The Project Gutenberg EBook of Toots and his Friends, by Kate Tannatt Woods This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Toots and his Friends Author: Kate Tannatt Woods Release Date: April 14, 2014 [EBook #45388] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOOTS AND HIS FRIENDS *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

PAUL'S VIEWS AT EIGHT YEARS OF AGE.

TOOTS is our baby. He is a queer one too; up early, and always in dread of bed-time. One morning, not long ago, we heard him singing, and on looking for him, found the little rogue in the very middle of our best bed in the guest chamber, where he was playing hand-organ with a long hairpin put through the pretty pillow covers which had just come home from the laundry. There he sat singing a droll medley of "Uncle Ned," "Blessed Desus," and "Down in the Coal Mine." He had been watching two soldiers with a hand-organ, and Toots likes to do everything he sees done. While we were putting the guest-room in order, Toots marched out as a blind man, with his eyes shut and a cane in his hand. This brought him to grief, for he was picked up at the foot of the stairs with two large bumps on his pretty white brow. Toots was quiet then for a little while, a very little while, for as soon as we decided that his bones were all sound and a doctor need not be called, he "played sick," and asked for "shicken brof" and toast.

One night mamma was imprudent, for she said to a visitor, who was praising the little fellow, "Oh, yes, Toots is always lovely and gentle at bed-time." That very night while mamma was resting on the lounge, and her friend was chatting, both ladies heard a mysterious clicking. "It can't be Toots," said mamma; "his eyes were closed when I left him." Then the clicking came again louder than ever, and suddenly a crash as of breaking glass. Mamma sprang up at once, and there was Toots seated on a bath-tub driving for dear life with two of his best sashes for reins. He had fastened one on each side of the mirror, and in his eagerness to drive fast, had tumbled down toilet-bottles, cushions, and all the pretty things his mamma loved to see. Toots was playing circus. Barnum had been in town the day before, and Toots had made a grand procession with chairs, books, bottles, pictures, and everything his little hands could reach. Such a happy, beaming face was never seen before. "Why, Toots, I thought you were asleep," said mamma. "No, I hab too much to do, my 'cession is coming up street fast."

When he was quite small, Toots used to spend hours in the garden safely fastened into the standing stool which his grandpa had when a little boy. The little fellow's face was so bright, and his large eyes so full of innocent fun, that no one could be angry with Toots even when he did very strange and unexpected things.

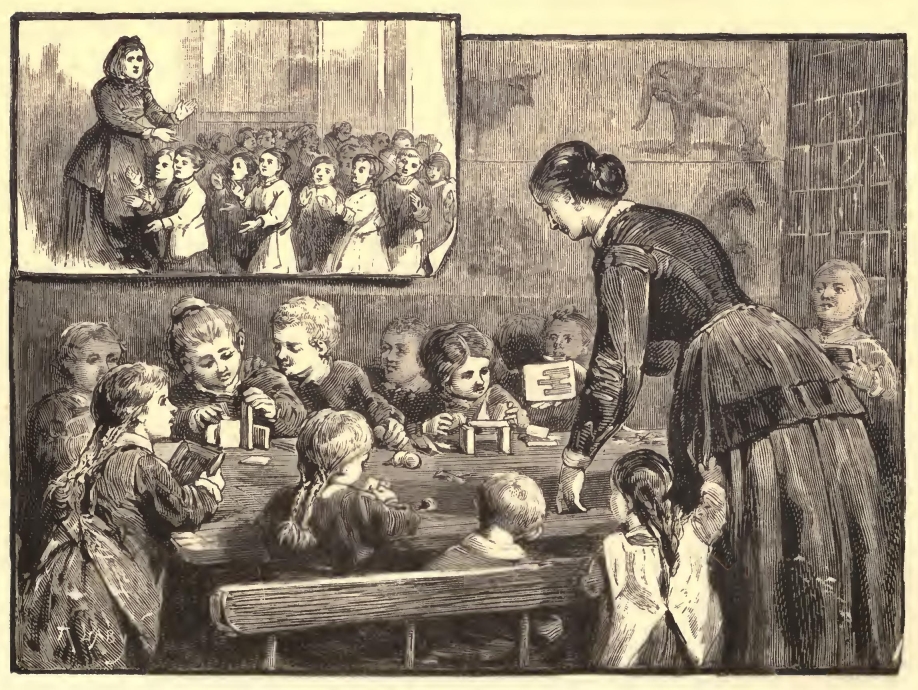

WHEN Toots was old enough to enter a little school, his mamma said he must go to a Kindergarten, which, you all know, is a delightful place for all children. Our good German friends first thought of it for their little people, and here in America we have found it an excellent fashion to follow. Block building, song singing, and drawing with pretty things in needlework, and forms in clay, not only teach the children to think but to do, and good thinking must always come before well doing, Toots' mamma knew a kind German lady who understood teaching the little ones, and after some delay a school was opened and Toots was a pupil. He cried hard at first. He was afraid of strangers, and he dreaded to speak aloud before them, although he was such a rogue at home. His mamma bought him a pretty lunch basket and put in it some little cakes for his lunch, and then they rode away in the horse car to the schoolroom. After the first day Toots was always ready to go. "It is only play," he said. But it was more than play, for every night Toots had something new to tell; sometimes he had watered the plants in the school-room, sometimes he talked of cubes and triangles, sometimes he sang a little song. Toots was learning without knowing it, and all the time he was very happy. No one was allowed to say a naughty word, no one was ever rude or unkind, and all the little eyes and hands were trained.

When Toots told his grandma about the seed germ of a plant and how it grew she said, "Ah, I wish I could have gone to such a school; the children are very fortunate now a days." One day Toots brought his grandma a pretty book-mark he had worked, and he could tell the names of all the colors in it and the names of the stitches. Such pretty things as he made in clay, such dainty shapes and forms, it really was quite wonderful to see them and hear the little fellow in kilt skirts talk about them. One day Toots did not come home from the Kindergarten as usual. His favorite car driver shook his head as he passed the house. Toots had not come out to ride home with him. Grandma was much worried. "Never mind," said mamma, "he is quite safe, perhaps they are all out for walk, or studying the trees or flowers in the garden; he will come in the next car, for his teacher always puts him on herself." When the next car came, there was the little boy, smiling and happy. The children had taken a long walk with their teacher, and when they returned Toots had fallen asleep, so the kind teacher would not disturb him, and the little fellow was well rested.

After dinner he had a long story to tell about the lungs of plants and the edges of leaves, which were like little saws, and a pretty pitcher-plant he had seen. When his story was complete he added, "All my children shall go to a Kindergarten, for it is the nicest place in the world 'cept mamma's room."

VERY night just before bedtime Toots and his mamma had a happy hour together.

Sometimes a friend or two would share the pleasures of this evening hour, and Toots enjoyed it much more if Bessie or Flossie, or some of his mates, could hear mamma's stories or verses written expressly for children. When Toots was quite small he was rude enough one day to strike his nurse, and after mamma had heard all the story, she read these lines about

My mamma's sorry, now, she is;

I don' know what I'se done;

S'pec' she feels sorry jess bekause

I slapped old nurse like fun.

Old nurse she digs and shates me too;

I wish I went to stool;

Teacher won't set me down so hard,

An' call me "little fool."

