Vol. I. Philadelphia, Seventh Month, 1820. No. 7.

FOR THE RURAL MAGAZINE.

Among the smooth faced urchins that were subject to my little kingdom about fifteen years ago, was a tall awkward boy, named Jonathan Gull. Jonathan was the son of an honest hard working farmer, who lived about two miles from the village, and who had by dint of frugality, acquired some property, and with it a proportional degree of consideration in the eyes of his neighbours. His crops of wheat were generally large, and he made a journey to the metropolis once a year, to dispose of his grain and produce. On these occasions his wife and a grown up daughter would usually accompany him to see the city and to buy cheap goods. It did one's heart good to witness the return of the honest farmer—the smile of self-complacency with which he greeted the members of his family, and the eagerness with which he inquired respecting the farm, Old Roan, and the young colt, and brindle, the cow, and the litter of young pigs; and the air of importance which he assumed towards his neighbours, who thronged around him to hear the latest news-what Boney was doing—the yellow fever—and the price of wheat. His hearty greeting of his acquaintance; the animation which sparkled in his sunburnt face; his short thick set figure, decked out in a suit of homespun grey, with large brass buttons; his arms a kimbo; and the broad burst of merriment, that, amidst the discussion of graver subjects, occasionally broke forth at some sly turn, or second hand joke of the traveller; altogether formed the beau ideal of homely rustic happiness, and prosperity. Nor was the greeting and excitation less on the part of the wife and daughter. As the wagon was emptied of its load, treasure after treasure met the eyes of the delighted group of children and neighbours. Here were a new set of milk pans, and a churn for the dairy; a dozen of pewter spoons, as smooth and as bright as silver, and scrubbing brushes, and knives and forks to repair the waste of years. There glittered lots of new calico, as fine as red and yellow could make them; papers of pins and needles, and all the sundry articles which complete the stock of an industrious housewife; while in another place were cautiously hid, lest they should excite undue envy, the silver teaspoons and teapot, and[242] the bundles of coffee and tea and white sugar, together with the tortoise shell combs and gold ear-rings which the good natured husband had been importuned to buy. Let not the reader turn away with contempt from this simple picture; the event was an important one in the family of farmer Gull, and supplied it with a stock, not only of necessities and luxuries, but of conversation and pleasure for a full season. But alas! in the train of all this prosperity and gladness marched the forerunners of decay. Farmer Gull's heavy purse of shining dollars had won the heart of many a knight of the counter, and many were the plans laid to obtain a a closer intimacy with their owner. Here Mrs. Gull was invited to sit down in the parlour to rest herself; and there was she pressed to stay to tea. One talked to her about her butter and her cheese, and another about her rosy faced children. In short, it so happened, that in the course of a few years, she had at least half a dozen acquaintances in the shopkeeping line, each of whom were under engagement to spend a short time during the Dog-days at Melrose; for so was the farm now styled. With these new acquaintances, new views and expectations filled the minds of the wife and daughters. The old family Bible and the Pilgrim's Progress were less frequently read and quoted; the calico short gowns in which they used to visit their neighbours of a summer evening gave place to dresses of silk and white muslin, and their talk was now of the fashions and the new novels. Among other changes it was determined to make a merchant of Jonathan, and a place was accordingly engaged for him with the particular friend of the family, Mr. Seersucker.——I was struck with the appearance of the lad when he came to bid me good bye and take his books from school. He was dressed in a suit of tidy homespun, made up by the hands of his mother and sisters, and which was, from the sheep that furnished the wool to the thread with which the garments were sewed, the produce of his father's farm. The good old fashioned notions of domestic industry were not then extinct. Our farmers had not then found that it was cheaper to keep a family of strapping daughters idle at home, and send the wool to one factory to be carded and spun, and to another to be wove and dyed, and then to a fop of a tailor to be made up into coats, than to have the cards, the wheel, and the loom at their own fire-side; giving wholesome occupation to their family, enlivening the gloomy hours of winter, and cementing by good humour and mutual assistance the ties of family and kindred. We had not then found out the grand modern secret of economy; that it is better to pamper a few inordinate manufacturing establishments, with all their consequences, of a degraded and dependant population and high taxes, than to let every individual pursue his own interests, and to encourage that best of domestic manufactures where the workshop is the kitchen of the farmer, and his wife and children the contented and uncorrupted labourers.

But I find myself perpetually digressing from my story, and must bid[243] a truce to these rambling thoughts. Jonathan, as I was saying, was tidily dressed; his hair was combed smooth on his forehead, and hanging long behind, and the awkwardness of his figure, was scarcely apparent in the expression of good health and contentment that animated him. It soon became apparent, however, that citizen Jonathan would not long be contented with his homely garb. At his first visit home I observed that he had been in the hands of a fashionable hair-dresser, who had given him the true Bonapartean topknot. His shirt collar was stretched up till it half covered his ears and cheeks, and he sported a clouded and twisted cane, while the remainder of his dress was yet unchanged. By degrees the exuvia of the clown fell off, as I have seen a snake in the spring slowly emerge from the shrivelled skin which she has cast, or as a locust may sometimes be seen breaking through his faded coat of mail and sporting in gaudy robes of green and gold; or as you may observe in the ponds a kind of doubtful animal, half frog and half tadpole. Jonathan became in a year or two the admiration of all the neighbouring milk maids, and was universally accounted a fine gentleman. He had not be sure ciphered further than Practice, and was but a dull hand, when a boy, at Murray's grammar; but so wonderfully had a city life sharpened his wits, that his old master himself was quite in the back ground when Jonathan was present; he poured forth such a torrent of words and discoursed so fluently about politics and trade and great men. Then came the days of delusion and speculation. Jonathan was now of age, and as he had what was called a good turn for business, and a strong back to support him, he was solicited to engage in trade. A partnership was accordingly formed, and "GULL, SNIPE, & Co." glittered in golden capitals across Market Street. A capital of some thousands was paid down, while goods to the amount of hundreds of thousands were bought and sold.

In the meantime farmer Gull was floating on the very spring tide of prosperity. His wealth, which was yearly increasing, gave him great weight in the neighbourhood; he was made overseer of the poor, and there was a talk of sending him to Congress. When that ill starred measure which created at a birth a swarm of banks, more greedy and more lean than Pharaoh's kine, was adopted, farmer Gull partook of the delusion. He was made a director of the bank of Potosi, which was located in our village, and from that moment gave himself up to dreams of imaginary wealth. He stocked his farm with merino sheep, at an average of fifty dollars a head, and calculated that in six years he should double his money. Six years have elapsed, and farmer Gull's whole flock will not now sell for the cost of a single ewe. He mortgaged his farm to the bank, that he might buy a neighbouring property, and prosecute some expensive improvements in the way of mills and factories. At home every thing was changed. Mistress Gull rode to church in a handsome carriage, which Jonathan had sent up from town; and Polly and Biddy, instead of being at the milk pail by sunrise, lay abed till breakfast time[244] and then came down with pale and languid countenances, and their hair buckled into "kill-beaus" and "heart breakers," to partake of coffee which unnerved their system, and rendered them feverish and nervous till dinner time. Why should I proceed with my story? The sequel may be read in the present circumstances of many a once thriving family. The lean kine of Simon devoured his fat kine, and distress and confusion covered the face of the country. Gull, Snipe, & Co., after a few years of fictitious prosperity, and proportional extravagance, went the way of half Market Street. Farmer Gull was their security, and had to make heavy payments to the bank. His own speculations had proved ruinous, the clouds became continually darker and thicker around him, and have at length burst upon his head. His whole property is insufficient to pay the mortgages, and his stock and furniture will be sold next week by the sheriff. Such is the termination of farmer Gull's career. His family is incapacitated for its present destitute situation, and has lost the inclination and the power of being frugal: he himself, I observe, bears his troubles with an appearance of unusual fortitude. He preserves his cheerful spirits, and has become the life of a circle of embarrassed farmers that frequent a tavern opposite the window of my study. I see him there daily—sometimes to be sure moody and disconsolate, but more often leading the chorus of some Bacchanalian song, or retailing the merry jests of some quondam acquaintance, of a lawyer, or bank director. Alas! for my countrymen;—when shall we see again the days of honest dealing, sturdy frugality, unsophisticated manners, and household industry?

