![[Figure 1]](images/p1t.jpg)

Project Gutenberg's Psychological Warfare, by Paul M. A. Linebarger This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Psychological Warfare Author: Paul M. A. Linebarger Release Date: March 30, 2015 [EBook #48612] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE *** Produced by Adam Buchbinder, Heike Leichsenring and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

By

PAUL M. A. LINEBARGER

School of Advanced International Studies

DUELL, SLOAN AND PEARCE

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT 1948, 1954, BY PAUL M. A. LINEBARGER

All rights reserved. No part of this book in excess of five hundred words may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 48-1799

SECOND EDITION

SECOND PRINTING

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FOR

GENEVIEVE, MY WIFE,

WITH LOVE

The present edition of this work has been modified to meet the needs of the readers of the mid-1950s. The material in the first edition following page 244 has been removed; it consisted of a chapter hopefully called "Psychological Warfare and Disarmament." A new Part Four, comprising three fresh chapters, has been added, representing some of the problems confronting students and operators in this field. Pages 1-243 are a reprint from the first edition.

This edition, like the first, is the product of field experience. The author has made nine trips abroad, five of them to the Far East, since 1949. He has profited by his meeting with such personalities as Sir Henry Gurney, the British High Commissioner for the Federation of Malaya, who was later murdered by the Communists, meetings with Philippine, Republic of Korea, Chinese Nationalist, captured Chinese Communist and other personalities, as well as by association with such veterans in the field as General MacArthur's chief psywar expert, Colonel J. Woodall Greene. To Colonel Joseph I. Greene, who died in 1953, the author is indebted as friend and colleague. He owes much to the old friends, listed in the original acknowledgment, who offered their advice and comment in many instances.

Many readers of the first edition wrote helpful letters of comment. Some of their suggestions have been incorporated here. The translators of the two Argentine editions of this book; the translator of the Japanese edition, the Hon. Suma Yokachiro; and the translator of the first and second Chinese editions, Mr. Ch'ên En-ch'êng—all of them have made direct or indirect improvements in the content or style of the work.

The author also wishes to thank his former student, later his former ORO colleague, now his wife, Dr. Genevieve Linebarger, for her encouragement and her advice.

The author hopes that, as U. S. agencies and other governments move toward a more settled definition of doctrine in this field, a third edition—a few years from now—may be able to reflect the maturation of psywar in international affairs. He does not consider the time appropriate for a fundamental restatement of doctrine; he hopes that readers who have suggestions for future definitions of scope, policy, or operations can communicate these to him for inclusion in later printings of this book.

P.M.A.L.

3 August 1954

This book is the product of experience rather than research, of consultation rather than reading. It is based on my five years of work, both as civilian expert and as Army officer, in American psychological warfare facilities—at every level from the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff planning phase down to the preparing of spot leaflets for the American forces in China. Consequently, I have tried to avoid making this an original book, and have sought to incorporate those concepts and doctrines which found readiest acceptance among the men actually doing the job. The responsibility is therefore mine, but not the credit.

Psychological warfare involves exciting wit-sharpening work. It tends to attract quick-minded people—men full of ideas. I have talked about psychological warfare with all sorts of people, all the way from Mr. Mao Tse-tung in Yenan and Ambassador Joseph Davies in Washington to an engineer corporal in New Zealand and the latrine-coolie, second class, at our Chungking headquarters. I have seen one New York lawyer get mentally befuddled and another New York lawyer provide the solution, and have seen Pulitzer Prize winners run out of ideas only to have the stenographers supply them. From all these people I have tried to learn, and have tried to make this book a patchwork of enthusiastic recollection. Fortunately, the material is non-copyright; unfortunately, I cannot attribute most of these comments or inventions to their original proponents. Perhaps this is just as well: some authors might object to being remembered.

A few indebtednesses stand out with such clarity as to make acknowledgment a duty. These I wish to list, with the caution that this list is not inclusive.

First of all, I am indebted to my father, Judge Paul M. W. Linebarger (1871-1939), who during his lifetime initiated me into almost every phase of international political warfare, whether covert or overt, in connection with his life-long activities on behalf of Sun Yat-sen and the Chinese Nationalists. On a limited budget (for years, out of his own pocket) he ran campaigns against imperialism and communism, and for Sino-American friendship and Chinese democracy, in four or five languages at a time. For five and a half years I was his secretary, and believe that this experience has kept me from making this a book of exclusively American doctrine. There is no better way to learn the propaganda job than to be whipped thoroughly by someone else's propaganda.

Second only to my debt to my father, my obligation to the War Department General Staff officers detailed to Psychological Warfare stands forth. By sheer good fortune, the United States had an unbroken succession of intelligent, conscientious, able men assigned to this vital post, and it was my own good luck to serve under each of them in turn between [Pg viii] 1942 and 1947. They are, in order of assignment: Colonel Percy W. Black, Brigadier General Oscar N. Solbert, Colonel Charles Blakeney, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Alexander Holmes Thomson, Colonel John Stanley, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hirsch, Lieutenant Colonel Bruce Buttles, Colonel Dana Johnston, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Tatum, and Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Edwards. Their talents and backgrounds were diverse but their ability was uniformly high. I do not attribute this to the peculiar magic of Psychological Warfare, nor to unwonted prescience on the part of The Adjutant General, but to plain good luck.

Especial thanks are due to the following friends, who have read this manuscript in whole or in part. I have dealt independently with the comments and criticism, so that none of them can be blamed for the final form of the book. These are Dr. Edward K. Merat, the Columbia-trained MIS propaganda analyst; Mr. C. A. H. Thomson, State Department international information consultant and Brookings Institution staff member; Professor E. P. Lilly of Catholic University and concurrently Psychological Warfare historian to the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Lieutenant Colonel Innes Randolph; Lieutenant Colonel Heber Blankenhorn, the only American to have served as a Psychological Warfare officer in both World Wars; Dr. Alexander M. Leighton, M.D., the psychiatrist and anthropologist who as a Navy lieutenant commander headed the OWI-MIS Foreign Morale Analysis Division in wartime; Mr. Richard Hirsch; Colonel Donald Hall, without whose encouragement I would never have finished this book; Professor George S. Pettee, whose experience in strategic intelligence lent special weight to his comment; Colonel Dana Johnston; Mr. Martin Herz, who may some day give the world the full account of the mysterious Yakzif operations; and Mrs. M. S. Linebarger.

Further, I must thank several of my associates in the propaganda agencies whose thinking proved most stimulating to mine. Mr. Geoffrey Gorer was equally brilliant as colleague and as ally. Dean Edwin Guthrie brought insights to Psychological Warfare which were as much the reflection of a judicious, humane personality as of preeminent psychological scholarship. Professor W. A. Aiken, himself a historian, provided data on the early history of U. S. facilities in World War II. Mr. F. M. Fisher and Mr. Richard Watts, Jr., of the OWI China Outpost, together with their colleagues, taught me a great deal by letting me share some of their tasks and my immediate chief in China, Colonel Joseph K. Dickey, was kind to allow a member of his small, overworked staff to give time to Psychological Warfare. Messrs. Herbert Little, John Creedy and C. A. Pearce have told me wonderful stories about their interesting end of propaganda. Mr. Joseph C. Grew, formerly Under Secretary [Pg ix] of State and Ambassador to Japan, showed me that the processes of traditional responsible diplomacy include many skills which Psychological Warfare rediscovers crudely and in different form.

Finally, I wish to thank Colonel Joseph I. Greene in his triple role of editor, publisher and friend, to whom this volume owes its actual being.

While this material has been found unobjectionable on the score of security by the Department of the Army, it certainly does not represent Department of the Army policy, views, or opinion, nor is the Department responsible for matters of factual accuracy. I assume sole and complete responsibility for this book and would be glad to hear the comment or complaint of any reader. My address is indicated below.

Paul M. A. Linebarger

2831 29th Street N.W.

Washington 8, D. C.

