It was here that Washington bade farewell to his officers, December 4, 1783. Purchased in 1904 by the New York Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, and now occupied by them as headquarters.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Revolutionary Reader, by Sophie Lee Foster

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Revolutionary Reader

Reminiscences and Indian Legends

Author: Sophie Lee Foster

Release Date: July 24, 2014 [EBook #46400]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REVOLUTIONARY READER ***

Produced by Greg Bergquist, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

COMPILED BY

SOPHIE LEE FOSTER

State Regent

Daughters of the American Revolution of Georgia

ATLANTA, GA.:

BYRD PRINTING COMPANY

1913

September 4, 1913.

Mrs. Sheppard W. Foster,

Atlanta, Georgia.

My Dear Mrs. Foster:—To say that I am delighted with your Revolutionary Reader is to state the sheer truth in very mild terms. It is a marvel to me how you could gather together so many charmingly written articles, each of them illustrative of some dramatic phase of the great struggle for independence. There is much in this book of local interest to each section. There is literally nothing which does not carry with it an appeal of the most profound interest to the general reader, whether in Georgia or New England. You have ignored no part of the map. I congratulate you upon your wonderful success in the preparation of your Revolutionary Reader. It is marvelously rich in contents and broadly American in spirit.

Sincerely your friend,

(Signed) Lucian Lamar Knight.

September 8, 1913.

Mrs. S. W. Foster,

711 Peachtree Street.

I like very much your plan of a Revolutionary reader. I hope it will be adopted by the school boards of the various states as a supplementary reader so that it may have a wide circulation.

Yours sincerely,

Joseph T. Derry.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | 9 |

| America | 11 |

| Washington's Name | 12 |

| Washington's Inauguration | 13 |

| Important Characters of the Revolutionary Period in American History | 14 |

| Battle of Alamance | 20 |

| Battle of Lexington | 22 |

| Signers of Declaration | 35 |

| Life at Valley Forge | 37 |

| Old Williamsburg | 46 |

| Song of the Revolution | 52 |

| A True Story of the Revolution | 53 |

| Georgia Poem | 55 |

| Forts of Georgia | 56 |

| James Edward Oglethorpe | 59 |

| The Condition of Georgia During the Revolution | 61 |

| Fort Rutledge of the Revolution | 65 |

| The Efforts of LaFayette for the Cause of American Independence | 72 |

| James Jackson | 77 |

| Experiences of Joab Horne | 79 |

| Historical Sketch of Margaret Katherine Barry | 81 |

| Art and Artists of the Revolution | 84 |

| "Uncle Sam" Explained Again | 87 |

| An Episode of the War of the Revolution | 88 |

| State Flowers | 93 |

| Georgia State History, Naming of the Counties | 95 |

| An Historic Tree | 100 |

| Independence Day | 101 |

| Kitty | 102 |

| Battle of Kettle Creek | 108 |

| A Daring Exploit of Grace and Rachael Martin | 111 |

| A Revolutionary Puzzle | 112 |

| South Carolina in the Revolution | 112 |

| Lyman Hall | 118 |

| A Romance of Revolutionary Times | 120 |

| [6]Fort Motte, South Carolina | 121 |

| Peter Strozier | 123 |

| Independence Day | 125 |

| Sarah Gilliam Williamson | 127 |

| A Colonial Hiding Place | 129 |

| A Hero of the Revolution | 131 |

| John Paul Jones | 132 |

| The Real Georgia Cracker | 135 |

| The Dying Soldier | 136 |

| When Benjamin Franklin Scored | 139 |

| A Revolutionary Baptising | 139 |

| George Walton | 140 |

| Thomas Jefferson | 143 |

| Orators of the American Revolution | 150 |

| The Flag of Our Country (Poem) | 154 |

| The Old Virginia Gentleman | 155 |

| When Washington Was Wed (Poem) | 160 |

| Rhode Island in the American Revolution | 162 |

| Georgia and Her Heroes in the Revolution | 168 |

| United States Treasury Seal | 173 |

| Willie Was Saved | 174 |

| Virginia Revolutionary Forts | 175 |

| Uncrowned Queens and Kings as Shown Through Humorous Incidents of the Revolution | 185 |

| A Colonial Story | 192 |

| Molly Pitcher for Hall of Fame | 195 |

| Revolutionary Relics | 196 |

| Tragedy of the Revolution Overlooked by Historians | 197 |

| John Martin | 204 |

| John Stark, Revolutionary Soldier | 206 |

| Benjamin Franklin | 209 |

| Captain Mugford | 211 |

| Governor John Clarke | 214 |

| Party Relations in England and Their Effect on the American Revolution | 221 |

| Early Means of Transportation by Land and Water | 228 |

| Colonel Benjamin Hawkins | 236 |

| Governor Jared Irwin | 240 |

| Education of Men and Women of the American Revolution | 243 |

| Nancy Hart | 252 |

| Battle of Kings Mountain (Poem) | 255 |

| William Cleghorn | 257 |

| [7]The Blue Laws of Old Virginia | 259 |

| Elijah Clarke | 264 |

| Francis Marion | 266 |

| Light Horse Harry | 274 |

| Our Legacy (Poem) | 276 |

| The Ride of Mary Slocumb | 277 |

| The Hobson Sisters | 284 |

| Washington's March Through Somerset County, N. J. | 289 |

| Hannah Arnett | 293 |

| Button Gwinnett | 298 |

| Forced by Pirates to Walk The Plank | 300 |

| Georgia Women of Early Days | 301 |

| Robert Sallette | 308 |

| General LaFayette's Visit to Macon | 312 |

| Yes! Tomorrow's Flag Day (Poem) | 317 |

| Flag Day | 319 |

| End of the Revolution | 328 |

| Indian Legends | |

| Counties of Georgia Bearing Indian Names | 330 |

| Story of Early Indian Days | 331 |

| Chief Vann House | 332 |

| Indian Tale | 334 |

| William White and Daniel Boone | 336 |

| The Legend of Lovers' Leap | 337 |

| Indian Mound | 344 |

| Storiette of States Derived from Indian Names | 346 |

| Cherokee Alphabet | 348 |

| The Boy and His Arrow | 351 |

| Indian Spring, Georgia | 353 |

| Tracing The McIntosh Trail | 367 |

| Georgia School Song | 369 |

| Index | 371 |

| Facing Page | |

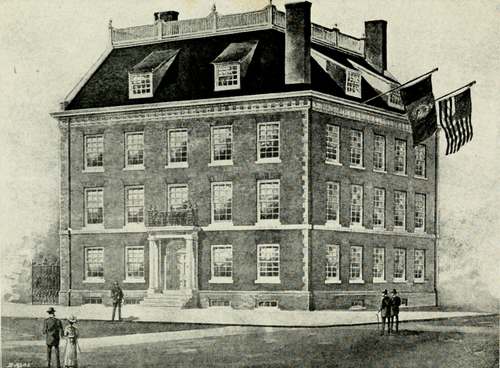

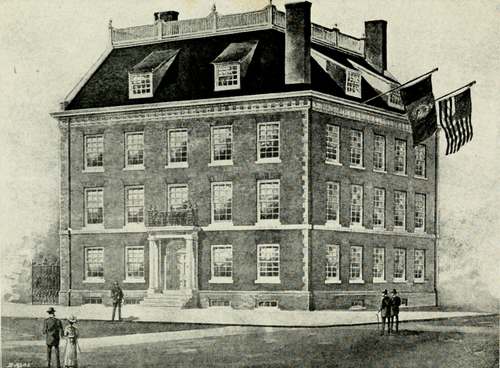

| Fraunces Tavern | 11 |

| Ruins of Old Fort at Frederica | 58 |

| Monument to Gen. Oglethorpe | 60 |

| Indian Treaty Tree | 98 |

| The Old Liberty Bell | 130 |

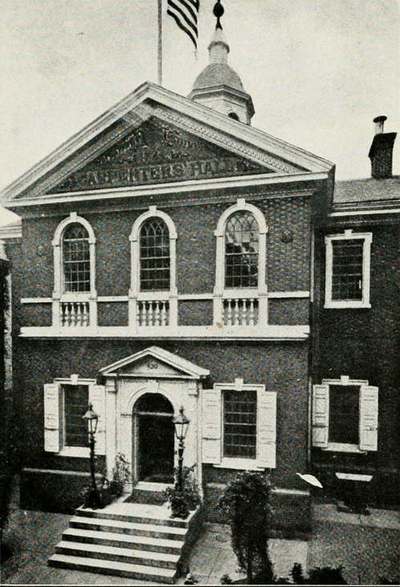

| Carpenter's Hall | 170 |

| Monument Site of Old Cornwallis | 266 |

| Birthplace of Old Glory | 318 |

| Chief Vann House | 330 |

| Map of McIntosh Trail | 366 |

| Map of Georgia, Showing Colonial, Revolutionary and Indian War Period Forts, Battle Fields and Treaty Spots | 370 |

