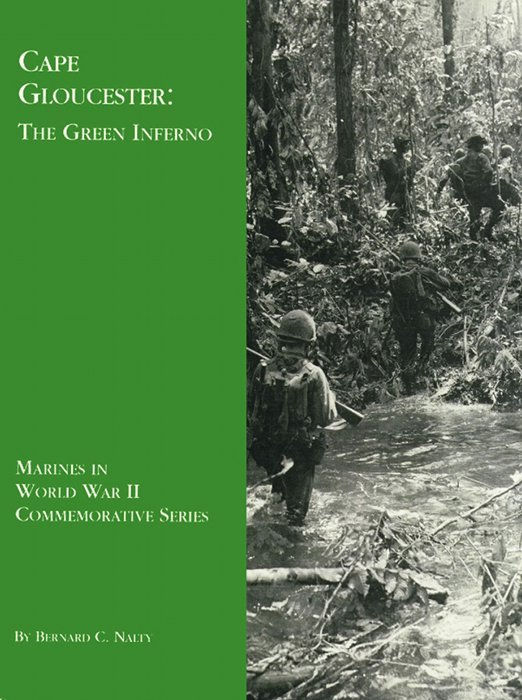

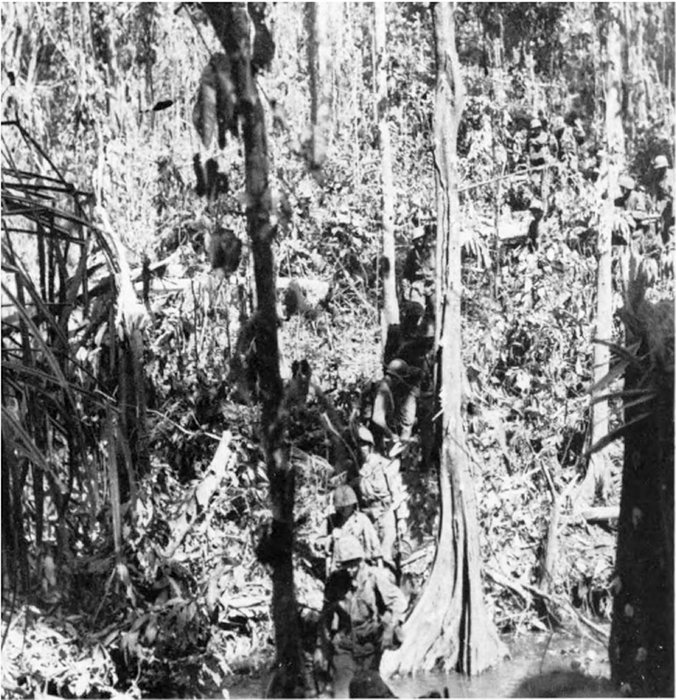

A Marine patrol crosses a flooded stream and probes for the enemy in the forests of New Britain. Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72290

A Marine patrol crosses a flooded stream and probes for the enemy in the forests of New Britain. Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72290

On 26 December 1943, Marines wade ashore from beached LSTs passing through a heavy surf to a narrow beach of black sand. Inland, beyond a curtain of undergrowth, lie the swamp forest and the Japanese defenders. Department of Defense (USMC) photo 68998

by Bernard C. Nalty

On the early morning of 26 December 1943, Marines poised off the coast of Japanese-held New Britain could barely make out the mile-high bulk of Mount Talawe against a sky growing light with the approach of dawn. Flame billowed from the guns of American and Australian cruisers and destroyers, shattering the early morning calm. The men of the 1st Marine Division, commanded by Major General William H. Rupertus, a veteran of expeditionary duty in Haiti and China and of the recently concluded Guadalcanal campaign, steeled themselves as they waited for daylight and the signal to assault the Yellow Beaches near Cape Gloucester in the northwestern part of the island. For 90 minutes, the fire support ships blazed away, trying to neutralize whole areas rather than destroy pinpoint targets, since dense jungle concealed most of the individual fortifications and supply dumps. After the day dawned and H-Hour drew near, Army airmen joined the preliminary bombardment. Four-engine Consolidated Liberator B-24 bombers, flying so high that the Marines offshore could barely see them, dropped 500-pound bombs inland of the beaches, scoring a hit on a fuel dump at the Cape Gloucester airfield complex and igniting a fiery geyser that leapt hundreds of feet into the air. Twin-engine North American Mitchell B-25 medium bombers and Douglas Havoc A-20 light bombers, attacking from lower altitude, pounced on the only Japanese antiaircraft gun rash enough to open fire.

The warships then shifted their attention to the assault beaches, and the landing craft carrying the two battalions of Colonel Julian N. Frisbie's 7th Marines started shoreward. An LCI [Landing Craft, Infantry] mounting multiple rocket launchers took position on the flank of the first wave bound for each of the two beaches and unleashed a barrage intended to keep the enemy pinned down after the cruisers and destroyers shifted their fire to avoid endangering the assault troops. At 0746, the LCVPs [Landing Craft, Vehicles and Personnel] of the first wave bound for Yellow Beach 1 grounded on a narrow strip of black sand that measured perhaps 500 yards from one flank to the other, and the leading elements of the 3d Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William K. Williams, started inland. Two minutes later, Lieutenant Colonel John E. Weber's 1st Battalion, on the left of the other unit, emerged on Yellow Beach 2, separated from Yellow 1 by a thousand yards of jungle and embracing 700 yards of shoreline. Neither battalion encountered organized resistance. A smoke screen, which later drifted across the beaches and hampered the approach of later waves of landing craft, blinded the Japanese observers on Target Hill overlooking the beachhead, and no defenders manned the trenches and log-and-earth bunkers that might have raked the assault force with fire.

The Yellow Beaches, on the east coast of the broad peninsula that culminated at Cape Gloucester, provided access to the main objective, the two airfields at the northern tip of the cape. By capturing this airfield [pg 2] complex, the reinforced 1st Marine Division, designated the Backhander Task Force, would enable Allied airmen to intensify their attack on the Japanese fortress of Rabaul, roughly 300 miles away at the northeastern extremity of New Britain. Although the capture of the Yellow Beaches held the key to the New Britain campaign, two subsidiary landings also took place: the first on 15 December at Cape Merkus on Arawe Bay along the south coast; and the second on D-Day, 26 December, at Green Beach on the northwest coast opposite the main landing sites.

Sidenote: (page 2)

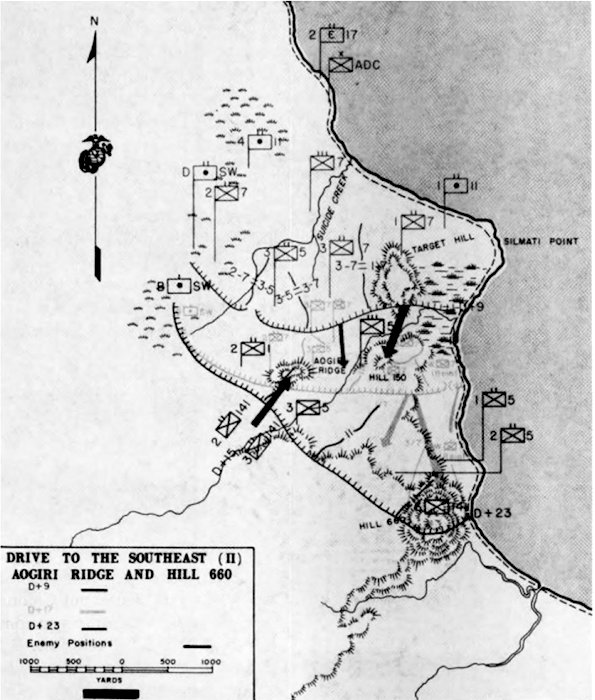

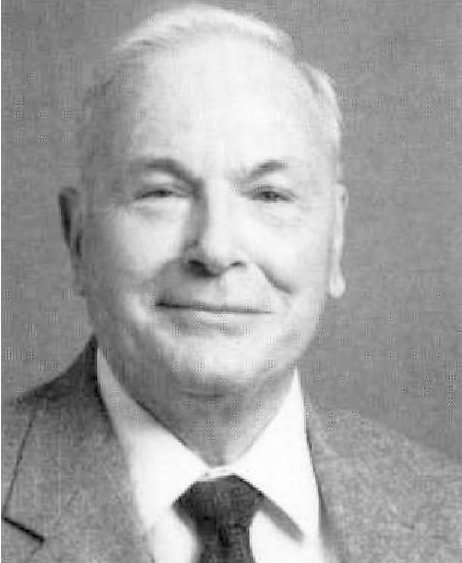

Major General William H. Rupertus, who commanded the 1st Marine Division on New Britain, was born at Washington, D.C., on 14 November 1889 and in June 1913 graduated from the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction. Instead of pursuing a career in this precursor of the U.S. Coast Guard, he accepted appointment as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. A vigorous advocate of rifle marksmanship throughout his career, he became a member of the Marine Corps Rifle Team in 1915, two years after entering the service, and won two major matches. During World War I, he commanded the Marine detachment on the USS Florida, assigned to the British Grand Fleet.

Between the World Wars, he served in a variety of assignments. In 1919, he joined the Provisional Marine Brigade at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, subsequently becoming inspector of constabulary with the Marine-trained gendarmerie and finally chief of the Port-au-Prince police force. Rupertus graduated in June 1926 from the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and in January of the following year became Inspector of Target Practice for the Marine Corps. He had two tours of duty in China and commanded a battalion of the 4th Marines in Shanghai when the Japanese attacked the city's Chinese defenders in 1937.

During the Guadalcanal campaign, as a brigadier general, he was assistant division commander, 1st Marine Division, personally selected for the post by Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, the division commander, whom he succeeded when Vandegrift left the division in July 1943. Major General Rupertus led the division on New Britain and at Peleliu. He died of a heart attack at Washington, D.C., on 25 March 1945, and did not see the surrender of Japan, which he had done so much to bring about.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 69010

MajGen William H. Rupertus, Commanding General, 1st Marine Division, reads a message of congratulation after the capture of Airfield No. 2 at Cape Gloucester, New Britain.

