TABLE OF CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.—Swiftwater First Hears of the Golden Find on Bonanza, in the Klondike.

CHAPTER II.—Lure of Great Wealth and Love of Gussie Lamore Starts Swiftwater on His Career—True Story of Famous Egg Episode in Dawson.

CHAPTER III.—Swiftwater Buys Gussie’s Love by Giving Her Virgin Gold to the Exact Amount of Her Weight—Fickle Girl Jilts Him in San Francisco and He Marries Her Sister, Grace—Burglarizes His Own Residence After Quarrel With Bride.

CHAPTER IV.—Our Hero, Now a Big Operator and Promoter, Meets His Future Mother-in-Law in Seattle for the First Time.

CHAPTER V.—Love on First Sight of Bera Beebe Is Followed by an Elopement, Which Ends Haplessly on the Hurricane Deck of the Steamer in Seattle Harbor.

CHAPTER VI.—Swiftwater Again Elopes With Bera, and They Are Married in the Yukon.

CHAPTER VII.—First Born of Swiftwater and Bera Sees Light of Day on Quartz Creek, Where [8]First Gold Was Found in the Klondike—Financial Entanglements Drive Swiftwater to Abandon Immensely Rich Property.

CHAPTER VIII.—Swiftwater Deserts His Child and Authoress in Dawson and Skips for the Nome Country.

CHAPTER IX.—Hard Lines for a Deserted Woman in Dawson—Driven From Shelter by Phil Wilson, Swiftwater’s Friend—Mounted Police Are Kind to Deserving Unfortunate.

CHAPTER X.—Swiftwater Elopes With Kitty Brandon, His Fifteen-Year-Old Niece, After Deserting Bera in Washington, D. C.—Is Pursued by Kitty’s Mother, but Escapes at Night from Seattle.

CHAPTER XI.—One Woman’s Ingratitude to Another, Who Had Befriended Her—Bera Is Sent Home Penniless—The Return to Seattle.

CHAPTER XII.—Swiftwater Returns, a Broken Man, to Seattle—Hides Under the Bed Clothes at His Hotel in Terror When Discovered by His Mother-in-Law—My Gems Are Pledged to Raise Money to Get Him a New Start in Alaska.

CHAPTER XIII.—Swiftwater Gives Business Men Swell Banquet on Borrowed Money and Then Decamps for the Tanana Country—A Spring Rush to the New Gold Fields Brings Picturesque Crowd to Seattle.

CHAPTER XIV.—Swiftwater Strikes It Rich on No. 6 Cleary Creek—Trip to the Interior Over the Ice—Swiftwater Promises to Make Reparation.

CHAPTER XV.—We Come Out Together From the Tanana—Bera Has Swiftwater Arrested on Landing in Seattle for Wife Desertion.

CHAPTER XVI.—How Swiftwater Secures His First Great Miscarriage of Justice—Remarkable Legal Transaction in a Seattle Hotel, Involving Court and Lawyers—Bill Persuades Bera to Secure a Divorce.

CHAPTER XVII.—Swiftwater, Again in His Familiar Role as the Artful Dodger—I Take Another Trip Over the Ice to the Yukon—Gates Makes More Fair Promises and Then Runs Away to the States.

CHAPTER XVIII.—Laws of Our Country Have Large Loopholes for Criminals of Wealth—Swiftwater Travels Scot Free and Makes Another Fortune in the New Mining Camp of Rawhide, Nevada.

CHAPTER XIX.—Nurse Abducts Clifford, Swiftwater’s Eldest Son, and Takes Him to Canada—Miner Fails to Make Any Effort to Recapture Child—Waiting to Get What Is My Own Out of the Northland—The End.

PREFACE.

IT may seem odd to Alaskans, and by that I mean, the men and women who really live in the remote, yet near, northern gold country, that “Swiftwater Bill”—known to both the old Sour Doughs and the Cheechacos—should have asked me to write the real story of his life, yet this is really the fact.

Bill Gates is in some ways, and indeed in many, one of the most remarkable men that the lust for gold ever produced in any clime or latitude.

Remarkable?

Yes—that’s the word—and possibly nothing more remarkable than that he, in a confiding moment said to me as he held his first born child in his arms in the little cabin on Quartz Creek, in the Klondike, where he had amassed and spent a fortune of $500,000:

“I’d like somebody to write my life story. Will you do it?”

I can only believe that the romantic element in Swift Water Bill’s character—a character as changeful and variegated as the kaleidoscope—led Swiftwater Bill to ask me to do him this service. I was then the mother of his wife—the grandmother of[11] his child. The sacredness of the relation must be apparent.

Probably a great many people—hundreds, perhaps—may say that my labor is one that can have no reward, and these may speak ill things of Swiftwater, saying, perhaps, that he is more inclined to do royally by strangers and to forget those who have aided and befriended him.

I am not to judge Swiftwater Bill, nor do I wish him to be judged except as the individual reader of this little work may wish so to do.

If he has turned against those near and dear to him—if he has preferred to give prodigally of gold to strangers, while at the same time forgetting his own obligations—I am not the one to point the finger of rebuke at his eccentricities.

For this reason, the narrative within these covers is confined to the facts relating to the career of Swiftwater Bill—a character worthy of the pen of a Dickens or a Dumas—with his faults and his virtues impartially portrayed as best I can do.

IOLA BEEBE,

Mother-in-law of Swiftwater Bill.

MRS. IOLA BEEBE,

Mother-in-law of Swiftwater Bill.

CHAPTER I.

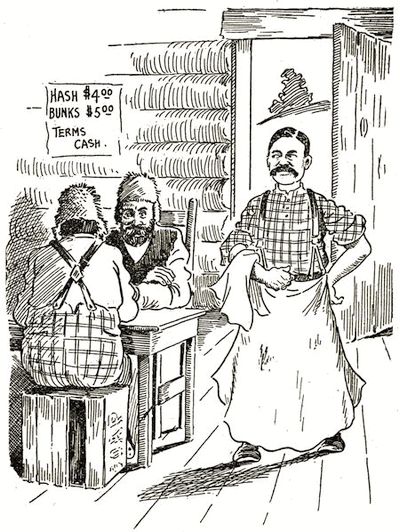

A LITTLE, low-eaved, common, ordinary looking road house, built of logs, with one room for the bunks, another for a kitchen and a third for miscellaneous purposes, used to be well known to travelers in the Yukon Valley in Alaska at Circle City. The straggling little mining camp, its population divided between American, French-Canadians of uncertain pedigree, and Indians with an occasional admixture of canny Scotchmen, whose conversation savored strongly of the old Hudson Bay Trading Company’s days in the far north, enjoyed no reputation outside of Forty Mile, Juneau and the Puget Sound cities of Seattle and Tacoma. From the wharves of these cities in 1895 there left at infrequent intervals, small chuggy, wobbly steamers for Southeastern Alaska points usually carrying in the spring months motley cargoes of yelping dogs, rough coated, bearded, tanned miners and prospectors from all points of the globe, and great quantities of canned goods of every description.

In those days the eager and hardy prospector who fared forth to the Yukon’s dangers in search of gold was usually indifferent to whatever fate befell him. He figured that at best the odds were overwhelmingly[14] against him, with just one chance, or maybe ten, in a hundred of striking a pay streak. It was inevitable that a great proportion of the venturous and ignorant Chechacos, or newcomers, who paid their dollars by the hundred to the steamship companies in Seattle, should, after failing in the search for gold, seek means of gaining a miserable existence in some wage paid vocation.

Were it in my power to bring my hero on the stage under more auspicious circumstances than those of which I am about to tell, I would gladly do it. But the truth must be told of Swiftwater Bill, and at the time of the opening of my narrative—and this was before the world had ever heard the least hint of the wonderful Klondike gold discovery—Swiftwater stood washing dishes in the kitchen of the road-house I have just described.

The place was no different from any one of a thousand of these little log shelters where men, traveling back and forth in the dead of winter with dog teams, find temporary lodging and a hurried meal of bacon and beans and canned stuff. It was broad daylight, although the clock showed eleven P. M., in August, 1896. The sun scarcely seemed to linger more than an hour beneath the horizon at nightfall, to re-appear a shimmering ball of light at three o’clock in the morning.

“Bring us another pot of coffee!” shouted one[15] of three prospectors, who sat with their elbows on the table, greedily licking up the remnants of a huge platter full of bacon and beans garnished with some strips of cold, canned roast beef and some evaporated potatoes, which had been made into a kind of stew.

The hero of my sketch wiped his hands on a greasy towel and, taking a dirty, black tin coffee pot from the top of the Yukon stove, he hurried in to serve his customers.

One of these was six feet two, broad shouldered, sparsely built, hatchet faced, with a long nose, keen blue eyes and with auburn colored hair falling almost to his shoulders. French Joe was the name he went by, and no more intrepid trapper and prospector ever lived in the frozen valley of the Yukon than he. The other two were nondescripts—one with a coarse yellow jumper, the other in a dark blue suit of cast off army clothes. The man in the jumper was bearded, short and chunky, of German extraction, while the other was a half-blood Indian.

