue eyes,—as he caught sight of the girl in the door-way. “Have you been on a hike?”

“Oh, no, just an afternoon at Mrs. Van Vorst’s. Nita had a lot of the girls there—” Nathalie stopped, for an expression, a sudden gleam in her brother’s eyes, caused her heart to give a wild leap. She drew in her breath sharply, but before the question that was forming could be asked, Dick waved the still flaming match hilariously above his head as he cried, “Well, sister mine, I’ve taken the plunge, and I’ve come off on top, 20 for I’ve joined the Flying Corps, and I’m going to be an army eagle!”

“Flying Corps?” repeated Nathalie dazedly. “What do you mean?”

“I mean, Blue Robin, that I’m going to be an aviator, a sky pilot,” replied the boy jubilantly. “I made an application some time ago to the chief signal officer at Washington. I was found an eligible applicant, for, you know, my course in the technical school in New York did me up fine. To-day I passed my physical examinations, and am now enlisted in the Signal Corps of the Signal Enlisted Reserve Corps. I’m off next week to the Military Aëronautics School at Princeton University. It’s an eight-weeks’ course. If I put it over,—and you bet your life I do,” Dick ground his teeth determinedly,—“I go into training at one of the Flying Schools, and then I’ll soon be a regular bird of the air; and if I don’t help Uncle Sam win the war, and manage to drop a few bombs on those Fritzies, I’ll go hang!”

For one awful moment Nathalie stood silent, staring at her brother in dumb despair. Then she turned, and with a blur in her eyes and a tightening of her throat, blindly groped for the stairway. But no! Dick’s hand shot out, he caught the hurrying figure in his grasp, and the next moment Nathalie was sobbing on his breast.

“That’s all right, little sis,” exclaimed the boy with a 21 break in his voice, as he pressed the brown head closer. Then he cried, in an attempt at jocularity, “Just get it all out of your system, every last drop of that salted brine, Blue Robin, and then we’ll talk business.”

This somewhat matter-of-fact declaration acted like a cold shower-bath on the girl, as, with a convulsive shiver, she caught her breath, and although she burrowed deeper into the snug of her brother’s arm her tears were stayed.

“Dick, how could you do it? Think of mother!” Then she raised her eyes, and went on, “Oh, I can’t bear the thought of your getting ki—” But the girl could not say the dreaded word, and again her head went down against the rough gray of Dick’s coat.

“Well, Blue Robin, I’m afraid you have lost that cheery little tru-al-lee of yours,” teased the boy humorously. “You’ve cried so hard you’re eye-twisted. In the first place, I don’t intend getting killed if I can help it. And I can’t help leaving mother. You must remember I’m a citizen of the United States—” the boy was thinking of his first vote cast the fall before—“and I am bound by my oath of allegiance to the country to uphold its principles, even if it means the breaking of my mother’s apron-strings,” he added jokingly.

“Oh, Dick, don’t try to be funny,” Nathalie managed to say somewhat sharply, as she drew away from her brother’s arm and dropped limply on the steps of the stairs, in such an attitude of hopeless despair that 22 Dick was at the end of his tether to know what to say. He stared down at the girl, unconsciously rubbing his hand through his hair, a trick the boy had when perplexed.

Suddenly a bit of a smile leaped into his eyes as he cried, in a hopelessly resigned tone, “All right, sis, seeing that you feel this way about it I’ll just send in my resignation. It will let the boys know I’ve laid down on my job, for if you and mother are going to howl like two cats, a fellow can’t do a thing but stay at home and be a sissy, a baby-tender, a dish-washer-er-er—”

“Oh, Dick, don’t talk nonsense,” broke in Nathalie sharply. “I didn’t say that you were not to go, but,—why—oh, I just can’t help feeling awfully bad when I read all those terrible things in the paper.” Her voice quivered pathetically as she finished.

“Well, don’t read them, then,” coolly rejoined Dick. “Just steer clear of all that hysterical gush and brace up. My job is to serve my country,—she wants me. By Jove, before she gets out of this hole she’ll need every mother’s son of us. And I’ve got to do it in the best way I can, by enlisting before the draft comes. I’ll not only have a chance to do better work, a prospect of quicker promotion, but, if you want to look at the sordid end of it, I’ll get more pay. And as to being killed, as you wailed, if you and mother will insist upon seeing it black, an aviator’s chance of life is ten to one better—if he’s on to his job—than that of the 23 fellow on the ground. So cheer up, Blue Robin. I’m all beat hollow, for I’ve been trying to cheer up mother for the last hour.”

“Oh, what does mother say?” asked a very faint voice, just as if the girl did not know how her mother felt, and had been feeling for some time.

“Say! Gee whiz! I don’t know what she would have said if she had voiced her sentiments,” replied Dick resignedly. “But the worst of the whole business was that she took it out in weeping about a tank of tears; all over my best coat, too,” he added ruefully. “You women are enough to make a fellow go stiff.

“Now see here, Blue Robin, don’t disappoint me!” suddenly cried the lad, as he stared appealingly into his sister’s brown eyes. “Why, I thought that you would be my right-hand man. I knew mother would make a time at first, but you,—I thought you had grit; you, a Pioneer, too. Don’t you know, girl—” added Dick, rubbing the back of his hand quickly across his eyes, “that I’ve got to go? Don’t you forget that. I’m on the job, every inch of it, but, thunderation, I’m no more keen to go ‘over there’ and have those Hun devils cut me up like sausage, than you or mother. But I’m a man and I’ve got to live up to the business of being a man, and not a mollycoddle.”

But Nathalie had suddenly come to her senses. Perhaps it was the brush of the boy’s hand across his eyes, or the quivering note in his voice, but she roused. She 24 had been selfish; instead of crying like a ninny she should have cheered. “Oh, Dick,” she exclaimed contritely, standing up and facing him suddenly, “I’m all wrong. I didn’t mean to cry, and I wouldn’t have either,” she explained excusingly, “if you had only let me go up-stairs.

“No, Dick, I would not have you be a slacker, or a mollycoddle, or wash the dishes,” she added with a faint attempt at a smile, “and we haven’t any babies to tend. Yes, old boy, I don’t want you to lie down in the traces, so let’s shake on it, and I’ll try to brace up mother, too,” added the girl, as she held out her hand to her brother.

“Now that’s the stuff, Nat, old girl,” cried the boy with gleaming eyes, as he took the girl’s hand and held it tightly, “and while I’m fighting to uphold the family honor and glory,—remember father was a Rough Rider,—you stay with dear old mumsie. Keep her cheered up, and see that everything is made easy for her. Do all you can to take my place here at home. Yes, Blue Robin, you be the home soldier. Gee whiz, you be the home guard!” added the boy in a sudden burst of inspiration.

“The home guard! Yes, that’s what I’ll be,” cried the girl, her eyes lighting with a sudden glow. “And then I’ll be doing my bit, won’t I? I’ll cheer up mother, and do all I can,” she added resolutely; “and don’t worry any more, Dick, for now,”—the girl drew 25 a long breath, “I’ll be on the job as well as you.”

