MY MAMIE ROSE

My Mamie Rose

The Story of My

Regeneration

By OWEN KILDARE

An Autobiography

New York

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1903, by THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY

Published, October, 1903

To

L. B. R.

CONTENTS.

Chapter

ILLUSTRATIONS.

Owen Kildare . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

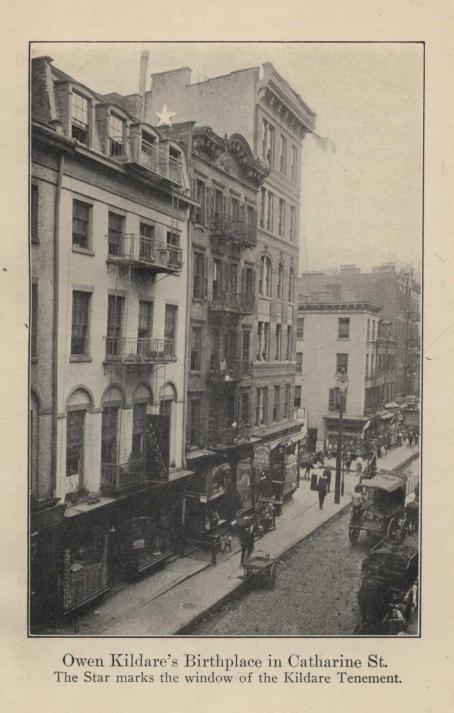

Mr. Kildare's Birthplace on Catharine Street

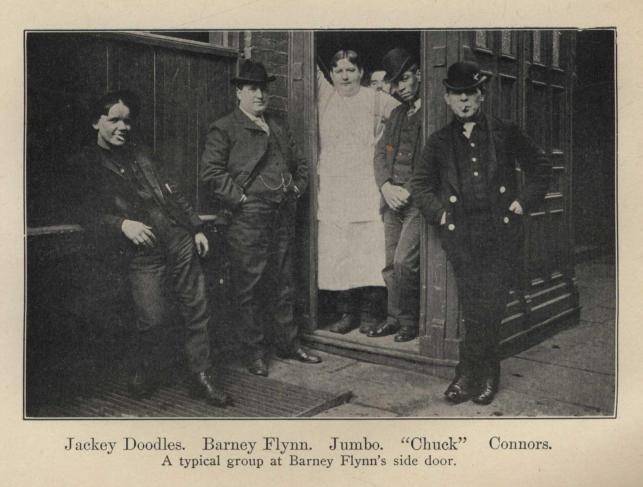

A Typical Group at Barney Flynn's Side-Door

THE KID OF THE TENEMENT.

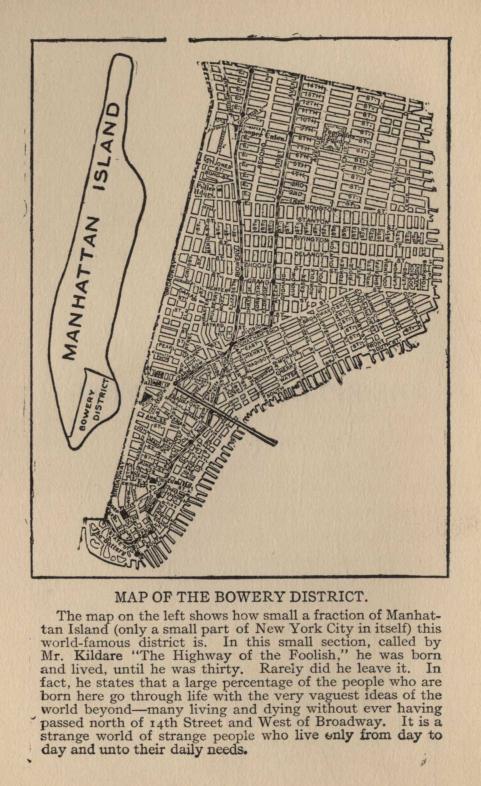

MAP OF THE BOWERY DISTRICT.

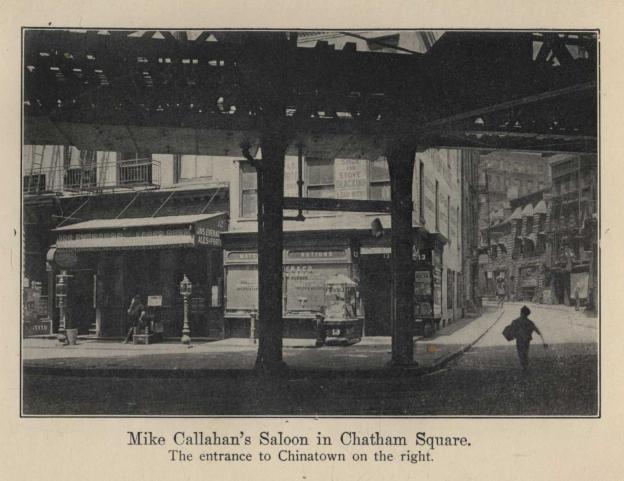

The map on the left shows how small a fraction of Manhattan Island (only a small part of New York City in itself) this world-famous district is. In this small section, called by Mr. Kildare "The Highway of the Foolish," he was born and lived, until he was thirty. Rarely did he leave it. In fact, he states that a large percentage of the people who are born here go through life with the very vaguest ideas of the world beyond—many living and dying without ever having passed north of 14th Street and West of Broadway. It is a strange world of strange people who live only from day to day and unto their daily needs.

MY MAMIE ROSE.

CHAPTER I.

THE KID OF THE TENEMENT.

Many men have told the stories of their lives. I shall tell you mine. Not because I, as they, have done great and important things, but because of the miracle which transformed me.

If lives may be measured by progress mine may have some interest to you. When a man at thirty cannot read or write the simplest sentence, and then eight years later is able to earn his living by his pen, his story may be worth the telling.

Before beginning, however, the recital of how I found my ambition awakened, let me make my position unmistakably definite. I am not a self-made man, having only contributed a mite in the making. A self-made man can turn around to the road traveled by him and can point with pride to the monuments of his achievements. I cannot do that. I have no record of great deeds accomplished. I am a man, reborn and remade from an unfortunate moral condition into a life in which every atom has but the one message, "Strive, struggle and believe," and I would be the sneakiest hypocrite were I to deny that I feel within me a satisfaction at being able to respond to the call with all the possible energy of soul and body. I have little use for a man who cloaks his ability with mock modesty. A man's conscience is the best barometer of his ability, and he who will pretend a disbelief in his ability is either untruthful or has an ulterior motif.

In spite of having, as yet, accomplished little, I have confidence in myself and my ability, because my aims are distinctly reasonable. I regret that in my story the first person singular will be so much in evidence, but it cannot be otherwise. Each fact, each incident mentioned, has been lived by me; the disgrace and the glory, the misery and the happiness, are all part of my life, and I cannot separate them from myself. I know you will not disbelieve me, and I am willing to be confronted by your criticism, which, for obvious reasons, will not be directed against my diction, elegance of style and literary quality. I am not an author. I only have a story to tell and all the rest remains with you.

There was nothing remarkable about my early childhood. Most of the boys of the tenements are having or have had the same experience.

The home which sheltered my foster parents (my own father and mother died in my infancy, as I will tell you later) and myself consisted of two rooms. The rental was six dollars a month. Located on the top floor of an old-style tenement house in Catharine street, our home was lighted and ventilated by one small window, which looked out into a network of wash-lines running from the windows to tall poles placed in the corners of the yard. By craning your neck out of the window you could look into the yard, six stories below, and discover the causes of the stenches which rose with might to your nostrils.

The "front room" was kitchen, dining-room, living room and my bedroom all in one. Beside the cooking range in winter and beside the open window in summer was the old soap box on its unevenly curved supports, which, as my cradle, bumped me into childhood.

As may be surmised, both of my foster parents were Irish. My father, a 'longshoreman, enjoyed a reputation of great popularity in the Fourth Ward, at that time an intensely Irish district of the city. Popularity in the Fourth Ward meant a great circle of convivial companions and a fair credit with the ginmill keepers. His earnings would have been considerable had he been a persistent worker. But men of popularity cannot afford to be constantly at work. It would perhaps fill their pocketbooks, but decrease their popularity. These periods of conviviality, hilarious intervals to my father, were most depressing to my mother.

