| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924023253143 |

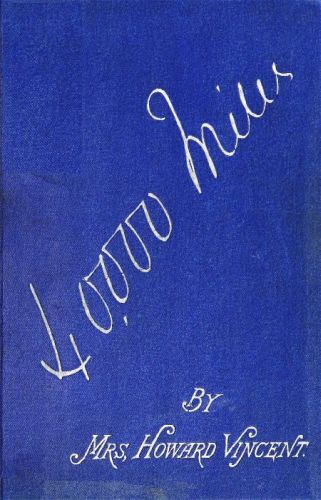

The White Terrace, Hot Lakes, New Zealand.

Frontispiece. Page 119.

THE JOURNAL OF A TOUR THROUGH THE

BRITISH EMPIRE AND AMERICA

BY

MRS. HOWARD VINCENT

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

THIRD AND CHEAPER EDITION.

London:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1886.

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, LIMITED,

ST. JOHN'S SQUARE.

TO

OUR FRIENDS,

THE CHILDREN OF THE METROPOLITAN AND CITY POLICE ORPHANAGE,

This Journal is Dedicated

BY

THEIR CONSTANT WELL-WISHERS.

My husband, during his six years' tenure of the office of Director of Criminal Investigations, took the greatest interest in the Metropolitan and City Police Orphanage.

In taking leave of his young friends he promised to keep for their benefit a record of our travels through the British Empire and America.

I have endeavoured to the best of my power to relieve him of this task.

It is but a simple Journal of what we saw and did.

But if the Police will accept it, as a further proof of our admiration and respect for them as a body, then I feel sure that others who may be kind enough to read it will be lenient towards the shortcomings of a first publication.

ETHEL GWENDOLINE VINCENT.

1, Grosvenor Square, London.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| Across the Atlantic | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| New York, Hudson River, and Niagara Falls | 4 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Dominion of Canada | 17 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The American Lakes, and the Centres of Learning, | |

| Fashion, and Government | 26 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| To the Far West | 43 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| San Francisco and the Yosemite Valley | 66 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Across the Pacific | 88 |

| [x] | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Coaching through the North Island of New Zealand; | |

| its Hot Lakes and Geysers | 102 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The South Island of New Zealand; its Alps and Mountain Lakes | 146 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Australia—Tasmania, and Victoria | 161 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Australia—New South Wales, and Queensland | 181 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Within the Barrier Reef, Through Torres Straits to Batavia | 200 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Netherlands India | 212 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Straits Settlements | 235 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Metropolis of India and its Himalayan Sanatorium | 250 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Shrines of the Hindu Faith | 274 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Scenes of the Indian Mutiny | 287 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Cities of the Great Mogul | 304 |

| [xxx] | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Gwalior and Rajputana | 332 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Home of the Parsees | 352 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Through Egypt—Homewards | 361 |

