Legends of the Land of the

Gods ![]() Re-told by Frank

Re-told by Frank

Rinder ![]() With Illustrations

With Illustrations

by T. H. Robinson

“The spirit of Japan is as the

fragrance of the wild cherry-blossom

in the dawn of the

rising sun”

London: George Allen

156 Charing Cross Road

1895

Old-World Japan

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

HISTORY and mythology, fact and fable, are closely interwoven in the texture of Japanese life and thought; indeed, it is within relatively recent years only that exact comparative criticism has been able, with some degree of accuracy, to divide the one from the other. The accounts of the God-period contained in the Kojiki and the Nihongi—“Records of Ancient Matters” compiled in the eighth century of the Christian era—profess to outline the events of the vast cycles of years from the time of Ame-no-mi-naka-nushi-no-kami’s birth in the Plain of High Heaven, “when the earth, young and like unto floating oil, drifted about medusa-like,” to the death of the Empress Suiko, A.D. 628.

[Pg vi] The first six tales in this little volume are founded on some of the most significant and picturesque incidents of this God-period. The opening legend gives a brief relation of the birth of several of the great Shinto deities, of the creation of Japan and of the world, of the Orpheus-like descent of Izanagi to Hades, and of his subsequent fight with the demons.

That Chinese civilisation has exercised a profound influence on that of Japan, cannot be doubted. A scholar of repute has indicated that evidence of this is to be found even in writings so early as the Kojiki and the Nihongi. To give a single instance only: the curved jewels, of which the remarkable necklace of Ama-terasu was made, have never been found in Japan, whereas the stones are not uncommon in China.

This is not the place critically to consider the wealth of myth, legend, fable, and folk-tale to be found scattered throughout Japanese literature, and represented in Japanese art: suffice it to say, that to the student and the lover of primitive [Pg vii] romance, there are here vast fields practically unexplored.

The tales contained in this volume have been selected with a view rather to their beauty and charm of incident and colour, than with the aim to represent adequately the many-sided subject of Japanese lore. Moreover, those only have been chosen which are not familiar to the English-reading public. Several of the classic names of Japan have been interpolated in the text. It remains to say that, in order not to weary the reader, it has been found necessary to abbreviate the many-syllabled Japanese names.

The sources from which I have drawn are too numerous to particularise. To Professor Basil Hall Chamberlain, whose intimate and scholarly knowledge of all matters Japanese is well known, my thanks are especially due, as also the expression of my indebtedness to other writers in English, from Mr. A. B. Mitford to Mr. Lafcadio Hearn, whose volumes on “Unfamiliar Japan” appeared last year. The careful text of [Pg viii] Dr. David Brauns, and the studies of F. A. Junker von Langegg, have also been of great service. The works of numerous French writers on Japanese art have likewise been consulted with advantage.

FRANK RINDER.

| PAGE | |

| THE BIRTH-TIME OF THE GODS | 1 |

| THE SUN-GODDESS | 15 |

| THE HEAVENLY MESSENGERS | 25 |

| PRINCE RUDDY-PLENTY | 35 |

| THE PALACE OF THE OCEAN-BED | 45 |

| AUTUMN AND SPRING | 57 |

| THE STAR-LOVERS | 67 |

| THE ISLAND OF ETERNAL YOUTH | 77 |

| RAI-TARO, THE SON OF THE THUNDER-GOD | 87 |

| THE SOULS OF THE CHILDREN | 97 |

| THE MOON-MAIDEN | 103 |

| THE GREAT FIR TREE OF TAKASAGO | 113 |

| THE WILLOW OF MUKOCHIMA | 121 |

| THE CHILD OF THE FOREST | 129 |

| THE VISION OF TSUNU | 141 |

| PRINCESS FIRE-FLY | 151 |

| THE SPARROW’S WEDDING | 161 |

| THE LOVE OF THE SNOW-WHITE FOX | 171 |

| NEDZUMI | 181 |

| KOMA AND GON | 189 |

| PAGE | |

| Heading to “The Birth-Time of the Gods” | 3 |

| When he had so said, he plunged his jewelled spear into the seething mass below | 5 |

| Heading to “The Sun-Goddess” | 17 |

| Ama-terasu gazed into the mirror, and wondered greatly when she saw therein a goddess of exceeding beauty | 21 |

| Heading to “The Heavenly Messengers” | 27 |

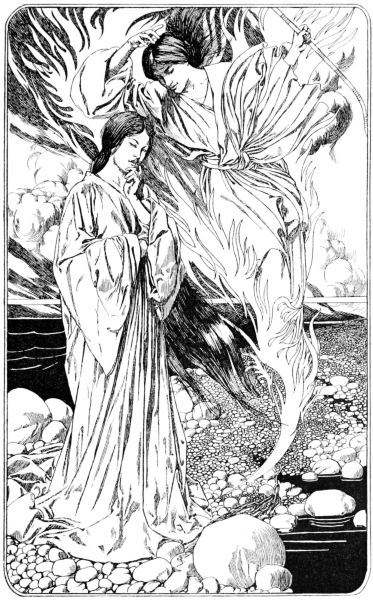

| As the Young Prince alighted on the sea-shore, a beautiful earth-spirit, Princess Under-Shining, stood before him | 29 |

| Heading to “Prince Ruddy-Plenty” | 37 |

| But the fair Uzume went fearlessly up to the giant, and said: “Who is it that thus impedes our descent from heaven?” | 39 |

| Heading to “The Palace of the Ocean-Bed” | 47 |

| Suddenly she saw the reflection of Prince Fire-Fade in the water | 51 |

| Heading to “Autumn and Spring” | 59 |

| One after the other returned sorrowfully home, for none found favour in her eyes | 63 |

| Heading to “The Star Lovers” | 69 |

| The lovers were wont, standing on the banks of the celestial stream, to waft across it sweet and tender messages | 71 |

| Heading to “The Island of Eternal Youth” | 79 |

| Soon he came to its shores, and landed as one in a dream | 83 |

| [Pg xii]Heading to “Rai-Taro, the Son of the Thunder-God” | 89 |

| The birth of Rai-taro | 93 |

| Heading to “The Souls of the Children” | 99 |

| Heading to “The Moon-Maiden” | 105 |

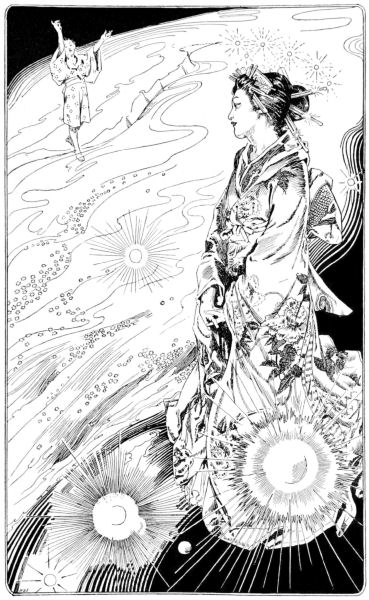

| At one moment she skimmed the surface of the sea, the next her tiny feet touched the topmost branches of the tall pine trees | 109 |

| Heading to “The Great Fir Tree of Takasago” | 115 |

| Heading to “The Willow of Mukochima” | 123 |

| Heading to “The Child of the Forest” | 131 |

| Kintaro reigned as prince of the forest, beloved of every living creature | 135 |

| Heading to “The Vision of Tsunu” | 143 |

| On a plot of mossy grass beyond the thicket, sat two maidens of surpassing beauty | 147 |

| Heading to “Princess Fire-Fly” | 153 |

| But the Princess whispered to herself, “Only he who loves me more than life shall call me bride” | 155 |

| Heading to “The Sparrow’s Wedding” | 163 |

| Heading to “The Love of the Snow-White Fox” | 173 |

| With two mighty strokes, he felled his adversaries to the ground | 177 |

| Heading to “Nedzumi” | 183 |

| Heading to “Koma and Gon” | 191 |

BEFORE time was, and while yet the world was uncreated, chaos reigned. The earth and the waters, the light and the darkness, the stars and the firmament, were intermingled in a vapoury liquid. All things were formless and confused. No creature existed; phantom shapes moved as clouds on the ruffled surface of a sea. It was the birth-time of the gods. The first deity sprang from an immense bulrush-bud, [Pg 4] which rose, spear-like, in the midst of the boundless disorder. Other gods were born, but three generations passed before the actual separation of the atmosphere from the more solid earth. Finally, where the tip of the bulrush points upward, the Heavenly Spirits appeared.

From this time their kingdom was divided from the lower world where chaos still prevailed. To the fourth pair of gods it was given to create the earth. These two beings were the powerful God of the Air, Izanagi, and the fair Goddess of the Clouds, Izanami. From them sprang all life.

