Project Gutenberg's The Pioneer Boys of the Columbia, by Harrison Adams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Pioneer Boys of the Columbia

or In the Wilderness of the Great Northwest

Author: Harrison Adams

Illustrator: Walter S. Rogers

Release Date: September 7, 2014 [EBook #46799]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE COLUMBIA ***

Produced by Beth Baran, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE OHIO, | |

| Or: Clearing the Wilderness | $1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS ON THE GREAT LAKES, | |

| Or: On the Trail of the Iroquois | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSISSIPPI, | |

| Or: The Homestead in the Wilderness | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSOURI, | |

| Or: In the Country of the Sioux | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE YELLOWSTONE, | |

| Or: Lost in the Land of Wonders | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE COLUMBIA, | |

| Or: In the Wilderness of the Great Northwest | 1.25 |

Copyright, 1916, by |

|

Dear Boys:—

The time has at last arrived when we must say good-bye to our pioneer friends, the Armstrongs. You will remember how we have followed their adventurous careers down the Ohio, along the Mississippi, then up the great Missouri to the wonder country of the Yellowstone; and now, between the covers of the present volume, are narrated the concluding incidents in the story of “Westward Ho!”

Our country is deeply indebted to the class of pioneers typified by the Armstrong boys. Restless spirits many of them were, always yearning for richer lands where game would be more plentiful. It was undoubtedly this desire that led them further and further into the “Country of the Setting Sun,” constantly seeking that which many of them never found; until at length the Pacific barred their further progress.

Bob and Sandy Armstrong, together with their sturdy sons, Dick and Roger, are but types of the settlers who opened up the rich territory of the Mississippi Valley, as well as the Great West. Their kind is not so numerous now, at least in our own country, since the need for such adventurous souls has become less acute. In many places, however, like the Canadian Northwest, they can still be met with, forging the links that will bind the wilderness to civilization.

If you boys have found one half the enjoyment in reading of the exploits of our young pioneers that the task has afforded the author in writing of them, his aim, which has been to instruct as well as to entertain, will have been accomplished.

Harrison Adams.

May 1, 1916.

|

CONTENTS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

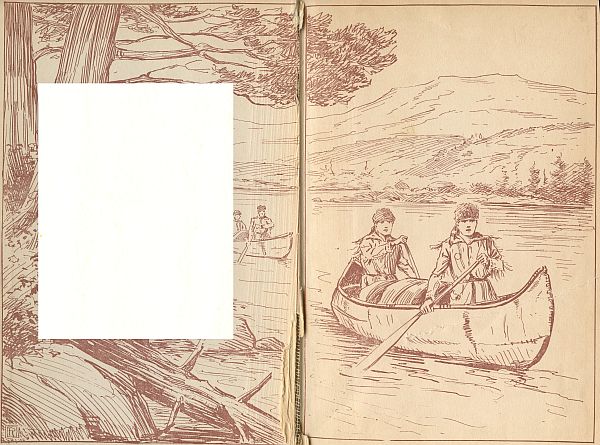

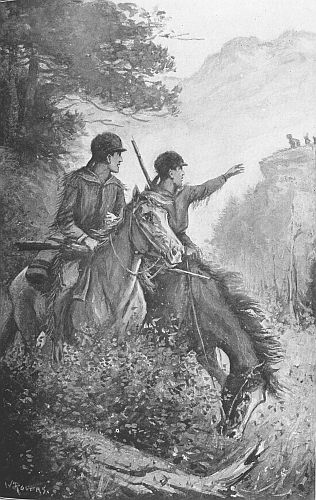

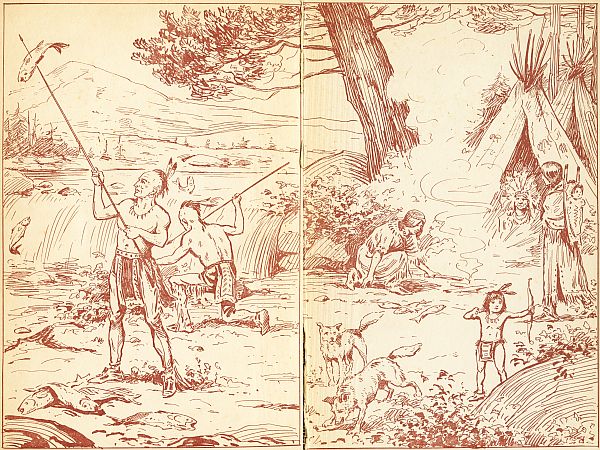

“The two boys had to . . . start upon the long journey into the northwest” (see page 148) |

Frontispiece |

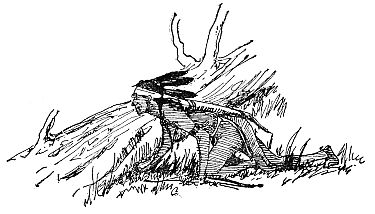

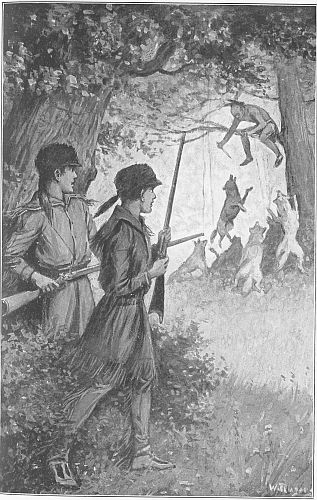

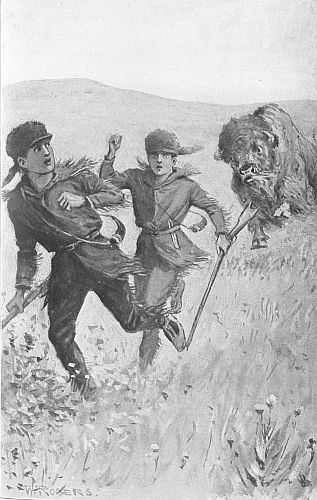

“‘He tries to strike them as they jump at him’” |

32 |

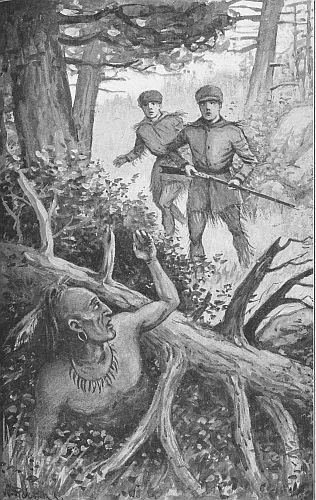

“‘Run for the trees, Roger!’ shouted Dick” |

74 |

“They pushed forward, and were soon at the fallen tree” |

192 |

“‘There! You can see him move’” |

235 |

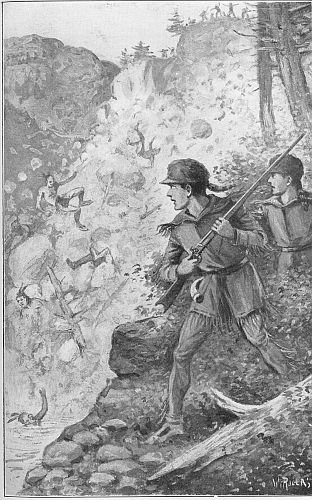

“Fully half of the Flat Head Indians went with the landslide” |

317 |

“It strikes me, Dick, the rapids are noisier to-day than ever before.”

“We have time enough yet, Roger, to paddle ashore, and give up our plan of running them.”

“But that would be too much like showing the white feather, Cousin; and you must know that we Armstrongs never like to do that.”

“Then we are to try our luck in the midst of the snarling, white-capped water-wolves, are we, Roger?”

“I say, ‘yes.’ We started to make the run, and a little extra noise isn’t going to frighten us off. Besides, we may not have another chance to try it.”

“You’re right there, Roger, for I heard Captain[2] Lewis say we’d have to start up the river again in a few days, heading into the great West, the Land of the Setting Sun.”

“I am ready, Dick. My paddle can be depended on to see us through. We’ll soon be at the head of the rapids, too.”

“Already the canoe feels the pull, and races to meet it. Steady now, Roger, and let us remember what the Indians told us about the only safe passage through the Big Trouble Water, as they call it. A little more to the left—now straight ahead, and both together!”

