TOTEMIC WRITING

INDIAN PETITION TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS

by

EDWARD CLODD

AUTHOR OF

"THE STORY OF PRIMITIVE MAN", "PIONEERS OF EVOLUTION", "THE STORY OF CREATION", ETC. ETC.

"The two greatest inventions of the human mind are writing and money—the common language of intelligence, and the common language of self-interest."—

WITH NINETY ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

GEORGE NEWNES, LIMITED

SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND

1900

THIS LITTLE HISTORY OF

A B C

IS DEDICATED TO

DOROTHY DAY

BY HER LOVING GRANDFATHER [Pg v]

If this little book does not supply a want, it fills, however imperfectly, a gap; for the only work in the English language on the subject—Canon Isaac Taylor's "History of the Alphabet"—is necessarily charged with a mass of technical detail which is stiff reading even for the student of graphiology. Moreover, invaluable and indispensable as is that work, it furnishes only a meagre account of those primitive stages of the art of writing, knowledge of which is essential for tracing the development of that art, so that its place in the general evolution of human inventions is made clear. Prominence is therefore given to this branch of the subject in the following pages.

In the recent reprint of Canon Taylor's book no reference occurs to the important materials collected by Professor Flinders Petrie and Mr. Arthur J. Evans in Egypt and Crete, the result of which is to revolutionise the old theory of the source of the Alphabet whence our own and others are derived. This opens up a big question for experts to settle; and here it must suffice to present a statement of the new evidence, and to point out its significance, so that the reader be not taken into the troubled atmosphere of controversy. That he may, further, not be distracted by footnotes, references to the authorities cited are printed in the text.

Rosemont, 19 Carleton Road,

Tufnell Park, N.

[Pg vi]

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | INTRODUCTORY | 9 |

II. |

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ALPHABET |

23 |

III. |

MEMORY-AIDS AND PICTURE-WRITING |

37 |

| (a) Mnemonic | 39 | |

| (b) Pictorial | 51 | |

| (c) Ideographic | 72 | |

| (d) Phonetic | 79 | |

IV. |

CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND COREAN SCRIPTS |

82 |

V. |

CUNEIFORM WRITING |

89 |

VI. |

EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS |

113 |

| (a) Hieroglyphic Writing | 115 | |

| (b) Hieratic Writing | 125 | |

| (c) Demotic Writing | 127 | |

VII. |

THE ROSETTA STONE |

128 |

VIII. |

EGYPTIAN WRITING IN ITS RELATION TO OTHER SCRIPTS |

134 |

IX. |

CRETAN AND ALLIED SCRIPTS |

157 |

X. |

GREEK PAPYRI |

198 |

| The Diffusion of the "Phœnician" Alphabet— | ||

| (a) Aramean | 207 | |

| (b) Sabean | 212 | |

| (c) Hellenic | 213 | |

XI. |

RUNES AND OGAMS |

223 |

INDEX |

229 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

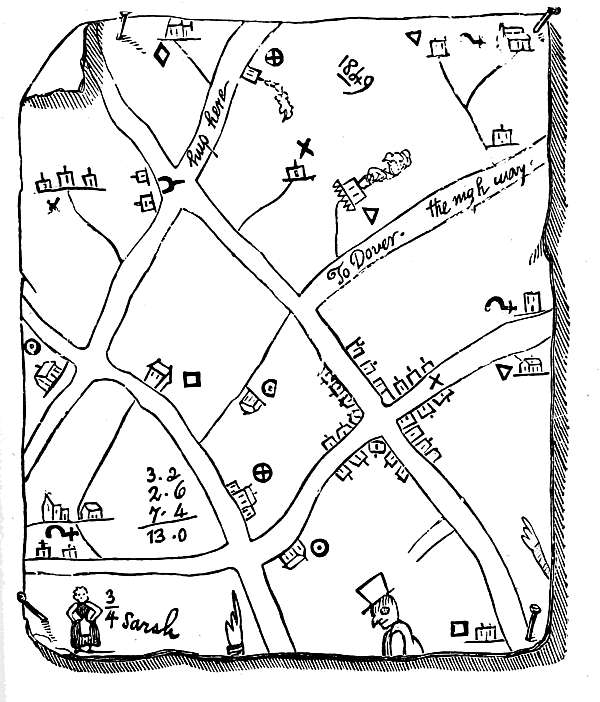

Indian Petition to the United States Congress |

Frontispiece |

|

FIG. |

PAGE |

|

| 1. | Magical Pictograph against Stings | 18 |

| 2. | Magical Device against Skin Disease | 20 |

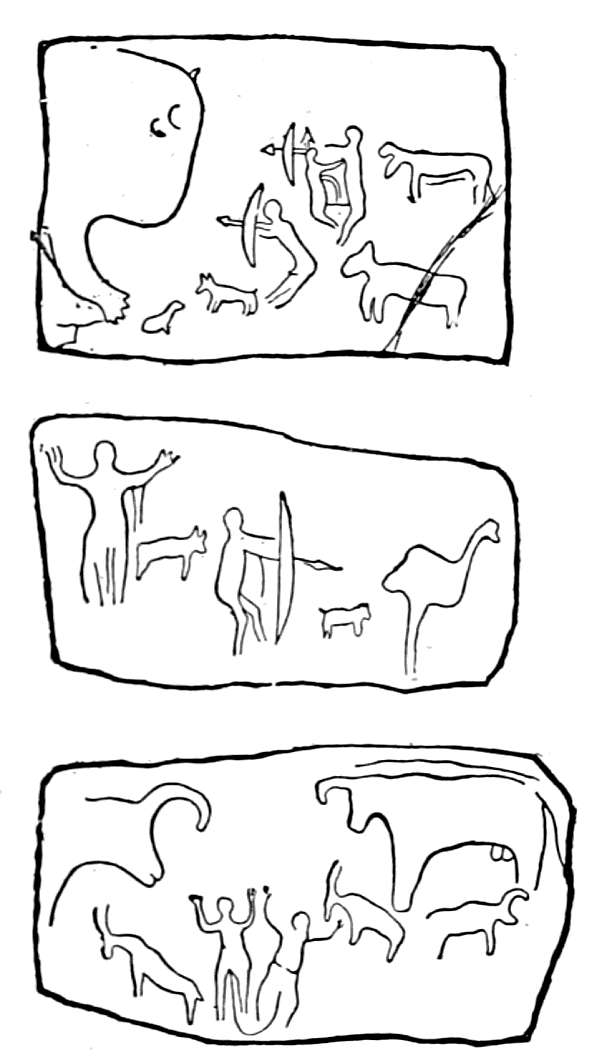

| 3. | Aboriginal Rock Carvings (Australia) | 27 |

| 3a. | Aboriginal Rock Paintings (Australia) | 28 |

| 4. | Bushman Paintings | 30 |

| 4a. | Bushman Paintings | 31 |

| 4b. | Specimen of Bushmen Rock Sculptures | 32 |

| 4c. | Engravings found on Rocks in Algeria | 33 |

| 5. | Bushman Rain-Charm | 34 |

| 6. | Semang Rain-Charm | 35 |

| 6a. | Record of Expedition | 35 |

| 6b. | Various Types of the Human Form | 36 |

| 7. | Quipu, for Reckoning, &c. | 39 |

| 8. | Double Calumet Wampum | 48 |

| 9. | Double Calumet Council Hearth | 48 |

| 10. | Jesuit Missionary Wampum | 49 |

| 11. | Four Nations' Alliance Wampum | 49 |

| 11a. | Penn Wampum | 50 |

| 12,13. | Indian Grave-posts | 53 |

| 14. | Tomb-board of Indian Chief | 54 |

| 15. | Hunter's Grave-post | 54 |

| 16. | A Cadger's Map of a Begging District | 57 |

| 17. | Ojibwa Love-letter | 58 |

| 18. | Love-song | 58 |

| 19. | Mnemonic Song of an Ojibwa Medicine-man | 59 |

| 20. | Wâbeno destroying an Enemy | 61 |

| 21. | Etching on Innuit Drill-bow | 62 |

| 22. | Ojibwa Hunting Record | 62 |

| 23. | Hidatsa Pictograph on a Buffalo Shoulder-blade | 63 |

| 24. | Alaskan Hunting Record | 63 |

| 25. | Record of Starving Hunter | 63 |

| 26. | Alaskan Hunting Life | 66 |

| 27. | Indian Expedition | 66 |

| 28. | Biography of Indian Chief | 66 |

| 29. | War-song | 68 |

| 30. | Letter offering Treaty of Peace | 70 |

| 31. | Census Roll of an Indian Band | 71 |

| 32. | Record of Departure (Innuit) | 72 |

| 33.[Pg viii] | Statue from Palenque | 76 |

| 34. | Itzcoatl | 80 |

| 35. | Rebus of Itzcoatl | 80 |

| 36. | Paternoster Rebus | 81 |

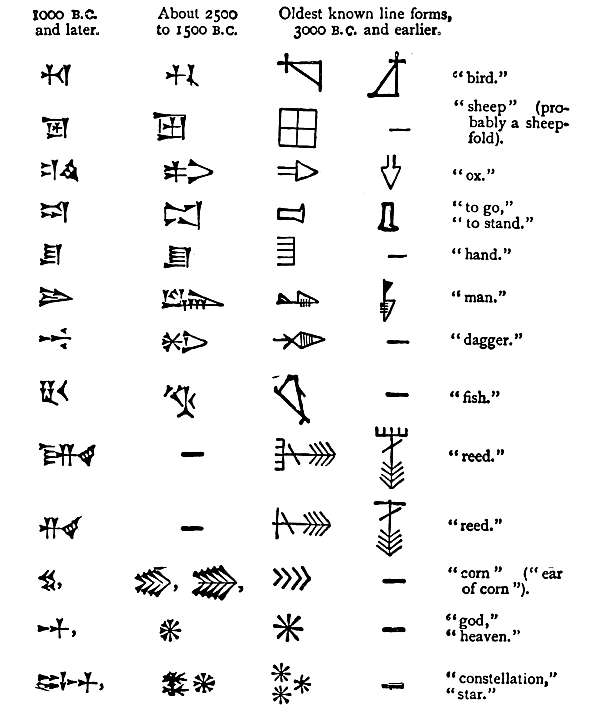

| 37. | Chinese Picture-writing and Later Uncial | 83 |

| 38. | Chinese and Tibetan Triglot | 88 |

| 39. | Rock Inscription at Behistun | 94 |

| 40. | Cylinder Seal of Sargon I. | 107 |

| 41. | Tell-el-Amarna Tablet | 109 |

| 42. | First Creation Tablet | 110 |

| 43,44. | Deluge Tablet (Chaldean Epic) | 111 |

| 45. | Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, and Demotic Signs for Man | 115 |

