This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Ireland Under the Tudors, Vol. II (of 3)

Author: Richard Bagwell

Release Date: February 21, 2015 [eBook #48334]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS, VOL. II (OF 3)***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/irelandundertudo02bagwiala |

PRINTED BY SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE LONDON

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS

WITH A SUCCINCT ACCOUNT OF THE EARLIER HISTORY

BY

RICHARD BAGWELL, M.A.

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. II.

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

1885

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| FROM THE ACCESSION OF ELIZABETH TO THE YEAR 1561. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Protestants rejoice at Elizabeth’s accession | 1 |

| Dispute as to the O’Neill succession | 2 |

| Sussex Lord Deputy—the Protestant ritual restored | 5 |

| Parliament of 1560—the royal supremacy | 6 |

| Expectations of a Catholic rising | 7 |

| Attitude of France, Spain, and Scotland | 8 |

| Clearsightedness of Elizabeth | 10 |

| Desmond, Ormonde, and O’Neill | 10 |

| Reform of the coinage | 12 |

| Fitzwilliam Lord Deputy | 14 |

| Claims and intrigues of Shane O’Neill | 15 |

| Conciliatory attitude of the Queen | 19 |

| Shane O’Neill supreme in Ulster | 21 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| 1561 AND 1562. | |

| Sussex completely fails in Ulster | 23 |

| He plots against Shane O’Neill’s life | 27 |

| A truce with Shane | 30 |

| Who goes to England | 32 |

| Shane O’Neill at Court | 33 |

| The Baron of Dungannon murdered | 38 |

| Shane in London—he returns to Ireland | 40 |

| Desmond and Ormonde | 41 |

| [Pg vi]Official corruption | 43 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| 1561-1564. | |

| Grievances of the Pale | 46 |

| Desmond and the Queen | 48 |

| Projects of Sussex | 49 |

| Elizabeth attends to the Pale | 50 |

| Shane O’Neill professes loyalty | 51 |

| Shane oppresses O’Donnell and his other neighbours | 52 |

| Sir Nicholas Arnold | 57 |

| Failure of Sussex | 58 |

| He attempts to poison Shane | 64 |

| Royal Commission on the Pale | 65 |

| Desmond and Ormonde | 66 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| 1564 AND 1565. | |

| Great abuses in the Pale | 68 |

| Extreme harshness of Arnold | 73 |

| Shane O’Neill in his glory | 74 |

| Shane’s ill-treatment of O’Donnell | 76 |

| Shane and the Scots | 79 |

| Nothing so dangerous as loyalty | 80 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| 1565. | |

| Desmond, Thomond, and Clanricarde | 82 |

| Ormonde will abolish coyne and livery | 83 |

| Private war between Desmond and Ormonde | 85 |

| Shane O’Neill and the Scots | 89 |

| Supremacy of Shane | 90 |

| Sidney advises his suppression | 91 |

| Desmond and Ormonde—Sidney and Sussex | 92 |

| Ireland is handed over to Sidney | 94 |

| Failure of Arnold | 98 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| 1566 AND 1567. | |

| Sidney prepares to suppress Shane | 102 |

| Who thinks an earldom beneath his notice | 103 |

| The Sussex and Leicester factions | 105 |

| Mission of Sir F. Knollys | 105 |

| [Pg vii]The Queen still hesitates | 106 |

| Shane’s last outrages | 107 |

| Randolph’s expedition reaches Lough Foyle | 108 |

| Sidney easily overruns Ulster | 109 |

| Randolph at Derry | 110 |

| Sidney in Munster—great disorder | 111 |

| Tipperary and Waterford | 112 |

| Horrible destitution in Cork | 113 |

| Sidney’s progress in the West | 114 |

| Failure of the Derry settlement | 115 |

| Defeat and death of Shane O’Neill | 117 |

| His character | 118 |

| Sidney and the Queen | 120 |

| Sidney and Ormonde | 121 |

| Butlers and Geraldines | 122 |

| The Queen’s debts | 123 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| 1567 AND 1568. | |

| Sidney in England—Desmond and Ormonde | 124 |

| Cecil’s plans for Ireland | 126 |

| The Scots in Ulster | 127 |

| Massacre at Mullaghmast | 130 |

| The Desmonds—James Fitzmaurice | 131 |

| Starving soldiers | 132 |

| Miserable state of the North | 133 |

| Abuses in the public service | 134 |

| Desmond in London—charges against him | 134 |

| Charges against Kildare | 138 |

| Sir Peter Carew and his territorial claims | 139 |

| He recovers Idrone from the possessors | 144 |

| James Fitzmaurice’s rebellion | 145 |

| The ‘Butlers’ war’ | 146 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| 1568-1570. | |

| Sidney’s plans for Ulster | 149 |

| Fitzmaurice and the Butlers | 150 |

| Parliament of 1569—the Opposition | 152 |

| The Bishops oppose national education | 155 |

| Fitzmaurice, the Butlers, and Carew | 156 |

| Atrocities on both sides | 161 |

| [Pg viii]Sinister rumours | 161 |

| Ormonde pacifies the South-East | 162 |

| Sidney and the Tipperary gentlemen | 163 |

| Sidney’s march from Clonmel to Cork and Limerick | 164 |

| The Butlers submit | 166 |

| Humphrey Gilbert in Munster | 167 |

| Fitzmaurice hard pressed | 168 |

| Ulster quiet | 169 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| 1570 AND 1571. | |

| The Presidency of Connaught—Sir Edward Fitton | 170 |

| Services of Ormonde | 171 |

| Thomond in France—diplomacy | 172 |

| Session of 1570—attainders and pardons | 174 |

| First attempt at national education | 176 |

| Commerce—monopolies—Dutch weavers | 177 |

| The Presidency of Munster—Sir John Perrott | 179 |

| Fitton fails in Connaught | 182 |

| Tremayne’s report on Ireland | 184 |

| Ormonde in Kerry—services of the Butlers | 184 |

| Perrott’s services in Munster | 186 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| FOREIGN INTRIGUES. | |

| Fitzmaurice proposes a religious war | 190 |

| Catholics at Louvain—suspicious foreigners | 190 |

| Archbishop Fitzgibbon and David Wolfe | 192 |

| Fitzgibbon’s own story | 193 |

| Philip II. hesitates | 196 |

| Thomas Stukeley | 196 |

| English and Irish parties in Spain | 199 |

| Ideas of Philip II. | 201 |

| Fitzgibbon, Stukeley, and Pius V. | 202 |

| Fitzgibbon negotiates with France and England | 205 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| 1571 AND 1572. | |

| Want of money—Perrott and Ormonde | 207 |

| Perrott will end the war by a duel | 209 |

| Proposal to colonise Ulster—Sir Thomas Smith | 211 |

| [Pg ix]Sir Brian MacPhelin O’Neill | 213 |

| Want of money—the army reduced | 214 |

| Fitton, Clanricarde, and Clanricarde’s sons | 216 |

| Fitton driven out of Connaught | 219 |

| Perrott’s activity in Munster | 221 |

| A mutiny | 223 |

| The Irish in Spain—Stukeley | 225 |

| Effects of the day of St. Bartholomew | 227 |

| Rory Oge O’More | 227 |

| Feagh MacHugh O’Byrne | 228 |

| Fitzwilliam cannot govern without men or money | 229 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| 1572 AND 1573. | |

| Smith’s failure in Ulster | 231 |

| Submission of James Fitzmaurice | 233 |

| Treatment of the Desmonds in England | 234 |

| Walter, Earl of Essex | 239 |

| Alarm at his colonisation project | 241 |

| Essex proposes to portion out Antrim | 242 |

| Smith is killed | 246 |

| Perrott’s government of Munster | 248 |

| Desmond escapes from Dublin | 252 |

| Wretched state of King’s and Queen’s Counties | 253 |

| Fitzwilliam and Fitton quarrel | 254 |

| Catholic intrigues | 257 |

| Failure of Essex | 258 |

| The Marward abduction case | 261 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| 1573 AND 1574. | |

| Threatening attitude of Desmond | 263 |

| Fitzwilliam and Essex | 268 |

| Essex governor of Ulster | 269 |

| Essex powerless | 272 |

| Troubles of Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam | 274 |

| Evil condition of Munster | 276 |

| Essex and Desmond | 278 |

| Ormonde solemnly warns Desmond | 281 |

| Campaign in Munster—Desmond plots | 283 |

| [Pg x]Essex struggles on in Ulster | 284 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| ADMINISTRATION OF FITZWILLIAM, 1574 AND 1575, AND REAPPOINTMENT OF SIDNEY. | |

| Essex wrongfully seizes Sir Brian MacPhelin | 288 |

| Violent disagreement of Essex and Fitzwilliam | 290 |

| The Essex scheme is finally abandoned | 294 |

| Profit versus honour | 295 |

| Official corruption | 296 |

| Arrest of Kildare | 297 |

| The revenue—a pestilence | 300 |

| General result of the grant to Essex | 301 |

| The Rathlin massacre | 301 |

| Ulster waste—Sidney’s advice | 304 |

| Bagenal’s settlement at Newry | 306 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| ADMINISTRATION OF SIDNEY, 1575-1577. | |

