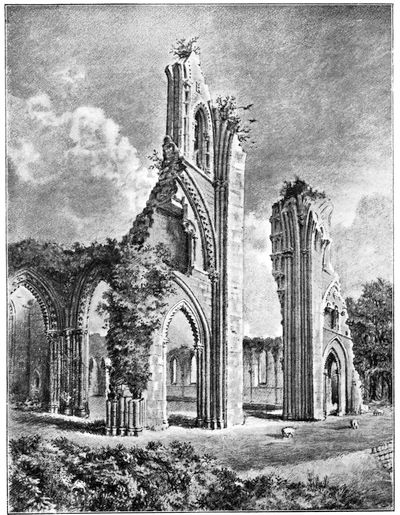

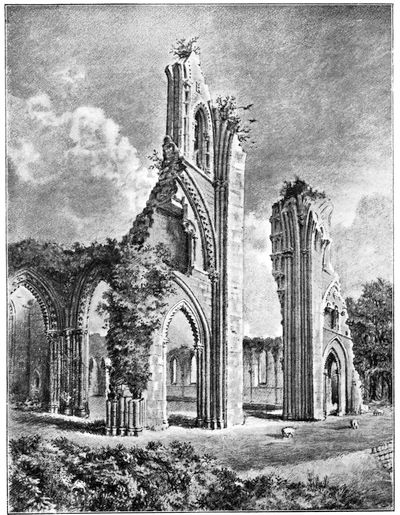

GLASTONBURY ABBEY.

View from the site of the north transept, looking towards the Quire.

Frontispiece to Part I.

THE GATE OF REMEMBRANCE

THE GATE OF REMEMBRANCE

A series of Seven Musical Impressions for

the Pianoforte, by the English composer

CARLYON DE LYLE,

based upon episodes in the life of Johannes,

the monk of Glastonbury, as given in the

well-known book of the same name, being

"MAGNUS ALBUM," No. 37

Published by SWAN & CO., 312, Regent Street,

London, W.

May be had of all Music-sellers

Price 2s. net

First edition, February, 1918

Second edition, July, 1918

Third edition, March, 1920

GLASTONBURY ABBEY.

View from the site of the north transept, looking towards the Quire.

Frontispiece to Part I.

THE STORY OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPERIMENT WHICH RESULTED IN THE DISCOVERY OF THE EDGAR CHAPEL AT GLASTONBURY

BY

FREDERICK BLIGH BOND, F.R.I.B.A.

DIRECTOR OF EXCAVATIONS AT GLASTONBURY ABBEY

AUTHOR OF "THE ARCHITECTURAL HANDBOOK OF GLASTONBURY ABBEY"

THIRD EDITION

WITH A RECORD OF THE FINDING OF THE

LORETTO CHAPEL IN 1919

BOSTON

MARSHALL JONES COMPANY

1920

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ARCHITECTURAL HANDBOOK OF

GLASTONBURY ABBEY. (Reprinting.)

The Glastonbury Press: Glastonbury. 4s. Net

THE HILL OF VISION.

A Forecast of the Great War, with subsequent events, gathered from automatic writings.

Constable & Co., 7s. 6d. net, and of all Booksellers.

ROODSCREENS AND ROODLOFTS.

With numerous illustrations of ancient ecclesiastical woodwork in English churches.

Two volumes, 4to., 32s. 6d. net.

Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Amen Corner, E.C.

v

Two problems in the script have engaged the serious attention of critics. The first and simpler of the two is that which is involved in the language and literary form of the messages. This is a curious patchwork of Low Latin, Middle English of mixed periods, and Modern English of varied style and diction. It is a mosaic of multi-coloured fragments cemented together in a strangely random fashion. This anomaly is the more remarkable from the contrast it presents to the sustained and consistent burden of the script itself, which, as though in obedience to some preordained intention and settled plan, seems to proceed to the presentment, line by line, of a completed whole, with absolute patience and indifference to interruptions. Lapse of time seems of no account. After a break of several hours, the thread is resumed at the point where it had been dropped. The unfinished communications about the Loretto Chapel in 1911 are picked up and spontaneously completed five years later. Nevertheless, the queer patchwork of language is again evident.

For this fact, the following explanation is offered. It will easily be conceded that whatever the source or inspiring influence of these messages, the language in which they are conveyed is the mechanical side of the matter, the most assuredly conventional element in the process of transmission. But the obvious instruments are the brains of F.B.B. and J.A. The reasoning and reflective faculties are at the time in abeyance or arevi otherwise engaged,[1] their attention being entirely diverted: but the storehouse of memories and subconscious impressions latent within are being used, and quite independently used, though concurrently in point of time with the normal use of the thinking faculties on a wholly different subject.

Consider for a moment the human brain as the repository of all impressions made on the mind from childhood upwards. Thus viewed, it becomes, as it were, an encyclopedia of all knowledge which the conscious mind has stored, each item recording an idea of a certain quality, in such language as circumstances may at the time have dictated. Suppose then—and it is not difficult to do so—that each of these records is responsive to the impulse of an Idea which is seeking expression, and whose instrument of expression is some sort of sympathetic vibration attuned to the original thought which recorded the particular memory or subject. The sympathetic vibration lays hold of the denser or physical particles of the record, causing them to respond and to emit their own proper voice.

In other words, the language of the script would be simply the product of the reaction of our brain-records to the sympathetic vibration of Idea, from whatever source arising.

Not that such conditions are always necessary or possible. There are, for example, many quite well-authenticated cases of automatic writing in which not only the idea conveyed is outside the consciousness of the writer, but the language itself is entirely unknown to him, or to her, as the case may be. Take, for example, the many recorded cases of automatic writing in languages unknown to the medium, and sometimes requiring special scholarship to appreciate. vii The explanation seems in this case to be that the mind of the medium is plastic to a more direct spiritual influence which can therefore mould its particles and create a new record for itself. This must have been so in the Gift of Tongues at the Pentecost, and later in the history of the Primitive Church.

The second problem noted by critics is a more difficult one. It concerns the intelligent source of the messages. As to this, I have propounded the view of a Greater Memory transcending, and interpenetrating our own. This theory is suggestive rather than explanatory. It does not, and cannot, explain many things which in our present state of knowledge are inexplicable. Neither does it pretend to cover the whole ground. It is, as I say, merely suggestive. Its virtue is that it excludes no other possible agencies, hence leaving room not only for the exercise of transcendental faculty, such as clairvoyance, but for any variety of primary impulse, and for any number or degree of directive agencies capable of employing it.

For as we are obliged by our own experience to acknowledge that our own latent memory is revived and brought out in these scripts by some intelligence working apart from our conscious minds; and to admit that telepathy between two is involved: so we are also bound to allow the possible presence of a further range of telepathic action working through our minds in the production of these messages. And if we are prepared to agree on the one hand that whereas the physical brain dissolves at death and its action ceases, yet, on the other hand, that a more inward and less material brain, the organ and vehicle of the subconscious or intuitive self, still persists and survives entirely the death of the physical body, and if we consider this more inward brain as composed of finer particles, responsive to the far more rapid movements of intuitive thought, then we shall have to allow that the memory-record of any defunct personality, if capable of response to the same stimulus of spiritual Will and Idea which canviii actuate our own, can be drawn upon in like manner by the energising Intelligence, and again, as in our own case, without evoking the conscious "spirit" or personality proper to it. This is surely the meaning of Johannes when he says (p. 95):

"Why cling I to that which is not? It is I, and it is not I, butt part of me which dwelleth in the past, and is bound to that which my carnal soul loved and called 'home' these many years. Yet I, Johannes, amm of many partes, and ye better part doeth other things—Laus, laus Deo!—only that part which remembreth clingeth like memory to what it seeth yet."

Thus it seems to me the problem of personality, in the sense of the conscious personal presence of individuals deceased, need not arise at all in connection with these writings. All that it seems vital to assume is the union of the deeper strata of our own latent mind or dream-consciousness with others of a kindred nature and tone, by virtue of their sympathetic and accordant motion in the presence of a greater and all-inclusive spiritual essence, Idea, or Will, omnipresent and all-permeating, waking into activity all dormant memory-records, and directing them into any channel of mind which by previous preparation on the conscious plane has become receptive and retentive of them.