Swiftwater, as he ambled into the room, one hand holding his dirty apron, the other holding the coffee pot, was not such a man as to excite the interest of even a wayfarer in the road-house at Circle. About 35 years old, five feet five inches tall, a scraggly growth of black whiskers on his chin, and long, wavy moustaches of the same color, curling from his upper lip, Swiftwater did not arouse even a passing glance from the trio at the table.

SWIFTWATER HEARS FROM FRENCH JOE THE FIRST NEWS OF THE GOLD DISCOVERY IN THE KLONDIKE.

“Boys, de’ done struck it, al’ right, ’cause Indian George say it’s all gold from ze gras’ roots, on Bonanza. An’ it’s only a leetle more’n two days polin’ up ze river from ze T’hoandike.”

It was French Joe who spoke, and then when he drew forth a little bottle containing a few ounces of gold nuggets and dust, Swiftwater Bill, as he poured the third cup of coffee, gazed open mouthed on the showing of yellow treasure.

It is only necessary to say that from that moment Swiftwater was attentive to the needs of his three guests, and when he had overheard all of their talk he silently, but none the less positively, made up his mind to quit his job forthwith and to “mush” for the new gold fields.

And this is why it was that, the next morning, the little Circle City road-house was minus a dishwasher and all round handyman. And before the little community was well astir, far in the distance, up the Yukon river, might have been seen the little, dark bearded man poling for dear life in a flat-bottom boat, whose prow was pointed in the direction of the Klondike river.

CHAPTER II.

IT WOULD be useless to encumber my story with a lengthy and detailed narrative of Swiftwater Bill’s experiences in the first mad rush of gold-seekers up the narrow and devious channels of Bonanza and Eldorado Creeks. The world has for eleven years known the entrancing story of George Carmack’s find on Bonanza—how, from the first spadeful of grass roots, studded with gold dust and nuggets, which filled a tiny vial, the gravel beds[19] of Bonanza and Eldorado and a few adjoining creeks, all situated within the area of a township or two, produced the marvelous sum of $50,000,000 within a few years.

Swiftwater struck gold from the very first. He located No. 13 Eldorado, and had as his neighbors such well known mining men as Prof. T. S. Lippy, the Seattle millionaire, who left a poorly paid job as physical director of the Y. M. C. A. in Seattle to prospect for gold in Alaska; Ole Oleson; the Berry Bros., who cleaned up a million dollars on two and a fraction claims on Eldorado; Antone Stander; Michael Dore, a young French-Canadian, who died from exposure in a little cabin surrounded by tin oil cans filled to overflowing with the yellow metal, and others equally well known.

Swiftwater’s ground on No. 13 Eldorado was fabulously rich—so rich that after he had struck the pay streak, the excitement was too much for him and he forthwith struck out for the trail that leads to Dawson. And now I am about to reveal to Alaskans and others who read this little book a quality about Swiftwater of which few people had any knowledge whatever, and this shows in a startling way how easy it was in those halcyon days in the Golden Klondike for a man to grasp a fortune of a million dollars in an instant and then throw it[20] away with the ease and indifference that a smoker discards a half-burned cigar.

Swiftwater, as may well be imagined, when he struck the rich layers of gold in the candle-lit crevices of bedrock on Eldorado a few feet below the surface, could have had a half interest in a half dozen claims on each side of him if he had simply kept his mouth shut and informed those he knew in Dawson of the strike, on condition that they would share half and half with him. This was a common transaction in those days and a perfectly legitimate one, and Swiftwater could have cleaned up that winter beyond question $1,000,000 in gold dust, after paying all expenses and doing very little work himself, had he exercised the most common, ordinary business ability.

Instead, Swiftwater, when he struck Dawson, threw down a big poke of gold on the bar of a saloon and announced his intention of buying out the finest gambling hall and bar in town. Dawson was then the roughest kind of a frontier mining camp, although the mounted police preserved very good order. There were at least a score of gambling halls in Dawson and as many more dance halls. The gambling games ran continually twenty-four hours a day, and the smallest wager usually made, even in the poorest games, was an ounce of gold, or almost $20.

When Bill laid down his poke of gold on the bar of a Dawson saloon—it was so heavy he could hardly lift it—he was instantly surrounded by a mob of thirty or forty men and a few women.

“Why, boys!” said Swiftwater, ordering a case of wine for the thirsty, while he chose appolinaris himself, “that’s easy enough! All you’ve got to do is to go up to Eldorado Creek and you can get all the gold you want by simply working a rocker about a week.”

That settled the fate of Eldorado, for the next day before three o’clock in the morning there was a stampede to the new find, and in twenty-four hours the whole creek had been staked from mouth to source.

Comfortably enjoying the knowledge that he had $300,000 or $400,000 in gold to the good, Swiftwater set about finding ways to spend it.

His first order “to the outside” was for a black Prince Albert coat and a black silk top hat, which came in in about five or six weeks and were immediately donned by Swiftwater. By this time he had become the owner of the Monte Carlo, the biggest gambling hall in Dawson.

“Tear the roof off, boys!” Swiftwater said when the players on the opening night swarmed in and asked what was the limit of the bets.

“The sky is the limit and raise her up as far as[22] you want to go, boys,” said Swiftwater, “and if the roof’s in your way, tear it off!”

Just about this time came the first of Swiftwater’s affaires d’l’amour, because a day or two previously five young women of the Juneau dance halls had floated down the river in a barge and gone to work in Dawson. There were two sisters in the group. Both of them were beautiful women, young, bright, entertaining and clever in the way such women are. They were Gussie and May Lamore.

“I am going to have a lady and the swellest that’s in the country,” Swiftwater told his friends, and then, donning his best clothes, the costliest he could buy in Dawson, Swiftwater went over to the dance hall, where the Lamore sisters were working, and ordered wine for everybody on the floor.

Gussie was dancing with a big, brawny, French-Canadian miner. Her little feet seemed scarcely to touch the floor of the dance hall as the miner whirled her around and around. She was little, plump, beautifully formed and with a face of more than passing comeliness.

You women of “the States”—when I say “the States” I simply speak of our country as do all the old-timers in Alaska, and not as if it was some foreign country, but as it really is to us, the home of ourselves and our forebears, yet separated from us by thousands of miles of iceclad mountain barriers[23] and storm swept seas have no conception of the dance hall girl as a type of the early days of Dawson. Many of them were of good families, young, comely, and fairly well educated. What stress or storm befell them, or other inhospitable element in their lives drove them to the northern gold mining country, God knows it is not my portion to tell. Nor could any one of them probably, in telling her own life story, give the reasons for the appearance in these dance halls of any of her sisters.

It is enough for you and me to understand—and it requires no unusual insight into the human heart and its mysteries to do so—that when a miner had spent a few months in the solitude of the hills and gold lined gulches of the Yukon Valley, if he finally found the precious gold on the rim of the bedrock, his first thought was to go back to “town.”

Back to town? Yes, because “town” meant and still means to those hardy men any place where human beings are assembled, and the dance hall, in those rough days, was the center of social activities and gaieties.

The sight of little Gussie Lamore, with her skirt just touching the tops of her shoes, spinning around in a waltz with that big French-Canadian, set all of Bill’s amorous nature aglow. He went to the hotel, filled his pockets with pokes of gold dust and came[24] quickly back to the dance hall, where he obtained an introduction to Gussie.

Bill’s wooing was of the rapid kind. Before the night was over he had told Gussie—

“I’ll give you your weight in gold tomorrow morning if you will marry me—and I guess you’ll weigh about $30,000.”

Pretty Gussie shook her head coquettishly. “We will just be friends, Swiftwater, and I guess that’ll be about all.”

Of course, it was only a day or two before all Dawson knew of Swiftwater’s infatuation. The two became fast friends and got along beautifully for a week or two. Then came a bitter quarrel, and from that arose the incident which gave Swiftwater Bill almost his greatest fame—it is the story of how he cornered the egg market in Dawson in a valiant effort to hold the love of his sweetheart, Gussie Lamore.

It was in the spring of 1898 and Dawson was very short of grub of every kind. The average meal of canned soup, a plate of beans garnished by a few slices of bacon or canned meat, with a little side dish of canned or dried potatoes stewed, hot cakes or biscuit and coffee, cost about $5 and sometimes more. The cheapest meal for two persons was $10, and Bill had seen to it, while trying to win Gussie for his[25] wife, that she had the best there was to eat in Dawson.

The two were inseparable on the streets. Then came the quarrel—it was simply a little lovers’ dispute, and then the break.

Swiftwater put in two days assiduously cultivating the friendly graces of the other dance hall girls in Dawson, but Gussie cared not.

One night an adventurous trader came down from the Upper Yukon in a small boat—there were no steamers then—and brought two crates of fresh eggs from Seattle.

