LETTERS

FROM A FARMER IN

PENNSYLVANIA.

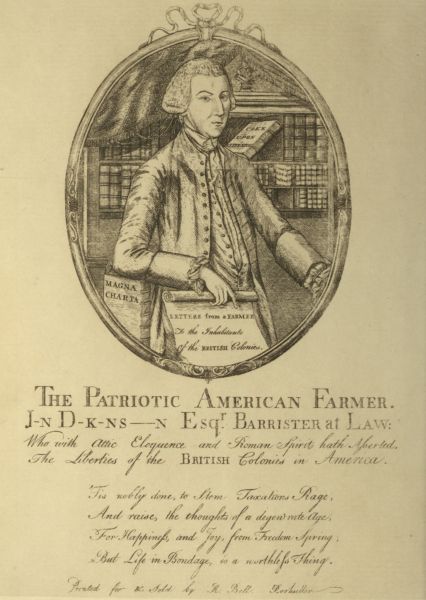

The Patriotic American Farmer

J-n D-k-ns—n Esqr. Barrister at Law:

Who with Attic Eloquence and Roman Spirit hath Asserted,

The Liberties of the British Colonies in America.

Printed for & Sold by R. Bell. Bookseller

BY

WITH AN HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

BY

R. T. H. HALSEY

NEW YORK

THE OUTLOOK COMPANY

1903

Copyright, 1903

By R. T. H. Halsey

TO THE MEMORY

OF ONE WHO LOVED HER COUNTRY

AND ALL THAT PERTAINED

TO ITS HISTORY

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xvii |

| Notes | xlix |

| Letter I | 5 |

| Letter II | 13 |

| Letter III | 27 |

| Letter IV | 37 |

| Letter V | 47 |

| Letter VI | 59 |

| Letter VII | 67 |

| Letter VIII | 79 |

| [xii]Letter IX | 87 |

| Letter X | 101 |

| Letter XI | 117 |

| Letter XII | 133 |

| Letter of Thanks from the Town of Boston | 147 |

The Patriotic American Farmer J-n D-k-ns-n, Esq^r, Barrister-at-Law | Frontispiece |

| Photogravure on copper. | |

Initial Letter from the Pennsylvania Chronicle of 1768 | Title |

| Line etching on copper. | |

Chelsea Derby Porcelain Statuette of Catherine Macaulay | xliii |

| Bierstadt process color print. |

In the issue of the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser of November 30th-December 3d, 1767, appeared the first of twelve successive weekly "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies," in which the attitude assumed by the British Parliament towards the American Colonies was exhaustively discussed. So extensive was their popularity that they were immediately reprinted in almost all our Colonial newspapers.

The outbursts of joy throughout America occasioned by the repeal of the Stamp Act had scarcely subsided when, the protracted illness of Lord Chatham having left the Ministry without a head, the indomitable Charles Townsend, to the amazement of his colleagues and unfeigned delight of his King, introduced measure after measure under the pretence that they were demanded by the necessities of the Exchequer; but in reality for the purpose of demonstrating the supremacy of the power of the Parliament of Great Britain over her colonies in America. Among these Acts were those which provided for the billeting of troops in the various colonies; others[xviii] called for duties upon glass, lead, paint, oil, tea, etc. Of dire portent was the provision therein, that the revenues thus obtained be used for the maintenance of a Civil List in America, and for the payment of the salaries of the Royal Governors and Justices, salaries which had hitherto been voted by the various Assemblies. The Assembly of New York, having failed to comply strictly with the letter of the law in regard to the billeting of the King's troops, was punished by having its legislative powers suspended.

This action boded ill for the future of any law-making body in America which should fail to carry out strictly any measure upon which the British Parliament might agree. The Colonies needed a common ground on which to meet in their opposition to these arbitrary Acts of Parliament. The deeds of violence and the tumultuous and passionate harangues in the northern colonies met with little sympathy among a large class in the middle and southern colonies, who, while chafing under the attacks upon their liberties, hesitated to favor resistance to the home government because of their unswerving loyalty to their King and their love for the country to whom and to which they owed allegiance. To these "The Farmer" appealed when he wrote, "The cause of liberty is a cause of too much dignity to be slighted by turbulence and tumult. It ought to be maintained in a manner suitable[xix] to her nature, those who engage in it should breathe a sedate yet fervent spirit animating them to actions of prudence, justice, modesty, bravery, humanity and magnanimity." The convincing logic of these letters clearly proved that the constitutional rights belonging to Englishmen were being trampled upon in the colonies, and furnished a platform upon which all those who feared their liberties were endangered could unite.

Under the date of the fifth of November, 1767, the seventy-ninth anniversary of the day on which the landing of William the Third at Torbay gave constitutional liberty to all Englishmen, John Dickinson, of Pennsylvania (for before long it became known that he was the illustrious author), in a letter addressed to his "beloved countrymen," called attention to the lack of interest shown by the Colonies in the act suspending the legislative powers of New York, and logically pointed out that the precedent thereby established was a blow at the liberty of all the other Colonies, laying particular emphasis upon the danger of mutual inattention by the Colonies to the interests of one another.

The education and training of the author well qualified him to handle his subject. Born in 1732 on his ancestral plantation on the eastern shore of Maryland, from early youth John Dickinson had had the advantages[xx] of a classical education.[1] His nineteenth year found him reading law in a lawyer's office in Philadelphia. Three years later, he sailed for England, where he devoted four important years to study at the Middle Temple, and then and there obtained that knowledge of English common law and constitutional history, and imbibed the traditions of liberty belonging to Englishmen on which he later founded his plea for the resistance of the Colonies to the ministerial attacks upon their liberty. On his return home he took up the practice of his profession at Philadelphia, and immediately won for himself a high place at the Bar. Elected in 1760 a member of the Assembly of Delaware, his reputation for ability and political discernment gained him its speakership. In 1762 he became a member of the Assembly of Pennsylvania, where he acquired great prominence and unpopularity, which later cost him his seat in that body, on account of his opposition to the Assembly's sending a petition to the King praying that the latter "would resume the government of the province, making such compensation to the proprietaries as would be equitable, and permitting the inhabitants to enjoy under the new government the privileges that have been granted to them by and under your Royal ministries."

Possibly Dickinson's knowledge of the personality of the Ministry and the dominant spirits in English political circles gained while abroad, led him bitterly to attack this measure, fathered and supported by Franklin, for subsequent events soon showed the far-sightedness which led him to distrust the wisdom of a demand for the revoking of the Proprietary Charter, even though it were a bad one. His part in the controversy forced even his bitterest opponents to admire his ability. The enormous debt incurred by Great Britain during the then recent war with France led the Ministry to look for some way of lightening taxation at home. It was decided that America must pay a share toward lifting the burden resting heavily on those in England, caused by the financing of the expenses of a war which drove France from North America. The fact that the colonies had furnished, equipped and maintained in the field twenty-five thousand troops and had incurred debts far heavier in proportion than those at home was forgotten. In 1764 was passed the "Sugar Act," which extended and enlarged the Navigation Acts and made England the channel through which not only all European, but also all Asiatic trade to and from the colonies must flow. At the same time an announcement was made that "Stamp Duties" would be added later on. The next year from Dickinson's[xxii] pen appeared a pamphlet entitled "The LATE REGULATIONS Respecting the BRITISH COLONIES on the Continent of AMERICA Considered, in a Letter from a Gentleman in Philadelphia to his Friend in London," in which these late regulations and proposed measures were discussed entirely from an economic standpoint. In it was clearly shown how dependent were the manufacturers and traders in England for their prosperity upon the trade of the colonies and that any restraint of American trade would naturally curtail the ability of those in the colonies to purchase from the home market. The Stamp Act was opposed on the ground that the already impoverished colonies would be drained of all their gold and silver which necessarily would have to go abroad in the payment for the stamps. This letter was conciliatory and persuasive, yet in the closing pages Dickinson asked:

"What then can we do? Which way shall we turn ourselves? How may we mitigate the miseries of our country? Great Britain gives us an example to guide us? She Teaches us to Make a Distinction Between Her Interests and Our Own.

