Project Gutenberg's The Truth About Jesus is He a Myth?, by M. M. Mangasarian

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Truth About Jesus is He a Myth?

Illustrated

Author: M. M. Mangasarian

Release Date: March 7, 2014 [EBook #45068]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRUTH ABOUT JESUS ***

Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by The Internet Archive

If it is not historically true that such and such things happened in Palestine eighteen centuries ago, what becomes of Christianity? —THOMAS HUXLEY.

By education most have been misled, So they believe because they were so bred; The priest continues what the nurse began, And thus the child imposes on the man.—DRYDEN.

CONTENTS

THE SILENCE OF PROFANE WRITERS

THE JESUS STORY A RELIGIOUS DRAMA

IS THE WORLD INDEBTED TO CHRISTIANITY?

SOME MODERN OPINIONS ABOUT JESUS.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

010 Picture in Herculaneum, of the Days Of Pompeii, Showing Cupid Crowned With a Cross.

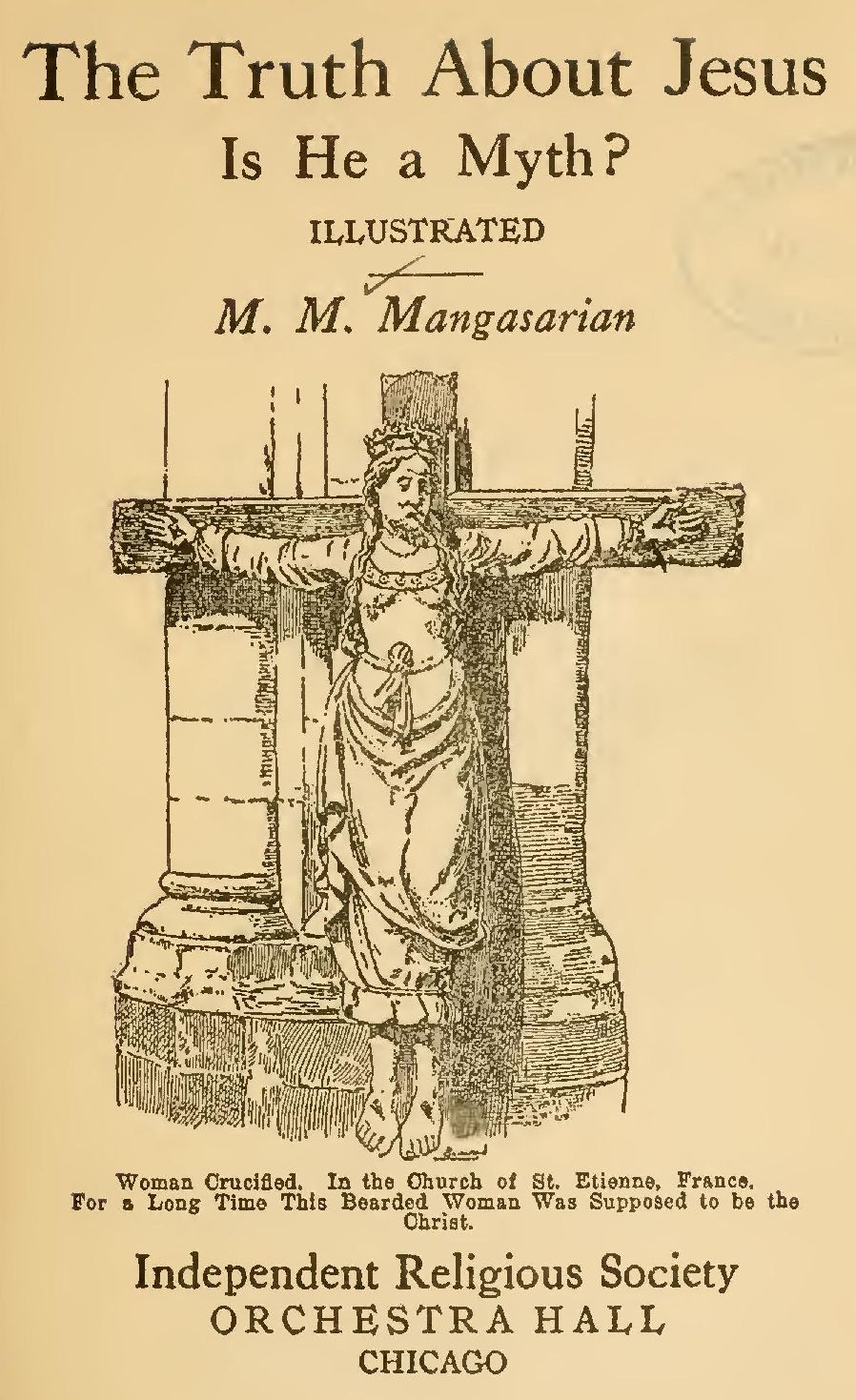

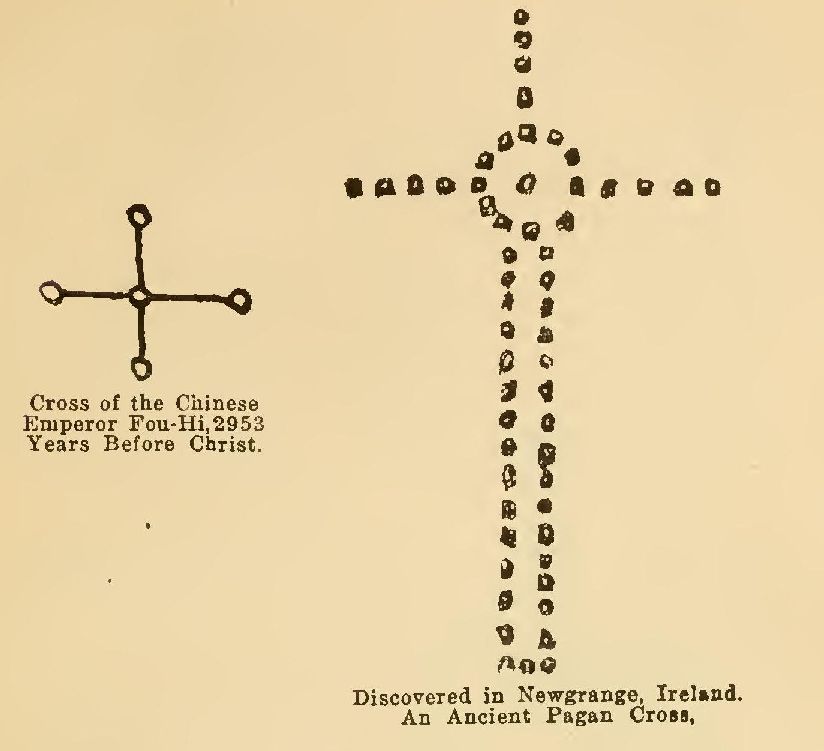

022 Swastika. Earlier Form of the Cross.

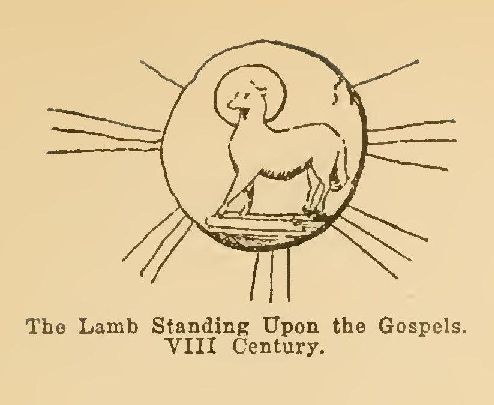

029 the Lamb Standing Upon The Gospels. Viii Century.

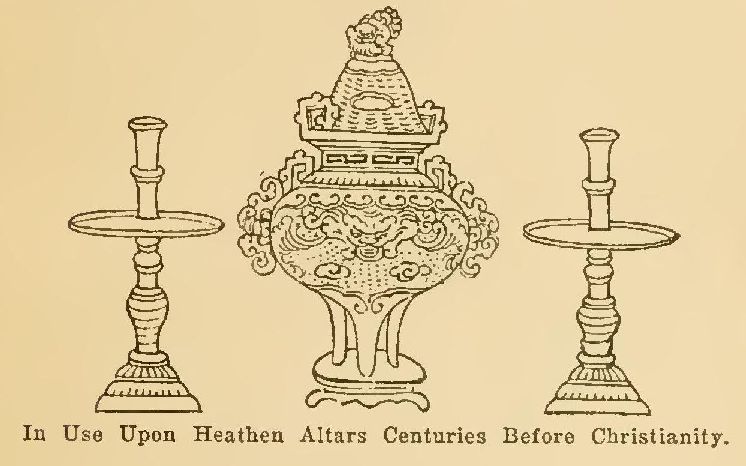

035 in Use Upon Heathen Altars Centuries Before Christianity.

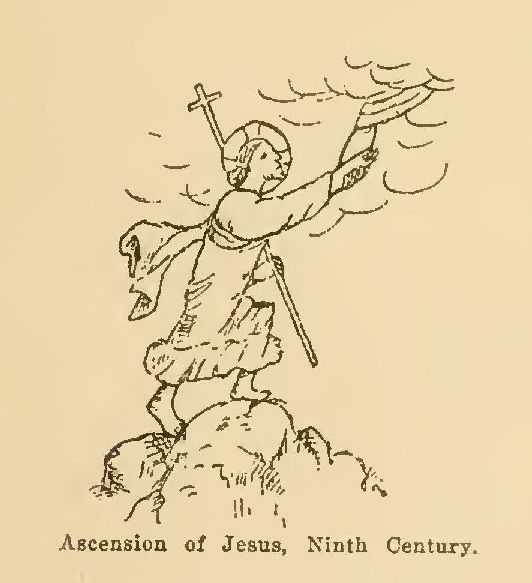

037 Ascension of Jesus, Ninth Century.

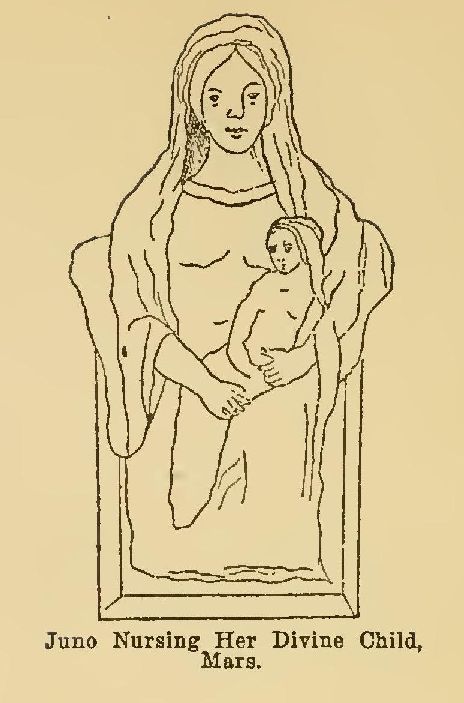

038 Juno Nursing Her Divine Child, Mars.

043 Isis Nursing Her Divine Child, 3000 B. C.

048 the Unsexed Christ, Naked in The Church of St. Antoine, Tours, France.

061 Portion of Manuscript Supposed to Be Copy Of Lost Originals.

073 the Goddess Mother in The Grecian Pantheon.

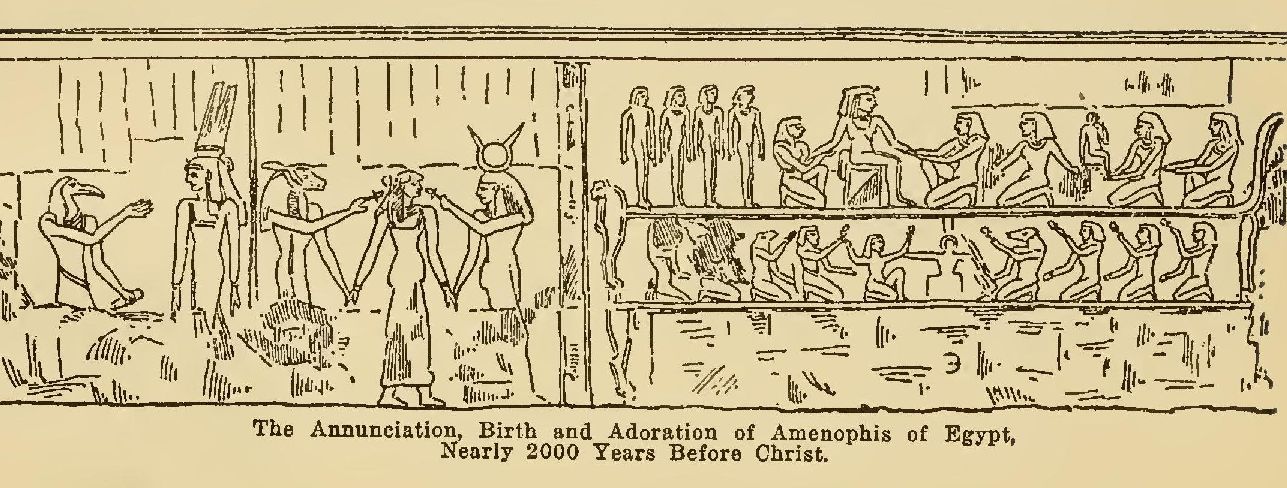

076 the Annunciation, Birth, and Adoration of Amenophis Of Egypt, Nearly 2000 Years Before Christ.