The first subsidiary landing took place on 15 December 1943 at distant Cape Merkus, across the Arawe channel from the islet of Arawe. Although it had a limited purpose—disrupting the movement of motorized barges and other small craft that moved men and supplies along the southern coast of New Britain and diverting attention from Cape Gloucester—it nevertheless [pg 3] encountered stiff resistance. Marine amphibian tractor crews used both the new, armored Buffalo and the older, slower, and more vulnerable Alligator to carry soldiers of the 112th Cavalry, who made the main landings on Orange Beach at the western edge of Cape Merkus. Fire from the destroyer USS Conyngham, supplemented by rocket-equipped DUKWs and a submarine chaser that doubled as a control craft, and a last-minute bombing by B-25s silenced the beach defenses and enabled the Buffaloes to crush the surviving Japanese machine guns that survived the naval and aerial bombardment. Less successful were two diversionary landings by soldiers paddling ashore in rubber boats. Savage fire forced one group to turn back short of its objective east of Orange Beach, but the other gained a lodgment on Pilelo Island and killed the handful of Japanese found there. An enemy airman had reported that the assault force was approaching Cape Merkus, and fighters and bombers from Rabaul attacked within two hours of the landing. Sporadic air strikes continued throughout December, although with diminishing ferocity, and the Japanese shifted troops to meet the threat in the south.

The other secondary landing took place on the morning of 26 December. The 1,500-man Stoneface Group—designated Battalion Landing Team 21 and built around the 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel James M. Masters, Sr.—started toward Green Beach, supported by 5-inch gunfire from the American destroyers Reid and Smith. LCMs [Landing Craft, Medium] carried DUKW amphibian trucks, driven by soldiers and fitted with rocket launchers. The DUKWs opened fire from the landing craft as the assault force approached the beach, performing the same function as the rocket-firing LCIs at the Yellow Beaches on the opposite side of the peninsula. The first wave landed at 0748, with two others following it ashore. The Marines encountered no opposition as they carved out a beachhead 1,200 yards wide and extending 500 yards inland. The Stoneface Group had the mission of severing the coastal trail that passed just west of Mount Talawe, thus preventing the passage of reinforcements to the Cape Gloucester airfields.

The trail net proved difficult to find and follow. Villagers cleared garden plots, tilled them until the jungle reclaimed them, and then abandoned the land and moved on, leaving a maze of trails, some faint and others fresh, that led nowhere. The Japanese were slow, however, to take advantage of the confusion [pg 4] caused by the tangle of paths. Not until the early hours of 30 December, did the enemy attack the Green Beach force. Taking advantage of heavy rain that muffled sounds and reduced visibility, the Japanese closed with the Marines, who called down mortar fire within 15 yards of their defensive wire. A battery of the 11th Marines, reorganized as an infantry unit because the cannoneers could not find suitable positions for their 75mm howitzers, shored up the defenses. One Marine in particular, Gunnery Sergeant Guiseppe Guilano, Jr., seemed to materialize at critical moments, firing a light machine gun from the hip; his heroism earned him the Navy Cross. Some of the Japanese succeeded in penetrating the position, but a counterattack led by First Lieutenant Jim G. Paulos of Company G killed them or drove them off. The savage fighting cost Combat Team 21 six Marines killed and 17 wounded; at least 89 Japanese perished, and five surrendered. On 11 January 1944, the reinforced battalion set out to rejoin the division, the troops moving overland, the heavy equipment and the wounded traveling in landing craft.

Sidenote: (page 3)

Located on Simpson Harbor at the northeastern tip of New Britain, Rabaul served as an air and naval base and troop staging area for Japanese conquests in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. As the advancing Japanese approached New Britain, Australian authorities, who administered the former German colony under terms of a mandate from the League of Nations, evacuated the Australian women and children living there. These dependents had already departed when the enemy landed on 23 January 1942, capturing Rabaul by routing the defenders, some of whom escaped into the jungle to become coastwatchers providing intelligence for the Allies. The Australian coastwatchers, many of them former planters or prewar administrators, reported by radio on Japanese strength and movements before the invasion and afterward attached themselves to the Marines, sometimes recruiting guides and bearers from among the native populace.

Once the enemy had seized Rabaul, he set to work converting it into a major installation, improving harbor facilities, building airfields and barracks, and bringing in hundreds of thousands of soldiers, sailors, and airmen, who either passed through the base en route to operations elsewhere or stayed there to defend it. Rabaul thus became the dominant objective of General Douglas MacArthur, who escaped from the Philippines in March 1942 and assumed command of the Southwest Pacific Area. MacArthur proposed a two-pronged advance on the fortress, bombing it from the air while amphibious forces closed in by way of eastern New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Even as the Allies began closing the pincers on Rabaul, the basic strategy changed. Despite MacArthur's opposition, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff decided to bypass the stronghold, a strategy confirmed by the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff during the Quadrant Conference at Quebec in August 1943. As a result, Rabaul itself would remain in Japanese hands for the remainder of the war, though the Allies controlled the rest of New Britain.

After the fierce battles at Guadalcanal in the South Pacific Area, the 1st Marine Division underwent rehabilitation in Australia, which lay within General MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area. Once the division had recovered from the ordeal of the Solomon Islands fighting, it gave MacArthur a trained amphibious unit that he desperately needed to fulfill his ambitions for the capture of Rabaul. Theoretically, the 1st Marine Division was subordinate to General Sir Thomas Blamey, the Australian officer in command of the Allied Land Forces, and Blamey's nominal subordinate, Lieutenant General Walter Kreuger, commanding the Sixth U.S. Army. But in actual practice, MacArthur bypassed Blamey and dealt directly with Kreuger.

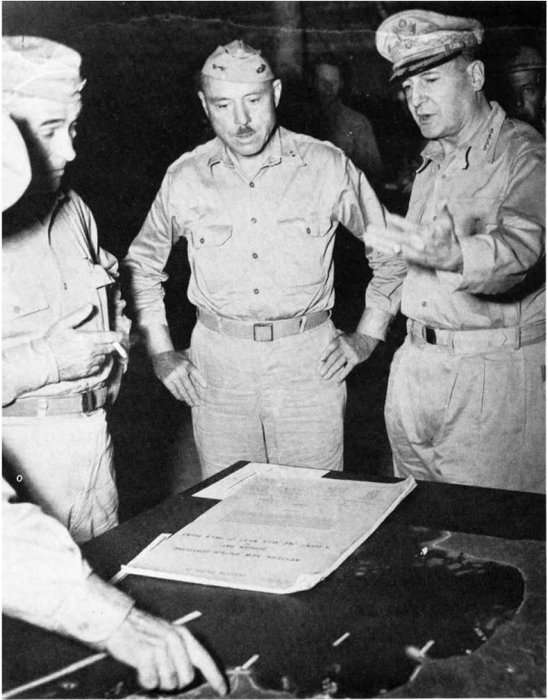

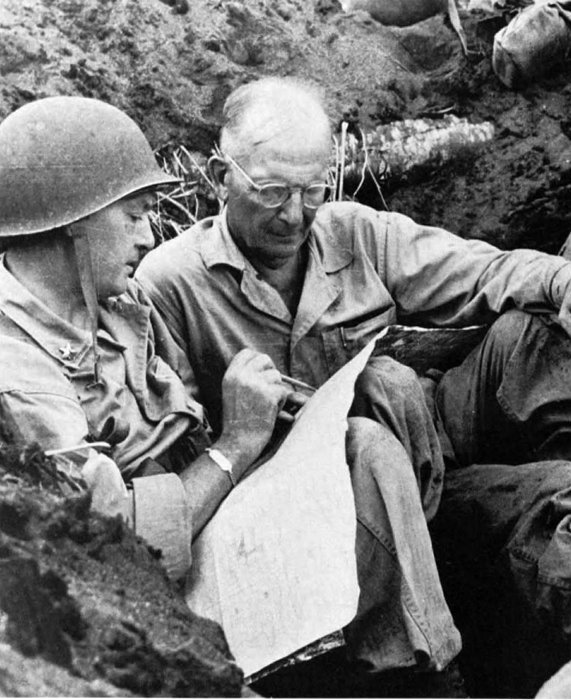

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 75882

During the planning of the New Britain operation, Gen Douglas MacArthur, right, in command of the Southwest Pacific Area, confers with LtGen Walter Kreuger, left, Commanding General, Sixth U.S. Army, and MajGen Rupertus, whose Marines will assault the island. At such a meeting, Col Edwin A. Pollock, operations officer of the 1st Marine Division, advised MacArthur of the opposition of the Marine leaders to a complex scheme of maneuver involving Army airborne troops.

When the 1st Marine Division became available to MacArthur, he still intended to seize Rabaul and break the back of Japanese resistance in the region. Always concerned about air cover for his amphibious operations, MacArthur planned to use the Marines to capture the airfields at Cape Gloucester. Aircraft based there would then support the division when, after a brief period of recuperation, it attacked Rabaul. The decision to bypass Rabaul eliminated the landings there, but the Marines would nevertheless seize the Cape Gloucester airfields, which seemed essential for neutralizing the base.

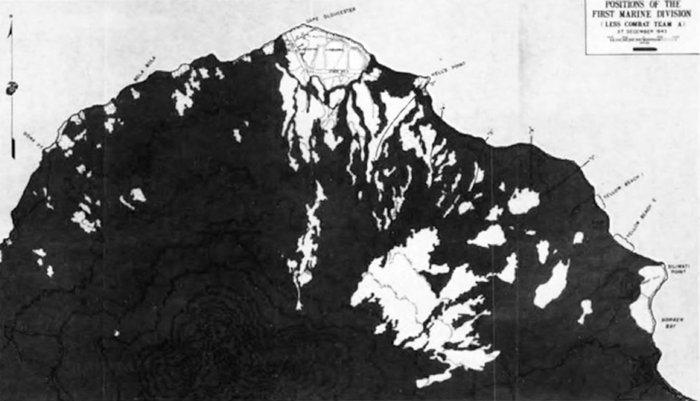

The initial concept of operations, which called for the conquest of [pg 5] western New Britain preliminary to storming Rabaul, split the 1st Marine Division, sending Combat Team A (the 5th Marines, reinforced, less one battalion in reserve) against Gasmata on the southern coast of the island, while Combat Team C (the 7th Marines, reinforced) seized a beachhead near the principal objective, the airfields on Cape Gloucester. The Army's 503d Parachute Infantry would exploit the Cape Gloucester beachhead, while Combat Team B (the reinforced 1st Marines) provided a reserve for the operation.

Revisions came swiftly, and by late October 1943 the plan no longer mentioned capturing Rabaul, tacit acceptance of the modified Allied strategy, and also satisfied an objection raised by General Rupertus. The division commander had protested splitting Combat Team C, and Kreuger agreed to employ all three battalions for the main assault, substituting a battalion from Combat Team B, the 1st Marines, for the landing on the west coast. The airborne landing at Cape Gloucester remained in the plan, however, even though Rupertus had warned that bad weather could delay the drop and jeopardize the Marine battalions already fighting ashore. The altered version earmarked Army troops for the landing on the southern coast, which Kreuger's staff shifted from Gasmata to Arawe, a site closer to Allied airfields and farther from Rabaul with its troops and aircraft. Although Combat Team B would put one battalion ashore southwest of the airfields, the remaining two battalions of the 1st Marines were to follow up the assault on Cape Gloucester by Combat Team C. The division reserve, Combat Team A, might employ elements of the 5th Marines to reinforce the Cape Gloucester landings or conduct operations against the offshore islands west of New Britain.