Now Izanagi and Izanami wandered on the Floating Bridge of Heaven. This bridge spanned the gulf between heaven and the unformed world; it was upheld in the air, and it stood secure. The God of the Air spoke to the Goddess of the Clouds: “There must needs be a kingdom beneath us, let us visit it.” When he had so said, he plunged his jewelled spear into the seething mass below. The drops that fell from the point of the spear congealed and became the island of [Pg 7] Onogoro. Thereupon the Earth-Makers descended, and called up a high mountain peak, on whose summit could rest one end of the Heavenly Bridge, and around which the whole world should revolve.

The Wisdom of the Heavenly Spirit had decreed that Izanagi should be a man, and Izanami a woman, and these two deities decided to wed and dwell together on the earth. But, as befitted their august birth, the wooing must be solemn. Izanagi skirted the base of the mountain to the right, Izanami turned to the left. When the Goddess of the Clouds saw the God of the Air approaching afar off, she cried, enraptured: “Ah, what a fair and lovely youth!” Then Izanagi exclaimed, “Ah, what a fair and lovely maiden!” As they met, they clasped hands, and the marriage was accomplished. But, for some unknown cause, the union did not prove as happy as the god and goddess had hoped. They continued their work of creation, but Awaji, the island that rose from the deep, was little more than a barren waste, and their first-born son, Hiruko, was a weakling. The Earth-Makers placed him in [Pg 8] a little boat woven of reeds, and left him to the mercy of wind and tide.

In deep grief, Izanagi and Izanami recrossed the Floating Bridge, and came to the place where the Heavenly Spirits hold eternal audience. From them they learned that Izanagi should have been the first to speak, when the gods met round the base of the Pillar of Earth. They must woo and wed anew. On their return to earth, Izanagi, as before, went to the right, and Izanami to the left of the mountain, but now, when they met, Izanagi exclaimed: “Ah, what a fair and lovely maiden!” and Izanami joyfully responded, “Ah, what a fair and lovely youth!” They clasped hands once more, and their happiness began. They created the eight large islands of the Kingdom of Japan; first the luxuriant Island of the Dragon-fly, the great Yamato; then Tsukushi, the White-Sun Youth; Iyo, the Lovely Princess, and many more. The rocky islets of the archipelago were formed by the foam of the rolling breakers as they dashed on the coast-lines of the islands already created. Thus China and the [Pg 9] remaining lands and continents of the world came into existence.

Now were born to Izanagi and Izanami, the Ruler of the Rivers, the Deity of the Mountains, and, later, the God of the Trees, and a goddess to whom was entrusted the care of tender plants and herbs.

Then Izanagi and Izanami said: “We have created the mighty Kingdom of the Eight Islands, with mountains, rivers, and trees; yet another divinity there must be, who shall guard and rule this fair world.”

As they spoke, a daughter was born to them. Her beauty was dazzling, and her regal bearing betokened that her throne should be set high above the clouds. She was none other than Ama-terasu, The Heaven-Illuminating Spirit. Izanagi and Izanami rejoiced greatly when they beheld her face, and exclaimed, “Our daughter shall dwell in the Blue Plain of High Heaven, and from there she shall direct the universe.” So they led her to the summit of the mountain, and over the wondrous bridge. The Heavenly Spirits were joyful when they saw [Pg 10] Ama-terasu, and said: “You shall mount into the soft blue of the sky, your brilliancy shall illumine, and your sweet smile shall gladden, the Eternal Land, and all the world. Fleecy clouds shall be your handmaidens, and sparkling dewdrops your messengers of peace.”

The next child of Izanagi and Izanami was a son, and as he also was beautiful, with the dream-like beauty of the evening, they placed him in the heavens, as co-ruler with his sister Ama-terasu. His name was Tsuku-yomi, the Moon-God. The god Susa-no-o is another son of the two deities who wooed and wed around the base of the Pillar of Earth. Unlike his brother and his sister, he was fond of the shadow and the gloom. When he wept, the grass on the mountainside withered, the flowers were blighted, and men died. Izanagi had little joy in this son, nevertheless he made him ruler of the ocean.

Now that the world was created, the happy life of the God of the Air and the Goddess of the Clouds was over. The consumer, the [Pg 11] God of Fire, was born, and Izanami died. She vanished into the deep solitudes of the Kingdom of the Trees, in the country of Kii, and disappeared thence into the lower regions.

Izanagi was sorely troubled because Izanami had been taken from him, and he descended in pursuit of her to the portals of the shadowy kingdom where sunshine is unknown. Izanami would fain have left that place to rejoin Izanagi on the beautiful earth. Her spirit came to meet him, and in urgent and tender words besought him not to seek her in those cavernous regions. But the bold god would not be warned. He pressed forward, and, by the light struck from his comb, he sought for his loved one long and earnestly. Grim forms rose to confront him, but he passed them by with kingly disdain. Sounds as of the wailing of lost souls struck his ear, but still he persisted. After endless search, he found his Izanami lying in an attitude of untold despair, but so changed was she, that he gazed intently into her eyes ere he could recognise her. Izanami was angry that Izanagi had not [Pg 12] listened to her commands, for she knew how fruitless would be his efforts. Without the sanction of the ruler of the under-world, she could not return to earth, and this consent she had tried in vain to obtain.

Izanagi, hard pressed by the eight monsters who guard the Land of Gloom, had to flee for his life. He defended himself valiantly with his sword; then he threw down his head-dress, and it was transformed into bunches of purple grapes; he also cast behind him the comb, by means of which he had obtained light, and from it sprang tender shoots of bamboo. While the monsters eagerly devoured the luscious grapes and tender shoots, Izanagi gained the broad flight of steps which led back to earth. At the top he paused and cried to Izanami: “All hope of our reunion is now at an end. Our separation must be eternal.”

Stretching far beyond Izanagi lay the ocean, and on its surface was reflected the face of his well-beloved daughter, Ama-terasu. She seemed to speak, and beseech him to purify himself in the great waters of the sea. As [Pg 13] he bathed, his wounds were healed, and a sense of infinite peace stole over him.

The life-work of the Earth-Maker was done. He bestowed the world upon his children, and afterwards crossed, for the last time, the many-coloured Bridge of Heaven. The God of the Air now spends his days with the Heaven-Illuminating Spirit in her sun-glorious palace.

AMA-TERASU, the Sun-Goddess, was seated in the Blue Plain of Heaven. Her light came as a message of joy to the celestial deities. The orchid and the iris, the cherry and the plum blossom, the rice and the hemp fields answered to her smile. The Inland Sea was veiled in soft rich colour.

Susa-no-o, the brother of Ama-terasu, who had resigned his ocean sceptre and now reigned as the Moon-God, was jealous of [Pg 18] his sister’s glory and world-wide sway. The Heaven-Illuminating Spirit had but to whisper and she was heard throughout her kingdom, even in the depths of the clear pool and in the heart of the crystal. Her rice-fields, whether situated on hill-side, in sheltered valley, or by running stream, yielded abundant harvests, and her groves were laden with fruit. But the voice of Susa-no-o was not so clear, his smile was not so radiant. The undulating fields which lay around his palace were now flooded, now parched, and his rice crops were often destroyed. The wrath and jealousy of the Moon-God knew no bounds, yet Ama-terasu was infinitely patient and forgave him many things.

Once, as was her wont, the Sun-Goddess sat in the central court of her glorious home. She plied her shuttle. Celestial weaving maidens surrounded a fountain whose waters were fragrant with the heavenly lotus-bloom: they sang softly of the clouds and the wind and the lift of the sky. Suddenly, the body of a piebald horse fell through the vast dome at their feet: the “Beloved of the Gods” had [Pg 19] been “flayed with a backward flaying” by the envious Susa-no-o. Ama-terasu, trembling at the horrible sight, pricked her finger with the weaving shuttle, and, profoundly indignant at the cruelty of her brother, withdrew into a cave and closed behind her the door of the Heavenly Rock Dwelling.

The universe was plunged in darkness. Joy and goodwill, serenity and peace, hope and love, waned with the waning light. Evil spirits, who heretofore had crouched in dim corners, came forth and roamed abroad. Their grim laughter and discordant tones struck terror into all hearts.

Then it was that the gods, fearful for their safety and for the life of every beautiful thing, assembled in the bed of the tranquil River of Heaven, whose waters had been dried up. One and all knew that Ama-terasu alone could help them. But how allure the Heaven-Illuminating Spirit to set foot in this world of darkness and strife? Each god was eager to aid, and a plan was finally devised to entice her from her hiding-place.

Ame-no-ko uprooted the holy sakaki trees [Pg 20] which grow on the Mountain of Heaven, and planted them around the entrance of the cave. High on the upper branches were hung the precious string of curved jewels which Izanagi had bestowed upon the Sun-Goddess. From the middle branches drooped a mirror wrought of the rare metals of the celestial mine. Its polished surface was as the dazzling brilliancy of the sun. Other gods wove, from threads of hemp and paper mulberry, an imperial robe of white and blue, which was placed, as an offering for the goddess, on the lower branches of the sakaki. A palace was also built, surrounded by a garden in which the Blossom-God called forth many delicate plants and flowers.

Ama-terasu gazed into the mirror, and wondered greatly when she saw therein a goddess of exceeding beauty.

