The Project Gutenberg EBook of Our Edible Toadstools and Mushrooms and How

to Distinguish Them, by William Hamilton Gibson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Our Edible Toadstools and Mushrooms and How to Distinguish Them

A Selection of Thirty Native Food Varieties Easily

Recognizable by their Marked Individualities, with Simple

Rules for the Identification of Poisonous Species

Author: William Hamilton Gibson

Release Date: August 5, 2014 [EBook #46514]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EDIBLE TOADSTOOLS AND MUSHROOMS ***

Produced by Peter Vachuska, Paul Marshall, Dave Morgan,

Illustration images from The Internet Archive (TIA) and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

The Deadly "Amanita".

A Selection of Thirty Native Food Varieties

Easily Recognisable by their Marked Individualities,

with Simple Rules for the

Identification of Poisonous Species

By W. HAMILTON GIBSON

WITH THIRTY COLORED PLATES

AND FIFTY-SEVEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS BY THE AUTHOR

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1895

THE WORKS OF W. HAMILTON GIBSON.

ILLUSTRATED BY THE AUTHOR.

SHARP EYES. A Rambler's Calendar among Birds, Insects, and Flowers. 8vo, $5.00.

HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS; or, Saunterings in New England. 4to, $7.50.

STROLLS BY STARLIGHT AND SUNSHINE. Royal 8vo, $3.50.

HAPPY HUNTING-GROUNDS. A Tribute to the Woods and Fields. 4to, $7.50.

PASTORAL DAYS; or, Memories of a New England Year. 4to, $7.50.

CAMP LIFE IN THE WOODS, and the Tricks of Trapping and Trap-making. 16mo, $1.00.

Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

"For those who do hunger after the earthlie

excrescences called mushrooms."—Gerarde.

Contents

| Page | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| THE DEADLY AMANITA | 43 |