FOR THE RURAL MAGAZINE.

It has been said by a writer, whose genius and scholarship are in the highest degree honourable to his country, that our Parnassus is fruitful only in weeds, or at best in underwood. Notwithstanding the general correctness of this assertion, a modest wild-flower now and then delights the eye, and points that rainbow adventurer HOPE to the brilliant future; in which some master of song shall disclose in a broad and clear light,

Such forms as glitter in the Muse's ray.

American literature, it must be admitted, is comparatively feeble in many of its branches; but while the names of Franklin and Rush, Dennie and Brown, of Walsh and Irving, are remembered, it is entitled to the respectful consideration, even of foreign criticism.

The extract given above is made from a writer, who has furnished some evidence of poetic talent in sundry occasional playful pieces, published originally in the New York Evening Post, under the signature of Croaker & Co. However unprepossessing may be the name which he has chosen to assume, his notes instead of reminding us, as might be inferred, of the frog[245] or the raven; at times successfully rival those of the favourite songsters of the grove. From this stanza, we learn that the author is a BACHELOR; who like too many of his brethren, delights to dwell on the fancied cruelty of the fair; and to pour the unheeded complaints of his sorrows on the dull and listless ear of indifference. To this portion of society, little commisseration is extended from any quarter; and the general sentiment is responsive to that contained in the following couplet of Pope:

Unpopular as such a doctrine might appear, this condition of life has had its advocates and defenders. Amongst these may be placed that truly great man, the eloquent and accomplished apostle Paul. When adverting to this subject, he discovers something of an unsocial disposition where he says, "For I would that all men were even as myself."[1] "But I speak this by permission, and not of commandment," says he, as if fearful that speculative opinion might be received from the weight of his character as authority perfectly valid and conclusive. Dryden has asserted, that "a true painter naturally delights in the liberty which belongs to the bachelor's estate." However specious this position may appear, the liberal arts are more indebted to the charities of life, and to the influence of female excellence, than the author of such a sentiment would be willing to admit. A vivid perception of physical and moral beauty, delicacy of feeling, and intellectual refinement, are indispensably requisite in the artist who aspires to eminence in his profession. Nothing has a more direct and efficient tendency to promote elegance and correctness of taste than the society of enlightened and polished females. The absence of care is another immunity which the BACHELOR is said to enjoy; but this as well as other assumptions in his favour, but serves to illustrate the fact, that on almost any subject whatever, to use the language of Sir Roger de Coverly, much may be said on both sides."

In all ages there have been from various causes, a formidable array of individuals of this class. The circumstances connected with the present times are, unfortunately, well calculated to increase their number. To the usual disastrous consequences produced by "beauty's frown," the disappointments and gloomy prospects in business, deep rooted habits of idleness and extravagance, by which the present period is peculiarly distinguished, may also be added. Active industry, frugality, and temperance, should be sedulously cultivated as moral virtues; having a most important agency in augmenting the stock of individual, social, and political happiness. But unamiable and repulsive as the character of a BACHELOR may too frequently be, is it necessarily so?

Can he contemplate the condition of childhood, surrounded with the pallid spectres of poverty, and shooting forth luxuriantly into all the noxious forms of ignorance and vice;—can he walk our streets or wharves when his ear is saluted with their lisping imprecations;—or witness their utter[246] disregard of the duties which appertain to the Sabbath,—without seriously interrogating his own bosom—In what way can any exertions of mine improve their condition, and promote their true interests?

Can he behold the increase of intemperance and crime in all the ramifications of society, without feeling the influence of those sacred ties which bind him to that community of which he is a member; and without resolving to use all diligence to arrest their further extension, so far as his influence and example may reach?

Can he listen with unconcern to the cries of oppressed humanity, and view without emotion, those objects of wretchedness which almost daily present themselves in the most affecting shapes, and forget the intimate relationship, and the reciprocity of duties which exist between every branch of the human family, and the justice and force of the claims of distress upon every generous and sympathetic heart?

He can no where in the moral or physical economy of the world, find an example of existences which are independent of all connection with the present, past, and future. The universe has been with great propriety compared to a complex machine, "a stupendous whole," every part of which has its relative and proper function to perform, and discord and confusion are the consequence of each irregularity of movement.

It should be the business of every one to cultivate such sentiments as those which are contained in the extract below, given from a work[2] which the celebrated Dugald Stewart declared when presenting a copy of it to one of our countrymen, now a resident of Philadelphia, to be the finest piece of composition in the English language: "That to feel much for others, and little for ourselves, that to restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent affections, constitutes the perfection of human nature; and can alone produce among mankind that harmony of sentiments and passions in which consists their whole grace and propriety." Even a BACHELOR, actuated by principles of this character, might emerge into the character of a worthy, useful, and amiable man!

☞

Cheap food for horses, from M'Arthur's Financial Facts, 8vo. p. 258.

The author lived in London and kept three horses which he fed as follows.

Two trusses and a half of clover or meadow hay cut and mixed with four trusses of wheat, or barley straw, when cut up, make nearly equal quantities in weight; two heaped bushels of this mixture equal to fourteen pounds weight, are given to each horse in twenty-four hours, being previously mixed with half a peck of corn, (in England oats) ground or chopped, weight 5lbs. with water to wet it; that is, 7 pounds of hay; 7 pounds of straw; 5 pounds of meal; given at six different times, each day and evening. Add 5 pounds of hay at night, makes 24 pounds to each[247] horse in twenty-four hours; and it kept them much fatter than with double the corn each day unground, two trusses of hay a week.

An ox, unworked, eats about 32 pounds of meadow hay per day.

An ox at work eats 40 pounds a day.

If fed in the stable each head of horned cattle will eat 130 pounds green clover just cut, or 30 pounds clover hay a day.

At work, 3 horses eat in all, 48 stones a week of hay, also 48 quarts of oats a week each horse.

At work 18 horses in 12 days, eat 430 stones of hay, which is 14 stones a week for each horse, also 64 quarts of oats a week for each.

An idle horse eat 14 stones of hay a week and no corn.

August 22, 1807.

In the garden of Joseph Cooper, Esq. of New Jersey, just opposite to Philadelphia, is one grape vine which with its branches, covers 2170 square feet of ground. On this one vine are now grapes supposed to be forty bushels, and probably much more. It produced last year one barrel of wine, which was made without sugar, and is judged to be quite as good as Madeira of the same age, by a man brought up in the Madeira wine trade. Under this vine the ground produced a good crop of grass this season. It is a native American vine, transplanted from that same neighbourhood.[3]

If 2170 square feet produced 32 gallons, then one acre which is 43,560 square feet would produce about 20 barrels, or 640 gallons but allowing space for avenues, say about 15 barrels, or 480 gallons.

It is expected that the crop of grapes for 1807 will produce much more than those of 1806.

One acre yielding 480 gallons,

at $1.00, is - - - $480.00

at $1.50, is - - - $720.00

This holds out a profitable culture to farmers.

C. E.

The "Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture," at a late meeting, passed a resolution to recommend the use of Malt Liquors, in preference to Ardent Spirits, on farms;—and appointed the subscribers a Committee to procure and publish Directions to enable Farmers to Brew Beer.—They have accordingly the pleasure to send a pamphlet published by the proprietors of a patent English brewing apparatus, which was imported by a gentleman of Philadelphia; and also some directions by an eminent brewer, to enable families to brew beer with the common household utensils. The apparatus was tried last year by one of our members, and found to answer perfectly.—It was imported with the view to general utility, not to private profit, and we understand may be purchased at first cost.[4]

RICHARD PETERS, }

JAMES MEASE, }

ROBERTS VAUX, }

ISAAC C. JONES, } Committee.

