Transcriber’s note: Table of Contents added by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

Marines in

World War II

Commemorative Series

By Henry I. Shaw, Jr.

by Henry I. Shaw, Jr.

In the early summer of 1942, intelligence reports of the construction of a Japanese airfield near Lunga Point on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands triggered a demand for offensive action in the South Pacific. The leading offensive advocate in Washington was Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). In the Pacific, his view was shared by Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CinCPac), who had already proposed sending the 1st Marine Raider Battalion to Tulagi, an island 20 miles north of Guadalcanal across Sealark Channel, to destroy a Japanese seaplane base there. Although the Battle of the Coral Sea had forestalled a Japanese amphibious assault on Port Moresby, the Allied base of supply in eastern New Guinea, completion of the Guadalcanal airfield might signal the beginning of a renewed enemy advance to the south and an increased threat to the lifeline of American aid to New Zealand and Australia. On 23 July 1942, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington agreed that the line of communications in the South Pacific had to be secured. The Japanese advance had to be stopped. Thus, Operation Watchtower, the seizure of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, came into being.

The islands of the Solomons lie nestled in the backwaters of the South Pacific. Spanish fortune-hunters discovered them in the mid-sixteenth century, but no European power foresaw any value in the islands until Germany sought to expand its budding colonial empire more than two centuries later. In 1884, Germany proclaimed a protectorate over northern New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the northern Solomons. Great Britain countered by establishing a protectorate over the southern Solomons and by annexing the remainder of New Guinea. In 1905, the British crown passed administrative control over all its territories in the region to Australia, and the Territory of Papua, with its capital at Port Moresby, came into being. Germany’s holdings in the region fell under the administrative control of the League of Nations following World War I, with the seat of the colonial government located at Rabaul on New Britain. The Solomons lay 10 degrees below the Equator—hot, humid, and buffeted by torrential rains. The celebrated adventure novelist, Jack London, supposedly muttered: “If I were king, the worst punishment I could inflict on my enemies would be to banish them to the Solomons.”

On 23 January 1942, Japanese forces seized Rabaul and fortified it extensively. The site provided an excellent harbor and numerous positions for airfields. The devastating enemy carrier and plane losses at the Battle of Midway (3–6 June 1942) had caused Imperial General Headquarters to cancel orders for the invasion of Midway, New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, but plans to construct a major seaplane base at Tulagi went forward. The location offered one of the best anchorages in the South Pacific and it was strategically located: 560 miles from the New Hebrides, 800 miles from New Caledonia, and 1,000 miles from Fiji.

The outposts at Tulagi and Guadalcanal were the forward evidences of a sizeable Japanese force in the region, beginning with the Seventeenth Army, headquartered at Rabaul. The enemy’s Eighth Fleet, Eleventh Air Fleet, and 1st, 7th, 8th, and 14th Naval Base Forces also were on New Britain. Beginning on 5 August 1942, Japanese signal intelligence units began to pick up transmissions between Noumea on New Caledonia and Melbourne, Australia. Enemy analysts concluded that Vice Admiral Richard L. Ghormley, commanding the South Pacific Area (ComSoPac), was signalling a British or Australian force in preparation for an offensive in the Solomons or at New Guinea. The warnings were passed to Japanese headquarters at Rabaul and Truk, but were ignored.

THE PACIFIC AREAS

1 AUGUST 1942

The invasion force was indeed on its way to its targets, Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the tiny islets of Gavutu and Tanambogo close by Tulagi’s shore. The landing force was composed of Marines; the covering force and transport force were U.S. Navy with a reinforcement of Australian warships. There was not much mystery to the selection of the 1st Marine Division to make the landings. Five U.S. Army divisions were located in the South and Southwest Pacific:2 three in Australia, the 37th Infantry in Fiji, and the Americal Division on New Caledonia. None was amphibiously trained and all were considered vital parts of defensive garrisons. The 1st Marine Division, minus one of its infantry regiments, had begun arriving in New Zealand in mid-June when the division headquarters and the 5th Marines reached Wellington. At that time, the rest of the reinforced division’s major units were getting ready to embark. The 1st Marines were at San Francisco, the 1st Raider Battalion was on New Caledonia, and the 3d Defense Battalion was at Pearl Harbor. The 2d Marines of the 2d Marine Division, a unit which would replace the 1st Division’s 7th Marines stationed in British Samoa, was loading out from San Diego. All three infantry regiments of the landing force had battalions of artillery attached, from the 11th Marines, in the case of the 5th and 1st; the 2d Marines drew its reinforcing 75mm howitzers from the 2d Division’s 10th Marines.

The news that his division would be the landing force for Watchtower came as a surprise to Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, who had anticipated that the 1st Division would have six months of training in the South Pacific before it saw action. The changeover from administrative loading of the various units’ supplies to combat loading, where first-needed equipment, weapons, ammunition, and rations were positioned to come off ship first with the assault troops, occasioned a never-to-be-forgotten scene on Wellington’s docks. The combat troops took the place of civilian stevedores and unloaded and reloaded the cargo and passenger vessels in an increasing round of working parties, often during rainstorms which hampered the task, but the job was done. Succeeding echelons of the division’s forces all got their share of labor on the docks as various shipping groups arrived and the time grew shorter. General Vandegrift was able to convince Admiral Ghormley and the Joint Chiefs that he would not be able to meet a proposed D-Day of 1 August, but the extended landing date, 7 August, did little to improve the situation.

An amphibious operation is a vastly complicated affair, particularly when the forces involved are assembled on short notice from all over the Pacific. The pressure that Vandegrift felt was not unique to the landing force commander. The U.S. Navy’s ships were the key to success and they were scarce and invaluable. Although4 the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway had badly damaged the Japanese fleet’s offensive capabilities and crippled its carrier forces, enemy naval aircraft could fight as well ashore as afloat and enemy warships were still numerous and lethal. American losses at Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, and Midway were considerable, and Navy admirals were well aware that the ships they commanded were in short supply. The day was coming when America’s shipyards and factories would fill the seas with warships of all types, but that day had not arrived in 1942. Calculated risk was the name of the game where the Navy was concerned, and if the risk seemed too great, the Watchtower landing force might be a casualty. As it happened, the Navy never ceased to risk its ships in the waters of the Solomons, but the naval lifeline to the troops ashore stretched mighty thin at times.

Tactical command of the invasion force approaching Guadalcanal in early August was vested in Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher as Expeditionary Force Commander (Task Force 61). His force consisted of the amphibious shipping carrying the 1st Marine Division, under Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, and the Air Support Force led by Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes. Admiral Ghormley contributed land-based air forces commanded by Rear Admiral John S. McCain. Fletcher’s support force consisted of three fleet carriers, the Saratoga (CV 3), Enterprise (CV 6), and Wasp (CV 7); the battleship North Carolina (BB 55), 6 cruisers, 16 destroyers, and 3 oilers. Admiral Turner’s covering force included five cruisers and nine destroyers.

On board the transports approaching the Solomons, the Marines were looking for a tough fight. They knew little about the targets, even less about their opponents. Those maps that were available were poor, constructions based upon outdated hydrographic charts and information provided by former island residents. While maps based on aerial photographs had been prepared they were misplaced by the Navy in Auckland, New Zealand, and never got to the Marines at Wellington.

On 17 July, a couple of division staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel Merrill B. Twining and Major William McKean, had been able to join the crew of a B-17 flying from Port Moresby on a reconnaissance mission over Guadalcanal. They reported what they had seen, and their analysis, coupled with aerial photographs, indicated no extensive defenses along the beaches of Guadalcanal’s north shore.

GUADALCANAL

TULAGI-GAVUTU

and

Florida Islands

This news was indeed welcome. The division intelligence officer (G-2), Lieutenant Colonel Frank B. Goettge, had concluded that about 8,4005 Japanese occupied Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Admiral Turner’s staff figured that the Japanese amounted to 7,125 men. Admiral Ghormley’s intelligence officer pegged the enemy strength at 3,100—closest to the 3,457 actual total of Japanese troops; 2,571 of these were stationed on Guadalcanal and were mostly laborers working on the airfield.

To oppose the Japanese, the Marines had an overwhelming superiority of men. At the time, the tables of organization for a Marine Corps division indicated a total of 19,514 officers and enlisted men, including naval medical and engineer (Seabee) units. Infantry regiments numbered 3,168 and consisted of a headquarters company, a weapons company, and three battalions. Each infantry battalion (933 Marines) was organized into a headquarters company (89), a weapons company (273), and three rifle companies (183). The artillery regiment had 2,581 officers and men organized into three 75mm pack howitzer battalions and one 105mm howitzer battalion. A light tank battalion, a special weapons battalion of antiaircraft and antitank guns, and a parachute battalion added combat power. An engineer regiment (2,452 Marines) with battalions of engineers, pioneers, and Seabees, provided a hefty combat and service element. The total was rounded out by division headquarters battalion’s headquarters, signal, and military police companies and the division’s service troops—service, motor transport, amphibian tractor, and medical battalions. For Watchtower, the 1st Raider Battalion and the 3d Defense Battalion had been added to Vandegrift’s command to provide more infantrymen and much needed coast defense and antiaircraft guns and crews.

