The Project Gutenberg EBook of Billy Topsail, M.D., by Norman Duncan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Billy Topsail, M.D.

A Tale of Adventure With Doctor Luke of the Labrador

Author: Norman Duncan

Release Date: October 15, 2014 [EBook #47128]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILLY TOPSAIL, M.D. ***

Produced by David Edwards, Joke Van Dorst and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

By NORMAN DUNCAN

Each Illustrated, 12mo, cloth, net $1.25

The Adventures of Billy Topsail

"There was no need to invent conditions or imagine situations. The life of any lad of Billy Topsail's years up there is sufficiently romantic. It is this skill in the portrayal of actual conditions that lie ready to the hand of the intelligent observer that makes Mr. Duncan's Newfoundland stories so noteworthy."—Brooklyn Eagle.

Billy Topsail and Company

"Another rousing volume of 'The Billy Topsail Books.' Norman Duncan has the real key to the boy heart and in Labrador he has opened up a field magnetic in its perils and thrills and endless excitements."—Examiner.

Billy Topsail, M. D.

A Tale of Adventure with "Doctor Luke of the Labrador."

The further adventures of Billy Topsail and Archie Armstrong on the ice, in the forest and at sea. In a singular manner the boys fall in with a doctor of the outposts and are moved to join forces with him. The doctor is Doctor Luke of the Labrador whose prototype as every one knows is Doctor Grenfell. Its pages are as crowded with brisk adventures as those of the preceding books.

BILLY TOPSAIL, M.D.

A Tale of Adventure With Doctor Luke of the Labrador

By

NORMAN DUNCAN

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1916, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 North Wabash Ave.

Toronto: 25 Richmond Street, W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

In this tale of the seas and ice-floes of Newfoundland and Labrador, Billy Topsail adventures with Doctor Luke of the Labrador. There are thrilling passages in the book. The author is frank to admit the hair-raising quality of them. Indeed, they have tickled his own scalp. Well, it is proper that the hair of the reader should sometimes stand on end and his eyes pop wide. The author would be a poor teller of tales if he could not manage as much—a charlatan if he did not. Yet these thrilling passages are not the work of a saucy imagination, delighting in shudders, no matter what, but are all decently founded upon fact, true to the experience of the coast, as many a Newfoundlander, boy and man, could tell you.

Doctor Luke has often been mistaken for Doctor Wilfred Grenfell of the Deep Sea Mission. That should not be. No incident in this book is a transcript from Doctor Grenfell's long and heroic service. What Billy Topsail and Doctor[6] Luke encounter, however, is precisely what the Deep Sea Mission workers must encounter. It should be said, too, that as the tale is told of the spring of the year, when the ice breaks up and the floes come drifting out of the north with great storms, Newfoundland presents herself in her worst mood. Yet the sun shines in Newfoundland, tender enough in summer weather—there are flowers on the hills and warm winds on the sea; and such as learn to know the land come quickly to love her for her beauty and for her friendliness.

N. D.

New York, March, 1916.

| Chapter I | 15 |

| In which it is hinted that Teddy Brisk would make a nice little morsel o' dog meat, and Billy Topsail begins an adventure that eventually causes his hair to stand on end and is likely to make the reader's do the same. | |

| Chapter II | 24 |

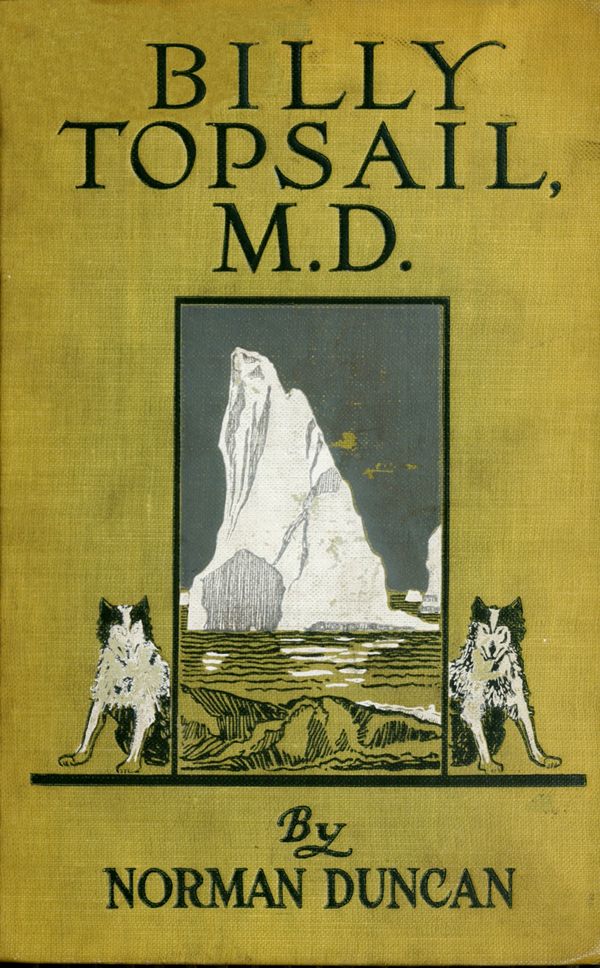

| In which Timothy Light's team of ten potential outlaws is considered, and there is a significant description of the career of a blood-guilty, ruined young dog, which is in the way of making desperate trouble for somebody. | |

| Chapter III | 33 |

| In which Timothy Light's famished dogs are committed to the hands of Billy Topsail and a tap on the snout is recommended in the probable case of danger. | |

| Chapter IV | 40 |

| In which the komatik is foundered, the dogs draw their own conclusions from the misfortune and prepare to take advantage, Cracker attempts a theft and gets a clip on the snout, and Billy Topsail and Teddy Brisk confront a situation of peril with composure, not knowing the ultimate disaster that impends. | |

| Chapter V | 50 |

| In which the wind goes to work, the ice behaves in an alarming way, Billy Topsail regrets, for obvious reasons, having to do with the dogs, that he had not brought an axe, and Teddy Brisk protests that his mother knew precisely what she was talking about. | |

| Chapter VI | 56 |

| In which the sudden death of Cracker is contemplated as a thing to be desired, Billy Topsail's whip disappears, a mutiny is declared and the dogs howl in the darkness. | |

| [8] | |

| Chapter VII | 64 |

| In which a blazing club plays a salutary part, Teddy Brisk declares the ways of his mother, and Billy Topsail looks forward to a battle that no man could win. | |

| Chapter VIII | 70 |

| In which Teddy Brisk escapes from the wolfskin bag and determines to use his crutch and Billy Topsail comes to the conclusion that "it looks bad." | |

| Chapter IX | 76 |

| In which attack is threatened and Billy Topsail strips stark naked in the wind in pursuit of a desperate expedient and with small chance of success. | |

| Chapter X | 82 |

| In which Teddy Brisk confronts the pack alone and Cracker leads the assault. | |

| Chapter XI | 87 |

| In which Teddy Brisk gives the strains of a Tight Cove ballad to the north wind, Billy Topsail wins the reward of daring, Cracker finds himself in the way of the evil-doer, and Teddy Brisk's boast makes Doctor Luke laugh. | |

| Chapter XII | 92 |

| In which Billy Topsail's agreeable qualities win a warm welcome with Doctor Luke at Our Harbour, there is an explosion at Ragged Run, Tommy West drops through the ice and vanishes, and Doctor Luke is in a way never to be warned of the desperate need of his services. | |

| Chapter XIII | 100 |

| In which Doctor Luke undertakes a feat of daring and endurance and Billy Topsail thinks himself the luckiest lad in the world. | |

| Chapter XIV | 104 |

| In which Billy Topsail and Doctor Luke take to the ice in the night and Doctor Luke tells Billy Topsail something interesting about Skinflint Sam and Bad-Weather Tom West of Ragged Run. | |

| [9] | |

| Chapter XV | 112 |

| In which Bad-Weather Tom West's curious financial predicament is explained. | |

| Chapter XVI | 118 |

| In which Doctor Luke and Billy Topsail proceed to accomplish what a cat would never attempt and Doctor Luke looks for a broken back whilst Billy Topsail shouts, "Can you make it?" and hears no answer. | |

| Chapter XVII | 126 |

| In which rubber ice is encountered and Billy Topsail is asked a pointed question. | |

| Chapter XVIII | 134 |

| In which discretion urges Doctor Luke to lie still in a pool of water. | |

| Chapter XIX | 140 |

| In which Doctor Luke and Billy Topsail hesitate in fear on the brink of Tickle-my-Ribs. | |

| Chapter XX | 149 |

| In which Skinflint Sam of Ragged Run finds himself in a desperate predicament and Bad-Weather Tom West at last has what Skinflint Sam wants. | |

| Chapter XXI | 158 |

| In which a Crœsus of Ragged Run drives a hard bargain in a gale of wind. | |

| Chapter XXII | 167 |

| In which Doctor Luke and Billy Topsail go north, and at Candlestick Cove, returning, Doctor Luke finds himself just a bit peckish. | |

| Chapter XXIII | 174 |

| In which, while Doctor Luke and Billy Topsail rest unsuspecting at Candlestick Cove, Tom Lute, the father of the Little Fiddler of Amen Island, sharpens an axe in the wood-shed, and the reader is left to draw his own conclusions respecting the sinister business. | |

