THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT

TYPICAL MOUNTAIN GOAT COUNTRY

FIVE GOAT MAY BE SEEN IN THE CLEFTS OF THE ROCKS.

Photographed in northern British Columbia by the late E. A. Stanfield.

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT

By

MADISON GRANT

SECRETARY OF THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY

REPRINTED FROM THE NINTH ANNUAL REPORT

OF THE

NEW YORK

OFFICE OF THE SOCIETY, 11 WALL STREET

1905

Copyright, 1905, by the

NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY

| PAGE | |

| Typical Mountain Goat Country | Frontispiece. |

| Rocky Mountain Goat and Sheep | 6 |

| Goat Country | 8 |

| Rocky Mountain Goat (Dead) | 10 |

| Rocky Mountain Goat (Head) | 11 |

| Rocky Mountain Goat (Mounted Specimen) | 14 |

| Rocky Mountain Goat (Mounted Specimen) | 15 |

| Rocky Mountain Goat and Sheep | 17 |

| Seven Mountain Goat Kids | 19 |

| Kids of Mountain Goat and Sheep | 21 |

| Two Goat Kids | 23 |

| Mounted Head (Front) | 26 |

| Mounted Head (Side) | 27 |

| Skull of Goat (Front) | 30 |

| Skull of Goat (Side) | 31 |

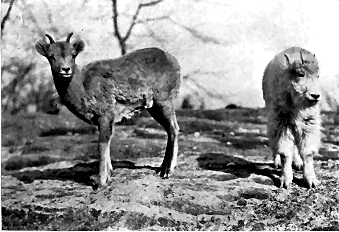

ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT AND SHEEP

IN THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL PARK.

Born in the spring of 1904, captured near Fort Steele and Michel, British Columbia.

REPRINTED FROM THE

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT.

By MADISON GRANT.

The white or Rocky Mountain goat shares with the musk-ox the honor of being the least known of the game animals of North America and descriptions of it written even as recently as ten years ago are valueless, as in many cases this animal is confused with white mountain sheep and even with deer. The explanation of this lack of knowledge lies in the extremely remote and inaccessible habitat of the goat, which begins in the northwestern United States, among the highest peaks of the Rocky Mountains and of the coast ranges and extends north, through British Columbia, into Alaska. The material in most natural histories, relating to this animal, is scanty and based on very inadequate information, since the opportunity to see and hunt it has not been granted to many. In captivity, we have had, on the Atlantic coast, only eight immature specimens, two in Boston in 1899, two in Philadelphia in 1893, and the four now (1905) living in the New York Zoological Park. One well grown male is living at this time in the London Zoological Garden.

As a result of this scarcity of direct knowledge, many myths have gathered around this mountain dweller, leading, as usual in our North American game animals, to an abundance of inappropriate names. The name “goat” is objectionable, but will have to stand until some better term can be found. The Stoney Indians in Alberta use the name “Waputehk,” and in Chinook, the universal jargon of the Northwest, the goat is called Snow Mawitch (white deer). Neither of these terms are likely to become common. It is not a goat, nor even closely related to them, but is the sole representative on this continent, of a very aberrant group of so-called mountain antelopes, known to science as the Rupicaprinæ, a Subfamily of the Bovidæ.

THE MOUNTAIN ANTELOPES.

The Rupicaprinæ comprise five widely scattered genera, extending from the Pyrenees of Spain, to the Rocky Mountains of the western United States, as enumerated below.

GOAT COUNTRY ON THE SUMMIT OF THE MAIN ROCKIES

EAST OF THE MAIN ROCKIES, INDICATING CHARACTER OF COUNTRY WHERE GOAT, SHOWN ON PAGE 14, WAS SHOT.

In western Europe we find first the chamois (Rupicapra), known in the Spanish Sierras and Pyrenees as the izard, and extending eastward through the Alps and Carpathians as far as the Caucasus. Throughout all this range only one species is recognized.

The next genus of this group is the goral (Cemas), with four species ranging throughout the Himalayas and parts of China, into Amurland.

In Tibet we have the third and decidedly most aberrant member of the Rupicaprinæ, the takin (Budorcas), the horns of which suggest those of the gnu. Only one species of this genus is known.

The fourth, and to Americans perhaps the most interesting Old World member of this Subfamily, is the serow (Næmorhedus), locally known as the forest goat. This genus is perhaps, more closely allied to Oreamnos than any of the preceding genera, and its horns resemble those of the mountain goat, but are shorter and thicker. The genus Næmorhedus inhabits the Himalayas, Tibet and China with outlying representatives in Burma, Sumatra, Formosa and Japan and it is divided into numerous species. The fifth genus is Oreamnos, the subject of this article.