Since it is customary to write a preface, should any one attempt the somewhat hazardous task of compiling a book, it is my wish, as the editor, in sending this book forth (to live or die according to its merits) to take advantage of this custom to offer a short explanation as to its mission. It is not to be expected that a volume, containing so many facts gathered from numerous sources, will be entirely free from criticism. The securing of material for compiling this book was first planned through my endeavors to stimulate greater enthusiasm in revolutionary history, biography of revolutionary period, Indian legends, etc., by having storiettes read at the various meetings of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and in this way not only creating interest in Chapter work, but accumulating much valuable heretofore unpublished data pertaining to this important period in American history; with a view of having same printed in book form, suitable for our public schools, to be known as a Revolutionary Reader.

At first it was my intention only to accept for this reader unpublished storiettes relating to Georgia history, but realizing this work could not be completed under this plan, during my term of office as State Regent, I decided to use material selected from other reliable sources, and endeavored to make it as broad and general in scope as possible that it might better fulfill its purpose.

To the Daughters of the American Revolution of Georgia this book is dedicated. Its production has been a labor of love, and should its pages be the medium through which American patriotism may be encouraged and perpetuated I shall feel many times repaid for the effort.

To the Chapters of the Daughters of American Revolution of Georgia for storiettes furnished, to the newspapers for clippings, to the American Monthly Magazine for articles, to Miss Annie M. Lane, Miss Helen Prescott, Mr. Lucian Knight and Professor Derry, I wish to express my deep appreciation for material help given.

Sophie Lee Foster.

At the celebration of Washington's Birthday, Maury Public School, District of Columbia, Miss Helen T. Doocy recited the following beautiful poem written specially for her by Mr. Michael Scanlon:

—American Monthly Magazine.

By Rev. Thomas B. Gregory.

On April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall, George Washington was duly inaugurated first President of the United States, and the great experiment of self-government on these Western shores was fairly begun.

The beginning was most auspicious. Than Washington no finer man ever stood at the forefront of a nation's life. Of Washington America is eminently proud, and of Washington America has the right to be proud, for the "Father of His Country" was, in every sense of the word, a whole man. Time has somewhat disturbed the halo that for a long while held the place about the great man's head. It has been proven that Washington was human, and all the more thanks for that. But after the closest scrutiny, from every part of the world, for a century and a quarter, it is still to be proven that anything mean, or mercenary, or dishonorable or unpatriotic ever came near the head or heart of our first President.

Washington loved his country with a whole heart. He was a patriot to the core. His first, last and only ambition was to do what he could to promote the high ends to which the Republic was dedicated. Politics, as defined by Aristotle, is the "science of government." Washington was not a learned man, and probably knew very little of Aristotle, but his head was clear and his heart was pure, and he, too, felt that politics was the science of government, and that the result of the government should be the "greatest good to the greatest number" of his fellow citizens.

From that high and sacred conviction Washington never once swerved, and when he quit his exalted office he did so with clean hands and unsmirched fame, leaving behind him a name which is probably the most illustrious in the annals of the race.

Rapid and phenomenal has been the progress of Washington's country! It seems like a dream rather than the soundest of historical facts. The Romans, after fighting "tooth and nail" for 300 years, found themselves with a territory no larger than that comprised within the limits of Greater New York. In 124 years the Americans are the owners of a territory in comparison with which the Roman Empire, when at the height of its glory, was but a small affair—a territory wherein are operant the greatest industrial, economic, moral and political forces that this old planet ever witnessed.

To make a subject interesting and beneficial to us we must have a personal interest in it. This is brought about in three ways: It touches our pride, if it be our country; it excites our curiosity as to what it really is, if it be history; and we desire to know what part our ancestors took in it, if it be war.

So, we see the period of the Revolutionary war possesses all three of these elements; and was in reality the beginning of true American life—"America for Americans."

Prior to this time (during the Colonial period) America was under the dominion of the lords proprietors—covering the years of 1663 to 1729—and royal governors—from 1729 to 1775—the appointees of the English sovereign, and whose rule was for self-aggrandizement. The very word "Revolutionary" proclaims oppression, for where there is justice shown by the ruler to the subjects there is no revolt, nor will there ever be.

We usually think of the battle of Lexington (April 19, 1775,) as being the bugle note that culminated in the Declaration of Independence and reached its final grand chord at Yorktown, October 19, 1781; but on the 16th[15] of May, 1771, some citizens of North Carolina, finding the extortions and exactions of the royal governor, Tryon, more than they could or would bear, took up arms in self-defense and fought on the Alamance River what was in reality the first battle of the Revolution.

The citizens' loss was thirty-six men, while the governor lost almost sixty of his royal troops. This battle of the Alamance was the seed sown that budded in the Declaration of Mecklenburg in 1775, and came to full flower in the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

There were stages in this flower of American liberty to which we will give a cursory glance.

The determination of the colonies not to purchase British goods had a marked effect on England. Commercial depression followed, and public opinion soon demanded some concession to the Americans.

All taxes were remitted or repealed except that upon tea; when there followed the most exciting, if not the most enjoyable party in the world's history—the "Boston Tea Party," which occurred on the evening of December 16, 1773.

This was followed in March, 1774, by the Boston Port Bill, the first in the series of retaliation by England for the "Tea Party."

At the instigation of Virginia a new convention of the colonies was called to meet September, 1774, to consider "the grievances of the people." This was the second Colonial and the first Continental congress to meet in America, and occurred September 5, 1774, at Philadelphia. All the colonies were represented, except Georgia, whose governor would not allow it.

They then adjourned to meet May 10, 1775, after having passed a declaration of rights, framed an address to the king and people of England, and recommended the suspension of all commercial relations with the mother country.

The British minister, William Pitt, wrote of that congress: "For solidity of reasoning, force of sagacity and wisdom of conclusion, no nation or body of men can stand in preference to the general congress of Philadelphia."

Henceforth the Colonists were known as "Continentals," in contradistinction to the "Royalists" or "Tories," who were the adherents of the crown.

No period of our history holds more for the student, young or old, than this of the Revolutionary war, or possesses greater charm when once taken up.

No man or woman can be as good a citizen without some knowledge of this most interesting subject, nor enjoy so fully their grand country!

Some one has pertinently said "history is innumerable biographies;" and what child or grown person is there who does not enjoy being told of some "great person?" Every man, private, military or civil officer, who took part in the Revolutionary war was great!

It is not generally known that the executive power of the state rested in those troublesome times in the county committees; but it was they who executed all the orders of the Continental Congress.

The provincial council was for the whole state; the district committee for the safety of each district, and the county and town committees for each county and town.

It was through the thought, loyalty and enduring bravery of the men who constituted these committees, that we of today have a constitution that gives us "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness"—in whatever manner pleases us, so long as it does not trespass on another's well being.

We do not give half the honor we should to our ancestry, who have done so much for us! We zealously seek and preserve the pedigrees of our horses, cows and chickens, and really do not know whether we come from a mushroom or a monkey!

When we think of it, it is a much more honorable and greater thing to be a Son or Daughter of the American[17] Revolution, than to be a prince or princess, for one comes through noble deeds done by thinking, justice-loving men, and the other through an accident of birth. Let us examine a little into a few of these "biographies" and see wherein their greatness lies, that they like righteous Abel, "though dead yet speak."

The number seven stands for completeness and perfection—let us see if seven imaginary questions can be answered by their lives.