| [10] | |

| Chapter XXIV | 184 |

| In which Bob Likely, the mail-man, interrupts Doctor Luke's departure, in the nick of time, with an astonishing bit of news, and the ice of Ships' Run begins to move to sea in a way to alarm the stout hearted. | |

| Chapter XXV | 190 |

| In which a stretch of slush is to be crossed and Billy Topsail takes the law in his own hands. | |

| Chapter XXVI | 196 |

| In which it seems that an axe and Terry Lute's finger are surely to come into injurious contact, and Terry Lute is caught and carried bawling to the block, while his mother holds the pot of tar. | |

| Chapter XXVII | 204 |

| In which Doctor Luke's flesh creeps, Billy Topsail acts like a bob-cat, and the Little Fiddler of Amen Island tells a secret. | |

| Chapter XXVIII | 212 |

| In which Sir Archibald Armstrong's son and heir is presented for the reader's inspection, highly complimented and recommended by the author, and the thrilling adventure, which Archie and Billy are presently to begin, has its inception on the departure of Archie from St. John's aboard the Rough and Tumble. | |

| Chapter XXIX | 221 |

| In which the crew of the Rough and Tumble is harshly punished, and Archie Armstrong, having pulled the wool over the eyes of Cap'n Saul, goes over the side to the floe, where he falls in with a timid lad, in whose company, with Billy Topsail along, he is some day to encounter his most perilous adventure. | |

| Chapter XXX | 226 |

| In which a little song-maker of Jolly Harbour enlists the affection of the reader. | |

| Chapter XXXI | 232 |

| In which a gale of wind almost lays hands on the crew of the Rough and Tumble, Toby Farr is confronted with the suggestion of dead men, piled forward like cord-wood, and Archie Armstrong joins Bill o' Burnt Bay and old Jonathan in a roar of laughter. | |

| [11] | |

| Chapter XXXII | 240 |

| In which Archie Armstrong and Billy Topsail say good-bye to Toby Farr for the present, and, bound down to Our Harbour with Doctor Luke, enter into an arrangement, from which issues the discovery of a mysterious letter and sixty seconds of cold thrill. | |

| Chapter XXXIII | 251 |

| In which the letter is opened, Billy and Archie are confronted by a cryptogram, and, having exercised their wits, conclude that somebody is in desperate trouble. | |

| Chapter XXXIV | 257 |

| In which Archie and Billy resolve upon a deed of their own doing, and are challenged by Ha-ha Shallow of Rattle Water. | |

| Chapter XXXV | 265 |

| In which Billy Topsail takes his life in his hands and Ha-ha Shallow lays hold of it with the object of snatching it away. | |

| Chapter XXXVI | 271 |

| In which Ha-ha Shallow is foiled, Archie Armstrong displays swift cunning, of which he is well aware, and Billy Topsail, much to his surprise, and not greatly to his distaste, is kissed by a lady of Poor Luck Barrens. | |

| Chapter XXXVII | 279 |

| In which Archie Armstrong rejoins the Rough and Tumble, with Billy Topsail for shipmate, and they seem likely to be left on the floe, while Toby Farr, with the gale blowing cold as death and dark falling, promises to make a song about the ghosts of dead men, but is entreated not to do so. | |

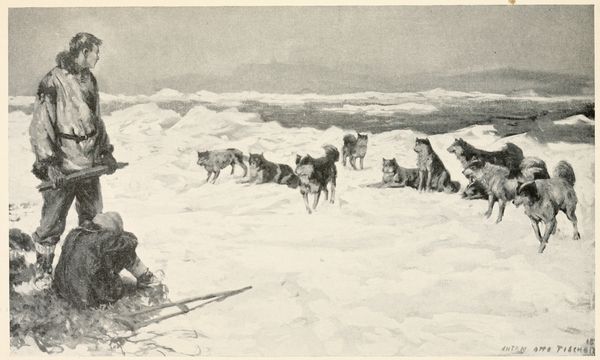

| Chapter XXXVIII | 287 |

| In which the wind blows a tempest, our heroes are lost on the floe, Jonathan Farr is encased in snow and frozen spindrift, Toby strangely disappears, and an heroic fight for life is begun, wrapped in bitter dark. | |

| Chapter XXXIX | 293 |

| In which one hundred and seventy-three men of the Rough and Tumble are plunged in the gravest peril of the coast, wandering like lost beasts, and some drop dead, and some are drowned, and some kill themselves to be done with the torture they can bear no longer. | |

| [12] | |

| Chapter XL | 298 |

| In which Toby Farr falls in the water, and, being soaked to the skin, will freeze solid in half an hour, in the frosty dusk of the approaching night, unless a shift of dry clothes is found, a necessity which sends Jonathan Farr and Billy Topsail hunting for dead men. | |

| Chapter XLI | 305 |

| In which a dead man is made to order for little Toby Farr. | |

| Chapter XLII | 311 |

| In which the tale comes to a good end: Archie and Billy make ready for dinner, Toby Farr is taken for good and all by Sir Archibald, and Billy Topsail, having been declared wrong by Archie's father, takes the path that leads to a new shingle, after which the author asks a small favour of the reader. |

In Which It Is Hinted that Teddy Brisk Would Make a Nice Little Morsel o' Dog Meat, and Billy Topsail Begins an Adventure that Eventually Causes His Hair to Stand on End and Is Likely to Make the Reader's Do the Same

One dark night in the fall of the year, the trading-schooner Black Bat, of Ruddy Cove, slipped ashore on the rocks of Tight Cove, of the Labrador. She was frozen fast before she could be floated. And that was the end of her flitting about. It was the end, too, of Billy Topsail's rosy expectation of an hilarious return to his home at Ruddy Cove. Winter fell down next day. A great wind blew with snow and frost; and when the gale was blown out—the sun out and the sky blue again—it was out of the question to rip the Black Bat out of her icy berth in Tight Cove Harbour and put her on the tumbled way to Ruddy.

And that is how it came about that Billy Topsail passed the winter at Tight Cove, with Teddy Brisk, and in the spring of the year, when the ice was breaking up, fell in with Doctor Luke of the Labrador in a way that did not lack the aspects of an adventure of heroic proportions. It was no great hardship to pass the winter at Tight Cove: there was something to do all the while—trapping in the back country; and there was no uneasiness at home in Ruddy Cove—a wireless message from the station at Red Rock had informed Ruddy Cove of the fate of the Black Bat and the health and comfort of her crew.

And now for the astonishing tale of how Doctor Luke and Billy Topsail fell in together——

When Doctor Luke made Tight Cove, of the Labrador, in the course of his return to his little hospital at Our Harbour, it was dusk. His dogs were famished; he was himself worn lean with near five hundred miles of winter travel, which measured his northern round, and his komatik (sled) was occupied by an old dame of Run-by-Guess Harbour and a young man of Anxious Bight. The destitute old dame of Run-by-[17]Guess Harbour was to die of her malady in a cleanly peace; the young man of Anxious Bight was to be relieved of those remnants of a shoulder and good right arm that an accidental gunshot wound had left to endanger his life.

It was not fit weather for any man to be abroad—a biting wind, a frost as cold as death, and a black threat of snow; but Doctor Luke, on this desperate business of healing, was in haste, and the patients on the komatik were in need too urgent for any dawdling for rest by the way. Schooner Bay ice was to cross; he would put up for the night—that was all; he must be off at dawn, said he in his quick, high way.

From this news little Teddy Brisk's mother returned to the lamp-lit cottage by Jack-in-the-Box. It was with Teddy Brisk's mother that Billy Topsail was housed for the winter.

"Is I t' go, mum?" said Teddy.

Teddy Brisk's mother trimmed the lamp.

"He've a ol' woman, dear," she replied, "from Run-by-Guess."

Teddy Brisk's inference was decided.

"Then he've room for me," he declared; "an' I'm not sorry t' learn it."

"Ah, well, dear, he've also a poor young feller from Anxious Bight."

Teddy Brisk nodded.

"That's all about that," said he positively. "He've no room for me!"

Obviously there was no room for little Teddy Brisk on Doctor Luke's komatik. Little Teddy Brisk, small as he was, and however ingenious an arrangement might be devised, and whatever degree of compression might be attempted, and no matter what generous measure of patience might be exercised by everybody concerned, including the dogs—little Teddy Brisk of Tight Cove could not be stowed away with the old dame from Run-by-Guess Harbour and the young man of Anxious Bight.

There were twenty miles of bay ice ahead; the dogs were footsore and lean; the komatik was overflowing—it was out of the question. Nor could Teddy Brisk, going afoot, keep pace with the Doctor's hearty strides and the speed of the Doctor's team—not though he had the soundest little legs on the Labrador, and the longest on the Labrador, of his years, and the sturdiest, anywhere, of his growth.

As a matter of fact, one of Teddy Bris[19]k's legs was as stout and willing as any ten-year-old leg ever you saw; but the other had gone bad—not so recently, however, that the keen Doctor Luke was deceived in respect to the trouble, or so long ago that he was helpless to correct it.

