Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

ESSENTIAL FACTS OF EVERYDAY INTEREST IN NATURE, GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, TRAVEL, GOVERNMENT, SCIENCE, INVENTION, EDUCATION, LANGUAGE, LITERATURE, FINE ARTS, PHILOSOPHY, RELIGION, INDUSTRY, BIOGRAPHY, HUMAN CULTURE, AND UNIVERSAL PROGRESS

Easy to Read; Easy to Understand; Easy to Retain

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

HENRY W. RUOFF, M.A., Litt.D., D.C.L.

Editor of “The Century Book of Facts,” “The Capitals of the

World,”

“Leaders of Men,” “The Standard Dictionary of Facts,”

“Masters of Achievement,” “The Volume Library,”

“The Human Interest Library,” Etc.

NUMEROUS TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS, MAPS

TABLES, DUOTONE AND COLOR PLATES

Exclusive Publishers for Canada and

Newfoundland:

THE JOHN A. HERTEL CO., Ltd.

TORONTO, ONTARIO

THE STANDARD PUBLICATION COMPANY

BOSTON · WASHINGTON · CHICAGO

1917

Copyright, 1916, by

THE STANDARD PUBLICATION COMPANY

Copyright, 1917, by

THE STANDARD PUBLICATION COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

All books that are really worth while may be divided into four classes: first, books of information; second, books of inspiration; third, books of entertainment; fourth, books of excitement. By far the most important and practical of these classes is the first. The next in importance is the second; while rather trivial importance attaches to the third and fourth.

THE CIRCLE OF KNOWLEDGE preëminently belongs to the first; but it is also designed to be both inspiring and entertaining. In its methods of presentation and in its editorship it typifies the modern, progressive spirit. Behind it lies a quarter of a century of successful editorial experience in selecting, adapting, and translating from highly technical treatises into simple, clear, understandable language the essentials as well as important sidelights of human knowledge. Its purpose is to answer the why, who, what, when, where, how, of the vast majority of inquiring minds, both young and mature, and to stimulate them to still further questionings. For it is only through this self-questioning process of the active mind that individual progress is possible.

It is a fact of singular interest that every human being born into the world must independently go through practically the same educative processes from childhood to maturity. No matter how great the storehouse of the world’s past knowledge, or how marvelous the multitude and wonder of new discoveries in every department of human endeavor, each individual must acquire and learn for himself the selfsame facts of nature, history, science, literature, human culture, and everyday needs.

In the present work special effort has been made to separate essentials from non-essentials; to distinguish human interest subjects of universal importance from those of minor concern; to present living facts instead of dead verbiage; and to bring the whole within the understanding of the average reader, without regard to age, in an acceptable and interesting form. The use of graphic outlines and tables; maps, drawings, and diagrams; the pictured works of great painters, sculptors, and architects—all combine in vizualizing and vitalizing both the useful and cultural knowledge of past and present. Indeed it is difficult to conceive how the purely pictorial interest of the work could be surpassed, with its veritable picture galleries illustrating the pageant of man’s progress; while the entire field of knowledge, from the measureless universe of space down to the simple fancy of a child, is sketched in its practical and essential outlines.

Never has there been greater demand for books of knowledge of the present type. The busy reader or consulter soon tires of the diffuse book or set of books of interminable words. He wants conciseness, directness, reasonable compass, reliability, with up-to-date treatment of topics of permanent usefulness. Above all he wants something that appeals to the eye, and, through the interest of its form and subject matter, stimulates thought and the imagination. While simplicity and clearness are undoubted virtues, great care has been exercised to prevent them from degenerating into those childish forms, all too frequent in certain books, that rob real knowledge of almost its entire value.

The best sources in the world of books have been laid under tribute in the preparation of this work, wisely supplemented by the wide experience of many eminent, practical, and progressive men and women—masters in their respective fields. It is earnestly hoped that this joint product will create for it a large sphere of usefulness and numerous satisfied readers.

The Editor desires to acknowledge his indebtedness to the following distinguished educators, scientists, writers and publicists for helpful suggestions, counsel, contributions, or revisions connected with the various departments of THE CIRCLE OF KNOWLEDGE.

EDWIN A. ALDERMAN, LL.D., D.C.L.

President University of Virginia; Editor-in-Chief Library of Southern Literature; author of Obligations and Opportunities of Citizenship, etc.

E. BENJAMIN ANDREWS, D.D., LL.D.

Educator and Historian; author of Institutes of General History, History of the United States, etc.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL.D.

Late President University of Michigan; author of The Higher Education, Progress in International Law, etc.

LIBERTY H. BAILEY, D.Sc., LL.D.

Cornell University; author of Plant Breeding, Manual of Gardening, Cyclopedia of American Horticulture, etc.

GEORGE F. BARKER, Sc.D., LL.D.

University of Pennsylvania; author of Text-book of Chemistry, Text-book of Physics, etc.

JOHN HENRY BARROWS, LL.D.

Late President Oberlin College; author of Christian Evidences, Lectures, etc.

CHARLES E. BESSEY, Ph.D., LL.D.

University of Nebraska; author of Essentials of Botany, Botany for High Schools and Colleges, Elementary Botany, etc.

FRANK W. BLACKMAR, Ph.D.

University of Kansas; author of The Story of Human Progress, Outlines of Sociology, etc.

DAVID J. BREWER, LL.D.

Jurist, Publicist; Associate Justice U. S. Supreme Court; author of American Citizenship, The Twentieth Century, etc.

ELMER ELLSWORTH BROWN, Ph.D., LL.D.

President N. Y. University; former U. S. Commissioner of Education; author of The Making of our Middle Schools, Origin of American State Universities, etc.

JAMES M. BUCKLEY, LL.D.

Late editor New York Christian Advocate; author of Travels in Three Continents, The Land of the Czar, etc.

JOHN W. BURGESS, Ph.D., LL.D.

Columbia University; author of The Civil War and the Constitution, Political Science and Comparative Constitutional Law, etc.

G. MONTAGUE BUTLER, M.E.

Colorado School of Mines; Geologist for Colorado Geological Survey; author of A Pocket Handbook of Minerals, etc.

JAMES McKEAN CATTELL, Ph.D.

Editor Popular Science Monthly; author of School and Society, American Men of Science, etc.

JOHN W. CAVANAUGH, C.S.C., LL.D.

President Notre Dame University; author of Priests of Holy Cross, etc.

EDWARD CHANNING, Ph.D., LL.D.

Harvard University; author of History of United States, English History for American Readers, etc.

SUSAN FRANCES CHASE, M.A., Ph.D.

Department of Psychology and Literature, Buffalo State Normal School; author of Talks to Teachers, Outlines of Literature, etc.

FOSTER D. COBURN, LL.D.

Former Secretary Kansas Department of Agriculture; author of Swine Husbandry, Alfalfa, The Farmer’s Encyclopedia, etc.

MAURICE F. EGAN, Litt.D., LL.D.

U. S. Minister to Denmark; author of Lectures on English Literature, Modern Novelists, etc.

CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D.

President Emeritus Harvard University; author of Educational Reform, The Durable Satisfactions of Life, etc.

EPHRAIM EMERTON, Ph.D.

Harvard University; author of Synopsis of the History of Continental Europe, Mediæval Europe, etc.

WILLIAM H. EMMONS, Ph.D.

University of Minnesota; Geologist of Minnesota; author of numerous Reports and Technical Papers on Geology.

ALCEE FORTIER, Litt.D., LL.D.

Tulane University; author of History of French Literature, Louisiana Folk Tales, History of France, etc.

ARTHUR L. FROTHINGHAM, Ph.D.

Author of History of Sculpture, Mediaeval Art Inventions of the Vatican, etc.; co-author Sturgis, History of Architecture, etc.

HORACE HOWARD FURNESS, Litt.D., LL.D.

Shakespearean Scholar, Critic; author of The Variorum Shakespeare, etc.

MERRILL E. GATES, LL.D., L.H.D.

Ex-President Amherst College; author of Land and Law as Agents in Educating the Indian, International Arbitration, etc.

JOHN F. GENUNG, D.D., Ph.D., Litt.D.

Amherst College; author of Practical Elements of Rhetoric, Working Principles of Rhetoric, The Idylls of the Ages, etc.

NICHOLAS PAINE GILMAN, L.H.D.

Meadville Theological School; author of Profit Sharing, A Dividend to Labor, Methods of Industrial Peace, etc.

WILLIAM W. GOODWIN, D.C.L., LL.D.

Harvard University; author of Greek Grammar, Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, etc.

EDWARD HOWARD GRIGGS, L.H.D.

Lecturer, Educator; author of Moral Education, Self-Culture through the Vocation, etc.

FRANK W. GUNSAULUS, D.D., LL.D.

President Armour Institute; author of Paths to Power, Higher Ministries of Recent English Poetry, etc.

G. STANLEY HALL, Ph.D., LL.D.

President Clark University; author of Adolescence, Youth—Its Education, Regimen and Hygiene, etc.; editor of the American Journal of Psychology, The Pedagogical Seminary, etc.

JOHN HAY, LL.D.

Diplomat, Historian; co-author of Life of Abraham Lincoln, Castilian Days, etc.

EMIL G. HIRSCH, L.H.D., LL.D., D.C.L.

University of Chicago; minister of Sinai Congregation, Chicago; associate editor Jewish Encyclopedia; author of many articles on religion, etc.

GEORGE HODGES, D.D., D.C.L.

Dean Episcopal Theological School, Cambridge, Mass.; author of The Episcopal Church, The Pursuit of Happiness, etc.

ARTHUR HOEBER, A.N.A.

Art Critic New York Globe; Art Editor New Encyclopedia Britannica; author of Painting in the Nineteenth Century, etc.

GEORGE S. HOLMESTED, K.C., Esq.

Registrar of the High Court of Justice of Ontario; editor of the Ontario Mechanics Lien Act, etc.

JAMES M. HOPPIN, D.D.

Yale University; author of Great Epochs in Art History, Old England: Its Art, Scenery and People, etc.

