The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Ashtabula Disaster, by Stephen D. Peet This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Ashtabula Disaster Author: Stephen D. Peet Release Date: November 16, 2014 [EBook #47359] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ASHTABULA DISASTER *** Produced by Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Cover created by Transcriber, using an illustration from the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

BY

Rev. Stephen D. Peet,

OF ASHTABULA, OHIO.

ILLUSTRATED.

CHICAGO, ILL.:

J. S. Goodman—Louis Lloyd & Co.

London, Ont.: J. M. Chute & Co.

1877.

Copyright, A. D. 1877,

By J. S. Goodman and Louis Lloyd & Co.

Ottaway & Colbert,

Printers,

147 & 149 Fifth Ave., Chicago.

Blomgren Bros. & Co.,

Electrotypers,

162 & 164 Clark St., Chicago.

The narrative of the greatest railroad disaster on record is a task which has been undertaken in the following pages. No event has awakened more wide-spread interest for many years, and the calamity will not cease to have its effect for a long time to come. The author has had unusual facilities for knowing the particulars, and has undertaken the record of them on this account. A familiarity with the locality, the place and the citizens, personal observation on the spot during the night, and a critical examination of the wreck before it was removed in the morning gave him an exact knowledge of the accident which few possessed. This, followed by intercourse with the survivors, with the friends of the deceased, and the representatives of the press, and by correspondence, which resulted from his assistance in identifying bodies, and searching for relics, all added to his acquaintance with the event and its consequences. The author is, however, happy in making an acknowledgment of assistance from the thorough investigation of the coroner’s jury, from the faithful presentation of facts by the reporters of the press, especially those of the “Inter-Ocean” and the “Cleveland Leader,” also from the pictures taken by the artist Frederick Blakeslee, and from the articles published and sent by various friends, which contained sermons, sketches and biographical notices. He has to acknowledge also encouragements received from Capt T. E. Truworthy of California, and his publishers J. S. Goodman and Louis Lloyd & Co.

iv The discussions before the country in reference to the cause of this accident, the author has not undertaken to give. These have been contained in the “Railroad Gazette,” the “Railway Age,” the “Springfield Republican,” the New York and Chicago dailies, and many other papers.

Prominent engineers, such as C. P. Buckingham, Clemans Herschel, E. C. Davis, L. H. Clark, Col. C. R. Morton, E. S. Cheseborough, Edward S. Philbrick, D. V. Wood, F. R. Smith and many others have passed their opinion upon it.

The accident at first seemed to involve the question of the use of iron for bridges, and whether the European system was not better than the American, and a comment upon this was given by Charles Collins, when he testified that $25,000 more would have erected a stone bridge. Yet as the discussions continued, the conclusion seems to have been reached that riveted iron bridges might be safe if properly constructed, and the engineers appointed by the State Legislature of Ohio, reported that they “find nothing in this case to justify our popular apprehension that there may be some inherent defect in iron as a material for bridges. We find no evidence of weakness in this bridge, which could not have been discovered and prevented.”

The erection of iron bridges with the trusses all below the track as contrasted with so-called “through” bridges has also been discussed. In this case the tendency to “buckling” where the track is supported by iron braces rather than suspended from them was most apparent, for engineer Gottleib testified there was not a single brace which was not buckled.

The danger from derailment and the fearful result which must follow in high bridges like this is sufficient argument for the addition of guards, or some other means to prevent trains from going off.

v These questions, however, are for railroad engineers to settle. The responsibility of the railroad companies to the American public is a point more important. The “Iron Age,” speaking of this disaster says, “it is a disquieting accident.” It says also that: “We know there are plenty of cheap, badly built bridges, which the engineers are watching with anxious fears, and which, to all appearance, only stand by the grace of God.”

The “Nation” of Feb. 15th says: “By such disasters and by shipwreck are lives in these days sacrificed by the score, and yet except through the clumsy machinery of a coroner’s jury, hardly any where in America is there the slightest provision made for inquiry into them.

“Here are wholesale killings. In four cases out of five some one is responsible for them; there was a carelessness somewhere, or a false economy has been practised, or a defective discipline maintained, or some appliances of safety dispensed with, or some one has run for luck and taken his chances.”

It may be said of this case that the coroner’s jury were as thorough and faithful in their investigation as the American public could ask; and yet from the class of reporters who conveyed so inadequately the results of that investigation from day to day no one was any wiser. The conclusion, however, has been reached, and the verdict corresponds with the evidence given in this book.

We have no space to give to the harsh words that have been spoken. These have come not only from the bereaved friends, but from papers of high standing, among manufacturers and others.

The accident has been bad enough, and the decision of the coroner’s jury sufficiently condemning. The action of the State Legislature has also made it a matter of investigation.

The letter of Charles Francis Adams also called attentionvi to a demand for a Railroad commission, and the subject has not been left, as the “Nation” intimates that it might, to a coroner’s jury, nor even to a legislative committee, but an enactment of Congress has already passed to bring the subject before the Committee on Railroads.

Doubtless the results will be, increased safety of travel, and the holding of railroad corporations to a strict account by the authority of law, for all accidents which may be caused by the want of skillful engineering or proper management. The Westenhouse brake may have caused the projectile force of the whole train to have fallen upon the centre of the defective bridge, but is there not some way of stopping trains from plunging entirely down into these fearful chasms?

Increased appliances for stopping trains, proper precautions in putting out fires, the frequent inspection of bridges, some method of keeping a strict account of the numbers on the train will be required.

The object of this book, however, has not been to discuss these points. As will be seen by the narrative, the religious lessons of the occasion are made most prominent.

The author’s sympathies were early called forth; access to the survivors enlisted all his sensibilities; correspondence also showed how much need of consolation there was; and the book was prepared under the shadow of the great horror; but if the reader shall find the same comfort from a view of the lovely characters and the Christian hopes which span this dark cloud with a bow of promise, the author will consider that his mission has been accomplished.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. | |

| Ashtabula | 9 |

| Chapter II. | |

| The River and the Bridge | 13 |

| Chapter III. | |

| The Night and the Storm | 18 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| The Wreck | 26 |

| Chapter V. | |

| The Startling Crash | 34 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| The Alarm in Town | 42 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| The Fire and the Firemen | 49 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| Care of the Survivor | 56 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| The Robbers | 61 |

| Chapter X. | |

| Midnight at the Wreck | 66 |

| Chapter XI. | |

| The Public Excitement | 72 |

| Chapter XII. | |

| Scenes at the Morgue | 81 |

| Chapter XIII. | |

| The Railroad Officials | 89 |

| Chapter XIV.viii | |

| The Arrival of Friends | 96 |

| Chapter XV. | |

| The Wave of Sorrow | 104 |

| Chapter XVI. | |

| The Search for Relics | 113 |

| Chapter XVII. | |

| The Passengers | 120 |

| Chapter XVIII. | |

| The Experience of Survivors | 131 |

| Chapter XIX. | |

| Personal Incidents | 138 |

| Chapter XX. | |

| Kindness shown | 144 |

| Chapter XXI. | |

| The Memorial Services | 152 |

| Chapter XXII. | |

| The Suicide | 159 |

| Chapter XXIII. | |

| The Character of Mr. Collins | 166 |

| Chapter XXIV. | |

| The Loved and Lost | 170 |

| Chapter XXV. | |

| Sketches of Character | 177 |

| Chapter XXVI. | |

| P. P. Bliss | 183 |

| Chapter XXVII. | |

| The Testimony of Witnesses | 197 |

| Chapter XXVIII. | |

| The Lessons of the Event | 203 |

| The Coroner’s Verdict | 207 |

The scene of this direful event is situated on the Lake Shore Railway, midway between the cities of Cleveland and Erie, and about two miles from Lake Erie.

