Project Gutenberg's Queen Moo's Talisman, by Alice Dixon Le Plongeon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Queen Moo's Talisman

The Fall of the Maya Empire

Author: Alice Dixon Le Plongeon

Release Date: January 1, 2015 [EBook #47842]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK QUEEN MOO'S TALISMAN ***

Produced by Julia Miller, Denis Pronovost, Linda Cantoni

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.) Music transcribed by Linda Cantoni.

Queen Moo’s Talisman

Entered according to act of Congress, June. 1902, by Alice Dixon Le Plongeon,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

To Doctor Augustus Le Plongeon,

whose works inspired these pages, their author

dedicates them: not as a worth offering, but as

A Small Token

Of loving endeavor to gratify his oft expressed desire.

Brooklyn, N. Y., May, 1902.

Engraved by F. A. Ringler & Co., of New York, from photographs

and drawings by

Dr. Augustus Le Plongeon.

| PLATE |

|

PAGE |

| I. |

Author’s portrait (Frontispiece). |

|

| II. |

Prince Coh in battle—tracing from fresco painting on walls of Coh’s funeral chamber, in Memorial Hall at Chicħen. |

35 |

| III. |

Mausoleum of High Priest Cay, at Chicħen. |

41 |

| IV. |

Queen Móo’s portrait—Demi-relief on entablature of east façade of Governor’s House at Uxmal. |

43 |

| V. |

Portrait of High Priest Cay. From a sculpture on the west side of the pyramid called the Dwarf’s House at Uxmal. (Discovered on June 1st, 1881, by Dr. Le Plongeon). |

47 |

| VI. |

Prince Coh’s portrait. His statue discovered by Dr. Le Plongeon at Chicħen in 1875. |

53 |

| VII. |

Prince Coh’s Memorial Hall at Chicħen. Restoration by Dr. Le Plongeon. |

55 |

| VIII. |

Prince Aac’s Portrait. From a sculptured wooden lintel over the door of the funeral chamber in Memorial Hall at Chicħen. |

61 |

| |

| Appendix—Music. |

| |

| IX. |

Invocation to the Sun. |

36 |

| X. |

He and She. |

36 |

| XI. |

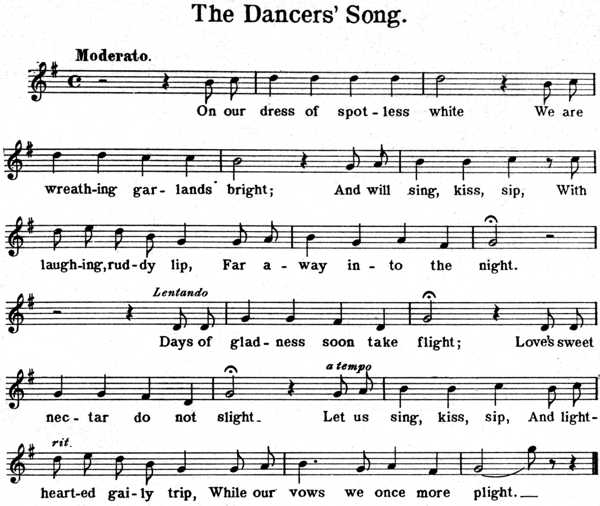

The Dancers’ Song. |

37 |

| XII. |

The Lover’s Song. |

38 |

| XIII. |

Funeral Chant. |

38 |

| |

| Head Pieces. |

| |

| I. |

Winged Circle—from Ococingo (Guatemala). |

25 |

| II. |

Winged Circle—from Egypt. |

65 |

| III. |

Queen Móo’s Talisman, found in the urn containing the charred heart and Viscera of Prince Coh, in his Mausoleum, at Chicħen in 1875, by Dr. Le Plongeon. |

77 |

PRONUNCIATION AND DEFINITION OF

MAYA PROPER NAMES.

| AAC |

(Ak, as in dark.) |

Name of a prince. |

| BALAM |

(Bǟ-läm, a as in far.) |

God of agriculture. |

| CAN |

(Kän, a as in far.) |

Title of kings. |

| CAY |

(Kǟ-ee.) |

Name of a high priest. |

| CHICĦEN |

(Chee-chen, chee as in cheek.) |

Name of a city. |

| COH |

(Kō.) |

Name of a prince consort. |

| HOMEN |

(Hō-men, o as in no.) |

God of volcanic forces. |

| KU |

(Koo, oo as in moon.) |

The Supreme Intelligence. |

| MAYA |

(Mǟ-yä, a as in far.) |

Name of a nation. |

| MÓO |

(Mō, o as in no.) |

Name of a queen. |

| MU |

(Moo, oo as in moon.) |

Name of a country. |

| NICTÉ |

(Nik-tay.) |

Name of a princess. |

| YUM CIMIL |

(Yoom Keémil.) |

God of death. |

| ZOƆ |

(Zŏdz.) |

Name of a queen. |

PREFACE.

In justice to the author of “Queen Móo’s Talisman”, it

may be recorded that at the time of its writing, there

was no intention of allowing the verses to go into print; they

were penned only for the one to whom they are dedicated.

The songs introduced have been arranged to the metre of the

two or three ancient melodies yet occasionally heard among the

natives of Yucatan. The one to the rain gods is a versification

(set to the tune even now used in a sun-dance) of an old Maya

prayer translated from that language by Dr. Le Plongeon and

published in his work “Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx.”

The melody to which the Love Song is set is not Maya. In

connection with the lines touching upon love and pain it may

be remarked that in the Maya language there is but one word to

express both.

In this poem are represented as nearly as possible, the religious

ideas of the Mayas, their belief in KU, the Supreme

Intelligence; in the immortality of the soul, and in successive

lives on earth before returning to the great Source whence all

emanate; also their rites and ceremonies as gathered from

traditions of the natives of Yucatan, the fresco paintings found

at Chicħen, and the books of ancient Maya authors.

As the general reader can hardly be expected to be familiar

with the peculiar customs and ideas of the natives of Central

America, these are sufficiently set forth in the Introduction, a

careful perusal of which will greatly contribute to an appreciation

of the poem.

Attention is also invited to the separate page containing a list

of the Maya names and their meanings.

The second part of this narrative poem must be regarded not

as a matter of belief on the part of the author, but solely as

having been suggested by the belief of the natives who worked

for Dr. Le Plongeon in his explorations among the ruins of

Chicħen.

INTRODUCTION.

The word Maya, though not familiar to modern ears, is a

most interesting one to the antiquary. It appears to have

originated with the great nation whose people, as well as their

language and country, bore that name, even thousands of years

back; their empire extended over the land comprised between

the isthmus of Tehuantepec and that of Darien; known collectively

to-day as Central America.

Dr. Le Plongeon has shown that in Yucatan and in Egypt the

radical MA, of the word Maya, meant earth and place. This

word was used by Hindoo sages to indicate matter, the earth, as

it is found in their cosmogonic diagram. All matter being regarded

as illusion, the word maya, in India, has that meaning.

The mother of Buddha was Maya Devi (Beautiful Illusion).

Maya is matter, the feminine energy of Brahma. But in the

Indian epic, “Ramayana”, Maya is spoken of as a great magician,

an architect, a terrible warrior and famous navigator,

who took forcible possession of, and settled in, the countries at

the south of the Hindostan peninsula. Plainly, the poet personified

as one hero the Maya colonists who long ago made their

way westward, across the Pacific, and settled there.

On the shores of the Mediterranean we find nations whose

ancestors seem to have been intimate with the Mayas, for the

names of their country, of their cities, and of their divinities can

be traced to the Maya tongue. Furthermore, their traditions,

customs, architecture, mode of dress, weapons, and even their

alphabetical letters are like those of the Mayas. From records

in stone and MSS. we learn something of the philosophy of the

Maya sages; and the same ideas are found among nations living

in Asia and Africa.

Nothing could be more significant than the universality of the

word Maya. In one country it is the name of a god or goddess;

in another that of a hero or heroine; elsewhere that of a cast,

tribe or country. This word is never used to indicate anything

unimportant. In Greece the goddess Maia was daughter of

Atlas, mother of Hermes, the good mother Kubéle, the Earth,

Mother of the gods. We see a vestige of her worship in the still

popular festival of the Maya or May Queen, fair goddess of spring,

May, that very month when the Earth, matter, Maya, lives

again, refreshed by the nourishing rain which, then particularly,

after a season of drought, pours down upon those latitudes where

the Maya nation had its birth.