The two sturdy, well-grown lads who crouched in the frail Indian craft, made of tanned buffalo skins, need no introduction to those who have read any of the preceding volumes of this series.

There may be those, however, who, in these pages, are making the acquaintance of Dick and Roger, the young pioneers, for the first time; and for their benefit a little explanation may be necessary.

While the pair are shooting downward, on the rapidly increasing current of the Yellowstone River, toward the roaring rapids, on this spring day in the year 1805, let us take a brief look backward. Who were these daring lads of the old frontier days, and how came they so far[3] from the westernmost settlements of the English-speaking race along the Mississippi, and about the mouth of the Missouri?

Dick Armstrong and his cousin, Roger, were the sons of two brothers whose adventures along the Ohio in the days of Daniel Boone occupied our attention in the earlier stories of border life. They were worthy of their fathers, for Dick had inherited the thoughtful character of Bob Armstrong, while Roger at times displayed the same bold disposition that had always marked Sandy, his parent, in the perilous days when they founded their homes in the then untrodden wilderness.

The families were now located at that spot which had first been taken up by the French, and called St. Louis in honor of the King of France. Their grandfather, David Armstrong, still lived, as did also his wife, hale and hearty, enjoying the increasing households of their children.

Bob and Sandy had both married, and besides Dick there was a smaller son, named Sam in the cabin of the former. Roger had a little sister, called Mary, in honor of her grandmother.

The two cousins had grown up, as did most lads of those early days, accustomed to think for themselves, and to meet danger bravely.[4] Both of them were accomplished in all the arts known to successful woodsmen. They learned from experience, as well as from the lips of old borderers who visited in their homes, and were able to hold their own with any boys of their age in the community.

A sudden calamity threatened to disturb the peace of the Armstrong circle, when it was learned that there was a flaw in the deed by which their property was held. An important signature was required in order to perfect this title, and, unless this could be obtained, and shown by the succeeding spring, everything would pass into the possession of a rich and unscrupulous French Indian trader, François Lascelles by name.

Inquiry developed the fact that Jasper Williams, the man whose signature was so important to the happiness of all the Armstrongs, had gone with the expedition undertaken by Captain Lewis and Captain Clark, which was headed into the unknown country of the Setting Sun, with the hope of finding a way to the far distant Pacific Ocean.

No white man had as yet crossed the vast stretches of country that lay west of the rolling Mississippi, and it was the boldest undertaking[5] ever known when President Jefferson influenced Congress to stand back of his proposition to learn the extent of the possessions that had recently come to the United States. (Note 1.)[1]

The President’s private secretary, Captain Lewis, headed the small party of adventurous spirits, assisted by an army officer, Captain Clark. They left St. Louis in the spring of 1804, and had been long on the way when the Armstrongs discovered that the one man whom they could depend on to save their homes was with the expedition.

Ordinarily Bob and Sandy Armstrong would have been quick to take upon themselves the duty of overtaking the expedition, and securing the necessary signature; but a recent injury prevented one of the brothers from going.

In the end the proposition of Dick and Roger to undertake the stupendous task was agreed to, and the boys started, mounted on two horses and equipped as well as the times permitted. The adventures they met with were thrilling in the extreme, and have been described at length in earlier volumes.[2]

The youths overtook the expedition after it had gone far up the “Great Muddy,” as the Missouri had already become known, and the coveted signature was obtained. Then the lads were tempted to continue with the party, since Captain Lewis was sending back one of his most trusted scouts with an account of what had already happened to the expedition, for the perusal of President Jefferson; and he could be trusted to see that the precious document reached the Armstrongs.

During the winter just passed the two boys were kept busy in the rôle of scouts and providers of fresh meat for the camp, a duty which their early training made them peculiarly fitted to assume.

The expedition had laid out a comfortable camp near the Indian village of the Mandan tribe, with whom peaceful relations had been established at the time of their first arrival in the neighborhood.

Some of the bolder spirits had ventured into the realm of natural wonders now known as Yellowstone Park, and had viewed with amazement and awe the strange geysers that spouted hot water hundreds of feet in the air at stated periods, as well as many other singular mysteries.

Dick and Roger had been among the fortunate few to view these marvels; but, as a rule, the soldiers and bordermen associated with the two captains were almost as superstitious as the ignorant red men, and actually feared to set eyes on these strange freaks of Nature which they could not understand. The Indians called the place the Bad Lands, and believed an evil Manitou dwelt there, who was ever ready to seize upon and enchain those reckless warriors who should invade his territory.

Slowly the long winter had passed away, and all seemed to be going well. There had been occasional signs of trouble, when hostile hunting parties of Indians were encountered; but, thus far, none of the expedition had been more than wounded in these frays.

Spring was at last at hand, and every one in the party looked forward with eagerness to the fresh start that was soon to be made. They had gathered much information concerning the vast stretch of plains and mountains that still lay between them and their goal; but, since only Indians had ever penetrated that wilderness, these stories were invariably untrustworthy, for the mind of the red man was very much like that of a child, and could[8] see things only from an imaginative standpoint.

About all that the adventurers really knew was that there was a tremendous barrier of mountains which they must climb before they could hope to attain their ambitious aim and gaze upon the Pacific Ocean, seen at that time only by those, following Balboa, who had crossed the narrow isthmus where the Panama Canal now joins the rival oceans.

Every evening, when the sun was setting in a maze of glowing colors, Dick and Roger were accustomed to stand and watch until the last fiery finger had finally faded from the skies. To them that mysterious West held out beckoning arms. They never tired of talking about the fresh wonders they might gaze upon once they started into the trackless wilds; and their young souls were aflame with eagerness as the days crept along, each one bringing them closer to the hour of departure.

For some time they had intended to take a canoe through the big rapids of the river, which they had passed in ascending the stream, before making the winter camp. From the Indians they had secured all possible information, and finally, knowing that their time here was now[9] short, they had set forth with the canoe that had been their property for months, bent upon undertaking the rather risky voyage.

If the daring canoe-man knows his course, the passing through a rapid, amidst all the foam and rush of hungry waters, is not the perilous thing it seems. Besides a knowledge of the way, all that is required is a bold heart, a quick eye, a stout paddle, and muscular arms to wield it.

The two lads soon entered the upper stretches of the white-capped water. They quickly picked out their course, and found themselves shooting downward with almost incredible speed. Around them on every hand was boiling, tumultuous water, curling and rushing and leaping as though eager to seize upon its prey.

Dick and his cousin were not at all dismayed. They had rubbed up against perils so often in their young lives that they could keep cool in the face of almost any danger. Roger crouched in the bow and fended off from the rocks, so that the glancing blows the boat received would not damage the tough skins of which the craft was made.

Dick occupied the stern, and his was the crafty hand that really guided the canoe, for Roger always[10] acknowledged that his cousin could handle a paddle better than he could.

They had passed more than two-thirds of the way down the rapids, and the worst seemed to be behind them, when something strange happened.

The canoe struck a partly submerged, but perfectly smooth, rock. It was only a slight blow, and glancing at that, but nevertheless the results were startling. No sooner had the accident occurred than the bottom of the boat gaped open and the water rushed in with terrible speed. One look convinced Dick that it was quite hopeless to try to keep the craft afloat with their weight to force this flood through the hole.

“Quick! snatch up your gun, and jump overboard, Roger!” he shouted. “And hold on to the boat, remember, like grim death!”

Roger was nothing if not catlike in his actions when an emergency arose; and the two lads leaped over into the swirling water as one, ready to battle for their lives with the rapids, where the superstitious red men said the evil spirits dwelt amidst continual strife and warring.

When they made this sudden plunge, the two boys were careful to maintain their grip upon the sides of the boat, one being on the right and the other on the left. Relieved of their weight, the buoyant canoe would probably float, and might yet prove of considerable help to them in navigating the remainder of the boisterous rapids.

All pioneer boys early learned to swim like fishes. It was as much a part of their education as handling a gun, or acquiring a knowledge of woodcraft. The lad who was not proficient in all these things would have been hard to find, and had he been discovered, the chances were he would have been deemed a true mollycoddle, and fit only to wear the dresses of his sister, or, as the Indians would have described it, be a “squaw.”

No sooner had Dick and Roger found themselves in the swift flowing waters than they[12] struck out most manfully to keep themselves and the boat afloat. It was no new experience in their adventurous career, for before now they had more than once found themselves battling with a flood.