The village itself contains nearly thirty-five hundred inhabitants. At the mouth of the river is another small village, making in all a population of nearly four thousand. Between these points of the village and harbor many families of the poorer classes have made their homes, the most of them being Swedes, Germans and Irish. There are a few fine residences in this part of the town, but the homes of the more prominent citizens are at least a mile away. Near the depot there are several small places of business, two or three saloons, three hotels: The American House,10 the Culver House, and the Eagle Hotel, kept by Patrick Mulligan. It was one of the worst places for a railroad disaster. Near the depot, not six hundred yards away to the eastward, was a deep and lonely gorge. Across this the ill-fated bridge was hung. It was just at the point where the trains from the East were likely to slacken speed. Below that bridge the stream ran darkly. The only access to the gorge was by a long flight of stairs which was at the time of the calamity covered with a deep bank of snow. No road existed to it, and the spot could be reached by teams, only as a track was broken through gardens and down steep banks and across the valley and along the stream. A solitary building was in this gorge. It was the engine house. Here were the massive boiler and engine which were used for pumping water from the stream to the heights above, and so to the tanks at either side of the station house, in the distance. Situated close by the river, and almost under the shadow of the bridge itself, this lone house became to the wrecked travelers a refuge from the fire and storm. On the heights above towards11 the depot, another engine house was situated. It was the place where the “Lake Erie,” a hand fire engine stood. Two cisterns for the supply of water were located near, one on either side of the railroad track. It is difficult to picture a place more retired and lonely than this gorge. So near the busy station and yet isolated, inaccessible, and seldom visited. Its distance from the village, and the nature of the surroundings, will account for many things which occurred on that awful night; but it is a strange tale we have to tell. In the midst of the habitations of men untold sufferings took place, and the loss of life and fearful burning.

The fire department consisted of three companies, two at the village and one at the depot. There was only one steamer, and that was a mile from the depot. These companies were under the control of the chief fireman, Mr. G. W. Knapp, who is a tinner by trade, and a man slow and lymphatic in temperament, and one who, for a long time, had been addicted to the constant use of intoxicating liquors; a man every way unfit for so trying an emergency. The re-organization12 of the fire department had begun. Many intelligent and prominent citizens were members of it, but these had not been successful in securing the removal of the chief, as several years of association had made many of the fireman satisfied with his services. It was unfortunate that the control was at the time in such incompetent hands, but no one could have anticipated such an event, and no emergency had heretofore shown the necessity for a change.

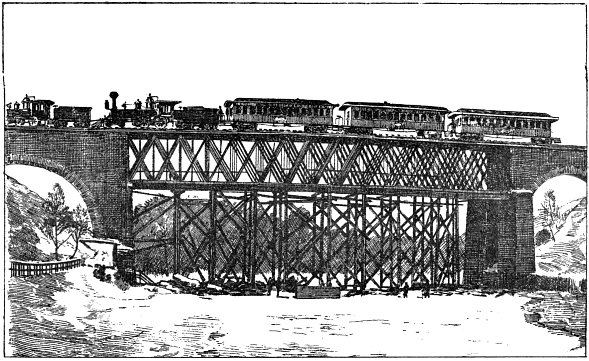

THE OLD BRIDGE.

[From a Photograph by T. T. Sweeny, Cleveland.]

The Ashtabula river is a shallow stream which runs through the county and the town. As it approaches the lake it widens and deepens into what constitutes the harbor.

The banks lining the valley of it are high and rocky precipices. They form in the rear or to the southward of the town a gorge which is called, by the inhabitants, by the significant name “the gulf.” Near the depot this gorge widens, and its banks become less precipitous; but, even at this point, the river flows at least seventy-six feet below the level of the road, and is four feet deep. Here the fatal, but far-famed, bridge was built. A grade on an arched viaduct conveyed the track to the abutments, but these stood by themselves, straight from the bottom of the gorge, two lofty pillars of stone seventy-six feet14 high and just wide enough for the two tracks of the road. Flanking these were the lower and smaller abutments of an older bridge, left standing, but, for a long time, unused. The span of the bridge across this gorge, from abutment to abutment, was the unusual length of one hundred and fifty feet. The bridge was very high, and loomed up in the distance, tall and dark and gloomy.

Travelers by the wagon road, at a distance up the river a mile away, would stop and look at this structure, apparently built high in air, and watch the cars as they passed in bold relief against the sky, almost as if a spectre train were traversing the blue vault above.

It was a dizzy height. There was something almost fearful in the sight. The recklessness of danger impressed the observer. As the full outline marked itself against the sky, the fascination at times almost reached a sense of the sublime.

Here, then, was the bridge suspended high in air, lofty and tall and dark, a mysterious thing. It was not an arch lifting high its springing sides,15 it was not a set of beams supported by abutments below; it was a web of iron netted and braced and bolted, heavy, dark and gloomy in appearance, and proving treacherous as death.

This bridge was erected in the year 1865, by Mr. Tomlinson, according to orders and patterns given by Mr. Amasa Stone, then president of the road. It was built after the pattern of the Howe Truss, but containing some elements introduced by the president himself. It was constructed of wrought iron, with long iron braces from lower cord to upper cord twenty feet in height. There were rods stretching from top to bottom and designed to carry the strain from brace to brace. The panels were eleven feet long, and between these the strength of the cords depended on three iron beams six inches thick and eight inches wide. The whole width of the bridge was nineteen and one-half feet; its height twenty feet; its length one hundred and sixty-five feet, in a single span.

When it was first erected it was discovered that the braces were placed wrong, so that they came upon the sides rather than upon the edges.16 The structure settled, as the edges were removed, about six inches, and necessitated the change of the process.

This error was remedied by the cutting away of iron, so that the braces could be turned, and this change occupied nearly a year. It was watched with interest by the citizens, and was regarded by the builders themselves as a doubtful experiment.

In its erection Mr. Tomlinson, the engineer, differed with the president so much that he resigned his position, and, even Mr. Charles Collins never acknowledged that it was a work of his inventing, or a bridge receiving his approval. Before the committee, appointed by the legislature of Ohio, he acknowledged that it was an “experiment,” and even when it was in process of erection he gave no orders, but rather left the responsibility with the president.

The deficiencies of the bridge, as acknowledged by Mr. Tomlinson, who made the drafts, were that the braces were smaller than was intended, and the weight was very great. Its dead weight was 3,000 pounds to the square foot, making17 an aggregate mass of iron of many tons.

The rods or braces had buckled or bent at the first trial, and there was danger that it would fall by its own weight into the creek. As it was changed, however, and the braces sprang back, by the elasticity of the iron, heavier braces were put into it, and in this shape it stood for eleven years in constant service.

The night was portentous. All nature conspired to make it prophetic of some direful event. The sympathy of the natural with the historic event was known and felt.

Ominous of evil, a furious storm had set in. It was one of the periodical snow storms for which the season had been remarkable. Every Saturday throughout the month it had returned, the same fearful blast and fall of snow. As if in warning, it had come three or four times during the season, and now with redoubled force appeared.

The snow had fallen all day long, and was, at the dusk of night, still falling with blinding fury. The powers of nature had seized it again, and were hurling it down as if in very vengeance against the abodes of men. Everything was covered19 with a weight of snow. The wreaths and fancy drapery which, during the first storm, had engaged the attention of children, and pleased the fancy with their forms of beauty and delicate tracery, had now increased until they were heavy blankets and burdensome loads. The feathery flakes, which at first were beds of down, had become solid banks. Everything was buried in the increasing drifts, even trees and houses and fences stood with muffled forms and burdened with a snowy mantle. The streets were covered with drifts which were piled high and wide.

