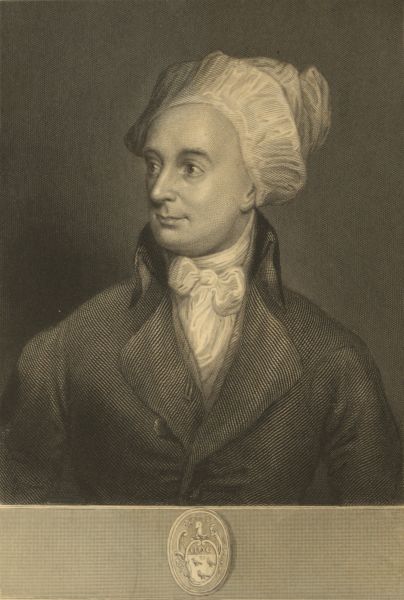

Drawn from the Life by Romney 1782. W. Greatbach.

WILLIAM COWPER.

BORN 1731 DIED 1800.

Drawn from the Life by Romney 1782. W. Greatbach.

WILLIAM COWPER.

BORN 1731 DIED 1800.

THE

LIFE AND WORKS

of

WILLIAM COWPER.

Complete

In one Volume.

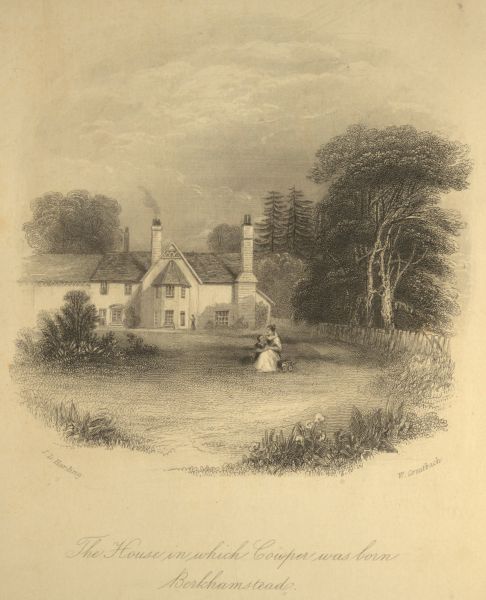

J. L. Harding W. Greatbach

The House in which Cowper was born

Berkhamstead.

London.

WILLIAM TEGG & Co.

THE WORKS

OF

WILLIAM COWPER:

HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND POEMS.

NOW FIRST COMPLETED BY THE INTRODUCTION OF

COWPER'S PRIVATE CORRESPONDENCE.

EDITED BY THE

REV. T. S. GRIMSHAWE, A.M., F.S.A., M.R.S.L.,

VICAR OF BIDDENHAM, BEDFORDSHIRE;

AND AUTHOR OF "THE LIFE OF THE REV. LEGH RICHMOND."

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

WILLIAM TEGG AND Co., CHEAPSIDE.

MDCCCXLIX.

LONDON:

J. HADDON, PRINTER, CASTLE STREET, FINSBURY.

The very extensive sale of the former editions of the Works of Cowper, in eight volumes, now comprising an issue of no less than seventy thousand volumes, has led the publishers to contemplate the present edition in one volume 8vo. This form is intended to meet the demands of a numerous class of readers, daily becoming more literary in taste, and more influential in their character on the great mass of our population. At a period like the present, when the great framework of society is agitated by convulsions pervading nearly the whole of continental Europe, and when so many elements of evil are in active operation, it becomes a duty of the highest importance to imbue the public mind with whatever is calculated to uphold national peace and order, and to maintain among us a due reverence for laws, both human and divine. The faculty also and taste for reading now exists to so great an extent, that it assumes a question of no small moment how this faculty is to be directed; whether it shall be the giant's power to wound and to destroy, or like the Archangel's presence to heal and to save? Many readers require to be amused, but it is no less necessary that they should be instructed. To seek amusement and nothing further, denotes a head without wit, and a heart and a conscience without feeling. An author, if he be a Christian and a patriot, will never forget to edify as well as to amuse. There are few writers who possess and employ this happy art with more skill than Cowper. His aim is evidently to interest his reader, but he never forgets the appeal to his heart and conscience. It is strange if amidst the flowers of his poetic fancy, and the sallies of his epistolary humour, the Rose of Sharon does not insinuate its form, and breathe forth its sweet fragrance. No one knows better than Cowper how to interweave the sportiveness of his wit with the gravity of his moral, and yet always to be gay without levity, and grave without[vi] dulness. He is also thoroughly English, in the structure of his mind, in the honest expression of his feelings, in his hatred of oppression, his ardour for true liberty, his love for his country, and for whatever concerns the weal and woe of man. Nor does he ever fail to exhibit National Religion as the only sure foundation for national happiness and virtue. The works of such a writer can never perish. Cowper has earned for himself a name which will always rank him among the household poets of England; while his prose has been admitted by the highest authority to be as immortal as his verse.[1]

In presenting therefore to the class of readers above specified, as well as to the public generally, this edition of the Works of Cowper, in a form accessible to all, the Publishers trust that the undertaking will be deemed to be both seasonable and useful. In this confidence they offer it with the fullest anticipations of its success. It remains only to state that it is a reprint of the former editions without any mutilation or curtailment.

It is gratifying to add that the Portrait, drawn from life by Romney in 1792, and now engraved by W. Greatbach in the first style of art, is esteemed by the few persons living who have a vivid recollection of the person and appearance of the Poet, as the most correct and happy likeness ever given to the public. The Illustrations, too, presented with this edition, are procured without regard to cost, so as to render the entire work, it is hoped, the most complete ever published.

December 3, 1848.

TO THE

DOWAGER LADY THROCKMORTON.

Your Ladyship's peculiar intimacy with the poet Cowper, and your former residence at Weston, where every object is embellished by his muse, and clothed with a species of poetical verdure, give you a just title to have your name associated with his endeared memory.

But, independently of these considerations, you are recorded both in his poetry and prose, and have thus acquired a kind of double immortality. These reasons are sufficiently valid to authorize the present dedication. But there are additional motives,—the recollection of the happy hours, formerly spent at Weston, in your society and in that of Sir George Throckmorton, enhanced by the presence of our common lamented friend, Dr. Johnson. A dispensation which spares neither rank, accomplishments, nor virtues, has unhappily terminated this enjoyment, but it has not extinguished those sentiments of esteem and regard, with which

I have the honour to be,

My dear Lady Throckmorton,

Your very sincere and obliged friend,

T. S. GRIMSHAWE.

Biddenham, Feb. 28, 1835.

In presenting to the public this new and complete edition of the Life, Correspondence, and Poems of Cowper, it may be proper for me to state the grounds on which it claims to be the only complete edition that has been, or can be published.

After the decease of this justly admired author, Hayley received from my lamented brother-in-law, Dr. Johnson, (so endeared by his exemplary attention to his afflicted relative,) every facility for his intended biography. Aided also by valuable contributions from other quarters, he was thus furnished with rich materials for the execution of his interesting work. The reception with which his Life of Cowper was honoured, and the successive editions through which it passed, afforded unequivocal testimony to the industry and talents of the biographer and to the epistolary merits of the Poet. Still there were many, intimately acquainted with the character and principles of Cowper, who considered that, on the whole, a very erroneous impression was conveyed to the public. On this subject no one was perhaps more competent to form a just estimate than the late Dr. Johnson. A long and familiar intercourse with his endeared relative had afforded him all the advantages of a daily and minute observation. His possession of documents, and intimate knowledge of facts, enabled him to discover the partial suppression of some letters, and the total omission of others, that, in his judgment, were essential to the development of Cowper's real character. The cause of this procedure may be explained so as fully to exonerate Hayley from any charge injurious to his honour. His mind, however literary and elegant, was not precisely qualified to present a religious character to the view of the British public, without committing some important errors. Hence, in occasional parts of his work, his reflections are misplaced, sometimes injurious, and often injudicious; and in no portion of it is this defect more visible than where he attributes the malady of Cowper to the operation of religious causes.

It would be difficult to express the painful feeling produced by these facts on the minds of Dr. Johnson and of his friends. Hayley indeed seems to be afraid of exhibiting Cowper too much in a religious garb, lest he should either lessen his estimation, alarm the reader, or compromise himself. To these circumstances may be attributed the defects that we have noticed, and which have rendered his otherwise excellent production an imperfect work. The consequence, as regards Cowper, has been unfortunate. "People," observes Dr. Johnson, "read the Letters with 'the Task' in their recollection, (and vice versâ,) and are perplexed. They look for the Cowper of each in the other, and find him not; the correspondency is destroyed. The character of Cowper is thus undetermined; mystery hangs over it, and the opinions formed of him are as various as the minds of the inquirers." It was to dissipate this illusion, that my lamented friend collected the "Private Correspondence,"[viii] containing letters that had been previously suppressed, with the addition of others, then brought to light for the first time. Still there remains one more important object to be accomplished: viz., to present to the British public the whole Correspondence in its entire and unbroken form, and in its chronological order. Then, and not till then, will the real character of Cowper be fully understood and comprehended; and the consistency of his Christian character be found to harmonize with the Christian spirit of his pure and exalted productions.

