The cover image was restored by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was restored by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

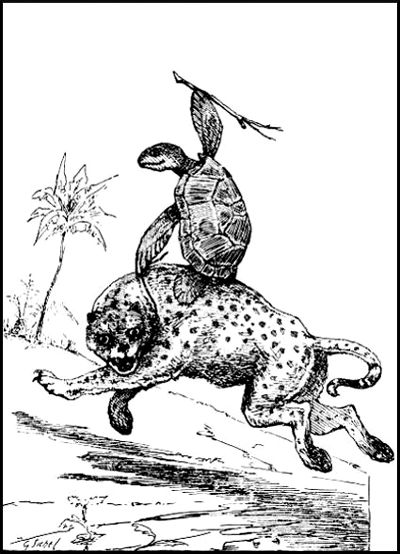

![A GHOST STORY. [See Chap. XI.]](images/image1.jpg)

A GHOST STORY.

Printed by The Motley Press, 18, Eldon Street, E.C.

This little volume is sent forth with many misgivings. It claims neither literary excellence nor an entrancing theme, but professes fidelity to truth, and a desire to call attention to certain quaint and interesting phases of the inner life of a much misunderstood race.

In the compilation of these folk-lore tales, the one aim has been to make them accessible to English readers, and at the same time to retain as much as possible of their native grace and quaintness.

To accomplish this aim, the stories have been told in the dialect used by the people in their intercourse with the English, and an attempt has been made to embody the tales in a native setting with local atmosphere and colour. In addition it has seemed necessary to make a rather copious use of footnotes and explanations.

Much care has been exercised not to modify the spirit and real content of the stories. The plots and the clever little inventions are wholly native. It has seemed advisable to select only a few of the more readable stories, in the hope that they may win the[vi] sympathy of the general reader, rather than to attempt an extended collection that would discourage all but special students of folk-lore.

The stories themselves possess much intrinsic merit; if they fail to enlist the reader, the fault must be ascribed to the compilers.

The sole credit for discovering and collecting the stories is due to Miss Cronise; the arrangements of the stories here presented, and their setting, have been largely the work of Mr. Ward.

The authors are under many obligations to Mr. Alfred Sumner, a native African now in this country at college, whose intimate acquaintance with the life and customs of his people proved most helpful; also to Rev. D. F. Wilberforce, a native missionary, who has long been interested in the oral literature of his country, and in consequence has been able to give us suggestions of unusual value. To Miss Minnie Eaton of Moyamba Mission, and to other friends, who spared no pains to place desired information within our reach, and especially to the Mission boys and girls in Africa whose sympathetic interest made this collection a possibility, the gratitude of the authors is due.

Florence M. Cronise.

Henry W. Ward.

The collection of folk-lore tales, from which the stories contained in the present volume have been selected, was made by Miss Cronise while a teacher in the mission school at Rotifunk, Protectorate of Sierra Leone, West Africa; a mission under the control of the Woman's Board of the United Brethren Church.

The stories were collected without the remotest thought of offering them for publication. The first motive was a desire to enter more intimately into the life and mental habits of the people whom she was to instruct. This motive was soon reinforced by the attractiveness of the stories themselves, and by the fascinating manner in which they were told.

The tales were gathered from the mission children, most of whom had been brought from native homes farther inland, and from[2] adult employees of the mission who had been long enough in contact with these white people to be found worthy of entire confidence, and to give their confidence in return.

Notwithstanding the many touches of English influence noticeable in the stories, it is believed that the ones here presented are, in all essentials, characteristically native. The same stories were heard from different persons, under different circumstances, and with every evidence of their being the spontaneous outflow of traditional lore. Sometimes a tale already heard in detail from an adult, would be told in mere outline by some child fresh from a hut of the forest.

A year or more had been spent among these people before it was discovered that they possessed a distinct oral literature, and considerably more time passed before any attempt was made to collect and record it.

Missionaries had been in this section for fifty years, but being wholly absorbed in more serious concerns, they were either unaware of this native literature, or more probably looked upon it as a part of the heathen superstition which they felt called upon to obliterate.

No one at all familiar with folk-lore, will[3] need to be told of the peculiar difficulties experienced in making the present collection. Natives are instinctively suspicious of foreigners, and uneasy in their presence, and not only must this natural barrier be broken down, but there must spring up mutual understanding and sympathy, and outward environments must be congenial before there can be any satisfactory story-telling. The collection was made as opportunity offered, after other duties were performed. Various devices had to be resorted to, the commonest being to offer some attractive little inducement to a child of the mission or adjacent town. The child, curled up on the floor, or perched on any convenient object, would at once evince the most sympathetic interest, and then it would be a simple matter to draw out stories heard in the native wilds. By rapid writing, so abbreviated as to approach shorthand, the narratives were taken down literally, word for word. Then again, familiarity made it possible to sit near a group of children gathered in the evening for talk and laughter, and there to overhear the conundrums they propounded, and the stories they related to one another. Sometimes an[4] adult could be induced to relate stories for an evening. One such story was a portion of a loosely connected narrative, the whole of which would occupy the evenings of an entire week.

Two years of patient endeavor brought to light one hundred and twenty-five distinct stories. There was positive assurance of unnumbered more being current among the people, and evidence was occasionally found of the existence of another class of stories, such as the missionary would not care to hear or to record.

It may be, then, that while the fables here given truthfully reflect the life of the people, they do not reflect the whole life, but only the better, purer part.

Strangely enough, during all the years that the English have been in possession of West Africa, no one has taken the pains to collect any considerable part of the oral literature that is particularly abundant there. So far as we have been able to learn, practically nothing has been done in all the Sierra Leone region, toward collecting and publishing this great body of traditional literature. Schlenker included seven tales in his "Temne Traditions" published in 1861,[5] and an occasional "Nancy Story" has appeared in Sierra Leone newspapers, but no serious effort has been made toward a collection; and yet perhaps no region of Africa is richer in native literature.

How completely this literature envelops the life of the people, may be inferred from the fact that the youngest children in the mission were found to possess the salient features of many stories, which they must have acquired before being taken from their people.

These stories seem to be the chief source of entertainment, not only of the young, but of the adult as well. The children of all races are fond of fables and fairy-tales, and the black man in his native state is always a child.

Whatever the distant origin of these legends and fables, it is plain that they now serve as a pleasing diversion for leisure hours, and gratify the natural hunger of the human mind for representations of its own desires as realized, without being hampered by literal fact. They fill even a larger place in the mental and ideal life of these unlettered people, than the great mass of fictitious literature does among more cultured[6] races. There are many close parallels between this native literature and fiction as it is found among civilized peoples. Both allow a delightful freedom to the genius of the story-teller—though the imagination of the African is representative rather than creative,—both please by depicting some form of ideal achievement, both make frequent appeals to the humorous and pathetic in experience, and both furnish entertainment for hours of idleness, or offer the soul an ideal refuge from life's hard and stern realities.

Among the Africans, story-telling is mainly a pastime. It flourishes only under congenial environments and favoring conditions. These are abundant leisure, a company of sympathizing listeners, and freedom from excitement.

Story-telling most often springs spontaneously from the chat, when a number of persons are together with nothing particular to do; sometimes, however, time and place are appointed. Stories may be told whenever circumstances are favorable, but as conditions are most inviting when darkness is in possession of the outer world, most of the story-telling takes place at night. If[7] the moon shines, its light is sufficient; should the night be dark or chill, fires are kindled, and in the flickering light of these, picturesque groups of natives may be seen, brought together by some impulse which they do not stop to question. Before the group breaks up, stories are quite likely to be started, and naturally one will draw out another, each furnishing the inspiration and the excuse for the next. The social instinct of the negro is very strong, and it leads him to seek the companionship of his fellows as often as possible. Crowded together in village communities, with few and irregular demands upon their time, and with instinctive hospitality and friendliness, the black tribes cultivate without conscious effort, their native traditions and fanciful literature. Any one may relate these tales, either as one is suggested to his mind, or on request of some one present; yet in many communities, there are persons so well versed in these common myths and legends, and so gifted in rehearsing them, that they are looked upon as the village story-tellers, and are expected to do most of the reciting. If the people know that a person so gifted is among them, they go and beg him for[8] a story, offering him some present—perhaps tobacco, kola nuts, cowry shells, which are used as currency, or some other small article. Then they build a great fire and sit around it while the story is told.

We have it also on good native authority, that there are occasionally professionals who make their living by going from village to village, and exchanging for food and shelter, stories interspersed with songs. Many of these African troubadours display remarkable dramatic power. Voice, eyes, face, hands, head, and indeed the whole person aid in giving force to the words.

The reader will greatly enhance his pleasure in the perusal of the following tales, if he will give his own imagination full play, and will supply what the narrator added by the manner of his delivery.

Riddles and story-telling are not infrequently continued throughout the entire night, and in connection with an unusual occasion, such as the funeral ceremonies of some distinguished person, or the marriage festivities of a similar personage. They may be protracted for several nights.

Many little songs, or rather choruses, occur in the stories. These are rendered[9] in a kind of chanting measure, a weird melody, usually accompanied by a rhythmical clapping of the hands. They are invariably short, usually in the minor key, and, in the longer stories, are repeated at intervals, seemingly to give variety and animation to the narrative. It makes a peculiar impression upon the distant listener to hear these periodical choruses break forth suddenly on the night air, and just as suddenly cease.

The songs are invariably given in the native language, and the crude attempt at translation given by the narrator, fails utterly to reproduce their musical qualities.

