The Project Gutenberg EBook of New York Times Current History: The European War, Vol. 8, Pt. 2, No. 1,, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: New York Times Current History: The European War, Vol. 8, Pt. 2, No. 1, July 1918 Author: Various Release Date: May 27, 2014 [EBook #45785] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NY TIMES CURRENT HISTORY; VOL. 8, PT. 2, NO. 1, JULY 1918 *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Roderick Humphreys and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Volume VIII.

[SECOND PART]

July-September, 1918

Pages 1-570

[Titles of articles appear in italics]

A

AERONAUTICS,

"Aerial Record," 51;

"The War in the Air," 80;

hospitals bombed, 83;

Lufbery's last fight, 85;

Richthofen's death, 85;

list of German aviators killed, 86;

ingenious devices for sending propaganda to

the enemy, 198;

German giant airplane described,

201;

casualties from bombing of hospitals,

204;

"War in the Air," 439;

number of enemy machines brought down

during year ended June 30, 439;

Allies' activities during period ending

Aug. 15, 439;

allied raids on German cities,

439.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

51, 223, 436.

AIMS of the War,

defined by Emperor of Germany,36;

stated by Pres. Wilson, July 4 at Mount

Vernon, 191;

reply of Austrian Foreign Minister,

194;

Chancellor von Hertling's reply in

Reichstag, 311;

Viscount Milner speaks of German domination

over her allies, 313;

Count Burian replies, 313.

See also

CAUSES of the War;

Peace.

AIRPLANES, see AERONAUTICS.

ALBANIA,

"Albanian and Slav," 201.

ALIEN Enemies, see ENEMY Aliens.

Allied Man Power Compared with That of Central Allies, 75.

ALMEREYDA, editor of "Bonnet Rouge,"

dies mysteriously in prison,

198.

Alsace-Lorraine: Its Relation to France, 308.

American Invasion of England, 433.

American Offensive a Success. First, 57.

American Soldiers in Action, 55.

Americans, Premier Lloyd George Lauds, 148.

Americans on the Battlefront, 226.

Americans' Defense of Chateau-Thierry, 62.

America's Answer, (poem,) 144.

America's Army, No Size Limit to, 70.

America's First Anniversary in France, 78.

America's First Field Army, 429.

Anniversary of the War, Fourth, 529.

ANNUNZIO, Gabriele d', 440.

ARMENIA,

Turkish invasion under Brest-Litovsk

Treaty, 131.

ARMIES,

"Armies Under Foreign Generals," 2;

allied war power compared with that of

Central Allies, 75.

See also under names of

countries.

ASPHYXIATING Gas, see GAS Warfare.

ASQUITH, Herbert H.;

"Final Phases of the War,"

301;

"President Wilson and the League of

Nations," 511;

address on occasion of silver wedding

anniversary of King George, 532.

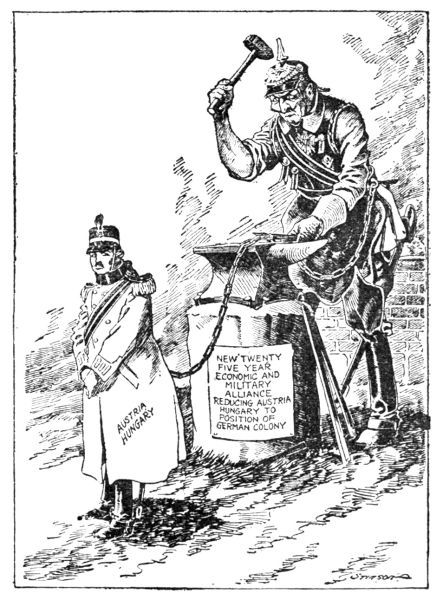

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY,

"New Austro-German Alliance." 91;

"Austrians at Grips with Italians,"

33;

Austria's leaders accept Germany's policy,

513.

See also

CAMPAIGN on Austro-Italian

Border;

JUGOSLAVIA;

PROGRESS of the War, 53.

Austria's Disastrous Offensive, 218.

B

BAKER, (Sec.) Newton D.,

"America's War Effort," 229.

BALFOUR, Arthur J.,

"The Basis of Peace"; "Belgium as a Pawn,"

516.

BALKAN States, see

CAMPAIGNS in Balkan States;

CZECHOSLOVAKS;

JUGOSLAVIA, and under names of

States.

BARRES, Maurice,

"Fraternity of English and French,"

533.

BASTILE, History of, 200.

BASTILE Day

in the United States, 244;

"Fraternity of English and French,"

533.

Battle, A, Seen from Above, 54.

BATTLES, see

CAMPAIGNS,

NAVAL Operations.

BEGBIE, Harold,

"The Living Line," (poem,) 149.

BELGIUM,

"Belgium as a Pawn," 312, 516;

Belgian courts superseded,

323;

"Belgium Under the Iron Heel,"

519;

zinc coins issued, 87;

"Saving Belgium from Starvation,"

521;

Germans seize church bells and organ pipes,

344.

Belleau Wood, Capture of, 65.

BENNETT, Arnold,

"A Peace League of Nations,"

355.

BERG, (Lieut.) von,

German official army report,

243.

Bessarabia, Rumania and, 326.

Bessarabia's Historical Background, 328.

BIDDLE (Gen.), 336.

Bombing Hospitals, 330.

BONNET Rouge,

proprietor and staff tried for treason,

198.

BORAH (Sen.),

criticises America's inaction with regard

to Russia, 260.

BORDEN, Sir Robert,

"Canada's War Achievements,"

306.

Boycotting Germany, 545.

BRIDGE, Admiral Sir Cyprian,

reviews debatable phases of Battle of

Jutland, 152.

Britain's Imperial Hopes Realized, 299.

BRYCE (Viscount),

"England and the War's Causes," 162;

speech at Fourth of July celebration,

336.

BUCHAREST, Treaty, see

PEACE—Rumanian Separate Peace.

BUCHET, Marguerite,

"Agony of the City of Lille," 281,

456.

BULLARD, (Maj. Gen.) R. L., 243.

BUNDY, (Maj. Gen.) Omar, 243.

BURIAN (Baron),

reply to American war aims,

194;

replies to Viscount Milner's reference to

German domination over her allies, 313.

BURR, Amelia Josephine,

"Pershing at the Tomb of Lafayette,"

(poem,) 329.

C

CAINE, (Sir) Hall,

"The World's Independence Day,"

342.

[Pg II]

CALDWELL, Charles Pope,

"War Record of the United States," 73.

CAMMAERTS, Emile,

"Another Cross for Belgium to Bear,"

344.

CAMPAIGN in Asia Minor—

Anglo-Indian advance blocked by Turks,

15.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

51.

CAMPAIGN on Austro-Italian border,

"The Austrian Defeat on the Piave,"

463;

unsuccessful Austrian offensive in Piave

region, 13;

"Austrians at grips with Italians, 33;

"Along the Piave," 210;

"Austria's Disastrous Offensive,"

218.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

51, 436.

CAMPAIGN in Balkan States,

Greeks take 1,500 Bulgar-German troops in

Macedonia, 15;

Allies' success, 211.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

51, 223, 436.

CAMPAIGN in Eastern Europe,

allied troops guard Murman coast,

252;

Czechoslovak Army fight Bolshevists in

Siberia and Volga region, 253.

CAMPAIGN in Western Europe,

review of month's fighting, 1,

9;

Germans cross the Aisne, 9;

second battle of the Marne, 10, 12;

description by Geo. H. Perris, 17;

"The German Offensive," 17;

"The Turning Point of the Battle," 28;

description of the French counterblow,

30;

"End of the Fourth Phase," 32;

Petain's tactics by W. Duranty, 32;

"A German View of Germany's Effort,"

35;

"A Battle Seen from Above," 54;

American soldiers in action in Champagne

and Picardy, 55;

capture of Cantigny by Americans, 57;

"First American Offensive a Success,"

57;

"Americans' Defense of Chateau-Thierry,"

62;

"Capture of Belleau Wood," 65;

"The War in the Air," 80;

hospitals bombed, 83;

Americans advance northwest of

Chateau-Thierry,

take Vaux and Belleau Wood,

197;

Australians and Americans take Hamel,

197;

French drive back Germans near Rheims,

197;

"Allied Successes on Three Fronts,"

205;

American troops check German advance

between

Chateau-Thierry and Jaulgonne,

213;

beginning of the allied offensive,

216;

"Americans on the Battlefront,"

226;

"Taking the Village of Vaux,"

233;

"Thorough American Work at Vaux,"

235;

"The Advance at Hamel," 237;

"Agony of the City of Lille," 281,

456;

"Nieuport, City of Desolation,"

286;

German offensive, 17;

enemy offensive in its fifth phase defeated

on the Marne, 389;

America's part in second battle of the

Marne described, 398;

account of the strategical plan which won

the

second battle of the Marne,

414;

"How Foch Outgeneraled the Germans,"

416;

German gains claimed, 425.

See also Progress of the War,

50, 221, 435.

CANADA,

war finance in Canada, 72;

war achievements, 306.

CANADA'S Four Years of War Effort, 451.

CANBY (Prof.), 336.

CARRE, (Dr.) P.,

"Chemists and Chemistry in the War,"

294.

CASUALTIES,

Chaplains on service, 8;

losses due to bombing of British hospitals

in France, 83;

list of German aviators killed, 86;

casualties of belligerents during four

years, 279;

losses from bombing of hospitals,

204;

estimate of German losses on western front,

389;

summary of American losses to Aug. 16,

431;

losses from air raids on Paris,

441.

See also PRISONERS of

War.

CAUCASUS Region, see ARMENIA.

CAUSES of the War,

Prince Lichnowsky's memorandum, 162;

Lord Haldane's report of his conciliatory

mission to

Germany in 1912, 166;

"Albanian and Slav," 201,

Dr. Wm. Muehlon lays responsibility for the

war on

German Government, 547.

See also AIMS of the

War.

Cavalry in Recent Battles, 387.

CENTRAL Powers,

"Austria's Leaders Accept Germany's

Policy," 513;

man power of, compared with that of the

Allies, 75.

See also

AUSTRIA—HUNGARY;

GERMANY.

CECIL, (Lord) Robert,

views on an economic league of nations,

297.

CHATEAU-THIERRY,

historical sketch, 6.

See also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

Chemists and Chemistry in the War, 294.

CHELMSFORD, Baron, 204.

CHINA,

Chinese-Japanese military alliance,

498.

CHURCHILL, Winston Spencer,

speech at Fourth of July celebration,

336;

"American Independence Day,"

535.

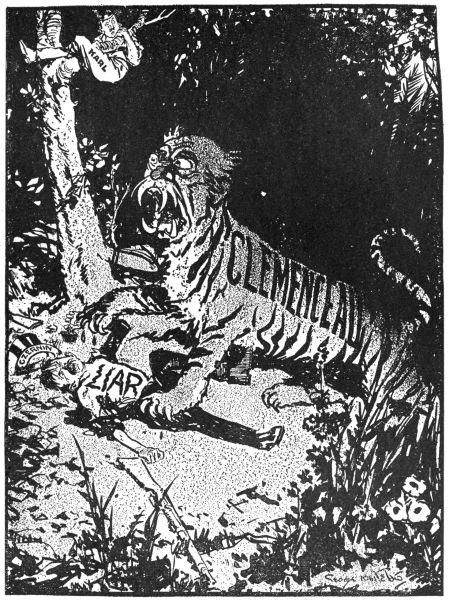

CLEMENCEAU (Premier),

text of speech of defiance to Socialist

pacifists, 307;

"Clemenceau's Defiance of Obstructors,"

149.

CIOTORI, D. N.,

"Bessarabia's Historical Background,"

328.

COLLEGE graduates in United States service, 203.

COMMERCE,

"American Exports Versus the U-boats,"

45;

"An Economic League of Nations to Govern

Trade After the War," 297;

"Trade After the War," 160;

world movement against German trade,

545.

See also SHIPPING.

COMMUNIST Party, see RUSSIA—Bolsheviki.

COMPIÉGNE,

historical sketch, 6.

See also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

Constantine's Treachery, 504.

COST of the War,

public debts of chief belligerent powers,

277.

See also FINANCES under names of

countries.

COSTA RICA

declares war on Germany, 8.

Current History Chronicled, 1, 191, 381.

CURZON, Earl,

on League of Nations, 352.

CZECHOSLOVAK Nation,

Austria-Hungary denounces British

recognition, 386.

CZECHOSLOVAKS,

role in Russian affairs, 265;

allied assistance, 465;

recognized as a nation, 489;

Czechoslovaks of Bohemia and Moravia,

491.

See also PROGRESS of the War—Russia,

437.

CZERNIN von Chudenitz, (Count) Ottokar,

"Austria's Leaders Accept Germany's

Policy," 513.