Still small Voices from a distant Time!—thrilling through the void and stirring faint resonances within the deeps of our own being—the great Telepathy, the true Communion of Mind, the gate of the Knowledge, the Gnosis of the apostle, whose key is Mental Sympathy, the key that the lawyers took away, neither entering themselves, nor suffering others to enter.

No discord can mar this communion, since love and understanding are its law. Death cannot touch it: rather is he Keeper of the Gate. Time, as we know it, here counts for naught, for to the deeper dream-consciousness, a day may be as a thousand years, and a period of trance or sleeping as one tick of the clock.

Bristol,

May, 1918.

ix

By SIR WILLIAM BARRETT, F.R.S.

As some readers of this remarkable book have thought it too incredible to be a record of fact, but rather deemed it a work of imagination, it may be useful to add my testimony to that given in the book as to the genuineness of the whole narrative.

The author has, I am sure, with scrupulous fidelity and care, presented an accurate record of the scripts obtained through the automatic writing of his friend, together with all the archæological knowledge of the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey that was accessible before the excavations were begun. In order to remove any doubt on this point, before further excavations were made, Mr. Bligh Bond has wisely asked representatives of certain societies to examine the later scripts which refer to the Loretto Chapel, note their contents, and see how far the further excavations may or may not verify any of the statements made in the later scripts.

From any point of view the present book is of great interest. To the student of psychology, who ignores any supernormal acquisition of knowledge and yet accepts the good faith of the author, the problem presents many difficulties. Chance coincidence may be suggested, but this does not carry us far. The question therefore arises, where did the veridical or truth-telling information given in some of these scripts come from? As is so often the case in automatic writing a dramatic formx is taken, and messages purport to come from different deceased people. The subconscious or subliminal self of the automatist, doubtless, is the source of much contained in the scripts, and may possibly be responsible for all the insight shown. But in that case we must confer upon the subconsciousness of the automatist faculties hitherto unrecognised by official science. The author has pointed out, on p. 156, some of the powers the subconscious mind must be assumed to possess; to these we may add a possible telepathic transfer of information between the author and the automatist, and also occasionally the faculty of clairvoyance, or a transcendental perceptive power; for, according to the investigations of the author, some of the statements made in the script were unknown to any living person, and not found in historical records, prior to their verification in subsequent excavation. We must, however, be on our guard against the too facile use of words such as "telepathy" and "subliminal consciousness" as a cloak to our ignorance. The history of physical science shows how progress has often been retarded by the use of phrases to account for obscure phenomena—words such as "Phlogiston," "Catalysis," etc., which explained nothing, and now are ridiculed, but which were once used by scientific authorities as unquestionable axioms. It is wiser to acknowledge our ignorance and convey our thanks to the author and his friend for the patient and laborious care with which they have furnished valuable material for future psychological explanation. Nor must we omit to recognise the courage shown by Mr. Bligh Bond in the publication of a work which might possibly jeopardise the high reputation he enjoys.xi

GLASTONBURY

.xii

"Even so ye, forasmuch as ye are zealous of spiritual gifts, seek that ye may excel to the edifying of the church.

"Wherefore let him that speaketh in an unknown tongue pray that he may interpret.

"For if I pray in an unknown tongue, my spirit prayeth, but my understanding is unfruitful.

"What is it then? I will pray with the spirit and I will pray with the understanding also."

I Cor. xiv. 12-15.

xiii

| PART | PAGE | |

| I. | THE LOST CHAPEL | 1 |

| (a) Introductory | 3 | |

| (b) Documentary | 6 | |

| (c) Psychological Methods applied to Research | 17 | |

| (d) On Automatism | 22 | |

| (e) Notes on the Automatic Script | 26 | |

| (f) Narrative of the Writings | 32 | |

| (g) Table of Veridical Passages | 70 | |

| (h) Testimonies | 79 | |

| II. | THE CHILD OF NATURE | 83 |

| (a) Johannes goes a-fishing | 86 | |

| (b) The Vat of Good Ale | 89 | |

| (c) Memories of His House | 93 | |

| (d) The Burden of the Flesh | 96 | |

| (e) The Gargoyle | 98 | |

| (f) Story of Eawulf | 105 | |

| III. | THE LORETTO CHAPEL | 109 |

| (a) Documentary | 111 | |

| (b) Story of Bere's Vow (1911 Script) | 119 | |

| (c) Camillus Thesiger speaks (1916 Script) | 125 | |

| (d) Architectural Details Descriptive of the Italian Chapel | 128 | |

| (e) Review | 142 | |

| (f) The 1917 Script | 144 | |

| (g) Reconstructions | 151 | |

| (h) Conclusion | 155 | |

| (i) Appendix: Table of Data and Constructive Argument | 160 | |

| IV. | INDEX AND SYNOPSIS | 169 |

xv

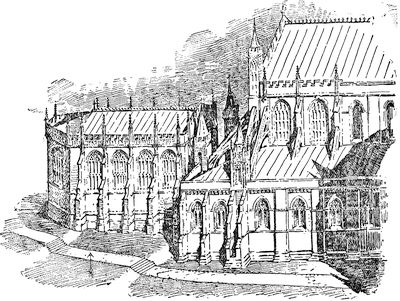

| PLATE | PAGE | ||

| I. | Ruins of Glastonbury Abbey viewed from North Transept, looking towards the Broken Arch of Quire. (F.B.B.) | frontispiece | |

| II. | Foundations of the Edgar Chapel, as Restored (from West) | to face | 56 |

| III. | Reconstruction of the Interior of Bere's Time (Early Sixteenth Century) from the Same Point as Plate I. (F.B.B.) (frontispiece to Part II.) | to face | 84 |

| IV. | Coney's View of the Abbey (1817) (frontispiece to Part III.) | to face | 111 |

| V. | Reconstruction of the North Transept with Loretto Chapel and Claustrum (from a Pencil Drawing by F.B.B.) | to face | 154 |

| —— | |||

| FIG. | |||

| 1. | Phelps's Plan | 5 | |

| 2. | Willis's Plan | 9 | |

| 3. | Archæological Institute's Plan of Retro-Quire | ||

| 4. | Plan of Gulielmus | 34 | |

| 5. | Second Plan, showing Edgar Chapel | 36 | |

| 6. | Plan of Apsidal Chapel, published before Discovery | 61 | |

| 7. | Plan of Apsidal Chapel after Excavation was completed | 64 | |

| 8. | Sketch Elevation of North Side of Edgar Chapel and Monington's Quire | 81 | |

| 9. | Abbot's Head (a Gargoyle in Profile) | 99 | |

| 10. | Stukeley's Panorama of the Ruins in 1723 | 115xvi | |

| 11. | Hollar's View, c. 1655 (Enlarged) | 116 | |

| 12. | Cannon's Sketch of the Ruins, c. 1746 | 117 | |

| Plans A to I: Nine Sheets of Details of the Loretto Chapel, being Facsimiles of those appearing in the Automatic Script | pages 129-142 | ||

| 13. | General Plan of the Abbey laid out on Squares of 74 Feet (1912) | 148a | |

| 14. | Geometric Plan of St. Mary's Chapel | 150 | |

| 15. | Tentative Plan of the Loretto Chapel, etc. | 152 | |

| 16. | Complete Plan of All Chief Features mentioned in the Work | 153 | |

1

2

Since the last issue of this work, the foundations of the Chapel of the Loretto at Glastonbury have been partly excavated, and are found to accord, so far, with the statements received in automatic writing. This discovery sets the seal upon the veridical nature of the writings, and emphasizes the importance of the method employed by the author for the recovery of latent knowledge.

3

THE GATE OF REMEMBRANCE

The green isle of Glaston, severed as it was from the outer world by its girdle of marsh and mere, was from old time a haunt of peace. Its history as a religious foundation goes back into the mists of antiquity, and is lost in legend and fable. To this quiet retreat, this secluded stronghold of a more ancient faith, the footsteps of the first Christian missioners were guided, and the company of Eastern pilgrims found rest in its green recesses and a well-guarded focus for the great work of evangelising the isle of Britain.

Successive waves of pagan immigration flooded the land, yet never was the lamp of truth extinguished here; and, stranger still, those who came, though of alien race and custom, cherished the older landmarks and sought not to destroy; for the heritage of Glaston was not the heritage of any individual race, but of all—a trust for Christendom.