| THE AGARICACEÆ | 77 |

| THE POLYPOREI | 181 |

| MISCELLANEOUS FUNGI | 231 |

| SPORE-PRINTS | 277 |

| RECIPES | 299 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 325 |

| INDEX | 329 |

| PAGE | |

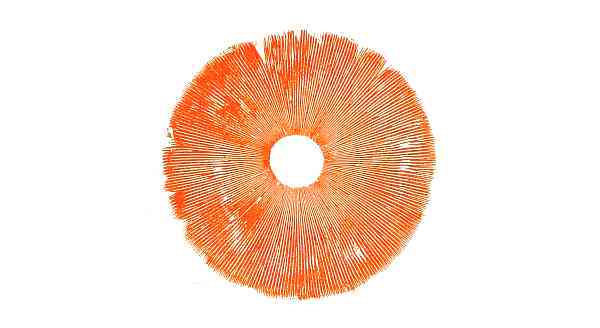

| 1. The Deadly "Amanita" | Frontispiece |

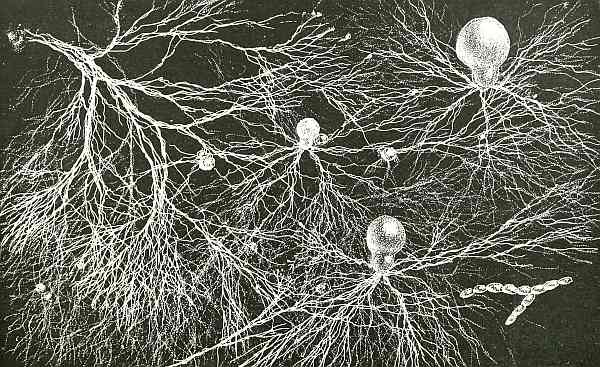

| 2. Mycelium, and early vegetation of a mushroom | 45 |

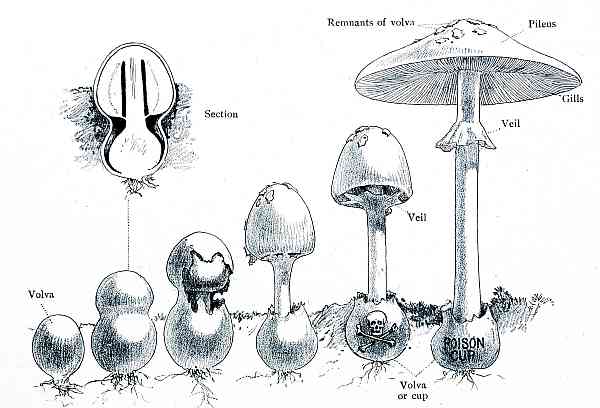

| 3. Amanita vernus—development | 49 |

| 4. Agaricus (Amanita) muscarius | 55 |

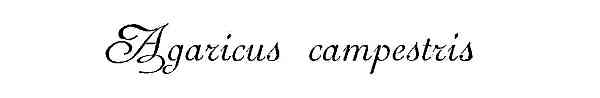

| 5. Agaricus campestris | 83 |

| 6. Agaricus campestris—various forms of | 89 |

| 7. Agaricus gambosus | 99 |

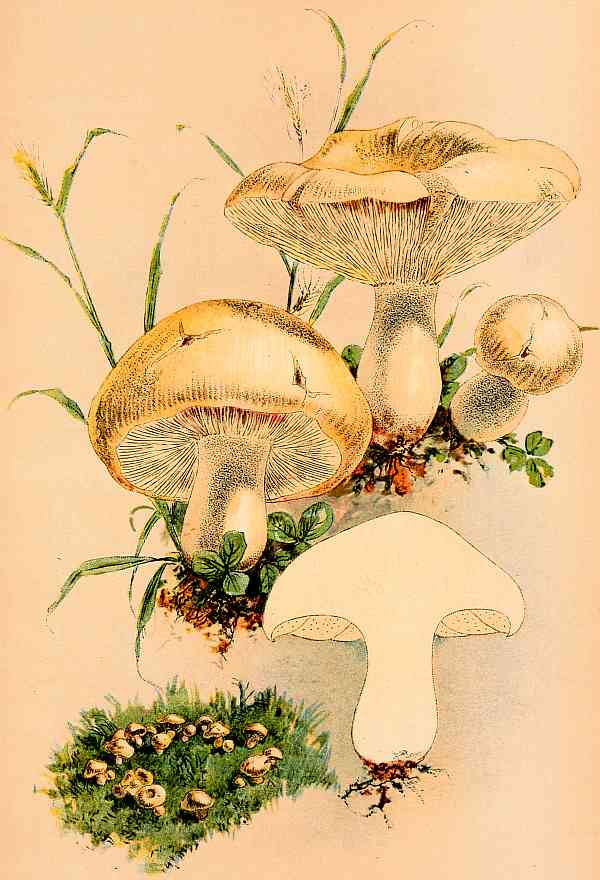

| 8. Marasmius oreades. "Fairy-ring" | 105 |

| 9. Poisonous Champignons. M. urens—M. peronatus | 111 |

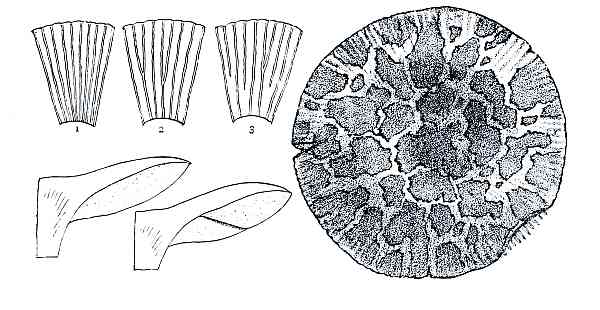

| 10. Agaricus procerus | 117 |

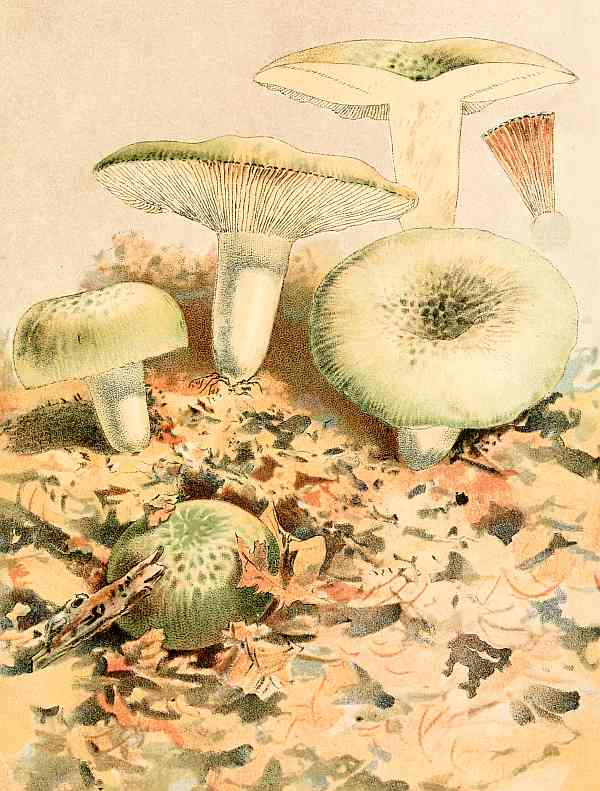

| 11. Agaricus (Russula) virescens | 123 |

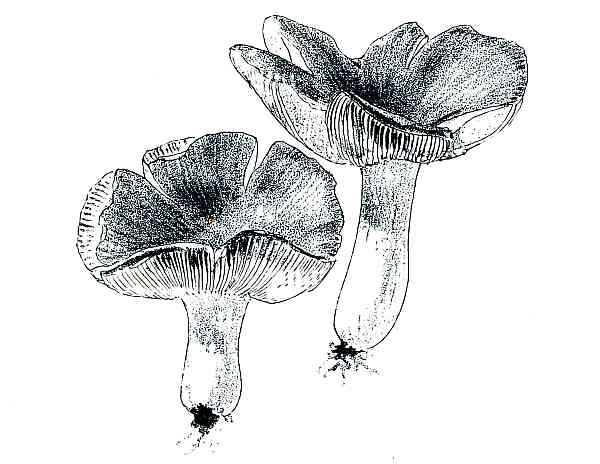

| 12. Edible Russulæ. R. heterophylla—R. alutacea—R. lepida | 131 |

| 13. Russula emetica | 139 |

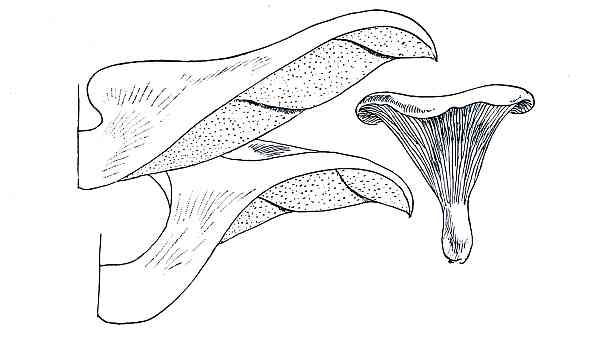

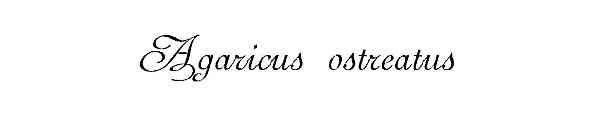

| 14. Agaricus ostreatus | 145 |

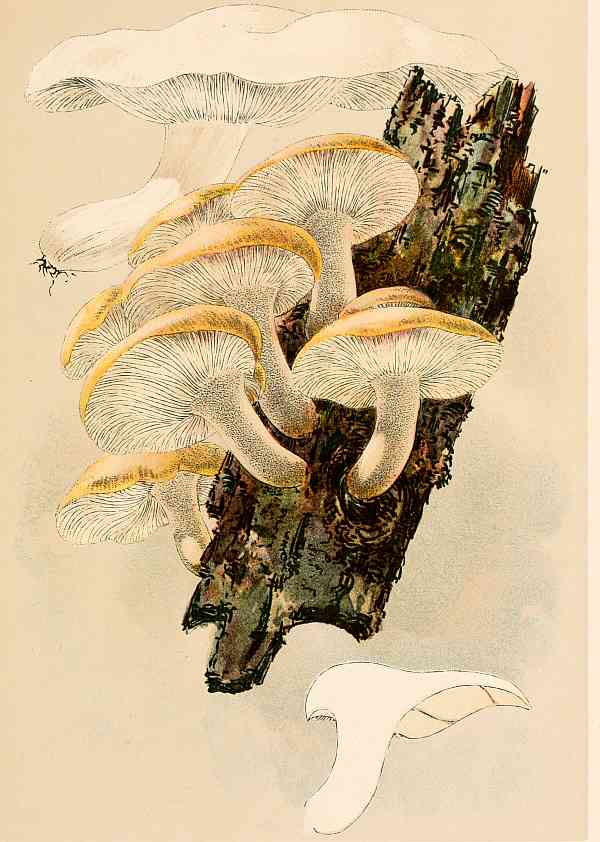

| 15. Agaricus ulmarius | 151 |

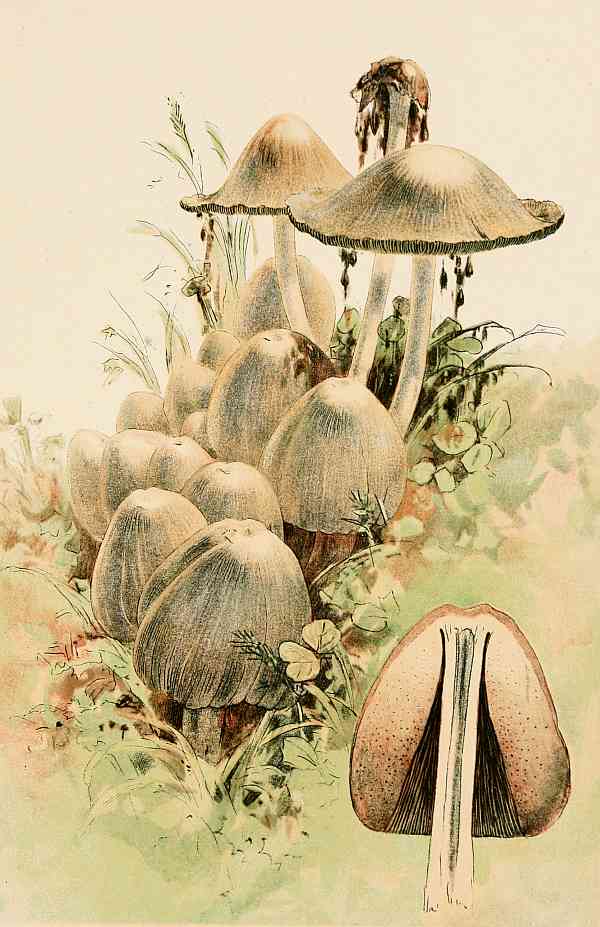

| 16. Coprinus comatus | 157 |

| 17. Coprinus atramentarius | 163 |

| 18. Lactarius deliciosus | 169 |

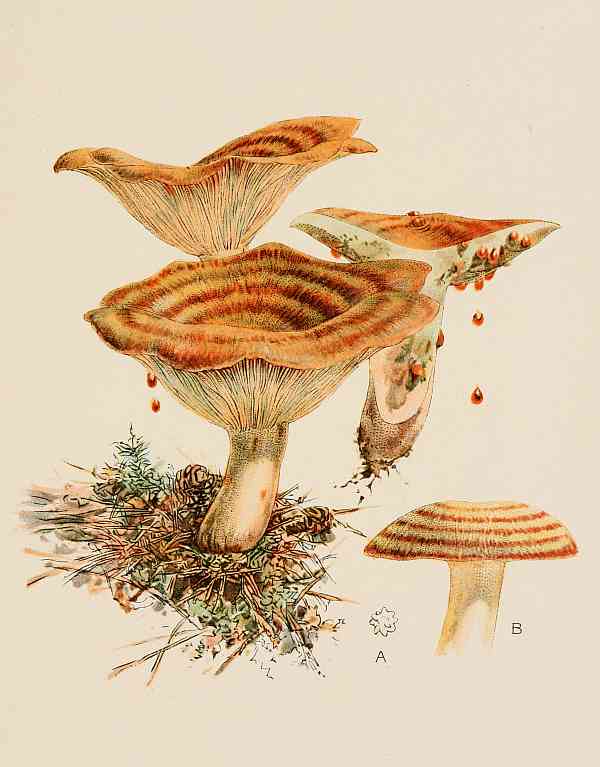

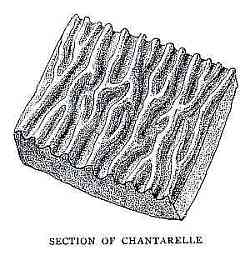

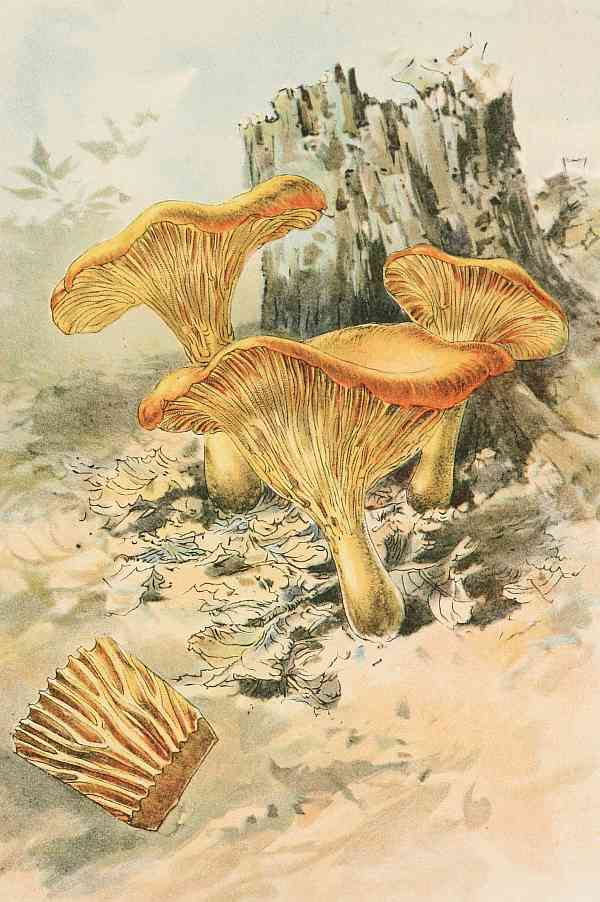

| 19. Cantharellus cibarius | 175 |

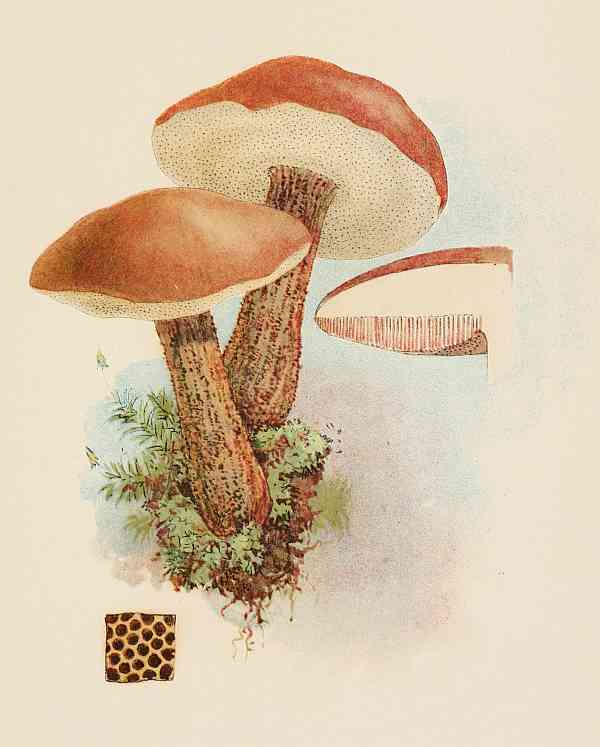

| 20. Boletus edulis | 187 |

| 21. Boletus scaber | 193 |

| 22. Edible Boleti. B. subtomentosus—B. chrysenteron | 199 |

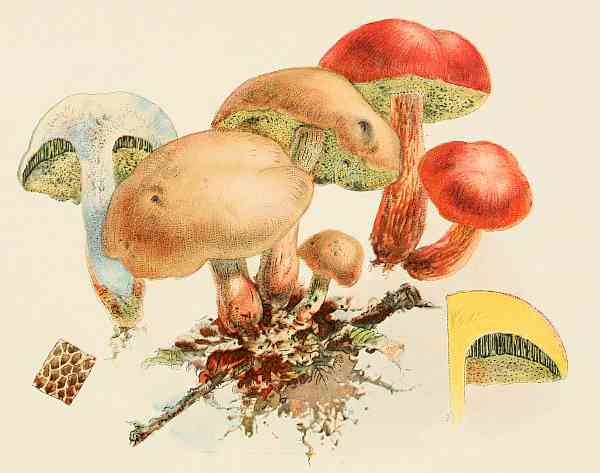

| 23. Strobilomyces strobilaceus | 205 |

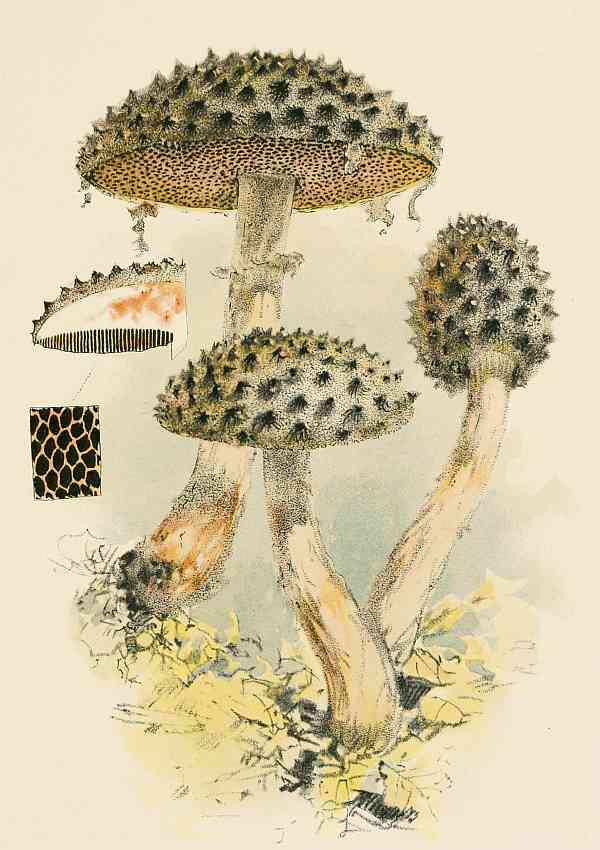

| 24. Suspicious Boleti. B. felleus—B. alveolatus | 211 |

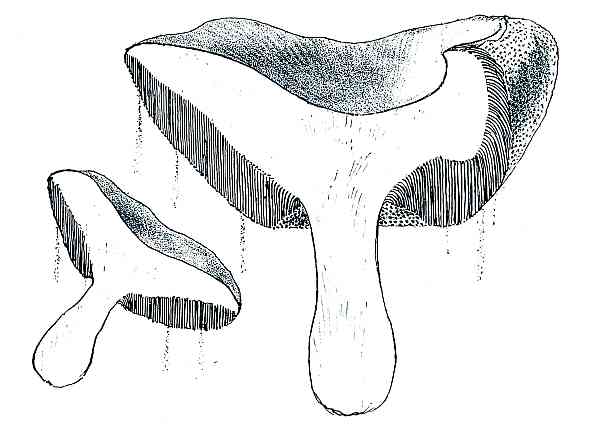

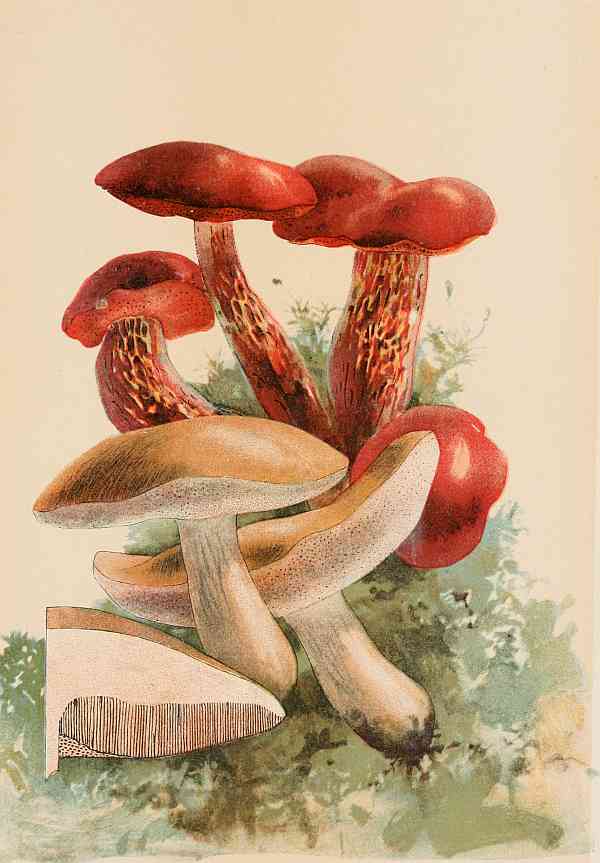

| 25. Fistulina hepatica | 217 |

| 26. Polyporus sulphureus | 225 |

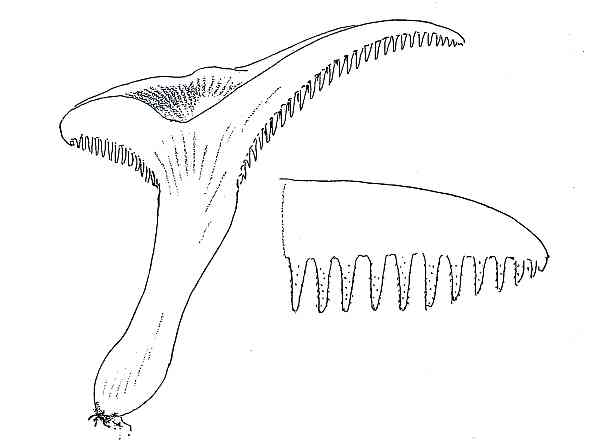

| 27. Hydnum repandum | 235 |

| 28. Hydnum caput-medusæ | 241 |

| 29. Hydnum caput-medusæ—habitat | 243 |

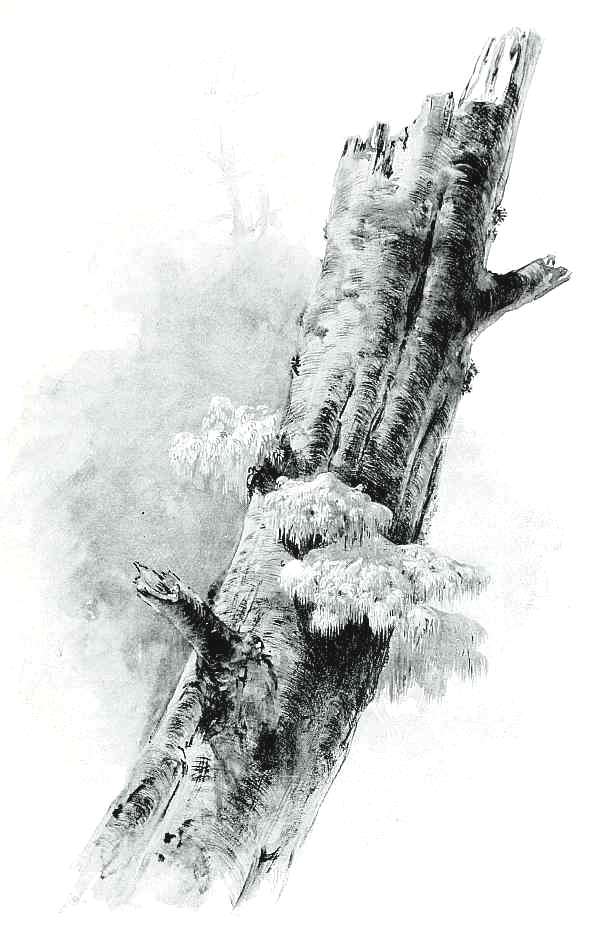

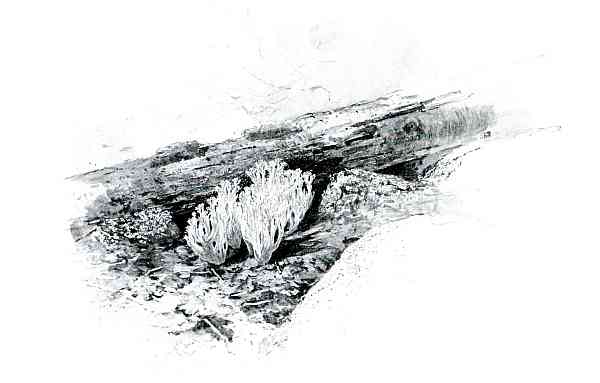

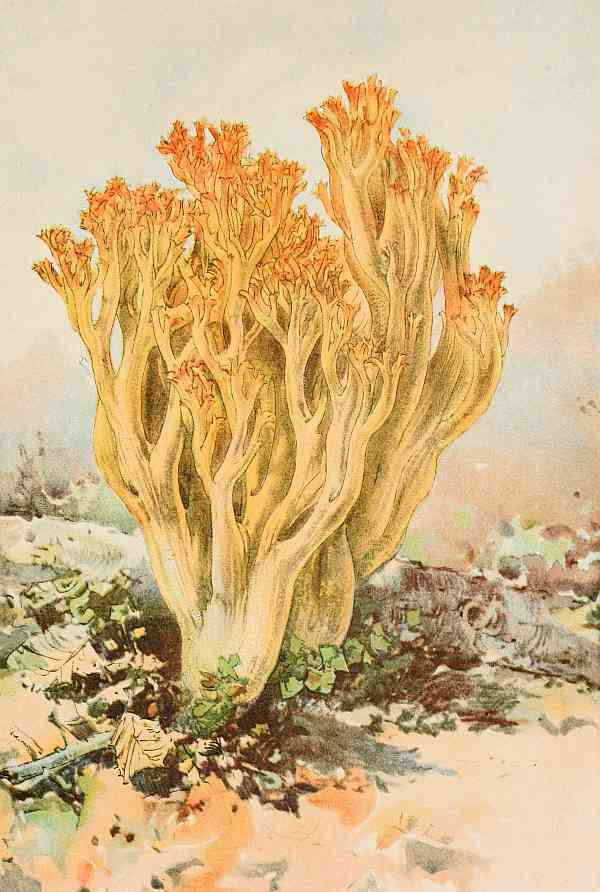

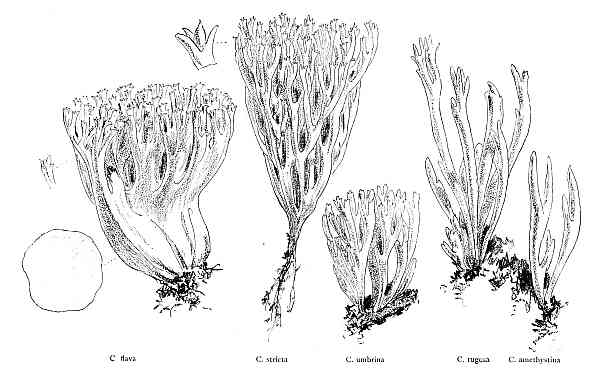

| 30. Clavaria formosa | 251 |