The Maypole dance is yet performed among the natives of

Yucatan, the land where it probably originated. The dancers

are invariably thirteen in number, which may be another reminiscence

of the land submerged beneath the waves of the

Atlantic on the thirteenth day of the Maya month of Zac.

This Maypole dance, called in Yucatan “Ribbon Dance” is

unquestionably a vestige of sun worship; the ancients, versed in

astronomy, thus celebrated the sun’s entrance into Taurus, and

the vernal equinox. The Maypole, as known in Europe, has

been satisfactorily shown to be the remains of an ancient institution

of Persia, India, and Egypt, where Maya civilization was

carried in past ages. The May Queen is a personification of the

goddess Maya, the feminine forces of nature; possibly too of that

Maya country whence it came. In Yucatan there is no queen

connected with the dance; there it is and was sun worship pure

and simple.

In Yucatan, as in the British Isles and elsewhere, the pole is

planted before the residences of leading citizens, and the dance

is performed for a recompense. In Ireland the dancers wore

over their other dress white shirts, a detail which becomes interesting

in view of the fact that the Maya people always dress exclusively

in white.

In Dr. Le Plongeon’s prolonged studies among the remarkable

Ruins on the Yucatan peninsula, after finding, by much patient

endeavor, a clue to the hieroglyphic signs covering the walls of

ancient palaces and temples, he clearly saw that the word CAN

was inscribed in a variety of ways on all the buildings, and as

he advanced in his studies, he learned that this had been the

title of several monarchs who constituted a powerful dynasty.

It is a remarkably interesting fact that the same title, spelled

Khan, is to-day given to rulers in many of the Asiatic nations;

furthermore, the principal emblem on the banners of those Khans

is the serpent or dragon.

Continued research, including excavations and a close study

of every object found, together with several tableaux of mural

paintings, convinced Dr. Le Plongeon that he had succeeded in

tracing certain incidents which occurred in the last family of the

CAN dynasty, and which led to its downfall. Upon studying

the famous Troano MS., he found the same story recorded there;

and the tragic events resulting from the acts of one member of

that family, Prince Aac, are the theme of the present poem.

The scene is laid at Chicħen, which appears to have been the

favorite city of the CANS, judging from certain indications,

among these the prevalence of the serpent as an ornament in all

the buildings. These serpents are represented covered with

feathers indicating that they were emblems of Maya potentates.

On ceremonial occasions royal personages and high officials wore

mantles of feathers, whose colors varied according to the rank of

the individual; yellow being that of the royal family, red that

of the nobility, and green that of the learned men. The word

CAN has in the Maya language a great variety of meanings,

as Dr. Le Plongeon explains in his works; it is the generic

name for serpent.

The personages whom Dr. Le Plongeon succeeded in tracing

were—the CAN, his Queen, Zoɔ; their three sons—Cay, Aac,

and Coh; and two daughters—Móo and Nicté. There was also

an aged man named Cay, the High Priest, elder brother of the

King. This venerable person is introduced in the early part of

the poem. When he died, his nephew and namesake, Cay, succeeded

to his position and title. Let it be noted that the High

Priest was, as among the Egyptians and the Hindoos of old,

superior in authority to the King himself.

At the death of King Can, his daughter Móo became Queen

of Chicħen. As among the Egyptians, and the Incas in Peru,

so among the Mayas, royal brothers and sisters were obliged to

marry each other; in Siam and some other places the same

custom exists to-day. One of Móo’s brothers had therefore to

be Prince consort. Aac aspired to her hand, but Coh, a valiant

leader in battle, and favorite with the people, was her own

choice. This gave rise to lamentable events which caused the

ruin of the dynasty, Aac refusing to be reconciled.

In a carving on stone, as well as in the Troano MS. and the

Codex Cortesianus, Dr. Le Plongeon has found records of the

destruction by earthquake, followed by submergence, of a great

island in the Atlantic ocean. The author of the Troano MS.

affirms that this land disappeared under the waves 8,060 years

before the inditing of that volume. It is not known when the

book in question was written, but judging from Egyptian

records, the cataclysm must have occurred between ten and

eleven thousand years ago. In the Maya books the lost land is

called MU.

Lately Dr. Le Plongeon has discovered, in translating the inscriptions,

written in Maya language with Egyptian and Maya

characters, which adorn the faces of the Pyramid of Xochicalco,

situated sixty miles to the southwest of the city of Mexico, in

the State of Morelos, eighteen miles from the city of Cuernavaca,

that said pyramid was a commemorative monument raised to

perpetuate the memory of the destruction of the land of Mu

among coming generations, and that it was made an exact model

of the sacred hill in Atlantis which Plato in his Timœus describes

as having been crowned by a temple dedicated to Cleito

and Poseidon.

Looking at scenes depicted in mural paintings, one is driven

to the conclusion that the Mayas were much addicted to the

study of occult forces; they certainly used magic mirrors and

appealed to haruspicy in their desire to foretell events. As may

be seen in Dr. Le Plongeon’s “Queen Móo”, one tableau

represents a wiseman examining the cracks induced by heat on

the shell of an armadillo and the marks made by the vapor;

from these signs he endeavors to read the fate of the young

Princess Móo. The soothsayer, of the imperial family of China

uses a turtle in the same way in a ceremony called Puu, for the

royal family only, and in state affairs of exceptional importance.

Another tableau, also reproduced in “Queen Móo”, represents

one man in his feather mantle, mesmerizing another, showing

that hypnotism was anciently made use of in Yucatan by priests

and wisemen.

There can be no doubt that certain stones were considered

efficacious, as talismans. Jadeite, particularly that of a beautiful

apple-green, mottled with grey, was held in high esteem by the

Mayas, if they did not regard it as sacred. They called it

“Bones of the Earth” because it was the hardest stone known

to them. Of the many varieties of jadeite, for which no less

than a hundred and fifty names have been found, according to

Fischer, the apple-green is the most rare.

In the great square of the old city of Chicħen, Dr. Le Plongeon

discovered, in the thick forest, two very ancient tombs with some

of their decorative sculptures yet in place; those on one, enabled

him to see that the tomb had been erected to the memory of Coh

by his widow, Queen Móo. In it he found a statue of the Prince

consort; also a large white stone urn, containing what proved,

by chemical analysis, to have been human flesh, charred and

preserved in red oxide of mercury. In the same urn, among

other relics, was a beautiful ornament of green jadeite, like

those decorating the necks of various personages portrayed in

the sculptures of certain edifices.

In connection with the statue it must be observed that the

ancient Mayas held a belief similar to that entertained by the

Egyptians, regarding the condition of the soul after death, and

in the same way made a statue of the deceased, with the idea

that this would give the individual a hold upon life. The

natives who aided in bringing Coh’s statue to light, out of the

mausoleum where it had remained concealed for thousands of

years, invariably spoke of it as the “Enchanted Prince”, and

frequently assured its discoverer that he had succeeded in finding

it because he himself had dwelt there in past ages, and was one

of the great men whose effigies were seen on all sides.

When the larger portion of the charred viscera found in the

urn was burned, to reduce it to ashes, the natives standing by

exclaimed—“A majestic shade ascends amid the smoke! It is

the form of the enchanted Prince, that seems to fade into nothingness.”

So impressed were the men by what their imagination

had evoked, that all ran from the spot in a state of agitation.

On the day when the statue, weighing three thousand pounds,

was taken out of the monument, a party of hostile Indians

suddenly emerged from the forest. One of their number was

aged, and he remarked to his companions, “This represents one

of our great men of antiquity.” Then the young men paid

homage to the statue by bending one knee, in a manner peculiar

to those people.

Traditions of their ancestors are not altogether lost among

the natives, as some travelers assert. Many still perform rites

and ceremonies in the depths of forests or in unexplored caverns,

in the darkness of the night, but keep their secrets to themselves,

remembering the tortures inflicted on their fathers by the

Spanish priests to oblige them to forego the religious observances

that had been dear to those of their race for countless

generations.