20 June 1947

| Acknowledgments | vii | |

| PART ONE: DEFINITION AND HISTORY | ||

| CHAPTER 1: | Historic Examples of Psychological Warfare | 1 |

| CHAPTER 2: | The Function of Psychological Warfare | 25 |

| CHAPTER 3: | Definition of Psychological Warfare | 37 |

| CHAPTER 4: | The Limitations of Psychological Warfare | 48 |

| CHAPTER 5: | Psychological Warfare In World War I | 62 |

| CHAPTER 6: | Psychological Warfare In World War II | 77 |

| PART TWO: ANALYSIS, INTELLIGENCE, AND ESTIMATE OF THE SITUATION | ||

| CHAPTER 7: | Propaganda Analysis | 110 |

| CHAPTER 8: | Propaganda Intelligence | 132 |

| CHAPTER 9: | Estimate of the Situation | 150 |

| PART THREE: PLANNING AND OPERATIONS | ||

| CHAPTER 10: | Organization for Psychological Warfare | 168 |

| CHAPTER 11: | Plans and Planning | 194 |

| CHAPTER 12: | Operations for Civilians | 203 |

| CHAPTER 13: | Operations Against Troops | 211 |

| PART FOUR: PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE AFTER WORLD WAR II | ||

| CHAPTER 14: | The "Cold War" and Seven Small Wars | 244 |

| CHAPTER 15: | Strategic International Information Operations | 268 |

| CHAPTER 16: | Research, Development and the Future | 283 |

| APPENDIX: | Military PsyWar Operations, 1950-53 | 301 |

| Index | 309 | |

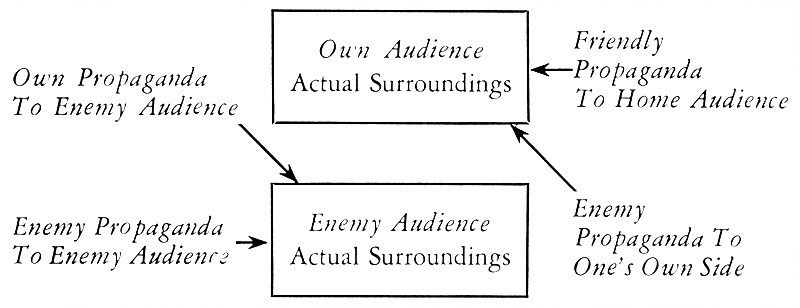

| 1: | A Basic Form of Propaganda | 2 |

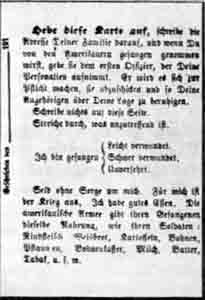

| 2: | Nazi Troop Morale Leaflet | 4 |

| 3: | One of the Outstanding Leaflets of the War | 5 |

| 4: | The Pass Which Brought them in | 6 |

| 5: | Revolutionary Propaganda | 9 |

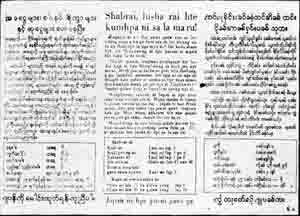

| 6: | Propaganda for Illiterates | 10-11 |

| 7: | Propaganda Through News | 13 |

| 8: | One of the Mongol Secret Weapons | 14 |

| 9: | Black Propaganda from the British Underground, 1690 | 18-19 |

| 10: | Secret American Propaganda Subverting the Redcoats | 20 |

| 11: | Desertion Leaflet from Bunker Hill | 21 |

| 12: | Money as a Carrier of Propaganda | 22-23 |

| 13: | Surrender Leaflet from the AEF | 70 |

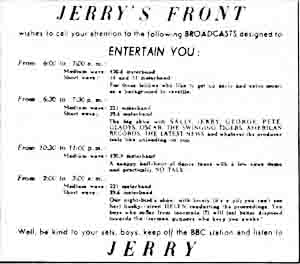

| 14: | Radio Program Leaflet, Anzio, 1944 | 82 |

| 15: | Radio Leaflet Surrender Form, Anzio, 1944 | 83 |

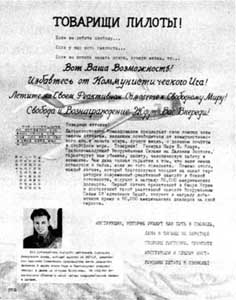

| 16: | Invitation to Treason | 84 |

| 17: | Anti-Radio Leaflet | 86 |

| 18: | Anti-Exhibit Leaflet | 96 |

| 19: | Propaganda Against Propaganda | 100 |

| 20: | Re-Use of Enemy Propaganda | 102 |

| 21: | Mockery of Enemy Propaganda Slogans | 118 |

| 22: | Mockery of Enemy Propaganda Technique | 119 |

| 23: | Direct Reply Leaflet | 120 |

| 24: | Black Use of Enemy Subversive Materials | 121 |

| 25: | Black Use of Enemy Information Materials | 122-123 |

| 26: | Religious Black | 124 |

| 27: | Malingerer's Black | 125 |

| 28: | Nostalgic Black | 133 |

| 29: | Nostalgic White, Misfire | 134 |

| 30: | Nostalgic White | 135 |

| 31: | Oestrous Black | 137 |

| 32: | Oestrous Grey | 138 |

| 33: | Oestrous Grey, Continued | 139 |

| 34: | Obscene Black | 141 |

| 35: | Informational Sheet | 142 |

| 36: | Counterpropaganda Instructions | 144 |

| 37: | Defensive Counterpropaganda | 146 |

| 38: | Black "Counterpropaganda" | 148 |

| 39: | Leaflet Production: Military Presses | 169 |

| 40: | Leaflet Production: Rolling | 169 |

| 41: | Leaflet Distribution: Attaching Fuzes | 170 |

| 42: | Leaflet Distribution: Packing the Boxes | 171 |

| 43: | Leaflet Distribution: Loading the Boxes | 172 |

| 44: | Leaflet Distribution: Bombs at the Airfield | 172 |

| 45: | Leaflet Distribution: Loading the Bombs | 173 |

| 46: | Leaflet Distribution: The Final Result | 174 |

| 47: | Consolidation Propaganda: The Movie Van | 175 |

| 48: | Consolidation Propaganda: Posters | 176 |

| 49: | Consolidation Propaganda: Photo Exhibit | 176 |

| 50: | Consolidation Propaganda: Door Gods | 188 |

| 51: | Basic Types: Start of War | 198 |

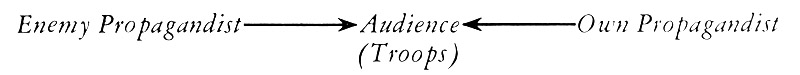

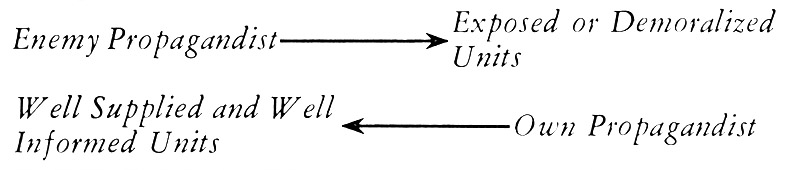

| 52: | Basic Types: Troop Morale | 212 |

| 53: | Paired Morale Leaflets | 213 |

| 54: | Troop Morale Leaflet, Grey | 214 |

| 55: | Chinese Communist Civilian Morale Leaflet | 215 |

| 56: | General Morale: Matched Themes | 215 |

| 57: | The Unlucky Japanese Sad Sack | 216-217 |

| 58: | Civilian Personal Mail | 218-219 |

| 59: | Basic Types: Newspapers | 220 |

| 60: | Basic Types: Spot-News Leaflets | 221 |

| 61: | Basic Types: Civilian Action | 222 |

| 62: | Basic Types: Labor Recruitment | 224 |

| 63: | Action Type: Air-Rescue Facilities | 231 |

| 64: | Pre-Action News | 232 |

| 65: | Direct Commands to Enemy Forces | 233 |

| 66: | Basic Types: Contingency Commands | 234 |

| 67: | Tactical Surrender Leaflets | 235 |

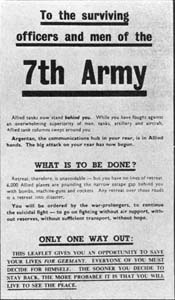

| 68: | Basic Types: Surrender Leaflet | 236 |

| 69: | Improved Surrender Leaflet | 239 |

| 70: | End of War | 241 |

| 71: | Official Chinese Letter | 250 |

| 72: | Intimidation Pattern | 256 |

| 73: | Communist Wall Propaganda | 258 |

| 74: | Divisive Propaganda, Korean Model | 266 |

| 75: | UN Propaganda | 302 |

| 76: | Korean Leaflet Bomb, Early Model | 303 |

| 77: | UN Themes | 305 |

| 78: | Home-front Morale | 306 |

| 79: | The Famous Airplane Surrender Leaflet | 308 |

| Chart | I | 92 |

| Chart | II | 95 |

| Chart | III | 112 |

| Chart | IV | 130 |

| Chart | V | 180 |

| Chart | VI | 181 |

| Chart | VII | 183 |

| Chart | VIII | 185 |

| Chart | IX | 190 |

| Chart | X | 248* |

Psychological warfare is waged before, during, and after war; it is not waged against the opposing psychological warfare operators; it is not controlled by the laws, usages, and customs of war; and it cannot be defined in terms of terrain, order of battle, or named engagements. It is a continuous process. Success or failure is often known only months or years after the execution of the operation. Yet success, though incalculable, can be overwhelming; and failure, though undetectable, can be mortal.

Psychological warfare does not fit readily into familiar concepts of war. Military science owes much of its precision and definiteness to its dealing with a well defined subject, the application of organized lawful violence. The officer or soldier can usually undertake his task of applying mass violence without having to determine upon the enemy. The opening of war, recognition of neutrals, the listing of enemies, proclamation of peace—such problems are considered political, and outside the responsibility of the soldier. Even in the application of force short of war, the soldier proceeds only when the character of the military operation is prescribed by higher (that is, political) authorities, and after the enemies are defined by lawful and authoritative command. In one field only, psychological warfare, is there endless uncertainty as to the very nature of the operation.

