The

STRAND MAGAZINE

An Illustrated Monthly

EDITED BY

GEO. NEWNES

Vol. I

JANUARY TO JUNE

London:

BURLEIGH STREET, STRAND

1891

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Strand Magazine - Vol. 1 - No. 5 - May

1891, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Strand Magazine - Vol. 1 - No. 5 - May 1891

An Illustrated Monthly

Author: Various

Editor: George Newnes

Release Date: July 30, 2014 [EBook #46452]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STRAND MAGAZINE, MAY 1891 ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Dianna Adair, Jonathan Ingram

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

EDITED BY

GEO. NEWNES

Vol. I

JANUARY TO JUNE

London:

BURLEIGH STREET, STRAND

1891

Table of Contents Added by Transcriber

An Eighteenth Century Juliet.

A Day With an East-end Photographer.

The Notorious Miss Anstruther.

The Guest of a Cannibal King.

Old Stone Signs of London.

Captain Jones of the "Rose."

Child Workers in London.

Portraits of Celebrities at Different Times of Their Lives.

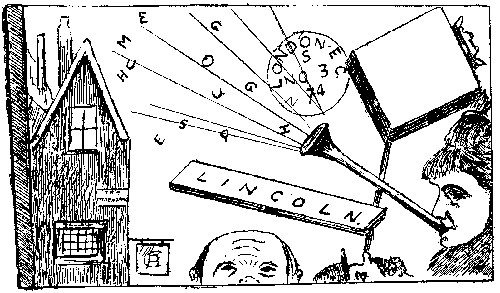

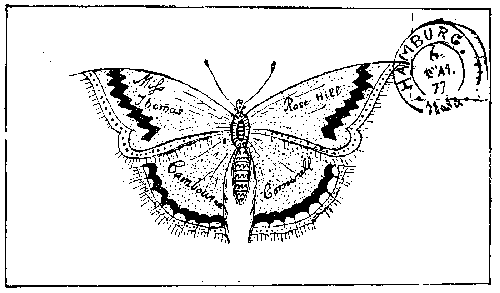

Humours of the Post Office.

Jenny.

The State of the Law Courts.

The Pastor's Daughter of Seiburg.

Stories of the Victoria Cross: Told by Those Who Have Won It.

The Enchanted Whistle.

"GABRIELLE JOINED HER PRAYERS TO HER LOVER'S."

(An Eighteenth Century Juliet.)

By James Mortimer.

French judicial annals are rich in strange and romantic episodes, but there are few narratives so replete with pathetic interest as the story of Gabrielle de Launay, a lady whose cause was tried before the High Court of Paris about the middle of the eighteenth century, and created a profound sensation throughout France at that epoch.

Mademoiselle de Launay was the only child of an eminent judge of Toulouse, where Gabrielle was born about the year 1730. M. de Launay, as the President of the Civil Tribunal of Toulouse, occupied a position of distinction, to which he was additionally entitled as a member of one of the leading families of the province. Between himself and the son of the late General de Serres, a deceased friend of the President de Launay, there existed an intimacy which gave colour to the belief entertained in the most exclusive social circles of Toulouse that young Captain Maurice de Serres was selected to be the future husband of the judge's beautiful daughter, then in her eighteenth year, whilst Maurice was nine years her senior. The birth and fortune of the two young people were equally in harmony, and the match thus appeared in every way suitable.

The surmises of the gossips were shortly confirmed by the formal announcement of the betrothal, and Maurice was on the point of asking the approval of his widowed mother, who resided in Paris, when an incident occurred which threatened to dash the cup of happiness from his lips. An official letter from the Minister of War reached Captain de Serres, instructing him, with all despatch, to rejoin his regiment, suddenly ordered abroad on active service in the far East.

The next morning, at an early hour, the young officer presented himself at the residence of President de Launay, greatly to the surprise of the worthy judge and his daughter, to whom he despairingly imparted the untoward tidings. The grief of Maurice and Gabrielle at the prospect of their sudden separation, for a long and uncertain period, was poignant in the extreme, and M. de Launay was himself profoundly distressed by this unexpected blow to his projects for his only child's happiness. After the first outburst, Maurice entreated the President to hasten the marriage and permit Gabrielle to accompany her husband to the Indies, if she would consent to undertake the voyage. Gabrielle joined her prayers to her lover's, but her father refused absolutely to listen to the proposal. Apart from his reluctance to part from his child for an indefinite term, the good President pointed out to the young man the hardships of a voyage to the most distant quarter of the globe, and the danger of exposure to a climate then regarded as fatal to many Europeans.

"Suppose Gabrielle, young as she is, were to sicken and die thousands of miles from her native land," said the President; "could you ever recover from the consequences of your rash imprudence, or could I forgive myself for my own weakness and folly?"

"Then, sir," exclaimed Maurice, passionately, "I only know of one alternative. I will at once resign my commission, and adopt a new profession—I care not what, so that it shall not separate me from the woman I love."

M. de Launay shook his head, and, with a grave smile, replied that such an act would be unworthy of a French soldier and a scion of the noble house of de Serres. As a last resort, Maurice implored the President to sanction the immediate celebration of the marriage, with the understanding that Gabrielle should remain under her father's protection until her husband's return from foreign service, which, he anticipated, would be in about two years. To[Pg 448] this request, also, M. de Launay returned an inflexible negative, without vouchsafing any reason, except that such was his decision.

Finding all his efforts vain, Maurice resigned himself to the inevitable, whilst Gabrielle sadly prepared to obey the command of one to whose behests she had ever yielded a dutiful submission, comforting herself, perchance, with the secret hope that her love and fidelity to Maurice would be more cherished, and invested with a greater heroism in his eyes, after two long, weary years of trial and separation.

In maintaining an attitude of firmness throughout the dilemma in which he had been placed by the inconsiderate passion of the young officer, M. de Launay manifested the possession of all the wisdom requisite in dealing with a difficult problem; but in adhering strictly to the French custom of decorously assisting at all interviews between unmarried young people of opposite sexes, and in failing to leave the lovers together alone for a short time, the President showed a deplorable want of knowledge of the human heart. The thought did not occur to him that a few tears, kisses, and vows of constancy would go far towards reconciling Maurice and Gabrielle to the sweet sorrow of parting, and that with these innocent crumbs of comfort the parental presence is totally uncongenial. Never in the history of love has it been deemed admissible that there should be witnesses to the tender words of farewell, the fond look in each other's eyes, the soft pressure of each other's hands, the whispered oath of eternal fidelity, and the many mysterious nothings which at such times are held sacred. Oblivious of these delicate considerations, the worthy President gave the young people no opportunity for a leave-taking which would have been to them a relief and a precious souvenir. Their parting was one of silence and dejection, but at the last moment Maurice found means to murmur in Gabrielle's ear, "I will be in the garden at midnight, under your window; meet me there to say good-bye." She spoke no word of reply, but a glance at her face assured him that his prayer had been heard and granted. With a tranquil smile, he bade farewell to the President, who again betrayed a sad lack of penetration in accompanying him to the gate, without the remotest suspicion that a clandestine midnight meeting of the lovers had been planned under his own eyes, and that the young officer's sudden composure arose from a joy he found it difficult to conceal.

"FAREWELL."

To both the lovers the hours seemed leaden indeed, until night came. At last, the church clock of Toulouse chimed three-quarters past eleven, and Gabrielle stole tremblingly down to the garden. The night was dark, and not a sound could the young girl hear but the tumultuous beating of her own heart, as she gently withdrew the bolts from the outer door and stepped lightly upon the soft green sward. Filled with dread of the consequences which might ensue if her secret meeting with Maurice should be[Pg 449] discovered by her father, the poor child's remorse for her act of disobedience, as she regarded it, caused her to pause more than once, undecided whether to keep her tacit promise, or to creep back swiftly to her chamber. Before she could adopt the course dictated by prudence and submission to her father's will, she heard a light step behind her, and in another instant she was clasped in her lover's arms. Gently releasing herself, she placed her hand in his, and led him to a low bench close by, under the shadow of a tree. Seated side by side, they spoke in low whispers of their approaching separation and of their mutual sorrow during Maurice's long absence from France. They talked of their occupations, and of the expedients each would adopt to make the time seem less wearisome. They arranged the employment of every day, and fixed the hours when each should breathe the other's name, and thus know that they were in communion of thought, though thousands of miles of ocean rolled between them, forgetting that in widely different climes the day to one would be night to the other. Then, perhaps, this geographical obstacle occurred to them, and they triumphantly vanquished it by promising to think of each other always, awake by day and in dreams by night, which would be the surest method of never being absent for an instant from each other's meditations.