All the members of these genera resemble the goat in tooth structure, but differ widely from them in the position and shape of the horns, face glands and other important details. The whole group is to be regarded as an early off-shoot of the Bovidæ, to some extent intermediate between the goats and the true bovine antelopes. The Rupicaprinæ must have pushed north, with their not distant ally the musk-ox, at a very early time and become adjusted to alpine and boreal conditions. At the close of the glacial period many of its members deserted the low country and retired to high altitudes so that in some instances, notably that of the chamois, we have an example of discontinuous distribution. Its sole American representative probably reached this continent by way of the Bering Sea land connection, during the middle Pleistocene, together with the other American genera of the Bovidæ.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT

KILLED, AUGUST, 1902, BY ANDREW J. STONE IN THE SCHESLEY MOUNTAINS, BRITISH COLUMBIA.

Measurements of the animal, in detail, are given on 35

HEAD OF THE GOAT SHOWN ON THE OPPOSITE PAGE.

GENERIC CHARACTERS.

Oreamnos as remarked above, while more closely related to Næmorhedus than to the other members of the group, has departed widely in structure from all of its relatives. Its most striking character is its almost pure white coat. This coloring is in perfect harmony with an environment of snow fields, but in some parts of its range it renders the animal unnecessarily conspicuous. Until white men appeared on the scene, it made very little difference to the goat whether his enemies could see him or not, as his home was beyond the reach of pumas, wolves, and for the most part of bears and until other game became scarce, the Indians did not hunt this inaccessible peak-dweller too closely. All the types of Oreamnos are characterized by this white coat and the only exception is the well authenticated occurrence of goat in the Selkirks of southern British Columbia, with a clearly-defined dark brown line extending along the center of the back and terminating in an almost black tail. This color variation « 12 » appears to be fixed in both the summer and winter pelage, as the markings were found on the skins of goats killed both in July and November. Reports of goat with these characters are widespread along the upper Columbia River, so that it would seem as though toward the southern limit of its range, a color variation were just beginning to appear. In addition to its uniformly white color, Oreamnos differs from the serow in the prominence of its eye sockets, in the elongated shape of the muzzle and face, in the position and shape of the horns and more particularly in the cannon bones, which are exceptionally short and stout. In this latter respect Oreamnos departs widely from all the other members of the Rupicaprinæ. The most striking character however, of Oreamnos, is the presence, situated in a half circle immediately behind each horn, of a large, black scent-gland, as large as half an orange. This gland is sometimes so tough as to wear deeply into the base of the horn. A horn worn away in this manner was secured by the writer in British Columbia.

The comparatively short duration of time since the appearance of Oreamnos in America and the somewhat uniform character of its habitat, probably account for the absence of much type variation.

TYPES OF OREAMNOS.

The first specimens of the mountain goat to be described, came from the Cascade Mountains on the Columbia River in Oregon and of course now stand as the type of Oreamnos montanus, having been first described by Rafinesque in 1817. This subspecies is intermediate in size between the eastern form of American goat, O. m. missoulæ, and the large Canadian O. m. columbianus, and, is characterized by a short but broad skull. The true Oreamnos montanus extends from about the Canadian boundary, south through Washington into Oregon. In the '70's a considerable number were found on Mt. Ranier in Washington, and they still occur on Mt. Baker to the northward. It is absent, however, from the Olympic Mountains, from Vancouver Island and from the southern Cascades in Oregon. Nothing is known of the northern limits of this subspecies, but it probably does not extend very far into British Columbia, merging at that point into O. m. columbianus. The most southerly Oregon records that the writer has been able to obtain is Mt. Jefferson in that State, latitude 44° 40´ north, in approximately the same latitude as the Sawtooth Mountains in Idaho.

Probably the only place where the goat exists to-day in the State of Oregon is the mountains in Wallowa County, in the extreme northeast corner of the State, and the animals from that locality are probably to be referred to as O. m. missoulæ. They have long since vanished from Mt. Hood and from the other peaks in the western part of the State, where they once abounded. In the State of Washington they exist in reduced numbers from the Canadian boundary as far south as Mt. Adams, although at the latter point they are possibly now extinct. Throughout the State the frequency of names, such as “goat rocks,” "goat paths," “goat buttes” and “goat creeks,” testify to their early abundance, and they were formerly shot from the decks of steamers on Lake Chelan by hunters who took a wanton delight in seeing the wounded animals fall down the precipitous banks.

In the Mt. Rainier Forest Reserve they are found in small numbers. In the isolated volcanic peaks along the coast the goat is too easily reached to be allowed to survive, and it is probable that before many years the interesting animal will be entirely exterminated in the United States except in the main Rockies.

The Alaskan form, at the extreme western limit of the genus, in the neighborhood of the Mt. St. Elias Alps and the Copper River, was described by Dr. D. G. Elliot, in 1900, as a second and valid species, under the name of Oreamnos kennedyi. It is strongly characterized by the lyrate shape of the horns and certain anatomical features.

