From the painting by W. H. Margetson.

HIS MAJESTY KING EDWARD VII.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cassellshistoryo01londuoft |

From the painting by W. H. Margetson.

HIS MAJESTY KING EDWARD VII.

FROM THE ROMAN INVASION

TO THE WARS OF THE ROSES

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS,

INCLUDING COLOURED

AND REMBRANDT PLATES

VOL. I

THE KING'S EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED

LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

MCMIX

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE ROMAN RULE IN BRITAIN. PAGE

Earliest Notices of the British Isles—The Celts—Their Settlement in Britain—Their Character and Customs—Druidism—Its Organisation and Authority—Its Tenets—Stonehenge and other Remains—Cæsar's Preparations—The First Invasion—Peril of the Romans and their Retirement—The Second Invasion—Cæsar's Battles with Cassivelaunus—Claudius in Britain—The Resistance of Caractacus—His Defeat and Capture—His Speech before Claudius—The Conquest of Anglesea—Boadicea's Rebellion—The Capture of Camulodunum and London—Her Defeat and Death—Agricola in Britain—His Campaigns and Administration—His Campaign against the Caledonians—His Recall—The Walls of Hadrian and Severus—Rivals to the Emperor—Constantine's Accession—Christianity in Britain—Invasions of the Picts and Scots—Dismemberment of the Roman Empire and Departure of the Romans—Divisions and Administration of Britain under the Romans 2

ROMAN REMAINS IN BRITAIN.

Two Varieties of Masonry—Dover Castle—Richborough Castle—Newport Gate, Lincoln—Hadrian's Wall—Its Direction and Construction—Outworks—Ornamental Detail—Roman Roads and Camps 19

THE FOUNDATION OF THE ENGLISH KINGDOMS AND THEIR CONVERSION TO CHRISTIANITY.

The Jutes, Angles, and Saxons—Their Village Communities—Larger Combinations, Gradations of Rank—Morality and Religion—Hengist and Horsa found the Kingdom of Kent—The Kingdoms of Sussex, Wessex, and Essex—The Anglian Kingdoms—Mercia—The Welsh—Gregory and St. Augustine—Augustine and Kent—Conversion of Northumbria—England becomes Christian—The Greatness of Mercia—King Offa 25

RISE OF WESSEX AND OF THE SOCIAL SYSTEM OF ENGLAND.

Ceawlin and his Successors—Cedwalla—Ina—Subjection to Mercia—Accession of Egbert—He subdues his Rivals—His Wars with the Welsh and Danes—Land-owning System—Local Assemblies—The Hundred Moot—The Shire Moot and its Business—Methods of Trial and Punishments—The Wergild—The Witena-gemot—Its Powers—The King—Class Distinctions—The Church 31

THE DANISH INVASIONS AND THE REIGN OF ALFRED.

Character of the Invaders—Reign of Ethelwulf—Reigns of Ethelbald and Ethelbert—The Conquest of East Anglia—Battles near Reading—The Accession of Alfred—The Extinction of the Kingdom of Mercia—The Invasion of Wessex—The Year 878—Alfred at Athelney—Death of Hubba—Victory of Alfred and the Treaty of Wedmore—Renewal of the War—Alfred's fleet—Expeditions of Hastings—Remainder of the Reign—Character of Alfred—His Rules of Life—His Legislation—Encouragement of Learning 38

EDWARD THE ELDER AND DUNSTAN.

Settlement of the Danes—Edward the Elder and his Cousin—Reconquest of the Danelagh—Edward becomes King of all England—Conspiracy of Alfred against Athelstan—Wars in Northumbria—The Death of Edwin—The Battle of Brunanburgh—The Power of Athelstan—Edmund's Wars with the Danes—Their Submission to Edmund—Rebellion and Reconquest—The Conquest of Cumberland—Death of Edmund—Final Conquest of Northumberland—The Rise of Dunstan—His Banishment—Edgar's Rebellion—His Accession to the Throne—Wars with the Welsh—Dunstan Archbishop of Canterbury—His Ecclesiastical Policy—The Reign of Edward the Martyr—Dunstan's Struggles with the Opposition—Death of the King 46

ETHELRED THE UNREADY.

The Retirement of Dunstan—Character of Ethelred—Sweyn in Denmark—Character of the Invasions and the Resistance—The Danegeld—The Arrival of Sweyn—Ethelred's Expedition—The Massacre of St. Brice's Day—Return of Sweyn—Defeats of the English—Edric Streona—Failure of the English Fleet—Treacheries of Edric—Death of St. Alphege—Sweyn's Conquest of England and his Death—Return of Ethelred and Departure of Canute—Misgovernment of the King—Canute's Return and the Death of Ethelred 57

EDMUND IRONSIDE AND CANUTE.

A Double Election—Battles of Pen Selwood and Sherstone—Treacheries of Edric—Division of the Kingdom—Death of Edmund—Election of Canute—His Treatment of his Rivals—The four Earldoms—Canute's Marriage with Emma—His Popular Government—His Expeditions to Northern Europe—Submission of the King of Scots—Canute at Rome—The Story of his Rebuke to his Courtiers—His Death 63

EARL GODWIN AND HAROLD.

Harold and Harthacanute—The Murder of Alfred—Accession of Harthacanute—His Reconciliation with Godwin—The Punishment of Worcester—Edward the Confessor—His Election—Influx of Normans—The Family of Godwin—Conduct of Sweyn—The Outbreak at Dover—Godwin's Rebellion and Outlawry—William of Normandy's Visit to England—Godwin's Attempt to Return—His Appearance in the Thames—His Restoration to Power—Death of Godwin—His Place taken by Harold—Siward's Invasion of Scotland and his Death—Death of Leofric and Punishment of Ælfgar—Church Building of Harold and Edward—Harold's Conquest of Wales—Turbulence of Tostig—Death of the Atheling Edward—Candidature of Harold 66

THE NORMAN INVASION.

The Normans—Their Settlement in France—Their Gradual Civilization—Richard the Good—Robert the Devil—William's earlier years—His Consolidation of Power—Harold's Adventures in Normandy and the Story of his Oath to William—Death and Character of Edward—Election of Harold—William's Claims—He Obtains the Sanction of the Church—His Preparations—Proceedings of Tostig—Harold's Forces dwindle—Invasion of Tostig and Harold Hardrada—Battle of Stamford Bridge—Landing of William—Harold in London—Desertion of Edwin and Morcar—Negotiations—Harold at Senlac—Account of the Battle—Death of Harold and Discomfiture of the English—His Burial—Legend of his Escape 75

ENGLISH AND NORMAN ARCHITECTURE AND CUSTOMS.

Saxon Architecture; Theories about it—Documentary Evidence—Ancient Churches—Characters of the Saxon Style—Illustrations from an Anglo-Saxon Calendar—Old Manuscripts—English Scholarship—Music and the Minstrels—Musical Instruments—Games and Sports—Costume—The Table—Household Furniture—Material Condition of the People—Norman Costumes—Condition of Learning and the Arts—Refinement of the Normans—The Bayeux Tapestry 83

THE REIGN OF WILLIAM I.

After Hastings—Election of Edgar Atheling—Submission of London and Accession of William—Tumult during his Coronation—Character of his Government—Return to Normandy—Affairs during his Absence—Suppression of the First English Rebellion—Rebellion in the North—The Last National Effort—The Reform of the Church—The Erection of Castles—Plan of a Norman Castle—End of Edwin and Morcar—"The Last of the Saxons"—Affairs in Maine—Conspiracy of the Norman Nobles—The Execution of Waltheof—Punishment of Ralph the Wader—The Story of Walcher of Durham—Expeditions to Scotland and Wales—Quarrels between William and his Sons—Domesday Book—The Creation of the New Forest—Punishment of Odo of Bayeux—The Death of William—Incidents at his Burial—Character of William 107

REIGN OF WILLIAM II.

William's Surname—How he obtained the Throne—Rising in favour of his Brother Robert—Bishop Odo's Ill-fortune—Surrender of Rochester Castle—Flight of Odo—Failure of the Conspiracy—Death of Lanfranc—William's Misrule—Randolf the Firebrand—Appointment of Anselm to Canterbury—Rufus Invades Normandy—Treaty between the Brothers—Siege of Mount St. Michael—Malcolm Canmore's Inroad into England—Building of Castle at Carlisle—Death of Malcolm—Illness of William—His Treachery towards Robert—Welsh Marauders—Earl Mowbray's Hard Fortune—The King's Exactions—He obtains possession of Normandy—The Hunt in the New Forest—Death of the Red King 123

THE FIRST CRUSADE.

The Institution of Chivalry—Affairs in the Holy Land—Pilgrimages—Persecution of Christians—Peter the Hermit—Crusade Decided on—Progress of Peter's Mission—The Council of Clermont—Attitude of Pope Urban—The Truce of God—Expedition of Walter the Penniless—Excesses of the Crusaders—Defeat of the Christians by the Turks—Conduct of the Emperor Alexius—Disaster in Hungary—Geoffrey de Bouillon—March of his Army—Robert of Normandy and his Troops—Imprisonment of Hugh of Vermandois—Arrival of Godfrey before Constantinople—The Byzantine Court—The Church of Santa Sophia—Scenes of Magnificence—Reception of Godfrey by the Emperor—Tancred's Army leaves Italy—Bohemond's Submission—Count Raymond at Constantinople—Arrival of Robert of Normandy—[v]Siege of Nicæa—Treachery of the Emperor—Severe Struggle with the Turks—Bravery of Robert—Flight of the Turks—Crusaders' Sufferings on their March—Siege and fall of Antioch—Defeat of the Persians—Pestilence at Antioch—Arrival of the Crusaders before Jerusalem—Fall of the City—Vengeance of the Crusaders—Godfrey elected King of Jerusalem—Hospitallers and Templars—Close of the First Crusade 132

THE REIGN OF HENRY I.