Philadelphia, June, 1820.

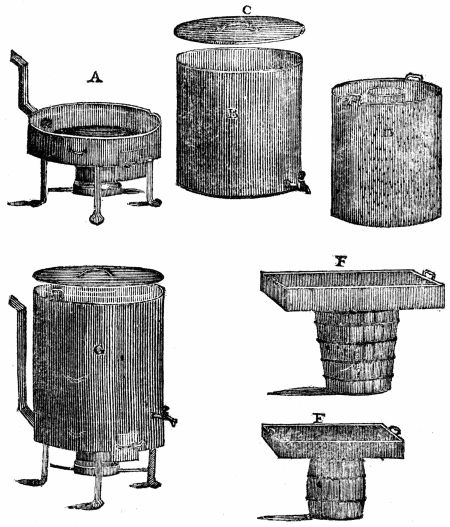

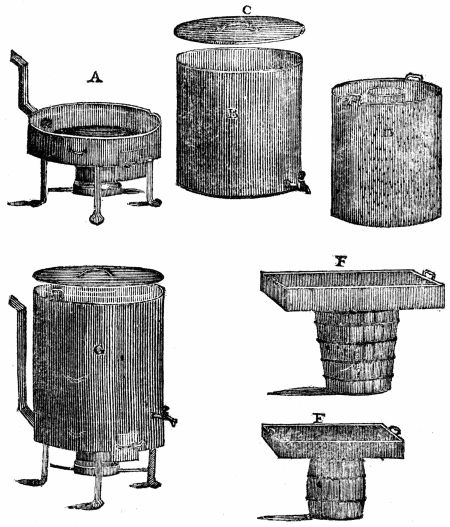

With Needham & Co.'s Patent Portable Family Brewing Machine.

As the attainment of good Malt Liquor greatly depends upon the quality of the materials from which it is produced, it may be useful to give a few general instructions for distinguishing the quality of malt and hops, of which it should be only composed; but considerable practice being requisite to form a ready judgment, it will generally be more safe to buy them of some reputable dealer.

Malt.—To judge of the quality of malt, you must chew it, and if sweet, tender, and mealy, with a brisk full flavour, it is good; in coloured malt particular care should be taken that it is neither smoky nor burnt.[5]

Hops should be of a bright colour, free from green leaves, of a quick pungent smell, and glutinous quality, which will be discoverable by their adhering together, and by rubbing them in the hands. New hops are preferable to old, after Christmas.

To Brew Ale with Table Beer after, from the same malt and hops.—The malt should be pale, sweet, and tender, ground coarse, and the hops of a pale bright colour and glutinous quality.

If the ale is for present use, 3⁄4 of a pound of hops to each bushel of malt will be sufficient, but for store ale use one pound per bushel.

The machine being placed ready

for use as described in the plate,

figure G,[6] put into it as much cold

water as will cover the perforated

bottom of the extracting cylinder, and

light the fire; then put as much

coarse ground malt into the perforated

cylinder, (see the plate, figure

D,) as will three parts fill it, taking

care that none goes into the centre,

(which centre should be covered,

(but only) while putting the malt in,

and when mashing the malt,) nor

any between the cylinder and boiler.—The

malt being put in, pour

through the centre as much more

cold water as will just cover the malt,[249]

[250]

then make the fire good, and in one

hour after stir the malt well up with

a strong mashing stick, for about ten

minutes, so that every particle of malt

may be divided from the other: let

the heat increase to 180 degrees,

which you must ascertain by holding

the thermometer a minute in the centre

part of the machine, and when at

180 degrees of heat, stir the malt

again, and after this second stirring,

try the heat, and if then at 180 degrees,

damp the fire well with some

wet ashes to prevent the heat of the

mash from increasing, and in 3 hours

and a half from the time of lighting

the fire, draw off the wort very gently

that it may run fine, and put it into

one of the coolers, and put all the

hops (rubbing them through your

hands to break the lumps) on the top

of the wort to keep it hot till the time

for returning it into the machine for

boiling; having drawn off this ale

wort, put into the machine through

the centre as much more cold water

as will cover the grains, brisken the

fire, and in half an hour stir up the

malt for about ten minutes, and make

it 180 degrees of heat as quick as

you can, then damp the fire to prevent

its getting hotter, and in one

hour and a half from the time of putting

in the water, draw off this table

beer wort gently, that it may run

fine, and put it into the other cooler,

and cover it over to keep it hot until

the time for returning it into the machine

for boiling; having drawn off

this table beer wort, if you wish to

make a third wort, put in as much

more cold water into the machine as

you think proper, and make it 170

degrees of heat as quick as you can,

and draw it off in about an hour after,

and put it to the last drawing off, or

wort: then take the grains out of the

cylinder with a hand shovel as clean

as you can, and after, take out the

cylinder,[7] and with a birch broom and

a little water rince out the boiler

clean, and put back the perforated

cylinder into the boiler, and then put

the first drawing off or ale wort, with

all the hops, into the machine cylinder

where you have taken the grains from,

and cover the machine, but be sure

the centre cover is off; make it boil

as quick as you can, and let it boil

well one hour, then damp the fire and

draw it off into a cooler or coolers,

which should be placed in the air

where it will cool quick. Having

drawn off this ale wort, return the

second drawing off, or table beer

wort, with the third, into the machine

to the hops left from the ale wort,

stir up the fire and make it boil as

quick as you can, and let it boil well

one hour, then put out the fire and

draw off the wort, and put it into a

cooler placed in the air to cool quick;

when the worts in the coolers are

cooled down to 70 degrees of heat by

the thermometer, put the proportion

of a gill of fresh thick yeast to every

9 gallons of wort in the coolers, first

thinning the yeast with a little of the

wort before you put it in that it may

the better mix; and when the ale

wort is cooled down to 60 degrees of

heat, draw it off from the coolers with

the yeast and sediment, and put it into

the machine boiler (the machine

boiler having been previously cleared

from the hops and cylinder,) which

forms a convenient vessel placed on

its stand for the ale to ferment in,

which must be kept fermenting in it

with the cover off until the head has

the appearance of a thick brown yeast

on the surface, an inch or two deep,

which will take 3 or 4 days;[8] when[251]

the head has this appearance, draw off

the beer free from the yeast and bottoms

into a clean cask, which must be

filled full,[9] and when done working,

put in a handful of dry hops, bung it

down tight, and stow it in a cool cellar.

This ale will be fit to tap in 3 or

4 weeks.

The second wort for table beer should be put from the coolers with yeast and sediment into an upright cask, with the cover off or top head out, at not exceeding 60 degrees of heat, and as soon as you perceive a brown yeast on the surface, draw it off free from the yeast and bottoms into a clean cask, which must be kept filled full, and when done working, put in a handful of dry hops, bung it down tight, and stow it in a cool cellar. This table beer will be fit to tap in a week, or as soon as fine.

To make Table Ale.—Mix the first and second worts together, and ferment, and treat it the same as the ale.

To Brew Porter or Brown Beer, with Table Beer after, from the same Malt and Hops.—Use pale and brown malt in equal quantities, ground coarse; and strong brown coloured hops of a glutinous quality. If the beer is for present draught, 3⁄4 pound of hops to each bushel of malt will be sufficient, but if intended for store beer, use one pound to each bushel of malt.

The process of brewing is the same as described for brewing ale with table beer after, except the heat of each mash must not be so high by 10 degrees, on account of the brown malt; the first wort fermented by itself will be stout porter, and fit to tap in 3 or 4 weeks; the second wort will be the table beer, and fit to tap in a week, or as soon as fine; but if you mix the first and second worts together, the same as for table ale, it will be good common porter.

To Brew Table Beer only.—Let your malt be of one sort, of a full yellow colour (not brown malt) ground coarse, and strong brown coloured hops, of a glutinous quality. If for present draught 1⁄2 a pound of hops to each bushel of malt will be sufficient, but if for keeping two or 3 months, use one pound of hops per bushel.

