This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: History of the Anglo-Saxons

From the Earliest Period to the Norman Conquest; Second Edition

Author: Thomas Miller

Release Date: April 12, 2014 [eBook #45366]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF THE ANGLO-SAXONS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/historyofanglos00mill |

Transcriber's notes

There are several "Parts" in this book. Only the last one

is listed in the Table of Contents. The titles of

the parts are shown as spaced, sans-serif headings (example:

The Saxon Invasion.).

The page numbers in the Table of Contents usually refer to the end of

the chapter, rather than to the beginning. The "CHAPTER" links are to the

beginnings of the chapters.

The List of Illustrations follows the

last chapter of the book. The

footnotes were moved to the end of this eBook.

The book cover image was created by the transcriber

and placed in the Public Domain.

Additional Transcriber's notes will be found after the footnotes.

BY

THOMAS MILLER,

AUTHOR OF "ROYSTON GOWER," "LADY JANE GREY,"

"PICTURES OF COUNTRY LIFE," ETC.

Second Edition.

LONDON:

DAVID BOGUE, FLEET STREET.

MDCCCL.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE DAWN OF HISTORY. | |

| Obscurity of early history—Our ancient monuments a mystery—The Welsh Triads—Language of the first inhabitants of Britain unknown—Wonders of the ancient world | p. 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE ANCIENT BRITONS. | |

| The Celtic Tribes—Britain known to the Phœnicians and Greeks—The ancient Cymry—Different classes of the early Britons—Their personal appearance—Description of their forest-towns—A British hunter—Interior of an ancient hut—Costume of the old Cymry—Ancient armour and weapons—British war-chariots—The fearful havoc they made in battle | p. 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

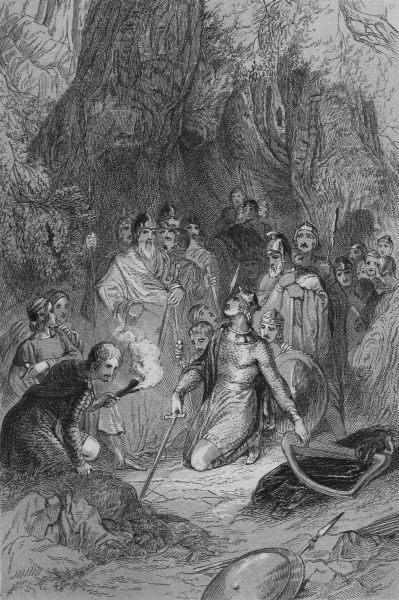

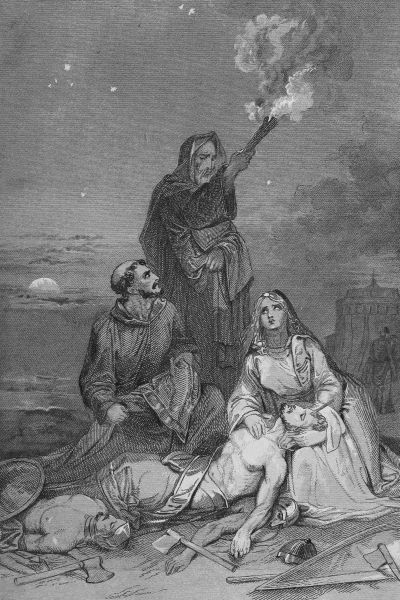

| THE DRUIDS. | |

| Interior of an old British forest—Druidical sacrifice—Their treasures—Their mysterious rites and ceremonies—The power they possessed—Their belief in a future state—Their wild superstitions—An arch-Druid described—Their veneration for the mistletoe—Description of the Druids offering up sacrifice—The gloomy grandeur of their ancient groves—Contrast between the idols of the Druids and the heathen gods of the Romans | p. 17 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| LANDING OF JULIUS CÆSAR. | |

| Cæsar's reasons for invading Britain—Despatches Volusenus from Gaul to ivreconnoitre the island—Is intimidated by the force he finds arranged along the cliffs of Dover—Lands near Sandwich—Courage of the Roman Standard-bearer—Combat between the Britons and Romans—Defeat and submission of the Britons—Wreck of the Roman galleys—Perilous position of the invaders—Roman soldiers attacked in a corn-field, rescued by the arrival of their general—Britons attack the Roman encampment, are again defeated, and pursued by the Roman cavalry—Cæsar's hasty departure from Britain—Return of the Romans at spring—Description of their armed galleys—Determination of Cæsar to conquer Britain—Picturesque description of the night march of the Roman legions into Kent—Battle beside a river—Difficulties the Romans encounter in their marches through the ancient British forests—Cæsar's hasty retreat to his encampment—The Roman galleys again wrecked—Cessation of hostilities—Cassivellaunus assumes the command of the Britons—His skill as a general—Obtains an advantage over the Romans with his war-chariots—Attacks the Roman encampment by night and slays the outer guard—Defeats the two cohorts that advance to their rescue, and slays a Roman tribune—Renewal of the battle on the following day—Cæsar compelled to call in the foragers to strengthen his army—Splendid charge of the Roman cavalry—Overthrow and retreat of the Britons—Cæsar marches through Kent and Surrey in pursuit of the British army—Crosses the Thames near Chertsey—Retreat of the British general—Cuts off the supplies of the Romans, and harasses the army with his war-chariots—Stratagems adopted by the Britons—Cassivellaunus betrayed by his countrymen—His fortress attacked in the forest—Contemplates the destruction of the Roman fleet—Attack of the Kentish men on the encampment of the invaders—The Romans again victorious—Cassivellaunus sues for peace—Final departure of Cæsar from Britain | p. 30 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

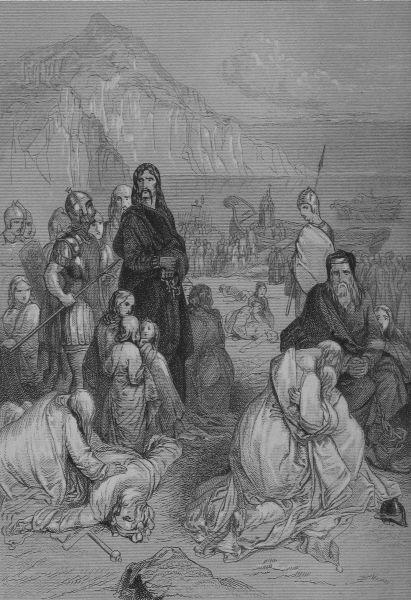

| CARACTACUS, BOADICEA, AND AGRICOLA. | |

| State of Britain after the departure of Cæsar—Landing of Plautius—His skirmishes with the Britons in the marshes beside the Thames—Arrival of the Roman emperor Claudius—Ostorius conquers and disarms the Britons—Rise of Caractacus—British encampment in Wales—Caractacus defeated, betrayed by his step-mother, and carried captive to Rome—Death of the Roman general Ostorius—Retreat of the Druids to the Isle of Anglesey—Suetonius attacks the island—Consternation of the Roman soldiers on landing—Massacre of the Druids, and destruction of their groves and altars—Boadicea, queen of the Iceni, assumes the command of the Britons—Her sufferings—She prepares for battle, attacks the Roman colony of vCamaladonum—Her terrible vengeance—Her march into London, and destruction of the Romans—Picturesque description of Boadicea and her daughters in her ancient British war-chariot—Harangues her soldiers—Is defeated by Suetonius, and destroys herself—Agricola lands in Britain—His mild measures—Instructs the islanders in agriculture and architecture—Leads the Roman legions into Caledonia, and attacks the men of the woods—Bravery of Galgacus, the Caledonian chief—Agricola sails round the coast of Scotland—Erects a Roman rampart to prevent the Caledonians from invading Britain | p. 40 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| DEPARTURE OF THE ROMANS. | |

| Adrian strengthens and extends the Roman fortifications—Description of these ancient barriers, and the combats that took place before them—Wall erected by the emperor Severus—He marches into Caledonia, reaches the Frith of Moray—Great mortality amongst the Roman legions—Severus dies at York—Picturesque description of the Roman sentinels guarding the ancient fortresses—Attack of the northern barbarians—Peace of Britain under the government of Caracalla—Arrival of the Saxon and Scandinavian pirates—The British Channel protected by the naval commander, Carausius—His assassination at York—Constantine the Great—Theodosius conquers the Saxons—Rebellion of the Roman soldiers; they elect their own general—Alaric, the Goth, overruns the Roman territories—British soldiers sent abroad to strengthen the Roman ranks—Decline of the Roman power in Britain—Ravages of the Picts, Scots, and Saxons—The Britons apply in vain for assistance from Rome—Miserable condition in which they are left on the departure of the Romans—War between the Britons and the remnant of the invaders—Vortigern, king of the Britons—A league with the Saxons | p. 50 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| BRITAIN AFTER THE ROMAN PERIOD. | |

| Great change produced in Britain by the Romans—Its ancient features contrasted with its appearance after their departure—Picturesque description of Britain—First dawn of Christianity—Progress of the Britons in civilization—Old British fortifications—Change in the costume of the Britons—Decline in their martial deportment—Their ancient mode of burial—Description viof early British barrows—Ascendancy of rank | p. 56 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE ANCIENT SAXONS. | |

| Origin of the early Saxons—Description of their habits and arms—Their religion—The halls of Valhalla—Their belief in rewards and punishments after death—Their ancient mythology described—Superstitions of the early Saxons—Their ancient temples and forms of worship—Their picturesque processions—Dreadful punishments inflicted upon those who robbed their temples—Different orders of society—Their divisions of the seasons—Their bravery as pirates, and skill in navigation | p. 64 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| HENGIST, HORSA, ROWENA, AND VORTIGERN. | |