Accession of Henry I.—Robert's Delay in Italy—The Charter of Liberties—Henry's Popularity—Offers his Hand to Matilda—Her Lineage—Obstacles to the Marriage—The Church decides in Favour of it—London at this Period—Coronation of Matilda—Roger of Salisbury—The Marriage—Punishment of William's Favourites—Arrival of Robert in Normandy—Prepares to Attack Henry—Anselm's Services to Henry—Peace effected between the Brothers—Henry's Dispute with Anselm—Strange Policy of the Pope—The Dispute Settled—Death of Anselm—The Earl of Shrewsbury Outlawed—Visit of Robert to England—Campaigns in Normandy—Robert and Edgar Atheling taken Prisoners—Fate of Edgar—Captivity and Death of Robert—Normandy in Possession of Henry—The English King and his Nephew—Return of the King to England—Betrothal of Henry's Daughter Matilda to the Emperor of Germany—War with the Welsh—Death of the Queen—Renewed War in Normandy—Henry before the Council of Rheims—Battle of Brenneville—Treaty of Peace—Shipwreck and Death of the King's Son—Henry's Grief—Character of Prince William—More Trouble in Normandy—The Empress Matilda declared Successor to the Throne—Her Marriage with the Count of Anjou—Death of William of Normandy—Last Years of the King's Life—Death of Henry 152

REIGN OF KING STEPHEN.

Stephen of Blois—Arrival in England—His Coronation—Pope Innocent's Letter—Claims of Matilda—The Earl of Gloucester's Policy—Revolt of the Barons—The King of Scotland Invades England—The Battle of Northallerton—Outrage on the Bishops of Salisbury, Lincoln, and Ely—The Synod of Winchester—Landing of the Empress Matilda—Outbreak of Civil War—Battle at Lincoln—Defeat and Capture of Stephen—Matilda's Arrogant Behaviour—Rising of the Londoners and Flight of Matilda—London Re-occupied by the King's Adherents—Matilda Besieged in Winchester—Exchange of the Earl of Gloucester for the King—Stephen Resumes the Crown—Reign of Terror—Siege of Oxford—Flight of Matilda—Desultory Warfare—Death of the Earl of Gloucester—Stephen's Quarrel with the Church—The Interdict Removed—Further Dangers from Normandy—Divorce of Eleanor—Her Marriage with Prince Henry—Landing of Henry in England—Unpopularity of the War—Violence and Death of Eustace—Treaty Arranged between Henry and the King—Death of Stephen 167

THE REIGN OF HENRY II.

Accession of Henry Plantagenet—Royal Entry into Winchester—Expulsion of the Flemings—Henry's Dealings with the Barons—Siege of Bridgenorth Castle—The King's Quarrel with Geoffrey—Henry's Magnificence—War with, and Submission of, the Welsh—The King in Brittany—Alarm of the King of France at Henry's Schemes of Aggrandisement—Henry's Designs on Toulouse—Origin of Scutage—Peace with Louis—The People of Languedoc—Louis' Third Marriage—Fresh Rupture between the Two Kings—Marriage of Henry's Son and Louis' Daughter—The Two Popes—Renewed Reconciliation 180

THE REIGN OF HENRY II.(continued).—CAREER OF THOMAS BECKET.

Early Life of Becket—Rapid Advance in the King's Service—Magnificence of his Embassy to Paris—The King, the Chancellor, and the Beggar—Depravity of the Clergy—Becket's Reforming Zeal—Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury—Extraordinary Change in his Habits—At Frequent Issue with the King—The Council of Clarendon—Becket Defies the King—Popularity with the People—His Flight from Northampton—Arrival at St. Omer—Obtains the Support of Louis and the Pope—Henry's Edict of Banishment—Defeat of the English by the Welsh—Insurrection in Brittany—Becket Excommunicates his Opponents—Henry's Anger—The Pope's Action against Becket—Interview between Becket and the King—The Two Reconciled—Return of Becket to England—His Christmas Sermon—The King's Fury—The Vow of the Conspirators—Scene in Becket's House—Murder of the Archbishop—Henry's Grief—Review of Becket's Career 187

THE REIGN OF HENRY II. (concluded).

Events in Ireland—The Irish People—Henry's Designs in Ireland—Nicholas Breakspeare (Pope Adrian IV.)—The King of Leinster's Outrage—Dermot obtains Henry's Patronage—Siege of Wexford—Strongbow in Ireland—Siege of Waterford—Henry and the Norman Successes in Ireland—Arrival of Henry near Waterford—His Court in Dublin—The King Returns to England—His Eldest Son Rebels—The Younger Henry at the French Court—The English King's Measures of Defence—Defeat of the Insurgent Princes—Success of the King's Cause in England—Henry's Penance—Capture of King William of Scotland—Revival of Henry's Popularity—The King Forgives his Rebellious Sons—Period of Tranquillity—Fresh Family Feuds—The King at Limoges—Death of Princes Henry and Geoffrey—Affairs in Palestine—The Pope's Call to Arms for the Cross—The Saladin Tithe—Richard's Quarrel with his Father—Henry Sues for Peace—The Conference at Colombières—Death of the King—Richard before his Father's Corpse—Character of Henry II.—The Story of Fair Rosamond 199

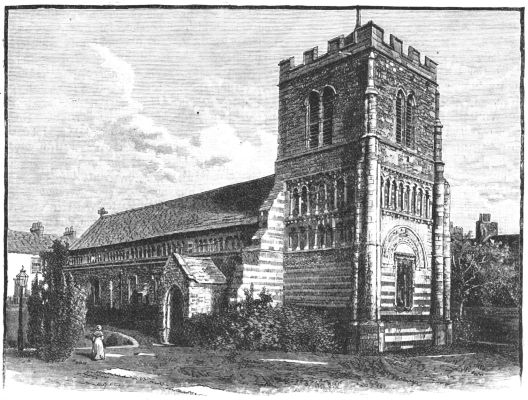

NORMAN ARCHITECTURE.

Introduction of Norman Architecture—Remains of Saxon Work—Canterbury Cathedral—St. Albans and other Edifices—Periods of Norman Architecture—Its Characteristics—Towers—Windows—Doorways—Porches—Arches—Piers and Pillars—Capitals—Mouldings and Ornaments 212

REIGN OF RICHARD I.: THE THIRD CRUSADE.

Richard's Show of Penitence—His Coronation—Massacre of the Jews—Results of the Second Crusade—Richard raises Money for the Third Crusade—The Regency—Departure for the Holy Land—The Sicilian Succession—The Quarrel concerning Joan's Dower—Richard's Prodigality—His Interview with the Monk, Joachim—Treachery of Philip, and Richard's Repudiation of Alice—Richard's Betrothal to Berengaria—Adventures on the Coast of Cyprus, and the Conquest of the Island—The Siege of Acre and its Fall—Dissension between Richard and Philip, and Return of the Latter to France—Massacre of Prisoners on Both Sides—The Battle of Azotus—Occupation of Jaffa—The Advance towards Jerusalem—Quarrels among the Crusaders, and Negotiations with Saladin—Chivalry of Saladin—Death of Conrad, and Charges brought against Richard—Last Advance upon Jerusalem—Battle of Jaffa—Truce with Saladin 217

REIGN OF RICHARD I. (concluded).

Shipwreck of Richard—His Arrival in Austria—His Capture by the Archduke Leopold—He is surrendered to the Emperor of Germany—Events in England—Renewed Persecution of the Jews—The Massacre at York—Quarrel between Longchamp and Pudsey—Stories about Longchamp—His Rupture with John, and Temporary Compromise—Imprisonment of Geoffrey of York—Longchamp takes Refuge in the Tower—His Deposition and Flight to France—Intrigues between John and Philip—Rumours of Richard's Imprisonment—The Story of Blondel—Richard before the Diet—Loyalty of Richard's Subjects, and Collection of the Ransom—Richard's Reception in England—His Expedition to France—Administration of Hubert Walter—William Fitz-Osbert—Recommencement of Hostilities with France—The Bishop of Beauvais—Defeat of Philip—Death of Richard before Chaluz—His Character 235

JOHN AND THE GREAT CHARTER.

Accession of John—His Position—Arthur of Brittany—Peace between John and Philip of France—John's Marriage with Isabella of La Marche—Rupture with France—The Struggle Begins—Capture of Arthur—The Stories of his Death—The Loss of Normandy—Peace with Philip—Quarrel with the Pope—The Kingdom Laid under an Interdict, and Excommunication of John—John's Desperate Measures—Expedition to Ireland—John is deposed—Arrival of Pandulph in England—Surrender of the Kingdom to the Pope—Successes of John—Langton Arrives in England—He Becomes Leader of the Baronial Party—The Battle of Bouvines—Insurrection in England—The Barons Confront John—His Intrigues—Meeting at Brackley—Occupation of London—The Meeting at Runnymede—Greatness of the Occasion—Provisions of the Charter—Duplicity of John—Siege of Rochester—John in the North—His Cause Supported by the Church—The Crown offered to Louis of France—He Enters London—Sieges of Dover and Windsor—Reported Conspiracy—John's Disaster at the Wash—His Death and Character 251

THE REIGN OF HENRY III.