These two were the only described forms, until 1904, when the attention of Dr. J. A. Allen, of the American Museum of Natural History, was called by the writer to the great difference in bulk of body and size of horns of the goat of British Columbia, and those of the Bitter Root Mountains in Montana. Upon comparing a number of specimens from the Cascade Mountains, the type locality of Oreamnos montanus, from the Bitter Root Mountains of Montana and Idaho, from the main Rockies in southern British Columbia and from the Schesley Mountains of northern British Columbia, it was found that all these specimens could be divided into three easily distinguishable groups each of subspecific rank.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT

KILLED IN SPILLAMACHENE VALLEY, SOUTH OF GOLDEN, BRITISH COLUMBIA, NOVEMBER, 1903

Total length with tail, following convolutions of body, 73 inches; tail, 7 inches; hind foot, 12 inches; height at shoulders, 41 inches; measurements taken after mounting. On exhibition in the American Museum of Natural History.

The skulls of animals killed in the Schesley Mountains by Andrew J. Stone in 1903, were found to be in all respects identical with those killed by the writer and Mr. Charles Arthur Moore, Jr., in the main Rockies, near the Columbia River the following year. Animals from these districts were characterized by great bulk and by a long and relatively narrow skull. This was the third type described and it received from Dr. Allen the name of O. m. columbianus. This subspecies probably extends from the American border up through the Canadian Rockies, to the northern limits of goat in that region, which is west of the Mackenzie River at about north latitude 63° 30´. The goat in the northern Rockies, may possibly be found to be specifically distinct from the goat on the coast of southern Alaska.

SIDE VIEW OF SPECIMEN SHOWN ON OPPOSITE PAGE.

In the midst of the distributional area of this large subspecies and in the vicinity of the Big Bend of the Columbia River, a very small goat is found. This animal, upon further investigation, may prove interesting. At present, however, all the Canadian goats must be provisionally assigned to O. m. columbianus.

A curious break in the range of this subspecies is found just north of the Liard River, where, according to no less an authority « 16 » than Andrew J. Stone, no goat are found for a distance of over a hundred miles. Probably the local topography, of which we have no knowledge, will explain the absence of goat from this territory. No goat have yet been found north of the Yukon River.

O. m. columbianus abounds along the coast ranges of British Columbia, and extends into Alaska, probably merging in the neighborhood of the Copper River into O. kennedyi, the western-most member of the genus. The extreme western record for goat is the Matanuska River, not far from the head of Cook Inlet. Horns from this locality, however, do not show the characteristics of Kennedy's goat. No goat are reported in the vicinity of Mt. McKinley, but they are found along the Copper River for a considerable distance inland, and there is some evidence of their occurrence on the north side of Mt. St. Elias. It may be well to remark here that while O. kennedyi is a valid species, founded on abundant material, no living specimens have been seen by a white man so far as is known, nor have we any information concerning the limits of its distribution. O. m. columbianus is by far the largest and handsomest member of the genus, unless O. kennedyi proves on further investigation, to excel in these respects. It is, therefore, surprising that the great differences in size and other characteristics, which distinguish this type from the goat in the United States have not been previously recognized.

The animals south of the Canadian border and still in the main range of the Rockies, upon comparison with the preceding types, were found to be much smaller, in fact the smallest of all the subspecies and were characterized by shorter but still relatively narrow skulls. The specimens of this type under consideration having been killed in the Bitter Root Mountains, the subspecific name of O. m. missoulæ was given them by Dr. Allen. This is the fourth and last type to be described, although these animals from the Bitter Root Mountains were the first goat known to transcontinental explorers. This is the goat usually hunted by American sportsmen and its range probably extends from the southeastern limits of the genus in Montana and Idaho to the Canadian border, where like O. montanus it passes imperceptibly into O. m. columbianus. The extreme southerly limit of the goat in the Rockies is the Sawtooth Mountains and the Salmon River in Idaho. It does not reach the Tetons, in Wyoming, nor does it occur in the Yellowstone Park. The question of its absence in these localities will be discussed later in this paper.

WHITE MOUNTAIN GOAT AND MOUNTAIN SHEEP

IN THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL PARK.

WHITE MOUNTAIN GOAT AND MOUNTAIN SHEEP

IN THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL PARK.

To sum up, the two American subspecies are smaller than their Canadian relatives and the type from the Cascade Mountains possesses a broad skull, in direct contrast to the narrow skulls of all other goats, both American and Canadian.

CAUSES GOVERNING DISTRIBUTION.