During a routine briefing on 14 December, just one day before the landings at Arawe, MacArthur off-handedly asked how the Marines felt about the scheme of maneuver at Cape Gloucester. Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, the division's operations officer, seized the opportunity and declared that the Marines objected to the plan because it depended on a rapid advance inland by a single reinforced regiment to prevent heavy losses among the lightly armed paratroops. Better, he believed, to strengthen the amphibious forces than to try for an aerial envelopment that might fail or be delayed by the weather. Although he made no comment at the time, MacArthur may well have heeded what Pollock said; whatever the reason, Kreuger's staff eliminated the airborne portion, directed the two battalions of the 1st Marines still with Combat Team B to land immediately after the assault waves, sustaining the momentum of their attack, and alerted the division reserve to provide further reinforcement.

A mixture of combat and service troops operated in western New Britain. The 1st and 8th Shipping Regiments used motorized barges to shuttle troops and cargo along the coast from Rabaul to Cape Merkus, Cape Gloucester, and across Dampier Strait to Rooke Island. For longer movements, for example to New Guinea, the 5th Sea Transport Battalion manned a fleet of trawlers and schooners, supplemented by destroyers of the Imperial Japanese Navy when speed seemed essential. The troops actually defending western New Britain included the Matsuda Force, established in September 1943 under the command of Major General Iwao Matsuda, a specialist in military transportation, who nevertheless had commanded an infantry regiment in Manchuria. When he arrived on New Britain in February of that year, Matsuda took over the 4th Shipping Command, an administrative headquarters that provided staff officers for the Matsuda Force. His principal combat units were the understrength 65th Infantry Brigade—consisting of the 141st Infantry, battle-tested in the conquest of the Philippines, plus artillery and antiaircraft units—and those components of the 51st Division not committed to the unsuccessful defense of New Guinea. Matsuda established the headquarters for his jury-rigged force near Kalingi, along the coastal trail northwest of Mount Talawe, within five miles of the Cape Gloucester airfields, but the location would change to reflect the tactical situation.

As the year 1943 wore on, the Allied threat to New Britain increased. Consequently, General Hitoshi Imamura, who commanded the Eighth Area Army from a headquarters at Rabaul, assigned the Matsuda Force to the 17th Division, under Lieutenant General Yasushi Sakai, recently arrived from Shanghai. Four convoys were to have carried Sakai's division, but the second and third lost one ship to submarine torpedoes and another to a mine, while air attack damaged a third. Because of these losses, which claimed some 1,200 lives, the last convoy did not sail, depriving the division of more than 3,000 replacements and service troops. Sakai deployed the best of his forces to western New Britain, entrusting them to Matsuda's tactical command.

The landings at Cape Merkus in mid-December caused Matsuda to shift his troops to meet the threat, but this redeployment did not account for the lack of resistance at [pg 6] the Yellow Beaches. The Japanese general, familiar with the terrain of western New Britain, did not believe that the Americans would storm these strips of sand extending only a few yards inland and backed by swamp. Matsuda might have thought differently had he seen the American maps, which labeled the area beyond the beaches as "damp flat," even though aerial photographs taken after preliminary air strikes had revealed no shadow within the bomb craters, evidence of a water level high enough to fill these depressions to the brim. Since the airfields were the obvious prize, Matsuda did not believe that the Marines would plunge into the muck and risk becoming bogged down short of their goal.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72833

Marines, almost invisible amid the undergrowth, advance through the swamp forest of New Britain, optimistically called damp flat on the maps they used.

Besides forfeiting the immediate advantage of opposing the assault force at the water's edge, Matsuda's troops suffered the long-term, indirect effects of the erosion of Japanese fortunes that began at Guadalcanal and on New Guinea and continued at New Georgia and Bougainville. The Allies, in addition, dominated the skies over New Britain, blunting the air attacks on the Cape Merkus beachhead and bombing almost at will throughout the island. Although air strikes caused little measurable damage, save at Rabaul, they demoralized the defenders, who already suffered shortages of supplies and medicine because of air and submarine attacks on seagoing convoys and coastal shipping. An inadequate network of primitive trails, which tended to hug the coastline, increased Matsuda's dependence on barges, but this traffic, hampered by the American capture of Cape Merkus, proved vulnerable to aircraft and later to torpedo craft and improvised gunboats.

The two battalions that landed on the Yellow Beaches—Weber's on the left and Williams's on the right—crossed the sands in a few strides, and plunged through a wall of undergrowth into the damp flat, where a Marine might be slogging through knee-deep mud, step into a hole, and end up, as one on them said, "damp up to your neck." A counterattack delivered as the assault waves wallowed through the damp flat might have inflicted severe casualties, but Matsuda lacked the vehicles or roads to shift his troops in time to exploit the terrain. Although immobile on the ground, the Japanese retaliated by air. American radar detected a flight of enemy aircraft approaching from Rabaul; Army Air Forces P-38s intercepted, but a few Japanese bombers evaded the fighters, sank the destroyer Brownson with two direct hits, and damaged another.

The first enemy bombers arrived as a squadron of Army B-25s flew over the LSTs [Landing Ships, Tank] en route to attack targets at Borgen Bay south of the Yellow Beaches. Gunners on board the ships opened fire at the aircraft milling overhead, mistaking friend for foe, downing two American bombers, and damaging two others. The survivors, shaken by the experience, dropped their bombs too soon, hitting the artillery positions of the 11th Marines at the left flank of Yellow Beach 1, killing one and wounding 14 others. A battalion commander in the artillery regiment recalled "trying to dig a hole with my nose," as the bombs exploded, "trying to get down into the ground just a little bit further."

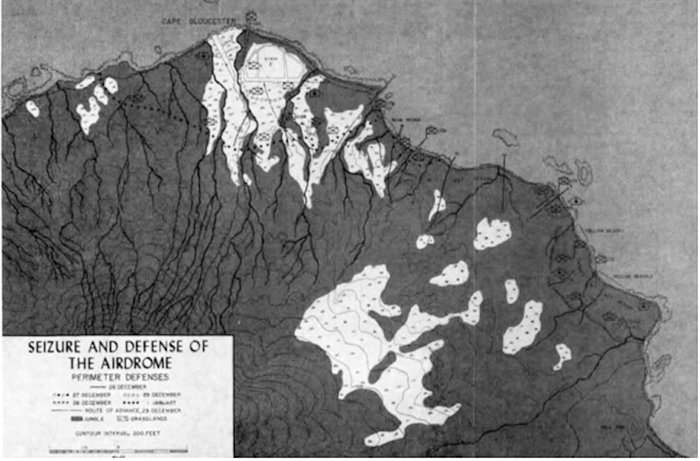

[pg 7] By the time of the air action on the afternoon of D-Day, the 1st Marine Division had already established a beachhead. The assault battalions of the 7th Marines initially pushed ahead, capturing Target Hill on the left flank, and then paused to await reinforcements. During the day, two more battalions arrived. The 3d Battalion, 1st Marines—designated Landing Team 31 and led by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Hankins, a Reserve officer who also was a crack shooter—came ashore at 0815 on Yellow Beach 1, passed through the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, and veered to the northwest to lead the way toward the airfields. By 0845, the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel Odell M. Conoley, landed and began wading through the damp flat to take its place between the regiment's 1st and 3d Battalions as the beachhead expanded. The next infantry unit, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, reached Yellow Beach 1 at 1300 to join that regiment's 3d Battalion, commanded by Hankins, in advancing on the airfields. The 11th Marines, despite the accidental bombing, set up its artillery, an operation in which the amphibian tractor played a vital part. Some of the tractors brought lightweight 75mm howitzers from the LSTs directly to the battery firing positions; others broke trail through the undergrowth for tractors pulling the heavier 105mm weapons.

Meanwhile, Army trucks loaded with supplies rolled ashore from the LSTs. Logistics plans called for these vehicles to move forward and function as mobile supply dumps, but the damp flat proved impassable by wheeled vehicles, and the drivers tended to abandon the trucks to avoid being left behind when the shipping moved out, hurried along by the threat from Japanese bombers. Ultimately, Marines had to build roads, corduroying them with logs when necessary, or shift the cargo to amphibian tractors. Despite careful planning and hard work on D-Day, the convoy sailed with about 100 tons of supplies still on board.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo

As the predicament of this truck and its Marine driver demonstrates, wheeled vehicles, like those supplied by the Army for mobile supply dumps, bog down in the mud of Cape Gloucester.

While reinforcements and cargo crossed the beach, the Marines advancing inland encountered the first serious Japanese resistance. Shortly after 1000 on 26 December, Hankins's 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, pushed ahead, advancing in a column of companies because a swamp on the left narrowed the frontage. Fire from camouflaged bunkers killed Captain Joseph A. Terzi, commander of Company K, posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for heroism while leading the attack, and his executive officer, Captain Philip A. Wilheit. The sturdy bunkers proved impervious to bazooka rockets, which failed to detonate in the soft earth covering the structures, and to fire from 37mm guns, which could not penetrate the logs protecting the occupants. An Alligator that had delivered supplies for Company K tried to crush one of the bunkers but became wedged between two trees. Japanese riflemen burst from cover and killed the tractor's two machine gunners, neither of them protected by armor, before the driver could break free. Again lunging ahead, the tractor caved in one bunker, silencing its fire and enabling Marine riflemen to isolate three others and destroy them in succession, killing 25 Japanese. A platoon of M4 Sherman tanks joined the company in time to lead the advance beyond this first strongpoint.

Japanese service troops—especially the men of the 1st Shipping Engineers and the 1st Debarkation Unit—provided most of the initial opposition, but Matsuda had alerted his nearby infantry units to converge on the beachhead. One enemy battalion, under Major Shinichi Takabe, moved into position late on the afternoon of D-Day, opposite Conoley's 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, which clung to a crescent-shaped position, both of its flanks sharply refused and resting on the marshland to the rear. After sunset, the darkness beneath the forest canopy became absolute, pierced only by muzzle flashes as the intensity of the firing increased.