In connection with the song to the rain-gods it may be said

that although the natives of Yucatan are to-day Catholic in

name, they really prefer to render homage to some statue of

their forefathers, and cling tenaciously to a few of their old

divinities. Among these may be mentioned Balam (tiger),

guardian of the crops, likewise appealed to as a rain-god. In a

subterranean cavern a few miles from Chicħen, there is an old

image of a man with long beard; this serves as a representation

of Balam, and to it offerings are made. The antiquity of the

carving cannot be doubted, similar ones existing on pillars at

the entrance of a very ancient castle at Chicħen. The figure in

the cavern is on its knees, its hands are raised to a level with

its head, palms upturned. On its back is a bag containing what

the natives say is a cake made of corn and beans. The statue

is now black, owing to the incense and candles with which its

devotees frequently smoke it. Previous to the planting of grain,

they place before it a basin of cool beverage made of corn, also

lighted wax candles and sweet-smelling copal, imploring the

god to grant an abundant harvest. When the crops ripen, the

finest ears are carried to the grimy divinity by men, women, and

children, who within the cavern dance and pray all day long,

some of their quaint instruments serving as accompaniment to

the Latin litanies which they chant, without having even the

vaguest idea of their meaning.

The sun-dance mentioned in the Preface, is occasionally performed

by Indians in Yucatan at the time of the vernal equinox.

Twenty men take part—corresponding to the number of days in

the ancient Maya month—but ten dress as women, whence it

may be inferred that in olden times the dancers were of both

sexes. All their faces are covered with masks of deer-skin, and

each has on his head the inverted half-shell of a calabash, with

turkey feathers standing up through a hole in the centre. They

wear their usual spotless white garments, and sandals. Those

clad as women are ornamented with large bead necklaces, principally

red, in imitation of old Maya coin, and all the dancers have

ear-rings. The hostile Indians[1] still pierce their ears as their

ancestors did; the rank of a chief being indicated by his having

a ring in the left ear only, or in the right, or in both.

The Master of the dance wears a stiff circular cap, surrounded

by upright peacock feathers that sway with every movement, towering

above all the dancers, and about his shoulders is a string of

big sea-shells. From his neck hangs a metallic representation of

the sun, in whose centre is an all-seeing eye within a triangle,

from which depends a large tongue, symbol of power and wisdom.

One man carries a white flag on which is painted an image of

the sun, and a man and woman on their knees worshiping it.

Three men, apart from the dancers, play a clarionet, a sacatan,

and a big turtle-shell beaten with deer-horns. The Master marks

time with a rattle, and in his other hand has a three-thonged

whip like the flagellum of Osiris in Egypt; throughout the performance

he remains standing close to the flag-staff.

Each dancer holds in his left hand a fan of turkey feathers

whose handle is a claw of that bird; and in his right a small

rattle made of a calabash shell, fancifully painted, containing

pebbles and dried seeds. These rattles remind us of the sistrums

used anciently in the temples of Egypt.

Around the pole on which the flag is furled, the dancers walk

three times, with solemn tread, groping their way as if in darkness.

Suddenly the flag is unfurled, the sun appears, all draw

themselves up to their full height, raise their eyes and hands,

and utter a unanimous shout of joy.

Now the dance commences, round and round the pole they go with

various steps and motions, not graceful, but energetic and

full of meaning. The dance is intended to represent, among

other things, the course and movement of our planet around the

sun. The chief and the dancers sing alternately:

“Take care how you step!”

“We step well, O Master!”

The melody and strange accompaniment are impressive and

stirring, the rattles being particularly effective, now imitating

the scattering of grain, then by a brisk motion of every arm

sending forth a sound like a sudden rainfall on parched leaves,

or a thunder clap in the distance, uniting with a shout raised by

the dancers at the conclusion of each chorus. The fans, kept in

motion, are emblematic of refreshing breezes.

The flag on the pole is undoubtedly a modern addition, simply

to indicate what the dance originally was; of old, the pole itself

represented the central orb; as the round towers did in Ireland,

Persia, and India; the conical stones in Phoenicia; the pyramids

and obelisks in Egypt, etc.—for in America, as in those countries,

sun worship was the religion of the people.

Finally, the expression “Will Supreme” in the opening line

of the poem is used in the sense of the Maya word UOL (or will)

as applied by the Mayas of ancient times to the First Great

Cause. This subject has been fully treated elsewhere by Dr. Le

Plongeon.

ARGUMENT.

I.

A soul returns to earth to live again in mortal form as

daughter of a potentate who rules over the Maya Empire.

When the Princess reaches womanhood, the High Priest

Cay, her father’s brother, describes to her the destruction of the

great land whence her people came; consults Fate regarding

her future; gives advice to the Princess, and presents her with a

talismanic stone, warning her that its loss might deprive her of

her throne.

II.

The Princess is wooed by two of her brothers, who thus become

rivals. Her preference is for Coh, whom she weds. Cay

prophesies to her that in another earthly incarnation she will

again be the sister and wife of him she has chosen for consort.

Aac, the unsuccessful suitor, is filled with jealous wrath.

The sovereign Can, and his brother the High Priest Cay, both

pass away. The Can’s eldest son, also named Cay, becomes High

Priest; Móo is Queen of Chicħen, and her consort the supreme

military chief.

III.

The Prince consort is treacherously slain by his brother Aac,

who admits his guilt, and is banished from the royal city, his

elder brother warning him that he, Aac, will cause the downfall

of the Can dynasty.

IV.

Multitudes assemble to bewail the death of Coh and witness

the funeral rites. His ashes are laid to rest and, with his

charred heart, deposited in a stone urn, the widowed Queen

places her talisman, hoping to thus link her destiny with that of

Coh. She builds a monument over his mortal remains and a

statue made to his likeness, and erects a memorial hall, upon

whose exterior walls she inscribes an invocation to the manes of

her consort.

V.

Notwithstanding his crime, Aac ventures to renew his entreaties.

Failing in his desire, he brings about a war that causes

the ruin of the country and people. Finally the Queen is captured

and imprisoned by Aac; but she is rescued by loyal subjects

and with them flees to foreign lands.

VI.

Aac, frustrated even in his hour of triumph, becomes a tyrant,

oppresses those under his sway, turns a deaf ear to better promptings,

and at last is killed in a contest with some of his own subjects,

who would restrain him. The famous CAN dynasty is

thus brought to its close.

VII.

The Queen and her rescuers find tranquillity in the land of the

Nile, where, long before, Maya colonists had made their homes.

Here, Móo is received with open arms, and reigns again to the

hour of her death.

SEQUEL.

I.

After many centuries have passed away, in a land far distant

from that of the Mayas, Death snatches a baby girl from a loving

brother. He stays upon earth; his lost sister again takes mortal

form in another family; they meet and are united; the prophecy

of the High Priest Cay being thus fulfilled. Together they

journey to the land of the Mayas where, in the tomb of Coh, they

find his heart and Móo’s talisman, in the urn in which she had

deposited it many centuries before.

II.

Among the ruins of his palace Aac’s spirit wanders desolate,

pleading for the blessing of forgetfulness in rebirth.

III.

The talisman brings visions of the long ago, voices of the

Past; Cay, the Wise, still lives, still leads the way to paths of

peace.

QUEEN MÓO’S TALISMAN.

I.

Moved by the Will Supreme to be reborn,—

In high estate a soul sought earthly morn;

Life stirred within a beauteous Maya queen

Of noble deeds, of gracious word and mien.

Beneath the wing of Can, just potentate

O’er Maya-land, of old an empire great,

The Princess Móo knew all the joys of youth,

Led on from day to day by Love and Truth.

Earth’s fairest blossoms at her feet were flung;

About her slender form rare pearls were hung.

The zephyr soft was music to her ear;

The tempest wild awaked in her no fear.

Within her being Past and Future slept,

And into guileless mind no phantom crept.

Heart sang with Nature’s harmonies its best,

Like warbling bird within a downy nest.

But soon ’mong roseate tints more sombre thought

Unto youth’s bubbling spring dark ripples brought.

An aged man, divine love in his face,

Led Princess Móo within a sacred place

And there relating many a tale of old,

Of years to come would something too unfold.

Faint echos even now reverberate

What he then told about the awful fate

Of Mu, imperial mistress of the seas,

Renowned for power and wealth thro’ centuries.

“O’erwhelmed was she in one appalling night

When Homen, raging in his fearful might,

Threw lofty peaks that lesser mountains crushed,

And every life was into silence hushed.

