This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Boy Scouts Along the Susquehanna

or, The Silver Fox Patrol Caught in a Flood

Author: Herbert Carter

Release Date: May 17, 2014 [eBook #45667]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY SCOUTS ALONG THE SUSQUEHANNA***

OR

The Silver Fox Patrol Caught in a Flood

By HERBERT CARTER

AUTHOR OF

“The Boy Scouts’ First Campfire,” “The Boy Scouts

In the Blue Ridge,” “The Boy Scouts On the

Trail,” “The Boy Scouts In the Maine

Woods,” “The Boy Scouts

Through the Big Timber,”

“The Boy Scouts In

the Rockies,”

Etc. Etc.

Copyright, 1915

By A. L. Burt Company

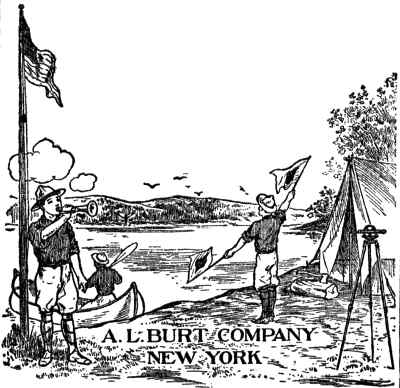

“CLOSE IN ON ALL SIDES AND KEEP THEM WELL COVERED, BOYS!” SAID THAD. Page 20

—The Boy Scouts Along the Susquehanna.

“I’m no weather sharp, boys; but all the same I want to remark that it’s going to rain like cats and dogs before a great while. Put a pin in that to remember it, will you?”

“What makes you say so, Davy?”

“Yes, just when we’re getting along splendidly, with the old Susquehanna not a great ways off, you have to go and put a damper on everything. Tell us how you know all that, won’t you, Davy Jones?”

“Sure I will, Giraffe, with the greatest of pleasure, while we’re sitting here on this log, resting up. In the first place just notice how gray the sky’s gotten since we had that snack at the farm house about noon!”

“Oh! shucks! that’s no positive sign; it often clouds up, and never a drop falls.”

“There’s going to be quite some drops come this time, and don’t you forget it, Step Hen. Why, can’t you feel the dampness in the air?”

“That brings it a little closer home, Davy; any more reasons?” demanded the boy answering to the singular name of “Step Hen,” but who, under other conditions, would have come just as quickly if someone had shouted “Steve!”

“Well, I was smart enough to look up the weather predictions before we left Cranford yesterday,” replied the active boy whom they called Davy, as he laughed softly to himself; “and they said heavy rains coming all along the line from out West; and that they ought to hit us here by to-night, unless held up on the road.”

“Whee! is that so? I guess you’ve made out your case, then, Davy,” admitted the boy called “Giraffe,” possibly on account of his unusually long neck, which he had a habit of stretching on occasion to abnormal dimensions.

“Mebbe Thad knew about what was in the air when he told us to fetch our rubber ponchos along this trip,” suggested Step Hen, whose last name was Bingham.

There were just eight boys in khaki sprawled along that log in various favorite positions suggestive of comfort. They constituted the full membership of the Silver Fox Patrol connected with the Cranford Troop of Boy Scouts, and the one designated as Thad Brewster had been the leader ever since the start of the organization.

Those of our readers who have been fortunate enough to possess any of the previous volumes in this Series need not be told just who these enterprising lads are; but for the purpose of introducing them to newcomers, a few words may be deemed necessary in the start.

Besides the patrol leader there were Allan Hollister, a boy whose former experiences in the woods of Maine and the Adirondacks made him an authority on subjects connected with outdoor life; a Southern boy, Robert Quail White, called “Bob White” by all his chums; Conrad Stedman, otherwise the “Giraffe,” previously mentioned; “Step Hen” Bingham; Davy Jones, an uneasy fellow, whose great specialty seemed to lie in the way of wonderful gymnastic feats, such as walking on his hands, hanging by his toes from a lofty limb, and kindred remarkable reckless habits; Cornelius Hawtree, a very red-faced, stout youth, with fiery hair and a mild disposition, and known as “Bumpus” among his set; and last though not least “Smithy,” whose real name was Edmund Maurice Travers Smith, and who had never fully overcome his dainty habits that at first had made him a subject of ridicule among the more rough-and-ready members of the Silver Fox Patrol.

There they were, as active a lot of scouts as could have been found from the Atlantic to the Pacific. They had been through considerable in the way of seeing life; and yet their experiences had not spoiled them in the least.

At the time we discover them seated on that big log they were a good many miles away from their home town; and seemed to be bent upon some object that might make their Easter holidays a season to be long remembered.

When Step Hen so naively hinted that the patrol leader may have suspected a spell of bad weather was due, when he ordered them to be sure and fetch along their rubber ponchos, there was a craning of necks, as everybody tried to set eyes on the face of Thad. Of course Giraffe had the advantage here, on account of that long neck of his, which he often thrust out something after the style of a tortoise when the land seems clear.

“How about that, Mr. Scout Master?” asked Bumpus.

Thad Brewster had a right to be called after that fashion, for he had duly qualified for the position, and received his commission from scout headquarters, empowering him to take the place of the regular scout master, when the latter could not be present. As Dr. Philander Hobbs, the young man who gave of his time and energies to help the cause along, found himself unable to accompany the scouts on many of their outings, the necessity of assuming command frequently fell wholly on Thad, who had always acquitted himself very well indeed.

Thad laughed as he noted their eagerness to hear his admission.

“I’ll have to own up, fellows,” he went on to say frankly, “that I did read the paper, just as Davy Jones says happened with him; and when I saw the chances there were of a storm coming down on us, I made up my mind we ought to go prepared. But even if we didn’t have a rubber poncho along I wouldn’t be afraid to wager we’d get through in pretty decent shape.”

“That’s right, Thad,” commented Giraffe; “after scouts have gone the limit, like we did down South last winter, when the schoolhouse burned, and we had a fine vacation before the new brick one was completed, they ought to be able to buck up against nearly anything, and come out of the big end of the horn.”

“Horn!” echoed Bumpus, involuntarily letting his hand fall upon the silver-plated bugle he carried so proudly, and the possession of which told that he must be the bugler of the troop—“Horn! that reminds me I haven’t had a chance to use my dandy instrument only at reveille and taps for quite some time now.”

“Well, don’t start in now, Bumpus, whatever you do,” remonstrated Step Hen. “To my mind a horn’s a good thing only on certain occasions. Now, when I’m just gettin’ the best sleep after sun-up it’s sure a shame to hear you tooting away to beat the band.”

“But none of us make any sort of a row when he blows the assembly at meal times, I notice,” Smithy remarked sagely; and not a protest was raised, showing that in this particular the members of the patrol were unanimously agreed.

The last exploit of the scouts had taken them into the Far South, in fact among the lagoons and swamps of Louisiana; and although some months had since passed, it would seem as though the events of that thrilling experience were still being threshed out whenever the eight boys came together.

Thad was an orphan, living with an uncle, a quaint old man whom everyone knew as “Daddy.” Acting from information that had been received in a round-about way, the leader of the scout patrol had organized an expedition to go South during the unexpected vacation, to look for a certain man who had once worked for his widowed mother, and was suspected of having been concerned in the mysterious disappearance of Thad’s little sister, Pauline, some years back.

The boys had carried this enterprise through to a successful termination; and after meeting with many thrilling, likewise comical adventures, had actually traced this man, and managed to recover the child; who was now a happy inmate of the Brewster home, the pride of old Daddy’s heart.

Judging from the numerous burdens with which the eight boys were weighted down it would seem that they must be in heavy marching order, after the manner of troops afield. Each fellow carried a blanket, folded so as to hang from his shoulder, and with the two ends secured under the other arm. Besides, he had a haversack that looked as though it might contain more or less food and extra clothing.

Giraffe also sported a frying-pan of generous dimensions; another scout carried a coffee pot; and doubtless the necessary tin cups, knives, forks, platters and spoons would be forthcoming whenever needed.

The convenient log which served the boys as a seat lay close to the road along which they had been tramping for hours that day, making inquiries whenever a chance offered, and picking up clews after the fashion of real scouts.