On D-Day, among the shadows on the jungle floor, Navy corpsmen administer emergency treatment to a wounded Marine.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 69009

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72599

The stumps of trees shattered by artillery and the seemingly bottomless mud can sometimes stymie even an LVT.

The Japanese clearly were preparing to counterattack. Conoley's battalion had a dwindling supply of ammunition, but amphibian tractors could not begin making supply runs until it became light enough for the drivers to avoid tree roots and fallen trunks as they navigated the damp flat. To aid the battalion in the dangerous period before the skies grew pale, Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. Puller, the executive officer of the 7th Marines, organized the men of the regimental Headquarters and Service Company into carrying parties to load themselves down with ammunition and wade through the dangerous swamp. One misstep, and a Marine burdened with bandoliers of rifle ammunition or containers of mortar shells could stumble and drown. When Colonel Frisbie, the regimental commander, decided to reinforce Conoley's Marines with Battery D, 1st Special Weapons Battalion, Puller had the men leave their 37mm guns behind and carry ammunition instead. A guide from Conoley's headquarters met the column that Puller had pressed into service and began leading them forward, when a blinding downpour, driven by a monsoon gale, obscured landmarks and forced the heavily laden Marines to wade blindly onward, each man clinging to the belt of the one ahead of him. Not until 0805, some twelve hours after the column started off, did the men reach their goal, put down their loads, and take up their rifles.

Conoley's Marines had in the meantime been fighting for their lives since the storm first struck. A curtain of rain prevented mortar crews from seeing their aiming stakes, indeed, the battalion commander described the men as firing "by guess and by God." Mud got on the small-arms ammunition, at times jamming rifles and machine guns. Although forced to abandon water-filled foxholes, the defenders hung on. With the coming of dawn, Takabe's soldiers gravitated toward the right flank of Conoley's unit, perhaps in a conscious effort to outflank the position, or possibly forced in that direction by the fury of the battalion's defensive fire. An envelopment was in the making when Battery D arrived and moved into the threatened area, forcing the Japanese to break off the action and regroup.

Sidenote (page 7)

On New Britain, the 1st Marine Division fought weather and terrain, along with a determined Japanese enemy. Rains brought by seasonal monsoons seemed to fall with the velocity of a fire hose, soaking everyone, sending streams from their banks, and turning trails into quagmire. The terrain of the volcanic island varied from coastal plain to mountains that rose as high as 7,000 feet above sea level. A variety of forest covered the island, punctuated by patches of grassland, a few large coconut plantations, and garden plots near the scattered villages.

Much of the fighting, especially during the early days, raged in swamp forest, sometimes erroneously described as damp flat. The swamp forest consisted of scattered trees growing as high as a hundred feet from a plain that remained flooded throughout the rainy season, if not for the entire year. Tangled roots buttressed the towering trees, but could not anchor them against gale-force winds, while vines and undergrowth reduced visibility on the flooded surface to a few yards.

No less formidable was the second kind of vegetation, the mangrove forest, where massive trees grew from brackish water deposited at high tide. Mangrove trees varied in height from 20 to 60 feet, with a visible tangle of thick roots deploying as high as ten feet up the trunk and holding the tree solidly in place. Beneath the mangrove canopy, the maze of roots, wandering streams, and standing water impeded movement. Visibility did not exceed 15 yards.

Both swamp forest and mangrove forest grew at sea level. A third form of vegetation, the true tropical rain forest, flourished at higher altitude. Different varieties of trees formed an impenetrable double canopy overhead, but the surface itself remained generally open, except for low-growing ferns or shrubs, an occasional thicket of bamboo or rattan, and tangles of vines. Although a Marine walking beneath the canopy could see a standing man as far as 50 yards away, a prone rifleman might remain invisible at a distance of just ten yards.

Only one of the three remaining kinds of vegetation seriously impeded military action. Second-growth forest, which often took over abandoned garden tracts, forced patrolling Marines to hack paths through the small trees, brush, and vines. Grasslands posed a lesser problem; though the vegetation grew tall enough to conceal the Japanese defenders, it provided comparatively easy going for the Marines, unless the grass turned out to be wild sugar cane, with thick stalks that grew to a height of 15 feet. Cultivated tracts, whether coconut plantations or gardens, posed few obstacles to vision or movement.

Sidenote (pag 10)

Driven by monsoon winds, the rain that screened the attack on Conoley's 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, drenched the entire island and everyone on it. At the front, the deluge flooded foxholes, and conditions were only marginally better at the rear, where some men slept in jungle hammocks slung between two trees. A Marine entered his hammock through an opening in a mosquito net, lay down on a length of rubberized cloth, and zipped the net shut. Above him, also enclosed in the netting, stretched a rubberized cover designed to shelter him from rain. Unfortunately, a gale as fierce as the one that began blowing on the night of D-Day set the cover to flapping like a loose sail and drove the rain inside the hammock. In the darkness, a gust of wind might uproot a tree, weakened by flooding or the effect of the preparatory bombardment, and send it crashing down. A falling tree toppled onto a hammock occupied by one of the Marines, who would have drowned if someone had not slashed through the covering with a knife and set him free.

The rain, said Lieutenant Colonel Lewis J. Fields, a battalion commander in the 11th Marines, resembled "a waterfall pouring down on you, and it goes on and on." The first deluge lasted five days, and recurring storms persisted for another two weeks. Wet uniforms never really dried, and the men suffered continually from fungus infections, the so-called jungle rot, which readily developed into open sores. Mosquito-borne malaria threatened the health of the Marines, who also had to contend with other insects—"little black ants, little red ants, big red ants," on an island where "even the caterpillars bite." The Japanese may have suffered even more because of shortages of medicine and difficulty in distributing what was available, but this was scant consolation to Marines beset by discomfort and disease. By the end of January 1944, disease or non-battle injuries forced the evacuation of more than a thousand Marines; more than one in ten had already returned to duty on New Britain.

The island's swamps and jungles would have been ordeal enough without the wind, rain, and disease. At times, the embattled Marines could see no more than a few feet ahead of them. Movement verged on the impossible, especially where the rains had flooded the land or turned the volcanic soil into slippery mud. No wonder that the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., compared the New Britain campaign to "Grant's fight through the Wilderness in the Civil War."

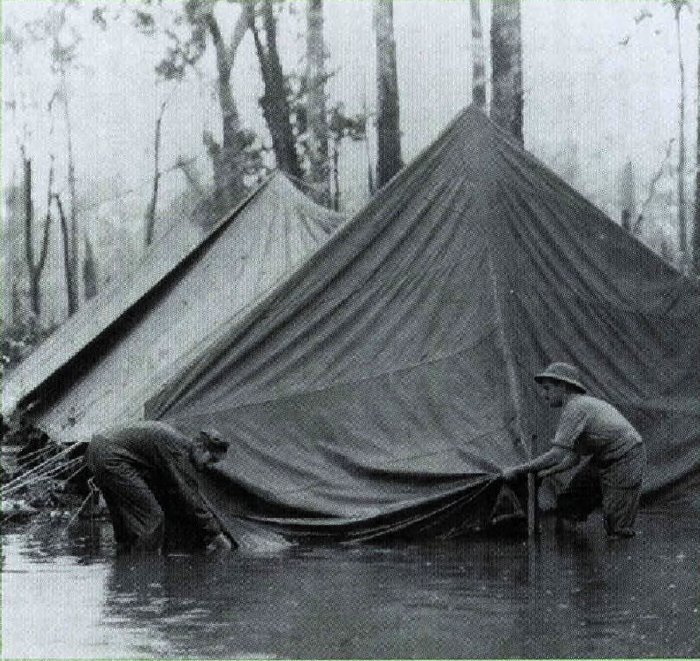

The monsoon rains flood a field kitchen at Cape Gloucester, justifying complaints about watery soup.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72821

Flooding caused by the monsoon deluge makes life miserable even in the comparative comfort of the rear areas.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72463

The 1st Marine Division's overall plan of maneuver called for Colonel Frisbie's Combat Team C, the reinforced 7th Marines, to hold a beachhead anchored at Target Hill, while Combat Team B, Colonel William A. Whaling's 1st Marines, reinforced but without the 2d Battalion ashore at Green Beach, advanced on the airfields. Because of the buildup in preparation for the attack on Conoley's battalion, General Rupertus requested that Kreuger release the division reserve, Combat Team A, Colonel John T. Selden's reinforced 5th Marines. The Army general agreed, sending the 1st and 2d Battalions, followed a day later by the 3d Battalion. The division commander decided to land the team on Blue Beach, roughly three miles to the right of the Yellow Beaches. The use of Blue Beach would have placed the 5th Marines closer to Cape Gloucester and the airfields, but not every element of Selden's Combat Team A got the word. Some units touched down on the Yellow Beaches instead and had to move on foot or in vehicles to the intended destination.

While Rupertus laid plans to commit the reserve, Whaling's combat team advanced toward the Cape Gloucester airfields. The Marines encountered only sporadic resistance at first, but Army Air Forces light bombers spotted danger in their path—a maze of trenches and bunkers stretching inland from a promontory that soon earned the [pg 11] nickname Hell's Point. The Japanese had built these defenses to protect the beaches where Matsuda expected the Americans to land. Leading the advance, the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel Hankins, struck the Hell's Point position on the flank, rather than head-on, but overrunning the complex nevertheless would prove a deadly task.

Rupertus delayed the attack by Hankins to provide time for the division reserve, Selden's 5th Marines, to come ashore. On the morning of 28 December, after a bombardment by the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, and strikes by Army Air Forces A-20s, the assault troops encountered another delay, waiting for an hour so that an additional platoon of M4 Sherman medium tanks could increase the weight of the attack. At 1100, Hankins's 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, moved ahead, Company I and the supporting tanks leading the way. Whaling, at about the same time, sent his regiment's Company A through swamp and jungle to seize the inland point of the ridge extending from Hell's Point. Despite the obstacles in its path, Company A burst from the jungle at about 1145 and advanced across a field of tall grass until stopped by intense Japanese fire. By late afternoon, Whaling abandoned the maneuver. Both Company A and the defenders were exhausted and short of ammunition; the Marines withdrew behind a barrage fired by the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, and the Japanese abandoned their positions after dark.