| Sidney and the Butlers | 307 |

| Ormonde and his accusers | 308 |

| Death and character of Carew | 309 |

| Sidney’s tour—Leinster | 310 |

| Munster | 312 |

| Fitzmaurice in France | 314 |

| Sidney in Limerick, Clare, and Connaught | 316 |

| Sidney on the Irish Church | 319 |

| Troubles in Connaught—Clanricarde’s sons | 321 |

| Sir William Drury Lord President of Munster | 322 |

| Essex in England | 324 |

| His return, death, and character | 325 |

| Leicester and Essex | 326 |

| Agitation in the Pale against the cess | 327 |

| The chiefs of the Pale under arrest | 332 |

| A composition agreed upon | 333 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| LAST YEARS OF SIDNEY’S ADMINISTRATION, 1577 AND 1578. | |

| Lord Chancellor Gerard’s opinions about the Pale | 334 |

| Drury’s opinions about Munster | 336 |

| Maltby’s opinions about Connaught | 338 |

| Rory Oge O’More | 340 |

| Rory is killed by the Fitzpatricks | 344 |

| Sidney’s last days in Ireland | 347 |

| [Pg xi]Character of Sir Henry Sidney | 350 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| THE IRISH CHURCH DURING THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS OF ELIZABETH’S REIGN. | |

| The Queen aims at outward uniformity | 353 |

| See of Armagh—Adam Loftus | 354 |

| Papal primates—Richard Creagh | 356 |

| See of Meath—Staples | 359 |

| Other sees of the Northern province | 360 |

| Province of Dublin | 361 |

| Province of Cashel | 364 |

| Province of Tuam | 367 |

| Spiritual peers—Papal and Protestant succession | 367 |

| David Wolfe, the Jesuit | 370 |

| INDEX | 373 |

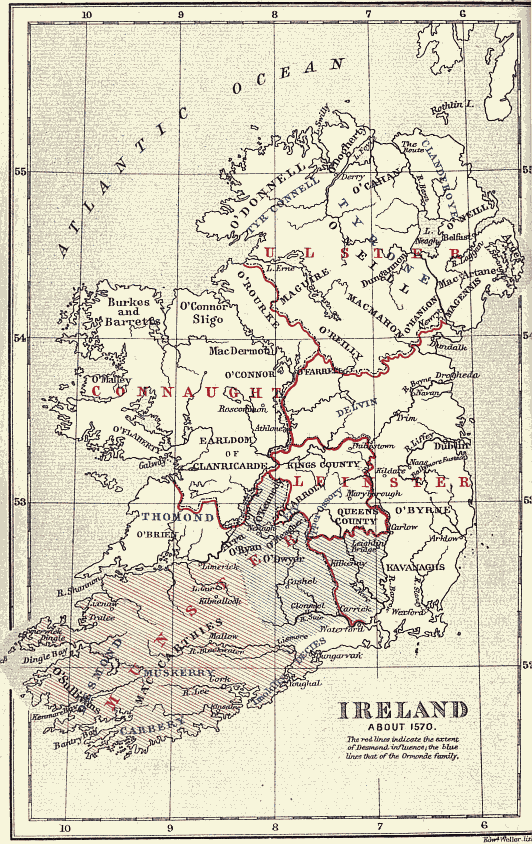

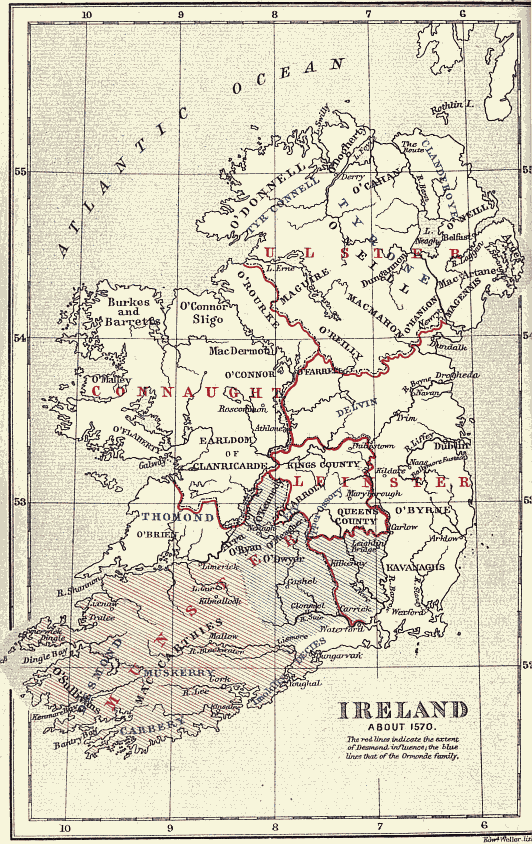

MAP.

| IRELAND ABOUT 1570 | To face p. 149. |

Errata.

| Page | 46, | line 2, for 1561 read 1562. |

| " | 47, | headline, for 1561 read 1562. |

| " | 156, | for Archbishop of Ross read Bishop of Ross. |

| " | 173, | for Henry III. read Charles IX. |

| " | 283, | for Thomas Butler read Theobald Butler. |

| " | 367, | for Dermot O’Diera read Cornelius O’Dea. |

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS.

The proclamation of Anne Boleyn’s daughter can hardly have caused general satisfaction in Ireland, but it was hailed with joy by Protestant officials whose prospects had been clouded during the late reign. Old Sir John Alen was soon in Dublin, whence he wrote to congratulate Cecil on his restoration to office, and to remind him of his own sufferings under Queen Mary. Thomas Alen, when reminding the new secretary of his great losses, rejoiced that God had sent light after darkness, and that he and his friends were going to have their turn. A sharp eye, he said, should be kept on Sir Oswald Massingberd, who was suspected of a design to pull down Kilmainham, lest its beauty and convenience should again attract the Lord Deputy. Massingberd should be sternly restricted to his revenue of 1,000 marks, and the great seal should be transferred to a lawyer of English birth. The prior was so far successful that Kilmainham soon afterwards ceased to be a royal residence. He probably sold the lead, and the damage being aggravated by a great storm, the commandery was not thought worth repairing, and the chief governor’s abode was transferred to Dublin Castle. Sir Ralph Bagenal, formerly lieutenant of Leix and Offaly, had been dismissed for denying the Papal supremacy, and had been forced to seek refuge in France, where he lived by selling at a great sacrifice a property worth 500l. a year. Queen[Pg 2] Elizabeth gave him the non-residence fines of twelve bishoprics; but there were legal obstacles, and he begged for something more substantial. Staples, the deprived Bishop of Meath, pointed out his griefs to Cecil, and thinking, no doubt, more of the Queen than of his correspondent, complained that Pole had made it a grievous article against him that he had presumed to pray for the soul of his old master. Pole probably hated Henry VIII. enough to wish his soul unprayed for, but the complaint is a very odd one from a Protestant divine.[1]

Sidney, whom most men spoke well of, was confirmed in the office of Lord Justice, and had soon plenty of work in the North. The old Earl of Tyrone was sinking fast, and the horrors of a disputed succession were imminent. Henry VIII. had conferred the Earldom on Con O’Neill for life, with remainder to Matthew Ferdorogh O’Neill and his heirs male for ever. The Barony of Dungannon was at the same time conferred upon the remainder man, with a proviso that it should descend upon the heir to the Earldom. Matthew’s mother was Alison Kelly, and at the time of his birth she was the wife of a smith at Dundalk. He was reputed to be Kelly’s son until he was sixteen, when his mother presented him to Con as his own child. ‘Being a gentleman,’ said his eldest son, ‘he never refused no child that any woman named to be his,’ and he accepted Matthew with a good grace. There was a Celtic law or doctrine that a child born in adultery should belong to its real father, but there is no evidence to show that the rule was actually binding in Ulster in the sixteenth century. Shane, the legitimate eldest son, made a plain statement to the contrary, and illustrated it by an Irish proverbial saying that a calf belongs to the owner of the cow, and not to the owner of the bull. Matthew became a good soldier, and Con was willing to have him for a successor. But as Shane grew up he learned to oppose this arrangement, and, having good abilities and boundless ambition, he was designated by a great portion of the clan as successor to the[Pg 3] tribal sovereignty. Shane oppressed his father, and perhaps ultimately induced him to acquiesce in the popular choice; but to make all safe, he took the precaution of murdering the Baron of Dungannon, whose prowess he had reason to remember, and whom he had no wish to meet again in the field. He steadily maintained that his victim was the smith’s son, and no relation; but the Irish annalists lend him no countenance, for they remark that the deed was ‘unbecoming in a kinsman.’ The Baron had left a young son, on whom his title devolved, and the government were bound by the patent to maintain his ultimate rights to the Earldom. It is uncertain whether Henry VIII. knew that Matthew Ferdorogh was born while his mother lived in wedlock with the smith, but probably he may be acquitted of having encouraged one of the worst Brehon doctrines.[2]