No attempt had been made to break the roads. The citizens had, for the third time, confined themselves to their houses, and had not even opened the paths from the doors to the gates. It was, in fact, one of those blinding, burying storms which occasionally come upon northern homes. The greatest comfort was in being at home and having the consciousness of the home feeling. Even the cares of the world were shut out, and many had remained in doors refusing to be called from the loved circle and comfortable fire. Those who were well housed felt a pleasure20 in their own security, and often looked out, grateful for the shelter of their homes.

But to the traveler it was a fearful storm. The same clouds which filled the sky with their fleecy masses, became portentous to his gaze. As the dusk of night settled down with more fury in the storm, a fearful foreboding filled his heart. There were many who were impressed with this indefinable sense of danger. It was not because they felt the discomfort of the journey, nor because they unconsciously acknowledged the difficulty of the way, but a strange presentiment continually haunted them and filled them with indefinable fear. Brave hearts sank within many, as the strange feeling came over them, that there was danger in the air. It was like a pall to the soul. It rested heavily upon the spirits. Stout men had to reason with themselves to nerve themselves to undertake the journey.

This presentiment of evil was the common one. Many of the friends urged the travelers to stay and not undertake the fearful journey. Parents at Buffalo are known to have persuaded a daughter to stay until the storm was over, and only21 yielded because a light heart was so buoyant and hopeful, in the prospect of a holiday approaching.

A wife at Rochester urged a loved husband to stay, and was only comforted by the promise of a speedy return. A young husband at Erie, away from his loved wife, was sadly impressed, and discussed the question a long time with parents and friends, and only went because absence might disappoint the expectant companion, and because affection for a little babe was stronger than the fear which haunted him.

Even the sweet singer of Israel was strangely impressed, and had so far yielded to his presentiments as to persuade the ticket agent, at the station where he was waiting, to exchange tickets and to give him passage by another route, and only the sudden appearance of the train, induced him to take it instead of another.

Among the many others the same forebodings were felt, but unexpressed. As the sun went down the air grew colder. A blast from the north arose and the snow ceased falling, but the roads and paths were still unbroken. Whoever undertook to breast the storm or to pass through22 the streets, plunged deeply into the untrodden snow. Horses were kept from their accustomed duties and were comfortably stabled from the storm. Nothing was stirring, apparently; only the strong iron horse and the solitary train, which slowly made its way along the snow-covered track.

Everything was behind time. The train which was due at Erie at a little after noon, was two and a half hours late. It should have reached Ashtabula before sundown, and it was now dark and the lamps had long been burning. But the engine pushed forward. The same train which had started from New York the night before, had divided at Albany; a portion of it was plunging through the snow-drifts of the mountains of Vermont, and now another portion was struggling amid the snow near the banks of Lake Erie. Both were destined to be wrecked.

Four engines had been used to push the train from the station at Erie. Two strong locomotives were straining every nerve to push forward and overcome the deep snow.

Within the cars there were many already anxious23 about the time. It was a long and well filled train, but it was greatly behind time. Those from a distance had been delayed throughout all their journey. Those from nearer cities were impatient to meet their friends. To some a long trip across the continent became an immense and gloomy undertaking. But the passengers were making the most of the comforts of the hour. It was a little world by itself. Men, women and children were mingled together in the precious load. Clergymen, physicians, professional men, business men and travelers, young men and women, those from all classes and places were there.

In the distant east and, even, the distant west, from north and south their homes were scattered.

The continent was represented by that train. It bore the hearts of many, many friends. It was a varied company. Each one was pursuing that which best suited the varied tastes, and were beguiling the weary hours. An unusual number of parties had gathered to drive away care and weariness by card playing. At least five such parties had cards in their hands at the hour of24 the sudden calamity. Others had been beguiling the time by tales of adventure, and by relating escapes from various dangers.

In the smoking car a group was discussing the weight of the engines and the amount of water used by each engine. Ladies in the sleeping coach were preparing to retire; some had already laid down in their berths. Gentlemen were quietly dozing in their seats; others were taking their last smoke, before settling themselves for the night. Even the sweet singer had just laid aside the Sacred Word, and was quietly meditating, with a song echoing in his heart. It was just the time when every one was seeking to make himself comfortable for the night, notwithstanding the storm which raged.

A few thought of danger as they looked out into the darkness of the night, but the sense of security pervaded the train; when suddenly! the sound of the wheels was stopped; the bell-rope snapped; the lights were extinguished; and in an instant all felt themselves falling, falling, falling. An awful silence seized the passengers; each one sat breathless, bracing and seizing the25 seats behind or before them. Not a word was spoken; not a sound was heard—nothing except the fearful crash. The silence of the grave had come upon them. It was the fearful pause before an awful plunge. It was the palsied feeling of those who were falling into a fathomless abyss. The sensation was indescribable, awful, beyond description. It seemed an age, before they reached the bottom. None could imagine what had happened or what was next to come. All felt as if it was something most dreadful. It was like a leap into the jaws of death, and no one can tell who should escape from the fearful doom.

The cars lay at the bottom of the gorge. That which had been such a thing of speed and a line of beauty, now lay wrecked and broken, and ready to be burned. It was indeed a beautiful train, and was well known for its elegance and beauty. At this time it consisted of two locomotives, one named “Socrates” and the other “Columbia;” two express cars, two baggage cars, two day passenger coaches, a smoking car, a drawing-room car called “Yokahama;” the New York sleeper named “Palatine;” the Boston sleeper named “City of Buffalo;” the Louisville sleeper called “Osceo.”

The bridge broke in the centre. The engineer of the Socrates suddenly heard a sharp crack, like the report of a torpedo, and looked out and saw the engine behind sinking. With great27 presence of mind he opened the throttle valve an instant, and putting on all steam drove his engine forward. It was “like going up hill,” but the Socrates reached the abutment and was safe. The Columbia, as it was drawn forward struck the abutment, and for an instant clung to its leader, held by the coupling rod, but as that broke, it fell. The first express car struck forward and downward, and landed at the foot of the abutment, while the locomotive fell on to it, completely reversed, with its headlight towards the train which it had been drawing. The other express and two baggage cars also fell to the side of the bridge, forming a line across the chasm with the rear baggage against the east abutment. The heavy iron bridge fell in the same instant with an awful crash, to the north, and lay, a great wall of iron rods and braces, ten feet high across the gorge. Singularly enough the track and top of the bridge remained long enough in situ for the bridge to sink and sway away beneath, and then fell straight down and lay at the bottom of the stream immediately below where it rested before, but 76 feet down,28 in the midst of the ice and the snow and water of the stream. Upon this the first passenger coach landed in an upright position in the middle of the stream and to the left, but close by the wreck of the bridge.

The second passenger coach followed, but struck around at an angle, and turning on to its side fell among the rods and braces, and was crushed and broken in the fall. The smoker broke its couplings at both ends, struck across and through the second passenger car, smashing it in its course, and then fell upon the top of the first, crushing it down and killing many as it fell. The palace cars followed, but as they fell they leaped clear of the abutment and flew out into the air to the left of the bridge with their trucks hurled beneath them, and dropped 76 feet down and 80 feet out, and landed in the centre of the chasm.

The first drawing-room car “Yokahama” landed on the ice, and the sleeper “Palatine” beside it to the right. The sleeper “City of Buffalo,” however, as it flew through the air struck across the two, knocking the “Yokahama”29 on its side and crushing it in through its whole length, and landed on its forward end, with its rear end resting on the other two and high in air.

As the different cars fell, every person for the instant was stunned, and the crashing of one car on another struck many dead in an instant, while the survivors waited in suspense, expecting death would also come to them at the next blow.

The work of death was owing mostly to the fall, and to the crashing of cars and heavy trucks on bodies and limbs, and even the very hearts of many.