She pinches awful! dess I know,

My arms is black an' blue;

She says she "hopes to do to Heaven

I hope I shan't do too.

I don't like nurses—do you now?

Dey is dest as mean as dirls;

When I dits big I'll let'em know

Dey musn't pull my turls.

My mamma she's real dood, she is;

On most the days I play

With her jess like she was a boy,

She hugs me every day.

My mamma she don't stold me none,

I dess she don't know how;

But nurse, oh, my! she spoke so loud;

Hush, she is toming now!

No, dat ain't nurse, an' ain't I glad?

I jess know what I'll do,

I'll do tell mamma I was bad,

An' I feel sorry too.

I dess Dod made my mamma sure,

She is so sweet and nice;

But who made nurse, s'pose you know?

I'll ask my Drandma Rice.

MONG Toots' friends was a little girl whose name was Elfie. She lived just across the way, and her papa's garden joined that of Toots' mamma. There was a large gate, between the gardens, and the children went back and forth in the summer. They seldom quarrelled, and both children were glad to share their playthings. When Toots had the scarlet fever and was shut up in a room with his mamma and nurse, Elfie cried to have the fever too, so she could see him. It was summer time when Toots was sick, and sometimes when he was tired and restless he would moan so Elfie could hear him in the garden. One day when it was very warm and every one was tired and cross, Auntie bathed Elfie and put her on the bed, but she did not stay there long; she began to think of Toots—how warm he must be, how tired of the bed and that ugly dark room. Suddenly Elfie remembered that people used to bring her mamma pretty flowers when she was ill.

Perhaps she might carry Toots some flowers; her auntie was fast asleep and the nurse was out. Yes, she would go into the garden and get the prettiest flowers there for poor Toots. She had no shoes—auntie had put them away—and no stockings; but it would not matter; plenty of children never had shoes or stockings, and it could not hurt very much, for they could run.

Just then a low moan was heard and that decided Elfie; she sprang up and ran down stairs; no one was in sight but Touser, and he was such a good dog, he only lapped her bare feet with his tongue, so little Elfie went into the garden and began to gather flowers.

Presently she heard another moan from the sick-room, and she ran as fast as she could through the gate and up to the door. One of the servants was just coming out. "Why, little Elfie!" said she, "you will hurt those poor bare feet and you must not come here now, did any one send you?"

"No, I runned away,'coz I wanted Toots to have some flowers, and I wish I could have the fever too, and be sick with him."

"Poor child!" said the maid, "Master Toots shall have your flowers and he is better to-day, only the great heat makes him moan; wait here a bit until I send them up to his room and then I will take you home."

The flowers were carried to the sick-room and Toots smiled when they told him what his little friend said. "Tell her not to wish for the fever," he said, "for I feel as if I were on fire, and there is no cool place in the bed; but when I am well again we will play together at the fountain and keep our store as we used to." Elfie was very happy when she heard this message, and after that she sent flowers to the sick boy every day.

HEN Toots first went to the Kindergarten he met there a little boy whose name was Paul Brown. He was a very bright little fellow, but he could not talk as well as Toots; some of his words were cut short and it sounded very cunning, for Paul did his best and the Kindergarten teacher told the boys and girls that no one could do better than his best. One day a little baby sister came to Paul's house and this is the story he told his grandpa when the old gentleman came in to see the stranger:

"Fink I don't know what dat fing is,

All wrapped up in gwanma's lap?

I does; nurse told me so to-day,

It's my sisser tatin' a nap.

"She's only a piece of a day old now,

But she looks like any fing;

Wight out of her great eyes all boo,

An', ganpa, she can sing:

"There, don't you hear her, naughty dirl?

She skuled dat way—because

I feeled her foots, to see if 'em gowed

Like mine or pussy's claws.

"Sissers ain't nice to sing dat way,

And gwanma holds her snug;

I wouldn't cuy if her holded me,

All up in dat pwetty rug.

"Oh, yes, me knows, she's a sisser, she is,

An' I'm jess a boy, dat's all;

Sissers ain't dood for much, I fink,

Why, her couldn't hold my ball.

"Dess if I was made a piece of a day,

I would know some more dan dat;

No, ganpa, sissers ain't dood for much,

I'll do and find my cat."

WHEN Paul grew older and the little sister could go with him to school he changed his mind about her value. Sometimes, I am sorry to say, he led her into mischief, and once they were lost a whole day in the woods because Paul wanted to show her how the flowers grew and the trees sang, but after all the little girl made him a better boy as we shall see.

What's that you say? "She's only a girl?"

Well, so much the better for that;

Her eyes are the prettiest I ever saw,

Just peep at them under her hat.

She talks in the funniest broken way,

Just as I did once! Well, who cares?

I never could smile the way she does,

Or pit-a-pat on the stairs.

I wonder at girls, I do, Jim Pool,

Let me try as hard as I will,

To put my feet down easy and soft,

They will pound and thump down still.

And I never yet tried to close the door

As gentle as sister pan do,

That it doesn't go bang and shake the house,

"That's queer; it's just so with you."

Well, Jim, we are boys, only boys you see,

And apt to be noisy and rough;

But my little sister, she just teaches me,

One look of her eyes is enough.

I can't tell just why, but as true as you live,

I am better since she came here;

"She's only a girl!" Yes, I know, Jim Pool,

And I'm only a boy, that's clear.

My mother was once a girl like her,

And she's just as good as gold;

What's that? oh, nonsense, I know, Jim Pool,

My mother won't ever "grow old."

What's that? False hair and teeth for her?

Go home, Jim Pool, I won't play

With a boy who says my mother dear

Will ever be "ugly and gray."

But never mind, Jim, you ain't to blame,

You've no sister or mother, you see;

If mine grows ugly, and wrinkled, and lame,

She will still be mother to me.

AX was not one of Toots' "really truly friends," so Toots said, but mamma and cousin Hattie were kind to Max. He needed friends badly. He had no mother, and his father was a cruel, wicked man. One day when Toots and his mother were spending the day with cousin Hattie, the latter said, "I have some very bad news to tell you. Some wicked boy has torn down my little bird-house which papa put in the maple tree for me, and my dear little birds have gone away."

"How cruel!" said Toots.

"Who could climb over your high wall?" asked his mamma.

"I cannot guess," replied cousin Hattie, "but my roses are trampled, and papa says it must be a boy, as he measured the footsteps."

"You had better watch for the thief, and, perhaps, we can coax him to behave better in future." Miss Hattie and the servants watched in vain for a week, but one day while the ladies were reading in the library the servant knocked to say that a queer-looking boy had just slid down the fence, and perhaps he was the thief.

The ladies went out at once and found him. He looked ragged and neglected, but his face was a good one if it had only been clean and happy.

"I am sorry you climbed over that way," said cousin Hattie; "whenever you would like to see my garden you shall come in if you will ring the bell." The boy looked very much ashamed. "Please tell me your name."

"Max," was the brief reply.

"It is a very nice name," said cousin Hattie. "Now Max, if you will come with me into the kitchen I will find some lunch for you." Max followed her in, but he could not eat much; the cook looked at him sharply.

"I know him, miss," said she, "he is called Max the Meddler. He never lets a poor bird or cat have any rest where he is, and he is prying about everywhere. I am sure he took your bird-house."