In these lover-like communings the night sped quickly, and over the tree-tops came the silver streaks in the clouds which herald the approach of dawn. They knew that their remaining time must now be short, and for a while they spoke no words. Still they sat side by side upon the bench, Maurice holding Gabrielle's hand folded within his own. Motionless, and with her head leaning forward, she wept in silence, tears of mingled joy and anguish. Maurice felt a strange thrill of rapture in his heart as he gazed in the sweet face of his beautiful betrothed, illumined by the soft rays of the moon, and as if seized with a sudden impulse, he fell upon his knees before her.

"Do you love me, dearest?" he murmured in trembling accents.

"God is my witness," she answered gently, "that I love you better than aught else on earth."

As if startled by the danger of discovery to which they were becoming every instant more and more exposed, the young man sprang hastily to his feet, clasped her in his arms, and kissed her passionately.

"Farewell, my own true love," he said softly. "Farewell until we meet again."

"Must you then leave me?"

"Alas, yes!"

She feared that her own gentleness and calmness at the supreme moment of parting would seem cold and tame in contrast with his exaltation, and, throwing her arms around his neck, she cried—

"Kiss me once more, Maurice; once more!"

Again he pressed his burning lips to hers in one long, last embrace.

"Farewell, Maurice," she sighed. "I feel that, if I were in my shroud, your kiss would recall me back to life!"

And with these prophetic words ringing strangely in his ears, he turned, and fled from her presence.

Four long and eventful years had passed since the lovers' clandestine parting, when Captain de Serres again set foot on the soil of his native land. The transport which brought a portion of his regiment home entered the harbour of Brest early one bright morning in June, and Maurice the same day set out for Paris, his first thought being to embrace his widowed mother, whom he idolised. He had taken the precaution to send her previous intelligence of his return to France, and of his safety, for the poor lady, during nearly two years, had mourned her only son as dead. Of his betrothal to Mademoiselle de Launay she had never known, though she knew of the President by name as one of her late husband's early friends.

When Maurice arrived in Paris, on the second morning after his departure from Brest, and it was vouchsafed to his mother to clasp in her arms the son she had thought gone from her for ever, her joy can only be pictured by those to whom it has been given to taste an unhoped-for happiness. Maurice, too, was happy; but still, after the first emotions of such a meeting, Madame de Serres' keenly observant glance detected in her son's face a strange expression of melancholy, and an air of abstraction in his replies to her anxious questions, which at once aroused all her solicitude. Alarmed at his singular demeanour, she tenderly pressed him to confide to her the cause of his sadness, that she might at least attempt to soothe and console him.

"It is nothing, mother," he said, with an effort to smile, "merely a childish folly, of which a man should be ashamed; but since you imagine that there is some serious cause for my ill-timed depression, I must do my best to reassure you, though I fear you will only laugh at me."

"No, no, my son, I shall not laugh, whatever it may be," replied Madame de Serres. "Explain yourself fully, Maurice, and trust my good sense to make all due allowances."

"Very well, mother," was the answer, "you shall know the exact truth. On my way home this morning, I passed before the church of St. Roch, the entire front of which was heavily hung with black, and decorated for the funeral of some person of note. Such a circumstance, I am aware, is of every-day occurrence in Paris, and would not likely attract the attention of an indifferent passerby. But upon me the sight of those mournful preparations had a strange and mystic effect, which seemed to chill my blood, and imbued me with a presentiment of evil. I feared—ah! you are smiling at my superstitious weakness, and you are right. But three years of captivity and horrible sufferings have so unstrung me that my restoration to liberty and home seems a miraculous dream, and I tremble to awake lest I should indeed find it to be only a vision after all."

"My dear Maurice," said his mother, imprinting a kiss on his brow, "let this convince you that it is no dream. The feelings you have described to me I can well understand, and they prove that you cling strongly to your recovered happiness, since you tremble lest it may again be snatched from you by relentless destiny. You must try to forget the trials of the past, and accustom yourself to the present, as if you had never known what it is to suffer. As for your mournful impression at the sight of a church hung with black, you have been so long absent from France that a very ordinary occurrence seems invested with a significance it really does not possess, except for those who have sustained the loss of a dear relative or friend. The funeral decorations you saw this morning were no doubt in honour of the young and beautiful Madame du Bourg, wife of the President du Bourg, chief judge of the Civil Tribunal of Paris."

"The beautiful Madame du Bourg?" repeated the young officer, inquiringly. "Was the fame of her beauty, then, so universal as to become proverbial?"

"Yes, poor young creature," replied Madame de Serres, "though she had only resided in Paris since her union with the President du Bourg, about eighteen months ago. Her husband was nearly thirty years her senior, and the unhappy lady died after an illness of only two days, so I was informed yesterday, leaving an infant six months old. The unfortunate lady herself was scarcely more than a child, and, before her marriage, was the belle of Toulouse, Mademoiselle Gabrielle de Launay."

DISASTROUS NEWS.

This disclosure, so simple and so brusque, of a terrible calamity to him, did not at once penetrate sharply and clearly the[Pg 451] mind of Maurice de Serres. He was so utterly unprepared for the blow that for a moment he was unable to realise the disastrous news thus unconsciously imparted to him by his mother. He gazed at her with the air of a man who had not fully grasped the meaning of the words she had spoken, and asked her to repeat them. Then Madame de Serres, remembering that her son had been stationed at Toulouse a few years previously, and might consequently have met the President de Launay and his daughter, framed an evasive reply; but the instant she again named Mademoiselle de Launay, and reverted to the story of her sudden death, Maurice fell, with a cry of anguish, at his mother's feet, as though struck by a mortal wound—a livid pallor overspread his features, his breathing was that of a man struggling against suffocation, and he might have died, had not a flood of tears come to his relief.

In this critical emergency Madame de Serres fortunately retained her presence of mind, and with the ingenuity of maternal instinct, she found means to alleviate the violent grief of her son. With his head pillowed upon her bosom, she talked to him of his lost bride, divining all that had occurred without a word of explanation from Maurice, and gently reproaching him for having failed to tell her, his mother, the story of his love. She found means to reconcile him to the death of Gabrielle—that, he said, was the will of God—but how could he ever forget the broken vow, or forgive the perfidy of her who had called Heaven to witness her promise of fidelity? Then, with admirable tact and delicacy, his mother recalled to his mind his capture by the enemy, and the official report of his death, which, no doubt, had reached Toulouse, and had left Mademoiselle de Launay no resource but resignation to the decree of Providence. Probably, she said, after a long resistance and many tears, the unhappy girl had at last yielded an unwilling obedience to her father's commands, and had consented to a marriage of convenience, in which her affections had borne no part. And so natural and plausible was this theory, that in devising these simple motives in mitigation of Gabrielle's conduct, Madame de Serres told her son the exact truth. Finally, she poured balm into his heart by asking him to consider whether the real cause of Mademoiselle de Launay's early death might not have been sorrow for Maurice's loss, and the bitter wretchedness of her forced marriage with a husband whom she could never love?

These wise arguments were, indeed, not without soothing effect. At all events, after listening to his mother's words for some time, he became more calm, though a keen observer would have divined that his silence was not that of resignation, but the refuge of a mind which conceives a desperate project, weighs its possibility, and resolves upon carrying it into immediate execution. Madame de Serres watched with deep anxiety the expression of her son's face, and, had he once raised his eyes despairingly to hers, she might have read in them a determination to put an end to his life. But she never suspected him of harbouring any design so terrible, and when he entreated that he might be left alone, she acquiesced without hesitation.

Towards nightfall she had the satisfaction of seeing him rejoin her, apparently almost restored to tranquillity. In her presence, and without disguise or concealment, he provided himself with a considerable sum in gold, kissed her, and left the house without uttering a word, nor did Madame de Serres ask for an explanation, or seek to detain him. It was quite dark when Maurice sallied forth into the street, and walked rapidly in the direction of the Rue St. Honoré. On reaching the church of St. Roch, he lost no time in finding the sacristan, and inquired the name of the place where Madame du Bourg had been buried that morning. The information was supplied to him without hesitation, and he set off immediately for the designated cemetery. On arriving at the gates, he found them closed for the night, and experienced some difficulty in rousing the janitor, who was asleep in his lodge. After some demur, the man opened the door to his nocturnal visitor, and inquired his business.

"Let me come in," said Captain de Serres, "and I will tell you."

Seeing before him a young man of aristocratic mien and appearance, the grave-digger, whose curiosity was now fairly aroused, offered no further objection, and showed the way to a little room on the ground floor of the lodge.

