*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 46917 ***

THE

POEM-BOOK OF THE GAEL

[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

at Paul's Work, Edinburgh

[Pg iv]

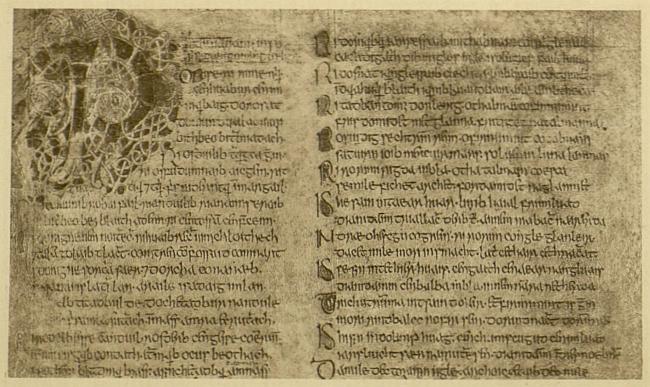

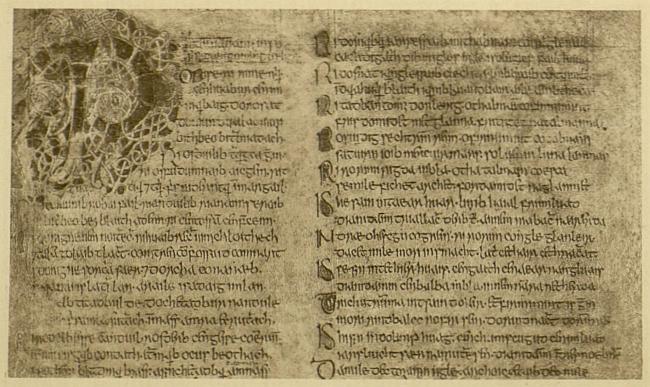

Opening passage of the "Saltair na Rann."

Opening passage of the "Saltair na Rann."

from the MS. in the Bodleian Library.

[Pg v]

THE POEM-BOOK OF

THE GAEL

Translations from Irish Gaelic Poetry into

English Prose and Verse

SELECTED AND EDITED BY

ELEANOR HULL

AUTHOR OF "THE CUCHULLIN SAGA IN IRISH LITERATURE,"

"A TEXT-BOOK OF IRISH LITERATURE," ETC.

WITH A FRONTISPIECE

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1913

[Pg vi]

A NEW IMPRESSION

All rights reserved

[Pg vii]

(Where not otherwise indicated, the translation or

poetic setting is by the author.)

| PAGE |

| |

Introduction

|

XV

|

THE SALTAIR NA RANN, OR PSALTER

OF THE VERSES

|

| I. |

The Creation of the Universe |

3 |

| II. |

The Heavenly Kingdom |

11 |

| III. |

The Forbidden Fruit |

20 |

| IV. |

The Fall and Expulsion from Paradise |

22 |

| V. |

The Penance of Adam and Eve |

31 |

VI.

|

The Death of Adam

|

43

|

ANCIENT PAGAN POEMS

|

The Source of Poetic Inspiration (founded on translation

by Whitley Stokes) |

53 |

Amorgen's Song (founded on translation by John

MacNeill) |

57 |

| [Pg viii]

The Song of Childbirth |

59 |

| Greeting to the New-born Babe |

61 |

| What is Love? |

62 |

| Summons to Cuchulain |

63 |

| Laegh's Description of Fairy-land |

65 |

| The Lamentation of Fand when she is about to

leave Cuchulain |

69 |

| Mider's Call to Fairy-land |

71 |

| The Song of the Fairies A. H. Leahy |

73 |

The great Lamentation of Deirdre for the Sons of Usna

|

74

|

OSSIANIC POETRY

|

| First Winter-Song Alfred Percival Graves |

81 |

| Second Winter-Song |

82 |

| In Praise of May T. W. Rolleston |

83 |

| The Isle of Arran |

85 |

| The Parting of Goll from his Wife |

87 |

| Youth and Age |

91 |

| Chill Winter |

92 |

| The Sleep-song of Grainne over Dermuid |

94 |

| The Slaying of Conbeg |

97 |

| The Fairies' Lullaby |

98 |

Song of the Forest Trees Standish Hayes O'Grady

|

99

|

[Pg ix]

EARLY CHRISTIAN POEMS

|

| St. Patrick's Breastplate Kuno Meyer |

105 |

| Patrick's Blessing on Munster Alfred Perceval Graves |

107 |

| Columcille's Farewell to Aran Douglas Hyde |

109 |

| St. Columba in Iona Eugene O'Curry |

111 |

| Hymn to the Dawn |

113 |

| The Song of Manchan the Hermit |

117 |

| A Prayer |

119 |

| The Loves of Liadan and Curithir |

121 |

| The Lay of Prince Marvan |

125 |

| The Song of Crede, daughter of Guare Alfred Perceval Graves |

130 |

| The Student and his Cat Robin Flower |

132 |

| The Song of the Seven Archangels Ernest Rhys |

134 |

| The Féilire of Adamnan P. J. McCall |

136 |

| The Feathered Hermit |

138 |

| An Aphorism |

138 |

| The Blackbird |

139 |

| Deus Meus George Sigerson |

140 |

| The Soul's Desire |

142 |

| Tempest on the Sea Robin Flower |

144 |

| The Old Woman of Beare |

147 |

| Gormliath's Lament for Nial Black-knee |

151 |

| [Pg x]

The Mother's Lament at the Slaughter of the Innocents Alfred Perceval Graves |

153 |

| Consecration |

156 |

| Teach me, O Trinity |

157 |

| The Shaving of Murdoch Standish Hayes O'Grady |

159 |

Eileen Aroon

|

161

|

POEMS OF THE DARK DAYS

|

| The Downfall of the Gael Sir Samuel Ferguson |

165 |

| Address to Brian O'Rourke "of the Bulwarks" to arouse him against the English |

169 |

| O'Hussey's Ode to the Maguire James Clarence Mangan |

172 |

| A Lament for the Princes of Tyrone and Tyrconnell James Clarence Mangan |

176 |

| The County of Mayo George Fox |

182 |

| The Outlaw of Loch Lene Jeremiah Joseph Callanan |

184 |

| The Flower of Nut-brown Maids |

186 |

| Roisín Dubh |

188 |

| My Dark Rosaleen James Clarence Mangan |

190 |

| The Fair Hills of Eire George Sigerson |

194 |

| Shule Aroon (Traditional) |

196 |

| Love's Despair George Sigerson |

198 |

| The Cruiskeen Lawn George Sigerson |

200 |

| [Pg xi]

Eamonn an Chnuic, or "Ned of the Hill" P. H. Pearse |

202 |

| O Druimin donn dilish |

204 |

| Do you Remember that Night? Eugene O'Curry |

206 |

| The Exile's Song |

208 |

| The Fisherman's Keen (Anonymous) |

210 |

| Boatman's Hymn Sir Samuel Ferguson |

213 |

| Dirge on the Death of Art O'Leary |

215 |

The Midnight Court (Prologue)

|

224

|

RELIGIOUS POEMS OF THE PEOPLE

|

| Hymn to the Virgin Mary |

229 |

| Christmas Hymn Douglas Hyde |

231 |

| O Mary of Graces Douglas Hyde |

232 |

| The Cattle-shed |

233 |

| Hail to Thee, O Mary |

234 |

| O Mary, O blessed Mother |

235 |

| I rest with Thee, O Jesus |

236 |

| Thanksgiving after Food |

236 |

| The Sacred Trinity |

237 |

| O King of the Wounds |

237 |

| Prayer before going to Sleep |

238 |

| I lie down with God |

239 |

| The White Paternoster |

240 |

| [Pg xii]

Another Version |

241 |

| A Night Prayer |

243 |

| Mary's Vision |

243 |

| The Safe-guarding of my Soul be Thine |

244 |

| Another Version |

244 |

| The Straying Sheep |

246 |

| Before Communion |

246 |

| May the sweet Name of Jesus |

247 |

| O Blessed Jesus |

248 |

| Another Version |

248 |

| Morning Wish |

249 |

| On Covering the Fire for the Night |

249 |

| The Man who Stands Stiff Douglas Hyde |

250 |

| Charm against Enemies Lady Wilde |

252 |

| Charm for a Pain in the Side Lady Wilde |

252 |

| Charm against Sorrow Lady Wilde |

253 |

The Keening of Mary P. H. Pearse

|

254

|

LOVE-SONGS AND POPULAR POETRY

|

| Cushla ma Chree Edward Walsh |

259 |

| The Blackthorn |

260 |

| Pastheen Finn Sir Samuel Ferguson |

263 |

| She |

265 |

| Hopeless Love |

266 |

| The Girl I Love Jeremiah Joseph Callanan |

267 |

| [Pg xiii]