Cousin Hattie said, "Never mind, cook; he will never do it again; perhaps he will earn a new name and a better one." After he had eaten his lunch the young lady took him out into the garden and told him the story of her birds—how much she loved them, how her papa put up their house, and how sorry she was to have them disturbed. Max looked more than ever ashamed. At last he said: "I will never do so again, lady, and if you will let me come and work in your garden I will pay you for the little house, which I sold to another boy."

ITTLE MAY is Toots' own cousin, and one of the dearest little girls you ever knew!

She is a tender-hearted child, and, like Toots, very fond of pets. Once on a cold winter day she found a poor little dead bird which the snow storm of the night before had killed. She brought it to cousin Toots, and together they buried it under a snowbank in the garden. One night during the "Happy Hour" May said "I wish you wrote some truly verses about me, dear auntie," and the very next night auntie did, and here they are:

In the early summer light,

Trampling down the red and white,

Eating clover, sweet and fair,

Happy child with floating hair;

Not a thought of injured hay.

That's our darling,

That's our May.

In the garret, on the stair,

Climbing haymows, everywhere;

Wearing glasses, teaching school,

Bringing dollies up by rule,

Working hard to call it play,

That's our darling,

That's our May.

In the parlor, on the floor,

Looking all the pictures o'er;

Making fun of grave old books,

Searching into sacred nooks—

Always cheerful, always gay.

That's our darling,

That's our May.

At the door, the first to see

Papa, as he comes to tea,

In his lap, with dancing eyes,

Searching pockets for a prize,

Asking "what you've done all day?"

That's our darling,

That's our May.

In the chamber just at night,

Nestled in her gown of white;

Eyelids closed on cheeks of red,

Kneeling by her little bed,

Lisping "teach me how to pray."

That's our darling,

That's our May.

Future woman, what maybe

Life with all its cares to thee?

Who shall say in after time,

Blessings on that head of thine?

Rich and good thy life we pray,

God's and ours,

Dear little May.

HEN Toots was four years old, his mamma thought she would let him have a birthday party. She wrote the invitations on the prettiest little paper, with funny frogs and dogs and cats in the corner, and each little envelope was made to match. Twenty-five pretty little notes to twenty-five dear little people, and every one came. No one else ever had such a party before. Large tables were covered with books and toys, all manner of games were waiting to be played, and in one corner of the children's play-room was a table with bowls, plates, and pipes, and all the children were invited to blow bubbles. Such fun as they had! Some blew large and some blew small, and those who laughed hard blew none at all. At last Toots and Robbie Mason began to see something in the soap bubble, "beautiful colors like the rainbow," said Toots.

"More of them," said Robbie, and then all the children began to wonder.

"What makes it?" asked Robbie, eagerly; "I wish I knew?"

"I will tell you," said mamma. "When a ray of light is divided, as it always is when it reaches an object on which to rest, it has different colors, because each color has different powers and is refracted or turned from its course. Let us cast a ray of light on this piece of glass called a prism; now examine it closely, here we have seven colors—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet The red is bent out of its course the least and it remains at the bottom; the blue is refracted most and goes to the top. Now blow a nice bubble, little Daisy, and I will explain the colors. You see the film is thicker in some places than in others, and that causes different powers of refraction or turning aside of the rays, and therefore, you observe different colors; as the soap bubble constantly changes its thickness, the rays vary or change also."

"There isn't any soap in the real rainbow in the clouds, is there?" asked thoughtful Robbie.

"Oh, no; when the clouds opposite the sun are dark and rain is still falling, the rays of the bright sun are divided by the rain drops as they would be here with my prism." #

After the children grew tired of bubbles they had many games and a nice supper, after which they went home saying it was the best party they ever went to.

LOSE by the window I saw her,

Only a bright young girl,

With a tear on her drooping lashes,

Half hid by a straying curl.

June sunshine was tempting her sorely,

The children were playing near by,

And still she sat with her sewing,

And the tear-drop in her eye.

At last in anger she muttered,

"So cruel, so hateful, and mean!

I lose all the brightness and beauty,

As I sit here sewing a seam.

"My thread grows tangled and dirty,

My needle is sure to stick fast,

And the girls are passing the window:

Please tell me that work-time has past."

Ah, Daisy, dear child, in the future,

As the shadows of life come and go,

You will find some duties as irksome

As the seam you are trying to sew.

Threads will knot, Daisy dear, and the needles

Will rust if you wet them with tears;

And seams will grow rough to your fingers,

When feeble and trembling with years.

Even brightness may pass like the sunshine,

Your life holding one little gleam;

But God is still watching my darling,

He knows we are sewing a seam.

Dear Grandma is wiser but cheerful,

She sits by the window to-day;

Where the sunlight is kissing her forehead,

And children are near her at play.

A smile in place of your tear-drop,

Grey locks where your golden are seen;

She says God's loved hath illumined

Her life, and made easy each seam.

She, too, can think of a summer day,

So sunny and bright in the past;

But her lips always say, "Father take me,

When play-time and work-time are past."

LL Toots' playmates among the boys and girls knew how very fond he was of his four-footed friends, and the children were very fond of watching him when he made his pets perform all sorts of tricks. Poor Toots was nearly ill one day when one of his pet cats was found dead in the stable. He cried and would not be comforted, but his mamma said that poor pussy had not been well for a long time, and she probably died in a fit. Not long after Pussy Meek's death, Toots was confined to his room with a bad cough, and his mamma went to a store to buy some cough drops which the doctor had ordered. When the old lady who kept the store heard that Toots was ill she said, "I wish I had something nice to send him; he is so polite and kind. Do you suppose he would like another kitten? We have three beauties now, and our cat mother is a fine old mouser."

"He would like it very much. I left him just now crying for his dear pet Pussy Meek."

"Dear little fellow!" said the old lady, "he shall have the very prettiest one we have."

Then she took a candy-box and made some holes in it and put the prettiest little kitty inside.

Toots was wild with pleasure; he sat up in bed and held her in his arms, then he fed her some warm milk, and at last she cuddled down with her little head peeping out of the bosom of his night-gown, and then she slept a long, long time. Toots was much troubled to find a pretty name for her. At last he said, "poor little Pussy, we cannot find a name good enough or sweet enough for you." His mamma said suppose we call her Psyche. This pleased Toots very much and the new kitty was duly named Pysche, and a nice ribbon was tied about her neck. For many days she lived in Toots' room and nestled close to him. As she grew older she grew wiser and very full of fun. All summer long she chased flies and grasshoppers, and when the children played ball, Pysche understood it all and took her place properly. She has two very cunning tricks—one was to never enter a door if she could make some one open a window to let her in, and the other was to hide away at bedtime and then come out to play when all the house was still. In the summer time Pysche went to the seaside with the family, where she was a great pet with the grown-up people as well as the children.

NLY a doll! I wouldn't cry,"

Said naughty, teasing Sandy;

"She's just a lot of rags and things

I'd rather have some candy."

But little sister cried and cried,

It was her "bestest" treasure;

While naughty Sandy tried and tried

To tease her for his pleasure.

"Don't cry, dear pet," the sister said,

"Some day he would be sorry

To have us treat his pretty boat

As he is treating Dolly."

"Only a doll," said he again,

"A boat is ten times better;

This thing can't sail; I'll go and see

If she can swim, I'll let her."