The process of brewing is the same as described for brewing porter and table beer, with the addition of another wort, that is, filling the machine a third time with water before you take out the grains, and treating the third mash the same as the second.

The first drawing off or wort, with part of the second wort, to be boiled (first) one hour with all the hops, and the remainder of the second wort with the third, to be boiled next one hour to the same hops; these two boilings, when cooled down to 60 degrees of heat, (having put your yeast to it in the coolers at 70 degrees) must be put together to ferment in the machine boiler, and as soon as it has the appearance of a brown yeast on the surface, draw it off into the casks, which must be kept filled full, and when done working, put into each cask a handful of dry hops, bung it down tight, and put it into a cool cellar. Tap it in a week, or as soon as fine.

General Remarks.—The season for brewing sound keeping beer, is from October to May.

All Beer should be stored in cool cellars or vaults, and kept as much as possible from the common atmosphere; and in drawing beer from a cask, if necessary to raise the vent-peg, it should be carefully tightened as soon as the beer is drawn.

When beer is intended to be kept many months, the bungs of the casks, and if bell casks are used, the whole of the head should be covered with sand or clay, which should be kept moist.

To preserve the Machine.—When the brewing is over, wash the machine and coolers with cold or hot water, then dry them, and put them away in a dry place. When wanted to be used, they should be washed with boiling water.

To keep Casks sweet.—It is recommended when a cask of beer is drawn off, to take out the head and scrub out the cask; then thoroughly dry and put it away in a dry place with the head out.

If it should be inconvenient to take out the head, and the cask is wanted to be filled again quickly, it may be washed quite clean with warm water, and afterwards with lime water; or the grounds being left in the cask, and every vent stopped, (bung, tap, and vent holes,) it may be kept in that state for a short time.

Casks of a bell shape are preferable for private brewing, and the patentees make them upon a principle by which the inside can be scrubbed out clean without removing the head, and at the same price as common casks of that shape.

The following comparative statement of the cost of Brewing Beer with Needham's apparatus, and of Beer when purchased, is given by the proprietor.—The references are to London prices, but an opinion may still be formed of the great economy of Domestic Brewing.

| Daily Consumption of | Yearly Consumption | Brewers' Prices. | Yearly expense | ||

| ale in a family, 3 pints | is 137 gallons | At 2s. 6d. per gal. | L.17 | 2 | 6 |

| Do. of table beer, 3 pints | Is 137 gallons | At 8d. | 4 | 11 | 4 |

| 21 | 13 | 10 | |||

| To Brew the above quantity of good Ale and Table Beer, 151⁄4 Bushels of Malt are required, the cost of which, at 10s. per Bushel, will be | L.7 | 12 | 6 | |||

| 111⁄2 lbs. best Hops, for ditto, at 5s. | 2 | 17 | 6 | ——10 | 10 | 0 |

| Yearly saving in the above quantity | 11 | 3 | 10 |

The above calculation sufficiently proves that the Patent Brewing Machine will, to the smallest Family who purchase Brewer's Beer, pay for itself in One Year, and those who have been accustomed to Brew by the old Method, will find the beer much stronger and better by using this Machine, and very considerably less likely to be spoiled in Brewing, with a great saving in Fuel, Labour, and Time.

As it may be inconvenient, or too expensive, for many private families to purchase a brewing machine, the following Directions are subjoined, which will enable them, by the aid of the vessels used in a family, to brew a barrel of beer; and by attention, and a few experiments, they will produce an excellent beverage.

Prepare a tub for making the extract, by fitting a false bottom with numerous holes, and raised about half an inch from the real bottom, in which fix a cock for drawing off the extract. Have four bushels of malt coarsely ground, and heat your water to about 170 or 175 degrees[10] of heat, of Fahrenheit's thermometer. Then pour in the tub about thirty-eight gallons of the water, and gently stir in the malt, until it is all mixed. Cover it, and let it stand about an hour and a half; draw off the extract into a vessel, and throw in about one and a quarter pounds of hops for liquor for present use, or about two or two and a half pounds for keeping liquors; cover the vessel to keep in the heat, and pour over the malt about 26 gallons of water, of about the same heat as the first, stirring it until it is well mixed with the malt; let it stand one hour, then draw off the extract, add it to the first extract, and put them on to boil in an open kettle: this will be your strong beer. Then pour over the malt about twenty gallons of water, for small beer, at about 160 or 170 degrees of heat. This last will not require stirring, and the extract[253] may remain covered until the kettle is ready for it. Keep the strong beer boiling smartly for about one hour and a quarter, or one hour and a half, for present use, or two hours for keeping: then pour it through a sieve or strainer, and set it to cool. Return the hops into the kettle with your third extract, or small beer, which set to boiling as soon as practicable, and continue it for about an hour and a half; then pour it through the strainer, and set it to cool. When cool, ferment according to the directions accompanying the brewing machine. The quantity of water used may be varied at the discretion of the person brewing. By diminishing the water, he may increase the strength of the liquor, or by increasing it, diminish the strength. Thus with the hops he may vary the quantity to suit his palate in the degree of bitter flavour that may be most agreeable.—For fomenting, a cask with one head taken out, will answer the same purpose as the machine boiler.

From Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, for April.

"'Tis only from the belief of the goodness and wisdom of a Supreme Being, that our calamities can be borne in that manner which becomes a man."—Henry Mackenzie.

In summer there is a beauty in the wildest moors of Scotland, and the wayfaring man who sits down for an hour's rest beside some little spring that flows unheard through the brightened moss and water-cresses, feels his weary heart revived by the silent, serene, and solitary prospect. On every side sweet sunny spots of verdure smile towards him from among the melancholy heather—unexpectedly in the solitude a stray sheep, it may be with its lambs, starts half alarmed at his motionless figure—insects large, bright, and beautiful come careering by him through the desert air—nor does the Wild want its own songsters, the grey linnet, fond of the blooming furze, and now and then the lark mounting up to heaven above the summits of the green pastoral hills.—During such a sunshiny hour, the lonely cottage on the waste seems to stand a paradise; and as he rises to pursue his journey, the traveller looks back and blesses it with a mingled emotion of delight and envy. There, thinks he, abide the children of innocence and contentment, the two most benign spirits that watch over human life.

But other thoughts arise in the mind of him who may chance to journey through the same scene in the desolation of Winter. The cold bleak sky girdles the moor as with a belt of ice—life is frozen in air and on earth. The silent is not of repose but extinction—and should a solitary human dwelling catch his eye half buried in the snow, he is sad for the sake of them whose destiny it is to abide far from the cheerful haunts of men, shrouded up in melancholy, by poverty held in thrall, or pining away in unvisited or untended sickness.

But, in truth, the heart of human life is but imperfectly discovered from its countenance; and before we can know what the summer, or what the winter yields for enjoyment or trial to our country's peasantry, we must have conversed with them in their fields and by their fire-sides; and make ourselves acquainted with the powerful ministry of the seasons, not over those objects alone that feed the eye and the imagination, but over all the incidents, occupations, and events that modify or constitute the existence of the poor.

I have a short and simple story to tell of the winter life of the moorland cottager—a story but of one evening—with a few events and no signal catastrophe—but which may haply please those hearts whose delight it is to think on the humble under-plots that are carrying on in the great Drama of life.