And then Nathalie, with a wave of her hand at the boy as he stood gazing up at her with his eyes fired with loyal determination, hurried up the stairs, straight on and up to the very top of the house to her usual weeping-place, for, oh, those hateful tears would not be restrained, and if she did not have her cry out she would strangle!

Ah, here she was in her den, the attic. Dimly she reached out her hand and pulled the little wooden rocker out from the wall and slumped into it, and a minute later, with her face buried in the fold of her arm, as it rested on the little sewing-table, she was weeping unrestrainedly.

Presently she gave a sudden start, raised her head and listened, and then was on her feet, for, oh, that was her mother’s step,—she was coming up after her. Oh, why hadn’t she waited until she had a hold on herself. The next moment the little wooden door with the padlock opened, and Mrs. Page was standing in the doorway gazing down at her.

“Why—oh, mother!” Nathalie cried in surprise and wonder, for her mother was smiling. The girl’s eyes bulged out from her tear-stained face in such a funny way that her mother broke into a little laugh. Then her face sobered and she came slowly towards her.

“No, daughter mine, mother is not weeping. Yes, 26 I heard what you and Dick said, and you are patriots, and have shamed mother into trying to be one, too.” Mrs. Page took the girl in her arms with tender affection.

“And Dick is a dear lad. Oh, Nathalie, in our grief at the thought of parting with him,—perhaps of losing him,—” her voice weakened slightly, “we have forgotten that he has been fighting a greater battle than we.

“It is surely a great thing,” continued Mrs. Page sadly, “for a young man in the buoyancy of youth and the very heyday of life, to give it all up. For youth clings more tenaciously to life than older people do, for to them it is an untried and shining pathway, flowered with hope, anticipation, and the luring glimmer of unfulfilled aims and ambitions.

“And then to have to face about,” her voice lowered, “and silently struggle with one’s self in the great battle of self-abnegation, to end by taking this glorious life and casting it far behind you,—this is what makes a hero. Then to face the dread ordeal of a battlefield, and go steadily forward, buoyed only with a feeling of bravery,—the heroism of doing what you believe to be right,—and, taking your one chance for life in your hands,—plunge into the unknown darkness and the horrifying perils of a No Man’s Land.”

There was a stifled sob in Nathalie’s throat, but her mother went steadily on: “No, Nathalie, we must 27 not weep. We must smile and be cheerful. We must inspire Dick with courage and hope, and if it is meant that he is to give his life, we must let him go with a ‘God speed you,’ his memory starred with the thought of a mother’s love and a sister’s courage, and with the soul-stirring song of the victor over death.

“And, Nathalie, Dick belongs to God; he was only loaned to me,—to you,—and if the time has come for God to call him home, we must not complain. We must gladly give him back. Then we must remember, too,” went on the patient mother-voice, “that, after all, life is not the mere living of it, but the things accomplished for the betterment of those who come after. And if Dick has been ‘on the job,’” Mrs. Page smiled, “no matter how small his share in this great warfare for the right, he will be the better prepared to enter into the Land where there is no more suffering, or horrible war, but just a glorious and eternal peace.”

The last word was almost whispered, but, with renewed effort, she said: “Now, Nathalie, let us be brave, as father would have had us,—the dear father,—and go down to Dick with a bright smile and inspiring words of cheer.” Mrs. Page bent and kissed the girl lightly, but solemnly, on the forehead, and then she had turned and was making her way towards the door.

“As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

Nathalie sat in the big rocker on the veranda, sewing a star on a service-flag. Yes, as soon as Dick had gone to do his “stunt,” as he called it, in the great warfare,—gone with all the honors of war, as his mother had laughingly declared as he kissed them a noisy good-by,—Nathalie had felt that it was incumbent upon her to sustain the honor of the family, and had run lightly up to the attic. Here, in the big piece-trunk she found a bundle of Turkey red, a bit of white, and then, after begging a snip of blue from Helen for the star, she had set to work.

She was sure that star would not come off, for she had double-stitched into every angle and on every point. She held up the patriotic square, bordered with red, and sorrowfully stared at that one lone star, although a thrill of pride stirred at her heart and caused her eyes to beam.

She must hang it up. And then she was busy tacking the little flag to a small staff, which she had fastened to the roof of the porch so it could be seen. 29 Ah, the wind had caught it, and it was waving in a salute to its many mates curling from the neighboring porches, and to the Red Cross insignias that starred a window here and there, ofttimes overshadowed by the graceful sweep of the Stars and Stripes.

But Nathalie’s heart was still sore, for although she had given up Dick with as good a grace as she could muster, and had tried to show that she possessed the true American spirit, yet it did seem as if it was a needless sacrifice. With a sudden turn on her heel, the girl burst into a new patriotic air that she had heard somewhere, as if hoping that it would drive away the rebellious thoughts that jarred her attempt at cheer, and hurried into the kitchen.

As Nathalie stepped to the window and stared carelessly out, her eyes were caught by the gleam of yellow crocus and purple hyacinth as they peeped up at her from their beds of green. Somehow their flaunting colors reminded her of the spring blooms that used to nod so gayly to her from the flower-beds in her beautiful city home in the upper part of New York.

She could hardly believe it was a year since her father’s death. The poignant grief she had suffered then again caused her eyes to fill with tears, and her mind dwelt upon the sorrowful circumstances surrounding her loss, the changes that had followed, in their financial losses, and the many sacrifices it had entailed.

30 She again saw the sorrowful farewell to the first and only home she had ever known; she again felt the grief that came to her in the giving up of the many things that had made life so happy,—her schoolmates, her many enjoyments, and her hope of going to college. She again experienced the dolefulness that had assailed her mother, her brother Dick, her younger sister, Dorothy, and herself, on their coming to the humble cottage home in Westport, the being associated with strangers, and the many people who at first had seemed so different from their city associates.

Yes, there was the tree where she had found the nest of bluebirds. The girl’s eyes gleamed amusedly as she peered down the garden at the old cedar tree, and remembered that she had called them blue robins, thus giving Dick an opportunity to nickname her, Blue Robin.

Nathalie attempted to smile, but the thought of Dick’s going away aroused her slumbering grief, and once more the tears flowed silently down her cheeks. But she bravely brushed them away and went on with her reminiscences,—the remembrance of spraining her ankle up in the woods, and how it had led to her meeting Helen Dame, her next-door neighbor, and now her dearest friend.

How lovely Grace Tyson had looked that day, and dear old Barbara with her near-sighted eyes, and the girls’ favorite, Lillie Bell, with her gracious charm 31 and dramatic poses. The girl smiled again as she remembered Edith Whiton, the sport, and her harum-scarum oddities. Yes, they were all dear girls. And how glad she was that she had become a Pioneer, and a real blue robin, by joining the Blue Bird group.

