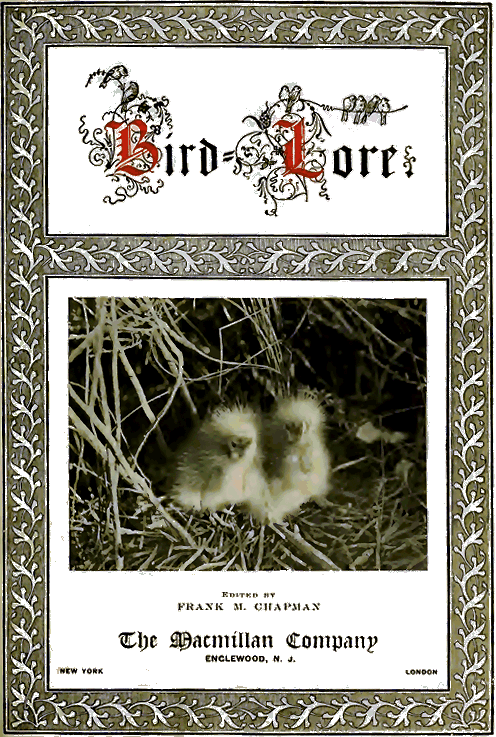

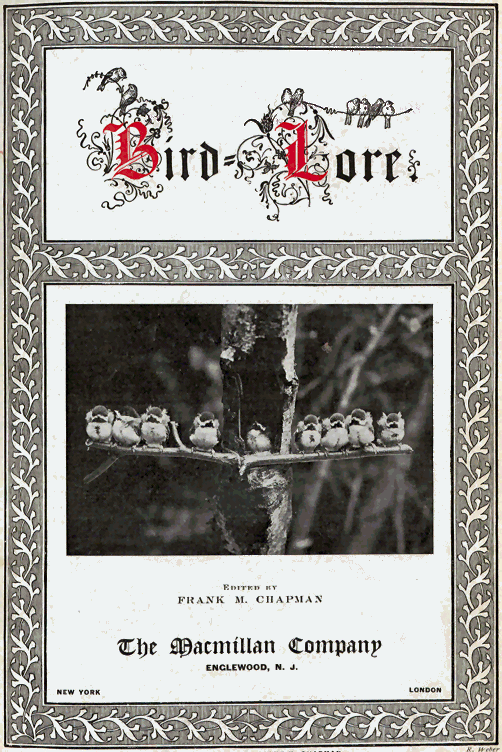

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bird Lore, Volume I--1899, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Bird Lore, Volume I--1899 Author: Various Editor: Frank M. Chapman Release Date: November 30, 2014 [EBook #47500] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRD LORE, VOLUME I--1899 *** Produced by David Garcia, Bryan Ness, Tom Cosmas and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Library of Congress)

AN ILLUSTRATED BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO

THE STUDY AND PROTECTION OF BIRDS

Edited by

FRANK M. CHAPMAN

Audubon Department Edited by

MABEL OSGOOD WRIGHT

VOLUME I—1899

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

ENGLEWOOD, N. J., AND NEW YORK CITY

Copyright, 1899

By FRANK M. CHAPMAN

INDEX TO ARTICLES IN VOLUME I BY AUTHORS

| VOL. 1 No. 1 |

February, 1899 | 20 c. a Copy $1 a Year |

February, 1899

| Frontispiece—John Burroughs at 'Slab Sides.' From a Flashlight Photograph. | ||

| In Warbler Time. | John Burroughs | 3 |

| John Burroughs at 'Slab Sides.' Illustrated | 5 | |

| The Camera as an Aid in the Study of Birds. Illustrated. | Dr. Thomas S. Roberts | 6 |

| From a Cabin Window. Illustrated | H. W. Menke | 14 |

| FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS | ||

| Bird-Studies for Children. | Isabel Eaton | 17 |

| Winter Bird Studies. | 19 | |

| FOR YOUNG OBSERVERS | ||

| Our Doorstep Sparrow. Illustrated | Florence. A. Merriam | 20 |

| A Prize Offered. | 23 | |

| NOTES FROM FIELD AND STUDY | ||

| An Accomplished House Sparrow. | J. L. Royael | 24 |

| A Nut-hatching Nuthatch. Illustrated | E. B. Southwick | 24 |

| Collecting a Brown Thrasher's Song. (With the gramophone) | S. D. Judd, Ph.D. | 25 |

| A Cover Design. Illustrated | 25 | |

| BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS | 26 | |

| Kearton's 'With Nature and a Camera;' De Kay's 'Bird Gods;' Mrs. Maynard's Birds of Washington; Bird-Life; Teachers' Edition; The Massachusetts Audubon Society's Bird Chart. | ||

| EDITORIALS | 28 | |

| AUDUBON DEPARTMENT | 29 | |

| Editorial; Reports from Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, and District of Columbia Societies. | ||

⁂ The Publication Office is in the Mount Pleasant Building, 208 Crescent Street, Harrisburg, Pa.

⁂ All communications in regard to contributions, etc., and all regular exchanges, should be addressed to the Editor, Frank M. Chapman, Englewood, New Jersey.

⁂ The subscription price is One Dollar per annum. Subscriptions and advertisements may be sent to the Publishers, The Macmillan Company, Harrisburg, Pa., or 66 Fifth Avenue, New York; or to the Editor, as above.

PUBLISHERS' ANNOUNCEMENT

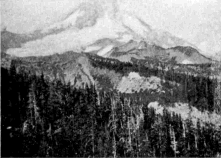

The April number of Bird-Lore will contain the conclusion of Dr. Roberts' interesting paper on 'The Camera as an Aid in the Study of Birds,' with photographs which surpass in merit even those presented in this issue; An article by Miss Merriam, entitled 'Oregon Jays and Clark's Crows on Mt. Shasta,' accompanied by photographs of the birds from life; A sketch of the home-life of Loons, by William Dutcher, illustrated by the author, and an illustrated account, by R. W. Hegner, of the manner in which he secured a unique picture of a Bluebird.

For 'Teachers and Students' Prof. Lynds Jones, of Oberlin College, will write on methods of bird-study, and a program suggesting appropriate exercises for Bird-day in the schools will be given.

Ernest Seton Thompson has written and illustrated some verses 'For Young Observers,' and there will be the usual departments.

A BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE

DEVOTED TO THE STUDY AND PROTECTION OF BIRDS

Official Organ of the Audubon Societies

| Vol. 1 | February, 1899 | No. 1 |

BY JOHN BURROUGHS

his morning, May 5, as I walked through the fields the west wind brought to me a sweet, fresh odor, like that of fragrant violets, precisely like that of our little white sweet violet (Viola blanda). I do not know what it came from,—probably from sugar maples, just shaking out their fringe-like blossoms,—but it was the first breath of May, and very welcome. April has her odors, too, very delicate and suggestive, but seldom is the wind perfumed with the breath of actual bloom before May. I said it is Warbler time; the first arrivals of the pretty little migrants should be noted now. Hardly had my thought defined itself when before me, in a little hemlock, I caught the flash of a blue, white-barred wing; then glimpses of a yellow breast and a yellow crown. I approached cautiously, and in a moment more had a full view of one of our rarer Warblers, the Blue-winged Yellow Warbler. Very pretty he was, too, the yellow cap, the yellow breast, and the black streak through the eye being conspicuous features. He would not stand to be looked at long, but soon disappeared in a near-by tree.

The Ruby-crowned Kinglet was piping in an evergreen tree near by, but him I had been hearing for several days. The Kinglets come before the first Warblers, and may be known to the attentive eye by their quick, nervous movements, and small greenish forms, and to the discerning ear by their hurried, musical, piping strains. How soft, how rapid, how joyous and lyrical their songs are! Very few country people, I imagine, either see them or hear them. The powers of observation of country people are not fine enough and trained enough. They see and hear coarsely. An object must be big and a sound loud, to attract their attention. Have you seen and heard the Kinglet? If not, the finer inner world of nature is - 4 - a sealed book to you. When your senses take in the Kinglet they will take in a thousand other objects that now escape you.

My first Warbler in the spring is usually the Yellow Redpoll, which I see in April. It is not a bird of the trees and woods, but of low bushes in the open, often alighting upon the ground in quest of food. I sometimes see it on the lawn. The last one I saw was one April day, when I went over to the creek to see if the suckers were yet running up. The bird was flitting amid the low bushes, now and then dropping down to the gravelly bank of the stream. Its chestnut crown and yellow under parts were noticeable.

The past season I saw for the first time the Golden-winged Warbler—a shy bird, that eluded me a long time in an old clearing that had grown up with low bushes. The song first attracted my attention, it is so like in form to that of the Black-throated Green Back, but in quality so inferior. The first distant glimpse of the bird, too, suggested the Green Back, so for a time I deceived myself with the notion that it was the Green Back with some defect in its vocal organs. A day or two later I heard two of them, and then concluded my inference was a hasty one.

Following one of the birds, I caught sight of its yellow crown, which is much more conspicuous than its yellow wing-bars. Its song is like this, 'n-'n de de de, with a peculiar reedy quality, but not at all musical, falling far short of the clear, sweet, lyrical song of the Green Back.