D

DALY, John,

"A Toast to the Flag," (poem,)

360.

Death Knell of Empire, 353.

DECORATIONS and honors,

distinguished service crosses, awarded to

100 Americans, 242;

Gen. Petain receives Military Medal,

382;

Gen. Foch becomes Marshal of France,

382;

conferring of foreign decorations on

Americans, 383;

Legion of Honor conferred on Lieut.

Nungesser, 442.

DEGOUTTE (Gen.),

sketch of career, 384.

DESCHANEL, Paul,

"American Ideals in the War,"

543.

DISTINGUISHED Service Crosses,

see DECORATIONS.

DOBRUDJA,

see PEACE—Rumanian Separate

Peace.

DRUNKENNESS,

reduced in England, 3.

DUBOST, Anthonin,

"What America Gives and Gains,"

542.

[Pg

III]

DURANTY, Walter,

"The Turning Point of the Battle," 28;

Petain's masterly tactics, 32;

"How Foch Outgeneraled the Germans,"

416.

DUVAL, Emile,

proprietor of Bonnet Rouge, shot for

treason, 198.

E

EDDY, Sherwood,

"Poison Gas in Warfare," 291.

"ENEMY Aliens in the United States," 249;

property of, 250;

"Rumely Propaganda Case," 251.

England and the War's Causes, 162.

ENGLAND:—

Achievements 1914-1918 reviewed by Premier

Lloyd George, 505.

Anniversary of the war, Fourth,

529.

Army, Irish volunteers, 1914-1917, 8.

Drunkenness reduced in, 3.

Finances, new vote of credit given,

8;

war pensions, 203.

"France's Tribute to Great Britain,"

77.

Germany, Relations with,

Lord Haldane's official report of his

conciliatory mission

prior to the war, 166;

Prince Lichnowsky's memorandum, 162;

"England and the War's Causes;" Prince

Lichnowsky's memorandum, 162;

Lord Haldane's report of his conciliatory

mission of 1912, 166;

British official statement issued in 1915,

169.

Exchanging Thousands of Prisoners, 94.

F

FERDINAND, (King) of Rumania,

accepts terms of treaty of Bucharest,

321.

Final Phases of the War, 301.

FINANCES, public debts of chief belligerent powers, 277.

See also under names of

countries.

FINLAND,

proposed constitution, 265;

German influence, 264.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

53.

Flame Throwers, 397.

FOCH, (Gen.) Ferdinand,

receives Marshal's baton, 382;

his use of cavalry, 387.

FOODSTUFFS:—

Belgium, "Saving Belgium from Starvation,"

521.

Canada's contribution, 307.

England, 7.

Ireland's food shipments to England,

90.

United States, "How America Has Fed the

Allies," 450.

United States assistance to Allies,

387.

FOURTH of July,

worldwide celebration, 335;

"The World's Independence Day,"

342;

addresses and papers, Cherioux Adolphe,

541;

Churchill, Winston Spencer,

535;

London Times editor, 538;

London Telegraph editor, 539;

Dubost, Anthonin, 543;

address and papers, Deschanel, Paul,

543.

FRANCE—

Premier Clemenceau receives vote of

confidence, 149;

Bastile Day greeting received from Pres.

Wilson, 245;

"Reconstructing the Life of France,"

286;

"Alsace-Lorraine: Its Relation to France,"

308.

See also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

Fraternity of English and French, 533.

French Armies at Close Range, 414.

G

GALEAZZI, (Prof.) Riccardo,

"Rebuilding Disabled Soldiers," 101.

GALSWORTHY, John,

"The Soldier Speaks," (poem), 79.

GAS Warfare,

sneezing powder in gas attacks, 102;

"Poison Gas in Warfare," 291;

gas masks for horses. 290;

U-boat makes mustard gas attack off North

Carolina, 448.

GASES, asphyxiating and poisonous, see GAS Warfare.

GEORGE V., (King of England,)

reviews American troops in London, 69;

Paris renames street in honor of,

204;

attends fourth anniversary of the war

ceremonies at

St. Margaret's, Westminster,

529;

congratulatory address on occasion of

silver wedding delivered by

Premier Lloyd George, and H. H. Asquith,

532, 248.

German Aims and Servile States, 313.

German Official View of the Americans, 243.

Germany and Great Britain in 1912, 166.

GERMANY:—

Army,

text of order for fraternization on Italian

front,

16;

estimate of losses on the western front,

389.

Austria-Hungary, Relations

with,

"New Austro-German Alliance," 91.

Commerce,

world movement against German trade,

545.

Demoralization and crime in

England;

Relations with, see

ENGLAND.

England, Relations with;

ENGLAND—Germany, Relations

with.

Finances,

"Germany's Debt and Credit,"

460.

Foreign relations,

von Kuhlmann's summary of war situation,

315;

criticised by Count Westarp,

318;

by Socialist leaders, 319;

Germany's financial burden,

550.

Infant welfare in, 7.

Population declining, 4.

Russia, relations with;

German Ambassador at Moscow assassinated,

258;

German intervention in Russia,

262.

South American States, relations with,

8.

See also CENTRAL

Allies.

Germany's Control of the Danube, 324.

"Germany's First Great Defeat," 389.

GIBBS, Philip,

"The Advance at Hamel," 237.

GOURAUD (Gen.), 385.

Great Britain's War Record, 505.

GREECE,

"Constantine's Treachery,"

504.

GREY of Falloden (Viscount),

"A League of Nations," 345.

H

HALDANE (Lord),

official report of his conciliatory mission

to

Germany prior to the war, 166.

Hamel, The Advance at, 237.

HAMEL,

see CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

HELSINGFORS, 8.

HENDERSON, Daniel M.,

"The Road to France," (poem,)

534.

HEROES, Pershing (Gen.)

cites many Americans for special acts of

bravery, 241.

See DECORATIONS and

Honors.

Heroic American Deeds, 239.

HERTLING, (Chancellor) George F. von,

outlines German official view on peace,

311.

HINTZE, (Admiral) von,

appointed German Foreign Secretary,

312.

HONORS, Military,

see Decorations and Honors.

HOOVER, Herbert C.,

"How America Has Fed the Allies,"

450.

HORVATH, Gen.,

declares himself dictator in East Siberia,

199, 254.

HOSPITAL ships,

sinkings, 447;

Llandovery Castle sunk, 246.

HOSPITALS

bombed, 83;

casualties, 204;

Col. Andrews describes attack on hospital

at Boulenes,

Chaplain describes it to King George,

330;

protest by Conan Doyle, 331;

by Prussian Order of St. John,

331.

How Foch Outgeneraled the Germans, 416.

How America Has Fed the Allies, 450.

I

"In Flanders Fields," (poem), 144.

INDEPENDENCE Day,

see FOURTH of July.

INDIA,

report on constitutional reforms,

204.

IRELAND,

food shipments to England, 90;

69 Sinn Feiners arrested, 88;

statistics of volunteers 1914-1917,

8.

Irish Plotters, Arrest of, 88.

ITALY,

"Italy's Third Year of War," 76;

address by Secretary Lansing in honor of

the

third anniversary of Italy's entrance into

the war,145;

speech of Count Macchi di Cellere, Italian

Ambassador,

at Italian anniversary celebration,

146.

Italy's Third Year of War, 76.

Italy's Troops, Trying to Corrupt, 16.

J

JAMES, Edwin L.,

"America's Part in a Historic Battle,"

398;

"Capture of Belleau Wood," 65;

"Defeating the German Offensive,"

213;

"The Enemy Outflanked and Beaten,"

216;

"Heroic American Deeds," 239;

"Thorough American Work at Vaux," 23.

JAPAN,

"Chinese-Japanese Military Alliance,"

498.

JOHNSON, Thomas F.,

"First American Offensive a Success,"

57.

JORDAN, E.,

"Czechoslovaks of Bohemia and Moravia,"

491.

JUGOSLAVIA,

project for a South Slavic State Threatens

to Disrupt

Austria-Hungary, 115;

Supreme War Council favors free Poland and

Jugoslavia, 126;

"Great Britain and the Jugoslav State,"

275;

conference of Poles, Jugoslavs, and

Italians at Rome, 119;

the case of Bohemia, 123;

the case of Transylvania, 125;

Supreme War Council at Versailles favors

free Poland and Jugoslavia, 126;

"Growth of the Jugoslav Movement," 115;

declaration of Czech members of Reichsrat,

115;

Jugoslav deputies and Croatian labor demand

independent States of

Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, 118.

Jutland, Battle of, 152.

K

KERENSKY, (ex-Premier) Alexander,

speech in London on Russian affairs,

259.

KIPLING, Rudyard,

"American Invasion of England,"

433.

KOLA,

see MURMAN District.

KROPOTKIN (Prince), speaks on Russian internal conditions, 263.

KUHLMANN, (Dr.) Richard von,

resignation, 312;

address leading to resignation,

315.

KUHLWETTER, (Capt.) von,

"Battle of Skagerrak as Germany Sees It,"

156.

L

LANSING, (Sec. of State) Robert,

address In honor of third anniversary of

Italy's

entrance into the war, 145.

LEAGUE of Nations,

views of Lord Robert Cecil,

297;

discussion by Viscount Grey of Falloden,

345;

by Premier Lloyd George, 351;

by Earl Curzon, 352;

"The Death of Empire," by H. G. Wells,

353;

French view, 350;

"Based on Population," by Arnold Bennett,

355;

"President Wilson and the League of

Nations," 511.

LEWIS, J. Hamilton,

"Price of Peace," 523.

LICHNOWSKY (Prince),

record of his conduct while German

Ambassador in England, 162.

LILLARD, R. W.,

America's answer, (poem), 144.

LILLE,

Agony of the city of, 281,

456.

LISLE, Claude Joseph Rouget de,

see ROUGET de LISLE, CLAUDE

JOSEPH.

LITHUANIA,

proclaimed an independent State allied to

Germany, 109.

Living Line, The, (poem), 149.

LLANDOVERY Castle (hospital ship) sunk, 246.

LLOYD GEORGE, (Premier) David,

congratulates Pershing on Fourth of July

celebration, 336;

"A Real League of Nations,"

351;

"Britain's Imperial Hopes Realized,"

299;

"Great Britain's War Record,"

505;

address on occasion of silver wedding

anniversary of King George, 532.

LUXEMBURG,

sketch of the history of, 202.

M

MACCHI DI CELLERE (Count),

speech at Italian anniversary celebration,

146.

McCRAE, (Lieut. Col.) John,

"In Flanders Fields," (poem), 144;

"America's Answer," (in honor of Lieut.

Col. John McCrae,) 144.

McCUDDEN, (Capt.) James B.,

awarded Victoria Cross, 87.

McCUDDEN, (Maj.) James B.,

death, 442.

McGILLICUDDY, Owen E.,

Canada's four years of war effort,

451.

MACKENZIE, Cameron,

"Taking the Village of Vaux,"

233.

MACLAY, (Sir) Joseph,

"Transporting America's Army Overseas,"

443.

MAETERLINCK, Maurice,

"Brute Force Versus Humanity," 150.

MALVY, Louis J.,

trial for treason by French Senate,

198;

banishment, 384.

MAN Power—

Allied man power compared with that of the

Central Powers, 75.

MANGIN, (Gen.) Joseph,

sketch of career, 385.

Marne, Second Battle of, 398.

MASARYK (Prof.),

receives message from Czechoslovaks,

469;

sends messages to Pres. Poincare and

Secretary Balfour on recognition

of the Czechoslovak Nation,

489.

MARSEILLAISE,

story of, 200.

MEXICO and the United States, 142.

MEYNELL, Alice,

"In Honor of America," (poem),

445.

MILITARY Medal,

see DECORATIONS and

Honors.

MILNER (Viscount), British War Secretary,

speaks on German aims, 313;

Count Burian replies, 313.

MIRBACH (Count) von, German Ambassador,

assassinated in Moscow, 259;

his duplicity, 261.

MONTAGUE, Edwin Samuel, 204.

Mount Vernon Address, 191.

MUEHLON, (Dr.) Wilhelm,

lays responsibility for the war on the

German Government, 547.

MURAVIEFF,

Bolshevist Commander in Chief,

266.

MURMAN District,

see RUSSIA—Murman

District.

MUSTARD gas,

see GAS Warfare.

N

NATIONS at war, 388, 461.

NAUDEAU, Ludovic,

"Russia's Constituent Assembly,"

267.

NAVAL operations,

Capt. Rizzo sinks Austrian dreadnoughts off

Trieste and Dalmatia, 15;

"The Battle of Jutland," 152;

Thomas G. Frotheringham's account of the

battle of Jutland reviewed

by Admiral Sir Cyprian Bridge, Vice Admiral

E. F. Fournier, and

Arthur Pollen, 152;

"Battle of Skagerrak (Jutland) as Germany

Sees It," 156.

