THE WORKS OF

Charles G. D. Roberts

PUBLISHED BY

L. C. Page & Company

Boston, Mass.

“Red Fox, meanwhile, had been watching the whole scene from that safe little ledge of rock.”

(See page 168)

The Story of His Adventurous Career in the Ringwaak Wilds and of His Final Triumph over the Enemies of His Kind

Told by

Charles G. D. Roberts

Author of “The Kindred of the Wild,” “The Watchers of the Trails,” “The Heart of the Ancient Wood,” “Barbara Ladd,” “Poems,” etc.

With Many Illustrations by

Charles Livingston Bull

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

BOSTON • • • MDCCCCV

Copyright, 1905, by The Outing Publishing Company

Copyright, 1905, by The Outlook Company

Copyright, 1905, by L. C. Page & Company (INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

Published, September, 1905

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U.S.A.

To

Henry Braithwaite

Master of Woodcraft

In the following story I have tried to trace the career of a fox of the backwoods districts of Eastern Canada. The hero of the story, Red Fox, may be taken as fairly typical, both in his characteristics and in the experiences that befall him, in spite of the fact that he is stronger and cleverer than the average run of foxes. This fact does not detract from his authenticity as a type of his kind. He simply represents the best, in physical and mental development, of which the tribe of the foxes has shown itself capable. In a litter of young foxes there is usually one that is larger and stronger, and of more finely coloured fur, than his fellows. There is not infrequently, also, one that proves to be much more sagacious and [viii] adaptable than his fellows. Once in awhile such exceptional strength and such exceptional intelligence may be combined in one individual. This combination is apt to result in just such a fox as I have made the hero of my story.

The incidents in the career of this particular fox are not only consistent with the known characteristics and capacities of the fox family, but there is authentic record of them all in the accounts of careful observers. Every one of these experiences has befallen some red fox in the past, and may befall other red foxes in the future. There is no instance of intelligence, adaptability, or foresight given here that is not abundantly attested by the observations of persons who know how to observe accurately. In regard to such points, I have been careful to keep well within the boundaries of fact. As for any emotions which Red Fox may once in a great while seem to display, these may safely be accepted by the most cautious as fox emotions, not as human emotions. In so far as man is himself an animal, he is subject to and impelled by many emotions which he must share with not a few other members of the animal kingdom. Any full presentation of an individual animal of one of the more highly developed species must depict certain emotions [ix] not altogether unlike those which a human being might experience under like conditions. To do this is not by any means, as some hasty critics would have it, to ascribe human emotions to the lower animals.

C. G. D. R. Fredericton, N. B., August, 1905.

Two voices, a mellow, bell-like baying and an excited yelping, came in chorus upon the air of the April dawn. The musical and irregularly blended cadence, now swelling, now diminishing, seemed a fit accompaniment to the tender, thin-washed colouring of the landscape which lay spread out under the gray and lilac lights of approaching sunrise. The level country, of mixed woodland and backwoods farm, still showed a few white patches here and there where the snow lingered in the deep hollows; but all over the long, wide southward-facing slope of the uplands, with their rough woods broken by occasional half-cleared, hillocky pastures, the spring was more advanced. [2] Faint green films were beginning to show on the birch and poplar thickets, and over the pasture hillocks; and every maple hung forth a rosy veil that seemed to imitate the flush of morning.

The music of the dogs’ voices, melodious though it was, held something sinister in its sweetness,—a sort of menacing and implacable joy. As the first notes of it came floating up from the misty lowlands, an old red fox started up from his sleep under a squat juniper-bush on the top of a sunny bank. Wide-awake on the instant, he stood listening critically to the sound. Then he came a few paces down the bank, which was open, dotted with two or three bushes and boulders, and its turf already green through the warmth of its sandy soil. He paused beside the mouth of a burrow which was partly screened by the evergreen branches of a juniper. The next moment another and somewhat smaller fox appeared, emerging briskly from the burrow, and stood beside him, intently listening.

The thrilling clamour grew louder, grew nearer, muffled now and then for a few moments as the trail which the dogs were following led through some dense thicket of spruce or fir. Soon an uneasy look came over the shrewd, grayish-yellow face of the old fox, as he realized that the trail [3] in question was the one which he had himself made but two hours earlier, on his return from a survey of a neighbouring farmer’s hen-roost. He had taken many precautions with that homeward trail, tangling and breaking it several times; but he knew that ultimately, for all its deviations and subtleties, it might lead the dogs to this little warm den on the hillside, wherein his mate had but yesterday given birth to five blind, helpless, whimpering puppies. As the slim red mother realized the same fact, her fangs bared themselves in a silent snarl, and, backing up against the mouth of the burrow, she stood there an image of savage resolution, a dangerous adversary for any beast less powerful than bear or panther.

To her mate, however, it was obvious that something more than valour was needed to avert the approaching peril. He knew both the dogs whose chiming voices came up to him so unwelcomely on the sweet spring air. He knew that both were formidable fighters, strong and woodswise. For the sake of those five helpless, sprawling ones at the bottom of the den, the mother must not be allowed to fight. Her death, or even her serious injury, would mean their death. With his sharp ears cocked very straight, one paw lifted alertly, and [4] an expression of confident readiness in his whole attitude, he waited a moment longer, seeking to weigh the exact nearness of the menacing cries. At length a wandering puff of air drawing up from the valley brought the sound startlingly near and clear. Like a flash the fox slipped down the bank and darted into the underbrush, speeding to intercept the enemy.

A couple of hundred yards away from the den in the bank a rivulet, now swollen and noisy with spring rains, ran down the hillside. For a little distance the fox followed its channel, now on one side, now on the other, now springing from rock to rock amid the foamy darting of the waters, now making brief, swift excursions among the border thickets. In this way he made his trail obscure and difficult. Then, at what he held a fitting distance from home, he intersected the line of his old trail, and halted upon it ostentatiously, that the new scent might unmistakably overpower the old.

“FOR A LITTLE DISTANCE THE FOX FOLLOWED ITS CHANNEL.”

The baying and yelping chorus was now very close at hand. The fox ran on slowly, up an open vista between the trees, looking over his shoulder to see what the dogs would do on reaching the fresh trail. He had not more than half a minute to wait. Out from a greening poplar thicket burst the dogs, running with noses to the ground. The one in the lead, baying conscientiously, was a heavy-shouldered, flop-eared, much dewlapped dog of a tawny yellow colour, a half-bred foxhound whose cur mother had not obliterated the instincts bequeathed him by his pedigreed and well-trained sire. His companion, who followed at his heels and paid less scrupulous heed to the trail, looking around excitedly every other minute and yelping to relieve his exuberance, was a big black and white mongrel, whose long jaw and wavy coat seemed to indicate a strain of collie blood in his much mixed ancestry.

Arriving at the point where the trail was crossed by the hot, fresh scent, the leader stopped so abruptly that his follower fairly fell over him. For several seconds the noise of their voices was redoubled, as they sniffed wildly at the pungent turf. Then they wheeled, and took up the new trail. The next moment they saw the fox, standing at the edge of a ribbon of spruce woods and looking back at them superciliously. With a new and wilder note in their cries, they dashed forward frantically to seize him. But his white-tipped, feathery brush flickered before their eyes for a fraction of a second, and vanished into the gloom of the spruce wood.

The chase was now full on, the quarry near, and [8] the old trail forgotten. In a savage intoxication, reflected in the wildness of their cries, the dogs tore ahead through brush and thicket, ever farther and farther from that precious den on the hillside. Confident in his strength as well as his craft, the old fox led them for a couple of miles straight away, choosing the roughest ground, the most difficult gullies, the most tangled bits of underbrush for his course. Fleeter of foot and lighter than his foes, he had no difficulty in keeping ahead of them. But it was not his purpose to distance them or run any risk of discouraging them, lest they should give up and go back to their first venture. He wanted to utterly wear them out, and leave them at last so far from home that, by the time they should be once more ready to go hunting, his old trail leading to the den should be no longer decipherable by eye or nose.

By this time the rim of the sun was above the horizon, mounting into a rose-fringed curtain of tender April clouds, and shooting long beams of rose across the level country. These beams seemed to find vistas ready everywhere, open lines of roadway, or cleared fields, or straight groves, or gleaming river reaches all appearing to converge toward the far-off fount of radiance. Down one of these [9] lanes of pink glory the fox ran in plain sight, looking strangely large and dark in the mystic glow. Very close behind him came the two pursuers, fantastic, leaping, ominous shapes. For several minutes the chase fled on into the eye of the morning, then vanished down an unseen cross-corridor of the woods.

