This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Life of Francis Thompson

Author: Everard Meynell

Release Date: March 10, 2014 [eBook #45106]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF FRANCIS THOMPSON***

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The Child | 1 |

| II. | The Boy | 15 |

| III. | Manchester and Medicine | 35 |

| IV. | London Streets | 61 |

| V. | The Discovery | 85 |

| VI. | Literary Beginnings | 111 |

| VII. | "Poems" | 135 |

| VIII. | Of Words; of Origins; of Metre | 152 |

| IX. | At Monastery Gates | 180 |

| X. | Mysticism and Imagination | 198 |

| XI. | Patmore's Death, and "New Poems" | 233 |

| XII. | Friends and Opinions | 245 |

| XIII. | The Londoner | 272 |

| XIV. | Communion and Excommunion | 291 |

| XV. | Characteristics | 308 |

| XVI. | The Closing Years | 316 |

| XVII. | Last Things | 339 |

| Index | 353 | |

| Francis Thompson in 1895 | Frontispiece | ||

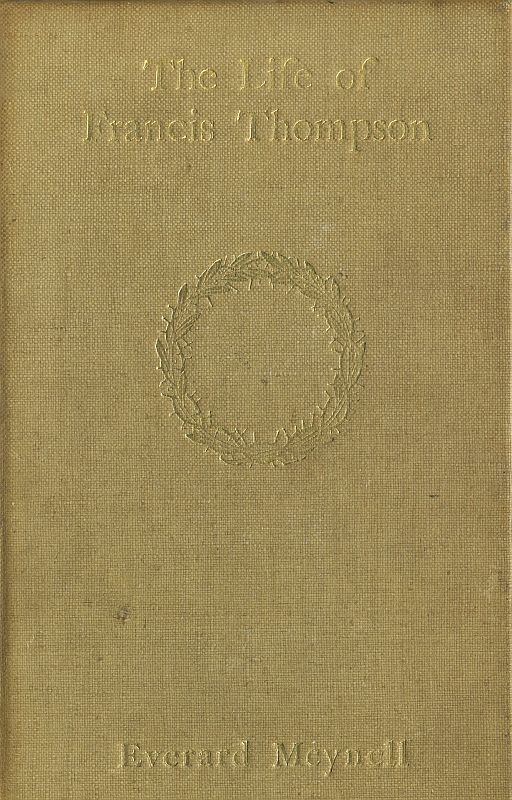

| His Birthplace | Facing | page | 4 |

| Francis, his Sisters and their Dolls, 1870 | " | " | 12 |

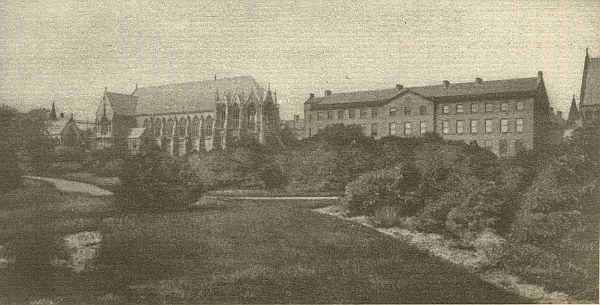

| St. Cuthbert's College, Ushaw | " | " | 26 |

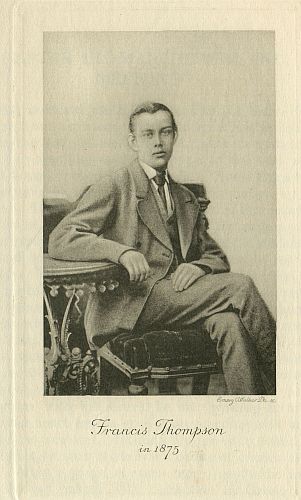

| Francis Thompson in 1875 | " | " | 34 |

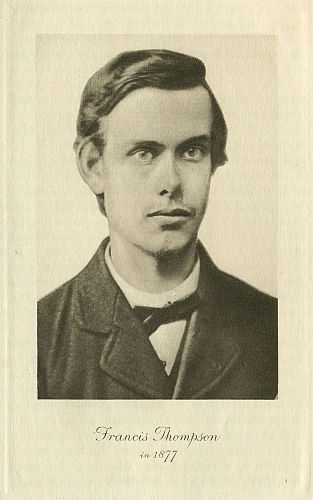

| Francis Thompson in 1877 | " | " | 54 |

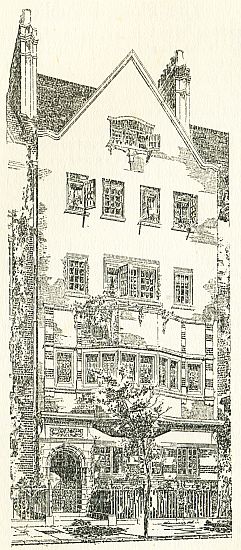

| No. 47 Palace Court | " | " | 134 |

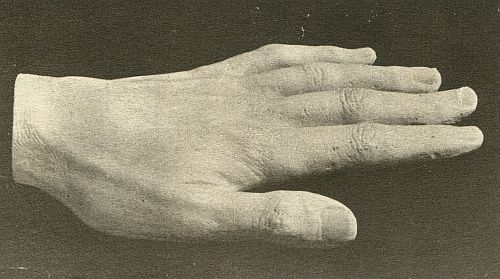

| Cast of the Poet's Hand | " | " | 144 |

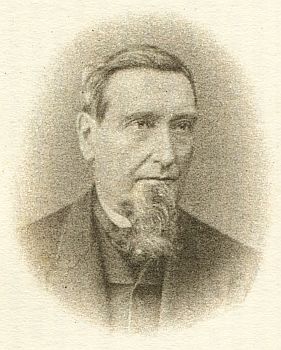

| His Parents | " | " | 186 |

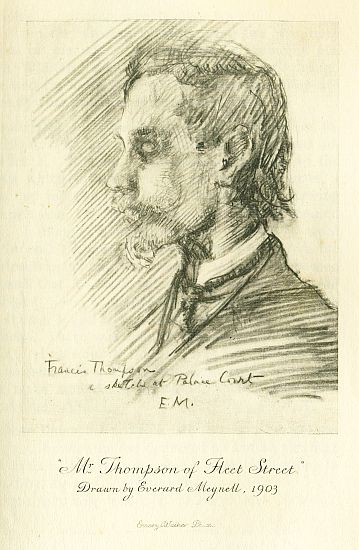

| "Mr. Thompson of Fleet Street" | " | " | 256 |

| (Drawn by Everard Meynell, 1903) | |||

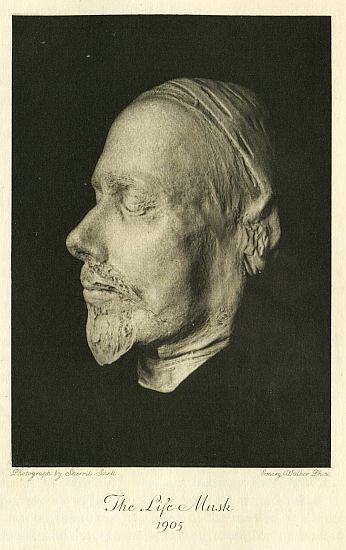

| The Life Mask, 1905 | " | " | 316 |

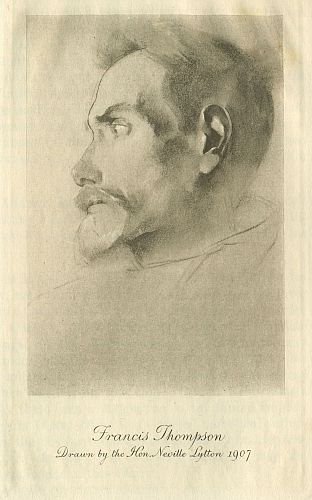

| Francis Thompson in 1907 | " | " | 328 |

| (Drawn by the Hon. Neville Lytton) | |||

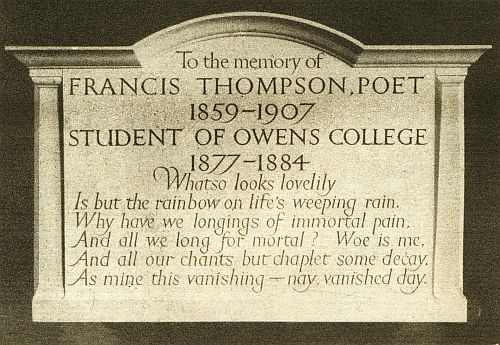

| The Memorial at Owens College | " | " | 344 |

The 16th of December 1859 was the day, 7 Winckley Street, a box of a house in a narrow road, the place of Francis Joseph Thompson's birth. He was the second son of Charles Thompson and his wife, Mary Turner Morton.[1] Charles Thompson's father (the poet's grandfather) was Robert Thompson, Surveyor of Taxes successively at Oakham in Rutlandshire, Bath, and Salisbury; he married Mary Costall, the daughter of a surgeon, at Oakham in 1812, and died at Tunbridge Wells in 1853. Charles, born in 1823, married Mary Morton in 1857.

