ANATOLE FRANCE — Bust by Lavergne

The true author is recognisable by the existence on every page of his works of at least one sentence or one phrase which none but he could have written.

Take the following sentence: "If we may believe this amiable shepherd of souls, it is impossible for us to elude divine mercy, and we shall all enter Paradise—unless, indeed, there be no Paradise, which is exceedingly probable." It treats of Renan. It must be written by a disciple of Renan's, whose humour perhaps allows itself a little more licence than the master's. More we cannot say.

But take this: "She was the widow of four husbands, a dreadful woman, suspected of everything except of having loved—consequently honoured and respected." There is only one man who can have written this. It jestingly indicates the fact that society forgives woman everything except a passion, and communicates this observation to the reader, as it were with a gentle nudge.

Or take the following: "We should not love nature, for she is not lovable; but neither should we hate her, for she is not deserving of hatred. She is everything. It is very difficult to be everything. It results in terrible heavy-handedness and awkwardness."

There is only one man who would excuse Nature for her indifference to us human beings in these words: "It is very difficult to be everything."

Read this passage: "It is a great infirmity to think. God preserve you from it, my son, as He has preserved His greatest saints and the souls whom He loves with especial tenderness and destines to eternal felicity."

It is an Abbé who speaks thus, and who speaks without a trace of irony. One is conscious of the author's smile behind the Abbe's seriousness.

Few are so pithy in their irony as France. He says: "Cicero was in politics a Moderate of the most violent description."

Few are so picturesque in their satire as he. Others have used the phrase: Equality before the law—that means equality before the laws which the well-to-do have made for the poor, and men for women. Others have maintained that the ideal of justice would be an inequality before the law adjusted to the differences between individuals. Others have said: If there is inequality in law itself, where is equality to be found?

But there is only one man who can have written: "The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread."

This one man is Anatole France. Most noticeable in this style is its irony; it stamps him as a spiritual descendant of Renan. But in spite of the relationship, France's irony is of a very different description from Renan's. Renan, as historian or critic, always speaks in his own name, and we are directly conscious of himself in the fictitious personages of his philosophic dramas, and even more so in those of his philosophic dialogues. France's irony conceals itself beneath naïveté. Renan disguises himself, France transforms himself. He writes from standpoints which are directly the opposite of his own—primitive Christian, or mediæval Catholic—and through what is said we apprehend what he means. Other writers may be as witty, may be or appear as delicately ironical—they still do not resemble him. If we enter the dépôt of some famous china manufactory with a piece of china from some other factory, as faultless and as beautiful in colour as those by which we are surrounded, the saleswoman takes it into her hand, looks at it, and says: "The paste is different."

In France's case we may search long for paste of the same quality as that which he has succeeded in producing after thirty-six years of labour.

Anatole France is no longer young, but his celebrity is of comparatively recent date. On April 16, 1904, he completed his sixtieth year, but only for the last eleven years has he really been famous.

He began as quite a young man to write literary and historical essays and tasteful poems, but he was thirty-seven when he first attracted attention by his simple tale, Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard, and it was not until 1892-93 that he gave proof of his originality.

His remaining so long in the shade is attributable in the first place to the tardy development of his complete individuality. He had not the courage to be completely himself; encouragement from without was necessary to him.

Another reason for it was the occupation of the foreground by great novelists who have now disappeared, story-tellers like Maupassant, Daudet, Zola; and yet another, that men of talent such as Bourget and Huysmans had not yet gone over to clericalism, or Jules Lemaître to nationalism, or Hervieu to the theatre. More-over—and this of prime importance—the great artist in style whose heir he is, Ernest Renan, was still with us.

Not until the acute sceptic and enthusiastically pious thinker in whose footsteps he trod, and those luxuriantly fertile authors whose books excited most attention had passed away, was the space round that tree of knowledge which Anatole France had planted sufficiently cleared to allow the sunlight to fall upon it and the tree to become visible from every side.

Those other Frenchmen were all born in the provinces—Daudet and Zola in Provence, Maupassant in Normandy, Renan in Brittany, Hervieu at Neuilly, Bourget at Amiens; Huysmans is of Flemish descent. France, who is cast in softer mould, and from the very beginning showed himself to be less sturdy than the Provençals and Normans, is a Parisian born, and bears the genuine Parisian stamp.

His master, Renan, did not become a Parisian until towards the close of his life, until he had lost the Breton stamp, and ceased to be a pupil of the Germans. France was a Parisian from the beginning.

The light and air of Paris were his native atmosphere, the Luxembourg Gardens were to him French nature, and the street was his school. As a child he watched the dairy-girls carrying milk and the coal-heavers coals into all the houses of the Quartier Latin. He knows the Parisian artisan and small shopkeeper well.

The windows of the stationers' shops riveted his attention with their pictures, and his first instruction was received in turning over the leaves of the books in the boxes of the poor salesmen on the Seine quays.

He himself was the son of a poor bookseller, or rather bookseller's assistant. He was born in a book-shop, and brought up amongst old, wise books, mysterious reminders of a life which was no more. From them he learned how ephemeral existence is, how little of the work of any generation survives; and this has inspired him with a fund of sadness, gentleness, and compassion.

It is extraordinary how many small book-shops he has described, in Paris and elsewhere—their books, their frequenters, the conversations held in them. Again and ever again does he occupy himself with these worthy booksellers on the banks of the Seine (who now look upon him as their guardian spirit), with their wretched life, as they stand there in the cold and rain, seldom selling anything.

We, to whom not one of the Frenchmen of to-day seems so French as Anatole France—for he embodies in himself the whole national tradition, descending from the romance-writers of the Middle Ages through Montaigne to Voltaire—we are not surprised that he should have boldly assumed the name of his country in place of his own. France, however, was also the Christian name of his unassuming father—he was France Thibaut. But to the humble people of the street in which he lives, the little Allée Villa Said, the author is not France; they call him Monsieur Anatole.

The streets by the Seine are always in his mind. He says somewhere: "I was brought up on this Quai, amongst books, by humble, simple people, whom I alone remember. When I am no more it will be as if they had never existed."

Elsewhere he calls these river-side streets the adopted country of all men of intellect and taste.

And in a third place he writes: "I was brought up on the quays, where the old books form part of the landscape. The Seine was my delight.... I admired the river, which by day mirrored the sky and bore boats on its breast, by night decked itself with jewels and sparkling flowers."

A book-lover he was and is.

One of the first characteristics which strikes the reader of France's works is this literary culture, unusual in a novelist and story-writer, and also its nature. Amongst French authors as a class we are accustomed to the unlearned, whose culture is restrictedly French, to the pupils of the Normal School, whose culture is one-sidedly classical, and to the learned, whose culture is European. But France's is a wide, ample culture, gained in a Europe from which the Germanic nations are excluded. He knows neither English nor German. This is the chief difference between his culture and Renan's. But the want is less felt in him than in others. Renan was the Oriental philologist. The Semitic languages were his field; his intellect had been nourished upon German science. What France is thoroughly at home in is Latin and Greek antiquity; but he is also well versed in the Latin and Italian literatures of the Middle Ages. Therefore he is, be it noted in passing, a keen supporter of classical school education. "I have," he says somewhere, "a desperate attachment to Latin studies. Without them the beauty of the French genius would be gone. We are Latins. The milk of the she-wolf is the best part of our blood."

He has made himself specially familiar with the age of ferment when Christianity was struggling with paganism in the ancient mind, with the Christian legends, which he retails with naïveté and well-concealed irony, and with Italian and even more particularly French history, from the days of Cæsar to the eighteenth century, the beginning of which lives in his Reine Pédauque.

His art occupies itself very frequently with religious feelings and situations. And here the contrast with Renan is strongest. For whereas Renan's mind was always religiously disposed and his language often unctuous, France, in treating of religious subjects, in spite of apparent reverence, is as callous in his inmost soul as Voltaire.

