A DICTIONARY OF MODERN SLANG, CANT, & VULGAR WORDS;

MANY WITH THEIR ETYMOLOGIES TRACED.

A 1, first rate, the very best; “she’s a prime girl she is; she is

A 1.“—Sam Slick. The highest classification of ships at

Lloyd’s; common term in the United States, also at Liverpool

and other English seaports. Another, even more

intensitive form, is “first-class, letter A, No. 1.”

ABOUT RIGHT, “to do the thing ABOUT RIGHT,” i.e., to do it

properly, soundly, correctly; “he guv it ’im ABOUT RIGHT,”

i.e., he beat him severely.

ABRAM-SHAM, or SHAM-ABRAHAM, to feign sickness or distress.

From ABRAM MAN, the ancient cant term for a begging

impostor, or one who pretended to have been mad.—Burton’s

Anatomy of Melancholy, part i., sec. 2, vol. i., p. 360.

When Abraham Newland was Cashier of the Bank of England,

and signed their notes, it was sung:—

“I have heard people say

That SHAM ABRAHAM you may,

But you mustn’t SHAM ABRAHAM Newland.”

ABSQUATULATE, to run away, or abscond; a hybrid American

expression, from the Latin ab, and “squat,” to settle.

ADAM’S ALE, water.—English. The Scotch term is ADAM’S WINE.

AGGERAWATORS (corruption of Aggravators), the greasy

locks of hair in vogue among costermongers and other

street folk, worn twisted from the temple back towards

the ear. They are also, from a supposed resemblance in

form, termed NEWGATE KNOCKERS, which see.—Sala’s Gas-light,

&c.

ALDERMAN, a half-crown—possibly from its rotundity.

ALDERMAN, a turkey.

ALDERMAN IN CHAINS, a turkey hung with sausages.

ALL OF A HUGH! all on one side, or with a thump; the

word HUGH being pronounced with a grunt.—Suffolk.

ALL MY EYE, answer of astonishment to an improbable story;

ALL MY EYE AND BETTY MARTIN, a vulgar phrase with similar

meaning, said to be the commencement of a Popish prayer

to St. Martin, “Oh mihi, beate Martine,” and fallen into

discredit at the Reformation.

ALL-OVERISH, neither sick nor well, the premonitory symptoms

of illness.

ALL-ROUNDERS, the fashionable shirt collars of the present

time worn meeting in front.

ALL-SERENE, an ejaculation of acquiescence.

ALLS, tap-droppings, refuse spirits sold at a cheap rate in gin-palaces.—See LOVEAGE.

ALL-THERE, in strict fashion, first-rate, “up to the mark;” a

vulgar person would speak of a spruce, showily-dressed

female as being ALL-THERE. An artizan would use the

same phrase to express the capabilities of a skilful fellow

workman.

ALL TO PIECES, utterly, excessively; “he beat him ALL TO

PIECES,” i.e., excelled or surpassed him exceedingly.

ALL TO SMASH, or GONE TO PIECES, bankrupt, or smashed to

pieces.—Somersetshire.

ALMIGHTY DOLLAR, an American expression for the “power

of money,” first introduced by Washington Irving in 1837.

AN’T, or AÏN’T, the vulgar abbreviation of “am not,” or “are

not.”

ANOINTING, a good beating.

ANY HOW, in any way, or at any rate, bad; “he went on ANY

HOW,” i.e., badly or indifferently.

APPLE CART, “down with his APPLE CART,” i.e., upset him.—North.

APPLE PIE ORDER, in exact or very nice order.

AREA-SNEAK, a boy thief who commits depredations upon

kitchens and cellars.—See CROW.

ARGOT, a term used amongst London thieves for their secret

or cant language. French term for slang.

ARTICLE, a man or boy, derisive term.

ARY, corruption of ever a, e’er a; ARY ONE, e’er a one.

ATTACK, to carve, or commence operations on; “ATTACK that

beef, and oblige!”

ATTIC, the head; “queer in the ATTIC,” intoxicated.—Pugilistic.

AUNT-SALLY, a favourite game on race-courses and at fairs,

consisting of a wooden head mounted on a stick, firmly

fixed in the ground; in the nose of which, or rather in that

part of the facial arrangement of AUNT SALLY which is

generally considered incomplete without a nasal projection, a

tobacco pipe is inserted. The fun consists in standing at a

distance and demolishing AUNT SALLY’S pipe-clay projection

with short bludgeons, very similar to the half of a broom-handle.

The Duke of Beaufort is a “crack hand” at smashing

pipe noses, and his performances two years ago on

Brighton race-course are yet fresh in remembrance. The

noble Duke, in the summer months, frequently drives the

old London and Brighton four-horse mail coach, “Age”—a

whim singular enough now, but common forty years ago.

AUTUMN, a slang term for an execution by hanging. When

the drop was introduced instead of the old gallows, cart, and

ladder, and a man was for the first time “turned-off” in

the present fashion, the mob were so pleased with the

invention that they spoke of the operation as at AUTUMN,

or the FALL OF THE LEAF (sc. the drop), with the man

about to be hung.

AVAST, a sailor’s phrase for stop, shut up, go away,—apparently

connected with the old cant, BYNGE A WASTE.

AWAKE, or FLY, knowing, thoroughly understanding, not

ignorant of. The phrase WIDE AWAKE carries the same

meaning in ordinary conversation.

AWFUL (or, with the Cockneys, ORFUL), a senseless expletive,

used to intensify a description of anything good or bad;

“what an AWFUL fine woman!” i.e., how handsome, or

showy!

AXE, to ask.—Saxon, ACSIAN.

BABES, the lowest order of KNOCK-OUTS (which see), who are

prevailed upon not to give opposing biddings at auctions, in

consideration of their receiving a small sum (from one

shilling to half-a-crown), and a certain quantity of beer.

Babes exist in Baltimore, U.S., where they are known as

blackguards and “rowdies.”

BACK JUMP, a back window.

BACK SLANG IT, to go out the back way.

BACK OUT, to retreat from a difficulty; the reverse of GO

AHEAD. Metaphor borrowed from the stables.

BACON, “to save one’s BACON,” to escape.

BAD, “to go to the BAD,” to deteriorate in character, be ruined.

Virgil has an exactly similar phrase, in pejus ruere.

BAGMAN, a commercial traveller.

BAGS, trowsers. Trowsers of an extensive pattern, or exaggerated

fashionable cut, have lately been termed HOWLING-BAGS,

but only when the style has been very “loud.” The

word is probably an abbreviation for b—mbags. “To have

the BAGS off,” to be of age and one’s own master, to have

plenty of money.

BAKE, “he’s only HALF BAKED,” i.e., soft, inexperienced.

BAKER’S DOZEN. This consists of thirteen or fourteen; the

surplus number, called the inbread, being thrown in for

fear of incurring the penalty for short weight. To “give a

man a BAKER’S DOZEN,” in a slang sense, means to give him

an extra good beating or pummelling.

BALAAM, printers’ slang for matter kept in type about monstrous

productions of nature, &c., to fill up spaces in newspapers

that would otherwise be vacant. The term BALAAM-BOX

has long been used in Blackwood as the name of the

depository for rejected articles.

BALL, prison allowance, viz., six ounces of meat.

BALLYRAG, to scold vehemently, to swindle one out of his

money by intimidation and sheer abuse, as alleged in a late

cab case (Evans v. Robinson).

BALMY, insane.

BAMBOOZLE, to deceive, make fun of, or cheat a person;

abbreviated to BAM, which is used also as a substantive,

a deception, a sham, a “sell.” Swift says BAMBOOZLE was

invented by a nobleman in the reign of Charles II.; but

this I conceive to be an error. The probability is that a

nobleman first used it in polite society. The term is derived

from the Gipseys.

BANDED, hungry.

BANDY, or CRIPPLE, a sixpence, so called from this coin being

generally bent or crooked; old term for flimsy or bad

cloth, temp. Q. Elizabeth.

BANG, to excel or surpass; BANGING, great or thumping.

BANG-UP, first-rate.

BANTLING, a child; stated in Bacchus and Venus, 1737, and

by Grose, to be a cant term.

BANYAN-DAY, a day on which no meat is served out for

rations; probably derived from the BANIANS, a Hindoo

caste, who abstain from animal food.—Sea.

BAR, or BARRING, excepting; in common use in the betting-ring;

“I bet against the field BAR two.” The Irish use of

BARRIN’ is very similar.

BARKER, a man employed to cry at the doors of “gaffs,” shows,

and puffing shops, to entice people inside.

BARKING IRONS, pistols.

BARNACLES, a pair of spectacles; corruption of BINOCULI?

BARNEY, a LARK, SPREE, rough enjoyment; “get up a BARNEY,”

to have a “lark.”

BARNEY, a mob, a crowd.

BARN-STORMERS, theatrical performers who travel the

country and act in barns, selecting short and frantic pieces

to suit the rustic taste.—Theatrical.

BARRIKIN, jargon, speech, or discourse; “we can’t tumble to

that BARRIKIN,” i.e., we don’t understand what he says.

Miege calls it “a sort of stuff.”

BASH, to beat, thrash; “BASHING a donna,” beating a woman;

originally a provincial word, and chiefly applied to the

practice of beating walnut trees, when in bud, with long

poles, to increase their productiveness. Hence the West

country proverb—

“A woman, a whelp, and a walnut tree,

The more you BASH ’em, the better they be.”

BAT, “on his own BAT,” on his own account.—See HOOK.

BATS, a pair of bad boots.

BATTER, “on the BATTER,” literally “on the streets,” or given

up to roistering and debauchery.

BATTLES, the students’ term at Oxford for rations. At Cambridge,

COMMONS.