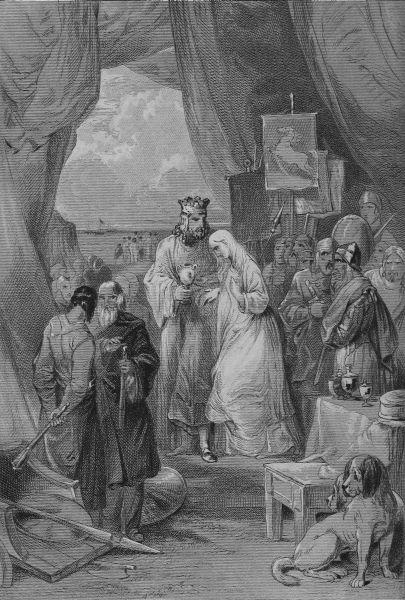

| Landing of Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs—Their treaty with Vortigern and the British chiefs—The British king allots them the Isle of Thanet as a residence, on condition that they drive out the Picts and Scots—Success of the Saxons—Arrival of more ships—Landing of the Princess Rowena—Marriage of Vortigern and Rowena—Quarrel between the Britons and Saxons—Description of their first battle by the old Welsh bards—The Britons led on by the sons of Vortigern—Death of Horsa, the Saxon chief—Rowena's revenge—Pretended reconciliation of the Saxons, and description of the feast where the British chiefs were massacred—Terrible death of Vortigern and the fair Rowena | p. 72 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| ELLA, CERDRIC, AND KING ARTHUR. | |

| Arrival of Ella and his three sons—Combat between the Saxons and Britons beside the ancient forest of Andredswold—Defeat of the Britons, and desolate appearance of the old forest town of Andred-Ceaster after the battle—Revengeful feelings of the Britons—Establishment of the Saxon kingdom of Sussex—Landing of Cerdric and his followers—Battle of Churdfrid, and death of the British king Natanleod—Arrival of Cerdric's kinsmen—The Britons again defeated—Arthur, the British king, arms in defence of his country—His adventures described—Numbers of battles in which he fought—Death of king Arthur in the field of Camlan—Discovery of his viiremains in the abbey of Glastonbury | p. 83 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SAXON OCTARCHY. | |

| Landing of Erkenwin—The establishment of the kingdom of Wessex—Description of London—Arrival of Ida and his twelve sons—The British chiefs make a bold stand against Ida—Bravery of Urien—Description of the battle of the pleasant valley, by Taliesin, the British bard—Llywarch's elegy on the death of Urien—Beautiful description of the battle of Cattraeth by Anenrin, the Welsh bard—Establishment of the kingdom of Mercia—Description of the divisions of England which formed the Saxon Octarchy—Amalgamation of the British and Saxon population—Retirement of the unconquered remnant of the ancient Cymry into Wales | p. 90 |

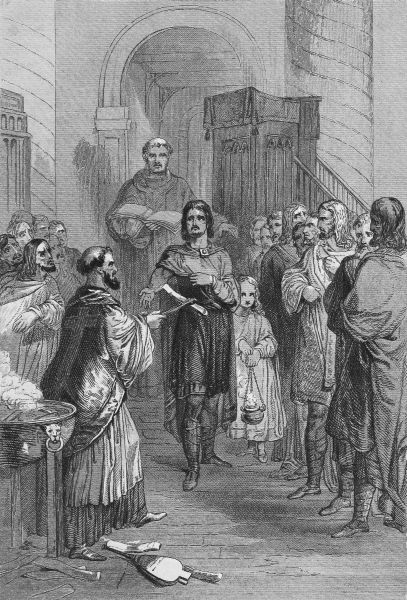

| CHAPTER XII. | |

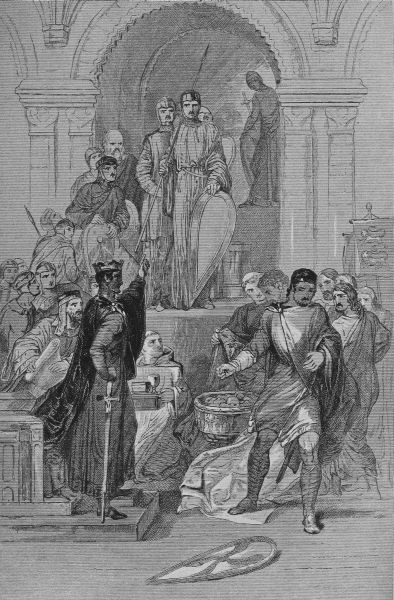

| CONVERSION OF ETHELBERT. | |

| Commencement of the civil war amongst the Saxons—Struggle between Ethelbert, king of Kent, and Ceawlin, king of Wessex, for the title of Bretwalda—Description of the slave-market of Rome—Monk Gregory's admiration of the British captives—Gregory becomes pontiff, and despatches Augustin with fifty monks to convert the inhabitants of Britain—Picturesque description of the landing of the Christian missionaries in the Isle of Thanet—Intercession of Bertha—Ethelbert's interview with Augustin and his followers—The missionaries take up their residence in Canterbury—Conversion of Ethelbert—Augustin is made Archbishop, by Pope Gregory—The rich presents sent to Britain by the Pope—Character of the Roman pontiff—His wise policy in not abolishing at once all outward forms of heathen worship—Eadbald ascends the throne of Kent—Marries his stepmother, and is denounced by the priests—He renounces the Christian faith—The monks are driven out of Essex—Eadbald again acknowledges the true faith, and the persecuted priests find shelter in the kingdom of Kent | p. 99 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| EDWIN, KING OF THE DEIRI AND BERNICIA. | |

| Adventures of Edwin, king of the Deiri—His residence in Wales with Cadvan, one of the ancient British kings—Ethelfrith having deprived him of his kingdom, seeks his life—Edwin flies from Wales, and seeks the protection of Redwald, king of East Anglia—Edwin's dream—The queen of East Anglia viiiintercedes in behalf of Edwin—Redwald prepares to wage war with Ethelfrith—Religion of the king of East Anglia—Description of the battle fought between Redwald and Ethelfrith on the banks of the river Idel—Death of Ethelfrith, and accession of Edwin to the throne of Northumbria—Edwin's marriage with Edilburga, daughter of Ethelbert—Journey of the Saxon princess from Kent to Northumbria—Attempted assassination of Edwin—Paulinus endeavours in vain to convert Edwin to the Christian faith—The king assembles his pagan priests and nobles to discuss the new religion—Speech of Coifi, the heathen priest—Beautiful and poetical address of a Saxon chief to the assembly—Coifi desecrates the temple of Woden—Peaceful state of Northumbria under the reign of Edwin—Death of Edwin at the battle of Hatfield-chase in Yorkshire—Victories of Cadwallon, the British king—Triumph of the Saxons under Oswald, and death of Cadwallon at the battle called Heaven-field | p. 111 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| PENDA, THE PAGAN MONARCH OF MERCIA. | |

| Description of the kingdom of Mercia—Character of Penda, the pagan king—Charity of Oswald—Barbarous cruelty of Penda—His desolating march through Northumbria—Attacks the castle of Bamborough—His march into Wessex—His invasion of East Anglia—Sigebert, the monk-king, leads on the East Anglians—Is defeated by Penda, who ravages East Anglia—The pagan king again enters Northumbria—Oswy offers all his treasures to purchase peace—Is treated with contempt by Penda—Oswy prepares for battle—Penda's forces driven into the river—Death of the pagan king—Great changes effected by his death—Courage of Saxburga, the widowed queen of Wessex—Perilous state of the Saxon Octarchy | p. 119 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| DECLINE OF THE SAXON OCTARCHY. | |

| Alfred, the learned king of Northumbria—His patronage of the celebrated scholar Aldhelm—Ceowulf, the patron of Bede—Mollo, brother of the king of Wessex, burnt alive in Kent—King Ina and his celebrated laws—Strange device of Ina's queen to induce him to resign his crown, and make a pilgrimage to Rome—Mysterious death of Ostrida, queen of the Mercians—Her husband, Ethelred, abandons his crown and becomes a monk after her violent death—Ethelbald ascends the throne of Mercia—Adventures of his early life—His residence with Guthlac, the hermit, in the island of Croyland—First founder of the monastery of Croyland—Ethelbald joins Cuthred, king of Wessex, and obtains a victory over the Welsh—Proclaims ixwar against Cuthred—Description of the battle, and defeat of Ethelbald—Independence of the kingdom of Wessex—Abdication of Sigebyhrt, king of Wessex—His death in the forest of Andredswold—Rapid accession and dethronement of the kings of Northumbria—Summary of their brief reigns | p. 129 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| OFFA, SURNAMED THE TERRIBLE. | |