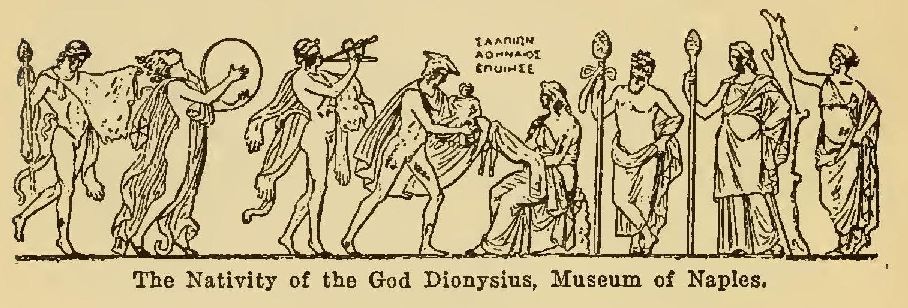

078 the Nativity of The God Dionysius, Museum Of Naples.

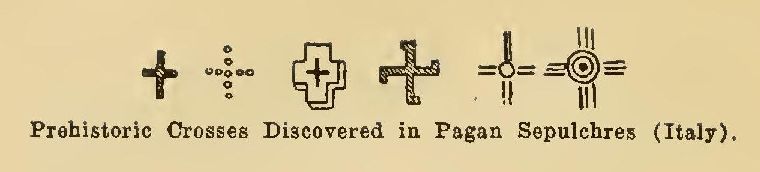

080 Prehistoric Crosses Discovered in Pagan Sepulchres (italy).

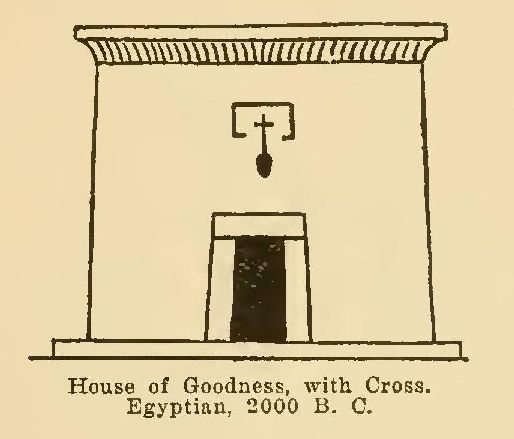

081 House of Goodness, With Cross. Egyptian, 2000 B. C.

082 Pagan Priest of Herculaneum Wearing the Cross.

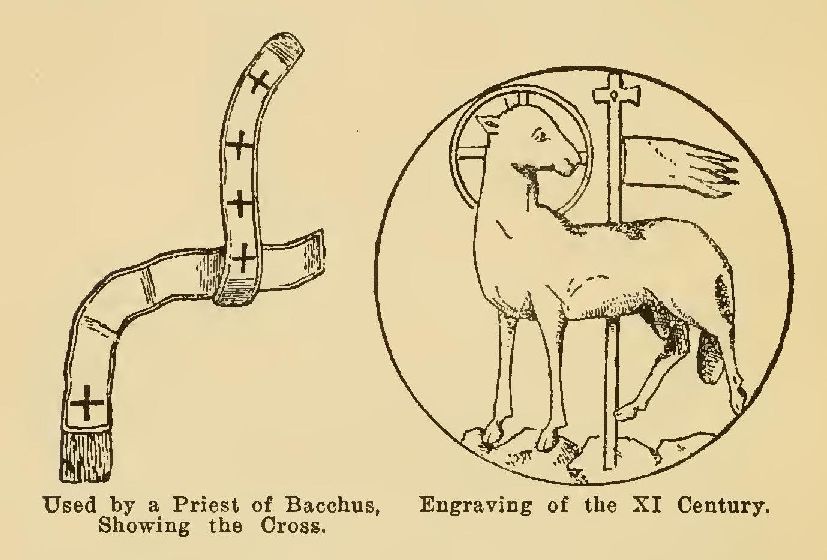

084 Used by a Priest of Bacchus, Showing the Cross.

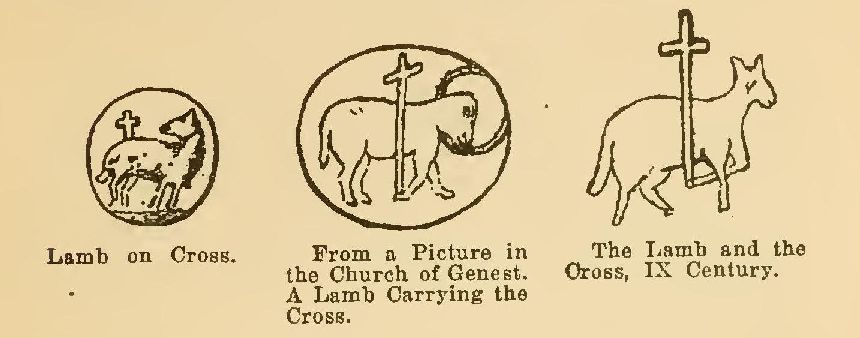

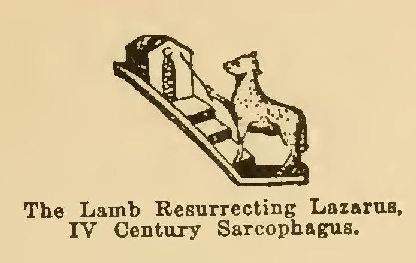

087 the Lamb Resurrecting Lazarus, Iv Century Sarcophagus.

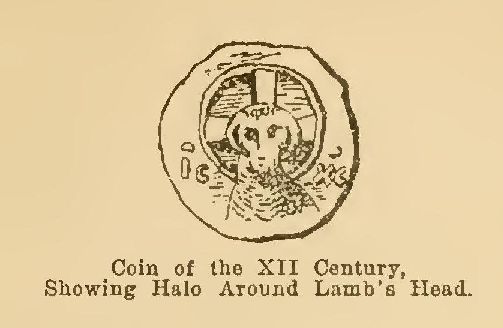

117 Coin of the Xii Century, Showing Halo Around Lamb's Head.

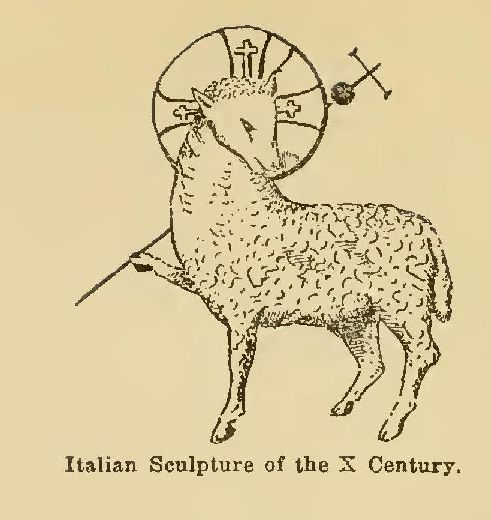

142 Italian Sculpture of the X Century.

170 Engraving of Xv Century Representing the Trinity.

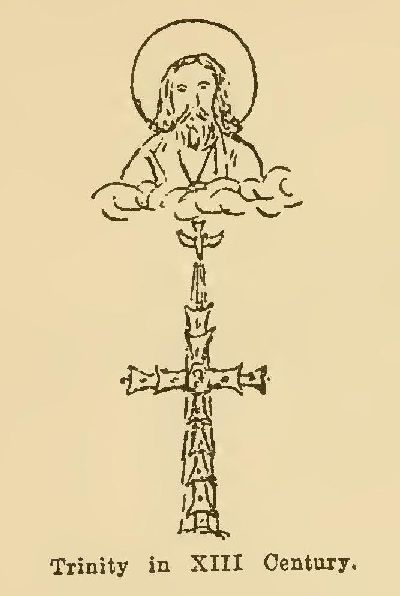

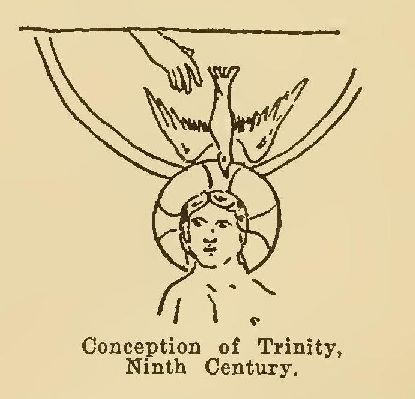

182 Conception of Trinity, Ninth Century.

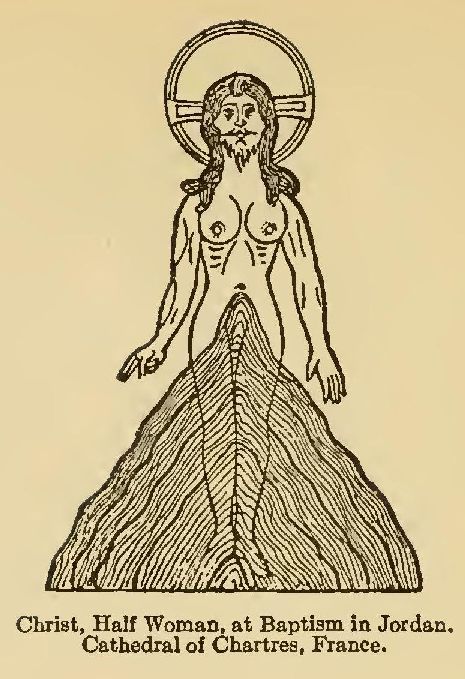

218 Christ, Half Woman, at Baptism in Jordan. Cathedral Of Chartres, France.

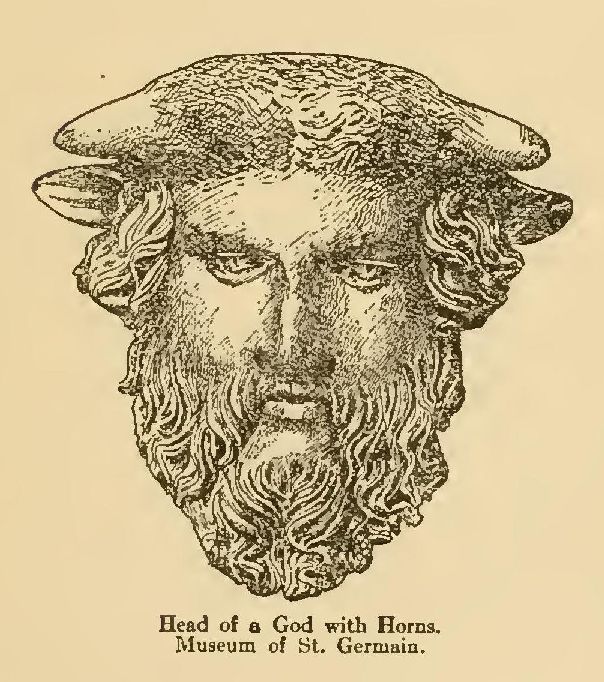

255 Head of a God With Horns. Museum Of St. Germain.

The following work offers in book form the series of studies on the question of the historicity of Jesus, presented from time to time before the Independent Religious Society in Orchestra Hall. No effort has been made to change the manner of the spoken, into the more regular form of the written, word.

I am today twenty-five hundred years old. I have been dead for nearly as many years. My place of birth was Athens; my grave was not far from those of Xenophon and Plato, within view of the white glory of Athens and the shimmering waters of the Aegean sea.

After sleeping in my grave for many centuries I awoke suddenly—I cannot tell how nor why—and was transported by a force beyond my control to this new day and this new city. I arrived here at daybreak, when the sky was still dull and drowsy. As I approached the city I heard bells ringing, and a little later I found the streets astir with throngs of well dressed people in family groups wending their way hither and thither. Evidently they were not going to work, for they were accompanied by their children in their best clothes, and a pleasant expression was upon their faces.

"This must be a day of festival and worship, devoted to one of their gods," I murmured to myself.

Looking about me I saw a gentleman in a neat black dress, smiling, and his hand extended to me with great cordiality. He must have realized I was a stranger and wished to tender his hospitality to me. I accepted it gratefully. I clasped his hand. He pressed mine. We gazed for a moment silently into each other's eyes. He understood my bewilderment amid my novel surroundings, and offered to enlighten me. He explained to me the ringing of the bells and the meaning of the holiday crowds moving in the streets. It was Sunday—Sunday before Christmas, and the people were going to "the House of God."

"Of course you are going there, too," I said to my friendly guide.

"Yes," he answered, "I conduct the worship. I am a priest."

"A priest of Apollo?" I interrogated.

"No, no," he replied, raising his hand to command silence, "Apollo is not a god; he was only an idol."