The rended mountains sent aloft their fire

To meet the lightning’s dart and then expire.

From earth and sky incessant thunder broke;

The bursting clouds forced back ascending smoke;

Soon over all the seething billows swept:

Death’s lullaby the waters purled, and crept.

Then towering seas that gleamed as with snowcap,

Tossed ships on land, while into Ocean’s lap

The land convulsed, her haughty mansions heaved.

Waves onward dashed, as roaring flames they cleaved.

In contest fierce, for mastery thus strove

The elements, as luckless Mu they drove,

With Death to battle, down in yawning hell;

By all her gods forsaken, doomed she fell!”

“In blind despair, brother ’gainst brother fought;

For feeble minds to frenzy soon were brought.

Upon their knees men grovelled in the mud;

In vain from crashing wall, from flame and flood,

A shelter sought, demented they, with fear;

And many a pleading eye met maniac leer.

Fond mothers left their babes and raving fled;

Thus fast and faster unto death all sped.

Men ran distracted; climbed the stalwart trees,

By earthquake rocked like craft on stormy seas.

Cast off, they rushed to find in caverns deep

A refuge safe; nor into those might creep;

For when they drew anear, with thunderous sound

The cavern mouths closed up as heaved the ground.

In cities rich and great the house-tops swarmed

With frantic men, by fear to brutes transformed.

Around, the blackened, angry waters surged

Till dwellings rocked, and melting soon were merged,

Engulfed in dark abyss with writhing woe,

All swiftly spent in one last awful throe!”

“The temples of the gods, the halls of state,

Quick fell, but failed Lord Homen’s greed to sate.

High towers of stone in fragments crumbled down—

Of perfect structure those, and wide renown.

About man’s shattered works the waters whirled,

And he, to Terror’s chariot lashed, was hurled

To deep repose or spheres to man unknown,

While mangled body lay in ocean prone.

Above the horrid sights and awful fear

Dark waters rolled, mud-laden many a year.

At dawn high crested waves, victorious,

Exulted over Mu long glorious!

Of what she was, some vestige yet may rest

In depth profound ’neath Ocean’s heaving breast.

Perchance, when ages shall have fled, that land,

Stripped bare—again unable to withstand

Volcanic force, that will her life-springs start—

May rise, and thus reborn again take part

On this small globe, mere cosmic spark! yet still

A universe whose powers await man’s will.”

“To Ku the Mighty, hosts of souls went back

Upon that thirteenth night in month of Zac.

The dross returned to nursery of Earth—

All form to fire and water owes its birth.

Our wisemen then by edict made that date

Each week, of thirteen days, to terminate.

And noble hearts that day, with sacred rite,

In urns are hid away from mortal sight;

Then during thirteen days we all lament.

When Maya nation mourns some dire event,

On thirteen altars we our offering make;

And thirteen guests at funeral board partake.

That famous Mu may ne’er forgotten be,

To grief belongs thirteen, by Can’s decree.”

“For many years Mu’s day of doom was feared,

When those who into magic mirrors peered

Saw visions grim; their minds were filled with dread.

Not all believed that into Ocean’s bed

A land of vast dimensions could be thrust

By Homen’s power, yet many felt mistrust.

But one there was more heedful than the rest,

In science versed and with discernment blest;

From Mu he sailed with those who deemed him wise—

Our ancestor was he, thou dost surmise.”

The Princess, deeply touched, in silence heard,

With close attention, not to lose a word.

“To Oracle that ancestor gave ear—

Yet he for self had not a thought of fear—

And thus were many saved, of noble race

That otherwise had left on earth no trace,

With him for guide to this kind shore they came,

Renewing here the glory of their name.

Then all agreed that Can should Sovereign be.

He earnestly desired they might be free

From failings he deplored in that great State

They’d left, because ’twas threatened by dark fate.

He warned them oft—‘Of luxury and pride

Beware!’—for well he knew how, side by side,

Such foes can plunge the soul of man in mire.

The arrogance of Mu roused Heaven’s ire;

At her debauchery shocked, the gods forth fled;

Deserted thus, in agony she bled.

Simplicity and virtue stern, Can taught;

With zeal his subjects held this righteous thought;

Rejoiced in peace, and in dominion grew,

Till far and near the Mayas throve anew.

Can passed away before proud Mu was crushed,

But his successor’s voice was yet unhushed.

Now, Princess dear, we reach, it seems to me,

Portentous years—come then, thy fate we’ll see.”

Thus spake the Sage, as o’er his raiment white

He threw an ample cloak of feathers bright,

Of royal yellow these and emerald-green,

Beneath the sky resplendent was their sheen

When forth he went, the Princess by his side,

To sacred place that had no roof to hide

The glorious light of day, but walled so high

That none could see within while passing by.

Móo’s simple mind was here struck with amaze,

For where the wiseman fixed his earnest gaze

An armadillo thence out crept, nor stayed

Till at her feet, as if it thus obeyed

A force unseen or was by fetter bound;

But none appeared upon that hallowed ground.

The aged man this creature gently placed

Above a brasier which the Princess faced;

As in its depth clear-burning charcoal lay,

With pity moved she cried aloud—“Nay! nay!”

But he—“Think not that I would torture this

Or aught that is; could I then hope for bliss?

Each being in Creation works its way

To perfect rest, all must this law obey.

From Ku all emanate, are thence divine;

Eternal law ordaineth all combine

To aid; each one of us must give and take.

This creature, serving us, will progress make,

And we are lifted up in reaching down;

Thus by endeavor we ourselves may crown.

Learn then, this little friend shall nothing feel,

Experience shall to thee a truth reveal.

Thy slender fingers I but touch, and lo!

All feeling goes, no heat therein doth glow.

Now move thy hand, ’tis free again dost find;

This holy law to suffering flesh is kind;

Who knoweth this, sensation can enchain,

And armadillo shall not suffer pain.”

’Twas true indeed, for tranquilly it stayed

Above the burning coal, quite undismayed;

While such the heat endured that soon its shell

O’erspread became with misty lines. To spell

What weighty meaning auspice might conceal

The seer watched, its purport to reveal.

What promised he—of what did he then warn—Could

she evade the fate foretold that morn?

For house of Can he prophesied defeat,

Through dark revenge its overthrow complete;

By jealousy brought on, and Móo its source,

Tho’ blameless she, herself bereft of force.

Then back to Cay’s sanctum both returned,

Móo’s heart oppressed by much that she had learned.

This mood the Sage rebuked and bade her hear

His words: “Dear child, thy path lies straight and clear;

Whate’er may hap, no thought of wrath outsend;

This breedeth ill and nothing doth amend.

In spite of many wrongs thou may’st endure,

Of fame this oracle doth thee assure.

’Twould seem a jest to bid thee do aright,

For man, alas! is in a woful plight!

He gropes along in quest of Wisdom’s ray

And, ever seeking, often goes astray.

In noble deeds exert thy human might;

Let acts of kindness be thy best delight.

To give advice for all life’s days who dare?

Can one foresee what pitfall may ensnare

Thy feet in paths where thou art bound to tread?

But come what may, thy soul must nothing dread.

Hate’s sting fear not; if thou no hatred give,

Its venom reacheth not what shall outlive

All trivial griefs and wrongs, thyself divine,

Bring what life will, let not thy soul repine.

Aid those who seek thy help; there is no joy

Surpassing this, unmingled with alloy.

We know that conflict is a law of life,

For matter feeds itself by constant strife;

The Will Eternal maketh this decree;

We feel results; the why we do not see.

The Heart of Heaven, throbbing with thine own,

Knows ALL IS WELL. The Infinite alone

Embraces all, and ever lures us on

To blissful rest where all return anon.

In paths of doubt and fear all onward go,

But knowing little, waver to and fro.

At times disconsolate, men yet aspire,

Labor and sigh for bauble they desire;

For riches, joys and honors, they contend;

But on the funeral pyre these all must end.

Let thy wish be to find the highest gift,

The Light Divine, ’t will ever thee uplift.

When grief shall rend thy heart, seek thine own soul;

Shut out life’s din, and find that sacred goal.

A talisman I give thee—jadeite green,

’Twill ever lend thee intuition keen.

Its wearer may with love herself surround,

For with attractive force it doth abound.

Would one deceive, and traitor prove to thee,

His mind with this thou wilt quite plainly see.