WILLIAM WIRT HOWE, LL.D.

Jurist, Lecturer; Justice Supreme Court of La.; author of Studies in Civil Law, etc.

GEORGE HOLMES HOWISON, LL.D.

University of California; author of Limits of Evolution, Philosophy: Its Fundamental Concepts and Methods, etc.

THOMAS WELBURN HUGHES, LL.D.

Dean Washburn College of Law; author of Hughes’ Cases on Evidence, Outline of Criminal Law, Commercial Law, etc.

JOHN F. HURST, D.D., LL.D.

Late Chancellor American University; author of History of the Christian Church, etc.

WILLIAM DeWITT HYDE, D.D., LL.D.

President Bowdoin College; author of The Teacher’s Philosophy In and Out of School, The Quest of the Best, etc.

MORRIS JASTROW, Ph.D.

University of Pennsylvania; author of Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria, The Study of Religion, etc.

JEREMIAH W. JENKS, Ph.D., LL.D.

New York University; author of The Trust Problem, Citizenship and the Schools, Government Action for Social Welfare, etc.

DAVID STARR JORDAN, Ph.D., LL.D.

Leland Stanford Jr. University; author of Science Sketches, Footnotes to Evolution, Animal Life, Food and Game Fishes of North America, etc.

ARTHUR B. LAMB, Ph.D.

Director Chemical Laboratory, Harvard University; translator of Haber’s Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reaction; author of many papers on chemical subjects.

JOSEPHUS N. LARNED, LL.D.

Librarian and Historian; author of History for Ready Reference, Literature of American History, etc.

HENRY C. LEA, LL.D.

Historian; author of Studies in Church History, Superstition and Force, etc.

SIMON LITMAN, Jur.D., Ph.D.

University of Illinois; author of Trade and Commerce, and of many articles on commerce and industry.

THOMAS H. MACBRIDE, Ph.D., LL.D.

Ex-President Iowa State University; author of Textbook of Botany, etc.

OTIS T. MASON, Ph.D., LL.D.

Ethnologist, Scientist; author of Origin of Inventions, Woman’s Share in Primitive Culture, etc.

HUGO MÜNSTERBERG, M.D., Ph.D., LL.D.,

Harvard University; author of Psychology and the Teacher, The Eternal Values, American Problems, etc.

CHARLES W. NEEDHAM, LL.D.

Educator, Lawyer; Ex-President George Washington University; associate counsel Interstate Commerce Commission; etc.

THOMAS NELSON PAGE, Litt.D., LL.D.

Lawyer, Diplomat, Novelist; U. S. Ambassador to Italy; author of Social Life in Old Virginia, Robert E. Lee: Man and Soldier, etc.

JOHN K. PAINE, Mus.D.

Harvard University; Musician, Composer; author of Realm of Fancy, Song of Promise, etc.

GEORGE H. PALMER, Litt.D., LL.D.

Harvard University; author of Self-Cultivation in English, The Teacher, Trades and Professions, etc.

HORATIO W. PARKER, Mus.D.

Yale University; Composer; author of the operas Mona, Fairyland, and much other music.

HARRY THURSTON PECK, Ph.D., L.H.D.

Co-editor New International Encyclopedia, editor of Harper’s Classical Dictionary, etc.

JOHN W. POWELL, Ph.D., LL.D.

Late Chief of Bureau of American Ethnology; author of Studies in Sociology, The Cañons of the Colorado, etc.

IRA REMSEN, Ph.D., LL.D.

Ex-President Johns Hopkins University; author of The Elements of Chemistry, Classical Experiments, etc.

HENRY A. ROWLAND, Ph.D., LL.D.

Late Professor Johns Hopkins University; author of Mechanical Equivalents of Heat, The Solar Spectrum, etc.

BOHUMIL SHIMEK, C.E., M.Sc.

Iowa State University; Botanist; author of numerous scientific papers.

AINSWORTH R. SPOFFORD, LL.D.

Late Librarian of Congress, Critic; editor of Library of Choice Literature, Book for All Readers, etc.

ROBERT H. THURSTON, LL.D., D.Eng.

Late Professor Cornell University; author of History of the Steam Engine, Materials of Construction, etc.

CRAWFORD H. TOY, M.A., LL.D.

Harvard University; author of The Religion of Israel, Judaism and Christianity, Quotations in the New Testament, etc.

JOHN C. VAN DYKE, L.H.D.

Rutgers College; author of New Guides to Old Masters, Studies in Pictures, etc.

LESTER F. WARD, Ph.D., LL.D.

Brown University; Scientist; author of Sociology and Economics, Pure Sociology, etc.

ROBERT M. WENLEY, Ph.D., Litt.D., D.Sc., LL.D.

University of Michigan; co-editor of The Dictionary of Philosophy, Dictionary of Theology, Religion and Ethics; author of Introduction to Kant, Contemporary Theology and Theism, etc.

BENJAMIN I. WHEELER, Ph.D., LL.D.

President University of California; author of Introduction to the History of Language, Life of Alexander the Great, etc.

JOHN SHARP WILLIAMS, LL.D.

Publicist, U. S. Senator; author of Permanent Influence of Thomas Jefferson on American Institutions, etc.

OWEN WISTER, Litt.D., LL.D.

Lawyer, Novelist, Critic; author of The Virginians, Biography of U. S. Grant, etc.

ROBERT S. WOODWARD, D.Sc., LL.D.

Director Carnegie Institute; Scientist; author of Higher Mathematics, etc.

CARROLL D. WRIGHT, Ph.D., LL.D.

Educator, Economist, Statistician; author of The Industrial Evolution of the United States, etc.

G. FREDERICK WRIGHT, D.D., LL.D.

Oberlin College; author of Man and the Glacial Period, Science and Religion, etc.

THE UNIVERSE—THE SOLAR SYSTEM—Sun—Planets—Moon—Constellations—Stars—Comets—Meteors—Nebulæ—NEBULAR HYPOTHESIS—ECLIPSES—MYTHOLOGY OF THE CONSTELLATIONS—DICTIONARY OF SCIENTIFIC TERMS USED IN ASTRONOMY—STAR CHARTS AND MAPS.

⁂Books of Reference about the Heavens.—Campbell: Handbook of Practical Astronomy. Young: Elementary Astronomy, Manual of Astronomy, and General Astronomy. Ball: Story of the Heavens. Turner: Modern Astronomy. Newcomb: Popular Astronomy. Todd: A New Astronomy. Gregory: Vault of Heaven.

OUR EARTH: ITS STRUCTURE AND SURFACE—GEOLOGICAL VIEW OF THE GROWTH OF THE EARTH—LAND FORMS OF THE WORLD—DISTRIBUTION OF LAND AND WATER—THE CONTINENTS—ISLANDS—MOUNTAINS—WATERS OF THE EARTH—FORMS OF WATER—RIVERS—WATERFALLS AND RAPIDS—LAKES—OCEANS—VOLCANOES—GEYSERS—ATMOSPHERE, CLIMATE, AND WEATHER—WINDS—CLOUDS—ATMOSPHERIC VAPOR, (Dew, Mist, Fog, Rain, Hail, Snow)—GLACIERS—ICEBERGS—DESERTS—NATURAL FORCES—MINERAL PRODUCTS—PRONOUNCING DICTIONARY OF SCIENTIFIC TERMS—MAPS AND CHARTS.

⁂Books of Reference about the Earth.—Dawson: Story of the Earth. Lyell: Principles of Geology. Geikie: Primer of Geology. Shaler: Sea and Land. Scott: Geology. Geikie: Text-Book of Geology. Chamberlin and Salisbury: Geology. Le Conte: Elements of Geology. Dana: Manual of Geology. Miers: Mineralogy. Dana: Text-Book of Mineralogy and System of Mineralogy (most comprehensive work in English). Brush and Penfield: Determinative Mineralogy. Rosenbusch-Iddings: Rock-Making Minerals. Hatch: Petrology. Butler: Pocket Handbook of Minerals. Mill: Realm of Nature. W. M. Davis: Physical Geography. Tarr: Physical Geography.

REALMS OF LIFE UPON THE EARTH—CHIEF DIVISIONS OF THE PLANT KINGDOM: (1) Cereals, Grasses and Forage Plants; (2) Kitchen Vegetables; (3) The Fruit Trees; (4) Fruit-bearing Shrubs and Plants; (5) Flowers and Other Ornamental Plants; (6) Wild Flowers and Flowerless Plants; (7) Trees of the Forest; (8) Fiber and Commercial Plants; (9) Poisonous Plants; (10) Some Wonders of Plant Life—BOTANICAL CLASSIFICATION OF PLANTS—SCIENTIFIC TERMS USED IN BOTANY, CLASSIFIED AND ILLUSTRATED—MAP OF THE PLANT KINGDOM.

⁂Books of Reference about the Vegetable Kingdom.—Gray: New Manual of Botany. Bessey: Synopsis of Plant Phyla. Small: Flora of the Southeastern United States. Coulter and Nelson: New Manual of the Botany of the Central Rocky Mountains. Gray: Synoptical Flora of North America. Britton: Manual of the Flora of the Northern States and Canada. Strasburger, Noll, Schenck and Karsten: Textbook of Botany. Pfeffer: Physiology of Plants. Ward: Disease in Plants. Schimper: Plant Geography. Campbell: Evolution of Plants. Green: Landmarks of Botanical History. Sach: History of Botany, 1530-1860. Green: History of Botany, 1860-1900. Baker: Elementary Lessons in Botanical Geography.

SCIENTIFIC CLASSIFICATION OF ANIMALS—TABULAR VIEW OF REPRESENTATIVE ANIMAL TYPES—ANIMALS IN CLASSIFIED GROUPS:

⁂Books of Reference about Animals.—Rolleston: Forms of Animal Life. Huxley: Anatomy of Invertebrated Animals and Anatomy of Vertebrated Animals. Lankester: Treatise on Zoölogy. Parker and Haswell: Text-Book of Zoölogy. Kingsley: The Standard Natural History and Elements of Comparative Zoölogy. Newton: A Dictionary of Birds. Headley: The Structure and Life of Birds. Wilson: American Ornithology. Audubon: Ornithological Biography. Coues: Key to North American Birds. Chapman: Handbook of Birds of East North America. Bendire: Life Histories of North American Birds. Comstock: Insect Life. Packard: Text-Book of Entomology and Guide to Study of Insects. Howard: The Insect Book. Beddard: Text-Book of Zoögeography. A. Heilprin: The Geographical and Geological Distribution of Animals.