And now it seemed to the brave and crafty old fox, a very Odysseus of his kind for valour and guile, that he had led the enemy almost far enough from home. It was time to play with them a little. Lengthening out his stride till he had secured a safer lead, he described two or three short circles, and then ran on more slowly. His pursuers were quite out of sight, hidden by the trees and bushes; but he knew very well by his hearing just when they ran into those confusing loops in the trail. As the sudden, excited confusion in their cries reached him, he paused and looked back, with his grayish-ruddy head cocked to one side; and, if laughter had been one of the many vulpine accomplishments, he certainly would have laughed at that moment. But presently the voices showed him that their owners had successfully straightened out the little snarl and were once more after him. So once more he ran on, devising further shifts.

Coming now to a rocky brook of some width, the fox stepped out upon the stones, then leaped back upon his own trail, ran a few steps along it, and finally jumped aside as far as he could, alighting upon a log in the heart of a patch of blueberry scrub. Slipping down from the log, he raced back a little way parallel with his tracks and lay down on the top of a dry hillock to rest. A drooping screen of hemlock branches here gave him effective hiding, while his sharp eyes commanded the brook-side and perhaps a hundred yards of the back trail.

“THE FOX STEPPED OUT UPON THE STONES.”

In a moment or two the dogs rushed by, their tongues hanging far out, but their voices still eager and fierce. Not thirty paces away the old fox watched them cynically, wrinkling his narrow nose with aversion as the light breeze brought him their scent. As he watched, the pupils of his eyes contracted to narrow, upright slits of liquid black, then rounded out again as anger yielded to interest. It filled him with interest, indeed, to watch the frantic bewilderment and haste of his pursuers when the broken trail at the edge of the brook baffled them. First they went splashing across to the other bank, and rushed up and down, sniffing savagely for the scent. Next they returned to the near bank and repeated the same tactics. Then they seemed to conclude that the fugitive had attempted to cover his tracks by travelling in the water, so they traced the water’s edge exactly, on both sides, for about fifty yards up and down. Finally they returned to the point where the trail was broken, and silently began to work around it in widening circles. At last the yellow half-breed gave voice. He had recaptured the scent on the log in the blueberry patch. As the noisy chorus rose again upon the morning air, the old fox got up, stretched himself somewhat contemptuously, and stood out in plain view with a shrill bark of defiance. Joyously the dogs accepted the challenge and hurled themselves forward; but in the same instant the fox vanished, leaving behind him a streak of pungent, musky scent that clung in the bushes and on the air.

And now for an hour the eager dogs found themselves continually overrunning or losing the trail. More than half their time and energy were spent in solving the riddles which their quarry kept propounding to them. Once they lost fully ten minutes racing up and down and round and round a hillocky sheep-pasture, utterly baffled, while the fox, hidden in the cleft of a rock on the other side of the fence, lay comfortably eying their performances. The sheep, huddling in a frightened mass in one [14] corner of the pasture, scared by the noise, had given him just the chance he wanted. Leaping lightly upon the nearest, he had run over the thick-fleeced backs of the whole flock, and gained the top of the rail fence, from which he had sprung easily to the cleft in the rock. To the dogs it was as if their quarry had suddenly grown wings and soared into the air. The chase would have ended there but for the mischance of the shifting of the wind. The light breeze which had been drawing up from the southwest all at once, without warning, veered over to the east; and with it came a musky whiff which told the puzzled dogs the whole story. As they raced joyously and clamorously toward the fence, the fox slipped down the other side of the rock and fled away.

A fox’s wits are full of resource, and he seldom cares to practise all his accomplishments in one run. But this was a unique occasion; and this fox was determined to make his work complete and thoroughly dishearten his pursuers. He now conceived a stratagem which might, possibly, prove discouraging. Minutely familiar with every inch of his range, he remembered a certain deep deadwater on the brook, bridged by a fallen sapling. The sapling was now old and partly rotted away. He had [15] crossed it often, using it as a bridge for his convenience; and he had noticed just a day or two ago that it was growing very insecure. He would see if it was yet sufficiently insecure to serve his purpose.

Without any more circlings and twistings, he led the way straight to the deadwater, leaving a clear trail. The tree was still there. It seemed to yield, almost imperceptibly, as he leaped upon it. His shrewd and practised perceptions told him that its strength would just suffice to carry him across, but no more. Lightly and swiftly, and not without some apprehension (for he loathed a wetting), he ran over, and halted behind a bush to see what would happen.

Arrived at the fallen tree, the dogs did not hesitate. The trail crossed. They would go where it went. But the tree had something to say in the matter. As the double weight sprang up it, it sagged ominously, but the excited hunters were in no mood to heed the warning. The next moment it broke in the middle with a punky, crumbling sound; and the dogs plunged, splashing and yelping, into the middle of the icy stream.

If the fox, however, had imagined that this unexpected bath would be cold enough to chill the [16] ardour of his pursuers, he was speedily disillusioned. Neither dog seemed to have his attention for one single moment distracted by the incident. Both swam hurriedly to land, scrambled up the bank, and at once resumed the trail. The fox was already well away through the underbrush.

By this time he was tired of playing tricks. He made up his mind to lead the enemy straight, distance them completely, and lose them in the rocky wilderness on the other side of the hill, where their feet would soon get sore on the sharp stones. Then he could rest awhile in safety, and later in the day return by a devious route to the den in the bank and his slim red mate. The plan was a good one, and in all ways feasible. But the capricious fate of the woodfolk chose to intervene.

It chanced that, as the fox passed down an old, mossy wood-road, running easily and with the whole game well in hand, a young farmer carrying a gun was approaching along a highway which intersected the wood-road. Being on the way to a chain of shallow ponds along the foot of the uplands, he had his gun loaded with duck shot, and was unprepared for larger game. The voices of the dogs—now much subdued by weariness and reduced to an occasional burst of staccato clamour—gave [17] him warning of what was afoot. His eyes sparkled with interest, and he reached for his pocket to get a cartridge of heavier shot. But just as he did so the fox appeared.

There was no time to change cartridges. The range was long for B B, but the young farmer was a good shot and had confidence in his weapon. Like a flash he lifted his gun and fired. As the heavy report went banging and flapping among the hills, and the smoke blew aside, he saw the fox dart lightly into the bushes on the other side of the way, apparently untouched. With a curse, devoted impartially to his weapon and his marksmanship, he ran forward and carefully examined the tracks. There was no smallest sign of blood. “Clean miss, by gum!” he ejaculated; and strode on without further delay. He knew the dogs could never overtake that seasoned old fox. They might waste their time, if they cared to. He would not. They crossed the road just as he disappeared around the next turning.

But the fox, though he had vanished from view so nonchalantly and swiftly, had not escaped unscathed. With the report, he had felt a sudden burning anguish, as of a white-hot needle-thrust, go through his loins. One stray shot had found [18] its mark; and now, as he ran, fierce pains racked him, and every breath seemed to cut. Slower and slower he went, his hind legs reluctant to stretch out in the stride, and utterly refusing to propel him with their old springy force. Nearer and nearer came the cries of the dogs, till presently he realized that he could run no farther. At the foot of a big granite rock he stopped, and turned, and waited, with bare, dangerous fangs gleaming from his narrow jaws.

The dogs were within a dozen yards of him before they saw him, so still he stood. This was what they had come to seek; yet now, so menacing were his looks and attitude, they stopped short. It was one thing to catch a fugitive in flight. It was quite another to grapple with a desperate and cunning foe at bay. The old fox knew that fate had come upon him at last. But there was no coward nerve in his lithe body, and the uncomprehended anguish that gripped his vitals added rage to his courage. The dogs rightly held him dangerous, though his weight and stature were scarcely half what either one of them could boast.