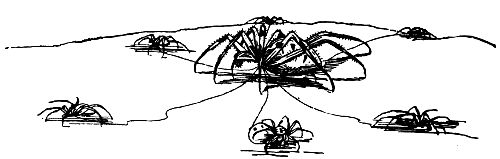

Negro folk-lore, whether in Africa or America, consists largely of animal stories, in which human qualities and characteristics are ascribed to the various animals. In the Temne legends, the Spider, the Cunning Rabbit, the Deer, the Leopard, the Turtle, the Elephant, the Lizard, the Chameleon, the Cat and the Hawk appear very frequently, while many other animals, birds and insects are introduced. It appears to be assumed, throughout the stories, that there was a time when all animals dwelt together in a single community, until some[10] of the animals began to prey upon the others, thus scattering them over the face of the earth, creating enmities, and destroying the power to understand one another. The communities were organized with king and headmen, and had houses and farms, occupations and wants, like the men of later times.

Several accounts are given of how the animals came to be dispersed. The one contained in this collection, of Mister Spider and his powerful witch medicine, is evidently, in part at least, a late invention. It represents Spider in his usual rôle of devising some cunning scheme for securing a supply of food for himself and family. In this instance he procures a gun and ammunition, and announces that he has secured a medicine to kill off the witches that infest the town; and thus, under pretence of rendering the community a valuable service, he begins to kill and to devour the animals one by one. They finally take alarm, and flee to different parts of the earth.

Another story, bearing the marks of greater antiquity, represents the animals as living together in peace and harmony, until the Leopard develops a taste for fresh meat,[11] and begins to prey upon the other animals. They hold a council, and finally decide to take the only boat in existence, and to remove to an island of the sea, leaving Mr. Leopard alone on the mainland. Every day some one is left to guard the boat, while the others are away procuring food. Once, while the Deer is left on guard, Leopard comes to the shore, and in a disguised voice calls for the boat to be brought across. Mr. Deer, always represented in these stories as being extremely stupid, is deceived, and rows the boat across. Of course Mr. Leopard devours the unfortunate Deer, seizes the boat and plans a general feast when the animals return to the village at night. To save themselves, they scatter in every direction, and thus animals become dispersed over the earth.

Hereafter the animals appear to have had dealings with each other, more or less, but were never again united, although there is mention of their gathering for special purposes on several occasions.

The stories frequently assume to account for the peculiar traits or physical characteristics of the various animals; as, for instance, why the Deer coughs, why the Leopard is[12] spotted, why the Spider is flat and why his waist is small, why the Elephant's tusks protrude, and why the Turtle's shell is rough and scarred.

Certain definite qualities and characteristics are ascribed to particular animals, and to these they hold consistently through all the stories. The Deer is always stupid and helpless; the Elephant enormously strong but lacking in mental acuteness; the Cunning Rabbit intelligent and lovable; and the Spider shrewd, designing, selfish, and sometimes vindictive and cruel.

It is noticeable that the weak and helpless creatures are made to prevail against the strong and mighty, not by any use of force, but by cleverness and cunning. Thus Mr. Spider defeats both the Elephant and the Hippopotamus in a pulling match, by the clever ruse of challenging them, in turn, to a trial of strength, proposing to draw the Elephant from the shore to the water, and the Hippopotamus from the water to the shore. The Spider procures a rope so long that neither antagonist can see the other. At the appointed time he ties one end of it to the Elephant, and says that when he is ready to begin the contest, he[13] will give the signal by shaking the rope; then going to the water's edge, he ties the other end to the Hippopotamus, giving the same instructions. Finally, going to the middle of the rope, he gives the signal, and the struggle begins, while Mr. Spider enjoys the sport from behind a tree, to which place of safety he has had the good judgment to retreat.

As the two monsters are so equally matched in strength, the struggle continues, with advantage to neither, until both are completely exhausted and fall down dead. Mr. Spider, viewing the results of his cleverness, soliloquises: "Yo' pass me fo' 'trong, but aintee I pass yo' fo' sense?"

The victims of this cunning supply food to Mr. Spider and his family throughout the famine, and that indeed was the Spider's purpose in the ruse. The story throws in the gratuitous information that the Spider cast into the water such portions of the carcasses as were not desirable for food, and from these pieces came fish, the first of their kind.

Mental superiority counts for more than mere brute force, even where there is a direct trial of strength, as in the story of[14] "Cunning Rabbit and his Well." The other animals come to wrestle with Cunning Rabbit for the privilege of taking water from his well, but on account of his "sense," Cunning Rabbit is always victor, even to hurling the Elephant into the air, although the latter tried to hold himself down by wrapping his trunk around a tree.

Sometimes a necromantic spell is called in to aid the weaker, as in the case of Goro, the Wrestler, in which the song of incantation chanted by the mother, enables the child to prevail.

It satisfies the ethical sense of all people, to represent helpless innocence as finally triumphant over the selfish power of might. Perhaps the black race has more than usual reason for representing in its imaginative literature, that cunning, craft and cleverness are the qualities most to be admired and cultivated. It has always been an oppressed people, defenceless in the contest with wild beasts, without adequate resources in the struggle with nature, and helpless against the cruelties of their more aggressive fellowmen. Little wonder that they exalt cunning, deception and craft. If there is a dash of viciousness in these, all the[15] better. It is only poetic retribution. Consequently the African is taught dissimulation as a fine art, and cunning as the most worthy of accomplishments.

The Spider appears to be the national hero, the impersonation of the genius of the race. To him are ascribed the qualities most characteristic of the people, or those most to be desired: cunning, sleeplessness, almost immortality, an unlimited capacity for eating, and an equal genius for procuring the necessary supplies. He possesses a charmed life, and escapes from all intrigue. He is a tireless weaver, and has spun the thread of his personality into all the warp and woof of the national life. With him the adults associate most of their traditions, while the children love him, and push him tenderly aside if he chances to come in their way. He is inclined to be lazy, and refuses to lift even the lightest burden if it is in the nature of work; if it is something to eat, he can carry the carcass of an elephant with the greatest ease.

The Spider occupies the same place in the folk-lore of West Africa, as does Brer Rabbit in the tales of the southern negro, and as Annancy holds among the negroes[16] of the West Indies, or Hlakanyana among the Kaffirs of South Africa. A comparative study of these several heroes and the literature gathered about them, would be extremely interesting and profitable, but would carry us beyond the bounds set for this introduction.

Mr. Harris, in his introduction to "Nights With Uncle Remus," has pointed out the essential identity of Brer Rabbit and Hlakanyana. There is perhaps a closer parallel between the Spider of the Temne tales, and Annancy, the hero of the West Indian stories. A comparison of Mr. Spider and Brer Rabbit reveals many similarities and some differences, the latter due no doubt to the mellowing influence of contact with a finer civilization, an influence that has softened the character of the transplanted negro, and wrought the same change in the hero of his stories. Both are exceedingly clever, and equal to any emergency. Brer Rabbit, however, is inoffensive in his mischief, and very properly gets out of every scrape without serious consequences. If ever he gets others into trouble, it is to save himself, or to settle an old score. Mr. Spider's cunning has at times a touch[17] of viciousness in it. It sometimes overreaches itself, and brings Mr. Spider to grief, though never to destruction.

Cunning Rabbit rivals Mr. Spider in shrewdness and wit, and in the reverence and esteem given him by the people. In pure intelligence and in amiability of disposition he is without a peer. He is uniformly pronounced "King of de beef fo' wise, oh!" He and Mr. Spider are usually on amicable terms, but when their interests clash there is a notable contest of wits. The natives say: "Two cunnie meet up, de one cunnie, de odder cunnie," but Cunning Rabbit always has a shade the better of it in the end.

We have found it very difficult to identify this little creature, called by the natives "Cunnie Rabbit." It is evidently not a rabbit at all, but the water deerlet or chevrotain, noted for its nimbleness and cunning. It is about eighteen inches long, slender and graceful in form, with a soft fawn-colored skin, and the daintiest of legs and feet. The little creature is very difficult to secure. Its shyness, fleetness and cunning have led the natives to invest it with a sort of veneration.

A fragment of skeleton submitted to Dr. F. W. True, Head Curator Department of Biology, Smithsonian Institution, was pronounced to belong to Hyomoschus Aquaticus, an animal peculiar to West Africa.

It would be the merest conjecture to surmise that this water deerlet, the Cunning Rabbit of African folk-lore, may be the ancestor of Brer Rabbit, as the negroes of the South portray him, and yet there is a shadow of evidence for such belief. The negroes might have transferred the qualities of their Cunning Rabbit to the American hare, because of the similarity of their popular names. It certainly requires a very friendly eye to see in the hare all the mental acumen accredited by the negroes to Brer Rabbit.

To students of comparative folk-lore, these little stories will furnish much food for reflection. They probably come as nearly fresh from the hearts of a primitive people, and are as little modified by outside influences, as any collection made in recent times.

To the oft-repeated question as to how the story was learned, and whence it came, the uniform answer was: "Oh, please, Missus, f'om f-a-r up country," with a much[19] prolonged emphasis on the "far," and an intonation that expressed wonder at such a question's being asked, as all such stories must come from the infinitely remote in space and time.

It will be observed that very many of the stories in this collection are almost identical with a number of the tales in the "Uncle Remus" series, and with a few in the "Annancy Stories," to say nothing of likenesses found in the folk-lore of the American Indians, and the very natural similarity between these tales and those current among the negroes of other portions of Africa.

The "Tar Baby" story, which seems to be in the oral literature of all African tribes, and a standard among the folk-lore tales of all peoples, appears here as the "Wax Girl."

The incidents leading up to the encounter of Mr. Spider with the Wax Girl, differ from the preliminaries in the story of Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby, but the encounter itself is the same in both. The outcome also differs in the two stories, but in each is entirely consistent with the story as a whole. Brer Rabbit has been guilty of no offence that deserves punishment, so he[20] suffers only temporary humiliation, and finally regains simultaneously his freedom and his prestige, by inducing Mr. Fox to fling him into the brier patch. Mr. Spider, on the other hand, has practised gross deception, and has appropriated to his own use what should have been shared with others, so he very appropriately receives as punishment an unmerciful flogging at the hands of the outraged community.