I. MAN AND THE HUMAN FAMILY—HOW MAN DIFFERS FROM OTHER ANIMALS—QUESTIONS OF MAN’S ORIGIN—HIS PRIMEVAL HOME—OLDEST EXTANT REMAINS OF THE HUMAN RACE—MAN’S ADVANCEMENT IN THE PRE-HISTORIC AGES—CHART SHOWING DEVELOPMENT OF THE RACE THROUGH THE AGES: (1) Dawn; Stone Age; (2) Old Stone Age; (3) New Stone Age; (4) Bronze Age; (5) Early Iron Age; (6) Late Iron Age; (7) Age of Letters.

II. HOW THE RACES ARE CLASSIFIED—CHART OF PHYSICAL AND MENTAL RACE CHARACTERISTICS—GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE RACES OF MANKIND—DICTIONARY OF THE HISTORICAL RACE GROUPS—COMPARATIVE CLASSIFICATION OF RACES AND PEOPLES.

⁂Books of Reference about Man.—Prichard: Researches into the Physical History of Mankind. Latham: Natural History of the Varieties of Man. Waitz: Anthropology. Darwin: The Descent of Man. Huxley: Essays and Man’s Place in Nature. Quatrefages: Classification des Races Humaines. Peschel: The Races of Man. Tylor: Anthropology. Lubbock: Prehistoric Times. Ratzel: History of Mankind. Keane: Ethnology and Man. Past and Present. Deniker: The Races of Man. Hutchinson: The Living Races of Mankind.

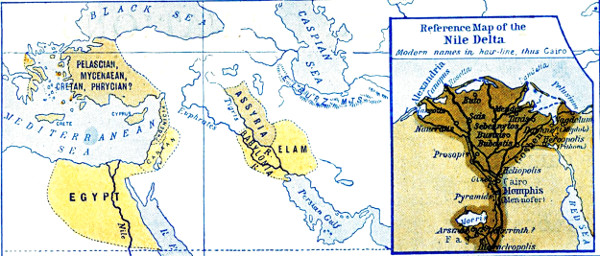

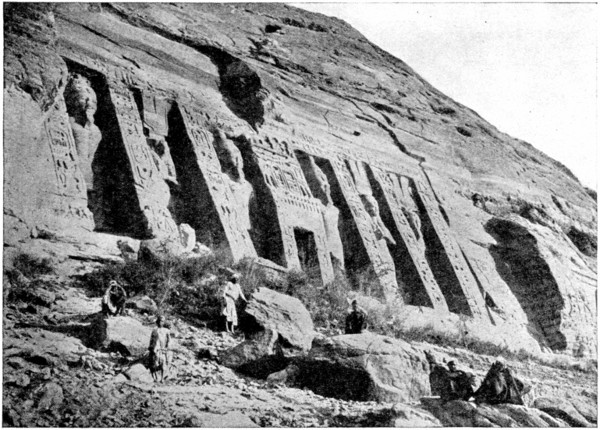

CHIEF HISTORICAL PEOPLES: Egyptians—Babylonians—Assyrians—Hebrews—Phœnicians—Medes and Persians—Hindus—Greeks—Romans—PROGRESS OF HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY AND DISCOVERY, B.C. 3800 TO THE PRESENT, WITH 16 MAPS—THE WORLD’S GREATEST EXPLORERS, B.C. 1400 TO 1917 A.D.—COMPARATIVE OUTLINE HISTORY OF ANCIENT NATIONS, B.C. 5000 TO 843 A.D.—DESCRIPTIVE GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT: The Spell of Egypt: Ancient and Modern—The Babylonian-Assyrian Empires—The Hebrews and the Holy Land—The Phœnicians: First Nation of Colonizers—The Medo-Persian Empire—The Greeks: Glory of the Ancient World—Rome: Mistress of the World—The Saracen Empire: Its Fanaticism, Art, and Learning—The Germanic Empire of Charlemagne.

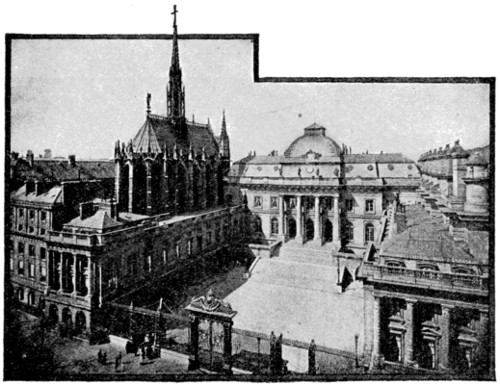

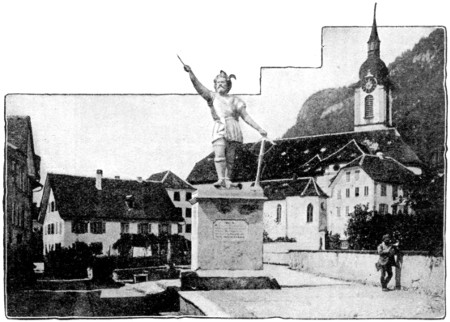

COMPARATIVE OUTLINE HISTORY OF MODERN NATIONS—TRANSITION PERIOD FROM THE ANCIENT TO THE MODERN—GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREAT POWERS: Great Britain—France—Germany—Italy—Austria—Hungary—Russia—United States—Japan—THE LESSER MODERN NATIONS: In Europe, Spain and Portugal—Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Denmark)—The Netherlands—Switzerland—The Balkan States (Bulgaria, Roumania, Turkey, Greece, Servia); In Asia, China—Persia—Turkey; In America, Brazil—Argentina—Chile—Mexico—Canada.

Including Great Wars, Great Battles, Dynasties, Rulers, Comparative Government, Biographical Facts Relating to the Presidents of the United States, Important Facts Concerning the States, etc.

⁂Books of Reference about the Nations.—HISTORY—Freeman: General Sketch. Haydn: Dictionary Dates. Rawlinson: Manual of Ancient History. Peck: Harper’s Classical Dictionary. Duncker: History of Antiquity. Brugsch-Bey: Egypt under the Pharaohs. Ewald: History of Israel. Allen: Hebrew Men and Times. Ranke: Universal History. Fisher: Outlines of Universal History. Mommsen: History of Rome. Gibbon: History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Grote: History of Greece. Duruy: History of Rome. Merivale: General History of Rome. Lecky: History of European Morals. Hallam: Middle Ages. Guizot: History of Civilization. Sybel: History of the Crusades. Cox: The Crusades. Emerton: Mediaeval Europe; Introduction to the Study of the Middle Ages. Harding: Essentials in Mediaeval and Modern History. Gieseler: Church History. Alzog: Manual of Universal Church History. Clarke: Events and Epochs of Religious History. Fisher: History of the Reformation. Ranke: History of the Popes. Dyer: History of Modern Europe. Fyffe: History of Europe. Sybel: History of the French Revolution. Acton: Cambridge Modern History. Larned: Topical Outlines of Universal History.

ATLASES.—Bartholomew: Atlas. Rand-McNally: Atlas; Century Dictionary and Atlas. Johnson: Historical Atlas. McClure: Historical Church Atlas.

GAZETTEERS.—Blackie: Imperial Gazetteer. Longman: Gazetteer of the World. Lippincott: Gazetteer. Baedecker: Guides.

GOVERNMENT AND LAW.—Aristotle: Politics. Bluntschli: Theory of the State. Burgess: Political Science and Comparative Constitutional Law. Freeman: Comparative Politics. Goodnow: Comparative Administrative Law. Lalor: Cyclopedia of Political Science. Locke: Treatises of Government. Maine: Popular Government. Montesquieu: Spirit of Laws. Morley: Ideal Commonwealths. Plato: Republic. Rousseau: The Social Contract. Sidgwick: Elements of Politics. Spencer: Man vs. the State. Wilson: The State. Bryce: The American Commonwealth. Hart: Actual Government. Robinson: Elements of American Jurisprudence. Thompson: English and American Encyclopedia of Law. Burdick: The Essentials of Business Law. Lowell: Governments and Parties in Continental Europe. Goodnow: Comparative Administrative Law. Dicey: The Law of the Constitution.

I. CLASSIFICATION OF LANGUAGES—WRITTEN AND SPOKEN ENGLISH—The Proper Use of Words, Sentences and Paragraphs—Figures of Speech—Poetics—Use of Capital Letters—Punctuation—Forms of Practical English Composition: Letters, Argument and Debate, News, Short Story, Fiction, Essay, Editorials, Reviews, Criticism, Addresses and Other Forms of Public Speech—ABBREVIATIONS—PRONOUNCING DICTIONARY OF CLASSIC WORDS AND PHRASES—PRONOUNCING DICTIONARY OF WORDS AND PHRASES FROM THE MODERN LANGUAGES.

II. ENGLISH AND AMERICAN LITERATURE—OUTLINE CHARTS OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN AUTHORS—DICTIONARY OF LITERARY ALLUSIONS: Famous Books, Poems, Dramas, Literary Characters, Plots, Pen Names, Literary Shrines and Geography, and other Miscellany—PRONOUNCING DICTIONARY OF MYTHOLOGY: Gods, Heroes, and Mythical Wonder Tales—CHART OF GREEK AND ROMAN MYTHS, their Origin, Relationship and Descent.