Swiftwater heard of this, and he knew that there would be a tremendous demand for those eggs, as the miners usually made their breakfasts of the evaporated article; so, shrewdly, he went immediately to the restaurant which had purchased the crates and called for the proprietor.

Now, this worthy knew Swiftwater to be immensely wealthy and a very good customer, so when the Eldorado miner demanded the right to buy every egg in the house, which meant every egg in town, the restaurant man stroked his chin and said:

“Swiftwater, those eggs cost me a big lot of money, and there hain’t no more. You can have the hull outfit for three dollars an egg, in dust.”

There was just one whole crate left, and Swiftwater weighed out $2,280 in gold dust.

“Those eggs are mine—keep them here and don’t let anybody have any.”

Now, Swiftwater and Gussie had been in the habit of breakfasting on fresh eggs some days before, when the first infrequent trader of the season had managed, after enduring several wrecks on the upper river, to reach Dawson. Fresh eggs were to Gussie what chocolates and bon bons are to the average girl in the States.

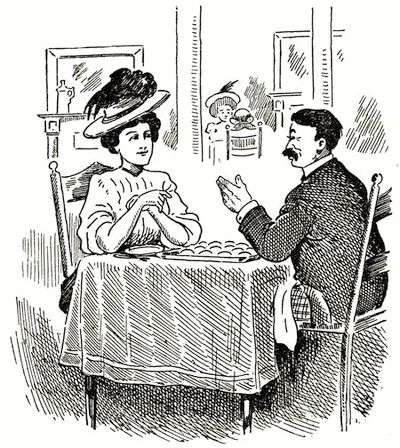

The next morning Swiftwater arrived at the restaurant for breakfast, a little earlier than usual, and in a few minutes the waiter placed before him a steaming hot platter containing an even dozen of the eggs, nicely poached and served on small strips of toast.

Just then Gussie came in for her breakfast and seated herself at the other end of the little dining room. It was long after the usual hour for breakfast, and they were the only two in the room. Without doing Swiftwater the honor of passing so much as a glance in his direction, Gussie said to the waiter:

“Bring me a full order of fried eggs.”

“We ain’t got no eggs, mum; they was all sold out last night,” said the waiter.

Gussie’s face flamed with anger, but only for an instant. Then she picked up her plate, her knife and fork and napkin and strode over to the table where Swiftwater sat.

SWIFTWATER AND GUSSIE LAMORE ARE RECONCILED OVER A HOT PLATTER OF FRESH EGGS, AT DAWSON.

“I guess I’ll have some eggs, after all,” said Gussie, without looking at Swiftwater, as she liberally helped herself from his platter.

Then both of them burst out laughing and peace reigned once more between them.

Of course, Swiftwater figured that he had won a substantial victory by reaching Gussie’s heart through her stomach. But, as a matter of fact, we all figured that the laugh was on Swiftwater, and I think every woman who reads this story will agree with me.

CHAPTER III.

SWIFTWATER has often told me that he never could quite understand why it was that the way to a woman’s heart, even his own way—Swiftwater’s—was so hard to travel and so devious and tortuous in its windings and interwindings.

“Why, Mrs. Beebe,” Swiftwater used to say, “I should think a man could do anything with gold! And for my own part, I used to always figure that money would buy anything,” said Swiftwater, “even the most beautiful woman in the world for your wife.”

Swiftwater’s mental processes were simple, as the foregoing will illustrate. It was hardly to be expected otherwise. Swiftwater decamped from the drudgery and slavish toil of a kitchen in the little road-house at Circle City to gain in less than three months more money than he had ever dreamed it possible for him to have.

Two hundred thousand dollars was the minimum of Swiftwater’s first big clean-up. If Gussie Lamore had lovers, Swiftwater figured, his money would win her heart away from all the rest.

All this relates very intimately to the really[30] interesting story of Swiftwater’s courtship of Gussie Lamore. The girl kept him at arm’s length, yet if ever Swiftwater became restive Gussie would cleverly draw the line taut and Swiftwater was at her feet.

“I am tired of this, Gussie,” said Swiftwater one day, and finally the “Knight of the Golden Omelette,” as he was often termed, was serious for once in his life.

“I am going back to Eldorado and I’ll bring down here a bunch of gold. It will weigh as much as you do on the scales, pound for pound. Gussie, that gold will be yours if you give me your word you will marry me.”

“All right, Bill, we’ll see. Go get your gold and show me that you really have it.”

Swiftwater was gone from Dawson about two days before he returned to the dance hall where Gussie was working. This time he kept away from the bar and merely waited until the morning dawned and the habitues of the dance hall had disappeared one by one. By that time the word had been sent out to Seattle of the rich findings of gold on Eldorado, and the early crop of newcomers was arriving over the ice from Dyea, in the days before the Skagway trail was known.

Swiftwater, in the early morning, carried to Gussie’s[31] apartments two tin coffee cans filled with the yellow gold.

“Here’s all you weigh, anyhow,” said Swiftwater. “Now, take this gold to the Trading Company’s office and bank it. Then I want you to buy a ticket to San Francisco and I will meet you there this summer and we will be married.”

Thus ended the curious story of Swiftwater’s wooing of Gussie Lamore. All the world knows how, when Gussie reached San Francisco, where her folks lived, she banked Swiftwater’s gold and turned him down cold.

Swiftwater reached the Golden Gate a month after Gussie had arrived at her home. All his entreaties for her to carry out her bargain came to nothing.

Bitter as he was towards Gussie, Swiftwater still seemed to love the girl. His first creed, “I can buy any woman with gold,” seemed to stick with him.

There was, for one thing, little Grace Lamore. It came to Swiftwater that he could marry Grace and punish Gussie for her inconstancy.

Now, this may seem to you, my reader, like an ill-founded story. Yet the truth is, Grace and Swiftwater were married within a month of his arrival in San Francisco, and the San Francisco papers were filled with the story of how Swiftwater bought his[32] bride a $15,000 home in Oakland and furnished it most beautifully with all that money could buy.

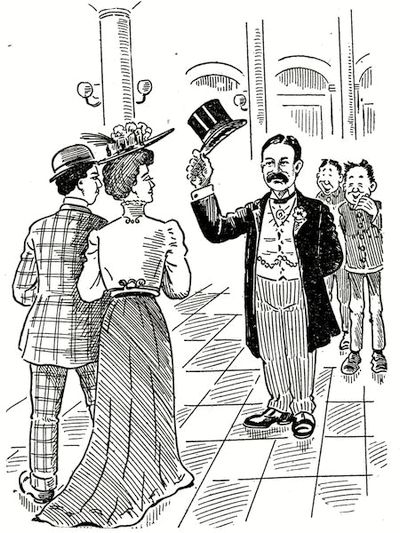

Swiftwater and Grace, after a two days’ wedding trip down the San Joaquin Valley leased the bridal chamber of the Baldwin Hotel, while their new home in Oakland was being fitted up. Old-time Alaskans will smile when I recall the impression that Swiftwater made on San Franciscans.

It was his invariable custom to stand in front of the lobby of the Baldwin every evening, smoothly shaved, his moustaches nicely brushed and curled, and wearing his favorite black Prince Albert and silk hat.

Probably few in the throng that came and went through the lobby of the Baldwin—in those days one of the most popular hostelries in San Francisco—would have paid any attention to Swiftwater. But Bill knew a trick or two and his old-time friends have told me that Swiftwater made it an unfailing custom to tip the bell-boys a dollar each a day to point to the dapper little man and have them tell both guests of the Baldwin and strangers:

“There is Swiftwater Bill Gates, the King of the Klondike.”

And Swiftwater would stand every evening, silk hat on his head, spick and span, and clean, and bow politely to everybody as they came in through the lobby to the dining hall.

SWIFTWATER GREETS STRANGERS IN THE LOBBY OF THE BALDWIN HOTEL, WHOM HE HAD NEVER SEEN BEFORE.

Isn’t it curious, that with all his money, and his confidence in the purchasing power of gold, Swiftwater’s dream of love with Grace Lamore should have lasted scarcely more than a short three weeks? It was not that Swiftwater was parsimonious with is money—the very finest of silks and satins, millinery, diamonds at Shreve’s, cut glass and silverware, were Grace’s for the asking. They will tell you in San Francisco to this day that Swiftwater and his bride worked overtime in a carriage shopping in the most expensive houses in the city of the Golden Gate.

Then came the break with Grace. I do not know the cause, but the girl threw Swiftwater overboard and left the bridal chamber of the Baldwin to return to her family, even before they had occupied the palatial home in Oakland.

Swiftwater’s rage knew no bounds. In his heart he cursed the whole Lamore family and quickly took means to vent his spite.