Having first practised at Bristol and later been house-surgeon in the Homeopathic Dispensary in Manchester, he set up a practice in Winckley Street shortly after his marriage. Like his wife, his sisters, and the majority of his brothers, Dr. Thompson was a convert to the Catholic Church; but, unlike his brothers, he never[2] committed himself to authorship, and is remembered only in the many good opinions of those who knew him. For his patients he had something of the pastoral feeling; his rounds were his diocese, and in the statistics of kindness which no man keeps—in deference perhaps to the thoroughness of the Recording Angel—his name is thought worthy to figure largely. Though he attended as many patients as the most successful members of his profession, his fees were smaller and fewer. He stood, like his clients of the poorer quarters, in fear of the Creator firstly, and of death secondly; and so it happened that, having ministered to mother and child, he would pour out the waters of baptism over infants who made as if to leave the world as soon as they had entered it. This much of his kindness will serve as a preface to the story of the part which, forced to a seeming severity, he played in the career of his son.

The verses of two of Charles Thompson's brothers (Francis's uncles[2]) supply no clue, not even a plebeian one, to the origin of Francis's muse. Edward Healy Thompson's sonnets and John Costall Thompson's Vision of Liberty show that not a dozen such rhyming uncles could endow a birth with poetry. Eugenists must accept an inexplicable hitch in the prosaic unfolding of the Thompson birth-roll. While there can be no chart made of Francis's intellectual lineage, it is not surprising that an occasional phrase in his uncle's Vision of Liberty and other Poems, privately printed in 1848, bears some resemblance to his form and diction.

A servant-maid destroyed John's autobiography—an unkind accident, since it left his career to be summed up by a relative in seven words: "An utter failure in life and literature." Gladstone and Sir Henry Taylor at one time interested themselves in his work, but neither so keenly nor so persistently as to secure his good fame with an exacting brother. Yet Edward Healy Thompson (born 1813, educated at Oakham and Emmanuel College, Cambridge) is duller in verse than John Costall. He never saw, or never used, even a second-rate vision. Before his conversion to Catholicism he was curate in the parish of Elia's "Sweet Calne in Wiltshire" from July 1838 to January 1840, and had for neighbour there the friend of Lamb and Wordsworth, to whom Coleridge, before a meeting, had written—

The paternal relative (a cousin once removed) who finds in Francis thoughts and yearnings habitual to other members of his father's family, is better able to note them than he was. She tracks them in a girl (never seen by Francis) whose tragedy, since seeking admittance to a convent and failing to take final vows, is that she is not physically fit for the only life tolerable to her. She recognises the family mannerism in a relative who is famous in the suburban street of his choice for reciting the Psalms in a mighty voice in his sleep, so that no rest visits the guest new to the household noises.[5] She sees the family characters in Francis's niece who is about to end her noviciate and take vows in a Canadian community. She notes them in the two aunts, the sisters of Charles Thompson, who as Sister Mary of St. Jane Frances de Chantal of the Order of the Good Shepherd, and Sister Mary Ignatius of the Order of Mercy, lived and died as nuns; of a third aunt nothing is known, but in a dozen other cases the inclination for a spiritual life or a disinclination for all the pleasures or successes of any other is apparent. She notes the same carelessness for worldly prosperity, the thoughtlessness for mundane concerns that goes with certain trains of spiritual speculation. In a family singularly scattered the family trait is for ever reappearing. The aloofness or vagueness that led Francis to lose himself in London was responsible for many lost addresses. As Francis wandered alone in the Strand, without knowing that he had relatives in Church Court within a stone's throw of his stony and uncovered bed, so do the brothers and sisters of the present generation inhabit London and its suburbs unknown to one another, but without real alienation or unkindness. She, the cousin here cited, has herself wished to enter a convent and failed, and knowing much of the family needs and inclinations, does not doubt that Francis's life-long trouble was that he failed in the attempt to be a priest. There is nothing to throw substantial discredit on such a reading of his career.

From Winckley Street, associated with none of Francis's conscious experiences of existence, the family moved to Winckley Square and to Lathom Street, Preston, and in 1864 to Ashton-under-Lyne, where they remained until Francis's flight to London twenty-one years later.

Having attended for two months the school of the Nuns of the Cross and the Passion—a name full of anticipations—he reached, in the cold phrase that admits to first Confession and Communion, the "age of discretion." At seven years he was reading poetry, and, overwhelmed by feelings of which he knew not the meaning, had found his way to the heart of Shakespeare and Coleridge: their three ages of discretion kept company.[7] Already seeking the highway and the highway's seclusion, he would carry his book to the stairs, where, away from the constraint of chairs and tables and the unemotional flatness of the floor, his sister Mary remembers him. It is on that household highway, where the voices and noises of the house, and the footsteps of passengers on the pavement beyond the dark front door, come and pass quickly into other regions, that the child meditates and learns. There he may contract the habit of loneliness, populate his fancy with the creatures of fear; and gather about him a company of thoughts that will be his intimates until the end. And all the thronging personages of the boy's imagination are perhaps darkly arrayed against him. The crowd will be of tremors rather than of smiles, of secret rather than open-handed truths; the lessons learnt in that steep college of childhood are not joyful. The "long tragedy of early experiences" of which he spoke was a tragedy adventured upon alone. With his mother and his sisters, their toys, his books, and his own inventions he was happy. He would give entertainments to a more or less patient and tolerant audience of sisters; conjuror's tricks, and a model theatre on whose stage he would dangle marionettes, were the favourite performances, to one of which he was beholden for amusement and occupation till the end of his life. His early experience of the tragedy cannot be traced to the nursery. It was not there he built his barricade, or became in his own words "expert in concealment, not expression, of myself. Expression I reserved for my pen. My tongue was tenaciously disciplined in silence." There befell some share of accidental alarm. In a note-book that he had by him towards the end of his life and in which there are many allusions to its beginnings, he wrote of the "world-wide desolation and terror of for the first time, realising that the mother can lose you, or you her, and your own abysmal loneliness and helplessness without her." Such[8] a feeling he compares to that of first fearing yourself to be without God.

His toys he never quite relinquished; among the few possessions at his death was a cardboard theatre, wonderfully contrived, seeing that his fingers never learnt the ordinary tricks of usefulness, and with this his play was very earnest, as is attested in a note-book query—"Sylvia's hairs shall work the figures(?)." That he was content with his childhood, its toys, and even its troubles, he has particularly asserted. "I did not want responsibility, did not want to be a man. Toys I could surrender, with chagrin, so I had my great toy of imagination whereby the world became to me my box of toys." It is remembered by a visitor to the Thompson household that at meal times the father would call upon the children to come out of their rooms. But they, for answer, would lock their doors against the dinner hour: they were playing with the toy theatre. Francis went on playing all his life; his sister has kept her heart young in a convent. And there is no discontent in this particular memory of early loneliness:—

"There is a sense in which I have always been and even now remain a child. But in another sense I never was a child, never shared children's thoughts, ways, tastes, manner of life, and outlook of life. I played, but my sport was solitary sport, even when I played with my sisters; from the time I began to read (about my sixth year) the game often (I think) meant one thing to me and another (quite another) to them—my side of the game was part of a dream-scheme invisible to them. And from boys, with their hard practical objectivity of play, I was tenfold wider apart than from girls with their partial capacity and habit of make-believe."

Crosses he also experienced, and the sense of injustice was awakened early. He lost the prize—a clockwork mouse, no less!—offered by his governess.[9] Although first in lessons, his brisker, punctual-footed sisters and governess would have to wait many times during a walk for him to come up with them. And so the mouse went to a sister. "I remembered the prize," she writes, "but had forgotten the reason of my luck. But Francis never forgot it; he could never see the justice of it, he said—and no wonder!" His tremulous, sudden "not ready!" jerked out at the beginning of a game of cards, is still heard in the same sister's memory, and also the leverage of calls and knockings that was required to get him from the house for church or a train; and his unrecognising progress in the street. Every detail of the boy recalls the man to one who had to get him forth from his chamber when he was a grown traveller, and has often seen him oblivious in the streets, and has heard his imperative appeals for "ten minutes more" in all the small businesses of his later life. His toys he could surrender, but he played the same games without them. As a youth during the Russo-Turkish war he built a city of chairs with a plank for drawbridge; "Plevna," his father said, would be found written in his heart for the interest he had in the siege. If Plevna was written there, then so was Ladysmith. He had no plank drawbridge during the Boer war, but he was none the less excited on that account.