See also

PROGRESS of the War, 224, 437;

SUBMARINE warfare.

NEW York Evening Mail, 251.

NICHOLAS, (Romanoff) ex-Czar of Russia,

"The Imprisoned ex-Czar in the Crimea,"

93;

biographical sketch, 381.

Nieuport, City of Desolation, 285.

NUNGESSER (Lieut.),

cited for Legion of Honor,

442.

P

PALLIS (Gen.),

sentenced for disloyalty, 204.

PARIS,

re-names streets in honor of allies,

204;

account of bombardments given by le Temps,

204.

Peace League of Nations, 355.

Peace, The Basis of, 303.

PEACE:—

"International Socialists' Peace Campaign,"

158.

General Chancellor von Hertling outlines

official view of

Berlin Government, 311;

"American Government's Peace Terms,"

523.

Rumanian separate peace ratified,

321;

view of Rumanian ex-Premier,

323;

Protest of Rumanians in exile against,

325.

Russo-German, views of Trotzky and

Savinkov,113.

See also AIMS of the

War.

PENSIONS, England, 203.

PERRIS, George H.,

"The German Offensive," 17;

description of the French counterblow,

30;

"French Armies at Close Range,"

414.

Pershing at the Tomb of Lafayette, (poem), 329.

PERSHING (Gen.),

cites Americans for special acts of

bravery, 241.

PETAIN (Gen.),

masterly tactics in allied counterattacks,

32;

receives Military Medal, 382.

PICARDY,

see CAMPAIGN in Western Europe,

423.

POINCARE, (Pres.) Raymond,

replies to Pres. Wilson's Bastile Day

greeting, 245;

congratulates Pres. Wilson on Fourth of

July celebration, 337.

POISON Gas,

see GAS Warfare.

POLAND,

Allies Supreme War Council favors

independent State, 126;

POLLEN, Arthur,

reviews debatable phases of Battle of

Jutland, 155.

PRISONERS of War, number taken in third German offensive, 1;

Franco-German agreement for release of,

94;

inhuman treatment of civilian prisoners in

Austrian prison camps, 97;

abuses in German prison camps, 100;

prisoners taken in Bouresches Sector,

German report on

examination of, 243;

appalling cruelty of Germans to,

288;

"Acme of German Cruelty," 314;

treatment of in German prison camps,

332.

Prisons, Horror of Austrian, 97.

Progress of the War, 49, 221, 434.

PROPAGANDA,

German, in the United States,

251;

sent to the enemy by balloons,

198.

PUTNAM, George Haven, 336.

R

RAILROADS,

Cairo to Jerusalem, 5;

Cape to Cairo, 5;

Kola to Petrograd, 255.

Rebuilding Disabled Soldiers, 101.

Reconstructing the Life of France, 286.

RED Cross,

second drive, 8;

President Wilson's address to inaugurate

second Red Cross campaign, 137;

"Remarkable Work of American Red Cross in

Italy," 472.

REHABILITATION,

see SOLDIERS and Sailors,

Rehabilitation.

RELIEF Work,

see Hospital Ships.

RHEIMS,

see CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

RICHTHOFEN, Capt. Baron von,

death, 85.

RIGGS, Edward G.,

estimates college graduates in United

States Service, 203.

RIZZO, Capt., 15.

Road (The) to France, (poem,) 534.

RODMAN (Admiral),

awarded the Order of the Bath,

383.

ROGERS, D. G.,

war finances, 277.

ROOSEVELT, (Lieut.) Quentin,

death, 441.

ROOSEVELT, Theodore,

sends letter to be read at Philadelphia

celebration of Bastile Day, 246.

ROSENBERG, von,

appointed German Ambassador in Moscow,

259.

ROUGET DE LISLE,

Claude Joseph, 200.

RUBIN, A.,

Rumania and Bessarabia, 326.

RUMANIA,

signs legal and political supplementary

agreement to

Peace of Bucharest, 127;

German control of Rumanian oilfields and

harvest, 129;

Ferdinand accepts terms of Treaty of

Bucharest, 321;

Rumanian peace treaty ratified,

321;

"Rumania and Bessarabia," 326;

"Rumania's Thralldom," 127;

"Rumania's Humiliation," 502.

RUMELY Propaganda Case,

see Enemy Aliens.

RUSSIA:—

Allied intervention discussed by Allies,

110;

Japan and China make treaty for

intervention in Siberia, 110;

Sen. King's resolution in favor of,

111;

"New Forces at Work to Save Russia,"

252.

"Czechoslovaks, Role of," 265.

Finances, Russia's debt, 277;

Germany, relations with, 258, 261,

262.

Internal conditions, 105, 259, 283.

Murman district, Anglo-American occupation

of Kem, 199;

German-Finnish forces attack Murman

railway, complete a railroad to

Kem, German submarines in White Sea,

255;

meaning of word "Murman," 256;

Murman railway, 257;

importance of the port of Kola,

257;

Allies intervene at request of Murman

inhabitants against Soviet, 259;

Bolshevist and Finno-German invasion,

259;

intervention of the Allies, 259,

465;

allied forces at Murmansk and Archangel,

470.

Revolution, Bolsheviki fail to make peace

with the Ukraine, 105;

"Russia under Many Masters," 103;

Czechoslovak Army fighting Bolsheviki in

Siberia and in

Volga region, 252;

attitude of Czechoslovaks toward Soviets,

254;

Armed allied intervention discussed,

110, 259, 260, 261;

German intervention, 262;

Russia's Constituent Assembly,

267;

non-Bolshevist Government established in

Siberia, 199, 254, 467;

anti-Bolshevists establish "Provisional

Government of the Country of the North," 470;

Japan sends aid to Czechoslovak troops,

466;

"Siberian Temporary Government"

established, 467.

See also

CAMPAIGN in Eastern Europe;

ESTHONIA—Finland;

GERMANY;

JAPAN—Chinese-Japanese Military

Alliance;

Relation with Russia;

UKRAINIA, LITHUANIA, POLAND;

PROGRESS of the War—RUSSIA.

RUSSIAN Situation, summary of, 265.

S

ST. JOHN of Jerusalem, Order of,

protest against bombing of hospitals,

331.

SAVINKOV, (ex-Minister) Boris,

on Bolshevist peace, 113.

SHERMAN, L. Y.,

"Germany Must Be Vanquished,"

527.

SHIPBUILDING,

new records in, 43;

statistics of allied output for Jan. to

May, 1918, 248;

American output Jan. to July, 1918,

203;

British and American output to August,

49.

SHIPPING,

"American Exports Versus the U-boats,"

45;

American losses, 203;

tonnage acquired from other nations,

204;

Allies' losses Jan. to May, 1918,

248;

losses to allied and neutral during

Jan.-Aug. 15, 446;

Canada's contribution, 307.

See also SHIPBUILDING.

SHIPYARDS, new American shipyards, 449.

SIBERIA,

temporary non-Bolshevist Government with

Gen. Horvath as President established, 254.

SIMS, Admiral, 336.

SINN FEIN,

see IRELAND.

SKAGGERRAK, Battle of,

see NAVAL Operations.

SLAVS,

account of Slavonic peoples, 3;

"Albanian and Slav," 201.

See also

CZECHOSLOVAKS;

JUGOSLAVIA.

SNEEZING Powder, see GAS Warfare.

SOCIALISTS,

"International Socialists Peace Campaign,"

158;

criticism of von Kuhlmann's summary of war

situation, 319;

view of Treaty of Bucharest,

322;

text of Premier Clemenceau's speech of

defiance to Socialist pacifists, 307.

SOISSONS, 21, 386;

see also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

Soldier Speaks, (poem), 79.

SOLDIERS and sailors,

rehabilitation of, "Rebuilding Disabled

Soldiers," 101;

pensions granted to British disabled

soldiers, 203.

Somme, Third Battle of, 423.

Stars and Stripes, (poem,) 225.

STEPHENS, Winifred,

"Reconstructing the Life of France,"

286.

STRESEMANN, (Dr.) Gustave,

criticises von Kuehlmann's summary of war

situation, 319.

STURGES, (Lieut.) R. S. H.,

"Fashions of the Firing Line,"

309.

SUBMARINE warfare,

"The U-boat Raid in American Waters,"

38;

other submarine activities of the month,

40;

"Out of the Sleep of Death," 42;

summary of losses, 49;

Llandovery Castle sunk, 246;

statistics of Allies' losses, January to

May, 1918, 248;

"The Submarine's Increasing Failure":

summary of recent activities, 446.

See also Hospital

Ships.

See also Progress of the War,

49, 221, 434.

SUPREME War Council, favors independent Poland and Jugoslavia, 126.

SWITZERLAND an oasis in wartime, 289.

T

Theodoric and Attila on the Marne, 427.

"Toast to the Flag, A," (poem,) 360.

TRADE, see COMMERCE.

TRANSATLANTIC Trust Company, 251.

Transporting America's Army Overseas, 443.

Troops, Transportation of, 2.

See also U. S. Army.

TROTZKY, Leon,

attitude on peace with Germany, 113.

TURKEY,

invasion of Caucasus under Brest

Treaty,131.

U

U-BOATS, see SUBMARINE Warfare.

UKRAINIA,

refuses to make peace with Bolshevist

Government, 105;

peace signed with Russia, 264.

UNITED STATES:—

Army,

number of troops in France, 1;

"Transportation of Troops," 2;

"Armies Under Foreign Generals," 2;

"First units of our new army reviewed by

King George," 69;

"No Limit to Size America's Army," 70;

"War Record of the United States," 73;

America's first anniversary in France,

78;

"Premier Lloyd George Lauds Americans,"

148;

number of negroes in, 204;

"America's War Effort," 229;

German official view of, 243;

reorganizations of, 429;

consolidation of all branches into one

"United States Army," 430;

"Transporting America's Army Overseas,"

443.

See also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

Commerce,

"American Exports Versus the U-boats,"

45;

finances, address by President Wilson on

Federal Revenue bill, 139.

See also COST of the

War.

French aid in the American Revolution,

201.

"Mexico and the United States," 142.

Navy, largest naval appropriation bill

passed, 431.

Russian Situation—Inaction criticised,

260.

SHIPPING, see

SHIPPING;

SHIPBUILDING.

War Dept.,

summary of achievements to July, 1918,

229;

war with Germany and Austria-Hungary, "War

Record of the United States," 73.

See also TITLES

Beginning

America,

American.

See also PROGRESS of the War,

49, 221, 434.

V

VAN DYKE, Henry,

"The Stars and Stripes," (poem,)

225.

Vaux, Taking the Village of, 233.

Vaux, Thorough American Work at, 235.

VERSAILLES Council, see SUPREME War Council.

VICTORIA Cross

awarded to Capt. James B. McCudden,

87.

VILLERS-COTTERETS,

historical sketch, 6.

See also CAMPAIGN in Western

Europe.

W

"War in the Air," 80.

WELLS, H. G.,

"Boycotting Germany," 545;

"The Death Knell of Empire,"

353.

WEST, Austin,

"Austrians at Grips with Italians,"

33.

WESTARP (Count), leader of Conservatives,

criticises von Kuhlmann's summary of war

situation, 318.

WHEELER, W. Reginald,

"Chinese-Japanese Military Alliance,"

498.

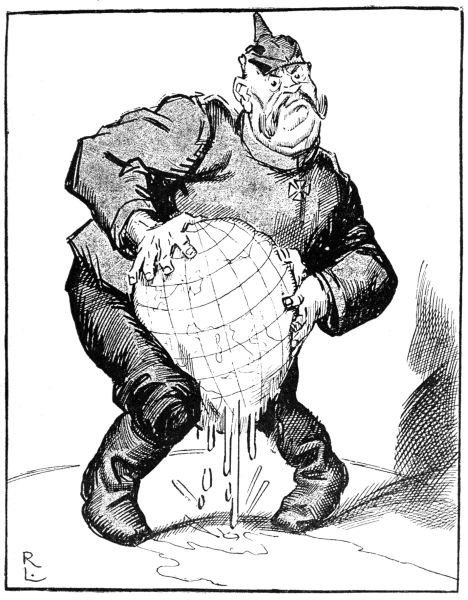

WILLIAM II., Emperor of Germany,

defines issues of the war, 36.

WILLIAMS, Harold,

summary of the Russian situation,

265.

WILSON, (Pres.) Woodrow,

Red Cross speech in New York, 137;

Federal Revenue Bill, 139;

appeals for economy, 141;

Memorial Day proclamation, 141;

address to Mexican editors, 142;

"Mount Vernon address"; a statement of

American war aims, 191;

reply of Baron Burian, 194;

Chancellor von Hertling's reply in

Reichstag, 311;

Paris renames street in honor of,

204;

sends greeting to France on Bastile Day,

245;

reply of Pres. Poincare, 245;

congratulated by Pres. Poincare on Fourth

of July celebration, 337;

reply, 337;

by King George of Greece, 340;

reply, 341;

denounces mob action, 384;

"President Wilson and the League of

Nations," 511.