| PAGE | ||

| The White Terrace, Hot Lakes, New Zealand | Frontispiece | |

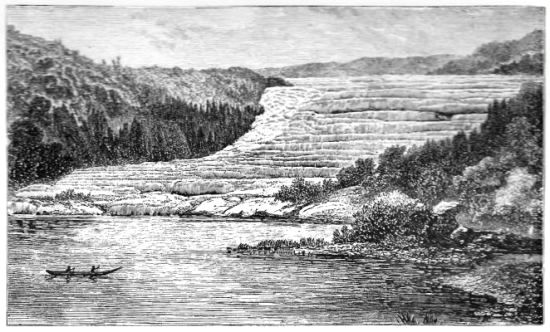

| Route Map | to face | 1 |

| "That horrible fog-horn!" | 1 | |

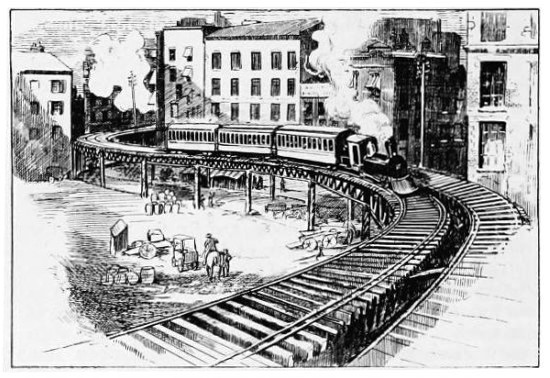

| Elevated-Railway, New York | 6 | |

| Parliament Buildings, Ottawa | to face | 22 |

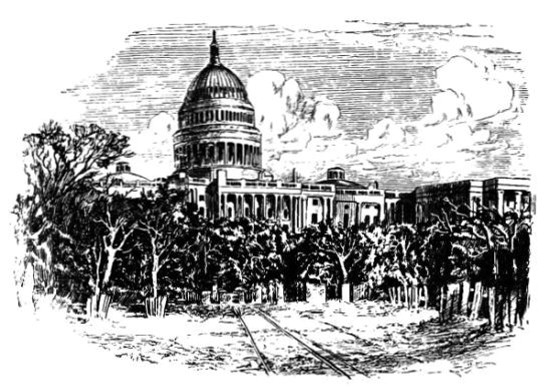

| The Capitol, Washington | 40 | |

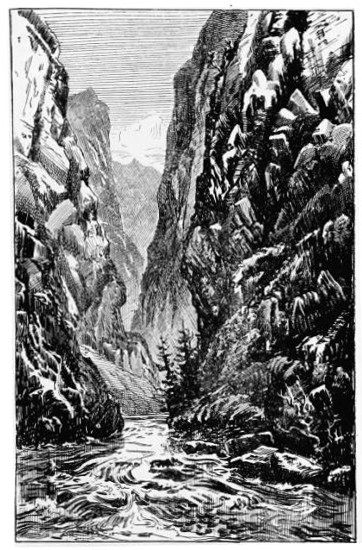

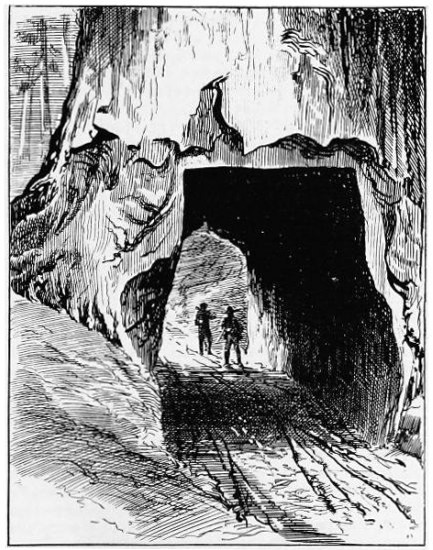

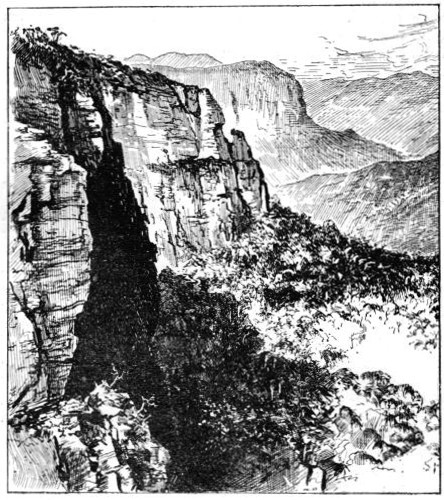

| The Royal Gorge of the Arkansas | to face | 58 |

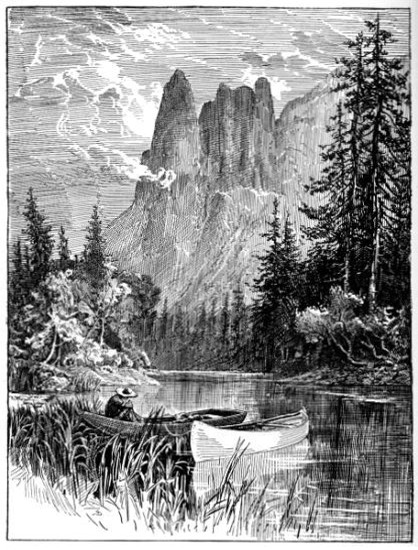

| The Sentinel, Yosemite Valley | " | 77 |

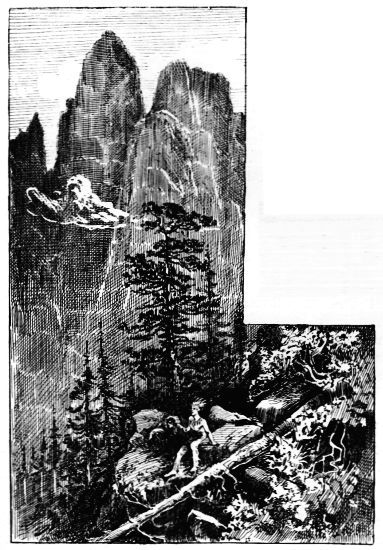

| The Cathedral Spires, Yosemite Valley | 79 | |

| Big Tree, California | 83 | |

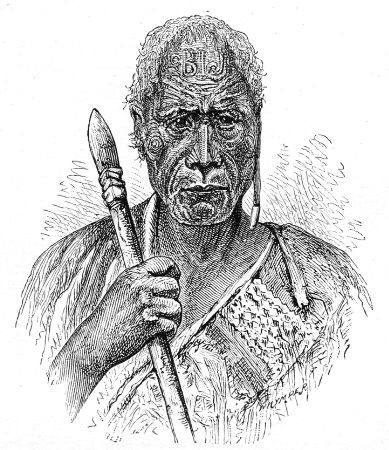

| Maori Chieftain | 110 | |

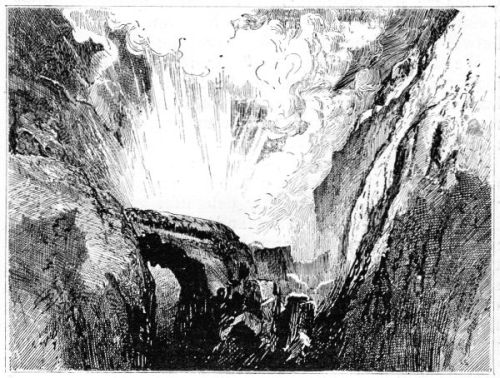

| Tuhuatahi Geyser, New Zealand | 128 | |

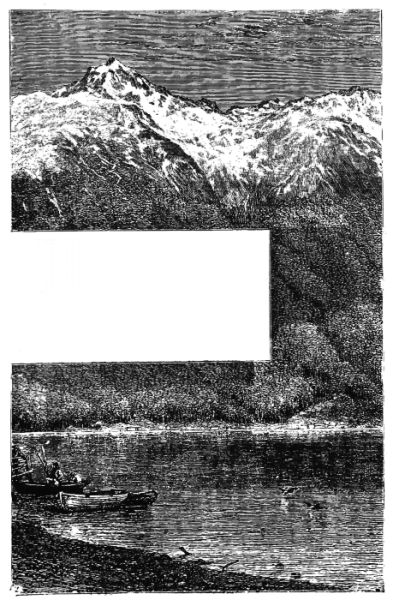

| Lake Wakitipu, New Zealand | 157 | |

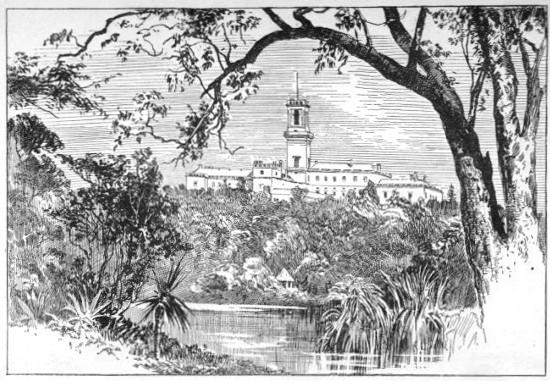

| Government House, Melbourne | to face | 165 |

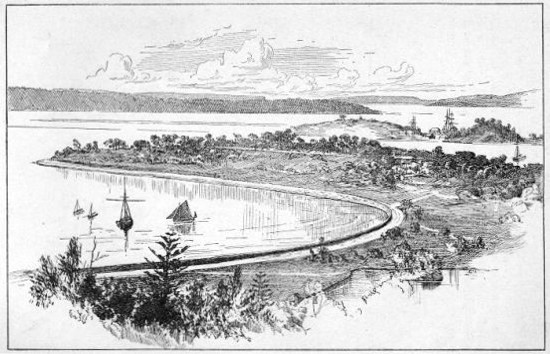

| Sydney Harbour | " | 182 |

| Govett's Leap, Blue Mountains | 191 | |

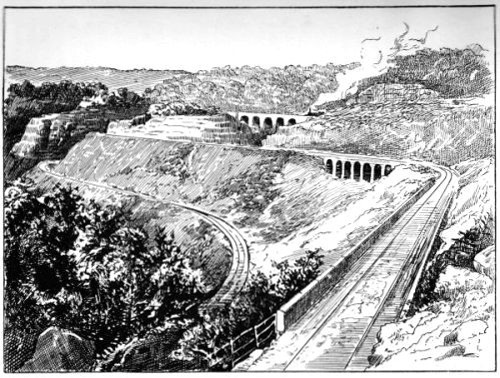

| Zig-zag on Railway, Blue Mountains | to face | 192 |

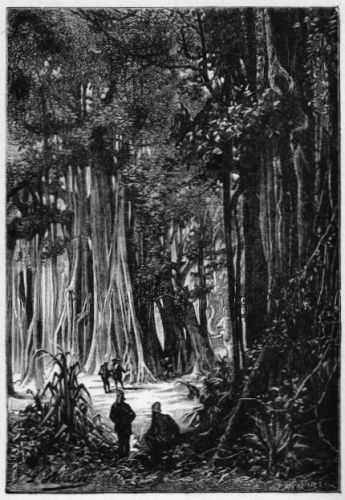

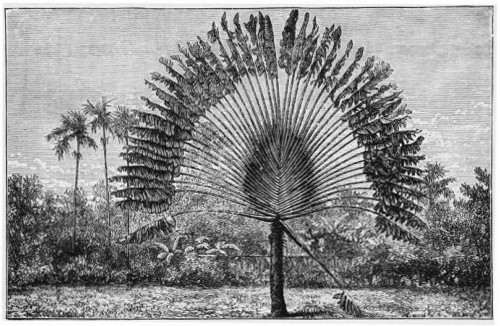

| Banyan Trees, Buitenzorg, Java | " | 227 |

| Traveller's Palm, Singapore | " | 236 |

| Jinricksha | 249 | |

| The Hooghley, Calcutta | to face | 251 |

| The Darjeeling and Himalayan Railway | " | 263 |

| Benares Bathing Ghât | " | 276 |

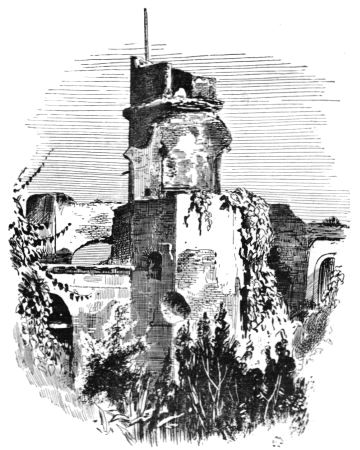

| The Residency, Lucknow | 288 | |

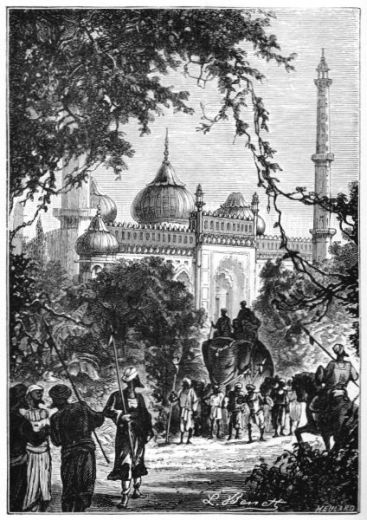

| The Imambara, Lucknow | to face | 291 |

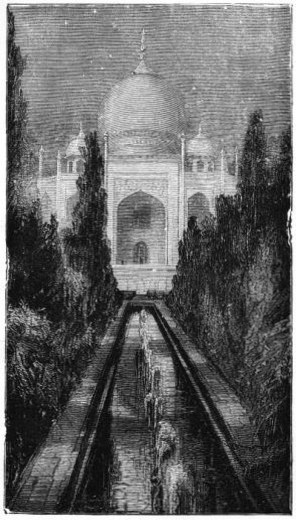

| The Taj Mahal, Agra | " | 312 |

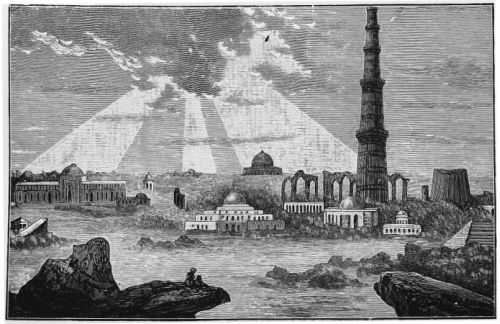

| Column, Kutub Minar, Delhi | " | 329 |

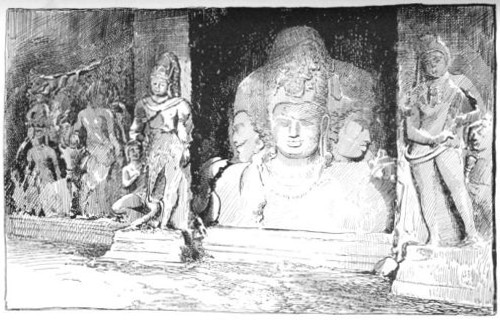

| The Caves of Elephanta, Bombay | " | 356 |

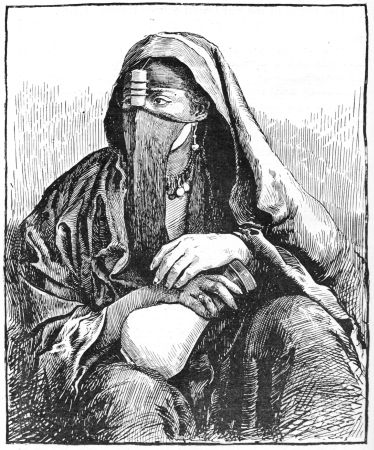

| Cairene Woman | 372 | |

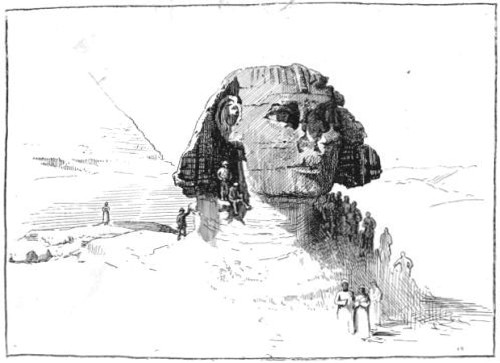

| The Sphinx | to face | 377 |

ROUTE MAP TO "FORTY THOUSAND MILES OVER LAND AND WATER" BY Mrs. HOWARD VINCENT.

Route marked thus ——

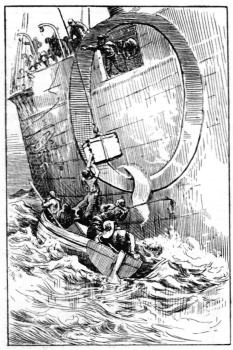

"That horrible fog-horn!"

Lat. 43° 15´ N., Long. 50° 12´ W. All is intensely quiet. The revolution even of the screw has ceased. We are wrapped in a fog so dense that we feel almost unable to breathe.