Now all was ready. Ame-no-ko stepped forward, and, in a loud voice, entreated Ama-terasu to show herself. His appeal was in vain. The great festival began. Uzume, the goddess of mirth, led the dance and song. Leaves of the spindle tree crowned her head; club-moss, from the heavenly mount Kagu, formed her sash; her flowing sleeves were bound with the creeper-vine; and in her [Pg 23] hand she carried leaves of the wild bamboo and waved a wand of sun-grass hung with tiny melodious bells. Uzume blew on a bamboo flute, while the eight hundred myriad deities accompanied her on wooden clappers and instruments formed of bow-strings, across which were rapidly drawn stalks of reed and grass. Great fires were lighted around the cave, and, as these were reflected in the face of the mirror, “the long-singing birds of eternal night” began to crow as if the day dawned. The merriment increased. The dance grew wilder and wilder, and the gods laughed until the heavens shook as if with thunder.

Ama-terasu, in her quiet retreat, heard, unmoved, the crowing of the cocks and the sounds of music and dancing, but when the heavens shook with the laughter of the gods, she peeped from her cave and said: “What means this? I thought heaven and earth were dark, but now there is light. Uzume dances and all the gods laugh.” Uzume answered: “It is true that I dance and that the gods laugh, because in our midst is a [Pg 24] goddess whose splendour equals your own. Behold!” Ama-terasu gazed into the mirror, and wondered greatly when she saw therein a goddess of exceeding beauty. She stepped from her cave and forthwith a cord of rice-straw was drawn across the entrance. Darkness fled from the Central Land of Reed-Plains, and there was light. Then the eight hundred myriad deities cried: “O, may the Sun-Goddess never leave us again.”

THE gods looked down from the Plain of High Heaven and saw that wicked earth-spirits peopled the lower world. Neither by day nor by night was there peace. Oshi-homi, whose name is His Augustness Heavenly-Great-Great-Ears, was commanded to go down and govern the earth. As he set foot on the Floating Bridge, he heard the sounds [Pg 28] of strife and confusion, so he returned, and said, “I would have you choose another deity to do this work.” Then the Great Heavenly Spirit and Ama-terasu called together the eight hundred myriad deities in the bed of the Tranquil River of Heaven. The Sun-Goddess spoke: “In the Central Land of Reed-Plains there is trouble and disorder. A deity must descend to prepare the earth for our grandson Prince Ruddy-Plenty, who is to rule over it. Whom shall we send?” The eight hundred myriad deities replied, “Let Ame-no-ho go to the earth.”

Now Ame-no-ho descended to the lower world. There he was so happy that the charge of the heavenly deities passed out of his mind. He lived with the earth-spirits, and confusion still reigned.

As the Young Prince alighted on the sea-shore, a beautiful earth-spirit, Princess Under-Shining, stood before him.

For three years the Great Heavenly Spirit and Ama-terasu waited for tidings, but none came. Then they said: “We will send Ame-waka, the Heavenly Young Prince. He will surely do our bidding.” Into his hands they gave the great heavenly deer-bow and the heavenly feathered arrows which fly straight [Pg 31] to the mark. “With these you shall war against the wicked earth-spirits, and bring order into the land.” But as the Young Prince alighted on the sea-shore, a beautiful earth-spirit, Princess Under-Shining, stood before him. Her loveliness bewitched him. He looked upon her, and could not withdraw his eyes. Soon they were wedded. Eight years passed. The Young Prince spent the time in revelry and feasting. Not once did he attempt to establish peace and order; moreover, he desired to place himself at the head of the earth-spirits, to defy the heavenly deities, and to rule over the Land of Reed-Plains.

Again the eight hundred myriad deities assembled in the bed of the Tranquil River of Heaven. The Sun-Goddess spoke: “Our messenger has tarried in the lower world. Whom shall we send to inquire the cause of this?” Then the gods commanded a faithful pheasant hen: “Go to Ame-waka, and say, ‘The Heavenly Deities sent you to the Central Land of Reed-Plains to subdue and pacify the deities of that land. For eight [Pg 32] years you have been silent. What is the cause?’” The pheasant flew swiftly to earth, and perched on the branches of a wide-spreading cassia tree which stood at the gate of the Prince’s palace. She spoke every word of her message, but no reply came. Again she repeated the words of the gods, again there was no answer. Now Ama-no-sagu, the Heavenly Spying-Woman, heard the call of the pheasant; she went to the Young Prince, and said, “The cry of this bird bodes ill. Take thy bow and arrows and kill it.” Then Ame-waka, in wrath, shot the bird through the heart.

The heavenly arrow fled upward and onward. Swift as the wind it sped through the air, it pierced the clouds and fell at the feet of the Sun-Goddess as she sat on her throne.

Ama-terasu saw that it was one of the arrows that had been entrusted to the Young Prince, and that the feathers were stained with blood. Then she took the arrow in her hands and sent it forth: “If this be an arrow shot by our messenger at the evil [Pg 33] spirits, let it not hit the Heavenly Prince. If he has a foul heart, let him perish.”

At this moment Ame-waka was resting after the harvest feast. The arrow flew straight to its mark, and pierced him to the heart as he slept. Princess Under-Shining cried aloud when she saw the dead body of the Young Prince. Her cries rose to the heavens. Then the father of Ame-waka raised a mighty storm, and the wind carried the body of the Young Prince to the Blue Plain. A great mourning-house was built, and for eight days and eight nights there was wailing and lamentation. The wild goose of the river, the heron, the kingfisher, the sparrow and the pheasant mourned with a great mourning.

When Aji-shi-ki came to weep for his brother, his face was so like that of the Young Prince that his parents fell upon him, and said: “My child is not dead, no! My lord is not dead, no!” But Aji-shi-ki was wroth because they had taken him for his dead brother. He drew his ten-grasp sabre and cut down the mourning-house, and scattered the fragments to the winds.

[Pg 34] Then the heavenly deities said: “Take-Mika shall go down and subdue this unruly land.” In company with Tori-bune he set forth and came to the shore of Inasa, in the country of Idzumo. They drew their swords and placed them on a crest of the waves. On the points of the swords Take-Mika and Tori-bune sat, cross-legged: thus they made war against the earth-spirits, and thus subdued them. The land once pacified, their mission was accomplished, and they returned to the Plain of High Heaven.

AMA-TERASU, from her sun-glorious palace, spoke to her grandson, Ninigi, Prince Rice-Ear-Ruddy-Plenty: “You must descend from your Heavenly Rock Seat and go to rule the luxuriant Land-of-Fresh-Rice-Ears.” She gave him many presents; precious stones from the mountain steps of heaven, crystal balls of purest whiteness, and the cloud-sword which her brother, Susa-no-o, had drawn from the tail of the terrible dragon. [Pg 38] She also entrusted to Ninigi the mirror whose splendour had enticed her from the cave, and said: “Guard this mirror faithfully; when you look into it you shall see my face.” A number of deities were commanded to accompany Prince Ruddy-Plenty, among them the beautiful Uzume, who had danced till the heavens shook with the laughter of the gods.

The great company broke through the clouds. Before them, at the eight-forked road of Heaven, stood a deity of gigantic stature, with his large and fiery eyes. The courage of the gods failed at sight of him, and they turned backward. But the fair Uzume went fearlessly up to the giant, and said: “Who is it that thus impedes our descent from heaven?” The deity, well pleased at the gracious mien of the goddess, made answer: “I am a friendly earth-spirit, the Deity of the Field-Paths. I come to meet Ninigi that I may pay homage to him and be his guide. Return and say to the august god that the Prince of Saruta greets him. I am this Prince, O Uzume.” The Goddess of Mirth rejoiced greatly when [Pg 41] she heard these words, and said: “The company of gods shall proceed to earth; there will Ninigi be made known to you.” Then the Deity of the Field-Paths spoke: “Let the army of gods alight on the mountain of Takachihi, in the country of Tsukushi. On its peak I shall await them.”

But the fair Uzume went fearlessly up to the giant, and said: “Who is it that thus impedes our descent from heaven?”

Uzume returned to the gods and delivered the message. When Prince Ruddy-Plenty heard her words he again broke through the eightfold spreading cloud, and floated on the Bridge of Heaven to the summit of Takachihi.

Now Ninigi, with the Prince of Saruta as his guide, travelled throughout the kingdom over which he was to rule. He saw the mountain ranges and the lakes, the great reed plains and the vast pine forests, the rivers and the valleys. Then he said: “It is a land whereon the morning sun shines straight, a land which the evening sun illumines. So this place is an exceeding good place.” When he had thus spoken, he built a palace. The pillars rested on the nethermost rock-bottom, and the cross-beams rose [Pg 42] to the Plain of High Heaven. In this palace he dwelt.

Again Ninigi spoke: “The God of the Field-Paths shall return to his home. He has been our guide, therefore he shall wed the beautiful goddess, Uzume, and she shall be priestess in his own mountain.” Uzume obeyed the commands of Ninigi, and is greatly honoured in Saruta for her courage, her mirth, and her beauty.