Would God I were Katharine Tynan-Hinkson |

268 |

| Branch of the Sweet and Early Rose William Drennan |

269 |

| Is truagh gan mise I Sasana Thomas MacDonagh |

270 |

| The Yellow Bittern Thomas MacDonagh |

271 |

| Have you been at Carrack? Edward Walsh |

273 |

| Cashel of Munster Sir Samuel Ferguson |

275 |

| The Snowy-breasted Pearl George Petrie |

277 |

| The Dark Maid of the Valley P. J. McCall |

279 |

| The Coolun Sir Samuel Ferguson |

281 |

| Ceann dubh dhileas Sir Samuel Ferguson |

283 |

| Ringleted Youth of my Love Douglas Hyde |

284 |

| I shall not Die for You Padraic Colum |

286 |

| Donall Oge |

288 |

| The Grief of a Girl's Heart |

291 |

| Death the Comrade |

294 |

| Muirneen of the Fair Hair Robin Flower |

296 |

| The Red Man's Wife Douglas Hyde |

298 |

| Another Version |

299 |

| My Grief on the Sea Douglas Hyde |

302 |

| Oró Mhór, a Mhóirín P. J. McCall |

304 |

| The little Yellow Road Seosamh Mac Cathmhaoil |

306 |

| Reproach to the Pipe |

308 |

| Lament of Morian Shehone for Miss Mary Bourke (Anonymous) |

311 |

| [Pg xiv]

Modereen Rue Katherine Tynan-Hinkson |

314 |

| The Stars Stand Up |

316 |

| The Love-smart |

318 |

| Well for Thee |

319 |

| I am Raftery Douglas Hyde |

320 |

| Dust hath Closed Helen's Eye Lady Gregory |

321 |

| The Shining Posy |

324 |

| Love is a Mortal Disease |

326 |

| I am Watching my Young Calves Sucking |

328 |

| The Narrow Road |

329 |

| Forsaken |

332 |

I Follow a Star Seosamh Mac Cathmhaoil

|

334

|

LULLABIES AND WORKING SONGS

|

| Nurse's Song (Traditional) |

337 |

| A Sleep Song P. H. Pearse |

339 |

| The Cradle of Gold Alfred Perceval Graves |

340 |

| Rural Song |

341 |

| Ploughing Song |

342 |

A Spinning-wheel Ditty

|

344

|

NOTES

|

349

|

[Pg xv]

"An air is more lasting than the voice of the birds,

A word is more lasting than the riches of the world."

The truth of this Irish proverb strikes us forcibly as we

glance through any such collection of Gaelic poetry as this,

and consider how these lays, the dates of whose composition

extend from the eighth to the present century, have

been preserved to us.

On the border of some grave manuscript, such as a Latin

copy of St. Paul's Epistles or a transcript of Priscian, a stray

quatrain may be found jotted down by the tired scribe,

recording in impromptu verse his delight at the note of a

blackbird whose song has penetrated his cell, his amusement

at the gambols of his cat watching a mouse, or his

reflections on a piece of news brought to him by some

wandering monk, about the terror of the viking raids, or a

change of dynasty "at home in Ireland."

Several of our Ossianic poems are taken from a manuscript

of lays collected in 1626-27 in and about the Glens

of Antrim, and sent out to while away the tedium of

camp life to an Irish officer serving in the Low Countries,

who wearied for the poems and stories of his youth. The

religious hymns of Murdoch O'Daly (Muredach Albanach),

called "the Scot" on account of his affection for

his adopted country, though he was born in Connaught,

[Pg xvi]

are preserved in a collection of poems gathered in the

Western Highlands, many Irish poems, even from so

great a distance as Munster, being found in it.

The Saltair na Rann or "Psalter of the Verses," the

most important religious poem of ancient Ireland, is

preserved in one copy only. It seems as though a

miracle had sometimes intervened to guard for later

generations some single version of a valuable tract at

home or abroad; but it is a miracle which we could

have wished to have taken place more often, when we

reflect upon the large number of manuscripts forever lost

to us.

Many of the most beautiful of the ancient poems, as

well as of the popular songs, are anonymous; they are

frequently found mixed up with material of the most

arid description, genealogies, annals, or miscellaneous

matter. It is easier to guess from the tone of the poems

under what mood of mind they were composed than to

tell exactly who wrote them. Even when they come

down to us adorned with the name of some well-known

saint or poet, we have an uncertain feeling about the

accuracy of the ascription, when we find a poem whose

language cannot be earlier than the tenth or eleventh

century confidently connected with a writer who lived

two or three centuries earlier. In some cases, no doubt,

the versions we possess, though modernised in language

and rhythm, are in reality old; in others the ascription

probably bears witness to the desire of the author or his

public to win esteem for his work by adorning it with

some famous name. Some of these poems, of which only

one copy has come down to us, were, however, well

known in an earlier day, and are quoted in old tracts on

Irish metric as examples of the metres used in the bardic

[Pg xvii]

schools. It is evident that though standards of taste

may change, the recognition of what is really beautiful

in poetry remains as a settled instinct in man's nature.

Many of those poems which now appeal most strongly

to ourselves took rank as verses of acknowledged merit

nearer to the time of their composition. This we can

deduce from their use as examples worthy of imitation

in these mediæval Irish text-books, where the names of

songs we still admire are quoted as specimens of good

poetry.

It is remarkable that a very large proportion of fine

poetry comes to us from the period of the Norse invasions,

a time which we are accustomed to think of as one continuous

series of wars, raids, and burnings; but which,

if we may judge by what has come down to us of its verse,

shows us that the Irish gentleman of that day had ideas

of refinement that raise him far above the mere fighting

clansman; his critical view of literature was a severe one.

The fine freedom shown in many of these poems is surprising,

both as regards the sentiments and the metres.

They possess a mastery of form that argues a high cultivation,

not only of the special art of poetry, but of the

whole intellectual faculties of the writers.

Some of these poems are strangely modern, even fin

de siècle in their tone. The poem of the "Old Woman

of Beare" has often been compared to Villon's "Regrets

de la Belle Heaulmière ja parvenue à viellesse," or to

Béranger's "Grand'mère." But the Irish poem is far

more artistically wrought than either of these comparatively

modern poems. For in the ancient verses, the old

woman is set, a lonely and forsaken figure, against the

background of the ebbing tide, and the slow throbs of

her heart, worn with age and sin, beat in unison with the

[Pg xviii]

retreating motion of the wave. There is also a further

significance in the poem which we must not miss. It is

the earliest of the long series of allegorical songs in which

Ireland is depicted under the form of a woman; though,

unlike her successors of a later day, she is here represented,

not as a fair maiden, a Grainne Mhaol, or Kathleen ni

Houlahan, or Little Mary Cuillenan, but as an aged joyless

hag, forlorn and censorious, bemoaning the loss of

bygone pleasures, and the gravity of her nun's veil. The

"Cailleach Bheara," the "Hag" or "Nun of Beare" is

known in many place-names in Ireland. It is on Slieve

na Callighe, or the "Hill of the Hag" or "Nun," in

Co. Meath that the great cairns and tumuli of Lough

Crew are found; it was evidently, like the neighbourhood

of the Boyne, a place of pagan sanctity; and such

names as Tober na Callighe Bheara, the "Well of the Hag

of Beare," are found in different parts of the country.