Thro’ centuries this talisman can bind

Two souls—desiring this, the way thou’lt find.

But keep it sacredly for thee alone;

If thou lose this a foe will seize thy throne.“

II.

The daughter of the Can was early wooed

By Aac, her brother, who with fervor sued;

A brother-prince by law must consort be;

In choice of one the future Queen was free.

And ’twas for Coh alone her own heart yearned;

Aac seeing this with jealous anger burned.

Those brothers fought as strangers cruel might;

Both wounded fell, a rueful, horrid sight!

Coh far and wide for valiant deeds was known;

The Princess Móo her courage oft had shown;

That they should mated be was right and just;

Thus by the Can, who in them put full trust,

Their nuptials sanctioned were, and many a day,

On pleasure bent, the people had their way;

For Can regaled them all with lavish grant.

At break of day was heard the deep-toned chant:

Lord of day we are Thine!

On our path deign to shine—

Holy Light!

Mortals glory in Thy might.

When night flees before Thy ray

We our voices lift, and pray—

Great Light!

Scarce rose the sun when crowds on sport intent,

From every door in quest of pleasure went;

All left their homes the time to pass away,

And on the air rang many a joyous lay

Of boy and girl who simple frolic sought,

And gaily sang with little care or thought.

Hear life’s jingle, come along!

All should mingle with the throng;

Clasp my hand, dear, haste with me—

Say not nay, for I love thee!

Quit thy nonsense or begone!

I am not thus lightly won.

Let’s go onward to the dance,

Give me but one tender glance!

Cease thy teasing, I’ll not go!

’Tis decided, thou must know.

Hear life’s jingle! join the throng;

Youth and pleasure stay not long.

With shades of eve came other dancers gay,

Their smiles enticing young and old away;

As in and out about the streets they roamed,

They joked and sang while many a goblet foamed:

On our dress of spotless white

We are wreathing garlands bright;

And will sing, kiss, sip,

With laughing, ruddy, lip,

Far away into the night.

Days of gladness soon take flight,

Love’s sweet nectar do not slight

Let us sing, kiss, sip,

And light-hearted gaily trip,

While our vows we once more plight.

And well they did to quaff the honeyed cup—

Why keep the mind with bitter thoughts filled up,—

The watchful gods no pity ever take

On those who sullen gloom will not forsake;

But on bright smiles, reflecting cheerful heart,

Frown not, e’en if gay Folly play a part.

O beauteous night! when lingering footfall strayed,

And stars reflected seemed where firefly played,

Each leaflet murmured lover’s tenderness;

Soul’s ecstasy was pure and fathomless.

O mystic Love! to every trivial thing

A new and holy charm dost ever bring,

With light and joy, to all touched by thy ray

Creation glows for him who feels thy sway.

Of one we love Perfection is the name,

For love is breath of God, all potent flame!

Thus ’twas a lover sang, with rapture filled,

When bird on leafy bough had softly trilled:

Ah! bird so gay,

Take not thy flight!

With dulcet lay

My heart delight!

Stay by me here,

For thou art dear—

Tho’ one I love is yet more dear!

Ah! floweret fair,

With breath of Morn

Upon the air

Thy perfume’s borne;

Thy life’s too fleet,

For thou art sweet—

Tho’ one I love is yet more sweet!

Ah! limpid dew,

Fair pearl of Night—

That doth anew

To petal bright

Give charm to lure—

Thou art so pure!

Tho’ one I love is just as pure.

In drowsy bud Night breathed. “May love here bide!”

But love and pain are one, so floweret sighed

When glistening dew to perfumed petal clung,

Imploring—“Wake me not! by zephyr swung,

Ah! let me linger in this happy state!

Ope not the way to pang that may await.”

But lovely Morn appeared with roseate ray,

And soon the god of day chased tears away;

Earth throbbed anew, leaves quivered with delight;

Flowers laughed, “We love! we live! thanks be to Night!”

In silent, sombre hour of deep repose

All form drinks in life’s force that ever flows;

And from the tranquil vale of balmy rest

Each being leaps—love’s joy they all attest.

On globes revolving night must follow day;

The universe doth this same law obey.

Pleasure with pain is mingled, gently kissed

By Sorrow, or regret for something missed;

As plaintive minor blends with major strain,

Fair Light’s attendant shades adorn her train.

And Móo upon her marriage day had mourned,

For she by Oracle had been forewarned

That Coh from her might in the future time

Be torn by dastard treachery and crime.

Beyond that time the wiseman too could see

That Móo, bereft and harshly wronged, would flee.

More strange than all, the Oracle foretold—

“In bitter woe this thought may thee uphold:

Both will return; the sister thou wilt be

And wife once more of him awaiting thee.”

The Prophet Cay taught Can’s eldest child;

With mystic lore their time was much beguiled;

For pupil would some day the High Priest be,

When his preceptor should from earth go free.

Surrounded by his volumes old, the Sage

In search of truth read over every page.

On rare occasions he before the crowd

Came forth to speak, and all to his will bowed.

Prophetic words were his, sincere and wise;

The Can obeyed when Cay deigned advise.

Revered by high and low, the honored Sage

Could by his will much pain and grief assuage—

Nor ever aid withheld, for he loved all—

But soon the Lord of life would him recall.

More than he did no one in mortal frame

Could do, aspiring to the Holy Flame,

To keep soul free from earth. His nourishment—

Whereon the sun its vital ray had sent—

Pure water, simple fruit, white flesh of bird,

Was more than he required, he oft averred.

In mystic posture he besought Mehen,

The Word, that he might wisdom pure attain.

He could at will ascend from solid ground

And float above, while crowds up looked spellbound.

Soon after Sovereign Can, without a throe,

Cay passed away, bewailed by high and low.

Around his flaming pyre, bowed in the dust,

All wept for him in whom they’d put their trust.

Can’s first-born son then filled the Pontiff’s place;

Thenceforth he would by every means efface

The jealous hatred rankling in Aac’s mind;

But he alas! with passion grew more blind;

For now that Móo was Queen, and consort Coh,

Her love he ne’er could win, nor him o’erthrow.

To Móo came other joys with baby lips;

Pure bliss from soft caressing finger tips.

III.

Beyond her palace wall Móo heard the chant

Of worshiper imploring Heaven to grant

Its bounteous rain, fresh life to Mother Earth,

The parched land to revive and save from dearth:

When the Master doth rise

To appear in the east

The four corners of heaven are released,

And my broken accents fall

Into the hands of Him who giveth all.

When clouds from east ascend

To the Orderer’s throne—

Ah Tzolan, who thirteen cloud-banks rules alone—

Where the lords cloud-tearers wait,

Biding the will of Ah Tzolan the Great,

Then the Keeper who sees

The gods’ nectar ferment,

With these guardians of crops is content;

They his holy offerings place

Before the Father, pleading for His grace.

I too my offering make,

Of beauteous virgin bird,

And myself lacerate, breathing holy word.

Thee I love! then heed my cry!

My offering place in hands of the Most High.

Could Móo in far off days forget that prayer?

Ah no! for as it died upon the air

A messenger appeared; his words sought vent—

Ill tidings had to him their fleetness lent.

Poor human heart! that blenches, quivers, shrinks,

Appalled at fatal stroke that swift unlinks

Two lives attuned to one harmonious breath.

O loving heart! thy cruel foe is Death.

With this compared all other anguish pales;

To soothe this pang no human aid avails.

Affrighted eyes met hers—“Speak! speak!” she cried.

Heart knew and leaped—“Thou art alone!” it sighed.

In broken words the dire event was told—

The herald was forbidden to withhold

The worst. Then fiercely battled in Móo’s breast

Wild rage and grief, while he obeyed her hest.

Scarce gone the man, when doubt brought some relief—

He must be mad! Allured by this belief

She fixed her gaze on Hope’s illusive beam—

“Untrue the tale! a frightful, ghastly dream!

He dead! Impossible! Sore wounded, yes,

As oft; his voice would ease her keen distress.

The valiant Coh could never vanquished be,

Victorious from every fight came he.”

Thus to herself, forbidding other thought,

And from her palace rushed, not caring aught

For those who would detain her steps, she fled

To meet the Prince; her servitors she led.

He came surrounded by a mighty crowd.

“Make way for us!” the Queen’s men cried aloud—

“The Queen is here!” Her breath was all but spent.