| 31. Various forms of Clavaria | 253 |

| 32. Morchella esculenta | 259 |

| 33. Helvella crispa | 265 |

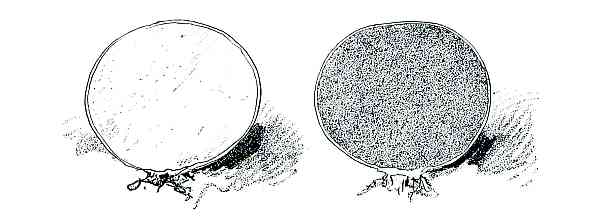

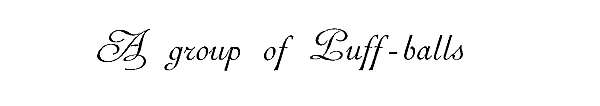

| 34. A group of Puff-balls | 271 |

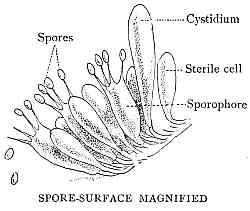

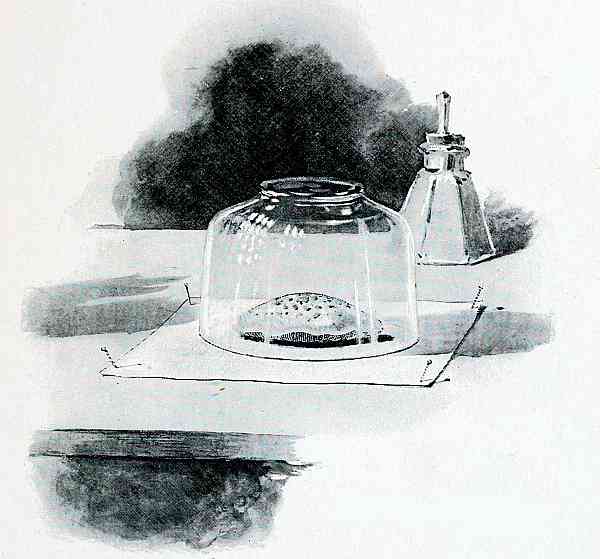

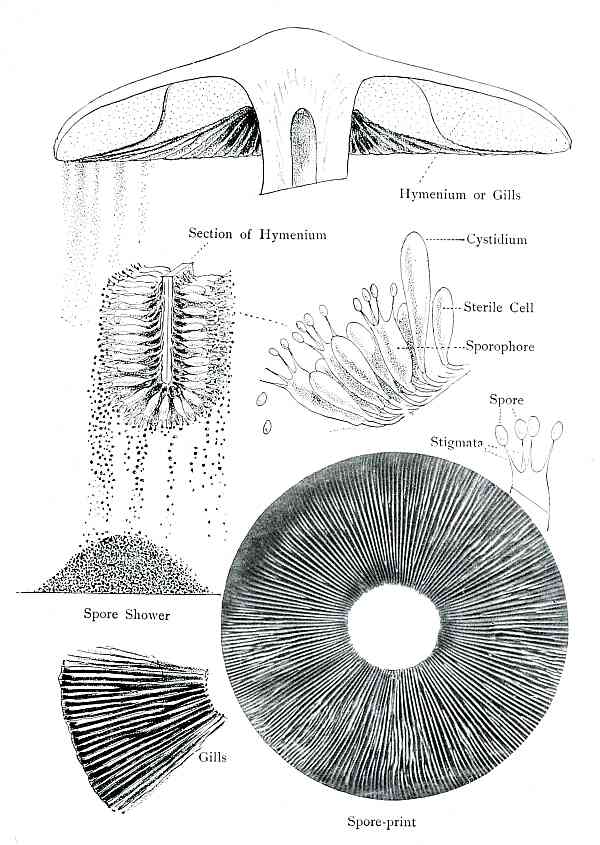

| 35. Spore-surface and spore-print of Agaricus | 283 |

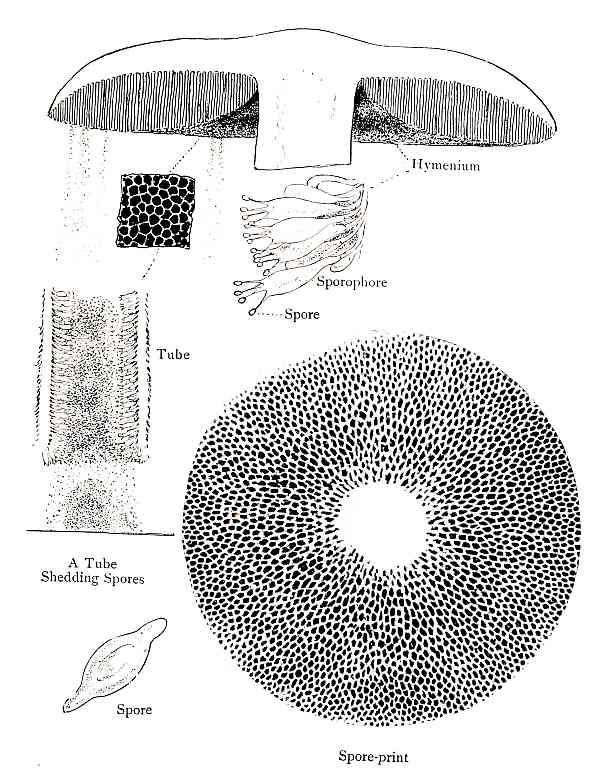

| 36. Spore-surface and spore-print of Polyporus (Boletus) | 285 |

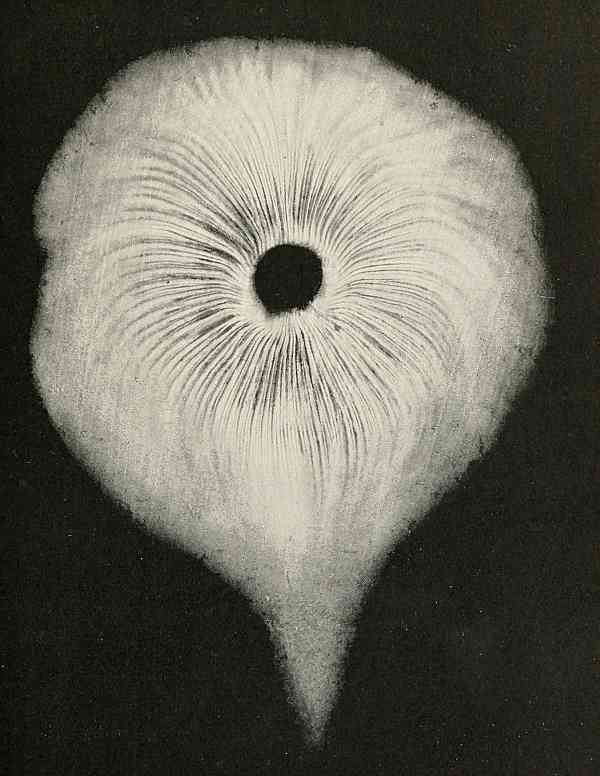

| 37. Spore-print of Amanita muscarius | 289 |

| 38. Action of slight draught on spores | 291 |

The Spurned Harvest

"Whole hundred-weights of rich, wholesome diet rotting under the trees; woods teeming with food and not one hand to gather it; and this, perhaps, in the midst of poverty and all manner of privations and public prayers against imminent famine."

A prominent botanical authority connected with one of our universities, upon learning of my intention of perpetrating a popular work on our edible mushrooms and toadstools, was inclined to take issue with me on the wisdom of such publication, giving as his reasons that, owing to the extreme difficulty of imparting exact scientific knowledge to the "general reader," such a work, in its presumably imperfect interpretation by the very individuals it is intended to benefit, would only result, in many instances, in supplanting the popular wholesome distrust of all mushrooms with a rash over-confidence which would tend to increase the labors of the family physician and the coroner. And, to a certain extent, in its appreciation of the difficulty of imparting exact science to the lay mind, his criticism was entirely reasonable, and would certainly apply to any treatise on edible mushrooms for popular circulation which contemplated a too extensive field, involving subtle botanical analysis and nice differentiation between species. [Pg 2]

But when we realize the fact—now generally conceded—that most of the fatalities consequent upon mushroom-eating are directly traceable to one particular tempting group of fungi, and that this group is moreover so distinctly marked that a tyro could learn to distinguish it, might not such a popular work, in its emphasis by careful portraiture and pictorial analysis of this deadly genus—placarding it so clearly and unmistakably as to make it readily recognizable—might not such a work, to that extent at least, accomplish a public service?