It happened that as the Son of the Gods walked along the sea-coast, he saw a maiden of exceeding loveliness. He spoke to her, and said: “By what name are you known?” She replied: “I am the daughter of the Deity Great-Mountain-Possessor, and my name is Ko-no-hane, Princess Tree-Blossom.” Ninigi loved the fair Princess. He went to the Spirit of the Mountains, and asked for her hand. But Oho-yama had an elder daughter, Iha-naga, Princess Long-as-the-Rocks, who was less fair than her sister. He desired that the offspring of Prince Ruddy-Plenty should live eternally like unto the rocks, and flourish as the blossom of the trees. Therefore [Pg 43] Oho-yama sent both his daughters to Ninigi in rich attire and with many rare presents. Ninigi loved the beautiful Princess Ko-no-hane. He would not look upon Iha-naga. She cried out in wrath: “Had you chosen me, you and your children would have lived long on earth; but as you love my sister all your descendants will perish rapidly as the blossom of the trees.” Thus it is that human life is so short compared with that of the earlier peoples that were gods.

For some time, Ninigi dwelt happily with Princess Tree-Blossom: then a cloud came over their lives. Ko-no-hane had the delicate grace, the morning freshness, the subtle charm of the cherry blossom. She loved the sunshine and the soft west wind. She loved the cool rain, and the quiet summer night. But Ninigi grew jealous. In anger Princess Tree-Blossom retired to her palace, closed up the entrance, and set it on fire. The flames rose higher and higher. Ninigi watched anxiously. As he looked, three little boys sprang merrily out of the flames and called for their father. Prince Ruddy-Plenty was [Pg 44] glad once more, and when he saw Ko-no-hane, unharmed, move towards him, he asked her forgiveness. They named their sons Ho-deri, Fire-Flash; Ho-suseri, Fire-Climax; and Ho-wori, Fire-Fade.

After many years, Ninigi divided his kingdom between two of his sons. Then Prince Ruddy-Plenty returned to the Plain of High Heaven.

HO-WORI, Prince Fire-Fade, the son of Ninigi, was a great hunter. He caught ‘things rough of hair and things soft of hair.’ His elder brother Ho-deri, Prince Fire-Flash, was a fisher who caught ‘things broad of fin and things narrow of fin.’ But, often, [Pg 48] when the wind blew and the waves ran high, he would spend hours on the sea and catch no fish. When the Storm God was abroad, Ho-deri had to stay at home, while at nightfall Ho-wori returned laden with spoil from the mountains. Ho-deri spoke to his brother, and said: “I would have your bow and arrows and become a hunter. You shall have my fish-hook.” At first Ho-wori would not consent, but finally the exchange was made.

Now Prince Fire-Flash was no hunter. He could not track the game, nor run swiftly, nor take good aim. Day after day Prince Fire-Fade went out to sea. In vain he threw his line; he caught no fish. Moreover, one day, he lost his brother’s fish-hook. Then Ho-deri came to Ho-wori, and said: “There is the luck of the mountain and there is the luck of the sea. Let each restore to the other his luck.” Ho-wori replied: “I did not catch a single fish with your hook, and now it is lost in the sea.” The elder brother was very angry, and, with many hard words, demanded the return of his treasure. Prince Fire-Fade was unhappy. He broke in pieces his good [Pg 49] sword and made five hundred fish-hooks which he offered to his brother. But this did not appease the wrath of Prince Fire-Flash, who still raged and asked for his own hook.

Ho-wori could find neither comfort nor help. He sat one day by the shore and heaved a deep sigh. The old Man of the Sea heard the sigh, and asked the cause of his sorrow. Ho-wori told him of the loss of the fish-hook, and of his brother’s displeasure. Thereupon the wise man promised to give his help. He plaited strips of bamboo so tightly together that the water could not pass through, and fashioned therewith a stout little boat. Into this boat Ho-wori jumped, and was carried far out to sea.

After a time, as the old man had foretold, his boat began to sink. Deeper and deeper it sank, until at last he came to a glittering palace of fishes’ scales. In front of it was a well, shaded by a great cassia tree. Prince Fire-Fade sat among the wide-spreading branches. He looked down, and saw a maiden approach the well; in her hand she carried a jewelled bowl. She was the lovely [Pg 50] Toyo-tama, Peerless Jewel, the daughter of Wata-tsu-mi, the Sea-King. Ho-wori was spellbound by her strange wave-like beauty, her long flowing hair, her soft deep blue eyes. The maiden stooped to fill her bowl. Suddenly, she saw the reflection of Prince Fire-Fade in the water; she dropped the precious bowl, and it fell in a thousand pieces. Toyo-tama hastened to her father, and exclaimed, “A man, with the grace and beauty of a god, sits in the branches of the cassia tree. I have seen his picture in the waters of the well.” The Sea-King knew that it must be the great hunter, Prince Fire-Fade.

Then Wata-tsu-mi went forth and stood under the cassia tree. He looked up to Ho-wori, and said: “Come down, O Son of the Gods, and enter my Palace of the Ocean-Bed.” Ho-wori obeyed, and was led into the palace and seated on a throne of sea-asses’ skins. A banquet was prepared in his honour. The hashi were delicate branches of coral, and the plates were of silvery mother-of-pearl. The clear-rock wine was sipped from cup-shaped ocean blooms with long [Pg 53] slender stalks. Ho-wori thought that never before had there been such a banquet. When it was ended he went with Toyo-tama to the roof of the palace. Dimly, through the blue waters that moved above, he could discern the Sun-Goddess. He saw the mountains and valleys of ocean, the waving forests of tall sea-plants, the homes of the shaké and the kani.

Ho-wori told Wata-tsu-mi of the loss of the fish-hook. Then the Sea-King called all his subjects together and questioned them. No fish knew aught of the hook, but, said the lobster: “As I sat one day in my crevice among the rocks, the tai passed near me. His mouth was swollen, and he went by without giving me greeting.” Wata-tsu-mi then noticed that the tai had not answered his summons. A messenger, fleet of fin, was sent to fetch him. When the tai appeared, the lost fish-hook was found in his poor wounded mouth. It was restored to Ho-wori, and he was happy. Toyo-tama became his bride, and they lived together in the cool fish-scale palace.

[Pg 54] Prince Fire-Fade came to understand the secrets of the ocean, the cause of its anger, the cause of its joy. The Storm-Spirit of the upper sea did not rule in the ocean-bed, and night after night Ho-wori was rocked to sleep by the gentle motion of the waters.

Many tides had ebbed and flowed, when, in the quiet of the night, Ho-wori heaved a deep sigh. Toyo-tama was troubled, and told her father that, as Ho-wori dreamt of his home on the earth, a great longing had come over him to visit it once more. Then Wata-tsu-mi gave into Ho-wori’s hands two great jewels, the one to rule the flow, the other to rule the ebb of the tide. He spoke thus: “Return to earth on the head of my trusted sea-dragon. Restore the lost fish-hook to Ho-deri. If he is still wroth with you, bring forth the tide-flowing jewel, and the waters shall cover him. If he asks your forgiveness, bring forth the tide-ebbing jewel, and it shall be well with him.”

Ho-wori left the Palace of the Ocean-Bed, and was carried swiftly to his own land. [Pg 55] As he set foot on the shore, he ungirded his sword, and tied it round the neck of the sea-dragon. Then he said: “Take this to the Sea-King as a token of my love and gratitude.”

A FAIR maiden lay asleep in a rice-field. The sun was at its height, and she was weary. Now a god looked down upon the rice-field. He knew that the beauty of the maiden came from within, that it mirrored the beauty of heavenly dreams. He knew that even now, as she smiled, she held converse with the spirit of the wind or the flowers.

[Pg 60] The god descended and asked the dream-maiden to be his bride. She rejoiced, and they were wed. A wonderful red jewel came of their happiness.

Long, long afterwards, the stone was found by a farmer, who saw that it was a very rare jewel. He prized it highly, and always carried it about with him. Sometimes, as he looked at it in the pale light of the moon, it seemed to him that he could discern two sparkling eyes in its depths. Again, in the stillness of the night, he would awaken and think that a clear soft voice called him by name.

One day, the farmer had to carry the mid-day meal to his workers in the field. The sun was very hot, so he loaded a cow with the bowls of rice, the millet dumplings, and the beans. Suddenly, Prince Ama-boko stood in the path. He was angry, for he thought that the farmer was about to kill the cow. The Prince would hear no word of denial; his wrath increased. The farmer became more and more terrified, and, finally, took the precious stone from his pocket and presented [Pg 61] it as a peace-offering to the powerful Prince. Ama-boko marvelled at the brilliancy of the jewel, and allowed the man to continue his journey.

The Prince returned to his home. He drew forth the treasure, and it was immediately transformed into a goddess of surpassing beauty. Even as she rose before him, he loved her, and ere the moon waned they were wed. The goddess ministered to his every want. She prepared delicate dishes, the secret of which is known only to the gods. She made wine from the juice of a myriad herbs, wine such as mortals never taste.