And what a dear Mrs. Morrow, the Pioneer director, was that day the Pioneers called. Oh, that was the day the “Mystic” had passed. Who would have thought she would turn out to be Mrs. Van Vorst, who was so lovely. And that ride with Dr. Morrow to the big gray house, and then she mentally saw herself, with that handkerchief over her eyes, talking to the Princess, Nita, the little hunchbacked girl. And what good friends they had become through those history lessons!

The many useful things she had learned from the Pioneer hikes and crafts, and the joys she had experienced from their many sports and activities had certainly proved worth while. And the “overcomes” she had fought for by adopting the Pioneer motto, “I can,” had certainly meant something in her life.

But they did have gloriously good times at Camp Laff-a-Lot at Eagle Lake, with the Boy Scouts, Miss Camphelia, Miss Dummy, and all the other good sports. Then, too, there was the surprise, on her return to learn the good that had come to Dick through the money so kindly loaned by Mrs. Van Vorst. Indeed, that one year had brought many new things into her 32 life, for—O dear, there was all that silver to be cleaned! For, now that her mother kept no maid, this duty, with many other menial tasks, had devolved upon Nathalie. Oh, how she hated that job!

With a resigned air, however, she managed to carry the basket of silver from the sideboard to the kitchen table, and then returned to the dining-room for the tea-service. After getting her cleaning cloths, her brushes, and the scouring-powder, with vigorous determination she began to rub and polish.

But somehow everything acted aggravatingly mean, for she dropped the polish, and the powder flew all over; then she knocked the tray and the knives and forks clattered to the floor. O dear! what ailed things anyway? And how her arms ached trying to polish those horrid tarnished stains on the teapot! The tableware had never seemed so obdurate, nor the means for making it bright so utterly ineffective.

“Oh, I guess I am the one who is ailing,” she exclaimed glumly, as she suddenly realized that her mind was not on her task, and that the elation of playing at being a patriot had departed, with Dick evidently, leaving her as limp as a rag. Oh, it does seem such a shame that we had to get into that war—Nathalie bit off her thought like a thread, resolved not to let her mind dwell on that forbidden topic. But how angelic her mother had acted when Dick went. Well, she was a dear, anyway, so brave. But suppose he never 33 should come back after all. Something suddenly seemed to snap in the girl’s breast, and down went her head on the tray, into a heap of powder, while a great sob strangled out of her throat.

O horrors! Nathalie’s brown head bobbed up from the tray, not very serenely either, for she had heard a step on the kitchen porch. Oh, Helen always came in that way! “Where is my handkerchief?” The girl grabbed desperately at something white lying on the tray, dimly seen through a blur of tears, and began to scrub her nose energetically with alas, not her handkerchief, but the powder-cloth with which she had been polishing the silver! “Ah chee! Ah chee!” sneezed Nathalie again and again, while groping frenziedly, but blindly, for her handkerchief. She must have dropped it. And then Helen’s arms were around her, and she was kissing the flushed cheek.

“What’s struck you, honey girl?” she asked in that gentle way of hers. “Have you got the influenza? But here’s a very necessary article at times, if that’s what you’re after,” she finished with a laugh, as she stooped and picked up Nathalie’s handkerchief from the floor.

“Influenza? No,” blurted out Nathalie savagely, tortured to a pitch of desperation at her unfortunate predicament. “I’ve been rubbing my nose with that dirty old piece of rag I clean the silver with. Serves me right, I suppose, for being such a fool as to cry 34 when I should be ‘on my job,’ as Dick says.” She shamefacedly tried to hide her red eyes from her friend’s keen gaze.

“Oh, well, it will do you good to cry, Nathalie, dear,” advised Helen softly, as she stroked the brown head caressingly, “for you were quite a heroine when Dick went away, so courageous and cheery. Mrs. Morrow says you are the nerviest Pioneer she knows.”

“But I’m not,” confessed Nathalie honestly, “in fact, I’m beginning to think that I’m a bluff. But anyway, I’m glad to get a bit of praise, something to warm me up, for I have felt like a congealed icicle for the last few days. Yes, I have smiled and smiled like the poor Spartan boy, while the fox of Grief was gnawing a hole into my internals. That sounds like one of Lillie Bell’s dramatics, doesn’t it?” she smiled pathetically into her friend’s kindly eyes.

“But, Helen, you are a dear, anyway,” cried Nathalie in a sudden burst of admiration for her tried and trusted friend, who was always such a stanch and timely comforter. “And do you know,” she added, swinging about in her chair with the teapot in one hand and the despised polishing-cloth in the other, “you grow better-looking every day. Oh, I think you are just lovely!”

“I lovely?” mocked Helen, opening her eyes in surprise at this unexpected praise. “Well, Blue Robin, what started you on that trail? You must have been 35 kissing the Blarney Stone, for you are handing me out ‘the stuff,’ as the boys say, for fair. Poor me, with a knob on my nose, a wide mouth, and green eyes—to call me lovely is a libel on the word.”

“Oh, Helen, your eyes are just lovely—every one says that, for they are so expressive,” retorted her friend loyally; “and as for the knob on your nose, no one would know it was there if you weren’t constantly telling them about it. But I don’t care what you look like anyway,” she added determinedly, “for I think you are a love of a friend. But when do you go to France?” she finished abruptly.

“I don’t quite know yet,” replied the girl; “perhaps not until a month or so. But mother is brave about letting me go. She says it will be a fine experience for me,—as long as I don’t have to go ‘over the top.’ Oh, you finished your service-flag! It’s a Jim Dandy!” Helen plunged recklessly into another topic, again blaming herself for her trick of alluding to forbidden subjects, for she had seen Nathalie’s lips quiver as she said “Over the top.”

“Yes, I finished it, and now the neighbors know where we stand, even if you consider me a pacifist,” said the girl a little defiantly. “Well, perhaps I shall think differently some day,” with a quickly repressed sigh.

“Yes, and that day is coming very soon, too, Blue Robin,” rejoined Helen; “for I’ll bet you a box of 36 candy that you won’t be a pacifist after you hear Mrs. Morrow talk on liberty. Surely you haven’t forgotten that we are to go to a Liberty Tea at her house this afternoon?” she inquired as she saw her friend’s face settle down into an expression of gloom.

“Oh, I don’t think I’ll go,” retorted Nathalie quickly, “for I don’t feel a bit Pioneery this morning, and then I have all this silver to clean.”

“But, Blue Robin,” returned her friend cheerily, “I’m going to help you finish up that silver, and then I’m going home to dress for this afternoon. Then I’m coming over here and just make you go to that Liberty Tea with me. You know, Nathalie, it would be mean for you to desert Mrs. Morrow,” she added wisely, “for you are the leader of the band and should help to entertain the girls.”

Whereupon, Helen caught up one of Nathalie’s kitchen-aprons, and a few moments later the two girls were laughing and chatting in the best of spirits, as they rubbed and polished with youthful ardor, every bone and muscle keyed to its task.