"Be seated, sir," he said, civilly, placing a chair. "You are, perhaps, fatigued with your walk."

"No," replied the young officer; "there is no time to be lost."

Then, to the terror and amazement of[Pg 452] the grave-digger, Maurice, placing in his trembling hands more gold than he had ever before seen in his whole life, implored him to accept it as a reward for committing an act of sacrilege—a crime then punishable with death. Maurice entreated him to remove the earth from the grave he had filled that day, to exhume the corpse of Madame du Bourg, and to break open the coffin which covered the remains of that most unhappy lady, that he, Maurice de Serres, her affianced husband, might look once again upon the woman he had so passionately loved.

MAURICE AND THE GRAVE-DIGGER.

Then ensued a long and painful discussion, for the glittering heap of gold, pressed upon the poor man by his tempter, did not succeed in overcoming either the fears or the scruples of the honest grave-digger. To the distracted young officer it was a maddening blow to find that the cupidity upon which he had counted to vanquish the obstacles in his way had no existence, or if it had, was less powerful than the grave-digger's dread of the consequences. Maurice gave full vent to his despair and his tears so moved the heart of the poor man, at whose feet he grovelled in agony, that out of the commiseration he succeeded in inspiring came a consent which neither gold nor entreaties had been able to obtain.

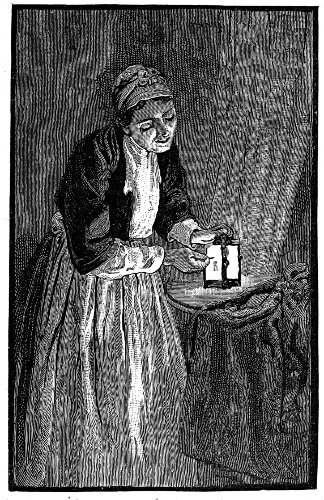

"Come!" said the grave-digger; "if it must be so, follow me!"

He led the way to the dark and silent cemetery, armed with a spade, a coil of rope, and a thick chisel, Maurice carrying his companion's lantern. Stumbling over many a mound of earth, they at last reached the grave in which the dead woman had been buried only a few hours previously. Taking off his jacket, the grave-digger set to work, without uttering a single syllable. In an hour, which to Maurice seemed years of torture, the hollow sound of the spade striking the top of the coffin told them that their sacrilegious task was nearly accomplished. A few moments more, and the united efforts of the two men had succeeded in raising the coffin to the surface. Maurice whispered to the man to remove the lid without noise, but as may well be imagined, such an injunction was needless. Proceeding with the utmost silence and precaution, the grave-digger was not long in loosening the fastenings of the coffin. Then, having now recovered his customary coolness and self-command, he sat down quietly upon a neighbouring tombstone, and mutely motioned to Maurice, who stood gazing at the corpse, as if petrified by the horrible sight. Finding the young man still remained immovable, the grave-digger pointed with his long, bony finger, to the still, white object, and muttered, "Look, 'tis she!"

But Maurice made no response, and[Pg 453] appeared no longer to remember why he was there, nor the crime he had instigated. He heard not the words of his companion, his gaze was fixed upon vacancy, the breath seemed to leave him, and he would have fallen to the ground, had not the other, alarmed at this strange lethargy, seized the young man's arm, and again whispered "Look!" Then slowly lifting the shroud from the face of the corpse, he added, "Convince yourself. Is it this lady?"

At this instant the moon burst forth from behind the clouds, and its pale, mysterious light fell full upon the lineaments of her whom Maurice had idolised, and for whose sake he had committed this horrible deed. Her features bore still the sad, sweet expression he knew so well; the colour of her cheeks had lost little of its rosy tint, and, though her eyes were closed, her lips were half parted, as if about to speak.

Flinging himself upon his knees beside the body, Maurice wept tears which brought his anguish some relief. With passionate sobs he recalled the story of their love, of their young hopes, of their betrothal, and of their sudden and piteous separation, and he bitterly reproached himself for having yielded obedience to her father's commands, and left her to be sacrificed a victim to that father's unbending will.

As he spoke he gently raised her in his arms and looked closely in her face. At that instant memory brought back to him her parting words, years before, when, as they said farewell, he had pressed his lips to hers. The scene flashed across his brain with the rapidity of lightning, and, as if urged by some sudden inspiration, he stooped and kissed her, as he had kissed her on that too well remembered night.

No sooner had his lips touched hers than he uttered a terrible cry, and rose to his feet, trembling convulsively. Then, with a wild laugh, he seized the body, and before the astonished grave-digger could interpose, the young officer fled from the spot with his burden in his arms, springing over the graves, and threading his rapid course among the tombs, as if the weight he bore were no more encumbrance to his flight than a flake of falling snow. With almost supernatural force and rapidity the madman, as the amazed and bewildered grave-digger now felt assured he was, made good his escape, like a tiger carrying off his prey.

"WITH A WILD LAUGH HE SEIZED THE BODY."

Seeing that pursuit was useless—even if[Pg 454] he had contemplated such a course—the poor man hastened to remove the evidence of the sacrilege in which he had played so prominent a part. Lowering the empty coffin into the open grave, he rapidly threw in the earth, and in a short time the spot showed no trace of having been disturbed since the interment of the preceding morning. Then the grave-digger gathered together the implements of his trade and stole back to his lodge, muttering imprecations upon his mad visitor, and upon himself for having assisted in committing a crime fraught with such formidable danger to its perpetrators, should the horrible deed ever be brought to light.

Nearly five years had passed away since that eventful night, and, during that long period, nothing had occurred to revive the fears of the conscience-stricken grave-digger, or to give rise to his misgivings that the theft of Madame du Bourg's corpse might by some means be discovered. In fact, after carefully weighing all the circumstances, he had finally come to the conclusion that he had been the victim of a conspiracy hatched by medical students, one having played the principal part in the abominable transaction, and the other or others waiting outside the cemetery to assist in making off with the "subject," should the nefarious plot succeed. The students (if this hypothesis were correct) would never betray the secret, for obvious reasons; and so long a time having now elapsed since the burial of the unhappy lady, the contingency of an authorised exhumation for any cause whatever became daily more and more remote.

On All Souls' Day the bereaved husband came regularly each year to pray at his dead wife's tomb, and each year the grave-digger observed him with feelings of remorse, as if it were adding to his weight of guilt in standing near while the worthy President du Bourg knelt reverently beside the mound beneath which was buried only an empty coffin. The sight of this futile annual pilgrimage possessed for the repentant grave-digger a fascination impossible to resist, and amongst all the mourners who visited the cemetery on that solemn day, he took note of none save M. du Bourg, before whom he more than once felt tempted to throw himself and confess all.

When the anniversary came round again, the grave-digger stationed himself at his usual post of observation, and saw the President draw near to his wife's tomb, over which he immediately bent in prayer. Both he and the contrite grave-digger were so deeply absorbed in thought that they did not notice the approach of a woman, who uttered a suppressed cry as she caught sight of the recumbent figure. Turning involuntarily and looking quickly up, M. du Bourg instantly recognised, in the person who had interrupted his meditations, no other than the wife whose death he had mourned so long. The grave-digger also remembered well the pale, beautiful face, from which he had removed the shroud five years before, and he instantly fell to the ground, insensible. But before the startled husband could recover from his amazement, Gabrielle, for it was she, swept past him like the wind and was gone. Following her retreating form in the distance, the President reached the cemetery gates in time to see her leap into a carriage with emblazoned panels, which, before he could reach the spot, was driven rapidly away towards the centre of Paris. M. du Bourg then returned to the place where he had seen the grave-digger fall in a swoon, hoping to derive some information from the stranger who had been thus terror-struck at sight of the unexpected apparition, but the man had been already carried to his lodge, and died an hour afterwards without recovering consciousness.

Losing no time, the President addressed himself to the Lieutenant-General of Police, by whom inquiries were set on foot without delay, and it was speedily established that the carriage, which many persons had observed in waiting at the cemetery gates, bore the arms of the noble house of de Serres. As M. du Bourg was aware of his late wife's early attachment to the young officer whose death abroad had been officially reported a few months previous to her marriage, the motive of her disappearance, if she were still alive, was clearly explained. But the mystery of her existence five years after her supposed death and burial must now be immediately unravelled.

By order of the authorities, the grave in which Madame du Bourg had been interred was opened, and the empty, broken coffin was found. This discovery fully confirmed the suspicions of the President du Bourg, and prompted him in the course he now resolved to pursue.