For a brief time it promised to be a most exciting experience, and one that would require their best endeavors if they hoped to come out alive at the foot of the rapids. To be hurled against some of the jutting spurs of rock with all the force of that speeding current would mean blows that would weaken their powers of resistance, and cause them to lose their grip on the side of the canoe.

There were times when they were almost overwhelmed by the dashing, foamy waters. In every instance, however, their pluck and good judgment served to carry them through the difficulty.

All the while they had the satisfaction of knowing that they must be drawing closer to the end of the rapids. Already Dick believed he could notice a little slackening of the fury with which they were beaten on all sides by the lashing waters. He managed to give a shout to encourage his cousin.

“Keep holding on, Roger; we are nearly at[13] the bottom! Another minute will take us into smoother water! Tighten your grip, and we shall win out yet!”

“I’m game to the finish!” was all Roger could say in reply, for every time he opened his mouth it seemed as though some of the riotous water would swoop over his head and almost choke him by forcing itself down his throat.

Before another minute was half over they had come to the foot of the rapids, and, still holding to the waterlogged canoe, floated out upon comparatively smooth water. Here amidst the foam and eddies they managed to push the boat toward the shore.

Roger was already laughing, a little hysterically it is true, for he had been tremendously worked up over the exciting affair. It might have ended in a tragedy for them; but, now that the peril was past, Roger could afford to act as if he saw only the humorous side of the accident.

“That was a very close call, Dick!” he ventured, as they continued to swim as best they could, holding their guns in the hands that at the same time clutched the gunwales of the boat.

“We rather expected it,” replied Dick, “and laid our plans to meet an upset; but it came with[14] a rush, after all. Who’d ever believe such a little knock against a rock would have burst the tough skin of our hide boat?”

“Yes, and a perfectly smooth rock at that,” added Roger, as though he knew this to a certainty, and it added to the mystery in his eyes. “I believed these boats were tough enough to stand ten times that amount of pounding. I believe after all I prefer our old style of dugout.”

“Yes, they may be clumsy, but you can depend on them all the time; and after this I think I’ll be suspicious about a hide boat,” Dick continued.

The shore was now close at hand, and they found little difficulty in making a landing. At the same time the half sunken Indian boat was dragged up on the bank, and tipped over to relieve it of the water, though that began to pour out through the rent in the bottom as soon as it left the river.

It was only natural that the two boys should first throw themselves down on the soft bank to regain some of their breath after such an exciting time. Then, having been brought up in the school of preparedness, their next act was to examine their guns, and to renew the priming of powder in the pan, so that the weapons, on[15] which, they always depended to defend themselves against sudden perils, would be in condition for immediate use in case of necessity.

In those days old heads were to be found on young shoulders. Responsibility caused lads, hardly entering their teens, to become the defenders of their families, as well as hunters and trappers. And the Armstrong cousins had long filled a position of trust of this description in the home circles.

“Well, we shot the rapids, all right,” remarked Roger, presently, with a whimsical smile; “but not exactly as we had planned. Now we can have the pleasure of walking back to camp. At least it saves us the bother of paddling all the way, after making a carry around the rapids. And we meant to give our boat to one of the Mandan boys, you remember, Dick.”

“I’m puzzled about that boat,” remarked the other, frowning.

“I suppose you mean you wonder what made it play such a treacherous trick on us, after standing the wear and tear of the winter,” Roger observed.

“Yes, for you remember we examined it closely only yesterday, and made sure it was in perfect condition. Suppose we take a look at[16] that break, and see how it happened to come.”

“Oh! the chances are,” said Roger, carelessly, “the old hide became worn or weak through age, and gave way. Still,” he added, “that was only a little bump, Dick, and I’m as bothered as you are how to explain it.”

In another minute they were bending over the upturned canoe. Immediately both boys uttered exclamations of astonishment, as though they had made a discovery that gave them an unexpected thrill.

“Why, it looks as if a sharp knife blade had been drawn straight down along here, and cut nearly through the skin, so that even a little blow would finish it!” exclaimed Roger, turning his troubled eyes upon his cousin as if to ascertain whether the other agreed with him.

“That is exactly what has been done,” added Dick, soberly. “See, you can even notice where the slit extends further than the break. This was not as much an accident as we thought, Roger. Some rascal, who knew what we expected to do, tried to bring about our destruction in the rapids!”

“But it must have been done since yesterday,” declared the other angrily, “for we looked over every inch of the skin of the boat[17] then, and surely would have noticed the deep scoring of a knife blade.”

“There can be no doubt about that,” agreed Dick. “And the work was skillfully done in the bargain. Whoever made that cut expected that the boat would strike against rocks many times during the run of the rapids, and took chances that one of the blows would tear open the weak place. And that is what happened.”

“It would have gone much harder with us if we had not been most of the way down the descent,” said Roger, with a frown on his face. “But, Dick, who could the treacherous rascal be? As far as we know, we have not made a single enemy among the members of the party. Would one of our Indian friends have played such a mean trick on us, do you think?”

“No one but an enemy could have done it, Roger, because there was nothing to gain; for while some Indians might envy us our rifles these would surely be lost with us in the rapids and never recovered.”

“That makes the mystery worse than ever, then,” fretted the other lad, who was so constituted that among his boy friends down along the Missouri he had often gone under the name of “Headstrong Roger.”

“I have a suspicion, although there is really nothing to back it up, that I can see,” remarked Dick, reflectively, as though at some time in the past winter he had allowed himself to speculate concerning certain things which were now again taking possession of his mind.

“Dick, tell me what it is about, please,” urged his cousin, “because I’m groping in the dark, myself.”

“There is only one man that I know of who hates us bitterly,” commenced Dick, and instantly a flash of intelligence overspread the face of the other.

“Do you mean that French trader, François Lascelles?” he demanded.

“I was thinking of him, and his equally unscrupulous son, Alexis,” Dick admitted.

“But, when we captured them last fall, they were held prisoners in the camp until Mayhew, the scout, was well on his way down the river and could not possibly be overtaken. Then the party of Frenchmen was let go, with the solemn warning from Captain Lewis that if any of them loitered around this region they would be shot on sight. And Dick, all winter long you remember we have seen nothing of Lascelles, or indeed for that matter any other white man.”

“Still,” urged the other, “he may have come back here again when he found he could not overtake Mayhew and secure that paper. A man like François Lascelles hates bitterly, and never forgives. To be beaten in his game by a couple of mere boys would make him gnash his teeth every time he remembered it. Yes, something seems to tell me, Roger, that our old enemy has returned, and is even now in communication with some treacherous member of the expedition.”

“You mean his money has hired some one to play this terrible trick that might have cost us our lives; is that it, Dick?”

“It is only a guess with me,” replied the other, soberly; “but I can see no other explanation of this mystery.”

“But who could be the guilty man in the camp?” asked Roger. “We believed every one was our friend, from the two captains down to the lowest in line. It is terrible to suspect any one of a crime like this. How will we ever be able to find out about it, do you think?”

“We must begin to keep our eyes about us and watch,” advised Dick. “One by one we can cross the names off our list until it narrows[20] down to two or three. Sooner or later we shall find out the truth.”

“Do you mean to tell Captain Lewis about the knife-slit along the bottom of our boat?” demanded Roger.

“It is our duty to tell him,” Dick declared. “The man who could stoop to such a trick as that, just for love of money, is not fit to stay in the ranks of honest explorers. Once we can show him the proof, I am sure Captain Lewis will kick the rascal out of camp. But I can see that you are beginning to shiver, Roger; so the first thing we ought to do now is to make a fire, and dry our clothes as best we may.”

“I was just going to say that myself, Dick, because this spring air is sharp, with little heat in the sun. To tell you the honest truth my teeth are beginning to rattle like those bones the Mandan medicine man shakes, when he dances to frighten off the evil spirit that has entered the body of a sick man. So let’s gather some wood and make a blaze.”

With that, both boys began to bestir themselves, first of all slapping their arms back and forth to induce circulation; after which they started to collect dry wood in a heap. At no time, however, did they let their precious guns[21] leave their possession, for they knew that when fire-arms were needed it was usually in a hurry, and to save life.

“Let me light the pile, Dick,” Roger pleaded, after they had made sufficient preparation.

They had selected only dry wood for various reasons. In the first place, this would burn more readily, and thus throw off the heat they wanted in order to dry their clothes. At the same time it was likely to make little smoke that could be seen by the eyes of any hostile Indians who might be within a mile or so of the spot.