BAWDYKEN, a brothel.—See KEN.

BAZAAR, a shop or counter. Gipsey and Hindoo, a market.

BEAK, a magistrate, judge, or policeman; “baffling the BEAK,”

to get remanded. Ancient cant, BECK. Saxon, BEAG, a

necklace or gold collar—emblem of authority. Sir John

Fielding was called the BLIND-BEAK in the last century

Query, if connected with the Italian BECCO, which means a

(bird’s) beak, and also a blockhead.

BEAKER-HUNTER, a stealer of poultry.

BEANS, money; “a haddock of BEANS,” a purse of money;

formerly BEAN meant a guinea; French, BIENS, property;

also used as a synonyme for BRICK, which see.

BEAR, one who contracts to deliver or sell a certain quantity of

stock in the public funds on a forthcoming day at a stated

place, but who does not possess it, trusting to a decline in

public securities to enable him to fulfil the agreement and

realise a profit.—See BULL. Both words are slang terms on

the Stock Exchange, and are frequently used in the business

columns of newspapers.

“He who sells that of which he is not possessed is proverbially

said to sell the skin before he has caught the BEAR. It was the

practice of stock-jobbers, in the year 1720, to enter into a contract

for transferring South Sea Stock at a future time for a certain

price; but he who contracted to sell had frequently no stock to

transfer, nor did he who bought intend to receive any in consequence

of his bargain; the seller was, therefore, called a BEAR, in allusion

to the proverb, and the buyer a BULL, perhaps only as a similar

distinction. The contract was merely a wager, to be determined by

the rise or fall of stock; if it rose, the seller paid the difference to

the buyer, proportioned to the sum determined by the same computation

to the seller.”—Dr. Warton on Pope.

BEARGERED, to be drunk.

BEAT, or BEAT-HOLLOW, to surpass or excel.

BEAT, the allotted range traversed by a policeman on duty.

BEAT-OUT, DEAD-BEAT, tired or fagged.

BEATER-CASES, boots: Nearly obsolete.

BEAVER, old street term for a hat; GOSS is the modern word,

BEAVER, except in the country, having fallen into disuse.

BE-BLOWED, a windy exclamation equivalent to an oath.—See

BLOW-ME.

BED-POST, “in the twinkling of a BED-POST,” in a moment, or

very quickly. Originally BED-STAFF, a stick placed vertically

in the frame of a bed to keep the bedding in its

place.—Shadwell’s Virtuoso, 1676, act i., scene 1. This was

used sometimes as a defensive weapon.

BEE, “to have a BEE in one’s bonnet,” i.e., to be not exactly

sane.

BEERY, intoxicated, or fuddled with beer.

BEESWAX, poor soft cheese.

BEETLE-CRUSHERS, or SQUASHERS, large flat feet.

BELCHER, a kind of handkerchief.—See BILLY.

BELL, a song.

BELLOWS, the lungs.

BELLOWSED, or LAGGED, transported.

BELLOWS-TO-MEND, out of breath.

BELLY-TIMBER, food, or “grub.”

BELLY-VENGEANCE, small sour beer, apt to cause gastralgia.

BEMUSE, to fuddle one’s self with drink, “BEMUSING himself

with beer,” &c.—Sala’s Gas-light and Day-light, p. 308.

BEN, a benefit.—Theatrical.

BEND, “that’s above my BEND,” i.e., beyond my power, too

expensive, or too difficult for me to perform.

BENDER, a sixpence,—from its liability to bend.

BENDER, the arm; “over the BENDER,” synonymous with

“over the left.”—See OVER. Also an ironical exclamation

similar to WALKER.

BENE, good.—Ancient cant; BENAR was the comparative.—See

BONE. Latin.

BENJAMIN, a coat. Formerly termed a JOSEPH, in allusion,

perhaps, to Joseph’s coat of many colours.—See UPPER-BENJAMIN.

BENJY, a waistcoat.

BEONG, a shilling.—See SALTEE.

BESTER, a low betting cheat.

BESTING, excelling, cheating. Bested, taken in, or defrauded.

BETTER, more; “how far is it to town?” “oh, BETTER ’n a

mile.”—Saxon and Old English, now a vulgarism.

BETTY, a skeleton key, or picklock.—Old cant.

B. FLATS, bugs.

BIBLE CARRIER, a person who sells songs without singing

them.

BIG, “to look BIG,” to assume an inflated dress, or manner; “to

talk BIG,” i.e., boastingly, or with an “extensive” air.

BIG-HOUSE, the work-house.

BILBO, a sword; abbrev. of BILBOA blade. Spanish swords

were anciently very celebrated, especially those of Toledo,

Bilboa, &c.

BILK, a cheat, or a swindler. Formerly in frequent use, now

confined to the streets, where it is very general. Gothic,

BILAICAN.

BILK, to defraud, or obtain goods, &c. without paying for

them; “to BILK the schoolmaster,” to get information or

experience without paying for it.

BILLINGSGATE (when applied to speech), foul and coarse

language. Not many years since, one of the London notorieties

was to hear the fishwomen at Billingsgate abuse each

other. The anecdote of Dr. Johnson and the Billingsgate

virago is well known.

BILLY, a silk pocket handkerchief.—Scotch.—See WIPE.

⁂ A list of the slang terms descriptive of the various

patterns of handkerchiefs, pocket and neck, is here subjoined:—

- Belcher, close striped pattern, yellow silk, and intermixed

with white and a little black; named from

the pugilist, Jim Belcher.

- Bird’s eye wipe, diamond spots.

- Blood-red fancy, red.

- Blue billy, blue ground with white spots.

- Cream fancy, any pattern on a white ground.

- Green king’s man, any pattern on a green ground.

- Randal’s man, green, with white spots; named after

Jack Randal, pugilist.

- Water’s man, sky coloured.

- Yellow fancy, yellow, with white spots.

- Yellow man, all yellow.

BILLY-BARLOW, a street clown; sometimes termed a JIM

CROW, or SALTIMBANCO,—so called from the hero of a slang

song.—Bulwer’s Paul Clifford.

BILLY-HUNTING, buying old metal.

BIRD-CAGE, a four-wheeled cab.

BIT, fourpence; in America 12½ cents is called a BIT, and a

defaced 20 cent piece is termed a LONG BIT. A BIT is the

smallest coin in Jamaica, equal to 6d.

BIT, a purse, or any sum of money.

BIT-FAKER, or TURNER OUT, a coiner of bad money.

BITCH, tea; “a BITCH party,” a tea-drinking.—University.

BITE, a cheat; “a Yorkshire BITE,” a cheating fellow from that

county.—North; also old slang, used by Pope. Swift says

it originated with a nobleman in his day.

BITE, to cheat; “to be BITTEN,” to be taken in or imposed

upon. Originally a Gipsey term.—See Bacchus and Venus.

BIVVY, or GATTER, beer; “shant of BIVVY,” a pot, or quart of

beer. In Suffolk, the afternoon refreshment of reapers is

called BEVER. It is also an old English term.

“He is none of those same ordinary eaters, that will devour three breakfasts,

and as many dinners, without any prejudice to their BEVERS,

drinkings, or suppers.”—Beaumont and Fletcher’s Woman Hater

1–3.

Both words are probably from the Italian, bevere, bere. Latin,

bibere. English, beverage.

BLACK AND WHITE, handwriting.

BLACKBERRY-SWAGGER, a person who hawks tapes, boot

laces, &c.

BLACK-LEG, a rascal, swindler, or card cheat.

BLACK-SHEEP, a “bad lot,” “mauvais sujet;” also a

workman who refuses to join in a strike.

BLACK-STRAP, port wine.

BLADE, a man—in ancient times the term for a soldier;

“knowing BLADE,” a wide awake, sharp, or cunning man.

BLACKGUARD, a low, or dirty fellow.

“A cant word amongst the vulgar, by which is implied a dirty fellow

of the meanest kind, Dr. Johnson says, and he cites only the

modern authority of Swift. But the introduction of this word into

our language belongs not to the vulgar, and is more than a century

prior to the time of Swift. Mr. Malone agrees with me in

exhibiting the two first of the following examples. The black-guard

is evidently designed to imply a fit attendant on the devil. Mr.

Gifford, however, in his late edition of Ben Jonson’s works, assigns

an origin of the name different from what the old examples

which I have cited seem to countenance. It has been formed,

he says, from those ‘mean and dirty dependants, in great houses,

who were selected to carry coals to the kitchen, halls, &c. To this

smutty regiment, who attended the progresses, and rode in the

carts with the pots and kettles, which, with every other article of

furniture, were then moved from palace to palace, the people, in

derision, gave the name of black guards; a term since become

sufficiently familiar, and never properly explained.’—Ben Jonson,

ii. 169, vii. 250”—Todd’s Johnson’s Dictionary.

BLARNEY, flattery, exaggeration.—Hibernicism.

BLAST, to curse.

BLAZES, “like BLAZES,” furious or desperate, a low comparison.

BLEST, a vow; “BLEST if I’ll do it,” i.e., I am determined not

to do it; euphemism for CURST.

BLEED, to victimise, or extract money from a person, to spunge

on, to make suffer vindictively.

BLEW, or BLOW, to inform, or peach.

BLEWED, got rid of, disposed of, spent; “I BLEWED all my

blunt last night,” I spent all my money.

BLIND, a pretence, or make believe.

BLIND-HOOKEY, a gambling game at cards.

BLINKER, a blackened eye.—Norwich slang.

BLINK FENCER, a person who sells spectacles.

BLOAK, or BLOKE, a man; “the BLOAK with a jasey,” the man

with a wig, i.e., the Judge. Gipsey and Hindoo, LOKE.

North, BLOACHER, any large animal.