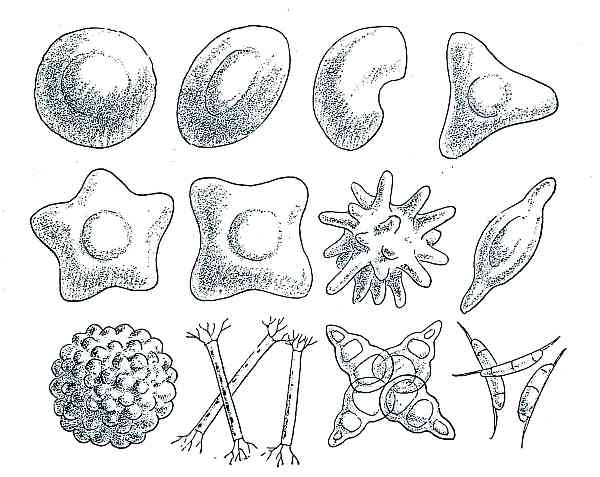

Moreover, even the most conservative mycologist will certainly admit that out of the hundred and fifty of our admittedly esculent species of fungi there might be segregated a few which bear such conspicuous characters of outward form and other unique individual features—such as color of spores, gills, and tubes, taste, odor, surface character, color of milky juice, etc.—as to render them easily recognizable even by the "general reader."

It is in the positive, affirmative assumption of these premises that the present work is prepared, comprising as it does a selection of a score or more, as it were, self-placarded esculent species of fungi, while putting the reader safely on guard against the fatal species and a few other more or less poisonous or suspicious varieties which remote possibility might confound with them.

Since the publication of a recent magazine article on this topic, and which became the basis of the present [Pg 3] elaboration, I have been favored with a numerous and almost continuous correspondence upon mushrooms, including letters from every State in the Union, to say nothing of Canada and New Mexico, evincing the wide-spread interest in the fungus from the gustatory point of view. The cautious tone of most of these letters, in the main from neophyte mycologists, is gratifying in its demonstration of the wisdom of my position in this volume, or, as one of my correspondents puts it, "the frightening of one to death at the outset while extending an invitation to the feast." "Death was often a consequence of toadstool eating," my friend continued, "but I never before realized that it was a certain result with any particular mushroom, and to the extent of this information I am profoundly thankful."

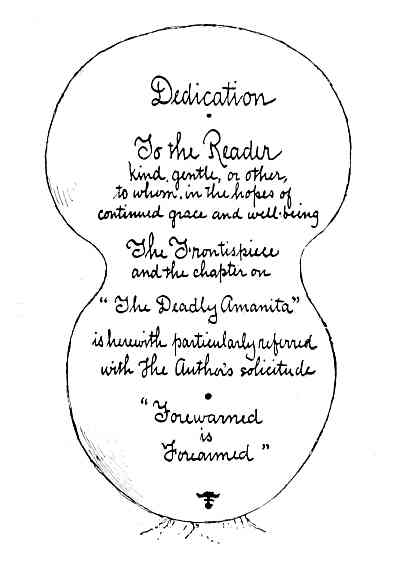

While, then, from the point of view of desired popularity of my book, the grim greeting of a death's-head upon the frontispiece might be considered as something of a handicap, the author confesses that this attitude is the result of "malice prepense" and deliberation, realizing that he is not offering to the "lay public," for mere intellectual profit, this scientific analysis of certain fungus species. Were this alone the raison d'être or the logical outcome of the work—mere identification of edible and poisonous species—the grewsome symbol which is so conspicuous on two of my pages might have been spared. But when it is remembered that with the selected list of esculent mushrooms herein offered is implied also an [Pg 4] invitation and a recommendation to the feast thereof, with the author as the host—that the digestive functions of his confiding friends or guests are to be made the final arbiters of the correctness of his botanical identification—the ban of bane may as well be pronounced at the threshold. Let the too eager epicurean be "scared to death at the outset," on the general principle pro bono publico, and to the conciliation of the author's conscience.

The oft-repeated queries of other correspondents suggest the wisdom of a clearer definition of the limitations of the present work. Several individuals have written in surprise of their discovery of a new toadstool which I "did not include in my pictured magazine list," with accompaniment of more or less inadequate description and somewhat enigmatical sketches, and desiring the name of the species and judgment upon its esculent qualities. Such correspondence is a pleasing tribute to an author, and is herewith gratefully acknowledged as to the past and, with some mental reservations, welcomed as to the future. The number of these communications—occasionally several in a day, and with consequent rapid accumulation—renders it absolutely impossible for a busy man to give them the prompt personal attention which courtesy would dictate. My "mushroom" pigeon-hole, therefore, is still plethoric with the unhonored correspondence of many weeks; and inasmuch as the continual accession more than balances the number of my responses, a fulfilment of my obligations in this direction seems hopeless in contemplation. [Pg 5] I would therefore beg the indulgence of such of my friends as have awaited in vain for my reply to their kind communications, even though the future should bring no tidings from me. All of these letters have been received, and are herewith acknowledged: many of them, too, if I may be pardoned what would seem to be a most ungracious comment, for which the "dead-letter" office would have been the more appropriate destination.

I refer to the correspondence "with accompanying specimens," the letter occasionally enclosed in the same box with the said specimens, which, upon its arrival, arouses a protest from the local postal authorities, and calls for a liberal use of disinfectants—a disreputable-looking parcel, which, indeed, would appear more consistently referable to the health-board than to the mycologist. So frequent did this embarrassing episode become that it finally necessitated the establishment of a morgue for the benefit of my mushroom correspondents, or rather for their "specimens," usually accompanied with the queries, "What is the name of this mushroom? Is it edible?" I have been obliged to write to several of my friends that identification of the remains was impossible, that the remnant was more interesting entomologically than botanically, and begging that in the future all such similar tokens shall be forwarded in alcohol or packed in ice.

"First impressions are lasting" and "a word to the wise is sufficient." I would suggest that correspondents hereafter consider the hazard of an introduction [Pg 6] under such questionable auspices. Most species of mushrooms are extremely perishable, and their "animal" character, chemically considered, and their tendency to rapid decomposition, render them unfit for transportation for any distance, unless hermetically sealed, or their decay otherwise anticipated.

In the possibility of a continuance of this correspondence, consequent upon the publication of this present book, the writer, in order to forefend a presumably generous proportion of such correspondence, would here emphasize the fact that he is by no means the authority on mycology, or the science of fungi, which the attitude of his inquiring friends would imply. Indeed, his knowledge of species is quite limited. An early fascination, it is true, was humored with considerable zeal to the accumulation of a portfolio of water-colors and other drawings of various fungi—microscopic, curious, edible, and poisonous—and this collection has been subsequently added to at intervals during his regular professional work.

More than one of the originals of the accompanying colored plates have been hidden in this portfolio for over twenty years, and a larger number for ten or fifteen years, awaiting the further accumulation of that knowledge and experience, especially with reference to the edibility of species, which should warrant the utterance of the long-contemplated book.

The reader will therefore kindly remember that out of the approximate 1000 odd species of fungi [Pg 7] entitled by their dimensions to the dignity of "toadstools" or "mushrooms"—after separating the 2000 moulds, mildews, rusts, smuts, blights, yeasts, "mother," and other microscopic species—and out of the 150 recommended edible species, the present work includes only about thirty. This selection has direct reference to popular utility, only such species having been included as offer some striking or other individual peculiarity by which they may be simply identified, even without so-called scientific knowledge.

The addition of color to the present list enables its extension somewhat beyond the scope of a series printed only in black and white, as in the distinction of mere form alone an uncolored drawing of a certain species might serve to the popular eye as a common portrait of a number of allied species, possibly including a poisonous variety.

While the study of "fungi" has a host of devotees, the mysteries which involve the origin of life in this great order of the cryptogamia having had fascinating attractions to microscopical students and specialists, the study of economic mycology has been almost without a champion in the United States. Thus we have many learned treatises on the nature, structure, and habits of fungi—vegetative methods, chemical constituents, specific characters, classification—learned dissertations on the microscopical moulds, mildews, rusts and smuts, blights and ferments, to say nothing of the medico-scientific and awe-inspiring potentialities of the sensational microbe, bacterium, [Pg 8] bacillus, etc., which are daily bringing humanity within their spell and revolutionizing the science of medicine. But among all the various mycological publications we look in vain for the great desideratum of the practical hand-book on the economic fungus—the mushroom as food! The mycologist who has been courageous enough to submit his chemical analysis and his botanical knowledge of fungi to the test of esculence in his own being is a rara avis among them; indeed, a well-known authority states that "one may number on the fingers of his two hands the entire list of mycophagists in the United States." The absence of such works upon the mushroom and "toadstool," greatly desired for reference at an early period of my career, and little better supplied to-day, led to a resolve of which this volume is but an imperfect fulfilment.

The special character of my volume, then—the collateral consideration of the fungus as food—will be sufficient excuse for the omission of a merely technical discourse upon the structure, classification, and vegetation of fungi as a class—a field so fully covered by other authors more competent to discuss these lines of special science, and to a selection of whose works the reader is referred in the list herewith appended, to a number of which I am indebted for occasional quotations. A general idea of the methods of dissemination and habitats of fungi will be found in the final chapter on "spore-prints," while under the discussion of the "Amanita," Agaricus [Pg 9] campestris, and the "Fairy Ring" the reader is referred to a condensed account of the methods of vegetation and growth of fungi sufficient for present purposes. Other references of similar character will be noted under "Fungi," in Index.

The most conspicuous disciple of mycophagy—almost the pioneer, indeed, in America—was the late Rev. M. A. Curtis, of North Carolina, whose name heads the bibliography on page 325. For the benefit of those of my readers who may wish to follow the subject further than my pages will lead them, I append the list of edible species of fungi contained in Curtis's Catalogue, each group alphabetically arranged, the esculent qualities of many of which he himself discovered and attested by personal experiment. The favorite habitat of each fungus is also given, and to avoid any possibility of confusion in scientific nomenclature or synonymes, the authority for the scientific name is also given in each instance:

LIST OF EDIBLE AMERICAN MUSHROOMS

FROM THE CATALOGUE OF DR. M. A. CURTIS

| Agaricus albellus. | De Candolle. | Damp woods. |

| A. (amanita) Cæsarea. | Scopoli. | In oak forests. |

| A. (amanita) rubescens. | Persoon. | Damp woods. |

| A. (amanita) strobiliformis. | Vittadini. | Common in woods. |

| A. amygdalinus. | M. A. Curtis. | Rich grounds, woods, and lanes. |

| A. arvensis. | Schaeffer. | Fields and pastures. |

| A. bombicinus. | Schaeffer. | Earth and carious wood. |

| A. campestris. | Linnæus. | Fields and pastures. |

| A. castus. | M. A. Curtis. | Grassy old fields. |

| A. cespitosus. | M. A. Curtis. | Base of stumps. |

| A. columbella. | Fries. | Woods. |

| A. consociatus. | Pine woods. | |

| A. cretaceus. | Fries. | Earth and wood. |

| A. esculentus. | Jacquin. | Dense woods. |

| A. excoriatus. | Fries. | Grassy lands. |

| A. frumentaceous. | Bulliard. | Pine woods. |

| A. giganteus. | Sowerby. | Borders of pine woods. |

| A. glandulosus. | Bulliard. | Dead trunks. |

| A. hypopithyus. | M. A. Curtis. | Pine logs. |

| A. mastoideus. | Fries. | Woods. |

| A. melleus. | Valmy. | About stumps and logs. |

| A. mutabilis. | Schaeffer. | Trunks. |

| A. nebularis. | Batsch. | Damp woods. |

| A. odorus. | Bulliard. | Woods. |

| A. ostreatus. | Jacquin. | Dead trunks. |

| A. personatus. | M. A. Curtis. | Near rotten logs. |

| A. pometi. | Fries. | Carious wood. |

| A. procerus. | Scopoli. | Woods and fields. |

| A. prunulus. | Scopoli. | Damp woods. |

| A. rachodes. | Vittadini. | Base of stumps and trees. |

| A. radicatus. | Bulliard. | Woods. |

| A. (russula). | Schaeffer. | Among leaves in woods. |

| A. salignus. | Persoon. | On trunks and stumps. |

| A. speciosus. | Fries. | Grassy land. |

| A. squamosus. | Muller. | Oak stumps. |

| A. sylvaticus. | Schaeffer. | Woods. |

| A. tessellatus. | Bulliard. | Pine trunks. |

| A. ulmarius. | Sowerby. | Dead trunks. |

| Boletus bovinus. | Linnæus. | Pine woods. |

| B. castaneus. | Bulliard. | Woods. |

| B. collinitus. | Fries. | Pine woods. |

| B. edulis. | Bulliard. | Woods. |

| B. elegans. | Fries. | Earth in woods. |

| B. flavidus. | Fries. | Damp woods. |

| B. granulatus. | Linnæus. | Woods and fields. |

| B. luteus. | Linnæus. | Pine woods. |

| B. scaber. | Bulliard. | Sandy woods. |

| B. subtomentosus. | Linnæus. | Earth in woods. |

| B. versipellis. | Fries. | Woods. |

| Bovista nigrescens. | Persoon. | Grassy fields. |

| B. plumbea. | Persoon. | Grassy fields. |

| Cantharellus cibarius. | Fries. | Woods. |

| Clavaria aurea. | Schaeffer. | Earth in woods. |

| C. botritis. | Persoon. | Earth in woods. |

| C. cristata. | Holmskiold. | Damp woods. |

| C. fastigiata. | Linnæus. | Grassy places. |

| C. flava.[Pg 11] | Fries. | Earth in woods. |

| C. formosa. | Persoon. | Earth in woods. |

| Clavaria fuliginea. | Persoon. | Shady woods. |

| C. macropus. | Persoon. | Earth. |

| C. muscoides. | Linnæus. | Grassy places. |

| C. pyxidata. | Persoon. | Rotten woods. |

| C. rugosa. | Bulliard. | Damp woods. |

| C. subtilis. | Persoon. | Shaded banks. |

| C. tetragona. | Schwartz. | Damp woods. |

| Coprinus atramentarius. | Bulliard. | Manured ground. |

| C. comatus. | Fries. | In stable-yards. |

| Cortinarius castaneus. | Fries. | Earth in woods. |

| C. cinnamomeus. | Fries. | Earth and wood. |

| C. violaceus. | Fries. | Woods. |

| Fistulina hepatica. | Fries. | Base of trunks and stumps. |

| Helvella crispa. | Fries. | Pine in woods. |

| H. infula. | Schaeffer. | Earth and pine logs. |

| H. lacunosa. | Afzelius. | Near rotten logs. |

| H. sulcata. | Afzelius. | Shady woods. |

| Hydnum caput-medusæ. | Bulliard. | Trunks and logs. |

| H. coralloides. | Scopoli. | Side of trunks. |

| H. imbricatum. | Linnæus. | Earth in woods. |

| H. laevigatum. | Schwartz. | Pine woods. |

| H. repandum. | Linnæus. | Woods. |

| H. rufescens. | Schaeffer. | Woods. |

| H. subsquamosum. | Batsch. | Damp woods. |

| Hygrophorus eburneus. | Fries. | Woods. |

| H. pratensis. | Fries. | Hill-sides. |

| Lactarius augustissimus. | Lasch. | Thin woods. |

| L. deliciosus. | Fries. | Pine woods. |

| L. insulsus. | Fries. | Woods. |

| L. piperatus. | Fries. | Dry woods. |

| L. subdulcis. | Fries. | Damp grounds. |

| L. volemus. | Fries. | Woods. |

| Lycoperdon bovista. | Linnæus. | Grassy lands. |

| Pachyma cocos. | Fries. | Underground. |

| Paxillus involutus. | Fries. | Sandy woods. |

| Polyporus Berkeleii. | Fries. | Woods. |

| P. confluens. | Fries. | Pine woods. |

| P. cristatus. | Fries. | Pine woods. |

| P. frondorus. | Fries. | Earth and base of stumps. |

| P. giganteus. | Fries. | Base of stumps. |

| P. leucomelas. | Fries. | Woods. |

| P. ovinus. | Schaeffer. | Earth in woods. |

| P. poripes. | Fries. | Wooded ravines. |

| P. sulphureus. | Fries. | Trunks and logs. |

| Marasmius oreades. | Fries. | Hill-sides.[Pg 12] |

| M. scorodoneus. | Fries. | Decaying vegetation. |

| Morchella Caroliniana. | Bosc. | Earth in woods. |

| M. esculenta. | Persoon. | Earth in woods. |

| Russula alutacea. | Fries. | Woods. |

| R. lepida. | Fries. | Pine woods. |

| R. virescens. | Fries. | Woods. |

| Sparassis crispa. | Fries. | Earth. |

| S. laminosa. | Fries. | Oak logs. |

| Tremella mesenterica. | Retz. | On bark. |

In the contemplation of such a generous natural larder as the above list implies, Dr. Badham's feeling allusion to the "hundred-weights of wholesome diet rotting under the trees," quoted in one of my earlier illustrated pages, will be readily appreciated.

In the purposely restricted scope of these pages I have omitted a large majority of species in Dr. Curtis's list, known to be equally esculent with those which I have selected, but whose popular differentiation might involve too close discrimination and possibly serious error; and while my list is probably not as complete as it might be with perfect safety, the number embraces species, nearly all of them what may be called cosmopolitan types, to be found more or less commonly throughout the whole United States and generally identical with European species. It will be observed that the list of Dr. Curtis is headed by three members of Amanitæ. The particular species cited are well known to be esculent, but they are purposely omitted from my list, which for considerations of safety absolutely excludes the entire genus Amanita of the "poison-cup" which is discussed at some length in the succeeding chapter.

[Pg 13] For popular utility from the food standpoint my selection presents, to all intents and purposes, a more than sufficient list, the species being easily distinguished, and, with proper consideration to their freshness, entirely safe and of sufficient frequency in their haunts to insure a continually available mushroom harvest throughout the entire fungus season.

The knowledge of their identities once acquired, it is perfectly reasonable to assert that in average weather conditions the fungus-hunter may confine himself to these varieties and still be confronted with an embarrassment of riches, availing himself of three meals a day, with the mere trouble of a ramble through the woods or pastures. Indeed, he may restrict himself to six of these species—the green Russula, Puff-ball, Pasture-mushroom, Campestris (meadow-mushroom), Shaggy-mane, and Boletus edulis—and yet become a veritable mycological gourmand if he chooses, never at a loss for an appetizing entrée at his table.

In the group of Russulæ and Boleti alone, more than one conservative amateur of the writer's acquaintance finds a sufficient supply to meet all dietary wants.

What a plenteous, spontaneous harvest of delicious feasting annually goes begging in our woods and fields!

The sentiment of Dr. Badham, the eminent British authority on mushrooms, years ago, in reference to the spontaneous perennial harvest of wild edible fungi which abounded in his country, going to waste by the ton, would [Pg 14] appear to be as true to-day for Britain as when he uttered it, and applies with even greater force to the similar, I may say identical, neglected tribute of Nature in our own American woods and fields, where the growth of fungi is especially rich.

The fungus-eaters of Britain, it is said, are even to-day merely a conspicuous coterie, while in America this particular sort of specialist is more generally an isolated "crank" who is compelled to "flock alone," contemplated with a certain awe by his less venturesome fellows, and otherwise variously considered, either with envy of his experience and scientific knowledge, or more probably as an irresponsible, who continually tempts Providence in his foolhardy experiments with poison.

But what a contrast do we find on the Continent in the appreciation of the fungus as an article of diet! In France, Germany, Russia, and Italy, for example, where the woods are scoured for the perennial crop, and where, through centuries of popular familiarity and tradition, the knowledge of its economic value has become the possession of the people, a most important possession to the poor peasant who, perhaps for weeks together, will taste no other animal food. I say "animal food" advisedly; for, gastronomically and chemically considered, the flesh of the mushroom has been proven to be almost identical with meat, and possesses the same nourishing properties. This animal affinity is further suggested in its physiological life, the fungus reversing the order of all [Pg 15] other vegetation in imbibing oxygen and exhaling carbonic acid, after the manner of animals. It is not surprising, therefore, that the analogy should be still further emphasized by the discrimination of the palate, many kinds of fungi when cooked simulating the taste and consistency of animal food almost to the point of deception.

But in America the fungus is under the ban, its great majority of harmless or even wholesome edible species having been brought into popular disrepute through the contamination, mostly, of a single small genus.

In the absence of special scientific knowledge, or, from our present point of view, its equivalent, popular familiarity, this general distrust of the whole fungus tribe may be, however, considered a beneficent prejudice. So deadly is the insidious, mysterious foe that lurks among the friendly species that it is well for humanity in general that the entire list of fungi should share its odium, else those "toadstool" fatalities, already alarmingly frequent, might become a serious feature in our tables of mortality.

But the prejudice is needlessly sweeping. A little so-called knowledge of fungi has often proven to be a "dangerous thing," it is true, but it is quite possible for any one of ordinary intelligence, rightly instructed, to master the discrimination of at least a few of the more common edible species, while being thoroughly equipped against the dangers of deadly varieties, whose identification is comparatively simple. [Pg 16]

It is idle to attempt an adjudication of the vexed "toadstool" and "mushroom" question here. The toad is plainly the only final, appealable authority on this subject. It may be questioned whether he is at pains to determine the delectable or noisome qualities—from the human standpoint—of a particular fungus before deciding to settle his comfortable proportions upon its summit—if, indeed, he even so honors even the humblest of them.

The oft-repeated question, therefore, "Is this fungus a toadstool or a mushroom?" may fittingly be met by the counter query, "Is this rose a flower or a blossom?"

The so-called distinction is a purely arbitrary, popular prejudice which differentiates the "toadstool" as poisonous, the "mushroom" being considered harmless. But even the rustic authorities are rather mixed on the subject, as may be well illustrated by a recent incident in my own experience.

Walking in the woods with a country friend in quest of fungi, we were discussing this "toadstool" topic when we came upon a cluster of mushrooms at the base of a tree-trunk, their broad, expanded caps apparently upholstered in fawn-colored, undressed kid, their under surfaces being stuffed and tufted in pale greenish hue.

"What would you call those?" I inquired.

"Those are toadstools, unmistakably," he replied.

"Well, toadstools or not, you see there about two pounds of delicious vegetable meat, for it is the common species of edible boletus—Boletus edulis." [Pg 17]

A few moments later we paused before a beautiful specimen, lifting its parasol of pure white above the black leaf mould.

"And what is this?" I inquired.

"I would certainly call that a mushroom," was his instant reply.

This mushroom proved to be a fine, tempting specimen of the Agaricus (amanita) vernus, the deadliest of the mushrooms, and one of the most violent and fatal of all known vegetable poisons, whose attractive graces and insidious wiles are doubtless continually responsible for those numerous fatalities usually dismissed with the epitaph, "Died from eating toadstools in mistake for mushrooms."

So much, therefore, for the popular distinction which makes "toadstool" a synonyme for "poisonous," and "mushroom" synonymous with "edible," and which often proves to be the "little knowledge" which is very dangerous.

The too prevalent mortality traceable to the mushroom is confined to two classes of unfortunates: 1. Those who have not learned that there is such a thing as a fatal mushroom; 2. The provincial authority who Can "tell a mushroom" by a number of his so-called infallible "tests" or "proofs." There is a large third class to whose conservative caution is to be referred the prevalent arbitrary distinction between "toadstool" and "mushroom," ardent disciples of old Tertullian, who believed in regard to toadstools that "For every different hue they display there is a pain to correspond to it, and just so many modes [Pg 18] of death as there are distinct species," and whose obstinate dogma, "There is only one mushroom, all the rest are toadstools," has doubtless spared them an occasional untimely grave, for few of this class, from their very conservatism, ever fall victims to the "toadstool."

And what a self-complacent, patronizing, solicitous character this rustic mushroom oracle is! Go where you will in the rural districts and you are sure of him, or perhaps her—usually a conspicuous figure in the neighborhood, the village blacksmith, perhaps, or the simpler "Old Aunt Huldy." Their father and "granther" before them "knew how to tell a mushroom," and this enviable knowledge has been their particular inheritance.

How well we more special students of the fungus know him! and how he wins our tender regard with his keen solicitude for our well-being! We meet him everywhere in our travels, and always with the same old story! We emerge from the wood, perhaps, with our basket brimful of our particular fungus tidbits, topped off with specimens of red Russula and Boletus, and chance to pass him on the road or in the meadow. He scans the basket curiously as he passes us. He has perhaps heard rumors afloat that "there's a city chap in town who is tempting Providence with his foolin' with tudstools;" and with genuine solicitude and superior condescension and awe, all betrayed in his countenance, he must needs pause in his walk to relieve his mind in our behalf. I recall one characteristic episode, of which the above is the prelude. [Pg 19]

"Ye ain't a-goin' to eat them, air ye?" he asks, anxiously, by way of introduction.

"I am, most certainly," I respond; "that is, if I can get my good farmer's wife to cook them without coming them and inundating them in lemon-juice."

"Waal, then, I'll say good-bye to ye," he responds, with emphasis. "Why, don't ye know them's tudstools, 'n' they'll kill ye as sartin as pizen? I wonder they ain't fetched ye afore this. You never larned tew tell mushrooms. My father et 'em all his life, and so hev I, 'n' I know 'em. Come up into my garden yender 'n' I'll show ye haow to tell the reel mushroom. There's a lot of 'em thar in the hot-bed naow. Come along. I'll give ye a mess on 'em if ye'll only throw them pizen things away."

"And how do you know that those in your garden are real mushrooms?" I inquire.

"Why, they ain't anything like them o' yourn. They're pink and black underneath, and peel up from the edge."

"How many kinds of mushrooms are there, do you suppose?" I ask.

"They's only the one kind; all the others is tudstools and pizen. It's easy to tell the reel mushroom. Come up and I'll show ye. Don't eat them things, I beg on ye! I vaow they'll kill ye!"

At this point he catches a glimpse of a Shaggy-mane mushroom, which comes to light as I tenderly fondle the specimens, and which is evidently recognized as an acquaintance. [Pg 20]

"What!" he exclaims, in pale alarm. "Ye ain't goin' t' eat them too?"

"Oh yes I am, this very evening," I respond. "I think I'll try them first."