James Edward Oglethorpe was born in 1696, and died in 1785—two years after the Revolutionary war. He planted the Colony of Georgia, in which the oppressed found refuge. He had served in the army of Prince Eugene of Savoy in the war with the Turks. He founded the city of Savannah, Georgia. He exported to England the first silk made in the colonies, of which the queen had a dress made. King George II gave him a seal representing a family of silk worms, with their motto: "Not for ourselves but for others." He forbade the importation of rum into the colony. He refused the command of the British forces sent in 1775 to reduce, or subdue the American Colonies. In this life told in seven questions, or rather answered, we find much—a religious man, a soldier, an architect (of a city), one versed in commerce, a wise legislator and a man who had the respect of the king—the head of England.

The next in chronological order is Benjamin Franklin (for whom our little city is named), born in 1706, died in 1790. He discovered the identity of lightning and electricity, and invented the lightning rods. He was an early printer who edited and published "Poor Richard's Almanac." Of him it was said, "He snatched the lightning from heaven and the sceptre from tyrants."

He founded the first circulating library in America. His portrait is seen to-day on every one-cent postage stamp. He was America's ambassador to France during the Revolutionary war.

He said after signing the Declaration of Independence, "We must all hang together or we shall all hang separately."

In him, we find an inventor and discoverer, an editor and author, a benefactor, a politician and statesman, and one whose face we daily see on account of his greatness.

George Washington was born 1732, and died 1799. He was the first president of the United States—"The Father of His Country," the commander-in-chief of the American forces in the Revolutionary war. He was the hero of Valley Forge, and the one to receive the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

He was the president of the convention that framed the United States constitution. The one of whom it was said, "He was the first in war, the first in peace, and the first in the hearts of his countrymen." It is his—and his only—birthday America celebrates as a national holiday. Of him Lord Byron said, "The first, the last, and the best, the Cincinnatus of the West." How much do seven short paragraphs tell!

Patrick Henry was born in 1736, died 1799, the same year that Washington "passed away;" and like his, this life can speak for itself. He was the most famous orator of the Revolution. He said, "give me liberty or give me death!" He also said, "We must fight. An appeal to arms and to the god of battles is all that is left us. I repeat it, sir, we must fight." Another saying of his was, "Caesar had his Brutus, Charles I his Cromwell, and George III—may profit by their example." Again, "The people, and only the people, have a right to tax the people." He won in the famous Parson's case, the epithet of "The Orator of Nature." He was the first governor of the Colony of Virginia after it became a state.

John Hancock was born in 1737, and died 1793. He first signed the Declaration of Independence. He was a rich Boston merchant as well as a Revolutionary leader. He was chosen president of the Continental congress in[19] 1775. He and Samuel Adams were the two especially excepted from pardon offered the "rebels" by the English.

As president of congress he signed the commission of George Washington as commander-in-chief of the army.

When he signed the Declaration of Independence he said, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles; let them double their reward." He was elected the first governor of the state of Massachusetts in 1780.

Anthony Wayne was born in 1745, and died in 1796. He was often called "Mad Anthony" on account of his intrepidity. He was the hero of Stony Point. He built a fort on the spot of St. Clair's defeat and named it Fort Recovery. He was made commander-in-chief of the Army of the Northwest in 1792. He gained a great victory over the Miami Indians in Ohio in 1794. He, as a Revolutionary general, banished whiskey from his camp calling it "ardent poison"—from whence came the expression "ardent spirits" when applied to stimulants. Major Andre composed a poem about him called the "Cow Chase," showing how he captured supplies for the Americans.

Alexander Hamilton was born in 1757, and died in 1804. He was aide-de-camp to Washington in 1777—the most trying year of the entire Revolutionary war. He succeeded Washington as commander-in-chief of the United States army. He was the first secretary of the treasury of the United States. He founded the financial system of the United States. He was the Revolutionary statesman who said, "Reformers make opinions, and opinions make parties"—a true aphorism to-day. He is known as the "prince of politicians, or America's greatest political genius." His brilliant career was cut short at the age of 43 by Aaron Burr—whose life is summed up in two sad, bitter lines:

Although John Paul Jones was not a Revolutionary soldier on the land, yet he was "the Washington of the Seas."

He was born in 1747 and died 1792. He was the first to hoist an American naval flag on board an American frigate. He fought the first naval engagement under the United States' national ensign or flag.

He commanded the Bon Homme Richard in the great sea fight with the Serapis in the English Channel.

He said, after the commander of the Serapis had been knighted, "if I should have the good fortune to meet him again, I will make a lord of him." He was presented with a sword by Louis XVI for his services against the English. He was appointed rear-admiral of the Russian fleet by Catherine II.

These are but a few of the many men who did so valiantly their part during the Revolutionary period.

Susie Gentry,

State Vice-Regent, D. A. R.

(A talk made to the public school teachers of Williamson County—at the request of the superintendent of instruction—in Franklin, Tennessee, January 13, 1906.)—American Monthly Magazine.

By Rev. Thomas B. Gregory.

At the battle of Alamance, N. C., fought May 16, 1771, was shed the first blood of the great struggle which was to result in the establishment of American independence.

All honor to Lexington, where the "embattled farmers" fired shots that were "heard around the world," but let it not be forgotten that other farmers, almost four years before the day of Lexington, opened the fight of which Lexington was only the continuation.

The principles for which the North Carolina farmers fought at Alamance were identified with those for which[21] Massachusetts farmers fought at Lexington. Of the Massachusetts patriots nineteen were killed and wounded, while of the Carolina patriots over 200 lay killed or crippled upon the field and six, later on, died upon the scaffold, yet, while all the world has heard of Lexington, not one person in a thousand knows anything to speak of about Alamance.

William Tryon, the royal Governor of North Carolina, was so mean that they called him the "Wolf." In the name of his royal master and for the furtherance of his own greedy instincts Tryon oppressed the people of his province to the point where they were obliged to do one or two things—resist him or become slaves. They resolved to resist and formed themselves into an organization known as "Regulators," a body of as pure patriots as ever shouldered a gun.

Having protested time and again against the unlawful taxation under which they groaned, they finally quit groaning, raised the cry of freedom and rose in arms against Tryon and King George.

To the number of 2,000 or 3,000 the Regulators, only partly armed and without organization, met the forces of the royal Governor at Alamance.

"Lay down your guns or I will fire!" shouted the British commander. "Fire and be damned!" shouted back the leader of the Regulators. At once the battle opened, and, of course, the Regulators were defeated and dispersed. But old Tryon received the lesson he had so long needed—that, while Americans could be shot down on the battlefield, they could not be made tamely to submit to the high-handed oppression of King George and his creatures.

On the afternoon of the day on which the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts adjourned, General Gage took the light infantry and grenadiers off duty and secretly prepared an expedition to destroy the colony's stores at Concord. The attempt had for several weeks been expected, and signals were concerted to announce the first movement of troops for the country. Samuel Adams and Hancock, who had not yet left Lexington for Philadelphia, received a timely message from Warren, and in consequence the Committee of Safety moved a part of the public stores and secreted the cannon.

On Tuesday, the eighteenth of April, ten or more British sergeants in disguise dispersed themselves through Cambridge and farther west to intercept all communication. In the following night the grenadiers and light infantry, not less than eight hundred in number, the flower of the army at Boston, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, crossed in the boats of the transport ships from the foot of the Common at East Cambridge.

Gage directed that no one else should leave the town, but Warren had, at ten o'clock, dispatched William Dawes through Roxbury and Paul Revere by way of Charlestown to Lexington.

Revere stopped only to engage a friend to raise the concerted signals, and two friends rowed him across the Charles River five minutes before the sentinels received the order to prevent it. All was still, as suited the hour. The Somerset, man-of-war, was winding with the young flood; the waning moon just peered above a clear horizon, while from a couple of lanterns in the tower of the North Church the beacon streamed to the neighboring towns as fast as light could travel.

A little beyond Charlestown Neck Revere was intercepted by two British officers on horseback, but being well mounted he turned suddenly and escaped by the road to[23] Medford. In that town he waked the captain and Minute Men, and continued to rouse almost every house on the way to Lexington, making the memorable ride of Paul Revere. The troops had not advanced far when the firing of guns and ringing of bells announced that their expedition had been heralded, and Smith sent back for a reinforcement.