| 46. | Comparative Ideographs | 122 |

| 47. | Ptolemy | 131 |

| 48. | Cleopatra | 131 |

| 49. | Kaisars (Cæsar)—A. Takrtr (Autokrator) | 131 |

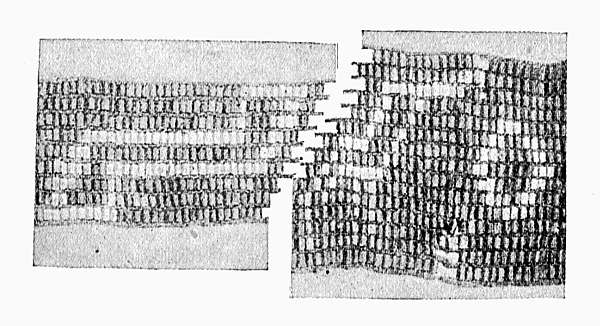

| 50. | Facsimile of Hieratic Papyrus Prisse | 140 |

| 51. | Inscription on the Eshmunazar Sarcophagus | 141 |

| 52. | Inscription on Sacred Bowls (Baal Lebanon) | 146 |

| 53. | The Moabite Stone | 147 |

| 54. | Maneh Weight | 151 |

| 55. | Vase with Incised Characters (Crete) | 160 |

| 56. | Incised Characters on Cup (Crete) | 160 |

| 57. | Characters on Vase (Crete) | 160 |

| 58. | Signs on Bronze Axe (Delphi) | 160 |

| 59. | Signs on Blocks of Mycenæan Buildings (Knôsos) | 166 |

| 60. | Symbols on Three-sided Cornelian (Crete) | 166 |

| 61. | Symbols on Four-sided Stone (Crete) | 166 |

| 62. | Symbols on Four-sided Stones, with larger faces (Central Crete) | 166 |

| 63. | Symbol on Single-faced Cornelian (Eastern Crete) | 166 |

| 64. | Symbol on Stone of ordinary Mycenæan type (Athens) | 166 |

| 65. | Egyptian Scarabs, XIIth Dynasty—Early Cretan Seal-stones | 178 |

| 66. | Signs on Potsherds at Tell-el-Hesy compared with Ægean Forms | 178 |

| 67. | Hittite Inscription at Hamah | 181 |

| 68. | Signs on Vase-handle (Mycenæ) | 183 |

| 69. | Signs on Amphora-handle (Mycenæ) | 183 |

Acknowledgments are gratefully tendered to Messrs. Macmillan, Messrs. Longmans, Mr. John Murray, Messrs. Eyre & Spottiswoode, Mr. Edward Arnold, Messrs. Witherby, the Cambridge University Press, and the Anthropological Institute for permission to reproduce Illustrations from their several publications. [Pg 9]

INTRODUCTORY

"What is ever seen is never seen," and it may be questioned if one in ten thousand of the readers of to-day ever pauses to ask what is the history of the conventional signs called the Alphabet, which, in their varying changes of position, make up the symbols of the hundred thousand words and more contained in a comprehensive dictionary of the English tongue.

Professor Max Müller says that "by putting together twenty-three or twenty-four letters in every possible variety. We might produce every word that has ever been used in any language of the world. The number of these words, taking twenty-three letters as the basis, would be 25,852,016,738,884,976,640,000, or, if we took twenty-four, would be 620,448,401,733,239,439,360,000; but," as the Professor warns us, in words the force of which will be manifest later on, "even these trillions, billions, and millions of sounds would not be words, [Pg 10] because they would lack the most important ingredient—that which makes a word to be a word—namely, the different ideas by which they were called into life, and which are expressed differently in different languages." (Lectures on Language, ii. 81.)

These words themselves, as will also be shown concerning the ear-pictures by which they are represented, reveal in their analysis a story of the deepest interest. In the happy simile quoted by the late Archbishop Trench in his Study of Words, they are "fossil history," and, as he adds, "fossil poetry and fossil ethics" also. To cite a few examples, more or less apposite to our subject, "book" is probably from the Anglo-Saxon bóc, a "beech," tablets of the bark of that tree being one of the substances on which written characters were inscribed. Parallel to this are the words "library" and "libel," both derived from the Latin liber, the inner bark or rind of a tree used for paper; while, as everybody knows, the word "paper" preserves the history of the manufacture of writing material in Egypt from the pith of the papyrus reed, the use of which goes back, as will be shown hereafter, to a high antiquity, and the classic name of which, biblos, has been applied to "bible." "Code" is derived from the Latin codex, "a tree-trunk"; "letters" comes through the French lettre from the Latin lino, litum, "to daub" or "besmear," an early mode of writing being the graving of characters on tablets smeared with wax. "Tablet" is the [Pg 11] diminutive of "table," which comes from the Latin tabula, "a board," and the ancient writing instrument, called a stylus, illustrates the passage of language from the concrete to the abstract in its application to the way in which a writer expresses his ideas. We speak of his "style," just as we say "he wields an able pen," this word being derived from the Latin penna, "a feather." The phrase lapsus calami, "a slip of the pen," preserves record of the use of the reed (Latin calamus), which also survives in "quill," from Old English quylle, "a reed." But the metal pen has a longer history than was suspected, since Dr. Waldstein has found one, cut and slit like our modern specimens, in a tomb of the third century b.c., at Eretria in the island of Eubœa in the Ægean. "Volume," from Latin volumen, "a roll," tells us what was the usual form of books in ancient times, the old form of preservation and custody of legal records surviving in "Rolls of Court," "Master of the Rolls," and so forth. So in "diploma," which, literally, is a paper folded double, from Greek diploō, "to fold." Both "diplomacy" and "duplicity" mean "doubling," but the force of the parallel may not be pursued here. Finally—for the list might be extended indefinitely—"parchment" is borrowed from Pergamus, a town in Asia Minor, where skin came into general use, Ptolemy V. (205-185 b.c.), so runs a doubtful story told by Pliny, having prohibited the export of papyrus from Egypt. [Pg 12]

As words, under the analyses now indicated, yield the history of their origin and of the changes both in spelling and meaning which follow their passage from older forms, and likewise reveal the reasons which governed the choice of them, so the letters of which they are made up bear witness to similar laws of development. The story which it is the purpose of this little book to endeavour to extract from them has mutilated and imperfect chapters, and, moreover, missing chapters which may never be recovered. But sufficing material survives for piecing together a narrative of the triumph of the human mind over one of the most difficult tasks to which it could apply itself; a task which, unwrought, would have made advance in the highest sense impossible beyond a certain point. In the highest sense, because man has gone a long way without knowledge either of reading or writing. These "two R's" are not necessary in matters of personal contact with his fellows, while in other ways progress is independent of them. An illiterate man may be an accomplished landscape artist, a skilful engineer, a successful farmer or trader, and prosperous in many ways where the aim of life is to "live by bread alone." It is true that much of the intellectual and spiritual record of man's past was long preserved in the form of oral tradition. But to the volume of such record there is a limit, while time and caprice alike work havoc in it. Memory, great as was its capacity of old, before dependence on books impaired it, was not infallible, nor, as the world's stock of knowledge increased, could it "pull down its barns and build greater [Pg 13] wherein to bestow its goods." We have, by an effort of the imagination well-nigh impossible to make, only to assume the absence of any means of material record of the involved and myriad events which fill the world's past, to conceive the intellectual poverty of the present. We have only to assume the absence of any medium whereby we could communicate with friends at a distance, or whereby the now complex and countless dealings between man and man could be set down and every transaction thus "brought to book," to realise the hopeless tangle of our social life. All that memory failed to overlap would be an absolute blank; the dateless and otherwise uninscribed monuments which the past had left behind would but deepen the darkness; all knowledge of the strivings and speculations of men of old would have been unattainable; all observation and experience through which science has advanced from guesses to certainties irretrievably lost; life could have been lived only from "hand to mouth," and the spectacle presented of an arrested world of sentient beings. Save in fragmentary echoes repeated by fugitive bards, the great epics of East and West would have perished, and the immortal literatures of successive ages never have existed. The invention of writing alone made possible the passage from barbarism to civilisation, and secured the continuous progress of the human race. It is solely through the marvellous perfecting, through stages of slow advance, [Pg 14] of a scripture that "cannot be broken," that the past is as eloquent, as real, as the present. "The pen is mightier than the sword" in accumulating and preserving for both gentle and simple the store of the world's intellectual wealth, unto which "all the things that can be desired are not to be compared."