Mr. Spider's feat of strength in his contest with the Elephant and the Hippopotamus, already referred to, is a variant of the same contest between Mr. Terrapin and Mr. Bear.

The Temne story of the Turtle making a riding-horse of Mr. Leopard, finds its parallel in Brer Rabbit's riding Brer Fox, as told by "Uncle Remus," and in the "Annancy Stories," by Pamela Colman Smith, where Annancy rides the Tiger.

In one instance Mr. Leopard feigns death, and when the other animals gather around to wail for him, he seizes and devours them. This is much like Mr. Wildcat's attempt to secure the wild turkey by the same ruse.

It must suffice to have mentioned a few variants only, although there are many[21] more of the same nature. If anything further were needed to prove that the folk-tales of the American negroes were brought with them from Africa, the striking parallels in the tales of the two countries ought to supply the proof.

The magic nuts, or eggs, or other articles, which appear in the folk-lore of most races, and which on being opened let out, at one time a profusion of all things desired—riches, fine houses, servants etc., and at other times, reptiles, insects, and cruel monsters, are also found among these tales. The story of the devil's magic eggs is a representative of this class. In another story the bangah-nuts take the place of the eggs.

There are also traces of the "half thing" conception. In one story a man's possessions consisted of half things of various kinds, a half pot, a half bowl, everything half. A bird that possessed magic power, befriended the poor man, and transformed the "bush" into a village filled with riches, to be his on condition of never disturbing the bird's egg. The condition is finally violated, and the man, made utterly destitute, learns that half a thing is better than none. In the story contained in this collection, in[22] which a young girl marries a devil, it will be noted that the devil in taking human form, was compelled to supply his hideous deficiency by borrowing half a head, one foot, one hand, everything half; and after his successful wooing, when he approached his own home, with his bride, all the half things that he had borrowed fell off one by one, until finally "all t'ing nah heen skin bin lef half."

In all the stories we possess, there is only one mention of the divining mirror. It is employed by a lover, and startles him by revealing his loved one lying dead.

It may aid the reader to appreciate these fables from Temne-Land, if a few paragraphs of this introduction be given to a brief discussion of the peculiar beliefs, customs, and environments of the people who have formulated the stories, and who repeat them with never-dying interest.

If we could get a true and complete picture of the black man's mental and moral world from his view point, we should be able to confer a measureless boon upon all those who must deal with him; but unfortunately we have no such good gift to offer. The negro character is so perverse[23] and enigmatical that it defies satisfactory analysis.

The stories themselves will furnish the best kind of information on these points, and to the serious student, this perhaps will be their chief value. However a summary of a few of the facts available will not be amiss. What is said, though applicable directly to the Temnes, will be true in a general sense of all the surrounding tribes, and in a limited way of all the race. As a people, the Temnes are filled exceedingly with innate pride and natural dignity, and love to be noticed and honored. They are fond of riches as they understand them, and are shrewd traders. Their wealth consists of wives, slaves, cows, and goats, and these they value in the order named. Mentally they are bright and quick-witted, though only as concerns the reproductive powers of the mind; for independent thinking they have little capacity. The memory powers are especially strong and persistent. The black man keeps in his head records that a white man would be compelled to write in a book.

The native African has few ambitions beyond the satisfying of his appetites, and the gratification of his sensual desires. Contentment[24] with his lot is the bane of his life, so far as any hope of improvement is concerned, and yet these stories reveal glimmerings of better things, and a capacity to formulate ideals. It is not an easy matter to know the impulses that lie deep within the breast of any people,—the central life impulses, out of which flow all desires and motives, and all standards of happiness. It is still more difficult to get at this central impulse in an uncivilized people, because heathenism renders the soul-life of its adherents extremely difficult to understand.

The literature of a people is the best revelation of its soul-life, especially of the ideals it would consciously or unconsciously set up. It is in this fact that such collections as the one here offered, find their greatest worth.

The inner life of the African is so completely under the control of his superstitious beliefs, that to comprehend it adequately, one must understand all the hideous network of superstitions that envelop the whole life of the people.

Mr. Alfred Sumner, an educated native, has kindly furnished us the following facts concerning this phase of the life of his people.

"All the people believe in signs and omens, good and bad; every occurrence that is a little beyond the ordinary, or seems a little strange, must receive some interpretation from the natives. In fact, occurrences that are not beyond the natural, so long as they do not happen every day, are the sign of something. The withering of a tree, the falling of a fence, the stumbling against something in the road, the ringing of the ear, the dancing of the eyelid, the itching palm, two babies laughing at each other; these and many more things that time would fail us to mention, mean something to the native; tokens of good, warnings of calamity near. The cry of the witch bird, and the "cluck, cluck, cluck" of the boa-constrictor, mean the certain death of someone. If one should be killed by lightning on the road, persons passing the spot from that time on, must pluck a leaf or a small branch and throw it there to avert the same death. Some parts of a road have been entirely abandoned and new paths made on this account. One dare not sew his cloth while it is on his body, lest a relative of his die. There are many more, to us silly superstitions, in which the natives fully believe.[26] To them they are signs and wonders. Some are easy to interpret, others must come under the prophetic eye of the "country-fashion" man—a man who interprets signs and wonders either by spiritual means, or on sand, or with stones. All sorts of charms are made and worn. Various articles are used in their composition—such as oil, leaves, beads, hair, finger-nails, toe-nails etc. Most of the charms the women put on in Africa, are merely small bits of paper with Mohammedan writing, wrapped in a piece of soft leather. They are either to ward off evil, or to bring about luck, according to the writing on the paper. All the "Sebbehs"—that is, the flat, regularly formed charms—are made in this way. Not all of the charms are to be seen by everybody; some are very private, and must be worn next the skin. The "hoodoos" and "fetiches" are of more importance than the ordinary charms, and their composition is more complex, consisting of leaves, barks, roots, horns and bones, either of man or beast, or of both, all carefully placed in a country-pot made of clay, and kept from every eye save that of the owners and perhaps near relatives. These fetiches may serve as[27] gods, and are believed to have the power to return evil for evil to any one who may harm their owners. What is called "gree-gree" is a fetich that is employed by its owner to revenge any wrong received by him. The "He-ge-de" is considered to have the power of self-motion, and of attacking in a death-combat the one to whom it is sent. These charms may be used by any one, irrespective of rank or age; but some of them are very costly, and only the rich can afford them. The leopard's teeth are considered very great and valuable ornaments—pearls of great price; and natives are loth to sell them. They may well be called their diamonds, as they not infrequently calculate their wealth by the number of leopard's teeth owned."

It is thus seen that the natives are born, reared, and die in nameless terror of unseen powers that teem in woods, fields and towns. Their spirits are legion. A few of these are believed to be good, the majority bad, exceedingly bad. It is the greater part of their existence to circumvent the evil spirits, and to win the favor of the good. The tiniest babe is decorated with strings, shells,[28] or bits of wood, supposed to possess the power to ward off evils which mother-arms cannot avert. Those of maturer years, even down to old age, often sacrifice to conciliate they know not what.

Sickness is believed to be caused by a witch. If one is seized with serious illness, a witch-doctor is called in to exorcise the evil spirit; failing in thus obtaining relief, the next resort is to incantations and ordeals, to discover who is guilty of bewitching the afflicted one, some individual being held guilty of bringing on the malady.

The power of the witch-doctor is considered absolute, and woe to the unfortunate one that falls under his ill-will. He is believed to possess the power of double vision, and to be able to see spirits, and to know their doings. Never is the power and efficiency of his incantations doubted. His exorbitant fees are paid with a cheerfulness that would quite astound a Christian doctor. A curse pronounced in the name of a witch-medicine is supposed to be relentless towards the one against whom it is directed. The following is a good example of a native curse.

"Oh, thou medicine, the person who stole this my rice, cloth, lamp, fruit, bed, or pot,[29] I give this person into your hands. If you leave this person you leave your fowl (used in sacrifice). I swear the person's lungs, heart and liver. If the person goes to work, let him cut himself, and if he goes to war let him be killed; everything he does, let evil come upon him."

The "Country-fashion" man, also, is supposed to possess the power of double vision, but of a slightly different kind. He can see the mysterious occult powers that operate beyond the reach of ordinary vision. He is therefore prophet and seer, the interpreter of signs and omens, and various mysterious occurrences.

In the social relations of the people, a loose caste system prevails, based chiefly upon might. The chief exacts obedience and service from all beneath him. Men make servants of women, and of other weaker men. In a polygamous household, the head wife regards the other wives as her inferiors and servants, while each wife makes practical slaves of her own children. The older children in turn exact service of the younger. He is poor indeed, who cannot find another weaker than himself to do his bidding. Society is a pyramid with the[30] weakest at the bottom, and the strongest at the top.

It remains to make the necessary explanations of the dialect of the stories, and with that this introduction must close.

The general reader may feel like protesting against the use of a dialect that presents so many difficulties, and the philologist will object to the form employed, as being too much influenced by English associations to represent the dialect of the people in its native purity.

To both classes of readers our apology may seem weak and inadequate. In the first place, the stories would lose much of their vitality and force if the flavor of the peculiar mental qualities of the people who tell them should be lost by an attempt at translation. The ideal means of expression would be the vigorous and picturesque native tongue, did it not exclude all but the initiated from sharing the stories. The next best thing is to allow the native mind to express itself in its own adaptation of a foreign language.

As to the form the dialect has been allowed to take, it may be said that it differs from that used by the people in daily conversation, only as formal English differs from[31] the colloquial. There is a little nearer approach to subordination of clauses than is found in ordinary conversation, and a larger per cent of English words is employed, as might be expected from those who have had some training in that language. This necessarily involves an inconsistency, inasmuch as the stories are represented as being told by natives in their native environment; but as the whole undertaking has presented peculiar difficulties, some degree of allowance may be expected.

