There are two footnotes, which have been moved to the end of the text and are linked for convenient reference.

Please see the transcriber’s notes at the end of this text for a more complete account of any other textual issues and their resolution.

“BROKE”

THE MAN WITHOUT THE DIME

BY

EDWIN A. BROWN

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

CHICAGO

BROWNE & HOWELL COMPANY

1913

COPYRIGHT, 1913

BY BROWNE & HOWELL COMPANY

Copyright in England

All rights reserved

PUBLISHED, NOVEMBER, 1913

THE · PLIMPTON · PRESS

NORWOOD · MASS · U·S·A

TO

THAT VAST ARMY, WHO, WITHOUT

ARMS OF BURNISHED STEEL, FIGHT

WITH BARE HANDS FOR EXISTENCE

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| Introductory | xi | |

| I | My Itinerary and Working Plan | 3 |

| II | The Welcome in the City Beautiful to its Builders | 8 |

| III | Chicago—A Landlord for Its Homeless Workers | 28 |

| IV | The Merciful Awakening of New York | 42 |

| V | Homeless—In the National Capital | 48 |

| VI | Little Pittsburg of the West and Its Great Wrong | 57 |

| VII | “Latter-Day Saints” Who Sin Against Society | 62 |

| VIII | Kansas City and Its Heavy Laden | 71 |

| IX | The New England “Conscience” | 82 |

| X | Philadelphia’s “Brotherly Love” | 95 |

| XI | Pittsburg and the Wolf | 104 |

| XII | Omaha and Her Homeless | 117 |

| XIII | San Francisco—The Mission, the Prison, and the Homeless | 123 |

| XIV | Experiences in Los Angeles | 136 |

| XV | In Portland | 144 |

| XVI | Tacoma | 160 |

| XVII | In Seattle | 164 |

| XVIII | Spokane | 172 |

| XIX | Minneapolis | 178 |

| XX | In the Great City of New York | 183 |

| XXI | New York State—The Open Fields | 197 |

| XXII | The Laborer the Farmer’s Greatest Asset | 207 |

| XXIII | Albany—In the Midst of the Fight | 218 |

| XXIV | Cleveland—The Crime of Neglect | 223 |

| XXV | Cincinnati—Necessity’s Brutal Chains | 244 |

| XXVI | Louisville and the South | 256 |

| XXVII | Memphis—A City’s Fault and a Nation’s Wrong | 279 |

| XXVIII | Houston—The Church and the City’s Sin Against Society | 288 |

| XXIX | San Antonio—Whose Very Name is Music | 296 |

| XXX | Milwaukee—Will the Philosophy of Socialism End Poverty? | 305 |

| XXXI | Toledo—The “Golden Rule” City | 310 |

| XXXII | Spotless Detroit | 314 |

| XXXIII | Conclusion | 318 |

| XXXIV | Visions | 328 |

| Appendix | 339 |

| The Author—As Himself and “Broke” | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| A half-frozen young outcast sleeping in a wagon-bed. He was beaten senseless by the police a few minutes after the picture was taken | 3 |

| A familiar scene in a Western city. The boy is “broke” but not willing to give up | 8 |

| A Municipal Lodging House. An average of seventy men slept each night in the brick ovens during the cold weather | 16 |

| At a Denver Employment Office. Many of these men slept in the brick ovens the night before | 24 |

| “Stepping up a little nearer to me he drew more closely his tattered rag of a coat” | 32 |

| Huddled on a stringer in zero weather | 32 |

| Just before Thanksgiving, 1911, leaving the Public Library, Chicago, after being ejected because of the clothes I wore | 40 |

| Municipal Lodging House, Department of Public Charities, New York City | 42 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Registering Applicants | 48 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Physicians’ Examination Room | 64 |

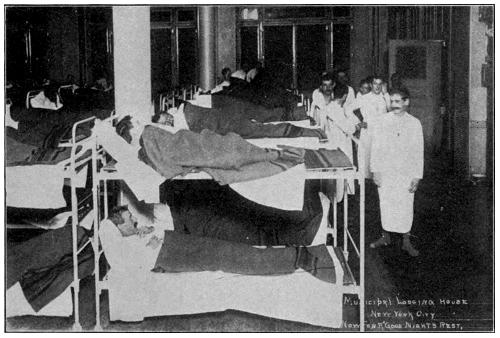

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: “Now for a good night’s rest” | 64 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Favorite Corner, Female Dormitory | 80 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Men’s Shower Baths | 96 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Female Showers and Wash Room | 96 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Men’s Dining Room | 112 |

| “The small dark door leads down under the sidewalk and saloon.” San Francisco Free Flop of Whosoever Will Mission | 128 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Women’s and Children’s Dining Room | 144 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Male Dormitory | 184 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Female Dormitory | 184 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Fumigating Chambers—loading up | 192 |

| Municipal Lodging House, New York City: Fumigating Chambers—sealed up | 192 |

| “I would have continued to ride on the top as less dangerous, if I had not been brutally forced on to the rods” | 268 |

| “I finally reached a point where I was hanging onto the corner of the car by my fingers and toes” | 268 |

| Riding a Standard Oil car | 272 |

| “After becoming almost helpless from numbness by coming in contact with the frozen steel shelf of the car I stood up and clung to the tank” | 272 |

| A sick and homeless boy with his dog on guard. He is sleeping on a bed of refuse thrown from a stable, with an old man lying near him | 288 |

| Waiting to crawl into a cellar for a free bed, unfed, unwashed. Fully clothed they spend the night on board bunks, crowded like animals | 320 |

I was born on the 28th day of April, 1857, in the village of Port Byron, Rock Island County, Illinois. The waves of the grand old Mississippi sang my lullaby through a long and joyful childhood. So near at hand was the stream that I learned to swim and skate almost before I was out of kilts. My father, A. J. Brown, at that time was the leading merchant and banker in the town. We were an exceedingly happy and prosperous family of six.

My father died when I was seven years of age. My mother, a woman of exceptionally brilliant intellect and lovable character, has been with or near me almost all my life. She died in 1909 at the ripe age of eighty-four.

When a boy in my teens I attended school in Boston, where I spent four years. In the early eighties I moved to Colorado and have lived there ever since. In 1897 I was married, and the intense interest and sympathy my wife has shown in my crusade for the homeless has been one of my greatest encouragements. With no children for company, it has meant a great sacrifice on her part, for it broke up our home and voluntarily separated us for nearly two years.

I have often wondered why I should have been the one to make this crusade, for all my life I have loved solitude, and have always been over-sensitive to the criticism and opinions of others. My mission is not based upon any personal virtue of goodness, but I have been inspired with the feeling that I had taken up a just and righteous cause, and the incentive of all my efforts has ever been that of compassion—not to question whether a hungry man has sinned against society, but to ask why he is not supplied with the necessities of existence.[A]

I am trying to solve these questions: Are our efforts to help the unfortunate through the medium of our “Charities,” our “Missions,” and our churches all failures? Why is crime rampant in our cities? Why are our hospitals, almshouses, our jails, and our prisons crowded to overflowing? And these questions have resolved themselves for me into one mighty problem: Why is there destitution at all,—why is there poverty and suffering amidst abundance and plenty?

I am convinced that poverty is not a part of the great Eternal plan. It is a cancerous growth that human conventions have created and maintained. I believe it was intended that every human being should have food and shelter. Therefore I have not only asked “Why?” but I have tried to find the remedy. My crusade has been constructive and not destructive.

My mission is not to censure but to disclose facts. I am without political or economic bias.

I shall ask my reader to go with me and see for himself the conditions existing in our great cities,—to view the plight of the homeless, penniless wayfarer, who, because of the shortsightedness of our municipalities, is denied his right to decent, wholesome food and to sanitary shelter for a night. And my concern is not only the homeless man, but the homeless woman, for there are many such who walk our streets, and often with helpless babes at their breasts and little children at their sides. And after my reader has comprehended the condition that I shall reveal to him, I shall ask him to enlist himself in the cause of a Twentieth Century Free Municipal Emergency Home in every city, that shall prove our claims to righteousness and enlightenment.