As the reason for their coming to this part of the country has everything to do with our story, it had better be explained before we follow Thad and his chums any further along the rather muddy road that led across country to the Susquehanna River.

Just a couple of days before the coming of the Easter holidays Thad had been asked over the ’phone to come and see Judge Whittaker, one of the most respected citizens of Cranford. Wondering what the strange request could mean, the patrol leader had immediately complied, after school that same afternoon.

He heard a most remarkable thing, and one that thrilled his nerves as they had not been stirred for many a day. The Judge first of all told him that he had long observed the doings of the scouts with growing admiration, and finding himself in need of assistance of a peculiar order, made bold to call upon Thad to help him.

Shorn of all unnecessary particulars, it would seem that the Judge, obeying a whim which he now called the height of foolishness, and while waiting for a new safe to be delivered from New York to take the place of the one that had to be opened by an expert because the time-lock had gone wrong, had actually sewed a very valuable paper in the red lining of an old faded blue coat which was hanging in his closet, and which he kept as a memento of the time his only son served in the engineer corps of the army.

It seemed that as the Judge had married again, his wife was not very fond of seeing that old blue army overcoat with the red lining hanging around; and thinking it a useless incumbrance, she had figured that it would be doing more good shielding some poor tramp from the cold than just tempting the moths in that closet.

And so it came about that one day, upon looking for the army coat, the Judge discovered to his utmost dismay that it could not be found. When he asked his wife, she was compelled to admit that three days before, after pitying a shivering hobo who came to the door and asked for food, she had obeyed a sudden generous instinct and given him the warm if faded blue overcoat.

The Judge was in a great predicament now. His first thought was to start out in search of “Wandering George” himself, and buy back the coat, which the hobo could not imagine would be worth more than a dollar or so at the most. Then, when he remembered his rheumatism, and how unfitted for such a chase he must be, the Judge gave this plan up.

His next idea was to send to the city and have a detective put on the track; but he had a horror of doing this, because he fancied that most of these professional detectives were only too ready to demand blackmail if given half a chance; and there was something about that paper which Judge Whittaker did not want known in a public way.

And just about that time he happened to think of Thad and his scouts; which gave him an inspiration. He felt sure they would be able to follow the hobo who wore the faded army overcoat, and in due time come up with him. Then Thad was to offer him a few dollars for the garment, using his discretion so that the suspicions of the tramp might not be aroused.

It promised to be a pretty chase, and already they had been on the road for the better part of two days, here and there learning that a man wearing such a coat had been seen to pass along. Part of the time they had tramped the ties of the railroad, but latterly the chase had stuck to the highway.

Now, acting on the suggestion of the sorrowful Judge, Thad had not told any one of the scouts, saving his close chum Allan, what the real reason of the hunt for the lost army coat meant. The others simply fancied that Judge Whittaker valued the old garment highly because his only son, now in Alaska, had worn it during the Spanish-American war, and was unwilling to have it come to such a disgraceful end. All they thought about was the fun of tracking the hobo and eventually bringing back the old engineer corps overcoat to its late owner. That was glory enough for Step Hen, Giraffe, Bumpus and the rest. It afforded them a chance to get in the open, and imagine for a time at least that they were outdoing some of those dusky warriors who, in the good old days of “Leatherstocking” and others of Cooper’s characters, roamed these very same woods.

“If you feel rested enough, fellows,” Thad now told them, “perhaps we’d better get a move on again. The last information we managed to pick up told us this Wandering George, as he likes to call himself, can’t be a great distance ahead of us now. In fact, I’m in hopes that we may run across him before night comes and forces us to go into camp somewhere along the river.”

Accordingly, the other scouts sprang to their feet, everyone trying to make out that he was as “fresh as a daisy,” though poor fat Bumpus gave an audible groan when he pried himself loose from that comfortable log. He was not built for long hikes, though possessed of a stubborn nature that made it hard for him to give up any object upon which he had set his heart.

“Yes, we’ve rested long enough,” admitted Giraffe, who, being tall and slim, was known as a fine runner, and long distance pedestrian. “Sorry to say there won’t be any wagon following us to pick up stragglers; so if you fall down, Bumpus, better stop at the first farmhouse you strike, and wait till we come back.”

This little slur only caused the fat scout to look at the speaker contemptuously; but from an unexpected quarter help came.

“Huh! you certainly do like to rub it into Bumpus, Giraffe, because he’s built on the heavy order,” Step Hen went on to say; “but go slow, my boy. Don’t you know the battle isn’t always to the swift or the strong? Have you forgotten all about the race between the hare and the tortoise; and didn’t the old slow-moving chap come in ahead, after all? I’ve known Bumpus to beat you out before this. You may have to use a crow-bar to get him started sometimes; but once he does move he don’t let little things balk him. Besides, it ain’t nice of you nagging him because he happens to weigh twice as much as you do. Bumpus is all right!”

“Thank you, Step Hen; I’ll remember that,” observed the freckled-face scout, as he gave his defender an appreciative grin.

Down the road they went, straggling along without any particular order, because Thad knew from past experiences he could get better work out of his followers when they relaxed. Still, they kept pretty well bunched, for whenever the conversation started up none of them wished to lose a word of what was said.

On the previous night they had been forced to make a temporary shelter with all manner of fence rails, boughs from trees, and such brush as they could find. Having their blankets along, and being cheered with a camp fire during the night, the experience had been rather delightful on the whole.

These energetic boys had been through so much during the time they belonged to the Cranford Scouts that nothing along ordinary lines seemed to daunt them. They were well equipped for meeting and overcoming such difficulties as might arise to confront them on a trip like the present one; in fact, they took keen delight in matching their wits against all comers, and a victory only served to whet their appetite for more problems to be solved along the line of woodcraft knowledge.

For something like half an hour they pushed steadily along. Bumpus, in order to positively prove to the sneering Giraffe that he was in the best of condition, had actually pushed ahead with the leaders. If he limped occasionally he did his best to conceal the fact by mumbling something about the nuisance of stepping on pebbles and being nearly thrown off his balance; a ruse that caused the said wily Giraffe to smile broadly, and wink toward Step Hen knowingly.

However, this disposition of their forces enabled Bumpus to make a discovery of apparently vast importance, which he suddenly communicated to the rest in what he intended to be a stage whisper:

“Hey! hold on here, what’s this I see ahead of us, boys? Unless my eyes have gone back on me, which I don’t believe they have, there’s the smoke of a fire rising over yonder alongside the road; and Thad, tell me, ain’t there a couple of trampy looking fellows sitting on stones cooking their grub? Bully for us, fellows, I wouldn’t be surprised a bit now if we’d gone and ketched up with our quarry right here and now!”

Every scout stared as Bumpus was saying all of this. They saw that smoke was undoubtedly rising close to the road, showing the presence of a fire; while their keen, practiced eyes, used to observing things at long distances, told them that in all probability the two men who occupied the roadside camp belonged to the order of hoboes; for their clothing showed signs of much wear and tear, and moreover they were heating their coffee in old tomato cans, after the time-tried custom of the tramp tribe the country over.

Naturally, under the circumstances, this discovery caused their hearts to beat with additional rapidity as they contemplated an early closing of their campaign.

“Well, I’m sorry, that’s all!” ejaculated Step Hen.

“What at?” demanded Giraffe; “we ought to be puffed up with pride over our success, and here you go to pulling a long face. What ails you, Step Hen?”

“It’s just this way,” muttered the scout addressed disconsolately; “we never did run across a better chance to have a great time than when we started out on this hobo chase; and here it’s turned out too easy for anything. Shucks! a tenderfoot might have followed that Wandering George right along to here; and now all we’ve got to do is to surround the camp, and make him fork over that old blue coat the judge loves so well. It’s a shame, that’s what!”

“I feel something the same way you do, Step Hen,” remarked Allan; “why, I figured on doing all sorts of smart stunts while we were on this hike; and here, before a chance comes along, we corral our game!”

“I’m just as sorry as you, suh,” observed the Southern boy, with the accent that stamped him a true Dixie lad; “but I reckon now you wouldn’t have Thad tell us to sheer off, and give the hoboes a chance to run away, just to let us keep up this chase. We promised to recover that old army coat for the judge, and for one I’d be ashamed to look him in the face again, suh, if we let it slip through our fingers on account of wanting to lengthen the sport.”