One appreciates how bright and gay the plumage of many of our Warblers is, when he sees one of them alight upon the ground. While passing along a wood road in June, a male Black-throated Green came down out of the hemlocks and sat for a moment on the ground before me. How out of place he looked, like a bit of ribbon or millinery just dropped there! The throat of this Warbler always suggests the finest black velvet. Not long after I saw the Chestnut-sided Warbler do the same thing. We were trying to make it out in a tree by the roadside, when it dropped down quickly to the ground in pursuit of an insect, and sat a moment upon the brown surface, giving us a vivid sense of its bright new plumage.

When the leaves of the trees are just unfolding, or, as Tennyson says, "When all the woods stand in a mist of green, and nothing perfect," the tide of migrating Warblers is at its height. They come in the night, and in the morning the trees are alive with them. The apple trees are just showing the pink, and how closely the birds inspect them in their eager quest for insect food! One cold, rainy day at this season Wilson's Black-cap,—a bird that is said to go north nearly to the arctic circle,—explored an apple tree - 5 - in front of my window. It came down within two feet of my face, as I stood by the pane, and paused a moment in its hurry and peered in at me, giving me an admirable view of its form and markings. It was wet and hungry, and it had a long journey before it. What a small body to cover such a distance!

The Black-poll Warbler, which one may see about the same time, is a much larger bird and of slower movement, and is colored much like the Black and White Creeping Warbler with a black cap on its head. The song of this bird is the finest, the least in volume, and most insect-like of that of any Warbler known to me. It is the song of the Black and White Creeper reduced, high and swelling in the middle and low and faint at its beginning and ending. When one has learned to note and discriminate the Warblers, he has made a good beginning in his or her ornithological studies.

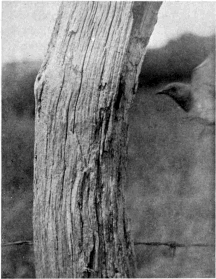

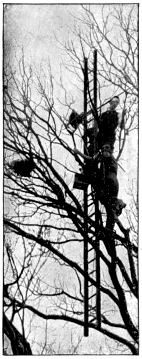

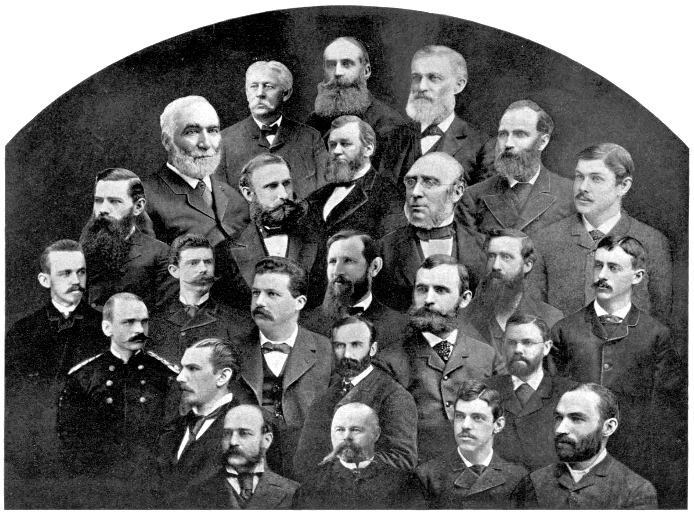

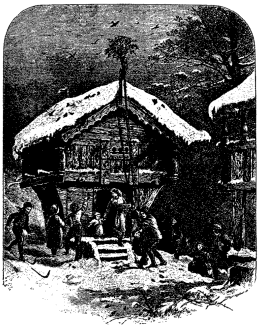

John Burroughs at 'Slab Sides'

ome years ago a favor to a neighbor resulted in Mr. Burroughs acquiring possession of a small 'muck swamp' situated in a valley in the hills, a mile or more west of his home at West Park, on the Hudson. To Mr. Burroughs, the agriculturist, this apparently worthless bit of ground promised a rich return after it had yielded to successive attacks of brush-knife, grubbing-hook, plough, and spade. To Burroughs, the literary naturalist and nature-lover, this secluded hollow in the woods offered a retreat to which he could retire when his eyes wearied of the view of nature tamed and trimmed, from his study on the bank of the Hudson.

In the spring of 1895 the muck swamp was a seemingly hopeless tangle of brush and bogs, without sign of human habitation. One year later its black bed was lined with long rows of luxuriant celery, while from a low point at one end of the swamp had arisen a rustic cabin fitting the scene so harmoniously that one had to look twice to see it.

This is 'Slab Sides,' a dwelling of Mr. Burroughs' own planning, and, in part, construction, its outer covering of rough sawn slabs, which still retain their bark, being the origin of its name. In a future number we hope to present a photograph of the exterior of Slab Sides, with an account of the birds its owner finds about it. Part of its interior is well shown by our photograph of Mr. Burroughs seated before the fireplace, in which, as head mason and stone-cutter, he takes a justifiable pride. Here, from April to November, Mr. Burroughs makes his home, and here his most sympathetic readers may imagine him amid surroundings which are in keeping with the character of his writings.

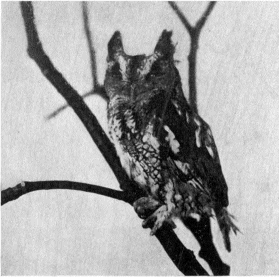

The Camera as an Aid in the Study of Birds

BY DR. THOS. S. ROBERTS

Director, Department of Birds, Natural History Survey of Minnesota.

With photographs from Nature, by the Author.

nyone having an earnest interest in both natural history and photography can find no more delightful and profitable way of spending leisure hours than by prying into the secrets of Dame Nature with an instrument capable of furnishing such complete and truthful information as the camera. Delightful and fascinating, because it not only gives worthy purpose and charming zest to all outing trips, but yields results that tell in no uncertain way of things and incidents that it would be well nigh impossible to preserve in any other manner. There is no department of nature-study in which the camera cannot be turned to excellent account, and while records of lasting and scientific value are being made, the devotee of amateur photography has at the same time full scope for the study of his art. What may, perhaps, be considered the greatest value, albeit an unrecognized one, of the present widespread camera craze, is the development of a love for the beautiful and artistic which may result, and along the line of study here suggested may surely be found abundant material to stimulate in the highest degree these qualities. Too much time is spent and too much effort expended by the average 'kodaker' in what has been aptly termed "reminiscent photography," the results being of but momentary interest and of no particular value to anybody.

In the present and subsequent articles, it is intended to illustrate by pictures actually taken in the field by the veriest tyro in the art of photography, what may be accomplished by any properly equipped amateur in the way of securing portraits of our native birds in their wild state and amid their natural surroundings. Supplemental to such portraits are the more easily taken photographs of the nests, eggs, young, and natural haunts of each species; the whole graphically depicting the most interesting epoch in the life-history of any bird. Words alone fail to tell the story so clearly, so beautifully, and so forcibly. And, best of all, this can be accomplished without carrying bloodshed and destruction into the ranks of our friends the birds; for we all love to call the birds our friends, yet some of us are not, I fear, always quite friendly in our dealings with them. To take their pictures and pictures of their homes is a peaceful and harmless sort of invasion of their domains, and the results in most cases are as satisfactory and far-reaching - 7 - as to bring home as trophies lifeless bodies and despoiled habitations, to be stowed away in cabinets where dust and insects and failing interest soon put an end to their usefulness. It is not intended, of course, to reflect in any way upon the establishment of orderly and well-directed collections, for such are absolutely necessary to the very existence of the science of ornithology. To such collections the great body of amateur bird students should turn for the close examinations necessary to familiarize themselves with the principles of classification and the distinctions between closely related species. Indeed, it is impossible for anyone to be intelligently informed as to the many varieties of birds, and their wonderful seasonal changes of plumage, without having actually handled specimens.

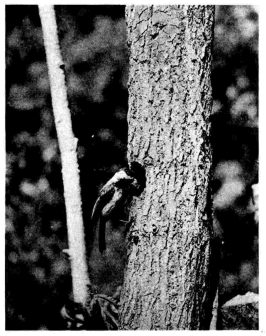

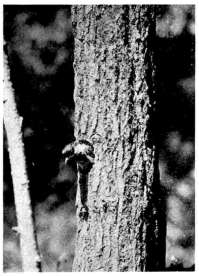

CHICKADEE AT NEST-HOLE, WITH FOOD FOR YOUNG

CHICKADEE AT NEST-HOLE, WITH FOOD FOR YOUNG

The growth of avian photography has been of short duration,—only a few years in this country and not much longer in England, where it seems to have had its inception. But there are already one or two good books dealing with the subject; and a goodly number of ornithological works of recent date, and especially the pages of the journal literature of the day, bear excellent testimony to the - 8 - merit and beauty of this method of securing bird pictures. Attention, however, has thus far been directed chiefly to obtaining illustrations of nests and eggs and captive birds, to the neglect of the more difficult but more interesting occupation of securing photographs of live birds in their wild state. Herein lies the chief fascination of this branch of photography, for good photographs from life of any of our birds, even the most common, are still novelties.