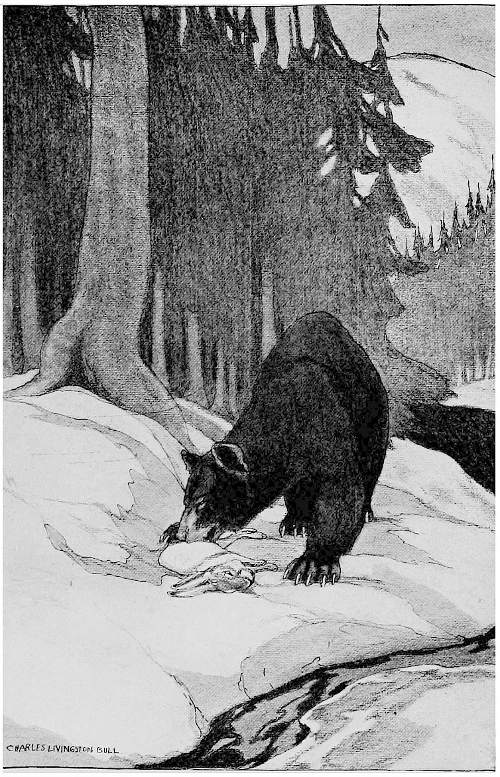

“SLOWER AND SLOWER HE WENT.”

Their hesitation, however, was but momentary. Together they flung themselves upon him, to get lightning slashes, almost simultaneously, on neck and jaw. Both yelped angrily, and bit wildly, but found it impossible to hold down their twisting foe, who fought in silence and seemed to have the strength and irrepressibility of steel springs in his slender body. Presently his teeth met through the joint of the hound’s fore paw, and the hound, with a shrill ki yi, jumped backward from the fight. But the black and white mongrel was of better grit. Though one eye was filled with blood, and one ear slit to the base, he had no thought of shirking the punishment. Just as the yelping hound withdrew from the mix-up, his long, powerful jaws secured a fair grip on the fox’s throat, just back of the jawbone. There was a moment of breathless, muffled, savage growling, of vehement and vindictive shaking. Then the valorous red body straightened itself out at the foot of the rock, and made no more resistance as the victors mauled and tore it. At a price, the little family in the burrow had been saved.

Night after night, for several weeks, the high, shrill barking of a she fox was heard persistently along the lonely ridges of the hills. The mother fox was sorrowing for her mate. When he came no more to the den, she waited till night, then followed the broad, mingled trail of the chase till she found out all that had happened. She was too busy, however—too much driven by the necessities of those five blind sprawlers in the musky depths of the burrow—to have much time for mourning. But when the softly chill spring night lay quiet about her hunting, her loneliness would now and then find voice.

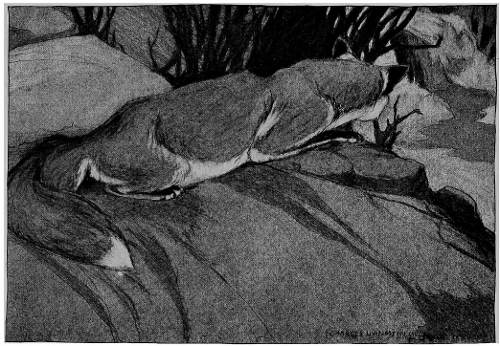

“NIGHT AFTER NIGHT, . . . THE HIGH SHRILL BARKING OF A SHE FOX WAS HEARD.”

Her hunting was now carried on with the utmost caution. For a time, while her puppies were still blind, she lay in her den all day long, nursing them, and never stirring abroad till the piping of the frogs in the valley pools proclaimed the approach of twilight. Then she would mount the hill and descend into the next valley before beginning to hunt. She would take every precaution to disguise her tracks while in the neighbourhood of her den. Wherever possible, she would steal through the pungent-scented, prickly dwarf-juniper bushes, whose smell disguised her own strong scent, and whose obstinate sharpness was a deterrent to meddlesome and inquisitive noses. Not until she had passed through a belt of particularly rough, stony ground near the top of the hill would she allow her attention to be absorbed in the engrossing labours of the hunt.

Once in what she held a safe region, however, she flung her precautions aside and hunted vehemently. The cubs as yet being entirely dependent upon her milk, it was her first care that she herself should be well fed. Her chief dependence was the wood-mice, whose tiny squeaks she could detect at an astonishing distance. Next in abundance and availability to these were the rabbits, whom she would lie in wait for and pounce upon as they went by. Once in awhile an unwary partridge afforded her the relish of variety; and once in awhile, descending to the marshy pools, she was cunning and swift enough to capture a wild duck. But the best and easiest foraging of all was that which, just now [26] when she most needed it, she least dared to allow herself. The hens, and ducks, and geese, and turkeys of the scattered backwoods farms were now, with the sweet fever of spring in their veins, vagrant and careless. But while she had the little ones to consider, she would not risk drawing to herself the dangerous attention of men. She did permit herself the luxury of a fat goose from a farmyard five miles away in the other valley. And a couple of pullets she let herself pick up at another farm half a mile beyond. But in her own valley, within a couple of miles of her lair, all the poultry were safe from tooth of hers. She would pass a flock of waddling ducks, near home, without condescending to notice their attractions. Notoriety, in her own neighbourhood, was the last thing she desired. She had no wish to advertise herself.

Thanks to this wise caution, the slim red mother saw no menace approach her den, and went on cherishing her little ones in peace. For a time she heard no more of that ominous hunting music down in the plain, for the hound’s well-bitten joint was long in healing. He could not hunt for the soreness of it; and the black and white mongrel did not care to hunt alone, or lacked the expertness to follow the scent. When at length the baying and barking [27] chorus once more came floating softly up to her retreat, somewhat muffled now by the young leafage which had burst out greenly over the hillside, she was not greatly disturbed. She knew it was no trail of hers that they were sniffing out. But she came to the door of her den, nevertheless, and peered forth. Then she emerged altogether, and stood listening with an air of intense hostility, untouched by the philosophic, half-derisive interest which had been the attitude of her slaughtered mate. As she stood there with bared fangs and green-glinting, narrowed gaze, a little group of pointed noses and inquiring ears and keen, mischievous, innocently shrewd eyes appeared in the doorway of the den behind her. The sound was a novel one to them. But their mother’s attitude showed plainly that it was also a dangerous and hateful sound, so they stayed where they were instead of coming out to make investigations. Thus early in their lives did they hear that music which is the voice of doom to so many foxes.

As spring ripened toward summer over the warm lowlands and windy uplands, and the aerial blue tones of far-off Ringwaak deepened to rich purples with the deepening of the leafage, the little foxes spent more and more of their time outside the door [28] of their den, and took a daily widening interest in the wonderful, radiant, outer world. Though they little knew it, they were now entering the school of life, and taking their first lessons from the inexorable instructress, Nature. Being of keen wits and restless curiosity, they were to be counted, of course, among Nature’s best pupils, marked out for much learning and little castigation. Yet even for them there was discipline in store, to teach them how sternly Nature exacts a rigid observance of her rules.

In mornings, as soon as the sun shone warm upon the face of the bank, the mother would come forth, still sluggish from her night’s hunting, and stretch herself out luxuriously on the dry turf a few paces below the mouth of the den. Then would come the cubs, peering forth cautiously before adventuring into the great world. As the mother lay there at full length, neck and legs extended and white-furred belly turned up to the warmth, the cubs would begin by hurling themselves upon her with a chorus of shrill, baby barking. They would nip and maul and worry her till patience was no longer a virtue; whereupon she would shake them off, spring to her feet with a faint mutter of warning, and lie down again in another place. This [29] action the puppies usually accepted as a sign that their mother did not want to play any more. Then there would be, for some minutes, a mad scuffle and scramble among themselves, with mock rages and infantile snarlings, till one would emerge on top of the rolling heap, apparently victor. Upon this, as if by mutual consent, the bunch would scatter, some to lie down with lolling tongues and rest, and some to set about an investigation of the problems of this entertaining world.

All five of these brisk puppies were fine specimens of their kind, their woolly puppy coats of a bright rich ruddy tone, their slim little legs very black and clean, their noses alertly inquisitive to catch everything that went on, their pale yellow eyes bright with all the crafty sagacity of their race. But there was one among them who always came out on top of the scramble; and who, when the scramble was over, always had something so interesting to do that he had no time to lie down and rest. He was just a trifle larger than any of his fellows; his coat was of a more emphatic red; and in his eyes there was a shade more of that intelligence of glance which means that the brain behind it can reason. It was he who first discovered the delight of catching beetles and crickets for himself [30] among the grass stems, while the others waited for their mother to show them how. It was he who was always the keenest in capturing the mice and shrews which the mother would bring in alive for her little ones to practise their craft upon. And he it was alone of all the litter who learned how to stalk a mouse without any teaching from his mother, detecting the tiny squeak as it sounded from under a log fifty feet or more from the den, and creeping up upon it with patient stealth, and lying in wait for long minutes absolutely motionless, and finally springing triumphantly upon the tiny, soft, gray victim. He seemed to inherit with special fulness and effectiveness that endowment of ancestral knowledge which goes by the name of instinct. But at the same time he was peculiarly apt in learning from his mother, who was tireless in teaching her puppies, to the best of her ability, whatever it behoved small foxes to know and believe.