| Offa ascends the throne of Mercia—Drida's introduction and marriage with the Mercian king—Character of queen Drida and her daughter Edburga—Offa's invasion of Northumbria—He marches into Kent—Is victorious—Defeats the king of Wessex—His victory over the Welsh—Description of Offa's dyke—Offa's friendly correspondence with Charlemagne—Adventures of Egbert—Murder of Cynewulf, at Merton, in Surrey—Brihtric obtains the crown of Wessex, and marries the daughter of Offa—Ethelbert, king of East Anglia, visits the Mercian court—Queen Drida plots his destruction—Description of a Saxon feast—Dreadful death of Ethelbert—Offa's daughter, Alfleda, seeks shelter in the monastery of Croyland—Murder of Queen Drida—Edburga poisons her husband, Brihtric, king of Wessex—She flies to France—Her reception at the court of Charlemagne—She dies a beggar in the streets of Pavia | p. 139 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| EGBERT, KING OF ALL THE SAXONS. | |

| Character of Egbert—His watchful policy—Death of Kenwulf, and decline of the kingdom of Mercia—Egbert annexes the kingdom of Kent to Wessex—Compels Wiglaf, king of Mercia, to pay him tribute—He conquers the kingdom of Northumbria, and subjects the whole of the Saxon kingdoms to his sway—Northumbria invaded by the Danes—They sack the abbey of Lindisfarne, and slay the monks—The Danes again land in Dorsetshire—Egbert presides over a council in London, to devise measures to prevent the ravages of the Danes—The remnant of the ancient Britons who have been driven into Wales, form a league with the Danes, and are defeated—Death of Egbert | p. 145 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE ANCIENT SEA-KINGS. | |

| Origin of the Danish invaders—Habits of the early Vikings—Their warlike education—Picturesque description of their wild life—Their hatred of the Saxons—Description of their ships and warlike weapons—Arrangement of their plans to plunder—Their vows on the golden bracelet—Power of xtheir leader only acknowledged in battle—Their rude festivities | p. 150 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| FIRST SETTLEMENT OF THE DANES IN NORTHUMBRIA. | |

| Ethelwulph, king of Kent—His unfitness to govern—The brave bishop of Sherbourne—The two characters contrasted—Boldness of the Danes—They occupy the Isle of Thanet—Battle of the field of Oaks—Character of Osberga, mother of Alfred the Great—Ethelwulph visits Rome in company with his son Alfred—The king of Kent marries Judith, daughter of Charles of France—His presents to the Pope—Returns to England with his youthful wife—Rebellion of his son Ethelbald—Death of Ethelwulph—Ethelbald marries his stepmother Judith—She elopes from a monastery with Baldwin, the grand forester—Death of Ethelbald—Brief reign of Ethelbert—Alfred begins to distinguish himself—The celebrated sea-king, Ragnar Lodbrog—His bravery—Builds a large ship—Is wrecked on the coast of Northumbria—Made prisoner by Ella, and dies in a dungeon—His celebrated death-song—The sons of Ragnar Lodbrog prepare to revenge their father's death—England invaded by their mighty fleet—Their march towards Northumbria—Ravage York—Horrible death of Ella, king of Northumbria—The Danes occupy the kingdoms of the Deiri and Bernicia—Nottingham taken by the Danes—Alfred accompanies his brother Ethelred, and the king of Mercia, in their attack upon the Danes—They enter into a treaty with the invaders—Alfred's marriage and attainments at this period | p. 159 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| RAVAGES OF THE DANES, AND DEATH OF ETHELRED. | |

| Ravages of the Danes in Lincolnshire—Destruction of the monastery of Bardney—Gallant resistance of the Mercians—Battle near Croyland Abbey—Destruction of Croyland Abbey, and murder of the monks—Sidroc, one of the sea-kings, saves a boy from the massacre—The abbey of Peterborough destroyed by the Danes—Description of the country through which the invaders passed—Their march into East Anglia—The Danes enter Wessex—Battle of Ash-tree hill, and victory of the Saxons—Death of Ethelred | p. 169 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| ACCESSION AND ABDICATION OF ALFRED THE GREAT. | |

| Miserable state of England when Alfred ascended the throne of Wessex—He is disheartened by the rapid arrival of the Danes—Enters into a treaty with them, and they abandon Essex—The Danes occupy London—Burrhed, xiking of Mercia, retires to Rome—The Danes now masters of all England, excepting Wessex—Alfred destroys their ships—Again enters into treaty with them—He encounters them at sea—Treaty at Exeter—His strange conduct at Chippenham—Vindication of the character of Alfred—His conduct during retirement—Alfred the Great in the cowherd's hut—Discovery of his retreat—His skirmishes with the Danes—Odin, the earl of Devonshire, captures the magical banner of Hubba, the sea-king—Alfred and his followers fortify their island retreat—Poverty of the great Saxon king | p. 179 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| ALFRED THE GREAT. | |

| Alfred in disguise visits the Danish camp near Westbury in Wiltshire—His interview with Godrun, the sea-king—Alfred musters the Saxon forces at Selwood forest—The arrival of his followers described—His preparation for battle—Description of the combat—Defeat of the Danes—Alfred besieges the Danish encampment—Surrender of Godrun—Policy and generosity of Alfred the Great—Peaceful appearance of England—Landing of Hastings, the famous sea-king—Alfred increases his navy—Character of Hastings, the sea-king, the most skilful of all the Danish invaders—Alfred marches his army between the Danish forces—His masterly generalship—Hastings offers to quit the kingdom—His treachery—Is again conquered by Alfred—The Danes of East Anglia and Northumbria rise up against Alfred—The wife and children of Hastings are taken prisoners by Alfred, and discharged with presents—After many struggles the Danes are at last defeated—Hastings quits England—Death of Alfred the Great | p. 192 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| CHARACTER OF ALFRED THE GREAT. | |

| His boyhood—Early love of poetry—Self-cultivation—Wisdom displayed in his conduct with the Danes—Difficulties under which he pursued his labour—His patronage of literary men—Method of study—Summary of his works—He reforms the Saxon nobles—Divides his time—Various purposes to which he appropriates his revenue—His invention for marking the hours—Cultivates an acquaintance with foreign countries—His severity in the administration of justice—Establishment of a rigid system of police—His laws—Intellectual character of Alfred the Great | p. 199 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| EDWARD THE ELDER. | |

| Ethelwold lays claim to the throne of Wessex—Is backed by the Danes, and xiicrowned at York—Battle of Axeholme and defeat of Ethelwold—Edward ravages Northumbria—The Danes attack Mercia—They enter the Severn—Battle of Wodensfield, and defeat of the Danes—Edward strengthens his frontier with fortresses—Their situation described—Bravery of his sister Ethelfleda—The Danes enter North Wales—Edward again victorious—Submission of the Welsh princes and the Danes of Northumbria—Death of Edward the Elder | p. 202 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| THE REIGN OF ATHELSTAN. | |

| Athelstan, the favourite grandchild of Alfred the Great—While but a boy his grandfather invests him with the honours of knighthood—He is educated by Alfred's daughter, Ethelfleda—Athelstan's sister married Sigtryg, a descendant of the famous sea-kings—The Dane repudiates his wife, and renounces his new religion—Athelstan invades his dominions—Death of Sigtryg, and flight of his sons—Preparation for the invasion of England—The force arrayed against Athelstan—Measures adopted by the Saxon king—Preparations for battle—Picturesque description of the battle of Brunanburg—Anglo-Saxon song on Athelstan's victory—High position attained by Athelstan—Otho the Great marries Athelstan's sister—The Saxon monarch forms an alliance with the emperor of Germany and the king of Norway—Harold of Norway suppresses piracy—Sends his son Haco to be educated at the Saxon court—Presents a beautiful ship to Athelstan—Death of Harold, king of Norway—List of the kings who were established on their thrones by Athelstan—His presents to the monasteries—His charity and laws for the relief of the poor—Cruelty to his brother Edwin—Death of Athelstan | p. 212 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| THE REIGNS OF EDMUND AND EDRED. | |

| Accession of Edmund the Elder—Anlaf, the Dane, invades Mercia, and defeats the Saxons—Edmund treats with Anlaf, and divides England with the Danes—Perilous state of the Saxon succession prevented by the death of Anlaf—Change in Edmund's character—His brilliant victories—Cruelty to the British princes—Edmund assassinated while celebrating the feast of St. Augustin, by Leof, the robber—Mystery that surrounds the murder of Edmund the Elder—Edred ascends the Saxon throne—Eric, the sea-king—His daring deeds on the ocean—Description of his wild life—Edred invades Northumbria—Eric attacks his own subjects—Edred's victory over the Danes—Scandinavian war-song on the death of Eric—Death xiiiof Edred | p. 218 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| EDWIN AND ELGIVA. | |