Early on the nineteenth of April the message from Warren reached Adams and Hancock, who at once divined the object of the expedition. Revere, therefore, and Dawes, joined by Samuel Prescott, "a high Son of Liberty" from Concord, rode forward, calling up the inhabitants as they passed along, till in Lincoln they fell upon a party of British officers. Revere and Dawes were seized and taken back to Lexington, where they were released, but Prescott leaped over a low stone wall and galloped on for Concord.

There, at about two hours after midnight, a peal from the bell of the meeting house brought together the inhabitants of the place, young and old, with their firelocks, ready to make good the resolute words of their town debates. Among the most alert was William Emerson, the minister, with gun in hand, his powder horn and pouch of balls slung over his shoulder. By his sermons and his prayers his flock learned to hold the defense of their liberties a part of their covenant with God. His presence with arms strengthened their sense of duty.

From daybreak to sunrise, the summons ran from house to house through Acton. Express messengers and the call of Minute Men spread widely the alarm. How children trembled as they were scared out of sleep by the cries! How women, with heaving breasts, bravely seconded their husbands! How the countrymen, forced suddenly to arm, without guides or counsellors, took instant counsel of their courage! The mighty chorus of voices rose from the scattered farmhouses, and, as it were, from the ashes of the dead. "Come forth, champions of liberty; now free your country; protect your sons and daughters, your wives and[24] homesteads; rescue the houses of the God of your fathers, the franchises handed down from your ancestors." Now all is at stake; the battle is for all.

Lexington, in 1775, may have had seven hundred inhabitants. Their minister was the learned and fervent Jonas Clark, the bold inditer of patriotic state papers, that may yet be read on their town records. In December, 1772, they had instructed their representative to demand "a radical and lasting redress of their grievances, for not through their neglect should the people be enslaved." A year later they spurned the use of tea. In 1774, at various town meetings, they voted "to increase their stock of ammunition," "to encourage military discipline, and to put themselves in a posture of defense against their enemies." In December they distributed to "the train band and alarm list" arms and ammunition and resolved to "supply the training soldiers with bayonets."

At two in the morning, under the eye of the minister, and of Hancock and Adams, Lexington Common was alive with the Minute Men. The roll was called and, of militia and alarm men, about one hundred and thirty answered to their names. The captain, John Parker, ordered everyone to load with powder and ball, but to take care not to be the first to fire. Messengers sent to look for the British regulars reported that there were no signs of their approach. A watch was therefore set, and the company dismissed with orders to come together at beat of drum.

The last stars were vanishing from night when the foremost party, led by Pitcairn, a major of marines, was discovered advancing quickly and in silence. Alarm guns were fired and the drums beat, not a call to village husbandmen only, but the reveille of humanity. Less than seventy, perhaps less than sixty, obeyed the summons, and, in sight of half as many boys and unarmed men, were paraded in two ranks a few rods north of the meeting house.

The British van, hearing the drum and the alarm guns, halted to load; the remaining companies came up, and, at[25] half an hour before sunrise, the advance party hurried forward at double quick time, almost upon a run, closely followed by the grenadiers. Pitcairn rode in front and when within five or six rods of the Minute Men, cried out: "Disperse, ye villains! Ye rebels, disperse! Lay down your arms! Why don't you lay down your arms and disperse?" The main part of the countrymen stood motionless in the ranks, witnesses against aggression, too few to resist, too brave to fly. At this Pitcairn discharged a pistol, and with a loud voice cried "Fire!" The order was followed first by a few guns, which did no execution, and then by a close and deadly discharge of musketry.

Jonas Parker, the strongest and best wrestler in Lexington, had promised never to run from British troops, and he kept his vow. A wound brought him on his knees. Having discharged his gun he was preparing to load it again when he was stabbed by a bayonet and lay on the post which he took at the morning's drum beat. So fell Isaac Muzzey, and so died the aged Robert Munroe, who in 1758 had been an ensign at Louisburg. Jonathan Harrington, Jr., was struck in front of his own house on the north of the common. His wife was at the window as he fell. With blood gushing from his breast, he rose in her sight, tottered, fell again, then crawled on hands and knees toward his dwelling; she ran to meet him, but only reached him as he expired on their threshold. Caleb Harrington, who had gone into the meeting house for powder, was shot as he came out. Samuel Hadley and John Brown were pursued and killed after they had left the green. Asabel Porter, of Woburn, who had been taken prisoner by the British on the march, endeavoring to escape, was shot within a few rods of the common. Seven men of Lexington were killed, nine wounded, a quarter part of all who stood in arms on the green.

There on the green lay in death the gray-haired and the young; the grassy field was red "with the innocent[26] blood of their brethren slain," crying unto God for vengeance from the ground.

These are the village heroes who were more than of noble blood, proving by their spirit that they were of a race divine. They gave their lives in testimony to the rights of mankind, bequeathing to their country an assurance of success in the mighty struggle which they began. The expanding millions of their countrymen renew and multiply their praise from generation to generation. They fulfilled their duty not from an accidental impulse of the moment; their action was the ripened fruit of Providence and of time.

Heedless of his own danger, Samuel Adams, with the voice of a prophet, exclaimed: "Oh, what a glorious morning is this!" for he saw his country's independence hastening on, and, like Columbus in the tempest, knew that the storm bore him more swiftly toward the undiscovered land.

The British troops drew up on the village green, fired a volley, huzzaed thrice by way of triumph, and after a halt of less than thirty minutes, marched on for Concord. There, in the morning hours, children and women fled for shelter to the hills and the woods and men were hiding what was left of cannon and military stores.

The Minute Men and militia formed on the usual parade, over which the congregation of the town for near a century and a half had passed to public worship, the freemen to every town meeting, and lately the patriot members of the Provincial Congress twice a day to their little senate house. Near that spot Winthrop, the father of Massachusetts, had given counsel; and Eliot, the apostle of the Indians, had spoken words of benignity and wisdom. The people of Concord, of whom about two hundred appeared in arms on that day, derived their energy from their sense of the divine power.

The alarm company of the place rallied near the Liberty Pole on the hill, to the right of the Lexington road, in the front of the meeting house. They went to the perilous[27] duties of the day "with seriousness and acknowledgment of God," as though they were to engage in acts of worship. The minute company of Lincoln, and a few men from Acton, pressed in at an early hour; but the British, as they approached, were seen to be four times as numerous as the Americans. The latter, therefore, retreated, first to an eminence eighty rods farther north, then across Concord River, by the North Bridge, till just beyond it, by a back road, they gained high ground about a mile from the center of the town. There they waited for aid.

About seven o'clock, under brilliant sunshine, the British marched with rapid step into Concord, the light infantry along the hills and the grenadiers in the lower road.

At daybreak the Minute Men of Acton crowded at the drum-beat to the house of Isaac Davis, their captain, who "made haste to be ready." Just thirty years old, the father of four little ones, stately in person, a man of few words, earnest even to solemnity, he parted from his wife, saying: "Take good care of the children," and while she gazed after him with resignation he led off his company.

Between nine and ten the number of Americans on the rising ground above Concord Bridge had increased to more than four hundred. Of these, there were twenty-five men from Bedford, with Jonathan Wilson for their captain; others were from Westford, among them Thaxter, a preacher; others from Littleton, from Carlisle, and from Chelmsford. The Acton company came last and formed on the right; the whole was a gathering not so much of officers and soldiers as of brothers and equals, of whom every one was a man well known in his village, observed in the meeting houses on Sundays, familiar at town meetings and respected as a freeholder or a freeholder's son.

Near the base of the hill Concord River flows languidly in a winding channel and was approached by a causeway over the wet ground of its left bank. The by-road from the hill on which the Americans had rallied ran southerly[28] till it met the causeway at right angles. The Americans saw before them, within gunshot, British troops holding possession of their bridge, and in the distance a still larger number occupying their town, which, from the rising smoke, seemed to have been set on fire.

The Americans had as yet received only uncertain rumors of the morning's events at Lexington. At the sight of fire in the village the impulse seized them "to march into the town for its defense." But were they not subjects of the British king? Had not the troops come out in obedience to acknowledged authorities? Was resistance practicable? Was it justifiable? By whom could it be authorized? No union had been formed, no independence proclaimed, no war declared. The husbandmen and mechanics who then stood on the hillock by Concord River were called on to act and their action would be war or peace, submission or independence. Had they doubted, they must have despaired. Prudent statesmanship would have asked for time to ponder. Wise philosophy would have lost from hesitation the glory of opening a new era for mankind. The small bands at Concord acted and God was with them.