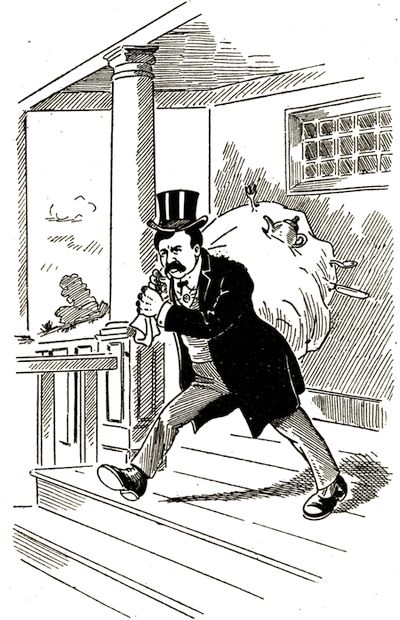

This is how it came about that scarcely a month after Swiftwater’s wedding bells had rung, the “Knight of the Golden Omelette” was seen to enter his Oakland home one evening and emerge therefrom a half hour later bearing on his back a heavy bundle wrapped in a bed sheet.

SWIFTWATER BILL CARRYING $7,000 WORTH OF WEDDING PRESENTS FROM HIS BRIDE’S HOME IN OAKLAND.

The burden was all that Swiftwater’s-strength could manage. Laboriously he toiled his way to the house of a friend in Oakland and wearily deposited his bundle on the front porch, where he sat and waited the coming of his friend.

When Swiftwater was finally admitted to the house, he untied the sheet and opened up the contents of the pack. There lay glittering on the floor $7,000 worth of solid silver plate and cut glass.

“That’s what I gave my bride,” he said, “and now she’s quit me and I’m d——d if she’ll have that.”

CHAPTER IV.

IT HAS always seemed a standing wonder to me that when Swiftwater had separated himself from about $100,000 or more in gold dust with the Lamore sisters as the chief beneficiaries, and after he had been divorced from Grace, following her refusal to live with him in San Francisco, he did not finally come within a rifle shot of the realization of the real value of money. There is no doubt but that Swiftwater was bitterly resentful towards Gussie and Grace Lamore after they had both thrown him overboard, and you will no doubt agree with me that to an ordinary man such experiences as these would have had a sobering effect.

Instead, however, the miner plunged more recklessly than ever into all manner of money-making and money-spending, and the only reason that Swiftwater Bill Gates is not ranked today with Flood, Mackay and Fair as one of a group of the greatest and richest mining men the Pacific Coast has produced, is that he did not have the balance wheel of caution and discretion that is given to the ordinary artisan or day laborer.

Swiftwater left San Francisco soon after his rupture[38] with Grace Lamore and went directly to Ottawa, Canada, where, marvelous as it may seem in the light of the ten years of mining history in the north, Swiftwater induced the Dominion government to grant him a concession on Quartz Creek, in the Klondike, worth today millions upon millions.

This concession covered an immense tract of ground at least three miles long and in some places two miles wide. Much of the ground was very rich, and today, ten years later, it is paying big dividends. Yet rich as it was and immensely valuable as was the enormous concession, Swiftwater induced the Dominion of Canada authorities to part with it for merely a nominal consideration. His success in this respect cannot be otherwise regarded than phenomenal. Although his money was nearly all gone, Swiftwater, taking a new grip on himself, and entirely disregardful of the fates which had been so lavish to him, went from Ottawa to London, England, where he obtained enough money to buy and ship to Dawson one of the largest and most expensive hydraulic plants in the country.

When this plant was shipped to Seattle in 1898, Swiftwater followed it to the city on Elliott Bay.

It was the day following Swiftwater Bill’s arrival in Seattle from San Francisco in the spring of 1899 that Mr. Richardson, an old Seattle friend of mine, who knew Gates well, telephoned me that[39] Swiftwater had an elegant suite of apartments at the Butler Hotel, and that he had asked him to arrange for an introduction. Mr. Richardson said over the telephone:

“You ought to know Swiftwater—he knows everybody in Dawson and the Klondike, and for a woman like you to go into that country with a big hotel outfit and no friends would be ridiculous.”

When I think of what happened to me and my daughters, Blanche and Bera, in the next few days following this incident, and of the years of wretchedness and misery and laying waste of human lives and happiness that came after, I am tempted to wonder what curious form of an unseen fate shapes our destinies and turns and twists our fortunes in all manner of devious and uncertain ways.

My whole hotel outfit had gone up to St. Michael the fall previous and I with it—and at great cost of labor and trouble I had seen to it, at St. Michael, that the precious shipment—representing all I had in the world—was safely stored aboard a river steamer bound for Dawson.

Now, spring had come again, and with it the big rush to the gold fields of the Yukon was on, and Seattle was again filled with a seething, surging, struggling, discontented, optimistic, laughing crowd of gold hunters of every nationality and color.

It was almost worth your life to try to break through the mob and gain admission to the lobby of the Hotel Butler in those days, for the place was absolutely packed at night with men as thick as sardines in a box, and all shouting and gesticulating and keeping up such a clatter that it drove one nearly crazy.

It was no place for a woman, and the few women whose fortunes or whose husbands had brought them thither were seated in a little parlor on the second floor, where they could easily hear the clamor and confusion that came from the noisy mob in the lobby.

In the crowd were such old-time sourdoughs as Ole Olson, who sold out a little piece of ground about as big as a city block on Eldorado for $250,000, after he had taken out as much more in three months’ work the winter previous; “French Curley” De Lorge, known from White Horse to the mouth of the Tanana, as one of the Yukon’s bravest and strongest hearted trappers and freighters; Joe Ladue, who laid out the town of Dawson; George Carmack, whose Indian brother-in-law, Skookum Jim, is supposed to have turned over the first spadeful of grass roots studded with gold on the banks of Bonanza; big Tom Henderson, who found gold before anybody, he always said on Quartz Creek; Joe Wardner[41] and Phil O’Rourke, both famous in the Coeur d’Alenes; Henry Bratnober, six feet two, black beard, shaggy black hair and black eyes, overbearing and coarse voiced, the representative in the golden north of the Rothschilds of London; and men almost equally well known from Australia, from South Africa and from continental Europe, including the vigilant and energetic Count Carbonneau of Paris.

By appointment, Swiftwater, attired in immaculate black broadcloth Prince Albert, low cut vest, patent leather shoes, shimmering “biled” shirt, with a four-karat diamond gleaming like an electric light from his bosom, stood waiting for us in the parlor. I had left Bera, who was fifteen years old, in my apartments in the Hinckley Block and had taken Blanche, my eldest daughter, with me.

“I am awfully glad to meet you, Mrs. Beebe,” said Swiftwater, advancing with step as noiseless as a Maltese cat, as he walked across the heavy plush carpet.

Swiftwater put out a soft womanish hand, grasped mine and spoke in a low musical voice, the kind of voice that instantly wins the confidence of nine women out of ten.

“I have heard that you were going in this spring, and as I know how hard it is for a woman to get along in that country without someone to befriend[42] her, I was very glad indeed to have the chance of extending you all the aid in my power,” continued Swiftwater, in the meantime glancing in an interested way at Blanche, who stood near the piano.

“This is my daughter, Blanche, Mr. Gates,” I said. Blanche was then nineteen years old, and I had taken her out of the Convent school in Portland to keep me company in the north, along with Bera.

It only took us a few minutes to agree that when I arrived in Dawson, if Swiftwater was there first, he should help me in getting a location for my hotel and settling down. Then, as I arose to go, he said, turning again to Blanche:

“Doesn’t your daughter play the piano, Mrs. Beebe? I am very fond of music.”

Blanche, at a nod from me, sat down and began to play some simple little thing, when Swiftwater said:

“Please excuse me, I have a friend with me.”

In a moment Swiftwater returned and introduced his friend, a tall, lithe, clean-cut, smooth shaven Englishman of about thirty-five—Mr. Hathaway.

Five minutes later, Blanche having pleased both men with her playing, arose from the piano.

“Now, we are just going down to dinner in the grill; won’t you please join us, ladies?” said Swiftwater[43] in those deliciously velvet tones which seemed to put any woman at perfect ease in his company.

A shivery feeling came over me, and I said: “No, I think we will go right home.”

Now, I never could tell for the life of me just what made me want to hurry away with my Blanche from the hotel and Swiftwater Bill. His friend Hathaway was a nice clean looking sort of a chap and very gentlemanly, and Swiftwater was the absolute quintessence of gentlemanly conduct and chivalry. But the papers had told all about Swiftwater and Gussie and Grace Lamore—only that the reporters, as well as the general public, seemed to regard it all as a joke—Gussie’s turning down Swiftwater after he had given her her weight in gold—about $30,000 in virgin dust and nuggets—and then Bill’s marrying Grace, her sister, for spite. The whole yarn struck me so funny, that as we walked, with difficulty, through the crowds on Second Avenue to our apartments, I could not think of anything mean or vicious about Swiftwater.

Nevertheless, I scrupulously avoided inviting Swiftwater to call, and after I had concluded my business with him, I determined to have nothing more to do with him until business matters made it necessary in Dawson. You women, who live “on the outside” and have never been over the trail and down the Yukon in a scow, can never know what[44] fortitude is necessary for a woman to cut loose from the States and make her own way in business in a new gold camp like Dawson was in 1899.