Unfortunately, the division’s heaviest ordnance had been left behind in6 New Zealand. Limited ship space and time meant that the division’s big guns, a 155mm howitzer battalion, and all the motor transport battalion’s two-and-a-half-ton trucks were not loaded. Colonel Pedro A. del Valle, commanding the 11th Marines, was unhappy at the loss of his heavy howitzers and equally distressed that essential sound and flash-ranging equipment necessary for effective counterbattery fire was left behind. Also failing to make the cut in the battle for shipping space, were all spare clothing, bedding rolls, and supplies necessary to support the reinforced division beyond 60 days of combat. Ten days supply of ammunition for each of the division’s weapons remained in New Zealand.

Naval Historical Photographic Collection 880-CF-117-4-63

Enroute to Guadalcanal RAdm Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of the Amphibious Force, and MajGen Alexander A. Vandegrift, 1st Marine Division commander, review the Operation Watchtower plan for landings in the Solomon Islands.

In the opinion of the 1st Division’s historian and a veteran of the landing, the men on the approaching transports “thought they’d have a bad time getting ashore.” They were confident, certainly, and sure that they could not be defeated, but most of the men were entering combat for the first time. There were combat veteran officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) throughout the division, but the majority of the men were going into their initial battle. The commanding officer of the 1st Marines, Colonel Clifton B. Cates, estimated that 90 percent of his men had enlisted after Pearl Harbor. The fabled 1st Marine Division of later World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, and Persian Gulf War fame, the most highly decorated division in the U.S. Armed Forces, had not yet established its reputation.

The convoy of ships, with its outriding protective screen of carriers, reached Koro in the Fiji Islands on 26 July. Practice landings did little more than exercise the transports’ landing craft, since reefs precluded an actual beach landing. The rendezvous at Koro did give the senior commanders a chance to have a face-to-face meeting. Fletcher, McCain, Turner, and Vandegrift got together with Ghormley’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, who notified the conferees that ComSoPac had ordered the 7th Marines on Samoa to be prepared to embark on four days notice as a reinforcement for Watchtower. To this decidedly good news, Admiral Fletcher added some bad news. In view of the threat from enemy land-based air, he could not “keep the carriers in the area for more than 48 hours after the landing.” Vandegrift protested that he needed at least four days to get the division’s gear ashore, and Fletcher reluctantly agreed to keep his carriers at risk another day.

On the 28th the ships sailed from the Fijis, proceeding as if they were headed for Australia. At noon on 5 August, the convoy and its escorts turned north for the Solomons. Undetected by the Japanese, the assault force reached its target during the night of 6–7 August and split into two landing groups, Transport Division X-Ray, 15 transports heading for the north shore of Guadalcanal east of Lunga Point, and Transport Division Yoke, eight transports headed for Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and the nearby Florida Island, which loomed over the smaller islands.

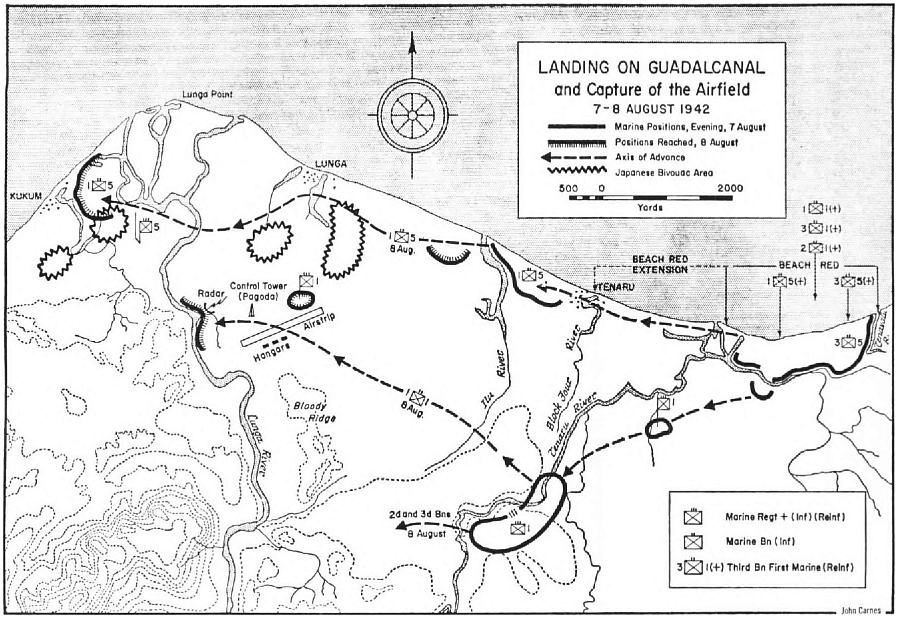

Vandegrift’s plans for the landings would put two of his infantry regiments (Colonel LeRoy P. Hunt’s 5th Marines and Colonel Cates’ 1st Marines) ashore on both sides of the Lunga River prepared to attack inland to seize the airfield. The 11th Marines, the 3d Defense Battalion, and most of the division’s supporting units would also land near the Lunga, prepared to exploit the beachhead. Across the 20 miles of Sealark Channel, the division’s assistant commander, Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, led the assault forces slated to take Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo: the 1st Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson); the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Harold E. Rosecrans); and the 1st Parachute Battalion (Major Robert H. Williams). Company A of the 2d Marines would reconnoiter the nearby shores of Florida Island and the rest of Colonel John A. Arthur’s regiment would stand by in reserve to land where needed.

As the ships slipped through the7 channels on either side of rugged Savo Island, which split Sealark near its western end, heavy clouds and dense rain blanketed the task force. Later the moon came out and silhouetted the islands. On board his command ship, Vandegrift wrote to his wife: “Tomorrow morning at dawn we land in our first major offensive of the war. Our plans have been made and God grant that our judgement has been sound ... whatever happens you’ll know I did my best. Let us hope that best will be good enough.”

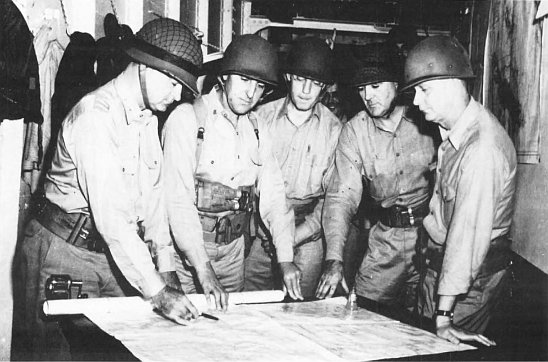

MajGen Alexander A. Vandegrift, CG, 1st Marine Division, confers with his staff on board the transport USS McCawley (APA-4) enroute to Guadalcanal. From left: Gen Vandegrift; LtCol Gerald C. Thomas, operations officer; LtCol Randolph McC. Pate, logistics officer; LtCol Frank B. Goettge, intelligence officer; and Col William Capers James, chief of staff.

National Archives Photo 80-G-17065

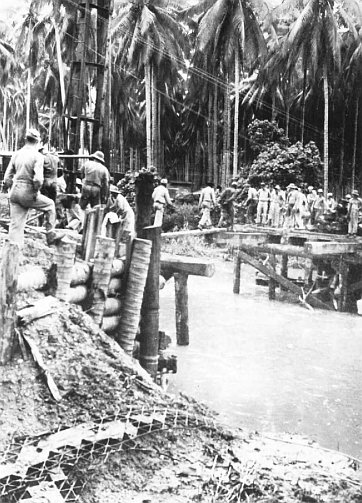

At 0641 on 7 August, Turner signalled his ships to “land the landing force.” Just 28 minutes before, the heavy cruiser Quincy (CA 39) had begun shelling the landing beaches at Guadalcanal. The sun came up that fateful Friday at 0650, and the first landing craft carrying assault troops of the 5th Marines touched down at 0909 on Red Beach. To the men’s surprise (and relief), no Japanese appeared to resist the landing. Hunt immediately moved his assault troops off the beach and into the surrounding jungle, waded the steep-banked Ilu River, and headed for the enemy airfield. The following 1st Marines were able to cross the Ilu on a bridge the engineers had hastily thrown up with an amphibian tractor bracing its middle. The silence was eerie and the absence of opposition was worrisome to the riflemen. The Japanese troops, most of whom were Korean laborers, had fled to the west, spooked by a week’s B-17 bombardment, the pre-assault naval gunfire, and the sight of the ships offshore. The situation was not the same across Sealark. The Marines on Guadalcanal could hear faint rumbles of a firefight across the waters.