The bearers stopped; with cries the air was rent.

Then bending low, her arms about him flung,

She gasped! To his, cold set, her hot lips clung.

Beneath an arch of warriors’ shields upraised,

She saw, she felt; in death Coh’s eyes were glazed.

Ah! woful sight! ’twas more than Móo could bear—

She fell, unconscious of the tender care

On her bestowed, as homeward borne apace;

Far happier had she been in Death’s embrace.

’Neath holy Ceiba tree, upon the ground,

Struck down by one unknown, Coh had been found.

Whence came the treacherous foe? From foreign land?

Beloved by all was Coh—Whose then the hand?

With brother’s blood would Aac himself imbrue?

This thought in vain she struggled to subdue.

“I rave!” she cried; her mind with doubt was torn;

Those brothers royal were from one womb born.

“O wretched man! O cruel, monstrous fate!

Our Prince was sacrificed to mortal hate!

Unarmed was he when came the stealthy foe

Behind, to strike unseen the vengeful blow.

Thrice stabbed, Coh reeled and fell. Then turned to flee

His slayer, who rejoiced alive and free!”

With passion’s anguish riven, loud she moaned—

Could she forgive? Must this crime be condoned?

A deed so foul by her own brother base—

What act could e’er such deep-set blot efface?

For brother-consort by a brother slain

Must she herself with bloody vengeance stain?

To dark despair the Queen bereft gave way,

Nor heeded anyone who tried to stay

Her grief, until the Pontiff Cay came—

Successor to the Sage who’d borne that name.

Alone with Móo he groaned, “’Tis Aac I see!

His life is ours to take; but this would be

With crime as infamous ourselves to brand—

Let not two fratricides accurse the land!

Our impulse to avenge must be suppressed;

Nor may our soul by anger be possessed.

Let Aac himself convict. Do thou, I pray,

Request his presence here—he’ll quick obey.”

Aac’s handsome face wore mask of grief until

The High Priest sternly thus expressed his will:

“Our dauntless Coh is slain by one unknown;

The coward’s blood for this crime should atone.

The Maya nation mourns—be thine the task

To see the culprit found—’tis all we ask.”

Aac’s features changed, with ardor he exclaimed—

“Not so! no blameless man shall be defamed

For what my passion wrought—all mine the guilt!

No clemency beg I—do as thou wilt.”

There spake Aac’s better self; just thought inbred

Outbreathed. With pity touched, Móo’s loathing fled.

Nor could a child of Can know aught of fear;

Aac boldly stood, the Pontiff’s word to hear.

“Thou shalt live on; hast made thyself accurst!

Not thus will we—let fools for vengeance thirst.

From Chicħen, go! thy face we would not see.

An edict from our hand shall safeguard thee;

For, mark this well, the people soon must know

Prince Aac alone hath dared to deal the blow.

I see that war upon us thou wilt bring,

And finally, thyself proclaim as king.

Afflicted Móo will feel thy cruel ire;

Thus wilt thou weave for thee a fate most dire.

Myself, thy elder brother, thou’lt degrade;

Cans’ dynasty shall fall, by thee betrayed.”

Thus forth from royal city Aac was sent,

Empowered on native soil where’er he went,

To live in princely state, with means endowed,

While unto law and Sovereign’s will he bowed.

IV.

Sun-Scorched, for tears athirst was Chicħen’s square;

The funeral bed ’mid wailing crowds rose there.

Here many noble structures had a place,

With carvings red and gold upon their face.

The lofty stronghold in their midst, appeared

Like pyramid of human beings reared;

From base to summit on each side were seen

Brave men who for their chief felt sorrow keen.

On temple’s mound crowds flocked to view the square,

And hum of million voices filled the air.

Each road that led within the city wall

Was packed with mourning populace; and all

Betrayed the grief they felt. The flowers fair

In well-kept beds, the burden seemed to share

Of nation’s woe; all drooped their dainty heads,

Entreating those sweet tears that heaven sheds.

With Priestess Nicté, Móo was near the pyre,

To light the cedar logs with sacred fire.

Piled high were these, with odorous plants between;

And many lovely garlands too were seen.

The priests in flowing robes were stationed round:

By solemn rite the rank of each was bound.

First those in yellow clad, the sun-god’s sheen;

Then soothing wisdom-ray, fair nature’s green;

The next in line of blue robes made display,

Grief sanctified—the mourners sad array,

Beyond stood many others all in white;

And last, full armed as ready for the fight,

The orators of war, in gowns of red.—

Their ardent words to victory oft had led.

Long lance they bore, as on the battle field

Where glowed their eloquence—nor would one yield,

Except to Yum Cimil, but onward pressed

And dauntless to the last urged on the rest.

These now restrained the crowd that thronged the ground:

In that vast square no tearless eye was found.

Móo’s sister Nicté, priestess of the Light,

Sustained the hapless Queen thro’ funeral rite.

Coh’s heart, concealed within a close shut urn,

Was near the corpse, to char while that should burn.

That flames might higher leap and quick consume,

Fine scented oils, the hot air to perfume,

By priestly hand were lavishly out-poured

Upon the shroud of him whom all deplored.

Around the pyre, with measured step and slow,

His comrades, arms reversed, must three times go

Unto the left, anear the funeral bed,

That evil spirits might not reach the dead.

Thrice round they went, their object to attain,

All chanting as they marched, a solemn strain.

At signal given by trumpets’ ringing sound,

Hushed was the wailing of the crowd around.

Móo grasped the torch that would, from body dead,

Release the soul yet linked to funeral bed.

Alone she set ablaze the corners four—

A sacred right none could dispute, nay more!—

Her duty ’twas as true and loving wife,

To light the wood, speeding the soul to life

Or dreamless sleep, the Will Supreme to bide.

The multitude, when Móo the torch applied,

Upon their knees, their brows to earth, were bowed

Until the priests, “Arise! All’s well!” cried loud.

The priests and mourners now, each one in place,

Around the pyre, with sad and measured pace,

Unto the right, three times the way must tread;

To honor thus the memory of their dead.

And when the hero’s form was wrapped in fire,

Two mated doves, pure white, loosed near the pyre,

Up soared—of liberated soul the sign,

From prison freed, no fetter to confine;

Yet more, fair symbols of creative force,

Of life and death and all that is, the Source.

The grace divine was fervently implored

While hissed the leaping flame and loudly roared.

Transparent burned the wood with ruddy glare;

Melodious voices rose o’er trumpet blare:

Thro’ earth-life our footsteps lead,

Guide us into peace eternal,

Till from all desire we’re freed,

And perceive Thy Light Supernal.

Down sank the pile; priests chanting nearer drew

And on expiring flames sweet incense threw.

Speed thee now to realm of bliss,

Cast aside the thought of strife,

Tho’ each eye thy face will miss

And we mourn thee all our life!

Intoned the priests and slow their bodies swayed,

The dying embers fanned, and singing stayed

While these by murm’ring winds were borne away—

List where they might, they would life’s law obey.

Afar they floated on the zephyr’s wing:

No triumph now would Coh to Mayas bring.

Disconsolate, the Queen in anguish cried:

“Would that I had with my beloved died!

Why tarry here? My soul entreats release!

I too will sleep on Death’s soft couch of peace.”

From thought so weak, by Nicté she was freed

And tottering reason saved from foolish deed.

Then came the date of Mu, the thirteenth day,

When hearts of noble men were laid away.

Where sacred fire had liberated Coh,

The people once again were lost in woe.

Beneath the earth, shut close in virgin urn,

Wherein it safe would bide the soul’s return,

The heart of hero slain was put to rest

By those who in its love were more than blest.

Before the marble lid closed o’er the urn,

Upon that heart for which she’d ever yearn

The widowed Queen with loving homage laid

Her Talisman, at Cay’s order made;

By his strong will invested for her sake

With qualities she ever might partake.

Thus from the day this gift became her own,

When she’d been warned its loss might her dethrone,

The gem had nestled close about her heart.

But now, most eager she with this to part;

For Cay had affirmed its force could bind

Two souls thro’ time, if she the way would find.

Coh gone, could Móo rejoice on sovereign throne?

Ah no! far rather than a Queen alone,

A fugitive she’d be in boundless space,

Assured she would at last behold his face.