We shudder as we look at the white pall drawn closely around us. The decks and rigging are dripping, and everything on board is saturated with moisture. We feel strangely alone. When hark! A discordant screech, a hideous howl belches forth into the still air, to be immediately smothered and lost in the fog. It is the warning cry of the fog-horn.

We are on board the White Star steamer Germanic, in mid-Atlantic, not far off the great ice-banks of Newfoundland.

It was on Wednesday, the 2nd of July, that we left London, and embarked from Liverpool on the 3rd.

I need not describe the previous bustle of preparation, the farewells to be gone through for a long absence of[2] nine months, the little crowd of kind friends who came to see us off at Euston, nor our embarkation and our last view of England.

I remember how dull and gloomy that first evening on board closed in, and how a slight feeling of depression was not absent from us.

The next morning we were anchoring in Queenstown Harbour, and whilst waiting for the arrival of the mails in the afternoon we went by train to Cork.

The mails were on board the Germanic by four o'clock. We weighed anchor, and our voyage to America had commenced. The often advertised quick passages across the Atlantic are only reckoned to and from Queenstown. The sea-sick traveller hardly sees the point of this computation of time, for the coasts of "ould Ireland" are as stormy and of as much account as the remainder of the passage.

And now we have settled down into the usual idle life on board ship, a life where eating and drinking plays the most important part. There is a superfluity of concerts and literary entertainments, the proceeds in one instance being devoted to the aid of a poor electrical engineer who has had his arm fearfully torn in the machinery, and whose life was only saved by the presence of mind of a comrade in cutting the strap.

Fine weather again at last, for we are past the banks so prolific in storms and fog. The story goes that a certain captain much harassed by the questioning of a passenger, who asked him "if it was always rough here?" replied, "How should I know, sir? I don't live here."

We are nearing America, and may hope to land to-morrow.

The advent of the pilot is always an exciting event. There was a lottery for his number and much betting upon the foot with which he would first step on deck.

A boat came in sight early in the afternoon. There was general excitement. But the captain refused this pilot as he had previously nearly lost one of the company's ships. At this he stood up in his dinghy and fiercely denounced us as we swept onwards, little heeding.

Another pilot came on board soon afterwards, but the news and papers he brought us were very stale. These pilots have a very hard life; working in firms of two or three, they often go out 500 miles in their cutters, and[3] lie about for days waiting to pick up vessels coming into port. The fee varies according to the draught of the ship, but often exceeds 30l.

At two o'clock a white line of surf is seen on the horizon. Land we know is behind, and great is the joy of all on board.

We watched and waited till behind the white line appears a dark one, which grew and grew, until Long Island and Fire Island lighthouse are plainly visible.

Three hours more and we see the beautiful Highlands of the Navesink on the New Jersey shore; then the long sandy plain with the lighthouse which marks the entrance—and we cross the bar of Sandy Hook. As we do so the sunset gun goes off, and tells us that we must pass yet another night on board, for it closes the day of the officer of health.

We pass the quarantine station, a white house on a lonely rock—then entering the Narrows, anchor in the dusk off lovely Statten Island.

The lights of Manhattan and New Brighton beach twinkle in the darkness. Steamers with flashing signals ply swiftly backwards and forwards. A line of electricity marks the beautiful span of Brooklyn Bridge, and over all a storm is gathering, making the surrounding hills resound with the cannon of its thunder and the sky bright with sheets of lightning.

And so we pass the night, within sight of the lights of New York, with pleasurable excitement looking forward to our first impressions on the morrow.

Sunday, July 13th.—By six o'clock all is life on board the Germanic, for a great steamer takes some time getting under weigh. Breakfast is a general scramble, interspersed with declarations to the revenue officials who are sitting in the saloon.

We pass the Old Fort on Governor's Island, now the military station, in our upward progress, see the round tower of Castle Garden, the emigrants' depôt, and by eight o'clock are safely moored alongside the company's pier.

On the wharf are presently to be seen passengers sitting forlorn on their trunks, awaiting the terrible inspection of the custom-house officer. The one detailed to us showed signs of becoming offensive, being unwilling to believe the statement that a dress some six months' old was not being[4] taken round the world for sale; but on making representations to his superior we were able to throw the things back into the boxes and "Express" them to the hotel.

As we drove over the rough streets of New York in the early hours of Sunday morning, it appeared as a city of the dead. There was no sign of life as our horses toiled along Broadway and up Fifth Avenue to the Buckingham Hotel, where we had secured rooms.

This hotel, though comfortable, had the disadvantage of being too far up town for short sojourners, but it has the merit of being conducted on the European system—that is, the rooms and meals are charged for separately. The American plan is to make an inclusive charge of from four to five dollars a day, and it is often troublesome only being able to have meals in the dining-room between certain hours. Besides, it is pleasant to be able to visit the restaurants of New York, which are admirable, and equal, if not superior to those of Paris. Delmonico's, where we dined one evening, is particularly excellent.

We were glad when eleven o'clock came and we could go to St. Thomas' Church, close by. It is one of the most frequented of the many beautiful churches of all denominations in New York, and of very fine interior proportions. Upon the dark oak carving is reflected in many hues the rich stained glass. The service was rendered according to the ritual of the English Church, which is followed by the Episcopal Church of America. They succeed in America in uniting a non-ceremonial service with a bright and hearty one. We listened to a very powerful sermon on St. Paul on the Hill of Mars, in which the eloquent preacher boldly declared that the political honesty of the Athenians 2000 years ago was superior to that of the United States of to-day.

On our way back we went into the Roman Catholic Cathedral, which was just opposite to our windows at the[5] "Buckingham," a very large marble building, but still unfinished.

We found four reporters waiting at the hotel to "interview" my husband. He had eluded them on the landing-stage, but they would take no denial here, and we were much harassed by others in the course of the day.

Our luggage arrived at noon. It is almost a necessity to employ the Express Company for the conveyance of "baggage" throughout America, as the hackney carriages and hotel omnibuses are not prepared to take it. The charges are very high, and it is often extremely inconvenient having to wait two, three, or even four hours for it, after arrival in a town.

The geography of New York is exceedingly simple, and is followed in nearly every American city. "Avenues" traverse the length of the town, which are called first, second, or third avenues, and the "streets" which intersect them are also numbered consecutively, so that you have—Third Street, Fifth Avenue, and know that it is the third street from the commencement of Fifth Avenue.

The houses are built in blocks, and for the most part in the upper portion of New York, of dark red sandstone.

There are ample means of cheap locomotion by two "elevated" railways, and innumerable tramways. Each of the former runs the whole length of the city, a distance of ten miles. They were built by rival companies who afterwards amalgamated. A double line is laid upon iron piers in the centre of the street on a level with the third stories of the houses on each side. One wonders how the necessary powers to build such a line were obtained, but in "free" America, vested interests and damage to property are not taken into account, when financiers have a scheme to carry out.

It is said that the value of the surrounding houses has been increased rather than otherwise by the proximity of the Elevated: more curiously, the tram lines running below it, and which were formerly insolvent, are now paying well.

The uniform fare is ten cents, except after four o'clock on Sundays, when it is reduced to five cents, the same as the fare of the "trams." The train consists of an engine and four light coaches, all of one class, and fitted with[6] comfortable cane seats. They succeed each other every five minutes. A conductor is on the platform of every carriage, and opens the iron gate at the end as soon as the train stops. There is a marked absence of all confusion and haste, partly attributable to there being no collection of tickets, which are dropped into a box on the platform immediately after purchase.

Cabs are few in number and very expensive. They charge four and a half dollars, or nearly 1l., from the quay to the hotels, without luggage, and one dollar a mile, or a dollar and a half per hour.

Elevated Railway, New York.

Independently of these exorbitant prices, driving is very unpleasant from the streets being paved with blocks of granite, and being kept in shocking repair.

It is alleged that the extremes of climate prevent the use of any other material, but there is probably more truth in the statement that the money voted by municipal councils for their paving finds its way into other channels. Washington and Boston were the only towns we afterwards saw with good pavements, without ruts or holes. Above the thoroughfares is a rose of telegraph and telephone[7] wires, and poles and standards abound in the streets. At nearly every house there is a telephone to put the inmates in connection with some place of business or some relative.

In the afternoon we went to Trinity Church, which may be called the cathedral of New York. The service was just ending, and the choir were filing out of the chancel under a blaze of golden glory from the sun shining through the east end window, singing the hymn, "Angels of Jesus, Angels of Light, Singing to welcome the pilgrims of the night."

The voices grew fainter and fainter, and finally died away on the breathless stillness of the air. Then the huge organ, blown by electricity, pealed forth, and the spell was broken.

Mr. Vanderbilt, Mr. Astor, and the Stewart family live in gorgeous palaces, and one is struck how even this Republic cannot prevent a monopoly of property and an accumulation of wealth. Mr. Vanderbilt has three adjoining houses, forming a block, in Fifth Avenue, for himself and his married children.

The squares and gardens are well kept, and it is pleasant to see them all open, full of people sitting in them, without the railings which make London squares so gloomy and of so little pleasure even to those who have the entrée.

We drove round Central Park—a perfect triumph of landscape gardening, with but little help from nature. The "Mall" and alleys were thronged with gay crowds, listening to the band, and boats were plying on the lake. There were not many carriages, the fashionable world having fled from the fagging heat of New York; but those we saw had servants in livery, a comparatively recent innovation, and one much disapproved of by the people.

The cross-bar waggons in general use, weighing little over two hundredweight, with their skeleton wheels, whirl along at a great pace, but the horses all have a check-rein passing over the head, which is far more cruel than even our gag bearing-rein.