| Edwin's marriage with Elgiva—Odo, the Danish archbishop—St. Dunstan—His early life—He becomes delirious—His intellectual attainments—His persecution—He falls in love—Is dissuaded from marriage by the bishop, Ælfheag—He is again attacked with sickness—Recovers, and becomes a monk—Lives in a narrow cell—Absurdity of his rumoured interviews with the Evil One—His high connexions—Analysis of his character—Dunstan's rude attack upon King Edwin, after the banquet—Dunstan again driven from court—Remarks on his conduct—Elgiva is cruelly tortured, and savagely murdered by the command of Odo, the archbishop of Canterbury—Dunstan recalled from his banishment—Supposed murder of Edwin | p. 227 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| THE REIGN OF EDGAR. | |

| Power of Dunstan—He is made Archbishop of Canterbury—He appoints his own friends counsellors to the young king—His encouragement of the fine arts—Enforces the Benedictine rules upon the monks—Speech of Edgar in favour of Dunstan's reformation in the monasteries—Romantic adventure of Elfrida, daughter of the Earl of Devonshire—Death of Athelwold—Personal courage of Edgar—His love of pomp, and generosity—His encouragement of foreign artificers—His tribute of wolves' heads—England infested with wolves long after the commencement of the Saxon period—Many of the Saxon names derived from the wolf—Death of Edgar—Elfric's sketch of his character—Changes wrought by Edgar | p. 233 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| EDWARD THE MARTYR. | |

| Dunstan still triumphant—Is opposed by the dowager-queen Elfrida—Her attempts to place her son, Ethelred, upon the throne, frustrated by Dunstan—Contest between the monks and the secular clergy—The Benedictine monks driven out of Mercia—The Synod of Winchester—Dunstan's pretended miracle doubted—The council of Calne—William of Malmesbury's description of the assembly—Dunstan's threat—Falling in of that portion of the floor on which Dunstan's opponents stood—Reasons xivfor supposing that the floor was undermined by the command of Dunstan—Death of his enemies, and triumph of the archbishop—Edward's visit to Corfe Castle—He is stabbed in the back while pledging his stepmother, Elfrida, at the gate—His dreadful death—Character of Elfrida | p. 238 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| ETHELRED THE UNREADY. | |

| Elfrida still opposed by Dunstan—Ethelred crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury—His malediction at the coronation—Dislike of the Saxons to Ethelred—Dunstan's power on the wane—Insurrection of the Danes—The Danish pirates again ravage England—Courageous reply of the Saxon governor of Essex—Single combat between the Saxon governor, and one of the sea-kings—Cowardly conduct of Ethelred—He pays tribute, and makes peace with the Danes—Alfric the Mercian governor, turns traitor, and joins the Danes with his Saxon ships—The Saxon army again commanded by the Danes, and defeated—Olaf, the Norwegian, and Swein, king of Denmark, invade and take formal possession of England—Ethelred again exhausts his exchequer, to purchase peace—Swein's second invasion of England—Cruel massacre of the Danes by the Saxons—Murder of Gunhilda, the sister of Swein, king of Denmark—Swein prepares to revenge the death of his countrymen—Description of his soldiers—Splendour of his ships—His magical banner described—His landing in England—Alfric again betrays the Saxons—Destruction of Norwich—Ethelred once more purchases peace of the Danes—-Ælfeg, archbishop of Canterbury, made prisoner by the sea-kings—He refuses to pay a ransom—Is summoned to appear before the sea-kings while they are feasting, and beaten to death by the bones of the oxen the pirates had feasted upon—Ethelred lays an oppressive tax upon the land—He raises a large fleet—Is again betrayed by his commanders—Sixteen counties are given up to the Danes—Ethelred deserted by his subjects—Escapes to the Isle of Wight, and from thence to Normandy—Swein, king of Denmark, becomes the monarch of England—Death of Swein—His son Canute claims the crown—Is opposed by Edmund Ironside—Canute's cruelty to the Saxon hostages—Miserable state of England at this period, as described by a Saxon bishop | p. 249 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| EDMUND, SURNAMED IRONSIDE. | |

| Courageous character of Edmund Ironside—His gallant defence of London—His prowess at the battle of Scearston—Obstinacy of the combat which is only terminated by the approach of night—Renewal of the battle in the xvmorning—Narrow escape of Canute, the Dane, from the two-handed sword of Edmund Ironside—Conduct of the traitor Edric—Retreat of the Danes—Battles fought by Edmund the Saxon—Ulfr, a Danish chief, lost in a wood—Meets with Godwin the cowherd, and is conducted to the Danish camp—Treaty between Canute the Dane and Edmund Ironside—The kingdom divided between the Danes and Saxons—Suspicious circumstances attending the death of Edmund—Despondency of the Saxons | p. 254 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| CANUTE THE DANE. | |

| Coronation of Canute the Dane—His treaty with the Saxon nobles—He banishes the relations of Ethelred, and the children of Edmund—Fate of Edmund's children—Canute's marriage with Emma, the dowager-queen of the Saxons—Death of the traitor, Edric—Canute visits Denmark—Death of Ulfr, the patron of Godwin the cowherd—Canute invades Norway—Habits of the Norwegian pirates—Canute erects a monument to Ælfeg, the murdered archbishop of Canterbury—Carries off the dead body of the bishop from London—Night scene on the Thames—Kills one of his soldiers—His penance—Establishes the tax of Peter's-pence—Picturesque description of Canute rebuking his courtiers—His theatrical display, and vanity—His pilgrimage to Rome—Canute's letter—His death | p. 264 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| REIGNS OF HAROLD HAREFOOT AND HARDICANUTE. | |

| Sketch of Canute's reputed sons—The succession disputed—Rise of earl Godwin—Refusal of the archbishop to crown Harold Harefoot—Harold crowns himself, and bids defiance to the church—Conduct of Emma of Normandy—Her letter to her son Alfred—He lands in England, with a train of Norman followers—His reception by earl Godwin—Massacre of the Normans at Guildford—Death of Alfred, the son of Ethelred—Emma banished from England—Her residence at Bruges—Hardicanute prepares to invade England—Death of Harold Harefoot—Accession of Hardicanute—Disinters the body of Harold—Summons earl Godwin to answer for the death of Alfred—Godwin's defence—Penalty paid by earl Godwin—Character of Hardicanute—His Huscarls—The inhabitants of Worcester refuse to pay the tax, called Dane-geld—They abandon the city—Reckless conduct of Hardicanute—He invites Edward, the son of Ethelred, to England—Hardicanute, the last of the sea-kings, dies drunk at a marriage-feast xviin Lambeth | p. 272 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| ACCESSION OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR. | |

| Edward established on the throne of England by the power of earl Godwin—Edward marries Editha, the earl's daughter—Description of the Lady Editha, by Ingulphus—Godwin's jealousy of the Norman favourites, who surrounded Edward—Friendless state of Edward the Confessor, when he arrived in England—Changes produced by the arrival of the Normans in the Saxon court—Independence of Godwin and his sons—Emma banished by her son Edward—Threatened invasion of Magnus, king of Norway—The Saxons and Danes alike jealous of the Norman favourites—Eustace, count of Boulogne, visits king Edward—His conduct at Dover—Several of the count's followers are slain—Earl Godwin refuses to punish the inhabitants of Dover for their attack on Count Eustace—The Normans endeavour to overthrow Earl Godwin—He refuses to attend the council at Gloucester—Earl Godwin and his sons have recourse to arms—The Danes refuse to attack the Saxons in king Edwin's quarrel—Banishment of the Saxon earl and his sons—Sufferings of queen Editha | p. 282 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| EDWARD THE CONFESSOR. | |

| Description of the English court, after the banishment of Earl Godwin—William, the Norman, surnamed the Bastard, and the Conqueror, arrives in England—William's parentage—Sketch of his father, surnamed Robert the Devil—His pilgrimage to Rome, and death—Bold and daring character of William the Norman—His cruel conduct to the prisoners of Alençon—His delight on visiting England—Circumstances in his favour for obtaining the crown of England—Return, and triumph of Earl Godwin—England again on the verge of a civil war—Departure of the Norman favourites—Sketch of the English court after the return of the Saxon earl—Death of Godwin—Siward the Strong—Rise of Harold, the son of earl Godwin—Imbecility of Edward the Confessor—Harold's victory over the Welsh—Conduct of Tostig, the brother of Harold—Coldness of the church of Rome towards England—struggle of Benedict and Stigand for the pallium—Mediation of Lanfranc—William the Norman becomes a favourite with the Roman pontiff—Suspicious death of Edward, the son of Edmund Ironside—Edward the Confessor suspects the designs of William the Conqueror—Harold, the son of Godwin, obtains permission to visit xviiNormandy | p. 296 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| EARL HAROLD'S VISIT TO NORMANDY. | |