Meanwhile Madame Julie de Serres, the young and lovely wife whom Captain Maurice de Serres had married abroad five years previously, and now brought to Paris for the first time, returned that day to her husband's house in a state of the utmost alarm and agitation. Pale and trembling, she begged to be conducted to Maurice, and the pair remained closeted together for several hours. At last, in outward semblance perfectly calm, she rejoined the Countess, her husband's mother, and from that day resumed the ordinary current of life as though nothing had arisen to mar its serenity.

About a fortnight had elapsed since the occurrences above related, and the incident in the cemetery appeared to have been forgotten, or if remembered by the chance witnesses of the scene, it was generally supposed that the mysterious lady who had been seen by M. du Bourg merely bore a fortuitous resemblance to the President's deceased wife. But during these few days, aided by all the power in the hands of the Lieutenant-General of Police, M. du Bourg instituted a searching and systematic investigation, firmly resolved as he was to know the truth. Without in the least suspecting that their every movement was watched, Captain de Serres and his wife were surrounded with spies, who rendered a daily report of their minutest actions. Maurice having come to the conclusion that it would be imprudent to leave Paris, there was no difficulty in keeping him under constant observation. Setting to work like an experienced lawyer, M. du Bourg rapidly collected evidence of the greatest importance. Through the Minister of War, he ascertained the exact date of Captain de Serres' return to France, after his captivity and supposed death in the Indies. At the passport office he found out the day of the young officer's departure shortly after his arrival in Paris. The postillions whom he had employed on his journey to Havre were discovered and interrogated. From them it was elicited that the traveller had been accompanied to the coast by a lady closely veiled, who never left the carriage until the pair reached their destination. The name of the vessel in which M. de Serres and a lady inscribed as his cousin had taken passage to South America was ferreted out, and the ship's journal was brought to Paris.

"SHE BEGGED TO BE CONDUCTED TO MAURICE."

Armed with these formidable proofs, the President du Bourg demanded from the High Court of Paris the dissolution of the illegal marriage between Captain Maurice de Serres and the pretended Julie de Serres, who, as M. du. Bourg solemnly declared, was Gabrielle du Bourg, his lawful wife.

The extraordinary novelty of this cause created an immense sensation throughout Europe, and pamphlets were exchanged by the faculty, some maintaining that a prolonged trance had given rise to the belief[Pg 456] in the apparent death of Madame du Bourg, whilst others as stoutly affirmed that resuscitation under such circumstances was an absolute impossibility. This latter theory secured the majority of partisans amongst medical men, and after calculating the number of hours which it was stated that Madame du Bourg had continued to exist in her grave, the fact was conclusively established that no case of a similar lethargy had ever previously been recorded. M. de Serres himself expressed the most profound and unaffected pity for his adversary, and acknowledged that when he had first met the lady who now bore his name, her marvellous likeness to Gabrielle de Launay had struck him with awe and amazement. This declaration was made with such evident sincerity that it carried conviction to the minds of all who heard it, and few doubted but that the President du Bourg had either lost his reason or was the instigator of a corrupt and knavish conspiracy.

"MAMMA, WON'T YOU KISS ME?"

In due course the hearing of this extraordinary suit came before the high tribunal of Paris, and Madame Julie de Serres was summoned to appear in court, and answer the questions of the judges. She was confronted with M. du Bourg, and was surprised and indignant at his pretensions. The father of Gabrielle de Launay came from Toulouse, and burst into tears at the sight of one who bore so wondrous a resemblance to his dead daughter; nor could he find words in which to address the lady who seemed the living image of his only child, and who calmly denied all knowledge of him. The judges, in much perplexity, looked at each other in troubled silence and indecision. Madame de Serres, in simple language, told the story of her entire life. She was an orphan, she said, born in South America, of a French father and a Spanish mother, and had never[Pg 457] left her native country until her marriage. The legal certificate was produced, attesting the marriage of Maurice de Serres and Julie de Nerval, and, with other formal documents, was laid before the court. After hearing the pleas of the distinguished advocates engaged on both sides, the judges consulted together for a short time, and announced that their decision would be given at the next sitting of the tribunal.

On the following day the court was crowded to excess, and it was rumoured amongst the many ladies and gentlemen of position who were present that a majority of the judges were so thoroughly convinced of the preposterous character of the President du Bourg's claim as to render certain a decree in favour of Captain de Serres and his wife. Amidst a sympathetic silence—for popular opinion was almost unanimously enlisted on the side of the defendants in this unprecedented case—the President of the High Court commenced in a grave voice the delivery of the judgment, when suddenly M. du Bourg, who had not been present at the commencement of that day's proceedings, entered the court, leading by the hand a little girl of five or six summers. At this moment Madame de Serres, her face lighted up with a smile of exultation, was seated by the side of her advocate, directly in front of the Bench, and in full view of the public. Conversing in animated tones with her counsel, she did not observe the entrance of M. du Bourg; but in a moment a tiny hand was placed in her own, and a child's soft voice said timidly—

"Mamma, won't you kiss me?"

Madame de Serres turned quickly, uttered a sharp cry, and, clasping the child in her arms, covered it with tears and caresses. The daughter and wife had complete control over the emotions of Nature, but the mother's heart had not the strength to resist the sudden strain.

From that moment the case before the court, and still undecided, assumed a totally different aspect. Springing to his feet in an instant, the advocate of the unhappy lady unhesitatingly proclaimed the identity of his client, and now called upon the judges to annul her marriage with M. du Bourg, which had been dissolved, he declared solemnly, by the hand of death. Turning towards M. du Bourg, he exclaimed with fiery eloquence—

"Sir, you have no right to demand from the earth the body you have consigned to the grave. Leave this woman to him by whose act, and by whose act alone, she lives. Her existence belongs to him, and you can only claim a corpse."

Had the brilliant advocate been pleading the cause of a beautiful woman before a modern Parisian jury, he might have indulged some hope of success, but a hundred and fifty years ago the law of France was not swayed by sentiment. The judges were unmoved by this vehement outburst, and prepared to alter their decree in conformity with the facts elicited through the presence of the child. The wretched wife and mother then entreated permission to spend the remainder of her days in the seclusion of a convent. This, too, was refused, and she was formally condemned to return to the house of her first husband.

Two days after this judgment had been rendered, she obeyed. The gates swung wide open before her, and, dressed in white, pale and weeping, she entered the great hall, where the President du Bourg, surrounded by his entire household, stood awaiting her arrival.

Approaching him, and pressing a phial to her lips, she gasped forth the words, "I restore to you what you lost"—and fell dead at his feet, poisoned.

The same night, despite his devoted mother's efforts to save him, Captain du Serres died by his own hand.

"Here y'are now, on'y sixpence for yer likeness, the 'ole thing, 'strue's life. Come inside now, won'tcher? No waitin'. Noo instanteraneous process."

Thus, with the sweet seductiveness of an East-end tout, was a photographer endeavouring to inveigle 'Arry and 'Arriet into his studio, which was situated—well, "down East som'ere," as the inhabitants themselves would describe the locality. It was somewhere near the Docks; somewhere, you may be sure, close bordering upon that broad highway that runs 'twixt Aldgate and the Dockgates, for within those boundaries the tide of human life flows most strongly, and the photographer hoped, by stationing himself there, to catch a few of the passers-by, thrown in his way like flotsam and jetsam. He was not disappointed in this expectation. While daylight lasted there was generally a customer waiting in his little back parlour, enticed thither by the blandishments of the tout outside.

The establishment was not prepossessing to an eye cultivated in the appearance of the artistic façades of photographers in the West. The frontage consisted of a little shop, with diminutive windows, which it was the evident desire of the proprietor to make the most of by engaging in other commercial pursuits.

THE ESTABLISHMENT.

There seemed to be an incongruity in the art of the photographer being associated with the sale of coals, firewood, potatoes, sweets, and ginger-beer, but the East-enders apparently did not trouble themselves to consider this in the least. There was, indeed, a homely flavour about this miscellaneous assortment of useful and edible articles, which commended itself to their mind. What was more natural than that 'Arry, having indulged in the luxury of a photograph, should pursue his day's dissipation by treating his 'Arriet to a bottle of the exhilarating "pop," to say nothing of a bag of sweets to eat on their holiday journey.

The coals, firewood, and potato department, so far from being regarded as in any way derogatory to the photographer's profession, was rather calculated to impress the natives, who were accustomed to look upon a heap of coals—to say nothing of the firewood and potatoes—as a material sign of prosperity.