These reflections are commonplace enough, but they may not be wholly needless, and an example or two of the impression made on the barbaric mind by written symbols may help us the better to appreciate what our case would be without them. In the narrative of his adventures in the Tonga Islands, published about ninety years ago, William Mariner tells how anxiety to escape from the place where, on the wreck of the ship Port au Prince, he and some other Englishmen had been cast ashore, led him to write, by means of a solution of gunpowder and a little mucilage for ink, a letter which he entrusted to a friendly native to give to the captain of any vessel that might happen to touch at Tonga. Finow, the king, came to hear of this, and got hold of the letter. But he could make "neither head nor tail" of it. However, by threats of death if he refused, one of Mariner's shipmates was made to interpret the mystic signs to Finow, who, still puzzled, sent for Mariner and ordered him to write down something else, saying, when Mariner asked for a subject, "Put down me." This done, Finow sent for another sailor, who read the royal name aloud, whereupon the king appeared more bewildered than ever, exclaiming. "This not like me; where are [Pg 15] my legs?" Then it slowly dawned upon him that it was possible to make signs of things which both the writer and the interpreter had seen. But the bewilderment returned when Mariner told him that he could write down a description of any one whom he had never seen, or of an event which happened long ago or far away, when these were told him. Thereupon Finow whispered to him the name of Tongoo Aho, a former king of Tonga, who, it had come to Mariner's knowledge, was blind in one eye. When Mariner set these things down, and the king had them read to him, it was explained that "in several parts of the world messages were sent to great distances through the same medium, and, being folded and fastened up, the bearer could know nothing of the contents; and that the histories of whole nations were thus handed down to posterity without spoiling by being kept. Finow acknowledged this to be a most noble invention, but added that it would not at all do for the Tonga Islands; that there would be nothing but disturbances and conspiracies, and he should not be sure of his life perhaps another month. He said, however, jocularly, that he should like to know it himself, and for all the women to know it, that he might make love with less risk of discovery, and not so much chance of incurring the vengeance of their husbands." (Mariner's Tonga Islands, i. 116, ed. 1827.) The Smithsonian Reports, 1864, tell a story of an Indian who was sent by a missionary to a colleague with four loaves of bread, accompanied by a [Pg 16] letter stating their number. The Indian ate one of the loaves, and was, of course, found out. He was sent on a similar errand and repeated the theft, but took the precaution to hide the letter under a stone while he was eating the bread, so that it might not see him!

Barbaric ideas fall into fundamentally-related groups, and the examples just given are connected with the widespread belief in the efficacy of written characters to work black or white magic, to effect cures, and otherwise act as charms—a belief largely derived from the legends which ascribe the origin of writing to the gods—legends themselves the product of Ignorance, the mother of Mystery. In an Assyrian inscription, Sardanapalus V. speaks of the cuneiform or wedge-shaped characters as a revelation to his royal ancestors from the god Nebo; among the Egyptians, Thoth was the scribe of the gods, and their oldest forms of writing were named "the divine." Chinese tradition ascribes the invention of writing to the dragon-faced, four-eyed sage Ts'ang Chien, who saw in the stars of heaven, the footprints of birds, and the marks on the back of the tortoise, the models on which he formed the written characters. At this invention "heaven caused showers of grain to descend from on high; the disembodied spirits wept in the darkness, and the dragons withdrew themselves from sight." On the altars raised to Ts'ang Chien throughout the Celestial Land, every scrap of fugitive paper which has writing on it is burned in his honour. In Hindu legend, Brahma, the supreme god of the Indian Trinity, gives knowledge of [Pg 17] letters to men; and Nâgari, in which alphabet the sacred books are written, is spoken of as "belonging to the city of the gods." The handwriting of Brahma, legend further says, is seen in the serrated sutures of men's skulls; and as Yahweh or Jehovah wrote the "Ten Words" with his own finger, so Brahma inscribed the holy texts of the Veda on leaves of gold. The story of the culture-hero, Cadmus, introducing the alphabet from Phœnicia into Greece is well known; while in Irish legend, Ogmios, the Gaelish Hercules, is familiar as the inventor of writing. But perhaps less familiar is that in the Northern Saga which attributes the invention of runes to Odin:—

Belief in the power of the spoken word, notably as a curse, has world-wide illustration; and not less is that in the power of the written word or of the pictorial symbol. Cabalistic formulæ and texts from sacred writings play a large part; the virtue in Jewish phylacteries and frontlets was believed to depend on the texts which they enclosed; the amulets worn by Abyssinians to avert the evil eye and ward off demons have the secret name of God chased on them; passages from the Koran are enclosed in bags and hung on Turkish and Arab horses to protect them against like maleficence; prayers to the Madonna are slipped into charm-cases to be worn by the Neapolitans; while not so many years back (indeed, so persistent are superstitions, that kindred practices obtain throughout Europe to this day) sick folk in the Highlands were fanned with the leaves of the Bible. [Pg 18]

Fig. 1.—Magical Pictograph against Stings

[Pg 19] In his instructive and entertaining book on Evolution in Art, Professor Haddon refers to a series of valuable observations on the use of picture-writing as a charm against diseases and stings of venomous animals, among the Semang tribes of East Malacca, made by Mr. H. Vaughan Stevens, and edited by Mr. A. Grünwedel. The women wear bamboo combs on which are drawn patterns of flowers or parts of flowers believed to be antidotes to fevers and other invisible diseases; for injuries and wounds such as those caused by a falling bough in the jungle, or the bite of a centipede, other means are employed. Among the magic-working devices incised in bamboo staves by the Semang magicians, Mr. Vaughan Stevens gives illustrations of one against the stings of scorpions and centipedes (Fig. 1), and of another against a skin disease (Fig. 2).

In the first-named there is depicted the figure of an Argus pheasant, the wheel-like patterns beneath which represent the eye-marks in the tail-feathers. On the left is an orange-coloured centipede, the head of which points to the tail of the pheasant. The dotted lines round the centipede are tracks which it leaves on a man's skin. On the other side of the Argus are two blue scorpions, the figures at the end of [Pg 20] their tails representing a swelling in the flesh of the persons stung by them. The female of this kind of scorpion is more poisonous than the male, and is said to cause double stings, which are denoted by the two rows of dots in the top figure. "The significance of this bamboo is that as the Argus pheasant feeds on centipedes and scorpions, so its help is invoked against them by striking the bamboo against the ground."

Fig. 2.—Magical Device against Skin Disease

The other example, which exhibits a much more complicated and conventionalised device, is designed as a charm against two kinds of skin disease, the one represented by fish scales indicating leprous [Pg 21] white ulcers, the other represented by oval figures indicating hard knots on and under the skin. The rows stand for the several parts of the body which are affected, and the figures increase in size to show that the disease will spread if not cured. Although the way in which the charm is applied is not clear, there is no doubt that belief in its virtue belongs to the large class of barbaric ideas grouped under sympathetic magic, i.e. that things outwardly resembling one another are thought by the barbaric or illiterate to possess the same qualities. The result is that effects are brought about in the individual himself by the production of similar effects in things belonging to him, or, what is more to the purpose, in images or effigies of him. Here it suffices to say that the most familiar examples of "sympathetic magic" are the making of an image of the person whose destruction is sought, of wax, clay, or other substance, so that as the wax is melted, or the clay dissolved in running water, his life may decline or wear away to its doom. Such examples are gathered alike from civilised and barbaric folk, from Devonshire and the Highlands to North America and Borneo.

Things are invested with mystery in the degree that their origins and causes are unknown; and the beliefs and customs, of which a few among the teeming illustrations have been given, invite the reflection that, had writing remained the monopoly of any caste or class, it would [Pg 22] have remained an engine of enslavement, instead of becoming an engine of liberation of the mind. "Knowledge is power," and whatever has ensured the possession and the retention of power over his fellows has been seized upon by man—notably by man as priest, from medicine-man to Pope, as wielder of weapons of authority, the more dreaded when unseen or intangible. Signs which were unadapted, and, things being what they then were, impossible, for general use, and moreover needing great expenditure of time and labour to master them, would come under this head, and it was only through their ultimate simplification that they could become serviceable to the many, and made vehicles of the diffusion of knowledge. How monstrous and penal an instrument of inequality learning itself long continued among ourselves is shown in the fact that "benefit of clergy"—one among many evidences of the old conflict between the civil and the sacerdotal powers—was not wholly repealed until the year 1827. Under this statute, exemption from trial for criminal offences before secular courts was extended, by law passed in the reign of Edward I., not only to ecclesiastics, but to any man who could read. A prisoner sentenced to death might be claimed by the bishop of the diocese as a clerk and haled before him, when the ordinary gave the man a Latin book from which to read a verse or two. If the ordinary said "Legit ut clericus"—i.e. "he reads like a clerk"—the offender was only burnt in the hand, and then set free. [Pg 23]

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ALPHABET

We may, without further preface, advance to our main purpose, which is to supply an account of the stages through which the alphabets of the civilised world passed before they reached their, practically, final form. Here, as in aught else that the wit of man has devised and the cunning of his hand applied, the law of development is seen at work. In the quest for traces of any fundamental differences between him and the animals to which he stands in nearest physical and psychical relation, he has been variously described as tool-maker, fire-maker, possessor of articulate speech, and so forth; but the further that observation and comparison have been made, the more apparent has it become that those differences are of degree and not of kind. Some evidence in support of this has been already summarised in previous volumes of this series; and here it suffices to say that it is in the inventive arts, as e.g. the production of fire, of the mode of which nature supplied the hints, and the making of pictorial signs, in which the mimetic instinct, shared by some of the lower animals, comes into play, [Pg 24] that, restricting the comparison to things material, man appears upon a higher plane. But this has been reached by processes of development involving no break in the continuity of things.