Oh, sister, make him div' her back;

He'll kill my darling pet;

Don't let him put her in the pond

And get her nice d'ess wet.

"You's very cruel, bruver, now-;

Please, div' her back to me;

'Tause she's my only darlin' child,

She sleeps upon my knee."

"Only a little, mean old doll,

Not worth my bat or ball;

Hark! take your baby; here comes pa;

I hear him in the hall."

"Teasing again? Ah! Sandy, lad,

Remember this, I pray:

Only a coward teases one

Too small to get away.

"Go to your room, my boy, and there

Think how this game would please,

If sister Nell should serve you so,

And always try to tease."

LOSSIE helps ever so much," said Toots, one day—"she dusts the chairs in her mother's room, waters the plants, and holds her auntie's worsted. Her auntie is knitting a new rug for the phaeton."

"Little hands should always help," said mamma, "they were made to be useful, and I know Flossie is happier when she is doing something to make home pleasant. One day I heard Flossie saying, "Oh dear! I wish I had something to do. I am tired of my dollies, I don't want to read, and there is no one here for me to play with." I said, "My dear little girl, your mamma has too much to do; she will give you something, and auntie will be glad to have you help her; those little hands must be kept busy every day." Soon after Flossie learned how to dust the chairs, then she picked the bits of thread from the carpet, then she gave the canary some food and water, and now she is making a dress for her dollie. In a few short months Flossie will learn to do a great many useful things and no one will hear her say, "I wish I had something to do."

"I always have enough to do," said Toots, "I cannot get time to read half the books I like, and then there are so many pets to take care of, beside the skating and sliding in winter, and the fun at the seaside in summer, and when I am at grandpa's he calls me 'a little worker.'"

Just then Flossie came running after Toots. "Would he go with her to buy some rolls for tea and take a book back to the library?"

Toots was very glad to go and carry some books for mamma, beside he must stop at the post-office for some stamps, and bring home a sheet of transparent paper to make some paper balloons for the children in the hospital. Such busy little people as they were! and how happy, too!

That night when Toots was fast asleep, his good mother said to his papa: "Children do more than we give them credit for; last week I kept an account of all the kind and useful things performed by our little boy, and it would surprise you to see how much it all amounts to. Beside the errands for me he has thought of others, and that is good for us all. I really think he has found more pleasure in mending old books and toys for sick children than in having them for himself, and Flossie is quite another little girl since she learned to help mamma."

E is lying on his pillows

All day, sweet Jamie Doon

His little back is crooked,

Yet he sings a merry tune.

For light of heart is Jamie,

Poor cripple though he be;

He is cheerful as the sunshine,

Or the birdies on the tree.

What makes you so contented,

My little Jamie boy?"

Asks a thoughtful lady, kindly,

When she carries him a toy.

I have so many blessings,"

Said gentle Jamie Doon,

I watch the flowers, and birdies

Oft sing for me a tune.

Then the children come to see me,

And every one is kind;

It might be worse you see, Miss,

If I were deaf and blind."

Ah, gentle little Jamie!

Count blessings day by day;

It might be worse, indeed, lad,

So smile and sing away.

Jamie had once been a very active boy and a good scholar, but his back was injured by a blow given him by a thoughtless playmate, and ever since he has been a great sufferer. It is a dreadful thing to injure any one for life, and boys cannot be too careful when playing with each other. I am sorry to say that the little boy who hurt Jamie does not seem to care for the terrible ruin he has wrought; perhaps he has not been taught at home to think kindly and tenderly of others.

FIVE little sparrows one sunny morn

Eating their breakfast out in the corn:

Five little boys, cruel as boys can be,

Longing to kill those birds blithe and free:

Five little stones that whizzed in the air,

And fell all at once where the sparrows were:

Five little sparrows that flew safe away

For sparrows are quicker than boys, any day:

Five little boys that looked quite forlorn

As they wandered on through the waving corn.

LIVER TWIST was the name of a fine rooster or gamecock which belonged to Toots' grandpa, and many were the stories told of him. He became quite famous in the family, and out of it, and none of the children wanted him killed or sold even if he grew too old to walk. When grandpa bought Oliver he carried him home between his knees in the carriage, while he drove Frisk, the pony. Toots' mamma sat by his side with a huge basket in her lap containing a fine old mother hen with ten little chicks. They were all going into grandpa's coop at the farm, and then he would take care of them for Toots.

"I suppose I have been very foolish to pay such a price for this fellow," said grandpa, "but he is smart enough to peck pretty hard."

All the way to the farm the new rooster made himself as disagreeable as he could, now biting grandpa's hands, and now his knees, until the dear old man wished he had never seen him. At last he was safe in the hen-house, where he soon began to eat, and, as he never seemed satisfied, he was called Oliver Twist.

"There has been an old fox about here stealing chicks," said the hired man, "but this Oliver will tackle him, I reckon."

The hired man was right. Only a few days after grandpa heard a great noise among the poultry, and there was a large fox trying to get into the chicken-yard from the barn. Grandpa stole softly into the house and got his gun. When he went back Oliver was pecking at the head and eyes of the fox with all his might. Oliver was very angry but did not show any signs of fear, while the fox tried in vain to get nearer. At last the old fox made up his mind to spring over and eat chicken for his lunch, but just then, bang! went grandpa's gun, and the sly enemy tumbled over on the barn floor.

When Oliver heard the gun he thought he was shot too, for he fell down and closed his eyes. When grandpa petted and praised him, and held out a dish of corn, he seemed to think better of it, and began to strut about, while all the hens cackled in chorus and seemed very proud of their defender.

Poor Oliver met with an accident during the cold winter weather; his beautiful red comb was frozen and fell off. He seemed so ashamed of it that he could not or would not hold up his head, but a nice new comb has grown now and he is as proud and lordly as ever. Indeed, only yesterday he was seen driving a strange cat out of the yard.

P at grandpa's farm the chicks were very happy since the old fox was killed, and as Toots wanted some more cunning little ones to play with and feed when he went up for a visit, grandpa decided to put some eggs under Mrs. White. Now, Mrs. White was a very fine hen, and although she had never raised any chicks of her own, she seemed so kind and gentle that grandpa was sure she would make a kind mother. He selected the eggs with great care, marking some very choice ones with a blue pencil. Mrs. White sat very quietly upon her nest for many days, until it was time for the little chicks to come out of their shell houses; then grandpa paid her a visit. Three little ones were already toddling about, and Mrs. White seemed to be in great distress concerning some others who were just trying to see what the world was made of. Grandpa helped the little fellows by picking away small bits of the shell, and then he hurried away to make some nice dough for them. When he returned, Mrs. White was nowhere to be seen, so grandpa covered the little new babies with some wool and then looked for the neglectful mother. He soon found her in the yard with Oliver Twist and a large flock of hens.

Grandpa caught her and carried her back, but Mrs. White hurt the little ones and refused to scratch for them. She covered them with her wings for a few moments while grandpa was there, and then ran away again.