To his pictures of the past have been added in the last stage of his development pictures drawn from the France of to-day, and portraits of personages who have as lately formed the subjects of conversation as Verlaine and Esterhazy.

It is not modern life, however, which he favours as author or man. One day, when a visitor to whom he was showing his books expressed surprise that there were so few, and apparently no modern works among them, France said: "I have no new books. I do not keep those which are sent me; I send them on to a friend in the country." (The "friend in the country" was very probably a French euphemism for one of those booksellers on the Seine quays whom France knows so well.) "But do you not care to make acquaintance with them?" "My contemporaries No! What they can tell me I know quite as well myself. I learn more from Petronius than from Mendès." It was, therefore, doubtless half unwillingly that France for several years undertook to discourse critically, in the feuilleton of the Temps, on the productions of his contemporaries. The four volumes in which he has collected his articles are, nevertheless, extremely interesting. In them, from beginning to end, he maintains that such a thing as pure, impersonal criticism is impossible, that the critic can never do anything but represent himself—that, consequently, when he speaks of Horace or Shakespeare it simply means that he is speaking, in connection with Horace or Shakespeare, of himself.

France, then, spoke always of himself. "I hope that when I speak of myself every one will think of himself." As critic he communicated his personal impressions, and often related anecdotes, chiefly of occurrences during his own childhood and early youth, which elucidated and explained these impressions. A critic in the strict sense of the word he was not, and when his books began to sell better he gave up criticism. His utterances in the four volumes referred to are most characteristic of his personality, revealing, as they do, its spirit, its limitations, and its prejudices—prejudices which he has gradually outgrown.

The friend to whom France replied, "I have no modern books in my house," asked, smiling: "Not even your own?" "No," answered France; "what a man has built himself—even supposing it to be a palace—he knows so well that he cannot endure the sight of it. I could not bear to have my own books in my hands. Why should I look at them?"

"To avoid repetition."

"I certainly do perpetually repeat myself."

This is unfortunately true—it is one of the besetting sins of the author. Too often does the same thought recur in his pages, expressed almost in the same words. At times he repeats in one book, page for page, what he has written in another.

We can see what a faithful portrait of himself France has given us in the person of the sculptor in Le Lys Rouge by comparing the above answer with the following passage.

Madame Martin-Bellême says: "I see none of your own works, not a single statue or relief."

Dechartre replies: "Do you imagine that it would be a pleasure to me to live among my own works? I know them far too well ... they bore me."

That Dechartre is only a mask for France is almost acknowledged in what follows: "Even though I have modelled a few bad figures, I am no sculptor—rather a bit of a poet and philosopher."

In France's literary life, after a preparatory stage which lasted fifteen years, there are two periods, which differ so much from each other that one might almost say: There are two Frances.

In the first of these periods he is the refined satirist, who, from a station high above the human crowd, observes its endeavours and struggles with a superior, compassionate smile. In the second he appears as the combatant. He not only attaches himself to a party, but affirms as he does so his belief in the very things at which he has jested and scoffed—the sound instinct of the people, the significance of the majority, the increasing reality of progress—in the doctrines which as a thinker he had declined to accept, those of democracy and socialism.

When a friend once politely but plainly reproached him with this attitude as not perfectly honourable, France answered in a manner which avoided the real point by asking: "Do you know any other power capable of opposing that of the Church and Nationalism in combination except the Socialist Labour party?"

He turned the theoretical into a practical question.

When the friend remarked that he himself, under similar circumstances, had plainly announced his practical adherence to a party, but at the same time his dissent from its doctrine, France turned to some ladies who were present, and said, laughing: "Is he not impossible? As honest and obstinate as a donkey!"

For more than half of his life France undoubtedly agreed with his Abbé Coignard, who had an affectionate contempt for mankind, and who would not have signed the Declaration of the Rights of Man, not a line of it, "because of the sharply defined and unjust distinction made in it between man and the gorilla." He in those days inclined, like Coignard, to the belief that men are mischievous animals who can be kept under control only by force or cunning.

Even many years later, after he has proclaimed himself a democrat, he makes his mouthpiece, Bergeret, say to his dog: "To-morrow you will be in Paris. It is an illustrious and noble city. The nobility, to tell the truth, is not common to all its inhabitants. It is, on the contrary, to be found in only a very small number of the citizens. But a whole town, a whole nation, exists in a few individuals who think with more power and more justice than the rest." And later, in the same book, when Biquet, with gaping jaws and flaming eyes, has flown at the heels of the clever workman who has been setting up Bergeret's book-shelves, his master explains to him that what exalts a nation is not the foolish cry that resounds in the streets, but the silent thought which is conceived in a garret, and one day changes the face of the earth.

France does not share the reactionary's fear of the power of the masses. But if he does not fear it, it is not because of their wisdom. It is because of their caution. He knows that fear of the unknown renders universal suffrage a perfectly safe institution. He has made too good use of his eyes and his reasoning powers to have more reverence for the sovereign people than for any of the other sovereigns to whom men throughout the ages have offered homage and flattery. He knows that knowledge is sovereign, not the people. He knows that a foolish cry, though taken up by thirty-six millions of voices, does not cease to be foolish, and that truth is irresistible and will make itself ruler of the earth, though it may be perceived and proclaimed only by a single man, and though millions may unite and shout in chorus against his "individualism."

France is no optimist. He has seen too much declension and apostasy around him in France and Europe generally, to believe in the fable of uninterrupted progress. He has lived through times of universal indifference and apathy, when no sting was sharp enough to stir men to think, much less to act. When men's souls are hungering and thirsting after unrighteousness, it is of little use offering them a refreshing draught of culture. As is said of the "people" in Bergeret: "It is not easy to make an ass which is not thirsty drink." France knows, too, what popularity means. He has good reasons for making one of his principal characters say: "If the crowd ever takes you lovingly into its arms, you will soon discover the vastness of its impotence and of its cowardice." And we have elsewhere his quiet, witty explanation of the election of a Nationalist candidate for the Municipal Council and the defeat of the Republican. The Nationalist candidate was entirely ignorant of all the subjects connected with the office, and this ignorance stood him in good stead; it rendered his oratory more spontaneous and eloquent. The Republican, on the contrary, lost himself in technical questions and details. Although he knew his public, he harboured some illusions regarding the intelligence of the electors who had nominated him. From a certain respect for them, he dared not venture on too much humbug, and entered into explanations. Consequently he seemed cold, obscure, tiresome—and all support was withdrawn.

But, on the other hand, France is no pessimist. He knows and says of the France of to-day: "The weak are in the wrong. That is the sum of our morality, my friend. Do you suppose that we are on the side of Poland or Finland? No, no! That is not the way the wind blows at present!" But he also knows that the earth will not finally belong to armed barbarity. Alone, unarmed, naked, truth is stronger than everything. Might and violence oppose it in vain. It strikes at injustice and annihilates it. The word of man changes the world. The alliance of strong reasons and noble thoughts is an indissoluble alliance, and against its onslaught nothing can stand. Bergeret, the tranquil philosopher, is absolutely certain of the final victory of reason. "The visions of the philosopher have in all ages aroused men of action, who have set to work to realise them. Our thoughts create the future. Statesmen work after the plans which we leave behind us."

Certain it is that the future is hidden from us. But we must, as France says, work at it as the weavers work who produce the Gobelin tapestry without seeing the pictures which they are weaving. Nor is it altogether true that the future is hidden. Or, granting it to be so to us, "we can conceive of more developed beings to whom to-morrow is realised as yesterday and to-day are. It makes it the easier to imagine beings who perceive simultaneously phenomena which appear to us separated by a long interval of time, when we remember that our own eyes, looking up to the night sky, receive, mingled beams of light which have left different stars at intervals of centuries, and centuries of centuries."

A man holding such views as these may be claimed as an adherent by both the Radical and the Conservative party, as Ibsen was for a time in Scandinavia. France actually was incorporated in the Conservative party. As late as 1897 he was the candidate for the Academy whom the Conservative party, the Dukes, opposed to Ferdinand Fabre, an author hostile to the power of the Church.