Supplemental to such an undertaking is the task of revising Hayley's Life of the Poet, purifying it from the errors that detract from its acknowledged value, and adapting it to the demands and expectations of the religious public. That this desideratum has been long felt, to an extent far beyond what is commonly supposed, the Editor has had ample means of knowing, from his own personal observation, and from repeated assurances of the same import from his lamented friend, the Rev. Legh Richmond.[2]

The time for carrying this object into effect is now arrived. The termination of the copyright of Hayley's Life of Cowper, and access to the Private Correspondence collected by Dr. Johnson, enable the Editor to combine all these objects, and to present, for the first time, a Complete Edition of the Works of Cowper, which it is not in the power of any individual besides himself to accomplish, because all others are debarred access to the Private Correspondence. Upwards of two hundred letters will be thus incorporated with the former work of Hayley, in their due and chronological order.

The merits of "The Private Correspondence" are thus attested in a letter addressed to Dr. Johnson, by a no less distinguished judge than the late Rev. Robert Hall.—"It is quite unnecessary to say that I perused the letters with great admiration and delight. I have always considered the letters of Mr. Cowper as the finest specimen of the epistolary style in our language; and these appear to me of a superior description to the former, possessing as much beauty, with more piety and pathos. To an air of inimitable ease and carelessness they unite a high degree of correctness, such as could result only from the clearest intellect, combined with the most finished taste. I have scarcely found a single word which is capable of being exchanged for a better. Literary errors I can discern none. The selection of[ix] words, and the construction of periods, are inimitable; they present as striking a contrast as can well be conceived to the turgid verbosity which passes at present for fine writing, and which bears a great resemblance to the degeneracy which marks the style of Ammianus Marcellinus, as compared to that of Cicero or of Livy. In my humble opinion, the study of Cowper's prose may on this account be as useful in forming the taste of young people as his poetry. That the Letters will afford great delight to all persons of true taste, and that you will confer a most acceptable present on the reading world by publishing them, will not admit of a doubt."

All that now remains is for the Editor to say one word respecting himself. He has been called upon to engage in this undertaking both on public and private grounds. He is not insensible to the honour of such a commission, and yet feels that he is undertaking a delicate and responsible office. May he execute it in humble dependence on the Divine blessing, and in a spirit that accords with the venerated name of Cowper! Had the life of his endeared friend, Dr. Johnson, been prolonged, no man would have been better qualified for such an office. His ample sources of information, his name, and his profound veneration for the memory of Cowper, (whom he tenderly watched while living, and whose eyes he closed in death,) would have awakened an interest to which no other writer could presume to lay claim. It is under the failure of this expectation, which is extinguished by the grave, that the Editor feels himself called upon to endeavour to supply the void; and thus to fulfil what is due to the character of Cowper, and to the known wishes of his departed friend. Peace be to his ashes! They now rest near those of his beloved Bard, while their happy spirits are reunited in a world, where no cloud obscures the mind, and no sorrow depresses the heart: and where the mysterious dispensations of Providence will be found to have been in accordance with his unerring wisdom and mercy.

It is impossible for the Editor to specify the various instances of revision in the narrative of Hayley, because they are sometimes minute or verbal, at other times more enlarged. The object has been to retain the basis of his work, as far as possible. The introduction of new matter is principally where the interests of religion, or a regard to Cowper's character seemed to require it; and for such remarks the Editor is solely responsible.

PART THE FIRST.

| Page | |

| The family, birth, and first residence of Cowper | 1 |

| His verses on the portrait of his mother | 1 |

| Epitaph on his mother by her niece | 2 |

| The schools that Cowper attended | 2 |

| His sufferings during childhood | 2 |

| His removal from Westminster to an attorney's office | 3 |

| Verses on his early afflictions | 4 |

| His settlement in the Inner Temple | 4 |

| His acquaintance with eminent authors | 4 |

| His translations in Duncombe's Horace | 4 |

| His own account of his early life | 4 |

| Stanzas on reading Sir Charles Grandison | 4 |

| His verses on finding the heel of a shoe | 5 |

| His nomination to the office of Reading Clerk in the House of Lords | 5 |

| His nomination to be Clerk of the Journals in the House of Lords | 5 |

| To Lady Hesketh. Journals of the House of Lords. Reflection on the singular temper of his mind. Aug. 9, 1763 | 5 |

| His extreme dread of appearing in public | 6 |

| His illness, and removal to St. Alban's | 6 |

| Change in his ideas of religion | 7 |

| His recovery | 7 |

| His settlement at Huntingdon to be near his brother | 7 |

| The translation of Voltaire's Henriade by the two brothers | 7 |

| The origin of Cowper's acquaintance with the Unwins | 7 |

| His adoption into the family | 8 |

| His early friendship with Lord Thurlow, and J. Hill, Esq | 8 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Account of his situation at Huntingdon. June 24, 1765 | 9 |

| To Lady Hesketh. On his illness and subsequent recovery. July 1, 1765 | 9 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Huntingdon and its amusements. July 3, 1765 | 10 |

| To Lady Hesketh. Salutary effects of affliction on the human mind. July 4, 1765 | 10 |

| To the same. Account of Huntingdon; distance from his Brother, &c. July 5, 1765 | 11 |

| To the same. Newton's Treatise on Prophecy; Reflections of Dr. Young, on the Truth of Christianity. July 12, 1765 | 12 |

| To the same. On the Beauty and Sublimity of Scriptural Language. Aug. 1, 1765 | 12 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Expected excursion. Aug. 14, 1765 | 13 |

| To Lady Hesketh. Pearsall's Meditations; definition of faith. Aug. 17, 1765 | 14 |

| To the same. On a particular Providence; experience of mercy, &c. Sept. 4, 1765 | 14 |

| To the same. First introduction to the Unwin family; their characters. Sept. 14, 1765 | 15 |

| To the same. On the thankfulness of the heart, its inequalities, &c. Oct. 10, 1765 | 16 |

| To the same. Miss Unwin, her character and piety. Oct. 18, 1765 | 16 |

| To Major Cowper. Situation at Huntingdon; his perfect satisfaction, &c. Oct. 18, 1765 | 17 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On those who confine all merits to their own acquaintance. Oct. 25, 1765 | 18 |

| To the same. Agreement with the Rev. W. Unwin. Nov. 5, 1765 | 18 |

| To the same. Declining to read lectures at Lincoln's Inn. Nov. 8, 1765 | 18 |

| To Lady Hesketh. On solitude; on the desertion of his friends. March 6, 1766 | 19 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. Mrs. Unwin, and her son; his cousin Martin. March 11, 1766 | 19 |

| To the same. Letters the fruit of friendship; his conversion. April 4, 1766 | 20 |

| To the same. The probability of knowing each other in Heaven. April 17, 1766 | 20 |

| To the same. On the recollection of earthly affairs by departed spirits. April 18, 1766 | 21 |

| To the same. On the same subject; on his own state of body and mind. Sept. 3, 1766 | 22 |

| To the same. His manner of living; reasons for his not taking orders. Oct. 20, 1766 | 23 |

| To the same. Reflections on reading Marshall. March 11, 1767 | 24 |

| To the same. Introduction of Mr. Unwin's son; his gardening; on Marshall. March 14, 1767 | 24 |

| To the same. On the motive of his introducing Mr. Unwin's son to her. April 3, 1767 | 25 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. General election. June 16, 1767 | 27 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. Mr. Unwin's death; doubts concerning Cowper's future abode. July 13, 1767 | 26 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Reflections arising from Mr. Unwin's death. July 16, 1767 | 26 |

| The origin of Cowper's acquaintance with Mr. Newton. | 26 |

| Cowper's removal with Mrs. Unwin to Olney. | 27 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Invitation to Olney. Oct. 10, 1767 | 27 |

| His devotion and charity in his new residence. | 27 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On the occurrences during his visit at St. Alban's. June 16, 1768 | 27 |

| To the same. On the difference of dispositions; his love of retirement. Jan. 21, 1769 | 27 |

| To the same. On Mrs. Hill's late illness. Jan. 29, 1769 | 28 |

| To the same. Declining an invitation. Fondness for retirement. July 31, 1769 | 28 |

| His poem in memory of John Thornton, Esq. | 28 |

| His beneficence to a necessitous child. | 29 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. His new situation; reasons for mixture of evil in the world. 1769 | 29 |

| To the same. The consolations of religion on the death of her husband. Aug. 31, 1769 | 30 |

| Cowper's journey to Cambridge on his brother's illness. | 30 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. Dangerous illness of his brother. March 5, 1770 | 30 |

| The death and character of Cowper's brother. | 31 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Religious sentiments of his brother. May 8, 1770 | 31 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. The same subject. June 7, 1770 | 32 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Expression of his gratitude for instances of friendship. Sept. 25, 1770 | 33 |