The "Hag of Beare" seems to be symbolic of pagan

Ireland, regretting the stricter regime of Christianity,

and the changes that time had brought about. The

curious legend which prefaces the poem suggests the

same idea. She is said to have seen seven periods of

youth, and to have outlived tribes and races descended

from her. For a hundred years of old age she wore the

veil of a nun. "Thereupon old age and infirmity came

upon her." We catch the same note of regret for the

days of paganism through many legends and poems. It

is mystical and veiled in such stories as that of "King

Murtough and the Witch-woman"; it is fierce, but also

often touched by the grotesque, in the innumerable

colloquies between Patrick and Oisín (Ossian), the last

of the ancient pagan heroes. But in all this there is a

note of apology. It is not so outspoken in its revolt

[Pg xix]

against the new system of life and thought as are the

Norse chronicles and the Icelandic Sagas. After all,

Christianity was an accomplished thing; quietly but

persistently it took its place, sweeping into its fold chiefs

and common folk alike. No resistance could stop this

universal progress. And the literary man or the peasant,

dwelling on his early legends, the outcome of a state of

thought passed or passing away, dared only half-heartedly

bemoan the former days, when wars and raids, the

"Creach" and the "Táin" were the highest way of

life for a brave man, and no Christian doctrine of forgiveness

of enemies and charity to foes had come in to perplex

his thoughts and confuse their issues. The Raid remained,

it was an essential part of actual life; and

burnings and wars went on as before, but they were

no longer, theoretically, at least, matters to win praise

and honour, they were condemned beforehand by the

Christian ethic. A chief, to hold his own, must still

throw open doors of hospitality to his tribe, must dispense

largesse to all-comers, must gather about his board the

neighbours and dependents in riotous assemblies and

festivals. But all this the Christian monk and priest

looked upon with suspicion; they bade him fill his

thoughts with a future Kingdom, rather than with the

earthly one to which he had been born, and to keep his

soul in humble readiness by prayers and fastings, by

seclusion and self-sacrifice. The great disjointure is

everywhere apparent; chiefs are seen flying from their

plain duties to their clans in order to win a heavenly

chiefdom, not of this world; kings retire into hermitages,

and whole villages take on the aspect and system of life

of the monastery. To escape a network of religious

service so closely spread throughout the country was

[Pg xx]

impossible; all that the half-convinced could do was to

relieve his soul in legend and song and jest. Hence the

large amount of this literature of protest, coming to us

curiously side by side with poems breathing the very

spirit of religious devotion, the work of peaceful recluse

or retired monk.

For the movement had its other aspect. If the warrior

or chief resigned much in becoming a Christian monk,

there is no doubt that he gained as well. Contemporaneous

religious poetry in the Middle Ages is elsewhere

overshadowed by the cast of theologic thought. The

"world" from which the saint must flee is no mere

symbol, denoting the perils of evil courses; it is the actual

visible earth, its hills and trees and flowers, and the beauty

of its human inhabitants that are in themselves a danger

and a snare. St. Bernard walking round the Lake of

Geneva, unconscious of its presence and blind to its

loveliness, is a fit symbol of the tendency of the religious

mind in the Middle Ages. Sin and repentance, the fall

and redemption, hell and heaven, occupied the religious

man's every thought; beside such weighty themes the

outward life became almost negligible. If he dared to

turn his mind towards it at all, it was in order to extract

from it some warning of peril, or some allegory of things

divine. In essence, the "world" was nothing else than a

peril to be renounced and if possible entirely abandoned.

But the Irish monk showed no such inclination,

suffered no such terrors. His joy in nature grew with his

loving association with her moods. He refused to mingle

the idea of evil with what God had made so good. If he

sought for symbols, he found only symbols of purity and

holiness. The pool beside his hut, the rill that flowed

across his green, became to his watchful eye the

[Pg xxi]

manifestation of a divine spirit washing away sin; if the birds

sang sweetly above his door, they were the choristers of

God; if the wild beasts gathered to their nightly tryst,

were they not the congregation of intelligent beings

whom God Himself would most desire? The friendly

badgers or foxes of the wood that came forth, undismayed

by the white or brown-robed figure who seemed to have

taken up his lasting abode amongst them, became to

his mind fellow-monks, authorised members of his

strange community. Amongst his feathered and furred

associates, he read his Psalms and Hours in peace; sang

his periodic hymn to St. Hilary or St. Brigit, and performed

his innumerable genuflexions and "cross-vigils."

Here, from time to time, he poured forth in spontaneous

song his joy in the life that he had elected as his own.

When King Guaire of Connaught stands at the door of

the hermitage in which his brother Marvan had taken

refuge from the bustle of court life, and asks him why he

had sacrificed so much, Marvan bursts forth into a poem

in praise of his hermit life, and the King is fain to confess

that the choice of the recluse was the wiser one;

when St. Cellach of Killala is dragged into the forest

by his comrades and threatened with death, not even the

sight of the four murderers lying at his feet with swords

ready drawn in their hands to slay him can prevent him

from greeting the Dawn in a beautiful song.

The saint who, like St. Finan, lived shut up within

his cell, in many cases lost his mental balance, and degenerated

into a mere Fakir, winning heaven by the

miseries of his self-imposed mortifications; but the

monk who trusted himself to untrammelled intercourse

with nature, preserved his underlying sanity. For

whether or no the hundreds of daily genuflexions were

[Pg xxii]

performed, the patch of ground around the solitary's

cell must be ploughed or sown or reaped; the apples

must be gathered or the honeysuckles twined. The

salmon or herring must be netted or angled for. Thus

nature and its needs kept the hermit on the straight and

simple paths of physical and mental healthfulness, however

he might try to escape into a wilderness of his own

imaginings.

The early poetry, we feel, is on the whole joyous;

whether pagan or Christian in tone, it arises from a happy

heart. The pagan is more robust, more vigorous; the

Christian gentler and more reflective; but alike they are

free from the mournful note of despair that throws a

settled gloom over much of the later literature.

The Ossianic poems have quite a distinctive tone;

in them we catch the abounding energy belonging to the

days of the hunt of the wild native boar or stag, when all

the country was one open hunting-ground, fit for men

whose ideal was that of the sportsman and the warrior.

Besides romantic tales, we have a whole body of poetry,

loosely strung together under the covering name of

Oisín, or Ossian, and usually ascribed to him or to

Fionn mac Cumhall, his father and chief, dealing with the

themes of war and of the chase. They are often in the

nature of the protest of the fighting and hunting-man

against the claims of religion. He is perpetually proclaiming

that the sounds and sights of the forest and seashore

are more dear to him than any others, and when he is

called upon to give the first place to the duties of religion,

placed before him, as it usually is, in its most enfeebling

aspect, he raises the stout protest that the hunting-horn

has greater attractions for him than the tinkling

bell which calls to prayer.

[Pg xxiii]

"I have heard music sweeter far

Than hymns and psalms of clerics are;

The blackbird's pipe on Letterlea,

The Dord Finn's wailing melody.

"The thrush's song of Glenna-Scál,

The hound's deep bay at twilight's fall,

The barque's sharp grating on the shore,

Than cleric's chants delight me more."

There is the ring of the obstinate pagan about such

verses; and many poems are wholly occupied by an unholy

wrangling between the representative of the old

order, Oisín, and the representative of the new, St.

Patrick. The poems themselves probably date from a

far later period than either.

More healthy are the true hunting songs. Many of

these are in praise of the Isle of Arran, in the Clyde, a

favourite resort during the sporting-season both for the

Scottish and Irish huntsman. In the poem we have

called "The Isle of Arran," from the "Colloquy of the

Ancient Men," the charm of the Isle is well described.

We have in it the same pure joy in natural scenery that

we find in the poems of the religious hermits, but the

tone is manlier and more emphatic.

Occasionally a fiercer note creeps into the hunter's

mood. The chase of the boar and deer was not without

its dangers. Winter, and the unfriendly clan hard by,

or the lean prowling wolf at night, were real terrors to

the small companies encamped on the open hill-side or

in the forest. Though the warrior in peaceful times

loved the chase of swine and stag, his hand had done and

was always ready to do sterner work when opportunity

offered. The poem "Chill Winter" has a note of almost

[Pg xxiv]

savage exultation; the old fighter turns from his present

perils and discomforts to remember the warrior onslaughts

which had left the glen below him silent, and its

once happy inhabitants cold in death; colder, as he

gladly reflects, than even he himself feels on this chill

winter's night. It is the voice of the ancient warrior,

who thought no shame of slaying, but thanked God when

he had knocked down his fellow. Whether he, in his

turn, were the undermost man, or whether he escaped,

he cared not at all.

Two difficulties face the modern reader in coming for

the first time upon genuine Irish literature, whether

poetry or prose. The first is the curious feeling that we

are hung between two worlds, the seen and the unseen;

that we are not quite among actualities, or rather that we

do not know where the actual begins or where it ends.

Even in dealing with history we may find ourselves

suddenly wafted away into some illusory spirit-world with

which the historian seems to deal with the same sober

exactness as in detailing any fact of ordinary life. The

faculty of discerning between the actual and the imaginary

is absent, as it is absent in imaginative children;

often, indeed, the illusory quite overpowers the real, as

it does in the life of the Irish peasant to-day.

There is, in most literatures, a meeting-place where the

Mythological and the Historic stand in close conjunction,

the one dying out as the other takes its place. Only in

Ireland we never seem to reach this point; we can never

anywhere say, "Here ends legend, here begins history."

In all Irish writing we find poetry and fact, dreams and

realities, exact detail and wild imagination, linked closely

hand in hand. This is the Gael as revealed in his literature.