Psychological warfare, by the nature of its instruments and its mission, begins long before the declaration of war. Psychological warfare continues after overt hostilities have stopped. The enemy often avoids identifying himself in psychological warfare; much of the time, he is disguised as the voice of home, of God, of the church, of the friendly press. Offensively, the psychological warfare operator must fight antagonists who never answer back—the enemy audience. He cannot fight the one enemy who is in plain sight, the hostile psychological warfare operator, because the hostile operator is greedily receptive to attack. Neither success nor defeat are measurable factors. Psychological strategy is planned along the edge of nightmare.

The best approach is perhaps afforded by a simplification of both a logical and historical approach. For concrete examples it is most worthwhile [Pg 2] to look at instances of psychological warfare taken out of history down to World War II.[Pg 3] Then the definitions and working relationships can be traced and—with these in mind—a somewhat more detailed and critical appraisal of World Wars I and II organizations and operations can be undertaken. If a historian or philosopher picks up this book, he will find much with which to quarrel, but for the survey of so hard-to-define a subject, this may be a forgivable fault.

![[Figure 1]](images/p1t.jpg)

Psychological warfare and propaganda are each as old as mankind; but it has taken modern specialization to bring them into focus as separate subjects. The materials for their history lie scattered through thousands of books and it is therefore impossible to brief them. Any reader contemplating retirement from the army to a sedentary life is urged to take up this subject.1 A history of propaganda would provide not only a new light on many otherwise odd or trivial historical events; it would throw genuine illumination on the process of history itself. There are however numerous instances which can be cited to show applications of psychological warfare.

The story is told in the seventh chapter of the Book of Judges. Gideon was in a tactically poor position. The Midianites outnumbered him and were on the verge of smiting him very thoroughly. Ordinary combat methods could not solve the situation, so Gideon—acting upon more exalted inspiration than is usually vouchsafed modern commanders—took the technology and military formality of his time into account.

Retaining three hundred selected men, he sought for some device which would cause real confusion in the enemy host. He knew well that the tactics of his time called for every century of men to have one light-carrier and one torch-bearer for the group. By equipping three hundred men with a torch and a trumpet each, he could create the effect of thirty thousand. Since the lights could not be turned on and off with switches, like ours, the pitchers concealed them, thus achieving the effect of suddenness.

![[Figure 2]](images/p2t.jpg)

![[Figure 3]](images/p3t.jpg)

![[Figure 4]](images/p4t.jpg)

He had his three hundred men equipped with lamps and pitchers. The lamps were concealed in the pitchers, each man carrying one, along with a trumpet. He lined his forces in appropriate disposition around the enemy camp at night and had them—himself setting the example—break the pitchers all at the same time, while blowing like mad on the trumpets.

The Midianites were startled out of their sleep and their wits. They fought one another throughout their own camp. The Hebrew chronicler modestly gives credit for this to the Lord. Then the Midianites gave up altogether and fled. And the men of Israel pursued after the Midianites.2 That settled the Midianite problem for a while; later Gideon finished Midian altogether.

This type of psychological warfare device—the use of unfamiliar instruments to excite panic—is common in the history of all ancient countries. In China, the Emperor-usurper Wang Mang on one occasion tried to destroy the Hunnish tribes with an army that included heavy detachments of military sorcerers, even though the Han Military Emperor had found orthodox methods the most reliable; Wang Mang got whipped[Pg 6][Pg 7] at this. But he was an incurable innovator and in 23 A.D., while trying to put down some highly successful rebels, he collected all the animals out of the Imperial menagerie and sent them along to scare the enemy: tigers, rhinoceri, and elephants were included. The rebels hit first, killing the Imperial General Wang Sun, and in the excitement the animals got loose in the Imperial army where they panicked the men. A hurricane which happened to be raging at the same time enhanced the excitement. Not only were the Imperial troops defeated, but the military propaganda of the rebels was so jubilant in tone and so successful in effect that the standard propaganda theme, "Depress and unnerve the enemy commander," was fulfilled almost to excess on Wang Mang. Here is what happened to him after he noted the progress of the enemy: "A profound melancholy fell upon the Emperor. It undermined his health. He drank to excess, ate nothing but oysters, and let everything happen by chance. Unable to stretch out, he slept sitting up on a bench."3 Wang Mang was killed in the same year, and China remained without another economic new deal until the time of Wang An-shih (A.D. 1021-1086), a thousand years later. Better psychological warfare would have changed history.

Themistocles, having selected the best sailing ships of the Athenians, went to the place where there was water fit for drinking, and engraved upon the stones inscriptions, which the Ionians, upon arriving the next day at Artemisium, read. The inscriptions were to this effect, 'Men of Ionia, you do wrong in fighting against your fathers and helping to enslave Greece. Rather, therefore, come over to us or if you cannot do that, withdraw your forces from the contest and entreat the Carians to do the same. But if neither of these things is possible, and you are bound by too strong a necessity, yet in action, when we are engaged, behave ill on purpose, remembering that you are descended from us and that the enmity of the barbarians against us originally sprang from you.'4

This text is very much like leaflets dropped during World War II on reluctant enemies, such as the Italians, the Chinese puppet troops, and others. (Compare this Greek text with Figure 5.) Note that the propagandist tries to see things from the viewpoint of his audience. His air[Pg 8] of reasonable concern for their welfare creates a bond of sympathy. And by suggesting that the Ionians should behave badly in combat, he lays the beginning of another line—the propaganda to the Persians, "black" propaganda making the Persians think that any Ionian who was less than perfect was a secret Athenian sympathizer. The appeal is sound by all modern standards of the combat-leaflet.