It was probably instantaneous to the large majority of those who perished. But a few were taken out of the wreck with any evidence of having perished from the flames which soon broke out. The wonder was that any escaped to tell the manner of their escape.

As the cars struck, splinters flew in every direction. The floor burst up from below. The seats were crushed in front and behind. The roofs were crushed from above. The sides opened and yawned, and, as one expressed it, it30 seemed as if every limb and sense were being scattered and only the soul was left in its solitariness.

More than one imagined that he was the only survivor, that all the rest had perished in an instant. Many thought their time had come. The thought of fire also arose in many minds, and the fear of a death that might be more dreadful than that by the crash.

Without, the wreck was strewn among the iron beams and columns of the broken bridge and scattered in terrible confusion.

Ice and water and snow were mingled with rods of iron, and heavy braces, and beams, and the debris of cars, and the bodies of men.

Danger threatened from all the elements. If they remained in the wreck, the fire threatened them with a horrid death. If they fled the fire, the water threatened to engulf them. If they escaped the water the darkness and chill of night, the storm and the awful stunning, bewildered and appalled.

The very sight of the lofty abutments towering high, impressed them with fear. The wild and31 lonely gorge strewn with snow and swept by the furious storm, conveyed a sense of wildness and strangeness in the extreme. It was a bewildering and an appalling scene.

As one after another of the stunned and stupefied survivors began to emerge from the broken wreck, they were dazed by the wildness of the place.

The experience of every one was different. Some dragged themselves from the debris and escaped through the broken windows, tearing clothes and flesh as they emerged. Others climbed through openings in the side or top and so made their way into the open air, and the gloomy night. Others broke the glass doors with their fists and dragged themselves through the openings thus made and sought to draw out others. Some became insensible and were only removed by force and taken by their friends to a place of safety.

Strong men were bruised and stunned and were led by their wives. Others found themselves bleeding before they knew they were hurt, and even hobbled with broken limbs, not knowing32 what was their wound. Some sank into the water and were with difficulty rescued by their companions and dragged out upon the ice and snow. Many, as they got out, found themselves amid the rods and braces and hardly knew which way to turn. Some emerged from the doors and fell into the snow and water. A lady climbed out a window and walked on the sides of the car that lay wrecked beneath, and climbed down the back of a man who was willing to become a ladder for her escape. Another escaped with broken limbs which by force she had dragged from beneath the wreck, and then by the rods and braces drew herself to shore through the water into which she had fallen. Another still was able to get out of the car where lay her child and nurse, and was dragged in her night clothes through the water and snow, and across the ice and then stood upon the bank in the storm like a spectre, exclaiming: “There is my child, I hear its voice.” A father rescued his little children, mere babies as they were, and placed them on the snow for strangers to take, and then returned for his wife. She is held by the wreck and is badly hurt and exclaims33 that she cannot be saved, but begs her husband to cut her throat lest the fire should reach her and she be burned to death. She is, however, rescued and the whole family is safe. A gentleman gets out but finds that his limbs will not obey his will, but sink beneath his weight, and he is obliged to crawl on hands and knees to a place of safety. After all others have escaped, something attracts the attention of those on the bank, as if a coat were flapping in the wind. Next a man appears as if attempting to arise, and then the man emerges from the region of the flames, and is helped to the shore by others.

Many became so exhausted and faint that they fell senseless upon the snow and were drawn by others to a place of safety. It is even thought that some were so bewildered that they wandered into the broken places in the ice and were drowned.

It was but a very few minutes before all who could, had escaped and the rest were still struggling to get out or were already dead.

The citizens were startled by a sudden crash. Those who lived near the bridge knew that the train was late. Many of them were in some way connected with the road, either as telegraph or baggage men or in some capacity of the railroad service.

For some reason there was an expectancy among them all. Those who dwelt on the banks of the gorge could look from their rear windows and see each train as it came. As the first awful crash was heard the whole neighborhood was startled. Then as the ominous sound of car following car fell upon the ear, crash after crash in quick succession, the horrible consciousness came to all with appalling force. Some started to their feet with alarm. Others rushed to the doors and hastened to the scene. One lady,35 Mrs. Apthorp, exclaimed to her husband in terror and great alarm: “My God, Henry, No. 5 has gone off the bridge.” As her husband seized his hat and coat and hastened out of the door, with a woman’s sympathy she put the camphor bottle into his hands, thinking of the wounded, and the suffering which must follow.

But a few minutes had passed before a number were at the depot. The engineer of the pump-engine was standing on the depot platform as the train approached. As he heard the sound he looked up and could see the cars from the middle of the train, plunge off to the side of the bridge, and fall into the abyss. The headlight of the engine was above the track, but the passenger cars were falling behind it. The head painter was also in his shop and heard the crash. The saloon keeper of one of the hotels, and the foreman of the fire engine “Lake Erie,” also heard and saw the fall. These were the first to start for the wreck, and reached it very soon. Mr. Apthorp also was early on the ground. These, as they approached were appalled at the awful scene. The engineer seized an axe and pail as36 the first things which were at hand, and hardly knowing what he was doing, attempted to break the doors and windows, for the wounded to escape. Mr. Tinlay plunged into the water and swam to the other side to rescue those who were at a distance in the wreck. The omnibus man began to chop to get an opening for those within, but cut an awful gash into his foot, and was obliged to cease. Mr. Apthorp, more deliberate and self-controlled, first thought of the bell and of giving the alarm, but hastened to the train. He went from car to car, entering such as were open and could be reached, and sought to help out those who might be left inside. Others arrived and helped the wounded to escape from the water and ice, and up the bank.

All were excited and hardly knew what they were doing and did not think of what next to do. The engineer fluttered to and fro, excited and uncontrolled. The saloon keeper assisted a few and then disappeared. Some who arrived stood on the bank amazed, and appalled, but idle and passive, amid the scene.

In the meantime the flames began to arise. It37 was only a little glimmering light at first, so small that as the passengers pass they throw snow and a portion of it is quenched. A few buckets of water thrown at this time, would have sufficed to have kept down the flame. But the critical moment was passed. The fire began at both ends of the wreck, and rapidly spread. It was just a little flame on the east side underneath the sleeper. It was brighter in the smoker and in the heap near the bridge, but it spread from car to car, and soon enveloped the whole. No one thought that the fire could be prevented. The desire to rescue the wounded, and save the living, was more urgent. It was too constraining for any deliberate thought. It crowded out every effort to prevent the spreading of the flames. Every one was appalled, and overwhelmed, and did that which seemed most pressing at the moment.

The brakeman, Stone, who had escaped unhurt, thought only of another train which was expected soon. He hastened to the telegraph office to tell of the wreck, and to stop the coming train. The conductor was almost paralyzed with terror and38 became frantic with excitement, and rushed to and fro, calling for help, and it is said was kept with difficulty from throwing himself into the fire.

The flames kept arising. They spread far and wide. They ascended high and still higher. They filled the valley. A cloud of smoke ascended, too. It was black and dense and pitchy. It came from the paint and varnish, and the materials of that gilded wreck. It was stifling to the breath and deadly to all who breathed it. It enveloped the ruins. It even darkened the sky and rolled a thick cloud through the awful gorge. The worst of fears began now to be realized. Horror seized the living, for death now claimed its victims, and man was powerless to deliver. Within the awful canopy the flames shot up, and from among them came forth groans and shrieks and cries of agony and despair.

Then followed the most heart-rending scenes and incidents. Those who were without, but who had friends still left in the burning cars, shouted loud and begged that the fire might be put out; they even sought to go back to get their39 friends. Yells arose from the valley, and were echoed in shouts from the top of the abutments, and one wild scene of excitement pervaded the spot. A little child was heard to exclaim, “Papa, O, Papa, take me!” A woman cried from within a car, “Oh save me, for God’s sake take my child!” A man had clasped a woman, to carry her from the flames, but her foot was caught, and he was obliged to leave her and save himself.