Accession of the King—Renewal of the Great Charter—Messages of Conciliation—Battle of Lincoln—Destruction of the French Fleet—Departure of Louis—Reduction of Albemarle—Resumption of the Royal Castles—War with France—Characters of Richard of Cornwall and Henry III.—Fall of Hubert de Burgh—Peter des Roches—Henry is his own Minister—The House of Provence—The King's Marriage Articles—The Marriage and Entry into London—Influx of Foreigners—Papal Aggressions—Persecution of the Jews—Oppression of the Londoners—A Religious Ceremony 277

THE REIGN OF HENRY III. (concluded).

The King's Misfortunes Abroad and Exactions at Home—Ambition and Rapacity of the Church of Rome—The Council of Lyons—The Kingdom of Sicily—Henry Accepts the Crown for his Son—Consequent Extortions—Richard becomes King of the Romans—Disputes between the King and the Barons—Simon de Montfort—He becomes Leader of the National Party—The Mad Parliament and the Provisions of Oxford—Banishment of Aliens—Government of the Barons—Peace with France—Henry is Absolved from the Provisions of Oxford—The Barons Oppose Him—Outbreak of Hostilities—The Award of Amiens—The Battle of Lewes—The Mise of Lewes—Supremacy of Leicester—The Exiles Assemble at Damme—The Parliament of 1265—Escape of Prince Edward—Battle of Evesham and Death of De Montfort—Continuance of the Rebellion—The Dictum de Kenilworth—Parliament of Marlborough—Prince Edward goes on Crusade—Deaths of Henry D'Almaine, Richard of Cornwall, and the King—Character of Henry 290

ARCHITECTURE OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY.

Transition from Norman to Gothic Architecture—The Period of Change—The Early English Style—Examples and Characteristics of the Style—Towers—Windows—Doorways—Porches—Buttresses—Pillars—Arches—Mouldings and Ornaments—Fronts 314

THE REIGN OF EDWARD I.

Accession of Edward—His Adventures while on Crusade—Death of St. Louis—Arrival of Edward at Acre—Fall of Nazareth—Events at Acre—Departure from Palestine—Edward in Italy—The "Little Battle of Châlons"—Dealings with the Flemings—Edward lands at Dover—Persecution of the Jews—Edward's Designs on Wales—Character of the Welsh—Rupture with Llewelyn—Submission of the Welsh—Conduct of David—Second Welsh Rising—Death of Llewelyn—Execution of David—Annexation of Wales—Edward on the Continent—Sketch of Scottish History—Attack of the Norwegians—Deaths in the Royal Family—Death of Alexander—Candidature of Robert Bruce—Death of the Maid of Norway—Candidates for the Throne—Meeting at Norham—Edward's Supremacy Acknowledged—He Decides in Favour of Balliol 319

REIGN OF EDWARD I. (concluded).

Banishment of the Jews—Edward's Restorative Measures—Edward's Continental Policy—Quarrel with France—Undeclared War—Edward Outwitted by Philip—Re-conquest of Wales—The War with France—Position of Balliol—He is placed under Restraint—Edward Marches Northwards—Fall of Berwick—Battle of Dunbar—Submission of Balliol and Scotland—Settlement of Scotland—Sir William Wallace—He heads the National Rising—Robert Bruce joins him—Submission of the Insurgents—Battle of Stirling Bridge—Invasion of England—Edward Defeats Wallace at Falkirk—Regency in Scotland—Oppression of the Clergy—The Barons refuse to help Edward—The Expedition to Flanders—A Constitutional Struggle—Peace with France—The Pope claims Scotland—Defeat of the English—Edward's Vengeance—Capture and Death of Wallace—Bruce takes his place—Death of Comyn—Defeats of the Scots—Death of Edward—His Character and Legislation—Sketch of the growth of the English Parliament 335

REIGN OF EDWARD II.

Character of the new King—Piers Gaveston—The King's Marriage—Gaveston is Dismissed to Ireland—His Return—Appointment of the Lords Ordainers—Their Reforms—Gaveston Banished—His Reappearance—Rebellion of the Nobles and Death of Gaveston—Successes of Bruce in Scotland—The Battle of Bannockburn—The Establishment of Scottish Independence—Edward Bruce in Ireland—Power of Lancaster—The Despensers—They are Banished—Sudden Activity of the King—Battle of Boroughbridge—The King's Vengeance—Peace with Scotland—Conspiracies against Edward—Machinations of the Queen—She Lands in England—Edward is Deserted and taken Prisoner—Dethronement of Edward—Indignation against Isabella—Murder of Edward—The Lessons of the Reign—Abolition of the Templars 363

THE REIGN OF EDWARD III.

The Regency—War with Scotland—Edward is Baffled—Peace with Scotland, and Death of Bruce—Kent's Conspiracy—Overthrow of Mortimer—Edward assumes Authority—Relations with Scotland—Balliol Invades Scotland—Battle of Dupplin Moor—Edward supports Balliol—Battle of Halidon Hill—Scottish Heroines—Preparations for War with France—The Claims of Edward—Real Causes of the Quarrel—Alliances and Counter-Alliances—Edward Lands in Flanders—Is Deserted by his Allies and Returns to England—Battle of Sluys—Dispute with Stratford—The Breton Succession Question—Renewal of the War—Derby in Guienne—Edward Lands in Normandy—Battle of Creçy 387

EDWARD III. (concluded).

Siege of Calais—Battle of Neville's Cross—Capture of the Scottish King—Institution of the Garter—The Black Death—Disturbances in France excited by the King of Navarre—Battle of Poitiers—The King of France taken Prisoner and brought to England—Disorders in France—Affairs in Scotland—Fresh Invasion of France—The Peace of Bretigny—Return of King John to France—Disorders of that Kingdom—The Free Companies—Expedition of the Black Prince into Castile—Fresh Campaign in France—Decline of the English Power there—Death of the Black Prince—Death of Edward III.—Character of his Reign and State of the Kingdom 420

THE REIGN OF RICHARD II.

Accession of the King—Attitude of John of Gaunt—Patriotic Government—Insurrection of the Peasantry—John Ball—The Poll-tax—Wat Tyler—The Attack on London—The Meeting at Mile End—Death of Wat Tyler, and Dispersion of the Insurgents—Marriage of the King—Expedition of the Bishop of Norwich—Death of Wycliffe—Unpopularity of Lancaster—He Retires to Spain—Gloucester Attacks the Royal Favourites—Committee of Reform—The[viii] Lords Appellant—The Wonderful Parliament—Richard sets Himself Free—His Good Government—Expedition to Ireland—Marriage with Isabella of France—The King's Vengeance—Banishment of Hereford and Norfolk—Arbitrary Rule of the King—His Second Visit to Ireland—Return of Hereford—Deposition and Murder of Richard 449

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

Power of the Church—Ecclesiastical Legislation—Rapacity of the Papacy—Resistance of the Clergy—The Bull "Clericis Laicos"—Contests between the Civil and Ecclesiastical Power—The Scottish Church—Literature, Science and Art—State of Learning—The Nominalists and Realists—Medicine—The Universities—Men of Learning and Science—Roger Bacon and his Contemporaries—Historians—Growth of the English Language—Poetry—Architecture—The Early Decorated Style and its Characteristics—Domestic Buildings—Sculpture and Painting—Music—Commerce, Coinage, and Shipping—Manners, Customs, Dress, and Diversions 486

REIGN OF HENRY IV.

His Coronation—The Insecurity of his Position—He courts the Clergy and the People—Sends an Embassy to France—Conspiracy to Assassinate him—Death of King Richard—Rumours of his Escape to Scotland—Expedition into Scotland—Revolt of Owen Glendower—Battle of Homildon Hill—The Conspiracy of the Percies—The Battle of Shrewsbury, where they are Defeated—Northumberland Pardoned—Accumulating Dangers—Second Rebellion of the Percies with the Archbishop of York—The North Reduced—The War in Wales—Earl of Northumberland flies thither—The Plague—Battle of Bramham Moor—Reduction of the Welsh—Expedition into France—Death of Henry 515

THE REIGN OF HENRY V.

Character of the King—Oldcastle's Rebellion—Attempts to Reform the Church—Henry's Reasons for the French War—Distracted Condition of France—Henry's Claims on the French Throne—Conspiracy of Cambridge—Fall of Harfleur—The March to Calais—The Battle-field of Agincourt—Events of the Battle—Visit of Sigismund to England—French Attack on Harfleur—Anarchy in France—Alliance between the Queen and the Burgundians—Henry's Second Invasion—Final Rebellion and Death of Oldcastle—Reduction of Lower Normandy—Siege and Capture of Rouen—Negotiations for Peace—Henry Advances on Paris—Murder of Burgundy—His Son Joins Henry—Treaty of Troyes—Defeat of the English at Beaugé—Henry in Paris—His Death 545

HENRY VI.