The dialect is that of the Temne people, and is essentially the dialect of Sierra Leone, from which it was derived. Each new tribe, in learning the dialect, modified it slightly, so that, although it is perfectly intelligible to all the tribes using it, an attempt to represent the words phonetically, reveals many differences. Wherever the pronunciation of common words, such as "make," "take," "come" etc., very closely approximates the English usage, we have not hesitated to give the correct English form.

The whole dialect is a hopeless jumble of English and African words. It is very much condensed, almost stenographic in its brevity, and requires the aid of voice and[32] gesture to round it out to like-life fulness. This requirement, the native temperament, being emotional and picturesque, meets to perfection. These accessories the imagination of the reader must supply, if he is to receive the keenest pleasure from the perusal of the stories.

With the native, a common device of expression is the repetition of the emphatic word or phrase, or else its very much prolonged utterance. The word "Sotáy"—accent on the last syllable—when used in the sense of "a long time," is prolonged until the very utterance conveys the impression desired. Naturally, the vocabulary is very meager. There are no words to express shades of meaning. Every thing that in any way pleases the eye is "fine." Every thing that pleases the taste, either literally or figuratively, is "sweet." Rice is "sweet," pepper is "sweet," and fighting is "sweet." Gender is ignored. "He" stands for "he," "she," or "it," indiscriminately. "Me Mammy he go bring yo' him son Mary, to-morrow." Idea of number is rudimentary. "He" is uniformly singular, and "dem" is usually plural. "Um" occurs often in the objective singular, but the[33] variation in number appears to be purely accidental. "Dey" is rarely used for the pronoun "they," although to avoid confusion it has been allowed to appear quite frequently in the stories. "Dem" and "den" are used interchangeably for "they," and since there is no distinction in case, they may also be used for them. "Den" is seldom used for "then," but is usually a pronoun. The reader will need to exercise special care on this point. For the adverb "there," the natives invariably use "deh." There is a peculiar use of an auxiliary that will need careful notice. Its sound is between that of "dey" and "duh;" the latter has been chosen. "He duh come" means "He is coming," or "He comes," in the historical present. However, laws of language are trampled on with utmost unconcern. "Go" is used occasionally as a sign of the future. "He go come" meaning "he will come," and "he go go," "he will go." Certain words are repeated to form a single expression, as "so-so," meaning "merely," "nothing but." "San'-san'" is sand, and "bug-a-bug" is the white ant. Idiomatic expressions occur frequently, and unless mastered at once, may prove confusing;[34] once understood, they are very expressive. "He no tay" means "it does not stay," that is, Time does not linger, or, It is but a short time. "Pass" is used in all comparisons, in the sense of surpass, excel, exceed, etc.; as—"Spider pass Elephan' fo' sense," "I pass yo' fo' 'trong." "Pull" is employed in the peculiar sense of "produce," "devise," "create," as: "He pull one big holler," "He pull dis sense," "God pull de people," referring to the creation of Adam and Eve. "No mo'" is an expression frequently found, and although no single English expression can cover the meaning in all of its uses, it signifies "only that and nothing more." "He de one man no mo'" means "only he and no one else." "So-so san'-san' no mo'," "entirely sand, nothing more."

But of these expressions there are not many, so the difficulty in mastering them will not be great. It has often been difficult to find a spelling that represents correctly the sound desired. The natives never say "house," but always "ho'se," giving "s" its sibilant sound. With the further aid of the vocabulary printed at the end of the volume, there should be little difficulty in reading the stories.

It may be said in conclusion, that no one can be more conscious of the fragmentary nature of the literature presented in this volume, or of the faulty manner of its presentation, than are the authors themselves.

F. M. C.

H. W. W.

Toledo, Iowa.

The African day was lingering for a brief moment in a tropical twilight, as if reluctant to give over a world of natural beauty to the impenetrable darkness of a moonless, forest night. The mud huts of the native village, with their conical, palm-thatched roofs, showed in the fading twilight like great shocks of harvested grain in a little field fenced in by a high hedge of trees. Narrow foot-paths—the only suggestion of streets—wound irregularly through the village, and in these, children, innocently nude, were romping, and chasing each other with all the noisy delight of that care-free age. Men and women, led by their inclination to gossip, or by an instinctive shrinking from the gathering darkness, were unconsciously drifting into groups about fires that had been kindled here and there in the irregular open spaces. Other light the village had[38] none, and the little fires seemed only to exaggerate the thick curtain of gloom that was now drawing around the place. The countless invisible and mysterious forces that control the destiny of the unfortunate black man, seemed to be taking on bodily shapes, and to be stealing forth under cover of the night to work their spells through forest and earth and air. Out of the stilly darkness came myriad voices of the night—familiar ones from within the village, the explosive chant and monotonous beat of the drum that accompanied a weird tribal dance, or the shouts of irrepressible childhood still at play, or more often the hum of conversation that told of the sway of gossip, or the fascination of myth and story. Anon came the awesome, half-terrifying voices from the outer night—the uncanny insect chorus, or the distant call of wild beasts, speaking to one another a language that seemed full of meaning, but which the human ear had lost the power to understand.

To-night the voices possessed a peculiar fascination for the group gathered around Sobah's fire. Coarse banter and desultory gossip had ceased to interest; the spirit of the night was upon them, and the voices[39] from the darkness seemed to address them personally, and to assert the kinship of all creatures. It scarcely needed the accumulated traditions of untold generations to convince these listeners that their ancestors had once possessed the ability to comprehend their fellow-creatures, and so had dwelt on terms of equality and friendship with them. As it was, Sobah and his friends did not trouble themselves about beliefs, but in imagination passed easily and naturally into that realm where all creatures spoke a common language, and possessed common needs and attributes.

For some time Sobah had been sitting in silence, wholly absorbed in his own mental processes. Suddenly an inspiration seemed to stir him. He tossed back his head, his eyes began to sparkle, and his face to glow with the anticipated delight of the story that had come to him from the depths of his capacious memory. These significant preliminaries were quickly noted. "He duh get story," was the warning exclamation passed around the group. Every eye was at once riveted upon Sobah's face, and every countenance took on a look of eager expectancy.

Konah, a bright-eyed, ebony-hued beauty of thirteen years, who all her life had seemed to possess the supernatural power of being present unnoted whenever anything new or marvellous was to be seen or heard, came up just at this moment, led by unerring instinct, and settled down unobserved in the shadow, ready to absorb every word.

Casting a dignified glance around the company, to assure himself that all were properly attentive, Sobah proceeded to relate the wonderful exploits of Mr. Spider, in meeting the requirements of his prospective mother-in-law.

"One ooman get girl pickin (pickaninny). Dis girl done do fo' married, but no man no deh (there) wey (who) able fo' married um, because de mammy no 'gree. Well, Spider come, he say he go married de girl, en de mammy answer um, say:

"'Yo' mus' fus' do dis t'ree t'ing; bring Lion teet' wey fresh wid blood 'pon um, en sass-wood palm-wine, en bowman'" (boa-constrictor).

Here the story was interrupted by a[41] chorus of "Eh! eh's!" and other exclamations of wonder at the impossibility of each of the three conditions imposed.

"Lion 'trong too much," protested Dogbah, who was sadly wanting in the imaginative quality, and demanded hard, prosaic fact, "Spider no able fo' get heen teet' fresh wid blood 'pon um."

Gondomah, who was of a rather silent and thoughtful turn, said meditatively, as if speaking to himself:

"Palm-tree no get banana, sass-wood no get palm-wine." It was his way of asserting the impossibility of securing palm-wine from the poisonous sass-wood.

"Spider leelee (little) too much fo' bring big, big bowman," was the verdict of Oleemah, and yet his tone contradicted his words.

Sobah silenced the interruptions with the pertinent question: "Aintee Spider pass all fo' cunnie? He able fo' do um." Then he proceeded:

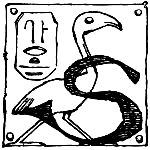

"Spider say he go try fo' all dem t'ing fo' get de girl. He go inside one big forest wey (where) all de beef (animals) duh (do) pass. He make leelee fiah by de road. De part wey de smoke duh go he make good bench, so de beef kin sit down. He[42] say: Make dem come wa'm fiah,[1] de cole too much, because nar (it is) rainy season. He say make dem no come togedder, make dem come one one. He kare (carried) one hammer, heaby one, wey he fo' hole wid two han'. He hide um. Well, den beef all duh come. De' one he no wan' he no hit um, he jus' duh coax, make dem go get de big beef fo' come. Well, w'en den beef all done come, w'en dey duh wa'm fiah, dey go call Lion fo' say: 'Eh! Spider one good man, dis make he duh make good fiah fo' we en we cumpin (companions).'

"Well, one day Lion come, en Spider he make de smoke good fashion; put plenty leaf deh. W'en Lion come he say:

"'Fren', I sorry fo' dah cole wey ketch yo'. Kahbo (welcome)! All day I duh make good fiah fo' yo'.'

"Well, he go wipe de bench good fashion, he say, make Lion sit down fo' wa'm fiah. De Lion sit down. Spider take mo' leaf, raw one, fo' make smoke come out plenty. Dis yeah big smoke go 'pon Lion; he shut he yi, he duh open he teet', he duh wa'm hese'f;[43] he no know say Spider duh watch um fo' hit um wid hammer 'pon heen teet'. Spider take de hammer soffle (softly), he hit Lion one tem, no mo', but dah hit wey he hit um! Lion he pull one big, big holler tay (until) all de groun' duh shake. He spit heen teet' out 'pon de groun', he run!"

Sobah had been telling his story with voice, countenance, hands and suggestive motions of his whole body, and as the climax approached, his impressiveness increased. The hearers were shaking with suppressed mirth, and when they saw the result of Spider's cunning, and Lion beating an ignominious retreat, leaving his teeth behind him, they could restrain the inevitable outburst of laughter no longer. Some of the more excitable threw themselves upon the ground in an ecstasy of delight. Konah had become so identified with her favorite, Mr. Spider, and was so pleased with his success, that she forgot her own art of cunning, and crept boldly out of the shadow.