Monday, July 14th.—We began our wanderings by going over the beautiful Brooklyn Bridge, which unites New York with its monster suburb, the home of half a million of people, principally of the working classes, of whom a large proportion are Irish. It is a marvellous structure, the finest[8] suspension bridge ever built, and a mile and a quarter long. So graceful and light is the curve it describes that from a distance it seems to be a spider's web suspended in mid-air. We had a long "tram" journey through the dull and dirty streets to Greenwood Cemetery, the great burial-place of New York. A gateway of much beauty marks the entrance, and over the centre arch are the words, "Weep not, for the dead shall be raised." A granite obelisk in the centre of a grass plot attracts our attention. Below it lie the bodies of 103 persons who perished in the burning of the Brooklyn Theatre in 1876. Under that green mound what a mass of human passions were laid to rest! Some of the monuments are very finely conceived in design, and execution; others were grotesque and ugly. Nothing, however, mars the beauty of the whole—the shining river running through this valley of the dead, the surroundings bright with marble, flowers, and shrubs—only, a sweet garden where the people come and walk in the evening cool, watching the sun sinking over the harbour, and thinking, it may be, of how they too will likewise join those who lie at rest here.

In the afternoon we paid a visit to Wall Street, the scene of so many fortunes lost and won. The din in the Stock Exchange was deafening, and the appearance of the frantic, yelling speculators anything but attractive.

The "stores," or shops, in Broadway are very fine inside, but the windows are not so well set out as in Paris or London. The goods for sale are also more general in character, and nearly double in price. This arises from the large duties or imposts in a great measure, but also because the unit of a dollar (4s. 2d.) is so high. It seems as easy to ask one dollar as one shilling or one franc, and the former coin scarcely goes farther than the latter throughout the States.

The New York Herald, Times, World, and other papers come out with long accounts of the interviews given yesterday. They went into the most precise details of dress, manners, and speech.

Tuesday, July 15th.—We had a pleasant morning in seeing the magnificent armoury of the "Seventh Regiment of the National Guard." The Seventh Regiment includes in its ranks some of the best men in New York, and the National Guard corresponds exactly to the Volunteer force[9] of England. The Drill Hall is 300 feet long and 200 feet broad, unbroken by a pillar, and large enough to manœuvre a battalion, having a solid oaken floor so constructed as to prevent reverberation in marching. Each company has a room for itself, and the officers' room, the library, and the veterans' room, where those who have left the regiment come to meet their sons and relatives now serving, are beautiful apartments, richly furnished.

In the afternoon Sir Roderick Cameron kindly took us over to his charming place on Statten Island. It is beautifully wooded, and when the salt marshes are drained, and the mosquitoes reduced in numbers, his farm will no doubt be the site of a populous suburb.

Wednesday, July 16th.—By nine o'clock we were waiting on the shores of the Hudson River for one of the floating palaces which ply to and from Albany. The C. Vibard was seen presently coming—a magnificent vessel of colossal size, with three decks towering one above the other, and yet drawing but six feet of water. What we were particularly struck with on these river and lake steamers was that, although there is no distinction of class, no inconvenience whatever results. All is orderly and quiet; everybody is well-dressed and well-behaved. Indeed, throughout the States, rowdyism seems to be as absent as pauperism, and the deference paid to ladies might well be imitated in older countries. They have a separate entrance at hotels, and a separate "guichet" at post-offices and railway stations. A lady may travel with perfect comfort alone, and walk in the streets without fear of any annoyance.

A fresh wind dappled the blue sky, and raised the muddy waters of the grand old Hudson. Across from New Jersey and Hoboken, those thriving suburbs of New York, came the busy hum of life. The well-wooded hills were clothed with villas, whose domes or towers peep out from amongst the dense foliage. Here and there, standing in a little park, were châlets, or a cottage with gilt minarets, or, even in still more incongruous taste, a Chinese pagoda. It is here the merchants from the great city take their rest and pleasure, within ear-shot and easy reach of their familiar haunts around Wall Street. On the opposite shore the great wall of basaltic trap-rock, known to the early settlers by the name of the "Great Chip Rock," but to their more practical successors as the "Palisades," forms an impenetrable[10] wall, rising in a sheer precipice from the river, a height of from 300 to 600 feet.

Meandering along by its mighty brother, unseen on the other side, there is another river, running at a lower level.

Historical associations crowd upon us as we sail up between the broad banks, stretching from the memory of the early band of settlers who under Hendrich Hudson, the Dutchman, made the first voyage of discovery up the river to which he afterwards gave his name; to the little villages of Tappan and Tarrytown, glowing with the memories of the brave but ill-fated Major André. Need I repeat his well-known story? In the dead of night he landed from the Vulture at Stony Point to meet Arnold, who had turned traitor, to arrange with him for the surrender of West Point, the key of the position. André was captured in returning by land, searched, the papers found on him, and executed, to the sorrow of both armies; whilst Arnold, escaping to the Vulture, was rewarded with 6000l., and became a Brigadier-General in the British army. Many know well the monument afterwards erected to André in Westminster Abbey.

Sunnyside, a little white cottage, the home of Washington Irving, lies on the hill, almost hidden by the surrounding trees. The front is covered with ivy grown from a sprig that Sir Walter Scott sent from Abbotsford. "Sleepy Hollow," the scene of so many of Washington Irving's charming romances, is quite near. Every side of life is here represented. All manner of men have found their greatest happiness in the quiet beauty of the Hudson's banks. Besides authors and actors, such as Forrest, the great tragedian—science, in the person of Professor Morse, of telegraph fame, and the great merchant princes, such as Stewart, Astor, and Jay Gould, have made their homes here. Miss Warner, authoress of the "Wide, wide World," has a cottage near Teller's Point.

At Tappan Zee the river opens out into a lake ten miles broad. The gloomy fortress of Sing Sing, the State prison, lies on an island near the shore. Croton Lake is close by, and supplies New York with from 40,000,000 to 60,000,000 gallons daily, through an aqueduct thirty-three miles long. The wooden sheds found at intervals along the banks are the great storehouses where in winter the ice is cut and kept, ready to supply the vast consumption of New York.

The beautiful bay of Haverstraw leads to the narrow defile and the northern gate of the Highlands. In rugged and varied beauty the mountains close us in on every side, overshadowing us with their wooded heights; maple and sycamore mingling with darker belts of pine, or a thick undergrowth of stunted oaks. They are so like the Highlands that you look—but in vain—for the bracken and the furze.

"The glory of the Hudson is at West Point," says a well-known author, and I suppose there could not be a more beautiful situation for the Military College of the United States, the Sandhurst of America, than at West Point. It stands on a commanding bluff, the river winding round three sides of the promontory in an almost impregnable position.

From the southern gate of the Highlands, green marshy fields, with weeping-willows trailing along the banks, form the chief feature of the landscape, and we pass several thriving towns like Peekskill and Poughkeepsie. In the afternoon, blue and purple in the far distance, we saw the glorious range of the mighty Catskill Mountains, forming one unbroken series of snow-capped domes, hiding in their deep recesses many of Nature's grandest secrets. The evening was closing in as the steamer passed under the swinging arch of the bridge at Albany, the chief town of New York State.

Albany is chiefly remarkable for its very fine Capitol, which has been in process of building since 1871, and is still far from finished, though it has already cost an enormous sum. At the present time every one is talking about Albany, owing to the fact that Grover Cleveland, the newly-selected Democratic candidate for the Presidency, is the Governor.

Delaware House gave us shelter for the night; and at 8 a.m. the next morning we were in the "cars" on our way to Niagara.

This was our first experience of American railways. There is no distinction of classes in the railway company's fares, but greater luxury is obtained by travelling in the drawing-room or sleeping car. The former belong to the Wagner, the latter to the Pullman Company, who make a separate charge, which is levied by the special conductor. This is his only duty, except to make himself a nuisance, and generally objectionable. The beds are made up by an obliging[12] coloured porter. The cars are very long, and run on sixteen wheels. There is communication through the train, but it is only used by the condescendingly grand officials and the numerous news and fruit vendors who torment you with repeated exhibitions of their varied wares. The windows are so large, that if opened dust and grit from the slack coal burnt by the engines smother everything, so that with the car full (and they hold from twenty to thirty) the atmosphere becomes terribly oppressive. In winter, and when the stoves are lighted it is even worse. The Americans are very proud of their railway system, but after travelling over most of their lines, it is impossible to see that we have much to learn from them. The traffic is conducted in a very happy-go-lucky style. There is an absence of civility, with a superabundance of officials, and a porter is not to be met with. The traveller must carry his hand-luggage himself. The system of checking the baggage is, however, admirable. A brass check attached to the trunk ensures its going safely to any destination, however distant, and only being given up on presentation of the duplicate, which is in possession of the passenger.

Our journey lay through the smiling valley of the Mohawk River. The operation of hay-making was going on in many of the fields we passed. The hay was cut, raked, turned over, unloaded, and stacked by machinery—the most convincing proof of the absence of hand-labour. Throughout the vast continent of America, from the farms of the east to the cattle ranches of the west, there is the same cry for labour. Still greater is the demand for domestic servants. American girls think nothing of serving in a "store" or at a railway buffet, or even in an hotel. They have their freedom at certain hours, and when their work is done they are their own mistresses; but domestic service they look upon as degrading. It is almost wholly confined to Irish immigrants. A gentleman told us of a large mountain hotel where the waiting during the summer months of the season was done by an entire school of young ladies, who at the end of the time returned with their "salaries" (the term of "wages" is never used) to pay for their winter's schooling.

At Syracuse we experienced for the first time the strange custom of running the train through a street in the heart of the city. Many lives are annually lost, and terrible accidents occur frequently at the level crossings.[13] "Look out for the locomotive" is on a large sign-board, but the public depend more upon the shrill whistle or the ringing of the engine bell. The effect of these engine bells is very melodious when, deep-toned and loud-voiced, coming and going in a station they chime to each other.

Friday, July 18th, Clifton House, Niagara Falls.—"What a moment in a lifetime is that in which we first behold Niagara!" And it is difficult with a very feeble pen to say anything superior to such a commonplace platitude, even when in the presence of one of Nature's most glorious works.