ARNIM, (Gen.) Sixt von, 47.

BERTHELOT, (Gen.) Henri, 410.

BOEHM, (Gen.) von, 47.

BOROEVIC (Field Marshal). 237.

BRITISH Imperial War Conference, Members, 474.

BULLARD, (Maj. Gen.) R. L., 191.

BUNDY, (Maj. Gen.) Omar, 191.

BURNHAM, (Maj. Gen.) W. P., 204.

BURTSEFF, Vladimir, 268.

CAMERON, (Maj. Gen.) G. H., 394.

CHAPMAN, Victor, 395.

DICKMAN, (Maj. Gen.) J. T., 14, 191.

DUNCAN, (Maj. Gen.) G. B., 204.

EICHHORN, (Field Marshal) von, 427.

FOSDICK, Raymond B., 269.

GLENN, (Maj. Gen.) E. F., 204.

GOURAUD (Gen.), 410.

GREENE, (Maj. Gen.) H. A., 14.

HAAN, (Maj. Gen.) W. A., 394.

HALDANE, Viscount, Lord High Chancellor of England, 47.

HALE, (Maj. Gen.) H. S., 14.

HARBORD (Maj. Gen.), 68, 191.

HINTZE, (Admiral) Paul von, 411.

HITCHCOCK, (Sen.) G. M.,15.

HOLUBOWICZ, H. M.,78.

HORVATH (Gen.), 268.

HUMBERT (Gen.), 410.

HUTIER, (Gen.) von, 47.

KITCHIN, (Congressman) Claude,

15.

KNIGHT, (Rear Admiral) Austin M., 205.

LENINE, Nikolai, 458.

LIGGETT, (Maj. Gen.) Hunter, 191.

LOMONOSSOFF, (Dr.) G. V., 268.

LUFBERY, (Maj. Gen.) Ravul, 395.

McMAHON, (Maj. Gen.) J. E., 394.

MANGIN, (Gen.) Joseph, 410.

MARWITZ, (Gen.) von der, 47.

MARTIN, (Maj. Gen.) C. T., 204.

MASARYK (Prof.), 78.

MAUD'HUY, (Gen.) de, 220.

MIRBACH, (Count) von, 427.

MITCHEL, (Maj.) J. Purroy, 395.

MUIR, (Maj. Gen.) C. H., 394.

NIBLOCK, (Rear Admiral) Albert T., 205.

NICHOLAS, Romanoff, 426.

OVERMAN, (Sen.) L. S., 15.

PETLJURA (Gen.), 78.

READ, (Maj. Gen.) George W., 381.

RODMAN, (Rear Admiral) Hugh, 205.

ROOSEVELT, (Lieut.) Quentin, 395.

SENATE Committee on Military Affairs, 475.

SIMMONS, (Sen.) F. M.,15

SIXTUS (Prince of Bourbon),79.

SKOROPADSKI, Pavel Petrovitch, 268.

SVINHUFVUD (Judge),78.

TALAAT Pasha, 236.

TCHITCHERIN, Georg, 459.

VALERA, (Prof.) Edward de, 79.

WILSON, (Rear Admiral) H. B., 205.

WOOD, (Maj. Gen.) Leonard, 14.

WRIGHT, (Maj. Gen.) Wm. M., 381.

ALBANIA, relation of, to other Balkan States, 212.

ARMENIA, 134.

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY, showing populations in threatened revolt, 117.

AUSTRO-ITALIAN

Campaign, 15;

Piave delta, 210;

Albania, Italo-French advance,

212;

Cairo-Jerusalem Railway, 4.

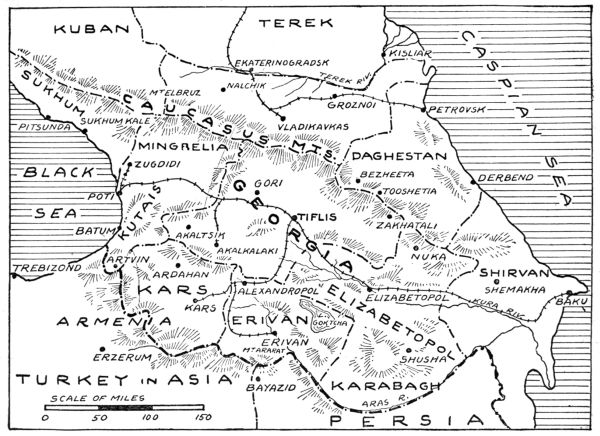

CAUCASUS region, 133.

EUROPE, showing territorial status of the war at the end of the

fourth year, 462.

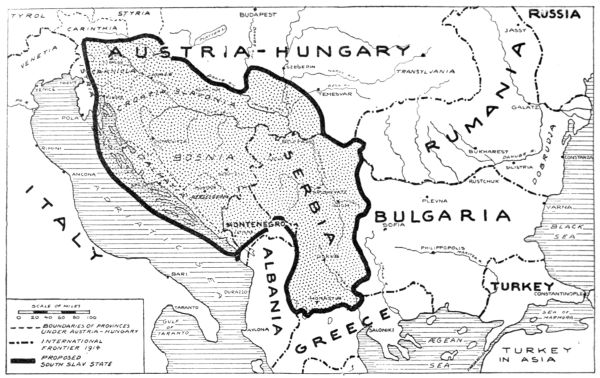

JUGOSLAVIA, projected States, 116.

MURMAN Coast, 256.

MURMAN District, 471.

MURMAN-PETROGRAD Railway, 255.

RUSSIA, showing points where Bolsheviki have been fighting, 260.

RUSSIA, showing positions of Allied Expeditionary Forces, 476.

RUSSIA, railway system, 262.

SIBERIA, showing Trans-Siberian Railway, 263.

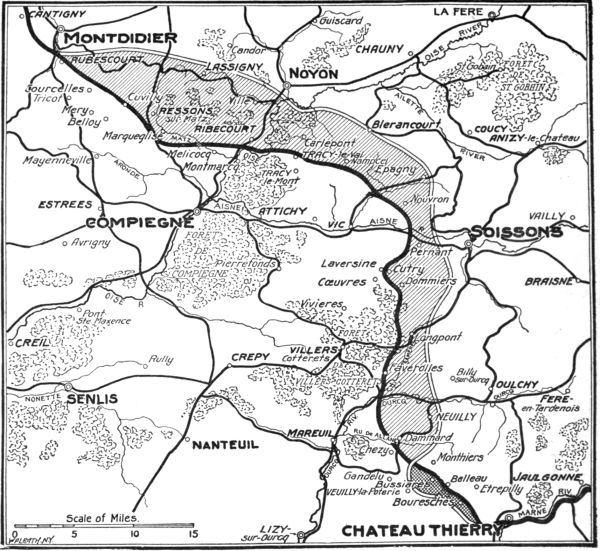

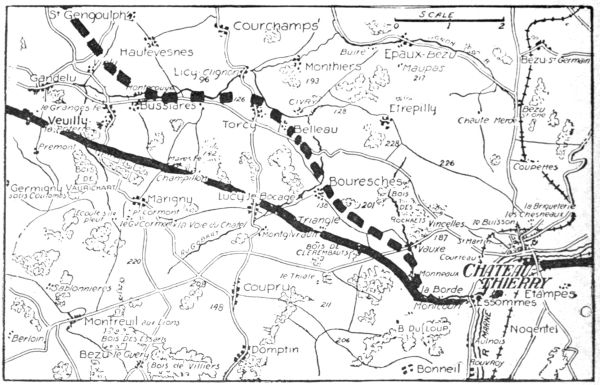

WESTERN Campaign:

German offensive of May, 10;

offensive of June 9, 12;

offensive of March to June, 18;

Cantigny captured by American troops,

59;

territory near Chateau-Thierry won back by

American soldiers, 66;

Aisne-Marne region showing Allies' gains

July, 1918, 206;

Marne front, 206;

Rheims, 207;

Allies' gains near Albert, Chateau-Thierry,

and Bethune, 208;

battlefront, August, 1918,

391;

Chateau-Thierry "pocket," 393;

Lys Salient, 395;

Montdidier Salient, 396.

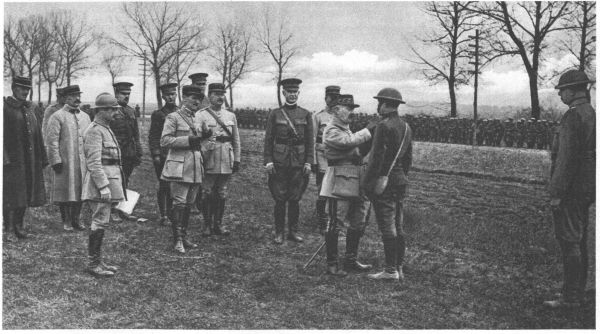

AMERICAN officers decorated by Gen. Philipot, 31.

AMERICAN patrol in trenches in France, 142.

AMERICAN troops on German soil, (Massevaux, Alsace,) 523.

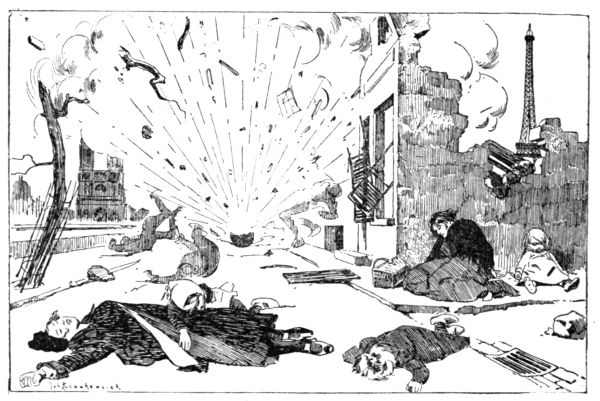

BATTLEFIELD in France, 316.

CAMP Jackson, 333.

CHATEAU-THIERRY, bridge across the Marne, 506.

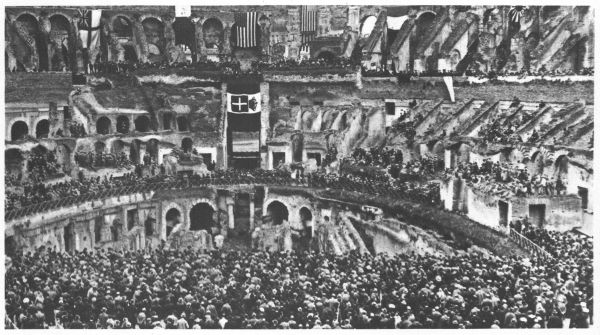

COLISEUM, Rome, during Italian celebration of anniversary of

America's

entry into the war,126.

DOGS trained for the British Army as dispatch bearers, 284.

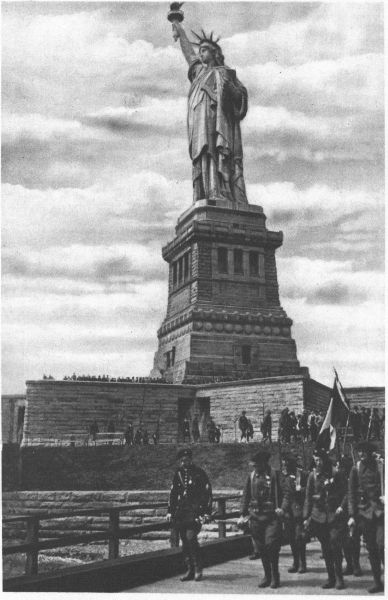

FRENCH Chasseurs Alpins visiting Statue of Liberty,

1.

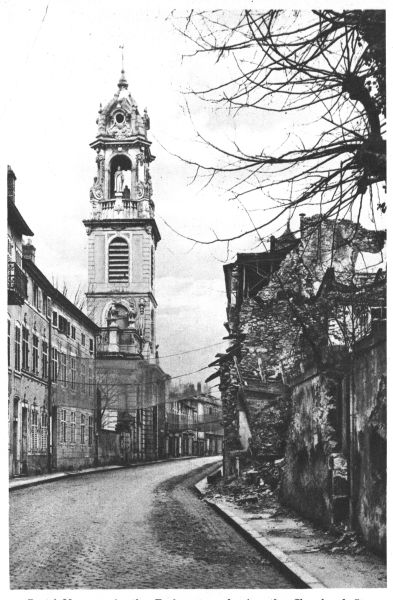

FRENCH town wiped out in German offensive,

95.

FRENCH town wrecked by retreating Germans, 506.

GAS attack as seen from an airplane, 317.

GAS masks, 317.