BLOB (from BLAB), to talk. Beggars are of two kinds,—those

who SCREEVE (introduce themselves with a FAKEMENT, or

false document), and those who BLOB, or state their case in

their own truly “unvarnished” language.

BLOCK, the head.

BLOCK ORNAMENTS, the small dark coloured pieces of meat

exposed on the cheap butchers’ blocks or counters,—debateable

points to all the sharp visaged argumentative old

women in low neighbourhoods.

BLOOD, a fast or high-mettled man. Nearly obsolete in the

sense in which it was used in George the Fourth’s time.

BLOOD-RED FANCY, a kind of handkerchief worn by pugilists

and frequenters of prize fights.—See BILLY.

BLOODY-JEMMY, a sheep’s head.—See SANGUINARY JAMES.

BLOW, to expose, or inform; “BLOW the gaff,” to inform

against a person. In America, to BLOW is slang for to taunt.

BLOW A CLOUD, to smoke a cigar or pipe—a phrase in use

two centuries ago.

BLOW ME, or BLOW ME TIGHT, a vow, a ridiculous and unmeaning

ejaculation, inferring an appeal to the ejaculator; “I’m

BLOWED if you will” is a common expression among the

lower orders; “BLOW ME UP” was the term a century ago.—See

Parker’s Adventures, 1781.

BLOW OUT, or TUCK IN, a feast.

BLOW UP, to make a noise, or scold; formerly a cant expression

used amongst thieves, now a recognised and respectable

phrase. Blowing up, a jobation, a scolding.

BLOWEN, a showy or flaunting prostitute, a thief’s paramour.

In Wilts, a BLOWEN is a blossom. Germ. BLUHEN, to bloom.

“O du blühende Mädchen viel schöne Willkomm!”—German Song.

Possibly, however, the street term BLOWEN may mean one

whose reputation has been BLOWN UPON, or damaged.

BLOWER, a girl; a contemptuous name in opposition to JOMER.

BLUBBER, to cry in a childish manner.—Ancient.

BLUDGERS, low thieves, who use violence.

BLUE, a policeman; “disguised in BLUE and liquor.”—Boots at

the Swan.

BLUE, or BLEW, to pawn or pledge.

BLUE, confounded or surprised; “to look BLUE,” to be astonished

or disappointed.

BLUE BILLY, the handkerchief (blue ground with white spots)

worn and used at prize fights. Before a SET TO, it is common

to take it from the neck and tie it round the leg as a garter,

or round the waist, to “keep in the wind.” Also, the refuse

ammoniacal lime from gas factories.

BLUE BLANKET, a rough over coat made of coarse pilot cloth.

BLUE-BOTTLE, a policeman. It is singular that this well

known slang term for a London constable should have been

used by Shakespere. In part ii. of King Henry IV., act v.,

scene 4, Doll Tearsheet calls the beadle, who is dragging

her in, a “thin man in a censer, a BLUE-BOTTLE rogue.”

BLUED, or BLEWED, tipsey or drunk.

BLUE DEVILS, the apparitions supposed to be seen by habitual

drunkards.

BLUE MOON, an unlimited period.

BLUE MURDER, a desperate or alarming cry. French, MORT-BLEU.

BLUE RUIN, gin.

BLUE-PIGEON FLYERS, journeymen plumbers, glaziers, and

others, who, under the plea of repairing houses, strip off the

lead, and make way with it. Sometimes they get off with

it by wrapping it round their bodies.

BLUES, a fit of despondency.—See BLUE DEVILS.

BLUEY, lead. German, BLEI.

BLUFF, an excuse.

BLUFF, to turn aside, stop, or excuse.

BLUNT, money. It has been said that this term is from the

French BLOND, sandy or golden colour, and that a parallel

may be found in BROWN or BROWNS, the slang for half-pence.

The etymology seems far fetched, however.

BLURT OUT, to speak from impulse, and without reflection.—Shakespere.

BOB, a shilling. Formerly BOBSTICK, which may have been the

original.

BOB, “s’help my BOB,” a street oath, equivalent to “so help me

God.” Other words are used in street language for a similarly

evasive purpose, i.e., CAT, GREENS, TATUR, &c., all

equally profane and disgusting.

BOBBISH, very well, clever, spruce; “how are you doing?”

“oh! pretty BOBBISH.”—Old.

BOBBY, a policeman. Both BOBBY and PEELER were nicknames

given to the new police, in allusion to the christian

and surnames of the late Sir Robert Peel, who was the prime

mover in effecting their introduction and improvement.

The term BOBBY is, however, older than the Saturday

Reviewer, in his childish and petulant remarks, imagines.

The official square-keeper, who is always armed with a cane

to drive away idle and disorderly urchins, has, time out of

mind, been called by the said urchins, BOBBY the Beadle.

Bobby is also, I may remark, an old English word for striking

or hitting, a quality not unknown to policemen.—See

Halliwell’s Dictionary.

BODMINTON, blood.—Pugilistic.

BODY-SNATCHERS, bailiffs and runners: SNATCH, the trick

by which the bailiff captures the delinquent.

BODY-SNATCHERS, cat stealers.

BOG or BOG-HOUSE, a water-closet.—School term. In the Inns

of Court, I am informed, this term is very common.

BOG-TROTTER, satirical name for an Irishman.—Miege. Camden,

however, speaking of the “debateable land” on the

borders of England and Scotland, says “both these dales

breed notable BOG-TROTTERS.”

BOILERS, the slang name given to the New Kensington Museum

and School of Art, in allusion to the peculiar form of the

buildings, and the fact of their being mainly composed of,

and covered with, sheet iron.—See PEPPER-BOXES.

BOLT, to run away, decamp, or abscond.

BOLT, to swallow without chewing.

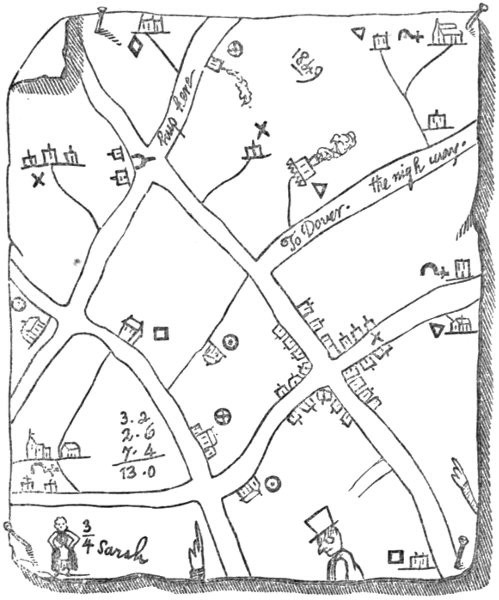

BONE, good, excellent. ![◇ [Diamond]](images/d_bone.gif) the vagabond’s hieroglyphic for

BONE, or good, chalked by them on houses and street

corners, as a hint to succeeding beggars. French, BON.

the vagabond’s hieroglyphic for

BONE, or good, chalked by them on houses and street

corners, as a hint to succeeding beggars. French, BON.

BONE, to steal or pilfer. Boned, seized, apprehended.—Old.

BONE-GRUBBERS, persons who hunt dust-holes, gutters, and

all likely spots for refuse bones, which they sell at the rag-shops,

or to the bone-grinders.

BONE-PICKER, a footman.

BONES, dice; also called ST. HUGH’S BONES.

BONES, “he made no BONES of it,” he did not hesitate, i.e.,

undertook and finished the work without difficulty, “found

no BONES in the jelly.”—Ancient, vide Cotgrave.

BONNET, a gambling cheat. “A man who sits at a gaming-table,

and appears to be playing against the table; when a

stranger enters, the BONNET generally wins.”—Times, Nov.

17, 1856. Also, a pretence, or make-believe, a sham bidder

at auctions.

BONNET, to strike a man’s cap or hat over his eyes and nose.

BONNETTER, one who induces another to gamble.

BOOK, an arrangement of bets for and against, chronicled in a

pocket-book made for that purpose; “making a BOOK upon

it,” common phrase to denote the general arrangement of a

person’s bets on a race. “That does not suit my BOOK,” i.e.,

does not accord with my other arrangements. Shakespere

uses BOOK in the sense of “a paper of conditions.”

BOOM, “to tip one’s BOOM off,” to be off, or start in a certain

direction.—Sea.

BOOKED, caught, fixed, disposed of.—Term in Book-keeping.

BOOZE, drink. Ancient cant, BOWSE.

BOOZE, to drink, or more properly, to use another slang term,

to “lush,” viz, to drink continually, until drunk, or nearly

so. The term is an old one. Harman, in Queen Elizabeth’s

days, speaks of “BOUSING (or boozing) and belly-cheere.”

The term was good English in the fourteenth century, and

comes from the Dutch, BUYZEN, to tipple.

BOOZE, or SUCK-CASA, a public-house.

BOOZING-KEN, a beer-shop, a low public house.—Ancient.

BOOZY, intoxicated or fuddled.

BORE, a troublesome friend or acquaintance, a nuisance, anything

which wearies or annoys. The Gradus ad Cantabrigiam

suggests the derivation of BORE from the Greek, Βαρος, a

burden. Shakespere uses it, King Henry VIII., i., 1—

“—— at this instant

He BORES me with some trick.”