Yes, it was enlivening to be so warmly welcomed by her hostess, Nathalie decided, as she greeted her a little later in the afternoon, and her depression vanished. And how perfectly lovely Mrs. Morrow looked in that blue gown; yes, it was just the color of her blue-gray eyes. Under the fascination of this lady’s charming personality Nathalie was soon flying about, 37 showing the girls how to start sweaters, or to purl, as this task had been delegated to her by the director, who herself had taught Nathalie.

When the tea was served it was Nathalie who occupied the place of honor at the little tea-table, decorated with the United States flag, and who dispensed the dainty little china cups filled with what was patriotically called Liberty Tea in honor of the young ladies who had given it its name over a hundred years ago, and who the Pioneers had impersonated last year in their entertainment of “Liberty Banners.”

After the teacups had been removed, and one or two announcements of coming events had been made, Mrs. Morrow, with sudden gravity, said:

“We have gathered here to-day, girls, to commemorate the Spirit of Liberty, the one great principle that has budded like Aaron’s rod, and brought forth other qualities as splendid and compelling as itself, as, for example, the principles represented in our national emblem. The principle of humanity, which means living the Golden Rule by taking thought for your neighbor; democracy, the equal rights of mankind, which in turn gives rise to justice, loyalty, and unity,—the principles that have not only given us that wonderful, mystical something called Americanism, but the principles that mean the Christianity of Christ.”

After the girls had discussed the meaning of liberty and summed it up as standing for man’s right to self-expression, 38 either by words or actions, and made it clear that it had to be governed by the law of self-control, as too much freedom would mean license or lawlessness, Mrs. Morrow continued her little talk.

“Liberty is not something that sprang into being with the coming of the settlers to America, for it is as old as man himself; but under the rule of king-ridden states it has been fighting its way through many long centuries, because the peoples of the Old World failed to grasp its meaning.

“Under the stimulus of the Reformation and the Revival of Learning, induced by the printing of the Bible and other books, the early comers to America, as they endeavored to worship God as they thought right, not only left the intolerant forms and bigoted narrowness of the Old World, but threw the first light on liberty by teaching man his right to freedom of the soul. The Pilgrims and Puritans were the Pioneers of liberty, for they not only gave us religious freedom, but, by establishing a government for and by the people without the aid of king or bishop, laid the cornerstone of a great commonwealth, and gave us democratic liberty.

“If you girls would make a study of the history of the Thirteen Colonies,” went on their director, “you would learn that not only each Colony contributed to the principles embodied in every stripe, star, and color of our spangled banner, but that a universal love of 39 freedom seems to have animated the settlers. Each individual group, to be sure, had its own peculiar belief, but, in the working-out of their cherished ideals and aspirations, liberty was the bone and sinew of every colony.

“It was under the influence of these early settlers—the giving of their best to mankind in their struggles for freedom—that the ideals and beliefs of the New World were molded into higher and better institutions, purified and strengthened by a new significance. Their ideals and aspirations were essentially different from anything known before,—ideals peculiar to this soil, which were absolutely American, not only in religious freedom, but in the institutions of local government and the union of all states into one, which gave rise to the United States of America.

“Now we have come to the great subject of the hour, the war, and a question I have heard several of you girls ask, ‘Why are we in the war?’”

Nathalie felt her face redden, and shifted uneasily in her seat. O dear! she did wish she had not come. Of course the talk was very interesting, but still she didn’t want to think of this terrible war.

“I have heard it said,” pursued Mrs. Morrow, “that we are in the war to avenge the sinking of the Lusitania, and that we must not allow the Germans to break the international law by killing our sailors and seamen. I have heard it said, too, that if they conquered 40 the Allies they would come over here and fight us. These are all sufficient reasons in a sense.”

The lady paused, and then, with grave solemnity, said: “And I have heard it put forth that we are in the war to maintain our national honor and integrity. I think I hear some of you girls say, ‘But we haven’t done any wrong: we have kept neutral; our principles are not involved.’”

Nathalie’s eyes were aglow as she bent forward, and with parted lips anxiously awaited Mrs. Morrow’s reply to this question.

“Now that we realize the depth and grandeur of the principles given to us by the founders of this nation, and know that every time our flag is unfurled it tells the world that religious and democratic liberty were born on these shores of America, are we going back on these principles? Are we going to allow other nations to say that our principles are just in the flying of our colors, that they stand for nothing but self-praise and the nation’s glorification?

“No,” cried the lady with grave emphasis, “by our love for our flag, by our love for our birth-land, by our reverence for the men who taught us these principles we swear to defend every time we hoist our colors, we must get into this war. We must prove that our flag is in the right place, and that we carry it in our hearts. We must strive to show with our 41 soul’s might that we are living these principles by being true to ourselves and to our nation’s honor, and carry our feelings into action.

“We must forget self, our desire for selfish ease and pleasure. We must align ourselves with the suffering masses of people across the sea, and help them to rid themselves of the iron-shod heel of one-man power. We must stand side by side with the Allies for humanity, democracy, and liberty. We must show the world that the so-called divine right of kings is a worn-out belief of savagery, and prove by the principles back of our flag, prove by the living of these principles, the sacredness of God’s heritage to man, the right of the world’s people to know, as we know, the principles that have made us the freest people in the world.

“Each one of you girls must not only do your bit, but must give of your best to your brothers and sisters over the sea. And if the best means the giving-up of those who are so dear to us, we must prove that we are true daughters of liberty, and send them forth cheerfully, to give freedom and liberty to the world.”

There was an impressive silence, and then Mrs. Morrow’s voice broke into song. In another moment the girls had joined their voices with hers, and were loudly sounding forth the old-time tune and the well-beloved words:

42

“In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in his bosom that transfigures you and me;

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

“He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before his judgment seat;

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet;

Our God is marching on!”

Later in the afternoon, as the girls hurried happily out from the white house on the corner, each one chatting merrily, intent on telling what she had done or intended to do for the war, Nathalie alone was silent, weighed down, as it were, by a strange sense of shame. Yes, she had been blindly selfish, and had failed to realize the momentousness of the great questions of the day. When she had been called upon, to give love and sympathy to her neighbors, the poor suffering masses of people over seas, she had selfishly turned her back to the call—she had failed to show herself a daughter of liberty. Why, she was not a patriot,—no, not even an American; and in the spirit, if not in the letter, she had dishonored Dick, yes, and her father, who had always been so steadfast and true to everything that was American.

That night Nathalie could not sleep, but tossed restlessly from side to side, as parts of Mrs. Morrow’s speech kept forcing themselves upon her memory. And just as she had succeeded in driving them away, 43 and also the remorseful thought that she had not given her best, that she had failed to show greatness, the song the girls had sung that afternoon, with the luring, old-time air and the soul-stirring words, flashed with vivid distinctness:

“As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.”

The girl sat up in bed, and in a crooning whisper hummed the whole verse through, repeating again and again,

“As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

The beauty as well as the significance of the words had made their appeal. Christ had died to make men holy; she must give of her best to make men free. She must show herself great, but what could she do?