⁂Books of Reference.—LANGUAGE.—Sayce: Introduction to the Science of Language. Whitney: Language and the Study of Language. Paul: Principles of the History of Language. Muller: Science of Language. Skeat: Philosophy. Jesperson: Progress in Language, with Special Reference to English. Giles: Manual of Comparative Philosophy for Classical Students. Oertel: Lectures on the Study of Language. Sweet: Primer of Spoken English. Skeat: Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Sweet: Grammar, Logical and Historical. Lewis: Applied English Grammar. Genung: Practical Elements of Rhetoric. Gummere: Poetics. Wendell: English Composition. Palmer: Self-Cultivation in English. Kittredge: Words and their Ways in English Speech. Trench: Study of Words. Fernald: Synonymns and Antonymns.

LITERATURE.—Jevons: History of Greek Literature. Mahaffy: Greek Literature. Crutwell: History of Roman Literature. Fortier: History of French Literature. Robertson: History of German Literature. Garnett: Short History of Italian Literature. Symonds: Italian Renaissance. Horn: History of Scandinavian Literature and Jewish Encyclopedia. Morley: Library of English Literature. Brooke: History of English Literature. Ward: English Poets. Gosse: Short History of English Literature. Tyler: History of American Literature. Matthews: History of American Literature. Stedman: An American Anthology. Johnson: Elements of Literary Criticism. Warner: Library of Universal Literature.

DICTIONARIES.—Webster: New International Dictionary. Worcester: Dictionary of the English Language. Funk and Wagnalls: Standard Dictionary. Whitney: The Century Dictionary. Murray: Oxford English Dictionary. Wright: Dialect Dictionary.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE SCIENCES IN PARALLEL OUTLINES—PRACTICAL MATHEMATICS—Arithematic and its Modern Applications—The Arithmetic of Business, Commercial and Industrial Transactions—Corporations, Stocks and Bonds—Table of Commercial Laws—Weights and Measures—PHYSICS: Laws and Properties of Matter—Mechanics and Inventions—Sound—Heat—Light and Color—Electricity and Magnetism—CHEMISTRY: Theory of Chemistry—Table of the Chemical Elements—The Chemistry of Common Things—REMARKABLE INVENTIONS AND DISCOVERIES—RECENT SCIENTIFIC PROGRESS, X-rays and Radium, Wireless Telegraphy, Wireless Telephone, Aeroplanes, Submarines, Airships, and Explosives.

⁂Books of Reference.—BIOLOGY.—Brooks: Foundations of Zoology. Morgan: Animal Behavior. Pearson: The Grammar of Science. Spencer: Principles of Biology. Thomson: The Science of Life. Verworn: General Physiology. Weismann: The Germ-Plasm.

PHYSICS.—Ames: General Physics. Ames and Bliss: Manual of Experiments. Hoadley: Measurements in Magnetism and Electricity. Preston: Theory of Heat and Theory of Light. Poynting and Thomson: Heat. Tyndal: Light. Schuster: Theory of Optics. Barker: Physics. Merrill: Theoretical Mechanics. Helmholtz: Sensations of Tone. Kapp: Electric Transmission of Energy. Crocker: Electric Lighting. Sewell: Elements of Electrical Engineering. Jackson: Elements of Electricity and Magnetism and Alternating Currents and Alternating Current Machinery.

CHEMISTRY.—Remsen: Introduction to the Study of Chemistry and Inorganic Chemistry. Roscoe: Lessons in Elementary Chemistry. Wurtz: Elements of Modern Chemistry. Ostwald: Inorganic Chemistry. Alexander Smith: Laboratory Outline of General Chemistry and General Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley: Chemistry of Foods and Agricultural Chemistry. Roscoe and Schorlemmer: Treatise on Chemistry. Watts: Dictionary of Chemistry. Thorp: Industrial Chemistry.

(Abridged in the Concise Edition.)

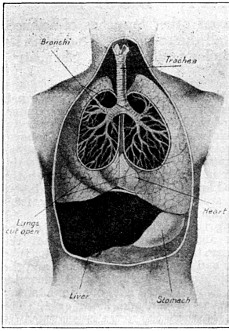

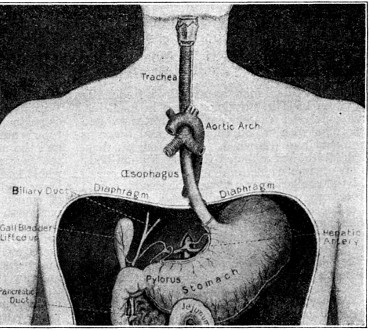

ITS STRUCTURE—ORGANIZATION INTO SYSTEMS—FUNCTIONS—SPECIAL SENSES—NERVOUS SYSTEM—PERSONAL HYGIENE—PREVENTION OF DISEASE—INTERDEPENDENCE OF BODY AND MIND—EUGENICS—ILLUSTRATIONS AND CHARTS.

⁂Books of Reference.—Morris: Treatise on Anatomy. Gray: Anatomy. Davidson: Human Body and Health. Martin: Human Body. Huxley and Youmans: Elements of Physiology and Hygiene. Wilson: The Cell in Development and in Inheritance. Thomson: Heredity. Loeb: Comparative Physiology of the Brain and Comparative Psychology. Sternberg: Manual of Bacteriology.

(Abridged in the Concise Edition.)

BIOGRAPHICAL CHART SHOWING THE WORLD’S MASTERS OF ACHIEVEMENT BY CENTURIES.

CHRONOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF BIOGRAPHY: (a) The World’s Immortals, specially treated; (b) Present-Day Biographies.

(The Biographical Chart only is included in the Concise edition.)

⁂Books of Reference.—Philips: Dictionary of Biographical Reference. Vincent: Dictionary of Biography. Thomas: Dictionary of Biography. Appleton: Dictionary of American Biography; Dictionary of National Biography; Who’s Who in Great Britain; Who’s Who in America. Ruoff: Masters of Achievement; American Statesmen Series; American Men of Letters; English Statesmen Series; English Men of Letters. Smith: Dictionary of Christian Biography.

(Omitted in the Concise Edition.)

PLAYLAND—STORYLAND—NATURE-LAND—SCHOOL-LAND: SIMPLE LESSONS ABOUT WORDS, READING, WRITING, NUMBERS, ETC.—MANNERS AND CONDUCT—THE PARENT AND CHILD—THE OUTLOOK UPON LIFE—EDUCATION AND MORAL GROWTH—CARE OF THE BODY.

⁂Books of Reference.—PRIMARY EDUCATION.—Arnold: Rhythms. Barnard: Kindergarten and Child-Culture Papers. Blow: Educational Issues; Letters to a Mother; Symbolic Education. Froebel’s translated Mother-Play Songs. Froebel: Education of Man; Education by Development; Last Volumes of Pedagogics; Pedagogics of the Kindergarten. Hailman: Laws of Childhood. Harrison: A Study of Child-Nature; Kindergarten Building Gifts; Misunderstood Children; Two Children of the Foothills. Hughes: Educational Laws. Peabody: Kindergarten Lectures. Snider: Commentary on Froebel’s Mother-Play Songs; Life of Froebel; Psychology of the Play-Gifts. Vanderwalker: The Kindergarten in American Education. Von Bulow: The Child; Reminiscences of Froebel.

(Abridged in the Concise Edition.)

Marvels of the Earth’s Rotation and Forces

Proud Color Beauties of the Land of Flowers

Three Celebrated Pictures of Animal Favorites

Washington, America’s City Beautiful

Architectural Glories of Famous Lands

Famous Historical Pictures by Oriental Artists

Tennyson’s Beautiful “Lady of Shalott”

“Open Sesame!” Ali Baba at the Cave

Picture Diagrams of Eye and Ear

The Fiery Furnace that Purifies Bessemer Steel

“The Ides of March”

Famous Masterpieces by Famous Painters

(Only six Color Plates are included in the single volume edition)

Color Diagram Showing the Ocean Beds

Diagram of Orbits of the Planets

Picture Diagram of the Moon’s Phases

Star Charts of the Chief Constellations

Maps of the Chief Constellations

Diagrams Showing Formation of Eclipses

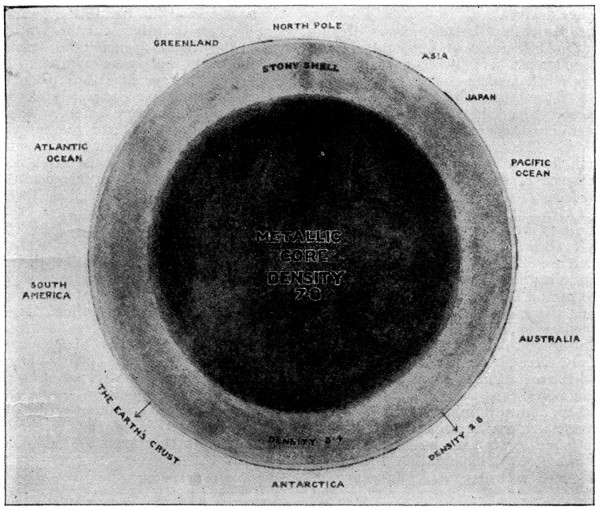

Diagram Showing a Bisection of the Earth

Chart Showing the Geological Growth of the Earth

Geological Map of the United States

Maps Showing Relative Size of Islands of the World

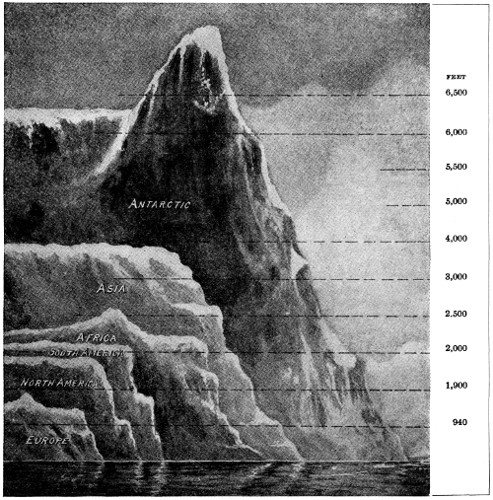

Diagram of the World’s Famous Rivers and Mountains

Maps Showing Relative Size of Lakes

Diagrams Explaining the Seasons, Day and Night

Pictorial Chart of Cloud Formations

Map Showing Distribution of Plant Life

Map Showing Range of Animal Life

16 Maps in Color Showing the Progress of Geographical Discovery

2 Picture Maps Presenting a Panoramic View of Paris

5 Picture Maps Giving a Panorama of the River Rhine

Picture Diagram Showing Parts of a Locomotive

Picture Diagram Explaining Wireless Telegraphy

Picture Diagram Explaining an Electric Battery

Picture Diagram Showing How Electricity is Generated

Picture Diagram Explaining Radioactivity

Map of Panama Canal and Connections

These include hundreds of beautiful and instructive reproductions illustrative of the heavens, earth, minerals, plants and plant products, animal life, races and peoples, famous examples of architecture, scenes in great cities, historic shrines and ruins, mythology, science, marvels of mechanism, great works of engineering, monuments, industries, etc., as well as numerous photographic and art pictures of famous persons and episodes in the history of progress.