Within the sacred precincts the dust of many holy men was preserved, and the church enshrined their relics. She grew great through the pious benefactions of kings and nobles whose memory she kept green. Among these the gifts of the great Saxon King, Edgar, "yclept The Peace4able,"2 were always gratefully remembered. In the great Abbey Church there was a chapel to his honour, well endowed, and, we doubt not, sumptuously furnished. But it was not esteemed sufficient, and in the day of Richard Bere, the last great building Abbot, it was decided that a new and more glorious monument should be erected to his memory. So we learn from Leland, who saw the chapel as it stood, a completed work, but a few years before the dissolution and ruin of the monastery. Then came, in 1539, the forced surrender, the barbarous execution of the last Abbot, Whiting, the violation of the shrines, and the dispersal of all the treasures of art and learning stored within the Abbey walls. But of the Edgar Chapel nothing more is heard, save that we can infer from a document we quote that it was standing in the days of Elizabeth. Yet it is doubtful whether it can have lasted through half her reign. And perhaps it was one of the first of the buildings to be utterly destroyed, since even its memory had perished and its form and grandeur were alike forgotten. Those who have seen the delicate and beautiful work at St. George's Chapel in Windsor Castle, or that masterpiece of stonecraft, the Chapel of King Henry VII. at Westminster, may form some idea of the general character of this Chapel of Edgar in its finished state.

Local memory and tradition generally preserve some traces, however dim or distorted, of an archi5tectural work of great magnitude and beauty, but it is a strange fact that this one had utterly faded out of knowledge save for some scattered and obscure notes in the pages of the old county antiquaries, which contained no hint of its identity.

Shewing in dotted lines the reminiscence of an eastward Lady's, or

Retro-Chapel, thought to have been built by Abbot Adam de

Sodbury in the early part of the fourteenth century.

Two different states are shewn, both lettered 'F' by these

authors, and here numbered 1 and 2. No. 1 shews by scale a

projection from the retro-choir of 30 feet; whilst No. 2 gives a

total length of 95 feet. This is called by Warner, "the chapel

according to its original proportions." The two measurements

are approximately harmonised by Leland's record of the lengthening

of the choir by Abbot Monington to the extent of two

bays, and the throwing out of his new retro-choir to the east,

which would absorb about two-thirds of the length of this chapel.

6

AN ACCOUNT OF A PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPERIMENT

The following is the story of the discovery which, in 1908, caused a good deal of public interest, and provided the archæological world with an object of attention.

Although known to a small circle of friends of the writer and his colleague in the research, and to the Secretary of the Society for Psychical Research, who was intimately acquainted with both, and in touch with them at the time, no publication of the circumstances has yet been made, and this was withheld largely for reasons more or less personal to the writer, though the intention had always been to make known the facts whenever the time should seem ripe for the disclosure.

The entire record has been preserved, and the testimony of both the writer and his friend being available, as well as the contemporary evidence of the Secretary of the S.P.R., it will be seen that the matter stands on a fairly good basis in respect of documentary witness.

For reasons of convenience, initials will be used7 in the ensuing account. F.B.B. will denote the writer, and J.A. his friend, John Alleyne.

In anticipation of an appointment to the position of Director of Excavations at Glastonbury Abbey on behalf of the Somerset Archæological Society, of which he was a member, F.B.B. had, during 1907, devoted considerable time to the study of the ruins and their history, and to that of the older religious foundations, and in this J.A. assisted him. Most of the surviving accounts of the Abbey were gone through, both the works of the mediæval writers and those of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, with the fragments collected by them from older sources. Among the first, the works of William of Malmesbury, Adam de Domerham, William Wyrcestre, and John of Glaston, were examined, whilst Leland was not overlooked, and the later antiquaries, Hearne, Dugdale, Hollar, and Stukeley, had their share of attention. Following these, Browne-Willis, Britton, Carter, Collinson, Phelps, Kerrich, and Warner, were consulted, and finally some careful attention was bestowed on the modern antiquaries, Parker, Freeman, and last, but not least in importance, Professor Willis, whose Architectural History was the standard book of reference on the subject during the latter half of the nineteenth century, and still remains of the greatest usefulness to students.

Glastonbury Abbey having passed out of private hands into the custody of a body of Trustees, acting on behalf of the National Church,8 it was hoped that a greatly increased opportunity for research and excavation would ensue. All published plans of the Great Church had been necessarily very incomplete, in the absence of visible remains and the lack of trustworthy evidence from documents. In particular the following features were in doubt:

1. The form of the retro-quire, and eastward termination of the Abbey Church.

2. The question of a north porch to the nave, and its probable position, if it existed.

Retro-quire and Chapels.

In 1866 Professor R. Willis published his invaluable Architectural History, being the substance of a communication he had made to the Archæological Institute in the year previous. He devotes two pages (40, 41) to a discussion of the number and arrangement of the chapels east of the processional path in the retro-quire, and arrives at the conclusion that they were five in number. And in his plan (Fig. 2), which appears as a frontispiece to his work, he shows these five, the central one projecting about 12 feet. On p. 43 he says:

"As Bere is also said to have built Edgar's Chapel at the east end of the church, it is probable that this chapel was one of those that we are considering, and that Bere fitted it up and completed it. The complete eradication of the east wall of the church in the centre may be accounted for by supposing that the central chapel projected eastward, as I have shown in the plan, and that this chapel was Edgar's; for if it had been only one of the ordinary9 chapels it would not have been worth mentioning as a distinct building."3

10

Professor Willis's conjecture represents the largest or most liberal interpretation yet placed by any antiquary upon the passage from Leland—which, it may be said, is the only known contemporary evidence of this work of the last two Abbots.

Parker,4 who reviewed the whole subject of the plan in his work for the Somerset Archæological Society (see his article in their Proceedings for 1880), does not support Willis's conclusions, inclining rather to the view that the Edgar Chapel was in the south transept, to the east of the nave, but it is within the writer's knowledge that Professor Freeman believed that the original quire, which, before Monington's addition of a fifth and sixth bay, must have been shorter by some 39 feet, was furnished with a large eastern chapel, prob11ably a Lady-chapel, and that this may have been of quite considerable dimensions and even co-extensive in total length with the plan as given by Willis. But this view does not appear to have gone farther than a mere expression of opinion verbally given at a meeting in the Abbey, and the writer only heard it quoted as a reminiscence some time after the discovery of the Edgar Chapel.

It appears to have been put forward as an explanation of the curious diagram given in Phelps's Somerset, where a plan of the church is published, showing in dotted lines a short projection at the point where Willis shows his chapel, and this is given a semicircular or apsidal end.5 Phelps calls this the "Lady's Chapel." And in the corner of the same sheet this author gives another long rectangular diagram, again with a semicircular end, which Warner, who reproduces the plan, calls the "Chapel according to its original dimensions." The apse being the constant feature, these additional dimensions would be to the west, and would answer to the difference in the former and the latter dimensions of the quire which Monington lengthened in 1344-5. And it will be clear that some such reasoning may have guided Parker or Freeman to the tentative conclusion mentioned, and have assisted Willis to form his definite theory of a slight prominence in the central chapel of the later retro-quire.

Among the documents which have been recovered whose period is that of the immediate12 post-Reformation, is one which would have been readily accessible to Willis and others, and which is preserved by Phelps and copied by Warner in his Glastonbury, published in the twenties of the last century. This is a transcript of a report made to Queen Elizabeth by a Commissioner, who was sent to make an inventory of the Abbey buildings, and he gives a series of measurements of the principal parts of the monastery, including the Abbey Church, as to which he says:

"The great church in the Aby was in length 594 as followeth:

The Chapter House, in length, 90 foot.

The Quier, in length, 159 foot; in breadth, 75 foot.

The bodie of the Church, in length, 228 foot.

The Joseph's chapell, in length, 117 foot."

In the seventeenth century we have the bare statements of Hollar and of Hearne, that the total length of the Abbey Church was 580 feet.

All the measures given by the Elizabethan Commissioner are very excessive, and perhaps for that reason, as well as for the confusion of idea suggested by the association of the Chapter-House measure with those of the Church, they have been rejected, or not regarded, by modern antiquaries. In like manner the bare statement of Hollar and Hearne, being without any description of what buildings were to be included in their measure, has not been taken into account.