| Harold shipwrecked upon the coast of France—Is made captive, and carried to the fortress of Beaurain—Is released by the intervention of William of Normandy—Harold's interview with Duke William at Rouen—Affected kindness of the Norman duke—William cautiously unfolds his designs on the crown of England—His proposition to Harold—Offers Harold his daughter, Adeliza, in marriage—Duke William's stratagem—Harold's oath on the relics of the saints—Description of William the Norman's courtship—Character of Matilda of Flanders—Harold's return to England—The English people alarmed by signs and omens—Appearance of a comet in England—Description of the death of Edward the Confessor | p. 304 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| ACCESSION OF HAROLD, THE SON OF GODWIN. | |

| Harold elected king of England by the Saxon witenagemot—Becomes a great favourite with his subjects—Restores the Saxon customs—Conduct of William the Norman on hearing that Harold had ascended the throne of England—Tostig, Harold's brother, forms a league with Harold Hardrada, the last of the sea-kings—Character of Harold Hardrada—His adventures in the east—He prepares to land in England—Tostig awaits his arrival in Northumbria—The duke of Normandy's message to Harold king of the Saxons—Harold's answer—He marries the sister of Morkar of Northumbria—Duke William makes preparations for the invasion of England—Arrival of Harold Hardrada with his Norwegian fleet—Superstitious feeling of the Norwegian soldiers—He joins Tostig, the son of Godwin—They burn Scarborough, and enter the Humber—Harold, by a rapid march, reaches the north—He prevents the surrender of York—Preparation for the battle—Harold surprises the enemy—Description of the combat—Harold offers peace to his brother—The offer rejected—Description of the battle—Deaths of Harold Hardrada and Tostig—Harold's victory | p. 314 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| ENGLAND INVADED BY THE NORMANS. | |

| Preparations in Normandy for the invasion of England—Description of duke William's soldiers—He obtains the sanction of the pope to seize the xviiicrown of England, and receives a consecrated banner from Rome—Meeting of the barons and citizens of Normandy—Policy of William Fitz-Osbern—Measures adopted by the Norman duke—His promises to all who embarked in the expedition—Vows of the Norman knights—Protest of Conan, king of Brittany—Death of Conan—The Norman fleet arrives at Dive—Conduct of duke William while wind-bound in the roadsteads of St. Valery—Consternation amongst his troops—Method pursued by the Norman duke to appease the murmurs of his soldiers—The Norman fleet crosses the Channel, and arrives at Pevensey-bay—Fall of the astrologer—Landing of the Norman soldiers—William's stumbling considered an ill omen—He marches towards Hastings—Alarm of the inhabitants along the coast—Tidings carried to Harold of the landing of the Normans | p. 325 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| BATTLE OF HASTINGS. | |

| Harold, king of the Saxons, marches from York—Despatches a fleet to intercept the flight of the Normans—Disaffection amongst his troops—He arrives in London—His hasty departure from the metropolis—Cause of Harold's disasters—Description of the Norman and Saxon encampments—William's message to Harold—Occupation of the rival armies the night before the battle—Gurth advises Harold to quit the field—Morning of the battle—The Saxon and Norman leaders—William the Norman's address to his soldiers—Inferiority of the Saxons in numbers—Strong position taken up by Harold—Commencement of the combat—Courage of the Saxons—The Normans driven back from the English intrenchments—Skill of the Norman archers—Cavalry of the invaders driven into a deep ravine—The battle hitherto in favour of the Saxons—Rumour that William the Norman was slain—The effect of his sudden appearance amongst his retreating forces—Unflinching valour of the Saxons—Stratagem adopted by the Norman duke—Its consequence—William again attempts a feigned flight, and the Saxons quit their intrenchments—Dreadful slaughter of the English—Death of Harold, the last Saxon king—Capture of the Saxon banner—Victory of the Normans—Retreat and pursuit of the remnant of the Saxon army—The field of Hastings the morning after the battle—The dead body of Harold discovered by Edith the Swan-necked | p. 338 |

| THE ANGLO-SAXONS. | |

| Their religion—Government and laws—Literature of Anglo-Saxons—Architecture, Arts, &c.—Costume, Manners, Customs, and Everyday life | p. 357 |

Almost every historian has set out by regretting how little is known of the early inhabitants of Great Britain—a fact which only the lovers of hoar antiquity deplore, since from all we can with certainty glean from the pages of contemporary history, we should find but little more to interest us than if we possessed written records of the remotest origin of the Red Indians; for both would alike but be the history of an unlettered and uncivilized race. The same dim obscurity, with scarcely an exception, hangs over the primeval inhabitants of every other country; and if we lift up the mysterious curtain which has so long fallen over and concealed the past, we only obtain glimpses of obscure hieroglyphics; and from the unmeaning fables of monsters and giants, to which the rudest nations trace their origin, we but glance backward and backward, to find that civilized Rome and classic Greece can produce no better authorities than old undated traditions, teeming with fabulous accounts of heathen gods and goddesses.2 What we can see of the remote past through the half-darkened twilight of time, is as of a great and unknown sea, on which some solitary ship is afloat, whose course we cannot trace through the shadows which everywhere deepen around her, nor tell what strange land lies beyond the dim horizon to which she seems bound. The dark night of mystery has for ever settled down upon the early history of our island, and the first dawning which throws the shadow of man upon the scene, reveals a rude hunter, clad in the skins of beasts of the chase, whose path is disputed by the maned and shaggy bison, whose rude hut in the forest fastnesses is pitched beside the lair of the hungry wolf, and whose first conquest is the extirpation of these formidable animals. And so, in as few words, might the early history of many another country be written. The shores of Time are thickly strown with the remains of extinct animals, which, when living, the eye of man never looked upon, as if from the deep sea of Eternity had heaved up one wave, which washed over and blotted out for ever all that was coëval with her silent and ancient reign, leaving a monument upon the confines of this old and obliterated world, for man in a far and future day to read, on which stands ever engraven the solemn sentence, "Hitherto shalt thou come, but no further!"—beyond this boundary all is Mine! Neither does this mystery end here, for around the monuments which were reared by the earliest inhabitants of Great Britain, there still reigns a deep darkness; we know not what hand piled together the rude remains of Stonehenge; we have but few records of the manners, the customs, or the religion of the early Britons; here and there a colossal barrow heaves up above the dead; we look within, and find a few bones, a few rude weapons, either used in the war or the chase, and these are all; and we linger in wonderment around such remains. Who those ancient voyagers were that first called England the Country of Sea Cliffs we know not; and while we sit and brood over the rude fragments of the Welsh Triads, we become so entangled in doubt and mystery as to look upon the son of Aedd the Great, and the Island of Honey to which he sailed, and wherein he found no man alive, as the pleasing dream of some old and forgotten poet; and we set out again, with no more success, to discover who were the earliest inhabitants of England, leaving the ancient Cymri and the country of Summer behind, and the tall, silent cliffs, to stand as they had done for ages, looking over a wide and mastless sea. We then3 look among the ancient names of the headlands, and harbours, and mountains, and hills, and valleys, and endeavour to trace a resemblance to the language spoken by some neighbouring nation, and we only glean up a few scattered words, which leave us still in doubt, like a confusion of echoes, one breaking in upon the other, a minglement of Celtic, Pictish, Gaulish, and Saxon sounds, where if for a moment but one is audible and distinct, it is drowned by other successive clamours which come panting up with a still louder claim, and in very despair we are compelled to step back again into the old primeval silence. There we find Geology looking daringly into the formation of the early world, and boldly proclaiming, that there was a period of time when our island heaved up bare and desolate amid the silence of the surrounding ocean,—when on its ancient promontories and grey granite peaks not a green branch waved, nor a blade of grass grew, and no living thing, saving the tiny corals, as they piled dome upon dome above the naked foundations of this early world, stirred in the "deep profound" which reigned over those sleeping seas. Onward they go, boldly discoursing of undated centuries that have passed away, during which they tell us the ocean swarmed with huge, monstrous forms; and that all those countless ages have left to record their flight are but the remains of a few extinct reptiles and fishes, whose living likenesses never again appeared in the world. To another measureless period are we fearlessly carried—so long as to be only numbered in the account of Time which Eternity keeps—and other forms, we are told, moved over the floors of dried-up oceans—vast animals which no human eye ever looked upon alive; these, they say, also were swept away, and their ponderous remains had long mingled with and enriched the earth; but man had not as yet appeared; nor in any corner of the whole wide world do they discover in the deep-buried layers of the earth a single vestige of the remains of the human race. What historian, then, while such proofs as these are before his eyes, will not hesitate ere he ventures to assert who were the first inhabitants of any country, whence they came, or at what period that country was first peopled? As well might he attempt a description of the scenery over which the mornings of the early world first broke,—of summit and peak which, they say, ages ago, have been hurled down, and ground and powdered into atoms. What matters it about the date4 when such things once were, or at what time or place they first appeared? We can gaze upon the gigantic remains of the mastodon or mammoth, or on the grey, silent ruins of Stonehenge, but at what period of time the one roamed over our island, or in what year the other was first reared, will for ever remain a mystery. The earth beneath our feet is lettered over with proofs that there was an age in which these extinct monsters existed, and that period is unmarked by any proof of the existence of man in our island. And during those not improbable periods when oceans were emptied and dried up, amid the heaving up and burying of rocks and mountains,—when volcanoes reddened the dark midnights of the world, when "the earth was without form, and void,"—what mind can picture aught but His Spirit "moving upon the face of the waters,"—what mortal eye could have looked upon the rocking and reeling of those chaotic ruins when their rude forms first heaved up into the light? Is not such a world stamped with the imprint of the Omnipotent,—from when He first paved its foundation with enduring granite, and roofed it over with the soft blue of heaven, and lighted it by day with the glorious sun, and hung out the moon and stars to gladden the night; until at last He fashioned a world beautiful enough for the abode of His "own image" to dwell in, before He created man? And what matters it whether or not we believe in all these mighty epochs? Surely it is enough for us to discover throughout every change of time the loving-kindness of God for mankind; we see how fitting this globe was at last for his dwelling-place; that before the Great Architect had put this last finish to His mighty work, instead of leaving us to starve amid the Silurian sterility, He prepared the world for man, and in place of the naked granite, spread out a rich carpet of verdure for him to tread upon, then flung upon it a profusion of the sweetest flowers. Let us not, then, daringly stand by, and say thus it was fashioned, and so it was formed, but by our silence acknowledge that it never yet entered into the heart of man to conceive how the Almighty Creator laid the foundation of the world.