“THE PUPPY FLUNG HIMSELF UPON IT WITHOUT A SIGN OF FEAR.”

At this stage in their development she brought in the widest variety of game, large and small, familiarizing the puppies with the varied resources of the forest. But large game, such as rabbits and woodchucks, she brought in dead, because a live rabbit might escape by one of its wild leaps, and a woodchuck, plucky to the last gasp and armed with formidable teeth, might kill one of its baby tormentors. Partridges, too, and poultry, and all strong-winged and adult birds, she brought in with necks securely broken, lest they should escape by timely flight. It was only young birds and very small animals that were allowed the privilege of helping along the education of the red fox litter.

One day she brought in a black snake, holding its head in her mouth uncrushed, while its rusty, writhing body twined about her head and neck. At her low call the cubs came tumbling eagerly from the burrow, wondering what new game she had for them. But at the sight of the snake they recoiled in alarm. At least, they all but one recoiled. The reddest and largest of the family rushed with a baby growl to his mother’s assistance, and tried to tear the writhing coils from her neck. It was a vain effort, of course. But when the old fox, with the aid of her fore paws, wrenched herself free and slapped the trailing length upon the ground, the puppy flung himself upon it without a sign of fear and arrested its attempt at flight. In an instant its tense coils were wrapped about him. He gave a startled yelp, while the rest of the litter backed yet farther off in their dismay. But the [34] next moment, remembering probably how he had seen his mother holding this strange and unmanageable antagonist, he made a successful snap and caught the snake just where the neck joined the head. One savage, nervous crunch of his needle-like young teeth, and the spinal cord was cleanly severed. The tense coils relaxed, fell away. And proudly setting both fore paws upon his victim’s body, the young conqueror fell to worrying it as if it had been a mere mouse. He had learned how to handle a snake of the non-poisonous species. As there were no rattlers or copperheads in the Ringwaak country, that was really all he needed to know on the subject of snakes. Emboldened by his easy victory, and seeing that the victim showed no sign of life except in its twitching tail, the other four youngsters now took a hand in the game, till there was nothing left of the snake but scattered fragments.

As the young foxes grew in strength and enterprise, life became more exciting for them. The mother still did her hunting by night, and still rested by day, keeping the youngsters still close about the door of the burrow. In her absence they kept scrupulously out of sight, and silent; but while she was there basking in the sun, ready to repel any dangerous intruder, they felt safe to roam a little, [35] along the top of the bank and in the fringes of the thickets.

One day toward noon, when the sky was clear and the shadows of the leaves lay small and sharp, a strange, vast shadow sailed swiftly over the face of the bank, and seemed to hover for an instant. The old fox leaped to her feet with a quick note of warning. The big red puppy, superior to his brothers and sisters in caution no less than in courage, shot like a flash under the shelter of a thick juniper-bush. The others crouched where they happened to be and looked up in a kind of panic. In what seemed the same instant there was a low but terrible rushing sound overhead, and the great shadow seemed to fall out of the sky. One of the little foxes was just on top of the bank, crouching flat, and staring upward in terrified amazement. The mother, well understanding the fate that impended, sprang toward him with a screeching howl, hoping to frighten away the marauder. But the great goshawk was not one to be scared by noise. There was a light blow, a throttled yelp, a sudden soundless spread of wide wings, then a heavy flapping; and just as the frantic mother arrived upon the spot the huge bird sprang into the air, bearing a little, limp, red form in the clutch of his talons. [36] When he was gone the rest of the puppies ran shivering to their mother,—all but Red Fox himself, who continued to stare thoughtfully from the covert of his juniper-bush for some minutes. For a long time after that experience he never failed to keep a sharp watch upon the vast blue spaces overhead, which looked so harmless, yet held such appalling shapes of doom.

It was not long after this event, and before the mother had begun to take her young ones abroad upon the serious business of hunting, that the Fate of the wood kindreds struck again at the little family of the burrow. It was just in the most sleepy hour of noon. The old fox, with one of the puppies stretched out beside her, was dozing under a bush some distance down the bank. Two others were digging fiercely in a sandy spot on top of the bank, where they imagined perhaps, or merely pretended to imagine, some choice titbit had been buried. A few paces away Red Fox himself, busy, and following his own independent whim as usual, was intent upon stalking some small creature, mouse or beetle or cricket, which had set a certain tuft of grains twitching conspicuously. Some live thing, he knew, was in that tuft of grains. He would [37] catch it, anyway; and if it was good to eat he would eat it.

Closer and closer he crept, soundless in movement as a spot of light. He was just within pouncing distance, just about to make his pounce and pin down the unseen quarry, when a thrill of warning ran through him. He turned his head,—but fortunately for him he did not wait to see what danger threatened him. Being of that keen temperament which can act as swiftly as it can think, even as he was turning his head he made a violent lightning-swift leap straight down the bank, toward his mother’s side. At the same instant he had a vision of a ghostly gray, crouching, shadowy form with wide green eyes glaring upon him from the embankment. The very next moment a big lynx came down upon the spot which he had just left.

Startled from their work of digging in the sand, the two puppies looked up in wonder. They saw their enterprising brother rolling over and over down the bank. They saw their mother leaping toward them with a fierce cry. They sprang apart, with that sound impulse to scatter which Nature gives to her weak children. Then upon one of them a big muffled paw, armed with claws like steel, came down irresistibly, crushing out the small, eager [38] life. He was snatched up by a pair of strong jaws; and the lynx went bounding away lightly over the bushes with his prize. Finding himself savagely pursued by the mother fox, he ran up the nearest tree, a spreading hemlock, and crouched in the crotch of a limb with his victim under one paw. As the mother circled round and round below, springing up against the trunk in voiceless rage, the lynx glared down on her with vindictive hissings and snarlings. He was really more than a match for her, both in weight and weapons; but he had no desire for a battle with her mother-fury. For perhaps ten minutes she raged against the base of the impregnable trunk. Then realizing her impotence, she turned resolutely away and went back to her three remaining little ones.

For some days now the fox family was particularly cautious. They kept close beside their mother all the time, trembling lest the flame-eyed terror should come back.

Among the wild kindreds, however, an experience of this sort is soon forgotten, in a way. Its lesson remains, indeed, but the shock, the panic fear, fades out. In a little while the green summer world of the hillside was as happy and secure as ever to the fox family, except that a more cunning caution, now grown instinctive and habitual, was carried into their play as into their work.

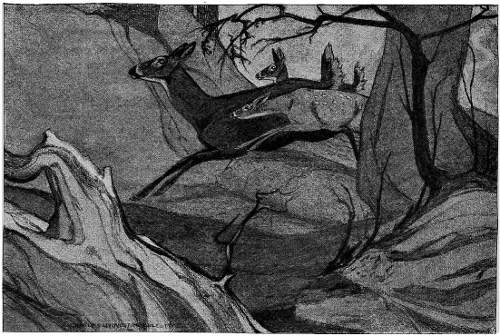

“HE RAN UP THE NEAREST TREE.”

Work, in fact, now began to enter the lives of the three little foxes, work which to them had all the zest of play. Their mother began to take them hunting with her, in the moonlight or the twilight. They learned to lie in wait beside the glimmering runways, and pounce unerringly upon the rabbit leaping by. They learned to steal up and catch the brooding partridge, which was a task to try the stealth of the craftiest stalker. They learned to trace the grassy galleries of the meadow mice, and locate the hidden scurriers by their squeaks and faint rustlings. And they learned to relish the sweet wild fruits and berries beginning to ripen in the valleys and on the slopes. The youngsters were now losing the woolly baby look of their fur, and beginning to show a desire of independence which kept their mother busy watching lest they should get themselves into mischief. With their independence came some unruliness and overconfidence, natural enough in men or foxes when they first begin to realize their powers. But of the three, Red Fox, who surpassed his brother and sister no less in stature and intelligence than in the vivid colouring of his young coat, was by far the least [42] unruly. It was no small part of his intelligence that he knew how much better his mother knew than he. When she signalled danger, or caution, or watchfulness, he was all attention instantly to find out what was expected of him; while the other two were sometimes wilful and scatter-brained. Taking it all in all, however, the little family was harmonious and contented, and managed, for all its tragedies, to get an immense amount of fun out of its life in the warm summer world.