Two cottagers, husband and wife, were sitting by their cheerful peat-fire one winter evening, in a small lonely hut, on the edge of a wide moor, at some miles distance from any other habitation. There had been, at one time, several huts of the same kind erected close together, and inhabited by families of the poorest class of day-labourers who found work among the distant farms, and at night returned to dwellings which were rent free, with their little gardens, won from the waste.—But one family after another had dwindled away, and the turf-built huts had all fallen into ruins, except one that had always stood in the centre of this little solitary village, with its summer walls covered with the richest honeysuckles and in the midst of the brightest of all the gardens. It alone now sent up its smoke into the clear winter sky—and its little end window, now lighted up, was the only ground star that shone towards the belated traveller, if any such ventured to cross, on a winter night, a scene so dreary and desolate. The affairs of the small household were all arranged for the night. The little rough pony that had drawn in a sledge, from the heart of the Black-Moss, the fuel by whose blaze the cottiers were now sitting cheerily and the little Highland cow, whose milk enabled them to live, were standing amicably together, under cover of a rude shed, of which one side was formed by the peat stack, and which was at once byre, and stable, and hen-roost. Within, the clock ticked cheerfully as the fire-light readied its old oak-wood case across the yellow sanded floor—and a small round table stood between, covered with a snow-white cloth, on which were milk and oat cakes, the morning, mid-day, and evening meal of these frugal and contented cottiers. The spades and the mattocks of the labourer were collected into one corner, and showed that the succeeding day was the blessed Sabbath—while on the wooden chimney-piece were seen lying an open Bible ready for family worship.

The father and mother were sitting together without opening their lips, but with their hearts overflowing with happiness, for on this Saturday-night they were, every minute, expecting to hear at the latch the hand of their only daughter, a maiden of about fifteen years, who was at service with a farmer over the hills. This dutiful child was, as they knew, to bring home to them "her sair-worn penny fee," a pittance which, in the beauty of her girl-hood, she earned singing at her work, and which, in the benignity of that sinless time, she would pour with tears into the bosoms she so dearly loved. Forty shillings a year were all the wages of sweet Hannah Lee—but though she wore at her labour a tortoise-shell comb in her auburn hair, and though in the kirk none were more becomingly arrayed than she, one half, at least, of her earnings were to be reserved for the holiest of all purposes, and her kind innocent heart was gladdened when she looked on the little purse that was, on the long expected Saturday-night, to be taken from her bosom, and put, with a blessing, into the hand of her father, now growing old at his daily toils.

Of such a child the happy cottiers were thinking in their silence. And well might they be called happy. It is at that sweet season that filial piety is most beautiful.—Their own Hannah, had just outgrown the mere unthinking gladness of childhood, but had not yet reached that time, when inevitable selfishness mixes with the pure current of love. She had begun to think on what her affectionate heart had felt so long; and when she looked on the pale face and bending frame of her mother, on the deepening wrinkles, and whitening hairs of her father, often would she lie weeping for their sakes on her midnight bed—and wish that she was beside[255] them as they slept, that she might kneel down and kiss them, and mention their names over and over again in her prayer. The parents whom before she had only loved, her expanding heart now also venerated. With gushing tenderness was now mingled a holy fear and an awful reverence. She had discerned the relation in which she, an only child, stood to her poor parents now that they were getting old, and there was not a passage in Scripture that spake of parents or of children, from Joseph sold into slavery, to Mary weeping below the Cross, that was not written, never to be obliterated, on her uncorrupted heart.

The father rose from his seat, and went to the door to look out into the night.—The stars were in thousands—and the full moon was risen.—It was almost light as day, and the snow, that seemed incrusted with diamonds, was so hardened by the frost, that his daughter's homeward feet would leave no mark on its surface. He had been toiling all day among the distant Castle-woods, and, stiff and wearied as he now was, he was almost tempted to go to meet his child, but his wife's kind voice dissuaded him, and returning to the fire-side, they began to talk of her whose image had been so long passing before them in their silence.

"She is growing up to be a bony lassie," said the mother, "her long and weary attendance on me during my fever last spring kept her down awhile—but now she is sprouting fast and fair as a lily, and may the blessing of God be as dew and as sunshine to our sweet flower all the days she bloometh upon this earth." "Aye Agnes," replied the father, "we are not very old yet—though we are getting older—and a few years will bring her to women's estate, and what thing on this earth, think ye, human or brute, would ever think of injuring her? Why I was speaking about her yesterday to the minister as he was riding by, and he told me that none answered at the Examination in the Kirk so well as Hannah.—Poor thing—I well think she has all the Bible by heart—indeed, she has read but little else—only some stories, too true ones, of the blessed martyrs, and some o' the auld sangs o' Scotland, in which there is nothing but what is good, and which, to be sure, she sings, God bless her, sweeter than any laverock." "Aye—were we both to die this very night, she would be happy—not that she would forget us, all the days of her life. But have you not seen, husband, that God always makes the orphan happy?—None so little lonesome as they! They come to make friends o' all the bonny and sweet things in the world around them, and all the kind hearts in the world make friends o' them. They come to know that God is more especially the father o' them on earth whose parents he has taken up to heaven—and therefore it is that they for whom so many have fears, fear not at all for themselves, but go dancing and singing along like children whose parents are both alive! Would it not be so with our dear Hannah? So douce and thoughtful a child—but never sad nor miserable—ready it is true to shed tears for little, but as ready to dry them up and break out into smiles! I know not why it is, husband, but this night my heart warms toward her, beyond usual. The moon and stars are at this moment looking down upon her, and she looking up to them, as she is glinting homewards over the snow. I wish she were but here, and taking the comb out o' her bonny hair, and letting it all fall down in clusters before the fire, to melt away the cranreuch!"

While the parents were thus speaking of their daughter a loud sugh of wind came suddenly over the cottage, and the leafless ash-tree under whose shelter it stood, creaked and groaned dismally, as it passed by.—The father started up, and going again to the[256] door, saw that a sudden change had come over the face of the night. The moon had nearly disappeared, and was just visible in a dim yellow, glimmering in the sky.—All the remote stars were obscured, and only one or two faintly seemed in a sky that half an hour before was perfectly cloudless, but that was now driven with rack, and mist, and sleet, the whole atmosphere being in commotion. He stood for a single moment to observe the direction of this unforseen storm, and then hastily asked for his staff. "I thought I had been more weather-wise—A storm is coming down from the Cairnbrae-hawse, and we shall have nothing but a wild night." He then whistled on his dog—an old sheep dog, too old for its former labours and set off to meet his daughter, who might then, for aught he knew, be crossing the Black-moss.

The mother accompanied her husband to the door, and took a long frightened look at the angry sky. As she kept gazing, it became still more terrible. The last shred of blue was extinguished—the wind went whirling in roaring eddies, and great flakes of snow circled about in the middle air, whether drifted up from the ground, or driven down from the clouds, the fear-striken mother knew not, but she at least knew, that it seemed a night of danger, despair, and death. "Lord have mercy on us James, what will become of our poor bairn!" But her husband heard not her words, for he was already out of sight in the snow storm, and she was left to the terror of her own soul in that lonesome cottage.

Little Hannah Lee had left her master's house, soon as the rim of the great moon was seen by her eyes, that had been long anxiously watching it from the window, rising like a joyful dream, over the gloomy mountain-tops; and all by herself she tripped along beneath the beauty of the silent heaven. Still as she kept ascending and descending the knolls that lay in the bosom of the glen, she sung to herself a song, a hymn, or a psalm, without the accompaniment of the streams, now all silent in the frost; and ever and anon she stopped to try to count the stars that lay in some more beautiful part of the sky, or gazed, on the constellations that she knew, and called them, in her joy, by the names they bore among the shepherds.—There were none to hear her voice, or see her smiles, but the ear and eye of Providence. As on she glided and took her looks from heaven, she saw her own little fire-side—her parents waiting for her arrival—the bible opened for worship—her own little room kept so neatly for her, with its mirror hanging by the window, in which to braid her hair by the morning light—her bed prepared for her by her mother's hand—the primroses in her garden peeping through the snow—old Tray, who ever welcomed her home with his dim white eyes—the poney and the cow; friends all, and inmates of that happy household. So stepped she along, while the snow diamonds glittering around her feet, and the frost wove a wreath of lucid pearls around her forehead.