Professor Willis's review of the probabilities of the plan of the east end seemed conclusive as regards the existence of five chapels in a row on13 the east wall of the retro-quire, for the construction he places upon William Wyrcestre's description must be admitted to be most reasonable, fortified as it is by the record of Wild's plan (1813), in which the bases of two piers with fragments of wall attached and running eastward are shown in precisely the position required as partitions for the forming of the three central chapels of the five.

These piers had evidently been recently discovered, and are figured in Britton's Architectural Antiquaries, vol. iv., p. 195. But all trace of them has been cleared away, and, as Willis himself says (op. cit., p. 42):

"Unfortunately, the practice in respect to these ruins until the beginning of this century and later was always to remove not merely the wrought stones, but also to eradicate the foundations. And although the remains have been for many years protected from this kind of destruction, THERE IS NO HOPE LEFT OF RECOVERING ANY DETAILS OF PLAN BY EXCAVATIONS." (Capitals mine.—F.B.B.)

So the matter remained until, in 1903-4, the Archæological Institute decided to make Glastonbury the scene of its labours, and Mr. (now Sir William) St. John Hope was deputed to prepare a paper for their annual meeting.

Mr. Hope, having in mind such plans as Abbey Dore, where four chapels appear against the east wall of the retro-quire, reviews William Wyrcestre's statement in this light, and places on his words an alternative construction such as would be correct if that writer had been habitually precise in his descriptions. But he is not precise, and a general14 inspection of his writings will sufficiently show that he has a peculiar method of representing facts where number, series, locality, or dimension are involved. In the present instance he says:

"IN ORIENTALI PARTE ALTARIS GLASTONIE.

"Spacium de le reredes ex parte orientali magne altaris sunt 5 columpnæ seriatim et inter quamlibet columpnam est capella cum altare."

Mr. Hope thought that Wyrcestre counted each respond as a whole column, which would mean three whole columns and two responds or piers engaged with the walls north and south, suggesting, of course, four chapels only. He caused trenches to be cut east and west along the site of his supposed central dividing wall, and one north and south immediately outside the east wall of the retro-quire and across the gap where the central chapel of Willis ought to have been. But nothing turned up which to his mind was indicative of an extension of building beyond the line of the two remaining fragments of walling marking the eastward end of the retro-quire, and his conclusion is definite—that there was not, and could never have been, any such extension of a central chapel. And he claimed to have found support for his view of a mid-partition giving a total of four, and not five, chapels, through the confirmatory results of his excavation. Such was the position in 1907 when the writer commenced his studies, and it will readily be seen that no prospect of success could reasonably be expected15 to attend further research by excavation beyond this point.

All the evidence was sifted and discussed by F.B.B. and J.A. F.B.B. attached perhaps as little weight to the conflicting records of a longer measure as had those who went before him. But he distinctly preferred Willis's solution to others, as there was no gainsaying the significance of16 Wild's plan with its two intermediate column-bases. And instinctively he felt, as his friend also felt, that the question was not solved, the last word not said. More than once, the feeling returned that a chapel which was thought worthy of special mention by Leland, and which, according to his account, was the work of two Abbots, must have been a work of some importance.

Still, nothing came uppermost in the mind which would tend to modify the writer's respect for Willis's view, nor, indeed, to challenge its probability. It was rather with the object of defending this view, as against the contradictory one more recently put forward, that the intention was formed to examine, as soon as circumstances might permit, the site of Wild's twin piers, and to dig deep around the spot in the hope of finding yet some trace of footings characteristic of a crypt; for Wild noted these as being "probably part of the crypt," and it did not appear that anyone had taken the trouble to investigate this matter.

Wild's plan, incorporated in Britton's "Antiquities," may be regarded as a standard work. In this respect it claims greater weight than others such as Phelps's or Stukeley's, which are vague and inaccurate. Warner copies Phelps, and claims a fourteenth-century Lady-Chapel at the east, but neither Britton nor Stukeley, whose plan is two hundred years old, supports his view. Warner's note is quoted by Professor Willis (ref. to p. 31 of his Architectural History).

17

It has been said that the great distinction between East and West in the matter of learning has been that whilst Western science deals with phenomena and builds upon deductions from observation of external things, Eastern wisdom looks always inwardly, seeking to find the answer to all enigmas of creation in the mind of man. The one develops the logical faculty, often, perhaps, at the sacrifice of the imaginative functions; whilst the other follows the intuitive powers, not regarding logical rules. But, as a matter of fact, neither method can be employed to the exclusion of the other, and any great discovery of Western science will be found the outcome of interaction between the two principles. It had always been clear, however, to the writer that the part played by the intuitive or, as Myers would say, subliminal powers of the mind is habitually set aside by the orthodox naturalist, who is apt to see little beyond his specimens and what can logically be inferred from them. And archæological research has been in such a manner hidebound, and, it must be admitted, with some reason; for, as a comparatively18 young science, it has had to protect itself against many a foolish fantasy launched by a half-instructed or over-enthusiastic devotee. To describe these as "vain imaginations" would be correct, as the word "vain" is a sufficient qualification, but the writer at all times deprecates the use of the noble word "imagination" in the debased sense of a mere fantasy. Imagination is a great gift, a Divine power of the mind, and may be trained and educated to receive and to create only that which is true. And this, maybe, is the secret of much of the spiritual understanding and wisdom of the East.

But we Western folks think it unpractical to cultivate this gift. We have no system for training it, and our bourgeois habit of mind despises it. In our slipshod way, we say of anything not founded on fact, "It is all imagination," and similarly we are wont to misuse the term "illusion" by employing it to characterise positive delusion.

The training of the imaginative faculty upon scientific lines and its application to archæological research had long been a favourite notion of the writer's, and he and J.A. had many a talk on the subject; but the difficulty was as to the method most likely to secure the results at which they aimed.

What was clear enough, however, was the need of somehow switching off the mere logical machinery of the brain which is for ever at work combining the more superficial and obvious19 things written on the pages of memory, and by its dominant activity excluding that which a more contemplative element in the mind would seek to revive from the half-obliterated traces below.

And it occurred to F.B.B. that in the faculty of automatism which his friend was believed to possess, but which he had never used deliberately (it had operated once or twice in his life spontaneously), there might be found the key to success in this direction. F.B.B. was a member of the Society for Psychical Research. Both he and J.A. were intimate with Mr. Everard Feilding, Secretary of the Society, who had been greatly interested in J.A.'s account of certain phenomena of automatism which he had experienced. And E.F. had been present at one or two experiments in the calling of these powers into play.

Before entering upon the actual narrative of the discovery in connection with Glastonbury, it must be further premised that neither F.B.B. nor J.A. favoured the ordinary spiritualistic hypothesis which would see in these phenomena the action of discarnate intelligences from the outside upon the physical or nervous organisation of the sitters. They would regard such a view as something like a reversal or turning inside-out of the truth. But that the embodied consciousness of every individual is but a part, and a fragmentary part, of a transcendent whole, and that within the mind of each there is a door through which Reality may enter as Idea—Idea presupposing a greater,20 even a cosmic Memory, conscious or unconscious, active or latent, and embracing not only all individual experience and revivifying forgotten pages of life, but also Idea involving yet wider fields, transcending the ordinary limits of time, space, and personality—this would be a better description of the mental attitude of the two friends.

The following may be quoted as indicating F.B.B's temper of mind and feeling at a time closely following the date of the experiments he made with J.A. It may be found as a passage in the Illuminated Address which he prepared for, and which was accepted by, the Queen on her visit as Princess of Wales to the Abbey in 1909, and was conceived as a part of the "lovynge Greetinge of ye monkes of Glaston to theyre Prince and Princesse. xxii Jun: Ao Mcmix." This extract runs as follows. It was not automatic, but was doubtless influenced to some extent by a strong feeling in more than one quarter that Glastonbury would be renewed as a centre of spiritual realisation and reconciliation between the various racial elements in these islands and their distinctive religious expressions, not yet co-ordinated (see the writer's article on "Glastonbury" in the Christmas number of the Treasury for 1908, also an address by Canon Masterman given in London in the same year). Glastonbury, as is well known, was a centre of pilgrimage from all parts of the world. In most ancient times it was compared with Rome and Jerusalem:

21

"For ye past dyeth not but slepeth, nay ffor perchaunce hit wakyth and hit ys they of ye present who doe slepe and dreme. Hit ys euen as a ffar countrie ffrom ye which they heare tydynges: Yet men will fare vnto londes ffarr distant and ye weelth hath bene theyr guerdon euen soe wayteth euer ffor man ye treasure of ye wisdom of past tymes and yeeldeth her vnto ye loue whych seekyth and ys ne wearyed; soe schal ye memorie of oldetyme thinges be reuealyd and of Glaston hit ys sayd yt when ye tymes ben ripe ye glorye schal return: May hit bee euen soe Gracious Prince and Princess yn youre tyme."