"I never heard from any person the least expression of a wish for a separation," Franklin, not long before, had said to Chatham. In October, 1774, Washington wrote: "No such thing as independence is desired by any thinking man in America." "Before the nineteenth of April, 1775," relates Jefferson, "I never heard a whisper of a disposition to separate from Great Britain." Just thirty-seven days had passed since John Adams published in Boston, "That there are any who pant after independence is the greatest slander on the province."

The American Revolution grew out of the souls of the people and was an inevitable result of a living affection for freedom, which set in motion harmonious effort as certainly as the beating of the heart sends warmth and color through the system.

The officers, meeting in front of their men, spoke a few words with one another and went back to their places. Barrett, the colonel, on horseback in the rear, then gave the order to advance, but not to fire unless attacked. The calm features of Isaac Davis, of Acton, became changed; the town schoolmaster of Concord, who was present, could never afterwards find words strong enough to express how deeply his face reddened at the word of command. "I have not a man that is afraid to go," said Davis, looking at the men of Acton, and, drawing his sword, he cried: "March!" His company, being on the right, led the way toward the bridge, he himself at their head, and by his side Major John Buttrick, of Concord, with John Robinson, of Westford, lieutenant-colonel in Prescott's regiment, but on this day a volunteer without command.

These three men walked together in front, followed by Minute Men and militia in double file, training arms. They went down the hillock, entered the by-road, came to its angle with the main road and there turned into the causeway that led straight to the bridge. The British began to take up the planks; to prevent it the Americans quickened their step. At this the British fired one or two shots up the river; then another, by which Luther Blanchard and Jonas Brown were wounded. A volley followed, and Isaac Davis and Abner Hosmer fell dead. Three hours before, Davis had bid his wife farewell. That afternoon he was carried home and laid in her bedroom. His countenance was pleasant in death. The bodies of two others of his company, who were slain that day, were brought to her house, and the three were followed to the village graveyard by a concourse of neighbors from miles around. Heaven gave her length of days in the land which his self-devotion assisted to redeem. She lived to see her country reach the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific; when it was grown great in numbers, wealth and power, the United States in Congress bethought themselves to pay[30] honors to her husband's martyrdom and comfort her under the double burden of sorrow and of more than ninety years.

As the British fired, Emerson, who was looking on from an upper window in his house near the bridge, was for one moment uneasy lest the fire should not be returned. It was only for a moment; Buttrick, leaping in the air and at the same time partially turning around, cried aloud: "Fire, fellow soldiers! for God's sake, fire!" and the cry "fire! fire! fire!" ran from lip to lip. Two of the British fell, several were wounded, and in two minutes all was hushed. The British retreated in disorder toward their main body; the countrymen were left in possession of the bridge. This is the world renowned "Battle of Concord," more eventful than Agincourt or Blenheim.

The Americans stood astonished at what they had done. They made no pursuit and did no further harm, except that one wounded soldier, attempting to arise if to escape, was struck on the head by a young man with a hatchet. The party at Barrett's might have been cut off, but was not molested. As the Sudbury company, commanded by the brave Nixon, passed near the South Bridge, Josiah Haynes, then eighty years of age, deacon of the Sudbury Church, urged an attack on the British party stationed there; his advice was rejected by his fellow soldiers as premature, but the company in which he served proved among the most alert during the rest of the day.

In the town of Concord, Smith, for half an hour, showed by marches and counter-marches his uncertainty of purpose. At last, about noon, he left the town, to retreat the way he came, along the hilly road that wound through forests and thickets. The Minute Men and militia who had taken part in the fight ran over the hills opposite the battle field into the east quarter of the town, crossed the pasture known as the "Great Fields," and placed themselves in ambush a little to the eastward of the village, near the junction of the Bedford road. There they were reinforced[31] by men from all around and at that point the chase of the English began.

Among the foremost were the Minute Men of Reading, led by John Brooks and accompanied by Foster, the minister of Littleton, as a volunteer. The company of Billerica, whose inhabitants, in their just indignation at Nesbit and his soldiers, had openly resolved to "use a different style from that of petition and complaint" came down from the north, while the East Sudbury company appeared on the south. A little below the Bedford road at Merriam's corner the British faced about, but after a sharp encounter, in which several of them were killed, they resumed their retreat.

At the high land in Lincoln the old road bent toward the north, just where great trees on the west and thickets on the east offered cover to the pursuers. The men from Woburn came up in great numbers and well armed. Along these defiles fell eight of the British. Here Pitcairn for safety was forced to quit his horse, which was taken with his pistols in their holsters. A little farther on Jonathan Wilson, captain of the Bedford Minute Men, too zealous to keep on his guard, was killed by a flanking party. At another defile in Lincoln, the Minute Men at Lexington, commanded by John Parker, renewed the fight. Every piece of wood, every rock by the wayside, served as a lurking place. Scarce ten of the Americans were at any time seen together, yet the hills seemed to the British to swarm with "rebels," as if they had dropped from the clouds, and "the road was lined" by an unintermitted fire from behind stone walls and trees.

At first the invaders moved in order; as they drew near Lexington, their flanking parties became ineffective from weariness; the wounded were scarce able to get forward. In the west of Lexington, as the British were rising Fiske's hill, a sharp contest ensued. It was at the eastern foot of the same hill that James Hayward, of Acton, encountered a regular, and both at the same moment fired; the regular[32] dropped dead; Hayward was mortally wounded. A little farther on fell the octogenarian, Josiah Haynes, who had kept pace with the swiftest in the pursuit.

The British troops, "greatly exhausted and fatigued and having expended almost all of their ammunition," began to run rather than retreat in order. The officers vainly attempted to stop their flight. "They were driven before the Americans like sheep." At last, about two in the afternoon, after they had hurried through the middle of the town, about a mile below the field of the morning's bloodshed, the officers made their way to the front and by menaces of death began to form them under a very heavy fire.

At that moment Lord Percy came in sight with the first brigade, consisting of Welsh Fusiliers, the Fourth, the Forty-seventh and the Thirty-eighth Regiments, in all about twelve hundred men, with two field pieces. Insolent, as usual, they marched out of Boston to the tune of Yankee Doodle, but they grew alarmed at finding every house on the road deserted.

While the cannon kept the Americans at bay, Percy formed his detachment into a square, enclosing the fugitives, who lay down for rest on the ground, "their tongues hanging out of their mouths like those of dogs after a chase."

After the juncture of the fugitives with Percy, the troops under his command amounted to fully two-thirds of the British Army in Boston, and yet they must fly before the Americans speedily and fleetly, or be overwhelmed. Two wagons, sent out to them with supplies, were waylaid and captured by Payson, the minister of Chelsea. From far and wide Minute Men were gathering. The men of Dedham, even the old men, received their minister's blessing and went forth, in such numbers that scarce one male between sixteen and seventy was left at home. That morning William Prescott mustered his regiment, and though Pepperell was so remote that he could not be in[33] season for the pursuit, he hastened down with five companies of guards. Before noon a messenger rode at full speed into Worcester, crying: "To arms!" A fresh horse was brought and the tidings went on, while the Minute Men of that town, after joining hurriedly on the common in a fervent prayer from their minister, kept on the march till they reached Cambridge.

Aware of his perilous position, Percy, resting but half an hour, renewed his retreat.

Beyond Lexington the troops were attacked by men chiefly from Essex and the lower towns. The fire from the rebels slackened till they approached West Cambridge, where Joseph Warren and William Heath, both of the committee of safety, the latter a provincial general officer, gave for a moment some appearance of organization to the pursuit, and the fight grew sharper and more determined. Here the company from Danvers, which made a breastwork of a pile of shingles, lost eight men, caught between the enemy's flank guard and main body. Here, too, a musket ball grazed the hair of Joseph Warren, whose heart beat to arms, so that he was ever in the place of greatest danger. The British became more and more "exasperated" and indulged themselves in savage cruelty. In one house they found two aged, helpless, unarmed men and butchered them both without mercy, stabbing them, breaking their skulls and dashing out their brains. Hannah Adams, wife of Deacon Joseph Adams, of Cambridge, lay in child-bed with a babe of a week old, but was forced to crawl with her infant in her arms and almost naked to a corn shed, while the soldiers set her house on fire. Of the Americans there were never more than four hundred together at any time; but, as some grew tired or used up their ammunition, others took their places, and though there was not much concert or discipline and no attack with masses, the pursuit never flagged.