So it was only natural, that, knowing Swiftwater to be one of the leading and richest men in that country, I should have accepted his offer of assistance and advice. God only knows how different would have been all our lives could I but have foreseen the awful misery and wretchedness and ruin which that man Swiftwater easily worked in the lives of three innocent people who had never done him wrong, or anyone else, for that matter.

Three days after my glimpse of Swiftwater Bill, Bera and myself were just finishing dressing for dinner in my big sitting room. It was rather warm for a spring evening in Seattle, and we were all hungry. Blanche was waiting near the door fully dressed, I was putting on my gloves, and little Bera, fifteen years old, stood in front of the mirror trying to fasten down a big bunch of wavy brown hair of silken glossy texture, which was doing its best to get from under her big white Leghorn hat, the child looking the very picture of beauty and innocence.

She was plump, with deliciously pink cheeks, great big blue eyes, regular features and she wore a dress I had had made at great expense in Victoria—it was of dark blue voile, close fitting, with a[45] lining of red silk, which showed the cardinal as the girl turned and walked across the room and then back again to the mirror. Her white Leghorn hat was trimmed with large red roses. I heard a noise, as if someone had knocked and Bera, turning quickly, said under her breath, as if alarmed:

“Mama! There is somebody there!”

I looked and there stood Swiftwater, silk hat in hand, smiling, bowing, one foot across the threshold, while behind him loomed the tall form of his friend Hathaway.

“Pardon us, won’t you, Mrs. Beebe, but we want you to go to dinner with us at the Butler. Won’t you do so and bring the girls?” and Swiftwater instantly turned his eyes from mine and looked at Bera standing in front of the mirror, her face flushed, her eyes sparkling with excitement and her form silhouetted against a red plush curtain which covered the door to the adjoining room.

Before I could gather my wits about me I had accepted Swiftwater’s invitation. It was the only thing I could do, because we were just about to go to dinner ourselves, and he seemed to know that instinctively, and that I could not very well refuse.

CHAPTER V.

MAMA,” said Bera to me, “Mrs. Ainslee is not nearly so well today, and Mr. Hathaway said when he came down from the hospital this afternoon that she wanted to see you sure this evening about seven o’clock.” Mrs. Ainslee had been desperately ill at Providence Hospital for weeks and she was a woman of whom I had known in earlier days and whose sad plight—her husband was dead and she was alone in the world—had induced me to do all I could for her.

It was scarcely more than a week following the evening that Swiftwater and Mr. Hathaway was host at dinner at the hotel, that Bera took, what I realized afterwards, was an unusual and unexpected interest in Mrs. Ainslee’s case. Since the dinner engagement, Swiftwater had been just ordinarily attentive to myself and my two daughters, although frequently asking us to go to the theatre with him and sending flowers almost daily to our apartments. I had not seen Mrs. Ainslee for two or three days, and my conscience rather troubled me about her, so that when, on this day—a day that will never fade[47] from my mind as long as I live, nor from that of Bera or Swiftwater—I quickly fell into Bera’s plans and determined to get some things together for Mrs. Ainslee, including a bunch of roses from a vase on my dresser, and go to the hospital after dinner.

Providence Hospital was scarcely more than five blocks from our apartments. I had not seen anything of Swiftwater or Hathaway all day. Tired even beyond the ordinary—it had been a long, hard fight to get my affairs in shape for the northern trip—I left the apartments a little before seven o’clock that fateful evening and walked up Second Avenue to Madison and thence up to Fifth Avenue to Providence Hospital.

“Mrs. Ainslee is feeling some better, Mrs. Beebe, but the doctor is in there now and you will have to wait for a few minutes,” the head nurse told me at the landing on the second floor. The steamer “Humboldt” was sailing for Alaska that night, and I had managed to get off a few things consigned to myself at Dawson and had seen them safely placed aboard ship.

As I sat waiting for the signal to come into Mrs. Ainslee’s room—it must have been a half hour or more before the nurse came to me and said I should enter—a curious feeling came over me regarding Bera. I had never known of her speaking about[48] Mrs. Ainslee and somehow or other I could not get out of my mind the thought that possibly Swiftwater and his friend Hathaway might leave for Skagway on the “Humboldt.”

Philosophers may talk of a woman’s sixth sense as some people talk of the cunning of a cat. Whatever it was, as the nurse beckoned me to come into Mrs. Ainslee’s room, I quickly arose, went in and said to the sick woman:

“Mrs. Ainslee, I am awfully glad to see that you are better and I wanted to visit with you for an hour, but I have overstayed my time already and I must hurry back to my rooms.”

Then I quickly turned and in another minute I was hurrying down the Madison Street hill to the Hinckley Block. In every step I took nearer my home there came a keener and more tense pulling at my heart strings—a feeling that something had happened in my own home. It was no wonder that the elevator boy in the Hinckley Block was dumb-founded to see me rush across Second Avenue and half way up the stairs to the second floor before he could call to me, saying he would take me up in the car if I was not in too big a hurry.

The next moment I was in my rooms, and for the life of me I cannot begin to describe their looks. My clothes and personal belongings were scattered all over the room, my big trunk had been emptied[49] of its contents and was missing. The bureau drawers were empty and the place really looked like a Kansas rancher’s house after a cyclone.

On the dresser was a little note—in Bera’s handwriting, held down by a bronze paperweight surmounted by a tiny, but beautiful miniature of a woman’s form. It was Bera’s last birthday gift to me.

“We have gone to Alaska with Swiftwater and Mr. Hathaway. Do not worry, mama, as when we get there we will look out for your hotel.”

“BERA.”

That was Bera’s note. I looked at my watch. It was 7:25 and I knew the “Humboldt” sailed at 8 o’clock. I rushed down four flights of stairs, never thinking of the elevator, gained the street and hailed a passing hackman.

“You can have this if you get to the ‘Humboldt’ at Schwabacher’s dock before she sails!” I cried as the cabby drew his team to the curb, and then I handed him a ten dollar gold piece.

Whipping his horses to a gallop, the hackman drove at a furious pace down First Avenue to Spring Street and thence to the dock. He all but knocked over a policeman as the horses under his whip surged through the crowd which stood around the dock waiting for the departure of the “Humboldt.”

“My two daughters are on that boat and Swiftwater Bill Gates has stolen them from me!” I shouted as I grabbed hold of the arm of a big policeman near the entrance to the dock. “I want you to get those girls off that boat before she sails, no matter what happens!”

In another minute the policeman was fighting his way with all the force of his 250 pounds through the mob of five thousand people that hung around the gang plank of the “Humboldt.” The ship’s lights were burning brightly and everybody was laughing and talking, and a few women crying as they said goodby to husbands, sweethearts or friends aboard the ship.

It was just exactly ten minutes before sailing time when we finally made our way to the main deck through the crowd. I fairly shouted to the captain on the bridge:

“My two daughters are on this ship hidden away, and I want them taken off this boat before you leave!”

Capt. Bateman looked at me a moment as if he wanted to throw me overboard.

“Who are your daughters and what are they doing on my ship?”

“My daughters are Blanche and Bera Beebe and Swiftwater Bill has stolen them and is taking them to Alaska. I am Mrs. Beebe, their mother.”

For the moment that ended the discussion with Capt. Bateman. Instantly turning to a quartermaster, he said:

“Help this woman find her daughters!”

A half an hour and then an hour passed as we worked our way from one stateroom to another on the saloon deck and the upper deck without avail. Capt. Bateman was furious at the delay.

“Mrs. Beebe, I do not believe your daughters are here,” he said. “Swiftwater has engaged one room, but we have not seen him yet.”

Just then the quartermaster turned to unlock the door of a stateroom on the starboard side near the stern of the ship. The lock failed to work.

“There is somebody in there,” he said, “and the dock is locked from the inside.”

“Break it in!” ordered Capt. Bateman.

The next instant the door flew off its hinges as the big quartermaster shoved a burly shoulder against it. The room was dark. I rushed in, to find Bera lying on the couch, sobbing as if her heart would break.

As quickly as possible, I got the girls out and turned them over to the custody of Capt. Bateman.

“These are my daughters, and I will not allow them to be taken from me.”

“Take ’em ashore!” ordered Capt. Bateman to the quartermaster.

“COME TO THE STATION WITH US,” SAID THE OFFICER, DRAGGING FORTH THE SHAPELESS MASS, AND HELPING SWIFTWATER ADJUST HIS SILK TILE.

“But I want you to find that scoundrel Swiftwater!” said I, turning on the policeman, who stood just behind me.

“You’ll not keep us here any longer,” angrily said the ship’s master.

“O, yes, we will!” said the officer, showing more grit than I expected.

Then began the search all over again. The hurricane deck was the last resort, the ship having been searched from her hold clear through the steerage and saloon cabins to the main deck.

