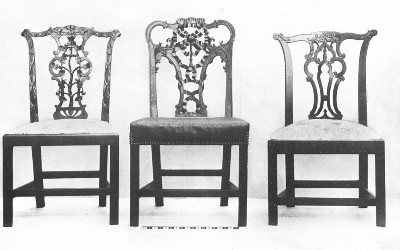

| PLATE XXXV | CHIPPENDALE CHAIRS |

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Brochure Series of Architectural

Illustration, vol. 06, No. 5, May 1900, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Brochure Series of Architectural Illustration, vol. 06, No. 5, May 1900

Chippendale Chairs

Author: Various

Release Date: January 6, 2015 [EBook #47893]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BROCHURE SERIES OF ARCHITECTURAL ILLUSTRATION ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Haragos Pál and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE BROCHURE SERIES

|

THE |

||

| 1900. | MAY | No. 5. |

It is only within recent times that movable chairs have become common and indispensable. Seats of some kind must have been used from the time when houses were first built, but it is not until the civilization of the last two or three centuries had transformed the old ways of living that we begin to find them in common use. Representations of seats are found in the sculptures and paintings of Egypt, Greece and Rome, and all through the middle ages—many of them elaborate and luxurious—but their use was confined to the noble and wealthy. In church furniture chairs are familiar throughout the middle ages, but they were usually fixed parts of the building. The seats of the common people were probably constructed of rude blocks, or of single planks joined together with little finish or skill.

In England, even so late as the sixteenth century, chairs as we know them were of so rare occurrence as to be handed down from generation to generation, and of such importance as to be frequently mentioned in wills and deeds. Such chairs were of the rudest forms, ornamented, however, with embroideries and costly stuffs. In the middle of the seventeenth century it was customary even at royal banquets for all but the king and queen to be seated upon benches without cushions. In the reign of Charles I., however, with the encouragement of luxurious living, chairs became more common among the favored classes, and under the Commonwealth, with its levelling of class distinctions, their use was extended. But in the latter period the revulsion against unnecessary ornament and display simplified the models. With the Restoration there was a return to the opposite extreme. The growing taste for ease and luxury brought into requisition the richest fabrics obtainable, and we find stuffed seats and backs, with Turkish embroideries and heavily brocaded velvets. Chairs were elaborately carved and gilded. French furniture was imported and copied, and the influence of Indian art, through the recent acquisition of Bombay, can be easily traced. Of the simpler patterns, those made of turned spindles became common at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Forms were borrowed and adapted from many sources, from France, Spain and Holland. In the time of William and Mary, under Dutch influence, the seats and backs were broadened, colored inlay introduced, and the "cabriole" legs commonly employed, suggesting the forms later adopted in the Chippendale period. The strong point of English furniture was not its originality, but its catholicity. It was a mirror which reflected the outcome of other times and countries in a frame of its own.

The period when Chippendale appeared on the scene seems to have been one very favorable to the success of his enterprise. The middle classes were already accumulating wealth and beginning to assume numerical and political importance. The troubles of civil war were over, the reigning dynasty had successfully overcome the last attempt at revolution, and the situation promised an age wherein the comforts of life might again be enjoyed in security. English trade with Holland, doubtless very largely fostered by the Dutch proclivities of William III., had helped to disseminate a love for pottery and lacquer work of the East; artificial works were multiplying, and the middle classes, above all, wanted for the furnishing of their rapidly rising, substantial dwellings something more sumptuous than the humble simplicity of the common Jacobean—something which would have a taste, at least, of the luxurious extravagances of the French reigning style.

English furniture of the time of Chippendale had profited by the best of the past and of the present. It closely resembled the French work of Louis XIV., but it had reached such a stage of perfection, though still made up of heterogeneous elements, that it was for the first time valued above the productions of other countries, and was even taken abroad to be copied, while the books of designs published by the English cabinet-makers were translated into other languages. In the preface to Hepplewhite's book of designs, published in 1789, there is this statement, which is of interest as indicating the esteem in which English cabinet work was held abroad, viz.: "English taste and workmanship have of late years been much sought for by surrounding nations; and the mutability of all things, but more especially of fashions, has rendered the labours of our predecessors in this line of little use; nay, in this day can only tend to mislead those foreigners who seek a knowledge of English taste in the various articles of household furniture."

Oak had been the prevailing material up to this time, but now mahogany took its place. An interesting account of the introduction of mahogany for furniture is given by Frederick Litchfield in his "History of Furniture." He says, "Mahogany may be said to have come into general use subsequent to 1720, and its introduction is asserted to have been due to the tenacity of purpose of a Dr. Gibbon, whose wife wanted a candle-box, an article of common domestic use at the time. The doctor, who had laid by in the garden of his house in King Street, Covent Garden, some planks sent to him by his brother, a West Indian captain, asked the joiner to use a part of the wood for this purpose; it was found too tough and hard for the tools of the period, but the doctor was not to be thwarted, and insisted on harder-tempered tools being found, and the task completed. The result was the production of a candle-box which was admired by every one. He then ordered a bureau of the same material, and when it was finished invited his friends to see the new work; amongst others the Duchess of Buckingham begged a small piece of the precious wood, and it soon became the fashion."