THE UNIVERSE: ITS MAGNITUDE AND MEANING

THE SOLAR SYSTEM: Sun, Planets, Moon, Constellations, Stars, Comets, Meteors, Nebulæ, and other Wonders of the Skies

ORIGIN OF THE WORLDS: THE NEBULAR HYPOTHESIS

ECLIPSES: CAUSES AND EXPLANATION

MYTHOLOGY OF THE CONSTELLATIONS

DICTIONARY OF SCIENTIFIC TERMS

STAR CHARTS AND MAPS

NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND TABLES

| 1. Crowded group of stars seen in the constellation Hercules. |  |

|

| 2. Beautiful circular group of stars in Aquarius. Very brilliant toward the center. | ||

| 3-4. Fan-shaped groups of stars, frequently to be observed. | ||

| 5. Round nebula of Ursa Major. | ||

| 6. A fine star in Gemini with a great, oval atmosphere. | ||

| 7. Star in Leo Major in the middle of nebula with very pointed ends. | ||

| 8-9. Nebulæ with luminous trains like the tail of a comet. | ||

| 10. Two stars in Canes Venatici joined by elliptical nebula. | ||

| 11. Elliptical nebula in Sagittarius with a star in each of the foci. | ||

| 12-13. Round nebula in Auriga with three stars in a triangle. | ||

| 14. Great nebula in Andromeda. | ||

| 15. Comet of 1819, of remarkable size. | ||

| 16-17. Great comet of 1811. | ||

| 18. Surface of the planet Mars, showing the supposed continents and seas. | ||

| 19. Disk of the great planet Jupiter with its dark streaks and masses. | ||

| 20. The wonderful planet Saturn with its remarkable rings. | ||

| Explanation of Figures in Diagram |

DIAGRAM SHOWING RELATIVE ORBITS OF THE PLANETS AROUND THE SUN |

Rate at which the Planets Travel |

Central diagram enlarged (245 kB)

Right-hand side illustration enlarged (181 kB)

DIAGRAM SHOWING RELATIVE ORBITS OF THE PLANETS AROUND THE SUN

Explanation of Figures in Diagram

1. Crowded group of stars seen in the constellation Hercules.

2. Beautiful circular group of stars in Aquarius. Very brilliant toward the center.

3-4. Fan-shaped groups of stars, frequently to be observed.

5. Round nebula of Ursa Major.

6. A fine star in Gemini with a great, oval atmosphere.

7. Star in Leo Major in the middle of nebula with very pointed ends.

8-9. Nebulæ with luminous trains like the tail of a comet.

10. Two stars in Canes Venatici joined by elliptical nebula.

11. Elliptical nebula in Sagittarius with a star in each of the foci.

12-13. Round nebula in Auriga with three stars in a triangle.

14. Great nebula in Andromeda.

15. Comet of 1819, of remarkable size.

16-17. Great comet of 1811.

18. Surface of the planet Mars, showing the supposed continents and seas.

19. Disk of the great planet Jupiter with its dark streaks and masses.

20. The wonderful planet Saturn with its remarkable rings.

Rate at which the Planets Travel

BOOK OF THE HEAVENS

THE UNIVERSE—THE SOLAR SYSTEM—PLANETS—SUN—MOON—CONSTELLATIONS—STARS—COMETS—METEORS—NEBULÆ—NEBULAR HYPOTHESIS—ECLIPSES—MYTHOLOGY OF THE CONSTELLATIONS—DICTIONARY OF SCIENTIFIC TERMS USED IN ASTRONOMY.

HOW THE PLANETS WOULD APPEAR IF GROUPED IN SPACE

In the above picture we have represented the planets of the Solar System as we should see them from the earth if the human eye could grasp a space of such immensity. The spectator is supposed to be standing on the earth, and the moon is in the foreground, 240,000 miles away. The planets are in their order outward from the sun, and vary in distance from 40,000,000 miles, in the case of Mars, to 2,700,000,000 miles in the case of Neptune. From the bottom upward, the planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and its rings, Uranus and Neptune.

The earth upon which we live is only one of many worlds that whirl through space. If we are to understand our own world, we must first learn something about the worlds in the skies. These bodies are arranged in groups, or systems, sweeping through circuits that baffle measurement; and such is the magnitude of the boundless space they occupy that our entire solar system is only a point in comparison. To this vast expanse of worlds, and systems and space we give the general name Universe.

First in importance to us in this immense space filled with stars is what astronomers call the Solar System, so-called because the sun is its center. It contains the planets, eight in number, of which our earth is one. They have been named after the ancient deities; the two interior ones, Mercury and Venus, and the exterior ones, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; the first three being smaller than our earth, and the remainder a great deal larger.

Mercury and Venus are known to be interior planets, that is, planets between us and the sun, because they appear to swing on either side of the sun. Mercury very seldom leaves the sun sufficiently to rise so early before the sun, or set so late after him, as to be visible. Venus, however, [14] gets so far away as to be seen long after sunset or before sunrise, and is called the Evening or Morning star, accordingly.

Besides the planets there are other members of the system, namely, comets and falling stars, which will be mentioned again more fully hereafter. All these bodies form a sort of family, having the sun for their head. The illustrations and drawings on separate pages give a view of the entire system.

Comparative Size. The size of the planets, in general, increases with their distance from the sun. The four composing the first group are all comparatively small, the earth being the largest. Those of the second group are all of great size. Jupiter, the largest, is not less than 1,390 times as large as the earth; but as it is much less dense, the amount of matter it contains is only a trifle more than 337 times that of the earth. All the planets together equal but one seven-hundredth part of the mass of the sun.

The Satellites, except our moon, and the two satellites of Mars, belong wholly to the second group of planets. Jupiter has eight; Saturn eight and several revolving rings; Uranus has four, and possibly more; while Neptune, so far as known with certainty, has but one.

Rotary Motion. The sun, all the primary planets, and their satellites, as far as known, rotate from west to east. Each rotation constitutes a day for the rotating body. The central line of rotary motion is called the axis of rotation, and the extremities of the axis are called the Poles.

Revolution Around the Sun. All the primary planets and asteroids revolve around the sun in the direction of their rotation, that is from west to east; and the planes of the orbits in which they revolve coincide very nearly with the plane of the sun’s equator. One revolution around the sun constitutes the year of a planet.

All the satellites, except those of Uranus and perhaps Neptune, also revolve from west to east.

Most of the comets revolve around the sun in very irregular and elongated orbits, only a few having their entire orbit within the planetary system. Some so move that after having entered our system and made their circuit around the sun, they seem to leave it, never to return.

Large illustration (258 kB)

Since the orbits of the planets are in most cases not far removed from the plane of the ecliptic, they are to be seen in a comparatively narrow belt of the heavens called,

The Zodiac. The belt of the sky which occupies 8° on each side of the ecliptic is called the Zodiac, and it is within this belt that the moon and the chief planets confine their movements, as none of their orbits is inclined to that of the earth by more than 8°. The Zodiac, which circles the celestial sphere, is divided into twelve signs each of which occupies 30°, and roughly coincides [15] with a constellation. The following lists give the signs of the Zodiac, with the seasons in which the sun passes through each of them:

Spring: Aries the Ram; Taurus the Bull; Gemini the Twins.

Summer: Cancer the Crab; Leo the Lion; Virgo the Virgin.

Autumn: Libra the Balance; Scorpio the Scorpion; Sagittarius the Archer.

Winter: Capricornus the Goat; Aquarius the Water-bearer; Pisces the Fishes.

Owing to the precession of the equinoxes, the signs of the Zodiac do not now correspond with the constellations of which they bear the names. Thus the sign Aries, in which the sun is seen on March 21st as it passes the vernal equinox, with which the solar year begins, is now in the constellation of Pisces, and in the course of the next 23,000 years it will move steadily backward through the constellations until it returns to the Ram, where it stood when its name was first given to it.

The laws under which the planets move were discovered through the genius of John Kepler, and are known as Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion. Kepler derived these laws from observation only, but Newton first explained them by showing that they were the necessary consequences of the laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

Kepler’s First Law states: “The earth and the other planets revolve in ellipses with the sun in one focus.”

Kepler’s Second Law states: “The radius vector of each planet moves over equal areas in equal times.”

Kepler’s Third Law states: “The squares of the periodic times of the planets are in proportion to the cubes of their mean distances from the sun.”

DIAGRAMS ILLUSTRATING KEPLER’S FIRST TWO LAWS OF PLANETARY MOTION

The diagram on the top illustrates the ellipse, and explains the first and second laws. The picture-diagram on the bottom illustrates the second law, which is that, as the planet moves round the sun, its radius vector describes equal areas in equal times. That is to say, a planet moves from A to B in the same time as it takes to move from C to D.

These laws cannot be fully understood without some acquaintance with mathematics. They may, however, be briefly explained for the comprehension of the non-mathematical reader. The figure in the diagram is an ellipse—what is known in popular language as an oval—which is symmetrical about the line AB, known as its major axis. It has two foci, S and S1. The fundamental law of the ellipse is that if we take any point P on it, and join this point by a straight line to the two foci, then the sum of these two lines SP and S1P is always the same—SP + S1P = C.

