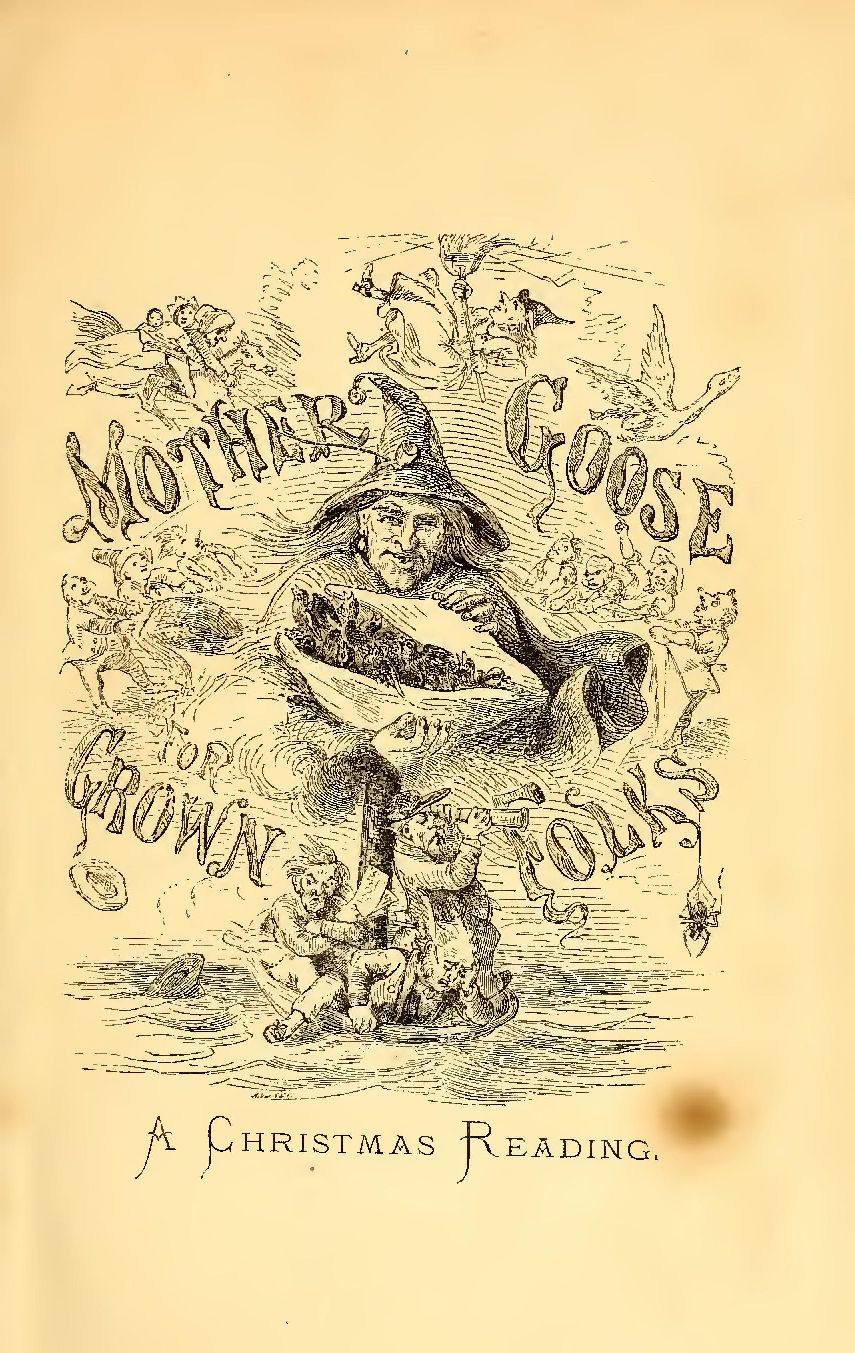

Project Gutenberg's Mother Goose for Grown Folks, by Mrs. A. D. T. Whitney This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Mother Goose for Grown Folks Author: Mrs. A. D. T. Whitney Illustrator: Augustus Hoppin Release Date: April 1, 2014 [EBook #45301] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOTHER GOOSE FOR GROWN FOLKS *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

Somewhere in that uncertain "long ago,"

Whose dim and vague chronology is all

That elfin tales or nursery fables know,

Rose a rare spirit,—keen, and quick, and quaint,—

Whom by the title, whether fact or feint,

Mythic or real, Mother Goose we call.

Of Momus and Minerva sprang the birth

That gave the laughing oracle to earth:

A brimming bowl she bears, that, frothing

high

With sparkling nonsense, seemeth non-

sense all;

Till, the bright, floating syllabub blown by,

Lo, in its ruby splendor doth upshine

The crimson radiance of Olympian wine

By Pallas poured, in Jove's own banquet-

hall.

The world was but a baby when she came;

So to her songs it listened, and her name

Grew to a word of power, her voice a spell

With charm to soothe its infant wearying

well.

But, in a later and maturer age,

Developed to a dignity more sage,

Having its Shakspeares and its Words-

worths now,

Its Southeys and its Tennysons, to wear

A halo on the high and lordly brow,

Or poet-laurels in the waving hair;

Its Lowells, Whittiers, Longfellows, to sing

Ballads of beauty, like the notes of spring,

The wise and prudent ones to nursery use

Leave the dear lyrics of old Mother Goose.

Wisdom of babes,—the nursery Shak-

speare stilly—

Cackles she ever with the same good-will:

Uttering deep counsels in a foolish guise,

That come as warnings, even to the wise;

As when, of old, the martial city slept,

Unconscious of the wily foe that crept

Under the midnight, till the alarm was heard

Out from the mouth of Rome's plebeian

bird.

Full many a rare and subtile thing hath

she,

Undreamed of in the world's philosophy:

Toss-balls for children hath she humbly

rolled,

That shining jewels secretly enfold;

Sibylline leaves she casteth on the air,

Twisted in fool's-caps, blown unheeded by,

That, in their lines grotesque, albeit, bear

Words of grave truth, and signal prophecy;

And lurking satire, whose sharp lashes hit

A world of follies with their homely writ;

With here and there a roughly uttered hint,

That makes you wonder at the beauty

in't;

As if, along the wayside's dusty edge,

A hot-house flower had blossomed in a

hedge.

So, like brave Layard in old Nineveh,

Among the memories of ancient song,

As curious relics, I would fain bestir;

And gather, if it might be, into strong

And shapely show, some wealth of its

lost lore;

Fragments of Truth's own architecture,

strewed

In forms disjointed, whimsical, and rude,

That yet, to simpler vision, grandly stood

Complete, beneath the golden light of

If a great poet think he sings,

Or if the poem think it's sung,

They do but sport the scattered plumes

That Mother Goose aside hath flung.

Far or forgot to me is near:

Shakspeare and Punch are all the same;

The vanished thoughts do reappear,

And shape themselves to fun or fame.

They use my quills, and leave me out,

Oblivious that I wear the wings;

Or that a Goose has been about,

When every little gosling sings.

Strong men may strive for grander thought,

But, six times out of every seven,

My old philosophy hath taught

All they can master this side heaven.

"Little boy blue! come blow your horn!

The sheep in the meadow, the cows in the corn!

Where's little boy blue, that looks after the sheep?

He's under the hay-mow, fast asleep!"

Of morals in novels, we've had not a few;

With now and then novel moralities too;

And we 've weekly exhortings from pulpit

to pew;

But it strikes me,—and so it may chance

to strike you,—

Scarce any are better than "Little Boy

Blue."

For the veteran dame knows her business:

right well,

And her quaint admonitions unerringly

tell:

She strings a few odd, careless words in a

jingle,

And the sharp, latent truth fairly makes

your ears tingle.

"Azure-robed Youth!" she cries, "up to

thy post!

And watch, lest thy wealth be all scattered

and lost:

Silly thoughts are astray, beyond call of

the horn,

And passion breaks loose, and gets into the

corn!

Is this the way Conscience looks after her

sheep?

In the world's soothing shadow, gone sound-

ly asleep?"

Is n't that, now, a sermon? No lengthened

vexation

Of heads, and divisions, and argumenta-

tion,

But a straightforward leap to the sure ap-

plication;

And, though many a longer harangue is

forgot,

Of which careful reporters take notes on

the spot,

I think,—as the "Deacon" declared of his

"shay,"

Put together for lasting for ever and aye,—

A like immortality holding in view,

The old lady's discourse will undoubtedly

"dew"!

"Hiccory, diccory, dock!

The mouse ran up the clock.

The clock struck one, and down she run:

Hiccory, diccory, dock!"

She had her simple nest in a safe and cun-

ning place,

Away down in the quiet of the deep, old-

fashioned case.

A little crevice nibbled out led forth into

the world,

And overhead, on busy wheels, the hours

and minutes whirled.