National Archives Photo 80-CF-112-5-3

First Division Marines storm ashore across Guadalcanal’s beaches on D-Day, 7 August 1942, from the attack transport Barnett (AP-11) and attack cargo ship Fomalhaut (AK-22). The invaders were surprised at the lack of enemy opposition.

LANDING ON GUADALCANAL

and Capture of the Airfield

7–8 AUGUST 1942

Photo courtesy of Col James A. Donovan, Jr.

When the 5th Marines entered the jungle from the beachhead, and had to cross the steep banks of the Ilu River, 1st Marine Division engineers hastily constructed a bridge supported by amphibian tractors. Though heavily used, the bridge held up.

Photographed immediately after a prelanding strike by USS Enterprise aircraft flown by Navy pilots, Tanambogo and Gavutu Islands lie smoking and in ruins in the morning sun. Gavutu is at the left across the causeway from Tanambogo.

National Archives Photo 80-C-11034

The Japanese on Tulagi were special naval landing force sailors and they had no intention of giving up what they held without a vicious, no-surrender battle. Edson’s men landed first, following by Rosecrans’ battalion, hitting Tulagi’s south coast and moving inland towards the ridge which ran lengthwise through the island. The battalions encountered pockets of resistance in the undergrowth of the islands thick vegetation and maneuvered to outflank and overrun the opposition. The advance of the Marines was steady but casualties were frequent. By nightfall, Edson had reached the former British residency overlooking Tulagi’s harbor and dug in for the night across a hill that overlooked the Japanese final position, a ravine on the islands southern tip. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, had driven through to the northern shore, cleaning its sector of enemy; Rosecrans moved into position10 to back up the raiders. By the end of its first day ashore, 2d Battalion had lost 56 men killed and wounded; 1st Raider Battalion casualties were 99 Marines.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 52231

After the battle, almost all palm trees on Gavutu were shorn of their foliage. Despite naval gunfire and close air support hitting the enemy emplacements, Japanese opposition from caves proved to be serious obstacles for attacking Marines.

Throughout the night, the Japanese swarmed from hillside caves in four separate attacks, trying to penetrate the raider lines. They were unsuccessful and most died in the attempts. At dawn, the 2d Battalion, 2d Marines, landed to reinforce the attackers and by the afternoon of 8 August, the mop-up was completed and the battle for Tulagi was over.

The fight for tiny Gavutu and Tanambogo, both little more than small hills rising out of the sea, connected by a hundred-yard causeway, was every bit as intense as that on Tulagi. The area of combat was much smaller and the opportunities for fire support from offshore ships and carrier planes was severely limited once the Marines had landed. After naval gunfire from the light cruiser San Juan (CL 54) and two destroyers, and a strike by F4F Wildcats flying from the Wasp, the 1st Parachute Battalion landed near noon in three waves, 395 men in all, on Gavutu. The Japanese, secure in cave positions, opened fire on the second and third waves, pinning down the first Marines ashore on the beach. Major Williams took a bullet in the lungs and was evacuated; 32 Marines were killed in the withering enemy fire. This time, 2d Marines reinforcements were really needed; the 1st Battalion’s Company B landed on Gavutu and attempted to take Tanambogo; the attackers were driven to ground and had to pull back to Gavutu.

After a rough night of close-in fighting with the defenders of both islands, the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, reinforced the men already ashore and mopped up on each island. The toll of Marines dead on the three islands was 144; the wounded numbered 194. The few Japanese who survived the battles fled to Florida Island, which had been scouted by the 2d Marines on D-Day and found clear of the enemy.

The Marines’ landings and the concentration of shipping in Guadalcanal waters acted as a magnet to the Japanese at Rabaul. At Admiral Ghormley’s headquarters, Tulagi’s radio was heard on D-Day “frantically calling for [the] dispatch of surface11 forces to the scene” and designating transports and carriers as targets for heavy bombing. The messages were sent in plain language, emphasizing the plight of the threatened garrison. And the enemy response was prompt and characteristic of the months of naval air and surface attacks to come.

At 1030 on 7 August, an Australian coastwatcher hidden in the hills of the islands north of Guadalcanal signalled that a Japanese air strike composed of heavy bombers, light bombers, and fighters was headed for the island. Fletcher’s pilots, whose carriers were positioned 100 miles south of Guadalcanal, jumped the approaching planes 20 miles northwest of the landing areas before they could disrupt the operation. But the Japanese were not daunted by the setback; other planes and ships were enroute to the inviting target.

On 8 August, the Marines consolidated their positions ashore, seizing the airfield on Guadalcanal and establishing a beachhead. Supplies were being unloaded as fast as landing craft could make the turnaround from ship to shore, but the shore12 party was woefully inadequate to handle the influx of ammunition, rations, tents, aviation gas, vehicles—all gear necessary to sustain the Marines. The beach itself became a dumpsite. And almost as soon as the initial supplies were landed, they had to be moved to positions nearer Kukum village and Lunga Point within the planned perimeter. Fortunately, the lack of Japanese ground opposition enabled Vandegrift to shift the supply beaches west to a new beachhead.

Marine Corps Personal Papers Collection

Immediately after assault troops cleared the beachhead and moved inland, supplies and equipment, inviting targets for enemy bombers, began to litter the beach.

Japanese bombers did penetrate the American fighter screen on 8 August. Dropping their bombs from 20,000 feet or more to escape antiaircraft fire, the enemy planes were not very accurate. They concentrated on the ships in the channel, hitting and damaging a number of them and sinking the destroyer Jarvis (DD 393). In their battles to turn back the attacking planes, the carrier fighter squadrons lost 21 Wildcats on 7–8 August.

The primary Japanese targets were the Allied ships. At this time, and for a thankfully and unbelievably long time to come, the Japanese commanders at Rabaul grossly underestimated the strength of Vandegrift’s forces. They thought the Marine landings constituted a reconnaissance in force, perhaps 2,000 men, on Guadalcanal. By the evening of 8 August, Vandegrift had 10,900 troops ashore on Guadalcanal and another 6,075 on Tulagi. Three infantry regiments had landed and each had a supporting 75mm pack howitzer battalion—the 2d and 3d Battalions, 11th Marines on Guadalcanal, and the 3d Battalion, 10th Marines on Tulagi. The 5th Battalion, 11th Marines’ 105mm howitzers were in general support.

That night a cruiser-destroyer force of the Imperial Japanese Navy reacted to the American invasion with a stinging response. Admiral Turner had positioned three cruiser-destroyer groups to bar the Tulagi-Guadalcanal approaches. At the Battle of Savo, the Japanese demonstrated their superiority in night fighting at this stage of the war, shattering two of Turners covering forces without loss to themselves. Four heavy cruisers went to the bottom—three American, one Australian—and another lost her bow. As the sun came up over what soon would be called “Ironbottom Sound,” Marines watched grimly as Higgins boats swarmed out to rescue survivors. Approximately 1,300 sailors died that night and another 700 suffered wounds or were badly burned. Japanese casualties numbered less than 200 men.

The Japanese suffered damage to only one ship in the encounter, the cruiser Chokai. The American cruisers Vincennes (CA 44), Astoria (CA 34), and Quincy (CA 39) went to the bottom, as did the Australian Navy’s HMAS Canberra, so critically damaged that she had to be sunk by American torpedoes. Both the cruiser Chicago (CA 29) and destroyer Talbot (DD 114) were badly damaged. Fortunately for the Marines ashore, the Japanese force—five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer—departed before dawn without attempting to disrupt the landing further.

When the attack-force leader, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, returned to Rabaul, he expected to receive the accolades of his superiors. He did get those, but he also found himself the subject of criticism. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese fleet commander, chided his subordinate for failing to attack the transports. Mikawa could only reply, somewhat lamely, that he did not know Fletcher’s aircraft carriers were so far away from Guadalcanal. Of equal significance to the Marines on the beach, the Japanese naval victory caused celebrating superiors in Tokyo to allow the event to overshadow the13 importance of the amphibious operation.

The disaster prompted the American admirals to reconsider Navy support for operations ashore. Fletcher feared for the safety of his carriers; he had already lost about a quarter of his fighter aircraft. The commander of the expeditionary force had lost a carrier at Coral Sea and another at Midway. He felt he could not risk the loss of a third, even if it meant leaving the Marines on their own. Before the Japanese cruiser attack, he obtained Admiral Ghormley’s permission to withdraw from the area.