Yet Shane’s case against the Government was a strong one; for it was not disputed that his father had known the facts, and he was thus able to contend that the King had been deceived, and that the limitation in the patent was void. Besides, it was asked, why was not the Earldom given in the usual way to Con and his heirs male? Whether Shane knew of the above-mentioned Brehon regulation or not, it was his interest to affect ignorance, to represent both his father and King Henry as the victims of deception, and to take his stand on strict hereditary right for the title, and on tribal election for his personal supremacy. About strict veracity he was no more scrupulous than Queen Elizabeth herself. The dilemma was complete, for English lawyers could not for very shame deny the moral claims of the legitimate heir, nor could politicians ignore those Irish captainries which the Crown had acknowledged over and over again. By Celtic usage Con had of course no power whatever to alienate or transmit the property of the tribe: in that he had only a life interest. Shane argued, moreover, that according to the law of the Pale no[Pg 4] lands could pass by patent without an inquisition previously taken. None could be taken in Tyrone, for it was no shire. If the English law were followed, there was, therefore, no power to divert the inheritance from him as rightful heir; if the Irish law prevailed, then he threw himself on the suffrages of the tribe.[3]

Shane O’Neill robbed his father and mother of all they possessed, and drove them into the Pale, where the unfortunate Con died early in 1559. Shane, who had recovered from his defeat by the O’Donnells, and secured himself by assassination against his most dangerous rival, claimed both the Earldom of Tyrone and the tribal sovereignty of the North. At first the Queen was strongly inclined to admit his pretensions. The patent was indeed fatal to them, but Elizabeth had an eminently practical mind, and the fact that Shane was in quiet possession weighed with her more than his legitimacy. In the absence of positive orders, Sidney did his best to maintain peace in the North. He repaired to Dundalk, and summoned Shane to attend him. The wily chief was loud in his professions of loyalty, but feared possible loss of reputation among his own people, and refused to go. Having less reason to regard appearances, Sidney visited Shane in his camp, and consented to act as god-father to his son, and to enter the mysteriously sacred bond of gossipred, or compaternity. O’Neill bound himself to keep the peace until the Queen should have pronounced on his claims, and Sussex, who hated him, expressed a belief that he would not keep his promise. Sidney could obtain nothing more, and Shane’s arguments were indeed such as could not easily be refuted.[4]

Sussex struggled hard to avoid returning to the hated Irish service, and pleaded occupations public and private. He declared, with perfect truth, that Sidney would govern Ireland much better than he could, and he was doubtless unwilling to leave the field clear to Lord Robert Dudley. But the Queen would take no denial, and he had to go. She was[Pg 5] at this time inclined to govern Ireland in her father’s cheap and rather otiose fashion, and the number of pardons granted during her first years shows that she aimed at a reputation for clemency. She understood the magnitude of the task awaiting her in Ireland, but declared herself unable to spare the necessary forces on account of the huge debt bequeathed by her sister, and of the expensive legacy of a Scotch and French war. The exchequer of Ireland had been much mismanaged, and its reform was urged on the restored governor, whose standing army was fixed at 1,500 men, 300 of them horse and 300 kerne. He was authorised to spend 1,500l. a month, but urged, if possible, to reduce the expense to 1,000l. The amount either of men or money was not to be exceeded, except under the pressure of necessity. The first duty of the new Lord Deputy and his council was to set the service of God before their eyes, and, pending a Parliamentary inquiry, all English-born officials were, at least in their own houses, to use the rites and ceremonies established in England.[5]

Sussex landed at or near Dalkey, and on the following day rode into Dublin. He was received on St. Stephen’s Green by the Mayor and Aldermen. Shaking hands with the chief magistrate, the Earl is reported to have said, ‘You be all happy, my masters, in a gracious queen.’ Three days later he was sworn in at Christ Church, Nicholas Darton, or Dardy, one of the vicars-choral, chanting the Litany in English before the ceremony, and the choir singing the Te Deum in English afterwards. Ormonde at the same time took the oath as a Privy Councillor and as Lord Treasurer of Ireland. Thus was the Protestant ritual quietly re-introduced, Sidney having been sworn with the full Roman ceremonial. The work of painting the two cathedrals, and of substituting texts of Scripture for ‘pictures and popish fancies,’ had begun three months before.[6]

Many important men had hastened to offer their services and forward their petitions to the new Queen. Conspicuous among them was Richard, second Earl of Clanricarde, called[Pg 6] Sassanagh, or the Englishman, of whose loyalty the Queen had a very good opinion, but who in one important respect fell short even of a Court standard of morals. The names of seven of his wives and sultanas have come down to us, and of these at least five were living at this time. He was acknowledged as captain of Connaught, his Earldom was confirmed by patent, and he received other marks of favour. The Queen also lent a favourable ear to Ormonde’s uncle, brother, and cousin, and to the new Earl of Desmond. Connor O’Brien, whom Sussex had established in the Earldom of Thomond, and MacCarthy More, were also well treated, and so were several of the corporate towns.[7]

The first Parliament of Elizabeth met on January 12, 1560, and was dissolved on February 1. It was attended by three archbishops, seventeen bishops, and twenty-three temporal peers, including all the earls then extant in Ireland. Ten counties sent two knights each, and twenty-eight cities and boroughs were represented by two burgesses each. Ten other counties, King’s and Queen’s among them, are mentioned, Connaught counting as one, and Down being divided into two; but they either received no writs or made no returns, and the same may be said of the borough of Kilmallock. James Stanihurst, Recorder of Dublin and member for that city, was chosen speaker. The chief business was to establish the Queen’s title, and to restore her father’s and brother’s ecclesiastical legislation. First-fruits were restored to the Crown, and so was the commandery of St. John. Massingberd’s alienations were annulled, and, as he was suspected of secret dealings with the Irish, he was attainted unless he should surrender within forty days.

So far English legislation was closely followed, but in two important respects the Church was made more dependent on the State than in England. Royal Commissioners, or Parliament in the last resort, were to be the judges of heresy without reference to any synod or convocation, and congés[Pg 7] d’élire were abolished as useless and derogatory to the prerogative. These matters having been arranged to his satisfaction, Sussex again went to England, and Sir William Fitzwilliam, who had just come over as Treasurer at War, was appointed Lord Justice in his room.[8]

Fitzwilliam, who was new to Ireland, at first found the Irish pretty peaceful, but admitted that the overtaxed people of the Pale were less so than they were bound in duty to be. Causes of disturbance were not long in coming. Old O’Connor escaped from Dublin Castle, and uneasiness was immediately observable in the districts where he had influence. Calvagh O’Donnell’s wife, who was Argyle’s half-sister, had brought over some 1,500 Scots, ‘not to her husband’s enrichment,’ as the Lord Justice supposed, but as a plague to Shane, who had married O’Donnell’s sister and ill-treated her. Shane had engaged a similar force, and all these combustibles could scarcely be stored without mischief. The priests who were beaten in England showed signs of an intention to transfer the struggle to Ireland, where they had many partisans and might create more. At all events, they were flocking across the Channel, ‘not for any great learning the universities of Ireland shall show them as I guess.’ The Government only was weak. There were but fifty hundredweight of lead in store, and Fitzwilliam thought he might have to strip the material for bullets from some house or church.[9]

Kildare, whose foreign education and connection made him more dangerous than any of his ancestors had been, was undoubtedly playing with edged tools. Desmond refused to pay cess. The two earls had met at Limerick, and would certainly join Donnell O’Brien if he landed with the expected foreign aid. There were rumours of French ships on the coast, and frequent messengers passed between Kildare, Desmond, and Shane O’Neill. Edmond Boy, a Geraldine who was usually employed on this dangerous service, warned a[Pg 8] relation who had married an Englishman to sell all and fly the realm, for if all promises were kept, her husband would never reap that he had sown. Kildare not only kept his followers under arms, but declared that he and his friends would be slaves no longer, presided at assemblies of Irishmen, and ostentatiously heard mass in public. Of all this there was ample evidence, and in addition, Lady Tyrone had sought interviews with the Lord Justice, and sworn the interpreter to secrecy. Laying the Bible first on her own head and then on his, ‘which is the surest kind of oath taken with them,’ she made a very positive statement as to the alliance of her son Shane and the two Geraldine earls. The Countess indeed, Fitzwilliam told Cecil, was ‘something busy-headed and largely-tongued, crafty and very malicious, no great heed to be given to her, unless some other thing might lend credit to the tale she telleth, as in this there is.’ There was quite enough to cause anxiety, and the Government were almost defenceless. ‘Send us over men,’ the Lord Justice cried, ‘that we may fight ere we die.’[10]

It was still the policy of Philip II. to appear as Elizabeth’s protector, anxious to save her from the consequences of her own rashness and to give her time to repent. This half contemptuous patronage was the result of mere statecraft, and the Queen gave no credit for kindliness to a man who had no such element in his nature. The first sighs of the great storm had been heard in the Netherlands. With France and Scotland united, and with England crushed as Philip thought she might be, the power of Spain in Northern Europe would be endangered. The Catholic King would therefore give no help to Catholic Ireland. The Christian King could give none; nor even maintain his ground in Scotland. The French fleet had been cast away, and the Huguenots were at no pains to hide their sympathy with English and Scotch reformers. The conspiracy of Amboise showed what might be expected. Francis II. was nought, and the hatred of Catherine de’ Medici for her lovely daughter-in-law paralysed the efforts of the states[Pg 9]men who ruled about him. Brave and full of resource, but without help or hope, D’Oysel was shut up in Leith, the national skill of his followers making the best of rats and horseflesh while Winter’s ships lay off Inchkeith, the unchallenged tyrants of the sea. Mary of Lorraine died with a Calvinist preacher by her bedside, and the power of Rome was for ever broken in Scotland. Under such circumstances no outbreak in Ireland could have a chance of success, and the plottings of the Geraldines with O’Briens and O’Neills came for the time to nothing.

