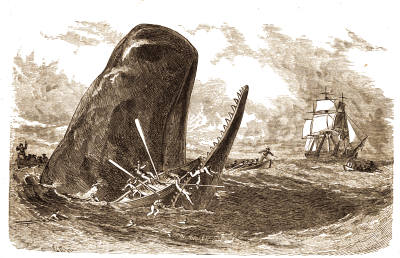

The First Whale. Page 67.

THERE SHE BLOWS!

OR,

THE LOG OF THE ARETHUSA.

BY

CAPT. W. H. MACY. OF NANTUCKET.

BOSTON

LEE & SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM

Copyright, 1877,

BY

LEE & SHEPARD.

THE AUTHOR TO HIS READERS.

The story embodied in these pages is not to be regarded as a mere "yarn." It is rather a series of illustrated sketches of actual life on the ocean, made up of real incidents and introducing for the most part real characters, many of which will be recognized. Indeed the author may truly say that in writing these "Leaves," he felt himself simply telling a story—not making one.

Since its first publication in serial form, nine years ago, he has been stricken with one of the heaviest of physical infirmities. Doomed to life-long blindness, the recollection of years spent at sea in the prime of manhood, come crowding upon him more thickly than ever, and he finds his chief solace in having still retained the ability to write them down for the benefit and amusement of others. His seafaring friends, as they overhaul the log of their own experience, will at once recognize the truthfulness of the pictures he has drawn here.

W. H. M.

Nantucket, Mass., August, 1877.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE. | |

| From Peck Slip to Nantucket Bar | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| In and Out over the Bar | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| From the Bar Round Great Point | 24 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Fairly at Sea.—The First Lookout.—Introduction | 38 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Western Islands.—"Yarns" and Anecdotes | 50 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The First Whale | 62 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| "Cutting In" | 73 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| [vi]Boiling.—Cutting the Line.—Dutch Courage.—"Man Overboard" | 85 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| "Gamming" with a "Homeward-Bounder" | 98 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Whaling Near the Falklands.—Death of Mr. Johnson | 112 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Promotion.—"Cooper's Novels."—The Mate Moralizes.—Cape Horn | 125 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Fishing at Juan Fernandez.—Fight with an Ugly Whale | 139 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Talcahuana | 153 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Bill-Fish.—The Marquesas.—A Prisoner among the Savages | 167 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Escape from the Savages.—Recovery of the Boat.—Magical Effects of Lynch Law | 181 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Cooper "Romances".—Incidents.—Byron's Island | 197 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Kingsmill's Group.—Singular Whaling Incident.—Hard and Fast.—A Perilous Position | 211 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Off the Rocks Again.—A Bad Leap.—Anecdotes.—The Run to the Caroline islands | [vii]225 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Strong's Island | 238 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| On Japan.—Ormsbee's Peak.—Whaling Incidents.—A Yankee Trick | 253 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Radack Chain.—Watering at Ocean Island.—Incidents on the Run to Sydney, N. S. W. | 267 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Sydney.—Up Anchor for Home.—"Galway Mike." | 280 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Homeward.—The Episode of Galway Mike.—Cape Horn.—The Last Whale | 294 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Homeward. The Whale Recognized as an Old Acquaintance.—Incidents of the Run Home.—Nantucket Again | 307 |

LEAVES

FROM THE

ARETHUSA'S LOG.

CHAPTER I.

FROM PECK SLIP TO NANTUCKET BAR.

"WANTED—500 able-bodied, enterprising young men, to go on whaling voyages of from twelve to twenty months' duration in first class ships. All clothing and other necessaries furnished on the credit of the voyage. To coopers, carpenters and blacksmiths, extra inducements offered."

This announcement, on a gigantic placard, in staring capitals, arrested my attention, and brought me to a stand, as I was strolling along South Street, near Peck Slip. I had just attained the susceptible age of eighteen, and had left my country home with the consent of my parents, to visit the great city of Gotham, like a modern Gil Blas, in quest of employment and adventures. As the old story-books have it, I had come "to seek my fortune." I have sought it ever since, but it has kept ahead of me, like an ignis fatuus. Like old Joe Garboard, I began the world with nothing, and have held my own ever since.

I had always a predilection for the sea, and had cultivated[2] my adventurous propensities by the study of all books of voyages and travels that I had access to. All the wanderings of famous navigators, from the days of Sinbad down to the present era, had been perused with delight, and I had always affected the sailor, as well as I knew how, in manner and dress. I had discovered, since I arrived in the city, however, that I was a miserable amateur; and not a ragged boy along the piers but would have spotted me for a "green one" at sight, while Jack himself, the real article, would have found my verdancy really refreshing after a long cruise.

Above the attractive placard to which I have alluded, in the form of a hanging sign projecting over the sidewalk, was a most stirring nautical piece, illustrating one of those agreeable little episodes which diversify the life of the whaleman. The principal figure in the foreground of this masterpiece of art was a huge sea monster, intended, doubtless, to represent something "very like a whale," but which, in truth, bore rather more resemblance to a magnified codfish with a specific gravity something less than that of a cork, as he floated on the water instead of in it. Fragments of a devoted whaleboat, which had been nearly pulverized by a blow of his tail, filled the air, and rained back in showers upon the unfortunate leviathan, at the imminent hazard, as it seemed, of inflicting serious splinter wounds, while several sailors, apparently dressed for the occasion in span new blue and red shirts, cut pirouettes among the wreck at various altitudes between sky and water, and made spread eagles[3] of themselves for the special diversion of a gaping public. From the head of the sea monster was ejected a stream of blood, which rose in a solid column to a height but little exceeding that of the topmasts of the ship, which appeared standing under all sail, in fearful proximity to the fast boats, and having no apparent intention of starting tack or sheet to avoid a collision. Hogarth's famous "Perspective" was quite eclipsed by this effort.

I stood, for a time, regarding this picture in silent admiration, and especially commiserating the situation of one luckless mariner, for whom the fate of Jonah seemed inevitable, as he appeared suspended in mid-air, directly over the jaws of the whale, which were widely distended in his agony.

"Now," said I to myself, "why wouldn't this be the sort of cruise for me? A long voyage, full of adventure and excitement. The very thing. I'll stop in here, and get some information about this business."

Following the direction of a hand painted on a tin sign, the finger of which, as well as the inscription, indicated that Ramsay's shipping office was "up stairs," I entered a room where a middle-aged gentleman, with a florid countenance, evidently the great Ramsay himself, was seated at a desk fenced in by a railing, while a shabby clerk, who looked as if he had been kept up all night, hovered, like a familiar spirit, near his elbow. Two youths, fresh from the country like myself, were negotiating for enlistment with the elder gentleman, who was all smiles and affability, and who, at my entrance, elevated his eyebrows, and said something,[4] sotto voce, to the sleepy clerk, whereat the latter smiled knowingly, and then, seeming fatigued by the exertion, relapsed into his former apathy.

"Take a seat, sir," said Mr. Ramsay. "I'm happy to see you, sir; and the fact of your being early in the day argues well for your success in life. I presume you would like to try a pleasant voyage, to see the world, and make some money at the same time."

"Yes, sir," said I; "I did think of trying a sea voyage, but I would like to make a few inquiries first."

"Quite right, sir," said Mr. Ramsay, lighting a cigar; "quite right. 'Look before you leap,' as the saying is. Have a cigar, sir?" at the same time extending a handful of cheap sixes, with a general invitation to the company present. "I shall be happy to afford you any information in my power, sir. I have never been whaling myself, but from my long experience in this business, and my extensive acquaintance with whalemen and shipowners, I may say that you could hardly have applied, in this city, to a better source; and, as I was observing to these two young gentlemen just before you entered, there is the finest opening just at this time that I have ever known. Indeed, I do not remember any period since I have been in the business when such inducements were offered to enterprising young men as now. A packet leaves this afternoon for Nantucket, and there are crews wanted there for four new ships, just launched, and all to be commanded by experienced captains. There will be more ships fitted this year than any previous[5] one; and, owing to the increased demand for young men, the lays are uncommonly high."

"The what, sir?" asked one of the country youths.