The second law is rather less easy to understand. The radius vector is the line joining the sun to the planet at any moment; if we suppose the sun to be at the focus S, and P to be the planet, the radius vector at various positions of the planet will be represented by the lines SP, SP1, SP2, and so on. If the positions P, P1, P2, and so on, represent those which the planet occupies after equal periods of time—say, once a month—then the sectors of the ellipse bounded by each pair of lines, SP and SP1, SP1 and SP2, will be equal. If a planet were to move in a circle round the sun, it is obvious that this law would imply that it moved with a uniform speed; but since the curvature of the ellipse varies in every part of its course, so must the speed of the planet, in order that its radius vector may describe equal areas in equal times. The planet will, in fact, be moving faster when it is near the sun, as at P, than when it is far off from the sun, as at P2.

The third law shows that there is a definite numerical relation between the motions of all the planets, and that the time which each of them takes to complete its orbit depends upon its distance from the sun.

On his discovery of his third law Kepler had written: “The book is written to be read either now or by posterity—I care not which; it may well wait a century for a reader, as God has waited six thousand years for an observer.” Twelve years after his death, on Christmas Day, 1642, near Grantham, England, the predestined “reader” was born. The inner meaning of Kepler’s three laws was brought to light by Isaac Newton.

The great luminary which warms, lights, and rules the solar system is, like the majority of its fellow stars, a gigantic bubble. In other words, it is a globe of [16] glowing gas, which is nowhere solid, though the immense pressure which must exist in its interior probably causes this gas to assume there a density greater than that of any solid which we know.

A PHOTOGRAPH OF THE SUN, SHOWING THE CLOUDS OF FIERY VAPOR WHICH SURROUND IT

Dimensions of the Sun. The sun appears to human vision as a brilliant globe of a little more than half a degree in diameter. It is about the same apparent size as the moon, since the size of the sun is to that of the moon very nearly in the same proportion as their relative distances from the earth. In reality, however, the sun is a gigantic orb, so huge that if the earth were at its center the whole orbit of the moon would lie well within its circumference. The diameter of the sun is about 866,500 miles.

The mass of the sun is about 332,000 times that of the earth, but its specific gravity is only about a quarter that of the earth, 1.41, if that of water be taken as unity. The mean distance of the sun from the earth is about 92,800,000 miles; but, as the earth’s orbit is not circular but elliptic, this distances varies by about 3,000,000 miles, being smallest in January and greatest in July.

The Physical Condition of the sun is very different from that of the earth, though we know it is composed of very similar materials. The white-hot surface that we see, called the photosphere, is believed to be largely a shell of highly heated metallic vapors surrounding the unseen mass beneath. Dark spaces seen in the photosphere are known as sun-spots, [17] and these are often surrounded by brighter patches, termed faculæ. Above the photosphere a shallow envelope of gases, rising here and there into huge prominences, and known as the chromosphere, is seen in red tints when the sun is totally eclipsed. Beyond the chromosphere, there is also seen, at the same time, a faint but far more extensive envelope called the corona.

This diagram illustrates the theory that sun-spots are formed by fragments struck from Saturn’s rings (which are in themselves nothing more than a great meteoric swarm) by the swarm of meteors known as the Leonids, which fragments fall into the solar furnace at a speed of four hundred miles a second.

The sun’s rays supply light and heat not only to the earth, but also to the [18] other planets which revolve round it. Its attraction confines these planets in their orbits and controls their motions.

The Moon, the satellite of the earth, is the nearest to us of all the heavenly bodies, being at a mean distance of 240,000 miles. Its diameter is 2,153 miles and, its density being little more than half that of the earth, the force of gravity at its surface is very much less than that at the surface of the earth. A body which weighs a pound here would only weigh about two and one-half ounces if taken to the moon.

THE SYSTEM OF MARS AND ITS MOONS CONTRASTED WITH THAT OF THE EARTH AND MOON

In this diagram the markings on the earth and Mars are to scale, the orbits of the planets are seen in perspective and the measurements are according to Prof. Percival Lowell.

The Moon’s Orbit. Her path is approximately an ellipse with the earth in one focus. Its apparent motion in the sky is from west to east, but she moves much faster than the sun, taking about twenty-seven days eight hours to travel all round the earth. The time between two successive new moons (synodic period or lunation) is twenty-nine and one-half days. The reason of the difference is that the sun moves slowly in his annual course through the stars in the same direction as the moon, which therefore in its revolution round the earth has to overtake him when it returns. The moon rotates on its axis in the same time as it performs a revolution in its orbit; hence the same half is always turned toward us.

When the moon in her orbit lies between the sun and the earth, she is said to be in conjunction with the sun; when the earth is between the moon and the sun, the moon is said to be in opposition to the sun. At either of the two points midway from conjunction and opposition, i. e. 90° from conjunction or opposition, the moon is said to be in quadrature.

The Phases of the Moon. Except at opposition—i. e. when the earth is between the moon and sun—the whole of the moon’s disc does not appear bright to us, and the amount of the bright surface seen by us is found to depend on the relative positions of moon and sun. Half of the moon is always illuminated by the sun; but when it is in conjunction between the earth and sun the whole of the bright surface is on the side away from us; so that the moon is invisible. As it moves farther from the line joining earth and sun, a small portion of the bright side comes into view as a narrow crescent. This increases till half the disc is illuminated, when the lines joining earth and moon and earth and sun are at right angles. From this time the moon loses its crescent shape and becomes convex on both sides, or gibbous (Lat. gibbus, a hump)—the maximum brightness, or full moon, occurring when sun and moon are on opposite sides of the [19] earth. After this the moon becomes gibbous, then crescent, and vanishes before the time of new moon.

It is worthy of note that the moon is higher in the heavens and longer above the horizon in the winter than in summer. This is owing to the plane of its orbit being at night high towards the south in winter and low in summer, as is the ecliptic. The moon’s orbit, like that of other planets, is elliptical, but irregular. When nearest to the earth, she is said to be in perigee; when at the greatest distance, in apogee.

DIAGRAM SHOWING HOW THE MOON’S PHASES ARE CAUSED

In the above diagram, the earth is in the center, and the circle ACFH the orbit of the moon. Since the inclination of the plane of the moon’s orbit to the plane of the ecliptic is only a few degrees, we may neglect it in this case, and suppose the two planes to coincide. Let the sun lie in the direction ES. Since the distance of the sun from the earth is about three hundred and eighty-seven times the distance of the moon from the earth, the lines ES, HS, BS, etc., drawn to the sun from different points of the moon’s orbit, may be considered to be sensibly parallel. Let us first suppose the moon to be in conjunction with the sun at the point A. Here only the dark portion of the moon is turned towards the earth, and the moon is therefore invisible. This is called new moon. As the moon moves on towards B, the enlightened part begins to be visible, and when it reaches C, half the enlightened part is visible, and the moon is at its first quarter. When the moon is at F, in opposition to the sun, all the illuminated part is turned towards the earth, and the moon is full. The moon wanes after leaving F, passes through its last quarter at H, and finally becomes again invisible at A.

Surface of the Moon. The moon is an opaque, cold globe, covered with mountains, extinct volcanoes, and plains. She has neither water nor atmosphere, and always presents the same surface to the earth in consequence of rotating on her axis in the same time as she revolves round the earth. Moonlight is only reflected sunlight, the illuminated hemisphere being always turned towards the sun.

The face of the moon has been studied and mapped on a large scale. Its chief features are three in number: (1) the [20] numerous volcanic craters, such as Tycho and Copernicus, which are mostly named after distinguished men of science; (2) the wide, dark plains which are known as seas, because they were formerly thought to consist of water; (3) the curious systems of bright streaks, which radiate from many of these craters, of which the most remarkable extend in all directions from the great crater Tycho, near the moon’s south pole, and are conspicuous even to the naked eye at the time of full moon.

The Moon and the Tides. The moon has long been known to have an effect upon the tides, and may perhaps influence the winds. It is of enormous importance to navigators for the determination of longitude, and hence its movements have been investigated with the greatest care and precision.

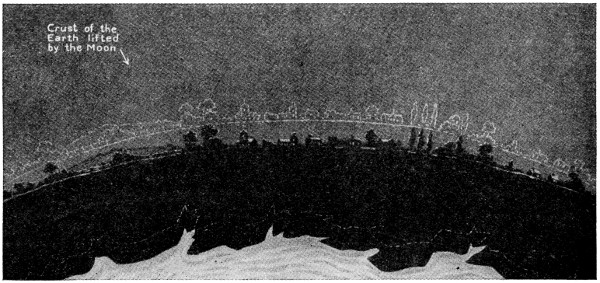

HOW THE MOON FORMS “TIDES” IN THE CRUST OF THE EARTH

By reason of its power of attraction, it is well recognized that the Moon exercises a greater influence on the side of the earth which is nearest to it. In consequence the earth is subject to a stress or pull that tends to lengthen it out toward the moon, and then to recede as the earth turns away on its axis.

The Planet Mars. Nearest to the earth, with the single exception of Venus, resembles the earth more closely than any other of the planets, and is most favorably situated for our observation of all the heavenly bodies, except the moon. It is a globe rather more than half the size of the earth. When Mars comes nearest to the earth its distance from us is about 35,000,000 miles. At these favorable moments its brightness is about equal to Jupiter, and only surpassed by that of Venus. Mars has a very pronounced red color, which is supposed to be due to the prevalence of a rock like our red sandstone on its surface, or possibly to the color of its vegetation.

Its density is much less—about three-quarters that of the earth; so a pound weight placed on its surface would not weigh much more than six ounces, and a ponderous elephant would, if there, be able to jump about with the agility of a fawn.

The heat and light which Mars receives from the sun, therefore, vary enormously, and so cause a difference in the lengths of winter and summer in his north and south hemispheres, the seasons in the north hemisphere being far more temperate than those in the south. Viewed with the telescope, large dark green spots are seen, the rest of the surface being of a ruddy tint, except at the two poles, where two white spots are observed and considered to be due to large masses of snow and ice. It has been supposed that the greenish spots are oceans, and the ruddy parts land. The spectroscope has shown that watery vapor is present in Mars’ atmosphere, and appearances like huge rain-clouds sometimes obscure a part of the planet for a considerable period. Physical processes seem to go on there much the same as on our planet; hence many believe that Mars is inhabited and forms, in fact, a miniature picture of the earth.