"Teaches! She requires—commands—insists upon it—threatens—compels—and even distresses us into it.

"We have our choice of these two things—to continue our present limited and[xxiii] disadvantageous commerce—or to promote manufactures among ourselves, with a habit of economy, and thereby remove the necessity we are now under of being supplied by Great Britain.

"It is not difficult to determine which of these things is most eligible. Could the last of them be only so far executed as to bring our demand for British manufactures below the profits of our foreign trade, and the amount of our commodities immediately remitted home, these colonies might revive and flourish. States and families are enriched by the same means; that is, by being so industrious and frugal as to spend less than what they raise can pay for."

The various Non-Importation Agreements signed during the next ten years, bear testimony to the popularity of the proposed plan.

This pamphlet circulated freely and increased Dickinson's reputation as that of a man capable of thoroughly discussing public measures; it also brought his name to the attention of the British public for whom the "Letter" was especially written.

At the call of Massachusetts, representatives of nine of the colonies met in New York in October, 1764, and after a long discussion (in which Dickinson's knowledge of constitutional law and English colonial policy enabled him to assume the leadership) issued a "Declaration of Rights," in[xxiv] which it was asserted that the inhabitants of the Colonies, standing on their rights as Englishmen, could not be taxed by the House of Commons while unrepresented in that body. Memorials were sent abroad protesting against the proposed acts, expressing, however, their willingness to meet loyally as in the past any properly accredited requisitions for funds sent to the various Assemblies. Notwithstanding this opposition, and the protests of all friends of America in England, the Stamp Act was passed. A year later it was repealed.

JUST PUBLISHED.

Printed on a large Type, and fine Paper,

And to be sold at the LONDON BOOK STORE

North Side of King-street

LETTERS

FROM

A FARMER in PENNSYLVANIA

To the INHABITANTS of the

BRITISH COLONIES.

(Price two Pistareens)

Among all the WRITERS in favor of the COLONIES, the FARMER shines unrivalled, for strength of Argument, Elegance of Diction, Knowledge in the Laws of Great Britain, and the true interest of the COLONIES: A pathetic and persuasive eloquence runs thro the whole of these Letters: They have been printed in every Colony from Florida to Nova Scotia; and the universal applause so justly bestowed on the AUTHOR, hath fully testified the GRATITUDE of the PEOPLE OF AMERICA, for such an able Adviser and affectionate Friend.

Written in a plain, pure style, with illustrations

and arguments drawn from ecclesiastical,

classical and English history, each

point proven with telling accuracy and convincing

logic, conciliatory to the English

people, and filled with expressions of loyalty

to the King, these essays, popularly known

as the "Farmer's Letters," furnished the

basis on which all those who resented the

attacks on their liberty were able to unite.

Town meetings[2] and Assemblies vied with

each other in their resolutions of thanks.

The "Letters" were published immediately

in book form in Philadelphia (three different

editions), New York, Boston (two different

editions), Williamsburgh, London (with a

preface written by Franklin), and Dublin.[xxv]

[xxvi]

Franklin was influential, also, in having

them translated into French, and published

on the Continent. Owing to the beauty of

its typography and the excellence of its

book-making, the Boston edition, published

by Messrs. Mein & Fleeming, has been selected

for republication, and has been reprinted

line for line and page for page, in

a type varying but slightly from that used

by Mein & Fleeming. A few typographical

errors have been corrected, but the irregularities

in spelling, wherever they exist

throughout the various editions, have been

retained. The binding also is a reproduction

of that of the original. Its publication[3]

was announced in the "Boston Chronicle,"

March 14-21, 1768, by the advertisement

reprinted on the preceding page.

Valuable as these "Letters" were at home in uniting all factions in their measures of resistance, yet their influence abroad was of even more far-reaching effect. Reprinted in London in June, 1768, this two-shilling pamphlet quickly circulated through coffee-house and drawing-room. In ministerial circles the "Farmer" caused great indignation. In a letter from Franklin, addressed to his son, dated London, 13th of March, 1768, appears the following: "My Lord Hillsborough mentioned the 'Farmer's Letters' to me, said that he had read[xxvii] them, that they were well written, and he believed he could guess who was the author, looking in my face at the same time, as if he thought it was me. He censured the doctrines as extremely wild. I have read them as far as Number 8. I know not if any more have been published. I should, however, think they had been written by Mr. Delancey, not having heard any mention of the others you point out as joint authors."

Groaning under their own heavy taxation, the troubles of America had hitherto appealed but slightly to the average Englishman and the sympathies of the English people had become involved in the long-drawn-out struggles of Wilkes to obtain his constitutional rights. The press published little American news. America was little discussed; conditions there were practically unknown to all but the trading class, whose members had prospered through the monopoly of the constantly increasing commerce with the growing colonies. This class, naturally fearing the loss of the magnificent trade which had been built up, had long bemoaned the constantly increasing friction between the two factions on each side of the water. Englishmen in general had hitherto paid little attention to the debates over the various acts raising revenue from the colonies. From the time the "Farmer's Letters" were published in England[xxviii] the differences between Parliament and colonies were better understood there. Untouched and yet alarmed by the political corruption so prevalent at the time, thinking men saw in these "Letters" a warning that if their Sovereign was successful in his attempt to take away constitutional liberty from their fellow Englishmen across the sea, their own prized liberty at home was in danger. "American" news became more frequent in the newspapers, "Letters to the Printer," the form of editorials of the day, discussed and criticised the measures of Parliament with great freedom. To the masses, John Dickinson's name soon became very familiar through the agency of the press, which under date of June 26-28, 1768, freely noted Isaac Barré's characterization in the House of Commons of Dickinson as "a man who was not only an ornament to his country but an honor to human nature." Almost immediately after the publication of the London edition, the Monthly Review of July, 1768, forcibly called the attention of the literary world to the "Farmer's Letters" in an exhaustive review which is reprinted in the Notes, page liii, for the purpose of showing the view held by the English Whigs regarding the doctrines laid down and arguments used by Dickinson in defence of his position.

The "London Chronicle," under date of September 1st, 1768, printed the popular[xxix] Liberty song, written by Mr. Dickinson, and which, set to the inspiring air of "Hearts of Oak," was being sung throughout the colonies. In order to give the accompanying letter of request for the republication of the song, a request which, from its wording demonstrates the enthusiasm which the song aroused, the latter is here reprinted from the issue of the Boston "Evening Post" of August 22, 1768.

MESSIRS FLEETS

The following Song being now much in Vogue and of late is heard resounding in almost all Companies in Town, and by way of eminence called "The Liberty Song," you are desired to republish in your 'circulating' Paper for the Benefit of the whole Continent of America.

[To the Tune of Hearts of Oak.]

The following extract from the London "Chronicle" of October 4, 1768, demonstrates how completely the arguments and logic of the "Farmer's Letters" gained popular approval; how constantly Dickinson's name was kept before the public, both at home and abroad; how his fame was toasted; how he was recognized as the leader of political thought in the colonies. It shows also the constantly increasing interest in American matters taken by the press of England since the advent of the "Farmer's Letters," for the "American News," published in this and other London papers, was extensively reprinted in the local journals throughout the kingdom.

Taken from the Boston, in New England, Evening Post of August 22, 1768

On Monday the fifteenth instant, the anniversary of the ever memorable Fourteenth of August, was celebrated by the Sons of Liberty in this Town, with extraordinary festivity. At this Dawn, the British Flag was displayed on the Tree of Liberty, and a Discharge of Fourteen Cannon, ranged under the venerable Elm, saluted the joyous Day. At eleven o'clock, a very large Company of the principal Gentlemen and respectable Inhabitants of the Town, met at the Hall under the Tree,[xxxii] while the Streets were crowded with a Concourse of People of all Ranks, public Notice having been given of the intended Celebration. The Musick began at high Noon, performed on various Instruments, joined with Voices; and concluding with the universally admired American Song of Liberty,[4] the Grandeur of its Sentiment, and the easy Flow of its Numbers, together with an exquisite Harmony of Sound, afforded sublime Entertainment to a numerous Audience, fraught with a noble Ardour in the cause of Freedom: The Song was clos'd with the Discharge of Cannon and a Shout of Joy; at the same time the Windows of the Neighbouring Houses, were adorned with a brilliant appearance of the fair Daughters of Liberty, who testified their Approbation by Smiles of Satisfaction. The following Toasts succeeded, viz.