The Jacobean and cognate styles, consisting fundamentally of "framing" based on rectangular forms and decorated with characteristic carving and turning, may be described as essentially suitable for oak, of which the open character of the grain forbids any extreme minuteness of detail. The particular qualities of the work of Chippendale and his successors demanded, on the other hand, the use of a very different material. Chippendale's delicate carving and his free use of curves, even in constructive members of his design, could have only been satisfactorily wrought out in a wood of fine, hard and close grain, and one which also possessed great lateral tenacity, such as mahogany. It is scarcely too much to say that, but for the introduction of this beautiful wood the specialty in the work of the cabinet-makers of the eighteenth century would have been impossible.

Together with the refinement of design came a perfection of construction and workmanship which has rendered the furniture of this period practically indestructible. It is said that Chippendale never carved a fret without gluing together three thicknesses of wood with opposing grain, and his work is so joined with tenons and pegs that it stands as well today as when first put together. Sheraton devoted whole pages of his book to constructive directions for the most simple table. This excellence of construction, and the eminently practical and usable character of the best of the eighteenth century work have been potent factors in helping to preserve the many examples of it which we fortunately possess today.

It will probably be a surprise to the reader who has had no occasion to inquire especially into the history of household furniture to know that a century and a half ago furniture makers, in England and elsewhere, resorted to much the same method of securing customers, by publishing illustrated catalogues, as do our own enterprising manufacturers. Among the earliest of these trade catalogues, as we now call them, was that of Thomas Chippendale, the first edition of which was published about 1750 (the exact date is in doubt), and two later editions are known. This catalogue has been reproduced in recent years and many of the plates have been frequently copied, until the Chippendale designs have become familiar, and the name applied broadly but loosely to all of the work of the period, including a great deal which by right has no connection whatever with Chippendale. The illustrations in this catalogue were elaborately engraved on copper, and it was entitled "The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director." It contained over two hundred engravings of useful and decorative designs, some of which, however, were probably never executed. It included designs "in the most fashionable taste" for a great variety of furniture "calculated to improve and refine the present taste, and suited to the fancy and circumstances of persons in all degrees of life." A great deal of the design is traceable to French influence, and may have been borrowed directly from similar books by French cabinet-makers.

Of Chippendale himself little of a personal nature is known. Both he and his father were carvers, and it is no doubt true that to the repute established by his father as a basis, he added superior skill and taste, and the shrewdness of a tradesman. It is by no means certain, however, that in his time, or immediately after it, his reputation was greater than that of other cabinet-makers. His present celebrity depends more upon the survival and later reproduction of his book of designs than upon any contemporary fame. That he had refinement of taste is proved by his designs; but that he was anxious, above all, to secure patrons is hardly open to question. Mr. J. A. Heaton ("Furniture and Decoration in England during the Eighteenth Century") calls him a "vulgar hawker" ready to make anything that would fill his purse. His book, the text of which is written in the bombastic style of the period, begins with an explanation of the classical orders of architecture, holding them up as the only basis of true design in furniture; but he later refers to certain designs "in the Chinese manner"—which were made, quite certainly, in response to the fashion introduced in England by Sir William Chambers,—as the most appropriate and successful of his whole collection.

Although much of the furniture of the middle and latter part of the eighteenth century is wrongly attributed to Chippendale, and he is now popularly held responsible for many excellencies as well as many faults which do not belong to him, the evidence of his book goes to prove that his work at its best was superior to that of his contemporaries, and vastly superior to that which either preceded or followed it.

Chippendale's ordinary furniture may be conveniently classified under three heads of very various artistic value. The first is the pure rococo. In this class of work we find, as Mr. Basil Champneys has happily described it, "intemperately flowing lines, wantonly twisting volutes, fantastic and unmeaning forms, suggestive about equally of organic and inorganic nature, bursting here into a gryphon's or sphynx's head, or there into a bunch of flowers; writhing into a mermaid, or culminating in a trophy; here the volutes are propped with an utterly dissipated and abandoned Gothic shaft, there is the ghost of a classic pediment; here a whole piece of ruin is bodily foisted in; a fortuitous interval is occupied by a sportsman or a flirtation, or by the conventional Chinaman, with an impossible mustache and inconceivable hat. The two sides of the design are seldom alike; symmetry is ostentatiously avoided; everything twists, twirls, writhes, changes, gets distorted like the images in a dyspeptic dream over a book of travels, from which the reader will be glad to awake."

Fortunately for Chippendale's fame this class of work forms but an insignificant portion of the remains of his furniture now extant—a fact which is owing in some measure to its constructive weakness. Its merits are purely those of a skilful carver.