Highly valuing moderation and tact, he at that time detested his future companion in arms, Zola—detested him, indeed, without moderation—wrote: "I do not envy him his disgusting celebrity. Never has a man so exerted himself to abase humanity and to deny everything that is good and right. Never has any one so entirely misunderstood the human ideal." There is more love of good taste here than appreciation of genius. It must be remembered that France afterwards publicly recanted this and many similar utterances. He did so in the beautiful and heartfelt speech which he made at Emile Zola's grave; but he had done it long before.

He overlooked the genius of the man who was to become his best comrade in arms because of that man's bad taste and exaggerations, and himself exaggeratedly praised the men with whom he was afterwards compelled to engage in mortal combat, and of whose narrowness and weaknesses he afterwards had ample experience.

He wrote in serious earnest: "I do not believe that more intelligent men than Paul Bourget and Jules Lemaître can ever have existed."

He had no perception then of Bourget's fear of hell, or of Lemaitre's want of moral equilibrium. Here is his testimonial to the latter, the future Nationalist fanatic: "He is one of the men who bear ill-will to none, but are long-suffering and benevolent. His is a fearless spirit, a smiling soul; he is all tolerance."

When this was written Jules Lemaître was already malicious and ungenerous, though perhaps not yet base. A few years later he was, as Vice-President of the Patrie Française, leader of the band which kept Dreyfus prisoner in the île du Diable and advocated the coup d'état against Loubet. A few years later Paul Bourget had returned to the bosom of the Roman Catholic Church, and was attacking with the utmost violence every progressive movement, even the enlightenment of the people and instruction for the working man. These were France's models of intelligence.

Compared with the attitude of these men, France's own attitude during the past six years may almost be termed exemplary.

It may be that as the popular orator—a career for which he was not intended by nature—he has proclaimed himself rather more strongly convinced than he is in his inmost soul; this does not prevent its being the real man who has come to light during the last decade—the man who was concealed behind the thinker's play of thought and the poet's metamorphoses.

Suddenly he stripped himself of all his scepticism and stood forth, with Voltaire's old blade gleaming in his hand—like Voltaire irresistible by reason of his wit, like him the terrible enemy of the power of the Church, like him the champion of innocence. But, taking a step in advance of Voltaire, France proclaimed himself the friend of the poor in the great political struggle.

That he did thus come forth was undoubtedly a consequence of the circumstance that the whole civilisation of France and her old position as protector of justice appeared to him to be endangered during a crisis in public morality; but, in the absence of some instigation from without, he might quite possibly have remained inactive. The person who influenced him more than any other at this time was a lady in whose house he has for years been the most welcome of daily visitors—whose house is, indeed, his second home.

France did not hesitate to bring the whole weight of his influence publicly to bear when it came in France to a trial of strength between a few chosen spirits on the one side, and the army, the Church, those in authority, and the misled masses on the other.

In his capacity as combatant France has written the last two volumes of his Histoire Contemporaine, published his speeches in the Cahier de la Quinzaine, spoken at the unveiling of Renan's statue and at Zola's grave, and written the Introduction to Combe's collected speeches It is one of the signs of the times that he should now be the man to whom the Prime Minister of France applies to have his utterances placed before the French reading public. It shows what a degree of influence is ascribed to him, and how definitely he has espoused a cause.

France has at times introduced himself into his books. He takes the retiring and wise element in his nature, and out of it creates Monsieur Bergeret. He takes the serene sensualism, and of it constructs Trublet, the doctor of the Histoire Comique. He takes his intensely beauty-loving ego, and we have the sculptor Dechartre in Le Lys Rouge. He introduces himself into this same novel in the person of the author Paul Vence, almost with the mention of his name—this, of course, to prevent its being observed that Anatole France is also the principal character, the sculptor; just as Mary Robinson is named in the book to conceal her identity with Miss Bell, the English authoress in it, and Oppert is referred to to prevent its being said that he is Schmoll, the antiquarian, as he undoubtedly is.

When Vence is introduced to us in the heroine's drawing-room we are told: "She considered Paul Vence to be the one really clever man who came to her house. She had appreciated him before his books had made him famous. She admired his profound irony, his sensitive pride, his talent, ripened in solitude."

And to such an extent is Paul Vence France himself that when, towards the end of the book, he remarks: "He was a wise man who said, 'Let us give to men for their witnesses and judges Irony and Compassion'"—an utterance to be found in more than one of France's books—Madame Martin-Bellême answers: "But, Monsieur Vence, it was yourself who wrote that."

Profound irony is, then, the first quality which he attributes to himself.

We have seen how this irony, unlike Renan's, is indirect; we only catch a glimpse of it through the naïveté of another person.

We are told, for instance, in Thaïs, of the heroine, a Grecian courtesan: "This woman showed herself at the festival games, and did not hesitate to dance publicly in such a manner that her excessively agile and artful movements suggested the most dreadful passions and excited to them." This is felt and spoken from the standpoint of a monk.

Pafnucius, in the same book, sees the devil torturing souls. The narrator of the occurrence expresses no doubt or incredulity; it is nowhere remarked that this was a vision, not reality. No! "Small green devils pierced his lips and his throat with red-hot irons."

This naïveté is a rare quality in French literature, the literary art of the French being (in spite of Lafontaine) as a rule not naïve, but even in Molière, and throughout his whole century, as well as the next, perfectly self-conscious. Yet naïveté is a powerful means of producing artistic effects—the indirect process which requires the reader's own co-operation being undoubtedly always more effective than the direct communication, which does not impart the useful little impetus to the intellect.

France, in his historical tales, writes ingenuously, as a contemporary would have spoken and thought. We are most conscious of this in the series collected and published under the title of Clio. Simple tales they are, yet this book, which bears the name of the goddess of history, concerns itself with some of the greatest historical personages—Homer, Cæsar, Dante, Joan of Arc, Napoleon. Of these only Homer and Napoleon are directly presented to us.

When the tale, The Singer of Kyme, first appeared, its seemingly arbitrary invention displeased many. Why take up this legend of the blind or half-blind old man? Why give this insignificant figure, this poor creature going from place to place earning his bread by his songs, the awe-inspiring name of Homer? But upon maturer reflection we acknowledge how correctly France has seen, and what wisdom there is in his view of the matter. The singer of his tale is unmistakably akin to the bards described in the Homeric poems; and it is only natural that his house should have been cramped and low in comparison with that of his neighbour, the wealthy soothsayer.

The secret of the art of France's historical style is, as already said, that he thinks and speaks in the spirit of the age which he is portraying, seems to share its views, to accept its beliefs and superstitions, its prejudices and ideas, without a trace of irony or of fatuity, but with an artistic skill which forcibly brings out the contrast between the spirit of those ages or countries and ours.

Take, for instance, in the story just mentioned, the way in which he communicates to the reader, by means of his description of the old singer's methods, his own conception of the genesis of the Homeric poems. When a king requests the old man to sing, but to let it be the truth that he sings, he answers: "What I know of the heroes I have from my father, who learned it from the Muses themselves; for of old the Muses were wont to visit the divine singers in caves and woods. I shall mingle no lies with the old histories." And the author adds: "He spoke thus from prudence. For to the songs which he had learned in his childhood he was in the habit of adding verses which he had taken from other songs or found within himself. But he did not confess this, fearing Jest he should be blamed for it. The chieftains almost always asked for the old tales, which they believed to have been dictated by a divinity, and mistrusted the new songs. Therefore he carefully concealed the origin of those which he had composed himself. And as he was a very good poet, and carefully observed the established customs, his verses were in no wise distinguishable from those of his forefathers; they resembled them in form and beauty, and from the moment of their conception were worthy of immortal fame." The singer is, we observe, praised, in the spirit of the age, for the quality which, according to modern ideas, detracts from his worth.