To-day there is everywhere a growing sense of and demand for political, social, and economic justice; there is a more general and definite aim to elevate the condition of the less fortunate of our fellow-citizens; there are united efforts of scientific investigators to discover and create a firm foundation for practical reforms. I am simply trying to show the way to one reform that is practical, feasible, and—since the test of everything is the dollar—good business.

If I can succeed in showing that old things are often old only because they are traditional; that in evolution of new things lies social salvation; that the “submerged tenth” is submerged because of ignorance and low wages; and that the community abounds in latent ability only awaiting the opportunity for development,—then this volume will have accomplished its purpose.

I am determined to create a systematic and popular sympathy for the great mass of unfortunate wage-earners, who are compelled by our system of social maladjustment to be without food, clothing, and shelter. I am determined our city governments shall recognize the necessity for relief.

Let me not be misunderstood as handing out a bone, for an oppressive system. “It is more Godly to prevent than to cure.”

In these pages I shall undertake to show by many actual cases that the so-called “hobo,” “bum,” “tramp,” “vagrant,” “floater,” “vagabond,” “idler,” “shirker,” “mendicant,”—all of which terms are applied indiscriminately to the temporarily out-of-work man,—the wandering citizen in general, and even many so-called criminals, are not what they are by choice any more than you or I are what we are socially, politically, and economically, from choice.

I shall call attention to the nature and immensity of the problem of the unemployed and the wandering wage-earner, as such problem confronts and affects every municipality.

We find the migratory wage-earner, the wandering citizen, at certain seasons traveling in large numbers to and from industrial centers in search of work. Most of these wandering wage-earners have exhausted their resources when they arrive at their destination, and are penniless—“broke.” Because of the lack of the price to obtain a night’s lodging, or food, or clothing, they are compelled to shift as best they may, and some are forced to beg, and others to steal.

For the protection and good morals of society in general, for the safety of property, it is necessary that every municipality maintain its own Municipal Emergency Home, in which the migratory worker, the wandering citizen, can obtain pure and wholesome food to strengthen his body, enliven his spirit, and imbue him with new energy for the next day’s task in his hunt for work. It is necessary that in such Municipal Emergency Home the wanderer shall receive not only food and shelter, but it is of vital importance that he shall be enabled to put himself into presentable condition before leaving.

The purpose of each Municipal Emergency Home, as advocated in this volume, is to remove all excuse for beggary and other petty misdemeanors that follow in the wake of the homeless man. The Twentieth Century Municipal Emergency Home must afford such food and lodging as to restore the health and courage and self-respect of every needy applicant, free medical service, advice, moral and legal, and help to employment; clothing, given whenever necessary, loaned when the applicant needs only to have his own washed; and free transportation to destination wherever employment is offered. The public will then be thoroughly protected. The homeless man will be kept clean, healthy, and free from mental and physical suffering. The naturally honest but weak man will not be driven into crime. Suffering and want, crime and poverty will be reduced to a minimum.

In looking over the field of social betterment, we find that America is far behind the rest of the civilized world in recognizing the problems of modern social adjustment. We find that England, Germany, Austria, France, Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, and other nations have progressed wonderfully in their system of protecting their wandering citizens. All these nations have provided their wage earners with old-age pensions, out-of-work funds, labor colonies, insurance against sickness, labor exchanges, and municipal lodging houses.

Because of the manifest tendency to extend the political activities of society and government to the point where every citizen is provided by law with what is actually necessary to maintain existence, I advocate a divorce between religious, private, and public charities, and sincerely believe that it is the duty of the community, and of society as a whole, to administer to the needs of its less fortunate fellow-citizens. Experience with the various charitable activities of the city, State, and nation, has proven conclusively to me that every endeavor to ameliorate existing conditions ought to be, and rightly is, a governmental function, just as any other department in government, such as police, health, etc. The individual cannot respect society and its laws, if society does not in return respect and recognize the emergency needs of its less fortunate individuals. Popular opinion, sentiment, prejudice, and even superstitions, are often influential in maintaining the present-day hypocritical custom of indiscriminate alms giving, which makes possible our deplorable system of street mendicancy.

The object of the personal investigation and experiences presented in this volume is to lay down principles and rules for the guidance and conduct of the institution which it advocates.

The reader has a right to ask: How does this array of facts show to us the way to a more economical use of private and public gifts to the needy? Are there any basic rules which will help to solve the problem of mitigating the economic worth of the temporary dependent? I shall give ample answers to these queries.

In the hope that the facts here presented may bring to my reader a sense of the great work waiting to be done, and may move him to become an individual influence in the movement for building and conducting Twentieth Century Municipal Emergency Homes throughout our land, I offer this volume in a spirit of good-will and civic fellowship.

E. A. B.

Denver, September, 1913.

“Broke”

“The heart discovers and reveals a social wrong, and then demands that reason step in and solve the problem.”

It was in the Winter of 1908–9 that a voice in the night prompted me to take the initiative for the relief of a great social wrong—to start on what to me was a great constructive social reform.

As mysterious as life itself was the following of that voice for three years. I realized fully the importance of actually putting myself in the place of the penniless man to gain the knowledge and fully grasp all that life meant to him. It came clearly to me that the shaking of hands through prison bars, and the regulation charity inquisition and investigation was idle and useless. Overcoming a sensitive dread of being looked upon as an eccentric poseur, I purchased a workingman’s suit of blue jeans, coarse shoes, and slouch hat, costing about four dollars, and became a voluntary wandering student in the haunts of the homeless and penniless.

I did not intend at first to investigate further than my own home city, Denver, but the demand reaching out, I felt compelled in the months of February and March, 1909, to visit Chicago, New York, and Washington. My visit to those cities being made exceedingly prominent by the Associated Press I received on my return home over one thousand letters from all parts of the country, and not a few from the Old World. I awakened to the fact that my plea for a Municipal Emergency Home for the city of Denver had become a national—yes, a world wide—issue. Many of these letters,—from the North, the East, the South and the West,—bore invitations to come and investigate the condition of the homeless among them. With such appeals I could not throw off the responsibilities which I had assumed, in trying to make the world a little better for having lived in it.

As the importance of my project grew upon me, my first thought was to obtain aid from influential institutions or individuals as a speedy way of realizing my dreams; but on second thought I realized fully that that was not in accord with my plan, for my institution was to be a governmental institution, and was to be created and maintained through that paternal medium. However, as an investigator I determined to test the heads of the great foundations, and the mighty masters of finance, to feel their attitude toward unemployment and governmental ownership and agencies for the betterment of social conditions. There were many champions of the crusade against tuberculosis and the white slave traffic, educational promoters, but the homeless, exposed, suffering, and penniless man or woman, boy or girl, standing ready to be employed, found no recognition nor were considered in their well-intentioned schemes. They could not see, or would not see, beyond their own useless, wasted efforts in meeting our problem of destitution.

My plan was brought to the notice of the Interstate Commerce Commission, which recognized my work as coming within the bounds of the law to the extent of granting me free railroad transportation, but left it optional with the railroads to give it or not. In my demands the New York Central absolutely ignored my request. The Pennsylvania—with smooth abuse—slapped me on the back and wished me good luck and God-speed, but could not think of carrying me for nothing. The Gould and Harriman lines were always generous, and a number of other roads occasionally.

It was a one-man, shoulder-to-shoulder battle. I carried no credentials. My plan of procedure was to go first to the leading hotel of each city I visited, because, after my investigations, I wanted to meet the leading people of that city. Arriving at my hotel I would don my emblems of honest toil—the blue jeans—and would make my study of the status of the homeless workingman of that particular city,—a study which held a message, and a message which usually startled the city. If an extended study, I usually lived at a workingman’s neat boarding or lodging house, where one in workingman’s clothes could walk in and out without comment. Armed with the array of facts I had collected, carrying my appeal for the Emergency Home, I would meet the various progressive civic societies of the city, and as far as possible leave something tangible in the minds of the members of “emergency home committees.” This plan I always carried out to the letter except, as described in my narrative, in my Hudson River study and in Cleveland, as well as my study from Cleveland to Memphis, Tenn.