Another type of early military propaganda was the political denunciation which, issued at the beginning of war, could be cited from then on as legal and ethical justification for one side or the other. In the Chinese San Kuo novel, which has probably been read by more human beings than any other work of fiction, there is preserved the alleged text of the proclamation of a group of loyalist pro-Han rebels on the eve of military operations (about A.D. 200). The text is interesting because it combines the following techniques, all of them sound: 1) naming the specific enemy; 2) appeal to the "better people"; 3) sympathy for the common people; 4) claim of support for the legitimate government; 5) affirmation of one's own strength and high morale; 6) invocation of unity; 7) appeal to religion. The issuance of the proclamation was connected with rather elaborate formal ceremony:

The House of Han has fallen upon evil days, the bonds of Imperial authority are loosened. The rebel minister, Tung Cho, takes advantage of the discord to work evil, and calamity falls upon honorable families. Cruelty overwhelms simple folk. We, Shao and his confederates, fearing for the safety of the imperial prerogatives, have assembled military forces to rescue the State. We now pledge ourselves to exert our whole strength, and to act in concord to the utmost limit of our powers. There must be no disconcerted or selfish action. Should any depart from this pledge may he lose his life and leave no posterity. Almighty Heaven and Universal Mother Earth and the enlightened spirits of our forefathers, be ye our witnesses.5

Any history of any country will yield further examples of this kind of material. Whenever it was consciously used as an adjunct to military operations, it may appropriately be termed military propaganda.

![[Figure 5]](images/p5t.jpg)

![[Figure 6]](images/p6_1t.jpg)

![[Figure 7]](images/p7t.jpg)

The expansion of the Islamic Faith-and-Empire provides a great deal[Pg 13] of procedural information which cannot be neglected in our time. It has been said that men's faith should not be destroyed by violence, and that force alone is insufficient to change the minds of men. If this were true, it would mean that Germany can never be de-Nazified, and that there is no hope that the democratic peoples captured by totalitarian powers can adjust themselves to their new overlords or, if adjusted, can be converted back to free principles. In reality warfare by Mohammed's captains and successors demonstrated two principles of long-range psychological warfare which are still valid today:

A people can be converted from one faith to the other if given the choice between conversion and extermination, stubborn individuals being rooted out. To effect the initial conversion, participation in the public ceremonies and formal language of the new faith must be required. Sustained counterintelligence must remain on the alert against backsliders, but formal acceptance will become genuine acceptance if all public media of expression are denied the vanquished faith.

If immediate wholesale conversion would require military operations that were too extensive or severe, the same result can be effected by toleration of the objectionable faith, combined with the issuance of genuine privileges to the new, preferred faith. The conquered people are left in the private, humble enjoyment of their old beliefs and folkways; but all participation in public life, whether political, cultural or economic, is conditioned on acceptance of the new faith. In this manner, all up-rising members of the society will move in a few generations over to the new faith in the process of becoming rich, powerful, or learned; what is left of the old faith will be a gutter superstition, possessing neither power nor majesty.

These two rules worked once in the rise of Islam. They were applied again by Nazi overlords during World War II, the former in Poland, the Ukraine and Byelorussia, the latter in Holland, Belgium, Norway and other Western countries. The rules will probably be seen in action again. The former process is difficult and bloody, but quick; the latter is as sure as a steam-roller. If Christians, or democrats, or progressives—whatever free men may be called—are put in a position of underprivilege and shame for their beliefs, and if the door is left open to voluntary conversion, so that anyone who wants to can come over to the winning side, the winning side will sooner or later convert almost everyone who is capable of making trouble. (In the language of Vilfredo Pareto,[Pg 14] this would probably be termed "capture of the rising elite"; in the language of present-day Marxists, this would be described as "utilization of potential leadership cadres from historically superseded classes"; in the language of practical politics, it means "cut in the smart boys from the opposition, so that they can't set up a racket of their own.")

![[Figure 8]](images/p8t.jpg)

Genghis even used the spies of the enemy as a means of frightening the enemy. When spies were at hand he indoctrinated them with rumors concerning his own forces. Let the first European biographer of Genghis tell, in his own now-quaint words, how Genghis put the bee on Khorezm (Carizme):

And a Historian, to describe their Strength and Number, makes the Spies whom the King of Carizme had sent to view them, speak thus: They are, say they to the Sultan, all compleat Men, vigorous, and look like Wrestlers; they breathe nothing but War and Blood, and show so great an Impatience to fight, that the Generals can scarce moderate it; yet though they appear thus fiery, they keep themselves within the bounds of a strict Obedience to Command, and are intirely devoted to their Prince; they are contented with any sort of Food, and are not curious in the choice of Beasts to eat, like Mussulmen [Mohammedans], so that they are subsisted without much trouble; and they not only eat Swines-Flesh, but feed upon Wolves, Bears, and Dogs, when they have no other Meat, making no distinction between what was lawful to eat, and what was forbidden; and the Necessity for supporting Life takes from them all the Dislike which the Mahometans have for many sorts of Animals; As to their Number, (they concluded) Genghizcan's Troops seem'd like the Grasshoppers, impossible to be number'd.

In reality, this Prince making a Review of his Army, found it to consist of seven hundred thousand men....7

Enemy espionage can now—as formerly—prove useful if the net effect of it is to lower enemy morale. The ruler and people of Khorezm put up a terrific fight, nevertheless, despite their expectation of being attacked by wolf-eating wrestlers without number; but they left the initiative in Genghis' hands and were doomed.

However good the Mongols were in strategic and tactical propaganda,[Pg 16] they never solved the problem of consolidation propaganda (see page 46, below). They did not win the real loyalty of the peoples whom they conquered; unlike the Chinese, who replaced conquered populations with their own people, or the Mohammedans, who converted conquered peoples, the Mongols simply maintained law and order, collected taxes, and sat on top of the world for a few generations. Then their world stirred beneath them, and they were gone.

Milton fell into the common booby-trap of refuting his opponents item by item, thus leaving them the strong affirmative position, instead of providing a positive and teachable statement of his own faith. He was Latin Secretary to the Council, in that Commonwealth of England which was—to its contemporaries in Europe—such a novel, dreadful, and seditious form of government. The English had killed their king, by somewhat offhanded legal procedures, and had gone under the Cromwellian dictatorship. It was possible for their opponents to attack them from two sides at once. Believers in monarchy could call the English murderous king-killers (a charge as serious in those times as the charge of anarchism or free love in this); believers in order and liberty could call the British slaves of a tyrant. A Frenchman called Claude de Saumaise (in Latin form, Salmasius) wrote a highly critical book about the English, and Milton seems to have lost his temper and his judgment.

In his two books against Salmasius, Milton then committed almost every mistake in the whole schedule of psychological warfare. He moved from his own ground of argument over to the enemy's. He wrote at excessive length. He indulged in some of the nastiest name-calling to be found in literature, and went into considerable detail to describe Salmasius in unattractive terms. He slung mud whenever he could. The books are read today, under compulsion, by Ph.D. candidates, but no one else is known to find them attractive. It is not possible to find that these books had any lasting influence in their own time. (In these texts written by Milton in Latin but now available in English, Army men wearying of the monotonous phraseology of basic military invective can find extensive additions to their vocabulary.) Milton turned to disappointment and poetry; the world is the gainer.

The vocabulary of seventeenth-century propaganda had a strident tone which is, perhaps unfortunately, getting to be characteristic of the twentieth century. The following epithets sound like an American Legion description of Communists, or a Communist description of the Polish democrats, yet they were applied in a book by a Lutheran to Quakers. The title of the tirade reads, in part:

... a description of the ... new Quakers, making known the sum of their manifold blasphemous opinions, dangerous practices, Godless crimes, attempts to subvert civil government in the churches and in the community life of the world; together with their idiotic games, their laughable action and behavior, which is enough to make sober Christian persons breathless, and which is like death, and which can display the lazy stinking cadaver of their fanatical doctrines....

In its first few pages, the book accuses the Quakers of obscenity, adultery, civil commotion, conspiracy, blasphemy, subversion and lunacy.8 Milton was not out of fashion in applying bad manners to propaganda. It is merely regrettable that he did not transcend the frailties of his time.

Such a list just begins to touch on subjects which can and should be investigated, either as staff studies or by civilian historians. Collection of the materials and framing of sound doctrines for psychological warfare are no minor task.