When ships carrying barbed wire and engineering tools needed ashore were forced to leave the Guadalcanal area because of enemy air and surface threats, Marines had to prepare such hasty field expedients as this cheval de frise of sharpened stakes.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 5157

At a conference on board Turner’s flagship transport, the McCawley, on the night of 8 August, the admiral told General Vandegrift that Fletcher’s impending withdrawal meant that he would have to pull out the amphibious force’s ships. The Battle of Savo Island reinforced the decision to get away before enemy aircraft, unchecked by American interceptors, struck. On 9 August, the transports withdrew to Noumea. The unloading of supplies ended abruptly, and ships still half-full steamed away. The forces ashore had 17 days’ rations—after counting captured Japanese food—and only four days’ supply of ammunition for all weapons. Not only did the ships take away the rest of the supplies, they also took the Marines still on board, including the 2d Marines’ headquarters element. Dropped off at the island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, the infantry Marines and their commander, Colonel Arthur, were most unhappy and remained so until they finally reached Guadalcanal on 29 October.

Ashore in the Marine beachheads, General Vandegrift ordered rations reduced to two meals a day. The reduced food intake would last for six weeks, and the Marines would become very familiar with Japanese canned fish and rice. Most of the Marines smoked and they were soon disgustedly smoking Japanese-issue brands. They found that the separate paper filters that came with the cigarettes were necessary to keep the fast-burning tobacco from scorching their lips. The retreating ships had also hauled away empty sand bags and valuable engineer tools. So the Marines used Japanese shovels to fill Japanese rice bags with sand to strengthen their defensive positions.

The Marines dug in along the beaches between the Tenaru and the ridges west of Kukum. A Japanese counter-landing was a distinct possibility. Inland of the beaches, defensive gun pits and foxholes lined the west bank of the Tenaru and crowned the hills that faced west toward the Matanikau River and Point Cruz. South of the airfield where densely jungled ridges and ravines abounded, the beachhead perimeter was guarded by outposts and these were manned in large part by combat support troops. The engineer, pioneer, and amphibious tractor battalion all had their positions on the front line. In fact, any Marine with a rifle, and that was virtually every Marine, stood night defensive duty. There was no place within the perimeter that could be counted safe from enemy infiltration.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 150993

Col Kiyono Ichiki, a battle-seasoned Japanese Army veteran, led his force in an impetuous and ill-fated attack on strong Marine positions in the Battle of the Tenaru on the night of 20–21 August.

Almost as Turner’s transports sailed away, the Japanese began a pattern of harassing air attacks on the beachhead. Sometimes the raids came during the day, but the 3d Defense Battalion’s 90mm antiaircraft guns forced the bombers to fly too high for effective bombing. The erratic pattern of bombs, however, meant that no place was safe near the airfield, the preferred target, and no place could claim it was bomb-free.16 The most disturbing aspect of Japanese air attacks soon became the nightly harassment by Japanese aircraft which singly, it seemed, roamed over the perimeter, dropping bombs and flares indiscriminately. The nightly visitors, whose planes’ engines were soon well known sounds, won the singular title “Washing Machine Charlie,” at first, and later, “Louie the Louse,” when their presence heralded Japanese shore bombardment. Technically, “Charlie” was a twin-engine night bomber from Rabaul. “Louie” was a cruiser float plane that signalled to the bombardment ships. But the harassed Marines used the names interchangeably.

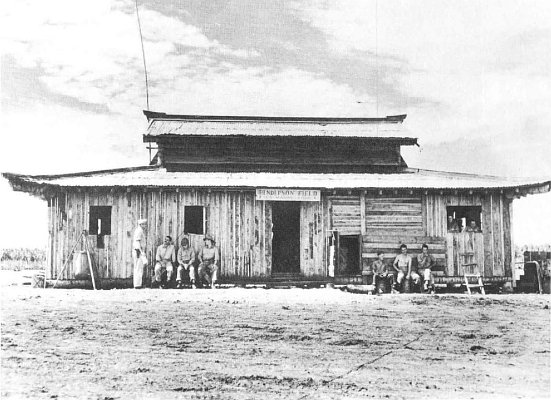

Even though most of the division’s heavy engineering equipment had disappeared with the Navy’s transports, the resourceful Marines soon completed the airfield’s runway with captured Japanese gear. On 12 August Admiral McCain’s aide piloted in a PBY-5 Catalina flying boat and bumped to a halt on what was now officially Henderson Field, named for a Marine pilot, Major Lofton R. Henderson, lost at Midway. The Navy officer pronounced the airfield fit for fighter use and took off with a load of wounded Marines, the first of 2,879 to be evacuated. Henderson Field was the centerpiece of Vandegrift’s strategy; he would hold it at all costs.

Although it was only 2,000 feet long and lacked a taxiway and adequate drainage, the tiny airstrip, often riddled with potholes and rendered17 unusable because of frequent, torrential downpours, was essential to the success of the landing force. With it operational, supplies could be flown in and wounded flown out. At least in the Marines’ minds, Navy ships ceased to be the only lifeline for the defenders.

While Vandegrift’s Marines dug in east and west of Henderson Field, Japanese headquarters in Rabaul planned what it considered an effective response to the American offensive. Misled by intelligence estimates that the Marines numbered perhaps 2,000 men, Japanese staff officers believed that a modest force quickly sent could overwhelm the invaders.

On 12 August, CinCPac determined that a sizable Japanese force was massing at Truk to steam to the Solomons and attempt to eject the Americans. Ominously, the group included the heavy carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku and the light carrier Ryujo. Despite the painful losses at Savo Island, the only significant increases to American naval forces in the Solomons was the assignment of a new battleship, the South Dakota (BB 57).

Of his watercolor painting “Instructions to a Patrol,” Capt Donald L. Dickson said that three men have volunteered to locate a Japanese bivouac. The one in the center is a clean-cut corporal with the bearing of a high-school athlete. The man on the right is “rough and ready.” To the one at left, it’s just another job; he may do it heroically, but it’s just another job.

Captain Donald L. Dickson, USMCR

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo had ordered Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army to attack the Marine perimeter. For his assault force, Hyakutake chose the 35th Infantry Brigade (Reinforced), commanded by Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. At the time, Kawaguchi’s main force was in the Palaus. Hyakutake selected a crack infantry regiment—the 28th—commanded by Colonel Kiyono Ichiki to land first. Alerted for its mission while it was at Guam, the Ichiki Detachment assault echelon, one battalion of 900 men, was transported to the Solomons on the only shipping available, six destroyers. As a result the troops carried just small amounts of ordnance and supplies. A follow-on echelon of 1,200 of Ichiki’s troops was to join the assault battalion on Guadalcanal.

National Archives Photo 80-G-37932

On 20 August, the first Marine Corps aircraft such as this F4F Grumman Wildcat landed on Henderson Field to begin combat air operations against the Japanese.

While the Japanese landing force was headed for Guadalcanal, the Japanese already on the island provided an unpleasant reminder that they, too, were full of fight. A captured enemy naval rating, taken in the constant patrolling to the west of the perimeter, indicated that a Japanese group wanted to surrender near the village of Kokumbona, seven miles west of the Matanikau. This was the area that Lieutenant Colonel Goettge considered held most of the enemy troops who had fled the airfield. On the night of 12 August, a reconnaissance patrol of 25 men led by Goettge himself left the perimeter by landing craft. The patrol landed near its objective, was ambushed, and virtually wiped out. Only three men managed to swim and wade back to the Marine lines. The bodies of the other members of the patrol were never found. To this day, the fate of the Goettge patrol continues to intrigue researchers.

After the loss of Goettge and his men, vigilance increased on the perimeter. On the 14th, a fabled character, the coastwatcher Martin Clemens, came strolling out of the jungle into the Marine lines. He had watched the landing from the hills south of the airfield and now brought his bodyguard of native policemen with him. A retired sergeant major of the British Solomon Islands Constabulary, Jacob C. Vouza, volunteered about this time to search out Japanese to the east of the perimeter, where patrol sightings and contacts had indicated the Japanese might have effected a landing.

The ominous news of Japanese sightings to the east and west of the perimeter were balanced out by the joyous word that more Marines had landed. This time the Marines were aviators. On 20 August, two squadrons of Marine Aircraft Group (MAG)-23 were launched from the escort carrier Long Island (CVE-1) located 200 miles southeast of Guadalcanal. Captain John L. Smith led 19 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF)-223 onto Henderson’s narrow runway. Smith’s fighters were followed by Major Richard C. Mangrum’s Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron (VMSB)-232 with 12 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers.

From this point of the campaign, the radio identification for Guadalcanal, Cactus, became increasingly synonymous with the island. The Marine planes became the first elements of what would informally be known as Cactus Air Force.

The first Army Air Forces P-400 Bell Air Cobras arrived on Guadalcanal on 22 August, two days after the first Marine planes, and began operations immediately.