| To the same. Congratulations on his marriage. Aug. 27, 1771 | 33 |

| To the same. Declining offers of service. June 27, 1772 | 33 |

| To the same. Acknowledging obligations. July 2, 1772 | 33 |

| To the same. Declining an invitation to London. Nov. 5, 1772 | 33 |

| The composition of the Olney Hymns by Mr. Newton and Cowper. | 34 |

| The interruption of the Olney Hymns by the illness of Cowper | 35 |

| His long and severe depression | 35 |

| His tame hares, one of his first amusements on his recovery. | 35 |

| The origin of his friendship with Mr. Bull. | 35 |

| His translations from Madame de la Mothe Guion. | 35 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On Mr. Ashley Cooper's recovery from a nervous fever. Nov. 12, 1776 | 36 |

| To the same. On Gray's Works. April 20, 1777 | 36 |

| To the same. On Gray's later epistles. West's Letters. May 25, 1777 | 36 |

| [vi]To the same. Selection of books. July 13, 1777 | 36 |

| To the same. Supposed diminution of Cowper's income. Jan. 1, 1778 | 37 |

| To the same. Death of Sir Thomas Hesketh, Bart. April 11, 1778 | 37 |

| To the same. Raynal's works. May 7, 1778 | 37 |

| To the same. Congratulations on preferment. June 18, 1778 | 37 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Disapproving a proposed application to Chancellor Thurlow. June 18, 1778 | 37 |

| To the same. Johnson's Lives of the Poets. May 26, 1779 | 38 |

| To the same. Remarks on the Isle of Thanet. July, 1779 | 38 |

| To the same. Advice on sea-bathing. July 17, 1779 | 38 |

| To the same. His hot house; tame pigeons; visit to Gayhurst. Sept. 21, 1779 | 39 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. With the fable of the Pine-apple and the Bee. Oct. 2, 1779 | 39 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Johnson's Biography; his treatment of Milton. Oct. 31, 1779 | 40 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. With a poem on the promotion of Edward Thurlow. Nov. 14, 1779 | 40 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Quick succession of human events; modern patriotism. Dec. 2, 1779 | 40 |

| To the same. Burke's speech on reform; Nightingale and Glow-worm. Feb. 27, 1780 | 41 |

| To Mrs. Newton. On Mr. Newton's removal from Olney. March 4, 1780 | 41 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Congratulations on his professional success. March 16, 1780 | 42 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. On the danger of innovation. March 18, 1780 | 42 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. On keeping the Sabbath. March 28, 1780 | 43 |

| To the same. Pluralities in the church. April 6, 1780 | 43 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. Distinction between a travelled man, and a travelled gentleman. April 16, 1780 | 44 |

| To the same. Serious reflections on rural scenery. May 3, 1780 | 44 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. The Chancellor's illness. May 6, 1780 | 45 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. His passion for landscape drawing; modern politics. May 8, 1780 | 45 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. On her brother's death. May 10, 1780 | 46 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. Pedantry of commentators; Dr. Bentley, &c. May 10, 1780 | 46 |

| To Mrs. Newton. Mishap of the gingerbread baker and his wife. The Doves. June 2, 1780 | 47 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Cowper's fondness of praise—Can a parson be obliged to take an apprentice?—Latin translation of a passage in Paradise Lost; versification of a thought. June 8, 1780 | 47 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. On the riots in 1780; danger of associations. June 12, 1780 | 48 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Latin verses on ditto. June 18, 1780 | 49 |

| To the same. Robertson's History; Biographia Britannica. June 22, 1780 | 49 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. Ingenuity of slander; lace-makers' petition. June 23, 1780 | 50 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. To touch and retouch, the secret of good writing; an epitaph; July 2, 1780 | 51 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On the riots in London. July 3, 1780 | 51 |

| To the same. Recommendation of lace-makers' petition. July 8, 1780 | 51 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Translation of the Latin verses on the riots. July 11, 1780 | 52 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. With an enigma. July 12, 1780 | 52 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. On the insensible progress of age. July 29, 1780 | 53 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Olney bridge. July 27, 1780 | 54 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. A riddle. July 30, 1780 | 54 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Human nature not changed; a modern, only an ancient in a different dress. August 6, 1780 | 54 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On his recreations. Aug. 10, 1780 | 55 |

| To the Rev. J. Newton. Escape of one of his hares. Aug. 21, 1780 | 56 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. Lady Cowper's death. Age a friend to the mind. Aug. 31, 1780 | 56 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Biographia; verses, parson and clerk. Sept. 3, 1780 | 57 |

| To the same. On education. Sept. 7, 1780 | 57 |

| To the same. Public schools. Sept. 17, 1780 | 58 |

| To the same. On the same subject. Oct. 5, 1780 | 59 |

| To Mrs. Newton. On Mr. Newton's arrival at Ramsgate. Oct. 5, 1780 | 60 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Verses on a goldfinch starved to death in his cage. Nov. 9, 1780 | 60 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On a point of law. Dec. 10, 1780 | 60 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. On his commendations of Cowper's poems. Dec. 21, 1780 | 60 |

| To J. Hill, Esq. With the memorable law-case between nose and eyes. Dec. 25, 1780 | 61 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. With the same. Dec. 1780 | 62 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Progress of Error. Mr. Newton's works. Jan. 21, 1781 | 62 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. On visiting prisoners. Feb. 6, 1781 | 63 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Hurricane in West Indies. Feb. 8, 1781 | 63 |

| To the same. On metrical law-cases; old age. Feb. 15, 1781 | 64 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. With Table Talk. On classical literature. Feb. 18, 1781 | 64 |

| To Mr. Hill. Acknowledging a present received. Feb. 19, 1781 | 64 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Mr. Scott's curacies. Feb. 25, 1781 | 65 |

| To the same. Care of myrtles. Sham fight at Olney. March 5, 1781 | 65 |

| To the same. On the poems, "Expostulation," &c. March 18, 1781. | 66 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Consolations on the asperity of a critic. April 2, 1781 | 67 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Requesting a preface to "Truth." Enigma on a cucumber. April 8, 1781 | 68 |

| To the same. Solution of the enigma. April 23, 1781 | 68 |

| Cowper's first appearance as an author. | 69 |

| The subjects of his first poems suggested by Mrs. Unwin. | 69 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Intended publication of his first volume. May 1, 1781 | 69 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. On the composition and publication of his first volume. May 9, 1781 | 70 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Reasons for not showing his preface to Mr. Unwin. May 10, 1781 | 70 |

| To the same. Delay of his publication; Vincent Bourne, and his poems. May 23, 1781 | 71 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. On the heat; on disembodied spirits. May 22, 1781 | 72 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Corrections of his proofs; on his horsemanship. May 28, 1781 | 72 |

| To the same. Mrs. Unwin's criticisms; a distinguishing Providence. June 5, 1781 | 73 |

| To the same. On the design of his poems; Mr. Unwin's bashfulness. June 24, 1781 | 73 |

| Origin of Cowper's acquaintance with Lady Austen. | 74 |

| Poetical epistle addressed to that lady by him. | 75 |

| Diffidence of the poet's genius. | 76 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. His late visit to Olney. Lady Austen's first visit. Correction in "Progress of Error." Intended portrait of Cowper. July 7, 1781 | 76 |

| To the same. Humorous letter in rhyme, on his poetry. July 12, 1781 | 77 |

| To the same. Progress of the poem, "Conversation." July 22, 1781. | 77 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Though revenge and a spirit of litigation are contrary to the Gospel, still it is the duty of a Christian to vindicate his right. Anecdote of a French Abbé, A fete champetre. July 29, 1781 | 77 |

| To Mrs. Newton. Changes of fashion. Remarks on his poem, "Conversation." Aug. 1781 | 78 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Conversion of the green-house into a summer-parlour. Progress of his work. Aug. 16, 1781 | 79 |

| To the same. State of Cowper's mind. Lady Austen's intended settlement at Olney. Lines on cocoa-nuts and fish. Aug. 21, 1781 | 80 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Congratulations on the birth of a son. Remarks on his poem, "Retirement." Lady Austen's proposed settlement at Olney. Her character. Aug. 25, 1781 | 81 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Progress of the printing of his poem, "Retirement." Mr. Johnson's corrections. Aug. 25, 1781 | 82 |

| To the same. Heat of the weather. Remarks on the opinion of a clerical acquaintance concerning certain amusements and music. Sept. 9, 1781 | 82 |

| [vii]To Mrs. Newton. A poetical epistle on a barrel of oysters. Sept. 16, 1781 | 83 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Dr. Johnson's criticism on Watts and Blackmore. Smoking. Sept. 18, 1781 | 83 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Thoughts on the sea. Character of Lady Austen. Sept. 26, 1781 | 84 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Religious poetry. Oct. 4, 1781 | 85 |

| To the same. Brighton amusements. His projected Authorship. Oct. 6, 1781 | 85 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Disputes between the Rev. Mr. Scott and the Rev. Mr. R. Oct. 14, 1781 | 86 |