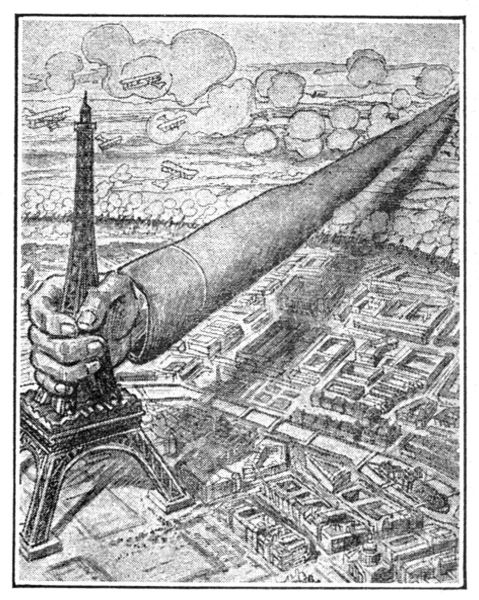

GUNS of the largest calibre, 285.

KENNELS of French war dogs, 284.

KING George's message to the soldiers of the United States, 69.

LOCRE, Ruins of village of, 221.

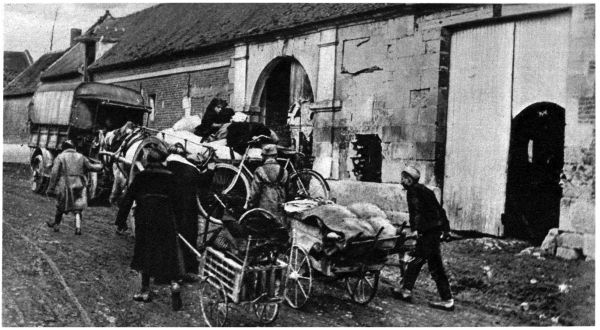

PICARDY inhabitants leaving their homes when German advance began, 94.

LUSITANIA'S victims' graves, 127.

PONT-A-MOUSSON, 143.

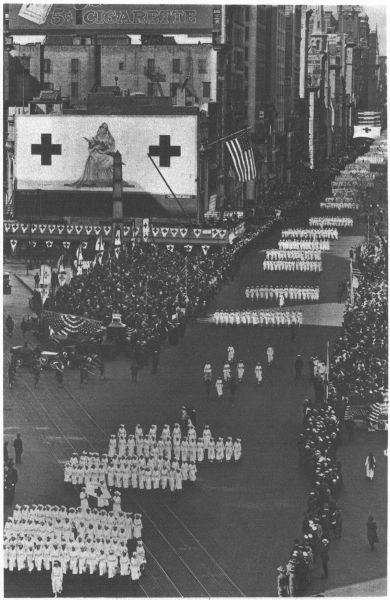

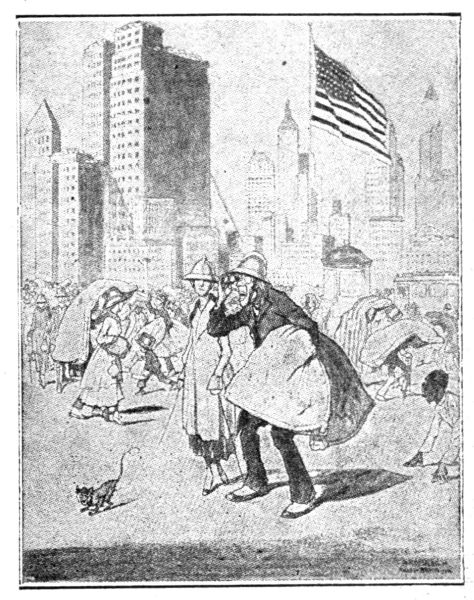

RED CROSS parade in New York reviewed by President Wilson, 1.

TANK, armored man power, 332.

TANK, new British type, 332.

UNITED STATES National Army men parade in London,30

VILLIERS-BRETONNEUX, entrance to chateau, 221.

WAR Dept. Building, Washington, 522.