Arrangements during the Minority—Condition of France—Death of Charles VI.—Bedford's Marriage—Battle of Crévant—Release of the Scottish King—Battle of Verneuil—Gloucester's Marriage and its Consequences—Rivalry of Gloucester and Beaufort—Siege of Orleans—Battle of the Herrings—Joan of Arc—The March to Orleans—Relief of the Town—March to Rheims—Coronation of Charles—The Repulse from Paris—Capture of the Maid—Her Trial and Death—Coronation of Henry—Bedford Marries again—Congress of Arras—Death of Bedford—The Tudors—Contests between Beaufort and Gloucester—Henry's Marriage—Deaths of Gloucester and Beaufort—Disasters in France—Fall and Death of Suffolk 576

IONA CATHEDRAL.

| page | |

| Landing of the Romans on the Coast of Kent | 1 |

| Stonehenge | 4 |

| Stonehenge (restored) | 4 |

| Druids inciting the Britons to oppose the Landing of the Romans | 5 |

| Julius Cæsar | 8 |

| Caractacus before Claudius | 9 |

| Britons with Coracle | 12 |

| Roman Soldiers passing over a Bridge of Boats | 13 |

| Roman Soldiers leaving Britain | 17 |

| Coins of the Roman Republic and the Empire | 20 |

| Newport Gate, Lincoln | 21 |

| Transverse Section of the Roman Wall | 22 |

| Longitudinal View of the Roman Wall | 22 |

| Cornice from Vendalana (Chesterholm) | 22 |

| Capital from Cilurnum (Walwick Chesters) | 23 |

| Doorway from Bird-Oswald | 23 |

| Roman Masonry at Colchester | 23 |

| Basement of Station on the Roman Wall | 23 |

| Roman Urns | 24 |

| Glastonbury Abbey | 25 |

| Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern | 28 |

| Edwin of Northumbria and the Christian Missionaries | 32 |

| Meeting of the Shire-Moot | 33 |

| Map of England showing the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms and Danish Districts | 37 |

| Danish Ships | 40 |

| Alfred in the Neat-Herd's Hut | 41 |

| The "Lady of the Mercians" Fighting the Welsh | 45 |

| Ethelwulf's Ring | 48 |

| Anlaff entering the Humber | 49 |

| Dunstan rebuking Edwy in the Presence of Elgiva | 52 |

| Edgar the Peaceable being rowed Down the Dee by eight Tributary Princes | 53 |

| Assassination of Edward the Martyr | 56 |

| Crucifixion of St. Peter and Martyrdom of other Saints | 57 |

| Martyrdom of Alphege | 61 |

| Meeting of Edmund Ironside and Canute on the Island of Olney | 64 |

| The Riot at Dover | 69 |

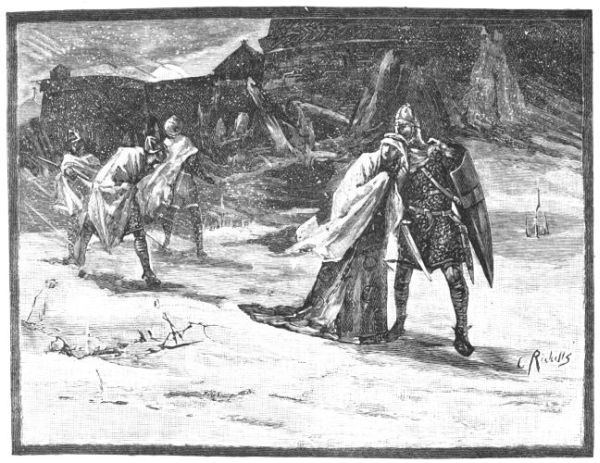

| The Death of Siward | 72 |

| Taking Sanctuary | 73 |

| Harold taken Prisoner by the Count of Ponthieu | 76 |

| Pevensey Castle | 77 |

| William I., surnamed the Conqueror | 80 |

| Death of Harold at the Battle of Hastings | 81 |

| Gateway of Battle Abbey | 84 |

| Building of the Tower of Babel | 85 |

| Tower of Sompting Church | 86 |

| Window (Saxon) of Deerhurst Church, Gloucester | 87 |

| Window (Saxon) of Jarrow Church, Durham | 87 |

| Doorway (Saxon) of Barnack Church, Northamptonshire | 87 |

| Anglo-Saxon Calendar | 88 |

| Anglo-Saxon Calendar | 89 |

| Anglo-Saxon Calendar | 90 |

| Saxon Calendar | 91 |

| Fragment of Copy of the Evangelists, in Latin | 91 |

| First Two Lines of Horace's Ode to Mæcenas | 92 |

| English Writing of the Sixth Century | 92 |

| English Dinner Party | 92 |

| Gleemen Juggling | 93 |

| Balancing | 93 |

| Musical Instruments | 93 |

| Dance with Lyre and Double Flute | 93 |

| Grand Organ, with Bellows and Double Keyboard | 94 |

| Harp of the Ninth Century | 94 |

| English Game of Bowls | 95 |

| Ladies Hunting | 95 |

| Norman Costumes of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries | 96 |

| Hawking Party in the Eleventh Century | 97 |

| Hawking | 98 |

| Harold | 98 |

| Umbrella for Hawks | 98 |

| The Lure | 99 |

| Sword Play | 99 |

| Ancient Quintain | 99 |

| Bob Apple | 100 |

| Saxon Costumes | 100 |

| Saxon Costumes | 100 |

| English Crowns | 100 |

| English Shoes | 101 |

| English Dinner Party | 101 |

| Cloak-pin, Buckle, and Pouch of the Twelfth Century | 101 |

| Early English Candlestick | 102 |

| English Bed | 102 |

| Chairs | 102 |

| Saxon Comb and Comb-Case | 102 |

| Norman Vessel of the Twelfth Century | 103 |

| Norman Soldiers | 103 |

| Norman Bowmen of the Eleventh Century | 103 |

| Woman Spinning | 104 |

| Sacramental Wafer Box of the Twelfth Century | 104 |

| Incidents copied from the Bayeux Tapestry | 105 |

| Incidents copied from the Bayeux Tapestry | 106 |

| Great Seal of William I. | 109 |

| Plan of a Norman Castle | 112 |

| Norman and Saxon Arms | 114 |

| Waltheof's Confession | 116 |

| Robert asking His Father's Pardon | 120 |

| Fitz-Arthur forbidding the Burial of William | 121 |

| Departure of Bishop Odo from Rochester | 124 |

| William II., surnamed Rufus | 125 |

| Great Seal of William II. | 128 |

| Surrender of Bamborough Castle | 129 |

| St. Helena discovering the True Cross | 132 |

| Initiation into the Order of Knighthood | 133 |

| Pope Urban II. preaching the First Crusade in the Market-Place of Clermont | 136 |

| The Mosque of Santa Sophia, Constantinople | 137 |

| Bird's-Eye View of Christian Constantinople | 140 |

| Circus and Hippodrome of Christian Constantinople | 141 |

| Statue of Godfrey de Bouillon, Brussels | 144 |

| Robert of Normandy rallying the Crusaders | 145 |

| Throne of the Emperor of Constantinople | 147 |

| Costume of Empress of Constantinople | 147 |

| Procession of the Crusaders round the Walls of Jerusalem | 148 |

| Pilgrim, Palmer, Hospitaller, Templar Knight, and Conventual Templar | 149 |

| Great Seal of Henry I. | 153 |

| Robert of Normandy paying Court to the Lady Sibylla | 156 |

| Marriage of Henry I. and Matilda | 157 |

| Duke Robert's Son before King Henry | 161 |

| Shipwreck of Prince William | 164 |

| Henry I. | 165 |

| Stephen | 168 |

| Great Seal of Stephen | 169 |

| Silver Penny of Stephen | 172 |

| Interview between the Empress Matilda and Queen Maud | 173 |

| Flight of Matilda from Oxford Castle | 176 |

| Great Seal of Henry II. | 177 |

| English Costumes in the Time of Henry II. | 181 |

| Silver Penny of Henry II. | 183 |

| Heroism of St. Clair at the Siege of Bridgenorth Castle | 184 |

| Becket before his Enemies in the Council Hall at Northampton | 185 |

| Henry II. | 189 |

| Repulse of the English at Corwen | 192 |

| Interview between Becket and King Henry | 193 |

| The Murder of Becket in Canterbury Cathedral | 197 |

| The Siege of Waterford | 200 |

| Henry on His Way to Becket's Tomb | 205 |

| Henry receiving the News of John's Treachery [x] | 209 |

| Crown of the Twelfth Century | 211 |

| St. Clement's, Sandwich, showing the Norman Tower | 212 |

| The Chapel in the White Tower, Tower of London | 213 |

| Portion of Doorway, Durham Cathedral | 215 |

| Castle Rising, Norfolk | 216 |

| Richard I. | 217 |

| Coronation of Richard in Westminster Abbey: the Procession along the Aisle | 220 |