“That’s the right sort of talk, Bob White,” said Thad, with a nod of his head, and a sparkle in his eyes. “Much as we all like the sport of showing what we know in the way of woodcraft, duty comes first. And we couldn’t shirk our responsibility in this case just to gratify our liking for action.”

“What’s the program, then, Thad?” asked Smithy, yawning as though he did not feel quite as much interest in the chase as some of the others; for Smithy of late, Thad noticed with regret, was apparently losing some of his former vigor, and acting as though ready to shirk his duty when it did not happen to appeal to him very strongly.

“We can have a little fun out of the thing by planning a complete surround, can’t we, Thad?” asked Step Hen eagerly.

“I hope you say yes to that, Mr. Scout Master,” added Giraffe; “because it’ll be apt to take some of the sting out, after having our game come to such a sudden end.”

“I was going to say something along those lines, boys, if you had let me,” Thad told them. “So far the tramps have given no sign that they suspect our being here. We’ll arrange it so as to surround the camp, and then at a signal from me everybody stand up and show themselves. I’ll arrange it so that we’ll make a complete circle around the fire, and to do that we’ll move in couples.”

He immediately paired them off, and each detachment was told what was expected of it in making the move a practical success.

Even in these apparently small matters Thad proved himself a capable commander, for he picked out the most able to undertake the difficult part of the work, while to Smithy and Bumpus was delegated the easier task of crawling along the side of the road until they found shelter close to the hoboes’ fire.

Giraffe and Step Hen were ordered to cross to the other side of the road and, making a little detour, came up from the north. The remaining four scouts branched off to the south, and it was the intention of Thad, taking Davy Jones along, to continue the enveloping movement until he could approach from the opposite quarter, which would mean along the road in the other direction.

Meanwhile Bob White and Allan would be taking positions to the south, and then curbing their impatience until Thad had signaled and learned that all of them were in place.

This was a most interesting piece of work for the boys. They delighted in just such practices, and for the simple reason that it enabled them to bring to bear on the matter all the knowledge they had managed to accumulate connected with the real tactics of scouting, as practiced by hunters and Indians, as well as the advance guard of an army sent out to “feel” of the enemy’s lines.

At a certain point Thad gave Allan and Bob White the sign that they were to turn to one side, and begin advancing toward the smoke again, while he and Davy would keep straight on.

They did not have to creep as yet, but kept bending low, in order to render the risk of being discovered as small as possible. Later on, however, as they headed toward the hub of the wheel, which was marked by the cooking fire, Thad and his companion did not hesitate to flatten themselves out on occasion, and do some pretty fine wriggling in passing from one patch of leafless bushes to another.

Every time they raised their heads cautiously to look, Davy would give one of his little chuckles, telling that the situation was eminently satisfactory, so far as he could see.

The two men were still hovering over their miserable little fire, which was such a poor excuse for a cooking blaze that any practical scout must curl his lip in disdain, knowing how easy it is to manage so as to have red coals, instead of smoky wood, when doing the cooking.

Davy could see that there was no longer the first question about their being genuine tramps. A dozen signs pointed to this fact; and he found himself wondering which of the pair would turn out to be Wandering George.

He did not see the faded blue army coat on either of them; but then it would be only natural for the possessor to discard this extra weight when keeping so close to a warm blaze. Doubtless, the object of their search would be found nearby, used in lieu of a blanket, to cover the form of the new owner as he slept in the open, or in some farmer’s haystack.

Several of the scouts carried guns, even Bumpus having so burdened himself in the hope that during their chase after the lost army coat they might happen to run across some game worth taking, in order to lend additional zest to the outing.

As Thad and Davy had chosen the longest task in making for the further side of the hobo camp, they could take it for granted when they finally reached the position the scout leader had in his eye, that all of the other detachments must by then have arrived.

To test this Thad gave a peculiar little sound that was as near like the bark of a fox as possible. Every member of the patrol had in times past perfected himself in making just that sort of sound, and of course they would immediately recognize it as the signal of the scout master, desirous of knowing whether all of them had gained their positions.

There came an immediate “ha! ha!” from across the road, and also from deeper in the woods, where Allan and Bob White were lying; but none from Bumpus and Smithy. Evidently, something had happened to cause a delay there. Thinking they had what they might call a “snap,” the two slow moving scouts covering this quarter had delayed their advance too long, and were now holding back.

As the tramps, however, had heard those strange barking sounds coming from three quarters, and jumped to their feet in alarm, Thad did not consider it wise to delay the exposure of their presence any longer. Accordingly, he gave a shrill whistle that was well known to the others.

Imagine the consternation of the hobo campers when from behind concealing bushes they saw figures in khaki rise up, some of them bearing threatening guns. Even Bumpus and Smithy followed suit, though not as near the fire as the rest.

Perhaps the first thought of the alarmed tramps was that they were surrounded by a detachment of the militia, for the sight of those khaki suits must have stunned them. Before they could gather their wits together to think of resistance Thad was heard to call out with military precision:

“Close in on all sides; and keep them well covered, boys!”

At that those who carried guns made out to aim them, and their manner was so threatening that both hoboes immediately elevated their hands, as though desirous of letting their captors see that they did not expect to offer the slightest resistance.

Slowly the scouts came forward, converging toward the common center, which of course was the smoky fire, alongside of which those two old tomato cans stood, each secured at the end of a bunch of metal ribs taken from a cast-off umbrella.

That successful surround would have made a picture worthy of being framed and hung upon the wall of their meeting room in the home town, some of the scouts may have proudly thought, as they walked slowly forward, thrilled with the consciousness of power.

The tramps kept turning around, to stare first at one pair of boys and then at another lot, as though hardly knowing whether they were awake or dreaming.

If they had guilty consciences, connected with stolen chickens, or other farm products, they must have believed that the strong arm of the law had found them out, and that the next thing on the program would be their being marched off to some country town lockup.

“Aw! it’s too, too easy, that’s what!” grumbled Step Hen disconsolately.

“Like taking candy from the baby!” added Giraffe, who always liked to have some spice connected with their adventures, and could not bear the idea of being on a team that outclassed its rival in every department; a tough struggle was what appealed to him every time, though of course he wanted the victory to eventually settle on the banner of the Silver Fox Patrol.

“Makes me think of that old couplet we used to say about old Alexander,” Bumpus here thought it policy to remark, just to show them that he too hoped there might have been some warm action before the tramps surrendered; “let’s see, how does she go? ‘Alexander with ten thousand men, marched up the Alps, and down again!’”

“Mebbe it was Hannibal you’re thinking about, Bumpus,” suggested Step Hen; “but it don’t matter much who did it, we’ve gone and copied after him. I say, we ought to go home by a roundabout course, so as to try and stir things up some. This is sure too easy a job for scouts that have been through all we have.”

The tramps were listening, and eagerly drinking in all that was said; perhaps a faint hope had begun to possess them that after all things might not turn out to be quite as bad as first appearances would indicate.

“Thad, it’s up to you to claim that coat now, so we can evacuate this camp,” observed Smithy, who was observed to be pinching his nose with thumb and forefinger, as though the near presence of the tattered hoboes offended his olfactory nerves; for as has been said before, the Smith boy had been a regular dude at the time he joined the patrol, and even at this late day the old trait occasionally cropped out.

Thad looked around at his comrades, and somehow when they saw the smile on his face a feeling bordering on consternation seized hold of them.

“What is it, Thad?” asked Davy Jones solicitously.

“Yes, why don’t you tell us to get what we came after, and fly the coop?” demanded Giraffe, who did not fancy being so close to the ill-favored tramps much more than the elegant Smithy did.

“There’s nothing doing, fellows,” said the acting scout master, with an eloquent shrug of his shoulders that carried even more weight than his words.

“What!” almost shrieked Step Hen, “do you mean to tell us that we’re on the wrong trail, and that neither of these gents is the one we want, Wandering George?”