Sobah chuckled contentedly, while the outburst was expending itself, then went on.

"Spider hese'f run, he mean say de Lion go grip um. W'en he see Lion no duh[44] follow, he turn back, he take de teet', he kare um go to de ooman, he say:

"'Look me, I done bring dah raw lion teet' wid de blood.'"

"De ooman say: 'All ret, but he lef' mo' t'ing fo' do. Go bring dah sass-wood palm-wine.'

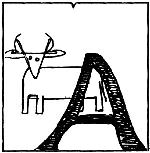

"Spider come out, he take heen ax, he sharp um, "Wahtah, wootah! wahtah, wootah!"[2] He fine one sass-wood 'tick (tree), he klim 'pon um, he dig hole, he come down. He go buy country-pot, big pot, he tie big rope 'pon um, make um 'trong; ef he no 'trong bimeby de pot go fa' down, he broke, because palm-wine go full um. W'en he done hang um he no sleep all net, he go 'roun' to den people all, he tief (steals) plenty palm-wine, he trow um 'way (empties it) inside de pot wey hang to dah dry sass-wood 'tick, en he full dis pot wid de people yown palm-wine[3] sotay he t'row 'way' nah groun'. He duh rub palm-wine inside de hole, en 'pon de 'tick all. He tell one man say:

"'Make yo' follow me, look ef de palm-wine run.'"

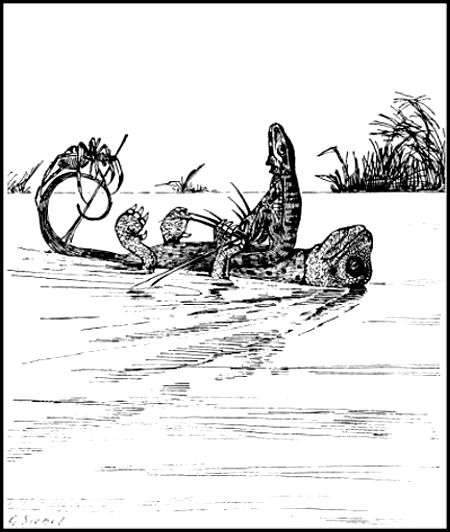

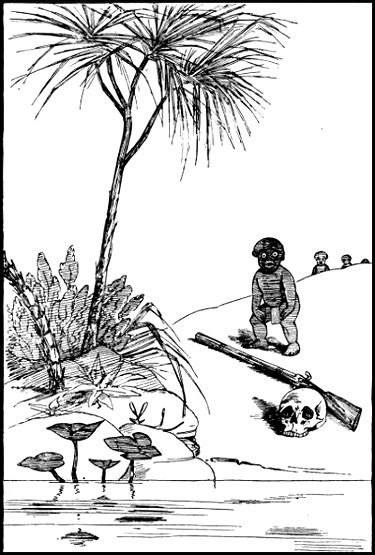

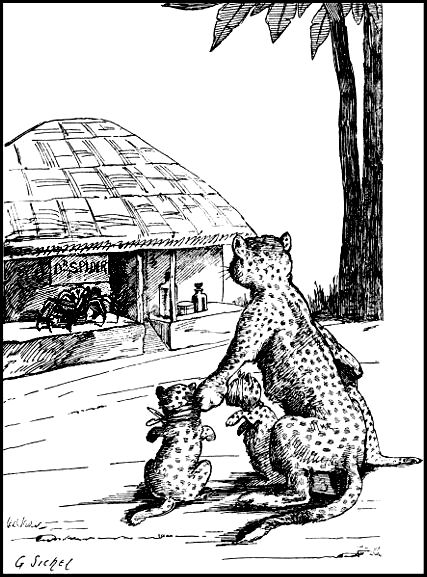

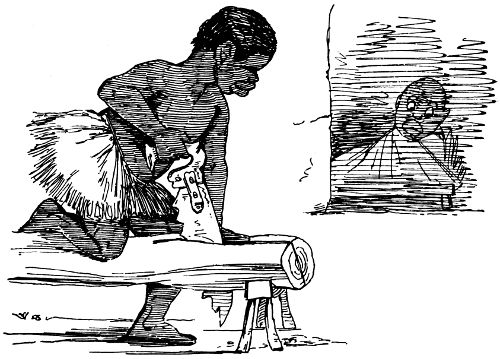

!["Spider takes the hammer soffle." [See p. 43, line 3.]](images/image3.jpg)

"Spider takes the hammer soffle."

This bit of shrewdness on the part of Mr. Spider, Sobah unfolded with intensest appreciation in tone and gesture, and was rewarded at this point with grunts of satisfaction and approval from the listeners, and with exclamations of unbounded admiration for the clever little hero who could both steal and deceive without detection. As soon as the silence told him they were ready for more, he proceeded.

"W'en dey go, dey meet de pot full. Spider tell heen cumpin fo' take um down, en dey two dey tote um sotay (until) dey reach de ole ooman. Spider pin (place) um down 'pon de groun', he say:

"'Mammy, look dah sass-wood palm-wine!'

"De ooman ax de man: 'Nar true?'

"He say: 'Yes, nar me see um wid me yown yi.'

"Well de ooman say:

"'Odder t'ing lef' yet fo' do befo' I gie yo' me pickin. Go bring live Bowman.'

"Spider go nah puttah-puttah,[4] he look sotay (until) he jus' meet Bowman, he say:

"'Fren', how do?'

"Bowman answer um: 'Tankee!'

"Spider kare one long 'tick, big one, he say:

"'One day me bin say Bowman long pass dis 'tick, but me cumpin done deny, dey say: "No, he no kin pass um fo' long." Make yo' lie down 'pon de 'tick fo' try ef yo' pass de 'tick fo' long, or de 'tick pass yo'.'

"Well, Bowman lie down; Spider take leelee rope, he begin fo' tie Bowman to heen neck, he say:

"'Nar play I duh play.[5] No make palaver, nar so I go tie yo' fo' make yo' no ben' ben' any place, fo' make yo' lie 'traight 'pon dis 'tick.'

"Bowman 'gree; he lie down soffle. Spider no tie um 'trong, he jus' tie um leelee tay he reach de tail side. He go back to de head, he draw de rope tight, he say:

"'Aintee I bin tell yo' nar play I duh play? I kare yo' fo' go to dem plenty people, fo' make den no deny me agin.'

"W'en Spider finish fo' tie um, Bowman[49] no get 'trenk (strength),[6] betty no dey agin fo' um. Spider tote um, he go gie um to dah mammy, he mudder-in-law. W'en de ooman see Spider done bring Bowman, he call plenty people, dey talk de palaver, dey say Spider do well, make de mammy gie um de girl fo' married, en he gie um. Nar so Spider do fo' he wef."

Cold type does scant justice to the sympathetic tone and expressive movements with which the story was told, or to the low chuckling laugh with which its finer points were enforced.

Gratified by the pleasure his story had given, Sobah was content to rest for the present, and after listening respectfully for some time to his less gifted companions, left the group and disappeared within his hut.

As the inclination seized them, the others strolled away into the darkness. Careful Mammy Mamenah covered the fire, and soon the night was given over to the undisputed possession of spirits and other creatures of darkness.

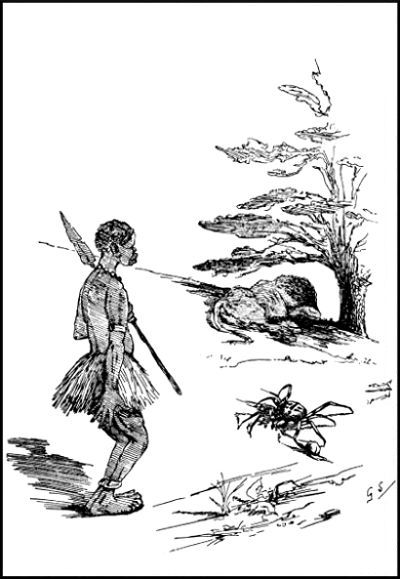

When one morning, not long after the story of Mr. Spider's successful courting, Sobah felt the hunter instinct strong upon him, he left the work of the little rice farm to Mammy Mamenah and some pickaninnies, took his trusted hunting-spear and sought the forest depths. He was a knowing hunter, artful and sure, and as familiar with the ways of the denizens of the woods as with the habits of his village neighbors.

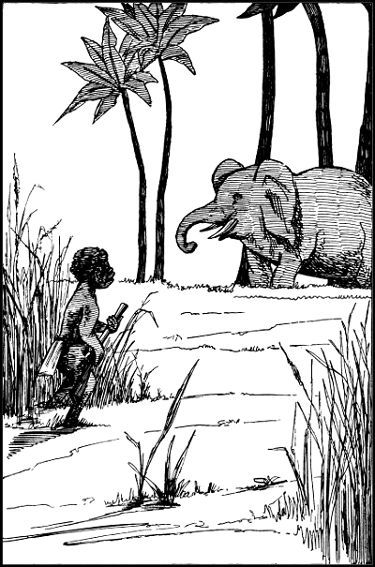

But through all the morning hours his skill and cunning proved of no avail. He sought the well-known haunts of the desired prey, and lay patiently in wait, or followed a fresh trail, with every faculty alert. All in vain, for the spirits of the forest seemed in league against him. Always some unseen presence would give warning of his approach, or bewitch his aim. Tired out at last, and[51] full of nameless dread, he threw himself down at the foot of a monkey-apple tree to think out the mystery. The cough of a deer from a neighboring thicket seemed to taunt his ill-success. A monkey swung down from a limb over his head, and chattered threateningly. A heavy body seemed to fall through the branches of a tree just behind him, and yet, as he turned, no object falling was visible. Starting up with the cry, "Now debble dat!" Sobah reached instinctively for the charm he always wore on his person as a safeguard against danger and an assurance of success. To his consternation he discovered that it was not in its accustomed place. The cause of his former ill-luck was now explained. This charm contained a potent medicine brought from afar, and had been consecrated as his personal guardian and helper. Greatly wrought up now at finding himself in this devil-haunted region without a charm so powerful, he made his way from the woods and to his hut with eager haste. To his great relief he found the precious little article hanging where he had carelessly left it. Much reassured when this object of his superstitious trust was again dangling from his neck, he started[52] out once more, and in a new direction, bent on retrieving his lost prestige as a hunter. Sustained by that feeling of confidence which is half of success in any undertaking, he, keen-eyed and alert, followed the path along the river. Sagaciously hiding in a covert that overlooked a little path leading down to the water's edge, he awaited developments. A little later his quick ear detected the lightest possible step approaching along the path; then a pair of intelligent eyes peeped around a tuft of rushes, and soon there appeared the most graceful little body Nature ever made, incased in a glossy coat of softest satin, and supported by the daintiest of feet. Even in repose the little creature suggested the very poetry of motion, and looked as if the working of a slight spell would transform it wholly into spirit and let it fly away.