High up in mystic glooms of space was

awful scenery

Of wires, and weights, and springs, and all

great Time's machinery;

But she had nought to do with these; a

blessed little mouse,

Whose only care beneath the sun was just

to keep her house.

For this was all she knew, or could; with-

out her, just the same

The earth's great centre drew the weight;

the pendulum went and came;

And days were born, and grew, and died;

and stroke by stroke were told

The hours by which the world and men

are ever growing old.

It suddenly occurred to her,—it struck her

all at once,—

That living among things of power, her-

self had been a dunce.

"Somebody winds the clock!" she cried

"Somebody comes and brings

An iron finger that feels through and fum-

bles at the springs;

"And then it happens; then the buzz is

stirred afar and near,

And the hour sounds, and everywhere the

great world stops to hear.

I don't think, after all, it seems so hard a

thing to do.

I know the way—I might run up and

make folks listen too."

She sprang upon the leaden weight; but

not the merest whit

Did all her added gravity avail to hurry it.

She clambered up the steady cord; it wav-

ered not a hair.

She got among the earnest wheels; they

knew not she was there.

She sat beside the silent bell; the patient

hammer lay

Waiting an unseen bidding for the word

that it should say.

Only a solemn whisper thrilled the cham-

bers of the clock,

And the mouse listened: "Hiccory! hie—

diccory! die—dock!"

Something was coming. She had hit the

ripeness of the time;

No tiny second was outreached by that ex-

ultant climb;

In no wise did the planet turn the faster to

the sun;

She only met the instant, but the great

clock sounded—"One!"

What then? Did she stand gloriously

among those central things,

Her eye upon the vibrant bell, her heel

upon the springs?

Was her soul grand in unison with that

resounding chime,

And her pulse-beat identical with the high

pulse of Time?

Ah, she was little! When the air first

shattered with that shock,

Down ran the mouse into her hole. "Hic,

diccory! die—dock!"

Too plain to be translated is the truth the

tale would show,

Small souls, in solemn upshot, had better

wait below.

"Little Bo-Peep

Has lost her sheep,

And does n't know where to find 'em;

Let 'em alone,

And they 'll come home,

And bring their tails behind 'em."

Hope beckoned Youth, and bade him keep,

On Life's broad plain, his shining sheep,

And while along the sward they came,

He called them over, each by name;

This one was Friendship,—that was Health;

Another Love,—another Wealth;

One, fat, full-fleeced, was Social Station;

Another, stainless, Reputation;

In truth, a goodly flock of sheep,—

A goodly flock, but hard to keep.

Youth laid him down beside a fountain;

Hope spread his wings to scale a mountain;

And, somehow, Youth fell fast asleep,

And left his crook to tend the sheep:

No wonder, as the legend says,

They took to very crooked ways.

He woke—to hear a distant bleating,—

The faithless quadrupeds were fleeting!

Wealth vanished first, with stealthy tread,

Then Friendship followed—to be fed,—

And foolish Love was after led;

Fair Fame,—alas! some thievish scamp

Had marked him with his own black stamp!

And he, with Honor at his heels,

Was out of sight across the fields.

Health just hangs doubtful,—distant Hope

Looks backward from the mountain slope,—

And Youth himself—no longer Youth—

Stands face to face with bitter Truth.

Yet let them go! 'T were all in vain

To linger here in faith to find 'em;

Forward!—nor pause to think of pain,—

Till somewhere, on a nobler plain,

A surer Hope shall lead the train

Of joys withheld to come again

With golden fleeces trailed behind 'em!

"Solomon Grundy

Born on Monday,

Christened on Tuesday,

Married on Wednesday,

Sick on Thursday,

Worse on Friday,

Dead on Saturday,

Buried on Sunday:

This was the end

Of Solomon Grundy."

So sings the unpretentious Muse

That guides the quill of Mother Goose,

And in one week of mortal strife

Presents the epitome of Life:

But down sits Billy Shakspeare next,

And, coolly taking up the text,

His thought pursues the trail of mine,

And, lo! the "Seven Ages" shine!

O world! O critics! can't you see

How Shakspeare plagiarizes me?

And other bards will after come,

To echo in a later age,

"He lived,—he died: behold the sum,

The abstract of the historian's page"

Yet once for all the thing was done,

Complete in Grundy's pilgrimage.

For not a child upon the knee

But hath the moral learned of me;

And measured, in a seven days' span,

The whole experience of man.

"Three wise men of Gotham

Went to sea in a bowl:

If the bowl had been stronger,

My song had been longer."

Mysteriously suggestive! A vague hint,

Yet a rare touch of most effective art,

That of the bowl, and all the voyagers in't,

Tells nothing, save the fact that they did

start.

There ending suddenly, with subtle craft,

The story stands—as 'twere a broken

shafts—'

More eloquent in mute signification,

Than lengthened detail, or precise relation.

So perfect in its very non-achieving,

That, of a truth, I cannot help believing

A rash attempt at paraphrasing it

May prove a blunder, rather than a hit.

Still, I must wish the venerable soul

Had been explicit as regards the bowl

Was it, perhaps, a railroad speculation?

Or a big ship to carry all creation,

That, by some kink of its machinery,

Failed, in the end, to carry even three?

Or other fond, erroneous calculation

Of splendid schemes that died disastrously?

It must have been of Gotham manufacture;

Though strangely weak, and liable to frac-

ture.

Yet—pause a moment—strangely, did I

say?

Scarcely, since, after all, it was but clay;—

The stuff Hope takes to build her brittle

boat,

And therein sets the wisest men afloat.

Truly, a bark would need be somewhat

stronger,

To make the halting history much longer.

Doubtless, the good Dame did but gener-

alize,—

Took a broad glance at human enterprise,

And earthly expectation, and so drew,

In pithy lines, a parable most true,—

Kindly to warn us ere we sail away,

With life's great venture, in an ark of

clay,

Where shivered fragments all around be-

token,

How even the "golden bowl" at last lies

broken!

"Rockaby, baby,

Your cradle is green;

Father's a nobleman,

Mother's a queen;

And Betty's a lady,

And wears a gold ring,

And Johnny's a drummer,

And drums for the king!"

O golden gift of childhood!

That, with its kingly touch,

Transforms to more than royalty

The thing it loveth much!

O second sight, bestowed alone

Upon the baby seer,

That the glory held in Heaven's reserve

Discerneth even here!

Though he be the humblest craftsman,

No silk nor ermine piled

Could make the father seem a whit

More noble to the child;

And the mother,—ah, what queenlier crown

Could rest upon her brow,

Than the fair and gentle dignity

It weareth to him now?

E'en the gilded ring that Michael

For a penny fairing bought,

Is the seal of Betty's ladyhood

To his untutored thought;

And the darling drum about his neck,—

His very newest toy,—

A bandsman unto Majesty

Hath straightway made the boy!

O golden gift of childhood!

If the talisman might last,

How the dull Present still should gleam

With the glory of the Past!

But the things of earth about us

Fade and dwindle as we go,

And the long perspective of our life

Is truth, and not a show!

"There was a man in our town,

And he was wondrous wise:

He jumped into a bramble-bush,

And scratched out both his eyes.

But when he saw his eyes were out,

With all his might and main

He jumped into another bush,

And scratched them in again!"

Old Dr. Hahnemann read the tale,

(And he was wondrous wise,)

Of the man who, in the bramble-bush,

Had scratched out both his eyes.

And the fancy tickled mightily

His misty German brain,

That, by jumping in another bush,

He got them back again.

So he called it "homo-hop-athy".

And soon it came about,

That a curious crowd among the thorns

Was hopping in and out.

Yet, disguise it by the longest name

They may, it is no use;

For the world knows the discovery

Was made by Mother Goose!

And not alone in medicine

Doth the theory hold good;

In Life and in Philosophy,

The maxim still hath stood:

A morsel more of anything,

When one has got enough,

And Nature's energy disowns

The whole unkindly stuff.

A second negative affirms;

And two magnetic poles

Of charge identical, repel,—

A

s sameness sunders souls.

Touched with a first, fresh suffering,

All solace is despised;

But gathered sorrows grow serene,

And grief is neutralized.

And he who, in the world's mêlée,

Hath chanced the worse to catch,

May mend the matter, if he come

Back, boldly, to the scratch;

Minding the lesson he received

In boyhood, from his mother.

Whose cheery word, for many a bump,

Was, Up and take another!

"I had a little pony,

His name was Dapple Gray:

I lent him to a lady

To ride a mile away.

She whipped him,

She lashed him,

She rode him through the mire;

I would n't lend my pony now,

For all the lady's hire."

Our hobbies, of whatever sort

They be, mine honest friend,

Of fancy, enterprise, or thought,

'T is hardly wise to lend.

Some fair imagination, shrined

In form poetic, maybe,

You fondly trusted to the World,—

That most capricious Lady.

Or a high, romantic theory,

Magnificently planned,

In flush of eager confidence

You bade her take in hand.