Yet after all, while I might enter in the life of the penniless and endure temporarily their privations, I could only assume on my part for I knew that at a moment’s notice, in case of accident or sickness, by revealing my identity every care and comfort would be given me. Consequently I was free from that mental suffering which is even greater than the physical suffering only those can understand who toil alone, homeless, penniless, and friendless in the world.

After my first visit to Chicago, New York, and Washington in 1909, I made a visit in the same year to Pueblo, Kansas City, Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Omaha, and Salt Lake City; and in the Winter of 1910, I visited San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Tacoma, Seattle, Spokane, and Minneapolis. This was followed by investigations through the South, which really ended my crusade in the Spring of 1911, although I made a brief study of conditions in Milwaukee, Toledo, and Detroit during the following Winter of 1911–12.

“And the gates of the city shall not be shut at all by day: for there shall be no night there.”—Rev. 21:25.

On a bitter winter night, when the very air seemed congealed into piercing needles, as I was hurrying down Seventeenth Street in the City of Denver—the City Beautiful, the City of Lights and Wealth,—a young man about eighteen years of age stopped me, and asked in a rather hesitating manner for the price of a meal. At a glance I took in his desperate condition. His shoes gaped at the toes and were run down at the heels; his old suit of clothes was full of chinks soiled and threadbare, frazzled at ankle and wrist; his faded blue shirt was open at the neck, where a button was missing, and where the pin had slipped out that had supplied its place. His face and throat were fair, and he was straight and sound in body and limb.

“You look strong and well,” I said to him, “why must you beg? Can’t you work for what you eat? I have to.”

His big, honest eyes took on a dull, desperate stare, as though all hope was crushed.

“This is the first time I have ever asked something for nothing,” he said, “and I don’t like to do it now, but I have been in Denver two days and I can’t find a job. I am hungry.” The last words trembled and he turned as though about to leave me. I stopped him.

“Wait a moment; I did not intend to turn you down. I am hungry myself; let us go across the street to the restaurant and get our dinner.”

I had made up my mind to study this strong, able-bodied boy, who was workless, homeless, penniless, and suffering in our city beautiful, which is famous for its spirit of Western hospitality and even displays it as soon as you enter its gate by a great sign, “Welcome.”

As we sat at the table he told me that his home was on a farm back East, that he and his stepmother didn’t get along very well, that his own mother died when he was ten years old and his stepmother had not been kind to him, but that he and dad were always great friends and had continued so up to the time he went away.

“I promised myself,” he continued, as his hunger was appeased, “that as soon as I was old enough I would go West. I thought there were great chances for a young fellow like me out here, and so I worked and beat my way, and here I am to-day without a cent in my pocket. I have five dollars to my credit in the bank back in the old town near our farm, and if I knew anybody here I could get that money, pay my employment-office and shipment fee, go down to some works in Nebraska, and be at a job to-morrow,” and he looked down in deep dejection.

“Well my lad,” I said, “cheer up; all life is before you. Meet me to-morrow and we will see what can be done.” On the following day I took him to my bank, signed a bit of paper, and the banker gave him the five dollars. As we left the bank and started down the street, he took an old brass watch out of his pocket and offered it to me.

“I want to give you something to show my appreciation of your kindness to me,” he said. “Here is a watch the pawnshop man wouldn’t give me anything on, but it keeps good time, and you are welcome to it if you will take it.”

“No, I will not take it; you will need it when you get down on the works,” I said. “Where did you sleep the night before I met you?” His face flushed and he hung his head. “Was it not in the city jail?”

“Yes, and it was the first time I was ever in a jail in my life.”

I did not question him further, but to-day I can not quite understand why he was not detained there the usual thirty days for the unforgivable crime of being homeless, as that was the way Denver had of treating her destitute visitors.

Then he looked up with the true spirit of conquest in his eyes. “I’ll tell you what I am going to do the first thing; I am going to get a clean, new suit of underclothing, then I am going to take a bath, and then get my shipment.”

“Come on, my boy,” I replied, and took him to a cheap store to buy his clean underwear. Afterward we went into a barber shop where he took his bath. Denver did not then have its public bath—the beautiful public bath later built through the efforts of the Denver Woman’s Club. I waited to go with him to the employment office to get his shipment. When this was accomplished, we shook hands in a good-bye, and I wished him God-speed.

Two weeks later I received a letter in which he said: “I have a place to work here on a farm at big wages, with one of the best men in the world, and I am going to stay and work and save my money to help dad back on the old farm to pay off the mortgage. It is nearly paid off now and the farm will be mine some day.”

After that incident I was haunted. The picture of that boy freezing and starving so far from home was constantly with me, and yet, I thought, how much more pitifully helpless a woman or girl placed in the same position. I fell to wondering about the many other boys and men and women who were homeless, and of what becomes of the homeless unemployed in our city. I knew I was not alone in this incidental help I had begun; there were hundreds of men and women helping cases just like this case of my boy. And thus I set out on my crusade.

Taking my initiative step into the forced resorts of the homeless of Denver, I one night drifted into one of the big beer dumps where they sell drinks at five cents a glass which costs a dollar a barrel to manufacture. Many men were in the place seeking shelter and a snack from the free lunch counter. Twenty-five stood at the bar drinking enormous schooners of chemicals and water under the name of beer containing just enough cheap alcohol to momentarily dull and lighten care. Not a few were drinking hot, strong drinks, which more quickly glazed the eye, confused the brain, and loosened the tongue. A few had already crept into the stifling odors of the dark rear rooms and had dropped down in the shadowed corners with the hope of being allowed to spend the night there. These rooms in earlier days had been “wine-rooms,” where the more “polite” and prosperous had gathered, but who took the “wine-room” with them further up town as the city grew.

Among the many gathered around the big warm stove was a man whose appearance told too plainly that the world was not dealing kindly with him. Stepping up to him I said in a tentative way, “Have a drink?”

I then asked, “Can you tell a fellow who is broke where he can get a free bed?”

He looked at me with an amused smile. “You are up against it, too, are you, Jack? Well, I am broke, too, and the only free bed I know of is the kind I am sleeping in, and that’s an oven at the brick yards. A lot of us boys go out there during these slack times.”

“An oven at the brick yards!” I said in astonishment. “How do you get there?”

“Well, you go out Larimer Street to Twenty-third, then you turn out Twenty-third and cross Twenty-third Street viaduct. It’s about two miles. You’ll know the kilns when you come to them; you can’t miss them. But don’t go before eleven o’clock; the ovens are not cool enough before that time.”

“To-night I sleep in an oven at the brick yards,” I said to myself, with cast-iron determination.

It was a very cold night, but at eleven o’clock I started out Larimer Street to find my free bed. Having crossed the Twenty-third Street viaduct I was lost in darkness; there were no lights save in the far distance. I stumbled along over the frozen ground, fearing at any moment an attack, for Denver is not free from hold-ups. I could hear men’s voices, but could see nothing. It was not a pleasure-outing except as the thrill caused by the swift approach of the unknown may be pleasurably exciting. Finally the lights of the brick yard shone upon me with its great, long rows of flaming kilns. I had arrived at my novel dormitory. Stepping up to a stoker at work near the entrance, I asked:

“Can you show a fellow where he can find a place to lie down out of the cold?”

He raised his head and looked at me, and said, “I’ll show you a place.” Leaning his shovel against the kiln, and picking up his lantern, he said, “Come with me.” He paused at a kiln. “Some of the boys are sleeping in here to-night.” I followed as he entered the low, narrow opening of a kiln and raised his light. We were in a round oven or kiln about forty feet in circumference. By the light of his lifted lantern I counted thirty men.