On the main deck there were a half dozen lifeboats securely lashed their proper places. It was dark by this time, but, curiously enough, there was a little fluttering electric arc light near the end of the warehouse on the dock, close to the after end of the boat.

That lamp must have been burning that night through some of the mysterious and indefinable laws of Providence or some other thing, because by its glare I could see a huddled, shapeless, black form underneath the last lifeboat on the upper deck.

“That’s him!” I said, pointing at the shapeless mass in the shadow of the lifeboat.

The policeman walked over to the boat, stretched forth a big muscular arm, grasped the formless object and drew forth—Swiftwater Bill.

“Come to the station with us,” said the officer, as he helped Bill adjust his silk tile.

CHAPTER VI.

A FULL thirty days after Swiftwater and Hathaway had left Seattle, following the affair on the decks of the steamer “Humboldt,” found the miner and his friend in Skagway. It was in the height of the spring rush to the gold fields, and there are undoubtedly few, if any, living today who will ever witness on this continent such scenes as were enacted on the terrible Skagway trail over the Coast Range of the Alaska mountains, which separated 50,000 eager, struggling, quarreling, frenzied men and women drawn thither by the mad rush for gold from the upper reaches of the Yukon River and the lakes which helped to form that mighty stream.

No pen can adequately portray the bitter clash, and struggling, and turmoil—man against man, man against woman, woman against man, fist against fist, gun against gun, as this mob of gold-crazed human beings surged into the vortex of the Yukon’s valley and found their way to the new Golconda of the north.

Skagway was a whirling, tumbling, seething whirlpool of humanity. Imagine the spectacle of[55] a mob of 40,000 half-crazed human beings assembled at the foot of the almost impassable White Pass, with the thermometer 90 degrees in the shade at the foot of the range, and ten feet of snow on the Summit, three miles away. Then picture to this, if you can, the innumerable crimes against humanity that broke out in this mob of half-crazy, fighting, excited, bewildered multitude of men and women.

There was no rest in the town—no sleep—no time for meals—no time for repose—nothing but a mad scramble and the devil take the hindmost.

There was one cheap, newly constructed frame hotel in Skagway and rooms were from $5 to $20 a day. The only wharf of the town was packed fifty feet high with merchandise of every description—65 per cent. canned provisions, flour and dried fruits and the rest of it hardware, mining tools and clothing for the prospectors. Teams of yelping, snarling, fighting malamutes added their cries to the eternally welling mass of sound.

And Swiftwater was there. Almost the first face I saw as I entered the hotel was that of Gates.

“Mrs. Beebe,” he said, “let us forget bygones. In another day or two I would have been over the Summit with my outfit. It is lucky that I am here, because possibly I can help you in some way.”

I could do nothing more than listen to what Swiftwater said. There was no other hotel, or indeed[56] any place in the town where I could get shelter for myself and my two girls. Knowing the black purpose in Swiftwater’s heart, I watched my girls Bera and Blanche day and night. My own goods were piled up unsheltered and unprotected on the beach.

Swiftwater, with all his cunning, could not deceive me of his real intent, yet my own perplexities and troubles made it easy for him to keep me in constant fear of him.

“Mrs. Beebe,” he would say, “you can trust me absolutely.”

With that, Swiftwater’s face would take on a smile as innocent as that of a babe. There was always the warm, soft clasp of the womanish hand—the low pitched voice of Swiftwater to keep it company.

And now, as I remember how innocent Bera was, how girlish she looked, how confiding she was in me, yet never for a moment forgetting, perhaps, the lure of the gold studded gravel banks of Eldorado which Swiftwater held constantly before her, it seems to my mind that no woman can be wronged as deeply and as eternally as that woman whose daughter is stolen from her through guile and soft deceit.

We had been in Skagway but a trifle more than a week, when, one evening, returning to the hotel, I found my room empty and Bera missing.

“I have gone with Swiftwater to Dawson, Mamma. He loves me and I love him.” This was what Bera had written and left on her dresser.

That was all. There was one chance only to prevent the kidnaping of Bera. That was for me to get to the lakes on the other side of the mountains, at the head of navigation on the Yukon and seek the aid of the Canadian mounted police.

At White Horse, there was trace of Swiftwater and Bera, but they had twenty-four hours the start of me and, when I finally found that they had gone through to Dawson, I simply quit.

Down the Upper Yukon there was a constant stream of barges, small boats and rafts. Miles Canyon, with its madly rushing, white-capped waters, extending over five miles of rock-ribbed river bed and sand bar, was scattered o’er with timbers, boards, boxes and casks containing the outfits and all the worldly possessions of scores of unfortunates.

“On, on, and ever and eternally on, down the Yukon to Dawson!” That was the cry in those days and it bore, as unresistingly and as mercilessly as the tide of the ocean carries the flotsam and jetsam of seacoast harbors, the brave and the strong, the weak and crippled, the wise and the foolish, in one inchoate mass of humanity to that magic spot where more gold lay underground waiting for the pick of[58] the poverty-struck miner than the world had ever known of—“The Klondike.”

All things finally come to an end. I was in Dawson. At the little temporary dock on the Yukon’s bank, stood Bera and Swiftwater. The miner did not wait till I landed from the little boat. He went up the gang plank and grasped me in his arms.

“Mrs. Beebe,” he said, “we’re married. Come with us to our cabin. We are waiting for you, and dinner is on the table.”

Swiftwater during all that summer and winter in Dawson was the very soul of chivalry and attention both to Bera and myself. There was nothing too good for us in the little market places at Dawson and a box of candy at $5 a box just to please Bera or to satisfy my own taste for sweetmeats was no more to Swiftwater than the average man spending a two-bit piece on the outside.

As the spring broke up the river and then summer took the place of spring in Dawson, the traders from the outside brought in supplies of fresh eggs, fresh oranges, lettuce, new onions—all the delicacies greatly to be prized and more esteemed after a long winter than the rarest fruits and dainties of the States.

When summer came, Dawson got its first shipment of new watermelons from the outside, Swiftwater[59] bought the first melon he could find and paid $40 in dust for it, and brought it home, simply to please Bera and to make his home that much happier.

CHAPTER VII.

HYDRAULIC mining in the Klondike country, by the time that Swiftwater had assembled his big outfit on Quartz Creek was in its very infancy, yet there were plenty of wise men in Dawson who knew that the tens of thousands of acres of hillside slopes and old abandoned creek beds would some day produce more gold when washed into sluice boxes with gigantic rams, than the native miner and prospector had been able to show, even with the figures, $50,000,000, output to his credit.

The Canadian government had given Swiftwater and his partner, Joe Boyle, a princely fortune in the three mile concession on Quartz Creek. So great was the reputation of Swiftwater Bill—so intimately was his name linked with the idea of immense quantities of gold—and so high was his standing as a practical miner, that Swiftwater was able to borrow money right and left to carry on his work on Quartz Creek. Thus it was that before anybody could realize it, including myself, Swiftwater’s financial standing actually was $100,000 worse off than nothing. This was about the amount of money that he used and in that tidy sum was all[61] the savings of my winter in Dawson and my dividends from my hotel, which aggregated at least $35,000.

“When Joe comes in this spring from London,” said Swiftwater to me, “we’ll have all the money we want and more, too, Mrs. Beebe. He has cabled twice to Seattle that our money is all raised and we will have a million-dollar clean-up on Quartz Creek this fall.”

As the spring came on and reports from the mines on Quartz Creek became brighter, Swiftwater became more enthusiastic and confident. The fact that his creditors were beginning to worry, and that there is a nasty law in Canada which affects debtors who seek to leave the country in a restraining way, did not seriously worry Swiftwater. He seemed to think more of the coming of his child than anything else, next to the work on Quartz Creek.

“That baby is going to be born on Quartz Creek, Mrs. B—” Swiftwater said. “It is my determination that my first child shall be born where I will make a greater fortune than anybody hereabouts.”

I told Swiftwater that he was talking arrant nonsense.

“It would be the death of Bera in her condition,” said I, “for her to take the trip up there in this cold, nasty weather, with the roads more like swamps than anything else and the hills still covered with[62] snow. More than that, there are doctors here in Dawson and on Quartz Creek we would be thirty miles from the nearest human settlement.”

But nothing would deter Swiftwater. He set about rigging up a big sled which could be pulled by two horses. It was made of heavy oaken timber, and the long low bed was filled with furs, blankets, bedding, etc. Swiftwater went to Dr. Marshall, our physician, when all arrangements had been practically completed for the journey to Quartz. He had effectually stopped my protests before he said to Dr. Marshall:

“I will give you $2,000 or more, if necessary, to take six weeks off and go with me up to Quartz Creek where my child will be born. Just name your figure if that is not enough.”

Bera was seventeen years old, immature and delicate, yet brave and strong, and willing to imperil her own life to gratify Swiftwater’s whim. So it finally came about that I was delegated to do the final shopping in advance of our journey.