Late that night, in the lamp-lit cottage by Jack-in-the-Box, the Doctor looked over the bad leg with a severely critical eye; and he popped more questions at Teddy Brisk, as Teddy Brisk maintained, than had ever before been exploded on anybody in the same length of time.

"Huh!" said he at last. "I can fix it."

"You can patch un up, sir?" cried Skipper Tom.

This was Thomas Brisk. The father of Teddy Brisk had been cast away, with the Brotherly Love, on the reef by Fly Away Head, in the Year of the Big Shore Catch. This old Thomas was his grandfather.

"No, no, no!" the Doctor complained. "I tell you I can fix it!"

"Will he be as good as new, sir?" said Teddy.

"Will he?" the Doctor replied. "Aha!" he laughed. "You leave that to the carpenter."

"As good as Billy Topsail's off shank?"

"I'll scrape that bad bone in there," said the Doctor, rubbing his hands in a flush of professional expectation; "and if it isn't as good as new when the job's finished I'll—I'll—why, I'll blush, my son: I'll blush all red and crimson and scarlet."

Teddy Brisk's mother was uneasy.

"Will you be usin' the knife, sir?"

"The knife? Certainly!"

"I'm not knowin'," said the mother, "what little Teddy will say t' that."

"What say, son?" the Doctor inquired.

"Will it be you that's t' use the knife?" asked Teddy.

"Mm-m!" said the Doctor. He grinned and twinkled. "I'm the butcher, sir."

Teddy Brisk laughed. "That suits me!" said he.

"That's hearty!" the Doctor exclaimed. He was delighted. The trust was recompense. God knows it was welcome! "I'll fix you, Teddy boy," said he, rising. And to Skipper Thomas: "Send the lad over to the hospital as soon as you can, Skipper Thomas. When the ice goes out we'll be crowded to the roof at Our Harbour. It's the same way every spring.[21] Egad! they'll sweep in like the flakes of the first fall of snow! Now's the time. Make haste! We must have this done while I've a cot to spare."

"I will, sir."

"We're due for a break-up soon, I suppose—any day now; but this wind and frost will hold the ice in the bay for a while. You can slip the lad across any day. It must be pretty fair going out there. You can't bring him yourself, Skipper Thomas. Who can? Somebody here? Timothy Light? Old Sam's brother, isn't he? I know him. It's all arranged, then. I'll be looking for the lad in a day or two. You've plenty of dogs in Tight Cove, haven't you?"

"Oh, aye, sir," Skipper Thomas replied; "we've dogs, sir—never you mind about that!"

"Whose dogs?"

"Timothy Light's dogs."

The Doctor grinned again.

"That pack!" said he.

"A saucy pack o' dogs!" said Teddy's mother. "It's mostly new this season. I don't like un! I'm fair afraid o' them, sir. That big Cracker, sir, that Timothy haves for bully an' leader—he've fair spoiled Timothy Light's whole team.[22] I'm none too fond o' that great dog, sir; an' I'll have my say about it."

Skipper Thomas laughed—as a man will at a woman's fears.

"No sheep's manners t' that pack," he drawled. "The team's all dawg."

"What isn't wolf!" the woman retorted.

"She've been afraid o' that Cracker," Skipper Thomas explained, "ever since he fetched a brace o' wolves out o' the timber. 'Twas as queer a sight, now, as ever you seed, sir. They hung round the harbour for a day an' a night. You might think, sir, that Cracker was showin' off his new quarters t' some friends from the back country. They two wolves seemed t' have knowed Cracker all their lives. I 'low that they had knowed——"

"He's half wolf hisself."

"I 'low he's all wolf," Skipper Thomas admitted. This was not true. Cracker was not all wolf. "I never heard o' nobody that knowed where Cracker was born. That dog come in from the timber."

"A wicked crew—the pack o' them!"

"We've had a lean winter at Tight Cove, sir," said Skipper Thomas. "The dogs have gone[23] marvellous hungry this past month, sir. They're just a wee bit savage."

"Spare your dog meat if you lack it," the Doctor advised. "I'll feed that team at Our Harbour."

Teddy Brisk put in:

"Timothy Light haves command o' that pack."

"I'm not so sure that he've command," Teddy Brisk's mother protested. "I'm not so sure that any man could command a shockin' pack like that. In case o' accident, now——"

Skipper Thomas chucked his ample, glowing daughter-in-law under the chin.

"You loves that lad o' yourn!" he bantered.

"I does!"

"You're thinkin' he'd make a nice little morsel o' dog meat?"

"As for me," she laughed, "I could eat him!"

She caught little Teddy Brisk in her arms and kissed him all over his eager little face. And then Doctor Luke, with a laugh and a boyish "So long, Teddy Brisk! See you soon, old soldier!" vanished to his lodgings for the night.

In Which Timothy Light's Team of Ten Potential Outlaws is Considered, and There is a Significant Description of the Career of a Blood-Guilty, Ruined Young Dog, Which is in the Way of Making Desperate Trouble for Somebody

Of all this Billy Topsail had been an observer. To a good deal of it he had listened with an awakened astonishment. It did not appear to him that he would be concerned in what might grow out of the incident. He did not for a moment imagine, for example, that he would find himself in a situation wherein his hair would stand on end—that he would stand stripped naked in the north wind, confronting Death in a most unpleasant form. Nor was it that Doctor Luke's personality had stirred him to admiration—though that was true: for Doctor Luke had a hearty, cheery twinkling way with him, occasionally mixed with a proper austerity, that would have won any boy's admiration; but what particularly engaged Billy Topsail was something else—it was Doctor[25] Luke's confident assertion that he could cure little Teddy Brisk.

Billy Topsail knew something of doctors, to be sure; but he had never before quite realized their power; and that a man, being only human, after all, could take a knife in his hand, which was only a man's hand, after all, and so employ the knife that the painful, hampering leg of Teddy Brisk, which had placed a dreadful limitation on the little boy, would be made whole and useful again, caused Billy Topsail a good deal of deep reflection. If Doctor Luke could do that, why could not Billy Topsail learn to do it? It seemed to Billy Topsail to be a more admirable thing to be able to do than to sail a hundred-tonner in a gale of wind.

"Who is that man?" he asked.

"That's Doctor Luke," said Teddy's mother. "You know that."

"Well, who's Doctor Luke?"

"I don't know. He's jus' Doctor Luke. He've a wee hospital at Our Harbour. An' he heals folk. You'll find un go anywhere he's asked t' go if there's a poor soul in need. An' that's all I know about un."

"What does he do it for?"

"I reckon he wants to. An' anyhow, I'm glad he does do it. An' I reckon you'd be glad, too, if you had a little boy like Teddy."

"I am glad!" said Billy. "I think 'tis the most wonderful thing ever I heard of. An' I wish——"

And the course of Billy Topsail's life moved inevitably on towards a nearing fate that he would have shuddered to contemplate had he foreseen it.

Well, now, there was but one team of dogs in Tight Cove. It was a happy circumstance. No dogs could have existed as a separate pack in the neighbourhood of Timothy Light's mob of potential outlaws. It was all very well for Timothy Light to pleasure his hobby and pride in the unsavoury collection. Timothy Light had command of his own team. It was quite another matter for the timid mothers of Tight Cove. Timothy Light's dogs had a bad name. As neighbours they deserved it, whatever their quality on the trail—a thieving, snarling crew.

To catch Timothy Light in the act of feeding his team was enough to establish an antipathy in the beholder—to see the old man beat off the[27] rush of the pack with a biting walrus whip while he spread the bucket of frozen fish; to watch him, then, leap away from the ferocious onset; and to be witness of the ravenous anarchy of the scramble—a free fight, dwindling, at last, to melancholy yelps and subsiding in the licking of the small wounds of the encounter. Timothy Light was a fancier of dog flesh, as a man may be devoted to horse-flesh; and the object of his selective taste was what he called go-an'-gumption.

"The nearer the wolf," said he, "the better the dog."

It was to accord with this theory—which is a fallacy as a generalization—that he had evolved the team of ten that he had.

"I'm free t' say," he admitted, "that this here Cracker o' mine is none too tame. He've the wolf in him—that's so. As a wolf, with the pack in the timber, he'd be a bad wolf; as a dog in harbour he's a marvellous wicked rogue. He've a eye as bitter as frost. Did you mark it? He leaves it fool all over a person in a laughin' sort o' fashion an' never stop on the spot he really wants t' look at—except jus' once in a while. An' then it darts t' the throat an' away again; an' Cracker thinks, jus' as plain as speech:

"'Oh, Lord, wouldn't I like t' fix my teeth in there!'

"Still an' all," the old man concluded, "he yields t' command. A tap on the snout goes a long way with Cracker. He've a deal o' wolf's blood—that one has; but he's as big a coward, too, as a wolf, an' there's no danger in him when he's overmastered. Still an' all"—with a shrug—"I'd not care t' lose my whip an' stumble an' fall on the trail in the dusk when he haven't been fed for a while."

Cracker had come to Tight Cove in a dog trade of questionable propriety. Cracker had not at once taken to the customs and dogs of Tight Cove; he had stood off, sullen, alert, still—head low, king-hairs lifted, eyes flaring. It was an attitude of distrust, dashed with melancholy, rather than of challenge. Curiosity alone maintained it through the interval required for decision. Cracker was deliberating.