“There are about seventy sleeping in the empty kilns to-night; I think you will find a place to lie down there,” he said, as he pointed to a place between two men.

I at once lay down, and with a “Good-night” he left me to the darkness and to the company of those homeless sleepers, who, in all our great city, could find no other refuge from death.

The kiln was so desperately hot that I could not sleep, and habit had not inured me to that kind of bed. Had I been half-starved, weak, and exhausted, as were most of my companions, I, too, could have slept, and perhaps would have wanted to sleep on forever. No one spoke to me. I endured the night by going at intervals to the kiln’s opening for fresh air. It was then when I looked up into the deep, dark, frozen sky, that I thought what a vast difference there is in being a destitute man from choice and a destitute man from necessity. At four o’clock the time for a fresh firing of the kilns, we were driven from the great heat of that place out into the bitter cold of the winter morning. Very few of the men had any kind of extra coat, but, thinly clad as they were, they must walk the streets until six o’clock, waiting for the saloons or some other public places to be opened. Their suffering was pitiful. I afterward learned that many of these men, from this exposure, contracted pneumonia, and from this and many other exposures filled to overflowing the hospitals of the city.

During the entire week I followed up my investigations. I found men sleeping in almost unthinkable places; in the sand-houses and the round-houses of the railroad companies, when they had touched the heart of the watchman.

I asked one of the railway men why the companies drove them away from this bit of comfort and shelter.

“Because they steal,” was his reply.

“What do they steal?” I asked.

“Oh, the supper pail of the man who comes to work all night, an old sack worth a nickel, a piece of brass or iron, or part of the equipment from a Pullman car, or anything they can sell for enough to buy a meal, or a bed, or a drink.”

“Do they steal those little things because they are hungry?” I questioned.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said with a shrug. “They are often so successful in not being detected, I expect that has made them bold. Some may have been hungry,” he said, after a thoughtful pause. “Work has been scarce and hard to find, you know.”

“Yes,” I replied, “they have, no doubt, tramped the streets for many a day, footsore, dirty, ragged, and penniless and worst of all, discouraged and desperate. They must have clothing and food as well as a place to sleep. Without this they must suffer and die. They are haunted by this fear of death, knowing well what hunger and exposure means and the utter impossibility of securing work with their ragged appearance.”

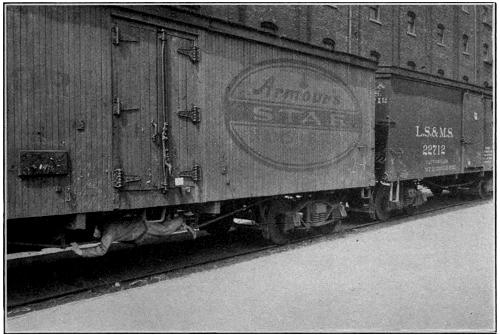

“Yes, I know,” said the man, patiently listening to my growing realization of their desperation. “When they become bolder and break into a freight car to steal something, if not of much real value, or something to eat, they are usually caught and thrown into jail. But they can’t stop to think of that, I suppose; the poor devils have got to live. You mustn’t give me away,” he added confidentially, “but I know a special agent for a big railroad company who made a boast of the number of men he had sent to the reformatory and put in the penitentiary the past year.”

I slept, or rather endured, the next night, with thirteen men who were sleeping in a box car on a bed of straw. Some were smoking. Is it any wonder that many thousands of dollars’ worth of property are destroyed by fire in one night? I found men asleep in vacant houses with old rags and paper for beds. They also smoked, and endangered not only this house but the entire city; besides, they often robbed the house of everything available, to satisfy their hunger. I found them sleeping in the loft of barns, the only covering the hay under which they crawled. I found them under platforms of warehouses with pieces of dirty old gunnysacks, or a piece of old canvas for a covering. I found them curled down in the tower of the switchmen, in empty cellars, in vat-rooms in breweries, in hallways, driven from one to the other, and some “carrying the banner”—walking the streets all night. I found them in the rear-ways of saloons, on and beneath their tables, and last, but not least, in that damnable, iniquitous hole, the bull-pen in the city jail.

A few short years ago—the date and name is of no moment—a young man eighteen years of age was shot to death by a policeman in Denver. I went to the morgue and looked on the white, silent face of the murdered boy. His mother wired, “Can’t come to bury him; too poor.” And so he was laid in a pauper’s grave; no, not a pauper’s grave, but a criminal’s.

I have noticed in my investigations in all the police systems of our various municipalities—I exempt none—that where someone has been murdered, or a sick man has been thrown into jail and his life taken there, or some other outrage has been committed by their wicked policies, they always try to blanket the wrong by making a public statement that the victim had “a record” and was well known to the police.

According to the newspapers, this young man’s diary showed that he had been in the State seventy-four days and out of the seventy-four days he had worked sixty-four; but—convincing proof of his outlawry—they found on him a match-safe that a man declared had been stolen from him. As I looked on that dead boy’s face I seemed to read, above all else, kindness. Had he been kind to someone; in return, had this match-safe been given to him? Hundreds of times have I seen these tokens of appreciation given: match-safes, knives, and even clothes from one out-of-work man to another—even an old brass watch that the pawnshop man considered of no value. The match-safe may have been given to this young fellow by a hardened criminal with whom circumstances had forced him to associate.

“He ran from the officer.” If you, my reader, had ever been forced, as a lodger or a suspect, to spend a night in a western city jail, you would take the chances of getting away by running rather than face that ordeal again.

I was so deeply impressed by the injustice of this legal murder that, under a nom de plume, I wrote a letter of defense for the boy to his mother, a copy of which I sent to the press. It reached the governing powers of the city, but not the public. Almost immediately the officer was arrested, tried,—and acquitted.

After my investigations in Denver had revealed such startling conditions of those who must toil and suffer, my first impulse was to fly to the Church. I thought I had reason to believe the Church stood for compassion, mercy, and pity. I approached, therefore, several of our leading clergymen. My first appeal was to the pastor of the Christian Church, and his reply was:

“My friend, if you succeed in getting a free Municipal Emergency Home for Denver, you will build a monument for yourself.”

To this I answered: “I have no desire to build a monument; I want our city to build a shelter for those who may be temporarily destitute among us.”

Another, a Baptist, asked if it were Christian. I turned from this reverend gentleman with the belief that in his study of the Scriptures he had omitted the thirteenth chapter of First Corinthians, in which, I believe, the substitution of the word love for charity is conceded correct by the highest authority.

To another, a Methodist, I said, “Won’t you speak a word to your people that an interest may be aroused to relieve the hardships of those who toil, who happen to be without money, and have no place to rest?” With a forced expression, he replied, “I don’t believe in the homeless and out-of-work. I have found them undeserving and dishonest.” I could only ask what our Savior meant by “the least of these,” and reminded him that the last words Christ spoke before His crucifixion were to a thief.

I then made my way to the home of the Presbyterian pastor of the largest and most influential church in the city. I did not succeed in seeing the leader of this ecclesiastical society, but as I passed, I could look into the basement of the brightly lighted church, and I saw approximately fifty Japanese being taught—aliens who did not want our religion, but did want our language and modern ideas.

Going to the president of the Ministerial Alliance, I asked to be heard, but they had no time to listen. I then went to the Y. M. C. A. and the president said, “You can’t expect every fellow to throw up his hat for your concern.” Paradoxical as it may seem, the only three societies whom I asked for aid, who turned me down, were the Ministerial Alliance, the Bartenders’ Union, and the Y. M. C. A. Later, the Women’s Clubs, Labor Councils, and the Medical Societies were my warmest friends.

I then went to those in authority in the administration of our city, and among the many objections raised to my plea, the first was there were other things that needed attention more. For instance, there were overcrowded hospitals, which must be enlarged. The sick, I was told, were lying on the floors, and several children were being placed in one bed, just as they are doing in Chicago to-day.