Life in tenements is a particularly busy one of its kind. When all efforts are directed toward the one end of providing the wherewithal for food and rent, each meal and each rent day is an epoch-making event.

As soon as one month's rent is paid, each succeeding day has its own thoughts of dread "against next rent day." The thrifty housekeeper lays aside a share of her daily allowance—increasing it during the last week of the month—until, with a sigh of relief, she can say, "Thank God, we got it this time."

I firmly believe that a great share of the dread is created by the aversion to a personal meeting with the rent collector or agent. People who have to measure the size of their meals by the length of their purses are very apt to become a trifle unsteady in their ethics concerning financial questions. They are willing to pay their grocer or butcher, but lose sight of the fact that the rent money is the payment for the most important purchase, the securing of their home. They are friendly with the shopkeeper, are often "jollied" by him into spending money otherwise needed, but regard the rent collector as their personal enemy.

There are many rent collectors, and, as in all greater numbers, quite a few are justly criticised for their manner. Many tenements are owned by men, who, though the owners, are only on a slightly different scale socially from their tenants. They are men, who, by great shrewdness or some fortunate chance, accumulated enough to make a real estate investment in their own ward. Naturally, they being familiar with the circumstances of their tenants and having a remnant of neighborly feeling for them, are more easily influenced.

Many blocks of tenements were then and are now owned by large estates. The management of these buildings is entrusted to real estate agents, who receive a commission on their collections, or to salaried representatives, who owe their position to the faculty of keeping rents up and keeping repairs down. These are the men who are hated by the poor.

It is said corporations have no souls, why then should a large estate, surely a corporation, have one? And there must be a soul to understand, to feel the woe, the pleading that comes to it in halting, sob-broken speech. How, then, is one whose feeling is long ago calloused by the repetition of these tales of misery, to be stirred to more than a sneer by another variation of the old, old wail: "Have pity on us this once, we are so poor, so ill, so miserable."

Here the poor could be reproached for shiftlessness in household matters, for not practising sufficiently the principles of economy. The reproach would be perfectly justified and would touch one of the most potent causes for the existing conditions among the poor. No one lives more lavishly and knows less how to save than the poor. Their expense account is not based on a sanitary or monetary basis, but shapes itself according to temporary income.

"Plenty of money in the house" and rent day far in the distance, and many families will absolutely gorge themselves at table with food and drink, only to return on perhaps the very next day to tea and dry bread.

For this reason no social movements on the East Side are worthier of hearty support than those carried on to teach children, and especially girls, "How to keep house." Teach them how to keep house, and they will make homes.

If rent days are the fearful anticipations of tenement house life, meals and their preparation are the pleasurable anticipations of it. At morning, noon and evening the smells of cooking and frying waft from the open doors of the apartments into the halls. The doors are open for two reasons—for ventilation and to "show" the neighbors that more than the tea kettle is bubbling away on the range. Behind the closed doors there is no feast, just the tea and the bread and scheming how to explain this unwelcome fact to the neighbors.

My mother found her best hold on her husband's affections by catering to his appetite, which was one of the marvels of the neighborhood. When working he was very exacting in the choice and preparation of his food; so, when idle his wife would strive still harder to cheer him into better humor by culinary feats.

Besides this promiscuous cooking, there were mending, washing, darning and other housework to be looked after, and little time was left for sentiment toward me beyond an occasional affectionate pat on the head.

Now, take the mind, the heart of a child, and then consider the influence of such a barren existence on it. A child can do without coddling—yes, most boys do not, or pretend not to like it—but a child's heart, sensitive as no other, hungers for a wealth of affection.

The child, a little ape, finding no outlet for his willing response to affection, seeks a field of mental activity in imitating the adults about him. And the models and patterns in tenement spheres are not those a child should imitate. All conditions there are primitive. To eat, drink, sleep and be clothed are the aims of life there, leaving but a small margin for emotions.

The forms of expression are also primitive and accepted. The worthy housewife, who, in a moment of anger at her husband's mellow state, should vent her feelings in an outburst of more emphatic than polite language, will not lose caste thereby, but will be told by sympathetic fellow-sufferers that "She did just right."

Among the men it is considered an indication of effeminacy or dudeism to utter one sentence without profanity. To be deemed manly one must curse and swear. Even terms of endearment are prefaced with an unintentionally opposite preamble.

There, not yet mentioning the other detrimental defects of environment, the child grows up, and then, when in the manhood days this foundation, faulty and vicious, breaks and crumbles to pieces and leaves naught but a being condemned by society and law, and seemingly by God, there is an army ready to pelt this creature, cursed by its own existence, with law, justice and punishment, but not with one iota of the spirit which even now, in our matter-of-fact days, echoes the grandest message, "He is thy brother."

Such was the setting of the stage on which the drama of my childhood began. The part I played in it was not very interesting.

An adult man or woman can do with a minimum of space, but a child must have much of it. To romp and play and scheme some mischief requires lots of room, and there being not an inch of room to spare in tenement apartments, the children in summer and winter claim the street as their very own realm.

It is bad that it is so, for there is much in the street which is of physical and moral danger to the child. Hardly a day passes without having a boy or girl hurt by some passing vehicle. It is almost impossible to guard against these accidents. The drivers are careful. No one can make me believe that these men would wantonly drive into a swarm of playing children, but there are so many, so many.

Convince yourself of this. You need not have to travel very far. Take any street, east or west of the Bowery, and the young generation, crowding before your very feet or jostling against you in innocent play, will tell you more effectively than my pen could of what the real need of the East Side is.

But then parks and play grounds do not bring rentals; tenement houses do, and, further, even the child-life of those districts is dependent on the whims of our patriotic ward politicians.

Among the very poor—and my parents were of that class—it is the custom to send out the children to pick up wood and coal for the fire. My mother, being constantly engaged in looking after the welfare of my father, had not very much time to spare on me, and I grew up very much by myself.

Even before it had become my duty to "go out for coal," I loved to take my basket and make my way to the river front to pick up bits of coal dropped in unloading from the canal boats or by too generously filled carts.

Among my playmates I held a very unimportant position, being neither very popular nor unpopular. I did not mind this much, as I felt, instinctively, that something was wrong and that I was not on a level footing with them. It is impossible for me to explain why I felt so at the time, but I can distinctly remember that quite often I felt myself entirely isolated.

No one minded me or censured me for my long absences from home, provided my basket was fairly well filled with coal. Then spells of envy often came to me. I envied the caresses given by mothers to their sons and, yes, I also envied the cuffs given to them for having spent too much time at the retail coal business.

I reasoned so then and I reason so now, that behind every whipping given to a child a father's or mother's love and justice is hidden. But even parental chastisement was denied me—a fact for which, according to popular opinion, I should have been thankful.

In this way I lived the dull life of a tenement house child, made more dull in my case by the lack of a certain inexplicable something in my relations to my parents and in my home conditions. I missed something, yet could not tell what it was.

It can hardly be termed a hidden sorrow, but make a boy ponder and worry about something, for which no explanation is vouchsafed to him, and he will get himself into a mental state not at all healthy for his years.

Close to the cooking range was an old box used as a receptacle for wood and coal. There was my seat, and from there I watched the little domestic comedies and tragedies played before me with my father and mother as chief actors.

My father's popularity made our home the calling place for many visitors. At these visits the most frequently used utensil was the "can," or "growler," and the functions usually assumed the character of an "ink pot." Several houses in the ward had well proven reputations as "mixed ale camps," meaning thereby places where certain cronies could meet nightly and "rush the growler" as long as the money lasted. If the friends were more than usually plentiful, the whisky bottle, called always the "bottle," besides the "can," was kept well filled, producing a continuation of effects, sometimes running to fighting; at other times running to maudlin sentimentality. These occasions—no one knows why—are called "ink pots."

My father's house was in a fair way to become listed among the well established "mixed ale camps." In those days no law had yet been passed making the selling of "pints" of beer to minors a punishable offense, and children of both sexes were employed until late in the night, when the bar-rooms were crowded with drunken and boisterous men, to "rush the growler" for their seniors at home. The children did not object to it, as a few pennies were always given to them for the errand.

I, also, had to make these journeys to the nearest saloon, and, also, did not mind it for the above mentioned reason. Sometimes, after returning from my trip, a man would ask me to sing him one of the popular songs of the day, but I would refuse with the diffidence of a boy. My father never missed these opportunities to inform his friends that "that brat ain't good for nothing. Don't bother with him."