“That’s just what ails us,” admitted Thad; “we counted our chickens before they were hatched, that’s all. Stop and remember the descriptions we’ve had of this Wandering George, and you’ll see how we’ve been barking up the wrong tree!”

All eyes were immediately and eagerly focused on the faces of the two wondering hoboes. At the same time, no doubt, there was passing through each boy’s mind that description of the man who had gone off with the faded army overcoat, and which had been their mainstay in the way of a clew, while following the trail.

A brief silence followed these words of the patrol leader. Then the boys were seen to nod their heads knowingly. It was evident that, once they had their suspicions aroused by Thad, every fellow could see what a dreadful mistake had been made.

“Well, I should say now that Wandering George was half a foot taller’n either of these fellows!” declared Bumpus, being the first to control his tongue, which was something remarkable, since as a rule he was as slow of speech as he was with regard to moving, on account of his weight.

“And had red hair in the bargain!” added Step Hen.

“Oh! everybody’s doing it now,” mocked Davy Jones; “and I can see that there ain’t the first sign of an old faded blue army overcoat anywhere around this camp.”

“After all, who cares?” exclaimed Giraffe, as he lowered his threatening gun; an act that doubtless gave the two tramps much solid satisfaction. “All of us felt mean and sore because our fine tracking game had come to such a sudden end. Now there’s still a chance we’ll meet up with a few crackerjack adventures before we pick the prize. I say bully all around!”

Davy Jones immediately threw himself into an acrobatic position, and waved both of his feet wildly in the air, as though he felt that the situation might be beyond weak words, and called for something stronger in order to express his exuberant feelings.

“Yes, all of those things would be enough to convince us we’ve made a mistake,” remarked Thad; “and if we want any further proof here it is right before us.”

He pointed to the ground as he spoke. There were a number of footprints in the half dried mud close to the border of the road, evidently made by the two men as they walked back and forth collecting dead wood for their cooking fire.

“You’re right, Thad,” commented Allan Hollister, who of course instantly saw what the other meant when he pointed in that way. “We settled it long ago that we ought to know Wandering George any time we came up with him, simply because he’s got a rag tied around his right shoe to keep it on his foot, it’s that old, and going to flinders. Neither of these men has need to do that; in fact, if you notice, they’ve both got shoes on that look nearly new!”

At that one of the tramps hastened to speak, as though he began to fear that as it was so remarkable a thing for a road roamer to be wearing good footgear, they were liable to arrest as having stolen the same.

“Say, we done a little turn for a cobbler two days back, over in Hooptown, an’ he give us the shoes. Said he fixed ’em fur customers what didn’t ever come back to pay the charges; didn’t we, Smikes?”

“We told him his barn was on fire, sure we did, an’ helped him trow water on, an’ keep the thing from burnin’ down. He gives us a hunky dinner, an’ trows de trilbies in fur good measure. But dey hurts us bad, an’ we was jest a-sayin’ we wishes we had de ole uns back agin. If it wa’n’t so cold we’d take ’em off right now, and go bare-footed, wouldn’t we, Jake?”

“Oh! well, it doesn’t matter to us where you got the shoes,” said Thad. “We happen to be looking for another man, and thought one of you might be him. So go on with your cooking; and, Giraffe, where’s that knuckle of ham you said you hated to lug any further, but which you thought it a sin to throw away? Perhaps we might hand the same over to Smikes and Jake, to pay up for having given them such a bad scare.”

This caused the two tramps to grin in anxious anticipation; and when Giraffe only too willingly extracted the said remnant of a half ham which the scouts had started with, they eagerly seized upon it.

“It’s all right, young fellers,” remarked the one who had been called Smikes, as he clutched the prize; “we ain’t a-carin’ if we gits the same kind o’ a skeer ’bout once a day reg’lar-like, hey, Jake? Talk tuh me ’bout dinner rainin’ down frum the clouds, this beats my time holler. Cum agin, boys, an’ do it sum more.”

Thad knew it was folly to stay any longer at the camp, but before leaving he wished to put a question to the men.

“We’re looking for a fellow who calls himself Wandering George,” he went on to say. “Just now he’s wearing an old faded blue army overcoat that was given to him by a lady who didn’t know that her husband valued it as a keepsake. So we just offered to find it for him, and give George a dollar or so to make up. Have either of you seen a man wearing a blue coat like that?”

“Nixey, mister,” replied Jake promptly.

“Say, I used to wear a blue overcoat, like them, when I was marchin’ fur ole Unc Sam in the Spanish war, fool thet I was; but honest to goodness now I ain’t set eyes on the like this three years an’ more,” the second tramp asserted.

“That settles it, then, fellows!” ejaculated Step Hen, with a note of joy in his voice; “we’ve got to go on further, and run our quarry down. And let me tell you I’m tickled nearly to death because it’s turned out so.”

“Who be you boys, anyhow?” asked Smikes. “Air ye what we hears called scouts?”

“Just what we are,” replied Allan. “That’s why we think it’s so much fun to follow this Wandering George, and trade him a big silver dollar for the old coat the lady gave him when she saw he made out to be cold. Scouts are crazy to do all kinds of things like that, you know.”

“Well, dew tell,” muttered the tramp, shaking his head; “I don’t git on ter the trick, fur a fact. If ’twar me now, I’d rather be a-settin’ in a warm room waitin’ tuh hear the dinner horn blow.”

“Oh! we all like to hear that, let me tell you,” asserted Giraffe, who was unusually fond of eating; “but we get tired of home cooking, and things taste so fine when you’re in camp.”

“Huh! mebbe so, when yuh got plenty o’ the right kind o’ stuff along,” observed the man who gripped the ham bone that Giraffe had tossed him, “but yuh’d think a heap different, let me tell yuh, if ever any of the lot knowed wat it meant tuh be as hungry as a wolf, and nawthin’ tuh satisfy it with. But then there seems tuh be all kinds o’ people in this ole world; an’ they jest kaint understand each other noways.”

Thad saw that the tramp was rather a queer customer, and something along the order of a hobo philosopher; but he had no more time just then to stand and talk with him out of idle curiosity.

So he gave the order, and the scouts, wheeling around, strode out upon the road, their faces set toward the east. The last they saw of the two tramps was just before turning a bend in the road they looked back and saw that the men were apparently hard at work dividing the remnant of the ham that had been turned over by the boys as some sort of solace to soothe their wounded feelings.

Half a mile further on and the woods gave place to cultivated fields and pastures, although of course it was too early in the season for much work to be done by the farmers, except where they were hauling fertilizer to make ready for the first plowing.

“If we get the chance, boys, to-night, let’s sleep in a barn,” suggested Giraffe, as he rubbed his right shank as though it might pain him. “Where we lay last night it seemed to me a million roots and stones kept pushing into my body till I was black and blue this morning. And I always did like to nestle down in good sweet hay. I don’t blame tramps for taking the chance every opportunity that opens. What do the rest of you say to that?”

“It strikes me favorably,” Step Hen quickly admitted.

“Oh! any old place is good enough for me,” sighed Bumpus.

“If you can only be sure there are no rats around, I believe I’d enjoy sleeping in a hay mow,” Davy told them.

“I’ve never had the experience,” remarked Smithy with a shrug of his shoulders, and a grimace; “and I must confess I don’t hanker much for it. Bad enough to have to roll up in your own blanket any old time; but spiders and hornets and all that horrible set are to be found in haylofts, they tell me. I’m more afraid of them than an alligator or a wild bull. A gypsy once told me I would die from poison bites, and ever since I’ve had to be mighty careful.”

Of course the rest of the scouts had to laugh to hear Smithy confess that he believed in the prophecy of a gypsy, or any other fake fortune-teller.

“I wouldn’t lie awake a minute,” ventured Step Hen, “if a dozen gypsies told me I was going to break my neck falling out of bed. Fact is, I’m built so contrary that like as not I’d hunt up the highest bed I could find to sleep on. I do everything on Friday I can think of; and when the thirteenth of the month comes around I’m always looking out to see how I can tempt fate. Ain’t an ounce of superstition in my whole body, I guess. Fortune-tellers! Bah! you ought to have been a girl, Smithy.”

“Oh! well, I didn’t say I believed I’d die by poison, did I?” demanded the other adroitly; “I’m only explaining that I don’t mean to let the silly prophecy come true by taking hazards that are quite unnecessary.”