"The lays, sir; that is to say, the shares. You will understand that in this business no one is paid wages by the day or month, but each receives a certain part, or lay, as it is called, of the proceeds of the cruise. By this arrangement, you will see, at once, that every one, from the captain to the cabin boy, has a personal interest in the success of the voyage. The lay is, of course, proportioned to his rank or station on board, and to his experience in the business. The lays, as I before observed, are high this season, uncommonly so."

"And what may be the lay of a new hand—one who has never been by water," I asked.

"Well, sir, the lays of green hands have ranged, in times past, from a two hundredth to a two hundred and fiftieth, but they are paying now a hundred and seventieth, and even as high as a hundred and fiftieth. By the way, have you any mechanical trade?" pursued the shipping-master, with the greatest urbanity.

"Well—yes, sir; I have served some time at the blacksmith's trade, though I can hardly call myself a finished workman," I answered.

"A blacksmith! ah, indeed! The very thing, sir. That reminds me that I have a special demand, at this time, for three or four blacksmiths, and as many carpenters. As to your being a finished workman, that is not at all essential, sir. If you can botch a little and do an indifferent sort of job, that is quite[6] sufficient. I may safely promise an able-bodied young man like you with some knowledge of the blacksmith's trade, as good as the hundred and thirtieth. That, however, is a matter to be arranged with the agent of the ship when you sign the articles. I shall mention the subject to my correspondents, Messrs. Brooks & Co., at Nantucket, and they will use their influence for you."

"The voyage, you say, will not be more than twenty months, sir?" I asked.

"Ye—no, sir—that is, they are seldom absent beyond that length of time, and, if very fortunate, you may finish a voyage in a year. Then your chances of promotion! Consider, sir—a young man of your ability ought certainly to command a third mate's berth on the second voyage, in which case, of course, your pay is more than doubled; and so on each successive voyage as you advance still higher on the ladder. That is, of course, supposing you should wish to follow the business. If not, why, a year or a year and a half is not much at your time of life. You would still be young enough to turn your attention to something else."

"How's the victuals on these whaling boats?" inquired one of the verdant youths.

"Excellent, sir," returned the voluble Mr. Ramsay. "I have reason to believe there are no ships on the ocean where the living is so good as in whalers. Even the luxuries of life are to be found in abundance. Cows are generally kept on board, so that the supply of milk and fresh beef scarcely ever fails."

Here the sleepy clerk knocked the ashes from his cigar, gave another knowing smile, and distended his cheek with his tongue, in keen enjoyment of the game. This action was not lost upon me, and, inexperienced though I was, I had already begun to surmise that the statements of his eloquent employer were to be received cum grano salis. Still, making due allowance for exaggeration, I thought this sort of voyage, from its very nature, full of excitement and adventure, would suit me better than any other.

"Do you furnish the outfit of clothes here, sir?" I inquired.

"No, sir," answered Mr. Ramsay, "that is not in my line. My correspondents, Messrs. Brooks & Co., will attend to that; and, from their perfect knowledge of the articles required, and their extensive facilities, cannot fail to give you satisfaction."

The sleepy clerk had the pleasure of registering the names of all three of us on the list of recruits to go on board the "Lydia Ann," and at four o'clock that afternoon, I found myself, in company with a score or more of others, on board the old sloop, with the mainsail hoisted, and dropped down to an outside berth; and, after the most affectionate farewells and hand-shaking from Mr. Ramsay and the sleepy clerk, the whole party were mustered and counted, and the roll being found correct, the Lydia Ann slipped the only fast by which she rode to the pier, and was fairly under way for Nantucket, amid the shouts and hurrahs of her passengers, who seemed to have bid adieu to all care and sorrow, and to consider themselves fairly enrolled in the ranks of the elect.

After taking our last looks at the great metropolis, I found ample amusement in studying human nature, and observing the peculiarities of my several companions, who were a motley crowd, composed of men of every stamp, from the fresh and innocent country youth, like myself, who had just left his mother and sisters, to the city rowdy, who had run himself "hard up" on a spree, and, unable longer to raise the wind, had shipped for a sea voyage as a last resort. It was surprising to note, now that we were brought together, and all bound on the same mission, how quickly we became acquainted with each other, and how quickly all distinctions were levelled. Many of my companions were more or less in liquor at starting, and some had brought suspicious bottles with them, and now were clustered in groups about the deck, roaring snatches of songs, breaking out into boisterous merriment, and cracking jokes on the old skipper, who only shook his head, and joined in the laugh, muttering:

"Hold on, my lads, till I get you out off Pint Judy, with a good stiff breeze and chopping sea on to shake up your stomachs, and I'll bet some of you will laugh out of the other side of your mouths."

The old gentleman was not at all averse to taking a stout pull at the bottles with those who offered them; and, after two or three applications of this sort, he grew communicative, and volunteered much information for our special behoof, touching the business in which we were about embarking. Many of his statements differed widely from those of the shipping-master, which is not strange; for it is well known[9] that two witnesses are seldom found to agree to their accounts of the same matter.

The Lydia Ann was an old time-worn and battered sloop, which ran as a regular transport between Nantucket and New York, having no accommodations for any considerable number of passengers, though she had carried so many human cargoes to the same consignees, all bound on the same errand, that she had acquired the pet name of "the Slaver."

When night came on, we were constrained to find lodgings in the hold as best we could; and, selecting the softest spots and most eligible corners among the casks and boxes which composed the freight list, we passed part of the night in much the same manner as before. But, as the skipper had predicted, the breeze freshened during the night, and the old sloop, feeling the benefit of it, and diving smartly into a head sea, furnished the majority of us employment in casting up our accounts, and admonished us that all bodies, not excepting the solid earth, are subject to upheavings when shaken to their centres. Some of us, who had crawled on deck to get the fresh air, furnished, by our own rueful and woe-begone appearance, rare food for merriment to the old mate, a veteran of nearly the same date as his commander, who in a rough pea-jacket and slouched sou'wester, stood, statue-like, braced up against the tiller, apparently as immovable as the rock of ages.

"Ah, boys," said the jolly old salt, "so the Liddy Ann is breaking you in, eh? Well, you've got to go through it, all of ye, and it's better to have it over[10] now, when you've got no duty to attend to, than to begin it in the Gulf stream, when there'll be, maybe, topsails to reef, and a slatting jib to be got in on a slippery boom."

He advised us, moreover, to try the experiment of attaching a piece of fat pork, previously dipped in molasses, to a string, swallowing the precious morsel and pulling it up again, repeating the operation as often as the symptoms returned, which mode of proceeding, he solemnly assured us, had been proved to be an invaluable specific, in cases of this kind, as could be attested by the experience of thousands of sufferers. The victims were slow to avail themselves of this information, not so much from any doubt of its efficacy, as from sheer inability to make the necessary exertion to prepare the medicine.

The utter prostration of all energy which attends sea-sickness is well known to those who have passed the ordeal. I was a sufferer with the rest, but not to the same extent as many others. When daylight broke, I was on deck, and stirring, and became accustomed to the Lydia Ann's antics with so little difficulty that the old skipper noticed me particularly; and finding I was the only one who could do full justice to an "able-bodied breakfast," he complimented me by averring his belief that I would be a sailor yet before my mother would. Which prophecy seemed in a fair way of fulfilment; for I gained so rapidly that before the sloop went in over Nantucket Bar, I was able to take an interest in all I saw and even to lend a hand about decks. I was rather vain of the[11] comparatively easy victory which my stomach had gained over old Neptune's medicine chest, and lost no opportunity of cracking jokes upon others, whose course of initiation had been more severe. Some of the boys who came over in the Lydia Ann will never forget the martyrdom they endured from this intolerable malady, which, when violent, makes even life and death seem a matter of indifference, and not the least irritating peculiarity of which is that it is a standing subject for joking by those who have passed through it, and that even the very pity which the initiated traveller bestows upon us is akin to ridicule.

CHAPTER II.

IN AND OUT OVER THE BAR.