To His great works must we ever come with reverential knee, and before them lowly bow; for the grey rocks, and the high mountain summits, and the wide-spreading plains, and the ever-sounding seas, are stamped with the image of Eternity,—a mighty shadow ever hangs over them. The grey and weather-beaten headlands still look over the sea, and5 the solemn mountains still slumber under their old midnight shadows; but what human ear first heard the murmur of the waves upon the beaten beach, or what human foot first climbed up those high-piled summits, we can never know.

What would it benefit us could we discover the date when our island was buried beneath the ocean; when what was dry land in one age became the sea in another; when volcanoes glowed angrily under the dark skies of the early world, and huge extinct monsters bellowed, and roamed, and swam, through the old forests and the ancient rivers which have perhaps ages ago been swept away? What could we find more to interest us were we in possession of the names, the ages, and the numbers, of the first adventurers who were perchance driven by some storm upon our sea-beaten coast, than what is said in the ancient Triad before alluded to? "there were no more men alive, nor anything but bears, wolves, beavers, and the oxen with the high prominence," when Aedd landed upon the shores of England. What few traces we have of the religious rites of the early inhabitants of Great Britain vary but little from such as have been brought to light by modern travellers who have landed in newly-discovered countries in our own age. They worshipped idols, and had no knowledge of the true God, and saving in those lands where the early patriarchs dwelt, the same Egyptian darkness settled over the whole world. The ancient Greeks and Romans considered all nations, excepting themselves, barbarians; nor do the Chinese of the present day look upon us in a more favourable light; while we, acknowledging their antiquity as a nation, scarcely number them amongst such as are civilized. We have yet to learn by what hands the round towers of Ireland were reared, and by what race the few ancient British monuments that still remain were piled together, ere we can enter those mysterious gates which open upon the History of the Past. We find the footprint of man there, but who he was, or whence he came, we know not; he lived and died, and whether or not posterity would ever think of the rude monuments he left behind concerned him not; whether the stones would mark the temple in which he worshipped, or tumble down and cover his grave, concerned not his creed; with his hatchet of stone, and spear-head of flint, he hewed his way from the cradle to the tomb, and under the steep barrow he knew that he should sleep his last sleep, and, with his arms folded upon his breast, he left "the dead past to bury its dead." He lived not for us.

Although the origin of the early inhabitants of Great Britain is still open to many doubts, we have good evidence that at a very remote period the descendants of the ancient Cimmerii, or Cymry, dwelt within our island, and that from the same great family sprang the Celtic tribe; a portion of which at that early period inhabited the opposite coast of France. At what time the Cymry and Celts first peopled England we have not any written record, though there is no lack of proof that they were known to the early Phœnician voyagers many centuries before the Roman invasion, and that the ancient Greeks were acquainted with the British Islands by the name of the Cassiterides, or the Islands of Tin. Thus both the Greeks and Romans indirectly traded with the very race, whose ancestors had shaken the imperial city with their arms, and rolled the tide of battle to those classic shores where "bald, blind Homer" sung. They were the undoubted offspring of the dark Cimmerii of antiquity, those dreaded indwellers of caves and forests, those brave barbarians whose formidable helmets were surmounted by the figures of gaping and hideous monsters; who wore high nodding crests to make them look taller and more terrible in battle, considering death on the hard-fought field as the crowning triumph of all earthly glory. From this race sprang those ancient British tribes who presented so bold a front to Julius Cæsar, when his Roman galleys first ploughed the waves that washed their storm-beaten shores. Beyond this contemporary history carries us not; and the Welch traditions go no further back than to state that when the son of Aedd first7 sailed over the hazy ocean, the island was uninhabited, which we may suppose to mean that portion on which he and his followers landed, and where they saw no man alive, for we cannot think that it would long remain unpeopled, visible as it is on a clear day from the opposite coast of Gaul, and beyond which great nations had then for centuries flourished. What few records we possess of the ancient Britons, reveal a wild and hardy race; yet not so much dissimilar to the social position of England in the present day, as may at a first glance appear. They had their chiefs and rulers who wore armour, and ornaments of gold and silver; and these held in subjection the poorer races who lived upon the produce of the chase, the wild fruits and roots which the forest and the field produced, and wore skins, and dwelt in caverns, which they hewed out of the old grey rocks. They were priest-ridden by the ancient druids, who cursed and excommunicated without the aid of either bell, book, or candle; burned and slaughtered all unbelievers just as well as Mahomet himself, or the bigoted fanatics, who in a later day did the same deeds under the mask of the Romish religion. For centuries after, mankind had not undergone so great a change as they at the first appear to have done; there was the same love of power, the same shedding of blood, and those who had not courage to take the field openly, and seize upon what they could boldly, burnt, and slew, and sacrificed their fellow-men under the plea that such offerings were acceptable to the gods.

By the aid of the few hints which are scattered over the works of the Greek and Roman writers, the existence of a few remaining monuments, and the discoveries which have many a time been made through numberless excavations, we can just make out, in the hazy evening of the past, enough of the dim forms of the ancient Britons to see their mode of life, their habits in peace and war, as they move about in the twilight shadows which have settled down over two thousand years. That they were a tall, large-limbed, and muscular race, we have the authority of the Roman writers to prove; who, however, add but little in praise of the symmetry of their figures, though they were near half a foot higher than their distant kindred the Gauls. They wore their hair long and thrown back from the forehead, which must have given them a wild look in the excitement of battle, when their long curling locks would8 heave and fall with every blow they struck; the upper lip was unshaven, and the long tufts drooped over the mouth, thus adding greatly to their grim and warlike appearance. Added to this, they cast aside their upper garments when they fought, as the brave Highlanders were wont to do a century or two ago, and on their naked bodies were punctured all kinds of monsters, such as no human eye had ever beheld. Claudian mentions the "fading figures on the dying Pict;" the dim deathly blue that they would fade into, as the life-blood of the rude warrior ebbed out, upon the field of battle.

How different must have been the landscape which the fading rays of the evening sunset gilded in that rude and primitive age. Instead of the tall towers and walled cities, whose glittering windows now flash back the golden light, the sinking rays gilded a barrier of felled trees in the centre of the forest which surrounded the wattled and thatched huts of those ancient herdsmen, throwing its crimson rays upon the clear space behind, in which his herds and flocks were pastured for the night; while all around heaved up the grand and gloomy old forest, with its shadowy thickets, and dark dingles, and woody vallies untrodden by the foot of man. There was then the dreaded wolf to guard against, the unexpected rush of the wild boar, the growl of the grizzly bear, and the bellowing of the maned bison to startle him from his slumber. Nor less to be feared the midnight marauder from some neighbouring tribe, whom neither the dreaded fires of the heathen druids, nor the awful sentence which held accursed all who communicated with him after the doom was uttered, could keep from plunder, whenever an opportunity presented itself. The subterraneous chambers in which their corn was stored might be emptied before morning; the wicker basket which contained their salt (brought far over the distant sea by the Phœnicians or some adventurous voyager) might be carried away; and no trace of the robber could be found through the pathless forest, and the reedy morass by which he would escape, while he startled the badger with his tread, and drove the beaver into his ancient home; for beside the druids there were those who sowed no grain, who drank up the beverage their neighbours brewed from their own barley, and ate up the curds which they had made from the milk of their own herds. These were such as dug up the "pig-nuts," still eaten by the children in the northern counties at the present day; who struck down the9 deer, the boar, and the bison in the wild unenclosed forest—kindled a fire with the dried leaves and dead branches, then threw themselves down at the foot of the nearest oak, when their rude repast was over, and with their war-hatchet, or hunting-spear, firmly grasped, even in sleep, awaited the first beam of morning, unless awoke before by the howl of the wolf, or the thundering of the boar through the thicket. They left the fish in their vast rivers untouched, as if they preferred only that food which could be won by danger; from the timid hare they turned away, to give chase to the antlered monarch of the forest; they let the wild goose float upon the lonely mere, and the plumed duck swim about the broad lake undisturbed. There was a wild independence in their forest life—they had but few wants, and where nature no longer supplied these from her own uncultivated stores, they looked abroad and harassed the more civilized and industrious tribes.