There was Tight Cove and a condition of servitude to Timothy Light; there were the free, wild, famishing spaces of the timber beyond. Cracker must choose between them.

All at once, then, having brooded himself to a[29] conclusion, Cracker began to wag and laugh in a fashion the most ingratiating to be imagined: and thereupon he fought himself to an established leadership of Timothy Light's pack, as though to dispose, without delay, of that necessary little preliminary to distinction. And subsequently he accepted the mastery of Timothy Light and fawned his way into security from the alarmed abuse of the harbour folk; and eventually he settled himself comfortably into the routine of Tight Cove life.

There were absences. These were invariably foreshadowed, at first, by yawning and a wretched depth of boredom. Cracker was ashamed of his intentions. He would even attempt to conceal his increasing distaste for the commonplaces of an existence in town by a suspiciously subservient obedience to all the commands of Timothy Light. It was apparent that he was preparing for an excursion to the timber; and after a day or two of whimpering restlessness he would vanish.

It was understood, then, that Cracker was off a-visiting of his cronies. Sometimes these absences would be prolonged. Cracker had been gone a month—had been caught, once, in a dis[30]tant glance, with a pack of timber wolves, from whom he had fled to hiding, like a boy detected in bad company. Cracker had never failed, however, to return from his abandoned course, in reasonable season, as lean and ragged as a prodigal son, and in a chastened mood, to the respectability and plenty of civilization, even though it implied an acquiescence in the exigency of hard labour.

Timothy Light excused the dog.

"He've got t' have his run abroad," said he. "I 'low that blood is thicker than water."

Cracker had a past. Timothy Light knew something of Cracker's past. What was respectable he had been told, with a good deal of elaboration—concerning Cracker's feats of endurance on the long trail, for example, accomplished with broken shoes, or no shoes at all, and bloody, frosted feet; and relating, with warm, wide-eyed detail of a persuasively conscientious description, to Cracker's cheerful resistance of the incredible pangs of hunger on a certain celebrated occasion.

Moreover, Cracker was a bully of parts. Cracker could bully a discouraged team into a forlorn endeavour of an amazing degree of power[31] and courage. "As clever a dog as ever you seed, sir! No shirkin'—ecod!—with Cracker t' keep watch on the dogs an' snap at the heels an' haunches o' the loafers." It was all true: Cracker was a powerful, clever, masterful, enduring beast in or out of harness, and a merciless driver of the dogs he led and had mastered.

"Give the devil his due!" Timothy Light insisted.

What was disreputable in Cracker's past—in the course of the dog trade of questionable propriety referred to—Timothy Light had been left to exercise his wit in finding out for himself. Cracker was from the north—from Jolly Cove, by the Hen-an'-Chickens. And what Timothy Light did not know was this: Cracker had there been concerned in an affair so doubtful, and of a significance so shocking, that, had the news of it got abroad in Tight Cove, the folk would have taken the customary precaution as a defensive measure, in behalf of the children on the roads after dark, and as a public warning to all the dogs of Tight Cove, of hanging Cracker by the neck until he was dead.

Long John Wall, of Jolly Cove, on the way to the Post at Little Inlet, by dog team, in January[32] weather, had been caught by the snow between Grief Head and the Tall Old Man; and Long John Wall had perished on the ice—they found his komatik and clean bones in the spring of the year; but when the gale blew out, Long John Wall's dogs had returned to Jolly Cove in a fawning humour and a suspiciously well-fed condition.

The Jolly Cove youngster, the other party to the dog trade, neglected to inform Timothy Light—whose eyes had fallen enviously on the smoky, taut, splendid brute—that this selfsame Cracker which he coveted had bullied and led Long John Wall's team on that tragic and indubitably bloody occasion.

His philosophy was ample to his need.

"In a dog trade," thought he with his teeth bare, when the bargain was struck, "'tis every man for hisself."

And so this blood-guilty, ruined young dog had come unsuspected to Tight Cove.

In Which Timothy Light's Famished Dogs Are Committed to the Hands of Billy Topsail and a Tap on the Snout is Recommended in the Probable Case of Danger

It is no great trick to make Tight Cove of the Labrador from the sea. There is no chart, of course. Nor is any chart of the little harbours needed for safe sailing, as long as the songs of the coast are preserved in the heads of the skippers that sail it. And so you may lay with confidence a bit west of north from the Cape Norman light—and raise and round the Scotchman's Breakfast of Ginger Head: whereupon a straightaway across Schooner Bay to the Thimble, and, upon nearer approach to the harbour water of the Cove—

and there you are: harboured within stone's throw of thirty hospitable cottages, with their stages and flakes clustered about, like offspring, and all clinging to the cliffs with the grip of a colony of mussels. They encircle the quiet, deep water of the Cove, lying in a hollow of Bill Pott's Point, Dane's Rock, and the little head called Brimstone.

Winter was near done, at Tight Cove, when Doctor Luke made the lights of the place from the north. Presently the sun and southwesterly winds of spring would spread the coast with all the balmy, sudden omens of summer weather, precisely as the first blast from the north, in a single night of the fall of the year, had blanketed the land with snow, and tucked it in, with enduring frost, for the winter to come. With these warm winds, the ice in Schooner Bay would move to sea, with the speed of a thief in flight. It would break up and vanish in a night, with all that was on it (including the folk who chanced to be caught on it)—a great, noisy commotion, and swift clearing out, this removal to the open.

And the ice would drift in, again, with contrary winds, and choke the bay, accompanied by Arctic ice from the current beyond, and depart[35] and come once more, and take leave, in a season of its own willful choosing, for good and all. When Doctor Luke made off across the bay, leaving Teddy Brisk to follow, by means of Timothy Light's komatik and scrawny dogs, Schooner Bay had already gone rotten, in a spell of southerly weather. The final break-up was restrained only by an interval of unseasonable frost.

A favourable wind would tear the field loose from the cliffs and urge it to sea.

Teddy Brisk could not go at once to Doctor Luke's hospital at Our Harbour. There came a mild spell—the wind went to the south and west in the night; a splashing fall of tepid southern rain swept the dry white coats in gusts and a melting drizzle; and, following on these untimely showers, a day or two of sunshine and soft breezes set the roofs smoking, the icicles dissolving, the eaves running little streams of water, the cliffs dripping a promise of shy spring flowers, and packed the snow and turned the harbour roads to slush, and gathered pools and shallow lakes of water on the rotting ice of the bay.

Schooner Bay was impassable; the trail was[36] deep and sticky and treacherous—a broken, rotten, imminently vanishing course. And sea-ward, in the lift of the waves, vast fragments of the field were shaking themselves free and floating off; and the whole wide body of ice, from Rattle Brook, at the bottom of the bay, to the great heads of Thimble and the Scotchman's Breakfast, was striving to break away to the open under the urge of the wind.

Teddy Brisk's adventure to Our Harbour must wait for frost and still weather; and wait it did—until in a shift of the weather there came a day when all that was water was frozen stiff overnight, and the wind fell away to a doubtful calm, and the cliffs of Ginger Head were a loom in the frosty distance across the bay.

"Pack that lad, mum," said Skipper Thomas then. "'Tis now or never."

"I don't like the look of it," the mother complained.

"I warns you, mum—you're too fond o' that lad."

"I'm anxious. The bay's rotten. You knows that, sir—a man as old as you. Another southerly wind would shatter——"

"Ecod! You'll coddle that wee lad t' death."

Teddy Brisk's mother laughed.

"Not me!" said she.

A cunning idea occurred to Skipper Thomas.

"Or cowardice!" he grumbled.

Teddy Brisk's mother started. She stared in doubt at old Skipper Thomas. Her face clouded. She was grim.

"I'd do nothin' so wicked as that, sir," said she. "I'll pack un up."

It chanced that Timothy Light was sunk in a melancholy regard of his physical health when Skipper Thomas went to arrange for the dogs. He was discovered hugging a red-hot bogie in his bachelor cottage of turf and rough-hewn timber by the turn to Sunday-School Hill. And a woebegone old fellow he was: a sight to stir pity and laughter—with his bottles and plasters, his patent-medicine pamphlets, his drawn, gloomy countenance, and his determination to "draw off" the indisposition by way of his lower extremities with a plaster of renowned power.

"Nothin' stronger, Skipper Thomas, knowed t' the science o' medicine an' the"—Skipper Timothy did not hesitate over the obstacle—"the[38] prac-t'-tie-on-ers thereof," he groaned; "an' she've begun t' pull too. Ecod! but she's drawin'! Mm-m-m! There's power for you! An' if she don't pull the pain out o' the toes o' my two feet"—Skipper Timothy's feet were swathed in plaster; his pain was elsewhere; the course of its exit was long—"I'm free t' say that nothin' will budge my complaint. Mm-m! Ecod! b'y, but she've sure begun t' draw!"

Skipper Timothy bade Skipper Thomas sit himself down, an' brew himself a cup o' tea, an' make himself t' home, an' feel free o' the place, the while he should entertain and profit himself with observing the operation of the plaster of infallible efficacy in the extraction of pain.