![[Figure 9]](images/p9_1t.jpg)

![[Figure 10]](images/p10t.jpg)

![[Figure 11]](images/p11t.jpg)

The Americans made extensive use of the press.9 When the newspaper proprietors veered too far to the Loyalist side, they were warned to keep to a more Patriotic line. If, in the face of counter-threats from the Loyalists, the newspaper threatened going out of business altogether, [Pg 22] it was warned that suspension of publication would be taken as treason to America.[Pg 23] The Whigs, before hostilities, and their successors, the Patriots of the war period, showed a keen interest in keeping the press going and in making sure that their side of the story got out and got circulated rapidly. In intimidation and control of the press, they far outdistanced the British, whose papers circulated chiefly within the big cities held as British citadels throughout the war. Political reasoning, economic arguments, allegations concerning the course of the war, and atrocity stories all played a role.

![[Figure 12]](images/p12_1t.jpg)

George Washington himself, as commander of the Continental forces, showed a keen interest in war propaganda and in his just, moderate political and military measures provided a policy base from which Patriot propagandists could operate.

Some wars are profoundly affected by a book written on one side or the other; the American revolutionary war was one of these. Thomas Paine's Common Sense (issued as a widely sold series of pamphlets) swept American opinion like wildfire; it stated some of the fundamentals of American thinking, and put its bold but reasonable revolutionary case in such simple terms that even conservatives in the Patriot group could not resist using it for propaganda purposes.10 Common Sense has become a classic of American literature, but it has its place in history too, as "the book that won the war." Other pamphleteers, with the redoubtable Sam Adams in the lead, also did well.

American experience in the Mexican war was less glorious. The Mexicans waged psychological warfare against us with considerable effect, ending up with traitor American artillerymen dealing out heavy murder to the American troops outside Mexico city. Historians in both[Pg 24] countries gloss over the treason and subversion which occurred on each side.

In the Civil War, psychological warfare was practised by both Lincoln and the Confederacy in establishing propaganda instrumentalities in England and on the continent of Europe. The Northern use of Negro troops, which was followed, at the end of the war by the Confederate plans for raising Negro troops, did not become the major propaganda issue it might have because of the community of feeling on the two sides, indecision on each side as to the purpose of the war (apart from the basic issue of union or disunion), and the persistence of politics-as-usual both North and South of the battle line.

The Boers, on the other hand, made a stir throughout the world. They got in touch with the Germans, Irish, Americans, French, Dutch, and everybody else who might criticize Britain. They stated their case loudly and often. They waged commando warfare, adding the word commando to international military parlance, and sent small units deep into the British rear, setting off a mad uproar and making the world press go crazy with excitement. When they finally gave in, it was on reasonable terms for themselves; they left the British with an internationally blacked eye.

Nobody remembered the Burmese; everybody remembered the Boers. The Boers used every means they could think of; they did everything they could. They even captured Winston Churchill.

These examples may show that the military role of propaganda and related operations is not as obscure or intangible as it may have seemed. They cannot be considered history but must be regarded as a plea for the writing of history. More recent experience is another question, and involves tracing the doctrines pertaining to psychological warfare which have now become established military procedure in the modern armies.

Psychological warfare in the broad sense, consists of the application of parts of the science called psychology to the conduct of war; in the narrow sense, psychological warfare comprises the use of propaganda against an enemy, together with such military operational measures as may supplement the propaganda. Propaganda may be described, in turn, as organized persuasion by non-violent means. War itself may be considered to be, among other things, a violent form of persuasion. Thus if an American fire-raid burns up a Japanese city, the burning is calculated to dissuade the Japanese from further warfare by denying the Japanese further physical means of war and by simultaneously hurting them enough to cause surrender. If, after the fire-raid, we drop leaflets telling them to surrender, the propaganda can be considered an extension of persuasion—less violent this time, and usually less effective, but nevertheless an integral part of the single process of making the enemy stop fighting.

Neither warfare nor psychology is a new subject. Each is as old as man. Warfare, being the more practical and plain subject, has a far older written history. This is especially the case since much of what is now called psychology was formerly studied under the heading of religion, ethics, literature, politics, or medicine. Modern psychological warfare has become self-conscious in using modern scientific psychology as a tool.

In World War II the enemies of the United States were more fanatical than the people and leaders of the United States. The consequence was that the Americans could use and apply any expedient psychological weapon which either science or our version of common sense provided. We did not have to square it with Emperor myths, the Führer principle or some other rigid, fanatical philosophy. The enemy enjoyed the positive advantage of having an indoctrinated army and people; we enjoyed the countervailing advantage of having skeptical people, with no inward theology that hampered our propaganda operations. It is no negligible matter to be able to use the latest findings of psychological science in a swift, bold manner. The scientific character of our psychology puts us ahead of opponents wrapped up in dogmatism who must check their propaganda against such articles of faith as Aryan racialism or the Hegelian philosophy of history.

What can psychology do for warfare?

In the first place, the psychologist can bring to the attention of the soldier those elements of the human mind which are usually kept out of sight. He can show how to convert lust into resentment, individual resourcefulness into mass cowardice, friction into distrust, prejudice into fury. He does so by going down to the unconscious mind for his source materials. (During world War II, the fact that Chinese babies remain unimpeded while they commit a nuisance, while Japanese babies are either intercepted or punished if they make a mess in the wrong place, was found to be of significant importance in planning psychological warfare. See below, page 154.)

In the second place the psychologist can set up techniques for finding out how the enemy really does feel. Some of the worst blunders of history have arisen from miscalculation of the enemy state of mind. By using the familiar statistical and questionnaire procedures, the psychologist can quiz a small cross section of enemy prisoners and from the results estimate the mentality of an entire enemy theater of war at a given period. If he does not have the prisoners handy, he can accomplish much the same end by an analysis of the news and propaganda which the enemy authorities transmit to their own troops and people. By establishing enemy opinion and morale factors he can hazard a reasoned forecast as to how the enemy troops will behave under specific conditions.

In the third place, the psychologist can help the military psychological warfare operator by helping him maintain his sense of mission and of proportion. The deadliest danger of propaganda consists of its being issued by the propagandist for his own edification. This sterile and ineffectual amusement can disguise the complete failure of the propaganda as propaganda. There is a genuine pleasure in talking back, particularly to an enemy. The propagandist, especially in wartime, is apt to tell the enemy what he thinks of him, or to deride enemy weaknesses. But to have told the Nazis, for example, "You Germans are a pack of murderous baboons and your Hitler is a demented oaf. Your women are slobs, your children are halfwits, your literature is gibberish and your cooking[Pg 27] is garbage," and so on, would have stiffened the German will to fight. The propagandist must tell the enemy those things which the enemy will heed; he must keep his private emotionalism out of the operation. The psychologist can teach the propaganda operator how to be objective, systematic, cold. For combat operations, it does not matter how much a division commander may dislike the enemy; for psychological warfare purposes, he must consider how to persuade them, even though he may privately thirst for their destruction. The indulgence of hatred is not a working part of the soldier's mission; to some it may be helpful; to others, not. The useful mission consists solely of making the enemy stop fighting, by combat or other means. But when the soldier turns to propaganda, he may need the advice of a psychologist in keeping his own feelings out of it.

Finally, the psychologist can prescribe media—radio, leaflets, loudspeakers, whispering agents, returned enemy soldiers, and so forth. He can indicate when and when not to use any given medium. He can, in conjunction with operations and intelligence officers, plan the full use of all available psychological resources. He can coordinate the timing of propaganda with military, economic or political situations.

The psychologist does not have to be present in person to give this advice. He does not have to be a man with an M.D. or Ph. D. and years of postgraduate training. He can be present in the manuals he writes, in the indoctrination courses for psychological warfare officers he sets up, in the current propaganda line he dictates by radio. It is useful to have him in the field, particularly at the higher command headquarters, but he is not indispensable. The psychologist in person can be dispensed with; the methods of scientific psychology cannot. (Further on, throughout this book, reference will be made to current psychological literature. The general history of psychology is described in readable terms in Gregory Zilboorg and George W. Henry, A History of Medical Psychology, New York, 1941, and in Lowell S. Selling, Men Against Madness, New York, 1940, cheap edition, 1942.)