He knew little of the technique of being a boy; childhood was an easier rôle. Brothers would have told him it was bad form to care for dolls. He writes, in "The Fourth Order of Humanity," that he was "withheld even in childhood from the youthful male's contempt for these short-lived parasites of the nursery. I questioned, with wounded feelings, the straitened feminine intolerance which said to the boy: 'Thou shalt not hold a baby; thou shalt not possess a doll.' In the matter of babies, I was hopeless to shake the illiberal prejudice; in the matter of dolls, I essayed to confound it. By eloquence and fine diplomacy I wrung from[10] my sisters a concession of dolls; whence I date my knowledge of the kind. But ineluctable sex declared itself. I dramatized them, I fell in love with them; I did not father them; intolerance was justified of her children. One in particular I selected, one with surpassing fairness crowned, and bowed before the fourteen inches of her skirt. She was beautiful. She was one of Shakespeare's heroines. She was an amity of inter-removed miracles; all wrangling excellencies at pact in one sole doll; the frontiers of jealous virtues marched in her, yet trespassed not against her peace; and her gracious gift of silence I have not known in woman. I desired for her some worthy name; and asked of my mother: Who was the fairest among living women? Laughingly was I answered that I was a hard questioner, but that perhaps the Empress of the French bore the bell for beauty. Hence, accordingly, my Princess of puppetdom received her style; and at this hour, though she has long since vanished to some realm where all sawdust is wiped for ever from dolls' wounds, I cannot hear that name but the Past touches me with a rigid agglomeration of small china fingers."

A housemaid remembers Francis on the top of the ladder in the book-cupboard, oblivious of her call to meals. Of this early reading he writes:—

"I read certain poetry—Shakespeare, Scott, the two chief poems of Coleridge, the ballads of Macaulay—mainly for its dramatic or narrative power. No doubt—especially in the case of Shakespeare, and (to a less extent) Coleridge—I had a certain sublatent, subconscious, elementary sense of poetry as I read. But this was, for the more part, scarce explicit; and was largely confined to the atmosphere, the exhalation of the work. To give some concrete instance of what I mean. In the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' I experienced profoundly[11] that sense of trance, of dream-like dimness, the moonlight glimmer and sleep-walking enchantment, embodied in that wonderful fairy epilogue 'Now the cat' &c., and suggested by Shakespeare in the lines, 'These things seem small and undistinguishable, like far off mountains turned into clouds.' I did indeed, as I read the last words of Puck, feel as if I were waking from a dream and rub my mental eyes. No doubt the sense of the lines 'These things' &c., was quickened (it may be created—I will not at this distance say) by an excellent note on them in the edition I read. But the effect on me of the close was beyond and independent of all notes. So, in truth, was it with the play as a whole. So, again, I profoundly experienced the atmospheric effect of 'Macbeth,' 'Lear,' 'The Tempest,' 'Coriolanus,' of all the plays in various degree. Never again have I sensed so exquisitely, so virginally, the aura of the plays as I sensed it then. Less often I may have drunk the effluence of particular passages, as in the case already instanced. But never, in any individual passage, did I sense the poetry of the poetry, the poetry as poetry. To express it differently, I was over young to have awakened to the poetry of words, the beauty of language which is the true flower of poetry, the sense of magic in diction, of words suddenly becoming a marvel and quick with a preternatural life. It is the opening of the eyes to that wonder which signalises the puberty of poetry. I was, in fact, as a child, where most men remain all their lives. Nay, they are not so far, for my elemental perception, my dawn before sunrise, had a passion and prophetic intensity which they (with rare exceptions) lack. It was not stunted, it was only nascent."

Another recollection:—

"I understood love in Shakespeare and Scott, which I connected with the lovely, long-tressed women of F. C. Selous' illustrations to Cassell's Shakespeare, my[12] childish introduction to the supreme poet.[4] Those girls of floating hair I loved; and admired the long-haired, beautiful youths whom I met in these pictures, and the illustrations of early English History. Shakespeare I had already tried to read for the benefit of my sisters and the servants; but both kicked against 'Julius Cæsar' as dry—though they diplomatically refrained from saying so. Comparing the pictures of mediæval women with the crinolined and chignoned girls of my own day, I embraced the fatal but undoubting conviction that beauty expired somewhere about the time of Henry VIII. I believe I connected that awful catastrophe with the Reformation (merely because, from the pictures, and to my taste, they seemed to have taken place about the same time)."

He "first beheld the ocean" at Colwyn Bay when he was five years old. It was there that the Thompsons spent their holidays, several excursions there during a year keeping them in touch with the sea. Its sunsets are still remembered by Mother Austin, his sister, in her convent in black Manchester, where her skies are for the most part locked behind bricks or otherwise tampered with. Remembered by this sister as particularly attracting Francis is "the phosphorescence on the crest of the waves at dusk." Her memory is good, for I find in a long mislaid note-book the following verse of an early epithalamium:—

He adds, "I do not know whether the image is altogether clear to the ordinary reader, as it was in my own mind. Anyone, however, who has ever seen on a dark night a phosphorescent sea breaking in long billows of light on the viewless beach, while, as the hidden pools and recessed waters of the strand are stirred by the onrush, they respond through the darkness in swarms of jewel-like flashes, will understand the image at once."

The sea was there, and Francis bathed, timidly and always with the consecrated medal that was still round his neck when he died. He would not strip it from its place, and his sister, only less pious, would laugh at his anxiety concerning it. On the beach brother and sister would score Hornby's centuries. That was the chief use and joy of the sands to the enthusiasts; the whole series of triumphs would be thus shiftingly writ in full particularity. To Colwyn Bay he went before Ushaw, during the holidays and after he left college, and he went also to Kent's Bank, near Ulverstone, to Holyhead and New Brighton, so that it may be wondered why his poetry harbours so few seas. Topographically, his verse is very bare of allusion. The chapter of his childhood must close without the benefits of such witness, unless, as indeed it should be, the whole body of his poetry is taken as the evidence of his teeming experiences. Only in a nonsense verse found in his note-book (where doggerel keeps close, as the grave-digger to Hamlet, to the exquisite fragments of his poetry, so that strings of puns must be disentangled from chains of images) does he confess the place-names of his childhood. Runs the doggerel:—

It may not be supposed that Francis was too busy collecting lore of Hornby's centuries or other boyish excitements to be moved by nature; he tells little of his early childhood's experiences because he was moved only to meditative dumbness, whereas later, when he knew he was a poet, each experience, however fleeting, smote upon his heart as a hammer on an anvil, and the words flew from each immediate stroke. He was too full of emotional adventures when he was sent, after his trials, to Storrington and Pantasaph to need to ransack the unmeaning confusion of his early impressions. Childhood proper was snatched from him when he became a schoolboy. His childhood he had called the true Paradisus Vitæ, and he would have combated the convention that school-days are the happiest of one's life. In an essay on his own childhood it had been his intention to include an account of his first year at Ushaw for the sake of contrast with his home existence, telling of the "refugium or sanctuary of fairy-tales, and dream of flying to the fairies for shelter" that he made there.

"I doubt if I ever saw F. Thompson since his boyhood. I well remember taking him up to Ushaw as a timid, shrinking little boy when he was first sent to college in the late sixties; and how the other boys in the carriage teased and frightened him—for 'tis their nature to—and how the bag of jam tarts in his pocket got hopelessly squashed in the process! I never thought there were the germs of divine poesy in him then. Strange that about the same time (but I think earlier) my classmate at Ushaw was the future Lafcadio Hearn—in those days he was 'Jack' or 'Paddy' Hearn; I never heard the Greek forename till the days of his fame."

Timid his journey must have been, for all the crises of his life were timidly and doubtfully encountered. Dr. Mann gives some account of the event and of his first impressions of the new boy:—

"Canon Henry Gillow—the Prefect of that time in the Seminary—assigned him his bedplace, and gave to him two ministering angels in the guise of play-fellows. Then, for initiation, a whinbush probably occupied his undivided attention, and he would emerge from it with a variant on his patronymic appellation! 'Tommy' was he then known to those amongst whom he lived for the next seven years.

"His mode of procedure along the ambulacrum was quite his own, and you might know at the furthest point from him that[16] you had 'Tommy' in perspective. He sidled along the wall, and every now and then he would hitch up the collar of his coat as though it were slipping off his none too thickly covered shoulder-blades. He early evinced a love for books, and many an hour, when his schoolfellows were far afield, would he spend in the well-stocked juvenile library. His tastes were not as ours. Of history he was very fond, and particularly of wars and battles. Having read much of Cooper, Marryat, Ballantyne, he sought to put some of their episodes into the concrete, and he organised a piratical band."

Another impression comes from Father George Phillips:—

"I was his master in Lower Figures, and remember him very well as a delicate-looking boy with a somewhat pinched expression of face, very quiet and unobtrusive, and perhaps a little melancholy. He always showed himself a good boy, and, I think, gave no one any trouble."