In this "story" we start with man as sign-maker. His prehistoric remains supply evidence of artistic capacity in a remote past, and set before us in vigorous, rapid outline what his life and surroundings must have been. On fragments of bone, horn, schist, and other materials, the savage hunter of the Reindeer Period, using a pointed flint flake, depicted alike himself and the wild animals which he pursued. From cavern-floors of France, Belgium, and other parts of Western Europe, whose deposits date from the old Stone Age, there have been unearthed rude etchings of naked, hardy men brandishing spears at wild horses, or creeping along the ground to hurl their weapons at the urus, or wild ox, or at the woolly-haired elephant. A portrait of this last named, showing the creature's shaggy ears, long hair, and upwardly curved tusks, its feet being hidden in the surrounding high grass, is one of the most famous examples of palæolithic art.

Here let us pause to say that the apparent absence of other indications of man's presence, showing passage from lower to higher stages of culture, led to the assumption that vast gaps have occurred in his occupancy of north-western and other parts of Europe. The theory of absolute disconnection between the Old Stone Age and the Newer Stone Age long held the field, but it has disappeared before the evidence [Pg 25] against tenantless intervals of areas in prehistoric times. And so with succeeding periods. There is no warrant for assuming entire effacement of one race, with resulting clear field for the immigration of another race; and modern archæological research is producing the links which connect the rude art of Northern with that of Southern Europe, and, what will be shown to be of great moment, with that of the Eastern Mediterranean. The examples of this must remain rare, since only pictographs on some durable material, or specimens of the fictile art, would survive the action of time. But, happily, if they are infrequent, they are widely distributed. For to those yielded by the bone-caverns already referred to are to be added rock-carvings in Denmark, and figures on limestone cliffs of the Maritime Alps; there are curious graphic signs, suggestive to some eyes of a primitive script, in the Marz d'Azil cave; while still more interesting are the animal and fylfot or swastika-like figures (the swastika is a solar symbol) "painted probably by early Slavonic hands on the face of a rock overhanging a sacred grotto in a fiord of the Bocche di Cattaro." To this last-named example, given by Mr. Arthur Evans in his paper on "Primitive Pictographs" (Journal of Hellenic Studies, xiv. ii. 1894) may be added some pregnant remarks by the same authority. "When we recall the spontaneous artistic qualities of the ancient race which has left its records in the carvings on bone and ivory in the caves of the 'Reindeer Period,' this evidence of at least partial continuity on [Pg 26] the northern shores of the Mediterranean suggests speculations of the deepest interest. Overlaid with new elements, swamped in the dull, though materially higher, Neolithic civilisation, may not the old æsthetic faculties which made Europe the earliest-known home of anything that can be called human art, as opposed to mere tools and mechanical contrivances, have finally emancipated themselves once more in the Southern regions, where the old stock most survived? In the extraordinary manifestations of artistic genius to which, at widely remote periods and under the most diverse political conditions, the later populations of Greece and Italy have given birth, may we not be allowed to trace the re-emergence, as it were, after long underground meanderings, of streams whose upper waters had seen the daylight of that earlier world?" (Presidential Address to the Anthropological Section, British Association. Nature, 1st Oct. 1896.)

But man at the same stage of culture being everywhere practically the same, there is, in the paucity of examples from the Europe of the past, compensation in the specimens of graphic art found among extant barbaric folk. It is probable that a good proportion of these lack significance, but the pictograph is the parent of the alphabet, and therefore the careful transcripts of rock and other paintings which explorers have made may yet prove to be of value when interpreted in the light of examples whose gradations have been traced. Since the extinction of the Tasmanians, whom anthropologists regard as the nearest approach to Palæolithic man, the Australians stand, in certain respects, at the bottom of the scale, although the ingenuity of their social organisations warrants hesitation in making them the nadir of human kind. But as the reproductions show (Figs. 3 and 3a), their attempts at art are inferior to the spirited designs of the prehistoric cave-dwellers. [Pg 27]

Fig. 3.—Aboriginal Rock Carvings (Australia)

Fig. 3a.—Aboriginal Rock Paintings (Australia)

Mr. R. H. Mathews, who has made an extensive survey of the rock-paintings and carvings, says that one type serves for another, so lacking are all in variety; "the stencilled and impressed hands, the outlines of men and animals rudely depicted in various colours, appearing to be universally distributed over the continent." He adds that "although it will be better not to attempt to suggest meanings to the groups of native drawings until a very much larger amount of information has been brought together ... still when we know that drawings such as these by uncivilised nations of all times, in various parts of the world, have ultimately been found to be full of meaning, it is not unreasonable for us to expect that the strange figures painted and carved upon rocks all over Australia will some day be interpreted. Perhaps some of these pictures are ideographic expressions of events in the history of the tribe; certain groupings of figures may portray some legend; many of the animals probably represent totems; and it is likely that a number of them were executed for pastime and amusement." (Journal of the Anthropological Institute, xxv. 2, p. 153.) In their recently published "Native Tribes of Central Australia," Messrs. Spencer and Gillen divide the rock-paintings into two series, those of ordinary type, and those which, found in places strictly taboo to women and children and uninitiated men, are associated with totems, i.e. with the natural object, whether living or non-living, from which the tribe believes itself to be descended. These totemistic figures, called Churinga (a general native term for sacred objects) Ilkinia, are frequently in the form of spiral and concentric circles, others being portraits of the totems themselves, as low in type as the centipede or witchetty grub. [Pg 30]

Fig. 4.—Bushman Paintings

Fig. 4a.—Bushman Paintings

The faces of sandstone caverns in South Africa are often covered with paintings which are the handiwork of Bushmen (Figs. 4, 4a, and 4b). With a skill showing some advance on the art of the Australian [Pg 32] aborigines there is depicted, usually in black or brownish-red colour, the hunting and other exploits which make up life among a people who represent the aboriginal races of the southern portion of the continent. Some of the drawings border on caricature; others, in the words of an observer, "suggest actual portraiture. The ornamentation of the head-dresses, feathers, beads tassels, &c., seemed to have claimed much care, while the higher class of drawings indicate correct appreciation of the actual appearance of objects, and perspective and foreshortening are well rendered." (Mark Hutchinson, Journal of the Anthropological Institute, xiv. p. 464.)

Fig. 4b.—Specimen of Bushmen Rock Sculptures

Fig. 4c.—Engravings found on Rocks in Algeria

(compare with Bushmen type)

These probably now degraded folk, who live on lizards, locusts, and roots when other food fails, have a good store of legend and folk-lore. Fig. 5 seems to portray their belief in "sympathetic magic," if, as conjectured, it represents the dragging of an hippopotamus or other amphibious animal across the land for the purpose of producing rain. The Semangs of the Malay Peninsula use a bamboo rain-charm (Fig. 6), on which the wind-driven showers are depicted in oblique lines, and, among many other examples wherein the higher and lower culture meet together, there is one supplied by old Rome, where it was the custom to throw images of the corn-spirit into the Tiber so that the crops might be drenched with rain. As showing the persistency of superstitions, here is a paragraph anent the severe drought in Russia last autumn: "In another village of the district of Bugulma some moujiks opened the grave of a peasant who had lately been buried, and then poured [Pg 34] water over the corpse, in the belief that this was the best method of bringing rain."—Daily Chronicle, 24th August 1899.

Fig. 5.—Bushman Rain-Charm.

Fig. 6.—Semang Rain-Charm.

Fig. 6a.—Record of Expedition.

The New World is rich in ancient monuments often adorned with symbolic devices, but older than these are the pictographs covering erratic blocks and cliff escarpments from Guiana to Nova Scotia, and westward to the Rockies. Some are incised in the hard stone to a depth of half an inch; others are traced in broad lines of red ochre or other colour, their weather-worn state witnessing to a high antiquity. Their purpose is often not easy to explain, but we know that therein lie the germs whence alphabets sprung. One picture (Fig. 6a) on the face of a [Pg 36] rock on the shore of Lake Superior, copied and interpreted by Schoolcraft, records an expedition across the lake, led by Myeengun, or "Wolf," a noted Indian chief. The crew of each canoe is denoted by a series of upright strokes, Myeengun's chief ally, Kishkemanusee, the "Kingfisher," being in the first canoe. The arch with three circles (three suns under heaven) shows that the voyage took three days. The tortoise (a frequent symbol of "land" in North American picture-writing) seems to indicate the arrival of the expedition, while the picture of the mounted chief evidences that the event took place after the introduction of horses into Canada. Some of the examples, less easy to explain, represent the migration of tribes; some, like the sculptured eagle near the borders of Quauhuahuac ("the place near the eagle") are symbolic boundary-marks; while others are direction-marks. Some have life-size human figures, rayed or horned; one engraved on a rock overlooking the Big Harpeth, in Tennessee, depicts a sun visible four miles off. Doubtless a large number of this class (Fig. 6b) are merely the outcome of that rude artistic fancy of man which, as has been seen, has had continuous expression from prehistoric times.