Another saw underneath the floor of a car, a man and a woman lying there and calling for help; he tried to extricate them, but, as the flames arose, he went to the firemen and begged them to put on water and save the living.

Mr. Apthorp saw a woman trying to get out of the window of a car, high up amid the ruins; she was half way out and called for help. He hastened to the rescue, but the flames arose between him and her, and she perished there.

Two men were seen, sitting in their seats, surrounded by the flames, but they perished and no one could save them. One man stood by his berth and burned to death, holding to its side. A gentlemen, supposed by some to be Mr.40 Brunner of Wisconsin, and by others, to be Mr. P. P. Bliss, the sweet singer, was seen to emerge and then to go back, saying that he will perish with his family.

A gentleman was seen in the midst of the flames, standing as if surrounded by a wall of fire, until he fell. The most appalling sounds and sights shock every heart, and send a shiver of horror through every frame. The howl of a poor wounded dog echoes through the valley.

A woman, whose children have already perished, was seen lifting up her hands and beseeching help, and was at last rescued, among the last, awfully burned, and died in a few days from her wounds. The last one removed was the fireman, and then this poor dog, which had kept up its piteous howling.

The living were driven from the wreck, and could only stand and look upon the awful scene. A cry arose—a horrid cry; it was not a shriek; it was not a groan, nor even a cry for help, but it was a plaintive, melancholy wail—the despairing cry of those who knew that they must die. It was a prolonged, an agonized, a heart-rending41 moan; it was the sound of Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Then all were dead, and silence settled down upon the scene—the awful silence which comes upon the dead.

The parched lips were sealed forever; the stifled breath could no longer send forth a cry or groan; the carnival of death had at last silenced all its victims; the slaughter was complete. “Blood and fire, and vapor of smoke.” The flames leaped and danced, and lifted high their heads, and death was exultant in all its forces. The canopy of blackness arched the snow-covered valley, while the fiery billows rolled between. All that man could do was to stand and look upon the scene, appalled.

The citizens of the village were sitting by their fires, or at their tables, or in their places of business. A sound was heard! It was a sudden, startling sound. To those who were living near the depot, it was a succession of sounds; first a crash, then a fall, then a distinct sound for every car. To those who were at a distance it was a single, but a prolonged and terrible crash. To those who were within doors it seemed like a sudden fall of a distant building, or the nearer slide of a heavy body of snow, but much more ominous. Some imagined they heard a sound that followed, which they supposed to be the wailing of the wind. It startled the inhabitants in many houses, and was heard more than a mile away. Presently the sharp alarm of fire was heard, and the bells rang out their pealing notes.

43 Many started from their seats, at the thought of fire on such a night. Presently the sky was illuminated: a strange glare filled the heavens. It was not like a distant flame, that cast its shadow on the sky. It was not like a nearer fire that shot up sparks and smoke. It was a glare that pervaded the whole horizon. It cast a pale and sickly color into the fleecy air. It covered even the snow with a pinkish, almost crimson, hue. It seemed like an extensive burning, as if the flames were suddenly arising from widespread structures. No one could tell, however, what it was, nor what was the matter.

The men who rushed into the street first whispered, it was an oil train, that had caught fire on the track. Others said that it was the building at the depot. Women who were kept at home were impressed that it was something more than a common fire. Uneasiness seized the aged who were residing in houses far distant. Many hastened for the engines; others ran in the direction of the light. All plunged into the deep snow, and, out of breath, could only follow in single file along the path which the foremost had broken.

44 A long line of men and boys reached from the main street toward the fatal spot. Horses and teams plunged madly by. Every available horse in one of the stables was put into use. The steamer was got out. The horses attached pulled and tugged the massive load.

“Protection” engine was also manned at first, but afterwards drawn by a team secured. Hose-carts were taken for a distance, and then horses were attached to these.

The villagers had become thoroughly aroused, and were straining every nerve to reach the fire. It had become known that the bridge was broken, and a passenger train was wrecked in the dreadful gorge. An unregulated crowd was rushing with all haste through the impeding drifts. The thought with all was to hasten forward, and save the living. It seemed an age before they could reach the spot. Many became exhausted by their efforts. The snow and drifts were so deep that none could make headway, except with difficulty. Even teams were detained by the snow. It was at least twenty minutes before the citizens arrived.

45 Time enough had then passed for the work of death. The wounded passengers had recovered from the stunning fall, and arisen to their feet and escaped to the shore, assisting one another from the wreck.

Nearly all who were in the forward car had escaped, except those who had been crushed by the trucks, which had broken through the roof, and fell upon them. One had even, after his escape, looked in the window, and put his face near the cheek of his companion, and found him dead. Those in the smoker, had climbed out and looked back to see how complete, the sweep of the burning stove had been, which had carried several before it to their death. One had fallen out of a gaping seam made in the side of that car, and looked back to see another man caught as the car closed again, and thought to himself that it had opened on purpose to let him out.

Those in the sleeping coaches who were alive, had also escaped, and made their way to land. One gentleman, Mr. Brewster, who was but little hurt, had assisted a man who was badly wounded46 and helpless amid the wreck, and laid him down at the east abutment, and then crossed the stream again and called out to others saying: “This way, here’s a house!” Women had escaped from the rear sleeping coach and were already at the shore.

Miss Sheppard, who was unhurt, had reached the bank and requested some one to help her up, and then made herself useful in aiding others. Those who had escaped on the north side were already making their way through the deep drifts and the lonely valley and up the steep embankment. Those who were near had done all they could to rescue the living, and the flames were already arising and nearly covered the scene. All this had occurred before the citizens from the town could reach the spot. It was then too late to do anything to save the wounded, or even to keep the flames from destroying life. To be sure the fire engine stood in that engine house upon the hill, but it was never moved. The pump engine also stood in the lonely valley, with its steam up, but it was not used. There was also hose in the upper engine house not six hundred47 yards away, which would fit a plug in the house by the river. But in the confusion of the moment no one had thought of engines, or of hose, and not even buckets had been brought down. Meanwhile, the teams from town were plunging on, dragging the steamer and the hose through the heavy drifts.

The station agent, who had received a telegram from the central office, to get surgeons and aid for the wounded, was also hastening to the spot—but it was too late.

The work was done. It was impossible for them now to rescue the living. Those who had reached the scene had already rescued nearly all the wounded and the living, though fearfully bruised, and some of them insensible, from the fire.

Others were standing and looking on from the banks, idle spectators of the scene. And, before the eyes of all, the fire had crept on and on, and was now enveloping the whole. The wounded lay in the snow, or on the damp, cold floor. The water dripped from their garments and ran upon the stone. Blood flowed from wounds and48 mingled with the water. Chill and damp and pain and wounds and the shock and fright were combined. Gashed and bruised and broken, they were crowding up that lonely, chilly bank. But the flames without were burning and eclipsing all their misery. Appalling death was shooting from car to car, and the dreadful valley had become an awful scene. It was too terrible for any human mind. The groans of the wounded were mingled with the groans of the dying, and shouts and groans and shrieks and cries echoed through the valley; then the plaintive wail and the awful silence.

The firemen arrived at last; the station agent had reached the spot before them. All was haste and confusion. No orders, and no one in command. The wounded were already coming up the bank. Citizens, as they came, had taken the survivors from the wreck, and were now helping them to a place of safety and comfort.

Appalled by the scene and confused by the horror, none knew what order was to be given or who was in command.

Mr. Apthorp was in the employ of the road, and was supposed to have some control. As Mr. Strong hastened to the rescue, he asked, “What shall we do?” The reply was, “Get men to help up the wounded.”