Grose speaks of this word as being much in fashion about

the year 1780–81, and states that it vanished of a sudden,

without leaving a trace behind. Not so, burly Grose, the

term is still in favour, and is as piquant and expressive as

ever. Of the modern sense of the word BORE, the Prince

Consort made an amusing and effective use in his masterly

address to the British Association, at Aberdeen, September

14, 1859. He said (as reported by the Times):—

“I will not weary you by further examples, with which most of you

are better acquainted than I am myself but merely express my

satisfaction that there should exist bodies of men who will bring

the well-considered and understood wants of science before the

public and the Government, who will even hand round the begging-box,

and expose themselves to refusals and rebuffs, to which all

beggars all liable, with the certainty besides of being considered

great BORES. Please to recollect that this species of “bore” is a

most useful animal, well adapted for the ends for which nature

intended him. He alone, by constantly returning to the charge,

and repeating the same truths and the same requests, succeeds in

awakening attention to the cause which he advocates, and obtains

that hearing which is granted him at last for self-protection, as

the minor evil compared to his importunity, but which is requisite

to make his cause understood.”

BOSH, nonsense, stupidity.—Gipsey and Persian. Also pure

Turkish, BOSH LAKERDI, empty talk. A person, in the

Saturday Review, has stated that BOSH is coeval with Morier’s

novel, Hadji Babi, which was published in 1828; but this is

a blunder. The term was used in this country as early as

1760, and may be found in the Student, vol. ii., p. 217.

BOSH, a fiddle.

BOSH-FAKER, a violin player.

BOS-KEN, a farm-house. Ancient.—See KEN.

BOSKY, inebriated—Household Words, No. 183.

BOSMAN, a farmer; “faking a BOSMAN on the main toby,” robbing

a farmer on the highway. Boss, a master.—American.

Both terms from the Dutch, BOSCH-MAN, one who lives in

the woods; otherwise Boschjeman or Bushman.

BOSS-EYED, a person with one eye, or rather with one eye

injured.

BOTHER, to teaze, to annoy.

BOTHER (from the Hibernicism POTHER), trouble, or annoyance.

Grose has a singular derivation, BOTHER, or BOTH-EARED,

from two persons talking at the same time, or to both ears.

Blother, an old word, signifying to chatter idly.—See

Halliwell.

BOTHERATION! trouble, annoyance; “BOTHERATION to it,”

confound it, or deuce take it, an exclamation when irritated.

BOTTLE-HOLDER, an assistant to a “Second,”—Pugilistic; an

abettor; also, the bridegroom’s man at a wedding.

BOTTY, conceited, swaggering.

BOUNCE, impudence.

BOUNCE, a showy swindler.

BOUNCE, to boast, cheat, or bully.—Old cant.

BOUNCER, a person who steals whilst bargaining with a tradesman;

a lie.

BOUNDER, a four-wheel cab. Lucus a non lucendo?

BOUNETTER, a fortune-telling cheat.—Gipsey.

BOW-CATCHERS, or KISS-CURLS, small curls twisted on the

cheeks or temples of young—and often old—girls, adhering

to the face as if gummed or pasted. Evidently a corruption

of BEAU-CATCHERS. In old times these were called love-locks,

when they were the marks at which all the puritan

and ranting preachers levelled their pulpit pop-guns, loaded

with sharp and virulent abuse. Hall and Prynne looked

upon all women as strumpets who dared to let the hair

depart from a straight line upon their cheeks. The French

prettily term them accroche-cœurs, whilst in the United

States they are plainly and unpleasantly called SPIT-CURLS.

Bartlett says:—“Spit Curl, a detached lock of hair curled

upon the temple; probably from having been at first

plastered into shape by the saliva. It is now understood

that the mucilage of quince seed is used by the ladies for

this purpose.”

“You may prate of your lips, and your teeth of pearl,

And your eyes so brightly flashing;

My song shall be of that SALIVA CURL

Which threatens my heart to smash in.”

Boston Transcript, October 30, 1858.

When men twist the hair on each side of their faces into ropes

they are sometimes called BELL-ROPES, as being wherewith

to draw the belles. Whether BELL-ROPES or BOW-CATCHERS,

it is singular they should form part of the prisoner’s paraphernalia,

and that a jaunty little kiss-me quick curl should,

of all things in the world, ornament a gaol dock; yet such

was formerly the case. Hunt, the murderer of Weare, on

his trial, we are informed by the Athenæum, appeared at the

bar with a highly pomatumed love-lock sticking tight to his

forehead. Young ladies, think of this!

BOWL-OUT, to put out of the game, to remove out of one’s

way, to detect.—Cricketing term.

BOWLAS, round tarts made of sugar, apple, and bread, sold in

the streets.

BOWLES, shoes.

BOX-HARRY, a term with bagmen or commercial travellers,

implying dinner and tea at one meal; also dining with

Humphrey, i.e., going without.—Lincolnshire.

BRACE UP, to pawn stolen goods.

BRACELETS, handcuffs.

BRADS, money. Properly, a small kind of nails used by cobblers.—Compare

HORSE NAILS.

BRAD-FAKING, playing at cards.

BRAGGADOCIO, three months’ imprisonment as a reputed

thief or old offender,—sometimes termed a DOSE, or a DOLLOP.—Household

Words, vol. i., p. 579.

BRAN-NEW, quite new. Properly, Brent, BRAND, or Fire-new,

i.e., fresh from the anvil.

BRASS, money.

BREAD-BASKET, DUMPLING DEPOT, VICTUALLING OFFICE, &c.,

are terms given by the “Fancy” to the digestive organ.

BREAK-DOWN, a jovial, social gathering, a FLARE UP; in

Ireland, a wedding.

BREAKING SHINS, borrowing money.

BREAKY-LEG, a shilling.

![[Egyptian hieroglyphs]](images/hieroglyph.gif) BREAKY-LEG, strong drink; “he’s been to Bungay fair, and BROKE BOTH HIS LEGS,” i.e., got drunk. In

the ancient Egyptian language the determinative character in the

hieroglyphic verb “to be drunk,” has the significant form of the leg

of a man being amputated.

BREAKY-LEG, strong drink; “he’s been to Bungay fair, and BROKE BOTH HIS LEGS,” i.e., got drunk. In

the ancient Egyptian language the determinative character in the

hieroglyphic verb “to be drunk,” has the significant form of the leg

of a man being amputated.

BREECHED, or TO HAVE THE BAGS OFF, to have plenty of

money; “to be well BREECHED,” to be in good circumstances.

BREECHES, “to wear the BREECHES,” said of a wife who

usurps the husband’s prerogative.

BREEKS, breeches.—Scotch, now common.

BRICK, a “jolly good fellow;” “a regular BRICK,” a staunch

fellow.

“I bonnetted Whewell, when we gave the Rads their gruel,

And taught them to eschew all their addresses to the Queen.

If again they try it on, why to floor them I’ll make one,

Spite of Peeler or of Don, like a BRICK and a Bean.”

The Jolly Bachelors, Cambridge, 1840.

Said to be derived from an expression of Aristotle, τετραγωνος ἀνηρ.

BRIEF, a pawnbroker’s duplicate.

BRISKET BEATER, a Roman Catholic.

BROADS, cards. Broadsman, a card sharper.

BROAD AND SHALLOW, an epithet applied to the so-called

“Broad Church,” in contradistinction to the “High” and

“Low” Church.—See HIGH AND DRY.

BROAD-FENCER, card seller at races.

BROSIER, a bankrupt.—Cheshire. Brosier-my-dame, school

term, implying a clearing of the housekeeper’s larder of provisions,

in revenge for stinginess.—Eton.

BROTHER-CHIP, fellow carpenter. Also, BROTHER-WHIP, a

fellow coachman; and BROTHER-BLADE, of the same occupation

or calling—originally a fellow soldier.

BROWN, a halfpenny.—See BLUNT.

BROWN, “to do BROWN,” to do well or completely (in allusion

to roasting); “doing it BROWN,” prolonging the frolic, or

exceeding sober bounds; “DONE BROWN,” taken in, deceived,

or surprised.

BROWN BESS, the old Government regulation musket.

BROWN PAPERMEN, low gamblers.

BROWN SALVE, a token of surprise at what is heard, and at

the same time means “I understand you.”

BROWN-STUDY, a reverie. Very common even in educated

society, but hardly admissible in writing, and therefore

must be considered a vulgarism. It is derived, by a writer

in Notes and Queries, from BROW study, from the old German

BRAUN, or AUG-BRAUN, an eye-brow.—Ben Jonson.

BROWN-TO, to understand, to comprehend.—American.

BRUISER, a fighting man, a pugilist.—Pugilistic. Shakespere

uses the word BRUISING in a similar sense.

BRUMS, counterfeit coins. Nearly obsolete. Corruption of

Brummagem (Bromwicham), the ancient name of Birmingham,

the great emporium of plated goods and imitation

jewellery.

BRUSH, or BRUSH-OFF, to run away, or move on.—Old cant.

BUB, drink of any kind.—See GRUB. Middleton, the dramatist,

mentions BUBBER, a great drinker.

BUB, a teat, woman’s breast.

BUCK, a gay or smart man, a cuckold.

BUCKHORSE, a smart blow or box on the ear; derived from

the name of a celebrated “bruiser” of that name.

BUCKLE, to bend; “I can’t BUCKLE to that,” I don’t understand

it; to yield or give in to a person. Shakespere uses the

word in the latter sense, Henry IV., i. 1; and Halliwell says

that “the commentators do not supply another example.”

How strange that in our own streets the term should be

used every day! Stop the first costermonger, and he will

soon inform you the various meanings of BUCKLE.—See

Notes and Queries, vols. vii., viii., and ix.

BUCKLE-TO, to bend to one’s work, to begin at once, and

with great energy.

BUDGE, to move, to inform, to SPLIT, or tell tales.

BUFF, to swear to, or accuse; to SPLIT, or peach upon. Old

word for boasting, 1582.

BUFF, the bare skin; “stripped to the BUFF.”

BUFFER, a dog. Their skins were formerly in great request—hence

the term, BUFF meaning in old English to skin. It is

still used in the ring, BUFFED meaning stripped to the skin.