In precisely the same manner is the dialogue entitled Farinata degli Uberti thrown into relief. With his unerring critical instinct France has selected the most interesting of all the figures in Dante's Inferno. And this figure has for us one element of interest in addition to those which it possessed for Dante? namely, the diametrical opposition between Farinata's views and ours. In our days it is a very honourable thing to fight for one's countrymen against foreign troops, and an abominable thing to stir up civil war. When Farinata is justifying himself for having fought on the side of Siena against his Florentine fellow countrymen, he says: "Undoubtedly it would have been better for us Florentines to have fought out the quarrel amongst ourselves. Civil war is such a fine and noble thing, a thing of such delicacy, that the implication of foreigners in it ought, if possible, to be avoided.... I do not maintain the same of wars with other States. They are useful, at times necessary, enterprises, undertaken to defend or to extend the frontiers of a country or to further its commerce. But as a rule there is neither much advantage nor much honour to be gained by fighting in these vulgar wars. For them a sensible people prefers to employ mercenary troops, under experienced leaders, who can do a great deal with a small force."

To appreciate the characteristic qualities of this dialogue the reader should compare it with the corresponding versified dialogue by Robert Browning, in which the old Italian passionateness finds expression. Browning's language is more vehement than France's, more spasmodic and more spontaneous.

France, as a rule, produces his effect entirely by the contrast between the inner logic of men's feelings in these old days and in ours.

The most fully elaborated of the tales is that entitled Commius, the Atrebate, which describes the career of a Gallic chieftain in the time of Cæsar. Although the author appears to have drawn as freely on his imagination here as in The Singer of Kyme, he has in this case built upon a sound historical foundation. The reader with Cæsar's Commentaries fresh in his memory will remember what they tell about the Atrebate chief, Commius. To France it has been a congenial task to probe the mind of a barbarian of those days—to describe Commius's care-free life as the chief of his tribe, to show how he is won over by the Romans and feels flattered by being called Cæsar's friend, but is gradually led to regard the loss of freedom as a disgrace, until his feeling towards the Romans becomes the barbarian's fierce hatred. Most readers will feel that not until they made acquaintance with this story had they a thorough understanding of the difference between the Roman methods of warfare and those of the barbarians, and in especial of the skill in engineering which had been acquired by the little dark soldiers who made war more with the pickaxe and the spade than with the javelin and the sword. Very masterly is the description of the barbarian king's astonishment and affright when, after an absence of a few years, he returns to his poor capital, Nemetoeenna (the Arras of to-day), and finds it transformed by the Romans into a magnificent town, with temples and colonnades. He cannot but believe them possessed of magic power. We follow him with keen interest as he wanders through the town disguised as a beggar; we watch his surprise at the paintings on the houses, of the subjects of which he understands nothing; we see him murder a young Roman who is sitting in the amphitheatre composing Latin verses in a Greek metre to his Phoebe. Here again France produces his effect by the silent throwing into relief of the difference between men's ideas in those days and in ours. He writes as follows, for instance, of the prefect of the Roman horse, Caius Volucenus Quadratus, who resolves to invite Commius to a friendly conference, and to have a deadly blow dealt him from behind whilst he himself is taking him by the hand.

"He was a good general, learned in mathematics and mechanics. In times of peace, under the terebinth trees of his Campanian villa, he conversed with other high officials upon the laws, manners, and customs of different races. He lauded the virtues of olden days, extolled liberty, read Greek history and philosophy. He was distinguished for nobility and refinement of mind. And as Commius the Atrabate was a barbarian, hostile to Rome and the Roman cause, he considered it right and wise to have him assassinated."

Although it is only in faint silhouette that Cæsar is presented to us, we are conscious here, as elsewhere, that Anatole France is deeply interested in him. He admires him without any cordial sympathy. His Abbé Coignard, who muses upon Cæsar, is repelled by his cruelty. The cutting off of the Gauls' hands at Uxellodunum is, of course, not forgotten. Yet Cæsar was more merciful than any other Roman general. But France, following his usual custom, puts into one book all that tells in favour of Cæsar, and into another what tells against him.

He has done the same with Napoleon. In Le Lys Rouge the shallowness of Napoleon's character is dwelt upon—nay, insisted upon to such an extent that poor Napoleon III. is actually maintained to be a more interesting figure. In the short story, La Muiron (the ship which conveyed Bonaparte from Egypt to France), we are, on the other hand, told of the young commander's inclination to mysticism, of his mysterious belief in his own future. And France puts into his mouth the following profound words: "No man escapes his fate. Brutus, who was a mediocrity, believed in the power of the human will. A greater man does not harbour that illusion. He sees the necessity which limits him.... Children are rebellious. A great man is not. What is a human life? The curve traced by a projectile." Bonaparte says this at the very moment when, with implicit faith in his own luck, he is venturing out on the Mediterranean among the English cruisers. The whole short story is based, as it were, upon his premonition of coming greatness.

But here, as always, France, with the unerring taste of the really great writer, avoids cheap effect. India-rubber in hand, he goes over all the outlines, erasing, toning down.

It is characteristic, and in harmony with the naïveté of the style, that naïveté should form a distinguishing quality of the most lifelike characters which France has produced. Another of their qualities is often strongly developed, sometimes very shameless sensuality, which is not repugnant to him, and which it amuses him to delineate.

Take Abbé Coignard in La Reine Pédauque, a man with an astoundingly able mind, a childlike soul, and a shameless body. Take Choulette in Le Lys Rouge, a childlike, drunken, shameless genius. This portrait of Verlaine we find again, with variations, in the Gestas of L'Étui de Nacre. In all three there is a mixture of simplicity and cynic voluptuousness—a half-childlike absence of shame.

Abbé Coignard undermines everything established with his doubts and leads an exceedingly loose life, but remains faithful in the very smallest particular to the Catholic religion. Even more childlike than he himself is his disciple, Tourne-broche. Choulette is the old, ruined Bohemian, eternally young as the poet, melting with drunken compassion for the poor and the mean—as is said of Coignard, "half a St. Francis of Assisi, half an Epicurean, a big, believing, shameless child."

It is in virtue of this combination—naïveté and shamelessness—that Riquet the dog becomes one of France's best characters. No man is as devoid of shame as a dog, and no child is more childlike.

Biquet has great difficulty in seeing things from Monsieur Bergeret's point of view. He flies at the heels of the worthy carpenter, merely because that workman wears a blouse and carries tools; he is steeped in all the old prejudices of the feudal age.

But his "Thoughts" are a little masterpiece of canine innocence and compressed irony. Let me give a few examples.

"Men, animals, and stones grow larger as they approach me, and become enormous when they are quite close. It is not so with me. I remain the same size wherever I am."

"The smell of a dog is a delicious smell."

"My master keeps me warm when I lie behind him in his arm-chair. That is because he is a god. In front of the fire there is a warm hearthstone. The hearthstone is divine."

"I speak when I choose. From my master's mouth, too, issue sounds which have a kind of meaning. But their meaning is less plain than that which I express with my voice. Everything uttered by my voice means something. But from my master's mouth comes much senseless noise."

"There are carriages which horses draw in the streets. They are terrible. There are carriages which move of themselves, puffing loudly. These, too, are full of malice."

"People in rags deserve to be hated, and also those who carry baskets on their heads or roll casks. Children who run about the streets, chasing each other and screaming, are hateful too."

"I love my master because he is powerful and terrible."

"An action for which one is thrashed is a bad action. An action for which one is caressed or given something to eat is a good action."

"Prayer.—O Bergeret, my master, god of carnage, I adore thee. Praised be thou when thou art terrible, praised when thou art gracious! I crawl to thy feet, I lick thy hands. Great art thou and beautiful when, seated at thy spread table, thou devourest quantities of food. Great art thou and beautiful when, bringing forth tire from a little chip of wood, thou changest night into day. Keep me, I pray thee, in thy house, and keep out every other dog!" This is a parody of human religion, good-natured and yet trenchant.