As the chief fireman met Mr. Strong, he asked “Where shall we put the hose?” “Where shall50 we apply the water?” The echo of Mr. Apthorp’s remark was the only response—“We want to get out the wounded, never mind the water.” A second time the question was asked, as the station agent appeared in another place, and a second time the response was, “We don’t want water, we want to get out the wounded.” “Get all the men to clear a road to the wreck.”

Again, as the firemen undertook to lay the hose, another official of the road used a vulgar illustration and saying there was no use in throwing water on the flames. The impression was thus given, by those in command of the wreck and the road, that water was not wanted. The chief fireman was not a man to assume the responsibility under such circumstances: he was dazed and confused and did not seem to know what to do. The horses stood hitched to the steamer. The hand engine “Protection,” also stood, with the men waiting for orders. Some one ran up from the wreck begging, for God’s sake, that water should be thrown, but both engines stood waiting.

The call for buckets, went up from below. One51 old man, seventy-six years old, was in the midst of the wreck, chopping for dear life and calling for buckets at the same time. His son, arriving late, plunged into the midst of the fire and began to work like one made desperate with despair. Others took pails and undertook to go out to rescue bodies that were burning.

The driver of the steamer took the engine to the cistern and stationed it there, but no orders were given; and the hose carts were ready to be unreeled, but no orders were given. The whistle of the steamer was sounded for hose and the men stood ready to lay it; many wondered at the delay and talked excitedly, but still no orders.

The captain of the steamer asked the station agent if he should apply water, but the same answer was returned. The chief fireman still remained stupid and passive, and gave no orders. At last he went, himself, to the wreck and began to help remove the wounded, while the men still waited and the engines were idle. The men became impatient, but they were held by the authority of their chief. The fire was still burning, but that answer of the station agent held the52 chief fireman and he yielded to the direction and abandoned the engines and his men.

A man who has seen two persons still living, underneath the wreck, comes up and begs that water be thrown, but the engines stand idle, and the firemen dare not work without orders. The more determined of them leave the engines and go down to the wreck to work without them. Pails are procured from the stores, and with them the firemen work. Great exertions are made to extinguish the flames in this way. Desperation has taken possession of the citizens.

An hour has passed, and it is stated that there are some still living, but the engines stand idle. There is talk, even, of disobeying orders and assuming command, but the law is quoted and that is prevented. Men fly here and there, anxious to save the living; others assist the wounded. Some stand on the banks, with hands in their pockets, and look on unmoved, but the fire still burns. A few seize a rope and fasten it to the locomotive, and try to lift it off from one poor wretch who lies beneath it, but the time passes and the flames are not subdued. A line is begun53 for the purpose of passing water, and so putting the fire out, but a voice was heard from the top of the abutment, saying: “You don’t want water there.” “Don’t put any water on the wreck.” A few rushed for the hand engine, thinking to take it down the steep bank to the creek; the arrangements are made and a hose is attached, but the decision of the foreman is, not to take it down. Still, a few persevere with their buckets; the flames in one place are put out by this means, but no effort is made by the engines, and the men stand waiting.

Horses become restive; the captain of the steamer remains at his post; the firemen await his command, but the order is never sent. Lives cannot now be saved, and the bodies are burning. A woman is seen in the midst of the wreck; life is extinct, but the body is held by the iron framework, high in air. Her clothes caught fire, and she begins to burn like a martyr at the stake. The spectators are horror-stricken by the sight. A few form a line and, with buckets, throw water in that direction, until the body falls and lies buried with others. The fire at the engine is54 next attacked, after the fireman is rescued. The poor dog, which has kept up his piteous howl, was also taken from the same place. This is the last living creature taken out, but the bodies still burn. The wind blows cold, but the fire burns on.

The strangest misunderstanding has taken possession of all. Whatsoever the motive of those in authority, the effect was, to keep the engines from playing upon the flames. There were tanks on both sides of the track; the engines were both on the ground; there was hose sufficient, but the misunderstanding made everything useless, and the department was held back and did nothing. The indignation of the citizens was openly expressed, but the fire continued. Mr. Stebbins, a citizen, asked the captain of the steamer, why water was not thrown? and was answered, that the chief would not order it. He exclaimed, “We had better hang him, then,” but the fire continued to burn until, in places, it burned itself out, and there was nothing more to feed upon; nothing was left except the bodies, and these were almost consumed. The fumes of55 the burning flesh filled the air, and the horrid consciousness haunted the hearts of the spectators, but the fire burned on, and the strange suspense held the people.

An engine house stood on the bank. It was the place where water was pumped from the river to the tank, at the depot buildings. It was a little brick building with a stone floor and a large boiler and engine occupying the middle of the room. Into this building, the wounded were taken, and were laid on the cold, damp floor,—a ghastly throng. As citizens came, they found them there, suffering from the cold as well as from the shock and wounds. The effort was made to take them to places of more comfort, but where to take them was the question. No one was there at the time to command. A few men were there to assist; some were there to plunder, and more had come not knowing for what they came. A long, weary flight of steps led from the gorge to the track above. Up this flight the wounded57 were taken. On the other side the access to the wreck was only through the deep snow and down the steep bank. A line of men was formed at last. Up both sides of the track the wounded are helped, passed from hand to hand where they are able to stand. Others were borne by the citizens, and so by degrees, with pains and groans and amid the wild excitement, the most of them were removed.

The nearest house to the scene was a place called the “Eagle Hotel,” kept by Patrick Mulligan. Into this, by some chance, eleven of the wounded were carried. It was a horrid place. A dirty bar-room. Rooms which had never known a carpet, but whose floors were soon covered with snow and water; little bed-rooms just large enough to hold a bed and wash-stand, without carpets or stove; beds that consisted of filthy sheets and miserable straw ticks. It was a house forbidding in every respect. Into this place the wounded were taken, bleeding and gashed, and laid two by two on the miserable pallets. There they lay in the clothes which they had on, covered with blood, cold and cheerless,58 while crowds of curious spectators trooped in and out through the weary hours of the long and dreadful night.

Others fortunately were taken to better quarters, but even some of these were robbed on the way of the money which they had in their pockets by the very persons who pretended to assist them in their helpless state.

Teams were secured. A road was broken. Into the gorge sleds are with difficulty taken down, and into these the badly wounded are placed. The two little children who had escaped are also taken in these, badly burned and insensible, and placed with their father in a private house. The mother is moved, and laid in another house, and lies in great agony. A young girl, timid and frightened, whose limbs are broken, is separated from her aunt, and placed among strangers. Amid great confusion those who are able, walk to the hotel, some of them pursued by those who would rob them. A father calls out from a stretcher for a daughter whom strangers are taking in another direction, and becomes almost frantic with excitement59 until the girl is brought back to him. The poor burned woman whose children are dead is borne to the “Culver House.”

The bruised, gashed and bleeding passengers are at last removed from the valley. They are distributed through the neighborhood. Upon couches and beds of the few hotels; upon the counters of stores; on the floors of private houses; and even in the saloons—they are scattered until the whole vicinity becomes a hospital. The surgeons are all at work. The wounds are hastily dressed. The blood is washed away. Many are wrapped in warm coverings. Comparative quiet and rest settle down. The spectators have left the smoking ruins, and in curious crowds have trooped through the houses and have gradually disappeared. Those on the abutment returned to their homes. The firemen themselves disperse. The last one in the engine house has gone. Only a very few are left to guard the dead.

A wild and lonely scene remains. The dead are left there alone. The snow drifts toward the smoking ruins. Nature weaves a white shroud.60 Night draws down a black pall. The silence of the grave settles upon the lonely spot. A flickering light from the funeral pyre sends up a glare through the darkness, and the dead stare from the blackened bars with eyeless sockets, and the bodies are left to burn.