From Dr. Mann's description, too, you get glimpses of the man. Those shoulder-blades were always ill-covered. The plucking-up of the coat behind was, after the lighting of matches, always the most familiar action of the man we remember; while the tragedy of the tarts seems strangely familiar to one who later had a thousand meals with him. Fires he always haunted, and his clothes were burnt on sundry occasions, as we are told they were before the class-room fire. But of the piracy what shall we say? Why, if he did not lose that habit of the collar and never shook off the crumbs of those tarts, why did he forget the way to be a pirate? There was no rollick in Francis, and his own talk of his childhood showed him to have always been a youth of most undaring exploits. A good picture of his person is to be had from his schoolfellows' recollections; for his mood we must go to his own recollections. In writing of Shelley he builds up a poet's boyhood from his own experience; there is no speculation here:—

"Now Shelley never could have been a man, for he never was a boy," is the argument. "And the reason lay in the persecution which overclouded his school-days. Of that persecution's effect upon him he has left us, in 'The Revolt of Islam,' a picture which to many or most people very probably seems a poetical exaggeration; partly because Shelley appears to have escaped physical brutality, partly because adults are inclined to smile tenderly at childish sorrows which are not caused by physical suffering. That he escaped for the most part bodily violence is nothing to the purpose. It is the petty malignant annoyance recurring hour by hour, day by day, month by month, until its accumulation becomes an agony; it is this which is the most terrible weapon that boys have against their fellow boy, who is powerless to shun it because, unlike the man, he has virtually no privacy. His is the torture which the ancients used, when they anointed their victim with honey and exposed him naked to the restless fever of the flies. He is a little St. Sebastian, sinking under the incessant flight of shafts which skilfully avoid the vital parts. We do not, therefore, suspect Shelley of exaggeration: he was, no doubt, in terrible misery. Those who think otherwise must forget their own past. Most people, we suppose, must forget what they were like when they were children: otherwise they would know that the griefs of their childhood were passionate abandonment, déchirants (to use a characteristically favourite phrase of modern French literature) as the griefs of their maturity. Children's griefs are little, certainly; but so is the child, so is its endurance, so is its field of vision, while its nervous impressionability is keener than ours. Grief is a matter of relativity: the sorrow should be estimated by its proportion to the sorrower; a gash is as painful to one as an amputation to another. Pour a puddle into a thimble, or an Atlantic into Etna; both thimble and mountain overflow.[18] Adult fools! would not the angels smile at our griefs, were not angels too wise to smile at them? So beset, the child fled into the tower of his own soul, and raised the drawbridge. He threw out a reserve, encysted in which he grew to maturity unaffected by the intercourses that modify the maturity of others into the thing we call a man."

When he recalls in a note-book his own first impressions of school he could not write as a boy, or of boys:

"The malignity of my tormentors was more heart-lacerating than the pain itself. It seemed to me—virginal to the world's ferocity—a hideous thing that strangers should dislike me, should delight and triumph in pain to me, though I had done them no ill and bore them no malice; that malice should be without provocative malice. That seemed to me dreadful, and a veritable demoniac revelation. Fresh from my tender home, and my circle of just-judging friends, these malignant school-mates who danced round me with mocking evil distortion of laughter—God's good laughter, gift of all things that look back the sun—were to me devilish apparitions of a hate now first known; hate for hate's sake, cruelty for cruelty's sake. And as such they live in my memory, testimonies to the murky aboriginal demon in man."

The word "reserve" is written large across the history of the schoolboy and the man; that he laid it aside in his poetry and with the rare friend only made its habitual observance the more marked. He was safest and happiest alone at Ushaw, and little would his schoolfellows understand the distresses of his mind there. One at least I know who could not recognise Thompson's painful memories as being conceivably based on actual experience. Teasing, at best, is an ignorant[19] occupation; at worst, not meant to inflict lasting wrong.

I have in mind two gay and gentle men, once his class-fellows, who are unfailingly merry at the mention of college hardships; they are now priests, whose profession and desires are to do kindness to their fellow-men, and I do not suspect them of ever having done a living creature an intentional hurt. Thompson's poetry they can understand, but not his unhappiness at school.

Nor does your normal boy, of Ushaw or any other school, admit that wrong is done him by the rod. The rod bears blossoms, says the schoolboy grown up; and the convention which makes men call their school-days the happiest of their lives likewise makes them smile at the punishments in the prefect's study. For the average schoolboy this attitude is perhaps an honest one. His school-days are happy; the cane is only an inconvenience to be avoided, or, if impossible of avoidance, to be grimaced at and tolerated. But every boy at school is not a school-boy, and the boy at school has to suffer generalisations about the school-boy and the rod. The commonweal spells some individual's woe, and doubtless the discipline proper for the normal child was hard for the abnormal. The boy at school, unlike the school-boy, is not brave, or, if he is brave, his courage is of a tragic quality that should not be required of him. The schoolboy's account of the punishment of the boy at school illustrates the difference between the two; for the one it is fit matter for an anecdote, for Francis it was an episode never to be alluded to. Dr. Mann writes:—

"Some old Ushaw men may wonder whether, in his passage through the Seminary, he ever fell into the hands of retributive justice. To the best of his schoolfellows' recollections he did. It fell on a certain day during our drilling-hour that Sergeant Railton dropt into confidential tones, and we had grouped round him to drink in his memories of the Indian Mutiny. 'Tommy,'[20] who scented a battle from afar, was with us. All went well until the steps of authority were heard coming round the corner near the music rooms, and with well-simulated sternness our Sergeant ordered us back into our ranks. 'Tommy,' who, doubtless, was already making pictures of Lucknow or Cawnpore on his mental canvas, was last to dress up, and was summarily taken off to Dr. Wilkinson's Court of Petty Sessions, where, without privilege of jury or advocate, he paid his penalty. He was indignant, naturally, not to say sore, over this treatment."

Such is the gallant and approved vein of school reminiscence, of which one of the classics is the jest about the Rev. James Boyer, the terror of Christ's Hospital: "It was lucky the cherubim who took him to Heaven were nothing but wings and faces, or he would infallibly have flogged them by the way."[6]

But Francis was neither cheerful, nor mock-heroic, like Lafcadio Hearn, whose "The boy stood on the bloody floor where many oft had stood" was conned by his class-mates at Ushaw. Nor did a sense of the grotesque assuage the sense of injury, as in the Daumier drawing of a small boy's agonised contortions under the stroke of a wooden spoon upon the palm of the hand. He did not join his past school-mates in the brave bursts and claps of laughter and winking silences that I have known break in upon the narration of ancient floggings. Says Lamb, in describing Mr. Bird's blister-raising ferule, "The idea of a rod is accompanied with something of the ludicrous": with Francis's school-mates it provokes a gaiety almost beyond the requirements of priestly light-heartedness. I am reluctant and ashamed to be less brave on the poet's behalf—to be out of the joke; and yet I find it difficult to put a better face on it. To remember Thompson's own extreme gentleness is to be intolerant of a small but over-early injury.

Being no observer, Francis failed to find the friends he might have found at Ushaw. Vernon Blackburn was his friend, but not till after-life. Henry Patmore, son of the poet, in a class above him, was as little known to him as he to Henry Patmore. Those who remember Francis as a shy and unusual boy, remember Henry Patmore—"Skinny" Patmore—in much the same terms. These two unusual boys had no more than the acquaintance of sight that is common in a school of over three hundred strong. Another schoolfellow was Mr. Augustine Watts, who married Gertrude Patmore, Henry's sister. It was from Ushaw, where he went in 1870 (Thompson's year), that Henry Patmore wrote to his step-mother:—

"I will begin by telling you I am very happy. I have been much happier during these last two or three months than ever before. . . . My bump of poetry is developing rapidly. For now poetry seems to me to be the noblest and greatest thing, after religion, on earth. . . . But what I mean by the development of my poetic bump is that I can now see the poetry in Milton, Wordsworth, Papa, and Dante as I never could till quite lately; and I really think that being able to enjoy poetry is a new source of happiness added to my life."

At Ushaw, then, were two readers in the conspiracy of spacious song. But Francis wrote no tidings of happiness home. Of schoolboys in general Henry Patmore wrote, and, in writing, disproved his belief:—

"It is quite sickening, after reading the 'Apologia,' to turn to those around me and to myself, and see how very frivolous and aimless and selfish our lives are; how we go on living from day to day for the day, as if we were animals put here to make the best of our time, and then 'go off the hooks' to make way for others. Of course, grown-up people often live for God, but I think nearly all my 'compeers' here (myself included) are animals."