I began to dislike my foster father, rather than hate him. More than once I met his casual glance with a bitter scowl.

A PAIR OF SHOES.

CHAPTER II.

A PAIR OF SHOES.

It was winter, still. I was running about bare-footed. This was preferred by me to having my feet shod with the old shoes of my mother. She had a small foot, yet her old shoes were miles too large for me, and furthermore, always made me the butt of the jeers and jibes of my playmates in the street. Therefore, I never wore the cast-off shoes unless snow or ice was on the ground.

But whether bare-footed or slouching along in my unwieldy cast-offs, the comments became so personal that I resolved to ask my father for a pair of real, new shoes.

The moment for presenting my petition anent the new shoes was ill chosen.

My father was experiencing a period of idleness, and had reached that intense state of feeling which prompted him to declare with much banging on the table that "there wasn't an honest day's work to be got no more, at all, by an honest, decent, laboring man." At the moment my mother was deeply engaged in the task of mollifying her husband's irascibility by preparing some marvelous feat of cooking, and was not at liberty to give me her most essential moral support.

My request was received in silence. It was an ominous silence, but I did not realize it.

I insisted.

"I want a pair of shoes all to myself, the same as other boys have."

"Oh, is it shoes you want? New shoes? Shoes that cost money, when there ain't enough money in the house to get a man a decent meal. I'll give you shoes; indeed I will."

Still I insisted. Then that which, perhaps, should have happened to me long before, was inflicted upon me. I was beaten for the first time, to be beaten often and often again afterward.

The whipping roused my temper. From a safe distance I upbraided my father for punishing me for demanding that which all children have a right to demand from their parents, to be properly clothed. This incited his humor; but, after his laugh had ended, he told me in the most direct and blunt way of my status in the family, and also informed me that if he felt so disposed he could at any time kick me into the street, where I, by right, belonged.

Without mincing his words he told me the story of my parentage. At least, he told me that I was no better than an orphan, picked from the gutter, and kept alive by the good nature of himself and his wife.

It was all true.

In the days to follow I learned more and more about my parents from the legendary lore of neighborly gossip. And even he, my foster-father, could say naught but good about my father and mother, if he did hate their son.

No, I should not say he hated me. Patrick McShane had a good heart, but permitted it too often to be poisoned by the poison of the can and bottle.

All I know about my own father is that he was a typical son of the Emerald Isle. Rollicking, carefree, ever ready with song or story, he was a universal favorite during his sojourn in the ward where he had made a home for himself and his wife for the short time from his arrival in this country until his death.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of meeting the owner of the building where our home had been and where I was born. In spite of his old age, he still remembered my father.

"Do you know, my boy, your father was a fine man? The same as any man, who lets nice apartments to tenants, I had to see that rents were regularly paid, and I always did that without being any too hard on them. But it was all different with your father. There were a few times when his rent was either short a few dollars or not there at all, but before I had the chance to get angry he'd tell me a story or sing me a ditty, and instead o' being mad I'd leave and forget all about my rent. Ah, indeed, Owney, boy, a fine man was your father."

Not much of an eulogy, but much, very much, to me, the son. I have nothing, no likeness, no photograph, to help my mind's eye see my parents; and, therefore, any tribute, no matter how trifling, paid to the memory of my father and mother goes toward perfecting the picture of them, fashioning in my soul.

My mother was a French woman, who married my father shortly before departing for this country from France, where he had gone to study art. They knew very little of her in the district. All her life seemed to be centered in her husband, and she was rarely seen out of her own rooms. The only breathing spells she ever enjoyed were had on the roof—quite convenient to the top floor, where the home was—and there she would get a whiff of fresh air, to the accompaniment of one of my dad's songs.

Why could I not know them?

Not being amply provided with funds, my parents, shortly after their arrival in this country, were compelled to take apartments on the top floor of the tenement house in Catharine street, where I was born.

My mother died at my birth; my father had preceded her by three months.

Sad is the fate of a baby orphaned in a tenement house. Each family has little, and many to subsist on it.

But I, the orphaned babe, was singularly fortunate.

Even the lives of the poor are not devoid of romance, and, owing to one, I found a home.

Not so very long before my parents made their domicile in the Fourth Ward, Patrick McShane, one of the most popular and finest looking young men of the neighborhood, had "gone to the bad." He had neglected his work to share in the many social festivities—otherwise, "mixed ale camps"—until his sober moments were very few and far between.

As soon as his status of confirmed drunkard was established, he was not as welcome as formerly at the many gatherings. The reason for it was his irascible temper while under the influence of drink.

Finding himself partly ostracized, he kept to the water front, spending his days and nights down there.

Facing the river is South street. At one of the corners was the gin mill and legislative annex of a true American patriot and assemblyman. Always anxious to pose before his constituents as a man whose charity knew no bounds, this diplomat, this statesman, had given a home to his niece, the daughter of his deceased brother. Perhaps it was just a coincidence that, on the same day, on which his niece became a member of the household the servant girl was discharged.

At any rate, Mary McNulty found little time to walk the sidewalks of Catharine street, as was the wont of the belles of the ward. Even would she have had the time for it, she would not have availed herself of it, for one very good reason. Mary McNulty was not beautiful.

During her first few weeks in the neighborhood she had been quickly christened "wart-face" by the boys on her appearance in the street, and, while not supersensitive, she determined to forego the pleasure of being a target for these personal comments.

Thereafter, she only left the house at nightfall to walk down to the end of the pier opposite to the gin mill of her uncle. During one of these nocturnal rambles she met Patrick McShane. He was lying in drunken stupor on the very edge of the dock, and in danger of losing his balance. Mary woke him up, lectured him and then gave him money. Before sending him away, she told him to be there on the following evening.

Regular meetings were soon in order, and it was not long before Mary conceived the idea of reforming Patrick McShane.

McShane was willing, and, one day the entire ward was startled into unusual surprise by hearing of the marriage of Patrick McShane and Mary McNulty.

To give credit where credit is due, it must be recorded that McShane, for quite a while, inspired by the devotion of his wife, improved wonderfully in his habits and walked along the narrow road of sobriety with nary a stumble. But, after about a year of wedded life, he permitted himself occasional relapses into the old ways, multiplying them in time. It is hard to tell if all the hope of his ultimate reformation died out in the heart of his wife. She became very quiet, catering more carefully to his creature comforts and never offering any remonstrance.

But there must have been a void, a yearning to receive and to give a little affection, and when "the lady in front"—my mother—died and left her orphan, Mary McShane would not let it go to the "institution," but took it into her own humble home.

And for this dear little woman, whose entire life was one of self-sacrifice, devotion and humiliation, a prayer goes from me at every thought of her.

It can hardly be expected that I, a boy of seven years of age, grasped the full significance of the information imparted by my foster father. Only two points appeared very grave to me. Should the fact become known to my playmates that I was an orphan—not distinguished from a foundling by them—and that I had sailed, so to speak, under false colors, my fate would have been one full of persecution and sneering contempt. I silently prayed and then beseeched my foster mother to keep the matter a profound secret.

The other point of importance was that the street, "where I, by right, belonged," assumed a new aspect. Having had plenty of evidence of the impulsive spirit which ruled our household, something seemed to tell me that it was not improbable that the threat of my expulsion would be fulfilled, and I began to consider my ultimate fate from all sides.

The bootblacks and newsboys and other young chaps, who were making their precarious living in the streets, became personages of great interest to me. I watched their ways, and even found myself calculating their receipts. It was quite clear to me that, should my foster father drive me from the house, I should have to resort to some makeshift living in the streets.

All this put me in a preoccupied state of mind, which does not sit naturally on a child. I became more quiet than ever, and, in the evening, from the wood box behind the cooking range, watched our home proceedings. Most times they were very noisy, and my quietness seemed to grate on the ears of him whom I had ceased to call "father," and was then addressing more formally as "Mr. McShane," which also annoyed him.

Can you not read here between the lines and understand how a certain something became more and more stifled within me? Perhaps I was unreasonable or lacking in gratitude, but I was a child and still hungered and hungered and longed for that which, as yet, had not come into my share.

But if Mr. McShane would not listen to my plea for shoes, my good, dear "mum" had heard my request and understood the motive of my insistence. Happily, children's shoes do not involve enormous expenditure, and so, on a certain eventful day, "mum" went to her savings bank, the proverbial stocking, took the larger part of it and made me the proud possessor of a pair of real, new shoes, the first of my life. Bitterness, sulking and wailing were all forgotten and wiped away as if by magic, and my feet, in their new casings, seemed to step on golden rays of sunshine. If I add to this that I had never had a toy of any kind you will be able to measure my sensation.