“Seems to me we’ve been walking like hot cakes ever since we said good-by to Smikes and Jake,” observed Bumpus, who was puffing a little from his exertions; “and Thad, would you mind if we took a little breathing spell about now? Just see how inviting this pile of old fence rails looks alongside the road. I hope you say yes, Thad, because I want to get fit to keep on the go till dark comes along.”

“No objections to favoring you, Bumpus,” Thad told him; “and if looks count for anything I rather think all the rest of us will be glad of a chance to rest up a little. So drop down, and take things easy, boys. I’ll give you ten minutes here.”

“Look sharp before you sit down!” warned Smithy, who had disengaged his blanket, as though meaning to use it for a soft cushion—time was when he invariably brushed a board or other intended resting-place with his handkerchief before sitting down; but the other scouts had long ago laughed him out of this habit, which jarred upon their nerves as hardly consistent with rough-and-ready scout life.

Giraffe had a most remarkable pair of eyes. He often discovered things that no one else had any suspicion existed. On this account, as well as the fact that he was able to see further and more accurately than his chums, he was sometimes designated as “Old Eagle Eye,” and the employment of that name invariably gave him more or less pleasure, since it proclaimed his superiority in the line of observation.

Giraffe was also a great hand for practical jokes. When some idea flashed into his mind he often gave little heed to the possible result, but immediately felt impelled to put his scheme into practice, with the sole idea of creating a laugh, of course with another scout as the victim.

They had hardly been sitting there five minutes when Giraffe might have been heard chuckling softly to himself, though no one seemed to pay any particular attention to him.

He elevated that long neck of his once or twice as if desirous of making sure concerning a certain point before going any further. Then, when satisfied on this score, he glanced from one to another of his companions, evidently seeking a victim.

When his gaze, after going along the entire line, returned once more to plump, good-natured Bumpus, who had now ceased puffing, and was looking rested, it might be set down as certain that there was trouble of some sort in store for the red-haired, freckle-faced scout.

Now Giraffe was a sharp schemer. He knew how to go about his business in a way least calculated to arouse suspicion.

Instead of immediately blurting out what he had in mind, he started to “beating around the bush,” seeking to first disarm his intended victim by drawing him into a little discussion.

Before another full minute had passed Thad noticed that Giraffe and Bumpus were warmly discussing some matter, and that the stout scout seemed to be unusually in earnest. Doubtless, this was on account of the sly assertions which Giraffe inflicted upon him, the tall scout being a past master when it came to giving little digs that hurt worse than pins thrust into one’s flesh.

“I tell you I can do it!” Bumpus was heard to say stubbornly.

“Don’t believe you’d ever come within a mile of making it, and that goes, Bumpus.” Giraffe went on as though he might be a Doubting Thomas who could only be convinced by actual contact; “and tell you what I’ll do to prove I’m in earnest. If you make it in three trials, straddling the limb while my watch is counting a whole minute, I’ll hand over that fine compass you always liked so much. How’s that, Bumpus; are you game to show us, or have I dared you to a standstill?”

“What, me back down for a little thing like that? Well, you just watch me make you eat your words, Giraffe!”

So saying the fat scout clambered up over the rail fence, and dropped in the open pasture beyond.

“What’s he going to do?” asked Thad, as they saw Bumpus start on a waddling sort of gait toward a tree that stood by itself some little distance from the fence, and with a clump of bushes not far away.

He looked a little suspiciously at Giraffe, who immediately stopped his chuckling, and tried to draw a solemn face, though he shut one eye in a humorous fashion.

“Why, he started to boast that he had been doing some fine climbing lately,” explained the tall scout; “and I dared him to go over and get up in that tree while I held the watch on him. He’s got to start climbing and make it inside of sixty seconds; and between you and me, Thad, I reckon now he might manage it in half that time—if hard pushed.”

“You’ve got some game started, Giraffe; what is it?” asked the patrol leader, as he turned again and watched the portly scout moving like a ponderous machine toward the tree which Giraffe had mentioned as a part of the contract.

Giraffe did not need to answer, for at that very second there came what seemed to be a loud bellow of rage from over in the field somewhere. Looking hastily through the bars of the fence, the seven boys saw a spectacle that thrilled them with various emotions.

From out of the sheltering bushes, where those keen roving eyes of Giraffe must have discovered her presence, came a dun-colored cow. Possibly her calf had recently been taken from her by the butcher, for she was furious toward all humankind. Her tail was held in the air, and as she ran straight toward poor Bumpus she stopped for a moment several times to toss a cloud of earth up with her hoofs, for she had no horns, Thad noted, which was at least one thing favoring Bumpus.

“Look out, Bumpus!” shrieked Davy Jones, as though instantly realizing what a perilous position the stout scout would be in if that angry cow succeeded in bowling him over with her hornless head.

“Run! run, Bumpus; a wild bull is after you!” shouted Step Hen, who may have really believed what he was saying with such a vim; or else considered that by magnifying the danger he might add more or less to the sprinting ability of the said Bumpus.

There was really little need to send all these warnings pealing over the field, because Bumpus had already glimpsed the oncoming enemy, and was in full flight.

At the moment of discovery he chanced to be fully two-thirds of the way over to the tree which had been the special object of his attention. It was therefore much easier for him to reach this haven of refuge than it would have been to dash for the fence with any hope of making that barrier.

“Go it, Bumpus, I’ll bet on you!” howled Giraffe, jumping up on the fence in his great excitement, so that he might not miss seeing anything of the amusing affair.

Now, possibly, the angry cow that had been bereft of her beloved calf by a late visit of the butcher might have readily overhauled poor Bumpus had she kept straight on without a stop, for she could cover two yards to his one. For some reason which only a cow or bull could understand, the animal seemed to consider it absolutely necessary that with every few paces she must come to a halt and paw the ground again, sending the earth flying about her.

That gave the stout runner his chance, and so he succeeded in gaining the tree, with his four-footed enemy still a little distance away.

Bumpus was evidently unnerved. He had seen that terrifying spectacle several times as he looked anxiously over his fat shoulder, and it had always caused him to put on an additional spurt.

When finally he banged up against the tree, having of course stumbled as usual, his one idea was to climb with lightning speed. His agreement with the scheming Giraffe called for an ascent in sixty seconds, but he now had good reason for desiring to shorten this limit exceedingly. He doubtless imagined that he would feel the crash of that butting head against his person before he had ascended five feet, and this completely rattled him.

Left to himself and possibly he could have climbed the smooth trunk within the limit of time specified in his arrangement with Giraffe; but such was his excitement now that he made a sorry mess of it.

The boys were shrieking all sorts of instructions to him to “hurry up,” or he was bound to become a victim; one was begging him with tears in his eyes to “get a move on him!” while another warned Bumpus of the near approach of the oncoming cow, and also the fact that she had “fire in her eyes!”

Twice did the scout manage to get part way up, when in his tremendous excitement he lost his grip, and in consequence slipped down again, amid a chorus of hollow groans from the watchers beyond the fence.

The avenging cow was now close up, and still enjoying the situation, as was evidenced by the way she made the earth fly. She could be heard giving a series of strange moaning sounds peculiarly terrifying; at least Bumpus evidently thought so, for after his second fall he just sat there, and stared at the oncoming enemy as if he had actually lost his wits.

“Get behind the tree, Bumpus!”

That was Thad shouting, and using both his hands in lieu of any better megaphone. Now, since Thad had always been the leader of the patrol ever since its formation, Bumpus was quite accustomed to obeying any order which the other might give. Doubtless, he recognized the accustomed authority in those tones; at any rate, it was noticed that he once more began to make a move, struggling to his feet in his usual clumsy way.

“Oh! he just missed getting struck!” ejaculated Smithy, as they saw Bumpus move around the tree, and heard a loud crash when the head of the charging cow smashed against the covering object.

The animal was apparently somewhat stunned by the contact, for she stood there, looking a little “groggy,” as Giraffe called it. Had Bumpus known enough to remain perfectly still, and allow the tree to shelter him the best it could, all might have gone well; but something that may have been boyish curiosity impelled the fat scout to thrust out his head. Why, he had so far recovered from his fright, thanks to the substantial aid of that tree-trunk, that he actually put his fingers to his nose, and wiggled them at the cow!