In Irish cant, BUFFER is a boxer. The BUFFER of a railway

carriage doubtless received its very appropriate name from

the old pugilistic application of this term.

BUFFER, a familiar expression for a jolly acquaintance, probably

from the French, BOUFFARD, a fool or clown; a “jolly

old BUFFER,” said of a good humoured or liberal old man.

In 1737, a BUFFER was a “rogue that killed good sound

horses for the sake of their skins, by running a long wire

into them.”—Bacchus and Venus. The term was once applied

to those who took false oaths for a consideration.

BUFFLE HEAD, a stupid or obtuse person.—Miege. German,

BUFFEL-HAUPT, buffalo-headed.

BUFFY, intoxicated.—Household Words, No. 183.

BUGGY, a gig, or light chaise. Common term in America and

in Ireland.

BUG-HUNTERS, low wretches who plunder drunken men.

BUILD, applied in fashionable slang to the make or style of

dress, &c.; “it’s a tidy BUILD, who made it?”

BULGER, large; synonymous with BUSTER.

BULL, term amongst prisoners for the meat served to them in

jail.

BULL, one who agrees to purchase stock at a future day, at a

stated price, but who does not possess money to pay for it,

trusting to a rise in public securities to render the transaction

a profitable one. Should stocks fall, the bull is then

called upon to pay the difference.—See BEAR, who is the

opposite of a BULL, the former selling, the latter purchasing—the

one operating for a fall or a pull down, whilst the

other operates for a rise or toss up.

BULL, a crown piece; formerly, BULL’S EYE.

BULL-THE-CASK, to pour hot water into an empty rum

puncheon, and let it stand until it extracts the spirit from

the wood. The result is drunk by sailors in default of

something stronger.—Sea.

BULLY, a braggart; but in the language of the streets, a man

of the most degraded morals, who protects prostitutes, and

lives off their miserable earnings.—Shakespere, Midsummer

Night’s Dream, iii. 1; iv. 2.

BUM, the part on which we sit.—Shakespere. Bumbags, trowsers.

BUM-BAILIFF, a sheriff’s officer,—a term, some say, derived

from the proximity which this gentleman generally maintains

to his victims. Blackstone says it is a corruption of

“bound bailiff.”

BUM-BOATS, shore boats which supply ships with provisions,

and serve as means of communication between the sailors

and the shore.

BUM-BRUSHER, a schoolmaster.

BUMMAREE. This term is given to a class of speculating

salesmen at Billingsgate market, not recognised as such by

the trade, but who get a living by buying large quantities

of fish of the salesmen and re-selling it to smaller buyers.

The word has been used in the statutes and bye-laws of

the markets for upwards of 100 years. It has been variously

derived, but is most probably from the French, BONNE

MAREE, good fresh fish! “Marée signifie toute sorte de

poisson de mer qûi n’est pas salé; bonne marée—marée

fraiche, vendeur de marée.”—Dict. de l’Acad. Franc. The

BUMMAREES are accused of many trade tricks. One of them

is to blow up cod-fish with a pipe until they look double

their actual size. Of course when the fish come to table

they are flabby, sunken, and half dwindled away. In Norwich,

TO BUMMAREE ONE is to run up a score at a public

house just open, and is equivalent to “running into debt

with one.”

BUNCH OF FIVES, the hand, or fist.

BUNDLE, “to BUNDLE a person off,” i.e., to pack him off, send

him flying.

BUNG, the landlord of a public-house.

BUNG, to give, pass, hand over, drink, or indeed to perform

any action; BUNG UP, to close up—Pugilistic; “BUNG

over the rag,” hand over the money—Old, used by Beaumont

and Fletcher, and Shakespere. Also, to deceive one by

a lie, to CRAM, which see.

BUNKER, beer.

BUNTS, costermonger’s perquisites; the money obtained by

giving light weight, &c.; costermongers’ goods sold by

boys on commission. Probably a corruption of bonus,

BONE being the slang for good. Bunce, Grose gives as the

cant word for money.

BURDON’S HOTEL, Whitecross-street prison, of which the

Governor is or was a Mr. Burdon.

BURERK, a lady. Grose gives BURICK, a prostitute.

BURKE, to kill, to murder, by pitch plaster or other foul

means. From Burke, the notorious Whitechapel murderer,

who with others used to waylay people, kill them, and sell

their bodies for dissection at the hospitals.

BURYING A MOLL, running away from a mistress.

BUSKER, a man who sings or performs in a public house.—Scotch.

BUSK (or BUSKING), to sell obscene songs and books at the bars

and in the tap rooms of public houses. Sometimes implies

selling any articles.

BUSS, an abbreviation of “omnibus,” a public carriage. Also,

a kiss.

BUST, or BURST, to tell tales, to SPLIT, to inform. Busting,

informing against accomplices when in custody.

BUSTER (BURSTER), a small new loaf; “twopenny BUSTER,” a

twopenny loaf. “A pennorth o’ BEES WAX (cheese) and a

penny BUSTER,” a common snack at beershops.

BUSTER, an extra size; “what a BUSTER,” what a large one;

“in for a BUSTER,” determined on an extensive frolic or

spree. Scotch, BUSTUOUS; Icelandic, BOSTRA.

BUSTLE, money; “to draw the BUSTLE.”

BUTTER, or BATTER, praise or flattery. To BUTTER, to flatter,

cajole.

BUTTER-FINGERED, apt to let things fall.

BUTTON, a decoy, sham purchaser, &c. At any mock or sham

auction seedy specimens may be seen. Probably from the

connection of buttons with Brummagem, which is often used

as a synonyme for a sham.

BUTTONER, a man who entices another to play.—See BONNETTER.

BUTTONS, a page,—from the rows of gilt buttons which adorn

his jacket.

BUTTONS, “not to have all one’s BUTTONS,” to be deficient in

intellect.

BUZ, to pick pockets; BUZ-FAKING, robbing.

BUZ, to share equally the last of a bottle of wine, when there

is not enough for a full glass for each of the party.

BUZZERS, pickpockets. Grose gives BUZ COVE and BUZ GLOAK,

the latter is very ancient cant.

BUZ-BLOAK, a pickpocket, who principally confines his attention

to purses and loose cash. Grose gives BUZ-GLOAK (or

CLOAK?), an ancient cant word. Buz-napper, a young pickpocket.

BUZ-NAPPER’S ACADEMY, a school in which young thieves

are trained. Figures are dressed up, and experienced tutors

stand in various difficult attitudes for the boys to practice

upon. When clever enough they are sent on the streets.

It is reported that a house of this nature is situated in a

court near Hatton Garden. The system is well explained

in Dickens’ Oliver Twist.

BYE-BLOW, a bastard child.

BY GEORGE, an exclamation similar to BY JOVE. The term is

older than is frequently imagined, vide Bacchus and Venus

(p. 117), 1737. “Fore (or by) GEORGE, I’d knock him

down.” A street compliment to Saint George, the patron

Saint of England, or possibly to the House of Hanover.

BY GOLLY, an ejaculation, or oath; a compromise for “by

God.” In the United States, small boys are permitted by

their guardians to say GOL DARN anything, but they are on

no account allowed to commit the profanity of G—d d——g

anything. An effective ejaculation and moral waste pipe

for interior passion or wrath is seen in the exclamation—BY

THE-EVER-LIVING-JUMPING-MOSES—a harmless phrase,

that from its length expends a considerable quantity of

fiery anger.

CAB, in statutory language, “a hackney carriage drawn by one

horse.” Abbreviated from CABRIOLET, French; originally

meaning “a light low chaise.” The wags of Paris playing

upon the word (quasi cabri au lait) used to call a superior

turn-out of the kind a cabri au crême. Our abbreviation,

which certainly smacks of slang, has been stamped with the

authority of “George, Ranger.” See the notices affixed

to the carriage entrances of St. James’s Park.

CAB, to stick together, to muck, or tumble up.—Devonshire.

CABBAGE, pieces of cloth said to be purloined by tailors.

CABBAGE, to pilfer or purloin. Termed by Johnson a cant

word, but adopted by later lexicographers as a respectable

term. Said to have been first used in this sense by Arbuthnot.

CABBY, the driver of a cab.

CAD, or CADGER (from which it is shortened), a mean or vulgar

fellow; a beggar; one who would rather live on other

people than work for himself; a man trying to worm something

out of another, either money or information. Johnson

uses the word, and gives huckster as the meaning, but I

never heard it used in this sense. Cager, or GAGER, the

old cant term for a man. The exclusives in the Universities

apply the term CAD to all non-members.

CAD, an omnibus conductor.

CADGE, to beg in an artful or wheedling manner.—North.

CADGING, begging of the lowest degree.

CAG-MAG, bad food, scraps, odds and ends; or that which no

one could relish. Grose gives CAGG MAGGS, old and tough

Lincolnshire geese, sent to London to feast the poor

cockneys.

CAGE, a minor kind of prison.—Shakespere, part ii. of

Henry IV., iv. 2.

CAKE, a flat, a soft or doughy person, a fool.

CAKEY-PANNUM-FENCER, a man who sells street pastry.

CALL-A-GO, in street “patter,” is to remove to another spot,

or address the public in different vein.

CAMESA, shirt or chemise.—Span. Ancient cant, COMMISSION.

CAMISTER, a preacher, clergyman, or master.

CANARY, a sovereign. This is stated by a correspondent to be

a Norwich term, that city being famous for its breed of

those birds.

CANISTER, the head.—Pugilistic.

CANISTER-CAP, a hat.—Pugilistic.

CANNIKEN, a small can, similar to PANNIKIN.—Shakespere.