When, in his turn, Monsieur Bergeret addresses the dog, he addresses in him the whole undeveloped portion of the human race.

"You too, poor little black being, so feeble in spite of your sharp teeth and your gaping jaws, you too adore outward appearances, and your worship is the ancient worship of injustice. You too allow yourself to be seduced by lies. You too have race hatreds.

"I know that there is an obscure goodness in you, the goodness of Caliban. You are pious; you have your theology and your morality. And you know no better. You guard the house, guard it even against those who are its protection and ornament. That workman whom you tried to drive away has, plain man though he be, most admirable ideas. You would not listen to him.

"Your hairy ears hear, not him who speaks best, but him who shouts loudest. And fear, that natural fear which was the counsellor of your ancestors and mine when they were cave-dwellers, the fear which created gods and crimes, makes you the enemy of the unfortunate and deprives you of pity."

The irony gains in power by being veiled in the innocence of the dog. The irony in France's writings is generally veiled in some such manner. In Monsieur Bergeret à Paris, for instance, the standpoint of the author's opponents is presented to us in two chapters which are read aloud by Monsieur Bergeret from a supposed work of the year 1538, in which France, with extraordinary skill, has imitated the language, style, and reasoning of the Trublions, the Nationalists of that age.

Just as something in France's intellectual qualities generally, reminds us of Voltaire as the narrator, so something in his principal characters and in the spirit of his novels recalls Candide. Candide, too, was naïve. France has read Voltaire again and again, and assimilated much of him. How often, for instance, does the story of Cosru's widow in Zadig crop up in France's pages! A Voltairean sentence such as: "The belief in the immortality of the soul is spreading in Africa along with cotton goods," sounds as if it might have been written by France. The naïveté of the modern writer is certainly the more genuine, though in greatness as an author he, of course, falls far short of his predecessor.

The four volumes of the Histoire Contemporaine, the last two of which, with their witty tirades oil the Dreyfus affair, were of no small assistance to the opponents of the Nationalists, are, though of unequal value, a very remarkable product of ripe experience and Olympian superiority. The principal character, the gentle and wise Monsieur Bergeret, unfortunate as a husband, fortunate in that he was able to obtain a divorce, is, as a type, in no respect inferior to the personages in whom other great French authors have embodied themselves. He is a worthy brother of Alceste, Figaro, and Mercadet.

More artistically perfect than this lengthy four-volume novel are the short modern stories published under the title of Crainquebille. The first of these, which gives its name to the book, is told placidly, simply, cuttingly, bitterly. The plot is so simple that it can be compressed into a few lines. A decent old man, a street vendor of vegetables, has stopped with his barrow in front of a shop in a very busy thoroughfare. He is waiting for payment for some leeks which he has sold. A policeman orders him to move on, and, heedless of the old man's muttered, "I'm waiting for my money," repeats the order twice in the course of a few moments, and then, enraged by Crainquebille's "resistance to authority," arrests him and accuses him before the magistrate of having made use of the insulting expression in which the common people give vent to their dislike of the police—a thing which the old man has certainly not done. The magistrate, who places more faith in the assertion of the policeman than in the denial of the poor man, sentences the latter to a fortnight's imprisonment and a fine of fifty francs.

When he comes out of prison Crainquebille finds that his customers have deserted him for another hawker, and will have nothing more to do with him because of his disgrace. He sinks deeper and deeper into poverty and misery, until at last he feels that the only way left him to provide himself with a shelter is to rush at a policeman shouting the offensive expression which he had before been unjustly accused of using. This policeman, however, leaning stoically against a lamp-post in pouring rain, despises the insult, and takes not the slightest notice of it, so that the poor man's last resort fails him.

Crainquebille is painfully touching; the next little story, Putois, is both witty and pregnant with meaning.

"Lucien," says Zoé to her brother, Monsieur Bergeret, "you remember Putois?"

"I should say so. Of all the familiar figures of our childhood, no other is still so vividly before my eyes. He had a peculiarly high head."

"And low forehead," adds Mademoiselle Zoé.

And now brother and sister intone in turn, with perfect seriousness, as if they were giving a description for legal purposes: "Low forehead," "Wall-eyed," "Unable to look one in the face," "Wrinkles at the corner of the eyes," "Thin," "Rather round-shouldered," "Feeble in appearance, but in reality extraordinarily strong—able to bend a five-franc piece between his first finger and thumb," "Thumb enormous," and many other particulars.

Monsieur Bergeret's daughter Pauline asks: "What was Putois?" and is told that he was a gardener, the son of respectable country people; that he started a nursery at Saint-Omer, but, proving unsuccessful with it, had to take work where he could find it; and that his character was none of the best. When Monsieur Bergeret the elder missed anything from his writing-table he always said: "I have a suspicion that Putois has been here."

"Is that all?" asks Pauline.

"No, my child, that is not all. The remarkable thing about Putois was that, well as we knew him, he nevertheless...."

"Did not exist," said Zoé.

"How can you say such a thing!" cried Monsieur Bergeret. "Are you prepared to answer for your words, Zoé? Have you sufficiently reflected upon the conditions of existence and all the modes of being?"

Then Monsieur Bergeret explains to his daughter that Putois was born as a full-grown man in the days when he himself and his sister were boy and girl. The Bergerets inhabited a small house in Saint-Omer, where they led a quiet, retired life, until they were discovered by a rich old grand-aunt of Madame's, Madame Cornouiller, the owner of a small property in the neighbourhood, who took advantage of the relationship to insist upon their dining with her every Sunday—a Sunday family dinner being, according to her, imperative among people of their position.

As Monsieur Bergeret was bored to death by these entertainments, he in time rebelled, refused to go, and left it to his wife to invent excuses for declining the invitations. And thus it came about that the usually truthful woman said one day: "We cannot come this week. I expect the gardener on Sunday." Putois had received his first attribute.

Glancing at the scrap of ground belonging to the house, Madame Cornouiller asked with astonishment if this were the garden in which he was to work, and on being told that it was, very naturally remarked that he might just as well do it on a weekday. This speech in its turn necessitated the reply that the man could only come on Sunday, as he was occupied all the week. Second qualification.

"What is your gardener's name, my dear?" "Putois" replied Madame Bergeret without hesitation. From the moment in which he received a name, Putois began to lead a kind of existence. When the old lady inquired where he lived, he necessarily became a species of itinerant workman—a vagrant, in fact. So now to existence had been added status.

When Madame Cornouiller decided that he should work for her too, he immediately proved to be undiscoverable. She made inquiries about him of all and sundry, to find that most of those she asked thought they had seen him, and others knew him, but were not certain where he was at the moment. The tax-collector was able to say with certainty that Putois had chopped firewood for him between the 19th and 23rd of October of the comet year.

The day came, however, when Madame Cornouiller was able to tell the Bergerets that she herself had seen him—a man of fifty or thereabouts, thin, round-shouldered, with a dirty blouse and the general appearance of a tramp. She had called "Putois!" in a loud voice, and he had turned round.

From this day onward Putois became ever more and more of a reality. Three melons were stolen from Madame Cornouiller. She suspected Putois. The police, too, believed him to be the culprit, and searched the neighbourhood for him. The Journal de Saint-Omer published a description of him, from which it appeared that he had the face of a habitual criminal. Ere long there was another theft on Madame Cornouiller's premises; three small silver spoons were stolen. She recognised Putois's handiwork. Henceforward he was the terror of the town.

When Gudule, her cook, was discovered to be enceinte, Madame Cornouiller jumped to the conclusion that she had been seduced by Putois, and was confirmed in her belief by the fact of the woman's weeping and refusing to answer her questions. As Gudule was ugly and bearded, the story occasioned much amusement, and in popular fancy Putois became a perfect satyr. Another servant in the town and a poor hump-backed girl being brought to bed that same year with children whose paternity was mysteriously concealed, Putois attained the reputation of a veritable monster.