Grandpa tried shutting her up, but still she hurt her little chicks and at last killed one. Then grandpa told her she was a cruel, wicked mother, and he carried the chicks into the kitchen and covered them over in a nice warm basket. There they nestled for several days until they began to hop out and get under grandma's feet. After that they had a little house in the shed and soon grew very fast. Toots called them the orphans, and never again liked Mrs. White, although she was so handsome. Soon after this grandpa put some eggs under a queer old hen which all the family called Mrs. Gummidge, she was so cross and queer. When her chicks came she was a very kind mother and scratched for them all day long. She was very proud of them, too, and seemed to say, "Did you ever see such little darlings?" Mrs. Gummidge went about with her children until they were large enough to take care of themselves, and then she sat quietly on some more eggs and raised another family, but none of them ever seemed quite so precious to Toots as the little neglected chicks of Mrs. White.

WO dear little girlies, born at the same time, with eyes, hair, and little faces so exactly alike that even their mother could not tell them apart; and when their pictures were taken and sent to Toots' papa, every one wondered which was Bud and which was Bunnie. The twins' papa was an old classmate of Toots' papa, and as soon as the baby girls came he wrote a very funny letter telling all about them. He said they were both like little rosebuds, and he was puzzled to know what to call them, so he simply nicknamed them Bud and Bunnie until the mamma could decide upon a name.

"They are dear little bits of womanhood," he said, when the children were three years old, "and I am ashamed to say that we still go on calling them by the old pet names. It would please you to see them at play, they are so very happy. Bunnie, who is a little more gentle than her sister, often gives up to her in their sports; and yet Bud is never cross. She takes the lead because she is fitted for it, while Bunnie nestles down and is content to do as she is told. They are into mischief every hour in the day—good-natured mischief of course. Sometimes we find them dressed in their mother's clothes, sometimes in my coats.

"Not long ago my wife and I determined to send a hamper of good things to her old nurse, who has been very unfortunate. We collected all our gifts and were about to pack them, when we chanced to think of a new prayer-book in large type, so away we went, to buy it, for she would not go without me and I would not know how to select without her. When we returned to the store-room where we were packing, what did we see but our twins, Bud and Bunnie, both seated in the hamper. They made such a charming picture that I sketched them on the spot."

Of course Toots' papa sent back a letter at once, and said they were the dearest little girlies in the world, and he wished he had some himself; but he was quite sure that his boys were just as good boys as ever grew, and he would send their pictures to prove it.

AISY DEAN is a little lass,

With rosy cheeks and eyes like glass;

When she sulks she is very queer,

When she smiles she is very dear;

Pretty and fair as a flower is she,

Busy and quick as a little bee.

Good or bad, do what she may,

We wash and dress her every day;

Comb her hair, and give her milk,

And dress her well with sash of silk.

With all her faults, we never have seen

A dearer girl than our Daisy Dean.

Daisy was much pleased with her little verses, "all her own," as she said, and I heard her whispering to her friend May that she would never sulk again if she could help it. Daisy has one serious fault: she never puts things in their places. One morning she could not find her hat anywhere, and her mamma made her go to school without it. Daisy cried and wanted to wear her best one, but her mamma said, "No; that would not teach her to remember." The girls were much amused when Daisy entered the dressing-room at school without any hat on.

"What have you done with it?" asked May.

"I don't know; it is lost somewhere."

"What a careless little girl! Why, I always hang mine up in one place when I go home from school or play," said May.

"So do I," said several of the girls, but some of the boys did not speak, and a little bird whispers to me that some of my kindest "little friends throw their caps down on the floor, table, lounge, chairs, or the first place they can find." Oh, oh, boys! this is too bad, for "order is heaven's first law."

COMMISSARY is one who furnishes supplies of food to an army or body of men, but I dare say you never heard of a dog commissary. He lived at the boarding-school where Toots' mamma went when a little girl, and his owner was the lady who kept the school. Her son brought him home one day and taught him many tricks. Every day he went to market for the family, and it was great fun for the younger girls to see "Captain Com" go out with his basket in his mouth. His errands were always faithfully done. No boy ever dared to meddle with Com, and although he went five blocks to market no one ever tried to get his note out of the basket. Every morning he waited until madam consulted with cook and wrote down the order, and then when it was put into his care he would trot away in a very happy frame of mind. "Com" was very good to the younger pupils. He would let them drive him in a little cart, or play tag with them by the hour. Once in the vacation, when nearly all the pupils had gone home, madam said: "We will not send an order to the butcher to-day; it is so warm, we will have a light lunch."

"Com" did not like this; he was very restless for a long time, and at last one of the children said, "I think Com has gone to market. He tried to get his basket from the nail and he could not; then he ran away."

"We will go out for a walk and see," said madam, "for 'Com' can do everything but talk, and he is greatly distressed because I did not order dinner."

When they reached the butcher's, there was "Com" with his paws on the cutting block, patiently waiting to be served.

"He deserves a nice dinner," said the butcher, and he gave him some meat; still "Com" was not satisfied; he wanted it put up in paper and laid in a basket before he would go away. "Com" never would touch a bit of meat until he went home to cook, with his marketing.

Where Com lived they did not have letter carriers or postmen, and his mistress made a little mail-bag for him which he carried to the office morning and night. He always entered by the back door, and the clerk would kindly wait upon him. Sometimes his bag would be full of letters and papers for the pupils, and then "Com" was very proud. Every night this wise dog guarded the house, and madam always felt quite happy about the younger children if "Com" was with them.

O wise person ever expects children to be perfect—grown people are not—still all can try to overcome their faults and grow wiser day by day.

Although little May was a very sweet child, as she grew older she began to fret about little things, and one day when she was urged to learn her lesson in arithmetic she said, "I wish I never had to see another old arithmetic; I hate them all!"

May's mother was very patient, and she had her own thoughts about punishing children. When her little daughter showed such ill-temper she said, quietly: "May dear, I am going out to do some errands; would you like to go?"

May was delighted; she would do any thing to get away from her hateful book. Their first visit was to a shop where fruit was sold, and then to a florist's where the lady bought some flowers.

"Now where shall we go, mamma?"

"You will see presently, my dear. We will take a car and make a call on a friend of mine."

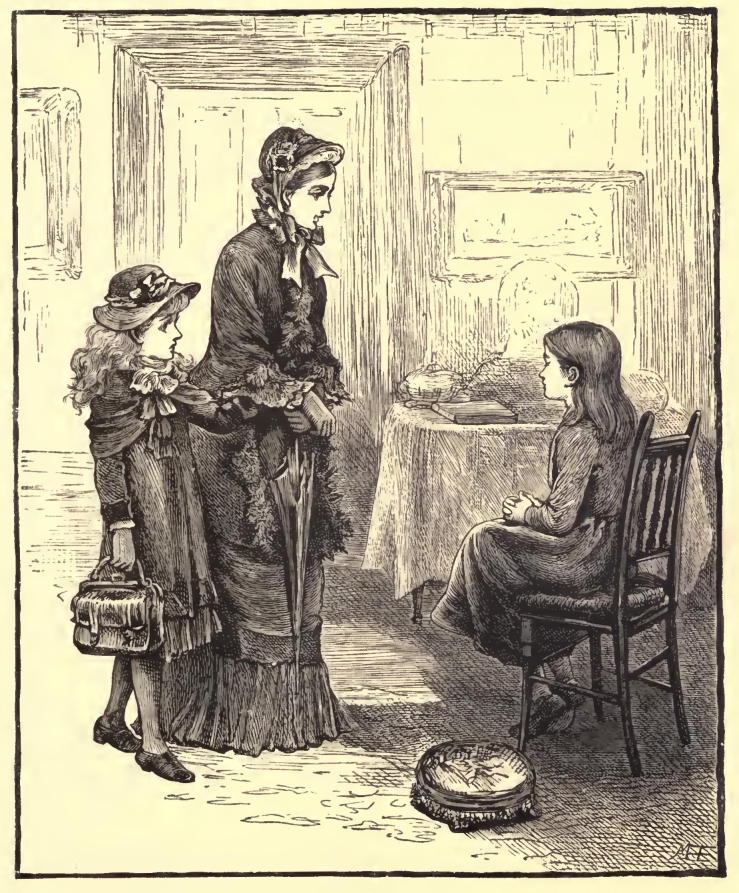

At last they got out and went up some steps, where a lad answered their ring at the door.