Two whaleships were lying at anchor outside the "bar" as the Lydia Ann passed in—one lately arrived from a long voyage, her rusty sides and rough bends nearly naked of copper, with the long grass clinging to the bare sheathing; her stump topmasts and general half-dismantled appearance presenting a striking contrast to the trim, newly-painted outward-bounder, which had just completed her preparations for sea, and, with everything aloft in its place, mainroyal yard crossed, and a full quota of showy, white-bottomed boats on the cranes and overhead, was to weigh anchor for the Pacific next morning. Loud rose the cheerful, measured sound of the hoisting song from the gang on board the inward-bound ship, as the heavy casks of oil were seen to rise slowly from her hatchway, and were discharged into the schooner lashed alongside of her to receive them, while another lighter, deeply loaded, had dropped astern, and was hoisting her mainsail.

"I thought the 'Pandora' had sailed before this time," said the old skipper, as we passed just out of hail of the ships. "They have been a long time fitting her for sea. I wonder," said he to his mate, "who that[13] is that has got in since we left. Get the glass, and see if you can make out her name when we cross her stern."

The mate brought an old battered telescope from a cleet in the companionway, and, after squinting for some time, muttered:

"P—her stern is so rusty that hang me if I can make out the letters—the name begins with a P; I can see that. There's a T in it, and the last letter looks like an H."

"Yes, that's all right," said the skipper. "That's the old 'Plutarch.' She has been expected some time, and has had a long passage home; but she is one of the old Anno Dominy ships, and sails about as fast as you can whip a toad though tar. I was in her two v'y'ges myself in my young days, and we never could drive more than six knot out of her in a gale of wind. She seems to have a foul bottom, too. But she has crawled home at last, and she has brought a good load of ile, too. She had twenty-one hund'ed at last accounts, and that ain't to be sneezed at, nowadays."

"No, indeed, it ain't," returned his partner. "But when was you in the Plutarch? Who had her then?"

"Old Hosea Coffin had her; that's when she was new, and was called a dandy ship at that time. Then I steered a boat in her next v'y'ge with 'Bimelech Swain—you knew him?"

"Yes, I remember; that's when I was in the 'Viper' on the Brazeel Banks."

I could not but look with admiration upon these old[14] veterans, who talked about long voyages round Cape Horn and on the "Banks" as though they had been mere pleasure trips across a harbor and back, or any such trifling matter. Two or three years in these old fellows' lives seemed like the same period in the history of nations, occupying but a line or two of the chronicler. But the vessel was rapidly drawing in round "Brant Point," and all my comrades, many of whom had not yet fully recovered from sea-sickness, had mustered on deck to see the low, sandy island and busy little town of Nantucket, which now lay fairly before us. Several more whaleships were lying at the wharves, some of them dismantled, and stripped to a girtline, others partly rigged for sea, and two or three hove down for coppering. This was in the summer of 1841, when Nantucket may be said to have been in the zenith of its prosperity. More new ships were built than in any previous season, and the general impression appeared to be that the partisan cries of "two dollars a day and roast beef to the laboring man" were to be literally fulfilled, and that the price of oil was to reach a standard positively fabulous. And so it did—fabulously low, as every poor whaleman can testify, who arrived in 1842-3, and sold his sperm oil for fifty or sixty cents a gallon.

As the sloop warped in alongside the wharf, a spruce young man jumped on deck, and, saluting the skipper, asked him when he left New York, and, in the same breath, how many men he had brought. "Twenty-five," said the old man. And, having thus satisfied himself that the cargo delivered corresponded with the[15] invoice, he invited us all to come up to "the store." Then, mounting into a one-horse cart—a sort of green box on two wheels—which stood in waiting, he called upon us to "jump up." We jumped up till the box was full of us, standing in solid phalanx, and the rest followed, as infantry of the rear guard; and thus, the admired of all beholders, we proceeded up the central or "Straight Wharf," and up Main Street to the store. The spruce young man informed us that his name was Richards, and that he was connected with the establishment as a sort of out-door clerk.

The store of Messrs. Brooks & Co. fronted directly on the square or grand plaza of Nantucket. They dealt in all kinds of ready-made clothing and dry goods, infitting as well as outfitting goods; and the store was a grand resort and rendezvous of seafaring men. At the time of our arrival, it was enlivened by the presence of numerous whalemen, of various grades in rank, from chief mates of ships, sedate, dignified-looking men, dressed in long togs in neat style, who sat smoking, comparing notes about matters and things, "round the other side of land," and re-killing, at a safe distance, many "forty barrel bulls," which they had years ago slaughtered, at imminent peril of life and limb, down to overgrown boys, who had made one voyage, aspirants for boatsteerers' berths, who wore fine blue round jackets and low-quartered morocco pumps, with a great superabundance of ribbon, as was the fashion at that period, carried flaming red handkerchiefs either awkwardly in their hands or hanging half out at their jacket pockets, masticated tobacco[16] in prodigious quantities, and in various ways aped the tar, to the great amusement of their elders, who passed remarks to each other in confidential tones.

"Here comes young Folger, rolling down to St. Helena, eighteen cloths in the lower studdingsail, and no change out of a dollar."

"What ship was he in?" asked another.

"In that plum pudd'ner that got in last week—what's her name?"

"O, that old brig over at the New North Wharf? The 'Sphynx.'"

"He wants a bilge pump in each pocket to pump the salt out."

"Yes—Lot's wife never was half as salt as some of these boys."

"They'll outgrow that after they have made two or three more voyages, and got the feather-edge rubbed off."

"Yes, they'll find it isn't all fun to come and go, 'happy go lucky,' when they have more to think about. Well, we've all had our thoughtless days."

The last speaker had lately married a young wife, and was to sail the next morning, mate of the Pandora.

"Well, Gardner, your time is getting short," said his next neighbor, with a careless laugh, slapping him on the back. "I'm sorry for you, boy, but it can't be helped, and I wish you a good voyage," continued the rough sympathizer, a powerful young man, who had just arrived second mate of the Plutarch, and had not yet begun to wear the bronze off his face.

"Never mind, Chase; you can blow for a short time, but you'll be travelling the same road soon."

"Not this winter," returned Chase, with a triumphant shake of the head. "I'll set my foot down on that."

"Don't be too sure of that," said Gardner. "I'll bet you'll be out again this fall."

"Not I."

"Well, I expect to see you in Talcahuano in the spring, and I'll put you in mind of this."

"If you see me there as soon as that, I'll stand treat."

"I see the old slaver has brought a lot of bran new sailors from New York to-day. I suppose, Gardner, you'll have the training of some of these young fellows," said another.

"No, not this lot; ours are all on board. These are to go in the Fortitude and the Arethusa."

"Well, Grafton's going in the Arethusa. They'll all find their right places there."

"There's a fellow will make a slashing midship oarsman," said one.

"Yes, and here's another for a bowman," replied his neighbor, with a glance at me, as I stood within ear shot, and overheard this colloquy.

I had no chance to hear more at present; for the whole party, after their names had been registered, were handed over to the tender mercies of the boarding-house keeper, and the procession moved off, in straggling order, "down under the bank" to dinner.

Mr. Loftus, the boarding-master, was an elderly[18] gentleman of pompous appearance, who had been whaling himself in his younger days, and thought himself quite an oracle in his way. He entertained his boarders with many thrilling reminiscences of his youth, interspersed with sage advice how to conduct ourselves so as to get ahead, and rise in our profession, as he himself had done, and regretted that ill health had prevented him from following it up until he got command of a ship, which must inevitably have been the case in a few more years. He informed us that the majority of us would probably be shipped the next day in the Arethusa, and we might consider ourselves truly fortunate in getting this opportunity, as the Arethusa was a new ship, with all the modern improvements, and a crack appointment, so that we might look upon the voyage as already made, before the ship left home. Furthermore the ship carried three maints' gall'nt sails, and had more backstays than any other ship in port, which fact, he said, had a material bearing on the success of the cruise.

All this produced a feeling of anxiety in the minds of the newly enlisted to be chosen on the roll of the Arethusa rather than to be left for the Fortitude and other less desirable ships.