Sobah's heart had been nurtured in savagery, yet it almost stayed the hand from striking.

"Cunnie Rabbit," he muttered to himself, for so the natives call this deerlet, "I go get yo' now."

Surely the charm was working, for there the shy creature stood, and moved not until[53] the well-directed spear from the hunter's hand laid it low.

While Sobah was gloating over his prize, a company of men from the village came along. After effusive congratulations, they tied Cunnie Rabbit upon a pole, covered the body with a white cloth, and eight men took up the burden and staggered along toward the village with it, as if the load were all they could possibly carry. "Eight man tote um," Mamenah explained later to the inquisitive Konah, "dem duh make as ef he heaby. Dey say he nar (is) king of de beas' fo' wise oh; not fo' stout, but fo' sense."

The stew that accompanied the usual boiled rice at that evening meal, was delicious enough to please a more fastidious palate.

With appetite richly satisfied for once, and in great good humor with himself and the world, Sobah was in a more genial mood than usual, when, later, a company of neighbors gathered around him. They had just come in from their little farms, and, remembering similar occasions, and knowing that if the hunter had been successful in the chase, his tongue would be "sweet" for story-telling, each man carried[54] on his back a bundle of wood. Throwing it in a heap suggestive of a fire, they remarked: "Lookee de wood fo' de fiah," thus making a covert request for a story, and paying the story-teller a delicate compliment. Sobah felt the beauty of this indirect appeal, and was much pleased by it, but there was no need for haste, so he allowed the talk to run on various topics before he made a formal response to the desire of his friends.

All chatted freely of the experiences of the day. A bit of war news from "up country" had drifted in, and was heard with relish. Most of all the behavior of the various animals Sobah had met that day, and the supposed connection between the little charm and that behavior, held awed attention. Out of this talk concerning the human-like actions of certain animals, grew, naturally, references to the animals that appear with human attributes in the many fireside tales so dear to the hearts of the people.

Sobah was recognized as the story-teller of the village, and so when mention was made of the deer that coughed, Oleemah proposed that Sobah should tell them the[55] story of how the deer acquired such a habit, adding diplomatically, "Yo' pass we all fo' pull story good fashion."

The story-teller was already in a gracious frame of mind, and, pleased with this last tribute to his art, lost no time in responding with a legend of Creation's early dawn.

"One tem all dem beef (animals) dey gadder to one place, all dem beef dis wuld, but de head of dem all, dat now one ooman en he pickin (pickaninny). De pickin name Goro. One net big rain fa' down, he out all de fiah. Now de mawnin' cole, all dem beef dey trimble, dey cole too much. No fiah no deh fo' make demse'f wa'm. Dey see one leelee place deh wey smoke duh come out. Dey sen' Deer, dem say:

"'Go bring fiah fo' we, over yandah to dat place.'

"Deer go, he meet de ooman en he pickin wey duh sit down close de fiah. Dey try wa'm demse'f by de fiah. W'en Deer reach he tell de ooman 'Mawnin'; he say: "I come beg fiah."

"De ooman say, 'I nebber greedy (begrudge) pusson fiah, but I get one law heah. Pusson wey wan' fiah mus' fet (fight) wid me pickin, mus' beat um. Yo' see de leelee girl? One place outside dah do', he nar (is) de fet place, he rub, he smooth. Go fet me pickin; ef yo' beat um yo' take de fiah.'

"De Deer he look de pickin foolish nah heen[7] yi, he say:

"'Mammy, yo' wan' make I kill yo' pickin?'

"De ooman say: 'Nebber min', kill um, de fault not yo' yown.'

"Deer say: 'All ret.'

"De pickin come, dey two grip, dey begin fo' fet, de ooman begin fo' sing; he duh sing fo' he pickin, he no duh sing fo' de Deer. He sing:

As if in sympathy with the rhythm of the song, Sobah's whole body began to sway back and forth, his voice rose and fell in musical cadences, and his hands began to clap in time to the movement of the song. All the listeners took up the rhythmic swaying[58] of the body and the measured clapping of the hands, and as soon as they caught the words, joined heartily in the chant. Not satisfied with the first result, Sobah led off with a repetition. This time there was no occasion for dissatisfaction, and the story proceeded with increasing animation.

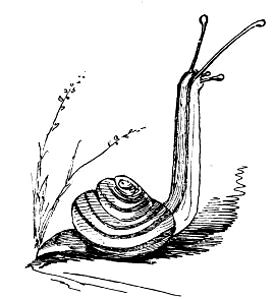

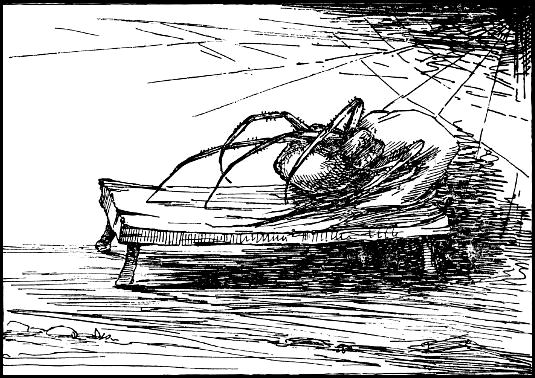

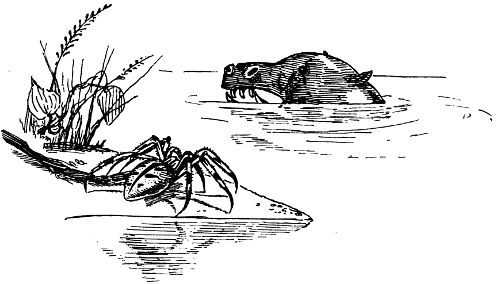

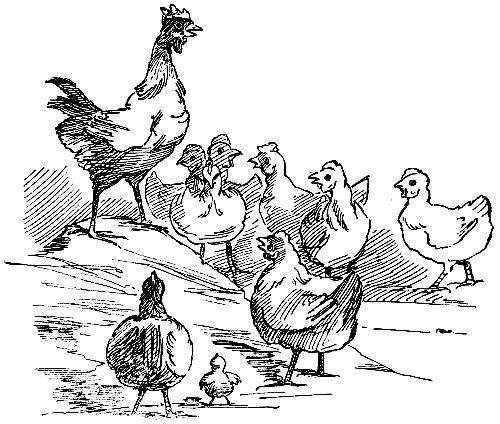

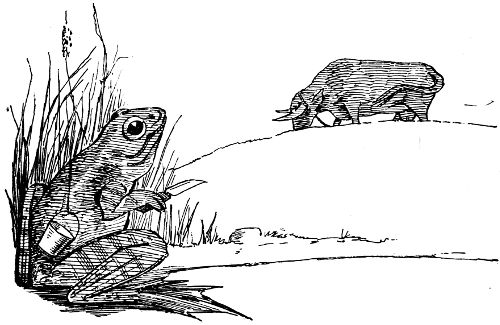

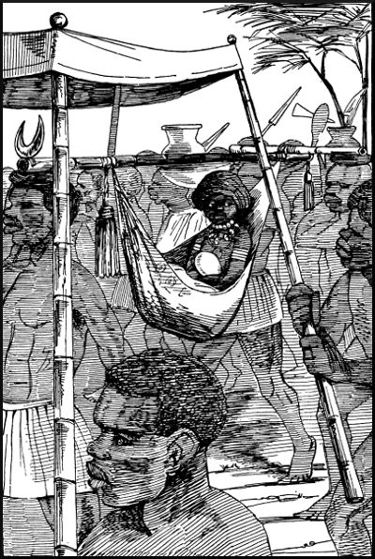

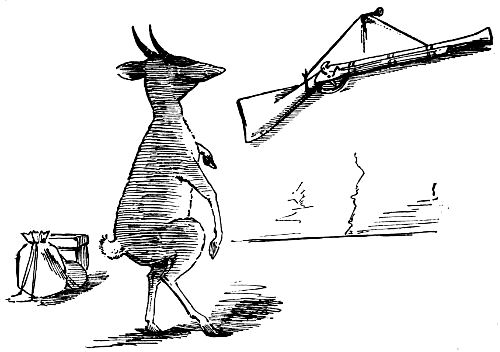

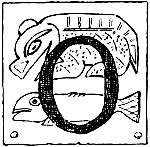

![The Deer after fighting with Goro. [See p. 56.]](images/image4.jpg)

The Deer after fighting with Goro.

"Goro fet, he fet. He hase (raised) de Deer up; de Deer go take one yeah up befo' he come down. W'en he fa' down he get cough. Some tem ef yo' deh nah (in) bush en Deer cough, yo' go say, 'Nar (is) pusson.'"