At first we are inclined to doubt the accuracy of

[Pg xxv]

any part of the story; but, as we continue our examination,

we are surprised at the substantial correctness of the

ancient records, so far as we are able to test them, whether

on the historical or on the social side. The poet is never

wholly poet, he is also practical man; and the historian

is never wholly chronicler and annalist, he is also at the

back of his mind folklorist, lover of nature, dreamer. It

is the puzzle and the charm of Ireland.

A good example of this is the very beautiful anonymous

Irish poem, rich in poetic imagery, addressed to Ragnall

or Reginald, son of Somerled, lord of the Isles from 1164-1204.

This poem, written for an historical prince,

begins with a description of the joys of the fairy palace,

"Emain of the Apples," whence this favoured prince is

supposed by the poet to have issued forth:

"Many, in white grass-fresh Emain,

Of men on whom a noble eye gazes

(The rider of a bay steed impetuously)

Through a countenance of foxglove hue,

Shapely, branch-fresh.

"Many, in Emain of the pastures,

From which its noble feast has not parted,

Are the fields ploughed in autumn

For the pure corn of the Lord's Body."

The poet's mind wanders from the ancient Emain,

capital of Ulster, to the allegorical Emain, the dwelling

of the gods or fairy-hosts, who were thought of as inhabiting

the great tumuli on the Boyne; again, he transplants

his fairy-land to the home of Ragnall, and seems

to place it in Mull or the Isle of Man, which was indeed

the especial abode of Manannan, the Ocean-god and

Ruler of Fairy-land.

[Pg xxvi]

"What God from Brugh of the Boyne,

Thou son of noble Sabia,

Thou beauteous apple-rod

Created thee with her in secret?

"O Man of the white steed,

O Man of the black swan,

Of the fierce band and the gentle sorrow,

Of the sharp blade and the lasting fame.

"Thy fair side thou hast bathed,

The grey branch of thy eyes like summer showers,

Over thy locks, O descendant of Fergus,

The wind of Paradise has breathed."[1]

We recognise that this is fine poetry, but we feel also

that it needs a specialised education thoroughly to understand

it. The world from which it hails is not our world,

and to comprehend it we must do more than translate, we

must add notes and glossary at every line; but no poetry,

especially poetry under the initial disadvantage of a translation,

could retain its qualities under such treatment.

In all the ancient verse we meet with these obstacles.

Even much of the most imaginative Ossianic poetry becomes

too difficult from this point of view for the

untrained reader.

Take the fine poem detailing the history of the Shield

of Fionn. Poetic addresses to noted weapons are common

enough, and are not confined to Irish literature;

but the adventures of this shield pass beyond the ordinary

uses of human battles, and enter the realm of mythology.

The very name given to it, the "Dripping Ancient

Hazel," carries us into a world of poetic imagination.

[Pg xxvii]

"Scarce is there on the firm earth, whether it be man or

woman, one that can tell why thy name abroad

is known as the Dripping Ancient Hazel.

"'Twas Balor that besought Lugh before his beheading:

'Set my head above thy own comely head and

earn my blessing.'

"That blessing Lugh Longarm did not earn; he set up

the head above a wave of the east in a fork of hazel

before him.

"A poisonous milk drips down out of that hardened

tree; through the baneful drip, it was not slight,

the tree split right in two.

"For full fifty years the hazel stood, but ever it was a

cause of tears, the abode of vultures and ravens.

"Manannan of the round eye went into the wilderness

of the Mount of White-Hazel; there he saw a

shadeless tree among the trees that vied in beauty.

"Manannan sets workmen without delay to dig it out of

the firm earth. Mighty was the deed!

"From the root of that tree arises a poisonous vapour;

there were killed by it (perilous the consequence)

nine of the working folk.

"Now I say to you, and let the prophecy be sought out:

Around the mighty hazel without reproach was

found the cause of many a woe."

"It was from that shield that Eitheor of the smooth

brown face was called 'Son of Hazel,'—for this was

the hazel that he worshipped."[2]

[Pg xxviii]

Or take again the strange mythological poem of the

"Crane-bag," made out of the skin of a wandering

haunted crane, which had once been a woman; condemned

for "two hundred white years" to dwell in "the house

of Manannan," i.e. in the wastes of the ocean, ever seeking

and never finding land. When the wanderings came to

an end, and the unhappy Crane-woman died, Manannan

(the Ocean-god) made of her skin a bag into which he put

"every precious thing he had; the shirt of Manannan

and his knife, the girdle of Goibniu (the Vulcan of Irish

legend); the king of Scotland's shears, the king of Lochlann's

helmet, and the bones of the swine of Asal—these

were the treasures that the Crane-bag held.... When

the sea was full, its treasures were seen in its midst;

when the fierce sea was on ebb, the Crane-bag was

empty." The story has the impress of great age, and

manifold changes; it belongs to the period when the

gods were not yet transformed into human beings, but

were still primæval elemental powers, impersonations of

fire and light and water, and the wisdom that is above

mankind. But the link is lost, and the story remains a

suggestion only, vague and indistinct. As an image of

the hollow ocean, holding the treasures of the Sea-god,

the idea is, however, full of force and beauty.[3]

The second difficulty, which is closely connected with

the first, lies in the retention of the ancient and unfamiliar

nomenclature; the old geographical and family

names, which have dropped out of actual use, being

everywhere found in the poetry.

Scotland is still Alba in Irish, as it was in the sixth

century; Éire (gen. Érinn) is the ordinary name for

Ireland, not only in poetry, as is commonly supposed, but

in the living language of the country. But it has besides

an abundance of specially poetic names, such as Inisfail,

"the island of Destiny," Banba, Fodla, &c., connected

with early legends, and these, if we are to understand

the poetry, we must accustom ourselves to.

[Pg xxix]

England is still to-day the land of the Saxons to the Gael, and

its inhabitants are the "Sassenachs"; the Irishman persists

in disregarding the coming of the Angles. We

may talk of the extinction of the Gaelic tongue, but in

his poetry, as in every place-name of stream or hill or

townland all over the country, it is about us still. In the

poetry we are back in Gaelic Ireland; the old tribal distinctions,

the old clan names, meet us on every page.

What does the modern man know of Leth Cuinn or Leth

Mogha, the ancient divisions of the North and South,

or of the stories which gave them birth? What of

Magh Breagh or Magh Murtheimne? What of Emain

Macha and Kincora? Who, again, are the Clann Fiachrach

or the Eoghanacht, or the Children of Ir or Eiber?

Even before the much later titles of Thomond and

Desmond, of Tyrconnell and Tyrowen he is somewhat

at a loss.

But to the bard the past is always present, the ancient

nomenclature is never extinct. The legend which caused

the River Boyne to be called "The forearm of Nuada's

wife," or the tumuli on its banks to be thought of as the

"Elfmounds of the wife of Nechtan," are familiar to him;

and to enter into the spirit of the mythological poetry

we must know something of Irish folklore and tradition.

Many of these expressions have a high imaginative significance,

as when the sea is called the "Plain of Ler" (the

elder Irish Sea-god), or its waves are "the tresses of

Manannan's wife" or the "Steeds of Manannan."

Of the large body of bardic poetry we have been unable

to give an adequate representation, partly from

considerations of space, but also because we are not yet,

until a larger quantity of this poetry has been published,

able to estimate its actual poetic value. Much fine poetry

[Pg xxx]

by the historic bards undoubtedly exists, but we have as

yet only a few published fragments to choose from. The

first specimen we give, Teigue Dall O'Higgin's appeal to

O'Rourke of the Bulwarks (na murtha), must stand as an

example of much similar poetry in and about his own day.

The call to union against England or against some local

enemy sounds loud and constant in the bardic poems.

There is much anti-English poetry; poetry which has for

its object the endeavour to unite for a single purpose the

chiefs who had split up the provinces into small divisions

under separate leaders, each fighting for his own hand.

To stir up the lagging or too peaceful chief was one of

the prime duties of the bard; to address to him congratulations

on his accession, or to bewail him when he

died, was his official function; and to judge by the quantity

of paper covered with these laudatory effusions and

elegies, he performed his task with punctilious care. It

was likely that he would do so, for the fees for a poem

that gave satisfaction were substantial. We miss the

family bard in these days; there is no one at hand to praise

indifferently all that we do.