Boys who lived in those pioneer days always carried flint and steel along with them, in order to kindle a blaze when necessary. Had these been lacking, Roger, no doubt, would have been equal to the occasion, for he could have flashed some powder in the pan of his gun, and thus accomplished his purpose. (Note 2.)

In a short time Roger, being expert in these lines, succeeded, by the use of flint and steel, as well as some fine tinder, which he always carried along with him in his ditty bag, in starting a fire.

The wood blazed up and sent out a most gratifying heat, so that both boys, by standing as close as they could bear it, began to steam, very much after the manner of some of the warm geysers, during the stated periods when they were not spouting, that the lads had looked upon in the Land of Wonders.

“What shall we do about the boat?” asked Roger, when they found that they were by degrees getting dry, though it took a long time to accomplish this desired end.

“I was thinking about that,” his cousin told him. “It is not worth while for us to try to patch the hole, because we expect to abandon it very soon. Captain Lewis asked us to be with him in his boat. We had better leave it here, and perhaps they may send a couple of Indians down to fetch it to camp.”

“You mean, Dick, if the captain wishes to see for himself the mark of the treacherous knife blade?”

“Which I think he will want to do, so as to settle it in his own mind,” returned the other. “This is, after all, the most terrifying thing that has as yet happened to us on our long journey up here into the heart of the wilderness.”

“That is just it, Dick. Open foes I can stand,[24] because you know what to expect; but it gives me a creep to think of some unknown person standing ready to stab us in the dark, or when our backs are turned. Perhaps, after all, we did wrong to decide on staying with Captain Lewis and Captain Clark, when we might have gone on home with Mayhew, carrying that precious paper.”

“Oh! I wouldn’t look at it that way, Roger,” said the other, striving to cheer him up, for Roger was subject to sudden fits of depression. “Just think of all the wonderful things we have seen while here; and then remember that there are still other strange sights awaiting us in the Land of the Setting Sun.”

“Yes, that’s so, Dick, and both of us decided that the chance to look upon the great ocean was one not to be lightly cast aside.”

“We’ve been lucky so far,” Dick told his chum, “and succeeded in everything we have undertaken; so even this new trouble mustn’t upset us. By keeping a sharp lookout we can expect to learn who the traitor is, and after that he will be forced to leave the party. And if that Lascelles is around here again he will have to look out for himself. Anyhow,” he added after a pause, “we have gone too far now to turn[25] back, no matter whether we made a mistake or not.”

“Yes, and as my father used to say,” continued Roger, “‘what can’t be cured must be endured.’ We have made our bed, and must lie in it, no matter how hard it may seem. I’m going to believe just as you do, Dick—that the same kind fate that has always watched over us in times past is still on duty.”

He glanced upward toward the blue sky as he said this, and Dick knew what he intended to imply; for boys in those days were reared in a religious atmosphere in their humble homes, and early learned to “trust in the Lord; but keep their powder dry,” as the Puritan Fathers used to do.

“Our fathers often had to meet situations just as dangerous as any that can come to us,” continued Dick, “and they grappled them boldly and came off victorious. So, from now on, we’ll devote ourselves to finding out whose was the unseen hand that held the knife with which our hide boat was slashed so cleverly.”

“How far are we from camp, do you think, Dick?”

“As the crow flies it may be five miles, though we came further than that on the river,” the[26] other boy replied without any hesitation, showing how completely he kept all these things in his mind, to be utilized on short notice.

“We came down with a swift current,” Roger admitted, “and it hardly seemed as if we could have been an hour on the way. It will take us some time to tramp back to camp, even if we take a short-cut to avoid the bends in the river.”

“What of that,” asked Dick, “since we expected to spend a good part of the day in paddling up the stream, after shooting the rapids? But, if you are dry enough now, I think we had better make a start.”

“Suppose we drag the boat into these bushes first, Dick,” suggested Roger.

“Not a bad idea either, for some passing Indian might think it worth while to mend the hole and carry the boat off. We would like to have Captain Lewis take a look at that knife mark, so as to prove our story. He trusts all his men, and it is going to make him feel badly to know that one among them has sold himself to an enemy.”

Between them they carried the hide canoe in among the bushes, where it was easily hidden away. Of course any one seeking it would[27] readily find its hiding-place; but at least it could not be seen by the ordinary passer-by.

Having accomplished this, the two lads set forth to cover the ground lying between their landing place on the shore of the river, below the rapids, and the camp of the explorers.

They anticipated no trouble in finding their goal, because of their familiarity with woods life. Besides, in their numerous hunting trips during the past winter they had covered nearly all the territory around that region, so that the chances of their getting lost were small indeed.

“We may run across game on the way back, don’t you think, Dick?” suggested Roger, just after they had left the ashes of their late fire, which had been dashed with water before they quitted the scene.

“You never can tell,” came the reply; “there is always a chance to sight a deer in this country. We got a number, you remember, within three miles of camp while the snow was deep on the ground. And already I have noticed signs telling that they use this section for feeding on the early shoots of grass.”

“Yes,” added Roger, “tracks there have been in plenty. And as I live! see here, where this tuft of reddish hair has caught on a pointed[28] piece of bark. I warrant you some buck rubbed himself against this tree good and hard. I would like to have been within gunshot of the rascal just then, for the marks are fresh, and I think they were made this very morning.”

This gave the two boys hope that they might at any minute run across the deer and bring him down with a lucky shot. As fresh venison was always welcome in the camp, such a possibility as this always spurred them on to do their best. They liked to hear the cheery voice of Captain Lewis telling them frankly that it had been a fortunate thing for the whole expedition when he tempted Dick and Roger to remain and see the enterprise through.

“Listen! what is all that noise ahead of us?” asked Roger, as a sudden burst of snarling and half-suppressed howling was borne to their ears.

“Wolves, as sure as you live!” exclaimed Dick, frowning, for if there was one animal upon which he disliked to waste any of his precious ammunition, that beast was a wolf.

Ordinarily these animals are not to be feared when met singly, or even in pairs; but, during the winter and early spring, they gather in packs, in order to hunt the better for food, and[29] at such times even the boldest hunter dislikes running across them.

“They are certainly on the track of something,” suggested Roger, as he listened, and then, shrugging his broad shoulders, he continued. “Like as not, it is that buck we were hoping to run across. A plague on the pests! If I had my way, and could spare the ammunition, I’d shoot every one of the lot!”

“Little good that would do,” Dick told him; “because they run to thousands upon thousands out on the plains and in the mountains where we are heading. A dozen or two would be no more than a grain of sand on that seashore we hope to set eyes on before snow flies again.”

“But listen to them carrying on, Dick,” continued the other, with growing excitement. “Come to think of it, I never heard wolves make those queer sounds when chasing a deer. You know they yap like dogs, and almost bark. These beasts are acting like those creatures did when they had me caught up in a tree, with my gun on the ground.”

“Yes, I remember the time well enough,” chuckled Dick. “You were mighty glad to see a fellow of my heft, too, when I came along. Twenty hours up a tree is no joke, when you’ve[30] got a healthy appetite in the bargain. But, just as you say, Roger, there is something queer about the way they are carrying on.”

“They’re not chasing anything now, that’s certain,” asserted the other positively; “because the sounds keep coming from the same place all the time. Dick, perhaps the beasts may have some one treed for all we know. They are savage with hunger, and would just as soon make a meal off a hunter, red or white, as off a deer or a wounded buffalo.”

“It happens to be right on our way to camp,” remarked Dick, tightening his grip on his long-barreled rifle, “so we can find out what’s up without going far out of our path.”

This, of course, pleased Headstrong Roger, always in readiness for adventure, it mattered little of what nature. He always maintained that he had a long-standing debt against the tribe of lupus on account of that terrible fast mentioned by his cousin, and, although powder and ball were not too plentiful, he seldom failed to take a shot at his four-footed enemies when the chance came to him.

So now he fancied that he would end the prowling of at least one red-tongued woods rover. Certainly he could spare a single charge,[31] and it would give him more satisfaction than almost anything else. You see, Roger had rubbed the old sore when he spoke of that bitter experience in the past, and it smarted again venomously.

As they pushed steadily on, the sounds increased in volume. They could even hear the thud of heavy bodies falling back to the ground after frantic leaps aloft, as though endeavoring to reach some tempting object among the branches of a tree.