When talisman touched heart, a great calm fell

O’er Móo; to think they would together dwell

Once more, they two, within her mind distilled

A solace sweet that all her being filled.

Should earth recall them, as in time it must,

Each would the other seek in perfect trust;

From spheres of bliss, if parted, they would strive

To meet again and keep love’s pain alive.

Close by the urn a counterpart of Coh

Was set; as long as that endured below,

Desiring thus, he could to earth return

If e’er his soul for mortal life should yearn.

Walled close around, cut from a solid block,

That statue could the fleeting ages mock.

Secure from tempest and from mortal eyes,

This form Coh’s will alone might bid arise.

The pose it had been given showed regal state,

The boundary lines of Maya Empire great;

Where Cans, for justice famed, long ruled; rich land

Of men renowned for actions brave and grand.

Now on the spot a monument was reared,

On four sides marble steps; and there appeared

The emblems royal carved in fine white stone;

A leopard crowning all, Coh’s name made known.

The tomb complete, Móo likewise built a shrine

In honor of the Prince now hailed divine.

Of grand proportions stood that edifice;

No charm that art could lend would one there miss.

Here faithful hearts might manes sometimes greet,

And on the altar lay an offering meet.

On walls within the artist toiled amain,

Portraying there the life of chieftain slain.

On outer wall was graved a loving thought—

Her Consort’s mem’ry thus the Queen besought:

“Cay witness beareth—earnestly doth Móo

Hereby invoke her warrior-prince, great Coh!”

V.

And yet again Aac dared his cause to plead,

His hand out reached that Móo might love concede.

Mad! mad! he surely was—Can one plant deep

The seed of hate, and then hope love to reap?

Events that Cay had foretold drew near;

For self-willed Aac cast o’er the land dark fear.

Enraged, a pretext he failed not to seek

For war; and soon he caused the soil to reek

With blood of men; for him they bravely fought,

And led by him dire devastation wrought.

When nearly all the land bowed ’neath his sway,

Once more he tried with her to have his way;

By messenger himself would thus demean:

“To Móo, Aac yields, if she will be his queen.”

Could mortal strive to rouse with greater zeal

Fierce hate and pity kill? Her fall, his weal,

He’d thus make one. His queen! O hateful thought!

’Twas plain the war that he ungrateful sought,

Had prompted been by fixed desire to reign,

And with the throne its Queen too he’d obtain.

With just wrath filled Móo scorned the victor’s plea—

Lose all she rather would, her palace flee.

Too soon indeed was this to come about,

Cay’s prophecy no longer one could doubt;

For Aac without delay acquired new force,

Nor cared who fell beneath his reckless course.

At last exulted he in Móo’s defeat,

And deeds were done that time could ne’er delete.

The noble Pontiff was at once abased

By Aac, who deeply thus himself disgraced.

When Móo’s defenders lay around her slain,

Her freedom she no longer could retain;

Then captive she was led to meet her fate.

Within Aac’s breast now battled love and hate.

Yet dared he not that heinous sin commit,

Compel what woman’s heart would not permit.

He hoped she soon would plead to be set free,

And since all else was lost for her could she

Withstand his ever strong desire? Relent

She must—to be his consort now consent.

Móo looked for death; she would surrender life,

Escaping thus all further pain and strife.

But jailers were by faithful friends embroiled;

At heavy cost Prince Aac’s designs they foiled.

Success was theirs, and guarding her with care,

They gained the coast, great oceans storms to dare.

“Dear native land, where tender mem’ries cling,

No other spot such happy years can bring!”

Thus to himself each, silent, said. The past

Knew no appeal; the lot of all was cast;

The future might, perchance, hold something yet.

And when the sun arose, the sails were set,

That all might find on distant, foreign shore,

New homes, where peace would bless their days once more.

Devoted subjects they, renouncing all

To rescue captive Queen, whose complete fall

From sovereign power forbade a hope of gain;

Their only wish to save her further pain.

Thus they with her now fled from Aac’s mad hate,

Untouched by fear of what might them await.

Afar the voyagers went from place to place,

And stayed at length where men of Maya race—

Bold navigators they for centuries back—

Had made a home, and nothing there could lack.

VI.

Thus Aac remained with power complete at last;

But all his triumph was by gloom o’ercast;

He writhed in torture when, each night, he thought

How great the cost at which his throne was bought.

Worse yet, he’d lost the stake for which he played—

To fail in winning Móo, all else outweighed.

Upon his soul wrath preyed till spent; and now

Dark melancholy hovered o’er his brow.

Unsatisfied, unresting, ne’er at ease,

Seek where he might, nothing in life could please.

Alone he ruled, none dared his word gainsay;

But this could not his discontent allay.

’Twas not remorse that ever brought him pain,

But fierce regret that he had failed to gain

That chief desire of his unyielding will:

This bitter thought his mind would ever fill.

Defied and baffled in his hour of might,

He hated all who had contrived Móo’s flight.

Each one suspected quickly met dark fate;

But cruel deeds could not Aac’s ire abate.

By passion swayed like tree in tempest blast,

All wish for good and right aside he cast.

One satisfaction yet remained to him—

The flight of time should not his victory dim;

His palace walls should bear upon their face,

In carvings deep that time would ne’er erase,

His triumph over all who strove in vain

To hold him back from what he would attain.

And thus ’twas writ above his palace door,

Above the polished, crimson-painted floor.

Now came the days when Mayas knew no peace

’Neath Aac’s harsh rule, and war that did not cease.

With sacred rite they strove to know the will

Of Can the Good; response came not, yet still

They plead; by holy fire would feign invoke

Some aid; and mystic power at last awoke

To seer’s gaze the mighty Can of old,

Whose visage stern and sad his sorrow told.

No hope or promise in that face was read;

The country still would be by tyrant bled.

Again the seers besought, and Coh appeared—

Brave prince who had to all himself endeared—

Averted was his gaze, his hands upraised,

Aggrieved he seemed to be and sore amazed;

But not a word expressed; no hope gave he

That from the tyrant Aac they might be free.

There came a final day of vengeance dire,

When subjects turned upon their haughty Sire.

E’en to this time may yet be seen the place

Where he was killed by one of Maya race;

Where last he took his stand upon that height

Within his palace grounds, there forced to fight

In self-defence or yield to prisoner’s lot;

Restraint his outraged subjects planned. ’T was not

Their wish, e’en now, to slay the wilful man

Whose being throbbed with blood of honored Can.

Aac towered there amid his fallen men,

Defiant, raging, livid, and ’twas then

That one named Pacab flung his arms aside,

Approached the Prince, and as he neared him cried—

“Now yield thyself; we would not do thee wrong;

Full well we know all rights to thee belong.

Thy safety we desire and not thy life,

Tho’ thou hast filled our land with grief and strife.”

With one fell blow Aac struck the speaker dead,

Then shook the dripping axe above his head.

But scarce the deed was done when from the crowd

An elder man leaped forth and wailed aloud—

“My son! my son! avenged thou now shalt be;

Thy life destroyed, no Prince is there for me!”

This said, he sprang upon the stalwart Aac

Like maddened brute and roared—“Thy soul is black!

Defend thy life; strike swift or breathe thy last!”

While yet he spake his blows fell thick and fast;

Then Aac, in flaming wrath, stabbed deep his foe;

Their blood in mingling stream was quick to flow.

’Twas fierce and brief, the Prince was first to fall,

But wounded unto death, beyond recall,

Was he who thus avenged his country’s woes

And brought the reign of Aac to tragic close.

VII.

Where flows the river Nile, the Queen found rest;

There once again her days with peace were blest.

Upon that soil where welcome frank was found,

Did Móo a giant Sphinx from out the ground

Cause to arise, and thus Coh’s fame renew?

Did she immortalize her consort true?

As child of Can the natives called her Queen;

Their ancestors Cans’ subjects all had been.

Móo reigned again, and many a year she dwelt

In Chem, the Land of Boats. There too she felt

Her call to liberty, and passed away,

Rejoiced at last the summons to obey.

“Now cometh bliss! the flesh doth loose its hold;

Death’s tender kiss will leave it still and cold.

Upon my weary brow the veil of Night

Descends; my soul leaps forth to joyous flight!

O touch my heart with thy all-healing balm

Oblivion sweet! now lull me in thy calm,”

Móo yearned for this. Then fell upon her ear

A voice—“Blessèd are they who know not fear!