"What's gone wrong along o' you?" Skipper Thomas inquired.

"I been singin' pretty hearty o' late," Skipper Timothy moaned—he was of a musical turn and given frequently to a vigorous recital of the Psalms and Paraphrases—"an' I 'low I've strained my stummick."

Possibly Skipper Timothy could not distinguish, with any degree of scientific accuracy, between the region of his stomach and the region of his lungs—a lay confusion, perhaps, in the[39] matter of terms and definite boundaries; he had been known to mistake his liver for his heart in the indulgence of a habit of pessimistic diagnosis. And whether he was right in this instance or not, and whatever the strain involved in his vocal effort, which must have tried all the muscles concerned, he was now coughing himself purple in the face—a symptom that held its mortal implication of the approach of what is called the lung trouble and the decline.

The old man was not fit for the trail—no cruise to Our Harbour for him next day; he was on the stocks and out of commission. Ah, well, then, would he trust his dogs? Oh, aye; he would trust his team free an' willin'. An' might Billy Topsail drive the team? Oh, aye; young Billy Topsail might drive the team an' he had the spirit for the adventure. Let Billy Topsail keep un down—keep the brutes down, ecod!—and no trouble would come of it.

"A tap on the snout t' mend their manners," Skipper Timothy advised. "A child can overcome an' manage a team like that team o' ten."

And so it was arranged that Billy Topsail should drive Teddy Brisk to Our Harbour next day.

In Which the Komatik is Foundered, the Dogs Draw Their Own Conclusions from the Misfortune and Prepare to Take Advantage, Cracker Attempts a Theft and Gets a Clip on the Snout, and Billy Topsail and Teddy Brisk Confront a Situation of Peril with Composure, Not Knowing the Ultimate Disaster that Impends

Billy Topsail was now sixteen years old—near seventeen, to be exact; and he was a lusty, well-grown lad, who might easily have been mistaken for a man, not only because of his inches, but because of an assured, competent glance of the eye. Born at Ruddy Cove of Newfoundland, and the son of a fisherman, he was a capable chap in his native environment. And what natural aptitude he possessed for looking after himself in emergencies had been developed and made more courageous and acute by the adventurous life he had lived—as anybody may know, indeed, who cares to peruse the records of those incidents as elsewhere set down. As assistant to the clerk[41] of the trader Black Bat, he had served well; and it is probable that he would some day have been a clerk himself, and eventually a trader, had not the adventure upon which he was embarking with Teddy Brisk interrupted his career by opening a new vista for his ambition.

Billy Topsail and Teddy Brisk set out in blithe spirits for Doctor Luke's hospital at Our Harbour. A dawn of obscure and disquieting significance; a hint of milder weather in the growing day; a drear, gray sky thickening to drab and black, past noon; a puff of southerly wind and a slosh of rain; a brisk gale, lightly touched with frost, running westerly, with snow, in a close, encompassing cloud of great wet flakes; lost landmarks; dusk falling, and a black night imminent, with high wind—and Billy Topsail's team of ten went scrambling over an unexpected ridge and foundered the komatik.

It was a halt—no grave damage done; it was nothing to worry a man—not then.

Young Billy Topsail laughed; and little Teddy Brisk chuckled from the tumbled depths of his dogskin robes; and the dogs, on their haunches now, a panting, restless half-circle—the Labrador[42] dogs run in individual traces—viewed the spill with shamefaced amusement. Yet Billy Topsail was confused and lost. Snow and dusk were impenetrable; the barricades and cliffs of Ginger Head, to which he was bound, lay somewhere in the snow beyond—a mere general direction. It is nothing, however, to be lost. Daylight and clearing weather infallibly disclose the lay of the land.

A general direction is good enough; a man proceeds confidently on the meager advantage.

It was interesting for the dogs—this rowdy pack from Tight Cove. They were presently curious. It was a break in the routine of the road. The thing concerned them nearly. What the mischief was the matter? Something was up! Here was no mere pause for rest. The man was making no arrangements to move along. And what now? Amusement gave place to an alert observation of the course of the unusual incident.

The dogs came a little closer. It was not an attitude of menace. They followed Billy Topsail's least movement with jerks of concern and starts of surprise; and they reflected—inquiring[43] amazed. Day's work done? Camp for the night? Food? What next, anyhow? It was snowing. Thick weather, this! Thick's bags—this palpable dusk! No man could see his way in a gale like this. A man had his limitations and customs. This man would camp. There would be food in reward of the day's work. Was there never to be any food? There must be food! Now—at last! Oh, sure—why, sure—sure—sure there'd be something to eat when the man went into camp!

Mm-m? No? Was the new man going to starve 'em all to death!

Big Cracker, of this profane, rowdy crew, sidled to the sled. This was in small advances—a sly encroachment at a time. His object was plain to the pack. It was theft. They watched him in a trance of expectant interest. What would happen to Cracker? Wait and see! Follow Cracker? Oh, wait and see, first, what happened to Cracker. And Cracker sniffed at the tumbled robes. The pack lifted its noses and sniffed, too, and opened its eyes wide, and exchanged opinions, and kept watch, in swift, scared glances, on Billy Topsail; and came squirming nearer, as though with some inten[44]tion altogether remote from the one precisely in mind.

From this intrusion—appearing to be merely an impudent investigation—Cracker was driven off with a quick, light clip of the butt of the walrus whip on the snout. "Keep the brutes down! Keep un down—ecod!—an' no trouble would come of it." And down went Cracker. He leaped away and bristled, and snarled, and crawled, whimpering then, to his distance; whereupon the pack took warning. Confound the man!—he was too quick with the whip. Cracker had intended no mischief, had he?

After that the big Cracker curled up and sulked himself to sleep.

"I 'low we're close t' Ginger Head," said Billy Topsail.

"Ah, no, b'y."

"I seed the nose o' the Scotchman's Breakfast a while back."

"We're t' the south o' that by three mile."

"We isn't."

"We is."

"Ah, well, anyhow we'll stop the night where we is. The snow blinds a man."

"That's grievous," Teddy Brisk complained.[45] "I wisht we was over the barricades an' safe ashore. The bay's all rotten. My mother says——"

"You isn't timid, is you?"

"Me? No. My mother says——"

"Ah, you is a bit timid, Teddy."

"Who? Me? I is not. But my mother says the wind would just——"

"Just a wee bit timid!"

"Ah, well, Billy, I isn't never been out overnight afore. An' my mother says if the wind blows a gale from the west, south or sou'west——"

"Never you mind about that, Skipper Teddy. We've something better t' think about than the way the wind blows. The wind's full o' notions. I've no patience t' keep my humour waitin' on what she does. Now you listen t' me: I got bread, an' I got 'lasses, an' I got tea, an' I got a kettle. I got birch all split t' hand, t' save the weight of an axe on the komatik; an' I got birch rind, an' I got matches. 'Twill be a scoff"—feast—"Skipper Teddy. Mm-m! Ecod! My belly's in a clamour o' greed. The only thing I isn't got is dog meat. Save for that, Skipper Teddy, we're complete."

Teddy Brisk renewed his complaint.

"I wisht," said he, "the wind would switch t' sea. Once on a time my grand——"

"Never you mind about that."

"Once on a time my grandfather was cotched by the snow in a gale o' wind off——"

"Ah, you watch how clever I is at makin' a fire on the ice! Never you mind about the will o' the wind. 'Tis a foolish habit t' fall into."

Billy Topsail made the fire. The dogs squatted in the offing. Every eye was on the operation. It was interesting, of course. Nothing escaped notice. Attention was keen and inclusive. It would flare high—a thrill ran through the wide-mouthed, staring circle—and expire in disappointment. Interesting, to be sure: yet going into camp on the ice was nothing out of the way. The man would spend the night where he was—that was all. It portended no extraordinary departure from the customs—no opportunity. And the man was alert and capable. No; nothing stimulating in the situation—nothing to be taken advantage of.

Billy Topsail was laughing. Teddy Brisk chattered all the while. Neither was in diffi[47]culty. Nor was either afraid of anything. It was not an emergency. There was no release of authority. And when the circumstances of the affair, at last, had turned out to be usual in every respect, interest lapsed, as a matter of course; and the pack, having presently exhausted the distraction of backbiting, turned in to sleep, helped to this good conduct by a crack of the whip.

"Not another word out o' you!" Billy Topsail scolded. "You'll be fed full the morrow."

Almost at once it fell very dark. The frost increased; the snow turned to dry powder and the wind jumped to half a gale, veering to the sou'west. Teddy Brisk, with the bread and tea and molasses stowed away where bread and tea and molasses best serve such little lads as he, was propped against the komatik, wrapped up in his dogskin robes as snug as you like. The fire was roaring, and the circle of the night was safe and light and all revealed, in its flickering blaze and radiant, warm red glow.

Billy Topsail fed the fire hot; and Billy Topsail gave Teddy Brisk riddles to rede; and Billy Topsail piped Teddy Brisk a song or two—such a familiar song of the coast as this:

Whatever was bitter and inimical in the wind and dark and driving mist of snow was chased out of mind by the warm fire and companionable behaviour.