“LEARNED TO STEAL UP AND CATCH THE BROODING PARTRIDGE.”

Now came the critical time when the young foxes showed a disposition to wander off and hunt by themselves; and at this stage of his education Red Fox, whose quickness had hitherto saved him from any sharp discipline in the school of Nature, came under the ferule more than once. Instinct could not teach him everything. His mother was somewhat overbusy with the other members of the family, who had shown themselves so much more in need of her care. And so it came about that he had to take some lessons from that rude teacher, experience.

The first of these lessons was about bumblebees. One afternoon, while he was hunting field-mice in a little meadowy pocket half-way up the hillside, his eager nose caught scent of something much more delicious and enticing in its savour than mice. It was a smell of warmth and sweetness, with a pungent [46] tang; and instinct assured him confidently that anything with a smell like that must be very good to eat. What instinct forgot to suggest, however, was that anything so delectable was likely to be expensive or hard to get. It is possible (though some say otherwise!) to expect too much of instinct.

Field-mice utterly forgotten, his mouth watering with expectation, the young fox went sniffing hungrily over the turf, following the vague allurement hither and thither, till suddenly it steamed up hot and rich directly under his nose. A big black and yellow bumblebee boomed heavily past his ears, but he was too busy to notice it. His slim pink tongue lolling out with eagerness, he fell to digging with all his might, heedless of the angry, squeaking buzz which straightway began under his paws.

The turf over the little cluster of comb was very thin. In a moment those busy paws had penetrated it. Greedily Red Fox thrust his nose into the mass of bees and honey. One taste of the honey, enchantingly sweet, he got. Then it seemed as if hot thorns were being hammered into his nose. He jumped backwards with a yelp of pain and astonishment; and as he did so the bees came swarming about his eyes and ears, stinging furiously. He ran for his life, blindly, and plunged into the nearest [47] clumps of juniper. It was the best thing he could do, for the stiff twigs brushed off those bees which were clinging to him, and the rest, like all of their kind, hated to take their delicate wings into the tangle of the branches. They hummed and buzzed angrily for awhile outside the enemy’s retreat, then boomed away to repair the damage to their dwelling. Within his shelter, meanwhile, the young fox had been grovelling with hot anguish, scratching up the cool, fresh earth and burying his face in it. In a few minutes, finding this remedy insufficient, he crept forth and slunk miserably down to the brook, where he could rub his nose and eyes, his whole tormented head, indeed, in a chilly and healing mess of mud. There was no better remedy in existence for such a hurt as his, and soon the fever of the stings was so far allayed that he remembered to go home. But he carried with him so strangely disfigured a countenance that the rest of the family regarded him with disapproval, and he felt himself an outcast.

For nearly two days Red Fox stayed at home, moping in the dark of the burrow, and fasting. Then his clean young blood purged itself of the acrid poison, and he came forth very hungry and bad-tempered. It was this bad temper, and the [48] recklessness of his unwonted hunger, that procured him the second taste of Nature’s discipline.

It was late in the afternoon, and the rest of the family were not yet ready to go a-hunting, so he prowled off by himself to look for a rabbit. His appetite was quite too large to think of being satisfied with mice. About a hundred yards above the den, as he crept stealthily through the underbrush, he saw a black and white striped animal moving sluggishly down a cattle path. It did not look at all formidable, yet it had an air of fearlessness which at any other time or in any other mood would have made so shrewd a youngster as Red Fox stop and think. Just now, however, he was in no sort of humour to stop and think. He crouched, tense with anticipation; waited till he could wait not another second; then bounded forth from his hiding-place, and flung himself upon the deliberate stranger.

“HE CROUCHED, TENSE WITH ANTICIPATION.”

Red Fox, as we have seen, was extraordinarily quick. In this case his rush was so quick that he almost caught the stranger unawares. His jaws were almost about to snap upon the back of that striped neck. But just before they could achieve this an astounding thing happened. The stranger whirled as if for flight. His tail went up in the air with a curious jerk. And straight in his eyes and nose and mouth Red Fox received a volley of something that seemed to slap and blind and choke him, all three at once. His eyes felt as if they were burnt out of his head. At the same time an overpowering, strangling smell clutched his windpipe and seemed almost to close up his throat in a paroxysm of repulsion. Gasping desperately, sputtering and staggering, the unhappy youngster rushed away, only to throw himself down and grovel wildly in the moss and leaves, coughing, tearing at mouth and eyes with frantic paws, struggling to rid himself of the hideous, throttling, slimy thing. And the skunk, not turning to bestow even one scornful glance upon his demoralized assailant, went strolling on indifferently down the cow-path, unafraid of the world. As for the Red Fox, it was many minutes before he could breathe without spasms. For a long time he rolled in the leaves and moss, scrubbing his face fiercely, getting up every minute and changing his place, till all the ground for yards about was impregnated with skunk. Then he betook himself to a mound of dusty soil, and there repeated his dry ablutions till his face was so far cleansed that he could breathe without choking, and his scalded eyes were once [52] more of some use to see with. This accomplished, he went sheepishly home to the burrow,—to be received this time with disgust and utter reprobation. His mother stood obstinately in the doorway and snarled him an unequivocal denial. Humiliated and heartsore, he was forced to betake himself to the hollow under the juniper-bush above the den, where his valiant father had slept before him. Not for three unhappy days was he allowed to enter the home den, or even come very close to the rest of the family. Even then an unprejudiced judge would have felt constrained to declare that he was anything but sweet. But it really takes a very bad smell to incommode a fox.

During the days when the curse of the skunk still lay heavy upon him, he found that his adversity, like most others, had its use. His hunting became distinctly easier, for the small wild creatures were deceived by his scent. They knew that a skunk was always slow in movement, and therefore they were very ready to let this unseen hunter, whose smell was the smell of a skunk, come within easy springing distance. In this way, indeed, Red Fox had his revenge for the grievous discomfiture which he had suffered. For presently, it seemed, word went abroad through the woods that some [53] skunks were swift of foot and terrible of spring as a wildcat; and thenceforth all skunks of the Ringwaak country found the chase made more difficult for them.

In the meantime, the mother fox was beginning to get very nervous because two of her litter were inclined to go foraging in the neighbourhood of the farmhouse in the valleys. In some way, partly by example and partly no doubt by a simple language whose subtleties evade human observation, she had striven to impress upon them the suicidal folly of interfering with the man-people’s possessions. Easy hunting, she conveyed to them, was not always good hunting. These instructions had their effect upon the sagacious brain of Red Fox. But to his brother and sister they seemed stupid. What were ducks and chickens for if not to feed foxes; and what were farmers for if not to serve the needs of foxes by providing chickens and ducks? Seeing the trend of her offspring’s inclinations, the wise old mother made up her mind to forsake the dangerous neighbourhood of the den and lead her little family farther back into the woods, out of temptation. Before she had quite convinced herself, however, of the necessity of this move, the [54] point was very roughly decided for her—and Red Fox received another salutary lesson.

It came about in this way. One afternoon, a little before sundown, Red Fox was sitting on a knoll overlooking the nearest farmyard, taking note of the ways of men and of the creatures dependent upon men. He sat up on his haunches like a dog, his head to one side, his tongue showing between his half-open jaws, the picture of interested attention. He saw two men working in the field just behind the little gray house. He saw the big black and white mongrel romping in the sunny, chip-strewn yard with the yellow half-breed, who had come over from a neighbouring farm to visit him. He saw a flock of fat and lazy ducks paddling in the horse-pond behind the barn. He saw, also, a flock of half-grown chickens foraging carelessly for grasshoppers along the edge of the hay-field, and thought wistfully what easy game they would be for even the most blundering of foxes. In a vague way he made up his mind to study the man-people very carefully, in order that he might learn to make use of them without too great risk.

As he watched, he caught sight of a small red shape creeping stealthily through the underbrush near the hay-field. It was his heedless brother; and [55] plainly he was stalking those chickens. Red Fox shifted uneasily, frightened at the audacity of the thing, but sympathetically interested all the same. Suddenly there was a rush and a pounce, and the small red shape landed in the midst of the flock. The next moment it darted back into the underbrush, with a flapping chicken swung over its shoulder; while the rest of the flock, squawking wildly with terror, fled headlong toward the farmyard.

At the sudden outcry, the dogs in the yard stopped playing and the men in the field looked up from their work.