Children caught glimpses of him everywhere. They saw him passing the door in the dusk, or climbing the garden wall; it was he who had inked the faces of Zoé's dolls; he howled at nights with the dogs and caterwauled with the cats; he stole into the bedroom; he became something between a hobgoblin, a brownie, and the dustman who closes little children's eyes. Monsieur Bergeret was interested in him as typical of all human beliefs; and, since all Saint-Omer was firmly convinced of Putois' existence, he, as a good citizen, would do nothing to shake their belief.

As to Madame Bergeret, she reproached herself sometimes for the birth of Putois; but, after all, she had done nothing worse than Shakespeare when he created Caliban. Nevertheless she turned quite pale one day when the maid came in and said that a man like a country labourer wished to speak to madame. "Did he give his name?" "Yes—Putois." "What?" "Putois, madame. He is waiting in the kitchen." "What does he want?" "He will tell no one but yourself, madame." "Go and ask him again." When the maid returned to the kitchen Putois was gone. But from that day Madame Bergeret herself began to have a kind of belief in his existence.

The story is both clever and of deep significance, it turns on the question of what an imaginary existence is. Putois' generation is the generation of a myth, and he exerts the influence which mythical characters do. No one can deny the rule of mythical beings over the minds of men, their influence on human souls. Gods and goddesses, spirits and saints, have inspired enthusiasm and terror, have had their altars, have counselled crimes, have, originated customs and laws. Satyrs and Silenuses have occupied the human imagination, have set chisels and brushes to work century after century. The Devil has his history, extending back for thousands of years—has been terrible, witty, foolish, cruel; has demanded human sacrifices; and has not only been worshipped by magicians and witches, but has, up to our own days, had his priests. France, however, has not the Devil alone in his mind; his thoughts range higher.

And he not only throws light in a bantering way on the formation of a myth, but also, and still more vividly, upon human verdicts. When Madame Cornouiller suspects Madame Bergeret of wishing to keep the vagrant gardener for herself, of not allowing other people to have any share in Putois, the writer remarks, as it were with a smile, that many historical conclusions which are accepted by every one are as well founded as this conclusion of Madame Cornouillers. Here, as elsewhere, France asserts that it is foolish to believe in the just judgment of posterity.

He has always thought it strange that Madame Roland should have appealed to "impartial posterity," without reflecting that if her contemporaries, who guillotined her, were cruel apes, there was every probability of their descendants being the same.

The world's history is the world's verdict, wrote Schiller. He is a naïve man who believes this. Posterity is just only to this extent, that the questions are of indifference to it; and as it is with the greatest difficulty that it can examine the dead, and as, moreover, it is itself not an impersonal thing, but an aggregate of more or less prejudiced human beings, the verdict takes shape accordingly. Historic justice is a Putois.

Fame is a Putois, an imaginary, impalpable being, that is pursued by thousands, and that melts into nothing just when it should display itself in full vigour—namely, after their death.

Everywhere we have imaginary, artificial existence, proclaimed to be real, and accepted as such. It is not at all necessary to confine ourselves to religion, where it is only too easy to discover Putois, whose huge shadow darkens theology in its entirety. Let us think of the illusions in politics, of the part played by titles in social life. Or let us remember the place occupied by imaginary existences in our own emotional life. Suppose that we could transfer to canvas the image of the beloved one which forms itself in the imagination of the lover at the moment when he sees all her supposed perfections, and afterwards place alongside of it the image of her which remains when love has evaporated and he has stripped her, one by one, of all the qualities which enchanted him—the description of the first picture would not seem less unreal than the description of Putois.

The reader who muses over the little story will feel how many ideas it sets in motion, and will, like the inhabitants of Saint-Omer, find traces of Putois everywhere.

The fault in most historical descriptions is that the pictures of the past are distorted in accordance with the significance which they have acquired for a later age. Gobineau makes Michael Angelo talk of Raphael as people did in the nineteenth century when they named them together. Wilde makes John the Baptist speak as he does in the Gospels, which were written, with an aim which led to distortion, long after his death. Wherever in modern poetry or art the figure of Jesus is treated, no matter in what spirit—let it be by Paul Heyse, by Sadakichi Hartmann the Japanese, or Edward Söderberg the Dane—He is the principal figure of His day, occupying the thoughts of all.

France, in his story, Judæas Procurator, has, in an extremely clever manner, indicated the place occupied by Jesus in the consciousness of a contemporary Roman. To any one who can read, the fact that the life and death of Jesus interested only a little band of humble people in Jerusalem, is sufficiently established by the circumstance that Josephus, who knows everything that happens in the Palestine of his day, does not so much as name Him. The man who argues that such an event as the Crucifixion must have made some impression forgets what a common and unheeded incident a crucifixion was in troublous times. During the Jewish war of the year 70, in the course of which 13.000 Jews were killed at Skythopolis, 50.000 in Alexandria, 40,000 at Jotapata—1,100,000 in all—Titus crucified on an average 500 Jews every day. When, impelled by hunger, they crept under the walls of Jerusalem, they were captured, tortured, and crucified. At last there was no more wood for crosses left in Palestine.

As his principal character, France has taken the Titus Ælius Lamia to whom the seventeenth ode of Horace's Third Book is addressed—a gay young Roman who, according to France, is banished by Tiberius for a flagrant love-affair with a consuls wife, goes to Palestine, and meets with a friendly reception in the house of Pontius Pilate. Forty years pass; Ælius Lamia has long been back in Italy; he is at Baiæ, taking the baths, and is sitting one day by a path upon a height reading Lucretius, when, in the occupant of a litter borne past by slaves, it seems to him that he recognises his old host, Pilate.

And it really is Pilate, who has come, accompanied by his eldest daughter, now a widow, to take the baths. They talk of old days—of all the trouble Pontius had with those wretched Jews, who refused to do homage to the image of the Emperor on the banners, and allowed themselves to be flogged to death rather than worship it. They continually came to him, too, demanding a sentence of death on some unfortunate creature whose crime he was unable to discover, and who appeared to him to be as mad as his accusers. Lamia declares that Pontius lacked appreciation of the Jews' good qualities, but confesses that his own predilection was in favour of the Jewesses. He recalls an evening on which he saw one of them dancing with uplifted arms to the clang of cymbals, on a ragged carpet in a miserably lighted, wretched drinking-booth. The dance was barbaric, the voice hoarse, but in the motion of the limbs there was sorcery, and the eyes were Cleopatra's. She had heavy red hair, this girl, whose charms enticed the young Roman to follow her everywhere. "But she ran away from me," he continued, when the young lay preacher and miracle-worker came from Galilee to Jerusalem. She became inseparable from him, and joined the little band of men and women who were always with him. "You remember him, of course?" "No," replies Pilate. "His name was Jesus, I think; he was from Nazareth" "I do not remember him," reaffirms Pilate. "You were obliged to have him crucified." "Jesus—" mutters Pilate, "from Nazareth—I have no recollection of it."

Here we have a characteristic example of Frances manner of producing his effects, and of his art in its profound truth.

So far is he from seeing Pilate's connection with Jesus in the light of later times that he represents him as completely forgetting the whole occurrence, which was an everyday one to him—whilst Lamia only remembers it because of Magdalene.

France has drawn Magdalene again in the tale of Læta Acilia, one of those composing the volume entitled Balthasar. Here he represents her as driven from Judæa, and arriving by ship at Marseilles, where she tries to convert her protectress, a Roman knight's wife. The Roman lady desires a child. Magdalene promises to pray for her. The next time she comes to the house Læta Acilia is pregnant. And now Magdalene tells her that she herself was a sinner when she first beheld the fairest of men, the Son of Man; that He drove seven devils out of her; and that she fell on her knees before Him in the house of one Simon and poured precious ointment from an alabaster box over His sacred feet. She repeats the words which the gentle Rabbi uttered in her defence when His disciples, with coarse taunts, would have driven her away. Since then she has lived in the shadow of the Master as in a new Paradise. And to her it was that He appeared first after His resurrection.