But, after a time, the Prince became proud and overbearing. He began to treat his faithful wife with cruel contempt. The goddess was sad, and said: “You are not worthy of my love. I will leave you and go to my father.” Ama-boko paid no heed to these words, for he did not believe that the threat would be fulfilled. But the beautiful goddess was in earnest. She escaped from the palace and fled to Naniwa, where she is still honoured as Akaru-hime, the Goddess of Light.

[Pg 62] Now the Prince was wroth when he heard that the goddess had left him, and set out in pursuit of her. But when he neared Naniwa, the gods would not allow his vessel to enter the haven. Then he knew that his priceless red jewel was lost to him for ever. He steered his ship towards the north coast of Japan, and landed at Tajima. Here he was well received, and highly esteemed on account of the treasures which he brought with him. He had costly strings of pearls, girdles of precious stones, and a mirror which the wind and the waves obeyed. Prince Ama-boko remained at Tajima, and was the father of a mighty race.

Among his children’s children was a princess so renowned for her beauty that eighty suitors sought her hand. One after the other returned sorrowfully home, for none found favour in her eyes. At last, two brothers came before her, the young God of the Autumn, and the young God of the Spring. The elder of the two, the God of Autumn, first urged his suit. But the princess refused him. He went to his younger brother, and said: “The princess does not [Pg 65] love me, neither will you be able to win her heart.” But the Spring God was full of hope, and replied: “I will give you a cask of rice wine if I do not win her, but if she consents to be my bride, you shall give a cask of saké to me.”

Now the God of Spring went to his mother, and told her all. She promised to aid him. Thereupon she wove, in a single night, a robe and sandals from the unopened buds of the lilac and white wisteria. Out of the same delicate flowers she fashioned a bow and arrows. Thus clad, the God of Spring made his way to the beautiful princess.

As he stepped before the maiden, every bud unfolded, and from the heart of each blossom came a fragrance that filled the air. The princess was overjoyed, and gave her hand to the God of the Spring.

The elder brother, the God of Autumn, was filled with rage when he heard how his brother had obtained the wondrous robe. He refused to give the promised cask of saké. When the mother learned that the god had broken his word, she placed stones and salt in the hollow [Pg 66] of a bamboo cane, wrapped it round with bamboo leaves, and hung it in the smoke. Then she uttered a curse upon her first-born son: “As the leaves wither and fade, so must you. As the salt sea ebbs, so must you. As the stone sinks, so must you.”

The terrible curse fell upon her son. While the God of Spring remains ever young, ever fragrant, ever full of mirth, the God of Autumn is old, and withered, and sad.

SHOKUJO, daughter of the Sun, dwelt with her father on the banks of the Silver River of Heaven, which we call the Milky Way. She was a lovely maiden, graceful and winsome, and her eyes were tender as the eyes of a dove. Her loving father, the Sun, was much troubled because Shokujo did not share in the youthful pleasures of the daughters of the air. A soft melancholy seemed to brood over her, but she never wearied of working [Pg 70] for the good of others, and especially did she busy herself at her loom; indeed she came to be called the Weaving Princess.

The Sun bethought him, that if he could give his daughter in marriage, all would be well; her dormant love would be kindled into a flame that would illumine her whole being and drive out the pensive spirit which oppressed her. Now there lived, hard by, one Kingen, a right honest herdsman, who tended his cows on the borders of the Heavenly Stream. The Sun-King proposed to bestow his daughter on Kingen, thinking in this way to provide for her happiness and at the same time to keep her near him. Every star beamed approval, and there was joy in the heavens.

The love that bound Shokujo and Kingen to one another was a great love. With its awakening, Shokujo forsook her former occupations, nor did she any longer labour industriously at the loom, but laughed, and danced, and sang, and made merry from morn till night. The Sun-King was sorely grieved, for he had not foreseen so great a change. Anger [Pg 73] was in his eyes, and he said, “Kingen is surely the cause of this, therefore I will banish him to the other side of the River of Stars.”

The lovers were wont, standing on the banks of the celestial stream, to waft across it sweet and tender messages.

When Shokujo and Kingen heard that they were to be parted, and could thenceforth, in accordance with the King’s decree, meet but once a year, and that upon the seventh night of the seventh month, their hearts were heavy. The leave-taking between them was a sad one, and great tears stood in Shokujo’s eyes as she bade farewell to her lover-husband. In answer to the behest of the Sun-King, myriads of magpies flocked together, and, outspreading their wings, formed a bridge, on which Kingen crossed the River of Heaven. The moment that his foot touched the opposite bank, the birds dispersed with noisy chatter, leaving poor Kingen a solitary exile. He looked wistfully towards the weeping figure of Shokujo, who stood on the threshold of her now desolate home.

Long and weary were the succeeding days, spent as they were by Kingen in guiding his oxen and by Shokujo in plying her shuttle. [Pg 74] The Sun-King was gladdened by his daughter’s industry. When night fell and the heavens were bright with countless lights, the lovers were wont, standing on the banks of the celestial stream, to waft across it sweet and tender messages, while each uttered a prayer for the speedy coming of the wondrous night.

The long-hoped-for month and day drew nigh, and the hearts of the lovers were troubled lest rain should fall: for the Silver River, full at all times, is at that season often in flood, and the bird-bridge might be swept away.

The day broke cloudlessly bright. It waxed and waned, and one by one the lamps of heaven were lighted. At nightfall the magpies assembled, and Shokujo, quivering with delight, crossed the slender bridge and fell into the arms of her lover. Their transport of joy was as the joy of the parched flower, when the raindrop falls upon it; but the moment of parting soon came, and Shokujo sorrowfully retraced her steps.

Year follows year, and the lovers still meet in that far-off starry land on the seventh [Pg 75] night of the seventh month, save when rain has swelled the Silver River and rendered the crossing impossible. The hope of a permanent reunion still fills the hearts of the Star-Lovers, and is to them as a sweet fragrance and a beautiful vision.

FAR beyond the faint grey of the horizon, somewhere in the shadowy Unknown, lies the Island of Eternal Youth. The dwellers on the rocky coast of the East Sea of Japan relate that, at times, a wondrous tree can be discerned rising high above the waves. It is the tree which has stood for all ages on the loftiest peak of Fusan, the Mountain of Immortality. Men rejoice when they catch a glimpse of its branches, though the glimpse be fleeting as a vision at dawn. On the island is endless spring: the [Pg 80] air is ever sweet and the sky blue. Celestial dews fall softly upon every tree and flower, and carry with them the secret of eternity. The delicate white bryony never loses its first-day freshness, the scarlet lily cannot fade. Ethereal pink blossoms enfold the branches of the sakuranoki; the pendulous fruit of the orange bears no trace of age. Irises, violet and yellow and blue, fringe the pool on whose surface float the heavenly-coloured lotus blooms. From day to day the birds sing of love and joy. Sorrow and pain are unknown, death comes not hither. The Spirit of this island it is who whispers to the sleeping Spring in every land, and bids her arise.

Many brave seafarers have sought Horaizan but have not reached its shores. Some have suffered shipwreck in the attempt, others have mistaken the heights of Fuji-yama for the blessed Fusan.

Now there once lived a cruel Emperor of China. So tyrannical was he that the life of his physician, Jofuku, was in constant danger. One day, Jofuku spoke to the Emperor, and said: “Give me a ship, and I will sail to the [Pg 81] Island of Eternal Youth. There I will pluck the herb of immortality and bring it back to you, that you may rule over your kingdom for ever.” The despot heard the words with pleasure. Jofuku, fully equipped, set sail and came to Japan; thence he steered his course towards the magic tree. Days, months, and years passed. Jofuku seemed to be drifting on the ocean of heaven, for no land was visible. At last, far in the distance, rose the dim outline of a hill such as he had never seen before; and when he perceived a tree on its summit, Jofuku knew that he neared Horaizan. Soon he came to its shores, and landed as one in a dream. Every thought of the Emperor, whose days were to be prolonged by eating of the sacred herb, passed from his mind. Life upon the beautiful island was so glorious that he had no wish to return. His story is told by Wasobiowe, a wise man of Japan, who, alone among mortals, can relate the wonders of that strange land.

Wasobiowe dwelt in the neighbourhood of Nagasaki. He loved nothing better than to spend his days far out at sea, fishing from a [Pg 82] little boat. Once, when the eighth full moon rose—which in Japan is called the “bean moon” and is the most beautiful of all—Wasobiowe started on a long voyage in order to be absent from Nagasaki during the festivals of the season. Leisurely he skirted the coast, and rejoiced in the bold outlines of the rocks seen by the light of the moon. But, without warning, black clouds gathered overhead. The storm burst, the rain poured down, and darkness fell. The waves were lashed into fury, and the little boat was driven swift as an arrow before the wind. For three days and nights the hurricane raged. As dawn broke on the fourth morning, the wind was stilled, the sea grew calm. Wasobiowe, who knew the course of the stars, saw that he was far from his home in Japan. He was at the mercy of the god of the tides. For months Wasobiowe ate the fish which he caught in his net, until his boat drifted into those black waters where no fish can live. He rowed and rowed; his strength was almost spent. Hope had left him, when, suddenly, a fragrant wind from the land played [Pg 85] about his temples. He seized the oars, and soon his boat reached the coast of Horaizan. Even as he landed, all remembrance of the dangers and privations of the voyage vanished.