A 75mm pack howitzer of the 11th Marines fires in support of the advance on the Cape Gloucester airfields.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 12203

Roughly 15 minutes after Company A assaulted the inland terminus of the ridge, Company I and the attached tanks collided with the main defenses, which the Japanese had modified since the 26 December landings, cutting new gunports in bunkers, hacking fire lanes in the undergrowth, and shifting men and weapons to oppose an attack along the coastal trail parallel to shore instead of over the beach. Advancing in a drenching rain, the Marines encountered a succession of jungle-covered, mutually supporting positions protected by barbed wire and mines. The hour's wait for tanks paid dividends, as the Shermans, protected by riflemen, crushed bunkers and destroyed the weapons inside. During the fight, Company I drifted to its left, and Hankins used Company K, reinforced with a platoon of medium tanks, to close the gap between the coastal track and Hell's Point itself. This unit employed the same tactics as Company I. A rifle squad followed each of the M4 tanks, which cracked open the bunkers, twelve in all, and fired inside; the accompanying riflemen then killed anyone attempting to fight or flee. More than 260 Japanese perished in the fighting at Hell's Point, at the cost of 9 Marines killed and 36 wounded.

With the defenses of Hell's Point shattered, the two battalions of the 5th Marines, which came ashore on the morning of 29 December, joined later that day in the advance on the airfield. The 1st Battalion, commanded by Major William H. Barba, and the 2d Battalion, under Lieutenant Colonel Lewis H. Walt, moved out in a column, Barba's unit leading the way. In front of the Marines lay a swamp, described as only a few inches deep, but the depth, because of the continuing downpour, proved as much as five feet, "making it quite hard," Selden acknowledged, "for some of the youngsters who were not much more than 5 feet in height." The time lost in wading through the swamp delayed the attack, and the leading elements chose a piece of open and comparatively dry ground, where they established a perimeter while the rest of the force caught up.

[pg 12] Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, attacking through that regiment's 3d Battalion, encountered only scattered resistance, mainly sniper fire, as it pushed along the coast beyond Hell's Point. Halftracks carrying 75mm guns, medium tanks, artillery, and even a pair of rocket-firing DUKWs supported the advance, which brought the battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Walker A. Reaves, to the edge of Airfield No. 2. When daylight faded on 29 December, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, held a line extending inland from the coast; on its left were the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, and the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, forming a semicircle around the airfield.

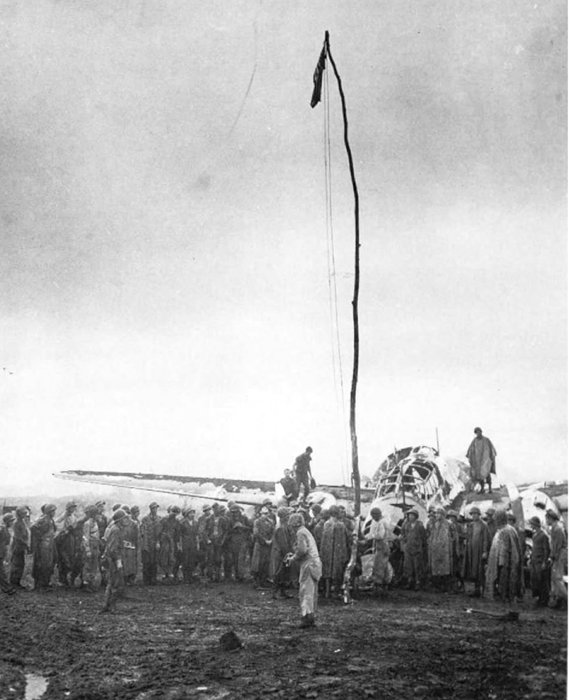

The Japanese officer responsible for defending the airfields, Colonel Kouki Sumiya of the 53d Infantry, had fallen back on 29 December, trading space for time as he gathered his surviving troops for the defense of Razorback Hill, a ridge running diagonally across the southwestern approaches to Airfield No. 2. The 1st and 2d Battalions, 5th Marines, attacked on 30 December supported by tanks and artillery. Sumiya's troops had constructed some sturdy bunkers, but the chest-high grass that covered Razorback Hill did not impede the attackers like the jungle at Hell's Point. The Japanese fought gallantly to hold the position, at times stalling the advancing Marines, but the defenders had neither the numbers nor the firepower to prevail. Typical of the day's fighting, one platoon of Company F from Selden's regiment beat back two separate banzai attacks, before tanks enabled the Marines to shatter the bunkers in their path and kill the enemy within. By dusk on 30 December, the landing force had overrun the defenses of the airfields, and at noon of the following day General Rupertus had the American flag raised beside the wreckage of a Japanese bomber at Airfield No. 2, the larger of the airstrips.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 71589

On 31 December 1943, the American flag rises beside the wreckage of a Japanese bomber after the capture of Airfield No. 2, five days after the 1st Marine Division landed on New Britain.

The 1st Marine Division thus seized the principal objective of the Cape Gloucester fighting, but the airstrips proved of marginal value to the Allied forces. Indeed, the Japanese had already abandoned the prewar facility, Airfield No. 1, which was thickly overgrown with tall, coarse kunai grass. Craters from American bombs pockmarked the surface of Airfield No. 2, and after its capture Japanese hit-and-run raiders added a few of their own, despite antiaircraft fire from the 12th Defense Battalion. Army aviation engineers worked around the clock to return Airfield No. 2 to operation, a task that took until the end of January 1944. Army aircraft based here defended against air attacks for as long as Rabaul remained an active air base and also supported operations on the ground.

While General Rupertus personally directed the capture of the airfields, the Assistant Division Commander, [pg 13] Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., came ashore on D-Day, 26 December, and took command of the beachhead. Besides coordinating the logistics activity there, Shepherd assumed responsibility for expanding the perimeter to the southwest and securing the shores of Borgen Bay. He had a variety of shore party, engineer, transportation, and other service troops to handle the logistics chores. The 3d Battalion of Colonel Selden's 5th Marines—the remaining component of the division reserve—arrived on 30 and 31 December to help the 7th Marines enlarge the beachhead.

Department of Defense (USA) photo SC 188250

During operations to clear the enemy from the shores of Borgen Bay, BGen Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., (left) the assistant division commander, confers with Col John T. Selden, in command of the 5th Marines.

Shepherd had sketchy knowledge of Japanese deployment west and south of the Yellow Beaches. Dense vegetation concealed streams, swamps, and even ridge lines, as well as bunkers and trenches. The progress toward the airfields seemed to indicate Japanese weakness in that area and possible strength in the vicinity of the Yellow Beaches and Borgen Bay. To resolve the uncertainty about the enemy's numbers and intentions, Shepherd issued orders on 1 January 1944 to probe Japanese defenses beginning the following morning.

In the meantime, the Japanese defenders, under Colonel Kenshiro Katayama, commander of the 141st Infantry, were preparing for an attack of their own. General Matsuda entrusted three reinforced battalions to Katayama, who intended to hurl them against Target Hill, which he considered the anchor of the beachhead line. Since Matsuda believed that roughly 2,500 Marines were ashore on New Britain, 10 percent of the actual total, Katayama's force seemed strong enough for the job assigned it.

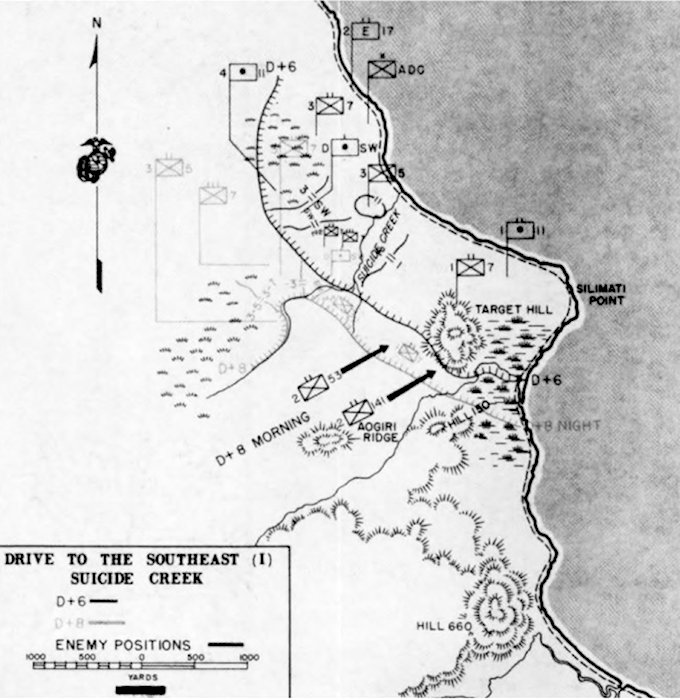

Katayama needed time to gather his strength, enabling Shepherd to make the first move, beginning at mid-morning on 2 January to realign his forces. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, stood fast in the vicinity of Target Hill, the 2d Battalion remained in place along a stream already known as Suicide Creek, and the regiment's 3d Battalion began pivoting to face generally south. Meanwhile, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, pushed into the jungle to come abreast of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, on the inland flank. As the units pivoted, they had to cross Suicide Creek in order to squeeze out the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, which would become Shepherd's reserve.

The change of direction proved extremely difficult in vegetation so thick that, in the words of one Marine: "You'd step from your line, take say ten paces, and turn around to guide on your buddy. And nobody there.... I can tell you, it was a very small war, and a very lonely business." The Japanese defenders, moreover, had dug in south of Suicide Creek, and from these positions they repulsed every attempt to cross the stream that day. A stalemate ensued, as Seabees from Company C, 17th Marines, built a corduroy road through the damp flat behind the Yellow Beaches so that tanks could move forward to punch through the defenses of Suicide Creek.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 69013

Marines and Seabees struggle to build a corduroy road leading inland from the beachhead. Without the log surface trucks and tanks cannot advance over trails turned into quagmire by the unceasing rain.

While the Marine advance stalled at Suicide Creek, awaiting the arrival of tanks, Katayama attacked Target Hill. On the night of 2 January, taking advantage of the darkness, Japanese infantry cut steps in the lower slopes so the troops could climb more easily. Instead of reconnoitering the thinly held lines of Company A, 7th Marines, and trying to infiltrate, the enemy followed a preconceived plan to the letter, advanced up the steps, and at midnight stormed the strongest of the company's defenses. Japanese mortar barrages fired to soften the defenses and screen the approach could not conceal the sound of the troops working their way up the hill, and the Marines were ready. Although the Japanese supporting fire proved generally inaccurate, one round scored a direct hit on a machine-gun position, killing two Marines and wounding the gunner, who kept firing the weapon until someone else could take over. This gun fired some 5,000 rounds and helped blunt the Japanese thrust, which ended by dawn of 3 January. Nowhere did the Japanese crack the lines of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, or loosen its grip on Target Hill.

The body of a Japanese officer killed at Target Hill yielded documents that cast new light on the Japanese defenses south of Suicide Creek. A crudely drawn map revealed the existence of Aogiri Ridge, an enemy strongpoint unknown to General Shepherd's intelligence section. Observers on Target Hill tried to locate the ridge and the trail network the enemy was using, but the jungle canopy frustrated their efforts.