The real, new shoes were not an altogether free gift. It had been agreed between "mum" and me that I was to pay the equivalent for them by increased collectibility in the retail coal business.

The following day saw me starting out for the coal docks with the very best of intentions. I began to fear that we would not be able to find room for all the coal I meant to carry home that day. Tons of coal began to heap themselves in my vision, until, perchance, my eyes fell on the real, new shoes.

It became my unavoidable duty to let my footgear be seen.

Many detours were made, and so much time was wasted in exhibiting my shoes to the thrilling envy of my comrades that the accumulation of coal suffered in consequence. The awakening from my dream of glory came with the end of the day, when it required all my remaining buoyant spirits to nerve me for my reception at home.

The coal basket was dreadfully light.

My home coming was very ill-timed. Mr. McShane was in the throes of another idle period, which did not preclude credit at the neighboring saloons. Had there been "company" I might have been able to escape his wrath, but, having sat there all alone—that is, without male companionship—and his wife never daring to reply to his sarcastic flings, I was just the red rag for the bull.

"Ah, and so you're home at last? Mary, have you no hot supper ready for this young gentleman, after him being hungry from working so hard at getting about ten pieces of coal? Oh, and new shoes are we wearing now, ain't that nice!" Then, with a quick change of tone and manner, "Come here, you brat, come here to me!"

"Leave the boy alone, Pat!" interposed "mum," but I knew, as she did, that it was futile.

I have no difficulty in remembering it all. In a dull, heavy way I felt that the crisis had come.

At the ending of the scene, my shoes, my real, new shoes, were torn from my feet. Everything within me rebelled against that. Life without those shoes was not worth living, and I stormed myself into a frenzy, which did not leave me until I found myself, propelled by a swift leg movement, on the floor of the dark hallway—minus my shoes.

The long expected had come. I had thought myself prepared for this moment, yet found myself stunned and bewildered. What was I to do? The street "where I belonged" now seemed to belong to me, but I did not look quite as stoically as before at the prospect before me.

"Besides, how can I go out without shoes?" I reasoned, forgetting the fact that, only quite recently, shoes had become necessities to me.

But the truth was—and will you blame me?—that from the crack at the bottom of the door came a tiny streak of light, which told a vivid tale of all I was in danger of forfeiting. How often I had growled at my fate; now, behind that door, lay a paradise.

I crouched there in the dark corner of the stairs leading to the roof. How long I shivered there I do not know. All my senses were alert and ready for the slightest alarm. Once I heard pleading and emphatic denial within, and then all was still—still for a long while.

My gaze was fixed on the door. It seemed hours—perhaps it was—before I heard a slight creaking and saw the reflection of more light on the hallway floor. It disappeared as quickly as it had appeared, and then it was dark and quiet again.

But why was that door opened? Something must have happened. I dragged myself to the threshold of my lost home, felt around and found—my shoes, my real, new shoes. And then I tried hard to cry, but could not. The crust had become too hardened.

The crisis had come, was passed, and the curtain fell on my childhood. Ages cannot be measured by years.

A NOMAD OF THE STREETS.

CHAPTER III.

A NOMAD OF THE STREETS.

Seven years old, I stepped into the street, where, by right, I belonged, no longer a child, to begin the journey, which, through many years in the valley, led me to the heights.

It was a bleak December night.

Can you not draw yourself the picture of the boy starting on his way—whither?

I stood for some time in the doorway. A policeman loomed in the distance. Boys cannot bear them in day time, how much less at night. To be "collared" by a "cop" at this hour meant a stay in the station house and a visit to the police court. I put myself in motion.

With cap pulled over my ears and hands pushed into my pockets, I started in the direction of the Bowery and Chatham Street, now called Park Row. I halted under a lamp-post to determine on my course.

"Uptown" was an entirely unknown region to me. "Downtown" was not much more familiar, but, somehow, I knew that that was the place where all the newsboys came from.

I turned to the left and walked and ran—the night was bitterly cold—down Chatham street until I came within view of the City Hall. So far I had been once or twice before on some adventurous trip, but not beyond that. Though I did not realize it at the time, I stood on my jumping-off place, ready to jump into the unknown.

I paused for a while, looking into the darkness before me. In those days, before the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge, City Hall Square was not as brilliantly lighted as now. I stood there until the biting cold made me move on.

My eyes were watery from the meeting blasts, and, stumbling on, I almost fell on top of a layer of diminutive humanity. Before I had time to draw my stiffened hands from the pockets to wipe my eyes, I felt a welcome sensation of warmth, thick, intense, damp, ink-permeated warmth.

The warm current came from the grating over the pressroom of a newspaper. This open-air radiator only measured a few feet, yet, at least, fifteen boys were hugging it as closely as their mothers' breasts. The iron frame was entirely invisible, and my share of warmth coming from it was very trifling. But, even so, only a few minutes of this straggling cheer was afforded to me.

Just as some of the numbness began to thaw out of my limbs, the cry—ever and ever familiar to the newsboy—"Cheese it, the cop!" rang out, and, like a horde of frightened sprites, the boys scampered away, I bringing up the rear.

We raced around the corner into Frankfort street and stopped in a dark hallway, which seemed to be the headquarters of this particular crowd. It was not warm in there, but, at any rate, it was a shelter against the cutting gusts of night winds, playing their stormy games of "hide-and-seek" around the blocks facing Park Row.

Following the example of the others, I cuddled up in a corner, and tried to forget my troubles in sleep. Just dozing, preliminary to falling into sounder sleep, I was suddenly and swiftly aroused by a grasp and a kick, and informed that I had usurped a corner "beeslonging" to a habitué of this dismal hostelry.

I had yet to learn that a newsboy will claim everything in sight, to relinquish it only by defeat in fight, and meekly submitted to my dispossession. The late comer took a bundle of newspapers from under his arm and carefully proceeded to prepare his bed. First, he spread a number of sheets on the floor; then built a pillow from the major part, and, at last, proceeded to cover himself with the remaining papers.

The light was dim, still, it was enough to show him my discomfiture.

"Say," he addressed me, "what's the matter, ain't you got no place to sleep? I'll tell you what I'll do. If you don't kick in your sleep, I'll let you lie down longside o' me." Then, as an afterthought, "It'll keep me warmer, anyhow."

Most emphatically and impressively did I assure him that my sleep was absolutely motionless, and from that night dated a partnership and friendship which lasted for many years.

In later years I have often wondered why I and all the other boys who comprised the newspaper-selling fraternity of that day always landed in Park Row, and in the midst of the future colleagues? It seemed to be a well defined destiny. Behind the coming of each new recruit was the little tragedy, which had made the leading actor therein a stray waif of the streets. And, no matter where the tragedy had happened, whether in Harlem or in the First Ward, the district along and above the Battery, they all found their way to Park Row.

The life of the newsboy is full of action. His personal struggle and business is so absorbing that he has no time for useless speculation. The advent of a newcomer is not signalized by a very warm reception. He is neither hampered by professional jealousy or suffered by tolerance. The field is open to all, and it rests with the boy how he will fare. However, in spite of this almost essential selfishness, impulsive outbursts of good nature are a characteristic of this most emotional creature, the newsboy. My apprenticeship in the fraternity owed its beginning to one of these spontaneous outbursts.

It was quite early when, chilled to the marrow, I awoke in the drafty hallway. My new and independent existence was begun with my first great sorrow. Here the temptation is very strong upon me to tell you that remorse, anguish and despair were racking my soul; that it was homesickness or a great longing for all I had left behind me. But putting this temptation behind me, I must confess that my sorrow was of the most material kind. I missed my coffee.

Across the street was Hitchcock's coffee and cake saloon. Through the shivery morning air, every time a patron entered or left the place, a cloud of greasy, spicy aromas came wafting to the frozen little troupe leaving their dreary abiding place. My future colleagues had so often had this torture inflicted on them that, now, with just an envious sniff, they could bear it with stoical fortitude. I, still a weakling, stopped, as if transfixed, inhaled the perfumed currents and most solemnly swore that, with my very first money, I would buy the entire stock; yes, even the entire coffee and cake saloon.

Alas, Hitchcock's is still doing business.