Below West Cambridge the militia from Dorchester, Roxbury and Brookline came up. Of these, Isaac Gardner,[34] of the latter place, one on whom the colony rested many hopes, fell about a mile west of Harvard College. The field pieces began to lose their terror, so that the Americans pressed upon the rear of the fugitives, whose retreat was as rapid as it possibly could be. A little after sunset the survivors escaped across Charlestown Neck.

The troops of Percy had marched thirty miles in ten hours; the party of Smith in six hours had retreated twenty miles; the guns of the ship-of-war and the menace to burn the town of Charlestown saved them from annoyance during the rest on Bunker Hill and while they were ferried across Charles River.

On that day forty-nine Americans were killed, thirty-four wounded and five missing. The loss of the British in killed, wounded and missing was two hundred and seventy-three. Among the wounded were many officers; Smith was hurt severely. Many more were disabled by fatigue.

"The night preceding the outrages at Lexington there were not fifty people in the whole colony that ever expected any blood would be shed in the contest"; the night after, the king's governor and the king's army found themselves closely beleaguered in Boston.

"The next news from England must be conciliatory, or the connection between us ends," said Warren. "This month," so wrote William Emerson, of Concord, late chaplain to the Provincial Congress, chronicled in a blank leaf of his almanac, "is remarkable for the greatest events of the present age." "From the nineteenth of April, 1775," said Clark, of Lexington, on its first anniversary, "will be dated the liberty of the American world."

Note.—The principal part of this account of the Battle of Lexington is taken from Banecroft's history.—American Monthly Magazine.

(Poem that embraces the names of the famous Americans.)

It will not be denied that the men who, on July 4, 1776, pledged "their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor" in behalf of our national liberty deserve the most profound reverence from every American citizen. By arranging in rhyme the names of the signers according to the colonies from which they were delegated it will assist the youthful learner in remembering the names of those fathers of American Independence.

Mrs. Harriet D. Eisenberg.

I have chosen to look up particulars concerning the daily life of the soldier at Valley Forge in the awful winter of 1777-8. And as no historian can picture the life of any period so vividly as it may be described by those who were participants in that life, or eye witnesses of it, I have gathered the materials for this paper from diaries of those who were there, from accounts by men whose friends were in the camp, from letters sent to and from the camp, and from the orderly book of a general who kept a strict report of the daily orders issued by the Commander-in-chief, from the fall campaign of 1777, to the late spring of 1778.

It is unnecessary to reiterate what all of us know,—that the winter of '77-8 was the blackest time of the war of Independence, and it was made so, not only by the machinations of the enemies of Washington who were striving to displace him as Commander-in-Chief, but by the unparalleled severity of the winter and the dearth of the commonest necessaries of life. The sombreness of the picture is emphasized by contrast with the brightness and gaiety that characterized the life in Philadelphia during that same winter when the British troops occupied the city. There a succession of brilliant festivities was going on, the gaieties culminating in the meschianza that most gorgeous spectacle ever given by an army to its retiring officer, when Peggy Shippen and Sallie Chew danced the night away with the scarlet-coated officers of the British army, while fathers and brothers were suffering on the hills above the Schuylkill.

Why did Washington elect to put his army in winter-quarters? He himself answers the question, which was asked by congress who objected to the army's going into winter quarters at all. The campaign, which had seen the battles of the Brandywine and of Germantown, was over; the British were in possession of Philadelphia; the army[38] was fatigued and there was little chance of recuperation from sources already heavily drained. Hence a winter's rest was necessary. And Washington's own words, as he issued the orders for the day on December 23d, tell us why Valley Forge was chosen.

"The General wishes it was in his power to conduct the troops into the best winter quarters; but where are those to be found? Should we retire into the interior portions of the country, we should find them crowded with virtuous citizens who, sacrificing their all, have left Philadelphia, and fled hither for protection. To their distress, humanity forbids us to add. This is not all. We should leave a vast extent of fertile country to be despoiled and ravaged by the enemy. These and other considerations make it necessary to take such a position (as this), and influenced by these considerations he persuades himself that officers and soldiers, with one heart and one mind, will resolve to surmount every difficulty with the fortitude and patience becoming their profession and the Sacred Cause in which they are engaged. He himself, will share in the hardships, and partake of every inconvenience."

And with this resolve on his part, kept faithfully through the long weeks, the bitter winter was begun.

It was on December 12th that a bridge of wagons was made across the Schuylkill and the army, already sick and broken down, moved over. On that day, Dr. Waldo, a surgeon from Connecticut made this entry in his diary:

"Sunset. We are ordered to march over the river. I'm sick—eat nothing—no whiskey—no baggage. Lord-Lord-Lord."

A few days later he makes this entry:

"The army, who have been surprisingly healthy hitherto, now begin to grow sickly. They still show alacrity and contentment not to be expected from so young troops.

"I am sick, discontented, out of humor. Poor food, hard lodging—cold weather—fatigue—nasty clothes—nasty cooking—smoked out of my senses, vomit half my time—the Devil's in it. I can't endure it.

"Here comes a bowl of soup—full of burnt leaves and dirt.—Away with it, boys. I'll live like the chameleon upon air. 'Pooh-pooh,' says Patience. You talk like a fool.—See the poor soldier—with what cheerfulness he meets his foes and encounters hardships. If bare of foot he labors through mud and cold, with a song extolling war and Washington. If his food is bad he eats it with contentment and whistles it into digestion.—There comes a soldier—his bare feet are seen through his worn out shoes. His legs are nearly naked from his tattered remains of an old pair of stockings—his shirt hanging in strings,—his hair dishevelled—his face meagre—his whole appearance pictures a person forsaken and discouraged. He comes and cries with despair—I am sick. My feet are lame—my legs are sore—my body covered with tormenting itch—my clothes worn out—my constitution broken. I fail fast. I shall soon be no more. And all the reward I shall get will be—'Poor Will is dead.'"

On the 21st of December this entry appears:

"A general cry through the camp this evening: 'no meat—no meat.' The distant vales echo back—'no meat.' 'What have you for dinner, Boys?' 'Nothing but fire-cake and water, sir! At night. 'Gentlemen, supper is ready.' 'What is your supper, lads?' 'Fire-cake and water Sir.'"

Again on December 22d:

"Lay excessive cold and uncomfortable last night. My eyes started out of their orbits like a rabbit's eyes, occasioned by a great cold and smoke. Huts go slowly. Cold and smoke make us fret.—I don't know anything that vexes a man's soul more than hot smoke continually blowing into one's eyes, and when he attempts to avoid it, he is met by a cold and freezing wind."

On December 25th, Xmas, this entry:

"Still in tents. The sick suffer much in tents. We give them mutton and grog and capital medicine it is once in a while."

January 1st:

"I am alive. I am well. Huts go on briskly."

I have quoted thus lengthily from this diary, which gives, perhaps, the most vivid picture we possess of that[40] dark period, simply because it touches upon almost all that concerns the life of the soldiers that winter,—upon their dwellings, their food, their health, their courage.