It seems to the Roman lady that Magdalene is endeavouring to impart to her a distaste for the pleasures of her placid life. Until now she has had no idea of there being any other happiness in the world except that which she knows.

"I have no desire to know your God. You have loved him too supremely. To please him one is to fall at his feet with unloosened hair! That is no posture for the wife of a Roman knight. Go, Jewess! Your God can never be mine. I have not lived the life of a sinner, and I have not been possessed with seven devils. I have not wandered in ways of error; I am a woman deserving of respect. Go!"

What attracts France in these characters is the contrast between the emotional life of the two women, between the religiously erotic rapture of the Asiatic and the tradition-sanctioned conjugal love of the Roman matron.

It is always as the creative writer that he touches history.

Among the many things in which France does not believe is history as a science. History, he says, is a representation of the events of the past. But what is an event? A remarkable fact. Who decides whether a fact is remarkable or not? The historian decides it, arbitrarily, according to his taste. A fact is, moreover, an exceedingly composite thing. Does the historian represent it in all its compositeness? That would be impossible. Hence he gives us it cropped and pruned. And yet again, the historic fact is the final consequence of unhistoric or unknown facts. How can the historian demonstrate their concatenation?

This line of argument appeals so forcibly to France that he sets it forth no fewer than three times—in the preface to La Vie Littéraire, in Les Opinions de M. Jérôme Coignard, and in Le Jardin d'Épicure. As the creative writer he chills the ardour of the investigator by his scepticism. It is, he says, impossible to know the past; no one is able to read everything that would require to be read. Twice he relates the same fable in illustration of his argument:

When young Prince Zemire succeeded his father on the throne of Persia, he summoned a convocation of all the learned men of his kingdom, and addressed them thus:

"My revered teacher has impressed upon me that kings would be less liable to error if they were acquainted with the history of the past. Write me a history of the world, and make certain that it is complete."

After the lapse of twenty years the learned men reappeared before the king, followed by a caravan composed of twelve camels, each bearing 500 volumes.

The secretary of the society made a short speech and presented the 6000 volumes.

The king, whose time was fully occupied with the affairs of the State, expressed his gratitude for the trouble taken, but added: "I am now middle-aged, and even if I live to be old I shall not have time to read such a long history. Abridge it!" After labouring twenty years longer the learned men returned, followed by three camels bearing 1500 volumes, and said: "Here is our new work; we believe that nothing essential is omitted."

"That may be; but I am an old man now. Abridge still further, and with all possible speed!"

After the lapse of only ten years they reappeared, followed by a young elephant, bearing only 500 volumes. "This time we have been exceedingly brief."

"Not yet sufficiently so," replied the king. "My life is almost over. Abridge again!"

Five years passed, and the secretary returned alone, walking with crutches, and leading a small ass, whose load was one large book.

"Hurry!" called an officer. "The king is at the point of death."

"I die," said the king, "without knowing the history of mankind."

"Not so, sire," answered the aged man of learning; "I can compress it for you into three words: They were born, suffered, and died."

We see how it is that France, in spite of his great gifts as an investigator, has not become a historian, but a novelist and story-writer.

He is not, however, so pessimistic as we might conclude from the closing words of his fable. The human beings whom he describes have pleasures as well as pains, and he invariably advocates pleasure as superior to every kind of abnegation of nature, and combats the theory that there is good in suffering.

But this scepticism with regard to history is typical of his sceptical spirit generally.

The danger of extreme intellectual refinement is that it disposes to doubt. The interest in humanity of the man who sees the many-sidedness of everything is apt to be swallowed up in contempt for humanity. And once this has happened he is quite likely, from sheer pessimistic reasonableness, to become the supporter of high-handed tyranny.

France has run this danger. Ten years ago it seemed as if the course of his development were quite as likely to lead him, practically, to reaction as to Radicalism.

When Abel Herman's book, Le Cavalier Miserey, a military novel of some ability which criticised the army, was forbidden to soldiers, France wrote: "I know only a few lines of the famous order of the day published by the colonel of the Twelfth Regiment of Chasseurs at Rouen. They are as follows: 'Every copy of Le Cavalier Miserey which is confiscated shall be burned on the dunghill, and every soldier in whose possession a copy is found shall be punished with imprisonment.' It is not a particularly elegant sentence, and yet I would rather have written it than the four hundred pages of the novel."

It was a crime in those days to utter a word against the army. Those who know what France has written about it since, know what a change has taken place in his views.

When the crisis came, it showed that in this man dwelt not merely, as in certain others, intellect and ability, but a determined will, and that in his inmost soul he was not such a doubter but that he had preserved one belief and one enthusiasm—belief in the justification of the great spiritual revolt of the eighteenth century, and enthusiasm for it.

As author he owns two main elements of effectiveness. The first is the ingenuousness which prevents his characters ever being—what Voltaire's often are—marionettes; they move freely on their own legs, and lead a life independent of their author and undisturbed by him. Their naïveté makes them natural.

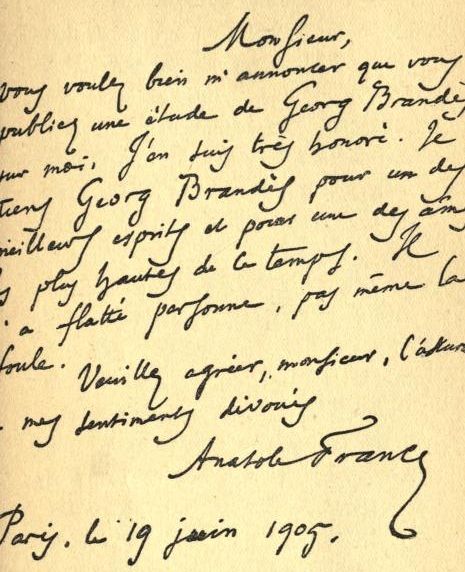

Manuscript of a letter.

The second element is art. France has what he himself calls the French writer's three great qualities—in the first place, lucidity; in the second, lucidity; in the third and last, lucidity. But this is only one fundamental quality of his art. He has proved himself possessed of moderation and tact, in which for him, as the true Frenchman (and to use his own words), "all art consists." His detestation of Zola as a novelist was due to that Italian's utter lack of moderation as an artist. He himself as narrator is always subdued.

He lacks passion, and he is never wanton; his eroticism is only Epicureanism. There is sensuality in his writing, and there is intellectuality—a good deal of the former, an overpowering amount of the latter.

He is, taken all in all, more the artistic and philosophic than the creative author. Delacroix has said that art is exaggeration in the right place. France's exaggeration lies in the wealth of ideas with which he endows his characters, a wealth which the books can hardly contain (vide Thaïs and Balthasar), and for which place must be made in whole additional volumes, such as Les Opinions de M. Jérôme Coignard, Le Jardin d'Épicure, and a part of Pierre Nozière. He has more ideas than feelings. He has ideas upon every subject, criticises everything—not only human prejudices and institutions, but nature herself.

He reproaches her, for instance, with giving us youth so early, and letting us live the rest of our life without it; it ought to come last, as the crown of life, like the butterfly stage, which in insects comes after the larva and cocoon stage, and ought, as the last, highest phase of development, to be directly followed by death.

France's own highest stage of development has come last. For in his latest phase, as combatant, he is far from having lost any of his satirical power, or of the artistic superiority which it confers. Never has his irony been so effective as in his most distinctly polemical work, L'Anneau d'Améthyste, where the most immoral actions, one breach of the Seventh Commandment after the other, become links in the cleverly woven chain of intrigues which, aiming at gratifying an ambitious young parvenu baron's desire to become member of an ultra-Conservative aristocrat's hunt, result in procuring the episcopal ring for a crafty, submissive priest. This priest has cringed to every one, and by his humility has prevailed on men and women to act. Hardly is he appointed before he reveals himself as the most warlike son of the Church, the irreconcilable enemy of the State.