Notwithstanding all written and said, imagined or described, Niagara cannot be put into words; cannot be conveyed to the imagination through the usual medium of pen and paper; can only be seen to be—even then but partially—understood.

There is a blue river, two miles wide, without ripple or ruffle on the surface, coming down from a great lake, pursuing its even course. There are breakers ahead—little clouds, then white foam sprayed into mid-air. The contagion spreads, until on the whole surface of the river are troubled waves, noisily hurrying down, down, with ever-increasing velocity, to the great Canadian fall. The mockery of those few yards of clear, still water! In a suction green as an uncut emerald, a volume of water, twenty fathoms deep, is hurled over a precipice 160 feet high. One hundred million tons of water pass over every hour, with a roar that can be heard ten miles away, and a reverberation that shakes the very earth itself, into the seething cauldron below, shrouded in an eternal mist:—"There is neither speech nor language, but their voices are heard."

In a minor key the American waters repeat the mighty cannonade, and blending their voices, mirror the sea-green colour of the wooded precipices as they flow on their onward course. Long serpent trails of foam alone bear witness to the late convulsion.

The gorge is narrowing; the waters are compressed into a smaller space; they are angry, and jostle each other. They hiss, they swirl; they separate to rush together in shooting shower of spray, and so struggle through the Rapids.

A gloomy pool, with darkling precipices of purple rocks, forms a basin. The waters are rushing too surely into that[14] iron-bound pool. The current is checked and turned back on itself, to meet the oncoming stream. A mighty Whirlpool forms. The waters divide under the current, and one volume returns to eddy and swirl helplessly against the great barrier, whilst the other volume, more happy, finds a cleft, broadened now into a wide gateway, and gurgling and laughing to itself, glides away on a smooth course, to lose its volume in Lake Ontario. What a world-renown that stream will always have—a short course full of awful incident.

On the 25th of July, 1883, Captain Webb was drowned while attempting to swim the rapids. Diving from a small boat about 300 yards above the new cantilever bridge, he plunged into the stream. The force of the current turned him over several times; then he threw up his arms and sank, crushed to death, it is supposed, by the pressure of the water. The enterprising owners of the restaurant at the rapids, have arranged with his widow to come over during the season to sell photographs opposite the spot where her husband perished.

Goat Island forms the division between the American and Canadian Falls. The waters are rapidly eating away the banks, and the rocky promontory, which forms such a principal feature, may some day disappear. What a glorious junction it would be! Four years ago a large piece of rock in the centre of the horse-shoe came away, and its symmetry was somewhat marred. The three pretty little Sister Islands are joined by their graceful suspension bridges to Goat Island. These islands, lying out as they do amidst the roughest and most tumultuous part of the rapids, have a magnificent view of the waters as they come tumbling down. The Hermit's Cascade is connected with the pathetic story of a young Englishman who, coming one day to see Niagara, remained day after day overpoweringly fascinated. Unable to tear himself away, he lived year after year for ever within sight and hearing of the falls. He is supposed to have perished in their waters whilst bathing one day, but whether intentionally or not was never known. I believe those who have sat and watched those tumultuous waters for any great length of time would understand the working of the spell on a sensitive brain.

Biddle's Stairs lead down to the "Cave of the Winds." It is awe-inspiring to watch the fall from below, and yet this[15] is only a streamlet of the great volume of the fall. What must it be inside, when the beating of the spray-like hail, the roaring of the winds, mingling with the thunder of the cataract, form a combination of the majesty of the elements on earth.

After a morning spent amongst these terrifying wonders, we had a quiet drive along the right bank of the river through Cedar Island. The thunder and roar was succeeded by quiet pools and swiftly-flowing currents, calm and clear, rippling in the afternoon sunlight. Weeping-willows, long grasses, and bending reeds whispered in the cool breezes. From the heights above we again surveyed the whole scene. And returning home once more came under the spell of the Mermaid, looming white and mysterious in the gloaming.

Niagara becomes very dear—a child of the affections; and to those who are unfortunate enough to have to picture Niagara from description, I should say efface mine quickly, quickly I say, and turn to that of Anthony Trollope:—

"Of all the sights on this earth of ours which tourists travel to see—at least, of all those which I have seen—I am inclined to give the palm to the Falls of Niagara. In the catalogue of such sights I intend to include all buildings, pictures, statues, and wonders of art made by men's hands, and also all beauties of nature prepared by the Creator for the delight of His creatures. I know no other one thing so beautiful, so glorious, and so powerful.

"We will go at once on to the glory, and the thunder, and the majesty, and the wrath of that upper belt of waters.

"Go down to the end of that wooden bridge, seat yourself on the rail, and there sit till all the outer world is lost to you. There is no grander spot about Niagara than this. The waters are absolutely around you. If you have that power of eye-control which is so necessary to the full enjoyment of scenery, you will see nothing but the water. You will certainly hear nothing else. And the sound, I beg you to remember, is not an ear-cracking, agonized crash and clang of noises, but is melodious and soft withal, though loud as thunder. It fills your ears, and, as it were, envelopes them; but at the same time you can speak to your neighbour without an effort. But at these places, and in these moments, the less of speaking I should say the better. There[16] is no grander spot than this. Here, seated on the rail of the bridge, you will not see the whole depth of the fall. In looking at the grandest works of nature, and of art too, I fancy, it is never well to see all. There should be something left to the imagination, and much should be half concealed in mystery.

"And so here, at Niagara, that converging rush of waters may fall down, down at once into a hell of rivers for what the eye can see. It is glorious to watch them in their first curve over the rocks. They come green as a bank of emeralds, but with a fitful flying colour, as though conscious that in one moment more they would be dashed into spray and rise into air, pale as driven snow. The vapour rises high into the air, and is gathered there, visible always as a permanent white cloud over the cataract; but the bulk of the spray which fills the lower hollow of that horse-shoe is like a tumult of snow.

"The head of it rises ever and anon out of that cauldron below, but the cauldron itself will be invisible. It is ever so far down—far as your own imagination can sink it. But your eyes will rest full upon the curve of the waters. The shape you will be looking at is that of a horse-shoe, but of a horse-shoe miraculously deep from toe to heel; and this depth becomes greater as you sit there. That which at first was only great and beautiful, becomes gigantic and sublime till the mind is at a loss to find an epithet for its own use. To realize Niagara, you must sit there till you see nothing else than that which you have come to see. You will hear nothing else, and think of nothing else. At length you will be at one with the tumbling river before you. You will find yourself among the waters as though you belonged to them. The cool liquid green will run through your veins, and the voice of the cataract will be the expression of your own heart. You will fall as the bright waters fall, rushing down into your new world with no hesitation and with no dismay; and you will rise again as the spray rises, bright, beautiful, and pure. Then you will flow away in your course to the uncompassed, distant, and eternal ocean.

"Oh! my friend, let there be no one there to speak to thee then; no, not even a brother. As you stand there speak only to the waters!"

Since our arrival at Niagara we had been on Canadian soil, and in view of the falls, which form Canada's greatest glory; but our first experience of the Dominion only really commenced when we left Niagara Station by the Grand Trunk Railway for Toronto.

It may have been prejudice, but we thought that the country bore signs of greater prosperity than over the American border.

The farms are more English in character and the cattle in greater abundance. The soil looks richer, and the pretty wooden zigzag fences, which take the place of hedges or railings, look most picturesque. In many places the blackened stumps of trees showed the recent clearing by fire.

From Hamilton, a prosperous town, we ran for nearly forty miles along the shores of Lake Ontario to Toronto.

Toronto is the capital of the province of Ontario, the chief city of Upper Canada, and the Queen City of the West. There is jealous rivalry between Montreal and Toronto. The former has the shipping interest, and for a long time held the lead; but Toronto is quickly gaining ground, and is the centre for a rapidly increasing commercial interest. Five lines of railway converge to her termini.

Hamilton and London, both rising places, centralize their commerce here. Lake Ontario supplies water transit to Montreal and the ocean; and the numerous banks do a thriving trade. In 1871 the census of the population was 50,600; ten years later it was 80,445. Wide streets of great length, avenues of trees, and churches are the chief characteristics of Toronto. The churches are built from the voluntary subscriptions of the congregations, the pastors being chosen and maintained by them. There is no State Church, and the Dissenters have as fine places of worship as the Episcopal body. The Metropolitan Methodist Church, with almost cathedral proportions, was built by Mr. Puncheon, the American Spurgeon, and it compares as[18] advantageously to the Tabernacle as do the Churches to the Chapels of England.

Toronto abounds in pretty suburbs, chief among them being Rosedale. The comfortable wooden houses of the upper and middle orders convey an idea of prosperity, with their neat gardens, a swinging hammock in the creeper-covered verandah, and the family sitting out in the cool of the evening.

The Provincial Parliament is a dingy building; but Osgood Hall—or the Law Courts—opened in 1860 by the Prince of Wales, and called after the Chief Justice of that day, is a very fine stone edifice, complete in all its arrangements. There are full-length portraits of the Chief Justices in succession, which being continued, will form a very complete legal gallery of local talent. There are fourteen judges, receiving 5000 dollars a year, nominated by the Governor-General from local men. The bar and solicitors are united as in America, and work together in firms, and are both eligible for judicial preferment, and have a like right of audience.

The Toronto University is second only to Harvard on the American Continent. The lecture-rooms, hall, museum, and library are all worthy of the fine Gothic building. There are 600 students, many of whose families coming to reside in Toronto, add much to the pleasantness of society. We stayed three days at Toronto. Mr. Hodgins, Q.C., Master in Chancery, was most kind in introducing my husband to some of the chief political men—to Mr. Mackenzie, the late Liberal Premier; Mr. Blake, the present leader of the Opposition; Mr. Ross, the Minister of Public Education, and others. The latter Minister showed us over the Normal School for the Instruction of Teachers. It has a well-arranged library and museum, and copies of many works of the old masters, and busts of the principal men in British history. Toronto is considered the most English of all the Canadian towns, and the Torontans pride themselves on this, and take a keen interest in home affairs. The previous night's debate in Parliament is on the breakfast-table: cabled over, and aided by the five hours' difference between the time of Greenwich and that of the Dominion, it appears in the first edition.