Then it was declared we would pauperize the people; we would encourage idleness instead of thrift. My investigations had taught me how useless it is to talk ethics to a man with an empty stomach. The Municipal Emergency Home I believed would encourage thrift instead of idleness.

And then our chief executive declared that something effectual should be done to keep out of our State the army of consumptives who come to Colorado. I could hardly see how that would be quite just or right. But I could see, I thought, how the Municipal Emergency Home, rightly built and conducted, with its sanitary measures would be a mighty influence in our combat against the great white plague. Then the all-powerful declared the city could not afford it—the old cry of every city administration, where the political boss and machine politics rule, when it comes to creating an institution that is not in tune with their policies.

Being abruptly asked what I knew about Municipal Emergency Homes, I was forced to confess that I had no knowledge whatever. I realized the need of information. I did not even know there was in existence on this whole earth of ours such an institution as I was asking Denver to build.

I have been greatly misunderstood in regard to the class and character of the destitute for whom I am asking favor. That I can now clearly explain, for what I found true in Denver in a small way I found true in every other city I visited. I classify them in two groups,—the unfortunate and the itinerant worker. Ninety per cent., taken as a whole throughout our country, are of the latter. The former and smaller percentage are chained by habits of vice, which our social system has forced upon them, or are physically weak, made so, many of them, in our prisons. And while, first, my plea is for the upright wage-earner, I am broad enough to feel that if we have been criminally thoughtless and negligent enough to allow social evils to exist and make derelicts and dependents, we certainly ought to be honest enough to stand the consequences and give them at least a place of shelter.

But the 4,000,000 homeless, honest toilers with us to-day affect the welfare of every home in our nation. They are an important force and factor in society. A moment’s reflection will show us quickly hundreds of good reasons why many of them at times should be moneyless and shelterless. As I throw back the curtain on these stories of human interest, I trust we may all of us catch forcibly the evident need of not sitting idly by, supinely asking a good God to help us, but rather of letting our petition in word and act be a living prayer in helping Him.

The boy whom I met on our Denver street, whose condition I have described, can justly go to the Lord and complain, as well as proclaim to the world, that the City Beautiful held no welcome for him while in need of life’s direst necessities. It is not to be wondered at that the so-called Christian people of the City and County of Denver have forgotten that it is not enough to have a twenty-five thousand dollar Welcome Arch of myriads of sparkling lights, heralding to the world its hospitality to those entering its gate, and then forget their Christian duty to their fellow-men in need, for the City and County of Denver has been in a political turmoil and has been concerned not so much with the preservation of human rights as with the preservation of property rights. There is no other city in the region of the Rocky Mountains that could better afford to give a real welcome to the wandering citizen, the harvester and the builder, than Denver.

A city whose tax payers have permitted waste and extravagance to the extent of hundreds of thousands of dollars, in the expenditure of the tax payer’s money, surely could afford to create and maintain an institution where the wandering citizen, the homeless wage earner, may find a Christian welcome and humane care.

If this boy should have attempted to go to the local charity organization, and had not been told that the Society did not help “floaters,” as I have known men in other cities to be told, he would undoubtedly have been informed, after going through a humiliating inquisition, that his case would be investigated and if found worthy relief afforded to him after such investigation. Imagine a hungry, homeless, penniless man, who must have whatever help he can get immediately, being told that his case will be investigated and relief afforded at some later date! What is a man in this condition to do? Did not the charity organization to whom the tax payers give money for the express purpose of relieving the needy and distressed, compel this very individual to beg, to accost the citizens on the streets who have already subscribed for his relief, and to still continue to beg from them? Does not such a charitable organization, by the acquiescence of the citizens of the city, put a premium on this hungry, homeless man to go and shift for himself as best he may, either by accosting citizens who have already been burdened by his relief, or by stealing, robbing, and if necessary demanding a life, to satisfy the needs whereby his existence may be made possible?

It is time that the citizens of the City and County of Denver, and for that matter, of all other municipalities of the United States, shall awaken to the call of duty in their respective communities in dealing rightly with those who are their wards, if they desire to minimize instead of increase the evils of pauperism brought about by indiscriminate alms-giving.

A great many times, through political intrigues, we find people at the head of charity organizations in our cities that have no business to be there. Their appointment to such places, in many instances, is purely political, and they are, therefore, not competent to dispense the money subscribed by the tax payers of the community. Very often only those individuals can receive consideration at the hands of such officials who bring a letter of introduction, or have some personal political “pull,” while an honest and deserving man, coming from some other portion of the City or State, without any acquaintance whatsoever in the community in which he finds himself stranded, may receive no consideration whatever at the hands of such so-called administrators of public charity.

It has been conclusively proven that the charitable endeavors of our so-called charity organization societies are extremely unscientific, wasteful, and have a detrimental and pauperizing effect in-so-far as the work of the charitable is devoted to reclamation and not to prevention, which is also one cause for its failure.

Consider a moment one startling fact evidencing the spirit shown by organized charity in its effort so evidently to refrain from helping the needy: I found during my personal investigations that the societies keep banking hours from nine to five o’clock, and are closed at noon on Saturdays! From noon on Saturday to nine on Monday, is it not possible that some needy one in distress may need help?

Readiness on the part of the private citizen to subordinate personal interests to the public welfare is a sure sign of political health; and readiness on the part of public officials to use public offices for private gain is an equally sure sign of disease. Every municipality, by reason of its organization, supported by all of its citizens, ought to supply all communal needs, instead of permitting certain special interests under the guise of “religious” and “charity” organizations to administer to the needs of the less fortunate members of the community.

There are two very important facts that occupy the center of the stage of our complex civilization, to which all other facts are tributary, and which for good or ill are conceded to be of supreme importance. They are the rise of scientific and democratic administration of all the needs of the people, and the decline of private, special interests, clinging to the preservation of property rights as against human rights.

Determined is the demand of the people for a controlling voice in their destinies. The disinherited classes are refusing to remain disinherited. Every device within the wit of man has been sought to keep them down, and all devices have come to naught. The efforts of the people to throw off their oppressors have not always been wise, but they have been noble, self-sacrificing.

The report of charities and corrections at Atlanta for 1903 states that from among thirty of the leading cities of our nation, Denver is the only city reported as being severe toward its toilers, particularly toward that class which it is pleased to call “beggars” and “vagrants.” Personal observation, however, proved to me that many other cities in the list were equally as cruel, and yet it is astounding to note in this report that the arrests in Denver for the crime of being poor—begging and vagrancy—which has undoubtedly correspondingly increased with the city’s growth in the following years, was 6763, while New York City’s for the corresponding crime, and same period of time was, for begging, 430; for vagrancy, 523; and Chicago, for begging, 338; for vagrancy, 523. This is approximately Denver’s ratio with all of the other cities in the report.

“These hints dropped as it were from sleep and night let us use in broad day.”—Emerson.

On a stormy night in February, 1909, I arrived at the Auditorium Annex in Chicago. Donning my worker’s outfit and covering my entire person with a large, long coat, unnoticed I left the hotel. Leaving the coat at a convenient place, I appeared an out-of-work moneyless man, seeking assistance in this mighty American industrial center. I made my way down Van Buren Street. Though the hour was late, there were many people abroad and almost every man, judging from his appearance, seemed to be needy. Stepping up to one on the corner of Clark Street, who seemed to be a degree less prosperous than all the rest, I said, in the language of the army who struggle:

“Say, Jack, can you tell a fellow where he can find a free flop?”

He raised his hand and pointed toward a stairway which led up over a large saloon, “You can flop on the floor up there for a nickle.”

“But I am up against it right, pal. I am shy the coin for even that to-night.”