Although there is but little doubt that the British chiefs, and those who dwelt on the sea-coast, and opened a trade with the Gaulish merchants, lived in a state of comparative luxury, when contrasted with the wilder tribes who inhabited the interior of the island, still there is something simple and primitive in all that we can collect of their domestic habits. Their seats consisted of three-legged stools, no doubt sawn crossways from the stem of the tree, and three holes made to hold the legs, like the seats which are called "crickets," that may be seen in the huts of the English peasantry in the present day. Their beds consisted of dried grass, leaves, or rushes spread upon the floor—their covering, the dark blue cloak or sagum which they wore out of doors; or the dried skins of the cattle they slew, either from their own herds or in the chase. They ate and drank from off wooden trenchers, and out of bowls rudely hollowed: they were not without a rough kind of red earthenware, badly baked, and roughly formed. They kept their provisions in baskets of wicker-work, and made their boats of the same material, over which they stretched skins to keep out the water. They kindled fires on the floors of their thatched huts, and appear to have been acquainted with the use of coal as fuel, though there is little doubt that they only dug up such as lay near the surface of the earth; but it was from the great forests which half covered their island that they principally procured their fuel. They had also boats, not unlike the canoes still in use amongst10 the Indians, which were formed out of the hollow trunk of a tree; and some of which have been found upwards of thirty feet in length; and in these, no doubt, they ventured over to the opposite coast of France, and even Ireland, when the weather was calm. Diodorus says, that amongst the Celtic tribes there was a simplicity of manners very different to that craft and wickedness which mankind then exhibited—that they were satisfied with frugal sustenance, and avoided the luxuries of wealth. The boundaries of their pastures consisted of such primitive marks as upright stones, reminding us of the patriarchal age and the scriptural anathema of "cursed is he who removeth his neighbour's land-mark." Their costume was similar to that worn by their kindred the Gauls, consisting of loose lower garments, a kind of waistcoat with wide sleeves, and over this a cloak, or sagum, made of cloth or skin; and when of the former, dyed blue or black, for they were acquainted with the art of dyeing; and some of them wore a cloth, chequered with various colours. The chiefs wore rings of gold, silver, or bronze, on their forefingers; they had also ornaments, such as bracelets and armlets of the same metal, and a decoration called the torque, which was either a collar or a belt formed of gold, silver, or bronze, and which fastened behind by a strong hook. Several of these ornaments have been discovered, and amongst them, one of gold, which weighed twenty-five ounces. It seems to have been something like the mailed gorget of a later day, worn above the cuirass or coat of mail, to protect the neck and throat in battle; their shoes appear to have been only a sole of wood or leather, fastened to the foot by thongs cut from off the raw hides of oxen they had slaughtered. The war weapons of the wilder tribes in the earlier times, were hatchets of stone, and arrows headed with flint, and long spears pointed with sharpened bone; but long before the Roman invasion, the more civilized were in possession of battle-axes, swords, spears, javelins, and other formidable instruments of war, made of a mixture of copper and tin. Many of these instruments have been discovered in the ancient barrows where they buried their dead; and were, no doubt, at first procured from the merchants with whom they traded—ignorant, perhaps, for a long period, that they were produced from the very material they were giving for them in exchange. In battle they also bore a circular shield, coated with the same metal; this they held in the hand by the11 centre bar that went across the hollow inner space from which the boss projected.

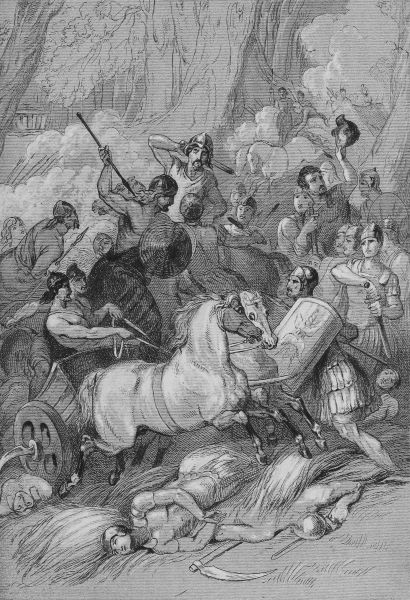

But the war-chariots which they brought into battle were of all things the most dreaded by the Romans. From the axles projected those sharp-hooked formidable scythes, which appalled even the bravest legions, and made such gaps in their well-trained ranks, as struck their boldest generals aghast. These were drawn by such horses as, by their fire and speed, won the admiration of the invaders; for fleet on foot as deer, and with their dark manes streaming out like banners, they rushed headlong, with thundering tramp, into the armed ranks of the enemy; the sharp scythes cutting down every obstacle they came in contact with. With fixed eyes the fearless warrior hurled his pointed javelins in every direction as he rushed thundering on—sometimes making a thrust with his spear or sword, as he swept by with lightning-speed, or dragged with him for a few yards the affrighted foeman he had grasped while passing, and whose limbs those formidable weapons mangled at every turn until the dreaded Briton released his hold. Now stepping upon the pole, he aimed a blow at the opponent who attempted to check his speed—then he stopped his quick-footed coursers in a moment, as if a bolt from heaven had alighted, and struck them dead, while some warrior who was watching their onward course fell dead beneath so unexpected a blow; and ere the sword of his companion was uplifted to revenge his death, the Briton and his chariot were far away, hewing a new path through the centre of veteran ranks, which the stormy tide of battle had never before broken. The form of the tall warrior, leaning over his chariot with glaring eye and clenched teeth, would, by his valour and martial deportment, have done honour to the plains of Troy, and won an immortal line from Homer himself, had he but witnessed those deeds achieved by the British heroes in a later day. What fear of death had they before their eyes who believed that their souls passed at once into the body of some brave warrior, or that they but quitted the battle-field to be admitted into the abodes of the gods? They sprang from a race whose mothers and wives had many a time hemmed in the back of battle, and with their own hands struck down the first of their tribe who fled,—sparing neither father, husband, brother, nor son, if he once turned his back upon the enemy: a race whose huge war-drums had, centuries before, sounded in Greek and Roman combats. And from this12 hardy stock, which drooped awhile beneath the pruning arms of civilized Rome, was the Gothic grandeur of the Saxon stem grafted, and when its antique roots had been manured by the bones of thousands of misbelieving Danes, and its exuberant shoots lopped by the swords of the Norman chivalry, there sprang up that mighty tree, the shadows of whose branches stretch far away over the pathless ocean, reaching to the uttermost ends of the earth.