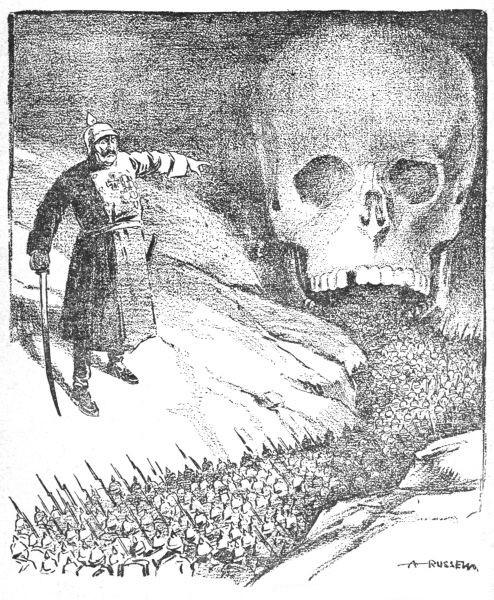

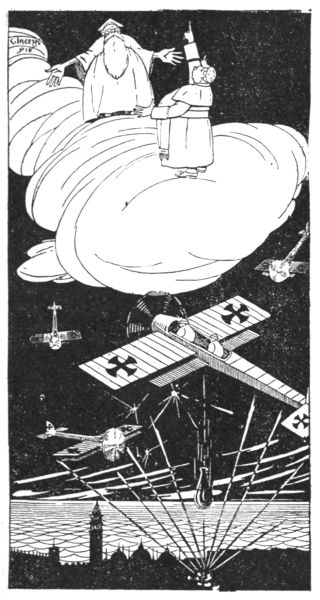

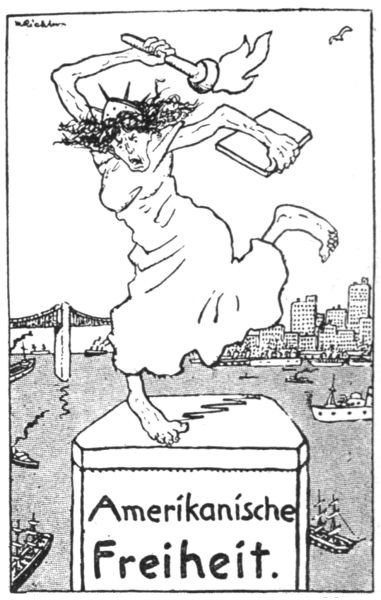

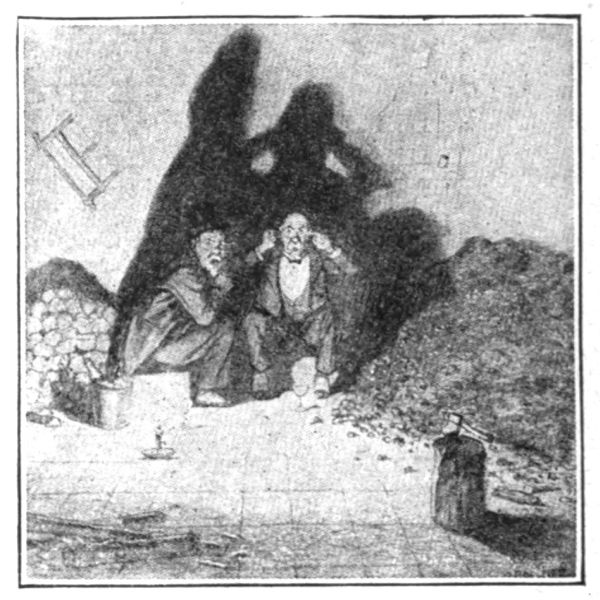

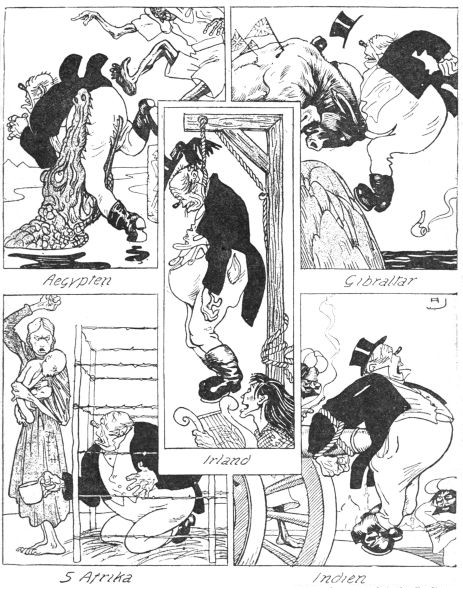

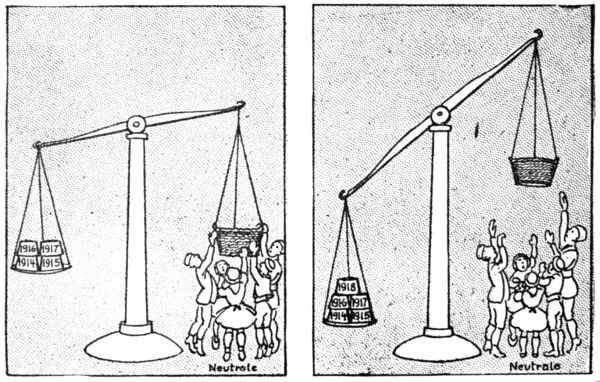

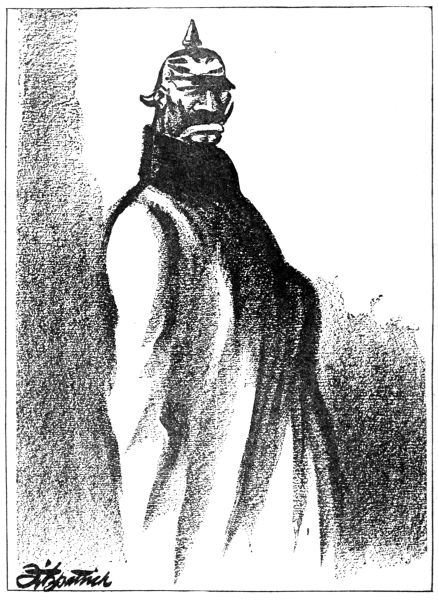

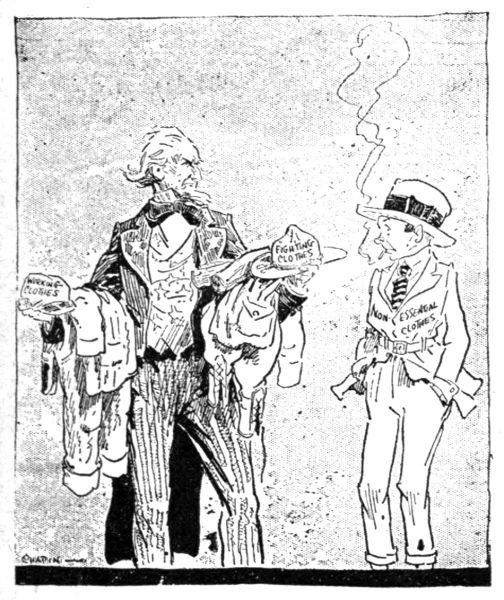

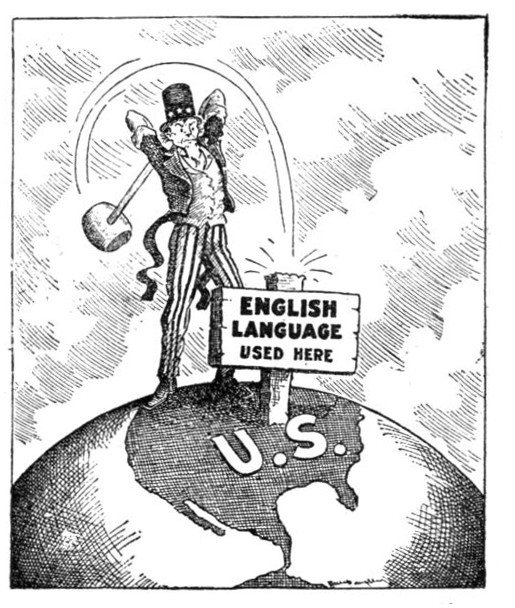

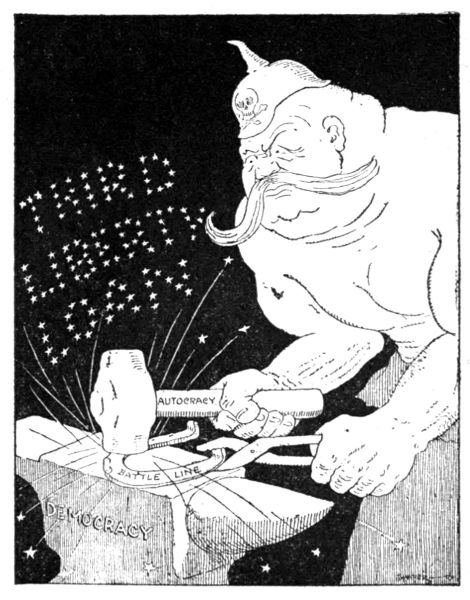

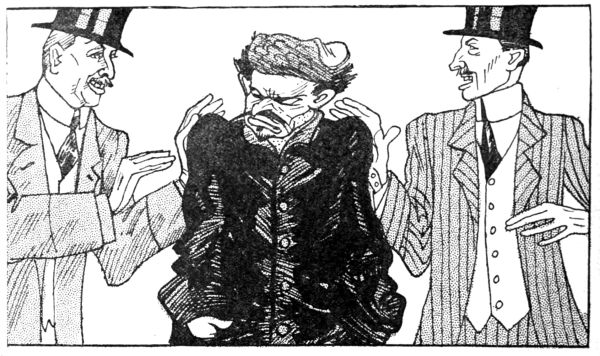

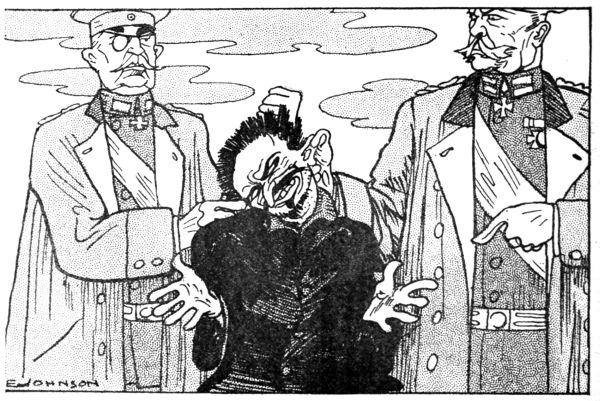

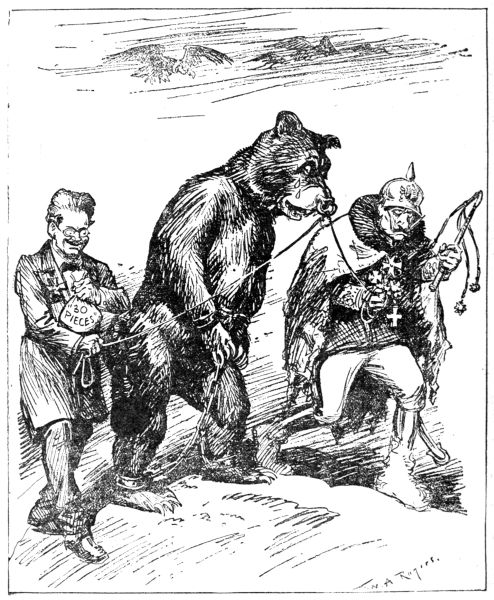

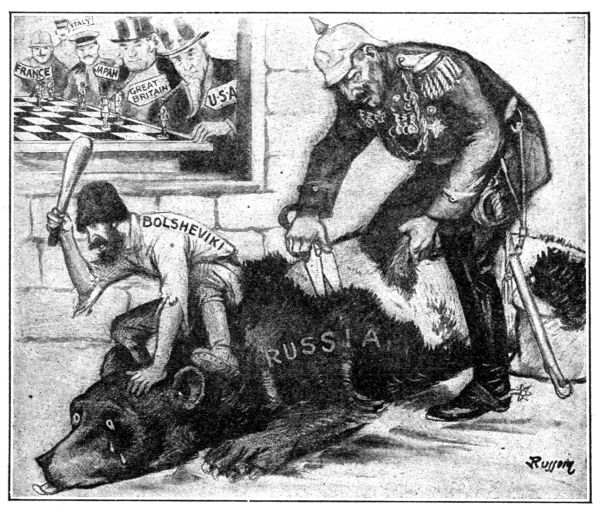

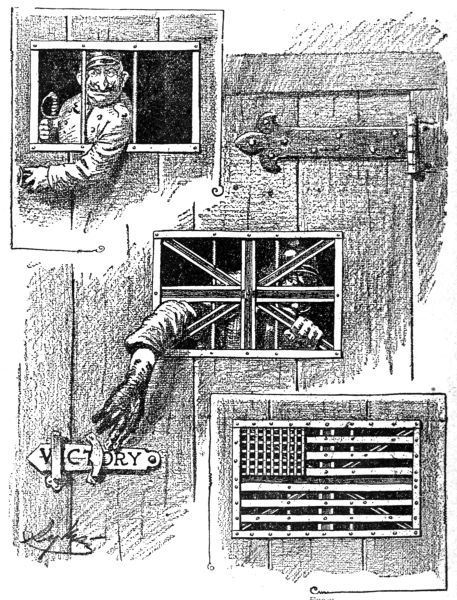

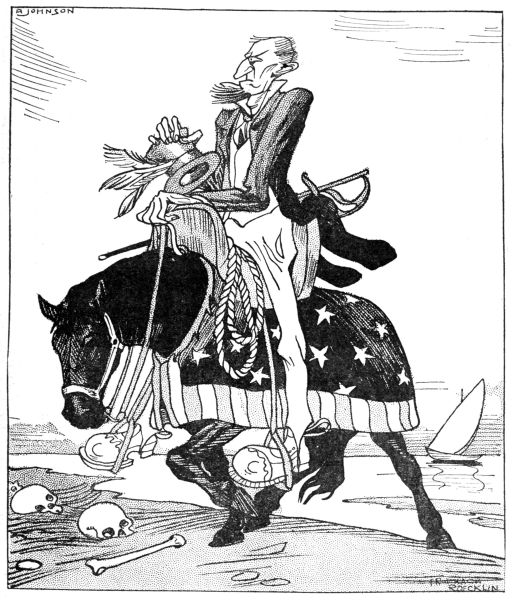

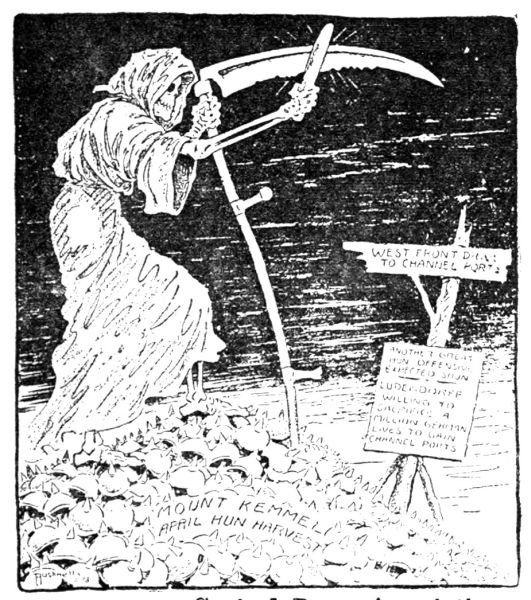

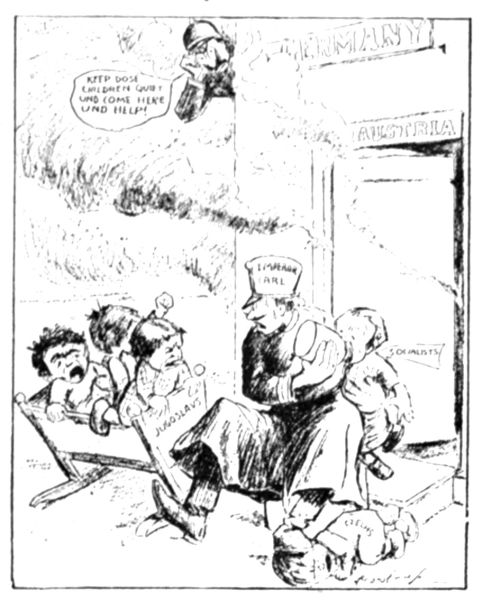

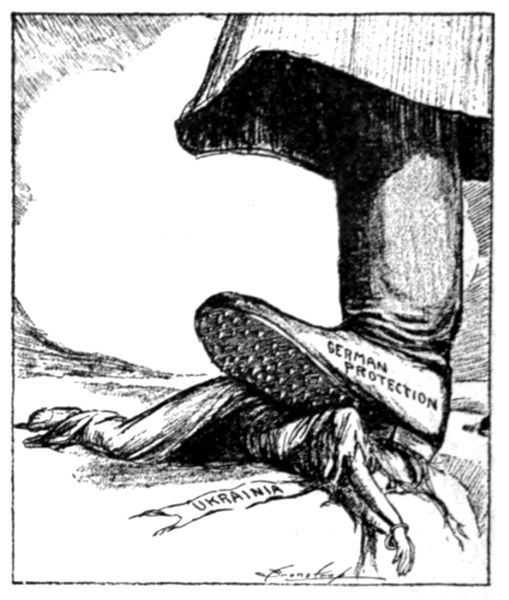

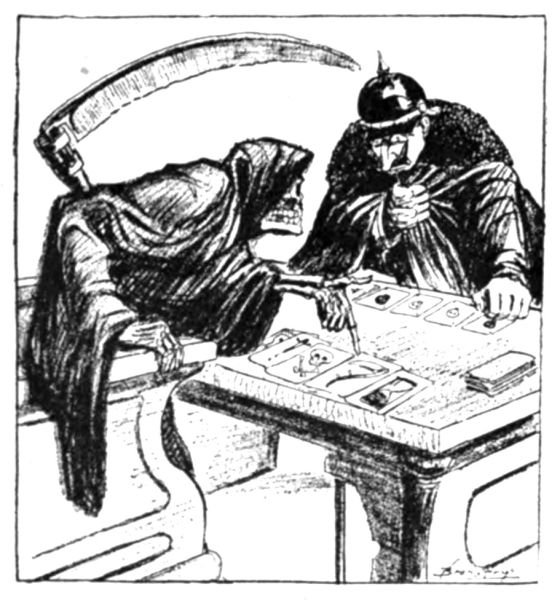

Cartoons

171-190; 361-380; 551-570.

(© International Film Service)

(Times Photo Service)

[Period Ended June 20, 1918]

Military activity superseded everything else during the month under review. Europe shook with the roar of battle. From May 27 to June 15 fully 3,000,000 men were engaged in deadly conflict along the battlefronts of France, with a ghastly toll of blood, while in Italy along a front of 100 miles more than 2,000,000 joined battle on June 15 and were furiously fighting when this issue went to press. The third German offensive, which continued for three weeks, did not break the front, nor did it divide the Allies, nor were the Channel ports reached, nor was Paris invested. In all these respects the drive failed, but important new territory was won by the Germans, and they claimed over 85,000 prisoners and an enormous amount of booty; the Allies declared that the failure of the Germans to obtain any of their objectives, coupled with the frightful price they had paid in killed and wounded, the shock to the army morale, and the disappointment in the enemy leadership, operated practically as a German defeat almost approaching disaster.

American co-operation in the war became profoundly significant during the month. The announcement was authorized early in June that more than 800,000 Americans were in France and that American soldiers were occupying important sectors on the front. Their brilliant stand on the Marne and at Belleau Wood, where they were victorious over crack Prussian divisions, created great enthusiasm throughout this country and evoked warmest encomiums from all the Allies. It was announced that American forces were holding a sector on German soil in the Vosges. It was understood that United States troops were crossing the Atlantic at the rate of nearly 40,000 a week, and that with the steady gain in shipping facilities an American Army in France of 1,500,000 was assured by Oct. 15, 1918. There was evidence that the Germans had realized the gravity of American intervention, and that their great offensive was based on the fear that ultimate defeat awaited them unless they could obtain immediate victory.

The offensive launched by the Austrians in Italy on June 15 was their most ambitious undertaking during the war. It was reported that they had 1,000,000 men engaged and 7,500 guns. At the end of the fourth day it was generally felt that the offensive had failed, as none of the objectives was obtained.

There were no important military activities on any of the other fronts.

German submarines invaded American waters late in May and within three weeks torpedoed twenty vessels, among them several steamships. There was no panic; the only effect was a fuller realization that the country was at war, with a marked speeding up of recruiting and a deepened determination that the war should be waged until victory was won. The raid caused no pause in the steady flow of troops to Europe. The submarine sinkings materially diminished in European waters, and the completion of new tonnage by the Allies during the month outstripped the losses by thousands of tons. It was clear during this period that the United States had attained its full stride in building ships, airplanes, and ordnance.

The growing importance of aerial warfare was universally recognized during the month, and the deadly efficiency of air squadrons in battle was demonstrated as never before.

The Russian situation became no clearer, though there was a growing impression that the Bolsheviki were steadily declining in power, while the forces of order and moderation were strengthening. The movement for intervention by Japan in Siberia gained momentum, but Washington gave no indication of giving its assent. The German progress into Russia continued, yet there were signs that [Pg 2] the Ukrainians were resenting German methods and were becoming a troublesome factor to the invaders. The Germanization of Finland and the other Russian border provinces proceeded apace. In the Caucasus the Turks continued to acquire new power over former Russian territory, and the spread of Turanian dominion was advanced.