But even as the question came, so flashed the answer, and Nathalie was again softly humming,

“Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet;

Our God is marching on.”

And then suddenly a thought stamped itself upon her mind. The girl caught her breath. Yes, she had given Dick up because she had been forced to do so, but now she would make the sacrifice, give the best of herself; she would stop once and forever all useless repining. She would keep herself cheered by the 44 thought that she was glad—she gritted her teeth determinedly—that she had Dick to give to help make people free.

Yes, but she must do something—she must give her best; no, it might not be anything very great or big, but she must show she was a true daughter of liberty. Ah, she knew what she could do, and then Nathalie fell back on her pillow, and although she lay very still, her brain was alert, thinking and planning. Yes, she could get the girls together; she would begin the very next morning. She would have every one in it, for liberty wouldn’t be liberty unless it was free to all. And then one thought and another kept popping into her mind, until finally the tired brain went on a strike and refused to register any more thoughts, and Nathalie, without a word of protest, tumbled into the land o’ dreams.

The next morning she was up betimes, and was soon singing cheerily at her work, every now and then stopping in the midst of some favored melody, to repeat softly,

“As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

In such a state of cheerfulness time flew swiftly, and soon Nathalie was up in the attic writing a note. Yes, it sounded all right, she decided as she read it over slowly. And then her hand was again flying 45 over the paper, and another note was written, and then another, and still another, until, with a sigh of relief, Nathalie found that she had them all finished. No, she wasn’t going to leave any one out. Quickly gathering up the notes the girl was off, running lightly down the stairs, and then flying swiftly across the lawn to see what Helen would think of the thing she had planned in the stillness of the night.

“Yes, we must prove that we have the true spirit of liberty, the spirit of humanity,” Nathalie spoke very earnestly, “and that is why I have asked Marie Katzkamof to belong to the club. She is the little lame girl, you know who she is; she sits at the news-stand on the corner of Main and West streets, and sells the papers when her father is at business. She is always knitting—sweaters for the soldiers, she says. It makes me feel ashamed when I realize how hard she works to do her ‘little bit.’”

“You are right, Nathalie,” replied Helen thoughtfully, “for you have struck something big in your idea that we are all Americans, and that the club should be free to all. But hurry over, and see what Mrs. Morrow has to say. I believe she’ll think the whole scheme is fine.”

But Nathalie was already at the door, her brown eyes sparkling with suppressed excitement, and her cheeks flushed with the soft pink that all the girls admired, and some envied. And then she was making her way across the road to the white house on the corner, still softly humming,

47 “As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

The Tuesday that Nathalie had designated in her notes to the invited girls had arrived, and the girl, somewhat pale from nervousness, was standing before a small table in the living-room of her home. Facing her were a dozen or more girls, all more or less in an attitude of expectant interest as they sat, some on chairs, others on the couch in the hall, while the Pioneers, as was their wont when chairs were limited, were seated in a circle on the floor.

“Now, girls,” cried Nathalie, determined to plunge ahead and get the thing started before her enthusiasm and nerves collapsed to a frazzle, as she told Helen afterward, “I have asked you all here to-day, to form a club in the interest of liberty. The Girl Pioneers know just how big a thing liberty is, for they had the pleasure of hearing Mrs. Morrow, our Pioneer director, in her little talk on liberty. Oh, Lillie Bell, would you mind repeating what you remember of Mrs. Morrow’s speech?” Nathalie broke off abruptly, turning towards that young lady, one of the most popular of the Pioneer girls. “I know you have a good memory, Lillie,” Nathalie pleaded, “and are such a good elocutionist that you can do it better than any one else I know.”

This calling upon Lillie Bell was a stroke of finesse on the part of Nathalie. For Lillie, when she had 48 learned that the club was to be so democratic that the daughter of her newsdealer, a Russian Jew, had been invited, had loftily declared that although she was a good American, and wanted to do all she could for liberty, well, she didn’t know that she cared to chum with all the Jews in the town.

Nathalie had been keenly alive to the desirability of having Lillie a member, because she was not only bright and efficient, but because she was such a good entertainer. This declaration of Lillie’s, however, had caused her spirits to fall below zero, and she began to fear that the whole thing would prove a fizzle. But when so many girls had responded to her invitation, all keyed to expectant curiosity—Lillie among them—her spirits had taken a leap into the nineties. Immediately her alert mind had begun to plan in what way, and how, she could interest Lillie in the club, so that she would take an active part in its doings. And here was her chance.

Lillie Bell, with her usual timely poise, gracefully and smilingly rose to the occasion. In her most luring manner she not only repeated Mrs. Morrow’s speech, but interpreted it with such a stirring American spirit, that not only was Nathalie electrified, but the whole audience were inspired to such a pitch of enthusiasm that they broke into hearty applause.

As soon as the clamor subsided, Nathalie cried earnestly, “Now that we all know what liberty means, 49 and the possibilities that lie before us, I propose that we form ourselves into a club to be known as ‘The Liberty Girls.’”

Another outburst of approval brought the speaker to a halt, but only for a moment, and then she went on smilingly, “Well, I am glad that you like the name, for it means something.” Then she briefly told of the seventeen young girls, who, over a hundred and fifty years ago, had formed a club called “The Daughters of Liberty.”

“They did their bit,” smiled the girl, “by sewing all day on homespun garments to prove that the colonies could be independent of the mother-country, and swore that they would drink no tea until the tax had been removed. They also declared that they would have nothing to do with any of their young gentlemen friends who dared to drink the detested beverage.

“But, girls,” said Nathalie rather hurriedly, as she stepped from behind the little table, “if we are to form ourselves into a club, we shall have to have a chairman, for although the idea originated with me, that does not mean that you have got to have me for a leader,” she ended modestly.

“But we don’t want any one but you,” called out some one enthusiastically, which cry was so emphatically echoed by others, that Nathalie stood hopelessly bewildered, a wave of color dyeing her face a rose-pink.

50 But in this crucial moment Helen came to her rescue, and jumping on her feet cried,—even Lillie, Grace, and Edith bobbed up too,—“Girls, I make the motion that we form ourselves into a club to be known as ‘The Liberty Girls,’ and that we elect for president, Miss Nathalie Page. All in favor of this motion stand up!”

There was a quick, simultaneous movement of many feet, and then, as Helen sensed that Nathalie had been duly elected leader by her mates, she called out, “Well, Nathalie, you will have to be president, for every one wants you.”

“Yes, and we won’t have any one else,” added Edith quickly, with a sudden clap of her hands. This was the signal for the girls to start up a loud clapping in approval of the newly elected president, whose rose-pink cheeks had deepened to scarlet as she stood bowing, somewhat confusedly, to them.

Whereupon Lillie Bell gracefully came to the fore, and dramatically seizing the hand of the young girl while leading her back to her seat, in an impressive manner cried, “Allow me, Miss Nathalie Page, to lead you to the seat of honor, as the president of the club, ‘The Liberty Girls.’”