When they entered they saw a little girl seated on a chair with her hands folded. She was blind. She heard their footsteps and said, "Please be seated, ladies."

"How long have you been blind, dear?" asked May's mother.

"Four years, madam. I was very ill and have never seen the light since."

"You must remember many things which you saw before your illness?"

"Oh, yes; and it makes me very happy. I know just how the grass looks, and how blue the sky is, and when I am tired I think of it over and over."

After some more conversation the matron came in and gladly welcomed May and her mother. "I would like to show my little girl through the school," said the latter, and the matron kindly took them into various rooms. Not one of the children could see, yet all seemed happy and busy. Some were getting lessons, some were knitting, the boys in the work-room were putting new seats into chairs, and yet all were blind.

It was a sad sight to little May, and after she had left the flowers and fruit she went away looking quite thoughtful: Since that day she never complains when asked to get a lesson, and even her music is not tiresome when she thinks of blind Maggie.

HE'S only an orphan," mother dear,

"Her father and mother are dead;

She hasn't a home to shelter her,

Or a hat to cover her head.

"I found her crying alone in the street,

And nobody seemed to care;

I know she is hungry and tired now—

Please give her all of my share.

"I am glad we have tea in the garden to-night

For she wouldn't go into our home;

I could hardly coax her up here, papa,

She hasn't a friend, not one."

"Come in, little girl, sit down here and eat,

We have plenty of food and to spare;

You are tired, poor child. Go Harry, my love,

And get your young friend a chair.

"There, now you have eaten, pray tell us why

You wander alone in the street;

And why there is none to look after your clothes,

And keep you more tidy and neat?"

"My mother just died, and they took her away,

And our landlady said I must go;

And all of our things belonged to her,

To pay up the rent we owe.

"I went to the river to sit down and think,

For no one cared for me now;

I wanted to die like my own dear ma,

But I could not—I did not know how.

"This boy he spoke kindly, and led me away,

He said he would bring me to you;

I knows I am dirty, not fit to be seen,

But, lady, my story is true."

So they took her in, as Harry had said,

And they cared for her kindly and well—

The good they have done and the good they will do,

Only angels in heaven can tell.

NE day in the summer Toots sat on the doorstep talking with his little friend, Fred Haldon, when a man came up to the gate with a hand-organ and asked if he might come in.

"Oh, mamma! mamma!" called Toots, "come as soon as you can, for he has a monkey with him."

His mother looked out of the window and nodded to the man. "Yes, he could play if he wished." Then she went out on the doorstep with the children. The monkey came to her at once. It looked so tired and sad, she said, "Poor little fellow!" He seemed to understand her, for he sprang into her lap and rubbed his head against her hand.

"How tired he is!" she said kindly, "do let him rest while we feed him."

The monkey would not eat much, he seemed too weary, but he bowed his thanks and then put his head on her hand again. When the man stopped playing the lady told him he would lose his monkey if he did not let it rest.

The man laughed and sat down under a tree. This seemed to please the monkey, for he went to him and kissed him and then returned to his new friend, nestling down in her lap like a tired child.

"He has danced too much when it was warm," said the man in broken English.

"Then you must be very good and let him sleep." After a good rest the organ-grinder went away with him, and soon after Toots went with all the family to the sea-side, where the monkeys in the park made them think of their tired little visitor. Long, long after, when winter came and all the family were in town and all the aunts and cousins were invited to meet grandpa Bergland—little May's grandpa from over the sea, the door opened just in the very midst of the Christmas festival, and in walked Leno, all dressed in his best suit.

"Where is his master?" asked Toots, "bring him in and let him show us the old tricks."

So the master came in. He said, "the kind ladies and gentlemen must excuse him, but he could not make Leno pass the gate where the lady was so kind to him when he was sick."

"He was quite sick then, poor thing!" said Toots' mamma.

"He was very sick, dear lady. I took him away in the cool country, but he was like to die, and for many days I thought I must leave him there, for he could neither eat nor sleep, only look in my face and make a sad noise. I could not Leno die, for he is my only friend."

"There, mamma," said grandpa Bergland, "you was kind to the dumb brute and it did thank you."

MAN who took charge of the park was very kind to Toots and allowed him to feed the parrots, birds, and rabbits. The rabbit-house was a favorite place with the children. They never tired of watching them, and the family was so large that the good keeper who cared for them called the old rabbit "Mr. Smith."

"You see he has so many children, his name must be Smith," said he.

The children fed them grass and clover, and many of the little creatures had pet names, but it was impossible to name them all, for the family increased so fast. One morning when the gardener went into the park to look at some plants he had set out the day before, he found them all out of the ground and the earth thrown about in every direction. "Ah!" said he, "those puppies must be shut up; they did all this mischief last night; I heard them barking."

Then the gardener took the three puppies and shut them in a cellar, while he hurried his garden-making, in order to get more plants in place before the superintendent came that way. He was so anxious to get the plants cared for before the sun was hot that he quite neglected the other pets.

While he was hard at work Toots ran to him crying, "Oh, Mr. Snyder, they are all out, the whole of Mr. Smith's family, and there is a big hole dug down under their house."

Sure enough, the house was empty and the family nowhere to be seen. Toots and the boys found them at last hiding under some steps. After some trouble and much chasing about over the grounds they were put into their cage and the big hole was securely fastened.

Toots released the puppies and fed them well, while Mr. Smith's family seemed tired out with their travels and were glad to lie down and rest.

That evening while the family sat on the piazza watching the moonlight on the water, something ran up the steps and hid in one corner.

"It must be one of those ugly rats," said Aunt Bell.

"No, indeed, it is some poor hunted thing seeking refuge," said mamma. "Bring me a lamp, Bridget, and let us see."

The lamp was brought and there in one corner of the piazza was a poor, lonely little rabbit. He had strayed from the rest, and now when it was dark he sought shelter where he heard familiar voices.

HAT shall we do with baby,

The bright-eyed mischievous one?

He wakens us all in the morning,

Two hours before the sun.

From the time that his peepers open,

He pinches and pulls at our nose;

Or, perhaps, by way of diversion,

He gives us a taste of his toes.

We find him rattles and clothes-pins,

We give him books by the score,

And make him a house in the corner

When lo! he is at the door.

We pile up a basket of playthings,

And seat the rogue in a chair;

We leave to order the dinner,

Behold! no baby is there.

He has found his way to the closet,

He is rattling our chinaware;

We run—he is clasping a goblet,

And trying to climb a chair.