Austria-Hungary was in a ferment during the month, and there was every indication that the Poles, Czechs, and Slavs were working in harmony and were threatening the existence of the Dual Empire.

In Great Britain, Italy, and France political matters were quieter, and a better feeling prevailed than for many months, while in our own country there was more war enthusiasm and less political discord than at any previous time in the nation's history.

The announcement on June 15 that the United States had successfully carried over three-quarters of a million troops to France, a distance of more than 3,000 miles by sea, with the statement, made at the same time, that the Allies had successfully transported the enormous number of 17,000,000 to and from the various battle zones, both with absolutely negligible losses, serves to bring up the interesting question of the movements of vast bodies of men in earlier wars. Leaving out the primitive wars, in which troops were moved only by land, and almost wholly on foot, to begin with the great Persian invasion of Europe, in the fifth century before our era: Xerxes transported an enormous army, fabled to number five millions, and certainly reaching nearly half a million combatants, across the water-barrier of Europe by building a pontoon bridge over the Hellespont, between three and four miles wide; but the Persians had also, at Salamis, between 1,000 and 1,200 ships, which was a sufficiently great achievement in transportation. On the return invasion of Asia by the Greeks, Alexander the Great likewise crossed the Hellespont, at the site of the Gallipoli fighting, by a bridge of boats; the latest crossing of a great army on pontoons being that of the Russians at the Danube, when they invaded Turkey in 1877. A feat in transportation of another kind was that of Hannibal, who carried his mixed army of Africans, Spaniards, and Gauls across the Alps, probably at Mont Genevre, in the Summer of 218; an achievement later repeated by Napoleon and the Russian General Suvoroff. A more recent feat in transportation was the bringing of British and French troops to America, in the days of Washington. But the closest analogy to the present achievement of the American Army and Navy is probably that of the transportation of British troops to South Africa, twenty years ago, the distance being over 6,000 miles, or about twice the distance of our Atlantic port from the landing place of our troops in France. The total British losses in South Africa have more than once been equaled by one week's British casualties in the present struggle in France, the ratio of killed to wounded being about the same, namely, one to five.

The brigading of American troops with French and English commands and the fact that the entire forces of England and Italy, as well as America, on the Continent, are commanded by a French soldier recall that in many past wars large forces of one nation served under leaders of another nation. In the Napoleonic wars there were numberless instances of these armies of composite nationality, the most striking example being, probably, the Grand Army which invaded Russia in 1811, in which there was only a minority of French soldiers, nearly all Western Europe contributing the majority. But these foreign troops served by compulsion, not of good-will. A better analogy is the war of the Spanish succession, in which both the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene commanded composite armies, voluntarily united; this war transferred Newfoundland and Nova Scotia from France to England. In the wars in India, English commanders have almost invariably had a majority of native troops in their[Pg 3] forces, and this was conspicuously the case in the second half of the eighteenth century, as in Clive's decisive victory at Plassey.

Considerable numbers of French troops served under an American Commander in Chief at an eventful period in this country's history; of the 16,000 who forced the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, about half were French troops, under Lafayette and Rochambeau. A generation later, when Napoleon was trying to subdue Spain, mixed forces of English, Portuguese, and Spanish troops fought, under the Duke of Wellington and his colleagues, against the invaders. At Waterloo also the Duke of Wellington had an army of several different nationalities under his command, though the Dutch and Belgian troops played no great part in the later stages of the battle. In the war of 1877, considerable Russian and Rumanian armies fought under a single commander who was, for a considerable period, Prince Charles (later King) of Rumania.

The conference at Rome, April 10, 1918, to settle outstanding questions between the Italians and the Slavs of the Adriatic, has once more drawn attention to those Slavonic peoples in Europe who are under non-Slavonic rule. At the beginning of the war there were three great Slavonic groups in Europe: First, the Russians with the Little Russians, speaking languages not more different than the dialect of Yorkshire is from the dialect of Devonshire; second, a central group, including the Poles, the Czechs or Bohemians, the Moravians, and Slovaks, this group thus being separated under the four crowns of Russia, Germany, Austria, and Hungary; the third, the southern group, included the Sclavonians, the Croatians, the Dalmatians, Bosnians, Herzegovinians, the Slavs, generally called Slovenes, in the western portion of Austria, down to Goritzia, and also the two independent kingdoms of Montenegro and Serbia.

Like the central group, this southern group of Slavs was divided under four crowns, Hungary, Austria, Montenegro, and Serbia; but, in spite of the fact that half belong to the Western and half to the Eastern Church, they are all essentially the same people, though with considerable infusion of non-Slavonic blood, there being a good deal of Turkish blood in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The languages, however, are practically identical, formed largely of pure Slavonic materials, and, curiously, much more closely connected with the eastern Slav group—Russia and Little Russia—than with the central group, Polish and Bohemian. A Russian of Moscow will find it much easier to understand a Slovene from Goritzia than a Pole from Warsaw. The Ruthenians, in Southern Galicia and Bukowina, are identical in race and speech with the Little Russians of Ukrainia.

Of the central group, the Poles have generally inclined to Austria, which has always supported the Polish landlords of Galicia against the Ruthenian peasantry; while the Czechs have been not so much anti-Austrian as anti-German. Indeed, the Hapsburg rulers have again and again played these Slavs off against their German subjects. It was the Southern Slav question, as affecting Serbia and Austria, that gave the pretext for the present war. At this moment, the central Slav question—the future destiny of the Poles—is a bone of contention between Austria and Germany. It is the custom to call these Southern Slavs "Jugoslavs," from the Slav word Yugo, "south," but as this is a concession to German transliteration, many prefer to write the word "Yugoslav," which represents its pronunciation. The South Slav question was created by the incursions of three Asiatic peoples—Huns, Magyars, Turks—who broke up the originally continuous Slav territory that ran from the White Sea to the confines of Greece and the Adriatic.

The result of the control of the liquor traffic in Great Britain is shown by the following figures of convictions for drunkenness in the years named, the upper line of figures referring to males, the lower line to females:

| Greater London—Population, (1911,) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7,486,964 | ||||

| 1913. | 1914. | 1915. | 1916. | 1917. |

| 48,535 | 49,077 | 35,866 | 19,478 | 10,931 |

| 16,953 | 18,577 | 15,970 | 9,975 | 5,736 |

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| 65,488 | 67,654 | 51,836 | 29,453 | 16,667 |

| Boroughs, (36,) England and Wales— | ||||

| Population, (1911,) 8,406,372 | ||||

| 41,380 | 38,577 | 27,041 | 17,233 | 9,870 |

| 11,399 | 11,258 | 9,959 | 6,097 | 3,679 |

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| 52,779 | 49,835 | 37,000 | 23,330 | 13,549 |

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| 89,915 | 87,654 | 62,907 | 36,711 | 20,801 |

| 28,352 | 29,835 | 25,929 | 16,072 | 9,415 |

| ————- | ————- | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| 118,267 | 117,489 | 88,836 | 52,783 | 30,216 |

In England and Wales the deaths due to or connected with alcoholism

(excluding cirrhosis of the liver) fell from 1,112 (males) and 719

(females) in 1913 to 358 (males) and 222 (females) in 1917; deaths due to

cirrhosis of the liver, from 2,215 (males) and 1,665 (females) to 1,475

(males) and 808 (females); cases of attempted suicide, from 1,458 (males)

and 968 (females) to 483 (males) and 452 (females); deaths from suffocation

of infants under one year declined from 1,226 to 704.

A careful study of the vital statistics of Germany and Great Britain reveals the fact that the population of Germany is declining, while that of Great Britain is increasing. The German Empire, which in June, 1919, at the previous rate of increase should have had 72,000,000 people, will have no more than 64,500,000. Germany as a whole will have 5 per cent. less population than when the war began. Of those who have been killed the greater number were men in the prime of life and energy, whom Germany could least spare. By deaths in the battle zone the empire has lost at least 3,000,000 men.

The birth rate has sunk to such a figure that by next year the number of births will have fallen short of what they would have been had there been no war by 3,333,000. In the same period the annual number of deaths among the German civilian population, owing to the stress and anxiety of the war, and sickness, which has been aggravated by hardships and food troubles, has increased by 1,000,000 over the normal.

While by next year the German Empire will be 7,500,000 lower in population than it would have been had the war not taken place, the vitality of the peoples of Austria and Hungary has suffered even more. The peoples of Austria will be 11 per cent. poorer in numbers next year than if the war had not taken place. They will be 8 per cent. lower in numbers than they were in 1914. Hungary will be still worse off. It will have a population 9 per cent. lower than before the war, and 13 per cent. lower than it would have been if there had been no war.

Meanwhile, despite the losses suffered in the war zone, the British population has been growing. By the middle of 1919 this population will be only 3 per cent. lower than it would have been without war. Great Britain in 1919 will have a larger population than in 1914.

It was officially announced May 11 that the swing bridge over the Suez Canal at Kantara was completed, and that on May 15, 1918, there was direct railway service from Cairo to Jerusalem. When the war broke out there were no railways between the Suez Canal and the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway, a distance of some 200 miles, mainly desert.

At that time a line ran along the western bank of the canal from Suez to Port Said. It was linked up with the main lines of the Egyptian State railways by a single track from Ismailia to Zagazig. [Pg 5]A few miles to the north of that track another line from Zagazig stopped some eighteen miles short of the canal at El Salhia. At the beginning of the war, to facilitate the transport of troops and supplies to the canal and beyond, the track from Zagazig to Ismailia was doubled, and a new line was pushed out from the dead end at El Salhia to the canal opposite Kantara, a village on the eastern, or Sinai, side of the canal. Later, when the British troops entered the Sinai Peninsula, a railway was begun from Kantara eastward, and as the British troops advanced so did the railway. It followed the northern track across Sinai, and had been taken within a few miles of Gaza when that town was captured last November. Meantime the Turks had built a branch from the Jaffa-Jerusalem line to a point only five miles north of Gaza, and by February General Allenby had joined the two systems, so that there was direct railway connection between Kantara and Jerusalem.

The annual ceremony of the Kindling of the Holy Fire took place May 4 in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In Turkish days it was the custom to provide a guard of not less than 600 soldiers in order to keep the peace between the Greeks and Armenians, as disorders almost invariably occurred. On this occasion there was no guard of any kind other than the ordinary police, and the ceremony took place without any sign of disturbance.

The ceremony of the Holy Fire—at which, it is held, flame comes by a miracle from heaven to kindle the lamps of the Holy Sepulchre—apparently began in the ninth century, and was formerly attended by leading representatives of all the churches. These have long ago withdrawn from it, and it is now attended by members of the Greek and Armenian Churches, mostly ignorant pilgrims of Eastern Christendom. Many enlightened members of the Greek Church discouraged the ceremony, as the vast crowds of frenzied people attending it had to be kept in some sort of order by Turkish soldiers. At the appointed time a bright flame of burning wood appears through a hole in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre; the rush to obtain this new fire is overwhelming, and it is handed on from taper to taper until thousands of lights appear. A mounted horseman takes a lighted torch to convey the sacred fire to the lamp of the Greek Church in the convent at Bethlehem. In 1834 hundreds of lives were lost in the violent pressure of the unruly crowd.

Notwithstanding the war, 200 miles of the Cape to Cairo Railway in Africa were laid in the last four years, and a total of 450 miles in the last eight years from the Rhodesian frontier to the navigable waterway of the Congo. The latest section of the Katanga Railway reached Bukama, on the Congo River, May 22.

The railway starts from Cape Town and crosses Bechuanaland and Rhodesia; it reached the Congo frontier in 1909. The first section (158 miles) reached the copper mines of the Star of the Congo in November, 1910, where Elizabethville, a populous town, inhabited by 1,400 white men, has since developed. The railway was pushed in 1913 as far as Kambové, another important mining district, (99 miles.) In spite of the difficulties caused by the war, a third section was open to traffic north of Kambové, reaching Djilongo (68 miles) in July, 1915. It was through this road that the two English monitors, under the direction of Commander G. B. Spicer Simson, reached the waters of Lake Tanganyika, which they cleared of enemy craft. Understanding the advantages which the line would afford, the Belgian Colonial Government opened new credits for the completion of the railway as far as Bukama, (125 miles.) The building started from Djilongo and Bukama at the same time, and, in spite of the difficulties of the ground and the scarcity of labor in the region traversed, has now been successfully completed. More than 30,000 tons of copper are annually transported from the Congo copper mines.