While the Marines on Target Hill tabulated the results of the fighting there—patrols discovered 40 bodies, and captured documents, when translated, listed 46 Japanese killed, 54 wounded, and two missing—and used field glasses to scan the jungle south of Suicide Creek, the 17th Marines completed the road that would enable medium tanks to test the defenses of that stream. [pg 15] During the afternoon of 3 January, a trio of Sherman tanks reached the creek only to discover that the bank dropped off too sharply for them to negotiate. The engineers sent for a bulldozer, which arrived, lowered its blade, and began gouging at the lip of the embankment. Realizing the danger if tanks succeeded in crossing the creek, the Japanese opened fire on the bulldozer, wounding the driver. A volunteer climbed onto the exposed driver's seat and took over until he, too, was wounded. Another Marine stepped forward, but instead of climbing onto the machine, he walked alongside, using its bulk for cover as he manipulated the controls with a shovel and an axe handle. By dark, he had finished the job of converting the impassable bank into a readily negotiated ramp.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72292

Target Hill, where the Marines repulsed a Japanese counterattack on the night of 2-3 January, dominates the Yellow Beaches, the site of the main landings on 26 December.

On the morning of 4 January, the first tank clanked down the ramp and across the stream. As the Sherman emerged on the other side, Marine riflemen cut down two Japanese soldiers trying to detonate magnetic mines against its sides. Other medium tanks followed, also accompanied by infantry, and broke open the bunkers that barred the way. The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, and the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, surged onward past the creek, squeezing out the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, which crossed in the wake of those two units to come abreast of them on the far right of the line that closed in on the jungle concealing Aogiri Ridge. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, thereupon joined the southward advance, tying in with the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, to present a four-battalion front that included the 2d Battalion and 3d Battalions, 7th Marines.

Once across Suicide Creek, the Marines groped for Aogiri Ridge, which for a time simply seemed to be another name for Hill 150, a terrain feature that appeared on American maps. The advance rapidly overran the hill, but Japanese resistance in the vicinity did not diminish. On 7 January, enemy fire wounded Lieutenant Colonel David S. MacDougal, commanding officer of the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines. His executive officer, Major Joseph Skoczylas, took over until he, too, was wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. Puller, temporarily in command of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, assumed responsibility for both battalions until the arrival on [pg 16] the morning of 8 January of Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W. Walt, recently assigned as executive officer of the 5th Marines, who took over the regiment's 3d Battalion.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72283

From Hell's Point, athwart the route to the airfields, to Suicide Creek near the Yellow Beaches, medium tanks and infantry team up to shatter the enemy's log and earthen bunkers.

Upon assuming command of the battalion, Walt continued the previous day's attack. As his Marines braved savage fire and thick jungle, they began moving up a rapidly steepening slope. As night approached, the battalion formed a perimeter and dug in. Random Japanese fire and sudden skirmishes punctuated the darkness. The nature of the terrain and the determined resistance convinced Walt that he had found Aogiri Ridge.

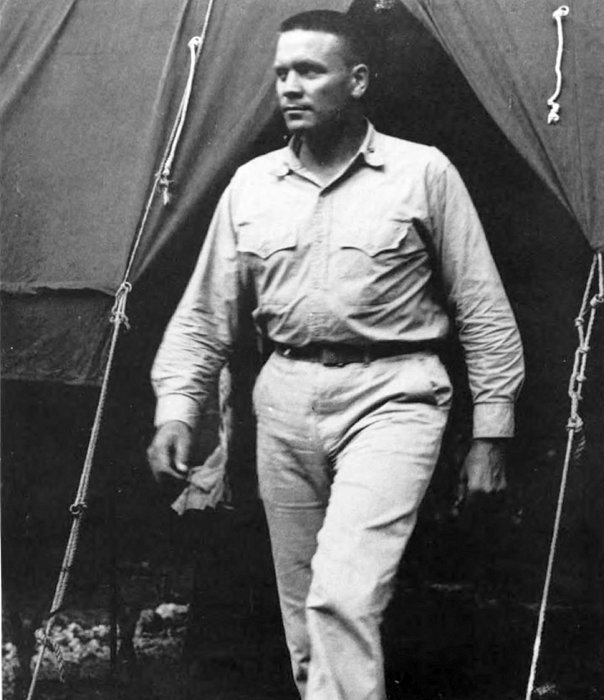

Walt's battalion needed the shock action and firepower of tanks, but drenching rain, mud, and rampaging streams stopped the armored vehicles. The heaviest weapon that the Marines managed to bring forward was a single 37mm gun, manhandled into position on the afternoon of 9 January, While the 11th Marines hammered the crest of Aogiri Ridge, the 1st and 3d Battalions, 7th Marines, probed the flanks of the position and Walt's 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, pushed ahead in the center, seizing a narrow segment of the slope, its apex just short of the crest. By dusk, said the 1st Marine Division's special action report, Walt's men had "reached the limit of their physical endurance and morale was low. It was a question of whether or not they could hold their hard-earned gains." The crew of the 37mm gun opened fire in support of the afternoon's final attack, but after just three rounds, four of the nine men handling the weapon were killed or wounded. Walt called for volunteers; when no one responded, he and his runner crawled to the gun and began pushing the weapon up the incline. Twice more the gun barked, cutting a swath through the undergrowth, and a third round of canister destroyed a machine gun. [pg 17] Other Marines then took over from Walt and the runner, with new volunteers replacing those cut down by the enemy. The improvised crew kept firing canister rounds every few yards until they had wrestled the weapon to the crest. There the Marines dug in, as close as ten yards to the bunkers the Japanese had built on the crest and reverse slope.

At 0115 on the morning of 10 January, the Japanese emerged from their positions and charged through a curtain of rain, shouting and firing as they came. The Marines clinging to Aogiri Ridge broke up this attack and three others that followed, firing off almost all their ammunition in doing so. A carrying party scaled the muddy slope with belts and clips for the machine guns and rifles, but there barely was time to distribute the ammunition before the Japanese launched the fifth attack of the morning. Marine artillery tore into the enemy, as forward observers, their vision obstructed by rain and jungle, adjusted fire by sound more than by sight, moving 105mm concentrations to within 50 yards of the Marine infantrymen. A Japanese officer emerged from the darkness and ran almost to Walt's foxhole before fragments from a shell bursting in the trees overhead cut him down. This proved to be the high-water mark of the counterattack against Aogiri Ridge, for the Japanese tide receded as the daylight grew brighter. At 0800, when the Marines moved forward, they did not encounter even one living Japanese on the terrain feature they renamed Walt's Ridge in honor of their commander, who received the Navy Cross for his inspirational leadership.

One Japanese stronghold in the vicinity of Aogiri Ridge still survived, a supply dump located along a trail linking the ridge to Hill 150. On 11 January, Lieutenant Colonel Weber's 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, supported by a pair of half-tracks and a platoon of light tanks, eliminated this pocket in four hours of fighting. Fifteen days of combat since the landings on 26 December, had cost the division 180 killed and 636 wounded in action.

LtCol Lewis W. Walt earned the Navy Cross leading an attack up Aogiri Ridge, renamed Walt's Ridge in his honor.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 977113

The next objective, Hill 660, lay at the left of General Shepherd's zone of action, just inland of the coastal track. The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, commanded since 9 January by Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Buse, Jr., got the assignment of seizing the hill. In preparation for Buse's attack, Captain Joseph W. Buckley, commander of the Weapons Company, 7th Marines, set up a task force to bypass Hill 660 and block the coastal trail beyond that objective. Buckley's group—two platoons of infantry, a platoon of 37mm guns, two light tanks, two half-tracks mounting 75mm guns, a platoon of pioneers from the 17th Marines with a bulldozer, and one of the Army's rocket-firing DUKWs—pushed through the mud and set up a roadblock athwart the line of retreat from Hill 660. The Japanese directed long-range plunging fire against Buckley's command as it advanced roughly one mile along the trail. Because of their flat trajectory, his 75mm and 37mm guns [pg 18] could not destroy the enemy's automatic weapons, but the Marines succeeded in forcing the hostile gunners to keep their heads down. As they advanced, Buckley's men unreeled telephone wire to maintain contact with higher headquarters. Once the roadblock was in place and camouflaged, the captain requested that a truck bring hot meals for his men. When the vehicle bogged down, he sent the bulldozer to push it free.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 71520

Advancing past Hill 660, a task force under Capt Joseph W. Buckley cuts the line of retreat for the Japanese defenders. The 37mm gun in the emplacement on the right and the half-track mounted 75mm gun on the left drove the attacking enemy back with heavy casualties.

Gaunt, weary, hollow-eyed, machine gunner PFC George C. Miller carries his weapon to the rear after 19 days of heavy fighting while beating back the Japanese counterattack at Hill 660. This moving photograph was taken by Marine Corps combat photographer Sgt Robert R. Brenner.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72273

After aerial bombardment and preparatory artillery fire, Buse's battalion started up the hill at about 0930 on 13 January. His supporting tanks could not negotiate the ravines that scarred the hillside. Indeed, the going became so steep that riflemen sometimes had to sling arms, seize handholds among the vines, and pull themselves upward. [pg 19] The Japanese suddenly opened fire from hurriedly dug trenches at the crest, pinning down the Marines climbing toward them until mortar fire silenced the enemy weapons, which lacked overhead cover. Buse's riflemen followed closely behind the mortar barrage, scattering the defenders, some of whom tried to escape along the coastal trail, where Buckley's task force waited to cut them down.

Apparently delayed by torrential rain, the Japanese did not counterattack Hill 660 until 16 January. Roughly two companies of Katayama's troops stormed up the southwestern slope only to be slaughtered by mortar, artillery, and small-arms fire. Many of those lucky enough to survive tried to break through Buckley's roadblock, where 48 of the enemy perished.

With the capture of Hill 660, the nature of the campaign changed. The assault phase had captured its objective and eliminated the possibility of a Japanese counterattack against the airfield complex. Next, the Marines would repulse the Japanese who harassed the secondary beachhead at Cape Merkus and secure the mountainous, jungle-covered interior of Cape Gloucester, south of the airfields and between the Green and Yellow Beaches.

At Cape Merkus on the south coast of western New Britain, the fighting proved desultory in comparison to the violent struggle in the vicinity of Cape Gloucester. The Japanese in the south remained content to take advantage of the dense jungle and contain the 112th Cavalry on the Cape Merkus peninsula. Major Shinjiro Komori, the Japanese commander there, believed that the landing force intended to capture an abandoned airfield at Cape Merkus, an installation that did not figure in American plans. A series of concealed bunkers, boasting integrated fields of fire, held the lightly armed cavalrymen in check, as the defenders directed harassing fire at the beachhead.