Fig. 6b.—Various Types of the Human Form

MEMORY-AIDS AND PICTURE-WRITING

The printed letters or sound-signs which compose our alphabet are about two thousand five hundred years old. "Roman type" we call them, and rightly so, since from Italy they came. They vary only in slight degree from the founts of the famous printers of the fifteenth century, these being imitations of the beautiful "minuscule" (so called as being of smaller size) manuscripts of four hundred years earlier. Minuscule letters are cursive (i.e. running) forms of the curved letters about an inch long called "uncials" (from Latin uncia, "an inch," or from uncus, "crooked"), which were themselves derived from the Roman letters of the Augustan age. These Roman capitals, to which those in modern use among us correspond, "are practically identical with the letters employed at Rome in the third century b.c.; such, for instance, as are seen in the well-known inscriptions on the tombs of the Scipios, now among the treasures of the Vatican. These, again, do not differ very materially from forms used in the earliest existing specimens of Latin writing, which may probably be referred to the end of the fifth century b.c. Thus it appears that our English alphabet is a member of that great Latin family of alphabets, whose [Pg 38] geographical extension was originally conterminous, or nearly so, with the limits of the Western Empire, and afterwards with the ancient obedience to the Roman See." (Canon Isaac Taylor's History of the Alphabet, vol. i. p. 71.)

The age of our own alphabet being thus indicated, we may postpone further remark on its lineal descent, and pass to inquiry into the primitive forms of which all alphabets are the abbreviated descendants, and also to reference to some primitive methods for which they are substitutes.

A survey of the long period which this development covers shows four well-marked stages, although in these, as in aught else appertaining to man's history, there are no true lines of division. The making of these, like the apparent lines of longitude and latitude of the cartographer, is justified by their convenience. These stages are:—

(a) The Mnemonic, or memory-aiding, when some tangible object is used as a message, or for record, between people at a distance, and also for the purpose of accrediting the messenger. As will be seen, it borders on the symbolic; indeed, it anticipates that stage.

(b) The Pictorial, in which a picture of the thing is given, whereby at a glance it tells its own story.

(c) The Ideographic, in which the picture becomes representative, i.e. is converted into a symbol. [Pg 39]

(d) The Phonetic, in which the picture becomes a phonogram, or sound-representing sign. The phonogram may be—(1) verbal, i.e. a sound-sign for a whole word; (2) syllabic, i.e. a sound-sign for syllables; or (3) alphabetic, a sound-sign for each letter.

To recapitulate stages (b), (c), and (d):—

In stage (b) the sign as eye-picture suggests the thing;

In stage (c) the sign as eye-picture suggests the name;

In stage (d) the sign as ear-picture suggests the sound;

and it is in the passage from (c) to (d), whereby constant signs are chosen to stand for constant sounds, that the progress of the human race was assured, because only thereby was the preservation of all that is of abiding value made possible.

Fig. 7.—Quipu, for Reckoning, &c.

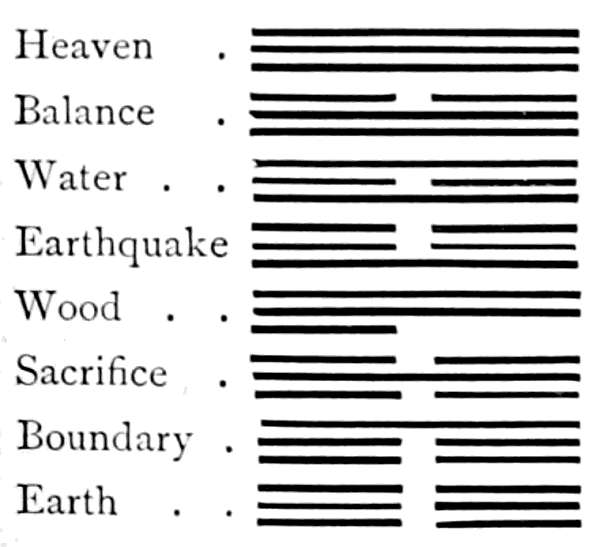

(a) The Mnemonic Stage.—This is well represented by "quipus" or knotted cords, and by wampums or shell-ornamented belts. The quipu (Fig. 7) has a long history, and is with us both in the rosary on which the Roman Catholic counts his prayers, in the knot which we tie in our handkerchief to help a weak memory, and in the sailor's log-line. Herodotus tells us that when Darius bade the Ionians remain to guard the floating bridge which spanned the Ister, he "tied sixty knots in a thong, saying: 'Men of Ionia ... do ye keep this thong and do as I shall say:—so soon as ye shall have seen me go forward against the Scythians, from that time begin and untie a knot on each day; and if within this time I am not here, and ye find that the days marked by the knots have passed by, then sail away to your own lands'" (iv. 98). And [Pg 40] the same obviously handy device is of widespread use, reaching its more elaborate form among the ancient Peruvians, from whose language the term "quipu," meaning "knot," is borrowed. It consists of a main cord, to which are fastened at given distances thinner cords of different colours, each cord being knotted in divers ways for special purposes, and each colour having its own significance. Red strands stood for soldiers, yellow for gold, white for silver, green for corn, and so [Pg 41] forth, while a single knot meant ten, two single knots meant twenty, double knots one hundred, and two double knots two hundred. Such simple devices served manifold purposes. Besides their convenience in reckoning, they were used for keeping the annals of the empire of the Incas; for transmitting orders to outlying provinces; for registering details of the army; and even for preserving records of the dead, with whom the quipu was buried, as in old Egypt the biography or titles of the deceased were set forth in hieroglyph and deposited in the tomb. Quoting from Von Tschudi's Peru, Dr. E. B. Tylor says that each town had its officer whose special function was to tie and interpret the quipus. They were called Quipucamayocuna, or knot-officers; but although they attained great facility in their work, they were seldom able to read a quipu without the aid of an oral commentary. When one came from a distant province, it was necessary to give notice with it whether it referred to census, tribute, war, and so forth. But by constant practice they so far perfected the system as to be able to register with their knots the most important events of the kingdom, and to set down its laws and ordinances. Although vain attempts to read the quipus have been made in the present day, Dr. Tylor adds that there are still Indians in Southern Peru "who are perfectly familiar with the contents of certain historical quipus preserved from ancient times; but they keep their knowledge a profound secret, especially from the white men." (Early History of Mankind, p. 160.) [Pg 42] This knot-reckoning is in use among the Puna herdsmen of the Peruvian plateaux. On the first strand of the quipu they register the bulls, on the second the cows, these again they divide into milch-cows and those that are dry; the next strands register the calves, the next the sheep and so forth, while other strands record the produce; the different colours of the cords and the twisting of the knots giving the key to the several purposes. Akin to this is the practice among the Paloni Indians of California, concerning whom Dr. Hoffman reports that each year a certain number are chosen to visit the settlement at San Gabriel to sell native blankets. "Every Indian sending goods provided the salesman with two cords made of twisted hair or wool, on one of which was tied a knot for every real received, and on the other a knot for each blanket sold. When the sum reached ten reals, or one dollar, a double knot was made. Upon the return of the salesman, each person selected from the lot his own goods, by which he would at once perceive the amount due, and also the number of blankets for which the salesman was responsible." The natives of Ardrah, in West Africa, use small cords, each knot in which has a meaning; and among the Jebus, the objects knotted into strings tell their separate tale, cowrie shells placed face to face denoting friendship; an arrow, war; and so forth. Other tribes have devised message-sticks somewhat after the well-known native Australian type. More highly-developed knot-reckoning is found among the Mexican Zuni, and in more primitive form among some North American Indians; but, not tarrying to detail these, we cross the [Pg 43] Pacific, noting, on our passage, that a generation ago the Hawaiian tax-gatherers kept accounts of the assessable property throughout the island on lines of cordage from four to five hundred fathoms long. Knots, loops, and tufts of different shape, size, and colour indicated the several districts, and the amount of tax to be paid by each inhabitant was defined by marks of the same character as those now specified, with such variety as to prevent confusion. The Shû-King, a sacred historical book of the Chinese, records the use of knotted cords prior to the invention of writing. The number and distances of the knots served as conventional mnemonics, and also as imperial records, until written characters replaced them. "Legend refers the tying of knots in strings to about 2800 b.c., when Fo-hi invented eight symbols, and at the same time pictorial representations of these knotted strings were taken to indicate the object thereby symbolised." These Morse-like symbols are:—

(C. Gardner, Journal Ethnological Society, 1870, vol. ii. p. 5)

Another Chinese legend says that "the most ancient forms were five hundred and forty characters, formed by a combination of knotted strings and the eight symbols, made in the form of birds' claws in [Pg 44] various states of tension, and that all these five hundred and forty characters were suggested to the inventor by the marks (left by the claws) upon the sand." The use of looped or knotted cords is depicted in Egyptian hieroglyph, and among other tribes of the African continent the Jebus of to-day evidence the survival of this primitive memoria technica, while from Melanesia to Formosa the knotted cord, as in Australia and Africa the message-stick, render service as means of communication between man and his fellows. The nine incisions, with a longer cut across them to denote ten, is a mode of decimal reckoning and of record found alike among Red Indians and London bargees. The same purpose explains the custom, in force well within the present century, of our Exchequer in keeping certain accounts by means of notched tallies. The tally was a squared stick of well-seasoned hazel or willow, in one side of which notches of different breadth, indicating pounds, shillings, and pence, were cut to mark the amount of money lent by any person to the Government, the same amount being cut in Roman numerals, together with the lender's name and date of the loan, on the two opposite sides. The stick was then split down the middle, and one half handed to the lender, the other half being kept in the Exchequer. When the money fell due, the lender surrendered his half for comparison with its fellow, and the two being found to "tally," the loan was repaid. It was through the overheating of stoves in the burning of heaps of accumulated tally-sticks that the Houses of [Pg 45] Parliament were destroyed in 1834. Fifty years ago in Scotland (and the like may happen in out-of-the-way hamlets to-day), the baker's boy took a "nick-stick" with his bread, and made a notch in the stick for every loaf he left on his rounds. So it was, Dr. Hoffman tells us, with the Pennsylvanian dairyman, who kept account of the milk which he sold by marking notches for pints and quarts on a stick. As these notches correspond to entries of transactions in our daybooks and ledgers, so the once widely-used Clog Almanack corresponded to our modern Whitaker. It consisted of a square-shaped "clog" or "block" of wood (sometimes of metal), and was designed chiefly to show when the Sundays and holidays fell, certain symbols or hieroglyphs being drawn against saint and other festal days—as, for example, an axe for Saint Paul, a true-lovers' knot for Saint Valentine, and a harp for Saint David. With this may be compared the hieroglyphic wheels named "record of the gods," formerly in use for recording time among the Indians of Virginia. "These wheels had sixty spokes, each for a year, as if to mark the ordinary age of man, and they were painted on skins kept by the priests. They marked on each spoke or division a hieroglyphic figure to show the memorable events of the year." (Tylor, p. 93.)