Fortified by constant intercourse with the Queen and Cecil, Sussex returned to Ireland with the title of Lord-Lieutenant, which had not been conferred since the death of Henry VIII.’s son, and which was not to be conferred again till it was given to the rash favourite whose fate darkened Elizabeth’s last days. He told the Queen that he was willing to surrender his post to anyone who would go against Shane O’Neill on easier terms. ‘She seeth,’ he said, ‘that I affect not that governance.’ He had repudiated with scorn the accusation that he had put to death those who surrendered under protection. ‘If the cause,’ he said, ‘were mine own I would ask trial like a gentleman, but it is the Queen’s. My word is not the Earl of Sussex’s word but Queen Elizabeth’s word, my lie her lie.’ Noble words: but too imperfectly remembered in the hour of trial.[11]

Sussex’s written instructions show no apprehension of foreign enemies, except that he was authorised to contribute a sum not exceeding 250l. to the fortification of Waterford. If Sorley Boy MacDonnell’s profession of loyalty were fulfilled, he might receive a grant of the lands he claimed. But Shane O’Neill was to be curbed either by fair means or force. There was no longer a disposition on the Queen’s part to accept him as an established fact, and the young Baron of Dungannon was if possible to be maintained against him. Noblemen and gentlemen were to be encouraged to surrender their estates and to receive them back by fresh grants, while Sussex was urged to proceed with the settlement of Leix and Offaly, which was visible only on paper. The garrisons were in fact the[Pg 10] only fixed inhabitants. The remaining instructions were such as were generally given to Irish governors, and were chiefly concerned with improvements in the revenue and with the satisfaction of private or official suits.[12]

But in private conversation with her representative Elizabeth held language of which her indefatigable secretary did not fail to make a minute, and which showed how deeply impressed she was with the magnitude of the Irish difficulty. The chief danger was evidently from Kildare’s dealings with the foreigners, and Sussex was to persuade him if possible to go to England. It was the habit of Irish lords on such occasions to plead the want of ready cash, and the Earl was to be authorised to draw to any reasonable amount on London on giving his bond for repayment in Dublin. Kildare would have been a gainer, and the Queen a loser by the exchange. If he would not cross the Channel by this golden bridge Sussex was authorised to use a letter written by the Queen herself to Kildare, in which she commanded his attendance at Court. A date was to be affixed which might make it appear that the royal missive had followed and not accompanied the Lord-Lieutenant to Ireland. If this failed, Kildare and his most prominent friends, including Desmond, were to be arrested at the earliest opportunity. ‘And for satisfaction of the subjects of the land the Lord-Lieutenant shall cause to be published by proclamation or otherwise the reasonable causes of his doings, leading only to the quiet of the realm.’[13]

The death of the Regent and the expulsion of the French from Scotland put an end for the time to any apprehensions from France. If Desmond and Ormonde were once at peace the Lord-Lieutenant would have leisure to settle Shane O’Neill’s account. The manors of Clonmel, Kilsheelan, and Kilfeacle had long been in dispute between the two earls, and a thousand acts of violence were the result. The lawsuit was now about to be decided in a pitched battle. Men came from the Lee[Pg 11] and the Shannon on one side and from Wexford on the other, and met near Tipperary, but separated without fighting, probably owing to the efforts of Lady Desmond. Sir George Stanley, Marshal of the Army, the veteran negotiator Cusack, and Parker the Master of the Rolls, were sent to Clonmel to decide the most pressing matters in dispute, which consisted chiefly of spoils committed by the tenants and partisans of the two earls on each other. The White Knight especially, whose lands bordered on Tipperary, was constantly at war with his Butler neighbours. An award was given, on the whole favourable to Desmond; but the peace thus obtained was not destined to endure.[14]

Meanwhile Shane O’Neill, in spite of his ‘misused’ MacDonnell wife, sought Argyle’s sister in marriage; but that chief was engaged in the English and Protestant interest, and sent the letter of proposal to Elizabeth. So far from allying himself with the O’Neills, Argyle offered to provide 3,000 Highlanders for immediate service in Ireland, if the Queen would pay them, and 1,000 for permanent garrison duty on the same terms. James MacDonnell was willing to serve in person. These were no empty promises, for Argyle and MacDonnell had the men ready in the following spring; and the Queen thought she saw her way to ‘afflict Shane with condign punishment to the terror of all his sept.’ Gilbert Gerrard, Attorney-General of England, who had been sent over to report on the revenues, told Cecil that Ireland would be difficult to govern, and that many people cared for nothing but the sword. O’Donnell, O’Reilly, and Maguire might be induced to act loyally in hopes of throwing off O’Neill’s tyranny, and the MacDonnells from the fear of losing their estates. All pointed to the necessity of vigorous action; but the summer passed and nothing was done.[15]

These were the days when everyone expected Elizabeth to marry. Cecil went to Scotland, where the general wish[Pg 12] was that the half-witted Arran should unite the two kingdoms. On his return he found that his policy had been thwarted by ‘back counsels;’ and he talked of resigning his place. Sussex wrote in horror at the prospect, for he thought the Queen would be but slenderly provided with counsel elsewhere, and under certain circumstances, such perhaps as a Dudley ministry, he himself would not serve ten months in Ireland—no, not for 10,000l. The dark tragedy on the staircase at Cumnor left Dudley free, and for a moment most men supposed that the Queen’s partiality would end in marriage. Sussex did not take so unfavourable a view of the match as the secretary. According to his view the great national requirement was an heir to the Crown, and there would be a better chance of one if Elizabeth married the object of her affections. Sussex declared himself ready to serve, honour, and obey any one to whom it might please God to direct the Queen’s choice. Had this advice been given to Elizabeth the writer might be suspected of flattery, and of seeking friends of the mammon of unrighteousness; but, spoken to such unwilling ears as Cecil’s, it must be considered highly honourable.[16]

In Ireland as in England, Elizabeth gained great and deserved credit by reforming the coinage. From the time of John till that of Edward IV. there had been no difference between the two standards; but in the latter reign that of Ireland suffered a depreciation of twenty-five per cent. An Irish shilling was henceforth worth no more than ninepence in England. There must have been a loss to the public and a gain to the Exchequer at first, but bullion finds its own level like water, and there were no further fluctuations. Having become a settled and understood thing, the difference caused little trouble. But when Henry VIII. began to tamper with the currency great loss and inconvenience followed. The quantity of silver—the common drudge ’twixt man and man—in any given piece of money could scarcely be guessed at by the ordinary citizen. Barrels full of counterfeit coin were imported, and added much to the confusion. Tradesmen raised prices to save themselves. All good coin was exported to[Pg 13] buy foreign wares, and the course was continually downwards, as it must inevitably be under similar circumstances. Inconvertible notes proved highly inconvenient in America and in Italy; but they were nothing to the metallic counters of the Tudors, which depended less upon credit than upon uncertain intrinsic values. Communications were difficult, there were no newspapers, and money dealers flourished. At every exchange a burden was imposed on industry. Those who have been in Turkish towns, and have seen a sovereign waste as it passes from one currency to another, can form an idea of what Dublin and Drogheda suffered through the ignorance and dishonesty of the English Government.