"An idol?" I whispered, taken by surprise.

"I perceive you are a Greek," he said to me, "and the Greeks," he continued, "notwithstanding their distinguished accomplishments, were an idolatrous people. They worshipped gods that did not exist. They built temples to divinities which were merely empty names—empty names," he repeated. "Apollo and Athene—and the entire Olympian lot were no more than inventions of the fancy."

"But the Greeks loved their gods," I protested, my heart clamoring in my breast.

"They were not gods, they were idols, and the difference between a god and an idol is this: an idol is a thing; God is a living being. When you cannot prove the existence of your god, when you have never seen him, nor heard his voice, nor touched him—when you have nothing provable about him, he is an idol. Have you seen Apollo? Have you heard him? Have you touched him?"

"No," I said, in a low voice.

"Do you know of any one who has?"

I had to admit that I did not.

"He was an idol, then, and not a god."

"But many of us Greeks," I said, "have felt Apollo in our hearts and have been inspired by him."

"You imagine you have," returned my guide. "If he were really divine he would be living to this day."

"Is he, then, dead?" I asked.

"He never lived; and for the last two thousand years or more his temple has been a heap of ruins."

I wept to hear that Apollo, the god of light and music, was no more—that his fair temple had fallen into ruins and the fire upon his altar had been extinguished; then, wiping a tear from my eyes, I said, "Oh, but our gods were fair and beautiful; our religion was rich and picturesque. It made the Greeks a nation of poets, orators, artists, warriors, thinkers. It made Athens a city of light; it created the beautiful, the true, the good—yes, our religion was divine."

"It had only one fault," interrupted my guide.

"What was that?" I inquired, without knowing what his answer would be.

"It was not true."

"But I still believe in Apollo," I exclaimed; "he is not dead, I know he is alive."

"Prove it," he said to me; then, pausing for a moment, "if you produce him," he said, "we shall all fall down and worship him. Produce Apollo and he shall be our god."

"Produce him!" I whispered to myself. "What blasphemy!" Then, taking heart, I told my guide how more than once I had felt Apollo's radiant presence in my heart, and told him of the immortal lines of Homer concerning the divine Apollo. "Do you doubt Homer?" I said to him; "Homer, the inspired bard? Homer, whose inkwell was as big as the sea; whose imperishable page was Time? Homer, whose every word was a drop of light?" Then I proceeded to quote from Homer's Iliad, the Greek Bible, worshipped by all the Hellenes as the rarest Manuscript between heaven and earth. I quoted his description of Apollo, than whose lyre nothing is more musical, than whose speech even honey is not sweeter. I recited how his mother went from town to town to select a worthy place to give birth to the young god, son of Zeus, the Supreme Being, and how he was born and cradled amid the ministrations of all the goddesses, who bathed him in the running stream and fed him with nectar and ambrosia from Olympus. Then I recited the lines which picture Apollo bursting his bands, leaping forth from his cradle, and spreading his wings like a swan, soaring sunward, declaring that he had come to announce to mortals the will of God. "Is it possible," I asked, "that all this is pure fabrication, a fantasy of the brain, as unsubstantial as the air? No, no, Apollo is not an idol. He is a god, and the son of a god. The whole Greek world will bear me witness that I am telling the truth." Then I looked at my guide to see what impression this outburst of sincere enthusiasm had produced upon him, and I saw a cold smile upon his lips that cut me to the heart. It seemed as if he wished to say to me, "You poor deluded pagan! You are not intelligent enough to know that Homer was only a mortal after all, and that he was writing a play in which he manufactured the gods of whom he sang—that these gods existed only in his imagination, and that today they are as dead as is their inventor—the poet."

By this time we stood at the entrance of a large edifice which my guide said was "the House of God." As we walked in I saw innumerable little lights blinking and winking all over the spacious interior. There were, besides, pictures, altars and images all around me. The air was heavy with incense; a number of men in gorgeous vestments were passing to and fro, bowing and kneeling before the various lights and images. The audience was upon its knees enveloped in silence—a silence so solemn that it awed me. Observing my anxiety to understand the meaning of all this, my guide took me aside and in a whisper told me that the people were celebrating the anniversary of the birthday of their beautiful Savior—Jesus, the Son of God.

"So was Apollo the son of God," I replied, thinking perhaps that after all we might find ourselves in agreement with one another.

"Forget Apollo," he said, with a suggestion of severity in his voice. "There is no such person. He was only an idol. If you were to search for Apollo in all the universe you would never find any one answering to his name or description. Jesus," he resumed, "is the Son of God. He came to our earth and was born of a virgin."

Again I was tempted to tell my guide that that was how Apollo became incarnate; but I restrained myself.

"Then Jesus grew up to be a man," continued my guide, "performing unheard-of wonders, such as treading the seas, giving sight, hearing and speech to the blind, the deaf and the dumb, converting water into wine, feeding the multitudes miraculously, predicting coming events and resurrecting the dead."

"Of course, of your gods, too," he added, "it is claimed that they performed miracles, and of your oracles that they foretold the future, but there is this difference—the things related of your gods are a fiction, the things told of Jesus are a fact, and the difference between Paganism and Christianity is the difference between fiction and fact."

Just then I heard a wave of murmur, like the rustling of leaves in a forest, sweep over the bowed audience. I turned about and unconsciously, my Greek curiosity impelling me, I pushed forward toward where the greater candle lights were blazing. I felt that perhaps the commotion in the house was the announcement that the God Jesus was about to make his appearance, and I wanted to see him. I wanted to touch him, or, if the crowd were too large to allow me that privilege, I wanted, at least, to hear his voice. I, who had never seen a god, never touched one, never heard one speak, I who had believed in Apollo without ever having known anything provable about him, I wanted to see the real God, Jesus.

But my guide placed his hand quickly upon my shoulder, and held me back.

"I want to see Jesus," I hastened, turning toward him. I said this reverently and in good faith. "Will he not be here this morning? Will he not speak to his worshippers?" I asked again. "Will he not permit them to touch him, to caress his hand, to clasp his divine feet, to inhale the ambrosial fragrance of his breath, to bask in the golden light of his eyes, to hear the music of his immaculate accents? Let me, too, see Jesus," I pleaded.

"You cannot see him," answered my guide, with a trace of embarrassment in his voice. "He does not show himself any more."

I was too much surprised at this to make any immediate reply.

"For the last two thousand years," my guide continued, "it has not pleased Jesus to show himself to any one; neither has he been heard from for the same number of years."

"For two thousand years no one has either seen or heard Jesus?" I asked, my eyes filled with wonder and my voice quivering with excitement.

"No," he answered.

"Would not that, then," I ventured to ask, impatiently, "make Jesus as much of an idol as Apollo? And are not these people on their knees before a god of whose existence they are as much in the dark as were the Greeks of fair Apollo, and of whose past they have only rumors such as Homer reports of our Olympian gods—as idolatrous as the Athenians? What would you say," I asked my guide, "if I were to demand that you should produce Jesus and prove him to my eyes and ears as you have asked me to produce and prove Apollo? What is the difference between a ceremony performed in honor of Apollo and one performed in honor of Jesus, since it is as impossible to give oracular demonstration of the existence of the one as of the other? If Jesus is alive and a god, and Apollo is an idol and dead, what is the evidence, since the one is as invisible, as inaccessible, and as unproducible as the other? And, if faith that Jesus is a god proves him a god, why will not faith in Apollo make him a god? But if worshipping Jesus, whom for the best part of the last two thousand years no man has seen, heard or touched; if building temples to him, burning incense upon his altars, bowing at his shrine and calling him 'God,' is not idolatry, neither is it idolatry to kindle fire upon the luminous altars of the Greek Apollo,—God of the dawn, master of the enchanted lyre—he with the bow and arrow tipped with fire! I am not denying," I said, "that Jesus ever lived. He may have been alive two thousand years ago, but if he has not been heard from since, if the same thing that happened to the people living at the time he lived has happened to him, namely—if he is dead, then you are worshipping the dead, which fact stamps your religion as idolatrous."

And, then, remembering what he had said to me about the Greek mythology being beautiful but not true, I said to him: "Your temples are indeed gorgeous and costly; your music is grand; your altars are superb; your litany is exquisite; your chants are melting; your incense, and bells and flowers, your gold and silver vessels are all in rare taste, and I dare say your dogmas are subtle and your preachers eloquent, but your religion has one fault—it is not true."

I shall speak in a straightforward way, and shall say today what perhaps I should say tomorrow, or ten years from now,—but shall say it today, because I cannot keep it back, because I have nothing better to say than the truth, or what I hold to be the truth. But why seek truths that are not pleasant? We cannot help it. No man can suppress the truth. Truth finds a crack or crevice to crop out of; it bobs up to the surface and all the volume and weight of waters can not keep it down. Truth prevails! Life, death, truth—behold, these three no power can keep back. And since we are doomed to know the truth, let us cultivate a love for it. It is of no avail to cry over lost illusions, to long for vanished dreams, or to call to the departing gods to come back. It may be pleasant to play with toys and dolls all our life, but evidently we are not meant to remain children always. The time comes when we must put away childish things and obey the summons of truth, stern and high. A people who fear the truth can never be a free people. If what I will say is the truth, do you know of any good reason why I should not say it? And if for prudential reasons I should sometimes hold back the truth, how would you know when I am telling what I believe to be the truth, and when I am holding it back for reasons of policy?

The truth, however unwelcome, is not injurious; it is error which raises false hopes, which destroys, degrades and pollutes, and which, sooner or later, must be abandoned. Was it not Spencer, whom Darwin called "our great philosopher," who said, "Repulsive as is its aspect, the hard fact which dissipates a cherished illusion is presently found to contain the germ of a more salutary belief?" Spain is decaying today because her teachers, for policy's sake, are withholding the disagreeable truth from the people. Holy water and sainted bones can give a nation illusions and dreams, but never,—strength.

A difficult subject is in the nature of a challenge to the mind. One difficult task attempted is worth a thousand commonplace efforts completed. The majority of people avoid the difficult and fear danger. But he who would progress must even court danger. Political and religious liberty were discovered through peril and struggle. The world owes its emancipation to human daring. Had Columbus feared danger, America might have slept for another thousand years.

I have a difficult subject in hand. It is also a delicate one. But I am determined not only to know, if it is possible, the whole truth about Jesus, but also to communicate that truth to others. Some people can keep their minds shut. I cannot; I must share my intellectual life with the world. If I lived a thousand years ago, I might have collapsed at the sight of the burning stake, but I feel sure I would have deserved the stake.

People say to me, sometimes, "Why do you not confine yourself to moral and religious exhortation, such as, 'Be kind, do good, love one another, etc.'?" But there is more of a moral tonic in the open and candid discussion of a subject like the one in hand, than in a multitude of platitudes. We feel our moral fiber stiffen into force and purpose under the inspiration of a peril dared for the advancement of truth.

"Tell us what you believe," is one of the requests frequently addressed to me. I never deliver a lecture in which I do not, either directly or indirectly, give full and free expression to my faith in everything that is worthy of faith. If I do not believe in dogma, it is because I believe in freedom. If I do not believe in one inspired book, it is because I believe that all truth and only truth is inspired. If I do not ask the gods to help us, it is because I believe in human help, so much more real than supernatural help. If I do not believe in standing still, it is because I believe in progress. If I am not attracted by the vision of a distant heaven, it is because I believe in human happiness, now and here. If I do not say "Lord, Lord!" to Jesus, it is because I bow my head to a greater Power than Jesus, to a more efficient Savior than he has ever been—Science!

"Oh, he tears down, but does not build up," is another criticism about my work. It is not true. No preacher or priest is more constructive. To build up their churches and maintain their creeds the priests pulled down and destroyed the magnificent civilization of Greece and Rome, plunging Europe into the dark and sterile ages which lasted over a thousand years. When Galileo waved his hands for joy because he believed he had enriched humanity with a new truth and extended the sphere of knowledge, what did the church do to him? It conspired to destroy him. It shut him up in a dungeon! Clapping truth into jail; gagging the mouth of the student—is that building up or tearing down? When Bruno lighted a new torch to increase the light of the world, what was his reward? The stake! During all the ages that the church had the power to police the world, every time a thinker raised his head he was clubbed to death. Do you think it is kind of us—does it square with our sense of justice to call the priest constructive, and the scientists and philosophers who have helped people to their feet—helped them to self-government in politics, and to self-help in life,—destructive? Count your rights—political, religious, social, intellectual—and tell me which of them was conquered for you by the priest.

"He is irreverent," is still another hasty criticism I have heard advanced against the rationalist. I wish to tell you something. But first let us be impersonal. The epithets "irreverent," "blasphemer," "atheist," and "infidel," are flung at a man, not from pity, but from envy. Not having the courage or the industry of our neighbor who works like a busy bee in the world of men and books, searching with the sweat of his brow for the real bread of life, wetting the open page before him with his tears, pushing into the "wee" hours of the night his quest, animated by the fairest of all loves, "the love of truth",—we ease our own indolent conscience by calling him names. We pretend that it is not because we are too lazy or too selfish to work as hard or think as freely as he does, but because we do not want to be as irreverent as he is that we keep the windows of our minds shut. To excuse our own mediocrity we call the man who tries to get out of the rut a "blasphemer." And so we ask the world to praise our indifference as a great virtue, and to denounce the conscientious toil and thought of another, as "blasphemy."