So far as the photographer was concerned it was a matter of necessity as well as choice that he came to be thus associated, for it transpired that he had married the buxom woman, whom we now see behind the counter, at a time when he was trying hard to make ends meet in the winter season, when photography is at a discount. She, on the[Pg 459] other hand, had a thriving little business of the general nature we have indicated, and was mourning the loss of the partner who had inaugurated the shop, and for a time had shared with her his joys and sorrows. The photographer had won her heart by practising his art on Hampstead Heath the last Bank Holiday, and the happy acquaintance thus formed had ripened into one of such mutual affection that the union was consummated, and another department was added to the little general business by the conversion of the yard at the back into a photographic studio.

The placards announcing the price of coals and firewood, and the current market rates of potatoes, were elevated to the topmost panes of the window, and the lower half was filled with a gorgeous array of specimen portraits in all the glory of their tinsel frames.

From that day the shop was a huge attraction, and the proprietor of the wax-work show over the way cast glances of ill-concealed envy and jealousy at the crowd which had deserted his frontage for the later inducements opposite.

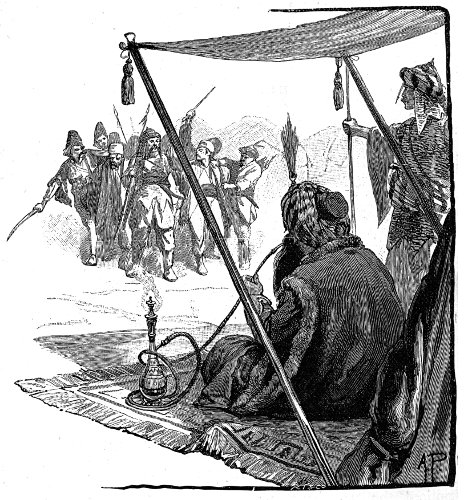

The incoming vessels from foreign ports brought many visitors, and generally a few customers. To the foreign element the window was especially fascinating. Many a face of strange mien stared in at the window, and the photographer being somewhat of an adept with an instantaneous camera, would often secure a "snap shot" of some curious countenance, the owner of which could not be enticed within. These would duly appear in the show cases, and served as decoys to others of the same nationality.

There was the solemn-faced Turk in showy fez, and with dainty cigarette 'twixt his fingers, who surveyed the window with immutable countenance, and was impervious to all the unction of the tout. This latter worthy was not aware that it was against the religion of the "unspeakable Turk" to be photographed, or he would not have wasted his energy on such an unpromising customer.

The negro sailor was apparently struck with the presentments of the other members of his race, but asseverated that he was "stone broke," and did not own a cent to pay for a photograph. He had spent such small earnings as he had received, and was now on his way back to his vessel. "Me no good, me no money," he told the tout, who turned away from him in disgust.

There has so far been a good many passers-by to-day for every likely customer, and the tout is almost in despair. "Rotters," he mutters; "not a blessed tanner among 'em."

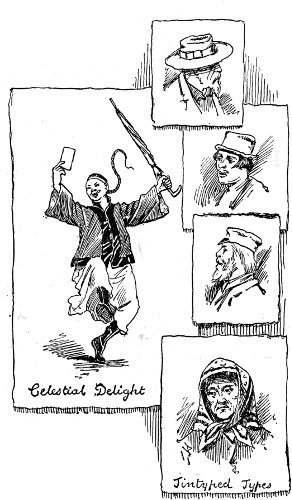

IN THE SHOW CASE.

Ah! here's his man, though, and he is on the alert for his prey, as he sees a[Pg 460] dapper little figure with unmistakable Japanese features come sauntering down the street. He is dressed in the most approved style of the East-end tailor, who no doubt has assured him that he is a "reg'lar masher." So evidently thinks the little Jap, as he shoots his cuffs forward, flourishes his walking cane, and displays a set of ivory white teeth in his guileless Celestial smile. The tout rubs his hands with a business-like air of satisfaction as he sees the victim safely handed over to the tender mercies of the operator within. "Safe for five bobs' worth, that 'un," he soliloquises, winking at no one in particular, but possibly just to relieve his feelings by the force of habit.

The next customer attracted was an Ayah, or Hindoo nurse, a type often to be seen in the show-case of the East-end photographer. These women find their way to England through engagements as nurses to Anglo-Indian families coming home, and they work their way back by re-engagements to families outward bound. Whenever a P. & O. boat arrives there will most probably be seen one or more of these women, whose stately walk and Oriental attire at once attract attention.

Prominent also among the natives who find their way up from the Docks are the Malay sailors, in their picturesque white dresses. Sometimes the photographer secures a couple for a photo, but as a rule they have little money. "Like all the rest o' them blessed haythens," says the tout, "not a bloomin' meg among a 'ole baker's dozen of 'em."

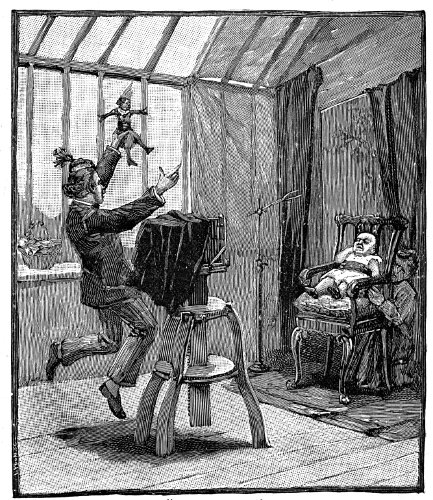

"NOW, LOOK PLEASANT!"

The faces of such types are not, however, interesting to the East-enders. Their interest in the window display is only heightened when familiar faces make their appearance in the tinsel frames. There was, for instance, positive excitement in the neighbourhood when a highly-coloured portrait of the landlord of a well-known beer-shop in the same street was added to the collection.

Everyone recognised the faithfulness at once, though it was irreverently hinted that in the colouring the exact shade of the gentleman's nose had not been faithfully copied.

One can imagine the feelings of pride with which the photographer had posed his worthy neighbour, who had arrayed himself in all the glory of his Sunday best suit.

"Head turned a little this way, please! Yes—now—look at this—yes—now, look pleasant!"

Everything would have gone well at this point, but the dog, which it was intended should form an important adjunct to the picture, and symbolically typify the sign of the house—"The Jolly Dog"—set up a mournful howl, and made desperate efforts to get away from the range of that uncanny instrument in front of him. However, the photographer waited for a more favourable moment, and while the dog was considering the force of his master's remarks, the exposure was successfully made. The result was regarded as quite a chef d'œuvre in the eyes of those who stopped to gaze at it as it hung in a place of honour in the window of the little front shop.

The "reg'lar" East-enders, as distinguished from the foreign element, were, indeed, very easy to please; but, unfortunately, they were not the mainstay of the photographer's business. He must needs look for other customers to eke out a living. And here his difficulties began. He had to be careful not to take a certain low type of Jewish features in profile, for the foreign Jew, once he has been acclimatised, does not like to look "sheeny"; and the descendants of Ham—euphemistically classed under the generic term of "gentlemen of colour"—were always fearful lest their features should come out too dark. One young negro who came to be photographed expressly stipulated that he should not be made to look black. To obviate this difficulty, the photographer wets his customer's face with water, so as to present a shiny appearance to the lens of the camera, and a brighter result is thus secured. On this particular occasion the ingenious dodge failed, and the vain young negro loudly denounced it as representing him a great deal blacker than he was in the flesh. Indeed, the tears sparkled in his eyes as he protested that he was "no black nigger." There is a subtle distinction, mark you, between a "nigger" and a "black nigger" in the mind of a "coloured person," and no greater insult can be levelled at him than to apply the latter epithet.

Too, too black.

The tout's thoughts are soon distracted by the appearance of a German fraulein, evidently of very recent arrival in England, who is admiring the photos in the window. She is arrayed in a highly-coloured striped dress, which is not of a length that would be accepted at the West-end, for it reaches only to the ankles, and shows her feet encased in a clumsy pair of boots. An abnormally large green umbrella which she carries is another characteristic feature that seems inseparable from women of this type.

The tout has a special method of alluring the women folk within the studio. He has a piece of mirror let into one of the tinsel frames which he carries in his hand as specimens. He holds this up before the woman's face, and asks her to observe what a picture she would make. This little artifice seldom fails to attract the women, whatever their nationality, for vanity is vanity all the world over.

John Chinaman is quite as easily satisfied, and the tout has no difficulty in drawing him within, but the drawback to his custom is that he seldom has any money, or, if he has any, is not inclined to part with it. It is just a "toss-up," as the tout says, whether he will pay, if he gets the Celestial inside, though it is worth the risk when business is not very brisk.