Everything spoke of joy and sunlight. The hum of the cicala, the whirr of the darting dragon-fly, the call of the bright-green tree-frog sounded in his ear. Sweet scents came from the pine-covered hills; everywhere was a flood of glowing colour.

Presently a man approached him. It was none other than Jofuku. He spoke to Wasobiowe, and told how the elect of the gods, who peopled those remote shores, filled their days with music and laughter and song.

Wasobiowe lived contentedly on the Island of Eternal Youth. He knew nothing of the flight of years, for where there is no birth, no death, time passes unheeded.

But, after many hundred years, the wise man of Nagasaki wearied of this blissful existence. He longed for death, but the dark river does not flow through Horaizan. He would wistfully follow the outward flight of the birds, [Pg 86] till they became mere specks in the sky. One day he spoke to a pure white stork: “I know that the birds alone can leave this island. Carry me, I pray you, to my home in Japan. I would see it once more and die.” Then he mounted upon the outstretched wings of the stork, and was carried across the sea and through many strange lands, peopled by giants and dwarfs and men with white faces. When he had visited all the countries of the earth, he came to his beloved Japan. In his hand he bore a branch of the orange which he planted. The tree still flourishes in the Mikado’s Empire.

AT the foot of the snowy mountain of Haku-san, in the province of Echizen, lived a peasant and his wife. They were very poor, for their little strip of barren mountain-land yielded but [Pg 90] one scanty crop a year, while their neighbours in the valley gathered two rich harvests. With unceasing patience, Bimbo worked from cock-crow until the barking of the foxes warned him that night had fallen. He laid out his plot of ground in terraces, surrounded them with dams, and diverted the course of the mountain stream that it might flood his fields. But when no rain came to swell the brook, Bimbo’s harvest failed. Often as he sat in his hut with his wife, after a long day of hard work, he would speak of their troubles. The peasants were filled with grief that a child had not been given to them. They longed to adopt a son, but, as they had barely enough for their own simple wants, the dream could not be realised.

An evil day came when the land of Echizen was parched. No rain fell. The brook was dried up. The young rice-sprouts withered. Bimbo sighed heavily over his work. He looked up to the sky and entreated the gods to take pity on him.

After many weeks of sunshine, the sky was overcast. Single clouds came up rapidly [Pg 91] from the west, and gathered in angry masses. A strange silence filled the air. Even the voice of the cicalas, who had chirped in the trees during the heat of the day, was stilled. Only the cry of the mountain hawk was audible. A murmur passed over valley and hill, a faint rustling of leaves, a whispering sigh in the needles of the fir. Fu-ten, the Storm-Spirit, and Rai-den, the Thunder-God, were abroad. Deeper and deeper sank the clouds under the weight of the thunder dragon. The rain came at first in large cool drops, then in torrents.

Bimbo rejoiced, and worked steadily to strengthen the dams and open the conduits of his farm.

A vivid flash of lightning, a mighty roar of thunder! Terrified, almost blinded, Bimbo fell on his knees. He thought that the claws of the thunder dragon were about him. But he was unharmed, and he offered thanks to Kwan-non, the Goddess of Pity, who protects mortals from the wrath of the Thunder-God. On the spot where the lightning struck the ground, lay a little rosy boy full of life, [Pg 92] who held out his arms and lisped. Bimbo was greatly amazed, and his heart was glad, for he knew that the gods had heard and answered his never-uttered prayer. The happy peasant took the child up, and carried him under his rice-straw coat to the hut. He called to his wife, “Rejoice, our wish is fulfilled. The gods have sent us a child. We will call him Rai-taro, the Son of the Thunder-God, and bring him up as our own.”

The good woman fondly tended the boy. Rai-taro loved his foster-parents, and grew up dutiful and obedient. He did not care to play with other children, but was always happy to work in the fields with Bimbo, where he would watch the flight of the birds, and listen to the sound of the wind. Long-before Bimbo could discern any sign of an approaching storm, Rai-taro knew that it was at hand. When it drew near, he fixed his eyes intently on the gathering clouds, he listened eagerly to the roll of the thunder, the rush of the rain, and he greeted each flash of lightning with a shout of joy.

Rai-taro had come as a ray of sunshine [Pg 95] into the lives of the poor peasants. Good fortune followed the farmer from the day that he carried the little boy home in his raincoat. The mountain stream was never dry. The land was fertile, and he gathered rich harvests of rice and abundant crops of millet. Year by year, his prosperity increased, until from Bimbo, ‘the poor,’ he became Kane-mochi, ‘the prosperous.’

About eighteen summers passed, and Rai-taro still lived with his foster-parents. Suddenly, they knew not why, he became thoughtful and sad. Nothing would rouse him. The peasants determined to hold a feast in honour of his birthday. They called together the neighbours, and there was much rejoicing. Bimbo told many tales of other days, and, finally, of how Rai-taro came to him out of the storm. As he ceased, a strange far-off look was in the eyes of the Son of the Thunder-God. He stood before his foster-parents, and said: “You have loved me well. You have been faithful and kind. But the time has come for me to leave you. Farewell.”

[Pg 96] In a moment Rai-taro was gone. A white cloud floated upward towards the heights of Haku-san. As it neared the summit of the mountain, it took the form of a white dragon. Higher still the dragon soared, until, at last, it vanished into a castle of clouds.

The peasants looked wistfully up to the sky. They hoped that Rai-taro might return, but he had joined his father, Rai-den, the Thunder-God, and was seen no more.

SAI-NO-KAWARA, the Dry Bed of the River of Souls. Far below the roots of the mountains, far below the bottom of the sea is the course of this river. Ages ago its current bore the souls of the blessed dead to the Land of Eternal Peace. The wicked oni were angry when they saw the good spirits pass out of their reach on the breast of the river. They muttered curses in their throats as the stream flowed on day by day, year by year. The snow-white soul of a [Pg 100] tender child came to the bank. A cup-shaped lotus bloom waited to carry the little one swiftly, through the dark cavernous region, to the kingdom of joy. The oni gnashed their teeth. The spirit of a kindly old man, whose heart was young, would thread his way unharmed, through the horde of demons, and float on the Heavenly-Bird-Boat to the unknown world. The oni looked on in wrath.

But the oni stemmed the River of Souls at its source, and now the spirits of the dead must wend their way, unaided, to the country that lies far beyond.

Jizo, The Never-Slumbering, is the god who guards the souls of little children. He is full of pity, his voice is gentle as the voice of the doves on Mount Hasa, his love is infinite as the waters of the sea. To him every child in the Land of the Gods calls for succour and protection.

In Sai-no-Kawara, The Dry Bed of the River of Souls, are the spirits of countless children. Babes of two and three years old, babes of four and five, children of eight and ten. Their wailing is pitiful to hear. They [Pg 101] cry for the mother who bore them. They cry for the father who cherished them. They cry for the brother and sister whom they love. Their cry is heard throughout Sai-no-Kawara, a cry that rises and falls, and falls and rises, rhythmic, unceasing. These are the words that they cry—

“Chichi koishi! haha koishi!——”

Their voices grow hoarse as they cry, and still they cry on—

“Chichi koishi! haha koishi!——”

While day lasts, they cry and they gather stones from the bed of the river, and heap them together as prayers.

A Tower of Prayer for the sweet mother, as they cry:

A Tower of Prayer for the father, as they cry:

A Tower of Prayer for brother and sister, as they cry:

From morning till evening they cry—

“Chichi koishi! haha koishi!——” and heap up the stones of prayer.

At nightfall come the oni, the demons, and say: “Why do you cry, why do you pray? Your parents in the Shaba-World cannot hear [Pg 102] you. Your prayers are lost in the strife of tongues. The lamentation of your parents on earth is the cause of all your sorrow.” So saying, the wicked oni cast down the Towers of Prayer, every one, and dash the stones into great caverns of the rocks.

But Jizo, with a great love in his eyes, comes and enfolds the little ones in his robe. To the babes who cannot walk, he stretches forth his shakujo. The children in Sai-no-Kawara gather round him, and he speaks sweet words of comfort. He lifts them in his arms and caresses them, for Jizo is father and mother to the little ones who dwell in the Dry Bed of the River of Souls.

Then they cease from their crying: they cease to build the Towers of Prayer. Night has come, and the souls of the children sleep peacefully, while The Never-Slumbering Jizo watches over them.

IT was early spring on the coast of Suruga. Tender green flushed the bamboo thickets. A rose-tinged cloud from heaven had fallen softly on the branches of the cherry tree. The pine forests were fragrant of the spring. Save for the lap of the sea, there was silence on that remote shore.