| To Mrs. Cowper. His first volume. Death of a friend. Oct. 19, 1781 | 87 |

| Reasons why the Rev. Mr. Newton wrote the Preface to Cowper's Poems | 87 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Remarks on the proposed Preface to the Poems. Mr. Scott and Mr. R. Oct. 22, 1781 | 87 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin. Brighton dissipation. Education of young Unwin. Nov. 5, 1781 | 88 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Cowper's indifference to Fame. Anecdote of the Rev. Mr. Bull. Nov. 7, 1781 | 89 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin. Apparition of Paul Whitehead, at West Wycombe. Nov. 24, 1781 | 90 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. In answer to his account of his landlady and her cottage. Nov. 26, 1781 | 90 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin. Origin and causes of social feeling. Nov. 26, 1781 | 91 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. Unfavourable prospect of the American war. Nov. 27, 1781 | 92 |

| To the same. With lines on Mary and John. Same date | 92 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Advantage of having a tenant who is irregular in his payments. Sale of chambers. State of affairs in America. Dec. 2, 1781 | 93 |

| To the Rev. John Newton. With lines to Sir Joshua Reynolds. Political and patriotic poetry. Dec. 4, 1781 | 93 |

| Circumstances under which Cowper commenced his career as an author | 94 |

| Letter to the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 17, 1781. Remarks on his poems on Friendship, Retirement, Heroism and Ætna; Nineveh and Britain | 95 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Dec. 19, 1781. Idea of a theocracy; the American war | 96 |

| To the Rev. John Newton; shortest day, 1781. On a national miscarriage; with lines on a flatting-mill | 96 |

| To the same, last day of 1781. Concerning the printing of his Poems; the American contest | 97 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 5, 1782. Dr. Johnson's critique on Prior and Pope | 97 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 13, 1782. The American contest | 98 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 17, 1782. Conduct of critics; Dr. Johnson's remarks on Prior's Poems; remarks on Dr. Johnson's Lives of the Poets; poetry suitable for the reading of a boy | 99 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Jan. 31, 1782. Political reflections | 101 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 2, 1782. On his Poems then printing; Dr. Johnson's character as a critic; severity of the winter | 102 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Feb. 9, 1782. Bishop Lowth's juvenile verses; acquaintance with Lady Austen | 102 |

| Attentions of Lady Austen to Cowper | 103 |

| Letter from him to Lady Austen | 103 |

| She becomes his next door neighbour | 103 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin. On Lady Austen's opinion of him; attempts at robbery; observations on religious characters; genuine benevolence | 104 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 16, 1782. Charms of authorship | 104 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Feb. 24, 1782. On the publication of his poems; his letter to the Lord Chancellor | 105 |

| To Lord Thurlow, Feb. 25, 1782, enclosed to Mr. Unwin | 105 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 1782. On Mr. N.'s Preface to his Poems. Remarks on a Fast Sermon | 105 |

| To the same, March 6, 1782. Political Remarks; character of Oliver Cromwell | 106 |

| Decision and boldness of Cromwell | 107 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, March 7, 1782. Remonstrance against Sunday routs | 107 |

| Remarks on the reasons for rejecting the Rev. Mr. Newton's Preface to Cowper's Poems | 107 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 14, 1782. On the intended Preface to his Poems; critical tact of Johnson the bookseller | 108 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., March 14, 1782. On the publication of his Poems | 108 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, March 18, 1782. On his and Mrs. Unwin's opinion of his Poems | 109 |

| Improvements in prison discipline | 109 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 24, 1782. Case of Mr. B. compared with Cowper's | 110 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, April 1, 1782. On his commendations of his Poems | 110 |

| To the same, April 27, 1782. Military music; Mr. Unwin's expected visit; dignity of the Latin language; use of parentheses | 111 |

| To the same, May 27, 1782. Dr. Franklin's opinion of his poems; remarkable instance of providential deliverance from dangers; effects of the weather; Rodney's victory in the West Indies | 111 |

| To the same, June 12, 1712. Anxiety of Authors respecting the opinion of others on their works | 112 |

| Reception of the first volume of Cowper's Poems | 113 |

| Portrait of the true poet | 113 |

| Picture of a person of fretful temper | 113 |

PART THE SECOND.

| To the Rev. Wm. Bull, June 22, 1782. Poetical epistle on Tobacco | 114 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin, July 16, 1782. Remarks on political affairs; Lady Austen and her project | 114 |

| To the same, August 3, 1782. On Dr. Johnson's expected opinion of his Poems; encounter with a viper; Lady Austen; Mr. Bull; Madame Guion's Poems | 116 |

| The Colubriad, a poem | 117 |

| Lady Austen comes to reside at the parsonage at Olney | 117 |

| Songs written for her by Cowper | 117 |

| His song on the loss of the Royal George | 118 |

| The same in Latin | 118 |

| Origin of his ballad of John Gilpin | 118 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Sept. 6, 1782. Visit of Mr. Small | 119 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin, Nov. 4, 1782. On the ballad of John Gilpin; on Mr. Unwin's exertions in behalf of the prisoners at Chelmsford; subscription for the widows of seamen lost in the Royal George | 119 |

| To the Rev. William Bull, Nov. 5, 1783. On his expected visit | 120 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 11, 1782. On the state of his health; encouragement of planting; Mr. P——, of Hastings | 120 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 1782. Thanks for a present of fish; on Mr. Small's report of Mr. Hill and his improvements | 121 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Nov. 18, 1782. Acknowledgments to a beneficent friend to the poor of Olney; on the appearance of John Gilpin in print | 121 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin. No date. Character of Dr. Beattie and his poems; Cowper's translation of Madame Guion's poems | 122 |

| To Mrs. Newton, Nov. 23, 1782. On his Poems; severity of the winter; contrast between a spendthrift and an Olney cottager; method recommended for settling disputes | 122 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Dec. 7, 1782. Recollections of the coffee-house; Cowper's mode of spending his evenings; political contradictions | 123 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 19, 1783. His occupations; beneficence of Mr. Thornton to the poor of Olney | 124 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 26, 1783. On the anticipations of peace; conduct of the belligerent powers | 124 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin, Feb. 2, 1783. Ironical congratulations on the peace; generosity of England to France | 125 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 8, 1783. Remarks on the peace | 125 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Feb. 13, 1783. Remarks on his poems | 126 |

| To the same. Feb. 20, 1783. With Dr. Franklin's letter on his poems | 126 |

| To the same. No date. On the coalition ministry; Lord Chancellor Thurlow | 127 |

| Neglect of Cowper by Lord Thurlow | 127 |

| Lord Thurlow's generosity in the case of Dr. Johnson, and Crabbe, the poet | 127 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 24, 1783. On the peace | 127 |

| To the Rev. William Bull, March 7, 1783. On the peace; Scotch Highlanders at Newport Pagnel | 128 |

| [viii]To the Rev. John Newton, March 7, 1783. Comparison of his and Mr. Newton's letters; march of Highlanders belonging to a mutinous regiment | 128 |

| To the same. April 5, 1783. Illness of Mrs. C.; new method of treating consumptive cases | 129 |

| To the same. April 20, 1783. His occupations and studies; writings of Mr. ——; probability of his conversion in his last moments | 129 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May 5, 1783. Vulgarity in a minister particularly offensive | 130 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, May 12, 1783. Remarks on a sermon preached by Paley at the consecration of Bishop L. | 130 |

| Severity of Cowper's strictures on Paley | 131 |

| Important question of a church establishment | 131 |

| Increase of true piety in the Church of England | 131 |

| Language of Beza respecting the established church | 132 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., May 26, 1783. On the death of his uncle's wife | 132 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May 31, 1783. On Mrs. C.'s death | 132 |

| To the Rev. William Bull, June 3, 1783. With stanzas on peace | 133 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, June 8, 1783. Beauties of the green-house; character of the Rev. Mr. Bull | 133 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 13, 1783. On his Review of Ecclesiastical History; the day of judgment; observations of natural phenomena | 133 |

| Extraordinary natural phenomena in the summer of 1783 | 134 |

| Earthquakes in Calabria and Sicily | 134 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 17, 1783. Ministers must not expect to scold men out of their sins | 135 |

| Tenderness an important qualification in a minister | 135 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 19, 1783. On the Dutch translation of his "Cardiphonia" | 135 |

| To the same, July 27, 1783. A country life barren of incident; Cowper's attachment to his solitude; praise of Mr. Newton's style as an historian | 136 |

| Remarks on the influence of local associations | 136 |

| Dr. Johnson's allusion to that subject | 137 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, August 4, 1783. Proposed inquiry concerning the sale of his Poems; remarks on English ballads; anecdote of Cowper's goldfinches | 137 |

| To the same, Sept. 7, 1783. Fault of Madame Guion's writings, too great familiarity in addressing the Deity 138 | |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Sept. 8, 1783. On Mr. Newton's and his own recovery from illness; anecdote of a clerk in a public office; ill health of Mr. Scott; message to Mr. Bacon | 138 |