The distribution of the genus is limited by the character of the mountain ranges, rather than any other consideration, and too much emphasis cannot be placed on the fact, that of all our North American animals the white goat is the only one absolutely confined to precipitous peaks and ridges, which even the mountain sheep seldom approach.

The extreme north and south ranges of Oreamnos in the main Rockies present several problems of great interest. The southern limit is clearly marked by a change in the formation and ruggedness of the mountains themselves, which, together with climatic conditions, and the lack of water in summer on the mountain tops, are sufficient to account for the absence of these animals much south of their present limit. A very different condition prevails in the north. At the extreme northern limit which is about 63° 30´, the mountains begin to lose their height but are still of considerable size and quite rugged enough to provide a suitable home for Oreamnos. White sheep are found all through these mountains, up to the very coast of the Arctic Ocean and westward through the Romanzoff Mountains in northern Alaska. These sheep are certainly not better equipped to resist arctic cold than are the goat, so we must seek for some cause other than climatic or topographical conditions. There must be some unknown and unfavorable condition of food supply which prevents Oreamnos from reaching the extreme north. This is perhaps the most interesting and difficult of the problems affecting the distribution of the genus.

Along the Pacific coast of the United States the mountains are not sufficiently precipitous to attract the goat, and consequently that animal is found only at some distance inland, but in northwestern British Columbia and southern Alaska, the Rockies approach the coast in stupendous chains, which swing westward through the Mt. St. Elias range. Through all this country the goat occupies the coast region from Prince William Sound south nearly to the American border. They are not found in any of the adjacent islands.

SEVEN MOUNTAIN GOAT KIDS

CAPTURED NEAR BANFF, ALBERTA, 1904, FOR THE NEW YORK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY.

Along these coast ranges goat are much more numerous than in the main Rockies, owing probably to the presence of forests high up in the mountains and in close contact with the cliffs where the goat lives, together with a copious supply of water. At all events the conditions are certainly favorable. North of Skagway goat do not extend inland much beyond the summit of the coast range, and do not again occur until the main Rockies are reached, hundreds of miles to the east. The goat in these eastern mountains are, in all likelihood, specifically distinct from the coast goat, as practically all the other mammals of these two distinct faunal areas are separate species.

LEGENDARY DISTRIBUTION.

The writer has carefully traced out the legends regarding the occurrence of goat in Colorado, Utah, and California. There are persistent stories about the existence of white goat in Colorado, which, when investigated seem to have their origin in some domestic goat which are known to have escaped from captivity. It is, however, a certainty that Oreamnos has not existed in Colorado since the arrival of the white man, and there is no proof of its previous existence there. This statement is made after a full examination of the evidence.

The purpose of this paper has been to gather and summarize the known facts about this interesting animal and it has been necessary to discard a large amount of data contained in the literature of the subject. Statements by certain writers regarding the existence of the goat in Wyoming, Colorado, California, and even New Mexico, are extremely misleading. It is positively known that no goat have ever existed on Mt. Shasta, although this mountain has been a favorite locality for stories about mountain goat and the mythical ibex. The origin of these fables is easily traced to the former existence on Mt. Shasta of mountain sheep, the horns and bones of which are still occasionally found there. The straight horns of the mountain sheep ewe are probably responsible for most of these legends. It is bad enough to suggest the occurrence of goat on Mt. Shasta, but it is utterly absurd to assert their existence on Mt. Whitney, 300 miles farther south, and it is still worse to include in the range of the goat New Mexico or the barren coast mountains of southern California.[A]

[A] See “Sport and Life in Western America and British Columbia,” by A. W. Baillie-Grohman, page 117, London, 1900, and “The Wilderness Hunter,” page 130, by Theodore Roosevelt.

KID OF MOUNTAIN GOAT (STANDING) AND MOUNTAIN SHEEP OF SAME AGE

CAPTURED IN 1904, NEAR MICHEL, BRITISH COLUMBIA.

Now on exhibition in the New York Zoological Park.

The above examples will suffice to show the loose manner in which this subject has been treated by writers who have not sifted the evidence sufficiently.

Within the United States the mountain goat is only found in Idaho, western Montana, Washington, and Oregon. There is no evidence whatever of the white goat having existed in Wyoming. In examining the rumors respecting the occurrence of goat one must remember that only a few years ago very little was known about this animal, and few people had seen it. In the south, escaped domestic goat and old mountain sheep ewes with bleached coats and straight horns, have probably been the basis of many such stories. In some places such animals have been mistaken for white goat and elsewhere, notably in Alaska, for the legendary ibex. Until the discovery and description of Dall's white sheep, in 1884, all white animals in the north were called goat and white mountain sheep meat is sold to-day in Dawson City restaurants under that name.

There is no reason whatever to believe that the limits of the distribution of the white goat were ever much different from what they are now, except in outlying localities along their southern limits. The center of the greatest abundance of goat appears to be in the coast ranges in British Columbia and southern Alaska and it is here that they are found low down the mountain sides and often close to salt water.