| View in Genoa: the Dogana | 221 |

| Isaac of Cyprus begging for the Release of His Daughter | 225 |

| Richard at the Battle of Azotus | 228 |

| Fountain near Jaffa | 229 |

| Jaffa, from the Sands | 232 |

| Richard landing at Jaffa | 233 |

| Richard assailed by the Austrian Soldiers | 237 |

| Arrest of Archbishop Geoffrey in a Monastery at Dover | 240 |

| South-West View of Old St. Paul's, showing the Chapter-House, &c. | 241 |

| Great Seal of Richard I. | 244 |

| Reception of Richard on His Return from the Continent | 245 |

| Map of the English Possessions in France | 248 |

| Bertrand in Presence of Richard | 249 |

| John | 253 |

| Great Seal of John | 256 |

| Murder of Prince Arthur | 257 |

| Interior of Rouen Cathedral | 261 |

| John doing Homage to the Pope's Legate | 264 |

| St. Peter's Church, Northampton | 265 |

| John refusing to sign the Articles of the Barons | 269 |

| Runnymede, from Cooper's Hill | 272 |

| Specimen of the Writing of the Great Charter | 273 |

| The Disaster to John's Army at the Wash | 276 |

| Winchester Cathedral | 277 |

| Defeat of the French Fleet in the English Channel | 281 |

| Great Seal of Henry III. | 284 |

| Banquet at the Marriage of Henry and Eleanor of Provence | 285 |

| Henry III. | 288 |

| Silver Penny of Henry III. | 292 |

| Gold Penny of Henry III. | 292 |

| View in Sicily: the Amphitheatre, Syracuse | 293 |

| Henry's Quarrel with De Montfort | 296 |

| The Barons submitting their Demands to Henry | 297 |

| Oxford Castle | 301 |

| Flight of Queen Eleanor: the Scene at London Bridge | 304 |

| Lewes (Sussex) | 305 |

| Battle of Evesham: King Henry in Danger | 309 |

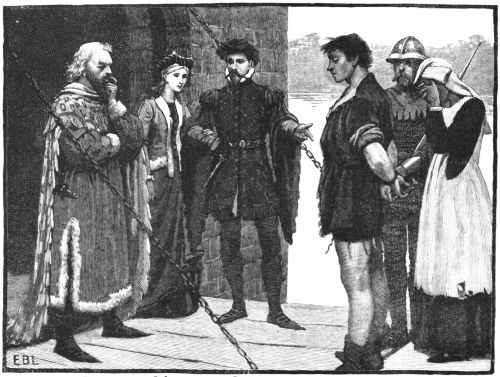

| Prince Edward introducing Adam Gourdon to the Queen | 312 |

| Interior of the Temple Church, London | 313 |

| The Choir of Lincoln Cathedral | 317 |

| Capital from Salisbury Cathedral | 318 |

| Capital from Lincoln Cathedral | 318 |

| Tooth Ornament from Lincoln Cathedral | 318 |

| View in Tunis | 321 |

| Great Seal of Edward I. | 324 |

| Edward I. | 325 |

| Llewelyn's Last Fight | 328 |

| Edward presenting his Infant Son to the Welsh | 329 |

| Norham Castle | 333 |

| Earl Warrenne showing his Title to his Estates | 336 |

| The Sailors' Quarrel near Bayonne | 337 |

| The Coronation Chair and "Stone of Destiny," Westminster Abbey | 341 |

| The Abbot of Arbroath before King Edward | 344 |

| The Abbey Craig and Wallace Monument, near Stirling, with the Ochil Hills | 345 |

| Revolt of the Barons against the King | 349 |

| Penny of Edward I. Groat of Edward I. Halfpenny of Edward I. | 352 |

| Dunfermline Abbey and Church | 353 |

| Wallace on his Way to Westminster Hall | 356 |

| Capture of Bruce's Wife and Daughter at Tain | 357 |

| South Transept, Westminster Abbey | 361 |

| Great Seal of Edward II. | 364 |

| Edward II. | 365 |

| Piers Gaveston and the Barons | 368 |

| Piers Gaveston before the Earl of Warwick | 369 |

| The Bore-Stone, Bannockburn, in which Bruce planted his Standard | 372 |

| Bannockburn: Bruce reviewing his Troops before the Battle | 373 |

| The Auld Brig, Stirling | 376 |

| Halfpenny of Edward II. Penny of Edward II. | 377 |

| Escape of Roger Mortimer from the Tower | 381 |

| Berkeley Castle | 385 |

| Great Seal of Edward III. | 388 |

| Robert Bruce's last Orders to Douglas | 392 |

| Melrose Abbey | 393 |

| Edward III. | 396 |

| Interrupting Balliol's Christmas Dinner | 397 |

| Black Agnes at the Siege of Dunbar Castle | 401 |

| Porch of the Golden Virgin: Amiens Cathedral | 404 |

| The Countess De Montfort inciting the People of Rennes to resist the French King | 409 |

| The Church of St. Etienne: Caen | 413 |

| Edward the Black Prince | 416 |

| The Black Prince at the Battle of Creçy | 417 |

| View in Calais: Rue de la Citadelle showing the Belfry | 421 |

| Queen Philippa interceding for the Burgesses of Calais | 425 |

| Edward receiving King John of France | 429 |

| Coins of the Reign of Edward III. | 432 |

| The Church of Notre Dame, Calais | 433 |

| The Cathedral, Coutances | 436 |

| Marcel and the Dauphin of France | 437 |

| The Black Prince and the French King's Herald | 441 |

| John Wycliffe appearing in St. Paul's Cathedral to answer the Charge of Heresy | 445 |

| Alice Perrers at the Death-bed of Edward III. | 448 |

| John Wycliffe | 453 |

| Great Seal of Richard II. | 456 |

| One of Wycliffe's "Poor Priests" preaching to the People | 457 |

| Coins of the Reign of Richard II. | 461 |

| John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster | 465 |

| Betrothal of the Princess Isabella to Richard | 469 |

| Arrest of the Duke of Gloucester | 473 |

| The Tower of London: the White Tower | 480 |

| Conway Castle | 481 |

| Arrest of King Richard | 485 |

| Costume of Bishop of the Fourteenth Century | 488 |

| Facsimile of part of the First Chapter of St. John's Gospel in Wycliffe's Bible | 489 |

| The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Colleges of Oxford University | 493 |

| Geoffrey Chaucer | 497 |

| Queen Eleanor's Cross, Northampton | 499 |

| Window from Meopham | 500 |

| Window from St. Mary's, Beverley | 500 |

| Decorated Capital, from Selby | 501 |

| Ball Flower, with Roll Moulding and Hollow | 502 |

| Four-leaved Flower, with Filleted, Round, and Hollow moulding | 502 |

| Minstrels at a Banquet in the Fourteenth Century | 504 |

| Fair at Westminster in the Fourteenth Century | 505 |

| English Ships of the Fourteenth Century | 509 |

| Costumes of the Fourteenth Century | 512 |

| English Merrymaking in the Fourteenth Century: riding at the Quintain | 513 |

| Henry IV. | 517 |

| Great Seal of Henry IV. | 520 |

| Arrest of the Conspirators at Cirencester | 521 |

| Charge of the Scots at Homildon Hill | 525 |

| Warkworth Castle | 529 |

| Shilling of Henry IV. | 532 |

| The French Fleet arriving at Milford Haven | 533 |

| The Dukes of Orleans and Burgundy, at the Church of the Augustines | 537 |

| Prince Henry before Judge Gascoigne | 541 |

| King at Table (Fourteenth Century) | 544 |

| Great Seal of Henry V. | 545 |

| Henry V. | 549 |

| The English before Harfleur | 553 |

| The Thanksgiving Service on the Field of Agincourt | 557 |

| Reception of the Emperor Sigismund | 561 |

| Rouen from St. Catherine's Hill | 564 |

| Cardinal Orsini's Visit to Henry | 565 |

| Henry's Wooing of the Princess Catherine | 569 |

| Monmouth Castle (Birthplace of Henry V.) | 573 |

| Henry VI. | 577 |

| Rothesay Castle | 581 |

| Great Seal of Henry VI. | 584 |

| Escape of Jacqueline | 585 |

| Joan of Arc before Charles | 589 |

| The Cathedral, Rheims | 593 |

| Trial of Joan of Arc | 596 |

| Place de la Pucelle, Rouen | 597 |

| Denbigh | 601 |

| Angel of Henry VI. | 604 |

| Arrest of the Duke of Suffolk | 605 |

| Illuminated Title Page. | ||

| King John Granting Magna Charta. (By Ernest Normand) | Frontispiece | |

| Phœnicians Bartering with the Ancient Britons. (By Lord Leighton) | To face p. | 2 |

| "The Romans Cause a Wall to be Built for the Protection of the South. | ||

| (By W. Bell Scott, R.H.A.) | " | 15 |

| The Danes Sailing up the English Channel. (By Herbert A. Bone) | " | 41 |

| William the Conqueror Granting a Charter to the Citizens of London. | ||

| (By J. Seymour Lucas, R.A.) | " | 118 |

| Peter the Hermit Preaching the First Crusade. (By James Archer, R.S.A.) | " | 135 |

| Crusaders on the March. (By Sir John Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 150 |

| The Battle of the Standard. (By Sir John Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 177 |

| Map of the Plantagenet Dominions in France, a.d. 1185 | " | 206 |

| St. Bernard Preaching the Second Crusade. (By James Archer, R.S.A.) | " | 219 |

| Prince Arthur and Hubert. (By W.F. Yeames, R.A.) | " | 257 |

| The Trial of Sir William Wallace. (By Daniel Maclise, R.A.) | " | 354 |

| Queen Philippa Interceding for the Burghers of Calais. (By J.D. Penrose) | " | 426 |

| Interview of Richard II. with his Uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, at the | ||

| Castle of Pleshy, in Essex. (From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum) | " | 449 |

| Tournament at St. Inglevere, near Calais. (From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum) | " | 465 |

| The Charity of Whittington. (By Henrietta Rue—Mrs. Normand) | " | 478 |

| The Coronation of Henry IV. in Westminster Abbey. (From the Froissart | ||

| MS. in the British Museum) | " | 515 |

| The Morning of Agincourt. (By Sir John Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 554 |

From the Design for the Cartoon in the Royal Exchange.

KING JOHN GRANTING MAGNA CHARTA.

By ERNEST NORMAND.

LANDING OF THE ROMANS ON THE COAST OF KENT. (See p. 6.)

THE ROMAN RULE IN BRITAIN.