It is a horrible, heart-sickening sight, the bodies still smoulder in the burning grave, and the smell of their flesh arises on the darkening air.

The fire continued to burn. For a time the wreck was left unguarded.

When it was, that so much plundering occurred no one knows. The flames were lifting up their lurid light, and covering the ghastly scene with a sickening glare. The dead lay in every direction amid the driving snow. A skull lay by itself amid a blackened heap, whitened by the fire. The heap of bodies lying in the sleeping-coaches were still burning, and yet this appalling scene did not intimidate the human vultures who were looking for their prey. The ravening wolf that prowls at night would be driven from such a horrid place by very fear. The hearts of men were on that fearful night more greedy than wolves or vultures are, for amid that awful wreck they sought for spoil. One and another of the62 wounded had been robbed. Men were more merciless to their fellows than the cruel flames.

One young man, who had lost both mother and sister, was suffering from four broken ribs and a severe gash in the head. As he looked up and saw the men standing and watching, the thought of robbers crossed his mind. He had a valuable watch, a present from his father, and two purses, one containing fifty dollars in bills, and the other a few dollars in change and his mother’s jewelry. As the thought of thieves came up, he turned around with his back to the crowd and dropped his watch down his neck inside his shirt, and there left it suspended by the chain next to his person. One purse he placed inside his vest and in an inside pocket, and the other was left in the pocket of his pantaloons.

Some one offered to assist him up the stairs. As he reached the top this person disappeared and another came. Taking him by the arm, the robber drew it out in such a way that the broken ribs gave intense pain and caused the poor boy to faint and fall. As he fell, he remembers to have felt a hand reached into his63 bosom, and then he became unconscious, and lay upon the snow. When he came to himself, his purses and his ticket to California were gone, and all he had left was the watch he had hidden and the clothes he wore. Among strangers, with mother and sister both dead, the poor young man was at last taken to a hotel and telegraphed the sad news to his father in the distant home. Another gentleman, as he was being helped to a hotel, was robbed of all that he had in his vest pocket, on the side towards the one who supported him. Still another was followed by a person who pretended to be a physician and offered to assist, but escaped by threats and such speed as he could command.

Much valuable property was removed from the bodies of the dead. One gentleman had upon his person a valuable diamond pin, a commander’s badge, a Sir Knight’s pin and other valuable jewelry, but when his body was found, nothing was left except a cheap pair of celluloid sleeve buttons.

Watches were removed from chains, and the jewelry in trunks was taken or mysteriously disappeared.64 More than $1,500 worth of valuable articles were afterwards recovered by the Mayor by a proclamation, and by detectives. A saloon keeper was found to have appropriated shawls and satchels, and others were found to have diamonds and jewelry in their possession which had been stolen.

A young man who had a splinter from the cornice of the car driven through his collar bone was robbed of $300 in money at the Eagle Hotel where he lay, and a gentleman from Hartford had his boots taken from his feet and carried away.

The dead in the valley and the wounded in the streets, and the survivors in other places were alike subject to this villainous pillaging. A pair of dominos, or black masks, were found, showing how deliberate had been the robbery with the villains who were out that night.

Scarcely anything of value was left after the wreck. One gentleman who had $7,000 on his person was killed and his pocket book found, but the money was gone. Trunks containing the wardrobes of brides, and the jewelry of the65 wealthy, were burned and destroyed. Watches were burned in the fierce flames until the gold was melted into nuggets, and everything that could be treasured by friends, whether it was the clothes of the dead or the precious keepsakes they had, or the bodies which were more precious than jewels, all disappeared and not a relic or trace could be found.

At twelve o’clock quietness had settled down upon the scene. The streets were deserted. All had formed the impression that the bodies were to be burned, and had gone to their homes, leaving the wreck still burning, and the dead to be consumed. The engines had been ordered to their houses. The lights glimmered from the homes where the wounded were lying. A few were at the wreck. The expressman guarding the treasures in the safe, sat solitary and alone through the long hours, while the flames which were burning precious bodies, crackled and threw their lurid light across the scene. The smell of burning flesh pervaded the air even half a mile away. A horrid sight was presented in the awful valley. The flames which had blazed so high had consumed the wood and67 furniture of the train. The gilded palaces were reduced to mere skeletons of iron. The bridge lay a mere network of blackened beams. The trucks and wheels and heavy rods were lying in every direction. But beneath these horrid ribs of death, lay the blackened bodies of men, women and children, burned, and still burning, amid the snow and ice. Blue tongues of fire shot here and there amid the blackened mass, as if some unseen monster were still licking up the life of its unburied victims. The white snow lay like a winding sheet along the valley, but the skeleton was in the midst with the tall abutments towering above and the precious bodies silent in death beneath the ruins.

A long line of bodies lay packed on the bridge just above the water of the stream. They were covered with trucks and brakes, and heavy bars, and the debris of wood and the ashes of the wreck. Packed in a horrid mass they lay, crushed and broken, and blackened by the smoke and heat. Ghastly forms lay in this open grave. Headless, armless trunks were packed with the broken limbs, and the heads from which the68 brains were oozing, while the stumps of arms seemed lifted from the blackened heaps as if in mute supplication—too shocking for any human heart. The delicate form of a mother lay beside her little child, but both reduced to mere black lumps with scarcely a semblance to a human form. A full sized woman lay amid the mass but with no sign of either legs or arms except the broken bones which had been crushed away by the fall. Bodies of men also lay cut completely asunder, and presenting only the half of the human form—an awful, sickening sight.

Everywhere through the valley there were bodies lying silent in death. The pale flames which flickered here and there, betokened where many of them lay. Underneath the horrid bars of iron, on the black, deceitful ice, in the watery depths of the unconscious stream, packed in heaps underneath the burning cars—were the dead! It was an appalling and terrifying scene. The darkness and loneliness, and the very desertion, were enough, but through the very nerves there came the horrid consciousness of the many, many dead.

69 Far away were their friends, the night was lonely, and the storm was pitiful, but scattered through that grave were the bodies of the dead. It was hard to realize it, but, to the hearts of friends, these unburied were no strangers, and yet they burned, in loneliness.

The railroad authorities came at half past one o’clock. Five surgeons from the Homœopathic College, in Cleveland, the superintendent, the assistant superintendent, the train-despatcher and others. The wounded were in their beds at the time. The fireman was at the Eagle Hotel. The engineer was at Mr. Apthorp’s, two other persons, also, who needed surgical operations, were at the same house. The surgeons of the road, as they arrived, sought first the employees—the fireman and the engineer—and to these, gave their professional attention. The surgeons of the village had already attended to the passengers, had dressed the wounds of most of them, and were waiting for the proper reaction, to perform the amputation on those whose limbs were broken.

Ten surgeons were, at one time, crowded into70 one small house, where the worst cases were placed. By morning, however, the amputation was performed by Dr. J. C. Hubbard, assisted by Drs. Fricker and Case, and about twenty of the wounded, including the fireman and engineer, were removed to the hospital in Cleveland. This relieved many of those who were at the Eagle Hotel, as they found comfortable quarters at the hospital, and the rest were taken into rooms where a fire could be built, and where a carpet covered the floor; but through all the night the fire continued to burn. The haggard dawn drove the darkness out of the valley of the shadow of death. Seldom was revealed a ghastlier sight. On either side of the ravine, frowned the dark and bare arches from which the treacherous bridge had fallen, while, at their base, the great mass of ruins covered the men and women and children, who had so suddenly been called to death. The cherished bodies lay where they had fallen, or where they had been placed, in the hurry and confusion of the night.