COMPARISON WITH SHEEP.

It is due to ignorance of the character of the country inhabited by mountain goat that so much has been written about an alleged antipathy between Oreamnos and the mountain sheep. It is singular that writers should go so far afield as to conjure up an imaginary mutual hatred to account for the undoubted fact that sheep and goat seldom live together. In some places, however, notably the Schesley Mountains, sheep and goat can be found on the same mountain side. Sheep belong to the rugged hills and lower slopes and at one time ranged far eastward into the plains wherever the character of the country was at all rough, as in the Black Hills and in the Bad Lands of the upper Missouri.

The sheep is furthermore, a grass-eating animal, while the goat is a browser, finding his food mainly on the buds and twigs of the forests that grow to the very foot of the goat rocks. All through the goat country occur patches of forest and it is there that the goat is found, between timber-line and the snow fields. So far as we know the only grazing done by the goat, beyond nibbling at small plants, is on the slides when the grass first appears and it is probable that to this habit the greatest mortality of this animal is due, as many are killed each spring by the avalanches on these snow slides.

TWO GOAT KIDS AND MOUNTAIN SHEEP LAMB, BORN IN THE SPRING OF 1904

CAPTURED NEAR FORT STEELE, BRITISH COLUMBIA.

Now living and on exhibition in the New York Zoological Park.

The sheep is an active, wary and fleet-footed animal, fully as well equipped as the deer to escape by agility from its enemies and is not dependent for safety on a refuge beyond the reach of other animals. The goat on the other hand, is heavy, powerful, clumsy, slow moving and somewhat stupid and does not dare to venture very far from its inaccessible rocks. It thrives among precipitous cliffs, which are everywhere known among hunters as “goat rocks” and are recognizable as such at a glance.

LOCAL DISTRIBUTION.

In a mountainous country it is perfectly easy to say where goat are to be found, if there are any in the neighborhood. They descend, of course, into the upper limits of the forests, but always keep near to cliffs to which they can retire when attacked. Sometimes swim rivers and have been killed while crossing the Stickine far into the forests. Salt-licks have been found in the hillsides, where great holes have been eaten out by these animals. The trails which lead to some of the licks in British Columbia are worn so deeply as to resemble buffalo trails. Goat pass through the forests and lower slopes of the mountains in moving from one locality to another, but this of course, is exceptional. They sometimes swim rivers and have been killed while crossing the Stickine River in British Columbia, a wide and rapid stream.

So complete is the protection the goat finds in broken rocks and precipices, that they are practically out of danger from any animal approaching from below, except bear, which frequently lie in wait for them and occasionally capture an unwary individual. The eagles take a very heavy toll from the young goat in the spring.

The difficulty of reaching the mountain tops is, of course, a protection against man, but the conspicuous color and the slow movements of the animal make it a comparatively easy victim when once reached by hard climbing.

WATER SUPPLY.

The question of water supply on the mountains inhabited by goat has a most important bearing on the distribution of the animal. In a large portion of the southern range of the goat, little « 25 » or no water is found from August to October, except what is furnished by such snow fields as persist throughout the year. All other animals can, during the dry season, venture down to the valleys and cañons for water, but the goat seldom leaves the rocks, even for water, relying on the snow of the mountain tops.

This fact alone, I believe, is sufficient to account for the absence of the goat, so often commented on by hunters, in many portions of its range, where other conditions appear to be entirely suitable. In southern British Columbia the great river valleys, such as those of the Kootenay, the Columbia and the Beaver, run almost north and south, and prevent communication from east to west between the goat inhabiting the adjacent mountains, while these same valleys offer no difficulties to the crossing of sheep and other large animals. Farther north in the Stickine country wide valleys are sometimes crossed.

The presence or absence of water on the higher ridges, taken together with the fact that the goat is not a very restless or migratory animal, accounts for many of the anomalies that are observed in its distribution. It is probable that in the course of its life the goat ranges over a smaller territory than any other of our game animals and unless seriously disturbed does not venture far from its native haunts as long as the food supply lasts. They can usually be found day after day on the same spot and goat have been watched, through glasses, which apparently scarcely moved for days at a time. Of course, in such a spot, food and water must be plentiful, and no danger threatening.

Along the Columbia River goat have been sometimes observed to get into positions on the face of the cliffs, from which they apparently could not escape. In spite of their great strength and climbing ability, their home must be an exceptionally dangerous one and it is probable that many lose their lives through accidents.