The next day we were all mustered at the store, and introduced in the aggregate, to the agent of the ship, and Captain Upton, the future commander, a middle-sized man, all bone and muscle, with keen eyes, and a peculiar stride in his gait, which might admit of a small wheelbarrow being driven between his legs without touching either. He seemed to have[19] his own way in the selection of his crew, the agent leaving the matter in his hands; and twelve of us having been called out, of whom I was flattered to find myself one, the rest were left for Captain Wyer, of the Fortitude, who, being a young man, just entering on his first command, was fain to content himself with what he could get in many particulars, where Captain Upton would have what he wanted. We were catechised, in brief, concerning our nativity and previous occupation, and the build and physical points of each were looked to, not forgetting the eyes, for a sharp-sighted man was a jewel in the estimation of the genuine whaling captain.

A formidable document lay on the desk, awaiting our signatures, and, almost before I knew it, I found myself entered on the Arethusa's articles, with the hundred an fiftieth, as blacksmith and green hand. Our outfits of "clothing and other necessaries" were put into our chests for us at the store; and most of us now donned some articles to replace such of our clothing as was in a dilapidated condition, while the best garments of which we happened to stand possessed were still retained in wear. The result was an incongruity in the various parts of our attire, which occasioned much merriment. Thus, one wore a check shirt under the shade of a glossy beaver; another a "claw-hammer" or dress-coat over bright red flannels; while tarpaulin hats surmounted with white shirts and dickeys, and patent leather peeped out under voluminous duck trowsers. The whalemen criticised us as "half-Jack half-gentlemen," as we took a stroll down[20] the busy wharves, to look at the shipping generally, and especially to inspect the noble vessel which was to be our future home.

We wound our tortuous way down through a labyrinth of old anchors and trypots, spars, timber and oil-casks, now diving under a capstan bar, and again making a detour to double a long pair of trucks or skids, backed up at a tier of oil to parbuckle its load on. We all fell in love with the Arethusa at sight, which might, in our case, be termed an illustration of "love after marriage," seeing that our names were already on her papers. She was indeed a fine specimen of naval architecture, and her model was much admired at that time, for this was before the day of extreme clippers. She was painted with the bright waist, a style more in vogue then than now, consisting of a broad yellow streak, relieved by narrow white moulding or ribbons. She appeared to justify all that the boarding-master had said of her; and, in the simplicity of our hearts, we had no doubt that his enumeration of her mainto'gall'nt-s'ls and backstays was perfectly correct.

It being a holiday afternoon, there was a crowd of boys on the wharf, who appeared to me to be quite a distinctive class of juveniles, accustomed to consider themselves as predestined mariners. Their fathers and grandfathers before them had spent the whole period of their lives "round Cape Horn;" their elder brothers were even now serving their apprenticeship in the same manner, and, as regarded themselves, it was only a question of time how soon they should[21] start. They climbed ratlines like monkeys—little fellows of ten or twelve years—and laid out on the yardarms with the most perfect nonchalance, shouting and laughing at our awkward attempts to perform the same feats. They ridiculed us as "greenies," and there was no help for it but to take it all in good part, and bear with their boyish impudence as philosophically as might be. Hostile advances were useless, for we might as well have kicked at the empty air.

We certainly could not complain of want of attention during our stay among these plain-hearted people. We could hardly turn a corner but we were saluted with the war-cry of some of these embryo circumnavigators. "See the greenies, come to go ileing;" while the smiles of beauty were extorted by our amphibious costumes wherever we strolled about town.

I understood that two of the boys were going with us in the ship. Wishing to know something of my future shipmates, I made inquiry of the landlord's daughter. Of course she knew them both. One was Kelly's son who lived away in Egypt, and the other was Obed B.

"And who is Obed Bee?" I asked.

"Why, he's a second cousin of ours."

"And does Mr. Bee live in Egypt, too?"

"Who?" she asked, with surprise.

"Why, Mr. Bee, Obed's father," said I innocently.

"Mr. Hoeg, you mean," said she, as soon as she could suppress her laughter so as to speak. "I forgot to tell you that his name was Obed B. Hoeg. No, he don't live in Egypt; he lives over in Guinea."

I was more and more mystified; I thought of Ledyard and Mungo Park, and pursued my African researches by inquiring:

"What part of the world is this where you live—Nubia or Abyssinia?"

"Neither," answered the young lady, now fairly screaming with laughter. "Why this is Newtown."

"Indeed!" said I. "And have you an 'Oldtown,' too?"

"Not in Nantucket," she replied; "that's on the Vineyard."

I did not learn, till long afterwards, that the name was universally used among the Nantucketers for Edgartown.

But our stay in this quaint old town was short, indeed, for the next afternoon we all reported ourselves on board, under the fatherly care and escort of Messrs. Brooks and Richards; and the Arethusa, with only topmasts aloft, and topsail yards crossed, dropped out from the wharf, in tow of the "Telegraph" steamer, for her station outside of the bar, there to complete rigging and loading for sea. She was at this time in charge of a pilot, and a superannuated whaling captain, who, having outlived active service, now found employment as chief stevedore and temporary captain, in cases where the regular officers preferred to pay for "lay days," and remain with their friends till the ship was quite ready for sea.

Directly on getting clear of the wharf, we poor bewildered green hands, whose senses had gone wool-gathering amid the confusion of unintelligible orders[23] connected with "hooking on," were set to work to heel the ship by rousing the chain cables and other ponderous articles all on one side, in order to lessen her draught of water; and this being accomplished, the ship, after rubbing for a few minutes on the flats, went over clear, and about dark came to, with both anchors ahead, in the berth vacated by the Pandora which had gone to sea the day before.

CHAPTER III.

FROM THE BAR ROUND GREAT POINT.

When the ship was righted, and all was made snug for the night, we proceeded to arrange the chaotic mass of sea-chests, bedding, kegs of oil soap, and miscellaneous sea-stores, and to perform the apparently impossible task of condensing sixteen men, with all their real and personal estate, into a little triangular space, called (by courtesy) the forecastle, so as to leave standing and dancing room at the foot of the ladder. This problem, however knotty it might seem to the uninitiated, was successfully solved, under the superintendence of the four "salts" who had been to sea before, two of whom were Portuguese from the Azores, one a gigantic negro who had been three voyages in the same employ, and the fourth a white American of some little intelligence—one of those sea-lawyers or "clock-setters," who are to be found in all sorts of ships, and who make more mischief then can well be imagined by people not conversant with matters of this sort. The stowage being completed, each one fitted up his own "bunk," the four veterans having, of course, appropriated the choice ones by marking them with their own hieroglyphics before the ship left[25] the wharf. Supper was then passed down, and a smart show of new tin-ware brought into requisition. Old Jeff swore at the tea, called it "frightened water" (it did certainly appear to have been mixed on homœopathy principles), and avowed his determination to have his brother African, the cook, over the windlass end before he had been a week in blue water, unless a decided improvement should be observed in this respect. In which threat he was ably seconded by Burley, the sea-lawyer, and the two Ghees, we green hands merely eating with eyes wide open, not yet daring to advance our opinions.

The remains of the banquet cleared away, most of us lighted our "half-Spanish" outfit cigars, but Old Jeff, disdaining such flummeries, produced his approved narcotic solace, in the shape of a well-worn and blackened "chunk," which being duly loaded and set on fire, he settled himself in a sort of Sir Oracle attitude, and prepared to give the attentive novices the benefit of his long experience.

"Now, boys," said Jeff, between the puffs, "you'll find you've got to toe the mark here. Our old man's a hard one, I can tell ye, for I've sailed with him afore. I can get along well enough with him, 'cause I know him, and he knows me, too, like a book. I haven't sailed ten years with him for nothing. Why, bless your souls, he wouldn't know how to get under way without me." This was one of Jeff's delusions—that he considered himself a necessary fixture or part of the ship. "He's a hard one," he continued, "and you lads will have to stand round when he gets among[26] ye. He wont trouble me, you know,'cause I know my duty, chock to the handle; but he's down on any man that don't know his duty."

"But, surely," I ventured to say, "he cannot be so unreasonable as to expect a green hand to know a seaman's duty by intuition. We don't profess to know anything; we come our first voyage to learn, and if we show ourselves willing to learn, we do all that can be reasonably expected of us."