Compiegne, the northern support of the French battlefront during the early part of June, goes back to Roman days. Its name is a modernization of Compendium, which seems to have meant the "short cut" between Soissons and Beauvais. The castle, which was founded by Charles the Bald, was rebuilt by Charles V. and Louis XV. It is now practically a historical museum of pictures, sculpture, vases, beautiful French furniture. The Hôtel de Ville, the Town Hall, was built under Louis XII., and is now adorned by a recent statue of Jeanne d'Arc, whose cult has been so widely revived in the last few years in France. And the old churches of Saint James and Saint Antony go back to the France of Charles VIII. and Louis XII. The magnificent forest of Compiègne, with its century-old oaks and beeches, covers some 36,000 acres, or almost sixty square miles, and has nearly ninety miles of parkways under its shady boughs. Within it, near Champlieu, are old Roman ruins, and the huge, many-towered Château of Pierrefonds, which was a favorite hunting lodge of the Kings of France. Built in the fourteenth century, it was rebuilt by Viollet-le-Duc. It is curious that the modern use of airplanes in military scouting, in conjunction with our powerful artillery, has given these forests a significance in battle which takes us back not merely to the days of mediaeval warfare with its forest ambushes but to the earlier fighting of primitive tribes.

The immense importance of forests in the present battle is only one among many returns to the machinery of mediaeval war, like the revival of helmets, bombs, mortars, the use of a trench knife, which is simply an adapted Roman broadsword. And, in exactly the same way, the pressure of races in the present war has brought the fighting back to the old, famous battle areas, on which the Latin races have fought against the barbarians any time these two thousand years. This is particularly true of the area of the fighting in the first half of June. Much of the history here goes back to old Roman times, much to the earliest Kings of France. Villers-Cotterets, in the old feudal territory of Valois, has developed from a sixth century hamlet, first named Villers-Saint-Georges. The great forest, which has been so strong a buttress for the French and American line, was then known as Col-de-Retz, and was a favorite hunting ground of the early Kings. The Château Malmaison, rebuilt by Francis I. in 1530, was really a magnificent hunting lodge; his son, Henry II., and Francis II. often sojourned there. Charles V. halted there during his campaign in Champagne. Charles IX. spent his honeymoon there with his young Queen Elizabeth. The castle was restored by the Duke of Orleans in 1750, at a cost of 2,000,000 francs, when the great walls of the park were built. He was the father of Philippe-Egalité and the grandfather of King Louis Philippe. Alexandre Dumas, who was born at Villers-Cotterets, described the castle as being "as big as the whole town." Later it became an orphanage, sheltering 800 children. In the forest is the "enchanted butte," 752 feet above sea level, which is dimly visible from Laon, forty-four miles away; here the fairies were traditionally believed to dance in the moonlight. Finally, in the last martial act of Napoleon's Hundred Days—on June 27, 1815, a week after Waterloo—Marshal Grouchy fought the Prussians under Pirch within sight of Villers-Cotterets.

Chateau-Thierry, which has added a splendid page to the martial history of the American Army, is another of the ancient strongholds whose strategic position has given it equal significance in the recent fighting. It was originally a Roman camp, Castrum Theodorici. The castle, built in 730 by Charles Martel, was given in 877 by Louis II., "the Stammerer," to Herbert, Count of Vermandois, from whose family it passed in the tenth century to the Counts of Troyes. At the end of the eleventh century the town, which had grown up under the shelter of the [Pg 7]fortress, was surrounded by a wall, and the Burgesses of the town, in 1520, received permission from Francis I. to found a leather and cloth fair, which was long famous. Often a battleground, Château-Thierry was captured by the English in 1421. It was sacked by the Spanish in 1591. It was a centre of French resistance in the invasion of 1814, and Napoleon with 24,000 veterans decisively beat Blücher with 50,000 men under the historic walls of the ancient fortress. The fabulist La Fontaine was born here on July 8, 1621.

The British Local Government Board issued a report on infant welfare in Germany, May 17, 1918, from which the following facts are taken:

During the war there has been a heavy fall in the number of births in Germany. The first three years alone of the war reduced by over 2,000,000 the number of babies who would have been born had peace prevailed. Some 40 per cent. fewer babies were born in 1916 than in 1913. The infantile death rate has been kept well down, but is 50 per cent. higher than in Great Britain.

The birth rate, which had risen from 36.1 per 1,000 inhabitants in the decade 1841-1850 to 39.1 per 1,000 in the period 1871-1880, fell in the succeeding decades to 36.8, 36.1, and 31.9. The rate for the last year of the period 1901-1910 was under 30 per 1,000, and the continuance of the fall brought the rate as low as 28.3 in 1912.

In 1913 there were 1,839,000 live births in Germany; in 1916 there were only 1,103,000—a decrease of 40 per cent. as compared with 1913. The corresponding figures for England and Wales (785,520 live births in 1916 against 881,890 in 1913) show a decrease of 10.9 per cent.

In 1913 the infant mortality rate for Germany was 151 per 1,000, as compared with 108 in England and Wales. The rates in 1914 for Prussia, Saxony, and Bavaria (comprising nearly 80 per cent. of the total population of Germany) were 164, 173, and 193 per 1,000 respectively. The abnormal increase in infant mortality during the first months of the war is shown by the fact that in Prussia in the third quarter of 1914 the rate rose from 128 to 143; in Saxony from 140 to 242; and in Bavaria from 170 to 239.

The principal measure adopted in Germany to promote infant welfare during the war has been the distribution of the imperial maternity grants. "Necessity" must first be proved, but instructions have been given that the term "necessity" is to be liberally interpreted. There was a general demand that some further provision should be made for soldiers' wives who could not meet the extra expenses connected with the birth of a child, and by a Federal Order, published on Dec. 3, 1914, provision was made for the payment (partly from imperial funds and partly from the funds of the sickness insurance societies) of the following allowances:

(a) A single payment of $6.25 toward the expenses of confinement.

(b) An allowance of 25 cents daily, including Sundays and holidays, for eight weeks, at least six of which must be after the confinement.

(c) A grant up to $2.50 for medical attendance during pregnancy if needed.

(d) An allowance for breast-feeding at the rate of 12½ cents a day, including Sundays and holidays, for 12 weeks after confinement.

These grants were afterward extended to women whose husbands were employed on patriotic auxiliary service and women who were themselves employed on such service. In addition to this special measure, steps were taken to encourage the formation of local societies for promoting infant welfare and the establishment by the societies of infant welfare centres. Steps were taken to protect illegitimate children by assisting unmarried mothers from municipal funds and to give expectant and nursing mothers additional rations of food.

As a result of intensive farming propaganda, the acreage of cereals and potatoes in England and Wales in 1917 was 8,302,000, an increase of 2,042,000 over 1916. It is estimated that the tillage in 1917 in Scotland increased 300,000 acres over 1916, and in Ireland the figures showed an increase of 1,500,000 acres, making a total of about 4,000,000 acres increase in the United Kingdom in the year. This was accomplished in the face of the fact that in England and Wales alone there were 200,000 fewer male laborers on the land in 1917 than before the war. It is estimated that the United Kingdom in 1918-19 will produce 80 per cent. of the total breadstuff requirements for the year, whereas in 1916-17 the production was but 20 per cent. of the needs.

The volunteers furnished by Ireland, divided between Ulster and the rest of the country, were as follows:

| Year. | Ulster. | Rest of Ireland. |

Total. |

| 1914 | 26,283 | 17,851 | 44,134 |

| 1915 | 19,020 | 27,351 | 46,371 |

| 1916 | 7,305 | 11,752 | 19,057 |

| 1917 | 5,830 | 8,193 | 14,023 |

| ——— | ——— | ——— | |

| 58,438 | 65,147 | 123,585 |

The Parliamentary Under Secretary to the British War Office, Mr. Macpherson, in a statement in Parliament, May 3, 1918, gave the following figures of Chaplains in the war, killed, died of wounds, or died of disease while on service in the war. The figures do not include colonial Chaplains or the Chaplains of the Indian Ecclesiastical Establishment:

| Church of England | 57 |

| Roman Catholic | 19 |

| Presbyterian | 4 |

| Methodist | 3 |

| United Board | 3 |

| Total | 86 |

The Government of Costa Rica declared war on Germany May 23, 1918, bringing the number of nations aligned against the Central Powers to a total of twenty-one. Of the other Central American States Panama, Nicaragua, and Guatemala had issued declarations of war. Honduras severed diplomatic relations, and San Salvador proclaimed neutrality, but explained that it was friendly to the United States. The Government of Peru seized 50,000 tons of interned German ships, and the Government of Chile is negotiating with the United States for the seizure, by appropriation or sale to this country, of 200,000 tons interned in its ports.

The Second American Red Cross drive was begun on May 20. The final subscriptions, as announced on May 28, were $148,833,367, an oversubscription of more than $48,000,000. The subscriptions in New York City exceeded $33,000,000; in the rest of New York State they were about $9,000,000. The oversubscription maintained a similar average in all parts of the country.

When the Germans came in possession of Helsingfors there were seven British submarines in the Baltic with stores, workshops, and barges for floating mechanics, which had been moved into the harbor from different parts of the Baltic as the Germans advanced into Russia. The British naval contingent was in charge of Lieut. Commander Downie, and when it was apparent that the Germans would come in possession of the harbor the entire property was destroyed, including all the submarines, repair shops, and supplies, estimated in value at $15,000,000.

Andrew Bonar Law, Chancellor of the British Exchequer, in introducing a new vote of credit in Parliament June 18, announced that it was felt that the German offensive in France had wholly failed and that the Austrian offensive in Italy was the war's worst initial failure. He extolled America's aid in the war and the brilliant part taken already by American troops. He moved a vote of credit of $2,500,000,000, which was promptly given. The vote brought the total British war credits to $36,500,000,000. It will cover expenditures to Sept. 1, 1918. Bonar Law stated that the daily cost of the war to Great Britain was $34,240,000. The debt due Great Britain from her allies was stated to be $6,850,000,000, and from the Dominions $1,030,000,000.

It was announced June 16 that an American contingent had been assigned to the Vosges Mountains in Alsace in territory which belonged to Germany prior to the war. Private W. J. Gwyton of Evart, Mich., of this force was the first American killed on former German soil, having met his death by machine-gun fire on the day after the unit entered the line, (May 27, 1918.) He was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

The third month of the great German offensive may be considered the complement of the second; it has been an attempt to accomplish south of the great Picardy salient what north of it had been tried and had failed. In the second month the Lys salient had been developed, but the barrier ridges of Ypres and Arras still held. At the end of the third month the southern barriers—the Chemin-des-Dames and the watershed of the Oise-Aisne—had been carried by the enemy, but the terrain of occupation was so constricted, the enemy troops so distributed, that neither of his ambitious objectives had been brought nearer attainment. These objectives were the reaching of the sea by the Somme via Amiens, with its corollaries, the isolation of the allied armies north of that river and the occupation of the Channel ports; the decisive defeat of the French armies in the field, with whatever moral and political corollary that eventuality might produce; the occupation of Paris, and the demoralization of the French body politic. [See map on Page 19.]

But the German failure of the third month is far more significant, has a far greater bearing on the war, than the failure of the second. The enemy has not only failed to broaden the Picardy front so as to permit a further advance down the Somme, to inflict vital losses on the Allies, to force the French back on the defenses of Paris, but, in attempting to do these things he has transformed all his potential resources into active resources, and these give evidence of approaching exhaustion.

Only one conclusion is possible: Ludendorff with an initial preponderance of men and war material, with the tactical advantage of being able to manoeuvre from the centre outward, has been outgeneraled both in tactics and in strategy by Foch, so that the former's gains of terrain, while being of no advantage whatever—even a danger in certain sectors—have been purchased at an expenditure of men and material utterly incommensurate with their area and position.

Ludendorff, on May 27, with a simultaneous diversion on the Lys salient and another at the southwest angle of the Picardy salient, northwest of Montdidier, began, with the most stupendous preparations ever concentrated, an attack on the southern barriers over a forty-mile front. He forced the Aisne the next day on an eighteen-mile front, and on May 31 he brought up at the Marne on a six-mile front, having made a penetration of thirty miles to the south. There he attempted to deploy both east and west, and was held.

Meanwhile his baseline had been extended twenty miles to the west—to near Noyon. He had occupied about 650 square miles of new territory and had reduced his nearest approach to Paris from sixty-two to forty-four miles.

Then, on June 9, with even a greater array of men and material, he attempted to invert the western bow-like side of the salient already formed by turning it outward. He made a fierce attack from a twenty-mile front between Montdidier and Noyon in the direction of Compiègne. With this objective attained, his Picardy front would have been sufficiently broadened to enable him to resume his journey down the Somme. Moreover, he would have been within striking distance of Paris. He gained seven miles, which was later reduced to less than six by French counterattacks. French counterattacks and a thrust of American marines on his flanks in the three succeeding days not only held him in a vise, but revealed his tremendous losses and the extraordinary means he had expended in preparations. By June 12 his failure, the ramifications of which actually demonstrated his defeat, was an established fact. Then, on the following Saturday, June 15, this failure was acknowledged by the sudden launching of an Austrian offensive in Italy. How this was an acknowledgment we shall see in the proper place.