Then Roger, who had the keenest eyesight of the pair, muttered:

“There, I can just begin to see them through the trees and brush yonder, Dick; and, as we believed, they have some human being treed, or else are trying to force conclusions with a panther, which would be a strange thing, to be sure.”

“We’ll soon know,” the other whispered, “for it’s only a little way. Yes, I can see them jumping up, just as you say. Roger, fasten your eyes on the tree above, and tell me what that dark object is.”

A minute later, as they still kept pushing forward, Roger uttered a low cry.

“Well, after all, it’s an Indian brave up there.[32] And he’s already shot a number of the brutes with his arrows; but I reckon his stock has given out. He tries to strike them as they jump at him, using his knife. And, Dick, I can see now that he isn’t a Mandan Indian at all, but more likely one of those Sioux who, under their sub-chief, Beaver Tail, did us such a good turn last fall, when we saved Jasper Williams from the French traders. But what can a Sioux warrior be doing here, in the land of his foes, the Mandans?”

“There, I could see him reach down then and strike at a leaping wolf!” exclaimed Dick, showing signs of excitement, something he seldom did, since he had wonderful control over his emotions for a boy of his age.

“Just as I told you,” continued Roger, trembling all over with eagerness, “he has used up his arrows, and is trying to cut down the number of his four-footed enemies by other means.”

“There, listen to that howl!”

“Oh! he made a splendid strike that time, Dick!”

“Yes, and you can see what that clever brave is up to, if you notice the wild scuffle at the foot of the tree,” the other replied.

“Why, the wolves seem to be fighting among themselves, Dick. What makes them act that way, do you know?”

“I can give a guess. These mad animals are almost starving, though just how that should be,[34] at this season of the year, I am not able to say. The scent of blood makes them wild, you see, and, every time the brave’s knife wounds one of the pack, the rest set upon the wretched beast to finish him.”

“In that way the Indian could clean them up in time, I should say, without any help from us,” Roger suggested, though he showed no sign that his intention of giving aid had changed in the least.

“But they might take warning, and stop jumping up at him,” Dick explained; “then his knife would be useless. And, too, other wolves hearing the noise are apt to hasten to the spot, so that there might be an increasing pack, a new one for every beast he helped to kill.”

“Dick, he is a brave fellow, even if his skin is red!”

“I agree with you there,” said the other, softly.

“Then are we not going to bring about his rescue, even if it does cost us some of our precious powder and shot?” Roger demanded.

“Yes, but I hope it will not be more than one load,” replied his cousin; for all their lives this question of a wastage of ammunition had been[35] impressed on their minds as the utmost folly, and on that account they seldom used their guns except to make sure of worthy game.

“Come, let us rush forward with loud yells, waving our arms, and doing everything we can to scare the animals off before we begin to fire. After we get close up, and they are hesitating what to do, that is the time for us to blaze away.”

“A good plan, Roger, and worthy of our fathers’ old friend, Pat O’Mara. Only as a last resort will we use our fire-arms.”

“And you be the one to say when, Dick, remember!”

“Depend on me for that,” Roger was told quickly. “Just as soon as I see that something is needed to force the ugly beasts to make up their minds, I’ll call out to you to give it to them.”

“Give me one last word of advice before we rush them, Dick.”

“Yes, what is it, Roger?”

“If, instead of taking to their heels, the pack turns on us, and starts to fight, what must we do?”

“There isn’t one chance in ten it will happen that way,” said Dick, “for wolves are too[36] cowardly. When they see us rushing boldly forward you’ll notice how every beast’s head will droop, and that he’ll begin to skulk away, showing his teeth, perhaps, but cowed and whipped.”

“But suppose it should?” urged Roger, as they paused, just before bursting out upon the strange scene.

“If it comes to the worst we may have to take to a tree just as the Indian brave has done,” Dick told him, “and then start to work killing them off as fast as we can load and fire. Now, are you ready to do a lot of yelling?”

“Just try me, that’s all, Dick!”

“Come on, then, with me!”

With the words Dick sprang boldly forth from his concealment, with his cousin alongside. Both of them started to make the woods ring with their strong young voices, and when two healthy boys yell and whoop they can produce a tremendous volume of sound!

Some of those predatory wolves must have conceived the idea that a whole company of the strange two-legged foes was rushing toward them, judging from the hasty manner of their exit from the scene. Others, however, either more bold or hungry, half crouched and, snarling,[37] showed their white teeth in a vicious manner.

Evidently these leaders of the pack were not as yet quite convinced that the game had gone against them, despite all the noise made by the oncoming boys. On seeing this, Dick and Roger tried to shout louder than ever, while they waved their arms in the most frantic manner.

It devolved upon Dick to decide whether or not they should keep on in this fashion until they came to close quarters with the wolves that lingered, loth to give up their chance of a dinner. Rushing forward at this rate, they would be on the scene in half a dozen seconds, and might find the ugly beasts springing up at their throats.

Never before had the boys seen wolves acting in this manner, for as a rule their nature is cowardly. There was nothing for it but to fall back upon their guns for the finishing stroke, and so Dick gave the word.

“We must shoot, Roger—take that big fellow in front!” he gasped, for he was by this time fairly out of breath after all those strenuous exertions of running, thrashing his arms, and shouting at the top of his voice.

Accordingly both of them halted just long enough to throw their long-barreled rifles to[38] their shoulders, and glance along the sights. They could actually hear the savage snarls of the defiant pack. Roger, always a bit faster than his companion, was the first to fire, and with the crash of his gun the big leader of the pack sprang upward, only to fall back again with his legs kicking.

Dick’s gun spoke fast on the heels of the first report, and he, too, succeeded in knocking over the beast his quick eye had selected.

Then with renewed shouts, Dick and Roger once more started forward, but there was a hasty scurrying of gray bodies, and presently not a wolf remained in sight save the pair that had gone down before the deadly fire of the guns.

The Indian up in the tree dropped to the ground, and the boys saw immediately from his manner of dress that he was, just as Roger had surmised, a Sioux warrior. From the fact that he was bleeding in various places the boys understood that he must have put up a valiant fight at close quarters against his four-footed enemies, before finally seeking refuge among the branches of the friendly tree.

Naturally both lads immediately began to wonder why a Sioux brave should thus venture[39] into the neighborhood of the Mandan village, since the two tribes had been at knives’ points for many years. Indeed, the preceding fall, when the boys had been aided by Beaver Tail and some of his Sioux warriors, who accompanied them later to their camp, it had required all the tact and diplomacy of which Captain Lewis was capable to prevent an open rupture between the old-time rivals.

“First we must make him let us look at his wounds,” suggested Dick, “because it is no child’s play to have the teeth of wolves draw blood. Some of his wounds look bad to me.”

“I think you are right, Dick,” agreed the other, always accustomed to leaving the decision to his cousin. “See if you can make him understand what we want to do. I’ll get some water in my hat, so you can wash the wounds.”

The boys always made it a practice to carry certain homely remedies with them, for in those pioneer days the family medicine chest consisted in the main of dried herbs, and lotions made from them, all put up by the wise housewife. Those who lived this simple life, and were most of the time in the open air, seldom found themselves in need of a doctor, and most of their troubles sprang either from accidents, or injuries[40] received in combats with wild beasts of the forest.

So it was that they had with them a salve they always used to soothe the pain, as well as neutralize the poison injected by bites or scratches received in struggles at close quarters with carnivorous beasts.

The Indian was looking at them as though puzzled. Whites were rarely seen by the dwellers in these far regions beyond the Mississippi; indeed, most of the natives had never as yet set eyes on a paleface.

This brave, however, may have been in company with Beaver Tail, the friendly chief, at the time he aided the two boys, and, if so, he undoubtedly recognized Dick and Roger.

Unable to speak the Sioux tongue, of which they knew but a few words, it would be necessary for Dick to make use of gestures in conducting a brief conversation with the other. Still, the smile on his face, as well as the fact of his recent acts, would readily tell the red wanderer that he was a friend.

“Ugh! Ugh!” was all the Indian could say, but he accepted the hand that was extended, though possibly this method of greeting was strange to him.

Dick pressed him to sit down, and the brave did so, though with increasing wonder. He speedily realized, however, what the white boys meant to do, and without offering any remonstrance continued silently to watch their labor, as they proceeded to look after his injuries.