The Doctor repeatedly speaks of the huts which were to shelter the men. In the order issued by Washington to his generals early in December, directions were given concerning the construction of these dwellings. According to these directions, the major-generals, accompanied by the engineers, were to fix on the proper spot for hutting. The sunside of the hills was chosen, and here they constructed long rows of log huts, and made numerous stockades and bristling pikes for defence along the line of the trench. For these purposes and for their fuel they cut off an entire forest of timber. Can't you hear the steady crash of the ax held by hands benumbed with the cold, as blow, by blow, they felled the trees on the hillside, eager to erect the crude huts which were to give better shelter than the tents in which they were yet shivering and choking? In cutting their fire wood, the soldiers were directed to save such parts of each tree as would do for building, reserving 16 or 18 feet of trunk for logs to rear their huts. "The quartermaster-general, (so says the order of December 20th) is to delay no time, but procure large quantities of straw, either for covering the huts or for beds." This last item would suggest the meagreness of the furnishing. Throughout the entire winter the soldier could look for few of the barest necessities of life. An order from headquarters directed that each hut should be provided with a pail. Dishes were a rarity. Each soldier carried his knife in his pocket, while one horn spoon, a pewter dish, and a horn tumbler into which whiskey rarely entered, did duty for a whole mess. The eagerness to possess a single dish is illustrated by an anecdote which has come down in my own family, if I may presume to narrate it. My Revolutionary ancestor was a manufacturer of pottery. In the leisure hours of this bitter time at Valley Forge, he built a kiln and burnt some pottery. Just as it was time to open the ovens, a band of[41] soldiers rushed upon them, tearing them down, and triumphantly marched off with their prize, leaving Captain Piercy as destitute of dishes as before.

As for the food that was meant to sustain the defenders of our liberty, the diary I have quoted, together with Washington's daily orders, gives us sufficient information to enable us to judge of its meagreness. Often their food was salted herring so decayed that it had to be dug 'en masse' from the barrels. Du Poncean, a young officer, aid to Baron Steuben, related to a friend, a few years after the war, some facts of stirring interest. "They bore," he says, "with fortitude and patience. Sometimes, you might see the soldiers pop their heads out from their huts and call in an undertone—'no bread, no soldier;' but a single word from their officer would still their complaint." Baron Steuben's cook left him at Valley Forge, saying that when there was nothing to cook, any one might turn the spit.

The commander-in-chief, partaking of the hardships of his brave men, was accustomed to sit down with his invited officers to a scanty piece of meat, with some hard bread and a few potatoes. At his house, called Moore Hall, they drank the prosperity of the nation in humble toddy, and the luxurious dessert consisted of a dish of hazel nuts.

Even in those scenes, Mrs. Washington, as was her practice in the winter campaign, had joined her husband, and always at the head of the table maintained a mild and dignified, yet cheerful manner. She busied herself all day long, with errands of grace, and when she passed along the lines, she would hear the fervent cry,—"God bless Lady Washington."

I need not go into details concerning the lack of clothing—the diary I have quoted is sufficiently suggestive. An officer said, some years after the war, that many were without shoes, and while acting as sentinels, had doffed their hats to stand in, to save their feet from freezing. Deserters to the British army—for even among the loyal American troops there were some to be found who could[42] not stand up against cold and hunger and disease and the inducement held out by the enemy to deserters—would enter Philadelphia shoeless and almost naked—around their body an old, dirty blanket, fastened by a leather belt around the waist.

One does not wonder that disease was rampant, that orders had to be issued from headquarters for the proper treatment of the itch; for inoculation against smallpox, for the care of those suffering from dysentery which was widespread in the camp. On January 8, an order was issued from the commander-in-chief to the effect that men rendered unfit for duty by the itch be looked after by the surgeon and properly disposed in huts where they could be annointed for the disease. Hospital provisions were made for the sick. Huts, 15 by 25 and 9 feet high, with windows in each end, were built, two for each brigade. They were placed at or near the center, and not more than 100 yards from the bridge. But such were the ravages of the disease that long trenches in the vale below the hill were dug, and filled in with the dead.

To turn to the activities of the camp,—its duties, privileges, and amusements, and even its crimes. Until somewhat late in the spring, when Baron Steuben arrived at Valley Forge, there was little system observed in the drilling of the several brigades. Yet each day's military duty was religiously attended to, that there might, at least, be some preparation for defence in case of an attack from the superior force at Philadelphia. The duties of both rank and file were strictly laid down by Washington, and any dereliction was punished with military strictness.

In the commands issued on February 8, the order of the day is plainly indicated. I give the words from Orderly book:

"Reveille sounded at daybreak—troop at 8—retreat at sunset—tattoo at 9. Drummers call to beat at the right of first line and answer through that line. Then through the second and corp of artillery, beginning at the left. Reserve shall follow[43] the second line immediately upon this. Three rolls, to begin, and run through in like manner as the call. Then all the drums of the army at the heads of their respective corps shall go through the regular beats, ceasing upon the right which will be a sign for the whole to cease."

Don't you imagine that you hear the rise and fall of the notes as they echoed and re-echoed over the frozen hills and thrilled the hearts that beat beneath the rags in the cold winter morning?

The daily drill on parade, the picket duty, the domestic duties incumbent upon the men in the absence of the women, the leisure hours, then taps, and the day's tale was told.

I should like to tell you of the markets established, for two days each, at three separate points on the outskirts of the camp, where for prices fixed by a schedule to prevent extortion, the soldiers, fortunate enough to possess some money might add to their meagre supplies some comforts in food or clothing. I should like to tell of the sutlers that followed each brigade, and the strict rules that governed their dealings with the army,—of the funerals, the simple ceremonies of which were fixed by orders from headquarters; of the gaming among the soldiers, which vice Washington so thoroughly abhorred that he forbade, under strictest penalties, indulgence in even harmless games of cards and dice. I should like to tell of the thanksgiving days appointed by congress for some signal victory of the northern army, or for the blessing of the French alliance, on which days the camp was exempt from ordinary duty and after divine service the day was given over to the men. Or I should like to tell of Friday the "Flag day" when a flag of truce was carried into Philadelphia and letters were sent to loved ones, and answers brought back containing disheartening news of the gaieties then going on, or encouraging accounts of the sacrifices of mothers and daughters in the cause of liberty. And finally I should like to tell you of the court martials, through the reports[44] of which we get such a vivid picture of the intimate life of the time: of the trial by court martial of Anthony Wayne, who was acquitted of the charge of conduct unbecoming an officer; of the trial of a common soldier for stealing a blanket from a fellow soldier, and the punishment by 100 lashes on his bare back; of the trial of a Mary Johnson who plotted to desert the camp and who, between the lined up ranks of the brigade, was drummed out of camp; of the trial of John Riley for desertion, and his execution on parade ground, with the full brigade in attendance; of the dramatic punishment of an officer found guilty of robbery and absenting himself, with a private, without leave, and who was sentenced to have his sword broken over his head on grand parade at guard mount. I should like to tell, too, of the foraging parties sent out to scour the country for food and straw; and the frequent skirmishes with detachments of the enemy; of the depredations made by the soldiers on the surrounding farmers, which depredations were so deplored by Washington and which tried so his great soul I wanted to speak of the greatness of the Commander-in-Chief in the face of all he had to contend with—the continued depredations of his men; the repeated abuse of privilege; the frequent disobedience of orders; the unavoidably filthy condition of the camp; the suffering of the soldiers; the peril from a powerful enemy,—all sufficient to make a soul of less generous mould succumb to fate, yet serving only in Washington's case to make him put firmer trust in an Almighty Power and in the justice of his cause.

At the opening of the spring a greater activity prevailed in the camp. With the coming of Baron Steuben, the army was uniformly drilled in the tactics of European warfare. With the new appropriation of congress, new uniforms were possible and gave a more military appearance to the army. It was no longer necessary, therefore, for Washington to issue orders that the men must appear on parade with beards shaven and faces clean, though[45] their garments were of great variety and ragged. And with the coming of the spring, and of greater comforts in consequence, Washington, in recognition of the suffering, fidelity and patriotism of his troops took occasion to commend them in these words:

"The Commander-in-Chief takes this occasion to return his thanks to the officers and soldiers of this army for that persevering fidelity and zeal which they have uniformly manifested in all their conduct. Their fortitude not only under the common hardships incident to a military life, but also, under the additional suffering to which the peculiar situation of these states has exposed them, clearly proves them to be men worthy the enviable privilege of contending for the rights of human nature—the freedom and independence of the country. The recent instance of uncomplaining patience during the late scarcity of provisions in camp is a fresh proof that they possess in eminent degree the spirits of soldiers and the magnanimity of patriots. The few who disgraced themselves by murmuring, it is hoped, have repented such unmanly behaviour and have resolved to emulate the noble example of their associates—Soldiers, American Soldiers, will despise the meanness of repining at such trifling strokes of adversity, trifling indeed when compared with the transcendent prize which will undoubtedly crown their patience and perseverance.