I went to Gandolfo’s and bought with my own money a case of oranges and a crate of apples. Each orange cost $3 in dust and the apples about the same. Next I ordered a barrel of bottled beer, for Swiftwater wanted to treat his men with a feast when the baby was born and the bottled beer was what he thought to be the proper thing. The barrel of beer cost me close to $500 in gold.

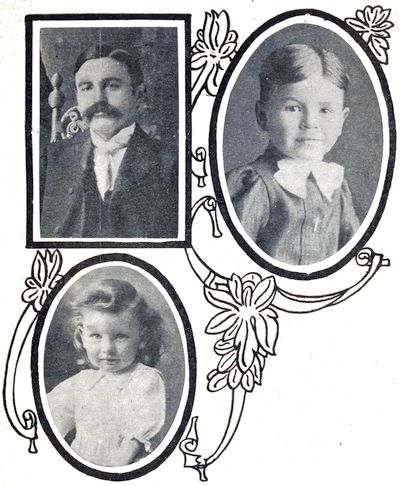

BERA BEEBE GATES

From a photograph taken at Washington, D. C., where she was deserted by Swiftwater Bill.

All this stuff was loaded on the sled. They started over the twenty-eight miles of crooked, winding, marshy trail to Quartz Creek. The journey was something terrible. The days were short and the wind from the hills and gulches was wet with the thawing of the snow and so cold that it seemed to make icicles of the drippings from the trees. Bera, wrapped a foot thick in furs, seemed to stand the trip all right, and in due time the baby was born and christened.

There was great rejoicing in the camp and Swiftwater weighed out $3,000 in dust to Dr. Marshall and sent him back to Dawson. A month afterwards one of our men brought from Dawson the word that the mail had arrived over the ice, but Swiftwater looked in vain for a letter from Joe Boyle. He had confidently expected a draft for $50,000.

For two days Swiftwater scarcely spoke. The cabin in which we lived was only a quarter of a mile from the nearest dump where the men were working. I used to go out every once in a while and take up a few shovels full of gravel which would wash out between $5 and $10 and if I had had the good common sense which comes only after years of hard knocks in this troublesome world, I could then and there[64] have protected myself against the bitter misfortunes which came to me in a few months afterwards.

I was washing some of the baby’s clothes in the kitchen and drying them on a line over the fire, when Swiftwater came in from the diggings, clad in his rubber boots which reached to his hips.

The miner asked for some hot water and a towel and began to shave the three weeks’ black growth from his chin.

“What are you going to do now, Swiftwater?” I asked.

“I’m going down to town.”

For two days the cabin had been without food except some mush and a few dried potatoes and a can of condensed milk for the baby. Swiftwater had sent a man over the trail to Dawson for food two days before.

“You’ll not go without Bera! You are not going to leave us here to starve,” said I.

“Bera cannot possibly go,” said Bill.

I turned and went to Bera’s room and told her to dress immediately. Then I washed the baby, put an entire new change of clothes on him, wrapped up his freshly ironed garments in a package, got a bottle of soothing syrup and a can of condensed milk.

It was always my belief and is now, that Swiftwater’s mind contained a plan to abandon Bera, the[65] baby and me, and to run away from the Yukon to escape his troubles.

We got a small boat and filled one end of it with fir boughs, covered them over with rugs, and put Bera and the baby there. Then Swiftwater and I got in the boat and pushed off down stream.

Swiftwater confessed to me for the first time that he was in serious trouble.

“There have been three strange men from Dawson out here on our claims,” said Swiftwater, “and I know who sent them out. They are watching me.”

As I look back upon that awful trip down Indian River, with poor, wan, white-faced Bera hugging the little three weeks’ old baby to her bosom, so sick that she could hardly talk, I wonder if there is any hardship, and peril, and privation, and suffering, a woman cannot endure.

The boat was heavy—terribly heavy. In the small stretches of still water it was desperately hard, bone-racking toil to keep moving.

In the rushes of the river, where rapids tore at mill-race speed over boulders and pebbly stretches, we were constantly in danger of being upset. An hour of this sort of work made me almost ready for any sort of fate.

Finally we struck a big rock and the current carried us on a stretch of sandy beach. Swiftwater and I got out and waded up to our armpits in the[66] cold stream to get the boat started again. Then we climbed aboard and once more shot down the rocky canyon to another stretch of still water beyond. By nightfall we had reached an old cabin half way to Dawson, in which the fall before Swiftwater had cached provisions. The baby’s food was all gone, and Bera, in a fit of anger, had thrown what little bread and butter sandwiches we had put up for ourselves, overboard. I had not eaten all day, nor had Swiftwater.

It was growing dusk when we painfully pulled the boat on the bank at Swiftwater’s cache. Gates went inside to get some grub and prepared to build a fire. He came out a moment later, his face ashy pale, his eyes downcast.

“They have stolen all I had put in here,” he said.

It seemed to me that night as if the very limit of human misery on this earth was my bitter portion as we waited all through the weary hours in the cabin huddled before a little fire, waiting (it is light all the time in summer) to resume our journey to Dawson.

The next day we reached Dawson shortly after noon, famished, cold, and completely exhausted. I actually believe the baby would have died but for the bottle of soothing syrup and water which I had brought along.

Swiftwater took us to the Fairview Hotel and sent for the doctor for Bera and the baby.

CHAPTER VIII.

TO THE people of Dawson, in those days, starving through weary winter months for want of frequent mail communication with the civilized world, and hungering for the ebb and flow of human tide that is a natural and daily part of the lives of those in more fortunate places, the arrival of the first steamer from “the outside” in the spring is an event even greater than a Fourth of July celebration to a country town in Kansas.

For days before our arrival down Indian River from Quartz Creek, the men and women of Dawson had eagerly discussed the probability of the coming of the Yukoner, the regular river liner from White Horse due any moment, with fresh provisions from Seattle and the first papers and letters from “the outside.”

For two days after Swiftwater had taken Bera to the Fairview Hotel, the doctor had cared for her so as to enable her to recover from the hardships of the trip down Indian River. I took the baby to my own rooms and carefully nursed him through all one day. This brought him quickly round, and he soon looked as bright and cheerful as a new twenty dollar gold piece.

It was on the third morning after we arrived in Dawson that the steamer Yukoner’s whistle sounded up the river, and the whole populace rushed to the wharves and river banks. Miners came from all points up the creeks to welcome friends or to get their mail that the Yukoner had brought. The little shopkeepers in Dawson, particularly the fruit venders, were extremely active, bustling amongst the crowd on the dock and fighting their way to get the first shipments of early vegetables, fruits, fresh eggs, fresh butter and other perishable commodities for which Dawson hungered.

But Swiftwater, keen eyed, nervous, straining, yet trying to be composed, saw none of this, nor felt the least interest in the tide of newcomers who stepped from the Yukoner’s decks and made their way up town surrounded by friends.

Swiftwater was looking for one face in the crowd—that of his partner, Joe Boyle, who had promised to bring him $100,000 from London, where the big concession on Quartz Creek had been bonded for $250,000.

Swiftwater stood at the gang plank and eagerly scanned every face until the last man had come ashore and only the deck hands remained on board.

“There is certainly a letter in the mail, anyhow,” said Swiftwater.

For the first time in all of this miserable experience[69] I realized that a heavy burden was on Swiftwater’s shoulders—a load that was crushing the heart and brain of him—and that would, unless relieved, destroy all of the man’s native capacity to handle his tangled affairs, even under the most unfavorable circumstances.

I decided to watch Swiftwater very closely. I noticed that he was not to be seen around town in his usual haunts. I did not dare ask him if he feared arrest, for that would show that I knew that his crisis had come.

Two hours after the Yukoner’s mail was in the postoffice, Swiftwater came to my room.

“There is no letter from Joe,” was all he said.

I made no reply except to say:

“Have you told Bera?”

“No, and I’m not going to—now,” said Swiftwater and then left the room.

Swiftwater had between $35,000 and $40,000 of my money in his Quartz Creek concession. I had felt absolutely secure for the reason that if the property was well handled my interest should be worth from $100,000 to $250,000. My faith in the property has been justified by subsequent events, as all well informed Dawson mining men will testify.

But the want of money was bitter and keen at that moment. Yet I scarcely knew what to advise Swiftwater to do.

Gates and Bera came to my rooms after dinner that night.

“Will this help you pay a few pressing little bills?” asked Swiftwater, as he threw two fifty dollar paper notes in my lap.

“My God, Swiftwater, can’t you spare any more than $100?” I gasped.

“Oh, that’s just for now—I’ll give you plenty more tomorrow,” said he.

As they arose to go, Bera kissed me on the mouth and cheek with her arms around my neck.

“You love the baby, don’t you mama?” said Bera, and I saw then, without seeing, and came afterwards to know that there were tears in Bera’s eyes and a smile dewy with affection on her lips.

Swiftwater put his arm around me and kissed me on the forehead.

“We’ll be over early for you for breakfast tomorrow,” said Swiftwater as they went down the stairs.