She had now reached the edge of the Black-moss, which lay half way between her master's and her father's dwelling, when she heard a loud noise coming down from Glen-Scrae, and in a few seconds, she felt on her face some flakes of snow. She looked up the glen, and saw the snow storm coming down, fast as a flood. She felt no fears; but she ceased her song; and had there been a human eye to look upon her there, it might have seen a shadow on her face. She continued her course, and felt bolder and bolder every step that brought her nearer to her parent's house. But the snow storm had now reached the Black-moss, and the broad line of light that had lain in the direction of her home, was soon swallowed up, and the child was in[257] utter darkness. She saw nothing but the flakes of snow, interminably intermingled, and furiously wafted in the air, close to her head; she heard nothing but one wild, fierce, fitful howl. The cold became intense, and her little feet and hands were fast, being benumbed into insensibility.

"It is a fearful change," muttered the child to herself, but still she did not fear, for she had been born in a moorland cottage, and lived all her days among the hardships of the hills.—"What will become of the poor sheep," thought she,—but still she scarcely thought of her own danger, for innocence and youth, and joy, are slow to think of ought evil befalling themselves, and thinking benignly of all living things, forget their own fear in their pity of others' sorrow.—At last, she could no longer discern a single mark on the snow, either of human steps, or of sheep track, or the foot print of a wild-fowl. Suddenly, too, she felt out of breath and exhausted,—and shedding tears for herself at last sank down in the snow.

It was now that her heart began to quake for fear. She remembered stories of the shepherds lost in the snow,—of a mother and child frozen to death on that very moor,—and, in a moment she knew that she was to die. Bitterly did the poor child weep, for death was terrible to her, who, though poor, enjoyed the bright little world of youth and innocence. The skies of heaven were dearer than she knew to her,—so were the flowers of earth. She had been happy at her work—happy in her sleep—happy in the kirk on Sabbath. A thousand thoughts had the solitary child,—and in her own heart was a spring of happiness, pure and undisturbed as any fount that sparkles unseen all the year through, in some quiet nook among the pastoral hills. But now there was to be an end of all this,—she was to be frozen to death—and lie there till the thaw might come; and then her father would find her body, and carry it away to be buried in the kirk-yard.

The tears were frozen on her cheeks as soon as shed—and scarcely had her little hands strength to clasp themselves together, as she thought of an overruling and merciful Lord came across her heart. Then, indeed, the fears of this religious child were calmed, and she heard without terror, the plover's wailing cry, and the deep boom of the bittern sounding in the moss. "I will repeat the Lord's prayer." And drawing her plaid more closely around her, she whispered beneath its ineffectual cover; "Our Father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name,—thy kingdom come—thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven." Had human aid been within fifty yards, it could have been of no avail—eye could not see her—ear could not hear her in that howling darkness. But that low prayer was heard in the centre of eternity—and that little sinless child was lying in the snow, beneath the all-seeing eye of God.

The maiden having prayed to her Father in Heaven—then thought of her Father on earth. Alas! they were not far separated! The father was lying but a short distance from his child; he too had sunk down in the drifting snow, after having in less than an hour, exhausted all the strength of fear, pity, hope, despair, and resignation, that could rise in a father's heart, blindly seeking to rescue his only child from death, thinking that one desperate exertion might enable them to die in each other's arms. There they lay, within a stone's throw of each other, while a huge snow drift was every moment piling itself up into a more insurmountable barrier between the dying parent and his dying child.

There was all this while a blazing fire in the cottage—a white spread table—and beds prepared for the family to lie down in peace. Yet was[258] she who sat thereon more to be pitied than the old man and the child stretched upon the snow. "I will not go to seek them—that would be tempting Providence—and wilfully putting out the lamp of life. No! I will abide here, and pray for their souls?" Then as she knelt down, looked she at the useless fire burning away so cheerfully, when all she loved might be dying of cold—and unable to bear the thought, she shrieked out a prayer, as if she might pierce the sky up to the very throne of God, and send with it her own miserable soul, to plead before Him for the deliverance of her child and husband.—She then fell down in blessed forgetfulness of all trouble, in the midst of the solitary cheerfulness of that bright-burning hearth—and the bible, which she had been trying to read in the pause of her agony, remained clasped in her hands.

Hannah Lee had been a servant for more than six months—and it was not to be thought that she was not beloved in her master's family. Soon after she had left the house, her master's son, a youth of about eighteen years, who had been among the hills, looking after the sheep, came home, and was disappointed to find that he had lost an opportunity of accompanying Hannah part of the way to her father's cottage. But the hour of eight had gone by, and not even the company of young William Grieve, could induce the kind-hearted daughter to delay sitting out on her journey, a few minutes beyond the time promised to her parents. "I do not like the night," said William—"there will be a fresh fall of snow soon, or the witch of Glen Scrae is a liar, for a snow-cloud is hanging o'er the birch-tree-linn, and it may be down to the Black-moss as soon as Hannah Lee." So he called his two sheep dogs, that had taken their place under the long table before the window, and set out, half in joy, half in fear, to overtake Hannah and see her safely across the Black-moss.

The snow began to drift so fast, that before he had reached the head of the Glen, there was nothing to be seen but a little bit of the wooden rail of the bridge across the Sauch burn. William Grieve was the most active shepherd in a large pastoral parish—he had often passed the night among the wintery hills for the sake of a few sheep, and all the snow that had ever fell from Heaven, would not have made him turn back when Hannah Lee was before him; and as his terrified heart told him, in imminent danger of being lost.—As he advanced, he felt that it was no longer a walk of love or friendship, for which he had been glad of an excuse. Death stared him in the face, and his young soul, now beginning to feel all the passions of youth, was filled with phrenzy. He had seen Hannah every day—at the fire-side—at work—in the kirk—on holydays—at prayers—bringing supper to his aged parents—smiling and singing about the house from morning till night. She had often brought his own meal to him among the hills—and he now found, that though he had never talked to her about love, except smilingly, and playfully, that he loved her beyond father or mother, or his own soul. "I will save thee, Hannah," he cried with a loud sob, "or lie down beside thee in the snow—and we will die together in our youth." A wild whistling wind went by him, and the snow-flakes whirled so fiercely round his head, that he staggered on for a while in utter blindness. He knew the path that Hannah must have taken, and went forward shouting aloud, and stopping every twenty yards to listen for a voice. He sent his well trained dogs over the snow in all directions—repeating to them her name "Hannah Lee," that the dumb animals might, in their sagacity, know for whom they were searching; and as they looked up in his face, and set[259] off to scour the moor, he almost believed that they knew his meaning, (and it is probable they did) and were eager to find in her bewilderment the kind maiden by whose hand they had so often been fed. Often went they off into the darkness, and as often returned, but their looks showed that every quest had been in vain. Meanwhile the snow was of a fearful depth, and falling without intermission or diminution. Had the young shepherd been thus alone, walking across the moor on his ordinary business, it is probable that he might have been alarmed for his own safety—nay, that in spite of all his strength and agility, he might have sunk down beneath the inclemency of the night and perished. But now, the passion of his soul carried him with supernatural strength along, and extricated him from wreath and pitfall. Still there was no trace of poor Hannah Lee—and one of his dogs at last came close to his feet, worn out entirely, and afraid to leave its master—while the other was mute, and, as the shepherd thought, probably unable to force its way out of some hollow or through some floundering drift.—Then he all at once knew that Hannah Lee was dead—and dashed himself down in the snow in a fit of passion.

It was the first time that the youth had ever been sorely tried—all his hidden and unconscious love for the fair lost girl had flowed up from the bottom of his heart—and at once the sole object which had blessed his life and made him the happiest of the happy, was taken away and cruelly destroyed—so that sullen, wrathful, baffled and despairing, there he lay, cursing his existence, and in too great agony to think of prayer. "God," he then thought, "has forsaken me—and why should he think on me, when he suffers one so good and beautiful as Hannah to be frozen to death." God thought both of him and Hannah—and through his infinite mercy forgave the sinner in his wild turbulence of passion. William Grieve had never gone to bed without joining in prayer—and he revered the Sabbath-day and kept it holy. Much is forgiven to the human heart by him who so fearfully framed it; and God is not slow to pardon the love which one human being bears to another, in his frailty—even though that love forget or arraign his own unsleeping providence. His voice has told us to love one another—and William loved Hannah in simplicity, innocence, and truth. That she should perish, was a thought so dreadful, that, in its agony God seemed a ruthless being—"blow—blow—blow—and drift us up for ever—we cannot be far asunder—O Hannah—Hannah—think ye not that the fearful God has forsaken us?"