But she whipped it, and she lashed it,

And bespattered it with mire,

Till your very soul felt stained within,

And scourged with stripes of fire.

Yet take this thought, and hold it fast,

Ye Martyrs of To-day!

That same great World, with all its scorn,

You 've lifted on its way!

"Hogs in the garden,—

Catch 'em, Towser!

Cows in the cornfield,—

Run, boys, run!

Fire on the mountains,—

Run, boys, run boys!

Cats in the cream-pot,—

Run, girls, run!"

Idon't stand up for Woman's Right

Not I,—no, no!

The real lionesses fight,—

I let it go.

Yet, somehow, as I catch the call

Of the world's voice,

That speaks a summons unto all

Its girls and boys;

In such strange contrast still it rings

As church-bells' bome

To the pert sound of tinkling things

One hears at home;

And wakes an impulse, not germane

Perhaps, to woman,

Yet with a thrill that makes it plain

'T is truly human;—

A sudden tingle at the springs

Of noble feeling,

The spirit-power for valiant things

Clearly revealing.

But Eden's curse doth daily deal

Its certain dole,—

And the old grasp upon the heel

Holds back the soul!

So, when some rousing deed's to do,

To save a nation,

Or, on the mountains, to subdue

A conflagration,

Woman! the work is not for you;

Mind your vocation!

Out from the cream-pot comes a mew

Of tribulation!

Meekly the world's great exploits leave

Unto your betters;

So bear the punishment of Eve,

Spirit in fetters!

Only, the hidden fires will glow,

And, now and then,

A beacon blazeth out below

That startles men!

Some Joan, through battle-field to stake,

Danger embracing;

Some Florence, for sweet mercy's sake

Pestilence facing;

Whose holy valor vindicates

The royal birth

That, for its crowning, only waits

The end of earth;

And, haply, when we all stand freed,

In strength immortal,

Such virgin-lamps the host shall lead

Through heaven's portal!

"There was an old man of Tobago,

Who lived on rice, gruel, and sago,

Till, much to his bliss,

His physician said this:

To a leg, sir, of mutton, you may go.

He set a monkey to baste the mutton,

And ten pounds of butter he put on."

Chain up a child, and away he will go";

I have heard of the proverb interpreted so;

The spendthrift is son to the miser,—and

still,

When the Devil would work his most piti-

less will,

He sends forth the seven, for such embas-

sies kept,

To the house that is empty and garnished

and swept:

For poor human nature a pendulum seems.,

That must constantly vibrate between two

extremes.

The closer the arrow is drawn to the

bow,

Once slipped from the string, all the further

't will go:

Let a panic arise in the world of finance,

And the mad flight of Fashion be checked

by the chance,

It certainly seems a most wonderful thing,

When the ropes are let go again, how it

will swing!

And even the decent observance of Lent,

Stirs sometimes a doubt how the time has

been spent,

When Easter brings out the new bonnets

and gowns,

And a flood of gay colors o'erflows in the

towns.

So in all things the feast doth still follow

the fast,

And the force of the contrast gives zest to

the last;

And until he is tried, no frail mortal can

tell,

The inch being offered, he won't take the

ell.

We are righteously shocked at the follies

of fashion;

Nay, standing outside, may get quite in a

passion

At the prodigal flourishes other folks put

on:

But many good people this side of Tobago,

If respited once from their diet of sago,

Would outdo the monkey in basting the

mutton!

"Leg over leg

As the dog went to Dover;

When he came to a stile,

Jump he went over."

Perhaps you would n't see it here,

But, to my fancy, 't is quite clear

That Mother Goose just meant to show

How the dog Patience on doth go:

With steadfast nozzle, pointing low,—

Leg over leg, however slow,—

And labored breath, but naught complaining,

Still, at each footstep, somewhat gaining,—

Quietly plodding, mile on mile,

And gathering for a nervous bound

At every interposing stile,—

So traversing the tedious ground,

Till all at length, he measures over,

And walks, a victor, into Dover.

And, verily, no other way

Doth human progress win the day;

Step after step,—and o'er and o'er,—

Each seeming like the one before,

So that't is only once a while,—

When sudden Genius springs the stile

That marks a section of the plain,

Beyond whose bound fresh fields again

Their widening stretch untrodden sweep,—

The world looks round to see the leap.

Pale Science, in her laboratory,

Works on with crucible and wire

Unnoticed, till an instant glory

Crowns some high issue, as with fire,

And men, with wondering eyes awide,

Gauge great Invention's giant stride.

No age, no race, no single soul,

By lofty tumbling gains the goal.

The steady pace it keeps between,—

The little points it makes unseen,—

By these, achieved in gathering might,

It moveth on, and out of sight,

And wins, through all that's overpast,

The city of its hopes at last.

"Hark, hark!

The dogs do bark;

Beggars are coming to town:

Some in rags,

Some in tags,"

And some in velvet gowns!"

Coming, coming always!

Crowding into earth;

Seizing on this human life,

Beggars from the birth.

Some in patent penury;

Some, alas! in shame;

And some in fading velvet

Of hereditary fame;

But all in deep, appeaseless want,

As mendicants to live;

And go beseeching through the world,

For what the world may give.

Beggars, beggars, all of us!

Expectants from "our youth:

With hands outstretched, and asking alms

Of Hope and Love and Truth.

Nor, verily, doth he escape

Who, wrapt in cold contempt,

Denies alike to give or take,

And dreams himself exempt;

Who never, in appeal to man,

Nor in a prayer to Heaven,

Will own that aught he doth desire,

Or ask that aught be given.

Whose human heart a stoic pride

Folds as a velvet pall;

Yet hides an eagreness within,

Worse beggary than all!

Coming, coming always!

And the bluff Apostle waits

As the throng pours upward from the earth

To Heaven's eternal gates.

In shreds of torn affection,

In passion-rended rags;

While scarcely at the portal

The great procession flags;

For the pillared doors of glory

On their hinges hang awide;

Where each asking soul may enter,

And at last be satisfied!

But a cold, calm shade arriveth,

In self-complacent trim,—

And Peter riseth up to see

Especially to him.

"Good morrow, saint! I'm going in

To take a stroll, you know;

Not that I want for anything,—

But just to see the show!"

"Hold!" thunders out the warden,

"Be pleased to pause a bit!

For seats celestial, let me say,

You 're not apparelled fit:

Yonder 's the brazen door that leads

Spectators to the pit!

Whatever may be thought on earth,

We've other rules in heaven;

And only poverty confessed

Finds free admittance given!"

"Sing a song o' sixpence, a pocket full of rye;

Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie:

When the pie was opened, they all began to sing,

And was n't this a dainty dish to set before the king?

The king was in his counting-house, counting out his

money;

The queen was in the parlor, eating bread and honey;

The maid was in the garden, hanging out the clothes,

And along came a blackbird, and nipt off her nose!"

It doesn't take a conjurer to see

The sort of curious pasty this might be;

A flock of flying rumors, caught alive,

And housed, like swarming bees within a

hive,—

Instead of what were far more wisely

done,

Having their worthless necks wrung, every

one;—

And so a dish of dainty gossip making,

Smooth covered with a show of secrecy,

That one but takes the pleasant pains of

breaking,

And out the wide-mouthed knaves pop,

eagerly.

Blackbirds, indeed! Each chattering on-

dit

Comes forth, full feathered, black as black

can be;

With quivering throats, all tremulous to

sing,

And please, forsooth, some little social

king;

Whose reign may last as long as he is able

To call his court around a dinner-table.

But, mark the sequel! When the laugh is

over,

Think not to get the varlets under cover:

The crust once broken, you may seek in vain

To catch the birds, or coax them in again;

Mrs. Pandora's famous box, I wis,

Was nothing worse than such a pie as this:

And so, some pleasant morning,—when,

down town,

The king is busy with his bags of money,

Leaving at home the queenly Mrs. Brown

Safe at her breakfast of fair bread and

honey,—

Some quiet, harmless soul, who never

knows

Of any matters, save the plain pursuing

Her daily round,—the hanging out of

clothes

Or other lawful work she may be doing,—

Finds, by the sudden nipping of her nose,

What sort of mischief is about her brew-

ing!

Not that, indeed, there's anything to hinder

The thieves from flying though the parlor

window;

For never yet could sentinel or warden

Keep scandals wholly to the kitchen gar-

den.

When, therefore, as not seldom it may be,

Even in the soberest community,

Strange revelations somehow get about,—

Like a mysterious cholera breaking out

Sudden, as Egypt's blains 'neath Aaron's rod,

Contagious by a whisper or a nod,—

When daily papers teem with many a hint

That daubs them darker even than their

print;

When it would seem, in short, the very D——,

Had let his little imps out on a spree;

Conclude, beyond a reasonable doubt,

Although, perhaps, you fail to trace it out,

Such plagues spring not unbidden from the

ground,

And, if the thing were sifted, 't would be

found

Somebody 's sown a pocket full of rye,

Or been regaling on a blackbird pie!