| To the same, Sept. 15, 1783. Cowper's mental sufferings | 139 |

| To the same, Sept. 23, 1783. On Mr. Newton's recovery from a fever; dining with an absent man; his niche for meditation | 139 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Sept. 29, 1783. Effect of the weather on health; comparative happiness of the natural philosopher; reflections on air balloons | 140 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 6, 1783. Religious animosities deplored; more dangerous to the interests of religion than the attacks of its adversaries; Cowper's fondness for narratives of voyages | 141 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Oct. 10, 1783. Cowper declines the discussion of political subjects; epitaph on sailors of the Royal George | 142 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 13, 1783. Neglect of American loyalists; extraordinary donation sent to Lisbon at the time of the great earthquake; prospects of the Americans | 142 |

| To the same, Oct. 20, 1783. Remarks on Bacon's monument of Lord Chatham | 143 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Oct. 20, 1783. Anticipations of winter | 144 |

| Cowper's winter evenings | 144 |

| The subject of his poem, "The Sofa," suggested | 144 |

| Circumstances illustrative of the origin and progress of "The Task" | 144 |

| Extracts from letters to Mr. Bull on that subject | 144 |

| Particulars of the time in which "The Task" was composed | 145 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 3, 1783. Fire at Olney described | 145 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Nov. 10, 1783. On the neglect of old acquaintance; invitation to Olney; exercise recommended; fire at Olney | 146 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 17, 1783. Humorous description of the punishment of a thief at Olney; dream of an air-balloon | 147 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 23, 1783. On his opinion of voyages and travels; Cowper's reading | 148 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Nov. 24, 1783. Complaint of the neglect of Lord Thurlow; character of Josephus's History | 148 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 30, 1783. Speculations on the employment of the antediluvians; the Theological Review | 149 |

| To the same, Dec. 15, 1783. Speculations on the invention of balloons; the East India Bill | 150 |

| To the same, Dec. 27, 1783. Ambition of public men; dismissal of ministers; Cowper's sentiments concerning Mr. Bacon; anecdote of Mr. Scott | 151 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, no date. Account of Mr. Throckmorton's invitation to see a balloon filled; attentions of the Throckmorton family to Cowper and Mrs. Unwin | 152 |

| Circumstances which obliged Cowper to relinquish his friendship with Lady Austen | 153 |

| Hayley's account of this event | 153 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 3, 1784. Dearth of subjects for writing upon at Olney; reflections on the monopoly of the East India Company | 154 |

| To Mrs. Hill, Jan. 5, 1784. Requesting her to send some books | 155 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Jan. 18, 1784. On his political letters; low state of the public funds | 155 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 18, 1784. Cowper's religious despondency; remark on Mr. Newton's predecessor | 156 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 1784. Proposed alteration in a Latin poem of Mr. Unwin's; remarks on the bequest of a cousin; commendations on Mr. Unwin's conduct; on newspaper praise | 156 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 25, 1784. Cowper's sentiments on East India patronage and East India dominion | 157 |

| State of our Indian possessions at that time | 158 |

| Moral revolution effected there | 158 |

| Latin lines by Dr. Jortin, on the shortness of human life | 158 |

| Cowper's translation of them | 158 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 1784. On Mr. Newton's "Review of Ecclesiastical History;" proposed title and motto; Cowper declines contributing to a Review | 158 |

| To the same, Feb. 10, 1784. Cowper's nervous state; comparison of himself with the ancient poets; his hypothesis of a gradual declension in vigour from Adam downwards | 159 |

| To the same, Feb. 1784. The thaw; kindness of a benefactor to the poor of Olney; Cowper's politics, those of a reverend neighbour; projected translation of Caraccioli on self-acquaintance | 160 |

| To the Rev. William Bull, Feb. 22, 1784. Unknown benefactor to the poor of Olney; political profession | 160 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Feb. 29, 1784. On Mr. Unwin's acquaintance with Lord Petre; unknown benefactor to the poor of Olney; diffidence of a modest man on extraordinary occasions | 161 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 8, 1784. The Theological Miscellany; abandonment of the intended translation of Caraccioli | 161 |

| To the same, March 11, 1784. Remarks on Mr. Newton's "Apology;" East India patronage and dominion | 162 |

| To the same, March 15, 1784. Cowper's habitual despondence; verse his favourite occupation, and why; Johnson's "Lives of the Poets" | 162 |

| To the same, March 19, 1784. Works of the Marquis Caraccioli; evening occupations | 162 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, March 21, 1784. Cowper's sentiments on Johnson's "Lives of the Poets;" characters of the poets | 163 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 29, 1784. Visit of a candidate and his train to Cowper; angry preaching of Mr. S | 164 |

| To the same, April 14, 1784. Remarks on divine wrath; destruction in Calabria | 165 |

| Effects of the earthquakes, and total loss of human lives | 165 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, April 5, 1784. Character of Beattie and Blair; speculation on the origin of speech | 166 |

| [ix]To the same, April 15, 1784. Further remarks on Blair's "Lectures;" censure of a particular observation in that book | 167 |

| To the same, April 25, 1784. Lines to the memory of a halybutt | 167 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, April 26, 1784. Remarks on Beattie and on Blair's "Lectures;" economy of the county candidates, and its consequences | 168 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, May 3, 1784. Reflections on face-painting; innocent in Frenchwomen, but immoral in English | 168 |

| To the same, May 8, 1784. Cowper's reasons for not writing a sequel to John Gilpin, and not wishing that ballad to appear with his Poems; progress made in printing them | 170 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May 10, 1784. Conversion of Dr. Johnson; unsuccessful attempt with a balloon at Throckmorton's | 170 |

| Circumstances attending Dr. Johnson's conversion | 171 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May 22, 1784. On Dr. Johnson's opinion of Cowper's "Poems;" Mr. Bull and his refractory pupils | 171 |

| To the same, June 5, 1784. On the opinion of Cowper's "Poems" attributed to Dr. Johnson | 171 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 21, 1784. Commemoration of Handel; unpleasant summer; character of Mr. and Mrs. Unwin | 172 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, July 3, 1784. Severity of the weather; its effects on vegetation | 172 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, July 5, 1784. Reference to a passage in Homer; could the wise men of antiquity have believed in the fables of the heathen mythology? Cowper's neglect of politics; his hostility to the tax on candles | 173 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, July 12, 1784. Remarks on a line in Vincent Bourne's Latin poems; drawing of Mr. Unwin's house; Hume's "Essay on Suicide" | 174 |

| To the same, July 13, 1784. Latin Dictionary; animadversions on the tax on candles; musical ass | 174 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, July 14, 1784. Commemoration of Handel | 175 |

| Mr. Newton's sermon on that subject | 175 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, July 19, 1784. The world compared with Bedlam | 176 |

| To the same, July 28, 1784. On Mr. Newton's intended visit to the Rev. Mr. Gilpin at Lymington; his literary adversaries | 176 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Aug. 14, 1784. Reflections on travelling; Cowper's visits to Weston; difference of character in the inhabitants of the South Sea islands; cork supplements; franks | 177 |

| Original mode of franking, and reason for the adoption of the present method | 178 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, August 16, 1784. Pleasures of Olney; ascent of a balloon; excellence of the Friendly islanders in dancing | 178 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Sept. 11, 1784. Cowper's progress in his new volume of poems; opinions of a visitor on his first volume | 178 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Sept. 11, 1784. Character of Dr. Cotton | 179 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Sept. 18, 1784. Alteration of franks; Cowper's green-house; his enjoyment of natural sounds | 179 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Oct. 2, 1784. Punctuation of poetry; visit to Mr. Throckmorton | 180 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 9, 1784. Cowper maintains not only that his thoughts are unconnected, but that frequently he does not think at all; remarks on the character and death of Captain Cook | 181 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Oct. 10, 1784. With the manuscript of the new volume of his Poems, and remarks on them | 182 |

| To the same, Oct. 20, 1784. Instructions respecting a publisher, and corrections in his Poems | 182 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 22, 1784. Remarks on Knox's Essays | 183 |

| To the same. Oct. 30, 1784. Heroism of the Sandwich islanders; Cowper informs Mr Newton of his intention to publish a new volume | 184 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Nov. 1, 1784. Cowper's reasons for not earlier acquainting Mr. Newton with his intention of publishing again; he resolves to include "John Gilpin" | 184 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 1784. On the death of Mr. Hill's mother; Cowper's recollections of his own mother; departure of Lady Austen; his new volume of Poems | 185 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 27, 1784. Sketch of the contents and purpose of his new volume | 185 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Olney, 1784. On the transmission of his Poems; effect of medicines on the composition of poetry | 185 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Nov. 29, 1784. Substance of his last letter to Mr. Newton | 186 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Dec. 4, 1784. Aërial voyages | 188 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 13, 1784. On the versification and titles of his new Poems; propriety of using the word worm for serpent | 188 |

| Passages in Milton and Shakespeare in which worm is so used | 189 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Dec. 18, 1784. Balloon travellers; inscription to his new poem; reasons for complimenting Bishop Bagot | 189 |

| To the Rev, John Newton, Christmas-eve, 1784. Cowper declines giving a new title to his new volume of Poems; remarks on a person lately deceased | 190 |