He is full of the funniest capers,

And scolds in the funniest way;

But never will own he is weary,

Or rest from his busy play.

He struggles and battles with slumber,

He scratches and picks at his eyes,

We fancy him quietly sleeping,

But baby is watching the flies.

We give him a seat at the table,

We make him a house of our chairs,

And while the coach is preparing,

The baby is tumbling down stairs.

The apples are thrown from the basket,

His milk is spilled on the floor;

Bread and butter sticks to the carpet,

And sugar sticks on the door.

We puzzle our brains to amuse him,

We bow to his lordly will;

But do what we may, the baby

Is never a moment still.

Oh, what shall we do with baby—

With his fun, and frolic, and fears?

He charms us all with his mischief,

And conquers us all with his tears.

T was a queer, very queer name, but the soldiers gave it to him, and when you hear how he conducted himself you will not wonder. Daddy Tough lived in a fort in the western country, and he belonged to the United States Government. On one side he had the letters "U. S." branded, in order to keep people from stealing him. The children in the fort all called those letters "Uncle Sam," and everything with that mark on it was said to belong to Uncle Sam, meaning the Government.

The children about the fort used to ride on his back in a sort of double saddle made of willow. One day the soldiers took him inside of a small gate in order to remove some ashes from a cellar. The cart was backed in and Daddy stood with his head just outside of the gate. He looked like a droll picture in a frame. There he stood winking his eyes and shaking his long ears. When the soldiers had the ashes all in the wagon they told Daddy to go on, but he would not move; then they coaxed him but he did not stir. His driver pelted and pulled, but Daddy winked and never moved a step.

"We must get him away somehow," said the soldiers, and at last they struck him. Daddy looked at them in the most reproachful manner, but he did not move an inch. For more than half an hour the poor soldiers tried to have him carry his burden away.

"We must be all cleared up before dress parade," said one.

"We must get him out of here somehow," said the other.

"Just think how the boys would laugh if they saw Daddy standing here winking while the colonel was issuing his orders at dress parade."

"It will never do," said the driver. "Come, Daddy, you must move on or you will disgrace the command."

Daddy looked knowing, but still stood firm. Other soldiers came and they tried, but Daddy would not yield even after hard whipping. Then the colonel came out and told them what to do, but Daddy winked at the colonel as if to say, "I like this place very much and I will not go even for you."

When all efforts had failed the colonel's wife said,

"Let me try; we cure horses of ill-temper by feeding them sugar."

"Nothing will cure Daddy," said her husband, "but you may try."

The lady brought out some sugar and gave Daddy a taste. He shook his ears and made a sort of grunt. Then she patted him and held it farther away and at last he marched after her out of the gate and ran so fast he upset part of the ashes. After that when Daddy grew sulky a little sugar would win him over.

OOTS had a brother much older than himself, and never were two boys better friends. Nothing pleased Toots more than stories of his brother's pranks when he was small. Then Toots' parents travelled nearly all the time, and their eldest boy saw a great deal of this busy world. All the soldiers in his father's regiment called him "Button Blue," for when they first saw him he wore little dresses with a good many buttons on them. After that he had a jacket and pants, or, as he called them, "Bocker-nickers." He was a droll little fellow, and always managed to twist words about. The soldiers were very fond of Button, and made him many presents. They taught him games of all kinds, and here we see him showing the major's little daughter how to play cat's cradle.

One day Button Blue was lost and all the camp was astir. The black man, whose duty it was to care for him, said he left him at the sutler's little store, and the sutler said he saw him playing with a dog near the flag-staff just before the general's door. The general was away on horseback and he had not taken the child, for some one had seen seen him riding away with one of his officers and their orderlies. The men were nearly wild over the lost boy, but Button's mother said she only feared his going to the river, and yet Button never went anywhere without permission. The dinner hour came and went, but no boy answered to the summons, and men were sent in different directions to find him. They had not returned when the general came up on horseback.

"We are in great trouble, sir," said the surgeon; "the colonel's boy is lost."

"Button, our little Button; it is impossible. Have you sent out men to search? Have you looked in all the men's quarters? Why, bless you, I kissed the little rogue good-bye the last thing before starting; we had a grand romp together. I will go myself to search for him." The general sprang off his horse and unlocked the door of the little house known as his headquarters. He threw his gloves on the table and said aloud in an anxious tone:

"Why, I love that rascal like one of my own. He must be somewhere about."

"We have searched everywhere, sir, and no trace can be found. Even the colonel is discouraged, but his mother will not give up. She says he will be found."

"Found! found! of course he will," replied the general. "Why, there isn't a man or boy that doesn't love Button."

"Here I am, General," piped a boy's voice; and there, just waking up from a sound sleep, was the boy who had slipped in as the general's servant locked the door, and then, tired with play, threw himself on a lounge behind a screen where his friend the general had often rested.

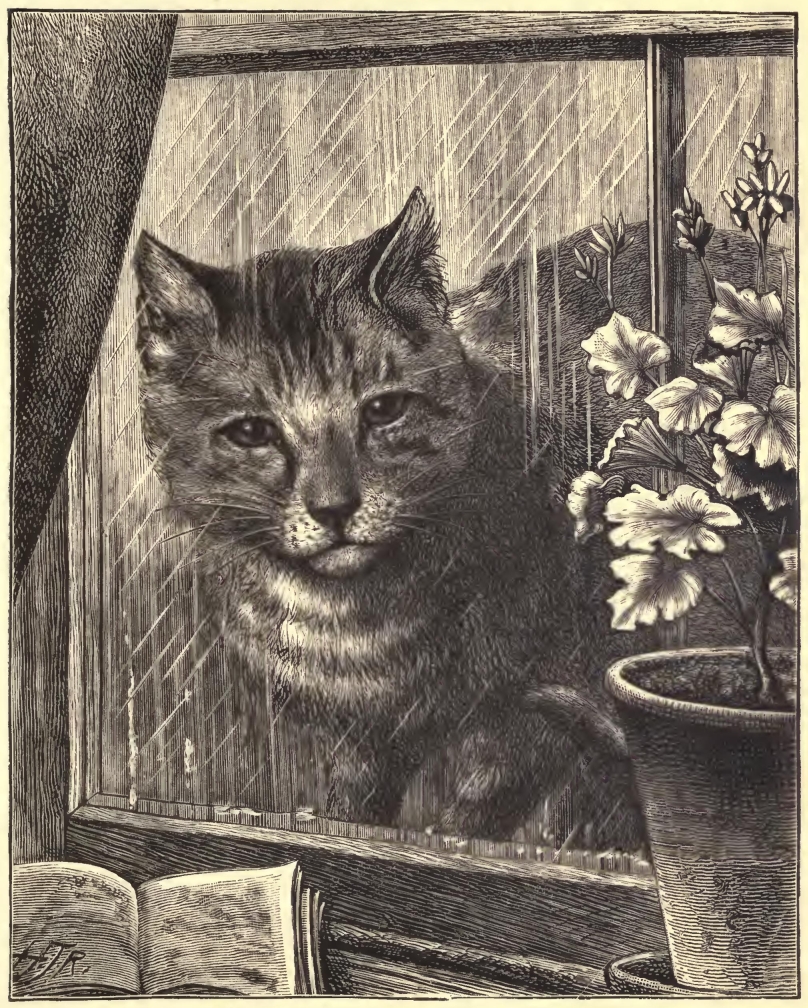

T was a dreary, rainy day, and Toots and his cousins were gathered in the library, where a cheerful open fire made them forget the chilling rain outside.