The successful bird photographer must possess a good camera, including a first-class lens, with at least an elementary knowledge of how to get the best results from it; some acquaintance with field and forest and their feathered inhabitants, and a fund of patience, perseverance, and determination to conquer that is absolutely inexhaustible. No matter how well equipped in other respects, this latter requisite cannot be dispensed with. As to the technique and many details of the art of photography, the writer is still too much of a novice to speak very intelligently. Suffice it to say, that the general principles governing other branches of photography are to be consulted here. One great difficulty to be encountered is that there is little opportunity to arrange the lighting or background of the object to be photographed, and as the latter is apt to be either green foliage or the dull ground, with the camera very near the object, the beginner will be much perplexed to determine the proper stop and the right time of exposure. With the usual appliances a wide open stop will be found necessary with the rapid exposure required, and this will detract in a disappointing manner from the beauty of the negative as a whole. But every determined student will try in his or her own way to lessen these defects, and will find in failure only increased incentive to discover better methods and better appliances. Cameras and lenses especially devised for this kind of work are promised in the near future. A rapid telephoto lens is a great desideratum, and there is reason to believe that in the near future such an one will be available. Those to be had at present increase the time of exposure too much to be generally useful in bird work. The writer has used a 4 × 5 long-focus 'Premo' with Bausch and Lomb Rapid Rectilinear lens (Zeiss-Anastigmat, Series II-A, 41/4 × 61/2), the focal length of the combination being about 61/4 inches. Many kinds of plates have been used, but any good rapid plate will do. For those who are willing to take the additional care necessary to handle them successfully, rapid isochromatic or orthochromatic plates are undoubtedly to be preferred, as they preserve quite clearly the color values.

A consideration of the actual field difficulties, rather than the more purely photographic problems to be encountered, is more within the scope of the present paper. To this end a rather detailed account is given of just how each of the following groups of photographs was secured, hoping that others better equipped, with a better knowledge of photography, and with more leisure, may be encouraged to go and do likewise and present us with the results.

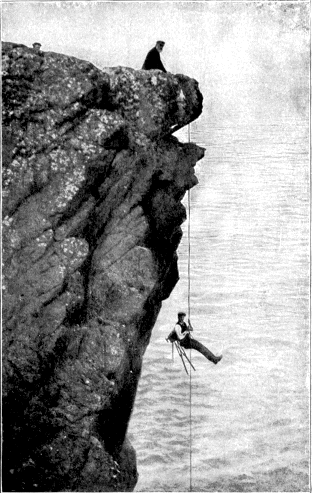

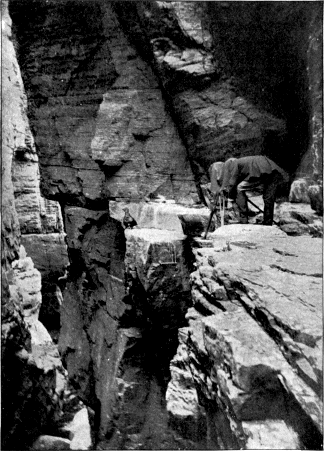

One of the greatest of these field difficulties is that the camera is rarely focused upon the bird to be taken, but is either snapped at random or focused upon some spot to which the bird is expected to return. The latter, in the great majority of cases, is the nest; at other times a much-used perching-place or feeding-ground. Success depends, therefore, very largely upon the nature, disposition, and habits, especially nesting habits, of the particular bird being dealt with. Some birds are of a confiding, unsuspicious nature, and easily reconciled to quiet intrusion; while others are so timid and wary that hours of time have to be expended, and all sorts of devices resorted to, in order to get the coveted 'snap.' Of the risk of life and limb necessary to reach rocky cliff and lofty tree-dwelling species, the recital must come from such daring and fearless devotees of this art as the Kearton brothers of England, and others nearer home.

The nest being the lure usually employed to bring the bird within range of the camera, it will follow that the nesting season is the time of year when most of this work must be done. Thus, spring and early summer are the harvest time of the bird photographer, and as it happens that these, of all the seasons, are the most delightful in which to be afield, the bird-lover, with glass, camera, and note-book, can leave care behind and find contentment, rest, and peaceful profit in the glorious days of June, so happily styled the rarest of all that come.

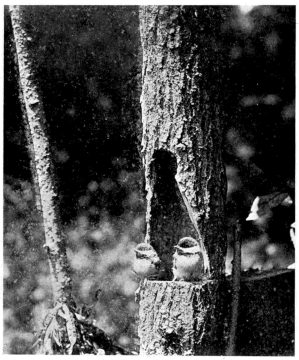

CHICKADEE LEAVING NEST

CHICKADEE LEAVING NEST

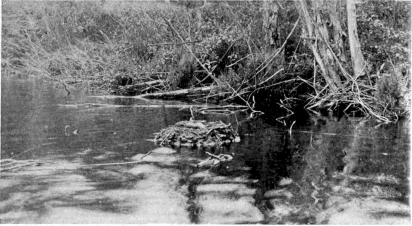

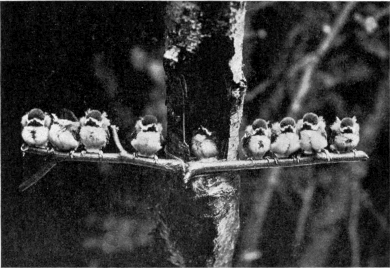

Leaving general considerations, let us first study a series of photographs that well illustrates what charming and dainty little pictures can sometimes be secured with most trifling effort. Success in this instance was easily attained because the little 'sitters' were not very unwilling and because the conditions under which they lived were more than usually favorable. The subject of these photographs, the little Black-capped Chickadee, or Titmouse,—Parus atricapillus, the scientists call him,—is familiarly known to almost every one who has given even casual attention to birds. Its generally common occurrence throughout the United States, cheery, happy disposition, and lively notes as the little band, for they usually travel in companies, goes roaming through woodland and - 10 - copse, endears it to all. All through the long, dreary winter, with its short days and perpetual snow and ice, they are the same sprightly, contented little fellows, and refreshing it is to meet and visit with them at such times as they come 'chick-a-de-dee'-ing right into your very presence in their familiar, confiding way. Springtime finds them with a mellow, long-drawn love whistle of two notes and thoughts of home and home-like things. Soon, down by the lake or brook-side, or in some moist woodland glade, where birch and willow trunks long since dead and soft with age stand sheltered among the growing trees, the little Black-cap and his chosen mate pick out a cozy retreat. This, perhaps, is some deserted Woodpecker den, decayed knothole, or more often it is a burrow of their own making, and here they assume the delights and cares of wedded life. A snug, warm nest of rabbit's hair or fern down is quickly built, and in this softest of beds the five or six rosy white, finely speckled little eggs are laid. Before very many days, eight or ten at most, the old stump exhibits unmistakable signs of being animated within, and in a wonderfully short time the little nestlings are as large as their parents, and full, indeed, is this family domicile. Owing to the cleanly habits and care of the old birds, the dresses of the youngsters are cleaner and brighter than those of their hard-worked, food-carrying parents. It was just at this stage in their progress that the little family, whose portraits are here shown, was discovered one late June day, snugly ensconced within the crumbling trunk of a long since departed willow tree. With a bird-loving companion, Mr. Leslie O. Dart, the writer was drifting idly in a little boat through one of the many channels of the Mississippi river, which cut up into innumerable islands, the heavily wooded bottomland of eastern Houston county, Minnesota. Being in search of the nests of numerous Prothonotary Warblers, which were flashing hither and thither across the channel, we skirted the shore closely, tapping on all likely-looking stubs. - 11 - Now the tapping brought to view a Downy Woodpecker, then a beautiful Golden Swamp Warbler; sometimes unexpectedly a great gray mouse scrambled out and plunged boldly into the water beneath; but this time the blow was followed by a subdued hum from within, and an inquiring, anxious parent Chickadee appeared suddenly on the scene, joined in a moment by a second, and we had the family complete. It was near noon, the sun was shining brightly, the hole was on the water side of the stub in the light, and we had no Chickadee pictures; so we camped at once and prepared to 'do' the situation. A little investigation showed the nest to be too high for setting up the camera satisfactorily, as the tripod legs sank deep in the mud and water. But our kit included a saw for just such an emergency, and sawing off the soft stub at the proper height, it was lowered gently until the hole came just on a level with the camera, placed horizontally and at a distance of about three feet. Propped with a forked stick, it rested quite securely on the soft bottom. This was better than tipping the camera and employing the 'swing back,' as the sun was nearly overhead. After focusing carefully on the opening in the stub, attaching to the camera fifty feet of small rubber tubing with large bulb, in place of the usual short tube and small bulb, setting carefully the trigger and other accessories of our harmless gun, and covering the whole camera with a hood of rough green cloth, the lens alone visible, we retreated to a convenient vantage point among the small willows close by. But a few minutes elapsed before the old birds were on the spot peering at us and the big green object from all sides. In an incredibly short space of time, considering the great liberties that had been taken with their habitation and door yard, they became resigned, and one of the birds, which we assumed to be the female, flew straight to the stub, and, with a last suspicious glance at the great glistening eye so near at hand, disappeared into the hole with a large brown worm in her bill. But that momentary delay was the looked-for opportunity, and all-sufficient; for with a quick squeeze of the bulb, click went the shutter, and in the twenty-fifth of a second the bird was ours; shot without so much as knowing it, without indeed the ruffling of a feather or the drawing of a drop of blood, and preserved life-like and true to nature for all time to come.