Stepping up a little nearer to me and drawing more closely his tattered rag of a coat about his frail, half-starved body, he replied:

“Honest to God, Shorty, I have only a dime myself, but say, this is a fierce night to carry the banner. If you don’t get a place, come back. I can get along without my ‘coffee and’ for once.”

There are many places in Chicago where a poor man can get a strengthless cup of coffee and rolls for a nickle. One-half of this man’s dime he proposed to spend for this supper, and the other half he would give me to provide the “flop” on the floor he had told me of.

He continued, “I am in line for a pearl-diver’s (dishwasher’s) job to-morrow. That means all a fellow can chew anyway. I can do better work than that, but when a fellow is down on his luck—but say, Shorty,” he added abruptly, as we moved to part, “if you don’t have a windfall like the Annex, Palmer, or the First National Bank, go over on the West Side; you’ll find a free flop, and maybe between the sheets, and maybe a bath and supper; but look out for bulls and fly cops, and don’t go too often, for you’re liable to be arrested and sent to the Bridewell. I have been out of a job for two weeks. I have been to the flop several times, and I am afraid to go any more. I have had so little to eat lately, and from all I hear, I don’t think I am strong enough for the battle of a workhouse; besides, I have never been in. Well, never mind, old man, you can find the place. It’s on Union Street, just off of West Madison, called ‘The City Lodging House.’”

How those last three words thrilled me! I who in fancy for months had been building a Municipal Emergency Home, rounding out and perfecting in my mind all of its wonderful possibilities! There was then such an institution in the world, and here in Chicago, and in a moment’s time I was to grasp the tangible fact!

As I made my way toward my destination I saw evidence of the brutal police system, so notoriously obvious throughout our entire country. I had seen a half-starved, homeless man knocked down on the streets of a Western city by an ignorant, rum-befouled bully of a policeman, simply because he stood a little too far out on the sidewalk, and with a desire to learn something of the spirit of the police force of Chicago, I made my way to the Desplains Street Police Station, although possessed with a foreboding that I might be arrested, and subjected to some insult or abuse.

With a thumping heart under a false air of complacency I entered and asked the Captain where I could find a free bed. He looked pleasantly enough upon me, and in words which held a tone of pride that he could do so, replied, “Why, yes, go to our Municipal Lodging House,” and turning to a subordinate, said, “Show this man the direction to North Union Street.” The under officer pointed out the proper course, and I was soon lost in a maze of brilliant, scintillating, cheap saloon, café, and playhouse signs along West Madison Street. The half-hidden, frost-covered windows of restaurants were filled with tempting, wholesome food. The sparkling bar-room signs were a guide to warmth and temporary shelter. I reached North Union Street, and looking down an almost black street with occasionally a dim distant light, I saw no sign guiding the homeless man or boy, woman or girl, to Chicago’s gift to its penniless toilers.

With fear and difficulty I found an old shell of a building. Arriving too late for a bed, I was allowed to lie down with sixty others, from boys of fifteen to old men of seventy, on the floor. In the foul air, unwashed, unfed, with my shoes for a pillow, with aching limbs, I endured, until daybreak, the sufferings which the temporarily homeless wanderer must suffer often many days until, if he does not find himself in some one of the other public institutions, he finds work and can again enjoy the comforts of a bed. And yet, how much this all meant to me! I did not sleep a moment of the night, yet above the dark side of it all, I caught the bright light of the golden thought behind this institution, for the establishment of which the City Homes Association, whose president was Mrs. Emmons Blaine, took the initiative, and which Raymond Robins worked into a tentative establishment.

Several years have passed since my first experience in Chicago. At that time I was deeply impressed with the fact that the city had not forgotten. My criticism was extremely friendly. The superintendent wrote, thanking me for my investigations, saying he believed it would help promote better things in Chicago in caring for its homeless workers. But I was disappointed. To-day you walk through West Madison Street to Union Street, to Chicago’s free “flop.” On your right you will notice a magnificent new railway station, which, its owners boast, cost twenty-five millions of dollars. Possibly at the very doorstep of this marvelous terminal, destitute men will ask you for help.

And a little further along, should you glance up at No. 623, you will read this sign, “The Salvation Army will occupy here a new six-story fireproof hotel, to be known as the Workingman’s Palace. Rates 15 cents to 30 cents per night, $1 to $2 per week.”

You have reached Union Street, and you enter the same dark old street and the same old makeshift of an old building which thirty-five years ago was a police station and later a storeroom for city wagons, until made into a “Municipal Emergency Home.” This shell accommodates only two hundred and fifty men, and on many a night during the last winter it has sheltered five hundred men, besides as many more in the “annex.” There are four thousand in Chicago every winter’s night without a bed or the money to buy a bed. There are five thousand men in Chicago who are willing to work ten long hours a day for a dollar a day, and this lodging-house can furnish two hundred men a day at that wage. Last year the ice companies, the street railway companies, and the packing-houses paid $1.75, and this past winter only $1.50, and out of that these men paid $4.50 a week for board. That these men are willing to work for such wages shows that a large proportion who seek this free shelter are honest workers. The chief of police gave orders and notice that men would no longer be sheltered in the police stations, and yet on one winter day an official of the Emergency Home marched sixty-eight down to a station and demanded they be taken in.

Follow this official through the institution and he will show you how he stores men away in every nook available, even allowing many to sit up all night on the stairs. He will show you how men lie down under and between the cots of those who are fortunate enough to get a cot itself. He will show you in one end of the dormitory, on filthy blankets and mattresses, men huddled and packed like swine, and he will tell you that in the morning these men receive a certain portion of a loaf of bread and a cup of a decoction called coffee; and yet those men are willing to go out and work in the storm and cold for a dollar or a dollar and a half a day. What a commentary on the humanity of a city that is willing to see this strength crippled! What a lack of ordinary business foresight to ignore the conservation of this human force!

You will find in this Municipal free “flop” of Chicago no department for women. Thank God for that! You will find no separation of the sick from the well; you will find no medical examination other than vaccination. Such a lodging-house is an institution driving men into intemperance, filling our hospitals, and spreading with frightful fatality the white plague.

Those who come from abroad to learn of Chicago, and what it has done and is doing to banish destitution and its specter of homeless suffering from its streets, may first visit the public institutions representing a city’s intelligence—the Art Institute, standing for its culture; its churches, charities and hospitals, representing its humanity. But they should also follow the course I traveled, to Chicago’s so-called Municipal Lodging House, even though it will mean a sad reflection upon a city’s care for its homeless workers.

Chicago is considered one of the greatest railroad centers of America; it is the hub of the fly wheel, East and West, North and South, of a mighty railroad industry. The old proverb, that “all roads lead to Rome,” can certainly be applied to this of the greatest, most remarkable of all modern industrial phenomena—the Metropolis without a peer. It is estimated that there are over half a hundred different railroad lines running in and out of the city, all bringing their quota of human energy and activity to be molded into the great mass of industrial humanity of the greatest of industrial giants—Chicago.

A very prominent railroad official of a Western railroad declared that the railroad “in a way may be called the chief citizen of the State.” If this statement be true, one cannot but acclaim that a mighty responsibility rests upon it. First of all it means that a transformation of heart and system must take place toward the wandering citizen, the homeless wage-earner,—an absolutely different method and a cessation of the present inhuman brutality.

The one wonderful and most hopeful sign of our day is that members of the great human family are beginning to recognize, in all phases of human endeavor, that our social life is absolutely dependent upon the co-operation and social service of one another. While the writer has a strong indictment to offer against the managements of the various American railroads in dealing with the more unfortunate members of society, nevertheless one cannot accept the already popularized beliefs that “the railroads lack the spark of human kindness.”

The extent of what so-called charitable experts are pleased to call the “vagrancy” of the homeless, wandering wage-workers in the United States, can easily be determined by the industrial and economic conditions existing throughout the country. The demand for laborers of all kinds continuously fluctuates in all industries and localities. The majority of the homeless, wandering wage-earners are unskilled laborers, and because of their unorganized condition they are the reserve of that great standing army which is being maintained through the unjust, inhuman, and wasteful economic system, that pushes human beings down to the lowest level.