As an artist, France, even when he is most combative, is Olympian and passionless.

That he is not lacking in passion, behind his art and apart from it, was revealed on the day when the serene sceptic suddenly faced round and as polemist adopted a party, as popular orator proclaimed himself a radical Socialist.

He was no born orator; according to French custom, he read his speeches. But his greatness as a writer stood him in good stead. He generally began by riveting the attention of the crowd by something graphic and tangible—perhaps some old fairy-tale. One day he told the story of the wonderful wrestler who could transform himself into a fire-breathing dragon, and when the dragon was overcome, into an inoffensive duck. "I could not help thinking of this wrestler the other day," he said, "when I read the programme which the Nationalists have affixed to the walls. We have seen them on our streets and boulevards ejecting fire from their eyes, their mouths, and their nostrils. Like the most frightful dragons, they flapped their wings and showed their terror-inspiring claws. They were, nevertheless, overcome; and now they have come to life again, to make a fresh trial of strength, with smooth feathers, with an appearance of belonging to our household, with a domestic animal's mild voice. What a remarkable transformation!"

The introduction was so amusing and popular that the audience, bursting into prolonged laughter and merry acclamation, was won at once.

One November evening in Paris, in the year 1904, when the delegates of the Scandinavian Parliaments were invited to an entertainment at the residence of M. Delcassé, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, where an opportunity was given them to see something of upper-class society, including the Diplomatic Corps, with its elegant and beautifully dressed ladies, I went, instead of accompanying them to this attractive sight, to the Trocadéro, where on the same evening, at the invitation of the Socialist party, three of the foremost men of France were to address a large meeting.

The hall had long been filled; but a seat had been kindly reserved for me, which, being on the platform beside the speakers, enabled me at a glance to view the 6000 human beings who crowded the floor of the enormous and beautiful building, and its galleries to the very roof. The hall is built like a huge theatre with the stage on a level with the dress circle. The audience, which had arrived early, sat in eager expectation.

The three speakers were Francis de Pressensé, Jean Jaurès, and Anatole France—the most strictly upright politician, the most eloquent orator, and the greatest writer of the France of to-day.

Francis de Pressensé's speech was distinguished by its simple, noble power. It was Huguenot oratory. He holds himself straight and still, speaks without a gesture, without an appeal to his audience, except that of his assertions to their sense of right. He communicates fact after fact and explains them. His command of language is so great that he has never to search for words, however quickly he speaks, and never mutilates a sentence, however hurriedly he flings it from him. In contrast to the usual custom of French orators, he makes not the slightest pause when he has said something particularly effective and applause breaks forth. He allows no time for the applause, but speaks on without a movement or a break, seemingly unconscious of it.

When the time came for Jaurès to speak, part of the platform was cleared, because he required its full length. The eloquence of the great Socialist is genuine Catholic eloquence. He recalls the most remarkable of the preachers in the churches of Naples. He, like them, is a Southern. And like them he requires a roomy stage, on which, whilst speaking, he can walk up and down, halt, and turn in all directions.

He has a voice like the trumpet of the Last Judgment. As soon as he opened his mouth its metallic clang made the windows in the roof of the hall ring. He does not use it with much skill, does not even moderate it to begin with, employs no crescendo or diminuendo, but is from the first to the last moment all ardour and passion. Hence even in a hall which holds 6000 persons his voice seems too strong, and not unfrequently produces a disturbing resonance. He would be heard better if he spared himself more.

He has the instincts of the actor. He charges, like a fighting ram, with bent head at an invisible enemy. Or he bends forwards with outstretched arms, and then with a jerk is erect again. Or he makes himself small, crouches down till he is almost sitting, and then suddenly starts up. He talks himself into a heat; in the end is bathed in perspiration. His style is emotional—the militant pathos of a man who loves his fellow men.

In his improvisations he is unable to keep himself in check. He goes on too long. Up and down, up and down in front of one marches the short, broadshouldered, strongly-built figure, large-limbed, thick-necked, with a round head and handsome bearded face. Beside him France and Pressensé looked like stag and horse beside a bull.

France did not really speak, but read, as he always does—perhaps because, as writer, he has too much tenderness for each sentence he has composed to deliver it up to the chance of the moment. His style, which does not permit of a word being omitted or transposed, is ironical; but the irony every here and there gives way to earnestness, which is the more effective from its rarity. And this style meets with approval; in all its subduedness it provokes laughter and carries conviction. He relates what has happened, interjects a point of interrogation—and his hearers smile; a point of exclamation—and they are compelled to reflect. He inserts a parenthesis, and between its curves one catches a glimpse of all the stupidity and insolence standing outside of them.

France spoke first of the state of matters produced by Bonaparte's Concordat, of the fact that the State pays the clergy of three creeds, the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish, but only of these three, although during the course of the nineteenth century the country has acquired far more Mohammedan subjects than it has Protestant or Jewish.

He said, with a playful allusion to the old story of the three rings, told by Boccaccio and employed by Lessing in Nathan der Wise:

"With us the Minister of Public Worship, like the father in the old Jewish parable, has three rings. He does not tell us which is the true one, and in this he is wise. But if he is to have more than one, why limit the number to three? Our Heavenly Father has given His sons more than three rings, and they are not able to discern which is the original, the true ring. Monsieur le Ministre, why have you not all your Heavenly Father's rings? You pay the clergy of certain creeds and not those of others. You surely do not make yourself the judge of religious truth? You cannot maintain that the three religions are in possession of the truth, seeing that each of them vigorously condemns both the others?"

As every one is aware, the encroachments of the Roman Catholic Church have led to the urgent demand by the Republican party for separation of Church and State. France maintained that this separation must take place at once. But what are to be its conditions? He scoffed at the old cry: A free Church in a free State. This would be equivalent to an armed Church in a disarmed State. "We undoubtedly owe the Church liberty," he said; "only not an absolute, theoretical liberty, which does not exist, but real liberty, a liberty which is bounded by all other liberties. You may be perfectly certain, however, that the Church will not be the least grateful to us for this. It will receive this liberty as an insult and mockery."

France then proceeded to speak of the relations between Europe and Eastern Asia, and in doing so said: "The European Powers have accustomed themselves, whenever any breach of order occurs in the great Empire of China, to send out troops—either one Power independently or several in combination—which troops restore order by means of theft, violence, plunder, slaughter, and incendiarism, and pacify the country with guns and cannons.

"The unarmed Chinese do not defend themselves, or defend themselves badly. They are slaughtered with agreeable facility. They are polite and ceremonious, but we reproach them with a want of goodwill towards Europeans. Our complaint against them is of the same nature as Monsieur Duchaillu's complaint of the gorilla.

"That gentleman shot a female gorilla. She died clasping her young one to her breast. He tore the young animal from its mother's arms, and dragged it after him across Africa to sell it in Europe. But it gave him just cause of complaint. It was unsociable. It preferred dying of hunger to living in his society, and refused to take food. 'I was,' he writes, 'unable to overcome its bad disposition.'

"We complain of the Chinese with as much right as M. Duchaillu complained of his gorilla."

France went on to speak of the yellow danger for Europe, and demonstrated that it was not to be compared with the white danger for Asia. The yellow men have not sent Buddhist missionaries to Paris, London, and St. Petersburg. Neither has any yellow military expedition landed in France and demanded a strip of territory within which the yellow men are not to be subject to the laws of the country, but to a court composed of Mandarins have come to the conclusion that, things being bad at the best, the existing state of matters was probably as good as the untried—that this man should proclaim himself a son of the Revolution, side with the working man, acknowledge his belief in liberty, throw away his load and draw his sword—this is what moves a popular audience, this is what plain people can understand and can prize.

It has shown them that behind the author there dwelt a man—behind the great author a brave man.