It was comfortable on the ice: it was a picnic—a bright adventure; and Teddy Brisk was as cozy and dry and content as——

"I likes it, Billy," said he. "I jus' fair loves it here!"

"You does, b'y? I'm proud o' you!"

"'Way out here on the ice. Mm-m! Yes, sirree! I'm havin' a wonderful happy time, Billy."

"I'm glad o' that now!"

"An' I feels safe——"

"Aye, b'y!"

"An' I'm's warm——"

"Sure, you is!"

"An' I'm's sleepy——"

"You go t' sleep, lad."

"My mother says, if the wind——"

"Never you mind about that. I'll take care o' you—never fear!"

"You would, in a tight place, wouldn't you, Billy, b'y?"

"Well, I 'low I would!"

"Yes, sirree! You'd take care o' me!"

"You go t' sleep, lad, an' show yourself an old hand at stoppin' out overnight."

"Aye, Billy; but my mother says——"

"Never you mind about that."

"Ah, well, my mother——"

And Teddy Brisk fell asleep.

FOOTNOTE:

[1] Sealing.

In Which the Wind Goes to Work, the Ice Behaves in an Alarming Way, Billy Topsail Regrets, for Obvious Reasons, Having to Do with the Dogs, that He Had Not Brought an Axe, and Teddy Brisk Protests that His Mother Knew Precisely What She was Talking About

Well, now, Teddy Brisk fell asleep, and presently, too, Billy Topsail, in his wolfskin bag, got the better of his anxious watch on the wind and toppled off. The dogs were already asleep, each covered with a slow-fashioning blanket of snow—ten round mounds, with neither snout nor hair to show. The fire failed: it was dark; and the wind blew up—and higher. A bleak place, this, on Schooner Bay, somewhere between the Thimble and the Scotchman's Breakfast of Ginger Head; yet there was no hardship in the night—no shivering, blue agony of cold, but full measure of healthful comfort. The dogs were warm in their coverings of snow and Billy Top[51]sail was warm in his wolfskin bag; and Teddy Brisk, in his dogskin robes, was in a flush and soft sweat of sound sleep, as in his cot in the cottage by Jack-in-the-Box, at Tight Cove.

It was a gale of wind by this time. The wind came running down the bay from Rattle Brook; and it tore persistently at the ice, urging it out. It was a matter of twenty miles from the Thimble, across Schooner Bay, to the Scotchman's Breakfast of Ginger Head, and a matter of thirty miles inland to Rattle Brook—wherefrom you may compute the area of the triangle for yourself and bestir your own imagination, if you can, to apply the pressure of a forty-mile gale to the vast rough surface of the bay.

Past midnight the ice yielded to the irresistible urge of the wind.

Crack! The noise of the break zigzagged in the distance and approached, and shot past near by, and rumbled away like a crash of brittle thunder. Billy Topsail started awake. There was a crackling confusion—in the dark, all roundabout, near and far—like the crumpling of an infinitely gigantic sheet of crisp paper: and then nothing but the sweep and whimper of the wind—those familiar, unportentous sounds,[52] in their mild monotony, like dead silence in contrast with the first splitting roar of the break-up.

Billy Topsail got out of his wolfskin bag. The dogs were up; they were terrified—growling and bristling; and they fawned close to Billy, as dogs will to a master in a crisis of ghostly fear. Billy drove them off; he whipped them into the dark. The ice had broken from the cliffs and was split in fields and fragments. It would move out and go abroad with the high southwest wind. That was bad enough, yet not, perhaps, a mortal predicament—the wind would not run out from the southwest forever; and an escape ashore from a stranded floe would be no new thing in the experience of the coast. To be marooned on a pan of ice, however, with ten famishing dogs of unsavoury reputation, and for God only knew how long—it taxed a man's courage to contemplate the inevitable adventure!

A man could not corner and kill a dog at a time; a man could not even catch a dog—not on a roomy pan of ice, with spaces for retreat. Nor could a man escape from a dog if he could not escape from the pan; nor could a man endure, in strength and wakefulness, as long as a dog. Billy Topsail saw himself attempt the[53] death of one of the pack—the pursuit of Cracker, for example, with a club torn from the komatik. Cracker would easily keep his distance and paw the ice, head down, eyes alert and burning; and Cracker would withdraw and dart out of reach, and swerve away. And Smoke and Tucker and Scrap, and the rest of the pack, would all the while be creeping close behind, on the lookout for a fair opportunity.

No; a man could not corner and kill a dog at a time. A man could not beat a wolf in the open; and these dogs, which roamed the timber and sprang from it, would maneuver like wolves—a patient waiting for some lapse from caution or the ultimate moment of weakness; and then an overwhelming rush. Billy Topsail knew the dogs of his own coast. He knew his own dogs; all he did not know about his own dogs was that Cracker had been concerned in a dubious affair on the ice off the Tall Old Man. These dogs had gone on short rations for a month. When the worst came to the worst—the pan at sea—they would attack.

Teddy Brisk, too, was wide awake. A thin little plaint broke in on Billy Topsail's reflections.

"Is you there, Billy?"

"Aye, I'm here. You lie still, Teddy."

"What's the matter with the dogs, Billy?"

"They're jus' a bit restless. Never you mind about the dogs. I'll manage the dogs."

"You didn't fetch your axe, did you, Billy?"

"Well, no, Skipper Teddy—no; I didn't."

"That's what I thought. Is the ice broke loose?"

"Ah, now, Teddy, never you mind about the ice."

"Is she broke loose?"

"Ah, well—maybe she have broke loose."

"She'll move t' sea in this wind, won't she?"

"Never you mind——"

"Won't she?"

"Ah, well, she may take a bit of a cruise t' sea."

Teddy Brisk said nothing to this. An interval of silence fell. And then Teddy plaintively again:

"My mother said——"

Billy Topsail's rebuke was gentle:

"You isn't goin' t' cry for your mother, is you?"

"Oh, I isn't goin' t' cry for my mother!"

"Ah, no! You isn't. No growed man would."

"All I want t' say," said Teddy Brisk in a saucy flash of pride, "is that my mother was right!"

In Which the Sudden Death of Cracker is Contemplated as a Thing to Be Desired, Billy Topsail's Whip Disappears, a Mutiny is Declared and the Dogs Howl in the Darkness

Past twelve o'clock and the night as black as a wolf's throat, with the wind blowing a forty-mile gale, thick and stifling with snow, and the ice broken up in ragged pans of varying, secret area—it was no time for any man to stir abroad from the safe place he occupied. There were patches of open water forming near by, and lanes of open water widening and shifting with the drift and spreading of the ice; and somewhere between the cliffs and the moving pack, which had broken away from them, there was a long pitfall of water in the dark. The error of putting the dogs in the traces and attempting to win the shore in a forlorn dash did not even present itself to Billy Topsail's experienced wisdom. Billy Topsail would wait for dawn, to be sure of his path and direction; and meantime—there[57] being no occasion for action—he got back into his wolfskin bag and settled himself for sleep.

It was not hard to go to sleep. Peril of this sort was familiar to Billy Topsail—precarious situations, with life at stake, created by wind, ice, reefs, fog and the sea. There on the ice the situation was completely disclosed and beyond control. Nothing was to be manipulated. Nothing threatened, at any rate, for the moment. Consequently Billy Topsail was not afraid. Had he discovered himself all at once alone in a city; had he been required to confront a garter snake—he had never clapped eyes on a snake——

Placidly reflecting on the factors of danger to be dealt with subsequently, Billy Topsail caught ear, he thought, of a sob and whimper from the midst of Teddy Brisk's dogskin robes. This was the little fellow's first full-fledged adventure. He had been in scrapes before—the little dangers of the harbour and the adjacent rocks and waters and wilderness; gusts of wind; the lap of the sea; the confusion of the near-by back country, and the like of that; but he had never been cast away like the grown men of Tight Cove. And these passages, heroic as they are,[58] and stimulating as they may be to the ambition of the little fellows who listen o' winter nights, are drear and terrifying when first encountered.

Teddy Brisk was doubtless wanting his mother. Perhaps he sobbed. Yet he had concealed his fear and homesickness from Billy Topsail; and that was stoicism enough for any lad of his years—even a lad of the Labrador. Billy Topsail offered him no comfort. It would have shamed the boy to comfort him openly. Once ashore again Teddy Brisk would want to boast, like his elders, and to spin his yarn:

"Well now, lads, there we was, ecod! 'way out there on the ice, me 'n' Billy Topsail; an' the wind was blowin' a gale from the sou'west, an' the snow was flyin' as thick as ever you seed the snow fly, an' the ice was goin' out t' sea on the jump. An' I says t' Billy: 'I'm goin' t' sleep, Billy—an' be blowed t' what comes of it!' An' so I falled asleep as snug an' warm; an' then——"

Billy Topsail ignored the sob and whimper from the depths of the dogskin robes.

"The lad haves t' be hardened," he reflected.

Dawn was windy. It was still snowing—a[59] frosty mist of snow. Billy Topsail put the dogs in the traces and stowed Teddy Brisk away in the komatik. The dogs were uneasy. Something out of the way? What the mischief was the matter? They came unwillingly. It seemed they must be sensing a predicament. Billy Topsail whipped them to their work and presently they bent well enough to the task.