Nathalie bowed and laughed with embarrassment, but she determined to carry off the honors bestowed upon her with a good grace, and as soon as the somewhat 51 noisy demonstrations of pleasure from the girls had ended, she said modestly, “Girls, I thank you for wanting me to be your leader, and only hope I will make a good one.”

There was more plaudits, and then Nathalie, with grave seriousness, said: “Girls, now that we have pledged ourselves not only as a club, but as individuals, to further the cause of liberty, I would suggest that our watchword be, ‘Liberty and humanity—our best.’ Humanity means to be helpful and kind to our neighbors, our best means to work with a strenuous will to do everything we can to that end. Our neighbors at the present moment loom very large and big as the needy and suffering ones overseas, as the sick, the wounded, the dying, the prisoners, the refugees, and all those who are fighting on land and sea: yes, and those in the air, and all those who are helping to care for the ones I have mentioned, as the doctors and nurses, for they, too, all need help. If we can’t fight, we have got to help those who are fighting in our stead. Yes,” she added solemnly, “and we must be prepared even to have the desire to do what we can for our enemies, for as liberty makes no discrimination as to who shall enjoy it, so in the doing of humane acts we should remember all.”

As Nathalie, highly elated by the enthusiasm shown by her audience, stood waiting for quietness, suddenly 52 her eyes rested on little lame Marie Katzkamof, whose big black eyes shone like two stars from her pale, sallow face. Nathalie had another inspiration.

She bent forward and in a low, earnest voice cried, “Do you think, little Marie, that you would enjoy being a member of this club? Wouldn’t you like to do something—yes, your best—to help the poor refugees in France and Belgium, and the brave soldier boys who are fighting, so that the whole world can enjoy liberty?”

“Yiss, ma’am; I have a glad on liberty,” the girl giggled nervously, “but it’s like this mit me, I likes I shure I don’t make you no trouble.”

“But it won’t be any trouble to us, Marie,” answered Nathalie with a smile. “We will all help you; humanity means to help others.”

“But, Missis Page,” the girl’s face was scarlet, her big eyes mournful. “It’s like this mit me, I ain’t stylish like these young ladies; I make nottings mit them, for I ain’t shmardt, hein? Und this leg it ain’t yet so healthy. Und, Missis Page, I’m lovin’ mit liberty, but I ain’t lovin’ much mit Krisht, for I’m a Jewess.”

Nathalie faltered a moment, for she had seen a smile creep into the eyes of the girls, which she knew would become a laugh if she did not say the right thing. “Yes, you may not love Christ, as we Christians,” she answered quickly, “but if you love the liberty, perhaps 53 you may learn to know what it means to love Him. And then, Marie, that will make no difference, for as long as you want to help the suffering ones, and show humanity, that makes you an American, no matter who, or what you are.”

“Thank you, Missis Page,” the girl’s face had lighted with repressed joy, “sure I’m an American. I can’t do nottings mit the fight, like the soldiers, but you bet yer life I can knit for them, hein?” And the little daughter of Israel held up a strip of wool with its two shiny needles. “Shure und my hands are straight,” she continued pathetically, “even if my legs ain’t healthy.”

Nathalie’s eyes blurred, but she answered smilingly, “Why, that will be lovely, Marie.” Then, turning towards the girls, she cried, “Every one in favor of appointing Marie Katzkamof captain of the Knitting Squad, please hold up her hand.” And every hand went up. “And we’ll call you Captain Molly,” went on Nathalie, “in memory of that brave young woman, Molly Pitcher, who, when her husband fell dead at the battle of Monmouth, during the Revolution, took his place,—she was carrying water to the soldiers,—seized the rammer of his gun, and fired it. And she kept on firing it,” cried Nathalie with glowing eyes, “with the shot and shell flying all about her, until the battle was over. And with that name and the bravery of that Molly—for I know you are brave, Marie—I 54 know you will do your best for liberty, and for the soldiers who are on the firing-line, doing their best, as the Sons of Liberty, for the right of every man in the world.”

After Lillie Bell had been duly elected vice-president of the club, and several other club matters had been disposed of, Nathalie proposed, as an inspiration to the girls, that they form a circle in the center of the room, and stand with clasped hands, to show the interdependence of one upon the other. “Then in turn,” she explained, “let each girl tell of some woman, or girl, who, by her bravery in doing what she could for some one else, or for the world, has given of her best to mankind, and shown that she was a true lover of humanity, and a daughter of liberty.”

The girls, quickly grasping Nathalie’s idea, were soon standing in a circle, hurriedly trying to concentrate their minds on some one woman who had given of her greatness to mankind.

“Can we tell about the Pioneer women?” asked a Girl Pioneer timidly.

“Yes, indeed,” answered the young president, “and we ought to hear about them first, too, for they were the ones who really taught us what it means to love liberty. Although they were not the first women who did great things for their fellow-beings, they were the ones who made clear to us that real liberty means humanity, justice, and democracy for all.”

55 Helen now started the liberty chain by clasping the hand of her neighbor on each side of her and telling of the women of the Mayflower, who, by their acts of sacrifice, and stern determination to worship God as they thought right, gave us religious freedom.

Nita told of the coming of the ship, the Arbella, to Gloucester with John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the two noted Puritan brides, the Lady Arbella and Anne Bradstreet, the latter our first American poetess. And gave testimony of their devotion to Puritanism, and their desire to benefit mankind.

One Pioneer told of America’s first club-woman, Anne Hutchinson, portraying her trial and banishment from Boston, in her efforts to benefit mankind by teaching them freedom of thought. Another told of Mary Dyer, the noted Quakeress, and how she was hanged from an old elm on Boston Common because she believed in freedom of religion.

Margaret, the wife of John Winthrop, the governor, and Susannah, the mother of John Wesley, both beloved for their sweet piety and charity, were cited as examples of having given of their best in being the ideal wife and mother. Lillie Bell told of Florence Nightingale, the young English woman who gave up a life of luxury to help the soldiers during the Crimean War in 1854. She became known as “The Lady of the Lamp,” from a statue of her as she stands with a 56 nurse’s lamp in her hand, erected in a church in London.

A Girl Scout told of Dorothy Dix, that wonderful woman who made it her life-work to visit prisons and insane asylums, in order to institute reforms for the care and comfort of the inmates. She also did much for the relief of wounded soldiers during the American Civil War.

Jenny Lind, the great Swedish singer, was cited as having given to humanity when she gave her time and voice to raise thousands of dollars for the benefit of broken-down musicians and writers. Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe gave of her best, Edith declared, when she wrote her book, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” and showed the world the evils of slavery; as also Mrs. Julia Ward Howe when she wrote that wonderful patriotic song, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The two noted women astronomers, Caroline Herschel and Maria Mitchell, when they studied the heavens in the interest of science, gave of their best. Also Charlotte Cushman, the great actress, who raised large sums of money by her acting, and gave it to the Sanitary Fund, during the Civil War, was quoted as a lover of humanity.