The bardic poetry attracted the genius of Mangan,

and his "Farewell to Patrick Sarsfield" and O'Hussey's

"Ode to the Maguire," are not only fine poetry, but

excellent representations of two of the finest of the bardic

poems. Elsewhere in his poems, we have usually too

much Mangan to feel that the tone of the original is

faithfully conveyed. His soaring poem, "The Dark

Rosaleen," can hardly be said to represent the Irish

"Roisín Dubh," of which, for purposes of comparison, we

give a literal rendering; beautiful as Mangan's poem is,

it has to our mind lost something of the exquisite grace

of the original.

[Pg xxxi]

It may be well to indicate here the relations between

Mangan's version and the original in the poem in which

he keeps most strictly to the words of the bard. "O'Hussey's

Ode to the Maguire," that fine address of the

Northern bard, O'Hussey, to his young chief, whose warlike

foray into Munster in the depth of winter filled his

mind with anxiety and distress. A literal translation of

the opening passage reads as follows:

"Too cold for Hugh I deem this night, the drops so

heavily downpouring are a cause for sadness;

biting is this night's cold—woe is me that such is

our companion's lot.

In the clouds' bosoms the water-gates of heaven are

flung wide; small pools are turned by it to seas,

all its destructiveness hath the firmament spewed

out.

A pain to me that Hugh Maguire to-night lies in a

stranger's land, 'neath lurid glow of lightning-bolts

and angry armed clouds' clamour;

A woe to us that in the province of Clann Daire (Southwest

Munster) our well-beloved is couched, betwixt

a coarse cold-wet and grass-clad ditch and the

impetuous fury of the heavens."[4]

But it is not, after all, the verses of the bards, even of

the best of them, that will survive. It is the tender religious

songs, the passionate love-songs, the exquisite addresses

to nature; those poems which touch in us the common

ground of deep human feeling. Whether it came to us

from the sixth century or from the sixteenth, the song

of Crede for the dead man, whom she had grown to love

only when he was dying, would equally move us; the

passionate cry of Liadan after Curithir would wring our

hearts whatever century produced it. The voice of love

is alike in every age. It has no date.

[Pg xxxii]

Having written so far, we begin to wonder whether it

was wise or necessary to set so much prose between the

reader and the poems which, as we hope, he wishes to

read. In an ordinary anthology, the interruption of a

long preface is a mistake and an intrusion, for, more

than any other good art, good poetry must explain itself.

The mood in which a poem touches us acutely may be

recorded, but it cannot be reproduced in or for the

reader. He must find his own moment. For the most

part, these Irish poems need no introduction. We need

no one to explain to us the beauty of the lines in the

"Flower of Nut-brown Maids":

"I saw her coming towards me o'er the face of the mountain,

Like a star glimmering through the mist";

or to remind us of the depth of Cuchulain's sorrow when

over the dead body of his son he called aloud:

"The end is come, indeed, for me;

I am a man without son, without wife;

I am the father who slew his own child;

I am a broken, rudderless bark

Tossed from wave to wave in the tempest wild;

An apple blown loose from the garden-wall,

I am over-ripe, and about to fall;"

or to tell us that the "Blackthorn," or "Donall Oge," or

"Eileen Aroon," are exquisite in their pathos and tenderness.

But there are, besides these enchanting things,

which we are prepared to expect from Irish verse, also

[Pg xxxiii]

things for which we are not prepared; unfamiliar themes,

treated in a new manner; and to judge of these, some

help from outside may be useful. The reader who does

not know Ireland or know Gaelic, is ready to accept

softness, the almost endless iteration of expressions conveying

the sense of woman's beauty and of man's affection,

in phrases that differ but little from each other; what he

is not prepared for is the sudden break into matter-of-fact,

the curt tone that cuts across much Irish poetry, revealing

an unexpected side of life and character. Even the

modern Irishman is tripped up by the swift intrusion of

the grotesque; the cold, cynical note that exists side

by side with the most fervent religious devotion, especially

in the popular poetry, displeases him. He resents

it, as he resents the tone of the "Playboy of the Western

World"; yet it is the direct modern representative of

the tone of mind that produced the Ossianic lays.

We find it in all the popular poetry; as an example take

the argument of the old woman who warns a young

man that if he persists in his evil ways, there will be no

place in heaven for such as he. The youth replies:

"If no sinner ever goes to Paradise,

But only he who is blessed, there will be wide empty places in it.

If all who follow my way are condemned

Hell must have been full twenty years and a year ago,

And they could not take me in for want of space."

The same chill, almost harsh tone is heard in the

colloquy between Ailill of Munster and the woman

whom he has trysted on the night after his death,[5] or in

the poem, "I shall not die for you" (p. 286), or in the

verses on the fairy-hosts, published by Dr. Kuno Meyer,

where, instead of praise of their ethereal loveliness, we

are told:

[Pg xxxiv]

"Good are they at man-slaying,

Melodious in the ale-house,

Masterly at making songs,

Skilled at playing chess."[6]

Could anything be more matter-of-fact than the clever

chess-playing of the shee-folk and their pride in it?

A collection of translations must always have some

sense of disproportion. It is natural that translators

should, as a rule, have been attracted, not only to the

poems that most readily give themselves to an English

translation, but to those which are most easily accessible.

The love-songs, such as those collected by Hardiman and

Dr. Douglas Hyde, have been attempted with more or

less success by many translators, while much good poetry,

not so easily brought to hand, has been overlooked.

Dr. Kuno Meyer's fine translations of a number of older

pieces, which came out originally either in separate

publications,[7] or in the transactions of the Arts Faculty

of University College, Liverpool, have now been rendered

more accessible in a separate collection; but the English

ear is wedded to rhyme, and a prose translation, however

careful and choice, often misses its mark with the

general reader. Long ago, Miss Brooke (in her Reliques

of Irish Poetry) and Furlong (in Hardiman's Irish

Minstrelsy) essayed the translation of a number of the

longer "bardic remains"; and these earlier collectors and

translators will ever retain the gratitude of their countrymen

for rescuing and printing, at a time when little value

was placed upon such things, these stores of Irish song.

[Pg xxxv]

But the translations suited better the taste of their own

day than of ours; we cannot read them now, nor do they

in the slightest way represent the verse they are intended

to reproduce. Naturally, too, it is easier to give the

spirit and language of a serious poem than that of a humorous

one in another tongue, so that the more playful

verse has been neglected.

It may be thought that this book is overweighted

by religious and love poems; but in a collection essentially

lyrical, religion and love must ever be the two

chief themes. In Ireland, the inner spirit of the national

genius ever spoke, and still speaks, through them.

Among the people of the quiet places where few

strangers come, and where night passes into day and

day again to night with little change of thought or outward

emotion, simple sorrows and simple pleasures have

still time to ripen into poetry. The grief that came

to-day will not pass away with a new grief to-morrow;

it will impress its groove, straight and deep, upon the

heart that feels it, lying there without hope of a summer

growth to hide its furrow. The long monotonous days,

the dark unbroken evenings are the nurseries of sorrow;

the white open roads are the highways of hope or the

paths for the wayfaring thoughts of despair. The

stranger who came one day comes again no more, though

we watch the long white track never so earnestly; the

boy or girl who went that way to foreign lands has not

thrown his or her shadow across the road again. Where

the turf fire rises curling and blue into the air, where the

young girl stands waiting by the winding "boreen,"

where the old woman croons over the hearth, there we

[Pg xxxvi]

shall surely find, if we know how to draw it forth, that

a well of poetry has been sunk, and that half-unconsciously

the thought of the heart has expressed itself in

simple verse, or in rhythmic prose almost more beautiful

than verse. The minds that produced the touching

melodies that wail and croon and sing to us out of Ireland,

have not the less expressed themselves in melodious

poetry. Here, if anywhere, we may look to find a style

unspoiled by imitation, and a sentiment moving because

it is perfectly sincere. It is thus that such poems as

"Donall Oge" or the "Roísin Dubh" or "My Grief

on the Sea" come into existence.

Where the outward distractions of life are few, the

grave monotony of sea and moor and bog-land, the

swirl of cloud and mist, and the loneliness of waste places

sink more deeply into the mind. The visible is less felt

than the invisible, and life is surrounded by a network

of fears and dreams to which the town-dweller is a

stranger. To-day, in the Western Isles of Ireland and

Scotland, the huntsman going out to hunt, the fisherman

to fish or lay his nets, the agriculturist to sow or reap

his harvest, and the weaver or spinner to wind his yarn,

go forth to their work with some familiar charm-prayer

or charm-hymn, often beautifully called "the Blessings,"

on their lips. The milkmaid calling her cows or churning

her butter, the young girl fearful of the evil-eye, and the

cottager sweeping up her hearth in the evening, laying

herself down to sleep at night, or rising up in the morning,

soothe their fears or smooth their way by some

whispered paider or ortha, a prayer or a verse or a blessing.