What is a myth? A myth is a fanciful explanation of a given phenomenon. Observing the sun, the moon, and the stars overhead, the primitive man wished to account for them. This was natural. The mind craves for knowledge. The child asks questions because of an inborn desire to know. Man feels ill at ease with a sense of a mental vacuum, until his questions are answered. Before the days of science, a fanciful answer was all that could be given to man's questions about the physical world. The primitive man guessed where knowledge failed him—what else could he do? A myth, then, is a guess, a story, a speculation, or a fanciful explanation of a phenomenon, in the absence of accurate information.

Many are the myths about the heavenly bodies, which, while we call them myths, because we know better, were to the ancients truths. The Sun and Moon were once brother and sister, thought the child-man; but there arose a dispute between them; the woman ran away, and the man ran after her, until they came to the end of the earth where land and sky met. The woman jumped into the sky, and the man after her, where they kept chasing each other forever, as Sun and Moon. Now and then they came close enough to snap at each other. That was their explanation of an eclipse. (Childhood of the World.—Edward Clodd.) With this mythus, the primitive man was satisfied, until his developing intelligence realized its inadequacy. Science was born of that realization.

During the middle ages it was believed by Europeans that in certain parts of the world, in India, for instance, there were people who had only one eye in the middle of their foreheads, and were more like monsters than humans. This was imaginary knowledge, which travel and research have corrected. The myth of a one-eyed people living in India has been replaced by accurate information concerning the Hindoos. Likewise, before the science of ancient languages was perfected—before archaeology had dug up buried cities and deciphered the hieroglyphics on the monuments of antiquity, most of our knowledge concerning the earlier ages was mythical, that is to say, it was knowledge not based on investigation, but made to order. Just as the theologians still speculate about the other world, primitive man speculated about this world. Even we moderns, not very long ago, believed, for instance, that the land of Egypt was visited by ten fantastic plagues; that in one bloody night every first born in the land was slain; that the angel of a tribal-god dipped his hand in blood and printed a red mark upon the doors of the houses of the Jews to protect them from harm; that Pharaoh and his armies were drowned in the Red Sea; that the children of Israel wandered for forty years around Mount Sinai; and so forth, and so forth. But now that we can read the inscriptions on the stone pages dug out of ancient ruins; now that we can compel a buried world to reveal its secret and to tell us its story, we do not have to go on making myths about the ancients. Myths die when history is born.

It will be seen from these examples that there is no harm in myth-making if the myth is called a myth. It is when we use our fanciful knowledge to deny or to shut out real and scientific knowledge that the myth becomes a stumbling block. And this is precisely the use to which myths have been put. The king with his sword and the priest with his curses, have supported the myth against science. When a man pretends to believe that the Santa Claus of his childhood is real, and tries to compel also others to play a part, he becomes positively immoral. There is no harm in believing in Santa Claus as a myth, but there is in pretending that he is real, because such an attitude of mind makes a mere trifle of truth.

Is Jesus a myth? There is in man a faculty for fiction. Before history was born, there was myth; before men could think, they dreamed. It was with the human race in its infancy as it is with the child. The child's imagination is more active than its reason. It is easier for it to fancy even than to see. It thinks less than it guesses. This wild flight of fancy is checked only by experience. It is reflection which introduces a bit into the mouth of imagination, curbing its pace and subduing its restless spirit. It is, then, as we grow older, and, if I may use the word, riper, that we learn to distinguish between fact and fiction, between history and myth.

In childhood we need playthings, and the more fantastic and bizarre they are, the better we are pleased with them. We dream, for instance, of castles in the air—gorgeous and clothed with the azure hue of the skies. We fill the space about and over us with spirits, fairies, gods, and other invisible and airy beings. We covet the rainbow. We reach out for the moon. Our feet do not really begin to touch the firm ground until we have reached the years of discretion.

I know there are those who wish they could always remain children,—living in dreamland. But even if this were desirable, it is not possible. Evolution is our destiny; of what use is it, then, to take up arms against destiny?

Let it be borne in mind that all the religions of the world were born in the childhood of the race.

Science was not born until man had matured. There is in this thought a world of meaning.

Children make religions.

Grown up people create science.

The cradle is the womb of all the fairies and faiths of mankind.

The school is the birthplace of science.

Religion is the science of the child.

Science is the religion of the matured man.

In the discussion of this subject, I appeal to the mature, not to the child mind. I appeal to those who have cultivated a taste for truth—who are not easily scared, but who can "screw their courage to the sticking point" and follow to the end truth's leading. The multitude is ever joined to its idols; let them alone. I speak to the discerning few.

There is an important difference between a lecturer and an ordained preacher. The latter can command a hearing in the name of God, or in the name of the Bible. He does not have to satisfy his hearers about the reasonableness of what he preaches. He is God's mouthpiece, and no one may disagree with him. He can also invoke the authority of the church and of the Christian world to enforce acceptance of his teaching. The only way I may command your respect is to be reasonable. You will not listen to me for God's sake, nor for the Bible's sake, nor yet for the love of heaven, or the fear of hell. My only protection is to be rational—to be truthful. In other words, the preacher can afford to ignore common sense in the name of Revelation. But if I depart from it in the least, or am caught once playing fast and loose with the facts, I will irretrievably lose my standing.

Our answer to the question, Is Jesus a Myth? must depend more or less upon original research, as there is very little written on the subject. The majority of writers assume that a person answering to the description of Jesus lived some two thousand years ago. Even the few who entertain doubts on the subject, seem to hold that while there is a large mythical element in the Jesus story, nevertheless there is a historical nucleus round which has clustered the elaborate legend of the Christ. In all probability, they argue, there was a man called Jesus, who said many helpful things, and led an exemplary life, and all the miracles and wonders represent the accretions of fond and pious ages.

Let us place ourselves entirely in the hands of the evidence. As far as possible, let us be passive, showing no predisposition one way or another. We can afford to be independent. If the evidence proves the historicity of Jesus, well and good; if the evidence is not sufficient to prove it, there is no reason why we should fear to say so; besides, it is our duty to inform ourselves on this question. As intelligent beings we desire to know whether this Jesus, whose worship is not only costing the world millions of the people's money, but which is also drawing to his service the time, the energies, the affection, the devotion, and the labor of humanity,—is a myth, or a reality. We believe that all religious persecutions, all sectarian wars, hatreds and intolerance, which still cramp and embitter our humanity, would be replaced by love and brotherhood, if the sects could be made to see that the God-Jesus they are quarreling over is a myth, a shadow to which credulity alone gives substance. Like people who have been fighting in the dark, fearing some danger, the sects, once relieved of the thraldom of a tradition which has been handed down to them by a childish age and country, will turn around and embrace one another. In every sense, the subject is an all-absorbing one. It goes to the root of things; it touches the vital parts, and it means life or death to the Christian religion.

Let me now give an idea of the method I propose to follow in the study of this subject. Let us suppose that a student living in the year 3000 desired to make sure that such a man as Abraham Lincoln really lived and did the things attributed to him. How would he go about it?

A man must have a birthplace and a birthday. All the records agree as to where and when Lincoln was born. This is not enough to prove his historicity, but it is an important link in the chain.

Neither the place nor the time of Jesus' birth is known. There has never been any unanimity about this matter. There has been considerable confusion and contradiction about it. It cannot be proved that the twenty-fifth of December is his birthday. A number of other dates were observed by the Christian church at various times as the birthday of Jesus. The Gospels give no date, and appear to be quite uncertain—really ignorant about it. When it is remembered that the Gospels purport to have been written by Jesus' intimate companions, and during the lifetime of his brothers and mother, their silence on this matter becomes significant. The selection of the twenty-fifth of December as his birthday is not only an arbitrary one, but that date, having been from time immemorial dedicated to the Sun, the inference is that the Son of God and the Sun of heaven enjoying the same birthday, were at one time identical beings. The fact that Jesus' death was accompanied with the darkening of the Sun, and that the date of his resurrection is also associated with the position of the Sun at the time of the vernal equinox, is a further intimation that we have in the story of the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus, an ancient and nearly universal Sun-myth, instead of verifiable historical events. The story of Jesus for three days in the heart of the earth; of Jonah, three days in the belly of a fish; of Hercules, three days in the belly of a whale, and of Little Red Riding Hood, sleeping in the belly of a great black wolf, represent the attempt of primitive man to explain the phenomenon of Day and Night. The Sun is swallowed by a dragon, a wolf, or a whale, which plunges the world into darkness; but the dragon is killed, and the Sun rises triumphant to make another Day. This ancient Sun myth is the starting point of nearly all miraculous religions, from the days of Egypt to the twentieth century.

The story which Mathew relates about a remarkable star, which sailing in the air pointed out to some unnamed magicians the cradle or cave in which the wonder-child was born, helps further to identify Jesus with the Sun. What became of this "performing" star, or of the magicians, and their costly gifts, the records do not say. It is more likely that it was the astrological predilections of the gospel writer which led him to assign to his God-child a star in the heavens. The belief that the stars determine human destinies is a very ancient one. Such expressions in our language as "ill-starred," "a lucky star," "disaster," "lunacy," and so on, indicate the hold which astrology once enjoyed upon the human mind. We still call a melancholy man, Saturnine; a cheerful man, Jovial; a quick-tempered man, Mercurial; showing how closely our ancestors associated the movements of celestial bodies with human affairs. * The prominence, therefore, of the sun and stars in the Gospel story tends to show that Jesus is an astrological rather than a historical character.

*Childhood of the World.—Edward Clodd.

That the time of his birth, his death, and supposed resurrection is not verifiable is generally admitted.

This uncertainty robs the story of Jesus, to an extent at least, of the atmosphere of reality.

The twenty-fifth of December is celebrated as his birthday. Yet there is no evidence that he was born on that day. Although the Gospels are silent as to the date on which Jesus was born, there is circumstantial evidence in the accounts given of the event to show that the twenty-fifth of December could not have been his birthday. It snows in Palestine, though a warmer country, and we know that in December there are no shepherds tending their flocks in the night time in that country. Often at this time of the year the fields and hills are covered with snow. Hence, if the shepherds sleeping in the fields really saw the heavens open and heard the angel-song, in all probability it was in some other month of the year, and not late in December. We know, also, that early in the history of Christianity the months of May and June enjoyed the honor of containing the day of Jesus' birth.

Of course, it is immaterial on which day Jesus was born, but why is it not known? Yet not only is the date of his birth a matter of conjecture, but also the year in which he was born. Matthew, one of the Evangelists, suggests that Jesus was born in King Herod's time, for it was this king who, hearing from the Magi that a King of the Jews was born, decided to destroy him; but Luke, another Evangelist, intimates that Jesus was born when Quirinus was ruler of Judea, which makes the date of Jesus' birth about fourteen years later than the date given by Matthew. Why this discrepancy in a historical document, to say nothing about inspiration? The theologian might say that this little difficulty was introduced purposely into the scriptures to establish its infallibility, but it is only religious books that are pronounced infallible on the strength of the contradictions they contain.

Again, Matthew says that to escape the evil designs of Herod, Mary and Joseph, with the infant Jesus, fled into Egypt, Luke says nothing about this hurried flight, nor of Herod's intention to kill the infant Messiah. On the contrary he tells us that after the forty days of purification were over Jesus was publicly presented at the temple, where Herod, if he really, as Matthew relates, wished to seize him, could have done so without difficulty. It is impossible to reconcile the flight to Egypt with the presentation in the temple, and this inconsistency is certainly insurmountable and makes it look as if the narrative had no value whatever as history.

When we come to the more important chapters about Jesus, we meet with greater difficulties. Have you ever noticed that the day on which Jesus is supposed to have died falls invariably on a Friday? What is the reason for this? It is evident that nobody knows, and nobody ever knew the date on which the Crucifixion took place, if it ever took place. It is so obscure and so mythical that an artificial day has been fixed by the Ecclesiastical councils. While it is always on a Friday that the Crucifixion is commemorated, the week in which the day occurs varies from year to year. "Good Friday" falls not before the spring equinox, but as soon after the spring equinox as the full moon allows, thus making the calculation to depend upon the position of the sun in the Zodiac and the phases of the moon. But that was precisely the way the day for the festival of the pagan goddess Oestera was determined. The Pagan Oestera has become the Christian Easter. Does not this fact, as well as those already touched upon, make the story of Jesus to read very much like the stories of the Pagan deities.