Earliest Notices of the British Isles—The Celts—Their Settlement in Britain—Their Character and Customs—Druidism—Its Organisation and Authority—Its Tenets—Stonehenge and other Remains—Cæsar's Preparations—The First Invasion—Peril of the Romans and their Retirement—The Second Invasion—Cæsar's Battles with Cassivelaunus—Claudius in Britain—The Resistance of Caractacus—His Defeat and Capture—His Speech before Claudius—The Conquest of Anglesea—Boadicea's Rebellion—The Capture of Camulodunum and London—Her Defeat and Death—Agricola in Britain—His Campaigns and Administration—His Campaign against the Caledonians—His Recall—The Walls of Hadrian and Severus—Rivals to the Emperor—Constantine's Accession—Christianity in Britain—Invasions of the Picts and Scots—Dismemberment of the Roman Empire and Departure of the Romans—Divisions and Administration of Britain under the Romans.

Separated from the continent of Europe by the sea, the British isles were not known to the nations of antiquity until a somewhat late date. Herodotus was ignorant of their existence; but Strabo, a contemporary of Cæsar, tells us that the Carthaginians had for a long period carried on a considerable commerce with the Cassiterides, or tin-islands, which are usually identified with the Scilly islands, and doubtless included also part of the Cornish coast. Again, Pytheas, a merchant of Marseilles, who lived about 332 B.C., visited this country in the course of his life, and fragments of his diary are still extant. He seems to have coasted round a considerable portion of what is now England, and his observations on the inhabitants are singularly acute. About two centuries later, Posidonius, another Greek traveller, visited Belerion, as he called it—that is, Cornwall; but, until the invasion of Cæsar, the extent of these islands, their main geographical features, and the tribes that inhabited them, were practically a matter of more or less complete ignorance to the civilised world that dwelt round the shores of the Mediterranean.

From the narrative of Cæsar, we gather that the bulk of the population of England, Scotland, and Wales at the time of his invasion was of Celtic origin; that is, it belonged to one of the branches of the great family of nations which is commonly known as the Indo-European, or Aryan, and which includes the Celts, the Greeks and Italians, the Germans, the Lithuanians and Slavs in Europe; and in Asia the Armenians, Persians, and the chief peoples of Hindustan. Of the Aryan nations, the Celts were probably the first to arrive in Europe from the East, though the date of their migration is purely conjectural. They pushed across the great central plateau, until the vanguard reached the ocean; and at first probably occupied a very large portion of Europe, but, being driven out by the stronger Germans, were gradually confined to the Iberian peninsula, France, Switzerland, and the British isles.

As it is impossible to fix the date of the Celtic migration into Europe, so it is equally impossible to conjecture the when and why of the Celtic invasion of Britain. It is pretty certain that they found other races here on their arrival; and that they did not succeed by any means in thoroughly exterminating them. It has been surmised, indeed, that the Silures, who played a prominent part in the resistance to the Romans, and who inhabited the south of Wales and Monmouthshire, belonged to some more primitive race than the Celts. After the Celts, in the same way came the Belgæ, who were of German origin, and who settled on the southern coast. But the mass of the population was, as we have said, purely Celtic, and was composed of two large divisions—the Gaels, who dwelt on the northern and western coasts of what are now called England and Scotland, and over the great part of Ireland; and the Britons, who occupied the country south of the Friths of Forth and Clyde, with the exception of what is now Hampshire and Sussex, where dwelt the Belgæ.

It was with the Britons, therefore, that the Romans were chiefly concerned, and we would fain have some information of their manners and customs other than that derived from the enemy, impartial though Cæsar and Tacitus were. But there was no British historian to chronicle the mighty deeds of the Celtic warriors, or to describe the home-life of the people. The picture we are able to construct, therefore, is derived almost entirely from the Romans; nevertheless, it is a fairly complete one. They describe a tall and finely built race, recklessly brave, strikingly patriotic, and faithful to the family tie; courteous also in manner, and eloquent of speech, and very[3] fond of novelty, especially when it took the form of the arrival of a stranger in the village. At the same time the Britons were an unpractical race, never constant to any one object, quarrelsome amongst themselves, and utterly unable to combine against a common enemy.

PHŒNICIANS BARTERING WITH THE ANCIENT BRITONS.

From the Wall Painting by Lord Leighton, in the Royal Exchange.

Such was the moral character of the Britons. They dwelt in villages, in which the cottages were wattled and thatched with straw, and in time of danger repaired to a fortified and entrenched stronghold, or dun. The name of London records the site of one of these ancient places of refuge. They had large quantities of cattle, and grew corn, which they stored, in some districts at any rate, underground. Their breed of hunting dogs was also celebrated. Pytheas informs us that they made a drink of mixed wheat and honey, which is still drunk in part of Wales under the name of mead; while other writers, probably deriving their information from him, tell us that they drank another liquor made of barley, which is also not unknown in these days. They fought under their kings and chiefs, and were well armed with sword, spear, axe, and shield. The chiefs also fought from chariots, which they managed with great skill, and the onslaught of the British host was accompanied by loud cries and the blowing of horns, with which each man was provided.

Religion was in the hands of the Druids, who combined the character of prophet and priest. It was dark and mysterious as the gloomy forests in which it first drew birth, and in whose deepest recesses they celebrated their cruel rites. Its ministers built no covered temples, deeming it an insult to their gods to attempt to enclose their emblems in an edifice surrounded by walls, and erected by mortal hands; the forest was their temple, and a rough unhewn stone their altar. They worshipped a god of the sky and thunder, whom they identified with Jupiter; a sun-god, whom, when they were Romanised, they called Apollo; a god of war, afterwards called Mars; and a goddess who presided over births, like the Latin Lucina; and Andate, the goddess of victory. Besides these, who may be regarded as their superior deities, they had a great number of inferior ones. Each wood, fountain, lake, and mountain had its tutelary genius, whom they were accustomed to invoke with sacrifice and prayer.

The Druids were ruled by a chief whom they elected; they were the interpreters of the laws, which they never permitted to be committed to writing, the instructors of youth, and the judges of the people—a tremendous power to be lodged in the hands of any peculiar class. There were also Bards, whose duty it was to preserve in verse the memory of any remarkable event; to celebrate the triumph of their heroes; and, by their exhortation and songs, excite the chiefs and people to deeds of courage and daring on the day of battle.

It is impossible not to be struck by the profound cunning which presided over the organisation of this terrible priesthood, and concentrated all authority in its hands. Its ministers placed themselves between man and the altar, permitting his approach only in mystery and gloom. They wrought upon his imagination by the sacrifice of human life, and the most terrible denunciations of the anger of their gods on all who opposed them. As the instructors of youth, they moulded the pliant mind, and fashioned it to their purpose; as the judges of the people, there was no appeal against their decisions, for none but the Druids could pronounce authoritatively what was the law, there being no written code to refer to; they alone possessed the right to recompense or punish: thus the present and future welfare of their followers alike depended upon them.

The severest penalty inflicted by the Druids was the interdiction of the sacrifice to those who had offended them. Woe to the unhappy wretch on whom the awful sentence fell! He ceased to be considered a human being. Like the beast of the forest, his life was at the mercy of any one who chose to take it. He lost all civil rights, and could neither inherit land nor sue for the recovery of debts; every one was at liberty to spoil his property; even his nearest kindred fled from him in horror. They were also accustomed to sacrifice human victims on their altars, or burnt them as offerings to the gods, in wicker baskets.

It is now time to give some account of the dogmas of this extinct religion, once the general faith of Britain. Like the monks of the Middle Ages, the Druids of the higher orders lived in community in the remote depths of the vast gloomy forests, where they celebrated their rites. In these retreats they initiated the youthful aspirants for the priesthood, who frequently passed a novitiate of twenty years before being admitted. Disciples of all ranks flocked to them, despite the severity of the probation, tempted, no doubt, by the honours and great privileges attached to the order, amongst which exemption from taxation and servitude was not the least. The mistletoe is said by Pliny to have been a peculiarly sacred plant in their rites.

The Druids taught the immortality of the soul,[4] and its transmigration from one body to another, till, by some extraordinary act of virtue or courage, it merited to be received into the assembly of the gods. Cæsar, in his "Commentaries," also informs us that they instructed their pupils in the movements of the heavenly bodies, and the grandeur of the universe. Their knowledge of mathematics must have been considerable, since we find it applied to the measurement of the earth and stars. In mechanics they were equally advanced, judging from the monuments which remain to us. Of these, the most remarkable in England are Stonehenge, consisting of 139 enormous stones, ranged in a circle; and that of Avebury, in Wiltshire, which covers a space of twenty-eight acres of land. But the largest of all the Druid temples is situated at Carnac, in the department of Morbihan, in France. It is formed of 400 stones, varying from five to twenty-seven feet in height, and ranged in eleven concentric lines. It should be mentioned, however, that some authorities consider these erections to belong to a period anterior to the arrival of the Celts in Europe, though they were probably utilised by them.

STONEHENGE FROM THE NORTH-WEST. (From a Photograph by Frith & Co, Reigate.)

STONEHENGE (RESTORED).

(From the Model in the Blackmore Museum, Salisbury, after the Restoration by Dr. Stukeley.)

Such was the country and such the condition of its inhabitants when in 55 B.C. Cæsar undertook its invasion, to which he was led not so much by the thirst of dominion as by the necessity he found himself under of doing something to acquire a great name at Rome. He had already partially subdued the Gauls, and determined on striking a blow at Britain. Having decided on the expedition,[5] the victorious general commenced his preparations with his accustomed energy. His first care was to obtain hostages from the Gauls: he questioned the merchants and others who had visited Britain as to its resources and extent, the natives which inhabited it, their manners, customs, and religion, and sent Commius, whom he had created King of the Atrabates in Gaul, to demand the submission of the islanders.