The next question presenting itself was, how was I to get the "first" money?

Newsboys work and play in cliques. The particular gang, with which I had thrown my lot, had its rendezvous in Theatre Alley. It was the assembling and meeting place for all the members, those who had slept in "regular" beds and those who had "carried the banner"[#] in the Frankfort street hallway. This distinction did by no means establish two different social strata among us. Fate was so uncertain that the aristocrat of the night before, who had rested his weary limbs on a "regular" bed, was very apt to fight on the following night for the possession of the corner in the hallway, which "beeslonged" to him.

[#] To spend the night without a bed.

Beyond giving me a scrutinizing look, none of the boys took heed of me, and did not object to my following them. Arrived in Theatre Alley, we met the leader of the gang, who had the proud distinction of being about the only one who had a "home to go to" whenever he felt like doing so. The same qualities, which, since then, have made him a leader in politics and have led him to membership in legislative bodies, were even in that day in evidence.

In parenthesis let me say that I am not blessed with personal beauty. Add to this that my appearance presented itself rather grotesquely and disheveled on that eventful morning, and you will understand why the leader's searching eye singled me out from the rest.

"Are you a new one?" he asked me.

I answered in the affirmative.

"Going to sell papers?"

Again the affirmative.

"Got any money?"

Now a convincing negative.

Then, as now, our leader was sparing in the use of words. At the end of our brief interview, I was "staked" to a nickel to buy my first stock of papers, and those who know Tim Sullivan will also know that I was not the first or the last to get "staked" by the Bowery statesman.

He not only furnished my working capital, but also taught me a few tricks of the trade and advised me to invest my five pennies in just one, the best selling paper of the period.

So, in less than twelve hours after leaving what had been for several years my home, I was fully installed as a vendor of newspapers.

Then began the usual existence of "newsies," eating and "sleeping" when lucky, and "pulling through somehow" when unlucky. I stuck to that business for over ten years.

The life of the streets did not at all disagree with me. My childhood had been full of bitterness, childish bitterness, and I had a dull longing to make the world at large feel my revenge for having dealt so unkindly with me. Whatever good traits there had been in me were quickly and willingly transformed into viciousness. This helped me to become a leading member of our gang of boys.

Among us there was none so absolutely orphaned as myself. Those who were orphans had, at least, their memories. I did not even have them.

In odd, emotional moments, one or another would let his thoughts stray back to some still loved and revered father or mother, or would confess to having crept up to his former home, at some safe time, to have a peep at forfeited comforts. I welcomed these references and day dreams of my colleagues, but solely because they were utilized by me as pretenses for inflicting my brutality on those who had uttered them.

There is a question, a number of questions, to be asked here. Why did I do this? Was it because I was naturally vicious, or because I wanted to stifle a certain gnawing in my heart by my ferociousness? A strange reasoning, the last, perhaps; but in years I was still a child, and if a child has but little in his life to love, and that little is taken out of his life, that child can turn into a veritable little demon. Those, whom I had believed my parents, turned out to be nothing more than charitably inclined strangers; that what I had believed to be my home, proved but a refuge, and my boyish logic saw in this sufficient cause to envy those, who had all this behind them and to give vent to this envy in the most ferocious manner.

That was the tenor of my life as a newsboy. I had enough callousness to bear all the hardships without a murmur. One ambition took possession of me. I wanted to be a power among newsboys. I wanted to be respected or feared. As I did not care which, I succeeded in the latter at the expense of the former. The heroes of newsboys are always men who owe their prominence to physical prowess. I chose as my models the best known fighters of the day.

As with all other "business men," there is keen rivalry and competition among newsboys. The only difference is that, among the boys, the most primitive and direct way is the most frequent one employed to settle disputes. Some men, after great sorrows or disappointments, seek forgetfulness in battle, being entirely indifferent to their ultimate fate, and they always make good fighters. My position was not altogether dissimilar from theirs. What little I had known of comfort and affection was behind me; my mode of life at that time had no particular attraction for me, and my only ambition was to conquer by fight, and, therefore, I made a good fighter.

In all those long years I cannot recall more than one incident which stirred the softer emotions of my heart.

A newcomer, a blue-eyed, light-haired little fellow, had come among us, and was immediately chosen by me as my favorite victim. Certain traces of refinement were discernible in him and this gave me many opportunities to hold him up to the ridicule of our choice gang of young ruffians. I hated him without knowing why.

One day I saw him standing at the corner of "the Row," offering his wares with the unprofessional cry: "Please, won't you buy a paper?"

It was a glorious chance to "plant" a kick on one of his shins, and thereby to relieve myself of some of my hatred. Stealthily I crept up behind him, and was on the point of sending my foot on its mission, when two motherly-looking women stopped to buy a paper from "the cherub." Wits are quickly sharpened in a life on the streets, and I realized at once that my intended assault, if witnessed by the two ladies, would evoke a storm of indignation.

I immediately changed front, and endeavored to create the impression that my hasty approach had been occasioned by my desire to sell a paper.

"Poipers, ladies, poipers," I cried, but was barely noticed.

The "cherub" claimed all their attention.

"What a pretty boy!" exclaimed one. "Have you no home, no parents? Too bad, too bad!"

All this was noted and registered by me for a future reckoning with the recipient of so much kindness.

My heart was shivering with acid bitterness.

"Never me, never me!" and the misery of many loveless years rang as a wail in my soul.

Just as the woman, who had spoken, was about to hand a dime to my intended scapegoat, her companion happened to turn and see me.

"Oh, just look at the other poor fellow."

The exclamation was justified. I was a sight. However, my dilapidated clothes and scratched face owed their pitiful condition to much "scrapping" and not to deprivations.

Again she spoke.

"Here, poor boy, here is a penny for you."

With a light pat on my grimy cheek and one of the sunniest smiles ever shed on me, she was gone before I could realize what had happened. There, penny in hand, I stood, dreaming and stroking the cheek she had touched, and asking myself why she had done so.

Somehow, I felt that, were she to come back, I could just have said to her: "Say, lady, I ain't got much to give, but I'll give you all me poipers, and me pennies, and me knife, if you'll only say and do that over again."

The "cherub" also was a gainer by this little touch of nature. I forgot to kick and abuse him that night.

There was nothing dwarfish about me, and my temperament made me enjoy the many "scraps" which belong to a street arab's routine.

Park Row was and is frequented by the lesser lights of the sporting world. Our boyish fights were not fought in seclusion, but anywhere. Being a constant participant in these "goes," as I was almost daily called upon to defend my sounding title of "Newsboy Champion of Park Row" against new aspirants for the honor, myself and my fighting "work" soon became familiar to the "sports," who were the most interested of the spectators.

I was of large frame, my face was of the bulldog type, my muscles were strong, my constitution hardened by my outdoor existence in all sorts of weather, and, without knowing it, my advance in the art of fisticuffs was eagerly watched, with the hope of discovering in me a new "dark horse" for the prize ring.

Among the men who had followed my progress in boxing were such renowned sports as Steve Brodie, Warren Lewis, "Fatty" Flynn, "Pop" Kaiser and others of equal prominence. In due time overtures were made to me. I was properly "tried out" on several third-rate boxers, and said good-by to the newsboy life to blossom out as a full-fledged pugilist.

Before long I began to have higher ambitions. It was the day of smaller purses and more fighting, and I determined to fight often so as to accumulate money quickly. I had no definite idea why I wanted to accumulate money with such feverish haste. I had some dim desire to wanting to have a lot of it, to having the sensation of being the possessor of a roll of bills, and, this being the only road open to me toward that goal, I was eager to travel it.

That was my ambition at the age of seventeen, the age when boys prepare themselves to be men in the fullest and only sense of the word. My boyhood, dreary as my childhood, closed behind me without a pang of regret on my part. I was aspiring according to my lights and my aspirations spelled nothing more or less than degradation.

LIVING BY MY MUSCLE.

CHAPTER IV.

LIVING BY MY MUSCLE.

The manly art of self-defense, as practised then, was unhampered by much law or refinement. Still, with all this license, I was too brutish to make a successful prizefighter. My sponsor in this sporting life soon learned that I had a violent temper.

Time and time again I was matched to fight men who were not physically my equals, only to be defeated by them. It was useless to endeavor to impress me with the argument that these fighting matches were merely business engagements, in the same way as the playing of a part by an actor.