The following toasts may need brief explanation.—R. T. H. H.:

1. Our rightful Sovereign George the Third.

2. The Queen, Prince of Wales, and the rest of the Royal Family.

3. The Sons of Liberty throughout the World.

4. The glorious Administration of 1766.

4. The Rockingham Ministry which repealed the Stamp Act.

5. A perpetual Union of Great Britain and her Colonies, upon the immutable Principles of Justice and Equity.

6. May the sinister Designs of Oppressors, both in Great Britain and America, be for ever defeated.

7. May the common Rights of Mankind be established on the Ruin of all their Enemies.

8. Paschal Paoli and his brave Corsicans. May they never want the Support of the Friends of Liberty.

8. The struggles of Paoli and the Corsicans excited great interest both in Great Britain and America. Constant references are made to these in the "Letters."

9. The memorable 14th of August, 1765.

9. The day of the demonstration in Boston against the Stamp Officers. Daybreak disclosed hanging on a tree an effigy of the Stamp Officer Oliver. After hanging all day, at nightfall it was taken down by the Sons of Liberty, who placed it on a bier and escorted it through the principal streets in Boston to the home of Oliver, where, in the presence of a large number of people, it was burned.

10. Magna Charta, and the Bill of Rights.

11. A speedy Repeal of unconstitutional Acts of Parliament, and a final Removal of illegal and oppressive Officers.

12. The Farmer.

12. John Dickinson.

13. John Wilkes, Esq.; and all independent Members of the British Parliament.

14. The glorious Ninety-Two who defended the Rights of America, uninfluenced by the Mandates of a Minister, and undaunted by the threats of a Governor.

14. On the 11th day of February, 1768, the Assembly of Massachusetts adopted and sent to the various Colonial Assemblies a circular letter drawn up by Samuel Adams, informing them of the contents of a petition which the Massachusetts Assembly had sent to the King. This letter also urged united action against the oppressive measures of the Ministry, and gave great offense to the King and Ministry. The Secretary for the Colonies, Lord Hillsborough, instructed Governor Bernard of Massachusetts to order the Assembly to rescind this letter, and in case of refusal to dissolve this body. After a thorough discussion this request was refused by a vote of "ninety-two" to "seventeen."

Which being finished, the French horns sounded; and after another discharge of the cannon, compleating the number Ninety-Two, the[xxxiv] gentlemen in their carriages repaired to the Greyhound Tavern in Roxbury, where a frugal and elegant entertainment was provided. The music played during the repast: After which the following toasts were given out, and the repeated discharge of cannon spoke the general assent.

1. The King.

2. Queen and Royal Family.

3. Lord Cambden.

3. A strenuous upholder of the Constitutional rights of the Colonies and a strong defender in the House of Lords of the doctrine, "No taxation without representation." Contemporary writers frequently spelt Camden's name as above.

4. Lord Chatham.

5. Duke of Richmond.

5. Another friend of America in the same body.

6. Marquis of Rockingham.

6. Under whose ministry the Stamp Act was repealed.

7. General Conway.

7. The leader in the House of Commons during the Rockingham Ministry.

8. Lord Dartmouth.

8. President of the Board of Trade in the Rockingham Ministry, much loved in the Colonies. Dartmouth College bears his name.

9. Earl of Chesterfield.

9. A warm adherent of America.

10. Colonel Barre.

10. The companion of Wolfe at Quebec; in replying to Townsend during one of the debates over the passage of the Stamp Acts he characterized the Americans as "Sons of Liberty," a term which immediately was applied throughout the Colonies to those who were resenting the interference of Parliament with their home government.

11. General Howard.

11. A member of Parliament from Stamford who was active in [xxxv]obtaining the repeal of the Stamp Act.

12. Sir George Saville.

12. Represented Yorkshire in the House of Commons; a strong supporter of the Rockingham Ministry.

13. Sir William Meredith.

13. Member of Parliament from Liverpool. Lord of the Admiralty

14. Sir William Baker.

14. Also energetic in securing the repeal of the Stamp Act.

15. John Wilkes, Esq., and a Speedy Reversal of his outlawry.

15. The struggles of Wilkes excited keen interest in America.

16. The Farmer of Pennsylvania.

16. It is noted that this was the second time Dickinson's health was drunk that day. No other American residing in this country was toasted.

17. The Massachusetts Ninety-Two.

18. Prosperity and Perpetuity to the British Empire, on Constitutional Principles.

19. North America: And her fair Daughters of Liberty.

20. The illustrious Patriots of the Kingdom of Ireland.

20. In Letter X Dickinson warns against the fate of Ireland.

21. The truly heroic Paschal Paoli, and all the brave Corsicans.

22. The downfall of arbitrary and despotic Power in all Parts of the Earth; and Liberty without Licentiousness to all mankind.

23. A perpetual Union and Harmony between Great Britain and the Colonies, on the Principles of the Original Compact.

24. To the immortal Memory of that Hero of Heroes William the Third.

25. The speedy Establishment of a wise and permanent [xxxvi]administration.

26. The right noble Lords, and very worthy Commoners, who voted for the Repeal of the stamp Act from Principle.

27. Dennis De Berdt, Esq; and all the true Friends of America in Great Britain, and those of Great Britain in America.

27. The agent of Massachusetts in London.

28. The respectable Towns of Salem, Ipswich and Marblehead, with all the Absentees from the late Assembly, and their constituents, who have publickly approved of the Vote against Rescinding.

28. Representatives of these towns voted in favor of rescinding. Town meetings, however, were held, and the citizens of these places recorded themselves as endorsing the action of the majority in refusing the "Ministerial Mandates" and condemned the position assumed by their own representatives. In letters which appeared in the press a number of absentees from the Assembly boldly endorsed the action of the majority.

29. May all Patriots be as wise as Serpents, and as harmless as Doves.

30. The Manufactories of North America, and the Banishment of Luxury, Dissipation and other Vices, Foreign and Domestic.

30. Referring to the proposal of Dickinson quoted on page xxiii of the Introduction.

31. The removal of all Task-Masters, and an effectual Redress of all other Grievances.

32. The Militia of Great Britain and of the Colonies.

33. As Iron sharpeneth Iron, so may the Countenance of every good and virtuous Son and Daughter of Liberty, that of his or her [xxxvii]Friend.

34. The Assemblies on this vast and rapidly populating Continent, who have treated a late haughty and "merely ministerial" Mandate "with all that Contempt it so justly deserves."

34. Referring to the replies of the various Assemblies to the circular letter and endorsements of the action of the Massachusetts Assembly.

35. Strong Halters and sharp axes to all such as respectively deserve them.

36. Scalping Savages let loose in Tribes, rather than Legions of Placemen, Pensioners, and Walkerizing Dragoons.

37. The Amputation of any Limb, if it be necessary to preserve the Body Politic from Perdition.

38. The oppressed and distressed foreign Protestants.

39. The free and independent Cantons of Switzerland.

40. Their High Mightinesses the States General of Seven United Provinces.

41. The King of Prussia.

42. The Republic of Letters.

43. The Liberty of the Press.

44. Spartan, Roman, British Virtue, and Christian Graces joined.

45. Every man under his own Vine! under his own Fig-Tree! None to make us afraid! And let all the People say, Amen!

45. See page 51.

Upon this happy occasion, the whole company with the approbation of their brethren in Roxbury, consecrated a tree in the vicinity; under the shade [xxxviii]of which, on some future anniversary, they say they shall commemorate the day, which shall liberate America from her present oppression! Then making an agreeable excursion round Jamaica Pond, in which excursion they received the kind salutation of a Friend to the cause by the discharge of cannon at six o'clock they returned to Town; and passing in slow and orderly procession through the principal streets, and the State-House, they retired to their respective dwellings. It is allowed that this cavalcade surpassed all that has ever been seen in America. The joy of the day was manly, and an uninterrupted regularity presided through the whole.