Paddy Hearn (referred to before)—the Lafcadio of later life—was an older schoolfellow. College can[22] be all things to all boys; some may find there a genial scene and cordial entertainment; others unfriendly and frightening surroundings. The case of Lafcadio Hearn, who arrived in Ushaw in 1863, a boy of thirteen, is not comparable to Thompson's, for Hearn mixed a strong rebelliousness with his nervousness; and he was neither unhappy nor unpopular, although peculiar, and even "undesirable" from the principal's point of view. Sent there, like Thompson, that he might discover if his inclination lay in the direction of the priesthood, like Thompson he drifted, after Ushaw, to London, and suffered there. The circumstances are strangely like those of Francis's case. But the invitation of the road and sea maintained Lafcadio's spirits. He endured his poverty mostly near the docks: "When the city roars around you, and your heart is full of the bitterness of the struggle for life, there comes to you at long intervals in the dingy garret or the crowded street some memory of white breakers and vast stretches of wrinkled sand, and far fluttering breezes that seem to whisper 'come.'" Thereafter the scope of his thought and action, with murder-case reporting in New York, with his unconfined sympathies for rebel blood, and contempt for "Anglo-Saxon prudery," might most easily be described as the opposite of Thompson's. A closer observer marks something more remarkable than dissimilarity. His Japanese biographer says of him that "he laughed with the flowers and the birds, and cried with the dying trees"—words which have an accidental likeness to "Heaven and I wept together."

Hearn's own words, in a letter to Krehbeil, the musician, show a much more deeply-rooted likeness. He says:—

"What you say about the disinclination to work for years upon a theme for pure love's sake touches me, because I have felt that despair so long and so often. And yet I believe that all the world's[23] art-work—all that is eternal—was thus wrought. And I also believe that no work made perfect for the pure love of art can perish, save by strange and rare accident. Yet the hardest of all sacrifices for the artist is this sacrifice to art, this trampling of self underfoot. It is the supreme test for admission into the ranks of the eternal priests. It is the bitter and fruitless sacrifice which the artist's soul is bound to make. But without the sacrifice, can we hope for the grace of heaven? What is the reward? the consciousness of inspiration only? I think art gives a new faith. I think, all jesting aside, that could I create something I felt to be sublime, I should feel also that the Unknowable had selected me for a mouthpiece, for a medium of utterance, in the holy cycling of its eternal purpose, and I should know the pride of the prophet that has seen the face of God."

"What shall I do with him? I am beginning to think that really much of the ecclesiastical education (bad and cruel as I used to imagine it) is founded on the best experience of man under civilisation; and I understand lots of things I used to think superstitious bosh, and now think solid wisdom."

When an enthusiastic critic said, at the time Thompson's first book was published, that Ushaw would be chiefly remembered in the future for her connexion with the poet, Ushaw smiled, counting the host of canons of the Church whom she had reared, her bishops, her archbishops, and her cardinals. Ushaw remembered, too, Cardinal Wiseman's saying: "Ushaw's sons are known not by words, but by deeds." But a few college friends did their best to keep Francis in sight during his early years in London, and if they did not help him, it was because he effectively hid himself among his[24] adversities. It would have been more pain to brook the conditions of assistance, more impossible to follow a régime of rescue than to shiver unobserved on the Embankment, or starve, with no invitation or punctuality to observe save the long and silent appeals of an empty stomach, in the Strand. He had privacies to keep intact, aloofness that made a law to him, and these he never abused, even in a doss-house. "What right have you to ask me that question?" he said to the gentleman who accosted him in the street, asking him if he were saved. He had then been fifteen nights upon the streets, a torture insufficient to curb the spirit.

Dr. Carroll, Bishop of Shrewsbury, Fr. Adam Wilkinson, and Dr. Mann were of the few who remembered or sought to renew acquaintance. It is said that Bishop Carroll, when he came to London, would search "with unaccustomed glance" the ranks of the sandwich-men for his face. And when later the poet had a friend, and was to be found at his house, Bishop Carroll sought him there in London, and at Pantasaph from time to time, and had the poet, if not in his diocese, almost within his fold. We have Dr. Mann's record of a visit to London and a meal with Francis at Palace Court, but I know of no other meeting with a college friend. Thompson had never been a schoolboy, nor did he grow into an "old boy."

Applicable to him are the words of Hawthorne, of which he was fond:—"Lingering always so near his childhood, he had sympathies with children, and kept his heart the fresher thereby like a reservoir into which rivulets are flowing, not far from the fountain-head."

The distractions of his imagination were the most pertinent to his needs at Ushaw. Some scraps from his class compositions and his note-books do not sufficiently illustrate the sway that literature already held in his heart and brain, for they are but exercises in expression, stiff words on parade, rather than the natural swinging[25] publication of his thoughts. A writer in the Ushaw magazine lends us some knowledge of his literary and other recreations:—

"He never fretted his hour upon the stage when our annual 'Sem play' delighted the senior house. A pity that was, for such an appearance might have helped to remove some of the awkward shyness which characterised him to the end. His recreation, as a rule, did not assume a vigorous form, though in the racquet houses he showed that at hand-ball he attained a proficiency above the average. At 'cat' his services were at times enlisted to make up the full complement of players. But here his muse was his undoing, for a ball sharply sent out in his direction would find him absent. He does not therefore figure as a party-game player. He seldom handled a bat or trundled a ball. Most of his leisure hours were spent in our small reading-room amongst the shades of dead and gone authors. It says a good deal for his perseverance and patience that he sometimes read and wrote when all around him was strife and turmoil of miniature battle. Thompson would be there, and pause was given to his dreamings; he was rudely brought down from his own peculiar empyrean. After the vacation of 1874 he automatically changes his surroundings, going from Seminary to College. The master who had then care of him exerted much influence over him; he was a man of reading and a rare discriminating taste. In Grammar Francis had a still larger selection of books, and many of his beloved poets were well represented."

Books that were not school-books compelled his attention in other places and at other times. It is remembered that

"He would deliberately take up his seat opposite Mr. F. S., who presided at the cross-table near the door, and, after erecting a pile of books in front of him, would devote his whole soul to a volume of poetry. But Mr. F. S. was not of a restless, suspicious nature. Or it may be that he saw out of his spectacles more than we supposed, and of set purpose did not interfere with the broodings of genius."

Glimpses of Francis in the social life of the college are few. He was not so social but that somebody[26] else sang his songs for him. Dr. Mann describes a picnic:—

"After regaling ourselves at Cornsay with tea, coffee, and toast, we did not leave the board till the old songs had been sung. I remember only the refrain. The first verse told of the virtues of our President (Dr. Tate), the second of the Vice (Dr. Gillow), the third of the Procurator (Mr. Croskell), and so on, each verse ending with—

Fill up your glass, here's to the ass

Who fancies his coffee is wine in a glass."

Another witness, in the Ushaw Magazine of March 1894, remembers Francis on one occasion himself speaking his composition, but it is said by some that he never put such a trial upon his courage:—

"During his later years at College his literary gifts were well known. He declaimed some of his own compositions—written in a clear, rich, vigorous prose—at the public exhibitions in the Hall for the 'speaking playday.' His verse we never heard, except a skit in Latin rhyme, bidding farewell to work before the vacation, and beginning:

Nunc relinquemus in oblivium

Cæsarem et Titum Livium.

We have, however, a vivid recollection of him as he was accustomed to come into the Reading-room, on the long dim half-playday afternoons, with a thick manuscript book under his arm, and there sit reading and copying poetry, nervously running one hand through his hair."

While Dr. Whiteside (later Archbishop of Liverpool) was Minor Professor at the College he had charge of Francis's dormitory. One night after lights were out he heard the sound of strictly forbidden talk. Searching for the offender, he found Francis reciting Latin poetry in his sleep. The Minor Professor awakened him and told him he was disturbing the dormitory. Ten minutes later he heard more noise, and found Francis, again asleep, reciting Greek poetry! I doubt if Francis's Greek, save in dream or anecdote, was fluent enough to waken his fellows.

The habit of humorous verse was already on him, and argues that he was light-hearted at school, even as the note-books, filled at the time of his greatest depression in after years, argue that he never wholly lacked[28] relief. His joke showed his independence; he was not under the thumb of his distresses. He could put them aside, or accept, or forget, or forbid, or do to them whatever may have been the armouring process.

Of all the essays, in verse or prose, of his Ushaw days, the verses aimed at an invalid master had caught out of the future the most characteristic note. I can hear him say his "Lamente Forre Stephanon" in the deep tremulous voice that he affected for reading, and it hardly comes amiss from the mature tongue:—

A copy of the verses fell into the hands of Stephanon, without ill effects; his mighty laugh is still raised when he remembers them. The resolve to be a poet is in some of the college verses; the word has not been made poetry, but the spirit is willing and anxious. "Yet, my Soul, we have a treasure not the banded world can take," was the stuff to fill the manuscript book he clutched in recreation hours:—

It was sowing-time and the soil rich, but an observer, in the exact sense, Francis never was. He would make any layman appear a botanist with easy questions about the commonplaces of the hedges, and a flowered dinner-table in London always kept him wondering, fork in air, as to kinds and names. On the other hand, he was essentially an observer: let him see but one sunset and the daily mystery of that going down would companion him for a life-time; let him see but one daisy, and all his paths would be strewn with white and gold. He had the inner eye, which when it lifts heavy lashes lets in immutable memories.