She must have seen him do it, and immediately resented the implied insult; for all of a sudden she was seen to be in motion again. There was a flash of dun-colored sides, and around the tree the cow sped, chasing Bumpus ahead of her.

Of course the scout did not have to cover as much ground as the animal, but the fact must be remembered that he was a very clumsy fellow, and apt to trip over his own feet when excited, so that the danger of his falling a victim to the rage of the mother cow was as acute as ever, despite the sheltering tree.

Giraffe seemed to be enjoying the game immensely. He sat there, perched on the rail fence, and clapped his hands with glee, while shouting all manner of brotherly advice at Bumpus. This of course fell on deaf ears, because just then the imperiled scout could think of only one thing at a time, and that was to keep out of reach of that battering ram.

Thad knew that something must be done to help Bumpus, who if left to his own resources never would be able to extricate himself from the bad fix into which he had stumbled, thanks to that love of a joke on the part of Giraffe, and his own blindness.

“Hi, there, Bumpus, she thinks you look like the butcher that took her calf away, that’s what’s the matter!” cried Step Hen.

“Pity you ain’t a cow puncher, Bumpus,” Giraffe went on to say; “because then you could throw that poor thing easy. Huh! think I could do it with one hand!”

“Then suppose you get off that fence and do it!” said Thad severely. “You got poor old Bumpus in that hole, and it ought to be your business to rescue him!”

Giraffe looked dubious. When he spoke so confidently about believing himself able to down the raging cow he certainly could not have meant it.

“Oh! he ain’t going to get hurt, Thad,” he started to say; “if I saw him knocked down, course I’d jump and run to help him. The exercise ought to do Bumpus good, for he’s been putting on too much flesh lately, you know. You’ll have to excuse me, Thad, sure you will. I’ll go if things look bad for him; but I hate to break up the game now by interfering.”

Thad paid no more attention to Giraffe, since he knew that the other’s inordinate love for practical joking made him blind to facts that as a true scout he should have kept before his mind.

“Hello! Bumpus!” the patrol leader once more shouted.

“Yes—T-had, what is it?” came back in a wheezy voice, for to tell the truth Bumpus was getting pretty well winded by now, thanks to the rapid manner in which he had to navigate around that tree again, with the active bovine in pursuit.

“Take off that red bandanna from your neck, and put it in your pocket!” ordered the patrol leader.

Strange to say no one else—saving possibly the artful Giraffe—had once considered this glaring fact, that much of the cow’s anger was excited by seeing the hated color so prominently displayed by the boy who had invaded the pasture at such an unfortunate time in her life of frequent bereavements.

Taking it for granted that Bumpus would obey the first chance he got to unfasten the knot by which his big bandanna was secured around his neck, Thad clambered over the fence and started to run.

He did not head directly for the tree around which this exciting chase was being carried on, but obliquely. In doing this Thad had several reasons, no doubt. First of all he was more apt to catch the attention of the angry cow, for he was waving his own red handkerchief wildly as he ran, and doing everything else in his power to attract notice. Then, if he did succeed in luring the animal toward him he would be taking her away from the tree at such an angle that when Bumpus headed for the spot where his other chums were gathered the cow would not be apt to see him in motion and give chase.

Thad knew how to work the thing nicely. He succeeded in attracting the attention of the cow, for he saw her stop in her pursuit of Bumpus, and start to pawing the turf again.

“She’s coming, Thad!” roared Allan.

As he spoke the cow started on a full run for the new enemy. That flaunting red rag bade her defiance, apparently, and no respectable bovine could refuse to accept such a gage of battle.

Thad had not gone far away from the fence at any time. He was not hankering to play the part of a bull-baiter, and run the chance of being tossed high in the air, or butted into the ground.

He had, like a wise general, also marked out the way of retreat, and when the onrushing animal was fully started, so that there seemed to be little likelihood of her stopping short of the fence, Thad nimbly darted along, and just at the proper time he was seen to make a flying leap that landed him on the top rail, from which he instantly dropped to the ground.

He continued to flaunt the red handkerchief as close to the nose of the cow as he could, so as to hold her attention; while she butted the fence again and again, as only an angry and baffled beast might.

Thad was meanwhile again shouting his directions to the dazed Bumpus, who, winded by his recent tremendous exertions, had actually sunk down at the base of the friendly tree as though exhausted.

“Get moving, Bumpus!” was what the patrol leader told him. “Back away, and try to keep the tree between the cow and yourself all you can. Don’t waste a single minute, because she may break away from me, and hunt you up again! Get a move on you, Bumpus, do you hear?”

Finally aroused to a consciousness of the fact that he was not yet “out of the woods” so long as no fence separated him from that fighting cow, Bumpus started in to obey the directions given by the leader of the Silver Fox Patrol.

It was no difficult matter to back away, keeping in a line that would allow the tree to cover him, and the fat scout in this manner drew steadily closer to where his comrades awaited him.

He was near the fence when the cow must have discovered him again, for the first thing Bumpus knew he heard Davy shrieking madly.

“Run like everything, Bumpus! Whoop! here she comes, licketty-split after you! To the fence, and we’ll help you over, Bumpus! Come on! Come on!”

Which Bumpus was of course doing the best he knew how, not even daring to look over his shoulder for fear of being petrified by the awful sight of that “monster” charging after him, and appearing ten times as big as she really was.

Arriving at the fence he found Davy and Giraffe awaiting him, for the latter, possibly arriving at the repentant stage, had begun to realize that a joke may often be very one-sided, and that “what is fun for the boys is death to the frogs.”

Assisted by their willing arms the almost breathless fat scout was hustled over the fence. There was indeed little time to spare. Hardly had Davy and Giraffe managed to follow after him, so that all three landed beyond the barrier, when the baffled bovine arrived on the spot, to bellow with rage as she realized that her intended prey had escaped for good.

Bumpus was hardly able to breathe. He was fiery red in the face, and quite wet with perspiration; but nevertheless he looked suspiciously at Giraffe, as though a dim idea might be taking shape in that slow-moving mind of his.

“Oh, no, Bumpus! You don’t get that compass this time,” asserted the tall scout, shaking his head in the negative, while he grinned at Bumpus. “You never climbed the tree at all, you know. Our little wager is off!”

“If I thought you knew—about that pesky cow, Giraffe—I’d consider that you played me a low-down trick!” said Bumpus, between gasps.

Giraffe made no reply. Perhaps the enormity of his offense had begun to trouble him, because Bumpus was such a good-natured fellow, with his sunny blue eyes, and his willing disposition, that it really seemed a shame to take advantage of his confiding nature. So Giraffe turned aside, and amused himself by thrusting his hand, containing his own red bandanna, through the openings between the rails of the fence, and tempting the cow to butt at him, when, of course, he would adroitly withdraw from reach in good time.

When Bumpus had fully recovered his breath, the march was resumed. Giraffe loitered behind a bit. He knew from the signs that he was in for what he called a “hauling over the coals” by the patrol leader, and fully expected to see Thad drop back to join him. The sooner the unpleasant episode was over with the better—that was Giraffe’s way of looking at it, and he was really inviting Thad to hurry up and get the scolding out of his system.

Sure enough, presently Thad dropped back and joined him. Looking up out of the tail of his eye, Giraffe saw that the other was observing him severely. He fully expected to hear something unpleasant about the duty one scout ought to assume toward his fellows. To his surprise Thad started on another tack entirely.

“I want to tell you a little story I read the other day, Giraffe,” he said quietly, “and, if the shoe fits, you can put it on.”

“All right, Thad; you know I like to hear stories first rate,” mumbled Giraffe, glad at least that the others of the party were far enough ahead so that none of them could hear what passed between himself and the patrol leader.

“I think,” began Thad, “it was told to illustrate the old saying that ‘curses, like chickens, come home to roost.’ The lecturer went on to say that when a boy throws a rubber ball against a wall it bounds back, and, unless he is careful, it’s apt to take him in the eye; and that’s the way everything we do comes back to us some time or other.”