CANT, a blow or toss; “a cant over the kisser,” a blow on the

mouth.—Kentish.

CANT OF TOGS, a gift of clothes.

CARDINAL, a lady’s cloak. This, I am assured, is the Seven

Dials cant term for a lady’s garment, but curiously enough

the same name is given to the most fashionable patterns of

the article by Regent-street drapers. A cloak with this

name was in fashion in the year 1760. It received its title

from its similarity in shape to one of the vestments of a

cardinal.

CARNEY, soft talk, nonsense, gammon.—Hibernicism.

CAROON, five shillings. French, COURONNE; Gipsey, COURNA,—PANSH

COURNA, half-a-crown.

CARPET, “upon the CARPET,” any subject or matter that is

uppermost for discussion or conversation. Frequently

quoted as sur le tapis, but it does not seem to be a correct

Parisian phrase.

CARRIER PIGEONS, swindlers, who formerly used to cheat

Lottery Office Keepers. Nearly obsolete.

CARROTS, the coarse and satirical term for red hair.

CARRY-ON, to joke a person to excess, to carry on a

“spree” too far; “how we CARRIED ON, to be sure!” i.e.,

what fun we had.

CART, a race-course.

CARTS, a pair of shoes. In Norfolk the carapace of a crab is

called a crab cart, hence CARTS would be synonymous with

CRAB SHELLS, which see.

CART WHEEL, a five shilling piece.

CASA, or CASE, a house, respectable or otherwise. Probably

from the Italian, CASA.—Old cant. The Dutch use the word

KAST in a vulgar sense for a house, i.e., MOTTEKAST, a brothel.

Case sometimes means a water-closet.

CASCADING, vomiting.

CASE, a bad crown piece. Half-a-case, a counterfeit half

crown. There are two sources, either of which may have

contributed this slang term. Caser is the Hebrew word for

a crown; and silver coin is frequently counterfeited by

coating or CASING pewter or iron imitations with silver.

CASE. A few years ago the term CASE was applied to persons

and things; “what a CASE he is,” i.e., what a curious

person; “a rum CASE that,” or “you are a CASE,” both

synonymous with the phrase “odd fish,” common half-a-century

ago. Among young ladies at boarding schools a

CASE means a love affair.

CASK, fashionable slang for a brougham, or other private

carriage.—Household Words, No. 183.

CASSAM, cheese—not CAFFAN, which Egan, in his edition of

Grose, has ridiculously inserted.—Ancient cant. Latin,

CASEUS.

CASTING UP ONE’S ACCOUNTS, vomiting.—Old.

CASTOR, a hat. Castor was once the ancient word for a

BEAVER; and strange to add, BEAVER was the slang for

CASTOR, or hat, thirty years ago, before gossamer came

into fashion.

CAT, to vomit like a cat.—See SHOOT THE CAT.

CAT, a lady’s muff; “to free a CAT,” i.e., steal a muff.

CATARACT, a black satin scarf arranged for the display of

jewellery, much in vogue among “commercial gents.”

CATCH ’EM ALIVE, a trap, also a small-tooth comb.

CATCHY (similar formation to touchy), inclined to take an

undue advantage.

CATEVER, a queer, or singular affair; anything poor, or very

bad. From the Lingua Franca, and Italian, CATTIVO, bad.

Variously spelled by the lower orders.—See KERTEVER.

CATGUT-SCRAPER, a fiddler.

CAT-LAP, a contemptuous expression for weak drink.

CAT’S WATER, old Tom, or Gin.

CAT AND KITTEN SNEAKING, stealing pint and quart pots

from public-houses.

CATCH-PENNY, any temporary contrivance to obtain money

from the public, penny shows, or cheap exhibitions.

CAT-IN-THE-PAN, a traitor, a turn-coat—derived by some

from the Greek, καταπαν, altogether; or from cake in

pan, a pan cake, which is frequently turned from side to

side.

CAUCUS, a private meeting held for the purpose of concerting

measures, agreeing upon candidates for office before an

election, &c.—See Pickering’s Vocabulary.

CAVAULTING, coition. Lingua Franca, CAVOLTA.

CAVE, or CAVE IN, to submit, shut up.—American. Metaphor

taken from the sinking of an abandoned mining shaft.

CHAFF, to gammon, joke, quiz, or praise ironically. Chaff-bone,

the jaw-bone.—Yorkshire. Chaff, jesting. In Anglo

Saxon, CEAF is chaff; and CEAFL, bill, beak, or jaw. In the

“Ancien Riwle,” A.D. 1221, ceafle is used in the sense of

idle discourse.

CHALK-OUT, or CHALK DOWN, to mark out a line of conduct

or action; to make a rule, order. Phrase derived from the

Workshop.

CHALK UP, to credit, make entry in account books of indebtedness;

“I can’t pay you now, but you can CHALK IT

UP,” i.e., charge me with the article in your day-book.

From the old practice of chalking one’s score for drink

behind the bar-doors of public houses.

CHALKS, “to walk one’s CHALKS,” to move off, or run away.

An ordeal for drunkenness used on board ship, to see

whether the suspected person can walk on a chalked line

without overstepping it on either side.

CHAP, a fellow, a boy; “a low CHAP,” a low fellow—abbreviation

of CHAP-MAN, a huckster. Used by Byron in his Critical

Remarks.

CHARIOT-BUZZING, picking pockets in an omnibus.

CHARLEY, a watchman, a beadle.

CHARLEY-PITCHERS, low, cheating gamblers.

CHATTER BASKET, common term for a prattling child

amongst nurses.

CHATTER-BOX, an incessant talker or chatterer.

CHATTRY-FEEDER, a spoon.

CHATTS, dice,—formerly the gallows; a bunch of seals.

CHATTS, lice, or body vermin.

CHATTY, a filthy person, one whose clothes are not free from

vermin; CHATTY DOSS, a lousy bed.

CHAUNTER-CULLS, a singular body of men who used to

haunt certain well known public-houses, and write satirical

or libellous ballads on any person, or body of persons, for a

consideration. 7s. 6d. was the usual fee, and in three hours

the ballad might be heard in St. Paul’s Churchyard, or other

public spot. There are two men in London at the present

day who gain their living in this way.

CHAUNTERS, those street sellers of ballads, last copies of

verses, and other broadsheets, who sing or bawl the contents

of their papers. They often term themselves PAPER

WORKERS. A. N.—See HORSE CHAUNTERS.

CHAUNT, to sing the contents of any paper in the streets.

Cant, as applied to vulgar language, was derived from

CHAUNT.—See Introduction.

CHEAP, “doing it on the CHEAP,” living economically, or

keeping up a showy appearance with very little means.

CHEAP JACKS, or JOHNS, oratorical hucksters and patterers of

hardware, &c., at fairs and races. They put an article up

at a high price, and then cheapen it by degrees, indulging

in volleys of coarse wit, until it becomes to all appearance a

bargain, and as such it is bought by one of the crowd. The

popular idea is that the inverse method of auctioneering

saves them paying for the auction license.

CHEEK, share or portion; “where’s my CHEEK?” where is my

allowance?

CHEEK, impudence, assurance; CHEEKY, saucy or forward.

Lincolnshire, CHEEK, to accuse.

CHEEK, to irritate by impudence.

CHEEK BY JOWL, side by side,—said often of persons in such

close confabulation as almost to have their faces touch.

CHEESE, anything good, first-rate in quality, genuine, pleasant,

or advantageous, is termed THE CHEESE. Mayhew thinks

CHEESE, in this sense, is from the Saxon, CEOSAN, to choose,

and quotes Chaucer, who uses CHESE in the sense of choice.

The London Guide, 1818, says it was from some young

fellows translating “c’est une autre CHOSE” into “that is

another CHEESE.” CHEESE is also Gipsey and Hindoo (see

Introduction); and Persian, CHIZ, a thing.—See STILTON.

CHEESE, or CHEESE IT (evidently a corruption of cease), leave

off, or have done; “CHEESE your barrikin,” hold your noise.

CHEESY, fine or showy.

CHERUBS, or CHERUBIMS, the chorister boys who chaunt in the

services at the abbeys.

CHESHIRE CAT, “to grin like a CHESHIRE CAT,” to display

the teeth and gums when laughing. Formerly the phrase

was “to grin like a CHESHIRE CAT eating CHEESE.” A

hardly satisfactory explanation has been given of this

phrase—that Cheshire is a county palatine, and the cats,

when they think of it, are so tickled with the notion that

they can’t help grinning.

CHICKEN, a young girl.

CHICKEN-HEARTED, cowardly, fearful.

CHI-IKE, a hurrah, a good word, or hearty praise.

CHINK, money.—Ancient.—See FLORIO.

CHINKERS, money.

CHIP OF THE OLD BLOCK, a child who resembles its father.

Brother chip, one of the same trade or profession.

CHIPS, money.

CHISEL, to cheat.

CHITTERLINGS, the shirt frills worn still by ancient beaux;

properly, the entrails of a pig, to which they are supposed

to bear some resemblance. Belgian, SCHYTERLINGH.

CHIVARLY, coition. Probably a corruption from the Lingua

Franca.

CHIVE, a knife; a sharp tool of any kind.—Old cant. This

term is particularly applied to the tin knives used in gaols.

CHIVE, to cut, saw, or file.

CHIVE, or CHIVEY, a shout; a halloo, or cheer, loud tongued.

From CHEVY-CHASE, a boy’s game, in which the word CHEVY

is bawled aloud; or from the Gipsey?—See Introduction.

CHIVE-FENCER, a street hawker of cutlery.

CHIVEY, to chase round, or hunt about.

CHOCK-FULL, full till the scale comes down with a shock.

French, CHOC. A correspondent suggests CHOKED-FULL.