We dined with Mr. Goldwin Smith, the distinguished Oxford Professor of History, who, after a long sojourn[19] in the United States and Canada, has settled with his wife at Toronto. Their house is delightfully old-fashioned. Though in the centre of the town, the garden and some of the original forest trees are still preserved to it; and it contains the tail-end of family collections, valuable bits of China, busts by Canova and Thorwaldsen, ivory carvings, morsels of jade, and some relics of the first settlers. Amongst the latter are some wine-glasses belonging to General Simcoe, the first Governor-General in 1794, which are without feet,—"To be returned when empty."

Wednesday, July 23rd.—We left Toronto in the afternoon by the steamer Algeria, coasting along the low-lying country of the left bank of Lake Ontario. Touching at the various thriving towns, we judged by the crowd who came down to the pier that it was the usual thing for the population to stroll down in the evening and watch for the arrival of the steamer.

All night we were crossing Lake Ontario, and at four o'clock the next morning, in the grey dawn, touched at Kingston. We waited here an hour for daylight, in which to approach the Thousand Islands. As we passed out we saw the gilt dome of the famous Military College.

In the freshness of the early morning, with the sun just flushing the waters and warming into life the bare and purple rocks, we wound in and out of the narrow channel of the Thousand Islands. It is the largest collective number of islands in the world. Some are formed of a few bare rocks just appearing on the surface of the water, others are large enough for a villa, a garden, and a boat-house, and others again for farming purposes. Their uniform flatness causes some disappointment and mars their collective beauty, though here and there one may be singled out for the prettiness of its woods.

At Alexandra Bay, a familiar summer resort, with two monster hotels, the St. Lawrence opens away from the lake, and we are descending between its monotonous banks for some hours.

The increasing swiftness of the current and the prevailing thrill of excitement of all on board, warns us of the approach of the Long Sault Rapids. We see a stormy sea, heaving and surging in huge billows.

All steam is shut off, four men are required at the wheel to keep the vessel steady, as we "shoot the rapid." One[20] minute we are engulfed; the next rising on the crest of the wave. Intense and breathless excitement is combined with the exhilaration of being carried in a few minutes down the nine miles of descent. Every now and again a peculiar motion is felt, as if the ship was settling down, as she glides from one ledge of rock to another.

We pass some smaller rapids; but it is late in the afternoon before Baptiste, the Indian pilot, comes on board for the shooting of the great Lachine Rapid. Whirlpools and a storm-lashed sea mingle in this reach, for the shoal-water is hurled about among the rocks. The greatest care and precision of skill are necessary, for with lightning speed we rush between two rocks, jagged and cruel, lying in wait for the broaching of the vessel. A steamer wrecked last year lies stranded away on the rocks as a warning. These natural barriers to the water communication between Montreal and the West, are overcome by canals running parallel with the rapids.

The Ottawa forms a junction with the St. Lawrence at the pretty village of St. Anne's, which has become famed by Moore's well-known Canadian boat-song,—

The Victoria Bridge, a triumph of engineering skill, spans the river above Montreal. It is built of solid blocks of granite, a mile and three quarters in length; and it is in passing under its noble arches that we get our first view of Montreal, the metropolis of the Dominion.

A filmy mist lay over the "city of spires," spreading up even to the sides of Mount Royal—the wooded mountain that rises abruptly and stands solitary guard behind the city. The golden dome of the old market of Bonsecours, and the twin spires of the cathedral of Notre Dame loomed faintly out from its midst. Before us there is a sea frontage of three miles—vessels of 5000 tons being able to anchor beside the quay.

One hundred and fifty years ago the French evacuated Montreal, but you might think it was but yesterday, so tenaciously do the lower orders cling to the tradition of their founder, Jacques Cartier. The quaint gabled houses and[21] crooked streets of the lower town, the clattering and gesticulating of the white-capped women marketing in Bonsecours, remind one of a typical Normandy town. Notices are posted in French and English, and municipal and local affairs are conducted in both languages.

The post-office, the bank, and the assurance company make a fine block of buildings as the nucleus of the principal street of Notre Dame, but all the others are crooked, narrow, and ill-paved.

The Catholic Cathedral in the quiet square is very remarkable for its double tier of galleries, and for being painted and decorated gaudily from floor to roof. The Young Men's Christian Association has erected another of its fine buildings at Montreal. The society seems to thrive and to be doing an enormous work of good throughout the length and breadth of the American Continent. We found it well-housed in every considerable town we visited, and what was our surprise when later we found it had penetrated even to the Sandwich Islands, and that the Y.M.C.A. was one of Honolulu's finest buildings!

Sunday, July 26th.—We went to morning service at the English Cathedral of Christ Church. The interior is bare and unfinished at present, but it is the best specimen of English Gothic architecture on the Western continent. There was a good mixed choir of men and women.

We had a charming drive in the afternoon, up Mount Royal from which the city takes its name. Fine houses and villas standing in their own gardens, lie around the base, and the ascent, through luxuriant groves of sycamore trees, is so well engineered as to be almost imperceptible. You do not realize how high you are till the glorious panorama opens out before you, and you stand on a platform—Montreal at your feet, the broad river flowing to right and left, and the blue mountains on the horizon line.

We returned by the cemetery, a square mile, laid out in avenues and shady walks. Flowers blossoming on the graves and smooth-shaven turf, made it a garden, and favourite drive and walk. At the entrance was a notice—a sarcasm on human nature—desiring persons "wishing to return from funerals by the mountain drive to remove their mourning badges!"

That evening we dined with Mr. and Mrs. George Stephen in their beautiful house in Drummond Street. He is the[22] President of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In two years time this railway will run from ocean to ocean, and will join the Atlantic and Pacific; opening up the unlimited lands of the great North-West, so rich in mineral wealth, and containing the best wheat-growing country in the world. This discovery of the North West has altered the whole aspect of affairs in Canada, and by bringing into habitation a country as large as the United States, laid the foundation of an immense future for our great possession. Thirty-six thousand men are now working on the railway, and it will be completed in half the time of the contract, viz. five years instead of ten.

Monday, July 27th.—Three hours by rail, through a thinly-populated district and backwoods roughly cleared by burning, brought us to a gloriously golden sunset against which rose the spires of the Dominion Houses of Parliament at Ottawa.

Ottawa was only a small town with about 4000 inhabitants in 1867. All ask, "Why was it chosen as the seat of government?" which previously had been at Quebec, Montreal, and Toronto alternately. A minister's wife travelling with us in the train, laughingly gave us the answer. Quebec refused to vote for Montreal, Montreal for Quebec, and between them there was always warring jealousy. Toronto "WOULD" have voted for Montreal if Quebec had been willing to do the same. The authorities at home—it is said the Queen herself—taking the map, pointed to Ottawa as being equidistant from all, and on the borders of both Upper and Lower Canada. A magnificent pile of buildings accordingly rose, containing two legislative halls for the Senate and the House of Commons (both the same size as their English originals), and other public offices. The Parliament buildings are built of buff freestone with many towers and miniature spires, and have a very fine frontage of 1200 feet, surmounted by the iron crown of the Victoria Tower. The Octagonal Tower contains a library of 40,000 books, open not only to members, but to all the inhabitants of the town. In the centre stands a full-length marble statue of the Queen, by Marshall Wood. The members speak in French or English at will, and all notices of motions are in both languages.

Parliament Buildings, Ottawa.

Page 22.

Timber-lugging is the great trade of Ottawa. As seen from the upper town, the lower presents the appearance of one vast timber-yard; masses of piles line the banks, and cover the surface of the stream. These piles are cut in the winter from the back forests, and floated down some 100 miles. At Ottawa they pass into the yards through what is called a timber-slide, to avoid the dangerous channel of the Chaudière Falls. Here they are lashed together to form rafts, houses being built for the men who drift down on them to Quebec. From thence they are shipped to all parts of the world, principally to England. We went over one of these large timber-mills and Eddy's match manufactory, both immensely interesting, with the perfection of machinery, entirely superseding any manual dexterity, and driven by the neighbouring water-power.

The La Chaudière Falls, so called from the cauldron into which they seethe and boil, though not of a great height, have been sounded to 300 feet without touching the bottom. They contain a very angry, copper-coloured element.

We drove out to Rideau Hall, the residence of the Governor-General, who was away at the time. We found a very deserted, miserable building, about which the only sign of life was a sleepy policeman. A tobogging-slide seemed to usurp the greater part of the garden. The Ottawa public was much offended by a recent prohibition forbidding entrance to the park, which has hitherto been free to all. There is a little occurrence which will always remain connected in our minds with Ottawa, an example which we certainly found followed nowhere else. Our driver, even after considerable pressure, refused to take more than his ordinary fare!

Ottawa, other than the Parliament buildings, which are alone worth coming to see, is the dullest and most primitive of towns. C. was, however, glad to have been there, as it gave him the opportunity of meeting the Ministers of Inland Revenue, and Agriculture, and other authorities, and hearing their views on the rapid development of Canada.

Returning to Montreal, we took the night boat to Quebec. A golden, glorious sunset, sinking behind purple clouds, was reflected in the water, and this was succeeded by a trail of silver light from the newly-risen crescent moon.

Tuesday, July 29th.—At 7 a.m. on a cloudy morning, from the deck of the steamer we were looking up at Quebec, perched, Gibraltar like, on an inaccessible promontory of precipitous rock, formed by the junction of the River St. Charles with the St. Lawrence.

The narrow streets of the lower town, with their picturesque red-tiled roofs and overhanging gables, seem at first sight as if they were entirely cut off from the upper town by a shelving mass of rocks.