The early Christians, Origin, for instance, in his reply to the rationalist Celsus who questioned the reality of Jesus, instead of producing evidence of a historical nature, appealed to the mythology of the pagans to prove that the story of Jesus was no more incredible than those of the Greek and Roman gods. This is so important that we refer our readers to Origin's own words on the subject. "Before replying to Celsus, it is necessary to admit that in the matter of history, however true it might be," writes this Christian Father, "it is often very difficult and sometimes quite impossible to establish its truth by evidence which shall be considered sufficient." * This is a plain admission that as early as the second and third centuries the claims put forth about Jesus did not admit of positive historical demonstration. But in the absence of evidence Origin offers the following metaphysical arguments against the sceptical Celsus: 1. Such stories as are told of Jesus are admitted to be true when told of pagan divinities, why can they not also be true when told of the Christian Messiah? 2. They must be true because they are the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. In other words, the only proofs Origin can bring forth against the rationalistic criticism of Celsus is, that to deny Jesus would be equivalent to denying both the Pagan and Jewish mythologies. If Jesus is not real, says Origin, then Apollo was not real, and the Old Testament prophecies have not been fulfilled. If we are to have any mythology at all, he seems to argue, why object to adding to it the mythus of Jesus? There could not be a more damaging admission than this from one of the most conspicuous defenders of Jesus' story against early criticism.

* Origin Contre Celse. 1. 58 et Suiv. Ibid.

Justin Martyr, another early Father, offers the following argument against unbelievers in the Christian legend: "When we say also that the Word, which is the first birth of God, was produced without sexual union, and that he, Jesus Christ, our teacher, was crucified, died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propound nothing different from what you believe regarding those whom you esteem sons of Jupiter." * Which is another way of saying that the Christian mythus is very similar to the pagan, and should therefore be equally true. Pressing his argument further, this interesting Father discovers many resemblances between what he himself is preaching and what the pagans have always believed: "For you know how many sons your esteemed writers ascribe to Jupiter. Mercury, the interpreting word (he spells this word with a small w while in the above quotation he uses a capital W to denote the Christian incarnation) and teacher of all; Aesculapius...who ascended to heaven; one Hercules...and Perseus;...and Bellerophon, who, though sprung from mortals, rose to heaven on the horses of Pegasus." ** If Jupiter can have, Justin Martyr seems to reason, half a dozen divine sons, why cannot Jehovah have at least one?

* First Apology, Chapter xxi (Anti-Nicene Library).

** Ibid.

Instead of producing historical evidence or appealing to creditable documents, as one would to prove the existence of a Caesar or an Alexander, Justin Martyr draws upon pagan mythology in his reply to the critics of Christianity. All he seems to ask for is that Jesus be given a higher place among the divinities of the ancient world.

To help their cause the Christian apologists not infrequently also changed the sense of certain Old Testament passages to make them support the miraculous stories in the New Testament. For example, having borrowed from Oriental books the story of the god in a manger, surrounded by staring animals, the Christian fathers introduced a prediction of this event into the following text from the book of Habakkuk in the Bible: "Accomplish thy work in the midst of the years, in the midst of the years make known, etc." * This Old Testament text appeared in the Greek translation as follows: "Thou shalt manifest thyself in the midst of two animals" which was fulfilled of course when Jesus was born in a stable. How weak must be one's case to resort to such tactics in order to command a following! And when it is remembered that these follies were deemed necessary to prove the reality of what has been claimed as the most stupendous event in all history, one can readily see upon how fragile a foundation is built the story of the Christian God-man.

* Heb. iii. 2.

Let us continue: Abraham Lincoln's associates and contemporaries are all known to history. The immediate companions of Jesus appear to be, on the other hand, as mythical as he is himself. Who was Matthew? Who was Mark? Who were John, Peter, Judas, and Mary? There is absolutely no evidence that they ever existed. They are not mentioned except in the New Testament books, which, as we shall see, are "supposed" copies of "supposed" originals. If Peter ever went to Rome with a new doctrine, how is it that no historian has taken note of him? If Paul visited Athens and preached from Mars Hill, how is it that there is no mention of him or of his strange Gospel in the Athenian chronicles? For all we know, both Peter and Paul may have really existed, but it is only a guess, as we have no means of ascertaining. The uncertainty about the apostles of Jesus is quite in keeping with the uncertainty about Jesus himself.

The report that Jesus had twelve apostles seems also mythical. The number twelve, like the number seven, or three, or forty, plays an important role in all Sun-myths, and points to the twelve signs of the Zodiac. Jacob had twelve sons; there were twelve tribes of Israel; twelve months in the year; twelve gates or pillars of heaven, etc. In many of the religions of the world, the number twelve is sacred. There have been few god-saviors who did not have twelve apostles or messengers. In one or two places, in the New Testament, Jesus is made to send out "the seventy" to evangelize the world. Here again we see the presence of a myth. It was believed that there were seventy different nations in the world—to each nation an apostle. Seventy wise men are supposed to have translated the Old Testament, sitting in seventy different cells. That is why their translation is called "the Septuagint" But it is all a legend, as there is no evidence of seventy scholars working in seventy individual cells on the Hebrew Bible. One of the Church Fathers declares that he saw these seventy cells with his own eyes. He was the only one who saw them.

That the "Twelve Apostles" are fanciful may be inferred from the obscurity in which the greater number of them have remained. Peter, Paul, John, James, Judas, occupy the stage almost exclusively. If Paul was an apostle, we have fourteen, instead of twelve. Leaving out Judas, and counting Matthias, who was elected in his place, we have thirteen apostles.

The number forty figures also in many primitive myths. The Jews were in the wilderness for forty years; Jesus fasted for forty days; from the resurrection to the ascension were forty days; Moses was on the mountain with God for forty days. An account in which such scrupulous attention is shown to supposed sacred numbers is apt to be more artificial than real. The biographers of Lincoln or of Socrates do not seem to be interested in numbers. They write history, not stories.

Again, many of the contemporaries of Lincoln bear written witness to his existence. The historians of the time, the statesmen, the publicists, the chroniclers—all seem to be acquainted with him, or to have heard of him. It is impossible to explain why the contemporaries of Jesus, the authors and historians of his time, do not take notice of him. If Abraham Lincoln was important enough to have attracted the attention of his contemporaries, how much more Jesus. Is it reasonable to suppose that these Pagan and Jewish writers knew of Jesus,—had heard of his incomparably great works and sayings,—but omitted to give him a page or a line? Could they have been in a conspiracy against him? How else is this unanimous silence to be accounted for? Is it not more likely that the wonder-working Jesus was unknown to them? And he was unknown to them because no such Jesus existed in their day.

Should the student, looking into Abraham Lincoln's history, discover that no one of his biographers knew positively just when he lived or where he was born, he would have reason to conclude that because of this uncertainty on the part of the biographers, he must be more exacting than he otherwise would have been. That is precisely our position. Of course, there are in history great men of whose birthplaces or birthdays we are equally uncertain. But we believe in their existence, not because no one seems to know exactly when and where they were born, but because there is overwhelming evidence corroborating the other reports about them, and which is sufficient to remove the suspicion suggested by the darkness hanging over their nativity. Is there any evidence strong enough to prove the historicity of Jesus, in spite of the fact that not even his supposed companions, writing during the lifetime of Jesus' mother, have any definite information to give.

But let us continue. The reports current about a man like Lincoln are verifiable, while many of those about Jesus are of a nature that no amount of evidence can confirm. That Lincoln was President of these United States, that he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and that he was assassinated, can be readily authenticated.

But how can any amount of evidence satisfy one's self that Jesus was born of a virgin, for instance? Such a report or rumor can never even be examined; it does not lend itself to evidence; it is beyond the sphere of history; it is not a legitimate question for investigation. It belongs to mythology. Indeed, to put forth a report of that nature is to forbid the use of evidence, and to command forcible acquiescence, which, to say the least, is a very suspicious circumstance, calculated to hurt rather than to help the Jesus story.

The report that Jesus was God is equally impossible of verification. How are we to prove whether or not a certain person was God? Jesus may have been a wonderful man, but is every wonderful man a God? Jesus may have claimed to have been a God, but is every one who puts forth such a claim a God? How, then, are we to decide which of the numerous candidates for divine honors should be given our votes? And can we by voting for Jesus make him a God? Observe to what confusion the mere attempt to follow such a report leads us.

A human Jesus may or may not have existed, but we are as sure as we can be of anything, that a virgin-born God, named Jesus, such as we must believe in or be eternally lost, is an impossibility—except to credulity. But credulity is no evidence at all, even when it is dignified by the name of faith. Let us pause for a moment to reflect: The final argument for the existence of the miraculous Jesus, preached in church and Sunday-school, these two thousand years, as the sole savior of the world, is an appeal to faith—the same to which Mohammed resorts to establish his claims, and Brigham Young to prove his revelation. There is no other possible way by which the virgin-birth or the godhood of a man can be established. And such a faith is never free, it is always maintained by the sword now, and by hell-fire hereafter.

Once more, if it had been reported of Abraham Lincoln that he predicted his own assassination; that he promised some of his friends they would not die until they saw him coming again upon the clouds of heaven; that he would give them thrones to sit upon; that they could safely drink deadly poisons in his name, or that he would grant them any request which they might make, provided they asked it for his sake, we would be justified in concluding that such a Lincoln never existed. Yet the most impossible utterances are put in Jesus' mouth. He is made to say: "Whatsoever ye shall ask in my name that will I do." No man who makes such a promise can keep it. It is not sayings like the above that can prove a man a God. Has Jesus kept his promise? Does he give his people everything, or "whatsoever" they ask of him? But, it is answered, "Jesus only meant to say that he would give whatever he himself considered good for his friends to have." Indeed! Is that the way to crawl out of a contract? If that is what he meant, why did he say something else? Could he not have said just what he meant, in the first place? Would it not have been fairer not to have given his friends any occasion for false expectations? Better to promise a little and do more, than to promise everything and do nothing. But to say that Jesus really entered into any such agreement is to throw doubt upon his existence. Such a character is too wild to be real. Only a mythical Jesus could virtually hand over the government of the universe to courtiers who have petitions to press upon his attention. Moreover, if Jesus could keep his promise, there would be today no misery in the world, no orphans, no childless mothers, no shipwrecks, no floods, no famines, no disease, no crippled children, no insanity, no wars, no crime, no wrong! Have not a thousand, thousand prayers been offered in Jesus' name against every evil which has ploughed the face of our earth? Have these prayers been answered? Then why is there discontent in the world? Can the followers of Jesus move mountains, drink deadly poisons, touch serpents, or work greater miracles than are ascribed to Jesus, as it was promised that they would do? How many self-deluded prophets these extravagant claims have produced! And who can number the bitter disappointments caused by such impossible promises?

George Jacob Holyoake, of England, tells how in the days of utter poverty, his believing mother asked the Lord, again and again—on her knees, with tears streaming from her eyes, and with absolute faith in Jesus' ability to keep His promise,—to give her starving children their daily bread. But the more fervently she prayed the heavier grew the burden of her life. A stone or wooden idol could not have been more indifferent to a mother's tears. "My mind aches as I think of those days," writes Mr. Holyoake. One day he went to see the Rev. Mr. Cribbace, who had invited inquirers to his house. "Do you really believe," asked young Holyoake to the clergyman, "that what we ask in faith we shall receive?"

"It never struck me," continues Mr. Holyoake, "that the preacher's threadbare dress, his half-famished look, and necessity of taking up a collection the previous night to pay expenses showed that faith was not a source of income to him. It never struck me that if help could be obtained by prayer no church would be needy, no believer would be poor." What answer did the preacher give to Holyoake's earnest question? The same which the preachers of today give: "He parried his answer with many words, and at length said that the promise was to be taken with the provision that what we asked for would be given, if God thought it for our good." Why then, did not Jesus explain that important proviso when he made the promise? Was Jesus only making a half statement, the other half of which he would reveal later to protect himself against disappointed petitioners. But he said: "If ye ask anything in my name, I will do it," and "If it were not so, I would have told you." Did he not mean just what he said? The truth is that no historical person in his senses ever made such extraordinary, such impossible promises, and the report that Jesus made them only goes to confirm that their author is only a legendary being.

When this truth dawned upon Mr. Holyoake he ceased to petition Heaven, which was like "dropping a bucket into an empty well," and began to look elsewhere for help. * The world owes its advancement to the fact that men no longer look to Heaven for help, but help themselves. Self-effort, and not prayer, is the remedy against ignorance, slavery, poverty, and moral degradation. Fortunately, by holding up before us an impossible Jesus, with his impossible promises, the churches have succeeded only in postponing, but not in preventing, the progress of man. This is a compliment to human nature, and it is well earned. It is also a promise that in time humanity will be completely emancipated from every phantom which in the past has scared it into silence or submission, and

"A loftier race than e'er the world

Hath known shall rise

With flame of liberty in their souls,

And light of science in their eyes."

* Bygones Worth Remembering.—George Jacob Holyoake

The documents containing the story of Jesus are so unlike those about Lincoln or any other historical character, that we must be doubly vigilant in our investigation.