CHOKE OFF, to get rid of. Bull dogs can only be made to

loose their hold by choking them.

CHOKER, a cravat, a neckerchief. White-choker, the white

neckerchief worn by mutes at a funeral, and waiters at a

tavern. Clergymen are frequently termed WHITE-CHOKERS.

CHOKER, or WIND-STOPPER, a garrotter.

CHONKEYS, a kind of mince meat baked in a crust, and sold

in the streets.

CHOP, to change.—Old.

CHOPS, properly CHAPS, the mouth, or cheeks; “down in the

CHOPS,” or “down in the mouth,” i.e., sad or melancholy.

CHOUSE, to cheat out of one’s share or portion. Hackluyt,

CHAUS; Massinger, CHIAUS. From the Turkish, in which

language it signifies an interpreter. Gifford gives a curious

story as to its origin:—

In the year 1609 there was attached to the Turkish embassy in

England an interpreter, or CHIAOUS, who by cunning, aided by his

official position, managed to cheat the Turkish and Persian

merchants then in London out of the large sum of £1,000, then

deemed an enormous amount. From the notoriety which attended

the fraud, and the magnitude of the swindle, any one who

cheated or defrauded was said to chiaous, or chause, or CHOUSE;

to do, that is, as this Chiaous had done.—See Trench, Eng. Past

and Present, p. 87.

CHOUT, an entertainment.

CHOVEY, a shop.

CHRISTENING, erasing the name of the maker from a stolen

watch, and inserting a fictitious one in its place.

CHUBBY, round-faced, plump.

CHUCK, a schoolboy’s treat.—Westminster school. Food, provision

for an entertainment.—Norwich.

CHUCK, to throw or pitch.

CHUCKING A JOLLY, when a costermonger praises the

inferior article his mate or partner is trying to sell.

CHUCKING A STALL, where one rogue walks in front of a

person while another picks his pockets.

CHUCKLE-HEAD, a fool.—Devonshire.

CHUFF IT, i.e., be off, or take it away, in answer to a street

seller who is importuning you to purchase. Halliwell

mentions CHUFF as a “term of reproach,” surly, &c.

CHUM, an acquaintance. A recognised term, but in such frequent

use with the lower orders that it demanded a place

in this glossary.

CHUM, to occupy a joint lodging with another person.

CHUMMING-UP, an old custom amongst prisoners when a fresh

culprit is admitted to their number, consisting of a noisy

welcome—rough music made with pokers, tongs, sticks, and

saucepans. For this ovation the initiated prisoner has to

pay, or FORK OVER, half a crown—or submit to a loss of

coat and waistcoat. The practice is ancient.

CHUMMY, a chimney sweep; also a low-crowned felt hat.

CHUNK, a thick or dumpy piece of any substance.—Kentish.

CHURCH A YACK (or watch), to take the works of a watch

from its original case and put them into another one, to

avoid detection.—See CHRISTEN.

CHURCHWARDEN, a long pipe, “A YARD OF CLAY.”

CLAGGUM, boiled treacle in a hardened state, Hardbake.—See

CLIGGY.

CLAP, to place; “do you think you can CLAP your hand on

him?” i.e., find him out.

CLAPPER, the tongue.

CLAP-TRAP, high-sounding nonsense. An ancient Theatrical

term for a “TRAP to catch a CLAP by way of applause from

the spectators at a play.”—Bailey’s Dictionary.

CLARET, blood.—Pugilistic.

CLEAN, quite, or entirely; “CLEAN gone,” entirely out of sight,

or away.—Old, see Cotgrave.—Shakespere.

CLEAN OUT, to thrash, or beat; to ruin, or bankrupt any one;

to take all they have got, by purchase, or force. De Quincey,

in his article on “Richard Bentley,” speaking of the lawsuit

between that great scholar and Dr. Colbatch, remarks

that the latter “must have been pretty well CLEANED OUT.”

CLICK, knock, or blow. Click-handed, left-handed.—Cornish.

CLICK, to snatch.

CLIFT, to steal.

CLIGGY, or CLIDGY, sticky.—Anglo Saxon, CLÆG, clay.—See

CLAGGUM.

CLINCHER, that which rivets or confirms an argument, an

incontrovertible position. Metaphor from the workshop.

CLINK-RIG, stealing tankards from public-houses, taverns, &c.

CLIPPING, excellent, very good.

CLOCK, “to know what’s O’CLOCK,” a definition of knowingness

in general.—See TIME O’DAY.

CLOD-HOPPER, a country clown.

CLOUT, or RAG, a cotton pocket handkerchief.—Old cant.

CLOUT, a blow, or intentional strike.—Ancient.

CLOVER, happiness, or luck.

CLUMP, to strike.

CLY, a pocket.—Old cant for to steal. A correspondent derives

this word from the Old English, CLEYES, claws; Anglo

Saxon, CLEA. This pronunciation is still retained in Norfolk;

thus, to CLY would mean to pounce upon, snatch.—See

FRISK.

CLY-FAKER, a pickpocket.

COACH, a Cambridge term for a private tutor.

COACH WHEEL, or TUSHEROON, a crown piece, or five shillings.

COALS, “to call (or pull) over the COALS,” to take to task,

to scold.

COCK, or more frequently now a days, COCK-E-E, a vulgar

street salutation—corruption of COCK-EYE. The latter is

frequently heard as a shout or street cry after a man or boy.

COCK AND A BULL STORY, a long, rambling anecdote.—See

Notes and Queries, vol. iv., p. 313.

COCKCHAFER, the treadmill.

COCK-EYE, one that squints.

COCKLES, “to rejoice the COCKLES of one’s heart,” a vulgar

phrase implying great pleasure.—See PLUCK.

COCKNEY, a native of London. Originally, a spoilt or effeminate

boy, derived from COCKERING, or foolishly petting a

person, rendering them of soft or luxurious manners.

Halliwell states, in his admirable essay upon the word, that

“some writers trace the word with much probability to the

imaginary land of COCKAYGNE, the lubber land of the olden

times.” Grose gives Minsheu’s absurd but comical derivation:—A

citizen of London being in the country, and

hearing a horse neigh, exclaimed, “Lord! how that horse

laughs.” A bystander informed him that that noise was

called neighing. The next morning, when the cock crowed,

the citizen, to show that he had not forgotten what was

told him, cried out, “do you hear how the COCK NEIGHS?”

COCK OF THE WALK, a master spirit, head of a party. Places

where poultry are fed are called WALKS, and the barn-door

cocks invariably fight for the supremacy till one has

obtained it.

COCKS, fictitious narratives, in verse or prose, of murders, fires,

and terrible accidents, sold in the streets as true accounts.

The man who hawks them, a patterer, often changes the

scene of the awful event to suit the taste of the neighbourhood

he is trying to delude. Possibly a corruption of cook,

a cooked statement, or, as a correspondent suggests, the

COCK LANE Ghost may have given rise to the term. This

had a great run, and was a rich harvest to the running

stationers.

COCK ONE’S TOES, to die.

COCK ROBIN SHOP, a small printer’s office, where low wages

are paid to journeymen who have never served a regular

apprenticeship.

COCKSHY, a game at fairs and races, where trinkets are set

upon sticks, and for one penny three throws at them are

accorded, the thrower keeping whatever he knocks off. From

the ancient game of throwing or “shying” at live cocks.

COCKSURE, certain.

COCKY, pert, saucy.

COCKYOLY BIRDS, little birds, frequently called “dickey

birds.”—Kingsley’s Two Years Ago.

COCK, “to COCK your eye,” to shut or wink one eye.

COCUM, advantage, luck, cunning, or sly, “to fight COCUM,” to

be wily and cautious.

CODDS, the “poor brethren” of the Charter house. At p. 133

of the Newcomes, Mr. Thackeray writes, “The Cistercian

lads call these old gentlemen CODDS, I know not wherefore.”

An abbreviation of CODGER.

CODGER, an old man; “a rum old CODGER,” a curious old

fellow. Codger is sometimes used synonymous with CADGER,

and then signifies a person who gets his living in a questionable

manner. Cager, or GAGER, was the old cant term for

a man.

COFFEE-SHOP, a water-closet, or house of office.

COG, to cheat at dice.—Shakespere. Also, to agree with, as one

cog-wheel does with another.

COLD BLOOD, a house licensed for the sale of beer “NOT to be

drunk on the premises.”

COLD COOK, an undertaker.

COLD MEAT, a corpse.

COLD SHOULDER, “to show or give any one the COLD

SHOULDER,” to assume a distant manner towards them,

to evince a desire to cease acquaintanceship. Sometimes it

is termed “cold shoulder of mutton.”

COLLAR, “out of COLLAR,” i.e., out of place, no work.

COLLAR, to seize, to lay hold of.

COLLY-WOBBLES, a stomach ache, a person’s bowels,—supposed

by many of the lower orders to be the seat of feeling

and nutrition; an idea either borrowed from, or transmitted

by, the ancients.—Devonshire.

COLT’S TOOTH, elderly persons of juvenile tastes are said to

have a colt’s tooth.

COMB-CUT, mortified, disgraced, “down on one’s luck.”—See

CUT.

COME, a slang verb used in many phrases; “A’nt he COMING

IT?” i.e., is he not proceeding at a great rate? “Don’t

COME TRICKS here,” “don’t COME THE OLD SOLDIER over

me,” i.e., we are aware of your practices, and “twig” your

manœuvre. Coming it strong, exaggerating, going a-head,

the opposite of “drawing it mild.” Coming it also means

informing or disclosing.

COME DOWN, to pay down.

COMMISSION, a shirt.—Ancient cant. Italian, CAMICIA.

COMMISTER, a chaplain or clergyman.