These verses were evolved one day in automatic writing. What their origin neither F.B.B. nor J.A. know—neither can recall having read them. Owing to their beauty and suggestiveness, they were incorporated in the Address in a form slightly modified from the original.

22

The essential objection to the methods and practices of the spiritualists, and the ground of that instinctive repugnance which is normally felt towards these methods, is undoubtedly that they imply a surrender of the will and powers of self-control to activities which, for good or evil, are outside the personal sphere of the medium. The higher spiritual gifts are those in which the recipient acts as a conscious participator in the act of transmission. Between these two extremes is a class intermediate in nature, which is apparently recognised by St. Paul in the first Epistle to the Corinthians,6 the typical instance quoted being that of the "gift of tongues" whose exercise, whilst not discouraged by him, was nevertheless noted as of inferior value, since it did not tend always to the edification of the Church. But it was one phase of a form of inspiration then known, probably as a common phenomenon, and there can be little or no doubt that it was accompanied by others of a similar sort, and that inspirational writing was possibly one of the most ordinary of these. The one necessarily follows from the other. There is even a possible element23 of the kind to be weighed in any satisfying theory of Biblical inspiration, and the prophetic utterances connected therewith, and it will have to be considered fairly and apart from theological preconceptions.

It is clear from the chapter in Corinthians (1 Cor. xiv.) that in the exercise of the gift of tongues the speaker generally knew little or nothing of the meaning of what he was saying, though it is not necessary to assume that the utterance was beyond his control. But it implies the action of what, in modern language, has been spoken of as a supraliminal part of the mind, when, to quote the Apostle, "the understanding is unfruitful."

The exercise of automatism—a controlled automatism—in the production of writing seems to the author a reasonable parallel, and, where the result is capable of ready interpretation, there, according to the Apostolic dictum, is the hope of "edification" by its means. And for those prepared and ready for its exercise the gift of prophecy in those days awaited manifestation through them. And it is not necessary to suppose that the gifts then bestowed were unique, in the sense that they were afterwards to be withdrawn for all time. On the contrary, it is quite clear from Scripture itself that a great revival of them was to be expected in later days, as Peter says in Acts ii. 17, quoting the prophet Joel:

"And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out My Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams."

24

Are we not led to believe that there is no limitation to the "liberal gifts" of the spirit nor to the variety in the nature of the spiritual gifts which may be exercised? They may be concerned with any possible branch of mental activity, and all new ideas, whether in art, science, philosophy, politics, religion, or what not, must be held to be included. Nor need the manner or method of such inspiration concern us as of primary importance, however unusual such may chance to appear. The one test is the quality of its message, whether it be truthful or otherwise, edifying or lacking in helpful qualities. If a message of this nature be found true, it cannot be dictated by a spirit of falsehood; if sane, then not by insanity; if wholesome and moral, then not by a vicious or depraved intelligence. Men do not gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles.

The germination of new and profitable ideas in the mind may in this respect be brought about, firstly, by a suitable system of mental exercise and culture; secondly, by a willingness to hold back all mental preferences and preconceptions, and to restrain also the surface activities of the brain, so that the channel of pure "idea" which resides in the subconscious mind may be maintained, and the finer activities allowed to percolate. Then surely may be hoped for the reaction of those energies sent forth by previous effort of the mind and will, and ideas will flow back, not singly and alone, but accompanied by a spiritual reinforcement which may include elements new and of25 great value, from sources beyond the ken of the individual mind.

These new elements may be of all conceivable kinds, moving instinct, intuition, imagination, affection, or will. They may be vague and abstract, or tinged, as in dreams, with a vivid sense of personality; dispassionate or pulsing with new enthusiasms; lighting the intelligence, or moving in the dark region of the subliminal mind—in this case perhaps incapable of being evoked save by automatism or the telepathy of other minds. From some inward and mysterious fount they come, borne in upon us by dynamic impulse carrying with it the fruition of memories and experiences long dormant and inaccessible to us, though within the range of the spiritual intelligence which is the Directive power. Man is a very complex being, and although, spiritually speaking, he lives and acts in relation with his fellow-men in, and by virtue of, his memories, personal and ancestral—for what are character and conscience but the fruition of all those memories and experiences which are his own or those of every pre-natal element in him?—yet, may it not be that when released from physical conditions, as at death, there will take place some dissociation of the strata of his personality, the mere brain-record, the husk, the mechanism of his memories of common things, being scattered as the chaff, or shaken off as a discarded coat, whilst their fruit is garnered as new spiritual power and knowledge in the soul's æonial treasury?

26

The decision to publish these writings was formed after much careful weighing of all reasons for and against, and their issue at the present juncture was largely influenced by the feeling that public interest in such matters had greatly ripened since the war, and that the fruits of the author's experiment should not be withheld, since they might serve to direct that interest into a new and perhaps profitable channel.

The script produced during the fairly long period of time (from the end of 1907 to 1911, and again in 1912 and more recently) was obtained under varying conditions, and was of very varied quality. A large proportion had reference to Glastonbury and to monastic affairs and history, and of this only a part would claim to possess any sort of evidential value. Some was of private interest only, and would be useless for publication. Occasionally the attempted communication was a failure. In a few cases there were noted some very obvious misstatements. The most serious of these was in the measures first given for the Edgar Chapel, "Et Capella extensit 30 virgas ad orientem et viginti virgas in latitudine(m)."27 A "virga" is a yard. The script was very obscure, and the measure was asked for again, with the result that "quinquaginta virgas" was written. A third time the confirmation was sought, and this time the "30 virgas" was repeated. "Quinquaginta" (50) was obviously a mistake, but the repetition of the 30 virgas, though indicating a length vastly in excess of anything we had ever thought possible for this chapel, made one less inclined to dismiss it without further attention. The "viginti virgas" given once for the width seemed quite out of the question. And as the event proved, no measure approaching 20 yards for the extreme width of the chapel could then be shown to have existed. It appeared absurd, and was then and there ruled out, together with the inconsistent and excessive "quinquaginta virgas" of length.7 This occurred at the close of the first sitting, which had been a long one. The writing was becoming less clear; the power was failing, and the sitters beginning to feel weary.

No further attempt was therefore made at the time to elucidate the measures, but it was resolved to try again on a subsequent occasion. There was a very cold spell in the early winter of 1907-8, and the attempts during this period were28 mostly failures. On the 13th December the sitting was abandoned for this reason. Another on the 21st produced nothing satisfactory. Again, on the 3rd January, 1908, when the cold was at its height, only a few cramped and uncertain words could be obtained, in which these were traced:

"Frigidus sum ... memoria oportet nullum ... nescio quid aut quo8 fecimus scriptum...."

Another and much more important cause of failure must now be noted. About the beginning of 1908 certain circumstances of a rather anxious and trying nature were affecting one of the sitters. This produced a preoccupation of mind unfavourable to the production of automatic writing; and it seems a well-established rule that the sitters' minds must be placid and their mood quiescent to obtain the best results. On the 30th January, 1908, a further attempt was made to obtain writing, but with entire lack of success from this cause, and all that was worth recording was a few words, ending with the following: "Eschew self. Something clogs the tones. Search yourselves straitly."

It was not until the 19th of February that any further really satisfactory results were attained, and at this sitting the unspoken desire of the sitters was met and a detailed description of the Edgar Chapel given, including its outside measure of width—namely, 34 feet. But it was not until Sitting XXXII. on the 16th June that the final29 confirmation came. This was in answer to a question, and it was given as follows:

"The width ye shall find is twenty and seven, and outside, thirty and four, so we remember.—BEERE ABBAS."

At the date of this sitting, the west wall of the chapel had been located, but its length not yet ascertained, so that there was nothing to guide opinion as to this save what could be inferred from the position of the small section opened, which showed it to be probably about 20 feet in the clear of the footings, if placed centrally with the quire. Then, in response to the further question, What was the clear internal length of the chapel? came the reply,

"Wee laid downe seventy and two, but they builded longer."