From this time on the birds came and went without hesitation, the only serious delays in our operations being due to the drifting clouds, which now and then obscured the sun and rendered the light too weak for the rapid exposures necessary. One of the birds, the one we took to be the female, was a little more courageous - 12 - than the other, and it is her picture that appears oftenest. The timid one,—the male,—even went so far on several occasions as to himself devour the worm he had brought rather than trust himself at close quarters with the unknown enemy, although his mate was at the time coming and going industriously and keeping the little folk well supplied with the great larvæ. Surely personal traits and individuality are quite as well marked in the bird world as higher in the scale! After we had made several more exposures similar to the first, one of the best of which shows the bird, worm-laden as before, balanced on the edge of the hole and taking the usual last look at the camera, we turned our attention to catching her as she was coming out. This required quicker coöperation between eye and hand, as the exit was generally made with a dash; but the accompanying picture, with head just emerging, will show that we were fairly successful.

|

|

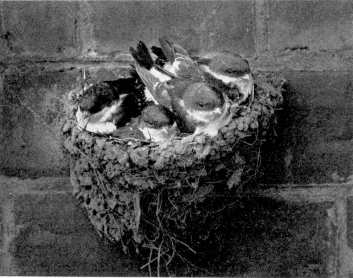

| YOUNG CHICKADEES. | CHICKADEE FEEDING YOUNG |

Having concluded from all indications, chief among which was the immense number of huge caterpillars carried in to the young, - 13 - that the latter must be fairly grown, we decided to expose the nest and complete our collection by securing the entire family. So carefully sawing away the front wall of the cavity with a keyhole saw carried for just such purposes, we gave the little fellows within their first view of the outside world. I fear they must have thought the manner of opening their second shell a rather rude one, and the outlook somewhat forbidding. They were pretty little youngsters, fully grown, with clean, jaunty coats, and a grown-up 'chickadee-dee,' just like the old folks. Though somewhat dazzled at first by the sudden flood of bright sunlight, they were, after a little coaxing, induced to sit out on the veranda that had been improvised for them; but, like youthful sitters generally, they were hard to pose, and after many exposures, we succeeded in getting no more than two of them at once. The prettiest one of all, showing two of the little fellows as they finally settled down contentedly in the warm sunshine, was obtained at the expense of much patient effort and a great deal of slushing back and forth in mud and water between boat and camera, and it was gratifying to find that one at least of the negatives did fair justice to the situation.

The old ones came and went after the mutilation of their home, just as before, and, indeed, apparently found the new arrangement much more convenient than the old. In one of the photographs here presented, domestic affairs that had before been entirely concealed from view are fully revealed, and had not the plate been light-struck by one of the many aggravating accidents likely to occur in the out-door work of the beginner, the picture would have been the best of the series. The courageous parent is attending to her maternal duties under circumstances which must appear most appalling. The little fellow sitting so contentedly by has undoubtedly had his share of the huge juicy caterpillars, and patiently recognizes that it is not his turn.

(To be concluded)

BY H. W. MENKE

With Photographs from Nature by the Author

uring the winter of 1897-8 I prospected for Jurassic fossils in Carbon and Albany counties, Wyoming. When cold weather and snow rendered field work impracticable as well as very disagreeable, I made permanent camp for the winter at Aurora, Wyoming,—a mere station on the Union Pacific R. R., an old abandoned section-house serving as my winter quarters.

This part of Wyoming,—at all times dreary and lonely,—is strikingly so during winter months. Then snow fills the ravines and lends a level, prairie-like aspect to the landscape. I doubt if there is to be found anywhere a more desolate country than this; at least such was my impression when the novelty of my surroundings had worn off.

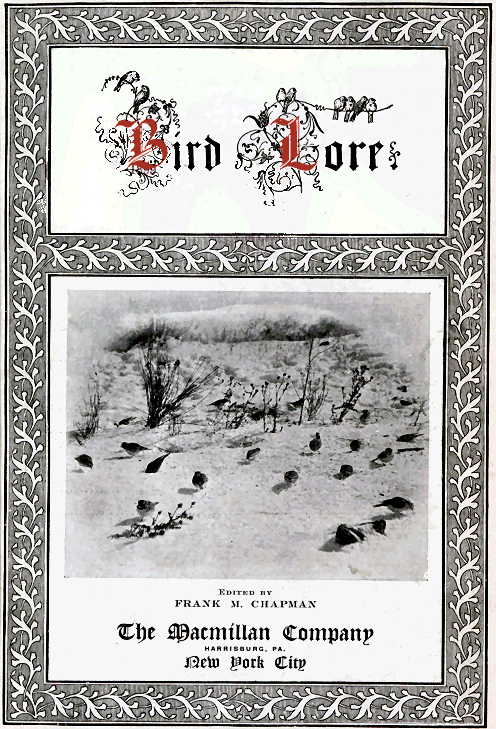

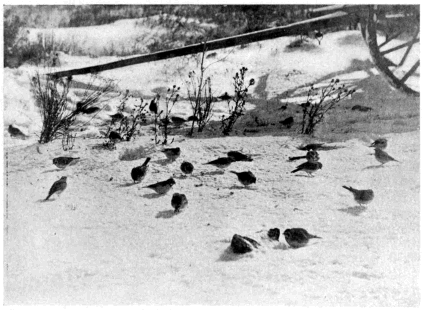

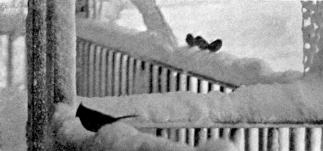

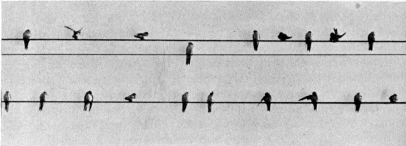

HORNED LARKS AND SNOWFLAKES

HORNED LARKS AND SNOWFLAKES

Among the various expedients to which I resorted for amusement, was photographing such birds as I could lure around the cabin. That I was not more successful in securing good negatives is due to the difficulties with which I had to contend. Chief of these were the - 15 - fierce, wintry blasts sweeping over the plains and filling the air with snow and dust.

A single experiment taught me the inadvisability of leaving the camera exposed for any length of time to these conditions. I had been trying to get a large photograph of Horned Larks. The camera was placed on the ground and a handful of oats scattered before it, while I waited within the cabin for nearly two hours for an opportunity to pull the thread attached to the camera shutter. But the birds persistently avoided the pebble marking the focal plane, and clouds continually obscured the sun when I wished to make an exposure. At last the right moment came, I pulled the thread, and hurried out to get the result. That plate was never developed. Snow had clogged the shutter, and I found it had remained wide open after being sprung.

HORNED LARKS AND SNOWFLAKES

HORNED LARKS AND SNOWFLAKES

By throwing oats on only one spot, and that close to the window, I soon gathered quite a flock of Horned Larks, who came regularly every morning to feed from the constantly replenished supply. Finally, after a week of gloomy, dark weather, a cloudless sky offered especially good chances for a photograph of my feathered friends. This time I placed the camera on the window-sill. Maneuvers attendant upon focusing and inserting a plate-holder, of course, - 16 - frightened the birds away. They were back again within a few minutes, but an unexpected source of annoyance interfered. A freight train stopped opposite the scene of my operations and belched great billows of smoke between the sun and the birds. Also the shadow of the cabin was gradually encroaching on the feeding ground. I made a trial exposure, however, and obtained a very good negative. But a shadow in the foreground and a wagon tongue in the rear, did not add to the pictorial effect of the group.

After much pulling and prying, I pushed the objectionable wagon out of the drifts, and put off further photographing until the next morning. The morning came as bright and sunny as I desired. My feathered subjects were early in the open air studio, and required no conventional admonition to 'look pleasant.' In fact, they were almost too lively for the camera shutter. The negative obtained proved very good, and well repaid me for all trouble and annoyance.

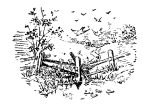

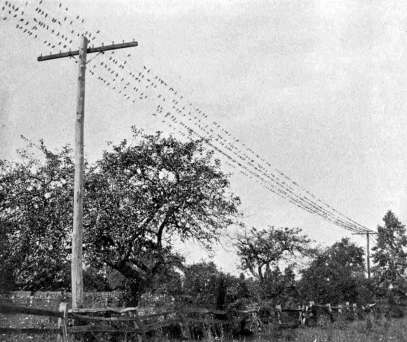

YELLOW-HEADED BLACKBIRDS

YELLOW-HEADED BLACKBIRDS

A few Yellow-headed Blackbirds were attracted by the food supply I furnished, and I made several negatives of them. The Yellow-heads were more wary than the Horned Larks, and flew away at the slightest disturbance. Only a few at a time gathered beneath the window, while the others perched on fence-posts at a safe distance and kept watch.

But it remained for a Northern Shrike to add 'insult to injury,' by seizing a dead mouse I had placed on a post and alighting on the camera with its capture!

BY ISABEL EATON

t is a simple matter enough, with the little folk who happily live in the country, to excite an interest and develop a familiar friendship with their bird neighbors. The birds can easily be coaxed to the piazza or the window-shelf by the judicious offer of free lunch, and so a speaking acquaintance, perhaps even a life-long friendship, with them may be gained.

But with city children, especially those of the poorer classes, the case is very different. The question how to teach them to know and care for birds is by no means so easy.

Look at their case: they have seen no birds but English Sparrows and caged Canaries and Parrots; few of them know the Robin; they practically never go to the country, and many of them never even go to the parks. How shall they be taught about birds? Observing the rule of advancing from known to unknown, would suggest Dick the Canary, as the obvious point of departure from a tenement into the world of birds; then, perhaps, the Summer Yellow-bird in the park, commonly known as the 'Wild Canary,' and then Mr. Goldfinch and his little olive-brown spouse, who would make a natural transition to the brown Sparrow family, and so on. The difficulty here is that it is so nearly impossible to get city children up to the park to see the Yellow-bird.