National Archives Photo 208-N-4932

Wasting no time, the Marine pilots were soon in action against the Japanese naval aircraft which frequently attacked Guadalcanal. Smith shot down his first enemy Zero fighter on 21 August; three days later VMF-223’s Wildcats intercepted a strong Japanese aerial attack force and downed 16 enemy planes. In this action, Captain Marion E. Carl, a veteran of Midway, shot down three planes. On the 22d, coastwatchers alerted Cactus to an approaching air attack and 13 of 16 enemy bombers were destroyed. At the same time, Mangrum’s dive bombers damaged three enemy destroyer-transports attempting to reach Guadalcanal. On 24 August, the American attacking aircraft, which now included Navy scout-bombers from the Saratoga’s Scouting Squadron (VS) 5, succeeded in turning back a Japanese reinforcement convoy of warships and destroyers.

On 22 August, five Bell P-400 Air Cobras of the Army’s 67th Fighter Squadron had landed at Henderson, followed within the week by nine20 more Air Cobras. The Army planes, which had serious altitude and climb-rate deficiencies, were destined to see most action in ground combat support roles.

The frenzied action in what became known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons was matched ashore. Japanese destroyers had delivered the vanguard of the Ichiki force at Taivu Point, 25 miles east of the Marine perimeter. A long-range patrol of Marines from Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines ambushed a sizable Japanese force near Taivu on 19 August. The Japanese dead were readily identified as Army troops and the debris of their defeat included fresh uniforms and a large amount of communication gear. Clearly, a new phase of the fighting had begun. All Japanese encountered to this point had been naval troops.

Alerted by patrols, the Marines now dug in along the Ilu River, often misnamed the Tenaru on Marine maps, were ready for Colonel Ichiki. The Japanese commander’s orders directed him to “quickly recapture and maintain the airfield at Guadalcanal,” and his own directive to his troops emphasized that they would fight “to the last breath of the last man.” And they did.

Too full of his mission to wait for the rest of his regiment and sure that he faced only a few thousand men overall, Ichiki marched from Taivu to the Marines’ lines. Before he attacked on the night of the 20th, a bloody figure stumbled out of the jungle with a warning that the Japanese were coming. It was Sergeant Major Vouza. Captured by the Japanese, who found a small American flag secreted in his loincloth, he was tortured in a failed attempt to gain information on the invasion force. Tied to a tree, bayonetted twice through the chest, and beaten with rifle butts, the resolute Vouza chewed through his bindings to escape. Taken to Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, whose 2d Battalion, 1st Marines held the Ilu mouth’s defenses, he gasped a warning that an estimated 250–500 Japanese soldiers were coming behind him. The resolute Vouza, rushed immediately to an aid station and then to the division hospital, miraculously survived his ordeal and was awarded a Silver Star for his heroism by General Vandegrift, and later a Legion of Merit. Vandegrift also made Vouza an honorary sergeant major of U.S. Marines.

At 0130 on 21 August, Ichiki’s troops stormed the Marines’ lines in a screaming, frenzied display of the “spiritual strength” which they had been assured would sweep aside their American enemy. As the Japanese charged across the sand bar astride the Ilu’s mouth, Pollock’s Marines cut them down. After a mortar preparation, the Japanese tried again to storm past the sand bar. A section of 37mm guns sprayed the enemy force with deadly canister. Lieutenant Colonel Lenard B. Cresswell’s 1st Battalion, 1st Marines moved upstream on the Ilu at daybreak, waded across the sluggish, 50-foot-wide stream, and moved on the flank of the Japanese. Wildcats from VMF-223 strafed the beleagured enemy force. Five light tanks blasted the retreating Japanese. By 1700, as the sun was setting, the battle ended.

Colonel Ichiki, disgraced in his own mind by his defeat, burned his regimental colors and shot himself. Close to 800 of his men joined him in death. The few survivors fled eastward towards Taivu Point. Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, whose reinforcement force of transports and destroyers was largely responsible for the subsequent Japanese troop buildup on Guadalcanal, recognized that the unsupported Japanese attack was sheer folly and reflected that “this tragedy should have taught us the hopelessness of bamboo spear tactics.” Fortunately for the Marines, Ichiki’s overconfidence was not unique among Japanese commanders.

Captain Donald L. Dickson, USMCR

Capt Donald L. Dickson said of his watercolor: “I wanted to catch on paper the feeling one has as a shell comes whistling over.... There is a sense of being alone, naked and unprotected. And time seems endless until the shell strikes somewhere.”

Following the 1st Marines’ tangle with the Ichiki detachment, General Vandegrift was inspired to write the Marine Commandant, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, and report: “These youngsters are the darndest people when they get started21 you ever saw.” And all the Marines on the island, young and old, tyro and veteran, were becoming accomplished jungle fighters. They were no longer “trigger happy” as many had been in their first days ashore, shooting at shadows and imagined enemy. They were waiting for targets, patrolling with enthusiasm, sure of themselves. The misnamed Battle of the Tenaru had cost Colonel Hunt’s regiment 34 killed in action and 75 wounded. All the division’s Marines now felt they were bloodied. What the men on Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo and those of the Ilu had done was prove that the 1st Marine Division would hold fast to what it had won.

Cactus Air Force commander, MajGen Roy S. Geiger, poses with Capt Joseph J. Foss, the leading ace at Guadalcanal with 26 Japanese aircraft downed. Capt Foss was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic exploits in the air.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 52622

While the division’s Marines and sailors had earned a breathing spell as the Japanese regrouped for another onslaught, the action in the air over the Solomons intensified. Almost every day, Japanese aircraft arrived around noon to bomb the perimeter. Marine fighter pilots found the twin-engine Betty bombers easy targets; Zero fighters were another story. Although the Wildcats were a much sturdier aircraft, the Japanese Zeros’ superior speed and better maneuverability gave them a distinct edge in a dogfight. The American planes, however, when warned by the coastwatchers of Japanese attacks, had time to climb above the oncoming enemy and preferably attacked by making firing runs during high speed dives. Their tactics made the air space over the Solomons dangerous for the Japanese. On 29 August, the carrier Ryujo launched aircraft for a strike against the airstrip. Smith’s Wildcats shot down 16, with a loss of four of their own. Still, the Japanese continued to strike at Henderson Field without letup. Two days after the Ryujo raid, enemy bombers inflicted heavy damage on the airfield, setting aviation fuel ablaze and incinerating parked aircraft. VMF-223’s retaliation was a further bag of 13 attackers.

On 30 August, two more MAG-23 squadrons, VMF-224 and VMSB-231, flew in to Henderson. The air reinforcements were more than welcome. Steady combat attrition, frequent damage in the air and on the ground, and scant repair facilities and parts kept the number of aircraft available a dwindling resource.

Plainly, General Vandegrift needed22 infantry reinforcements as much as he did additional aircraft. He brought the now-combined raider and parachute battalions, both under Edson’s command, and the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, over to Guadalcanal from Tulagi. This gave the division commander a chance to order out larger reconnaissance patrols to probe for the Japanese. On 27 August, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, made a shore-to-shore landing near Kokumbona and marched back to the beachhead without any measurable results. If the Japanese were out there beyond the Matanikau—and they were—they watched the Marines and waited for a better opportunity to attack.

Admiral McCain visited Guadalcanal at the end of August, arriving in time to greet the aerial reinforcements he had ordered forward, and also in time for a taste of Japanese nightly bombing. He got to experience, too, what was becoming another unwanted feature of Cactus nights: bombardment by Japanese cruisers and destroyers. General Vandegrift noted that McCain had gotten a dose of the “normal ration of23 shells.” The admiral saw enough to signal his superiors that increased support for Guadalcanal operations was imperative and that the “situation admits no delay whatsoever.” He also sent a prophetic message to Admirals King and Nimitz: “Cactus can be a sinkhole for enemy air power and can be consolidated, expanded, and exploited to the enemy’s mortal hurt.”

On 3 September, the Commanding General, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, Brigadier General Roy S. Geiger, and his assistant wing commander, Colonel Louis Woods, moved forward to Guadalcanal to take charge of air operations. The arrival of the veteran Marine aviators provided an instant lift to the morale of the pilots and ground crews. It reinforced their belief that they were at the leading edge of air combat, that they were setting the pace for the rest of Marine aviation. Vandegrift could thankfully turn over the day-to-day management of the aerial defenses of Cactus to the able and experienced Geiger. There was no shortage of targets for the mixed air force of Marine, Army, and Navy flyers. Daily air attacks by the Japanese, coupled with steady reinforcement24 attempts by Tanaka’s destroyers and transports, meant that every type of plane that could lift off Henderson’s runway was airborne as often as possible. Seabees had begun work on a second airstrip, Fighter One, which could relieve some of the pressure on the primary airfield.

National Archives Photo 80-G-29536-413C

This is an oblique view of Henderson Field looking north with Ironbottom Sound (Sealark Channel) in the background. At the left center is the “Pagoda,” operations center of Cactus Air Force flyers throughout their first months of operations ashore.