The two illustrations in this volume were selected for the purpose of recording prevalent contemporary opinions of Dickinson.

The frontispiece is a reproduction (slightly reduced in size)[5] of the very scarce print in which John Dickinson is crudely portrayed as the author of the "Farmer's Letters." It was first advertised for sale in the Pennsylvania "Chronicle" under date of October 12-17, 1768, as follows:

Lately published and sold by R. Bell

at James Emerson's, in Market-street,

near the river, and at John

Hart's vendue store, in Southward

(Price One Shilling)

an elegant engraved COPPER PLATE PRINT

of the Patriotic American Farmer;

The same glazed and framed, price Five Shillings.

This specimen of early American engraving, the work of some unknown artist and engraver, was undoubtedly inspired by the following article which appeared in the Pennsylvania "Chronicle" for May, 9-16, 1768, as well as the many other newspapers in the colonies, so eager was the press to publish any information concerning the author of the "Farmer's Letters." The inscription is thus explained as well as the elimination of the vowels from Dickinson's name.

PHILADELPHIA

On Tuesday last, by order of the Governor and Society of Fort St. David's, fourteen Gentlemen, members of that Company, waited upon J-n D-ck-nson Esq; and presented the following address, in a Box of Heart of Oak.

Respected Sir,

When a Man of Abilities, prompted by Love of his Country, exerts them in her Cause, and renders her the most eminent Services, not to be sensible, of the Benefits received, is Stupidity; not to be grateful for them, is Baseness.

Influenced by this Sentiment, we, the Governor and Company of Fort St. David's, who among other Inhabitants of British America, are indebted to you for your most excellent and generous Vindication of Liberties dearer to us than our Lives, beg Leave to return you our heartiest Thanks, and offer to you the greatest Mark of Esteem, that, as a Body, it is in our Power to bestow, by admitting you, as we hereby do, a Member of our Society.

When that destructive Project of Taxation, which your Integrity and Knowledge so signally contributed to baffle about two years ago, was lately renewed under a Disguise so artfully contrived as to delude Millions, You, sir, watchful for the Interests of Your Country, perfectly acquainted with them, and undaunted in asserting them, Alone detected the Monster concealed from others by an altered Appearance, exposed it, stripped of its insidious covering, in its own horrid Shape, and, we firmly trust by the Blessing of God on Your Wisdom and Virtue, will again extricate the British Colonies on this Continent from the cruel Snares of Oppression; for we already perceive these Colonies ROUSED by your strong and seasonable Call, pursuing the salutary Measures advised by You for obtaining Redress.

Nor is this all that you have performed for Your native Land. Animated by a sacred Zeal, guided by Truth and supported by Justice, You have penetrated to the Foundations of the Constitution, have poured the clearest Light on the important Points, hitherto involved in a Darkness bewildering even the Learned, and have established with an amazing Force and Plainness of Argument, the TRUE DISTINCTIONS and GRAND PRINCIPLES, that will fully instruct Ages YET UNBORN, what Rights belong to them, and the best Methods of defending them.

To Merit far less distinguished, ancient Greece or Rome would have decreed Statues and Honours without Number: But it is Your Fortune and your Glory, Sir, that You live in such Times, and possess such exalted Worth, that the Envy of those, whose Duty it is to applaud You, can conceive no other Consolation, than by withholding those Praises in Public, which all honest Men acknowledge in Private that you have deserved.

We present to you, sir, a small gift of a Society not dignified by any legal authority; But when you consider this gift as expressive of the sincere Affection of many of your Fellow Citizens for Your Person, and of their unlimited Approbation of the noble Principles maintained in your unequalled[xli] Labours, we hope this Testimony of our Sentiments will be acceptable to you.

May that all-gracious Being, which in kindness to these colonies gave your valuable Life Existence at the critical Period when it will be most wanted, grant it a long Continuance, filled with every Felicity; and when your Country sustains its dreadful loss, may you enjoy the Happiness of Heaven, and on Earth may your Memory be cherished, as we doubt not it will be, to the latest Posterity.

Signed by the Order of the Society,

John Bayard, Secretary.

The box was finely decorated, and the Inscription neatly done in Letters of Gold. On the Top was represented the Cap of Liberty on a Spear, resting on a Cypher of the Letters I. D. Underneath the Cypher in a semicircular Label——Pro Patria——Around the whole the following words:

The Gift of the Governor and Society of Fort St. David's to the Author of the Farmer's Letters, in grateful Testimony of the very eminent Services thereby rendered to this Country, 1768.

On the Inside of the Top—

The Liberties of

The British Colonies in America

Asserted

With Attic Eloquence,

And Roman Spirit,

by

J-n D-k-ns-n[6] Esqr.;

Barrister at Law.

On the Inside of the Bottom—

Ita Cuique Eveniat

ut de Republica Meruit.On the Outside of the Bottom—A sketch of Fort St. David's.

To which the following Answer was returned.

Gentlemen,

I very gratefully receive the Favour you have been pleased to bestow upon me, in admitting me a Member of your Company; and I return you my heartiest Thanks for your Kindness.

The "Esteem" of worthy Fellow Citizens is a Treasure of greatest Price; and as no man can more highly value it than I do, Your Society in "expressing the Affection" of so many respectable Persons for me, affords Me the sincerest Pleasure.

Nor will this Pleasure be lessened by reflecting, that you may have regarded with a generous Partiality my Attempts to promote the Welfare of our Country; for the Warmth of your Praises in commending a Conduct you suppose to deserve them, gives Worth to these Praises, by proving your Merit, while you attribute Merit to another.

Your Characters, gentlemen, did not need this Evidence to convince Me, how much I ought to prize Your "Esteem" or how much You deserved Mine.

I think myself extremely fortunate, in having obtained your favorable Opinion, which I shall constantly and carefully endeavor to preserve.

I most heartily wish you every Kind of Happiness, and particularly that you may enjoy the comfortable Prospect of transmitting to your Posterity those "Liberties" dearer to You than your Lives, "which God gave to you, and which no inferior Power has a Right to take away."

The potter's art, which from time immemorial

has been the means of transmitting

history, furnishes the other illustration and

also perpetuates the estimate of Dickinson's

character held by William Duesbury, England's

greatest manufacturer of porcelain. It

pictures a porcelain statuette of Mrs. Catherine[xliii]

[xliv]

[xlv]

Macaulay, a well-known historian, whose

"History of England from the Accession of

James the First to that of the Brunswick

Line" and other historical writings met with

great approval among the Whig party in

England and whose decided approval of the

stand taken by the colonies, gave her great

popularity in America. This statuette, measuring

131⁄2 inches in height, is modeled to a

certain extent after the statue of this lady

which was erected in 1777 in the Church of

St. Stephen, Walbrook, London. Mrs.

Macaulay appears leaning upon her "Histories

of England," which rest on the top of

a pedestal, on the front of which is the inscription,

"Government a Power Delegated

for the Happiness of Mankind conducted by

Wisdom, Justice and Mercy." Beneath are

the words, "American Congress." On the side

of the pedestal the name of Dickinson appears,

preceded by the names of those noble

writers, England's great advocates and expounders

of Constitutional liberty, Sydney,

Hampden, Milton, Locke, Harrington,

Ludlow and Marvel. This beautiful porcelain

statuette was moulded at the Chelsea

factory in 1777, the same year in which

Boswell chronicles Dr. Johnson's visit there,

noting, "The china was beautiful, but Dr.