And of Religion: more pressing than the invitation to the northern road would be the invitation to Ushaw's Chapel. His lessons in ceremonial were not the least he was taught. Eton could have given him his Latin, but his Liturgy was more important. His singing-gown[31] was a vestment, and he learnt its fashioning at college. He learnt the hymns of the Church and became her hymn-writer; he learnt his way in the missal, and came to write his meditation in "The Hound of Heaven." A priest, who was his schoolfellow, writes:

"No Ushaw man need be told how eagerly all, both young and old, hailed the coming of the 1st of May. For that day, in the Seminary, was erected a colossal altar at the end of the ambulacrum nearest the belfry, fitted and adorned by loving zeal. Before this, after solemn procession from St. Aloysius', with lighted tapers, all assembled, Professors and students, and sang a Marian hymn. In the College no less solemnity was observed. At a quarter past nine the whole house, from President downwards, assembled in the ante-chapel before our favourite statue. A hymn, selected and practised with great care, was sung in alternate verses by the choir in harmony, and the whole house in unison. 'Dignare me laudare, te, Virgo Sacrata,' was intoned by the Cantor; 'Da mihi virtutem contra hostes tuos' thundered back the whole congregation; and the priest, robed already for Benediction, sang the prayer 'Concede, misericors Deus,' etc. Singing Our Lady's Magnificat, we filed into St. Cuthbert's, and then, as in the Seminary, Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament followed. For thirty-one days, excepting Sundays and holy days, this inspiring ceremonial took place—its memory can never be effaced."

Although it is somewhere affirmed that Francis betrayed no singular piety, we know how devout was his young heart. It was intended for him that he should enter the Church, and he studied for the priesthood. Letters written to his parents by those who had him under observation go to make the history of the case; on September 6, 1871, Father Yatlock wrote:—

"I am sure, dear Mrs. Thompson, that it will be a pleasure and a consolation to you and Dr. Thompson that Frank gives the greatest satisfaction in every way; and I sincerely trust, as you said the other evening, that he will become one day a good and holy priest."

But at the last his ghostly advisers found him unfitted. They held his absent-mindedness to be too grave a[32] disability, and in his nineteenth year he was advised to relinquish all idea of the priesthood. In June 1877 the President wrote a letter proving the good will, a quality that may easily collapse before a silent, strange, evasive child, which was felt for Francis.

The President wrote:—

"With regard to Frank, I can well appreciate the regret and disappointment which you and his mother must feel. Frank has always been a great favourite of mine ever since he came as a child to the Seminary. He has always been a remarkably docile and obedient boy, and certainly one of the cleverest boys in his class. Still, his strong, nervous timidity has increased to such an extent that I have been most reluctantly compelled to concur in the opinion of his Director and others that it is not the holy will of God that he should go on for the Priesthood. It is only after much thought, and after some long and confidential conversations with Frank himself, that I have come to this conclusion: and most unwillingly, for I feel, as I said, a very strong regard and affection for your boy. I earnestly pray God to bless him, and to enable you to bear for His sake the disappointment this has caused. I quite agree with you in thinking that it is quite time that he should begin to prepare for some other career. If he can shake off a natural indolence which has always been an obstacle with him, he has ability to succeed in any career."

Indolence is one name of many for the abstraction of Francis's mind and the inactivities of his body. He was not of the stuff to "break ice in his basin by candlelight," and no doves fluttered against his lodging window to wake him in summer, but he was not indolent in the struggle against indolence. Not a life-time of mornings spent in bed killed the desire to be up and doing. In the trembling hand of his last months he wrote out in big capitals on pages torn from exercise books such texts as were calculated to frighten him into his clothes. "Thou wilt not lie a-bed when the last trump blows"; "Thy sleep with the worms will be long enough," and so on. They were ineffectual. His was a long series of broken[33] trysts—trysts with the sunrise, trysts with Sunday mass, obligatory but impossible; trysts with friends. Whether it was indolence or, as he explained it, an insurmountable series of detaining accidents, it is certain that he, captain of his soul, was not captain of his hours. They played him false at every stroke of the clock, mutinied with such cunning that he would keep an appointment in all good faith six hours after it was past. Dismayed, he would emerge from his room upon a household preparing for dinner, when he had lain listening to sounds he thought betokened breakfast. He was always behindhand with punctual eve, and in trouble with strict noon.

And yet there were the makings of the parish priest, or the hint of them, in his demeanour. "Is that the Frank Thompson I quarrelled about with my neighbouring bishop?" asked Cardinal Vaughan (then Bishop of Salford) when many years later he heard the name of the poet from my father; "each of us wanted him for his own diocese."

The ritual of the Church ordered his unorderly life; he was priestly in that he preached her faith and practised her austerities. Nature he ignored till she spoke the language of religion; and he, though secretly much engrossed in his own spiritual welfare, was, priest-like, audible at his prayers—or poetry. His muse was obedient and circumspect as the voice that proclaims the rubrics. He was often merely in Roman orders, so to say, when the critics accused him of breaking the laws of English and common-sense. At the same time he failed signally in the practical service of his fellows. His rhymes were the only alms he gave; but annoyances he seemed at times to distribute as lavishly as St. Anthony his loaves.

Having done no wrong, he bore home a disappointment for his parents. It is no light thing to have a son, destined for the sheltered rallying-place of the Church, thrust back into a world he had been well rid of. Nor[34] did his indifference as to his prospects (the disguise, perhaps, of his own disappointment) inspire them with confidence. I have already mentioned that it is thought by many persons well-versed in the spiritual affairs of the family that his failure in the Seminary was with him an acute and lasting grief.

On the other hand, he was from his childhood a prophet in his own strange land, and it is probable that while his family were solicitous for him to enter the Church, he recognised the justice of his confessor's opinion. The "A.M.D.G." inscribed in his exercise books was none the less the perfect dedication. "To the Greater Glory of God" was already his pen's motto. He saw "all the world for cell," and he made much of the pains he thought necessary for his poetry.

He had been seven years at Ushaw when he left in July 1877. The photographs of the time show him to have arrived at the most robust and perhaps most normal period of his life. But awaiting him at home were the traps of personality. There the opportunity to be himself set on foot and gave courage to all the essential peculiarities of his character. If he had evaded at Ushaw the claims of the community, he now evaded them much more. Although he resumed his play and make-believe with his sisters, he was growing further and further apart from a good understanding with any of his fellow-creatures. Holding himself little bounden to his duties, he soon started on a career of evasion and silence. After a pause of some more months he was examined, and passed with distinction in Greek, for admission as a student of medicine to Owens College. For six years he studied or attempted to study in Manchester, making the journey from Ashton-under-Lyne under the compulsion of the family eye. But once round the corner he was safe from the too strict inquiry by a[36] father never stern. The hours of his actual attendance at lectures were comparatively few. "I hated my scientific and medical studies, and learned them badly. Now even that bad and reluctant knowledge has grown priceless to me," he wrote in after life.

The Manchester of his studies had little hold of him, and keeps few memories of him. In the wide but mean street leading to Owens College you may, it is true, picture him making a late and lingering way to work, or entering the cook-shops which even then had initiated him in the consumption of bad food (but he long remembered the excellence of one underground restaurant for modest commercial classes), or nervously awaiting the offer of the bookseller for some volume superfluous to a truant student's needs. The thoroughfare is so busy as to disregard the abstracted walk and expression of an eccentric wayfarer. Francis soon learned the art of being lonely in a multitude, and would only occasionally perceive one of the passers who turned and looked after him. Boys provoked to jeer at him he met to his own satisfaction, sometimes with a complete disregard, sometimes with a threatening show of anger. He would congratulate himself upon his tactics, not knowing that he, a young man, was more timid and abashed than any seven-year-old rough of the pavement. The college building, oppressive and awesome in its arches, halls, and corridors, is difficult to reconcile with the timidity with which Francis faced it. Your footsteps "hullo!" at you in the passages, and must ring with self assurance or with carelessness if they are not to echo and exaggerate your doubtful mood. Laughter, the ungentle laughter of medical students—whither, asked Stevenson, go all unpleasant medical students, whence come all worthy doctors?—swings down on you or bars you from a corner that you must needs pass. Among the sheltering cases of the deserted museum there is more room for the would-be solitary. Silent mineralogies,[37] fragments, fossils, tell the poet more than the boisterous tongues of the young men. Yorkshire delivered up to the museum a vast saurian and other creatures of the past of whom we hear in the "Anthem of Earth."