The deep religious feeling of the Celtic mind, with its

far-stretching hands groping towards the mysterious and

the infinite, comes out in these spontaneous and simple

[Pg xxxvii]

ejaculations; I have therefore endeavoured to bring

together a few others to add to the groups gathered by

Dr. Hyde in the west of Ireland and by Dr. Carmichael

in the Western Hebrides; but in their original Gaelic

they are the fruit of others' collections, not of my own.[8]

They are the thoughts of such humble people as the poor

farm-servant who "had so many things to do from dark

to dark" that she had no time for long prayers, and knew

only a little prayer taught her by her mother, which laid

"our caring and our keeping and our saving on the

Sacred Trinity."

I desire to inscribe here my sincere gratitude to the

living authors and authoresses who have kindly given

me permission to use their work, and my gratitude to

those authors who have gone, that they have left us so

much good work to use. Especially I desire to thank

my friends, Mr. Alfred Perceval Graves and Mr. Ernest

Rhys, for permitting the use of unpublished poems.

Many friends have given a ready helping hand in

elucidating difficult words and phrases, and it is a pleasant

task to thank them here. Dr. D. Hyde, Rev. Michael

Sheehan, Rev. P. S. Dinneen, Mr. Tadhg O'Donoghue,

Mr. R. Flower, Miss Hayes, especially, have always

readily come to my assistance; to Miss Eleanor Knott

I am indebted for valuable help in the translation of

the "Saltair na Rann," and to Dr. R. Thurneysen for

suggesting some readings in this difficult poem.

I gratefully acknowledge permission accorded to me

by the following publishing houses to include poems or

extracts from books published by them:—

[Pg xxxviii]

Messrs. Constable & Co., Ancient Irish Poetry, by

Professor Kuno Meyer. T. Fisher Unwin, Bards of the

Gael and Gall, by Dr. George Sigerson, F.N.U.I.

Maunsel & Co., Irish Poems, by Alfred Perceval Graves;

Sea-Spray, by T. W. Rolleston; The Gilly of Christ, by

Seosamh mac Cathmhaoil. David Nutt, Heroic Romances

of Ireland, by A. H. Leahy. Herbert & Daniel, Eyes of

Youth, for a poem by Padraic Colum. Sealy, Bryers and

Walker, Lays of the Western Gael, by Sir Samuel Ferguson;

Irish Nóinins, by P. J. McCall. H. M. Gill & Son,

Irish Fireside Songs and Pulse of the Bards, by P. J.

McCall. Williams & Norgate, Silva Gadelica, by Standish

Hayes O'Grady. Chatto & Windus, Legends, Charms,

and Cures of Ireland, by Lady Wilde.

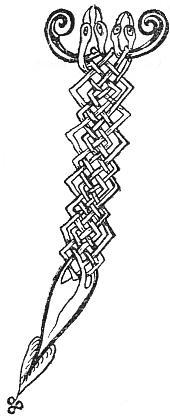

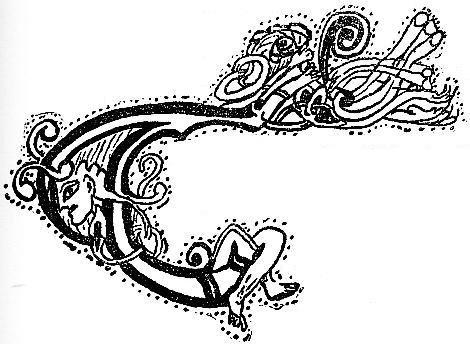

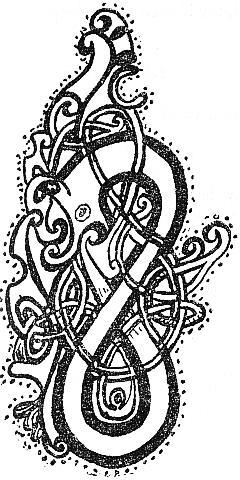

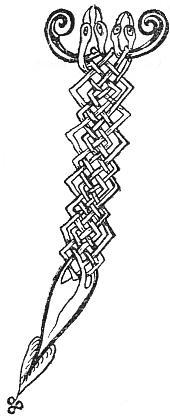

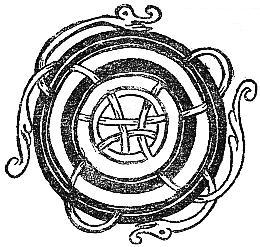

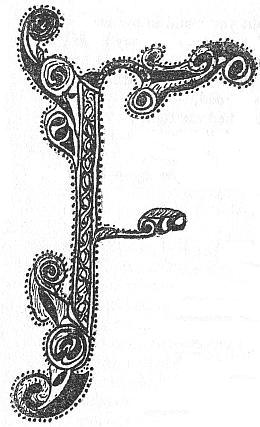

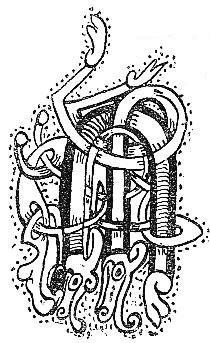

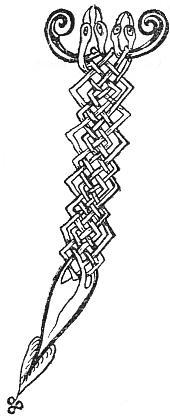

I also desire to acknowledge the courtesy of His

Majesty's Stationery Department in permitting the use

of drawings taken from initial letters in Sir John T.

Gilbert's Facsimiles of Irish National MSS. Others of

the initial letters used in the book are drawn from the

Book of Lindisfarne and other Celtic manuscripts in the

British Museum. I have to thank the Librarian of the

Bodleian Library for permitting the reproduction of

the photograph of the initial lines from the "Saltair na

Rann" as a frontispiece to the book.

[Pg 1]

THE SALTAIR NA RANN, OR PSALTER

OF THE VERSES

[Pg 2]

The Saltair na Rann, or Psalter of the Verses, so-called because

it is divided into 150 poems in imitation of the Psalms of David, is

undoubtedly the most important religious poem of early Ireland.

It may justly be regarded as the Irish Paradise Lost and Paradise

Regained, for it opens with an account of the Creation of the

Universe, the founding of Heaven and Hell, the fall of Lucifer,

the creation of the Earthly Paradise and of man, the temptation

and fall and the penance of Adam and Eve. After this it sketches

the Old Testament History, leading up to the birth and life of

Christ and closing with His death and resurrection. Though in

general it follows the Bible narrative, it is peculiarly Irish in tone,

and its additions and variations are of the greatest interest to

students of mediæval religious literature. The conception of the

universe in the first poem, with its ideas of the seven heavens,

the coloured and fettered winds, and the sun passing through the

opening windows of the twelve divisions of the heavens, is curious;

the earth, enclosed in the surrounding firmament, "like a shell

around an egg," being regarded as the centre of the universe.

In the portions which relate the life of Adam and Eve, the

author evidently had before him the Latin version of the widely

known Vita Adae et Euae, which he follows closely, introducing

from it several Latin words into his text; but even here the colouring

is purely Irish. The poem is ascribed to Oengus the Culdee,

who lived early in the ninth century; but its language is later,

probably the end of the tenth century.

In 1883 Dr. Whitley Stokes published[9] the text from the only

existing complete copy, that contained in the Bodleian MS. Rawl.

B. 502, but no part of it has hitherto been published in English.

The present translation of the sections dealing with the Creation and

with the life of Adam and Eve is purely tentative; the poem

presents great difficulties, and we suffer from the lack of a second

copy with which to compare it.[10] Miss Eleanor Knott has read

the translations and has helped me with many difficulties; and I

had the advantage of reading parts of the poem in class with

Dr. Kuno Meyer. For the errors which the translation must

undoubtedly contain, I am myself, however, alone responsible.

[Pg 3]

Attributed to Oengus the Culdee, ninth century; but the

date is probably the close of the tenth century.

I. THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE

y own King, King of the pure heavens,

without pride, without contention,

who didst create the folded[11] world,

my King ever-living, ever victorious.

King above the elements, surpassing the sun,

King above the ocean depths,

King in the South and North, in the West and East,

with whom no contention can be made.

King of the Mysteries, who wast and art,

before the elements, before the ages,

King yet eternal, comely His aspect,

King without beginning, without end.

[Pg 4]

King who created lustrous heaven,

who is not arrogant, not overweening,

and the earth, with its multitudinous delights,

strong, powerful, stable.

King who didst make the noble brightness,

and the darkness, with its gloom;

the one, the perfect day,

the other, the very perfect night.