What Henry began Edward and Mary continued, and Ireland was deluged with innumerable varieties of bad money. Some of Mary’s shillings were worth little more than the copper they contained. She also by proclamation authorised the adulterated rose-pence of her father and brother to be used in Ireland, though they were prohibited in England. In a paper drawn up for Elizabeth’s Council, five kinds of small coins are enumerated, of every degree of baseness, and of values between 5-1/3d. and 1-1/3d. English. One of these, the old Irish groat, was worth threepence, but had several varieties. Thus Dominus groats were those struck before Henry VIII. assumed the royal title, Rex groats were those struck after; none were of a good standard. The quantity of coin no more than three ounces fine was estimated at from 60,000 to 100,000 lbs. To cleanse the Augean stables it was proposed to restore the Irish mint, which had been abandoned for want of silver at the end of Edward VI.’s reign. The repair of the furnaces was begun, wood was cut, and the mixed money was cried down for a recoinage. But the inducements offered proved insufficient, and the merchants hoarded the Irish money instead of bringing it in. The plan was then changed. A reward was offered for bringing in the bad coin, and fresh money was struck in England on the basis of the practice which prevailed from Edward IV. to Henry VIII. Ninepence sterling was fixed as the value of an Irish shilling; some of the old money, particularly that of the lower denominations,[Pg 14] seems to have been put in circulation, but it was used merely as counters and was not complained of. The currency question slumbered until 1602, when Elizabeth fell away somewhat from her early virtue, and partially revived the grievance which she had redressed.[17]

Kildare had the wit to see that times were changed, and that the Crown would be too strong for any possible combination; but others were less well informed, or more sanguine. Some of the O’Mores held a meeting at Holy Cross in Tipperary, where Neill M’Lice was chosen chief of Leix. The object of this unfortunate clan was of course the retention of their lands, to which they clung with desperate resolution. Shane sent a rymer, one of those improvisatori who were always at hand to carry dangerous messages, bidding them to trust no man’s word, but to wait for orders from him. Desmond was also consulted. According to one account he offered the conspirators a refuge in the last resort; according to another, he had promised to send actual assistance. The matter came to Ormonde’s ears, and he appeared suddenly at Holy Cross, dispersed the meeting, and took three of the principal men prisoners.[18]

Elizabeth saw that nothing of importance could be done without an effort, and being in one of her frugal moods, she was disinclined to make that effort. She summoned Sussex over for a personal conference, reminding him that she had formerly been charged with other items besides his salary, and suggesting that part of it should now be devoted to the payment of a Lord Justice, ‘which, considering our other charges, we think you cannot mislike.’ As soon as Fitzwilliam’s commission arrived, Sussex left Ireland; but Shane[Pg 15] O’Neill did not wish to let the Lord-Lieutenant have the sole telling of the story. Shane was in communication with Philip, who bade him not be discouraged, for that he should not want help. Letters to this effect were brought by the parish priests of Howth and Dundalk, and O’Neill then wrote to the Queen in a very haughty strain. He asked leave to correspond freely with the Secretary, and solicited the admission of his messenger to the Queen’s presence. ‘There is nothing,’ he said, ‘I inwardly desire of God so much’ as that ‘the Queen should know what a faithful subject I mean to be to her Grace.’ For her Majesty’s information, he stated forcibly his case against the Dungannon branch, invariably calling his rival Matthew Kelly, and laying great stress on his own election by the tribe. ‘According,’ he wrote, ‘to the ancient custom of this county of Tyrone time out of mind, all the lords and gentlemen of Ulster assembled themselves, and as well for that I was known to be the right heir unto my said father, as also thought most worthiest to supply my father’s room, according to the said custom, by one assent and one voice they did elect and choose me to be O’Neill, and by that name did call me, and next under your Majesty took me to be their lord and governor, and no other else would they have had.’ The effect had been magical. All the North for eighty miles had been waste, without people, cattle, or houses, ‘save a little that the spirituality of Armagh had,’ and now there was not one town uninhabited. If the Queen would give Ireland into his keeping, she would soon have a revenue where she had now only expense.

As to Matthew Kelly, he had tried to turn him out of lands which his father had long ago given him, in which the bastard pretender was ‘maintained and borne up by the chin’ by Sussex. Had he not been wholly occupied in hunting Matthew up and down, he would long since have expelled the Scots, who had been reinforced by Lady Tyrone, and supported by Sussex. The Lord-Lieutenant had given them MacQuillin’s land, ‘which time out of mind hath been mere Englishman,’ having held his estate since the first conquest. The Queen was thus answerable for the strength of the Scots,[Pg 16] and without her help he could not undertake to drive them out. Kelly had been killed in a skirmish by chance of war, and he was not to be held answerable for so usual an accident. In fact, he was a blameless subject, who had committed no fault knowingly; ‘but through being wild and savage, not knowing the extremity of her Majesty’s laws, nor yet brought up in any civility whereby he might avoid the same, having also many wild and unruly persons, and hard to be corrected in his country.’ By a stretch of legal ingenuity their misdeeds might possibly be laid at his door, and to avoid that, and ‘not for any mistrust of his own behaviour,’ he asked for protection. Unable to trust Sussex, he had sent over the respectable Dean of Armagh to bring a safe-conduct from the Queen herself, which would enable him to lay his case in person before the English Council, and to return safely. For his expenses he should require 8,000l. sterling, which, with a fine irony, he declared himself quite willing to repay in Irish currency. For fear of mischances, the Earl of Kildare and other men of rank should be directed to put him safely on board, and to deliver him at Holyhead into Sir Henry Sidney’s charge. After his return Sussex should not be allowed to molest him for three months.

Besides the main grievance about Matthew Kelly, Shane had fault to find with governors in general, and Sussex in particular. When a very young man he had discovered a plot to attack the Pale, and having respect to the common weal of his native country, he had gone boldly to Sir Anthony St. Leger without any safe-conduct. St. Leger had been so much impressed with his virtue that he and all his Council had signed a contract, ‘which I have to be showed,’ to give him 6s. 8d. sterling a day. Since that he had suffered much, but not a groat of the pension had ever been paid. Still he bore no malice, and had offered his services to Sussex against the Scots. The Lord-Lieutenant was nevertheless firmly prejudiced in favour of Matthew Kelly, and determined that he, the legitimate chief, should be no officer of his. He accused Sussex of putting innocent men to death, and thus making it impossible for any one to trust him. Sussex[Pg 17] always indignantly denied this charge, and he was borne out by Kildare and by the Irish Council.

Shane proudly contrasted the state of his country with that of the Pale, and suggested that the Queen should send over two incorruptible men joined in commission with the mayor and aldermen of Dublin and Drogheda, ‘which are worshipful and faithful subjects,’ to judge which country was the better governed. They might hear the charges against him, and also the complaints of the families of the Pale, ‘what intolerable burdens they endure of cess, taxes, and tallages both of corn, beefs, muttons, porks, and baks.’ Not only did the soldiers live at free quarters, but they had ‘their dogs and their concubines all the whole year along in the poor farmers’ houses, paying in effect nothing for all the same.’ Not less than 300 farmers had gone into Shane’s county out of the Pale. These men were once rich, and had good houses, but they dared not so much as tell their griefs to the Queen, ‘yet the birds of the air will at length declare it unto you.’ Shane considered it ‘a very evil sign that men shall forsake the Pale, and come and dwell among wild savage people.’

Besides his pretensions to the Earldom, or to the captaincy of Tyrone, Matthew Kelly also advanced a claim to the manor of Balgriffin, in the county of Dublin, which had been granted to Con O’Neill, with remainder to his son, Matthew O’Neill, and in default of him and his heirs, with remainder to the right heirs of Con. Shane had taken legal opinions, and was advised that he had a title to Balgriffin, because there was no Matthew O’Neill at the time of the grant. ‘It follows plainly,’ he argued, ‘that I am my father’s right heir, legitimate begotten, and although my said father accepted him as his son, by no law that ever was since the beginning, he could not take him from his own father and mother which were then in plain life.’ Besides which he had inherited the land of ‘his own natural father the smith.’ If the premise that Matthew was Kelly and not an O’Neill be admitted, the reasoning is irrefragable.