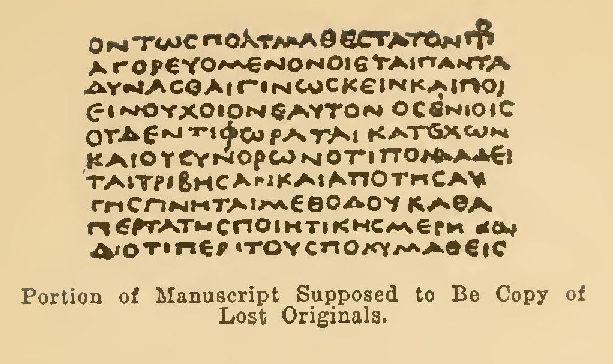

The Christians rely mainly on the four Gospels for the historicity of Jesus. But the original documents of which the books in the New Testament are claimed to be faithful copies are not in existence. There is absolutely no evidence that they ever were in existence. This is a statement which can not be controverted. Is it conceivable that the early believers lost through carelessness or purposely every document written by an apostle, while guarding with all protecting jealousy and zeal the writings of anonymous persons? Is there any valid reason why the contributions to Christian literature of an inspired apostle should perish while those of a nameless scribe are preserved, why the original Gospel of Matthew should drop quietly out of sight, no one knows how, while a supposed copy of it in an alien language is preserved for many centuries? Jesus himself, it is admitted, did not write a single line. He had come, according to popular belief, to reveal the will of God—a most important mission indeed, and yet he not only did not put this revelation in writing during his lifetime, and with his own hand, which it is natural to suppose that a divine teacher, expressly come from heaven, would have done, but he left this all-important duty to anonymous chroniclers, who, naturally, made enough mistakes to split up Christendom into innumerable factions. It is worth a moment's pause to think of the persecutions, the cruel wars, and the centuries of hatred and bitterness which would have been spared our unfortunate humanity, if Jesus himself had written down his message in the clearest and plainest manner, instead of leaving it to his supposed disciples to publish it to the world, when he could no longer correct their mistakes.

Moreover, not only did Jesus not write himself, but he has not even taken any pains to preserve the writings of his "apostles," It is well known that the original manuscripts, if there were any, are nowhere to be found. This is a grave matter. We have only supposed copies of supposed original manuscripts. Who copied them? When were they copied? How can we be sure that these copies are reliable? And why are there thousands upon thousands of various readings in these, numerous supposed copies? What means have we of deciding which version or reading to accept? Is it possible that as the result of Jesus' advent into our world, we have only a basketful of nameless and dateless copies and documents? Is it conceivable, I ask, that a God would send his Son to us, and then leave us to wander through a pile of dusty manuscripts to find out why He sent His Son, and what He taught when on earth?

The only answer the Christian church can give to this question is that the original writings were purposely allowed to perish. When a precious document containing the testament of Almighty God, and inscribed for an eternal purpose by the Holy Ghost, disappears altogether there is absolutely no other way of accounting for its disappearance than by saying, as we have suggested, that its divine author must have intentionally withdrawn it from circulation. "God moves in a mysterious way" is the last resort of the believer. This is the one argument which is left to theology to fight science with. Unfortunately it is an argument which would prove every cult and "ism" under the heavens true. The Mohammedan, the Mazdaian, and the Pagan may also fall back upon faith. There is nothing which faith can not cover up from the light. But if a faith which ignores evidence be not a superstition, what then is superstition? I wonder if the Catholic Church, which pretends to believe—and which derives quite an income from the belief—that God has miraculously preserved the wood of the cross, the Holy Sepulchre, in Jerusalem, the coat of Jesus, and quite a number of other mementos, can explain why the original manuscripts were lost. I have a suspicion that there were no "original" manuscripts. I am not sure of this, of course, but if nails, bones and holy places could be miraculously preserved, why not also manuscripts? It is reasonable to suppose that the Deity would not have permitted the most important documents containing His Revelation to drop into some hole and disappear, or to be gnawed into dust by the insects, after having had them written by special inspiration.

Again, when these documents, such as we find them, are examined, it will be observed that, even in the most elementary intelligence which they pretend to furnish, they are hopelessly at variance with one another. It is, for example, utterly impossible to reconcile Matthew's genealogy of Jesus with the one given by Luke. In copying the names of the supposed ancestors of Jesus, they tamper with the list as given in the book of Chronicles, in the Old Testament, and thereby justly expose themselves to the charge of bad faith. One evangelist says Jesus was descended from Solomon, born of "her that had been the wife of Urias." It will be remembered that David ordered Urias killed in a cowardly manner, that he may marry his widow, whom he coveted. According to Matthew, Jesus is one of the offspring of this adulterous relation. According to Luke, it is not through Solomon, but through Nathan, that Jesus is connected with the house of David.

Again, Luke tells us that the name of the father of Joseph was Heli; Matthew says it was Jacob. If the writers of the gospels were contemporaries of Joseph they could have easily learned the exact name of his father.

Again, why do these biographers of Jesus give us the genealogy of Joseph if he was not the father of Jesus? It is the genealogy of Mary which they should have given to prove the descent of Jesus from the house of David, and not that of Joseph. These irreconcilable differences between Luke, Matthew and the other evangelists, go to prove that these authors possessed no reliable information concerning the subjects they were writing about. For if Jesus is a historical character, and these biographers were really his immediate associates, and were inspired besides, how are we to explain their blunders and contradictions about his genealogy?

A good illustration of the mythical or unhistorical character of the New Testament is furnished by the story of John the Baptist. He is first represented as confessing publicly that Jesus is the Christ; that he himself is not worthy to unloose the latchet of his shoes; and that Jesus is the Lamb of God, "who taketh away the sins of the world." John was also present, the gospels say, when the heavens opened and a dove descended on Jesus' head, and he heard the voice from the skies, crying: "He is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased."

Is it possible that, a few chapters later, this same John forgets his public confession,—the dove and the voice from heaven,—and actually sends two of his disciples to find out who this Jesus is, * The only way we can account for such strange conduct is that the compiler or editor in question had two different myths or stories before him, and he wished to use them both.

* Matthew xi.

A further proof of the loose and extravagant style of the Gospel writers is furnished by the concluding verse of the Fourth Gospel: "There are also many other things which Jesus did, the which, if they should be written, every one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that should be written." This is more like the language of a myth-maker than of a historian. How much reliance can we put in a reporter who is given to such exaggeration? To say that the world itself would be too small to contain the unreported sayings and doings of a teacher whose public life possibly did not last longer than a year, and whose reported words and deeds fill only a few pages, is to prove one's statements unworthy of serious consideration.

And it is worth our while to note also that the documents which have come down to our time and which purport to be the biographies of Jesus, are not only written in an alien language, that is to say, in a language which was not that of Jesus and his disciples, but neither are they dated or signed. Jesus and his twelve apostles were Jews; why are all the four Gospels written in Greek? If they were originally written in Hebrew, how can we tell that the Greek translation is accurate, since we can not compare it with the originals? And why are these Gospels anonymous? Why are they not dated? But as we shall say something more on this subject in the present volume, we confine ourselves at this point to reproducing a fragment of the manuscript pages from which our Greek Translations have been made. * It is admitted by scholars that owing to the difficulty of reading these ancient and imperfect and also conflicting texts, an accurate translation is impossible. But this is another way of saying that what the churches call the Word of God is not only the word of man, but a very imperfect word, at that.

* See page 57.

The belief in Jesus, then, is founded on secondary documents, altered and edited by various hands; on lost originals, and on anonymous manuscripts of an age considerably later than the events therein related—manuscripts which contradict each other as well as themselves. Such is clearly and undeniably the basis for the belief in a historical Jesus. It was this sense of the insufficiency of the evidence which drove the missionaries of Christianity to commit forgeries.

If there was ample evidence for the historicity of Jesus, why did his biographers resort to forgery? The following admissions by Christian writers themselves show the helplessness of the early preachers in the presence of inquirers who asked for proofs. The church historian, Mosheim, writes that, "The Christian Fathers deemed it a pious act to employ deception and fraud." *

* Ecclesiastical Hist., Vol. I, p. 247.

Again, he says: "The greatest and most pious teachers were nearly all of them infected with this leprosy." Will not some believer tell us why forgery and fraud were necessary to prove the historicity of Jesus. Another historian, Milman, writes that, "Pious fraud was admitted and avowed" by the early missionaries of Jesus. "It was an age of literary frauds," writes Bishop Ellicott, speaking of the times immediately following the alleged crucifixion of Jesus. Dr. Giles declares that, "There can be no doubt that great numbers of books were written with no other purpose than to deceive." And it is the opinion of Dr. Robertson Smith that, "There was an enormous floating mass of spurious literature created to suit party views." Books which are now rejected as apochryphal were at one time received as inspired, and books which are now believed to be infallible were at one time regarded as of no authority in the Christian world. It certainly is puzzling that there should be a whole literature of fraud and forgery in the name of a historical person. But if Jesus was a myth, we can easily explain the legends and traditions springing up in his name.

The early followers of Jesus, then, realizing the force of this objection, did actually resort to interpolation and forgery in order to prove that Jesus was a historical character.

One of the oldest critics of the Christian religion was a Pagan, known to history under the name of Porphyry; yet, the early Fathers did not hesitate to tamper even with the writings of an avowed opponent of their religion. After issuing an edict to destroy, among others, the writings of this philosopher, a work, called Philosophy of Oracles, was produced, in which the author is made to write almost as a Christian; and the name of Porphyry was signed to it as its author. St. Augustine was one of the first to reject it as a forgery. * A more astounding invention than this alleged work of a heathen bearing witness to Christ is difficult to produce. Do these forgeries, these apocryphal writings, these interpolations, freely admitted to have been the prevailing practice of the early Christians, help to prove the existence of Jesus? And when to this wholesale manufacture of doubtful evidence is added the terrible vandalism which nearly destroyed every great Pagan classic, we can form an idea of the desperate means to which the early Christians resorted to prove that Jesus was not a myth. It all goes to show how difficult it is to make a man out of a myth.

* Geo. W. Foote. Crimes of Christianity.

Stories of gods born of virgins are to be found in nearly every age and country. There have been many virgin mothers, and Mary with her child is but a recent version of a very old and universal myth. In China and India, in Babylonia and Egypt, in Greece and Rome, "divine" beings selected from among the daughters of men the purest and most beautiful to serve them as a means of entrance into the world of mortals. Wishing to take upon themselves the human form, while retaining at the same time their "divinity," this compromise—of an earthly mother with a "divine" father—was effected. In the form of a swan Jupiter approached Leda, as in the guise of a dove, or a Paracletus, Jehovah "overshadowed" Mary.

A nymph bathing in a river in China is touched by a lotus plant, and the divine Fohi is born.

In Siam, a wandering sunbeam caresses a girl in her teens, and the great and wonderful deliverer, Codom, is born. In the life of Buddha we read that he descended on his mother Maya, "in likeness as the heavenly queen, and entered her womb," and was "born from her right side, to save the world." * In Greece, the young god Apollo visits a fair maid of Athens, and a Plato is ushered into the world.

* Stories of Virgin Births. Reference: Lord Macartney.

Voyage dans "interview de la Chine et en Tartarie." Vol. I,

p. 48. See also Les Vierges Meres et les Naissance

Miraculeuse. p. Saintyves. p. 19, etc.

In ancient Mexico, as well as in Babylonia, and in modern Corea, as in modern Palestine, as in the legends of all lands, virgins gave birth and became divine mothers. *

* Stories of Virgin Births. Reference: Lord Macartney.

Voyage dans "interview de la Chine et en Tartarie." Vol. I,

p. 48. See also Les Vierges Meres et les Naissance

Miraculeuse. p. Saintyves. p. 19, etc.

But the real home of virgin births is the land of the Nile. Eighteen hundred years before Christ, we find carved on one of the walls of the great temple of Luxor a picture of the annunciation, conception and birth of King Amunothph III, an almost exact copy of the annunciation, conception and birth of the Christian God. Of course no one will think of maintaining that the Egyptians borrowed the idea from the Catholics nearly two thousand years before the Christian era. "The story in the Gospel of Luke, the first and second chapters is," says Malvert, "a reproduction, 'point by point,' of the story in stone of the miraculous birth of Amunothph." *

* Science and Religion p. 96.

Sharpe in his Egyptian Mythology, page 19, gives the following description of the Luxor picture, quoted by G. W. Foote in his Bible Romances, page 126: "In this picture we have the annunciation, the conception, the birth and the adoration, as described in the first and second chapters of Luke's Gospel." Massey gives a more minute description of the Luxor picture. "The first scene on the left hand shows the god Taht, the divine Word or Loges, in the act of hailing the virgin queen, announcing to her that she is to give birth to a son. In the second scene the god Kneph (assisted by Hathor) gives life to her. This is the Holy Ghost, or Spirit that causes conception....Next the mother is seated on the midwife's stool, and the child is supported in the hands of one of the nurses. The fourth scene is that of the adoration. Here the child is enthroned, receiving homage from the gods and gifts from men." * The picture on the wall of the Luxor temple, then, is one of the sources to which the anonymous writers of the Gospels went for their miraculous story. It is no wonder they suppressed their own identity as well as the source from which they borrowed their material.