"Why, man, yure crazy! You don't know nothin' about 'em. I'd as soon think o' eatin' pizen outright. Them's what we call black-slime tudstools. They come up out o' manure. I've seen my muck-heap in my barnyard covered with the nasty things time 'n' ag'in. They look nice 'n' white naow, but they rot into the onsiteliest black mess ye ever see. I know wut I'm sayin'. Ye can't tell me nothin' 'baout them tudstools! They keep comin' up along my barn-fence all thro' the fall—bushels of 'em."

"Well, my good friend, it's a great pity, then, that you have not learned something about toadstools as well as mushrooms, for you might have saved many a butcher's bill, and may in the future if you will only take my word that this much-abused specimen is as truly a mushroom as your pink-gilled peeler, and to my mind far more delicious."

"What! Do you mean to tell me thet you have reely eaten 'em?"

"Yes, indeed; often. Why, just look at its clean, shaggy cap, its creamy white or pink gills underneath; take a sniff of its pleasant aroma; and here! just taste a little piece—it's as sweet as a nut!" I conclude, offering him the white morsel.

"Not much! I'll make my will first, thank'ee! You let me see ye eat a mess of 'em, and if the coroner don't get ye, p'r'aps I'll try on't." [Pg 21]

Experiences similar to this one are frequent in the career of every mycophagist, and serve to illustrate the pity and solicitude which he awakens among his fellow-mortals, as well as to emphasize the prevalent superstitions regarding the comparative virtues of the mushroom and toadstool—a prejudice which, by-the-way, in the absence of available popular literature on the subject, and the actual dangers which encompass their popular distinction, is a most beneficent public safeguard.

The mushroom which "he can tell" is generally the Agaricus campestris, or one of its several varieties; and knowing this alone, and tempted by no other, this sort of village oracle escapes the fate which often awaits another class, who are not thus conservative, and who extend their definition of mushroom (a word supposed to be synonymous with "edible"), and this mainly through the indorsement of certain so-called infallible tests handed down to them from their forefathers, and by which the esculent varieties may be distinguished from the poisonous. By these so-called "tests" or "proofs" the identification of certain species is gradually acquired. The rural fungus epicure now "knows them by sight," or perhaps has received his information second-hand, and makes his selection without hesitation, with what success may be judged from the incident in my own experience already noted—one which, knowing as I did the frequency and confidence with which my country friend sampled the fungi at his [Pg 22] table, filled me with consternation and anxiety for his future.

"How, then, shall we distinguish a mushroom from a toadstool?"

There is no way of distinguishing them, for they are the same.

"How, then, shall we know a poisonous toadstool from a harmless one?" the reader hopelessly exclaims.

This discrimination is by no means as difficult as is popularly supposed, but in the first place, the student must entirely rid himself of all preconceived notions and traditions, such as the following almost world-wide "tests," many of which are easily demonstrated to be worse than worthless, and have doubtless frequently led to an untimely funeral. Some of these are merely local, and in widely separated districts are supplanted by others equally arbitrary and absurd, while many of them are as old as history.

WORTHLESS TRADITIONAL TESTS FOR THE

DISCRIMINATION OF POISONOUS AND EDIBLE MUSHROOMS

FAVORABLE SIGNS

1. Pleasant taste and odor.

2. Peeling of the skin of the cap from rim to centre.

3. Pink gills, turning brown in older specimens.

4. The stem easily pulled out of the cap and inserted in it like

a parasol handle.

5. Solid stems.

6. Must be gathered in the morning.

7. "Any fungus having a pleasant taste and odor, being found

similarly agreeable after being plainly broiled without the least seasoning, is perfectly safe."

[Pg 23]

UNFAVORABLE SIGNS

8. Boiling with a "silver spoon," the staining of the

silver indicating danger.

9. Change of color in the fracture of the fresh mushroom.

10. Slimy or sticky on the top.

11. Having the stems at their sides.

12. Growing in clusters.

13. Found in dark, damp places.

14. Growing on wood, decayed logs, or stumps.

15. Growing on or near manure.

16. Having bright colors.

17. Containing milky juice.

18. Having the gill plates of even length.

19. Melting into black fluid.

20. Biting the tongue or having a bitter or nauseating taste.

21. Changing color by immersion in salt-water,

or upon being dusted with salt.

These present but a selection of the more prevalent notions. Taken in toto, they would prove entirely safe, as they would practically exclude every species of mushroom or toadstool that grows. But as a rule the village oracle bases his infallibility upon two or three of the above "rules," and inasmuch as the entire list absolutely omits the only one test by which danger is to be avoided, it is a seven-days' wonder that the grewsome toadstool epitaph is not more frequent.

I once knew an aged dame who was accepted as a village oracle on this as well as other topics, such as divining, palmistry, and fortune-telling, and who ate and dispensed toadstools on a few of the above rules. Strange to say, she lived to a good old age, and no increased mortality is credited to her memory as a result of her generosity. [Pg 24]

How are these popular notions sustained by the facts? Let us analyze them seriatim and confront each with its refutation, the better to show their entire untrustworthiness.

Pleasant taste and odor (1) is a conspicuous feature in the regular "mushroom" (Agaricus campestris), and most other edible fungi, but as a criterion for safety it is a mockery. The deadly Agaricus amanita, already mentioned, has an inviting odor and to most people a pleasant taste when raw, and being cooked and eaten gives no token of its fatal resources until from six to twelve hours after, when its unfortunate victim is past hope. (See p. 68.)

The ready peeling of the skin (2) is one of the most widely prevalent proofs of probation, and is often considered a sufficient test; yet the Amanita will be found to peel with a degree of accommodation which would thus at once settle its claims as a "mushroom." Indeed, a large number of species, including several poisonous kinds, will peel as perfectly as the Campestris.

The pink gills turning brown(3) is a marked characteristic of the "mushroom" (A. campestris, Plate 5), and, being a rare tint among the fungus tribe, is really one of the most valuable of the tests, especially as it is limited by rules affecting other pink-gilled species.

The stem being easily pulled out of the cap (4) applies to several edible species, but equally to the poisonous. [Pg 25]

The notion that edible mushrooms have solid stems (5) would be a very unsafe talisman for us to take to the woods in our search for fungus-food. Many poisonous species are thus solid—the emetic Russula, for example—while the alleged importance of the morning specimens (6) is without the slightest foundation.

The passage quoted here (7), or a statement to the same effect, was quite widely circulated in the newspapers a dozen or more years ago, in an article which bore all the indications of authoritative utterance, the assumption being that the poisonous mushroom would invariably give some forbidding token to the senses by which it might be discriminated.

Woe to the fungus epicure who should sample his mushrooms and toadstools on such a criterion as this, as the most fatal of all mushrooms, the Amanita vernus, would fulfil all these requisites.

The discoloration of silver (8) is a test as old as Pliny at least, a world-wide popular touchstone for the detection of deleterious fungi, but useful only in the fact that it will often exclude a poison not contemplated in the discrimination. On this point, especially as it affords opportunity to emphasize a common disappointment of the mushroom-eater, I quote from a recent work by Julius A. Palmer (see Bibliography, No. 3): "Mushrooms decay very rapidly. In a short time a fair, solid fungus becomes a mass of maggots which eat its tissue until its substance is [Pg 26] honey-combed; these cells, on a warm day, are charged with the vapors of decomposition. Now you put such mushrooms as these (and I have seen just such on the markets of Boston and London) over the fire. In boiling, sulphuretted hydrogen or other noxious gases are liberated; you stir with a bright spoon and it is discolored; proud of your test, you throw away your stew. Now this is right, but if from this you conclude that all fungus which discolors silver is poisonous and that which leaves it bright is esculent, you are in dangerous error. It is the same with fish at sea. Tradition says that you must fry a piece of silver with them and throw them away if it discolors. Certainly the experiment does no harm, and shows a decomposition in both cases which might have been detected without the charm." Opposed to this so-called talisman, how grim is the fact that the deadliest of all mushrooms, the Amanita, in its fresh condition, has no effect upon silver.

The change of color in fracture (9) has long been a ban to the fungus as food. But this would exclude several very delicious species, which turn bluish, greenish, and red when broken—viz., Boletus subtomentosus (Plate 22), Boletus strobilaceus (Plate 23), and Lactarius (Plate 18).

The "toadstools" with "sticky tops" thus discriminated against (10) include a number of esculent species, Boleti and Russulæ, and others, as do also the varieties with side-stems (11)—viz., Agaricus ulmarius (Plate 15), Fistulina hepatica (Plate 25), Agaricus ostreatus (Plate 14), etc. [Pg 27]

The clustered fungi (12) have long been included in the black-list without reason, as witness the following esteemed esculent species: The Shaggy-mane (Plate 16), Coprinus atramentarius (Plate 17), Oyster mushroom (Plate 14), Elm mushroom (Plate 15), Puff-balls (Plate 34), and Champignon (Plate 8).

To exclude all fungi which grow in dark, damp places (13) is a singular inconsistency, as in some localities this would eliminate the very one species of "mushroom" admittedly eatable by popular favor. In many countries these are regularly cultivated for market in dark, damp, subterranean caverns or in cellars. Indeed, the "dark, damp place" would appear to be the ideal habitat of this the "only mushroom!"

Equally absurd is the discrimination against those growing on wood (14), which again deprives us of the delicious Hydnum (Plate 27), the Beefsteak (Plate 25), Oyster mushroom (Plate 14), Elm mushroom (Plate 15), and many others, including Puff-balls (Plate 34). If we exclude those growing upon or near manure (15), we shall be obliged to omit the Coprinus group (Plates 16 and 17), and often the "reel mushroom" as well.

Among the bright-colored species (16), it is true, are many dangerous individuals, as, for instance, the deadly Fly Amanita of Plate 4, and the emetic Russula (Plate 13), but on this fiat we should have to reject the other brilliant esculent Russulæ (Plates 11 and 12), the brilliant yellow Chantarelle (Plate 19), the Lactarius (Plate 18), and various other equally palatable and wholesome species. [Pg 28]

The objection against milky mushrooms (17) would serve to exclude the poisonous species of Lactarius, but would thus include at least two of the delicious species of the group, L. deliciosus, with orange milk (Plate 18), and L. piperatus, another species with white milk not figured in this volume.

The group of Russulæ, most of which are esculent, is notable for their gills of even length (18), though not all the species are thus characterized. This discrimination, however, especially applies to the Shaggy-mane (Plate 16), which is conspicuously even-gilled, and is a decided delicacy.

This species, together with its congener, the edible Coprinus atramentarius (Plate 17), are notorious for their melting into black fluid (19), which is thus of no significance as a test, although the mushrooms are not supposed to be eaten in this stage of deliquescence.

A fungus which bites the tongue (20) when tasted would naturally be excluded from our mushroom diet, as would also, of course, those of a bitter or nauseating taste; but several species, notably the Lactarius piperatus, as its name implies, is very hot and peppery when raw—a characteristic which disappears in cooking, after which it is perfectly esculent. The same applies in a scarcely less degree to the Agaricus melleus, and less so to the Hydnum repandum (Plate 27), and other mushrooms. But the poisonous Russula emetica (Plate 13) gives this same hot, warning tang, and this rule (17) would at least thus exclude the harmful species, and is thus contributive to popular safety. [Pg 29]

The salt test (21), with that of the silver charm, is also a relic of the dim past, but is absolutely useless as a touchstone. Many poisonous species, notably the Amanita, fail to answer to it. All authorities agree, however, that the addition of salt in cooking, or the preparatory soaking of specimens in brine, has a tendency to render poisonous species innocuous. Indeed, it is claimed that in Russia and elsewhere on the Continent many admittedly poisonous species, even the deadly Fly Amanita, is habitually eaten subsequent to this semi-corning process, by which the poisonous chemical principle is neutralized.

Among this long list, and many other equally arbitrary and ignorant prejudicial traditions, many of which date back to the earliest times, it is indeed astonishing to note the conspicuous absence of the one and only valuable sign by which the fatal species could be unmistakably determined—a symbol which was reserved for botanical science to discover: the presence of the "cup" in the Amanita, which is pointedly emphasized in my Frontispiece, and the importance of which as a botanical and cautionary distinction is considered at more length in the following chapter.

It is well to consider for a moment what is implied in [Pg 30]

A fungus may be poisonous in various ways:

1. A distinct and certain deadly poison.

2. The cause of violent digestive or other functional

disturbance, but not necessarily fatal.

3. The occasion of more or less serious physical

derangement through mere indigestibility.

4. Productive of similar disorders through the employment

of decayed or wormy specimens of perfectly

esculent species.

5. These same esculent species, even in their fresh

condition, may become highly noxious by contact or

confinement with specimens of the Amanita by the

absorption of its volatile poison, as further described

on p. 69.

And lastly comes the question of idiosyncrasy, a consideration which is of course not taken into account in our recommendation of certain well-established food varieties.

"One man's food another man's poison." The scent of the rose is sometimes a serious affliction, and even the delicious strawberry has repeatedly proven a poison. Even the most wholesome mushroom will occasionally require to be discriminated against, as certain individuals find it necessary to exclude cabbage, milk, onions, and other common food from their diet. When we reflect, moreover, that in its essential chemical affinities the fungus simulates animal flesh, and many of the larger and more solid varieties are similarly subject to speedy decomposition, it is obviously important that [Pg 31] all fungi procured for the table should be collected in their prime, and prepared and served as quickly as possible. More than one case of supposed mushroom poisoning could be directly traced to carelessness in this regard, when the species themselves, in their proper condition, had been perfectly wholesome.