Roger fetched his hat full of cool water from a running brook close by, and one by one Dick washed the numerous scratches and ugly furrows where those wolfish fangs had torn the flesh of the stoical brave’s lower limbs.

He gave no sign of flinching, though the pain must have been more than a trifle. The boys knew enough of Indian character to feel sure that, if it had been ten times as severe, he would have calmly endured it, otherwise he could not have claimed the right to wear the feather they could see in his scalplock, and which signified that he was a warrior, or brave.

Finally the task was completed. There had been nothing further heard from the remnant of the baffled wolf pack all this while, proving that the loss of their powerful leaders must have taken the last bit of courage from the animals, known never to be very brave.

All the while the Sioux continued to keep those black eyes of his glued on Dick Armstrong. It[42] was as though he was in search of some one and had made up his mind that, since there could be no other paleface boys within a thousand miles of the spot, these must be the ones he had been commissioned to find.

Just about the time Dick, with another of his rare smiles, indicated that the work of looking after his injuries had been completed, the Sioux fumbled in his snake-skin ditty bag, where he kept his little stock of pemmican, and numerous other necessary articles, perhaps his war paint as well. To the astonishment of the boys he drew out a small roll of birch bark, secured far to the north, and handed it to Dick.

Filled with curiosity, the boy opened it with trembling fingers, to find, just as he had anticipated, that it was covered with a series of queer characters, painted after the Indian fashion and representing men and animals.

“It’s Indian picture writing, you see, Roger!” Dick declared, “and must be meant for us, or else this brave would not give it over. He has been sent here from the far-away Sioux village to find us, and deliver a message.”

“Yes,” added Roger, excitedly. “And look, Dick, there is what seems to be the awkward but plain picture of a beaver at the end of the message.[43] It must have been sent by our good friend, the chief of the Sioux.”

“You are right that far, Roger, for it is meant to be the signature of Beaver Tail, himself. Now to see if we can make out what it says!”

It was with the utmost eagerness that the two boys studied the strange characters depicted on the strip of bark. The hand that had drawn them there must have been accustomed to the task, and doubtless the story the message was meant to tell could have been easily read by the eyes of any Indian.

Dick and his cousin had seen samples of this queer picture writing before that time, and understood how the Indians depend on the natural sagacity of a woodsman, whether red or white, to decipher the meaning of the various characters. (Note 3.)

“What can it all stand for?” demanded Roger, as he gazed blankly at the several lines of characters. “Perhaps we may have to call on some of the Mandans in the village to explain it to us.”

“We will do that in the end, anyway,” Dick said, “in order to make certain; but, if we look[45] this over closely, right now, we may get an idea of what Beaver Tail meant by sending it.”

“You don’t think then, Dick, it was intended just as a greeting to us, so as to let us know the chief has not forgotten his young paleface brothers?”

“No, I feel sure it has a more serious meaning than that,” the other declared. “In fact, Roger, something tells me it may be in the nature of a warning.”

“A warning, Dick! Do you mean the Sioux chief wants us to tell Captain Lewis it will be all his life is worth to keep heading into the land of the West, now that spring has come?”

“I was thinking only of ourselves when I said that, Roger.”

“And that the warning would be for our benefit, you mean? But, Dick! how could Beaver Tail, so far away from here, know of any danger that hung over our heads?”

“Let us examine the bark message, and perhaps we shall learn something that may explain the mystery. The first thing we see is what looks to be a man facing the sun that is half hidden by the horizon.”

“Yes, that hedgehog-looking half circle is meant for the sun, I can see that. And, further[46] along, we find it again, only on the left side of the man who is now creeping toward it. What do you make that out to be?”

“It is plain that one represents the rising, and the other the setting sun,” Dick explained, with lines of deep thought marked across his forehead. “Now, an Indian always faces the north when he wants to represent the points of the compass, so it is plain that the first sun lies in the east.”

“And he wanted us to know that this man was heading into the east first of all; is that what you mean, Dick?”

“Yes, and look closer at the figure, Roger. It is not intended to be an Indian, you can see, for he has a hat on his head. It strikes me we ought to know that hat, cleverly imitated here; what do you say about it?”

“Oh! it must be the odd-looking hat that French trader, François Lascelles, always wore, Dick. He means that it was toward the rising sun François started last fall, just as we know happened. And now here he is, again, the same hat and all, creeping straight toward the setting sun. Does that mean the trader came back again, in spite of the warning Captain Lewis gave him?”

“I am sure it means that, and nothing else,” replied the other, calmly. “Stop and think, Roger. Only a little while ago, we were wondering whether such a thing had come about, because we found reason to believe some member of the expedition had been hired to do us an injury. Yes, that bitter Frenchman has dared to return, believing that he can keep out of the reach of our protectors, and manage in some way to get his revenge.”

“If that is what Beaver Tail is trying to tell us in this picture writing, Dick, the rest of the screed must simply go on to explain it a little further.”

“You notice that the same figure with the hat occurs always,” continued Dick, as he examined the message again. “Here is what must stand for a fire, and two persons are sitting beside it, as if cooking. In what seems to be a clump of bushes close by he has drawn that man again, this time lying flat.”

“That must mean that François is spying on the pair by the fire,” suggested Roger, “and as he has made both of them wear caps with ’coon or squirrel tails dangling down behind, I think they are meant to represent us.”

“There can be no question about it,” admitted[48] the other, deeply interested. “And, going further, we see the snake in the grass creeping up as if he meant to surprise the two, who are now sleeping, for they lie flat on the ground.”

“Yes, even the fire burns low, for there is hardly any blaze,” added Roger, “which indicates that the hour is late. Why, Dick, we can read the story as easily as any sign in the woods we ever tackled.”

“Then comes another scene,” continued Dick, “where the creeper has evidently sprung with uplifted knife, upon his intended prey, taken unawares. After that, we can see him crawling away, and there are two figures lying stretched out on the ground close to the now dead fire. That needs no explanation, Roger; François Lascelles seeks our lives, because we baffled him in his scheme to win a fortune at the expense of our folks at home!”

The two boys looked at each other. Their eyes may have seemed troubled, but there was no sign of flinching about them. The lads had met too many perils in times past to shrink, now that they were face to face with another source of danger.

“Shall we keep on now for the camp, and show[49] this message on the bark to Captain Lewis?” asked Roger.

“It would be the best thing to do, for he can advise us,” his companion admitted. “Besides, he will surely order every one in the camp to keep an eye out for François Lascelles.”

“We ought to take this brave with us, Dick, because he has come a long way, and is hardly fit to return without rest and food.”

Once again did Dick endeavor to make the Sioux warrior comprehend what he wished him to do. He urged him to get upon his feet, then thrust an arm through that of the brave, after which he nodded his head, pointed to the north, made gestures as though feeding himself, and then started to walk away, still holding on to the other.

Of course it was easy for the Indian to understand that they wished him to accompany them to their camp, where he would receive food and attention. He simply gave a guttural grunt, nodded his head, and fell in behind Dick, after the customary Indian method of traveling in single file. Then they moved along, Roger bringing up the rear.

Little was said while they tramped onward, heading for the camp. Dick occupied himself[50] with making sure that he held to the right direction. He also found much food for thought in the startling information that Beaver Tail had taken the pains to send all these miles to his young friends.

In due time they came in sight of the camp where the expedition had passed the preceding winter. Rude cabins had sheltered them from the cold and the snow, both of which had been quite severe in this northern latitude. Some distance beyond lay the Mandan village, always a source of deepest interest to the two boys. It contained so many strange things, and the lads had never become weary of trying to understand the ways of these “White Indians.” (Note 4.)

Upon seeing the boys come in with a strange Indian in their company, many curious glances were cast in their direction. Going straight to the cabin where the two leaders of the expedition lived, the boys were fortunate enough to find Captain Lewis busily engaged in making up his log for the preceding day, though of course there was little that was new to record.

To the surprise of the boys the Sioux Indian produced another bark scroll from his ditty bag, which he handed to Captain Lewis. This fact convinced Dick that the brave must have been[51] with the party in the fall, for he seemed to know that the white man he faced was the “big chief.”

“What does all this mean, my boys?” asked the captain, looking puzzled.