Most of General Kawaguchi’s brigade had reached Guadalcanal. Those who hadn’t, missed their landfall forever as a result of American air attacks. Kawaguchi had in mind a surprise attack on the heart of the Marine position, a thrust from the jungle directly at the airfield. To reach his jumpoff position, the Japanese general would have to move through difficult terrain unobserved, carving his way through the dense vegetation out of sight of Marine patrols. The rugged approach route would lead him to a prominent ridge topped by Kunai grass which wove snake-like through the jungle to within a mile of Henderson’s runway. Unknown to the Japanese, General Vandegrift planned on moving his headquarters to the shelter of a spot at the inland base of this ridge, a site better protected, it was hoped, from enemy bombing and shellfire.

Marine ground crewmen attempt to put out one of many fires occuring after a Japanese bombing raid on Henderson Field causing the loss of much-needed aircraft.

Marine Corps Personal Papers Collection

The success of Kawaguchi’s plan depended upon the Marines keeping the inland perimeter thinly manned while they concentrated their forces on the east and west flanks. This was not to be. Available intelligence, including a captured enemy map, pointed to the likelihood of an attack on the airfield and Vandegrift moved his combined raider-parachute battalion to the most obvious enemy approach route, the ridge. Colonel Edson’s men, who scouted Savo Island after moving to Guadalcanal and destroyed a Japanese supply base25 at Tasimboko in another shore-to-shore raid, took up positions on the forward slopes of the ridge at the edge of the encroaching jungle on 10 September. Their commander later said that he “was firmly convinced that we were in the path of the next Jap attack.” Earlier patrols had spotted a sizable Japanese force approaching. Accordingly, Edson patrolled extensively as his men dug in on the ridge and in the flanking jungle. On the 12th, the Marines made contact with enemy patrols confirming the fact that Japanese troops were definitely “out front.” Kawaguchi had about 2,000 of his men with him, enough he thought to punch through to the airfield.

Japanese planes had dropped 500-pound bombs along the ridge on the 11th and enemy ships began shelling the area after nightfall on the 12th, once the threat of American air attacks subsided. The first Japanese thrust came at 2100 against Edson’s left flank. Boiling out of the jungle, the enemy soldiers attacked fearlessly into the face of rifle and machine gun fire, closing to bayonet range. They were thrown back. They came again, this time against the right flank, penetrating the Marines’ positions. Again they were thrown back. A third attack closed out the night’s action. Again it was a close affair, but by 0230 Edson told Vandegrift his men could hold. And they did.

The raging battle of Edson’s Ridge is depicted in all its fury in this oil painting by the late Col Donald L. Dickson, who, as a captain, was adjutant of the 5th Marines on Guadalcanal. Dickson’s artwork later was shown widely in the United States.

Captain Donald L. Dickson, USMCR

On the morning of 13 September, Edson called his company commanders together and told them: “They were just testing, just testing. They’ll be back.” He ordered all positions improved and defenses consolidated and pulled his lines towards the airfield along the ridge’s center spine. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, his backup on Tulagi, moved into position to reinforce again.

EDSON’S (BLOODY) RIDGE

12–14 SEPTEMBER 1942

Edson’s or Raider’s Ridge is calm after the fighting on the nights of 12–13 and 13–14 September, when it was the scene of a valiant and bloody defense crucial to safeguarding Henderson Field and the Marine perimeter on Guadalcanal. The knobs at left background were Col Edson’s final defensive position, while Henderson Field lies beyond the trees in the background.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 500007

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 310563

Maj Kenneth D. Bailey, commander of Company C, 1st Raider Battalion, was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for heroic and inspiring leadership during the Battle of Edson’s Ridge.

The next night’s attacks were as fierce as any man had seen. The Japanese were everywhere, fighting hand-to-hand in the Marines’ foxholes and gun pits and filtering past forward positions to attack from the rear. Division Sergeant Major Sheffield Banta shot one in the new command post. Colonel Edson appeared wherever the fighting was toughest, encouraging his men to their utmost efforts. The man-to-man battles lapped over into the jungle on either flank of the ridge, and engineer and pioneer positions were attacked. The reserve from the 5th Marines was fed into the fight. Artillerymen from the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, as they had on the previous night, fired their 105mm howitzers at any called target. The range grew as short as 1,600 yards from tube to impact. The Japanese finally could take no more. They pulled back as dawn approached. On the slopes of the ridge and in the surrounding jungle they left more than 600 bodies; another 600 men were wounded. The remnants of the Kawaguchi force staggered back toward their lines to the west, a grueling, hellish eight-day march that saw many more of the enemy perish.

The cost to Edson’s force for its epic defense was also heavy. Fifty-nine men were dead, 10 were missing in action, and 194 were wounded. These losses, coupled with the casualties of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo, meant the end of the 1st Parachute Battalion as an effective fighting unit. Only 89 men of the27 parachutists’ original strength could walk off the ridge, soon in legend to become “Bloody Ridge” or “Edson’s Ridge.” Both Colonel Edson and Captain Kenneth D. Bailey, commanding the raider’s Company C, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic and inspirational actions.

On 13 and 14 September, the Japanese attempted to support Kawaguchi’s attack on the ridge with thrusts against the flanks of the Marine perimeter. On the east, enemy troops attempting to penetrate the lines of the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, were caught in the open on a grass plain and smothered by artillery fire; at least 200 died. On the west, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, holding ridge positions covering the coastal road, fought off a determined attacking force that reached its front lines.

The Pagoda at Henderson Field, served as headquarters for Cactus Air Force throughout the first months of air operations on Guadalcanal. From this building, Allied planes were sent against Japanese troops on other islands of the Solomons.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 50921

28 The victory at the ridge gave a great boost to Allied homefront morale, and reinforced the opinion of the men ashore on Guadalcanal that they could take on anything the enemy could send against them. At upper command echelons, the leaders were not so sure that the ground Marines and their motley air force could hold. Intercepted Japanese dispatches revealed that the myth of the 2,000-man defending force had been completely dispelled. Sizable naval forces and two divisions of Japanese troops were now committed to conquer the Americans on Guadalcanal. Cactus Air Force, augmented frequently by Navy carrier squadrons, made the planned reinforcement effort a high-risk venture. But it was a risk the Japanese were prepared to take.

On 18 September, the long-awaited 7th Marines, reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, and other division troops, arrived at Guadalcanal. As the men from Samoa landed they were greeted with friendly derision by Marines already on the island. The 7th had been the first regiment of the 1st Division to go overseas; its men, many thought then, were likely to be the first to see combat. The division had been careful to send some of its best men to Samoa and now had them back. One of the new and salty combat veterans of the 5th Marines remarked to a friend in the 7th that he had waited a long time “to see our first team get into the game.” Providentially, a separate supply convoy reached the island at the same time as the 7th’s arrival, bringing with it badly needed aviation gas and the first resupply of ammunition since D-Day.

The Navy covering force for the American reinforcement and supply convoys was hit hard by Japanese submarines. The carrier Wasp was torpedoed and sunk, the battleship North Carolina (BB 55) was damaged, and the destroyer O’Brien (DD 415) was hit so badly it broke up and sank on its way to drydock. The Navy had accomplished its mission, the 7th Marines had landed, but at a terrible cost. About the only good result of the devastating Japanese torpedo attacks was that the Wasp’s surviving aircraft joined Cactus Air Force, as the planes of the Saratoga and Enterprise had done when their carriers required combat repairs. Now, the Hornet (CV 8) was the only whole fleet carrier left in the South Pacific.

As the ships that brought the 7th Marines withdrew, they took with them the survivors of the 1st Parachute Battalion and sick bays full of badly wounded men. General Vandegrift now had 10 infantry battalions, one understrength raider battalion, and five artillery battalions ashore; the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, had come over from Tulagi also. He reorganized the defensive perimeter into 10 sectors for better control, giving the engineer, pioneer, and amphibian tractor battalions sectors along the beach. Infantry battalions manned the other sectors, including the inland perimeter in the jungle. Each infantry regiment had two battalions on line and one in reserve. Vandegrift also had the use of a select group of infantrymen who were training to be scouts and snipers under the leadership of Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Whaling, an experienced jungle hand, marksman, and hunter, whom he had appointed to run a school to sharpen the division’s fighting skills. As men finished their training under Whaling and went back to their outfits, others took their place and the Whaling group was available to scout and spearhead operations.

Vandegrift now had enough men ashore on Guadalcanal, 19,200, to expand his defensive scheme. He decided to seize a forward position along the east bank of the Matanikau River, in effect strongly outposting his west flank defenses against the probability of strong enemy attacks from the area where most Japanese troops were landing. First, however, he was going to test the Japanese reaction with a strong probing force.