King who fashioned the vast deeps

out of the primary stuff of the elements,

who ...

the wondrous formless mass.

King who formed out of it each element,

who confirmed them without restriction, a lovely mystery,

both tempestuous and serene,

both animate and inanimate.

King who hewed, gloriously, with energy,

out of the very shapely primal stuff,

the heavy, round earth,

with foundations, ... length and breadth.[12]

King who shaped within no narrow limits

in the circle of the firmament

the globe, fashioned

like a goodly apple, truly round.

[Pg 5]

King who formed after that with fixity

the fresh masses about the earth;

the very smooth currents above the world

of the chill watery air.

King who didst sift the cold excellent water

on the earth-mass of the noble cliffs

into rills, with the reservoirs[13] of the streams,

according to their measures, with moderation.

Creation of the winds with their colours

King who ordained the eight winds

advancing without uncertainty, full of beauty,

the four prime winds He holds back,

the four fierce under-winds.

There are four other under-winds,

as learned authors say,

this should be the number, without any error,

of the winds, twelve winds.

King who fashioned the colours of the winds,

who fixed them in safe courses,

after their manner, in well-ordered disposition,

with the varieties of each manifold hue.

The white, the clear purple,

the blue, the very strong green,

the yellow, the red, sure the knowledge,

in their gentle meetings wrath did not seize them.

[Pg 6]

The black, the grey, the speckled,

the dark and the deep brown,

the dun, darksome hues,

they are not light, easily controlled.

King who ordained them over every void,

the eight wild under-winds;

who laid down without defect

the bounds of the four prime winds.

From the East, the smiling purple,

from the South, the pure white, wondrous,

from the North, the black blustering moaning wind,

from the West, the babbling dun breeze.

The red, and the yellow along with it,

both white and purple;

the green, the blue, it is brave,

both dun and the pure white.

The grey, the dark brown, hateful their harshness,

both dun and deep black;

the dark, the speckled easterly wind

both black and purple.

Rightly ordered their form,

their disposition was ordained;

with wise adjustments,[14] openly,

according to their position and their fixed places.

[Pg 7]

The twelve winds,

Easterly and Westerly, Northerly and Southerly,

the King who adjusted them, He holds them back,

He fettered them with seven curbs.

King who bestowed them according to their posts,

around the world with many adjustments,

each two winds of them about a separate curb,

and one curb for the whole of them.

King who arranged them in habitual harmony,

according to their ways, without over-passing their limits;

at one time, peaceful was the space,

at another time, tempestuous.

Measurements of the Universe

King who didst make clear the measure of the slope[15]

from the earth to the firmament,

estimating it, clear the amount,

along with the thickness of the earth-mass.

He set the course of the seven Stars[16]

from the firmament to the earth,

Saturn, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars,

Sol, Venus, the very great moon.

[Pg 8]

King who numbered, kingly the space,

from the earth to the moon;

twenty-six miles with a hundred miles,

they measure them in full amount.

This is that cold air

circulating in its aerial series(?)

which is called ... with certainty

the pleasant, delightful heaven.

The distance from the moon to the sun

King who measured clearly, with absolute certainty,

two hundred miles, great the sway,

with twelve and forty miles.

This is that upper ethereal region,

without breeze, without greatly moving air,[17]

which is called, without incoherence,

the heaven of the wondrous ether.

Three times as much, the difference is not clear(?)

between the firmament and the sun,

He has given to calculators;[18]

my King star-mighty! most true is this!

This is the perfect Olympus,

motionless, immovable,

(according to the opinion of the ancient sages)

which is called the Third Holy Heaven.

[Pg 9]

Twelve miles, bright boundary,

with ten times five hundred miles,

splendid the star-run course, separately

from the firmament to the earth.

The measure of the space

from the earth to the firmament,

it is the measure of the difference

from the firmament to heaven.

Twenty-four miles

with thirty hundred miles

is the distance to heaven,

besides the firmament.

The measure of the whole space

from the earth to the Kingly abode,

is equal to that from the rigid earth

down to the depths of hell.

King of each Sovereign lord, vehement, ardent,

who of His own force set going the firmament

as it seemed secure to Him over every space,

He shaped them from the formless mass.

The poem goes on to speak of the division of the

universe into five zones, a torrid, two temperate, and

two frigid zones, and of the earth revolving in the centre

of the universe, with the firmament about it, "like a shell

encircling an egg." The passage of the sun through the

constellations is then described, each of the twelve

divisions through which it passes being provided with

six windows, with close-fitting shutters, and strong

[Pg 10]

coverings, which open to shed light by day. The constellations

are then named, and the first section of the

poem ends as follows:—

For each day five items of knowledge

are required of every intelligent person,

from every one, without appearance of censure,[19]

who is in ecclesiastical orders.

The day of the solar month, the age of the moon,

the sea-tide, without error,

the day of the week, the festivals of the perfect saints,

after just clearness, with their variations.

[Pg 11]

II. THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM

l. 337

King who formed the pure Heaven,

with its boundaries, according to His pleasure,

a habitation choice, songful, safe,

for the wondrous host of Archangels.

Heaven with its multitude of hosts,

noble, durable, exceeding spacious,

a strong mighty city with a hundred graces,

a tenth of it the measure of the world.

Therein are three ramparts undecaying,

fixedly they surround heaven,

a rampart of emerald crystal,

a rampart of gold, a rampart of amethyst.[20]

A wall of emerald, without obscurity, outside,

a wall of gold next to the city,

between the two, with bright fair glory,

a mighty rampart of stainless purple.

[Pg 12]

There, with a strong-flowing sea (?)

is a spacious, perfect city,

in it, with the light of peace,[21]

is the eternal way of the four chief doors.

The measure of each door severally

of the four chief doorways,

(placed) side by side, by calculation,

is a mile across each single door.

In each doorway a cross of gold

before the eyes of the ever-shining host;

the King wrought them without effort,

they are massive, very lofty.

Overhead, on each cross, a bird of red gold,

full-voiced, not unsteady;

in every cross

a great gem of precious stone.

Every day an archangel

with his host from Heaven's king,

with harmony, with pure melody,

(gather) around each several cross.

Before each doorway is a lawn,

fair ..., of sure estimation,

I liken each one of them in extent[22]

to the earth together with its seas.

[Pg 13]

The circuit of each single lawn

with its silvern soil,[23]

with its swards, covered with goodly blossom,

with its beauteous plants.

Vast though you may deem

the extent of the spacious lawns,

a rampart of silver, undecaying,

has been formed about each several lawn.

The portals of the walls without

around the fortress on every side,

with its dwellings soundly placed,

affording abodes (?) for many thousands.

Eight portals in a series

so that they come together around the city,

I have not, in the way of knowledge,[24]

a simile for the extent of each portico.

Each portal abounding in plants,

with their bronze foundations,

a rampart of fair clay has been established

strongly about each portal.

Twelve ramparts—perfect the boundary (?)

of the portals, of the lawns,

without counting the three ramparts that are outside

around the chief city.

[Pg 14]

There are forty gateways in the heavenly habitation

with its kingly thrones;

three to each tranquil lawn,

and three to each portal.

Gratings (or doors) of silver, fair in aspect,

to each gateway of that lawn,

gracious bronze doors

to the gateways of the portals.

The corresponding walls from the fortress outwards

of all the portals

are comparable in height[25]

(to the distance) from the earth to the moon.

The ramparts of the lawns, as is meet,

wrought of white bronze,

their height—mighty in brilliance—

is as that from the earth to the pure sun.

The measure of comparison of the three ramparts

which surround the chief city,

their height shows (a distance equal

to that) from the earth to the firmament.

The entrance bridges[26] of the perfect gates,

a fair way, shining with red gold,

they are irradiated—pure the gathering—

each step ascending above the other.

[Pg 15]

From step to step—brave the progress,

pleasant the ascent into the high city;

fair is that host, on the path of attainment (?)

many thousands, a hundred of hundreds.

In the circuit of the ramparts—great its strength (?)—

in the interior of the chief city,

bright glossy galleries,

firm red-gold bridges.

Therein are flowering lands

ever fresh in all seasons,

with the produce of each well-loved fruit

with their thousand fragrances.

The nine grades of heaven,

around the King of all causation,

without loss of glory, with vigour of strength,

without pride, without envy.

In abundant profusion (?) under the lawful King

this their exact number,

seventy-two excellent hosts

in each grade of the grades.

The number of each host, unmeasured gladness,

there is none that could know it,

except the King should know it

who created them out of nothing.