“We met with an accident in the rapids, and had to swim out,” replied Dick. “Then, on the way back to camp, we came upon this Sioux brave in a tree with a dozen hungry wolves jumping up at him. We chased the wolves off, and looked after his wounds, when to our surprise he handed us this message from his chief, Beaver Tail.”

The captain examined the picture writing with considerable interest. He had been taking considerable pains since mingling with the Mandans to understand their ways, and this crude but effective method of communication had aroused his curiosity on numerous occasions.

“Read it to me, if you managed to make it out, Dick,” he told the boy, who only too willingly complied.

The captain frowned upon learning that, despite his solemn warning, the French trader had returned to the neighborhood. That look boded ill for François Lascelles, should he ever have the hard luck to be caught in the vicinity of the camp.

The captain’s own communication from the Sioux chief was merely meant for an expression of goodwill. Two figures, one plainly a Sioux chieftain, and the other a soldier, were seen to be grasping hands as though in greeting. Beaver Tail by this crude method of picture writing evidently intended to convey the meaning that he had not forgotten his friend, the white chief, and, also, that he had kept his word that the Sioux should remain on peaceful terms with the travelers.

“But you spoke of meeting with an accident in the rapids,” Captain Lewis presently remarked. “That is something strange for clever boys like you to experience. Did you miscalculate the danger, or was it something that could not be helped?”

“We closely examined our buffalo hide canoe yesterday, and it was in perfect condition, Captain,” said Dick. “Yet, with only a slight blow against a perfectly smooth rock, it split open, and we had to jump overboard. We managed to get through the rough water safely, and drew the damaged boat ashore. Imagine our surprise and consternation, sir, when we found that a sharp-pointed knife blade had been run along the bottom of the canoe, making a deep cut that[53] had easily given way when we struck the rock.”

“You startle me when you say that, Dick,” remarked the captain, looking uneasy, though almost immediately afterward his jaws became set in a determined fashion, while his eyes gleamed angrily. “It must mean that we have a traitor in the camp; some one who has been bought by the gold of François Lascelles.”

“That was what we began to fear, Captain,” Dick continued, “and we believed it only right to let you know what happened to us. We hope you will send some of the Indians, and one of our men, for the canoe. It could be brought secretly to the camp and examined, without the guilty one knowing about it.”

“A good idea, my boy, and one I shall act upon at once. Say nothing to a single soul concerning this outrage. If we expect to catch the traitor napping, he must not be put on his guard. But none of us could feel safe, knowing we had a snake in our midst. Depend upon it, the truth is bound to come out, and, when once we learn his identity, the traitor will be kicked out of the camp, if nothing worse happens to him.”

With this assurance the two boys rested content. They knew Captain Lewis was a man of his word, and felt sure that the man who had[54] sold his loyalty for a sum of money offered by the French trader would before long rue the evil day he allowed himself to be thus tempted.

Soon afterward they saw Captain Clark and his companion officer in conference, after which the former went over to the Mandan village, and, later on, vanished in the dense forest accompanied by two stalwart braves. They had gone, the boys knew to secure the hide canoe that told the story of treachery in the camp.

On the following day orders were given to prepare to start once more in the direction of the beckoning West. There was not much to be done, for, knowing that their departure would soon be ordered, the men had for some time past been getting things in readiness.

Dick and Roger had looked their few possessions over, and were ready to move on short notice. It gave the boys a little feeling of distress to realize that they would be thus placing additional ground between themselves and those dear ones left at home near the mouth of the Missouri.

“But we have embarked on the trip,” said Dick, when his chum was speaking of this as something he did not like very much, “and must see it through now. When we do get back home again, if we are so fortunate, think of all the wonderful things we shall be able to describe.”

The coming of Captain Lewis just then interrupted[56] their confidential talk. Dick expected that their leader had something of importance to communicate, and he could give a pretty accurate guess concerning its nature.

Sure enough, the first words spoken by the President’s private secretary explained the nature of his visit to the cabin of the Armstrong boys.

“I had an opportunity to examine your canoe, and there can be no reason to doubt that some unknown miscreant planned to have you lose your lives in the rapids. It was cleverly done, and at night-time doubtless, when no one would be apt to notice him working with your boat. The knife went in just deep enough to weaken the whole skin of the bottom, and only a slight blow was needed to finish the treacherous work.”

“Of course you have not been able to place your hand on the guilty party, Captain, have you?” asked Roger, eagerly.

“Nothing has been found out so far,” came the reply. “One of my reasons for joining you just now is to ask if either of you have any suspicions. Although of course we could not accuse any one on such grounds alone, at the same time it might narrow our search, and focus attention[57] on the guilty one, so that he could be watched, and caught in the act.”

“We do not feel able to say positively, Captain Lewis,” said Dick, “but when we came to look over the entire membership of the company we finally figured it out that it must lie between three men. All the others seemed to be above suspicion in our eyes.”

“Tell me who they are, so that I can have them watched,” demanded the commander.

“There is, first of all, Drewyer, the Canadian scout. He never seemed to be very friendly with us, for some reason or other, though we have had no quarrel. You are surprised to hear me mention his name, because you have always trusted him fully. And the chances are, Captain, that Drewyer is as faithful as the needle to the pole. I only include him because we know so little about him.”

“Who is the next one you have on your list?” asked Captain Lewis. “I count considerably on your natural sagacity to help in running this traitor to earth. You boys have learned pretty well how to judge men from their actions and looks, rather than from their fair speech. Tell me the other names, please, Dick.”

“Fields is the second man. I base my right[58] to include him in the group from the fact that there was a time when my cousin, here, and Fields had hot words over something the trapper had been doing in the village, and which Roger took him to task for. Since that time they have been on speaking terms, but I do not think Fields likes us over much.”

“I should regret very much to learn that Fields had turned traitor, for I have in the past been ready to trust him to any extent,” remarked Captain Lewis.

“The third and last man is Andrew Waller,” continued Dick. “Now, we have never had a word with Andrew except in the best of ways. We have always looked on him as a loyal friend, and faithful to the trust you put in him. It has only been of late that both of us noticed that Andrew seems to try to avoid us, and when we do meet face to face he lets his eyes drop.”

“That is indeed a suspicious fact,” commented the other, quickly. “If money has tempted him to play the part of a traitor it is easy to understand how he cannot look you squarely in the eye. Conscience flays him every time he sees you near by. I shall certainly bear in mind what you have told me, and in due time[59] results may spring from keeping a close watch on the movements of these three men.”

With that Captain Lewis left the boys, but they felt sure he would not allow the matter to drop. The man whom President Jefferson had personally selected to manage this big enterprise, and who had been his own private secretary, was accustomed to getting results whenever he attempted anything.

It was on the following morning that camp was broken, and the expedition once more started forward—down the Yellowstone to the Missouri, and up that muddy stream again. That was an event of vast importance in the lives of those daring souls who were thus venturing to plunge deeper into the mysteries of the country that up to then had never known the imprint of a white man’s foot.

Although filled with exultation, as were the rest of the travelers, Dick and his cousin looked back to see the last of the weird Mandan village which had long been a source of delight to their eyes. It was with considerable regret that they took their farewell view of the painted lodges, as well as the Indian cemetery on the side of the hill, where all those platforms, bearing their mummy-like burdens wrapped in buffalo hides,[60] told of superstitions that were a part of the Mandan nature.

During that day they made considerable progress, and the first camp of the new trail was pitched on a ridge close to the river. Here the horses were put out to graze, and the boats drawn up on the shore, though a guard was constantly kept to insure against treachery.

Despite the apparent friendship shown by many of the Indian tribes they encountered on their long journey of thousands of miles, the two captains never fully put their trust in the red men. They believed them as a rule to be treacherous, and unable to resist pilfering if the opportunity offered. Especially was this true when the coveted object was a horse or a “stick that spat fire,” as the wonderful “shooting-irons” of the explorers were generally called.

Several days passed with nothing to break the monotony of the journey. Of course they often met with minor difficulties, but these were speedily overcome by a display of that generalship which had so far made the trip a success.

All this while the boys had not forgotten about the spy in the camp. Without appearing to do so, they kept a watch upon the three men upon whom suspicion had fallen. Had any one of[61] them offered to leave camp after nightfall, he would have been trailed by Dick and Roger, bent on learning what could be the object of his wandering, and whether he had an appointment with François Lascelles, the Indian trader.

But, as the days drifted along, and nothing happened, they began to cherish hopes that perhaps the accident to their canoe had been rather an act of vandalism and malice than part of a deep plan to bring about their death.