COMMON SEWER, a DRAIN, or drink.

COMMONS, rations, because eaten in common.—University.

Short commons (derived from the University slang term), a

scanty meal, a scarcity.

CONK, a nose; CONKY, having a projecting or remarkable nose.

The Duke of Wellington was frequently termed “Old

CONKY” in satirical papers and caricatures.

CONSTABLE, “to overrun the CONSTABLE,” to exceed one’s

income, get deep in debt.

CONVEY, to steal; “CONVEY, the wise it call.”

CONVEYANCER, a pick-pocket. Shakespere uses the cant expression,

CONVEYER, a thief. The same term is also French

slang.

COOK, a term well known in the Bankruptcy Courts, referring to

accounts that have been meddled with, or COOKED, by the

bankrupt; also the forming a balance sheet from general

trade inferences; stated by a correspondent to have been

first used in reference to the celebrated alteration of the

accounts of the Eastern Counties Railway, by George

Hudson, the Railway King.

COOK ONE’S GOOSE, to kill or ruin any person.—North.

COOLIE, a soldier, in allusion to the Hindoo COOLIES, or day

labourers.

COON, abbreviation of Racoon.—American. A GONE COON—ditto,

one in an awful fix, past praying for. This expression is

said to have originated in the American war with a spy, who

dressed himself in a racoon skin, and ensconced himself in a

tree. An English rifleman taking him for a veritable coon

levelled his piece at him, upon which he exclaimed, “Don’t

shoot, I’ll come down of myself, I know I’m a GONE COON.”

The Yankees say the Britisher was so flummuxed, that he

flung down his rifle and “made tracks” for home. The

phrase is pretty usual in England.

COOPER, stout half-and-half, i.e., half stout and half porter.

COOPER, to destroy, spoil, settle, or finish. Cooper’d, spoilt,

“done up,” synonymous with the Americanism, CAVED IN,

fallen in and ruined. The vagabonds’ hieroglyphic ![▽ [Downward pointing triangle]](images/e_cooper.gif) ,

chalked by them on gate posts and houses, signifies that the

place has been spoilt by too many tramps calling there.

,

chalked by them on gate posts and houses, signifies that the

place has been spoilt by too many tramps calling there.

COOPER, to forge, or imitate in writing; “COOPER a moneker,”

to forge a signature.

COP, to seize or lay hold of anything unpleasant; used in a

similar sense to catch in the phrase “to COP (or catch) a

beating,” “to get COPT.”

COPER, properly HORSE-COUPER, a Scotch horse-dealer,—used to

denote a dishonest one.

COPPER, a policeman, i.e., one who COPS, which see.

COPPER, a penny. Coppers, mixed pence.

COPUS, a Cambridge drink, consisting of ale combined with

spices, and varied by spirits, wines, &c. Corruption of

HIPPOCRAS.

CORINTHIANISM, a term derived from the classics, much in

vogue some years ago, implying pugilism, high life, “sprees,”

roistering, &c.—Shakespere. The immorality of Corinth was

proverbial in Greece. Κορινθίαζ εσθαι, to Corinthianise,

indulge in the company of courtesans, was a Greek slang expression.

Hence the proverb—

Οὐ παντὸς ἀνδρὸς εἰς Κόρινθον ἔσθ' ὁ πλοῦς,

and Horace, Epist. lib. 1, xvii. 36—

Non cuivis homini contingit adire Corinthum,

in allusion to the spoliation practised by the “hetæræ” on

those who visited them.

CORK, “to draw a CORK,” to give a bloody nose.—Pugilistic.

CORKS, money; “how are you off for corks?” a soldier’s term

of a very expressive kind, denoting the means of “keeping

afloat.”

CORNED, drunk or intoxicated. Possibly from soaking or pickling

oneself like CORNED beef.

CORNERED, hemmed in a corner, placed in a position from

which there is no escape.—American.

CORPORATION, the protuberant front of an obese person.

CORPSE, to confuse or put out the actors by making a mistake.—Theatrical.

COSSACK, a policeman.

COSTERMONGERS, street sellers of fish, fruit, vegetables,

poultry, &c. The London costermongers number more than

30,000. They form a distinct class, occupying whole

neighbourhoods, and are cut off from the rest of metropolitan

society by their low habits, general improvidence,

pugnacity, love of gambling, total want of education, disregard

for lawful marriage ceremonies, and their use of a

cant (or so-called back slang) language.

COSTER, the short and slang term for a costermonger, or

costard-monger, who was originally an apple seller. Costering,

i.e., costermongering.

COTTON, to like, adhere to, or agree with any person; “to

cotton on to a man,” to attach yourself to him, or fancy

him, literally, to stick to him as cotton would. Vide Bartlett,

who claims it as an Americanism; and Halliwell, who

terms it an Archaism; also Bacchus and Venus, 1737.

COUNCIL OF TEN, the toes of a man who turns his feet inward.

COUNTER JUMPER, a shopman, a draper’s assistant.

COUNTY-CROP (i.e., COUNTY-PRISON CROP), hair cut close and

round, as if guided by a basin—an indication of having

been in prison.

COUTER, a sovereign. Half-a-couter, half-a-sovereign.

COVE, or COVEY, a boy or man of any age or station. A term

generally preceded by an expressive adjective, thus a “flash

COVE,” a “rum COVE,” a “downy COVE,” &c. The feminine,

COVESS, was once popular, but it has fallen into disuse.

Ancient cant, originally (temp. Henry VIII.) COFE, or

CUFFIN, altered in Decker’s time to COVE. Probably connected

with CUIF, which, in the North of England, signifies

a lout or awkward fellow. Amongst Negroes, CUFFEE.

COVENTRY, “to send a man to COVENTRY,” not to speak to or

notice him. Coventry was one of those towns in which the

privilege of practising most trades was anciently confined to

certain privileged persons, as the freemen, &c. Hence a

stranger stood little chance of custom, or countenance, and

“to send a man to COVENTRY,” came to be equivalent to

putting him out of the pale of society.

COVER-DOWN, a tossing coin with a false cover, enabling

either head or tail to be shown, according as the cover is

left on or taken off.

COWAN, a sneak, an inquisitive or prying person.—Masonic

term. Greek, κύων, a dog.

COW’S GREASE, butter.

COW-LICK, the term given to the lock of hair which costermongers

and thieves usually twist forward from the ear; a

large greasy curl upon the cheek, seemingly licked into

shape. The opposite of NEWGATE-KNOCKER, which see.

COXY-LOXY, good-tempered, drunk.—Norfolk.

CRAB, or GRAB, a disagreeable old person. Name of a wild

and sour fruit. “To catch a CRAB,” to fall backwards by

missing a stroke in rowing.

CRAB, to offend, or insult; to expose or defeat a robbery, to

inform against.

CRABSHELLS, or TROTTING CASES, shoes.—See CARTS.

CRACK, first-rate, excellent; “a CRACK HAND,” an adept; a

“CRACK article,” a good one.—Old.

CRACK, dry firewood.—Modern Gipsey.

CRACK, “in a CRACK (of the finger and thumb),” in a moment.

CRACK A BOTTLE, to drink. Shakespere uses CRUSH in the

same slang sense.

CRACK A KIRK, to break into a church or chapel.

CRACK-FENCER, a man who sells nuts.

CRACK-UP, to boast or praise.—Ancient English.

CRACKED-UP, penniless, or ruined.

CRACKSMAN, a burglar.

CRAM, to lie or deceive, implying to fill up or CRAM a person

with false stories; to acquire learning quickly, to “grind,”

or prepare for an examination.

CRAMMER, a lie; or a person who commits a falsehood.

CRANKY, foolish, idiotic, ricketty, capricious, not confined to

persons. Ancient cant, CRANKE, simulated sickness. German,

KRANK, sickly.

CRAP, to ease oneself, to evacuate. Old word for refuse; also

old cant, CROP.

CRAPPING CASE, or KEN, a privy, or water-closet.

CRAPPED, hanged.

CREAM OF THE VALLEY, gin.

CRIB, house, public or otherwise; lodgings, apartments.

CRIB, a situation.

CRIB, to steal or purloin.

CRIB, a literal translation of a classic author.—University.

CRIB-BITER, an inveterate grumbler; properly said of a horse

which has this habit, a sign of its bad digestion.

CRIBBAGE-FACED, marked with the small pox, full of holes

like a cribbage board.

CRIKEY, profane exclamation of astonishment; “Oh, CRIKEY,

you don’t say so!” corruption of “Oh, Christ.”

CRIMPS, men who trepan others into the clutches of the recruiting

sergeant. They generally pretend to give employment

in the colonies, and in that manner cheat those

mechanics who are half famished. Nearly obsolete.

CRIPPLE, a bent sixpence.

CROAK, to die—from the gurgling sound a person makes when

the breath of life is departing.—Oxon.

CROAKER, one who takes a desponding view of everything;

an alarmist. From the croaking of a raven.—Ben Jonson.

CROAKER, a beggar.

CROAKER, a corpse, or dying person beyond hope.

CROAKS, last dying speeches, and murderers’ confessions.

CROCODILES’ TEARS, the tears of a hypocrite. An ancient

phrase, introduced into this country by Mandeville, or other

early English traveller.—Othello, iv., 1.

CROCUS, or CROAKUS, a quack or travelling doctor; CROCUS-CHOVEY,

a chemist’s shop.

CRONY, a termagant or malicious old woman; an intimate

friend. Johnson calls it cant.

CROOKY, to hang on to, to lead, walk arm-in-arm; to court or

pay addresses to a girl.

CROPPIE, a person who has had his hair cut, or CROPPED, in

prison.

CROPPED, hanged.

CROSS, a general term amongst thieves expressive of their