Holding the baby in my arms at the window, I watched Swiftwater and Bera go down the street, Bera turning now and again to wave her hand and throw a kiss to me, Swiftwater lifting his hat.

Now, what I am about to relate may seem almost incredible to any normal human mind and heart; and especially so to those thousands of Alaskans who knew Swiftwater in the early days to be jolly,[71] though impractical, yet always generous, whole-souled, brave and honest.

An hour after Swiftwater and Bera had gone, there was a knock at my door. I opened it and there stood Phil Wilson—an old associate and friend of Swiftwater’s.

“Is Bill Gates here?” asked Wilson.

“Why, no,” said I. “They went over an hour ago.”

“Thank you,” said he, and lumbered heavily down the stairs.

The next morning I waited until 11 o’clock for Swiftwater and Bera to come for me to go to breakfast. I had slept little or none the night before and my nerves were worn down to the fine edge that comes just before a total collapse.

When it seemed as if I could not wait longer, there came a knock at the door.

When I opened the door there stood George Taylor, a friend of Swiftwater’s of some years’ standing.

“Mrs. Beebe, I came to tell you that Swiftwater and Bera left early this morning to go to Quartz Creek on horseback. I promised Swiftwater I would help you move to his cabin and get everything ready for their return on Saturday.”

“In Heaven’s name, what is Swiftwater trying to do—kill Bera?” I exclaimed. “That ride to[72] Quartz Creek in her condition, through the mud and mire of that trail, will kill her.”

Taylor merely looked at me and did not answer.

“Are you telling me the truth?” I demanded.

“I am,” he said.

Taylor walked away and I closed the door and went back to the baby.

“Baby,” said I, “I guess we’re left all alone for a while and you haven’t any mama but me.”

Although I afterward learned of the fact, it did me no good at that trying moment that Swiftwater had told Bera, before she would consent to leave me, that he had sent me $800 in currency by Wilson. Of course, Swiftwater did nothing of the kind, yet his story was such as to lead Bera to believe that I was well protected and comfortable.

Then I set to work to move my little belongings into Swiftwater’s cabin, there to wait for four days hoping that every minute would bring some word from Bera and Gates. There was little to eat in the cabin and the $100 that Swiftwater had given me had nearly all gone for baby’s necessities. The little fellow had kept up well and strong in spite of everything, and when I undressed him at night and bathed him and got him ready for his bed, he seemed so brave and strong and sweet that I could not, for the life of me, give way to the[73] feeling of desolation and loss that my circumstances warranted.

On the third day after Bera and Swiftwater had gone and I was getting a little supper for the baby and myself in the cabin, there came a clatter of heavy boots on the gravel walk in front of the house and a boisterous knock on the door.

Jumping up from the kitchen table, I nearly ran to the door, believing that Bera and Swiftwater were there. Instead there stood a messenger from the McDonald Hotel in Dawson with a letter for me. It simply said:

“We have gone down the river in a small boat to Nome with Mr. Wilson. I will send you money immediately on arrival there, so that you can join us.

SWIFTWATER.”

That was all.

I read the letter through again and then the horror of it came over me—I all alone in Dawson with Swiftwater’s four weeks’ old baby, broke and he owing me nearly $40,000.

Then everything seemed to leave me and I fell to the floor unconscious. Hours afterward—they said it was 9 o’clock at night, and the messenger had been there at 4 in the afternoon—I came to. The baby was crying and hungry. It seemed to me I had been in a long sickness and I could not[74] for a while quite realize where I was or what ill shape of a hostile fate had befallen me. And, when I think of it now, it seems to me any other woman in my place would have gone crazy.

For two months I stayed in that cabin, trying my best to find a way out of Dawson and unable to move a rod because of the fact that I had no money. Swiftwater, as I learned afterwards, took a lay on a claim on Dexter Creek and cleaned up in a short time $4,000.

When I heard this, I wrote to him for money for the baby, but none came.

A month passed and then another and no word from Swiftwater. I felt as long as I had a roof over my head, I could make a living for myself and the baby by working at anything—manicuring, hairdressing or sewing. Then, one evening, just after I had finished dinner, came a rap at the door.

It was Phil Wilson.

“Swiftwater has given me a deed to this house and power of attorney over his other matters,” said he. “I shall move my things over here and occupy one of these three rooms.”

I knew better than to make any objection then, but the next day I told Wilson:

“You will have to take your things down town—you cannot stay here.”

“I guess I’ll stay all right, Mrs. Beebe,” said he.[75] “And it will be all winter, too. And, I think it would be better for you, Mrs. Beebe, if you stayed here with me.”

I knew just what that meant. I said:

“Mr. Wilson, I understand you, but you will go and take your things now.”

Wilson left in another minute and I did not see him for two days. On the second afternoon I locked the door with a padlock and went down town to do some shopping for the baby, who I had left with a neighbor. I also wanted to send a fourth letter to Swiftwater, begging him to send me some money to keep me and his baby from starving.

When I got back at dusk that evening, the door to the cabin was broken open, and the chain and padlock lay on the ground shattered into fragments.

I went inside. All my clothes, the baby’s and even the little personal belongings of the child were piled together in a disordered heap in the center room.

CHAPTER IX.

IT WAS pitch dark when I left the cabin and made my way directly, as best I could, to the town with its dimly lighted streets. It seemed to me that I had never had a friend in all this world. Friend? Yes, FRIEND. That is to say—a human being who could be depended upon in any emergency and who was right—right all the time in fair as well as in foul weather.

There was only one thought in my mind—that was to find some man or woman in all that country to whom I could go for shelter and for aid. I knew naught of Swiftwater and Bera, except that they had left me. Swiftwater’s child, I felt as if he was my own—that little babe smiling up into my face as I had held him in my arms but a few minutes before, seemed to me as if he was my own.

I knew instinctively that there was none in all that multitude of carefree or careworn miners who thronged the three cafes and the dance halls of Dawson who could do much, if anything, to help me.

Past the dance halls and saloons and gambling halls of Dawson I went my way, down beyond the town and finally found the dark trail that led to[77] the barracks of the mounted police. I told the captain exactly what had happened. I said:

“Captain, I am left all alone here by Swiftwater Bill and I have to find some place to shelter his little two months’ old child and to feed and clothe him. He told me to live in his cabin. But I have no home there now as long as that man Wilson lives there.”

No woman who has never known the hard and seamy side of life in Dawson can possibly understand how good are the mounted police to every human being, man, woman or child, who is in trouble without fault of their own. The captain said.

“Mrs. Beebe, I have long known of you, and I do not doubt that a wrong has been done you. You and your little grandson shall not suffer for want of shelter or food tonight.”

With that the captain detailed two officers with instructions to accompany me to Swiftwater’s cabin and to see that I was comfortably and safely housed there, no matter what the circumstances. We went back that long, dark way, a mile over the trail to the cabin. When we arrived there, the two officers went inside.

“Place this woman’s clothes and belongings where they were before you came in here, and do it at once,” commanded one of the mounted police.

Wilson looked at me in amazement, and then his face was flushed with an angry glow as he saw that the two officers meant business.

Without a word, he picked up all the baby’s clothes and my own and put them back where they had been before. Then he took his pack of clothes and belongings and left without a word.

It would merely encumber my story to tell how I was summoned into court by Phil Wilson, and how the judge, after hearing my story of Swiftwater’s brutality—of his leaving me in Dawson penniless with his baby—said that he could hardly conceive how a man could be so inhuman as Swiftwater was, to leave the unprotected mother of his wife and his baby alone in such a place as Dawson and in such hands as those of the man who stood before him. He said that such brutality, in his judgment, was without parallel in Dawson’s annals and that, while he felt the deepest sympathy for me, left as I had been helpless and with Swiftwater’s baby, yet the law gave Phil Wilson the right to the cabin.

This ended the case. I turned to go from the courtroom when the Presbyterian minister, Dr. McKenzie, came to me and said:

“Mrs. Beebe, I do not know anything about the circumstances that have brought you to this condition,[79] but if you will let me have the child I will see that he has a good home and is well cared for.”

But this was not necessary, as it turned out afterwards, because Dr. McKenzie took the matter up with the council, where it was threshed out in all its details. The council voted $125 a month for sustenance for the nurse and the baby. The mounted police took me to the barracks and there provided a cabin and food, with regular supplies of provisions from the canteen.

I do not doubt but that the monthly expense during the winter that I lived there with the baby is still a matter of record in Dawson in the archives of the government, and I am equally certain that, although Swiftwater Bill has made hundreds of thousands of dollars since that day and is now reputed to be worth close to $1,000,000, he has never liquidated the debt he owes to the Canadian government for the care and sustenance and shelter they gave his own boy. All of the facts stated in this chapter can easily be verified by recourse to the records of the court and mounted police in Dawson.

Although I knew that Swiftwater was making money in Nome, I placed no more dependence in him from that moment and managed to sustain myself by manicuring and hairdressing in Dawson.