| General remarks on the particulars of Cowper's personal history | 190 |

| Remarks on the completion of the second volume of Cowper's Poems | 190 |

| Gibbon's record of his feelings on the conclusion of his History | 191 |

| Moral drawn from the evanescence of life | 191 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 5, 1785. On the renouncement of the Christian character; epitaph on Dr. Johnson | 191 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 15, 1785. On delay in letter-writing; sentiments of Rev. Mr. Newton; Cowper's contributions to the Gentleman's Magazine; Lunardi's narrative | 192 |

| Explanations respecting Cowper's poem, entitled "The Poplar Field" | 192 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Jan. 22, 1785. Breaking up of the Frost; anticipations of proceedings in Parliament | 193 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Feb. 7, 1785. Progress of Cowper's second volume of Poems; his pieces in the Gentleman's Magazine; sentiments of a neighbouring nobleman and gentleman respecting Cowper | 193 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 19, 1785. An ingenious bookbinder; poverty at Olney; severity of the late winter | 194 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Feb. 27, 1785. Inquiry concerning his health, and account of his own | 195 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 19, 1785. Uses and description of an old card table; want of exercise during the winter; petition against concessions to Ireland | 195 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, March 20, 1785. Remarks on a Nobleman's eye; progress of his new volume; political reflections; celebrity of "John Gilpin" | 196 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, April 9, 1785. On the prediction of a destructive earthquake, by a German ecclesiastic | 197 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, April 22, 1785. On the popularity of "John Gilpin" | 197 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, April 30, 1785. On the celebrity of "John Gilpin;" progress of Cowper's new volume; Mr. Newton's sentiments in regard to him; mention of some old acquaintances; discovery of a bird's nest in a gate-post | 198 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May, 1785. Sudden death of Mr. Ashburner; remarks on the state of Cowper's mind; reference to his first acquaintance with Newton | 199 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 4, 1785. Character of the Rev. Mr. Greatheed; completion of Cowper's new volume; Bacon's monument to Lord Chatham | 200 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., June 25, 1785. Cowper's summer-house; dilatoriness of his bookseller | 200 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 25, 1785. Allusion to the mental depression under which Cowper laboured; Nathan's last moments; complaint of Johnson's delay; effects of drought; tax on gloves | 201 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, July 9, 1785. Mention of letters in praise of his Poems; conduct of the Lord Chancellor and G. Colman; reference to the commemoration of Handel; cutting down of the spinney | 202 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, July 27, 1785. Violent thunder-storm; courage of a dog; on the love of Christ | 203 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Aug. 6, 1785. Feelings on the subject of authorship; reasons for introducing John Gilpin in his new volume | 204 |

| [x]To the Rev. John Newton, Aug. 17, 1785. Reasons for not writing to Mr. Bacon; Dr. Johnson's Diary; illness of Mr. Perry | 205 |

| Character of Dr. Johnson's Diary | 206 |

| Extracts from it | 207 |

| Arguments for the necessity of conversion | 207 |

| Johnson's neglect of the Sabbath | 207 |

| Testimony of Sir William Jones respecting the Holy Scriptures | 208 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Aug. 27, 1785. Thanks for presents; his second volume of Poems; remarks on Dr. Johnson's Journal; claims of who and that | 208 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Sept. 24, 1785. Recollections of Southampton; recovery of Mr. Perry; proposed Sunday School | 209 |

| Origin of Sunday Schools | 210 |

| Their utility | 210 |

| Sentiments of the late Rev. Andrew Fuller on the Bible Society and on Sunday Schools | 210 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Oct. 11, 1785. Cowper excuses himself for not visiting Wargrave; on his printed epistle to Mr. Hill | 210 |

| Renewal of Cowper's intimacy with his cousin, Lady Hesketh | 211 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Oct. 12, 1785. Recollections revived by her letter; account of his own situation; allusion to his uncle's health; necessity of mental employment for himself | 211 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 16, 1785. On the death of Miss Cunningham; expected removal of the Rev. Mr. Scott from Olney; Mr. Jones, steward of Lord Peterborough, burned in effigy | 212 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Oct. 22, 1785. Progress of his translation of Homer; course of reading recommended for Mr. Unwin's son | 213 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 5, 1785. On his tardiness in writing; remarks on Mr. N.'s narrative of his life; strictures on Mr. Heron's critical opinions of Virgil and the Bible; lines addressed by Cowper to Heron | 214 |

| Remarks on Heron's "Letters on Literature" | 215 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 7, 1785. On the interruptions experienced by men of business from the idle | 215 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Nov. 9, 1785. Reference to his poems; he signifies his acceptance of her offer of pecuniary aid; his translation of Homer; description of his person | 215 |

| To the same, without date. His feelings towards her allusion to his translation of Homer | 217 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Nov. 9, 1785. On Bishop Bagot's Charge | 217 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 3, 1785. Causes which led him to undertake the translation of Homer; visit from Mr. Bagot; renewal of his correspondence with Lady Hesketh; complains of indigestion | 217 |

| To the same, Dec. 10, 1785. On the favourable reports of his last volume of poems; censure of Pope's Homer | 218 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Dec. 24, 1785. On his translation of Homer | 219 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Dec. 24, 1785. On his translation of Homer | 219 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Dec. 31, 1785. On his negotiation with Johnson respecting the Translation of Homer; want of bedding among the poor of Olney | 220 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 10, 1786. His consciousness of defects in his poems; on his Translation of Homer | 221 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Jan. 14, 1786. On Mr. Unwin's introduction to Lady Hesketh; specimen of Cowper's translation of Homer, sent to General Cowper; James's powder; what is a friend good for? unreasonable censures | 221 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 14, 1786. On his translation of Homer | 222 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Jan. 15, 1786. Explanation of the delay in the publication of his proposals; allusion to Bishop Bagot | 222 |

| To the same, Jan. 23, 1786. Dr. Maty's intended review of "The Task;" Dr. Cyril Jackson's opinion of Pope's Homer | 223 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 31, 1786. Acknowledgment of presents from Anonymous; state of his health; progress of his translation of Homer; correspondence with General Cowper | 223 |

| To the same, Feb. 9, 1786. Anticipations of a visit from her; description of the vestibule of his residence | 224 |

| To the same, Feb. 11, 1786. He announces that he has sent off to her a portion of his translation of Homer; effect of criticisms on his health; promise of Thurlow to Cowper | 225 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Feb. 18, 1786. On their correspondence; his translation of Homer; proposed mottoes | 226 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Feb. 19, 1786. Preparations for her expected visit; character of Homer; criticism on Cowper's specimen | 226 |

| To the Walter Bagot, Feb. 27, 1786. Condolence on the death of his wife | 227 |

| To Lady Hesketh, March 6, 1786. On elisions in his Homer; progress of the work | 227 |

| To the Rev. W. Unwin, March 13, 1786. Character of the critic to whom he had submitted his Homer | 229 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, April 1, 1786. Expected visitors | 229 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., April 5, 1786. Reasons for declining to make any apology for his translation of Homer | 229 |

| Motives which induced Cowper to undertake a new version | 230 |

| To Lady Hesketh, April 17, 1786. Description of the vicarage at Olney, where lodgings had been taken for her; Mrs. Unwin's sentiments towards her; letter from Anonymous; his early acquaintance with Lord Thurlow | 230 |

| To Lady Hesketh, April 24, 1786. On her letters; anticipations of her coming; General Cowper | 231 |

| To the same, May 8, 1786. On Dr. Maty's censure of Cowper's translation of Homer; Colman's opinion of it; Cowper's stanzas on Lord Thurlow; invitation to Olney; specimen of Maty's animadversions; recommendation of a house at Weston; blunder of Mr. Throckmorton's bailiff; recovery of General Cowper | 232 |

| To the same, May 15, 1786. Anticipations of her arrival at Olney; proposed arrangements for the occasion; presumed motive of Maty's censures; confession of ambition | 233 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, May 20, 1786. His translation of Homer; reasons for not adopting Horace's maxim about publishing, to the letter | 235 |

| Secret sorrows of Cowper | 235 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, May 20, 1786. Cowper's unhappy state of mind; his connexions | 236 |

| Remarks on Cowper's depression of spirit | 237 |

| Delusion of supposing himself excluded from the mercy of God | 237 |

| Religious consolation recommended in cases of disordered intellect | 237 |

| To Lady Hesketh, May 25, 1786. Delay of her coming; visit to a house at Weston; the Throckmortons; anecdote of a quotation from "The Task;" nervous affections | 238 |

| To the same, May 29, 1786. Delay of her coming; preparations for it; allusion to his fits of dejection | 239 |

| To the same, June 4 and 5, 1786. Cowper rallies her on her fears of their expected meeting; dinner at Mr. Throckmorton's | 240 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., June 9, 1786. Relapse of the Lord Chancellor; renewal of correspondence with Colman; the Nonsense Club; expectation of Lady Hesketh's arrival | 241 |