And the veridical nature of these figures was shown by later knowledge. (See Table, p. 76.)

But to return to the subject of errors. At Sitting XXXVI., on the 19th September, 1908, there was given the story of a Saxon Earl, one Eawulf, or Eanwulf, who was slain by a certain Radulphus, Norman knight of the time of Turstin, first Norman Abbot. The story is quite a good one and contains what appears to be veridical matter, but it is marred by a peculiarity. Halfway through the script a strange mistake is noted. The name of Turstin is substituted for Radulphus, and the script says, "Eawulf and Turstinus did fight, and the Norman did slay the Saxon." Now such an error is tiresome, as it spoils the clearness30 of the story. Yet, in another way, it is interesting, for the light that it throws on the mechanical action of the brain as the probable source of error in automatic writing or speaking.

It is a fact well known to those who are called upon to speak in public, or who are engaged in literary work, that unless the attention be fixed and concentrated on the subject in hand, the brain will act mechanically, causing repetition of any word recently impressed on the mental tympanum, and such word may easily be substituted for another. Where there is fatigue, this may happen very easily. In the case of automatic writing, the mind is relaxed, and there is probably a predisposition to such errors. The example given seems a proof of it. It seems, indeed, a matter for surprise that such mistakes are not more numerous in the script obtained by us. On the contrary, another phenomenon has been frequently observed in connection with it. This is, that at the commencement of a sitting the thread of a former communication, broken by the termination of a previous séance, would be resumed almost as though no interval of time had elapsed.

It had been intended in the present work that only the veridical matter concerning the Edgar Chapel should appear in print; but the scope was enlarged by the inclusion of Johannes, whose personality seemed attractive. Later, it was decided to allow the remarkable reminiscence of the "Loretto" Chapel also to see the light of day, in anticipation of further knowledge. But readers31 will understand that nothing like a wholesale reproduction of the script in the author's possession would be possible. At the same time it may be clearly stated that in what is reserved there is nothing which contradicts or negatives the value of what is given, and of this the fact that the author has been able with success to follow out the indications given may be held sufficient warrant.

No apology seems needed for the quality of the "Latin" in the script, which is very much what one might imagine to be the colloquial jargon of illiterate members of the community, whose knowledge of the tongue would be chiefly confined to the service-books, or what they understood of them.

The author would here record his indebtedness to his friend J.A., not only for that cordial interest and co-operation without which the new line of research could not have been undertaken, nor this work have seen the light of day; but also for the verses he has written on the subject of Plate III., and on the final Envoi. His thanks are also due to Miss A. M. Buckton for her sonnet (Plate I.) and for many valued suggestions; to Mr. T. H. Felton for his permission to use material from the Cannon MS.; to the Council of the Somerset Archæological Society for loan of several blocks (including Plate II.); and to Mr. Edward Everard for the loan of Coney's and Stukeley's plates; also to Mr. Everard Feilding for his constant interest in the work and many helpful suggestions.

32

It was on the 7th of November that F.B.B. and J.A. had their first sitting for the purpose of furthering the Glastonbury research. This took place at 4.30 p.m. in F.B.B.'s office. J.A. held a pencil, F.B.B. provided foolscap paper, which he steadied with his left hand, whilst placing his right lightly on the back of J.A.'s, so that his fingers lay evenly across its surface.

F.B.B. started by asking the question, as though addressed to some other person:

"Can you tell us anything about Glastonbury?"

J.A.'s fingers began to move, and one or two lines of small irregular writing were traced on the paper. He did not see what was written, nor did F.B.B. decipher it until complete. The agreed method was to remain passive, avoid concentration of the mind on the subject of the writing, and to talk casually of other and indifferent matters, and this was done. The writing turned out to be a sort of abstract dictum—viz.:

"All knowledge is eternal and is available to mental sympathy."

Then followed:

"I was not in sympathy with monks—I cannot find a monk yet."

33

F.B.B. suggested that one of their living monk-friends might be a sympathetic link, and the writing was resumed. After a short interval J.A.'s hand moved and began to trace a line, ultimately making a drawing which on inspection looked like a recumbent cross, but which when examined proved to be a fairly correct outline of the main features of the Abbey Church traced by a single continuous line, but at the east was a long rectangular addition, nearly as long again as the quire, and this was given in a double line as though to emphasise it. Down the middle of the plan were written the words—

"Gulielmus Monachus." (See Fig. 4.)

Next followed what appeared to be an elaborate plan of the great enclosure of the Abbey Church, with a sketch of a central tower, with square pinnacled top, a west front or gabled façade, with two peaked turrets and a large arched light between. Across the middle of the surrounding enclosure a line was drawn, and at one point something like an ornamental turret with two curved diverging lines below appeared, and the words, "linea bifurcata"9 were written. Then something looking like a gabled building was sketched, from which a line was traced to two rows of arches,34 perhaps representing a cloister, and thence another straight line to a drawing recognised as being intended for St. Mary's Chapel, and approaching it from the south. The plan of the chapel showed a large square projection (? turret) on the south, and two doors on the north side.

Note.—The drawing has all the marks of a blindfold tracing. The line is continuous, commencing at A, and the north transept is first drawn, very small. Next the line runs east, and the north-east angle of the retro-quire is traced, and, following this, the Edgar Chapel, extending east for about half the length of the quire. Here the line is drawn three times over, as though to emphasise the feature, and it then returns over the old ground, the north transept being again drawn, but larger and further removed, and the whole outline of the church is completed, to the junction south-west of the Edgar Chapel, ending with the signature Gulielmus Monachus (William the Monk).

Q. (by F.B.B.). "What does this drawing represent?"35

A. "Guest Hall ... St. Maria Capella ... Rolf monachus."

The first drawing was now examined, and both F.B.B. and J.A. expressed a view unfavourable to the possibility of so large a chapel at the east of the church. It was resolved to try again.

F.B.B. "Please give us a more careful drawing of the chapel sketched just now at the east end of the great church."

In reply, a new sketch of the rectangular chapel was given (see Fig. 5), with an attempt to indicate the position of two smaller chapels on the north. Again the line was drawn double, and below was written the following, in cramped characters not easy to decipher:

"Capella St. Edgar. Abbas Beere fecit hanc capellam Beati Edgari ... martyri et hic edificavit vel fecit voltam ... fecit voltam petriam quod vocatur quadripartus sed Abbas Whitting ... destruxit ... et restoravit eam cum nov ... multipart ... nescimus eam quod vocatur.

"Portus10 introitus post reredos post altarium quinque36 passuum et capella extensit 30 virgas ad orientem et (? viginti)11 in latitudine cum fen (?) ... (?)."

F.B.B. "Please repeat; we cannot read this."

(Repeated.) "Quinquaginta12 virgas et fenestrae transomatae."

The line starts at the east, and again it is repeated for emphasis. The chapel is shown at first, clear of the east wall, but there is a subsequent loss of position which brings the little chapels beyond their prescribed limit and makes the plan appear confused. Below is written "Capella St. Edgar, Abbas Beere fecit hanc capellam" (Chapel of Saint Edgar, Abbot Beere built this chapel).

37

F.B.B. "Please give length again."

A. "30 virgas ... et fenestrae (cum) lapide horizontali quod vocatur transome et vitrea azurea; et fecit altarium ornat(um) cum auro et argento et ... et tumba ante altarium gloriosa aedificavit ad memoriam Sanct ... Edgar...."

F.B.B. "Which Abbot did this?"

A. "Ricar(d)us Whitting.... Ego Johannes Bryant monachus et lapidator."

This concluded the sitting.

SITTING II. 11th November, 1907, 1 p.m.

"The material influences were at fault when last ... I think active influences were overpowering my will. Those monks were anxious to communicate.... They want you to know about the Abbey. They say the times are now ripe for the glory to return and the curse is departing. I do not know about these things. They have been wishing to influence you for a long time, and they have been (endeavouring to?) reproduce things in your minds."

Here the influence changes.

"Benedicite. Go unto Glaston soon. Gloria reddenda antiqua. Laus Deo in saecula seculorum. Nubes evaserunt ... memoria rerum manet et red ... Ecclesia catholica extensit et comprehensit latera (sic,? latentia) vera et res occultas sapientibus.

"JOHANNES."