Jupiter. By far the largest of the planets is second in brilliancy to Venus, unlike which, however, it is a “superior” planet, having its orbit outside that of the earth. It is about five times as brilliant as Sirius, the brightest of the fixed stars.

The planet is a beautiful object when viewed with a telescope; it is probable that the markings are entirely due to its atmosphere, and that the actual surface of the planet is rarely visible. Jupiter has hardly yet cooled from the condition of incandescence, and it is only slightly solidified. It possesses eight satellites, four of which were discovered by Galileo when he applied the telescope first to the investigation of the heavens. By means of these satellites the first observations of the velocity of light were made. A fifth was discovered in 1892 at the Lick Observatory.

Saturn was recognized as a planet by the ancients, and was the outside member of the solar system as known by them. His diameters at the equator and poles differ considerably, the protuberance at the equator giving him there a diameter of 74,000 miles, while at the poles it is only 68,000. In size Saturn is the largest of the planets except Jupiter, being in fact seven hundred times larger than our earth, but his density is so small that he would be able to float on water far more easily than an iceberg. From this it follows that he cannot consist of solid or liquid matter, and in fact we can only view a mass of clouds intensely heated within, the whole being probably a planet in the early stage of development—younger even than Jupiter.

The most remarkable characteristic of Saturn, which makes him an object of such interest in the sky, is his possession of a luminous ring. The ring is only luminous on account of its reflection of the sun’s light; hence is invisible to us when, for instance, we are endeavoring to look at the ring from below while the sun is shining above. It also sometimes happens that the plane of the rings passes through the sun or through the center of the earth, in which case only the thin edge of the rings can be seen. The ring is divided into two parts, the inner being the wider, while another faint division appears to divide the outer part into two smaller rings. In 1850 another ring was discovered; this is quite different from the outer rings, being dark, and generally known as the dusky ring of Saturn. The outer ones, though far from solid, can receive a shadow of Saturn, and themselves cast one on his disc. The rings are not continuous masses of matter, but consist of countless myriads of tiny satellites, so close together that to the observer they appear as one body. The planet has eight satellites which seldom pass behind or in front of the planet’s disc, and therefore are not objects of great interest.

Uranus is the next planet beyond Saturn. His mass is about fifteen times as much as that of the earth, an amount which makes him more than outweigh Mercury, Venus, the Earth, and Mars combined. All astronomers do not agree in their estimation of these numbers, Uranus being too far away for measurements to be more than approximate. Gravity on his surface is only three-quarters of what it is here. Uranus has four satellites, and possibly faint rings like those which encircle Saturn.

Neptune is farthest from the sun, the distance between the two bodies being about 2,750,000,000 miles. At this immense distance it will, according to Kepler’s laws, take a long time to travel once around its orbit, and this time has been found to be one hundred and sixty-five of our years. Although it is ninety-seven times as large as the earth, yet, on account of its enormous distance from us it can only just be seen, even with a powerful telescope. Neptune possesses one satellite, which moves around the planet in rather less than six days.

Mercury is the smallest planet, except the planetoids, in the solar system, and the one nearest the sun. It is never seen for more than two hours before sunrise or after sunset, and is not always visible then; but when it does appear, it is extremely brilliant. Even when it is most distant the sun appears four and a half times as big to it as it does to us, and when the two are at their nearest, this small planet gets ten times as much light and heat as we do. It is, however, so small and difficult to observe, that comparatively little is known of it.

Venus appears to us as the most brilliant of all the planets, sometimes [22] heralding the sun’s approach in the morning and sometimes following him at night. Hence she has been called the “morning” and the “evening” star; and the ancient Greeks, believing her to be two bodies, and not one, called her Hesperus (Vesper) when she appeared at night, but Phosphorus when she preceded the dawn, this last name having been translated in the Latin, Lucifer. We know very little of the actual surface of Venus, for her envelope of clouds remains constantly in front of us to baffle curiosity, and never lifts to give us a glimpse of the planet beneath. These clouds send on to us the light they borrow from the sun, and shine to us with a brilliant silvery lustre interrupted here and there with shadowy markings of short duration. But when Venus shines to us in crescent-form, certain spots near the ends of the horns can be seen more definitely, and the effects of light and shadow round these points suggest that they are lofty peaks, reaching above the clouds.

The Minor Planets or Asteroids. The space between Mars and Jupiter is occupied by a strange and numerous swarm of minor planets or asteroids. The first of these singular bodies was discovered by an Italian astronomer, Piazzi, on the first night of the nineteenth century. Three others were discovered within the course of the next seven years, and the number now known is upward of 600, most of which have been recognized by the record of their motion on photographs of the sky. The four asteroids first discovered, Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta, are naturally the largest, ranging in diameter from four hundred to one hundred and eighteen miles.

Vesta, though not the largest, is considerably the brightest of the minor planets, and is occasionally visible to the naked eye. None of the other asteroids has a diameter so great as one hundred miles, and probably the majority of them are only ten or twenty miles in diameter.

In addition to the planets and their satellites, the sun is attended by numerous other bodies, moving with far less regularity, and generally much less conspicuous in the heavens. These are known as comets and meteorites or shooting stars. One of the most interesting of recent astronomical discoveries is that an intimate physical connection exists between these two classes of bodies.

Comets. Comets have been known from the earliest times, because every now and then a very large and conspicuous one hastens up to the sun from the remote regions of space, and perplexes monarchs with the fear of change. They are called comets, from the Latin coma, meaning hair, because when they are bright enough to be seen with the naked eye they look like stars attended by a long stream of hazy light, which was thought to resemble a woman’s hair flowing down her back. This train of light is known as the comet’s tail. Such bright comets are sometimes as brilliant as Venus; their tails have been known to stretch halfway across the visible sky.

These comets are very beautiful and conspicuous objects, which usually appear in the sky without any warning from astronomers, and invariably create a great popular sensation. By far the greater number of comets, however, are only visible through a telescope, and it is rare that a year passes without at least half a dozen of these being reported. Up to the present time nearly a thousand comets of all sizes have been recorded. Not more than one in five of these visitors is visible to the naked eye.

Cometary Orbits. In all cases in which a comet has been observed sufficiently often for its orbit to be calculated, it is found that it moves in one of the curves which are known to the geometer as conic sections. Less than a hundred of the known comets move like the planets in elliptical orbits, and consequently their periodical return to visibility can be predicted. As a rule the eccentricity of these cometary orbits is very much greater than that of any planetary orbit, which means that the comet approaches fairly close to the sun at one end of its orbit, but at the other flies away far beyond the outermost planet, and for a long period disappears from the view of our most powerful telescopes.

The great majority of comets have only been seen once, and their orbits appear to be either parabolic or hyperbolic. Neither of these is a closed curve, and what seems to happen in such cases [23] is that a comet travelling in such an orbit dashes up to the sun from the remote parts of space, swings round it, often at very close quarters, and flies away again forever. Only those comets which have elliptical orbits can be said to belong to the solar system. The others are visitors from space, which in the course of their motion come near the sun and are deflected by it, but then fly away until after a lapse of ages they perhaps come within the sphere of another star’s attraction. Of the comets which move in elliptical orbits, about twenty have been observed at more than one return to the sun. Some of these complete their orbits in quite a short period, like Encke’s comet, which has the shortest period of all, less than three and a half years; the longest periodical comet is known as Halley’s, which returns to the sun after seventy-six years, and last appeared in 1910; it is a bright and conspicuous object.

The Constitution of Comets. The nature of comets was long in doubt, and even today their physical characteristics are not fully understood. They are certainly formed of gravitational matter, because they move in orbits which are subject to the same laws as those of the planets. But they also appear to be acted upon by powerful repulsive forces emanating from the sun, to which is due the remarkable phenomenon of cometary tails. Perhaps there is not much exaggeration in the statement once made by a well-known astronomer that the whole material of a comet stretching halfway across the visible heavens, if properly compressed, could be placed in a hatbox. The old fear that the earth might suddenly be annihilated by a comet striking it is thoroughly dispelled by modern investigation, which leads us to believe that the worst results of such an encounter would be an extremely beautiful display of shooting stars.

Meteors, or Fireballs, are bodies which do not belong to the earth, but come from other parts of space into our atmosphere, and are seen as bright balls of fire crossing the sky, with a train of light behind. Suddenly they are seen to go out, and very often a fall of stones occurs. Sometimes they are observed to break in two, and loud explosions like thunder are heard. They move very fast—ten or twelve miles per second, and are visible when between forty and eighty miles above the earth.

Other meteors dart across the sky and disappear, all in a very short time. These are known as shooting stars, and are sometimes big and bright, like planets. It is estimated that about six or eight meteors which drop stones come into our atmosphere every year; but some 20,000,000 of small bodies pass through the air every day—these would all appear as shooting stars if they occurred at night.

At some periods of the year there are so many shooting stars that they appear like a shower of fire. On November 14th this happens, the shower being greatest every thirty-three years. A stream of meteors is travelling round the sun, and every thirty-three years the earth just comes through them. Meteoric showers also occur about August 9th to 11th, and smaller ones in April.

The luminosity of meteors is due to the intense heat caused by the resistance of the air to their passage, and in support of this theory it is found that meteoric stones are always covered, either wholly or in part, with a crust of cement that has recently been melted.

We shall now study the so-called fixed stars, those stars, namely, which preserve the same relative position and configuration from night to night, only varying, and that with perfect regularity, in the times at which they reach the meridian. For this reason they have been known from the dawn of astronomy as fixed stars, in contrast with the planets or wandering stars.

The observer who watches the nightly changes in the sky with close attention will soon perceive that all these fixed stars appear to move in circles or parts of circles. Some of them describe larger circles than others, and the further south a star is when it passes the meridian, the larger circle will it describe.