In British Columbia, during the early summer, the streams from the melting snow on the mountain tops are found in every draw and gulch. During this season small bands of females and kids, or solitary males, are scattered everywhere in favorable localities, from the upper timber to the summits of the mountains. As the season advances however and the snow-fed streams dry up, the only water available is found in the larger basins where the snow has accumulated in large quantities. These basins become the feeding ground of the goat and the rest of the mountain side is deserted, except for an occasional individual traveling along the summit from one such feeding ground to another, or during the autumn rutting season, when both sexes are almost constantly on the move. Connecting two favorite feeding grounds in the Palliser Rockies was found, in 1903, a well beaten path along the summit-ridge, passing close to the snow fields and showing constant usage.

FRONT VIEW OF MOUNTED HEAD OF GOAT SHOWN ON PAGE 14

PROPERTY OF MADISON GRANT.

On exhibition in the American Museum of Natural History

SIDE VIEW OF HEAD SHOWN ON THE OPPOSITE PAGE.

WINTER RANGES.

In winter the goat suffers from the severity of the storms on the mountain tops and the limit of its increase is, in the long run, dependent on the food supply available during this season. This is also true of most of our large animals and the elimination of the weak takes place during the terrible blizzards of winter and early spring.

In much of the southern range of the goat the use of the larger valleys for farming has undoubtedly interfered seriously with their lower feeding grounds. While the loss of these winter ranges is more serious for other game, even the goat feels the approach of civilization. The high valleys, however, still remain untouched and a certain number of hardy individuals will winter successfully in close proximity to settlements if not too much hunted. This is notably the case in the Bitter Root Valley, where goat are often found within sight of the town of Hamilton, Montana.

In winter the question of water supply is, of course, eliminated and at this season many ranges are well stocked with goat which, in summer, are deserted on account of lack of water. The goat travels so slowly that, aside from the danger of venturing far from the rocks, long daily journeys to and from a feeding ground are quite impossible.

As to food supply, we are apt to think of the mountain tops as barren in comparison with the valleys; but in a very mountainous region, such as British Columbia, the reverse is often true. On the higher mountain slopes and ridges are to be found the best pasturage and the most sunny resting places. The valleys receive the sun for a much shorter portion of the day than do the higher ridges and while the mountain tops are above the fogs, mists and clouds often darken the low country. It is noticeable that domestic cattle, sheep and horses in a mountainous country, are very partial to the high lands, seldom remaining voluntarily in the valleys and river bottoms. In such a country the first impulse of a grazing animal is to climb high. Anyone who has tried to hunt horses which have strayed from camp, is apt to be familiar with this habit.

It is the inaccessible character of the country inhabited by the goat and not his wariness or agility, which has made goat hunting « 29 » a test of sportsmanship. Only those sound of wind and limb can venture after Oreamnos. The first rule in goat hunting is to go to the highest point that can be found and this point is apt to be very high.

HABITS.

The sight of a man does not seriously disturb a goat and it seems to be of indifferent power of vision. Sounds affect it even less. The constant falling of rocks and stones and the rumble and breaking up of the glaciers, close to which it finds its home, has led the goat to distrust the warning of its ears. Shouting at a goat only arouses a slight curiosity and the report of a rifle has scarcely more effect. The hunter may sometimes stand for an hour in plain view of a goat without disturbing it, but its sense of smell is highly developed and the slightest trace of human scent will alarm it.

These characters, together with confidence in the inaccessible nature of its habitat, born of long experience with animals other than man, have all combined to give the goat its reputation for stupidity. It probably is stupid, but less so than would appear to those accustomed to the nervousness of other game animals. The goat, like the skunk, has a serene reliance in its ability to protect itself and is accustomed to gaze with indifference at enemies who threaten it from below. The large males are not lacking in bravery and will savagely fight off a dog when attacked. Stories are told of wounded goat attacking man when cornered, but most of the danger to the hunter lies in missing a foothold, or in the stones rolled down from above by a fleeing animal.

Goat are marvelously tough and can carry more lead even than a grizzly. It sometimes seems almost impossible to kill them and in some cases when hopelessly wounded, they show a tendency to throw themselves from a cliff. That this is a deliberate act on their part is generally believed by goat hunters, but it is doubtful whether it is more than a last desperate effort to get out of harm's way.

Goat, like moose, are inclined to be solitary, but are often found in small family groups. They occasionally assemble in larger numbers in some favorite feeding ground, as many as twenty-seven having been seen together.

SKULL OF A GOAT

KILLED BY MADISON GRANT, SEPTEMBER, 1903.

Main Rocky Mountains, east side of Columbia River, south of Golden, British Columbia. Measurements in inches: Right horn, 101⁄8 inches; left, 103⁄16 inches; spread of horns, 47⁄8 inches. These measurements are the largest on record, with a known history. Same specimen as on pages 26 and 27.

SIDE VIEW OF SKULL SHOWN ON THE OPPOSITE PAGE.