Wampum-belts are of much narrower geographical distribution than quipus. They consist of hand-made beads or perforated shells arranged in various more or less conventionalised patterns on bark filaments, [Pg 46] hemp, or deerskin strips or sinews, the ends of the belts being selvedged by sinews or hempen fibres. The patterns are pictorial symbols recording events in the history of the tribe or treaties between tribes; the belts being also used to note land boundaries or personal property, sometimes even passing, in the old days, as shell-money in all parts of New England from one end of the coast to the other. As illustrating a common purpose for which the wampum record was used, Peter Clarke tells us, in his Origin and Traditional History of the Wyandotts (a tribe of the Huron-Iroquois stock), that "in the last decade of the eighteenth century, the king or head chief, Sut-staw-ra-tse, called a meeting at the house of Chief Adam Brown, who had charge of the archives, which consisted of wampum belts, parchments, &c., contained in a large trunk. One by one they were brought out and shown to the assembled chiefs and warriors. Chief Brown wrote on a piece of paper and tacked it to each wampum belt, designating the compact or treaty it represented, after it had been explained from memory by the chiefs appointed for that purpose. There sat before them the venerable king, in whose head were stored the hidden contents of each wampum belt, listening to the rehearsal, and occasionally correcting the speaker and putting him on the right track whenever he deviated." Clarke goes on to say that "when the majority of the people removed to the south-west, they demanded to have the belts, as these might be a safeguard to them. Some of these belts recorded treaties of alliance or of peace with other tribes which [Pg 47] were now residing in that region, and it might be of great importance to the Wyandotts to be able to produce and refer to them. The justice of this claim was admitted, and they were allowed to have the greater part of their belts." And modern inquirers tell us that, in so far as the wampums still possess utility, it is as evidence of a subsisting treaty or a title-deed. Few examples, however, of the vast number of belts once in the possession of the North American tribes (and these almost exclusively confined to the Iroquois country) survive, since in the displacement of the red man by the white their value from the land-right point of view has disappeared. Four interesting specimens, known as the "Hale Series of Huron Wampum Belts," which were presented by Dr. Tylor to the Pitt-Rivers Museum at Oxford in 1897, form the subject of lengthy memoirs by the donor and the late Horatio Hale in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute (xxvi. 3, pp. 221-54). Of these only the barest summary is needful. The first and oldest example, dating from before the middle of the seventeenth century, is named the "Double Calumet Treaty Belt" (Figs. 8, 9). It is nine beads in width, and although imperfect, is still nearly four feet long. On a dark ground of the costly purple wampum there is the device of a council-hearth in what was probably the centre of the belt, flanked on one side by four and on the other side by three double calumets, i.e. double-headed peace-pipes, each possessing a bowl at both ends. Of course a pipe of this sort is of no use for smoking. It is a creation of [Pg 48] the heraldic imagination, like the double-headed eagle of some modern European powers. This, first appearing on the arms of the German Emperor in the middle of the fourteenth century, may have been derived through contact with the East from Hittite bas-reliefs, as the cherub of our grave-stone cutters is derived through the Hebrews from the Assyrians, and the symbolic design of the Good Shepherd from the old type of Hermes, the ram-bearing god.

Fig. 8.—Double Calumet Wampum

Fig. 9.—Double Calumet Council Hearth

[Pg 49] Returning to the "double calumet," Mr. Hale was told by Mandorong, an Indian chief, that it was a peace-belt, representing an important treaty or alliance of ancient times. The second example is called Peace-Path Belt, which name indicates its purpose; the third, of which a good portion has probably vanished, is named the Jesuit Missionary Belt (Fig. 10), and is believed "to commemorate the acceptance by the Hurons of the Christian religion" as taught by the Jesuits.

Fig. 10.—Jesuit Missionary Wampum

Fig. 11.—Four Nations' Alliance Wampum

The figures are worked on fifteen rows of white beads on a dark ground, the oval or lozenge-shaped design near the centre representing a council. On each side of this are religious emblems—on one side the dove, on the other side the lamb—and beyond each are Greek crosses representing the Trinity. "The latest date which can be ascribed to this belt is the year 1648, the eve of the expulsion of the Hurons by the Iroquois." The fourth example (Fig. 11), called the "Four Nations' Alliance Belt," is sixty years younger, and, as denoted by the four squares forming the chief device, is a land-treaty made between the Wyandotts and three Algonquin tribes. [Pg 50]

Fig. 11a.—Penn Wampum

This reference to records which mark a certain approach to the ideographic stage of writing would be incomplete if no account was given of the most celebrated wampum record in existence (Fig. 11a), the Penn Belt, preserved in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It derives its name from a well-authenticated tradition that it is the identical belt given, probably in 1701, to William Penn by the Iroquois "to confirm the friendly relations then permanently established between them." It is composed of eighteen strings of white wampum, thus evidencing its relation to an important transaction, and has in the centre two figures delineated in dark-coloured beads, one an Indian grasping the hand of a man who, as wearing a hat, is doubtless intended to represent a European. The oblique bands are the symbol of the federation of Iroquois known as the "Five Nations," and represent by synecdoche (or the putting of a part for the whole) the entire native Iroquois "long-house," as the communal dwelling is called. "The Iroquois league is spoken of in their Book of Rites as Kanastat-sikowa, the 'great framework.' It was this mighty structure, which, when the belt in question was given, overshadowed the greater [Pg 51] part of North America, that was indicated by the rafters, shown as oblique bands." (Hale, J.A.I. xxvi. p. 244.)

(b) The Pictorial Stage.—The necessity of identifying personal as well as tribal property, especially in land and live stock, led to the employment of various characters more or less pictographic, which have their representatives in signaries used in ancient commerce and in manufacturers' trade marks. Professor Ernst of Caracas believes that he can recognise survivals of Indian picture-writing in the marks used for branding cattle; and among Mr. Arthur Evans's remarkable discoveries of pre-Mycenæan relics in Crete, the significance of which will be dealt with later on, are seal-stones engraved with signs which are not merely fanciful or ornamental, but designed to convey information about their owners. "For example, a boat with a crescent moon on either side of the mast may have been the signet of an ancient mariner who ventured on long voyages;" perchance a feat to be proud of, since even a one-moon voyage seems to have been too much for the average Homeric mariner (cf. Iliad, II. 292-4). "Another signet, with a gate and a pig on one of its faces, would be proper to a well-to-do swineherd." Other seals bearing the device of a fish may indicate a fisherman; of a harp, a musician, and so on. (The Mycenæan Age, p. 270: Tsountas and Manatt.) The painful operation of tattooing is known to have symbolic and religious, even more than decorative, significance, as marking the connection of the man with his clan-totem or individual totem. But it [Pg 52] has also a utilitarian purpose, as among certain Red Indian tribes, who tattoo both sexes, so that in case of war the captured individuals may be identified and ransomed. Totemic and mythic animals are tattooed upon various parts of the body; in one case the design worn by a landowner among the Kavuya Indians of California was used as his property mark by being cut or painted upon boundary trees and posts, so that his title to his possessions was proved by the portable title-deed which he bore, reminding us of the leading incident in Rider Haggard's Mr. Meeson's Will. "In New Zealand the facial decorations of a dead man were reproduced upon the trees near his grave; while among the Yakuts and Bushmen the facial marks, or even totems, were furthermore employed as property marks, the Bushmen carving them upon growing squashes and melons." (Hoffman, p. 39.) The various Indian tribes appear to have made more frequent use of the totem name rather than of the personal name, perhaps because of the common barbaric notion that a man's name is an integral part of himself, through which, whether he be living or dead, mischief may be wrought by the sorcerer who knows the name—a notion the force of which would be lessened where the name is generic and shared in common. On the grave-posts of both Australian black fellows and North American Indians the totem symbol is reversed, as in our mediæval chronicles the leopards of English kings are [Pg 53] reversed on the scutcheon drawn opposite the record of their death. With this we may connect the classic symbol of the inverted torch which the modern sculptor depicts on funereal monuments. In his great work on the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes, published over fifty years ago (a work, however, which needs checking from other authorities), Schoolcraft gives some illustrations of the red man's grave-posts, of which three are here reproduced.