Most American railroads are to blame for the industrial conditions in which the unskilled laboring class finds itself. They offer starvation wages, shelter under unsanitary conditions, and permit the “canteen” and “padroni system” to pilfer, rob, and exploit the men working on the sections. And after the job at which they have been employed has been completed, they are left stranded whereever they have finished their work, instead of being given transportation to the nearest city or place where other work can be obtained.

Hundreds of thousands of able-bodied, economically useful citizens of the country are being put to immature death by the railroads of America, and an equally appalling number are being maimed and crippled by “accidents,” and thereby made dependent charges on an already overburdened community.

From among the victims of the present-day railroad system (for it is a system) by which men are being crippled, maimed, and killed, there is a silent but earnest appeal, from the builders of our cities, the harvesters of the nation’s crops, the miners of the nation’s resources, the scholars and teachers of the future republic, for a more scientifically humane treatment, and for a guarantee that “Life, Liberty, and Happiness” shall not be a by-word but a living reality.

The great public, that pays the “freight,” and even the officials of the American railroad systems themselves, are awakening to a realization of the fact that the torn-out rail, the misplaced switch, the obstructing tie, the burned bridge, the cut wire, petty thefts, and air-brake troubles, are all too often the result of retaliation for the inhuman abuse of the homeless, wandering wage-earner. Even that portion of the great public that rides “the velvet” are beginning to demand more protection, for their own self-preservation. The spirit of the various commonwealths of the Union to co-operate and demand by legislative provisions for safety is steadily on the increase.

Thousands of wandering wage-earners in search of work are killed on American railroads, because society as a whole, and the railroad as a public carrier in particular, are ignorantly uninterested in the welfare of the less fortunate members of society. The number of so-called “trespassers” killed annually on American railroads exceeds the combined total of passengers and trainmen killed annually. From 1901 to 1903, inclusive, 25000 “trespassers” were killed, and an equal number were maimed, crippled, and injured. From one-half to three-quarters of the “trespassers” according to the compilers of these figures were “vagrants,” wandering, homeless wage-earners in search of work to make their existence possible.

Let us examine the economic loss and the financial cost to the railroads alone, not considering the loss to the community of the so-called “vagrants” killed and injured. Even the railroads are unable to give accurate figures on this matter. Sometimes the trains stop and pick up the injured and dying victims of their system, and bear them to hospitals, where the hospital and burial charges must, in most cases, be paid or guaranteed by the railroads. In many of the States of the Union, a number of law-suits have been successfully fought against railroads by so-called “vagrants” who have been thrown off a fast-moving train and injured, or maimed. Think of the barbarous orders of a railroad superintendent, to push or throw people from a fast running train, or leave them on the vast plains of the West in a desperate blizzard, as I have seen done.

How much cheaper would it be for the railroads to furnish these less fortunate members of the working-class with transportation to their respective destination, the nearest place where work is possible for them, and thereby suffer fewer depredations, petty thefts, delays to traffic, hospital and burial charges, and other expenses.

How much would the respective communities, and society as a whole, be the gainer, were the State, the municipality, to assume the expense for the creation and maintenance of Municipal Emergency Homes, and thereby make it possible for the homeless, wandering wage-earner to receive the hospitality of the community and be furnished with those necessities upon which human life depends, thus co-operating with the railroads, reducing vice, crime, and pauperism, and abolishing the existence of burdensome public charges.

In addition to the Municipal Emergency Home, provided with up-to-date sanitary facilities, the respective communities should furnish transportation to those desiring to leave for other parts of the country where work can be obtained or may await them. Such a Municipal Emergency Home ought to be the clearing-house for employers of labor and employees alike. Instead of the unemployed being exploited by the grafting employment bureaus existing in the various cities, the business men, the men who need help, and the railroads especially, could make their drafts for workingmen on such Municipal Emergency Homes, which would be always in a position to assist them, while at the same time assisting the honest laborer who seeks work to sustain himself and make existence possible for those dependent upon him.

One of the greatest remedial agencies in solving this very serious problem is pre-eminently that of governmental and railroad co-operation, by which the land shall be taken out of the hands of the speculator, and reclaimed for those who desire to make immediate use of it and to live upon the fruit of their toil. Thus the many thousands of homeless, wandering American wage-earners, the itinerant and occasional helpers in our agricultural industry, as well as the casual, unskilled laborers of our cities, could be given a real lift on the road to economic independence.

In most of the European countries, the so-called crime of “stealing a ride” is almost unknown, because there the governments have established a chain of Municipal Emergency Homes where the itinerant workers are reasonably well taken care of,—provided not only with necessary food, shelter, and clothing, but given transportation to the nearest point where employment may be secured.

Would it not be a wise financial move on the part of the American railroads, while they are investing millions in useless and superficial adornments on fifty-million-dollar terminals, to consider the advisability of building an Emergency Home in every station where the wandering, homeless wage-worker can find comfortable shelter and be given food to strengthen him on his way toward honest employment without having to “beat” the railroads?

American railroads will be forced sooner or later to see that it is up to them to take care of the homeless, wandering wage-worker, or the homeless, wandering wage-worker will take care of the railroads.

“I said, I will walk in the country. He said, walk in the city. I said, but there are no flowers there. He said, but there are crowns.”

In New York I repeated my Chicago plan. I left the Waldorf-Astoria at ten o’clock, dressed in my blue jeans and with my cloak covering my outfit until I could reach unobserved a place to leave it. The police were courteous and directed me to New York City’s “House of God.”

Before entering I stepped back and looked at the wonderful building, beautifully illuminated. As I stood there with a heart full of thankfulness for this gift to those in need, I saw a young girl about fifteen years of age approach the woman’s entrance. Her manner indicated that this was her first appeal for help. She hesitated to enter and stood clinging to the side of the door for support. At my right was the long dark street leading to New York’s Great White Way; on my left the dark East River. I could see the lights of the boats and almost hear the splash of the water. As she raised her face and the light fell upon it, I read as plainly as though it were written there, those lines of Adelaide Procter’s:

Then the door opened and I saw a motherly matron take the girl in her arms and disappear. This incident brought to me a startling revelation. This home was a haven between sin and suicide.

The night I slept in New York’s Emergency Home I was told a mother, with seven children, one a babe in arms, at one o’clock in the morning, had sought shelter there. And as the door was opened to receive her, she said, in broken, trembling words, “My man’s killed himself—he’s out of work.”

Many men were seeking admission. I entered with the rest. At the office we gave a record of ourselves, who we were and where we were from, and what our calling was. Then we were taken into a large and spotless dining-room, where we were given a supper of soup, and it was real soup, too, soup that put health and strength into a man’s body and soul. We also had coffee with milk and sugar, hot milk, and delicious bread and butter, as much as anyone wanted of it. After supper we were shown to a disrobing-room, where our clothes were put into netted sanitary trays and sent to a disinfecting-room. In the morning they came to us sweet and clean, purified from all germ or disease. From the disrobing-room we went into the bathroom where were playing thirty beautiful shower-baths of any desired temperature, and each man was given a piece of pure Castile soap. As we entered the bath a man who sat at the door with a pail of something, gave each one of us on the head as we passed him, a paddle full of the stuff. I said to the attendant, “What is that for?” “That’s to kill every foe on you,” he said, with an emphasis that was convincing. As he was about to give me another dose, I protested. “That’s enough; I have only half my usual quantity tonight.” But I got another dab nevertheless.

After our bath and germicide, we were shown into a physician’s room, where two skilled physicians examined each man carefully. The perceptibly diseased man was given a specially marked night-robe and sent to an isolation ward, where he received free medical treatment. Those who were sound in health and body, were given a soft, clean night-robe and socks, and were taken in an elevator up to the wonderful dormitories. I was assigned to bed 310. There were over three hundred beds in this dormitory, accommodating more than three hundred men. They were of iron and painted white, and placed one above the other, that is, “double-deck,” and furnished with woven wire springs. The mattresses and pillows were of hair, and exceedingly comfortable. The linen was snowy white.