Johnson justly observed it was too dear, for

he could have vessels of silver as cheap as

were here made of porcelain."

The space at my disposal prevents my[xlvi] quoting many a "Letter to the Printer" appealing for justice for the Colonials as well as numerous contributed articles which appeared during the next few years in the English press, the contents of which clearly show how strongly Dickinson's arguments had influenced their respective authors. While it is true that these sentiments were attacked both at home and abroad, the attacks soon lost their vehemence. Strange as it may seem, more protests against the course of the ministry than denunciations of the doings of the colonial Assemblies are found in the columns of the English press of the period. The demand for the arguments contained in the "Farmer's Letters" was not lessened by subsequent events as their popularity demanded the publishing of another London edition in 1774.

Certainly to John Dickinson for his masterly defence of the rights of the Colonies America owes an everlasting debt of gratitude. The logic of his claims and his warnings as to what must be the ultimate result of the ministerial encroachments upon the liberties of Englishmen did much to win over to the American cause in England that strong ally, the support of a large body of thoughtful Englishmen. These men actively condemned the ministerial actions and during the war which followed caused the course of the government to be bitterly opposed by an influential and constantly[xlvii] growing minority in Parliament. Through their efforts was fostered a public sentiment which caused the war to be prosecuted in a half-hearted manner and obliged a power-loving King to fill the depleted ranks of his army with German mercenaries, so impossible was it to force a sufficient number of his own liberty-loving subjects to fight against their kindred living in the land so happily alluded to by a contributor to the London "Chronicle" (June 3-6, 1769), in the following poem:

The Genius of America to her Sons

An address from the Moderator and Freemen of the Town of Providence in the Colony of Rhode-Island, and Providence Plantation convened in open Meeting the 20th day of June, 1768, to the Author of a Series of Letters signed

A FARMER.

Sir,

In your Retirement, "near the Banks of the River Delaware," where you are compleating, in a rational way, the Number of Days allotted to you by Divine Goodness, the consciousness of having employed those Talents which God hath bestowed upon You, for the Support of our Rights, must afford you a Satisfaction vastly exceeding that, which is derived to you from the universal Approbation of Your Letters,—However amidst the general Acclamation of your Praise, we the Moderator and Freemen of the ancient Town of Providence cannot be silent; although we would not offend your Delicacy, or incur the Imputation of Flattery in expressing our Gratitude to you.

Your Benevolence to Mankind, fully discoverable from your Writings, doubtless caused you to address your countrymen, whom you tenderly call Dear and Beloved, in a Series of Letters, wherein you have with a great Judgment, and in the most spirited and forcible Manner explained their Rights and Privileges; and vindicated them against such as would reduce these extensive Dominions[lii] of His Majesty to Poverty, Misery, and Slavery. This Your patriotic Exertion in our Cause and indeed in the Cause of all the human Race in some Degree, hath rendered you very dear to us, although we know not your Person.

We deplore the Frailty of human Nature, in that it is necessary that we should be frequently awakened into Attention to our Duty in Matters very plain and incontrovertible, if we would suffer ourselves to consider them. From this Inattention to Things evidently the Duty and Interest of the World, we suppose despotic Rule to have originated, and all the Train of Miseries consequent thereupon.

The virtuous and good Man, who rouses an injured Country from their Lethargy, and animates them into active and successful Endeavours for casting off the Burdens imposed on them, and effecting a full Enjoyment of the Rights of Men, which no Human Creature ought to violate, will merit the warmest Expressions of Gratitude from his Countrymen, for his Instrumentality in saving them and their Posterity.

As the very Design of instituting civil Government in the World was to secure to Individuals a quiet Enjoyment of their native Rights, wherever there is a Departure from this great and only End, impious Force succeeds. The Blessings of a just Government, and the Horror of brutal Violence are both inexpressible. As the latter is generally brought upon People by Degrees, it will be their Duty to watch against even the smallest attempt to "innovate a single Iota" in their Privilege.

With Hearts truly loyal to the King, we feel the greatest concern at divers Acts of the British Parliament, relative to these colonies. We are clear and unanimous in Sentiment that they are[liii] subversive of our Liberties, and derogatory to the Power and Dignity of the several Legislatures established in America.

Permit us, Sir, to assure you that we feel an ineffable Gratitude to you, for sending forth your Letters at a Time when the Exercise of great Abilities was necessary. We sincerely wish that You may see the Fruit of your Labours. We on our parts shall be ready at all Times to evince to the World that we will not surrender our privileges to any of our Fellow Subjects, but will earnestly contend for them, hoping that the "Almighty will look upon our righteous contest with gracious approbation." We hope that the Conduct of the Colonies on this Occasion will be "peaceable, prudent, firm, and joint; and such as will show their Loyalty to the best of Sovereigns, and that they know what they owe to themselves as well as to Great-Britain."

Signed by Order

JAMES ANGELL, Town Clerk.

"Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies. 8vo. 2s. Almon. 1768.

"We have, in the Letters now before us, a calm yet full inquiry into the right of the British parliament, lately assumed, to tax the American colonies; the unconstitutional nature of which attempt is maintained in a well-connected chain of close and manly reasoning; and though from this character, it is evident that detached passages[liv] must appear to a disadvantage, yet it is but just to give our Readers some specimens of the manner in which the author asserts the rights of his American brethren; subjects of the British government, as he pleads, carrying their birthrights with them wherever they settle as such.

'Colonies, says he, were formerly planted by warlike nations, to keep their enemies in awe; to relieve their country overburthened with inhabitants; or to discharge a number of discontented and troublesome citizens. But in more modern ages, the spirit of violence being, in some measure, if the expression may be allowed, sheathed in commerce, colonies have been settled by the nations of Europe for the purposes of trade. These purposes were to be attained, by the colonies raising for their mother country those things which she did not produce herself; and by supplying themselves from her with things they wanted. These were the national objects in the commencement of our colonies, and have been uniformly so in their promotion.

'To answer these grand purposes, perfect liberty was known to be necessary; all history proving, that trade and freedom are nearly related to each other. By a due regard to this wise and just plan, the infant colonies, exposed in the unknown climates and unexplored wildernesses of this new world, lived, grew, and flourished.

'The parent country, with undeviating prudence and virtue, attentive to the first principles of colonization, drew to herself the benefits she might reasonably expect, and preserved to her children the blessings, upon which those benefits were founded. She made laws, obliging her colonies to carry to her all those products which she wanted for her own use; and all those raw materials which she chose herself to work up. Besides this restriction, she forbade them to procure manufactures from any other part of the globe, or even the products of European countries, which alone could rival her,[lv] without being first brought to her. In short, by a variety of laws, she regulated their trade in such a manner as she thought most conducive to their mutual advantage and her own welfare. A power was reserved to the crown of repealing any laws that should be enacted: the executive authority of government was also lodged in the crown, and its representatives; and an appeal was secured to the crown from all judgments in the administration of justice.

'For all these powers, established by the mother country over the colonies; for all these immense emoluments derived by her from them; for all their difficulties and distresses in fixing themselves, what was the recompense made them? A communication of her rights in general, and particularly of that great one, the foundation of all the rest—that their property, acquired with so much pain and hazard, should be disposed of by none but themselves—or, to use beautiful and emphatic language of the sacred scriptures, "that they should sit every man under his vine, and under his fig-tree, and none should make them afraid."

'Can any man of candour and knowledge deny that these institutions form an affinity between Great Britain and her colonies, that sufficiently secures their dependence upon her? Or that for her to levy taxes upon them is to reverse the nature of things? Or that she can pursue such a measure without reducing them to a state of vassalage?

'If any person cannot conceive the supremacy of Great Britain to exist, without the power of laying taxes to levy money upon us, the history of the colonies, and of Great Britain, since their settlement, will prove the contrary. He will there find the amazing advantages arising to her from them—the constant exercise of her supremacy—and their filial submission to it, without a single rebellion, or even the thought of one, from their first emigration to this moment—and all these things have happened, without one instance of[lvi] Great Britain's laying taxes to levy money upon them.