As the boy groaned these words passionately through his quivering lips, there was a sudden lowness in the air, and he heard the barking of his absent dog, while the one at his feet hurried off in the direction of the sound, and soon loudly joined the cry. It was not a bark of surprise—or anger—or fear—but of recognition and love. William sprung up from his bed in the snow and with his heart knocking at his bosom even to sickness, he rushed headlong through the drifts, with a giant's strength, and fell down half dead with joy and terror beside the body of Hannah Lee.

But he soon recovered from that fit, and lifting the cold corpse in his arms, he kissed her lips, and her cheeks, and her forehead, and her closed eyes, till, as he kept gazing on her face in utter despair, her head fell back on his shoulder, and a long deep sigh came from her inmost bosom.—"She is yet alive thank God!"—and as that expression left his lips for the first time that night, he felt a pang of remorse:" "I said, O God, that thou hadst forsaken us—I am not worthy to be saved; but let not this maiden perish, for the sake of her parents, who have no other child."

The distracted youth prayed to God with the same earnestness as if he had been beseeching a fellow creature, in whose hand was the power of life and of death. The presence of the Great Being was felt by him in the dark and howling wild, and strength was imparted to him as to a deliverer. He bore along the fair child in his arms, even as if she had been a lamb. The snow drift blew not—the wind fell dead—a sort of glimmer, like that of an upbreaking and departing storm, gathered about him—his dogs barked and jumped, and burrowed joyfully in the snow—and the youth, strong in sudden hope, exclaimed, "With the blessing of God, who has not deserted us in our sore distress, will I carry thee, Hannah, in my arms, and lay thee down alive in the house of thy father."—At this moment there were no stars in Heaven, but she opened her dim blue eyes upon him on whose bosom she was unconsciously lying, and said, as in a dream, "Send the riband that ties up my hair, as a keepsake to William Grieve." "She thinks that she is on her death bed, and forgets not the son of her master. It is the voice of God that tells me she will not now die, and that, under His grace, I shall be her deliverer."

The short lived rage of the storm was soon over, and William could attend to the beloved being on his bosom. The warmth of his heart seemed to infuse life into her's; and as he gently placed her feet on the snow, till he muffled her up in his plaid, as well as in her own, she made an effort to stand, and with extreme perplexity and bewilderment, faintly inquired, where she was, and what fearful catastrophe had befallen them? She was, however, too weak to walk; and as her young master carried her along, she murmured, "O William! what if my father be in the moor?—For if you, who need care so little about me, have come hither, as I suppose to save my life, you may be sure that my father sat not within doors during the storm." As she spoke it was calm below, but the wind was still alive in the upper air, and cloud, rack, mist, and sleet, were all driving about in the sky. Out shone for a moment the pallid and ghostly moon, through a rent in the gloom, and by that uncertain light, came staggering forward the figure of a man.—"Father—Father," cried Hannah—and his gray hairs were already on her cheek. The barking of the dogs and the shouting of the young shepherd had struck his ear, as the sleep of death was stealing over him, and with the last effort of benumbed nature, he had roused himself from that fatal torpor and prest through the snow wreath that had separated him from his child. As yet they knew not of the danger each had endured—but each judged of the other's suffering from their own, and father and daughter regarded one another as creatures rescued, and hardly yet rescued from death.

But a few minutes ago, and the three human beings who loved each other so well, and now feared not to cross the Moor in safety, were, as they thought, on their death beds. Deliverance now shone upon them all like a gentle fire, dispelling that pleasant but deadly drowsiness; and the old man was soon able to assist William Grieve in leading Hannah along through the snow. Her colour and her warmth returned, and her lover—for so might he well now be called—felt her heart gently beating against her side. Filled as that heart was with gratitude to God, joy in her deliverance, love to her father, and purest affection for her master's son, never before had the innocent maiden known what was happiness—and never more was she to forget it. The night was now almost calm, and fast returning to its former beauty—when the party saw the first twinkle of the fire through the low window of the Cottage of the Moor. They soon were[261] at the garden gate—and to relieve the heart of the wife and mother within, they talked loudly and cheerfully—naming each other familiarly, and laughing between, like persons who had known neither danger nor distress.

No voice answered from within—no footsteps came to the door which stood open, as when the father had left it in his fear, and now he thought with affright, that his wife, feeble as she was, had been unable to support the loneliness, and had followed him out into the night, never to be brought home alive.—As they bore Hannah into the house, his fear gave way to worse, for there upon the hard clay floor lay the mother upon her face, as if murdered by some savage blow. She was in the same deadly swoon into which she had fallen on her husband's departure, three hours before. The old man raised her up, and her pulse was still—so was her heart—her face pale and sunken—and her body cold as ice. "I have recovered a daughter," said the old man, "but I have lost a wife;" and he carried her, with a groan, to the bed on which he laid her lifeless body. The sight was too much for Hannah, worn out as she was, and who had hitherto been able to support herself in the delightful expectation of gladdening her mother's heart by her safe arrival. She, too, now swooned away, and, as she was placed on the bed beside her mother, it seemed, indeed that death, disappointed of his prey on the wild moor, had seized it in the cottage, and by the fire-side. The husband knelt down by the bed-side, and held his wife's icy hand in his, while William Grieve appalled, and awe-stricken, hung over his Hannah, and inwardly implored God that the night's wild adventure might not have so ghastly an end. But Hannah's young heart soon began once more to beat—and soon as she came to her recollection, she rose up with a face whiter than ashes, and free from all smiles, as if none had ever played there, and joined her father and young master in their efforts to restore her mother to life.

It was the mercy of God that had struck her down to the earth, insensible to the shrieking winds, and the fears that would otherwise have killed her. Three hours of that wild storm had passed over her head, and she heard nothing more than if she had been asleep in a breathless night of the summer dew. Not even a dream had touched her brain, and when she opened her eyes which, as she thought had been but a moment shut, she had scarcely time to recal to her recollection the image of her husband rushing out into the storm, and of a daughter therein lost, till she beheld that very husband kneeling tenderly by her bed-side, and that very daughter smoothing the pillow on which her aching temples reclined. But she knew from the white steadfast countenances before her that there had been tribulation and deliverance, and she looked on the beloved beings ministering by her bed, as more fearfully dear to her from the unimagined danger from which she felt assured they had been rescued by the arm of the Almighty.

There is little need to speak of returning recollection, and returning strength. They had all now power to weep, and power to pray. The Bible had been lying in its place ready for worship—and the father read aloud that chapter in which is narrated our Saviour's act of miraculous power, by which he saved Peter from the sea. Soon as the solemn thoughts awakened by that act of mercy so similar to that which had rescued themselves from death had subsided, and they had all risen up from prayer, they gathered themselves in gratitude round the little table which had stood so many hours spread—and exhausted nature was strengthened and restored by a frugal and simple meal partaken of in silent thankfulness.

The whole story of the night was then calmly recited—and when the mother heard how the stripling had followed her sweet Hannah into the storm, and borne her in his arms through a hundred drifted heaps—and then looked upon her in her pride, so young, so innocent, and so beautiful, she knew, that were the child indeed to become an orphan, there was one, who, if there was either trust in nature, or truth in religion, would guard and cherish her all the days of her life.

It was not nine o'clock when the storm came down from Glen Scrae upon the Black-moss, and now in a pause of silence the clock struck twelve. Within these three hours William and Hannah had led a life of trouble and of joy, that had enlarged and kindled their hearts within them—and they felt that henceforth they were to live wholly for each other's sakes. His love was the proud and exulting love of a deliverer, who, under Providence, had saved from the frost and the snow the innocence and the beauty of which his young passionate heart had been so desperately enamoured—and he now thought of his own Hannah Lee ever more moving about in his father's house, not as a servant, but as a daughter—and when some few happy years had gone by, his own most beautiful and most loving wife. The innocent maiden still called him her young master—but was not ashamed of the holy affection which she now knew that she had long felt for the fearless youth on whose bosom she had thought herself dying in that cold and miserable moor. Her heart leapt within her when she heard her parents bless him by his name—and when he took her hand into his before them, and vowed before that Power who had that night saved them from the snow, that Hannah Lee should ere long be his wedded wife—she wept and sobbed as if her heart would break in a fit of strange and insupportable happiness.