SITTING III. 13th November, 1907.

Writing commenced without any direction by sitters.

"I think I am wrong in some things. Other influences cross my own.... Those monks are trying to make themselves felt by you both. Why do they want to talk Latin?... Why can't they talk English?... Bene38dicite. Johannes.... It is difficult to talk in Latin tongue (repeated, being illegible). Seems just as difficult to talk in Latin language."

"Ye names of builded things are very hard in Latin tongue—transome, fanne tracery, and the like. My son, thou canst not understande. Wee wold speak in the Englyshe tongue. Wee saide that ye volte was multipartite yt was fannes olde style in ye este ende of ye choire and ye newe volt in Edgares chappel.... Glosterfannes (repeated). Fannes ... (again) yclept fanne ... Johannes lap ... mason."

Q. "What is meant by 'lap mason'?"

A. "Lapidator ... stonemason."

Having this signature "Johannes" now again repeated, F.B.B. felt curious to know how far this dramatisation or memory of a personality might be developed.

Q. by F.F.B. "Tell us more about yourself."

A. "I ... died in 1533." (Repeated because almost illegible.) "Yn 1533 obitus ... curator capellae et laborans in mea ecclesia pro amore ecclesiae Dei ... sculptans et supervisor ... yn Henricum septem13 ... anno 1497 et defunctus anno 1533."

NOTE ON THE FIRST THREE SITTINGS.

We observe in these communications an individual tone, as of a directing influence, at first manifesting without intermediate links, but almost immediately yielding place to the monkish elements introducing themselves as "Gulielmus Monachus," "Rolf Monachus," and "Johannes Bryant." There appears something like a clash of intention, a strain which reacts on the physical39 condition of the sitters, and which seems to account for the rapid exhaustion of power towards the end of the first sitting, and the consequent lack of clearness and consistency in the results.

In the second sitting the directive agency speaks of the monks as "active influences"—an expression to be noted. And it is explained that "the material influences were at fault." Then in the third sitting we get, "I think I am wrong in some things. Other influences cross my own."

It seems very much like a man trying to make a trunk call on a telephone, who is worried because the local office will either persist in switching him off at critical moments, or else because the wires are out of order and imperfectly isolated, so that fragments of other conversation are interjected.

When we come to consider the matter of the monkish communications, under the name Johannes, we are at once confronted by the question, "Is this a piece of actual experience transmitted by a real personality, or are we in contact with a larger field of memory, a cosmic record latent, yet living (the "eternal knowledge" of the first writing we record), and able to find expression in human terms related to the subject before us, by the aid of something furnished by the culture of our own minds, and by the aid of a certain power of mental sympathy which allows such records to be sensed and articulated?"

As to this, it is too early to dogmatise, but in either case room must be left for the presence of a Directive Power accessible to man, capable of40 stimulating and energising dormant consciousness, and directing it into such channels as man has developed for its reception and expression.

SITTING IV. 19th November, 1907.

The result was interesting, but contained nothing important as regards the Abbey.

SITTING V. 22nd November, 1907.

A further plan was produced of the general range of Abbey buildings, signed "Johannes." This was followed by a short script as here given:

"When you dig, excavate the pillars of the crypt, six feet below the grass—they will give you a clue. The direction of the walls ... eastwards (this word might almost as easily have been 'westwards,' or even 'outwards,' and it was so ill written that nothing could be decided from it) ... was at an angle ... clothyards twenty seven long, nineteen wide."

It would have been just as easy to read the last as "thirteen." The pencilled original of the plan is preserved, but not the script, as it was not regarded as of value at the time, but the mention of the "walls at an angle," referring, as it would appear, to some part of the chapel whose dimensions are in the context, is an interesting point.

The mention of the crypt seemed simply the mentality of the sitters—a reflex of their study of Wild's plan. It is again referred to, however, in later writings.

41

SITTING VI. 26th November, 1907.

F.B.B. "Perhaps Johannes will tell us something more?"

A. "Johannes Bryant is striving for the glory of Glaston. There is much under the grass deep down and unrifled. The east of St. Mary's has a vault under the stairs and under the nave there are vaults14—the destroyers feared, and the ruin of the walls hid the entrance in. Under the tower the volt is perfect, and many names of those buried therein very deep down."

Q. "Where should we commence to dig?"

A. "The east end. Seek for the pillars, and the wall(s) at an angle. The foundations are deep."

SITTING IX. 30th December, 1907.

Commencement of writing quite illegible.

"... (the) end of the time approaches. The year is big with issues and Glastonbury will engage much of your attention....

"JOHANNES, MONACHUS."

"Wait, and the course will open in the spring. You will learn as you proceed. We have much to do this season...."

"... The chapel of Our Lady of Glaston—type of spiritual things which are not manifest to you. The changes need not alarm you. The reconstructions will be more perfect. Let the State fall in ruins and the outward garments of Faith perish—fear not!"

"... For greater things will rise into being—great nations and great ideals. We work for it. Be willing, and strive not against the tide. Up on the crest and prosper. All will work for the best.... The spark will live thro' the rains and re-light dead fires, fire which is still fire but with purer flame. We cannot hasten the time,42 but it is sure and is not delayed. You are between two influences. Earth and spirit mingle not. Losing earthly grasp leaves you without earthly support. Hold fast to earth's duties. Work as men for man's meat. Keep open ears for spiritual help and whisperings. Assimilate and combine both forces. Stand in the market-place and cry your wares, but listen for the still small voice in the silence of your chamber. Work in the sun. Listen in the starlight...."

Both F.B.B. and J.A. expressed a good deal of surprise at the nature of the first part of this communication, as any idea of impending revolution in Church or State had been utterly remote from our minds and not in any way the subject of conversation. The passage was an intrusion and a puzzle. But we did not regard it as of any special interest; more as a curiosity for which a psychological explanation was lacking.

Later there occurred more such intrusions, pointing with increasing definiteness to the nature of that which we were warned to anticipate, but they belong to another story and have no connection with the discovery of the Edgar Chapel. Hence the record of many sittings will be omitted, and we pass to the nineteenth, held 19th February, 1908, after a visit to the Abbey. F.B.B. had not yet received his appointment, but was steadily preparing, and at the moment was engaged in working out the probable appearance of the approaches to the central chapel of the retro-quire, and the work of Bere's time had been discussed.

N.B.—All the 1907 sittings were at Bristol. The next to be recorded (Sitting XIX.) was held at Glastonbury.

43

SITTING XIX. 19th February, 1908. At Glaston

"The arche is flatte—three ells from side to side—ten feet high—all panellae. All ye midst of ye est ende was panellae and the grete chappell was15 ...

"... we have told you long tyme sins—panellae everywhere ... thin walls and poore foundations in the new work.

"Two capellae north and south and between them a greate space with a tall doore in the midst, of four centres, all panelled under ye fann-tracery over ye lintel. And there were two altares on either side and much carven woode very blacke which was took away for the panellae. And the holes in ye walls were covered with the panellae so that they shewed not, and yt was all of stone very white and faire and in ye doore was a greate stairway with two windowes on either hand that did rise one above the other of equal height above ye stairway.... And ye stairway was divided in ye midst by a grete rail of stone so that they who went upp might not meet with they who came down ye said stair.

"And beyond rose a Capella of Edgar ye sainte, faire and high with grete windowes with transomes and between ye windowes were pillars as panellae the whych did holde ye roofe of stone vaultid very faire in panellae which were fanwise very fine much like carven yvorie and carvings ypainted in ye bosses and in ye spandrels and there was a grete windowe in ye est parte of eight lights all ye arches and ye roofe being flatte as of the period and the chamber was yflagged with tiles of many colours and in ye midst was a tumbe of silver and precious stones and pictures in the panellae over against ye est window. And ye chamber was in length seventy feet in four bayes and in width it was thirty and foure16 ... and the walls were thin and all of faire squared stone and newe carven soe that they who did destroy this ... first, even before the great church.

"And soe hyt was not. There were faire steppes of marble and ye fannes over ye doore did hold a lyttel galerie44 the whych did open close on ye stairway looking down on them that passed there and a lytell windowe was above for to lyte ye chapell in ye church at back of ye two altares for hyt was darke.

"Forty and two feete was the hight of ye newe chapelle and yt was ybuttressed with faire buttresses and walls slantwise at ye cornere."