'How many British authors have demonstrated, that the present wealth, power and glory of their country, are founded upon these colonies? As constantly as streams tend to the ocean have they been pouring the fruits of all their labours into their mother's lap. Good heaven! and shall a total oblivion of former tendernesses and blessings, be spread over the minds of a good and wise nation by the sordid arts of intriguing men, who, covering their selfish projects under pretences of public good, first enrage their countrymen into a frenzy of passion, and then advance their own influence and interest, by gratifying the passion, which they themselves have basely excited.

'Hitherto Great Britain has been contented with her prosperity, moderation has been the rule of her conduct. But now, a generous, humane people, that so often have protected the liberty of strangers, is inflamed into an attempt to tear a privilege from her own children, which if executed, must, in their opinion, sink them into slaves: and for what? for a pernicious power, not necessary to her as her own experience may convince her; but horribly dreadful and detestable to her.

'It seems extremely probable, that when cool, dispassionate prosperity, shall consider the affectionate intercourse, the reciprocal benefits, and the unsuspecting confidence, that have subsisted between these colonies and their parent country, for such a length of time, they will execrate, with the bitterest curses, the infamous memory of those men, whose pestilential ambition unnecessarily, wantonly, first opened the sources of civil discord between them; first turned their love into jealousy; and first taught these provinces, filled with grief and anxiety, to enquire.'

"As every community possessed of valuable privileges, and desirous to preserve the enjoyment of them, ought to be very cautious of admitting[lvii] innovations from their established forms of political administration, our Author does not confine his views to the immediate effects of the laws lately passed regarding America; but considers the necessary tendency of the precedents; thus he says,

'I have looked over every statute relating to these colonies, from their first settlement to this time; and I find everyone of them founded on this principle, till the stamp-act administration. All before, are calculated to regulate trade, and preserve or promote a mutually beneficial intercourse between the several constituent parts of the empire; and though many of them imposed duties on trade, yet those duties were always imposed with design to restrain the commerce of one part, that was injurious to another, and thus to promote the general welfare. The raising a revenue thereby was never intended. Thus, the king by his judges in his courts of justice, impose fines, which altogether amount to a very considerable sum, and contribute to the support of government; but this is merely a consequence arising from restrictions, that only meant to keep peace, and prevent confusion; and surely a man would argue very loosely, who should conclude from hence, that the king has a right to levy money in general upon his subjects. Never did the British parliament, till the period above mentioned, think of imposing duties in America, for the purpose of raising a revenue. Mr. Grenville first introduced this language, in the preamble to the fourth of George III. chap. 15, which has these words—"and whereas it is just and necessary that a revenue be raised in your majesty's said dominions in America, for defraying the expenses of defending, protecting and securing the same: We your majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the commons of Great Britain, in Parliament assembled, being desirous to make some provisions in this present session of parliament, towards raising the said revenue in America, have resolved to give and grant unto your majesty the several rates and duties hereinafter mentioned," etc.

'A few months after came the stamp-act, which reciting this, proceeds in the same strange mode of expression, thus—"And whereas it is just and necessary, that provision be made for raising a further revenue within your majesty's dominions in America, towards defraying the said expenses, we your majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the commons of Great Britain, etc., give and grant," etc., as before.

'The last act, granting duties upon paper, etc., carefully pursues these modern precedents. The preamble is, "Whereas it is expedient, that a revenue should be raised in your majesty's dominions in America for making a more certain and adequate provision for defraying the charge of the administration of justice, and the support of civil government in such provinces, where it shall be found necessary; and towards the further defraying of the expences of defending, protecting, and securing the said dominions, we your majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the commons of Great Britain, etc. give and grant," etc. as before.

'Here we may observe an authority expresly claimed and exerted to impose duties on these colonies; not for the regulation of trade; not for the preservation or promotion of a mutually beneficial intercourse between the several constituent parts of the empire, heretofore the sole objects of parliamentary institutions; but for the single purpose of levying money upon us.'

"Again in another place,

'What but the indisputable, the acknowledged exclusive right of the colonies to tax themselves, could be the reason, that in this long period of more than one hundred and fifty years, no statute was ever passed for the sole purpose of raising a revenue from the colonies? And how clear, how cogent must that reason be, to which every parliament, and every ministry for so long a time submitted, without a single attempt to innovate?

'England, in part of that course of years, and[lix] Great Britain, in other parts, was engaged in several fierce and expensive wars; troubled with some tumultuous and bold parliaments; governed by many daring and wicked ministers; yet none of them ever ventured to touch the Palladium of American liberty. Ambition, avarice, faction, tyranny, all revered it. Whenever it was necessary to raise money on the colonies, the requisitions of the crown were made, and dutifully complied with. The parliament, from time to time, regulated their trade, and that of the rest of the empire, to preserve their dependence and the connections of the whole in good order.'

"The amount of present duties exacted in an unusual way is no part of the object in question; for our Pennsylvanian Farmer observes:

'Some persons may think this act of no consequence, because the duties are so small. A fatal error. That is the very circumstance most alarming to me. For I am convinced, that the authors of this law would never have obtained an act to raise so trifling a sum as it must do, had they not intended by it to establish a precedent for future use. To console ourselves with the smallness of the duties, is to walk deliberately into the snare that is set for us, praising the neatness of the workmanship. Suppose the duties imposed by the late act could be paid by these distressed colonies with the utmost ease, and that the purposes to which they are to be applied, were the most reasonable and equitable that can be conceived, the contrary of which I hope to demonstrate before these letters are concluded; yet even in such a supposed case, these colonies ought to regard the act with abhorrence. For who are a free people? Not those, over whom government is reasonably and equitably exercised, but those, who live under a government so constitutionally checked and controuled, that proper provision is made against its being otherwise exercised.

'The late act is founded on the destruction of this constitutional security. If the parliament have a right to lay a duty of four shillings and eight pence on a hundred weight of glass, or a ream of paper, they have a right to lay a duty of any other sum on either. They may raise the duty, as the author before quoted says has been done in some countries, till it "exceeds seventeen or eighteen times the value of the commodity." In short, if they have a right to levy a tax of one penny upon us, they have a right to levy a million upon us; for where does their right stop? At any given number of pence, shillings or pounds? To attempt to limit their right, after granting it to exist at all, is as contrary to reason—as granting it to exist at all, is contrary to justice. If they have any right to tax us—then, whether our own money shall continue in our pockets or not, depends no longer on us, but on them, "There is nothing which "we" can call our own; or, to use the words of Mr. Locke—what property have "we" in that which another may, by right, take, when he pleases, to himself?"

'These duties which will inevitably be levied upon us—which are now levying upon us—are expresly laid for the sole purpose of taking money. This is the true definition of "taxes." They are therefore taxes. This money is to be taken from us. We are therefore taxed. Those who are taxed without their own consent, expressed by themselves or their representatives are slaves. We are taxed without our own consent, expressed by ourselves or representatives. We are therefore slaves.'

"Further,

'Indeed nations in general are more apt to feel than to think; and therefore nations in general have lost their liberty: for as the violation of the rights of the governed are commonly not only specious, but small at the beginning, they spread over the multitude in such a manner, as to touch individuals but slightly; thus they are disregarded. The[lxi] power or profit that arises from these violations, centering in a few persons, is to them considerable. For this reason, the Governors having in view their particular purposes, successively preserve an uniformity of conduct for attaining them: they regularly increase and multiply the first injuries, till at length the inattentive people are compelled to perceive the heaviness of their burthen. They begin to complain and inquire—but too late. They find their oppressions so strengthened by success, and themselves so entangled in examples of express authority on the part of their rulers, and of tacit recognition on their own part, that they are quite confounded: for millions entertain no other idea of the legality of power, than that it is founded on the exercise of power. They then voluntarily fasten their chains by adopting a pusillanimous opinion "that there will be too much danger in attempting a remedy"—or another opinion no less fatal, "that the government has a right to treat them as it does." They then seek a wretched relief for their minds, by persuading themselves, that to yield their obedience, is to discharge their duty. The deplorable poverty of spirit, that prostrates all the dignity bestowed by Divine Providence on our nature—of course succeeds.'