I fully understood all that was pointed out to me; would adhere to my instructions for two, perhaps three, rounds of fighting, then would forget all, rules, time limits and all else, to "sail in" with most deadly determination to "do" my opponent at all hazards.

During my brief career as pugilist I only met one man who was of the same brutish temperament as myself—Tommy Gibbons, of Pittsburg—and we fought four encounters.

Of the same age as myself, Gibbons had earned for himself a well-founded reputation for viciousness. He had never been defeated in his own state, and the promoters of this "manly" form of sport were anxious to find a more vicious brute than he to vanquish him.

I was chosen for this mission.

A paper manufacturer, still doing business in New York City, after seeing me "perform" in trial bouts, was induced to "put up" the necessary money for my side of the purse, and we were matched to fight in Pittsburg.

We "weighed in" at one hundred and forty pounds.

This, our first encounter, lasted twenty-seven rounds. The "humanity" of our seconds and backers prevented us from going any further. Our physical condition was the cause for stirring that "humanity."

We were smeared with blood, but that alone would not have been sufficient to terminate the fight. A broken arm, a torn ear, a gash from eye to lower part of cheek, constituted Tommy Gibbons' principal injuries. I was damaged to the extent of two broken thumbs and a broken nose, not mentioning minor disfigurements. But, what of that? Had not the noble cause of sport derived a new impetus from our performance? Had not the hearts and aspirations of the "select" crowd of spectators been moved to higher emotions?

We had behaved so right manfully, that, at the ringside, we were matched again for another meeting. In that, after seventeen rounds, I was declared the winner on a "foul" of Gibbons.

Again we were matched, this time to fight according to London prize ring rules—they permitting more latitude for our brutish instincts. It resulted in a "draw," but not until we had entertained the very flower of the sporting world for forty-three rounds.

Not yet satisfied as to which one of us was the greater brute, another meeting was arranged, and I had the proud distinction of being the victor in this fight of eleven rounds.

Poor Tommy Gibbons took his defeat very much to heart. His fistic prestige was gone, and he went speedily to "the bad." He ended his busy life at the hands of the hangman, paying therewith the penalty for one of the most horrible murders ever committed.

Too bad that such a promising light in the sporting world should meet with such ignoble end!

My backer, the paper manufacturer, who did so much, by effort and expenditure, for the cause of sport, is still on my list of acquaintances. He is eminently respectable, the father of an adoring family, the model for striving young men, a pillar of his church, a power in commercial life, and, withal, an enthusiastic follower of the Manly Art of Self-Defense, provided the specimen of it is not too tame.

Apropos of the manly art of self-defense I want to record my individual opinion that it is a lost art, if it really has ever been an art. In the knightly art of fencing, skill, artful skill, is necessary and acquired. Not so in boxing; at least not in that branch of boxing which is only practised for money. Men who step into the ring for a "finish fight" are not prompted by the desire of giving a clever exhibition of boxing. Their only desire—if the fight "is on the level"—is to "put out" their man somehow, as quickly as possible, and to collect their end of the purse as promptly as possible. I have seen my quota of fights in my life time, but never one in which claims of "fouls" were not made.

Is it not logical to suppose that leading exponents of their art should be able to give a demonstration of it without resorting to foul means?

Although I have given "physical culture lessons" of a certain kind I have but little knowledge of how boxing lessons are conducted in academies and reputable gymnasiums. The popularity of this branch of athletics indicates that the lessons are conducive to corporal perfection, and teach men how to use their strength to best advantage when driven to the point of defense.

This principle is not observed by "scrappers." They pay less, if any attention to boxing than to learning tricks of their trade. It is all very well for sporting writers to speak about Fitzsimmons' and Sullivan's art, but I am quite sure that one or more efficient tricks is the real mainspring of many pugilistic reputations.

The rules of the prize ring are fair and formed to protect men from foul methods. For that very reason, all the tricks learned—and they are many and efficient—are, if not absolutely fouls, so near the dividing line that the margin of distinction is almost nil.

Through the press of the country we are informed that prizefighters now-a-days make considerable fortunes. Then they did not, and having a surprisingly healthy appetite in a healthy body, the fighting profession sadly delayed the perfect development of my embonpoint.

LIVING BY MY WITS.

CHAPTER V.

LIVING BY MY WITS.

True, my fights with Tommy Gibbons and others had brought me some money, but the social obligations were so many and the celebrations so frequent that, after a short time of plenty, I always found myself "dead broke" and compelled to resort to my "wits" for making a living.

All Chatham street—now Park Row—and the Bowery teemed with "sporting houses," which offered opportunities to men of my class. In many of these places boxing was the real or pretended attraction.

On an elevated stage from three to six pairs of boxers and wrestlers furnished nightly entertainment for a roomful of foolish men, and—more's the pity!—women. The real purpose of these gatherings must remain nameless here, but this fact we must note, that all of these "sporting-houses," these hells of blackest iniquity, were run by so-called statesmen, patriots, politicians, many of them lawmakers, or else by their figureheads.

The figureheads were chosen with great carefulness. To become a proxy owner of a "sporting-house" one had to have a reputation, sufficient to attract that particularly silly and morbid crowd of habitués. Some of the reputations were made in the prize ring, viz: Frank White, manager of the Champion's Rest, on the Bowery, two doors north of Houston street; Billy Madden, Mike Cleary and other "prominent" prizefighters. A few of them, as Billy Madden and Frank Stevenson, later branched out as backers of pugilists, policy shops and gambling houses.

Reputations made in prisons were also accepted as qualifications, and "Fatty" Flynn, Billy McGlory, Tommy Stevenson, Jimmy Nugent, of Manhattan Bank robbery fame, and other ex-inmates of jails owed their wide popularity and money-making capacity to their terms spent behind the bars. An isolated position of especially luminous glamor was acceptably filled by the famous Mr. Steve Brodie, the bridge-jumper, and greatest "fake" and fraud of the period.

In places where boxing was not the attraction, the vilest passions of human nature were vainly incited by painted sirens, who, by experience and compulsion of their employers, had become perfect in their shrewd wickedness. In front of these "joints"—frequently called "bilking houses"—glaring posters, picturing the pleasures within, were displayed in most garish array.

In addition to these places described, a number of dance-halls, notably Billy McGlory's Armory Hall, and "Fatty" Flynn's place in Bond street, completed the boast of the day that New York City was a "wide-open town," and the "only place in the world fit to live in."

It was not very difficult for one, accustomed to the environment, to "make a living" in it by his "wits."

Any one, not minding a short spell of strenuousness, could always get from a dollar and a half to two dollars for "donning the mitts" in the "sporting-houses," where boxing was the special feature. Others, having neither the training or inclinations to take part in these "set-to's," officiated as waiters—"beer-slingers"—and found it more remunerative, if more tedious work.

It seems to be a distinct trait of people who visit these "dives" and "joints" to leave their small allowance of intelligence at the door. Men, who, in their daily occupation, are fairly alert and awake to their interests, permit themselves to be cheated by the most transparent devices of the "beer-slingers."

To give these fellows a bill in payment of drinks is simply inviting them to experiment on you. Over charging, "palming"—retaining a coin in the palm of the hand between ball of thumb and fleshy part—"flim-flamming"—doubling a bill in a number of them, and counting each end of it as one separate bill—are the most common means of cheating employed. Whenever any of these tricks failed, the money was either withheld or taken away by force, and the victim—the "sucker"—bodily thrown into the streets as a "disorderly person."

Such were the glories of the "open town."

Although a recognized factor in the world pugilistic, I was not above seeking occasional employment in these resorts, and it helped me to create for myself another reputation. I did not work in these places for the purpose of study or observation, yet, every night my contempt for the patrons of these "joints" increased.

Men, whose names I had heard and mentioned with awe; men, whose positions and station should have been guarantees of every sterling quality, came there, not once, but night after night, to enjoy that seemingly harmless pastime known as "slumming"—to have a "good time."

A "good time" in the midst of moral and physical filth; a "good time" in the company of jailbirds, fallen men and women; a "good time" of grossest selfishness, for, over and over again, I have seen men there for whose education I would have gladly given years of my life, and who, by one word of sympathy or encouragement, could have rekindled the dying flame of hope, of self-respect, in some fellow-being, but that word was never spoken, because it would have brought discord into the "good time," and would have jangled the croaking melody chanted by that chorus of human scum in praise of their host—the "sightseer"—of the evening!