To Julius Cæsar we are indebted for the clearest description of the religious rites and ceremonies of the Druids; and as he beheld them administered by these Priests to the ancient Britons, so they had no doubt existed for several centuries before the Roman invasion, and are therefore matters of history, prior to that period. There was a wild poetry about their heathenish creed, something gloomy, and grand, and supernatural in the dim, dreamy old forests where their altars were raised: in the deep shadows which hung over their rude grey cromlechs, on which the sacred fire burned. We catch glimpses between the gnarled and twisted stems of those magnificent and aged oaks of the solemn-looking druid, in his white robe of office, his flowing beard blown for a moment aside, and breaking the dark green of the underwood with the lower portion of his sweeping drapery, while he stands like a grave enchanter, his deep sunk and terrible eyes fixed upon the blue smoke as it curls upward amid the foliage—fixed, yet only to appearance; for let but a light and wandering expression13 pass over one single countenance in that assembled group, and those deep grey piercing eyes would be seen glaring in anger upon the culprit, and whether it were youth or maiden they would be banished from the sacrifice, and all held accursed who dared to commune with them—a curse more terrible than that which knelled the doom of the excommunicated in a later day. There were none bold enough to extinguish the baleful fire which was kindled around the wicker idol, when its angry flames went crackling above the heads of the human victims who were offered up to appease their brutal gods. In the centre of their darksome forests were their rich treasures piled together, the plunder of war; the wealth wrested from some neighbouring tribe; rich ornaments brought by unknown voyagers from distant countries in exchange for the tin which the island produced; or trophies won by the British warriors who had fought in the ranks of the Gauls on the opposite shore—all piled without order together, and guarded only by the superstitious dread which they threw around everything they possessed; for there ever hung the fear of a dreadful death over the head of the plunderer who dared to touch the treasures which were allotted to the awful druids. They kept no written record of their innermost mysteries, but amid the drowsy rustling of the leaves and the melancholy murmuring of the waters which ever flowed around their wooded abodes, they taught the secrets of their cruel creed to those who for long years had aided in the administration of their horrible ceremonies, who without a blanched cheek or a quailing heart had grown grey beneath the blaze of human sacrifices, and fired the wicker pile with an unshaken hand—these alone were the truly initiated. They left the younger disciples to mumble over matters of less import—written doctrines which taught how the soul passed into other bodies in never-ending succession; but they permitted them not to meddle in matters of life and death; and many came from afar to study a religion which armed the druids with more than sovereign power. All law was administered by the same dreaded priests; no one dared to appeal from their awful decree; he who was once sentenced had but to bow his head and obey—rebellion was death, and a curse was thundered against all who ventured to approach him; from that moment he became an outcast amongst mankind. To impress the living with a dread of their power even after death, they hesitated not in their doctrines to proclaim, that they held14 control over departed and rebellious souls; and in the midnight winds that went wailing through the shadowy forests, they bade their believers listen to the cry of the disembodied spirits who were moaning for forgiveness, and were driven by every blast that blew against the opening arms of the giant oaks; for they gave substance to shadows, and pointed out forms in the dark-moving clouds to add to the terrors of their creed. They worshipped the sun and moon, and ever kept the sacred fire burning upon some awful altar which had been reddened by the blood of sacrifice. They headed the solemn processions to springs and fountains, and muttered their incantations over the moving water, for, next to fire, it was the element they held in the highest veneration. But their grand temples—like Stonehenge—stood in the centre of light, in the midst of broad, open, and spacious plains, and there the great Beltian fire was kindled; there the distant tribes congregated together, and unknown gods were evoked, whose very names have perished, and whose existence could only be found in the wooded hill, the giant tree, or the murmuring spring or fountain, over which they were supposed to preside. There sat the arch-druid, in his white surplice, the shadow of the mighty pillars of rough-hewn stone chequering the stony rim of that vast circle—from his neck suspended the wonderful egg which his credulous believers said fell from twined serpents, that vanished hissing high in the air, after having in vain pursued the mounted horseman who caught it, then galloped off at full speed—that egg, cased in gold, which could by its magical virtues swim against the stream. He held the mysterious symbol of office, in his hands more potent than the sceptre swayed by the most powerful of monarchs that ever sat upon our island throne, as he sat with his brow furrowed by long thought, and ploughed deep by many a meditated plot, while his soul spurned the ignorant herd who were assembled around him, and he bit his haughty lip at the thought that he could devise no further humiliation than to make them kneel and lick the sand on which he stood.

They held the mistletoe which grew on the oak sacred, and on the sixth day of the moon came in solemn procession to the tree on which it grew, and offered up sacrifice, and prepared a feast beneath its hallowed branches, adorning themselves with its leaves, as if they could never sufficiently reverence the tree on which the mistletoe grew, although they named themselves15 druids after the oak. White bulls were dragged into the ceremony; their stiff necks bowed, and their broad foreheads bound to the stem of the tree, while their loud bellowings came in like a wild chorus to the rude anthem which was chaunted on the occasion: these were slaughtered, and the morning sacrifice went streaming up among the green branches. The chief druid ascended the oak, treading haughtily upon the bended backs and broad shoulders of the blinded slaves, who struggled to become stepping-stones beneath his feet, and eagerly bowed their necks that he might trample upon them, while he gathered his white garment in his hand, and drew it aside, lest it should become sullied by touching their homely apparel. Below him stood his brother idolators, their spotless garments outspread ready to catch the falling sprigs of the mistletoe as they dropped beneath the stroke of the golden pruning-knife. Doubtless the solemn mockery ended by the assembled multitude carrying home with them a leaf or a berry each, of the all-healing plant, as it was called, while the druids lingered behind to consume the fatted sacrifice, and forge new fetters to bind down their ignorant followers to their heathenish creed. Still it is on record that they taught their disciples many things concerning the stars and their motion; that they pretended to some knowledge of distant countries, and the nature of the gods they worshipped. Gildas, one of the earliest of our British historians, seeming to write from what he saw, tells us that their idols almost surpassed in number those of Egypt, and that monuments were then to be seen (in his day) of "hideous images, whose frigid, ever-lowering, and depraved countenances still frown upon us both within and outside the walls of deserted cities. We shall not," he says, "recite the names that once were heard on our mountains, that were repeated at our fountains, that were echoed on our hills, and were pronounced over our rivers, because the honours due to the Divinity alone were paid to them by a blinded people." That their religion was but a system of long-practised imposture admits not of a doubt; and as we have proof that they possessed considerable knowledge for that period, it is evident that they had recourse to these devices to delude and keep in subjection their fellow-men, thereby obtaining a power which enabled them to live in comparative idleness and luxury. Such were the ancient Egyptian priests; and such, with but few exceptions, were all who, for many centuries, held mighty nations in thrall16 by the mystic powers with which they cunningly clothed idolatry. True, there might be amongst their number a few blinded fanatics, who were victims to the very deceit which they practised upon others, whose faculties fell prostrate before the imaginary idols of their own creation, and who bowed down and worshipped the workmanship of their own hands.

All the facts we are in possession of show that they contributed nothing to the support of the community; they took no share in war, though they claimed their portion of the plunder obtained from it; they were amenable to no tribunal but their own, but only sat apart in their gloomy groves, weaving their dangerous webs in darker folds over the eyes of their blinded worshippers. We see dimly through the shadows of those ancient forests where the druids dwelt; but amongst the forms that move there we catch glimpses of women sharing in their heathen rites; it may be of young and beautiful forms, who had the choice offered them, whether they would become sacrifices in the fires which so often blazed before their grim idols, or share in the solemn mockeries which those darksome groves enshrouded—those secrets which but to whisper abroad would have been death.

The day of reckoning at last came—as it is ever sure to come—and heavy was the vengeance which alighted upon those bearded druids; instead of such living and moving evils, the mute marble of the less offensive gods which the Romans worshipped usurped the places where their blood-stained sacrifices were held. Jupiter frowned coldly down in stone, but he injured not. Mars held his pointed spear aloft, but the dreaded blow never descended. They saw the form of man worshipped, and though far off, it was still a nearer approach to the true Divinity than the wicker idol surrounded with flames, and filled with the writhing and shrieking victims who expired in the midst of indescribable agonies. Hope sat there mute and sorrowful, with her head bowed, and her finger upon her lip, listening for the sound of those wings which she knew would bring Love and Mercy to her aid. She turned not her head to gaze upon those heathenish priests as they were dragged forward to deepen the inhuman stain which sunk deep into the dyed granite of the altar, for she knew that the atmosphere their breath had so long poisoned must be purified before the Divinity could approach; for that bright star which was to illume the world had not yet arisen in the east. The civilized heathen was17 already preparing the way in the wilderness, and sweeping down the ruder barbarism before him. There were Roman galleys before, and the sound of the gospel-trumpet behind; and those old oaks jarred again to their very roots, and the huge circus of Stonehenge shook to its broad centre; for the white cliffs that looked out over the sea were soon to echo back a strange language, for Roman cohorts, guided by Julius Cæsar, were riding upon the waves.

Few generals could put in a better plea for invading a country than that advanced by Julius Cæsar, for long before he landed in this island, he had had to contend with a covert enemy in the Britons, who frequently threw bodies of armed men upon the opposite coasts, and by thus strengthening the enemy's ranks, protracted the war he had so long waged with the Gauls. To chastise the hardy islanders, overawe and take possession of their country, were but common events to the Roman generals, and Cæsar no doubt calculated that to conquer he had but to show his well-disciplined troops. He was also well aware that the language and religion of the Britons and Gauls were almost the same, and that the island on which his eye was fixed was the great centre and stronghold of the druids; and, not ignorant of the power of these heathen priests, whose mysterious rites banded nation with nation, he doubtless thought, that if he could but once overthrow their altars, he could the more easily march over the ruins to more extended conquests. He had almost the plea of self-defence for setting out to invade England as he did, and such, in reality, is the reason he assigns; and not to18 possess the old leaven of ambition to strengthen his purpose, was to lack that which, in a Roman general, swelled into the glory of fame. Renown was the pearl Julius Cæsar came in quest of; he was not a general to lead his legions back to the imperial city, when, after having humbled the pride of the Gauls, he still saw from the opposite coast the island of the presumptuous Britons—barbarians, who had dared to hurl their pointed javelins in the very face of the Roman eagle;—not a man to return home, when, by stretching his arm over that narrow sea, he could gather such laurels as had never yet decked a Roman brow.