Badly as he had been treated, Shane declared himself ready to make restitution wherever anything could be proved against[Pg 18] him. His savagery, which he confessed again and again, he thought could best be eradicated by an English wife, ‘some gentlewoman of some noble blood meet for my vocation, whereby I might have a friendship towards your Majesty.’ This impossible she would indeed be much more than an intermediary between him and the Queen to declare his grief and those of his country. ‘By her good civility and bringing up, the country,’ he hoped, ‘would become civil, and my generation so mixed, I and my posterity should ever after know their duties.’ Some educated companion was necessary to him; for the men of the Pale would not even show him how to address his letters properly, and he feared to offend, whereas he desired nothing so much as her Majesty’s approbation and favour. How Shane treated an accomplished woman when he had her in his power will appear hereafter.[19]

To enforce his demands, and to show how disagreeable he could be, Shane burned three villages on the borders of the Pale. Their crime was giving asylum to Henry, son of Phelim Roe O’Neill, who had offended by his loyalty. With much difficulty and many smooth words, the invader was prevented from spreading his ravages further; but he went so far as to threaten the town of Dundalk for sheltering his disobedient namesake, and he demanded an authority equal to that which Desmond had over the western seaports.[20]

Shane’s proposal to go to Court was accepted in order to gain time. A safe-conduct was sent, and Fitzwilliam was instructed to make his departure easy. Either really suspicious, or anxious to make it appear that he was ill-treated, the troublesome chief then began to make excuses, the most valid being that he had no money. Fitzwilliam wrote him a soothing letter, and Shane then said his retinue could not be ready for nearly two months. He held out stoutly for 3,000l. at least, but it was feared that he would rebel on receipt of[Pg 19] it, ‘conduct,’ said the Lord Justice, ‘which to his kind best belongeth.’ In the meantime he amused himself by plundering the O’Reillys and those on the borders of the Pale.[21]

While Fitzwilliam was temporising with Shane in Ireland, Sussex was intriguing against him in Scotland. His messenger carried credentials to the Ambassador Randolph, to Argyle, and to James MacDonnell. He was directed to visit them all, and if possible to see O’Donnell’s wife, a sister of Argyle, who continually hovered between Ireland and Scotland. He was then to cross the Channel, find his way to O’Donnell, and offer him the Earldom of Tyrconnel in the Queen’s name. To Argyle Cecil wrote as to a friend whom he had learned to value when in Scotland, urging him to ‘use stoutness and constancy, or the adversary will double his courage, where contrariwise the Papist being indeed full of cowardness ... will yield.’ Large offers were made to James MacDonnell and his brother Sorley Boy, and it was hoped that all the most powerful men in the North might thus be united against the redoubtable Shane.[22]

Sir Henry Radclyffe, the Lord-Lieutenant’s brother, thought Shane had money enough if he would be contented with reasonable expenses, but that he had sought counsel of those who were against the journey, and was chiefly anxious to gain time. He daily muddled his ‘unstable head’ with wine, and every boon companion could affect his judgment. That drunken brain was nevertheless clear enough to baffle Elizabeth for a long time. Perhaps Shane really expected help from Philip. Radclyffe thought him hopeless, and quoted Ovid as to the desirability of cutting out incurable sores before they had time to poison the blood. These opinions prevailed, and warlike preparations were swiftly and silently made. Six hundred additional men were sent to Ireland, and a general hosting was ordered. O’Reilly was encouraged to hope for the Earldom of Brefny, and robes and coronets for[Pg 20] him and for O’Donnell were actually sent. O’Madden and O’Shaughnessy in Connaught, were thanked for former services, and exhorted to deserve thanks in the future. Shane, wrote the Queen, was the common disturber. He had offered to go to Court and then drew back, though she had with her own hands given the required safe-conduct to his messenger. Conciliation had been tried in vain; and she was now obliged to resort to force. They were directed in all things to be guided by Sussex, whom her Majesty quite exonerated from Shane’s slanders.[23]

While his official superior was at Court, Fitzwilliam had no easy time in Dublin. He disliked and distrusted Kildare, who declined all responsibility for his bastard kinsfolk, the old scourges of the marches living at free quarters and disdaining honest industry. The MacCoghlans surprised one of the Earl’s innumerable castles, in which they were assisted by Ferdinando O’Daly, an Irishman in Fitzwilliam’s service. Kildare made a prisoner of O’Daly, and the Lord Justice thought his position as the Queen’s representative required his liberation. They were ‘tickle times, and many evil and rude men depend upon his Lordship, who with one wink might stir mischief.’ The Lord Justice offered to make good any harm that O’Daly might have done, but insisted on his enlargement, because it did not stand with the credit of his office that any servant of his should lie in gyves. Kildare at first refused to give the man up, and on the Lord Justice persisting, said he was in the custody of his captor, who had been promised a ransom of forty marks. O’Daly was ultimately released, and probably Fitzwilliam paid the forty marks. In the meantime Shane had been acting while his opponents talked.[24]

The O’Donnells, under a son of the chief, besieged an island in Lough Veagh, occupied by one of those pretenders who were never wanting in any Irish country. The chief himself lay at a Franciscan friary, eleven miles from his son, and with only ‘a few soldiers, besides women and poets.’ Among the women was his wife, by birth a Maclean, widow of an Earl of Argyle, noted for her wisdom and sobriety, a good French scholar with a knowledge of Latin, and a smattering of Italian, but at heart a rake who had been dazzled by Shane’s successful career. She contrived to let the object of her admiration know her husband’s defenceless condition, and he was only too ready to take the hint. A meeting of the two chiefs was arranged for May 15. O’Neill was not far off, and on the night of the 14th he appeared in force at the monastery gates. Had they been shut defence might have been possible, for O’Donnell had 1,500 Scots mercenaries within five miles; but they had been left open, probably on purpose, and O’Donnell and his wife were carried off into Tyrone. The night attack of four years before was thus amply avenged. Calvagh was kept in close and cruel confinement, and as Shane’s mistress the wise countess soon had reason to deplore her folly and perfidy.[25]

A messenger whom O’Neill had sent to Fitzwilliam used very insolent language, such as he had no doubt been accustomed to hear from his chief’s mouth. The Lord Justice complained, and Shane, whose cue was not to offend the Queen or her representative, said that his envoy was a scamp who had exceeded his instructions, and that he had tortured him and slit his ear. But the Government thought Shane incorrigible, and in this at least they were supported by Kildare. O’Neill was proclaimed a rebel and traitor. Either on this or some later occasion an Irish jester remarked that, except traitor was a more honourable title than O’Neill, he would never consent to Shane’s assumption of it, a joke which gained point from the feebleness of the proceedings against him. In the eyes of the Lord Justice he was the bully of the North;[Pg 22] in the eyes of the Irish he was King of Ulster from Drogheda to the Erne, with power very little diminished by the opposition of the English.[26]

[1] Sir John Alen to Cecil, Dec. 16, 1558; Staples to same, Dec. 16; T. Alen to same, December 18. Harris’s Dublin, chap. ii.

[2] Ancient Laws and Institutes of Ireland, vol. iii.; Preface to Book of Aicill, p. cxlviii.; Shane O’Neill to Queen Elizabeth, Feb. 8, 1561; Campion’s History; Four Masters, 1558. Maine’s Early History of Institutions, chap. ii.

[3] See the arguments in Carew, 1560, vol. i. p. 304.

[4] There is an account of the interview in Hooker.

[5] Instructions to Sussex, 1559, in Carew, pp. 279 and 284.

[6] Mant from Loftus MS.; Ware’s Annals.

[7] Memorial of answers by the Queen, July 16, 1559, and Instructions to Sussex, July 17, both in Carew; note of the Earl of Clanricarde’s wives and concubines now alive, Feb. 1559 (No. 18).

[8] The list of this Parliament is in Tracts relating to Ireland, vol. ii., Appendix 2; Printed Statutes, 2 Elizabeth; Collier, vol. vi. p. 296 (ed. 1846); Ware’s Annals; Leland, book iv. chap. i.

[9] Fitzwilliam to Sussex, March 8 and 15, 1560.

[10] Fitzwilliam to Cecil, April 11, 1560; Advertisements out of Ireland, May (No. 15), and many other papers about this time.

[11] Memorial by the Earl of Sussex for the Queen, May 1560 (No. 21).

[12] See the two sets of Instructions in Carew, vol. i. May 1560, Nos. 223, 225.

[13] Memorial of such charge as the Queen’s Majesty has given by her own speech to the Earl of Sussex, &c., May 27, 1560, in Carew.

[14] Orders taken by the Lord-Lieutenant and Council, Aug. 1, 1560. Award for the Earl of Desmond, Aug. 23.

[15] The Queen to Sussex, Aug. 15, 1560, and Aug. 21; list of plain rebels, July 19. Gerrard, A.G., to Cecil, Sept. 5.

[16] Sussex to Cecil, Oct. 24 and Nov. 2.

[17] Ware’s Antiquities, by Harris, chap. xxiii.; ‘Le case de mixt moneys’ in Davies’s Reports. There are a great many letters on this subject in the R.O., 1560 and 1561. See particularly the valuation of silver coins, &c., Dec. 1560 (No. 62), several of Feb. 23, 1561; Fitzwilliam to Cecil, May 4; to the Queen May 5; and the Queen’s letter of June 16. See also Queen’s Instructions to Sussex, May 22, 1561, in Carew, and the proclamations near the end of the last volume of that collection.

[18] Queen to Sussex, Dec. 15; to Ormonde, Dec. 16, 1560. Examinations of Donell MacVicar, Jan. 14, 1561.

[19] The whole of Shane’s statements are from his letter to the Queen, Feb. 8, 1561. For the refutation of his charge against Sussex, see the Queen to the Nobility and Council of Ireland, May 21, and the Council’s answer, June 12.

[20] Lord Justice Fitzwilliam to Cecil, Feb. 8, 1561; Jaques Wingfield to Sussex, Feb. 23.

[21] Protection for Shane O’Neill, March 4, 1561; Fitzwilliam to the Queen, April 5, 8, and 26.

[22] Sir William Cecil to Argyle, April 2, 1561 (not sent till the 27th); Instructions by Sussex to William Hutchinson, sent into Scotland, April 27.