“That’s one o’ them blame foxes, or I’ll be jiggered!” exclaimed one of the men, the farmer-woodsman named Jabe Smith, whose knowledge of wilderness lore had taught him the particular note of alarm which fowls give on the approach of a fox. “We’ll make him pay dear for that chicken, if he’s got one!” and the two hurried up toward the house, whistling for the dogs. The dogs came bounding toward them eagerly, well knowing what fun was afoot. The men got their guns from the kitchen and led the dogs across the hay-field to the spot where the chickens had been feeding. In five minutes the robber’s trail was picked up, and the dogs were in full cry upon it. Red Fox, [56] watching from his knoll behind the house, cocked his ears as the musical but ominous chorus arose on the sultry air; but he knew it was not he the dogs were hunting, so he could listen more or less philosophically.

The reckless youngster who had stolen the chicken was terrified by the outcry which he had excited at his heels; but he was plucky and kept hold of his prize, and headed straight for the den, never stopping to think that this was one of the deadliest sins on the whole of the fox kins’ calendar. Running for speed only, and making no attempt at disguising his trail, he was nevertheless lucky enough to traverse a piece of stony ground where the trail refused to lie, and then to cross the brook at a point where it was wide and shallow. Here the pursuers found themselves completely at fault. For a time they circled hither and thither, their glad chorus hushed to an angry whimpering. Then they broke into cry again, and started off madly down along the brook instead of crossing it. They had a fresh fox trail; and how were they to know it was not the trail of the fox which had taken the chicken?

“RED FOX, SITTING SOLITARY ON HIS KNOLL, HEARD THE NOISE OF THE CHASE.”

Red Fox, sitting solitary on his knoll, heard the noise of the chase swerve suddenly and come clamouring in his direction. At first this did not disturb him. Then all at once that subtle telepathic sense which certain individuals among the wild kindreds seem to possess signalled to him that the dogs were on a new trail. It was his trail they were on. He was the hunted one, after all. And doom was scarcely a hundred yards away. He fairly bounced into the air at the shock of this realization. Then he ran, lengthened straight out and belly to the ground, a vivid ruddy streak darting smoothly through the bushes.

It was not in the direction of home that Red Fox ran, but straight away from it. For awhile the terror of the experience made his heart thump so furiously that he kept losing his breath, and was compelled to slow up from time to time. In spite of his bursts of great speed, therefore, he was unable to shake off these loud-mouthed pursuers. The suddenness and unexpectedness of it all were like a hideous dream; and added to his panic fear was a sense of injury, for he had done nothing to invite this calamity. When he reached the brook—which was shallow at this season and split up into pools and devious channels—his sheer fright led him to forget his keen aversion to a wetting, and he darted straight into it. In midstream, however, as he [60] paused on a gravelly shoal, inherited lore and his own craft came timely to his aid. Instead of seeking the other shore, he turned and kept on straight up mid-channel, leaping from wet rock to rock, and carefully avoiding every spot which might hold his scent. The stream was full of windings, and when the dogs reached its banks the fugitive was out of sight. His trail, too, had vanished completely from the face of the earth. Round and round in ever widening circles ran the dogs, taking in both sides of the stream, questing for the lost scent; till at last they gave up, baffled and disgusted.

Red Fox continued up the stream bed for fully a mile, long after he had satisfied himself that pursuit was at an end. Then he made a long détour to the rocky crest of the ridge, rested awhile under a bush, and descended through the early moonlight to the home den in the bank. Here he found his scatter-brained brother highly elated, having escaped the dogs without difficulty and brought home his toothsome prize in triumph. But his mother he found so anxious and apprehensive that she would not enter the burrow at all, choosing rather to take her nap in the open, under a juniper-bush, before setting out for the night’s hunting. Here Red Fox curled up beside her, while the other [61] two youngsters, ignorantly reckless, stuck to the old home nest.

That night Red Fox contented himself with catching mice in the little wild meadow up the slope. When he returned home, on the gray-pink edge of dawn, his mother and sister were already back, and sleeping just outside the door of the den, under the sheltering bush. But the triumphant young chicken-hunter was still absent. Presently there floated up on the still, fragrant air that baleful music of dogs’ voices, faint and far off but unmistakable in its significance. The yellow half-breed and the black and white mongrel were again upon the trail. But what trail? That was the question that agitated the little family as they all sat upon their brushes, and cocked their ears, and listened.

With astonishing rapidity the noise grew louder and louder, coming straight toward the den. To the wise old mother there was no room to mistake the situation. Her rash and headstrong whelp had once more got the dogs upon his trail and was leading them to his home refuge. Angry and alarmed, she jumped to her feet, darted into the burrow and out again, and raced several times round and round the entrance; and first Red Fox, and then his less quick-witted sister, followed her in these tactics, [62] which they dimly began to comprehend. Then all three darted away up the hillside, and came out upon a well-known bushy ledge from which they could look back upon their home.

They had been watching but a minute or two when they saw the foolish fugitive run panting up the bank and dive into the burrow. At his very heels were the baying and barking dogs, who now set up a very different sort of chorus, a clamour of mingled impatience and delight at having run their quarry at last to earth. The black and white mongrel at once began digging furiously at the entrance, hoping to force his way in and end the whole matter without delay. But the half-breed hound preferred to wait for the men who would, he knew, soon follow and smoke the prisoner out. He contented himself with sitting back on his haunches before the door, watching his comrade’s futile toil, and every now and then lifting his voice to signal the hunters to the spot. Meanwhile, the wise old mother fox on the ledge above knew as well as he what would presently happen. Having no mind to wait for the inevitable conclusion of the tragedy, she slunk away dejectedly and led the two surviving members of her litter over the ridge, [63] across the next broad valley, and far up the slope of lonely and rugged Ringwaak, where they might have time to mature in strength and cunning before pitting their power against men.

For some days after this sudden flight into exile, the diminished family wandered wide, having no fixed lair and feeling very much adrift. In a curious outburst of bravado or revenge, or perhaps because she for the moment grew intolerant of her long self-restraint, the mother fox one violet sunset led her two young ones in fierce raid upon the barnyard of one of the remoter farms. It seemed a reckless piece of audacity; but the old fox knew there were no dogs at this farm save a single small and useless cur; and she knew, also, that the farmer was no adept with the gun.

All was peace about the little farmyard. The golden lilac light made wonderful the chip-strewn yard and the rough, weather-beaten roofs of cabin and barn and shed. The ducks were quacking and bobbing in the wet mud about the water-trough, [65] where some grain had been spilled. The sleepy chickens were gathering in the open front of the shed, craning their necks with little murmurings of content, and one by one hopping up to their roosts among the rafters. From the sloping pasture above the farmyard came a clatter of bars let down, and a soft tunk-a-tonk of cowbells as the cows were turned out from milking.

Into this scene of secure peace broke the three foxes, rushing silently from behind the stable. Before the busy ducks could take alarm or the sleepy chickens fly up out of danger, the enemy was among them, darting hither and thither and snapping at slim, feathered necks. Instantly arose a wild outcry of squawking, quacking, and cackling; then shrill barking from the cur, who was in the pasture with the cows, and angry shouting from the farmer, who came running at top speed down the pasture lane. The marauders cared not a jot for the barking cur, but they had no mind to await the arrival of the outraged farmer. Having settled some grudges by snapping the necks of nearly a dozen ducks and fowls, each slung a plump victim across his back and trotted leisurely away across the brown furrows of the potato-field toward the woods. Just as they were about to disappear under [66] the branches they all three turned and glanced back at the farmer, where he stood by the water-trough shaking his fists at them in impotent and childish rage.

This audacious exploit seemed in some way to break up the little family. In some way, at this time, the two youngsters seemed to realize their capacity for complete independence and self-reliance; and at the same moment, as it were, the mother in some subtle fashion let slip the reins of her influence. All three became indifferent to each other; and without any misunderstanding or ill will each went his or her own way. As for Red Fox, with a certain bold confidence in his own craft, he turned his face back toward the old bank on the hillside, the old den behind the juniper-bush, and the little mouse-haunted meadow by the friendly brook.

“THEY ALL THREE TURNED AND GLANCED BACK.”