It cannot be too often repeated that this motion of the stars is only apparent, being due to the real rotation of the earth, along with the observer on its surface, in the contrary direction. It is estimated that there are about three thousand stars visible to the naked eye [24] in our latitude, though not all these are visible at the same time, many of them being below the horizon, while others are elevated in the sky at different times and seasons.

In beginning our study of the stars, let us put ourselves in the position of the earliest observers. Let us first, like them, watch the stars, and see how they appear from night to night.

We see, at the first glance, that the stars vary much in brightness. The brightest ones—like Sirius, Capella, Arcturus, and Vega—are called stars of the first magnitude. Those less brilliant, like the six brightest of “the Dipper,” are said to be of the second magnitude. All the stars which can be seen with the unaided eye are thus divided into six classes or magnitudes, according to their brightness.

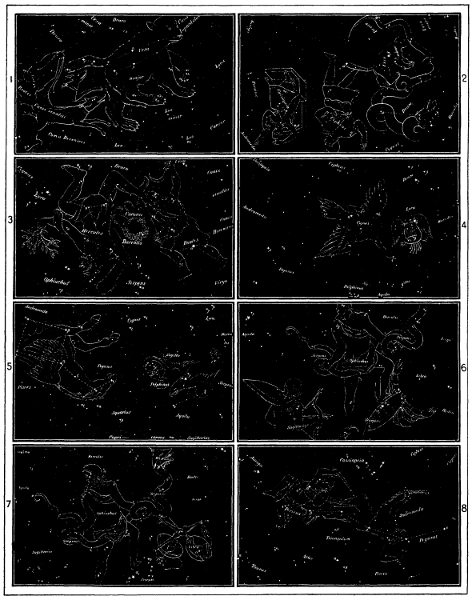

Constellations. We also see that the stars are not uniformly distributed over the sky. They seem to be arranged in groups, some of which take the form of familiar objects. Every one knows the seven bright stars which are called “the Dipper.” Another group resembles a sickle, another a cross, and so on. All the stars in the heavens have been divided into groups called constellations. Many of these were recognized and named at a very early period.

We should become familiar with these constellations in order to study the stars with any profit.

It is necessary, in the first place, to have some way of designating the stars in each constellation. Many of the brighter stars have proper names as Sirius, Arcturus, and Vega; but the great majority of them are marked by the letters of the Greek alphabet. The brightest star in each constellation is called α (alpha); the next brightest, β (beta); the next, γ (gamma); and so on. The characters and names of the Greek alphabet are as follows:

| α, | Alpha. |

| β, | Beta. |

| γ, | Gamma. |

| δ, | Delta. |

| ε, | Epsilon. |

| ζ, | Zeta. |

| η, | Eta. |

| θ, | Theta. |

| ι, | Iota. |

| κ, | Kappa. |

| λ, | Lambda. |

| μ, | Mu. |

| ν, | Nu. |

| ξ, | Xi. |

| ο, | Omicron. |

| π, | Pi. |

| ρ, | Rho. |

| σ, | Sigma. |

| τ, | Tau. |

| υ, | Upsilon. |

| φ, | Phi. |

| χ, | Chi. |

| ψ, | Psi. |

| ω, | Omega. |

These letters are followed by the Latin name of the constellation. Thus Aldebaran is called α Tauri; Rigel, β Orionis; Sirius, α Canis Majoris.

If there are more stars in a constellation than can be named from the Greek alphabet, the Roman alphabet is used in the same way; and when both alphabets are exhausted, numbers are used.

Circumpolar Constellations. One of the most important constellations, and one easily recognized, is the Great Bear, or Ursa Major. It is represented in Plate 1 on the Star Chart. It may be known by the seven stars forming “the Dipper.” The Bear’s feet are marked by three pairs of stars. These and the star in the nose can be readily found by means of the lines drawn on the chart. It may be remarked here, that in all cases the stars thus connected by lines are the leading stars of the constellation. The stars α and β are called the Pointers. If a line be drawn from β to α, and prolonged about five times the distance between them, it will pass near an isolated star of the second magnitude known as the Pole Star, or Polaris. This is the brightest star in the Little Bear, or Ursa Minor (Plate 2). It is in the end of the handle of a second “dipper,” smaller than the one in the Great Bear.

On the opposite side of the Pole Star from the Great Bear, and at about the same distance, is another conspicuous constellation, called Cassiopeia. Its five brightest stars form an irregular W, opening towards the Pole Star (Plate 2).

About half-way between the two Dippers three stars of the third magnitude will be seen, the only stars at all prominent in that neighborhood. These belong to Draco, or the Dragon. The chart will show that the other stars in the body of the monster form an irregular curve around the Little Bear, while the head is marked by four stars arranged in a trapezium. Two of these stars, β and γ, are quite bright. A little less than half-way from Cassiopeia to the head of the Dragon is a constellation known as Cepheus, five stars of which form an irregular K.

These five constellations never set in our latitude, and are called circumpolar constellations.

Constellations Visible in September. At this time the Great Bear will be low down in the northwest, and the Dragon’s head nearly in the zenith. If we draw a line from ζ to η of the Great Bear and prolong it, we shall find that it will pass near a reddish star of the first magnitude. This star is called Arcturus, or α Boötis, since it is the brightest star in the constellation Boötes. Of its other conspicuous stars, four form a cross. These and the remaining stars of the constellation can be readily traced with the aid of Plate 3.

Near the Dragon’s head (Plate 4) may be seen a very bright star of the first magnitude, shining with a pure white light. This star is Vega, or α Lyræ.

If we draw a line from Arcturus to Vega (Plate 3), it will pass through two constellations, the Crown, or Corona Borealis and Hercules. The former is about one-third of the way from Arcturus to Vega, and consists of a semicircle of six stars, the brightest of which is called Alphecca or Gemma Coronæ,—“the gem of the crown.”

Hercules is about half-way between the Crown and Vega. This constellation is marked by a trapezoid of stars of the third magnitude. A star in one foot is near the Dragon’s head; there is also a star in each shoulder, and one in the face.

Just across the Milky Way from Vega (Plate 5) is a star of the first magnitude, called Altair, or α Aquilæ. This star marks the constellation Aquila, or the Eagle, and may be recognized by a small star on each side of it. These are the only important stars in this constellation.

In the Milky Way, between Altair and Cassiopeia (Plate 4), there is a large constellation called Cygnus, or the Swan. Six of its stars form a large cross, by which it will be readily known. α Cygni is often called Deneb. It forms a large isosceles triangle with Altair and Vega.

Low down in the south, on the edge of the Milky Way (Plate 6), is a constellation called Sagittarius, or the Archer. It may be known by [25] five stars forming an inverted dipper, often called “the Milk-dipper.” The head is marked by a small triangle. The other stars, as seen by the map, may be grouped so as to represent a bow and an arrow.

I. STAR CHART OF THE PRINCIPAL CONSTELLATIONS

Large illustrations (all less than 100 kB):

Plate 1,

Plate 2, Plate 3, Plate 4,

Plate 5, Plate 6, Plate 7,

Plate 8

Low in the southwest is a bright red star called Antares, or α Scorpionis.

The space between Sagittarius and Hercules and Scorpio is occupied by the Serpent (Serpens) and the Serpent-bearer, or Ophiuchus (Plates 6 and 7). The head of the Serpent is near the Crown, and marked by a small triangle. The head of Ophiuchus is close to the head of Hercules, and may be known by a star of the second magnitude. Each shoulder is marked by a pair of stars. His feet are near the Scorpion.

Nearly on a line with Arcturus and γ Ursæ Majoris (Plate 1), and rather nearer the latter, is an isolated star of the third magnitude, called Cor Caroli, or Charles’ Heart. This is the only prominent star in the constellation of Canes Venatici, or the Hunting Dogs.

Cassiopeia is almost due east of the Pole Star. A line drawn from the latter through β Cassiopeiæ [26] and prolonged, passes through two stars of the second and third magnitude. These, with two others farther to the south, form a large square, called the Square of Pegasus. Three of these, as seen by the chart (Plate 5), belong to the constellation Pegasus, or the Winged Horse. α Pegasi is called Markab, and β is called Algenib. The bright stars in the neck and nose can be found by the chart.

II. STAR CHART OF THE PRINCIPAL CONSTELLATIONS

Large illustrations (all less than 100 kB):

Plate 9,

Plate 10, Plate 11, Plate 12,

Plate 13, Plate 14, Plate 15,

Plate 16

The fourth star in the Square of Pegasus belongs (Plate 8) to the constellation Andromeda. Nearly in a line with α Pegasi and this star are two other bright stars belonging to Andromeda. The stars in her belt may be found by the chart.

Following the direction of the line of stars in Andromeda just mentioned, and bending a little towards the east, we come to Algol, or β Persei, a remarkable variable star. This star may be readily recognized from the fact, together with β and γ Andromeda and the four stars in the Square of Pegasus, it forms a figure similar in outline to the Dipper in Ursa Major, but much larger. If the handle of this great Dipper is made straight instead of being bent, the star in the end of it is α [27] Persei, of the second magnitude. This star has one of the third magnitude on each side of it. The other stars in Perseus may be found by the chart.

Just below θ in the head of Pegasus (Plate 9) are three stars of the third and fourth magnitudes, forming a small arc. These mark the urn of Aquarius, the Water-bearer. His body consists of a trapezium of four stars of the third and fourth magnitudes. Small clusters of stars show the course of the water flowing from his urn.

This stream enters the mouth of the Southern Fish, or Piscis Australis. The only bright star in this constellation is Fomalhaut, which is of the first magnitude, and at this time will be low down in the southeast.

To the south of Aquarius is Capricornus, or the Goat. He is marked by three pairs of stars arranged in a triangle. One pair is in his head, another in his tail, and the third in his knees.

Near Altair (Plate 5), and a little higher up, is a small diamond of stars forming the Dolphin, or Delphinus.

A little to the west of the Dolphin, in the Milky Way, are four stars of the fourth magnitude, which form the constellation Sagitta, or the Arrow.