The Heart of Heaven e’er radiates love’s light,

And soul released finds nothing to affright

Save visions false of terror, bred by creeds,

And deep remorse that gnaws at evil deeds.”

Soul stirred, awoke and saw! Herself Móo found.

Was this the law, tho’ not to body bound,

To still live on? What time in nothingness

Had fled? Since she besought unconsciousness

Had ages sped? And now appeared her guide,

Cay, whom long she mourned when he had died.

His clear calm eyes again she searched amazed;

Their power thrilled and drew her as she gazed.

Then murmured she—“If this be happy dream

Let me dream on.” O Light! thy wondrous beam

Throughout creation glows, now and for aye,

If Will Omnipotent ordaineth day.

Thy rays are harmonies, celestial Light!

Because thou art, there is no endless night.

Earth’s weary children long for deep repose;

But from the glorious light all music flows.

As night and day forever alternate,

In darkest silence life doth germinate.

No mortal can conceive th’ entrancing sounds

That greet the spirit freed from terrene bounds.

Could love’s effulgence from supernal spheres

But reach the mortal eye bedimmed with tears,

A solace sweet as rain on sun-parched leaf

Would fall on those bereft and bowed with grief.

No more would Death a bitter foe appear;

Kind Hope and Faith would banish Doubt and Fear.

To Móo awaked another rapture flowed—

Coh’s eyes with love unquenched before her’s glowed.

O Love! thou art the power of life, the force

That lifts the soul; Divinity thy source.

Ignoble things thy presence doth redeem,

Sweet breath of God! most holy and supreme!

Eternal thou, throughout the boundless space;

Thy purity no act can e’er abase.

Deep passion broods pent up, in matter dark;

Death comes, and there upon his gliding bark

Reality appears; soul finds its own—

Pure Love released, unmasked, stands forth alone.

By man has time been made the gauge of Earth.

What cares the soul in realm of spirit birth

How oft around spin globes above, below?

Of happiness do beings weary grow?

Must they return—again to feel the throes

Of matter’s strife—from passionless repose?

SEQUEL.

Ages Later.

I.

While mortals slept and stars lit up its bed,

Ere Phoebus smiled the infant’s soul had fled.

Kissed by the god of day, a blue-eyed boy

Sprang from his couch, with eager love and joy.

White twinkling feet then ran across the floor

To Natalie, as many a morn before.

Death’s mystery to him was yet untaught;

The lifeless babe no dread to his mind brought;

To mother’s arms he bore the drooping form—

“Poor baby cold! make pretty sister warm.”

The lustrums sped. A girl of lightsome heart

Was told, “He comes! with him thou must depart.”

To find her in the East, he sailed from West,

Responsive to the power of soul’s request.

Resistless forces bade her go fulfill

The part that she, by her own human will

Had planned upon a day, when swayed by love

She would her consort find, on earth, above,

Wherever might he dwell there too would she:

Attachments deep can bind like stern decree.

To learn the past, to Maya-land both turned,

But no faint ray of mem’ry in them burned.

Altho’ he murmured in a certain place—

“Familiar ’tis, there’s something I would trace.”

As Maya chief reborn, men of the soil

Hailed him, and led by him would patient toil

In forest depths, ’mid desert mansions old

And temples drear—their history to unfold.

Within a white stone urn in ancient tomb,

Charred heart and talisman lay in the gloom.

To her he gave the gem,—“Now take thine own,

I pray; henceforth it must be thine alone.”

In dancing flame the mortal dust from urn

Was thrown. “A form ascends from what doth burn!”

The natives loud exclaimed, “A princely shade

That into nothingness doth quickly fade.”

When evening came, and all from work reposed,

They told the white man why the things inclosed

Were found by him: “Thou art returned once more

From long enchanted sleep; wast here before.”

To this, both earnestly responded—“Nay,”

But nothing changed; the men thought their own way.

II.

Fantastic thought cut loose from reason cool

Are dreams wherein the wisest play the fool.

Can dreams be memories? Are some portents?

Who knows? His ignorance man still laments.

The woman dreamed among the Ruins gray,

Where moon shines in at night and sun by day

On crumbling floors where powdered bones thick lie

And glistening serpents glide with gleaming eye.

Now as she seemed to roam in palace drear,

A man in rich and strange attire drew near,

Bemoaning thus: “May every wind and leaf

Re-echo now my wail of hopeless grief!

In mercy shine upon my endless woe,

Great Sun! from whom all life and light outflow.

Here crouches Aac, alone from age to age—

Absorb me now, my wretchedness assuage!

Remorse, to thee I said, ‘Return no more’—

Thou shalt not stay to goad me as before!

O Light Eternal! bid this mem’ry die

While penitent upon the ground I lie.

Tho’ long the years of anguish I have spent,

The worm gnaws on as if ’twould ne’er relent.”

He prayed and wept. Response came from above—

A woman’s voice replied with pitying love.

Up started he—“Hush! hush! thou knowest not,

But I know who thou art. O bitter lot!

To jealous frenzy I became a slave

And vilely slew my brother true and brave,

Thus casting o’er my sister’s life a blight.

Still mad with rage and lost to sense of right,

I crushed my elder brother in my wrath;

Tho’ Pontiff he, I swept him from my path.”

“My vicious mood led many where they fell;

I lied to them that they might serve me well.

No fiery couch was lit for heroes slain;

Now I could crawl o’er moldering bones, and fain

Would lick their dust—so low my haughty head—

I, lord of all! for whom their blood was shed.

A tyrant harsh, imbittered I became;

Nor could my soul’s rebuke awaken shame.

O Mother! drop thy tears; accurst for aye

Am I! the drouth of this, my land, allay.

Send down thy light, Great Sun!” he cried aloud,

“Let me forget! with mortal form endowed.”

To her he turned again:—“Forgive! forgive!

Earth-born thro’ thee, ah! let me once more live.

My crimes and victories, my soul’s defeat,

My anguish and remorse, wilt thou repeat;

For thus alone new life may dawn for me—

In solitude I’ve long awaited thee.”

A falling tear the sighing dreamer woke:

No mem’ry of the past could she evoke.

III.

Again the Talisman, now set in gold,

Was worn by woman as in days of old.

She asked herself, “Doth mystery lurk herein?

Can we from this some hidden knowledge win?

Perhaps for us there is a task to do,

Of bygone times some link to find anew.

Cold stone! if dowered thou by magic deep,

What then—if silence thou must ever keep?

Jadeite grey-green, by ancients called divine,

Till Earth grow cold this talisman may shine;

As it hath seen long eons in the past,

So may it yet man’s memory outlast.”

’Twas thus the dreamer meditating thought,

Till by her strong desire some rays were caught.

A mystic clue this stone of magic, yea,

To scenes of long ago—but find the way.

Like other million forms, stone hath a soul,

A spark divine of God the Perfect Whole.

Then heard the woman toying with the stone:

“With power was this endowed for thee alone.”

What voice thus spake from mind to mind? No sound

The silence broke, wherein her thought was bound.

“’Tis I, among Earth’s men thy friend of old;

In times long past this page I thee foretold;

For thou hast been in this, his present life,

His sister one brief year; thou art his wife.

Attachments deep and strong are ties that bind;

We ever take the skein again to wind

Ourselves about with bonds that draw us back,

And which none other than ourselves can slack.

He came to give the ancient Maya race

Its right—on history’s page a noble place.

He would to light restore what’s hid away,

And throw upon the past a clearer ray.”

“When we outgrow desire for mundane things—

Which are but means—our spirit finds its wings.

When universal love and light are all

We crave, no power of earth can us inthrall.

Peace comes alone through matter, which is strife;

Right effort lifts the soul to purer life.

To do his best is all man knows of right—

Observing this, he finds the spirit’s might.

To dread the Great Unknown is bondage vile

For man; this fear’s a sin that doth defile

The thought and deed of multitudes. In space

No depth is found where evil can efface

Love’s holy, constant, all-pervading ray;

Go where soul will, it need feel no dismay.

Peace dwells in Heart of Heaven, eternal Ku;

But in the rugged paths that lead thereto

With turmoil finite being makes its way—

Tho’ none know why or whither, all obey.”

The clasping hand let fall the talisman

Placed centuries agone, by child of Can,

To serve as link with mortal heart in urn.