* Natural Genesis. Massey, Vol. II, p. 398

Not only the idea of a virgin mother, but all the other miraculous events, such as the stable cradle, the guiding star, the massacre of the children, the flight to Egypt, and the resurrection and bodily ascension toward the clouds, have not only been borrowed, but are even scarcely altered in the New Testament story of Jesus.

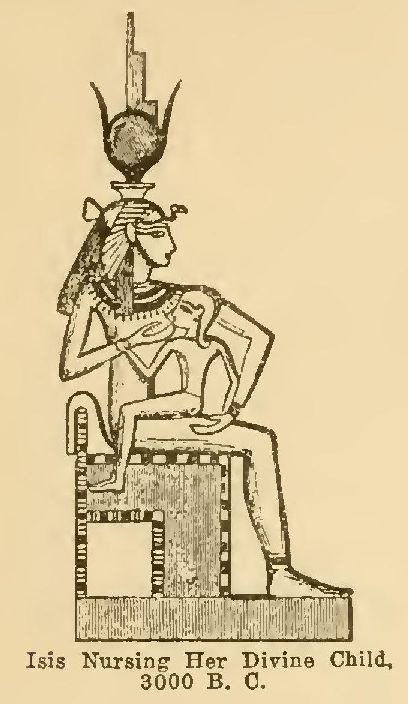

That the early Christians borrowed the legend of Jesus from earthly sources is too evident to be even questioned. Gerald Massey in his great work on Egyptian origins demonstrates the identity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, with Isis, the mother of Horus. He says: "The most ancient, gold-bedizened, smoke-stained Byzantine pictures of the virgin and child represent the mythical mother as Isis, and not as a human mother of Nazareth." * Science and research have made this fact so certain that, on the one hand ignorance, and on the other, interest only, can continue to claim inspiration for the authors of the undated and unsigned fragmentary documents which pass for the Word of God. If, then, Jesus is stripped of all the borrowed legends and miracles of which he is the subject; and if we also take away from him all the teachings which collected from Jewish and Pagan sources have been attributed to him—what will be left of him? That the ideas put in his mouth have been culled and compiled from other sources is as demonstrable as the Pagan origin of the legends related of him.

* Natural Genesis. Massey, Vol. ii, p. 487.

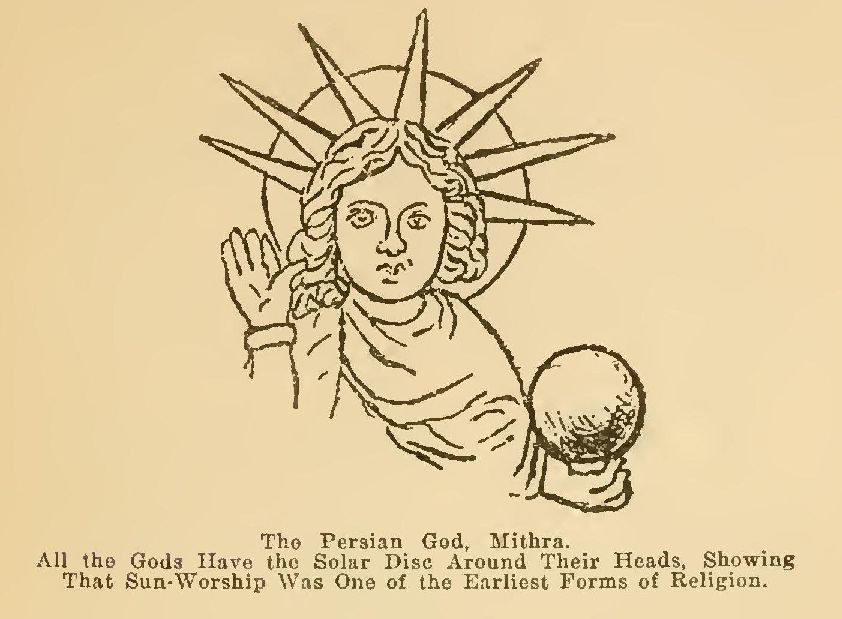

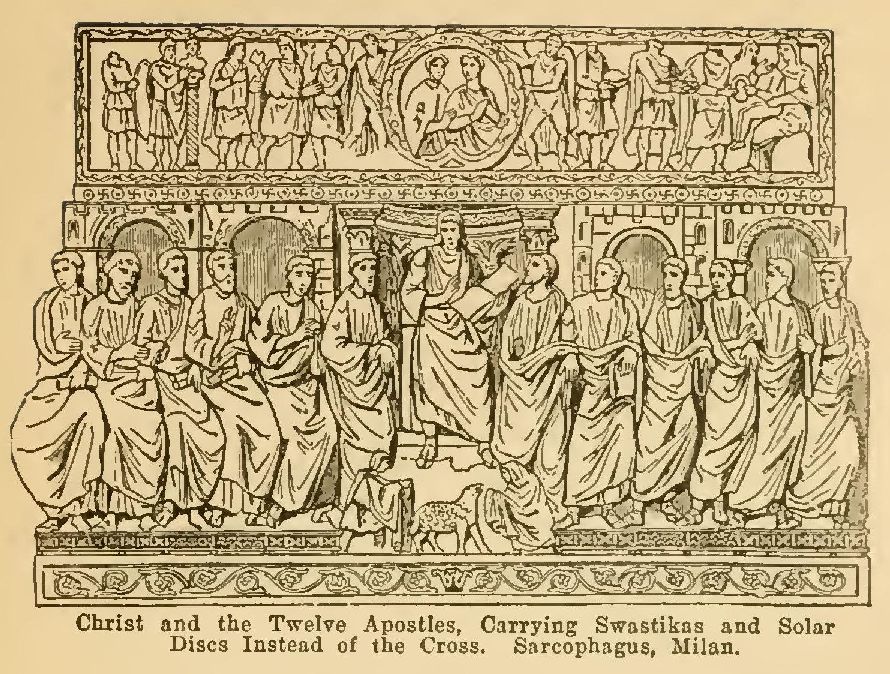

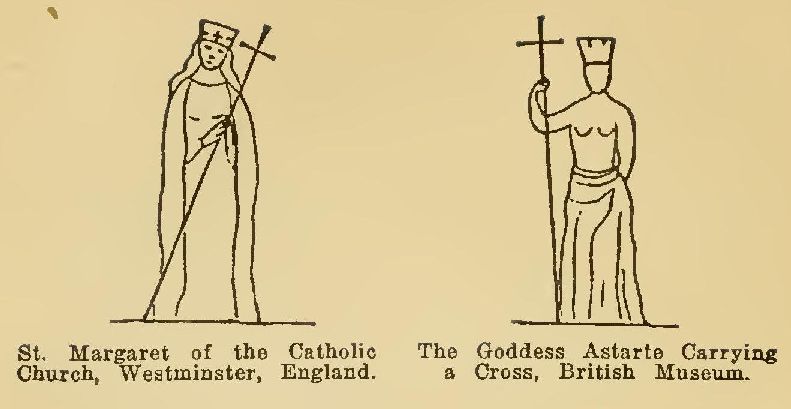

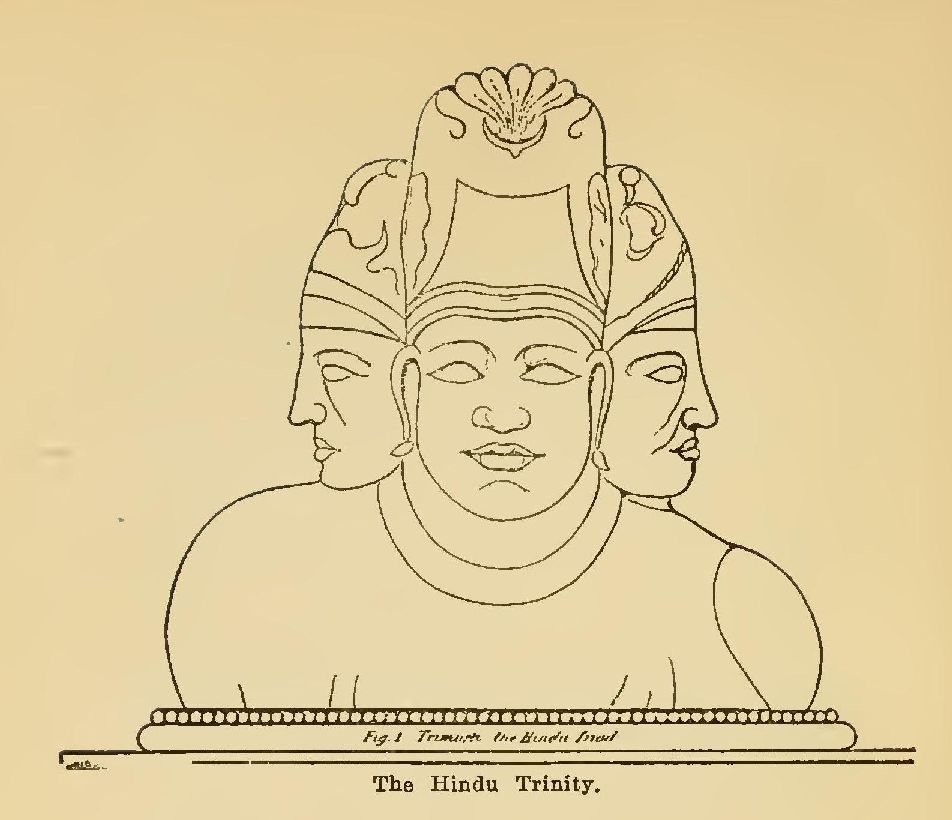

Nearly every one of the dogmas and ceremonies in the Christian cult were borrowed from other and older religions. The resurrection myth, the ascension, the eucharisty, baptism, worship by kneeling or prostration, the folding of the hands on the breast, the ringing of bells and the burning of incense, the vestments and vessels used in church, the candles, "holy" water,—even the word Mass were all adopted and adapted by the Christians from the religions of the ancients. The Trinity is as much Pagan, as much Indian or Buddhist, as it is Christian. The idea of a Son of God is as old as the oldest cult. The sun is the son of heaven in all primitive faiths. The physical sun becomes in the course of evolution, the Son of Righteousness, or the Son of God, and heaven is personified as the Father on High. The halo around the head of Jesus, the horns of the older deities, the rays of light radiating from the heads of Hindu and Pagan gods are incontrovertible evidence that all gods were at one time—the sun in heaven.

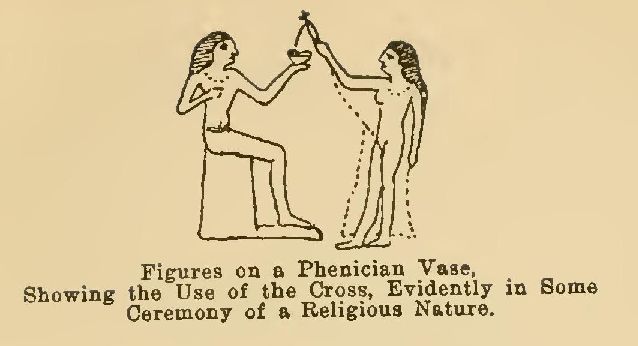

Only the uninformed, of whom, we regret to say, there are a great many, and who are the main support of the old religions, still believe that the cross originated with Christianity. Like the dogmas of the Trinity, the virgin birth, and the resurrection, the sign of the cross or the cross as an emblem or a symbol was borrowed from the more ancient faiths of Asia. Perhaps one of the most important discoveries which primitive man felt obliged never to be ungrateful enough to forget, was the production of fire by the friction of two sticks placed across each other in the form of a cross. As early as the stone age we find the cross carved on monuments which have been dug out of the earth and which can be seen in the museums of Europe. On the coins of later generations as well as on the altars of prehistoric times we find the "sacred" symbol of the cross. The dead in ancient cemeteries slept under the cross as they do in our day in Catholic churchyards.

In ancient Egypt, as in modern China, India, Corea, the cross is venerated by the masses as a charm of great power. In the Musee Guimet, in Paris, we have seen specimens of pre-Christian crosses. In the Louvre Museum one of the "heathen" gods carries a cross on his head. During his second journey to New Zealand, Cook was surprised to find the natives marking the graves of their dead with the cross. We saw, in the Museum of St. Germain, an ancient divinity of Gaul, before the conquest of the country by Julius Caesar, wearing a garment on which was woven a cross. In the same museum an ancient altar of Gaul under Paganism, had a cross carved upon it. That the cross was not adopted by the followers of Jesus until a later date may be inferred from the silence of the earlier gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, on the details of the crucifixion, which is more fully developed in the later gospel of John. The first three evangelists say nothing about the nails or the blood, and give the impression that he was hanged. Writing of the two thieves who were sentenced to receive the same punishment, Luke says, "One of the malefactors that was hanged with him." The idea of a bleeding Christ, such as we see on crosses in Catholic churches, is not present in these earlier descriptions of the crucifixion; the Christians of the time of Origin were called "the followers of the god who was hanged." In the fourth gospel we see the beginnings of the legend of the cross, of Jesus carrying or falling under the weight of the cross, of the nail prints in his hands and feet, of the spear drawing the blood from his side and smearing his body. Of all this, the first three evangelists are quite ignorant.