Those were years of anything but the making of a doctor. To have conformed so little to the style of the medical student promised little for the expected practitioner. He would even leave his father's reputable doorstep with untied laces, dragging their length on the pavement past the windows of curious and critical neighbours. He did not work, and his idleness was all unlike the idleness proper to his class. He read poetry in the public library. One sort of idleness, an idleness that gave business to his thoughts for all his life, took him to the museums and galleries. In an essay of the 'nineties he remembers

"The statue which thralled my youth in a passion such as feminine mortality was skill-less to instigate. Nor at this let any boggle; for she was a goddess. Statue I have called her; but indeed she was a bust, a head, a face—and who that saw that face could have thought to regard further? She stood nameless in the gallery of sculptural casts which she strangely deigned to inhabit; but I have since learned that men call her the Vatican Melpomene. Rightly stood she nameless, for Melpomene she never was: never went words of hers from bronzèd lyre in tragic order; never through her enspelled lips moaned any syllables of woe. Rather, with her leaf-twined locks, she seems some strayed Bacchante, indissolubly filmed in secular reverie. The expression which gave her divinity resistless I have always suspected for an accident of the cast; since in frequent engravings of her prototype I never met any such aspect. The secret of this indecipherable significance, I slowly discerned, lurked in the singularly diverse set of the two corners of the mouth; so that her profile wholly shifted its meaning according as it was[38] viewed from the right or left. In one corner of her mouth the little languorous firstling of a smile had gone to sleep; as if she had fallen a-dream, and forgotten that it was there. The other had drooped, as of its own listless weight, into a something which guessed at sadness; guessed, but so as indolent lids are easily grieved by the prick of the slate-blue dawn. And on the full countenance these two expressions blended to a single expression inexpressible; as if pensiveness had played the Maenad, and now her arms grew heavy under the cymbals. Thither each evening, as twilight fell, I stole to meditate and worship the baffling mysteries of her meaning: as twilight fell, and the blank noon surceased arrest upon her life, and in the vaguening countenance the eyes broke out from their day-long ambuscade. Eyes of violet blue, drowsed-amorous, which surveyed me not, but looked ever beyond, where a spell enfixed them,

Waiting for something, not for me.

And I was content. Content; for by such tenure of unnoticedness I knew that I held my privilege to worship: had she beheld me, she would have denied, have contemned my gaze. Between us, now, are years and tears; but the years waste her not, and the tears wet her not; neither misses she me or any man. There, I think, she is standing yet; there, I think, she will stand for ever: the divinity of an accident, awaiting a divine thing impossible, which can never come to her, and she knows this not. For I reject the vain fable that the ambrosial creature is really an unspiritual compound of lime, which the gross ignorant call plaster of Paris. If Paris indeed had to do with her, it was he of Ida. And for him, perchance, she waits."

Here already was the artist, the actor in unreal realities. Already he had been thrice in love—with the heroines of Selous' Shakespeare, with a doll, with a statue.

Before he knew that his lot was to be more chipped and filled with blanks than the ladies of the Parthenon, he had set about furnishing the gaps with complementing fragments of fancy. He was winning consolation prizes before any races had been lost. "No youth expects to get a heroine of romance for a mistress," he avers, but I doubt if many youths court woodcut and wax on that account. They look for their heroines in living replica; Francis, the artist, went to book and toy-box. And he went walking often to the accompaniment of his father's talk of buds, and trees, and flowers. Mr. J. Saxon Mills, his neighbour, writes:—

"Some few may remember him when, a good many years ago, he used to take his walks up Stalybridge Road, and in the semi-rural outskirts of Ashton. They will recall the quick short step, the sudden and apparently causeless hesitation or full stop, then the old quick pace again, the continued muttered soliloquy, the frail and slight figure. Such was the poet during his studentship at Owens College. An intellectual temperament less adapted to the career of a doctor and surgeon could not be imagined. To such a profession, however, Frank was destined by a careful and practical father."

Besides the public galleries, the libraries, and the roads, he had the cricket-field. From the writing of his own and his sister's heroes' scores upon the sands at Colwyn Bay, he and she had taken to back-garden practice of the game. At school he had not played, but neither had he lost his enthusiasm there. Returning from Ushaw, he would, his sister tells me, go to a friend's garden and play for hours by himself, and bowl for hours at the net, which meant that he had, after each delivery, to retrieve his own ball. He was much at the Old Trafford ground, and there he stored memories that would topple out one over another in his talk at the end of his life. The most historic of the matches he witnessed was that between Lancashire and Gloucestershire in 1878. His sister remembers it, and he celebrates it[40] in the following poem, written in the clear but tragic light that his devotion to the game shed upon the distant scene of whites and greens:—

Nor did Francis's cloistered sister forget. On reading Mr. E. V. Lucas's criticisms on her brother's cricket verses (Cornhill Magazine, 1907) she wrote to me:—"The article stirred up many old memories, thank God. I can remember seven names out of the Lancashire XI of that match." For thirty years she remembered the seven jolly cricketers, with the seven joyful mysteries of the Rosary, to keep her young.

Francis in 1900 could draw up the whole of the Lancs. XI and name eight of the other XI, with a guess at a ninth man. Mr. E. V. Lucas knows all about the match. "It was an historic contest, for the two counties had never met before, and was played on July 25, 26, 27, 1878, when the poet was eighteen. The fame of the Graces was such that 16,000 people were present on the Saturday, the third day—of whom, by the way, 2000 did not pay but took the ground by storm. The result was a draw a little in Lancashire's favour. It was eminently Hornby's and Barlow's match. In the first innings the amateur made only five, but Barlow went right through it, his wicket falling last for 40. In the second innings Hornby was at his best, making with incredible dash 100 out of 156 while he was in, Barlow supporting him while he made eighty of them. The note-book in which these verses are written contains numberless variations upon several of the lines. 'O my Hornby and my Barlow long ago!' becomes in one case 'O my Monkey and Stone-Waller long ago!' Monkey was, of course, Mr. Hornby's nickname. 'First he runs you out of breath,' said the professional, possibly Barlow himself, 'then he runs you out, and then he gives you a sovereign!' A brave summary!"

Other Lancashire heroes and other worship were here recorded:—

Vernon Royle, says the sister, was one of them; nor did the brother forget him. I quote from his review of Ranjitsinhji's Jubilee Book of Cricket (The Academy, September 4, 1897):—

"'From what one hears,' Prince Ranjitsinhji says, 'Vernon Royle must have been a magnificent fielder.' He was. A ball for which hardly another cover-point would think of trying he flashed upon, and with a single action stopped it and returned it to the wicket. So placed that only a single stump was visible to him, he would throw that down with unfailing accuracy, and without the slightest pause for aim. One of the members of the Australian team in Royle's era, playing against Lancashire, shaped to start for a hit wide of cover-point. 'No, no!' cried his partner, 'the policeman is there!' There were no short runs anywhere in the neighbourhood of Royle. He simply terrorised the batsmen. In addition to his swiftness and sureness, his style was a miracle of grace. Slender and symmetrical, he moved with the lightness of a young roe, the flexuous elegance of a leopard. . . . To be a fielder like Vernon Royle is as much worth any youth's endeavours as to be a batsman like Ranjitsinhji or a bowler like Richardson."

The cricket verses are all lamentations for the dead. I doubt if he was ever so happy as when mourning his heroes. To decorate his boyish memories of the departed with rhymed requiems and mature rhythms was one of his few luxuries. The note-books were full of fragments:—

He had projects beyond cricket verses and reviewing. At a late London period he proposed to write his cricket memories, gravely justifying his connoisseurship and his qualifications:—

"For several years, living within distance of the O. T. Ground, where successively played each year the chief cricketers of England, where the chief cricketers of Australia played in their periodic visits, and where one of the three Australian test-matches was latterly decided, I saw all the great cricketers of that day, and it was a very rich day. Naturally, I have a few things to say about cricket now and then. . . . Thousands of others have the same basis, but it happens that I have what they have not—some trained faculty of expression. The few remarks that follow carefully avoid the province of purely technical criticism, which is rightly engrossed by those who are themselves great cricketers. The only technical criticism worth having in poetry is that of poets, and the same is true of cricket."

Of the true historian of the game he writes: "Nyren—at once the Herodotus and Homer of cricket—an epic writer if ever there was one."

His Lancastrian ardour had suffered no diminution[44] when, after an absence from the north and from cricket fields of twenty years, he and I talked cricket. There was a well-established understanding between us that he was for the red rose, I for the white. It was make-believe, but served during many seasons and in many letters. More chivalrous than a knight of Arthur in rivalry he would write thus:—

"Well done, Yorkshire! your county is coming up hand over hand I see by the placards. I said how it would be, so I am not surprised. Our tail is not plucky. Love to all, dear Ev.

F.T."

That was about a match lost by Lancashire in 1905. The year before, Thompson's fellow-lodgers, with an eye to comedy as much as to cricket, had persuaded him to meet them at a cricket-net near Wormwood Scrubbs. Of seven men and boys who met there, six had made some compromise with the conventional costume of the game; they could boast a flannelled leg, soft collar, or at least a stud unfastened in deference to a splendid sun; and they were active, and their shadows on the green quite playful. But he was dingy from boot laces to hat band. Timorously excited and wonderfully intent upon all the preparations, he stiffly waited his turn to bat. When it came he remembered he had no pads on and stayed to strap them with fingers so weak that they were hurt by the buckle with which they fumbled. And then, supremely grave, he batted for the first time since he had faced his sister's bowling on the sands of Colwyn Bay.