As he neared the old home, with the memory of tragic events strong upon him, Red Fox went very circumspectly, as if he thought the dogs might still be frequenting the place. But he found it, of course, a bright solitude. The dry slope lay warm in the sun, the scattered juniper-bushes stood prickly and dark as of old, and unseen behind its screen of leafage the brook near by babbled pleasantly as of old over its little falls and shoals. But where had been the round, dark door of his home was now a gaping gash of raw, red earth. The den had been dug out to its very bottom. Being something of a philosopher in his young way, and quite untroubled by sentiment, Red Fox resumed possession of the bank. For the present he made his lair under the bush on top of the bank, where his father had been wont to sleep. He knew the bank was a good place for a fox to inhabit, being warm, dry, secluded, and easy to dig. Well under the shelter of another juniper, at the extreme lower end of the bank and quite out of sight of the old den, he started another burrow to serve him for winter quarters.

Engrossed in the pursuit of experience and provender, Red Fox had no time for loneliness. Every hour of the day or night that he could spare from sleep was full of interest for him. The summer had been a benignant one, favourable to all the wild kindreds, and now the red and saffron autumn woods were swarming with furtive life. With a flicker of white fluffy tails, like diminutive powder-puffs, the brown rabbits were bounding through the underbrush on all sides. The dainty wood-mice, delicate-footed as shadows, darted and squeaked among the brown tree roots, while in every grassy [70] glade or patch of browning meadow the field-mice and the savage little shrews went scurrying in throngs. The whirring coveys of the partridge went volleying down the aisles of golden birch, their strong brown wings making a cheerful but sometimes startling noise; and the sombre tops of the fir groves along the edges of the lower fields were loud with crows. In this populous world Red Fox found hunting so easy that he had time for more investigating and gathering of experience.

At this time his curiosity was particularly excited by men and their ways; and he spent a great deal of his time around the skirts of the farmsteads, watching and considering. But certain precautions his sagacious young brain never forgot. No trail of his led between the valley fields and his burrow on the hillside. Before descending toward the lowlands he would always climb the hill, cross a spur of the ridge, and traverse a wide, stony gulch where his trail was quickly and irretrievably lost. Descending from the other side of this gulch, his track seemed always as if it came over from the other valley, below Ringwaak. Moreover, when he reached the farms he resolutely ignored ducks, turkeys, chickens,—and, indeed, in the extremity of his wisdom, the very rats and mice which frequented [71] yard and rick. How was he to know that the rats which enjoyed the hospitality of man’s fodder stack were less dear to him than the chickens who sheltered in his shed? He had no intention of drawing down upon his inexperienced head the vengeance of a being whose powers he had not yet learned to define. Nevertheless, when he found beneath a tree at the back of an orchard a lot of plump, worm-bitten plums, he had no hesitation in feasting upon the juicy sweets; for the idea that man might be interested in any such inanimate objects had not yet penetrated his wits.

Another precaution which this young investigator of man and manners very carefully observed was to keep aloof from the farm of the yellow half-breed hound. That was the chief point of danger. The big black and white mongrel, whose scent was not keen, he did not so very much dread. But when he saw the two dogs playing together, then he knew that the most likely thing in the world was a hunting expedition of some kind; and he would make all haste to seek a less precarious neighbourhood. Toward dogs in general he had no very pronounced aversion, such as his cousin the wolf entertained; but these two dogs in particular he feared and hated. Whenever, gazing down from one of his [72] numerous lookouts or watch-towers, he saw the two excitedly mussing over one of his old, stale trails—which straggled all about the valley—his thin, dark muzzle would wrinkle in vindictive scorn. In his tenacious memory a grudge was growing which might some day, if occasion offered, exact sharp payment.

Among the animals associated in the young fox’s mind with man there was only one of which he stood in awe. As he was stealing along one day in the shadow of a garden fence, he heard just above him a sharp, malevolent, spitting sound, verging instantly into a most vindictive growl. Very much startled, he jumped backward and looked up. There on top of the fence crouched a small, grayish, dark striped animal, with a round face, round, greenish, glaring eyes, long tail fluffed out, and high-arched back. At the sound of that bitter voice, the glare of those furious eyes, Red Fox’s memory went back to the dreadful day when the lynx had pounced at him from the thicket. This spitting, threatening creature on the fence was, of course, nothing like the lynx in size; and Red Fox felt sure that he was much more than a match for it in fair fight. He had no wish to try conclusions with it, however. For some seconds he stood eying it nervously. Then the cat, divining his apprehensions, advanced slowly along the top of the fence, spitting explosively and uttering the most malignant yowls. Red Fox stood his ground till the hideous apparition was within five or six feet of him. Then he turned and fled ignominiously; and the cat, the instant he was gone, scurried wildly for the house as if a pack of fiends were after her.

“GLARING EYES, LONG TAIL FLUFFED OUT, AND HIGH-ARCHED BACK.”

Among the man creatures whom Red Fox amused himself by watching at this period, there were two who made a peculiar impression upon him, two whom he particularly differentiated from all the rest. One of these was the farmer-hunter, Jabe Smith, who owned the black and white mongrel,—he whose stray shot had caused the death of Red Fox’s father. This fact, of course, Red Fox did not know,—nor, indeed, one must confess, would he have greatly considered it had he known. Nevertheless, in some subtle way the young fox came to apprehend that this Jabe Smith was, among all the man creatures of the settlement, particularly dangerous and implacable,—a man to be assiduously studied in order to be assiduously avoided. It was from Jabe Smith that the furry young investigator got his first idea of a gun. He saw the man come out of the house with a long [76] black stick in his hands, and point it at a flock of ducks just winging overhead. He saw red flame and blue-white smoke belch from the end of the black stick. He heard an appalling burst of thunder which flapped and roared among the hills. And he saw one of the ducks turn over in its flight and plunge headlong down to earth. Yes, of a certainty this man was very dangerous. And when, a few evenings later, as the colour was fading out of the chill autumn sky, he saw the man light a fire of chips down in the farmyard, to boil potatoes for the pigs, his dread and wonder grew ten-fold. These red and yellow tongues that leaped so venomously around the black pot—terrible creatures called forth out of the chips at the touch of the man’s hand—were manifestly akin to the red thing which had jumped from the end of the stick and killed the voyaging duck. Even when away over in the other valley, hunting, or when curled up safely under his juniper-bush on the bank, Red Fox was troubled with apprehensions about the man of the fire. He never felt himself quite secure except when he had the evidence of his own eyes as to what the mysterious being was up to.

The one other human creature whom Red Fox honoured with his interest was the Boy. The Boy [77] lived on one of the farther farms, one of the largest and most prosperous, one equipped with all that a backwoods farm should have except, as it chanced, a dog. The Boy had once had a dog, a wise bull terrier to which he was so much attached that when it died its place was kept sacredly vacant. He was a sturdy, gravely cheerful lad, the Boy, living much by himself, playing by himself, devoted to swimming, canoeing, skating, riding, and all such strenuous outdoor work of the muscles, yet studious, no less of books than of the fascinating wilderness life about him. But of all his occupations woodcraft was that which most engrossed his interest. In the woods he moved as noiselessly as the wild kindreds themselves, saw as keenly, heard as alertly, as they. And because he was quiet, and did not care to kill, and because his boyish blue eyes were steady, many of the wild kindreds came to regard him with a curious lack of aversion. It was not that the most amiable of them cared a rap for him, or for any human being; but ceasing to greatly fear him, they became indifferent. He was able, therefore, to observe many interesting details of life in that silent, populous, secretive wilderness which to humanity in general seems a solitude.

To Red Fox the Boy became an object of interest [78] only second to Jabe Smith. But in this case fear and antagonism were almost absent. He watched the Boy from sheer curiosity, almost as the Boy might have watched him if given the same sort of chance. It puzzled Red Fox to see the Boy go so soundlessly through the woods, watching, listening, expectant, like one of the wild folk. And in an effort to solve the puzzle he was given to following warily in the Boy’s trail,—but so warily that his presence was never guessed.

For weeks Red Fox kept studying the Boy in this way, whenever he had a chance; but it was some time before the Boy got a chance to study Red Fox. Then it came about in a strange fashion. One afternoon, some time after Red Fox had discovered and enjoyed the fallen plums in the orchard, he came upon a wild grape-vine on the edge of the valley, loaded with ripe fruit. Grape-vines were a rare growth in the Ringwaak region; but this one, growing in a sheltered and fertile nook, was a luxuriant specimen of its kind. It had draped itself in serpentine tangles over a couple of dying trees; and the clusters of its fruit were of a most alluring purple.