"Ride a fine horse

To Banbury Cross,

To see a young woman

Jump on a white horse.

Rings on her fingers,

And bells on her toes,

And she shall have music

Wherever she goes."

Prophetic Dame! What hadst thou in

view?

A modern wedding in Fifth Avenue?

Where,—like the goddess of a heathen

shrine,

With offerings heaped in such a glittering

show

As must have emptied a Peruvian mine,

And would suggest, but that we better

know,

Marriage must be a bitter thing indeed,

And, like the Prophet of the Eastern tale,

Must wear a very ugly face, to need

Such careful shrouding in the silver

veil,—

Her bridal pomp, as a white palfrey, mount-

ing,

Caparisoned at cost beyond all counting,

With diamond-jewelled fingers, and the

toes

Ditto, for all that anybody knows,

The smiling damsel goeth to the Banns?

(Why add the "bury," or suggest the

"cross,"

As if such brilliant ringing of the hands

Preluded aught of trial or of loss?)

Shall not Life's golden bells still tinkle

sweet,

And merry music make about her feet?

Shall not the silver sheen around her spread,

A lasting light along her pathway shed?

No mocking satire, surely, hides a sting,

Nor bitter irony a truth foreshows,

In the gay chant the cheery dame doth

sing,—

"She shall have music wheresoe'er she

goes"?

She shall have music! Shall she sit apart,

And let the folly-chimes outvoice the

tone

That comes up wailing to the listening

heart,

From the great world, where misery

maketh moan?

Ah, Mother Goose! if such the tale it tells,

Sing us no more your rhyme of rings and

bells!

But may not—'twere a rare device in-

deed!—

The wondrous oracle in both ways read?

And call up, as a fair beatitude,

The gracious vision of true womanhood,

That with pure purpose, and a gentle might,

Upheld and borne, as by the steed of white,

Pledged with her golden ring, goes nobly

forth

To trace her path of joy along the earth,—

And, as she moves, makes music, silver-shod

"With preparation of the peace" of God,

That holds the key-note of celestial cheer,

And hangs heaven's echoes round her foot-

steps here?

"Two little blackbirds sat upon a hill,

One named Jack, the other named Jill

Fly away, Jack! fly away, Jill!

Come again, Jack! come again, Jill!"

I half suspect that, after all,

There's just the smallest bit

Of inequality between

The witling and the wit.

'Tis only mental nimbleness:

No language ever brought

A living word to soul of man

But had the latent thought.

You may meet, among the million,

Good people every day,—

Unconscious martyrs to their fate,—

Who seem, in half they say,

On the brink of something brilliant

They were almost sure to clinch,

Yet, by some queer freak of fortune,

Just escape it by an inch!

I often think the selfsame shade,—

This difference of a hair,—

Divides between the men of nought

And those who do and dare.

An instant cometh on the wing,

Bearing a kingly crown:

This man is dazzled and lets it by—

That seizes and brings it down.

Winged things may stoop to any door

Alighting close and low;

And up and down, 'twixt earth and sky,

Do always come and go.

Swift, fluttering glimpses touch us all,

Yet, prithee, what avails?

'Tis only Genius that can put

The salt upon their tails!

"There was an old woman

Who lived in a shoe;

She had so many children

She did n't know what to do:

To some she gave broth,

And to some she gave bread,

And some she whipped soundly,

And sent them to bed."

Do you find out the likeness?

A portly old Dame,—

The mother of millions,—

Britannia by name:

And—howe'er it may strike you

In reading the song—

Not stinted in space

For bestowing the throng;

Since the Sun can himself

Hardly manage to go,

In a day and a night,

From the heel to the toe.

On the arch of the instep

She builds up her throne,

And, with seas rolling under,

She sits there alone;

With her heel at the foot

Of the Himmalehs planted,

And her toe in the icebergs,

Unchilled and undaunted.

Yet though justly of all

Her fine family proud,

'Tis no light undertaking

To rule such a crowd;

Not to mention the trouble

Of seeing them fed,

And dispensing with justice

The broth and the bread.

Some will seize upon one,—

Some are left with the other,

And so the whole household

Gets into a pother.

But the rigid old Dame

Has a summary way

Of her own, when she finds

There is mischief to pay.

She just takes up the rod,

As she lays down the spoon,

And makes their rebellious backs

Tingle right soon:

Then she bids them, while yet

The sore smarting they feel,

To lie down, and go to sleep,

Under her heel!

Only once was she posed,—

When the little boy Sam,

Who had always before

Been as meek as a lamb,

Refused to take tea,

As his mother had bid,

And returned saucy answers

Because he was chid.

Not content even then,

He cut loose from the throne,

And set about making

A shoe of his own;

Which succeeded so well,

And was filled up so fast,

That the world, in amazement,

Confessed, at the last,—

Looking on at the work

With a gasp and a stare,—

That't was hard to tell which

Would be best of the pair.

Side by side they are standing

Together to-day;

Side by side may they keep

Their strong foothold for aye:

And beneath the broad sea,

Whose blue depths intervene,

May the finishing string

Lie unbroken between!

"There once was a woman,

And what do you think?

She lived upon nothing

But victuals and drink.

Victuals and drink

"Were the chief of her diet,

And yet this poor woman

Scarce ever was quiet."

And were you so foolish

As really to think

That all she could want

Was her victuals and drink?

And that while she was furnished

With that sort of diet,

Her feeling and fancy

Would starve, and be quiet?

Mother Goose knew far better;

But thought it sufficient

To give a mere hint

That the fare was deficient;

For I do not believe

She could ever have meant

To imply there was reason

For being content.

Yet the mass of mankind

Is uncommonly slow

To acknowledge the fact

It behooves them to know;

Or to learn that a woman

Is not like a mouse,

Needing nothing but cheese,

And the walls of a house.

But just take a man,—

Shut him up for a day;

Get his hat and his cane,—

Put them snugly away;

Give him stockings to mend,

And three sumptuous meals;—

And then ask him, at night,

If you dare, how he feels!

Do you think he will quietly

Stick to the stocking,

While you read the news,

And "don't care about talking?"

O, many a woman

Goes starving, I ween,

Who lives in a palace,

And fares like a queen;

Till the famishing heart,

And the feverish brain,

Have spelled to life's end

The long lesson of pain.

Yet, stay! To my mind

An uneasy suggestion

Comes up, that there may be

Two sides to the question.

That, while here and there proving

Inflicted privation,

The verdict must often be

"Wilful starvation."

Since there are men and women

Would force one to think

They choose to live only

On victuals and drink.

O restless, and craving,

Unsatisfied hearts,

Whence never the vulture

Of hunger departs!

How long on the husks

Of your life will ye feed,

Ignoring the soul,

And her famishing need?

Bethink you, when lulled

In your shallow content,

'Twas to Lazarus only

The angels were sent;

And 't is he to whose lips

But earth's ashes are given,

For whom the full banquet

Is gathered in heaven!

"There was an old woman

Tossed up in a blanket,

Seventeen times as high as the moon;

What she did there

I cannot tell you,

But in her hand she carried a broom.

Old woman, old woman,

Old woman, said I,

O whither, O whither, O whither so high?

To sweep the cobwebs

Off the sky,

And I 'll be back again, by and by."

Mind you, she wore no wings,

That she might truly soar; no time was lost

In growing such unnecessary things;

But blindly, in a blanket, she was tost!

Spasmodically, too!

'T was not enough that she should reach

the moon;

But seventeen times the distance she must

do,

Lest, peradventure, she get back too

soon.

That emblematic broom!

Besom of mad Reform, uplifted high,

That, to reach cobwebs, would precipitate

doom,

And sweep down thunderbolts from out

the sky!

Doubtless, no rubbish lay

About her door,—no work was there to

do,—

That through the astonished aisles of Night

and Day,

She took her valorous flight in quest of

new!

Lo! at her little broom

The great stars laugh, as on their wheels

of fire

They go, dispersing the eternal gloom,

And shake Time's dust from off each

blazing tire!