So another method, involving no country walks and no live birds, has to be resorted to. We may use pictures,—drawn before the class and colored, if possible,—and, trusting to the children's powers of imagination and idealization, may connect with their experience at some other point. After studying about the carpenter, in kindergarten or primary school, for instance, it is easy to interest children in the Woodpecker by proposing to tell them about a "little carpenter bird;" after talking of the fisherman, a promise to tell them of a bird who is a fisherman is sure to stir their imaginations of the doings of the Kingfisher, and so with the weaver (Oriole), mason (Robin) and others.

When several birds have been learned, the best kind of review for little people is probably some game like the following, which has been - 18 - played with most tumultuous enthusiasm and eager interest in a certain New York school of poor children. The teacher says:

"Let's play 'I'm thinking of a bird.' All shut your eyes tight and think. Now, I'm thinking of a bird nearly as large as a Pigeon; he is brownish, with black barring on the back, black spots all over the breast," etc., etc., giving a description of the Yellow Hammer, or Flicker, but leaving the characteristic marks until the end of the description. Before the teacher has gone far, a dozen hands are waving wildly and several vociferous whispers are heard, proclaiming in furious pianissimo: "I know," "I know what it is." Then the child who gets it right is allowed to describe a bird for the class to guess, and if the description fails in any point the class may offer corrections.

This appeal to the play instinct excites great interest, which is the thing chiefly to be desired.

When a number of birds have been learned in this way, a trip to the Natural History Museum would be of very great value, especially noticing the wonderful reproductions of actual scenes from bird-life there displayed. In this way city children could see in a single day more real bird-life than they could otherwise get in a year, as their few country days are generally populous picnics, from which the birds flee aghast.

The children should take their kindergarten principles of observation and conversational description to the Museum with them, and, on returning to school, should draw and color some bird they have seen. To observe and describe and, perhaps, draw each new bird whose picture is shown in the classroom is also a good thing. The writer passed a mounted Flicker through a class of fifty children of kindergarten age, let them look and carefully handle, and then asked for "stories" about it. One child said: "I know—Oh—I know seven stories—no, eight—nine stories about Mr. Yellow Hammer," and she really did know her nine "stories."

When they have gone as far as this, most bird stories will interest them, especially if the birds are humanized for them by the teller of the tale.

To sum up, it may be said that the best way to begin is to teach a few birds well,—a dozen or so,—by connecting with the child's experience, in some way, the information to be given, and then employing the play instinct by having bird games of various kinds, both kindergarten bird games and others; observation, description and drawing of birds may follow, and first and last, and all the time, all descriptions and stories given to children should be in terms of human nature.

Although we have fewer birds during the winter than at any other season, at no other time during the year do the comparative advantages of ornithology as a field study seem so evident. The botanist and entomologist now find little out of doors to attract them, and, if we except a stray squirrel or rabbit, birds are the only living things we may see from December to March. Winter, therefore, is a good time to begin the study of birds, not only because flowers and insects do not then claim our attention, but also because the small number of birds then present is a most encouraging circumstance to the opera-glass student, who, in identifying birds, is at the mercy of a 'key.'

Indeed, the difficulty now lies not in identification, but in discovery; unless one is thoroughly familiar with a given locality and its bird-life, one may walk for miles and not see a feather—a particularly unfortunate state of affairs if one has a bird-class in charge. This dilemma, however, may be avoided by catering to the dominant demand of bird-life at this season, the demand for food. Given a supply of the proper kind of food, and birds in the winter may nearly always be found near it. Bird seed and grain may be used, but a less expensive diet, and one which will doubtless be more appreciated, consists of sweepings from the hay-loft containing the seeds to which our birds are accustomed. This may be scattered by the bushel or in a sufficient quantity to insure a hearty meal for all visiting Juncos and Tree Sparrows, with perhaps less common winter seed-eaters.

The bark-hunting Woodpeckers, Nuthatches, and Chickadees will require different fare, and meat-bones, suet, bacon-rinds and the like have been found to be acceptable substitutes for their usual repast of insects' eggs and larvæ.

Winter, strange as it may seem, is an excellent season for bird-nesting. The trees and bushes now give up the secrets they guarded from us so successfully during the summer, and we examine them with as much interest as we pore over the 'Answers to Puzzles in Preceding Number' department of a favorite magazine.

Immediately after a snow storm is the best time in which to hunt for birds' nests in the winter. Then all tree and bush nests have a white cap, which renders them more conspicuous.

When walking with children, the spirit of competition may be aroused by saying "Who'll see the first nest," or "Who'll see the next nest first," as the case may be, and the number discovered under this impetus is often surprising.

Boys and girls who study birds are invited to send short accounts of their observations to this department.

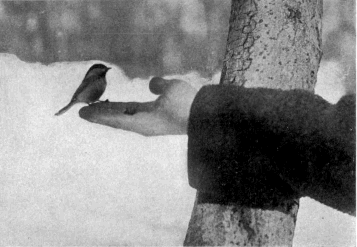

BY FLORENCE A. MERRIAM.

on't think that I mean the House, or English Sparrow, for he is quite a different bird. Our little doorstep friend is the very smallest of all the brown Sparrows you know, and wears a reddish brown cap, and a gray vest so plain it hasn't a single button or stripe on it. He is a dear, plump little bird, who sits in the sun and throws up his head and chippers away so happily that people call him the Chipping Sparrow.

He comes to the doorstep and looks up at you as if he knew you wanted to feed him, and if you scatter crumbs on the piazza he will pick them up and hop about on the floor as if it were his piazza as well as yours.

One small Chippy, whom his friends called Dick, used to light on the finger of the kind man who fed him, and use his hand for dining-room, and sometimes when he had had a very nice breakfast, he would hop up on a finger, perch, and sing a happy song!

Dick was so sure his friends were kind and good, that as soon as his little birds were out of the nest, he brought them to be fed too. They did not know what a nice dining-room a hand makes, so they wouldn't fly up to it, but when the gentleman held their bread and seeds close to the ground, they would come and help themselves.

CHIPPY'S NEST.

If you were a bird and were going to build a nest, where would you put it? At the end of a row of your brothers' nests, as the Eave Swallows do? Or would that be too much like living in a row of brick houses in the city? Chipping Sparrows don't like to live too close to their next door neighbors. They don't mind if a Robin is in the same tree, on another bough, but they want their own branch all to themselves.

TAMING A CHIPPY

TAMING A CHIPPY

Photographed by Mr. George Wood at the home of Lieutenant Wirt Robinson, in Virginia. Lieutenant Robinson writes that a pair of Chipping Sparrows placed their nest in the climbing rose bush at the end of the piazza. One of the pair, supposed to be the female, was easily tamed with the aid of bread crumbs, and for three successive years she returned to the piazza, always immediately resuming her habits of familiarity.

And they want it to be a branch, too. Other birds may build their nests on the ground, or burrow in the ground, or dig holes in tree trunks, or even hang their nests down inside dark chimneys if they like, but Chippy doesn't think much of such places. He wants plenty of daylight and fresh air.

But even if you have made up your mind to build on a branch, think how many nice trees and bushes there are to choose from, and how hard it must be to decide on one. You'd have to think a long time and look in a great many places. You see you want the safest, best spot in all the world in which to hide away your pretty eggs, and the precious birdies that will hatch out of them. They must be tucked well out of sight, for weasels and cats, and many other giants like eggs and nestlings for breakfast.

If you could find a kind family fond of birds, don't you think it would be a good thing to build near them? Perhaps they would drive away the cats and help protect your brood. Then on hot summer days maybe some little girl would think to put out a pan of water for a drink and a cool bath. Some people, like Dick's friends, are so thoughtful they throw out crumbs to save a tired mother bird the trouble of having to hunt for every morsel she gets to give her brood. Just think what work it is to find worms enough for four children who want food from daylight to dark!

The vines of a piazza make a safe, good place for a nest if you are sure the people haven't a cat, and love birds. I once saw a Chippy's nest in the vines of a dear old lady's house, and when she would come out to see how the eggs were getting on she would talk so kindly to the old birds it was very pleasant to live there. In such a place your children are protected, they have a roof over their little heads so the rains won't beat down on them, and the vines shade them nicely from the hot sun.

When you are building your house everything you want to use will be close by. On the lawn you will find the soft grasses you want for the outside, and in the barnyard you can get the long horse hairs that all Chipping Sparrows think they must have for a dry, cool nest-lining. Hair-birds, you know Chippies are called, they use so much hair. The question is how can they ever find it unless they do live near a barn? You go to look for it, someday, out on a country road or in a pasture. It takes sharp eyes and a great deal of patience, I guess you'll find them. But if you live on the piazza of a house, with a barn in the back yard, you can find so many nice long hairs that you can sometimes make your whole nest of them. I have seen a Chippy's nest that hadn't another thing in it—that was just a coil of black horse hair.

After you have built your nest and are looking for food for your young it is most convenient to be near a house. The worms - 23 - you want for your nestlings are in the garden, and the seeds you like for a lunch for yourself are on the weeds mixed up with the lawn grass. You needn't mind taking them, either, for the people you live with will be only too glad to get rid of them, because their flowers are killed by the worms, and their lawns look badly when weeds grow in the grass, so you will only be helping the kind friends who have already helped you. Don't you think that will be nice?

CHIPPY'S FAMILY.

Did you ever look into a Chippy's nest? The eggs are a pretty blue and have black dots on the larger end.