"Dat nar true," broke in Dogbah eagerly, a spark of understanding falling on his dull mind. "Mese'f bin hearee um cough to-day nah bush. Dah fa' wey he bin fa' long tem make he cough so," and he shook with laughter, as if Mr. Deer's hard fall were highly amusing.

Sobah, taking up the interrupted thread of the narrative, said: "Well, Deer go home widout no fiah."

"Elephan' he say: 'I go go, I jus' wrap me mout' 'pon dis girl I twis' um, I hase (raise) um up, I wop um down, I take de fiah.' Well he begin root dem big, big[59] 'tick wid he teet' fo' show how he 'trong; he say: 'Nar so I go meet de girl.'

"Well, w'en Elephan' go, he tell de ooman how do, he meet de fiah, he wan' take um. De ooman say: 'All ret,' he say: 'Look me pickin. Go fet.' De pickin begin, de ooman sing de same sing w'en dey grip fo' fet.

This time the apt imitators caught up the refrain at once, and gave it with great zest. "Soon," continued Sobah, after a momentary pause, "de girl he hase de Elephan' up, he sen' um up; but since de Elephan' stout he no able, he jus' sen' um up as far as one week. De one week finish, de Elephan' come down. W'en he fa' down 'pon de groun' he hurt he teet', en he teet' swell. Dat make Elephan' he teeth big."

At this point Sobah struck an attitude suggestive of the Elephant's state of general dilapidation. His face took on a look of mingled pain and disgust, and this in turn was succeeded by a smile of self-approbation, and ended in a peculiar chuckling laugh that carried infectious mirth to all the circle of listeners.

The Elephant after the fight with the Goro.

Settling back once more to his usual air of serious dignity, Sobah continued his recital.

"Elephan' he go back, he no kare any fiah.

"Well, Lepped come, he tell de ooman say: 'I come fo' fiah.'

"De ooman say, 'All ret,' he say, 'Look me pickin, he go fet yo.'

"Dey begin fo' fet, Goro en Lepped. Dey fet en fet. De girl he hase (raise) de Lepped up; he sen' um, he go, he take t'ree mont'; he come down, he fa' down 'pon 'tone, he cut hese'f, de blood sprinkle all 'pon um. Dat make de Lepped he spot, spot."

This explanation of the Leopard's spots, seemed reasonable enough to these simple-minded people, who ask only that some cause out of the ordinary should account for ordinary things. Dogbah was about to offer a comment again, but before his slow wits could formulate his words, the story-teller had plunged into the next sentence.

"De Lepped he go widout no fiah. De beef, w'en dey see um, dey say:

"'Eh! We no get no fiah to-day.'

"Now Puss he get up, he say: 'I go go.'

"Dem beef dey laugh um, dey say: 'All ret.' Dey say: 'Yo' see all dem big beef? Dey go, dey no able fo' bring fiah. Yo' say yo' duh go? All ret, go try.'

"De Cat he go, he say: 'Mammy, I come fo' fiah.'

"De ooman say: 'All ret, go try wid me pickin.'

"De Cat go, de ooman begin fo' sing. De girl he jus' take de Cat wid one han', he hebe (raise) um up, he go take one yeah en ha'f befo' he come down. He fa' hard, he begin fo' cry 'Meouw! meouw!' Dat make Puss duh cry anytem, net or day tem he duh cry. He go home widout no fiah.

"Now Spider go, he say, 'Mammy, I come fo' fiah.'

"De ooman say: 'All ret, oonah (you) go fet wid me pickin.' De ooman he no even se'f sing. Dah girl take Spider wid one fingah, he hebe (raise) um up fo' two yeah."

A murmur of dissent caused the story-teller to pause and cast a look of inquiry around the company. It was evident that the ardent admirers of crafty little Mr. Spider could not bear to have him disposed of so easily. But Sobah checked the rising protest by a commanding gesture, and a look that seemed to say: "I am sorry, but I must tell the story just as it is." When the silence assured him of a hearing, he continued.

"W'en Spider come he fa' down, he[63] broke he foot. Dat make Spider duh crawl now; dat make he walker wid four foot, sometem six. Long tem[8] he walker wid two foot 'traight lek pusson. Spider go home widout no fiah.

"Cunnie Rabbit he go, he say: 'Mammy, I come fo' fiah.'

"De ooman say: 'All ret, go to dah pickin, fet wid um.'

"W'en dey fet, de girl come hebe (raise) um up, he take six mont.' De t'ing wey make he no go far, he get too much sense."

This was uttered with peculiar emphasis, and was answered by a prolonged "Y-a-h-oh; y-a-h-oh!" of assent that indicated a keen appreciation of Cunnie Rabbit's superior mental qualities. The next sentence was almost equally satisfactory, and regained for the story what favor it had lost by the humiliation of Mr. Spider.

"W'en Cunnie Rabbit come down he fa' down, he get up one tem (at once), he begin fo' run, he run. Dat make tay (until) to-day he hard fo' ketch. He kin run fas' pass all dem beef.

"All de odder beef duh go, dey no able fo' beat de pickin. Conk (snail) he get up, he go, he walker 'bout slow, slow. W'en he tell dem beef: 'I go go fo' fiah,' Cunnie Rabbit take um en hebe (threw) um nah (out) de do'. He fa' down, he hurt hese'f, he get blood 'pon um. De blood mark, mark um, but he say: 'Nebber min', I go go.'

De Conk.

"He go, he tell de ooman, 'How do;' he say, 'Mammy I come fo' fiah, en I mus' kare dis fiah go home.'

"De ooman say: 'All ret; look de place wey fo' fet wid me pickin.

"De Conk do lek he duh walk 'roun de place slow, slow; but he duh get slipple (slippery) spit, he duh rub all de place. W'en he done finis' fo' rub, he say: 'Come fet now.'

"De girl come, he duh boas', he no know de cunnie wey de Conk bin pull fo' beat um. Den grip fo' fet, he en[65] de Conk. De Conk he hase (raise) de girl up, he go fo' five yeah. De ooman no see he pickin, he duh cry. Conk take de fiah, he go home. Dey cook, dey yeat, dey gladee. Dey done finis' fo' cook en yeat befo' de girl fa' down. W'en de ooman see how de Conk hebe (raise) he pickin up, he begin fo' cry. Nar (It is) de ooman bring cry nah (into) de wuld.

"Story come, story go."

This well-known form of ending was followed by a long silence. The night was already far advanced, but the black man is a creature of the night. Deeper than the color of his skin lies his kinship with the darkness, however much he may dread the powers of evil that creep forth as soon as the day is gone.

At last the silence was broken by Gondomah, a man of modest bearing, who, though seldom essaying the rôle of a story-teller, could not yet be reconciled to the place assigned to Spider in the last story. Half to himself he said: "Spider nar smart man, nobody no go pass um." Then, emboldened by the sound of his own voice, and by the encouraging silence, he proceeded in the fewest possible words to relate how.

"One tem Spider say he go go far up country fo' buy plenty cow. Early mawnin', fus' fowl crow, he grap (got up), he walker tay (until) de sun middle de sky. He done tire. W'en he reach to one big, big grass-fiel' he go lay down. He close to one lion, but he no know. Dey all two, dey duh sleep. Well, soon de Foulah people dey bring plenty cow wey dem duh kare down fo' go sell. De Foulah people dey no sabbee lion, dey nebber see um yet. W'en dey meet dis lion heah de one man say:

"'Eh, lookee! Wey t'ing dat?'

"Odder one say: 'He big dog, aintee?'

"Den 'tan' up wid wonder. Dey no see Spider fo' long tem, because he leelee so. W'en dey fus' meet up nah grass-fiel' Spider bin hearee um, he come out heen sleep. He hearee how dey say dat de lion one big dog. W'en he look de plenty cow he t'ink: 'How I go do fo' get dem cow? I mus' get um.'

"He grap (got up), he tell dem Foulah man 'How do.' Dey answer um 'tankee.' Dey ax um say:

"'Daddy, now dis dog heah, yo' get um?'

Mr. Spider sells a very fine dog.

"Spider say: 'Yes, nar me yown dog dat.'

"De Foulah man wan' fo' buy um, dey talk de palaver, dey bargain fo' gie um all de cow fo' buy dis dog. Spider say: 'All ret, but no wake dis dog yeah, oh! because he done use me too much.[9] Bimeby w'en yo' wake um, he go follow me, he no 'gree fo' follow oonah (you). W'en I done go far 'way, den oonah mus' wake um.'"

By this time Gondomah was warming to his theme, and surprised even himself with his unwonted eloquence. The listeners, ever ready to see a rich point, had for some time been quivering with intense appreciation of Spider's rascally shrewdness, and just here gave expression to their delight in a fit of uncontrollable laughter, and exclamations of approval.

Gondomah, elated beyond measure, paused long enough to regain his composure, and then went on.

"So den people dey gie Spider all de cow. Dey wait tay (until) he done get far 'way, dey begin fo' call de dog. Jus' de Lion wake he open he yi, he 'tretch hese'f, he raise he tail, take um put um 'pon he[70] back. He jus' grip one of de Foulah people, he kill um; de odder all run go. Spider he done get de cow.

"So ef Spider tell yo' say he go do anyt'ing, no deny.[10]

Sobah, a little jealous of the attention that had been paid to this upstart story-teller, had been searching in the vast storehouse of his memory for a fitting tale with which to bring himself again into favorable notice. The one which came to his mind caused a broad smile to spread over his face, and a chuckle of satisfaction to rise in his throat. Oleemah, noticing these signs of pleasure, and suspecting that they foreshadowed a good story, asked encouragingly:

"Wey t'ing make yo' gladee so? Do, yah? tell we."

Not needing further urging, Sobah launched into his narrative with much animation.