Here is one fine specimen of a Celestial coming along. Western civilisation, as yet, has made no impression upon him, and he looks for all the world the Chinaman of the willow-pattern plate in the window of the tea shop. John falls an easy prey to the tout, who ushers him inside, and whispers to the "Guv'nor" in a mysterious aside: "Yew du 'im for nothin', if ye can't get him to brass up. Lots o' Chaneymen about to-day, an' 'e'll advertise the business." The customer is thereupon posed with especial favour, the photographer feeling that the reputation of the business in the Celestial mind depends on the success of this effort. Chinese accessories are called into play; John Chinaman is seated in a bamboo chair, against a bamboo table, supporting a flower vase which looks suspiciously as though it had once served as a receptacle for preserved ginger. Overhead is hung a paper lantern, and the background is turned round so that the stretcher frame[Pg 462] of the canvas may give the appearance of a Chinese interior. There is no need to tell the sitter to look pleasant, for his features at once expand into that peculiar smile which Bret Harte has described as "child-like and bland."

The photo is duly completed and handed over to the customer for his inspection and approval. He manifests quite a childish delight, and is about to depart with it, when he is reminded by word and sign that he has not paid. John very well understands the meaning of it all, but smiles vacuously. When, however, the photographer begins to look threatening, he whines in his best English that he has no money. The photographer slaps him all round in the hope of hearing a jingle of concealed coins, but to no purpose. "Another blessed specimen, gratis!" he mutters, as he allows his unprofitable customer to depart with the photo, in the hope that it will attract some of his fellow-countrymen to the studio. This seems quite likely, for the Chinaman goes off in a transport of delight. He stops now and again to survey the photo, and the appearance of it evidently gives such satisfaction that he goes dancing off like a child to show it to his Celestial brethren. They straightway resolve also to go and have a photograph for nothing.

A group of chattering Chinamen soon appear in front of the photographer's shop, with the late customer in the midst explaining how the trick is done. It seems to be finally resolved that they should go in one at a time, the others waiting outside. One young member of the party accordingly steps forward, and the tout, delighted to find the bait has so soon taken, never considers the possibility that this customer likewise has no money.

The same scene is enacted as in the previous case, but when it comes to the point of paying for the photo, and John Chinaman is found to be absolutely penniless, there is an unrehearsed ending to the little comedy. The proprietor of the photographic establishment seizes the Chinaman by the collar and drags him into the front shop, where the tout, in instant comprehension of the state of affairs, takes the offender in hand and very neatly kicks him over the doorstep, whence he falls into the midst of his compatriots, who all take to their heels, screaming in a high-pitched key. The tout looks at their rapidly retreating figures with a countenance eloquently expressive of mingled sorrow and anger, vowing vengeance on any other of "them haythen Chaynees" who might choose to try the game of securing photos for nothing. "Ought to be all jolly well drownded in the river," he remarks to his colleague indoors.

"KICKED OUT."

On the other hand, the heavy-browed, gaunt-cheeked, male Teuton is not[Pg 463] so easy to attract, but the photographer can trust the course of things to bring him eventually to the studio. When first imported he stares in at the window in a stolid, indifferent manner. His face has a hungry look, and is shadowed by a heavily slouched hat; his hair is unkempt; he wears an untidy and unclean scarf; his boots are big and heavy, and his trousers several inches too short for him.

A TEUTON.

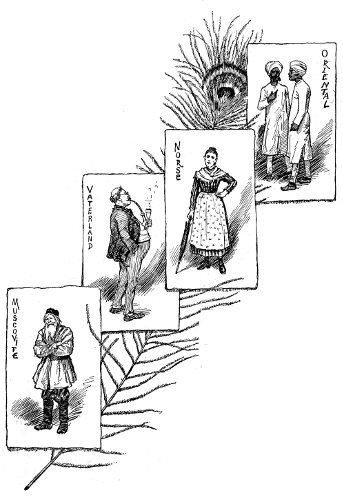

SOME FOREIGN IMMIGRANTS.

AN ORIENTAL.

In a short time, however, he will blossom forth into a billycock hat, with broad and curly brim of the most approved East-end cut; patent leather boots to match, and a very loud red tie. The hungry look has by this time given way to a sleek, well-fed nature, and he will stroll along with a Teuton sweetheart, likewise transformed very much from her former self. The short, gaudily-striped dress has given way to the latest "'krect thing" in East-end[Pg 464] fashion, and the green stuff umbrella has gone the way of the striped skirt, to be replaced by the latest novelty in "husband beaters." Then it is that the Teutonic 'Arry and 'Arriet patronise the photographer, and rejoice his heart with, perhaps, a five-shilling order.

The show-case of the East-end photographer gives one a very fair idea of the evolution of the foreign immigrant.

The tout seemed to know the history of every person whose photograph was displayed in the show-case, and he was rattling it off to us at a rate which precluded any possibility of storing it up in our memory, when a slight diversion was created by a coster's barrow, drawn by a smart little pony, being driven up to the front of the photographer's. The driver was Mr. Higgins, we learnt, and the other occupants of the barrow were Mrs. Higgins and the infant son and heir to the Higgins' estate, which was reputed to be something considerable in the costermongers' way, as was evidenced by the fact that Mr. Higgins was enabled to keep a pony to draw his barrow. Mrs. Higgins had determined that 'Enery—ætat one year and eight months—should have his photograph taken and afterwards be glorified in a coloured enlargement. Mr. Higgins had assented to this being done regardless of expense. It was a weighty responsibility for the photographer, who always considered the taking of babies was not his strong point. But he reflected upon the increased fame which would accrue to his business if he was successful, and he determined to do it or perish in the attempt.

"YOUNG HIGGINS."

He made hasty preparations by selecting the most tempting stick of toffy he could find in the sweet-stuff window, and the tout was instructed to procure from a neighbouring toy shop a doll, a rattle, a penny trumpet, and other articles dear to the juvenile mind.

The youthful Higgins was duly placed in a chair, behind which Mrs. Higgins was ensconced with a view to assisting the photographer by preserving a proper equilibrium in the sitter, and also ensuring confidence in the infantile mind.

So far, the child had been quietly sucking his thumb and surveying the studio with an interested air, but no sooner was his attention directed to the photographer than a distrustful frown settled upon his face, and his irritation at the photographer's presence found expression in a yell of infantile wrath. The more the photographer tried to conciliate by flourishing the toys the more the child yelled. The photographer danced and sung, and blew the penny trumpet, and was about to give up the operation in despair, when it dawned on him that he had forgotten the toffy stick. It was produced, and had its effect. On being assured by Mrs. Higgins, behind the chair, that the "ducksy darling would have its toffy stick," the youthful sitter held that prospective joy with his tear-glistening eye, and the photographer seizing a favourable moment performed the operation with a sigh of satisfaction. Baby Higgins had its toffy stick, Mrs. Higgins had a pleasing photo of her infant offspring, and the photographer proudly congratulated himself on[Pg 465] having so successfully performed his task. The production of such elaborate efforts as the coloured enlargements was, however, attended with disadvantages and disappointments at times. It was hard to give entire satisfaction to such exacting critics in these matters as the East-end folk, and there was always the risk that the picture might be thrown upon his hands if not liked.

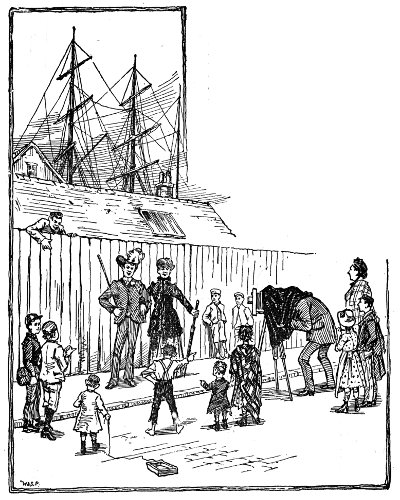

Taking it all round, his time was much more profitably employed out of doors on high days and holidays, in taking sixpenny "tintypes" "while you wait."

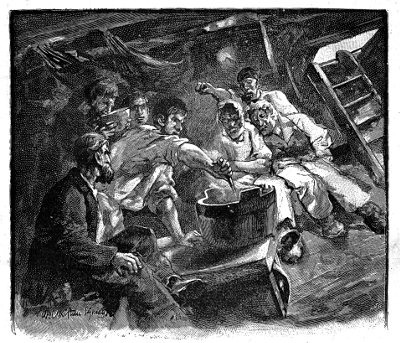

We have seen him on a Bank Holiday beaming with good luck. He has started out early in the morning with the intention of proceeding to Hampstead, but instead of going direct thither, he pitches his camera near the walls of the Docks, and manages to catch a good many passers-by before they have had the opportunity of spending their money in the pleasures of a London Bank Holiday. Here he has succeeded in inducing 'Arry and 'Arriet to have their photos taken.