I was never at Lord's or the Oval with him, in spite of many plans, and he himself passed the turnstile on very few occasions. But he was always thinking of the cricket he would see, and always for some good reason postponing the day, as for instance in a note written in 1905:—

"I did not go to Lord's. Could not get there before lunch; and getting a paper at Baker Street saw Lancashire had collapsed and Middlesex were in again. So turned back without getting my ticket—luckily kept from another disappointing day."

Mr. E. V. Lucas has written of the incongruity of Thompson's appearance and his enthusiasm:—

"If ever a figure seemed to say, 'Take me anywhere in the world so long as it is not to a cricket match,' that figure was Francis Thompson's. And his eye supported it. His eye had no brightness: it swung laboriously upon its object; whereas the enthusiasts of St. John's Wood dart their glances like birds. But Francis Thompson was born to baffle the glib inference."

It was his unpromising figure that, making its way late at night from Granville Place to Brondesbury, would pass through St. John's Wood and be stirred with thoughts of the game. Had his mutterings reached the ear of the policeman on the Lord's beat, it would have been known that they were not always so tragically engendered as his mien suggested. The following lines he wrote out for me and posted in the early hours after such a journey:—

At the end of two years at Owens College he went to London for the first time, staying with his cousin, Mr. May, in Tregunter Road, Fulham.[8] The trials of examination were partly compensated for by a visit to the opera.

In 1879 Francis fell ill, and did not recover until after a long bout of fever. He looks stricken and thin in photographs taken at his recovery, and it is probably at this time that he first tasted laudanum. It was at this time too, during his early courses at Owens College, that Mrs. Thompson, without any known cause or purpose, gave her son a copy of The Confessions of an English Opium Eater.[9] It was a last gift, for she died December 19, 1880. Apart from the immediate consequences of this momentous introduction, fraught with suggestions and sympathies for which there was a gaping readiness in the young man, it greatly serves in the understanding of the opium-eater in general, of the Manchester opium-eater in particular, and of Francis Thompson, to make or renew acquaintance with de Quincey. Indeed if there is one favour that must be asked by the biographer of Francis Thompson, it is that his readers should also be readers of the Confessions, for, without the mighty initiation of that masterly prose, the gateways into the strange and tortuous landscape of dreams can hardly be forced, nor half the thickets and valleys be conquered, of the poet's intellectual history.[47] As a sight of the pictures of Tintoretto would serve to make known, to one entirely ignorant of the style, the possibilities and achievements of the Venetian School; would serve to make known, not Titian, but the possibility of a Titian, so the style of de Quincey, the habit of his mind, the manner of his confessing, his concealments and sincerities, his association of passion and idleness, his fretfulness and his habit of presaging dole, his manner of complaining of being cold a-bed, his bulletins, his conscious style and repetitions, serve to bring the personality of Thompson to the memory of those who knew him and into the ken of those who did not. For the family likeness, for the school manner, there are passages, too, in the history of Coleridge that will be found suggestive and explanatory. In knowing these cousins of the habit, you come, as you cannot come by any single and uncorroborated experience, into very convincing touch with him whom you are seeking. If, apart from the special significance of Francis's communion with de Quincey, these two are linked, and in them the family likeness is apparent, what of the likeness and the linking when we find how strong was the allegiance sworn by Francis to the spirit of de Quincey; when we track allusions and words and mannerisms in the "Anthem of Earth" back to the Confessions; when coincidence of actualities as well as the coincidence of intellect, such as the two flights from Manchester and the two lives in the streets of London, clashed upon the attention of the young man who was withdrawn from the companionship of contemporaries?

De Quincey, like Francis, had spent much time in the Manchester library. There both made their vocabularies robust and rare from the same Elizabethans, both fattened to the marrow the bones of their English from Sir Thomas Browne. And both stumbled headlong down a precipice of despondency. De Quincey has[48] said many things on his own behalf, in that despondency and in the recourse to opium, that may well be said on Thompson's.

It happened as if in giving Francis the Confessions Mrs. Thompson had found for him a guardian, a spokesman, as if she had borne to him an elder brother. For Francis's feeling for de Quincey soon came to be that of a younger for an elder brother who has braved a hazardous road, shown the way, conquered, and left it strewn with consolations and palliations. From de Quincey he received the passport, the royal introduction set forth in Sir Walter Raleigh-like language ringing with at least the assurance of its own stateliness and power:—

"O just, subtle, and all-conquering opium! that to the hearts of rich and poor alike, for the wounds that will never heal and for the pangs of grief that 'tempt the spirit to rebel,' bringest an assuaging balm:—eloquent opium! that with thy potent rhetoric stealest away the purposes of wrath, pleadest effectually for relenting pity, and through one night's heavenly sleep callest back to the guilty man the visions of his infancy, and hands washed pure from blood;—O just and righteous opium! that to the chancery of dreams summonest for the triumphs of despairing innocence false witnesses, confoundest perjury, and dost reverse the sentences of unrighteous judges; then buildest upon the bosom of darkness, out of the fantastic imagery of the brain, cities and temples, beyond the art of Phidias and Praxiteles—beyond the splendours of Babylon and Hekatòmpylos; and, 'from the anarchy of dreaming sleep' cullest into sunny light the faces of long-buried beauties, and the blessed household countenances, cleansed from the 'dishonours of the grave.' Thou only givest those gifts to man; and thou hast the keys to Paradise, O just, subtle, and mighty opium!"

Opium indeed was in the air of Manchester, the cotton-spinners being much addicted to its use. And it called aloud to Francis in these words of de Quincey. Damnable things become reasonable or tolerable in a city. It harbours such a multitude of distresses,[49] such a conflict of right and wrong—the purposes of nature stand confused, instincts go haltingly along the streets, conscience and reasonings are stunned between stone walls. In one thing, then, did Francis mishear the edict of lawfulness. He took opium—a very pitiful and, surely, very excusable misunderstanding. Constitutionally he was a target for the temptation of the drug; doubly a target when set up in the mis-fitting guise of a medical student, and sent about his work in the middle of the city of Manchester, long, according to de Quincey, a dingy den of opium, with every facility of access, and all the pains that were de Quincey's excuse. He took opium at the hands of de Quincey and his mother. That she, "giver of life, death, peace, distress," should thus have confirmed and renewed her gifts was a strange thing to befall. From her copy of the Confessions of an English Opium Eater he learnt a new existence at her hands. That the life that opium conserved in him triumphed over the death that opium dealt out to him shall be part argument of this book. On the one hand, it staved off the assaults of tuberculosis; it gave him the wavering strength that made life just possible for him, whether on the streets or through all those other distresses and discomforts that it was his character deeply to resent but not to remove by any normal courses; if it could threaten physical degradation he was able by conquest to tower in moral and mental glory. It made doctoring or any sober course of life even more impractical than it was already rendered by native incapacities, and to his failure in such careers we owe his poetry. On the other hand, it dealt with him remorselessly as it dealt with Coleridge and all its consumers. It put him in such constant strife with his own conscience that he had ever to hide himself from himself, and for concealment he fled to that which made him ashamed, until it was as if the fig-leaf were of necessity plucked from the Tree of the Fall. It killed in him[50] the capacity for acknowledging those duties to his family and friends which, had his heart not been in shackles, he would have owned with no ordinary ardour.

It is on account of a hundred passages of the Confessions that the friendship was established. What solace of companionship must Francis have discovered when de Quincey told him, "But alas! my eye is quick to value the logic of evil chances. Prophet of evil I ever am to myself; forced for ever into sorrowful auguries that I have no power to hide from my own heart, no, not through one night's solitary dreams." Here was a boon though sorrowful companion. For here was one who could translate his distresses into a brave art; one who could extract good writing out of his disabilities. Doubtless it was he who first showed to Francis the profitableness of bitter experiences, and that, if gallant prose might come of weakness, poetry might be sown in the fields of failure, and the crown of thorns be turned to the chaplet of laurel. As it serves us in following the friendship that Francis had imagined for himself, a passage in which no immediate relation to him can be traced may perhaps be pardoned on this page. It is necessary inasmuch as it shows the equal ground trodden by the two men; they were going the same road, the stride of their thoughts was equal. It occurs in the part of the Confessions telling of the eve of de Quincey's flight from school. Evening prayers are being said, and with nerves highly strung by the responsibilities of the morrow there comes to de Quincey the higher meanings and motives of the school devotions. He feels how "the marvellous magnetism of Christianity" has gathered into her service the wonders of nature, and builded her temple with the bricks of Creation:—