He chose the fresh 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, to move inland along the slopes of Mt. Austen and patrol north towards the coast and the Japanese-held area. Puller’s battalion ran into Japanese troops bivouacked on the slopes of Austen on the 24th and in a sharp firefight had seven men killed and 25 wounded. Vandegrift sent the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, forward to reinforce Puller and help provide the men needed to carry the casualties out of the jungle. Now reinforced, Puller continued his advance, moving down the east bank of the Matanikau. He reached the coast on the 26th as planned, where he drew intensive fire from enemy positions on the ridges west of the river. An attempt by the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, to cross was beaten back.

About this time, the 1st Raider Battalion, its original mission one of establishing a patrol base west of the Matanikau, reached the vicinity of the firefight, and joined in. Vandegrift sent Colonel Edson, now the commander of the 5th Marines, forward to take charge of the expanded force. He was directed to attack on the 27th and decided to send the raiders inland to outflank the Japanese defenders. The battalion, commanded by Edson’s former executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith II, ran into a hornet’s nest of Japanese who had crossed the Matanikau during the night. A garbled message led Edson to believe that Griffith’s men were advancing according to plan, so he decided to land the companies of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, behind the enemy’s Matanikau position and strike the Japanese from the rear while Rosecran’s men attacked across the river.

The landing was made without incident29 and the 7th Marines’ companies moved inland only to be ambushed and cut off from the sea by the Japanese. A rescue force of landing craft moved with difficulty through Japanese fire, urged on by Puller who accompanied the boats on the destroyer Ballard (DD 660). The Marines were evacuated after fighting their way to the beach covered by the destroyer’s fire and the machine guns of a Marine SBD overhead. Once the 7th Marines companies got back to the perimeter, landing near Kukum, the raider and 5th Marines battalions pulled back from the Matanikau. The confirmation that the Japanese would strongly contest any westward advance cost the Marines 60 men killed and 100 wounded.

Shortly after becoming Commander, South Pacific Area and Forces, VAdm William F. Halsey visited Guadalcanal and the 1st Marine Division. Here he is shown talking with Col Gerald C. Thomas, 1st Marine Division D-3 (Operations Officer).

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 53523

The Japanese the Marines had encountered were mainly men from the 4th Regiment of the 2d (Sendai) Division; prisoners confirmed that the division was landing on the island. Included in the enemy reinforcements were 150mm howitzers, guns capable of shelling the airfield from positions near Kokumbona. Clearly, a new and stronger enemy attack was pending.

As September drew to a close, a flood of promotions had reached the division, nine lieutenant colonels put on their colonel’s eagles and there were 14 new lieutenant colonels also. Vandegrift made Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, his former operations30 officer, the new division chief of staff, and had a short time earlier given Edson the 5th Marines. Many of the older, senior officers, picked for the most part in the order they had joined the division, were now sent back to the States. There they would provide a new level of combat expertise in the training and organization of the many Marine units that were forming. The air wing was not quite ready yet to return its experienced pilots to rear areas, but the vital combat knowledge they possessed was much needed in the training pipeline. They, too—the survivors—would soon be rotating back to rear areas, some for a much-needed break before returning to combat and others to lead new squadrons into the fray.

On 30 September, unexpectedly, a B-17 carrying Admiral Nimitz made an emergency landing at Henderson Field. The CinCPac made the most of the opportunity. He visited the front lines, saw Edson’s Ridge, and talked to a number of Marines. He reaffirmed to Vandegrift that his overriding mission was to hold the airfield. He promised all the support he could give and after awarding Navy Crosses to a number of Marines, including Vandegrift, left the next day visibly encouraged by what he had seen.

Visiting Guadalcanal on 30 September, Adm Chester W. Nimitz, CinCPac, took time to decorate LtCol Evans C. Carlson, CO, 2d Raider Battalion; MajGen Vandegrift, in rear; and, from left, BGen William H. Rupertus, ADC; Col Merritt A. Edson, CO, 5th Marines; LtCol Edwin A. Pollock, CO, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines; Maj John L. Smith, CO, VMF-223.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 50883

The next Marine move involved a punishing return to the Matanikau, this time with five infantry battalions and the Whaling group. Whaling commanded his men and the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, in a thrust inland to clear the way for two battalions of the 7th Marines, the 1st and 2d, to drive through and hook toward the coast, hitting the Japanese holding31 along the Matanikau. Edson’s 2d and 3d Battalions would attack across the river mouth. All the division’s artillery was positioned to fire in support.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 61534

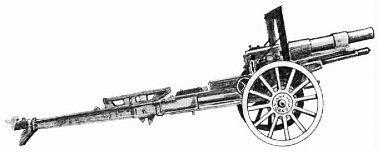

A M1918 155mm howitzer is fired by artillery crewmen of the 11th Marines in support of ground forces attacking the enemy. Despite the lack of sound-flash equipment to locate hostile artillery, Col del Valle’s guns were able to quiet enemy fire.

On the 7th, Whaling’s force moved into the jungle about 2,000 yards upstream on the Matanikau, encountering Japanese troops that harassed his forward elements, but not in enough strength to stop the advance. He bypassed the enemy positions and dug in for the night. Behind him the 7th Marines followed suit, prepared to move through his lines, cross the river, and attack north toward the Japanese on the 8th. The 5th Marines’ assault battalions moving toward the Matanikau on the 7th ran into Japanese in strength about 400 yards from the river. Unwittingly, the Marines had run into strong advance elements of the Japanese 4th Regiment, which had crossed the Matanikau in order to establish a base from which artillery could fire into the Marine perimeter. The fighting was intense and the 3d Battalion, 5th, could make little progress, although the 2d Battalion encountered slight opposition and won through to the river bank. It then turned north to hit the inland flank of the enemy troops. Vandegrift sent forward a company of raiders to reinforce the 5th, and it took a holding position on the right, towards the beach.

Rain poured down on the 8th, all day long, virtually stopping all forward progress, but not halting the close-in fighting around the Japanese pocket. The enemy troops finally retreated, attempting to escape the gradually encircling Marines. They smashed into the raider’s position nearest to their escape route. A wild hand-to-hand battle ensued and a few Japanese broke through to reach and cross the river. The rest died fighting.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 50963

More than 200 Japanese soldiers alone were killed in a frenzied attack in the sandspit where the Tenaru River flows into Ironbottom Sound (Sealark Channel).

On the 9th, Whaling’s force, flanked by the 2d and then the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, crossed the Matanikau and then turned and followed ridge lines to the sea. Puller’s battalion discovered a number of Japanese in a ravine to his front, fired his mortars, and called in artillery, while his men used rifles and machine guns to pick off enemy troops trying to escape what proved to be a death trap. When his mortar ammunition began to run short, Puller moved on toward the beach, joining the rest of Whaling’s force, which had encountered no opposition. The Marines then recrossed the Mantanikau, joined Edson’s troops, and marched back to the perimeter, leaving a strong combat outpost at the Matanikau, now cleared of Japanese. General Vandegrift, apprised by intelligence sources that a major Japanese attack was coming from the west, decided to consolidate his positions, leaving no sizable Marine force more than a day’s march from the perimeter. The Marine advance on 7–9 October had thwarted Japanese plans for an early attack and cost the enemy more than 700 men. The Marines paid a price too, 65 dead and 125 wounded.

32 There was another price that Guadalcanal was exacting from both sides. Disease was beginning to fell men in numbers that equalled the battle casualties. In addition to gastroenteritis, which greatly weakened those who suffered its crippling stomach cramps, there were all kinds of tropical fungus infections, collectively known as “jungle rot,” which produced uncomfortable rashes on men’s feet, armpits, elbows, and crotches, a product of seldom being dry. If it didn’t rain, sweat provided the moisture. On top of this came hundreds of cases of malaria. Atabrine tablets provided some relief, besides turning the skin yellow, but they were not effective enough to stop the spread of the mosquito-borne infection. Malaria attacks were so pervasive that nothing short of complete prostration, becoming a litter case, could earn a respite in the hospital. Naturally enough, all these diseases affected most strongly the men who had been on the island the longest, particularly those who experienced the early days of short rations. Vandegrift had already argued with his superiors that when his men eventually got relieved they should not be sent to another tropical island hospital, but rather to a place where there was a real change of atmosphere and climate. He asked that Auckland or Wellington, New Zealand, be considered.

For the present, however, there was to be no relief for men starting their third month on Guadalcanal. The Japanese would not abandon their plan to seize back Guadalcanal and gave painful evidence of their intentions near mid-October. General Hyakutake himself landed on Guadalcanal on 7 October to oversee the coming offensive. Elements of Major General Masao Maruyama’s Sendai Division, already a factor in the fighting near the Matanikau, landed with him. More men were coming. And the Japanese, taking advantage of the fact that Cactus flyers had no night attack capability, planned to ensure that no planes at all would rise from Guadalcanal to meet them.