The Baroness Burdett-Coutts and Miss Helen Gould, two of the world’s noted philanthropists, as well as Miss Louisa Alcott, in her writings for the youth of America, and other women writers were 57 added to the growing list of Liberty Daughters. Dolly Madison, the beautiful First Lady of the Land, showed herself a true American during the War of 1812. When the British burned Washington she refused to leave the White House until the portrait of Washington was carried to a place of safety, while she herself took the Declaration of Independence, with its autographs of the signers, away with her, so that it would not be lost to America.

Even Marie, alias Captain Molly, caught the inspiration of the Liberty Chain, and told of a young Russian girl, who, rather than betray the secrets of a great man, from a paper that had fallen into her hands, allowed herself to be exiled to Siberia. Then came the war stories, as that of the noted Quakeress, Lydia Darrach, who, during the Revolution, on learning the secrets of the British officers who were quartered at her house, endured untold hardship in traveling many miles in the dead of winter to reveal them to the American patrol, so as to save the Continental Army from disaster.

Hannah Weston, who filled a pillow-case with pewter-ware when she heard that a certain town was in need of ammunition, and carried it many miles through the woods at night, was cited for her bravery and her sacrifice, in her effort to help others. The story of Betty Zane and how she ran from the palisade of a Western fort to her brother’s hut for a keg of powder 58 in the fire of a tribe of Indians, although a familiar one, was listened to with glowing interest.

Ruth Wyllis, who hid the charter of Connecticut in an oak tree, and Katy Brownell, the color-bearer at the battle of Bull Run, who stood by the flag in the face of the advancing foe, and who would have been shot to death if a soldier had not pulled her away, were but two recitals of brave deeds for the sake of humanity.

But at last the liberty chain came to an end by Nathalie telling of Saint Margaret, a plain, uneducated Irish woman, who, after losing her husband and child, devoted her life and every penny she made to the cause of orphan children. A statue, she said, had been erected in New Orleans to this noble woman, who gave of her best to humanity when she devoted her life to these little waifs.

After the girls had returned to their seats, Nathalie appointed seven squads. She had made it seven, she said, not only because it was a lucky number, but because there were just seven letters in the name, Liberty. Helen was made the captain of the Florence Nightingale Squad, since she had gained many honors, as a Girl Pioneer, as an expert maker of bandages.

Nita, with a Girl Scout as a running mate, was made captain of the Scrap-Book Squad, which meant the making of scrap-books for the convalescing soldiers in the hospitals. Lillie Bell and a Camp Fire Girl were placed at the head of the Garments Squad for the cutting 59 and sewing of garments for the refugee children of France and Belgium. Two Girl Scouts were made captains of the Flower Squad, with the purpose of raising and selling flowers for the Liberty Loan fund.

Jessie Ford had charge of the comfort-kits for the soldier-boys, while Barbara Worth, who was an expert knitter, was appointed to work with Captain Molly, the Russian Jewess. Nathalie was unanimously chosen as the captain of the Liberty Garden, with Edith Whiton and several other Girl Pioneers. They were not only to raise vegetables and fruits in their garden-to-be, but they were to do canning as well.

After some discussion it was decided that the club members wear a uniform consisting of a white shirtwaist, with the letters L. G. in red on the arm, on the corners of their white sailor-collars, and on the hatbands of their white sailor-hats, and to wear white or khaki skirts.

Nathalie had just appointed a committee to scour the town for a parcel of ground to use as a flower and Liberty garden, when a sudden noise was heard. The girl looked quickly up, to see Mrs. Morrow standing in the doorway leading from the dining-room, with her arms filled with flowers. In her hand was a large bell, which she was jingling softly, while her blue eyes smiled down upon the girls with radiant good-will.

Nathalie stared in amazement, and then, recovering her usual poise, she cried, “Oh, Mrs. Morrow, please come right in, for I want you to meet my Liberty Girls.” As the girl spoke she advanced towards her unexpected guest, who was coming slowly forward, as if not assured of her welcome. But the cordiality expressed in the tones of Nathalie’s voice and the fact that the girls had all risen on their feet,—her own girls at attention in the Pioneer salute,—with their faces aglow with pleasure, quickly assured her that her welcome was a hearty one.

With a sudden movement she turned to Nathalie and asked, “May I have the floor a moment, Miss President?” As the girl assented, although somewhat mystified, Mrs. Morrow took her place behind the small table, and with a quick nod of greeting to the faces upturned to hers, cried: “Girls, I am greatly pleased to see you here to-day, and to know that our Pioneer Blue Robin’s little plan to make you all work with a keener zest for liberty, has succeeded so well. I also want to assure you of my hearty cooperation, 61 and my wish that all of you, those who are Pioneers, and those who belong to other clubs, will be inspired to better work in your own organizations by the fact that you have banded together to stand unitedly as Daughters of Liberty, in order to show that you are all loyal Americans. In proof of my good wishes I am going to present the club with a bell. It is needless to say that it is not the Liberty Bell, but a facsimile in miniature.

“Wait, I have not finished,” laughingly protested the lady as she held up her hand,—for some of the girls had started to clap. “I want you to know before your president rings it,—it is to be rung to call you together in the sacred cause of liberty,—that way up in the top has been inserted a very tiny chip from the real Liberty Bell,—the bell that was rung over a hundred years ago to announce that the thirteen colonies had become the United States of America. I hope, girls, that when you hear this bell ring you will feel the same inspiration to do your best as animated the patriots in the war of 1776.”

As Mrs. Morrow paused, the long-delayed clapping burst forth with such vigor that she and Nathalie—she had drawn the girl to her and was pressing the bell into her hand—had to smile and bow again and again. But the clapping only halted for a space, for when Nathalie saw that quietness reigned, she rang the liberty bell so loudly and determinedly, while a mischievous 62 twinkle glowed in her eyes, that it broke forth again.

As soon as the demonstration was over and the bell-ringing had subsided, Mrs. Morrow’s voice was heard again: “Now, Liberty Girls, I am going to ask your president to take a vote to get your opinion as to who you think told the best story about great women in your liberty chain.

“Perhaps you do not know,” the gray-blue eyes deepened, “but I was in the dining-room, although not purposely an eavesdropper, and had the pleasure of hearing the stories told. I have formed an opinion as to the best story-teller, but would like to know if your opinion coincides with mine.”

But alas, there were so many different opinions as to the best story, and as to who was the best narrator, that to even matters Mrs. Morrow had to take her big bouquet of flowers and divide it into three or four nosegays. But a smile of satisfaction gleamed in the eyes of many when Marie, the little Jewess, received a bouquet and a few words of commendation from the giver. The little captain’s delight was so genuine, and her eyes beamed so joyously, that every one rejoiced with her.

After the flowers were distributed, and the girls had sung a few patriotic songs, they filed out into the sunshine, happily aglow with the joy of the meeting and the inspiration it had brought to them.