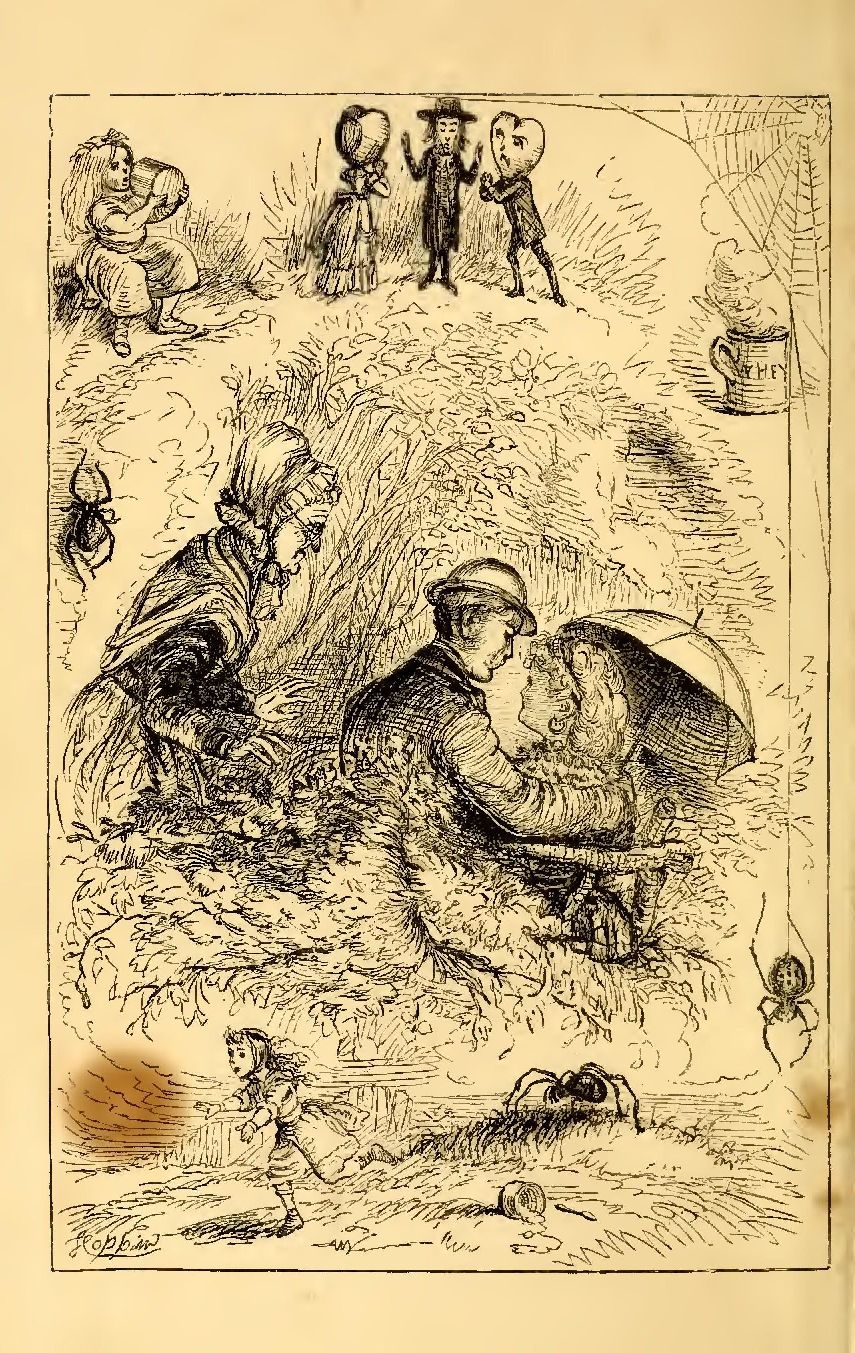

"Little Miss Muffet

Sat on a tuffet,

Eating curds and whey:

There came a black spider,

And sat down beside her,

And frightened Miss Muffet away,"

To all mortal blisses,

From comfits to kisses,

There's sure to be something by way of

alloy;

Each new expectation

Brings fresh aggravation,

And a doubtful amalgam's the best of our

You may sit on your tuffet;

Yes,—cushion and stuff it;

And provide what you please, if you don't

fancy whey;

But before you can eat it,

There 'll be—I repeat it—

Some sort of black spider to come in the

way.

"Daffy-down-dilly

Is new come to town,

With a petticoat green,

And a bright yellow gown,

And her little white blossoms

Are peeping around."

Now don't you call this

A most exquisite thing?

Don't it give you a thrill

With the thought of the spring,

Such as once, in your childhood,

You felt, when you found

The first yellow buttercups

Spangling the ground?

When the lilac was fresh

With its glory of leaves,

And the swallows came fluttering

Under the eaves?

When the bluebird flashed by

Like a magical thing,

And you looked for a fairy

Astride of his wing?

When the clear, running water,

Like tinkling of bells,

Bore along the bare roadside

A song of the dells,—

And the mornings were fresh

With unfailing delight,

While the sweet summer hush

Always came with the night?

O' daffy-down-dilly,

With robings of gold Î

As our hearts every year

To your coming unfold,

And sweet memories stir

Through the hardening mould,

We feel how earth's blossomings

Surely are given

To keep the soul fresh

For the spring-time of heaven!

"Baa, baa, black sheep!

Have you any wool?

Yes, sir,—no, sir,—

Three bags full.

One for my master,

One for my dame,

And one for the little boy

That lives in the lane."

T is the same question as of old;

And still the doubter saith,

"Can any good be made to come

From out of Nazareth?"

No sheep so black in all the flock,—

No human heart so bare,—

But hath some warm and generous stock

Of kindliness to share.

It may be treasured secretly

For dear ones at the hearth;

Or be bestowed by stealth along

The by-ways of the earth;—

And though no searching eye may see,

Nor busy tongue may tell,

Perchance, where largest love is laid,

The Master knoweth well!

A twister, in twisting, would twist him a twist,

And, twisting his twists, seven twists he doth twist:

If one twist, in twisting, untwist from the twist,

The twist, untwisting, untwists the twist."

A ravelled rainbow overhead

Lets down to life its varying thread:

Love's blue,—Joy's gold,—and, fair be-

tween,

Hope's shifting light of emerald green;

With, either side, in deep relief,

A crimson Pain,—a violet Grief.

Wouldst thou, amid their gleaming hues,

Clutch after those, and these refuse?

Believe,—as thy beseeching eyes

Follow their lines, and sound the skies,—

There, where the fadeless glories shine,

An unseen angel twists the twine.

And be thou sure, what tint so e'er

The broken rays beneath may wear,

It needs them all, that, broad and white,

God's love may weave the perfect light!

"I have a little sister,

They call her peep, peep;

She wades through the water,

Deep, deep, deep;

She climbs up the mountains,

High, high, high; '

My poor little sister,

She has but one eye!"

Rough Common Sense doth here confess

Her kinship to Imagination;

Betraying also, I should guess,

Some little pride in the relation.

For even while vexed, and puzzled too,

By the vagaries of the latter,—

Fearful what next the child may do,—

She looks with loving wonder at her.

Plain Sense keeps ever to the road

That's beaten down and daily trod;

While Fancy fords the rivers wide,

And scrambles up the mountain-side:

By which exploits she's always getting

Either a tumble or a wetting.

While simple Sense looks straight before,

Fancy "peeps" further, and sees more;

And yet, if left to walk alone,

May chance, like most long-sighted people,

To trip her foot against a stone

While gazing at a distant steeple.

Nay, worse! with all her grace erratic,

And feats aerial and aquatic,

Her flights sublime, and moods ecstatic,

She of the vision wild and high

Hath but a solitary eye!

And,—not to quote the Scripture, which

Forebodes the falling in the ditch,—

Doubtless by following such a guide

Blindly, in all her wanderings wide,

The world, at best, would get o' one side.

What then? To rid us of our doubt

Is there no other thing to do

But we must turn poor Fancy out,

And only downright Fact pursue?

Ah, see you not, bewildered man!

The heavenly beauty of the plan?

'T was so ordained, in counsels high,

To give to sweet Imagination

A single deep and glorious eye;

But then't was meant, in compensation,

That Common Sense, with optics keen,—

As maid of honor to a queen,—

On her blind side should always stay,

And keep her in the middle way.

"Little Jack Jingle

Used to live single.

But when he got tired

Of that kind of life,

He left off being single,

And lived with his wife."

Your period's pointed, most excellent Moth-

er!

Pray what did he do when he tired of the

other?

For a man so deplorably prone to ennui

But a queer sort of husband is likely to be.

The fatigue might recur,—and, in case it

should be so,

Why not take a wife on a limited lease, O?

Grant the privilege, pray, to his idiosyn-

crazy,—

Some natures won't bear to be too closely

pinned, you see,—

And, at worst, the poor Benedict might

advertise,

When weary, at length, of the light of his

eyes,—

Or failing to find her, it may be, in salt,—

"Disposed of, indeed, for no manner of

fault,"

(To borrow a figure of speech from the

mart,)

"But because the late owner has taken a

start!"

I believe once before you have cautiously

said

Something quite as concise on this delicate

head,

When distantly hinting at "needles and

pins,"

And that "when a man marries, his trouble

begins";

But I don't recollect that you ever pretend

To prophesy anything as to the end.

Unless we may learn it of Peter,—the

bumpkin,

Renowned for naught else but his eating

of pumpkin;

Whose wife—I don't see how he happened

to get her—

Had a taste, very likely, for things that

were better:

Since, fearing to lose her, at last it be-

fell

He bethought him of shutting her up in a

shell;

By which brilliant contrivance she kept very

well!