There appears throughout this communication a tendency to older forms of spelling never quite achieved, and constantly slipping back into the normal. The phrasing seems more consistently old-fashioned.

Note the further reference to "walls slantwise at ye cornere," recalling the "walls at an angle" mentioned in an earlier script.

SITTING XXIV. 5th March, 1908.

"... Wold I could tell you of the great Est window in the gabell. It is hard to say its many parts but ye shall see it a noon. (This is of the quire.—F.B.B.)

"The buildings on the south side of the east end were two. One was a chapell, the other for the priest to robe in.

"Saint Edgar was buried in the window where ye see the cross. Afterwards Beer moved him to the new chapell that he builded. Chapell was like unto Wells but more faire."

This obviously alludes to Bishop Stillington's Chapel, a fan-vaulted structure of rich sixteenth-century work, now destroyed.

SITTING XXV. 10th March, 1908.

F.B.B. obtained the appointment as representative of the Somerset Archæological Society, with licence to excavate, in the month of May, 1908.

45

SITTING XXVII. 17th March, 1908. At Bristol.

"The time is ripe for the stones to be studied. Go ye soone."

"The corbel-stones are full large." (This refers to a sketch reconstruction of the transept wall by F.B.B.) "Put ye ten between each buttress."

Q. "Is the parapet right?"

A. "The parapet is right."

Q. "What about the quire vaulting shown?"

A. "Ye volte is welnigh righte for what ye see, but over Arthur's tombe to the Est window it was fayrer and much ygilt soe that the lightes of the Altar shold shine thereon and make a glory."

"Looke for ye ribs of the choir, plain ones and carven, and ye bosses. Some be at the East End. Enow has been left from the destroyer, just enow and no more: it was so ordained lest they should destroy for ever. Make ye yourselves a scheme—enow left everywhere."

"Why destroyed they not the walls that came to hande? They cared not, but indeed they left it and digged deepe for stones.

"They could not an they would."

"Why left they the altar stones when they might have digged up? say, why?"

Q. "You say, 'Saxon, Norman, and Native, all strive together for the glory of Glaston.' Can you put us in touch with any of these early influences?"

A. "What wold they tell ye? Their works were rude, and have departed. The Abbey is not of them—nothing save certain books—and we wold that the books were againe, only the Church as it was wont to be. We who speke are of its different orders: Gulielmus of old tyme, and Johannes later, and he who builded last—our Abbot Beere. What more is needed? Wee point the way; to you it is to follow, and all that is needed is given you. Worke wyth brain and handes, and all is there. So it is ordained, for what ye desire, that is good that ye shall strive for. Wee worked in our day: ye must work in yours. Ne work, ne wages,—ne what you call honour."

46

Q. "It is St. Patrick's Day to-day. Can you tell us anything of his time and of his work, and St. Brigit's? No doubt there was much in the great Library of the Abbey."

A. "Olde legends, meet for the people—but what value? They were, and didde, much among the heathen. We know not more, save that their workes were old and very dry to rede." (This passage is signed with a cross in a circle, and a capital letter, not clearly identified.)

Q. "Please write your name."

A. "Reginaldus, qui obiit 1214—one thousand, two hundred and 14."

The identity of this Reginald is not clear. Bishop Reginald of Wells, who consecrated the Chapel of St. Mary at Glastonbury, died in 1191 according to the chronicles. The Chapel is said to have been completed in 1216.

The script has been retraced, as it was done in soft pencil and could not be preserved.

SITTING XXIX. 20th April, 1908.

"Gloria in excelsis tibi Deo. Pax vobiscum, filii.

"The time is near. Dig well and those things which ye seek shall be given you but serche carefully lest ye eradicate those things that be left for your guidance....

"... the est end will be the first, and then ye shall find proof of ye goodly towers at ye west end.17 Serche the ruins for the way they were finished. There is much left to guide you...."

"... Influence man, and that which was before decreed shall aid you and they who are around you shall feel your influence and ours.

"In very truth it was a goodly church and it is said that ye of your time shall know what works we did pro gloria Dei.

47

"We were mistaken in some things—all men are—but the thought that made the great church of Glaston was not bounded by ye mind and that thought must live and prevail.

"Move, work, and unceasingly persist, and in time there will be a place for what once was and ye shall know its buildings yet again as they were wont to be. The lesser works first: and then cometh one who will build the great church—a son of Glaston from beyond the sea. Even now he waits and watches. We wait and watch and hope with the knowledge that comes to men on the other side. The church is always the church, and in the great schema of the world we come soon and our instrument Glaston shall find a mighty place.... Thus Johannes saith."

At this point the sequence of the writing is broken by the story of Johannes going a-fishing, and lingering in the lanes. This we give in Part II.

Q. "We should like to know something of the nature of the old foundations which were found under the Quire in the 1904 excavations, also whether any light can be thrown upon the subterranean piers, their date and purpose?"

"... The window was straight as we knew it, but18 was somewhat changed by Abbot Beere when he made the chapell. Ye are right about ye end walls. Johannes saw to the building thereof for they were five years before they builded the last part because there was nothing in the coffers—so the church was perfect without the new parts.

"What was it Beere performed? We will remember. The olde church had a chapell going east like to Edgar's and the corners were cut off most like. The foundations ye mean remain. We know but that which we heard and that which they who followed after did, we know not, save only we can enquire.

"Beere, Abbot, is not with us now. He has a work to48 perform. There are others who build in your England and he hath to lead them as they should be led. They who builded in our day and were masters, lead ye now.

"ROBERT. ANNO 1334. GLASTON."

NOTE ON SITTING XXIX.

The blending of influences is again very marked, but the dominant thought is that of one of the inmates of the great abbatial House. The signature "Robert" (anno 1334) does not help us. This was the year that witnessed the election of John de Breynton as Abbot, vice Adam de Sodbury, and it was an era of great building activities. But Robert speaks, or is made to speak, for those of an era two hundred years later, or nearly, and it is strange to find a voice from the fourteenth century recalling the "window" as it then was, and going on to describe alterations made at the beginning of the sixteenth.

And the allusion to Abbot Beere's living influence is of peculiar interest. Among the best modern exponents of the Gothic English styles, the call of the past, and the influence of the past, is vital as an element in their work, and it is precisely in the measure in which they are able to translate the spirit of the past, that they can claim inspiration in what they strive to produce.19 Occasionally a sincere student will obtain some mental pictures of a bygone time of singular clearness and fidelity, whence, he knows not; only that they are spontaneously apparent to him when in a49 state of mental passivity after intellectual exertion in the particular direction needed. It may be of interest here to quote an experience once related to the writer by an old friend, W., now retired from practice, but who in the 80's of the last century was responsible for a good deal of scholarly restoration work in the west country. W. was very partial to the Early English forms, and if he had a fault, it was the fault of his day, when restorers were a little ruthless, as we should think nowadays, in substituting Early English detail for the fifteenth century "vernacular" of the district. On one occasion he was called upon to undertake "restoration"—which, in this case, meant a partial rebuilding—of a decayed church in the very decayed town of I. The south wall of the nave, a work of the ordinary "Perpendicular" sort, had to be rebuilt, and he had to construct a new arcade for the aisle adjoining. Somehow he felt disinclined to do this in the fifteenth-century style, but was prompted to design afresh, in the manner of the thirteenth. And for his pillars he imagined a form of capital having rather a complex moulding. There was nothing visible to guide him, but it appealed to him as suitable. Nor was it a local type—at least, this would be the writer's recollection of the impression he derived from the drawing which W. showed him.

The capitals were provided of this pattern, the old wall was pulled down, and hidden within it and built into its substance was found a pier-capital of a moulding identical in detail. I myself50 was satisfied that he had never seen any particle of this early work, and he allows me to retell the story here. As to the story of Johannes, the truant monk and nature-lover, it takes the form of an interpretation of his memory-record by another. Whether we are dealing with a singularly vivid imaginative picture or with the personality of a man no one can really decide. But later examples will elucidate the part he plays in the scheme, and it is one of much interest from the psychological point of view.

SITTING XXIX.—Continued. 20th April, 1908.

"Ye crypt was mere a chamber under the stairs and it was at the west end of the chapel. It was not for sepulture and it is gone long syne by reason of the fall of the floor of ye chapel.

"Yt wasne underground and was low—a man might hardly walk sans stooping."