A glorious sport this "sightseeing," these "good times," when men of "respectability" and position feast with gloating eyes on all that is vile and look on the unfortunates of a great city as if they were some strange beasts, some freaks in human shape. That almost every creature in these "dives" and "joints" has left behind a niche in the world's usefulness, or a home, to which his or her daily thoughts stray back, is not considered by the "sightseer." One does not like unpleasant reflections when at a circus.

Vile, very vile, are the men and women who constitute the population of divedom, but how about the representatives of respectability, who come among them to spend their "good time" with them?

Were I at liberty to give the names of men whom I have seen hobnobbing with the most fearful riff-raff, you would shrug your shoulders and say: "I cannot believe it of them." Yet, I do not lie.

There is no need for lying, and there is much corroboration, not the least being the conscience of those men.

We want you—you men and women of respectability—to come to these "dives," but we want you to come for another purpose. Even at this very moment there is a scope for your efforts in spite of all change of administration and Christian endeavor has done for that part of the city. The stamping out of vice is carried on vigorously, but vice is a proverbially obstinate disease.

Only a few nights ago I saw a scene in a widely known pest hole, reeking with stench beyond its very doors, which I can only hint at in describing it.

At one of the tables sat a youth, a mere boy, who had been coaxed into the dirty hole by the persuasion of the wily "barker" at the side door. The boy seemed from the country, his ruddy complexion and "store clothes" indicated it. The drink, which he had been forced to buy, was standing untasted before him. Without being afraid, he kept wide awake and resented all overtures made to him. But he looked too much like an easy victim to escape the usual procedure.

Before he was aware of it, a woman had dropped into the chair on the other side of the table. At least more than fifty years of age, the toothless wretch assumed the coquetry of a young girl.

The gray hair, devoid of comb or ribbon, hung in straggling strands to her shoulders. The front of her dress was unbuttoned. Still, this witch of lowest depravity, lulled her Lorelei song, hoping to transfix the gaze of the boy—young enough perhaps to be her grandson—by the leer of her bleary eyes.

I do not dare, and if I dared, could not tell you the horridness of this scene, yet it was only a detail in the grander spectacle, the "good time," seen and enjoyed nightly by thousands of the "better" class.

Forerunners of the eventually coming overthrow of "open" vice made themselves felt during some of the more important elections and for a few weeks preceding election day the ukase was sent out by the mysterious hidden powers: "Lie low for a while."

These periods of restriction, while not welcome, did not involve great hardships for us, the "sports" of the Bowery. If the blare of the wheezy cornet and the thumping of the piano had to be silenced for the time being, there were other channels in which the services of the men, who did not care, could be utilized.

One of the most flourishing industries carried on was the confidence game in its many guises.

"Ah, all the 'easy marks' go up to the Tenderloin now," is the cry of the few remaining Bowery grafters. Then it was different.

The Bowery was famed from Atlantic to Pacific for what it offered. Every day a new consignment of lambs unloaded itself on this highway of the foolish and miserable, to be devoured by the expectant wolves. The recognized headquarters of the wolves was at the corner of Pell street.

A few among them were men of some education and refinement, but the most of them were beetle-browed ruffians, who seemed ill at ease in their fine raiment, the emblem of their calling.

To get the stranger's money many means were used.

Sailors, immigrants, farmers and out-of-town merchants were approached in most suitable manner, generally by a claim of former acquaintanceship. To celebrate the renewal of their old friendship it was necessary to adjoin to the nearby gin-mill. Here, the stranger, the "refound old friend," would not be permitted to spend one cent of his money—"dear, no, you're my guest."

Next move: The two reunited friends—the wolf and the lamb—are joined by a third—"an old friend o' mine," says the wolf.

The newcomer sings one of the many variations of the old, old theme. He has just won a lot of money at a game where no one can lose; or has a telegram promising beyond a doubt that a certain horse was to win that day; or has a hundred dollar bill, which he wants to change; or is broke, and offers his entire outlay of jewelry, watch, studs and rings, each one flashing with fire-spitting jewels, for a mere bagatelle of fifty dollars; or offers to bet on some mechanical trick toy in his possession, trick pocketbook or snuff box, and loses every bet to the wolf—but not to the lamb; or offers to take both, wolf and lamb, to a "regular hot joint," hinting at the beautiful sights to be beheld there, which, in reality, is a "never-lose" gambling device.

Should the lamb prove impervious to all these temptations, the pleasing concoction called "knock-out drops" is introduced as most effective tonic.

Sometimes there is a slip in the proceedings, and the lamb "tumbles to the game" before he is shorn. This is entirely against the rules of the industry, and cannot be permitted without being rebuked. Therefore, the confidence industry was always willing to draw its apprentices from the class in which muscularity and brutality were the only qualifications.

Other industries, now much retrograded, were the "sawdust," "green goods" and "gold brick" games. All these games were vastly entertaining to all, and vastly profitable to some. Besides, in their lower stages, and technically inside of the law, they gave employment to many young men, who, like me, were unwilling to use their strength in more honorable occupation, preferring to be the slaves of crooked masters and schemes.

Those were not all the ways in which a well-known tough could earn an honest dollar. To our "hang out," sheltering always a large number of choice spirits, frequently came messengers calling for a quota for some expedient mission. We were the "landsknechts" of the day, willing to serve any master, without inquiring into the ethics of the cause, for pay.

Electoral campaigns in this and other cities furnished much employment. Capt B——, of Hoboken, a notorious "guerrilla" chief, was a frequent employer. During a heated contest in a small town near Baltimore, he shipped fifty of us to the scene of strife to "help elect" his patron. Five "Bowery gents," in rough and ready trim, were stationed near each doubtful polling place, and, somehow, induced voters, unfriendly to their master of the moment, to keep away from the ballot boxes.

Local primaries and conventions, regardless of politics, could never afford to do without us. To-day we would fight the men, who, to-morrow, would pay us to turn the tables on our masters of yesterday.

Still, we were loyal to our temporary bosses. We offered our strength and brutality in open market. We asked a price, and, if it was paid, we did our "work" with a faithfulness worthier of a better cause. That this was so is proven by the fact that not only John Y. McKane, the "Czar of Coney Island," recruited his police force from among us, but even reputable concerns, like the Iron Steamboat Company, and others, engaged men of our class to preserve order and peace at designated posts.

A number of railroad companies and detective bureaus, in times of strikes, invited us to aid them in protecting property and temporary employees, but, for some reason or other, these offers were never greedily accepted.

Among the rest of these unlisted occupations must be mentioned playing pool and cards. I do not mean the out-and-out experts of these games hung around to win money from unwary strangers. Quite a number of the more "straight" saloons on the Bowery did not object to having about the place a crowd of fellows who were fair players of pool or the games of cards in vogue. If, by any chance they lost a game, the proprietor would stand the loss, and, if they proved exceedingly lucky, he would give them a percentage of the receipts of the game.

It is rather difficult to enumerate all the different ways in which a man, who had to live by his "wits," could make a living on the Bowery. They were many and variegated in their nature. It was a saying of the day that all a man had to do then was to leave his "hang-out" for an hour to return with enough money to pay his expenses for the day.

AT THE SIGN OF CHICORY HALL.

CHAPTER VI.

AT THE SIGN OF CHICORY HALL.

I have several times mentioned "hang-out." Most of these "hang-outs" were ginmills (saloons) of the better class, but the real Bowery Bohemian chose odd spots for his haunts. The most unique resort in this Bohemia of the nether world was at Chicory Hall, where my particular gang had established itself.

It was a basement at the corner of Fourth street and Bowery. Originally a bakeshop, it had been unoccupied for some time, until a coffee merchant rented it to prepare his chicory there. One man constituted the entire working force of the plant, and it so happened that Tom Noseley, the chicory baker, was imbued with sporting proclivities.

Do not let us forget that, at the time, the prize-fighter was a man of consequence to the youths of the East Side. To know a pugilist, to have spoken to him, to have shaken his hand, was an event never to be forgotten.

Tom Noseley was a very young man. In the immediate neighborhood of his basement were many "sporting-houses." Tom Noseley was earning eighteen dollars a week. What is more natural than that one of sporting proclivities should become an enthusiastic patron of "sporting-houses"?

Tom Noseley wanted to number some well-known pugilists among his acquaintances. Several well-known pugilists, I among the number, did not resent his many invitations to drink with him, and, ere long, the dream of Noseley seemed fully realized, for we consented, after much coaxing, to call at his basement for the pleasant task of "rushing the growler."