Red Fox looked on this unknown fruit and felt sure that it was good. He remembered the plums, [79] and his lips watered. One small bunch, swinging low down on a vagrant shoot of vine, he sampled. It was all that he had fancied it might be. But the rest of the bursting, purple clusters hung out of reach. Leap as he might, straight up in the air, with tense muscles and eagerly snapping jaws, he could reach not a single grape. Around and around the masses of vine he circled, looking for a point of attack. Then he attempted climbing, but in vain. His efforts in this direction were as futile as his jumping; and the grapes remained inviolate.

Red Fox was resourceful and persistent; but there are occasions when resourcefulness and persistence prove a snare. He sat down on his haunches and carefully thought out the situation. At one place he had found that, owing to the twists of the great vine around its supporting tree, he could scale the trunk for a distance of five or six feet. This seemed useless, however, as there were no grapes within reach at that point; but he observed at length a spot that he might jump to after climbing as high as he could,—a spot where a tangle of vines might afford him foothold, and where the luscious bunches would hang all about his head. He lost no more time in considering, but [80] climbed, poised himself carefully, gathered his muscles, and sprang out into the air.

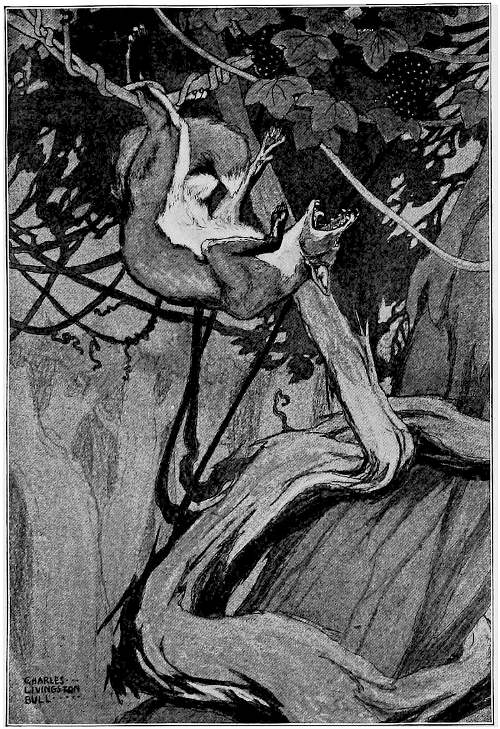

The feat was well calculated and exactly accomplished, and Red Fox alighted safely among the grapes. But what he had not allowed for, or even guessed at, was the yielding elasticity of the vines. They gave way in all directions, quite eccentrically and inconsistently. For several seconds he made a frantic struggle to keep up, clutching with paws and jaws. Then, squirming and baffled, he fell through.

Unhappily for him, however, he did not fall through completely. The tangle of stems that would not sustain him seemed equally resolved not to let him go. An obstinate twist of vine hooked itself about one hind leg, above the joint, and held him fast, swinging head downward.

The luckless adventurer writhed up against himself, striving to loose that relentless clutch with his teeth. But the facile yielding of the vines gave him no purchase, and every struggle he made but drew the snare the tighter. When he realized his predicament, he became panic-stricken, and fell to a violent kicking and struggling and swinging which made loud disturbance in the leafage. This he kept up for several minutes, till at last, utterly exhausted, he hung motionless, swaying in the brown-green shadow, his tongue out piteously and his eyes half-shut.

“HE BECAME PANIC-STRICKEN, AND FELL TO A VIOLENT KICKING AND STRUGGLING.”

Just at this moment, by chance, arrived the Boy. His quick ear had caught from a distance the unwonted thrashing of leafage at a time when all the air was still. Drawing near very stealthily, in order to miss nothing of what there might be to be seen, he came up just as the captive seemed to be dying. One fresh struggle of fright convulsed the young fox’s limbs; then, realizing that the situation was hopeless, he relaxed to apparent lifelessness, his eyes closed to a narrow, deathlike slit.

The Boy, with instant commiseration, sprang forward and loosed the coil, grieving that he had not come in time to save the handsome creature’s life. He had a rather special interest in foxes, admiring their cleverness and self-possession. Now, his gray eyes full of pity, he held up the limp form in his arms, smoothing the brilliant, vivid, luxuriant fur. He had never before had a chance to examine a fox so rich in colour. Finally, deciding that he could now have a splendid fox-skin without any qualms of conscience, he turned his face homeward, flinging the body carelessly over his shoulder by the hind legs.

At this moment, however, just as he was leaving, there flashed across his mind’s eye a vision of the great purple grape-clusters, which he had seen when quite too much preoccupied to notice them. Could he leave those ripe grapes behind him? No, indeed! He turned back again eagerly, flung the dead fox down, and fell to feasting till mouth and fingers were purple. His appetite satisfied, satiated indeed, he then filled his hat, and at last, with a sigh of content, faced about to pick up the dead fox. For a moment he stared in amazement, and rubbed his eyes. The fox he had flung down so carelessly was the deadest looking fox he had ever seen. But now, there was no fox there. Then, swiftly, because he understood the wild creatures, it flashed upon him how cunningly he had been fooled. With a quiet little chuckle of appreciation he went home, bearing no trophy but his hatful of wild grapes.

Immeasurably elated by his success in outwitting the Boy, Red Fox now ran some risk of growing overbold and underrating the superiority of man. Fortunately for himself, however, he presently received a sharp lesson. He was stealthily trailing Jabe Smith, one crisp morning, when the latter was out with his gun, looking for partridges. A whirr of unseen wings chancing to make Jabe turn sharply in his tracks, he caught sight of a bright red fox shrinking back into the underbrush. Jabe was a quick shot. He up with his gun and fired instantly. His charge, however, was only in for partridges, and the shot was a long one. A few of the small leaden pellets struck Red Fox in the flank. They penetrated no deeper than the skin; but the shock was daunting, and they stung most viciously. In his amazement and fright he sprang straight into the [86] air. Then, straightening himself out, belly to earth, he fled off in a red streak among the trunks of the young white birches. For days he was tormented with a smarting and itching in his side, which nothing could allay; and for weeks he kept well away from the haunts of men.

About this time the young fox met with several surprises. One morning, emerging from under his juniper-bush in the first pale rose of dawn, he found a curious, thin, sparkling incrustation on the dead leaves, and the brown grasses felt stiff and brittle under his tread. Much puzzled, he sniffed at the hoarfrost, and tasted it, and found it had nothing to give tongue or nose but a sensation of cold. The air, too, had grown unwontedly cold, so that his thoughts reverted to the burrow which he had been digging. Both the cold and the sparkling hoarfrost fled away as the sun got high; but Red Fox set himself at once to work completing his burrow. Thereafter he occupied it, and forgot all about the lair beneath the juniper-bush.

Shortly after this he made his first acquaintance with the miracle of the ice. One chilly morning in the half-light, when the upper sky was just taking on the first rose-stains of dawn, he stopped to drink at a little pool. To his amazement, his muzzle came [87] in contact with some hard but invisible substance, intervening between his nose and the water. At first he backed off in wary suspicion, and glanced all about him to see if anything else had gone wrong in the world. Then he sniffed at the ice, and lapped it tentatively; and finally, growing bolder, thrust at it so hard with his nose that it broke. This seemed to solve the mystery to his satisfaction, so he slaked his thirst and went about his hunting. Later in the day, however, happening to drink again at the same pool, he was surprised to find that the strange, hard, invisible, breakable substance had all gone. He hunted for it anxiously, and was utterly mystified until he found some remnants still unthawed; whereupon he was once more content, seeming to think the phenomenon quite adequately explained.

This surprise over hoarfrost and ice, however, was nothing to his troubled astonishment on the coming of the first snow. One morning, after a hard hunting expedition which had occupied the first half of the night, he slept till after daylight. During his sleep the snow had come, covering the ground to the depth of about an inch. When he poked his nose out from the burrow, the flurry was [88] about over, but here and there a light, belated flake still loitered down.

At his first sight of a world from which all colour had been suddenly wiped out, Red Fox started back—shrank back, indeed, to the very bottom of his den. The universal and inexplicable whiteness appalled him. In a moment or two, however, curiosity restored his courage, and he returned to the door. But he would not venture forth. Cautiously thrusting his head out, he stared in every direction. What was this white stuff covering everything but the naked hardwood branches? It looked to him like feathers. If so, there must have been great hunting. But no, his nose soon informed him it was not feathers. Presently he took up a little in his mouth, and was puzzled to find that it vanished almost instantly. At last he stepped out, to investigate the more fully. But, to his disgust, he found that he got his feet wet, as well as cold. He hated getting his feet wet, so he slipped back at once into the den and licked them dry.