On 11 October, U.S. Navy surface ships took a hand in stopping the “Tokyo Express,” the nickname that had been given to Admiral Tanaka’s almost nightly reinforcement forays. A covering force of five cruisers and five destroyers, located near Rennell Island and commanded by Rear Admiral Norman Scott, got word that many ships were approaching Guadalcanal. Scott’s mission was to protect an approaching reinforcement convoy and he steamed toward Cactus at flank speed eager to engage. He encountered more ships than he had expected, a bombardment33 group of three heavy cruisers and two destroyers, as well as six destroyers escorting two seaplane carrier transports. Scott maneuvered between Savo Island and Cape Esperance, Guadalcanal’s western tip, and ran head-on into the bombardment group.

Alerted by a scout plane from his flagship, San Francisco (CA 38), spottings later confirmed by radar contacts on the Helena (CL 50), the Americans opened fire before the Japanese, who had no radar, knew of their presence. One enemy destroyer sank immediately, two cruisers were badly damaged, one, the Furutaka, later foundered, and the remaining cruiser and destroyer turned away from the inferno of American fire. Scott’s own force was punished by enemy return fire which damaged two cruisers and two destroyers, one of which, the Duncan (DD 485), sank the following day. On the 12th too, Cactus flyers spotted two of the reinforcement destroyer escorts retiring and sank them both. The Battle of Cape Esperance could be counted an American naval victory, one sorely needed at the time.

Maj Harold W. Bauer, VMF-212 commander, here a captain, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor after being lost during a scramble with Japanese aircraft over Guadalcanal.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 410772

Its way cleared by Scott’s encounter with the Japanese, a really welcome reinforcement convoy arrived at the island on 13 October when the 164th Infantry of the Americal Division arrived. The soldiers, members of a National Guard outfit originally from North Dakota, were equipped with Garand M-1 rifles, a weapon of which most overseas Marines had only heard. In rate of fire, the semiautomatic Garand could easily outperform the single-shot, bolt-action Springfields the Marines carried and the bolt-action rifles the Japanese carried, but most 1st Division Marines of necessity touted the Springfield as inherently more accurate and a better weapon. This did not prevent some light-fingered Marines from acquiring Garands when the occasion presented itself. And such an occasion did present itself while the soldiers were landing and their supplies were being moved to dumps. Several flights of Japanese bombers arrived over Henderson Field, relatively unscathed by the defending fighters, and began dropping their bombs. The soldiers headed for cover and alert Marines, inured to the bombing, used the interval to “liberate” interesting cartons and crates. The news that the Army had arrived spread across the island like wildfire, for it meant to all Marines that they eventually would be relieved. There was hope.

Department of Defense (USMC) Photos 304183 and 302980

Two other Marine aviators awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism and intrepidity in the air were Capt Jefferson J. DeBlanc, left, and Maj Robert E. Galer, right.

As if the bombing was not enough grief, the Japanese opened on the airfield with their 150mm howitzers also. Altogether the men of the 164th got a rude welcome to Guadalcanal. And on that night, 13–14 October, they shared a terrifying experience with the Marines that no one would ever forget.

Determined to knock out Henderson Field and protect their soldiers landing in strength west of Koli Point, the enemy commanders sent the battleships Kongo and Haruna into Ironbottom Sound to bombard the Marine positions. The usual Japanese flare planes heralded the bombardment, 80 minutes of sheer hell which had 14-inch shells exploding with such effect that the accompanying cruiser fire was scarcely noticed. No one was safe; no place was safe. No dugout had been built to withstand 14-inch shells. One witness, a seasoned veteran demonstrably cool under enemy fire, opined that there was nothing worse in war than helplessly being on the receiving end of naval gunfire. He remembered “huge trees being cut apart and flying about like toothpicks.” And he was on the frontlines, not the prime enemy target. The airfield and its environs were a shambles when dawn broke. The naval shelling, together with the night’s artillery fire and bombing, had left Cactus Air Force’s commander, General Geiger, with a handful of aircraft still flyable, an airfield thickly cratered by shells and bombs, and a death toll of 41. Still, from Henderson or Fighter One, which now became the main airstrip, the Cactus Flyers had to attack, for the morning also revealed a shore and sea full of inviting targets.

The expected enemy convoy had gotten through and Japanese transports and landing craft were everywhere near Tassafaronga. At sea the escorting cruisers and destroyers provided a formidable antiaircraft screen. Every American plane that could fly did. General Geiger’s aide, Major Jack Cram, took off in the general’s PBY, hastily rigged to carry two torpedoes, and put one of them into the side of an enemy transport as it was unloading. He landed the lumbering flying boat with enemy aircraft hot on his tail. A new squadron of F4Fs, VMF-212, commanded by Major Harold W. Bauer, flew in during the day’s action, landed, refueled, and took off to join the fighting. An hour later, Bauer landed again, this time with four enemy bombers to his credit. Bauer, who added to his score of Japanese aircraft kills in later air battles, was subsequently lost in action. He was awarded34 the Medal of Honor, as were four other Marine pilots of the early Cactus Air Force: Captain Jefferson J. DeBlanc (VMF-112); Captain Joseph J. Foss (VMF-121); Major Robert E. Galer (VMF-224); and Major John L. Smith (VMF-223).

The Japanese had landed more than enough troops to destroy the Marine beachhead and seize the airfield. At least General Hyakutake thought so, and he heartily approved General Maruyama’s plan to move most of the Sendai Division through the jungle, out of sight and out of contact with the Marines, to strike from the south in the vicinity of Edson’s Ridge. Roughly 7,000 men, each carrying a mortar or artillery shell,35 started the trek along the Maruyama Trail which had been partially hacked out of the jungle well inland from the Marine positions. Maruyama, who had approved the trail’s name to indicate his confidence, intended to support this attack with heavy mortars and infantry guns (70mm pack howitzers). The men who had to lug, push, and drag these supporting arms over the miles of broken ground, across two major streams, the Mantanikau and the Lunga, and through heavy underbrush, might have had another name for their commander’s path to supposed glory.

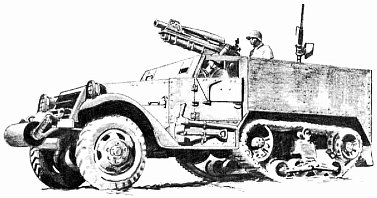

A Marine examines a Japanese 70mm howitzer captured at the Battle of the Tenaru. Gen Maruyama’s troops “had to lug, push, and drag these supporting arms over the miles of broken ground, across two major streams and through heavy underbrush” to get them to the target area—but they never did. The trail behind them was littered with the supplies they carried.

Photo courtesy of Col James A. Donovan, Jr.

General Vandegrift knew the Japanese were going to attack. Patrols and reconnaissance flights had clearly indicated the push would be from the west, where the enemy reinforcements had landed. The American commander changed his dispositions accordingly. There were Japanese troops east of the perimeter, too, but not in any significant strength. The new infantry regiment, the 164th, reinforced by Marine special weapons units, was put into the line to hold the eastern flank along 6,600 yards, curving inland to join up with 7th Marines near Edson’s Ridge. The 7th held 2,500 yards from the ridge to the Lunga. From the Lunga, the 1st Marines had a 3,500-yard sector of jungle running west to the point where the line curved back to the beach again in the 5th Marines’ sector. Since the attack was expected from the west, the 3d Battalions of each of the 1st and 7th Marines held a strong outpost position forward of the 5th Marines’ lines along the east bank of the Matanikau.

In the lull before the attack, if a time of patrol clashes, Japanese cruiser-destroyer bombardments, bomber attacks, and artillery harassment could properly be called a lull, Vandegrift was visited by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb. The Commandant flew in on 21 October to see for himself how his Marines were faring. It also proved to be an occasion for both senior Marines to meet the new ComSoPac, Vice Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey. Admiral Nimitz had announced Halsey’s appointment on 18 October and the news was welcome in Navy and Marine ranks throughout the Pacific. Halsey’s deserved reputation for elan and aggressiveness promised renewed attention to the situation on Guadalcanal. On the 22d, Holcomb and Vandegrift flew to Noumea to meet with Halsey and to receive and give a round of briefings on the Allied situation. After Vandegrift had described his position, he argued strongly against the diversion of reinforcements intended for Cactus to any other South Pacific venue, a sometime factor of Admiral Turner’s strategic vision. He insisted that he needed all of the Americal Division and another 2d Marine Division regiment to beef up his forces, and that more than half of his veterans were worn out by three months’ fighting and the ravages of jungle-incurred diseases. Admiral Halsey told the Marine general: “You go back there, Vandegrift. I promise to get you everything I have.”

Department of Defense (USMC) Photo 13628

During a lull in the fight, a Marine machine gunner takes a break for coffee, with his sub-machine gun on his knee and his 30-caliber light machine gun in position.