"With regard to the proper conduct of the colonies on this occasion he premises the following questions:

'Has not the parliament expressly avowed their intention of raising money from us for certain purposes? Is not this scheme popular in Great Britain? Will the taxes imposed by the late act, answer those purposes? If it will, must it not take an immense sum from us? If it will not, is it to be expected, that the parliament will not fully execute their intention, when it is pleasing at home, and not opposed here? Must not this be done by imposing new taxes? Will not every addition thus made to our taxes, be an addition to the power of the British legislature, by increasing the number of officers employed in the collection?[lxii] Will not every additional tax therefore render it more difficult to abrogate any of them? When a branch of revenue is once established, does it not appear to many people invidious and undutiful, to attempt to abolish it? If taxes sufficient to accomplish the intention of the parliament, are imposed by the parliament, what taxes will remain to be imposed by our assemblies? If no material taxes remain to be imposed by them, what must become of them, and the people they represent?'

"Our Author all along, however, asserts that the real interest of English America consists in its proper dependence on the mother country, at the same time that he strenuously exhorts his countrymen to oppose, by all the suitable means in their power, every incroachment on those constitutions under the sanction of which they settled on those remote and uncultivated shores, whereon they have so industriously established themselves. He remarks with a spirit which no one, it is apprehended, can condemn:

'I am no further concerned in anything affecting America, than any one of you; and when liberty leaves it, I can quit it much more conveniently than most of you: but while divine providence, that gave me existence in a land of freedom, permits my head to think, my lips to speak, and my hands to move, I shall so highly and gratefully value the blessing received, as to take care, that my silence and inactivity shall not give my implied assent to any act, degrading my brethren and myself from the birthright, wherewith heaven itself "hath made us free.'

"The consequence of Great Britain exerting this disagreeable power, he shews, in a long train of arguments, to have a tendency very fatal to the liberty of America, which he illustrates by examining into the application of the pensions on the[lxiii] Irish establishment; and sums up his reasoning with the following positions:

'Let these truths be indelibly impressed on our mind—that we cannot be happy, without being free—that we cannot be free, without being secure—in our property—that we cannot be secure in our property, if, without our consent, others may, as by right, take it away—that taxes imposed on us by parliament, do thus take it away—that duties laid for the sole purposes of raising money, are taxes—that attempts to lay such duties should be instantly and firmly opposed—that this opposition can never be effectual, unless it is the united effort of those provinces—that therefore benevolence of temper towards each other, and unanimity of counsels, are essential to the welfare of the whole—and lastly, that for this reason, every man amongst us, who in any manner would encourage either dissention, diffidence, or indifference, between these colonies, is an enemy to himself, and to his country.

'The belief of these truths, I verily think, my countrymen, is indispensably necessary to your happiness. I beseech you, therefore, "teach them diligently unto your children, and talk of them when you sit in your houses, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down and when you rise up."

'What have these colonies to ask, while they continue free? or what have they to dread, but insidious attempts to subvert their freedom? Their prosperity does not depend on ministerial favours doled out to particular provinces. They form one political body, of which each colony is a member. Their happiness is founded on their constitution; and is to be promoted by preserving that constitution in unabated vigour, throughout every part. A spot, a speck of decay, however small the limb on which it appears, and however remote it may seem from the vitals, should be alarming. We have all the rights requisite for our prosperity. The legal authority of Great Britain may indeed lay hard restrictions[lxiv] upon us; but, like the spear of Telephus, it will cure as well as wound. Her unkindness will instruct and compel us, after some time to discover, in our industry and frugality, surprising remedies—if our rights continue unviolated: for as long as the products of our labour, and the rewards of our care, can properly be called our own, so long will it be worth our while to be industrious and frugal. But if we plow—sow—reap—gather and thresh—we find, that we plow—sow—reap—gather and thresh for others, whose pleasure is to be the SOLE limitation how much they shall take and how much they shall leave, WHY should we repeat the unprofitable toil? Horses and oxen are content with that portion of the fruits of their work, which their owners assign to them, in order to keep them strong enough to raise successive crops; but even these beasts will not submit to draw for their masters, until they are subdued with whips and goads. Let us take care of our rights, and we therein take care of our property. "Slavery is ever preceded by sleep." Individuals may be dependent on ministers if they please. States should scorn it; and if you are not wanting to yourselves, you will have a proper regard paid you by those, to whom if you are not respectable, you will infallibly be contemptible. But—if we have already forgot the reasons that urged us, with unexampled unanimity, to exert ourselves two years ago—if our zeal for the public good is worn out before the homespun cloaths which it caused us to have made—if our resolutions are so faint, as by our present conduct to condemn our own late successful example—if we are not affected by any reverence for the memory of our ancestors, who transmitted to us that freedom in which they had been blest—if we are not animated by any regard for posterity, to whom, by the most sacred obligations, we are bound to deliver down the invaluable inheritance—THEN, indeed, any minister, or any tool of a minister, or any creature of a tool of a minister—or any lower instrument of administration, if lower there be, is a personage whom it may be dangerous to offend.'

"In justification of the Letter-writer's loyalty, and the integrity of his intentions, he declares in a note:

'If any person shall imagine that he discovers in these letters the least disaffection towards our most excellent sovereign, and the parliament of Great Britain, or the least dislike of the dependence of these colonies on that kingdom, I beg that such person will not form any judgment on particular expressions, but will consider the tenour of all the letters taken together. In that case, I flatter myself that every unprejudiced reader will be convinced, that the true interests of Great Britain are as dear to me as they ought to be to every good subject.

'If I am an enthusiast in anything, it is in my zeal for the perpetual dependance of these colonies on the mother country.—A dependance founded on mutual benefits, the continuance of which can be secured only by mutual affections. Therefore it is, that with extreme apprehension I view the smallest seeds of discontent, which are unwarily scattered abroad. Fifty or sixty years will make astonishing alterations in these colonies; and this consideration should render it the business of Great Britain more and more to cultivate our good dispositions toward her: but the misfortune is, that those great men, who are wrestling for power at home, think themselves very slightly interested in the prosperity of their country fifty or sixty years hence; but are deeply concerned in blowing up a popular clamour for supposed immediate advantages.

'For my part, I regard Great Britain as a bulwark happily fixed between these colonies and the powerful nations of Europe. That kingdom is our advanced post or fortification, which remaining safe, we under its protection enjoying peace, may diffuse the blessings of religion, science, and liberty, through remote wildernesses. It is, therefore, incontestably our duty and our interest to support the strength of Great Britain. When, confiding[lxvi] in that strength, she begins to forget from whence it arose, it will be an easy thing to shew the source. She may readily be reminded of the loud alarm spread among her merchants and tradesmen, by the universal association of these colonies, at the time of the stamp-act, not to import any of her MANUFACTURES. In the year 1718, the Russians and Swedes entered into an agreement, not to suffer Great Britain to export any naval stores from their dominions, but in Russian or Swedish ships, and at their own prices. Great Britain was distressed. Pitch and tar rose to three pounds a barrel. At length she thought of getting these articles from the colonies; and the attempt succeeding, they fell down to fifteen shillings. In the year 1756, Great Britain was threatened with an invasion: An easterly wind blowing for six weeks, she could not MAN her fleet; and the whole nation was thrown into the utmost consternation. The wind changed. The American ships arrived. The fleet sailed in ten or fifteen days. There are some other reflections on this subject worthy of the most deliberate attention of the British parliament; but they are of such a nature that I do not chuse to mention them publicly. I thought I discharged my duty to my country, by taking the liberty, in the year 1765, while the stamp-act was in suspence, of writing my sentiments to a man of the greatest influence at home, who afterwards distinguished himself by espousing our cause in the debates concerning the repeal of that act.'