Because the cavalry unit lacked heavy weapons, a call went out for those of the 1st Marine Division's tanks that had remained behind at Finschhafen, New Guinea, because armor enough was already churning up the mud of Cape Gloucester. Company B, 1st Marine Tank Battalion, with 18 M5A1 light tanks mounting 37mm guns, and the 2d Battalion, 158th Infantry, arrived at Cape Merkus, moved into position by 15 January and attacked on the following day. A squadron of Army Air Forces B-24s dropped 1,000-pound bombs on the jungle-covered defenses, B-25s followed up, and mortars and artillery joined in the bombardment, after which two platoons of tanks, ten vehicles in all, and two companies of infantry surged forward. Some of the tanks bogged down in the rain-soaked soil, and tank retrievers had to pull them free. Despite mud and nearly impenetrable thickets, the tank-infantry teams found and destroyed most of the bunkers. Having eliminated the source of harassing fire, the troops pulled back after destroying a tank immobilized by a thrown track so that the enemy could not use it as a pillbox. Another tank, trapped in a crater, also was earmarked for destruction, but Army engineers managed to free it and bring it back.

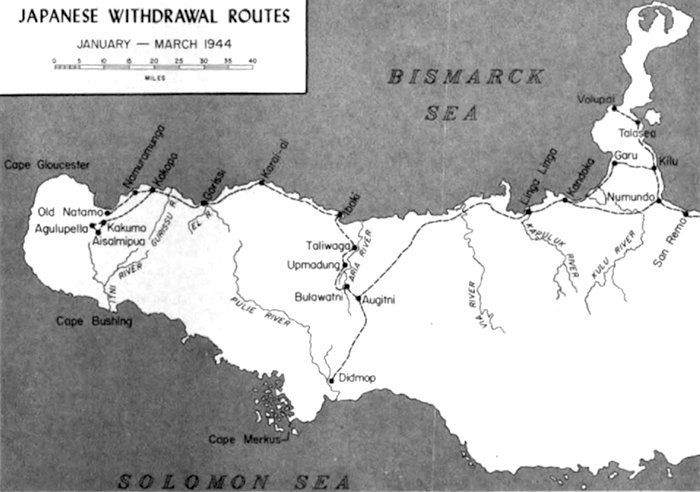

The attack on 16 January broke the back of Japanese resistance. Komori ordered a retreat to the vicinity of the airstrip, but the 112th Cavalry launched an attack that caught the slowly moving defenders and inflicted further casualties. By the time the enemy dug in to defend the airfield, which the Americans had no intention of seizing, Komori's men had suffered 116 killed, 117 wounded, 14 dead of disease, and another 80 too ill to fight. The Japanese hung on despite sickness and starvation, until 24 February, when Komori received orders to join in a general retreat by Matsuda Force.

Across the island, after the victories at Walt's Ridge and Hill 660, the 5th Marines concentrated on seizing control of the shores of Borgen [pg 20] Bay, immediately to the east. Major Barba's 1st Battalion followed the coastal trail until 20 January, when the column collided with a Japanese stronghold at Natamo Point. Translations of documents captured earlier in the fighting revealed that at least one platoon, supported by automatic weapons had dug in there. Artillery and air strikes failed to suppress the Japanese fire, demonstrating that the captured papers were sadly out of date, since at least a company—armed with 20mm, 37mm, and 75mm weapons—checked the advance. Marine reinforcements, including medium tanks, arrived in landing craft on 23 January, and that afternoon, supported by artillery and a rocket-firing DUKW, Companies C and D overran Natamo Point. The battalion commander then dispatched patrols inland along the west bank of the Natamo River to outflank the strong positions on the east bank near the mouth of the stream. While the Marines were executing this maneuver, the Japanese abandoned their prepared defenses and retreated eastward.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 75970

Maj William H. Barba's 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, prepares to outflank the Japanese defenses along the Natamo River.

Success at Cape Gloucester and Borgen Bay enabled the 5th Marines to probe the trails leading inland toward the village of Magairapua, where Katayama once had his headquarters, and beyond. Elements of the regiment's 1st and 2d Battalions and of the 2d Battalion, 1st Marines—temporarily attached to the 5th Marines—led the way into the interior as one element in an effort to trap the enemy troops still in western New Britain.

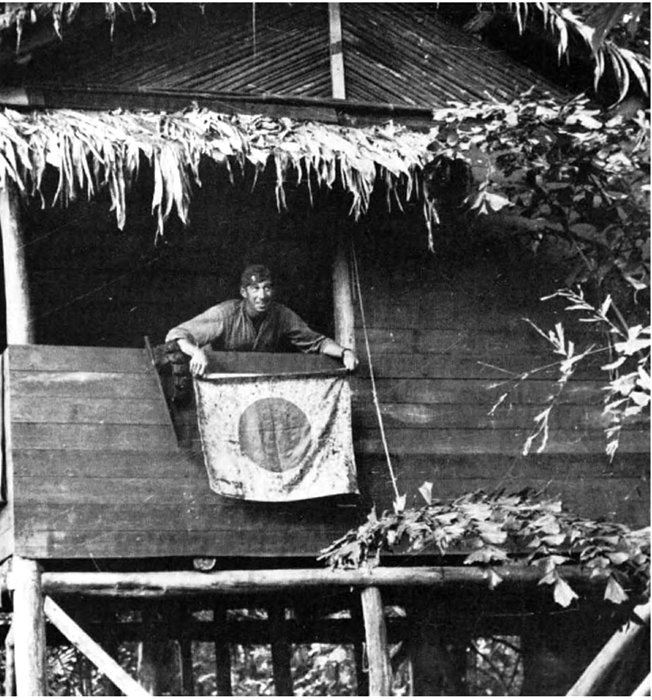

An officer of Maj Gordon D. Gayle's 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, displays a captured Japanese flag from a window of the structure that served as the headquarters of MajGen Iwao Matsuda.

Department of Defense (USA) photo SC 188246

In another part of this effort, Company L, 1st Marines, led by Captain Ronald J. Slay, pursued the Japanese retreating from Cape Gloucester toward Mount Talawe. Slay and his Marines crossed the mountain's eastern slope, threaded their way through a cluster of lesser outcroppings like Mount [pg 21] Langila, and in the saddle between Mounts Talawe and Tangi encountered four unoccupied bunkers situated to defend the junction of the track they had been following with another trail running east and west. The company had found the main east-west route from Sag Sag on the coast to the village of Agulupella and ultimately to Natamo Point on the northern coast.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 77642

The capture of Matsuda's headquarters provides Marine intelligence with a harvest of documents, which the enemy buried rather than burned, presumably to avoid smoke that might attract artillery fire or air strikes.

To exploit the discovery, a composite patrol from the 1st Marines, under the command of Captain Nickolai Stevenson, pushed south along that trail Slay had followed, while a composite company from the 7th Marines, under Captain Preston S. Parish, landed at Sag Sag on the west coast and advanced along the east-west track. An Australian reserve officer, William G. Wiedeman, who had been an Episcopal missionary at Sag Sag, served as Parish's guide and contact with the native populace. When determined opposition stopped Stevenson short of the trail junction near Mount Talawe, Captain George P. Hunt's Company K, 1st Marines, renewed the attack.

On 28 January, Hunt concluded he had brought the Japanese to bay and attacked. For three hours that afternoon, his Marines tried unsuccessfully to break though a line of bunkers concealed by jungle growth, losing 15 killed or wounded. When Hunt withdrew beyond reach of the Japanese mortars that had scourged his company during the action, the enemy emerged from cover and attempted to pursue, a bold but foolish move that exposed the troops to deadly fire that cleared the way for an advance to the trail junction. Hunt and Parish joined forces and probed farther, only to be stopped by a Japanese ambush. At this point, Major William J. Piper, Jr., the executive officer of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, assumed command, renewed the pursuit on 30 January, and discovered the enemy had fled. Shortly afterward Piper's combined patrol made contact with those dispatched inland by the 5th Marines.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 77436

LtCol Lewis H. Puller, left, and Maj William J. Piper discuss the route of a patrol from the village of Agulupella to Gilnit on the Itni River, a two-week operation.

Thus far, a vigorous pursuit along the coast and on the inland trails had failed to ensnare the Japanese. The Marines captured Matsuda's abandoned headquarters in the shadow of Mount Talawe and a cache of documents that the enemy buried rather than burned, perhaps because smoke would almost certainly bring air strikes or artillery fire, but the Japanese general and his troops escaped. Where had Matsuda Force gone?

Since a trail net led from the vicinity of Mount Talawe to the south, General Shepherd concluded that Matsuda was headed in that direction. The assistant division commander therefore organized a composite battalion of six reinforced rifle companies, some 3,900 officers and men in all, which General Rupertus entrusted to Lieutenant Colonel Puller. This patrol was to advance from Agulupella on the east-west track, down the so-called Government Trail all the way to Gilnit, a village on the Itni River, inland of Cape Bushing on New Britain's southern coast. Before Puller could set out, information discovered at Matsuda's former headquarters and translated revealed that the enemy actually was retreating to the northeast. As a result, Rupertus detached the recently arrived 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, and reduced Puller's force from almost 4,000 to fewer than 400, still too many to be supplied by the 150 native bearers assigned to the column for the march through the jungle to Gilnit.

During the trek, Puller's Marines depended heavily on supplies dropped from airplanes. Piper Cubs capable at best of carrying two cases of rations in addition to the pilot and observer, deposited their loads at villages along the way, and Fifth Air Force B-17s dropped cargo by the ton. Supplies delivered from the sky made the patrol possible but did little to ameliorate the discomfort of the Marines slogging through the mud.

Marine patrols, such as Puller's trek to Gilnit, depended on bearers recruited from the villages of western New Britain who were thoroughly familiar with the local trail net.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 72836

Despite this assistance from the air, the march to Gilnit taxed the ingenuity of the Marines involved and hardened them for future action. This toughening-up seemed especially desirable to Puller, who had led many a patrol during the American intervention in Nicaragua, 1927-1933. The division's supply clerks, aware of the officer's disdain for creature comforts, were startled by requisitions from the patrol for hundreds of bottles of insect repellent. [pg 24] Puller had his reasons, however. According to one veteran of the Gilnit operation, "We were always soaked and everything we owned was likewise, and that lotion made the best damned stuff to start a fire with that you ever saw."