What he did with her next, the old rhyme

does n't say,

But she seems to be somehow got out of

the way,

For the ill-fated Peter was wedded once

more,

To find his bewilderment worse than be-

fore;

"If the first for her spouse had but small

predilection,

Now 't was his turn, alas! to fall short in

affection.

And how do you think that he conquered

the evil?

Why, simply by lifting himself to her level;

By leaving his pumpkins, and learning to

spell,

He came, saith the story, to love her right

well;

And the mythical memoir its moral con-

trives

For the lasting instruction of husband*

and wives.

"There was an old woman in Surrey,

Who was morn, noon, and night in a hurry;

Called her husband a fool,

Drove the children to school,

The worrying old woman of Surrey."

T was an ancient earldom over the sea,

And it must be now as it used to be;

Yet the sketch is of one I have known

before,—

The very old woman that lives next door.

One thing is unquestionable,—she 's

"smart,"—

As they say of an apple that's rather tart;

For her nearest friends, I think, would

allow her

To be, at her best, but a "pleasant sour."

There's a certain electrical atmosphere

That you feel beforehand, when she's near:

And—unless you 'ye a wonderful deal of

pluck—

A shrinking fear that you might be

"struck."

She moves with such a bustle and rush,—

Such an elemental stir and crush,

As makes the branches bend and fall

In the breeze that blows up a thunder-squall.

And yet, it is only her endless "hurry";

She's not so bad if she would n't "worry."

And, for all the worlds that she has to make.

If the six days' time she 'd only take.

You may talk about Surrey, or Devon, or

Kent,

But I doubt if a special location was meant;

It may sound severe,—but it seems to me

That a "representative" woman was she;

And that here and there you may chance

to trace

Some specimens extant of the race:

For a slip of the stock, as I've a notion,

Somehow "in the Mayflower" crossed the

ocean.

"Peter Piper picked a peck of pickle peppers;

And a peck of pickle peppers Peter Piper picked;

If Peter Piper picked a peck of pickle peppers

Where's the peck of pickle peppers Peter Piper

picked?"

P oor Peter toiled his life away,

That afterward the world might say

"Where is the peck of peppers he

Did gather so industriously?"

The peppers are embalmed in metre,—

But who, alas! inquires for Peter?

In sun or storm, by night and day,

Scant time for sleep, and none for play,

Still the poor fool did nothing reck,

If only he might pick his peck:

And what result from all hath sprung,

But just to bite somebody's tongue?

Or,—Lady Fortune playing fickle,—

Get some one in a precious pickle?

"Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall;

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall:

Not all the king's horses nor all the king's men

Could set Humpty Dumpty up again."

Full many a project that never was hatched

Falls down, and gets shattered beyond be-

ing patched;

And luckily, too! for if all came to chick-

ens,

Then things without feathers might go to

the dickens.

If each restless unit that moves among men

Might climb to a place with the privileged

"ten,"

Pray tell us where all the commotion would

stop!

Must the whole pan of milk, forsooth, rise

to the top?

If always the statesman attained to his hopes,

And grasped the great helm, who would

stand by the ropes?

Or if all dainty fingers their duties might

choose,

Who would wash up the dishes, and polish

the shoes?

Suppose every aspirant writing a book

Contrived to get published, by hook or by

crook;

Geologists then of a later creation

Would be startled, I fancy, to find a forma-

tion

Proving how the poor world did most wo-

fully sink

Beneath mountains of paper, and oceans of

ink!

Or even suppose all the women were mar-

ried;

By whom would superfluous babies be car-

ried?

Where would be the good aunts that should

knit all the stockings?

Or nurses, to do up the singings and rock-

ings?

Wise spinsters, to lay down their wonderful

rules,

And with theories rare to enlighten the

fools,—

Or to look after orphans, and primary

schools?

No! Failure's a part of the infinite plan;

Who finds that he can't, must give way to

who can;

And as one and another drops out of the

race,

Each stumbles at last to his suitable place.

So the great scheme works on,—though,

like eggs from the wall,

Little single designs to such ruin may fall,

That not all the world's might, of its horses

or men,

Could set their crushed hopes at the sum-

mit again.

"As Tommy Snooks and Bessy Brooks

Were walking out one Sunday,

Says Tommy Snooks to Bessy Brooks,

To-morrow will be Monday."

No doubt you are smiling at such a remark.

And thinking poor Snooks but a pitiful

spark;

But the words have a meaning, worth look-

ing for, too,

As I'll presently try and demonstrate for you.

'Twas a pity, indeed, in that moment of

leisure,

To dampen poor Bessy's hebdomadal pleas-

ure,

Suggesting that close on the beautiful Sun-

day

Must come all the common-place horrors

of Monday;

That he to his toiling, and she to her

tub,

Must turn, and take up with another week's

rub;

Yet a truth for us all, since the shade of

the real

Follows fast on the track of each sunny

ideal.

Now and then we may pause on Life's

pleasant oases;

But between lie the desert's grim, desolate

spaces;

And our feet, with all patience, must trav-

erse them still,

Reaching forward to blessing, through

bearing of ill.

Yet for Snooks and his Bessy,—for me

and for you,—

Comes a Saturday night when the wage

will be due;

And we'll say to each other, in ecstasy,

one day,

"To-morrow—the endless to-morrow—is

Sunday!"

"There was a mad man,

And he had a mad wife,

And the children were mad beside;

So on a mad horse

They all of them got,

And madly away did ride."

Sagacious Goose! Fresh wonders yet!

"What spell had power to help you get

Those seven-leagued spectacles, that see

Down to the nineteenth century?

"The mad world, and his madder wife!"

That, in your earlier time of life,—

Though quite demented now,?t is plain,—

Were sober, grave, and almost sane!

And all the tribes, a motley brood

Sprung into being since the flood,

With their hereditary bent

To cerebral bewilderment!

If some old ghost, precise and slow,

Who died a hundred years ago,—

Always supposing he himself

Has lain, meanwhile, upon the shelf,—

Things as they are might only see,

Surely his inference would be

A simultaneous bursting out

Of lunacy the earth about.

The world is mad; his wife is mad;

The rising generation's madder;"

And when a charter can be had,

Up to the moon they 'll build a ladder!

They caught a horse awhile ago,—

They called him Steam,—but he was

slow;

After the lightning then they ran,

Caught him,—and now they drive the

span!—1860.

P. S.—1870.

The great Pacific railroad's done;

They've poured two oceans into one:

Two shores with whispering cable tied,

And cut a path for ships to ride,

Where camel-tracks had used to be,

Through desert sands, from sea to sea.

Moon, quoth I? Faith, they 've made a

moon!

Leastwise, they 've thought one; * and so

soon

* E. E. Hale's Brick Moon: likewise Jules

Verne's Projectile.=

Upon man's whim his stroke succeeds,

And turns his dreams into his deeds,

Look sharply! for with word and blow,

They 'll swing one up before you know!

1882.

Why put a double P. S. in?

'T would need a daily bulletin

To tell how fast the craze goes on,

With Keeley and with Edison;

With things to eat, and things to travel,—

Bicycles spinning o'er the gravel,—

Great guns to simplify the fights,—

Suns outshone with electric lights,—

The whisper in the closet stirred

In sooth across the housetops heard,

And when the airy tangle tires

Earth to be veined with throbbing wires.

Women to physic and to preach,

And help the national bird to screech;

One man on Wall-Street curb to stand,

With twenty railroads in his hand;

Schools for the mass, effecting this,

That all may know what most must miss

Ah, who so sage that can pretend

To pre-sage of such tale the end?

I press the limit of my page;

So, haply, may this frantic age!

"Little girl, little girl, where have you been?

Gathering roses to give to the queen.

Little girl, little girl, what gave she you?

She gave me a diamond as big as my shoe."

If the old could share with the young

again,—

If worn could borrow of new,—

If faces could wear their roses again.

And hearts be sweetened with dew,—

If a child might bring the joy of a child,

And give it to us to-day,—

What glory of gem, or what weight of gold

Would we think too precious to pay?

"Little Jack Horner

Sat in a corner

Eating a Christmas Pie:

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

And said, "What a great boy am I!"

Ah, the world hath many a Horner,

Who, seated in his corner,

Finds a Christmas Pie provided for his

thumb:

And cries out with exultation,

"When successful exploration

Doth discover the predestinated plum!

Little Jack outgrows his tier,

And becometh John, Esquire;

And he finds a monstrous pasty ready made,

Stuffed with stocks and bonds and bales,

Gold, currencies and sales,

And all the mixed ingredients of Trade.

And again it is his luck

To be just in time to pluck,

By a clever "operation," from the pie

An unexpected." plum";

So he glorifies his thumb,

And says, proudly, "What a mighty man

am I!"