"One day Trorkey (Turtle) bin walker close to Lepped he ho'se (house), en he[71] see de ooman lepped 'tan' up nah de do'-(door) mout'. He tell um say:

"'How do, Mammy? How yo' kin 'tan'?'

"De Mammy answer um: 'Tankee, I well leelee bit, how yo'se'f, Daddy? I no bin see yo' long tem.'

"Trorkey answer um: 'I no so well, Mammy; dis de hour w'en feber duh walker all 'bout, en me skin all duh hurt. I duh go to de bush fo' pull med'cin', fo' make leelee tea. Which side Mr. Lepped to-day?'

"He wef answer: 'He done go walker; I duh wait um jus' now. Yo' no bin see um nah road?'

"Trorkey say: 'No, I no bin see um. I sorry he done go, because ef he here I go ride um lek hoss.'

"Lepped he wef deny, he say:

"'No, yo' won' do um, yo' no go able ride me man lek hoss.'

"Den Trorkey go home. W'en Lepped come nah ho'se he wef tell um say:

"'Trorkey bin pass heah to-day, he say he go ride yo' lek hoss.'

"Well, den de man lepped vex, he run go to Trorkey, he go ax um ef he bin say he go ride um lek hoss. Trorkey deny, he say:

"'I no say so.'

"Den Lepped say: 'All ret. Come, we go ax me wef.'

"Den de Trorkey say: 'I no able fo' walk. De sick too 'trong 'pon me.'

"Dat de cunnie he duh do.

"De Lepped say: 'Come, I go tote yo', I go ax me wef.'

"Den de Trorkey say: 'Gie me one leelee rope, make I tie um 'roun yo' mout', make I hole um, so w'en I duh shake, shake, make I no fa' down.'

"En de Lepped gie um de rope.

"Well, de Trorkey say: 'Gie me one leelee 'tick, make I go flog dem fly, make I go dribe dem w'en dey duh follow we.'

This bit of apparently artless guile on the part of Mr. Turtle, threatened to convulse the audience, but interest in the development of the story had become so intense as to check the rising tide of mirth for the present, while the story-teller went on with growing enthusiasm.

"Well, de Lepped gie um de 'tick.'

"Den Trorkey he say, 'Come go now.'

"Well, w'en de Lepped done kare Trorkey go, Trorkey duh joomp, he duh flog de Lepped, he duh make lek pusson wey duh ride hoss.'

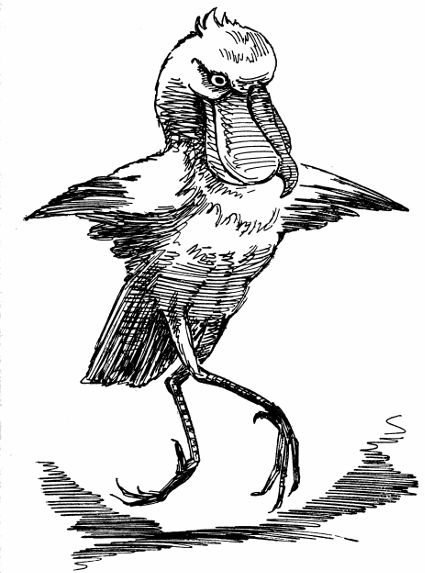

Mr. Turtle makes a riding-horse of Mr. Leopard.

Sobah described this little episode with inimitable drollery in tone and manner, and ended the 'wey duh ride hoss', with a peculiar nasal explosion that served to emphasize the humor of the situation. The result was instantaneous, and convulsive laughter continued many minutes, breaking out afresh every time anyone would remark: 'Aintee he flog um good fashion?' When the laughter had subsided sufficiently, the story proceeded:

"W'en dey go meet Lepped he wef nah road, de ooman laugh en say:

"'Oh! Nar true wey dis Trorkey bin talk, say he go ride me man lek hoss, so nar true.'

"W'en Lepped reach, he hebe Trorkey down, den he tell he wef, he say:

"I done bring Trorkey come, fo' de word he duh talk, say he go ride me lek hoss.'

"He wef say: 'Wey t'ing Trorkey do so? He no ride yo' lek hoss'? en de ooman laugh agin.

"Now Lepped see Trorkey bin make he fool; he ketch Trorkey, he tie um 'pon one big 'tick, he flog um sotay (until) he back all cut, cut. Dat make sotay to-day de mark all lef 'pon Trorkey he back."

There was more laughter at the retribution that overtook Mr. Turtle, and then the talk drifted to personal matters.

Finally, as if led by some common impulse, the company began to disperse, some to the solid comfort of a hard mud bed, and some to consort with the hideous spirits of darkness and the night.

Sobah had gone with his boat on a trading trip to Freetown, but he was a thoughtful husband and father, and had left a generous supply of rice and dried fish.

Mammy Mamenah and Konah were leisurely preparing their evening meal, for once alone. No, not entirely alone, for in their kitchen, which was also the back-yard, was gathered just at this time a strangely assorted group of creatures more or less intimately connected with the household. By mutual consent, some precedence of rights seemed to be granted to the two human beings, but they did not seem to be inclined to exercise their rights to any oppressive degree. In dress and bearing they were almost as simple and blissfully unconscious as the other creatures that shared their back-yard space with them. Konah's sole attire was a string[78] of beads fastened around her waist, while Mammy Mamenah had the conventional piece of cloth, three feet wide, wrapped around her body, tucked deftly beneath her arms, and extending to her knees. Chickens roamed over the place with the air of rightful ownership. Goats nibbled the bits of grass that grew around the edge of the bare spot, and climbed over or peered into anything that appealed to their curiosity. A monkey, limited in his activities by the length of string fastened around his slender body, was going through various evolutions in the endeavor to reach the tail feathers of a parrot that was shrilly scolding at a mangy little dog. The furnishings of the kitchen were few and simple in the extreme. The stove consisted of three stones so arranged as to support a pot of rice, and at the same time to allow a fire to be kindled beneath. A large pot for the rice, a smaller one for the stew, some calabashes and a large mortar and pestle for pounding the rice, completed the outfit. The rice had been set to boil, and Mammy Mamenah had nothing to do but wait for it to cook. She had seated herself upon one end of a small log, the other[79] end of which was in the fire. Konah had squatted upon the ground in front of her mother, and by artful and suggestive questions was endeavoring to draw out a story about some of her animal friends. A heathen mother does not concern herself about the pleasure of her child, and takes no trouble for the child's happiness, unless there is some amusement in it for herself, but Konah was the third child, the two older ones having died of small-pox, and on that account was treated more nearly with indulgence than were other children. A spirit of comradeship, almost of affection, had grown up between this black mother and her story-loving child. The many hours they had passed together had tended to deepen the feeling of fellowship and sympathy.

Finally Konah put her desire in the form of a direct entreaty, 'Mammy, do yah (please) pull story.'

In response Mammy Mamenah drew the child's head down upon her lap, and, loosening the kinky wool, proceeded to replait it in innumerable little braids that caused the jet-black hair on the shapely head to stand out in regular rows like the ridges of a cantaloupe.

"'Yo' lek story too much,' she said reprovingly; then, repenting almost immediately, added: 'Wey t'ing yo' wan'?'

The question was unnecessary, for the child's very pronounced preference for Cunning Rabbit, above all the creatures of her fairy world, was well known to her mother. So in a low crooning voice she began the story of

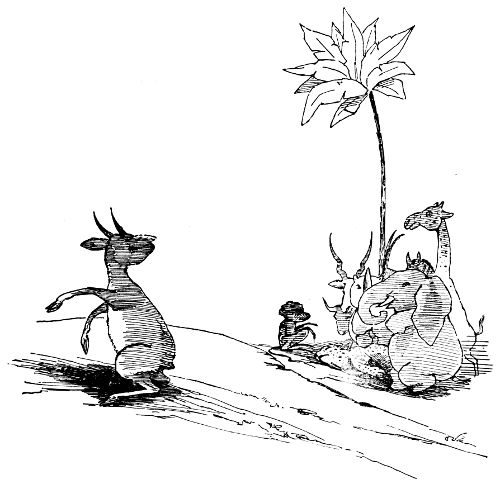

"Long tem, Cunnie Rabbit en all dem beef bin gadder. Den meet up to one place fo' talk palaver, because de country dry too much. Dey no get one grain (drop) wattah sotay (until) all man wan' fo' die. Dey all get word fo' talk, f'om de big beef to de small, but nobody no able fo' fine sense fo' pull dem f'om dis yeah big trouble. Cunnie Rabbit he no bin say notting, he jus' listen wey dem beef talk; he t'ink say: 'Wey ting I go do fo' get wattah?'

"Bimeby he grap (get up), he go home, he begin fo' dig well. He dig, he dig, he dig. De wattah come plenty. He drink sotay (until) he done satisfy.

Cunning Rabbit and his well.

"Now dem beef hearee dat Cunnie Rabbit get well. Spider he grap fo' go walker to Cunnie Rabbit. He say:

"'Fren', we no get one grain wattah fo' drink, we go die. Make yo' gie we.

"Cunnie Rabbit tell um, he say:

"'De pusson wey wan' make me gie um wattah, make he come fet me.'

"Spider say: 'All ret.'

"Now Spider en Cunnie Rabbit dey fet. Cunnie Rabbit hase (raise) Spider up to dah sky. He come down, he lay down flat. He grap (get up), he hase Cunnie Rabbit up. Cunnie Rabbit go to de sky; he blow one horn wey (which) he hole nah (in) he han'. W'en he blow um dark come, w'en he blow um agin, do' clean.[11] He fa' down, he grip de wuld, VIP! He han' long, dey go inside de groun'. Cunnie Rabbit get up back, he hase Spider up. One rainy season, one dry season he stay 'pon top de sky. W'en he come down, w'en he too fa' down 'pon de groun', he say: 'Ee! Ee! Ee! Fren', I no able agin. Den he shake Cunnie Rabbit he han'; he say: 'Oonah (you) 'trong man.'"