Snow fell all that day. There were glimpses of Ginger Head. In a rift of the gale Teddy Brisk caught sight of the knob of the Scotchman's Breakfast.

Always, however, the way ashore was barred by open water. When Billy Topsail caught sight of the Scotchman's Breakfast for the last time it was in the southwest. This implied that the floe had got beyond the heads of the bay and was moving into the waste reaches of the open sea. At dusk Billy had circled the pan twice—hoping for chance contact with another pan, to the east, and another, and still another; and thus a path to shore. It was a big pan—a square mile or more as yet. When the pinch came, if the pinch should come, Billy thought, the dogs would not be hampered for room.

Why not kill the dogs? No; not yet. They[60] were another man's dogs. In the morning, if the wind held offshore——

Wind and snow would fail. There would be no harsher weather. Billy Topsail made a little fire with his last billets of birchwood. He boiled the kettle and spread a thick slice of bread with a meager discoloration of molasses for Teddy Brisk. What chiefly interested Teddy Brisk was the attitude of the dogs. It was not obedient. There was swagger in it. A crack of the whip sent them leaping away, to be sure; but they intruded again at once—and mutinously persisted in the intrusion.

Teddy Brisk put out a diffident hand towards Smoke. Smoke was an obsequious brute. Ashore he would have been disgustingly grateful for the caress. Now he would not accept it at all. He snarled and sprang away. It was a defiant breach of discipline. What was the matter with the dogs? They had gone saucy all at once. The devil was in the dogs. Nor would they lie down; they withdrew, at last, in a pack, their hunger discouraged, and wandered restlessly in the failing light near by.

Teddy Brisk could not account for this singular behaviour.

It alarmed him.

"Ah, well," said Billy Topsail, "they're all savage with hunger."

"Could you manage with nine, Billy?"

Billy Topsail laughed.

"With ease, my son," said he, "an' glad of it!"

"Is you strong enough t' kill a dog?"

"I'll find that out, Teddy, when the time comes."

"I was 'lowin' that one dog would feed the others an' keep un mild till we gets ashore."

"I've that selfsame thing in mind."

Teddy said eagerly:

"Kill Cracker, Billy!"

"Cracker! Already? 'Twould be sheer murder."

"Aye, kill un now, Billy—ah, kill un right away now, won't you, b'y? That dog haves a grudge on me. He've been watchin' me all day long."

"Ah, no! Hush now, Teddy!"

"I knows that dog, Billy!"

"Ah, now! The wind'll change afore long. We'll drift ashore—maybe in the mornin'. An then——"

"He've his eye on me, Billy!"

Billy Topsail rose.

"You see my whip anywhere?"

"She's lyin' for'ard o' the komatik."

"She's not."

"She was."

"She've gone, b'y!"

"Ecod! Billy, Cracker haves her!"

It was not yet dark. Cracker was sitting close. It was an attitude of jovial expectation. He was on his haunches—head on one side and tail flapping the snow; and he had the walrus whip in his mouth. Apparently he was in the mood to pursue a playful exploit. When Billy Topsail approached he retreated—a little; and when Billy Topsail rushed he dodged, with ease and increasing delight. When Billy Topsail whistled him up and patted to him, and called "Hyuh! Hyuh!" and flattered him with "Good ol' dog!" he yielded nothing more than a deepened attention to the mischievous pleasure in hand.

Always he was beyond reach—just beyond reach. It was tantalizing.

Billy Topsail lost his temper. This was a blunder. It encouraged the dog. To recover[63] the whip was an imperative precaution; but Billy could not accomplish it in a temper. Cracker was willful and agile and determined; and when he had tired—it seemed—of his taunting game, he whisked away, with the pack in chase, and was lost to sight in the gale. It fell dark then; and presently, far away a dog howled, and there was an answering howl, and a chorus of howls. They were gone for good. It was a mutiny. Billy knew that his authority had departed with the symbol of it.

He did not see the whip again.

In Which a Blazing Club Plays a Salutary Part, Teddy Brisk Declares the Ways of His Mother, and Billy Topsail Looks Forward to a Battle that No Man Could Win

Next night—a starlit time then, and the wind gone flat—Billy Topsail was burning the fragments of the komatik. All day the dogs had roamed the pan. They had not ventured near Billy Topsail's authority—not within reach of Billy's treacherously minded flattery and coaxing. In the exercise of this new freedom they had run wild and fought among themselves like a mutinous pirate crew. Now, however, with night down, they had crept out of its seclusion and were sitting on the edge of the firelight, staring, silent, pondering.

Teddy Brisk was tied up in the wolfskin bag. It was the best refuge for the lad. In the event of a rush he would not be torn in the scuffle; and should the dogs overcome Billy Topsail—which was not yet probable—the little boy would be none the worse off in the bag.

Had the dogs been a pack of wolves Billy would have been in livid fear of them; but these beasts were dogs of his own harbour, which he had commanded at will and beaten at will, and he was awaiting the onset with grim satisfaction. In the end, as he knew, the dogs would have an advantage that could not be resisted; but now—Billy Topsail would "l'arn 'em! Let 'em come!"

Billy's club, torn from the komatik, was lying one end in his little fire. He nursed it with care.

Cracker fawned up. In the shadows, behind, the pack stared attentive. It was a pretense at playfulness—Cracker's advance. Cracker pawed the ice, and wagged his tail, and laughed. This amused Billy. It was transparent cunning. Billy gripped his club and let the fire freely ignite the end of it. He was as keen as the dog—as sly and as alert.

He said:

"Good ol' dog!"

Obviously the man was not suspicious. Cracker's confidence increased. He moved quickly, then, within leaping distance. For a flash he paused, king-hairs rising. When he rushed, the pack failed him. It started, quivered, stopped, and cautiously stood still. Billy[66] was up. The lift of Cracker's crest and the dog's taut pause had amply warned him.

A moment later Cracker was in scared, yelping flight from the pain and horror of Billy's blazing club, and the pack was in ravenous chase of him. Billy Topsail listened for the issue of the chase. It came presently—the confusion of a dog fight; and it was soon over. Cracker was either dead or master again. Billy hoped the pack had made an end of him and would be content. He could not be sure of the outcome. Cracker was a difficult beast.

Released from the wolfskin bag and heartened by Billy's laughter, Teddy Brisk demanded:

"Was it Cracker?"

"It was."

Teddy grinned.

"Did you fetch un a fatal wallop?"

"I left the dogs t' finish the job. Hark! They're not feastin', is they? Mm-m? I don't know."

They snuggled up to the little fire. Teddy Brisk was wistful. He talked now—as often before—of the coming of a skiff from Our Harbour. He had a child's intimate knowledge of his own mother—and a child's wise and abounding faith.

"I knows my mother's ways," he declared. "Mark me, Billy, my mother's an anxious woman an' wonderful fond o' me. When my mother heard that sou'west wind blow up, 'Skipper Thomas,' says she t' my grandfather, 'them b'ys is goin' out with the ice; an' you get right straight up out o' bed an' tend t' things.'

"An' my grandfather's a man; an' he says:

"'Go to, woman! They're ashore on Ginger Head long ago!'

"An' my mother says:

"'Ah, well, they mightn't be, you dunder-head!'—for she've a wonderful temper when she's afeared for my safety.

"An' my grandfather says:

"'They is, though.'

"An' my mother says:

"'You'll be off in the bait skiff t'-morrow, sir, with a flea in your ear, t' find out at Our Harbour.'

"An' she'd give that man his tea in a mug (scolding) until he got a Tight Cove crew t'gether an' put out across the bay. Ecod! but they'd fly across the bay in a gale o' wind like that! Eh, Billy?"

"All in a smother—eh, Teddy?"

"Yep—all in a smother. My grandfather's fit an' able for anything in a boat. An' they'd send the news up an' down the coast from Our Harbour—wouldn't they, Billy?"

"'Way up an' down the coast, Teddy."

"Yep—'way up an' down. They must be skiffs from Walk Harbour an' Skeleton Cove an' Come-Again Bight searchin' this floe for we—eh, Billy?"

"An' Our Harbour too."

"Yep—an' Our Harbour too. Jus' the way they done when ol' Bad-Weather West was cast away—eh, Billy? Don't you 'low so?"

"Jus' that clever way, Teddy."

"I reckon my mother'll tend t' that." Teddy's heart failed him then. "Anyhow, Billy," said he weakly, "you'll take care o' me—won't you—if the worst comes t' the worst?"

The boy was not too young for a vision of the worst coming to the worst.

"None better!" Billy replied.

"I been thinkin' I isn't very much of a man, Billy. I've not much courage left."

"Huh!" Billy scoffed. "When we gets ashore, an' I tells my tale o' these days——"

Teddy started.

"Billy," said he, "you'll not tell what I said?"

"What was that now?"

"Jus' now, Billy—about——"

"I heard no boast. An I was you, Teddy, I wouldn't boast too much. I'd cling t' modesty."

"I takes it back," said Teddy. He sighed. "An' I'll stand by."