DRUIDS INCITING THE BRITONS TO OPPOSE THE LANDING OF THE ROMANS. (See p. 6)

On the first news of the intended descent, the[6] Britons, excited by the Druids and Bards, assembled in arms, in order to defend their coasts, but at the same time did not neglect other means of warding off the danger which threatened their independence, and despatched ambassadors to Cæsar with offers of alliance. They were received courteously, although the wily Roman knew that, incited by their priests, they had arrested his messenger, and kept him in chains. Meanwhile Cæsar prepared his fleet, and assembled his soldiers for the expedition. He embarked the infantry of two of his legions in eighty vessels, which he assembled at Itius Portus, supposed by some writers to be Calais, by others the village of Wissant, between that place and Boulogne. He divided the vessels amongst his principal officers, and set sail with a favourable wind during the night. Eighteen galleys at a distant part of the coast had received his cavalry, and sailed about the same time. At ten the following morning the expedition appeared off the coast, where the inhabitants were seen in arms, ready to receive it. The spot, it would seem, was unfavourable for landing, and Cæsar hesitated, and dropped anchor till three in the afternoon, hoping for the arrival of his other galleys. Disappointed in this expectation, he sailed along the coast, and finally decided on disembarking at Deal, where the shore was comparatively level, and presented less difficulty for such an enterprise. But here, too, the Britons were prepared, a considerable force being collected to oppose him. The galleys drew too much water to permit the invaders to land at once upon the beach, and the soldiers hesitated. There was a momentary confusion amongst them. "Follow me, comrades!" exclaimed the standard-bearer, "if you would not see the eagle in the hands of the enemy. For myself, if I perish, I shall have done my duty to Rome and to my general." At these words he plunged into the waves, and was followed by the men, who leaped tumultuously after him, ashamed, most likely, of their previous cowardice and hesitation. On reaching the shore, they fell with the utmost fury on the enemy, whose undisciplined ranks could ill sustain the shock of the Roman legion; still, they fought desperately, incited by their bards and priests, who sang the songs of victory, and exhorted them to renew the combat each time they seemed to waver. At last they were compelled to give way, and retreat to the shelter of the woods, with their chariots and broken ranks. Cæsar himself informs us that he was prevented from pursuing the victory by the absence of his cavalry, a circumstance which he bitterly laments, since its presence alone was wanting to crown his fortune.

Although he did not venture to follow the fugitives, they sent ambassadors, accompanied by Commius, whom the Britons released from prison and chains, to sue for peace. The victor complained, and with some show of justice, of the reception he had met with, after they had sent envoys to him in Gaul with offers of submission, and also of the arrest of his ambassador; and lamented the blood that had been shed. To this harangue the Britons artfully replied that they had imprisoned Commius in order to preserve him from the fury of the people, and with this excuse Cæsar either was, or affected to be, content. He granted the peace they came to solicit, and demanded hostages, which were promised, for the future.

A storm dispersed the eighteen galleys which were to transport the cavalry of Cæsar, and drove them back upon the coast of Gaul. This was not the only misfortune the Romans endured. That same night the moon was at its full; it was the season of the equinox, and the tide rose to an unusual height, filling the vessels which Cæsar had drawn out of the reach of danger, as he imagined, on the sands. The larger ships, which had served him as a means of transport, were driven from their anchors, and many of them wrecked.

Although perfectly aware of the perils which menaced their invaders, the Britons appear to have proceeded with the utmost caution. Whilst a league was secretly being formed to crush the Romans, their chiefs appeared daily in their camp, professing unbroken friendship. Suddenly they fell upon the seventh legion, which had been sent to a distance to forage. The plan was well contrived to defeat the enemy in detail. Many of their leaders remained in camp, in order to lull suspicion, whilst their confederates surprised the Romans, who, having laid aside their arms, were soon surrounded, and must have been cut off but for the timely arrival of Cæsar, who, warned by his outposts that a cloud of dust thicker than usual had been seen at a distance, guessed immediately what had occurred. With a portion of his army he fell upon the assailants, and, after a desperate struggle, disengaged the threatened legion, and returned with it to the camp in safety. The lesson was a sharp one, and the rains soon afterwards setting in, the invader did not attempt to renew the battle.

The islanders, meanwhile, had not been idle: messengers had been despatched in every direction,[7] calling on the various nations to take arms; the Druids preached war to the death; and a sufficient force was soon assembled to attack the Romans in their camp. Discipline, however, again prevailed against the courage of the barbarians, as Tacitus contemptuously calls them; although he admits at the same time their bravery, and adds that it was a fortunate thing for Cæsar that the country was so divided into petty states that the jealousies of their respective rulers prevented the unity of action which alone could ensure success. Had the Britons been united, they might have bid defiance to the legions of Rome. Once more the islanders demanded peace, which Cæsar granted them; in fact, he was scarcely in a position to do otherwise, for he already meditated a retreat. He embarked the army suddenly in the night, and retired to Gaul, taking the hostages he had received with him. Although the senate of Rome ordered a thanksgiving of twenty days for the triumph of the Roman arms, the first expedition against the island cannot be regarded as other than a failure.

For the second invasion, which took place in the following year, preparations were made commensurate with the importance of the task proposed. Cæsar having assembled 800 vessels, on board of which were five legions, and 2,000 horsemen of the noblest families in Gaul, set sail, and landed without opposition at Ryde. This time there was no enemy to oppose him; for the Britons, terrified at the appearance of this immense armament, had retreated to their natural fastnesses, the forests. Leaving ten cohorts and 300 horsemen to guard the camp and fleet, under the orders of Quintus Atrius, Cæsar set forward in search of the enemy, whom he discovered, after a march of twelve miles, on the banks of a river, where they had drawn up their chariots and horsemen. Profiting by their elevated position, they accepted, or rather engaged, the combat, and when repulsed withdrew into an admirably fortified camp, which was not taken without much difficulty. The Britons, as usual after a defeat, retreated once more to their woods, where it was impossible for the legions of Rome to follow, or the cavalry to act against them.

On the following morning, just as the victorious leader was about to re-commence his march, news arrived from the camp that a violent tempest had seriously damaged the fleet. Many of his vessels were wrecked, and others rendered unfit for service. Like a prudent general, Cæsar at once returned to the camp, to assure himself of the extent of the injury done to his fleet, and found it more considerable than he imagined. Forty vessels were lost; the rest could be repaired, though not without great labour and time. Every artificer in his army was set to work; others were sent for from the continent; and instructions written to Labienus in Gaul to construct new galleys to replace those which were lost. The next step was worthy the genius and reputation of Cæsar. After having repaired his ships, he caused his legions to draw them out of reach of the tide, high up on the shore, and enclosed the whole of them in a fortified camp—an immense work, when we consider that it was executed in an enemy's country, and the scanty means at his command for such an undertaking.

Meanwhile the Britons had united under Cassivelaunus, head-king of the tribes north of the Thames, and Cæsar advanced to meet him. The king proved a doughty opponent, seldom venturing upon a pitched battle, but harassing the Romans by sudden attacks, in which the chariots proved particularly formidable. At length Cæsar managed, with difficulty, to cross the Thames somewhere above London, and ravaged the king's territory. Fortunately the powerful tribe of the Trinobantes, who inhabited part of Middlesex and Essex, came over to him at this juncture, having old scores to pay off against Cassivelaunus, and they were followed by other tribes. Cæsar was therefore able to storm Verulam, the stronghold of the British king, and then, finding that his camp on the coast was being besieged by the four kings of Kent, that his troops were being wearied out by the constant alarms, and having, in addition, received unpleasant news from Gaul, he accepted the offers of peace made by Cassivelaunus, and departed. So ended Cæsar's invasions of Britain.

For nearly a century, that is, until A.D. 43, Britain remained undisturbed by the Romans; but at length the Emperor Claudius determined that the island should be thoroughly conquered. Accordingly his general, Aulus Plautius, landed with an army, and, after gaining considerable successes, wrote to Claudius inviting him to pass over to the island and conclude the war himself. The emperor accepted the invitation, and took the command of his legions in Britain. He crossed the Thames, and seized upon the fortress of Camulodunum (Colchester or Malden, authorities are divided as to which), receiving in his progress the submission of a number of petty kings and chiefs. This had been the stronghold of Cunobelinus, the Cymbeline of Shakespeare. Having reduced a[8] part of the country to the condition of a Roman province, Claudius returned to enjoy the honours of a triumph in Rome. It was celebrated with a degree of unusual magnificence, splendid games, and rejoicings.

JULIUS CÆSAR.

(From the Bust in the British Museum.)

After passing four years on the island, Plautius was recalled to Rome, where the jealousy of the emperor limited the honours decreed to the victorious general to a simple ovation. He was succeeded by Ostorius Scapula, who found, on his arrival, the affairs of his countrymen in the greatest disorder. The Britons, trusting that a general newly arrived in the island would not enter on a campaign in the beginning of winter, had divided their forces, to plunder and lay waste the territories of such persons as were in alliance with Rome. Ostorius, however, contrary to their expectations, pursued the war with vigour, gave the dispersed bands no time to unite or rally, and commanded the people whom he suspected of disaffection to give up their arms. As a further precaution, he erected forts on the banks of the Avon and the Severn.

CARACTACUS BEFORE CLAUDIUS. (See p. 10.)