There can be no general rule laid down for the discrimination of an edible fungus. Each must be learned as a species, or at least familiarized as a kind, even as we learn to recognize certain flowers, trees, or birds.

Within a certain range this discrimination is practised by the merest child. How are the robin, the chippy, and the swallow recognized, or the red clover, and white clover, and yellow clover?

Even in the instances of species which bear a very close outward similarity, how simple, after all, does the distinction become. Here, for instance, is the wild-lettuce, and its mimic, the mulgedium, growing side by side—to ninety-nine out of a hundred observers absolutely alike, and apparently the same species. But how readily are they distinguished, I will not say by the botanist merely, but by any one who will take the small pains of contrasting their specific botanical characters—perfectly infallible, no matter how various the masquerade of their foliage. The lettuce has yellow blossoms, and a seed prolonged into a long beak, to whose tip the feathery pappus is attached. The mulgedium has dull bluish flowers, and its pappus is attached to the seed by a hardly perceptible elongation. As with the birds and wild-flowers, so with the fungi: we must learn them as species, even [Pg 32] as we learn to distinguish the difference between the trefoil of the clover and that of the wood-sorrel, or between the innocuous wild-carrot and the poison-hemlock, the harmless stag-horn sumach and its venomous congener, the Rhus venenata. There are parallel outward resemblances between esculent and poisonous fungi, but each possesses otherwise its own special features by which it may be identified—variations of gills, pores, spores, taste, odor, color, juice, consistency of pulp, method of decay, etc.

It must not be presumed that the list of edible species just cited from the catalogue of Dr. Curtis includes all the esculents among the fungi. Dr. Harkness has discovered and classified many others. Mr. Palmer and Prof. Charles Peck are never at a loss for their "mess of mushrooms" among their list of nearly a hundred species, while Mr. Charles McIlvaine, whose name, so far as its practical authority is concerned, should appear more prominently in my bibliographical list, but who has not yet incorporated his many mycological essays in book form, writes me that he has tested gastronomically a host of species, and has found over three hundred to be edible, or at least harmless. It may be said that the probabilities would include a large majority of the thousand species in the same category. But this is a matter which, in the absence of absolute knowledge, is mere conjecture.

Of the forty-odd species which the writer enjoys with more or less frequency at his table, he is satisfied that he can select at least thirty which possess such distinct and strongly marked characters of form, [Pg 33] structure, and other special qualities as to enable them, by the aid of careful portraiture and brief description, to be easily recognized, even by a tyro.

As previously emphasized, the present work does not aim to be complete, nor does it contemplate a practical utility beyond its specific recommendations, nor will the author assume any responsibility for the hazard which shall exceed its restricted list of species.

On general principles, however, considering the proneness of humanity towards the acquisition of forbidden fruit, and reasoning from my own actual experience, and that of many others to whom this fascinating hobby of epicurean fungology has become a growing passion, it may almost be assumed that the fungus appetite with many of my readers will increase by what it feeds on, and the sufficiency herewith offered will scarcely suffice. Like Oliver Twist, they must needs have more. The glory of a new acquisition to the fungus menu, and emulation of other rival tyro mycophagists, will doubtless lead many enthusiasts to more or less hazardous experiment among the legion of the unknown species. This logical tendency, then, must be met ere my book can safely and conscientiously be launched upon its career, to which purpose I would append the following condensed [Pg 34]

1. Avoid every mushroom having a cup, or suggestion

of such, at base (see Frontispiece,

and Plates 3 and 4);

the distinctly fatal poisons are thus excluded.

2. Exclude those having an unpleasant odor, a

peppery, bitter, or other unpalatable flavor, or tough consistency.

3. Exclude those infested with worms, or in advanced age or decay.

4. In testing others which will pass the above probation

let the specimen be kept by itself, not in contact

with or enclosed in the same basket with other species,

for reasons given on page 69.

Begin by a mere nibble, the size of a pea, and gentle mastication, being careful to swallow no saliva, and finally expelling all from the mouth. If no noticeable results follow, the next trial, with the interval of a day, with the same quantity may permit of a swallow of a little of the juice, the fragments of the fungus expelled as before.

No unpleasantness following for twenty-four hours, the third trial may permit of a similar entire fragment being swallowed, all of these experiments to be made on "an empty stomach." If this introduction of the actual substance of the fungus into the stomach is superseded by no disturbance in twenty-four hours, a larger piece, the size of a hazel-nut, may be attempted, and thus the amount gradually increased day by day until the demonstration of edibility, or at least harmlessness, is complete, and the species thus admitted into the "safe" list. By following this method with the utmost caution the experimenter can at best suffer but a slight temporary indisposition as the result of his hardihood, in the event of a noisome species having [Pg 35] been encountered, and will at least thus have the satisfaction of discovery of an enemy if not a friend.

It may be said that any mushroom, omitting the Amanita, which is pleasant to the taste and otherwise agreeable as to odor and texture when raw, is probably harmless, and may safely be thus ventured on with a view of establishing its edibility. A prominent authority on our edible mushrooms, already mentioned, applies this rule to all the Agarics with confidence. "This rule may be established," he says: "All Agarics—excepting the Amanitæ—mild to the taste when raw, if they commend themselves in other ways, are edible." This claim is borne out in his experience, with the result, already told, that he now numbers over one hundred species among his habitual edible list out of the three hundred which he has actually found by personal test to be edible or harmless. "So numerous are toadstools," he continues, "and so well does a study of them define their habits and habitats, that the writer never fails upon any day from April to December to find ample supply of healthy, nutritious, delicate toadstools for himself and family." The italicized portion is my own, as I would thus emphasize the similar possibilities amply afforded even in the present condensed list of about thirty varieties herein described.

In gathering mushrooms one should be supplied with a sharp knife. The mushroom should be carefully cut off an inch or so below the cap, or at least sufficiently far above the ground to escape all signs of dirt on the stem. They should then be laid gills [Pg 36] upward in their receptacle, and it is well to have a special basket, arranged with one or two removable bottoms or horizontal partitions, which are kept in place by upright props within, thus relieving the lower layers of mushrooms from the weight of those above them. Such a basket is almost indispensable.

Before preparing mushrooms for the table, the specimens should be carefully scrutinized for a class of fungus specialists which we have not taken into account, and which have probably anticipated us. The mushroom is proverbial for its rapid development, but nature has not allowed it thus to escape the usual penalties of lush vegetation, as witness this swarming, squirming host, minute grubs, which occasionally honey-comb or hollow its entire substance ere it has reached its prime; indeed, in many cases, even before it has fully expanded or even protruded above ground.

Like the carrion-flies, the bees, and wasps, which in early times were believed to be of spontaneous origin—flies being generated from putrefaction, bees from dead bulls, and the martial wasps from defunct "war-horses"—these fungus swarms which so speedily reduce a fair specimen of a mushroom to a melting loathsome mass, were also supposed to be the natural progeny of the "poisonous toadstool." But science has solved the riddle of their mysterious omnipresence among the fungi, each particular swarm of grubs being the witness of a former visit of a [Pg 37] maternal parent insect, which has sought the budding fungus in its haunts often before it has fully revealed itself to human gaze, and implanted within its substance her hundred or more eggs. To the uneducated eye these larvæ all appear similar, but the specialist in entomology readily distinguishes between them as the young of this or that species of fly, gnat, or beetle.

As an illustration of the assiduity with which the history of these tiny scavenger insects has been followed by science, I may mention that in the gnat group alone over seven hundred species have been discovered and scientifically described, many of them requiring a powerful magnifier to reveal their identities.

Specimens of infected or decaying mushrooms preserved within a tightly closed box—and, we would suggest, duly quarantined—will at length reveal the imago forms of the voracious larvæ: generally a swarm of tiny gnats or flies, with an occasional sprinkling of small glossy black beetles, or perhaps a beautiful indigo-blue insect half an inch in length, of most nervous habit, and possessed of a long and very active tail. This insect is an example of the curious group of rove-beetles—staphylinus—a family of insect scavengers, many of whose species depend upon the fungi for subsistence.

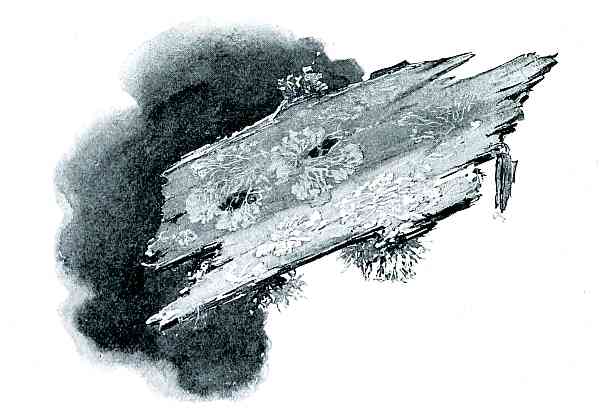

Even the large woody growth known as "punk" or "touch-wood," so frequently seen upon decaying trunks, is not spared. A huge specimen in my keeping was literally reduced to dust by a single species of beetle. [Pg 38]

Considering the prevalence of these fungus hosts, it is well in all mushrooms to take the precaution of making a vertical section through stem and cap, excluding such specimens as are conspicuously monopolized, and not being too critical of the rest, for the over-fastidious gourmet will often thus have little to show for his morning walk. I have gathered a hundred specimens of fungi in one stroll, perhaps not a quarter of which, upon careful scrutiny, though fair of exterior, would be fit for the table. The fungus-hunter par excellence has usually been there before us and left his mark (see page 135)—a mere fine brown streak or tunnel, perhaps, winding through the pulp or stem, where his minute fungoid identity is even yet secreted. But we bigger fungus-eaters gradually learn to accept him—if not too outrageously promiscuous—as a natural part and parcel of our Hachis aux Champignons, or our simple mushrooms on toast, even as we wink at the similar lively accessories which sophisticate our delectable raisins, prunes, and figs, to say nothing of prime old Rochefort!

In conclusion, lest these pages, in spite of the impress of caution with which they are weighted, should lead to discomfiture, distress, or more serious results among their more careless readers, it is well to devote a few lines to directions for medical treatment where such should seem to be required. To this end I quote a passage from an article in the Therapeutic Gazette [Pg 39] of May, 1893, from the pen of Mr. McIlvaine, whose many years' experience with gastronomic fungi entitles his words to careful consideration:

"The physician called upon to treat a case of toadstool poisoning need not wait to query after the variety eaten; he need not wish to see a sample. His first endeavor should be to ascertain the exact time elapsing between the eating of the toadstools and the first feeling of discomfort. If this is within four or five hours one of the minor poisons is at work, and rapid relief must be given by the administration of an emetic, followed by one or two moderate doses of sweet-oil and whiskey, in equal parts. Vinegar is effective as a substitute for sweet-oil. If from eight to twelve hours have elapsed, the physician may rest assured that amanitine is present, and should administer one-sixtieth of a grain of atropine at once."

This atropine is intended to be injected hypodermically, and the treatment repeated every half-hour until one-twentieth of a grain has been given, or the patient's life saved.

Further consideration of the Amanita and its deadly poison and antidote, with details as to treatment in a notable case, will be reserved for the following chapter.

The colored plates in the volume were prepared from pencil drawings tinted in water-color, many of them direct from nature, several dating back fifteen years, and many of them over twenty years, for their original sketch. The colors as presented indicate those of typical individuals of the various species, and [Pg 40] each, in addition to the extended description in the text of the volume, is faced by a condensed description for ready reference, the usual troublesome necessity of turning the pages being thus avoided.

In each plate dimension marks are shown which indicate the expansion of the pileus or cap of the fungus in an ideal specimen.

In the preparation of this work, acknowledgments are specially due to Messrs. Julius A. Palmer and Charles McIlvaine for the privilege of liberal quotations from their published works, especially with reference to the poisonous fungi. The volume is also further indebted for occasional extracts from the standard works of Prof. Chas. Peck, Mrs. T. J. Hussey, Rev. Dr. C. D. Badham, Rev. Dr. M. C. Cooke, Rev. J. M. Berkeley, Worthington Smith, and Rev. M. A. Curtis, all of whose volumes and various other contributions on the special subject of mycophagy are included in my bibliography on a later page.

October 1, 1894

The frequency of this terrible foe in all our woods, and the ever-recurring fatalities which are continually traced to its seductive treachery (some twenty-five deaths having been recorded in the public journals during the summer of 1893 alone), render it important that its teeth should be drawn, and its portrait placarded and popularly familiarized as an archenemy of mankind.

As we have seen, from every superficial standpoint, this species is self-commendatory. It is, without doubt, in comeliness, symmetry, and structure, the ideal of all our mushrooms, as it is, indeed, the botanical type of the tribe Agaricus, as well as its most notorious genus. Since the time of that carousing young lunatic Nero, who, doubtless, was wont to make merry with its "convenient poison," upon one occasion, it is recorded by Pliny, to the presumably amusing extinction of the entire guests of a banquet, together with the prefect of the guard and a small host of tribunes and centurions, the Amanita has claimed an army of victims.

While giving no superficial token of its dangerous [Pg 44] character to the casual observer, the Amanita, as a genus and a species, is nevertheless easily identified, if the mushroom collector will for the moment consider it from the botanical rather than the sensuous or gustatorial standpoint.