Such is a chapter in the life of an East-end photographer. To-day he may be doing a "roaring" business, but to-morrow he may be reduced to accepting the twopences and threepences of children who club together and wait upon him with a demand that he will take "Me, an' Mary Ann, an' little Mickey all for thruppence." He invariably assents, knowing that, though there can be little profit, the photo will create a feeling of envy in the minds of other children who will decide on having a "real tip topper" at sixpence.

The stock-in-trade of an East-end photographer is not a very elaborate one. He may pick up the whole apparatus second-hand for about £5, and the studio and fittings are not expensive. The thin metal plates cost not more than 10s. per gross, and the tinsel binding frames about 3s. per gross, while the chemicals amount to an infinitesimal sum on each plate. On a good day a turnover of £2 to £3 may be made, but there are many ups and downs, and trials of temper and patience, to say nothing of the unhealthy nature of the business, all going to make up many disadvantages associated with the life of an East-end photographer.

By E. W. Hornung.

It is prejudicial to the nicest girl in this unjust world to be asked in marriage too frequently. Things come out, and she gets the name of being a heartless flirt; her own sex add, that she cannot be a very nice girl. A flirt she is, of a surety, but why heartless, and why not a nice girl? So grave defects do not follow. The flirt who doesn't think she is one—the flirt with a set of sham principles and ideals, and a misleading veneer of soul—is heartless, if you like, and something worse. Now the girl who gets herself proposed to regularly once a week in the season is far less contemptible; she is not contemptible at all, for how could she know that you meant so much more than she did? She only knows a little too much to take your word for this.

A sweetly pretty and highly accomplished young girl, little Miss Anstruther came to know too much to dream of taking any man's word on this point. She was reputed to have refused more offers than a good girl ought to get; for what in the very beginning conferred a certain distinction upon her, made her notorious at a regrettably early stage of her career. The finger of feminine disapproval pointed at her, presently, in an unmistakable way; and this is said—by women—to be a very bad sign. Men may not think so. Intensely particular ladies, in the pride of their complete respectability, tried to impress upon very young men in whom they were interested that Miss Anstruther was not at all a nice girl. But this had a disappointing effect upon the boys. And Miss Anstruther by no means confined herself to rejecting mere boys.

The moths that singed themselves at this flame were of every variety. They would have made a rare collection under glass, with pins through them; Miss Anstruther herself would have inspected them thus with the liveliest interest. Her detractors also could have enjoyed themselves at such an exhibition. But the more generous spirits among them—those who had been young and attractive too long ago to pretend to be either still—might have found there some slight excuse for Miss Anstruther. Of course, it was no excuse at all, but it was notable that almost every moth had some salient good point—something to "account for it" on her side, to some extent—say a twentieth part of the extent to which she had gone. Nearly all the moths had something to be said for them—looks,[Pg 467] intellect, a nice voice, an operatic moustache, or an aptitude for the informal recitation of engaging verses; their strong points, sorted out and fitted together, would have made a dazzling being—whom Miss Anstruther would have rejected as firmly and as finally as she had rejected his integral parts.

For there was no pleasing the girl. Apparently she did not mean to be pleased—in that way. She had neither wishes nor intentions, it became evident, beyond immediate flirtation of the most wilful description. Her depravity was shocking.

Her accomplishment was singing. She sang divinely. Also she had plenty of money; but the money alone was not at the bottom of many declarations; her voice was the more infatuating element of the two; and her "way" did more damage than either. She was not, indeed, aware what a "way" she had with her. It was a way of seeming desperately smitten, and a little unhappy about it; which is quite sufficient to make a man of tender years or acute conscientiousness "speak" on the spot. Thus many a proposal was as unexpected on her part as it was unpremeditated on his. He made a sudden fool of himself—heard some surprisingly sensible things from her frivolous lips—decided, upon reflection and inquiry, that these were her formula—and got over the whole thing in the most masterly fashion. This is where Miss Anstruther was so much more wholesome than the flirt who doesn't think she flirts: Miss Anstruther never rankled.

She had no mother to check her notorious propensity in its infancy, and no brother to bully her out of it in the end. Her father, an Honourable, but a man of intrinsic distinction as well, was queer enough to see no fault in her; but he was a busy man. She had, however, a kinsman, Lord Nunthorp, who used to talk to her like a brother on the subject of her behaviour, only a little less heavily than brothers use. Nunthorp knew what he was talking about. He had once played at being in love with her himself. But that was in the days when his moustache looked as though he had forgotten to wash it off, and before Miss Anstruther came out. There had been no nonsense between them for years. They were the best and most intimate of friends.

"Another!" he would say, gazing gravely upon her as the most fascinating curiosity in the world, when she happened to be telling him about the very latest. "Let's see—how many's that?"

There came a day when she told Nunthorp she had lost count; and she really had. The day was at the fag-end of one season; he had been lunching at the Anstruthers' and Miss Anstruther had been singing to him.

"LET'S SEE—HOW MANY'S THAT?"

"I'm afraid I can't assist you," said he, with amused concern. "I only remember the first eleven, so to speak. First man in was your rector's son in the country, young Miller, who was sent out to Australia on the spot. He was the first, wasn't he? Yes, I thought that was the order; and by Jove, Midge, how fond you were of that boy!"

"I was," said Miss Anstruther, glancing out of the window with a wistful look in her pretty eyes; but her kinsman said to himself that he remembered that wistful look—it went cheap.

"The next man in," said Nunthorp, who was an immense cricketer, "was me!"

"I like that!" said Miss Anstruther, taking her eyes from the window with rather a jerk, and smiling brightly. "You've left out Cousin Dick!"

"So I have; I beg Dick's pardon. It was very egotistical of me, but pardonable, for of course Dick never stood so high in the serene favour as I did. I came after Dick then, first wicket down, and since then—well, you say yourself that you've lost tally, but you must have bowled out a pretty numerous team by this time. My dear Midge," said Nunthorp, with a sudden access of paternal gravity, "don't you think it about time that somebody came in and carried his bat?"

"Don't talk nonsense!" said Miss Anstruther, briskly. She added, almost miserably: "I wish to goodness they wouldn't ask me! If only they wouldn't propose I should be all right. Why do they want to go and propose? It spoils everything."

Her tone and look were quite injured. She was more indignant than Nunthorp had ever seen her—except once—for the girl was of a most serene disposition. He looked at her kindly, and as admiringly as ever, though rather with the eye of a connoisseur; and he found she had still the most lovely, imperfect, uncommon, and fragrant little face he had ever seen in his life. He said candidly:

"I really don't blame them, and I don't see how you can. If you are to blame anybody, I'm afraid it must be yourself. You must give them some encouragement, Midge, or I don't think they'd all come to the point as they do. I never saw such sportsmen as they are! They walk in and walk out again one after the other, and they seem to like it——"

"I wish they did!" said Miss Anstruther, devoutly. "I only wish they'd show me that they liked it; I should have a better time then. They wouldn't keep making me miserable with their idiotic farewell letters. That's what they all do. Either they write and call me everything—rudely, politely, sarcastically, all ways—or they say their hearts are broken, and they haven't the faintest intention of getting over it—in fact, they wouldn't get over it if they could. That's enough to make any person feel low, even if you know from experience what to expect. At one time I daren't look in the paper for fear of seeing their suicides; but I've only seen their weddings. They all seem to get over it pretty easily; and that doesn't make you think much better of yourself, you know. Of course I'm inconsistent!"

"Of course you are," said Nunthorp, cordially. "I approve of you for it. I'd rather see you an old maid, Midge, than going through life in a groove. Consistency's a narrow groove for narrow minds! I can do better than this about consistency, Midge; I'm hot and strong on the subject. But you're not listening."

"Ah!" cried Miss Anstruther, who had not listened to a word, "they're driving me crazy, between them! There's Mr. Willimott, you know, who writes. Of course he had no business to speak to me. There were a hundred things against him at the time—even if I'd cared for him—though he's getting more successful now. Well, I do believe he's put me into every story he's written since it happened! I crop up in some magazine or other every month!"

"'Into work the poet kneads them,'" murmured Nunthorp, who was not a professional cricketer. "Well, you needn't bother yourself about him. You've made the fellow. He now draws a heroine better than most men. It's a pity you don't take to writing, Midge, you'd draw your heroes better than women do as a rule; for don't you see that you must know more about us than we know about ourselves?"

"They wouldn't be much of heroes!" laughed the girl. "But I heartily wish I did write. Wouldn't I show up some people, that's all! It would give me something to do, too; it would keep me out of mischief, and really I'm sick of men and their ridiculous nonsense. And they all say the same thing. If only they wouldn't say anything at all! Why do they? You might tell me!"