As Puller's Marines pushed toward Gilnit on the Itni River, they killed perhaps 75 Japanese and captured one straggler, along with some weapons and odds and ends of equipment. An abandoned pack contained an American flag, probably captured by a soldier of the 141st Infantry during Japan's conquest of the Philippines. After reaching Gilnit, the patrol fanned out but encountered no opposition. Puller's Marines made contact with an Army patrol from the Cape Merkus beachhead and then headed toward the north coast, beginning on 16 February.

To the west, Company B, 1st Marines, boarded landing craft on 12 February and crossed the Dampier Strait to occupy Rooke Island, some fifteen miles from the coast of New Britain. The division's intelligence specialists concluded correctly that the garrison had departed. Indeed, the transfer began on 6 December 1943, roughly three weeks before the landings at Cape Gloucester, when Colonel Jiro Sato and half of his 500-man 51st Reconnaissance Regiment, sailed off to Cape Bushing. Sato then led his command up the Itni River and joined the main body of the Matsuda Force east of Mount Talawe. Instead of committing Sato's troops to the defense of Hill 660, Matsuda directed him to delay the elements of the 5th Marines and 1st Marines that were converging over the inland trail net. Sato succeeded in checking the Hunt patrol on 28 January and buying time for Matsuda's retreat, not to the south, but, as the documents captured at the general's abandoned headquarters confirmed, along the northern coast, with the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment initially serving as the rear guard.

On 12 February 1944, infantrymen of Company B, from LtCol Walker A. Reaves's 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, advance inland on Rooke Island, west of New Britain, but find that the Japanese have withdrawn.

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 79181

Once the Marines realized what Matsuda had in mind, cutting the line of retreat assumed the highest priority, as demonstrated by the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, from the Puller patrol on the very eve of the march toward [pg 25] Gilnit. As early as 3 February, Rupertus concluded that the Japanese could no longer mount a counterattack on the airfields and began devoting all his energy and resources to destroying the retreating Japanese. The division commander chose Selden's 5th Marines, now restored to three-battalion strength, to conduct the pursuit. While Petras and his light aircraft scouted the coastal track, landing craft stood ready to embark elements of the regiment and position them to cut off and destroy the Matsuda Force. Bad weather hampered Selden's Marines; clouds concealed the enemy from aerial observation, and a boiling surf ruled out landings over certain beaches. With about 5,000 Marines, and some Army dog handlers and their animals, the colonel rotated his battalions, sending out fresh troops each day and using 10 LCMs in attempts to leapfrog the retreating Japanese. "With few exceptions, men were not called upon to make marches on two successive days," Selden recalled. "After a one-day hike, they either remained at that camp for three or four days or made the next jump by LCMs." At any point along the coastal track, the enemy might have concealed himself in the dense jungle and sprung a deadly ambush, but he did not. Selden, for instance, expected a battle for the Japanese supply point at Iboki Point, but the enemy faded away. Instead of encountering resistance by a determined and skillful rear guard, the 5th Marines found only stragglers, some of them sick or wounded. Nevertheless, the regimental commander could take pride in maintaining unremitting pressure on the retreating enemy "without loss or even having a man wounded" and occupying Iboki Point on 24 February.

Meanwhile, American amphibious forces had seized Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls in the Marshall Islands, as the Central Pacific offensive gathered momentum. Further to complicate Japanese strategy, carrier strikes proved that Truk had become too vulnerable to continue serving as a major naval base. The enemy, conscious of the threat to his inner perimeter that was developing to the north, decided to pull back his fleet units from Truk and his aircraft from Rabaul. On 19 February—just two days after the Americans invaded Eniwetok—Japanese fighters at Rabaul took off for the last time to challenge an American air raid. When the bombers returned on the following day, not a single operational Japanese fighter remained at the airfields there.

The defense of Rabaul now depended exclusively on ground forces. Lieutenant General Yusashi Sakai, in command of the 17th Division, received orders to scrap his plan to dig in near Cape Hoskins and instead proceed to Rabaul. The general believed that supplies enough had been positioned along the trail net to enable at least the most vigorous of Matsuda's troops to stay ahead of the Marines and reach the fortress. The remaining self-propelled barges could carry heavy equipment and those troops most needed to defend Rabaul, as well as the sick and wounded. The retreat, however, promised to be an ordeal for the Japanese. Selden had already demonstrated how swiftly the Marines could move, taking advantage of American control of the skies and the coastal waters, and a two-week march separated the nearest of Matsuda's soldiers from their destination. Attrition would be heavy, but those who could contribute the least to the defense of Rabaul seemed the likeliest to fall by the wayside.

The Japanese forces retreating to Rabaul included the defenders of Cape Merkus, where a stalemate had prevailed after the limited American attack on 16 January had sent Komori's troops reeling back beyond the airstrip. At Augitni, a village east of the Aria River southwest of Iboki Point, Komori reported to Colonel Sato of the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment, which had concluded the rear-guard action that enabled the Matsuda Force to cross the stream and take the trail through Augitni to Linga Linga and eastward along the coast. When the two commands met, Sato broke out a supply of sake he had been carrying, and the officers exchanged toasts well into the night.

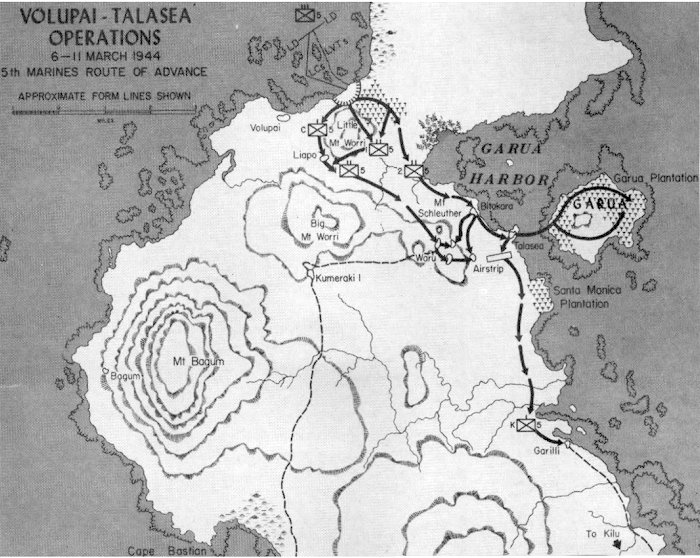

Meanwhile, Captain Kiyomatsu Terunuma organized a task force built around the 1st Battalion, 54th Infantry, and prepared to defend the Talasea area near the base of the Willaumez Peninsula against a possible landing by the pursuing Marines. The Terunuma Force had the mission of holding out long enough for Matsuda Force to slip past on the way to Rabaul. On 6 March, the leading elements of Matsuda's column reached the base of the Willaumez Peninsula, and Komori, leading the way for Sato's rear guard, started from Augitni toward Linga Linga.

Sidenote: (page 23)

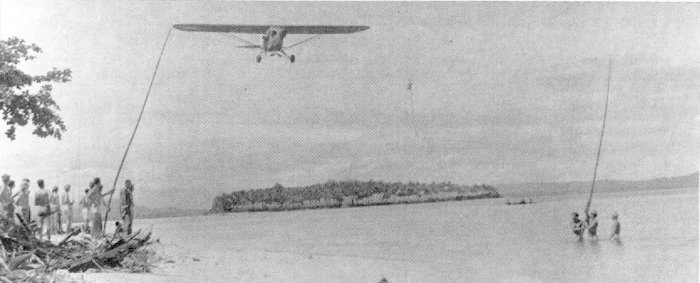

Department of Defense (USMC) photo 86249

A Piper Cub of the 1st Marine Division's improvised air force snags a message from a patrol on New Britain's north coast.

At Cape Gloucester, the 1st Marine Division had an air force of its own consisting of Piper L-4 Cubs and Stinson L-5s provided by the Army. The improvised air force traced its origins to the summer of 1943, before the division plunged into the green inferno of New Britain. Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth H. Weir, the division's air officer, and Captain Theodore A. Petras, the personal pilot of Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, then the division commander, concocted a plan for acquiring light aircraft mainly for artillery spotting. The assistant division commander at that time, Brigadier General Rupertus, had seen Army troops making use of Piper Cubs on maneuvers, and he promptly presented the plan to General MacArthur, the theater commander, who promised to give the division twelve light airplanes in time for the next operation.

When the 1st Marine Division arrived at Goodenough Island, off the southwestern tip of New Guinea, to begin preparing for further combat, Rupertus, now a major general and Vandegrift's successor as division commander, directed Petras and another pilot, First Lieutenant R. F. Murphy, to organize an aviation unit from among the Marines of the division. A call went out for volunteers with aviation experience; some sixty candidates stepped forward, and 12 qualified as pilots in the new Air Liaison Unit. The dozen Piper Cubs arrived as promised; six proved to be in excellent condition, three needed repair, and another three were fit only for cannibalization to provide parts to keep the others flying. The nine flyable planes practiced a variety of tasks during two months of training at Goodenough Island. The airmen acquired experience in artillery spotting, radio communications, and snagging messages, hung in a container trailing a pennant to help the pilot see it, from a line strung between two poles.

The division's air force landed at Cape Gloucester from LSTs on D-Day, reassembled their aircraft, and commenced operating. The radios installed in the L-4s proved too balky for artillery spotting, so the group concentrated on courier flights, visual and photographic reconnaissance, and delivering small amounts of cargo. As a light transport, a Piper Cub could drop a case of dry rations, for example, with pinpoint accuracy from an altitude of 200 feet. Occasionally, the light planes became attack aircraft when pilots or observers tossed hand grenades into Japanese positions.

Before the Marines pulled out of New Britain, two Army pilots, flying Stinson L-5s, faster and more powerful than the L-4s, joined the division's air arm. One airplane of each type was damaged beyond repair in crashes, but the pilots and passengers survived. All the Marine volunteers received the Air Medal for their contribution, but a specially trained squadron arrived from the United States and replaced them prior to the next operation, the assault on Peleliu.

By coincidence, 6 March was the day chosen for the reinforced 5th Marines, now commanded by Colonel Oliver P. Smith, to land on the west coast of the Willaumez Peninsula midway between base and tip. The intelligence section of division headquarters believed that Japanese strength between Talasea, the site of a crude airstrip, and Cape Hoskins, across Kimbe Bay from Willaumez Peninsula, equaled that of the Smith's command, but that most of the enemy troops defended Cape Hoskins. The intelligence estimate proved correct, for Sakai had been preparing a last-ditch [pg 26] defense of Cape Hoskins, when word arrived to retreat all the way to Rabaul.