However, we were soon wending our way upwards by a street so steep that it could only be likened to climbing a mountain. The houses on either side seemed also to be climbing the roof of the houses above, the upper storey being on a level with the second floor of its neighbour. Any sand there ever has been was long ago washed down by the rain, leaving a stony surface as a precarious foothold for the poor struggling horses. This was the more circuitous route for carriages. A nearer one for pedestrians lay in the perpendicular flight of steps cut out in the face of the rocks leading immediately to Dufferin Terrace. This terrace was called after Lord Dufferin, the most popular of Governors-General, and is built on the old buttresses and platform formerly occupied by the Château of St. Louis. It is a favourite resort of the townspeople, perhaps as being the only level ground, so far as we could see in the town, but probably more so on account of the beautiful view it commands over the river. Vessels of all classes and sizes, coming from all parts of the world, but more especially from England, were anchoring in the broad basin formed by the confluence of the two rivers. Immediately beneath us were the wharves of the old town, where we could see two or three colliers discharging coal, and even hear in the still morning air the rattling of the chains as the crane was swung to and fro. On the opposite side rose the fortified bluff of Point Levy, and on the other the St. Charles winding away up its peaceful valley. The white houses of Beaufort form a straggling line almost as far as the Montmorenci Falls, which latter seem only a speck in the distance. There was a light morning mist floating away over the opposite heights, and the murmur of the busy hum of life reached us from below.

The Governor's garden, facing the road on the opposite side, is only an enclosure overgrown with rank weeds and grass, but it contains the obelisk erected to the joint memory of Wolfe and Montcalm. It is a novel idea to combine the names of the victorious and conquered, but it shows a true appreciation of the two generals who each gave up their life for their country in the hour of battle. In the[25] Ursuline Convent, near by, we see Montcalm's grave, said to have been made by the bursting of one of the enemy's shells during the bombardment, with the inscription in French—

Honour to Montcalm.

Fate,

In depriving him of Victory,

rewarded him by

A glorious Death.

There are some very quaint old buildings and curious bits of architecture in out-of-the-way corners, and the town altogether has an old-world look, as if life were passing it by. The outside of the Catholic Cathedral is homely and irregular, and very damp and musty inside; but attached to one of the pillars is a fine "Crucifixion" by Van Dyke; and the adjoining seminary has quite a large collection of pictures highly prized by the inhabitants, though by artists unknown to fame. The Laval University, chartered by the Queen in 1852, is the most modern building in Quebec.

The population is almost entirely French, and the maintenance of their language and institutions was guaranteed to them at the conquest. Descendants of the old noblesse still linger here, preserving among themselves the traditions of their forefathers in a circle of society renowned for its polish and refinement; preserving, too, in its entirety the purity of the mother language. They do not mix at all with the English.

The Citadel is gloriously situated on the high ground above the town, surrounded by walls and ramparts, but our approach to it was under the following untoward circumstances. We hired an ungainly cabriolet, a vehicle on two wheels, with a narrow board in front, on which the driver—a raw-boned Irish boy in our case—driving a sorry steed, was seated. After going up a very steep hill, the entrance to the fortress is over a wooden drawbridge guarded by massive chain gates. The hollow sound of the wood frightened the horse beyond control, and we discovered then that he could go, when he turned and bolted down the hill. We only prevented ourselves from being pitched out head-foremost by clinging on to the sides of the old-fashioned hood. The driver was powerless, and C. eventually stooped over and jerked the reins happily with success. We must have caused[26] much amusement to the soldiers looking out from the guard-house window.

The Governor-General's residence is part of the low stone building in the courtyard, the remainder of the Citadel being used for barracks; the windows on the river side command a superb view.

In the absence of Lord Lansdowne, Lord and Lady Melgund entertained us most hospitably, and very kindly took us on the river in the police launch after luncheon, near enough to obtain a good view of the beautiful Montmorenci Falls. The volume of water is powerful in the first instance, but dwindles into fringes, and evaporates altogether in mist at the base.

A storm was gathering on the heights as we returned, and a dense bank of fog rolled down the river. The thunder muttered overhead, and a rift in the clouds let a curious light stream over the roofs of the town; and then, closing up, the black cloud swept towards us, creeping up Diamond Cape, till the Citadel above loomed out white and ghostly from the surrounding clearness. In a downpour of tropical rain we reached the wharf.

We should liked to have managed an expedition from Quebec to the beautiful Saguenay River, combining a visit to Sir John Macdonald, the present Premier; but that great Nemesis, time, was already beginning to pursue us. We left Quebec the next morning, passing again through Montreal at five in the afternoon, and sleeping at Plattsburg, on the shores of Lake Champlain.

It was a great disappointment to us not to be able to see more of Canada, but we shall hope to pay it a more extended visit on some future occasion. It offers as great attractions to the lover of nature as to the sportsman, and affords a glorious and unlimited field for the emigration of men and women since the opening up of the Far West by the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Thursday, July 31st.—Up at 6 a.m. this morning to[27] catch the steamer. However early we rise for these matutinal starts there is always a rush in the end to catch the train or boat. It is a depressing thought when we think of what frequent occurrence they will be for the next few months.

We were soon plying our way over the placid bosom of Lake Champlain, holding a central course. The shores on either side are flat and ugly, for the beauty of the lake lies in the broad expanse of unruffled waters reflecting the various changes of the sky, generally of a heavenly blue, but on this morning taking the leaden hue of the low-lying clouds.

Numberless islands lay dotted on the calm surface, kept fresh and green from the continued lapping of the waters around their indented shores.

The range of the green mountains of Vermont lay hidden by a transparent haze, the sun shining brightly behind, and presently piercing through, rising to gladden the gloomy morning.

After crossing the broad bay and touching at a further point in the eastern shore—at Burlington, a thriving town—the waters narrowed and flowed on the one side through flat green meadows, pretty though uninteresting; but, on the other, rose in the full beauty of their verdant summer foliage, the mountains of the Adirondacks. The steamer threaded its way through the narrow channels, and we lay right under their mighty shadows, looking into the calm depths of the quiet pools formed by the boulders of rock, that in the course of ages have loosened their hold and slipped down the precipitous sides.

We looked up into dark ravines, piercing through the heart of the mountains, dividing one rounded peak from another. We followed the undulating outline of the mountains, now bare and stony, or more often fringed to the summit with pine forests. The dark green of these pines, and the bright foliage of the stunted oaks, formed a brilliant contrast to the orange lichen covering the grey protruding boulders.

Here and there we came upon a wall of rocks, descending in a sheer precipice to the lake, reflecting purple shadows on the still water.

And so we passed on, one scene of beauty succeeding another, till we reached Fort Ticonderoga. It was here[28] during the Revolutionary War, that the brave Eathan Allen with his celebrated band of Green Mountain Boys surprised the British commander in the dead of night, and appearing at his bedside demanded the immediate surrender of the fort. "In whose name?" demanded De le Place. "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress," replied Allen,—and the fort was surrendered.

An hour by rail brought us to the head of Lake George. The Indians gave it the poetical name of "Horicon," or "Silvery Waters," from the great purity of the water. Its peaceful shores have been the scene of many a bloody battle in the great conflict between the Indian and the white man, and the mountains have oft resounded to the war-whoop and battle-cry of the savages and the despairing shriek of the captives whom they scalped alive. Now a death-like stillness broods over the scene. The scenery of Lake George is far grander than that of Champlain. The other only leads up to and forms a preparation for this one. The mountains which surround Lake George and close it in on all sides have a bolder, more sweeping outline. Here and there one projects lone and solitary, forming a promontory round which the steamer creeps, seeming to cling to its densely-wooded sides. The dark whispering pine forests grow down to the very edge of the waters, mingling their sighings with the rustling of the waters over a shallow bottom. There are numberless islands, some mere strips of sandy beach and rocks, dividing the silvery rapids on either side, and others are wooded with a stunted undergrowth. We noticed one curious conical-shaped mountain, formed of a sharp escarpment of rock from the summit to the base, which is called "Roger's Slide." The story goes that an Englishman, Major Rogers, being hotly pursued by the Indians to the edge of the cliffs, suddenly bethought himself of reversing his snow-shoes and retracing his steps by this means leaving no foot-prints. The Indians tracked him to the brink of the precipice, and then concluded he had slid down into the lake, under the protection of the "Great Spirit."

As the steamer turned into the "Narrows" we saw a beautiful little waterfall, falling down the ravine in a feathery shower of spray, spanned in the afternoon light by a vivid rainbow. At Sabbath Day Point the scenery is more[29] striking and majestic. Think of the "Trosachs" in the Highlands, and that will give the best idea of the grandeur of the scene before us.

Adding to the beauty of all we saw that afternoon was the ceaseless play of light and shadow on the mountains. I tried to carry away with me in the mind's eye the picture of those mountains, dark and powerful as a background, the quiet beauty and picturesqueness along the banks as a foreground, and the deep calm blue waters of the lake all around.

Alas! a sudden storm came up and obscured the view before us, and we ended our journey at Fort William in a blinding hurricane of rain and wind. We were glad to find shelter from it in the train, which brought us to Saratoga Springs by the evening.

Friday, August 1st.—Saratoga is the Ems or Baden-Baden of America, the most fashionable resort as a watering-place, only equalled by the more select charms of Newport.

Seen on a sunny morning such as we had, nothing can surpass the brightness and gaiety of the scene in Broadway. Along its broad shady avenues stroll the collected beauty and fashion gathered at Saratoga, and light cross-bar waggons and buggies bowl swiftly by. There are no villas, but life is confined entirely to pensions, and the three colossal hotels in Broadway. The "United States" is perhaps the finest of them. It covers seven acres of ground, accommodates 1200 guests, and gives employment to 150 black waiters. Built round three sides of a quadrangle, there are broad covered piazzas running the entire length of the building, opening on to a large and beautifully kept garden, gay with flowers. Morning and evening the band plays here, when the piazza becomes a fashionable promenade, visitors from all the other hotels congregating in it.