WEIGHT AND SIZE.

The strength of the goat is enormous and while its weight is far greater than one would at first suppose, it is a matter about which we have little definite information. An average specimen from the Cascade Mountains appears to weigh about 150 pounds. A six-year-old goat killed near Skagway, Alaska, showed an actual weight of 329 pounds. A much smaller animal killed at the same time and probably a female, weighed 250 pounds. Large goat from the main Rockies, in British Columbia and Schesley Mountains, have been estimated to weigh as high as 350 and 400 pounds. Mr. Baillie-Grohman publishes an account of a full grown male goat captured near Deerlodge, Montana, which was weighed after its capture and “was found to turn the scales at 480 pounds!” This, however, must be an error.

The size of the goat is emphasized by the long and shaggy coat, which at the shoulders rises in a hump. This, taken in connection with the low-carried head, gives the animal the appearance of a pigmy bison. Careful measurements of goat are hard to obtain, but authentic figures which were taken by Mr. Stone, of four goat killed in August, 1902, in the Schesley Mountains, British Columbia, are to be found at the end of this article.

HORNS.[B]

[B] Measurements of horns are given at the end of this paper.

The horns of the female are slightly longer and much more slender than those of the male. A little over eleven inches appears to be the extreme limit of horns for the male. The longest horns known are from British Columbia, attaining a length of something over ten inches up to an extreme measurement of eleven and one-half, which appears to be the record. The horns from the Bitter Root Mountains average at least an inch shorter, as do those from the coast ranges in the United States. Any horn measuring over nine inches is to be considered of good size and anything over ten inches is very exceptional. All measurements of horns and antlers are subject to considerable variation, owing to the material of the tape and zeal of the man holding it and this must be taken into consideration in the measurements of record horns. In the measurement of the basal girth of sheep horns a variation of as much as an inch has been found to occur in the recorded size of the same horn taken by different persons, all quite conscientious in their efforts to be accurate.

PROTECTION.

The mountain goat has probably a better chance of survival in a wild state than any other American game animal, except possibly the Virginia deer. It is protected even from man by the extreme ruggedness of its mountain habitat and although it will probably be exterminated in certain localities, if given a moderate amount of protection it can hold its own throughout most of its range. Its history will probably be like that of the chamois in Europe, as the country grows more populated.

In some localities it is in great need of protection. In southern British Columbia, the Indians, who are not amenable to the laws governing the white man, but are protected by treaty rights secured by the Dominion government, kill right and left with impunity. In Canada, even more than in the United States, solicitude for the noble red man works great injury to all our game animals. In the early days, from motives of self-interest, the Indian may have been moderate in his killing, but, having abandoned his archaic weapons in favor of modern fire-arms, he is now an unmitigated butcher.

The Kootenays on the upper Columbia and the Stoneys on the east face of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta, are game murderers and it is the boast of the latter that no game can live where they hunt. In the interest of game protection in British Columbia, it is greatly to be regretted that the enforcement of stringent laws cannot be extended to the Indians. Curiously enough, many persons, who would ordinarily be friendly to game protection, have become so interested in the natives, that they advocate hunting privileges for Indians which they deny to the white man, under the mistaken impression that the Indian kills only what he needs. The strange delusion has recently led to an attempt by a benevolent United States Senator to repeal the game laws for Alaska and leave that great game region to the mercy of the native and meat hunter.

SALE OF GAME HEADS.

The hunting of the Stoney Indians has been somewhat discouraged by a wise law recently enacted in the Northwest Provinces, prohibiting the sale of game heads. This law is especially beneficial to sheep, since the demand for heads of large rams has been steadily increasing. Oreamnos has not suffered greatly from head hunting, as its horns do not offer much of a trophy except « 34 » when needed to complete a collection of American game animals. The marketing of game heads cannot be too strongly condemned by genuine hunters and by those interested in the protection of wild animal life.

INTRODUCTION OF FOREIGN ANIMALS.

In this connection a word should be said about a proposition to establish chamois in the Rocky Mountains. Efforts, to introduce European game, instead of protecting the native American animals, are constantly cropping out. Why anyone should prefer a chamois to the far finer native animal is somewhat of a mystery. Nature has provided for every portion of our country, mammals, birds and fish well adapted to the needs of the locality, and the introduction of foreign animals simply means, in case they survive, the crowding out of some native form.