“Sure thing it does; and p’raps some day I expect Bumpus will be getting one over on me to pay the score,” admitted Giraffe; but Thad did not pay any attention to what he said, only went on with his story.

“There was once a boy, a thoughtless boy, with a little cruel streak in his make-up, who always wanted to find a chance for a good laugh, without thinking of what pain he might be causing others,” Thad went on, at which Giraffe winced, for the shaft went home. “One day he was playing on a hillside with their big dog, Rover. He would roll a stone down the hill, and Rover would obediently run after it, and bring it back. He seemed to be enjoying the sport as much as the boy.

“Then all at once the boy discovered a big hornet’s nest almost a foot in diameter, hanging low down on a bush. He saw a chance to have a great lark. He would roll a stone so as to hit the nest, and send Rover after it. Then the hornets would come raging out, and it would be such a lark to see them chasing poor Rover down the hill.

“Well, the stone he rolled went true to the mark, and came slam against the hornet’s nest. Rover was in full pursuit, and he banged up against it, too. Out came a black swarm of furious hornets, and of course they tackled poor Rover like everything.

“The boy up on the hill laughed until he nearly doubled up, to hear Rover yelp, and whirl around this way and that. He thought he had never had such a bully time in all his life as just then. Rover was a fine dog, and the boy thought just heaps of him; but then it was so comical to see how he twisted, and bit at himself, and he howled so fiercely, too, that the boy could hardly get his breath for laughing.

“But all at once he saw to his alarm that poor Rover, unable to help himself, was running up the hill straight to his master, as though thinking that the boy could save him. Then the boy stopped laughing. It didn’t seem so funny then. And, Giraffe, inside of ten seconds there was a boy running madly down the hill, fighting a thousand mad hornets that stung him everywhere, and set him to yelling as if he were half crazy. When he got home finally, and saw his swollen face in the glass, and felt Rover licking his hand as if the good fellow did not dream that his master had betrayed him so meanly, what do you suppose that boy said to himself, if he had any conscience at all?”

Giraffe looked up. He was as red in the face as any turkey that ever strutted and gobbled. Giraffe at least had a conscience, as his words proved beyond any doubt.

“Served him right, Thad; that’s what I say! And I thank you for telling me that story. It’s a hummer, all right, and I won’t ever forget it, either, I promise you. It was a cruel joke, and some time I’m going to make up for playing it. That’s all I want to say, Thad.”

And the wise patrol leader, knowing that it would do Giraffe a lot more good to commune with himself just then, rather than to be taken to task any further, walked away, to rejoin Allan, who was at the head of the expedition. Nor did Giraffe make any effort to hasten his footsteps so as to catch up with the rest, until quite some little time had elapsed.

“There’s a farmhouse over yonder, Thad; and night’s coming on pretty fast now!” called out Davy Jones later on, after the expedition had covered several more miles of ground, and seemed to be descending an incline that would very likely shortly take them to the bank of the winding Susquehanna.

“I hope we decide to bunk in a haymow, and not out in the open to-night,” added Step Hen. “Not having any tents along makes it a poor business trying to keep off the rain, if she should drop in on us. How about it, Thad?”

“I reckon, suh, we’re all of one mind there,” remarked Bob White.

“Just as you say, boys,” Thad announced. “We’ll turn in here, and see if the farmer will allow us to camp in his barnyard.”

“And mebbe he might sell us a couple of fat chickens, and some fresh milk or cream to go with our coffee. That would be about as fine as silk, I’m telling you,” and Giraffe, who had rejoined his comrades, looking just the same as ever, rubbed his stomach as he said this, by that means implying that the prospect pleased him even more than words could tell.

Accordingly the line of march was changed. They abandoned the road, and started up the lane that led to the farmhouse. A watchdog began barking furiously, and at the sound several people came out of the house, and the big barn as well; so that while the scouts had clustered a little closer together, as though wishing to be ready for an attack, they knew there was now nothing to fear.

Three minutes later and they were talking with the grizzled farmer, his good wife, a couple of girls, and the stout young hired help named Hiram, all of whom were fairly dazzled by the sight of eight khaki-clad young fellows, some of whom carried shotguns, grouped in their dooryard.

Thad explained that they were a patrol of Boy Scouts from Cranford, on a hike, and not having tents along with them, made bold to ask the farmer if they might sleep in his haymow, and cook their supper in the open space before the barns.

There was something inviting about Thad Brewster’s manner that drew most people toward him. That same farmer might have been tempted to say no under ordinary conditions, for he looked like a severe man; but somehow he was quite captivated by the manly appearance of these lads. Besides, he had doubtless read considerable about the activities of the scouts, and felt that the chance of hearing something concerning them at first hand was too good to be lost.

“I ain’t got the least objection to you boys sleeping in my hay, if you promise me not to light matches, or do any smokin’ there,” he said.

“I’ll look out for that, sir,” replied Thad promptly, “and we all promise you that there will be no damage done from our staying over. We will want to make a cooking fire somewhere, but it can be done at a safe distance from the barn, and to leeward, so that any sparks will go the other way.”

“And if so be you could spare us a couple of chickens, mister,” put in Giraffe, “we’d be glad to pay you the full market price; as also for any milk or cream or eggs you’d let us have.”

“Oh! you can fix that with the missus,” returned the farmer; “she runs that end of the farm. I look after the crops and the stock. Now, if you wanted a four-hundred-pound pig I’ve got a beauty to offer you.”

“Thanks, awfully,” returned Step Hen quickly, giving Giraffe, who was a big eater, a meaning look; “but I reckon we’re well supplied in that way already.”

Arrangements were quickly made with the farmer’s wife, and under charge of the willing Hiram, who never could get over staring at the uniforms of the scouts with envy in his pale eyes, some of the boys gave chase to a couple of ambitious young roosters that were trying their first crow on a nearby fence, finally capturing and beheading the same.

Thad meanwhile accompanied the good woman to her dairy, and returned with a brimming bucket of morning’s milk, as well as a pitcher of the thickest yellow cream any of them had ever gazed upon.

The girls brought out some fresh eggs, and altogether the sight of so much riches caused Giraffe to smile all over.

Giraffe was the acknowledged leader when it came to making fires, and that duty as a rule devolved upon him. He had made a particular study of the art, and in pursuing his hobby to the limits was able to get fire at his pleasure, whether he had a match or not. And in more than a few times in the past this knowledge had proved very useful to the tall scout, as the record in previous stories concerning the doings of the Silver Fox Patrol will explain.

Accordingly Giraffe had chosen to make a neat little fireplace out of smooth blocks of stone which happened to lie handy. This he had built at the spot selected by Thad as perfectly safe; for what little wind there was would blow the sparks in a direction where they could do no possible damage.

When Hiram came back he forgot all about any chores that might be waiting. Never before had he been given such a glorious chance to witness the smart doings of Boy Scouts. He observed everything Giraffe did when he made that cunning little out-of-doors cooking range, and noted that while the double row of stones spread wide apart at one end, just so the big frying pan would set across, they drew much closer at the other terminus, like the letter V, so that the coffee pot could be laid there without spilling.

Then Giraffe started his fire. Hiram noticed how he picked certain kinds of wood from the abundant supply over at the chopping block. Giraffe liked to be in the lime light; and he was also an accommodating chap. He saw that the farmhand was intensely interested, as well as quite green at all such things; but the fact of his “wanting to know” was enough to start the scout to imparting information.

So he told Hiram how certain kinds of wood are more suitable for cooking purposes, since they make a fierce heat, and leave red ashes that hold for a long time; and it is over such a bed that the best cooking can be done, and not when there is more or less flame and smoke to interfere.

Allan and Davy had been very busy plucking the fowls during this time, while Bumpus busied himself getting some fresh water from the well near by, and fixing the coffee ready to go on the fire when Giraffe gave the word that he was prepared.

One of the girls brought a loaf of fresh homemade bread, and a roll of genuine country butter that was as sweet as could be. Fancy with what impatience those boys waited while supper was being cooked. The odors that arose when the cut-up chicken was browning in the pan along with some slices of salt pork, and the coffee steaming on one of the stones alongside the fire, made a combination that fairly set several of the fellows wild, so that they had to walk away in order to control themselves.