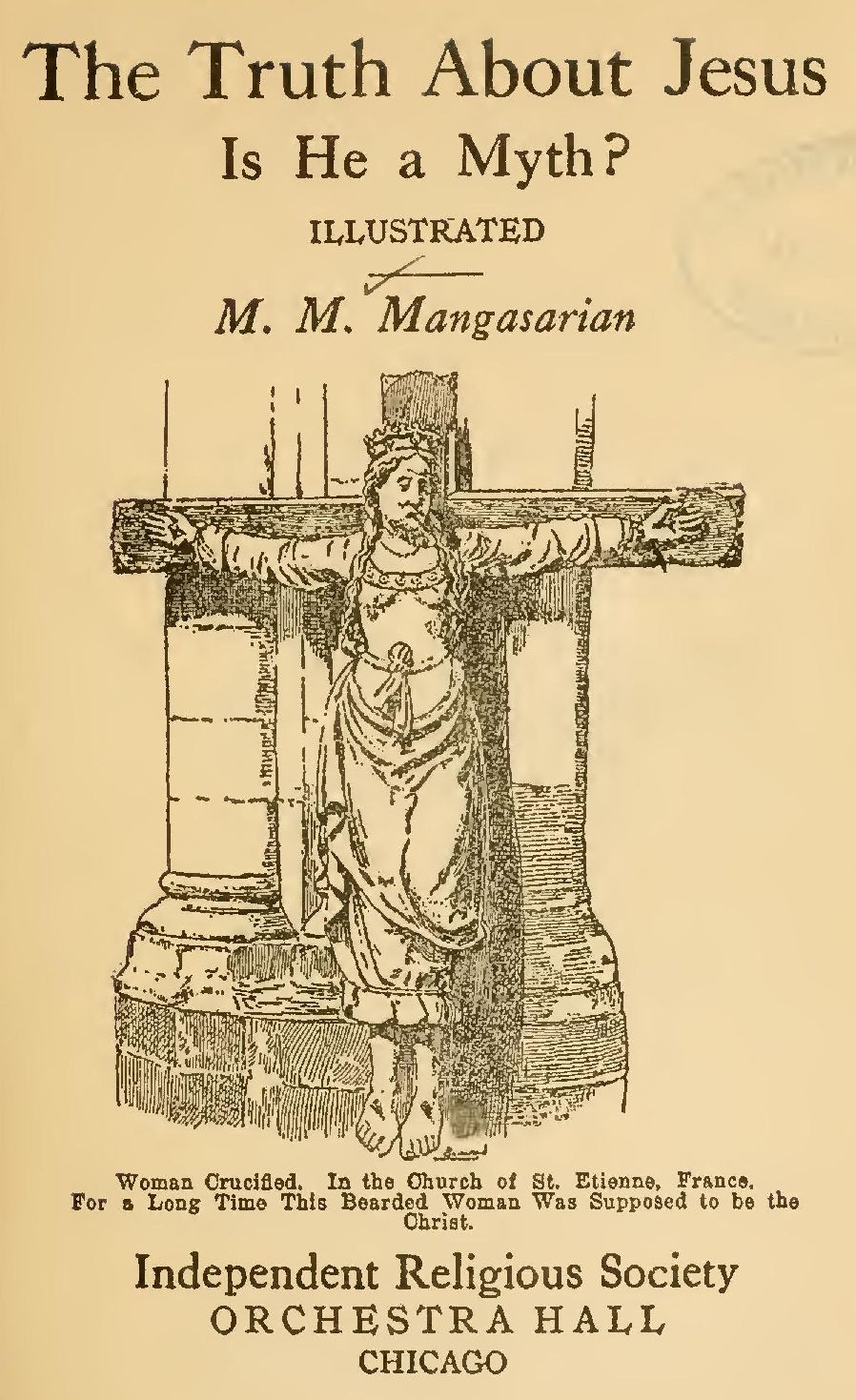

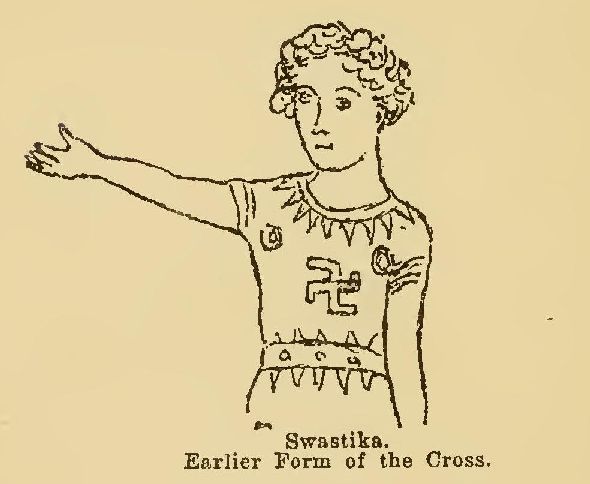

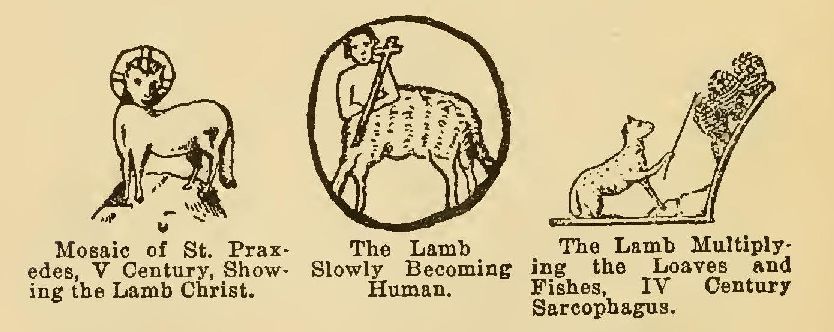

Let it be further noted that it was not until eight hundred years after the supposed crucifixion that Jesus is seen in the form of a human being on the cross. Not in any of the paintings on the ancient catacombs is found a crucified Christ. The earliest cross bearing a human being is of the eighth century. For a long time a lamb with a cross, or on a cross, was the Christian symbol, and it is a lamb which we see entombed in the "holy sepulchre." In more than one mosaic of early Christian times, it is not Jesus, but a lamb, which is bleeding for the salvation of the world. How a lamb came to play so important a role in Christianity is variously explained. The similarity between the name of the Hindu god, Agni and the meaning of the same word in Latin, which is a lamb, is one theory. Another is that a ram, one of the signs of the zodiac, often confounded by the ancients with a lamb, is the origin of the popular reverence for the lamb as a symbol—a reverence which all religions based on sun-worship shared. The lamb in Christianity takes away the sins of the people, just as the paschal lamb did in the Old Testament, and earlier still, just as it did in Babylonia.

To the same effect is the following letter of the bishop of Mende, in France, bearing date of the year 800 A. D.: "Because the darkness has disappeared, and because also Christ is a real man, Pope Adrian commands us to paint him under the form of a man. The lamb of God must not any longer be painted on a cross, but after a human form has been placed on the cross, there is no objection to have a lamb also represented with it, either at the foot of the cross or on the opposite side." * We leave it to our readers to draw the necessary conclusions from the above letter. How did a lamb hold its place on the cross for eight hundred years? If Jesus was really crucified, and that fact was a matter of history, why did it take eight hundred years for a Christian bishop to write, "now that Christ is a real man," etc.? Today, it would be considered a blasphemy to place a lamb on a cross.

* Translated from the French of Didron. Quoted by Malvert.

On the tombstones of Christians of the fourth century are pictures representing, not Jesus, but a lamb, working the miracles mentioned in the gospels, such as multiplying the loaves and fishes, and raising Lazarus from the dead.

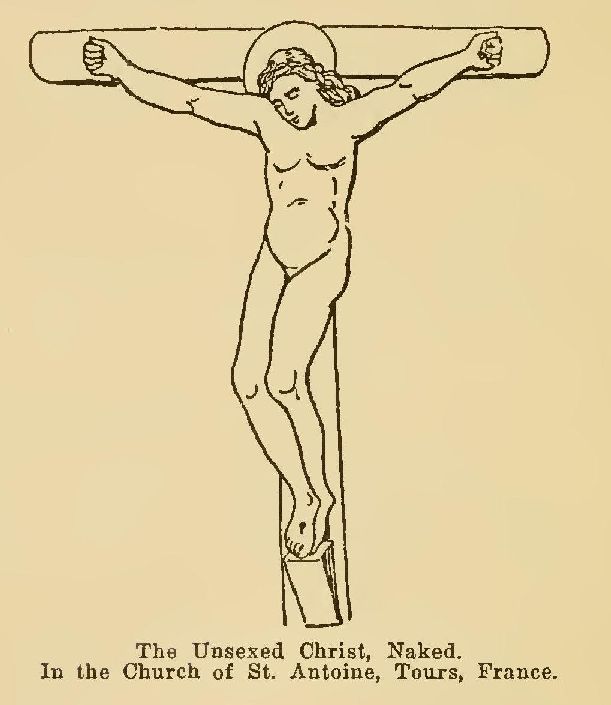

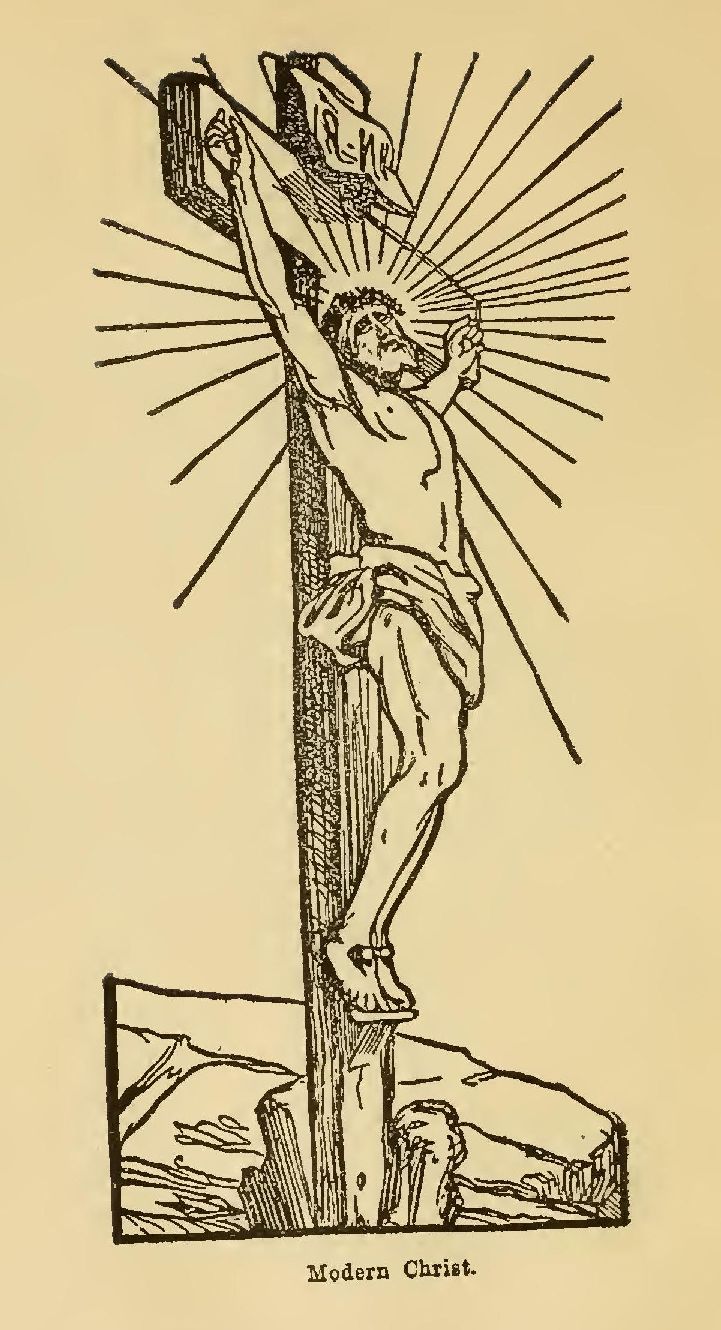

The first representations of a human form on the cross differ considerably from those which prevail at the present time.

While the figure on the modern cross is almost naked, those on the earlier ones are clothed and completely covered. Wearing a flowing tunic, Jesus is standing straight against the cross with his arms outstretched, as though in the act of delivering an address. Frequently, at his feet, on the cross, there is still painted the figure of a lamb, which by and by, he is going to replace altogether. Gradually the robe disappears from the crucified one, until we see him crucified, as in the adjoining picture, with hardly any clothes on, and wearing an expression of great agony.