"I don't know nothing about your inter-ition," returned Old Jeff, showing the whites of his eyes to a frightful extent. "That's further into the booktionary that ever I overhauled. But I know this old man, and it's no use for a lad like you to argy about things that you don't understand. If you and me was going to talk in 'long-shore company, now, I s'pose I'd have to strike my flag, 'cause you could launch some three-deckers, like that one just now; but here, you know, I'm to home. You just hold on a bit; he'll let you know who's who, when he gets you off soundin's!"

"I aint afraid he'll do me anything," said the sea-lawyer, Burley, his voice coming with a sepulchral sound from the depths of the bunk, where he was already stretched at full length. "I don't allow any live man to do me anything. I've been in all sorts of ships, men-of-war, merchantmen, and—well, I wont say what else. But I always stood up for my rights."

"That's all well enough, you know," replied the negro, speaking with less assumption of superiority now that he was addressing a man of experience. "That's all well enough to stand up, if all hands would[27] hang together standin' up"—(quite unconscious of the bull, of course). "But they wont, 'cause they don't know their duty. Now, you see, you and me's got to do 'bout all the duty here—"

"What you talk about?" said one of the two Ghees, a swarthy, big-whiskered fellow, with that restless eye so common among his countrymen. "What you talk about—do all dutee? I no want you do my work. S'pose you do your own work, me all e' same."

"Ah, well! I don't mean nothin' 'bout you and Antone, of course!" said Jeff, turning nearly white at the interruptions. "I s'pose you two can do your duty well enough. What I mean to say is," thus ingeniously shifting his ground, "there'll be only two of us in each watch to do all the duty. 'The doctor' he don't count nobody, 'cause he don't stand watch, and he's got enough to do to look after his galley. Now, when I first went a whaling, they used to have some men aboard of a ship; but now-a days they send them out filled with a lot of children. I expect if I go two or three voyages more, I'll see 'em bring their mothers out with 'em. I don't know, for my part, what they ship such spindle-legged boys for!"

"I do!" shouted the clock-setter, from the recesses of the bunk. "Because they can do just what they like with 'em, and they don't know their rights. If they were to ship a whole crew of old hands that knew their rights and stood up for them, they'd get brought up with a round-turn."

"R-r-r-ights!" muttered Manoel the Portuguese.[28] "What that you talk 'bout r-r-rights? What for you begin gr-r-owl now, no got ship out sea yet? Time enough gr-r-owl, s'pose old man no do r-r-right by-'m-by."

"But it's always well enough to have these things understood in the beginning," insisted Burley. "I want a man to use me like a man, and I mean he shall, too. I don't know what you Dagos mean to do, but I'll have my rights."

"R-r-rights!" echoed Manoel, with infinite contempt. "All 'e time r-r-rights!"

"I tink s'pose have row 'board dis ship—you no do more's 'nother mans," said the little Portuguese, Antone, with that quick perception of character, which, in many of his class, seems to supply the place of both theoretical knowledge and worldly experience.

"Well, you'll see," returned the sea-lawyer. "Time will show. I sha'n't ask any Dago to tell me what to do."

"Dago no tell you, s'pose you ask," answered the quiet little Portuguese, sarcastically.

He had already conceived a disgust for one, at least, of his shipmates. Though having no desire, at present, to quarrel with him, he took in good part the epithet of "Dago," which Burley had always at his tongue's end.

"Well," said I, "I shall not believe that the captain—"

"Who's the captain?" interrupted Old Jeff.

"Why, Captain Upton."

"O! the old man you mean. If you was talking[29] about the skipper of another ship, it might do to say the cap'n, but ours is always the old man—mind that."

"Very well—the old man, then," I resumed. "I shall not believe that he will misuse or ill-use a man for not knowing what he can't be expected to know without some practice and experience. It's an old saying that the devil is not so black as he is painted; and the only way for us new hands is to go to work cheerfully, and try to learn our duty. I'm sure I am willing to learn, and would be obliged to any one who would teach or help me."

This view of the matter, and my expression of it, at once found an echo from all the other youngsters, while, at the same time, it secured for me the better opinion of Old Jeff himself; who, though a notorious growler, was not a bad-hearted man in the main. In deed, this negro was a specimen of a class which every seaman will recognize at once, who growl rather from confirmed habit than from any evil motive; and nothing could be further from his mind than to be the intentional cause of trouble on board any ship in which he served. Not so with Burley, whom I set down at once as a man to be instinctively avoided and distrusted. Growling, with Old Jeff, was a weakness, and, from long indulgence in the practice had become, as it were, an essential part of his existence; but the sea-lawyer was a deliberate mischief-maker. In one respect, as I afterwards discovered, they were much on a par, being both arrant cowards when put to the test.

The cook now made his appearance down the ladder—a merry, simple-hearted African, of a shining bottlegreen[30] complexion, between whom and Old Jeff a harmless sort of skirmishing feud existed, they having sailed together on the previous voyage with Captain Upton, and contracted a habit of cracking coarse jokes upon each other to such an extent that a stranger might have supposed them to be in a towering rage at times, when they were in reality fast friends.

"Halloo, Jeff, aint you turned in yet?" said the cook, showing his ivory from ear to ear. "Here you be, boys; all de bunks taken up, and I's left like dey say de Son o' Man in de Scriptur', nowhere to lay my head. De old man says he's going to have an extra bunk put up for me in de steerage. S'pose he wont do it till after we get out to sea."

"Take your black mug out of this!" thundered Old Jeff, who was stripping off preparatory to retiring for the night. "You make the fo'castle so dark a man can't see to turn in. You'll put the lights out if you stay here five minutes."

"Now don't trouble yourself to get in a puncheon when a hogshead's big enough to hold ye," retorted the "doctor" in a tantalizing way. "Some people might think you's dangerous, if dey didn't know ye as well as I do. You can't frighten Kentucky Sam, you know. Lord sakes! You might run loose till kingdom come, 'thout any muzzle; you wouldn't bite nobody. Might bark some, though."

"I'll bark your crooked shins for you, if you don't shut up. I'm goin' to turn in; we shall have two lighters alongside to-morrow morning and Uncle Brock will be turning us to, as soon as he can see daylight through a ladder."

"Well, now, don't be flyin' off de handle, altogedder," said the cook with provoking coolness, "'cos I's goin' to turn in myself, soon's I fix up a bed on dese two donkeys." (Sea chests.)

"I'll settle your hash for you to-morrow," roared Jeff, extending his herculean fist from the bunk, and shaking it apparently in a state of great excitement.

"All right. Call at my office any time before dinner. Sha'n't have no hash to settle tho'. 'Taint hash day to-morrow, anyhow."

By this time the sable functionary was stretched at his ease on his temporary shake down, and the sparring ended for the night. Some of the boys were already snoring off the fatigues of the day, and the rest were making a movement bedward; so I had leisure to reflect a little upon the sudden change in my situation and the new and strange society into which I was thrown. Yet though my meditations kept me wakeful for some time, they were by no means of a despondent cast. I was on board a first-rate ship, new and stanch, and as I had every reason to believe, well appointed for a successful voyage; and though I had already found out that the chances were in favor of three years' absence instead of one (the statements of the polite Mr. Ramsay to the contrary notwithstanding), even this did not deter me from following my bent. I should see much of the Pacific side of the world in that length of time, would so conduct myself as to ensure promotion, and my calculations as well as my observation at Nantucket, had satisfied me that the business must prove quite lucrative to captains and[32] officers who could command high lays. As for my shipmates they were probably an average of rough men, and I could soon adapt myself to their humors.

I fell asleep, dreamed of piles of gold doubloons, all besmeared with whale oil, but shining the brighter for it, and was roused at the first peep of dawn by the stentorian voice of Uncle Brock exhorting us to "muster up and get the lighter alongside." Old Jeff brought his immense flat feet from his bunk to the deck with a bound, calling to us youngsters to "show a leg!" and also administering a smart kick to his ebony friend the cook, by way of a gentle hint to "bear a hand and get the grub under way." Burley, to support consistently his character as an old man-of-wars man, asserted his "rights" by standing three or four calls.