It did not appear to Billy Topsail how this guardianship of the boy was to be accomplished. Being prolonged, it was a battle, of course, no man could win. The dogs were beaten off for the time. They would return—not that night, perhaps, or in the broad light of the next day; but in the dark of the night to come they would return, and, failing success then, in the dark of the night after.

That was the way of it.

In Which Teddy Brisk Escapes From the Wolfskin Bag and Determines to Use His Crutch and Billy Topsail Comes to the Conclusion that "It Looks Bad"

Next day the dogs hung close. They were now almost desperately ravenous. It was agony for them to be so near the satisfaction of their hunger and in inhibitive terror of seizing it. Their mouths dripped. They were in torture—they whimpered and ran restless circles; but they did not dare. They would attack when the quarry was weak or unaware. Occasionally Billy Topsail sallied on them with his club and a loud, intimidating tongue, to disclose his strength and teach them discretion; and the dogs were impressed and restrained by this show. If Billy Topsail could catch and kill a dog he would throw the carcass to the pack and thus stave off attack. Having been fed, the dogs would be in a mild humour. Billy might then entice and kill another—for himself and Teddy Brisk.

Cracker was alive and still masterful. Billy went out in chase of Smoke. It was futile. Billy cut a ridiculous figure in the pursuit. He could neither catch the dog nor overreach him with blandishments; and a cry of alarm from the boy brought him back to his base in haste to drive off Cracker and Tucker and Sling, who were up to the wolf's trick of flanking. The dogs had reverted. They were wolves again—as nearly as harbour dogs may be. Billy perceived that they could no longer be dealt with as the bond dogs of Tight Cove.

In the afternoon Billy slept. He would need to keep watch through the night.

Billy Topsail had husbanded the fragments of the komatik. A fire burned all that night—a mere glow and flicker of light. It was the last of the wood. All that remained was the man's club and the boy's crutch. Now, too, the last of the food went. There was nothing to eat. What Billy had brought, the abundant provision of a picnic, with something for emergencies—the bread and tea and molasses—had been conserved, to be sure, and even attenuated. There was neither a crumb nor a drop of it left.

What confronted Billy Topsail now, however,[72] and alarmed his hope and courage, was neither wind nor frost, nor so much the inevitable pangs of starvation, which were not immediate, as a swift abatement of his strength. A starved man cannot long continue at bay with a club. Billy could beat off the dogs that night perhaps—after all, they were the dogs of Tight Cove, Cracker and Smoke and Tucker and Sling; but to-morrow night—he would not be so strong to-morrow night.

The dogs did not attack that night. Billy heard them close—the sniffing and whining and restless movement in the dark that lay beyond the light of his feeble fire and was accentuated by it. But that was all.

It was now clear weather and the dark of the moon. The day was bright and warm. When night fell again it was starlight—every star of them all twinkling its measure of pale light to the floe. The dogs were plain as shifting, shadowy creatures against the white field of ice. Billy Topsail fought twice that night. This was between midnight and dawn. There was no maneuvering. The dogs gathered openly, viciously, and delivered a direct attack. Billy[73] beat them off. He was gasping and discouraged, though, at the end of the encounter. They would surely come again—and they did. They waited—an hour, it may have been; and then they came.

There was a division of the pack. Six dogs—Spunk and Biscuit and Hero in advance—rushed Billy Topsail. It was a reluctant assault. Billy disposed of the six—after all, they were dogs of Tight Cove, not wolves from the rigours of the timber; and Billy was then attracted to the rescue of Teddy Brisk, who was tied up in the wolfskin bag, by the boy's muffled screams. Cracker and Smoke and Tucker and Sling were worrying the wolfskin bag and dragging it off. They dropped it and took flight when Billy came roaring at them with a club.

When Billy released him from the wolfskin bag the boy was still screaming. He was not quieted—his cries and sobbing—until the day was broad.

"Gimme my crutch!" said he. "I'll never go in that bag no more!"

"Might as well wield your crutch," Billy agreed.

To survive another night was out of the ques[74]tion. Another night came in due course, however, and was to be faced.

It was a gray day. Sky and ice and fields of ruffled water had no warmth of colour. All the world was both cold and drear. A breeze was stirring down from the north and would be bitter in the dusk. It cut and disheartened the castaways. It portended, moreover, a black night.

Teddy cried a good deal that day—a little whimper, with tears. He was cold and hungry—the first agony of starvation—and frightened and homesick. Billy fancied that his spirit was broken. As for Billy himself, he watched the dogs, which watched him patiently near by—a hopeless vigil for the man, for the dogs were fast approaching a pass of need in which hunger would dominate the fear of a man with a club. And Billy was acutely aware of this much—that nothing but the habitual fear of a man with a club had hitherto restrained the full fury and strength of the pack.

That fury, breaking with determination, would be irresistible. No man could beat off the attack of ten dogs that were not, in the beginning, already defeated and overcome by awe of him.[75] In the dark—in the dark of that night Billy could easily be dragged down; and the dogs were manifestly waiting for the dark to fall.

It was to be the end.

"It looks bad—it do so, indeed!" Billy Topsail thought.

That was the full extent of his admission.

In Which Attack is Threatened and Billy Topsail Strips Stark Naked in the Wind in Pursuit of a Desperate Expedient and with Small Chance of Success

Teddy Brisk kept watch for a skiff from Our Harbour or Come-Again Bight. He depended for the inspiration of this rescue on his mother's anxious love and sagacity. She would leave nothing to the indifferent dealings and cold issue of chance; it was never "more by good luck than good conduct" with her, ecod!

"I knows my mother's ways!" he sobbed, and he repeated this many times as the gray day drew on and began to fail. "I tells you, Billy, I knows my mother's ways!"

And they were not yet beyond sight of the coast. Scotchman's Breakfast of Ginger Head was a wee white peak against the drab of the sky in the southwest; and the ragged line of cliffs running south and east was a long, thin[77] ridge on the horizon where the cottages of Walk Harbour and Our Harbour were.

No sail fluttered between—a sail might be confused with the colour of the ice, however, or not yet risen into view; but by and by, when the misty white circle of the sun was dropping low, the boy gave up hope, without yielding altogether to despair. There would be no skiff along that day, said he; but there would surely be a sail to-morrow, never fear—Skipper Thomas and a Tight Cove crew.

In the light airs the floe had spread. There was more open water than there had been. Fragments of ice had broken from the first vast pans into which Schooner Bay ice had been split in the break-up. These lesser, lighter pans moved faster than the greater ones; and the wind from the north—blown up to a steady breeze by this time—was driving them slowly south against the windward edge of the more sluggish fields in that direction.

At sunset—the west was white and frosty—a small pan caught Billy Topsail's eye and instantly absorbed his attention. It had broken from the field on which they were marooned and was under way on a diagonal across a quiet[78] lane of black water, towards a second great field lying fifty fathoms or somewhat less to the south.

Were Billy Topsail and the boy aboard that pan the wind would ferry them away from the horrible menace of the dogs. It was a small pan—an area of about four hundred square feet; yet it would serve. It was not more than fifteen fathoms distant. Billy could swim that far—he was pretty sure he could swim that far, the endeavour being unencumbered; but the boy—a little fellow and a cripple—could not swim at all.

Billy jumped up.

"We've got t' leave this pan," said he, "an' forthwith too."

"Have you a notion, b'y?"

Billy laid off his seal-hide overjacket. He gathered up the dogs' traces—long strips of seal leather by means of which the dogs had drawn the komatik, a strip to a dog; and he began to knot them together—talking fast the while to distract the boy from the incident of peculiar peril in the plan.

The little pan in the lane—said he—would be a clever ferry. He would swim out and crawl aboard. It would be no trick at all. He would[79] carry one end of the seal-leather line. Teddy Brisk would retain the other. Billy pointed out a ridge of ice against which Teddy Brisk could brace his sound leg. They would pull, then—each against the other; and presently the little pan would approach and lie alongside the big pan—there was none too much wind for that—and they would board the little pan and push off, and drift away with the wind, and leave the dogs to make the best of a bad job.

It would be a slow affair, though—hauling in a pan like that; the light was failing too—flickering out like a candle end—and there must be courage and haste—or failure.

Teddy Brisk at once discovered the interval of danger to himself.

"I'll be left alone with the dogs!" he objected.

"Sure, b'y," Billy coaxed; "but then you see——"

"I won't stay alone!" the boy sobbed. He shrank from the direction of the dogs towards Billy. At once the dogs attended. "I'm afeared t' stay alone!" he screamed. "No, no!"

"An we don't leave this pan," Billy scolded, "we'll be gobbled up in the night."

That was not the immediate danger. What confronted the boy was an immediate attack, which he must deal with alone.

"No! No! No!" the boy persisted.

"Ah, come now——"

"That Cracker knows I'm a cripple, Billy. He'll turn at me. I can't keep un off."

Billy changed front.

"Who's skipper here?" he demanded.

"You is, sir."

"Is you takin' orders or isn't you?"

The effect of this was immediate. The boy stopped his clamour.

"I is, sir," said he.

"Then stand by!"

"Aye, sir!"—a sob and a sigh.

It was to be bitter cold work in the wind and water. Billy Topsail completed his preparations before he began to strip. He lashed the end of the seal-leather line round the boy's waist and put the club in his hand.