63 Several weeks later we find Nathalie coming slowly down the garden-walk with its old-time hedge, from the big gray house. The tall pines—now good old friends—that bordered the path bowed their tops in a cheery good-morning, as she walked beneath their shade.

She had just given her usual morning lesson of two hours to her young friend, for Nathalie, on her return from Camp Laff-a-Lot last summer, had found that her studies with Nita were to be continued. Yes, and she had banked every penny that she could spare from her weekly salary of ten dollars. It had seemed such a big sum at first, but alas, now that her mother’s income had slowly dwindled, and she had been compelled to use it for her own personal needs, and to lay part of it aside every week to repay Mrs. Van Vorst the loan for Dick’s operation, it seemed a mere pittance.

But to-day she felt unusually joyful, for the last penny of that haunting debt had been paid, and she was now free to call her money her own. If there had been many disappointments in life—the going to college was still a luring hope—and self-denials, added to the unpleasantness of doing housework since their coming to Westport, there had been several compensations that had cast their rosy shadows across the darkness.

One was the joy and the profit she had gained from 64 being a Pioneer, and the other was the great pleasure that had come to her in the knowledge that she had a purpose in life. Yes, she had told Helen many times, “I think it is one of the delights of life to be legitimately busy, and to know that you are really doing something that is a help to yourself or some one else.” And now, added to these compensating joys had come the thrills and joys from the new organization, the Liberty Girls, for that little patriotic club now numbered almost a hundred. And it had thrived so well, and Nathalie had gained so many honors from being its founder, that sometimes she feared that she, too, would become a bird of the air, like Dick, only in a different way, from sheer conceit.

But if she had been overmuch praised, and had found it a pleasant diversion to plan and dream over the club’s future successes, she had also found hard work and great discouragement. Discouragement, too, over such small things, when the girl came to face them in the coolness of after-thought, that she had felt like throwing the whole thing up, or else just letting things drift, and taking what pleasure she could, without so much conscientious worry over doing her best.

But through all the storm and stress Helen had buoyed her with the frequent, sensible remark, that if it had taken the world thousands of years to comprehend the true meaning of democracy and liberty, she 65 must expect her girls would be slow in realizing many things. But it was tiresome to hold the reins of government, and yet sometimes be unable to stop their silly chatter, or useless argument over mere trifles, all the while holding back the legitimate work by their dallying.

Yes, and it had been an awful strain to manage that Liberty Garden. Of course the Pioneers were all good workers, and she had given each one some one thing to study over, but still she had had to know about these things herself, so as to be sure they would do the right thing.

But it was something worth while, she reflected sagely, to know that there are three kinds of soil, how to test it with litmus paper to see if it was sour or not, and, if it was, how to neutralize it, or sweeten its acidity. Then she had had to know what kind of chemicals acted as food to the soil, so as to know what each plant or vegetable required to enrich it and to sustain life. She had also learned how to draw moisture from the land and how to fertilize it.

By placing seeds on wet blotting-paper in saucers she had demonstrated how long it would take them to germinate, so as to be able to to write her germinating-table for the girls. How old seeds should be before planting, how deep to plant each kind, the method of planting, and how many seeds to plant, and the distance apart, had all seemed tiresome and trivial things 66 to many, but it was necessary knowledge to a would-be farmer.

Ah, she had reached the bank. She was going to get that ten dollars deposited before it melted away. Suddenly her eyes became pools of brightness, and the dimples twinkled in the red glow of her cheeks, for there, right in front of her, stood Mrs. Morrow, with a kiddie boy, as the girl called the twins, on each side of her. There was such genuine pleasure in the lady’s smiling blue eyes, that Nathalie impulsively cried, “Oh, Mrs. Morrow, this is just lovely! I’m so glad to see you! When did you get back?” for her good friend had been away for several weeks.

“Last night, Nathalie, and I am so pleased to meet you,” was the cordial greeting, “for I have heard so many reports about the Liberty Girls’ club that I am anxious to hear all about it from you.”

“Oh, it is just the dandiest thing, Mrs. Morrow,” cried the girl jubilantly. And then, lured by the kindly interest in her friend’s eyes, her tongue unloosened, and she was soon busy telling about the club’s many experiences, and the good that had come from the industry of its members.

“And Helen is a dear,” Nathalie rattled on, “for she has taught her girls the most wonderful things, and now they have all enrolled as Red Cross members. She had been reading to them from Florence Nightingale’s ‘Notes on Nursing,’ and now she has taken 67 up other works on the same subject. Lillie, too, reads to the girls at the club meetings about great women, while I inspect the work. The Garment and Comfort-Kit squads meet together, and Jessie Ford not only tells them about the French villages and the towns that have been destroyed by the Germans, but reads to them from the ‘Prince Albert Book.’

“We are to have our Liberty Pageant to-morrow, and all the people who live on the line of parade have been perfectly lovely, for they have sold tickets for the seats on their verandas, and are to give the money to us for the Liberty Fund, so we can buy Liberty bonds. And the day after,” continued Nathalie, “we are to have a liberty sale on Mrs. Van Vorst’s grounds, the Pioneers’ meeting-place, you know. Indeed, we are almost over the tops of our heads in work, and we have enough plans to last the rest of the summer. Mother declares I am the busiest girl she knows.”

“And the Liberty Garden, has that turned out well? I understand it is the work of my girls, the Pioneers.”

“Indeed, yes,” returned her companion: “it has been said to be one of the beauty spots of Westport. We have bordered it with nasturtiums, poppies, marigold, sweet peas, and all sorts of old-time posies. But we had a time getting the ground, for this year every one was hysterically wild to cultivate every inch of ground for a war-garden, and nobody wanted to loan any. Finally, however, Edith and Lillie tried their 68 powers of persuasion on old Deacon Sawyer,—you know he’s one of the pillars of the old Presbyterian church, and he let us have an old lot of his on Summer Street, about a hundred feet or so square.

“And how we have worked over it, for of course it had to be plowed. Peter, Mrs. Van Vorst’s gardener,—he’s the kindest-hearted thing alive,—offered to plow it for us, but we declined with a vote of thanks, for we felt that wouldn’t be our work. So Edith scoured the town until finally she borrowed an old nag from the livery-stable man,—he was just ready to crumble to pieces,—and Nita got a plow from Peter, and we plowed it ourselves.

“But the time we had with that old steed,” Nathalie’s eyes gleamed humorously, “for just as he would be going nicely across the field, he would be inspired to take the ‘rest-cure’ and stand stock-still, and no amount of pulling—we all got behind him and pushed—or coaxing would induce him to budge a hair. O dear, we worked over him until we thought we should expire with the heat, our faces all red and perspiring.

“Then Edith took to pulling his tail; she said she had read that would make a balky horse go. Oh, it was funny to see her!” Nathalie laughed outright. “But, dear me, it only made him lift one leg, very slowly, and then the other, and then settle down in the same old rut, as still as the wooden horse of Troy.