Propaganda can be conducted by rule of thumb. But only a genius can make it work well by playing his hunches. It can become true psychological warfare, scientific in spirit and developed as a teachable skill, only by having its premises clearly stated, its mission defined, its instruments put in systematic readiness, and its operations subject to at least partial check, only by the use of techniques borrowed from science. Of all the sciences, psychology is the nearest, though anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, area studies and other specialties all have something to contribute; but it is psychology which indicates the need of the others.

How much the traditional doctrines may be altered in the terrible light of atomic explosion, no one knows; but though the weapons are novel, the wielders of the weapons will still be men. The motives and weaknesses within war remain ancient and human, however novel and dreadful the mechanical expedients adopted to express them.

Warfare as a whole is traditionally well defined, and psychological warfare can be understood only in relation to the whole process. It is no mere tool, to be used on special occasion. It has become a pervasive element in the military and security situation of every power on earth.

Psychological warfare is a part of war. The simplest, plainest thing which can be said of war—any sort of war, anywhere, anytime—is that it is an official fight between men. Combat, killing, and even large-scale group struggle are known elsewhere in the animal kingdom, but war is not. All sorts of creatures fight; but only men declare, wage, and terminate war; and they do so only against other men.

Formally, war may be defined as the "reciprocal application of violence by public, armed bodies."

If it is not reciprocal, it is not war, the killing of persons who do not defend themselves is not war, but slaughter, massacre, or punishment.

If the bodies involved are not public, their violence is not war. Even our enemies in World War II were relatively careful about this distinction, because they did not know how soon or easily a violation of the rules might be scored against them. To be public, the combatants need not be legal—that is, constitutionally set up; it suffices, according to international usage, for the fighters to have a reasonable minimum of numbers, some kind of identification, and a purpose which is political. If you shoot your neighbor, you will be committing mere murder; but if you gather twenty or thirty friends, together, tie a red handkerchief around the left arm of each man, announce that you are out to overthrow the government of the United States, and then shoot your neighbor as a counterrevolutionary impediment to the new order of things, you can have the satisfaction of having waged war. (In practical terms, this means that you will be put to death for treason and rebellion, not merely for murder.)

Finally, war must be violent. According to the law of modern states, all the way from Iceland to the Yemen, economic, political, or moral[Pg 29] pressure is not war; war is the legalization, in behalf of the state, of things which no individual may lawfully do in time of peace. As a matter of fact, even in time of war you cannot kill the enemy unless you do so on behalf of the state; if you had shot a Japanese creditor of yours privately, or even shot a Japanese soldier when you yourself were out of uniform, you might properly and lawfully have been put to death for murder—either by our courts or by the enemies'. (This is among the charges which recur in the war trials. The Germans and Japanese killed persons whom even war did not entitle them to kill.)

The governments of the modern world are jealous of their own monopoly of violence. War is the highest exercise of that violence, and modern war is no simple reversion to savagery. The General Staffs would not be needed if war were only an uncomplicated orgy of homicide—a mere getting-mad and throat-cutting season in the life of man. Quite to the contrary, modern war—as a function of modern society—reflects the institutional, political complexity from which it comes. A modern battle is a formal, ceremonialized and technically intricate operation. You must kill just the right people, in just the right way, with the right timing, in the proper place, for avowed purposes. Otherwise you make a mess of the whole show, and—what is worse—you lose.

Why must you fight just so and so, there and not here, now and not then? The answer is simple: you are fighting against men. Your purpose in fighting is to make them change their minds. It is figuratively true to say that the war we have just won was a peculiar kind of advertising campaign, designed to make the Germans and Japanese like us and our way of doing things. They did not like us much, but we gave them alternatives far worse than liking us, so that they became peaceful.

Sometimes individuals will be unpersuadable. Then they must be killed or neutralized by other purely physical means—such as isolation or imprisonment. (Some Nazis, perhaps including the Führer himself, found our world repellent or incomprehensible and died because they could not make themselves surrender. In the Pacific many Japanese had to be killed before they became acceptable to us.) But such is man, that most individuals will stop fighting at some point short of extinction; that point is reached when one of two things happens:

Sometimes these things are mixed. The people might wish to make peace, but may find that their government is not recognized by the enemy. Or the victors may think that they have smashed the enemy government, when the new organization is simply the old one under a slightly different name, but with the old leaders and the old ideas still prevailing.

It is plain that whatever happens wars are fought to effect a psychological change in the antagonist. They are then fought for a psychological end unless they are wars of extermination. These are rare. The United States could not find a people on the face of the earth whose ideas and language were unknown to all Americans. Where there is a chance of communication, there is always the probability that one of the antagonistic organizations (governments)—which have already cooperated to the extent of meeting one another's wishes to fight—will subsequently cooperate on terms of primary advantage to the victors. Since the organizations comprise human beings with human ways of doing things, the change must take place in the minds of those specific individuals who operate the existing government, or in the minds of enough other people for that government to be overthrown.

The fact that war is waged against the minds, not the bodies, of the enemy is attested by the comments of military writers of all periods. The dictum of Carl von Clausewitz that "war is politics continued by other means" is simply the modern expression of a truth recognized since antiquity. War is a kind of persuasion—uneconomical, dangerous, and unpleasant, but effective when all else fails.

If our difference of opinion is so inclusive that we can agree on nothing political, our differences have gone from mere opinion into the depths of ideology. Here the institutional framework is affected. You and I would not want to live in the same city; we could not feel safe in one another's presence; each would be afraid of the effect which the other might have on the morals of the community. If I were a Nazi, and you a democrat, you would not like the idea of my children living next door to yours. If I believed that you were a good enough creature—poor deluded devil—but that you were not fit to vote, scarcely to be trusted with property, not to be trusted as an army officer, and generally subversive and dangerous, you would find it hard to get along with me.

It was not metaphysical theories that made Protestants and Catholics burn one another's adherents as heretics in early wars. In the seventeenth century, the Protestants knew perfectly well what would happen if the Catholics got the upper hand, and the Catholics knew what would happen if the Protestants came to power. In each case the new rulers, fearful that they might be overthrown, would have suppressed the former rulers, and would have used the rack, the stake, and the dungeon as preventives of counterrevolution. Freedom cannot be accorded to persons outside the ideological pale. If an antagonist is not going to respect your freedom of speech, your property, and your personal safety, then you are not obliged to respect his. The absolute minimum of any ideology is the assumption that each person living in an ideologically uniform area (what the Nazi General Haushofer, following Rudolf Kjellen, would call a geo-psychic zone) will respect the personal safety, etc., of other individuals in the same area.

In our own time, we have seen Spaniards get more and more mistrustful of one another, until years of ferocious civil war were necessary before one of the two factions could feel safe. Spain went from republican unity to dictatorial unity in four years; in neither case was the unity perfect, but it was enough to give one government and one educational system control of most of the country. The other countries of[Pg 32] the world vary in the degree of their ideological cohesion. Scandinavia seemed serene until the German invasion brought to the surface cleavages, latent and unseen, which made Quisling a quisling. Russia, Italy, Germany and various other states have made a fetish of their ideologies and have tried to define orthodoxy and heresy in such a way as to be sure of the mentality of all their people. But most of the countries of the world suffer from a considerable degree of ideological confusion—of instability of basic beliefs—without having any immediate remedy at hand, or even seeking one.

In the states which are ideologically self-conscious and anxious to promote a fixed mentality, the process of education is combined with agitation and regulation, so that the entire population lives under conditions approximating the psychological side of war. Heretics are put to death or are otherwise silenced. Historical materialism and the Marxian "objectivity," or the Volk, or Fascismo, or Yamato-damashii, or "new democracy" is set up as the touchstone of all good and evil, even in unrelated fields of activity. Education and propaganda merge into everlasting indoctrination. And when such states go to war against states which do not have propaganda machinery, the more liberal states are at a disadvantage for sheer lack of practice in the administrative and mechanical aspects of propaganda. Education is to psychological warfare what a glacier is to an avalanche. The mind is to be in both cases captured, but the speed and techniques differ.