When the little birds first come out of the shell their eyes are shut tight, like those of little kittens when they are first born.

If you are very gentle you can stroke the backs of the little ones as they sit waiting for the old birds to feed them.

I remember one plum tree nest on a branch so low that a little girl could look into it. One day when the mother bird was brooding the eggs the little girl crept close up to the tree, so close she could look into Mother Chippy's eyes, and the trustful bird never stirred, but just sat and looked back at her. "Isn't she tame?" the child cried, she was so happy over it.

There was another Chippy's nest in an evergreen by the house, and when the old birds were hunting for worms we used to feed the nestlings bread crumbs. They didn't mind the bread not being worms so long as it was something to eat. It would have made you laugh to see how wide they opened their bills! It seemed as if the crumbs could drop clear down to their boots! Wouldn't you like to feed a little family like that sometime?

We want the boys and girls who read Bird-Lore to feel that they have a share in making the journal interesting. Young eyes are keen and eager when their owner's attention is aroused; so we ask the attention of every reader of Bird-Lore of fourteen years or under to the following offer: To the one sending us the best account of a February walk we will give a year's subscription to this journal. The account should contain 250 to 300 words, and should describe the experiences of a walk in the country or some large park, with particular reference to the birds observed.

In June, six or seven years ago, my daughters found in the courtyard of our home, a young House or English Sparrow who had evidently fallen from the nest, and had broken its leg in the fall. They took it in and cared for it, binding up the injured limb and feeding it as experience with other birds of the same family had taught them to do. Happily, the bird recovered, and in a short time became quite a pet of the household.

At that time we had two Canary Birds, both beautiful singers, and in almost constant song. The Sparrow was in the same room with them, and very soon (making use of its imitative power, which we have observed is a strong characteristic of the Sparrow) acquired the full and complete song of the Canaries. We followed with much pleasure the unfolding of his musical ability, which was gradual, and found that he had surpassed his teachers, producing melodies much richer and stronger, as all who had the pleasure of listening to him freely admitted.

The bird retained his song to the last, although as age came upon him, as with all other pet birds, his singing was less and less frequent till he passed away, some few months ago. Besides imitating the song of the Canary, he acquired the song of a bird in our collection known as the 'Strawberry Finch,' which he gave perfectly. His plumage was greatly improved by his confinement and the very great care given him, so much so, that one almost doubted his being an English Sparrow till convinced upon closer examination.

We have had a large experience with these birds; they become very affectionate with petting, and show a wonderful degree of intelligence.

I would further say that our Sparrow had all the notes common to the English Sparrow, beside his acquired accomplishments, and there was sadness in our home when his little life went out.—John L. Royael, Brooklyn, N. Y.

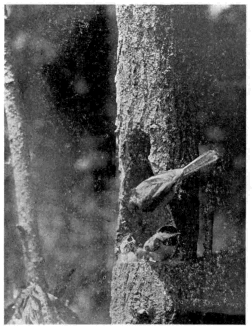

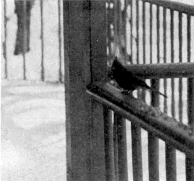

On October 14, 1898, while on a short visit to my old home, at New Baltimore, New York, I sat down near a clump of trees and shrubs to enjoy the bird-life so abundant there.

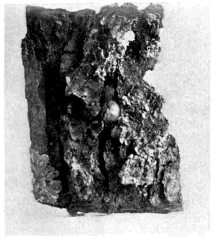

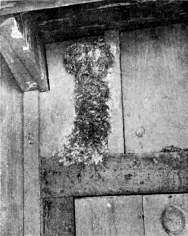

ACORN WEDGED IN BARK BY WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH

ACORN WEDGED IN BARK BY WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCHHere I saw the Chickadee carefully examining the fruit-heads of the smooth sumach, and twice take from them a mass of spider-web; then, flying to a limb, dissect it and obtain from it the mass of young or eggs. It was with difficulty that the food was disentangled from the silk, and I found on examination that much of it had been so crushed, that it was impossible to determine whether the web contained eggs or young.

While thus engaged, I saw a White-breasted Nuthatch, with something in its - 25 - beak, alight on the trunk of a wild cherry tree. While running about over the bark, the bird dropped what proved to be an acorn, but immediately flew down and picked it from the long grass, and returned to the tree. A second time it dropped it, and then, after carrying it again to the tree, thrust it into a crevice in the bark with considerable force, and began to peck at it vigorously. This it did for a few seconds, when I jumped up quickly and, with wild gesticulations, frightened it away. It proved to be the acorn of the pin Oak (Quercus palustris), and as no fruiting tree of this species was nearer than the Island, in the river opposite, I concluded that the bird had carried it across the water from that point.

After photographing the acorn on the tree, I cut the section of bark off, glued the acorn in its cavity, and the photograph shows the result.—E. B. Southwick, New York City.

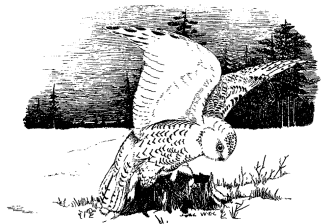

This interesting sketch was contributed by a prominent ornithologist as an appropriate cover design for this magazine at a time when it was proposed to call it "The Bird World." The appearance of a book bearing this title renders it necessary for us to abandon its use, but we do not, for the same reason, feel justified in depriving the world of this remarkably artistic effort, and therefore present it for the edification of our readers, and we trust, to the delight of its author!

Collecting a Brown Thrasher's Song

Rustler, my pet Brown Thrasher, was pouring out his loud, long, spring song. A phonograph, or rather a graphophone, had been left on a table by the cage. Everything seemed to favor the collection of a bird song. I placed the instrument so that the open funnel of the horn came within less than a foot of the Thrasher's swelling throat, and touching a lever, set the wax cylinder revolving below a sapphire-tipped style, which cut the bird notes into the wax. Just as the medley changed from that of a Catbird to that of a Wood Thrush, a Robin flew past the window. Rustler stopped short, but the style continued to cut and ruin the wax cylinder. When Rustler started in again he hopped to the opposite side of the cage, rudely turning his back upon the graphophone.

More than a little vexed at the perversity of dumb animals, I quickly covered over the end of the cage farthest from the graphophone; then Rustler sulked beneath the cloth in silence. Next I removed the perch from that side and then Rustler absolutely refused to sing any more. Some hours later, however, I made another attempt, but each time the graphophone was started the whir of the revolving cylinder cut short my Thrasher's rich, rippling notes, so that the only thing to do was to remove the recording style and accustom him to the noise of the cylinder, and when this had been accomplished, I replaced the recording style. I found that by shutting off the graphophone the instant Rustler's notes became weak or stopped, I could catch a continuous series of notes. I succeeded the following morning in getting a pretty fair song. It was not so loud as it might have been, but in pitch and timbre it was perfect.

In September dear old Rustler died. For nine long years he had enlivened my northern New Jersey home with his cheery music. In November, at a meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union, the notes of Rustler's love song fell sweetly upon sympathetic ears.—Sylvester D. Judd, Ph. D., Washington, D. C.

With Nature and a Camera. By Richard Kearton, F. Z. S. Illustrated by 180 Pictures from Photographs by Cherry Kearton: Cassell & Co., London, Paris and Melbourne [New York, East 18th St.], 1898. 8vo. Pages xvi + 368. Price, $5.

Authors may or may not be indebted to reviewers of their works, but it is not often that reviewers are under obligations to the authors of the works they review. In the present instance, however, we feel that we must express our gratitude to the Messrs. Kearton for furnishing us with such an admirable demonstration of the kind of ornithology for which this journal stands. If, following the same lines, we can bring Bird-Lore to the high standard reached in 'With Nature and a Camera,' we shall have nearly approached our ideal.

Briefly, this book is a record of observation and photography by two ornithologists in Great Britain. Doubtless, no birds in the world have been more written about than the birds of this region, and still this book is filled with fresh and original matter, which is always interesting, and often of real scientific value.

Asked to explain how it was that in such a well-worked field the author of this volume had succeeded in securing so much new material, we should reply that we believed it was because he was an observer rather than a collector. Apparently realizing that to collect specimens of British birds would add but little to the store of our knowledge concerning them, he has devoted his time to a study of their habits, and in presenting the results of his labors, he has been most ably seconded by his brother, whose photographs of birds in nature have not, so far as we know, been excelled.

Perhaps the most forcible lesson taught by this book is the pleasure to be derived from photographing wild birds in nature, and the surprisingly good results which may be achieved by patient, intelligent effort. We do not recall a more adequately illustrated nature book, and its pictures not only claim our admiration because of their beauty, but also because they carry with them an assurance of fidelity to nature which no artist's pencil can inspire.

Bird Gods. By Charles de Kay. With decorations by George Wharton Edwards. A. S. Barnes & Co., New York. 12mo, pages xix + 249. Price, $2.

So singular a combination of ornithologist and mythologist is the author of 'Bird Gods' that students of birds, as well as of myths, will find his pages of interest. "Why," he asks himself, "should certain birds have been allotted to certain gods and goddesses in the Greek and Roman mythology? Why should the Eagle go with Zeus, the Peacock with Hera, the Dove with Venus, the Swan with Apollo, the Woodpecker with Ares, the Owl with Pallas Athené?" And his search for a reply to these questions has led him into many little-frequented by-paths of early European literature, in which he has found much curious information concerning the influence of birds on primitive religions. Impressed by the "share birds have had in the making of myth, religion, poetry and legend" he wonders at their wholesale destruction to-day, and ventures the hope that "recollection of what our ancestors thought of birds and beasts, of how at one time they prized and idealized them, may induce in us, their descendants, some shame at the extermination to which we are consigning these lovable but helpless creatures, for temporary gains or sheer brutal love of slaughter."