I had been in bed but a short time when an old man about seventy years of age took the bed next to mine. As he lay down in that public place I heard him breathe a little prayer, ever so softly and almost inaudibly, but I heard it—“Oh, God, I thank Thee!” And I said to myself, “That prayer ought to build a Municipal Emergency Home in every city of our land.” It came to me then what a great and wonderful social clearing-house it was or could be.

I did not sleep, I did not want to sleep, but lay there taking mental notes of the soul’s activity. The room was quiet and restful except for the restless man who silently walked the floor. As he came over near me I said to him, “Man, what is the matter?”

He came close to my bed and said, with a hot, flushed face, “I was not considered a subject for the isolation ward, but I am on the verge of delirium tremens. Feel my pulse, isn’t it jumping to beat the devil?”

I felt his pulse; it was jumping like a trip-hammer. But in the way of assurance I answered, “No, your pulse is normal.”

“Have we been up here four hours? They gave me some medicine downstairs to take every four hours, and if I was restless, I was to send down for it and take a dose.”

“No, I think we have been up here about two hours. You might send down for it, and if it is a good thing to take a full dose every four hours, you might take a half-dose in two hours.”

He hesitated for a moment, then agreed. I advised him to cut out the drink, and he went to the attendant for his medicine, received it, and slept like a babe until dawn. There is an attendant in each dormitory all night long, and he must report to the office by telephone every hour, not being allowed to sleep one moment on duty.

A few days later, after my visit was made public, I received many letters at my hotel, and among them was one from this man. He thanked me for my bit of advice to cut out the drink, and said that he had braced up and had not drunk a drop since that night, and that he had determined to be a man and fill a man’s place in the world. His resolution was not due to my advice at all. It was due to the influence of "God’s House," to New York’s Municipal Emergency Home, and had turned him back to his true inheritance.

At six o’clock in the morning we were called. Every man took the linen from his bed and put it in a pile where it was all gathered up and taken afterward to the laundries. Every day fresh and spotless linen is supplied.

We then went down and dressed and were given our breakfast—as fine a dish of oatmeal as I ever ate, and again most delicious hot coffee with milk and sugar, bread and butter. And again every man had abundance. I said to a boy who sat on my right, “How do you feel this morning?”

“I tell you I feel as if someone cared for me,” he answered, “I feel like getting out and hustling harder than ever for a job to-day.”

This Municipal Emergency Home of New York’s is absolutely fire-proof and accommodates one thousand men and fifty women. The health of its occupants is more guarded than at the most costly private hotels. The ventilation is by the modern forced-air system, in which every particle of air is strained before entering the dormitories. The humane consideration of the comfort of the broken and weary wayfarer is always in evidence, and speaks volumes for New York’s intelligence. There are no open windows on one side, freezing one portion of the sleeping-hall, while the other may be stifling with the heat. The method of fumigating is of the best, as it does not injure in the least the leather of hat, suspender, glove, or shoe, or weaken the texture of the cloth. The sick man’s nightclothes are not even laundered with the well man’s clothing. The size, and degree of careful detail, of this wonderful home was an outgrowth of the awful and fatal unsanitary old police station lodgings, and yet the Commissioner of Police of New York recently told me that notwithstanding the extensive character of the institution, it was often pitifully inadequate, especially during the winter months. New York already needs at least four such homes.

“What is strange, there never was in any man sufficient faith in the power of rectitude, to inspire him with the broad design of renovating the state on the principle of right and love.”—Emerson.

It was late in the afternoon when I arrived at the Nation’s Capital, and rode to my hotel between tiers of newly erected seats, and banners and flags and festooned arches, and myriads of many-colored lights which soon were to burst forth in royal splendor. Already the prodigal display, costing half a million dollars, to inaugurate a president, was nearing completion. Already people were coming from far and near, spending five million more.

The New Willard hotel had assumed that air of distinction it always does just before a happening of some national import. In the faces of the handsome men I saw and read the character of decision and intellect, and the many beautiful ladies, gowned in fabrics of priceless value, made an exceedingly pleasant study; and with this vision before me I was proud to be an American. But I had not come to study this side; it was “the other half” I wanted to know. I wanted to learn how our Capital helps its poor, how a man out of work, penniless, and homeless, is cared for in Washington.

At about ten o’clock I went to my room to change my evening clothes for my workingman’s outfit. Walking down the stairs and slipping out a side door, I was not noticed, and was soon lost in the avalanche of humanity on the streets.

I asked of the first policeman I met where I could get a free bed, and he looked at me seemingly in surprise and said, “A free bed?” then continued, “Go to the Union Mission.” I asked, “Do they charge for a bed there?” and he replied, “Yes, 10 or 15 cents.” “But I haven’t even that tonight,” I answered.

Then he seemed to remember that Washington had a municipal lodging house, and told me I would find it on Twelfth Street, next to the police station. I asked two other policemen with similar results, and started in search of my desired object. I looked down Pennsylvania Avenue, a blaze of lights, and for one mile I could see and read guiding signs of theaters, breweries, hotels, and cafés.

Presently I came to Twelfth Street, dark and gloomy, but there was no sign as in Chicago to guide the homeless man or woman, boy or girl, to the door of the free home. It was with difficulty I found it. There was a three-cornered box over the door, intended for a light, but it was not illuminated. Through smoke-dimmed windows there came a feeble light by which I could just discern the words, “Municipal Lodging House,” and on the door the inscription, “To the Office.”

Before entering I stepped back into the street and looked up at the building. It was an old three-story brick building, with no sign of a fire escape. I entered and found myself in a low and very narrow passageway. I applied to the “office” through a small window-door for my bed. There was an honest-faced, comfortably dressed young man just ahead of me, who gave his occupation as machinist, received his bed check, and passed on.

When I stepped to the window and asked for a bed, I received no word of welcome from a woman seated at her desk, her demeanor being decidedly unwelcome. Abruptly a man’s voice asked from within, “Are you willing to work for it?” I replied earnestly that I was. The woman then snatched up a pen and asked, “Were you ever here before? Where were you born? Where do you live? What is your business?”

My answers apparently being satisfactory, she thrust me a bed check, and said something about a light and something else which I did not understand, and slammed the door in my face. I stepped along and found myself in the woodyard among piles of wood, saws, sawbucks, and sawdust. I tried several doors, and finally found one that admitted me. A narrow flight of stairs let me to a bathroom, where a number of men were already trying to get a bath. There were two attendants, one who was working for his bed and breakfast, and the other, I judged a paid attendant. I was told to go into a closet and strip, and to hang on a hook all of my clothes except my shoes and stockings and hat. Having done this, I stepped out into the bathroom. It was heated by a stove, which emitted no heat, however, as the fire was almost dead. There were two bathtubs, and six of us were standing nude in that cold room waiting each for his turn. The boy working for his bed made a pretense with a mop of cleaning the tubs after each bather, but left them nasty and unsanitary. I got into about six inches of water, and hurriedly took my bath, because of the others waiting. I did not want to wash my head, so omitted that, but just as I got out of the tub the Superintendent came in and said, “You haven’t washed your head yet; get back in there and wash your head.” I immediately and meekly complied.

Shivering with the cold, I got out, was given a towel to dry myself, and then a little old cotton nightshirt with no buttons on it. Several of us being ready, we were led by the Superintendent up another flight of narrow stairs, through another long hall, and up two more series of steps to a small dormitory. I would have suffered with the cold if I had not seized an extra blanket from an unoccupied bed, and I slept very little. I was afraid to go to sleep, for if the building had taken fire not one man could have escaped. So I lay and took mental notes and soul thoughts of my companions and surroundings, and of all I had seen and heard since I left Denver.