Allegiance in war is a matter of ideology, not of opinion. A man cannot want his own side to lose while remaining a good citizen in all[Pg 33] other respects. The desire for defeat—even the acceptance of defeat—is of tragic importance to any responsible, sane person. A German who wanted the Reich to be overthrown was a traitor to Germany, just as any American who wished us to pull out of the war and exterminate American Jews would have been a traitor to his own country. These decisions cannot be compared with the choice of a toothpaste, a deodorant, or a cigarette.

Advertising succeeds in peacetime precisely because it does not matter; the choice which the consumer makes is of slight importance to himself, even though it is of importance to the seller of the product. A Dromedary cigarette and an Old Coin cigarette are both cigarettes; the man is going to smoke one anyhow. It does not matter so much to him. If Dromedaries are associated in his mind with mere tobacco, while Old Coins call up unaccountable but persistent memories of actresses' legs, he may buy Old Coins. The physical implements of propaganda were at hand in 1941-1942, but we Americans had become so accustomed to their use for trivial purposes that much of our wartime propaganda was conducted in terms of salesmanship.

In a sense, however, salesmanship does serve the military purpose of accustoming the audience to appeals both visual and auditory. The consequence is that competing, outside propaganda can reach the domestic American audience only in competition with the local advertising. It is difficult for foreign competition to hold attention amid an almost limitless number of professionally competent commercial appeals. A Communist or Fascist party cannot get public attention in the United States by the simple expedient of a "mass meeting" of three hundred persons, or by the use of a few dozen posters in a metropolitan area. Before the political propagandist can get the public attention, he must edge his media past the soap operas, the soft drink advertisements, the bathing beauties advertising Pennsylvania crude or bright-leaf tobacco. The consequence is that outside propaganda either fails to get much public attention, or else camouflages itself to resemble and to exploit existing media. Clamorous salesmanship deadens the American citizen to his own government's propaganda, and may to a certain extent lower his civic alertness; but at the same time, salesmanship has built up a psychological Great Wall which excludes foreign or queer appeals and which renders the United States almost impervious to sudden ideological penetration from overseas.

It is not possible to separate public relations from psychological warfare when they use the same media. During World War II, the Office of War Information prepared elaborate water-tight plans for processing war news to different audiences; at their most unfortunate, such plans seemed to assume that the enemy would listen only to the OWI stations, and that the American public releases issued from Army and Navy would go forth to the world without being noted by the enemy. If a radio in New York or San Francisco presented a psychological warfare presentation of a stated battle or engagement, while the theater or fleet public relations officer presented a very different view, the enemy press and radio were free to choose the weaker of the two, or to quote the two American sources against each other.

It must be said, however, that propaganda by any other name is just as sweet, and that the conviction of the propagandist that he is not a propagandist can be a real asset. Morale services provided the American forces with news, entertainment, and educational facilities. Most of the time these morale facilities had huge parasitical audiences—the global kibitzers who listened to our broadcasts, read our magazines, bought our paper-bound books on the black markets. (It was a happy day for Lienta University at Kunming, Yünnan, when the American Information and Education set-up began shipping in current literature. The long-isolated Chinese college students found themselves deluged with good American books.)

The morale services lost the opportunity to ram home to their G.I.-plus-foreign audience some of the more effective points of American psychological warfare, but they gained as propagandists by not admitting, even to themselves, that they were propagandists. Since the United States has no serious inward psychological cleavages, the general morale services function coordinated automatically with the psychological warfare function simply because both were produced by disciplined, patriotic Americans.

In the experience of the German and Soviet armies, morale services were parts of a coordinated propaganda machine which included psychological warfare, public relations, general news, and public education. In the Japanese armies, morale services were directed most particularly to physical and sentimental comforts (edible treats, picture postcards, good luck items) which bore little immediate relation to news, and less to formal propaganda.

News becomes propaganda when the person issuing it has some purpose in doing so. Even if the reporters, editors, writers involved do not have propaganda aims, the original source of the news (the person giving the interview; the friends of the correspondents, etc.) may give the[Pg 36] news to the press with definite purposes in mind. It is not unknown for government officials to shift their rivalries from the conference room to the press, and to provide on-the-record or off-the-record materials which are in effect ad hoc propaganda campaigns. A psychological warfare campaign must be planned on the assumption that these civilian facilities will remain in being, and that they will be uncoordinated; the plan must allow in advance for interference, sometimes of a very damaging kind, which comes from private operations in the same field. The combat officers can get civilian cars off the road when moving armored forces into battle but the psychological warfare officer has the difficult task of threading his way through civilian radio and other communication traffic over which he has no control.

Psychological warfare is also closely related to diplomacy. It is an indispensable ingredient of strategic deception. In the medical field, psychological warfare can profit by the experiences of the medical corps. Whenever a given condition arises among troops on one side, comparable troops on the other are apt to be facing the same condition; if the Americans are bitten by insects, the same insects will bite the enemy, and enemy soldiers can be told how much better the American facilities are for insect repulsion. Finally, psychological warfare is intimately connected with the processing of prisoners of war and with the protection of one's own captured personnel.

Psychological warfare is a field to itself, although it touches on many sciences and overlaps with all the other functions of war. It is generally divisible into three topics: the general scheme of psychological warfare, the detection and analysis of foreign psychological warfare operations, and the tactical or immediate conduct of psychological warfare. Sections of this book deal with each of these in turn. In each case it must be remembered, however, that psychological warfare is not a closed operation which can be conducted in private, but that—to be effective—psychological warfare output must be a part of the everyday living and fighting of the audiences to which it is directed.

Psychological warfare seeks to win military gains without military force. In some periods of history the use of psychological warfare has been considered unsportsmanlike.12 It is natural for the skilled soldier to rely on weapons rather than on words, and after World War I there was a considerable reluctance to look further into that weapon—propaganda—which Ludendorff himself considered to be the most formidable achievement of the Allies. Nevertheless, World War II brought a large number of American officers, both Army and Navy, into the psychological warfare field: some of the best work was done without civilian aid or sponsorship. (Capt. J. A. Burden on Guadalcanal wrote his own leaflets, prepared his own public-address scripts, and did his own distributing from a borrowed Marine plane, skimming the tree tops until the Japanese shot him down into the surf. He may have heard of OWI at the time, but the civilians at OWI had not heard of him.)

Psychological warfare has become familiar. The problems of psychological warfare for the future are problems of how better to apply it, not of whether to apply it. Accordingly, it is to be defined more for the purpose of making it convenient and operable than for the purpose of finding out what it is. The whole world found out by demonstration, during World Wars I and II.

Psychological warfare is not defined as such in the dictionary.13 Definition is open game. There are three ways in which "psychological warfare" and "military propaganda" can be defined:

Plainly, the staff officer needs a different definition from the one used by the combat officer; the political leader would use a broader definition than the one required by soldiers; the fanatic would have his own definition or—more probably—two of them; one (such as "promoting democracy" or "awakening the masses") for his own propaganda and[Pg 38] another (such as "spreading lies," "corrupting the press," or "giving opiates to the people") for antagonistic propaganda.14 Definition is not something which can be done once and forever for any military term, since military operations change and since military definitions are critically important for establishing a chain of command.

The first method of definition is satisfactory for research purposes; it may help break a politico-military situation down into understandable components. The second method—the organizational—is usable when there exists organization with which to demonstrate the definition, such as, "Propaganda is what OWI and OSS perform." The third method, the operational or historical, is useful in evaluating situations after the time for action has passed; thus, one may say, "This is what the Germans did when they thought they were conducting propaganda."

Since the first lesson of all propaganda is reasoned disbelief, it would be sad and absurd for anyone to believe propaganda about propaganda. The "propaganda boys" in every army and government are experts at building up favorable cases, and they would be unusual men indeed if they failed to work up a fine account of their own performance. Propaganda cannot be given fair measurement by the claims made for it. It requires judicious proportioning to the military operations of which it is (in wartime) normally a part.