Or perchance, to Science turning,

And with weary labor learning

All the formulas and phrases that oppress

her,—

For the fruit of others' baking

So a fresh diploma taking,

Comes he forth, a full accredited Profes-

sor!

Or he's not too nice to mix

In the dish of politics;

And the dignity of office he puts on;

And he feels as big again

As a dozen nobler men,

While he writes himself the Honorable

John!

Ah, me, for the poor nation!

In her hour of desperation

Her worst foe is that unsparing Horner-

Thumb!

To which War, and Death, and Hate,

Right, Policy, and State,

Are but pies wherefrom his greed may

grasp a plum!

Oh, the work was fair and true,

But't is riddled through and through.

And plundered of its glories everywhere;

And before men's cheated eyes

Doth the robber triumph rise

And magnify itself in all the air.

"Why, if even a good man dies,

And is welcomed to the skies

In the glorious resurrection of the just,

They must ruffle it below

"With some vain and wretched show,

To make each his little mud-pie of the dust!

Shall we hint at Lady-Horners,

Who in their exclusive corners

Think the world is only made of upper-

crust?

Who in the queer mince-pie

That we call Society,

Do their dainty fingers delicately thrust;

Till, if it come to pass,

In the spiced and sugared mass,

One should compass,—do n't they call it

so?—a catch,

By the gratulation given

It would seem the very heaven

Had outdone itself in making such a

match!

Or the "Woman-Horner, now,

Who is raising such a row

To prove that Jack's no bigger boy than

Jill;

And that she wo n't sit by

With her little saucer pie,

While he from the Great Pasty picks his

fill.

Jealous-wild to be a sharer

In the fruit she thinks the fairer,

Flings by all for the swift gaining of her

wish;

Not discerning in her blindness,

How a tender Loving-Kindness

Hid the best things in her own rejected

dish!

O, the world keeps Christmas Day

In a queer, perpetual way;

Shouting always, w What a great big boy

am I!"

Yet how many of the crowd

Thus vociferating loud,

And their honors or pretensions lifting

high,

Have really, more than Jack,

With their boldness or their knack,

Had a finger in the making of the Pie?

"Inty, minty,

Cutey, corn!

Apple-seed,

Apple-thorn!

Wire, brier,

Limber lock;

Seven geese

In a flock,

Sit and sing, by the spring;

O-u-t, out, and in again."

Inklings and meanings,

Sprinklings and gleanings,

Shimmers and glints.

That's how the light comes

Down from the sides;

That's how the beauty

Is born to our eyes.

The seed is within,

And the thorn is without:

Nature's sweet secret

Is guarded about.

Yet briers are slender,

Locks are but slight,

To touch of a genius

That searches with light.

White by the fountain

Sit the calm seven;

Unto their joyance

Its music is given.

The world looketh on,

And still wonders in vain,

As they go out and in,

And find pasture again.

"Hey, rub-a-dub!

Three maids in a tub!

And who do you think was there?

The butcher, the baker,

The candlestick-maker,

And all of them gone to the fair."

Strong hands are in the washing-tubs;

Gay heads, the labor scorning,

Make holiday between the rubs,

And sport of Monday morning.

Three maids? That's your arithmetic.

The child that met the poet

Would still to her own counting stick:

"We 're seven; I surely know it!"

The boatman ferried over three

Across the haunted river;

And only guessed it by his fee,

And wondered at the giver.

And Betsey, Jane, and Mary Ann,—

If more your sense discovers?

Well, rub your insight if you can,

And reckon up the lovers!

Count Jane with her stout cleaver knight,

And Betsey with the baker;

And Mary Ann in dreamy light

Beside the candle-maker.

Yet of the six no soul is there,

For all your wakened vision!

In the charmed circle of the Fair

They walk their Fields Elysian!

The work goes on by board and bench,—

Hard tax of human sinning,—

But hearts thro' labor-chinks still wrench

Some joy of their beginning.

In the close limit that confines

Our getting and our giving,

Unless we read between the lines,

What should we do with living?

"Ding, dong, bell,

The cat's in the well!

Who put her in? Little John Green.

Who pulled her out? Great John Stout!"-

There was never a drama of sorrow

<>But good folks might be found, I'm afraid,

Who a queer satisfaction could borrow

From the parts of importance they played.

There is war for four years in the nation:

There are havoc and panic abroad:

Comes a tempest; a wild conflagration:

Great souls go up home to their God.

How the tall I's spring thick in the spell-

ing!—

I knew, or I saw, or I said!—

How the small ones turn out to the swelling

Each splendor of final parade!

How many are left, we may wonder,

Heart-mournful for that which befell?

How many would wish back the blunder

"When the Cat has got into the Well!

Nay, more; if with infinite bother

And peril, poor Puss is got out,

Somehow, one boy seems famous as t' other,

John Green is as big as John Stout!

See, now! let me tell you a story

Of something which happened in sooth;

That shows with how fearless a glory

The children and simple speak truth.

Biddy came to her mistress refulgent;

A whole sunrise of smiles on her face;

'With w M'am, could ye be so indulgent

Jist to shpare me the day, if ye plase?

"It 's me cousin that 's dead,—Kate

M'Gawtherin,—

Was married to Barnaby Roach;

An' I 'd want,—but I hates to be both-

erin',—

Three shillings to pay for the coach!"

And so we were minus our dinners;

And all that deplorable day

We fasted, like penitent sinners,

While Biddy the cook was away.

But she came when the sunset was gleam-

ing;

And her story she gleefully told;

Disdaining all dolorous seeming,

In a way that was good to behold.

Each loving and sad recollection

Of the late Mrs. Barnaby Roach

Quite absorbed in the single reflection

That she "wint wid himsel' in the coach!"

"For he thrated me, faith, like a lady,

An' he paid me me fare, an' ahl;

An' he tould me that I, Bridget Brady,

Was the charm of the funeral!"

"There was a little woman, as I've heard tell,

She went to market her eggs for to sell:

She went to market all on a market day,

And she fell asleep on the king's highway.

"There came a little peddler, his name was Stout;

He cut off her petticoats round about:

He cut off her petticoats up to her knees,

And the poor little woman began for to freeze.

"She began to shiver, and she began to cry,

Lawk-a-mercy on me! sure it is n't I!

But if it be I, as I think it ought to be,

I 've got a little dog at home, and he knows me!"

I think of a poor, tired Soul,

That has trodden, up and down,

The tradeways of this busy life,

To and from its market town,

Till, traffic and toil all past,

At the silent close of the day,

She lies down, weary and worn, at last,

On the king's highway;—

The highway that brings all home,

Never a one left out;—

And in her sleep doth a Stranger come

Who cuts her garments about.

Cuts the life-tatters away,

All the old rags and the stain;

And leaves the Soul 'twixt her night and

day,

To waken again.

Slowly she wakens, and strange;

Strange and scared she doth seem;

Marvelling at the mystical change

Come over her in her dream.

"Where is my life?" she cries,

"That which I knew me by?

Something is here in an unknown guise:

Can it be I?

"I wonder if anything is:

Or if I am anything:

Did ever a Soul come bare as this

From its earthward marketing?

Let me think down into the past;

Bethink me hard in the cold;

Find me something to stand by fast;

Something to hold!"

She thinks away back to the morning,

To something she loved and knew;

And over her doubt comes dawning

Sense of the dear and true.

"I do n't know if it be I," she sighs;

"But if after all it be,

There 's a little heart at home in the skies,

And he 'll know me!"

"Jack and Jill

Went up the hill,

To draw a pail of water:

Jack fell down

And broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after."

Jack and Jill went up the hill,

When the world was young, together.

Jack and Jill went up the hill,

In Eden ways and weather.

She to seek out blessed springs,

He to bear the burden:

Nature their sole choice of things,

Love their only guerdon.

That was all the simple creatures knew.

Jack and Jill come down the hill,

In the world's fall years, together.

Jack and Jill come down the hill,

And there is stormy weather.

'T is all about the pail, you see;

The sweet springs are behind them:

Empty-handed seemeth she

Who only helped to find them.

Jill would like to swing a bucket, too.

O'er the hillside coming down,

Eagerly and proudly,

Sparkling trophies to the town

To bear, she clamors loudly.

But, in face of all the town,

Challenging its laughter,

Many a Jack comes tumbling down.

Shall the Jills come after?

Is that what the women want to do?

Listen! When on heights of life

Hidden pools He planted,

God to Adam and his wife

Wise division granted.

Gave his son the pitcher broad

For wealth and weight of water;

But the quick divining-rod

Confided to his daughter.

Ah, if men and women only knew!

Impromptu, July, 1870.

"The sow came in with the saddle;

The little pig rocked the cradle;

The dish jumped up on the table

To see the pot swallow the ladle;

The spit that stood behind the door

Threw the pudding-stick on the floor.

"Odsplut!" said the gridiron,

Can't you agree?

I'm the head constable,

Bring 'em to me.'"