[23] Sir Henry Radclyffe to Cecil, May 3. The lines from Ovid are:—

They were quoted by Sir Edward Dering in his speech against Bishops, &c., in the Long Parliament. The Queen to the Nobility and Council of Ireland, May 21. Sussex to Cecil, July 17.

[24] Wingfield to Sussex, Feb. 23; Fitzwilliam to Cecil, April 5, and the enclosures.

[25] Fitzwilliam to Cecil, May 30, 1561, and to Sussex same date. The Four Masters incorrectly place the event under the year 1559.

[26] Shane O’Neill to the Lord Justice, June 8. He calls his messenger ‘nebulo,’ and says ‘diversis torquidibus torturavi eum et auriculam ejus fidi.’ Campion. Four Masters, 1561.

Sussex landed on June 2, and advanced within three weeks to Armagh, where he fortified the cathedral and posted a well-provided garrison of 200 men. Shane could do nothing in the field, but withdrew with his cattle to the border of Tyrconnel. Calvagh O’Donnell was hurried about from one lake-dwelling to another; and Hutchinson, the confidential agent of Sussex in Scotland and Ulster, retired to Dublin in despair. Believing that the possession of Armagh would give him an advantage in negotiation, Sussex made overtures through the Baron of Slane; but O’Neill refused to come near him until he had seen the Queen, who had given his messenger a superlatively gracious answer. In the meantime he demanded withdrawal of the garrison, maintaining that the war was unjust and unprovoked. He had not, he said, libelled the Lord-Lieutenant, and had he done so he would have scorned to deny his authorship. He professed great readiness to go to London, but repeated that money was necessary, and laid upon the Viceroy the whole responsibility of nullifying the Queen’s good intentions. In future, he grandly declared, he would communicate only with head-quarters, and he hoped that her Majesty would support his efforts to civilise his wild country. He was not such a fool as to put himself in the power of an Irish Government, and he gave a long list of Irishmen who had suffered torture or death through their reliance on official promises. Sussex replied that the money was ready for Shane if he would come for it before the campaign began, and he issued a proclamation calling on the O’Neills to support the young heir to the Earldom of Tyrone. Shane merely warned the Baron of Slane to look out for[Pg 24] something unpleasant; for Earl of Ulster he intended to be. That great dignity had long been merged in the Crown, and the Baron could hardly fail to see what Shane was aiming at.[27]

When all was ready the army encamped near Armagh, which it was proposed to make a store-house for plunder. Five hundred cows and many horses were taken in a raid northwards; but the Blackwater was flooded, and nothing more could be done for several days. Not to be quite idle, Sussex sent Ormonde to Shane, who offered worthless hostages for his prompt departure to England, but refused to give up O’Donnell. An attempt was then made against some cattle which were discovered on the borders of Macmahon’s country. In compliance with a recognised Irish custom, Macmahon was probably obliged to support a certain number of his powerful neighbour’s stock. Sir George Stanley, with Fitzwilliam and Wingfield, went on this service with 200 horse, seven companies and a half of English foot, 200 gallowglasses, 100 Scots, and all the kerne in camp. Ormonde was ill, and Sussex in an evil hour, as he himself says, stayed to keep him company. The cattle were driven off, and no enemy appeared. On their return Shane overtook the troops with twelve horse, 300 Scots, and 200 gallowglasses. Wingfield, who commanded the rear guard of infantry, allowed himself to be surprised, and for a time all was confusion. The column was long, and some time passed before Stanley and Fitzwilliam knew what had happened. They at once attacked the Irish in flank, and Shane in turn suffered some loss; indeed, the annalists say, with a fine rhetorical vagueness, that countless numbers were slain on both sides. But the cattle, the original cause of the expedition, were not brought into Armagh. The moral effect of the check was disastrous, and Sussex, though he put the best face on the matter when writing to Elizabeth, exaggerating Shane’s losses and making light of his own, did[Pg 25] not conceal the truth from Cecil. ‘By the cowardice of some,’ he wrote, ‘all were like to have been lost, and by the worthiness of two men all was restored.’ Wingfield was chiefly blamed, but the Lord-Lieutenant bitterly reproached himself for remaining behind when so large a force was in the field. Fifty of his best men were killed and fifty wounded, and it was impossible to take that prompt revenge which alone can restore the reputation of an army when defeated in a hostile country by a barbarian enemy. ‘This last July,’ said the unhappy Viceroy, ‘having spent our victuals at Armagh, we do return to the Newry to conduct a new mass of victuals to Armagh.’[28]

When Cecil heard the evil tidings he says himself that he was so appalled that he had much ado to hide his grief, the rather that Lord Pembroke being away there was no one with whom he could share it. To the Queen he spoke as lightly as he could of a little bickering in which Shane had the greater loss, which to the letter was true. For the benefit of the general public Cecil gave out that Shane had been overthrown with the loss of two or three captains. Privately he urged Sussex to use strong measures with those who had shown cowardice. But it was seldom possible to hide the truth from Elizabeth, and she soon knew all. She gave orders that Wingfield should be deprived of all his offices, and dismissed her service with ignominy. But the wrath of Sussex soon cooled, or perhaps his conscience made him generous. It was discovered that Wingfield’s patent as Master of the Ordnance could not be voided, because he had acted only as a simple captain. His services among the O’Byrnes were remembered, and both Sussex and Ormonde interceded for him. At his own urgent request he was summoned to Court, when he probably succeeded in rebutting the charge of actual cowardice, and he remained Master of the Ordnance till his death in 1587.[29]

Having driven the English out of his country, Shane O’Neill proposed to treat with Ormonde, no doubt with the deliberate intention of insulting Sussex. To Ormonde accordingly he sent his messenger, Neal Gray, with power to make terms. Shane was ready to go to the Queen, and to repair the church at Armagh. But he would not make peace while the soldiers remained there, and he declared that no one in his senses would believe in the peace while such a sign of war remained. To show his own idea of peace and friendship he asked Sussex to be his gossip, and to give him his sister’s hand. The Lord-Lieutenant declined to withdraw the garrison until the Queen’s pleasure should be known. Fitzwilliam had gone to her, and Ormonde, knowing that nothing would be done till his return, had gone home. If Shane hurt any of his neighbours in the meantime, he was warned that he could never hope to see the Queen’s face. Sussex marvelled at the constant changes in Shane’s answers. ‘O’Neill desired me to procure the Queen’s pardon and protection, for the which at his request we have already sent Mr. Treasurer, and now he desireth to send his own messengers, whereby it seemeth he should seek delays, for that his messengers cannot go and return with such speed as Mr. Treasurer will do. And we know not to what other purpose he should send his messenger thither. Therefore we will him to send us word by writing directly whether he will go to the Queen’s Majesty, according his oath taken, if Mr. Treasurer bring him the Queen’s pardon and protection.’ To this Shane haughtily answered that he would make no peace with any of his vassals (urraghs) but at his own time and in his own way, and that he would receive neither pardon nor protection from the Queen unless they were delivered to his own messenger. In his natural anger at such an answer, Sussex called loudly for strong measures: ‘if Shane be overthrown, all is settled; if Shane settle, all is overthrown.’ It was no fault of his that the arch-[Pg 27]rebel would not go to the Queen. Indeed, it was well known that Kildare had first advised that step to gain time, and then prevented its being taken for the same reason.[30]

Fitzwilliam was instructed to ask for an immediate aid of 200 men, and 3,000l. The men were ordered from Berwick, and 2,000l. of the money was sent. Transports were pressed upon the Lancashire coast, and the Queen wrote in her best style to encourage Sussex. His ill success, she was sure, had come from no want of goodwill, and the chances of war were to be borne patiently; but she marvelled that the General had not punished those who showed cowardice. Traitors and cowards were to be sent to gaol without favour or affection. The Queen impressed the value of patience upon Sussex, her own principle being rather to recover the subject by persuasion than force. She was willing to give Ormonde a reasonable sum for Shane’s expenses, leaving the question of security to Sussex. She would not withdraw the garrison, but would undertake that it should molest no one except notorious traitors proclaimed before last March. In the meantime Sussex was to prepare for war by discharging unserviceable men, and by withholding the pay of runaways. The Lord-Lieutenant was required to forget his private dislike to Kildare, and to work with him loyally for the good of the service.[31]