Nunthorp put on his thinking-cap. "You see, you are quite pretty," said he.

"Thanks."

"Then you sing like an angel."

"Please don't! That's what they all say."

"Ah, the singing has a lot to do with it; you oughtn't to sing so well; you should cultivate less expression. And then—I'm afraid you like attention."

"Well, perhaps I do."

"And I'm sure it must be very hard not to be attentive to you," said Nunthorp, with a rather brutal impersonality; "for I should fancy you have a way—quite unconscious, mind—of giving your current admirer the idea that he's the only one who ever held the office!"

"Thanks," said she, with perfect good-humour; "that's a very pretty way of putting it."

"What, Midge?"

"That I'm a hopeless flirt—which is the root of the whole matter, I suppose!"

She burst out laughing, and he joined her. But there had been a pinch of pathos in her words, and he was weak enough to make a show of contradicting them. She would not listen to him, she laughed at his insincerity. The conversation had broken down, and, as soon as he decently could, he went.

That was at the very end of a season; and Lord Nunthorp did not see his notorious relative again for some months. In the following February, however, he heard her sing at some evening party; he had no chance of talking with her properly; but he was glad to find that he could meet her at a dance the next night.

"Well, Midge!" he was able to say at last, as they sat out together at this dance. "How many proposals since the summer?"

She gravely held up three fingers. Nunthorp laughed consumedly.

"SHE GRAVELY HELD UP THREE FINGERS."

"Any more scalps?" he inquired.

This was an ancient pleasantry. It referred to the expensive presents with which some young men had paved their way to disappointment. It was a moot point between Miss Anstruther and her noble kinsman whether she had any right to retain these things. She considered she had every right, and declared that these presents were her only compensation for so many unpleasantnesses. He pretended to take higher ground in the matter. But it amused him a good deal to ask about her "scalps."

She told him what the new ones were.

"And I perceive mine—upon your wrist!" Nunthorp exclaimed, examining her bracelet; and he was genuinely tickled.

"Well!" said she, turning to him with the frankest eyes, "I'd quite forgotten whose it was—honestly I had!"

He was vastly amused. So his bracelet—she had absolutely forgotten that it was his—did not make her feel at all awkward. There was a healthy cynicism in the existing relations between these two.

She had nothing very new to tell him. Two out of the last three had proposed by letter. She confessed to being sick and tired of answering this kind of letter.

"I'll tell you what," said her kinsman, looking inspired, "you ought to have one printed! You could compose a very pretty one, with blanks for the name and date. It would save you a deal of time and trouble. You would have it printed in brown ink and rummy old type, don't you know, on rough paper with coarse edges. It would look charming. 'Dear Mr. Blank, of course I'm greatly flattered'—no, you'd say 'very'—'of course I'm very flattered by your letter, but I must confess it astonished me. I thought we were to be such friends.' Really, Midge, it would be well worth your while!"

Miss Anstruther did not dislike the joke, from him; but when he added, "The pity is you didn't start it in the very beginning, with young Ted Miller"—she checked him instantly.

"Now don't you speak about him," she said, in a firm, quiet little way; but he appreciated the look that swept into her soft eyes no better than he had appreciated it six months before.

"Why not?" asked Nunthorp, merely amused.

"Because he meant it!"

Nunthorp wondered, but not seriously, whether that young fellow, who had gone in first, was to be the one, after all, to carry out his bat. And this way of putting it, in his own head, which was half full of cricket, carried him back to their last chat, and reminded him of a thing he had wanted to say to her for the last twenty-four hours.

"Do you remember my telling you," said he, "when I last had the privilege of lecturing you, that you sang iniquitously well? Then I feel it a duty to tell you that your singing is now worse than ever—in this respect. No wonder you have had three fresh troubles; I consider it very little, with your style of singing. Your songs have much to answer for; I said so then, I can swear to it now. Your voice is heavenly, of course; but why pronounce your words so distinctly? I'm sure it isn't at all fashionable. And why strive to make sense of your sounds? I really don't think it's good form to do so. And it's distinctly dangerous. It didn't happen to matter last night, because the rooms were so crowded; but if you sing to one or two as you sing to one or two hundred, I don't wonder at them, I really don't. You sing as if you meant every word of the drivel—I believe you humbug yourself into half meaning it, while you're singing!"

"I believe I do," Miss Anstruther replied, with characteristic candour. "You've no idea how much better it makes you sing, to put a little heart into it. But I never thought of this: perhaps I had better give up singing!"

"I'll tell you, when my turn comes round again," said he, leading her back to the ballroom. "I'll think of nothing else meanwhile."

He did not dance; he was not a dancing man; but he did think of something else meanwhile. He thought of a young fellow with a pale face, darkly accoutred, with whom Miss Anstruther seemed to be dancing a great deal. Lord Nunthorp hated dancing, and he had only come here to sit out a couple of dances with his amusing relative. He had to wait a good time between them; he spent it in watching her; and she spent it in dancing with the pale, dark boy—all but one waltz, during which Nunthorp removed his attention from the bow to its latest string, who, for the time being, looked miserable.

"Who," he asked her, as they managed to get possession of their former corner in the conservatory, "is your dark-haired, pale-faced friend?"

"Well," whispered Miss Anstruther, with grave concern, "I'm very much afraid that he is what you would call the next man in!"

"Good heaven!" ejaculated Nunthorp, for once aghast. "Do you mean to say he is going to propose to you?"

"I feel it coming; I know the symptoms only too well," she replied, in cold blood.

"Then perhaps you're going to make a different answer at last?"

"My dear man!" said Lord Nunthorp's[Pg 471] sisterly little connection; and her tone was that of a person rather cruelly misjudged.

The noble kinsman held his tongue for several seconds. Man of the world as he was, he looked utterly scandalised. Here, in this fair, frail, beautiful form, lay a depth of cynicism which he could not equal personally—which he could not fathom in another, and that other a quite young girl.

"Midge," he said at last, with sincere solemnity, "you horrify me! You've often told me the kind of thing, but this is the first time I've seen you with a fly actually in the web: for I don't think I myself counted, after all. That boy is helplessly in love with you! And you were smiling upon him as though you liked him too!"

Nunthorp was touched tremulously upon the arm. "Was I?" the girl asked him, in a frightened voice. "Was I looking—like that?"

"I think you were," said Nunthorp, frankly. "And now you calmly scoff at the bare notion of accepting him! You make my blood run cold, Midge! I think you can have no heart!"

"Do you think that?" she asked, strenuously, as though he had struck her.

"No, no; you know I don't; only after seeing you look at him like that——"

"Honestly, I didn't know I was looking in any particular way." Miss Anstruther added in a lowered, softened voice: "If I was—well, it wasn't meant for him."

Lord Nunthorp dropped his eye-glass.

"And it wasn't meant for you, either!" she superadded, smartly enough.

Lord Nunthorp breathed again, and ventured to recommend an immediate snub, in the pale boy's case.

"BUT I'VE GOT IT DOWN."

When he had led her back to her chaperone, he felt easier on her account than he had been for a long time. It was obvious to him that the biter was bit at last. The right man was evidently in view, though he was not there at the dance—which was hard on the white-faced youth. Perhaps she was not the right girl for the right man—perhaps he refused to be attracted by her. That would be odd, but not impossible; and a girl who had refused to fall in love with every man who had ever fallen in love with her, was the likeliest girl in the world to care for some man who cared nothing for her—primarily to make him care. That is a woman, through and through, reflected Lord Nunthorp, out of the recesses of a recherché experience. But Midge would most certainly make him care:[Pg 472] she was fascinating enough to capture any man—except himself—if she seriously tried: and he sincerely hoped she was going to try, to succeed, and to live happily ever after. For Nunthorp had now quite a paternal affection for the girl, and he wished her well, from the depths of his man-of-the-world's prematurely grey heart. But he did not like a little scene, with her in it, which he witnessed just before he quitted that party.

"My dance!" said a boy's confident, excited voice, just behind him; and the voice of Miss Anstruther replied, in the coldest of tones, that he "must have made a mistake, for it was not his dance at all."

"But I've got it down," the boy pleaded, as yet only amazed; his face was like marble as Nunthorp watched him; Miss Anstruther was also slightly pale.

"She's doing her duty, for once," thought Nunthorp, to whom the pathos of the incident lay in its utter conventionality. "But she plays a cruel game!"

"You've got it down?" said Miss Anstruther, very clearly, examining her card with ostentatious care. "Excuse me, but there is really some mistake; I haven't got your name down for anything else!"