This may be called the broad definition, since it would include an appeal to buy Antident toothpaste, to believe in the theological principle of complete immersion,16 to buy flowers for Uncles on Uncles' Day, to slap the Japs, to fight fascism at home, or to smell nice under the arms. All of this is propaganda, by the broad definition. Since War and Navy Department usage never put the Corps of Chaplains, the PX system, the safety campaigns, or the anti-VD announcements under the rubric of propaganda, it might be desirable to narrow down the definition to exclude those forms of propaganda designed to effect private or nonpolitical purposes, and make the definition read:

Propaganda consists of the planned use of any form of public or mass-produced communication designed to affect the minds and emotions of a given group for a specific public purpose, whether military, economic, or political.

This may be termed the everyday definition of propaganda, as it is used in most of the civilian college textbooks.17 For military purposes, however, it is necessary to trim down the definition in one more direction, applying it strictly against the enemy and making it read:

Military propaganda consists of the planned use of any form of communication designed to affect the minds and emotions of a given enemy, neutral or friendly foreign group for a specific strategic or tactical purpose.

Note that if the communication is not planned it cannot be called propaganda. If a lieutenant stuck his head out of a tank turret and yelled at some Japs in a cave, "Come on out of there, you qwertyuiop asdfgs, or we'll zxcvb you all to hjkl, you etc.'s!," the communication[Pg 40] may or may not work, but—in the technical sense—it is not propaganda because the lieutenant did not employ that form of communication planned and designed to affect the minds or emotions of the Japanese in the cave. Had the lieutenant given the matter thought and had he said, in the Japanese language, "Enemy persons forthwith commanded to cease resistance, otherwise American Army regrets inescapable consequences attendant upon operation of flamethrower," the remark would have been closer to propaganda.

Furthermore, propaganda must have a known purpose. This element must be included in the definition; a great deal of communication, both in wartime and in peacetime, arises because of the pleasure which it gives to the utterer, and not because of the result it is supposed to effect in the hearers. Sending the Japanese cartoons of themselves, mocking the German language, calling Italians by familiar but inelegant names—such communications cropped up during the war. The senders got a lot of fun out of the message but the purpose was unintelligently considered. The actual effect of the messages was to annoy the enemy, stiffening his will-to-resist. (Screams of rage had a place in primitive war; in modern military propaganda they are too expensive a luxury to be tolerated. Planned annoyance of the enemy does, of course, have its role—a minor, rare and special one.)

"Psychological warfare" is simple enough to understand if it is simply regarded as application of propaganda to the purposes of war, as in the following definition:

Psychological warfare comprises the use of propaganda against an enemy, together with such other operational measures of a military, economic, or political nature as may be required to supplement propaganda.

In this sense, "psychological warfare" is a known operation which was carried on very successfully during World War II under the authority of the Combined and Joint Chiefs of Staff. It is in this sense that some kind of a "Psychological Warfare Unit" was developed in every major theater of war, and that the American military assimilated the doctrines of "psychological warfare."

However, this is only one of several ways of using the term, "psychological warfare." There is, in particular, one other sense, in which the term became unpleasantly familiar, during the German conquest of Europe, the sense of warfare psychologically waged. In the American use of the term, psychological warfare was the supplementing of normal military operations by the use of mass communications; in the Nazi sense of the term, it was the calculation and execution of both political and military strategy on studied psychological grounds. For the American [Pg 41] uses, it was modification of traditional warfare by the effective, generous use of a new weapon; for the Germans it involved a transformation of the process of war itself. This is an important enough distinction to warrant separate consideration.

After the excitement had died down, it was found that the novelty of the German war effort lay in two special fields:

The Germans set the pace, in the prewar and early war period and United Nations psychological warfare tried to keep up, even though the two efforts were different in scope and character.

In conquering Europe, the German staff apparently used opinion analysis. Much of this analysis has turned out to have been superb guesswork; at the time, it looked as though the Nazis might have found some scientific formula for determining just when a nation would cave in. In the conduct of war, the Germans waged a rapid war—which was industrially, psychologically and militarily sound, as long as it worked. Their "diplomacy of dramatic intimidation" used the war threat to its full value, with the result that the Czechoslovaks surrendered the Sudetenland without a shot and then submitted themselves to tyranny half a year later; the Germans wrung every pfennigs worth of advantage out of threatening to start war, and when they did start war, they deliberately tried to make it look as horrible as it was. The psychologists had apparently [Pg 42] taught the German political and military intelligence people how to get workable opinion forecasts; German analysis of anti-Nazi counterpropaganda was excellent. Add all this to strategy and field operations which were incontestably brilliant: the effect was not that of mere war, but of a new kind of war—the psychological war.

The formula for the psychological war is not to be found in the books of the psychologists but in the writings of the constitutional lawyers. The totality of war is a result of dictatorship within government; total coordination results from total authority. The "secret weapon" of the Germans lay in the power which the Germans had openly given Hitler, and in his use of that power in a shrewd, ruthless, effective way. The Führer led the experts, not the experts the Führer. If the Germans surprised the world by the cold calculation of their timing, it was not because they had psychological braintrusters inventing a new warfare, but because they had a grim political freak commanding the total resources of the Reich. Even in wartime, no American President has ever exercised the authority which Hitler used in time of peace; American Cabinet members, military and naval figures, press commentators and all sorts of people are free to kibitz, to offer their own opinions, to bring policy into the light of day. That is as it should be. The same factors which made "psychological warfare" possible in the beginning of the war were the ones which led to Germany's futile and consummate ruin in 1944-45: excessive authority, an uninformed public, centralized propaganda, and secret political planning.

That kind of "psychological warfare"—war tuned to the needs of fanatically sought lusts for power, war coordinated down to the nth degree, waged in the light of enemy opinion and aiming at the political and moral weaknesses of the enemy—is not possible within the framework of a democracy. Even from within Imperial Japan, Pearl Harbor had to be waged secretly as a purely naval operation; those Japanese who would have told the Board of Field Marshals and Fleet Admirals that an unannounced attack was the best way to unify all American factions against Japan were obviously not brought into the planning of the Pearl Harbor raid. The Japanese still had too much of their old parliamentary spirit left over, as Ambassador Grew's reports show; the military had to outsmart the home public, along with the foreigners. In the Western dictatorships, the home public is watched by élite troops, secret police, party cells, and is made the subject of psychological warfare along with the victim nations. Hitler could turn the war spirit on and off; the Japanese did not dare do so to any effective extent. "Psychological warfare" was too dictatorial a measure even for prewar Japan; it is therefore permanently out of reach of the authorities of the United[Pg 43] States. After war starts, we are capable of surprising the enemy with such things as incendiary raids, long-range bombers, and nuclear fission; but we cannot startle with the start of war. The United States is not now capable and—under the spirit of the Constitution, can never be capable—of surprising an enemy by the timing of aggression. If the same were true of all other nations, peace would seem much nearer than it does.

German psychological warfare, in the broad sense of warfare psychologically waged, depended more on political background than on psychological techniques. Disunity among the prospective victims, the complaisance of powers not immediately affected, demonstration of new weapons through frightful applications, use of a dread-of-war to harness pacifism to appeasement, the lucky geographic position of Germany at the hub of European communications—such factors made the German war of nerves seem new. Such psychological warfare is not apt to be successful elsewhere except for aggressions by dictatorships against democracies; where the democracies are irritable, tough, and alert, it will not work at all.

The psychological warfare which remains as a practical factor in war is therefore not the Hitlerian war of nerves, but the Anglo-American application of propaganda means to pre-decided strategy. Let him who will advocate American use of the war of nerves! He will not get far with commentators publishing his TOP SECRET schedule of timing, with legislators very properly catechizing him on international morality, with members of his own organization publishing their memoirs or airing their squabbles right in the middle of the operation. He would end up by amusing the enemy whom he started out to scare. Psychological warfare has its place in our military and political system, but its place is a modest one and its methods are limited by our usages, morality, and law.

These factors are given in approximate order of importance to the analyst, and provide a good working breakdown for propaganda analysis when expert staffs are not available. The five factors can be remembered by memorizing the initial letters in order: S-T-A-S-M. The last factor, "Mission," covers the presumed effect which the enemy seeks by dissemination of the item.

Without going into the technique of field propaganda analysis (described below, page 115), it is useful to apply these analysis factors to the definition of some subordinate types of military propaganda.