Stung by failure, and fearing to be outwitted after all, Sussex now devised a safer and surer method than either war or diplomacy. There had perhaps already been one attempt to stab O’Neill, which he attributed to Sussex; but we are not bound to believe this, for a chief who punished unsuccessful agents by torturing them and slitting their ears was not[Pg 28] likely to gain much affection. Neill Gray now declared that he was ready to serve the Queen, if Sussex would write to her on his behalf. The nature of the service required was not such as could be publicly avowed, and Gray swore on the Bible to keep it secret, on pain of death, if it became known during the continuance of the Earl’s government. ‘For the benefit of his country and his own assurance,’ he agreed to do whatever Sussex wished, and ‘in fine I brake with him to kill Shane, and bound myself by my oath to see him have 100 marks of land by the year to him and his heirs for his reward. He seemed desirous to serve your Highness, and to have the land, but fearful to do it, doubting his own escape after. I told him the way how he might do it, and how to escape after with safety;’ and at last Gray promised to do it if he saw a prospect of security. Sussex assured the Queen that his accomplice might do it without danger if he chose, ‘and if he will not do what he may in your service, there will be done to him what others may. God send your Highness a good end.’ To hire a man to murder your enemy, and to determine to murder that hireling in the event of failure, are hardly matters deserving of divine favour, and it is deeply to be regretted that no letter is extant from Elizabeth expressing horror at the scheme. Such a letter may nevertheless have been written, for it would have been the interest of Sussex to destroy all evidence of the contemplated crime. On the same day that the Lord-Lieutenant attempted to make his sovereign an accessory before the fact, he informed her of the way in which he had received Shane’s matrimonial proposal. ‘I told him he should at his coming find my sister at the Court, and if I liked the other, I would further it as much as I could.’ The treachery of Judas was hardly more dramatically complete. It must not, however, be forgotten that Shane was a proclaimed traitor, and that the political morality of the day was very different from ours. Sussex may have thought he was doing little more than putting a price upon an outlaw’s head.[32]

Nothing came of the plot; but Neill Gray was too deeply implicated to venture on a double treason, and the Lord-Lieutenant’s secret was kept. But ‘slanderous bruits’ against him were rife on other accounts; for the feeling on the border was in Shane’s favour, and there was a general hesitation about putting him down effectually. It was said that Sussex would be superseded, and the date of his intended departure was named positively. The hundred tongues of rumour were busy in giving the sword to one man to-day and to another to-morrow. Everything was believed but the truth, and as a natural consequence orders were badly obeyed. Sussex urged strongly that the campaign must be prosecuted, or that everything must be left to Shane, who claimed jurisdiction over all inhabitants of the northern province, including those who held direct of the Queen, and had never been subject to any O’Neill. ‘So as we see, Ulster is the scope he challengeth,’ and if he once gained that there was no reason why he should not shoot even higher. Amid the general disaffection Sussex was afraid to carry out the Queen’s orders about punishing Wingfield and the other delinquents in the affair of July, when, as common report affirmed, the army was overthrown with small loss to Shane.[33]

With a heavy heart the Lord-Lieutenant led an unusually large force to Armagh. The magnitude of the effort may be estimated from the fact that four out of the five earls then in Ireland took part in the expedition, Thomond and Clanricarde being left to defend the principal camp, eight miles north of Dundalk. From Armagh Sussex made a rapid march across Slieve Gullion to the head of Glenconkein, a wild forest tract near the southern boundary of what is now the county of Londonderry. No resistance was offered, and 4,000 head of cattle, with many ponies and stud mares, were driven back, ‘so that they might see them who would otherwise have been hard of belief.’ Knowing by experience how hard it was to progress when thus encumbered, the Lord-Lieutenant ordered[Pg 30] all the beasts to be slaughtered, except a few which were kept for provisions. All the country between Armagh and the mountains was destroyed, and the army then proceeded to Omagh, and thence to Lough Foyle, where Con O’Donnell and others were expected to appear, and where a victualling fleet was supposed to be in waiting. But the ill fortune which attended Sussex in Ireland did not desert him here. The ships, which had been forty days at sea, were not to be seen, and the Earl, having had the poor satisfaction of seeing Lough Foyle, returned to Newry with 500 cows which he picked up on the march. ‘Man,’ he said, ‘by his policy doth propose, and God at His will doth dispose.’ Con O’Donnell and Maguire, who were already well affected, had been sworn to continue so; but no general confederacy had been formed against Shane, and the impotence of the military administration had been demonstrated once more. Yet Sussex thought himself justified in saying that the credit of the army had been restored, though no enemy had been seen, because Shane had lost 5,000 cows, and had been forced to fly from wood to wood. The cunning chief was only waiting till the transient effort of civilisation was exhausted, and he soon attacked Meath, in fulfilment of his promise to Lord Slane. Some villages were burned, and Sir James Garland, a gentleman of importance who had ventured to stray from his armed company, was taken prisoner. A brother of Macmahon was with Shane, and we are told that 1,000 cows were taken from his tribe in revenge; but the result of all the operations was to prove that Sussex could neither conquer Ulster nor even defend the Pale.[34]

When Shane was returning practically victorious to Tyrone, Kildare brought a letter authorising him to treat and coax O’Neill to visit England. Fitzwilliam had already brought a conditional pardon. Sussex was ordered to co-operate cordially with the Earl, who lost no time in seeking a meeting with Shane. Accompanied by Lords Baltinglass, Slane, and Louth, he came to Carrickbradagh, the usual place of meeting;[Pg 31] but Shane was in bad humour, and would listen to nothing. Next day he proved more amenable, and the conversation resulted in his making a written offer of terms, to which Kildare agreed with a readiness for which he was afterwards blamed. The arrangement was generally condemned in official circles, and was, with difficulty, accepted by the Lord-Lieutenant and Council. Yielding everything and suggesting nothing, it was said that Kildare had shown no regard for the Queen’s honour, taken no pains to fight her battle, and consented to abandon Armagh, for the retention of which he should have held out to the last. The Earl merely answered that the thing was done and could not be undone, and he had certainly full power to treat.[35]

It was agreed that Kildare and Ormonde should meet Shane, and remain in his company till he came to the Queen’s presence. His passport to go and return safely was to be signed by the five Irish Earls, who were to undertake for the safety of his dependents in his absence. Kildare in particular undertook that the soldiers of Armagh, upon whose immediate withdrawal Shane did not insist, should do no harm until after the appointed meeting. A sum of money was to be advanced by Ormonde and Kildare, and paid through the latter. No Irishman owing Shane allegiance was to be maintained against him, and if such a person drove his cattle into the Pale it was to be restored. In return he was to go to the Queen, giving the very hostages which had been before rejected, and to forbear taking vengeance on Maguire and others. Shane refused any alteration in these terms; what he had written he had written. It was retorted that ‘seeing he would put no more in writing than was in writing already, he should look for the performance of all things written and of nothing else.’ Shane’s own terms were granted, but there was little goodwill or sincerity on either side.[36]

Having practically humiliated the Lord-Lieutenant, Kil[Pg 32]dare had enough address to give the Queen the appearance of a diplomatic triumph. It had been agreed that the garrison should be withdrawn from Armagh, but the Earl persuaded Shane that by not insisting strictly on this article he would put her Majesty in good humour and make her favourable to his suits. After expressing some indignation that any attempt should be made to vary the written letter, Shane was at last graciously pleased to humour the Queen, ‘but as to th’erle of Sussex he would not molefye one yoote of his agrements; and hereupon sent his man the garison to remaynge.’ Five hundred pounds were paid over to Shane before starting, 1,000l. awaited him at Chester, and a second 500l. in London.

Shane came to Dublin and waited upon Sussex, who received him graciously; but this outward politeness scarcely concealed the real feelings of the two men. Shane perhaps feared that the Lord-Lieutenant, who now had him in his power, might after all send him over as a prisoner. For the same reason an encouraging letter from Mary Stuart, which only reached him in Dublin, had not the desired effect of preventing his journey. And thus, accompanied by Kildare and Ormonde, without whose escort he had positively refused to stir, and with a train suitable to his pretensions, the uncrowned monarch of Ulster took ship to visit that great princess whose authority even he was ready to acknowledge, upon the sole condition that she should never exercise it. Shane afterwards complained that he was treated as a prisoner on the journey, and that Sussex had charged the Earls on their allegiance to secure him by handcuffs.[37]

Sussex did not conceal from the Queen his mortification at the treaty which he had been obliged to sign, at the powers given to Kildare, and at the abandonment of the campaign,[Pg 33] from which so much had been hoped, and for which such great preparations had been made. Her Majesty’s letters had contained expressions of disgust which not only reflected on himself, but discredited the whole English interest of which he was the head, and he bitterly resented the small thanks given him for five years of arduous service. ‘Our nation in this realm,’ he said, ‘is likened to the French in Scotland. We be railed on at tables with terms not sufferable. The people be incensed to wax mad, and this is hoped to be the jubilee year.’ He complained that the Queen’s Irish policy was as useless and unprogressive as Penelope’s web, woven by one governor only to be picked to pieces by the next. It would be for the Queen’s honour either to support her representative cordially, or to recall him honourably and employ him in some other place, ‘where I can do her better service than I can now do here.’ These criticisms were well deserved. The peace with Shane was of Elizabeth’s own making, and yet, with that want of generosity which she sometimes showed, she tried to make out that its terms were not sufficiently favourable to her. Sussex showed conclusively that he had done the best thing possible under the circumstances which the Queen had thought proper to create.[38]