A week after leaving the winter camp the party found itself on the border of a wide plain. Dick and Roger were mounted and were on a slight elevation down which they expected to pass to the level ground near the river, and await the coming of the boats. From here they could see for a considerable distance around.

“Look at the herds of buffaloes feeding here and there, Dick!” exclaimed Roger, whose hunting instincts were easily aroused. “It strikes me we heard Captain Clark say the fresh meat was getting low again. What do you say to trying to knock over one or two of those fine fellows?”

“We would have to go a considerable distance to do it, then,” the other told him, “and leave our horses in the bargain, because they are not[62] used to approaching such fierce-looking animals as buffalo bulls.”

“But we might be lucky enough to get one or two yearlings,” persisted Roger, who dearly loved the excitement of the hunt, as well as the taste of the well-cooked meat when meal time came. “I think we could manage to load our animals down with the spoils, and easily reach the place where our friends mean to camp for the night.”

Dick looked around him before replying to this tempting proposal. He remembered that they had need to use particular care while away from the main body of explorers; but so far as indications went he could not discover the slightest sign of danger. Certainly there was nothing to be feared from François Lascelles out there on that wide stretch of plains, where in various places they could see timid antelopes and clumsy buffaloes feeding amidst the isolated stands of timber which dotted the landscape.

“I see nothing to hinder our making the attempt, Roger,” he finally remarked.

“Then you agree, do you, Dick?” eagerly demanded the other young explorer, as he caressed his gun, and cast a happy look over the panorama that was spread in front of them.

“Let’s figure out just where our best chance lies, before we make a start,” he was told. “We have to keep in mind that it’s necessary to hide our mounts, so we can creep up on the herd close to some motte of timber.”

The boys had more than once shot the great, shaggy animals that in those early days abounded in countless thousands on the prairies of the Far West. Their fathers had hunted buffaloes while on the trail from Virginia to the banks of the Ohio when boys no older than Dick and Roger. Hence they were familiar with the habits of the animals which they now meant to stalk.

Choosing their course so as to keep a patch of cottonwoods between themselves and the small herd they had picked out as their prey, the two boys urged their horses on at a smart pace. In several quarters they could see the swift-footed antelopes vanishing at a surprising pace, frightened by the approach of these strange animals, bearing riders on their backs, the like of which they possibly had never beheld before that day.

The buffaloes, however, were not so easily alarmed. Unless they saw an enemy for themselves, or scented something that caused them[64] uneasiness, they were likely to hold their ground where they chanced to be feeding. (Note 5.)

Finally the boys decided it was no longer safe to take their horses with them. The animals were accordingly secured in a patch of timber, and the lads, still screened by the other motte, set forth on foot.

They had possibly a quarter of a mile to walk before reaching their intended shelter, from the other side of which they hoped to be able to fire upon some of the nearest of the herd. The old grass still lay on the ground, dead and brown; but shoots of the new spring crop had begun to thrust their heads up between. It was on this tender green stuff that the buffaloes were browsing, and, as it grew more freely in certain places, such a fact would account for their presence near the timber.

The one thing Dick and Roger had to be careful about was the chance of any straggler from the herd discovering them, and with a bellow giving the alarm. In order to avoid this if possible, Dick and his chum bent low as they advanced, and kept a wary lookout on either side of the timber.

The breeze blew from the trees toward them. This fact they had made sure of before starting,[65] because, otherwise, such is the sense of smell in the buffaloes they would not have had the least chance of getting within shooting distance of the wary animals, who generally feed facing the wind.

When finally the boys arrived at the edge of the timber they believed everything was working as well as they could wish. As yet no sound had come to their ears that would indicate alarm on the part of their intended quarry; and Roger allowed himself to indulge in high hopes of a hunters’ feast that night, with buffalo meat in plenty as the main dish.

“Look, Dick, we are not the only hunters,” whispered Roger, as he tugged at the sleeve of his cousin’s tunic, and pointed with his rifle.

There was a slight movement in the undergrowth just ahead of them. Dick, looking in that direction, was surprised to see a crouching animal slink away. He instantly recognized it as a gray timber wolf, and knew the animal must have been hiding there in hopes of seizing upon some sort of game.

As a single wolf, however daring, would never attempt to attack a buffalo, Dick could not understand at first what the animal meant to do. He judged, however, that, as this was the spring of the year, possibly there were calves in the herd, which would be just the tender sort of food that the sleek prowler would delight to secure.

The animal drew back his lips at the boys, disclosing the cruel white fangs; but he knew better[67] than to attack such enemies and slunk swiftly away. After he slid into a thicker part of the brush the boys lost sight of him, for the time at least.

Bent upon finding a place where they could get a fair shot at such animals as seemed best suited to their needs, the boys crept along. The patch of timber was not of any great size, and already they could see the open prairie between the standing trees.

Again did the keen-eyed Roger make a sudden discovery that caused him to grip once more the arm of his companion and point. This time, however, he did not speak even in a whisper, for they were very close to the edge of the motte, and for all they knew some buffalo might be lying within twenty feet of them.

What Dick saw, as he turned his eyes in the direction indicated, surprised him very much. Apparently the tempting bait had drawn another savage hunter to the spot in hopes of securing a meal.

It was no Indian brave who sprawled upon the lowermost limb of that tree, but the lithe figure of a gray animal which Dick instantly recognized as a panther, and an unusually big one at that.

The beast was staring hard at them. It did not move, or offer to attack them, but, just as the wolf had done, it bared its teeth.

The boys were not looking for trouble with a brute of this type just then. Food alone held their thoughts and governed their movements. On that account Dick did a very wise thing when, drawing his companion aside, he made a little detour.

The boys crept as softly as though born spies. Hardly a leaf fluttered as they moved along, and certainly no stick cracked under their weight, for these lads had long ago learned all that woodcraft could teach them.

Both cast many a curious glance to the right and to the left, as though wondering what next they would come upon in the way of hungry, envious beasts.

After a little while Dick turned again toward the front, and began to make his way to the edge of the timber. He had noticed that, at a certain point, the dead grass extended some thirty feet away from the trees, and offered splendid shelter to any one who knew how to utilize it.

Taking an observation after he had crawled forward to the very edge of the timber, Dick found that the nearest animals were some little[69] distance away. He could count a dozen of them in sight, and there were two small calves frisking about their mothers.

Although the grass might be exceptionally fine close up to the trees, the temptation to feed in closer was resisted by the buffaloes. They seemed to know by some intuition that danger was apt to lurk where timber grew, especially for the tender calves.

In order to make sure of their shots, it was desirable for the boys to crawl out amidst that dead grass. Dick could see that it offered the finest kind of shelter, and, once they reached its furthermost limit, the chances of making sure shots would be just that much enhanced.

Flattening themselves out upon the ground they crept along on their hands and knees. An inexperienced hunter could never have performed the task without attracting the attention of the feeding buffaloes, and causing a stampede; but the Armstrong boys had learned how to accomplish the feat.

Now and then a cautious observation was taken, and these glances painted the scene vividly on the minds of the creeping boys. They could see the coveted yearling cows that it was their object to secure, the other, older members[70] of the herds, and, towering above all, the old bull who ruled the herd.

This last was a terrible object, with the shaggiest mane the boys had ever seen on a buffalo. He showed the scars of numerous fierce battles, and one of his short black horns had been twisted out of shape in some former combat, so that it gave him a peculiarly wicked appearance.

Of course, when picking out their game, neither of the hunters had the slightest idea of aiming for the patriarch of the herd. He would be much too tough a morsel for any one to chew, unless reduced to the point of actual starvation, when he might be preferable to slicing up one’s moccasins for soup.

The old fellow seemed to understand his business as acknowledged guardian of the herd. He moved hither and thither, and, every once in so often, stopped to look around him, as though in search of signs of trouble.

Then he would shake his great head, give a proud snort of conscious power, strike at the ground several times with one of his forefeet, and finally go on with his feeding.

By this time the hunters had arrived at the point where to proceed further would be to accept unnecessary risk of detection. They knew[71] well that, once the alarm was given, the whole herd would quickly be in motion.

While they might possibly succeed in a shot taken at a moving target, the chances of a miss were much greater than they cared to take. So Dick concluded the time had come for them to pick out their quarry, take deliberate aim, and then fire as close together as possible.