Birds of Washington and Vicinity. By Mrs. L. W. Maynard, with Introduction by Florence A. Merriam. Washington, D. C., 1898. 12 mo, pages 204. Cuts in the text, 18. Price, 85 cents.

In a prefatory note the author states that this book "has been prepared at the suggestion of the Audubon Society - 27 - of the District of Columbia, in the belief that a local work giving untechnical descriptions of all birds likely to be seen in this vicinity, with something of the haunts and habits of those that nest here, will be useful to many who desire an acquaintance with our own birds, but do not know just how to go about making it."

The book seems admirably adapted to achieve this end. The opening pages by Miss Merriam are a capital introduction to the study of birds in the District of Columbia. They are followed by 'A Field Key to Our Common Land Birds,' and attractively written biographical sketches of the breeding species. The migrants and winter residents are treated more briefly, and an annotated 'List of All Birds Found in the District of Columbia,' by Dr. C. W. Richmond, is given. There are also nominal lists of winter birds, birds that nest within the city limits, etc., and an 'Observation Outline,' abridged from Miss Merriam's 'Birds of Village and Field.'

The book is, in fact, a complete manual of ornithology for the District of Columbia, and will undoubtedly prove an efficient guide to the study of the birds of that region.

Bird-Life: A Guide to the Study of Our Common Birds. Teachers' Edition. By Frank M. Chapman. With 75 full-page plates and numerous text-drawings by Ernest Seton Thompson. D. Appleton & Co. New York. 1899. 12mo, pages xiv + 269 + Appendix, pages 87.

This is the original edition of 'Bird-Life,' with an Appendix designed to adapt the work for use in schools. The new matter consists of questions on the introductory chapters of 'Bird-Life,' as, for instance, 'The Bird, its Place in Nature and Relation to Man,' 'Form and Habit,' 'Color,' 'Migration,' etc.; and, under the head of 'Seasonal Lessons,' a review of the bird-life of a year based on observations made in the vicinity of New York City. This includes a statement of the chief characteristics of each month, followed by a list of the birds to be found during the month, and, for the spring and early summer months, a list of birds to be found nesting.

For the use of teachers and students residing in other parts of the eastern United States there are annotated lists of birds from Washington, D. C., by Dr. C. W. Richmond; Philadelphia, Pa., by Witmer Stone; Portland, Conn., by J. H. Sage; Cambridge, Mass., by William Brewster; St. Louis, Mo., by Otto Widmann; Oberlin, Ohio, by Lynds Jones, and Milwaukee, Wis., by H. Nehrling.

The Appletons have also issued this book in the form of a 'Teachers' Manual,' which contains the same text as the 'Teachers' Edition,' but lacks the seventy-five uncolored plates.

This 'Teachers' Manual' is intended to accompany three 'Teachers' Portfolios of Plates,' containing in all one hundred plates, of which ninety-one, including the seventy-five plates published in 'Bird-Life,' are colored, while nine are half-tone reproductions of birds' nests photographed in nature. The one hundred plates are about equally divided in portfolios under the titles of 'Permanent Residents and Winter Visitants,' 'March and April Migrants,' and 'May Migrants and Types of Nests and Eggs.'

A most practical step in Audubon educational work is the publication, by the Massachusetts Audubon Society, of a chart giving life-size, colored illustrations of twenty-six of our common birds. On the whole, both in drawing and coloring, these birds are excellent, and while a severe critic might take exception to some minor inaccuracies, the chart may be commended as the best thing of the kind which has come to our attention. It is accompanied by a pamphlet containing well written biographies, by Mr. Ralph Hoffmann, of the species figured. The chart is published by the Prang Educational Company, of Boston, from whom, with Mr. Hoffmann's booklet, it may be purchased for one dollar.

A Bi-monthly Magazine

Devoted to the Study and Protection of Birds

OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE AUDUBON SOCIETIES

Edited by FRANK M. CHAPMAN

Published by THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

| Vol. 1 | February, 1899 | No. 1 |

SUBSCRIPTION RATES.

Price in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, twenty cents a number, one dollar a year, postage paid.

Subscriptions may be sent to the Publishers, at Harrisburg, Pa., 66 Fifth avenue, New York City, or to the Editor, at Englewood, New Jersey.

Price in all countries in the International Postal Union, twenty-five cents a number, one dollar and a quarter a year, postage paid. Foreign agents, Macmillan and Company, Ltd., London.

Manuscripts for publication, books, etc., for review, should be sent to the Editor at Englewood, New Jersey.

Advertisements should be sent to the Publishers at 66 Fifth avenue, New York City.

COPYRIGHTED, 1899, BY FRANK M. CHAPMAN.

During the past six years New York and Boston publishers have sold over 70,000 text-books on birds, and the ranks of bird students are constantly growing. With this phenomenal and steadily increasing interest in bird-studies, there has arisen a widespread demand for a popular journal of ornithology which should be addressed to observers rather than to collectors of birds, or, in short, to those who study "birds through an opera-glass."

The need of such a journal has also been felt by the Audubon societies, and in concluding his report for the year 1898, Mr. Witmer Stone, chairman of the American Ornithologists' Union's Committee on Bird Protection, remarks on the necessity of a "magazine devoted to popular ornithology which could serve as an organ for the various societies and keep the members in touch with their work. All societies which have reached a membership of several thousand realize that it is impossible to communicate with their members more than once or twice a year, owing to the cost of postage, and the success of the societies depends largely upon keeping in communication with their members."

It is to supply this want of bird students and bird protectors that Bird-Lore has been established. On its behalf we promise to spare no effort to make it all that the most ardent bird student could desire, and, in the event of our success, we would appeal to all bird-lovers for such support as we may be deemed worthy to receive.

We have issued a 'Prospectus,' setting forth in part the aims of Bird-Lore, and as a matter of permanent record, we enter its substance here. It stated that Bird-Lore would attempt to fill a place in the journalistic world similar to that occupied by the works of Burroughs, Torrey, Dr. van Dyke, Mrs. Miller, and others in the domain of books. This is a high standard, but our belief that it will be reached will doubtless be shared when we announce that, with one or two exceptions, every prominent American writer on birds in nature has promised to contribute to Bird-Lore during the coming year. The list of contributors includes the authors just mentioned, Mabel Osgood Wright, Annie Trumbull Slosson, Florence A. Merriam, J. A. Allen, William Brewster, Henry Nehrling, Ernest Seton Thompson, Otto Widmann, and numerous other students of bird-life.

The Audubon Department, under Mrs. Wright's care, will be a particularly attractive feature of the magazine, one which, we trust, is destined to exert a wide influence in advancing the cause of bird-protection.

The illustrations will consist of half-tone reproductions of birds and their nests from nature, and on the basis of material already in hand, we can assure our readers that, whether judged separately or as a whole, this volume of Bird-Lore will contain the best photographs of wild birds which have as yet been published in this country.

At present Bird-Lore will contain from thirty-two to forty pages, but should our efforts to produce a magazine on the lines indicated be appreciated, we trust that the near future will witness a material increase in the size of each number.

"You cannot with a scalpel find the poet's soul,

Nor yet the wild bird's song."

Edited by Mrs. Mabel Osgood Wright (President of the Audubon Society of the State of Connecticut), Fairfield, Conn., to whom all communications relating to the work of the Audubon and other Bird Protective Societies should be addressed.

DIRECTORY OF STATE AUDUBON SOCIETIES

With names and addresses of their Secretaries.

| New Hampshire | Mrs. F. W. Batchelder, Manchester. |

| Massachusetts | Miss Harriet E. Richards, care Boston Society of Natural History, Boston. |

| Rhode Island | Mrs. H. T. Grant, Jr., 187 Bowen street, Providence. |

| Connecticut | Mrs. Henry S. Glover, Fairfield. |

| New York | Miss Emma H. Lockwood, 243 West Seventy-fifth street, New York City. |

| New Jersey | Miss Mary A. Mellick, Plainfield. |

| Pennsylvania | Mrs. Edward Robins, 114 South Twenty-first street, Philadelphia. |

| District of Columbia | Mrs. John Dewhurst Patten, 3033 P street, Washington. |

| Wheeling, W. Va. (branch of Penn Society) |

Elizabeth I. Cummins, 1314 Chapline street, Wheeling. |

| Ohio | Miss Clara Russell, 903 Paradrome street, Cincinnati. |

| Indiana | Amos W. Butler, State House, Indianapolis. |

| Illinois | Miss Mary Drummond, Wheaton. |

| Iowa | Miss Nellie S. Board, Keokuk. |

| Wisconsin | Mrs. George W. Peckham, 646 Marshall street, Milwaukee. |

| Minnesota | Mrs. J. P. Elmer, 314 West Third street, St. Paul. |

This department will be devoted especially to the interests of active Audubon workers, and we earnestly solicit their assistance, as our success in making it a worthy representative of the cause for which it stands largely depends upon the heartiness of their coöperation. Others also, who are lovers and students of nature in many forms, but who have never, for divers reasons, engaged in any bird protective work, may, through reading of the systematic and effective methods of the societies, become convinced of the necessity of personal action.