The first sound that greeted my ears, as I emerged from the scuttle, was an invocation from the leathern lungs of the skipper of the lighter. "Arethusa aho-o-oy! Rouse and bitt, you youngsters! I know you've got strong constitutions. You can stand more sleep than a polar bear in winter time! Get your lines ready. I'm coming alongsi-i-de!" and the gruff response of old Captain Brock mounted on the rail. "What the devil ails you, Uncle Dan? You've turned out wrong end foremost! That polar bear of yours has got a sore head by the way he growls! You talk about sleeping! Why, anybody knows that you can sleep twenty-two hours out of twenty-four, and then d—n the dogwatch."

But the war of words between these old salts was[33] quite as harmless as that of the two black shipmates; and the sloop being soon lashed alongside, the noisy old skipper came on board the ship to breakfast. The hands were then turned to again, and the work of taking in stores and provisions, and filling salt-water ballast in the ground tier went briskly on. I was selected, with one other green hand, to work in the hold under the direction of another old whaleman, who filled the second mate's place pro tempore, and the boatsteerers, two of whom were promising young men, natives of the island, and the third, or captain's boatsteerer, was a mulatto, who was ex-officio, third mate, and had the handle to his name, being addressed as Mr. Johnson. These worthies all messed in the cabin, as well as the cooper, who had not yet come on board. There were no bunks in the steerage; the Arethusa being, in this respect, an exception to the generality of ships at that time. But it was a favorite expression with Captain Upton, "that he had but two ends to his ship, and wanted every man to keep in his own end." I succeeded so well in satisfying the petty officers, that, before we had finished loading the ship, they were all agreed that it was expedient to retain me as one of the regular "hold gang," provided no objection should be raised by those higher in authority.

The quantity of stores put on board a whaleship, for a long voyage, would astonish any one not acquainted with the business. A ship is literally crammed full when she sails, and one is tempted to ask, "Where is the oil to be put when we get it?" Every[34] cranny and crevice is filled with wood or lumber of some sort, and to add to the puzzle, the ship carries from a thousand to fifteen hundred barrels or casks in the form of shooks, or packed bundles of staves, which, in the event of a successful voyage, are all, of course, to be set up, filled with oil and stowed away. But, as the gradual consumption of provisions and stores keeps pace with the gradual accumulation of oil, and as some space is gained in restowing, each time, it is managed, somehow, and a whaleship is always full, or nearly so, all the voyage. Still it seems, in some sort, a mystery, even to old whalemen themselves.

In about ten days the stowage was completed, the topgallant-masts and yards sent aloft, in which process we boys found opportunity to display our agility in fetching and carrying, as well as to acquire some knowledge of seamanship, and to unravel other puzzling questions as to "how those long poles were to be put up so high?" and "what kept them there when up?", the spare sails, boats, etc., received on board, and the ship reported ready for a start. Mr. Richards, the out-door agent of Messrs. Brooks & Co., had never relaxed his fatherly vigilance, visiting his protégés every day, praising and encouraging us, and prophesying a short voyage and "greasy luck" to the Arethusa.

The day of departure arrived, with a fair wind and plenty of it; the last boats came alongside at three o'clock in the morning, bringing the captain and officers, with their luggage, and the agent of the ship, with several other friends, who had come to "see us[35] off" and return in the pilot-boat; and who, of course, burst into enthusiastic praises of the new ship, and the arrangement of all on board, protesting that it almost made them wish they were going themselves. The windlass was soon after manned; the topsails loosed (not exactly in man-of-war style, with a simultaneous fall), green hands were hurried here and there, ropes pointed out to them and put into their hands; the anchors slowly but steadily rose to the bows; and, by sunrise, the gallant Arethusa, feeling the impulse of the fresh breeze, was fairly underway, and her course shaped to clear Great Point.

I had anticipated another course of martyrdom from sea-sickness; but I soon found that the gallant Lydia Ann had broken me in completely, and I was destined to suffer no more from that intolerable malady. It was a great relief to feel that my stomach had gained the victory in the conflict with old Neptune's medicine chest. There was something exhilarating in the sensation of feeling the lively ship springing under my feet, and driving onward under the impulse of her distended wings; in looking back at the low, receding island, the cradle whence had issued so many stout hearts and strong arms to vex every sea with their fisheries, and feeling that I, too, was now embarking in this adventurous and romantic business; and in observing how Captain Upton, with his mate and the owner, grouped together on the quarterdeck, watched the behavior and movements of the new vessel, from time to time commenting, as they found occasion for so doing, and comparing her[36] qualities and merits with those of other time-worn and well-tried ships. I myself began to feel a little of that pride in my floating home springing up within me, which every seaman feels for his vessel. Then, as I looked again astern, at the dim outline of Nantucket, fast sinking towards the horizon, my thoughts reverted to my pleasant country home, to my parents and my much loved sister left there, and a prayer went up—yes, a prayer; a silent one, but none the less sincere. A glance of the captain's eye aloft; a word, "Port!" to Old Jeff at the wheel; another word in an under tone to the mate; and then the loud order, "Square in the yards!" chased away these gentle thoughts, and recalled my mind to the voyage before me.

As we had rounded Great Point, the ship was kept away with the wind nearly aft, and standing more stiffly up to her work, went booming off at a rate which promised to leave home far out of sight before nightfall. Old Jeff, when relieved by Manoel, came forward in ecstacies. He had quite forgotten his growling propensity, in the excitement of the moment, and vowed she was the most perfect beauty that ever swam under his flat feet; that she steered like a pilot-boat; and, as for sailing! why she'd go round and round the old Colossus (his last ship), and not half try herself.

"Now," said the negro, "I only want to see her work on a wind, and go in stays once or twice. But I know—confound it—I know she'll tack in a pint of water. I can tell by the way she feels under me. If[37] we don't get a load of oil this time, it wont be the ship's fault. Hurrah! twenty-five months—twenty-five hundred barrels! that's all we want to give her a bellyful! that's all! twenty-five;"—and went off into a shuffle step of cadence.

CHAPTER IV.

FAIRLY AT SEA.—THE FIRST LOOKOUT.—INTRODUCTIONS.

By noon the ship had run the land nearly down to the horizon line, and having sufficient offing, with the open sea before her, and all being well satisfied with her performance, she was brought to the wind with the maintopsail thrown aback for the pilot-boat; and after the most affectionate leave-takings and handshakings, the owner and the rest of our shore friends left us; many of them with, literally, very turbulent feelings. Mr. Richards was not so indisposed but that he was able to take the hand of each of his young friends in turn, and bid us godspeed, at the same time leaving in our hands copies of our outfit bills (receipted in full by order on the owners), as a parting token of his esteem. Three cheers were given as they shoved off from the ship—or rather attempted, with but indifferent success, and somewhat more feeble returned by the stay-at-homes; and in a few minutes we again filled away on our course to the eastward. The anchors were stowed and well secured, the chain cables run down into the lockers, and the breeze freshening[39] in the afternoon, the ship was brought down to double-reefed topsails; an operation requiring considerable time for its performance, with new sails and running gear, and a green crew; and one adapted to develop not only our agility, but the power of grip in our hands; while the rigging was embraced so affectionately that I had no reason to wonder at the complaint of the second mate that we had robbed all the tar from it, and transferred it to our clothes. Jeff had his fill of growling at the "children," as if they were to blame that they had not been born able seamen, or trained as "reefers" in the district school; while Manoel was kind enough to undo all my part of the work and do it over again, instructing me at the same time how not to tie a "gr-r-r-annee-knot," enunciating the r with a noise like that made in tearing a strong rag.

At sundown, all hands were called aft, and requested to "spread" ourselves in full view of the officers, and the process of choosing watches was gone through with, the mate and second mate selecting a man alternately, till all were disposed of except the "idlers," such as the cook, steward, cooper, etc. As we were chosen, we were formed in two divisions, one each side of the deck, according as we were billeted in the starboard or larboard watch. Next came the choice of oarsmen for the respective boats, a still more important matter in a whaler; and here there was much competition among the officers, and evidently some anxiety, with a little ill-concealed jealousy of feeling. I found myself a member of the larboard watch, and[40] also assigned to the bow oar of the larboard, or chief mate's boat.

When we all understood our places, Captain Upton introduced his officers in form, as Mr. Grafton, his mate, Mr. Dunham his second mate, and Johnson, his third mate.