Piles of iron lay on the thick ice or bedded in the shallow stream. The fires smouldered in great71 heaps where many of the helpless victims had been consumed; while men went about, in wild confusion, seeking some trace of their friends among the wounded or dead.

The morning dawned. Those who had known of the event, awoke as if from a fearful dream. The horror of the great calamity haunted the sleeping hours, and came back with returning consciousness. The dream was, indeed, a sad reality. The bodies, which were wrapped in the sleep of death and whose bed was the driven snow, were the first thought at the awakening of the living; nothing else was thought of in the village. Those who had not heard of it were startled by the news, but those who had seen and known, were strangely impressed. The smell of the burning flesh seemed to pervade the air. The sight of dead bodies seemed to fill the eye. The flames—the fearful flames—the ghastly wounds, the blackened bodies and the unknown, unburied dead were before the mind.

73 Death had descended like a bird of night, and flapped a dark wing over the abodes of the living, casting a shadow over the whole place, and then descended into the valley and was still watching its victims. There was something fearful in such an awful devastation by the dread monster.

But with this sense of the nearness of death, came another still more fearful to the mind. There was mingled with the thoughts of the dead, another of the living, which was even more horrible to the mind. A great shadow hovered over the place. It was not the shadow of the angel, which had descended, with its dark wings; it was not the unseen messenger of God; it was not of the horror that walked in darkness, or the destruction that wasted at noon of night, but a horrible suspicion had seized the people; the horrid selfishness of men haunted the waking thoughts as terrible death had the sleep of night. Cruelty was ascribed to men, worse, even, than the awful fall and death.

That burning of the bodies was ascribed to design. The impression was a general one. Indignation74 was mingled with horror; that retiring to homes, while the bodies burned, was not the result of indifference. Few were so heartless as to care more for sleep than for the safety of the dead. Many could not sleep that night, but, somehow, the impression had taken possession of the people that the burning was designed.

As the citizens returned to their homes late at night, they had talked their suspicion, and grown sick at heart. The firemen themselves had laid the blame somewhere else than upon their chief. It seemed too inhuman, and yet it was believed. The station agent was known and trusted. His character was well established. His humane and kindly heart was not impeached. His Christian life and courtesy were well known to all. But the feeling was universal, and the suspicion strong. The control of the company over the cars, and all the contents, was taken for granted. The responsibility of common carriers was known, and no one could understand why orders should be given to withhold the water, except it was to destroy the traces of those who were on the train. For the time this was believed. The75 sentiment was so common that even an employee of the road was heard to say that “ashes did not count,” but bodies did.

There was no foundation for the report. It was all the result of that strange mistake. As was afterwards shown, no such order had been given, and the persons in command were not responsible for the mistake; but for the time it had its effect. That midnight hour showed how strong this conviction had become. The deserted streets, the silent engines, the stabled horses—all betokened a thought which ruled the night. A strange misunderstanding had controlled that fatal hour, yet none the less powerful because so strange. As men met in the morning, this was the first thought which they expressed. It was the main subject of remark. Many supposed that the order had been given from the central office, but had no means of correcting or confirming their belief. Others maintained that there was a reason for the order, as the throwing of water upon hot iron was likely to create steam, and this, it was said, “would destroy more lives than even the flames, and would deface the76 bodies.” It was held by some to be the general policy of railroad companies to allow wrecks to be burned, and this was given as the reason: “that steam would be generated which would immediately cover the wreck, and drive away those who would rescue the living.” Gentlemen of intelligence and caution discussed that point with earnest warmth.

Little knots of men would gather and express their pent-up feelings. Others supposed that this popular indignation was the result of the terrible pressure and that weighed on the spirits, as if indignation were the safety valve for the oppressed heart.

These convictions of the people arose above all other feelings. The better sympathies were awakened and rebuked the very selfishness which was abhorred. The passions which were excited were to the praise of the better feelings of the heart. The kind and generous emotions were protesting against a cruelty which was imagined. It was not supposed, at the time, that the same humane feelings existed in the hearts of those in command. It was a “soulless corporation,” it77 was said, and men did not stop to reason. A horrible thing had occurred. A fatal mistake! The awful negligence and the fearful burning were combined. Somebody was responsible! The citizens felt that it could not be themselves, and yet the corporation remained unconscious of the charge. For several days the popular feeling continued. It was even reflected back in the reports of the press. As the friends arrived they partook of the feeling, and swelled its force. The sentiment came back from distant places, and the little village was intensely moved.

It was because the heart of a great nation was moved, and the shock which appalled and paralyzed the whole land, sent back its chilling horror to the very centre. Far and wide over the long wires the startling message had made its way. Families on the distant hill tops of the New England States; men in the green valleys of the California shores; at the distant south and in the snowy north; in the great city and in the little hamlet—the fact was known. Everywhere the shock was felt. Every eye was fixed upon the startling head lines. Every heart was moved as78 the news was read. All other things were forgotten in the great horror. The greatest railroad disaster on record had taken place. The Brooklyn horror was eclipsed by a greater. Angola was surpassed. Norwalk and the many other catastrophies were all forgotten. Ashtabula was known, and became the synonym, for the event. But mingled with this startling news was the silent question which the citizens were discussing on that gloomy morning—“Why was not the fire put out?” Nor did the feeling cease, or the surprise and sad suspicion die away for many a day.

As the tidings reached the neighboring counties, vast numbers began at once to flock in. Trains arrived by other roads. Each train came laden with passengers. The streets were filled with people. All were excited. Sooner, even, than the friends of the lost these crowds reached the wreck. The friends at a distance were, however, detained as it was not the purpose to allow them to come to witness the horrid scene until a suitable disposal of the dead was made. The police stationed on the ground endeavored to keep back the curious crowds, but in many79 cases found it impossible. It was not known whether the control was in the hands of the railroad company, or of the village authorities. They were mostly railroad men who were superintending the work. The excitement of the citizens was not diminished, as it seemed so doubtful who were in control. The fact that the Mayor of the city was in the employ of the road as assistant engineer only increased this feeling. At the time of the accident there was no coroner in the place. The proper officer had previously declined. Another had to be appointed in his place. Access being denied to the spot, and the supposition having obtained that the control was in the hands of the Company rather than of the village corporation the suspicion increased. The very efforts of the authorities to protect the place and keep back the curious strengthened the conviction. A strange feeling pervaded the place and was spread throughout many parts of the country. It was the element which most excited the people and which called attention from the widespread public.

The only answer is that the calamity was too80 appalling for man’s reason, and those in command seemed to have lost their judgment in the excitement of the hour and were held by the misunderstanding which so unjustly arose.

There was no evidence that this burning was intended. It is not reasonable to suppose it. The report was entirely untrue, the suspicion wrong, but in the excitement of the hour, it was felt, and was a strange feature in the event.

At eight o’clock, work was begun upon the wreck. Guards were stationed about the spot. Planks were placed upon the ice. Men were employed to remove the debris of wood and iron. Boxes were procured, in which to place the dead. A special policeman was stationed at the head of the stairway; no one was permitted to go on the ice, except the workmen, who were engaged in removing the debris.

The mayor of the city was on the ground; the stationing of the police was at his request, but the removal of bodies and the preservation of relics, was in the charge of an official of the road.

The superintendent of bridges and the train-dispatcher, assisted in the work. Even Mr. Collins, himself, the chief engineer, was there, and worked in the water, and forgot himself, in the82 sympathy he felt. Throughout the day the work continued, and the crowds passed to and fro.

Men were employed who, in long rubber boots and water-proof coats, worked all day long in the ice and snow; it was a difficult and tedious task. The wind blew cold, the water was deep, the beams were heavy, the iron was netted together, and the wreck was imbedded in the stream. The bodies were frozen, they were packed among the debris, and buried in the snow, but they were, by degrees, removed.