A far-off sound became audible: it might be [Pg 106] the song of falling waters, it might be the voice of the awakening wind, it might be the melody of the clouds. The strange sweet music rose and fell: the cadence was as the cadence of the sea. Slowly, imperceptibly, the music came nearer.

Above the lofty heights of Fuji-yama a snow-white cloud floated earthwards. Nearer and nearer came the music. A low clear voice could be heard chanting a lay that breathed of the peace and tranquillity of the moonlight. The fleecy cloud was borne towards the shore. For one moment it seemed to rest upon the sand, and then it melted away.

By the sea stood a glistening maiden. In her hand she carried a heart-shaped instrument, and, as her fingers touched the strings, she sang a heavenly song. She wore a robe of feathers, white and spotless as the breast of the wild swan. The maiden looked at the sea. Then she moved towards the belt of pine trees that fringed the shore. Birds flocked around her; they perched on her shoulder, and rubbed their soft heads against her cheek. [Pg 107] She stroked them gently and they flew away full of joy. The maiden hung her robe of feathers on a pine branch, and went to bathe in the sea.

It was mid-day. A fisher sat down among the pines to eat his dumpling. Suddenly, his eye fell on the dazzling white robe. “Perhaps it is a gift from the gods,” said Hairukoo as he went up to it. The robe was so fragile that he almost feared to touch it, but at last he took it down. The feathers were wondrously woven together, and slender curved wings sprang from above the shoulder. “I will take it home, and we shall be happy,” he thought.

Now the maiden came from the sea. Hairukoo heard no sound until she stood before him. Then a soft voice spoke: “The robe is mine, good fisher, pray give it to me.” The man stood awestruck, for never had he seen so lovely a being. She seemed to come from another world. He said, “What is your name, beautiful maiden, and whence do you come?” She answered, “I am one of the virgins who attend the moon. I come with a message of peace to the ocean. I have [Pg 108] whispered it into his ear, and now I must fly heavenward.” But Hairukoo replied, “I would see you dance before you leave me.” The moon-maiden answered: “Give me my feather robe, and I will dance a celestial dance.” The peasant refused. “Dance and I will give you your robe.” Then the glittering virgin was angry: “The wicked oni will take you for their own, if you doubt the word of a goddess. I cannot dance without my robe. Each feather has been given to me by the Heavenly Birds. Their love and trust support me.” As she thus spoke the fisher was ashamed, and said, “I have done wrong, and I ask your forgiveness.” Then he gave the robe into her hands. The moon-maiden put it around her.

And now she rose from the ground. She touched the stringed instrument and sang. Clear and infinitely sweet came the notes. It was her farewell to the earth and the sea. It ceased. She broke into a merry trilling song, and began to dance. At one moment she skimmed the surface of the sea, the next her tiny feet touched the topmost branches of [Pg 111] the tall pine trees. Then she sped past the fisher and smiled as the long grass rustled beneath her. She swept through the air, in and out among the trees, over the bamboo thicket, and under the branches of the blossoming cherry. Still the music went on. Still the maiden danced. Hairukoo looked on in wonder: he thought it must all be a beautiful dream.

At one moment she skimmed the surface of the sea, the next her tiny feet touched the topmost branches of the tall pine trees.

But now the music changed. It was no longer merry. The dance ended. The maiden sang of the moonlight, and of the quiet of evening.

She began to circle in the air. Slowly at first, then more swiftly, she floated over the woods towards the distant mountain. The music and the song rang in the ears of the fisher. The maiden was wafted farther and farther away. Hairukoo watched until he could no longer discern her snow-white form in the sky. But still the music reached him on the breeze. At last it too died away. The fisher was left alone: alone with the sound of the sea, and the fragrance of the pines.

THE cherry tree has blossomed many times since O-Matsue lived with her father and mother on the sandy coast of the Inland Sea. The home at Takasago was sheltered by a tall fir tree of great age; a god had planted it as he passed that way. O-Matsue was beautiful, for her mother had taught her to love the sea, and the birds, the trees, and every living thing. [Pg 116] Her eyes were like a clear deep ocean-pool on a summer day. Her smile was as the sunshine on the surface of Lake Biwa.

The fallen needles of the fir made a soft couch on which O-Matsue sat for hours at a time, plying her shuttle, weaving robes for the peasants around. Sometimes, she would go to sea with the fishers, and peer into the depths to try and catch a glimpse of the Palace of the Ocean Bed; the fishers would tell her the story of the poor jelly-fish who lost his shell, or of the Blessed Island of Eternal Youth, whose tree could at times be discerned from the coast.

The steep shore of Sumi-no-ye is many leagues distant from Takasago, but a youth who dwelt there took a long journey. Teoyo said, “I will see what lies beyond the mountains. I will see the country to which the heron wings his way across the plain.” He travelled through many provinces, and at last came to the land of Harima. One day he passed by Takasago. O-Matsue sat in the shade of the fir tree. She was weaving, and [Pg 117] sang as she worked. These are the words of her song:—

Teoyo heard the sweet song, and said, “It is like the song of a spirit,—and how beautiful the maiden is!” For some time he watched her as she wove. Then her song ceased, he moved towards her, and spoke: “I have travelled far. I have seen many fair maidens, but not one so fair as you. Take me to your father and mother that I may speak with them.” Teoyo asked the peasants for the hand of their daughter, and they gave their consent.

There was great rejoicing. O-Matsue received many presents, and, as the wedding-day approached, a great feast was prepared. Bride and bridegroom drank thrice of three cups of saké which made them man and wife, and the feast went on.

Now Teoyo said, “This country of Harima [Pg 118] is a good land. Let us stay here with your father and mother.” O-Matsue was glad. So they dwelt with the old people under the great fir tree. At last, the father and mother died. O-Matsue and Teoyo still lived beneath the shelter of the tree. They were very happy. Summer, autumn and winter passed over the land of Harima many times. Their love was always in its spring. The “waves of age” furrowed their brows, but their hearts remained young and tender, green as the needles of the pine. Even when their eyes had grown dim, they went to the shore to listen to the waters of the Inland Sea, or together they gathered, with rakes of bamboo, the fallen needles of the fir.

A crane came and built in the topmost branches of the tree, and for many years they watched the birds rear their young. A tortoise also dwelt beside them. O-Matsue said, “We are blessed with a fir tree, a crane, and a tortoise. The God of Long Life has taken us under his care.”

When, at last, at the same moment, Teoyo and O-Matsue died, their spirits withdrew into [Pg 119] the tree which had for so long been the witness of their happiness. To this day the pine tree is called “The Pine of the Lovers.”

On moonbright nights, when the coast wind whispers in the branches of the tree, O-Matsue and Teoyo may sometimes be seen, with bamboo rakes in their hands, gathering together the needles of the fir.

Despite the storms of time, the old tree stands to this hour eternally green on the high shore of Takasago.

NOT far from Matsue, the great city of the Province of the Gods, there once dwelt a widow and her son. Their wooden hut looked upon the Shinji Lake set in a framework of mountain peaks. Ayame was true to the old religion, the worship of the descendants of Izanagi and Izanami. Long ere the sun rose above the chain of hills, she was up, and, with Umewaki’s hand clasped closely in her own, went down to the verge of the lake. First they laved their faces in the cool water, then, [Pg 124] turning towards the east, they clapped their hands four times and saluted the sun. “Konnichi Sama! All hail to thee, Day-Maker. Shine and bring joy to the Place of the Issuing of Clouds.” Then, having turned towards the west, mother and son blessed the holy, immemorial shrine of Kitzuki; towards the north and the south they turned and prayed to the gods, unto each one, who dwell in the blue Plain of High Heaven.

Umewaki’s father had been dead many years, and the love of the mother was centred upon her son. He was in the open air from sunrise to nightfall; sometimes by Ayame’s side, sometimes alone, watching the heron or the crane, or listening to the sweet call of the yamabato. The hut was in a remote spot, but Ayame felt that her son was safe in the keeping of the good gods.

It was a beautiful summer morning. Ayame and Umewaki awakened soon after dawn. Hand in hand they went to the shore of Lake Shinji. It still slept beneath the faintly-tinged haze. The Lady of Fire had not whispered of her approach to the soft mists that veiled [Pg 125] the hills. Mother and son waited patiently. As the Day-Maker appeared, they cried, “Konnichi Sama! Great Goddess, shine upon thy land. Give it beauty and peace and joy.” Then mother and son returned to the hut. Ayame plied her shuttle, and Umewaki left her to wander in the woods.

Noon came. “My boy has met some woodcutter; he talks with him in the shade of the pine trees,” she thought. As the evening drew on, she said, “He is with little Kime, his playmate, but I shall soon hear his soft footstep.” Night fell. “Once only has he been so late; when he went to Matsue with the good Shijo.” She looked through the paper window, and then stepped out. The hills cast a mysterious shadow on the surface of the lake. Still there was no sign of Umewaki. The mother called his name. No response came save the echo of her own voice. Now she searched far and near. To every peasant she put the question, “Have you seen my Umewaki?” But she always received the same answer. At last she returned home weary: “He may be there waiting for me,” she thought. It [Pg 126] was midnight: the hut was empty. Ayame was heavy at heart, and as she lay upon her mat she wept bitterly, and cried to the gods to give her back her son. So the night passed. In the morning she learned that a band of robbers had been seen among the mountains.