| Arrival of Lady Hesketh at Olney | 241 |

| Influence of that event on Cowper | 241 |

| Extract from a letter from him to Mr. Bull | 241 |

| Description of a thunder-storm, from a letter to the same | 242 |

| Cowper's House at Olney | 242 |

| His intimacy with Mr. Newton | 242 |

| His pious and benevolent habits | 242 |

| He removes from Olney to the Lodge at Weston | 242 |

| His acquaintance with Samuel Rose, Esq. and the late Rev. Dr. Johnson | 242 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., June 19, 1786. His intended removal from Olney | 242 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 22, 1786. His employments; interruption given to them by Lady Hesketh's arrival; Newton's Sermons | 243 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin, July 3, 1786. Lady Hesketh's arrival and character; state of his old abode and description of the new one at Weston; books recommended for Mr. Unwin's son | 243 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, July 4, 1786. Particulars relative to the translation of Homer | 244 |

| [xi]To the Rev. John Newton, Aug. 5, 1786. His intended removal from Olney; its unhealthy situation; his unhappy state of mind; comfort of Lady Hesketh's presence | 245 |

| Cowper's spirits not affected apparently by his mental malady | 246 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, Aug. 24, 1786. Progress of his Translation; the Throckmortons | 246 |

| To the same, (without date.) His lyric productions; recollections of boyhood | 246 |

| Extract of a letter to the Rev. Mr. Unwin | 247 |

| Lines addressed to a young lady on her birth-day | 247 |

| Proposed plan of Mr. Unwin for checking sabbath-breaking and drunkenness | 247 |

| To the Rev. Wm. Unwin, (no date.) Cowper's opinion of the inutility of Mr. Unwin's efforts | 247 |

| Exhortation to perseverance in a good cause | 248 |

| Hopes of present improvement | 248 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, (no date.) State of the national affairs | 248 |

| To the Rev. William Unwin, (no date.) Character of Churchill's poetry | 249 |

| To the same, (no date.) Cowper's discovery in the Register of poems long composed and forgotten by him | 250 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Aug. 31, 1786. Defence of elisions; intended removal to Weston | 250 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Sept. 30, 1786. Defence of his and Mrs. Unwin's conduct | 251 |

| Explanatory remarks on the preceding letter | 251 |

| Amiable spirit and temper of Newton | 251 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq. Oct. 6, 1786. Loss of the MS. of part of his translation | 251 |

| Cowper's removal to Weston | 251 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Nov. 17, 1786. On his removal from Olney; invitation to Weston | 253 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 17, 1786. Excuse for delay in writing; his new residence; affection for his old abode | 253 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Nov. 26, 1786. Comforts of his new residence; the cliffs; his rambles | 254 |

| Unexpected death of the Rev. Mr. Unwin | 254 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Dec. 4, 1786. On the death of Mr. Unwin | 255 |

| To the same, Dec. 9, 1786. On a singular circumstance relating to an intended pupil of Mr. Unwin's | 255 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Dec. 9, 1786. Death of Mr. Unwin; Cowper's new situation at Weston | 256 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 16, 1786. Death of Mr. Unwin; forlorn state of his old dwelling | 256 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Dec. 21, 1786. Cowper's opinion of praise; Mr. Throckmorton's chaplain | 257 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Jan. 3, 1787. Reason why a translator of Homer should not be calm; praises of his works; death of Mr. Unwin | 257 |

| Cowper has a severe attack of nervous fever | 258 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 8, 1787. State of his health; proposal of General Cowper respecting his Homer; letter from Mr. Smith, M.P. for Nottingham; Cowper's song of "The Rose" reclaimed by him | 258 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 13, 1787. Inscription for Mr. Unwin's tomb; government of Providence in his poetical labours | 258 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 18, 1787. Suspension of his translation by fever; his sentiments respecting dreams; visit of Mr. Rose | 259 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., July 24, 1787. On Burns' poems | 260 |

| Remarks on Burns and his poetry | 260 |

| Passages from his poems | 261 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Aug. 27, 1787. Invitation to Weston; state of Cowper's health; remarks on Barclay's "Argenis," and on Burns | 261 |

| To Lady Hesketh, August 30, 1787. Improvement in his health; kindness of the Throckmortons | 262 |

| To the same, Sept. 4, 1787. Delay of her coming; Mrs. Throckmorton's uncle; books read by Cowper | 262 |

| To the same, Sept. 15, 1787. His meeting with her friend, Miss J——; new gravel-walk | 263 |

| To the same, Sept. 29, 1787. Remarks on the relative situation of Russia and Turkey | 263 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 2, 1787. Cowper confesses that for thirteen years he doubted Mr. N.'s identity; acknowledgments for the kind offers of the Newtons; preparations for Lady Hesketh's coming | 263 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Oct. 19, 1787. State of his health; strength of local attachments | 264 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Oct. 20, 1787. His miserable state during his recent indisposition; petition to Lord Dartmouth in behalf of the Rev. Mr. Postlethwaite | 264 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Nov. 10, 1787. On the delay of her coming; Cowper's kitten; changes of weather foretold by a leech | 265 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Nov. 16, 1787. On his own present occupation | 266 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Nov. 27, 1787. Walks and scenes about Weston; application from a parish clerk for a copy of verses; papers in "The Lounger;" anecdote of a beggar and vermicelli soup | 266 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Dec. 4, 1787. Character of the Throckmortons | 267 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Dec. 6, 1787. Visit to Mr. B.'s sister at Chichely; Bishop Bagot; a case of ridiculous distress | 267 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Dec. 10, 1787. Progress of his Homer; changes in life | 268 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Dec. 13, 1787. Requisites in a translator of Homer | 268 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 1, 1788. Extraordinary coincidence between a piece of his own and one of Mr. Merry's; "The Poet's New Year's Gift;" compulsory inoculation for small-pox | 269 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Jan. 5, 1788. Translation of the commencing lines of the Iliad, by Lord Bagot; revisal of Cowper's translation; the clerk's verses | 270 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 19, 1788. His engagement with Homer prevents the production of occasional poems; remarks on a new print of Bunbury's | 270 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Jan. 21, 1788. Reasons for not writing to him; expected arrival of the Rev. Mr. Bean; changes of neighbouring ministers; narrow escape of Mrs. Unwin from being burned | 271 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Jan. 30, 1788. His anxiety on account of her silence | 272 |

| To the same, Feb. 1, 1788. Excuse for his melancholy; his Homer; visit from Mr. Greatheed | 272 |

| Causes of Cowper's correspondence with Mrs. King | 273 |

| To Mrs. King, Feb. 12, 1788. Reference to his deceased brother; he ascribes the effect produced by his poems to God | 273 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Feb. 14, 1788. A sense of the value of time the best security for its improvement; Mr. C——; brevity of human life illustrated by Homer | 273 |

| Commencement of the efforts for the abolition of the slave trade | 274 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Feb. 16, 1788. On negro slavery; Hannah More's poem on the Slave Trade; extract from it; advocates of the abolition of slavery; trial of Warren Hastings | 274 |

| To Lady Hesketh, Feb. 22, 1788. Remarks on Burke's speech impeaching Warren Hastings, and on the duty of public accusers | 276 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 1, 1788. Excuse for a lapse of memory in regard to a letter of Mr. Bean's | 276 |

| To the same, March 3, 1788. Arrival of Mr. Bean at Olney; Cowper's correspondence with Mrs. King | 276 |

| To Mrs. King, March 3, 1788. Brief history of his own life | 277 |

| To Lady Hesketh, March 3, 1788. Catastrophe of a fox-chace; Cowper in at the death | 278 |

| To the same, March 12, 1788. Remarks on Hannah More's works, and on Wilberforce's book; the Throckmortons | 278 |

| Cowper is solicited to write in behalf of the negroes | 279 |

| To General Cowper. 1788. Songs written by him on the condition of negro slaves | 279 |

| "The Morning Dream," a ballad | 279 |

| Efforts for the abolition of the Slave Trade | 280 |

| Wilberforce, the Liberator of Africa | 280 |

| Cowper's ballads on Negro slavery | 280 |

| The Negro's Complaint | 280 |

| The question why Great Britain should be the first to sacrifice interest to humanity answered by Cowper | 280 |

| Lines from Goldsmith's "Traveller," on the English character | 281 |

| Exposition of the cruelty and injustice of the slave trade, by Granville Sharp | 281 |

| Proof of the slow progress of truth | 281 |

| Extracts from Cowper's poems on Negro slavery | 282 |

| Case of Somerset, a slave, and Lord Mansfield's judgment | 282 |

| Final abolition of slavery by Great Britain, and efforts making for the religious instruction of the Negroes | 282 |

| Probability that Africa may be enlightened by their means | 283 |

| [xii]Cowper's lines on the blessings of spiritual liberty | 283 |

| Letter to Mrs. Hill, March 17, 1788. Thanks for a present of a turkey and ham; Mr. Hill's indisposition; inquiry concerning Cowper's library | 284 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, March 17, 1788. With a Song, written at Mr. N.'s request, for Lady Balgonie | 284 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, March 19, 1788. Coldness of the spring; remarks on "The Manners of the Great;" progress of his Homer | 284 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., March 29, 1788. He expresses his wonder that his company should be desirable to Mr. R.; Mrs. Unwin's character; acknowledges the receipt of some books; Clarke's notes on Homer; allusion to his own ballads on Negro slavery | 285 |