"When we review a performance well written, and founded upon laudable principles, if we do not restrain ourselves to a general approbation, which may be given in few words, the article will unavoidably contain more from the author of it, than from ourselves; this, if any excuse is needful for enabling our Readers, in some measure, to judge for themselves, is pleaded as an apology for our copious extracts from these excellent letters.[lxvii] To conclude; if reason is to decide between us and our colonies, in the affairs here controverted, our Author, whose name the advertisements inform us is Dickenson,[7] will not perhaps easily meet with a satisfactory refutation."

LETTERS

FROM

A FARMER.

LETTERS

FROM

A FARMER in Pennsylvania,

To the INHABITANTS

OF THE

BRITISH COLONIES.

—————

BOSTON:

Printed by Mein and Fleeming, and to

be sold by John Mein, at the

London Book-store, north-side

of King-street.

M DCC LXVIII.

My Dear Countrymen,

I am a farmer, settled after a variety of fortunes, near the banks, of the river Delaware, in the province of Pennsylvania. I received a liberal education, and have been engaged in the busy scenes of life: But am now convinced, that a man may be as happy without bustle, as with it. My farm is small, my servants are few, and good; I have a little money at interest; I wish for no more: my employment in my own affairs is easy; and with a contented grateful mind, I am compleating the number of days allotted to me by divine goodness.

Being master of my time, I spend a good deal of it in a library, which I think the most valuable part of my small estate; and[6] being acquainted with two or three gentlemen of abilities and learning, who honour me with their friendship, I believe I have acquired a greater share of knowledge in history, and the laws and constitution of my country, than is generally attained by men of my class, many of them not being so fortunate as I have been in the opportunities of getting information.

From infancy I was taught to love humanity and liberty. Inquiry and experience have since confirmed my reverence for the lessons then given me, by convincing me more fully of their truth and excellence. Benevolence towards mankind excites wishes for their welfare, and such wishes endear the means of fulfilling them. Those can be found in liberty alone, and therefore her sacred cause ought to be espoused by every man, on every occasion, to the utmost of his power: as a charitable but poor person does not withhold his mite, because he cannot relieve all the distresses of the miserable, so let not any honest man suppress his sentiments concerning freedom, however small their influence is likely to be. Perhaps he may "[8]touch some wheel" that will have an effect greater than he expects.

These being my sentiments, I am encouraged to offer to you, my countrymen, my thoughts on some late transactions, that in[7] my opinion are of the utmost importance to you. Conscious of my defects, I have waited some time, in expectation of seeing the subject treated by persons much better qualified for the task; but being therein disappointed, and apprehensive that longer delays will be injurious, I venture at length to request the attention of the public, praying only for one thing,—that is that these lines may be read with the same zeal for the happiness of British America, with which they were wrote.

With a good deal of surprise I have observed, that little notice has been taken of an act of parliament, as injurious in its principle to the liberties of these colonies, as the Stamp-act was: I mean the act for suspending the legislation of New-York.

The assembly of that government complied with a former act of parliament, requiring certain provisions to be made for the troops in America, in every particular, I think, except the articles of salt, pepper, and vinegar. In my opinion they acted imprudently, considering all circumstances, in not complying so far, as would have given satisfaction, as several colonies did: but my dislike of their conduct in that instance, has not blinded me so much, that I cannot plainly perceive, that they have been punished in a manner pernicious to American freedom, and justly alarming to all the colonies.

If the British Parliament has a legal authority to order, that we shall furnish a single article for the troops here, and to compel obedience to that order; they have the same right to order us to supply those troops with arms, cloaths, and every necessary, and to compel obedience to that order also; in short, to lay any burdens they please upon us. What is this but taxing us at a certain sum, and leaving to us only the manner of raising it? How is this mode more tolerable than the Stamp Act? Would that act have appeared more pleasing to Americans, if being ordered thereby to raise the sum total of the taxes, the mighty privilege had been left to them, of saying how much should be paid for an instrument of writing on paper, and how much for another on parchment?

An act of parliament commanding us to do a certain thing, if it has any validity, is a tax upon us for the expence that accrues in complying with it, and for this reason, I believe, every colony on the continent, that chose to give a mark of their respect for Great-Britain, in complying with the act relating to the troops, cautiously avoided the mention of that act, lest their conduct should be attributed to its supposed obligation.

The matter being thus stated, the assembly of New-York either had, or had not a right to refuse submission to that act. If they[9] had, and I imagine no American will say, they had not, then the parliament had no right to compel them to execute it.—If they had not that right, they had no right to punish them for not executing it; and therefore had no right to suspend their legislation, which is a punishment. In fact, if the people of New-York cannot be legally taxed but by their own representatives, they cannot be legally deprived of the privileges of making laws, only for insisting on that exclusive privilege of taxation. If they may be legally deprived in such a case of the privilege of making laws, why may they not, with equal reason, be deprived of every other privilege? Or why may not every colony be treated in the same manner, when any of them shall dare to deny their assent to any impositions that shall be directed? Or what signifies the repeal of the Stamp-Act, if these colonies are to lose their other privileges, by not tamely surrendering that of taxation?

There is one consideration arising from this suspicion, which is not generally attended to, but shews its importance very clearly. It was not necessary that this suspension should be caused by an act of parliament. The crown might have restrained the governor of New-York, even from calling the assembly together, by its prerogative in the royal governments. This step, I suppose, would have[10] been taken, if the conduct of the assembly of New-York, had been regarded as an act of disobedience to the crown alone: but it is regarded as an act of "disobedience to the authority of the British Legislature." This gives the suspension a consequence vastly more affecting. It is a parliamentary assertion of the supreme authority of the British legislature over these colonies in the part of taxation; and is intended to COMPEL New-York unto a submission to that authority. It seems therefore to me as much a violation of the liberty of the people of that province, and consequently of all these colonies, as if the parliament had sent a number of regiments to be quartered upon them till they should comply. For it is evident, that the suspension is meant as a compulsion; and the method of compelling is totally indifferent. It is indeed probable, that the sight of red coats, and the beating of drums would have been most alarming, because people are generally more influenced by their eyes and ears than by their reason: But whoever seriously considers the matter, must perceive, that a dreadful stroke is aimed at the liberty of these colonies: For the cause of one is the cause of all. If the parliament may lawfully deprive New-York of any of its rights, it may deprive any, or all the other colonies of their rights; and nothing can possibly so much encourage such attempts, as a mutual inattention to the interest[11] of each other. To divide, and thus to destroy, is the first political maxim in attacking those who are powerful by their union. He certainly is not a wise man, who folds his arms and reposeth himself at home, seeing with unconcern the flames that have invaded his neighbour's house, without any endeavours to extinguish them. When Mr. Hampden's ship-money cause, for three shillings and four-pence, was tried, all the people of England, with anxious expectation, interested themselves in the important decision; and when the slightest point touching the freedom of a single colony is agitated, I earnestly wish, that all the rest may with equal ardour support their sister. Very much may be said on this subject, but I hope, more at present is unnecessary.

With concern I have observed that two assemblies of this province have sat and adjourned, without taking any notice of this act. It may perhaps be asked, what would have been proper for them to do? I am by no means fond of inflammatory measures. I detest them.——I should be sorry that any thing should be done which might justly displease our sovereign or our mother-country. But a firm, modest exertion of a free spirit, should never be wanting on public occasions. It appears to me, that it would have been sufficient for the assembly, to have ordered our agents to represent to the King's ministers, their sense of the suspending act, and[12] to pray for its repeal. Thus we should have borne our testimony against it; and might therefore reasonably expect that on a like occasion, we might receive the same assistance from the other colonies.

A FARMER.

Beloved Countrymen,

There is another late act of parliament, which seems to me to be as destructive to the liberty of these colonies, as that inserted in my last letter; that is, the act for granting the duties on paper, glass, &c. It appears to me to be unconstitutional.