"These are my officers," said he, "and I look for you all to respect and obey them as you do myself; and remember that when either of them is on deck in charge of the ship, he represents me, and his orders are mine."

He told us he should allow no fighting among ourselves, he wanted to see no sogering, and, above all, to hear no "back answers." He wound up with a peroration after the most approved and stereotyped form, which has been handed down from ancient sea-captains; indeed, it is supposed to date back to the patriarchal system of government, and to have originated with Noah when he first closed the doors of the ark:

"All you've got to do is, go when you are sent, and come when you are called; and if you don't have enough to eat, come aft and let me know. Set the watch, Mr. Grafton."

The starboard watch had eight hours on deck, following the established seaman's rule that the captain must take the ship out, and the mate take her home. When our watch was summoned at eleven o'clock, the ship was still under double reefs, but the wind had hauled round to the northward-and-east-ward, causing an ugly cross sea, and she was braced sharp on the[41] port tack, and plunging into it smartly. The weather was quite chilly, and as our end of the deck was "all afloat," we naturally made our way aft to explore for drier quarters. Mr. Grafton was on hand to meet and count us at the mainmast. Being satisfied the quota was full:

"Now, boys," said he, "you will remember this. In your watch on deck, you are expected to stay on deck; and so that you are all ready for a call when I want you, you may pass the time about as you please, and make yourselves as comfortable as you can—except one man at the wheel and one looking out ahead. I shall want one of you always on the lookout at night, and you must arrange the tricks among yourselves so that I may always find one there. I want him mounted up somewhere where he can see all around on both bows, and where I can see him if I come forward. If I find him asleep, I'll—never mind—I'll fix him so that he will keep his eyes open next time. Now go forward, one of you; and mind, all the rest of you keep above deck. You understand the wheel and lookout are to be relieved every two hours, and whoever has the next trick, I expect him to be travelling along at once when the bell rings; if he don't—he'll hear from me."

I volunteered to take the first lookout, and my offer was accepted with enthusiasm. I struggled forward, clutching at the weather-rail, and finding some difficulty in keeping my equilibrium on the wet, slippery deck, as the buoyant ship rose and fell, rolling at times heavily, and righting with a sudden recoil. I[42] looked at the station between the knight-heads; but just at that moment she made a heavy pitch forward, and meeting a head sea in full career, sent it flying high over the bows, and rushing down the heel of the bowsprit, inboard; giving ocular evidence that I should be more than half drowned as the reward of my temerity, if I ventured up there. The foretopsail sheet bitts presented the next eligible place, and here I "mounted guard." Planting myself in a Colossus-of-Rhodes attitude, with my back against the foremast, and one arm round each chain sheet for a firm hold, I stared intently into the black void ahead of the ship, regardless of the drenching sprays which every now and then flew over the weather bow upon my head, rattling down my sou'wester, and penetrating my new monkey jacket, which, so far from being water-proof, might have been aptly classified with Mr. Weller's hat, as "wentilatin' gossamer." I was the possessor of an oil-cloth suit, but it was below in the forecastle; and so profoundly was I impressed with a sense of the responsibility resting upon me, that I would not for an instant have stirred from my post until relieved, for anything short of an earthquake; a contingency not likely to occur so far out in the Atlantic Ocean, in this latitude. No one came near me during the two hours, but I had been reconnoitred from time to time by Mr. Johnson, who was skilled in working traverses round the tryworks, and saw a great deal without being seen himself. At one o'clock the relief bell struck, and soon after a voice issued from the darkness:

"Hallo! Blacksmith, where you?"

"Here!" I answered, turning half round.

"Come down! I 'lieve you!" hailed Antone, from the fore-hatches.

"Leave me? what for? I've been left here two hours now."

"No, I 'lieve you! I take you place!" shouted the Portuguese. "You wet, no?"

Just at the moment a gush of water came flying in over the galley, and I jumped down on deck, gasping for breath, and streaming from every thread. The Portuguese roared with laughter.

"What for you stop up dere? You no sabe stand lookout. By'mby you see me no all e' same," continued Antone, who was favoring himself under the lee of the foremast, and all ready for a rapid retreat, if necessary.

But this was my first lookout. I proved myself, in time, an apt scholar, and learned to "favor myself" in many particulars; and while I obeyed orders, and gave satisfaction to my superiors, to leave responsibility, like a true Jack, to those who were better paid for it, and to cultivate close acquaintances with the softest planks about the decks on all convenient occasions.

Those who predicted a good voyage for the Arethusa did not, in this instance, as in many others, do so without reason; and they did no more than justice to Captain Upton and his officers when they pronounced her well appointed. The captain himself was a man of great energy and undaunted courage, still in the[44] prime of life, who always headed his own boat, and took the initiative himself in whaling. He was rather taciturn, saying little more than was really necessary on any occasion, but possessed great firmness and an iron will. There was nothing of the Tartar about him, and very little to justify Old Jeff's bugbear statement as to his being "a hard one." He had his peculiarities, however, not to say failings. No man could study more closely the interest of his owners; and as he was now identified with them, being a part owner himself in the new ship, we felt the effects of it in the commissariat department. Moreover, he was very proud of his vessel; so much so as to be old-maidish in regard to the neatness of her appearance, and devoted more time and labor to this end than was at all agreeable either to his crew or officers. On the whole, however, he was justly regarded as a most efficient man for his station, and ranked A. 1. on the list of crack whaling captains.

His chief-executive and prime minister, Mr. Grafton, was a tall, massive-looking man, of fine personal appearance, something older than his superior. He had made three voyages in the same capacity, being one of those choice mates, who, by some chance, never get command of a ship, perhaps in virtue of a saying much in vogue among shipowners, and in many instances acted upon, "that it is a pity to spoil a good mate by making him master." A man of rather thoughtful cast of mind, of much intelligence, and possessed of an extensive stock of information upon many subjects, with a habit of generalizing and a clearness,[45] of expression which rendered him an agreeable companion to all with whom he came in contact. Though a good whaleman, Grafton was not what is known to the connoisseur as a "fishy man;" he had no lungs to blow his own trumpet, and sometimes distrusted his own powers, though generally found equal to any emergency after it arose. This want of confidence sometimes led him to hesitate, where a more impulsive or less thoughtful man would act at once. In the course of his career he had seen many "fishy" young men lifted over his head; but as he was very highly esteemed in his station, and received nearly a captain's pay, he was well contented as he was. He was devotedly attached to his family at home, personated the gentleman in all he said and did, and well sustained the character.

Dunham, the second officer, was a smart young fellow of two-and-twenty, active, strong, and "fishy to the backbone." His chief fault, as an officer, lay in his being an inveterate sleeper; he could never, upon any consideration, keep awake a whole four-hour watch.

The mulatto Johnson had steered a boat with Captain Upton before in the Colossus, and was well known in Nantucket as "a long-dart man." He was somewhat of the Shanghai build—tall and long-shanked, with great strength of limb, and could plug a whale better if four fathoms distant than he could "wood and blackskin." He had an eye like a hawk, and could see a spout as far with his natural optics as most men could through a telescope. He[46] was ignorant of everything out of his own immediate line, and sometimes rather overbearing. He was not disliked, in the main, by the crew, if we except Jeff and the cook, who being old shipmates of his, and themselves of the pure blood, were averse to tolerating anything of a mongrel description, or "milk-and-molasses color," as they termed it. "No compromise" was their platform, on this particular issue.

The cooper of the Arethusa was an important personage, as, indeed, the cooper always is in a whaler. The duties of this functionary are of a peculiar character, and about as independent of all the rest as those of a surgeon in a man-of-war. He is neither officer nor man, strictly speaking, his lay or pay being nearly equal to that of a second mate. He lives aft with the officers, but makes himself at home in all parts of the ship, occupying a sort of neutral ground—a kind of connecting link between republicanism and oligarchy, neither too high nor too low to consort or joke with anybody and everybody. As a general rule, he stands no watch, but does his day's work and sleeps all night, and in many ways evinces consciousness of his own value, and of the indispensable character of his services. For a whaler may, and, in fact, often does, go to sea without a blacksmith or without a carpenter; but the cooper is an essential part of her equipage. An officer or a boatsteerer may, in case of emergency, be created at sea, by promotion; but the cooper is not so easily replaced.