American women are the best dressers in the world; for taste and skilful combination, particularly in pale colours, they are unsurpassed. A change of costume thrice daily is absolutely de rigueur at Saratoga, and it becomes at last quite exciting to see how many more varied dresses are going to appear.

Illustrating a great feature in American life is the wing devoted to the cottages where families come and live during the season, in separate suites, everything being provided by[30] the hotel. A good example of the attendance which it is expected you will require can be gathered from the notice in each room: "Ring once for the bell-man, twice for stationery, and three times for iced water." The chamber-maid plays a very unimportant part in any hotel, and a "bell-man" is attached to each floor. The consumption of iced water is prodigious; not only is it placed at your elbow at every meal, but large jugs of it are brought at stated hours of the day to every room. At the "United States" it was quite formidable walking the immense length of the dining-room, or venturing across the vast spaces of the yellow satin-lined drawing-room. The lift has been known to go up and down 300 times in the course of the afternoon.

Amid the shady groves and green lawns of Congress Park we found the mineral springs bubbling up into artificial wells, with a few drinkers idling about, and languidly sipping their waters, but we came to the conclusion that visitors were not here so much for the purposes of health as of amusement. The springs are of all kinds, Vichy, sulphur, iron, magnesia, soda, &c., and it has often been necessary to bore down several hundred feet before finding the water. Two or three of the most powerful medicinal springs are some miles away, and these are bottled and brought in fresh daily for the drinkers in town.

The fashionable afternoon drive is to the lake, some two miles away, and is reached by a straight dusty road, bordered for the most part by rushes and long grass, where the frogs maintain a cheerful chorus of chirping. When you arrive there you find a primitive café, with groups sitting about the tables under the trees, and the lake, pretty enough, lying in the hollow, with small excursion steamers constantly plying from the landing.

In the evening there is generally a "hop," or dance, advertised in one or other of the hotels, but I confess that that evening we preferred the good-humoured crowd and the fireworks in Congress Park to the hop at Congress Hall Hotel. Alternating with the fireworks were the strains of the band wafted from the pagoda in the centre of the lake, and all sat about heedless of the heavy dew lying on the grass.

We were very sorry to leave Saratoga the next morning, and undergo a very hot and dusty journey to Boston. We passed Pittsburg, as famed for its great ladies' college, as its[31] southern namesake is for its iron-works, and late in the afternoon reached Boston, Massachusetts. A red and yellow coach, suspended by straps to C springs, such as were in use in the last century, conveyed us to the Hotel Vendôme.

I think Boston the most charming of all the American towns. The broad sweeping avenues are bordered by houses of red sandstone, a soft mellow colour, that contrasts well with the green avenues of trees and grass borders. Commonwealth Avenue is the finest of these continuous "parks," and is a mile and a half long. The Common, with its avenues of fine elm-trees, forms a large open space in the middle of the town, and separated only by a road are the public gardens. A bronze statue of Washington rises in the middle, surrounded by a brilliant flower-bed, the colours blending in carpet-gardening to form a Moorish inscription, which translated means "God is all-powerful," a very fitting motto for the great hero. The gilded dome of the Massachusetts State House dominates them from the eminence of Beacon Hill; but far more interesting than this new erection is the venerable time-worn building of the "Old State House," where some of the most stirring scenes of the Revolution were enacted. From this balcony the Declaration of Independence was read to the people. Our troops occupied the buildings during the Stamp Riots, but at the close of the war Washington stood on its steps the chosen hero of the exultant populace. So many of the buildings are closely associated with humiliating remembrances of that fatal epoch in British history when these fair provinces, owing to the lack of foresight and imbecility of her leaders, were for ever lost to England.

There is the old Scotch church, so famous as the political meeting-place of the Boston Tea Party; Tancred Hall, the "Cradle of Liberty," nurtured by the patriotic orations of Adams, Everett, and above all of Daniel Webster; the harbour, with its numerous shipping, where was lighted the first straw of that great conflagration of the "Rebellion," by the throwing overboard of those few chests of tea.

The city is rich in churches, there being no less than 150 belonging to all denominations, who raise their spires heavenwards within its precincts. But Trinity Church surpasses all in beauty and design. It is built of granite and freestone in the form of a Latin cross, in Romanesque[32] style. The stained glass is rich in harmonious colouring, depicting no subject, but blending into a mystery of blue, orange, and purple. Some lancet windows, filled with iridescent glass of pale blue, gave the appearance of shining steel.

We started early on that quiet Sunday morning for a drive to Cambridge in one of the "Herdic Hansoms." These curious vehicles with their jolting motion can only be described as covered two wheeled carts. We passed the green hill on which stands Bunker's Hill Monument. It is inexpressibly grand in its massive simplicity, being only huge blocks of granite narrowing in such imperceptible proportion to the summit, that the pyramidal ending seems in perfect accord with the broad base. No railing surrounds it. There is no decoration or inscription: it stands alone in its majesty, sufficiently raised to be a landmark to the whole town. Our road led through Charlestown, where the seafaring population chiefly live close to the harbour. A long, straight, dusty road, under a blazing sun for three miles, brought us to Cambridge, the immediate approach to which is through stately avenues of elm-trees.

The colleges of Harvard University are clustered together, forming an irregular quadrangle. There was a delightfully quiet and studious look about the dull red-brick buildings, low latticed windows, and ivy-covered walls,—a look of antiquity unusual to America. In this comparatively newly-risen continent so much is thought of age, that Harvard College, the oldest of the fifteen of which the University consists, is prized most highly for its foundation dating from 1636.

Chief amongst the colleges for beauty is the Gothic tower of Memorial Hall, erected by the alumni in memory of the students who perished in the War of Secession. It contains the great dining-hall with carved screens and galleries, busts and portraits of the founders of the college, and has stained-glass windows bearing the college and State arms. A theatre, library, museum, scientific school, and chapel are in different parts of the irregularly laid-out square, which is sacred to the University buildings.

It was vacation time, and the place was utterly deserted, save by a few straggling church-goers, their footsteps resounding on the narrow paved walk, and lingering amongst the tenantless walls. It must be a different scene in term,[33] when 1300 students and forty-seven professors gather under the classic shades of a university already numbering among its former students such men as John Adams the second President of the United States, Edward Everett, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Lathrop Motley, J. Russell Lowell, and Wendell Phillips. The University course extends over four years. It may be interesting to know, in face of the recent agitation at our own universities on the subject, that women are not as yet admitted to the University lectures, though allowed to matriculate and pass the different examinations.

Quite near the University is a battered elm-tree, whose shattered branches are sustained by iron stanchions, and which marks the place where General Washington took command of the rebellious colonists. Further on we passed a plain, square, wooden house, with pointed roof, and a small garden, surrounded by a high laurel hedge, a gravel path, and little white gate leading to the verandah and entrance. There was nothing particular to mark a house, homely enough in its exterior. But yet it was here that in 1775 Washington established his headquarters, when it was the scene of many warlike preparations and much enthusiasm. Later it has been hallowed by the quiet presence of the great poet Longfellow.

And it was in this quiet retreat that he passed away in 1882.

We followed the winding road, almost an avenue of willow-trees, to Mount Auburn Cemetery, and with great difficulty found his last resting-place. We were terribly disillusioned. Not a garden of flowers, tended by loving hands; not a simple marble monument with short inscription, prompted by a knowledge of the gentle, retiring, nature; but we found a great, ugly block of sandstone, a huge sarcophagus, with a name and date on one side, and an ingenious pattern on the other, taking X as a centre letter, and forming a senseless device, and utterly inappropriate to the memory of the great poet.

No more beautiful garden than this cemetery could be conceived: grassy slopes, planted with waving palms and the choicest plants; bright flower-beds interspersed among the white marble crosses and memorials of the dead; an air of quiet beauty and repose, mingling with the many signs of respectful care on the different graves, such as bunches of newly-cut flowers. Those who have served their country had a miniature flag of the stars and stripes waving over their heads. The mortuary chapel stands on the high ground, and opposite to it there is a magnificent marble sphinx with this soul-stirring inscription,—

Throughout the length and breadth of America this intense respect to the dead may be seen in regard to their last resting-place. In strange contrast is the irreverence shown in the removal of bodies. Several times we saw coffins, travelling at first-class fares, placed in the luggage-vans, piled under Saratoga trunks, and with the party of mourners in the same train.

In returning from the cemetery we passed Mr. Russell Lowell's country-house, standing in grounds fairly hidden by surrounding trees.

Boston is the great literary and scientific centre of America. The saying goes that at Boston they ask you "what you know," in New York "what you have," and at Philadelphia "who you are."

Fostered by its close neighbourhood to Harvard, Boston boasts more literary institutions than any other town in America; whether in its remarkably fine Public Library, its Atheneum (which corresponds to our Royal Institution), its two museums, or the English High and Latin School, the first public school in the States.

One of the celebrated steamers of the Fall River Line took us that evening to Newport.

What fascination the word exercises over "the aristocracy" of America! Filled throughout the summer months with society—select and fashionable, hospitable to foreigners, but difficult of access to new-comers, and closed to those who[35] do not belong to the upper circle of finance. The gay butterfly life is carried on in "cottages," or villas, as we should call them—small houses, unattractive outside, standing in gardens adjoining the road, too public and suburban for English taste. So also is the life, entirely without privacy; morning calls are customary; and beginning society thus early, does not prevent its being carried on at high pressure for the remainder of the day.

There is a well-known and accommodating Frenchman, who undertakes not only to supply a "cottage," but all the elaborate necessaries, servants, linen, plate, &c., for a stay at Newport. The Ocean Drive and Bellevue Avenue are daily crowded with joyous equipages and neat phætons, driven by their fair owners, and equestrians.