A majestic King over them all,

King of flowery heaven,

a goodly, righteous, steadfast King,

King of royal generosity in His regal dwelling.

[Pg 16]

King very youthful, King aged long ago,[27]

King who fashioned the heavens about the pure sun,

King of all the gracious saints,

a King gentle, comely, shapely.

The King who created the pure heavenly house

for the angels without transgression,

land of holy ones, of the sons of life,[28]

a plain fair, long, spacious.

He arranged a noble, peaceful[29] abode,

stable, under the regal courses,

a comely, clear, perfect, bright circuit,

for the wondrous folk of penitence.

My King from the beginning over the host,

"sanctus Dominus Sabaoth,"

to whom is chanted upon the heights, with loving guidance, (?)

the melody of the four-and-twenty white-robed saints.

The King who ordained the perfect choir

of the four-and-twenty holy ones,

sweetly they chant the chant to the host

"sanctus Deus Sabaoth."

[Pg 17]

King steadfast, bountiful, goodly, noble,

abode of peace, ... (?)

with whom is the flock of lambs

around the Pure Spotless Lamb.

Bright King, who appointed the Lamb

to move forward upon the Mount (of Sion)[30]

four thousand youths following Him,

(with) a hundred and forty (thousand) in a pure progress,

A perfect choir, with glories of form,

of the stainless virgins,

chants pure music along with them

following after the shining Lamb.

Equal in beauty, in swiftness, in brightness,

across the Mount surrounding the Lamb;

the name inscribed on their countenances, with grace,

is the name of the Father.

The King who ordained the voice

of the heavenly ones by inspiration,

full, strong-swelling,

as the mighty wave of many waters;

Or like the voice of sound-loving harps

they sing, without fault, full tenderly,

(like) multitudinous great floods over every land,

or like the mighty sound of thunder.[31]

[Pg 18]

King of the flowering tree of life,

a way for the ranks of the noble grades;

its top, its droppings, on every side,

have spread across the broad plain of heaven.

On which sits the splendid bird-flock

sustaining a perfect melody of pure grace,

without decay, with gracious increase

of fruit or of foliage.

Beauteous the bird-flock which sustains it, (i.e. the melody)

each choice bird with a hundred wings;

they chant without guile, in bright joyousness,

a hundred melodies for every wing.

King who created many splendid dwellings,[32]

many comely, just, perfect works,

through (the care of) my rich King,[33] over every sphere,

no lack is felt by any of the vast array.

His are the seven heavens, perfect in might,

without prohibition, without evil, whitely moving

around the earth, great the wonder (?)

with the names of each heaven.

Air, ether, over all

Olympus, the firmament,

heaven of water, heaven of the perfect angels,

the heaven where is the fair-splendid Lord.

The amount of good which our dear God,

has for His saints in their holy dwelling,

according to the skill of the wise(?)

there is none who can relate a hundredth part of it.

The Lord, the head of each pure grade,

who gathered (?) the host to everlasting life,

may He save me after my going out of the body of battles,

the King who formed Heaven.

King who formed the pure Heaven.

[Pg 20]

III. THE FORBIDDEN FRUIT. (vii.)

rince who gave a clear admonition to Eve and to Adam,

that they should eat of the produce of Paradise

according to God's command:

"Eat ye of them freely,

of the fruits of Paradise—sweet the fragrance—

many, all of them (a festival to be shared)[34]

are lawful for you save one tree.

"In order that you may know that you are under authority,

without sorrow, without strife,

without anxiety, without long labour,

without age, evil, or blemish;

"Without decay, without heavy sickness;

with everlasting life, in everlasting triumph

on your going to heaven (joyous the festival)

at the choice age of thirty years."

[Pg 21]

A thousand years

and six hours of the hours,

without guile, without danger, it has been heard,

Adam was in Paradise.[35]

O God our help, whom champions prove,

who fashioned all with perfect justice,

not bright the matter of our theme (?)[36]

the King who spake an admonition with them.

Prince who gave a clear admonition.

(The figures in brackets after the title of the chapters

are the numbers of the poems or cantos in the text.)

[Pg 22]

IV. THE FALL AND EXPULSION FROM

PARADISE. (viii.)

The Devil was jealous thereat

with Adam and his children,

their being here, without evil,

in their perfect bodies (on their passage) to heaven.

All the living creatures in the flesh

my Holy King has created them,

outside Paradise without strife

Adam it is who used to order them.

At the time when out of every quarter

the hosts of the seven heavens used to gather round my High King,

every fair corporeal creature

used to come together to Adam.

Each of them out of this place cheerfully,[37]

at his call to adore him;

to Adam, joyous the custom,

they used to come to delight him.

[Pg 23]

From heaven God ruled

all the living things

that they should come out of every district without fierceness[38]

till they arrived before (the gate of) Paradise.

Then they would return right-hand-wise

without seed of pride or any murmuring,

each of them to its very pure abode

after taking leave of Adam.

The very fierce, double-headed beast,

was subtle and watchful, with (his) twenty hosts,

how under heaven he shall find a way

to bring about the destruction of Adam.

Lucifer, many his clear questions,[39]

went amongst the animals,

amongst the herds outside Paradise

until he found the serpent.

"Is it not useless (i.e. unworthy of you) thy being outside?"

said the Devil to the serpent;

"with thy dexterous cunning,

with thy cleverness, with thy subtlety?

"Great was the danger and the wickedness

that Adam should have been ordained over thee;

the downfall[40] of him, the youngest of created things,

and his destruction, would be no crime to us.

[Pg 24]

"Since thou art more renowned in warfare,

first of the twain thou wast created,

thou art more cunning, more agreeable in every way (?)

do not submit to the younger!

"Take my advice without shrinking,[41]

let us make an alliance and friendship;

listen to my clear reasoning:

do not go forth to Adam.

"Give me a place in thy body,

with my own laws, with my own intellect,

so that we both may go from the plain

unexpectedly[42] to Eve.

"Let us together urge upon her

the fruit of the forbidden tree,

that she afterwards may clearly

press the food upon Adam.

"Provided that they go together

beyond the commandment of his Lord,

God will not love them here,

they will leave Paradise in evil plight."[43]

"What reward is there for me above every great one?"

said the serpent to the devil;

"on my welcoming thee into my fair body,

without evil, as my fellow-inhabitant?

[Pg 25]

"For guiding thee on that road

to destroy Eve and Adam,

for going with thee truly to the attack

whatever act thou mayest undertake?"[44]

(Lucifer replies)

"What greater reward shall I give to thee

according to the measure of our great crime

(than that) our union in our habits, in our wrath,

shall be for ever spoken of?"

When he found a place for the betrayal

in the likeness of the serpent's shape,

slowly he went tarrying[45]

directly to the gate of Paradise.

The serpent called outside,

"dost thou hear me, O wife of Adam?

come and converse with me, O Eve of the fair form,

beyond[46] every other."

"I have no time to talk with anyone,"

said Eve to the serpent;

"I am going out to feed

the senseless animals."

"If you are the Eve whose fame was heard

with honour in Paradise,

wife of Adam, beautiful, wide-minded,

in her I desire[47] my full satisfaction."[48]

"Whenever Adam is not here,

I am guardian of Paradise,

without weariness, O smooth, pale creature,

I attend to the needs of the animals."

(The Serpent speaks)

"How long does Adam go from thee,

on which side does he make his fair circuit,

when at any time he is not here

feeding the herds in Paradise?"

"He leaves it to me, bright jewel;

I feed the animals,

while he goes with pure unmeasured renown

to adore the Lord."

"I desire to ask a thing of thee,"

said the slender, very affable serpent,

"because bright and dear is thy clear reasoning,

O Eve, O bride of Adam!"

"Whatever it be that you contemplate saying,

it will not vex me, O noble creature;

certainly there will be no obscurity here,

I will narrate it to thee truthfully."

[Pg 27]

"Tell me, O glorious Eve,

since it chances that we are discoursing together,

in your judgment, is the life in Paradise,

with your lordship here, pleasant?"

(Eve replies)

"Until we go faultless in our turn, (or "ranks")

in our bodies to heaven,

we do not ask here greater lordship

than what there is of good in Paradise.

"Every good thing,[49] as it was heard,

that God created in Paradise,

save one tree, all without reserve,

is thus under our control.[50]

"It is He, the dear God, who committed to us,

O pale, bashful creature,

Paradise as a solace[51] for His people (?)

except the fruit of the one tree.

"'Let alone the very pure tree,'

He cautioned myself and Adam,

'the fruit of the rough tree, if thou eatest of it

against my command, thou shalt die.'"

"Though on the plain[52] you be equal,

yourself and Adam, O Eve,