We intend at once to establish the more practical side of the department by printing in an early issue a bibliography of Audubon Society publications, in order that anyone interested may know exactly what literature has appeared and is available. For this reason we ask the secretaries of all the societies to send us a complete set of their publications, stating, if possible, the number of each which has been circulated, and, when for sale, giving the price at which they may be obtained.

We also request the secretaries to send us all possible news of their plans and work, not merely statistics, but notes of anything of interest, for even the record of discouragements, as well as of successes, may often prove full of suggestion to workers in the same field, and aid toward developments that will broaden and strengthen the entire movement. A movement in complete harmony with the great desire of thinking people for a broader life in nature, which is one of the most healthful and hopeful features of the close of this century.

M. O. W.

Reports of Societies[A]

[A] The editor acknowledges the receipt from Mr. Witmer Stone, chairman of the Committee on Bird Protection of the American Ornithologists' Union, of a number of the following reports, which, before the establishment of an official organ for the Audubon Societies, had been sent to Mr. Stone for inclusion in his annual report to the A. O. U., from which, through lack of space, they were necessarily omitted.

THE MASSACHUSETTS SOCIETY

The Massachusetts Audubon Society has reissued the Audubon Calendar of last year and it is having a good sale. The drawings were made especially for - 30 - the calendar by a member of the society: the originals are painted in water colors on Japanese rice paper, and are very artistic bird portraits. The same artist is now at work on drawings of new birds for a calendar for 1900, which the directors hope will be reproduced by a more accurate and satisfactory process.

The Bird Chart of colored drawings of twenty-six common birds, which the Directors undertook last spring, is now ready. The drawings have all been especially made for the chart by E. Knobel and are reproduced by the Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing Co., on twelve stones. Some of our best ornithologists have seen the color proof and pronounce it good. The society has published a descriptive pamphlet to accompany the chart which has been prepared by Ralph Hoffmann. His sketches of the birds are delightfully written, and the book is valuable in itself.[B]

[B] See note on this chart and pamphlet in Book News and Reviews.

The Directors have recently sent out a new circular mainly in Boston and vicinity, which briefly describes the work undertaken and asks for further coöperation from interested persons, and states that "in addition to our first object, the support of other measures of importance for the further protection of our native birds has been assumed by the Society." Among such measures may be mentioned:

1. Circulation of literature.

2. Improved legislation in regard to the killing of birds, and the better enforcement of present laws.

3. Protection during the season for certain breeding places of Gulls, Herons and other birds, which, without such protection will soon be exterminated.

4. Educational measures. This includes the publication of colored wall charts of birds, Audubon Calendars and other helps to bird study.

The response to this circular has been gratifying.

The society now numbers over twenty-four hundred persons, twenty-six of these are Life Associates, having paid twenty-five dollars at one time; four hundred and seventy-five are Associates, paying one dollar annually; the remaining are Life Members, having paid twenty-five cents.

While the rage for feather decoration is unabated, we feel that there is steadily growing a sentiment among our best people in condemnation of the custom. There is a noticeable decrease in the use of aigrettes and of our native birds, excepting the Terns and the plumage of the Owl; and a marked increase in the employment of the wings and feathers of the barnyard fowl. While the latter continue to feed the fashion they are harmless in themselves.

Harriet E. Richards, Sec'y.

THE RHODE ISLAND SOCIETY

The Audubon Society of Rhode Island was organized in October, 1897, and has now about 350 members.

The purposes of the society, according to its by-laws, are: the promotion of an interest in bird-life, the encouragement of the study of ornithology, and the protection of wild birds and their eggs. Some work has been done in the schools, abstracts of the state laws relating to birds have been circulated throughout the state, lectures have been given, and a traveling library has been purchased for the use of the branch societies.

Nearly five thousand circulars of various kinds have been distributed, and it is evident that the principles of the society are becoming well known and are exerting an influence, even in that difficult branch of Audubon work, the millinery crusade.

Annie M. Grant, Sec'y.

THE CONNECTICUT SOCIETY

A score of ladies met in Fairfield on January 28, 1898, and formed "The Audubon Society of the State of Connecticut." Mrs. James Osborne Wright was chosen president and an executive committee provisionally elected, representing so far as possible at the beginning, the State of Connecticut.

An effort was made to find every school district in the state, and a Bird-Day programme - 31 - was sent to 1,350 of these schools. Care was naturally used to see that the rural schools, at least, should be reached. Through the kindness of Congressman Hill of this district, one of our vice-presidents, 740 copies of Bulletin No. 54, 'Some Common Birds in their Relation to Agriculture,' issued by the United States Department of Agriculture, were received by the secretary, and 600 of these have been mailed to individuals.

The Society has had two lectures prepared, one by Willard G. Van Name, entitled 'Facts About Birds That Concern the Farmer,' illustrated by sixty colored lantern slides, and one by Mrs. Mabel Osgood Wright, on 'The Birds About Home,' illustrated by seventy colored slides. A parlor stereopticon has been purchased for use in projecting the slides.

The lectures and slides are intended primarily for the use of the local secretaries of the society, and after these for such members of the society as desire to give educational entertainments in the interest of bird protection.

The only expense connected with the use of the lectures and slides will be the expressage from Fairfield to place and return.

Under no circumstances will the outfit be allowed to go outside of the State of Connecticut.

The oil lantern accompanying the slides is suitable for a large parlor or school room, and can be worked by anyone understanding the focussing of a photographic camera, but it is advised that when the audience is to be composed of more than fifty people the exhibitor should secure a regular stereopticon.

Applications should be made at least two weeks before the outfit is desired.

No admission fee is to be charged at any entertainment at which the outfit is used, the intention of the Audubon Society of the State of Connecticut being to furnish free information about our birds, and so win many, who may never have given the matter a thought, to a sense of the necessity and wisdom of their protection.

The secretary is glad to report on January 1, 1899, that the society has had practical proof of the success of its experiment in sending out these free illustrated lectures. Much interest has been awakened by them, and the State Board of Agriculture has listed both lectures for the Farmers' Institutes, held during the winter months. Much enterprise is being shown by local secretaries. An illustrated lecture by Mrs. Kate Tryon, having been given in Bridgeport, November 19, under the auspices of Miss Grace Moody (local secretary), Mrs. Howard N. Knapp, and Mrs. C. K. Averill. While Mr. Frank M. Chapman lectured before a large audience at the Stamford High School, on December 2, under the auspices of Mrs. Walter M. Smith, the local secretary of that city.

Harriet D. C. Glover,

Cor. Sec'y and Treas.

NEW YORK SOCIETY

Since November, 1897, the society has distributed 13,465 leaflets, making a total distribution of over 40,000 since its organization on February 23, 1897.

In spite of this large circulation of literature, the society has only 529 members, including 9 patrons, 7 sustaining members, 356 members, 157 junior members.

Financially, the society is now in a sound condition.

During the year two public meetings have been held in the large lecture hall of the American Museum of Natural History, at both of which the hall was well filled. Addresses were made by Dr. Henry van Dyke, Dr. Heber Newton, and others.

A 'Bird Talk' was also given by Mr. W. T. Hornaday, at the house of one of the honorary vice-presidents, which was well attended.

In educational work we have secured the publication of a paper on 'The Relation of Birds to Trees,' by Florence A. Merriam, in the annual Arbor Day Manual of New York State, and Mr. Chapman, chairman of our Executive Committee, - 32 - reports that in connection with Professor Bickmore, of the American Museum's Department of Public Instruction, and a committee representing the science teachers of the fourteen normal colleges of the State, he has prepared a course in bird study for the normal colleges for the present year.

Further interest in birds was shown by the science teachers of the State in their invitation to Mr. Chapman to address them on the subject of 'The Educational Value of Bird Study,' during their convention, held in New York City, December 29-30, 1898.

That the good work accomplished cannot be gauged by the number of members is proved by the constant reports received from local secretaries and others, telling of classes formed for bird study, of clubs that have taken up the subject, of bird exercises in schools, etc. If all these silent sympathizers would only realize how much the cause might be strengthened by open, concerted action, shown by a large membership roll of the Audubon Society, its influence would be greatly increased.

Emma H. Lockwood, Sec'y.

NEW JERSEY SOCIETY

We have at present 124 members and have distributed over 1,000 general circulars in regard to the work, and 1,000 aigrette circulars written by Mr. Chapman. We expect to have new literature issued during the coming year, and are now having the State bird-laws printed for distribution.

Mary A. Mellick, Sec'y.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Mrs. John Dewhurst Patten, secretary of the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia, reports much valuable work. A course of six lectures was given by Mrs. Olive Thorne Miller, and others by Mr. Chapman and Dr. Palmer.

A successful and fashionably attended exhibit of millinery was held in April. Nine of the leading milliners contributed hats and bonnets, which, of course, were entirely free from wild bird feathers. The society has designed an Audubon pin after a drawing of the Robin, by Mr. Robert Ridgway. This has already been adopted by the Pennsylvania and Massachusetts societies. At the suggestion of the secretary of the Pennsylvania society, efforts have been directed towards the establishment of societies in the south.

In response to a great demand for a cheap book of information about local birds, this society has been instrumental in issuing 'Birds of Washington and Vicinity,'[C] by Mrs. L. W. Maynard—200 pages 12mo, illustrated, which may be had for the small sum of 85 cents. The price placing the volume within the reach of teachers and pupils in the public schools.

[C] See a review of this book in Book News and Reviews.

OHIO SOCIETY