| To Lady Hesketh, March 31, 1788. He makes mention of his song, "The Morning Dream;" allusion to Hannah More on the "Manners of Great" | 286 |

| Character of and extracts from Mrs. More's work | 286 |

| To Mrs. King, April 11, 1788. Allusion to his melancholy, and necessity for constant employment; improbability of their meeting | 286 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, April 19, 1788. Remarks on the conduct of government in regard to the Slavery Abolition question | 287 |

| To Lady Hesketh, May 6, 1788. Smollett's Don Quixote; he thanks her for the intended present of a box for letters and papers; renewal of his correspondence with Mr. Rowley; remarks on the expression, "As great as two inkle weavers" | 288 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., May 8, 1788. Lament for the loss of his library; progress of his Homer | 288 |

| To Lady Hesketh, May 12, 1788. Mrs. Montagu and the Blue-Stocking Club; his late feats in walking | 288 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., May 24, 1788. Thanks for the present of prints of the Lacemaker and Crazy Kate; family of Mr. Chester; progress of Homer; antique bust of Paris | 289 |

| To the Rev. William Bull, May 25, 1788. He declines the composition of hymns, which Mr. B. had urged him to undertake | 290 |

| To Lady Hesketh, May 27, 1788. His lines on Mr. Henry Cowper; remarks on Mrs. Montagu's Essay on the Genius of Shakespeare; antique head of Paris; remarks on the two prints sent him by Mr. Hill | 290 |

| To the same, June 3, 1788. Sudden change of the weather; remarks on the advertisement of a dancing-master of Newport-Pagnell | 291 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 5, 1788. His writing engagements; effect of the sudden change of the weather on his health; character of Mr. Bean; visit from the Powleys; he declines writing further on the slave-trade; invitation to Weston; verses on Mrs. Montagu | 291 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., June 8, 1788. On the death of his uncle, Ashley Cowper | 292 |

| To Lady Hesketh, June 10, 1788. On the death of her father, Ashley Cowper | 292 |

| To the same, June 15, 1788. Recollections of her father | 293 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, June 17, 1788. Coldness of the season; reasons for declining to write on slavery; contrast between the awful scenes of nature and the horrors produced by human passions | 293 |

| To Mrs. King, June 19, 1788. He excuses his silence on account of inflammation of the eyes; sudden change of weather; reasons why we are not so hardy as our forefathers; his opinion of Thomson, the poet | 294 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., June 23, 1788. Apology for an unanswered letter; providence of God in regard to the weather; visitors at Weston; brevity of human life | 294 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, June 24, 1788. Difficulties experienced by Mr. Bean in enforcing a stricter observance of the Sabbath at Olney; remarks on the slave trade | 295 |

| To Lady Hesketh, June 27, 1788. Anticipations of her next visit; allusion to Lord Thurlow's promise to provide for him; anecdote of his dog Beau; remarks on his ballads on slavery | 296 |

| The Dog and the Water Lily | 297 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq, July 6, 1788. He gives Mr. H. notice that he has drawn on him; allusion to an engagement of Mr. H.'s | 297 |

| To Lady Hesketh, July 28, 1788. Her talent at description; the lime-walk at Weston; remarks on the "Account of Five Hundred Living Authors" | 297 |

| To the same, August 9, 1788. Visitors at Weston; motto composed by Cowper for the king's clock | 298 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., August 18, 1788. Circumstances of their parting; he recommends Mr. R. to take due care of himself in his pedestrian journeys; strictures on Lavater's Aphorisms | 298 |

| Remarks on physiognomy, and on the merits of Lavater as the founder of the Orphan House at Zurich. Note | 299 |

| To Mrs. King, August 28, 1788. He playfully guesses at Mrs. King's figure and features | 299 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Sept. 2, 1788. Reference to Mr. N.'s late visit; his own melancholy state of mind; Mr. Bean's exertions for suppressing public houses | 300 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Sept. 11, 1788. Remarkable oak; lines suggested by it; exhortation against bashfulness | 300 |

| To Mrs. King, Sept. 25, 1788. Thanks for presents; invitation to Weston | 301 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Sept. 25, 1788. A riddle; superior talents no security for propriety of conduct; progress of Homer; Mrs. Throckmorton's bullfinch | 302 |

| To Mrs. King, Oct. 11, 1788. Account of his occupations at different periods of his life | 302 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Nov. 29, 1788. Declining state of Jenny Raban; Mr. Greatheed | 303 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Nov. 30, 1788. Vincent Bourne; invitation to Weston | 303 |

| To Mrs. King, Dec. 6, 1788. Excuse for not being punctual in writing; succession of generations; Cumberland's "Observer" | 304 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 9, 1788. Mr. Van Lier's Latin MS.; Lady Hesketh and the Throckmortons; popularity of Mr. C. as a preacher | 304 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Jan. 19, 1789. Local helps to memory; Sir John Hawkins' book | 305 |

| To the same, Jan. 24, 1789. Accidents generally occur when and where we least expect them | 305 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, Jan. 29, 1789. Excuse for irregularity in correspondence; progress of Homer; allusion to political affairs | 305 |

| To Mrs. King, Jan. 29, 1789. Thanks for presents; Mrs. Unwin's fall in the late frost; distress of the Royal Family on the state of the King, and anecdote of the Lord Chancellor | 306 |

| To the same, March 12, 1789. Excuse for long silence, and for not having sent, according to promise, all the small pieces he had written; his poem on the King's recovery | 306 |

| To the same, April 22, 1789. He informs Mrs. K. that he has a packet of poems ready for her; his verses on the Queen's visit to London on the night of the illuminations for the King's recovery; disappointment on account of her not coming to Weston; Twinings' translation of Aristotle | 307 |

| To the same, April 30, 1789. Thanks for presents; his brother's poems | 308 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., May 20, 1789. Reference to his lines on the Queen's visit; character of Hawkins Brown | 309 |

| To Mrs. King, May 30, 1789. He acknowledges the receipt of a packet of papers; reference to his poem on the Queen's visit | 309 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., June 5, 1789. He commissions Mr. R. to buy him a cuckoo-clock; Boswell's Tour to the Hebrides; Hawkins' and Boswell's Life of Johnson | 309 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot, June 16, 1789. On his marriage; allusion to his poem on the Queen's visit | 310 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., June 20, 1789. He expresses regret at not receiving a visit from Mr. R.; acknowledges the arrival of the cuckoo-clock; remark on Hawkins' and Boswell's Life of Johnson | 310 |

| To Mrs. Throckmorton, July 18, 1789. Poetic turn of Mr. George Throckmorton; news concerning the Hall | 310 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., July 23, 1789. Importance of improving the early years of life; anticipations of Mr. R.'s visit | 311 |

| To Mrs. King, August 1, 1789. Grumbling of his correspondents on his silence; his time engrossed by Homer; he professes himself an admirer of pictures, but no connoisseur | 311 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., August 8, 1789. Mrs. Piozzi'sTravels; remark on the author of the "Dunciad" | 312 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., August 12, 1789. Unfavourable weather and spoiled hay; multiplicity of his engagements; Sunday school hymn | 312 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, August 16, 1789. Excuse for long silence; progress of Homer | 313 |

| Remarks on Cowper's observation that authors are responsible for their writings | 313 |

| [xiii]To Samuel Rose, Esq., Sept. 24, 1789. Coldness of the season | 313 |

| To the same, Oct. 4, 1789. Description of the receipt of a hamper, in the manner of Homer | 314 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot (without date). Excuse for long silence; why winter is like a backbiter; Villoison's Homer; death of Lord Cowper | 314 |

| To the Rev. Walter Bagot (without date). Remarks on Villoison's Prolegomena to Homer | 314 |

| Note on the reveries of learned men | 315 |

| To the Rev. John Newton, Dec. 1, 1789. Apology for not writing; Mrs. Unwin's state of health; reference to political events | 315 |

| To Joseph Hill, Esq., Dec. 18, 1789. Political reflections | 316 |

| Character of the French Revolution | 316 |

| Burke on the features which distinguish the French Revolution from that of England in 1688 | 316 |

| Political and moral causes of the French Revolution | 317 |

| Origin of the Revolution in America | 317 |

| The Established Church endangered by resistance to the spirit of the age | 318 |

| To Samuel Rose, Esq., Jan. 3, 1790. Excuses for silence; inquiry concerning Mr. R.'s health; laborious task of revisal | 318 |

| To Mrs. King, Jan. 4, 1790. His anxiety on account of her long silence; his occupations; Mrs. Unwin's state | 319 |

| To the same, Jan. 18, 1790. He contradicts a report that he intends to quit Weston; reference to his Homer | 319 |

| Commencement of Cowper's acquaintance with his cousin the Rev. John Johnson | 320 |