Figs. 12, 13.—Indian Grave-posts

Fig. 14.—Tomb-board

of Indian Chief

Fig. 12 shows the dead warrior's totem, a tortoise, and beside it a headless man, which is a common symbol of death among Indian tribes. [Pg 54] Below the trunk are three marks of honour. The next and more elaborated figure (13) records the achievements of Shingabawassin, a celebrated chief of the St. Mary's band. His totem, the crane, is shown reversed. The three marks on the left of the totem represent important general treaties of peace to which he had been a party; the six strokes on the right probably indicate the number of big battles which he fought. The pipe appears to be a symbol of peace, and the hatchet a symbol of war. In like manner head-boards erected over a woman have the various articles used by her in life, as cutting and sewing instruments and weaving utensils, depicted upon them. The third example (14) represents the adjedatig or tomb-board of Wabojeeg, a celebrated war chief, who died on Lake Superior about 1793. His totem, the reindeer, is reversed, and his own name, which means the White Fisher, is not recorded. The seven strokes note the seven war parties whom he led; the three upright strokes as many wounds received in battle. The horned head tells of a desperate fight with a moose.

Fig. 15.—Hunter's

Grave-post

Fig. 15 is a reduced copy (Hoffman) of the grave-board of an Innuit hunter. The vocation of the dead man is shown in the baidarka, or boat, in which he is depicted as rowing with a companion. The object beneath represents a rack for drying fish and skins. Next to this are figures of a fox and a land otter, and the network drawing at the bottom is a copy of the hunter's summer dwelling. These temporary structures denote the abode of a skin-hunter, those used by fishermen [Pg 55] being dome-shaped. Hoffman adds that "this differentiation in the shape of roofs of habitations applies to their pictorial representation and not to their actual form." In close connection with these mortuary boards there is the ornamentation of door-posts which we find among British Columbian, Polynesian, and Maori tribes; also the carvings on canoes and other personal effects to mark ownership or to identify the property with the totem. But to pursue this would take us into the domain of savage art generally, reference to which is warranted here only in its mnemonic uses as keeping alive knowledge of events which would otherwise perish. Obviously, the examples given above can fulfil only a limited purpose, because only the initiated can know their meaning. As Dr. Tylor remarks, such mode of record "may be compared to the elliptical forms of expression current in all societies whose attention is given specially to some narrow subject of interest, and where, as all men's minds have the same framework set up in them, it is not necessary to go into an elaborate description of the whole state of things; but one or two details are enough to enable the hearer to understand the whole. Such expressions as 'new white at 48,' 'best selected at 92' ('futures fairly active' is a good example), though perfectly understood in the commercial circles where they are current, [Pg 56] are as unintelligible to any one who is not familiar with the course of events in those circles, as an Indian record of a war-party would be to an ordinary Londoner." (Early History of Mankind, p. 86.) This applies with even greater force to the large group of symbolic mnemonics whose purpose is more restricted, whether it be as help to the singer in his verses, to the medicine-man in his incantation, to the hunter in his quest, or, as among ourselves, to the tramp on his rounds. The subjoined copy of a cadger's map (Fig. 16), given in Hotten's Slang Dictionary (1869), is an addition to the number of survivals which are found in so-called civilised communities, and has fit place among the examples of pictorial mnemonics in matters of 1, love; 2, sorcery; 3, the chase; 4, war; and 5, politics which follow it.

Fig. 16.—A Cadger's Map of a Begging District

Explanation of the Hieroglyphics

1. Love.—Fig. 17 is a reduced copy of a love-letter, drawn upon birch bark (a material used elsewhere, as among the Yukaghirs of Siberia), which an Ojibwa girl sent to her sweetheart at White Earth, Minnesota. She was of the "Bear" totem, he of the "Mud Puppy" totem; hence the picture of these animals as representing the addresser and the addressee. The two lines from their respective camps meet and are continued to a point between two lakes, another trail branching off towards two tents. Here three girls, Catholic converts, as denoted by the three crosses, are encamped, the left-hand tent having an opening from which an arm protrudes with beckoning gesture. The arm is that of the writer of the letter, who is making the Indian sign of welcome to her lover. "This is done by holding the palm of the hand down and forward, and drawing the extended index finger towards the place occupied by the speaker, thus indicating the path upon the ground to be followed by the person called." [Pg 57]

Fig. 17.—Ojibwa Love-letter

Fig. 18.—Love-song

Fig. 18 is the record of a love-song. 1, represents the lover; 2, he is singing and beating a magic drum; in 3, he surrounds himself with a secret lodge, denoting the effects of his necromancy; in 4, he and his mistress are joined by a single arm to show that they are as one; in [Pg 59] 5, she is on an island; in 6, she sleeps, and as he sings, his magical power reaches her heart; and in 7, the heart itself is shown. To each of these figures a verse of the song corresponds.

Fig. 19.—Mnemonic Song of an Ojibwa Medicine-man.

2. Sorcery.—Fig. 19 is the song of an Ojibwa medicine-man incised upon birch bark. These conjurers, who correspond to the Siberian shamans, affect the usual mystery of the priestly craft all the world over, and affirm, like those who know better, that their thaumaturgic powers are the direct gift of the god. Him they name Manabozho—probably some ancestral deity, since he is the great uncle [Pg 60] of the anish'inabēg or "first people." In 1, Manabozho holds his bow and arrow; 2, represents the medicine-man's drum and drumsticks used in chanting and in initiation ceremonies; 3, a bar or rest observed while chanting the incantation; 4, the medicine-bag, made of an otter skin, in which is preserved the white cowrie shell as the sacred emblem of the cult; 5, the medicine-man himself, horned to show his superior power; 6, a funnel-like object, known as a "jugglery," used in legerdemain and other hocus pocus; 7, a woman, signifying the admission of her sex to "the society of the grand medicine"; 8, a bar or rest, as at 3; 9, the sacred snake-skin medicine bag, which has magic power; 10, another woman; 11, another otter-skin "bag o' tricks," showing that women members are allowed to use it; 12, a female figure, holding a branch of some sacred plant used in the exorcism of the demon of disease. In any reference to savage therapeutics it cannot be too often insisted upon that diseases are never ascribed to natural causes. "The Indians believed that diseases were caused by unseen evil beings and by witchcraft, and every cough, every toothache, every headache, every fever, every boil, and every wound, in fact all their ailments, were attributed to such a cause. Their so-called medical practice was a horrible system of sorcery, and to such superstition human life was sacrificed on an enormous scale.... In fact, a natural death in a savage tent is a comparatively rare phenomenon; but death by sorcery, [Pg 61] medicine, and blood-feud arising from a belief in witchcraft is exceedingly common." (Professor Powell's Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico, p. 39.)

Fig. 20.—Wâbeno destroying an Enemy

Fig. 20 records the destruction of an enemy by an Ojibwa wâbeno or bad medicine-man. The box-like objects represent the four degrees of the cult society to which the wâbeno belonged, the number of posts indicating the series. The figure next to these is that of the assistant to the wâbeno, who is shown with a waving line extending from his mouth to the oval-like object intended to represent a lake upon an island in which the victim lives. He is shown prostrate beneath the wâbeno with a spot upon his breast, the small oblong figure between the two being the sacred drum. (See 2 in the foregoing illustration.) The meaning of the pictograph is that the wâbeno was employed to work black magic on the man. He took a piece of birch bark and cut upon it the effigy of the victim, then, after beating the drum to the chanting of incantations, he pierced the breast of the effigy, applying red paint to the puncture. This, under the principle of "sympathetic magic," was believed to bring about the death of the victim, whom, through [Pg 62] his living on the island, the wâbeno could not reach.

Fig. 21.—Etching on Innuit Drill-bow

White magic, in which the beneficent powers are at work, is illustrated by the Innuit pictograph on an ivory drill-bow (Fig. 21), on the right of which are two huts, nearest to which stands the medicine-man who has been called in to exorcise the disease from a couple of sufferers. He is catching hold of the animal by whose help the disease-demon is expelled, or to whom, mayhap, as a sort of scapegoat, the disease is transferred. In the second exorcism, the medicine-man is grasping the patient by the arm, while he chants the formulæ wherewith to cast out the demon. The figure on the left is making a gesture of surprise at his relief, while beyond him are two demons struggling to escape beyond the power of the medicine man.

Fig. 22.—Ojibwa Hunting Record

3. The Chase.—Fig. 22 records a hunting expedition. The two lines represent a wave-tossed river, on which floats a bark canoe, guided by the owner. In the bow a piece of birch bark shields a fire of pine [Pg 63] knots to light up the course taken by the steersman. By this means the game, as it comes to the water to drink, can be seen from the shaded part of the canoe, in front of which two deer are shown. Next to these is a circle representing a lake, from which peep the head and horns of a third deer. To the right of the lake a doe appears, and beyond her the two wigwams of the hunter. The four animals may represent the quarry secured.

Fig. 23.—Hidatsa

Pictograph on a

Buffalo Shoulder-blade

Fig. 23, drawn on a buffalo shoulder-blade by a Hidatsa Indian, tells his efforts to track companions who had gone buffalo-hunting. The trail of the animal and the pursuers is shown in the dotted lines. Of the three heads the lowest is that of the seeker, who is depicted shouting after his missing friends; then he is shown advancing and still shouting, till his call is returned from the spot where the hunters have camped.