In the East the mountain goat never can be more than an object of temporary curiosity, as he cannot long survive the rigors of our Atlantic summer. A number of young goat have been captured in British Columbia for exhibition in the New York Zoological Park, but while very docile, and taking readily to the milk of domestic ewes, they all died before shipment except the four now on exhibition at the Park. The proper place for the exhibition and breeding of mountain goat is in the Canadian National Park at Banff, Alberta, where there is an unsurpassed opportunity to secure and breed not only goat, but also mountain sheep, bison and even moose in their native environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

The writer desires to acknowledge his indebtedness for assistance in the preparation of the above article to Mr. Charles Arthur Moore, Jr., to Mr. Andrew J. Stone, to Dr. J. A. Allen, to Mr. Charles H. Townsend, to Mr. Wilfrid H. Osgood, and to members of the Geological Survey, notably Mr. A. H. Sylvester.

MEASUREMENTS.

Four goat killed in the Schesley Mountains of British Columbia, in August, 1902, and measured with extreme accuracy, ran as follows:

| No. 43. inches |

No. 44. inches |

No. 57. inches |

No. 60. inches |

|

| Total length, end of nose to end of tail vertebra | 61 | 65 | 57 | 66 |

| Tail vertebra | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7½ |

| Tarsus | 13½ | 14 | 13 | 14½ |

| Height at shoulder | 40½ | 39 | 36 | 43 |

No. 57 was about a half-grown animal.

No. 60 was the largest specimen and its estimated weight was over 400 pounds.

Detail measurements in millimeters of No. 60[C] are as follows:

| End of nose to lower corner of right eye | 220 |

| End of nose to base of ear | 297 |

| End of nose to base of right horn | 265 |

| Width of head just over eyes | 147 |

| Width of nose above nostril | 65 |

| Width of nostril | 81 |

| Greatest depth of head | 193 |

| Depth of nose | 156 |

| Depth of chin | 119 |

| Between the eyes | 110 |

| Circumference of horn at base | 153 |

| Length of horn | 260 |

| Width between point of horns | 210 |

| Length of ear | 150 |

| Width of ear | 65 |

| Length of beard | 110 |

| Length of front foot | 83 |

| Width of front foot | 72 |

| Extreme width of dew claws outside | 80 |

| Length of front of front hoof | 52 |

| Hind foot, length | 71 |

| Hind foot, width | 72 |

| Length of dew claw | 52 |

| Width of dew claws | 34 |

MEASUREMENTS OF MOUNTAIN GOAT HORNS IN INCHES.

Four large specimens in the United States National Museum, Washington, D. C., selected and measured by Madison Grant on February 4, 1905, gave the following dimensions:

| Right. | Left. | ||||

| ♂ | 10 | 9 | ¾ | Lake Chelan, Washington. | |

| ♀ | 8 | ½ | 8 | ½ | ” ” |

| ♀ | 8 | 5⁄8 | 8 | ¼ | Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho. |

| ♀ | 7 | 5⁄8 | 7 | ¾ | ” ” |

Fifteen specimens in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City, were measured by Dr. J. A. Allen, with the following result:

| Right. | Left. | Spread. | ||||||

| 15752 | — | 7 | ½ | 7 | ½ | 4 | ¾ | O. m. missoulæ, Missoula, Montana. |

| 22694 | ♂ | 9 | 9 | 1⁄16 | 4 | 7⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” | |

| 22695 | ♂ | 9 | ¾ | 8 | 5⁄8 | 4 | ¼ | ” ” ” ” ” |

| 19335 | ♂ | 9 | — | — | ” ” ” ” ” | |||

| 19337 | ♀ | 9 | 13⁄16 | 9 | ¾ | 4 | 7⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” |

| 19836 | ♂ jnr. | 7 | 3⁄16 | 8 | ¼ | 6 | ½ | ” ” columbianus, Schesley Mts., B. C. |

| 19837 | ♂ | — | 9 | 1⁄8 | — | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” | ||

| 19838 | ♂ | 9 | 7⁄8 | 10 | 8 | 1⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” | |

| 19839 | ♂ | 9 | 1⁄8 | 8 | 7⁄8 | 5 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” | |

| 19858 | ♀ | 8 | ½ | 8 | ½ | 5 | 7⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” |

| 21504 | ♀ | 9 | ¾ | 9 | 4 | 5⁄8 | ” ” ” Main Rockies, ” ” | |

| 21505 | ♀ | 9 | 7⁄8 | 9 | 7⁄8 | 5 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” | |

| 21506 | — | 7 | 5⁄8 | 7 | 3⁄8 | 4 | 7⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” |

| Mt. | ||||||||

| [D]Head | ♂ | 10 | 1⁄8 | 10 | 3⁄16 | 4 | 7⁄8 | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” |

| [E]Mt. | ♂ | 9 | 7⁄8 | 9 | 5⁄8 | 6 | ½ | ” ” ” ” ” ” ” |

[E] Property of Charles Arthur Moore, Jr.

All occurrences of O.m.columbianus were changed to O. m. columbianus.

Illustrations were moved so as not to split paragraphs.

On p. 13, “as” was added in “... to be referred to as O. m. missoulæ.”