The cooper in question was a stout, grave-looking man of forty or thereabouts, with a shaggy mass of[47] grey hair, and a patriarchally long beard. His mechanical work was of excellent quality, what little he accomplished; for he always worked on the principle of the tortoise in the race—"slow and sure." He scraped indifferently well on the violin, but delighted especially in drawing a longer bow. In virtue of this latter accomplishment, he might have claimed near relationship with a certain gentleman known in classic lore as Thomas Pepper, without having his title questioned for a moment. He always told his yarns as gospel truth, and would back them with any oath, if required.

The two young boatsteerers, Bunker and Fisher, with the Portuguese steward, completed the "afterguard." In the forecastle there was, in addition to the personages already mentioned, the usual variety of character and disposition to be found among a dozen young men, recruited at random in this manner. Now that we were getting initiated to a sea life, we were beginning to have opinions, and to express them, no longer leaving the whole field to Jeff and the sea-lawyer. As for the Nantucket boys, Kelly and Hoeg (or Obed B., as I still persisted in calling him), they made rapid progress in knowledge and confidence. As I have before intimated, these young "natives to the manor born" seemed to look upon this life with the eye of fatalists. It was foreordained that they should be sailors, and nothing in their new way of life seemed to surprise or disturb them for a moment. Everything took place as a matter of course with them. They never seemed to think they could, by[48] any possibility, have followed any other business for a livelihood; and each new event or circumstance of the voyage was merely another link in the chain of their inevitable destiny. They were born to go whaling and a station on the quarterdeck was the goal of their ambition.

They had not been more than a week at sea before they had taken some of the starch out of the sea-lawyer, who had attempted to assert his "rights" by hazing them about, and calling upon them to perform various menial services for him, which he said it was a "boy's place to do."

One morning he ordered Kelly, in a very arbitrary way, to go on deck and bring him down some water, which Kelly flatly refused to do. The sea-lawyer declared he would "make him do it;" and upon Kelly's expressing a doubt as to his ability to perform that feat, he proceeded to enforce his command, vi et armis. But he was met by the boy with a spirit that he had not looked for, and before he could get a good hold upon the youngster, so as to chastise him, as he expected easily to do, he was attacked in the rear by Obed B., who arrived on the field just in time to reinforce his chum and schoolmate. This gave Kelly a chance to rally and assume the offensive; and Burley, who was a most arrant coward, finding himself roughly handled between the two, was fain to call for an armistice. A parley ensued, and the boys gave him to understand that they did not come to sea to be boys, but to make themselves men, and that they would not submit to be bullied by him. And the upshot of the[49] matter was, that the champion of "rights" made rather an ignominious retreat from the field, as compared with the vigor of his first attack. All this was nuts, of course, to the rest of us youngsters, who desired nothing more earnestly than to see the bully humbled a little; while the emotion of Manoel was too powerful to find utterance—in intelligible English. He patted the two boys on the shoulder, in the exuberance of his spirits, while his tongue rattled until I thought all his teeth were loose in the jaws; but to save my life, I could not have told what he was trying to say.

There was plenty of work for all hands on the passage out, as every one will understand who has ever performed a voyage in a new ship. We found our duties very fatiguing, as we were kept at work all day, and had a watch to stand at night. There was all the new rigging to be stretched and set up over and again, in addition to the thousand and one other matters to be attended to, to put everything in trim for whaling against the opening of the campaign. The old salts growled night and day in the forecastle about having no "watch below;" but as we verdant ones had but a vague idea of what they meant by it, we had but little to say about this grievance.

CHAPTER V.

THE WESTERN ISLANDS.—"YARNS" AND ANECDOTES.

On the eighteenth day out from Nantucket, the high peak of Pico was visible from the masthead, and having a fair breeze, we were lying off and on at the port of Fayal the same afternoon. The captain, with the starboard boat's crew, went ashore, and the ship made short boards to await his return, the Pandora and two whaleships from New Bedford in company. Two more ships were at anchor having taken some oil on the outward passage and put in to land it to be shipped home. Several Portuguese boats came alongside, of the most clumsy and primitive construction imaginable, characteristic of a people who are a couple of centuries behind the times. The boatmen appeared to be, "like Captain Copperthorne's crew, all officers," and jabbered and shouted all at once, in most admirable discord, and at such a furious rate that I found myself wondering whether they really could understand each other or not, and certainly never contemplated the possibility of any American having the remotest idea what they were talking about. But I found that Mr. Grafton could converse with them quite fluently whenever he could make himself heard in the din and confusion. These boats brought[51] a few inferior oranges, sour enough to make a pig squeal (if he would touch them at all, which of course he wouldn't, if a sensible pig), with some miniature cheeses, which, with a little more drying, might have been made available as sheaves for small blocks without much alteration in size, form or consistency of material. These they either sold for money or bartered for various articles of ship's provisions, and were perfect Jews at a bargain.

Just before sundown a large launch, deeply loaded, was seen coming out, with a rag hoisted on a pole as a signal. This launch was of even more primitive appearance than the smaller ones. She might have been the longboat of one of Vasco de Gama's fleet, of four centuries ago; at any rate, if his ship had any longboats, they were exactly of this model. We stood well in to meet her, and wearing off shore with the maintopsail aback, took her alongside. Her cargo of potatoes, onions and live stock was to be taken on board and stowed away, and, as the captain arrived soon afterwards, with his boat laden to the gunwale streak with vegetables, it was quite dark before she was again in her place on the cranes, and sail made on the ship.

Among the live stock brought on board was a handsome little boy, who was to help the steward in the cabin, much to the enhancement of that functionary's importance, as he could now attend to many calls by deputy which before he was compelled to answer in person; and would also have some one to lay all little mishaps to, such as dishes broken and lamps untrimmed.

The Pandora braced full about the same time as the Arethusa, but it was soon apparent that she could not compete in sailing qualities with the new ship, and she gradually dropped astern. The breeze was light from the north-west, with fine weather, and we now had leisure to get supper, and to listen, to the yarns of those who had been ashore.

Manoel and Antone had seen their relatives and friends—meeting them after years of absence, to part again in an hour or two—and had found time to visit the priest and get full absolution, balancing the account up to date, and opening a new page, ready to run up another score. Farrell, a young Irishman who pulled the captain's bow oar, had become considerably elevated by imbibing too much sour wine and aguardiente, and was full of stories of his own prowess in knocking over a "Portinghee" who had dared to remonstrate against his kissing a pretty, black-eyed girl, his sister, he supposed; for, like a true Milesian, he had been the hero of a drinking bout, a love intrigue and a knockdown row, all within half an hour after he landed.

"I jist took him a nate clip betwane the eyes," said Farrell, "and laid him out foreninst the door of his shanty. Thin you see, five or six murtherin' Portinguese pitched intil me, and was afther carryin' me off, body and sowl, to the lock-up; but the ould man interfared, and settled it somehow. Afther he'd paid me fine, he tould me I'd betther go down to the boat, and not lave her again. So I went and got int'l her and shoved her off the length of her tather, and there was a crowd[53] of the nagurs jabberin' and squintin' at me wid their corkindile eyes; but I knowed I was in sanctyeary thin. I'd half a bottle of that blackguard potteen what they call dent, so I jist sot and looked at 'em back again, and dhrank their healths. I suppose the ould man'll be chargin' me the fine on the ship's books."

"Yes, you can bet high on that," said Jeff, "and the interest, too."

"Yes," said the sea-lawyer, "but you needn't be fool enough to pay it. If every man stood up for his rights, they wouldn't gouge him in that style. A man can't go ashore and drink a drop, and have a bit of a time—and that's what he goes ashore for, of course—but he must have a long bill of calaboose fees tacked to his account; and that d—d twenty-five per cent added on. If they charge it to me, they'll never get it, that's all. I know what they've got a right to do."

"I don't know nothin' about the rights," said Jeff, "but I know the old man will charge it to you, and make you pay it, too."

"Well, you'll see," said Burley. "I'll have my rights."