"Auntie," said May, "please tell me why you keep that pretty bird always sitting above your desk?"

"Toots has something to do with that. It is his bird, and perhaps you would like to hear about it; wait one moment until I get you a dish of fruit, and I will tell you how the pretty bird came here:

"One summer when Toots was quite small and not very strong, our family doctor said, 'Couldn't you go and camp out in the pine woods somewhere for a few weeks?' At first it seemed quite impossible to take all the family, but Button Blue was so active and helpful, and the cook said she would like the fun of it, so at last we went, taking care to be near a house where we could get pure water. We had two tents. One was our parlor by day and the boys' bedroom by night; the other held my bed and an easy camp cot for Toots. We were very cosey and happy. The birds sang over our heads all day, and at night we could hear the whip-poor-will's note only a few feet from our tent door."

"What did you do when it rained?" asked one of the boys.

"We drew the tent curtains close, made little ditches outside to carry off the water, and read, played games, or told stories. One day a party of gentlemen came to our camp. They were out hunting, and one of them had in his game bag a pretty cuckoo he had just killed. Poor Toots felt terribly when he saw it. Only the day before he had heard its pretty note, 'Cuckoo! cuckoo!' and we had told him that its name was given it because it made that peculiar song."

"I think he was wicked to shoot it," said Toots.

"We all felt very sorry," said his mother, "and I think the hunters did, too, for they promised to keep away from our camp and avoid shooting any of our pets. When they left us, they told Toots he would hear from them again, but we forgot all about it until one day a small box was brought to our house by the expressman. It was directed to Toots and marked 'with care.' On opening it we found our little friend the cuckoo handsomely stuffed and mounted on a branch. Toots was very much pleased and it has stood where it now is ever since it came."

"I wish he could fly once more, and say 'Cuckoo, cuckoo,' as he used to," said Toots.

KIND lady and dear friend of Toots and his mother owns a bright little dog named Benjamina. Its mother was blind and lame when the little puppy was born, and the good lady thought it was the child of the dog mother's old age; so she called it Benjamina, and a very cunning, wise little creature she is.

Benjamina likes to curl up on a sofa pillow and take life easy. Nearly every day she takes a walk with her mistress and frisks about here and there. Once when they were out walking, naughty Bennie ran too near the horse car and was kicked by one of the horses. She lay quite still for a moment, and all who saw her feared she was dead. Before any one could reach her, a large, strong dog who belonged to a neighbor sprang across the street and carried her to her mistress. Poor doggie had a bad cut in her side which the doctor sewed up, and it was so very sore that she could not lie down for many days. It was quite pitiful to see it walk around and around in a circle, trying to go to sleep. Old Major came every day to see her, and when he was allowed to come into the room he would sit down gravely and look at her. He evidently wanted to say, "I am very, very sorry for you and shall be glad to see you out again."

After a time poor Benjamina grew well enough to sit in a chair at the window, and Major would sit outside on the piazza and look at her. They really seemed to understand each other perfectly. If anything went wrong in the street Major would run down the steps and attend to it, and then come back to his station before the window. At last Bennie was taken out for a drive and Major ran all the way by the side of the carriage, barking with pleasure.

Once Bennie's mistress found a large bone put on her piazza, which Major had brought for his friend's breakfast, and great was the good fellow's delight when it was carried to Bennie.

Major went to church every Sunday and sat in the porch until his master came out; he tried very hard to go inside but was never allowed to do so. When the sexton went out to open the doors Major would shake himself and take his position on the steps. Once he came on Sunday and tried to coax Bennie out, but her mistress said no. When I last saw Bennie she was sitting in her mistress' lap while she wrote some letters. Major is still the same faithful friend and visits her every day.

OW happy the little people were at the seashore! There was so much to see and so much to do that the long days ran quickly away.

Toots and his friend learned many things. They caught hermit crabs, and were told how they stole shell houses to live in. They found star fish, and horse-shoe crabs, and beautiful sea anemones, and sometimes a kind old sailor would tell them about trawls, lobster traps, nets, and the queer tricks of the various fish they caught.

Away out on a point of rocks near the water lived some very bright little boys who often came to play with Toots. One day their parents were invited to visit a beautiful yacht lying in the harbor. The ladies and gentlemen were much pleased, and when they returned from their visit they told the children all about it. Two little boys, Philip and Harry, who lived in the cottage at the point, heard the story with much pleasure; so did Toots, who wished he could see it. One morning when the wind blew hard and the water was covered with white caps, Philip's mother missed both her little boys. "Perhaps they have gone over to Toots'," she said. Their sister inquired, but Toots was swinging in the hammock with another little friend. He had not seen Philip or Harry all the morning. Then the nurse and all the family began to look, but no boys could they find.

At last an old sailor said, "There's a little boat a-bob-bing up and down out there, and I think it has two little chaps in it."

The ladies took a glass, and there indeed were the two little rogues liable to be drowned at any moment; but two kind sailors went after them and brought them safe on shore.

"Where were you going?" asked their mamma.

"To visit the Tommodore's pretty water-house."

Both boys were very small and could not speak distinctly.

"But how strange! you were not invited," said their mother.

"Oh, yes, I 'vited 'Ilip and 'Ilip Vited me!"

"What would you have done if you had reached the yacht?"'

"I was going to 'duce 'Ilip to the Tommodore and 'Ilip was going to 'duce me."

"But you must not introduce people anywhere unless you are welcome yourself and invited. When the Commodore invites my little boys, I will take them out to his yacht and introduce them myself. Besides, the water is very rough and you are too young to row a boat so far."

"We could do it;'cause 'Ilip rowed one oar and I rowed the other. We like it."

Their mother was very glad to get them back again, and the good Commodore never knew what funny little guests he missed seeing that summer morning.

RAIN, plenty of grain,

Sang the birds in the harvest field;

Grain, plenty of grain;

H ow grandly it doth yield!

Grain, plenty of grain,

Eat, and chirp, and sing;

Come one and all to the harvest field,

Each with buoyant wing.

Grain, plenty of grain,

The reapers are out to-day;

And every bird from far and near,

Must sing a roundelay.

Grain, plenty of grain,

And not a farmer near;

Chirp, chirp, how glad are we,

To find this harvest here!

Over the top of the stack,

Down on the bundle bound;

Swoop and pick, and sing your songs;

Such a feast is seldom found.

Chirp, chirp, chirp,

Sing with all your might,

The glorious day will soon be done,

And the harvest ends to-night.

Grain, plenty of grain,

Eat your fill, my friends;

Let us gladly, cheerfully take,

The food the dear God sends.

"I think," said Toots, "that every song you read is the best one, and I wish birds could talk.

"They certainly talk to each other," said his mother, "and the robins in our apple-tree try very hard to answer me when I talk to them."

End of Project Gutenberg's Toots and his Friends, by Kate Tannatt Woods

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOOTS AND HIS FRIENDS ***

***** This file should be named 45388-h.htm or 45388-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/5/3/8/45388/

Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the