Poor Umewaki had, in truth, been stolen by the robbers. He was watched night and day, and had no chance of escape. From town to town they travelled. Through strange villages where the name of Buddha was upon the lips of the people, across great plains unsheltered by mountains. The summer passed, and autumn came. Still the men would not let Umewaki go. They treated him cruelly, and he began to pine away. Then the robbers knew that he was of no use to them. As they neared Yedo, they left him, faint and weary, on the roadside. A kind man of Mukochima found the poor little fellow and carried him to his home. But Umewaki had not long to live. On the fifteenth day of the third month, the day sacred to the awakening of the Spring, he opened his eyes, and called to the good [Pg 127] woman who tended him, “Tell my dear mother that I love her, and would stay with her, but the Lady of the Great Light calls me, and I must obey.”

Ayame had left her quiet hut by the lake of Shinji to follow the men who had stolen her son. The autumn and the winter had gone by, and still she persevered. As she passed through Mukochima, she heard that a poor boy was dead, and soon found that it was her son. She went to the house where he had been cared for, and the woman gave her Umewaki’s message.

In the evening, when all was quiet, Ayame crept to the graveside of her child. Near it a sacred willow was planted. The slender tree moved in the wind. There was a whispered sound: the voice of Umewaki speaking softly to the mother from his place of rest. She was happy.

Every evening she came to listen to the sighing of the willow. Every evening she lay down happy to have spoken to her son.

On the fifteenth day of the third month, the day of the awakening of the Spring, many [Pg 128] pilgrims visit the resting-place of Umewaki. If it rains on that day, the people say, “Umewaki weeps.”

The willow is under the protection of the gods. Storm and rain can do it no hurt.

SAKATO-NO-TOKI-YUKI was a brave warrior at the court of Kyōto. He fought for the Minamoto against the Taira, but the Minamoto were defeated, and Sakato’s last days were spent as a wandering exile. He died of a broken heart. His widow, the daughter of a noble house, escaped from Kyōto, and fled eastward to the rugged Ashigara mountains. No one knew of her hiding-place, and she had no enemies [Pg 132] to fear save the wild beasts who lived in the forest. At night she found shelter in a rocky cave.

A son was born to her whom she named Kintaro, the Golden Boy. He was a sturdy little fellow, with ruddy cheeks and merry laughing eyes. Even as he lay crowing in his bed among the fern, the birds that alighted on his shoulder peeped trustfully into his eyes, and he smiled. Thus early the child and the birds were comrades. The butterfly and the downy moth would settle upon his breast, and tread softly over his little brown body.

Kintaro was not as other children—there was something strange about him. When he fell, he would laugh cheerily; if he wandered far into the wood, he could always find his way home; and, when little more than a chubby babe, he could swing a heavy axe in circles round his head. In the remote hills he had no human companions, but the animals were his constant playfellows. He was gentle and kind-hearted, and would not willingly hurt any living creature; therefore it was that the birds [Pg 133] and all the forest people looked upon Kintaro as one of themselves.

Among Kintaro’s truest friends were the bears who dwelt in the woods. A mother bear often carried him on her back to her home. The cubs ran out and greeted him joyfully, and they romped and played together for hours. They wrestled and strove in friendly rivalry. Sometimes Kintaro would clamber up the smooth-barked monkey tree, sit on the topmost branch, and laugh at the vain attempts of the shaggy little fellows to follow him. Then came supper-time and the feast of liquid honey.

But the Golden Boy loved best of all to fly through the air with his arms round the neck of a gentle-eyed stag. Soon after dawn, the deer came to awaken the sleeper, and, with a farewell kiss to his mother and a morning caress to the stag, Kintaro sprang on his back and was carried, with swift bounds, up mountain side, through valley and thicket, until the sun was high in the heavens. When they came to a leafy spot in the woods and heard the sound of falling water, the stag grazed [Pg 134] among the high fern while Kintaro bathed in the foaming torrent.

Thus mother and son lived securely in their home among the mountains. They saw no human being save the few woodcutters who penetrated thus far into the forest, and these simple peasants did not guess their noble birth. The mother was known as Yama-uba-San, “The Wild Nurse of the Mountain,” and her son as “Little Wonder.”

Kintaro reigned as prince of the forest, beloved of every living creature. When he held his court, the bear and the wolf, the fox and the badger, the marten and the squirrel, and many other courtiers were seated around him. The birds, too, flocked at his call. The eagle and the hawk flew down from the distant heights; the crane and the heron swept over the plain, and feathered friends without number thronged the branches of the cedars. He listened as they told of their joys and their sorrows, and spoke graciously to all, for Kintaro had learned the language and lore of the beasts, and the birds, and the flowers, from the Tengus, the wood-elves.

[Pg 137] The Tengus, who live in the rocky heights of the mountains and in the topmost branches of lofty trees, befriended Kintaro and became his teachers. As he was truthful and good, he had nothing to fear from them; but the Tengus are dreaded by deceitful boys, whose tongues they pull out by their roots and carry away.

These elves are strange beings: with the body of a man, the head of a hawk, long, long noses, and two powerful claws on their hairy hands and feet. They are hatched from eggs, and, in their youth, have feathers and wings: later, they moult and wear the garb of men. On their feet are stilt-like clogs about twelve inches high. They stalk proudly along with crossed arms, head thrown back, and long nose held high in the air; hence the proverb, “He has become a Tengu.”

The headquarters of the tribe are in the Ōyama mountain, where lives the Dai-Tengu, their leader, whom all obey. He is even more proud and overbearing than his followers, and his nose is so long that one of his ministers always precedes him that it may [Pg 138] not be injured. A long grey beard reaches to his girdle, and moustaches hang from his mouth to his chin. His sceptre is a fan of seven feathers, which he carries in his left hand. He rarely speaks, and is thus accounted wondrous wise. The Raven-Tengu is his chief minister; instead of a nose and mouth, he has a long beak. Over the left shoulder is slung an executioners axe, and in his hand he bears the book of Tengu wisdom.

The Tengus are fond of games, and their long noses are useful in many ways. They serve as swords for fencing, and as poles on the point of which to balance bowls of water with gold-fish. Two noses joined together form a tight-rope on which a young Tengu, sheltered by a paper umbrella and leading a little dog, dances and jumps through hoops; the while an old Tengu sings a dance-tune and another beats time with a fan. Some among the older Tengus are very wise. The most famous of all is he who dwells on the Kurama mountain, but hardly less wise is the Tengu who undertook the education of [Pg 139] Kintaro. At nightfall he carried the boy to the nest in the high rocks. Here he was taught the wisdom of the elves, and the speech of all the forest tribes.

One day, Little Wonder was at play with some young Tengus, but they grew tired and flew up to their nest, leaving Kintaro alone. He was angry with them, and shook the tree with all his strength, so that the nest fell to the ground. The mother soon returned, and was in great distress at the loss of her children. Kintaro’s kind heart was touched, and, with the little ones in his arms, he swarmed up the tree and asked pardon. Happily they were unhurt, and soon recovered from their fright. Kintaro helped to rebuild the nest, and brought presents to his playfellows.

Now it happened that, as the hero Raiko, who had fought so bravely against the oni, passed through the forest, he came upon Little Wonder wrestling with a powerful bear. An admiring circle of friends stood around. Raiko, as he looked, was amazed at the strength and courage of the boy. The combat over, he asked Kintaro his name and his story, but [Pg 140] the child could only lead him to his mother. When she learned that the man before her was indeed Raiko, the mighty warrior, she told him of her flight from Kyōto, of the birth of Kintaro, and of their secluded life among the mountains. Raiko wished to take the boy away and train him in arms, but Kintaro loved the forest. When, however, his mother spoke, he was ready to obey. He called together his friends, the beasts and the birds, and, in words that are remembered to this day, bade them all farewell.

The mother would not follow her son to the land of men, but Kintaro, when he became a great hero, often came to see her in the home of his childhood.

The peasants of the Ashigara still tell of The Wild Nurse of the Mountains and Little Wonder.

WHEN the five tall pine trees on the windy heights of Mionoseki were but tiny shoots, there lived in the Kingdom of the Islands a pious man. His home was in a remote hamlet surrounded by mountains and great forests of pine. Tsunu had a wife and sons and daughters. He was a woodman, and his days were spent in [Pg 144] the forest and on the hillsides. In summer he was up at cock-crow, and worked patiently, in the soft light under the pines, until nightfall. Then, with his burden of logs and branches, he went slowly homeward. After the evening meal, he would tell some old story or legend. Tsunu was never weary of relating the wondrous tales of the Land of the Gods. Best of all he loved to speak of Fuji-yama, the mountain that stood so near his home.