The young shepherd rose to bid them farewell—"my father will think I am lost," said he, with a grave smile, "and my Hannah's mother knows what it is to fear for a child." So nothing was said to detain him, and the family went with him to the door. The skies smiled serenely as if a storm had never swept before the stars—the moon was sinking from her meridian, but in cloudless splendour—and the hollow of the hills was hushed as that of heaven. Danger there was none over the placid night-scene—the happy youth soon crost the Black-moss, now perfectly still—and, perhaps, just as he was passing, with a shudder of gratitude, the very spot where his sweet Hannah Lee had so nearly perished, she was lying down to sleep in her innocence, or dreaming of one now dearer to her than all on earth but her parents.

EREMUS.

I went this afternoon to pay a visit to my neighbour Ephraim; indeed I find his cheerful fire-side so much more pleasant than my own little solitary dwelling, that I am afraid I go there rather too often; however, as yet I have not remarked any coldness or distance in their reception of me. Ephraim had been a little indisposed, and I found him reclining on the sofa; his wife was preparing something comfortable for him by the fire, and his daughter, having arranged his pillow to his mind, sat with her work at his feet, while Ezekiel read to him—his other son was engaged in superintending the business of the farm; but when the hour of tea approached, he joined the circle in the parlour with a smiling countenance, cheeks glowing with health, and an appetite which appeared in no wise diminished by the exercise of the day. When I returned to my own lonely habitation, I could not avoid contrasting a little my situation with that of my old[263] friend. Happy Ephraim! said I, thou hast an excellent wife and dutiful daughter, to smooth the pillow of thy aching head, to hover with feathery footsteps around thy peaceful couch, and watch over thy slumbers with the assiduity of anxious love—thou hast two manly intelligent sons, to attend to thy business, to protect thy interests, and support thy tottering steps; whose only strife is that of kindness, whose only rivalship, which shall be most attentive to thee, each of whom would gladly say with the poet,

And when at last, in a good old age, thou shalt be gathered to thy fathers, a train of mourning relatives shall deposit with decent care thy cherished remains in the narrow house appointed for all living; while I stand alone in the world, an insulated, insignificant being, for whom no one feels an interest, and whose pains and pleasures are of consequence to no one; whose approach is greeted with no smile, and whose departure excites no regret, and when the closing scene approaches, no kindred hand shall support my throbbing temples, or prepare the potion for my feverish lip, but mercenary eyes alone mark with ill disguised impatience the uncertain flutter of the lingering pulse, mercenary attendants only receive, with frigid indifference, the last farewell of the departing spirit—

Lost in a train of such like melancholy musings, and pondering on the past, the present and the future, I had suffered my fire to become nearly extinguished, and the feeble glimmer of my untrimmed taper faintly illumined my little study, when I was roused from my revery by the entrance of Ezekiel and his sister: The good girl said she had remarked that I was more silent than usual, and as the evening was fine, they had come over to see if I was unwell: this little act of kindness, though in itself no way remarkable, yet coming at such a moment, affected me not a little.—But I must shake off this gloom and depression of spirit, I am not now to learn that the world had much rather laugh with or at a man than mourn with him; I did not sit down to lament the desolation of my own situation, which cannot now be remedied; but to exhort the young to get married, to encourage them by the example of Ephraim, and to warn them of my own: "Do nothing in a hurry," is an excellent maxim in the main, but in some cases it is possible to use too much deliberation; in the important business of taking a wife, many a man has debated and deliberated, until the season for acting has passed away. An old fellow like myself has little to do in the world, but to talk for the benefit of his neighbours; and I would willingly devote my experience to the service of the rising generation. I should feel no objection to narrate the disastrous consequences of my own superabundant caution in the affair of matrimony, and to enumerate the many eligible matches which have slipped through my fingers; the opportunities to form advantageous connexions which have been unimproved in consequence of my hesitation and indecision, for I have now no plans to be defeated or prospects blasted by a knowledge of my failings, and no vanity to be mortified by the exposure of my disappointments, but I am apprehensive the detail might prove rather tedious and uninteresting; I may, however, mention a few circumstances attending my last attempts to obtain a help mate, if attempt it may be called. I had become acquainted in the family of a respectable farmer, who had a daughter of a suitable age, and although I cannot say that

yet her correct and orderly deportment[264] seemed to promise that she would make an excellent wife; I was therefore pretty frequent in my visits, and though on these occasions my discourse was principally, if not entirely, addressed to the parents, yet I kept a sharp eye upon the daughter, in order to endeavour to form a tolerable estimate of her disposition and character; and as I had in those days a handsome little estate at my own disposal, and was upon the whole considered rather a promising young man, my company seemed always very acceptable, to the father and mother at least.

In this manner, eight or ten months, perhaps, passed pleasantly away, and I was beginning to think that I might before long venture to address her with a little freedom and familiarity, preparatory to a serious negotiation when all my plans were defeated, and my visionary castle crumbled into dust, by the precipitation of others.

One evening I was sitting with them as usual, when after a little time the father and mother, on some occasion, absented themselves from the room, and left the daughter and myself together. As I had not the most distant suspicion that there was any design in their movements, and expected their return every moment, I took up the almanack, (being fond of reading) and had just got cleverly through it, when they returned. I thought I remarked something particularly scrutinizing in the looks of the mother, but I believe she soon discovered that I had done nothing but read the almanack. On my next visit, I felt no small trepidation, having a strong suspicion of what might occur; and, in fact, we were again soon left alone together—and now the consciousness of what was expected, kept me as silent as ignorance had done before. In my distress I looked about for the almanack, but they had taken it away. In vain I endeavoured to find something to say, my faculties seemed spell bound; and I sat, I know not how long, in a pitiable state of confusion and embarrassment, until my companion made some remark respecting the weather—this was a great relief. I immediately proceeded to treat of the weather in all its bearings, past, present and to come, and strove to prolong the discussion until some one might come in, but in vain—the subject at length became exhausted, and silence again took place; which lasted so long, and became so glaringly ridiculous, that in utter despair, I was upon the point of having recourse to the weather again, when we were relieved by the entrance of company.

Determined never again to cut so silly a figure, I resolved to provide against my next visit a fund of agreeable conversation. I accordingly brushed up my acquaintance with the philosophy of Aristotle, and of the peripatetics generally; collected some anecdotes of the wise men of Greece, and, not to lack matters of more recent date, stored my memory with a few amusing particulars respecting Mary Queen of Scots, and of the court of Elizabeth: thus prepared, I ventured once more to make my appearance, but I had no opportunity to say a word about Aristotle or the Queen of Scots; it was rather late when I entered the room, and I found my intended in earnest conversation with a young man who had drawn his chair very near to her: their discourse seemed to be of an interesting nature, but they spoke in so low a tone, that I was unable to profit by their remarks; I observed at last, that they frequently smiled when looking towards me, and as I love a cheerful countenance, and smiling is certainly contagious, I smiled a good deal too. This seemed wonderfully to promote their risibility, and my laughter increasing in the same proportion, we had a deal of merriment, although little or nothing was said: how long this might have continued I know not, had not my intended father-in-law[265] called me aside, and hinted that as the night was dark, and there was some appearance of rain, I had perhaps better return. I thanked him for his truly paternal care, and accordingly took my departure in high good humour, and the next week was informed that the young people were married.

[Rural Visiter.

Mr. Editor—I send you the following account of a short inspection of a fellow creature, which, if it will convey any information to your readers, you are at liberty to publish.