Our first call at the cellar convinced us of its many attractions. It seemed just the place for an ideal "hang-out." Then, also, there was Tom Noseley's weekly stipend of eighteen dollars a week, which he was willing to spend to the last cent for the "furthering of sport."

Tom Noseley was a hunter of Bowery lions. I have been told that in higher social strata different lions are hunted by different hunters. Still, the species do not differ very much from each other.

Men who had "done" a long term in prison; men who had a reputation for crookedness; men who were known to make their living without having to descend to the ignoble manner of working for it, all these had been fads of Noseley. Then, the sporting spirit of the Bowery flared up with great spluttering, and Noseley, for the nonce, took the poor, shiftless boxers to his heart of hearts.

We named the cellar "Chicory Hall," and quickly succeeded in making it known.

The cellar consisted of two large rooms. Descending from Fourth street, about a dozen steps led to the bakeshop. Four small windows, grimed with impenetrable dirt, suggested the presence of light. The sunlight or cloudy sky found no token there. At night one dim flame of gas gave a sort of humorous weirdness to the filthy hole.

Adjoining the bakeshop was a dark apartment of the same size as the first room, used as storing place for the bags of bran, which were used in the manufactory of chicory. Shortly after establishing our headquarters at Chicory Hall, we chose the storage room as our sleeping chamber, making unwieldy couches from the heavy, unclean bags.

Certainly we had conveniences, a "front room" and a "bedroom," what more could we desire? And we appreciated it. Did not I, myself, spend ten entire days and nights in Chicory Hall without ever leaving it?

But while Tom Noseley's eighteen dollars a week, earned by his intermittent labors in baking chicory, were not to be despised as the substantial nucleus of our treasury, they were not enough to provide a little food and much drink for about six able-bodied prizefighters out of work. The regular staff included Jerry Slattery, the Limerick Terror; Mike Ryan, the Montana Giant; Tom Green and his brother, Patsy Green; Charlie Carroll and myself.

On Saturday, Tom Noseley's pay day, two or three of the staff appointed themselves a committee to accompany our host to the office and to prevent him from falling into other hands. His return was celebrated by feasting on many pounds of raw chopped meat and drinking many gallons of beer. Sunday morning found the exchequer very much depleted, containing, perhaps, just enough to reflicker our drooping and aching spirits by purchasing several pints of the vilest fusel oil, parading under the name of whiskey, ever manufactured.

Sabbath day, the day of rest, as appointed by the Master, was spent by us in quiet peace. That the peace was a consequence of the turbulent hilarity of the night before, and not a desire to live according to divine dictates is a mere detail.

At the beginning of our sojourn at Chicory Hall our feast of Saturday was generally followed by a famine until the next week's end. This was somewhat palliated by a happy inspiration of "Lamby," a character of the locality.

"Lamby"—no one knew him by any other name—had some mysterious hiding and sleeping place, but was infatuated with our Subterranean Bohemia and spent all his spare time—which practically was all his time, excepting the hours dedicated to sleep—with the Knights of Chicory Hall. He was a boy of about seventeen years of age, over six foot tall, of piping voice and full of most unexpected opinions and ideas.

There was good stuff in "Lamby," as in many of the East Side boys, who are, by environment and circumstances, led into evil, or, at least, useless lives. "Lamby's" heart was bigger than all his carcass. To be his friend, meant that "Lamby" thought it his duty to give three-fourths of all his temporary possessions to the cementing of this friendship.

I made "Lamby's" acquaintance under inconvenient conditions. He was not yet entitled to vote. This did not prevent him from formulating the strongest opinions on political personages and principles. During the election which made me acquainted with him, "Lamby" for some unknown reason, was doing the most enthusiastic individual "stumping" for the candidate of one of the labor parties. It was conceded by the supporters of the labor ticket that the candidate in question stood absolutely no chance of being elected and that their entire list of nominees was only in the field as a means of making propaganda, of paving the way for future possibilities. All this did not deter "Lamby" from sounding the labor-man's praises on all and every occasion.

In one of his many eulogies "Lamby" was opposed by a ward-heeler of the local organization, who laughing offered to bet any amount that the much praised candidate would not poll fifty votes. This roused the ire of the champion of labor.

"Say," cried "Lamby" at his adversary, "you know I ain't got no money to bet and that's why you're so anxious to bet me. If you're on the level in this, I'll tell you what I'll do. You put up your money and if Kaltwasser don't get elected I won't speak to no human being for a month."

The politician accepted this odd bet and, a few weeks later, "Lamby," by his own decree, found himself sentenced to one month's silence.

And "Lamby" loved to talk!

It was a fearful dilemma, but leave it to a Bowery boy to wriggle out of a scrape.

In one of his rambles, "Lamby" had met Rags, and, impressed by some similarity in their appearance and disposition, had appointed him forthwith his chum and inseparable companion.

Rags was a cur of nondescript origin and breed. His long, wobbly and ungainly legs barely balanced a long and shaggy body, draped with a frowsy, kaleidoscopic mass of wiry hair. The color of Rags' eyes could not be determined, bangs of matted locks wholly screening them from view.

For some obscure reason, "Lamby" conceived the idea that the use of the lower extremities would prove injurious to Rags, and the mongrel—surely weighing at least fifty pounds—spent most of his time in the loving arms of his adoring friend.

The opportunity to return some of his friend's devotion, by making himself useful to him, came to Rags during the period in which "Lamby's" tongue was restrained from its favorite function for a month of silence. "Lamby's" pledge not to speak to a human being for a month was never broken, but he found a way of expressing himself to Rags in such loud and distinct tones that no one had any difficulty in following the train of conversation.

There was so much ingenuity in the plan that the ward politician declared the bet off and presented "Lamby" with a part of the stake money.

On a Monday, when the feast of Saturday was but a sweet memory and the famine of the week had set in with convincing force, Tom Noseley and his staff of friends—including "Lamby" and Rags, who hugged the shadowy recess of a corner—sat disconsolately in the dingy dimness of Chicory Hall.

"Ain't none of you fellows got any money at all?" queried Jerry Slattery against hope.

The question was too absurd to deserve an answer.

"Well, what are we going to do?" pursued the Limerick Terror; "I'm hungry as blazes and can't stand this any longer. Nothing to eat and nothing to drink; this is worse than being on the bum in the country among the hayseeds. If I don't get something here pretty soon, I'll go out into the Bowery and see if I can't pick up something."

The harangue passed our ears without comment. More deep and dark silence. Then everybody turned to where "Lamby's" preambling cough heralded a monologistic dialogue.

"Rags," began the silent sage of Chicory Hall, "what would you and me do, if we was hungry and wasn't as delicate as we are? Wouldn't you and me go up to Lafayette alley and look them chickens over that don't seem to belong to nobody? Couldn't you and me use them in the shape of one o' them nice chicken stews with plenty of potatoes and onions in it? Ain't it too bad that you and me is too delicate to be chasing round after them chickens and that we aren't allowed to speak so's we could tell other people how to get a meal that'll tickle them to death?"

Bully "Lamby."

In less than five minutes a small, but determined gang of marauders made their stealthy way through Lafayette alley. Every one of the husky pilferers endeavored to shrink his big body into the smallest compass. The alley ended in a hamlet of ramshackle stables in the rear of a famous bathing establishment. The place was deserted in day time as all men and animal occupants were in the streets pursuing the energetic calling of peddling. As said, the place was deserted, save for those chickens. Dating from our first call, the chickens, young and old, began to disappear.

For over a week we feasted on chicken. We had them in all known styles of cooking. Our bill of fare included fried, baked, stewed, broiled and fricasseed chicken. But a day came when naught was left of the flock of chicks excepting one big, black rooster.

I shall never forget him, because it was my fate to be his captor.

He surely was a general of no mean order. We had often hunted him, but he had always succeeded in eluding us by some cleverly executed movement.

This survivor of his race irritated my determination and, supported and flanked by my cohorts, I set out to exterminate the last of the clan. Sounding his defy in many cackles and muffled crows the black hero raced up and down the yard, dodging, whenever possible, under some of the unused wagons and trucks standing about. But escape was impossible.

Driven into a corner he faced me and my bag with splendid heroism. He met the lowering deathtrap by an angry leap, and, when I and bag fell on top of him, we were greeted by a shower of furious picking and clawing.