The moment appeared favourable to the victorious general to subdue the Silures, a fierce and warlike nation, who, under their king, Caractacus, still held out against the Roman arms (A.D. 50). Hitherto clemency and force had alike proved unavailing to reduce them to submission, and Ostorius prepared his expedition with a prudence and foresight worthy of the struggle on which the establishment of the supremacy of Rome in the island, in a great measure, depended. He first settled a strong colony of his veteran soldiers at Camulodunum, on the conquered lands, to keep in check the neighbouring tribes, and spread by their example a knowledge of the useful arts. He then set forth at the head of his bravest legions in search of Caractacus, who had retreated from his own states, and transported the war into the[10] country of the Ordovices, in the middle of Wales. The warlike Briton had assembled under his command all who had vowed an eternal resistance to the invaders, and fortified his position by entrenchments of earth, in imitation of the Roman military works. In Shropshire, where the great struggle is supposed to have taken place, there is a hill which the inhabitants still call Caer Caradoc. It corresponds exactly with the description which Tacitus has given of the fortifications erected by Caractacus, and answers to the Latin words Castra Caractaci. This warrior, whose devotion to the liberties of his country merited a better fate, did all that a patriot and a soldier could do to excite the spirit of his countrymen. He reminded the chiefs under his command that the day of battle would be the day of deliverance from a degrading bondage, and at the same time appealed to their patriotism, by reminding them that their ancestors had defeated the attempts of Cæsar. The address was received with acclamation, and the excited Britons bound themselves by oaths not to shrink from the darts of their enemies.

The cries of rage with which the invaders were received, the resolute bearing of the Silures, astonished the Roman general, who examined with disquietude the river which defended the rude entrenchment on one side, the ramparts of earth and stone, not unskilfully thrown up, and the rugged rock, which towered above them, crowned with numberless defenders. His soldiers demanded to be led on, urging that nothing was impossible to true courage; the tribunes held the same language, and Ostorius led on his army to the attack. Under a shower of arrows it crossed the river, and arrived at the foot of the rude entrenchment, but not without suffering severely. Then was seen the advantage of discipline over untrained courage. The Roman soldiers serried their ranks, and raising their bucklers over their heads, formed with them an impenetrable roof, which securely sheltered them whilst they demolished the earthworks. That once accomplished, the victory was assured. The half-naked Britons, with their clubs and arrows, were no match against the well-armed legions of Rome; but from the summit of the rocks still poured death upon their enemies, till the light troops succeeded in slaying or dispersing them. The victory of the Romans was complete. The wife and daughter of Caractacus were taken prisoners, and the illustrious chief of the Silures soon afterwards shared a similar destiny. His mother-in-law, Cartismandua, Queen of the Brigantes, to whom he had fled for shelter, delivered him in chains to his enemies. Ostorius sent him and his family to Rome, as the noblest trophies of his conquest.

The fame of Caractacus had penetrated even to Italy. The Roman citizens were anxious to behold the barbarian who had so long braved their power. Although defeated and a captive, the natural greatness of his soul did not abandon him. Tacitus relates that his first remark on beholding the imperial city was surprise that those who possessed such magnificent palaces at home should envy him a poor hovel in Britain. He was conducted before the Emperor Claudius, who received him seated on his throne, with the Empress Agrippina by his side. The prætorian guard were drawn up in line of battle on either side. First came the servants of the captive prince; then were borne the spoils of the vanquished Britons; these were followed by the brothers, the wife, and daughter of Caractacus, and last of all by Caractacus himself, calm and unsubdued by his misfortune.

Advancing to the throne, he pronounced the following remarkable discourse, which Tacitus has preserved for us:—"If I had had, O Cæsar, in prosperity, a prudence equal to my birth and fortune, I should have entered this city as a friend, and not as a captive; and possibly thou wouldest not have disdained the alliance of a man descended from illustrious ancestors, who gave laws to several nations. My fate this day appears as sad for me as it is glorious for thee. I had horses, soldiers, arms, and treasures; is it surprising that I should regret the loss of them? If it is thy will to command the universe, is it a reason we should voluntarily accept slavery? Had I yielded sooner, thy fortune and my glory would have been less, and oblivion would soon have followed my execution. If thou sparest my life, I shall be an eternal monument of thy clemency." To the honour of Claudius, he not only spared the life of his captive, but the lives of his brothers, wife, and daughter, and treated them with respect. Their chains were removed, and they expressed their thanks, not only to the emperor, but to Agrippina, whose influence is supposed, not without reason, to have been exerted in their favour.

The public life of Caractacus ended with his captivity; for the tradition that he afterwards returned to Britain, and ruled over a portion of the island, rests on so uncertain a foundation as to be unworthy of belief. The senate, in its pompous harangues, compared the subjection of this formidable chief to that of Syphax by Scipio, and decreed the honours of a triumph to his conqueror,[11] Ostorius, who died, however, shortly afterwards, worn out by the perpetual attacks of the Silures.

Ostorius was succeeded in the government of Britain by Avitus Didius Gallus, who, unlike his warlike predecessor, sought to establish the Roman dominion in the island by fomenting internal dissension. He made an alliance with the perfidious mother-in-law of Caractacus, Cartismandua, Queen of the Brigantes, whose subjects had revolted. His government lasted but four years, during which period the armies of Rome made but little progress on the isle. Nero assigned the government of Britain to Veranius, who died a year afterwards, in a campaign he had undertaken against the Silures.

Suetonius Paulinus, who was despatched to Britain by Nero in 58, proved himself fully equal to the task he had undertaken. Hitherto the Britons had been excited to revolt by the exhortations of the Druids, whose principal sanctuary was in the island of Anglesea, which, up to the period of his government, had preserved its independence, and served as a refuge to the malcontents and vanquished. Of this important spot Suetonius resolved to obtain possession, as the most effectual means of crushing the spirit of resistance still existing amongst the people. By means of a number of flat-bottomed boats, which he had constructed for the purpose, he crossed the arm of the sea which separates Anglesea from Britain. Tacitus has left a vivid description of the effect produced upon the Romans on approaching the island: the army of the enemy drawn up like a living rampart on the shore, to oppose their landing; the women, in mournful robes of a sombre colour, rushing wildly along the sands, brandishing their torches and muttering imprecations; the Druids, with their arms extended in malediction. The invaders were appalled; and, but for the exhortations of their leaders, the expedition, in all probability, must have suffered a defeat. Excited by their reproaches, the standard-bearers advanced, and the army, ashamed to desert their eagles, followed them, striking madly with their swords, and crushing all who opposed them. Finally, they succeeded in surrounding the Britons, who perished, with their wives and children, in the fires which the Druids had commanded to be kindled for their hideous sacrifices. The victory was a terrible blow to the influence of the Druids, who never recovered their power in the island; and its consequences would have been even more severely felt, but for an insurrection which shortly afterwards broke out in that portion of Britain which had been reduced to the condition of a Roman colony.

The imposts were excessive, and exacted with rigour. Hundreds of distinguished families saw themselves reduced to indigence, and, consequently, to servitude. Their sons were torn from their hearths, and compelled to serve on the continent in the auxiliary cohorts. All these evils, great as they were, might have been borne, had not an outrage been added more infamous than any the insolent invaders had yet ventured to perpetrate: an outrage which filled the hearts of the Britons with fury, and drove them once more to rebellion. Prasutagus, a king of the nation of the Iceni, had for many years been the faithful ally of Rome; on his death, the better to ensure a portion of his inheritance to his family, he named the emperor and his daughters as his joint heirs. The Roman procurator, however, took possession of the whole in the name of his imperial master, a proceeding which naturally aroused the indignation of Boadicea, the widow of the deceased prince. Being a woman of resolute character, she complained bitterly of the spoliation, and for redress was not only beaten with rods like a slave, but her daughters were dishonoured before her eyes. On hearing of these indignities, the Iceni flew to arms; the Trinobantes and several other tribes followed their example, and a league was formed between them to recover their lost liberties.

The first object of their attack was the colony of veterans established at Camulodunum, where a temple, dedicated to Claudius, had been raised, the priests of which committed infamous exactions, under the pretence of thus honouring religion. It was affirmed, as is generally the case on the eve of any great event, that numerous omens preceded the catastrophe. The statue of Victory fell in the temple with its face upon the ground; fearful howlings were heard in the theatre; and it is even pretended that a picture of the colony in ruins had been seen floating in the waters of the Thames. The report of all these prodigies, which, if they really took place, were doubtless the contrivances of the Druids, froze the veterans with terror, and raised the courage of the Britons to the highest pitch. In the absence of Suetonius, the colonists demanded succour of the procurator, who sent them only 200 men, and those badly armed; and with this feeble reinforcement, the garrison shut themselves up in the temple.

With the cunning which seems peculiar to all semi-barbarous nations, the Britons continued to reassure their enemy of their pacific intentions. The consequence was that instead of raising a rampart and digging a ditch round the building,[12] which they might easily have done, the Romans remained in a state of fancied security, neglecting even to send away their women and children, and such as from age and sickness were unable to bear arms. Suddenly the mask was thrown off. The insurgents, who had gained sufficient time to collect their forces and mature their plans, fell upon the colony, destroying everything before them, and sparing neither sex nor age. After a siege of several days, the temple was taken by assault, and the garrison put to the sword.

BRITONS WITH CORACLES.

Emboldened by their success, the victors marched to meet Petillius Cerealis, who, at the head of the ninth legion, was hastening to the assistance of his countrymen. After a bloody battle, in which the Britons massacred all his infantry, the Roman lieutenant was compelled to seek refuge with his cavalry in the camp. Terrified at the disaster which his avarice and cruelty had caused, the procurator, Cato Decianus, fled to Gaul, followed by the maledictions of the inhabitants of the province on which he had brought so many evils.