Spain came in with an empty throne;

The little prince rocked his German cradle

"No, no," he said;

And he shook his head;

"I am well content to be let alone."

All the dishes on pantry-ledge

And shelf, and table, were up on edge,

To see how the Pot,

Simmering hot,

Would foam at the dip of the threatening

ladle.

Nothing befell for a minute or so,

(Nobody chose to be first, you know),

Till the royal spit, with an angry frown,

Threw a little pudding-stick down.

"Odsplut!" shouts Emperor Gridiron,

Hissing for a broil,

"Those folks that stand behind the door

Are getting up a coil!

I 've red Fire panting at my feet;

I thought how things would be!

I?m creation's constable,

Bring the world to me!"

"I'll sing you a song

Of the days that are long;

Of the woodcock and the sparrow;

Of the little dog

That burnt his tail,

And he shall be whipt to-morrow."

That is the song the world sings

Of the long bright days:

That is the way she evens things,

Portions, and pays.

The dog that let his tail burn,

Proving one pain,

Shall be whipt next day, that he may learn

Wisdom again.

That is the song the world sings

To sin and sorrow:

Over her limit her hard lash flings

Into God's morrow.

Measures His dear divine grace

In compass narrow:

Counts for nothing the infinite days;

Forgets the sparrow.

The world sings only a half song;

Leaves our hearts sore:

Heaven, in the time that is tender and long,

Will sing us more.

"How many miles to Babylon?

Threescore and ten.

Can I get there by candle-light?

Yes, and back again."

How many miles of the weary way?

Threescore miles and ten.

Where shall I be at the end of the day?

Yon shall be back again.

You shall prove it all in the lifelong round;

The joy, and the pain and the sinning;

And at candle-light your soul shall be found

Back—at its new beginning.

Down in his grave the old man lies;

In from the earthward wild,

At the open door of Paradise

Enters a little child.

"Two little blackbirds sat upon a stone;

One flew away, and then there was one;

The other flew after and then there was none;

So the poor stone was left all alone."

One of these little birds back again flew;

The other came after, and then there were two;

Says one to the other, pray, how do you do?

Very well, thank you, and, pray, how are you?

A stone is the barest fact:

But living and wonderful things

Gather to earthly occasion and act

With folded or parting wings.

Birds of the air are they,—

Our knowledge, our thought, our love,—

And the ethers in which they win their way

Are breaths of the heaven above.

Some place and point of the hour,—

The same little fact for two,—

Who knoweth the lasting wonder and power

It holdeth for me and you;

Away in the long-past years,

With trifle of merest chance,

Keeping, through losing, and blinding, and

tears,

The key of its circumstance?

I, left to the narrowed earth,—

You into the great heaven gone,—

And things of our sharing,—our work, our

mirth,—

So lonely to brood upon!

Yet ever, when thought recurs,

With hardly a reckoning why,

To some old, small memory, straightway stirs

That sound of wings in the sky;

And like birds to a resting-place,—

No longer one, but the two,—

Alight the remembrances, face to face,

Alive between me and you;

And heaven grows real and dear,

And earth widens up to heaven;

And all that had vanished, and stayed so

near,

In one marvellous glimpse is given.

For memory is return:

Ourselves are what we have been:

And what we have been together, we learn

Our life doth continue in.

Spread, then, the angel wings!

I lose you not as you go;

Since heart finds heart in the uttermost

things

Two thoughts may revisit so!

'Taffy was a Welshman,

Taffy was a thief;

Taffy came to my house

And stole a piece of beef:

I went to Taffy's house,

Taffy was n't at home;

Taffy came to my house

And stole a marrow bone:

I went to Taffy's house,

Taffy was in bed;

I took the marrow bone,

And beat about his head."

Old Time came unto my house of clay,

And pilfered its pride of flesh away:

I knocked at the doors of the years in vain

To ask for its goodliness again.

Old Time came unto me yet once more,

For crueller theft than he thieved before;

Stealing the very marrow and bone

That the strength of my life was builded on.

Old Time! At last thou shalt lie in thy bed,

And thy years and days be buried and

dead;

And the strength of the life to come shall

be

In the great revenge I will have of thee!

"See, saw! Margery Daw

Sold her bed, and lay upon straw;

Sold her straw, and lay upon dirt;

Was n't she a good-for-naught?"

O Margery Daw! Mistress Margery Daw!

Not yours the sole lapse that the world ever

saw!

In precisely such willful gradation

I fear me religion and morals and law

Go down, step by step, to the dirt through

the straw,

In the church and the mart and the nation.

A yielding of that, and a dropping of this,—

("With straw fresh and plenty, pray what

is amiss?

The bed may be wider and cleaner;" )

Ah, that's as you make it, and shake it,

you 'll find;

And with slumber forgetful, and luxury

blind,

What you rest in grows meaner and

meaner.

"In righteousness walking," the Scripture

verse goes,—

"They rest in their beds," and find blessed

repose;

And the beautiful contrary diction

Is neither Isaiah's mistake, nor a word

At random declared, to be scoffingly heard,

But a truth in the freedom of fiction.

O Margery Daw! Mistress Margery Daw!

It shall always be gospel, what always was

law:

Some bed-making none may dispense

with,—

In dust of the earth, or in heart of the

heaven,—

And to soul of mankind shall no Sabbath be

given

Save that it lies down and contents with.

"Pretty John Watts,

We are troubled with rats;

Will you drive them out of the house?

There are mice, too, in plenty,"

Who feast in the pantry;

But let them stay,

And nibble away;

What harm in a little brown mouse?"

A curious puzzle haunts

The brain of the commentator,

Whether John Watts, perchance,

Be preacher or legislator.

We 're troubled with rats, we cry:

And who shall drive out the vermin?

Let senate and pulpit try:

Urge edict, and scourge with sermon.

They steal, they riot, they slay:

They are noisy, they are noisome:

Mice in the pantry, you say?

Ah, those little things are toysome!

They only nibble, you see;

They only frolic and scamper:

What harm can it possibly be

A little brown mouse to pamper?

They 're not of the race, John Watts!

From them we need no protection;

They will never develop to rats,

By survival or selection.

And yet, John Watts! John Watts!

Whether in closet or highway,

I doubt me that mice and rats

Are akin, in some sort of sly way;

And as long as the world sins on,

That the odds will be but a quibble

Between the deeds that are done

By brutes that devour—or nibble!

"Little Robin Redbreast sat upon a tree;

Up went the pussy-cat, down came he:

Down came the pussy-cat, away Robin ran;

Says little Robin Redbreast, catch me if you can!

Little Robin Redbreast hopped upon a spade;

Pussy-cat jumped after him, and then he was afraid;

Little Robin chirped and sung, and what did pussy say?

Pussy said, Me-ow! Me-ow! and Robin flew away."

Little Robin Redbreast sat upon a tree,

Heartsome and glad;

The cheer of life, in the green of life, what-

ever so blithe may be?

Fol de roi, de rol, lad!

Up went the pussy-cat, and down came

he,—

Woe befall for the claws, lad!

The care of life, and the fear of life, it

creepeth so stealthily,—

So threatsome and sad!

And woe befall for the claws, lad!

Down came the pussy-cat, away Robin

ran,

In his scarlet clad;

There may be a day for running away, for

redcoated bird or man.

Fol de roi, de rol, lad!

Says little Robin Redbreast, Catch me if

you can!

Two merry legs to the four, lad!

A quick, bold pair, that scampers fair, is

part of the saving plan,

And a match for the pad

Aprowl on the pitiless four, lad!

Little Robin Redbreast hopped upon a

spade;

This is n't so bad!

All of leafy green, and for joy, I ween, the

world was never made.

Fol de roi, de rol, lad!

Pussy-cat jumped after him, and then he

was afraid;

Ah, what's the use of all, lad?

There 's death in our work, there's fear to

lurk in the places where we played.

What help 's to be had?

And what is the use of all, lad?

Little Robin chirped and sung, the same

brave roundelay;

There's room to be glad!

There's always a light behind the night;

there's never a will but a way;

Fol de roi, de rol, lad!

Little Robin chirped and sung, and what did

pussy say?

Creeping, and stretching the claws, lad?

Pussy said, O-w! P-shaw i Me-ow! for

Robin was off and away.

There's wings to be had!

And fol de rol for the claws, lad!

"When I was a bachelor, I lived by myself,

And all the bread and cheese I got I put upon a shelf.

The rats and the mice, they made such a strife,

I was forced to go to London to get me a wife.

The streets were so broad, and the lanes were so nar-

row

I was forced to bring my wife home in a wheelbarrow.

The wheelbarrow broke, and my wife had a fall,

Down came wheelbarrow, wife, and all."

Of course it did. Whatever could you pos-

sibly expect, sir?

You chose a quite peculiar style to cherish

and protect, sir!

Your resource in emergency commands my

admiration,