"Glory and freedom, peace and plenty, the admiration of the world, the love of their country and the gratitude of posterity."—American Monthly Magazine.

By Emily Hendree Park.

The screeching of the steam whistle at the Williamsburg station seemed a curious anachronism, a noisy, pushing impertinence, a strident voice of latter-day vulgar haste. But when the big engine had rolled away, puffing and blowing and screaming as if in mischievous and irreverent effort to disturb the archaic dreams of the fast-asleep town, the "exceeding peace" which always dwells in Williamsburg, fell upon our hilarious spirits. We wandered about the streets with hushed voices and reverent eyes. The throbbing pulse of the gay, stirring, rebellious heart of the old capital of Virginia had been still for a century.

On entering Bruton church, the eye is first attracted on the right of the chancel to the novel sight of the governor's seat, high canopied and richly upholstered in crimson and gilt. The high-backed chair is railed off from the "common folk," and the name Alexander Spotswood in gold lettering runs around the top of the canopy. At once you realize that this was indeed the court church of the vice-regal court at Williamsburg, and that you are in old Colonial Virginia. The lines "He rode with Spotswood and Spotswood men," the knights of the "Golden Horse Shoe," run through the brain, and the knightly figure of Raleigh, the chivalric founder of the colony, and brave John Smith and a score of others, heroes of that elder day, come from out the shadowy past, and hover about one. You look at the quaint old pulpit, on the left of the church, with its high-sounding board, and then glance down at the pew on your right, which bears the name of George Washington, and opposite the plate on the pew reads Thomas Jefferson, and next are James Madison and the seven signers of the Declaration of Independance, and Peyton Randolph and Patrick Henry and the doughty members of the house of burgesses who worshiped here,[47] and whose liberty-loving spirits fired the world with their brave protests against tyranny. When you read these names, suddenly the church seems full of the men who bore them, and you are surrounded by that goodly company of heroes who made Virginia and America, the cradle of liberty. The magic spell is upon you. You turn cold and burning hot with high enthusiasm and the glory of the vision. You are roused from your trance by the pleasant voice of the young minister, Mr. John Wing, who is saying: "Now we will go down into the crypt."

There are treasures in the crypt indeed. We follow in a dazed fashion, and are shown the Jamestown communion service; the communion silver bearing the coat-of-arms of King George III; the ancient communion silver of the College of William and Mary; the Colonial prayer book, with the prayer for the president pasted over the prayer for King George III; a parish register of 1662, the pre-Revolutionary Bible; coins found while excavating in the church, and brass head-tack letters and figures by which some of the graves in the aisles and chancel were identified. We are told that the date of parish was 1632, first brick church, 1674-83; present church 1710-15. Precious and deeply interesting, but I imagined that I could hear the tread of that "knightly company" upstairs, who let neither silver nor gold nor the glitter of the vice-regal court at Williamsburg seduce them from their love of liberty, nor dull their hatred of tyranny in its slightest exercise. Ah! there were giants in those days among those Virginia pioneers, in whose veins ran the hot blood of the cavalier, who loved truth and hated a lie, who loved life and despised danger, and feared not death nor "king nor kaiser," descendants of the valiant Jamestown colonists to whom Nathaniel Bacon cried one hundred years before: "Come on, my hearts of gold!"

The tombstones in the aisle and chancel of the church include the tombs of two Colonial governors—Francis Fauquier and Edmund Jennings—and the graves of the great-grandfather,[48] the grandfather and grandmother of Mrs. Martha Washington. After reading the quaint inscription on the marble mural tablet in memory of Colonel Daniel Parke and the inscriptions on the bronze mural tablets memorial to Virginia churchmen and patriots, we climb to "Lord Dunmore's gallery," where, tradition says, the boys of William and Mary College used to be locked in for their soul's edification until service was over, and where we sat in Thomas Jefferson's accustomed place, from whence he looked down upon the heads of the members of the house of burgesses and the Colonial vestrymen of distinguished memory. Is it any wonder that in such environment the boy's dreamy aspirations crystallized into the high resolve of becoming a patriot and statesman? For in those stormy days preceding the Revolution this little Bruton parish church was a very Pantheon of living heroes.

Fiske, the New England historian, says that "the five men who more than any others have shaped the future of American history were Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Marshall and Hamilton." All but Hamilton were Virginians and worshipers at Bruton church, and two of them were students of the College of William and Mary. Distinction unrivaled for the state, the church, the college.

And now we walk into the church yard, under venerable trees, among crumbling grave stones and see the Pocahontas baptismal font and the tombs of the Custis children and Colonial Governor Knott.

We are shown the home of George Wythe, the signer of the Declaration, the teacher of Jefferson, Monroe and Marshall. Great teacher of greater pupils! Inspirer of high thoughts and immortal deeds! One of the students at William and Mary, Jefferson, wrote the declaration, three were presidents, and another, John Marshall, was Chief Justice of the United States. The headquarters of Washington, the site of the first theater in America, 1732, the Ancient Palace green on the right hand of which is the fictional home of Audrey, and several ancient colonial[49] homes are pointed out to us. If any vestige remains of the old Raleigh tavern, whose "Apollo" room was famous as the gathering place of the burgesses, who, after their dismissal in 1769 asked an agreement not to use or import any article upon which a tax is laid—it was not shown to us.

The old powder horn or powder magazine, a curious hexagonal building, has been admirably restored and stands as a reminder of that dramatic scene in Virginia history in 1775 when, after Lord Dunmore had removed the powder from the magazine into one of the vessels in the James, fearing an uprising of the colonists, Patrick Henry, with an armed force from Hanover, stalked into the governor's presence and demanded the return of the powder or its equivalent in money. Lord Dunmore, looking into those dauntless eyes, beholds the dauntless soul of the "Firebrand of the Revolution" behind them, and yields at once and pays down £330 sterling. Patrick Henry, with splendid audacity, seizes a pen and signs the receipt, "Patrick Henry, Jr." making himself alone responsible for this act of high treason, and then, that there may be no doubt as to his signature, he has it attested by two distinguished gentlemen. What heroic daring! What impassioned love of liberty! While Peyton, Randolph and Richard Henry Lee counsel caution, Patrick Henry acts and becomes the inspired genius of the revolution, fusing the disunited and hesitating colonies into a nation by the white heat of his burning passion for freedom.

First in importance of all the historic places in Williamsburg is the venerable college of William and Mary. Founded in 1693, next to Harvard the oldest college in the United States, it soon became the "intellectual center of the colony of Chesapeake Bay," the alma mater of the patriots who fought for the life of the young republic and of the statesmen who formed its constitution and guided its course in its infant years. It has furnished to our country fifteen senators and seventy representatives in congress; thirty-seven[50] judges, and Chief Justice Marshall; seventeen governors of states and three presidents of the United States—Jefferson, Monroe and Tyler. James Blair, a Scotchman, was its first president and remained so for fifty years. The ivy-clad buildings of the old college nestle among ancient trees on a wide campus, and so venerable is the look of the place that the new hall seems a modern intruder, though of quiet and well-mannered architecture. The quiet air of scholarly seclusion reminds one of Oxford. It was commencement day, and we found the buildings decorated with white and yellow, the college colors. The chapel, with its oil paintings of presidents, donors and patriots, and the library with its rare volumes and priceless old documents and portraits and engravings, are full of interest. A marble statue of one of the old governors—Botetourt, I believe—stands in the silence of the centuries in front of the old college.

"Yas'm ris de place, de house er buggesses, dey call it, 'cause de big bugs of ole Virginny sot dere er making laws. 'Fo de Lawd, marm, dey wuz big bugs; quality folks, quality folks." And John Randolph, our colored coachman, waved his hand with a proud air of ownership, as if he were displaying lofty halls with mahogany stairs and marble pillars, instead of the mortar and brick foundation, in its bare outline, of the old capitol, or House of Burgesses.

"Walk right in, suh. Bring de ladies dis way, boss," John Randolph urged, in a tone of lordly hospitality. "Right hyah is the charmber (room) whar Marse Patrick Henry made dat great speech agin de king—old Marse King George—or bossin' uv de colonies. He wuz er standing on dis very spot, and he lif' up his voice like a lion and he sez, sez he—"

"What did he say?" as the old man paused.