Finally the welcome signal was given by Bumpus, and never had those silver notes of the “assembly” sounded sweeter in mortal ears than they did that night in the barnyard of that Susquehanna farm, with the eight khaki-clad scouts sitting on logs, and any other thing that offered, and every inmate of the farmhouse gathered near by to watch operations.

They had a feast indeed, and there was plenty for every one and to spare. Indeed, Hiram had accepted the invitation of Giraffe to hold off supper, and join them, and the big fellow seemed to be enjoying his novel experience vastly, if one could judge from the broad grin that never once left his rosy face.

After the meal was over they found seats, and as the fire sparkled and crackled merrily Thad told them all that he possibly could about the aims and ambitions of the scout movement. He found a very attentive and appreciative audience; and it was possible that seeds were planted in the mind of Hiram on that occasion calculated to bear more or less good fruit later on in his life.

Of course Thad had to explain to some extent why they were so far away from home, and this necessitated relating the story about the old army overcoat that had been turned over to a tramp through the desire of the judge’s second wife to get rid of it. Thad of course only went so far as to say that the judge mourned the loss of an article which he really valued highly on account of its association with his only son’s army life years before; and he made out such a strong case that those who heard the story could easily understand why the gentleman should wish to recover the garment again, if it were possible.

None of them could remember having seen any party wearing such a coat; and it would seem that if the hobo had passed along that way, he might have applied at the farmhouse for a meal, though the presence of the dog usually deterred those of his kind from bothering the good farm wife.

“Guess they’ve got the chalk mark on your gate post, mister,” commented Step Hen, when he heard this; “I’ve been told these hoboes leave signs all along the way for the next comer to read. Some places they say are good for a square meal; then at another place you want to look sharp, for the farmer’s wife will ring pies on you that are guaranteed to break off a tooth in trying to bite ’em. Now, like as not there’s a sign on your post that says: ‘Beware of the dog; he’s a holy terror!’”

“I hope there is,” replied the farmer; “and if I knew what it was I’d see it got on every post I own, for if there’s one thing I hate it’s a tramp. I’ve had my chickens stolen, my hogs poisoned, and my haymow out in the pasture burned twice by some of that worthless lot. They kind of know me by now, and that I ain’t to be trifled with.”

The evening passed all too quickly; and when Step Hen happened to mention that Bumpus was the possessor of a beautiful soprano voice of course the country girls insisted that he entertain them. Bumpus, as has been remarked before, was an accommodating fellow, and he allowed himself to be coaxed to sing one song after another, with all of them joining in the chorus, until he was too hoarse to keep it up. Then they spied his lovely silver-plated bugle, and nothing would do but he must sound all the army calls he knew, which added to the enjoyment considerably.

Taken in all, that was the most novel entertainment any of them had ever experienced; and especially those who lived in the lonely farmhouse. It must have been a tremendous and pleasant break in the monotony that usually hangs like a pall upon all farm work. No wonder, Thad thought, all of them looked so happy when they were bidding the boys good night, and admitted that they had enjoyed the coming of the expedition greatly.

Hiram could not be “pried loose,” as Giraffe said. He insisted on seeing all he could of these new and remarkable friends, and had announced his intention of accompanying the scouts to the hay, and sleeping near them.

No one offered the least objection. Indeed, by this time, after such an exhausting march as they had been through since sun-up, all of them were pretty tired, and their one thought was to snuggle down in the hay, with their blankets wrapped around them, and get some sleep.

“Still cloudy and threatening,” remarked Allen, as he and Thad took a last look around ere turning in.

“Yes, it’s holding off in a queer way,” replied the other, “but when it does hit us, look out for a downpour. I’d be glad if we ran on that Wandering George before the rain starts in, because it’ll be hard getting around when the whole country is soaked and afloat.”

“I’m told the river is already close to flood stage, owing to so much snow melting at headwaters,” observed Allan.

“Yes, we had an unusual lot last winter, you remember; and when the weather turned actually hot a few days back it must have started the snow melting at a furious rate. If we get a hard rain now there’ll be a whopping big flood all along the Susquehanna this spring.”

“Everything seems all right around here, doesn’t it?” asked Allan, as he bent down over Giraffe’s fireplace, with the caution of a hunter who knew how necessary it always is to see that no glowing embers have been forgotten that a sudden wind could carry off to cause a disastrous conflagration.

“I saw Giraffe throw some water over the coals,” remarked Thad. “He loves a fire better than anyone I know, but you never find him neglecting to take the proper precautions. Yes, it’s cold to the touch. Let’s hunt a place to bunk for the night, Allan. With our blankets, a bed in the soft hay ought to feel just prime.”

Nine of them burrowed into the big haymow, with all sorts of merry remarks, and a flow of boyish badinage. Finally they began to get settled in their various nooks and the talking died down until in the end no one said a single word, and already Bumpus and perhaps several others began to breathe heavily, thus betraying the fact that they had passed over the border of dreamland.

Thad of course had more to think about than most of his mates, because, as the patrol leader, and head of the present expedition, he found problems to study out that did not present themselves to such happy-go-lucky fellows as Bumpus, Step Hen, Davy, and perhaps Giraffe. So Thad lay there for quite some time, thinking, and trying to lay out some plan of campaign to be followed in case the expected rain did strike them before they came up with the fugitive tramp.

It was very comfortable, and the hay was sweet-smelling, so that even the fastidious Smithy had not been heard to utter the least complaint, but had burrowed with the rest. Possibly he may have swathed his face, as well as his body, in the folds of his blanket, in order to prevent any roving spider from carrying out the gypsy’s evil prophecy; but if so no one knew it, since all of them but Allan and Thad had made separate burrows.

The young scout master remembered that his thoughts became confused, and then he lost his grip on things.

It seemed to him that his dreams must be wonderfully vivid, for as he suddenly struggled up to a sitting position he could fancy that he heard some one calling at the top of his voice. Then shrill screams in girlish tones added to the clamor.

“What’s that mean, Thad?” demanded Allan, as he clutched the arm of his chum, at the same time sitting up.

“I don’t know,” replied Thad shortly. “There must be something wrong up at the farmhouse. The other fellows are stirring now, so let’s crawl out of this in a big hurry, Allan!”

Both scouts made all haste to escape from the tunnel under the hay, kicking their way to freedom. No sooner had they gained their feet than they started out of the barn, for the haymow was under the shelter of a roof.

Only too well did Thad know what was the matter, when he burst from the door of the barn, and saw that the darkness of the night was split by a glare from up in the direction of the farmhouse on the rise. Through the bare branches of the trees he could see tongues of flames.

“The house is on fire, Allan!” he shouted. “We must get all the boys out, and do what we can to fight the flames. Hi! everybody on deck—Giraffe, Step Hen, Davy, and the rest of you, hurry out here and lend a hand! You’re wanted, and wanted badly into the bargain!”

Feeling sure that the rest of the scouts, as well as Hiram, the overgrown country boy who worked on the farm, would be along shortly, Thad and Allan seized upon a couple of buckets, filled them at the watering trough near by, and hastened toward the burning building.

The farmer, partly dressed, was doing valiant work already, and his wife kept up a constant pounding of the pump, filling buckets as fast as the man of the house emptied them.

When the two scouts got to work things began to look more hopeful, though with the flames making such rapid headway it promised to be a hard fight to win out.

Thad wondered why the fire should have gained such a tremendous headway, but later on the mystery was explained, and he understood the reason. When kerosene is dashed around it offers splendid food for fire, once the flame is applied.

Now came all of the other fellows, eager to lend a helping hand. The farmer had been neighborly and kind, and his folks had helped to make a pleasant night for their unexpected but nevertheless welcome guests, and on this account alone Thad and his chums felt that they must do all in their power to save the house. Then again they were scouts, and as such had cheerfully promised to always assist those in trouble, whether friends, strangers, or even enemies.

They found all manner of vessels capable of holding more or less water. Bumpus even manipulated a footbath, although on one or two occasions he had to stumble as usual, and came very near being drowned in consequence, since he deluged himself from head to foot with the contents.

When such a constant stream of water was being poured upon the fire it could not make much headway.