A second important characteristic style was that which may be described as "fret work." Some pieces coming under this description, shelves and cabinets for china, amongst others, are constructed almost wholly of thin slabs of wood pierced with a great variety of small patterns, many of them very intricate. These are dainty pieces of furniture, well suited for the drawing-room and boudoir; and it speaks volumes for the care and finish in the workmanship that any of them have been handed down to us in a perfect state during so long an existence.

What is sound of the reputation that Chippendale has earned, however, apart from the excellence of his workmanship, lies in the furniture coming under the last head of our division—in pieces wherein we find the decoration applied, a little lavishly it is true, with a certain admixture of straight lines and plain surfaces with which to contrast it. In these, members otherwise square and straight are enriched with delicate and shallow sunk carved work, sometimes based on geometrical patterns. The backs of chairs, although consisting of curved forms, have commonly a rectilinear disposition of the principal lines, and the curvatures of the constructional members are so subtle and restrained that the impression of strong wooden construction is not wholly destroyed. The supporting members, such as legs of tables and chairs, are often kept straight, and the carving, where applied, is kept so shallow that it does not interfere with the apparent or real capacity of the parts for the function for which they are designed.

In appraising his merits it must always be remembered that Chippendale was pre-eminently a carver; and as a carver producing work applied to objects of utility he holds an unchallenged position.

Mr. K. Warren Clouston, describing the work of this period (The Architectural Record, Vol. VIII.), says: "Chippendale, above all things, was a chairmaker, and his chairs are full of variety, at first with the high back, cabriole leg and claw-and-ball foot of the so-called Dutch taste; then rising to lighter fancies, either with vase-shaped ornament, flowing ribbon bows, interlacing frets of Gothic tracery. But what matters it whether the rococo ornament then prevailing on the continent, the Chinese leanings of Sir William Chambers, or Strawberry Hill Gothic were adopted, when the different sources are blended in one harmonious whole? We give Chippendale the first place simply from his book, for the squat backs and ungainly chairs of Manwaring and the Society of Upholsterers, and the badly designed seats of Ince and Mayhew only serve to accentuate the work of the master hand."

The chairs chosen for illustration in this number are of the simpler patterns. It will be seen that they have very little ornament, and that this is almost entirely confined to the backs, the legs being in most cases square and plain. In the backs the same lines occur as in those made in the time of William III., but instead of the frame of the back being covered with silk, tapestry or other material, Chippendale's are cut open with fanciful patterns. Those with cabriole legs usually have claw feet and a shell or leaf at the top. The chairs in Chippendale's book are much more elaborate than those here illustrated or than those he ordinarily produced. This is naturally accounted for by the desire to induce customers to purchase the more expensive pieces. The simple square leg without taper is one of the distinctive marks of Chippendale's time. Later in the century, in the work of Hepplewhite and others, the legs were made more tapering and the whole chair much lighter and more elaborately ornamented to correspond with the Renaissance forms then in vogue. The turned leg is rarely found, although much used later. The shaping and ornamentation is generally confined to the front legs. Mahogany, as has been stated, was the wood most used, and the ornamentation was confined as a rule to carving. Inlay and marquetry, brass and ormolu were employed on other articles of furniture, but the chairs rarely have such ornament.

The rococo of Chippendale's earlier work, corresponding to the French of Louis XV. and XVI., was succeeded by a modification tending towards the severer Renaissance, influenced by the designs of the architects, Robert and James Adam, who gave their attention to the minutest details of interior decoration and furnishing, as well as the larger problems of architecture. Of Chippendale's contemporaries, Ince and Mayhew, who also published a book of designs, are now looked upon as most deserving to share his fame, although there are records of many others.

Hepplewhite forms a connecting link between this period and that of the more severe lines of Sheraton and Shearer. Sheraton was a skilled and cultivated man and an excellent draughtsman. Among the subscribers to his book, "The Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing Book," published in 1793, are the names and addresses of no less than four hundred and fifty cabinet-makers, chairmakers and carvers, not including musical instrument makers, upholsterers and other kindred trades. This gives some idea of the extent to which such books were then employed, and the number of makers whose work is not now distinguishable and whose names are lost in oblivion. Following the work of these men came the "Empire" style introduced in France after the French Revolution.

Readers interested in the subject of the furniture of the Georgian period are referred to the recently published large collection of photographic plates, entitled "English Household Furniture" (see announcement in our advertising pages) from which our present illustrations have been reproduced.

Note.—The illustrations in this issue are reduced from large photographic plates in the recently published work, entitled "English Household Furniture, mainly designed by Chippendale, Sheraton, Adam and others of the Georgian Period. 100 Plates, illustrating 348 Examples." Bates & Guild Company, publishers, Boston. See advertisement on another page.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Brochure Series of Architectural

Illustration, vol. 06, No. 5, May 1900, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BROCHURE SERIES OF ARCHITECTURAL ILLUSTRATION ***

***** This file should be named 47893-h.htm or 47893-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/7/8/9/47893/

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Haragos Pál and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.