The deadly Amanita need no longer impose upon the fastidious feaster in the guise of the dainty "legume" of his menu, or as a contaminating, fatal ingredient in the otherwise wholesome ragoût.

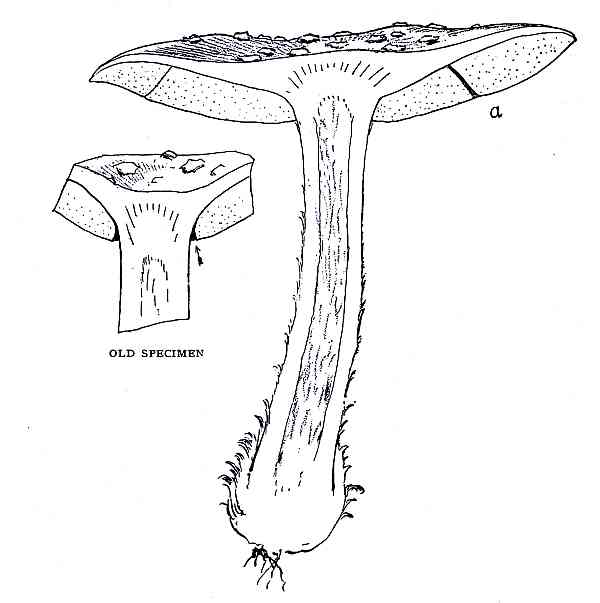

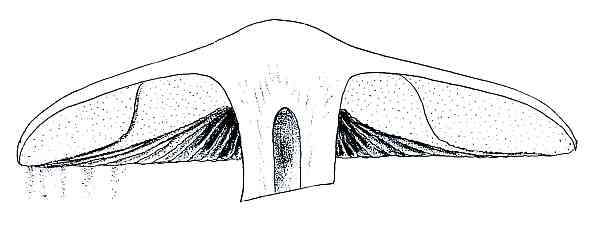

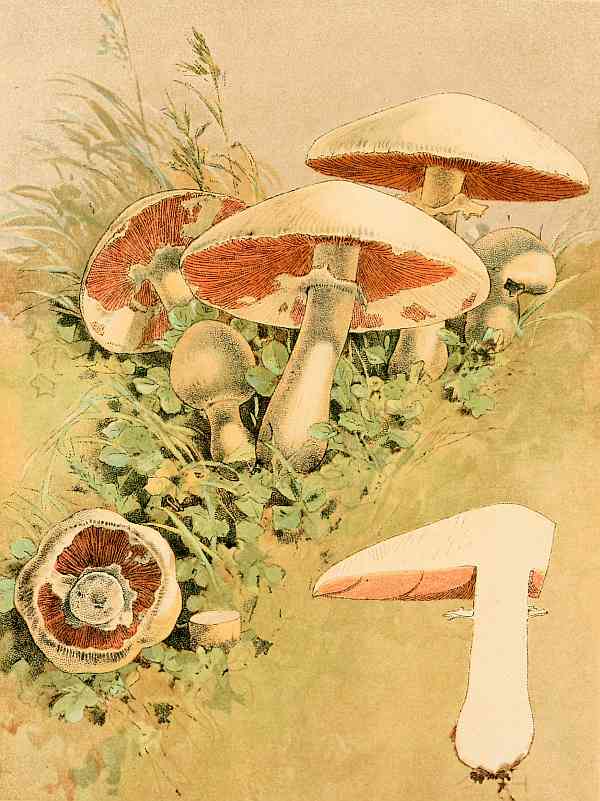

In Plate 3 I have presented the reprobate Amanita vernus in its protean progressive proportions from infancy to maturity. This is especially desirable, in that the fungus is equally dangerous as an infant, and also because the development of its growth specially emphasizes botanically the one important structural character by which the species or genus may be easily distinguished. Let us, then, consider the specimen as a type of the tribe Agaricus (gilled mushroom, see p. 79), genus Amanita.

Year after year we are sure of finding this species, or others of the genus, especially in the spring and summer, its favorite haunt being the woods. Its spores, like other mushrooms, are shed upon the ground from the white gills beneath, as described in our chapter on "Spore-prints," or wafted to the ends of the earth on the breeze, and eventually, upon having found a suitable habitat, vegetate in the form of webby, white, mould-like growth—mycelium—which threads through the dead leaves, the earth, or decaying wood. This running growth is botanically considered as the true fungus, the final mushroom being the fruit, whose function is the dissemination of the spores. After a rain, or when the conditions are otherwise suitable, a certain point among this webby tangle beneath the ground becomes suddenly quickened into astonishing cell-making energy, and a small rounded nodule begins to form, which continues to develop with great rapidity (Plate 2). In a few hours more it has pushed its head above ground, and now appears like an egg, as at A, Plate 3. The successive stages in its development are clearly indicated in the drawings. Each represents an interval of an hour or two, or more, the most suggestive and important feature being the outer envelope, or volva, which encloses the actual mushroom—at first completely, then in a ruptured condition, until in the mature growth the only vestige of it which appears above ground are the few shreds generally, though not always, to be seen on the top of the cap. The most important character of this deadly Amanita is, therefore, apparently with almost artful malice prepense, often concealed from our view in the mature specimen, the only remnant of the original outer sack being the cup or socket about the base of the stem, which is generally hidden under ground, and usually there remains after we pluck the specimen. [Pg 45]

Plate II.—MYCELIUM, AND EARLY VEGETATION OF A MUSHROOM

This "poison-cup" may be taken as the cautionary symbol of the genus Amanita, common to all the species. Any mushroom or toadstool, therefore, whose stem is thus set in a socket, or which has any suggestion of such a socket, should be labelled "poison"; for, though [Pg 48] some of the species having this cup are edible, from the popular point of view, it is wiser and certainly safer to condemn the entire group. But the cup must be sought for. We shall thus at least avoid the possible danger of a fatal termination to our amateur experiments in gustatory mycology; for, while various other mushrooms might, and do, induce even serious illness through digestive disturbance, and secondary, possibly fatal, complications, the Amanita group are now conceded to be the only fungi which contain a positive, active poisonous principle whose certain logical consequence is death.

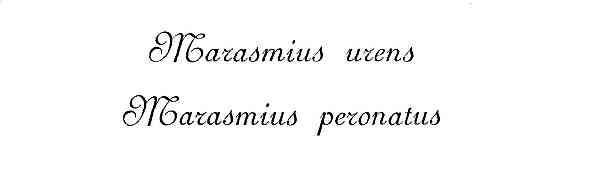

Another structural feature of the Amanita is shown in the illustration, but has been omitted from the above consideration to avoid confusion. This is the "veil" which, in the young mushroom, originally connected the edge of the cap, or pileus, with the stem, and whose gradual rupture necessarily follows the expansion of the cap, until a mere frill or ring is left about the stem at the original point of contact.

But this feature is a frequent character in many edible mushrooms, as witness the several examples in the edible species of our plates, and therefore of no dangerous significance per se, being merely a membrane which protects the growing gills. [Pg 49]

Plate III.—DEVELOPMENT OF AMANITA VERNUS

Nor are the other features, the remnants of the volva on the summit of the cap, to be considered of primary importance from the popular point of view, for the reason—firstly, that these fragments, while conspicuous and constant in Amanita muscarius (Plate 4), are not thus permanent in several other species of Amanitæ, notably the white-satin-capped Amanita vernus, Amanita phalloides, and Amanita Cæsarea, in which the fragments are deciduous; and, secondly, because the same general effect of these warty scales is so clearly imitated in other mushrooms which are distinctly edible, as in examples Plate 10 and Plate 16. It is to the volva or cup, then, that we must devote our special attention as the only safe and constant character. And this leads me to the prominent and necessary consideration of another common species of Amanita, mentioned above, in which even this cup is more or less obscure.

Agaricus (Amanita) muscarius

This, one of the most strikingly beautiful of our toadstools, is figured in Plate 4. Its brilliant cap of yellow, orange, or even scarlet, studded with white or grayish raised spots, can hardly be unfamiliar to even the least observant country walker. Its favorite habitat is the woods, and, in the writer's experience especially, beneath hemlocks and poplars, where he has seen this species year after year in whole companies, and in all stages shown in the plate at the same time, from the globular young specimen almost covered with its white warts just lifting its head above the brown carpet to the fully expanded [Pg 52] individual, in which the spots have assumed a shrunken and brownish tint.

The consideration of this species is of the utmost importance, as its beauty is but an alluring mask, which has enticed many to their destruction; among the more recent of its conspicuous victims having been the Czar Alexis of Russia. For this is another cosmopolitan type of mushroom, common alike in America, Great Britain, Europe, and Asia, in all of which countries it is notorious for its poisonous resources. It is commonly known as the "Fly-agaric," its substance macerated in milk having been employed for centuries as an effectual fly-poison. After the reader's introduction to the botanical character of the Amanita, he would, presumably, be somewhat suspicious of the present species. The suggestive white or dingy fragments upon its cap, it is true, would alone arouse his suspicions, but in the examination of the stem for the telltale volva or cup its verification might be somewhat in doubt. It is for this reason that the species is emphasized in these pages, as the Amanita muscarius, judging from the great dissimilarity of its numerous portraits from all countries, would seem to be remarkably protean, especially with reference to its stalk. The majority of the portraits of this reprobate presents the volva as distinct and as clean cut as in the A. vernus just described, and the stalk above as equally smooth, features which are usually at variance with the associated botanical description of the species, which often characterizes the volva as "incomplete" or "obscure," and the stem as "rough and scaly." If the portraits in these works are correct, the Amanita qualities of the species are clearly displayed, but if their accompanying descriptions are to be credited, and such seem to be in perfect accord with the specimens which I have always found, the A. muscarius would seem in need of a more authentic historian. [Pg 53]

PLATE IV

FLY MUSHROOM

Agaricus (Amanita) muscarius

Pileus: Diameter three to six inches, quite flat at maturity; color brilliant yellow, orange, or scarlet, becoming pale with age, dotted with adhesive white, at length pale brownish warts, the remnants of the volva.

Gills: Pure white, very symmetrical, various in length, the shorter ones terminating under the cap with an almost vertical abruptness.

Spores: Pure white. A spore-print of this species is shown in Plate 37.

Stem: White, yellowish with age, becoming shaggy, at length scaly, the scales below appearing to merge into the form of an obscure cup.

Volva: Often obscure, indicated by a mere ragged line of loose outward curved shaggy scales around a bulbous base.

Flesh: White.

Habitat: Woods and their borders, especially favoring pine and hemlock.

Season: Summer and autumn.

PLATE IV

Amanita Muscaria. (POISONOUS.)

The example figured in the plate presents the stem and volva as they have always appeared in specimens obtained by the writer. In the young individuals the stem is waxy-white, becoming later a dull, pale ochre hue, the lower half being shaggy and torn, and beset with loose projecting woolly points which resolve themselves below into scales with loose tips curved outward, and so distantly disposed upon the bulbous base as to leave no marked definition of the continuous rim or opening of a cup. But the cup is there, and in a section of the bud state of the mushroom could have been seen, even as in the white warts upon the surface of the younger specimens we note the evidences of the upper portion of the same white volva. In many other species of Amanita, notably A. vernus, as already mentioned, these volva fragments generally wither and are shed from the cap. They are thus not to be counted on as a permanent token. But in the fly-mushroom they form a distinct character, as they adhere firmly to the smooth skin of the pileus, and in drying, instead of shrivelling and curling and falling off, simply shrink, turn brownish, and in the maturely expanded [Pg 58] mushroom appear like scattered drops of mud which have dried upon the pileus. Another peculiar structural feature of this mushroom is shown in the sectional drawing herewith given. The shorter gills, instead of rounding off as they approach the pileus (see a), terminate abruptly almost at right angles to their edge. The contrast from the usual form will be more apparent by comparison with the section of the parasol-mushroom on page 114.

SECTION OF FLY-AMANITA

Few species of mushrooms have such an interesting history as this. Its deadly properties were [Pg 59] known to the ancients. From the earliest times its deeds of notoriety are on record.

This is quite possibly the species alluded to by Pliny as "very conveniently adapted for poisoning," and is not improbably the mushroom referred to by this historian in the following quotation from his famous Natural History: "Mushrooms are a dainty food, but deservedly held in disesteem since the notorious crime committed by Agrippina, who through their agency poisoned her husband, the Emperor Claudius; and at the same moment, in the person of her son Nero, inflicted another poisonous curse upon the whole world, herself in particular."

Notwithstanding its fatal character, this mushroom, it is said, is habitually eaten by certain peoples, to whom the poison simply acts as an intoxicant. Indeed, it is customarily thus employed as a narcotic and an exhilarant in Kamchatka and Asiatic Russia generally, where the Amanita drunkard supplants the opium fiend and alcohol dipsomaniac of other countries. Its narcotizing qualities are commemorated by Cooke in his Seven Sisters of Sleep, wherein may be found a full description of the toxic employment of the fungus.

The writer has heard it claimed that this species of Amanita has been eaten with impunity by certain individuals; but the information has usually come from sources which warrant the belief that another harmless species has been confounded with it. The warning of my Frontispiece may safely be extended [Pg 60] to the fly-amanita. Its beautiful gossamer veil may aptly symbolize a shroud.