Fig. 24.—Alaskan Hunting Record

Fig. 25.—Record of Starving Hunter

Fig. 24, incised on an ivory drill-bow, is a pictograph of an Alaskan sea-lion hunt. In 1, the speaker points with his left hand in the direction to be taken, and, 2, holds a paddle to show that a voyage is intended. In 3, the right hand to the side of the head denotes sleep, while the left hand with one finger elevated means one night. The circle with two dots in the middle, 4, signifies an island with huts; [Pg 64] 5 is the same as 1; 6 is another island; 7 is the same as 3, but with two fingers elevated to indicate two nights. In 8 the speaker with his harpoon makes the sign of a sea-lion with his left hand, which he thrusts outward and downward in a slight curve to represent the animal swimming; 9, 10, a sea-lion shot at with bow and arrow; 11, two men in a boat, the paddles pushed downwards; and 12, the speaker's hut. The native account, as translated, reads thus: "I there go that island, one sleep there; then I go another that island, there two sleeps; I catch one sea-lion, then return mine." (Colonel Mallery, quo. Hoffman, Transactions of the Anthropological Society, Washington, vol. ii. p. 134, 1883.) "Hunters who have been unfortunate, and are starving, scratch or draw upon a piece of wood characters like those in Fig. 25, and place the lower end of the stick in the ground on the trail where it is most likely to be discovered," the stick being inclined towards the hunter's dwelling. The horizontal line 1, denotes a canoe, [Pg 65] 2, the gesture of the man with both arms extended, signifies "nothing," while the uplifting of the right hand to the mouth, 3, means "food" or "to eat," and the left hand outstretched points to 4, the hut of the famished man. Here we are actually within the ideographic stage, and, as will be shown in due course, handling material identical in character with that found in Egypt and other nations of antiquity. But, as already remarked, and as will be evidenced in abundance throughout these pages, there are no well-marked divisions between the stages of development.

A varied interest attaches to Fig. 26, which depicts some general features of Alaskan life on a piece of walrus tusk. In 1, a native is resting against his house, and on his right stands a pole surmounted by a bird, apparently a totem-post. 2. A reindeer. 3. One man shooting at another with an arrow. 4. An expedition in a dog-sledge, and, 5, in a boat with sail and paddle. 6. A dog-sledge, with the sun above; perhaps indicating the coming of summer. 7. A sacred lodge. The four figures at each outer corner represent young men armed with bows and arrows to keep off the uninitiated from the forbidden precincts. The members of the occult society are dancing round a fire in the centre of the lodge. 8. A pine tree up which a porcupine is climbing. 9. Another pine tree, from which a woodpecker is extracting larvæ. 10. A bear. 11, 12. Men driving fish into, 13, the net, above them being a captured whale, with harpoon and line attached. [Pg 66]

Fig. 26.—Alaskan Hunting Life

4. War.—Schoolcraft, who has been already drawn upon for an example (page 53), records the finding of the bark letter copied in Fig. 27. It was fastened to the top of a pole so as to attract the notice of other Indians who might happen to be passing. Beginning on the right of the middle row we have 1, the officer in command, sword in hand; 2, his secretary, and 3, the geologist of the party, indicated by his hammer. Then follow 4, 5, two attachés; 6, the interpreter; and 7, 8, two Chippewa guides. In the top row is 9, 10, a group of seven soldiers, armed with muskets. A prairie hen and tortoise, 11, 12, represent the animals secured for food.

Fig. 27.—Indian Expedition

Fig. 28.—Biography of Indian Chief

Fig. 28 gives the biography of Wingemund, a noted Delaware chief. To the left is 1, the tortoise totem of the tribe; then 2, the [Pg 67] chief-totem; and 3, the sun, beneath which are ten strokes representing the ten expeditions in which Wingemund took part. On the opposite side are indicated, 4, 5, 6, 7, the prisoners of both sexes taken, and also the killed, these last being drawn as headless. In the centre are the several positions attacked, 8, 9, 10, 11; and the slanting strokes at the bottom denote the number of Wingemund's followers. [Pg 68]

Fig. 29.—War-song

Fig. 29 is a war-song. Wings are given to the warrior, 1, to show that he is swift-footed; in 2 he stands under the morning star, and in 3 under the centre of heaven, with his war-club and rattle; in 4, the eagles of carnage are flying round the sky; in 5, the warrior lies slain on the battlefield; while in 6 he appears as a spirit in the sky. The words of the song are as follows:—

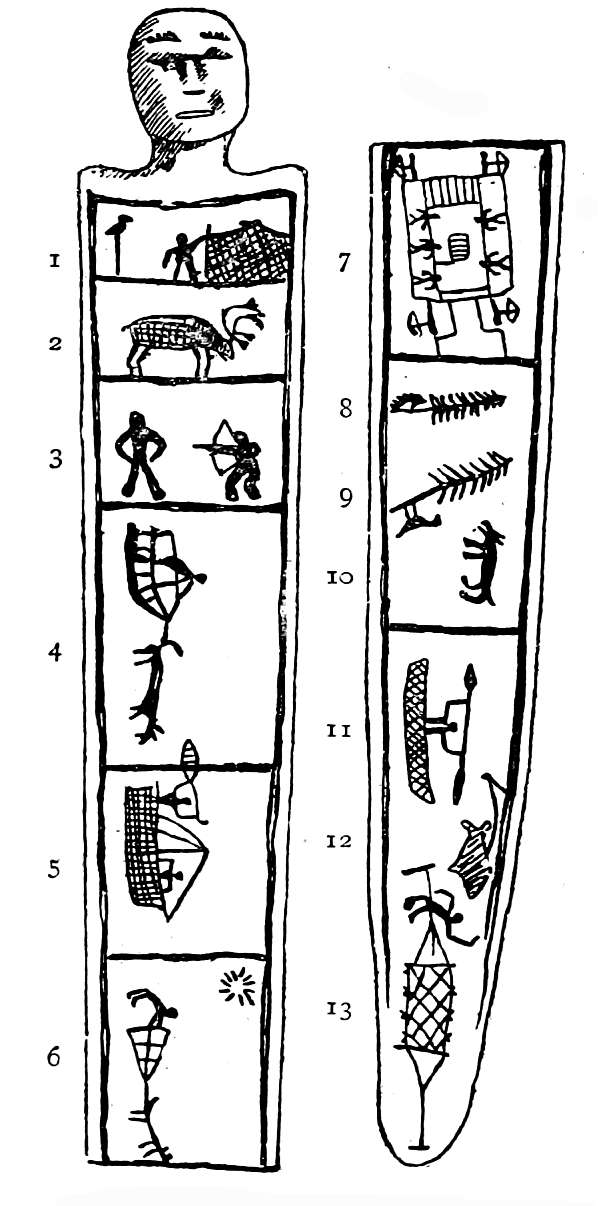

5. Political and Social.—The frontispiece is a copy of a petition sent by a group of Indian tribes to the United States Congress for fishing rights in certain small lakes near Lake Superior. The leading clan is represented by Oshcabawis, whose totem is 1, the crane; then follow 2, Waimitligzhig; 3, Ogemagee; and 4, a third, all of the marten totem; 5, Little Elk, of the bear totem; 6, belongs to the manfish totem; 7, to the catfish totem. [Pg 69]

From the eye and heart of each of the animals runs a line connecting them with the eye and heart of the crane to show that they are all of one mind, and the eye of the crane has also a line connecting it with the lakes on which the tribes want to fish, while another line runs towards Congress.

Fig. 30 is a copy of a letter found above St. Anthony's Falls in 1820. "It consisted of white birch bark, and the figures had been carefully drawn. 1, Denotes the flag of the Union; 2, the cantonment then recently established at Cold Spring, on the western side of the cliffs; 4 is the symbol of Colonel Leavenworth, the commanding officer, under whose authority a mission of peace had been sent into the Chippewa country; 11 is the symbol of Chakope, the leading Sioux chief, under whose orders the party moved; 8 is the second chief, named Wabedatunka, or, 10, the Black Dog, who has fourteen lodges, 7 is a chief also subordinate to Chakope, with thirteen lodges, and 9 is a bale of goods devoted by the Government to the objects of the peace. The name of 6, whose wigwam is 5, with thirteen subordinate lodges, was not given." [Pg 70]

The letter was written to make known the fact that Chakope and his followers, accompanied or supported by the American officer, had come to the spot to make peace with the Chippewa hunters. "The Chippewa chief, Babesacundabee, who found the letter, read off its meaning without doubt or hesitation." (Schoolcraft, vol. i. p. 352.)

Fig. 30.—Letter offering Treaty of Peace

Fig. 31 represents the census roll of an Indian band at Mille Lac, in the territory of Minnesota, sent in to the United States agent by Nagonabe, a Chippewa Indian, during the annuity payments in 1849. [Pg 71]

Fig. 31.—Census Roll of an Indian Band

As the Indians were all of the same totem, Nagonabe "designated each family by a sign denoting the common name of the chief. Thus 5 denotes a catfish, and the six strokes indicate that the Catfish's family consisted of six individuals; 8 is a beaver skin; 9, a sun; 13, an eagle; 14, a snake; 22, a buffalo; 34, an axe; 35, the medicine-man, and so on." (Lubbock, Origin of Civilisation, p. 47.)

Fig. 32.—Record of Departure (Innuit)

Fig. 32 supplies a striking example of the cumbersomeness of the pictograph as contrasted with the sound-symbol. It is a copy of a record which an Innuit placed over the door of his dwelling to notify to his friends that he had gone on a journey. The persons thus notified are indicated in 1, 3, 5, 7; 2 is the speaker, who denotes the direction in which he is leaving by his extended left hand; 4 is the gesture sign for "many," and 6 for sleep, the upraising of the left hand showing that he will be some distance away; 8, his intended return is denoted by the right hand being pointed homeward, while the left arm is bent to denote return.